KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. - Clouds of exhaust form around a Boeing Delta II expendable launch vehicle as it blasts NASA's Swift spacecraft on its mission at Complex 17A, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, on Nov. 20 at 12:16:00.611 p.m. EST. Swift is a first-of-its-kind multi-wavelength observatory dedicated to the study of gamma-ray burst science. Its three instruments will work together to observe GRBs and afterglows in the gamma ray, X-ray, ultraviolet and optical wavebands.

![KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. - Clouds of exhaust form around a Boeing Delta II expendable launch vehicle as it blasts NASA’s Swift spacecraft on its mission from Complex 17-A, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, at 12:16:00.611 p.m. EST Nov. 20 . Swift is a first-of-its-kind multi-wavelength observatory dedicated to the study of gamma-ray burst science. Its three instruments will work together to observe GRBs and afterglows in the gamma ray, X-ray, ultraviolet and optical wavebands. [Photo courtesy of Scott Andrews]](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/04pd2356/04pd2356~medium.jpg)

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. - Clouds of exhaust form around a Boeing Delta II expendable launch vehicle as it blasts NASA’s Swift spacecraft on its mission from Complex 17-A, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, at 12:16:00.611 p.m. EST Nov. 20 . Swift is a first-of-its-kind multi-wavelength observatory dedicated to the study of gamma-ray burst science. Its three instruments will work together to observe GRBs and afterglows in the gamma ray, X-ray, ultraviolet and optical wavebands. [Photo courtesy of Scott Andrews]

ISS024-E-014559 (14 Sept. 2010) --- Hurricane Igor is featured in this Sept. 14 image photographed by an Expedition 24 crew member on the International Space Station. At the time this image was taken, Hurricane Igor was about 648 miles east of Barbuda Island in the Lesser Antilles. It was travelling to the northeast (290 degrees) at 6.2 mph (6 kts). The winds were already 132.5 mph (115 kts) gusting to 161.3 mph (140 kts) and forecast to intensify. Igor?s well-defined eye was a dynamic area of swift rising winds in the outer wall and sinking winds in the center. His strong eye wall surrounded a low level cloud deck of clouds containing additional vortices.

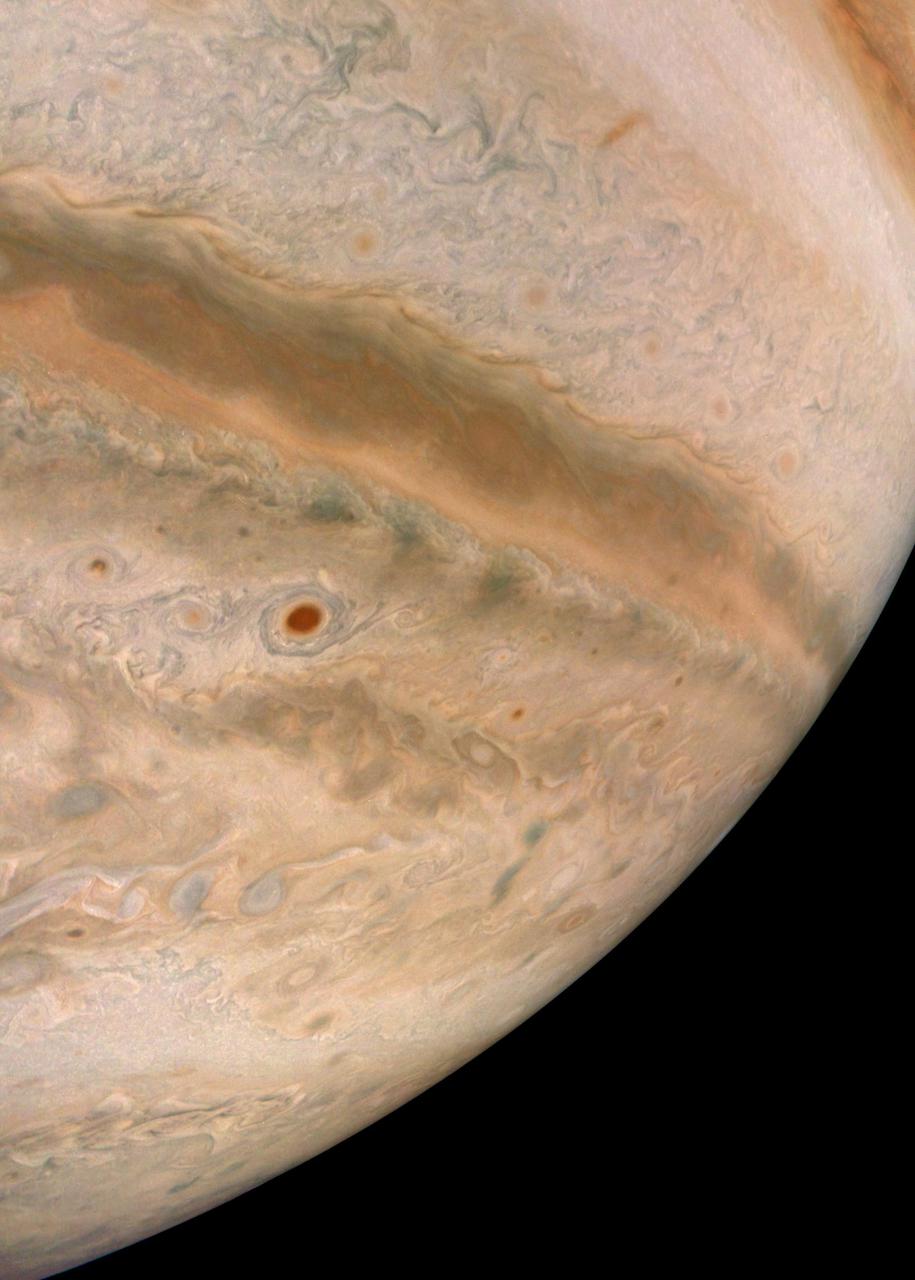

The three-dimensional character of Jupiter's cloud decks is captured in this image of the planet's North Equatorial Belt. Orange storms peek out from under banks of dark gray clouds. Lighter tan and gray clouds cast narrow shadows on the dark gray cloud bank below. At the top are the "pop-up clouds," parcels of air pushed up to the altitude at which ammonia ice condenses to make small, bright clouds. Jupiter appears to have a pastel hue to the naked eye through an Earth-based telescope. The color in this image from the JunoCam imager aboard NASA's Juno spacecraft has been "exaggerated," processed by citizen scientist Brian Swift to bring out subtle differences. The result is that the cloud layering is more obvious than in the original image. This image was taken Oct. 16, 2021, at 10:07 a.m. PDT (1:07 p.m. EDT) as Juno performed its 37th close flyby of Jupiter. At the time the image was taken, the spacecraft was about 3,738 miles (6,016 kilometers) from the tops of the clouds of the planet at a latitude of 49.17 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24972

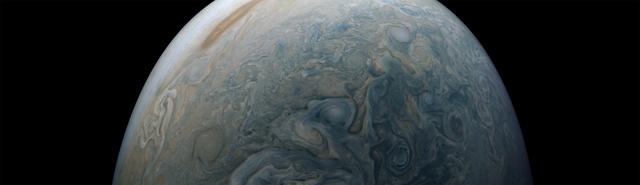

During its 36th low pass over Jupiter, NASA's Juno spacecraft captured this view of striking cloud bands and swirls in the giant planet's mid-southern latitudes. The dark, circular vortex near the center of the image is a cyclone that spans roughly 250 miles (about 400 kilometers). The color at its center is likely to be the result of descending winds that cleared out upper-level clouds, revealing darker material below. Citizen scientist Brian Swift used a raw JunoCam image digitally projected onto a sphere to create this view. It has been rotated so that north is up. The original image was taken on Sept. 2, 2021, at 4:09 p.m. PDT (7:09 p.m. EDT). At the time, the spacecraft was about 16,800 miles (about 27,000 kilometers) above Jupiter's cloud tops, at a latitude of about 31 degrees south. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23610

NASA Dryden aerospace engineer Michael Allen hand-launches a model motorized sailplane during a study validating the use of heat thermals to extend flight time.

A NASA model motorized sailplane catches a thermal during one of 17 flights to demonstrate that updrafts can extend flight time and save energy for small UAVs.

A NASA remote-controlled model motorized sailplane lies over Rogers Dry Lake to test the theory that catching heat thermals extends flight time for small UAVs.

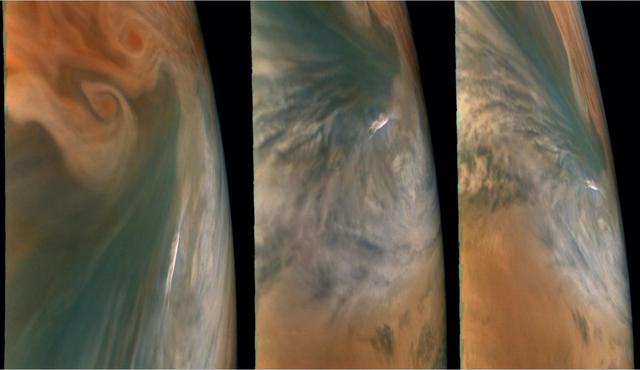

These images from NASA's Juno mission show three different views of a Jupiter "hot spot" — a break in Jupiter's cloud deck that provides a glimpse into Jupiter's deep atmosphere. Hot spots are flanked by clouds and active storms, and fueled by high-altitude electrical discharges recently discovered by Juno known as "shallow lightning." The pictures were taken by the JunoCam imager during its 29th close flyby of the giant planet on Sept. 16, 2020. Not all of Jupiter's clouds are the same. The planet is composed mostly of hydrogen and helium, and the vivid colors that appear in thick bands across Jupiter are likely plumes of sulfur compounds and phosphorus-containing gases rising from the planet's warmer interior. The small, bright cloud feature seen here is likely made of ammonia ice and water ice rising to a higher altitude than the surrounding features. The original JunoCam images used to produce these views were taken from altitudes between about 2,700 and 4,500 miles (4,300 and 7,200 kilometers) above Jupiter's cloud tops. Citizen scientist Brian Swift processed the images to enhance the color and contrast. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24298

Clouds in a Jovian jet stream, called Jet N5, swirl in the center of this color-enhanced image from NASA's Juno spacecraft. A brown oval known as a "brown barge" can be seen in the North North Temperate Belt region in the top-left portion of the image. This image was taken at 5:58 p.m. PDT on Sept. 6, 2018 (8:58 p.m. EDT) as the spacecraft performed its 15th close flyby of Jupiter. At the time, Juno was 7,600 miles (12,300 kilometers) from the planet's cloud tops, above a northern latitude of approximately 52 degrees. Citizen scientists Brian Swift and Seán Doran created this image using data from the spacecraft's JunoCam imager. The view has been rotated 90 degrees to the right from the original image. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22689

During its 65th close flyby of Jupiter on Sept. 20, 2024, NASA's Juno spacecraft captured this series of images as it approached the giant planet and swung low over its north polar region. Juno's recent orbits have provided exceptionally clear views of Jupiter's circumpolar cyclones. At closest approach in this series of images, the Juno spacecraft was about 6,800 miles (11,000 kilometers) above the cloud tops, at a latitude of 82 degrees north of the equator. Citizen scientist Brian Swift made this image using raw data from the JunoCam instrument, applying digital processing techniques to enhance color and clarity. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25730

The main image and the inset image were taken by the JunoCam imager about NASA's Juno spacecraft a few hours before its closest approach to Jupiter on its 38th perijove pass, on Nov. 29, 2021, during an encounter with the Jovian moon Io. After snapping a series of Io images, JunoCam acquired this picture of Jupiter and Io together. Much fainter and more distant is Jupiter's moon Callisto, barely visible below and to the right of Io. The original JunoCam image used to produce this view was taken from an altitude of 15,404 miles (24,791 kilometers) above Jupiter's cloud tops near its north pole. At the time, Io was at a distance of 270,648 miles (435,567 kilometers), and Callisto was almost 1.2 million miles (2 million kilometers). Citizen scientist Brian Swift processed the main image and inset to enhance the color and contrast. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25032

This composite image shows a hot spot in Jupiter's atmosphere. In the image on the left, taken on Sept. 16, 2020, by the Gemini North telescope on the island of Hawaii, the hot spot appears bright in the infrared at a wavelength of 5 microns. In the inset image on the right, taken by Juno's JunoCam visible-light imager, also on Sept. 16 during Juno's 29th perijove pass, the hot spot appears dark. Scientists have known of Jupiter's hot spots for a long time. On Dec. 7, 1995, the Galileo probe likely descended into a similar hot spot. To the naked eye, Jupiter's hot spots appear as dark, cloud-free areas in Jupiter's equatorial belt, but at infrared wavelengths, which are invisible to the human eye, they are extremely bright, revealing the warm, deep atmosphere below the clouds. High-resolution images of hot spots such as these are key both to understanding the role of storms and waves in Jupiter's atmosphere. Citizen scientist Brian Swift processed the images to enhance the color and contrast, with further processing by Tom Momary to map the JunoCam image to the Gemini data. The international Gemini North telescope is a 26.6-foot-diameter (8.1-meter-diameter) optical/infrared telescope optimized for infrared observations, and is managed for the NSF by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA). https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24299

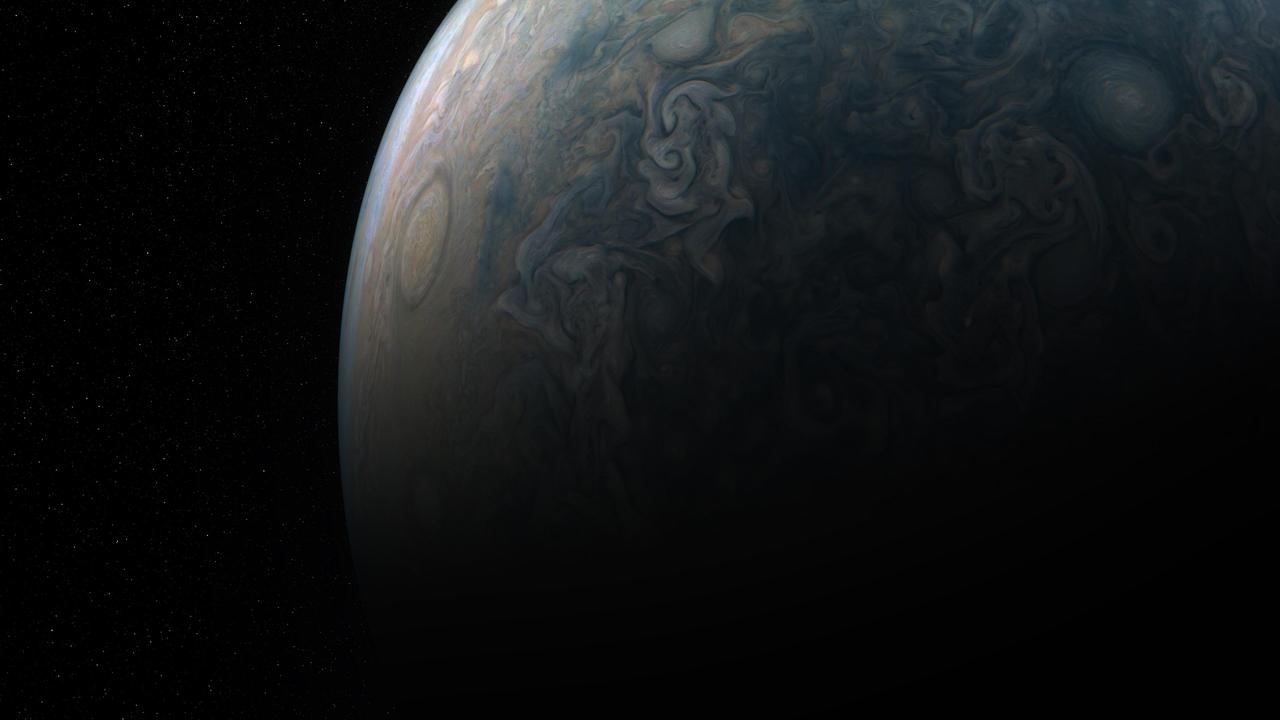

Tumultuous tempests in Jupiter's northern hemisphere are seen in this portrait taken by NASA's Juno spacecraft. Like our home planet, Jupiter has cyclones and anticyclones, along with fast-moving jet streams that circle its globe. This image captures a jet stream, called Jet N6, located on the far right of the image. It is next to an anticyclonic white oval that is the brighter circular feature in the top right corner. The North North Little Red Spot is also visible in this view. The image was taken at 10 p.m. PDT on July 15, 2018 (1 a.m. EDT on July 16), as the spacecraft performed its 14th close flyby of Jupiter. At the time, Juno was about 10,600 miles (17,000 kilometers) from the planet's cloud tops, above a latitude of 59 degrees. Citizen scientists Brian Swift and Seán Doran created this image using data from the spacecraft's JunoCam imager. The image has been rotated clockwise so that north is to the right. The stars were artfully added to the background for effect. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22428

As NASA's Juno mission completed its 43rd close flyby of Jupiter on July 5, 2022, its JunoCam instrument captured this striking view of vortices – hurricane-like spiral wind patterns – near the planet's north pole. These powerful storms can be over 30 miles (50 kilometers) in height and hundreds of miles across. Figuring out how they form is key to understanding Jupiter's atmosphere, as well as the fluid dynamics and cloud chemistry that create the planet's other atmospheric features. Scientists are particularly interested in the vortices' varying shapes, sizes, and colors. For example, cyclones, which spin counter-clockwise in the northern hemisphere and clockwise in the southern, and anti-cyclones, which rotate clockwise in the northern hemisphere and counter-clockwise in the southern hemisphere, exhibit very different colors and shapes. A NASA citizen science project, Jovian Vortex Hunter, seeks help from volunteer members of the public to spot and help categorize vortices and other atmospheric phenomena visible in JunoCam photos of Jupiter. This process does not require specialized training or software, and can be done by anyone, anywhere, with a cellphone or laptop. As of July 2022, 2,404 volunteers had made 376,725 classifications using the Jovian Vortex Hunter project web site at https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/ramanakumars/jovian-vortex-hunter. Another citizen scientist, Brian Swift, created this enhanced color and contrast view of vortices using raw JunoCam image data. At the time the raw image was taken, the Juno spacecraft was about 15,600 miles (25,100 kilometers) above Jupiter's cloud tops, at a latitude of about 84 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25017

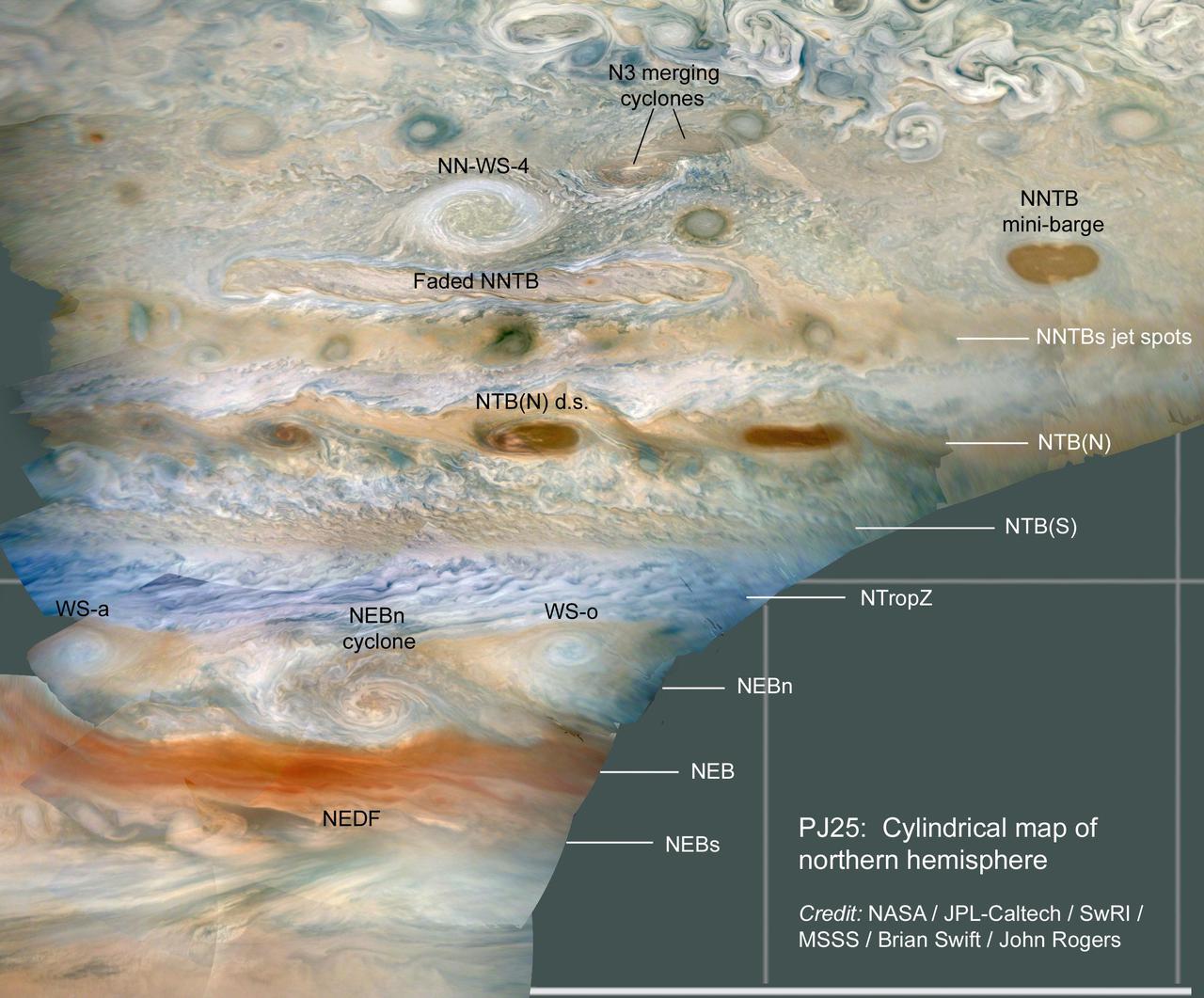

JunoCam imaged numerous storms in Jupiter's atmosphere on Juno's 25th close pass, in the region just north of Jupiter's equator. Amateurs and professional observers track these storms routinely to study the dynamics of Jupiter's atmosphere. Near the top of the image, two cyclones can be seen merging in the N3 jet stream. The next storm down is NN-WS-4 (the North North White Spot 4), rotating in an anticyclonic (clockwise rotation) direction. For scale this storm is about 4,000 miles (6,500 kilometers) across, roughly the distance between Cedar Rapids, Iowa to Honolulu, Hawaii. The elongated brown storms are familiar cyclonic (counterclockwise rotation) features, called "mini-barges." WS-a and WS-o are White Spots "a" and "o," anticyclonic storms that have persisted for over a year, separated by the North Equatorial Belt (NEB) north (NEBn) cyclone. The NEDF is the dark formation on the south edge of the NEB. Latitudinal belts and zones are labeled on the right with the conventions used by the amateur astronomy community and professional observers: NNTBs - North North Temperate Belt south; NTB(N) - North Temperate Belt (North); NTB(S) - North Temperate Belt (South); NTropZ - North Tropical Zone; NEBn - North Equatorial Belt north; NEB - North Equatorial Belt; NEBs - North Equatorial Belt south. The original JunoCam images used to produce these views were taken from altitudes between about 2,900 and 6,300 miles (4,600 and 10,200 kilometers) above Jupiter's cloud tops. Citizen scientist Brian Swift processed the images to produce a cylindrical map and enhance the color and contrast. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24236

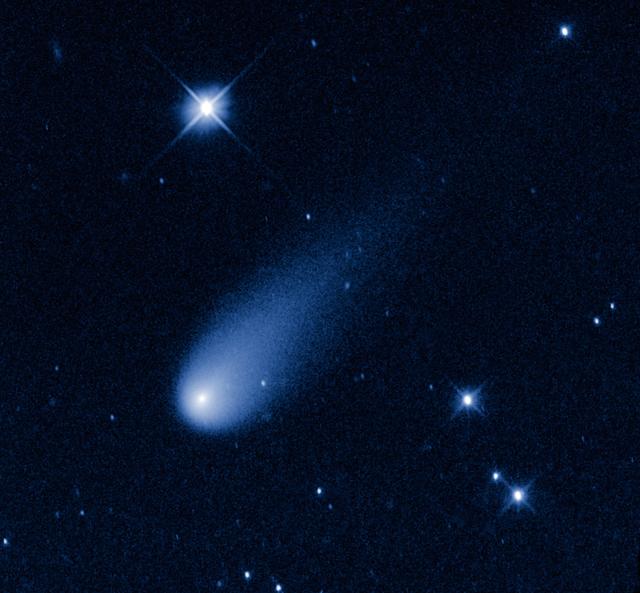

Superficially resembling a skyrocket, Comet ISON is hurtling toward the Sun at a whopping 48,000 miles per hour. Its swift motion is captured in this image taken May 8, 2013, by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. At the time the image was taken, the comet was 403 million miles from Earth, between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Unlike a firework, the comet is not combusting, but in fact is pretty cold. Its skyrocket-looking tail is really a streamer of gas and dust bleeding off the icy nucleus, which is surrounded by a bright, star-like-looking coma. The pressure of the solar wind sweeps the material into a tail, like a breeze blowing a windsock. As the comet warms as it moves closer to the Sun, its rate of sublimation will increase. The comet will get brighter and the tail grows longer. The comet is predicted to reach naked-eye visibility in November. The comet is named after the organization that discovered it, the Russia-based International Scientific Optical Network. This false-color, visible-light image was taken with Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3. Credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA) -------- More details on Comet ISON: Comet ISON began its trip from the Oort cloud region of our solar system and is now travelling toward the sun. The comet will reach its closest approach to the sun on Thanksgiving Day -- 28 Nov 2013 -- skimming just 730,000 miles above the sun's surface. If it comes around the sun without breaking up, the comet will be visible in the Northern Hemisphere with the naked eye, and from what we see now, ISON is predicted to be a particularly bright and beautiful comet. Catalogued as C/2012 S1, Comet ISON was first spotted 585 million miles away in September 2012. This is ISON's very first trip around the sun, which means it is still made of pristine matter from the earliest days of the solar system’s formation, its top layers never having been lost by a trip near the sun. Comet ISON is, like all comets, a dirty snowball made up of dust and frozen gases like water, ammonia, methane and carbon dioxide -- some of the fundamental building blocks that scientists believe led to the formation of the planets 4.5 billion years ago. NASA has been using a vast fleet of spacecraft, instruments, and space- and Earth-based telescope, in order to learn more about this time capsule from when the solar system first formed. The journey along the way for such a sun-grazing comet can be dangerous. A giant ejection of solar material from the sun could rip its tail off. Before it reaches Mars -- at some 230 million miles away from the sun -- the radiation of the sun begins to boil its water, the first step toward breaking apart. And, if it survives all this, the intense radiation and pressure as it flies near the surface of the sun could destroy it altogether. This collection of images show ISON throughout that journey, as scientists watched to see whether the comet would break up or remain intact. The comet reaches its closest approach to the sun on Thanksgiving Day -- Nov. 28, 2013 -- skimming just 730,000 miles above the sun’s surface. If it comes around the sun without breaking up, the comet will be visible in the Northern Hemisphere with the naked eye, and from what we see now, ISON is predicted to be a particularly bright and beautiful comet. ISON stands for International Scientific Optical Network, a group of observatories in ten countries who have organized to detect, monitor, and track objects in space. ISON is managed by the Keldysh Institute of Applied Mathematics, part of the Russian Academy of Sciences. <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scienti