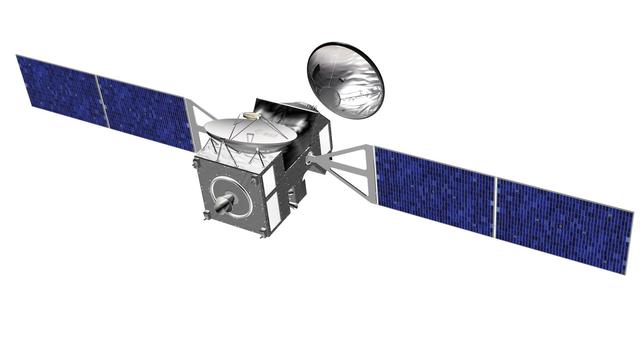

The European Space Agency ExoMars 2016 mission, combining the Trace Gas Orbiter and Schiaparelli landing demonstrator, launches on a Proton launch vehicle from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

NASA and the European Space Agency are jointly developing the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter mission for launch in 2016.

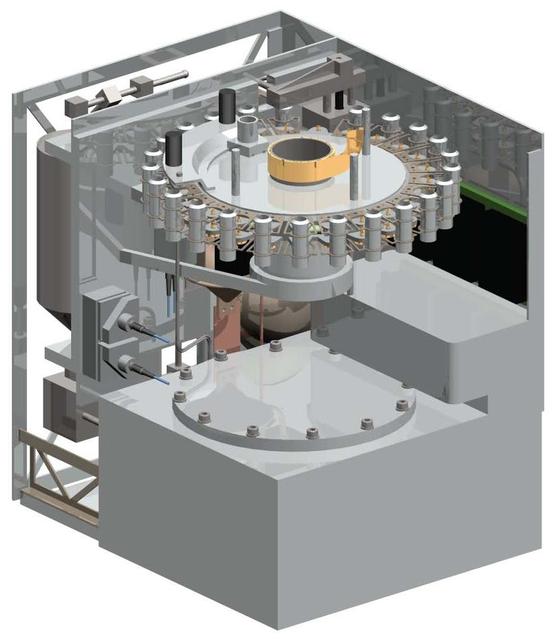

Some key components of a NASA-funded instrument being developed for the payload of the European Space Agency ExoMars mission stand out in thisillustration of the instrument

The European Space Agency ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, being assembled in France for a 2016 launch opportunity, will carry two Electra UHF relay radios provided by NASA.

This June 2014 image from the clean room at Thales Alenia Space, in Cannes, France, shows ongoing assembly of the European Space Agency ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, including the first of the orbiter two Electra UHF relay radios provided by NASA.

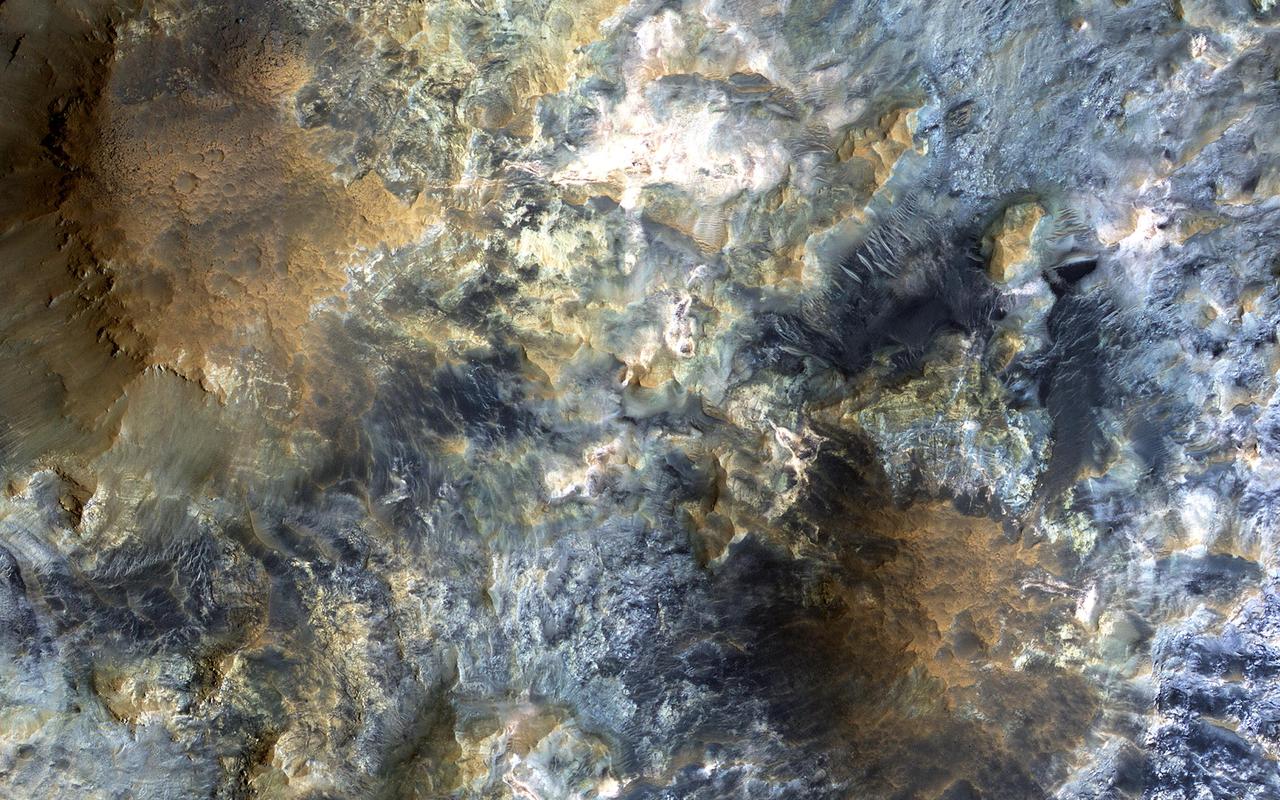

HiRISE plays an important role in finding suitable landing sites for future rover missions. Scientists have narrowed down the candidate landing sites for the upcoming European ExoMars rover mission to two regions: the plains of Oxia and Mawrth Vallis. Images covering these areas aid scientists in picking a location that will be both scientifically interesting and a safe place to land and operate. HiRISE pictures help to assess the risk for each particular location so that a final landing site can be selected. If you look very closely, the image may appear hazy. This is due to additional dust lingering in the atmosphere from the massive summer global dust storm at the time we acquired this observation. ExoMars is due to launch to Mars in 2020. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22805

Oxia Planum is an ancient Noachian epoch terrain situated to the east of Chryse Planitia at about 18 degrees north. This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiteris of a proposed ExoMars Landing Site.

This image captured by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is of an area called Aram Dorsum also known by its old name, Oxia Palus that has been suggested for the 2018/2020 ExoMars Rover because it contains an ancient, exhumed alluvial system.

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is part of a proposed landing site in Aram Dorsum for the ExoMars Rover, planned for launch in 2018. Upper layers of light toned sediments have been eroded, leaving a lower surface which appears dark. The retreating sediment scarp slopes would be an important target for the rover if it ends up going to Aram Dorsum. The retreating scarps will be relatively recent compared to the ancient age of the terrain. That means that organic compounds-which is what ExoMars is designed to drill to 2 meters depth and analyze-will not have been exposed to the full effects of solar and galactic radiation for their entire history. Such radiation can break down organic compounds. Prior to this later erosion, the rocks formed in the ancient, Noachian era as alluvial deposits of fine grained sediment. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19859

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft is of a landing site that the flattest, safest place on Mars: part of Meridiani Planum, close to where the Opportunity rover landed. In March 2016, the European Space Agency in partnership with Roscosmos will launch the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter. This orbiter will also carry an Entry, Descent, and Landing Demonstration Module (EDM): a lander designed primarily to demonstrate the capability to land on Mars. The EDM will survive for only a few days, running on battery power, but will make a few environmental measurements. The landing site is the flattest, safest place on Mars: part of Meridiani Planum, close to where the Opportunity rover landed. This image shows what this terrain is like: very flat and featureless. A full-resolution sample reveals the major surface features: small craters and wind ripples. HiRISE has been imaging the landing site region in advance of the landing, and will re-image the site after landing to identify the major pieces of hardware: heat shield, backshell with parachute, and the lander itself. The distribution of these pieces will provide information about the entry, descent and landing. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20159

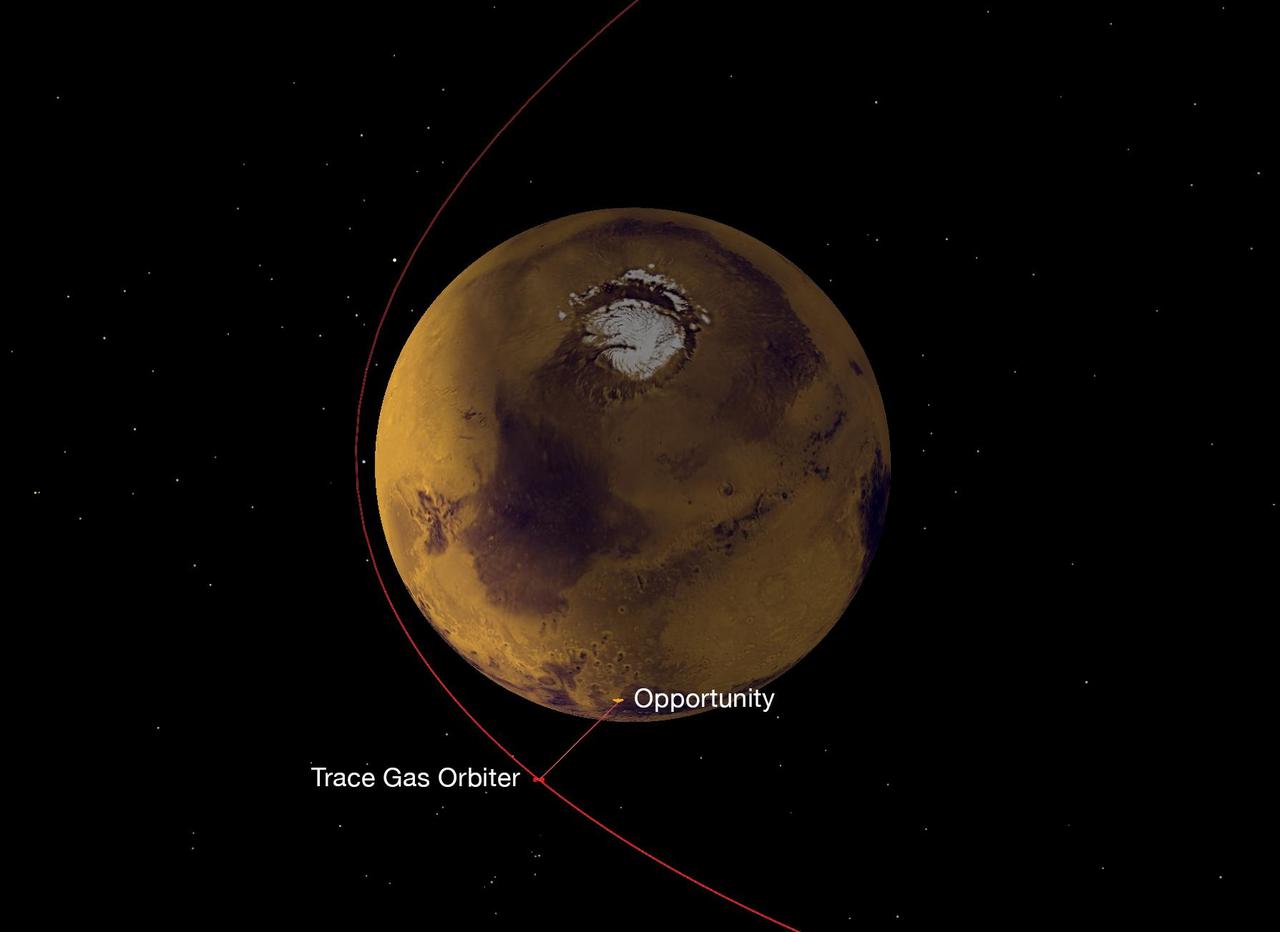

On Nov. 22, 2016, a NASA radio aboard the European Space Agency's (ESA's) Trace Gas Orbiter, which arrived at Mars the previous month, succeeded in its first test of receiving data transmitted from NASA Mars rovers, both Opportunity and Curiosity. This graphic depicts the geometry of Opportunity transmitting data to the orbiter, using the ultra-high frequency (UHF) band of radio wavelengths. The orbiter received that data using one of its twin Electra UHF-band radios. Data that the orbiter's Electra received from the two rovers was subsequently transmitted from the orbiter to Earth, using the orbiter's main X-band radio. The Trace Gas Orbiter is part of ESA's ExoMars program. During the initial months after its Oct. 19, 2016, arrival, it is flying in a highly elliptical orbit. Each loop takes 4.2 days to complete, with distances between the orbiter and the planet's surface ranging from about 60,000 miles (about 100,000 kilometers) to less than 200 miles (less than 310 kilometers). Later, the mission will reshape the orbit to a near-circular path about 250 miles (400 kilometers) above the surface of Mars. Three NASA orbiters and one other ESA orbiter currently at Mars also have relayed data from Mars rovers to Earth. This strategy enables receiving much more data from the surface missions than would be possible with a direct-to-Earth radio link from rovers or stationary landers. Successful demonstration of the capability added by the Trace Gas Orbiter strengthens and extends the telecommunications network at Mars for supporting future missions to the surface of the Red Planet. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21139

Scientists from NASA's Mars 2020 and ESA's ExoMars projects study stromatolites, the oldest confirmed fossilized lifeforms on Earth, in the Pilbara region of North West Australia. The image was taken on Aug. 19, 2019. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23551

Scientists with NASA's Mars 2020 mission and the European-Russian ExoMars mission traveled to the Australian Outback to hone their research techniques before their missions launch to the Red Planet in the summer of 2020. The trip was designed to help them better understand how to search for signs of ancient life on Mars. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23275

There is a candidate landing site in the Mawrth Vallis region for the European Space Agency's ExoMars rover, planned to launch in 2020. This is one of the HiRISE images acquired to evaluate this site. Mawrth Vallis has some of the most spectacular color variations seen anywhere on Mars. This color variability is due to a range of hydrated minerals -- water caused alteration of these ancient deposits -- which is why this site is of interest to study the past habitability of Mars. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21029

This observation from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbite shows a candidate 2018 European Space Agency ExoMars landing site in Hypanis Vallis. Instead of imaging ancient fluvial deposits (thought to be the remnants of a delta feed lake), the image shows patchy concentrations of dust clouds. These clouds are part of the annually occurring Acidalia storm track, a regional dust storm system that originates in the Acidalia-Chryse-Kasei region and propagates southward into equatorial Valles Marineris and beyond. While this image is only partially obscured by dust, many others captured around this time frame were completely dominated by think clouds of dust. For example, this image in Capri Chasma was rendered useless for geology and will have to be reacquired. Landing by the ExoMars rover in these kinds of atmospheric conditions would be complicated. That mission is set to touchdown on Mars in January 2019, hopefully with clear skies. HiRISE will continue to image Hypanis Vallis and other interesting sites on Mars despite the changing weather. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19846

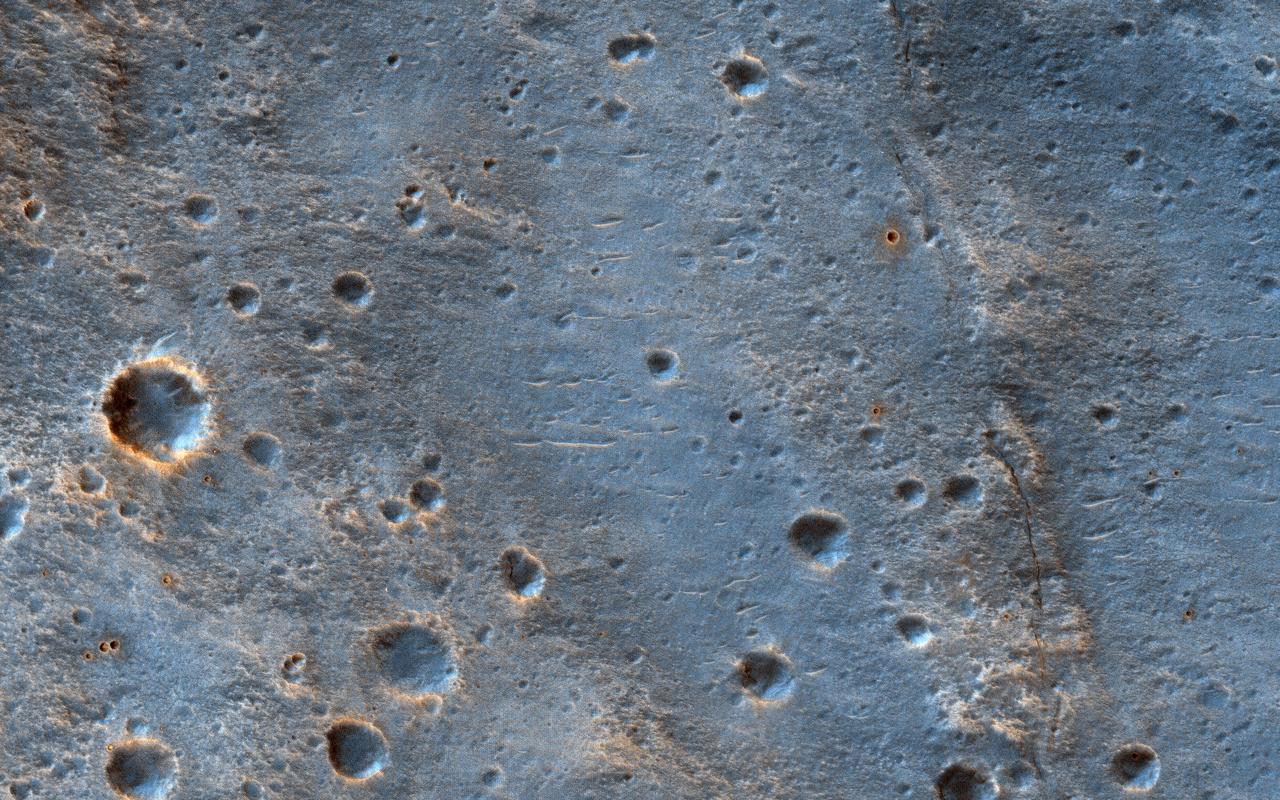

This image shows a cratered area to the southeast of the ExoMars 2020 Rosalind Franklin rover landing site at Oxia Palus. Selecting and characterizing landing sites is a balance between having science targets and avoiding potential obstacles, and HiRISE is used for both purposes. Craters like this one excavate material from within the crust, including both sedimentary and igneous rocks, and scatter this material far from the crater itself. This is one of the ways that so-called "float rocks" (rocks that are not connected to their original outcrop) can occur across a landing site: they are often ejecta from distant impacts. Here, an ejecta blanket is visible in the rays of material surrounding this 2-kilometer diameter crater. The ExoMars rover has a suite of cameras and a close-up imager (called CLUPI) that will be used to study these float rocks. Studying such samples has been an important way of learning about the deep crust of Mars on previous missions, notably the Spirit and Opportunity rovers and now, Curiosity. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23289

This image was acquired on May 15, 2018 by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. This observation shows relatively bright mounds scattered throughout darker and diverse surfaces in Chryse Planitia. These mounds are hundreds of meters in size. The largest of the mounds shows a central pit, similar to the collapsed craters found at the summit of some volcanoes on Earth. The origins of these pitted mounds or cratered cones are uncertain. They could be the result of the interaction of lava and water, or perhaps formed from the eruption of hot mud originating from beneath the surface. These features are very interesting to scientists who study Mars, especially to those involved in the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter mission. If these mounds are indeed mud-related, they may be one of the long sought after sources for transient methane on Mars. More information is available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22682

![This is one of three views of locations where hardware from the European Space Agency's Schiaparelli test lander reached the surface of Mars on Oct. 19, 2016, combine two orbital views from different angles as a stereo pair. The view was created to appear three-dimensional when seen through red-blue glasses with the red lens on the left, though the scene is too flat to show much relief. The stereo preparation uses images taken on Oct. 25, 2016, [PIA21131] and Nov. 1, 2016, [PIA21132] by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The left-eye (red-tinted) component of the stereo is from the earlier observation, which was taken from farther west than the second observation. These views shows three sites where parts of the Schiaparelli spacecraft hit the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The parachute's shape on the ground changed between the two observation dates, cancelling the three-dimensional effect of having views from different angles. The scale bar of 20 meters (65.6 feet) applies to all three portions. Schiaparelli was one component of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. The ExoMars project received data from Schiaparelli during its descent through the atmosphere. ESA has reported that the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). More views are available at http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21135](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21135/PIA21135~thumb.jpg)

This is one of three views of locations where hardware from the European Space Agency's Schiaparelli test lander reached the surface of Mars on Oct. 19, 2016, combine two orbital views from different angles as a stereo pair. The view was created to appear three-dimensional when seen through red-blue glasses with the red lens on the left, though the scene is too flat to show much relief. The stereo preparation uses images taken on Oct. 25, 2016, [PIA21131] and Nov. 1, 2016, [PIA21132] by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The left-eye (red-tinted) component of the stereo is from the earlier observation, which was taken from farther west than the second observation. These views shows three sites where parts of the Schiaparelli spacecraft hit the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The parachute's shape on the ground changed between the two observation dates, cancelling the three-dimensional effect of having views from different angles. The scale bar of 20 meters (65.6 feet) applies to all three portions. Schiaparelli was one component of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. The ExoMars project received data from Schiaparelli during its descent through the atmosphere. ESA has reported that the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). More views are available at http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21135

![On Nov. 1, 2016, the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter observed the impact site of Europe's Schiaparelli test lander, gaining the first color view of the site since the lander's Oct. 19, 2016, arrival. These cutouts from the observation cover three locations where parts of the spacecraft reached the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The heat shield location was outside of the area covered in color. The scale bar of 10 meters (32.8 feet) applies to all three cutouts. Schiaparelli was one component of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. The ExoMars project received data from Schiaparelli during its descent through the atmosphere. ESA reports that the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). Information gained from the Nov. 1 observation supplements what was learned from an Oct. 25 HiRISE observation, at PIA21131, which also shows the locations of these three cutouts relative to each other. Where the lander module struck the ground, dark radial patterns that extend from a dark spot are interpreted as "ejecta," or material thrown outward from the impact, which may have excavated a shallow crater. From the earlier image, it was not clear whether the relatively bright pixels and clusters of pixels scattered around the lander module's impact site are fragments of the module or image noise. Now it is clear that at least the four brightest spots near the impact are not noise. These bright spots are in the same location in the two images and have a white color, unusual for this region of Mars. The module may have broken up at impact, and some fragments might have been thrown outward like impact ejecta. The parachute has a different shape in the Nov. 1 image than in the Oct. 25 one, apparently from shifting in the wind. Similar shifting was observed in the parachute of NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission during the first six months after the Mars arrival of that mission's Curiosity rover in 2012 [PIA16813]. At lower right are several bright features surrounded by dark radial impact patterns, located where the heat shield was expected to impact. The bright spots appear identical in the Nov. 1 and Oct. 25 images, which were taken from different angles, so these spots are now interpreted as bright material, such as insulation layers, not glinting reflections. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21132](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21132/PIA21132~thumb.jpg)

On Nov. 1, 2016, the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter observed the impact site of Europe's Schiaparelli test lander, gaining the first color view of the site since the lander's Oct. 19, 2016, arrival. These cutouts from the observation cover three locations where parts of the spacecraft reached the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The heat shield location was outside of the area covered in color. The scale bar of 10 meters (32.8 feet) applies to all three cutouts. Schiaparelli was one component of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. The ExoMars project received data from Schiaparelli during its descent through the atmosphere. ESA reports that the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). Information gained from the Nov. 1 observation supplements what was learned from an Oct. 25 HiRISE observation, at PIA21131, which also shows the locations of these three cutouts relative to each other. Where the lander module struck the ground, dark radial patterns that extend from a dark spot are interpreted as "ejecta," or material thrown outward from the impact, which may have excavated a shallow crater. From the earlier image, it was not clear whether the relatively bright pixels and clusters of pixels scattered around the lander module's impact site are fragments of the module or image noise. Now it is clear that at least the four brightest spots near the impact are not noise. These bright spots are in the same location in the two images and have a white color, unusual for this region of Mars. The module may have broken up at impact, and some fragments might have been thrown outward like impact ejecta. The parachute has a different shape in the Nov. 1 image than in the Oct. 25 one, apparently from shifting in the wind. Similar shifting was observed in the parachute of NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission during the first six months after the Mars arrival of that mission's Curiosity rover in 2012 [PIA16813]. At lower right are several bright features surrounded by dark radial impact patterns, located where the heat shield was expected to impact. The bright spots appear identical in the Nov. 1 and Oct. 25 images, which were taken from different angles, so these spots are now interpreted as bright material, such as insulation layers, not glinting reflections. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21132

![This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) captures details of an approximately 1-kilometer inverted crater west of Mawrth Vallis. A Context Camera image provides context for the erosional features observed at this site. The location of this HiRISE image is north of the proposed landing ellipse for the ExoMars 2020 rover mission that will investigate diverse rocks and minerals related to ancient water-related activity in this region. Prolonged erosion removed less resistant rocks leaving behind other rocks that stand up locally such as the crater seen here and other nearby remnants. These resistant layers may belong to a phase of volcanism and/or water-related activity that carved Mawrth Vallis and filled in existing craters, and other lower-lying depressions, with darker materials. Erosion has also exposed these layers down to older, more resistant lighter rocks that are clay-bearing. The diversity of exposed bedrock made this location an ideal candidate for exploring a potentially water-rich ancient environment that might have once harbored life. The map is projected here at a scale of 25 centimeters (9.8 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 28.7 centimeters (11.3 inches) per pixel (with 1 x 1 binning); objects on the order of 86 centimeters (33.9 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22117](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA22117/PIA22117~medium.jpg)

This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) captures details of an approximately 1-kilometer inverted crater west of Mawrth Vallis. A Context Camera image provides context for the erosional features observed at this site. The location of this HiRISE image is north of the proposed landing ellipse for the ExoMars 2020 rover mission that will investigate diverse rocks and minerals related to ancient water-related activity in this region. Prolonged erosion removed less resistant rocks leaving behind other rocks that stand up locally such as the crater seen here and other nearby remnants. These resistant layers may belong to a phase of volcanism and/or water-related activity that carved Mawrth Vallis and filled in existing craters, and other lower-lying depressions, with darker materials. Erosion has also exposed these layers down to older, more resistant lighter rocks that are clay-bearing. The diversity of exposed bedrock made this location an ideal candidate for exploring a potentially water-rich ancient environment that might have once harbored life. The map is projected here at a scale of 25 centimeters (9.8 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 28.7 centimeters (11.3 inches) per pixel (with 1 x 1 binning); objects on the order of 86 centimeters (33.9 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22117

This Oct. 25, 2016, image shows the area where the European Space Agency's Schiaparelli test lander reached the surface of Mars, with magnified insets of three sites where components of the spacecraft hit the ground. It is the first view of the site from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter taken after the Oct. 19, 2016, landing event. The Schiaparelli test lander was one component of ESA's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. This HiRISE observation adds information to what was learned from observation of the same area on Oct. 20 by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's Context Camera (CTX). Of these two cameras, CTX covers more area and HiRISE shows more detail. A portion of the HiRISE field of view also provides color information. The impact scene was not within that portion for the Oct. 25 observation, but an observation with different pointing to add color and stereo information is planned. This Oct. 25 observation shows three locations where hardware reached the ground, all within about 0.9 mile (1.5 kilometer) of each other, as expected. The annotated version includes insets with six-fold enlargement of each of those three areas. Brightness is adjusted separately for each inset to best show the details of that part of the scene. North is about 7 degrees counterclockwise from straight up. The scale bars are in meters. At lower left is the parachute, adjacent to the back shell, which was its attachment point on the spacecraft. The parachute is much brighter than the Martian surface in this region. The smaller circular feature just south of the bright parachute is about the same size and shape as the back shell, (diameter of 7.9 feet or 2.4 meters). At upper right are several bright features surrounded by dark radial impact patterns, located about where the heat shield was expected to impact. The bright spots may be part of the heat shield, such as insulation material, or gleaming reflections of the afternoon sunlight. According to the ExoMars project, which received data from the spacecraft during its descent through the atmosphere, the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). At mid-upper left are markings left by the lander's impact. The dark, approximately circular feature is about 7.9 feet (2.4 meters) in diameter, about the size of a shallow crater expected from impact into dry soil of an object with the lander's mass -- about 660 pounds (300 kilograms) -- and calculated velocity. The resulting crater is estimated to be about a foot and a half (half a meter) deep. This first HiRISE observation does not show topography indicating the presence of a crater. Stereo information from combining this observation with a future one may provide a way to check. Surrounding the dark spot are dark radial patterns expected from an impact event. The dark curving line to the northeast of the dark spot is unusual for a typical impact event and not yet explained. Surrounding the dark spot are several relatively bright pixels or clusters of pixels. They could be image noise or real features, perhaps fragments of the lander. A later image is expected to confirm whether these spots are image noise or actual surface features. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21131