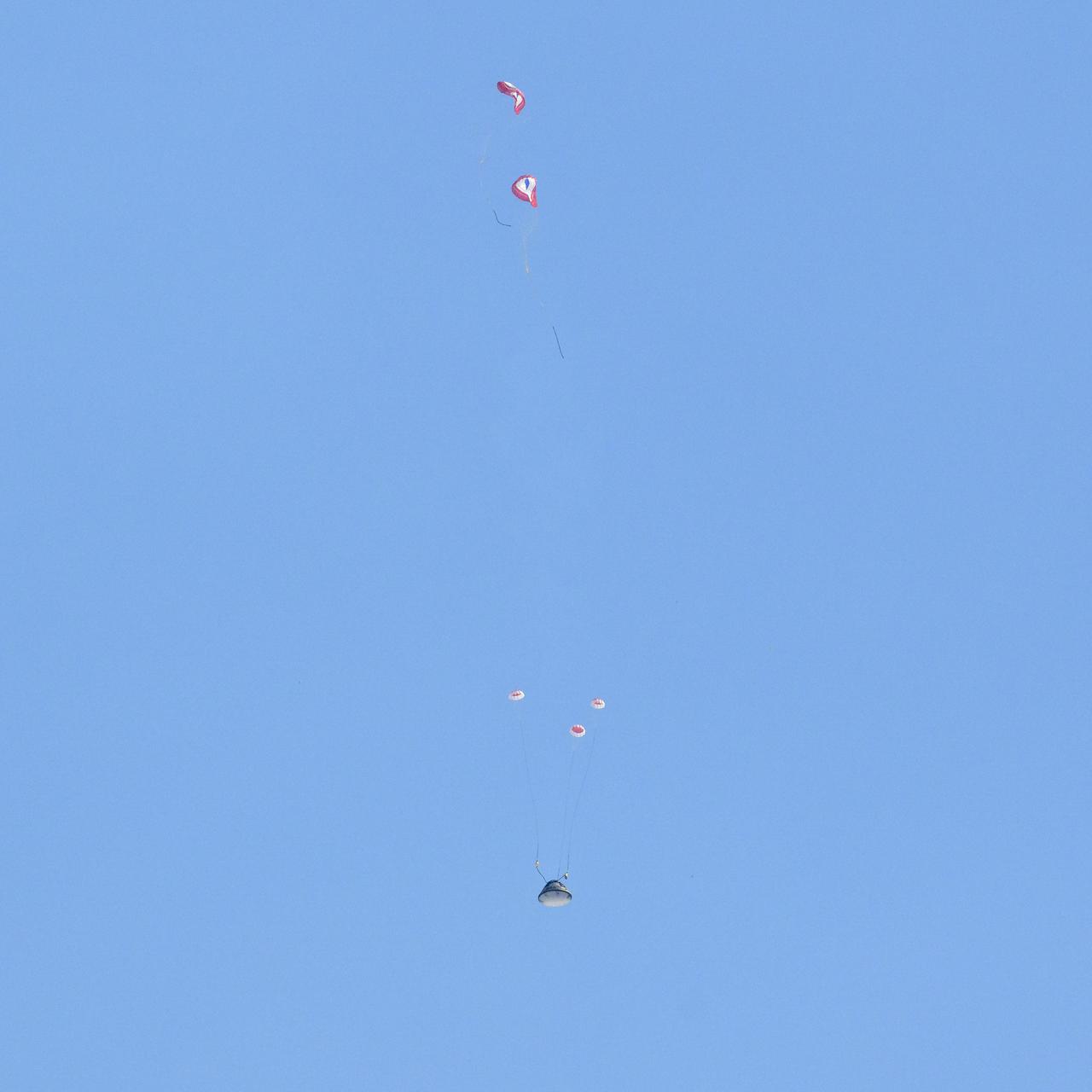

The Soyuz MS-26 spacecraft drogue parachute is seen during the landing of the Soyuz MS-26 spacecraft in a remote area near the town of Zhezkazgan, Kazakhstan with Expedition 72 NASA astronaut Don Pettit, and Roscosmos cosmonauts Alexey Ovchinin and Ivan Vagner aboard, Sunday, April 20, 2025, (April 19 Eastern). The trio are returning to Earth after logging 220 days in space as members of Expeditions 71 and 72 aboard the International Space Station. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

The Soyuz MS-26 spacecraft, lower left, and it’s drogue parachute, are seen as the spacecraft lands in a remote area near the town of Zhezkazgan, Kazakhstan with Expedition 72 NASA astronaut Don Pettit, and Roscosmos cosmonauts Alexey Ovchinin and Ivan Vagner aboard, Sunday, April 20, 2025, (April 19 Eastern). The trio are returning to Earth after logging 220 days in space as members of Expeditions 71 and 72 aboard the International Space Station. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

The drogue parachute of the Soyuz MS-11 spacecraft is seen during the landing of Expedition 59 crew members Anne McClain of NASA, David Saint-Jacques of the Canadian Space Agency, and Oleg Kononenko of Roscosmos near the town of Zhezkazgan, Kazakhstan, Tuesday, June 25, 2019 Kazakh time (June 24 Eastern time). McClain, Saint-Jacques, and Kononenko are returning after 204 days in space where they served as members of the Expedition 58 and 59 crews onboard the International Space Station. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

The drogue parachute of the Soyuz MS-17 spacecraft is seen as the capsule lands in a remote area near the town of Zhezkazgan, Kazakhstan with Expedition 64 crew members Kate Rubins of NASA, Sergey Ryzhikov and Sergey Kud-Sverchkov of Roscosmos, Saturday, April 17, 2021. Rubins, Ryzhikov and Kud-Sverchkov returned after 185 days in space having served as Expedition 63-64 crew members onboard the International Space Station. Photo Credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls

The drogue parachute of the Soyuz MS-12 spacecraft is seen coming down after the capsule landed with Expedition 60 crew members Nick Hague of NASA and Alexey Ovchinin of Roscosmos, along with visiting astronaut Hazzaa Ali Almansoori of the United Arab Emirates, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2019. Hague and Ovchinin are returning after 203 days in space where they served as members of the Expedition 59 and 60 crews onboard the International Space Station. Almansoori logged 8 days in space during his first flight as an astronaut. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

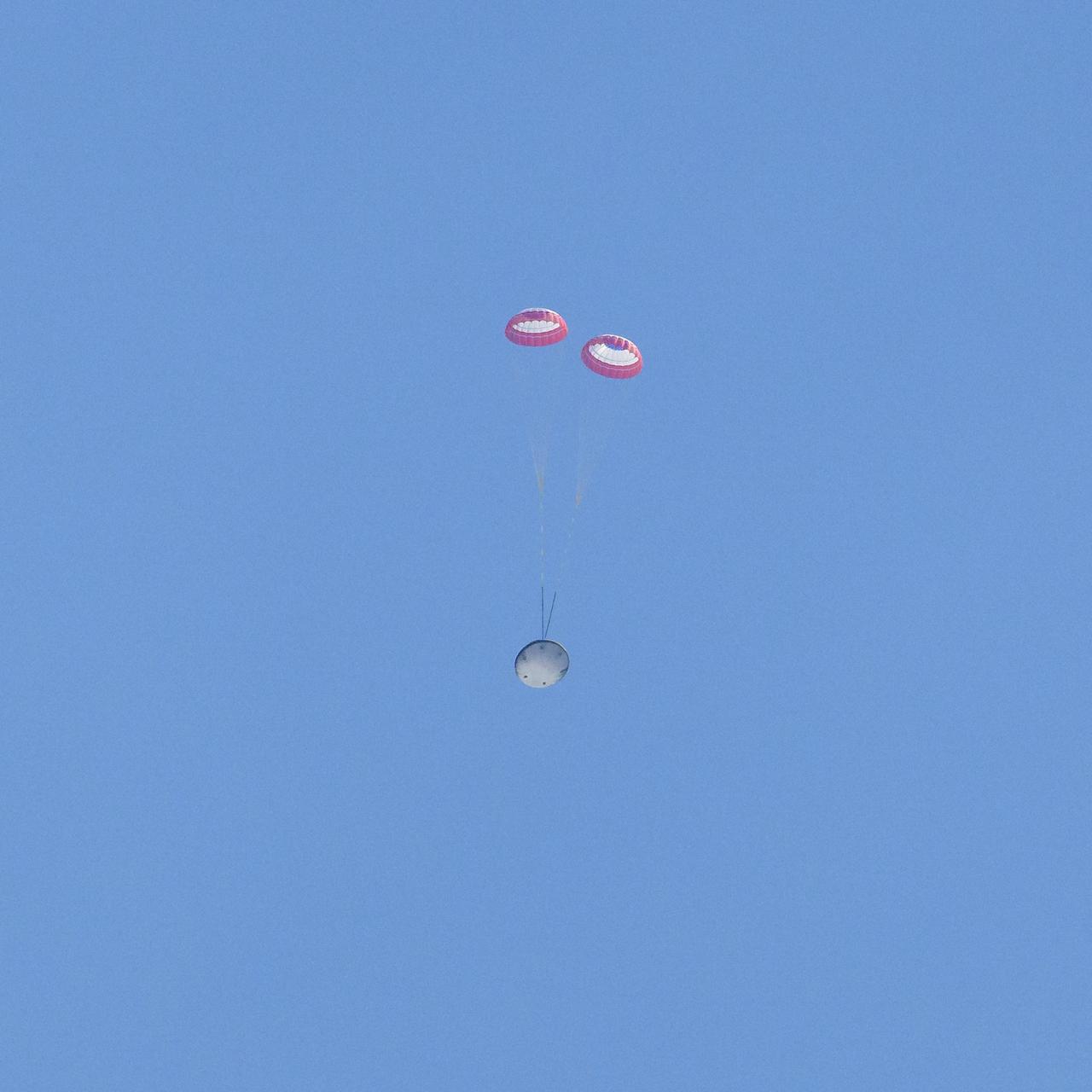

The drogue parachutes of the SpaceX Crew Dragon Freedom spacecraft are seen after being released during the landing of NASA astronauts Kjell Lindgren, Robert Hines, Jessica Watkins, and ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti aboard in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Jacksonville, Florida, Friday, Oct. 14, 2022. Lindgren, Hines, Watkins, and Cristoforetti are returning after 170 days in space as part of Expeditions 67 and 68 aboard the International Space Station. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Support teams work around the SpaceX Dragon Endurance spacecraft shortly after it landed with NASA astronauts Anne McClain and Nichole Ayers, JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) astronaut Takuya Onishi, and Roscosmos cosmonaut Kirill Peskov aboard in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of San Diego, Calif., Saturday, Aug. 9,2025. McClain, Ayers, Onishi, and Peskov are returning after 147 days in space as part of Expedition 73 aboard the International Space Station. The drogue parachutes can also be seen in the sky behind the SpaceX Dragon Endurance spacecraft as they land in the Pacific Ocean. Photo Credit: (NASA/Keegan Barber)

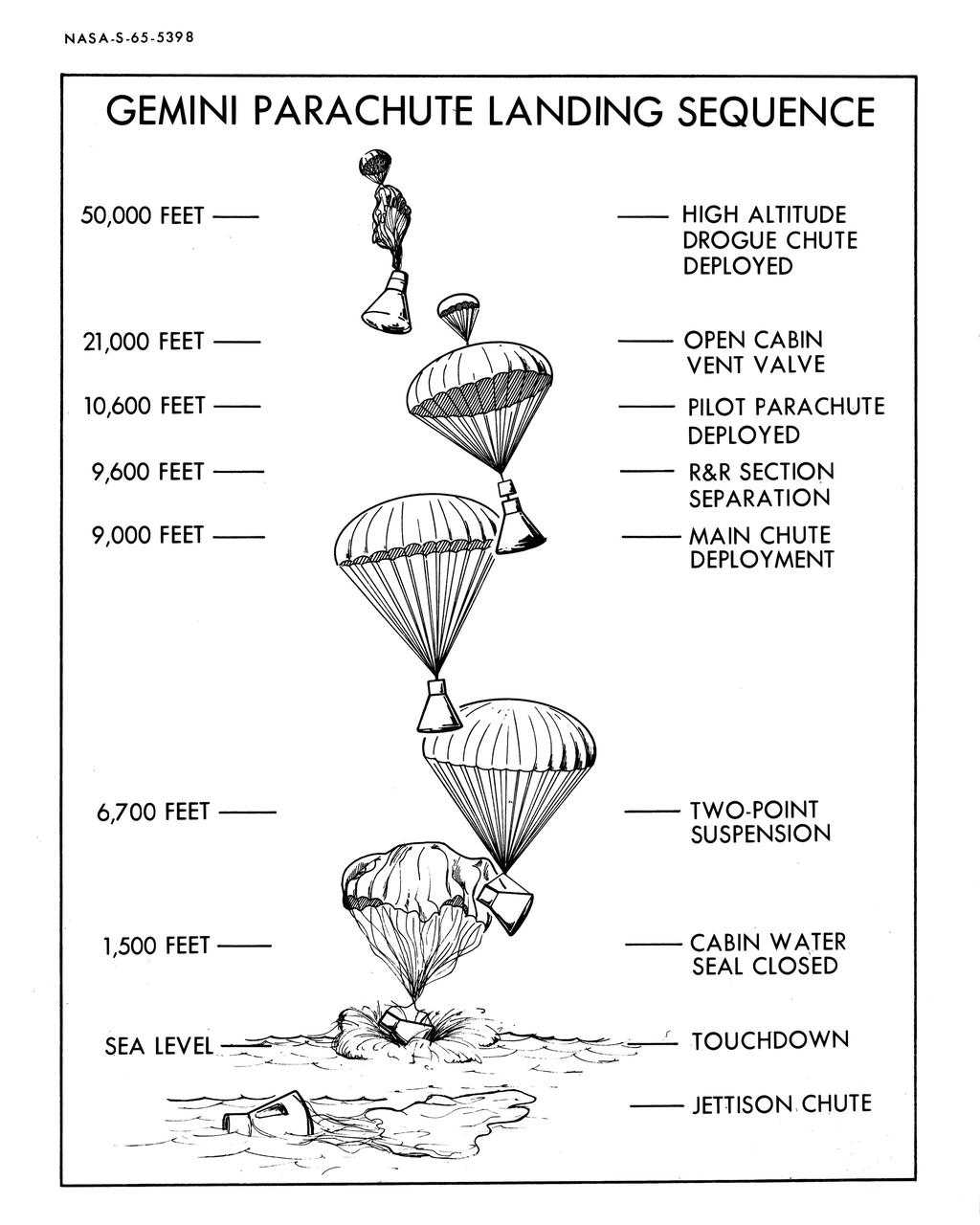

S65-05398 (1965) --- Artist concept of Gemini parachute landing sequence from high altitude drogue chute deployed to jettison of chute.

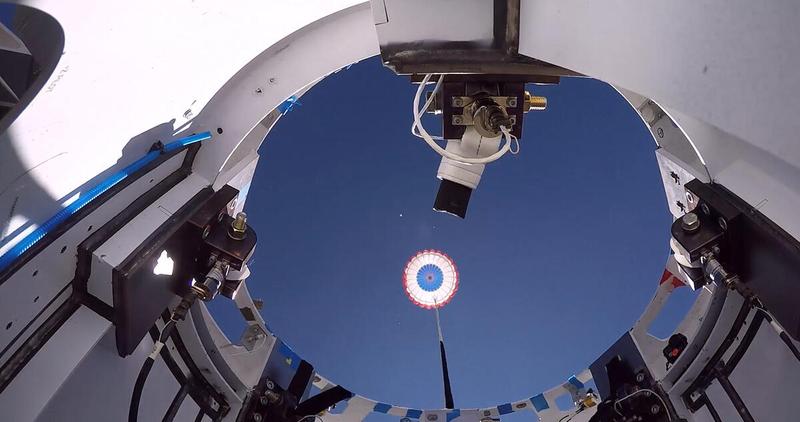

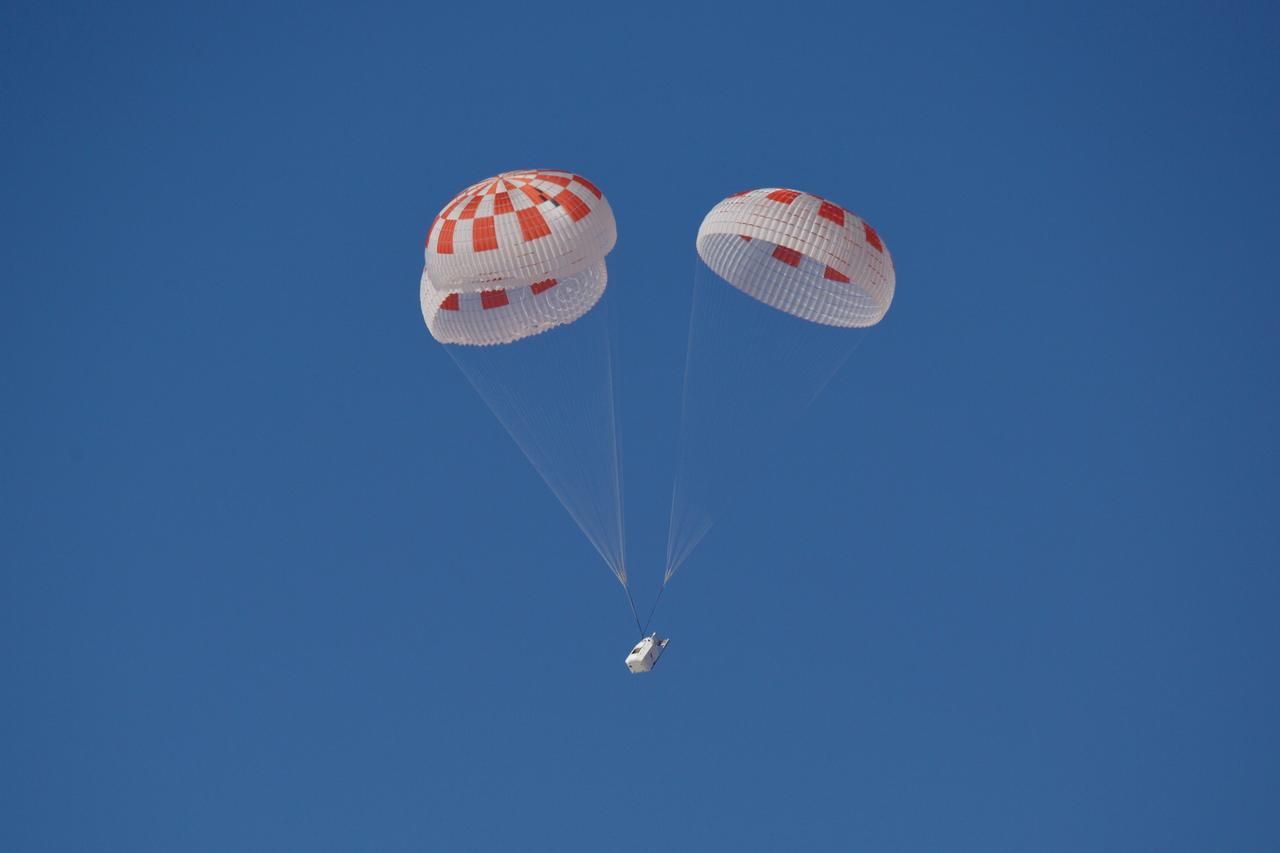

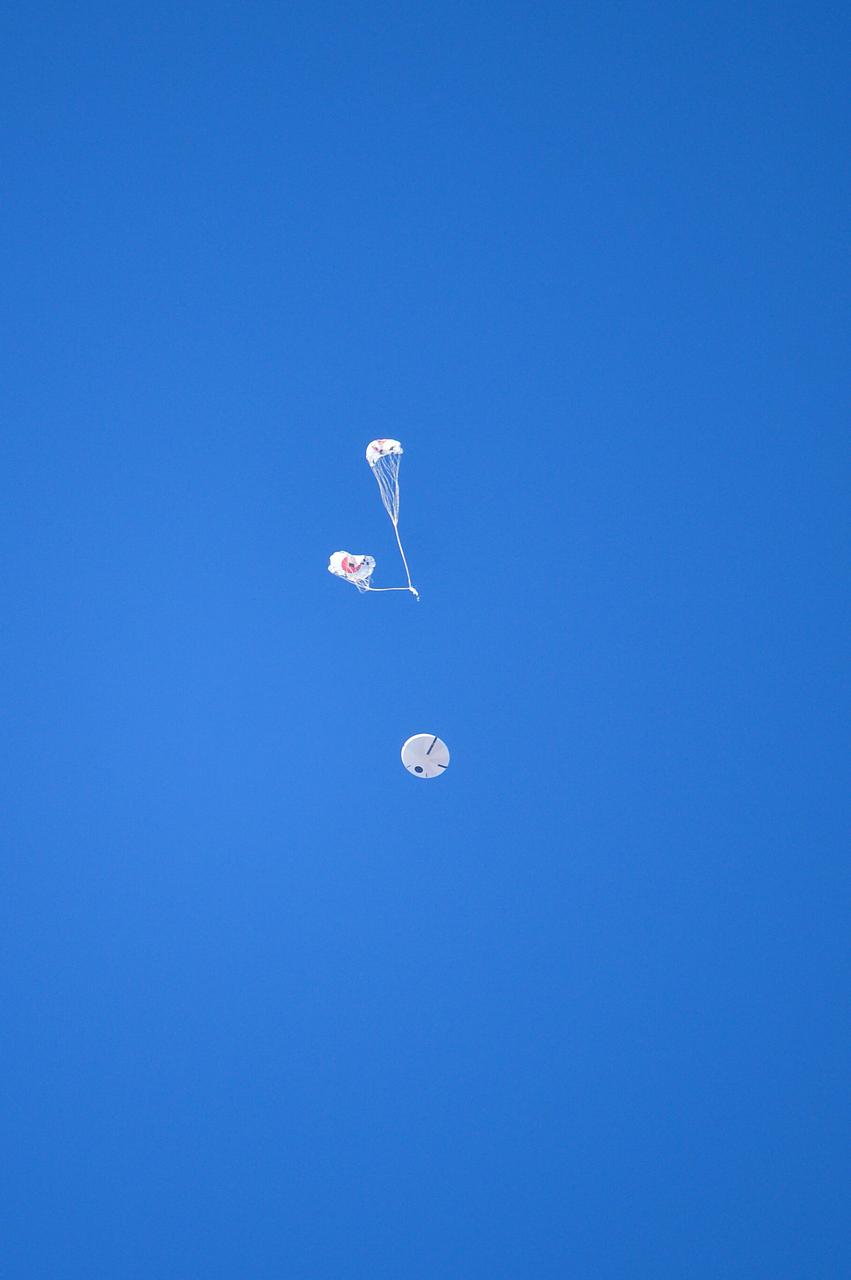

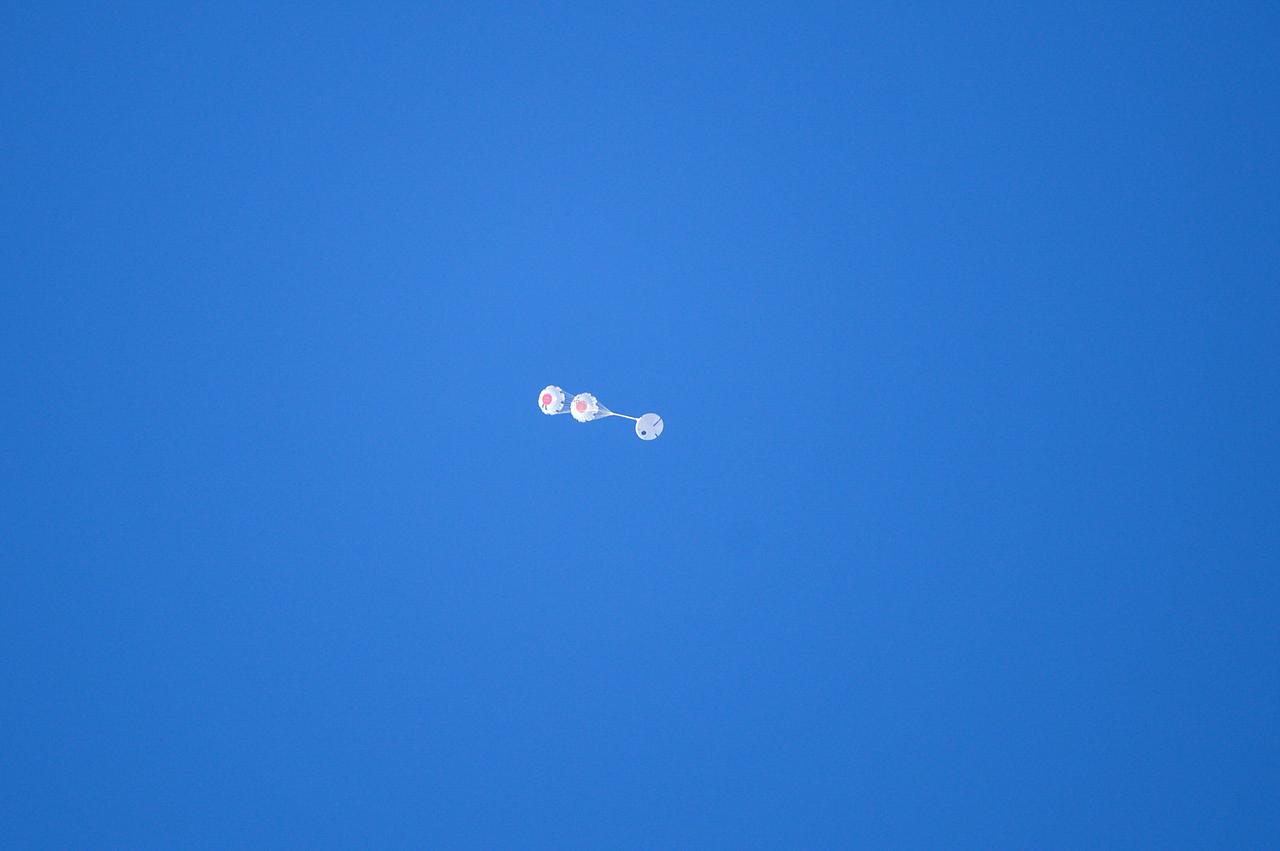

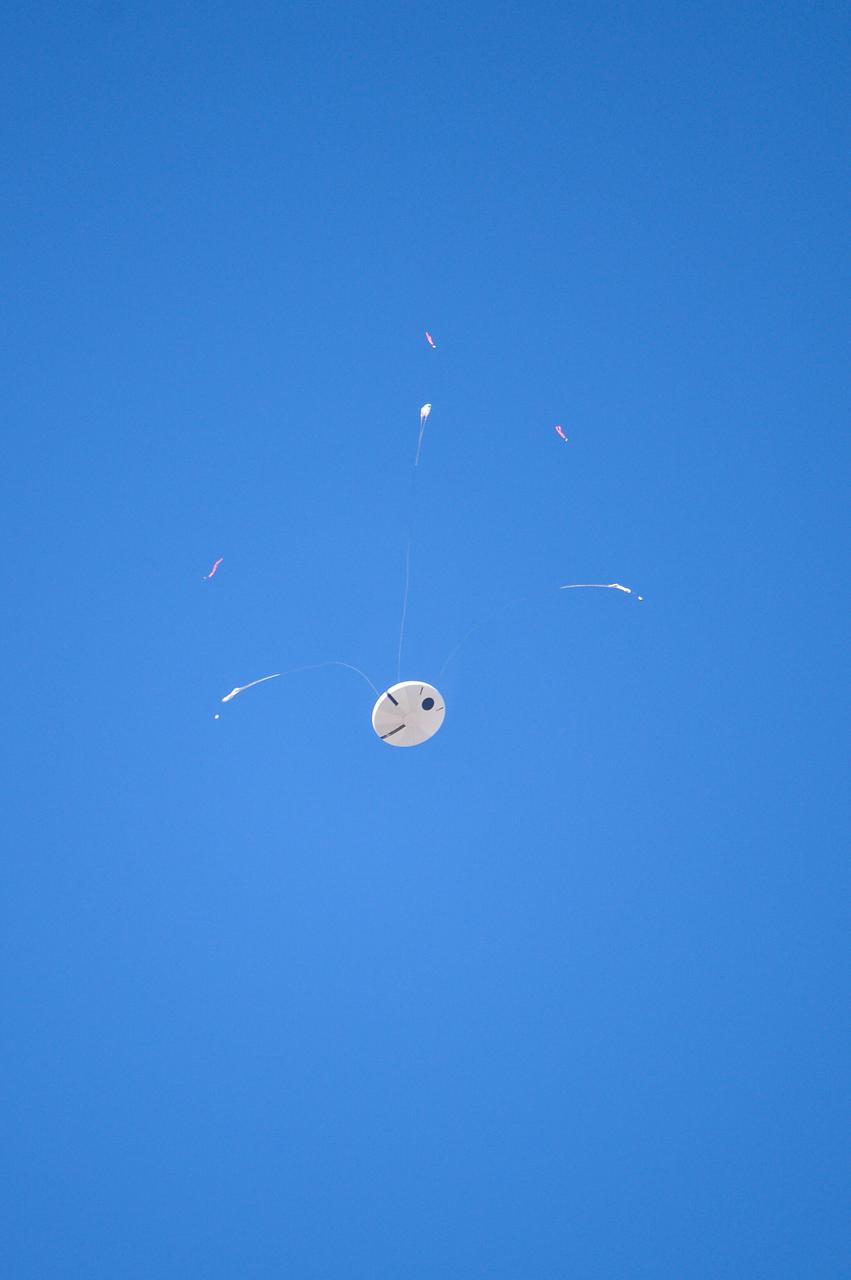

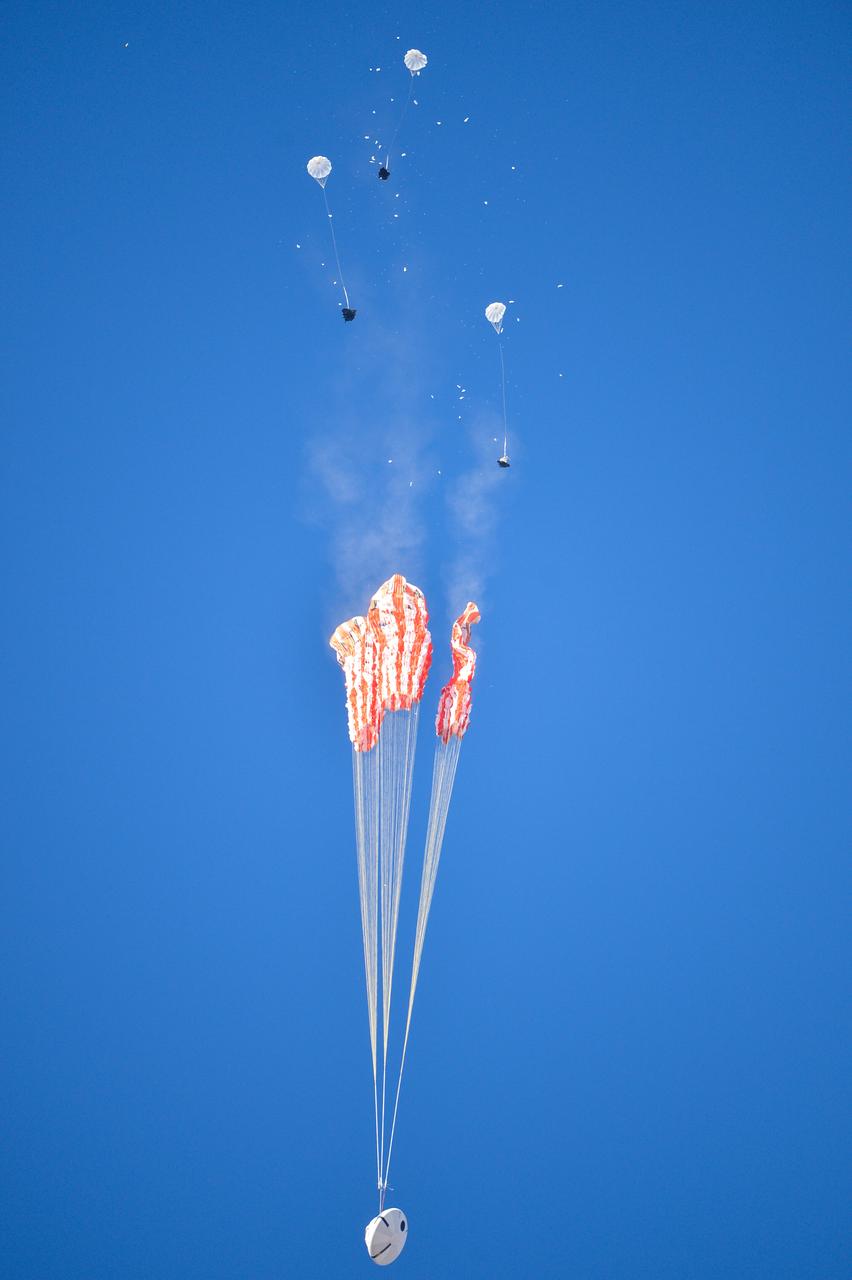

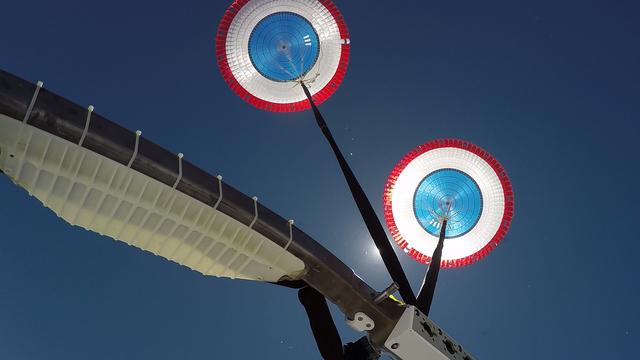

MORRO BAY, Calif. – Drogue chutes open above Dragon test article during a test to evaluate the spacecraft's parachute deployment system. The drogue chutes stabilized the vehicle, in preparation for main chute deployment as part of a milestone under SpaceX's Commercial Crew Integrated Capability agreement with NASA's Commercial Crew Program. Photo credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

MORRO BAY, Calif. – Drogue chutes open above Dragon test article during a test to evaluate the spacecraft's parachute deployment system. The drogue chutes stabilized the vehicle, in preparation for main chute deployment as part of a milestone under SpaceX's Commercial Crew Integrated Capability agreement with NASA's Commercial Crew Program. Photo credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

MORRO BAY, Calif. – Drogue chutes open above Dragon test article during a test to evaluate the spacecraft's parachute deployment system. The drogue chutes stabilized the vehicle, in preparation for main chute deployment as part of a milestone under SpaceX's Commercial Crew Integrated Capability agreement with NASA's Commercial Crew Program. Photo credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

NASA engineers prepare for the test of the Orion spacecraft’s parachutes on Wednesday, Aug. 26 at the U.S. Army’s Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. An engineering model of the spacecraft will drop from an airplane 35,000 feet up to evaluate how it fares when the parachute system does not perform as expected...During the test, Orion engineers will carry out a scenario in which one of the spacecraft’s two drogue parachutes and one of its three main parachutes fail. This high-risk assessment is the penultimate drop test of the scheduled engineering evaluations leading up to next year’s tests to qualify the parachute system for crewed flights. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

A reused drogue parachute deploys from Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner test article during the final balloon drop parachute test above White Sands, New Mexico, on Sept. 19, 2020. The test is part of a reliability campaign that will help strengthen the spacecraft’s landing system ahead of crewed flights to and from the International Space Station as part of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program.

A full-scale Boeing CST-100 Starliner test article, known as a boiler plate, successfully lands at the U.S. Army’s White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico during parachute system testing on June 24, 2019. Boeing conducted the test, which involved intentionally disabling one of the parachute system’s two drogue parachutes and one of the three main parachutes to evaluate how the remaining parachutes handled the additional loads during deployment and descent. This was one of a series of important parachute tests to validate the system is safe to carry astronauts to and from the International Space Station as part of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. Boeing is targeting an uncrewed Orbital Flight Test to the space station this summer, followed by its Crew Flight Test. Starliner will launch atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner’s parachute systems are successfully tested at the U.S. Army’s White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico on June 24, 2019. Boeing conducted the test using a full-scale Starliner test article, known as a boiler plate, designed to simulate the actual spacecraft. The test involved intentionally disabling one of the parachute system’s two drogue parachutes and one of the three main parachutes to evaluate how the remaining parachutes handled the additional loads during deployment and descent. This was one of a series of important parachute tests to validate the system is safe to carry astronauts to and from the International Space Station as part of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. Boeing is targeting an uncrewed Orbital Flight Test to the space station this summer, followed by its Crew Flight Test. Starliner will launch atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner’s parachute systems are successfully tested at the U.S. Army’s White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico on June 24, 2019. Boeing conducted the test using a full-scale Starliner test article, known as a boiler plate, designed to simulate the actual spacecraft. The test involved intentionally disabling one of the parachute system’s two drogue parachutes and one of the three main parachutes to evaluate how the remaining parachutes handled the additional loads during deployment and descent. This was one of a series of important parachute tests to validate the system is safe to carry astronauts to and from the International Space Station as part of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. Boeing is targeting an uncrewed Orbital Flight Test to the space station this summer, followed by its Crew Flight Test. Starliner will launch atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

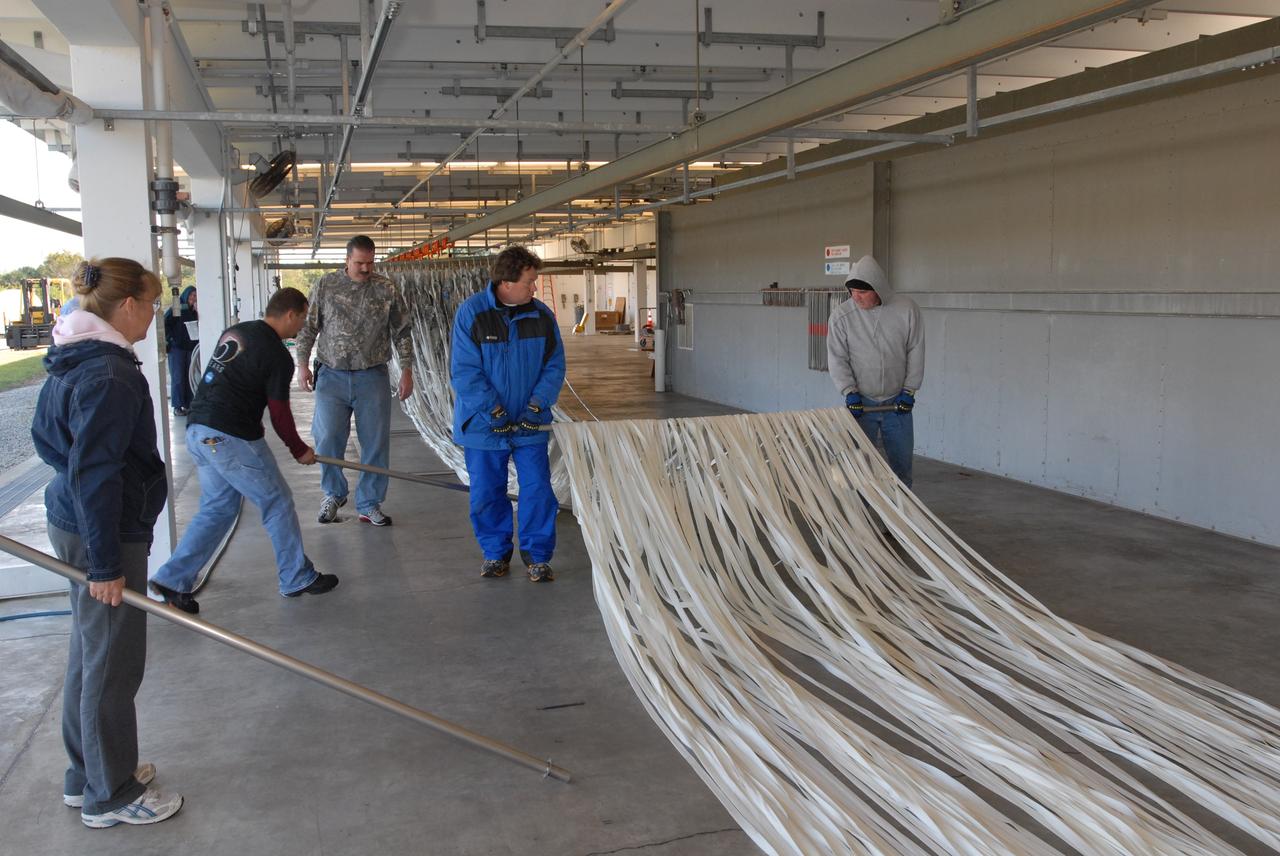

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – At the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, workers spread out the parachutes recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission to detangle them. The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be carefully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

SpaceX performed its fourteenth overall parachute test supporting Crew Dragon development. This most recent exercise was the first of several planned parachute system qualification tests ahead of the spacecraft’s first crewed flight and resulted in the successful touchdown of Crew Dragon’s parachute system. During this test, a C-130 aircraft transported the parachute test vehicle, designed to achieve the maximum speeds that Crew Dragon could experience on re-entry, over the Mojave Desert in Southern California and dropped the vehicle from an altitude of 25,000 feet. The test demonstrated an off-nominal situation, deploying only one of the two drogue chutes and intentionally skipping a reefing stage on one of the four main parachutes, proving a safe landing in such a contingency scenario.

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – At the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, a worker checks the parachute lines suspended from the monorail system. The parachutes were recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. The monorail will transport each parachute into a 30,000-gallon washer and a huge dryer heated with 140-degree air at 13,000 cubic feet per minute. One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be carefully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – At the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, workers place rods under the lines of the parachutes recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission to hang them on a monorail system. Behind them, the parachutes are suspended from the monorail. The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. The monorail will transport each parachute into a 30,000-gallon washer and a huge dryer heated with 140-degree air at 13,000 cubic feet per minute. One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be carefully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

SpaceX performed its fourteenth overall parachute test supporting Crew Dragon development. This most recent exercise was the first of several planned parachute system qualification tests ahead of the spacecraft’s first crewed flight and resulted in the successful touchdown of Crew Dragon’s parachute system. During this test, a C-130 aircraft transported the parachute test vehicle, designed to achieve the maximum speeds that Crew Dragon could experience on re-entry, over the Mojave Desert in Southern California and dropped the vehicle from an altitude of 25,000 feet. The test demonstrated an off-nominal situation, deploying only one of the two drogue chutes and intentionally skipping a reefing stage on one of the four main parachutes, proving a safe landing in such a contingency scenario.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

SpaceX performed its fourteenth overall parachute test supporting Crew Dragon development. This most recent exercise was the first of several planned parachute system qualification tests ahead of the spacecraft’s first crewed flight and resulted in the successful touchdown of Crew Dragon’s parachute system. During this test, a C-130 aircraft transported the parachute test vehicle, designed to achieve the maximum speeds that Crew Dragon could experience on re-entry, over the Mojave Desert in Southern California and dropped the vehicle from an altitude of 25,000 feet. The test demonstrated an off-nominal situation, deploying only one of the two drogue chutes and intentionally skipping a reefing stage on one of the four main parachutes, proving a safe landing in such a contingency scenario.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

SpaceX performed its fourteenth overall parachute test supporting Crew Dragon development. This most recent exercise was the first of several planned parachute system qualification tests ahead of the spacecraft’s first crewed flight and resulted in the successful touchdown of Crew Dragon’s parachute system. During this test, a C-130 aircraft transported the parachute test vehicle, designed to achieve the maximum speeds that Crew Dragon could experience on re-entry, over the Mojave Desert in Southern California and dropped the vehicle from an altitude of 25,000 feet. The test demonstrated an off-nominal situation, deploying only one of the two drogue chutes and intentionally skipping a reefing stage on one of the four main parachutes, proving a safe landing in such a contingency scenario.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

Engineers prepare to test the parachute system for NASA’s Orion spacecraft at the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona on Aug. 24, 2015. During the test, planned for Wednesday, Aug. 26, a C-17 aircraft will carry a representative Orion capsule to 35,000 feet in altitude and then drop it from its cargo bay. Engineers will test a scenario in which one of Orion’s two drogue parachutes, used to stabilize it in the air, does not deploy, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the capsule during the final stage of descent, also does not deploy. The risky test will provide data engineers will use as they gear up to qualify Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts. On Aug. 24, a C-17 was loaded with the test version of Orion, which has a similar mass and interfaces with the parachutes as the Orion being developed for deep space missions but is shorter on top to fit inside the aircraft. Part of Batch image transfer from Flickr.

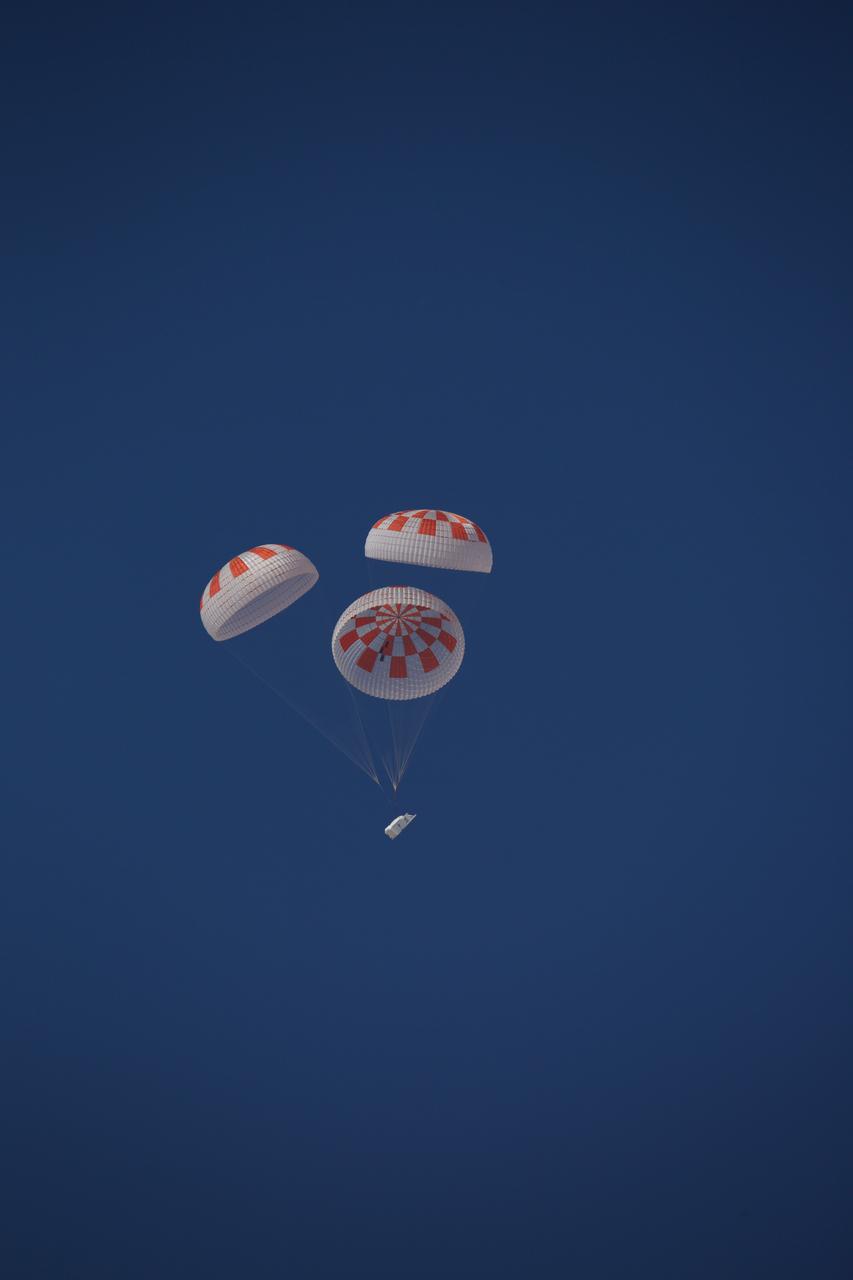

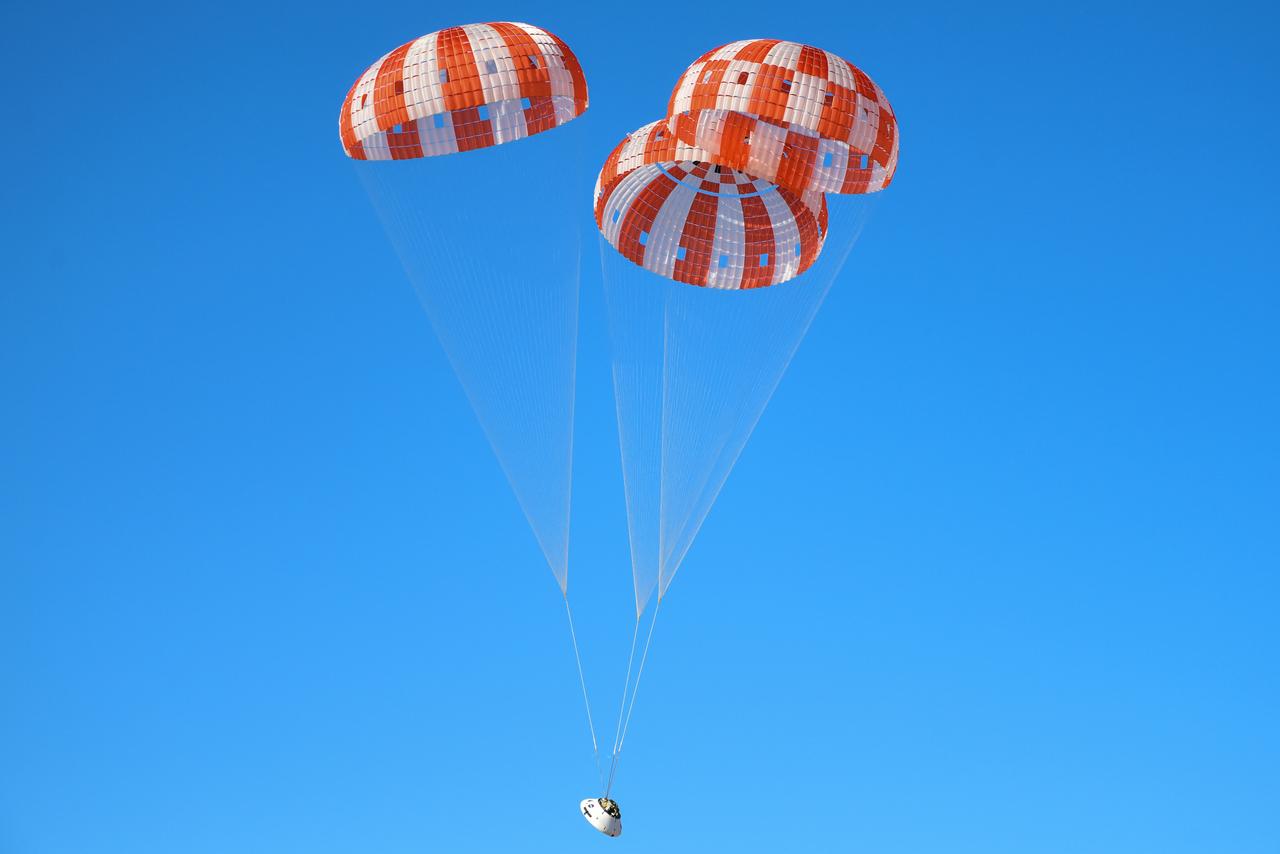

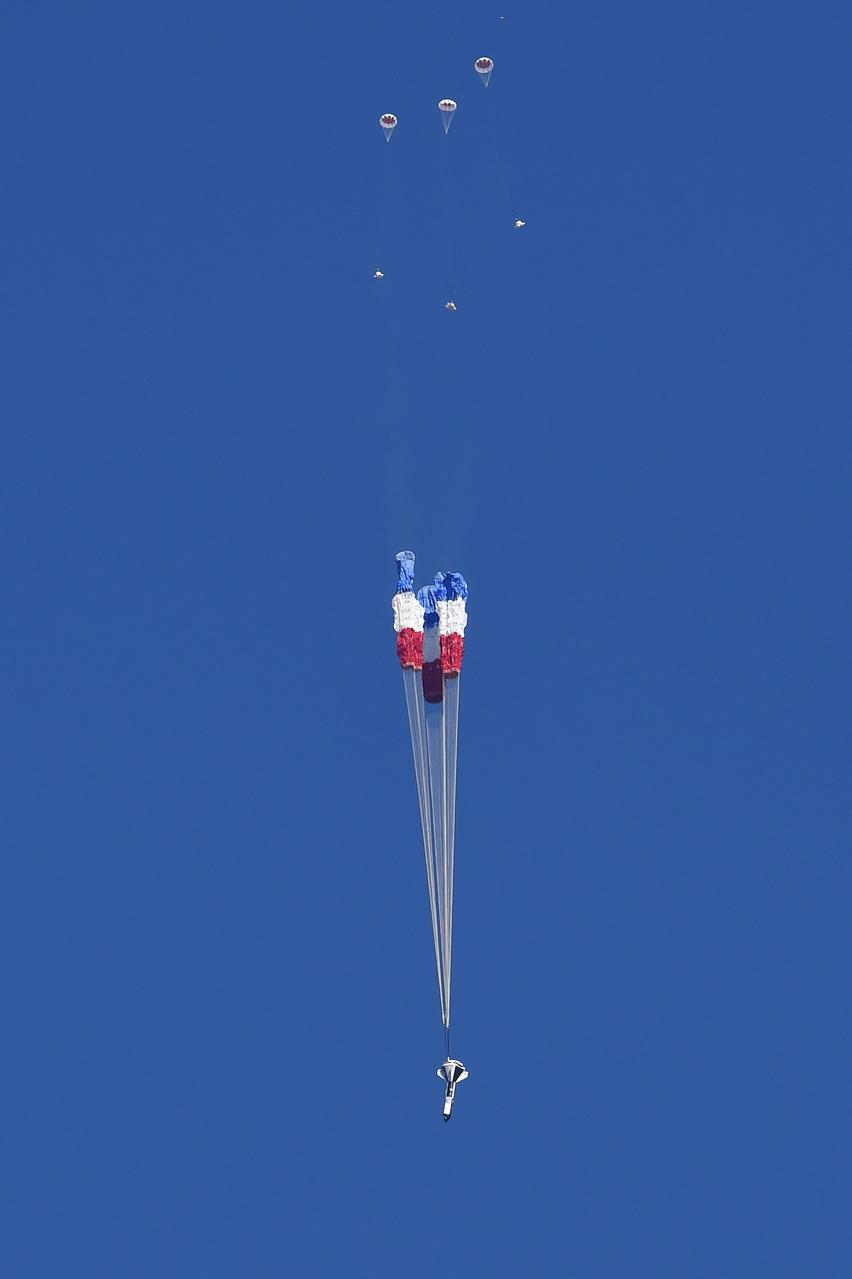

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

Orion’s three main orange and white parachutes help a representative model of the spacecraft descend through sky above Arizona, where NASA engineers tested the parachute system on Sept. 13, 2017 at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma. NASA is qualifying Orion’s parachutes for missions with astronauts.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – At the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, workers begin hanging the parachutes recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission onto a monorail system. The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. The monorail will transport each parachute into a 30,000-gallon washer and a huge dryer heated with 140-degree air at 13,000 cubic feet per minute One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be carefully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – At the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the parachutes recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission are moved through the 30,000-gallon washer. The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. After washing, the monorail will move the parachutes into a huge dryer heated with 140-degree air at 13,000 cubic feet per minute. One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be carefully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – At the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, another parachute recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission is unwound from a large turnstile. After their recovery, the parachutes are untangled, hung on a monorail system and transported into a 30,000-gallon washer and a huge dryer heated with 140-degree air at 13,000 cubic feet per minute. The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be carefully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – At the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, workers begin hanging the parachutes recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission onto a monorail system. The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. The monorail will transport each parachute into a 30,000-gallon washer and a huge dryer heated with 140-degree air at 13,000 cubic feet per minute. One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be carefully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – Parachutes recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission are suspended from a hanging monorail system at the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. The monorail will transport each parachute into a 30,000-gallon washer and a huge dryer heated with 140-degree air at 13,000 cubic feet per minute. One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be carefully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – At the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, a worker checks the parachute lines, recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission, as they move into the 30,000-gallon washer. The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. After washing, the monorail will move the parachutes into a huge dryer heated with 140-degree air at 13,000 cubic feet per minute. One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be carefully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – In the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, workers repair the parachutes recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission. Typically, each main canopy requires hundreds of repairs after each use. The smaller chutes and the parachute deployment bags they are packed in also require repairs. The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be carefully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – Parachutes recovered from sea after the launch of space shuttle Endeavour on the STS-126 mission are stretched out at the Parachute Refurbishment Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida to detangle them. The parachutes are used to slow the descent of the solid rocket boosters that are jettisoned during liftoff. After the chutes are returned to the facility following launch, a hanging monorail system is used to transport each parachute into a 30,000-gallon washer and then into a huge dryer heated with 140-de¬gree air at 13,000 cubic feet per minute. One pilot, one drogue and three main canopies per booster slow the booster’s fall from about 360 mph to 50 mph. After the chutes are cleaned and repaired, they must be care¬fully packed into their bags so they will deploy correctly the next time they are used. Photo credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

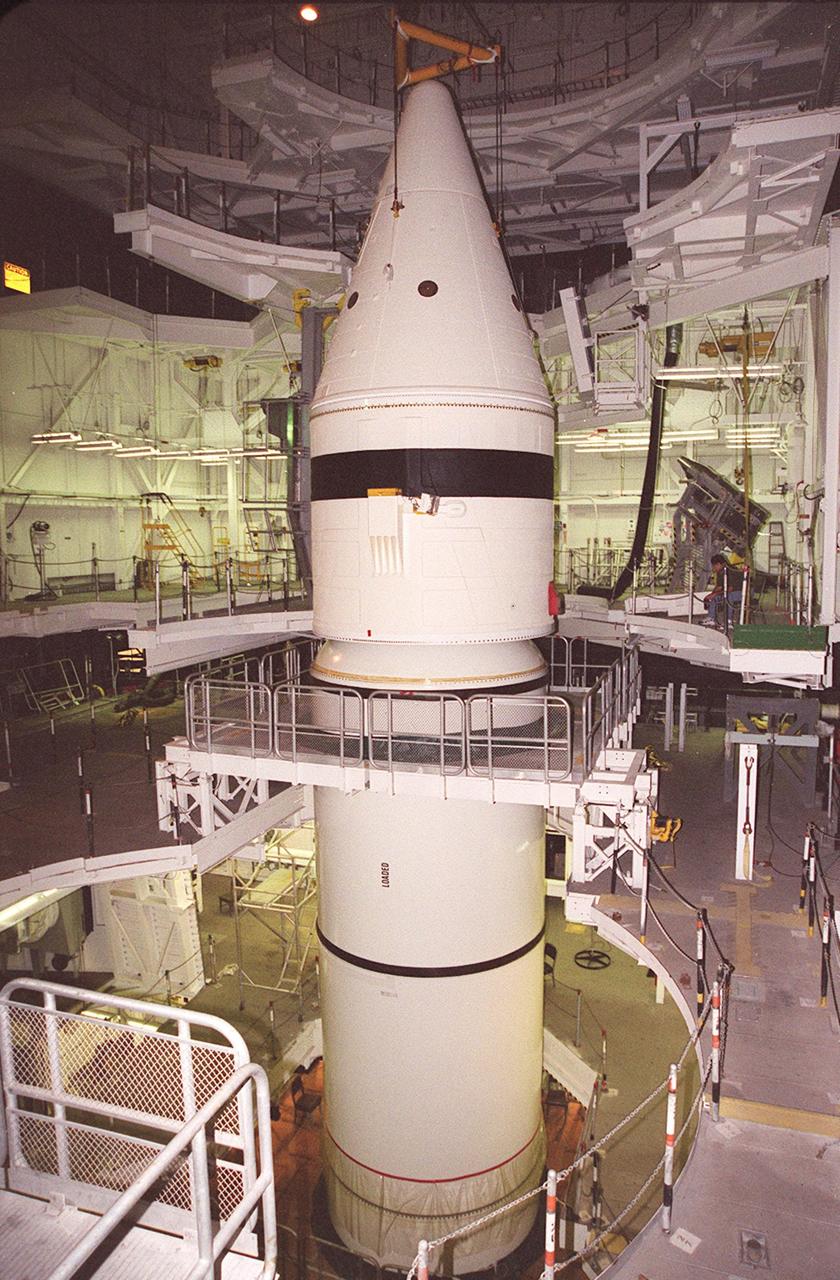

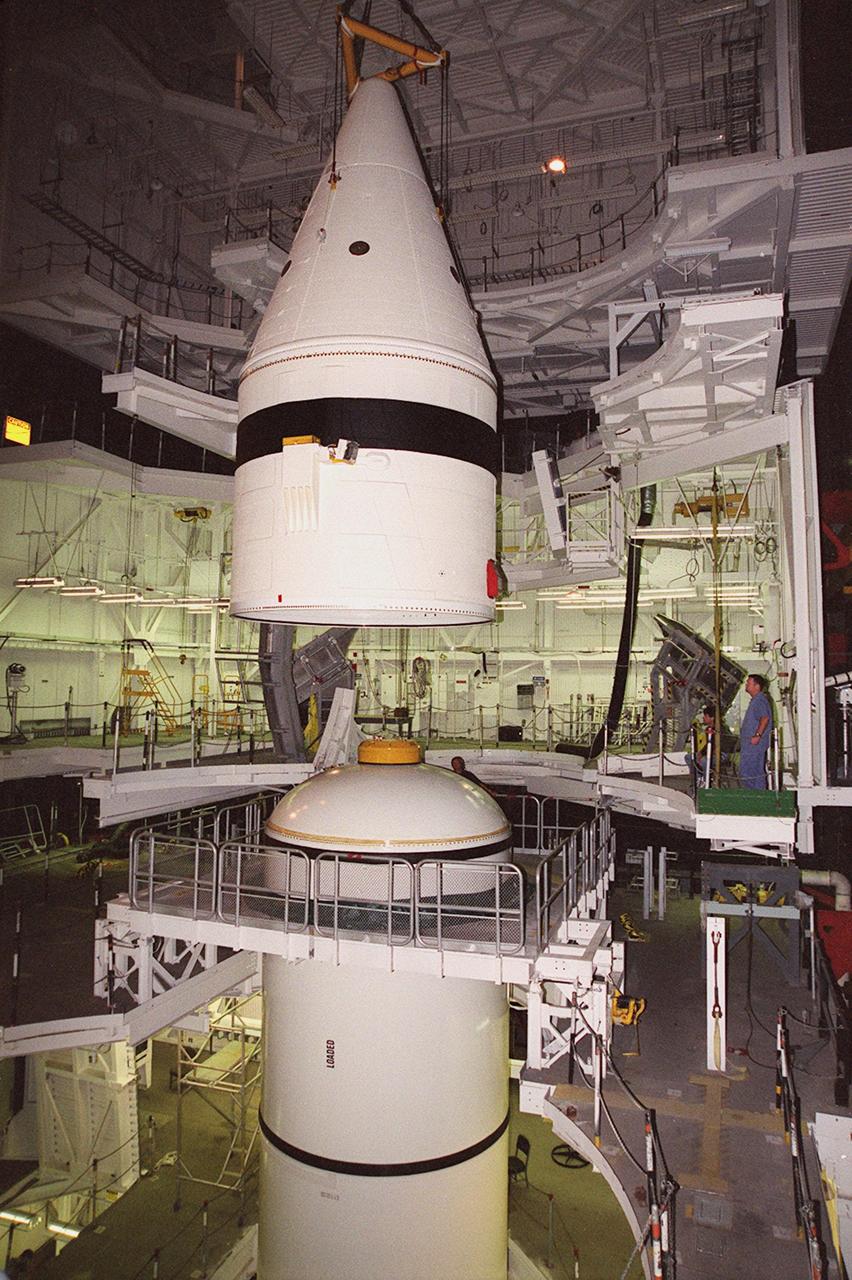

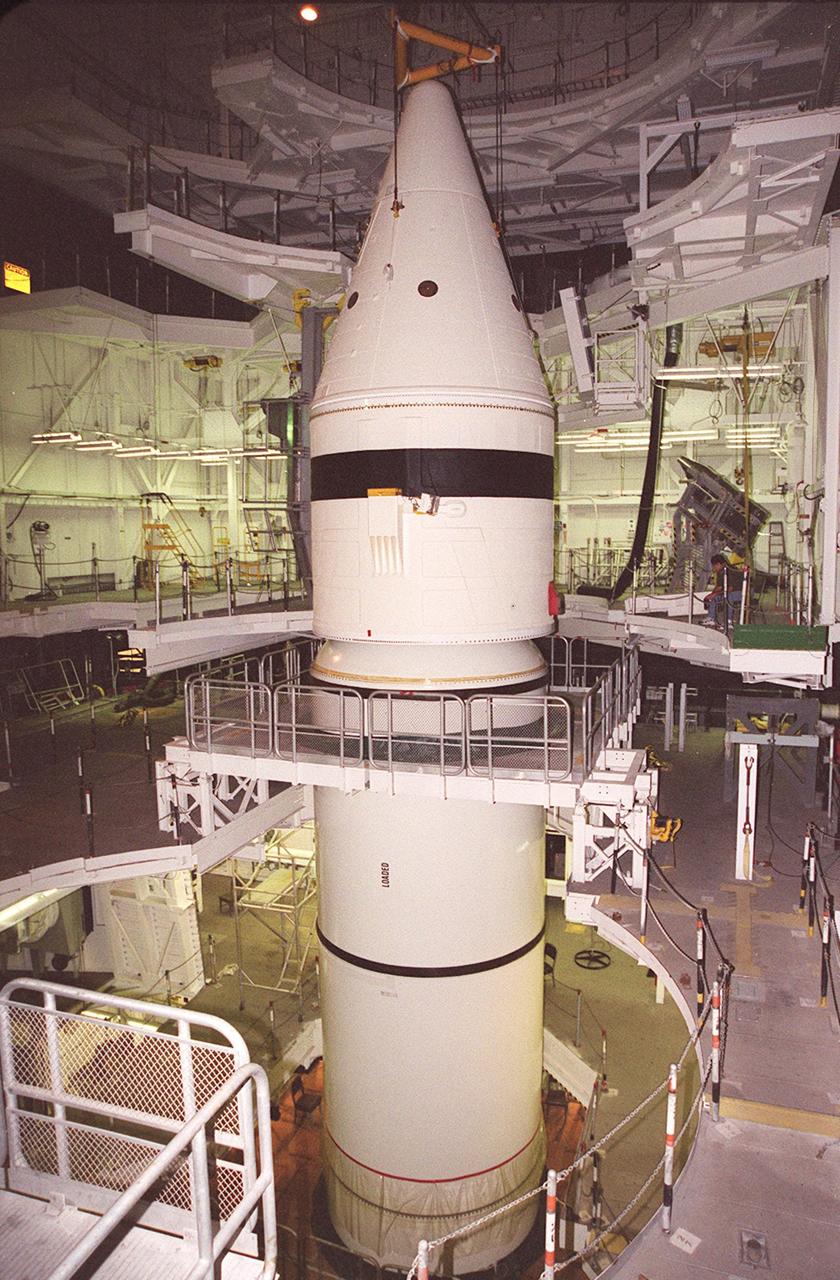

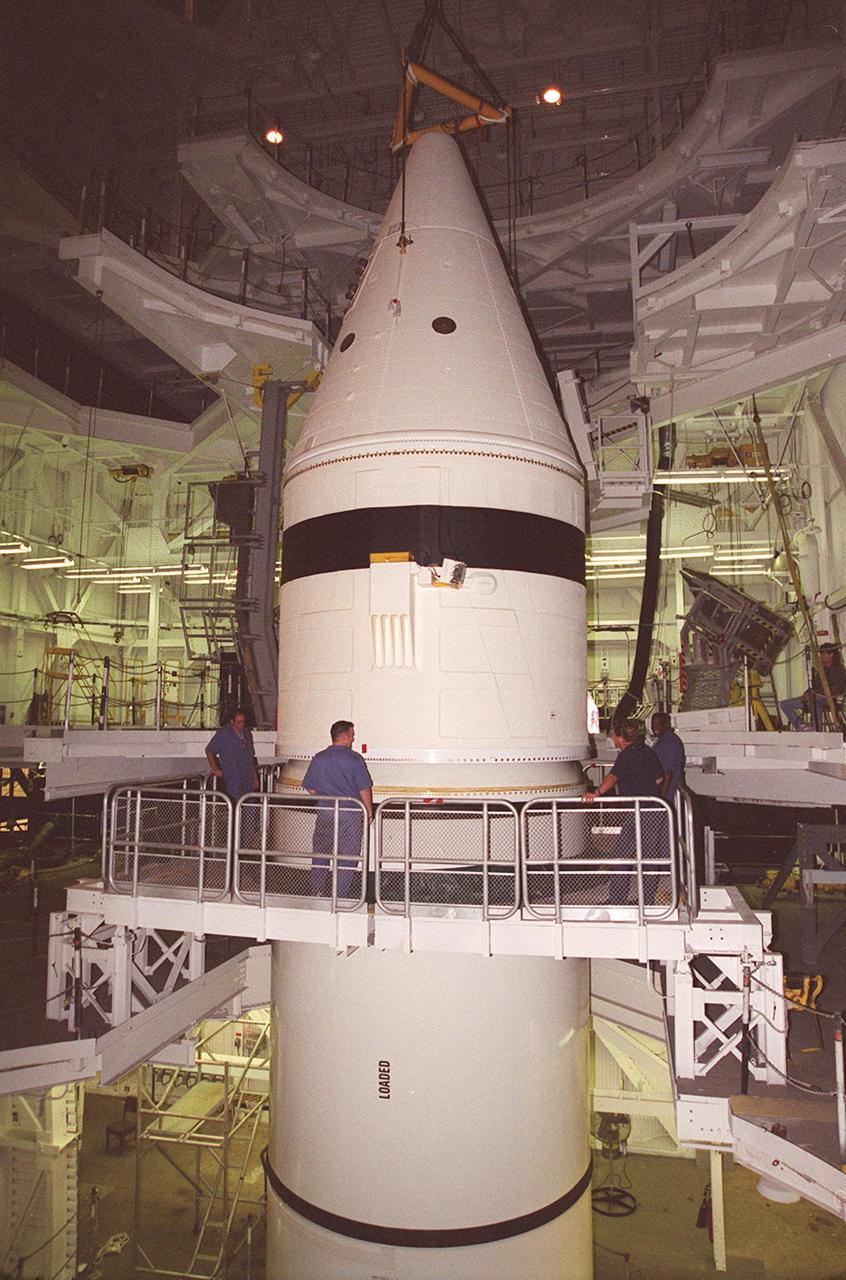

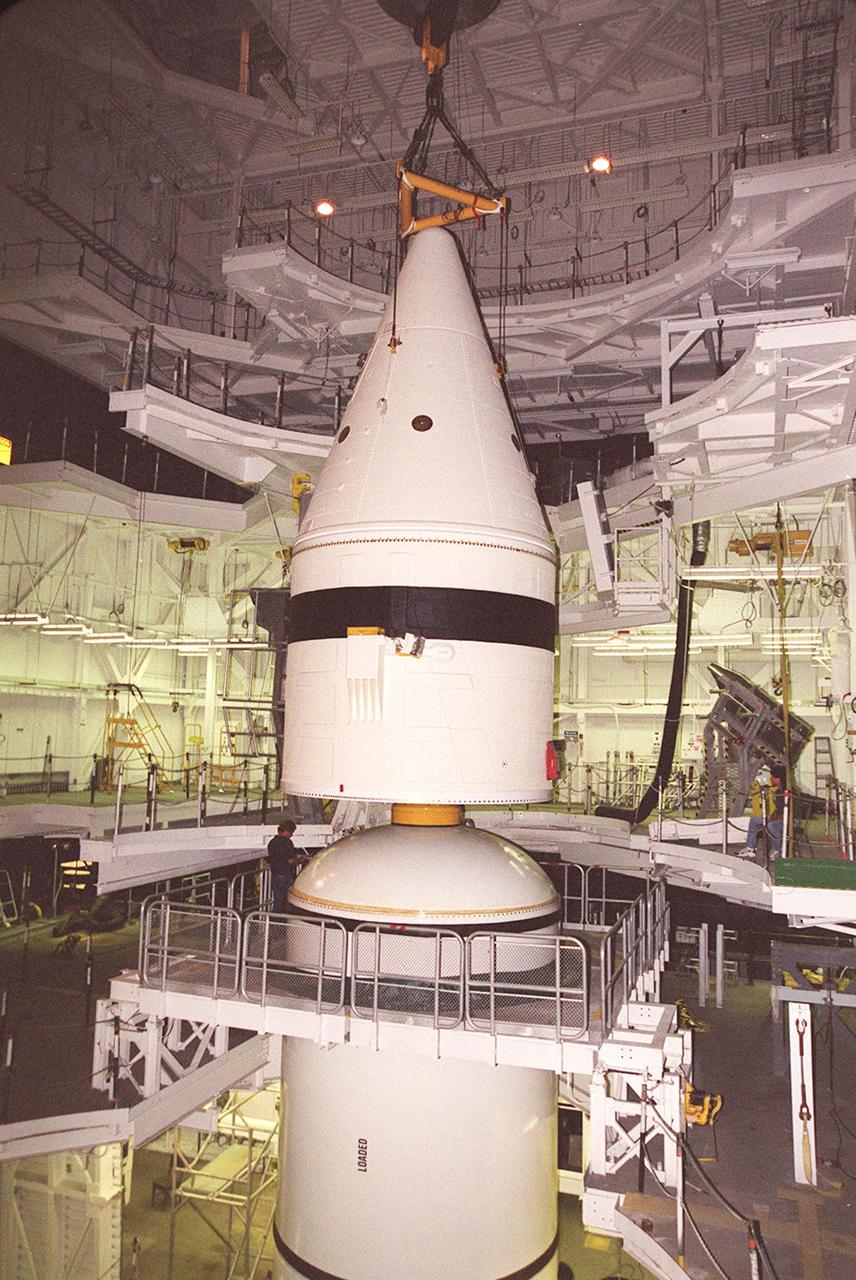

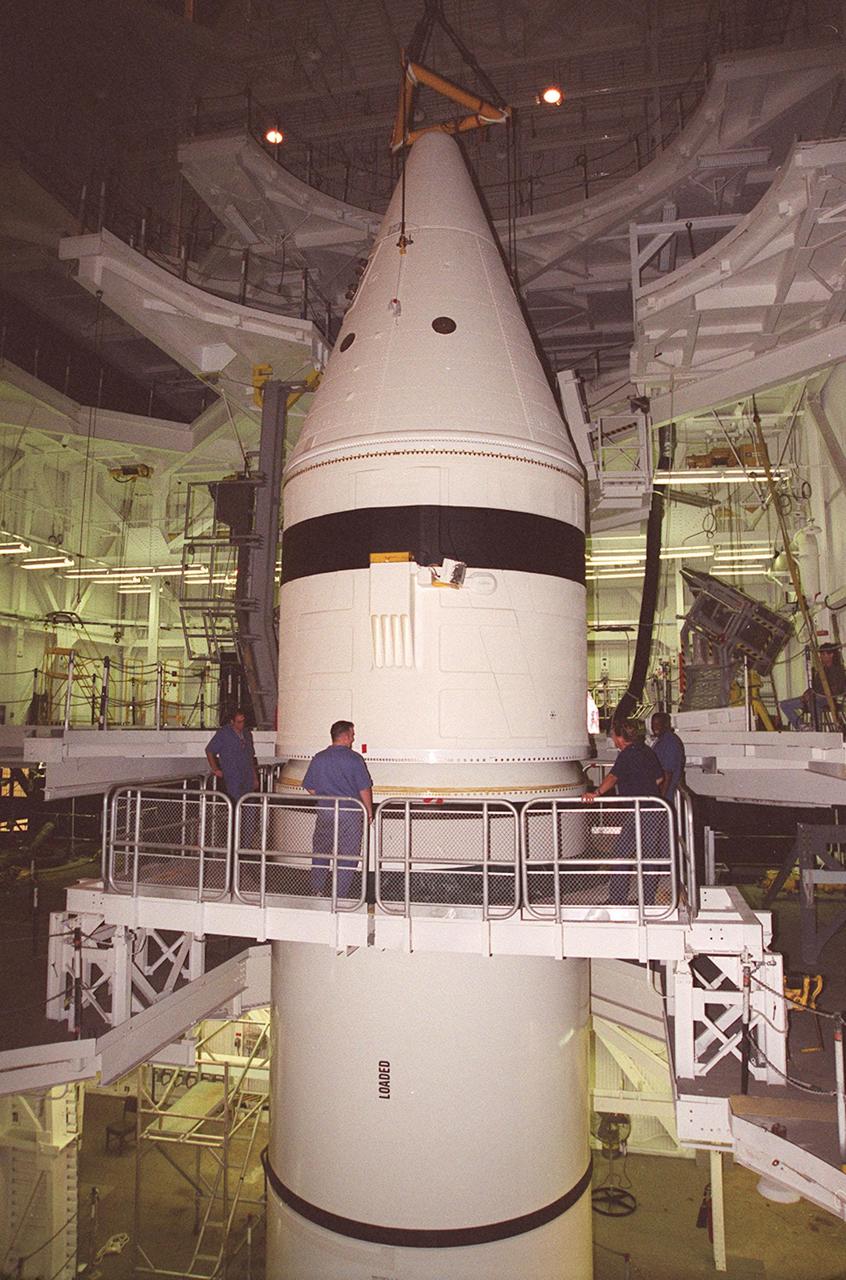

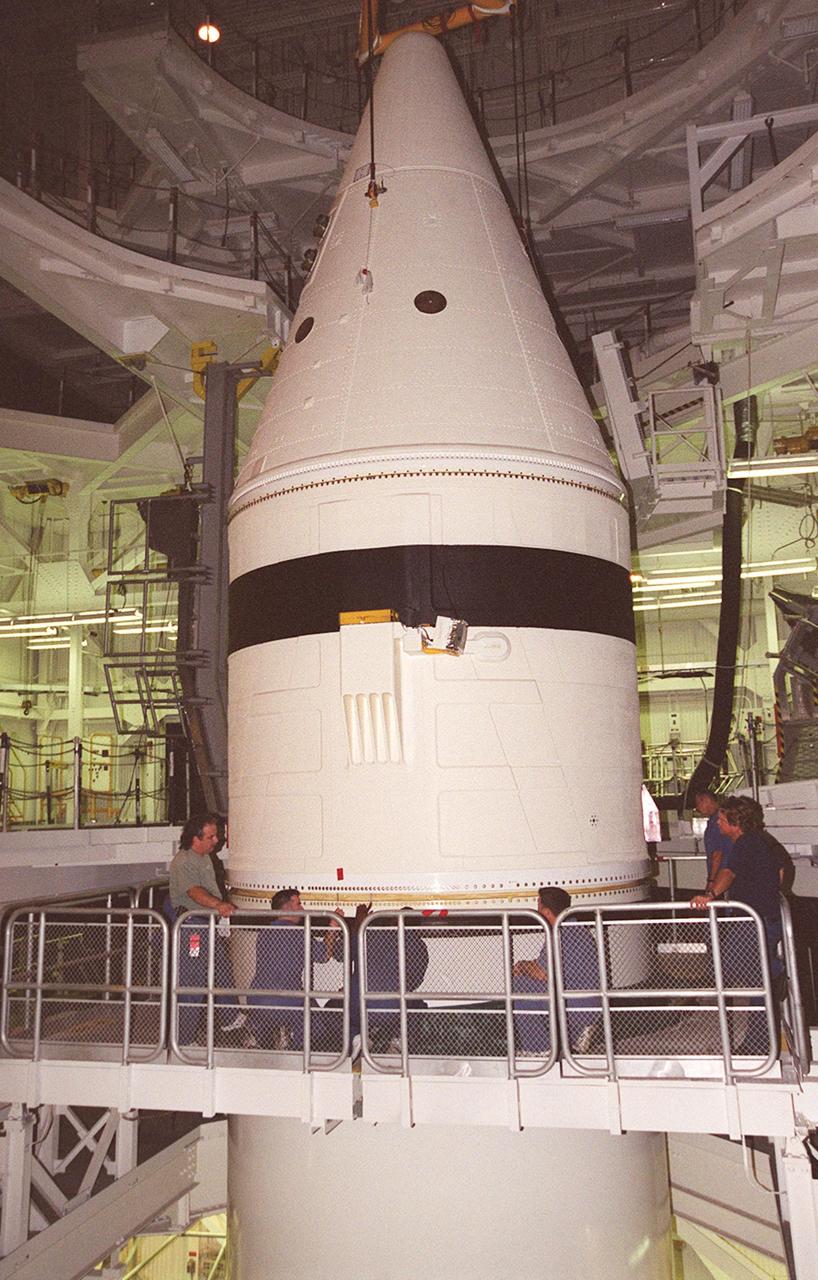

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) is lowered onto the rest of the stack for mating. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

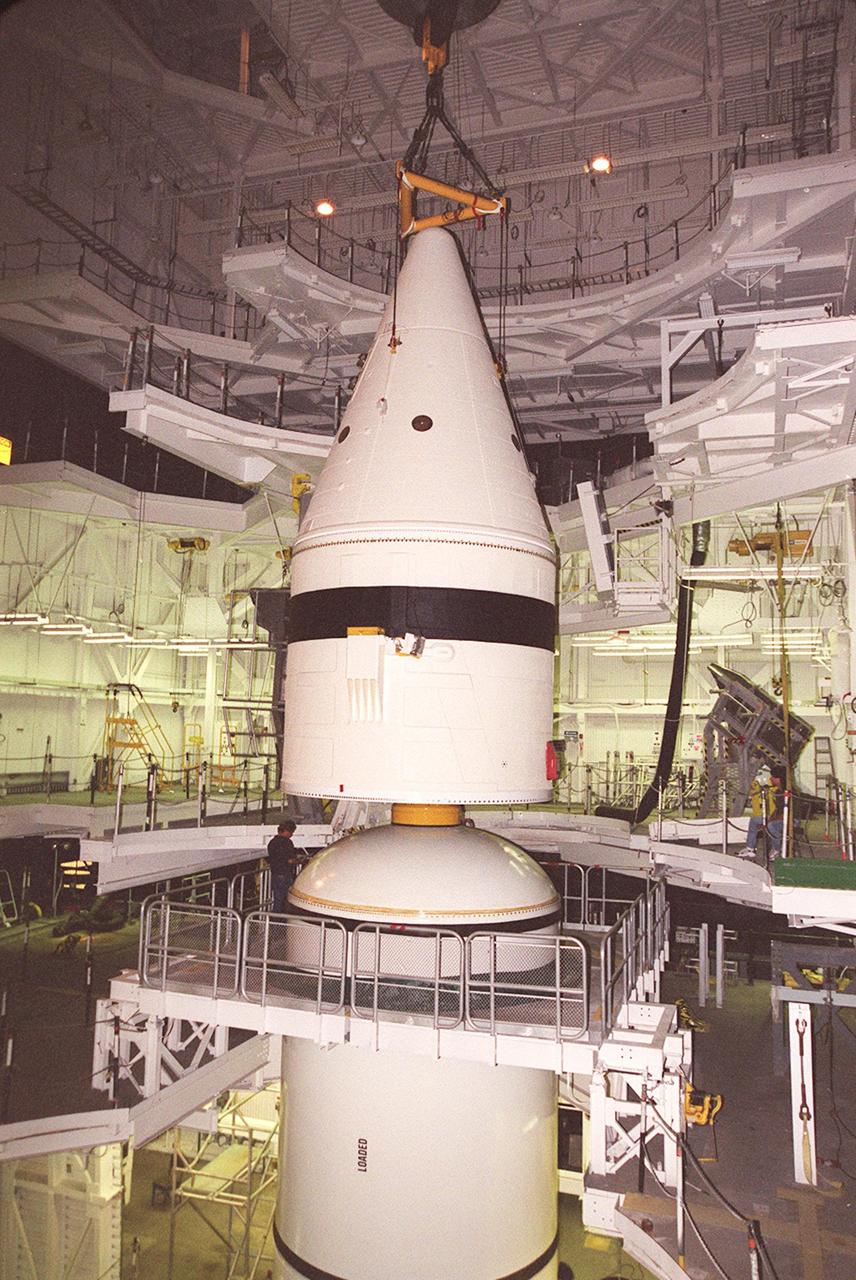

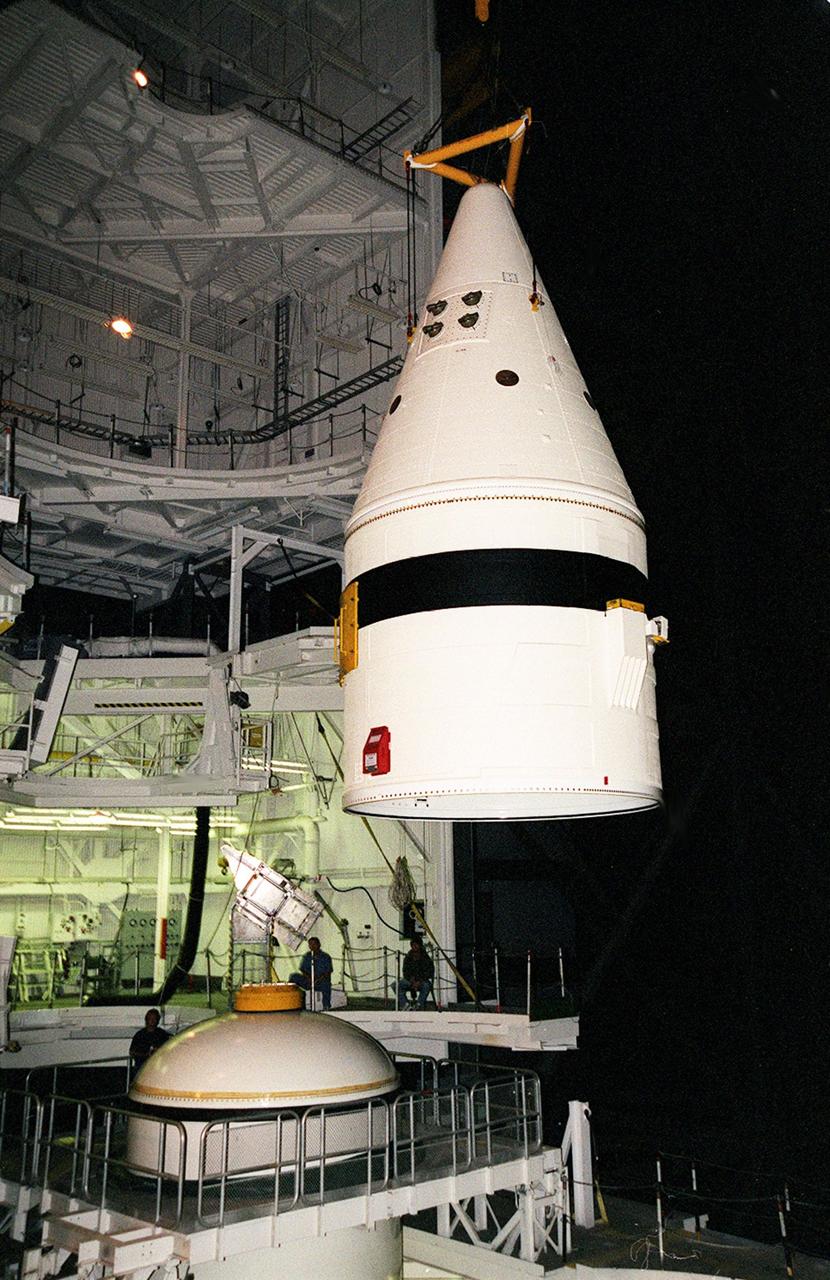

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, an overhead crane lifts the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) to mate it with the components seen at lower left in the photo. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, an overhead crane moves the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) toward the previously stacked elements at lower left in the photo. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

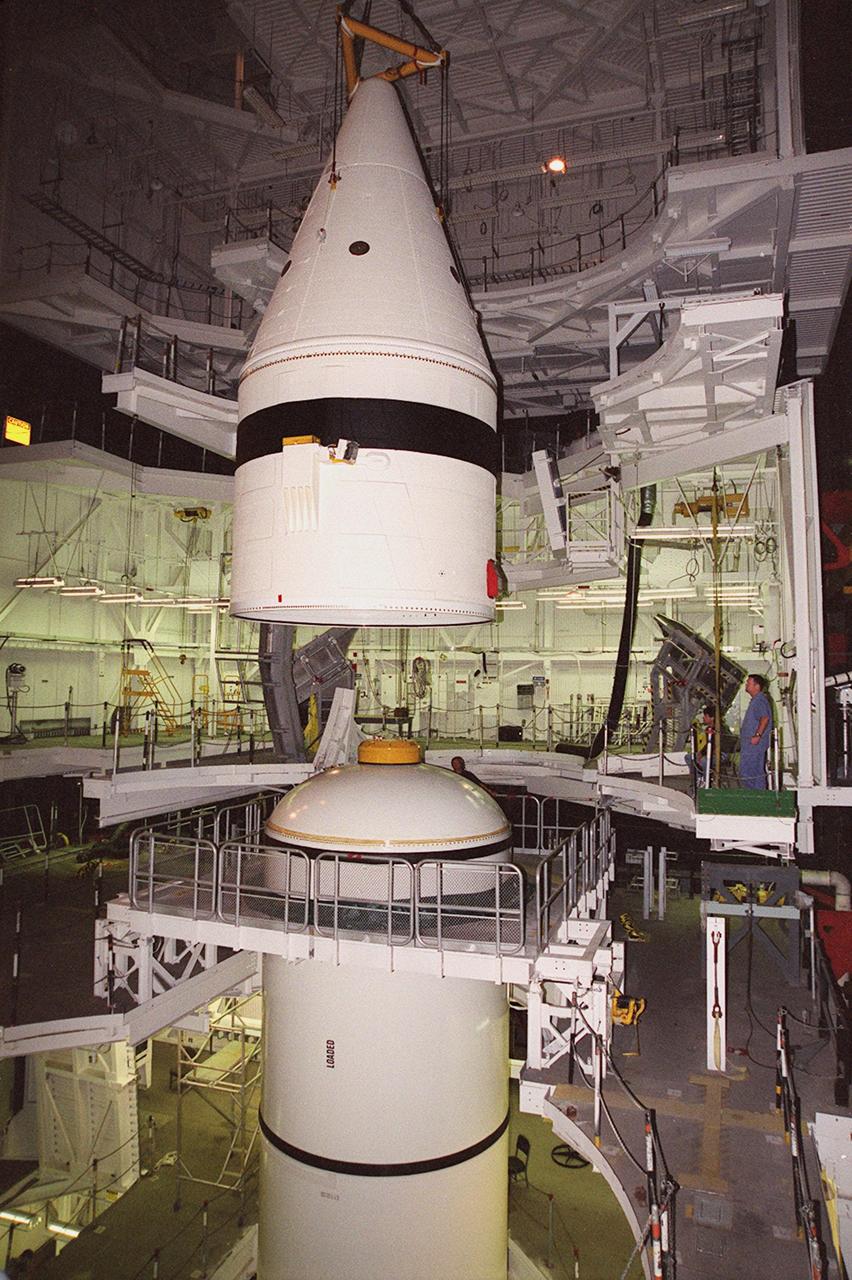

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, an overhead crane lowers the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) toward the rest of the stack for mating. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, an overhead crane centers the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) above the rest of the stack it will be mated to. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, an overhead crane lifts the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) to mate it with the components seen at lower left in the photo. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) is lowered onto the rest of the stack for mating. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) sits on top of the rest of the stack for mating. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, an overhead crane lowers the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) toward the rest of the stack for mating. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, an overhead crane moves the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) toward the previously stacked elements at lower left in the photo. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

The X-38, a research vehicle built to help develop technology for an emergency Crew Return Vehicle (CRV), descends under its steerable parachute during a July 1999 test flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California. It was the fourth free flight of the test vehicles in the X-38 program, and the second free flight test of Vehicle 132 or Ship 2. The goal of this flight was to release the vehicle from a higher altitude -- 31,500 feet -- and to fly the vehicle longer -- 31 seconds -- than any previous X-38 vehicle had yet flown. The project team also conducted aerodynamic verification maneuvers and checked improvements made to the drogue parachute.

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) sits on top of the rest of the stack for mating. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

Inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, an overhead crane centers the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) above the rest of the stack it will be mated to. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station

Engineers testing the parachute system for Orion during a Sept. 13, 2017 evaluation at the U.S. Army Proving Ground in Yuma.. .During this test, engineers replicated a situation in which Orion must abort off the Space Launch System rocket and bypasses part of its normal parachute deployment sequence that typically helps the spacecraft slow down during its descent to Earth after deep space missions. The capsule was dropped out of a C-17 aircraft at more than 4.7 miles in altitude and allowed to free fall for 20 seconds, longer than ever before, to produce high aerodynamic pressure before only its pilot and main parachutes were deployed, testing whether they could perform as expected under extreme loads. Orion’s full parachute system includes 11 total parachutes -- three forward bay cover parachutes and two drogue parachutes, along with three pilot parachutes that help pull out the spacecraft’s three mains.

In this view looking up, Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner’s parachutes deploy above the U.S. Army’s White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico during parachute system testing on June 24, 2019. Boeing conducted the test using a full-scale Starliner test article, known as a boiler plate, designed to simulate the actual spacecraft. The test involved intentionally disabling one of the parachute system’s two drogue parachutes and one of the three main parachutes to evaluate how the remaining parachutes handled the additional loads during deployment and descent. This was one of a series of important parachute tests to validate the system is safe to carry astronauts to and from the International Space Station as part of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. Boeing is targeting an uncrewed Orbital Flight Test to the space station this summer, followed by its Crew Flight Test. Starliner will launch atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

In this view looking up, Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner’s parachutes deploy above the U.S. Army’s White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico during parachute system testing on June 24, 2019. Boeing conducted the test using a full-scale Starliner test article, known as a boiler plate, designed to simulate the actual spacecraft. The test involved intentionally disabling one of the parachute system’s two drogue parachutes and one of the three main parachutes to evaluate how the remaining parachutes handled the additional loads during deployment and descent. This was one of a series of important parachute tests to validate the system is safe to carry astronauts to and from the International Space Station as part of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. Boeing is targeting an uncrewed Orbital Flight Test to the space station this summer, followed by its Crew Flight Test. Starliner will launch atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft transitions to main chutes from drogue parachutes as it lands at White Sands Missile Range’s Space Harbor, Wednesday, May 25, 2022, in New Mexico. Boeing’s Orbital Flight Test-2 (OFT-2) is Starliner’s second uncrewed flight test to the International Space Station as part of NASA's Commercial Crew Program. OFT-2 serves as an end-to-end test of the system's capabilities. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft is seen under drogue parachutes as it lands at White Sands Missile Range’s Space Harbor, Wednesday, May 25, 2022, in New Mexico. Boeing’s Orbital Flight Test-2 (OFT-2) is Starliner’s second uncrewed flight test to the International Space Station as part of NASA's Commercial Crew Program. OFT-2 serves as an end-to-end test of the system's capabilities. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Boeing conducted the first in a series of reliability tests of its CST-100 Starliner flight drogue and main parachute system by releasing a long, dart-shaped test vehicle from a C-17 aircraft over Yuma, Arizona. Two more tests are planned using the dart module, as well as three similar reliability tests using a high fidelity capsule simulator designed to simulate the CST-100 Starliner capsule’s exact shape and mass. In both the dart and capsule simulator tests, the test spacecraft are released at various altitudes to test the parachute system at different deployment speeds, aerodynamic loads, and or weight demands. Data collected from each test is fed into computer models to more accurately predict parachute performance and to verify consistency from test to test.

Boeing conducted the first in a series of reliability tests of its CST-100 Starliner flight drogue and main parachute system by releasing a long, dart-shaped test vehicle from a C-17 aircraft over Yuma, Arizona. Two more tests are planned using the dart module, as well as three similar reliability tests using a high fidelity capsule simulator designed to simulate the CST-100 Starliner capsule’s exact shape and mass. In both the dart and capsule simulator tests, the test spacecraft are released at various altitudes to test the parachute system at different deployment speeds, aerodynamic loads, and or weight demands. Data collected from each test is fed into computer models to more accurately predict parachute performance and to verify consistency from test to test.

Boeing conducted the first in a series of reliability tests of its CST-100 Starliner flight drogue and main parachute system by releasing a long, dart-shaped test vehicle from a C-17 aircraft over Yuma, Arizona. Two more tests are planned using the dart module, as well as three similar reliability tests using a high fidelity capsule simulator designed to simulate the CST-100 Starliner capsule’s exact shape and mass. In both the dart and capsule simulator tests, the test spacecraft are released at various altitudes to test the parachute system at different deployment speeds, aerodynamic loads, and or weight demands. Data collected from each test is fed into computer models to more accurately predict parachute performance and to verify consistency from test to test.

Boeing conducted the first in a series of reliability tests of its CST-100 Starliner flight drogue and main parachute system by releasing a long, dart-shaped test vehicle from a C-17 aircraft over Yuma, Arizona. Two more tests are planned using the dart module, as well as three similar reliability tests using a high fidelity capsule simulator designed to simulate the CST-100 Starliner capsule’s exact shape and mass. In both the dart and capsule simulator tests, the test spacecraft are released at various altitudes to test the parachute system at different deployment speeds, aerodynamic loads, and or weight demands. Data collected from each test is fed into computer models to more accurately predict parachute performance and to verify consistency from test to test.

Boeing conducted the first in a series of reliability tests of its CST-100 Starliner flight drogue and main parachute system by releasing a long, dart-shaped test vehicle from a C-17 aircraft over Yuma, Arizona. Two more tests are planned using the dart module, as well as three similar reliability tests using a high fidelity capsule simulator designed to simulate the CST-100 Starliner capsule’s exact shape and mass. In both the dart and capsule simulator tests, the test spacecraft are released at various altitudes to test the parachute system at different deployment speeds, aerodynamic loads, and or weight demands. Data collected from each test is fed into computer models to more accurately predict parachute performance and to verify consistency from test to test.

Workers in the Vehicle Assembly Building check the connections on the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) being mated to the rest of the stack below it. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station. Payloads on the mission include the Z-1 truss and Pressurized Mating Adapter-3, components of the Space Station

Workers in the Vehicle Assembly Building check the connections on the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) being mated to the rest of the stack below it. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station. Payloads on the mission include the Z-1 truss and Pressurized Mating Adapter-3, components of the Space Station

Workers in the Vehicle Assembly Building check the connections on the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) being mated to the rest of the stack below it. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station. Payloads on the mission include the Z-1 truss and Pressurized Mating Adapter-3, components of the Space Station

Workers in the Vehicle Assembly Building check the connections on the forward section of a solid rocket booster (SRB) being mated to the rest of the stack below it. The forward section of each booster, from nose cap to forward skirt contains avionics, a sequencer, forward separation motors, a nose cone separation system, drogue and main parachutes, a recovery beacon, a recovery light, a parachute camera on selected flights and a range safety system. Each SRB weighs approximately 1.3 million pounds at launch. The SRB is part of the stack for Space Shuttle Discovery and the STS-92 mission, scheduled for launch Oct. 5, from Launch Pad 39A, on the fifth flight to the International Space Station. Payloads on the mission include the Z-1 truss and Pressurized Mating Adapter-3, components of the Space Station

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. - The Freedom Star is berthed at the Turn Basin near the Vehicle Assembly Building. The ship has recently returned to KSC after refurbishment at Fort George Island, Fla., including new paint. Freedom Star is one of the solid rocket booster (SRB) retrieval ships built to recover the SRB casings released over the Atlantic Ocean after launch of a Space Shuttle. In addition to the SRBs, the ship recovers the drogue and main parachutes that slow the boosters’ speed before splashdown. Some of the retrieval equipment can be seen on the rear deck. The ships also tow the external tanks built at the Michoud Space Systems Assembly Facility near New Orleans to Port Canaveral, Fla. Freedom Star was brought to KSC today for a visit by NATO Parliamentarians.

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. - The Freedom Star is berthed at the Turn Basin near the Vehicle Assembly Building. The ship has recently returned to KSC after refurbishment at Fort George Island, Fla., including new paint. Freedom Star is one of the solid rocket booster (SRB) retrieval ships built to recover the SRB casings released over the Atlantic Ocean after launch of a Space Shuttle. In addition to the SRBs, the ship recovers the drogue and main parachutes that slow the boosters’ speed before splashdown. Some of the retrieval equipment can be seen on the rear deck. The ships also tow the external tanks built at the Michoud Space Systems Assembly Facility near New Orleans to Port Canaveral, Fla. Freedom Star was brought to KSC today for a visit by NATO Parliamentarians.

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. - The Freedom Star is berthed at the Turn Basin near the Vehicle Assembly Building. The ship has recently returned to KSC after refurbishment at Fort George Island, Fla., including new paint. Freedom Star is one of the solid rocket booster (SRB) retrieval ships built to recover the SRB casings released over the Atlantic Ocean after launch of a Space Shuttle. In addition to the SRBs, the ship recovers the drogue and main parachutes that slow the boosters’ speed before splashdown. Some of the retrieval equipment can be seen on the rear deck. The ships also tow the external tanks built at the Michoud Space Systems Assembly Facility near New Orleans to Port Canaveral, Fla. Freedom Star was brought to KSC today for a visit by NATO Parliamentarians.