Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., conducts a biological study on two tanks of water, filled with green dye, in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. The tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

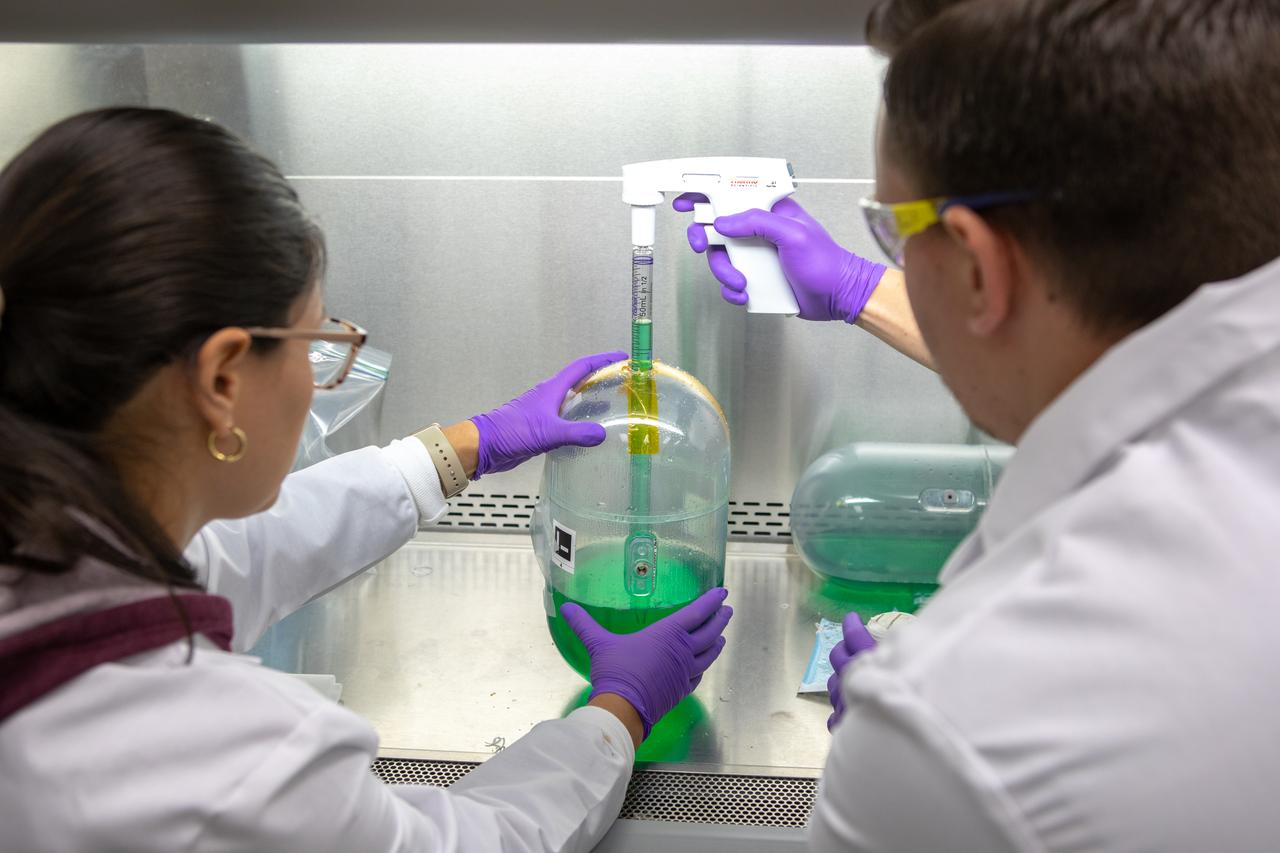

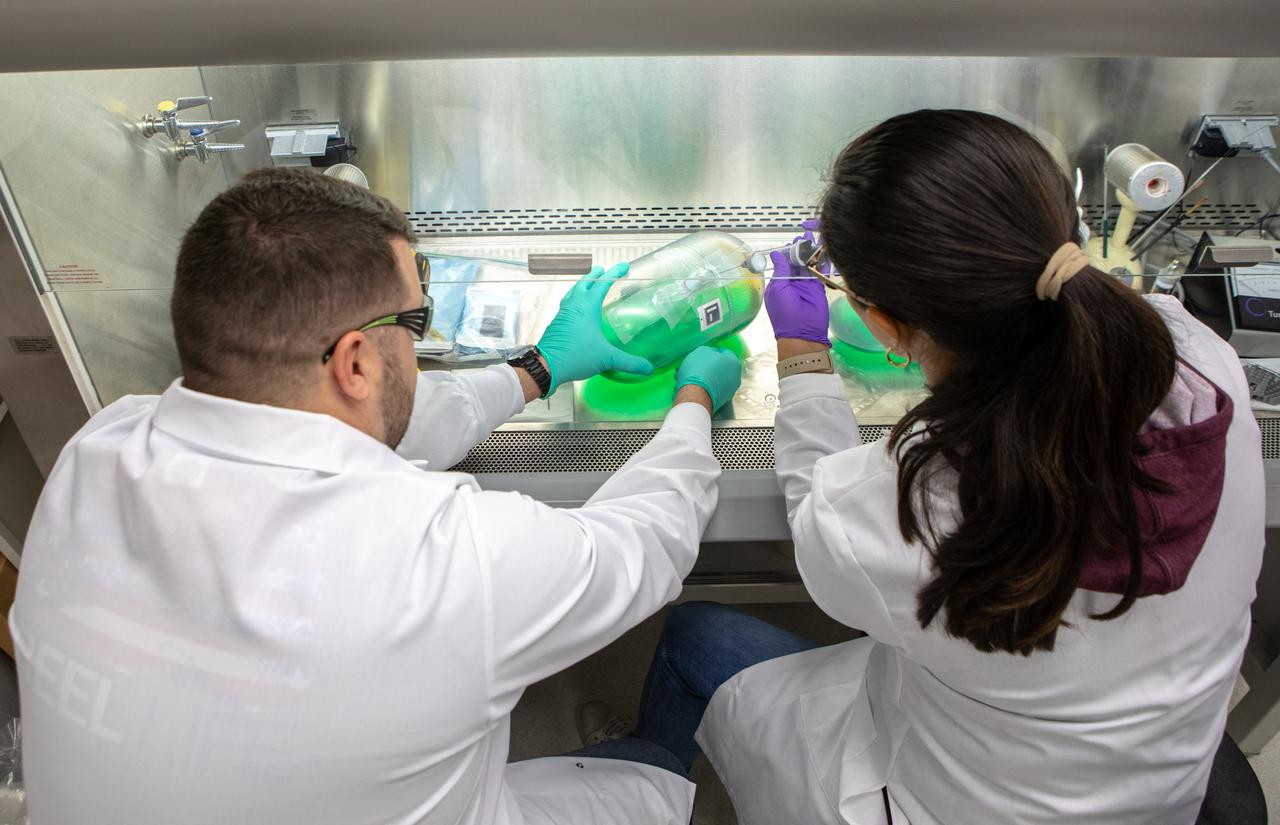

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., left, and Jason Fischer collect samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

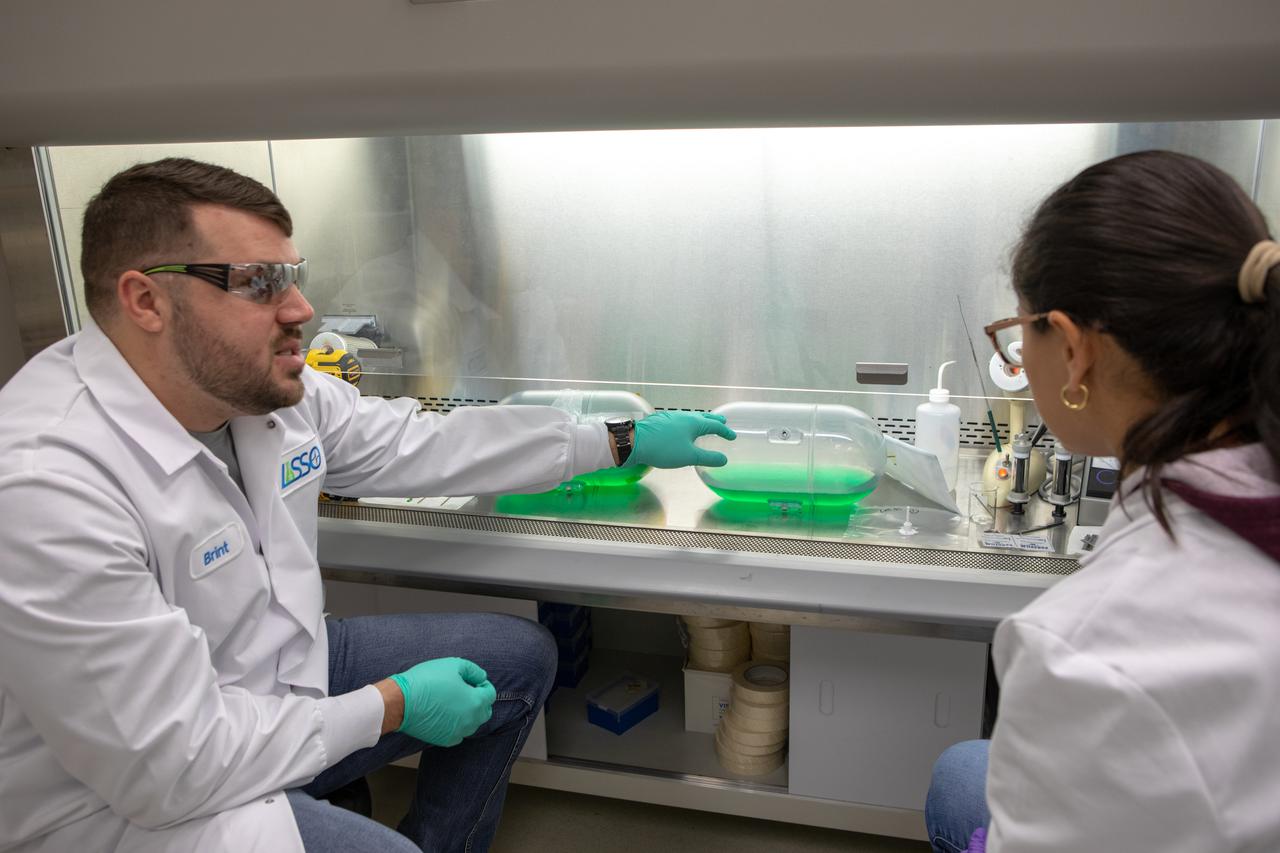

Kennedy Space Center’s Brint Bauer drills into a water tank, filled with green dye, in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

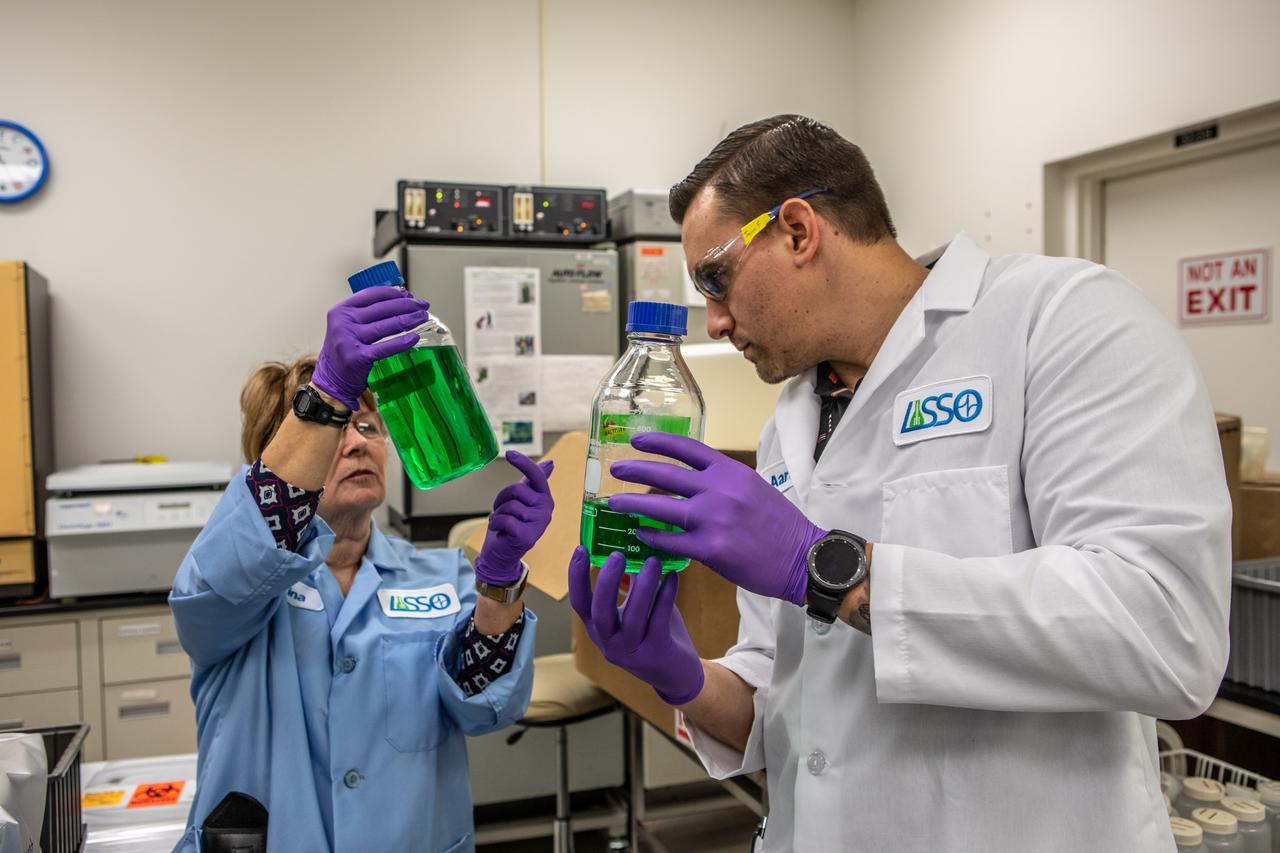

Kennedy Space Center’s Christina Khodadad, Ph.D., left, and Jason Fischer hold samples of water in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks of water have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

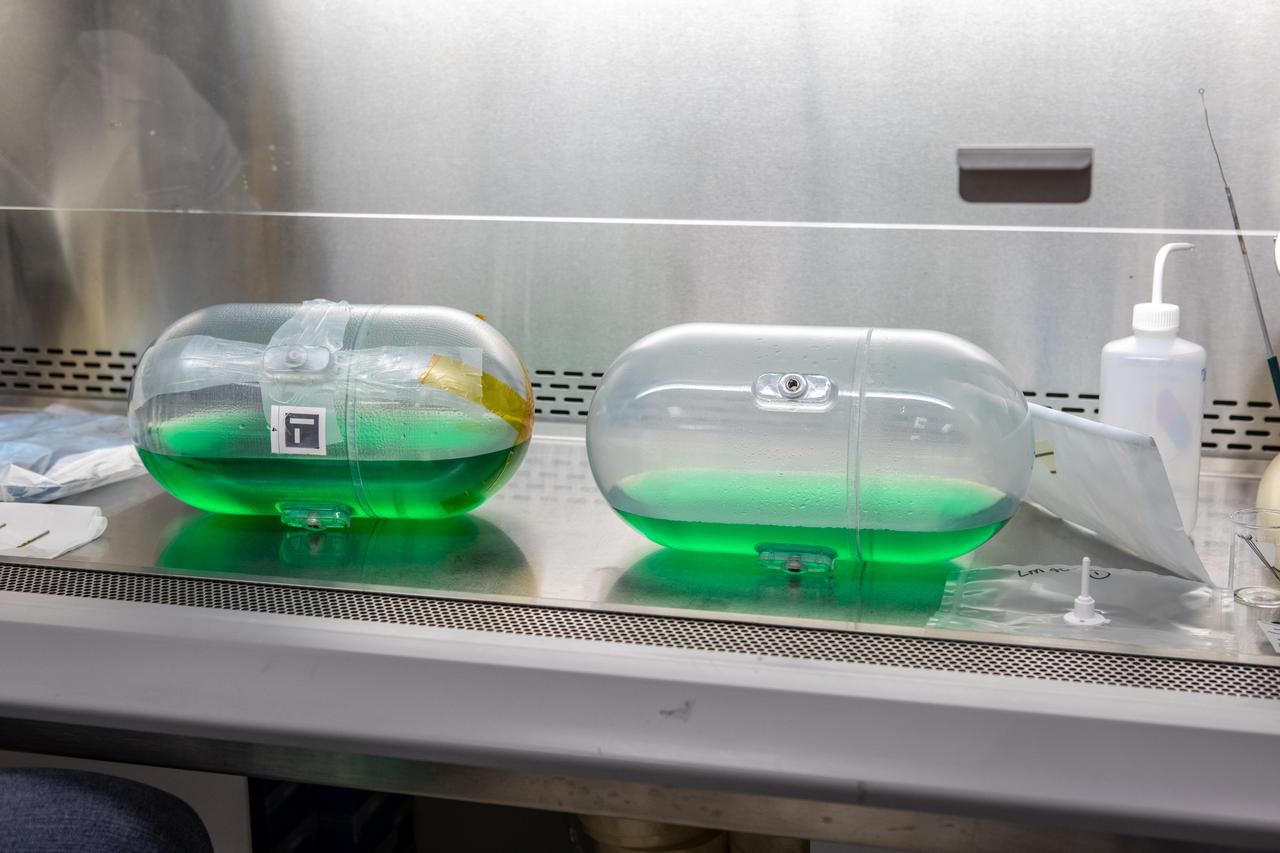

Kennedy Space Center’s Brint Bauer, left, and Carolina Franco, Ph.D., conduct a biological study on two tanks of water, filled with green dye, in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. The tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

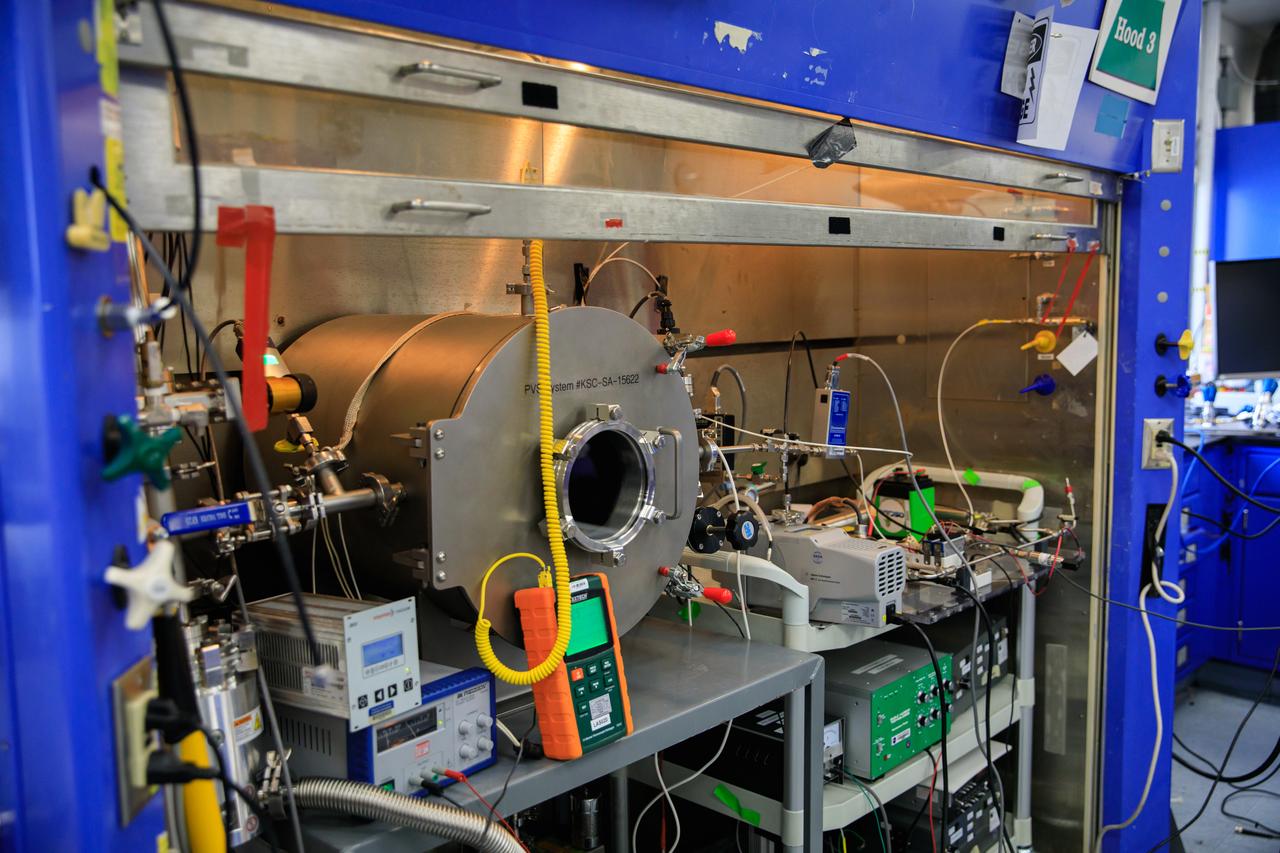

Inside a laboratory in the Neil A. Armstrong Operations and Checking Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, testing is underway on the Molten Regolith Electrolysis (MRE) on Aug. 30, 2022. This is a high-temperature electrolytic process which aims to extract oxygen from the simulated lunar regolith. Extraction of oxygen on the lunar surface is critical to the agency’s Artemis program. Oxygen extracted from the Moon can be utilized for propellent to NASA’s lunar landers., breathable oxygen for astronauts, and a variety of other industrial and scientific applications for NASA’s future missions to the Moon.

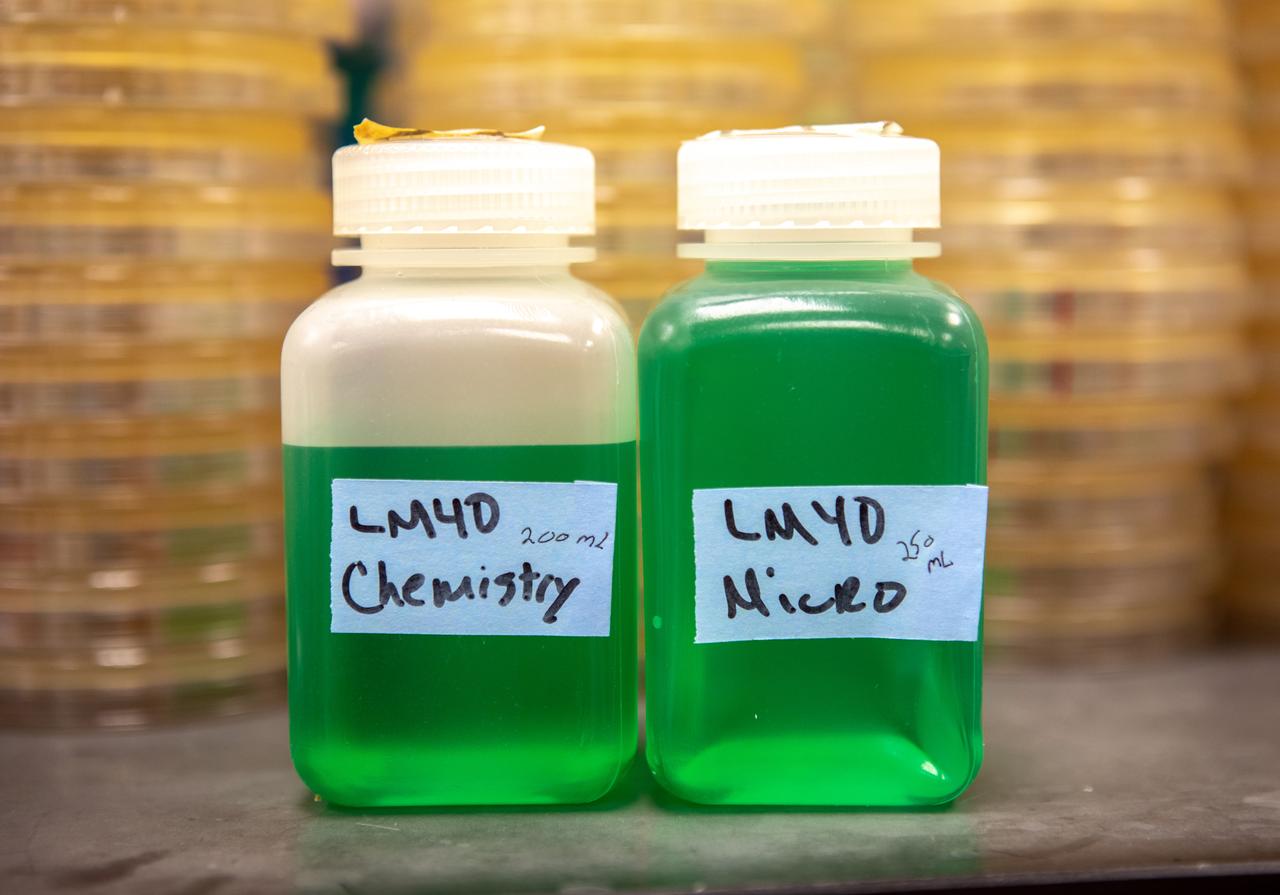

Samples of water, filled with green dye, gathered from two water tanks that have spent the past five years in space, are photographed inside the Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Nov. 13, 2019. The tanks were first sent to the International Space Station in 2014 to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded and the tanks recently returned to Kennedy, they are being utilized for a biological study to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

An engineer conducts testing of the Molten Regolith Electrolysis (MRE) inside a laboratory in the Neil A. Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Aug. 30, 2022. This is a high-temperature electrolytic process which aims to extract oxygen from the simulated lunar regolith. Extraction of oxygen on the lunar surface is critical to the agency’s Artemis program. Oxygen extracted from the Moon can be utilized for propellent to NASA’s lunar landers., breathable oxygen for astronauts, and a variety of other industrial and scientific applications for NASA’s future missions to the Moon.

A Kennedy Space Center employee collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Engineers conduct testing of the Molten Regolith Electrolysis (MRE) inside a laboratory in the Neil A. Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Aug. 30, 2022. This is a high-temperature electrolytic process which aims to extract oxygen from the simulated lunar regolith. Extraction of oxygen on the lunar surface is critical to the agency’s Artemis program. Oxygen extracted from the Moon can be utilized for propellent to NASA’s lunar landers., breathable oxygen for astronauts, and a variety of other industrial and scientific applications for NASA’s future missions to the Moon.

An engineer conducts testing of the Molten Regolith Electrolysis (MRE) inside a laboratory in the Neil A. Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Aug. 30, 2022. This is a high-temperature electrolytic process which aims to extract oxygen from the simulated lunar regolith. Extraction of oxygen on the lunar surface is critical to the agency’s Artemis program. Oxygen extracted from the Moon can be utilized for propellent to NASA’s lunar landers., breathable oxygen for astronauts, and a variety of other industrial and scientific applications for NASA’s future missions to the Moon.

A Kennedy Space Center employee collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, the tanks are being utilized to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Inside a laboratory in the Neil A. Armstrong Operations and Checking Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, testing is underway on the Molten Regolith Electrolysis (MRE) on Aug. 30, 2022. This is a high-temperature electrolytic process which aims to extract oxygen from the simulated lunar regolith. Extraction of oxygen on the lunar surface is critical to the agency’s Artemis program. Oxygen extracted from the Moon can be utilized for propellent to NASA’s lunar landers., breathable oxygen for astronauts, and a variety of other industrial and scientific applications for NASA’s future missions to the Moon.

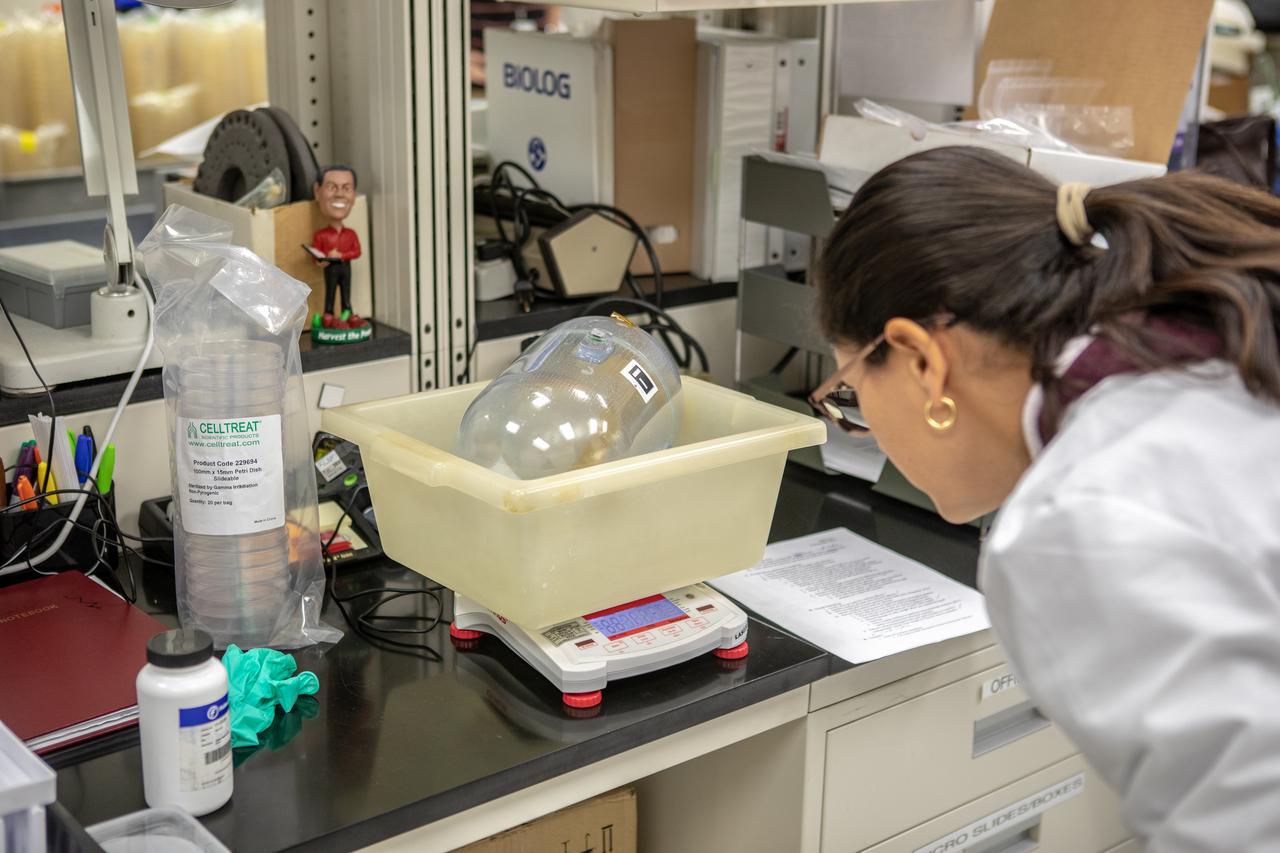

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., weighs one of the water tanks, recently returned to the center after remaining on the International Space Station for the past five years, in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks containing water were first sent to the orbiting laboratory in 2014 to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., left, and Jason Fischer collect samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

A Kennedy Space Center employee collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Jason Fischer holds a sample of water in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks of water have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Brint Bauer, left, and Carolina Franco, Ph.D., collect samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Researchers from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center Air and Water Revitalization lab are studying two tanks, containing water with green dye, inside the Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building in Florida on Nov. 13, 2019. The tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after remaining on the International Space Station for the past five years, originally sent to space to study slosh – the movement of water – in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, the tanks are being examined to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Engineers conduct testing of the Molten Regolith Electrolysis (MRE) inside a laboratory in the Neil A. Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Aug. 30, 2022. This is a high-temperature electrolytic process which aims to extract oxygen from the simulated lunar regolith. Extraction of oxygen on the lunar surface is critical to the agency’s Artemis program. Oxygen extracted from the Moon can be utilized for propellent to NASA’s lunar landers., breathable oxygen for astronauts, and a variety of other industrial and scientific applications for NASA’s future missions to the Moon.

Kennedy Space Center’s Jason Fischer collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.