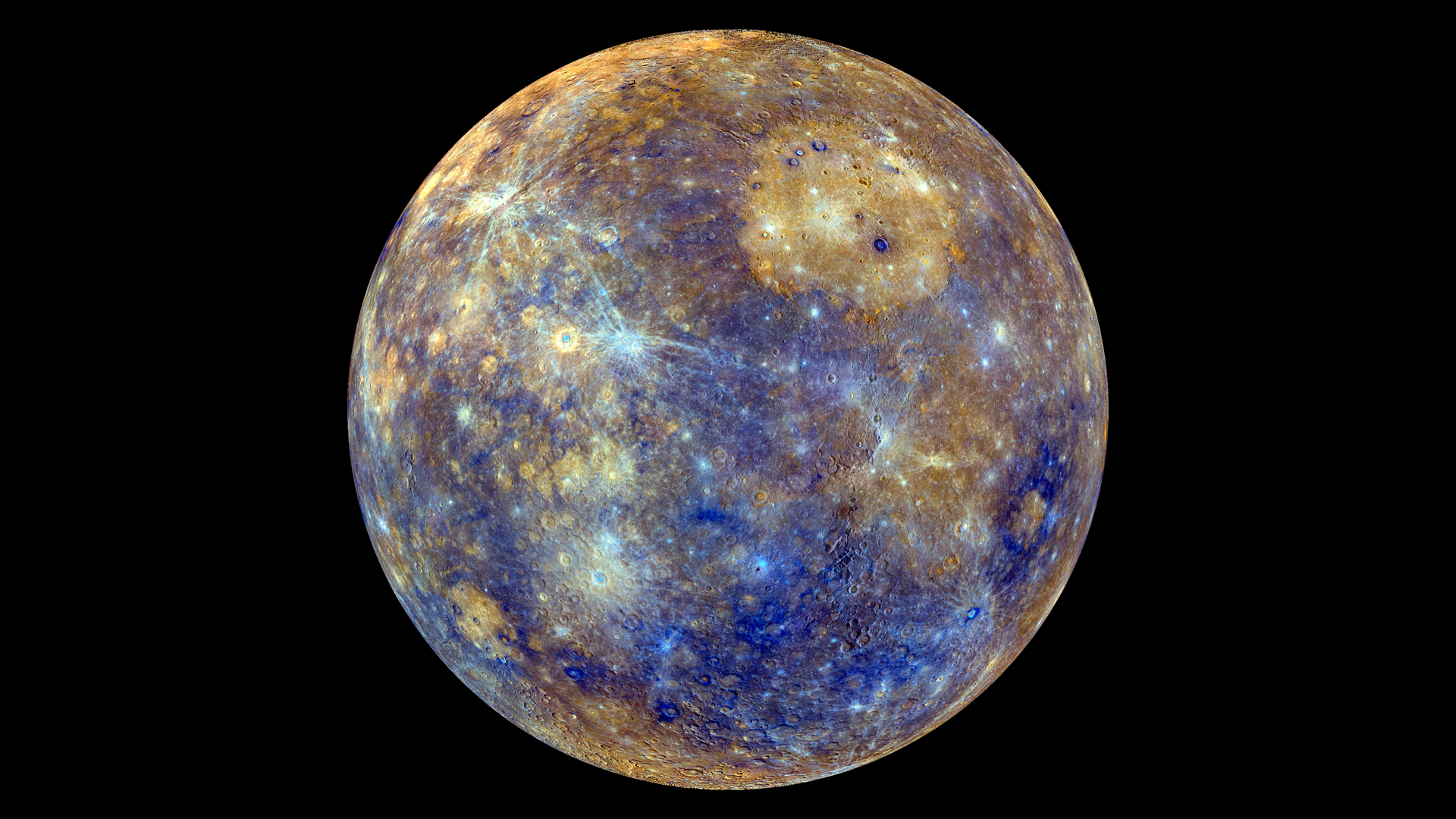

This colorful view of Mercury was produced by using images from the color base map imaging campaign during MESSENGER's primary mission. These colors are not what Mercury would look like to the human eye, but rather the colors enhance the chemical, mineralogical, and physical differences between the rocks that make up Mercury's surface. <b>To watch a movie of this colorful view of Mercury as a spinning globe go here: <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/gsfc/8497927473">www.flickr.com/photos/gsfc/8497927473</a></b> Young crater rays, extending radially from fresh impact craters, appear light blue or white. Medium- and dark-blue areas are a geologic unit of Mercury's crust known as the "low-reflectance material", thought to be rich in a dark, opaque mineral. Tan areas are plains formed by eruption of highly fluid lavas. The giant Caloris basin is the large circular tan feature located just to the upper right of center of the image. The MESSENGER spacecraft is the first ever to orbit the planet Mercury, and the spacecraft's seven scientific instruments and radio science investigation are unraveling the history and evolution of the Solar System's innermost planet. Visit the Why Mercury? section of this website to learn more about the key science questions that the MESSENGER mission is addressing. During the one-year primary mission, MESSENGER acquired 88,746 images and extensive other data sets. MESSENGER is now in a yearlong extended mission, during which plans call for the acquisition of more than 80,000 additional images to support MESSENGER's science goals. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASA_GoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagram.com/nasagoddard?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

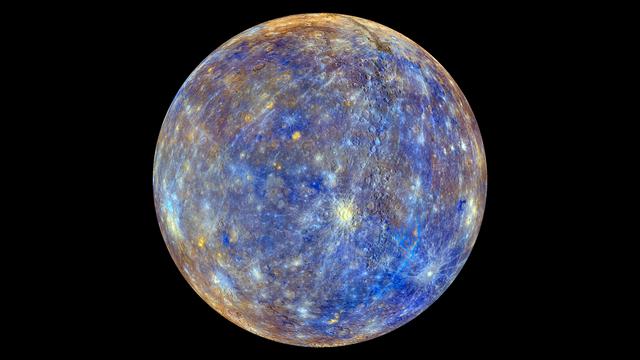

This colorful view of Mercury was produced by using images from the color base map imaging campaign during MESSENGER's primary mission. These colors are not what Mercury would look like to the human eye, but rather the colors enhance the chemical, mineralogical, and physical differences between the rocks that make up Mercury's surface. Young crater rays, extending radially from fresh impact craters, appear light blue or white. Medium- and dark-blue areas are a geologic unit of Mercury's crust known as the "low-reflectance material", thought to be rich in a dark, opaque mineral. Tan areas are plains formed by eruption of highly fluid lavas. The crater in the upper right whose rays stretch across the planet is Hokusai. <b>To watch a movie of this colorful view of Mercury as a spinning globe go here: <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/gsfc/8497927473">www.flickr.com/photos/gsfc/8497927473</a></b> Young crater rays, extending radially from fresh impact craters, appear light blue or white. Medium- and dark-blue areas are a geologic unit of Mercury's crust known as the "low-reflectance material", thought to be rich in a dark, opaque mineral. Tan areas are plains formed by eruption of highly fluid lavas. The giant Caloris basin is the large circular tan feature located just to the upper right of center of the image. The MESSENGER spacecraft is the first ever to orbit the planet Mercury, and the spacecraft's seven scientific instruments and radio science investigation are unraveling the history and evolution of the Solar System's innermost planet. Visit the Why Mercury? section of this website to learn more about the key science questions that the MESSENGER mission is addressing. During the one-year primary mission, MESSENGER acquired 88,746 images and extensive other data sets. MESSENGER is now in a yearlong extended mission, during which plans call for the acquisition of more than 80,000 additional images to support MESSENGER's science goals. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagram.com/nasagoddard?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

As it sped away from Venus, NASA's Mariner 10 spacecraft captured this seemingly peaceful view of a planet the size of Earth, wrapped in a dense, global cloud layer. But, contrary to its serene appearance, the clouded globe of Venus is a world of intense heat, crushing atmospheric pressure and clouds of corrosive acid. This newly processed image revisits the original data with modern image processing software. A contrast-enhanced version of this view, also provided here, makes features in the planet's thick cloud cover visible in greater detail. The clouds seen here are located about 40 miles (60 kilometers) above the planet's surface, at altitudes where Earth-like atmospheric pressures and temperatures exist. They are comprised of sulfuric acid particles, as opposed to water droplets or ice crystals, as on Earth. These cloud particles are mostly white in appearance; however, patches of red-tinted clouds also can be seen. This is due to the presence of a mysterious material that absorbs light at blue and ultraviolet wavelengths. Many chemicals have been suggested for this mystery component, from sulfur compounds to even biological materials, but a consensus has yet to be reached among researchers. The clouds of Venus whip around the planet at nearly over 200 miles per hour (100 meters per second), circling the globe in about four and a half days. That these hurricane-force winds cover nearly the entire planet is another unexplained mystery, especially given that the solid planet itself rotates at a very slow 4 mph (less than 2 meters per second) — much slower than Earth's rotation rate of about 1,000 mph (450 meters per second). The winds and clouds also blow to the west, not to the east as on the Earth. This is because the planet itself rotates to the west, backward compared to Earth and most of the other planets. As the clouds travel westward, they also typically progress toward the poles; this can be seen in the Mariner 10 view as a curved spiral pattern at mid latitudes. Near the equator, instead of long streaks, areas of more clumpy, discrete clouds can be seen, indicating enhanced upwelling and cloud formation in the equatorial region, spurred on by the enhanced power of sunlight there. This view is a false color composite created by combining images taken using orange and ultraviolet spectral filters on the spacecraft's imaging camera. These were used for the red and blue channels of the color image, respectively, with the green channel synthesized by combining the other two images. Flying past Venus en route to the first-ever flyby of Mercury, Mariner 10 became the first spacecraft to use a gravity assist to change its flight path in order to reach another planet. The images used to create this view were acquired by Mariner 10 on Feb. 7 and 8, 1974, a couple of days after the spacecraft's closest approach to Venus on Feb. 5. Despite their many differences, comparisons between Earth and Venus are valuable for helping to understand their distinct climate histories. Nearly 50 years after this view was obtained, many fundamental questions about Venus remain unanswered. Did Venus have oceans long ago? How has its atmosphere evolved over time, and when did its runaway greenhouse effect begin? How does Venus lose its heat? How volcanically and tectonically active has Venus been over the last billion years? This image was processed from archived Mariner 10 data by JPL engineer Kevin M. Gill. The Mariner 10 mission was managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23791