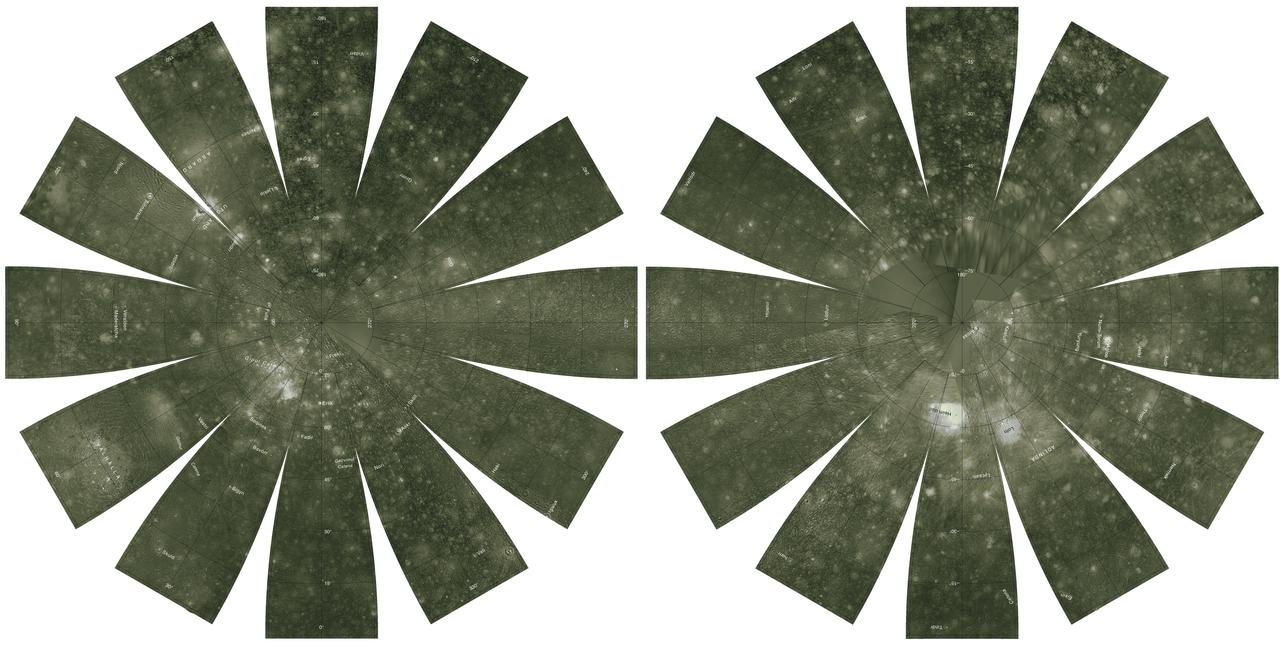

Galileo Regio Mosaic - Galileo over Voyager Data

View of Callisto from Voyager and Galileo

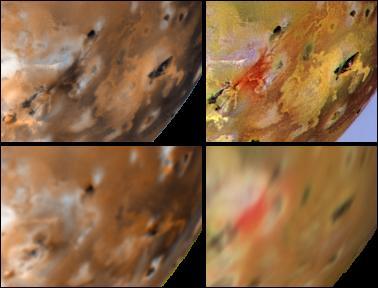

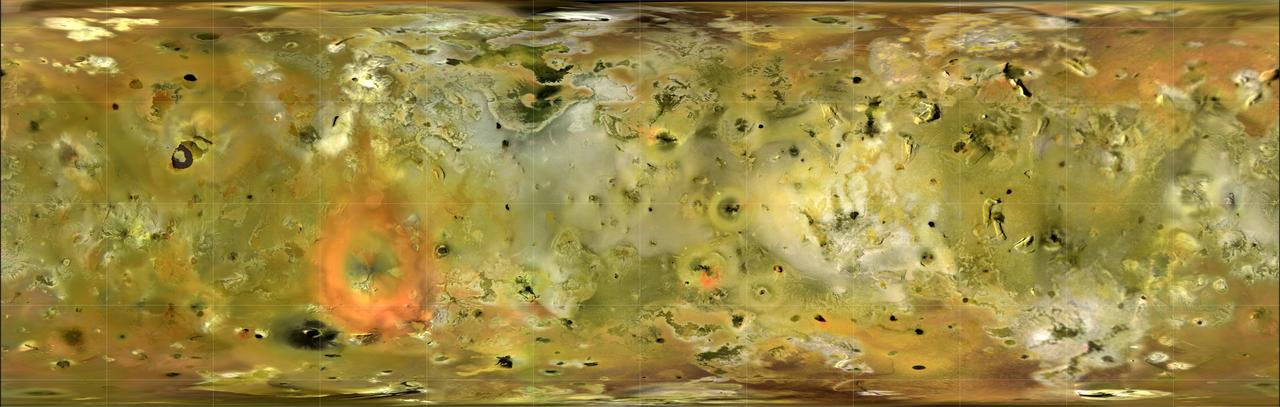

Voyager-to-Galileo Changes, Io Anti-Jove Hemisphere

Uruk Sulcus Mosaic - Galileo over Voyager Data

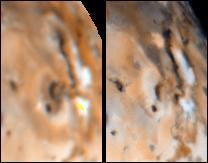

Changes on Io around Volund between Voyager 1 and Galileo Second Orbit

Changes around Marduk Between Voyager, and Galileo First Two Orbits

Detail of Ganymede Uruk Sulcus Region as Viewed by Galileo and Voyager

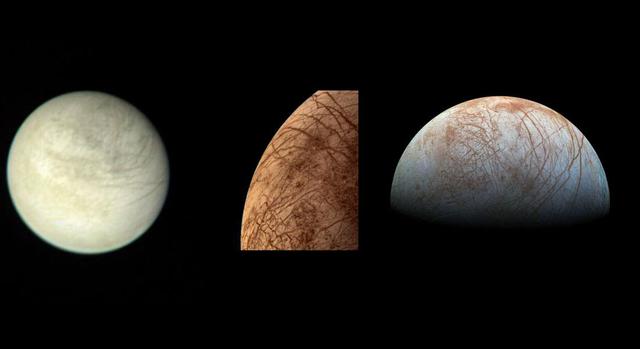

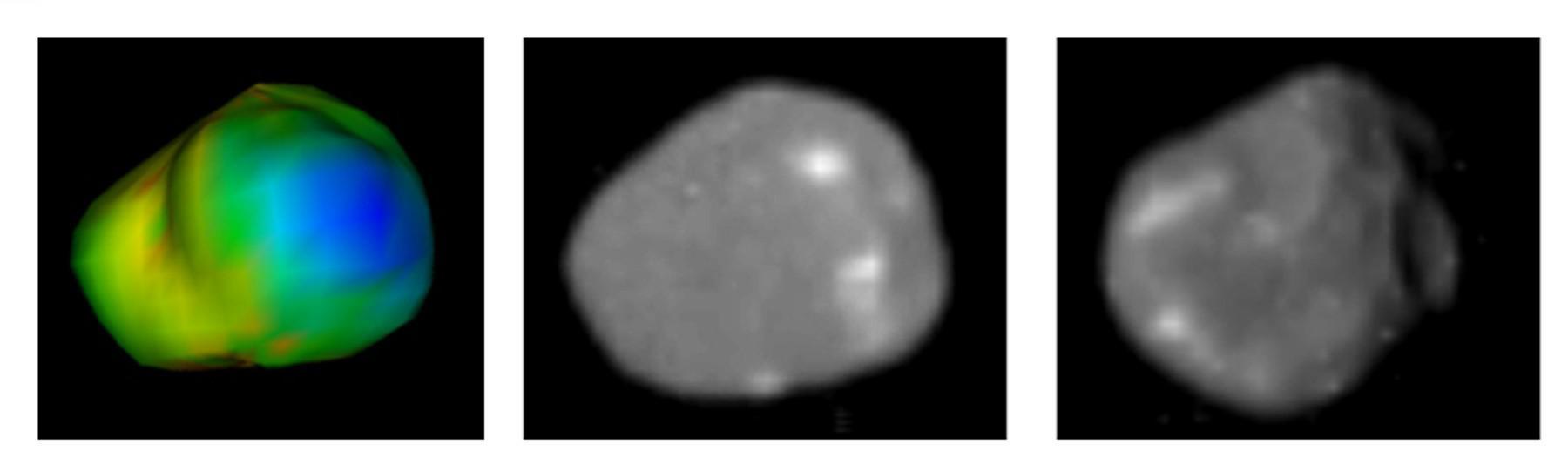

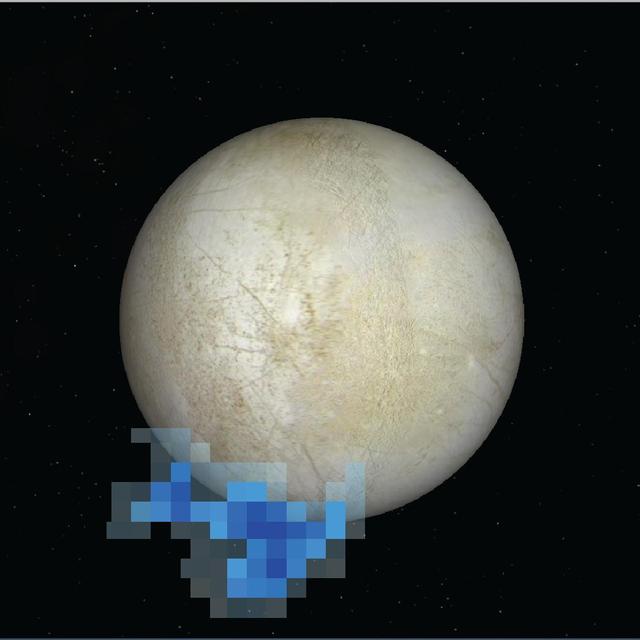

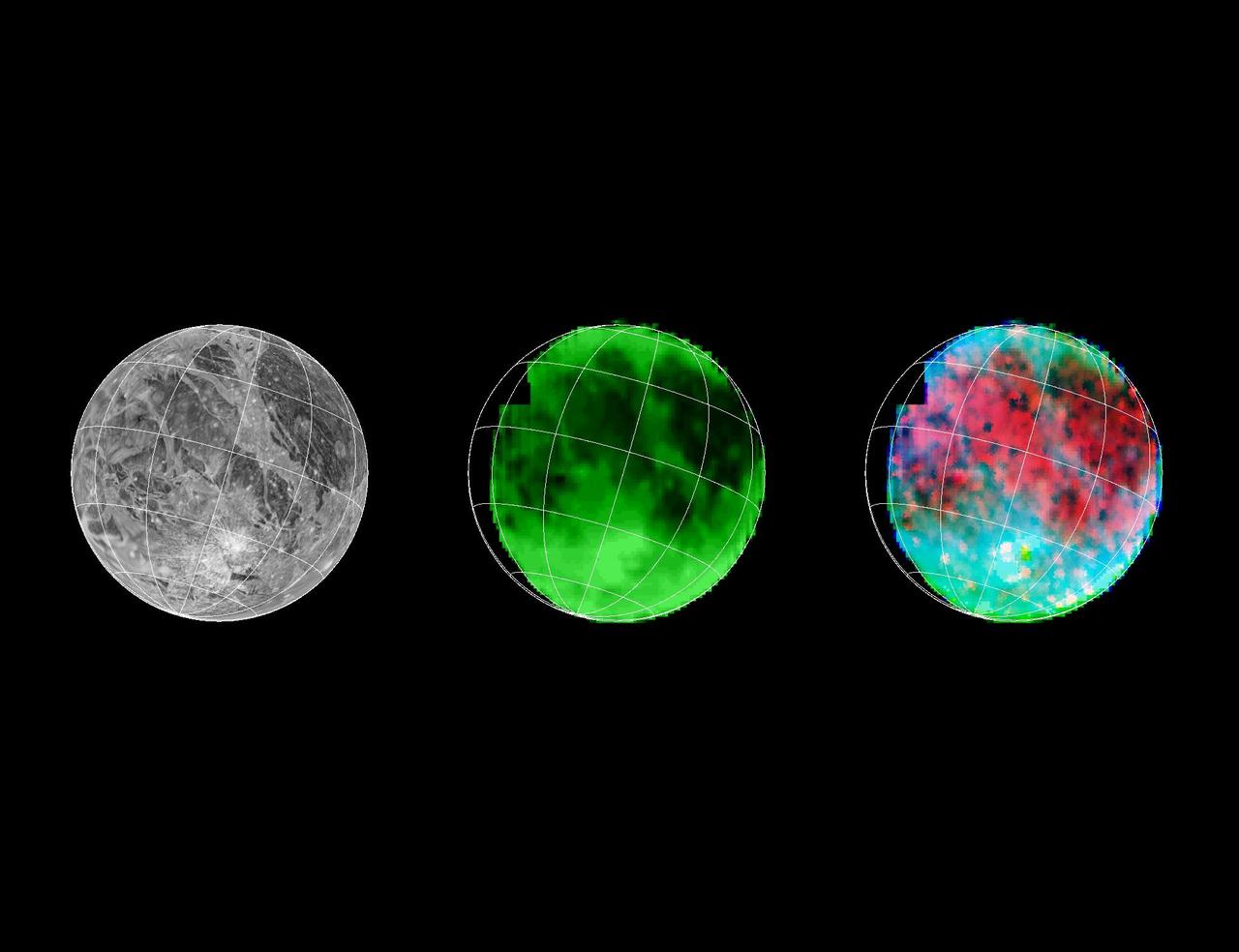

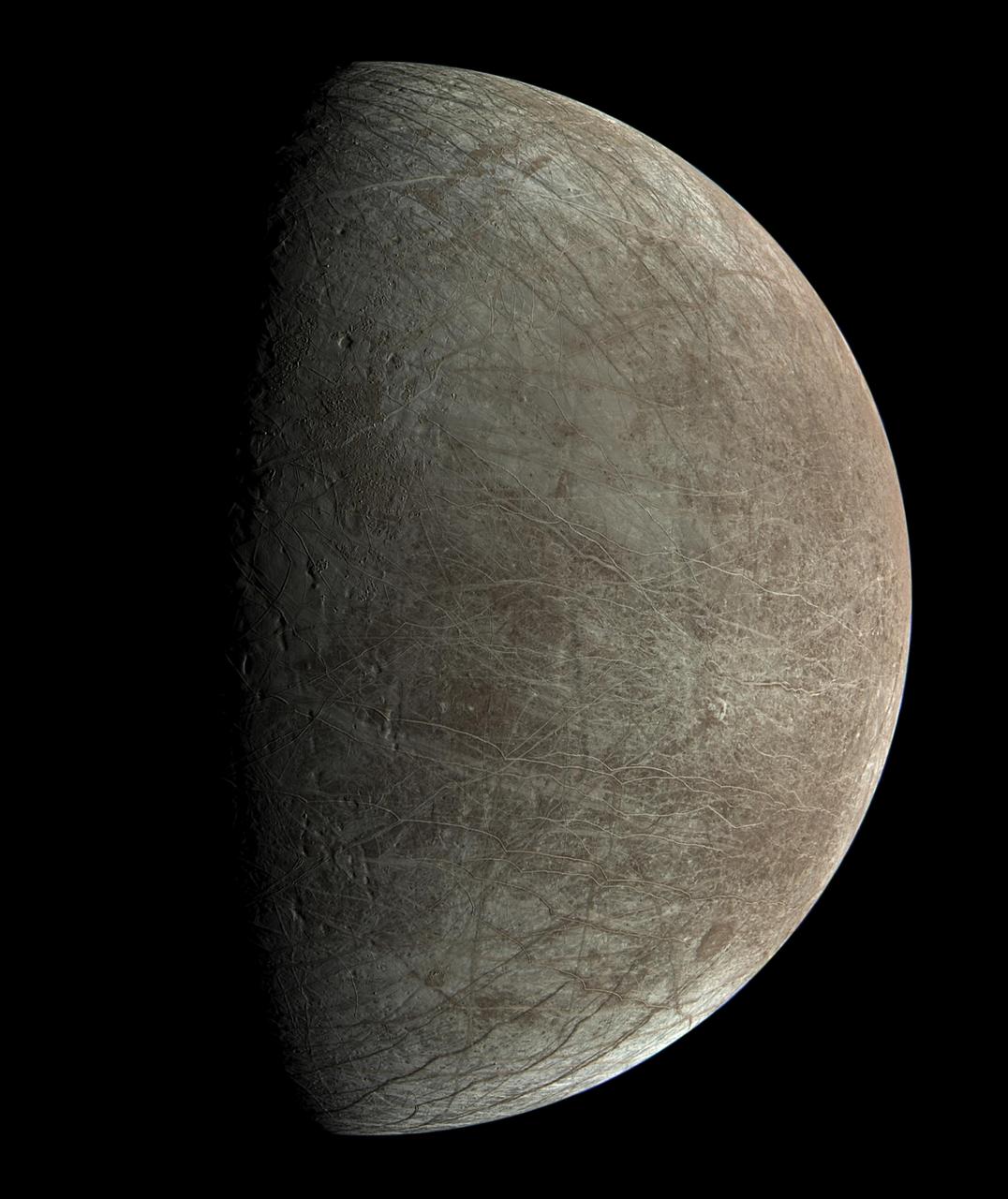

On the left is a view of Jupiter's moon Europa taken on March 2, 1979, by NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft. In the middle is a color image of Europa taken by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft during its close encounter on July 9, 1979. On the right is a view of Europa made from images taken by NASA's Galileo spacecraft in the late 1990s. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24895

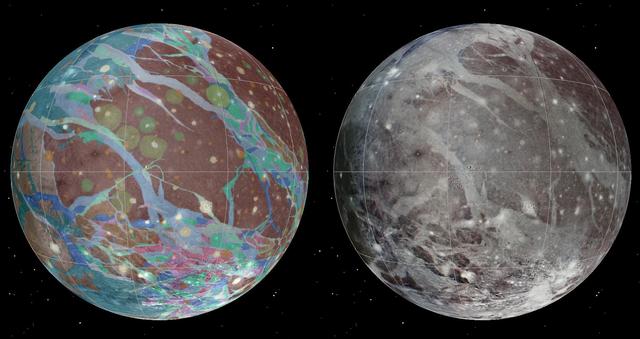

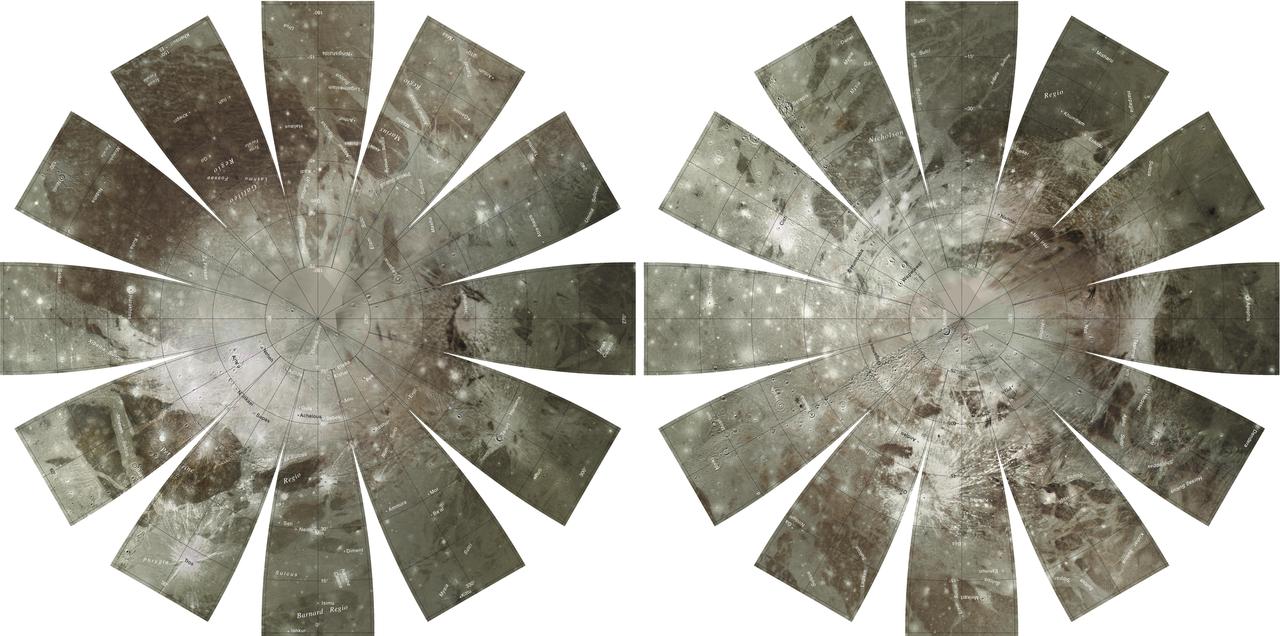

To present the best information in a single view of Jupiter moon Ganymede, a global image mosaic was assembled, incorporating the best available imagery from NASA Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft and NASA Galileo spacecraft.

These images of Jupiter moon Amalthea were taken with NASA Galileo and Voyager spacecraft. Amalthea is almost pure water ice, hinting that it may not have formed where it now orbits.

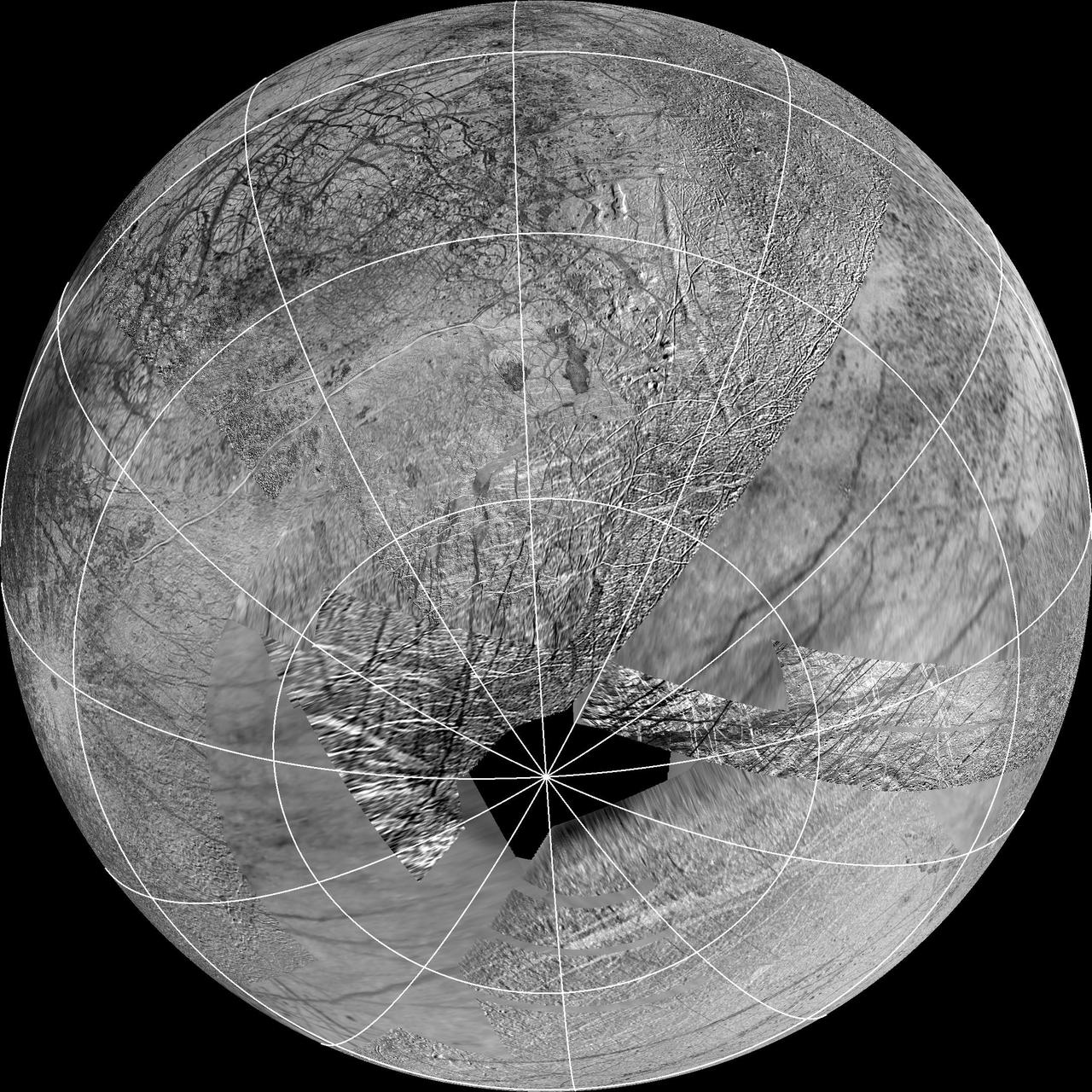

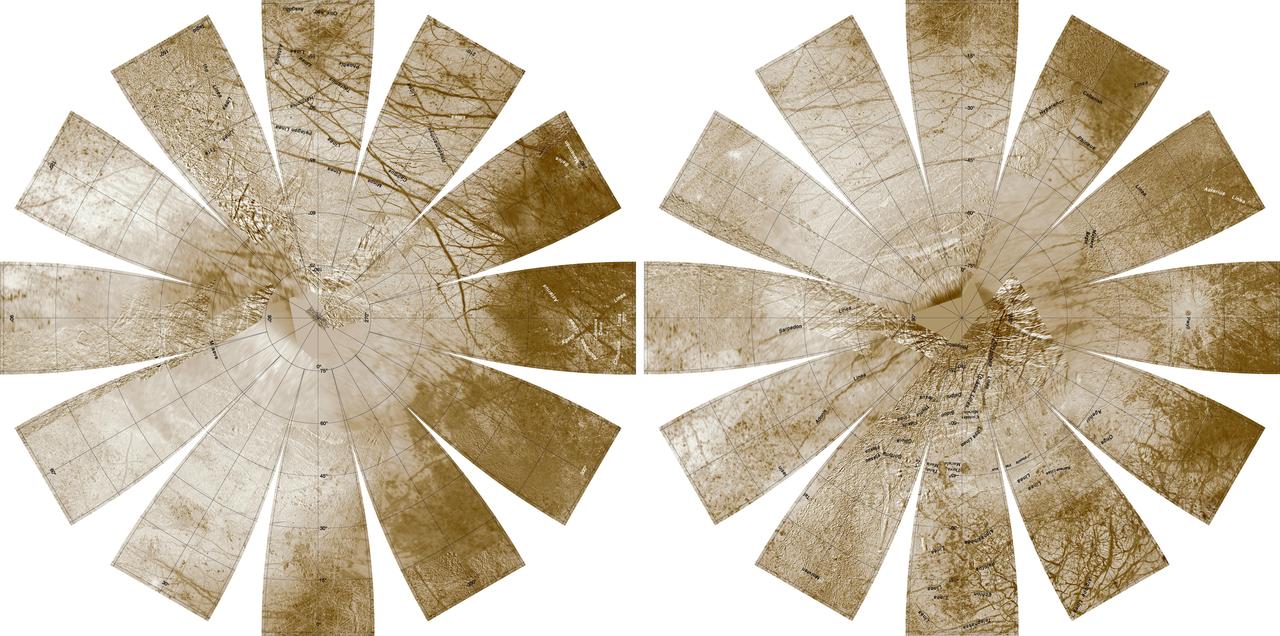

This map composed of images NASA Galileo and Voyager missions shows the hemisphere of Europa that might be affected by plume deposits. The view is centered at -65 degrees latitude, 183 degrees longitude.

This is a frame from an animation of a rotating globe of Jupiter moon Ganymede, with a geologic map superimposed over a global color mosaic, incorporating the best available imagery from NASA Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, and Galileo spacecraft.

Changes on Io between Voyager 1 and Galileo Second Orbit Around an Unnamed Vent North of Prometheus

Changes on Io around Maui and Amirani between Voyager 1 and Galileo Second Orbit

A mosaic of four Galileo high-resolution images of the Uruk Sulcus region of Jupiter moon Ganymede is shown within the context of an image of the region taken by Voyager 2 in 1979. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00281

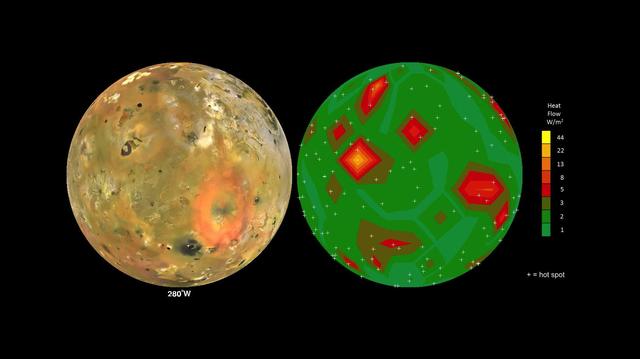

This frame from an animation shows Jupiter volcanic moon Io as seen by NASA Voyager and Galileo spacecraft (at left) and the pattern of heat flow from 242 active volcanoes (at right). The red and yellow areas are places where local heat flow is greatest -- the result of magma erupting from Io's molten interior onto the surface. The map is the result of analyzing decades of observations from spacecraft and ground-based telescopes. It shows Io's usual volcanic thermal emission, excluding the occasional massive but transient "outburst" eruption; in other words, this is what Io looks like most of the time. This heat flow map will be used to test models of interior heating. The map shows that areas of enhanced volcanic heat flow are not necessarily correlated with the number of volcanoes in a particular region and are poorly correlated with expected patterns of heat flow from current models of tidal heating -- something that is yet to be explained. This research is published in association with a 2015 paper in the journal Icarus by A. Davies et al., titled "Map of Io's Volcanic Heat Flow," (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2015.08.003.) http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19655

Volcanic hot spots are seen in this color temperature map of the Prometheus volcano on Jupiter moon Io created with data obtained by NASA Galileo and Voyager spacecraft.

This mosaic of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede consists of more than 100 images acquired with NASA’s Voyager and Galileo spacecrafts, showing irregular lumps beneath the icy surface.

This global view of Europa shows the location of a four-frame mosaic of images taken by NASA Galileo spacecraft in 1996, set into low-resolution data obtained by NASA Voyager spacecraft in 1979.

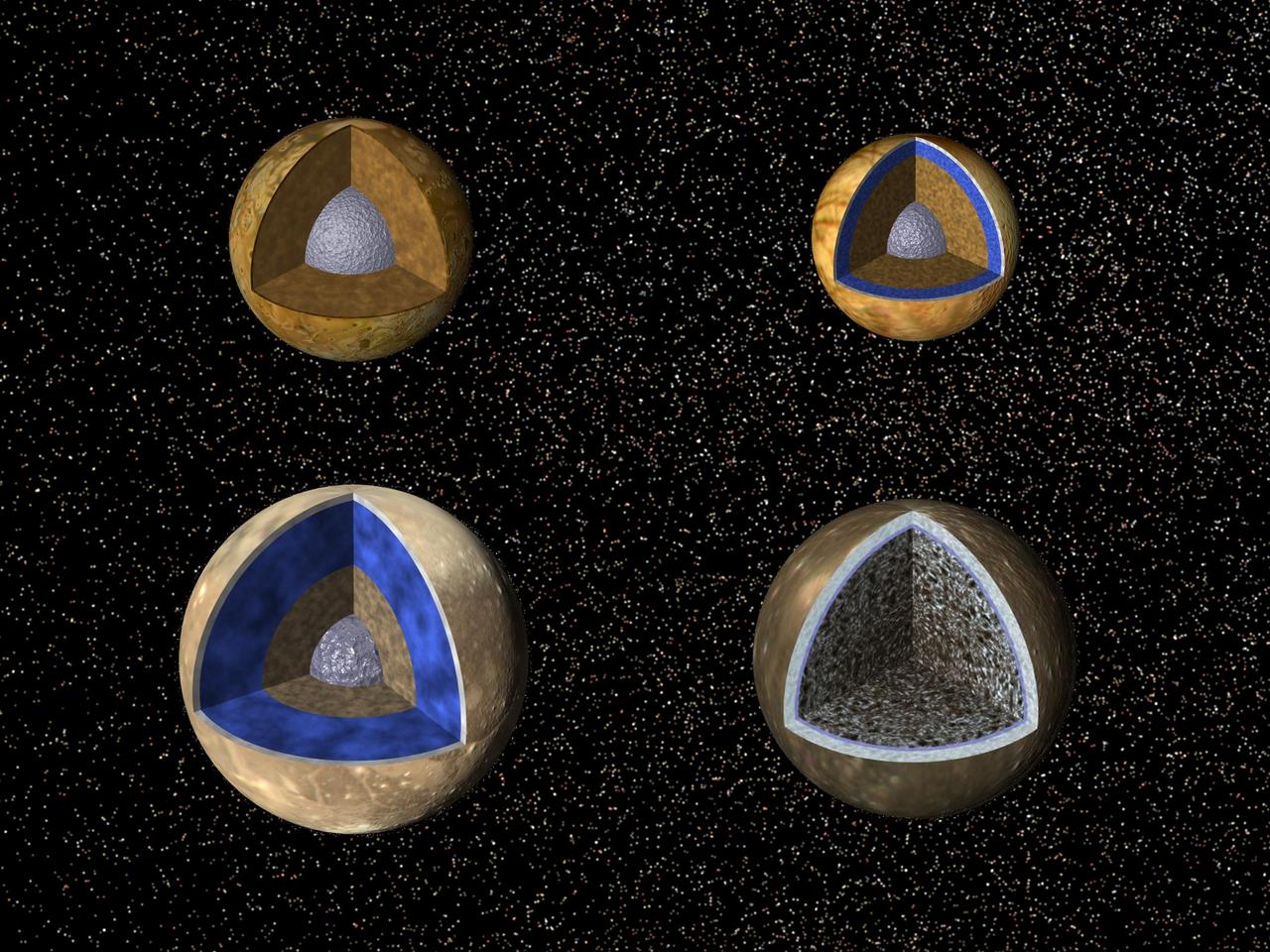

Cutaway views of the possible internal structures of the Galilean satellites. Ganymede at lower left, Callisto at lower right, Io on upper left, and Europa on upper right in a combined biew from NASA Galileo and Voyager spacecraft.

The left image is an airbrush map of the surface of Ganymede from NASA Voyager data. The small square shows the location of Antum crater, target of the image from NASA Galileo spacecraft on the right.

Artist concept shows Galileo spacecraft while still approaching Jupiter having a satellite encounter. Galileo is flying about 600 miles above Io's volcano-torn surface, twenty times closer than the closest flyby altitude of Voyager in 1979.

These images demonstrate the dramatic improvement in the resolution of pictures that NASA Galileo spacecraft returned compared to previous images of the Jupiter system. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00277

Global Map of Ganymede

Io in Motion

Europa Hemispherical Globes

Callisto Hemispherical Globes

NASA's Voyager images are used to create a global view of Ganymede. The cut-out reveals the interior structure of this icy moon. This structure consists of four layers based on measurements of Ganymede's gravity field and theoretical analyses using Ganymede's known mass, size and density. Ganymede's surface is rich in water ice and Voyager and Galileo images show features which are evidence of geological and tectonic disruption of the surface in the past. As with the Earth, these geological features reflect forces and processes deep within Ganymede's interior. Based on geochemical and geophysical models, scientists expected Ganymede's interior to either consist of: a) an undifferentiated mixture of rock and ice or b) a differentiated structure with a large lunar sized "core" of rock and possibly iron overlain by a deep layer of warm soft ice capped by a thin cold rigid ice crust. Galileo's measurement of Ganymede's gravity field during its first and second encounters with the huge moon have basically confirmed the differentiated model and allowed scientists to estimate the size of these layers more accurately. In addition the data strongly suggest that a dense metallic core exists at the center of the rock core. This metallic core suggests a greater degree of heating at sometime in Ganymede's past than had been proposed before and may be the source of Ganymede's magnetic field discovered by Galileo's space physics experiments. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00519

This graphic shows the location of water vapor detected over Europa south pole in observations taken by NASA Hubble Space Telescope in December 2012. This is the first strong evidence of water plumes erupting off Europa surface.

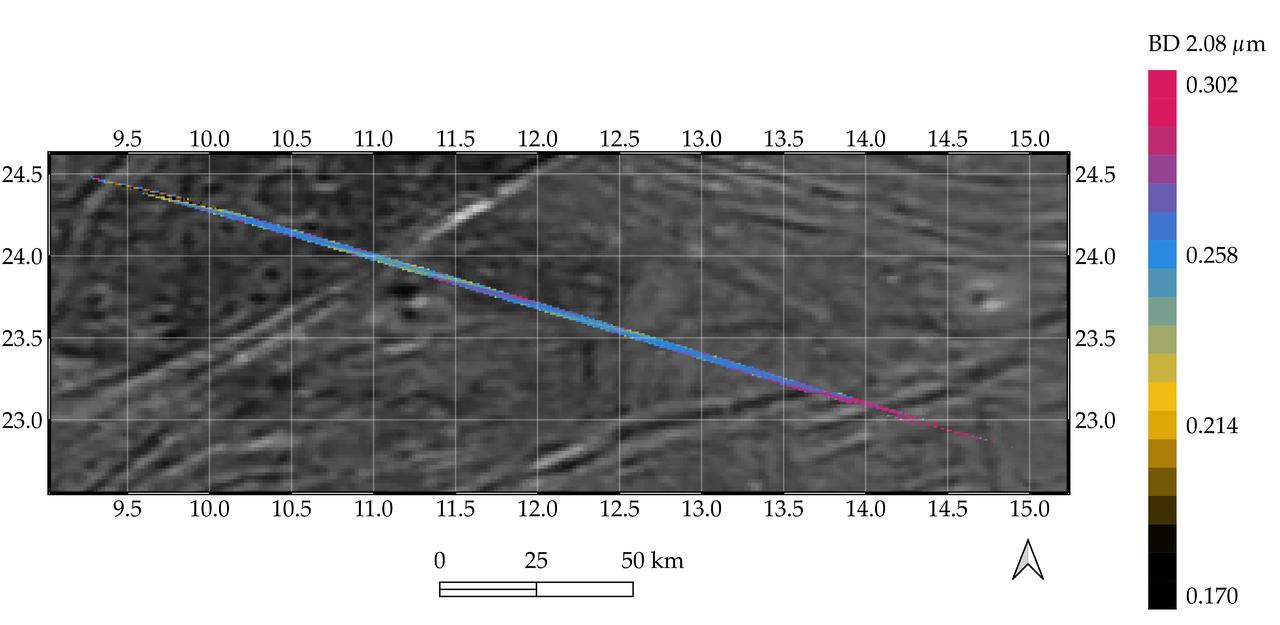

Processed data from the Jovian InfraRed Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) spectrometer aboard NASA's Juno mission is superimposed on a mosaic of optical images from the agency's Galileo and Voyager spacecraft that shows grooved terrain on Jupiter's moon Ganymede. This composite image covers a portion of Phrygia Suclus, northeast of Nanshe Catena, on Ganymede. The data was taken by Juno during its June 7, 2021, flyby of the icy moon. The JIRAM data is represented by the colored line running from the upper left to lower right in the graphic. The line depicts an increase in intensity of the spectral signature of a non-ice compound, possibly ammonium chloride, in the groove at the lower right of the image. JIRAM "sees" infrared light not visible to the human eye. It measures heat radiated from the planet at an infrared wavelengths. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26075

Galileo has eyes that can see more than ours can. By looking at what we call the infrared wavelengths, the NIMS (Near Infrared Mapping Spectrometer) instrument can determine what type and size of material is on the surface of a moon. Here, 3 images of Ganymede are shown. Left: Voyager's camera. Middle: NIMS, showing water ice on the surface. Dark is less water, bright is more. Right: NIMS, showing the locations of minerals in red, and the size of ice grains in shades of blue. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00500

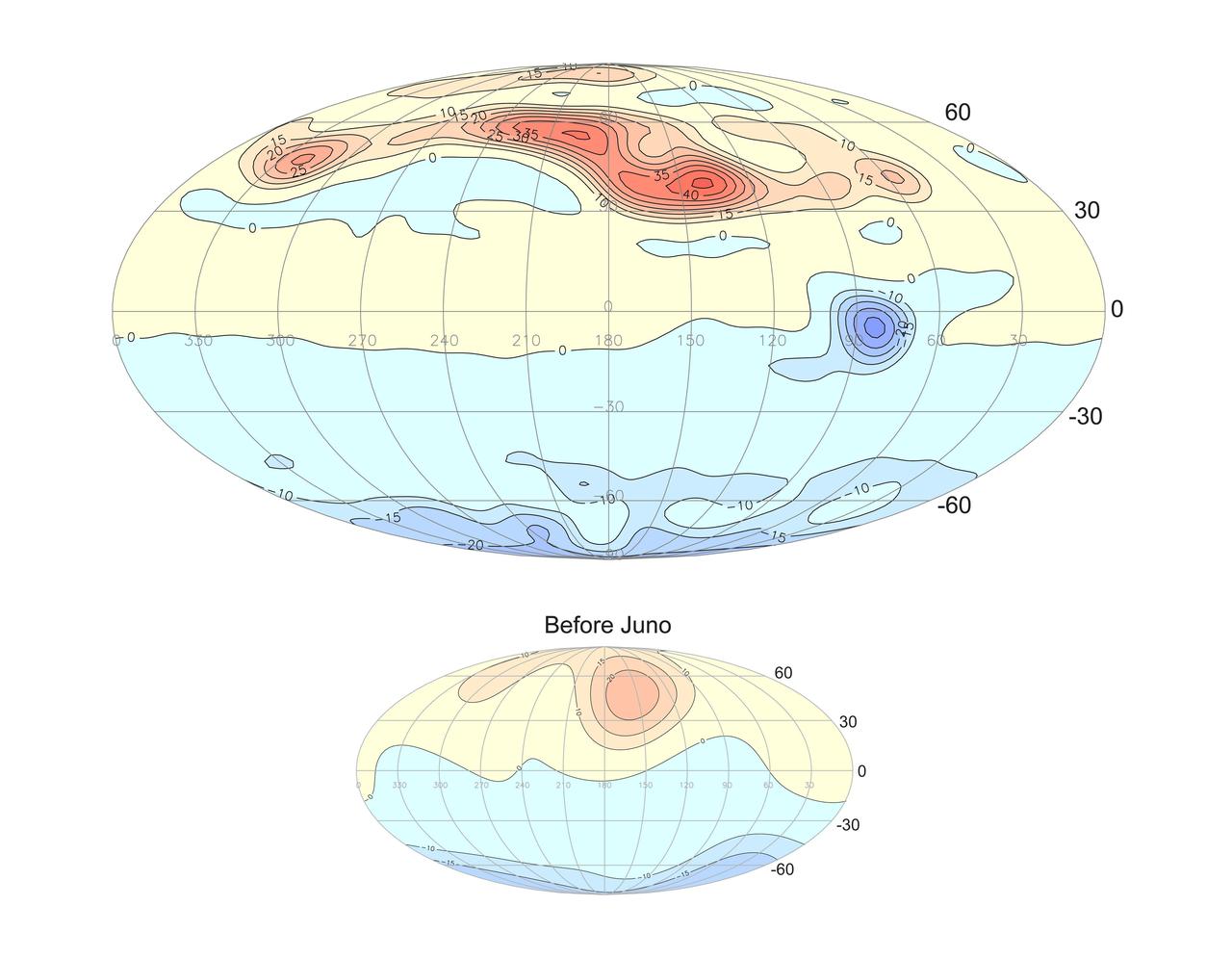

This projection of the radial magnetic field of Jupiter (top) uses a new magnetic field model based on data from Juno's orbits during its prime mission. Magnetic field lines emerge from yellow and red regions and enter the planet in the blue regions. The new model represents a vast improvement in spatial resolution compared to prior knowledge (bottom) provided by earlier missions, including Pioneer 10 and 11, Voyager 1 and 2, Ulysses, and Galileo. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25040

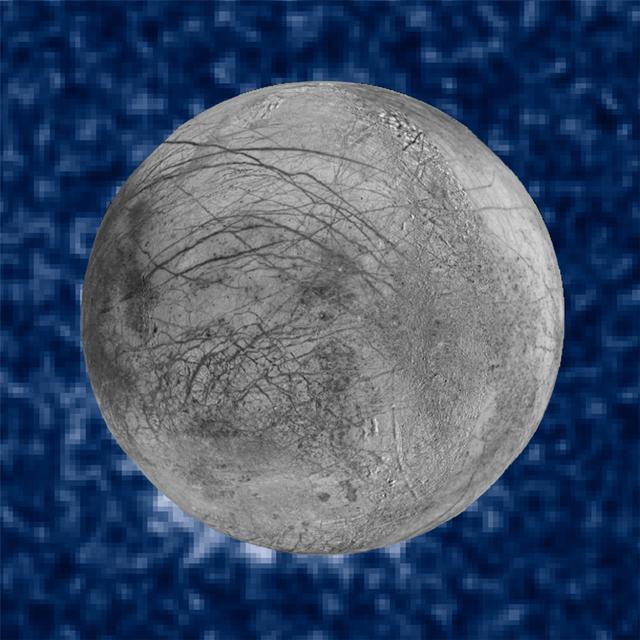

This composite image shows suspected plumes of water vapor erupting at the 7 o’clock position off the limb of Jupiter’s moon Europa. The plumes, photographed by NASA’s Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph, were seen in silhouette as the moon passed in front of Jupiter. Hubble’s ultraviolet sensitivity allowed for the features -- rising over 100 miles (160 kilometers) above Europa’s icy surface -- to be discerned. The water is believed to come from a subsurface ocean on Europa. The Hubble data were taken on January 26, 2014. The image of Europa, superimposed on the Hubble data, is assembled from data from the Galileo and Voyager missions.

This image revealing the north polar region of the Jovian moon Io was taken on October 15, 2023, by the JunoCam imager aboard NASA's Juno spacecraft. Since the high latitudes were not well covered in imagery gathered by NASA's Voyager and Galileo missions, three of the peaks captured here were observed for the first time. Those mountains are seen at the upper part of the image, near the terminator (the line dividing day and night). At the time the image was taken, the Juno spacecraft was about 7,270 miles (11,700 kilometers) above Io's surface. Citizen scientist Ted Stryk made this image using raw data from the JunoCam instrument, processing the data to enhance details. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26234

A sequence of full disk Io images was taken prior to Galileo's second encounter with Ganymede. The purpose of these observations was to view all longitudes of Io and search for active volcanic plumes. The images were taken at intervals of approximately one hour corresponding to Io longitude increments of about ten degrees. Because both the spacecraft and Io were traveling around Jupiter the lighting conditions on Io (e.g. the phase of Io) changed dramatically during the sequence. These images were registered at a common scale and processed to produce a time-lapse "movie" of Io. This movie combines all of the plume monitoring frames obtained by the Solid State Imaging system aboard NASA's Galileo spacecraft. The most prominent volcanic plume seen in this movie is Prometheus (latitude 1.6 south, longitude 153 west). The plume becomes visible as it moves into daylight, crosses the center of the disk, and is seen in profile against the dark of space at the edge of Io. This plume was first seen by the Voyager 1 spacecraft in 1979 and is believed to be a geyser-like eruption of sulfur dioxide snow and gas. Although details of the region around Prometheus have changed in the seventeen years since Voyager's visit, the shape and height of the plume have not changed significantly. It is possible that this geyser has been erupting nearly continuously over this time. Galileo's primary 24 month mission includes eleven orbits around Jupiter and will provide observations of Jupiter, its moons and its magnetosphere. North is to the top of all frames. The smallest features which can be discerned range from 13 to 31 kilometers across. The images were obtained between the 2nd and the 6th of September, 1996. The animation can be viewed at http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01073

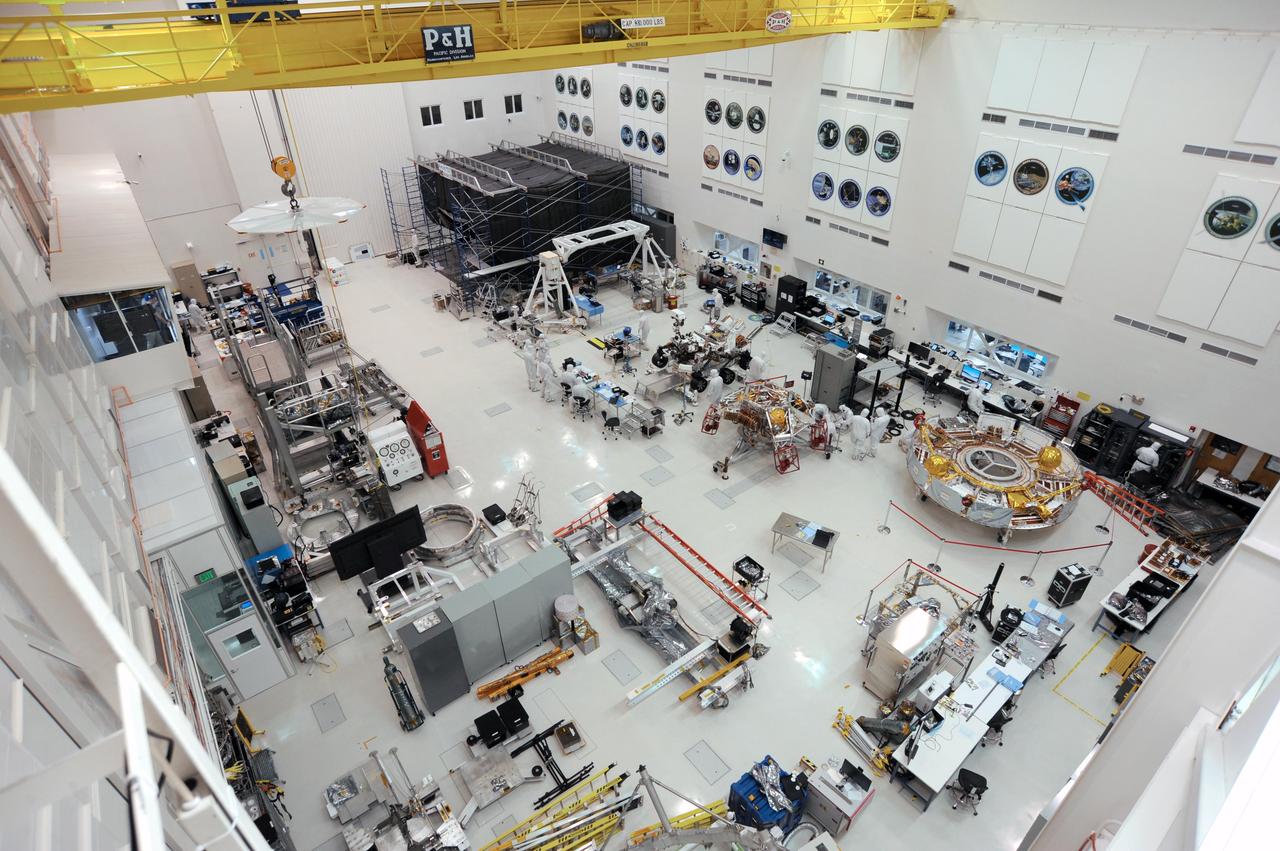

The Mars 2020 rover is visible (just above center) in this image — taken on Nov. 12, 2019 — of the High Bay 1 clean room floor in JPL's Spacecraft Assembly Facility. Many of NASA's most famous robotic spacecraft were assembled and tested in High Bay 1, including most of the Ranger and Mariner spacecraft; Voyager 1; the Galileo and Cassini orbiters; and all of NASA's Mars rovers. An annotated version of the image points to the facility's Wall of Fame, featuring emblems of those and other spacecraft that successfully launched after being built in the room. It also points to other features of the room, including the facility's gallery, which hosts about 30,000 members of the public each year. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23519

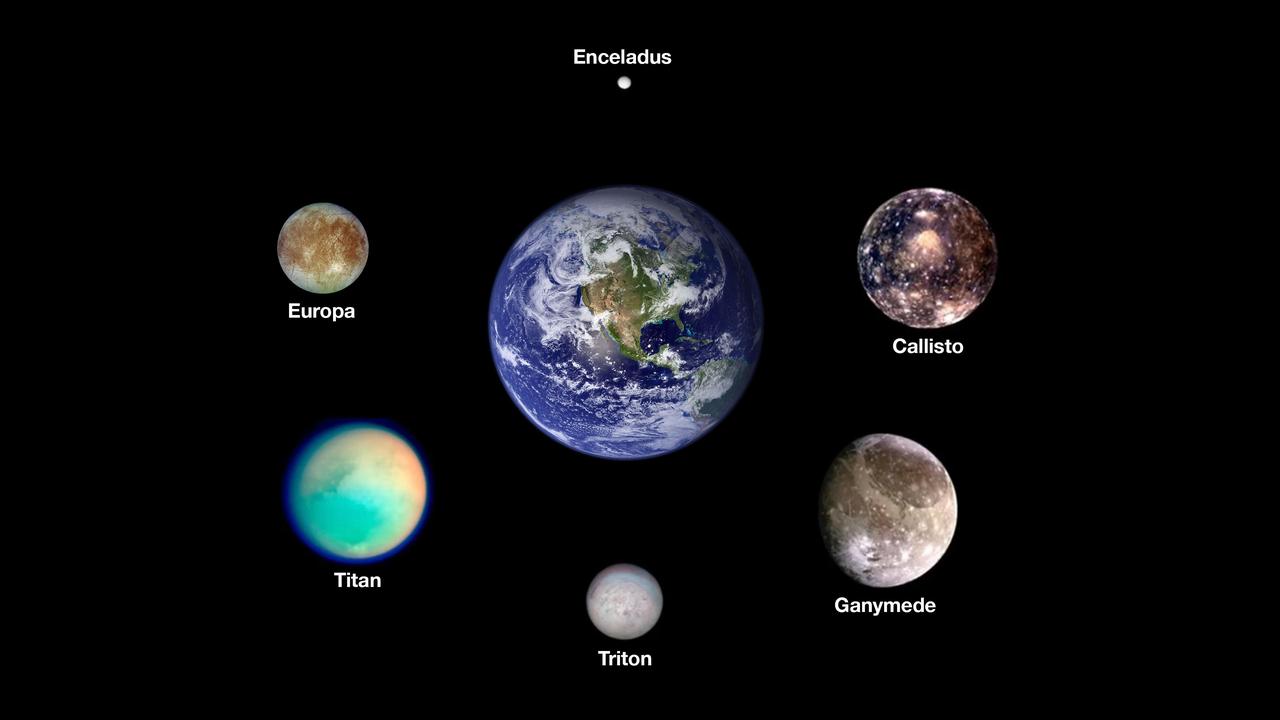

Scientists think six icy moons in our solar system may currently host oceans of liquid water beneath their outer surfaces. Arranged around Earth are images from NASA spacecraft of, clockwise from the top, Saturn's moon Enceladus, Jupiter's moons Callisto and Ganymede, Neptune's moon Triton, Saturn's moon Titan, and Jupiter's moon Europa, the target of NASA's Europa Clipper mission. The worlds here are shown to scale. The images of the Saturnian moons were taken by NASA's Cassini mission. The images of the Jovian moons were taken by NASA's Galileo mission. The image of Triton was taken by NASA's Voyager 2 mission. The image of Earth was stitched together using months of satellite-based observations, mostly using data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra satellite. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26103

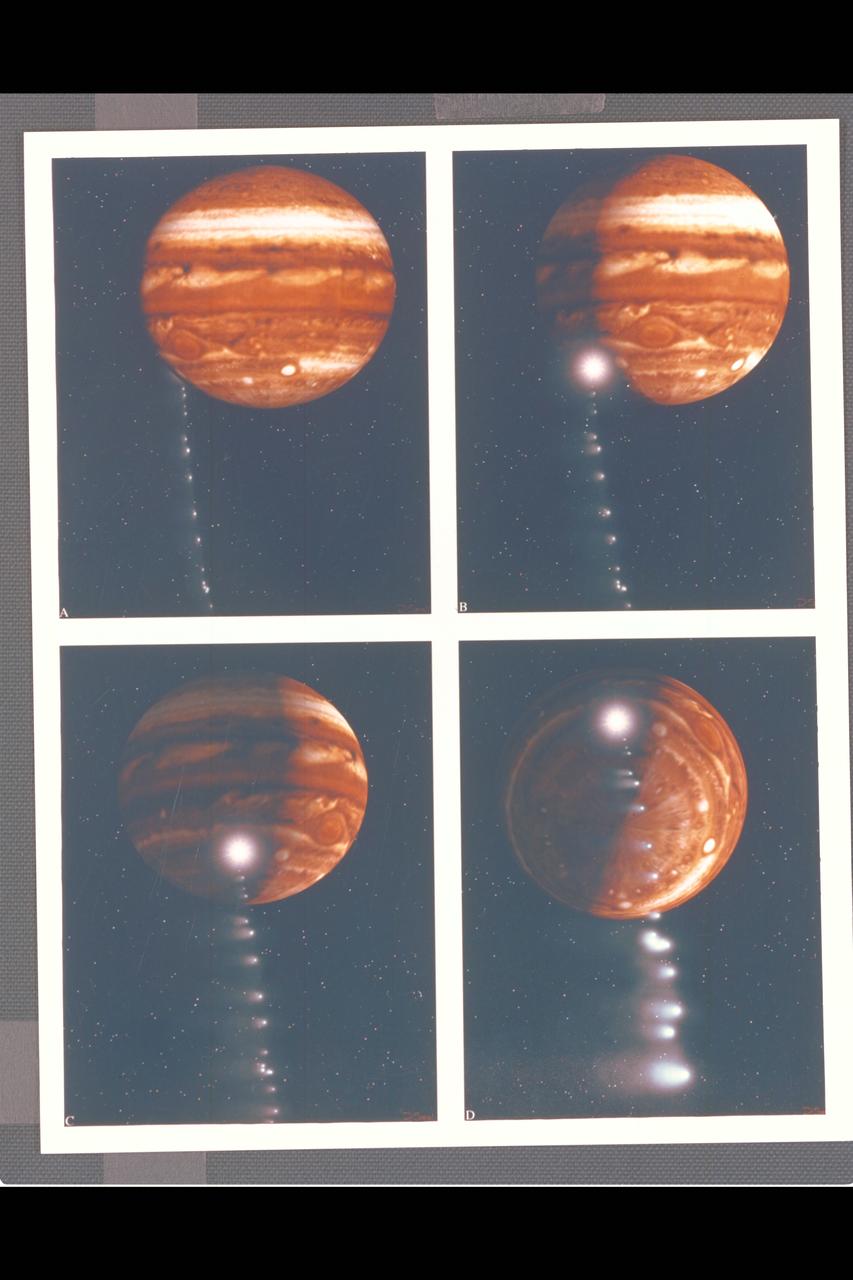

Photo Artwork composite by JPL This depiction of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 impacting Jupiter is shown from several perspectives. IMAGE A is shown from the perspective of Earth based observers. IMAGE B shows the perspective from Galileo spacecraft which can observe the impact point directly. IMAGE C is shown from the Voyager 2 spacecraft, which may observe the event from its unique position at the outer reaches of the solar system. IMAGE D depicts a generic view from Jupiter's south pole. For visual appeal, most of the large cometary fragments are shown close to one another in this image. At the time of Jupiter impact, the fragments will be separated from one another by serveral times the distances shown. This image was created by D.A. Seal of JPL's Mission Design Section using orbital computations provIded by P.W. Chodas and D.K. Yeomans of JPL's Navigation Section.

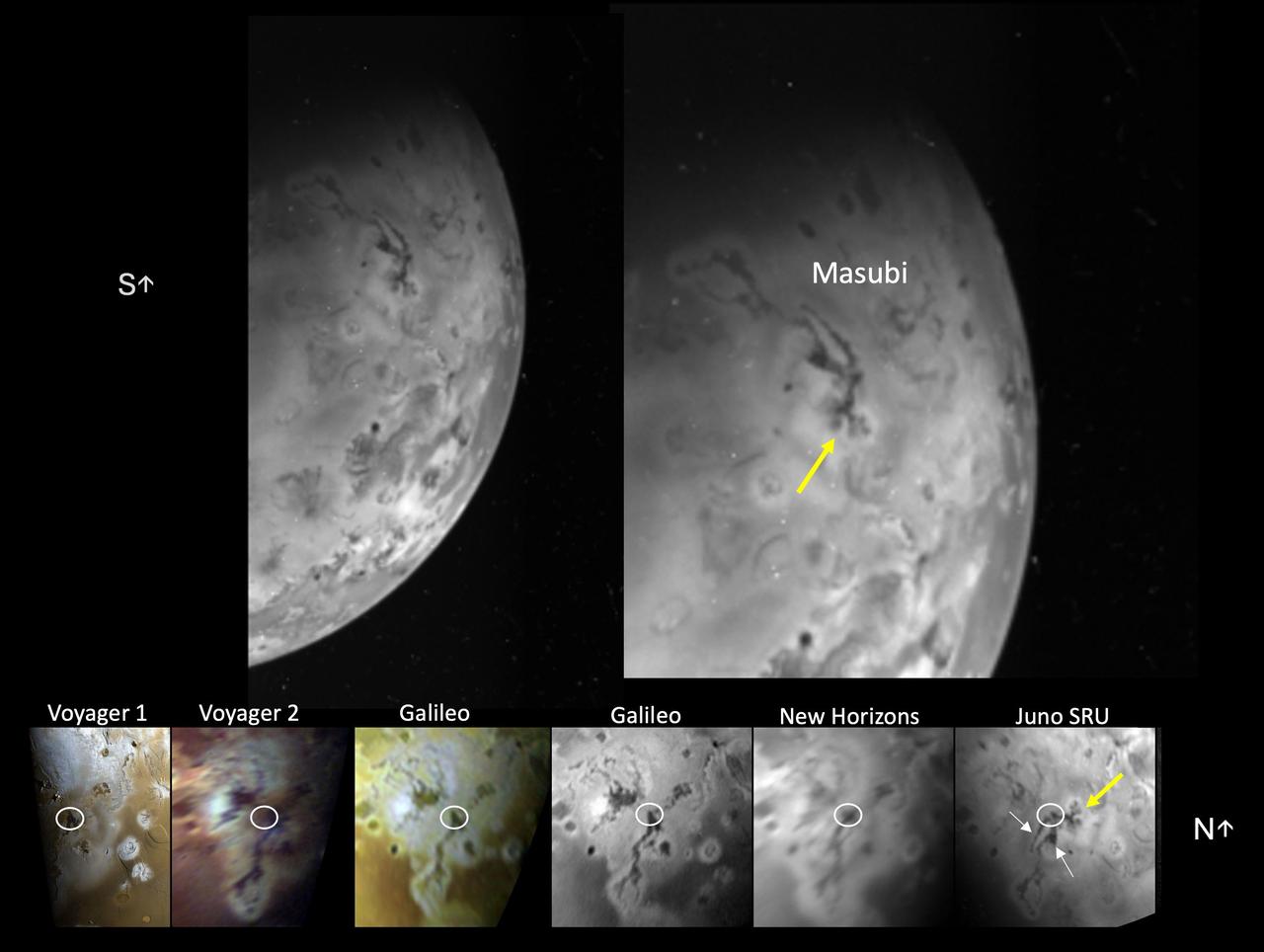

The Stellar Reference Unit (SRU) on NASA's Juno spacecraft collected this visible wavelength image of Io's night side while the surface was illuminated by Jupiter-shine on April 4, 2024. The image features the large compound flow field, Masubi, located on Io's southern hemisphere. Masubi was first observed by NASA's Voyager 1 in 1979 and has continued to expand ever since. A co-registered time sequence of Masubi observations covering 45 years is shown in the bottom panel. The location of the plume first observed by Galileo is circled in white in each image of the time sequence. The SRU observed even further expansion of pre-existing flows (white arrows) and two new flows with multiple lobes (yellow arrow). As of April 4, 2024, Masubi's total compound flow length is about 994 miles (1,600 kilometers), making it the longest currently active lava flow in the solar system. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26524

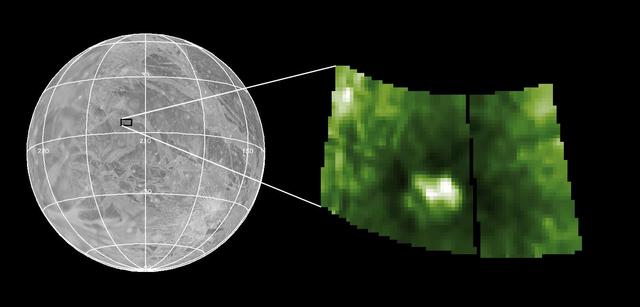

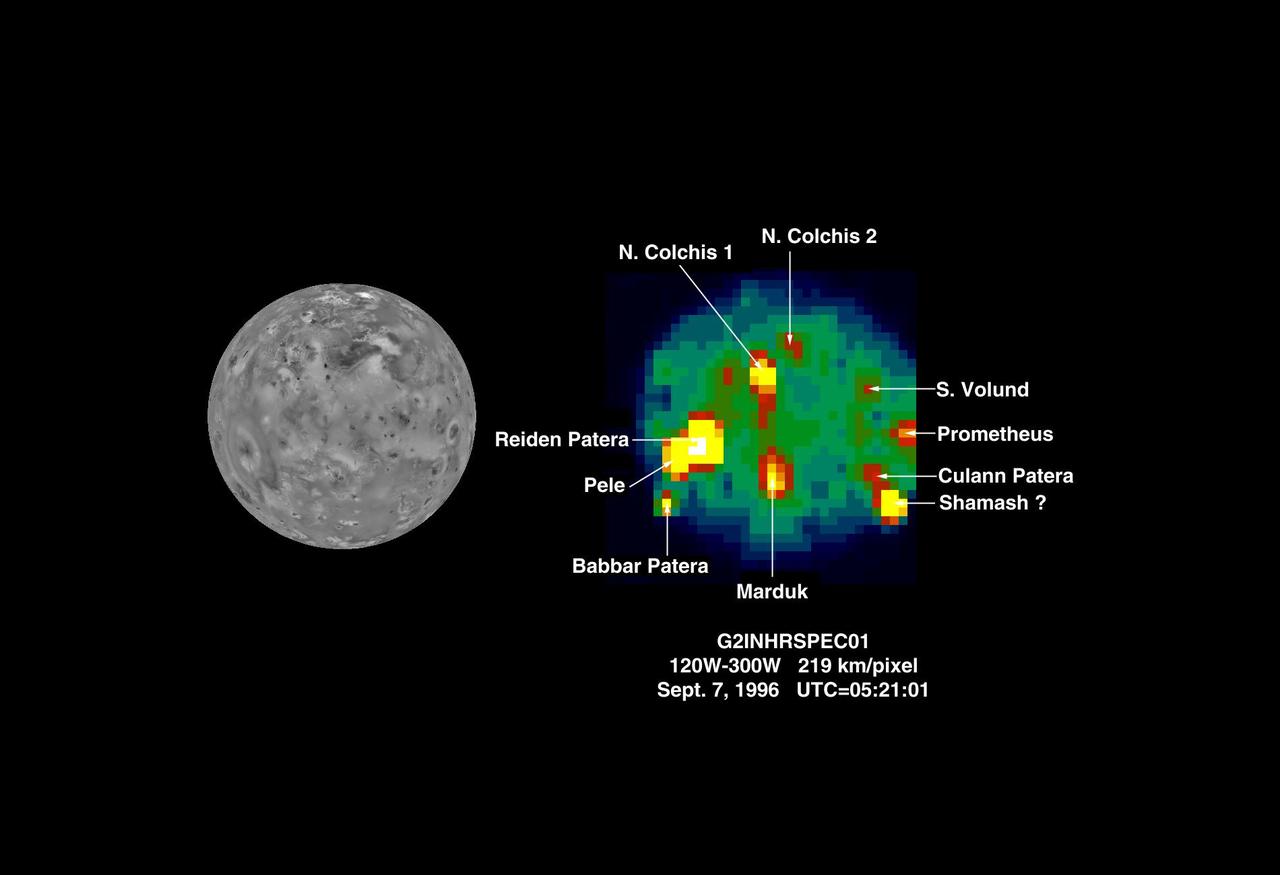

The Near Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (NIMS) on the Galileo spacecraft imaged Io at high spectral resolution at a range of 439,000 km (275,000 miles) during the G2 encounter on 7 September 1996. This image shows (on the right) Io as seen in the infrared by NIMS. The image on the left shows the same view from Voyager in 1979. This NIMS image can be compared to the NIMS images from the G1 orbit (June 1996) to monitor changes on Io. The NIMS image is at 4.9 microns, showing thermal emissions from the hotspots. The brightness of the pixels is a function of size and temperature. At least 10 hotspots have been identified and can be matched with surface features. An accurate determination of the position of the hotspot in the vicinity of Shamash Patera is pending. Hotspots are seen in the vicinity of Prometheus, Volund and Marduk, all sites of volcanic plume activity during the Galileo encounters, and also of active plumes in 1979. Temperatures and areas have been calculated for the hotspots shown. Temperatures range from 828 K (1031 F) to 210 K (- 81.4 F). The lowest temperature is significantly higher than the Io background (non-hotspot) surface temperature of about 100 K (-279 F). Hotspot areas range from 6.5 square km (2.5 sq miles) to 40,000 sq km (15,400 sq miles). The hottest hotspots have smallest areas, and the cooler hotspots have the largest areas. NIMS is continuing to observe Io to monitor volcanic activity throughout the Galileo mission. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00520

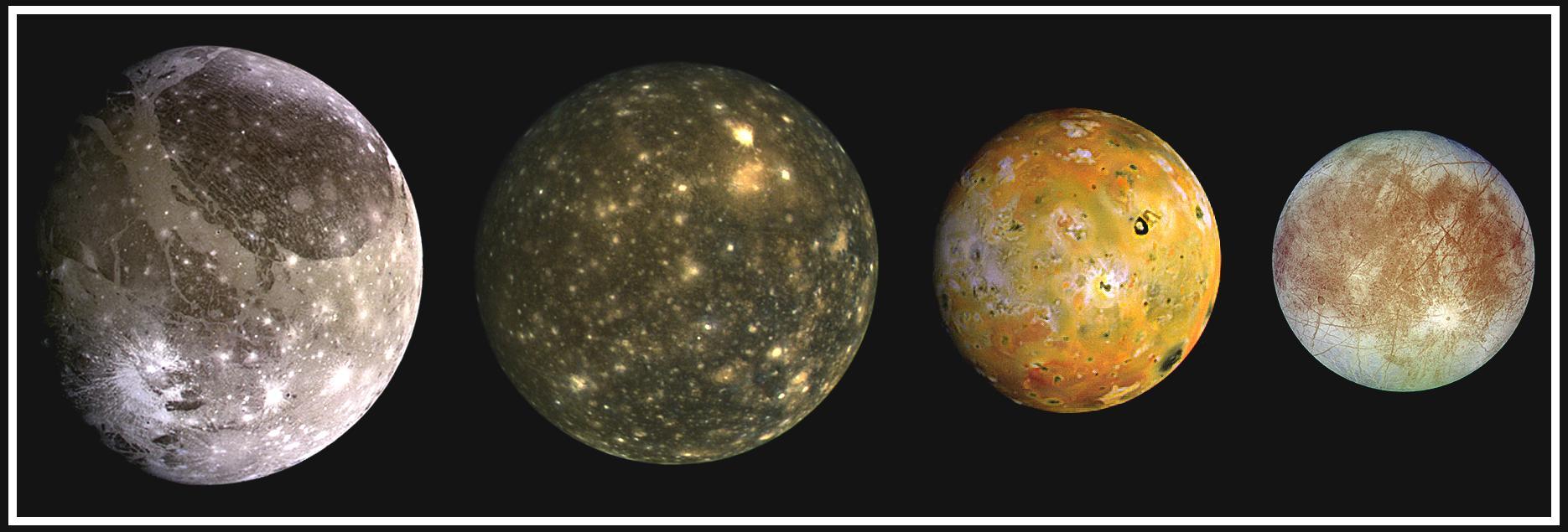

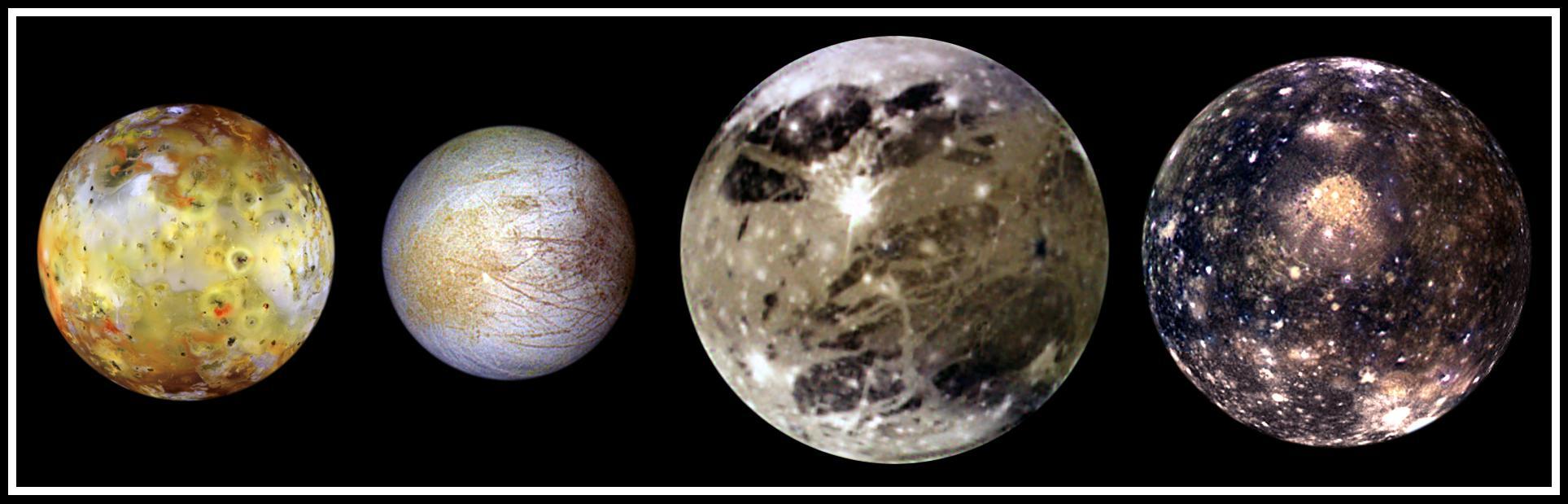

This composite includes the four largest moons of Jupiter which are known as the Galilean satellites. From left to right, the moons shown are Ganymede, Callisto, Io, and Europa. The Galilean satellites were first seen by the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei in 1610. In order of increasing distance from Jupiter, Io is closest, followed by Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. The order of these satellites from the planet Jupiter helps to explain some of the visible differences among the moons. Io is subject to the strongest tidal stresses from the massive planet. These stresses generate internal heating which is released at the surface and makes Io the most volcanically active body in our solar system. Europa appears to be strongly differentiated with a rock/iron core, an ice layer at its surface, and the potential for local or global zones of water between these layers. Tectonic resurfacing brightens terrain on the less active and partially differentiated moon Ganymede. Callisto, furthest from Jupiter, appears heavily cratered at low resolutions and shows no evidence of internal activity. North is to the top of this composite picture in which these satellites have all been scaled to a common factor of 10 kilometers (6 miles) per picture element. The Solid State Imaging (CCD) system aboard NASA's Galileo spacecraft obtained the Io and Ganymede images in June 1996, while the Europa images were obtained in September 1996. Because Galileo focuses on high resolution imaging of regional areas on Callisto rather than global coverage, the portrait of Callisto is from the 1979 flyby of NASA's Voyager spacecraft. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00601

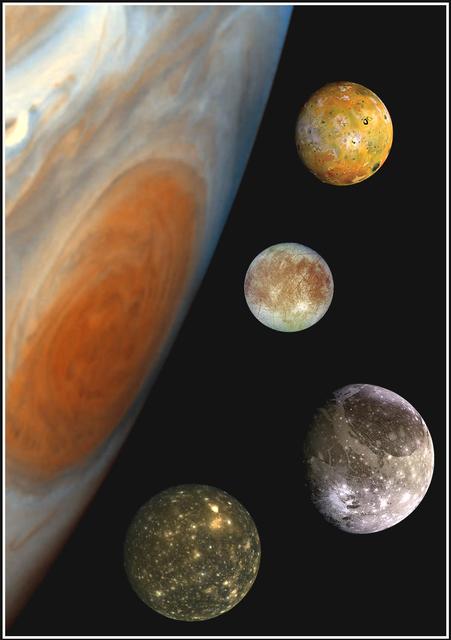

This "family portrait," a composite of the Jovian system, includes the edge of Jupiter with its Great Red Spot, and Jupiter's four largest moons, known as the Galilean satellites. From top to bottom, the moons shown are Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. The Great Red Spot, a storm in Jupiter's atmosphere, is at least 300 years old. Winds blow counterclockwise around the Great Red Spot at about 400 kilometers per hour (250 miles per hour). The storm is larger than one Earth diameter from north to south, and more than two Earth diameters from east to west. In this oblique view, the Great Red Spot appears longer in the north-south direction. Europa, the smallest of the four moons, is about the size of Earth's moon, while Ganymede is the largest moon in the solar system. North is at the top of this composite picture in which the massive planet and its largest satellites have all been scaled to a common factor of 15 kilometers (9 miles) per picture element. The Solid State Imaging (CCD) system aboard NASA's Galileo spacecraft obtained the Jupiter, Io and Ganymede images in June 1996, while the Europa images were obtained in September 1996. Because Galileo focuses on high resolution imaging of regional areas on Callisto rather than global coverage, the portrait of Callisto is from the 1979 flyby of NASA's Voyager spacecraft. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00600

In this "family portrait," the four Galilean Satellites are shown to scale. These four largest moons of Jupiter shown in increasing distance from Jupiter are (left to right) Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. These global views show the side of volcanically active Io which always faces away from Jupiter, icy Europa, the Jupiter-facing side of Ganymede, and heavily cratered Callisto. The appearances of these neighboring satellites are amazingly different even though they are relatively close to Jupiter (350,000 kilometers for Io; 1, 800,000 kilometers for Callisto). These images were acquired on several orbits at very low "phase" angles (the sun, spacecraft, moon angle) so that the sun is illuminating the Jovian moons from completely behind the spacecraft, in the same way a full moon is viewed from Earth. The colors have been enhanced to bring out subtle color variations of surface features. North is to the top of all the images which were taken by the Solid State Imaging (SSI) system on NASA's Galileo spacecraft. Io, which is slightly larger than Earth's moon, is the most colorful of the Galilean satellites. Its surface is covered by deposits from actively erupting volcanoes, hundreds of lava flows, and volcanic vents which are visible as small dark spots. Several of these volcanoes are very hot; at least one reached a temperature of 2000 degrees Celsius (3600 degrees Fahrenheit) in the summer of 1997. Prometheus, a volcano located slightly right of center on Io's image, was active during the Voyager flybys in 1979 and is still active as Galileo images were obtained. This global view was obtained in September 1996 when Galileo was 485,000 kilometers from Io; the finest details that can be discerned are about 10 km across. The bright, yellowish and white materials located at equatorial latitudes are believed to be composed of sulfur and sulfur dioxide. The polar caps are darker and covered by a redder material. Europa has a very different surface from its rocky neighbor, Io. Galileo images hint at the possibility of liquid water beneath the icy crust of this moon. The bright white and bluish parts of Europa's surface are composed almost completely of water ice. In contrast, the brownish mottled regions on the right side of the image may be covered by salts (such as hydrated magnesium-sulfate) and an unknown red component. The yellowish mottled terrain on the left side of the image is caused by some other, unknown contaminant. This global view was obtained in June 1997 when Galileo was 1.25 million kilometers from Europa; the finest details that can be discerned are 25 kilometers across. Ganymede, larger than the planet Mercury, is the largest Jovian satellite. Its distinctive surface is characterized by patches of dark and light terrain. Bright frost is visible at the north and south poles. The very bright icy impact crater, Tros, is near the center of the image in a region known as Phrygia Sulcus. The dark area to the northwest of Tros is Perrine Regio; the dark terrain to the south and southeast is Nicholson Regio. Ganymede's surface is characterized by a high degree of crustal deformation. Much of the surface is covered by water ice, with a higher amount of rocky material in the darker areas. This global view was taken in September 1997 when Galileo was 1.68 million kilometers from Ganymede; the finest details that can be discerned are about 67 kilometers across. Callisto's dark surface is pocked by numerous bright impact craters. The large Valhalla multi-ring structure (visible near the center of the image) has a diameter of about 4,000 kilometers, making it one of the largest impact features in the Solar System. Although many crater rims exhibit bright icy "bedrock" material, a dark layer composed of hydrated minerals and organic components (tholins) is seen inside many craters and in other low lying areas. Evidence of tectonic and volcanic activity, seen on the other Galilean satellites, appears to be absent on Callisto. This global view was obtained in November 1997 when Galileo was 684,500 kilometers from Callisto; the finest details that can be discerned are about 27 kilometers across. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01400

This view of Jupiter's icy moon Europa was captured by JunoCam, the public engagement camera aboard NASA's Juno spacecraft, during the mission's close flyby on Sept. 29, 2022. Citizen scientist Björn Jónsson processed the view to create this image. Jónsson processed the image to enhance the color and contrast. The resolution is about 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) per pixel. JunoCam took the image at an altitude of 945 miles (1,521 kilometers) above a region of the moon called Annwn Regio. In the image, terrain beside the day-night boundary is revealed to be rugged, with pits and troughs. Numerous bright and dark ridges and bands stretch across a fractured surface, revealing the tectonic stresses that the moon has endured over millennia. The circular dark feature at the lower right is Callanish Crater. JunoCam images of Europa help fill in gaps in the maps from images obtained during by NASA's Voyager and Galileo missions. In processing raw images taken by JunoCam, members of the public create deep-space portraits of the Jovian moon that aren't only awe-inspiring but also worthy of further scientific scrutiny. Juno citizen scientists have played an invaluable role in processing the numerous JunoCam images obtained during science operations at Jupiter. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25334