Hellas Basin

Hellas Basin Dunes

Regional Topographic Model of the Hellas Basin

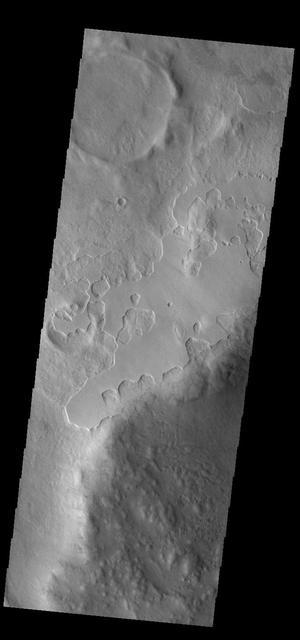

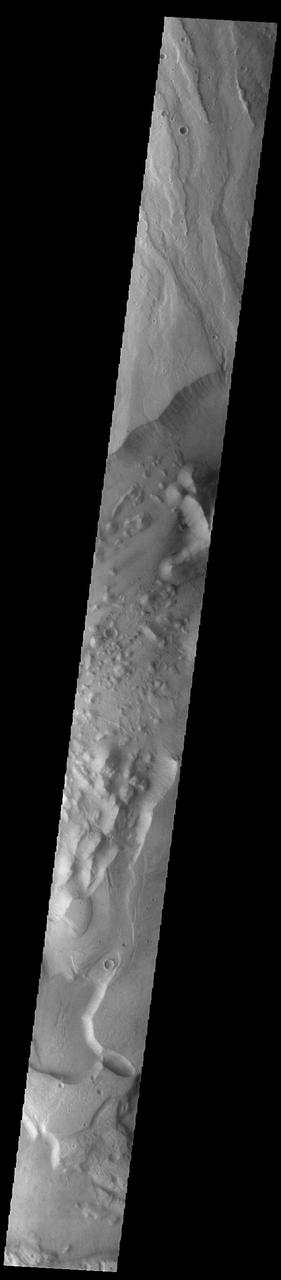

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter covers a small portion of the northwest quadrant of Hellas Basin, or Hellas Planitia, on southern Mars; Hellas is one of the largest impact craters in the solar system.

This NASA Mars Odyssey image was taken during winter in the southern hemisphere, meaning that the usually cloudy Hellas Basin is relatively free from clouds.

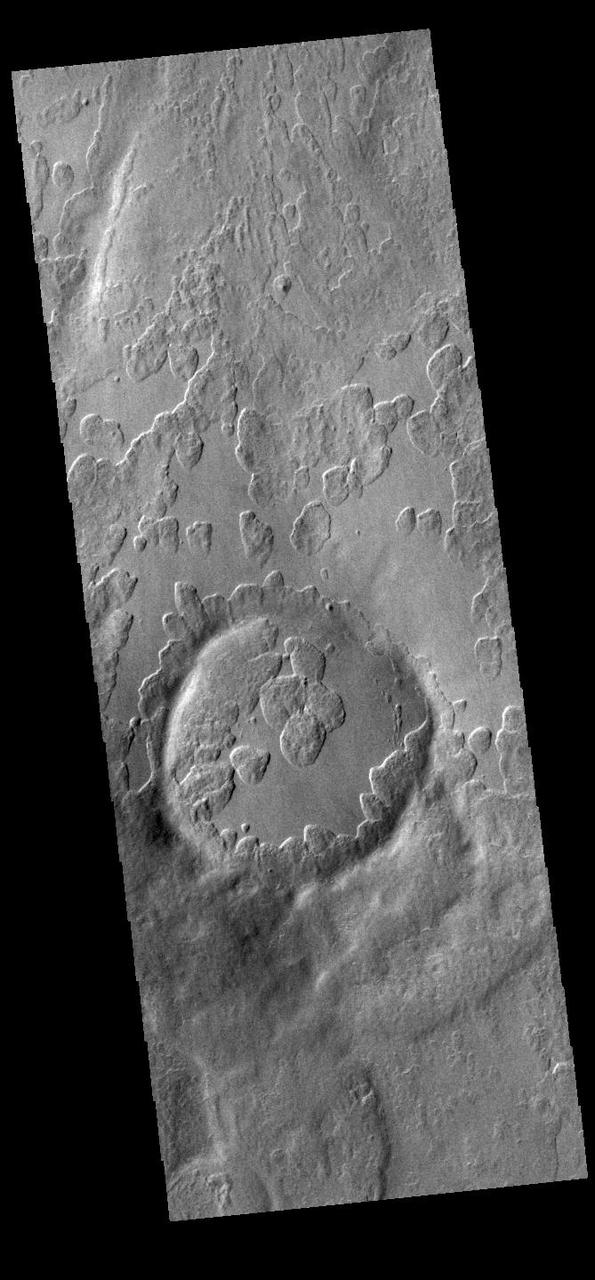

![Hellas is an ancient impact structure and is the deepest and broadest enclosed basin on Mars. It measures about 2,300 kilometers across and the floor of the basin, Hellas Planitia, contains the lowest elevations on Mars. The Hellas region can often be difficult to view from orbit due to seasonal frost, water-ice clouds and dust storms, yet this region is intriguing because of its diverse, and oftentimes bizarre, landforms. This image from eastern Hellas Planitia shows some of the unusual features on the basin floor. These relatively flat-lying "cells" appear to have concentric layers or bands, similar to a honeycomb. This "honeycomb" terrain exists elsewhere in Hellas, but the geologic process responsible for creating these features remains unresolved. The map is projected here at a scale of 50 centimeters (19.7 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 52.2 centimeters (20.6 inches) per pixel (with 2 x 2 binning); objects on the order of 157 centimeters (61.8 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21570](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21570/PIA21570~medium.jpg)

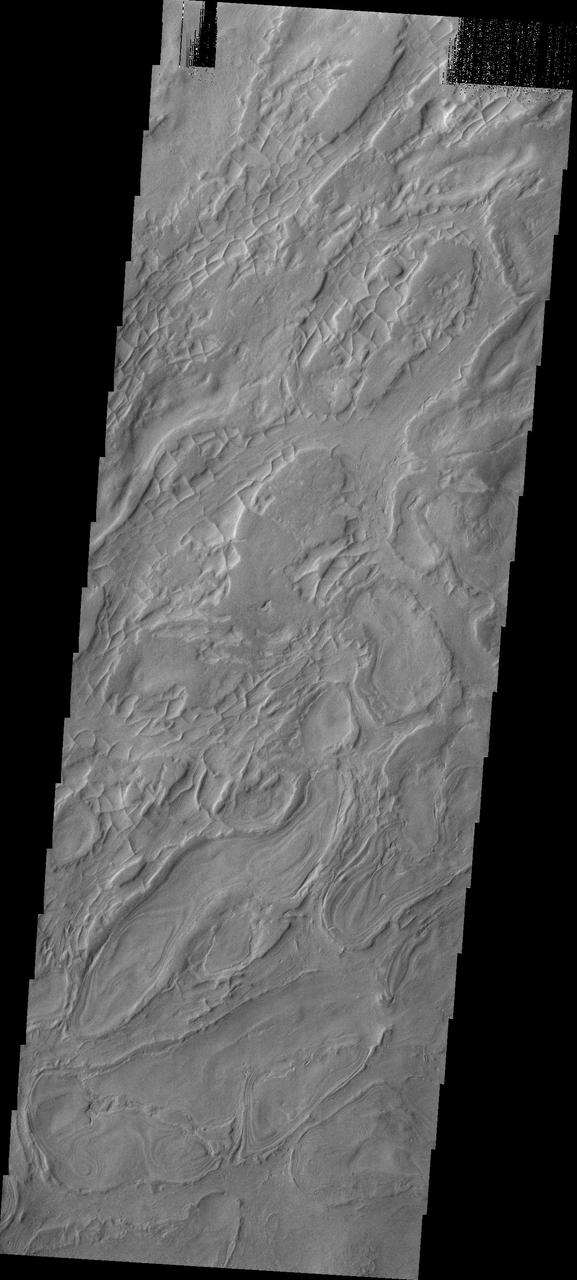

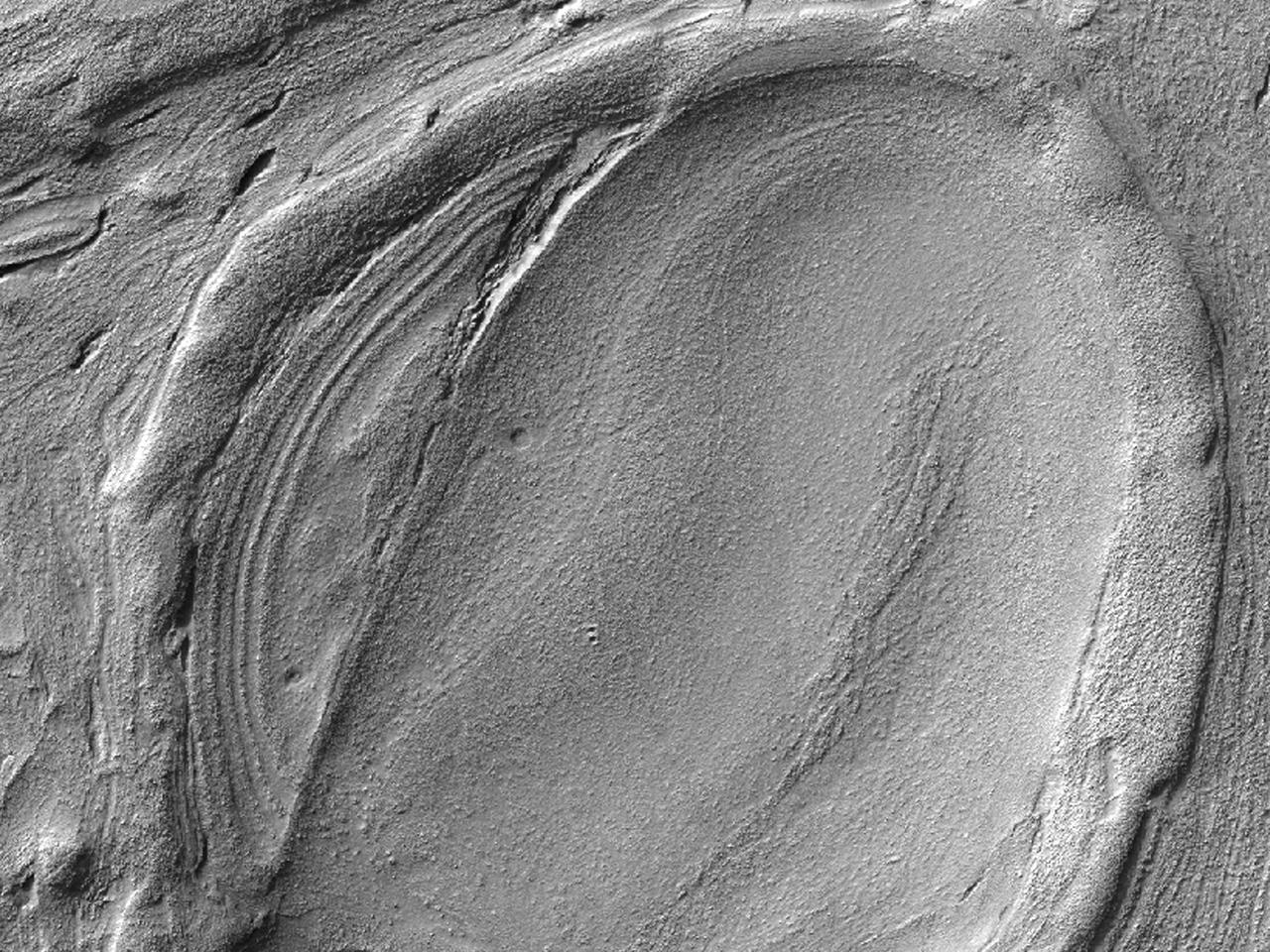

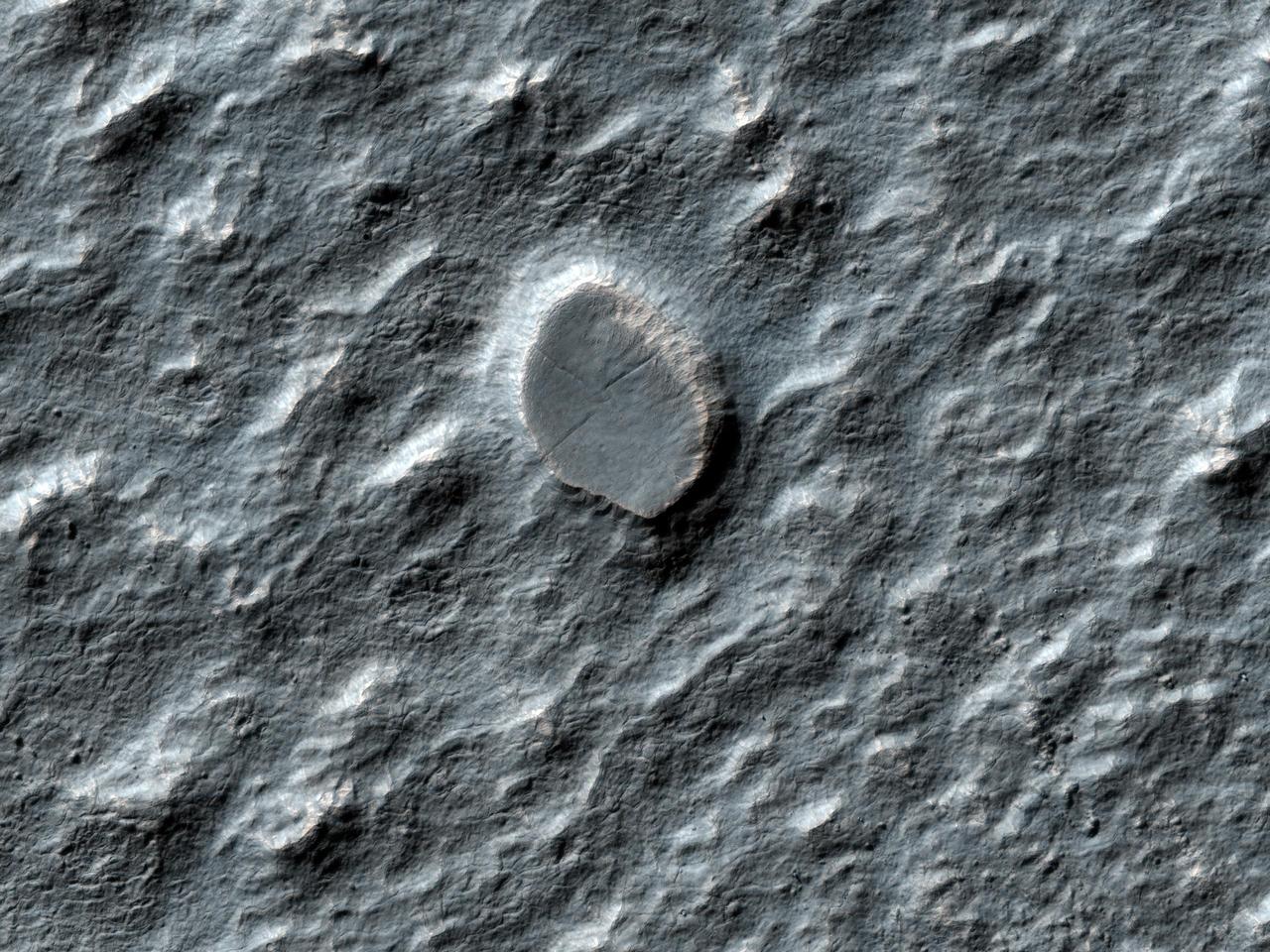

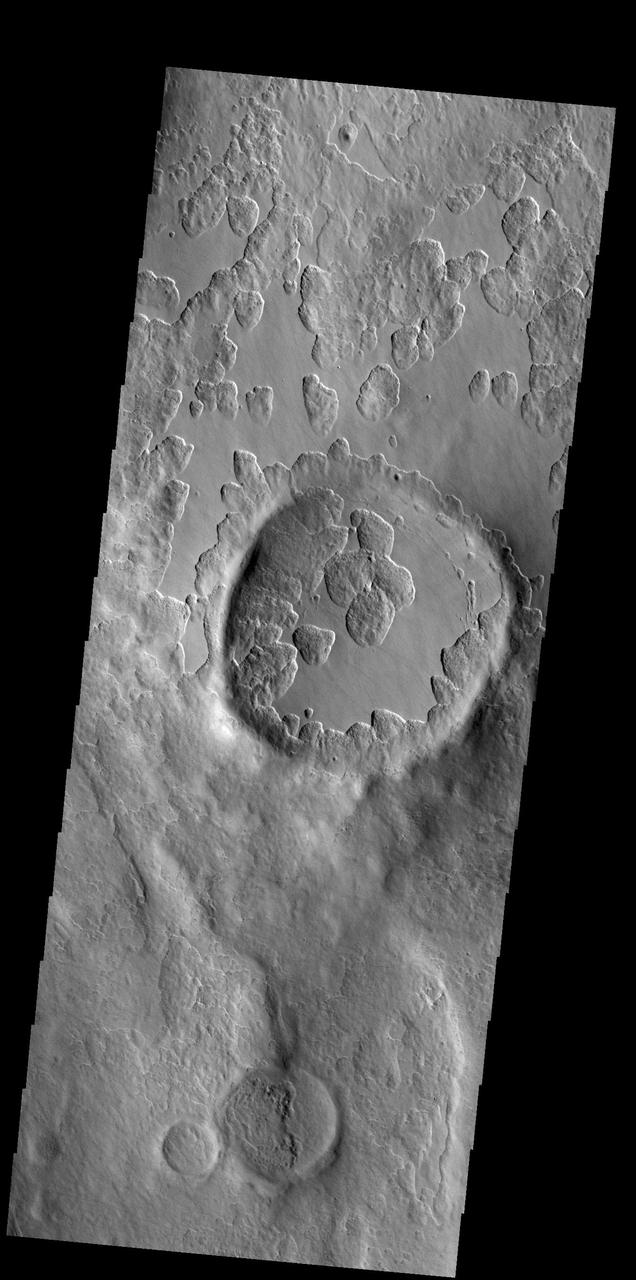

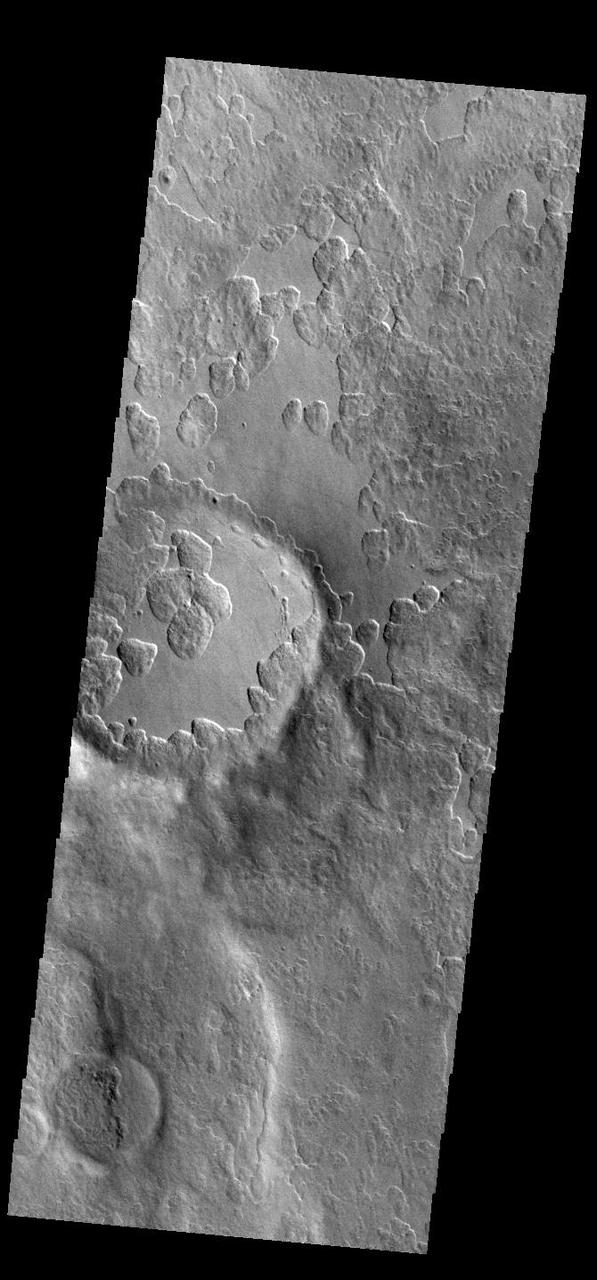

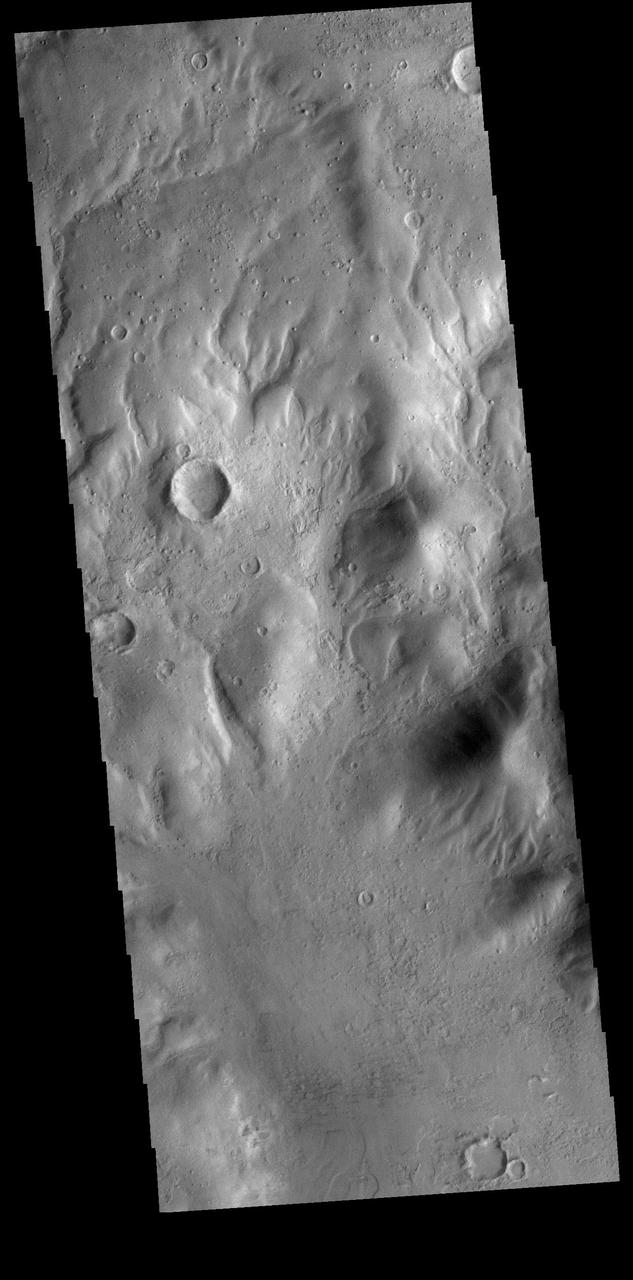

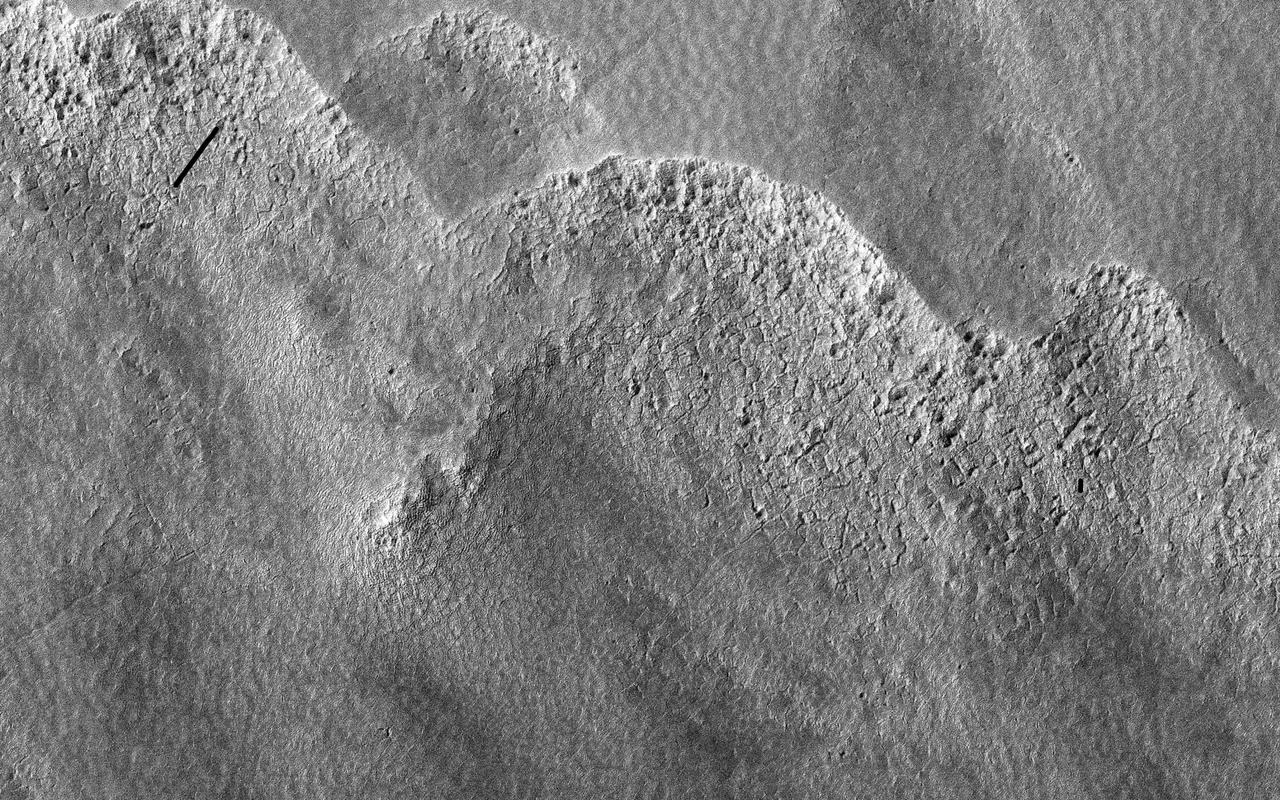

Hellas is an ancient impact structure and is the deepest and broadest enclosed basin on Mars. It measures about 2,300 kilometers across and the floor of the basin, Hellas Planitia, contains the lowest elevations on Mars. The Hellas region can often be difficult to view from orbit due to seasonal frost, water-ice clouds and dust storms, yet this region is intriguing because of its diverse, and oftentimes bizarre, landforms. This image from eastern Hellas Planitia shows some of the unusual features on the basin floor. These relatively flat-lying "cells" appear to have concentric layers or bands, similar to a honeycomb. This "honeycomb" terrain exists elsewhere in Hellas, but the geologic process responsible for creating these features remains unresolved. The map is projected here at a scale of 50 centimeters (19.7 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 52.2 centimeters (20.6 inches) per pixel (with 2 x 2 binning); objects on the order of 157 centimeters (61.8 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21570

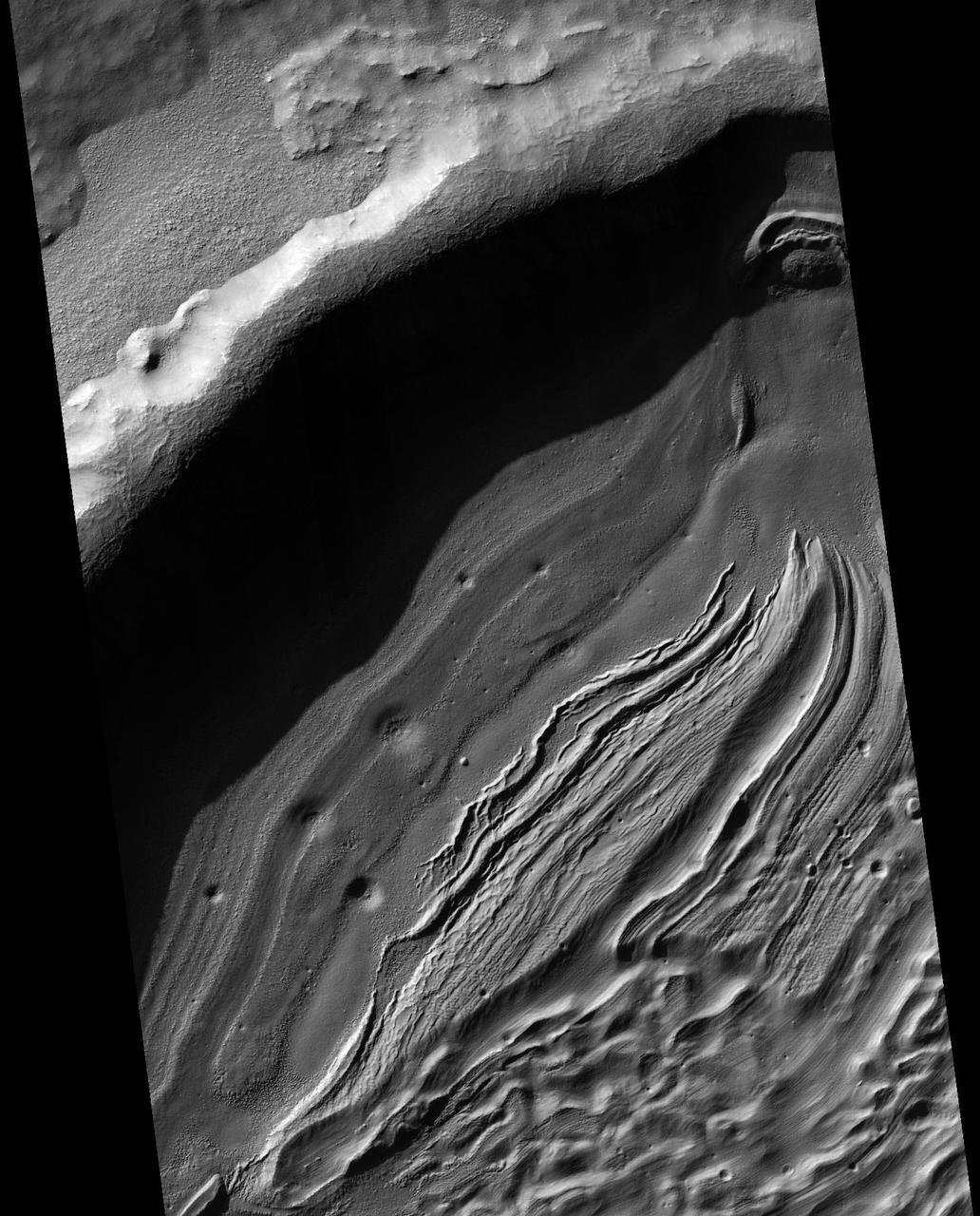

Excellent exposures of light-toned layered deposits occur along the northern edge of Hellas Basin as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

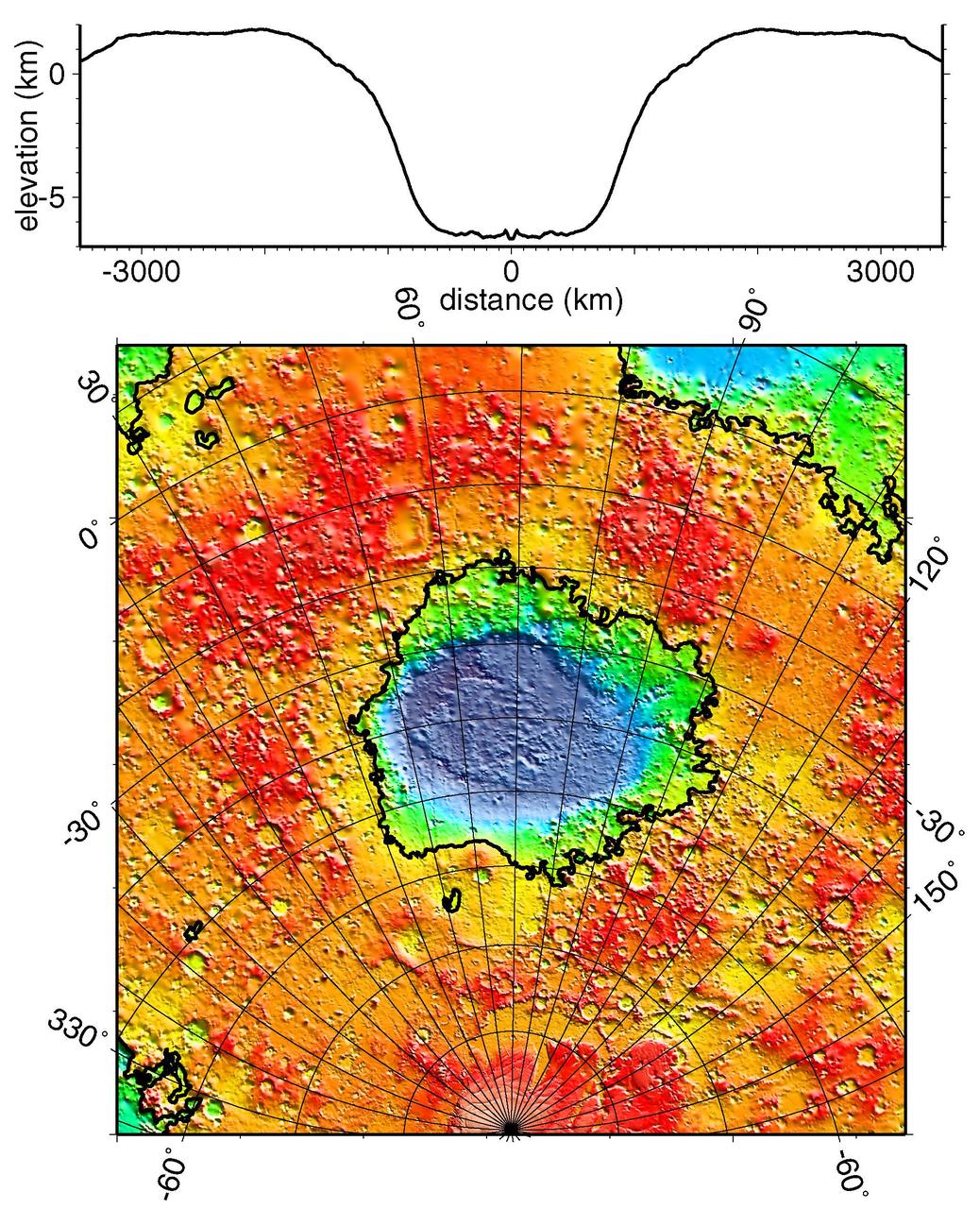

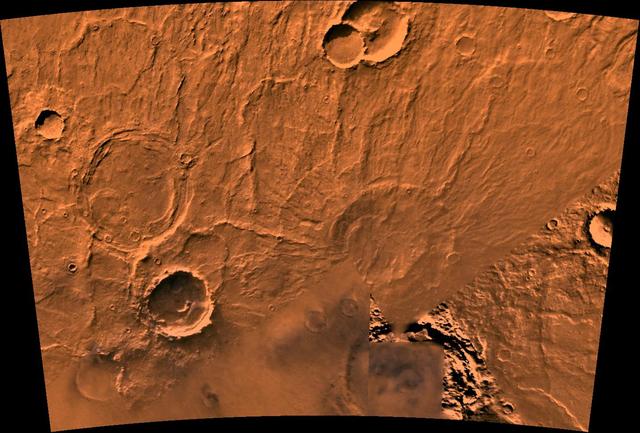

With a diameter of roughly 2,000 km 1,243 miles and a depth of over 7 km more than 4 miles, the Hellas Basin, shown in this image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft, is the largest impact feature on Mars.

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows some of the weirdest and least-understood landscapes on Mars are on the floor of the deep Hellas impact basin.

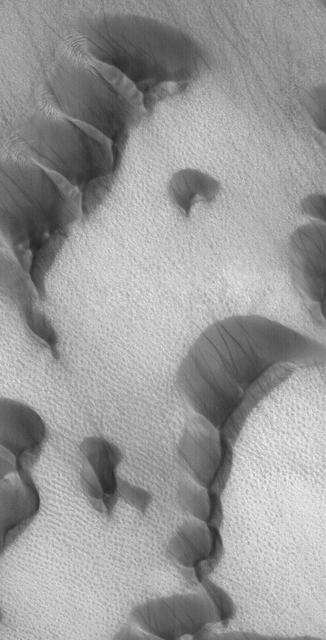

These sand dunes are located on the floor of an unnamed crater west of Hellas Basin

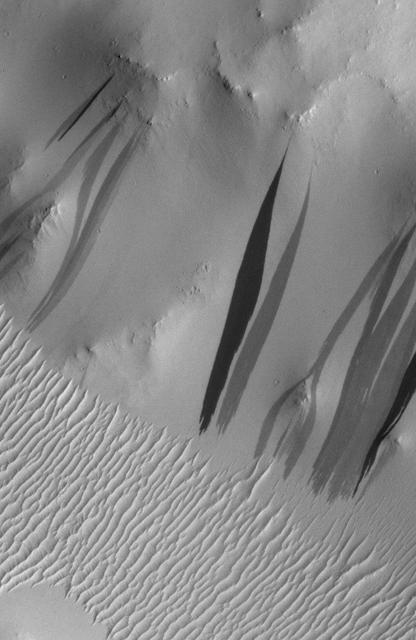

This Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) image of dunes in the martian north polar region is important because it shows one of the highest northern latitude views of streaks thought to be made by passing dust devils. The dark, thin, filamentary streaks on the dunes and on the adjacent plains were probably formed by dust devils. The dunes occur near 76.6°N, 62.7°W. Dust devil streaks are observed on Mars at very high latitudes, such as this, all the way down to the equator. They are also seen at all elevations, from the deepest parts of the Hellas Basin to the summit of Olympus Mons. This picture covers an area about 3 km (1.9 mi) wide. Sunlight illuminates the scene from the lower left. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA06334

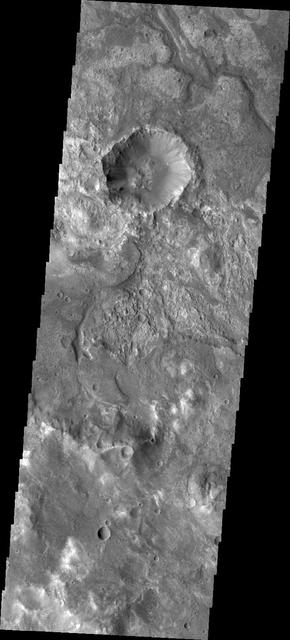

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows the southwestern floor of a 50-kilometer diameter unnamed crater, about 100 kilometers northeast of Hellas Basin. The crater's rim is breached on both the north and south by a valley system that previously flowed across the crater floor, leaving behind an interesting array of channel patterns and deposits as it transported water and sediments into and out of the crater. In this image, we see a portion of the channel system along the southwestern crater floor near where the valley breaches the southern rim. The darker-toned surface has a pattern similar to the texture of a basketball, and blankets the region both in the channel belt and in the basin below the cliffs. Superposed on this patterned surface are clusters of larger, circular mounds that may be related to the thawing and freezing of ice-rich sediment, which is unusual at this relatively low latitude. Extensional cracks and clusters of pits make this topography more complicated. The southern part of this image reveals a prominent irregular scarp with light-toned layered deposits exposed along the margin beneath this textured surface. The light-toned layers look like an ancient mosaic in some areas as they are irregularly fractured and brecciated. Individual blocks and large boulders of this material are visible at full-resolution near the scarp, just about to fall and already lying on the debris slopes below the scarp. Some are brighter than the others: these may be dust-free, indicating that they have detached from the cliff more recently. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19850

This image covers a 26-kilometer-wide impact crater northeast of the Hellas impact basin as observed by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

The layered ridge and mesas in this image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft are located on the northern margin of Hellas Basin.

The erosion of the western rim of Hellas Basin has exposed a surface composed of layered material

A conspicuous fretted channel, Reull Valles, Mars which dissects wall deposits of the large Hellas impact basin, trends southeast towards the basin floor as seen by NASA's Viking Orbiter 2. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00154

This VIS image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows part of the floor of an unnamed crater located between the Hellas and Argyre Basins.

This somewhat cloudy image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows a stunning example of layered deposits in Terby crater, just north of the Hellas impact basin.

This observation from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows part of the floor of a large impact crater in the southern highlands, north of the giant Hellas impact basin.

This MOC image shows an example of the extremely odd, seemingly scrambled layered rocks exposed by erosion near the deepest part of the deepest basin on Mars, Hellas

Terby Crater, sitting on the northern rim of Hellas Basin, has been filled by sedimentary deposits, perhaps deposited by or in water, as observed by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Heavily cratered highlands dominate this view from NASA's Viking Orbiter 1. Toward the lower right, a conspicuous light-colored circular depression marks the ancient large Hellas impact basin. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00191

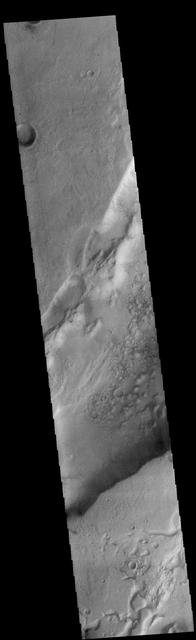

This Mars Global Surveyor MGS Mars Orbiter Camera MOC image shows gullies formed in the wall of a depression located on the floor of Rabe Crater west of the giant impact basin, Hellas Planitia

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows a swath of a debris apron east of Hellas Basin. Features like this are often found surrounding isolated mountains in this area. Original release date March 3, 2010.

This pair of craters seen by NASA Mars Odyssey just north of the Hellas Basin demonstrate the rugged topography that can result when an impact occurs on the rim of an existing crater. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04027

Low lying areas in the Hellas region, which is the largest impact basin on Mars, often show complex groups of banded ridges, furrows, and pits as seen in this observation from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

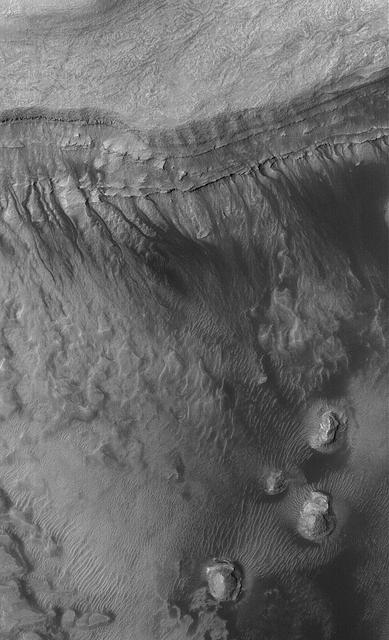

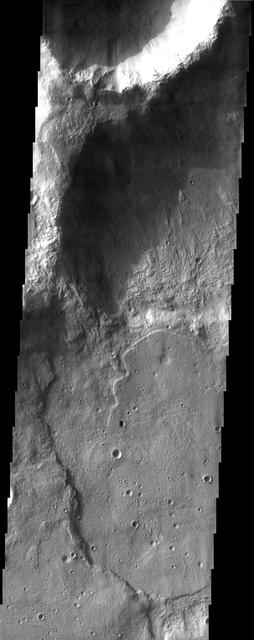

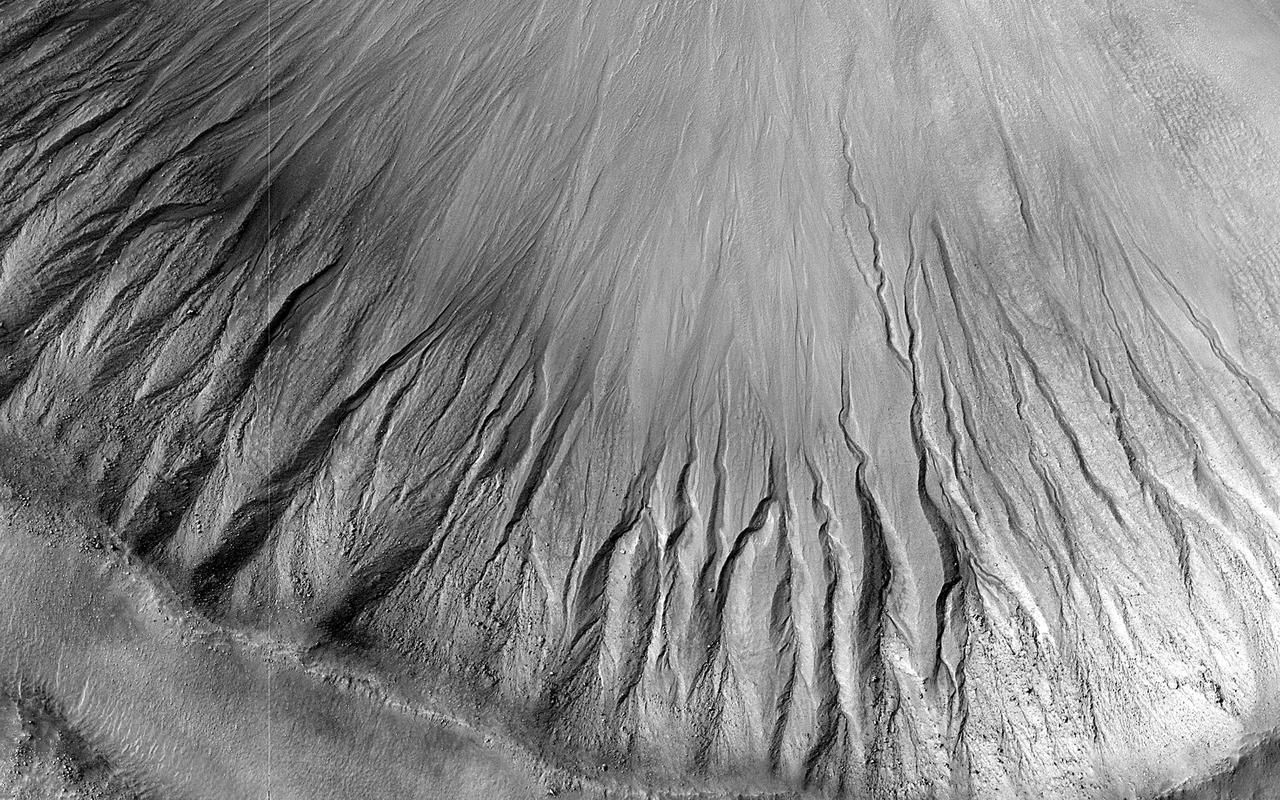

This NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows many channels on a scarp in the Hellas impact basin. On Earth we would call these gullies. Some larger channels on Mars that are sometimes called gullies are big enough to be called ravines on Earth.

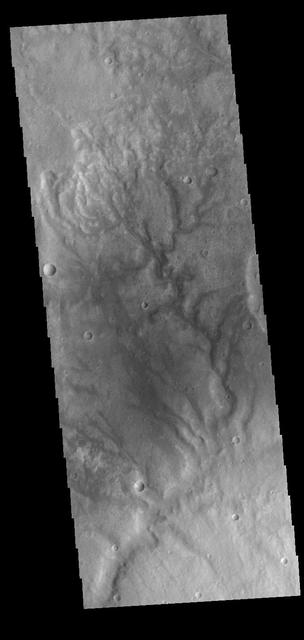

This image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows several large channels emptying into the eastern Hellas Basin. These southern channels are filled with material today. Whether the material contains volitiles like ice is unknown.

This image captured by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft shows several smaller craters that formed on the floor of Saheki Crater, an 85-kilometer diameter impact crater north of Hellas Basin.

It is sometimes difficult to figure out the history of the surface of Mars as seen in visible wavelength images. This image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey is located on the northern margin of Hellas Basin and hints at a layered surface.

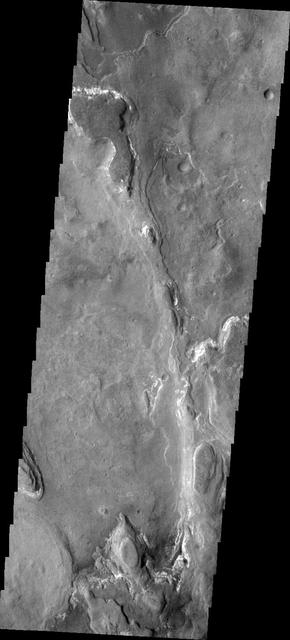

This image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows an unnamed channel draining from the highlands of Promethei Terra to lowlands of the Hellas Basin. Orbit Number: 59120 Latitude: -36.2289 Longitude: 100.566 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2015-04-12 15:39 http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19499

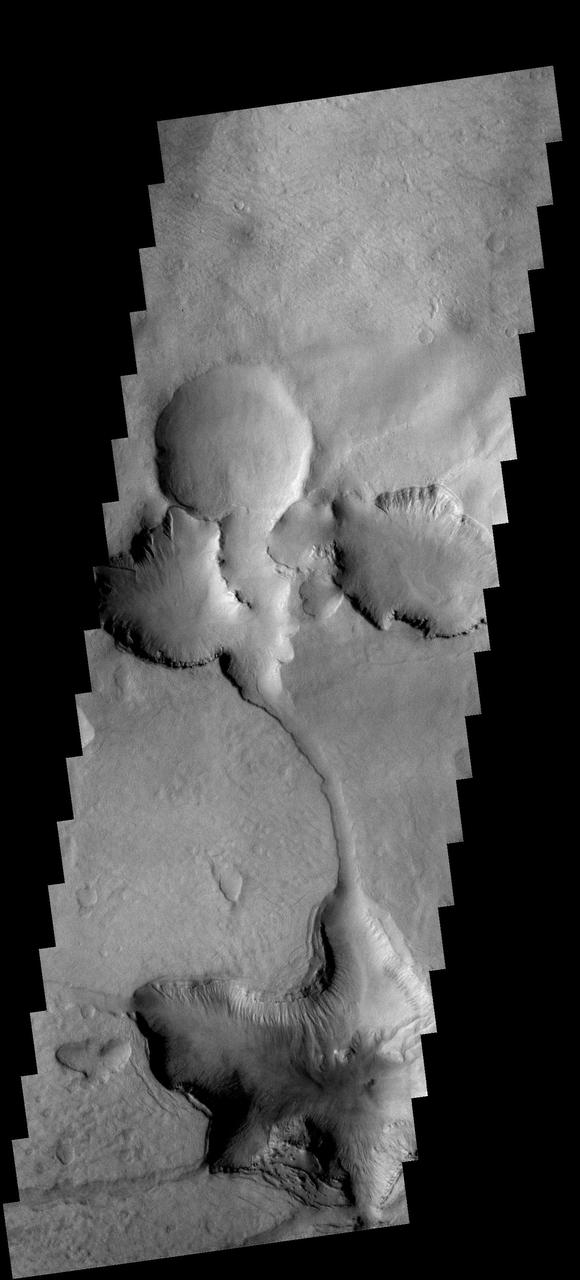

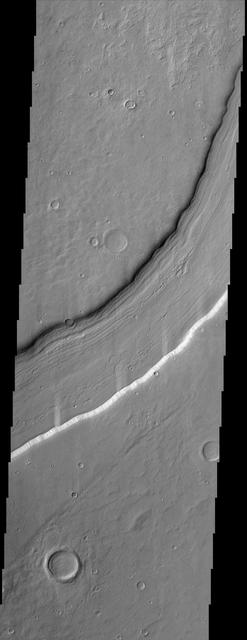

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft shows a channel system flowing to the southwest toward the huge Hellas impact basin. We're not sure if this channel-inside-a-channel was carved by flowing water or lava. Flowing water erodes channels, and flowing lava both erodes and melts surrounding rock to form channels. It's not clear whether a huge surge of water or lava first formed the wide channel and then subsided into a trickle to form this narrow, inner channel, or if a trickle formed the inner channel and a subsequent surge formed the wider one. Detailed analysis of the shape could reveal which scenario is most likely, as well as whether water or lava is responsible. Relevant observations for such a determination would include, for example, the facts that the channels lack levees (ridges along the banks) and that the inner channel diverts around a mound, which at one time was an island. This channel system flowed to the southwest toward the huge Hellas impact basin.

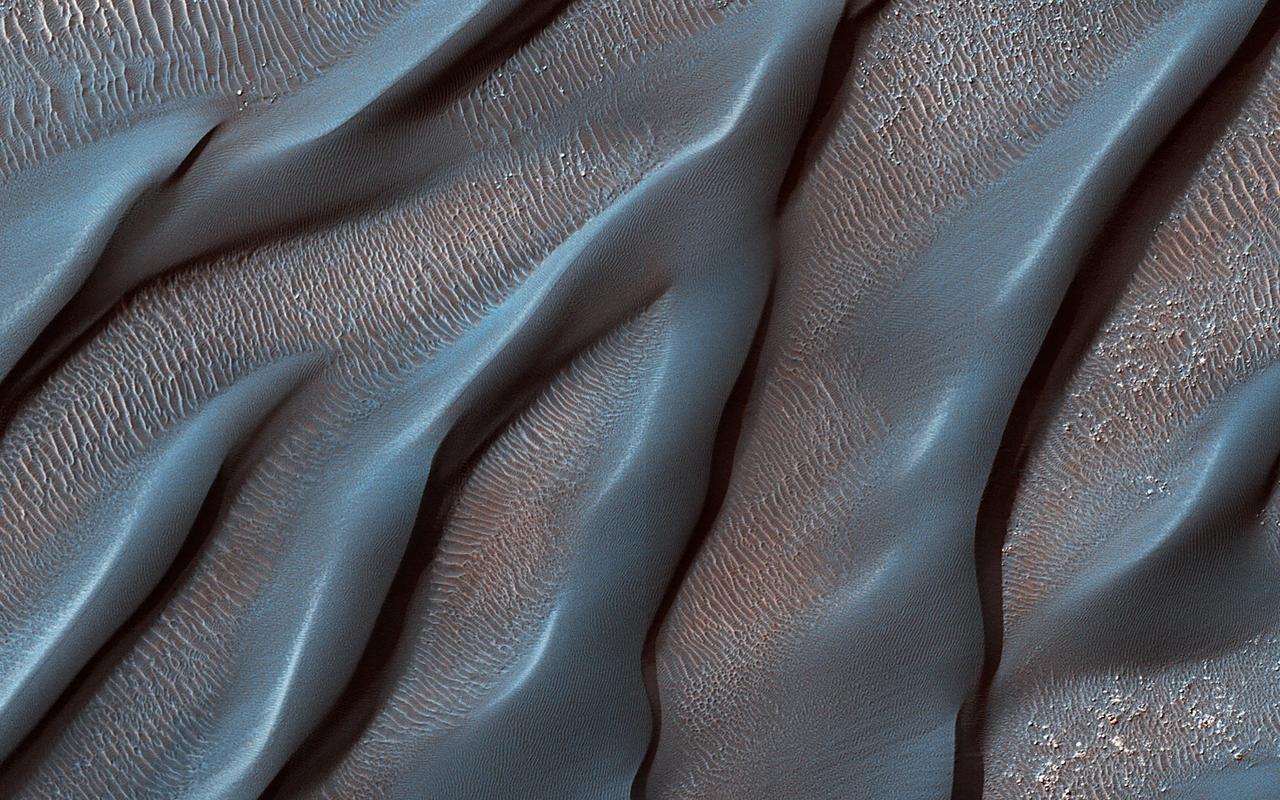

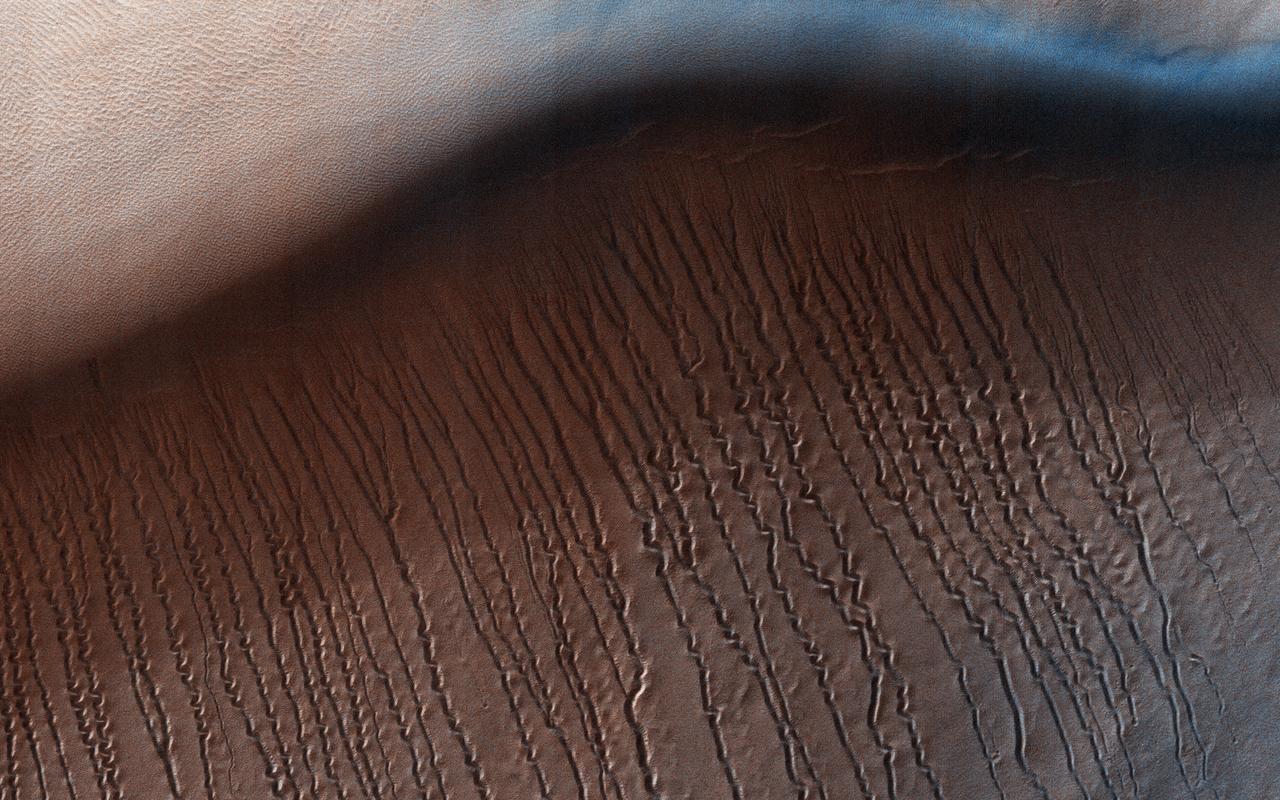

The Hellespontus Montes is a rugged mountain range located on the western rim of one of the largest impact basins in the Solar System: Hellas Basin. The 7-kilometer depth of Hellas and its location in the Southern Hemisphere form an active atmospheric system that directly impacts local landscape evolution. Hellespontus has a large accumulation of sand dunes and other wind-created bedforms that have been migrating on a continual basis since HiRISE began imaging Mars. A dune's steepest area, called a "slip face," indicates the down-wind side of the dune and its migration direction as driven by local winds. At this location, there are many dunes influenced by eastward winds that were draining into Hellas. Meanwhile, other locations show that migration had shifted towards the opposite direction to the west. In certain cases, we see these opposing dune directions in proximity. The complex patterns are not due to winds that are constant in magnitude or direction, but rather they wax and wane over the course of the Martian year. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25899

This NASA Mars Odyssey image shows Dao Vallis, a large outflow channel that starts on the southeast flank of a large volcano called Hadriaca Patera and runs for 1,000 kilometers about 620 miles southwest into the Hellas impact basin. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04009

The central portion of this image features a mildly-winding depression that was carved by water, likely around four billion years ago shortly after the Hellas basin formed following a giant asteroid or comet impact. Water would have flowed from the uplands (to the east) and drained into the low-lying basin, carving river channels as it flowed. The gentle curves-called "meanders" by geomorphologists-imply that this paleoriver carried lots of sediment along with it, depositing it into Hellas. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20815

Dunes of sand-sized materials have been trapped on the floors of many Martian craters, as seen in this view captured by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. This is one example, from a crater in Noachis Terra, west of the giant Hellas impact basin.

Reull Vallis, located in Mars cratered southern hemisphere, flows for over 1,000 km about 620 miles toward the Hellas basin. This NASA Mars Odyssey image shows a portion of the channel with its enigmatic lineated floor deposits.

An unusual layer of smooth material covers the flanks of the volcano Peneus Patera just south of the Hellas Basin. Though smooth on its upper surface, the layer is pitted by a process of erosion that produces steep scarps facing the south pole and more gentle slopes in the direction of the equator. The style of erosion of the smooth layer suggests that ice of some form plays a role in shaping this terrain. Orbit Number: 83810 Latitude: -57.2811 Longitude: 54.3276 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2020-11-05 04:51 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24289

An unusual layer of smooth material covers the flanks of the volcano Peneus Patera just south of the Hellas Basin. Though smooth on its upper surface, the layer is pitted by a process of erosion that produces steep scarps facing the south pole and more gentle slopes in the direction of the equator. The style of erosion of the smooth layer suggests that ice of some form plays a role in shaping this terrain. Orbit Number: 84434 Latitude: -58.8716 Longitude: 52.6886 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2020-12-26 13:56 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24401

An unusual layer of smooth material covers the flanks of the volcano Peneus Patera just south of the Hellas Basin. Though smooth on its upper surface, the layer is pitted by a process of erosion that produces steep scarps facing the south pole and more gentle slopes in the direction of the equator. The style of erosion of the smooth layer suggests that ice of some form plays a role in shaping this terrain. Orbit Number: 91422 Latitude: -57.3055 Longitude: 54.5279 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-07-24 23:11 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25578

An unusual layer of smooth material covers the flanks of the volcano Peneus Patera, located south of the Hellas Basin. Though smooth on its upper surface, the layer is pitted by a process of erosion that produces steep scarps facing the south pole and more gentle slopes in the direction of the equator. The style of erosion of the smooth layer suggests that ice of some form plays a role in shaping this terrain. Orbit Number: 91366 Latitude: -57.1932 Longitude: 54.3735 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-07-20 08:53 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25535

A color image of the Amphitrites Patera region of Mars; north toward top. The scene shows several indistinct ring structures and radial ridges of an old volcano named Amphitrites Patera. A patera (Latin for shallow dish or saucer) is a volcano of broad areal extent with little vertical relief. This image is a composite of NASA's Viking medium-resolution images in black and white and low-resolution images in color. The image extends from latitude 55 degrees S. to 62 degrees S. and from longitude 292 degrees to 311 degrees; Lambert projection. Amphitrites Patera is a 138-km-diameter feature on the south rim of Hellas impact basin and is one of many indistinct ring structures in the area. The location of the paterae in this area of Hellas indicates that their source magma may have been influenced by the transition fractures of the basin. The radial ridges of Amphitrites extend for about 400 km north into the Hellas basin. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00410

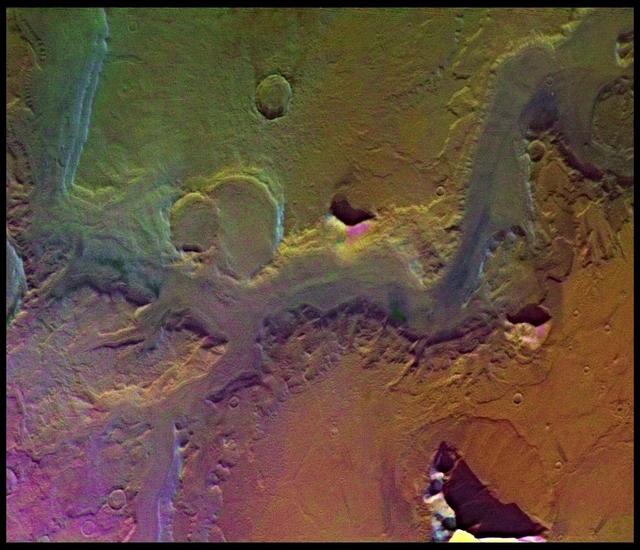

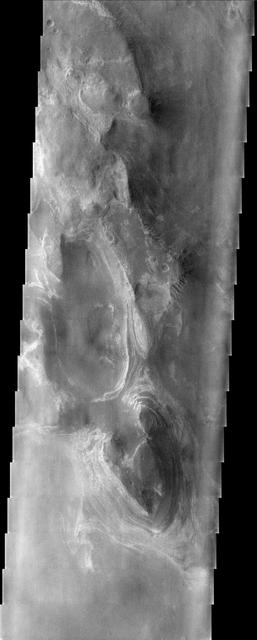

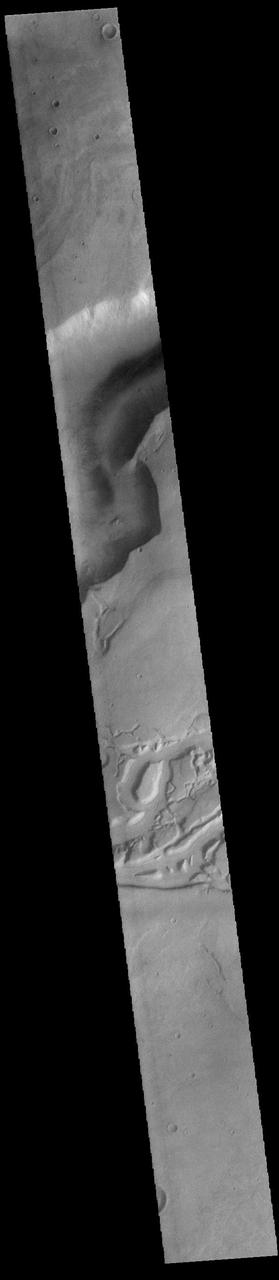

This image shows a portion of an enigmatic formation called banded terrain, which is only observed in the northwest of the Hellas basin. This basin was formed by a giant impact around 4 billion years ago. It is the deepest impact basin on the planet, and banded terrain is in the deepest part of the basin (at elevations around 7 kilometers). This terrain is characterized by smooth bands of material separated by ridges or troughs, with circular and lobe shapes that are typically several kilometers long and a few hundred meters wide. A closeup shows banded terrain deforming around a mesa (bottom) and the transition of smooth banded terrain into surrounding rough terrain (top). Other banded terrain appears to have undergone deformation, like by a glacier, though it is not quite like terrestrial landforms. There are several ideas for what it could be, including a thin, flowing, ice-rich layer or sediment that was deformed beneath a former ice sheet. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24947

Sand dunes like those seen in this image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have been observed to creep slowly across the surface of Mars through the action of the wind.

Sand dunes such as those seen in this image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have been observed to creep slowly across the surface of Mars through the action of the wind.

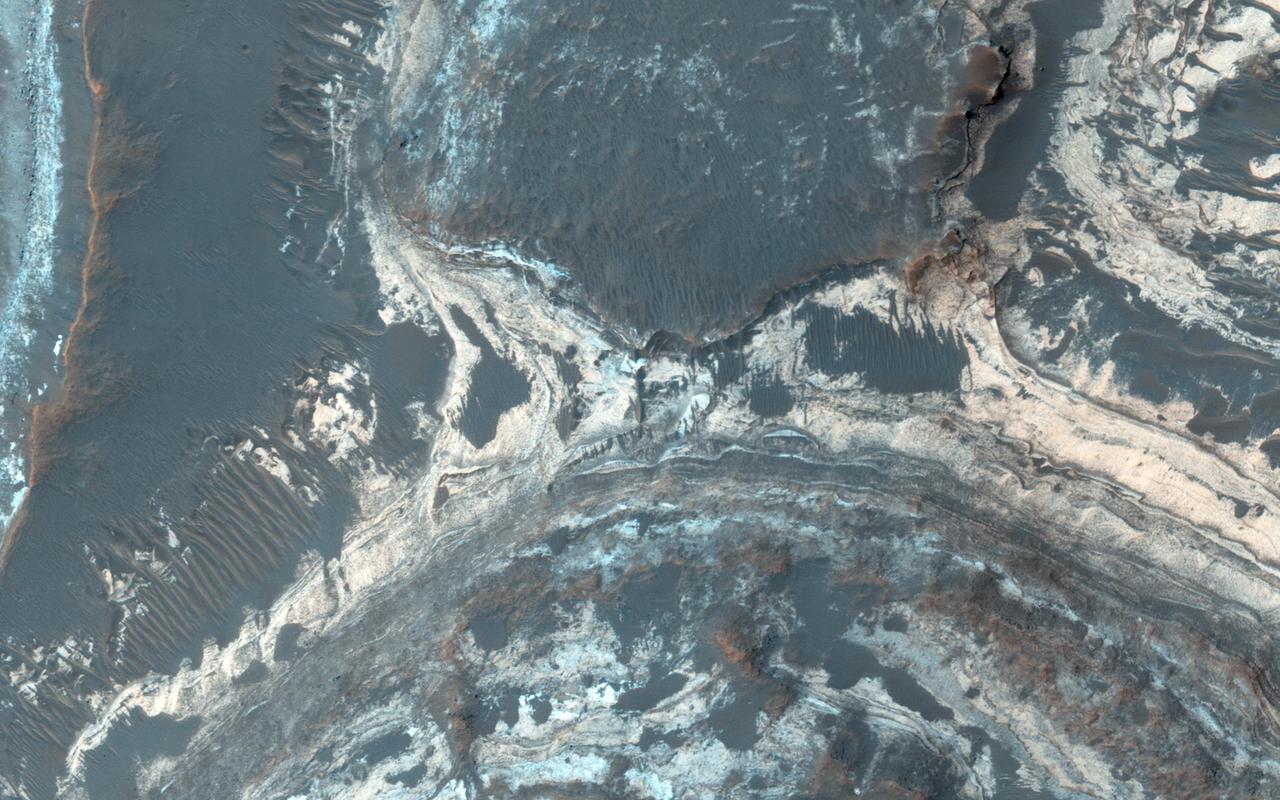

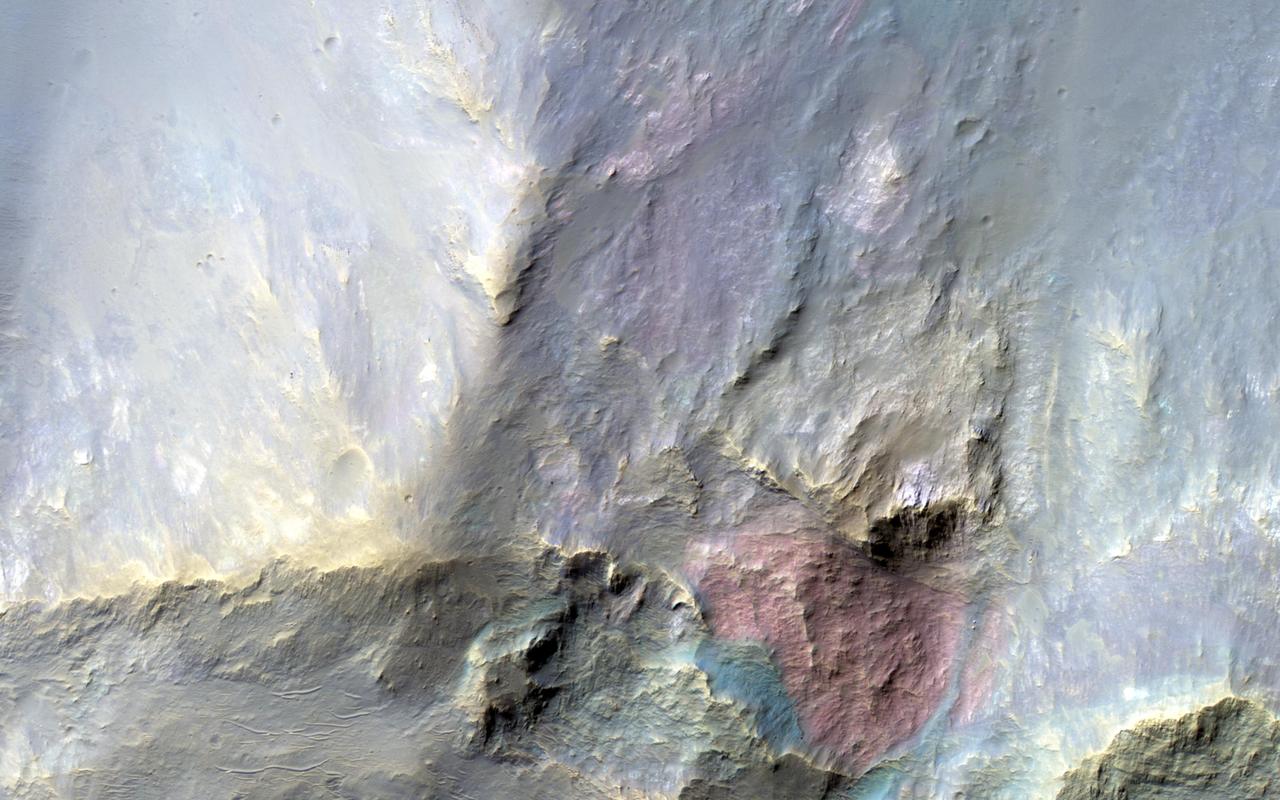

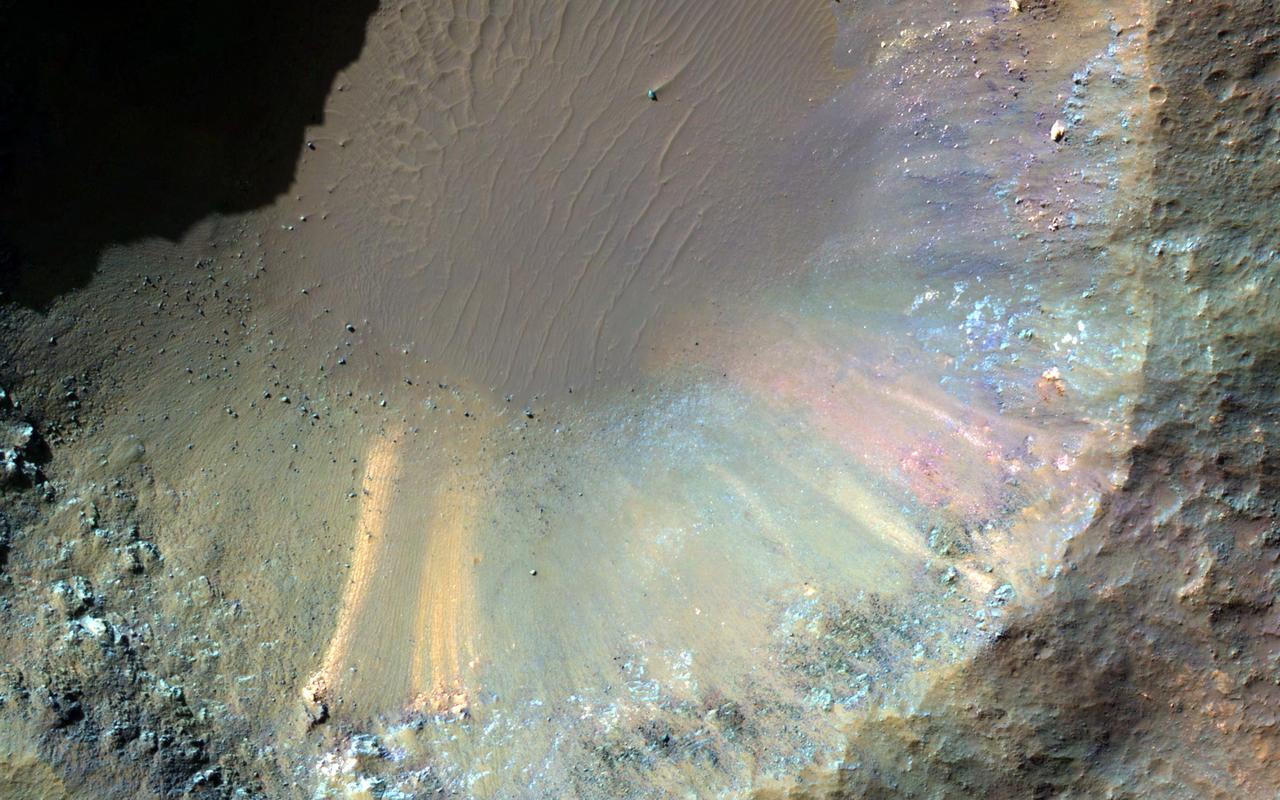

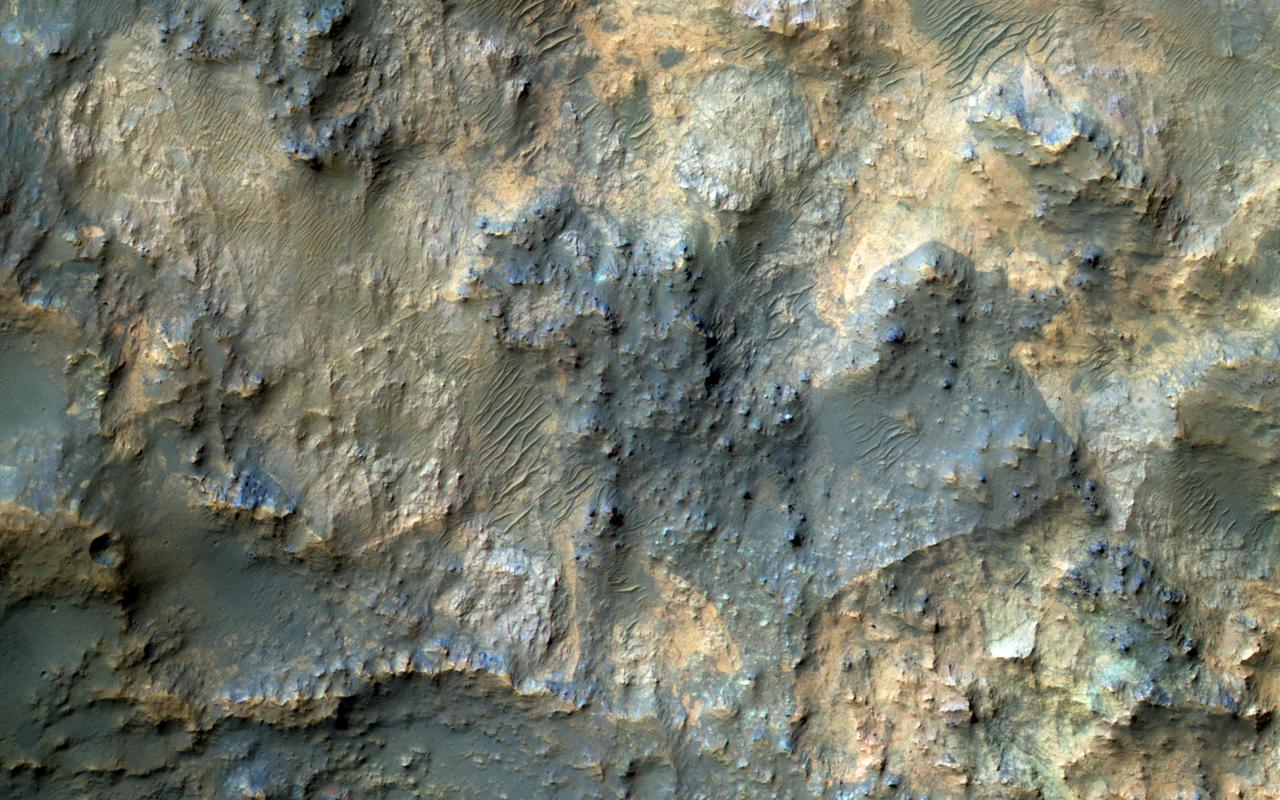

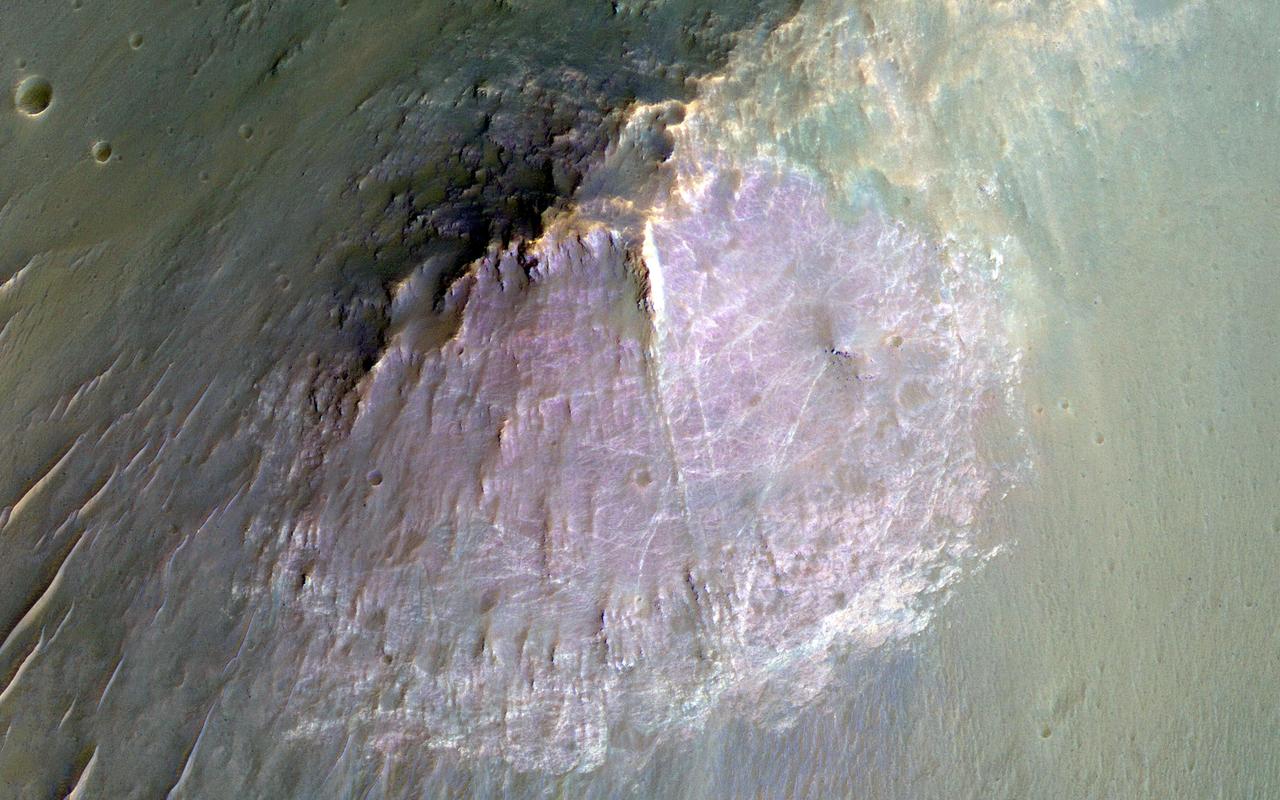

This image samples the excellent bedrock exposures north of Terby Crater, which lies on the northern rim of the giant Hellas basin. An enhanced-color cutout shows a sample of this bedrock, which has a variety of colors and textures. The warm-colored bedrock probably contains hydrated minerals such as clays, whereas the blue-green bedrock is dominated by unaltered mafic minerals. These may be some of the oldest rocks exposed at the Martian surface. Such ancient rocks are extremely rare on Earth. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20737

An unusual layer of smooth material covers the flanks of the volcano Peneus Patera just south of the Hellas Basin, seen here in a crater on the patera rim. Though smooth on its upper surface, the layer is pitted by a process of erosion that produces steep scarps facing the south pole and more gentle slopes in the direction of the equator. The style of erosion of the smooth layer suggests that ice of some form plays a role in shaping this terrain. Orbit Number: 84409 Latitude: -57.5964 Longitude: 54.2339 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2020-12-24 12:31 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24400

Gullies are commonly found in the Martian mid-latitudes, particularly in the Southern Hemisphere. However, they are rare in the deepest parts of the massive Hellas impact basin. One likely reason for this is that gullies are found on steep slopes, which seem to be less common in Hellas. For this image, HiRISE targeted a relatively fresh crater where previous images from the MRO Context Camera appeared to show gullies. This high-resolution look confirms the gullies and will allow scientists to compare them in detail with gullies elsewhere on the planet. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26329

This VIS image shows several channels located in Terra Sabaea. The flow was from the top of the image towards the bottom. These channels are located north of Hellas Planum and are following the topographic gradient down into the Hellas basin. None of these channels have been named. Orbit Number: 81919 Latitude: -17.5776 Longitude: 65.3522 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2020-06-02 12:33 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24112

Perched on the northern rim of the enormous Hellas Basin, Terby Crater, imaged by NASA Mars Odyssey, is host to an impressive range of landforms. As is common for many Martian craters, Terby has been filled with layered material, presumably sediments. The process of erosion has exposed some of these layers along with strange, rectilinear ridges. Sinuous channels, collapse pits, and a scoured-looking cap rock are some of the other interesting landforms in Terby. Such a variety of landforms attests to a diversity of rock types and geologic processes in the relatively small area of this THEMIS image. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04024

This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows Malea Planum,a polar region in the Southern hemisphere of Mars, directly south of Hellas Basin, which contains the lowest point of elevation on the planet. The region contains ancient volcanoes of a certain type, referred to as "paterae." Patera is the Latin word for a shallow drinking bowl, and was first applied to volcanic-looking features, with scalloped-edged calderas. Malea is also a low-lying plain, known to be covered in dust. These two pieces of information provide regional context that aid our understanding of the scene and features contained in our image. The area rises gradually to a ridge (which can be seen in this Context Camera image) and light-colored dust is blown away by gusts of the Martian wind, which accelerate up the slope to the ridge, leading to more sharp angles of contact between light and dark surface materials. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21784

Today's VIS image shows a small portion of Dao Vallis. Located south of Hadriacus Mons (a volcano), this channel is approximately 1200km (750 miles) long. It has been proposed that heating of the region due to volcanic activity melted subsurface ice which was released to the surface to carve the channel. Dao Vallis empties into the Hellas Planitia basin. Orbit Number: 83191 Latitude: -34.7957 Longitude: 91.6287 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2020-09-15 06:07 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24241

Today's VIS image shows several small channels. These channels are along the break in topography, that leads down into Argyre Planitia. Argyre Planitia and Hellas Planitia are deep basins in the southern hemisphere. Orbit Number: 74586 Latitude: -34.8073 Longitude: 318.916 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2018-10-07 16:02 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22857

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft shows a channel system flowing to the southwest toward the huge Hellas impact basin. Click on the image for larger version The scarp at the edge of the North Polar layered deposits of Mars is the site of the most frequent frost avalanches seen by HiRISE. At this season, northern spring, frost avalanches are common and HiRISE monitors the scarp to learn more about the timing and frequency of the avalanches, and their relationship to the evolution of frost on the flat ground above and below the scarp. This picture managed to capture a small avalanche in progress, right in the color strip. See if you can spot it in the browse image, and then click on the cutout to see it at full resolution. The small white cloud in front of the brick red cliff is likely carbon dioxide frost dislodged from the layers above, caught in the act of cascading down the cliff. It is larger than it looks, more than 20 meters across, and (based on previous examples) it will likely kick up clouds of dust when it hits the ground. The avalanches tend to take place at a season when the North Polar region is warming, suggesting that the avalanches may be triggered by thermal expansion. The avalanches remind us, along with active sand dunes, dust devils, slope streaks and recurring slope lineae, that Mars is an active and dynamic planet. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19961

At around 2,200 kilometers in diameter, Hellas Planitia is the largest visible impact basin in the Solar System, and hosts the lowest elevations on Mars' surface as well as a variety of landscapes. This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaisance Orbiter (MRO) covers a small central portion of the basin and shows a dune field with lots of dust devil trails. In the middle, we see what appears to be long and straight "scratch marks" running down the southeast (bottom-right) facing dune slopes. If we look closer, we can see these scratch marks actually squiggle back and forth on their way down the dune. These scratch marks are linear gullies. Just like on Earth, high-latitude regions on Mars are covered with frost in the winter. However, the winter frost on Mars is made of carbon dioxide ice (dry ice) instead of water ice. We believe linear gullies are the result of this dry ice breaking apart into blocks, which then slide or roll down warmer sandy slopes, sublimating and carving as they go. The linear gullies exhibit exceptional sinuosity (the squiggle pattern) and we believe this to be the result of repeated movement of dry ice blocks in the same path, possibly in combination with different hardness or flow resistance of the sand within the dune slopes. Determining the specific process that causes the formation and evolution of sinuosity in linear gullies is a question scientists are still trying to answer. What do you think causes the squiggles? https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22052

NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbite observed this image of an isolated mountain in the Southern highlands reveals a large exposure of purplish bedrock. Since HiRISE color is shifted to longer wavelengths than visible color and given relative stretches, this really means that the bedrock is roughly dark in the broad red bandpass image compared to the blue-green and near-infrared bandpass images. In the RGB (red-green-blue) color image, which excludes the near-infrared bandpass image, the bedrock appears bluish in color. This small mountain is located near the northeastern rim of the giant Hellas impact basin, and could be impact ejecta. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19854

Today's VIS image shows a small portion of both Dao Vallis (top of image) and Niger Vallis (middle of image). Arising from the volcano Hadriacus Mons, Dao Vallis is approximately 1200km (750 miles) long. Niger Vallis is 333 km (207 miles) long. It has been proposed that heating of the region due to volcanic activity melted subsurface ice which was released to the surface to carve the two channels. Niger Vallis merges with Dao Vallis just off the image and then flow southwestward into the Hellas Planitia basin. Orbit Number: 91427 Latitude: -36.3071 Longitude: 90.4526 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-07-25 09:32 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25601

![Sand dunes are scattered across Mars and one of the larger populations exists in the Southern hemisphere, just west of the Hellas impact basin. The Hellespontus region features numerous collections of dark, dune formations that collect both within depressions such as craters, and among "extra-crater" plains areas. This image displays the middle portion of a large dune field composed primarily of crescent-shaped "barchan" dunes. Here, the steep, sunlit side of the dune, called a slip face, indicates the down-wind side of the dune and direction of its migration. Other long, narrow linear dunes known as "seif" dunes are also here and in other locales to the east. NB: "Seif" comes from the Arabic word meaning "sword." The map is projected here at a scale of 25 centimeters (9.8 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 25.5 centimeters (10 inches) per pixel (with 1 x 1 binning); objects on the order of 77 centimeters (30.3 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21571](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21571/PIA21571~medium.jpg)

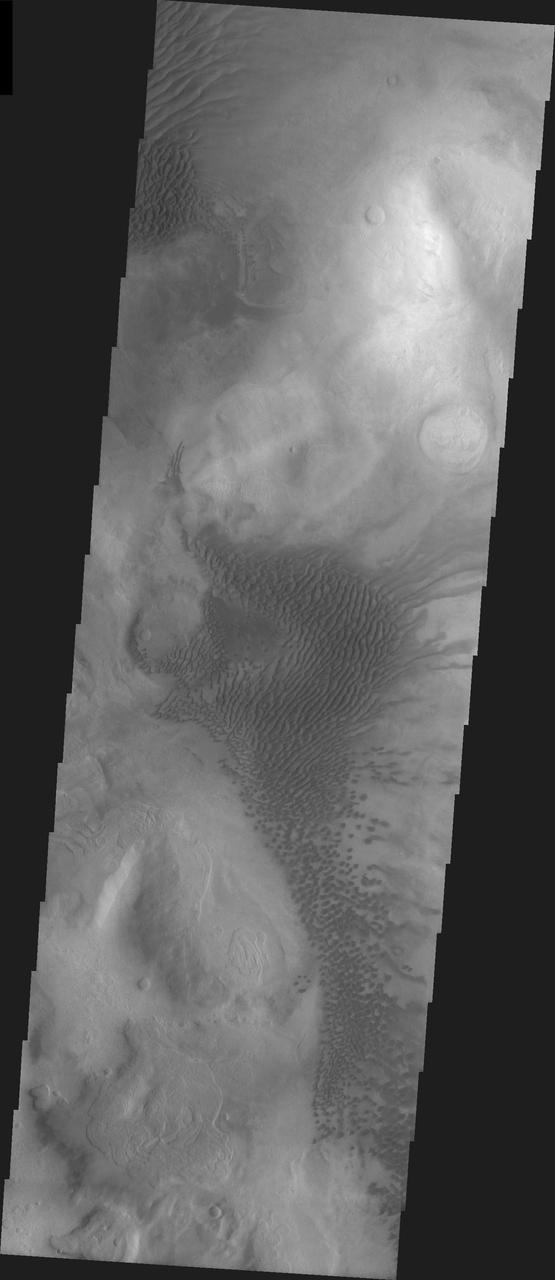

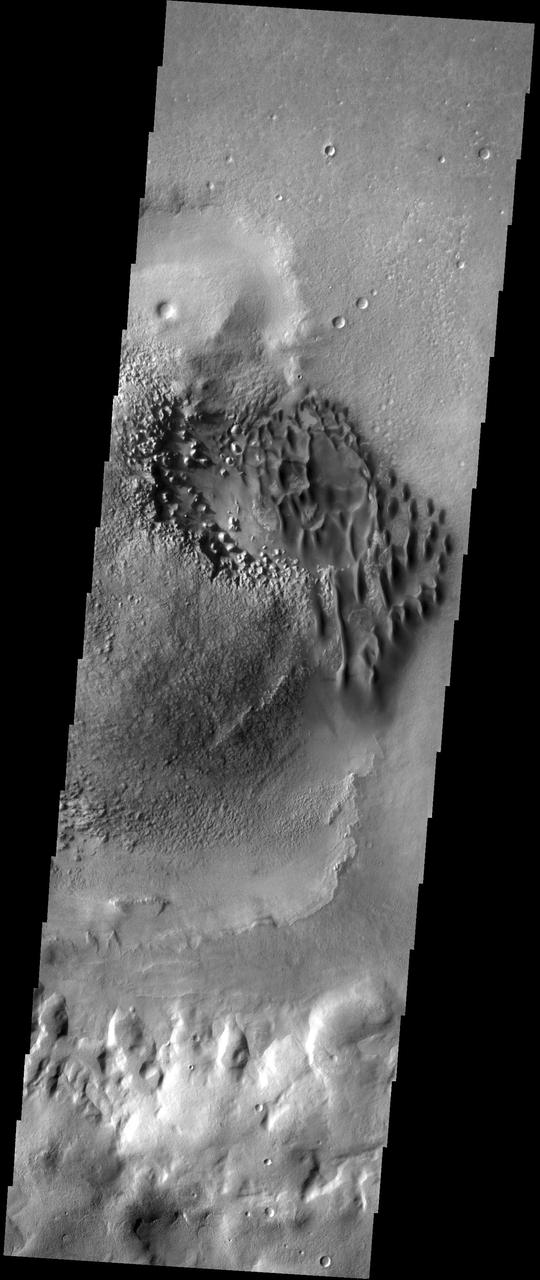

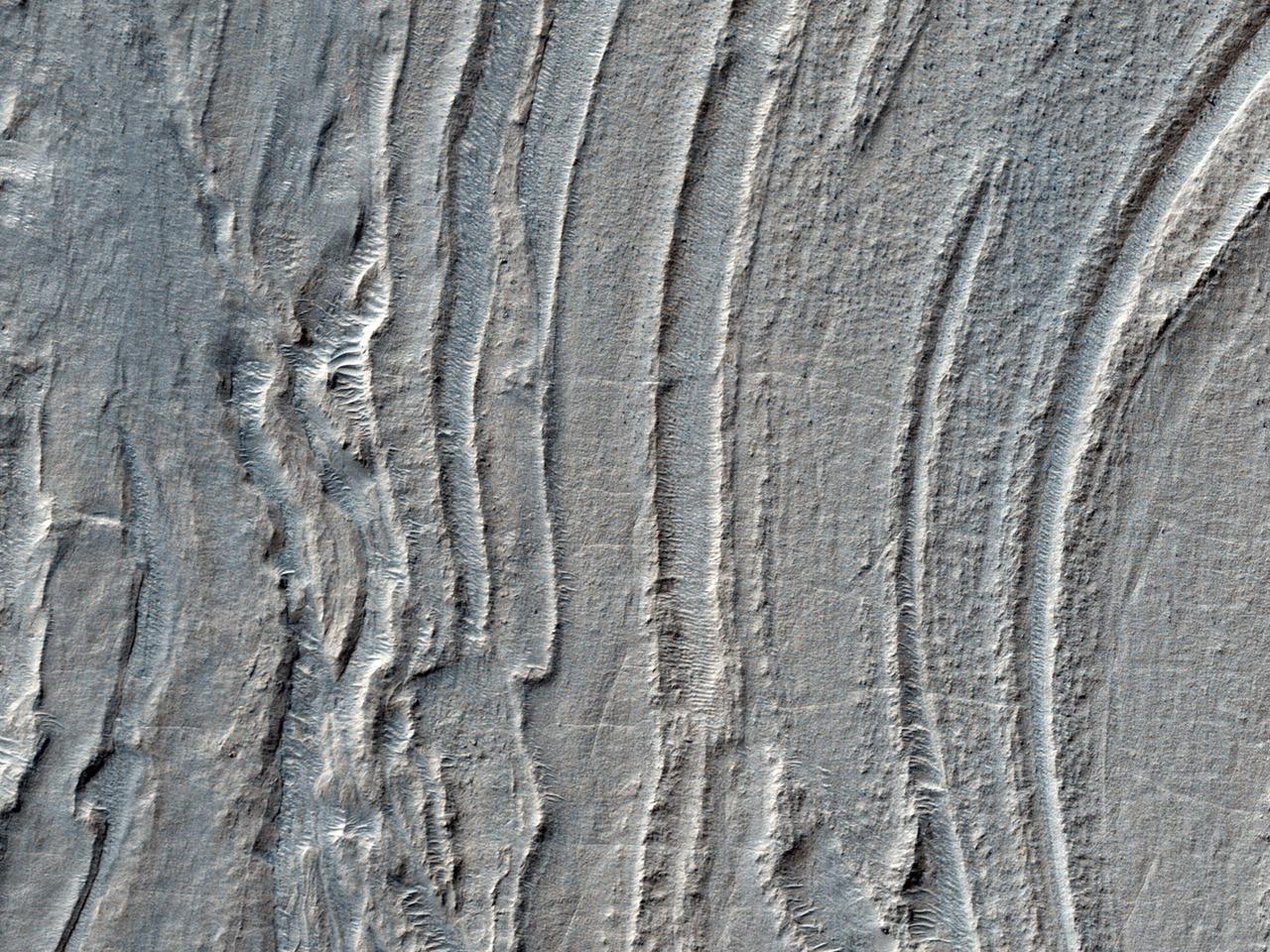

Sand dunes are scattered across Mars and one of the larger populations exists in the Southern hemisphere, just west of the Hellas impact basin. The Hellespontus region features numerous collections of dark, dune formations that collect both within depressions such as craters, and among "extra-crater" plains areas. This image displays the middle portion of a large dune field composed primarily of crescent-shaped "barchan" dunes. Here, the steep, sunlit side of the dune, called a slip face, indicates the down-wind side of the dune and direction of its migration. Other long, narrow linear dunes known as "seif" dunes are also here and in other locales to the east. NB: "Seif" comes from the Arabic word meaning "sword." The map is projected here at a scale of 25 centimeters (9.8 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 25.5 centimeters (10 inches) per pixel (with 1 x 1 binning); objects on the order of 77 centimeters (30.3 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21571

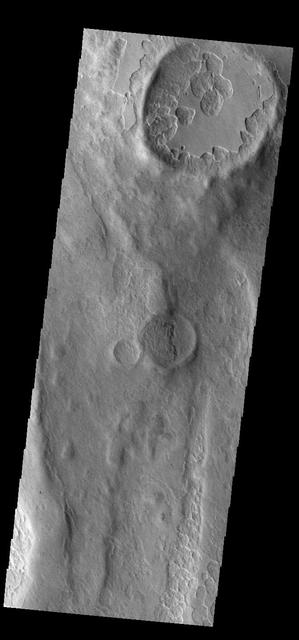

![This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) targets a portion of a group of honeycomb-textured landforms in northwestern Hellas Planitia, which is part of one of the largest and most ancient impact basins on Mars. In a larger Context Camera image, the individual "cells" are about 5 to 10 kilometers wide. With HiRISE, we see much greater detail of these cells, like sand ripples that indicate wind erosion has played some role here. We also see distinctive exposures of bedrock that cut across the floor and wall of the cells. These resemble dykes, which are usually formed by volcanic activity. Additionally, the lack of impact craters suggests that the landscape, along with these features, have been recently reshaped by a process, or number of processes that may even be active today. Scientists have been debating how these honeycombed features are created, theorizing from glacial events, lake formation, volcanic activity, and tectonic activity, to wind erosion. The map is projected here at a scale of 50 centimeters (19.7 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 53.8 centimeters (21.2 inches) per pixel (with 2 x 2 binning); objects on the order of 161 centimeters (23.5 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22118](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA22118/PIA22118~medium.jpg)

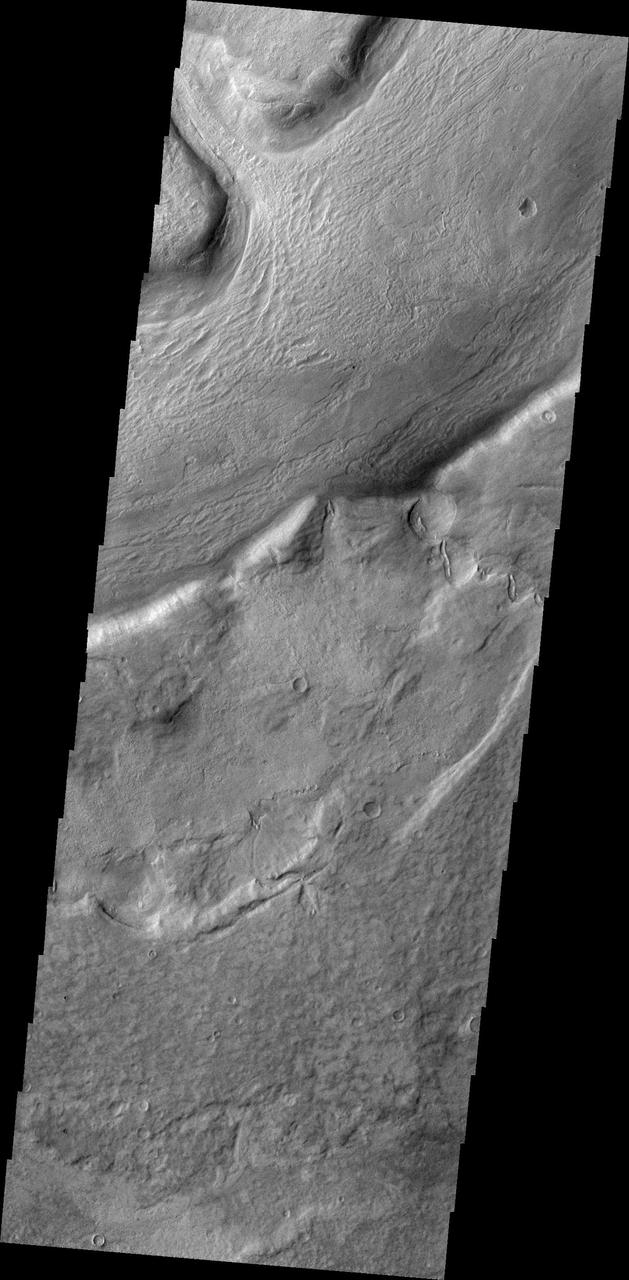

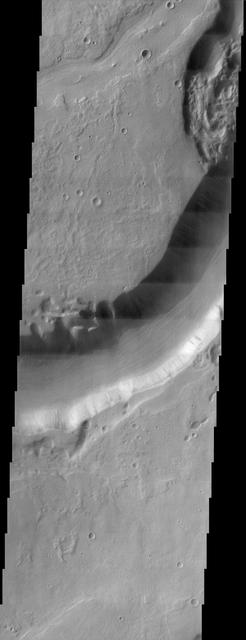

This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) targets a portion of a group of honeycomb-textured landforms in northwestern Hellas Planitia, which is part of one of the largest and most ancient impact basins on Mars. In a larger Context Camera image, the individual "cells" are about 5 to 10 kilometers wide. With HiRISE, we see much greater detail of these cells, like sand ripples that indicate wind erosion has played some role here. We also see distinctive exposures of bedrock that cut across the floor and wall of the cells. These resemble dykes, which are usually formed by volcanic activity. Additionally, the lack of impact craters suggests that the landscape, along with these features, have been recently reshaped by a process, or number of processes that may even be active today. Scientists have been debating how these honeycombed features are created, theorizing from glacial events, lake formation, volcanic activity, and tectonic activity, to wind erosion. The map is projected here at a scale of 50 centimeters (19.7 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 53.8 centimeters (21.2 inches) per pixel (with 2 x 2 binning); objects on the order of 161 centimeters (23.5 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22118

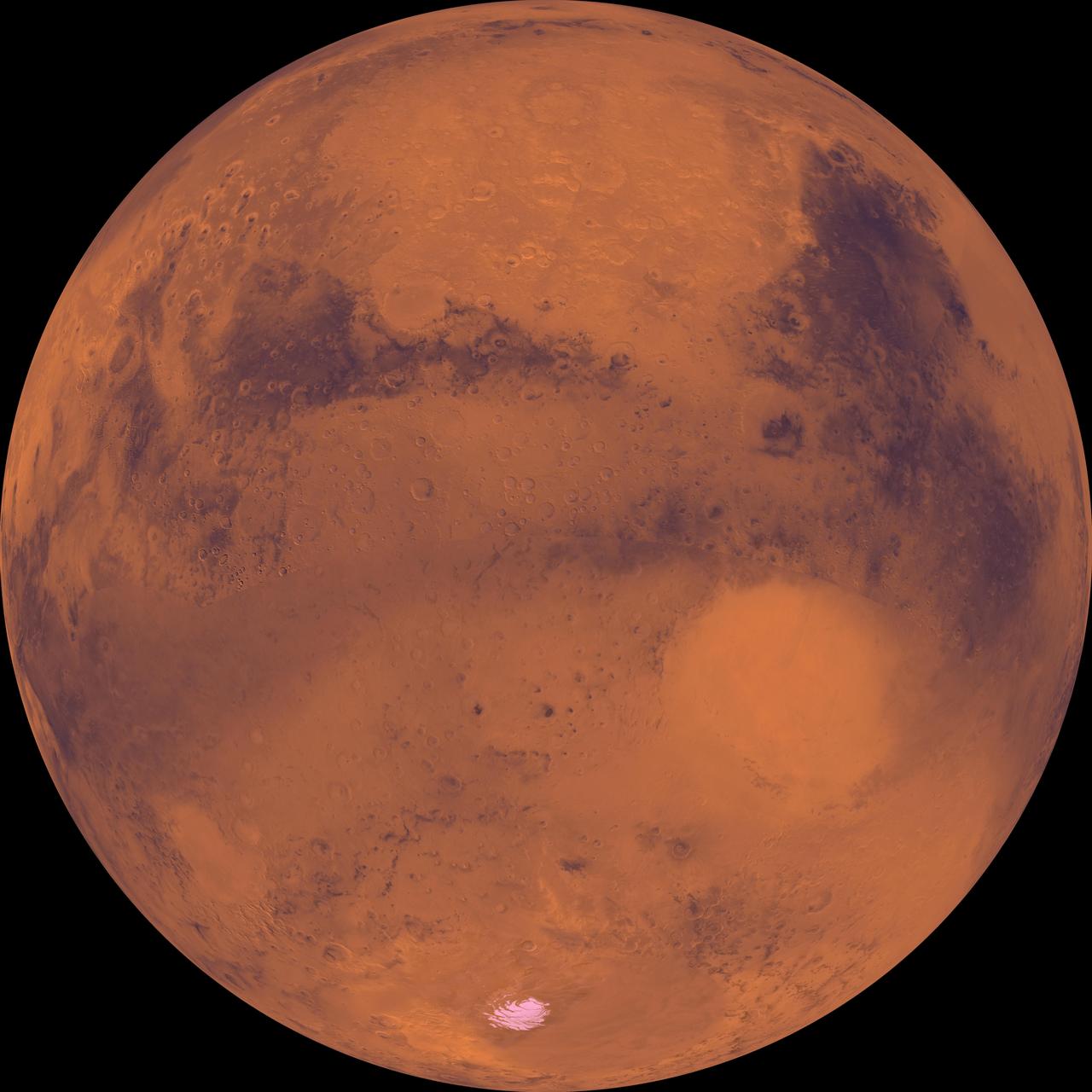

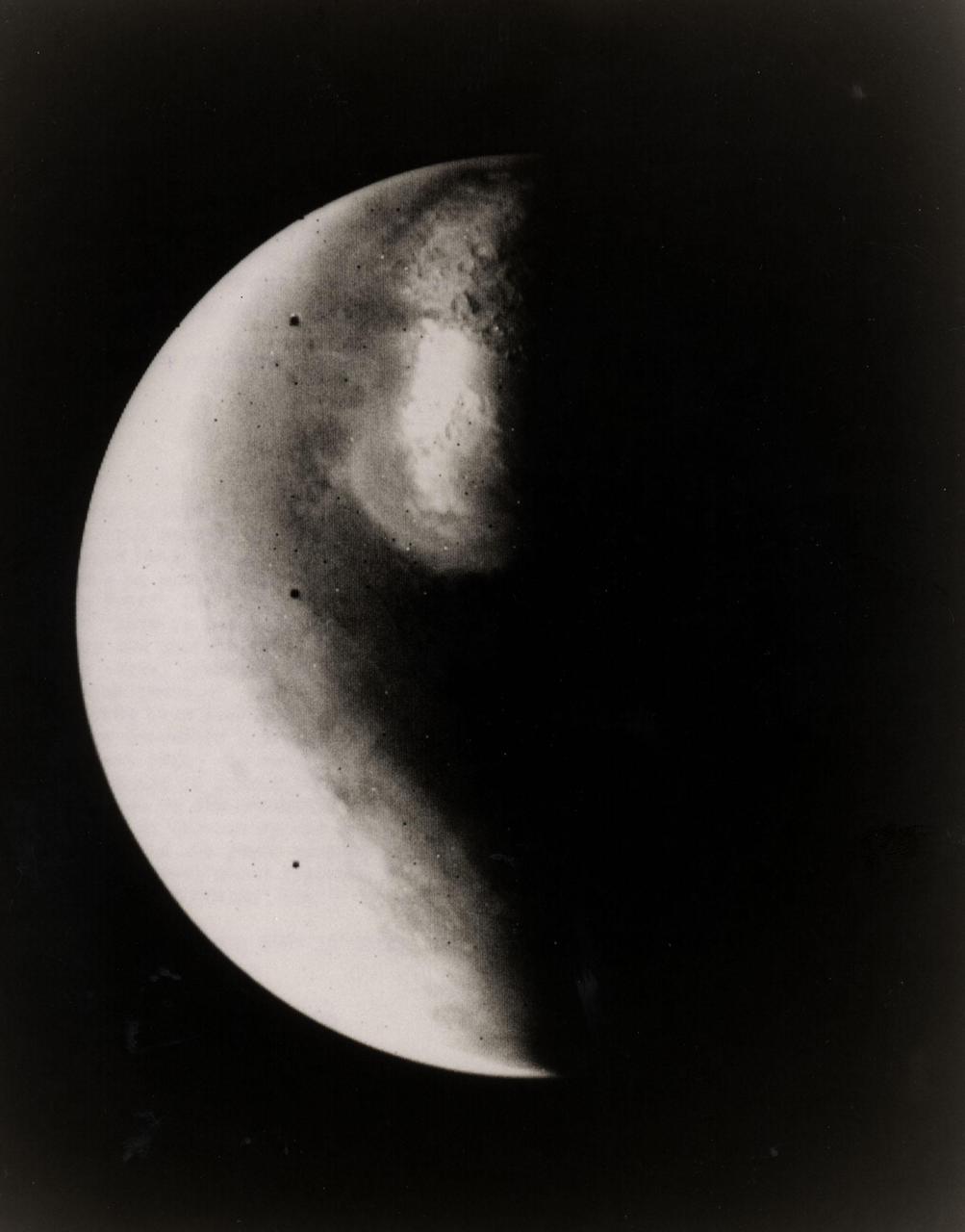

Half-Mars hangs in space 685,000 kilometers (425,000 miles) above Viking 1 as the spacecraft approaches the planet. This picture was taken at 6:40 p.m. PDT on June 16 by one of two telescope-equipped TV cameras aboard the Viking 1 Orbiter. A violet filter was used. Resolution is approximately 17 kilometers (10.5 miles) at center of disk. North is toward upper right and the south pole is in the dark to the lower left. We are looking at the morning side of the planet; that is, the planet is rotating from left to right. Toward the bottom of the image is a very bright irregular feature within a somewhat less bright circular feature. The circular feature is Hellas, a 2,000-kilometer(1,250-mile) diameter impact basin. Numerous craters are just visible within the frost-covered region. To the south of Hellas is another brighter area. This is probably an area of discontinuous frost cover around the south pole. The image is very bright toward the edge of the planet because of atmospheric scattering in the violet. Viking 1 will begin orbiting Mars on Saturday, June 19, with the landing planned for July 4. The Viking Project is managed by the NASA Langley Reseach Center, Hampton, Va.

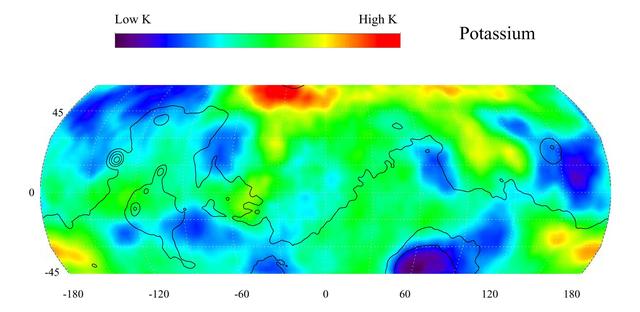

This gamma ray spectrometer map of the mid-latitude region of Mars is based on gamma-rays from the element potassium. Potassium, having the chemical symbol K, is a naturally radioactive element and is a minor constituent of rocks on the surface of both Mars and Earth. The region of highest potassium content, shown in red, is concentrated in the northern part of Acidalia Planitia (centered near 55 degrees N, -30 degrees). Several areas of low potassium content, shown in blue, are distributed across the mid-latitudes, with two significant low concentrations, one associated with the Hellas Basin (centered near 35 degrees S, 70 degrees) and the other lying southeast of Elysium Mons (centered near 10 degrees N, 160 degrees). Contours of constant surface elevation are also shown. The long continuous line running from east to west marks the approximate separation of the younger lowlands in the north from the older highlands in the south. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04255

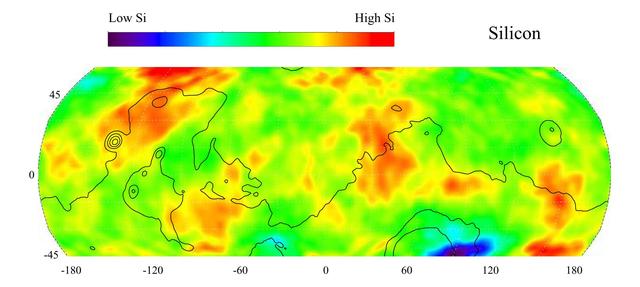

This gamma ray spectrometer map of the mid-latitude region of Mars is based on gamma-rays from the element silicon. Silicon is one of the most abundant elements on the surface of both Mars and Earth (second only to oxygen). The most extensive region of highest silicon content, shown in red, is located in the high latitudes north of Tharsis (centered near 45 degrees latitude, -120 degrees longitude). The area of lowest silicon content, shown in blue, lies just to the east of the Hellas Basin (-45 degrees latitude, 90 degrees longitude). Contours of constant surface elevation are also shown. The long continuous contour line running from east to west marks the approximate separation of the younger lowlands in the north from the older highlands in the south. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04256

The light-toned deposits that formed in two gully sites on Mars during the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) mission in the 1999 to 2005 period are considered to be the result of sediment transport by a fluid with the physical properties of liquid water. The young, light-toned gully deposits were found in a crater in Terra Sirenum (see PIA09027 or MOC2-1618) and in a crater east of the Hellas basin in the Centauri Montes region (see PIA09028 or MOC2-1619). In their study of how the light-toned gully deposits may have formed, the MOC team considered their resemblance to light- and dark-toned slope streaks found elsewhere on Mars. Slope streaks are most commonly believed to have formed by downslope movement of extremely dry, very fine-grained dust, through processes thought by some to be analogous to terrestrial snow avalanche formation. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA09030

Today's VIS image shows a small portion of both Dao Vallis (middle of image) and Niger Vallis (bottom of image). Arising from the volcano Hadriacus Mons (top of image), Dao Vallis is approximately 1200km (750 miles) long. Niger Vallis is 333 km (207 miles) long. It has been proposed that heating of the region due to volcanic activity melted subsurface ice which was released to the surface to carve the two channels. Niger Vallis merges with Dao Vallis south of this image and then flow southwestward into the Hellas Planitia basin. Orbit Number: 93355 Latitude: -33.4749 Longitude: 93.0394 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-12-31 02:58 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25852

MarCO-B, one of the experimental Mars Cube One (MarCO) CubeSats, took this image of Mars from about 11,300 miles (18,200 kilometers) away shortly before NASA's InSight spacecraft landed on Mars on Nov. 26, 2018. MarCO-B flew by Mars with its twin, MarCO-A, to serve as communications relays for InSight spacecraft as it touched down around noon PST (3 p.m. EST). This image was taken at 10:35 a.m. PST (1:35 p.m. EST). Mars' north pole is at the top. A lighter-toned circular feature known as Hellas Basin is visible in the southern hemisphere. MarCO-B's antenna reflector can be seen at left. The blue dot on the right is a glint of sunlight off the antenna feed (not visible in the picture). https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22831

This image covers channels cutting through the ancient rim of Savich Crater, a 188 kilometer-wide depression near the northeastern edge of the much larger Hellas impact basin. The channels were likely eroded by water flowing into Savich Crater long ago. Our image reveals layers of varying brightness and texture exposed along the channels. Individual boulders are visible within the brighter layers (appearing blue-white in this enhanced color view), while redder layers lack distinct boulders. The meter-scale boulders could have been transported by floodwaters, or perhaps could be an even more ancient rock unit broken apart by impacts that these channels subsequently exposed. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25502

This image is of a portion of the Southern plains region within Hellas, the largest impact basin on Mars, with a diameter of about 2300 kilometers 1400 miles, as observed by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. There are three main phenomena apparent in this image. First, the faint dark streaks that criss-cross the terrain are dust devil tracks that clear the bright dust along their way. Second, the subtle overall bumpy "basketball" texture of the surface is formed by repeated seasonal freezing and thawing of the ice-rich regolith and is common at higher latitudes. Third, the large, elliptical, scalloped depressions are common in permafrost terrains in both hemispheres, where thick, latitude-dependent sedimentary mantles comprise the surface units. These mantles are composed of ice-rich sediments that degrade as the ice sublimates away and is heated either by the Sun or by locally higher geothermal gradients. Sublimation, or the direct change in phase from ice to gas, occurs on Mars because of its low density atmosphere. These depressions have steeper pole-facing slopes, whereas the equator-facing slopes gently fade into the surrounding terrain. At full resolution (see close up view), numerous sublimation pits and networks of polygonal cracks are visible on the steeper, unstable pole-ward facing slopes. The overall morphology of this terrain is characteristic of what is called "thermokarstic degradation processes," which is a term used to describe the formation of pits in an ice-rich terrain due to loss of ice creating pits and collapse features. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19350

The ancient highland channels in this image empty into the Eridania Basin (not visible), a large topographically low enclosure with smooth-appearing terrains that may have once contained a large paleolake or ancient sea. Water in these channels flowed to the east into Ariadnes Basin, a smaller basin located within the confines of Eridiana. Light-toned knobs are exposed in the northern channel, while the other channels are partially filled with smooth appearing lobe-shaped surface flows that are extensively fractured when viewed at high-resolution. Although the origin of these knobs is not known, interpretations include fumarolic mounds, erosional remnants, pingos, mud volcanoes and spring mounds. The movement of the once ice-rich, channel-filling flows over the knobby terrains likely created radial tension stresses producing the cracks that we see on the surface of these deposits. As the material slowly thinned, it eventually led to the formation of an elephant skin-like texture. This texture is different from the surrounding eroding mantling deposit that has become pitted as the ice sublimated causing the overlying surface to collapse. The combination of such knobby terrain and smooth, channel-filling deposits are seen only in a few places on Mars. One such example is the Navua Valles channels northeast of the Hellas Basin that may have also hosted a large, ice-covered lake in the past. Their morphological similarities, particularly in their surface materials, suggest that they formed under similar paleoclimatic conditions. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA12968

This mosaic is composed of about 100 red- and violet- filter Viking Orbiter images, digitally mosaiced in an orthographic projection at a scale of 1 km/pixel. The images were acquired in 1980 during mid northern summer on Mars (Ls = 89 degrees). The center of the image is near the impact crater Schiaparelli (latitude -3 degrees, longitude 343 degrees). The limits of this mosaic are approximately latitude -60 to 60 degrees and longitude 280 to 30 degrees. The color variations have been enhanced by a factor of two, and the large-scale brightness variations (mostly due to sun-angle variations) have been normalized by large-scale filtering. The large circular area with a bright yellow color (in this rendition) is known as Arabia. The boundary between the ancient, heavily-cratered southern highlands and the younger northern plains occurs far to the north (latitude 40 degrees) on this side of the planet, just north of Arabia. The dark streaks with bright margins emanating from craters in the Oxia Palus region (to the left of Arabia) are caused by erosion and/or deposition by the wind. The dark blue area on the far right, called Syrtis Major Planum, is a low-relief volcanic shield of probable basaltic composition. Bright white areas to the south, including the Hellas impact basin at the lower right, are covered by carbon dioxide frost. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00004

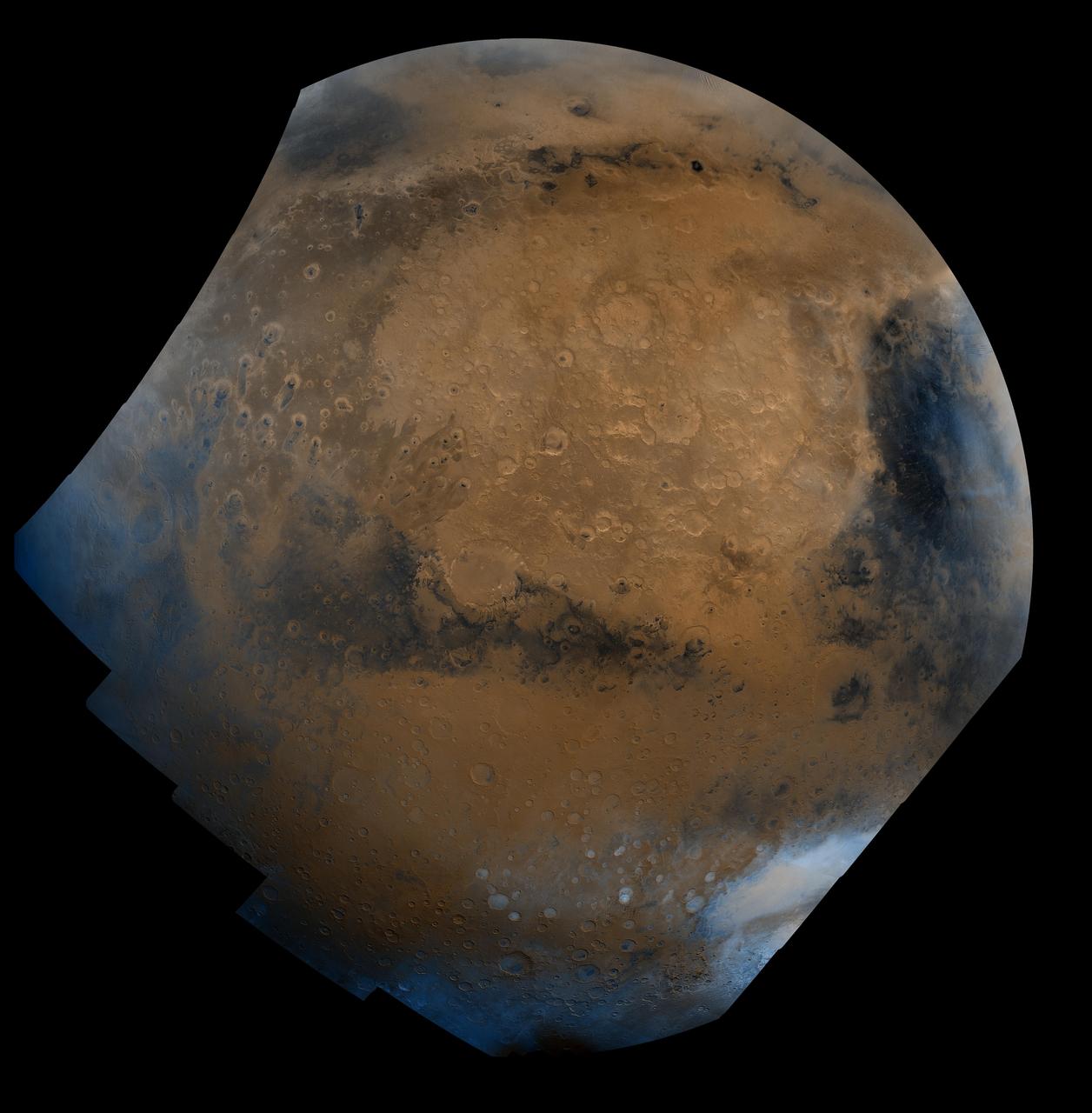

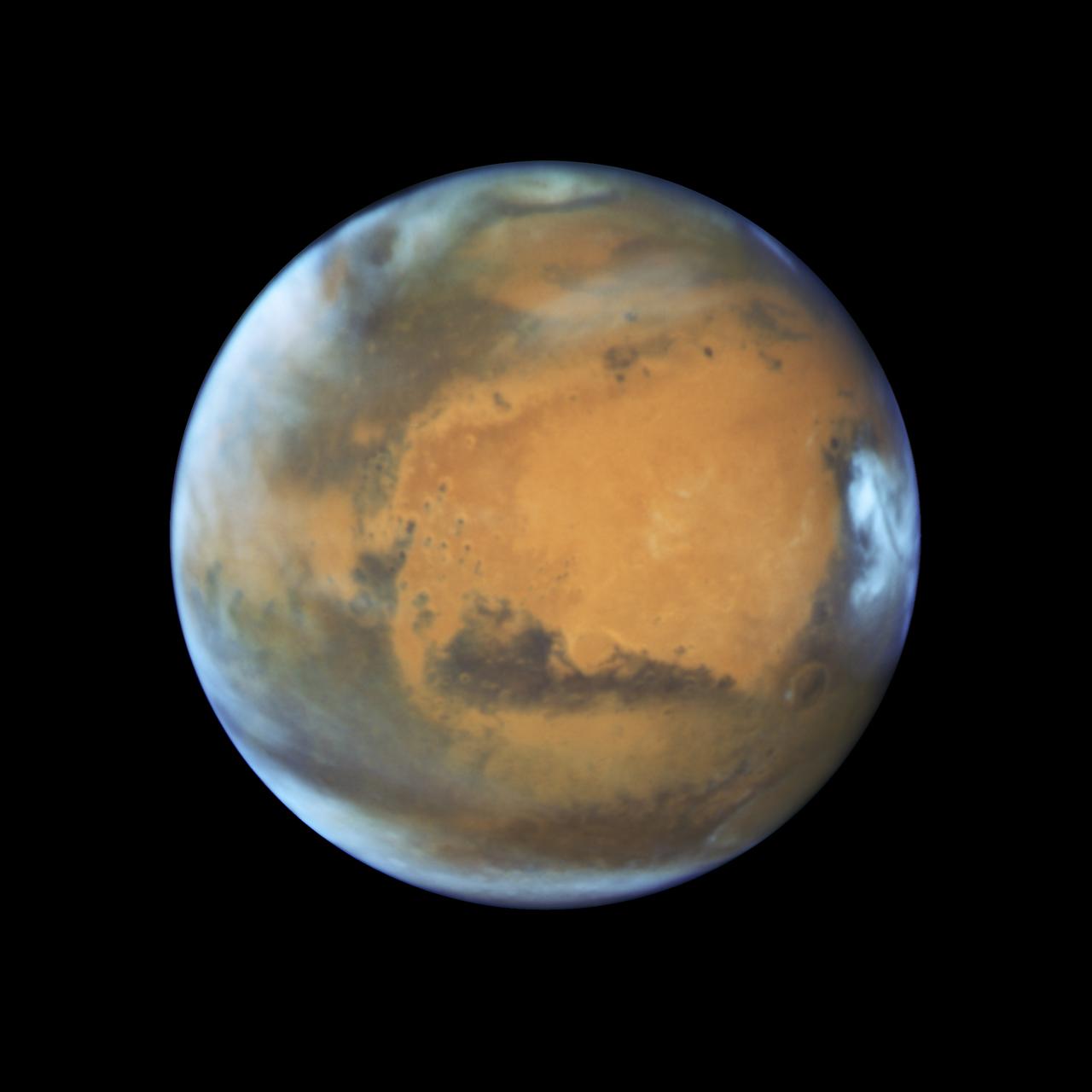

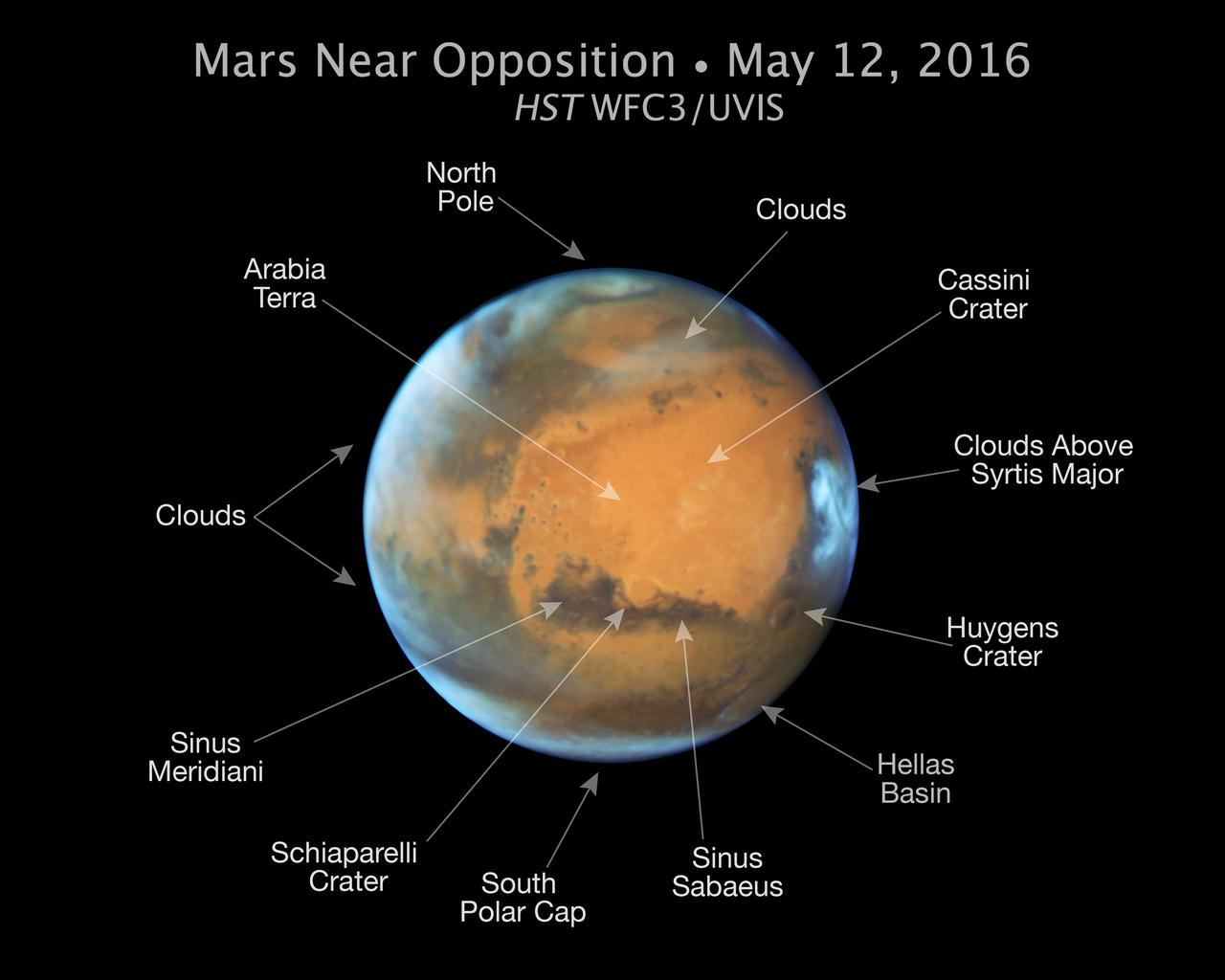

Mars is looking mighty fine in this portrait nabbed by the Hubble Space Telescope on a near close approach! Read more: <a href="http://go.nasa.gov/1rWYiBT" rel="nofollow">go.nasa.gov/1rWYiBT</a> The Hubble Space Telescope is more well known for its picturesque views of nebulae and galaxies, but it's also useful for studying our own planets, including Mars. Hubble imaged Mars on May 12, 2016 - ten days before Mars would be on the exact opposite side of the Earth from the Sun. Bright, frosty polar caps, and clouds above a vivid, rust-colored landscape reveal Mars as a dynamic seasonal planet in this NASA Hubble Space Telescope view taken on May 12, 2016, when Mars was 50 million miles from Earth. The Hubble image reveals details as small as 20 to 30 miles across. The large, dark region at far right is Syrtis Major Planitia, one of the first features identified on the surface of the planet by seventeenth-century observers. Christiaan Huygens used this feature to measure the rotation rate of Mars. (A Martian day is about 24 hours and 37 minutes.) Today we know that Syrtis Major is an ancient, inactive shield volcano. Late-afternoon clouds surround its summit in this view. A large oval feature to the south of Syrtis Major is the bright Hellas Planitia basin. About 1,100 miles across and nearly five miles deep, it was formed about 3.5 billion years ago by an asteroid impact. The orange area in the center of the image is Arabia Terra, a vast upland region in northern Mars that covers about 2,800 miles. The landscape is densely cratered and heavily eroded, indicating that it could be among the oldest terrains on the planet. Dried river canyons (too small to be seen here) wind through the region and empty into the large northern lowlands. Credit: NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA), J. Bell (ASU), and M. Wolff (Space Science Institute) #nasagoddard #mars #hubble #space <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagrid.me/nasagoddard/?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

Mars is looking mighty fine in this portrait nabbed by the Hubble Space Telescope on a near close approach! Read more: <a href="http://go.nasa.gov/1rWYiBT" rel="nofollow">go.nasa.gov/1rWYiBT</a> The Hubble Space Telescope is more well known for its picturesque views of nebulae and galaxies, but it's also useful for studying our own planets, including Mars. Hubble imaged Mars on May 12, 2016 - ten days before Mars would be on the exact opposite side of the Earth from the Sun. Bright, frosty polar caps, and clouds above a vivid, rust-colored landscape reveal Mars as a dynamic seasonal planet in this NASA Hubble Space Telescope view taken on May 12, 2016, when Mars was 50 million miles from Earth. The Hubble image reveals details as small as 20 to 30 miles across. The large, dark region at far right is Syrtis Major Planitia, one of the first features identified on the surface of the planet by seventeenth-century observers. Christiaan Huygens used this feature to measure the rotation rate of Mars. (A Martian day is about 24 hours and 37 minutes.) Today we know that Syrtis Major is an ancient, inactive shield volcano. Late-afternoon clouds surround its summit in this view. A large oval feature to the south of Syrtis Major is the bright Hellas Planitia basin. About 1,100 miles across and nearly five miles deep, it was formed about 3.5 billion years ago by an asteroid impact. The orange area in the center of the image is Arabia Terra, a vast upland region in northern Mars that covers about 2,800 miles. The landscape is densely cratered and heavily eroded, indicating that it could be among the oldest terrains on the planet. Dried river canyons (too small to be seen here) wind through the region and empty into the large northern lowlands. Credit: NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA), J. Bell (ASU), and M. Wolff (Space Science Institute) #nasagoddard #mars #hubble #space <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagrid.me/nasagoddard/?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

Mars is looking mighty fine in this portrait nabbed by the Hubble Space Telescope on a near close approach! Read more: <a href="http://go.nasa.gov/1rWYiBT" rel="nofollow">go.nasa.gov/1rWYiBT</a> The Hubble Space Telescope is more well known for its picturesque views of nebulae and galaxies, but it's also useful for studying our own planets, including Mars. Hubble imaged Mars on May 12, 2016 - ten days before Mars would be on the exact opposite side of the Earth from the Sun. Bright, frosty polar caps, and clouds above a vivid, rust-colored landscape reveal Mars as a dynamic seasonal planet in this NASA Hubble Space Telescope view taken on May 12, 2016, when Mars was 50 million miles from Earth. The Hubble image reveals details as small as 20 to 30 miles across. The large, dark region at far right is Syrtis Major Planitia, one of the first features identified on the surface of the planet by seventeenth-century observers. Christiaan Huygens used this feature to measure the rotation rate of Mars. (A Martian day is about 24 hours and 37 minutes.) Today we know that Syrtis Major is an ancient, inactive shield volcano. Late-afternoon clouds surround its summit in this view. A large oval feature to the south of Syrtis Major is the bright Hellas Planitia basin. About 1,100 miles across and nearly five miles deep, it was formed about 3.5 billion years ago by an asteroid impact. The orange area in the center of the image is Arabia Terra, a vast upland region in northern Mars that covers about 2,800 miles. The landscape is densely cratered and heavily eroded, indicating that it could be among the oldest terrains on the planet. Dried river canyons (too small to be seen here) wind through the region and empty into the large northern lowlands. Credit: NASA, ESA, the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA), J. Bell (ASU), and M. Wolff (Space Science Institute) #nasagoddard #mars #hubble #space <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagrid.me/nasagoddard/?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>