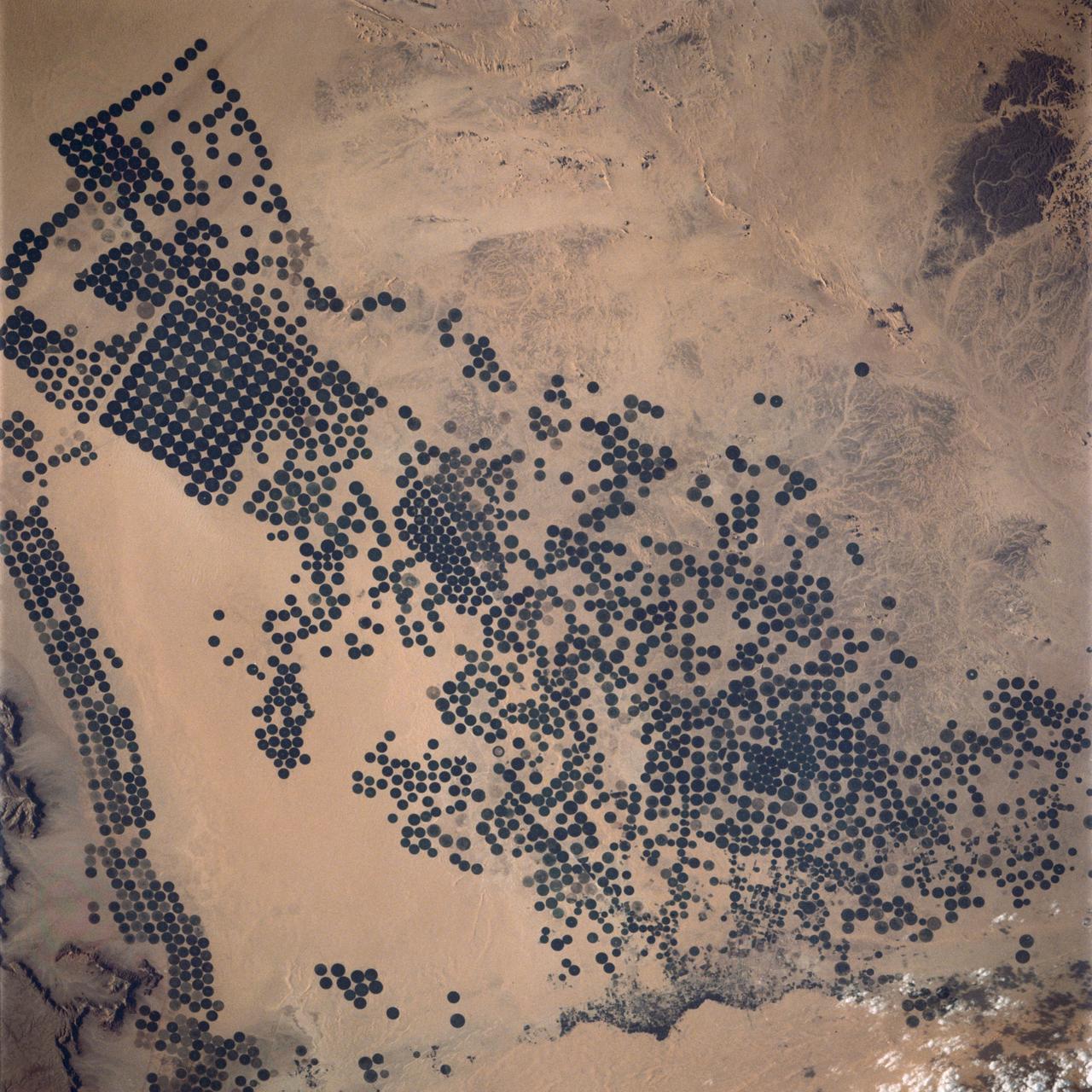

The Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System is the world's largest fossil water aquifer system. It covers an estimated area of 2.6 million square kilometers, including parts of Sudan, Chad, Libya, and most of Egypt. In the southwestern part of Egypt, the East Oweinat development project uses central pivot irrigation to mine the fossil water for extensive agricultural development. Crops include wheat and potatoes; they are transported via the airport on the eastern side. The image was acquired October 12, 2015, covers an area of 33.3 by 47.2 km, and is located near 22.6 degrees north, 28.5 degrees east. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24616

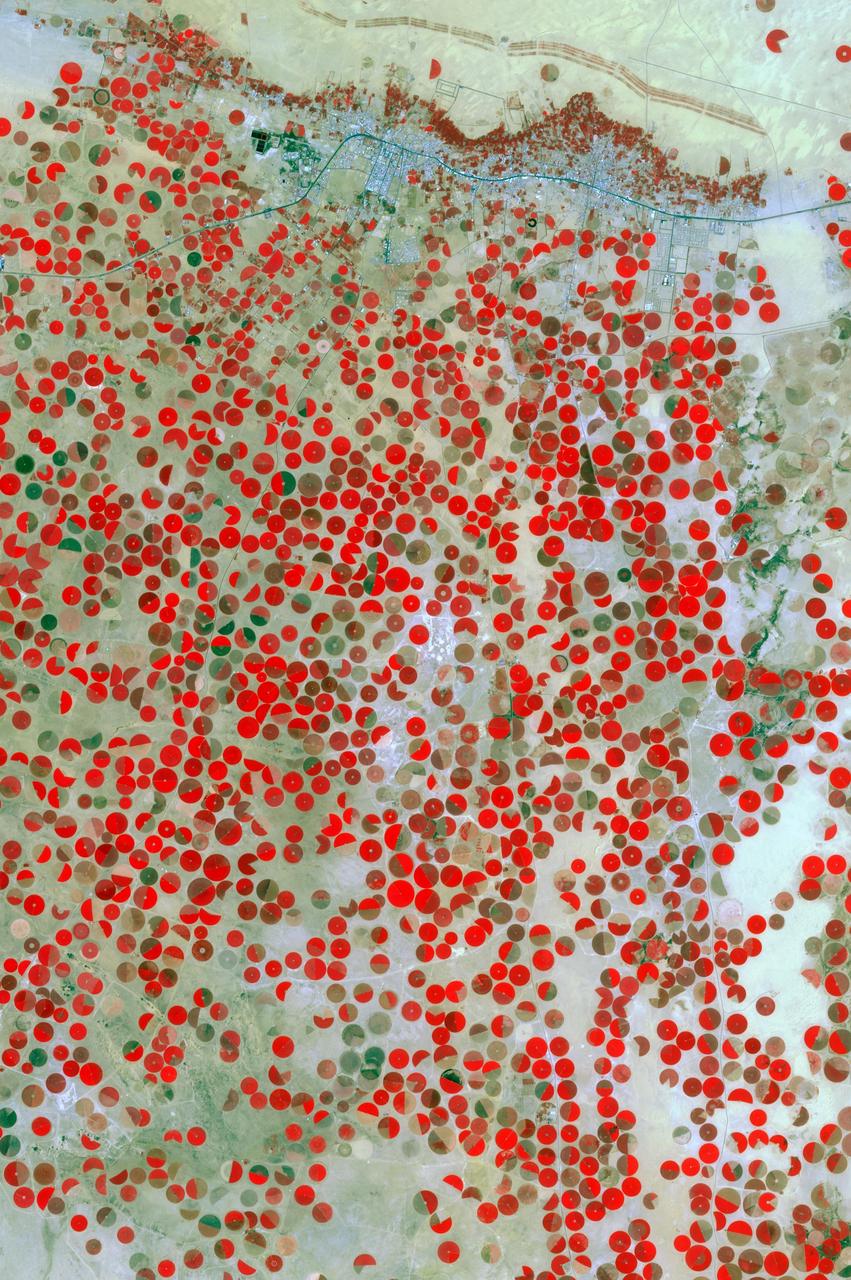

The Wajid Aquifer in Saudi Arabia underlies about 450,000 square kilometers in Saudi Arabia and Yemen. The area around Wadi Al Dawasir, Saudi Arabia, relies on the aquifer to provide water for the extensive development of agriculture. As a result the water level in the aquifer system has dropped 6m/yr for the past 20 to 30 years. Heavy use of water has led to the exhaustion of the aquifer in some areas (Inventory of Shared Water Resources in Western Asia. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.18356/d8517580-en). The images were acquired June 30, 2000, and April 26, 2017, cover an area of 34.6 by 43.9 kilometers, and are located at 20.1 degrees north, 44.7 degrees east. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23490

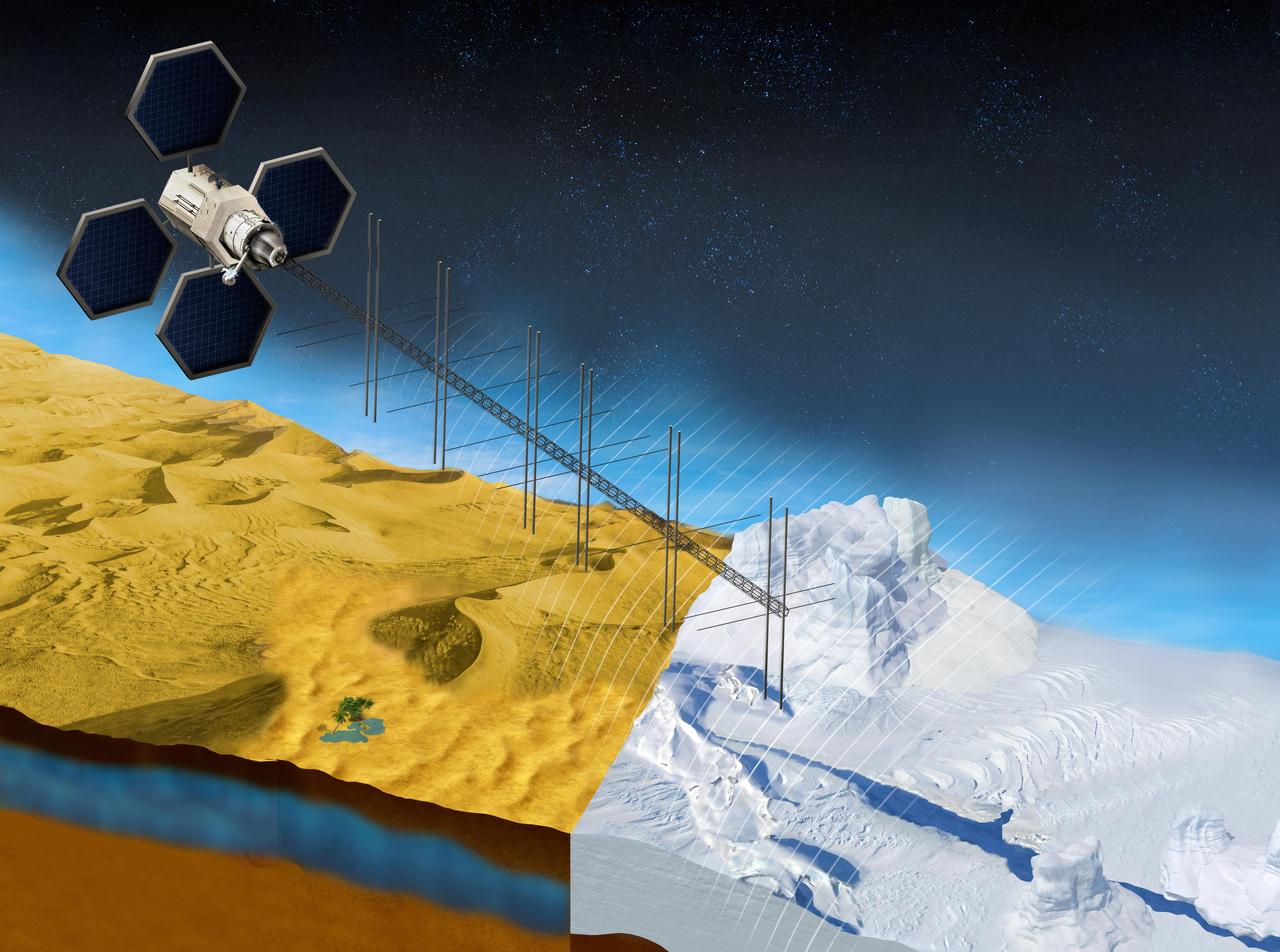

The OASIS project seeks to study fresh water aquifers in the desert as well as ice sheets in places like Greenland. This illustration shows what a satellite with a proposed radar instrument for the mission could look like. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23790

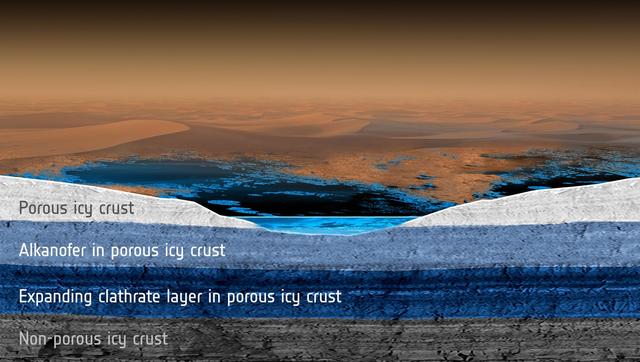

Scientists modeled how methane rainfall runoff would interact with the porous, icy crust of Saturn moon Titan and found that a subsurface methane aquifer might have its composition changed over time due to the formation of materials called clathrates.

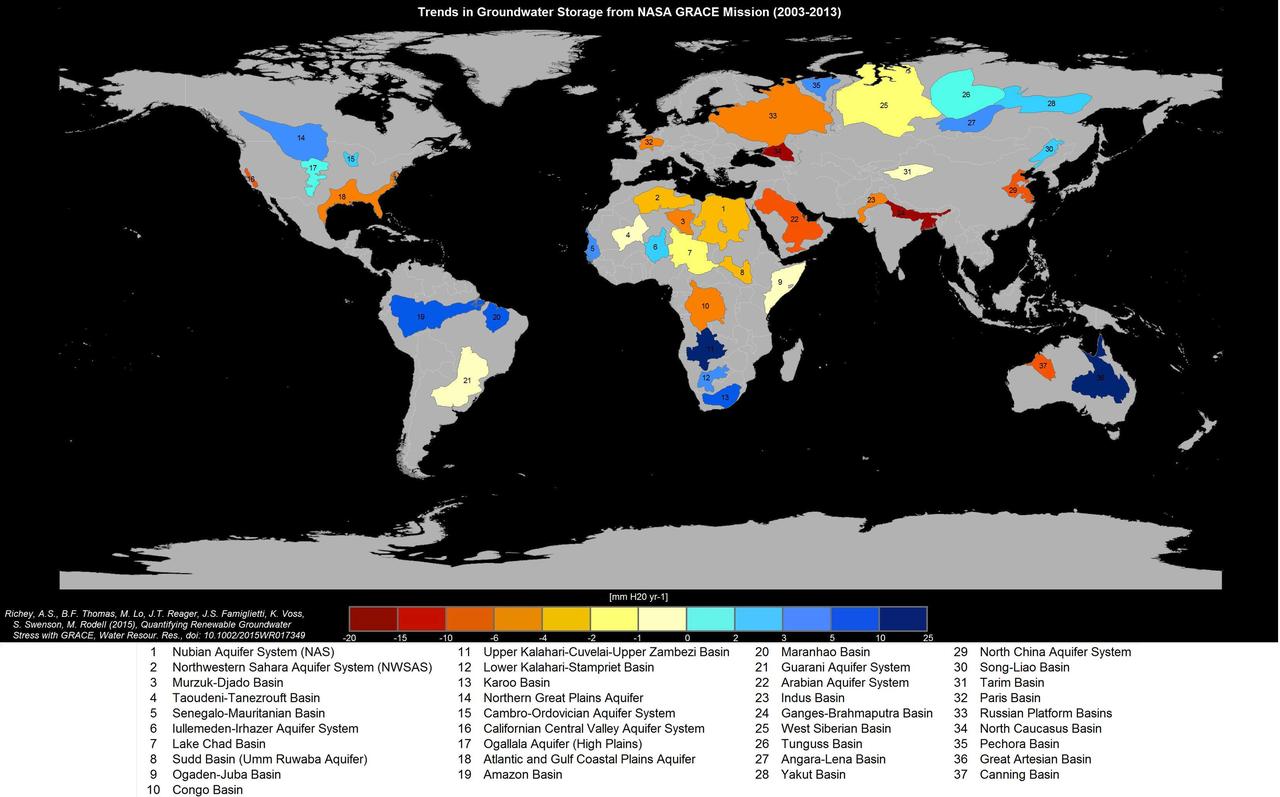

Groundwater storage trends for Earth's 37 largest aquifers from UCI-led study using NASA GRACE data (2003-2013). Of these, 21 have exceeded sustainability tipping points and are being depleted, with 13 considered significantly distressed, threatening regional water security and resilience. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19685

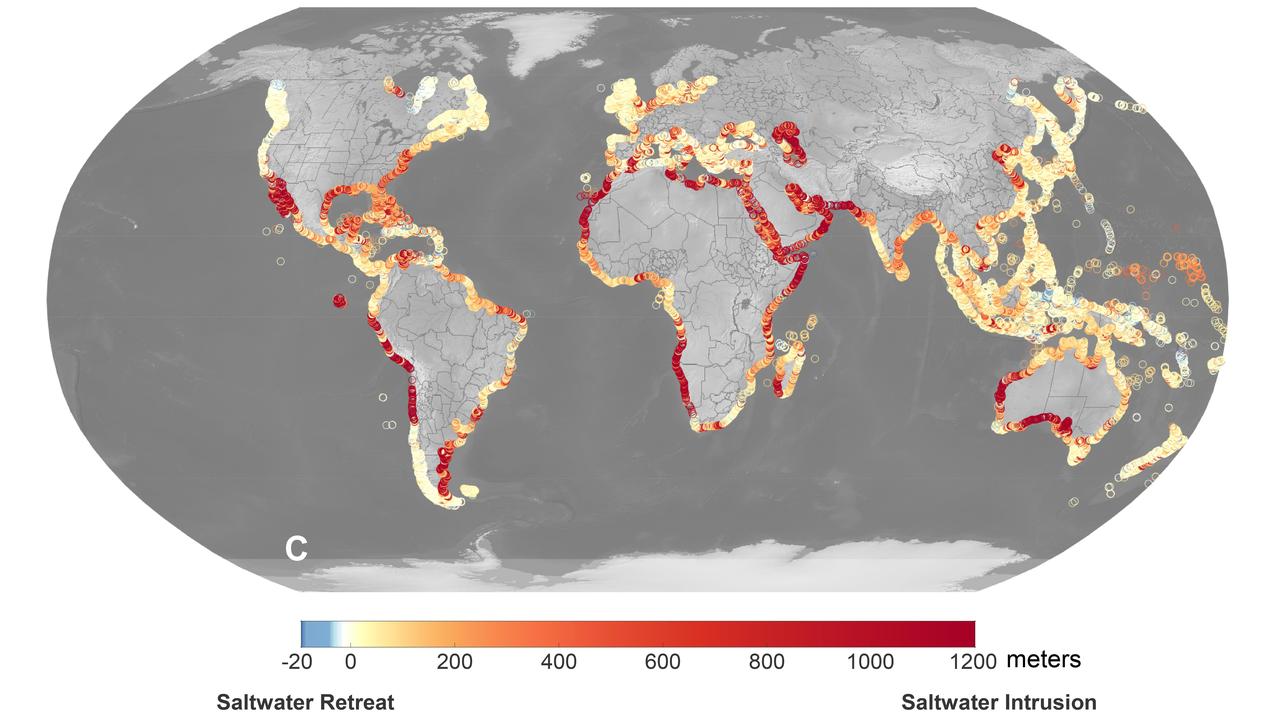

A recent study led by researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California that seawater will infiltrate underground fresh water supplies in about 77% of coastal watersheds around the world by the year 2100, as illustrated in this graphic. Called saltwater intrusion, the phenomenon will result from the combined effects of sea level rise and slower replenishment of groundwater supplies due to warmer, drier regional climates, according to the study, which was funded by NASA and the U.S. Department of Defense and published in Geophysical Research Letters in November 2024. In the graphic, areas that the study projected will experience the most severe saltwater intrusion are marked with red, while the few areas that will experience the opposite phenomenon, called saltwater retreat, are marked with blue. Saltwater intrusion happens deep below coastlines, where two masses of water naturally run up against each other. Rainfall on land replenishes, or recharges, fresh water in coastal aquifers (essentially, underground rock and dirt that hold water), which tends to flow underground toward the ocean. Meanwhile, seawater, backed by the pressure of the ocean, tends to push inland. Although there's some mixing in the transition zone where the two meet, the balance of opposing forces typically keeps the water fresh on one side and salty on the other. Spurred by melting ice sheets and glaciers, sea level rise is causing coastlines to migrate inland and increasing the force pushing underground salt water landward. At the same time, slower groundwater recharge resulting from reduced rainfall and warmer weather patterns is weakening the force behind the fresh water in some areas. Saltwater intrusion can render water in coastal aquifers undrinkable and useless for irrigation. It can also harm ecosystems and damage infrastructure. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26491

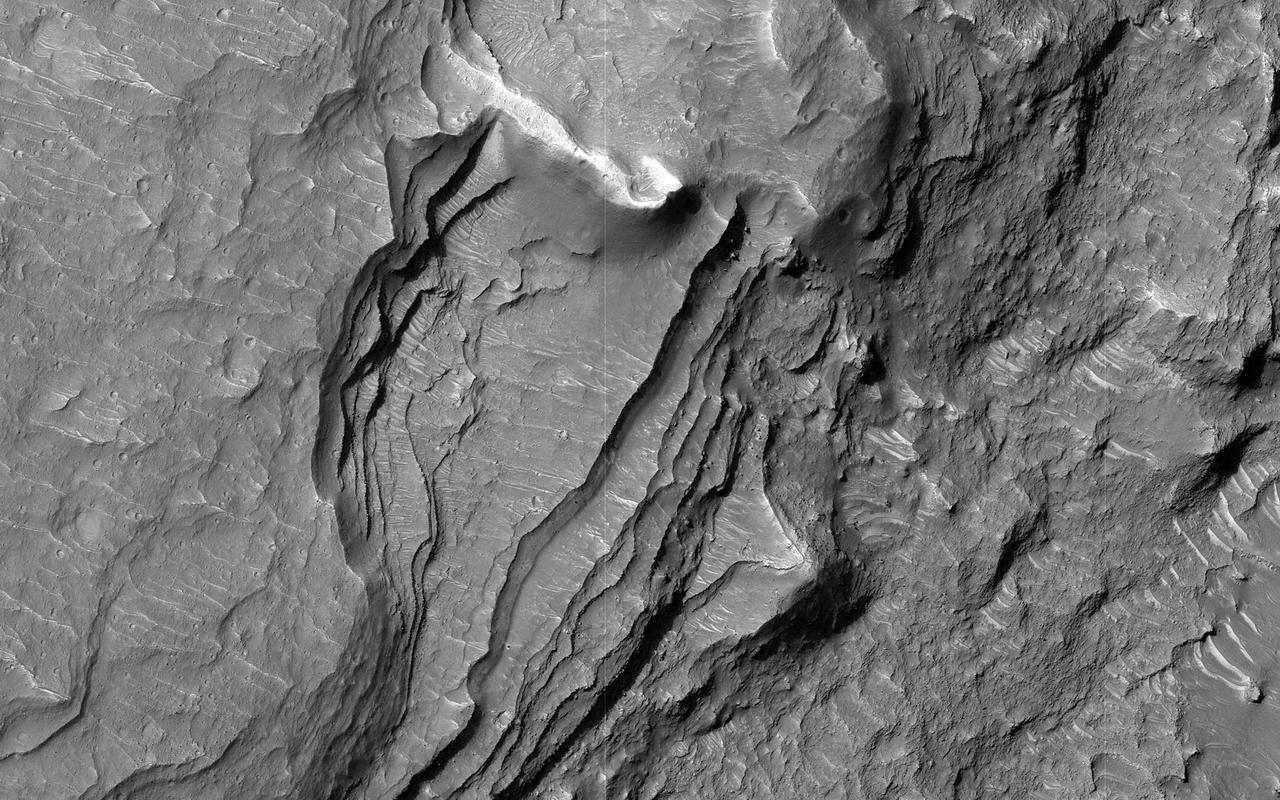

North of Ganges Chasma lies Orson Welles Crater, whose floor contains broken up blocks we call chaotic terrain and which is the source for the major outflow channel Shalbatana Vallis. Between Orson Welles and Ganges Chasma is a region where materials subsided and collapsed over underground cavities that had once held aquifers. This image shows an elongated collapse pit. There is evidence that the pit was once filled with water as the groundwater erupted to the surface. A closer view shows fine sedimentary layers exposed by erosion. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25082

In the middle of the Arabian desert the city Green Oasis Wadi Al Dawasir is being developed as a new urban center for the Wadi Al Dawasir region of Saudi Arabia, as shown in this image from NASA Terra spacecraft. Huge solar fields supply the entire city and the surrounding region with energy. Hundreds of circular agricultural fields are fed by center pivot irrigation apparatus, drawing water from subterranean aquifers. The image was acquired March 30, 2013, covers an area of 30 x 45 km, and is located at 20.2 degrees north, 44.8 degrees east. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20077

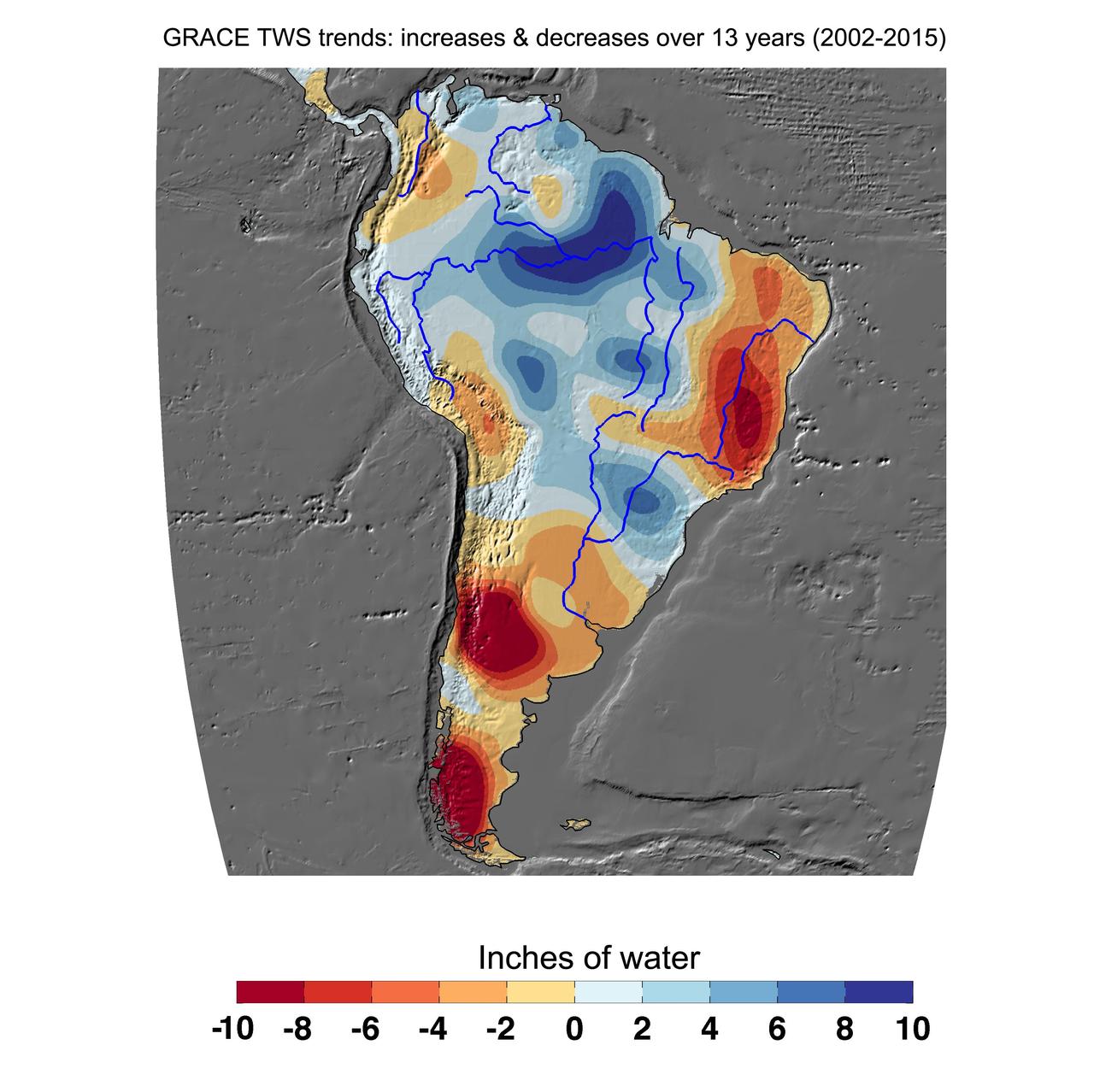

Cumulative total freshwater losses in South America from 2002 to 2015 (in inches) observed by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission. Total water refers to all of the snow, surface water, soil water and groundwater combined. Much of the Amazon River basin experienced increasing total water storage during this time period, though the persistent Brazilian drought is apparent to the east. Groundwater depletion strongly impacted total water losses in the Guarani aquifer of Argentina and neighboring countries. Significant water losses due to the melting ice fields of Patagonia are also observed. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20205

In Saudi Arabia, center-pivot, swing-arm irrigated agriculture complexes such as the one imaged at Jabal Tuwayq (20.5N, 45.0 E) extract deep fossil water reserves to achieve food crop production self sufficiency in this desert environment. The significance of the Saudi expanded irrigated agriculture is that the depletion of this finite water resource is a short term solution to a long term need that will still exist when the water has been extracted.

ISS021-E-026475 (14 Nov. 2009) --- Ounianga Lakes in the Sahara Desert, in the nation of Chad are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 21 crew member on the International Space Station. This view features one of the largest of a series of ten, mostly fresh water lakes in the Ounianga basin in the heart of the Sahara Desert of northeastern Chad. According to scientists, the lakes are the remnant of a single large lake, probably tens of kilometers long that once occupied this remote area approximately 14,800 to 5,500 years ago. As the climate dried out during the subsequent millennia, the lake was reduced in size and large wind-driven sand dunes invaded the original depression dividing it into several smaller basins. The area shown in this image measures approximately 11 x 9 kilometers, with the dark water surfaces of the lake segregated almost completely by orange linear sand dunes that stream into the depression from the northeast. The almost year-round northeast winds and cloudless skies make for very high evaporation (an evaporation rate of greater than six meters per year has been measured in one of the nearby lakes). Despite this, only one of the ten lakes is saline. According to scientists, the reason for the apparent paradox of fresh water lakes in the heart of the desert lies in the fact that fresh water from a very large aquifer reaches the surface in the Ounianga depression in the form of the lakes. The aquifer is large enough to keep supplying the small lakes with water despite the high evaporation rate. Mats of floating reeds also reduce the evaporation in places. The lakes form a hydrological system that is unique in the Sahara Desert. Scientists believe the aquifer was charged with fresh water, and the large original lake evolved, during the so-called African Humid Period (approximately 14,800 to 5,500 years ago) when the West African summer monsoon was stronger than it is today. Associated southerly winds brought Atlantic moisture well north of modern limits, producing sufficient rainfall in the central Sahara to foster an almost complete savanna vegetation cover. Pollen data from lake sediments of the original 50-meters-deep Ounianga Lake suggests to scientists that a mild tropical climate with a wooded grassland savanna existed in the region. This vegetation association is now only encountered 300 kilometers further south. Ferns grew in the stream floodplains which must have been occasionally flooded. Even shrubs that now occur only on the very high, cool summits (greater than 2,900 meters, greater than 9,500 feet) of the Tibesti Mts. have been found in the Ounianga lake sediments.

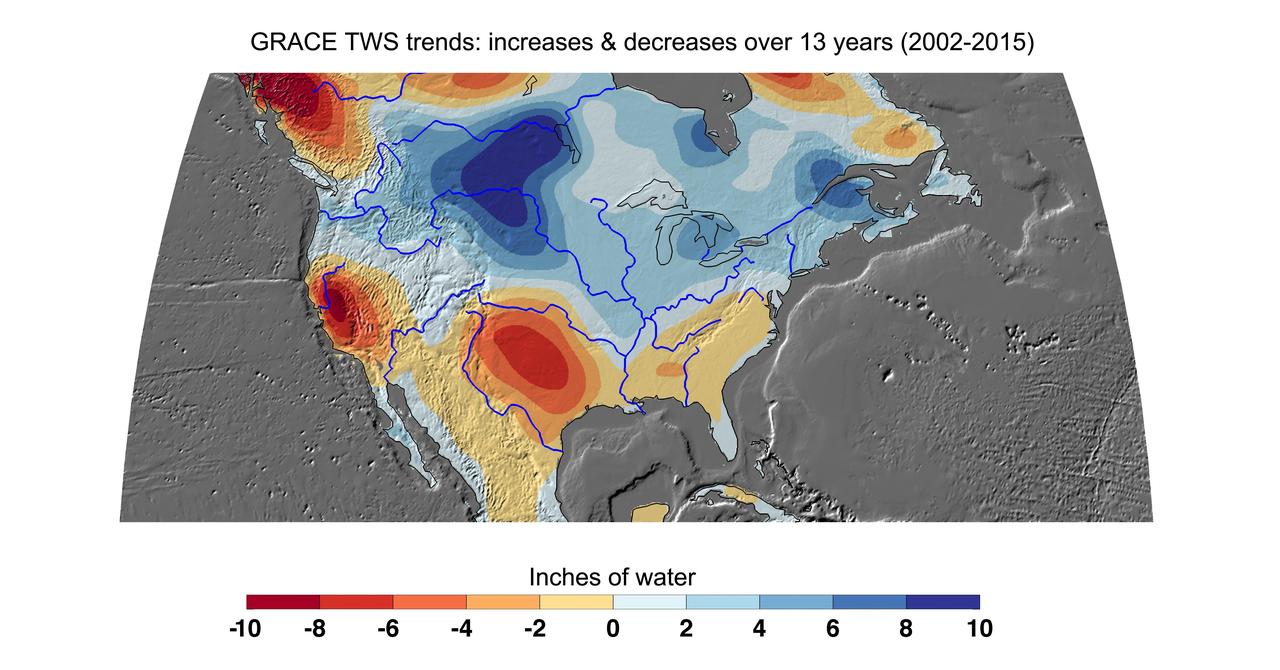

Cumulative total freshwater losses in the United States from 2002 to 2015 (in inches) observed by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission. Total water refers to all of the snow, surface water, soil water and groundwater combined. Much of the northern half of the country experienced increasing total water storage during this time period, while total water storage in the southern half decline. Areas where groundwater depletion strongly impacted total water losses include California's Central Valley, and the southern High Plains aquifer beneath the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles. Total water storage in the Upper Missouri River basin increased signficantly and contributed to considerable flooding during the 2002-15 time period. Image updated from Famiglietti and Rodell, 2013. Citation of Record: Famiglietti, J. S., and M. Rodell, Water in the Balance, Science, 340, 1300-1301. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20204

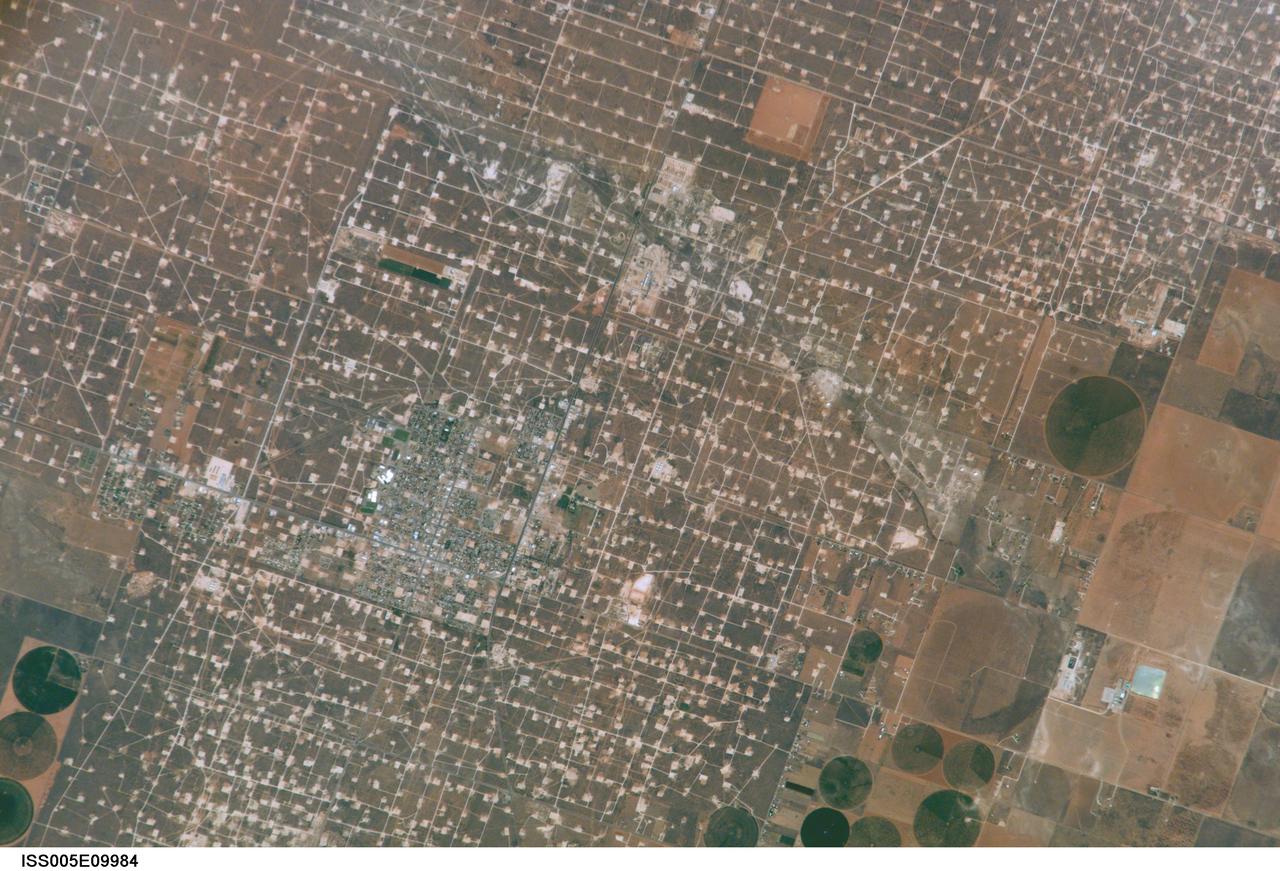

ISS005-E-9984 (17 August 2002) --- This digital still photograph, taken from the International Space Station (ISS) during its fifth staffing, depicts both agriculture and the petroleum industry, which compete for land use near Denver City, Texas. The photo was recently released by the Earth Sciences and Image Analysis Laboratory at Johnson Space Center. The area is southwest of Lubbock near the New Mexico border. According to analysts studying the station imagery, the economy of this region is almost completely dependent on its underground resources of petroleum and water. Both resources result in distinctive land use patterns visible from space. Historically this area has produced vast quantities of oil and gas since development began in the 1930s. A fine, light-colored grid of roads and pipelines connect well sites over this portion of the Wasson Oil Field, one of the state’s most productive. Since the 1940s, agricultural land use has shifted from grazing to irrigated cultivation of cotton, sorghum, wheat, hay, and corn. The water supply is drawn from wells tapping the vast Ogallala Aquifer. Note the large, circular center-pivot irrigation systems in the lower corners of the image. The largest is nearly a mile in diameter.

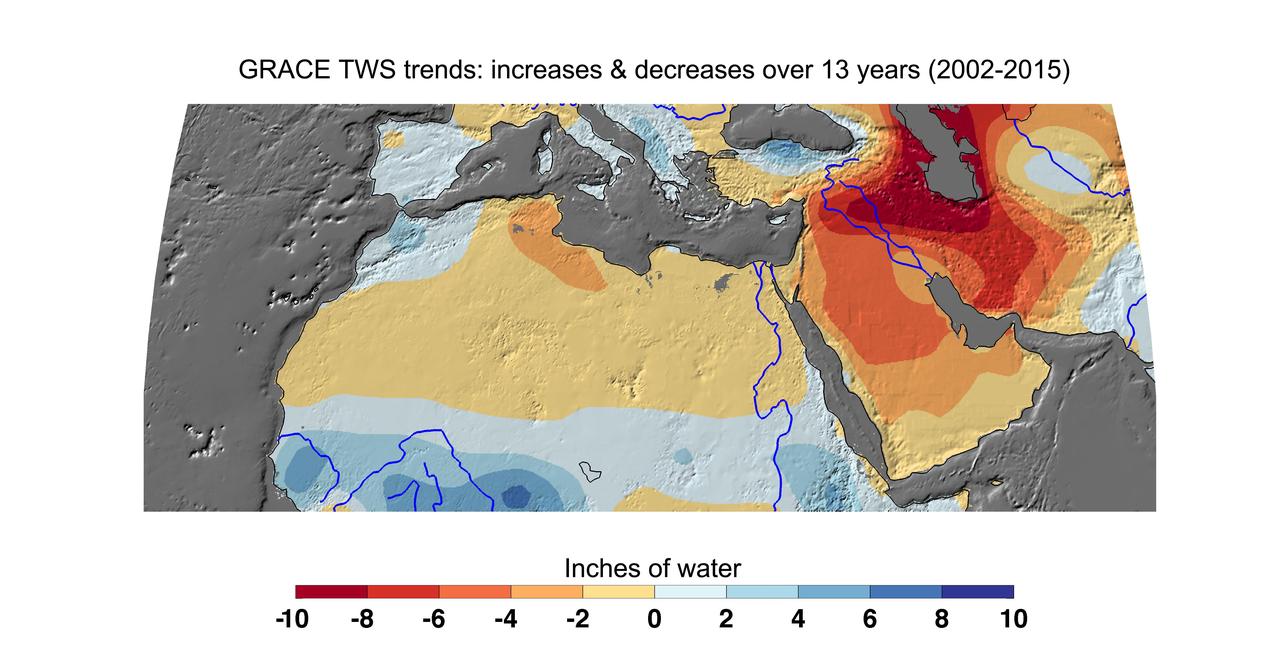

Cumulative total freshwater losses in North Africa and the Middle East from 2002 to 2015 (in inches) observed by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission. Total water refers to all of the snow, surface water, soil water and groundwater combined. Groundwater depletion in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, and along the Arabian Peninsula, are leading to large changes in total water storage in the region. Likewise, drought and groundwater pumping is contributing to the drying of the Caspian Sea Region. The Northwest Sahara Aquifer System, which underlies Tunisia and Libya, is also experiencing increasing water stress as shown in the map. Image updated from Voss et al., 2013. Citation of Record: Voss, K. A., J. S. Famiglietti, M. Lo, C. R. de Linage, M. Rodell and S. C. Swenson, Groundwater depletion in the Middle East from GRACE with Implications for Transboundary Water Management in the Tigris-Euphrates-Western Iran Region, Wat. Resour. Res., 49(2), 904-914, DOI: 10.1002/wrcr.20078. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20207

STS062-151-220 (4-18 March 1994) --- Great numbers of circular, center-pivot irrigation plots appear in this west-looking view of the northern Saudi Arabia (center to lower left). So many plots now exist that the face of Saudi Arabia as seen from low earth orbit has changed. Until a few years ago, there were only a few scattered center-pivots. Now the entire swath of country between the shifting sands of the Ad Dahna Sand Sea (light colors center and right) and the almost soilless Nejd Plateau (left) has been darkened by thousands of these agricultural fields. The Nejd Plateau is a mass of dark rocks, some volcanic, in NW Saudi Arabia. Water from this higher country flows east towards the agricultural region where it is pumped up from underground aquifers. The weep of the Ad Dahna Sand Sea is one of the major features of Saudi Arabia (center and right) as seen from the orbiter. The dunes follow the trend of regional winds (northwesterly in the center of the view) which circulate around the Nejd plateau. The north end of the Red Sea can be seen top left with the Sinai Peninsula and Mediterranean are just visible center top. Iraq is under cloud top right.

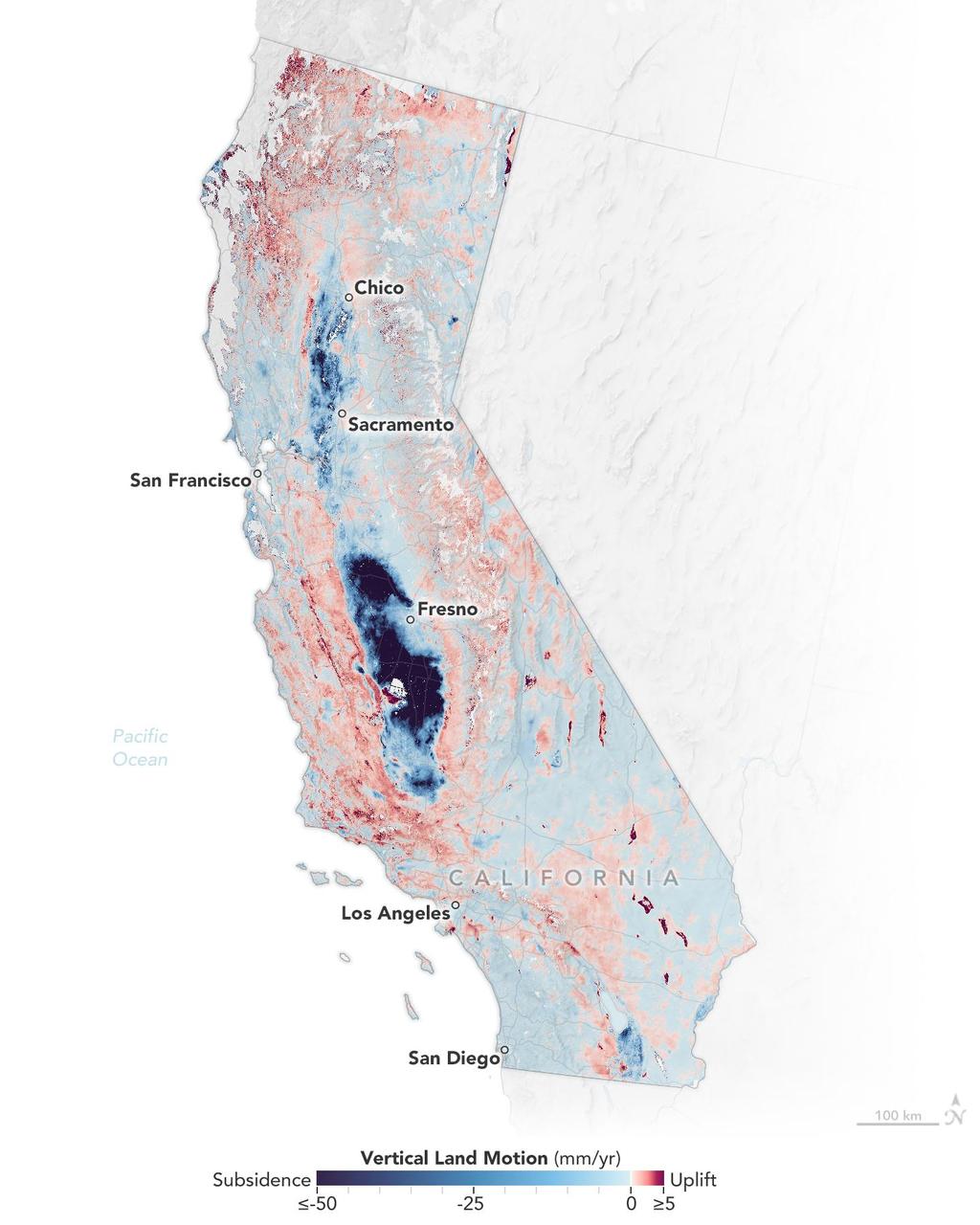

Researchers from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) analyzed vertical land motion – also known as uplift and subsidence – along the California coast between 2015 and 2023. They detailed where land beneath major coastal cities, including parts of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego, is sinking (indicated in blue in this visualization of the data). Locations of uplift (shown in red) were also observed. Causes for the motion include human-driven activities such as groundwater withdrawal and wastewater injection as well as natural dynamics like tectonic activity. Understanding these local elevation changes can help communities adapt to rising sea levels in their area. The researchers pinpointed hot spots – including cities, beaches, and aquifers – at greater exposure to rising seas in coming decades. Sea level rise can exacerbate issues like nuisance flooding and saltwater intrusion. To gather the data, the researchers employed a remote sensing technique called interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR), which combines two or more 3D observations of the same region to reveal surface motion down to fractions of inches. They used the radars on the ESA (European Space Agency) Sentinel-1 satellites, as well as motion velocity data from ground-based receiving stations in the Global Navigation Satellite System. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25530

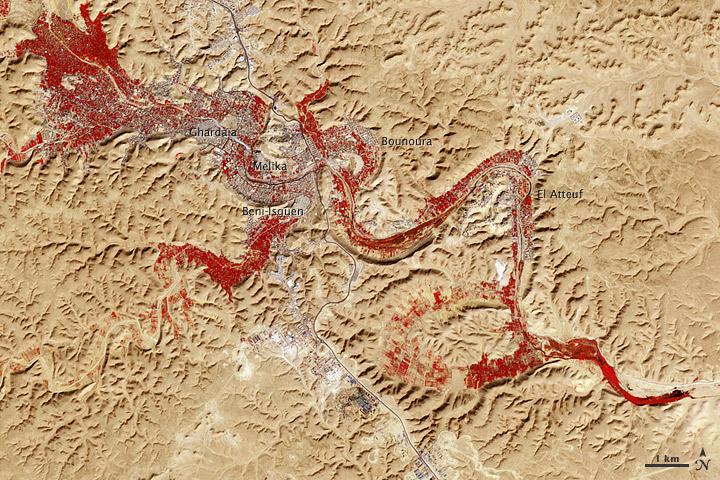

NASA image acquired Feb. 9, 2011 Less than 5 percent of Algeria’s land surface is suitable for growing crops, and most precipitation falls on the Atlas Mountains along the coast. Inland, dust-laden winds blow over rocky plains and sand seas. However, in north central Algeria—off the tip of Grand Erg Occidental and about 450 kilometers (280 miles) south of Algiers—lies a serpentine stretch of vegetation. It is the M’zab Valley, filled with palm groves and dotted with centuries-old settlements. The Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this image of M’zab Valley on February 9, 2011. ASTER combines infrared, red, and green wavelengths of light. Bare rock ranges in color from beige to peach. Buildings and paved surfaces appear gray. Vegetation is red, and brighter shades of red indicate more robust vegetation. This oasis results from water that is otherwise in short supply in the Sahara Desert, thanks to the valley’s approximately 3,000 wells. Chemical analysis of Algerian aquifers, as well studies of topography in Algeria and Tunisia, suggest this region experienced a cooler climate in the late Pleistocene, and potentially heavy monsoon rains earlier in the Holocene. The M’zab region shows evidence of meandering rivers and pinnate drainage patterns. The vegetation lining M’zab Valley highlights this old river valley’s contours. Cool summer temperatures and monsoon rains had long since retreated from the region by eleventh century, but this valley nevertheless supported the establishment of multiple fortified settlements, or ksours. Between 1012 A.D. and 1350 A.D., locals established the ksours of El-Atteuf, Bounoura, Melika, Ghardaïa, and Beni-Isguen. Collectively these cities are now a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage site. NASA Earth Observatory image by Robert Simmon and Jesse Allen, using data from the GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team. Caption by Michon Scott. Instrument: Terra - ASTER <b>To download the full high res file go <a href="http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=51296" rel="nofollow"> here</a></b>

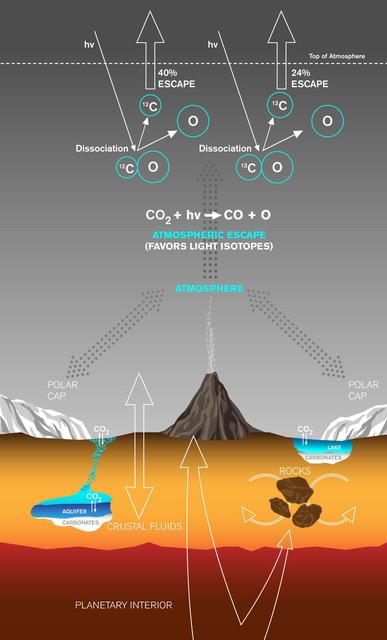

This graphic depicts paths by which carbon has been exchanged between Martian interior, surface rocks, polar caps, waters and atmosphere, and also depicts a mechanism by which carbon is lost from the atmosphere with a strong effect on isotope ratio. Carbon dioxide (CO2) to generate the Martian atmosphere originated in the planet's mantle and has been released directly through volcanoes or trapped in rocks crystallized from magmas and released later. Once in the atmosphere, the CO2 can exchange with the polar caps, passing from gas to ice and back to gas again. The CO2 can also dissolve into waters, which can then precipitate out solid carbonates, either in lakes at the surface or in shallow aquifers. Carbon dioxide gas in the atmosphere is continually lost to space at a rate controlled in part by the sun's activity. One loss mechanism is called ultraviolet photodissociation. It occurs when ultraviolet radiation (indicated on the graphic as "hv") encounters a CO2 molecule, breaking the bonds to first form carbon monoxide (CO) molecules and then carbon (C) atoms. The ratio of carbon isotopes remaining in the atmosphere is affected as these carbon atoms are lost to space, because the lighter carbon-12 (12C) isotope is more easily removed than the heavier carbon-13 (13C) isotope. This fractionation, the preferential loss of carbon-12 to space, leaves a fingerprint: enrichment of the heavy carbon-13 isotope, measured in the atmosphere of Mars today. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20163

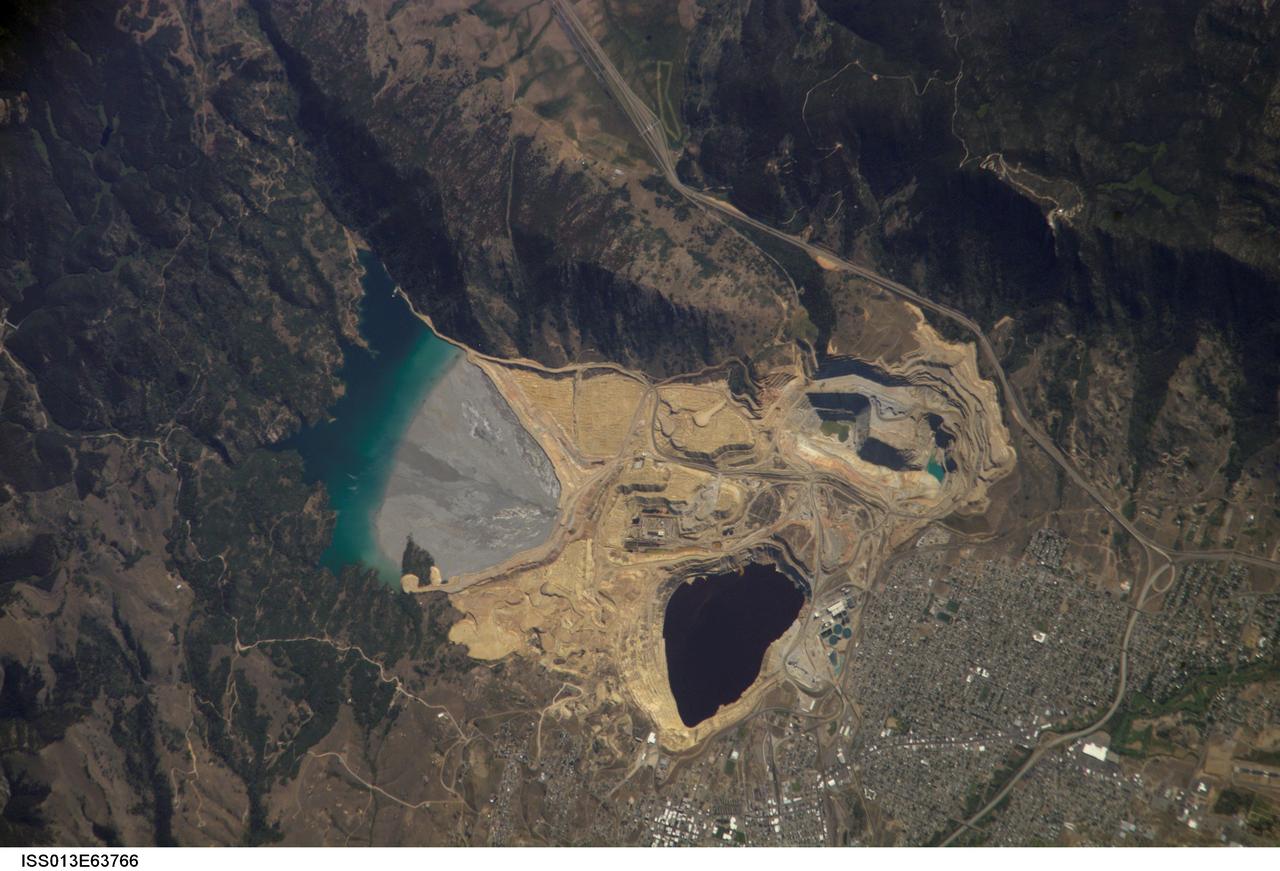

ISS013-E-63766 (2 Aug. 2006) --- Berkeley Pit and Butte, Montana are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 13 crewmember on the International Space Station. The city of Butte, Montana has long been a center of mining activity. Underground mining of copper began in Butte in the 1870s, and by 1901 underground workings had extended to the groundwater table. Thus began the creation of an intricate complex of underground drains and pumps to lower the groundwater level and continue the extraction of copper. Water extracted from the mines was so rich in dissolved copper sulfate that it was also "mined" (by chemical precipitation) for the copper it contained. In 1955, the Anaconda Copper Mining Company began open-pit mining for copper in what is now know as the Berkeley Pit (dark oblong area in center). The mine took advantage of the existing subterranean drainage and pump network to lower groundwater until 1982, when the new owner ARCO suspended operations at the mine. The groundwater level swiftly rose, and today water in the Pit is more than 900 feet deep. Many features of the mine workings are visible in this image such as the many terraced levels and access roadways of the open mine pits (gray and tan sculptured surfaces). A large gray tailings pile of waste rock and an adjacent tailings pond are visible to the north of the Berkeley Pit. Color changes in the tailings pond are due primarily to changing water depth. The Berkeley Pit is listed as a federal Superfund site due to its highly acidic water, which contains high concentrations of metals such as copper and zinc. The Berkeley Pit receives groundwater flowing through the surrounding bedrock and acts as a "terminal pit" or sink for these heavy metal-laden waters. Ongoing efforts include regulation of water flow into the pit to reduce filling of the Pit and potential release of contaminated water into local aquifers or surface streams.

The diagram – based on data used in a July 2024 NASA-funded study – shows polar motion, a phenomenon that results from the combined action of several physical processes that broadly shift the distribution of mass around the globe or create forces in its mantle and core that cause the planet to wobble as it rotates. These changes cause the spin axis to meander over time. The blue line starts at the position of the spin axis near the North Pole in 1900, the first year polar motion data was collected, and tracks it until 2023. The spin axis now sits about 30 feet (10 meters) from where it was in 1900, in the direction of Canada's Baffin Bay. Around 2000, the axis took a sudden eastward turn, which researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California in a 2016 study attributed to faster melting of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets and groundwater depletion in Eurasia. Surendra Adhikari, a JPL geophysicist who co-authored that study, used measurements from the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service to create the animation. Adhikari and collaborators from Switzerland, Canada, and Germany found in a July 2024 paper in Nature Geoscience that about 90% of repeated oscillations in polar motion between 1900 and 2018 could be explained by large-scale mass redistribution at Earth's surface due to the melting of ice sheets and glaciers and the depletion of aquifers. It also found that nearly all of the long-term, non-repeating drift of the axis was due to dynamics in the mantle. Animation available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26120

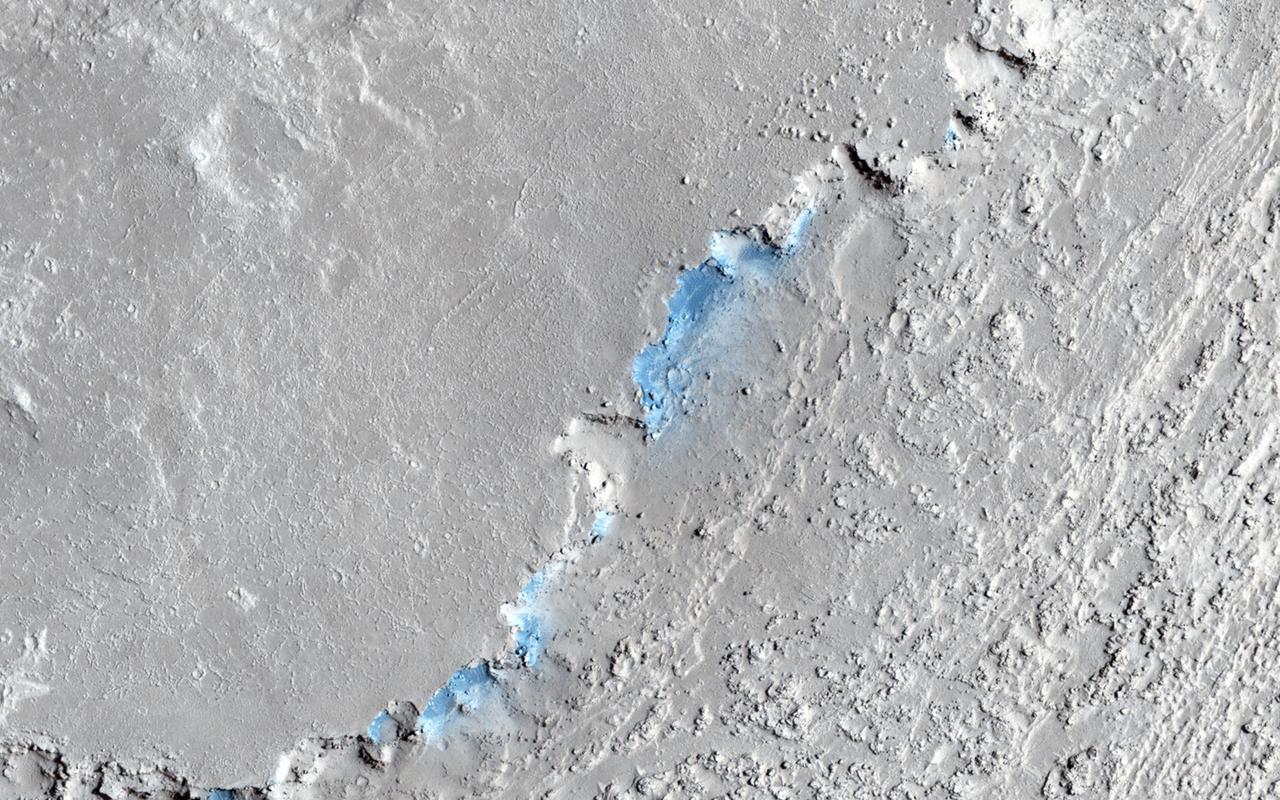

This image captured by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows a small channel cutting into young volcanic lavas in a region where massive catastrophic flooding took place in the relatively recent past. The Athabasca Valles region includes a vast lava flow, thought to be the youngest on Mars, with even younger outflow channels that were carved by running water. The source of the water is believed to be the Cerberus Fossae valleys to the north, which may have penetrated to an over-pressurized aquifer in the subsurface. Nowadays, erosion by gravity, wind, and frost gradually wears down the rims of the outflow channels. In this scene, we see dark materials along the channel rim that were probably exposed by this erosion. The dark materials are less red than the surrounding surface and so they appear blue in this enhanced color picture. Viewed close up, the dark materials show ripples that suggest they are made up of mobile sand. It is possible that this sand originated elsewhere and simply collected where we see it today, but the fact that sand is not found elsewhere in the scene suggest to us that it is eroding out of the volcanic layers at the retreating rim of the channel. Sand sources are important because mobile sand grains have only a limited lifetime, wearing down and chipping apart each time they impact the surface. Erosion of the volcanic materials in this region may provide sands to replace those that are destroyed. Few such sand sources have so far been identified on Mars. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18889

ISS030-E-090918 (21 Feb. 2012) --- Agricultural fields in the Wadi As-Sirhan Basin in Saudi Arabia are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 30 crew member on the International Space Station. Northern Saudi Arabia hosts some of the most extensive sand and gravel deserts in the world, but modern agricultural technology has changed the face of some of them. This photograph presents the almost surreal image of abundant green fields in the midst of a barren desert ? specifically the Wadi As-Sirhan Basin of northwestern Saudi Arabia. As recently as 1986 there was little to no agricultural activity in the area, but over the subsequent 26 years agricultural fields have been steadily developed, largely as a result of investment of oil industry revenues by the Saudi government. The fields use water pumped from subsurface aquifers and is distributed in rotation about a center point within a circular field ? a technique known as center-pivot agriculture. This technique affords certain benefits relative to more traditional surface irrigation such as better control of water use and application of fertilizers. The use of this so-called ?precision agriculture? is particularly important in regions subject to high evaporative water loss; by better controlling the amount and timing of water application, evaporative losses can be minimized. Crops grown in the area include fruits, vegetables, and wheat. For a sense of scale, agricultural fields in active use (dark green) and fallow (brown to tan), are approximately one kilometer in diameter. While much of the Wadi As-Sirhan Basin shown here is sandy (light tan to brown surfaces) and relatively flat, low hills and rocky outcrops (dark gray) of underlying sedimentary rocks are visible at left and right.