The Encke Gap as Never Seen Before

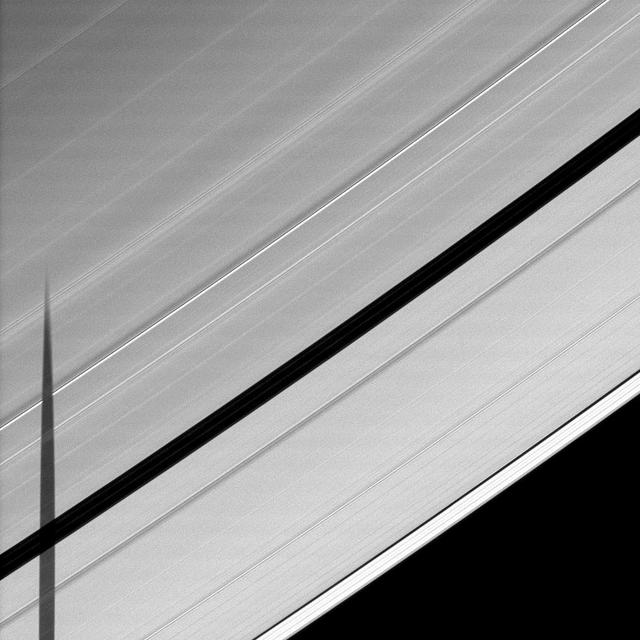

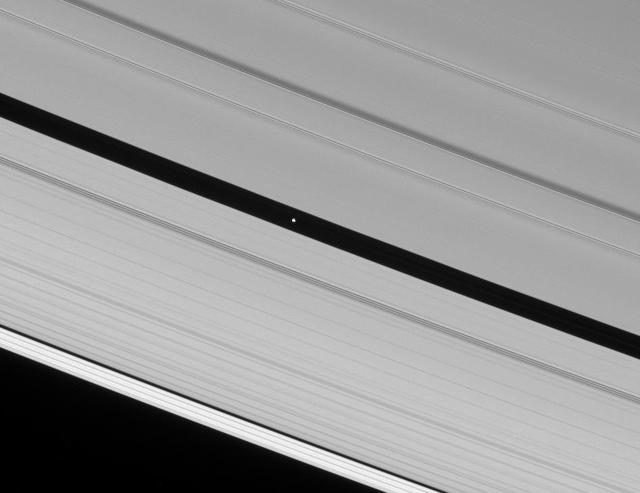

Seen from the unlit side of Saturn A ring, the shadow of the moon Janus is cast across the Encke Gap.

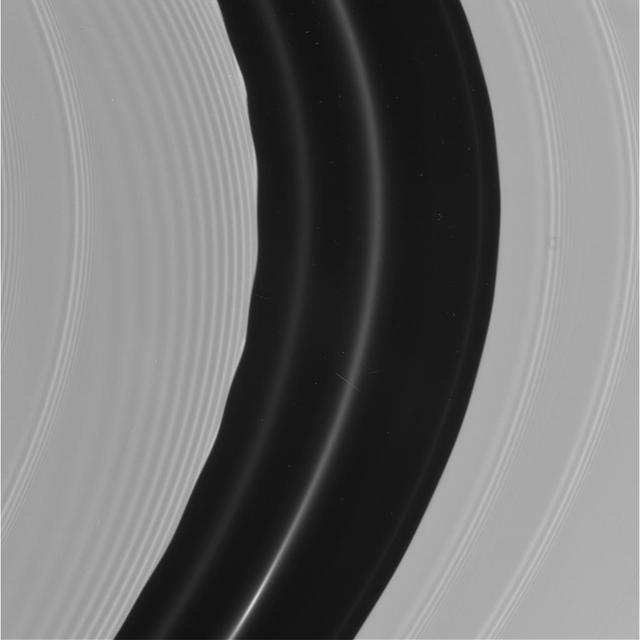

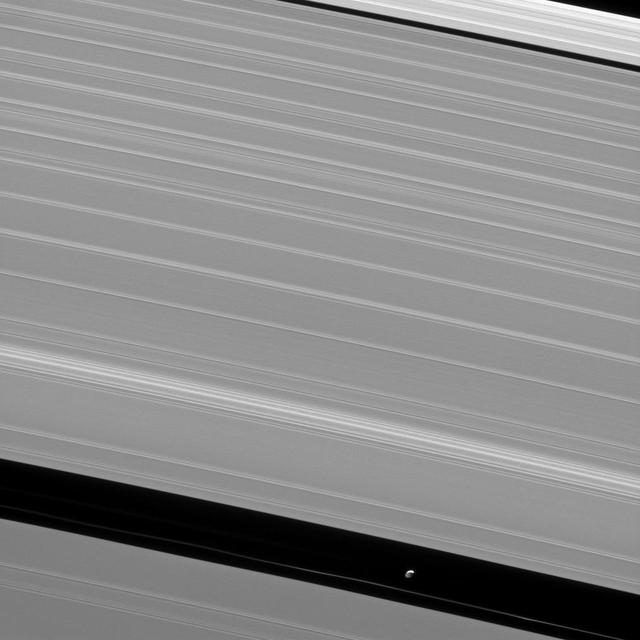

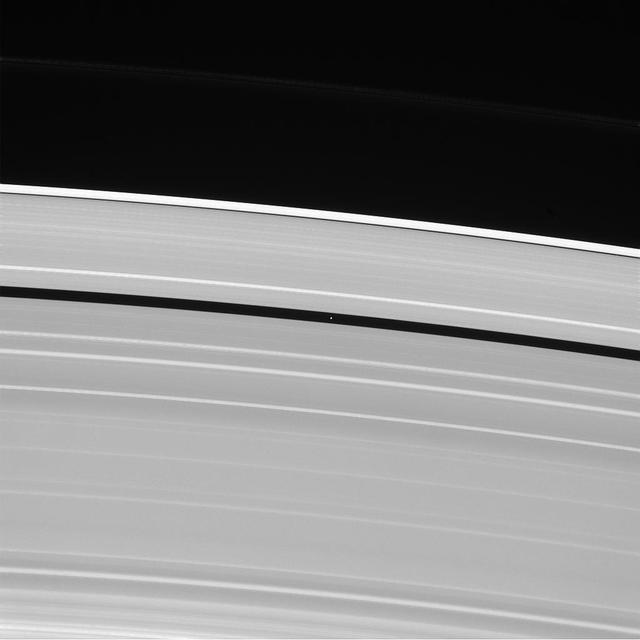

Kinky, discontinuous ringlets occupy the Encke Gap in Saturn A ring in the middle of this NASA Cassini spacecraft image; parts of these thin ringlets cast shadows onto the A ring.

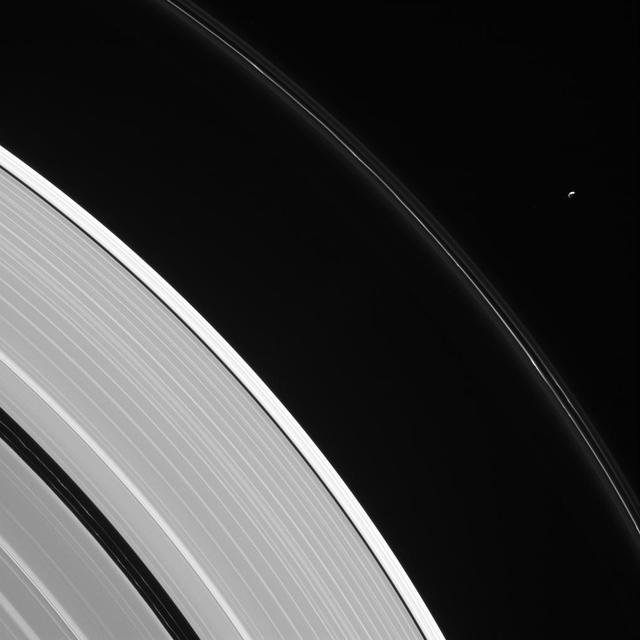

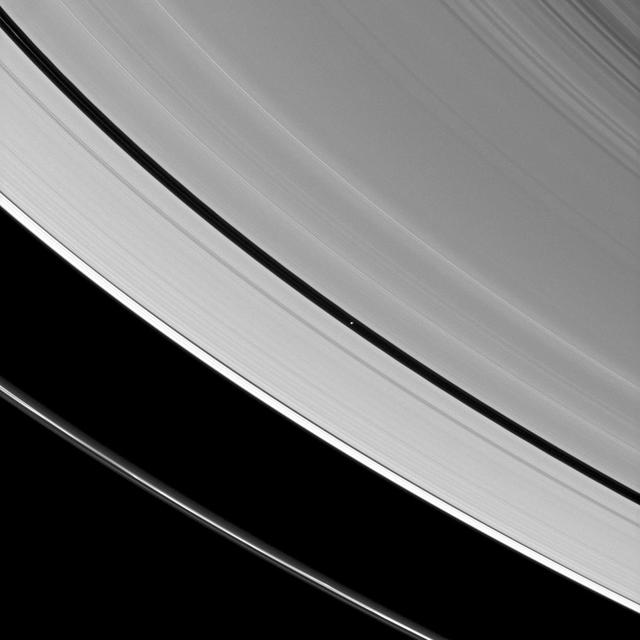

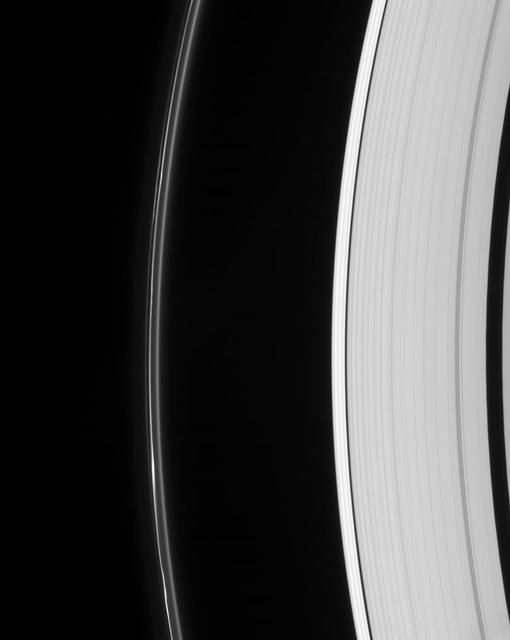

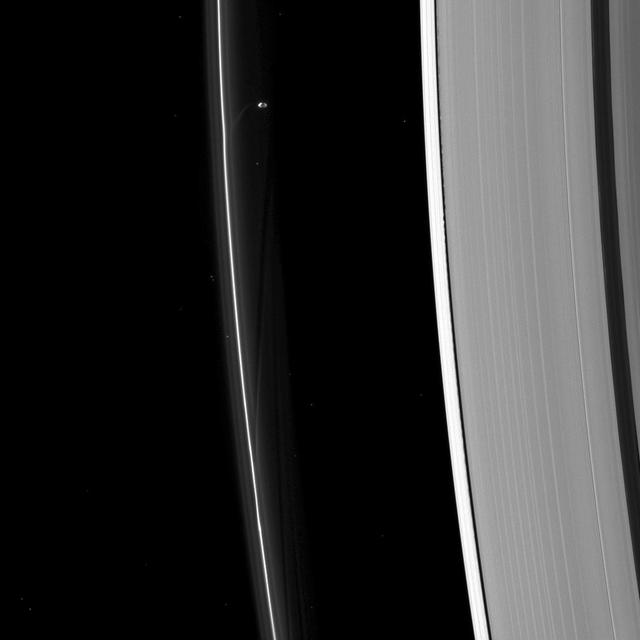

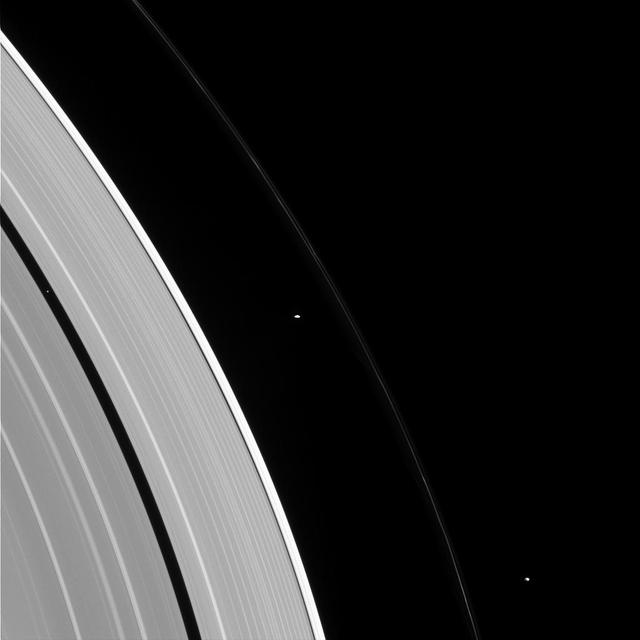

Pandora is seen here, in isolation beside Saturn's kinked and constantly changing F ring. Pandora (near upper right) is 50 miles (81 kilometers) wide. The moon has an elongated, potato-like shape (see PIA07632). Two faint ringlets are visible within the Encke Gap, near lower left. The gap is about 202 miles (325 kilometers) wide. The much narrower Keeler Gap, which lies outside the Encke Gap, is maintained by the diminutive moon Daphnis (not seen here). This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 23 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Aug. 12, 2016. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 907,000 miles (1.46 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 113 degrees. Image scale is 6 miles (9 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20504

The Encke Gap moon, Pan, has left its mark on a scalloped ringlet of the Encke Gap. The moon creates these perturbations as it sweeps through the 325-kilometer 200-mile gap in the A ring

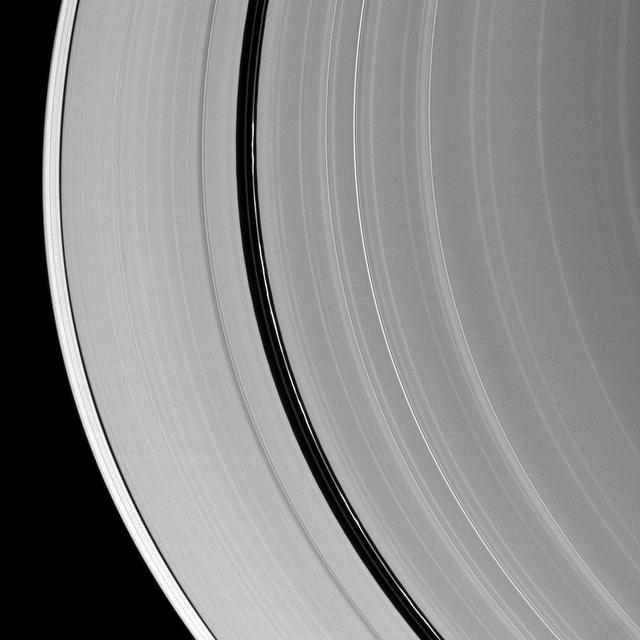

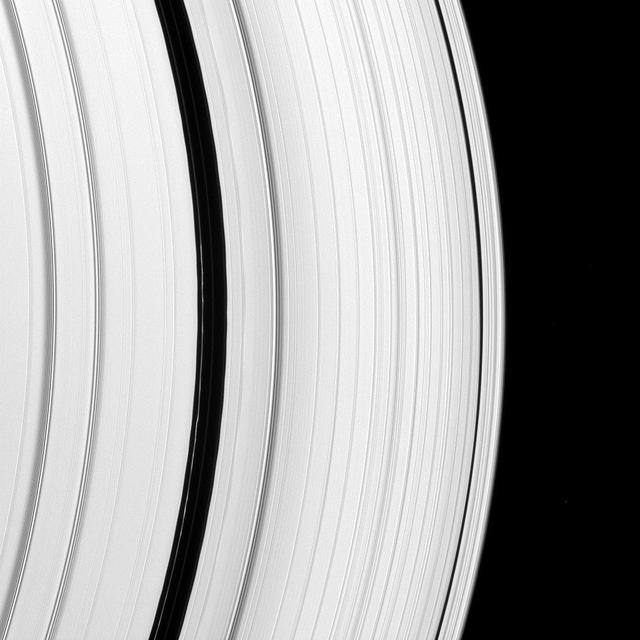

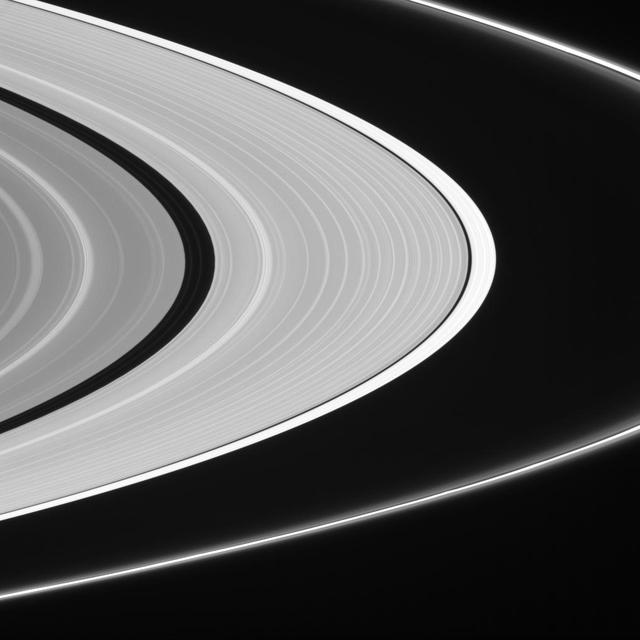

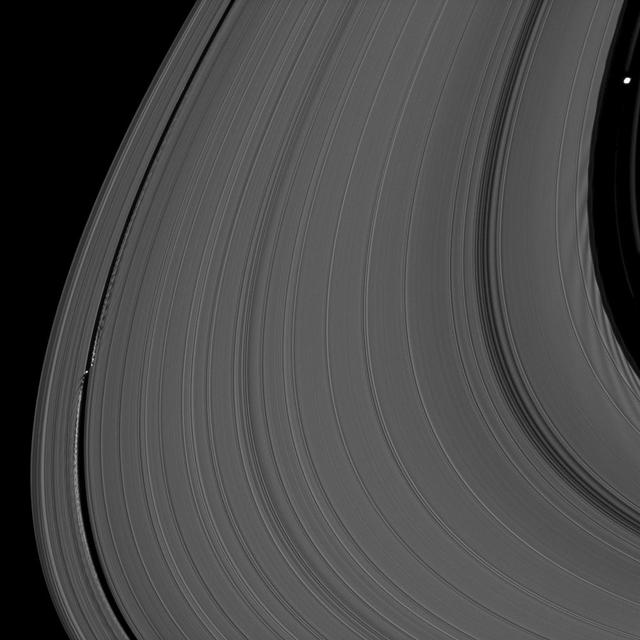

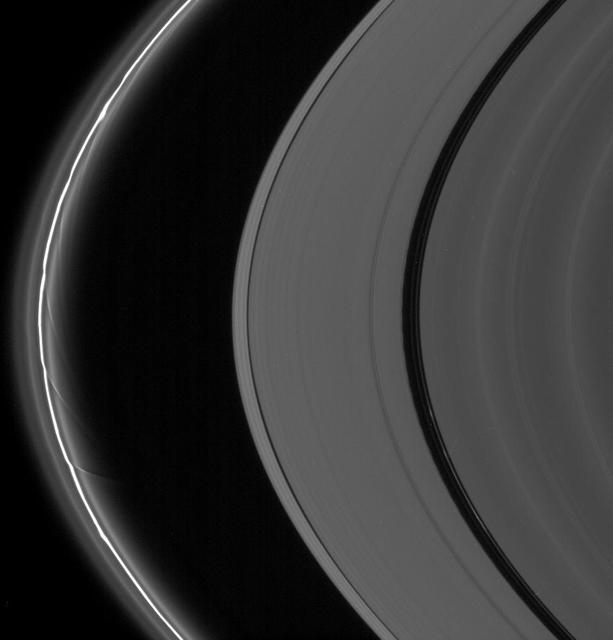

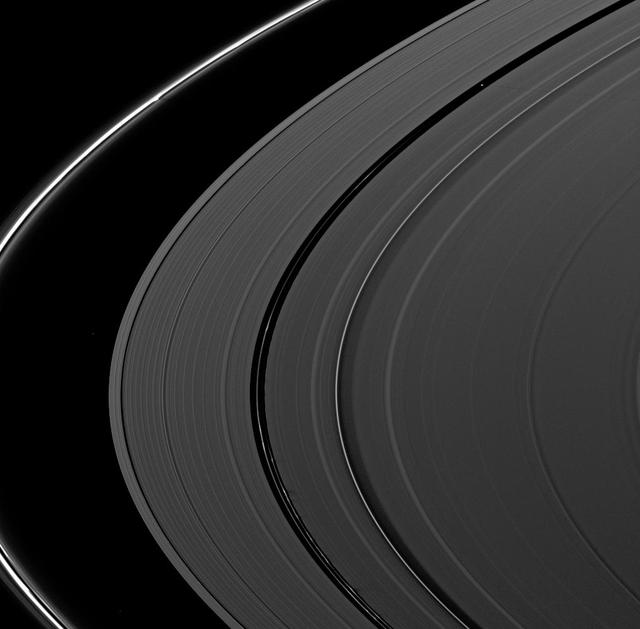

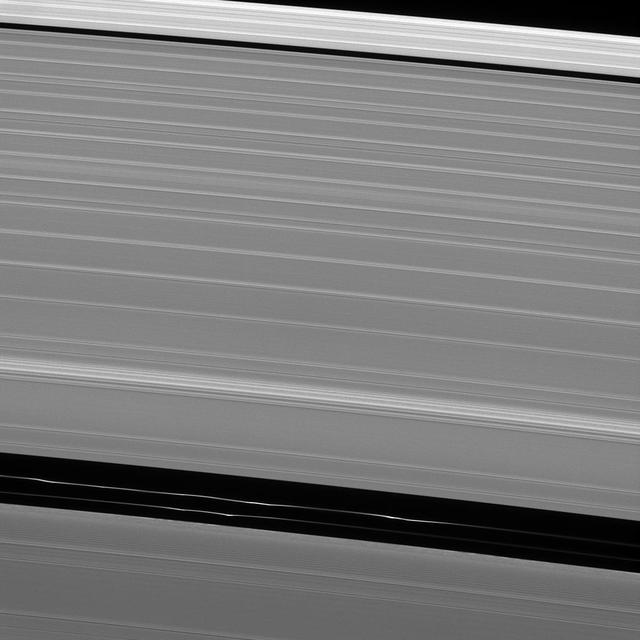

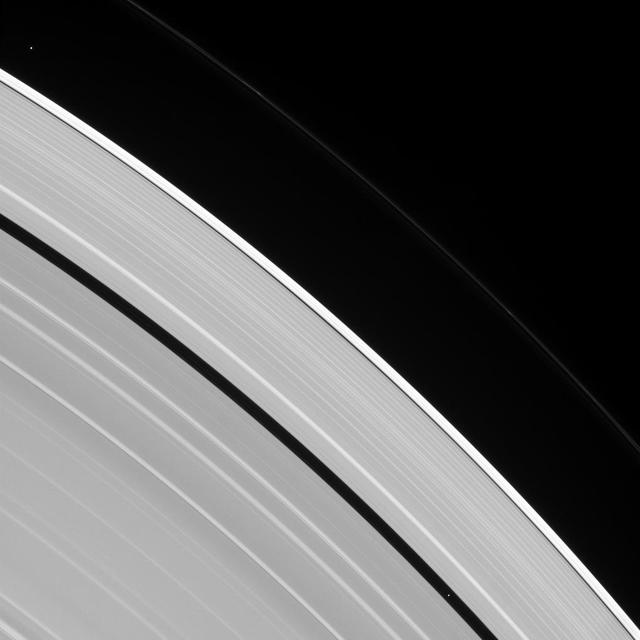

This Cassini spacecraft view shows details of Saturn outer A ring, including the Encke and Keeler gaps. The A ring brightens substantially outside the Keeler Gap

Saturn moon Pan, orbiting in the Encke Gap, casts a slender shadow onto the A ring.

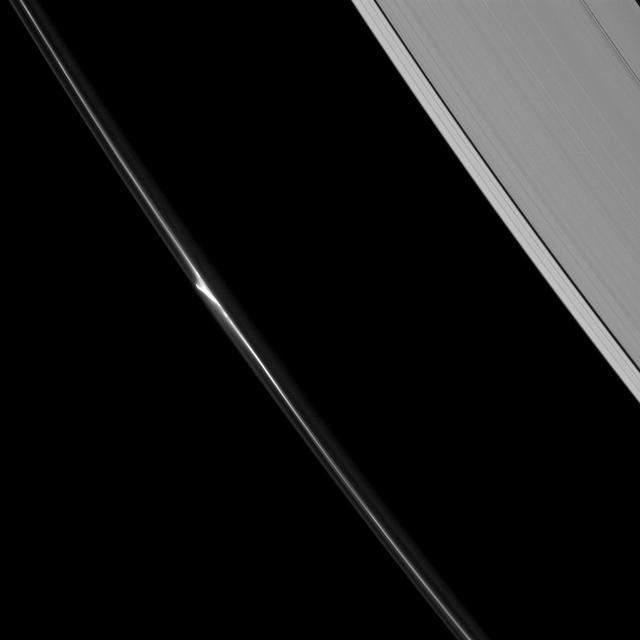

Bright undulations disturb a faint ringlet drifting through the center of the Encke Gap. This ring structure shares the orbit of the moon Pan

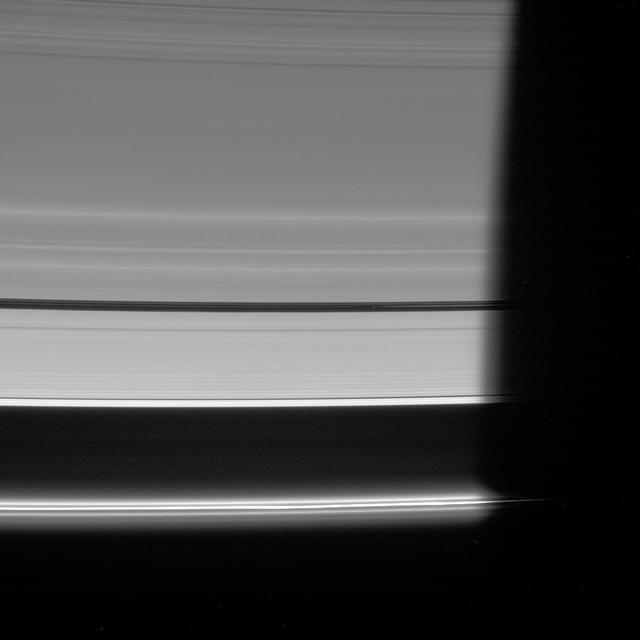

Ringlets in the Encke Gap and flanking the bright F ring core are clearly visible here

The Cassini spacecraft looks toward the unilluminated side of Saturn rings to spy on the moon Pan as it cruises through the Encke Gap

An intriguing knotted ringlet within the Encke Gap is the main attraction in this image captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft.

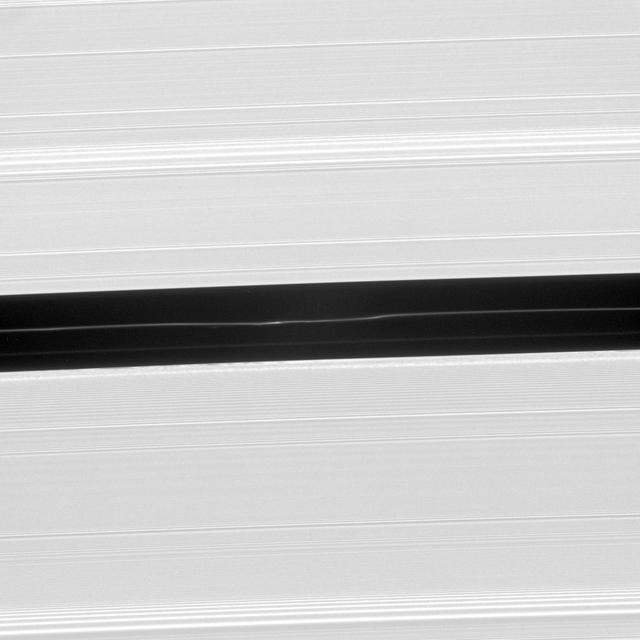

The Encke gap displays gentle waves in its inner and outer edges that are caused by gravitational tugs from the small moon Pan

The Cassini spacecraft spies Pan speeding through the Encke Gap, its own private path around Saturn

This image, taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft, shows A beautiful mini-jet appearing in the dynamic F ring of Saturn. Saturn A ring including the Keeler gap and just a hint of the Encke gap at the upper-right also appears.

Saturn moons Daphnis and Pan demonstrate their effects on the planet rings in this view from NASA Cassini spacecraft. Daphnis, at left, orbits in the Keeler Gap of the A ring; Pan at right, orbits in the Encke Gap of the A ring.

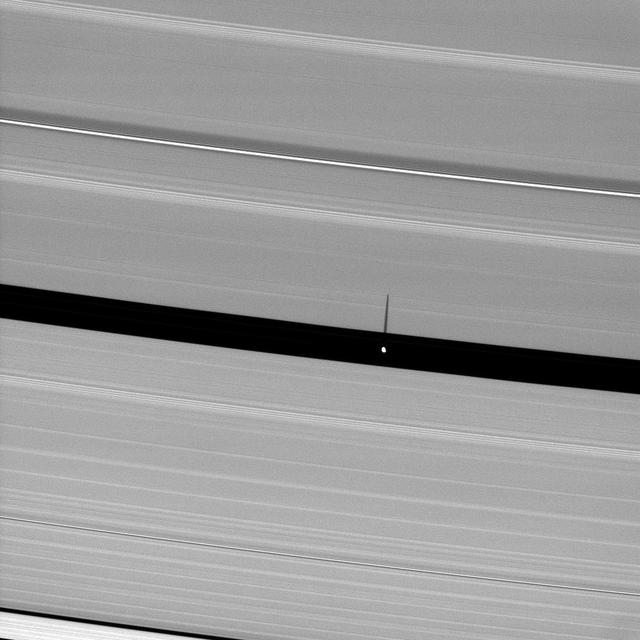

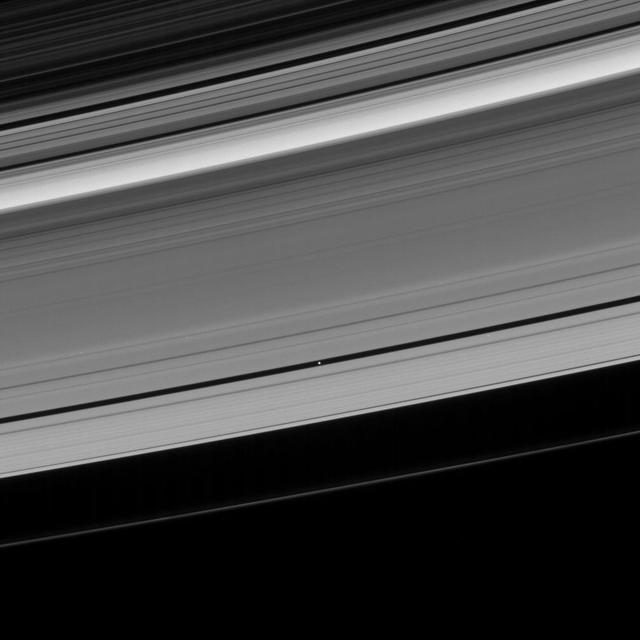

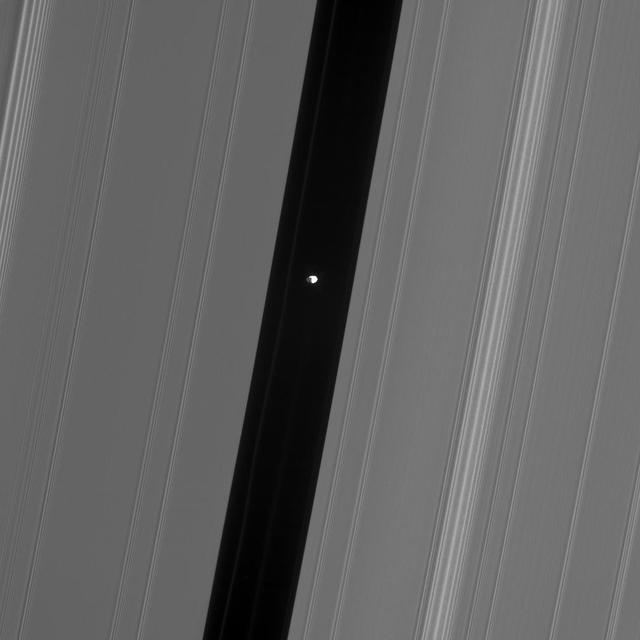

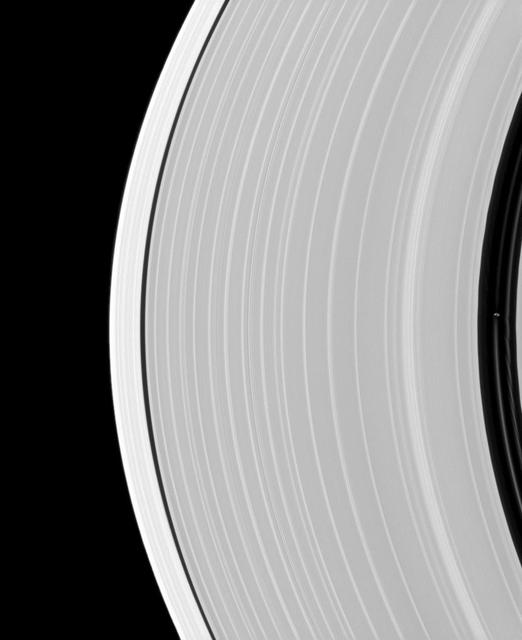

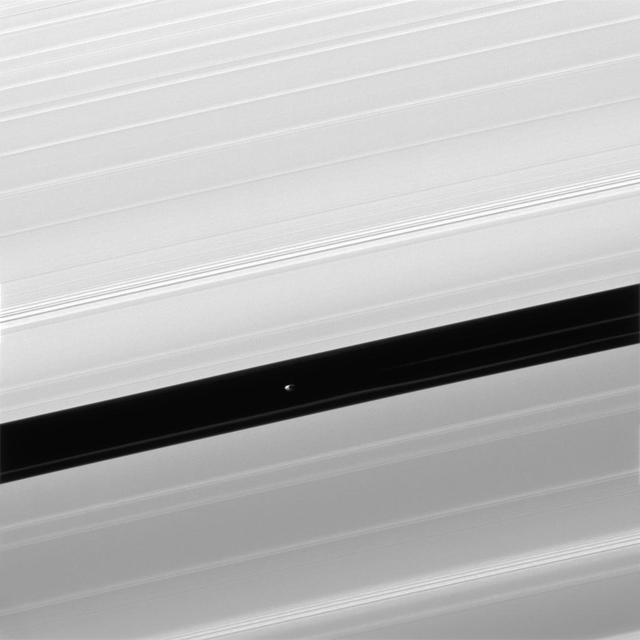

Saturn tiny moon Pan orbits in the middle of the Encke Gap of the planet A ring in this image from the Cassini spacecraft. Pan is visible as a bright dot in the gap near the center of this view.

The shepherd moon Pan orbits Saturn in the Encke gap while the A ring surrounding the gap displays wave features created by interactions between the ring particles and Saturnian moons in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft.

The shadow of the moon Janus crosses the Encke Gap as it strikes the plane of Saturn rings in this image taken as the planet approached its August 2009 equinox.

NASA Cassini spacecraft looks down at the unlit side of the rings as Pan heads into Saturn shadow. The moon is accompanied by faint ringlets in the Encke Gap.

Saturn odd but ever-intriguing F ring displays multiple lanes and several bright clumps. The Keeler and Encke gaps are visible in the outer A ring, at right

Bright, kinked ringlets fill the Encke Gap, while the F ring glows brilliantly and displays its signature knots and flanking, diffuse ringlets

This Cassini spacecraft view of Pan in the Encke gap shows hints of detail on the moon dark side, which is lit by saturnshine -- sunlight reflected off Saturn.

Prometheus, seen here by NASA Cassini spacecraft, sculpting the F ring while Daphnis too small to discern in this image raises waves on the edges of the Encke gap.

The A and F rings are alive with moving structures in this Cassini spacecraft view. Graceful drapes of ring material created by Prometheus are seen sliding by at left, while clumpy ringlets slip through the Encke Gap

Orbiting in the Encke Gap of Saturn A ring, the moon Pan casts a shadow on the ring in this image taken about six months after the planet August 2009 equinox by NASA Cassini spacecraft.

Although the embedded moon Pan is nowhere to be seen, there is a bright clump-like feature visible here, within the Encke Division. Also discernable are periodic brightness variations along the outer right side gap edge

An unusually large propeller feature is detected just beyond the Encke Gap in this Cassini image of Saturn’s outer A ring taken a couple days after the planet’s August 2009 equinox.

Saturn moon Pan, orbiting in the Encke Gap near the top of the image, casts a short shadow on the A ring in this image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft about six months after the planet August 2009 equinox.

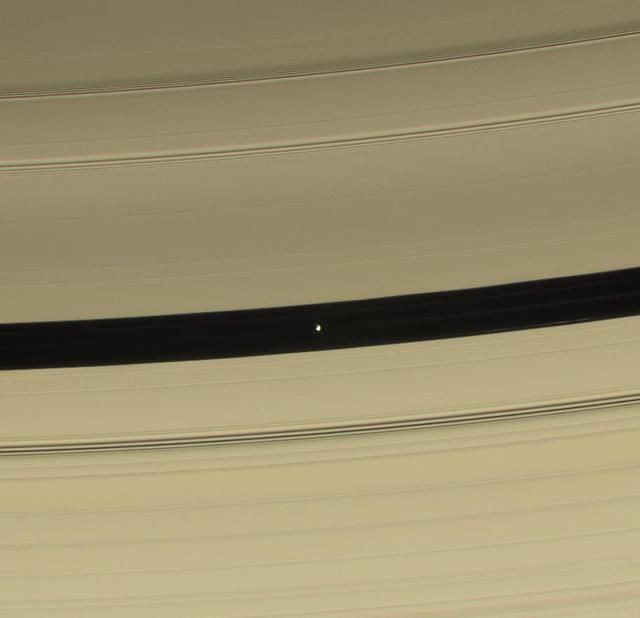

Pan is seen in this color view as it sweeps through the Encke Gap with its attendant ringlets. As the lemon-shaped little moon orbits Saturn, it always keeps its long axis pointed along a line toward the planet

Saturn moon Pan, named for the Greek god of shepherds, rules over quite a different domain: the Encke gap in Saturn rings. This image is from NASA Cassini spacecraft.

Shadows seem ubiquitous in this view from NASA Cassini spacecraft of Saturn rings. The moon Pan casts a long shadow towards the right from where it orbits in the Encke Gap of the A ring in the upper right of the image.

Several structures in Saturn A ring are exposed near the Encke Gap in this image captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft. A peculiar kink can be seen in one particularly bright ringlet at the bottom right.

Saturn small, ring-embedded moon Pan, on the extreme right of this NASA Cassini spacecraft image, can be seen interacting with the ringlets that share the Encke Gap of the A ring with this moon.

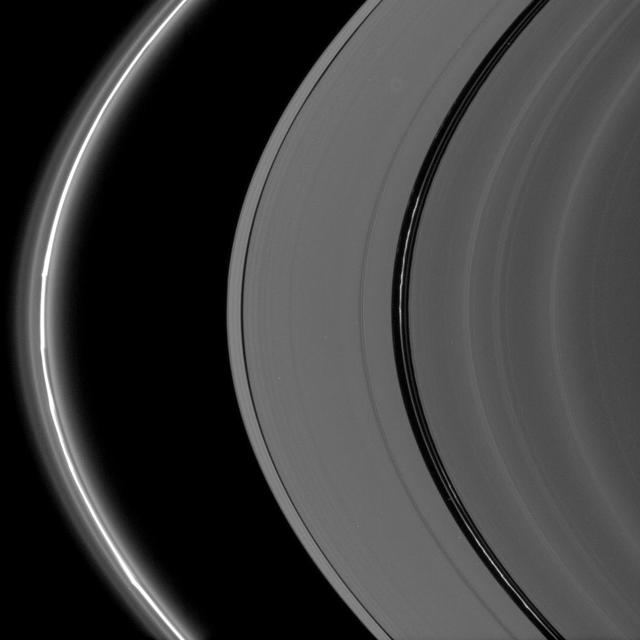

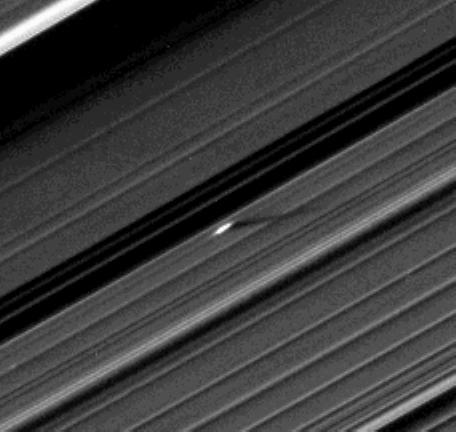

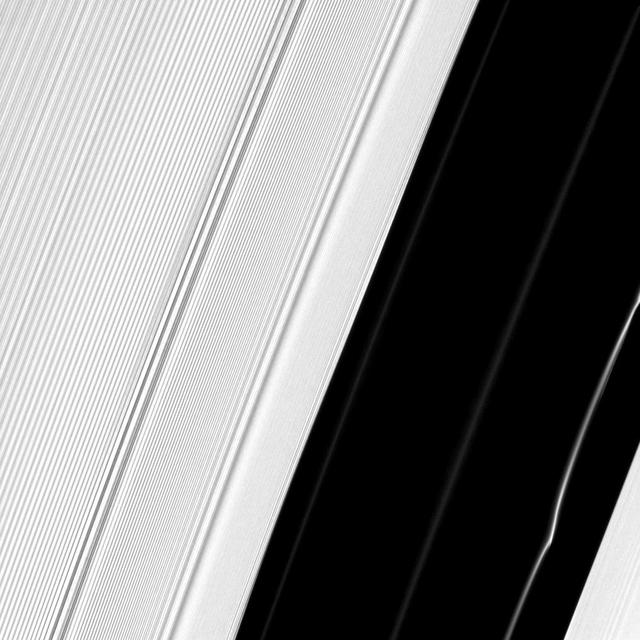

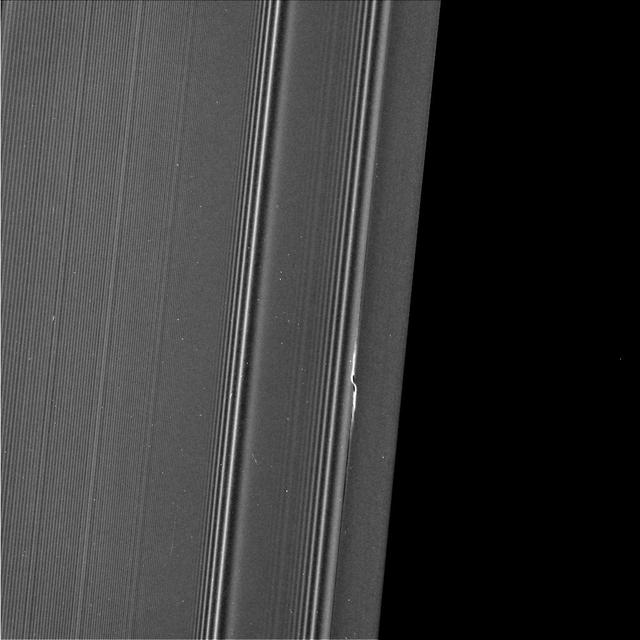

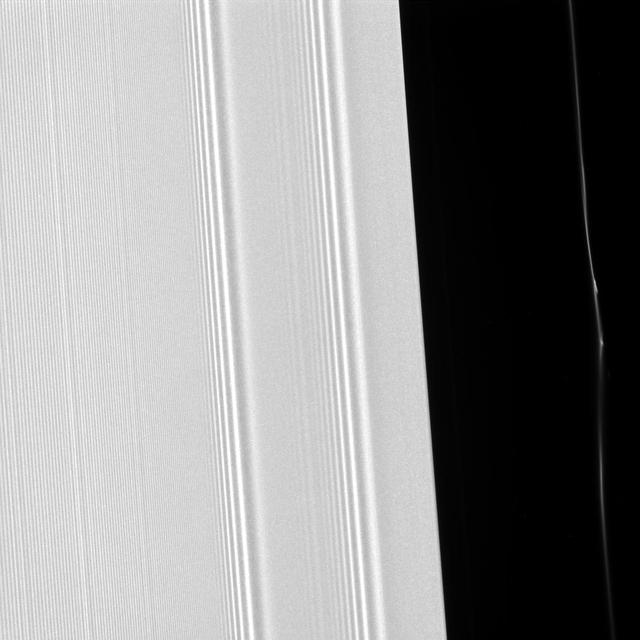

The propeller informally named "Earhart" is seen in this view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft at much higher resolution than ever before. This view, obtained on March 22, 2017, is the second time Cassini has deliberately targeted an individual propeller for close-up viewing during its ring-grazing orbits, after its images of Santos-Dumont (PIA21433) a month earlier. The biggest known propeller, informally named "Bleriot," is slated for the third and final propeller close-up in April 2017. Propellers are disturbances in the ring caused by a central moonlet. The moonlet itself would be a few pixels wide in this view, but it is difficult to distinguish from (and may be obscured by) the disturbed ring material that surrounds it. (See PIA20525 for more info on propellers.) The detailed structure of the Earhart propeller, as seen here, differs from that of Santos-Dumont. It is not clear whether these differences have to do with intrinsic differences between Earhart and Santos-Dumont, or whether they have to do with different viewing angles or differences in where the propellers were imaged in their orbits around Saturn. Earhart is situated very close to the 200-mile-wide (320-kilometer-wide) Encke Gap, which is held open by the much larger moon Pan. In this view, half of the Encke Gap is visible as the dark region at right. The gap and the propeller are a study in contrasts. The propeller is nothing more than Earhart's attempt to open a gap like Encke using its gravity. However, Earhart's attempt is thwarted by the mass of the ring, which fills in the nascent gap before it can extend very far. Pan is a few thousand times more massive than Earhart, which enables it to maintain a gap that extends all the way around the ring. To the left of the propeller are wave features in the rings caused by the moons Pandora, Prometheus and Pan. The visible-light image was acquired by the Cassini narrow-angle camera at a distance of 69,183 miles (111,340 kilometers) from the propeller feature. Image scale is 0.4 mile (670 meters) per pixel in the radial, or outward-from-Saturn, direction. The view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21437

<p> The Cassini spacecraft looks toward the unilluminated side of Saturn rings to spy on the moon Pan as it cruises through the Encke Gap. </p> <p> This view looks toward the rings from about 13 degrees above the ringplane. At the top of the image

Hiding within the Encke gap is the small moon Pan, partly in shadow and party cut off by the outer A ring in this view. Similar to Atlas, Pan appears to have a slight ridge around its middle; and like Atlas, Pan orbit also coincides with a faint ringlet

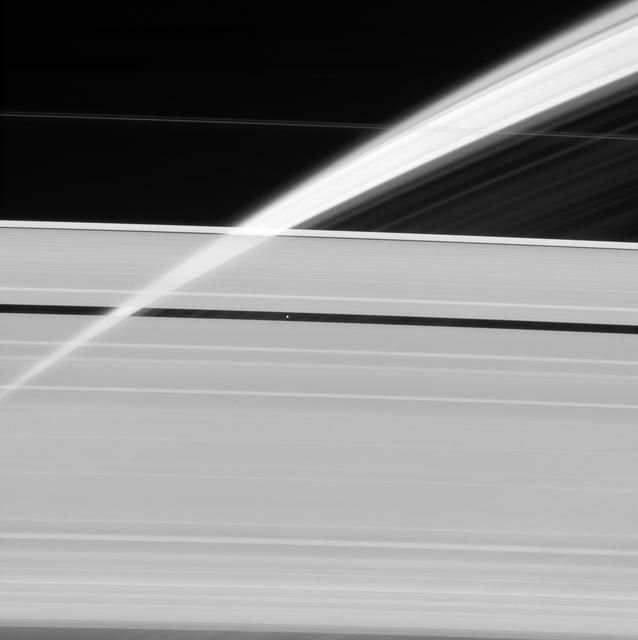

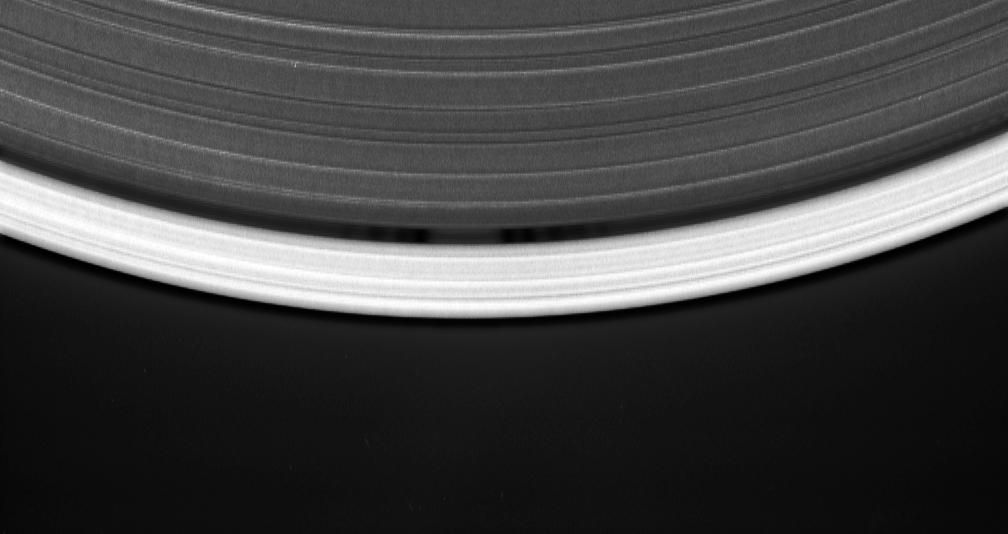

Saturn's rings, made of countless icy particles, form a translucent veil in this view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft. Saturn's tiny moon Pan, about 17 miles (28 kilometers) across, orbits within the Encke Gap in the A ring. Beyond, we can see the arc of Saturn itself, its cloud tops streaked with dark shadows cast by the rings. This image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 12, 2016, at a distance of approximately 746,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from Pan. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21901

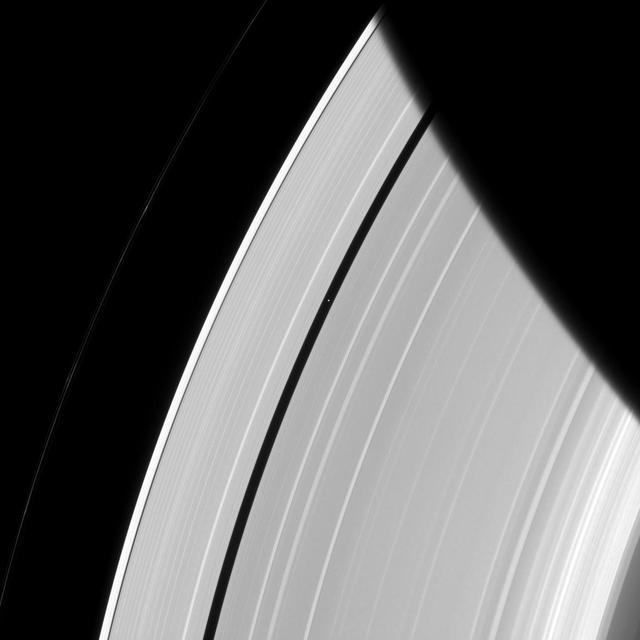

Saturn's innermost moon Pan orbits the giant planet seemingly alone in a ring gap its own gravity creates. Pan (17 miles, or 28 kilometers across) maintains the Encke Gap in Saturn's A ring by gravitationally nudging the ring particles back into the rings when they stray in the gap. Scientists think similar processes might be at work as forming planets clear gaps in the circumstellar disks from which they form. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 38 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on May 3, 2014. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 2 million miles (3.2 million kilometers) from Pan and at a Sun-Pan-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 56 degrees. Image scale is 12 miles (19 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18281

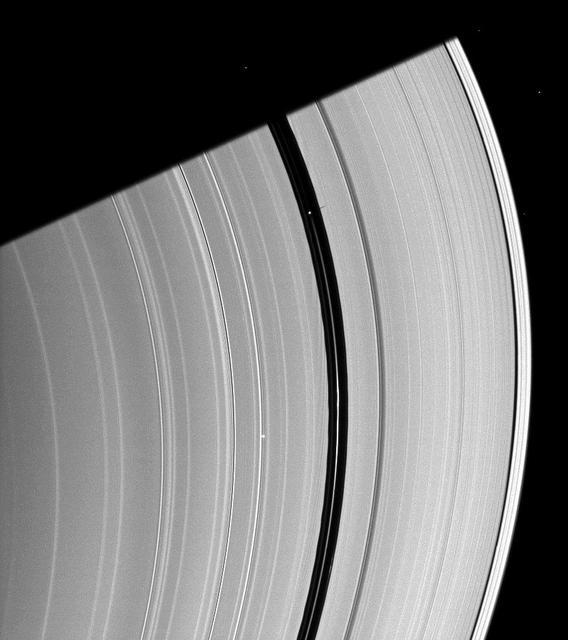

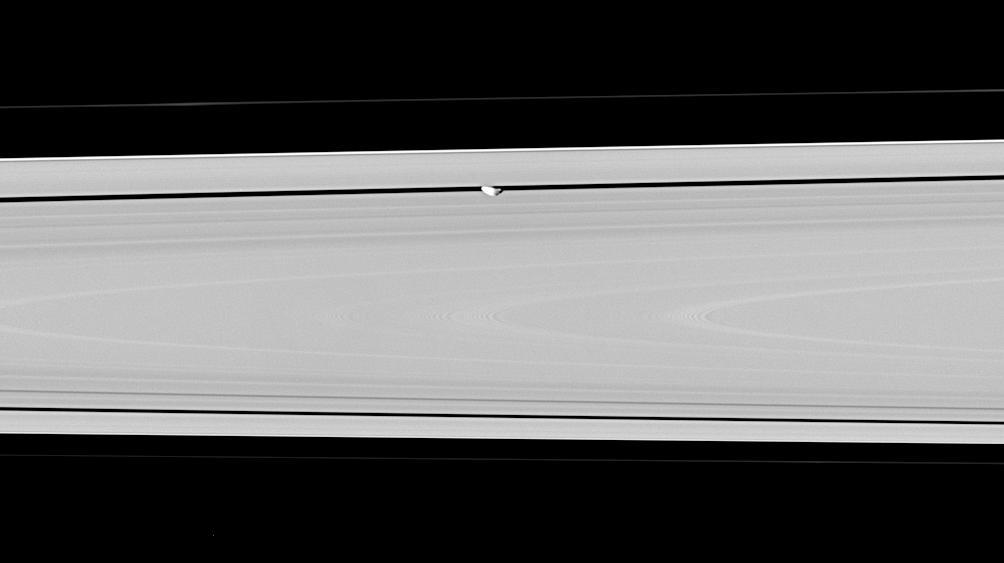

Pan and moons like it have profound effects on Saturn's rings. The effects can range from clearing gaps, to creating new ringlets, to raising vertical waves that rise above and below the ring plane. All of these effects, produced by gravity, are seen in this image. Pan (17 miles or 28 kilometers across), seen in image center, maintains the Encke Gap in which it orbits, but it also helps create and shape the narrow ringlets that appear in the Encke gap. Two faint ringlets are visible in this image, below and to the right of Pan. Many moons, Pan included, create waves at distant points in Saturn's rings where ring particles and the moons have orbital resonances. Many such waves are visible here as narrow groupings of brighter and darker bands. Studying these waves can provide information on local ring conditions. The view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 22 degrees below the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on April 3, 2016. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 232,000 miles (373,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 140 degrees. Image scale is 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20490

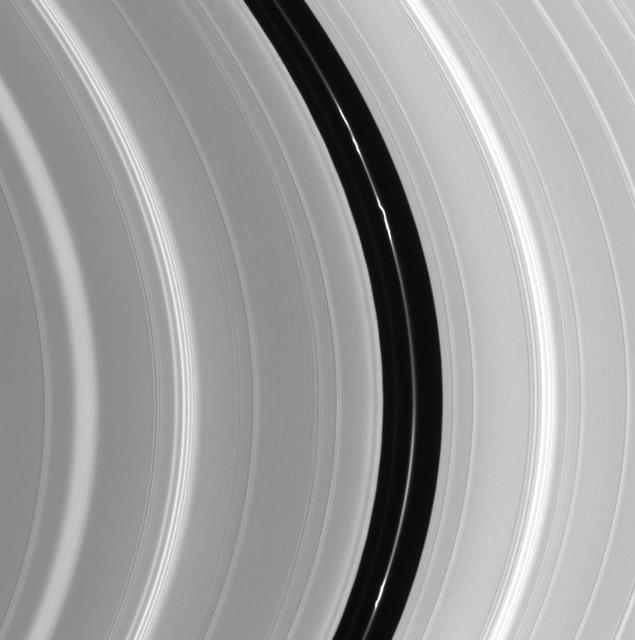

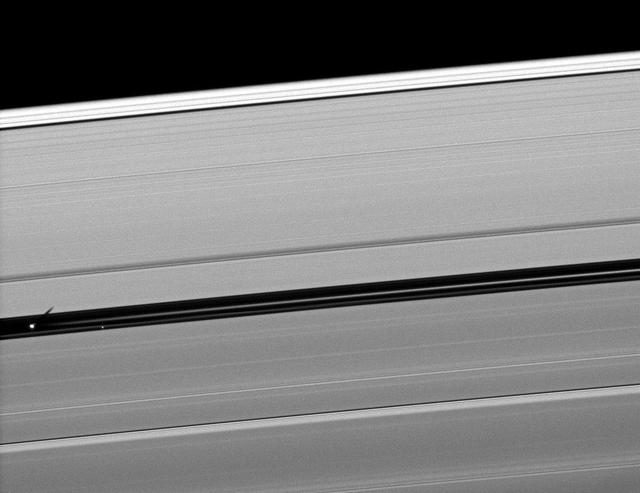

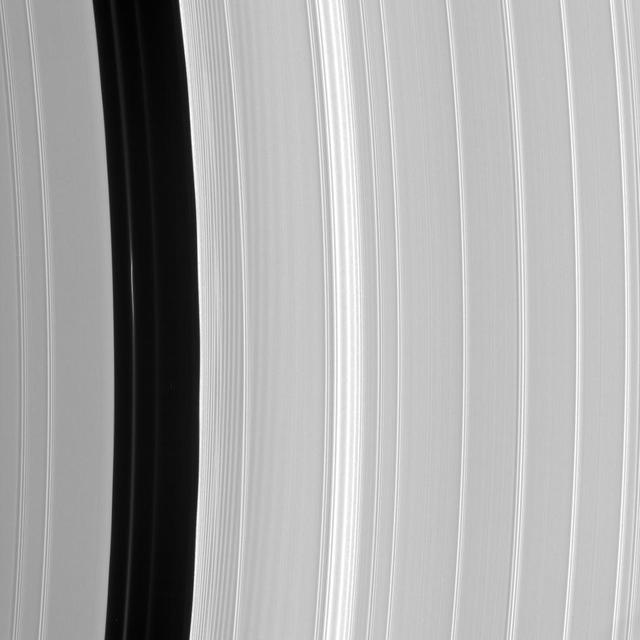

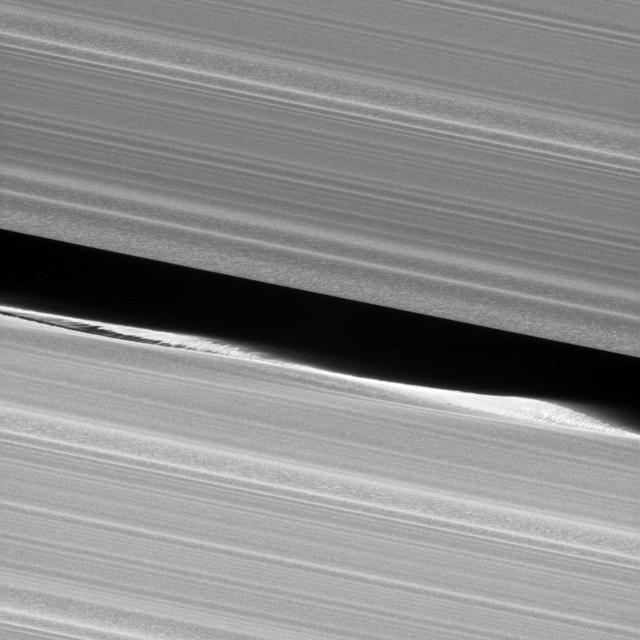

Many of the features seen in Saturn's rings are shaped by the planet's moons. This view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft shows two different effects of moons that cause waves in the A ring and kinks in a faint ringlet. The view captures the outer edge of the 200-mile-wide (320-kilometer-wide) Encke Gap, in the outer portion of Saturn's A ring. This is the same region features the large propeller called Earhart. Also visible here is one of several kinked and clumpy ringlets found within the gap. Kinks and clumps in the Encke ringlet move about, and even appear and disappear, in part due to the gravitational effects of Pan -- which orbits in the gap and whose gravitational influence holds it open. The A ring, which takes up most of the image on the left side, displays wave features caused by Pan, as well as the moons Pandora and Prometheus, which orbit a bit farther from Saturn on both sides of the planet's F ring. This view was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on March 22, 2017, and looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 22 degrees above the ring plane. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 63,000 miles (101,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a phase angle (the angle between the sun, the rings and the spacecraft) of 59 degrees. Image scale is 1,979 feet (603 meters) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21333

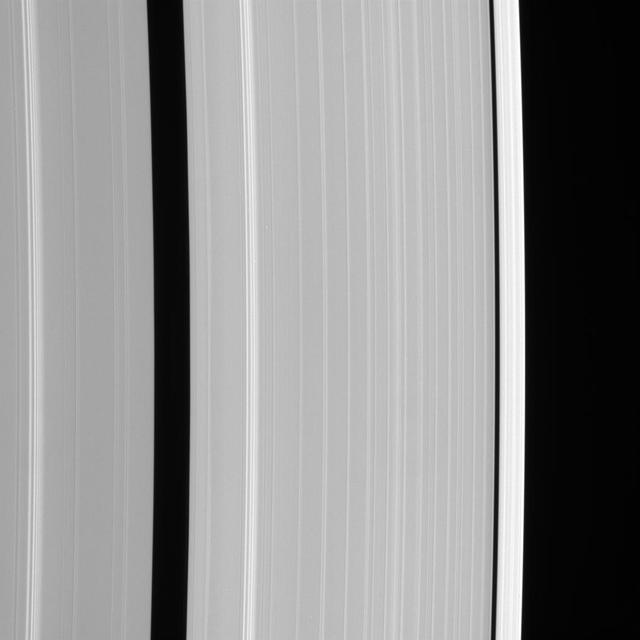

Although it appears empty from a distance, the Encke gap in Saturn A ring has three ringlets threaded through it, two of which are visible here from NASA Cassini spacecraft. Each ringlet has dynamical structure such as the clumps seen in this image. The clumps move about and even appear and disappear, in part due to the gravitational effects of Pan. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 27 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on May 11, 2013. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 199,000 miles (321,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 121 degrees. Image scale is 1 mile (2 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18277

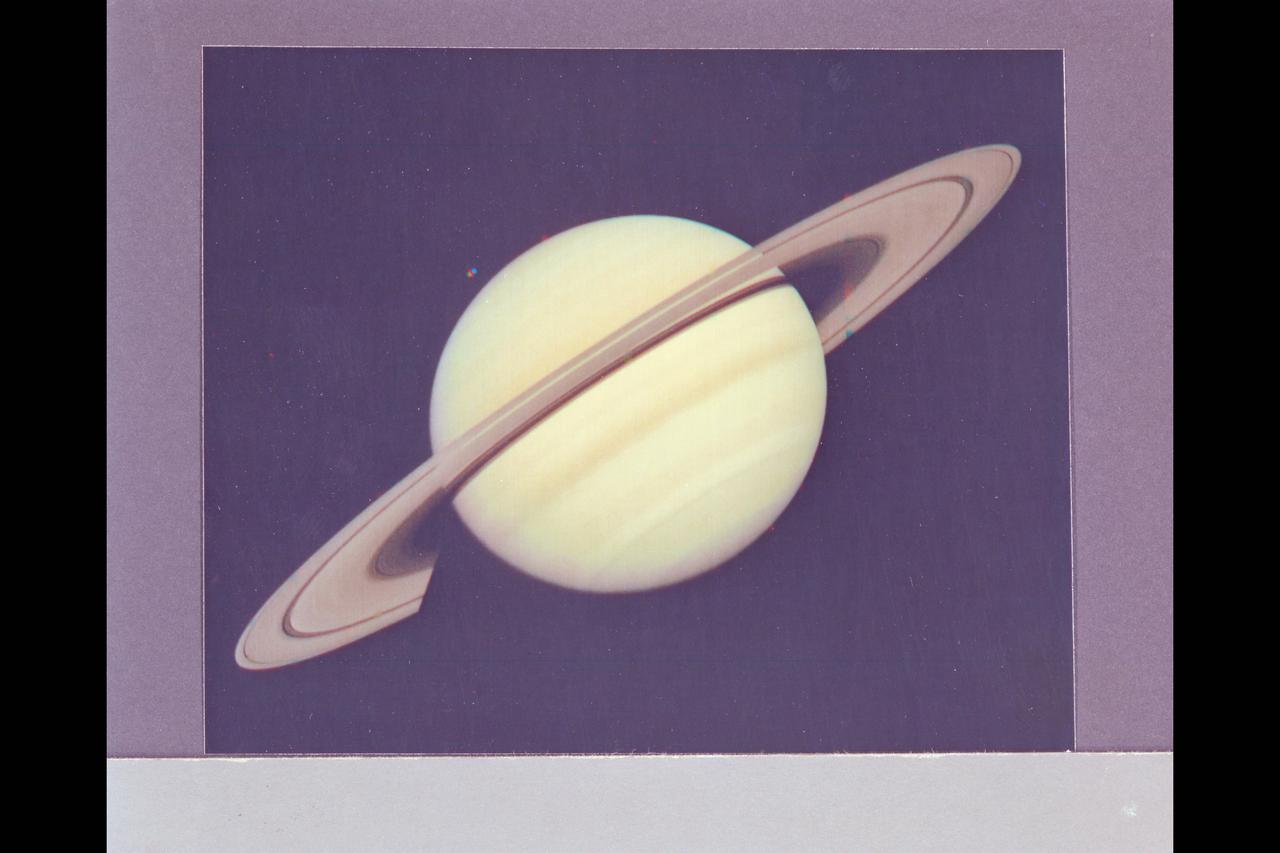

Range : 1.2 million km. ( 740,000 miles ) P-23954C Voyager 2 obtained this color image of Saturn's F-ring and its small inner sheparding satellite (1990S27) against the full disk of the planet. TheA-ring and the Encke Gap appear in the lower left corner. This view shows that the shepard is more refective than Sturn's clouds, suggesting that it is an icy, bright surfaced object like the larger satellites and the ring particles themselves.

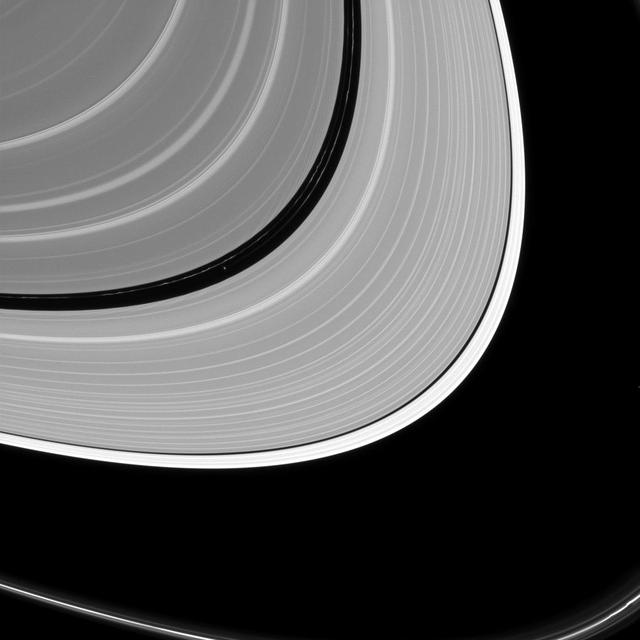

Cassini's celestial sleuthing has paid off with this time-lapse series of images which confirmed earlier suspicions that a small moon was orbiting within the narrow Keeler gap of Saturn's rings. The movie sequence, which consists of 12 images taken over 16 minutes while Cassini gazed down upon the sunlit side of the A ring, shows a tiny moon orbiting in the center of the Keeler gap, churning up waves in the gap edges as it goes. The pattern of waves travels with the moon in its orbit. The Keeler gap is located about 250 kilometers (155 miles) inside the outer edge of the A ring, which is also the outer edge of the bright main rings. The new object is about 7 kilometers across (4 miles) and reflects about 50 percent of the sunlight that falls upon it -- a brightness that is typical of particles in the nearby rings. The new body has been provisionally named S/2005 S1. Imaging scientists predicted the moon's presence and its orbital distance from Saturn after July 2004, when they saw a set of peculiar spiky and wispy features in the Keeler gap's outer edge. The similarities of the Keeler gap features to those noted in Saturn's F ring and the Encke gap led the scientists to conclude that a small body, a few kilometers across, was lurking in the center of the Keeler gap, awaiting discovery. Also included here is a view of the same scene created by combining six individual, unmagnified frames used in the movie sequence. This digital composite view improves the overall resolution of the scene compared to that available in any of the single images. The images in this movie sequence were obtained with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on May 1, 2005, at a distance of approximately 1.1 million kilometers (708,000 miles) from Saturn. Resolution in the original image was 8 kilometers (5 miles) per pixel. The images in the movie sequence have been magnified in (the vertical direction only) by a factor of two to aid visibility of features caused within the gap by the moonlet. An animation is available at http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA06238

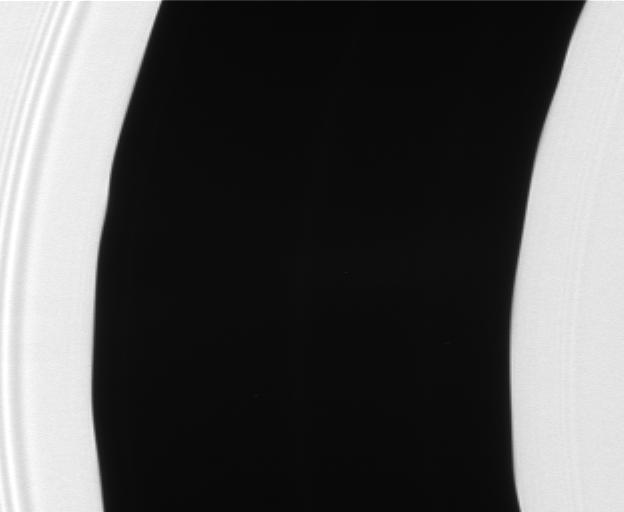

Before NASA's Cassini entered its Grand Finale orbits, it acquired unprecedented views of the outer edges of the main ring system. For example, this close-up view of the Keeler Gap, which is near the outer edge of Saturn's main rings, shows in great detail just how much the moon Daphnis affects the edges of the gap. Daphnis creates waves in the edges of the gap through its gravitational influence. Some clumping of ring particles can be seen in the perturbed edge, similar to what was seen on the edges of the Encke Gap back when Cassini arrived at Saturn in 2004. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 3 degrees above the ring plane. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 18,000 miles (30,000 kilometers) from Daphnis and at a Sun-Daphnis-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 69 degrees. Image scale is 581 feet (177 meters) per pixel. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Jan. 16, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21329

Pan may be small as satellites go, but like many of Saturn's ring moons, it has a has a very visible effect on the rings. Pan (17 miles or 28 kilometers across, left of center) holds open the Encke gap and shapes the ever-changing ringlets within the gap (some of which can be seen here). In addition to raising waves in the A and B rings, other moons help shape the F ring, the outer edge of the A ring and open the Keeler gap. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 8 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 2, 2016. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 840,000 miles (1.4 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 128 degrees. Image scale is 5 miles (8 kilometers) per pixel. Pan has been brightened by a factor of two to enhance its visibility. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20499

Range : 34 million km. ( 21.1 million miles) P-22993C This Voyager 1 photograph of Saturn was taken on the last day it could be captured within a single narrow angle camera frame as the spacecraft neared the planet for it's closest approach on Nov. 12, 1980. Dione, one of Saturn's innermost satellites, appears as three color spots just below the planet's south pole. An abundance of previously unseen detail is apparent in the rings. For example, a gap in the dark, innermst ring, C-ring or Crepe Ring, is clearly shown. Also, material is seen inside the relatively wide Cassini Division, seperating the middle, B-ring from the outermost ring, the A-ring. The Encke division is shown near the outer edge of A-ring. The detail in the ring's shadows cast on the planet is of particular interest. The broad dark band near the equator is the shadow of B-ring. The thinner, brighter line just to the south is the shadow of the less dense A-ring.

P-34712 Range: 1.1 million kilometers (683,000 miles) This wide-angle Voyager 2 image, taken through the camera's clear filter, is the first to show Neptune's rings in detail. The two main rings, about 53,000 km (33,000 miles) and 63,000 km (39,000 miles) from Neptune, are 5 to 10 times brighter than in earlier images. The difference is due to lighting and viewing geometry. In approach images, the rings were seen in light scattered backward toward the spacecraft at a 15° phase angle. However, this image was taken at a 135° phase angle as Voyager left the planet. That geometry is ideal for detecting microscopic particles that forward scatter light preferentially. The fact that Neptune's rings are so much brighter at that angle means the particle-size distribution is quite different from most of Uranus' and Saturn's rings, which contain fewer dust-size grains. However, a few componenets of the Saturian and Uranian ring systems exhibit forward-scattering behavior: The F ring and the Encke Gap ringlet at Saturn and 1986U1R at Uranus. They are also narrow, clumpy ringlets with kinks, and are associated with nearby moonlets too small to detect directly. In this image, the main clumpy arc, composed of three features each about 6 to 8 degrees long, is clearly seen. Exposure time for this image was 111 seconds.

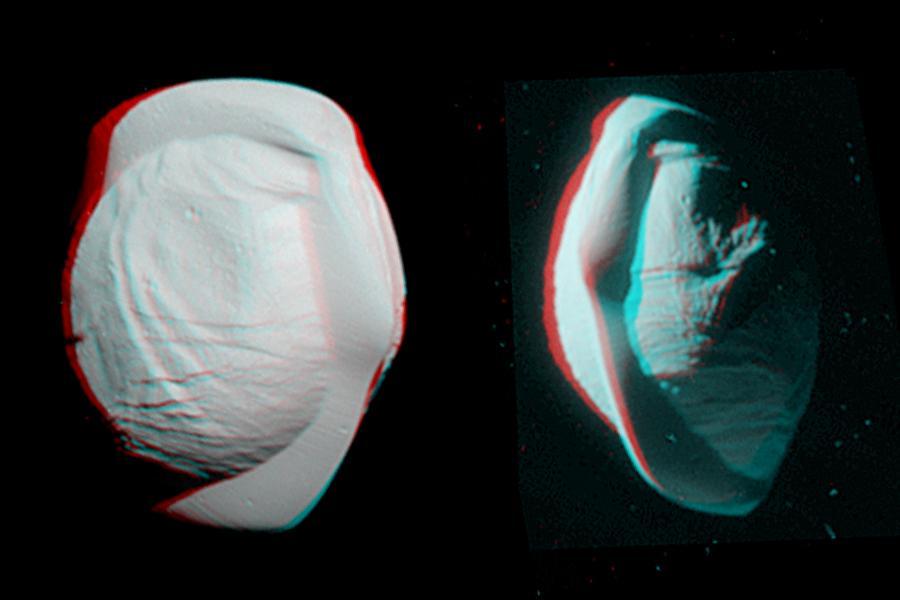

These stereo views, or anaglyphs, highlight the unusual, quirky shape of Saturn's moon Pan. They appear three-dimensional when viewed through red-blue glasses with the red lens on the left. The views show the northern and southern hemispheres of Pan, at left and right, respectively. They have been rotated to maximize the stereo effect. Pan has an average diameter of 17 miles (28 kilometers). The moon orbits within the Encke Gap in Saturn's A ring. Both of these views look toward Pan's trailing side, which is the side opposite the moon's direction of motion as it orbits Saturn. These views were acquired by the Cassini narrow-angle camera on March 7, 2017, at distances of approximately 16,000 miles or 25,000 kilometers (left view) and 21,000 miles or 34,000 kilometers (right view). Image scale in the original images is about 500 feet (150 meters) per pixel (left view) and about 650 feet (200 meters) per pixel (right view). The images have been magnified by a factor of two from their original size. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21435

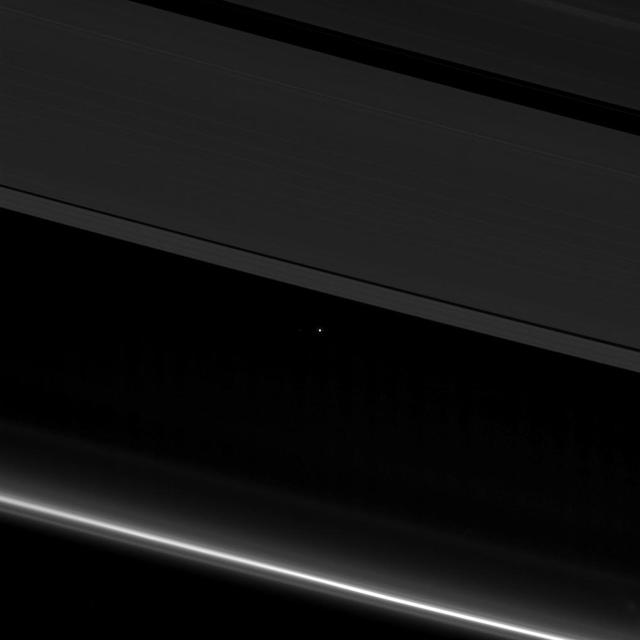

This view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft shows planet Earth as a point of light between the icy rings of Saturn. The spacecraft captured the view on April 12, 2017 at 10:41 p.m. PDT (1:41 a.m. EDT). Cassini was 870 million miles (1.4 billion kilometers) away from Earth when the image was taken. Although far too small to be visible in the image, the part of Earth facing toward Cassini at the time was the southern Atlantic Ocean. Earth's moon is also visible to the left of our planet in a cropped, zoomed-in version of the image (Figure 1). The rings visible here are the A ring (at top) with the Keeler and Encke gaps visible, and the F ring (at bottom). During this observation Cassini was looking toward the backlit rings, making a mosaic of multiple images, with the sun blocked by the disk of Saturn. Seen from Saturn, Earth and the other inner solar system planets are all close to the sun, and are easily captured in such images, although these opportunities have been somewhat rare during the mission. The F ring appears especially bright in this viewing geometry. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21445

Two tiny moons of Saturn, almost lost amid the planet's enormous rings, are seen orbiting in this image. Pan, visible within the Encke Gap near lower-right, is in the process of overtaking the slower Atlas, visible at upper-left. All orbiting bodies, large and small, follow the same basic rules. In this case, Pan (17 miles or 28 kilometers across) orbits closer to Saturn than Atlas (19 miles or 30 kilometers across). According to the rules of planetary motion deduced by Johannes Kepler over 400 years ago, Pan orbits the planet faster than Atlas does. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 39 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 9, 2016. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 3.4 million miles (5.5 million kilometers) from Atlas and at a Sun-Atlas-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 71 degrees. Image scale is 21 miles (33 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20501

People with similar jobs or interests hold conventions and meetings, so why shouldn't moons? Pandora, Prometheus, and Pan -- seen here, from right to left -- also appear to be holding some sort of convention in this image. Some moons control the structure of nearby rings via gravitational "tugs." The cumulative effect of the moon's tugs on the ring particles can keep the rings' edges from spreading out as they are naturally inclined to do, much like shepherds control their flock. Pan is a prototypical shepherding moon, shaping and controlling the locations of the inner and outer edges of the Encke gap through a mechanism suggested in 1978 to explain the narrow Uranian rings. However, though Prometheus and Pandora have historically been called "the F ring shepherd moons" due to their close proximity to the ring, it has long been known that the standard shepherding mechanism that works so well for Pan does not apply to these two moons. The mechanism for keeping the F ring narrow, and the roles played -- if at all -- by Prometheus and Pandora in the F ring's configuration are not well understood. This is an ongoing topic for study by Cassini scientists. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 29 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Jan. 2, 2015. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.6 million miles (2.6 million kilometers) from the rings and at a Sun-ring-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 86 degrees. Image scale is 10 miles (15 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18306

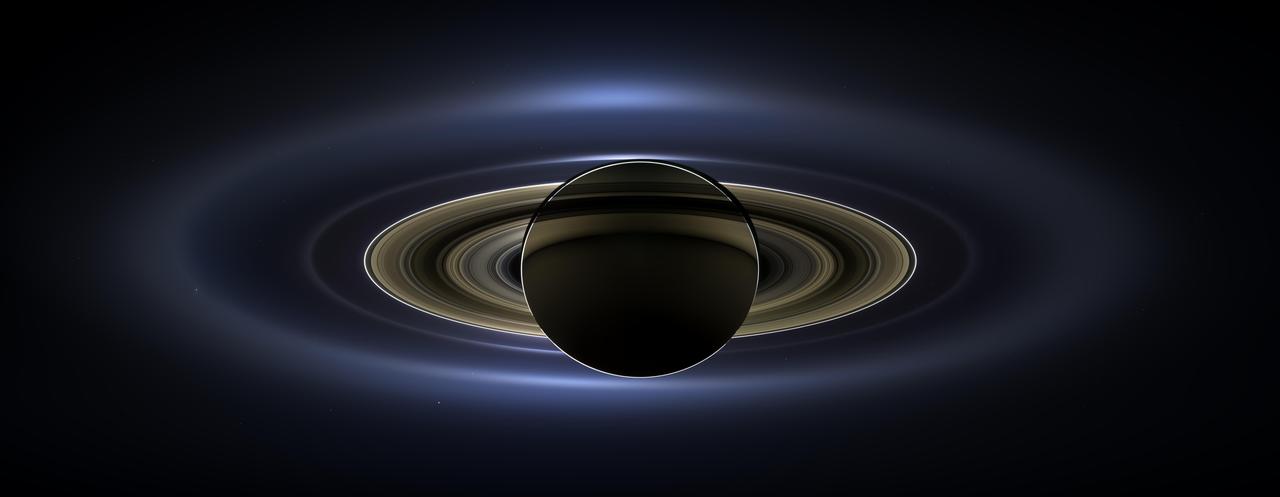

On July 19, 2013, in an event celebrated the world over, NASA's Cassini spacecraft slipped into Saturn's shadow and turned to image the planet, seven of its moons, its inner rings -- and, in the background, our home planet, Earth. With the sun's powerful and potentially damaging rays eclipsed by Saturn itself, Cassini's onboard cameras were able to take advantage of this unique viewing geometry. They acquired a panoramic mosaic of the Saturn system that allows scientists to see details in the rings and throughout the system as they are backlit by the sun. This mosaic is special as it marks the third time our home planet was imaged from the outer solar system; the second time it was imaged by Cassini from Saturn's orbit; and the first time ever that inhabitants of Earth were made aware in advance that their photo would be taken from such a great distance. With both Cassini's wide-angle and narrow-angle cameras aimed at Saturn, Cassini was able to capture 323 images in just over four hours. This final mosaic uses 141 of those wide-angle images. Images taken using the red, green and blue spectral filters of the wide-angle camera were combined and mosaicked together to create this natural-color view. A brightened version with contrast and color enhanced (Figure 1), a version with just the planets annotated (Figure 2), and an annotated version (Figure 3) are shown above. This image spans about 404,880 miles (651,591 kilometers) across. The outermost ring shown here is Saturn's E ring, the core of which is situated about 149,000 miles (240,000 kilometers) from Saturn. The geysers erupting from the south polar terrain of the moon Enceladus supply the fine icy particles that comprise the E ring; diffraction by sunlight gives the ring its blue color. Enceladus (313 miles, or 504 kilometers, across) and the extended plume formed by its jets are visible, embedded in the E ring on the left side of the mosaic. At the 12 o'clock position and a bit inward from the E ring lies the barely discernible ring created by the tiny, Cassini-discovered moon, Pallene (3 miles, or 4 kilometers, across). (For more on structures like Pallene's ring, see PIA08328). The next narrow and easily seen ring inward is the G ring. Interior to the G ring, near the 11 o'clock position, one can barely see the more diffuse ring created by the co-orbital moons, Janus (111 miles, or 179 kilometers, across) and Epimetheus (70 miles, or 113 kilometers, across). Farther inward, we see the very bright F ring closely encircling the main rings of Saturn. Following the outermost E ring counter-clockwise from Enceladus, the moon Tethys (662 miles, or 1,066 kilometers, across) appears as a large yellow orb just outside of the E ring. Tethys is positioned on the illuminated side of Saturn; its icy surface is shining brightly from yellow sunlight reflected by Saturn. Continuing to about the 2 o'clock position is a dark pixel just outside of the G ring; this dark pixel is Saturn's Death Star moon, Mimas (246 miles, or 396 kilometers, across). Mimas appears, upon close inspection, as a very thin crescent because Cassini is looking mostly at its non-illuminated face. The moons Prometheus, Pandora, Janus and Epimetheus are also visible in the mosaic near Saturn's bright narrow F ring. Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers, across) is visible as a faint black dot just inside the F ring and at the 9 o'clock position. On the opposite side of the rings, just outside the F ring, Pandora (50 miles, or 81 kilometers, across) can be seen as a bright white dot. Pandora and Prometheus are shepherd moons and gravitational interactions between the ring and the moons keep the F ring narrowly confined. At the 11 o'clock position in between the F ring and the G ring, Janus (111 miles, or 179 kilometers, across) appears as a faint black dot. Janus and Prometheus are dark for the same reason Mimas is mostly dark: we are looking at their non-illuminated sides in this mosaic. Midway between the F ring and the G ring, at about the 8 o'clock position, is a single bright pixel, Epimetheus. Looking more closely at Enceladus, Mimas and Tethys, especially in the brightened version of the mosaic, one can see these moons casting shadows through the E ring like a telephone pole might cast a shadow through a fog. In the non-brightened version of the mosaic, one can see bright clumps of ring material orbiting within the Encke gap near the outer edge of the main rings and immediately to the lower left of the globe of Saturn. Also, in the dark B ring within the main rings, at the 9 o'clock position, one can see the faint outlines of two spoke features, first sighted by NASA's Voyager spacecraft in the early 1980s and extensively studied by Cassini. Finally, in the lower right of the mosaic, in between the bright blue E ring and the faint but defined G ring, is the pale blue dot of our planet, Earth. Look closely and you can see the moon protruding from the Earth's lower right. (For a higher resolution view of the Earth and moon taken during this campaign, see PIA14949.) Earth's twin, Venus, appears as a bright white dot in the upper left quadrant of the mosaic, also between the G and E rings. Mars also appears as a faint red dot embedded in the outer edge of the E ring, above and to the left of Venus. For ease of visibility, Earth, Venus, Mars, Enceladus, Epimetheus and Pandora were all brightened by a factor of eight and a half relative to Saturn. Tethys was brightened by a factor of four. In total, 809 background stars are visible and were brightened by a factor ranging from six, for the brightest stars, to 16, for the faintest. The faint outer rings (from the G ring to the E ring) were also brightened relative to the already bright main rings by factors ranging from two to eight, with the lower-phase-angle (and therefore fainter) regions of these rings brightened the most. The brightened version of the mosaic was further brightened and contrast-enhanced all over to accommodate print applications and a wide range of computer-screen viewing conditions. Some ring features -- such as full rings traced out by tiny moons -- do not appear in this version of the mosaic because they require extreme computer enhancement, which would adversely affect the rest of the mosaic. This version was processed for balance and beauty. This view looks toward the unlit side of the rings from about 17 degrees below the ring plane. Cassini was approximately 746,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from Saturn when the images in this mosaic were taken. Image scale on Saturn is about 45 miles (72 kilometers) per pixel. This mosaic was made from pictures taken over a span of more than four hours while the planets, moons and stars were all moving relative to Cassini. Thus, due to spacecraft motion, these objects in the locations shown here were not in these specific places over the entire duration of the imaging campaign. Note also that Venus appears far from Earth, as does Mars, because they were on the opposite side of the sun from Earth. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17172