This image shows two merging galaxies known as Arp 302, also called VV 340. It is composed of images from three Spitzer Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) channels: IRAC channel 1 in blue, IRAC channel 2 in green and IRAC channel 3 in red. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23008

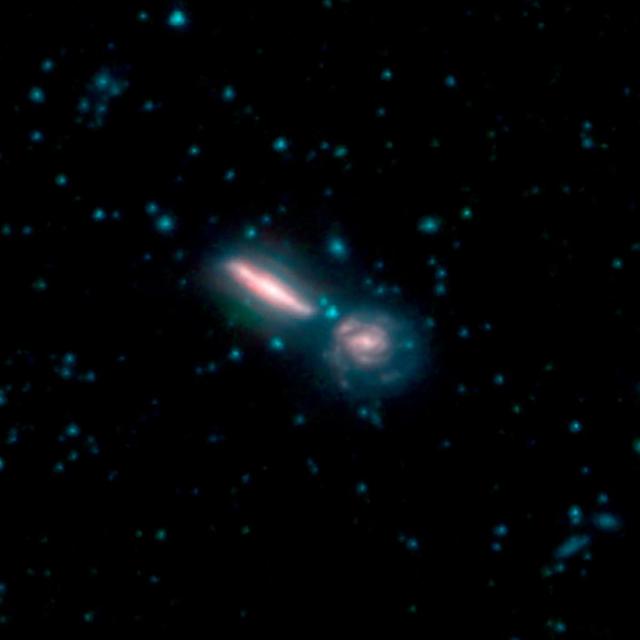

This image shows the merger of two galaxies, known as NGC 6786 (right) and UGC 11415 (left), also collectively called VII Zw 96. It is composed of images from three Spitzer Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) channels: IRAC channel 1 in blue, IRAC channel 2 in green and IRAC channel 3 in red. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23007

This image shows the merger of two galaxies, known as NGC 7752 (larger) and NGC 7753 (smaller), also collectively called Arp86. It is composed of images from three Spitzer Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) channels: IRAC channel 1 in blue, IRAC channel 2 in green and IRAC channel 3 in red. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23006

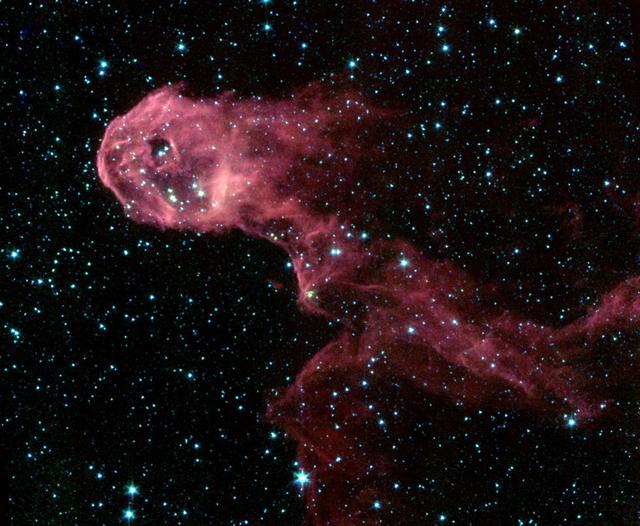

Thin, red veins of energized gas mark the location of the supernova remnant HBH 3 in this image from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope. The puffy, white feature in the image is a portion of the star forming regions W3, W4 and W5. Infrared wavelengths of 3.6 microns have been mapped to blue, and 4.5 microns to red. The white color of the star-forming region is a combination of both wavelengths, while the HBH 3 filaments radiate only at the longer 4.5 micron wavelength. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22564

This image from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope shows the spiral galaxy NGC 2841, located about 46 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Ursa Major. The galaxy is helping astronomers solve one of the oldest puzzles in astronomy: Why do galaxies look so smooth, with stars sprinkled evenly throughout? An international team of astronomers has discovered that rivers of young stars flow from their hot, dense stellar nurseries, dispersing out to form large, smooth distributions. This image is a composite of three different wavelengths from Spitzer's infrared array camera. The shortest wavelengths are displayed inblue, and mostly show the older stars in NGC 2841, as well as foreground stars in our own Milky Way galaxy. The cooler areas are highlighted in red, and show the dusty, gaseous regions of the galaxy. Blue shows infrared light of 3.6 microns, green represents 4.5-micron light and red, 8.0-micron light. The contribution from starlight measured at 3.6 microns has been subtracted from the 8.0-micron data to enhance the visibility of the dust features.The shortest wavelengths are displayed inblue, and mostly show the older stars in NGC 2841, as well as foreground stars in our own Milky Way galaxy. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA12001

NASA Spitzer Space Telescope image of a glowing stellar nursery provides a spectacular contrast to the opaque cloud seen in visible light inset.

This image was compiled using data from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope using the Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) and the Multiband Imaging Photometer (MIPS) during Spitzer's "cold" mission, before the spacecraft's liquid helium coolant ran out in 2009. The colors correspond with IRAC wavelengths of 3.6 microns (blue), 4.5 microns (cyan) and 8 microns (green), and 24 microns (red) from the MIPS instrument. The green-and-orange delta filling most of this image is a nebula, or a cloud of gas and dust. This region formed from a much larger cloud of gas and dust that has been carved away by radiation from stars. The bright region at the tip of the nebula is dust that has been heated by the stars' radiation, which creates the surrounding red glow. The white color is the combination of four colors (blue, green, orange and red), each representing a different wavelength of infrared light, which is invisible to human eyes. The massive stars illuminating this region belong to a star cluster that extends above the white spot. On the left side of this image, a dark filament runs horizontally through the green cloud. A smattering of baby stars (the red and yellow dots) appear inside it. Known as Cepheus C, the area is a particularly dense concentration of gas and dust where infant stars form. This region is called Cepheus C because it lies in the constellation Cepheus, which can be found near the constellation Cassiopeia. Cepheus-C is about 6 light-years long, and lies about 40 light-years from the bright spot at the tip of the nebula. The small, red hourglass shape just below Cepheus C is V374 Ceph. Astronomers studying this massive star have speculated that it might be surrounded by a nearly edge-on disk of dark, dusty material. The dark cones extending to the right and left of the star are a shadow of that disk. The smaller nebula on the right side of the image includes a blue star crowned by a small, red arc of light. This "runaway star" is plowing through the gas and dust at a rapid clip, creating a shock wave or "bow shock" in front of itself. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23126

![This image from NASA Spitzer Space Telescope, shows the wispy filamentary structure of Henize 206, is a four-color composite mosaic created by combining data from an infrared array camera IRAC. The LMC is a small satellite galaxy gravitationally bound to our own Milky Way. Yet the gravitational effects are tearing the companion to shreds in a long-playing drama of 'intergalactic cannibalism.' These disruptions lead to a recurring cycle of star birth and star death. Astronomers are particularly interested in the LMC because its fractional content of heavy metals is two to five times lower than is seen in our solar neighborhood. [In this context, 'heavy elements' refer to those elements not present in the primordial universe. Such elements as carbon, oxygen and others are produced by nucleosynthesis and are ejected into the interstellar medium via mass loss by stars, including supernova explosions.] As such, the LMC provides a nearby cosmic laboratory that may resemble the distant universe in its chemical composition. The primary Spitzer image, showing the wispy filamentary structure of Henize 206, is a four-color composite mosaic created by combining data from an infrared array camera (IRAC) at near-infrared wavelengths and the mid-infrared data from a multiband imaging photometer (MIPS). Blue represents invisible infrared light at wavelengths of 3.6 and 4.5 microns. Note that most of the stars in the field of view radiate primarily at these short infrared wavelengths. Cyan denotes emission at 5.8 microns, green depicts the 8.0 micron light, and red is used to trace the thermal emission from dust at 24 microns. The separate instrument images are included as insets to the main composite. An inclined ring of emission dominates the central and upper regions of the image. This delineates a bubble of hot, x-ray emitting gas that was blown into space when a massive star died in a supernova explosion millions of years ago. The shock waves from that explosion impacted a cloud of nearby hydrogen gas, compressed it, and started a new generation of star formation. The death of one star led to the birth of many new stars. This is particularly evident in the MIPS inset, where the 24-micron emission peaks correspond to newly formed stars. The ultraviolet and visible-light photons from the new stars are absorbed by surrounding dust and re-radiated at longer infrared wavelengths, where it is detected by Spitzer. This emission nebula was cataloged by Karl Henize (HEN-eyes) while spending 1948-1951 in South Africa doing research for his Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Michigan. Henize later became a NASA astronaut and, at age 59, became the oldest rookie to fly on the Space Shuttle during an eight-day flight of the Challenger in 1985. He died just short of his 67th birthday in 1993 while attempting to climb the north face of Mount Everest, the world's highest peak. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05517](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA05517/PIA05517~medium.jpg)

This image from NASA Spitzer Space Telescope, shows the wispy filamentary structure of Henize 206, is a four-color composite mosaic created by combining data from an infrared array camera IRAC. The LMC is a small satellite galaxy gravitationally bound to our own Milky Way. Yet the gravitational effects are tearing the companion to shreds in a long-playing drama of 'intergalactic cannibalism.' These disruptions lead to a recurring cycle of star birth and star death. Astronomers are particularly interested in the LMC because its fractional content of heavy metals is two to five times lower than is seen in our solar neighborhood. [In this context, 'heavy elements' refer to those elements not present in the primordial universe. Such elements as carbon, oxygen and others are produced by nucleosynthesis and are ejected into the interstellar medium via mass loss by stars, including supernova explosions.] As such, the LMC provides a nearby cosmic laboratory that may resemble the distant universe in its chemical composition. The primary Spitzer image, showing the wispy filamentary structure of Henize 206, is a four-color composite mosaic created by combining data from an infrared array camera (IRAC) at near-infrared wavelengths and the mid-infrared data from a multiband imaging photometer (MIPS). Blue represents invisible infrared light at wavelengths of 3.6 and 4.5 microns. Note that most of the stars in the field of view radiate primarily at these short infrared wavelengths. Cyan denotes emission at 5.8 microns, green depicts the 8.0 micron light, and red is used to trace the thermal emission from dust at 24 microns. The separate instrument images are included as insets to the main composite. An inclined ring of emission dominates the central and upper regions of the image. This delineates a bubble of hot, x-ray emitting gas that was blown into space when a massive star died in a supernova explosion millions of years ago. The shock waves from that explosion impacted a cloud of nearby hydrogen gas, compressed it, and started a new generation of star formation. The death of one star led to the birth of many new stars. This is particularly evident in the MIPS inset, where the 24-micron emission peaks correspond to newly formed stars. The ultraviolet and visible-light photons from the new stars are absorbed by surrounding dust and re-radiated at longer infrared wavelengths, where it is detected by Spitzer. This emission nebula was cataloged by Karl Henize (HEN-eyes) while spending 1948-1951 in South Africa doing research for his Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Michigan. Henize later became a NASA astronaut and, at age 59, became the oldest rookie to fly on the Space Shuttle during an eight-day flight of the Challenger in 1985. He died just short of his 67th birthday in 1993 while attempting to climb the north face of Mount Everest, the world's highest peak. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05517

This image shows data from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, from the IRAC instrument, with colors corresponding to wavelengths of 3.6, 4.5, 5.8 and 8.0 µm (shown as blue, green, orange and red). The grand red delta filling most of the image is a far-away nebula, or a cloud of gas and dust. A second nebula is located in the lower right portion of the image. Within the first nebula, on the left side of this image, a dark filament runs horizontally through the green cloud. A smattering of baby stars (the red and yellow dots) appear inside it. Known as Cepheus C, the area is a particularly dense concentration of gas and dust where infant stars form. This region is called Cepheus C because it lies in the constellation Cepheus, which can be found near the constellation Cassiopeia. Cepheus-C is about 6 light years long, and lies about 40 light-years from the bright spot at the tip of the nebula. Two features identified in the annotated image are visible only in the multi-instrument version of the image, found here. The first is V374 Ceph in the larger nebula. The second is the "runaway star" in the smaller nebula. A second star cluster is located just above the second large nebula on the right side of the image. Known as Cepheus B, the cluster sits within a few thousand light-years of our Sun. A study of this region using Spitzer found that the dramatic collection is about 4 million to 5 million years old — slightly older than those in Cepheus C. Also found in the second nebula is a small cluster of newborn stars that illuminates the dense cloud of gas and dust where they formed. It appears as a bright teal splash. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23127

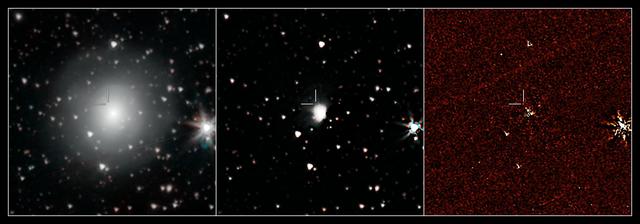

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope has provisionally detected the faint afterglow of the explosive merger of two neutron stars in the galaxy NGC 4993. The event, labeled GW170817, was initially detected in gravitational waves and gamma rays. Subsequent observations by dozens of telescopes have monitored its afterglow across the entire spectrum of light. The event is located about 130 million light-years from Earth. Spitzer's observation on September 29, 2017, came late in the game, just over 6 weeks after the event was first seen. But if this weak detection is verified, it will play an important role in helping astronomers understand how many of the heaviest elements in the periodic table are created in explosive neutron star mergers. The left panel is a color composite of the 3.6 and 4.5 micron channels of the Spitzer IRAC instrument, rendered in cyan and red. The center panel is a median-filtered color composite showing a faint red dot at the known location of the event. The right panel shows the residual 4.5 micron data after subtracting out the light of the galaxy using an archival image that predates the event. An annotated version is at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21910

The Cat's Paw Nebula, imaged here by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, is a star-forming region inside the Milky Way Galaxy and is located in the constellation Scorpius. Its distance from Earth is estimated to be between 1.3 kiloparsecs (about 4,200 light years) to 1.7 kiloparsecs (about 5,500 light years). The image was taken as part of the Galactic Legacy Infrared Midplane Survey Extraordinaire (GLIMPSE), a survey of the Milky Way Galaxy. It was taken using Spitzer's Infrared Array Camera (IRAC). The colors correspond with wavelengths of 3.6 microns (blue), 4.5 microns (green), and 8 microns (red). The bright, cloudlike band running left to right across the image shows the presence of gas and dust that can collapse to form new stars. The black filaments running through the nebula are particularly dense regions of gas and dust. The entire star-forming region is thought to be between 24 and 27 parsecs (80-90 light years) across. New stars may heat up the pressurized gas surrounding them causing the gas to expand and form "bubbles." https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22567

The Cat's Paw Nebula, imaged here by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, lies inside the Milky Way Galaxy and is located in the constellation Scorpius. Its distance from Earth is estimated to be between 1.3 kiloparsecs (about 4,200 light years) to 1.7 kiloparsecs (about 5,500 light years). The bright, cloudlike band running left to right across the image shows the presence of gas and dust that can collapse to form new stars. The black filaments running through the nebula are particularly dense regions of gas and dust. The entire star-forming region is thought to be between 24 and 27 parsecs (80-90 light years) across. The stars that form inside the nebula heat up the pressurized gas surrounding them, such that the gas may expand and form "bubbles", which appear red in this image. Asymmetric bubbles may "burst," creating U-shaped features. The green areas show regions where radiation from hot stars collided with large molecules and small dust grains called "polycyclic aromatic hydocarbons" (PAHs), causing them to fluoresce. This image was compiled using data from two Spitzer instruments, the Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) and the Multiband Imaging Photometer (MIPS). The colors correspond with wavelengths of 3.6 microns (blue), 4.5 microns (cyan), 8 microns (green) and 24 microns (red). https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22568

What looks like a red butterfly in space is in reality a nursery for hundreds of baby stars, revealed in this infrared image from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope. Officially named W40, the butterfly is a nebula - a giant cloud of gas and dust in space where new stars may form. The butterfly's two "wings" are giant bubbles of hot, interstellar gas blowing from the hottest, most massive stars in this region. The material that forms W40's wings was ejected from a dense cluster of stars that lies between the wings in the image. The hottest, most massive of these stars, W40 IRS 1a, lies near the center of the star cluster. W40 is about 1,400 light-years from the Sun, about the same distance as the well-known Orion nebula, although the two are almost 180 degrees apart in the sky. They are two of the nearest regions in which massive stars - with masses upwards of 10 times that of the Sun - have been observed to be forming. The W40 star-forming region was observed as part of a Spitzer Legacy Survey, and the resulting mosaic image was published as part of the MYStIX (Massive Young stellar clusters Study in Infrared and X-rays) survey of young stellar objects. The Spitzer picture is composed of four images taken with the telescope's Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) in different wavelengths of infrared light: 3.6, 4.5, 5.8 and 8.0 µm (shown as blue, green, orange and red). Organic molecules made of carbon and hydrogen, called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are excited by interstellar radiation and become luminescent at wavelengths near 8.0 microns, giving the nebula its reddish features. Stars are brighter at the shorter wavelengths, giving them a blue tint. Some of the youngest stars are surrounded by dusty disks of material, which glow with a yellow or red hue. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23121

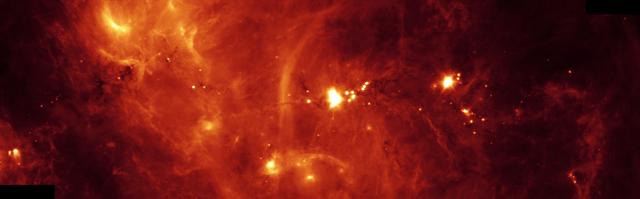

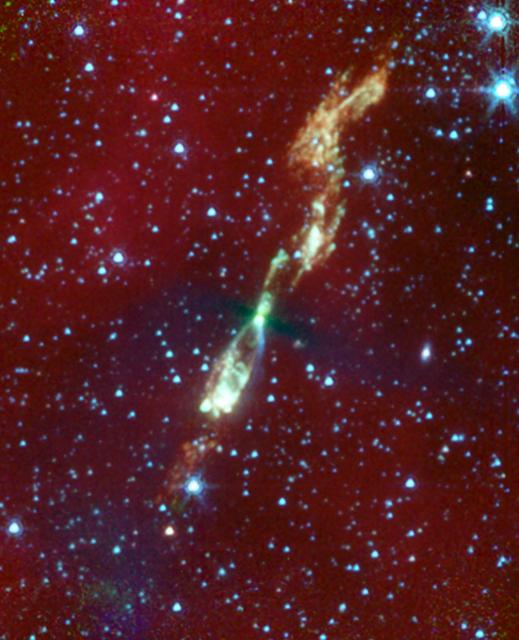

Hidden behind a shroud of dust in the constellation Cygnus is an exceptionally bright source of radio emission called DR21. Visible light images reveal no trace of what is happening in this region because of heavy dust obscuration. In fact, visible light is attenuated in DR21 by a factor of more than 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000, 000,000,000,000 (ten thousand trillion heptillion). New images from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope allow us to peek behind the cosmic veil and pinpoint one of the most massive natal stars yet seen in our Milky Way galaxy. The never-before-seen star is 100,000 times as bright as the Sun. Also revealed for the first time is a powerful outflow of hot gas emanating from this star and bursting through a giant molecular cloud. This image shows a 24-micron image mosaic, obtained with the Multiband Imaging Photometer aboard Spitzer (MIPS). This image maps the cooler infrared emission from interstellar dust found throughout the interstellar medium. The DR21 complex is clearly seen near the center of the strip, which covers about twice the area of the IRAC image. Perhaps the most fascinating feature in this image is a long and shadowy linear filament extending towards the 10 o'clock position of DR21. This jet of cold and dense gas, nearly 50 light-years in extent, appears in silhouette against a warmer background. This filament is too long and massive to be a stellar jet and may have formed from a pre-existing molecular cloud core sculpted by DR21's strong winds. Regardless of its true nature, this jet and the numerous other arcs and wisps of cool dust signify the interstellar turbulence normally unseen by the human eye. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05733

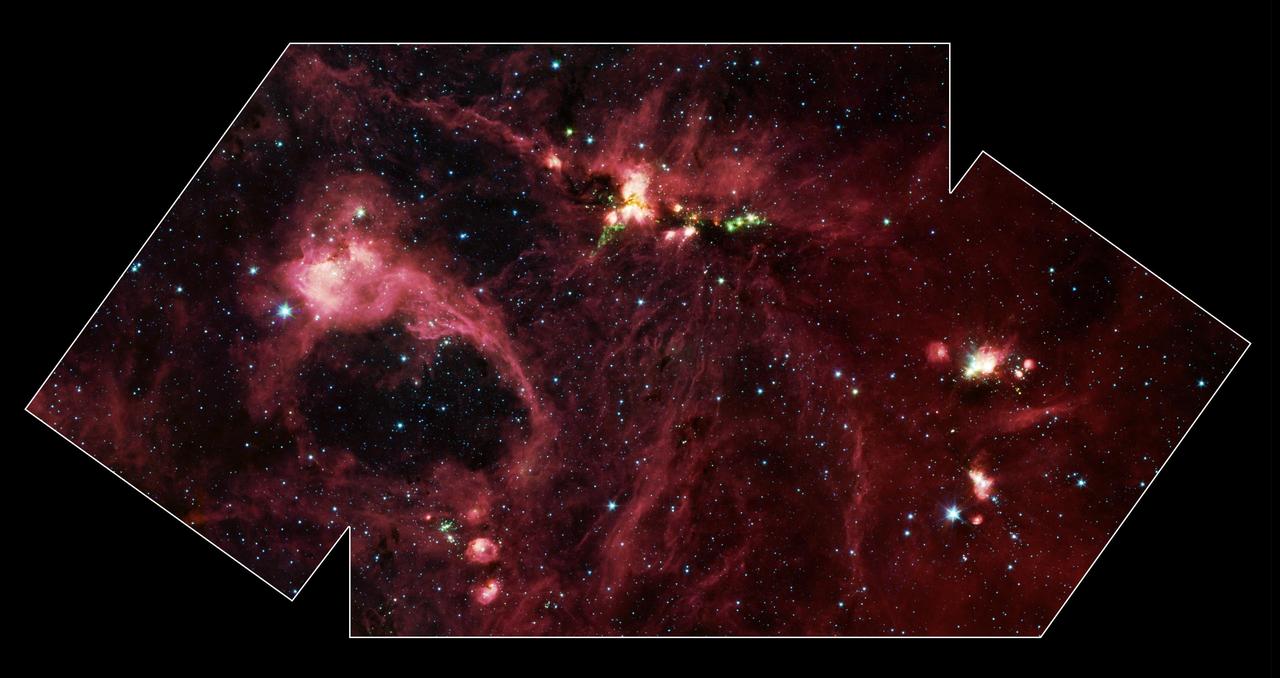

Hidden behind a shroud of dust in the constellation Cygnus is a stellar nursery called DR21, which is giving birth to some of the most massive stars in our galaxy. Visible light images reveal no trace of this interstellar cauldron because of heavy dust obscuration. In fact, visible light is attenuated in DR21 by a factor of more than 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (ten thousand trillion heptillion). New images from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope allow us to peek behind the cosmic veil and pinpoint one of the most massive natal stars yet seen in our Milky Way galaxy. The never-before-seen star is 100,000 times as bright as the Sun. Also revealed for the first time is a powerful outflow of hot gas emanating from this star and bursting through a giant molecular cloud. The colorful image is a large-scale composite mosaic assembled from data collected at a variety of different wavelengths. Views at visible wavelengths appear blue, near-infrared light is depicted as green, and mid-infrared data from the InfraRed Array Camera (IRAC) aboard NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope is portrayed as red. The result is a contrast between structures seen in visible light (blue) and those observed in the infrared (yellow and red). A quick glance shows that most of the action in this image is revealed to the unique eyes of Spitzer. The image covers an area about two times that of a full moon. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05734

Hidden behind a shroud of dust in the constellation Cygnus is a stellar nursery called DR21, which is giving birth to some of the most massive stars in our galaxy. Visible light images reveal no trace of this interstellar cauldron because of heavy dust obscuration. In fact, visible light is attenuated in DR21 by a factor of more than 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (ten thousand trillion heptillion). New images from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope allow us to peek behind the cosmic veil and pinpoint one of the most massive natal stars yet seen in our Milky Way galaxy. The never-before-seen star is 100,000 times as bright as the Sun. Also revealed for the first time is a powerful outflow of hot gas emanating from this star and bursting through a giant molecular cloud. This image is a large-scale mosaic assembled from individual photographs obtained with the InfraRed Array Camera (IRAC) aboard Spitzer. The image covers an area about two times that of a full moon. The mosaic is a composite of images obtained at mid-infrared wavelengths of 3.6 microns (blue), 4.5 microns (green), 5.8 microns (orange) and 8 microns (red). The brightest infrared cloud near the top center corresponds to DR21, which presumably contains a cluster of newly forming stars at a distance of 10,000 light-years. Protruding out from DR21 toward the bottom left of the image is a gaseous outflow (green), containing both carbon monoxide and molecular hydrogen. Data from the Spitzer spectrograph, which breaks light into its constituent individual wavelengths, indicate the presence of hot steam formed as the outflow heats the surrounding molecular gas. Outflows are physical signatures of processes that create supersonic beams, or jets, of gas. They are usually accompanied by discs of material around the new star, which likely contain the materials from which future planetary systems are formed. Additional newborn stars, depicted in green, can be seen surrounding the DR21 region. The red filaments stretching across this image denote the presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. These organic molecules, comprised of carbon and hydrogen, are excited by surrounding interstellar radiation and become luminescent at wavelengths near 8.0 microns. The complex pattern of filaments is caused by an intricate combination of radiation pressure, gravity and magnetic fields. The result is a tapestry in which winds, outflows and turbulence move and shape the interstellar medium. To the lower left of the mosaic is a large bubble of gas and dust, which may represent the remnants of a past generation of stars. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05732

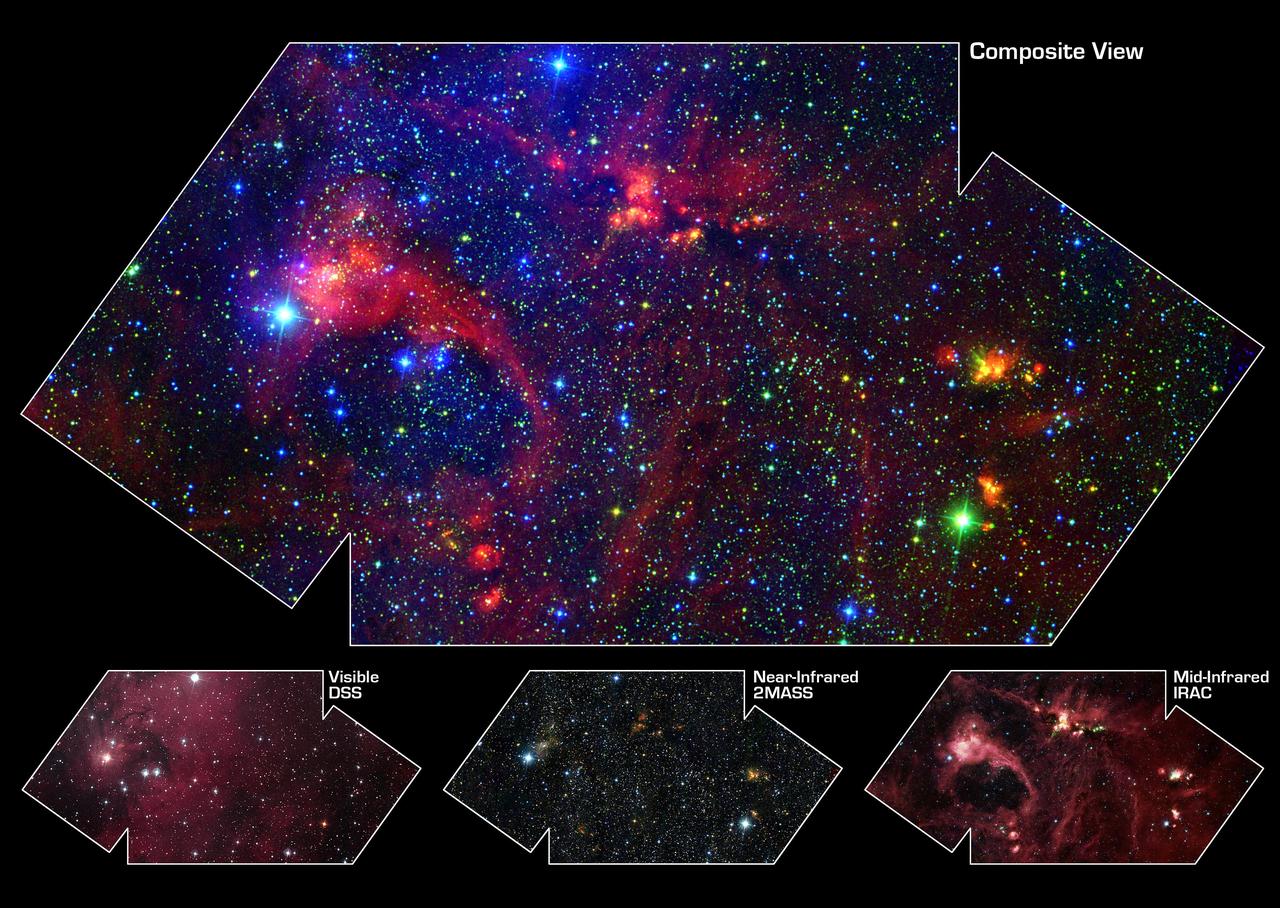

Hidden behind a shroud of dust in the constellation Cygnus is a stellar nursery called DR21, which is giving birth to some of the most massive stars in our galaxy. Visible light images reveal no trace of this interstellar cauldron because of heavy dust obscuration. In fact, visible light is attenuated in DR21 by a factor of more than 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (ten thousand trillion heptillion). New images from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope allow us to peek behind the cosmic veil and pinpoint one of the most massive natal stars yet seen in our Milky Way galaxy. The never-before-seen star is 100,000 times as bright as the Sun. Also revealed for the first time is a powerful outflow of hot gas emanating from this star and bursting through a giant molecular cloud. The colorful image (top panel) is a large-scale composite mosaic assembled from data collected at a variety of different wavelengths. Views at visible wavelengths appear blue, near-infrared light is depicted as green, and mid-infrared data from the InfraRed Array Camera (IRAC) aboard NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope is portrayed as red. The result is a contrast between structures seen in visible light (blue) and those observed in the infrared (yellow and red). A quick glance shows that most of the action in this image is revealed to the unique eyes of Spitzer. The image covers an area about two times that of a full moon. Each of the constituent images is shown below the large mosaic. The Digital Sky Survey (DSS) image (lower left) provides a familiar view of deep space, with stars scattered around a dark field. The reddish hue is from gas heated by foreground stars in this region. This fluorescence fades away in the near-infrared Two-Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS) image (lower center), but other features start to appear through the obscuring clouds of dust, now increasingly transparent. Many more stars are discerned in this image because near-infrared light pierces through some of the obscuration of the interstellar dust. Note that some stars seen as very bright in the visible image are muted in the near-infrared image, whereas other stars become more prominent. Embedded nebulae revealed in the Spitzer image are only hinted at in this picture. The Spitzer image (lower right) provides a vivid contrast to the other component images, revealing star-forming complexes and large-scale structures otherwise hidden from view. The Spitzer image is composed of photographs obtained at four wavelengths: 3.6 microns (blue), 4.5 microns (green), 5.8 microns (orange) and 8 microns (red). The brightest infrared cloud near the top center corresponds to DR21, which presumably contains a cluster of newly forming stars at a distance of nearly 10,000 light-years. The red filaments stretching across the Spitzer image denote the presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. These organic molecules, comprised of carbon and hydrogen, are excited by surrounding interstellar radiation and become luminescent at wavelengths near 8 microns. The complex pattern of filaments is caused by an intricate combination of radiation pressure, gravity, and magnetic fields. The result is a tapestry in which winds, outflows, and turbulence move and shape the interstellar medium. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05735

A rare, infrared view of a developing star and its flaring jets taken by NASA Spitzer Space Telescope shows us what our own solar system might have looked like billions of years ago.

This infrared image from NASA Spitzer Space Telescope shows a galaxy that appears to be sizzling hot, with huge plumes of smoke swirling around it. The galaxy is known as Messier 82 or the Cigar galaxy.

This majestic false-color image from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope shows the "mountains" where stars are born. Dubbed "Mountains of Creation" by Spitzer scientists, these towering pillars of cool gas and dust are illuminated at their tips with light from warm embryonic stars. The new infrared picture is reminiscent of Hubble's iconic visible-light image of the Eagle Nebula, which also features a star-forming region, or nebula, that is being sculpted into pillars by radiation and winds from hot, massive stars. The pillars in the Spitzer image are part of a region called W5, in the Cassiopeia constellation 7,000 light-years away and 50 light-years across. They are more than 10 times in the size of those in the Eagle Nebula (shown to scale here). The Spitzer's view differs from Hubble's because infrared light penetrates dust, whereas visible light is blocked by it. In the Spitzer image, hundreds of forming stars (white/yellow) can seen for the first time inside the central pillar, and dozens inside the tall pillar to the left. Scientists believe these star clusters were triggered into existence by radiation and winds from an "initiator" star more than 10 times the mass of our Sun. This star is not pictured, but the finger-like pillars "point" toward its location above the image frame. The Spitzer picture also reveals stars (blue) a bit older than the ones in the pillar tips in the evacuated areas between the clouds. Scientists believe these stars were born around the same time as the massive initiator star not pictured. A third group of young stars occupies the bright area below the central pillar. It is not known whether these stars formed in a related or separate event. Some of the blue dots are foreground stars that are not members of this nebula. The red color in the Spitzer image represents organic molecules known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. These building blocks of life are often found in star-forming clouds of gas and dust. Like small dust grains, they are heated by the light from the young stars, then emit energy in infrared wavelengths. This image was taken by the infrared array camera on Spitzer. It is a 4-color composite of infrared light, showing emissions from wavelengths of 3.6 microns (blue), 4.5 microns (green), 5.8 microns (orange), and 8.0 microns (red). http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA03096