Epimetheus Alone

Epimetheus in the Way

Epimetheus on the Outside

Staying with Epimetheus

Epimetheus Revealed

Brush with Epimetheus

Epimetheus: Up-Close and Colorful

Shade from Epimetheus

Looking Down on Epimetheus

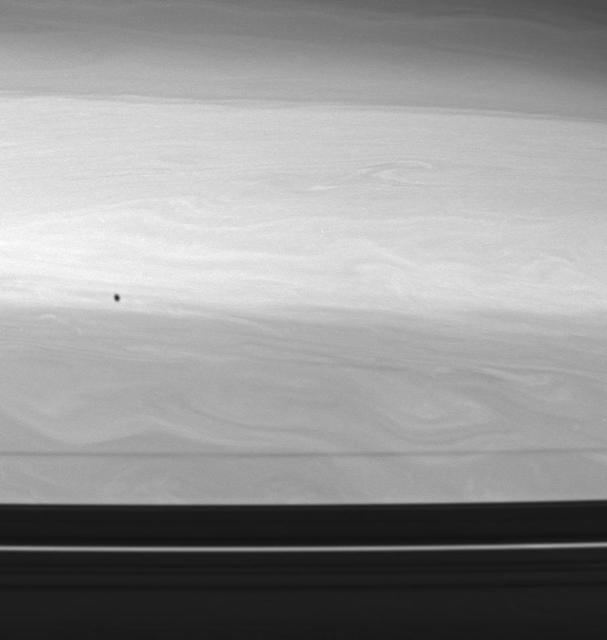

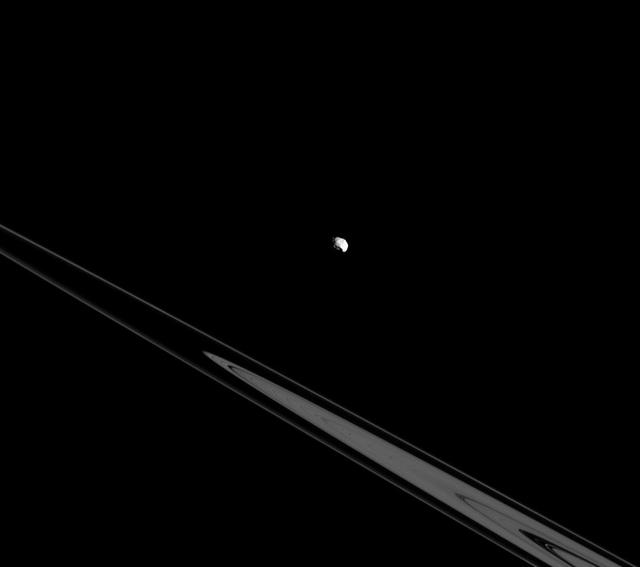

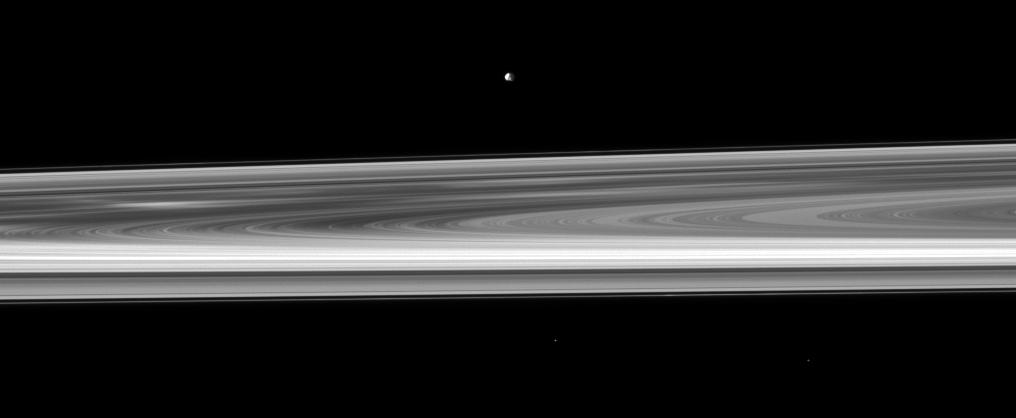

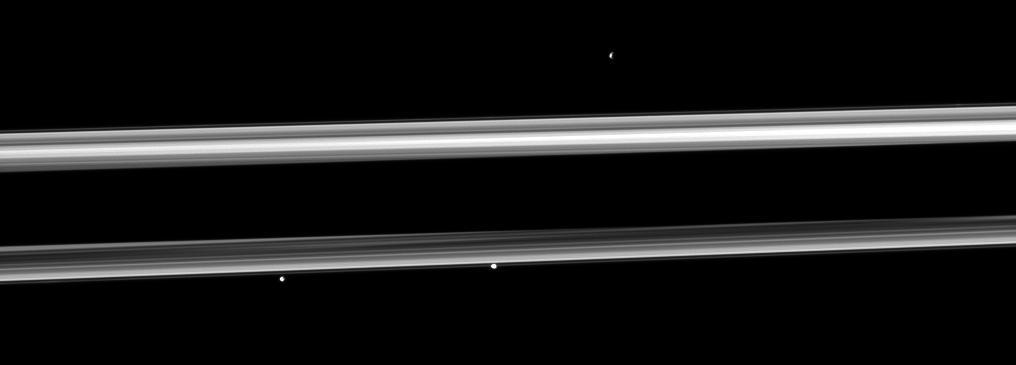

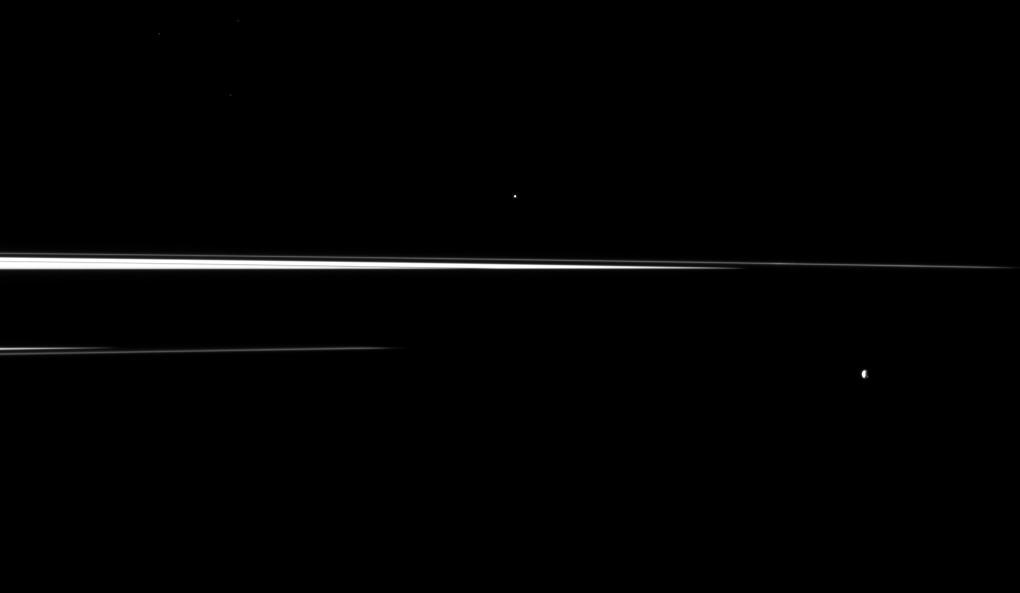

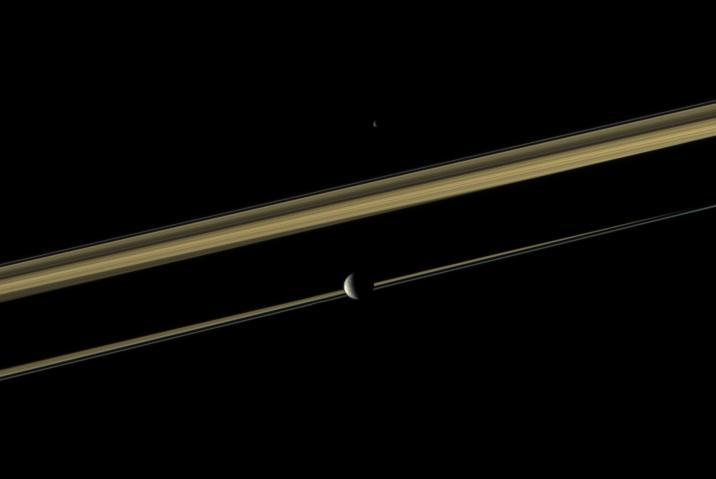

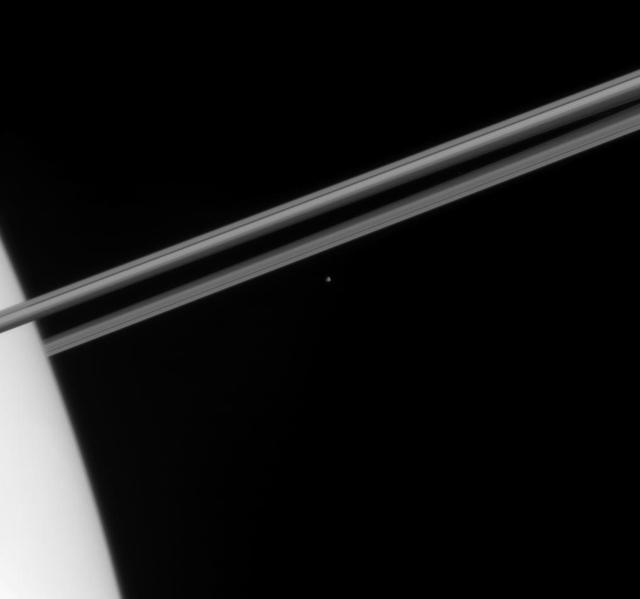

NASA Cassini spacecraft watches Saturn small moon Epimetheus orbiting beyond the planet rings. Epimetheus orbits beyond the thin F ring near the bottom center of this view.

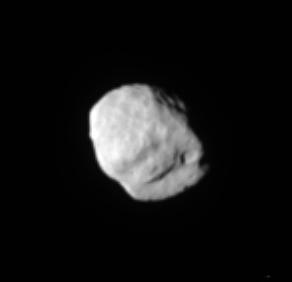

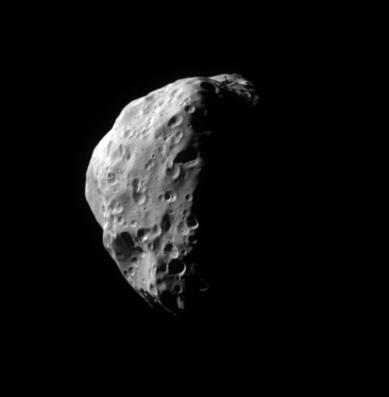

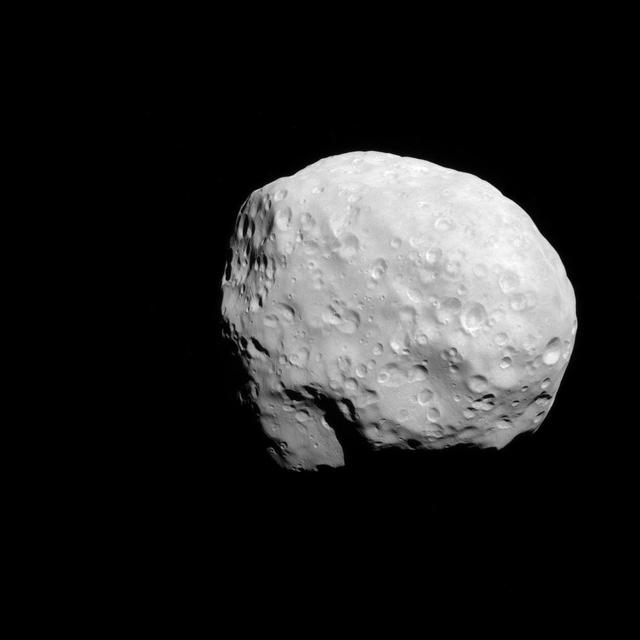

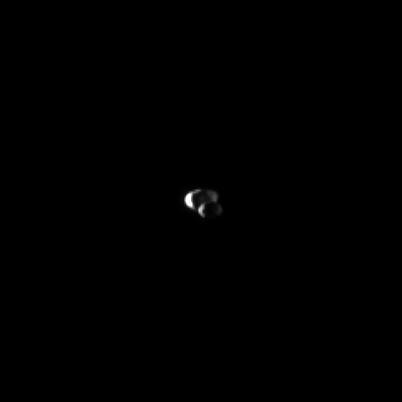

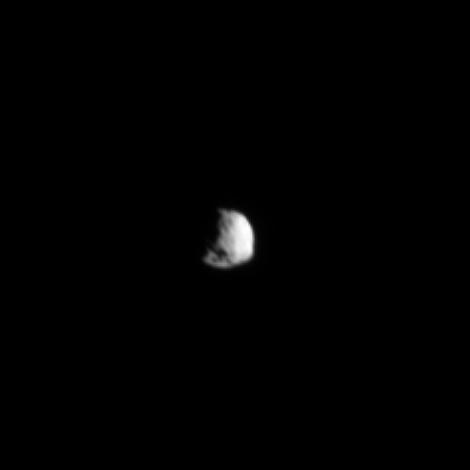

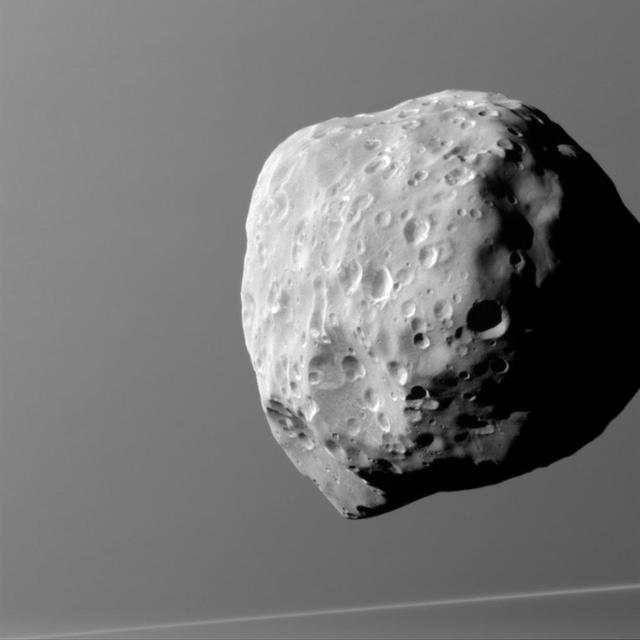

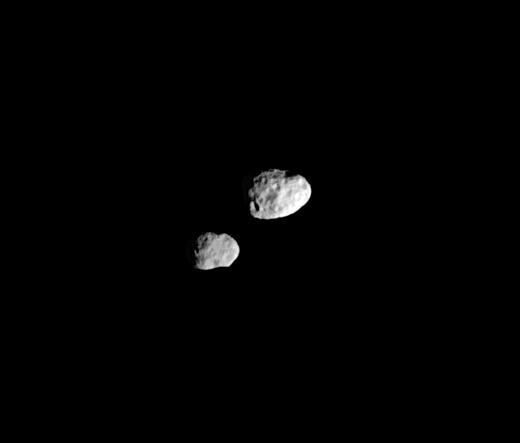

This zoomed-in view of Epimetheus, one of the highest resolution ever taken, shows a surface covered in craters, vivid reminders of the hazards of space. Epimetheus (70 miles or 113 kilometers across) is too small for its gravity to hold onto an atmosphere. It is also too small to be geologically active. There is therefore no way to erase the scars from meteor impacts, except for the generation of new impact craters on top of old ones. This view looks toward anti-Saturn side of Epimetheus. North on Epimetheus is up and rotated 32 degrees to the right. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 21, 2017 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 939 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 9,300 miles (15,000 kilometers) from Epimetheus and at a Sun-Epimetheus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 71 degrees. Image scale is 290 feet (89 meters) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21335

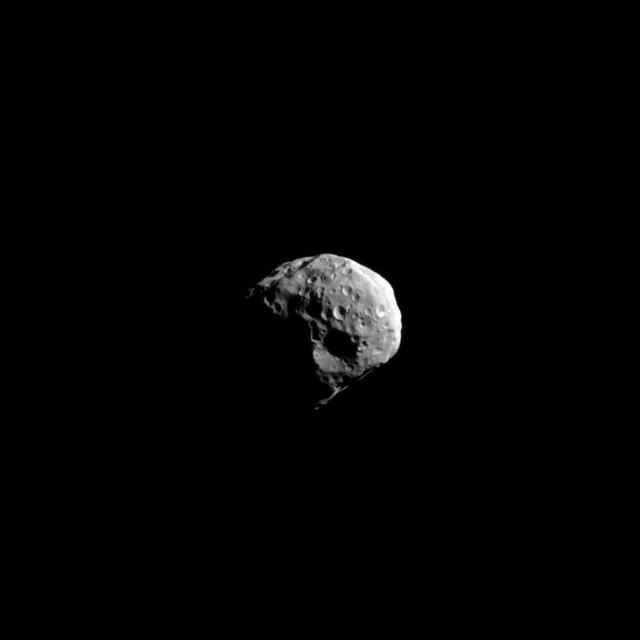

Swinging by Saturn small moon Epimetheus, NASA Cassini spacecraft snapped this shot during the spacecraft April 7, 2010, flyby.

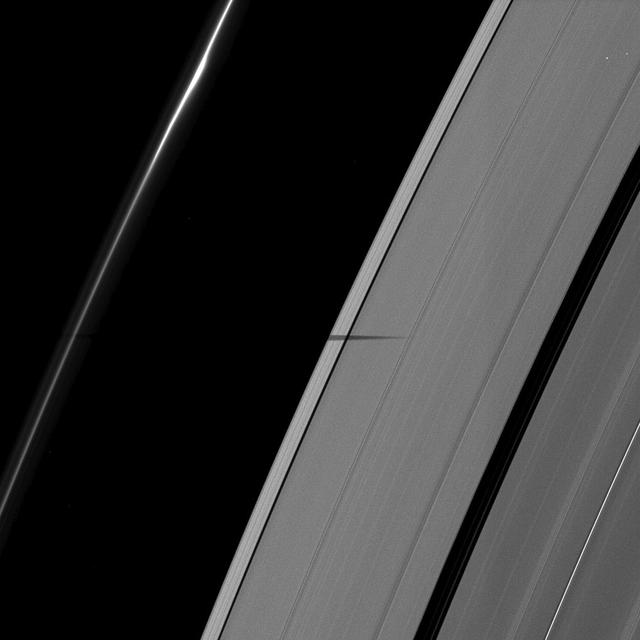

The shadow of the moon Epimetheus is cast onto Saturn rings, striking the outer-most part of the A ring and only just nipping the F ring.

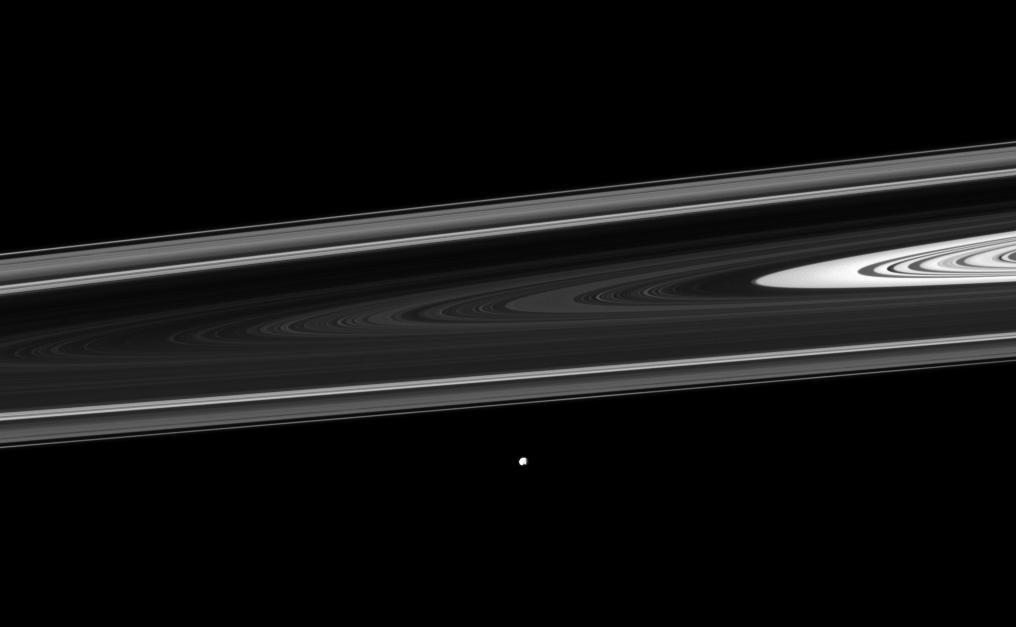

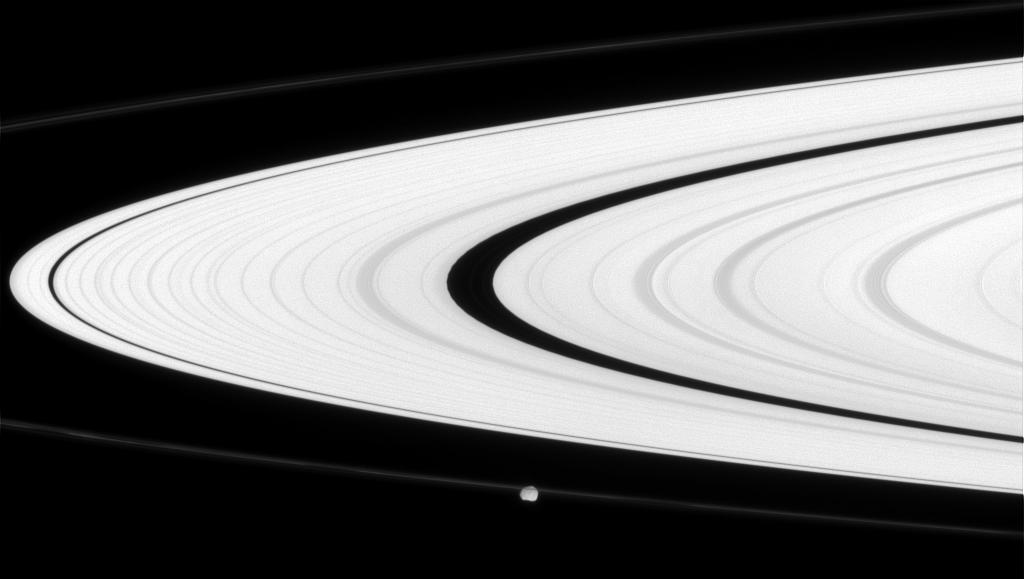

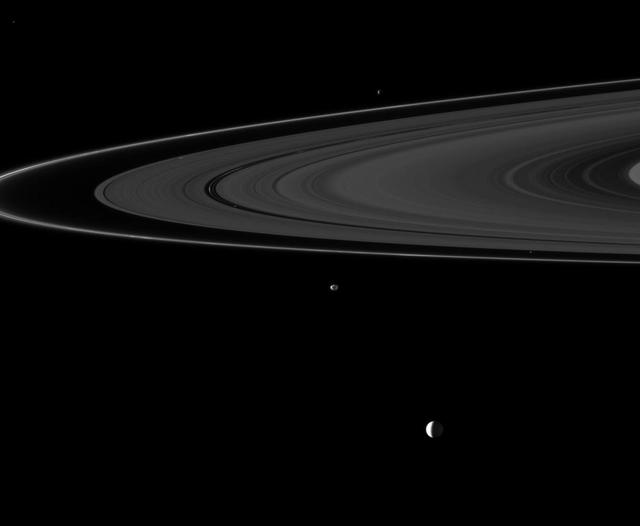

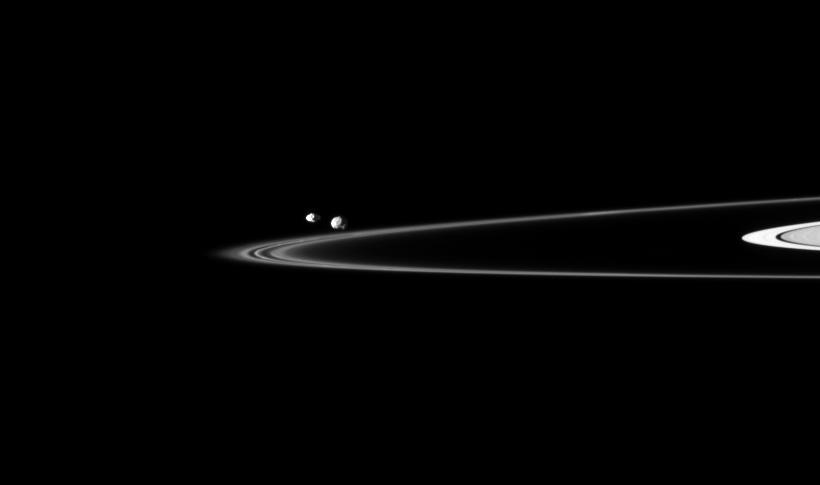

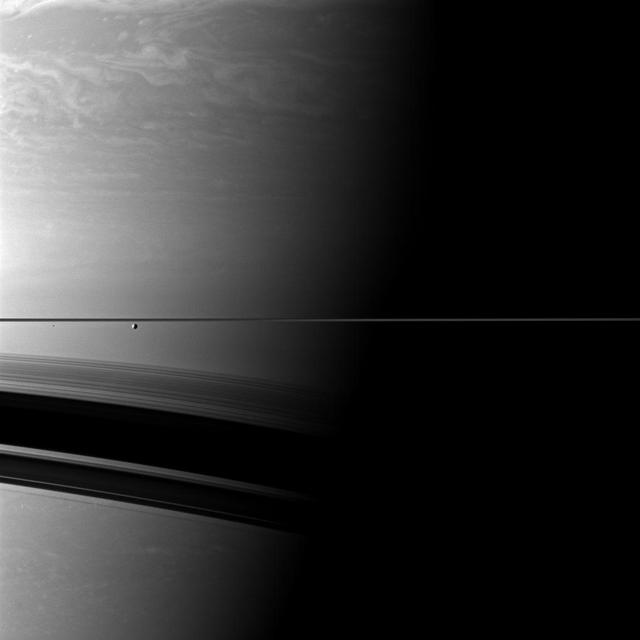

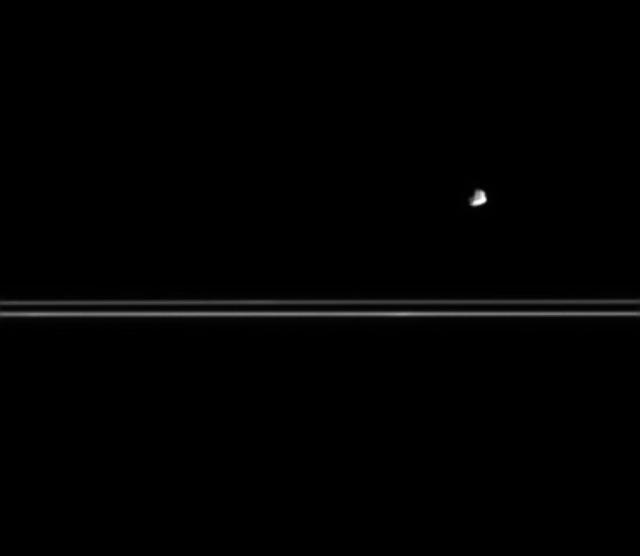

Although Epimetheus appears to be lurking above the rings here, it's actually just an illusion resulting from the viewing angle. In reality, Epimetheus and the rings both orbit in Saturn's equatorial plane. Inner moons and rings orbit very near the equatorial plane of each of the four giant planets in our solar system, but more distant moons can have orbits wildly out of the equatorial plane. It has been theorized that the highly inclined orbits of the outer, distant moons are remnants of the random directions from which they approached the planets they orbit. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about -0.3 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 26, 2015. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 500,000 miles (800,000 kilometers) from Epimetheus and at a Sun-Epimetheus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 62 degrees. Image scale is 3 miles (5 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18342

NASA Cassini spacecraft captured this view of Saturn moon Epimetheus 116 kilometers, or 72 miles across during a moderately close flyby on Dec. 6, 2015. This is one of Cassini highest resolution views of the small moon.

NASA Cassini spacecraft snapped this high-resolution image of Saturn small moon Epimetheus during the spacecraft non-targeted flyby on April 7, 2010.

Obscuring Epimetheus

Orbiting near the plane of Saturn rings, NASA Cassini spacecraft looks across the span of the rings to spy the small moon Epimetheus. The brightest spoke is visible on the left of the image.

Saturn moon Epimetheus moves in front of the larger moon Janus as seen by NASA Cassini spacecraft. The moons are lit by sunlight on the left and light reflected off Saturn on the right.

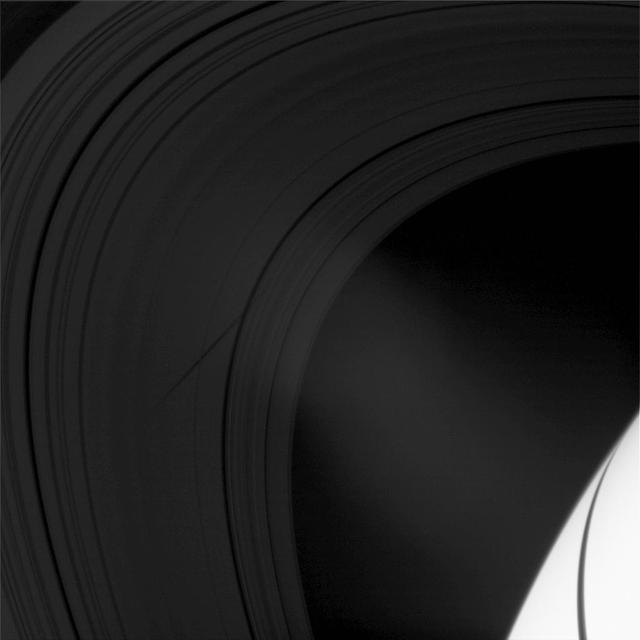

The Janus/Epimetheus Ring

Epimetheus Long Shadow

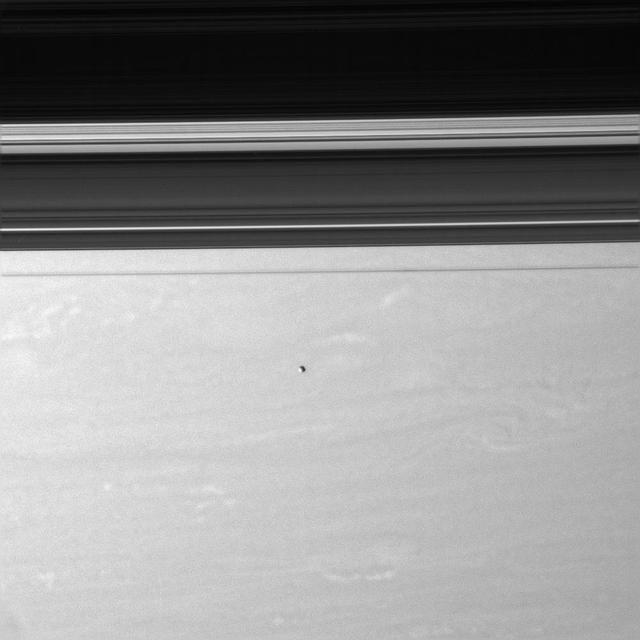

Epimetheus floats above Saturn swirling skies

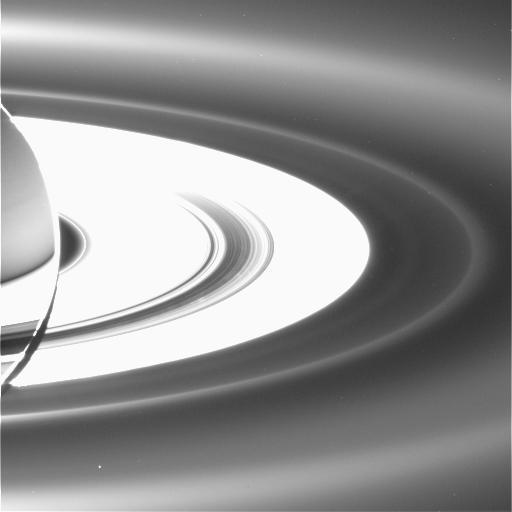

Saturn moon Epimetheus casts a shadow across colorful rings in this image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft before the planet August 2009 equinox. Epimetheus is visible as a small dot at the center of the bottom of the image.

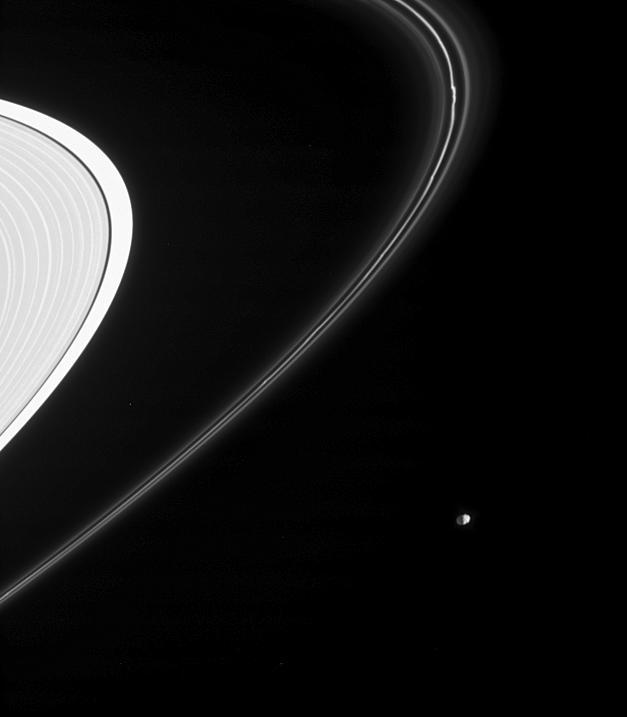

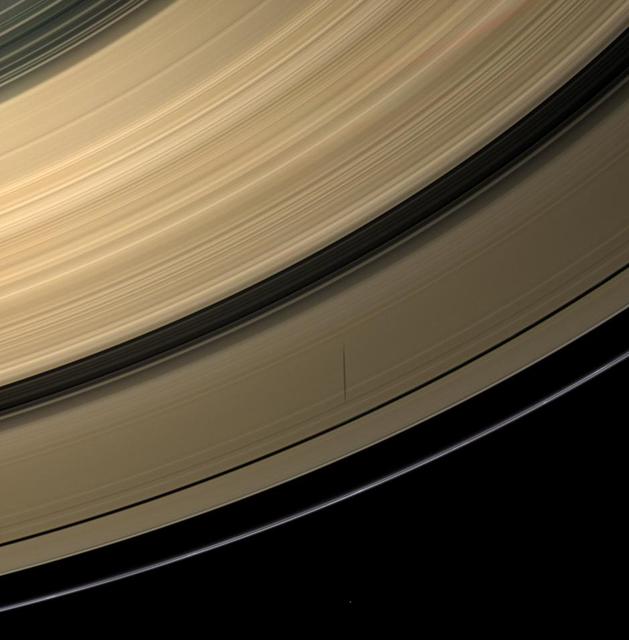

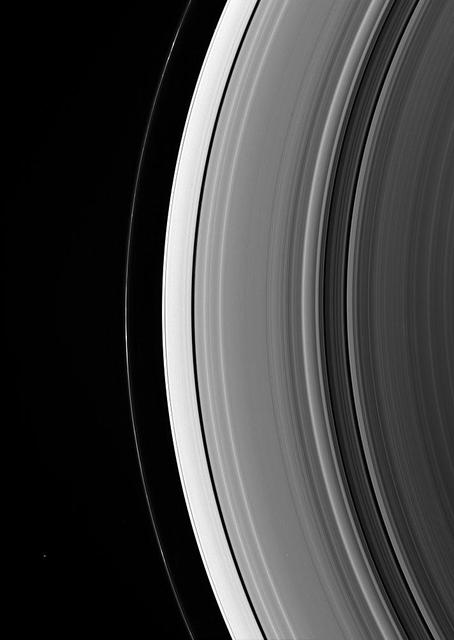

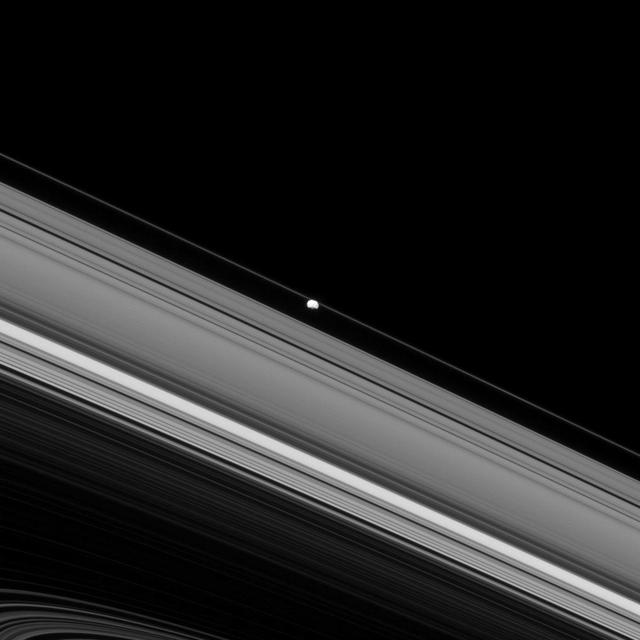

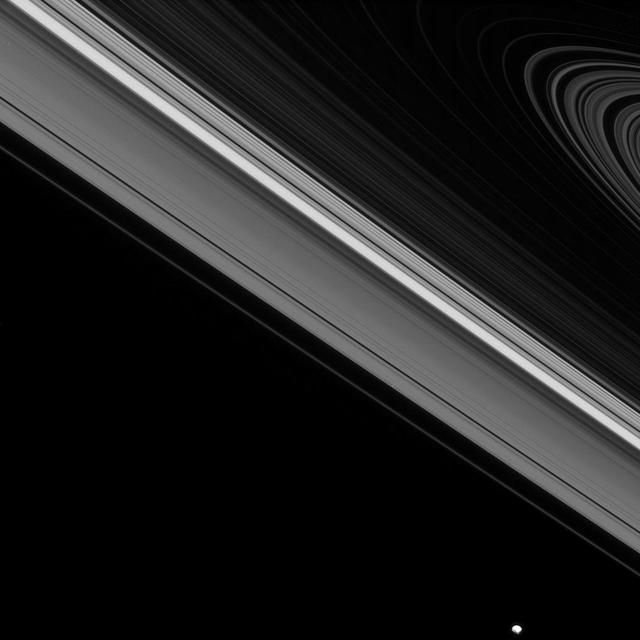

Tiny Epimetheus is dwarfed by adjacent slivers of the A and F rings. But is it really? Looks can be deceiving! There is approximately 10 to 20 times more mass in that tiny dot than in the piece of the A ring visible in this image! In total, Saturn's rings have about as much mass as a few times the mass of the moon Mimas. (This mass estimate comes from measuring the waves raised in the rings by moons like Epimetheus.) The rings look physically larger than any moon because the individual ring particles are very small, giving them a large surface area for a given mass. Epimetheus (70 miles or 113 kilometers across), on the other hand, has a small surface area per mass compared to the rings, making it look deceptively small. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Dec. 5, 2014. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (2 million kilometers) from Epimetheus and at a Sun-Epimetheus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 40 degrees. Image scale is 7 miles (12 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18302

The Cassini spacecraft looks toward the flattened south pole of Saturn small moon Epimetheus.

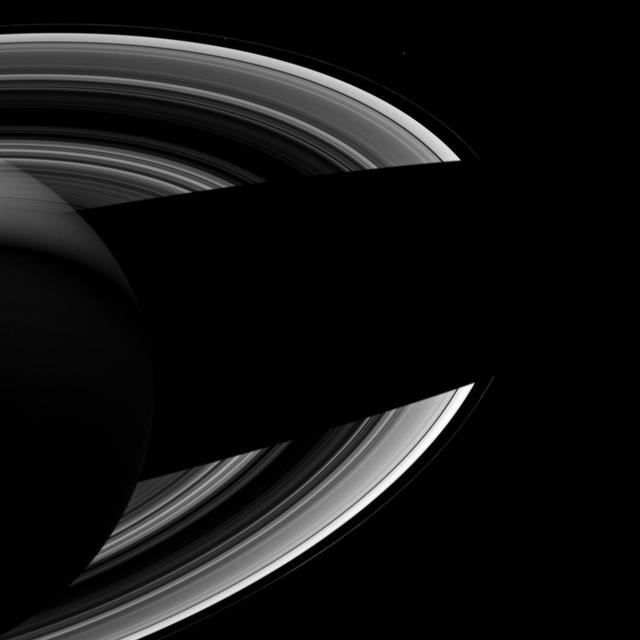

The shadow of the moon Epimetheus stretches across the B ring in this image taken by Cassini as Saturn approaches its 2009 equinox.

The shadow of the moon Epimetheus crosses Saturn rings in this image taken as the planet approached its August 2009 equinox.

Epimetheus, seen here by NASA Cassini spacecraft, with Saturn in the background, is lumpy and misshapen, thanks in part to its size and formation process. Bombardment over the eons has left this tiny moon surface heavily pitted.

Epimetheus is a lonely dot beyond Saturn rings. The little moon appears at lower left, outside the narrow F ring. Several very faint spokes lurk in the B ring, at right

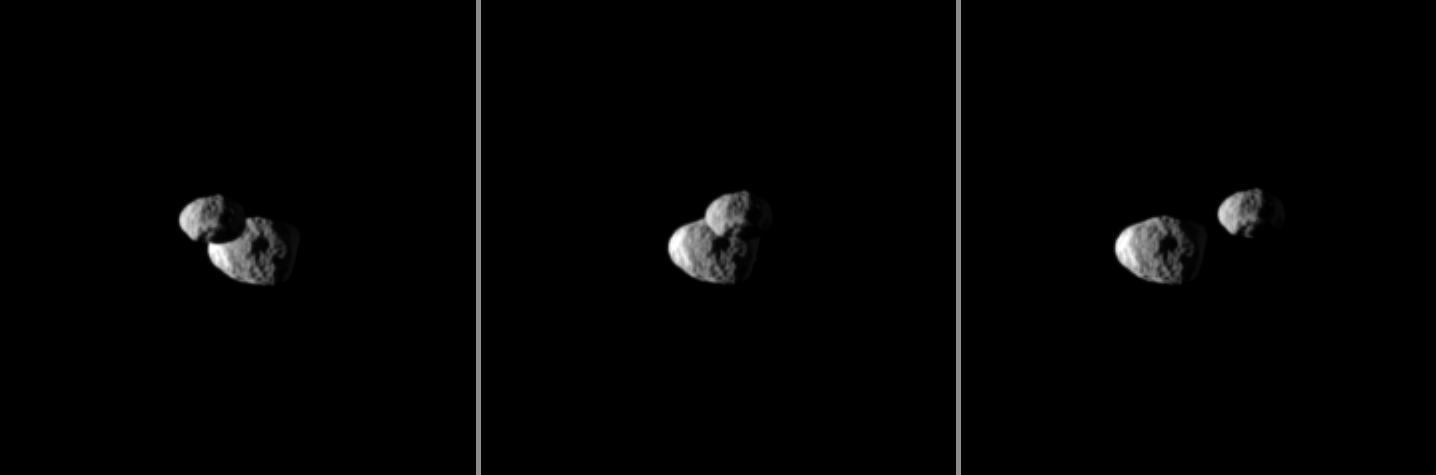

Janus and Epimetheus continue to separate, following their orbital swap in January 2006. Until 2010, Janus will remain the innermost of the pair, whose orbits around Saturn are separated by only about 50 kilometers 31 miles on average

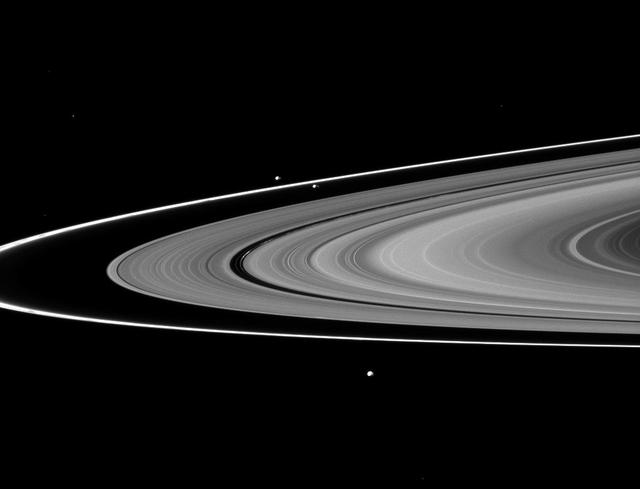

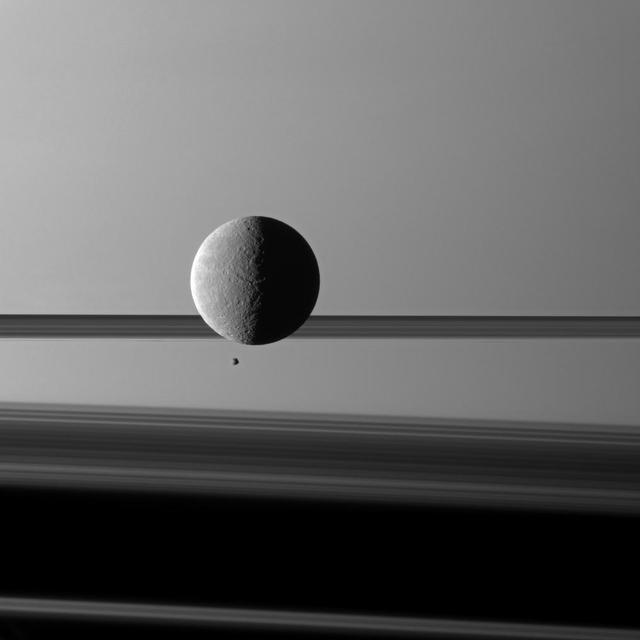

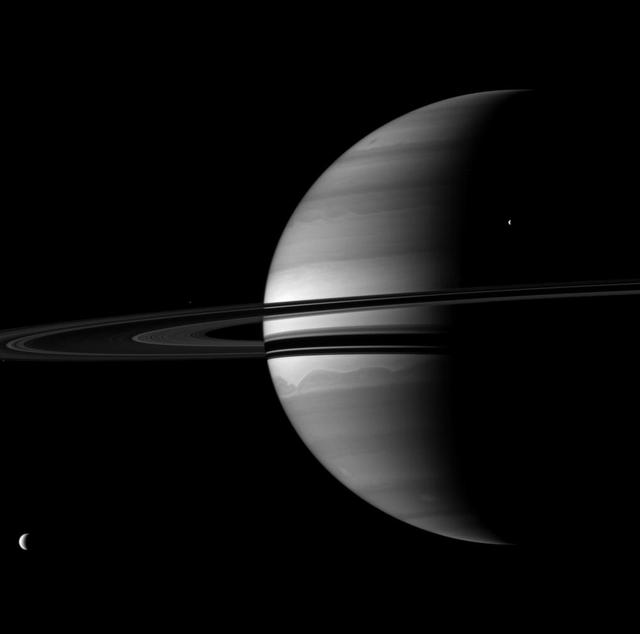

Much as its name implies, tiny Epimetheus (Greek for hindsight) was discovered in hindsight. Astronomers originally thought that Janus and Epithemeus were the same object. Only later did astronomers realize that there are in fact two bodies sharing the same orbit. Janus (111 miles or 179 kilometers across) and Epimetheus (70 miles or 113 kilometers) have the same average distance from Saturn, but they take turns being a little closer or a little farther from Saturn, swapping positions approximately every 4 years. See PIA08348 for more. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 29 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Jan. 1, 2015. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.8 million miles (2.9 million kilometers) from Epimetheus and at a Sun-Epimetheus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 89 degrees. Image scale is 11 miles (17 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18305

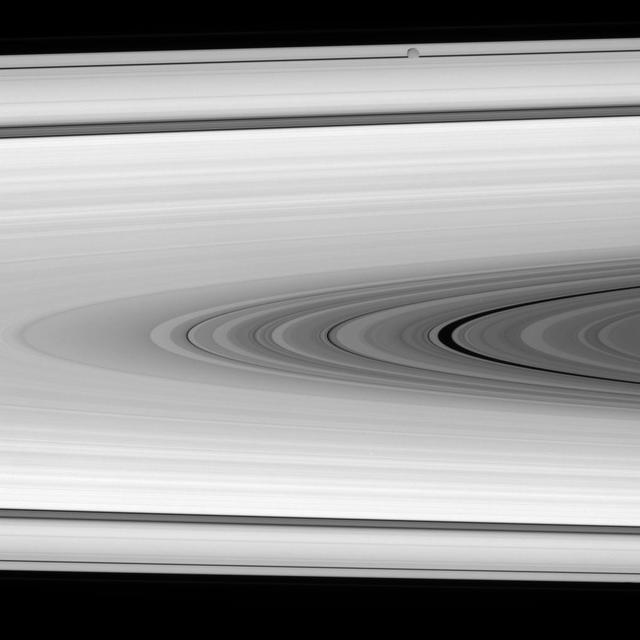

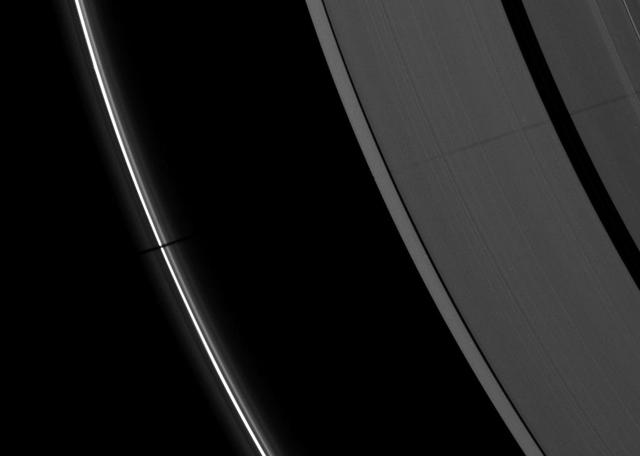

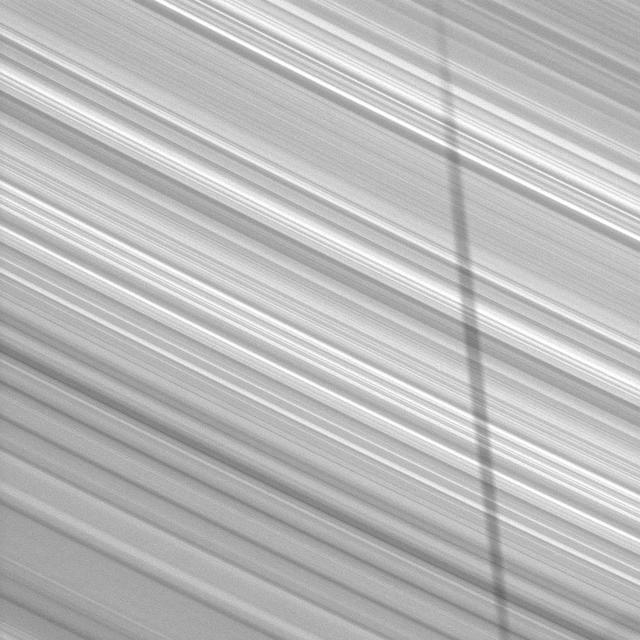

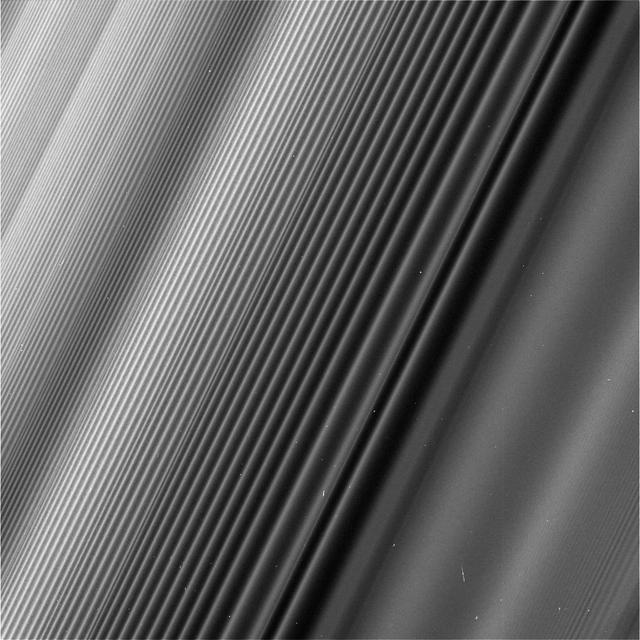

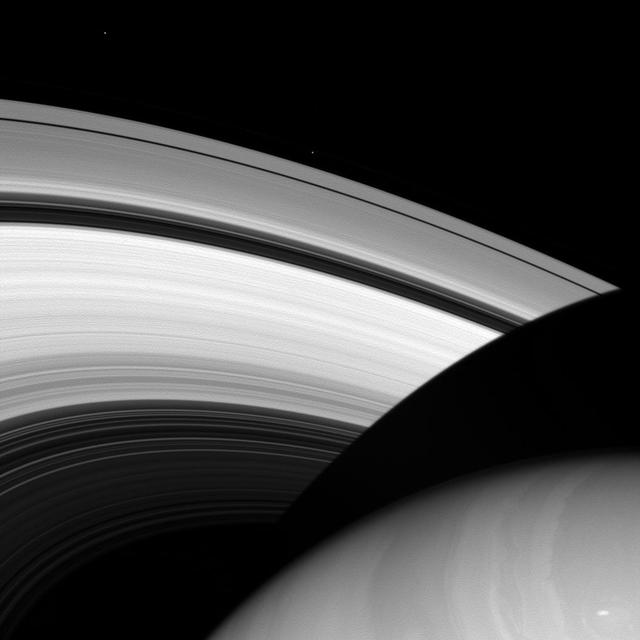

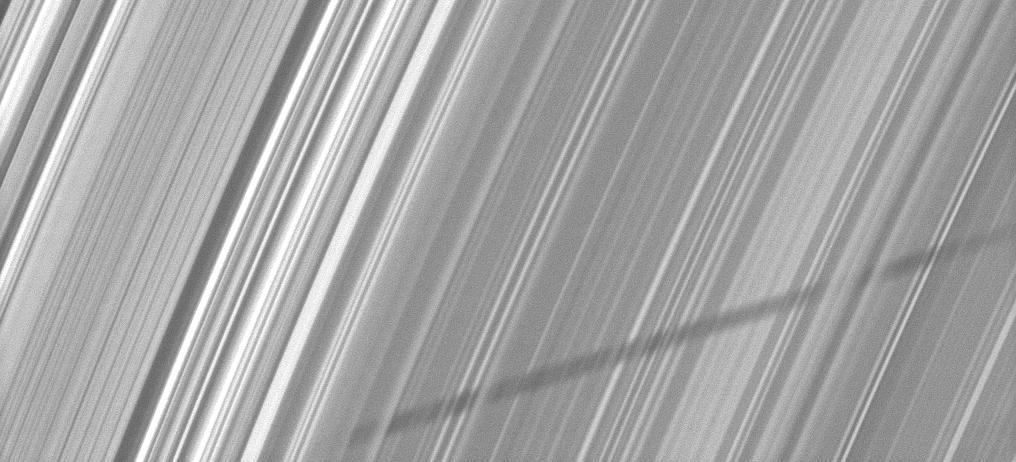

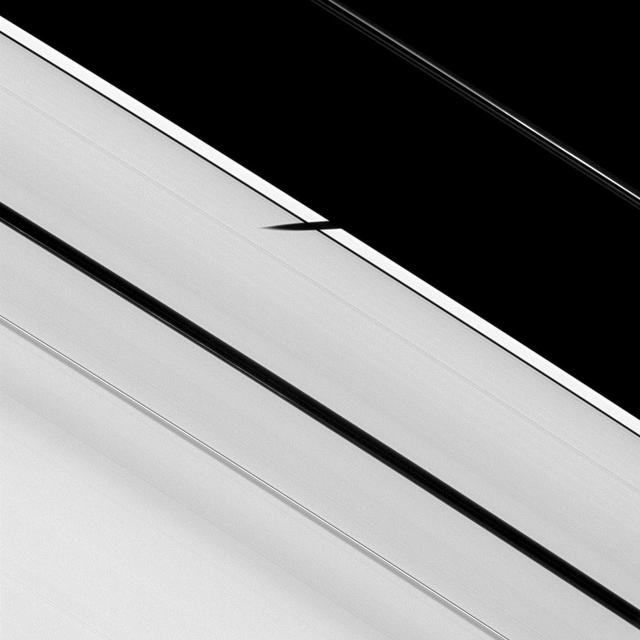

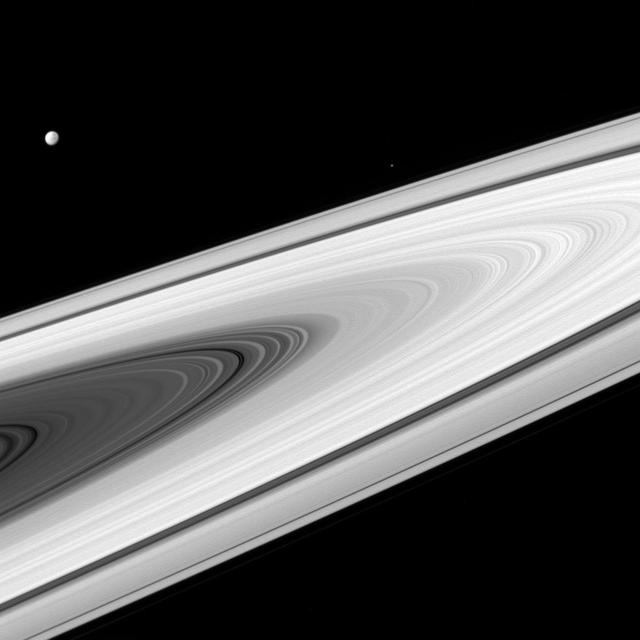

This view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft shows a wave structure in Saturn's rings known as the Janus 2:1 spiral density wave. Resulting from the same process that creates spiral galaxies, spiral density waves in Saturn's rings are much more tightly wound. In this case, every second wave crest is actually the same spiral arm which has encircled the entire planet multiple times. This is the only major density wave visible in Saturn's B ring. Most of the B ring is characterized by structures that dominate the areas where density waves might otherwise occur, but this innermost portion of the B ring is different. The radius from Saturn at which the wave originates (toward lower-right in this image) is 59,796 miles (96,233 kilometers) from the planet. At this location, ring particles orbit Saturn twice for every time the moon Janus orbits once, creating an orbital resonance. The wave propagates outward from the resonance (and away from Saturn), toward upper-left in this view. For reasons researchers do not entirely understand, damping of waves by larger ring structures is very weak at this location, so this wave is seen ringing for hundreds of bright wave crests, unlike density waves in Saturn's A ring. The image gives the illusion that the ring plane is tilted away from the camera toward upper-left, but this is not the case. Because of the mechanics of how this kind of wave propagates, the wavelength decreases with distance from the resonance. Thus, the upper-left of the image is just as close to the camera as the lower-right, while the wavelength of the density wave is simply shorter. This wave is remarkable because Janus, the moon that generates it, is in a strange orbital configuration. Janus and Epimetheus share practically the same orbit and trade places every four years. Every time one of those orbit swaps takes place, the ring at this location responds, spawning a new crest in the wave. The distance between any pair of crests corresponds to four years' worth of the wave propagating downstream from the resonance, which means the wave seen here encodes many decades' worth of the orbital history of Janus and Epimetheus. According to this interpretation, the part of the wave at the very upper-left of this image corresponds to the positions of Janus and Epimetheus around the time of the Voyager flybys in 1980 and 1981, which is the time at which Janus and Epimetheus were first proven to be two distinct objects (they were first observed in 1966). Epimetheus also generates waves at this location, but they are swamped by the waves from Janus, since Janus is the larger of the two moons. This image was taken on June 4, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of 47,000 miles (76,000 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,730 feet (530 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 90 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21627

This image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft shows Epimetheus, which orbits Saturn well outside of the F ring orbit.

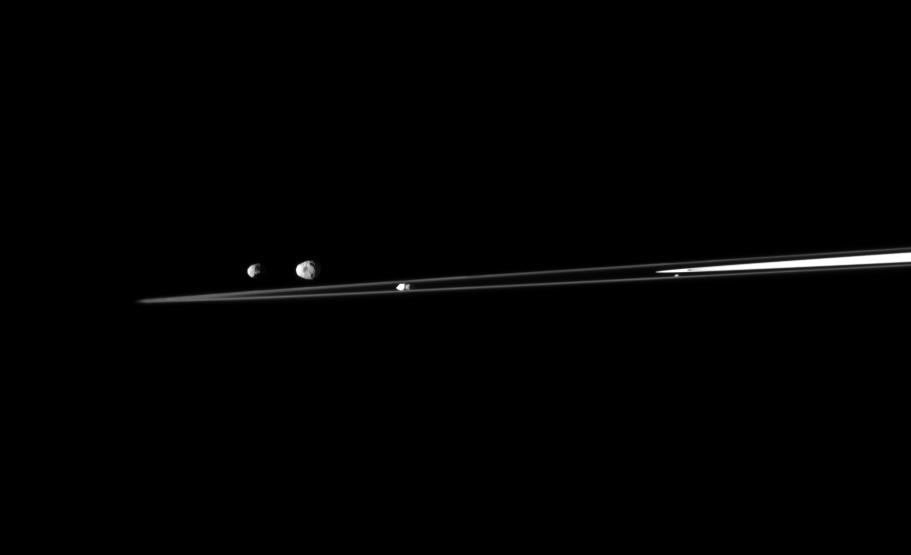

The F ring shepherds, Prometheus and Pandora, join Epimetheus in this image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft of three of Saturn moons and the rings.

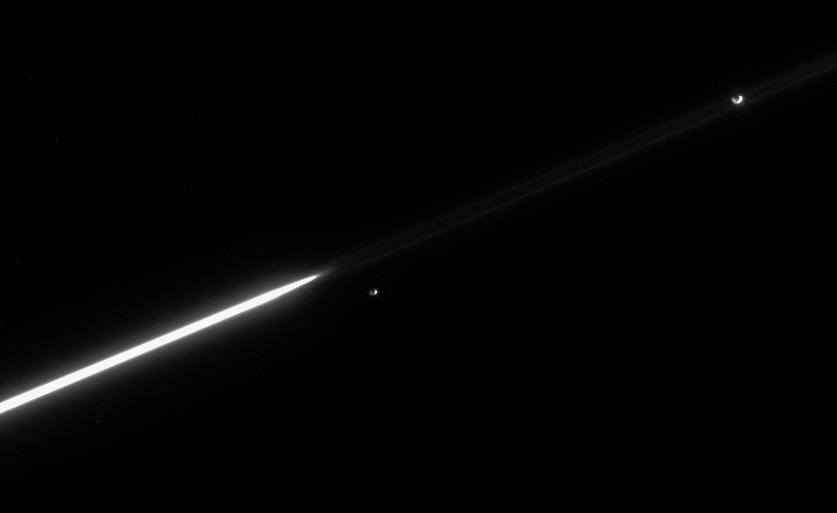

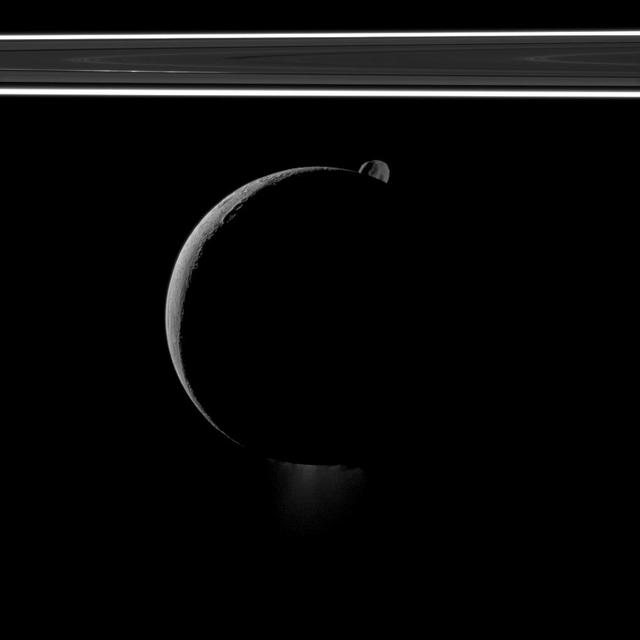

During a flyby of Saturn moon Enceladus on Oct. 1, 2011, NASA Cassini spacecraft snapped this portrait of the moon joined by its sibling Epimetheus and the planet rings.

Three of Saturn small moons straddle the rings in this image captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft. From left to right are Pandora, Prometheus and, near the top right, Epimetheus.

This fortunate view sights along Saturn ringplane to capture three moons aligned in a row: Dione at left, Prometheus at center and Epimetheus at right

Six of Saturn moons orbiting within and beyond the planet rings are collected in this Cassini spacecraft image; they include Enceladus, Epimetheus, Atlas, Daphnis, Pan, and Janus.

A quartet of Saturn moons are shown with a sliver of the rings in this view from NASA Cassini spacecraft. From left to right in this image are Epimetheus, Janus, Prometheus, and Atlas.

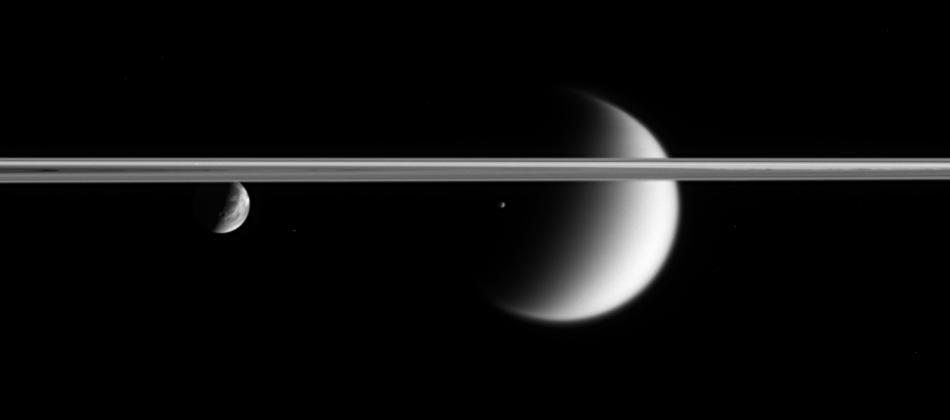

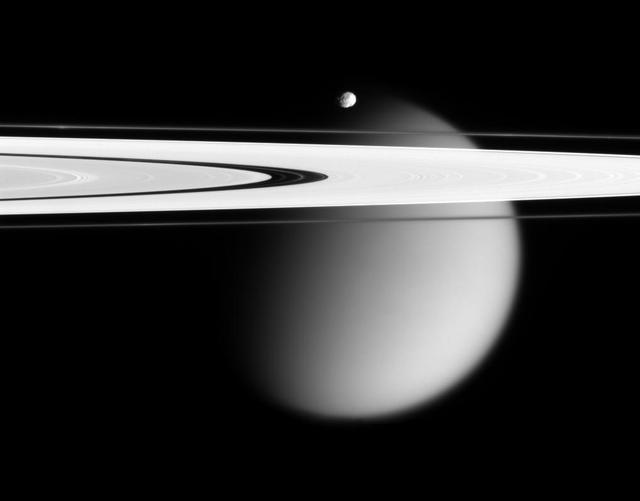

The Cassini spacecraft delivers this stunning vista showing small, battered Epimetheus and smog-enshrouded Titan, with Saturn A and F rings stretching across the scene

Flying past Saturn moon Dione, NASA Cassini captured this view which includes two smaller moons, Epimetheus and Prometheus, near the planet rings.

Saturn moon Epimetheus passes in front of Janus in this mutual

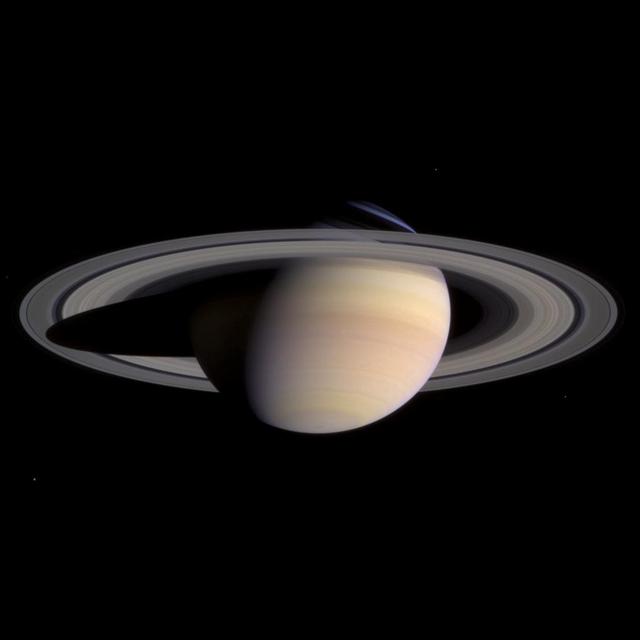

Befitting moons named for brothers, the moons Prometheus and Epimetheus share a lot in common. Both are small, icy moons that orbit near the main rings of Saturn. But, like most brothers, they also assert their differences: while Epimetheus is relatively round for a small moon, Prometheus is elongated in shape, similar to a lemon. Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers across) orbits just outside the A ring - seen here upper-middle of the image - while Epimetheus (70 miles, 113 kilometers across) orbits farther out - seen in the upper-left, doing an orbital two-step with its partner, Janus. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 28 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on July 9, 2013. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 557,000 miles (897,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 11 degrees. Image scale is 33 miles (54 kilometers) per pixel. Prometheus and Epimetheus have been brightened by a factor of 2 relative to the rest of the image to enhance their visibility. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18286

While the moon Epimetheus passes by, beyond the edge of Saturn main rings, the tiny moon Daphnis carries on its orbit within the Keeler gap of the A ring in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft.

Saturn moon Rhea looms over a smaller and more distant Epimetheus against a striking background of planet and rings. The two moons arent actually close to each other.

Saturn shadow interrupts the planet rings, leaving just thin slivers of the rings visible in this image, which shows a pair of the planet small moons. Helene is in the center top of the image, Epimetheus is in the lower right.

Two of Saturn small moons can be seen orbiting beyond the planet thin F ring in this image captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft. Pandora is on the left, and Epimetheus is on the right.

In their orbital ballet, Janus and Epimetheus swap positions every four years -- one moon moving closer to Saturn, the other moving farther away. The two recently changed positions

Epimetheus 116 kilometers, or 72 miles across, at right and Janus 181 kilometers, or 113 miles across, at left are lit here by reflected greylight from Saturn. The Sun brightens only thin slivers of the moons surfaces.

Part of the shadow of Saturn moon Epimetheus appears as if it has been woven through the planet rings in this image taken about a month and a half before the planet August 2009 equinox by NASA Cassini spacecraft.

Two of Saturn moons straddle the planet rings in this color view from NASA Cassini spacecraft. Mimas is closest to NASA Cassini spacecraft here. Epimetheus is on the far side of the rings. Saturn shadow cuts across the middle of the rings.

The irregularly shaped moon Janus keeps up its lonely orbit as seen by NASA Cassini spacecraft. Even though Janus shares its orbit with the moon Epimetheus, they never get very close to one another.

Four of Saturn moons join the planet for a well balanced portrait. Titan, Saturn largest moon, is in the lower left. Tethys appears in upper right. The smaller moons Pandora and Epimetheus are barely visible here.

Saturn second largest moon Rhea pops in and out of view behind the planet rings in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft, which includes the smaller moon Epimetheus.

A pair of Saturn moons appear insignificant compared to the immensity of the planet. Enceladus is at left, Epimetheus appears as a tiny black speck on the far left in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft.

Epimetheus floats in the distance below center, showing only the barest hint of its irregular shape. Pandora hides herself in the ringplane, near upper right, appearing as little more than a bump

Five moons, dominated by Rhea in the foreground, share NASA Cassini spacecraft view with Saturn rings seen nearly edge-on. Also seen here are Dione, Epimetheus, Prometheus, and Tethys.

During super-close flybys of Saturn's rings, NASA's Cassini spacecraft inspected the mini-moons Pan and Daphnis in the A ring; Atlas at the edge of the A ring; Pandora at the edge of the F ring; and Epimetheus, which is bathed in material that fans out from the moon Enceladus. The mini-moons' diameter ranges from 5 miles (8 kilometers) for Daphnis to 72 miles (116 kilometers) for Epimetheus. The rings and the moons depicted in this illustration are not to scale. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22772

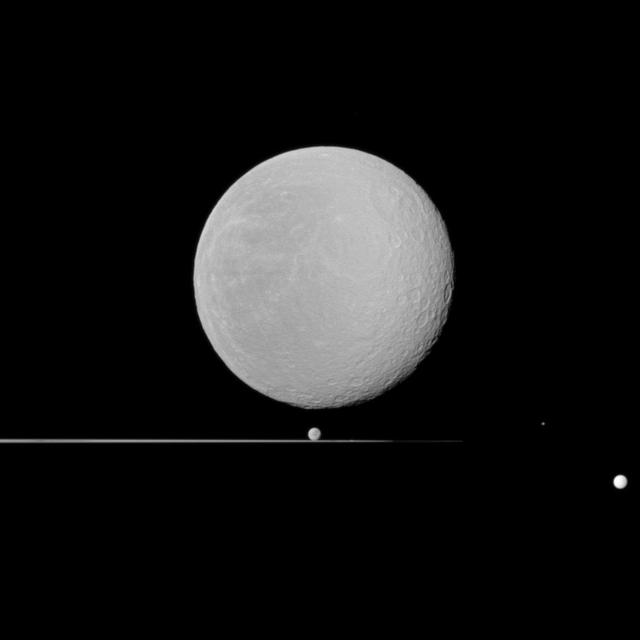

Although Janus should be the least lonely of all moons -- sharing its orbit with Epimetheus -- it still spends most of its orbit far from other moons, alone in the vastness of space. Janus (111 miles or 179 kilometers across) and Epimetheus have the same average distance from Saturn, but they take turns being a little closer or a little farther from Saturn, swapping positions approximately every 4 years. See PIA08348 for more. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 4, 2015. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.6 million miles (2.5 million kilometers) from Janus and at a Sun-Janus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 91 degrees. Image scale is 9 miles (15 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18315

Epimethean Profile

Big Boulder

Lonely Gem

Belittled Moon

Iceberg Beyond the Rings

Rubble Moon?

Groundhog Day on Saturn

Saturn small moons Atlas, Prometheus, and Epimetheus keep each other company in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft of the planet night side. It seems fitting that they should do so since in Greek mythology, their namesakes were brothers.

This poetic scene shows the giant, smog-enshrouded moon Titan behind Saturn nearly edge-on rings. Much smaller Epimetheus 116 kilometers, or 72 miles across is just visible to the left of Titan 5,150 kilometers, or 3,200 miles across

These two moons are locked in a gravitational tango that causes them to swap positions about every four years, with one becoming the innermost of the pair and the other becoming the outermost

This colorful view, taken from edge-on with the ringplane, contains four of Saturn's attendant moons. Tethys (1,071 kilometers, 665 miles across) is seen against the black sky to the left of the gas giant's limb. Brilliant Enceladus (505 kilometers, 314 miles across) sits against the planet near right. Irregular Hyperion (280 kilometers, 174 miles across) is at the bottom of the image, near left. Much smaller Epimetheus (116 kilometers, 72 miles across) is a speck below the rings directly between Tethys and Enceladus. Epimetheus casts an equally tiny shadow onto the blue northern hemisphere, just above the thin shadow of the F ring. Images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this natural color view. The images were acquired with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on July 24, 2007 at a distance of approximately 2 million kilometers (1.2 million miles) from Saturn. Image scale is 116 kilometers (72 miles) per pixel on Saturn. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA08394

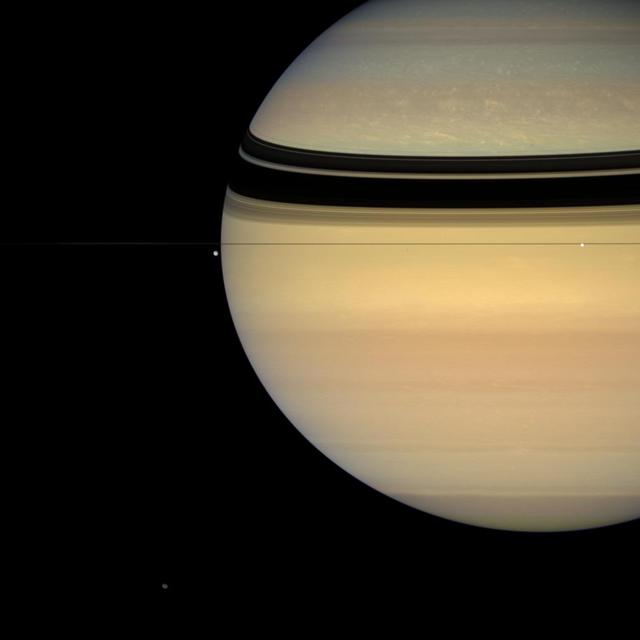

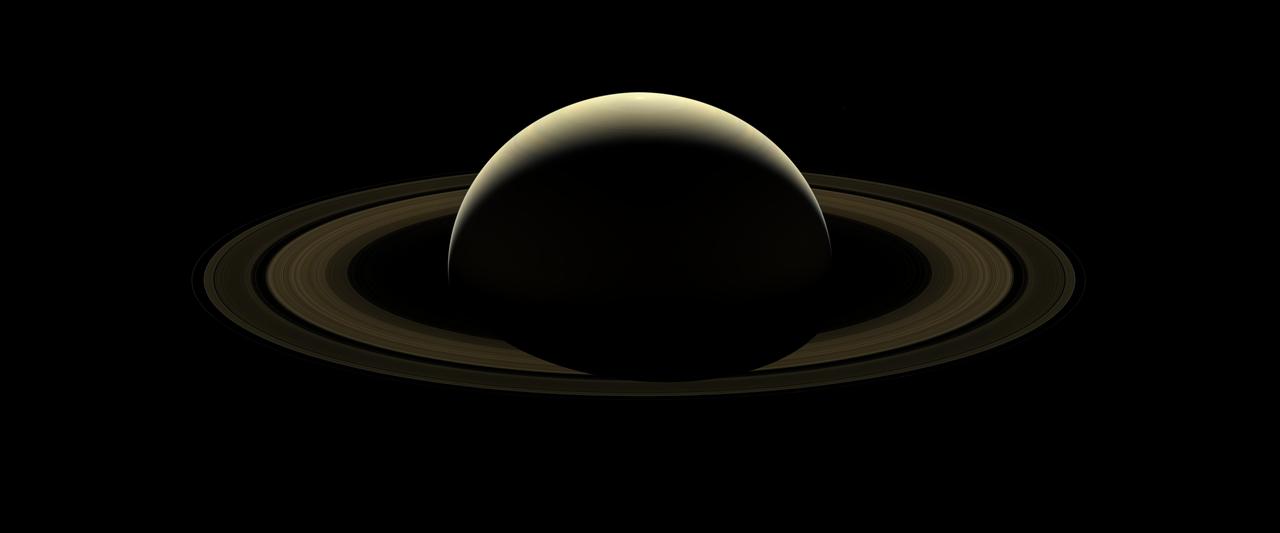

After more than 13 years at Saturn, and with its fate sealed, NASA's Cassini spacecraft bid farewell to the Saturnian system by firing the shutters of its wide-angle camera and capturing this last, full mosaic of Saturn and its rings two days before the spacecraft's dramatic plunge into the planet's atmosphere. During the observation, a total of 80 wide-angle images were acquired in just over two hours. This view is constructed from 42 of those wide-angle shots, taken using the red, green and blue spectral filters, combined and mosaicked together to create a natural-color view. Six of Saturn's moons -- Enceladus, Epimetheus, Janus, Mimas, Pandora and Prometheus -- make a faint appearance in this image. (Numerous stars are also visible in the background.) A second version of the mosaic is provided in which the planet and its rings have been brightened, with the fainter regions brightened by a greater amount. (The moons and stars have also been brightened by a factor of 15 in this version.) The ice-covered moon Enceladus -- home to a global subsurface ocean that erupts into space -- can be seen at the 1 o'clock position. Directly below Enceladus, just outside the F ring (the thin, farthest ring from the planet seen in this image) lies the small moon Epimetheus. Following the F ring clock-wise from Epimetheus, the next moon seen is Janus. At about the 4:30 position and outward from the F ring is Mimas. Inward of Mimas and still at about the 4:30 position is the F-ring-disrupting moon, Pandora. Moving around to the 10 o'clock position, just inside of the F ring, is the moon Prometheus. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 15 degrees above the ring plane. Cassini was approximately 698,000 miles (1.1 million kilometers) from Saturn, on its final approach to the planet, when the images in this mosaic were taken. Image scale on Saturn is about 42 miles (67 kilometers) per pixel. The image scale on the moons varies from 37 to 50 miles (59 to 80 kilometers) pixel. The phase angle (the Sun-planet-spacecraft angle) is 138 degrees. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17218

Saturn and its rings completely fill the field of view of Cassini's narrow angle camera in this natural color image taken on March 27, 2004. This is the last single 'eyeful' of Saturn and its rings achievable with the narrow angle camera on approach to the planet. From now until orbit insertion, Saturn and its rings will be larger than the field of view of the narrow angle camera. Color variations between atmospheric bands and features in the southern hemisphere of Saturn, as well as subtle color differences across the planet's middle B ring, are now more distinct than ever. Color variations generally imply different compositions. The nature and causes of any compositional differences in both the atmosphere and the rings are major questions to be investigated by Cassini scientists as the mission progresses. The bright blue sliver of light in the northern hemisphere is sunlight passing through the Cassini Division in Saturn's rings and being scattered by the cloud-free upper atmosphere. Two faint dark spots are visible in the southern hemisphere. These spots are close to the latitude where Cassini saw two storms merging in mid-March. The fate of the storms visible here is unclear. They are getting close and will eventually merge or squeeze past each other. Further analysis of such dynamic systems in Saturn's atmosphere will help scientists understand their origins and complex interactions. Moons visible in this image are (clockwise from top right): Enceladus (499 kilometers or 310 miles across), Mimas (398 kilometers or 247 miles across), Tethys (1060 kilometers or 659 miles across) and Epimetheus (116 kilometers or 72 miles across). Epimetheus is dim and appears just above the left edge of the rings. Brightnesses have been exaggerated to aid visibility. The image is a composite of three exposures, in red, green and blue, taken when the spacecraft was 47.7 million kilometers (29.7 million miles) from the planet. The image scale is 286 kilometers (178 miles) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05389

Saturn's main rings, along with its moons, are much brighter than most stars. As a result, much shorter exposure times (10 milliseconds, in this case) are required to produce an image and not saturate the detectors of the imaging cameras on NASA's Cassini spacecraft. A longer exposure would be required to capture the stars as well. Cassini has captured stars on many occasions, especially when a target moon is in eclipse, and thus darker than normal. For example, see PIA10526 . Dione (698 miles, 1123 kilometers across) and Epimetheus (70 miles, 113 kilometers across) are seen in this view, above the rings at left and right respectively. This image looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 3 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on April 2, 2016. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 257,000 miles (413,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20489

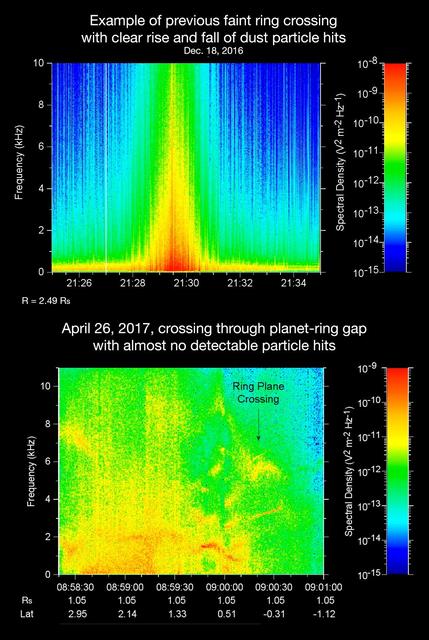

The sounds and spectrograms in these two videos represent data collected by the Radio and Plasma Wave Science, or RPWS, instrument on NASA's Cassini spacecraft, as it crossed the plane of Saturn's rings on two separate orbits. As tiny, dust-sized particles strike Cassini and the three 33-foot-long (10-meter-long), RPWS antennas, the particles are vaporized into tiny clouds of plasma, or electrically excited gas. These tiny explosions make a small electrical signal (a voltage impulse) that RPWS can detect. Researchers on the RPWS team convert the data into visible and audio formats, like those seen here, for analysis. Ring particle hits sound like pops and cracks in the audio. The first video (top image in the montage) was made using RPWS data from a ring plane crossing on Dec. 18, 2016, when the spacecraft passed through the faint, dusty Janus-Epimetheus ring (see PIA08328 for an image that features this ring). This was during Cassini's 253rd orbit of Saturn, known as Rev 253. As is typical for this sort of ring crossing, the number of audible pops and cracks rises to a maximum around the time of a ring crossing and trails off afterward. The peak of the ring density is obvious in the colored display at the red spike. The second video (bottom image in the montage) was made using data RPWS collected as Cassini made the first dive through the gap between Saturn and its rings as part of the mission's Grand Finale, on April 26, 2017. Very few pops and cracks are audible in this data at all. In comparing the two data sets, it is apparent that while Cassini detected many ring-particles striking Cassini when passing through the Janus-Epimetheus ring, the first Grand Finale crossing -- in stark contrast -- was nearly particle free. The unexpected finding that the gap is so empty is a new mystery that scientists are eager to understand. On April 26, 2017, Cassini dove through the previously unexplored ring-planet gap at speeds approaching 75,000 mph (121,000 kph), using its large, dish-shaped high-gain antenna (or HGA) as a shield to protect the rest of the spacecraft and its instruments from potential impacts by small, icy ring particles. Two of Cassini's instruments, the magnetometer and RPWS, extend beyond the protective antenna dish, and were exposed to the particle environment during the dive. The Cassini team used this data from RPWS, along with inputs from other components on the spacecraft, to make the decision of whether the HGA would be needed as a shield on most future Grand Finale dives through the planet-ring gap. Based on these inputs the team determined this protective measure would not be needed, allowing the team's preferred mode of science operations to proceed, with Cassini able to point its science instruments in any direction necessary to obtain scientists' desired observations. (Four of the 21 remaining dives pass through the inner D ring. The mission had already planned to use the HGA as a shield for those passes.) The colors on the spectrogram indicate the emitted power of the radio waves, with red as the most powerful. Time is on the x-axis, and frequency of the radio waves is on the y-axis. The audible whistle in the April 26 data, just before ring plane crossing, is due to a type of plasma wave that will be the subject of further study. In addition, there is an abrupt change beginning at the 09:00:00 mark on the spectrogram that represents a change in the RPWS antenna's operational configuration (from monopole mode to dipole mode). The videos can be viewed at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21446

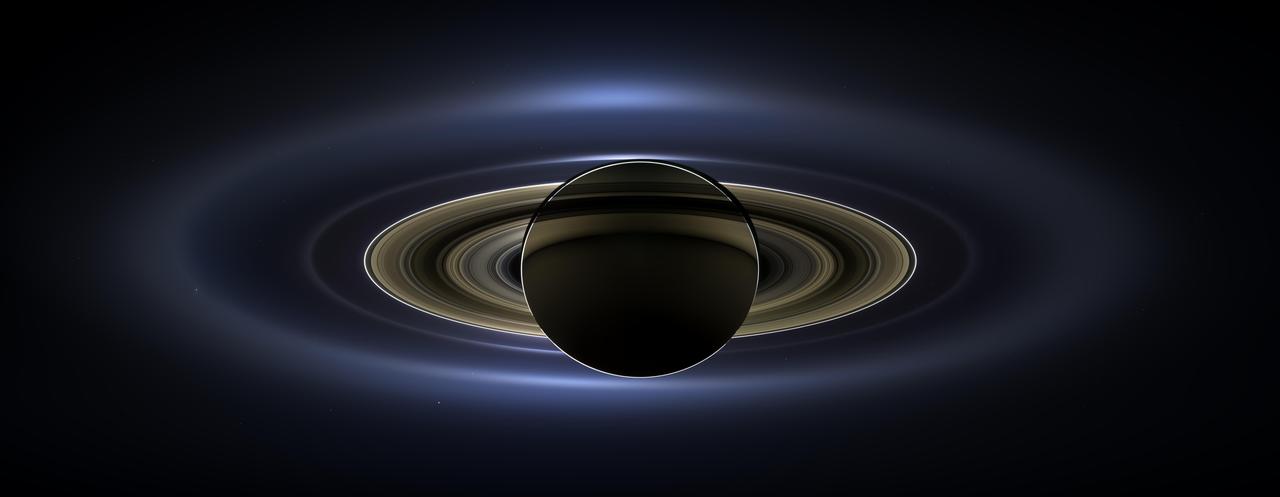

On July 19, 2013, in an event celebrated the world over, NASA's Cassini spacecraft slipped into Saturn's shadow and turned to image the planet, seven of its moons, its inner rings -- and, in the background, our home planet, Earth. With the sun's powerful and potentially damaging rays eclipsed by Saturn itself, Cassini's onboard cameras were able to take advantage of this unique viewing geometry. They acquired a panoramic mosaic of the Saturn system that allows scientists to see details in the rings and throughout the system as they are backlit by the sun. This mosaic is special as it marks the third time our home planet was imaged from the outer solar system; the second time it was imaged by Cassini from Saturn's orbit; and the first time ever that inhabitants of Earth were made aware in advance that their photo would be taken from such a great distance. With both Cassini's wide-angle and narrow-angle cameras aimed at Saturn, Cassini was able to capture 323 images in just over four hours. This final mosaic uses 141 of those wide-angle images. Images taken using the red, green and blue spectral filters of the wide-angle camera were combined and mosaicked together to create this natural-color view. A brightened version with contrast and color enhanced (Figure 1), a version with just the planets annotated (Figure 2), and an annotated version (Figure 3) are shown above. This image spans about 404,880 miles (651,591 kilometers) across. The outermost ring shown here is Saturn's E ring, the core of which is situated about 149,000 miles (240,000 kilometers) from Saturn. The geysers erupting from the south polar terrain of the moon Enceladus supply the fine icy particles that comprise the E ring; diffraction by sunlight gives the ring its blue color. Enceladus (313 miles, or 504 kilometers, across) and the extended plume formed by its jets are visible, embedded in the E ring on the left side of the mosaic. At the 12 o'clock position and a bit inward from the E ring lies the barely discernible ring created by the tiny, Cassini-discovered moon, Pallene (3 miles, or 4 kilometers, across). (For more on structures like Pallene's ring, see PIA08328). The next narrow and easily seen ring inward is the G ring. Interior to the G ring, near the 11 o'clock position, one can barely see the more diffuse ring created by the co-orbital moons, Janus (111 miles, or 179 kilometers, across) and Epimetheus (70 miles, or 113 kilometers, across). Farther inward, we see the very bright F ring closely encircling the main rings of Saturn. Following the outermost E ring counter-clockwise from Enceladus, the moon Tethys (662 miles, or 1,066 kilometers, across) appears as a large yellow orb just outside of the E ring. Tethys is positioned on the illuminated side of Saturn; its icy surface is shining brightly from yellow sunlight reflected by Saturn. Continuing to about the 2 o'clock position is a dark pixel just outside of the G ring; this dark pixel is Saturn's Death Star moon, Mimas (246 miles, or 396 kilometers, across). Mimas appears, upon close inspection, as a very thin crescent because Cassini is looking mostly at its non-illuminated face. The moons Prometheus, Pandora, Janus and Epimetheus are also visible in the mosaic near Saturn's bright narrow F ring. Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers, across) is visible as a faint black dot just inside the F ring and at the 9 o'clock position. On the opposite side of the rings, just outside the F ring, Pandora (50 miles, or 81 kilometers, across) can be seen as a bright white dot. Pandora and Prometheus are shepherd moons and gravitational interactions between the ring and the moons keep the F ring narrowly confined. At the 11 o'clock position in between the F ring and the G ring, Janus (111 miles, or 179 kilometers, across) appears as a faint black dot. Janus and Prometheus are dark for the same reason Mimas is mostly dark: we are looking at their non-illuminated sides in this mosaic. Midway between the F ring and the G ring, at about the 8 o'clock position, is a single bright pixel, Epimetheus. Looking more closely at Enceladus, Mimas and Tethys, especially in the brightened version of the mosaic, one can see these moons casting shadows through the E ring like a telephone pole might cast a shadow through a fog. In the non-brightened version of the mosaic, one can see bright clumps of ring material orbiting within the Encke gap near the outer edge of the main rings and immediately to the lower left of the globe of Saturn. Also, in the dark B ring within the main rings, at the 9 o'clock position, one can see the faint outlines of two spoke features, first sighted by NASA's Voyager spacecraft in the early 1980s and extensively studied by Cassini. Finally, in the lower right of the mosaic, in between the bright blue E ring and the faint but defined G ring, is the pale blue dot of our planet, Earth. Look closely and you can see the moon protruding from the Earth's lower right. (For a higher resolution view of the Earth and moon taken during this campaign, see PIA14949.) Earth's twin, Venus, appears as a bright white dot in the upper left quadrant of the mosaic, also between the G and E rings. Mars also appears as a faint red dot embedded in the outer edge of the E ring, above and to the left of Venus. For ease of visibility, Earth, Venus, Mars, Enceladus, Epimetheus and Pandora were all brightened by a factor of eight and a half relative to Saturn. Tethys was brightened by a factor of four. In total, 809 background stars are visible and were brightened by a factor ranging from six, for the brightest stars, to 16, for the faintest. The faint outer rings (from the G ring to the E ring) were also brightened relative to the already bright main rings by factors ranging from two to eight, with the lower-phase-angle (and therefore fainter) regions of these rings brightened the most. The brightened version of the mosaic was further brightened and contrast-enhanced all over to accommodate print applications and a wide range of computer-screen viewing conditions. Some ring features -- such as full rings traced out by tiny moons -- do not appear in this version of the mosaic because they require extreme computer enhancement, which would adversely affect the rest of the mosaic. This version was processed for balance and beauty. This view looks toward the unlit side of the rings from about 17 degrees below the ring plane. Cassini was approximately 746,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from Saturn when the images in this mosaic were taken. Image scale on Saturn is about 45 miles (72 kilometers) per pixel. This mosaic was made from pictures taken over a span of more than four hours while the planets, moons and stars were all moving relative to Cassini. Thus, due to spacecraft motion, these objects in the locations shown here were not in these specific places over the entire duration of the imaging campaign. Note also that Venus appears far from Earth, as does Mars, because they were on the opposite side of the sun from Earth. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17172