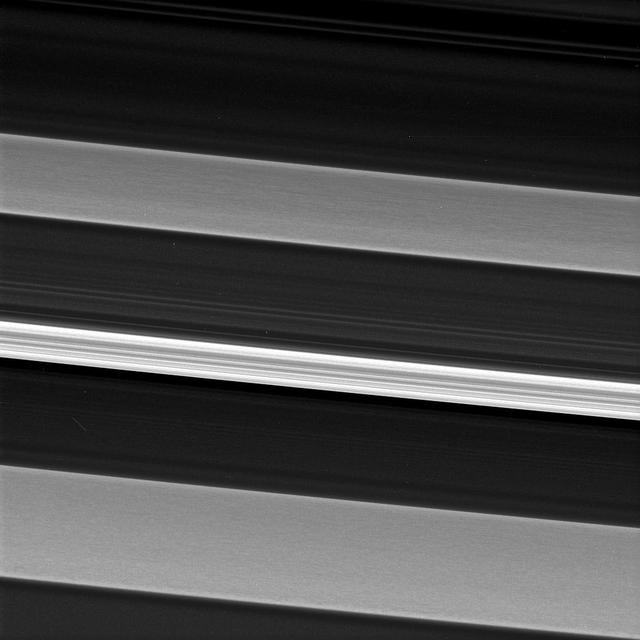

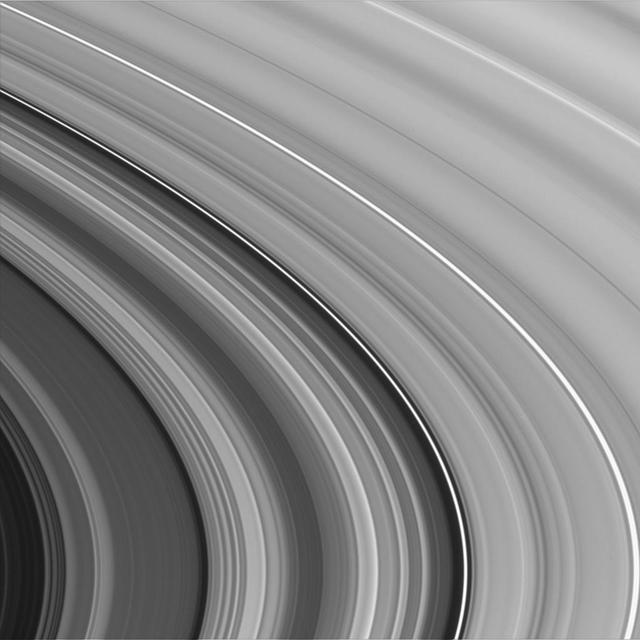

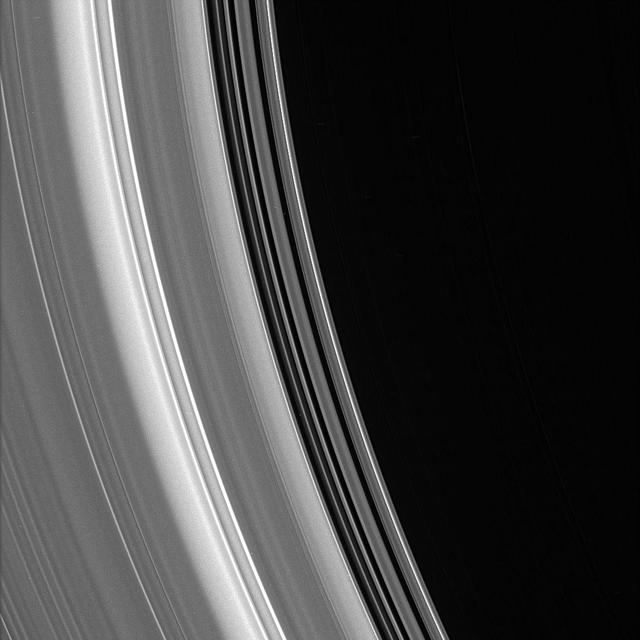

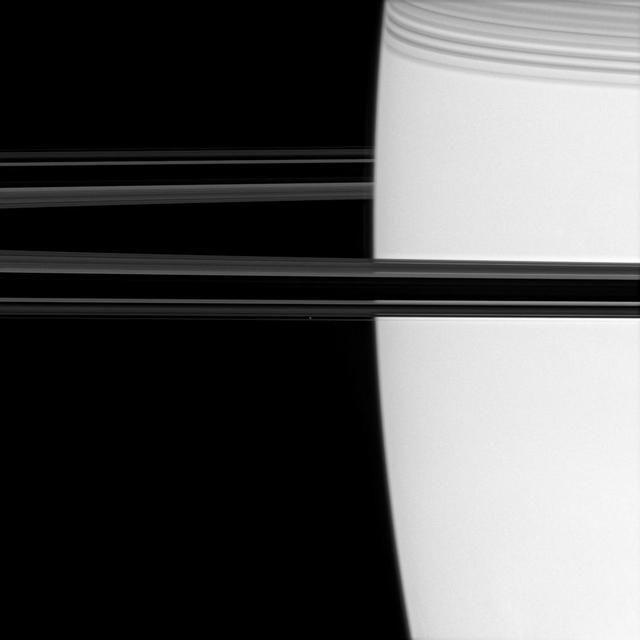

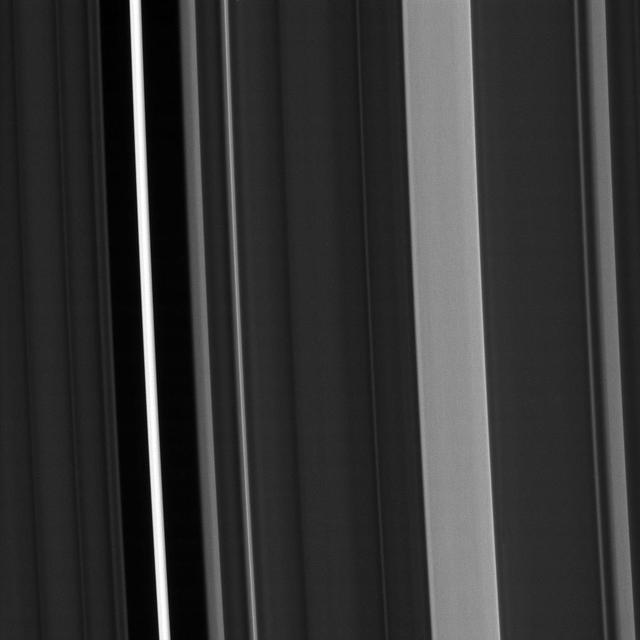

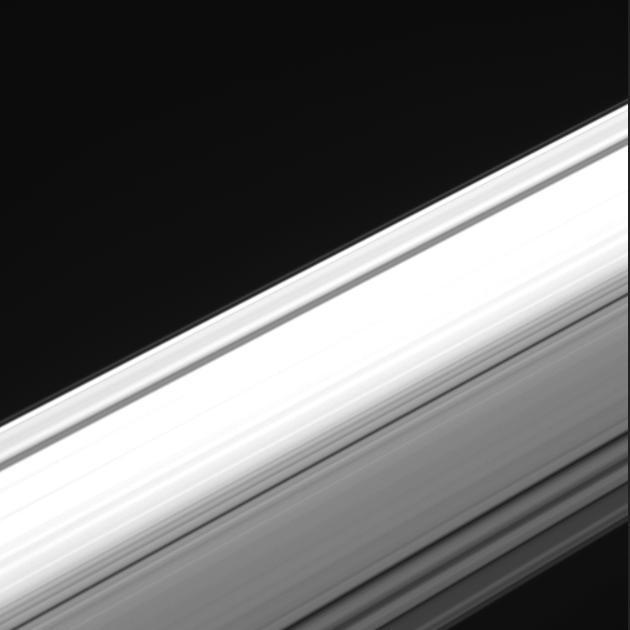

Saturn's C ring is home to a surprisingly rich array of structures and textures. Much of the structure seen in the outer portions of Saturn's rings is the result of gravitational perturbations on ring particles by moons of Saturn. Such interactions are called resonances. However, scientists are not clear as to the origin of the structures seen in this image which has captured an inner ring region sparsely populated with particles, making interactions between ring particles rare, and with few satellite resonances. In this image, a bright and narrow ringlet located toward the outer edge of the C ring is flanked by two broader features called plateaus, each about 100 miles (160 kilometers) wide. Plateaus are unique to the C ring. Cassini data indicates that the plateaus do not necessarily contain more ring material than the C ring at large, but the ring particles in the plateaus may be smaller, enhancing their brightness. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 53 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in green light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Aug. 14, 2017. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 117,000 miles (189,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 74 degrees. Image scale is 3,000 feet (1 kilometer) per pixel. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21356

Saturn Outer C Ring

Many Faces of the C Ring

Saturn B and C-rings

C-Ring Variations

Intricate C Ring Details

Framing the C Ring

Seeing the C Ring

Outer C Ring Detail

Saturn C and B Rings From the Inside Out

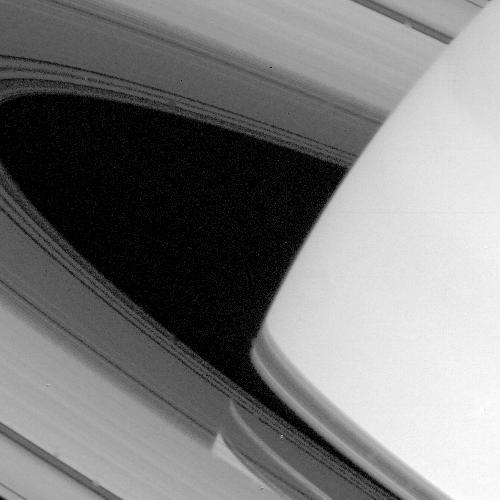

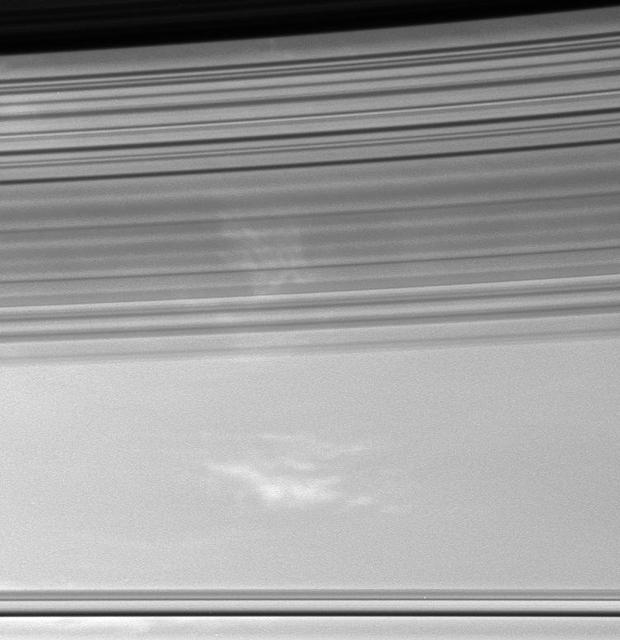

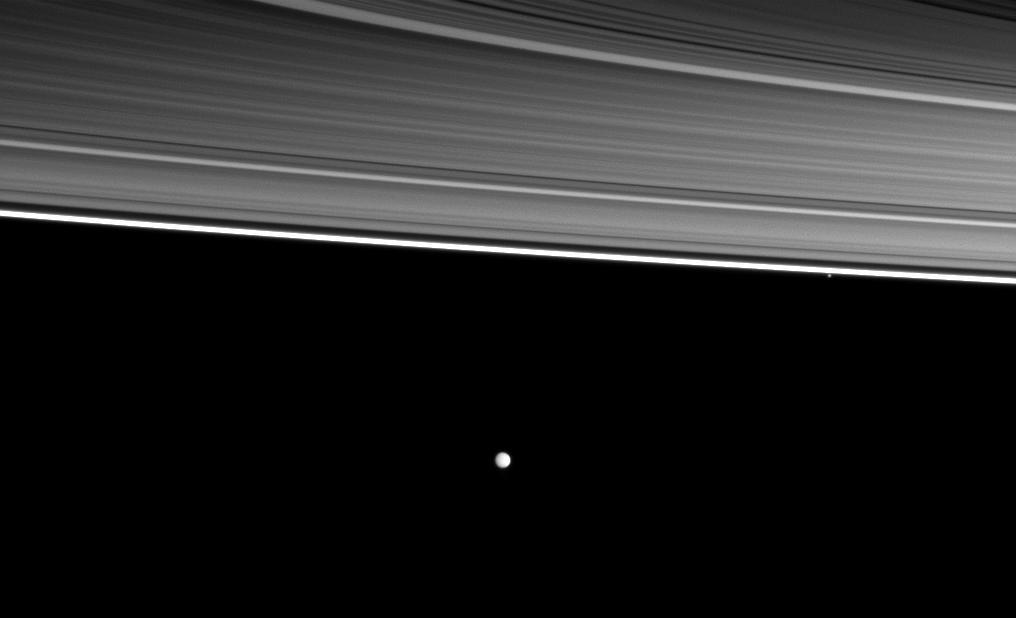

The shadow of the moon Tethys cuts across the C ring in this image taken as Saturn approaches its August 2009 equinox.

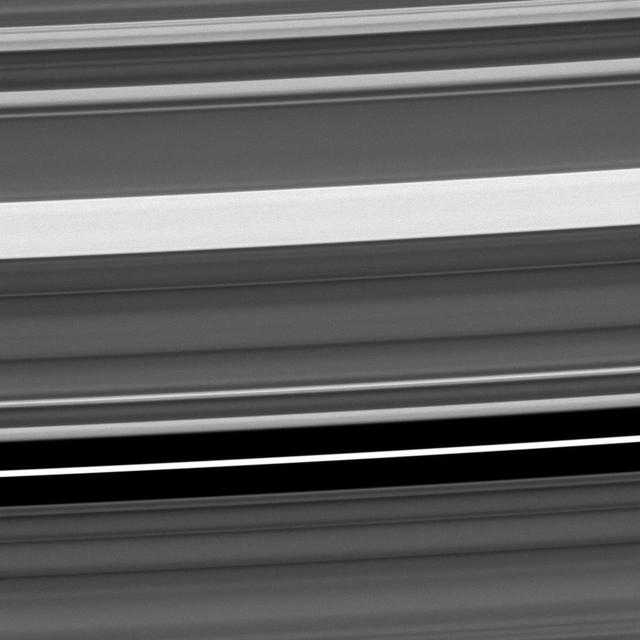

Bright ringlets and dark gaps at the inner edge of the C ring sweep across this scene. The C ring contains numerous plateaus -- broad ring regions that are bright and surrounded by fainter material

![Recent images of features in Saturn's C ring called "plateaus" have deepened the mystery surrounding them. It turns out that these bright bands have a streaky texture that is very different from the textures of the regions around them. The central feature in this image, called Plateau P5, is found approximately 52,700 miles (84,800 kilometers) from Saturn's center. It is situated amid some undulating structure that characterizes this region of the C ring. None of this structure is well understood. This image reveals that the plateau itself is shot through with elongated streaks. This provides information about ways in which the ring particles are interacting with each other, though scientists have not yet worked out what it all means. A more clumpy texture, similar to the "straw" seen previously in the A ring. Plateau regions are brighter than their surroundings, and have sharp edges. Recent evidence indicates that the plateaus do not actually contain more material than their surroundings, nor are they different in their chemical composition, which would mean that their greater brightness is likely due to smaller particle sizes. (If a given amount of mass is broken into smaller particles, it will spread out more [i.e., it will have more surface area].) These texture differences may give a clue about processes at the particle level that create the larger structures that Cassini has observed from greater distance throughout its mission at Saturn. These images were taken with the camera moving in sync with the orbits of individual ring particles. Therefore, any elongated structures are truly there in the rings, and are not an artifact of particles moving during the exposure (i.e., smear). This image was taken on the unilluminated side of the rings, with sunlight filtering through the rings as it would through a translucent bathroom window. Brighter regions in the image indicate more material scattering light toward the camera. This image was taken on May 29, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of about 39,800 miles (64,100 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,460 feet (445 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 137 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21619](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21619/PIA21619~small.jpg)

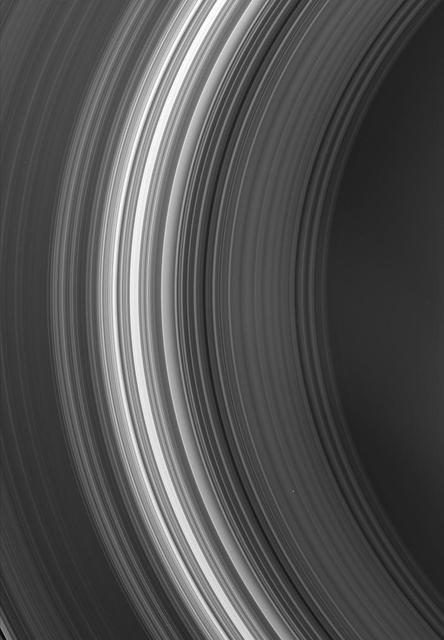

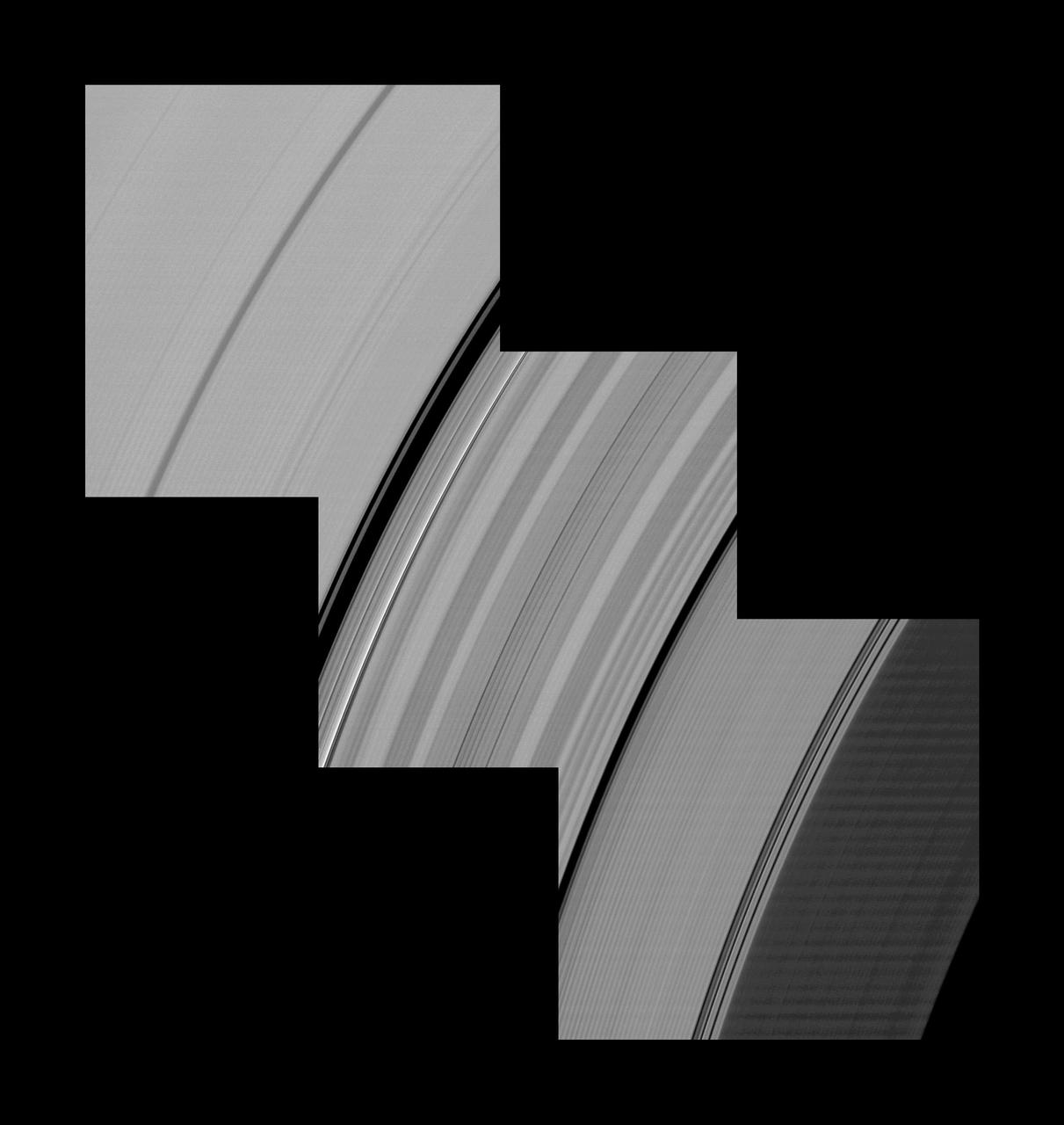

Recent images of features in Saturn's C ring called "plateaus" have deepened the mystery surrounding them. It turns out that these bright bands have a streaky texture that is very different from the textures of the regions around them. The central feature in this image, called Plateau P5, is found approximately 52,700 miles (84,800 kilometers) from Saturn's center. It is situated amid some undulating structure that characterizes this region of the C ring. None of this structure is well understood. This image reveals that the plateau itself is shot through with elongated streaks. This provides information about ways in which the ring particles are interacting with each other, though scientists have not yet worked out what it all means. A more clumpy texture, similar to the "straw" seen previously in the A ring. Plateau regions are brighter than their surroundings, and have sharp edges. Recent evidence indicates that the plateaus do not actually contain more material than their surroundings, nor are they different in their chemical composition, which would mean that their greater brightness is likely due to smaller particle sizes. (If a given amount of mass is broken into smaller particles, it will spread out more [i.e., it will have more surface area].) These texture differences may give a clue about processes at the particle level that create the larger structures that Cassini has observed from greater distance throughout its mission at Saturn. These images were taken with the camera moving in sync with the orbits of individual ring particles. Therefore, any elongated structures are truly there in the rings, and are not an artifact of particles moving during the exposure (i.e., smear). This image was taken on the unilluminated side of the rings, with sunlight filtering through the rings as it would through a translucent bathroom window. Brighter regions in the image indicate more material scattering light toward the camera. This image was taken on May 29, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of about 39,800 miles (64,100 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,460 feet (445 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 137 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21619

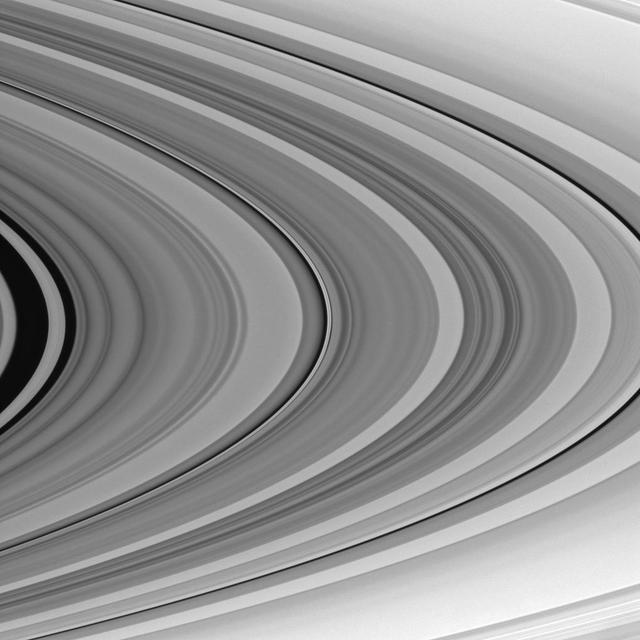

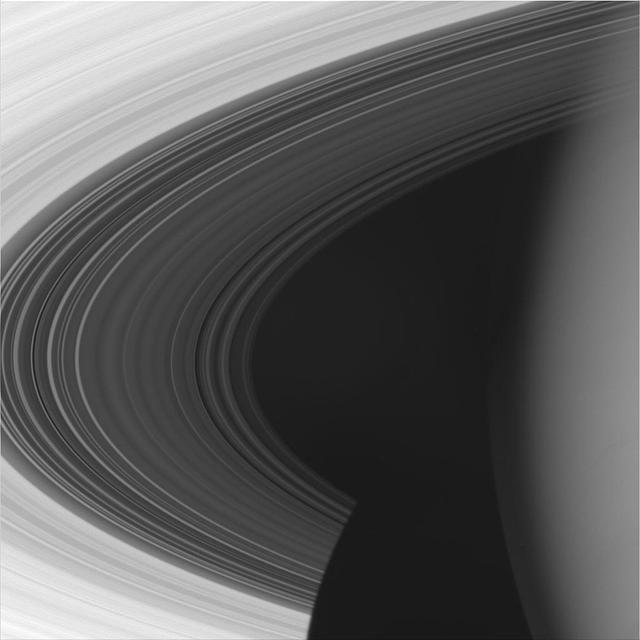

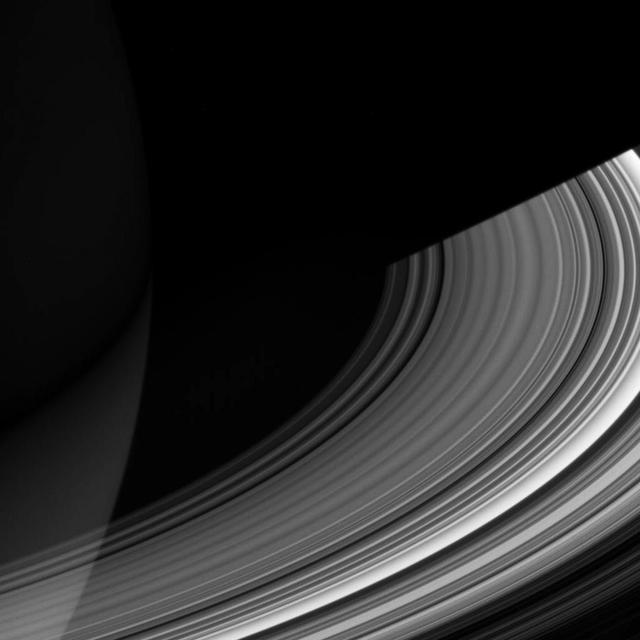

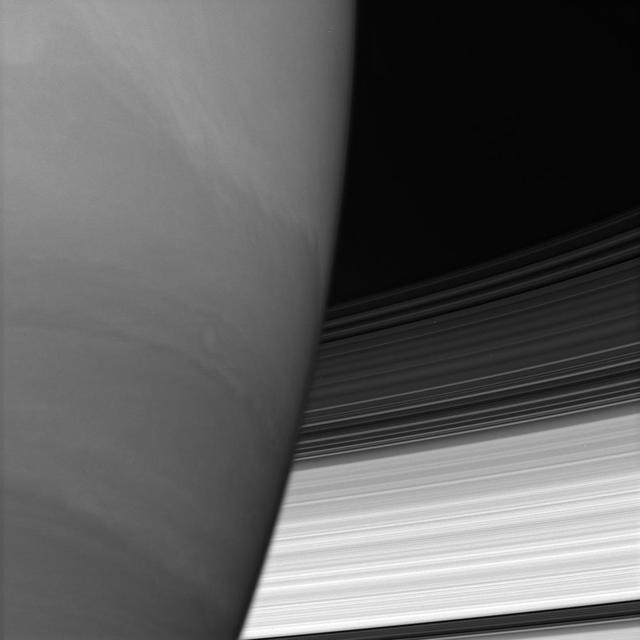

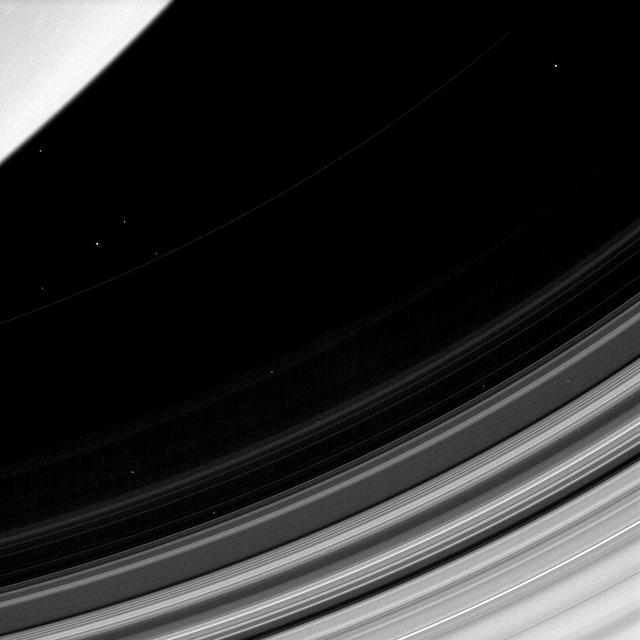

Both luminous and translucent, the C ring sweeps out of the darkness of Saturn's shadow and obscures the planet at lower left. The ring is characterized by broad, isolated bright areas, or "plateaus," surrounded by fainter material. This view looks toward the unlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. North on Saturn is up. The dark, inner B ring is seen at lower right. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Dec. 15, 2006 at a distance of approximately 632,000 kilometers (393,000 miles) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 56 degrees. Image scale is 34 kilometers (21 miles) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA08855

![Recent images of features in Saturn's C ring called "plateaus" have deepened the mystery surrounding them. It turns out that these bright bands have a streaky texture that is very different from the textures of the regions around them. The central feature in this image, called Plateau P1, is found approximately 47,300 miles (76,200 kilometers) from Saturn's center. It is situated amid some undulating structure that characterizes this region of the C ring. None of this structure is well understood. This image reveals three different textures with different kinds of structure. The plateau itself is shot through with elongated streaks, while the brighter parts of the undulating structure have more clumpy texture that is similar to the "straw" seen previously in the A ring, and the dimmer parts of the undulating structure have no apparent texture at all. These textures provide information about different ways in which the ring particles are interacting with each other, though scientists have not yet worked out what it all means. Plateau regions are brighter than their surroundings, and have sharp edges. Recent evidence indicates that the plateaus do not actually contain more material than their surroundings, nor are they different in their chemical composition, which would mean that their greater brightness is likely due to smaller particle sizes. (If a given amount of mass is broken into smaller particles, it will spread out more [i.e., it will have more surface area].) These texture differences may give a clue about processes at the particle level that create the larger structures that Cassini has observed from greater distance throughout its mission at Saturn. These images were taken with the camera moving in sync with the orbits of individual ring particles. Therefore, any elongated structures are truly there in the rings, and are not an artifact of particles moving during the exposure (i.e., smear). This image was taken on June 4, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of (51,830 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,070 feet (325 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 80 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21618](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21618/PIA21618~small.jpg)

Recent images of features in Saturn's C ring called "plateaus" have deepened the mystery surrounding them. It turns out that these bright bands have a streaky texture that is very different from the textures of the regions around them. The central feature in this image, called Plateau P1, is found approximately 47,300 miles (76,200 kilometers) from Saturn's center. It is situated amid some undulating structure that characterizes this region of the C ring. None of this structure is well understood. This image reveals three different textures with different kinds of structure. The plateau itself is shot through with elongated streaks, while the brighter parts of the undulating structure have more clumpy texture that is similar to the "straw" seen previously in the A ring, and the dimmer parts of the undulating structure have no apparent texture at all. These textures provide information about different ways in which the ring particles are interacting with each other, though scientists have not yet worked out what it all means. Plateau regions are brighter than their surroundings, and have sharp edges. Recent evidence indicates that the plateaus do not actually contain more material than their surroundings, nor are they different in their chemical composition, which would mean that their greater brightness is likely due to smaller particle sizes. (If a given amount of mass is broken into smaller particles, it will spread out more [i.e., it will have more surface area].) These texture differences may give a clue about processes at the particle level that create the larger structures that Cassini has observed from greater distance throughout its mission at Saturn. These images were taken with the camera moving in sync with the orbits of individual ring particles. Therefore, any elongated structures are truly there in the rings, and are not an artifact of particles moving during the exposure (i.e., smear). This image was taken on June 4, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of (51,830 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,070 feet (325 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 80 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21618

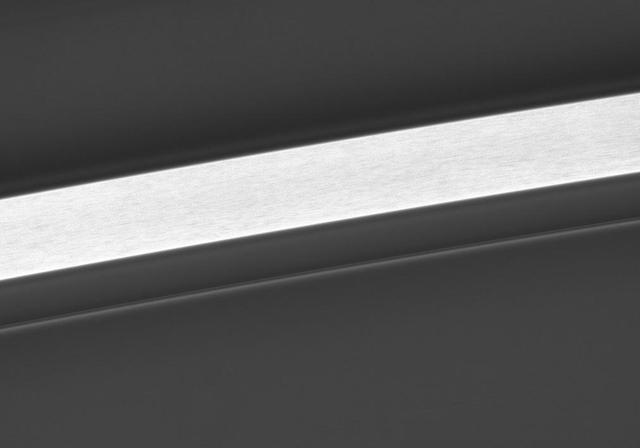

Not all of Saturn's rings are created equal: here the C and D rings appear side-by-side, but the C ring, which occupies the bottom half of this image, clearly outshines its neighbor. The D ring appears fainter than the C ring because it is comprised of less material. However, even rings as thin as the D ring can pose hazards to spacecraft. Given the high speeds at which Cassini travels, impacts with particles just fractions of a millimeter in size have the potential to damage key spacecraft components and instruments. Nonetheless, near the end of Cassini's mission, navigators plan to thread the spacecraft's orbit through the narrow region between the D ring and the top of Saturn's atmosphere. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 12 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 11, 2015. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 372,000 miles (599,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 133 degrees. Image scale is 2.2 miles (3.6 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18313

Both the limb of Saturn and the shadow of its ring system are seen through the transparent C-ring in this striking picture taken by NASA Voyager 1 on Nov. 9, 1980. Gaps and regions of high transparency are seen throughout the C-ring, especially in the a

Saturn B and C rings disappear behind the immense planet. Where they meet the limb, the rings appear to bend slightly owing to upper-atmospheric refraction

The soft, sweeping shadows of Saturn C ring cover bright patches of clouds in the planet atmosphere. The shadow-throwing rings stretch across the view at bottom. The dark inner edge of the B ring is visible at top

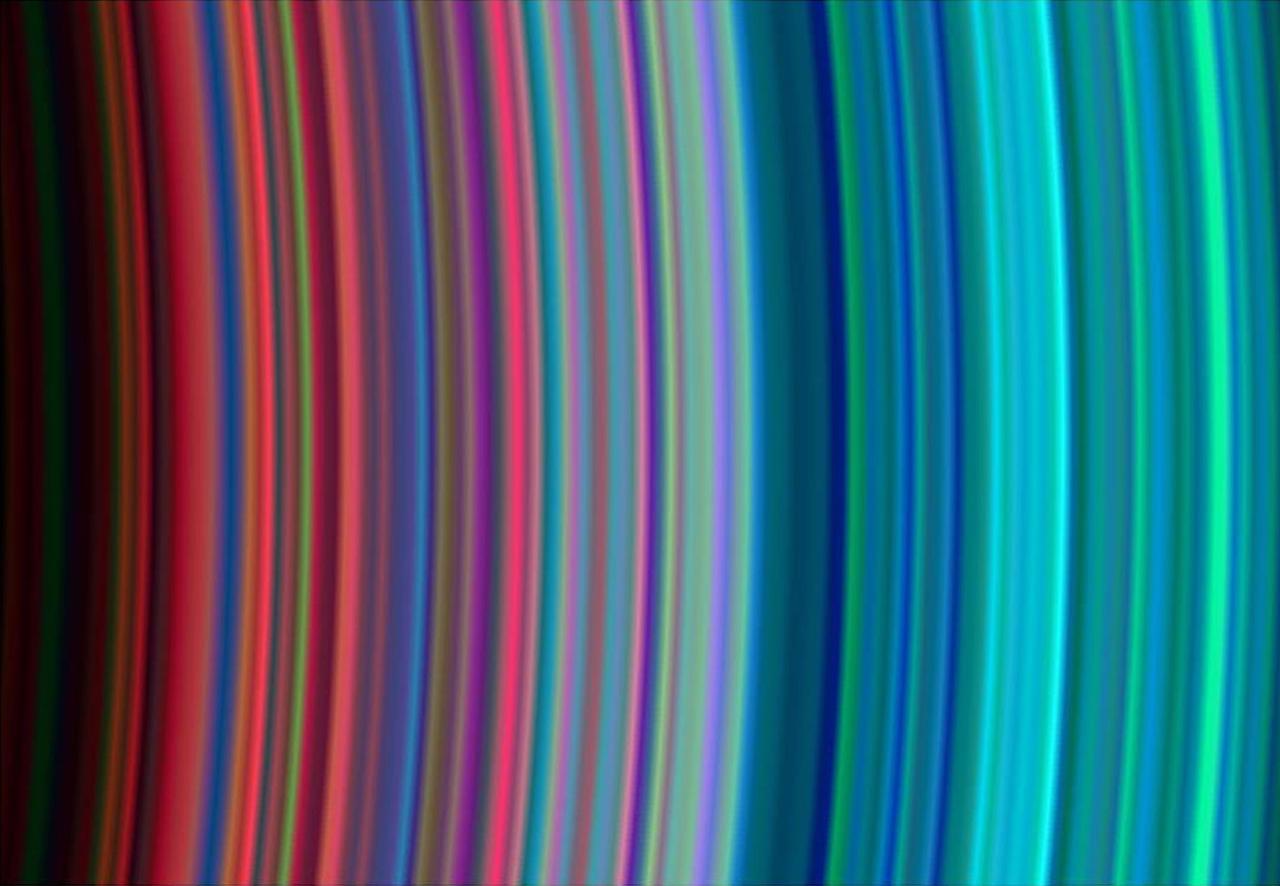

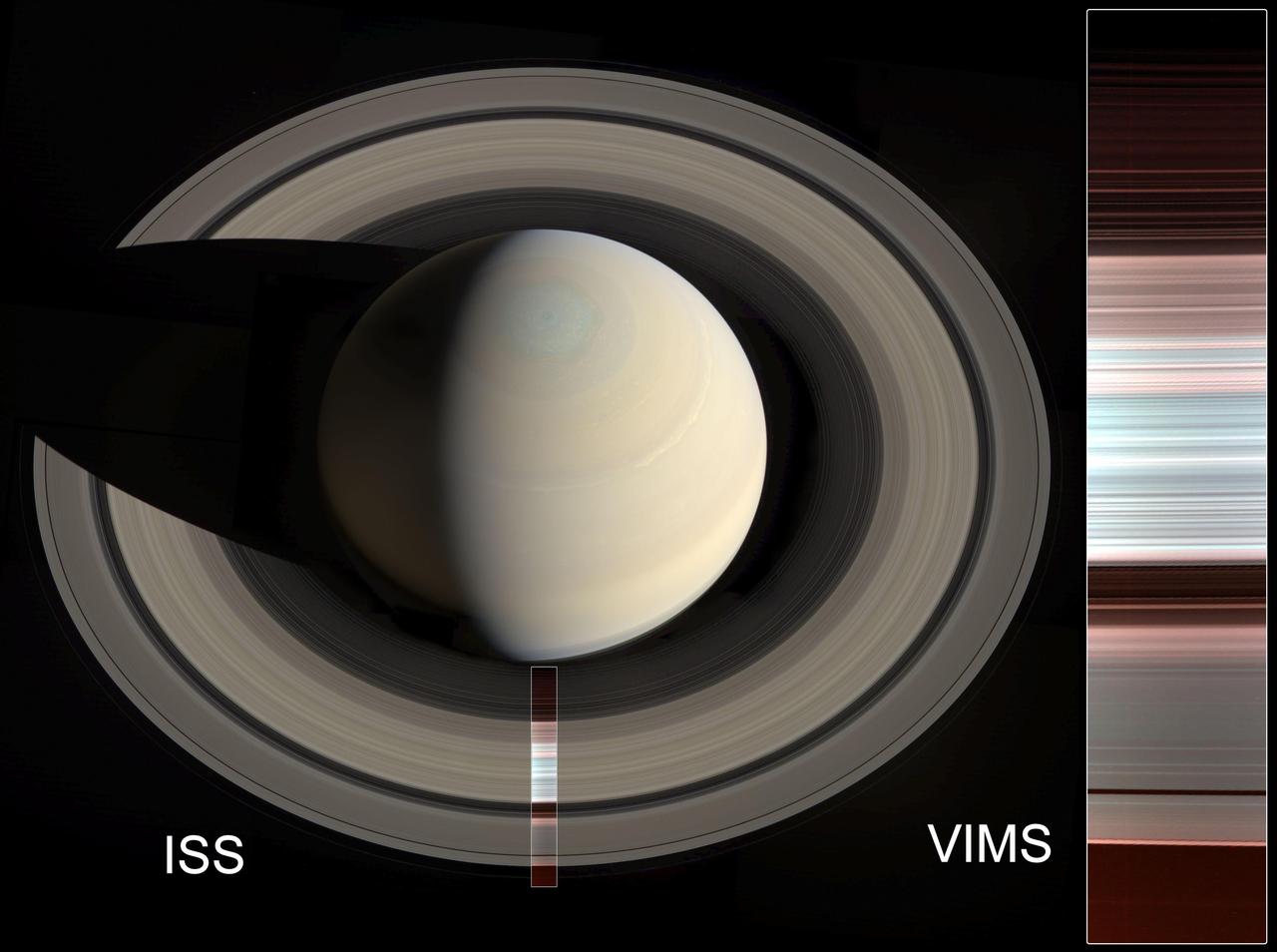

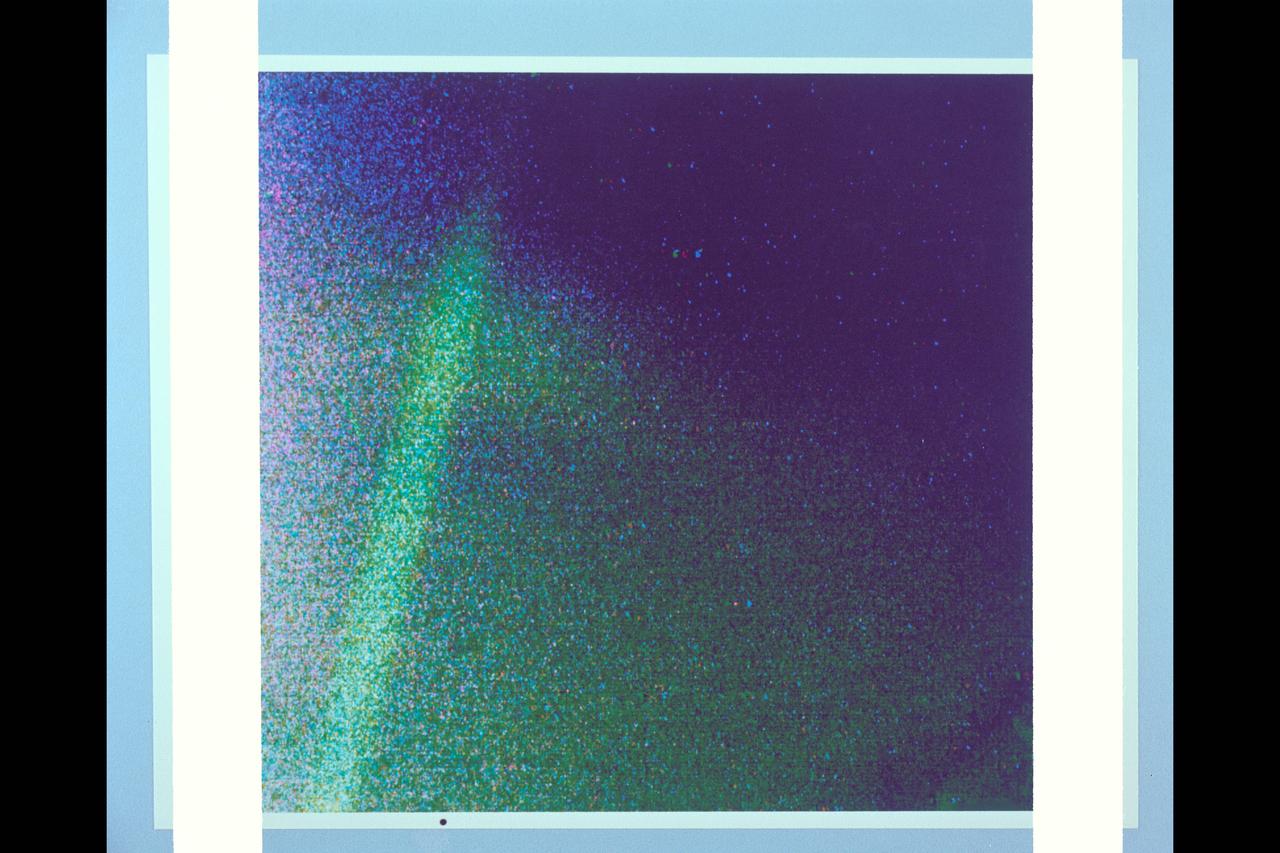

The false-color image at right shows spectral mapping of Saturn's A, B and C rings, captured by Cassini's Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS). It displays an infrared view of the rings, rather than an image in visible light. The blue-green areas are the regions with the purest water ice and/or largest grain size (primarily the A and B rings), while the reddish color indicates increasing amounts of non-icy material and/or smaller grain sizes (primarily in the C ring and Cassini Division). At left, the same image is overlaid on a natural-color mosaic of Saturn taken by Cassini's Imaging Science Subsystem. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23170

The shadow of the moon Tethys is revealed on Saturn B and C rings in this image which also includes the planet.

Off the shoulder of giant Saturn, a bright pinpoint marks the location of the ring moon Atlas image center. Shadows cast by the C ring adorn the planet at upper right

The Cassini spacecraft looks toward the innermost region of Saturn rings, capturing from right to left the C and B rings. The dark, inner edge of the Cassini Division is just visible in the lower left corner

Saturn D ring is easy to overlook since it trapped between the brighter C ring and the planet itself. In this view from NASA Cassini spacecraft, all that can be seen of the D ring is the faint and narrow arc as it stretches from top right of the ima

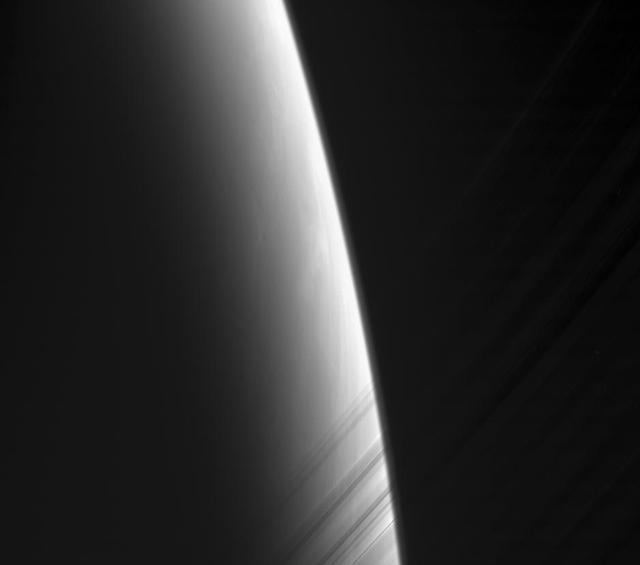

The Cassini spacecraft looks toward daybreak on Saturn through the delicate strands of the C ring. Some structure and contrast is visible in the clouds far below

Saturn's C ring isn't uniformly bright. Instead, about a dozen regions of the ring stand out as noticeably brighter than the rest of the ring, while about half a dozen regions are devoid of ring material. Scientists call the bright regions "plateaus" and the devoid regions "gaps." Scientists have determined that the plateaus are relatively bright because they have higher particle density and reflect more light, but researchers haven't solved the trickier puzzle of how the plateaus are created and maintained. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 62 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken Jan. 9, 2017 in green light with the Cassini spacecraft's narrow-angle camera. Cassini obtained the image while approximately 194,000 miles (312,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 67 degrees. Image scale is 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20529

Although solid-looking in many images, Saturn's rings are actually translucent. In this picture, we can glimpse the shadow of the rings on the planet through (and below) the A and C rings themselves, towards the lower right hand corner. For centuries people have studied Saturn's rings, but questions about the structure and composition of the rings lingered. It was only in 1857 when the physicist James Clerk Maxwell demonstrated that the rings must be composed of many small particles and not solid rings around the planet, and not until the 1970s that spectroscopic evidence definitively showed that the rings are composed mostly of water ice. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 17 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Aug. 12, 2014 in near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.4 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 24 degrees. Image scale is 85 miles (136 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18295

Two of Saturn moons orbit beyond four of the planet rings in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft. From the top right of the picture are the C, B , A, and thin F rings, the small moon Pandora and, near the middle of the image, the moon Enceladus.

Alternating light and dark bands, extending a great distance across Saturn’s D and C rings taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft one month before the planet’s August 2009 equinox.

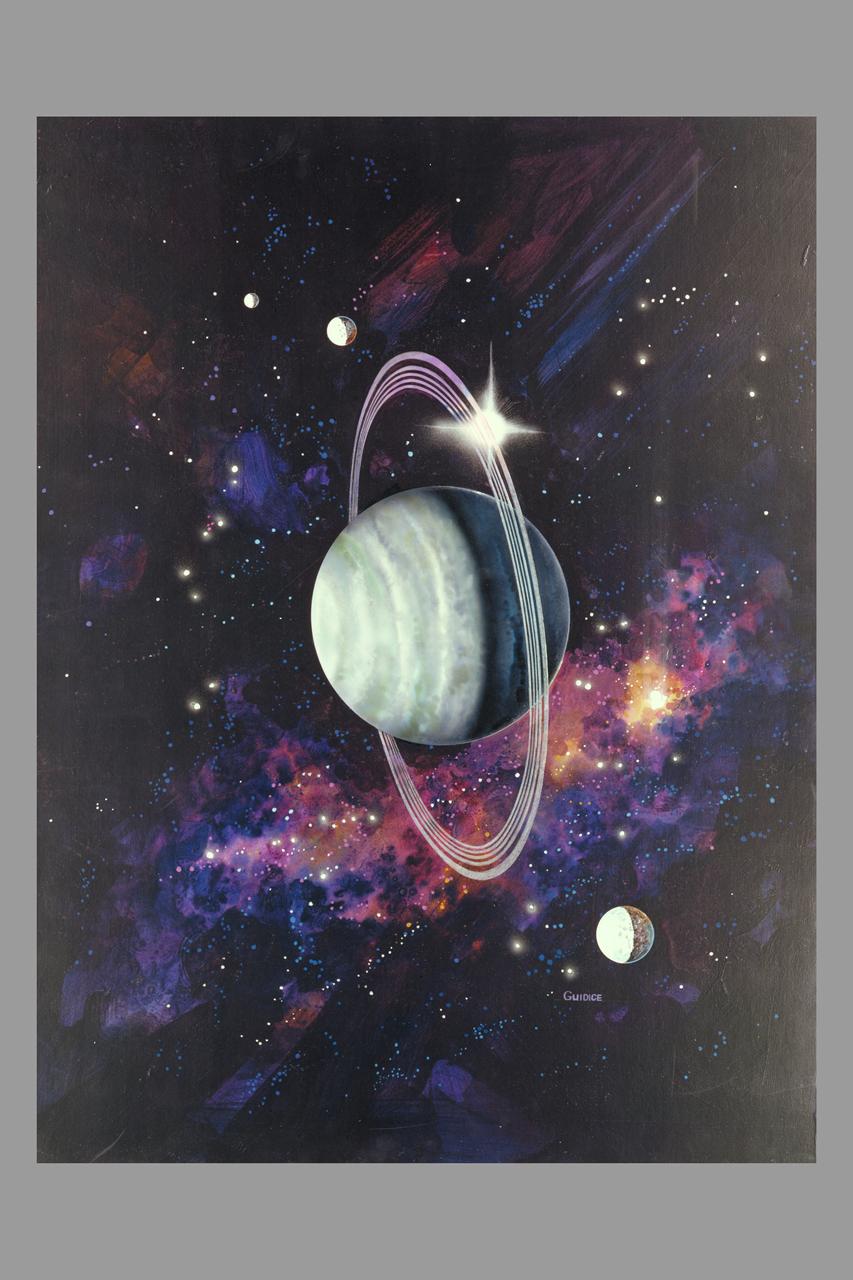

Artist: Rick Guidace This artist concept depicts the rings of Uranus in polar rotation as discovered by NASA Ames C-141 Kuiper Airborne Observatory

P-21763 C Range: 1,400,000 kilometers (870,000 miles) Jupiter's thin ring of particles was photographed by Voyager 2's telescope-equipped TV camera through three color filters to provide this color representation. During the three long exposures the spacecraft drifted, smearing out the ring image. The linear feature just above the ring is a star trail. True color of the ring cannot be deduced from this photo.

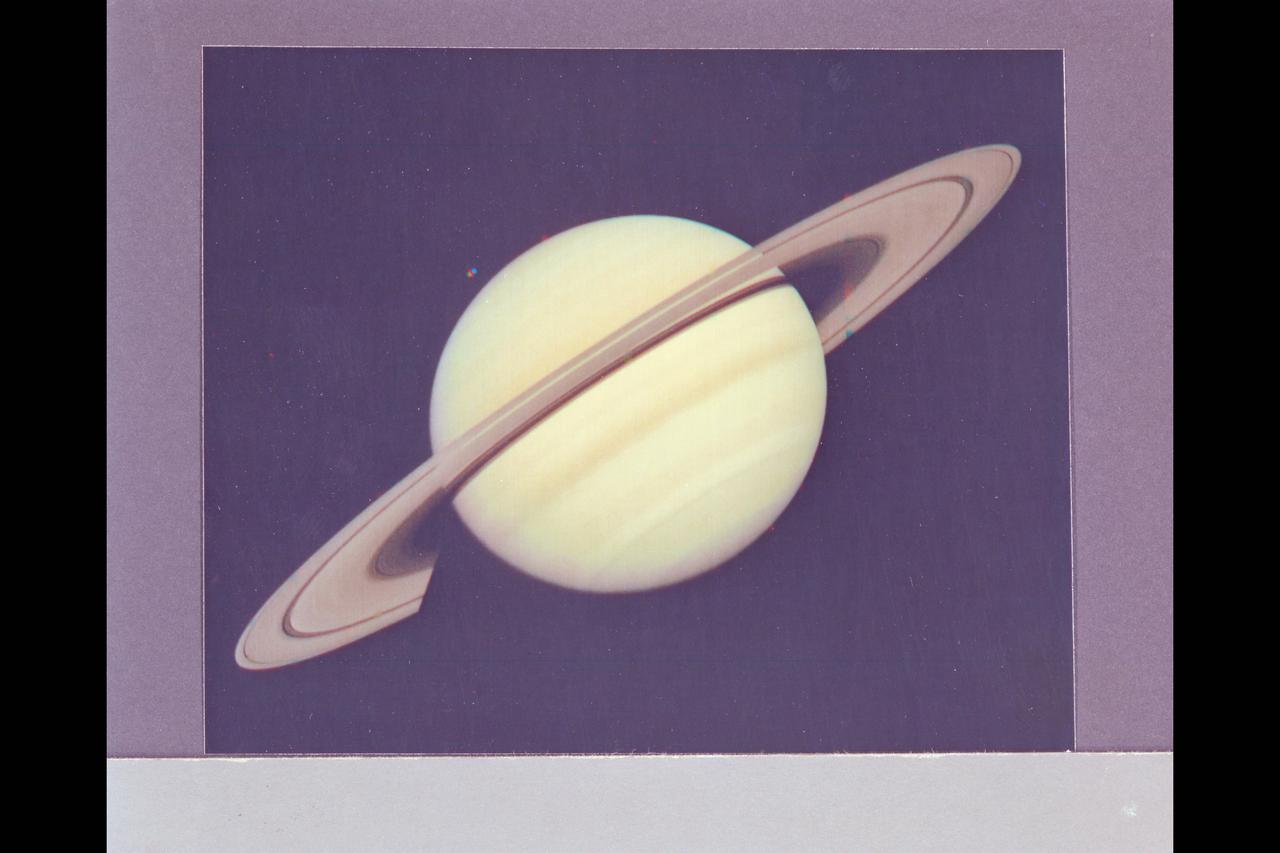

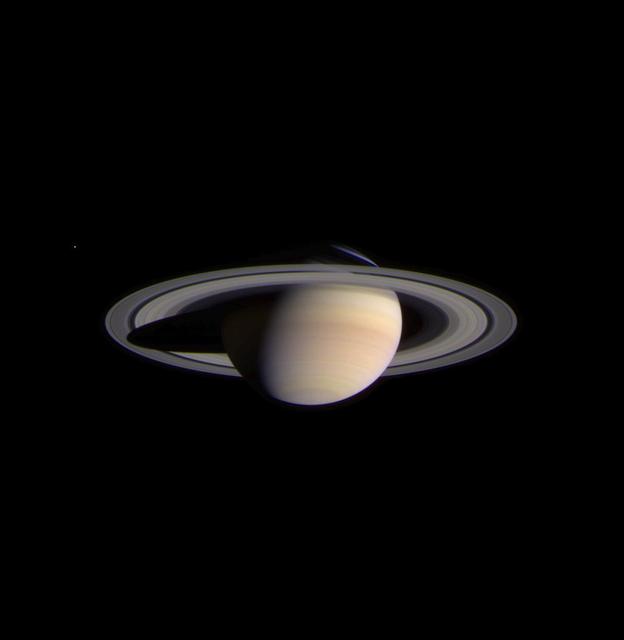

Range : 34 million km. ( 21.1 million miles) P-22993C This Voyager 1 photograph of Saturn was taken on the last day it could be captured within a single narrow angle camera frame as the spacecraft neared the planet for it's closest approach on Nov. 12, 1980. Dione, one of Saturn's innermost satellites, appears as three color spots just below the planet's south pole. An abundance of previously unseen detail is apparent in the rings. For example, a gap in the dark, innermst ring, C-ring or Crepe Ring, is clearly shown. Also, material is seen inside the relatively wide Cassini Division, seperating the middle, B-ring from the outermost ring, the A-ring. The Encke division is shown near the outer edge of A-ring. The detail in the ring's shadows cast on the planet is of particular interest. The broad dark band near the equator is the shadow of B-ring. The thinner, brighter line just to the south is the shadow of the less dense A-ring.

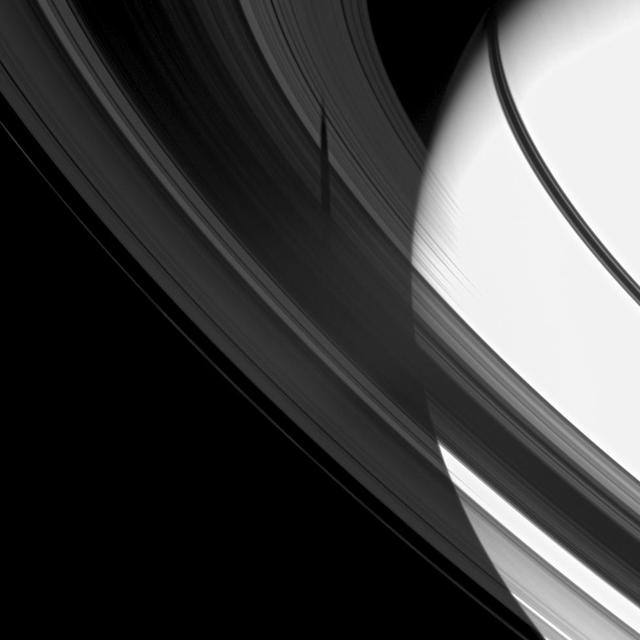

Cassini obtained this panoramic view of Saturn's rings on Sept. 9, 2017, just minutes after it passed through the ring plane. The view looks upward at the southern face of the rings from a vantage point above Saturn's southern hemisphere. The entirety of the main rings can be seen here, but due to the low viewing angle, the rings appear extremely foreshortened. The C ring, with its sharp, bright plateaus (see PIA20529), appears at left; the B ring is the darkened region stretching from bottom center toward upper right; the A ring is seen at far right. This view shows the rings' unilluminated face, where sunlight filters through from the other side. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21898

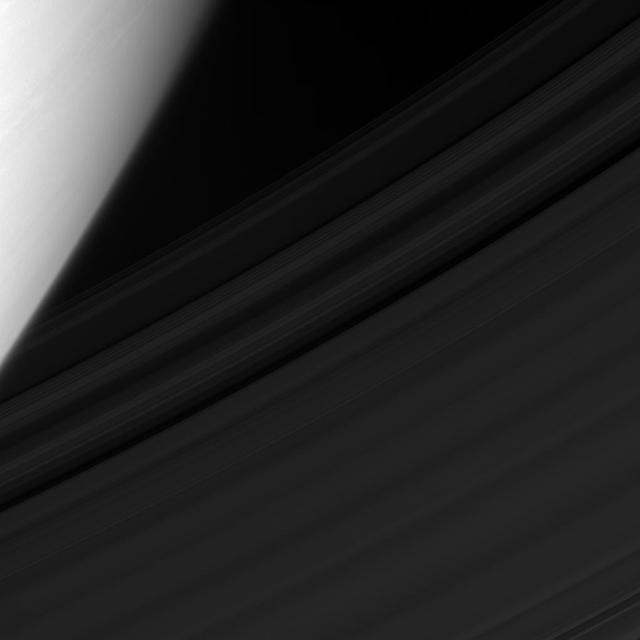

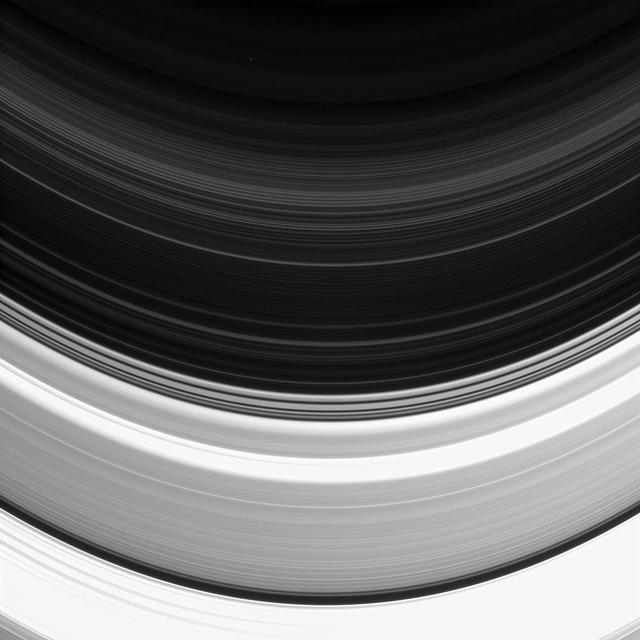

Although only a sliver of Saturn's sunlit face is visible in this view, the mighty gas giant planet still dominates the view. From this vantage point just beneath the ring plane, the dense B ring becomes dark and essentially opaque, letting almost no light pass through. But some light reflected by the planet passes through the less dense A ring, which appears above the B ring in this photo. The C ring, silhouetted just below the B ring, lets almost all of Saturn's reflected light pass right through it, as if it were barely there at all. The F ring appears as a bright arc in this image, which is visible against both the backdrop of Saturn and the dark sky. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 7 degrees below the ring plane. The image was taken in green light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Jan. 18, 2017. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 630,000 miles (1 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 38 miles (61 kilometers) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20530

This image from NASA's Cassini spacecraft offers a unique perspective on Saturn's ring system. Cassini captured images from within the gap between the planet and its rings, looking outward as the spacecraft made one of its final dives through the gap as part of the mission's Grand Finale. Using its wide-angle camera, Cassini took the 21 images in the sequence over a span of about four minutes during its dive through the gap on Aug. 20, 2017. The images have an original size of 512 x 512 pixels; the smaller image size allowed for more images to be taken over the short span of time. The entirety of the main rings can be seen here, but due to the low viewing angle, the rings appear extremely foreshortened. The perspective shifts from the sunlit side of the rings to the unlit side, where sunlight filters through. On the sunlit side, the grayish C ring looks larger in the foreground because it is closer; beyond it is the bright B ring and slightly less-bright A ring, with the Cassini Division between them. The F ring is also fairly easy to make out. A movie is available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21886

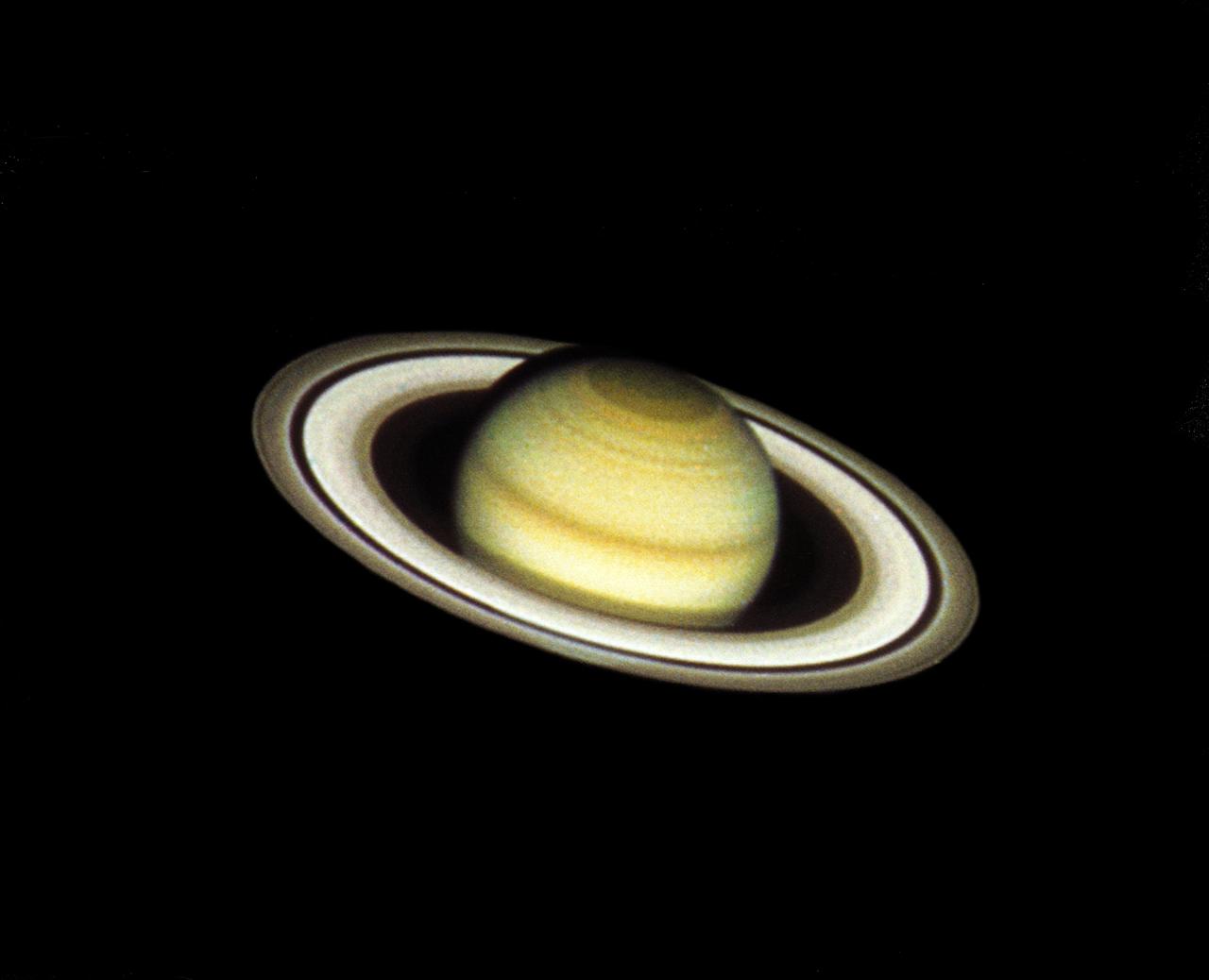

This color image of Saturn was taken with the Hubble Space Telescope's (HST's) Wide Field Camera (WFC) at 3:25 am EDT, August 26, 1990, when the planet was at a distance of 2.39 million km (360 million miles) from Earth. The color in the image is reconstructed by combining three different pictures, taken in blue, green and red light (4390, 5470 and 7180 angstroms). Because Saturn's north pole is currently tilted toward Earth (24 degrees), the HST image reveals unprecedented detail in atmospheric features at the northern polar hood, a region not extensively imaged by the Voyager space probes. The classic features of Saturn's vast ring system are also clearly seen from outer to irner edge; the bright A and B rings, divided by the Cassini division, and the very faint inner C ring. The Enche division, a dark gap near the outer edge of the A ring, has never before been photographed from Earth.

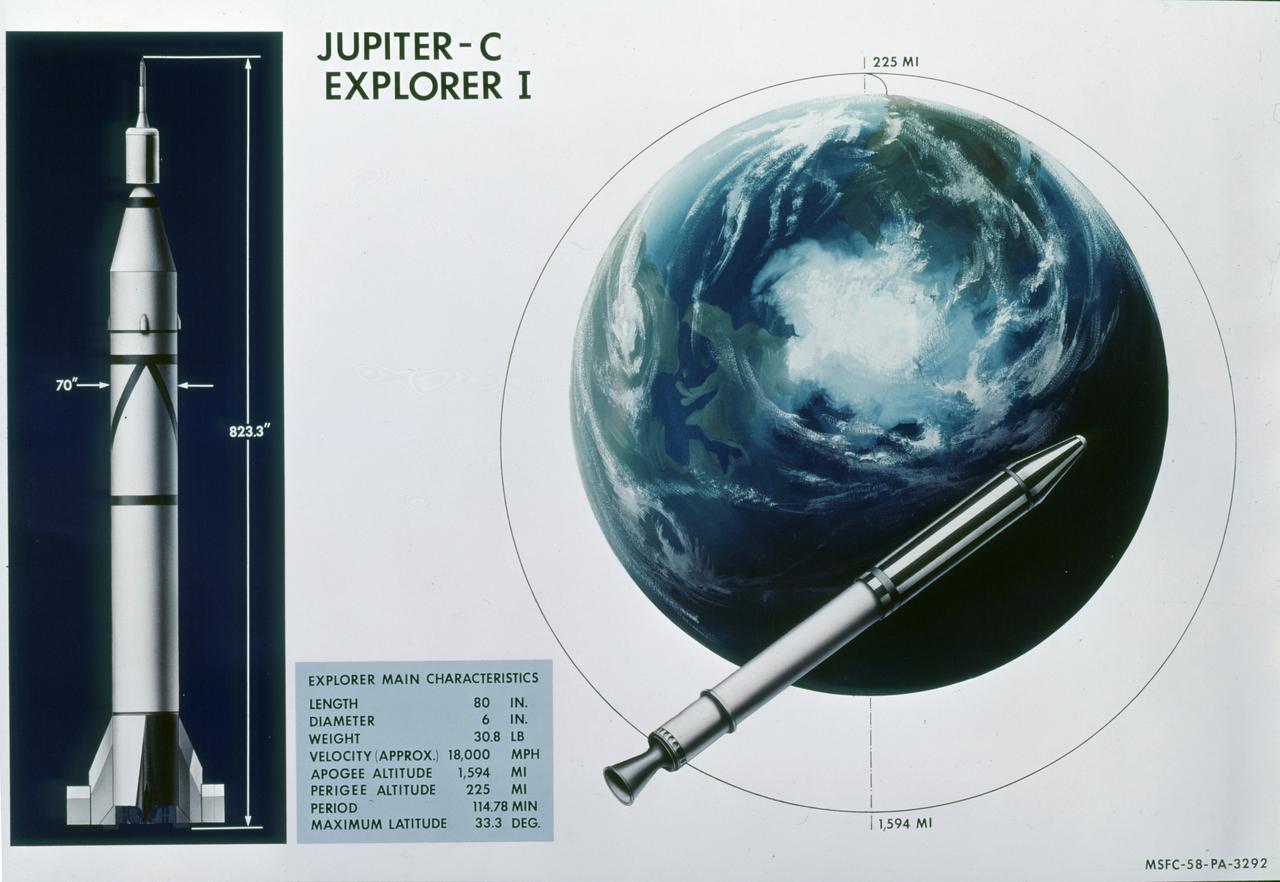

This illustration shows the main characteristics of the Jupiter C launch vehicle and its payload, the Explorer I satellite. The Jupiter C, America's first successful space vehicle, launched the free world's first scientific satellite, Explorer 1, on January 31, 1958. The four-stage Jupiter C measured almost 69 feet in length. The first stage was a modified liquid fueled Redstone missile. This main stage was about 57 feet in length and 70 inches in diameter. Fifteen scaled down SERGENT solid propellant motors were used in the upper stages. A "tub" configuration mounted on top of the modified Redstone held the second and third stages. The second stage consisted of 11 rockets placed in a ring formation within the tub. Inserted into the ring of second stage rockets was a cluster of 3 rockets making up the third stage. A fourth stage single rocket and the satellite were mounted atop the third stage. This "tub", all upper stages, and the satellite were set spirning prior to launching. The complete upper assembly measured 12.5 feet in length. The Explorer I carried the radiation detection experiment designed by Dr. James Van Allen and discovered the Van Allen Radiation Belt.

Technicians and engineers put finishing touches on the Orion Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1) crew module and service module stack in the Operations and Checkout (O&C) Building at Kennedy Space Center on Sept. 7, 2014. The crew module is covered by protective foil as it and the service module are lifted for the installation of the Orion-to-stage adapter ring. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Technicians and engineers put finishing touches on the Orion Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1) crew module and service module stack in the Operations and Checkout (O&C) Building at Kennedy Space Center on Sept. 7, 2014. The crew module is covered by protective foil as it and the service module are lifted for the installation of the Orion-to-stage adapter ring. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Technicians and engineers put finishing touches on the Orion Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1) crew module and service module stack in the Operations and Checkout (O&C) Building at Kennedy Space Center on Sept. 7, 2014. The crew module is covered by protective foil as it and the service module are lifted for the installation of the Orion-to-stage adapter ring. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

The narrow angle camera onboard NASA's Cassini spacecraft took a series of exposures of Saturn and its rings and moons on February 9, 2004, which were composited to create this stunning, color image. At the time, Cassini was 69.4 million kilometers (43.1 million miles) from Saturn, less than half the distance from Earth to the Sun. The image contrast and colors have been slightly enhanced to aid visibility. The smallest features visible in this image are approximately 540 kilometers across (336 miles). Fine details in the rings and atmosphere are beginning to emerge, and will grow in sharpness and clarity over the coming months. The optical thickness of Saturn's B (middle) ring and the comparative translucence of the A (outer) ring, when seen against the planet, are now apparent. Subtle color differences in the finely banded Saturnian atmosphere, as well as structure within the diaphanous, inner C ring can be easily seen. Noticeably absent are the ghostly spoke-like dark markings in Saturn's B ring, first discovered by NASA's Voyager spacecraft on approach to the planet 23 years ago. The icy moon Enceladus (520 kilometers or 323 miles across) is faintly visible on the left in the image. Its brightness has been increased seven times relative to the planet. Cassini will make several very close approaches to Enceladus, returning images in which features as small as 50 meters (165 feet) or less will be detectable. The composite image signals the start of Cassini's final approach to the ringed planet and the beginning of monitoring and data collection on Saturn and its environment. This phase of the mission will continue until Cassini enters orbit around Saturn on July 1, 2004. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05380

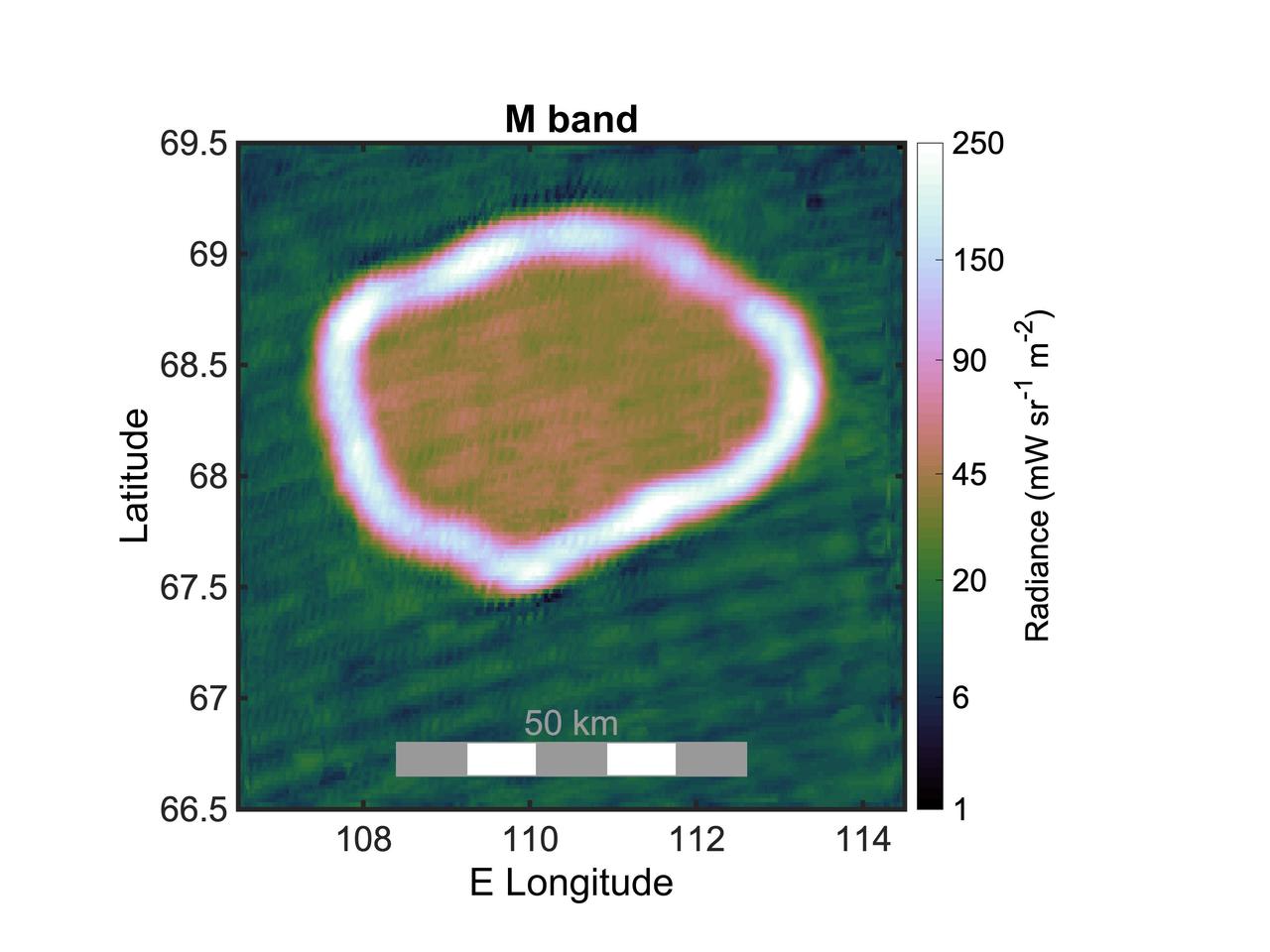

This graphic shows the infrared radiance of Chors Patera, a lava lake on Jupiter's moon Io. It was created using infrared data collected by the JIRAM (Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper) instrument aboard NASA's Juno spacecraft during a flyby of the moon on Oct. 15, 2023. The lake is about 31 miles (50 kilometers) wide. Juno scientists believe the majority of the lake is covered with a thick crust of molten material (appearing red/green in graphic, inside the white ring) that is approximately minus 45 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 43 degrees Celsius) at its surface. The white ring indicates where lava from Io's interior is directly exposed to space, providing the geologic feature's hottest thermal signature: between 450 and 1,350 F (232 and 732 C). The area in green, outside the lava lake, is very cold: about minus 225 F (minus 143 C). JIRAM "sees" infrared light not visible to the human eye. In this composite image, the measurements of thermal emissions radiated from the planet were in the infrared wavelength between 4.5 and 5 microns. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26371

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, Calif. -- At Vandenberg Air Force Base's processing facility in California, this separation ring, installed on the aft end of NASA's Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array, or NuSTAR, is the mating interface between the spacecraft and the upper stage of the Orbital Sciences Pegasus XL rocket which will place it in orbit. Behind the ring is part of the turnover rotation fixture, the C-plate, which protects the spacecraft during mating operations. The conjoining of the spacecraft with the rocket is a major milestone in prelaunch preparations. After processing of the rocket and spacecraft are complete, they will be flown on Orbital's L-1011 carrier aircraft from Vandenberg to the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site on the Pacific Ocean’s Kwajalein Atoll for launch. The high-energy x-ray telescope will conduct a census of black holes, map radioactive material in young supernovae remnants, and study the origins of cosmic rays and the extreme physics around collapsed stars. For more information, visit http://www.nasa.gov/nustar. Photo credit: NASA/Randy Beaudoin, VAFB

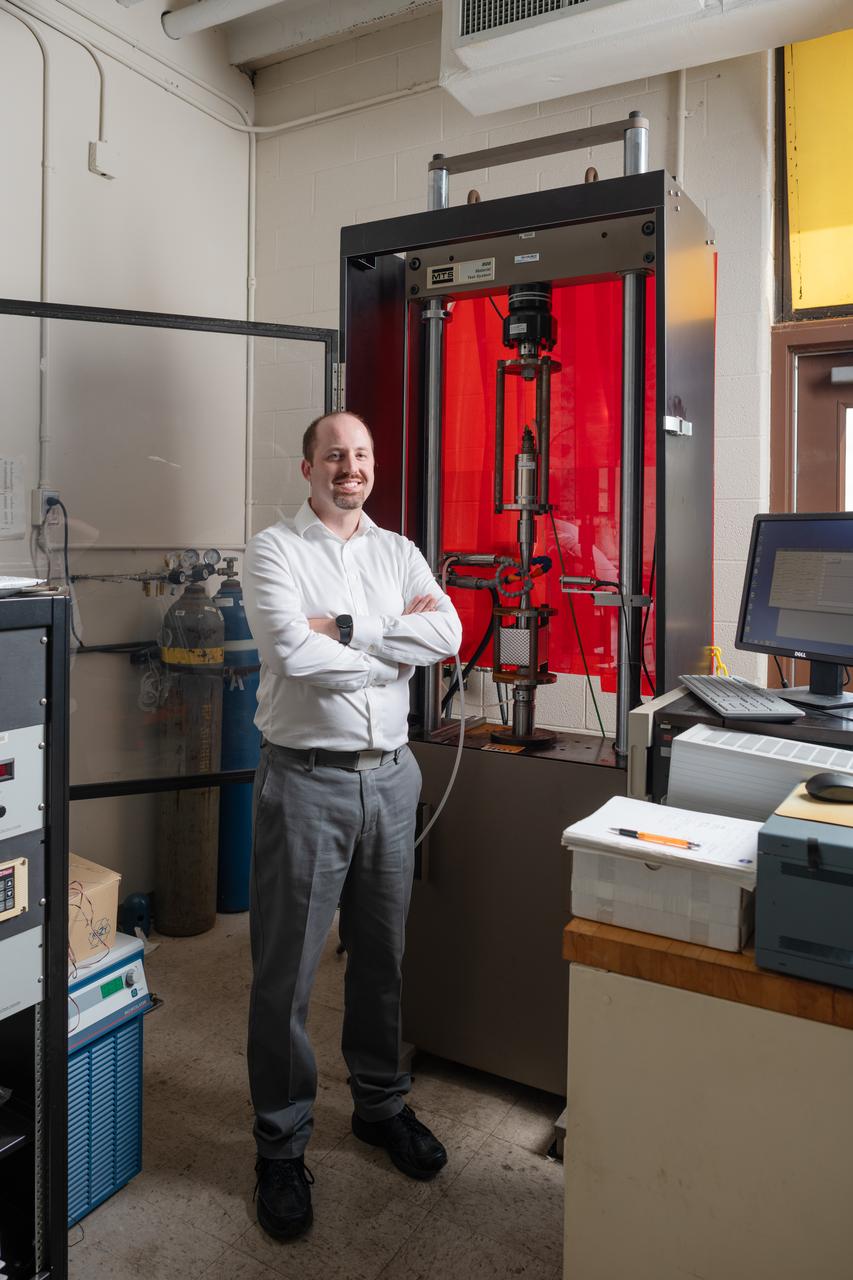

Each year, the NESC produces the NESC Technical Update, which highlights two or three individuals from each Center and includes assessments throughout the year. Because of the critical contributions to the NESC mission this year, Rob Jankovsky, NESC Chief Engineer at GRC, chose two individuals to be highlighted. This year, it is Andrew Ring and Michael Cooper. Mr. Ring, pictured here, performs stress and fatigue testing on all manner of materials in various environments and research on jet engine materials, looking for ways to increase the performance and safety of turbine blades and disks. Several NESC assessments have benefited from his expertise, most recently in understanding crack initiation and propagation in the aluminum-magnesium alloys that make up the modules of the ISS. He has also used image processing techniques to quantify the variables in parachute energy modulator production and performance and investigate flaws in the composite weave of overwrapped pressure vessels.

Each year, the NESC produces the NESC Technical Update, which highlights two or three individuals from each Center and includes assessments throughout the year. Because of the critical contributions to the NESC mission this year, Rob Jankovsky, NESC Chief Engineer at GRC, chose two individuals to be highlighted. This year, it is Andrew Ring and Michael Cooper. Mr. Ring, pictured here, performs stress and fatigue testing on all manner of materials in various environments and research on jet engine materials, looking for ways to increase the performance and safety of turbine blades and disks. Several NESC assessments have benefited from his expertise, most recently in understanding crack initiation and propagation in the aluminum-magnesium alloys that make up the modules of the ISS. He has also used image processing techniques to quantify the variables in parachute energy modulator production and performance and investigate flaws in the composite weave of overwrapped pressure vessels.

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLORIDA STS-82 PREPARATIONS VIEW --- In the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Vertical Processing Facility (VPF), the STS-82 crew members familiarize themselves with some of the hardware they will be handling on the second servicing mission to the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). Looking over the Flight Support System (FSS) Berthing and Positioning System (BAPS) ring are astronauts Joseph R. Tanner (far left), Mark C. Lee (third left) and Gregory J. Harbaugh (fourth left); along with several HST processing team members. Tanner, Lee and Harbaugh, along with Steven L. Smith, will perform spacewalks required for servicing of the HST. The telescope was deployed nearly seven years ago and was initially serviced in 1993.

Caption: In this composite image, visible-light observations by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope are combined with infrared data from the ground-based Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona to assemble a dramatic view of the well-known Ring Nebula. Credit: NASA, ESA, C.R. Robert O’Dell (Vanderbilt University), G.J. Ferland (University of Kentucky), W.J. Henney and M. Peimbert (National Autonomous University of Mexico) Credit for Large Binocular Telescope data: David Thompson (University of Arizona) ---- The Ring Nebula's distinctive shape makes it a popular illustration for astronomy books. But new observations by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope of the glowing gas shroud around an old, dying, sun-like star reveal a new twist. "The nebula is not like a bagel, but rather, it's like a jelly doughnut, because it's filled with material in the middle," said C. Robert O'Dell of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. He leads a research team that used Hubble and several ground-based telescopes to obtain the best view yet of the iconic nebula. The images show a more complex structure than astronomers once thought and have allowed them to construct the most precise 3-D model of the nebula. "With Hubble's detail, we see a completely different shape than what's been thought about historically for this classic nebula," O'Dell said. "The new Hubble observations show the nebula in much clearer detail, and we see things are not as simple as we previously thought." The Ring Nebula is about 2,000 light-years from Earth and measures roughly 1 light-year across. Located in the constellation Lyra, the nebula is a popular target for amateur astronomers. Read more: <a href="http://1.usa.gov/14VAOMk" rel="nofollow">1.usa.gov/14VAOMk</a> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASA_GoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagram.com/nasagoddard?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

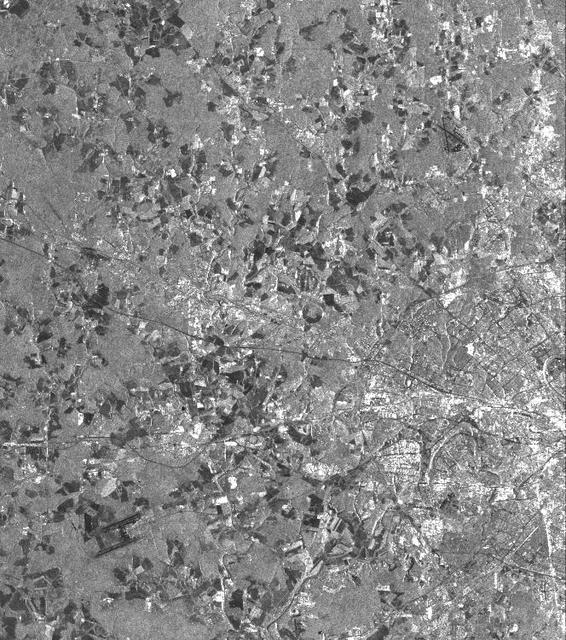

This is a vertically polarized L-band image of the southern half of Moscow, an area which has been inhabited for 2,000 years. The image covers a diameter of approximately 50 kilometers (31 miles) and was taken on September 30, 1994 by the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C/X-band Synthetic Aperture Radar aboard the space shuttle Endeavour. The city of Moscow was founded about 750 years ago and today is home to about 8 million residents. The southern half of the circular highway (a road that looks like a ring) can easily be identified as well as the roads and railways radiating out from the center of the city. The city was named after the Moskwa River and replaced Russia's former capital, St. Petersburg, after the Russian Revolution in 1917. The river winding through Moscow shows up in various gray shades. The circular structure of many city roads can easily be identified, although subway connections covering several hundred kilometers are not visible in this image. The white areas within the ring road and outside of it are buildings of the city itself and it suburban towns. Two of many airports are located in the west and southeast of Moscow, near the corners of the image. The Kremlin is located north just outside of the imaged city center. It was actually built in the 16th century, when Ivan III was czar, and is famous for its various churches. In the surrounding area, light gray indicates forests, while the dark patches are agricultural areas. The various shades from middle gray to dark gray indicate different stages of harvesting, ploughing and grassland. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01752

Workers begin unloading the Cassini orbiter from a U.S. Air Force C-17 air cargo plane after its <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">arrival</a> at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers prepare to tow away the large container with the Cassini orbiter from KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility. The orbiter <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">just arrived</a> on the U.S. Air Force C-17 air cargo plane, shown here, from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers prepare to move the shipping container with the Cassini orbiter inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) for prelaunch processing, testing and integration. The <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">orbiter arrived</a> at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility in a U.S. Air Force C-17 air cargo plane from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers prepare to move the shipping container with the Cassini orbiter inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) for prelaunch processing, testing and integration. The <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">orbiter arrived</a> at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility in a U.S. Air Force C-17 air cargo plane from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers prepare to move the shipping container with the Cassini orbiter inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) for prelaunch processing, testing and integration. The <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">orbiter arrived</a> at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility in a U.S. Air Force C-17 air cargo plane from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers offload the shipping container with the Cassini orbiter from what looks like a giant shark mouth, but is really an Air Force C-17 air cargo plane which <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">just landed</a> at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

STS045-S-001 (October 1991) --- Designed by the crew members, the patch depicts the space shuttle launching from the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) into a high inclination orbit. From this vantage point, the Atmospheric Laboratory for Applications and Science (ATLAS) payload can view Earth, the sun, and their dynamic interactions against the background of space. Earth is prominently displayed and is the focus of the mission's space plasma physics and Earth sciences observations. The colors of the setting sun, measured by sensitive instruments, provide detailed information about ozone, carbon dioxide and other gases which determine Earth's climate and environment. Encircling the scene are the names of the flight crew members: Charles F. Bolden Jr., commander; Brian Duffy, pilot; C. Michael Foale, David C. Leestma, and Kathryn D. Sullivan, all mission specialists; Dirk Frimout and Byron K. Lichtenberg, payload specialists. The additional star in the ring is to recognize Charles R. Chappell and Michael Lampton, alternate payload specialists, and the entire ATLAS-1 team for its dedication and support of this "Mission to Planet Earth" (MTPE). The NASA insignia design for space shuttle flights is reserved for use by the astronauts and for other official use as the NASA Administrator may authorize. Public availability has been approved only in the form of illustrations by the various news media. When and if there is any change in this policy, which is not anticipated, it will be publicly announced. Photo credit: NASA

This planetary nebula's simple, graceful appearance is thought to be due to perspective: our view from Earth looking straight into what is actually a barrel-shaped cloud of gas shrugged off by a dying central star. Hot blue gas near the energizing central star gives way to progressively cooler green and yellow gas at greater distances with the coolest red gas along the outer boundary. Credit: NASA/Hubble Heritage Team ---- The Ring Nebula's distinctive shape makes it a popular illustration for astronomy books. But new observations by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope of the glowing gas shroud around an old, dying, sun-like star reveal a new twist. "The nebula is not like a bagel, but rather, it's like a jelly doughnut, because it's filled with material in the middle," said C. Robert O'Dell of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. He leads a research team that used Hubble and several ground-based telescopes to obtain the best view yet of the iconic nebula. The images show a more complex structure than astronomers once thought and have allowed them to construct the most precise 3-D model of the nebula. "With Hubble's detail, we see a completely different shape than what's been thought about historically for this classic nebula," O'Dell said. "The new Hubble observations show the nebula in much clearer detail, and we see things are not as simple as we previously thought." The Ring Nebula is about 2,000 light-years from Earth and measures roughly 1 light-year across. Located in the constellation Lyra, the nebula is a popular target for amateur astronomers. Read more: <a href="http://1.usa.gov/14VAOMk" rel="nofollow">1.usa.gov/14VAOMk</a> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagram.com/nasagoddard?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

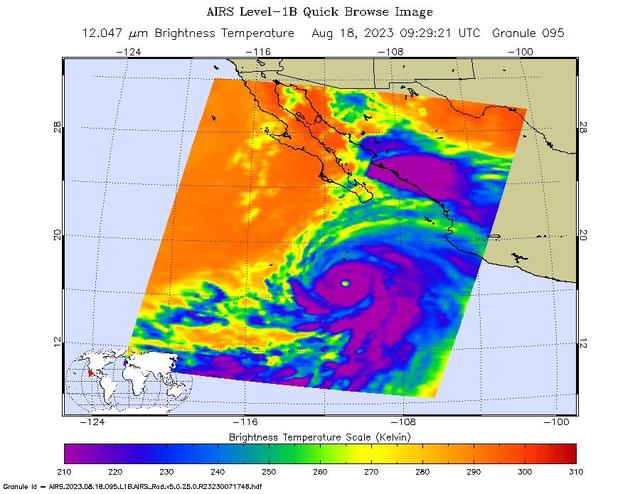

NASA's Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) captured Hurricane Hilary on the morning of Aug. 18, 2023, when it was a Category 4 storm roughly 470 miles (760 kilometers) south of Baja California. Hilary could be the first tropical storm to make landfall in California since 1939, according to the National Weather Service. Hilary grew from a tropical storm into a Category 2 hurricane within 24 hours on Aug. 17. Another period of rapid intensification – an increase in maximum sustained wind speed of at least 30 knots (35 mph) within 24 hours – occurred Aug. 17-18. The animation shows some of this rapid growth, with images taken by AIRS Aug. 15-18. This intensification was driven by very warm ocean surface waters and weak wind shear, a term for vertical changes in wind speed. Strong wind shear can keep hurricanes from forming, or can tear them apart. AIRS measures cloud temperatures in infrared wavelengths, which can reveal information about the atmosphere not visible to the human eye. Hilary shows several indicators of a powerful hurricane: a well-defined eye surrounded by a ring of very cold clouds in purple, with warmer outer regions seen in yellows and oranges. Purple and violet areas are colder, between about minus 82 degrees Fahrenheit and minus 46 F (minus 63 degrees Celsius to minus 44 C). Blue and green regions are roughly minus 28 F to 26 F (minus 33 C to minus 3 C). The cooler parts of the clouds are associated with very heavy rainfall. Most hurricanes in the Pacific Ocean off Mexico travel westward, following tropical trade winds. Occasionally, one of these storms will head northward. Hurricane Hilary is being steered by a weak low-pressure system off the coast of California, an area normally dominated by high pressure and an atmospheric circulation pattern that would deflect storms from the region. The current forecast from the National Hurricane Center has Hilary closely following the western coastline of the Baja California peninsula, weakening as it moves north. Rainfall projections for Southern California range from 2 inches (5 centimeters) in coastal areas to 8 or more inches (20 or more centimeters) in local mountains. For comparison, San Diego and Los Angeles receive no rain in August most years, and the wettest parts of the local mountains receive about 1 inch (3 centimeters) of rain over a normal summer. In conjunction with the Advanced Microwave Sounding Unit (AMSU), AIRS senses emitted infrared and microwave radiation from Earth to provide a 3D look at the planet's weather and climate. Working in tandem, the two instruments make simultaneous observations down to Earth's surface. With more than 2,000 channels sensing different regions of the atmosphere, the system creates a global, 3D map of atmospheric temperature and humidity, cloud amounts and heights, greenhouse gas concentrations, and many other atmospheric phenomena. Launched into Earth orbit in 2002 aboard NASA's Aqua spacecraft, the AIRS and AMSU instruments are managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, under contract to NASA. JPL is a division of Caltech. Animation available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25779