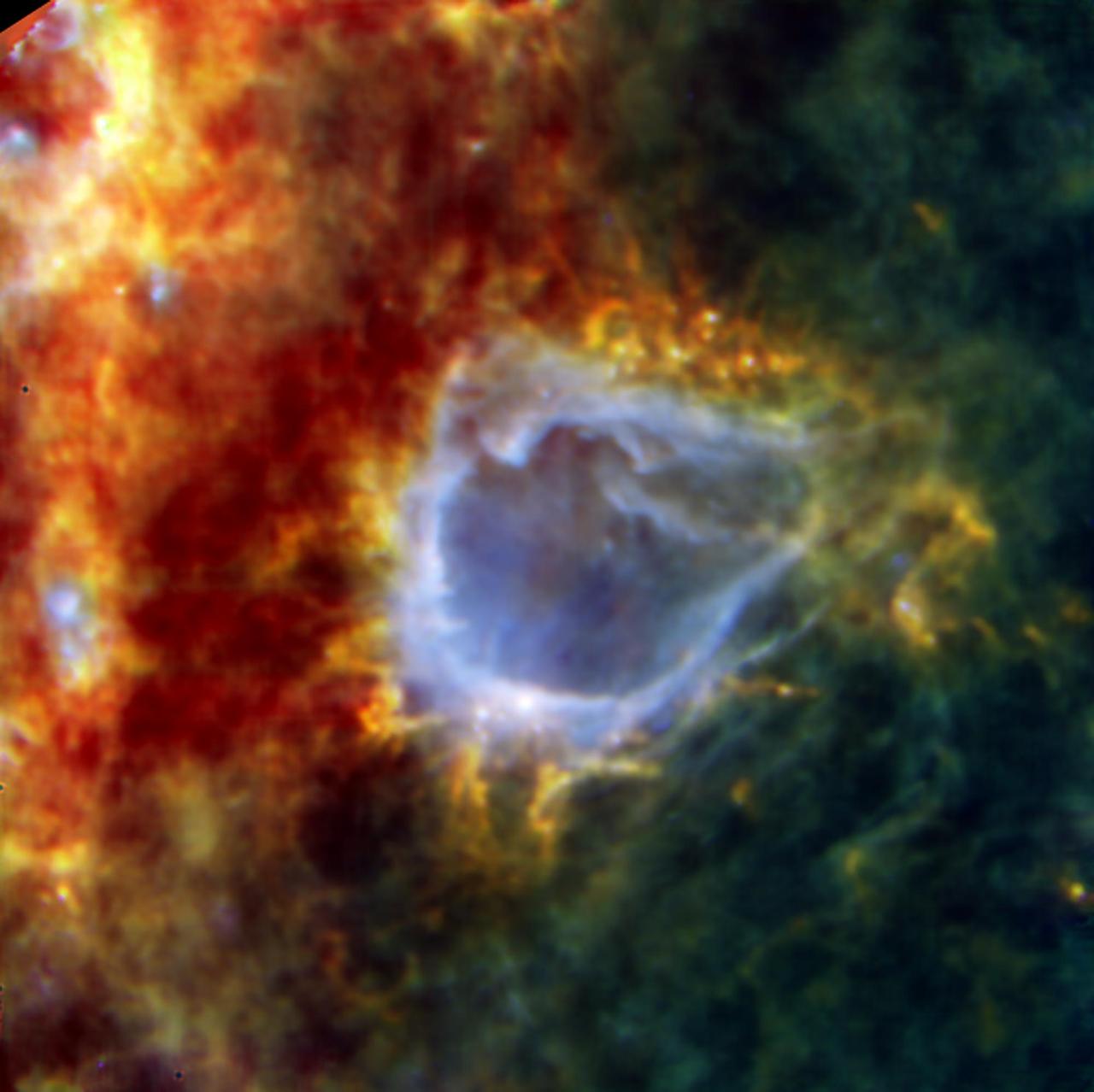

The large bubble is an embryonic star that looks set to turn into one of the brightest stars in our Milky Way galaxy in this infrared image from the Herschel Space Telescope.

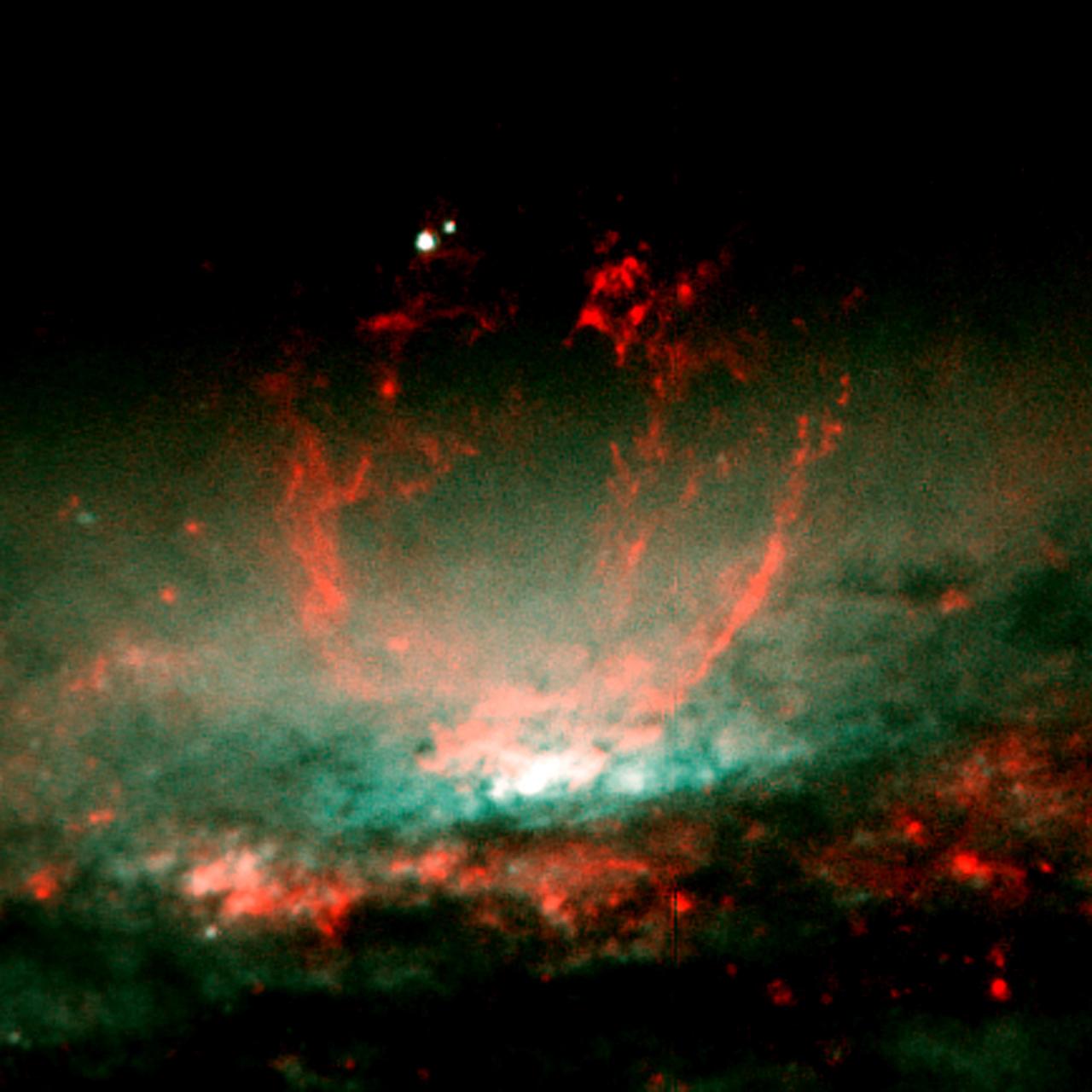

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope (HST) captures a lumpy bubble of hot gas rising from a cauldron of glowing matter in Galaxy NGC 3079, located 50 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Ursa Major. Astronomers suspect the bubble is being blown by "winds" or high speed streams of particles, released during a burst of star formation. The bubble's lumpy surface has four columns of gaseous filaments towering above the galaxy's disc that whirl around in a vortex and are expelled into space. Eventually, this gas will rain down on the disc and may collide with gas clouds, compress them, and form a new generation of stars.

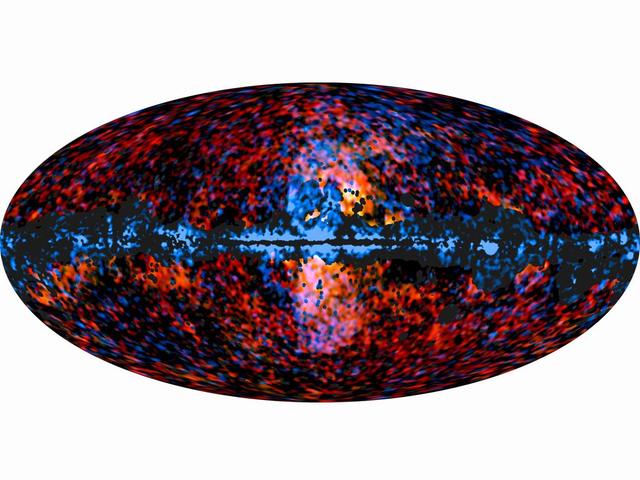

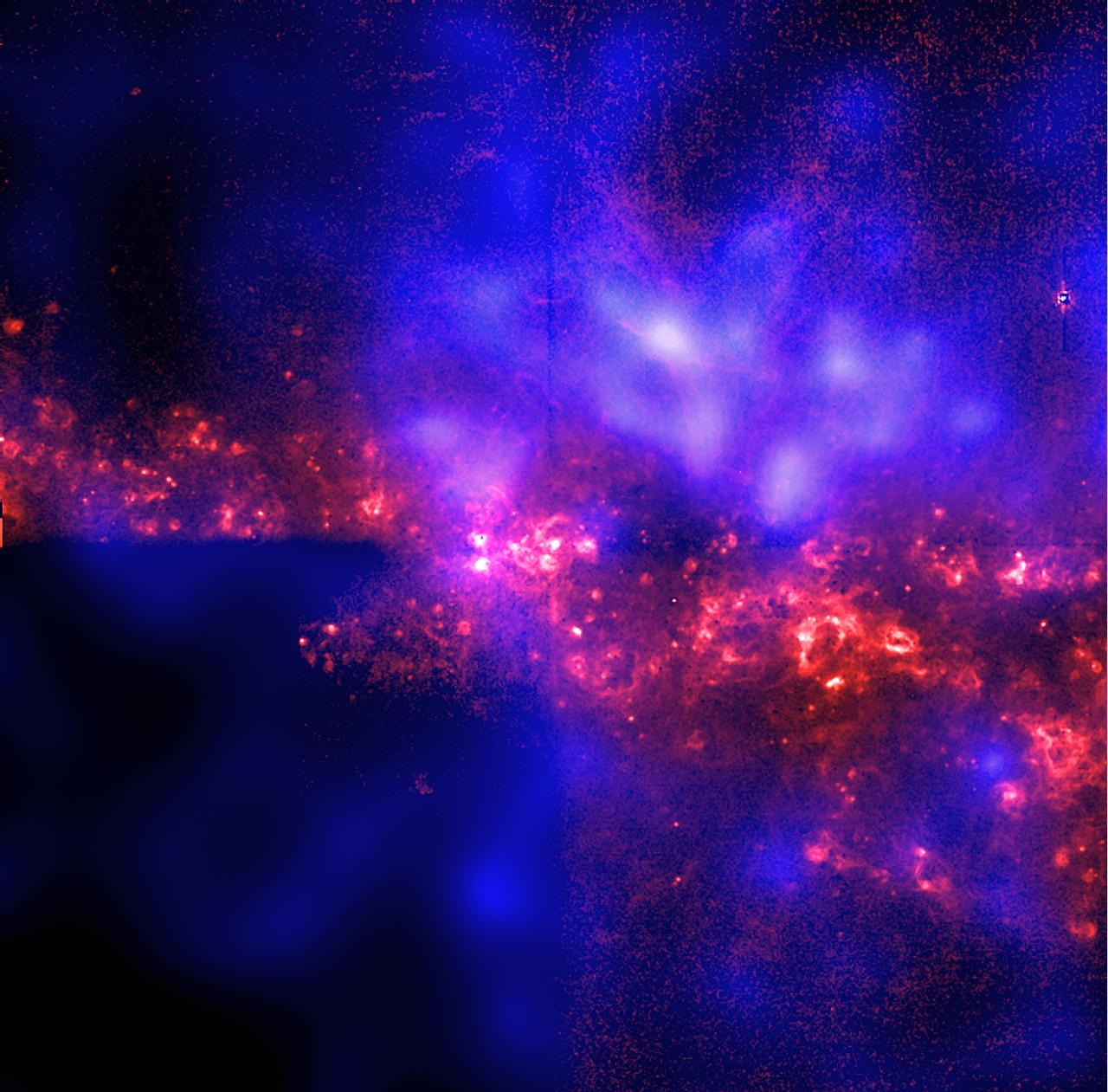

This all-sky image shows the distribution of the galactic haze seen by ESA Planck mission at microwave frequencies superimposed over the high-energy sky, as seen by NASA Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope.

This new image taken with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is of the nearby dwarf galaxy NGC 1569. This galaxy is a hotbed of vigorous star birth activity which blows huge bubbles that riddle its main body. The bubble structure is sculpted by the galactic super-winds and outflows caused by a colossal input of energy from collective supernova explosions that are linked with a massive episode of star birth. The bubbles seen in this image are made of hydrogen gas that glows when hit by the fierce wind and radiation from hot young stars and is racked by supernova shocks. Its "star factories" are also manufacturing brilliant blue star clusters. NGC 1569 had a sudden onset of star birth about 25 million years ago, which subsided about the time the very earliest human ancestors appeared on Earth. The Marshall Space Flight Center had responsibility for the design, development, and construction of the HST.

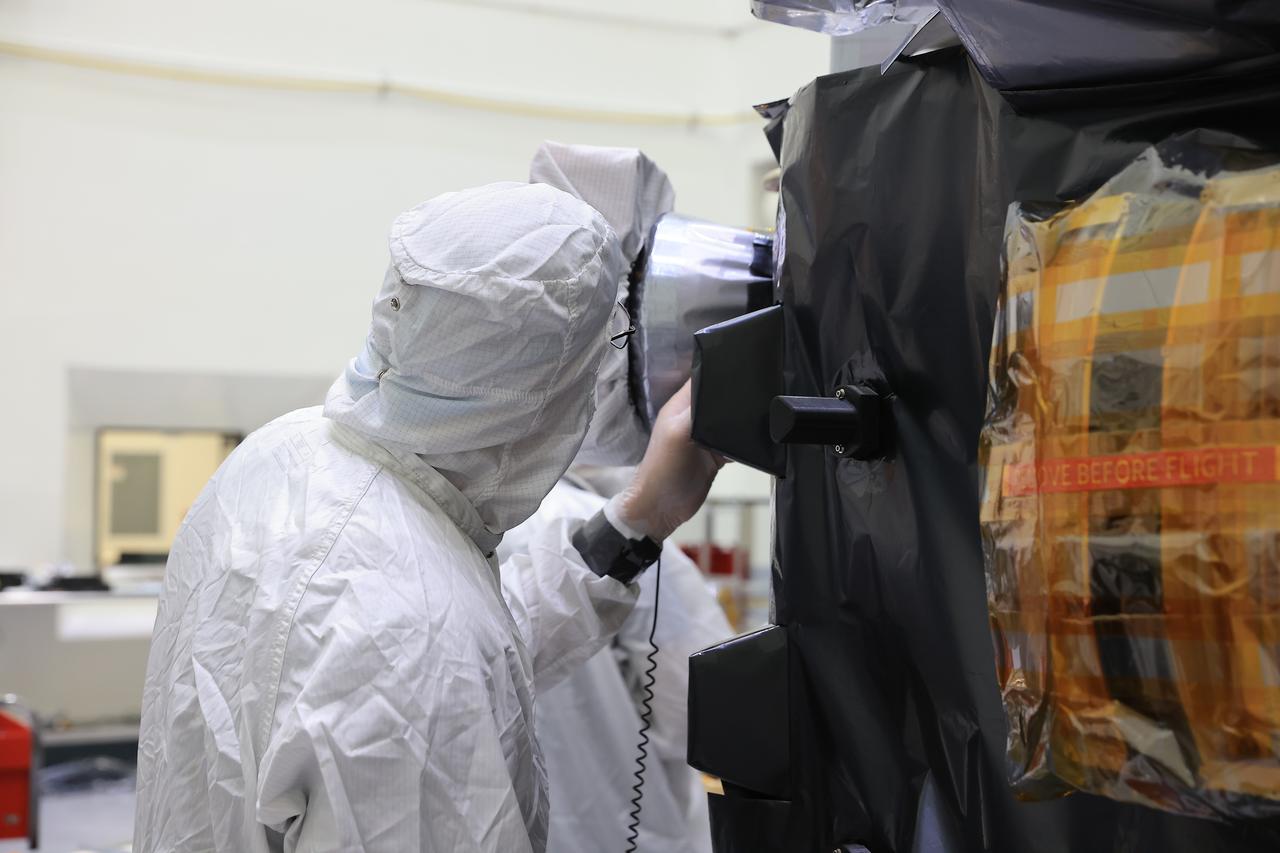

Technicians conduct blanket closeout work on NASA’s IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) observatory at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. IMAP will explore and map the boundaries of the heliosphere — a huge bubble created by the Sun’s wind that encapsulates our entire solar system — and study how the heliosphere interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond.

Technicians conduct blanket closeout work on NASA’s IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) observatory at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. IMAP will explore and map the boundaries of the heliosphere — a huge bubble created by the Sun’s wind that encapsulates our entire solar system — and study how the heliosphere interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond.

Technicians conduct blanket closeout work on NASA’s IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) observatory at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. IMAP will explore and map the boundaries of the heliosphere — a huge bubble created by the Sun’s wind that encapsulates our entire solar system — and study how the heliosphere interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond.

Technicians conduct blanket closeout work on NASA’s IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) observatory at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. IMAP will explore and map the boundaries of the heliosphere — a huge bubble created by the Sun’s wind that encapsulates our entire solar system — and study how the heliosphere interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond.

Technicians conduct blanket closeout work on NASA’s IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) observatory at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. IMAP will explore and map the boundaries of the heliosphere — a huge bubble created by the Sun’s wind that encapsulates our entire solar system — and study how the heliosphere interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond.

Technicians conduct blanket closeout work on NASA’s IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) observatory at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. IMAP will explore and map the boundaries of the heliosphere — a huge bubble created by the Sun’s wind that encapsulates our entire solar system — and study how the heliosphere interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond.

Technicians conduct blanket closeout work on NASA’s IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) observatory at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 15, 2025. IMAP will explore and map the boundaries of the heliosphere — a huge bubble created by the Sun’s wind that encapsulates our entire solar system — and study how the heliosphere interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond.

NASA’s IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) observatory arrives at Building 2 where technicians will load 317 pounds (or 144 kilograms) of hydrazine into three tanks into the spacecraft at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Tuesday, Aug. 12, 2025. IMAP will explore and map the boundaries of the heliosphere — a huge bubble created by the Sun’s wind that encapsulates our entire solar system — and study how the heliosphere interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond.

Technicians transport NASA’s IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) observatory to Building 2 where they will load 317 pounds (or 144 kilograms) of hydrazine into three tanks into the spacecraft at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Tuesday, Aug. 12, 2025. IMAP will explore and map the boundaries of the heliosphere — a huge bubble created by the Sun’s wind that encapsulates our entire solar system — and study how the heliosphere interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond.

Technicians prepare to transport NASA’s IMAP (Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe) observatory to Building 2 where they will load 317 pounds (or 144 kilograms) of hydrazine into three tanks into the spacecraft at the Astrotech Space Operations Facility near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Tuesday, Aug. 12, 2025. IMAP will explore and map the boundaries of the heliosphere — a huge bubble created by the Sun’s wind that encapsulates our entire solar system — and study how the heliosphere interacts with the local galactic neighborhood beyond.

The CTB 1 supernova remnant resembles a ghostly bubble in this image, which combines new 1.5 gigahertz observations from the Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope (orange, near center) with older observations from the Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory’s Canadian Galactic Plane Survey (1.42 gigahertz, magenta and yellow; 408 megahertz, green) and infrared data (blue). The VLA data clearly reveal the straight, glowing trail from pulsar J0002+6216 and the curved rim of the remnant’s shell. CTB 1 is about half a degree across, the apparent size of a full Moon. Credits: Composite by Jayanne English, University of Manitoba, using data from NRAO/F. Schinzel et al., DRAO/Canadian Galactic Plane Survey and NASA/IRAS More info: https://go.nasa.gov/2TKpyWF

Images of the Milky Way and the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) are overlaid on a map of the surrounding area, our galaxy's galactic halo. Dark blue represents a low concentration of stars; lighter blues indicate increasing stellar density. The map spans from about 200,000 light-years to 325,000 light-years from the galactic center and provides the first clear view of the major features in this region. The LMC is orbiting the Milky Way and will eventually merge with it. The high concentration in the lower half is a wake created by the LMC as it sails through the galactic halo. In the upper half of the image, astronomers observed an apparent excess of stars compared to the southern hemisphere. This is evidence that the Large Magellanic Cloud has pulled the Milky Way disk significantly off-center. The galactic halo can be thought of as a bubble surrounding the disk. The number of stars per area is highest near the center of the bubble, and drops off moving away from the center. If the Milky Way were in the center of the halo, astronomers would see an approximately equal number of stars in both hemispheres. But because the Milky Way has been pulled away from the center, when astronomers look into the northern hemisphere, they see more of the central, highly populated area. Comparing these two views, there is an apparent excess of stars in the northern hemisphere. The image of the Milky Way used here is from the ESA (European Space Agency) Gaia mission: https://www.eso.org/public/images/eso1908e/. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24571

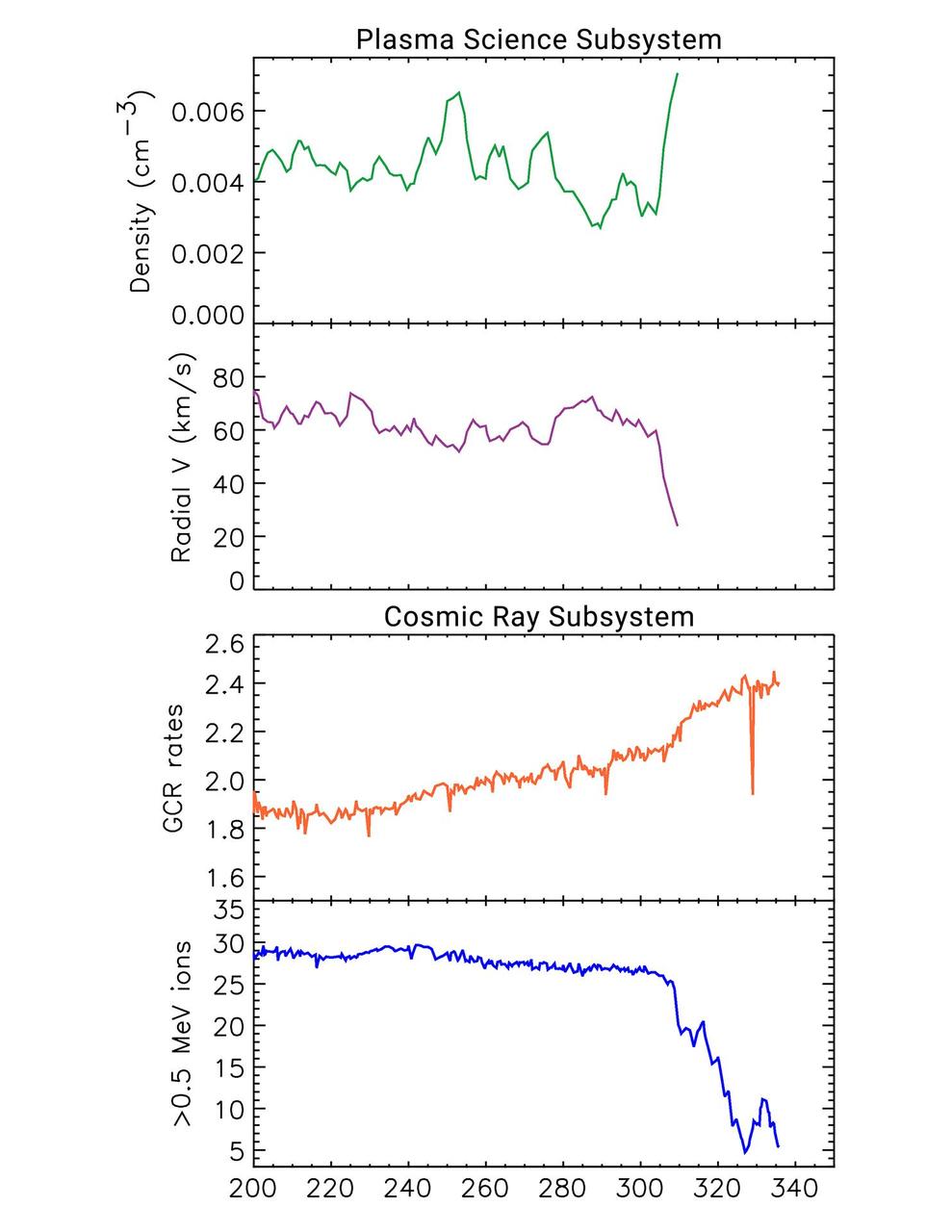

This set of graphs illustrates how data from two key instruments point to NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft entering interstellar space, or the space between the stars, in November 2018. The top two plots come from the plasma science experiment (PLS). The plasma -- or ionized gas -- of interstellar space is significantly denser than the plasma inside the bubble of plasma the Sun blows around itself (the heliosphere). There is a jump on the graph in November 2018. At the same time, the measurements show that the outward speed (radial velocity) of the plasma the Sun is blowing (also known as the solar wind) sharply decreased. The bottom two plots come from the cosmic ray subsystem, which counts hits per second of higher-energy particles that originate from outside the solar bubble and lower-energy particles that originate from inside the solar bubble. The outsideparticles (also known as galactic cosmic rays or GCRs) increased and the inside particles (greater than 0.5 MeV) decreased at the same time the plasma science instrument detected its changes. The horizontal axis proceeds according to the numbered days of the year in 2018. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22923

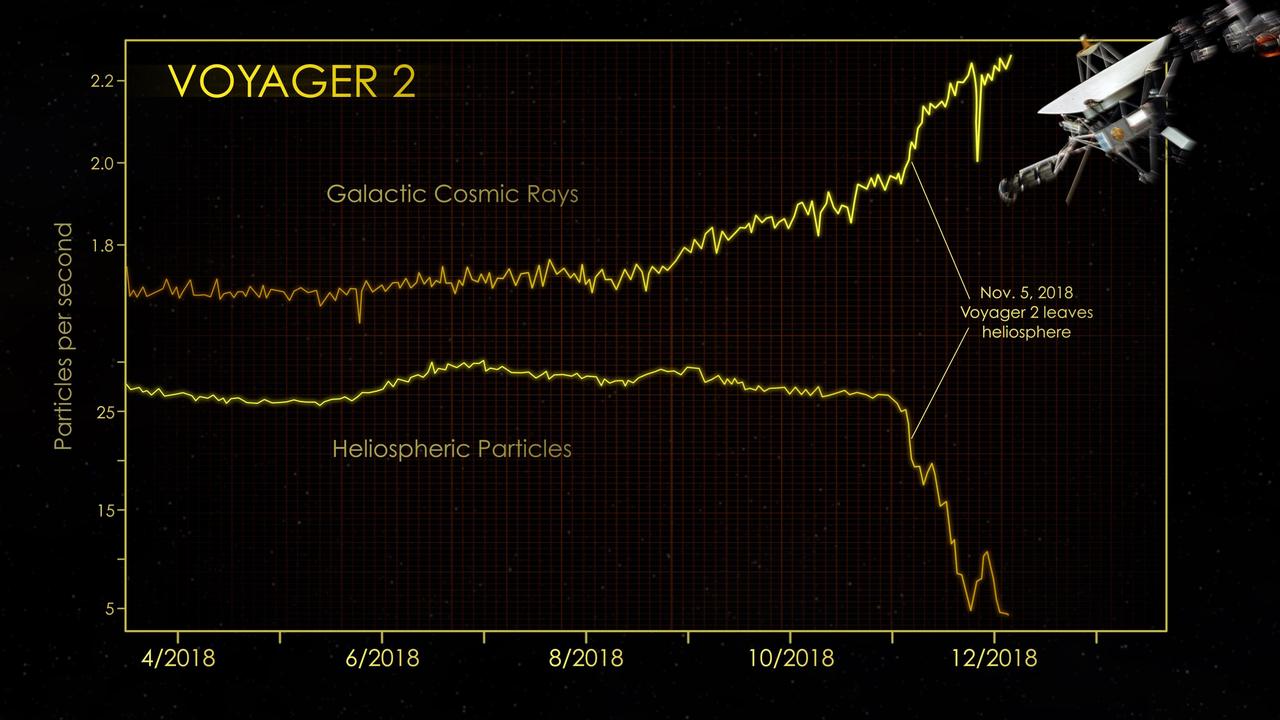

At the end of 2018, the cosmic ray subsystem (CRS) aboard NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft provided evidence that Voyager 2 had left the heliosphere (the plasma bubble the Sun blows around itself). There were steep drops in the rate at which particles that originate inside the heliosphere hit the instrument's radiation detector. At the same time, there were significant increases in the rate at which particles that originate outside our heliosphere (also known as galactic cosmic rays) hit the detector. The graphs show data from Voyager 2's CRS, which averages the number of particle hits over a six-hour block of time. CRS detects both lower-energy particles that originate inside the heliosphere (greater than 0.5 MeV) and higher-energy particles that originate farther out in the galaxy (greater than 70 MeV). https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22924

The Cat's Paw Nebula, imaged here by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, is a star-forming region inside the Milky Way Galaxy and is located in the constellation Scorpius. Its distance from Earth is estimated to be between 1.3 kiloparsecs (about 4,200 light years) to 1.7 kiloparsecs (about 5,500 light years). The image was taken as part of the Galactic Legacy Infrared Midplane Survey Extraordinaire (GLIMPSE), a survey of the Milky Way Galaxy. It was taken using Spitzer's Infrared Array Camera (IRAC). The colors correspond with wavelengths of 3.6 microns (blue), 4.5 microns (green), and 8 microns (red). The bright, cloudlike band running left to right across the image shows the presence of gas and dust that can collapse to form new stars. The black filaments running through the nebula are particularly dense regions of gas and dust. The entire star-forming region is thought to be between 24 and 27 parsecs (80-90 light years) across. New stars may heat up the pressurized gas surrounding them causing the gas to expand and form "bubbles." https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22567

This image shows the central region of the spiral galaxy NGC 4631 as seen edge-on from the Chandra X-Ray Observatory (CXO) and the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). The Chandra data, shown in blue and purple, provide the first unambiguous evidence for a halo of hot gas surrounding a galaxy that is very similar to our Milky Way. The structure across the middle of the image and the extended faint filaments, shown in orange, represent the observation from the HST that reveals giant bursting bubbles created by clusters of massive stars. Scientists have debated for more than 40 years whether the Milky Way has an extended corona, or halo, of hot gas. Observations of NGC 4631 and similar galaxies provide astronomers with an important tool in the understanding our own galactic environment. A team of astronomers, led by Daniel Wang of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, observed NGC 4631 with CXO's Advanced Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) Imaging Spectrometer (ACIS). The observation took place on April 15, 2000, and its duration was approximately 60,000 seconds.