This view shows the confluence of the Amazon and the Topajos Rivers at Santarem, Brazil (2.0S, 55.0W). The Am,azon flows from lower left to upper right of the photo. Below the river juncture of the Amazon and Tapajos, there is considerable deforestation activity along the Trans-Amazon Highway.

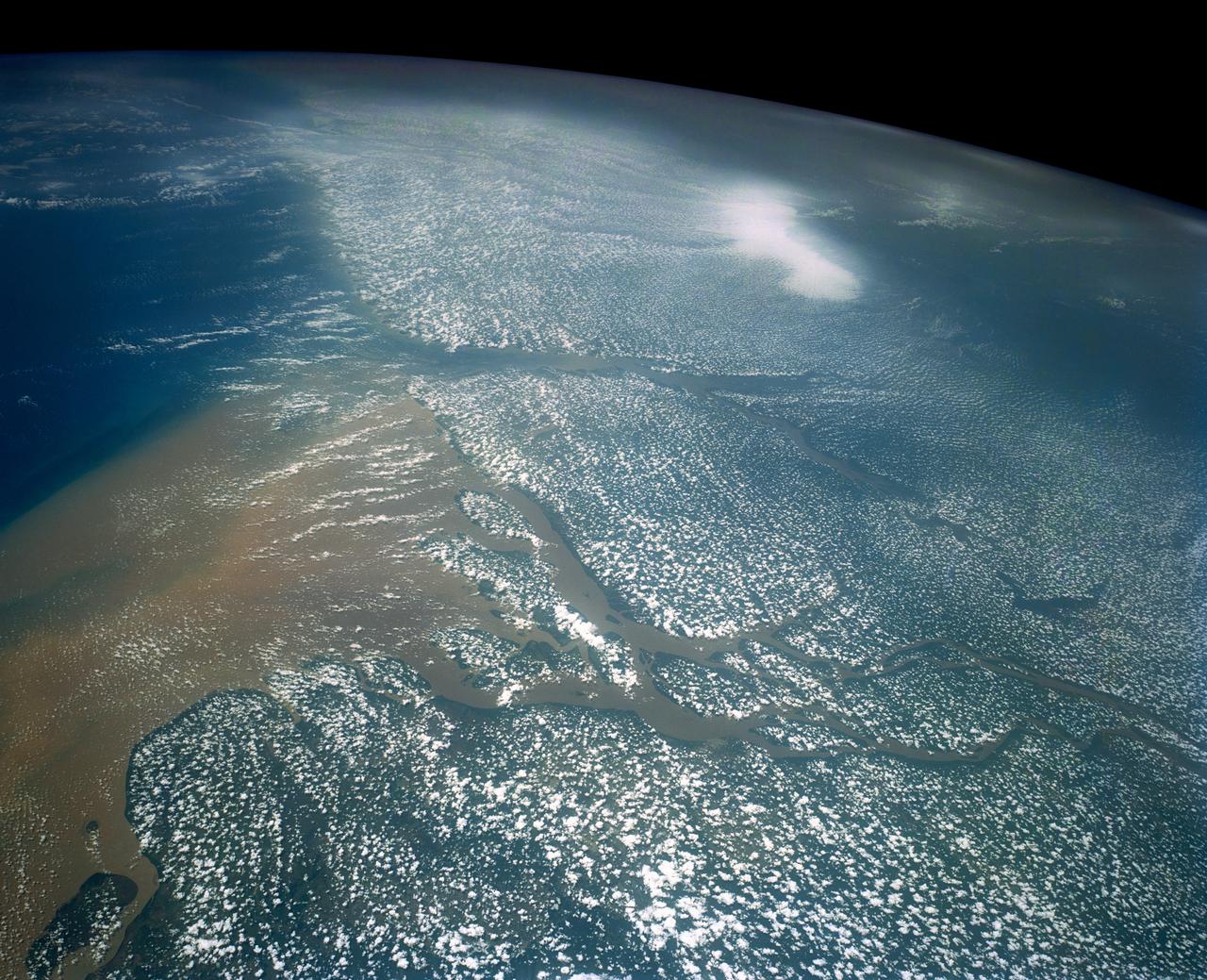

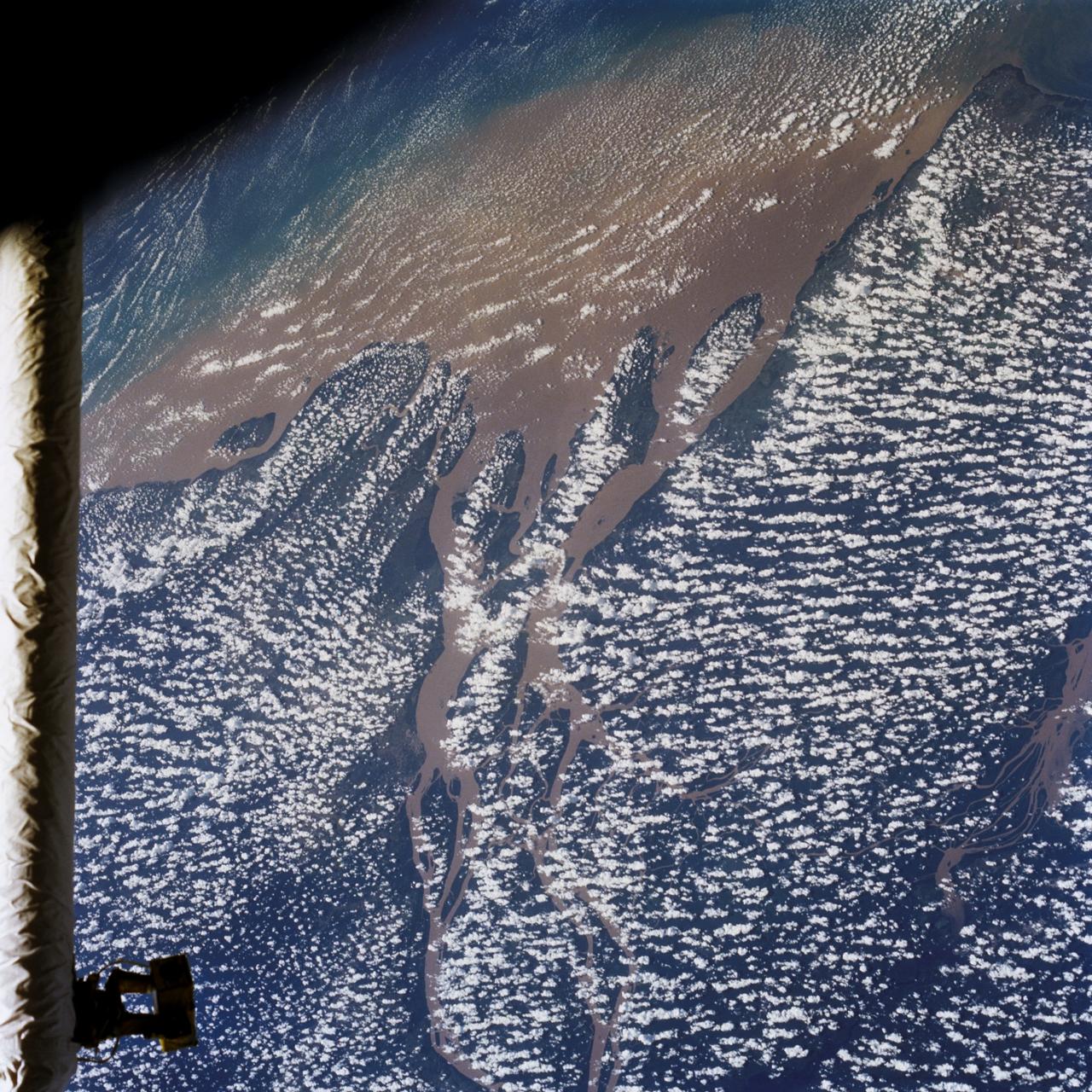

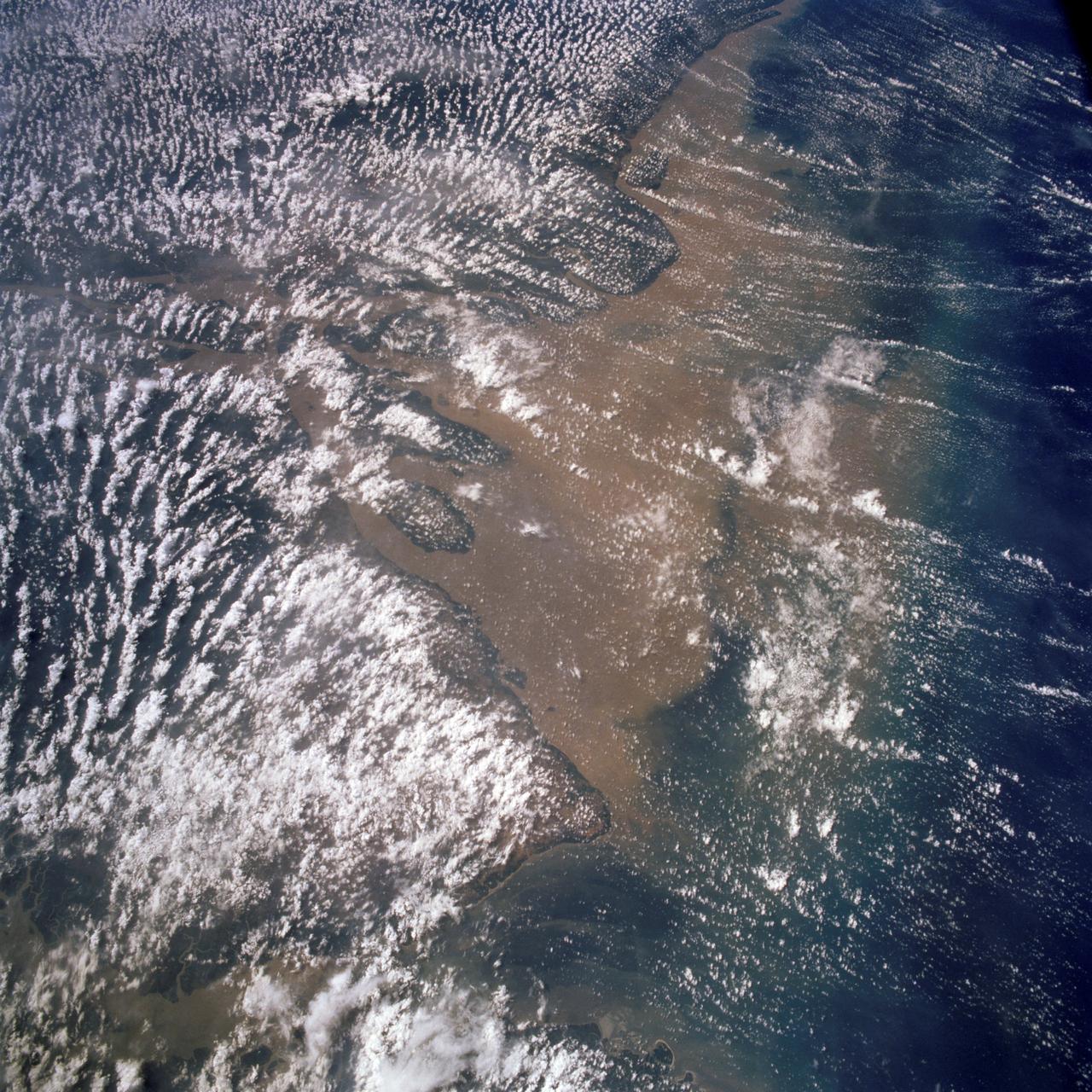

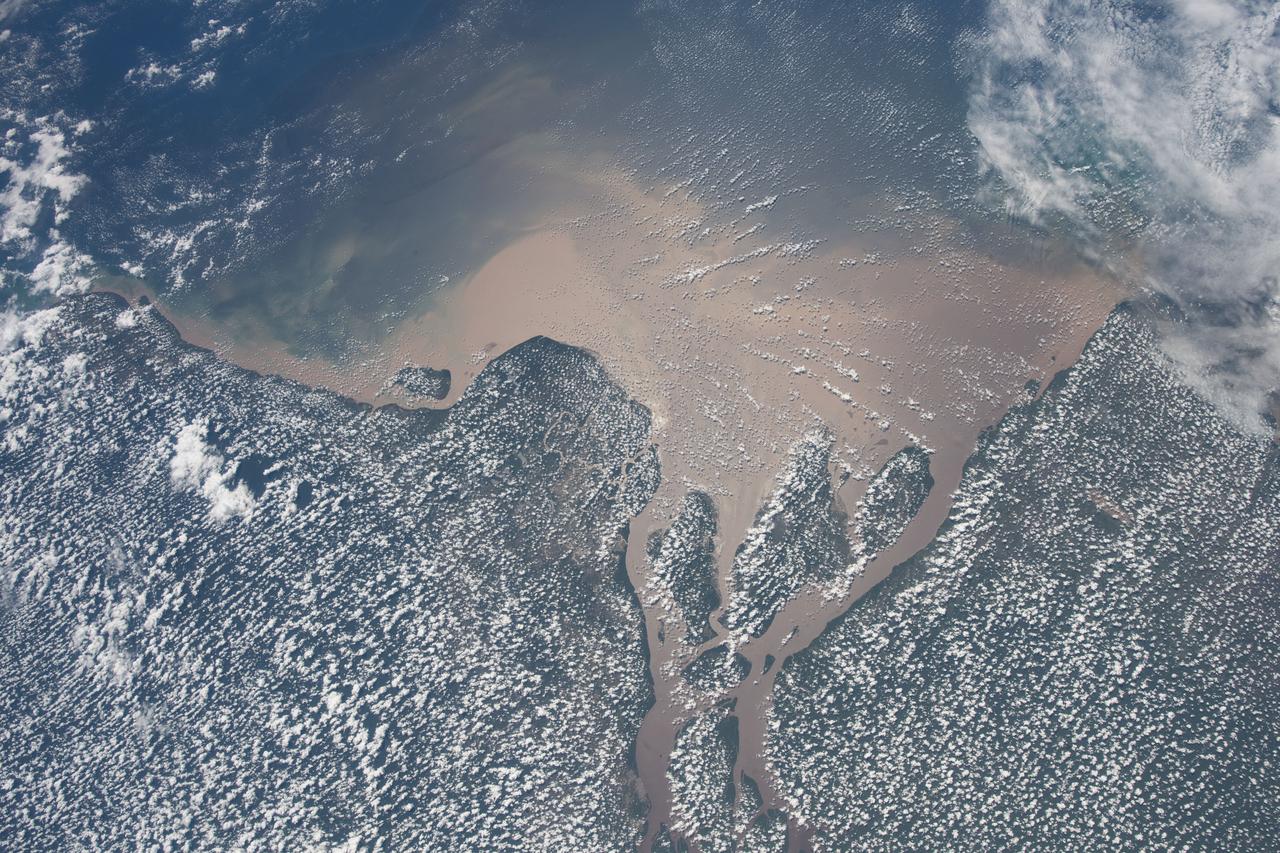

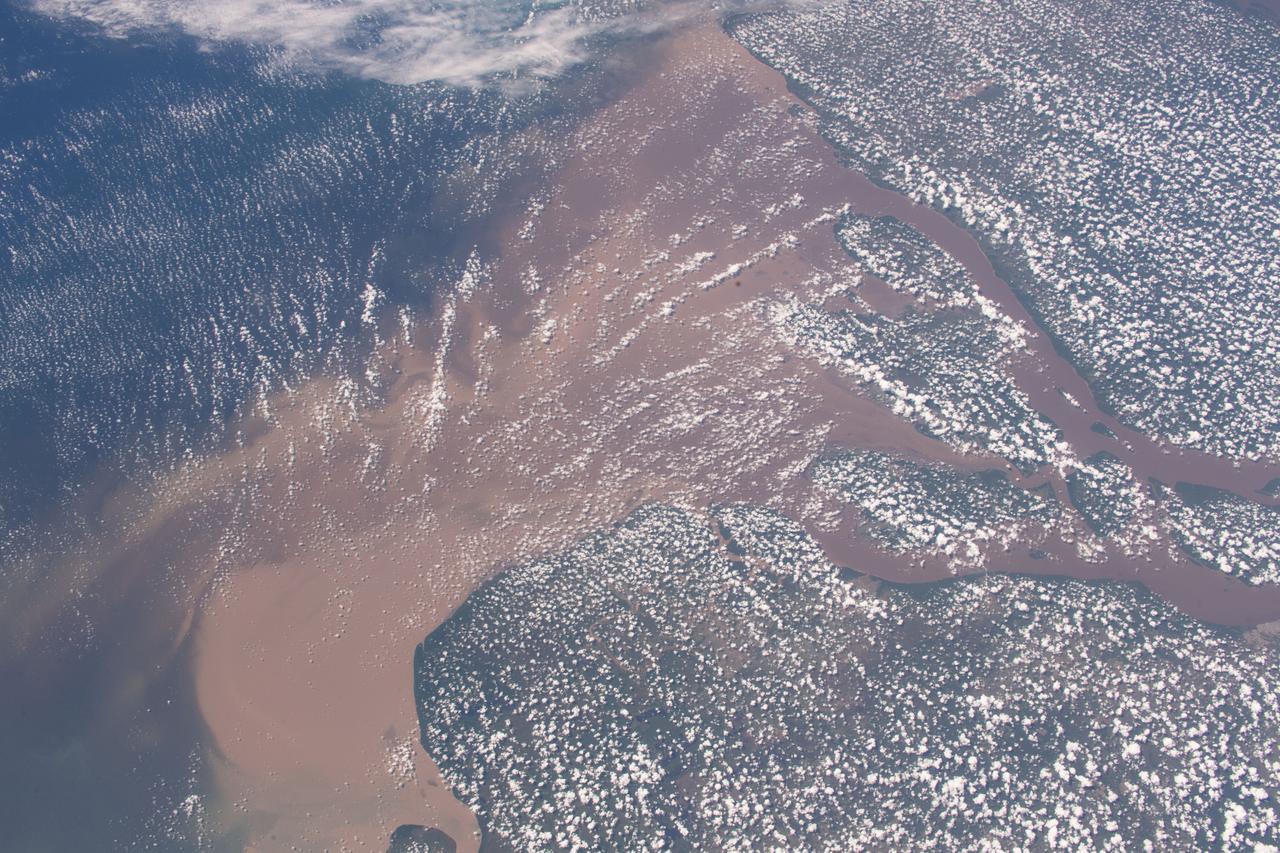

Huge sediment loads from the interior of the country flow through the Mouths of the Amazon River, Brazil (0.5S, 50.0W). The river current carries hundreds of tons of sediment through the multiple outlets of the great river over 100 miles from shore before it is carried northward by oceanic currents. The characteristic "fair weather cumulus" pattern of low clouds over the land but not over water may be observed in this scene.

STS046-80-009 (31 July-8 Aug. 1992) --- A view of the mouth of the Amazon River and the Amazon Delta shows a large sediment plume expanding outward into the Atlantic Ocean. The sediment plume can be seen hugging the coast north of the Delta. This is caused by the west-northwest flowing Guyana Current. The large island of Marajo is partially visible through the clouds.

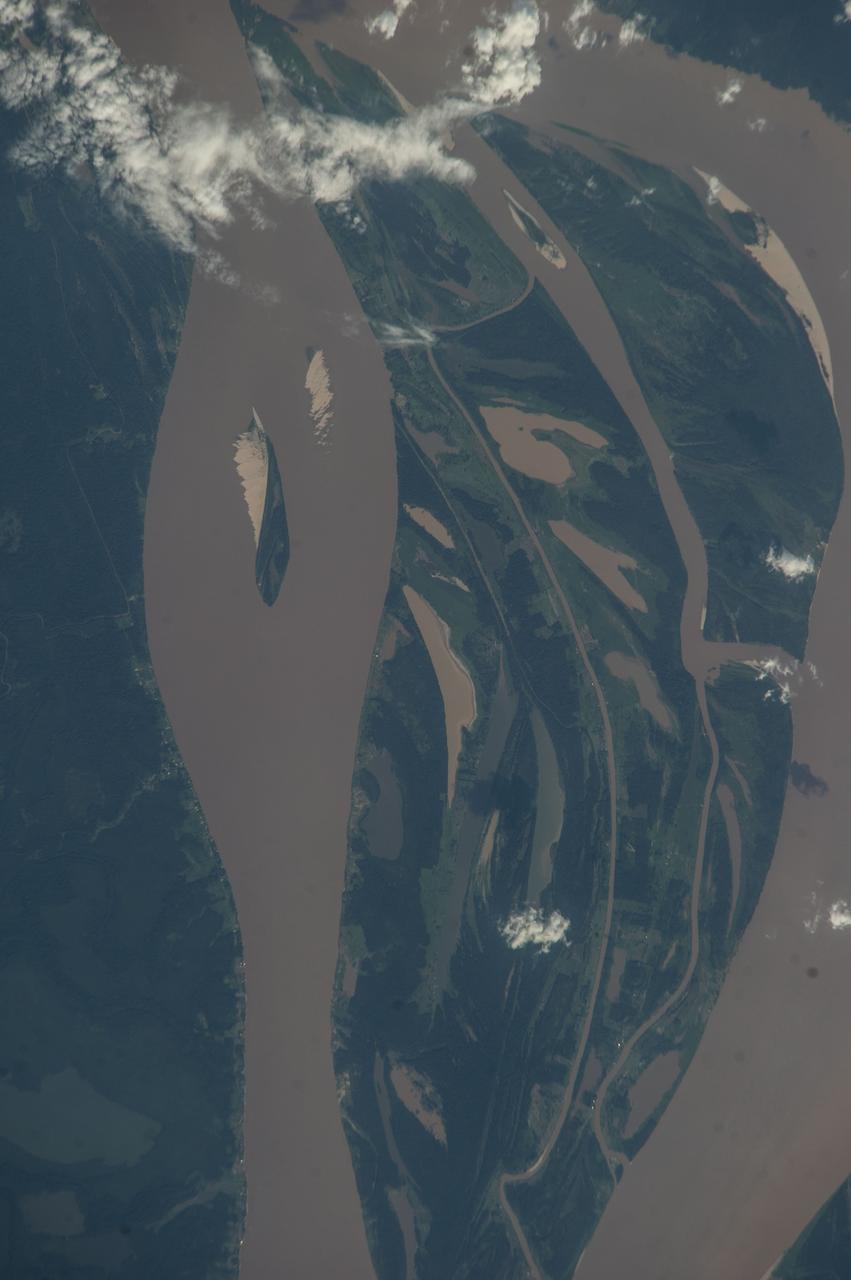

iss069e033689 (July 19, 2023) -- Curves of the Amazon River are pictured from the International Space Station as it orbited 260 miles above Bolivia.

STS058-107-083 (18 Oct.-1 Nov. 1993) --- A near-nadir view of the mouth of the Amazon River, that shows all signs of being a relatively healthy system, breathing and exhaling. The well-developed cumulus field over the forested areas on both the north and south sides of the river (the view is slightly to the west) shows that good evapotranspiration is underway. The change in the cloud field from the moisture influx from the Atlantic (the cloud fields over the ocean are parallel to the wind direction) to perpendicular cloud fields over the land surface are normal. This change in direction is caused by the increased surface roughness over the land area. The plume of the river, although turbid, is no more or less turbid than it has been reported since the Portuguese first rounded Brasil's coast at the end of the 15th Century.

This striking image of Skylab was photographed by Astronaut Jack Lousma (Skylab-3), as the second crew reached the orbiting laboratory over the delta of the mighty Amazon River. Skylab's solar arrays were exposed directly to the Sun's rays. Solar energy was transformed into electrical power for operation of all spacecraft systems. The proper operation of these solar arrays was vital to the mission.

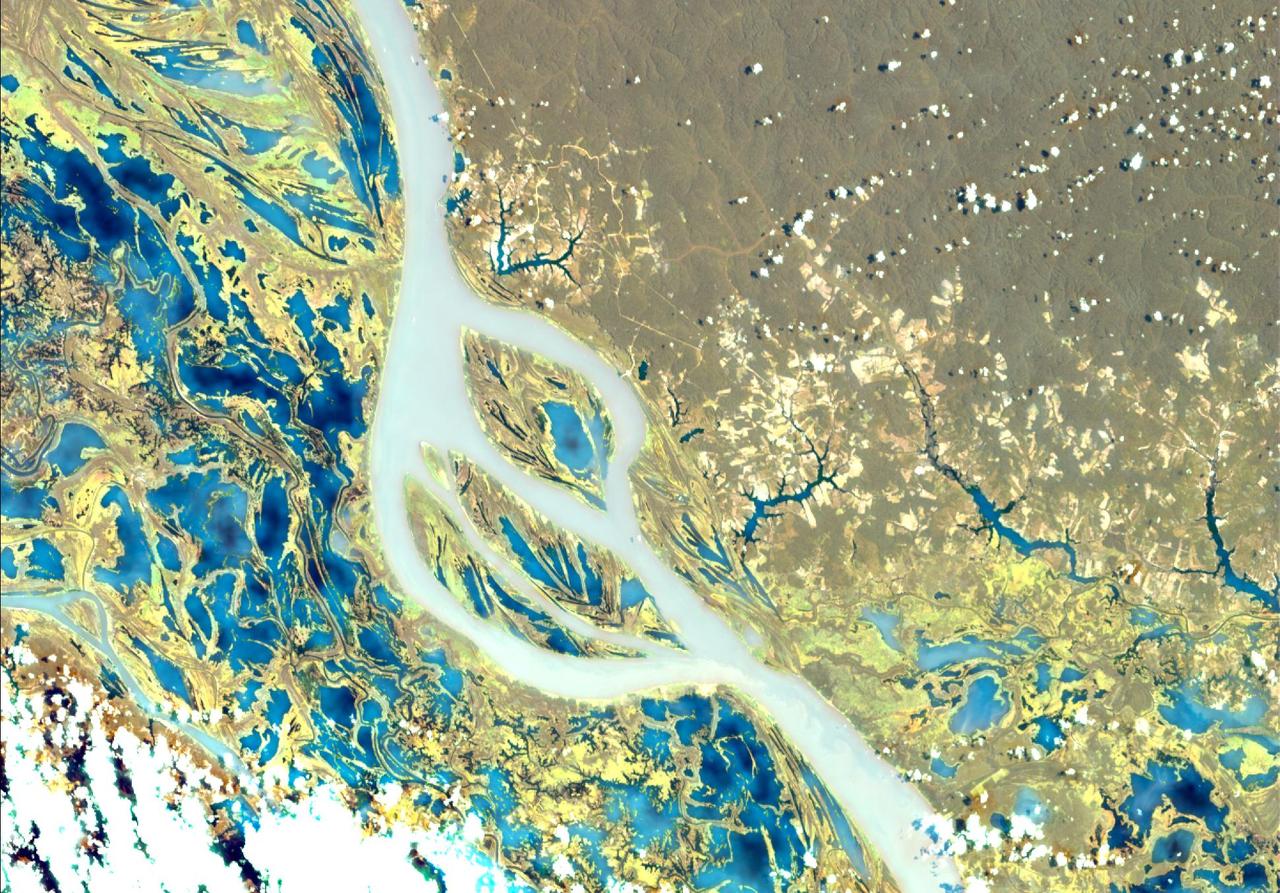

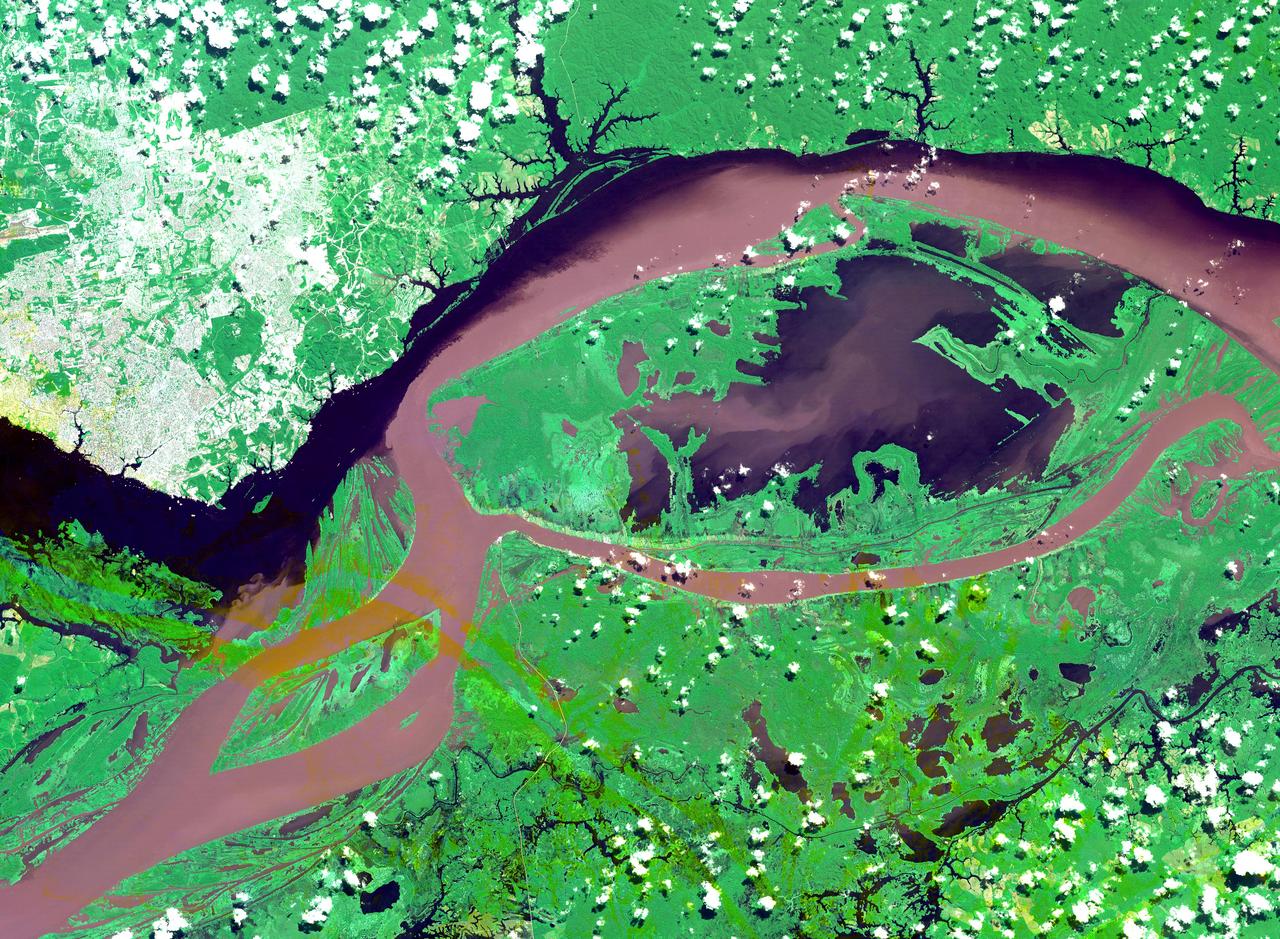

NASA's Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation (EMIT) collected this hyperspectral image of the Amazon River in the northern Brazilian state of Pará on June 30, 2024. The tan and yellow colors represent vegetated land, while the blue and turquoise hues signify water. Clouds are white. This image is part of a new dataset providing new information on global ecosystem biodiversity. EMIT, installed on the International Space Station in 2022, was originally tasked with mapping minerals over Earth's desert regions to help determine the cooling and heating effects that dust can have on regional and global climate. Since early 2024 the instrument has been on an extended mission in which its data is being used in research on a diverse range of topics including agricultural practices, snow hydrology, wildflower blooming, phytoplankton and carbon dynamics in inland waters, ecosystem biodiversity, and functional traits of forests. Imaging spectrometers like EMIT detect the light reflected from Earth and then separate visible and infrared light into hundreds of wavelength bands. Scientists use patterns of reflection and absorption at different wavelengths to determine the composition of whatever the instrument is observing. EMIT is laying the groundwork for NASA's future Surface Biology and Geology-Visible Shortwave Infrared satellite mission. SBG-VSWIR will cover Earth's land and coasts more frequently than EMIT, with finer spatial resolution. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26417

Flowing over 6450 kilometers eastward across Brazil, the Amazon River originates in the Peruvian Andes as tiny mountain streams that eventually combine to form one of the world mightiest rivers as shown in this image from NASA Terra satellite.

The junctions of the Amazon and the Rio Negro Rivers at Manaus, Brazil. The Rio Negro flows 2300 km from Columbia, and is the dark current forming the north side of the river. It gets its color from the high tannin content in the water. The Amazon is sediment laden, appearing brown in this simulated natural color image. Manaus is the capital of Amazonas state, and has a population in excess of one million. The ASTER image covers an area of 60 x 45 km. This image was acquired on July 16, 2000 by the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) on NASA's Terra satellite. With its 14 spectral bands from the visible to the thermal infrared wavelength region, and its high spatial resolution of 15 to 90 meters (about 50 to 300 feet), ASTER will image Earth for the next 6 years to map and monitor the changing surface of our planet. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA03851

Close to the city of Manaus, Brazil the Rio Solimoes and the Rio Negro converge to form the Amazon River. This image from NASA Terra satellite was acquired on July 23, 2000 during Terra orbit 3178.

A paper led by researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory estimates the total volume of water in Earth's rivers – called river storage – on average between 1980 and 2009, and maps out the results for the planet's major hydrological regions. This graphic, adapted from data gathered for the paper, indicates the amount of storage by hydrologic regions that contain one or more river basins, with shades of blue deepening as the amount of storage increases. The paper, published in Nature Geoscience in April 2024, calculated Earth's river storage at about 539 cubic miles (2,246 cubic kilometers), and found that the Amazon River basin, shown in dark blue in South America, was the region with the most storage, with 204 cubic miles (850 cubic kilometers), or about 38% of the global total. The study also estimated the flow of water through more than 3 million segments of river around the world and identified several locations marked by intense human water use, including parts of the Colorado River basin in the United States, portions of the Amazon basin in South America, the Orange River basin in southern Africa, and the Murray-Darling basin in southeastern Australia. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26119

ISS017-E-013856 (19 Aug. 2008) --- Amazon River, Brazil is featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 17 crewmember on the International Space Station. This image shows the huge sunglint zone, common to oblique views from space, of the setting sun shining off the Amazon River and numerous lakes on its floodplain. About 150 kilometers of the sinuous Amazon course is shown here, as it appears about 1,000 kilometers from the Atlantic Ocean. The Uatuma River enters on the north side of the Amazon (top). A small side channel of the very large Madeira River enters the view from the left. Tupinambarama Island occupies the swampy wetlands between the Amazon and Madeira rivers. Sunglint images reveal great detail in waterbodies -- in this case the marked difference between the smooth outline of the Amazon and the jagged shoreline of the Uatuma River. The jagged shoreline results from valley sides being eroded in relatively hard rocks. The Uatuma River has since been dammed up by the sediment mass of the Amazon floodplain. Because the Amazon flows in its own soft sediment, its huge water discharge smooths the banks. Another dammed valley (known as a ria) is visible beneath the cirrus cloud of a storm (bottom). Although no smoke plumes from forest fires are visible in the view, two kinds of evidence show that there is smoke in the atmosphere. The coppery color of the sunglint is typically produced by smoke particles and other aerosols scattering yellow and red light. Second, a small patch of cloud (top right) casts a distinct shadow. The shadow, say scientists, is visible because so many particles in the surrounding sunlit parts of the atmosphere reflect light to the camera.

iss056e085377 (July 7, 2018) --- Altocumulus clouds blanket the northeast coast of Brazil where the Amazon River flows into the Atlantic Ocean.

iss056e084566 (July 7, 2018) --- Altocumulus clouds blanket the northeast coast of Brazil where the Amazon River flows into the Atlantic Ocean.

iss055e086505 (May 25, 2018) --- The Amazon River, and its surrounding lakes, cuts through the South American country of Brazil.

iss070e015233 (Oct. 29, 2023) --- A portion of the Amazon River in northwestern Brazil is pictured from the International Space Station as it orbited 260 miles above.

iss064e014990 (Dec. 23, 2020) --- The Amazon River is pictured from the International Space Station as it orbited 260 miles above Brazil in South America.

ISS009-E-15488 (7 July 2004) --- Solimoes-Negro River confluence at Manaus, Amazonia is featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 9 crewmember on the International Space Station (ISS). The largest river on the planet, the Amazon, forms from the confluence of the Solimoes (the upper Amazon River) and the Negro at the Brazilian city of Manaus in central Amazonas. At the river conjunction, the muddy, tan colored waters of the Solimoes meet the “black” water of the Negro River. The unique mixing zone where the waters meet extends downstream through the rainforest for hundreds of kilometers, and is a famous attraction for tourists all over the world. It is the vast quantity of sediment eroded from the Andes Mountains that gives the Solimoes its tan color. By comparison, water in the Negro derives from the low jungles where reduced physical erosion of rock precludes mud entering the river. In place of sediment, organic matter from the forest floor stains the river the color of black tea.

iss067e300317 (Aug. 30, 2022) --- Clouds border the Amazon River as it empties into the Atlantic Ocean in this photograph from the International Space Station taken from 258 miles above Brazil. As the sun rises, the land heats up faster than the river preventing the formulation of small cumulus clouds above the cooler water.

ISS020-E-034693 (25 Aug. 2009) --- Lake Erepecu and Rio Trombetas in Brazil are featured in this sun glint image photographed by an Expedition 20 crew member on the International Space Station. The 38 kilometers long Lake Erepecu runs parallel to the lower Rio (river) Trombetas which snakes along the lower half of this photograph. Waterbodies in the Amazon rainforest are often so dark they can be difficult to distinguish. In this image, however, the lake and river stand out from the uniform green of the forest in great detail as a result of sun glint on the water surface. Sun glint is light reflected off of a surface directly back towards the viewer, in this case a crew member onboard the space station. Soil color beneath the forest is red, as shown by airfield clearings near Porto Trombetas (upper left), a river port on the south side of the Trombetas River. The Trombetas flows into the Amazon River from the north about 800 kilometers from the Amazon mouth. Despite being so far from the sea, seagoing ore ships export most of Brazil?s bauxite from Porto Trombetas. Bauxite is the raw material formed in these tropical soils for the production of aluminum (the Trombetas bauxite mine is outside the upper margin of the image). Central Amazonia has many lakes like Erepecu?relatively straight, large waterbodies located just off the main axis of the large rivers. These lakes, as distinct from smaller floodplain lakes next to the large rivers, were created as rivers cut down during the repeated low global sea levels of the recent geological past (according to scientists, related to the ice ages of the last 1.7 million years). River water filled the valleys to form lakes during intervening periods of high sea level. Many larger rivers like the Trombetas and Amazon carried enough sediment to fill their immediate valleys?rivers flowing in unconsolidated sediment produce sinuous courses like those along the upper part of the image?but not enough to fill tributary valleys further from the axis of flow, so that lakes like Erepecu are formed.

iss070e099548 (Feb. 23, 2024) --- The Amazon River and its tributaries flow through Brazil in this photograph from the International Space Station as it orbited 259 miles above the South American nation.

iss063e077259 (Aug. 21, 2020) --- The International Space Station was orbiting above Brazil when an external high-definition camera pictured the Marine Extractive Reserve of Tracuateua near the mouth of the Amazon River located on the northeast coast of the South American nation.

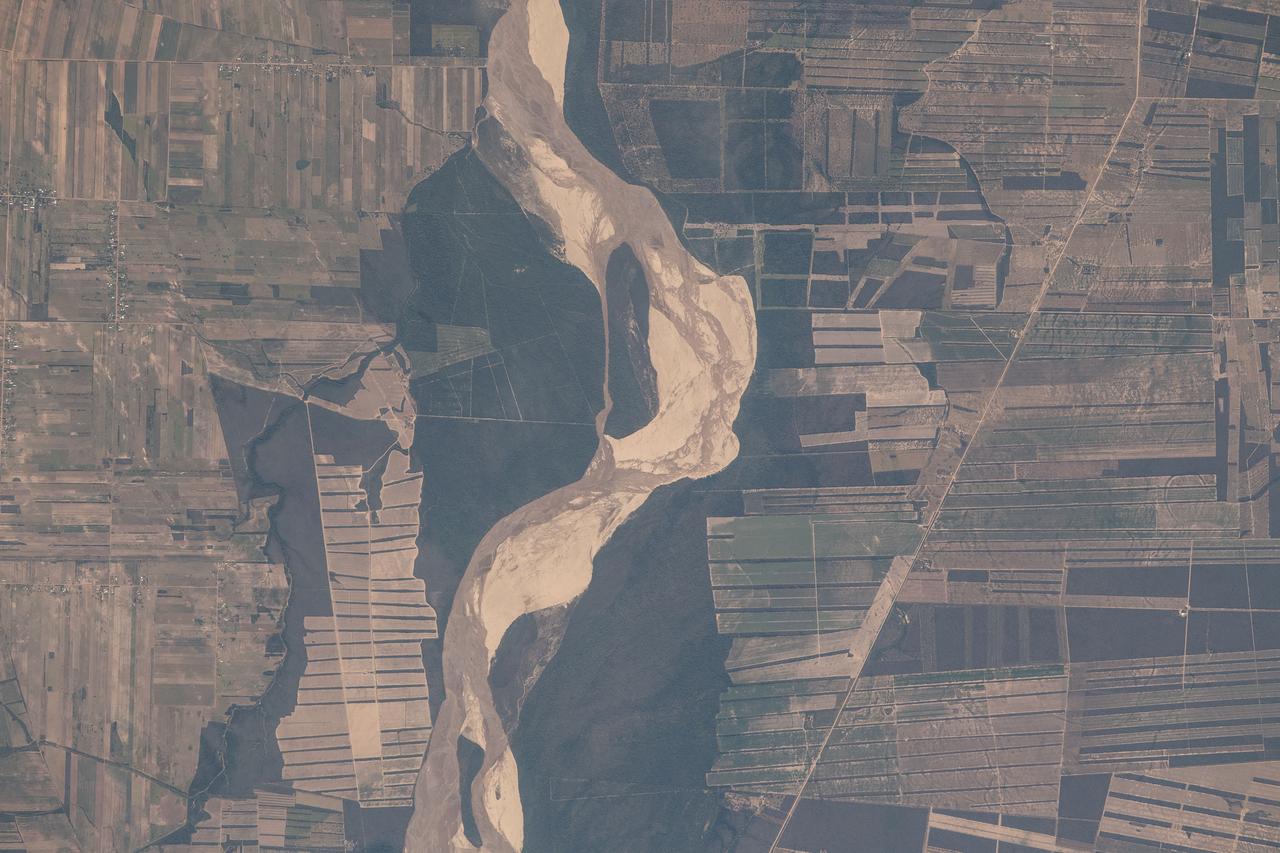

iss056e094532 (July 10, 2018) --- This portion of Bolivia's Rio Grande is about 27 miles east of downtown Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the country's largest city. The river in the Amazon Basin and the sub-tropical climate support navigation, fishing and agriculture.

iss056e094533 (July 10, 2018) --- This portion of Bolivia's Rio Grande is about 27 miles east of downtown Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the country's largest city. The river in the Amazon Basin and the sub-tropical climate support navigation, fishing and agriculture.

S66-38191 (4 June 1966) --- The mouth of the Amazon River on the northern coast of Brazil, looking southwest, as seen from the Gemini-9A spacecraft during its 18th revolution of Earth. The image was taken with a 70mm Hasselblad camera, using Eastman Kodak, Ektachrome MS (S.O. 217) color film. Photo credit: NASA

iss056e094531 (July 10, 2018) --- This portion of Bolivia's Rio Grande in the Amazon Basin is about 27 miles east of downtown Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the country's largest city. The river and the region's sub-tropical climate support navigation, fishing and agriculture.

ISS038e014408 (10 Dec. 2013) --- What at first glance might appear to be a piece of modern art is actually a nadir perspective of part of the Amazon River system in South America, as photographed by one of the Expedition 38 crew members aboard the International Space Station. The astronaut used an 800mm lens to record the image on Dec. 10, 2013.

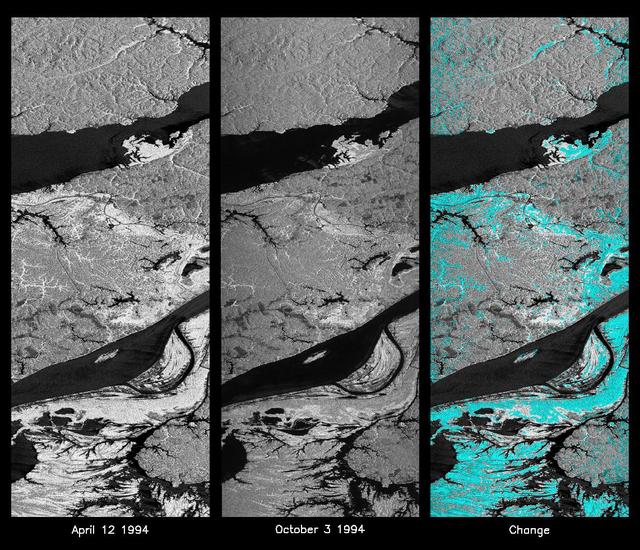

These L-band images of the Manaus region of Brazil were acquired by the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C and X-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SIR-C/X-SAR) aboard the space shuttle Endeavour. The left image was acquired on April 12, 1994, and the middle image was acquired on October 3, 1994. The area shown is approximately 8 kilometers by 40 kilometers (5 miles by 25 miles). The two large rivers in this image, the Rio Negro (top) and the Rio Solimoes (bottom), combine at Manaus (west of the image) to form the Amazon River. The image is centered at about 3 degrees south latitude and 61 degrees west longitude. North is toward the top left of the images. The differences in brightness between the images reflect changes in the scattering of the radar channel. In this case, the changes are indicative of flooding. A flooded forest has a higher backscatter at L-band (horizontally transmitted and received) than an unflooded river. The extent of the flooding is much greater in the April image than in the October image, and corresponds to the annual, 10-meter (33-foot) rise and fall of the Amazon River. A third image at right shows the change in the April and October images and was created by determining which areas had significant decreases in the intensity of radar returns. These areas, which appear blue on the third image at right, show the dramatic decrease in the extent of flooded forest, as the level of the Amazon River falls. The flooded forest is a vital habitat for fish and floating meadows are an important source of atmospheric methane. This demonstrates the capability of SIR-C/X-SAR to study important environmental changes that are impossible to see with optical sensors over regions such as the Amazon, where frequent cloud cover and dense forest canopies obscure monitoring of floods. Field studies by boat, on foot and in low-flying aircraft by the University of California at Santa Barbara, in collaboration with Brazil's Instituto Nacional de Pesguisas Estaciais, during the first and second flights of the SIR-C/X-SAR system have validated the interpretation of the radar images. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01740

STS043-151-159 (2-11 August 1991) --- This photograph looks westward over the high plateau of the southern Peruvian Andes west and north of Lake Titicaca (not in field of view). Lima, Peru lies under the clouds just north of the clear coastal area. Because the high Andes have been uplifted 10,000 to 13,000 feet during the past 20 million years, the rivers which cut down to the Pacific Ocean have gorges almost that deep, such as the Rio Ocona at the bottom of the photograph. The eastern slopes of the Andes are heavily forested, forming the headwaters of the Amazon system. Smoke from burning in the Amazon basin fills river valleys on the right side of the photograph. A Linhof camera was used to take this view.

ISS010-E-05070 (25 October 2004) --- Corrientes, Argentina, and the Parana River are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 10 crewmember on the International Space Station (ISS). Corrientes, Argentina sits on the east bank of the Parana River, South America’s third largest river (after the Negro and Amazon Rivers). From its headwaters in southeastern Brazil, the river flows southwestward around southern Paraguay, and then into Argentina. Corrientes is located just inside Argentina, across the river from the southwestern tip of Paraguay. The bridge over the Parana, built in the 1970s, connects Corrientes to its sister city, Resistencia, (beyond the left edge of image) on the western bank of the river. Sun glint on the river gives it a silvery glow and emphasizes channel islands in the river, side channels, and meander scars on the floodplain opposite the city, and even reveals the pattern of disturbed flow downstream of the bridge pylons. The old part of the city appears as a zone of smaller, more densely clustered city blocks along the river to the north of a major highway, which runs through Corrientes from the General Belgrano Bridge to the northeast (upper right of image). Larger blocks of the younger cityscape, with more green space, surround these core neighborhoods.

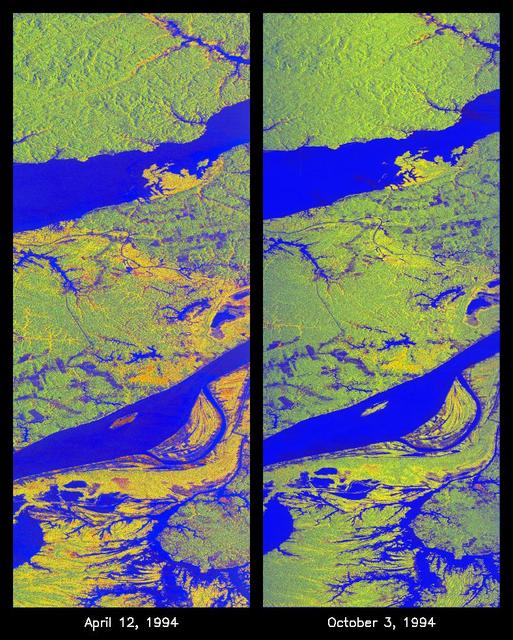

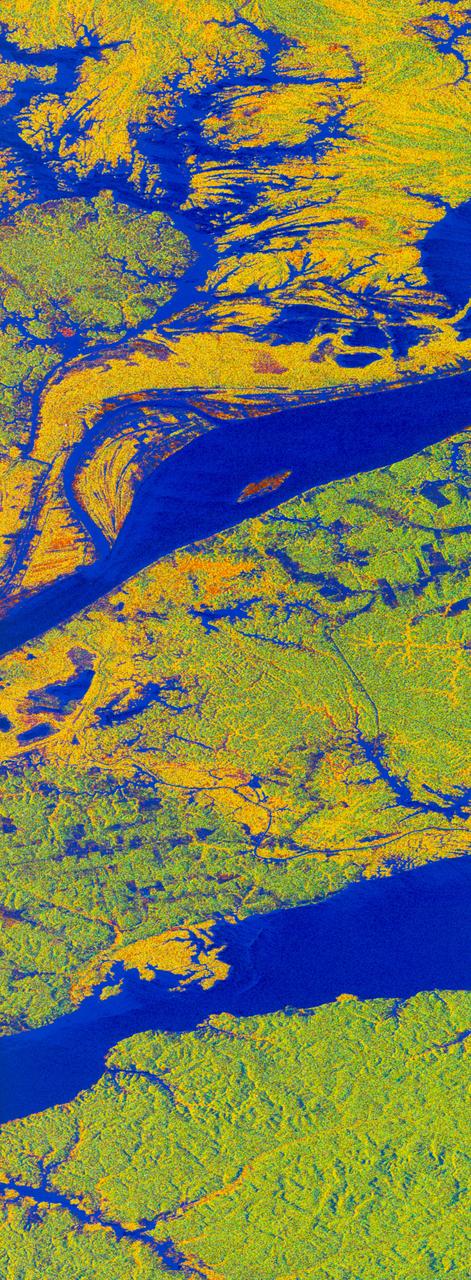

These two false-color images of the Manaus region of Brazil in South America were acquired by the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C and X-band Synthetic Aperture Radar on board the space shuttle Endeavour. The image at left was acquired on April 12, 1994, and the image at right was acquired on October 3, 1994. The area shown is approximately 8 kilometers by 40 kilometers (5 miles by 25 miles). The two large rivers in this image, the Rio Negro (at top) and the Rio Solimoes (at bottom), combine at Manaus (west of the image) to form the Amazon River. The image is centered at about 3 degrees south latitude and 61 degrees west longitude. North is toward the top left of the images. The false colors were created by displaying three L-band polarization channels: red areas correspond to high backscatter, horizontally transmitted and received, while green areas correspond to high backscatter, horizontally transmitted and vertically received. Blue areas show low returns at vertical transmit/receive polarization; hence the bright blue colors of the smooth river surfaces can be seen. Using this color scheme, green areas in the image are heavily forested, while blue areas are either cleared forest or open water. The yellow and red areas are flooded forest or floating meadows. The extent of the flooding is much greater in the April image than in the October image and appears to follow the 10-meter (33-foot) annual rise and fall of the Amazon River. The flooded forest is a vital habitat for fish, and floating meadows are an important source of atmospheric methane. These images demonstrate the capability of SIR-C/X-SAR to study important environmental changes that are impossible to see with optical sensors over regions such as the Amazon, where frequent cloud cover and dense forest canopies block monitoring of flooding. Field studies by boat, on foot and in low-flying aircraft by the University of California at Santa Barbara, in collaboration with Brazil's Instituto Nacional de Pesguisas Estaciais, during the first and second flights of the SIR-C/X-SAR system have validated the interpretation of the radar images. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01735

This view of deforestation in Rondonia, far western Brazil, (10.0S, 63.0W) is part of an agricultural resettlement project which ultimately covers an area about 80% the size of France. The patterns of deforestation in this part of the Amazon River Basin are usually aligned adjacent to highways, secondary roads, and streams for ease of access and transportation. Compare this view with the earlier 51G-37-062 for a comparison of deforestation in the region.

STS076-708-031 (22 - 31 March 1996) --- Clouds over Brazil form the backdrop for this 70mm image showing the Spektr Module and other components of Russia's Mir Space Station. The photograph was taken after Space Shuttle Atlantis docked with the Mir Space Station on March 23, 1996. The delta of the giant Amazon River is at frame center.

iss064e006446 (Nov. 27, 2020) --- This picture was taken from a window on the SpaceX Crew Dragon vehicle as the International Space Station orbited above the Atlantic Ocean just off the coast of Brazil near the mouth of the Amazon River. Two other spacecraft, including the Cygnus cargo craft with its two prominent cymbal-shaped solar arrays, and behind it, Russia's Soyuz MS-17 crew ship with its rectangular solar arrays, are also pictured docked to the orbiting lab.

iss059e104296 (June 17, 2019) --- A set of three CubeSats are ejected from the Japanese Small Satellite Orbital Deployer attached to a robotic arm outside of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's Kibo laboratory module. The tiny satellites from Nepal, Sri Lanka and Japan were released into Earth orbit for technology demonstrations. The International Space Station was orbiting 256 miles above the Amazon River in Brazil when an Expedition 59 crewmember took this photograph.

ISS037-E-001606 (18 Sept. 2013) --- What at first glance might appear to be a piece of abstract art is actually a photo made using a 180mm lens from approximately 226 nautical miles above Earth featuring the very wide Amazon River floodplain at Santarem, Brazil. One of the Expedition 37 crew members aboard the International Space Station took the photograph on Sept. 18, 2013. Center coordinates of the area pictured are located at approximately 2.1 degrees south latitude and 54.9 degrees west longitude.

ISS020-E-047807 (6 Oct. 2009) --- Thunderstorms on the Brazilian horizon are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 20 crew member on the International Space Station. A picturesque line of thunderstorms and numerous circular cloud patterns filled the view as the station crew members looked out at the limb and atmosphere (blue line on the horizon) of Earth. This region displayed in the photograph (top) includes an unstable, active atmosphere forming a large area of cumulonimbus clouds in various stages of development. The crew was looking west southwestward from the Amazon Basin, along the Rio Madeira, toward Bolivia when the image was taken. The distinctive circular patterns of the clouds in this view are likely caused by the aging of thunderstorms. Such ring structures often form during the final stages of a storm?s development as their centers collapse. Sunglint is visible on the waters of the Rio Madeira and Lago Acara in the Amazon Basin. Widespread haze over the basin gives the reflected light an orange hue. The Rio Madeira flows northward and joins the Amazon River on its path to the Atlantic Ocean. Scientists believe that a large smoke plume near the bottom center of the image may explain one source of the haze.

STS054-86-001 (13-19 Jan. 1993) --- This 70mm view shows a spectacular multiple spit on the coast of Brazil, about halfway between Rio de Janeiro and the mouth of the Amazon River. Over a few thousand years, according to NASA scientists, shifting regimes of wave and current patterns piled up sand onto a series of beach ridges and tidal lagoons. The present swirls of sediment along the coast evidently were derived from beach erosion, because streams flowing into the Atlantic contain dark, clear water. Offshore, reefs and sandbanks parallel the coast. The largest is the Recife da Pedra Grande (Big Rocks Reef).

ISS007-E-15177 (21 September 2003) --- This view, photographed by an Expedition 7 crewmember onboard the International Space Station (ISS), features a small part of the coastal dune field which is now protected as the Lencois Maranhenses National Park, on Brazil’s north coast, about 700 kilometers east of the Amazon River mouth. Persistent winds blow off the equatorial Atlantic Ocean onto Brazil from the east, driving white sand inland from 100 kilometers stretch of coast, to form a large field of dunes. The dark areas between the white dunes are fresh water ponds that draw fishermen to this newly established park.

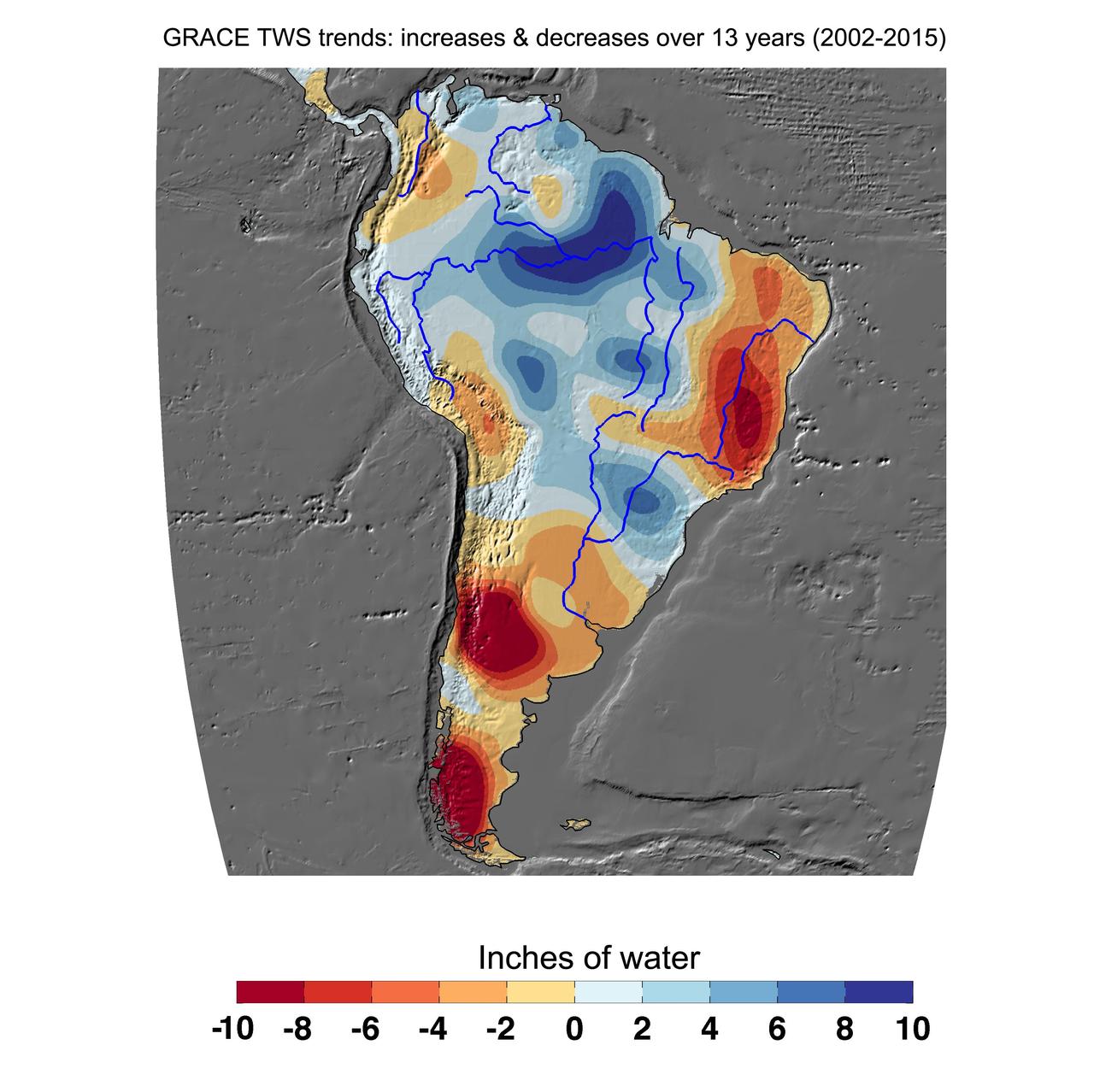

Cumulative total freshwater losses in South America from 2002 to 2015 (in inches) observed by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission. Total water refers to all of the snow, surface water, soil water and groundwater combined. Much of the Amazon River basin experienced increasing total water storage during this time period, though the persistent Brazilian drought is apparent to the east. Groundwater depletion strongly impacted total water losses in the Guarani aquifer of Argentina and neighboring countries. Significant water losses due to the melting ice fields of Patagonia are also observed. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20205

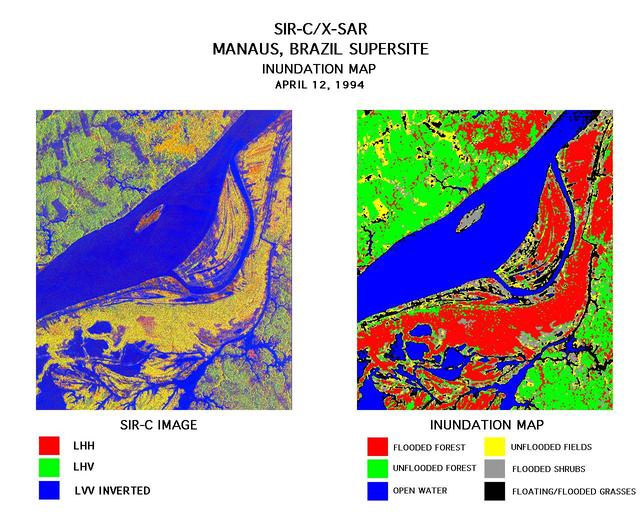

These two images were created using data from the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C/X-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SIR-C/X-SAR). On the left is a false-color image of Manaus, Brazil acquired April 12, 1994, onboard space shuttle Endeavour. In the center of this image is the Solimoes River just west of Manaus before it combines with the Rio Negro to form the Amazon River. The scene is around 8 by 8 kilometers (5 by 5 miles) with north toward the top. The radar image was produced in L-band where red areas correspond to high backscatter at HH polarization, while green areas exhibit high backscatter at HV polarization. Blue areas show low backscatter at VV polarization. The image on the right is a classification map showing the extent of flooding beneath the forest canopy. The classification map was developed by SIR-C/X-SAR science team members at the University of California,Santa Barbara. The map uses the L-HH, L-HV, and L-VV images to classify the radar image into six categories: Red flooded forest Green unflooded tropical rain forest Blue open water, Amazon river Yellow unflooded fields, some floating grasses Gray flooded shrubs Black floating and flooded grasses Data like these help scientists evaluate flood damage on a global scale. Floods are highly episodic and much of the area inundated is often tree-covered. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01712

ISS013-E-74843 (2 Sept. 2006) --- Rio Negro in Amazonia, Brazil is featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 13 crewmember onboard the International Space Station. The wide, multi-island zone in the Rio Negro (Black River) shown in this image is one of two, long "archipelagoes" upstream of the city of Manaus (not shown) in central Amazonia. Ninety kilometers of the total 120 kilometers length of this archipelago appear in this view. On the day the photo was taken, air temperatures over the cooler river water of the archipelago were just low enough to prevent cloud formation. Over the neighboring rainforest, temperatures were warm enough to produce small convection-related clouds, known to pilots as "popcorn" cumulus. Several zones of deforestation, represented by lighter green zones along the river banks, are also visible. Two different types of river appear in this image. Flowing east-southeast (left to right) is the multi-island, Rio Negro, 20 kilometers wide near the right of the view. Two other "black" rivers, Rio Caures and Rio Jufari, join Rio Negro downstream. The second river type is the Rio Branco (White River; right) which is the largest tributary of the Rio Negro. The difference in water color is controlled by the source regions: black-water rivers derive entirely from soils of lowland forests. Water in these rivers has the color of weak tea, which appears black in images from space. By contrast, white-water rivers like the Branco carry a load of sand and mud particles, mudding the waters. The reason for the tan color is that white-water rivers rise in mountainous country where headwater streams erode exposed rock. The Amazon itself rises in the Andes Mts., where very high erosion occurs, and it is thus the most famous white river in Amazonia. This image was taken in September, near low-water stage. Pictures taken at other times show the channels much wider during high-water season (May--July) when water levels rise several meters. It was discovered recently, from high resolution GPS measurements at Manaus, that the land surface actually rises vertically a small amount in compensation when this vast mass of water drains away each season. Although small, the vertical displacement--50-70 mm--was unexpectedly large according to the scientists who performed the study.

ISS010-E-13029 (13 January 2005) --- The Perigoso Channel and Amazon River mouth are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 10 crewmember on the International Space Station (ISS). According to NASA scientists studying the Expedition 10 imagery, between 2000 and 2005 the channel on the west side of the island has shifted to the northwest – by eroding ~200 meters of the mainland shoreline and accreting sediment on the west side of the island, broadly maintaining the width of the channel. The North Channel (right) has been significantly widened. This has resulted in the erosional removal of almost 1 kilometer of the north end of the island, as well narrowing of a smaller island downstream (lower right). A more important but subtler visual effect has been the accumulation of sediment on the upstream (left) two-thirds of the island, accompanied by the establishment of permanent vegetation (dark green).

STS059-S-068 (13 April 1994) --- This false-color L-Band image of the Manaus region of Brazil was acquired by the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C and X-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SIR-C/X-SAR) aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour on orbit 46 of the mission. The area shown is approximately 8 kilometers by 40 kilometers (5 by 25 miles). At the top of the image are the Solimoes and Rio Negro Rivers just before they combine at Manaus to form the Amazon River. The image is centered at about 3 degrees south latitude, and 61 degrees west longitude. The false colors are created by displaying three L-Band polarization channels; red areas correspond to high backscatter at HH polarization, while green areas exhibit high backscatter at HV polarization. Blue areas show low returns at VV polarization; hence the bright blue colors of the smooth river surfaces. Using this color scheme, green areas in the image are heavily forested, while blue areas are either cleared forest or open water. The yellow and red areas are flooded forest. Between Rio Solimoes and Rio Negro a road can be seen running from some cleared areas (visible as blue rectangles north of Rio Solimoes) north towards a tributary of Rio Negro. SIR-C/X-SAR is part of NASA's Mission to Planet Earth (MTPE). SIR-C/X-SAR radars illuminate Earth with microwaves allowing detailed observations at any time, regardless of weather or sunlight conditions. SIR-C/X-SAR uses three microwave wavelengths: L-Band (24 cm), C-Band (6 cm), and X-Band (3 cm). The multi-frequency data will be used by the international scientific community to better understand the global environment and how it is changing. The SIR-C/X-SAR data, complemented by aircraft and ground studies, will give scientists clearer insights into those environmental changes which are caused by nature and those changes which are induced by human activity. SIR-C was developed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). X-SAR was developed by the Dornire and Alenia Spazio Companies for the German Space Agency, Deutsche Agentur fuer Raumfahrtangelegenheiten (DARA), and the Italian Space Agency, Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (ASI). JPL Photo ID: P-43895

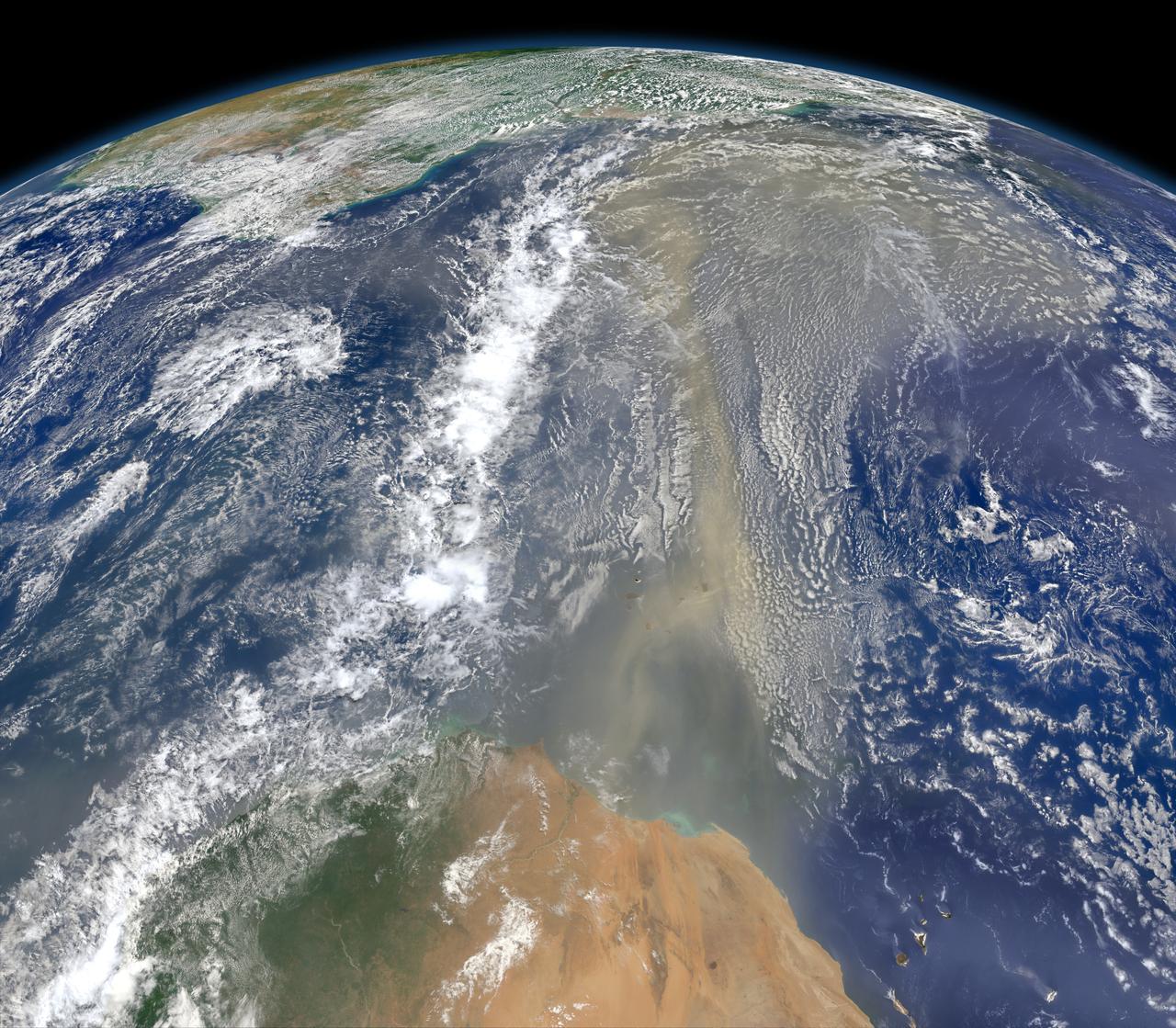

A piece of Africa—actually lots of them—began to arrive in the Americas in June 2014. On June 23, a lengthy river of dust from western Africa began to push across the Atlantic Ocean on easterly winds. A week later, the influx of dust was affecting air quality as far away as the southeastern United States. This composite image, made with data from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on Suomi NPP, shows dust heading west toward South America and the Gulf of Mexico on June 25, 2014. The dust flowed roughly parallel to a line of clouds in the intertropical convergence zone, an area near the equator where the trade winds come together and rain and clouds are common. In imagery captured by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), the dust appeared to be streaming from Mauritania, Senegal, and Western Sahara, though some of it may have originated in countries farther to the east. Saharan dust has a range of impacts on ecosystems downwind. Each year, dust events like the one pictured here deliver about 40 million tons of dust from the Sahara to the Amazon River Basin. The minerals in the dust replenish nutrients in rainforest soils, which are continually depleted by drenching, tropical rains. Research focused on peat soils in the Everglades show that African dust has been arriving regularly in South Florida for thousands of years as well. In some instances, the impacts are harmful. Infusion of Saharan dust, for instance, can have a negative impact on air quality in the Americas. And scientists have linked African dust to outbreaks of certain types of toxic algal blooms in the Gulf of Mexico and southern Florida. Read more: <a href="http://1.usa.gov/1snkzmS" rel="nofollow">1.usa.gov/1snkzmS</a> NASA images by Norman Kuring, NASA’s Ocean Color web. Caption by Adam Voiland. Credit: <b><a href="http://www.earthobservatory.nasa.gov/" rel="nofollow"> NASA Earth Observatory</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagram.com/nasagoddard?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>