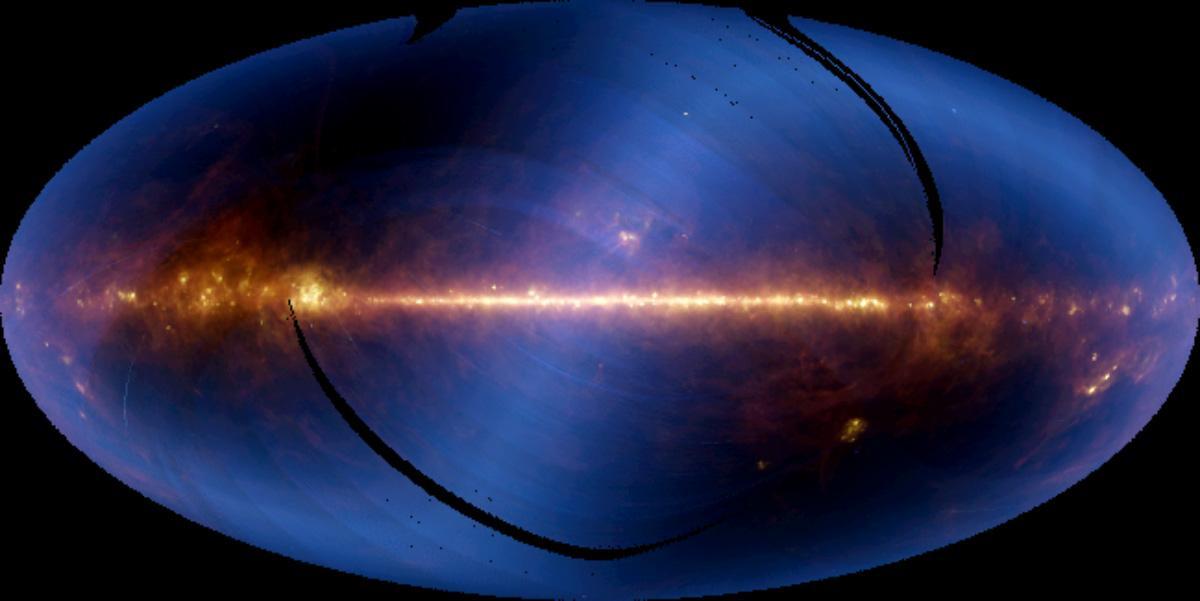

Nearly the entire sky, as seen in infrared wavelengths and projected at one-half degree resolution, is shown in this image, assembled from six months of data from the NASA Infrared Astronomical Satellite, or IRAS.

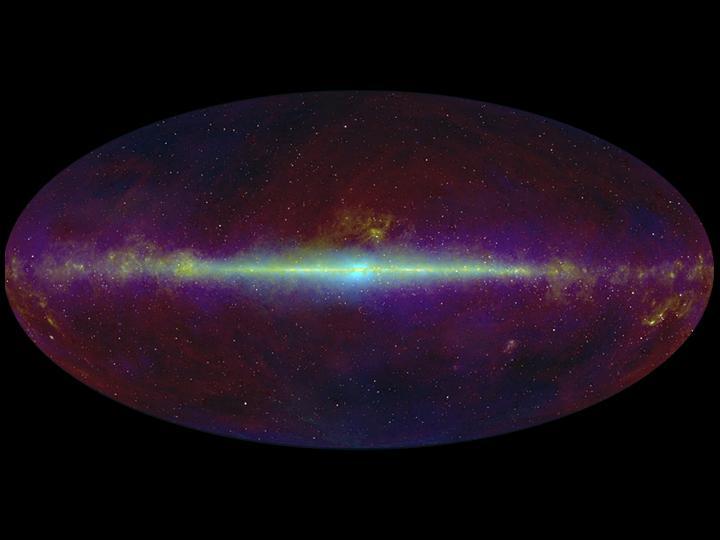

This infrared view of the whole sky highlights the flat plane of our Milky Way galaxy line across middle of image. NASA WISE, will take a similar infrared census of the whole sky, only with much improved resolution and sensitivity.

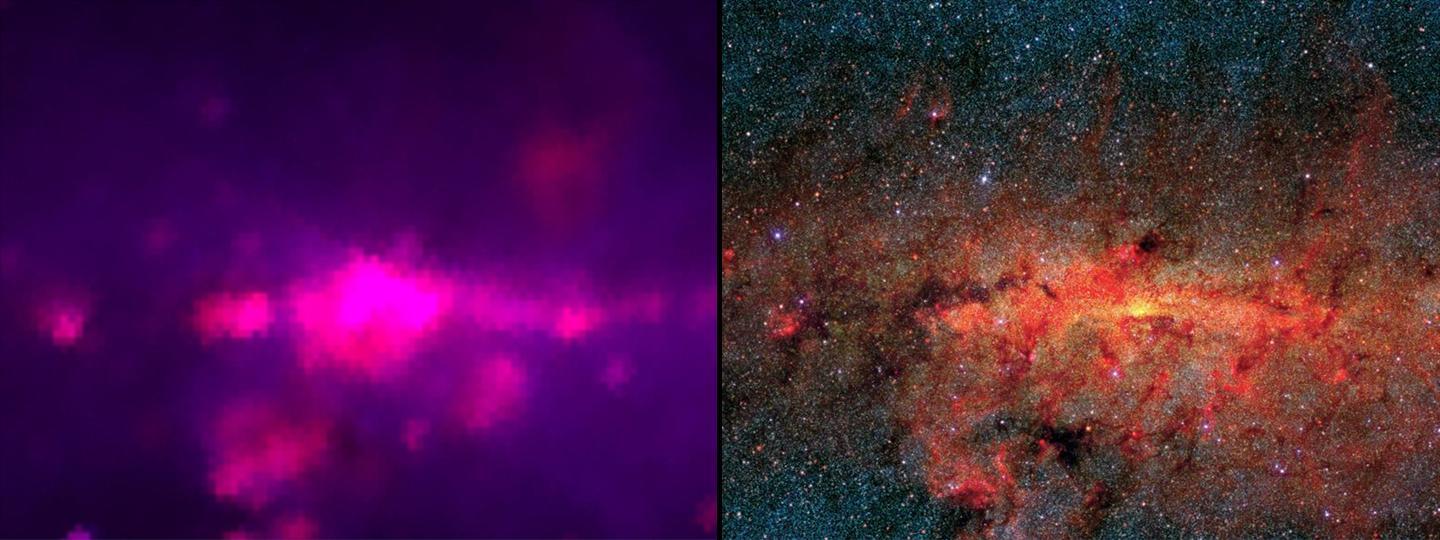

The image on the left shows an infrared view of the center of our Milky Way galaxy as seen by the 1983 Infrared Astronomical Satellite, which surveyed the whole sky with only 62 pixels. The image on the right shows an infrared view similar to what NASA

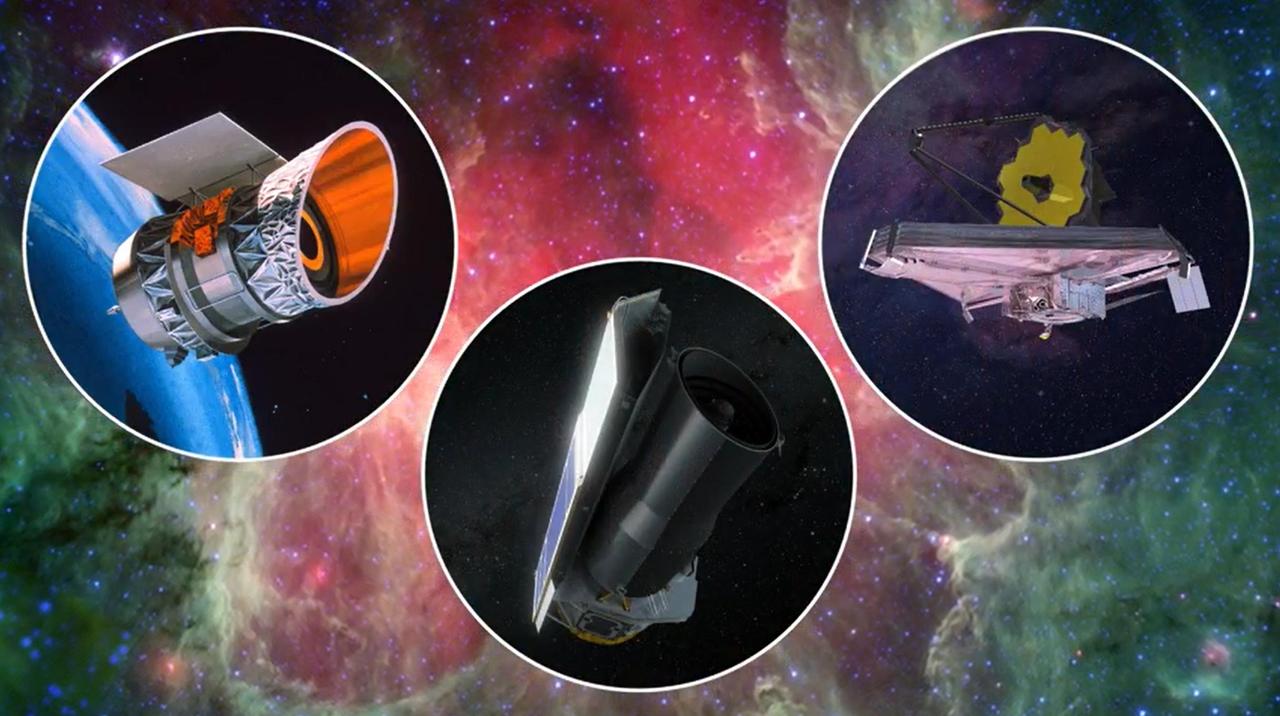

This artist's concept shows three space telescopes that observe infrared light, wavelengths slightly longer than what human eyes can see. On the right is NASA's James Webb Space Telescope. Launched in 2021, it is the largest and most powerful space observatory in history. On the left is NASA's Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS), the first infrared telescope in Earth orbit, launched in 1983. In the middle is NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, launched in 2003. The background image is from Spitzer and shows the Eagle Nebula. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25790

This image of the star-forming region Rho Ophiuchi was taken in 1983 by the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS), the first infrared telescope ever launched into Earth orbit. Infrared light refers to wavelengths slightly longer than what human eyes can see. Most infrared wavelengths are blocked by Earth's atmosphere, so infrared space telescopes are essential for observing the full breadth of infrared light from cosmic sources. Rho Ophiuchi's thick clouds of gas and dust block visible light, but IRAS' infrared vision made it the first observatory to be able to pierce those layers to reveal newborn stars nestled deep inside. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26271

This artist's concept illustrates the ring of material discovered by the Infrared Astronomical Satellite around the star Vega. IRAS scientists believe the material probably consists of dust and small objects resembling meteors. As depicted here, the ring of particles is thin enough toallow light from distant stars to shine through. The plane of the Milky Way is to the right.

Milky way - This image of the center of our galaxy was produced from observtons made by the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS). The infrared telescope carried by IRAS sees through the dust and gas that obscures stars and other objects when viewed by optical telescopes. The bulge in the band is the center of the galaxy. The knots and blobs scattered along the band are giant clouds of interstellar gas and dust heated by nearby stars. Some are wrmed by newly formed stars in the surrounding cloud and some are heated by nearby massive, hot, blue stars tens of thousands of times brighter than our Sun.

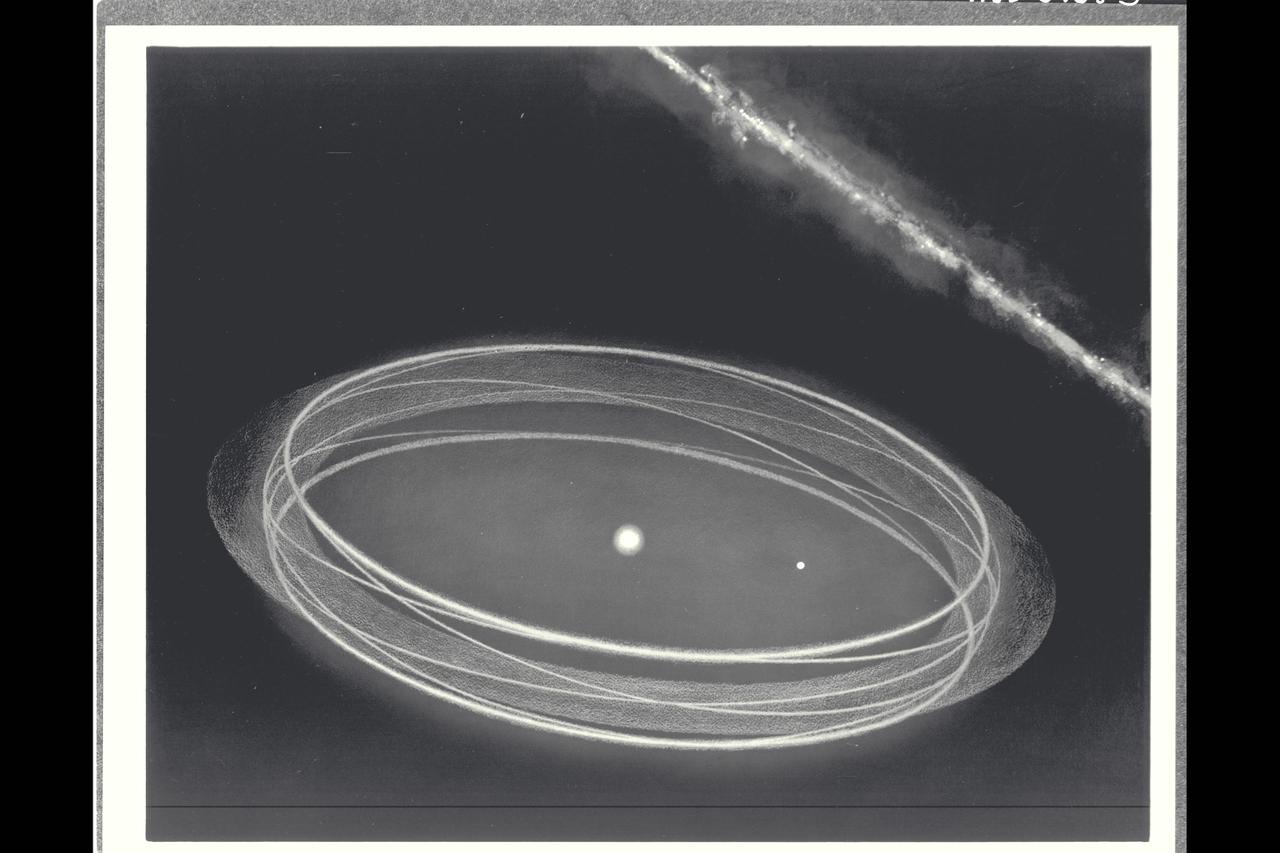

This artist's concept show how it is possible for a single collection of particles, which share a common family of orbits around the Sun, to produce the appearance of identical bands on either side of the zodical or ecliptic plane. The bands were discovered in data from the Infrared Astronomical Satellite. Also illustrated is the concept of a comet/asteroid collision which could have created a cloud of debris. The dust cloud, as depicted here, has the orbital parameters needed to produce the band structure observed by IRAS.

This artist's concept show how it is possible for a single collection of particles, which share a common family of orbits around the Sun, to produce the appearance of identical bands on either side of the zodical or ecliptic plane. The bands were discovered in data from the Infrared Astronomical Satellite. Also illustrated is the concept of a comet/asteroid collision which could have created a cloud of debris. The dust cloud, as depicted here, has the orbital parameters needed to produce the band structure observed by IRAS.

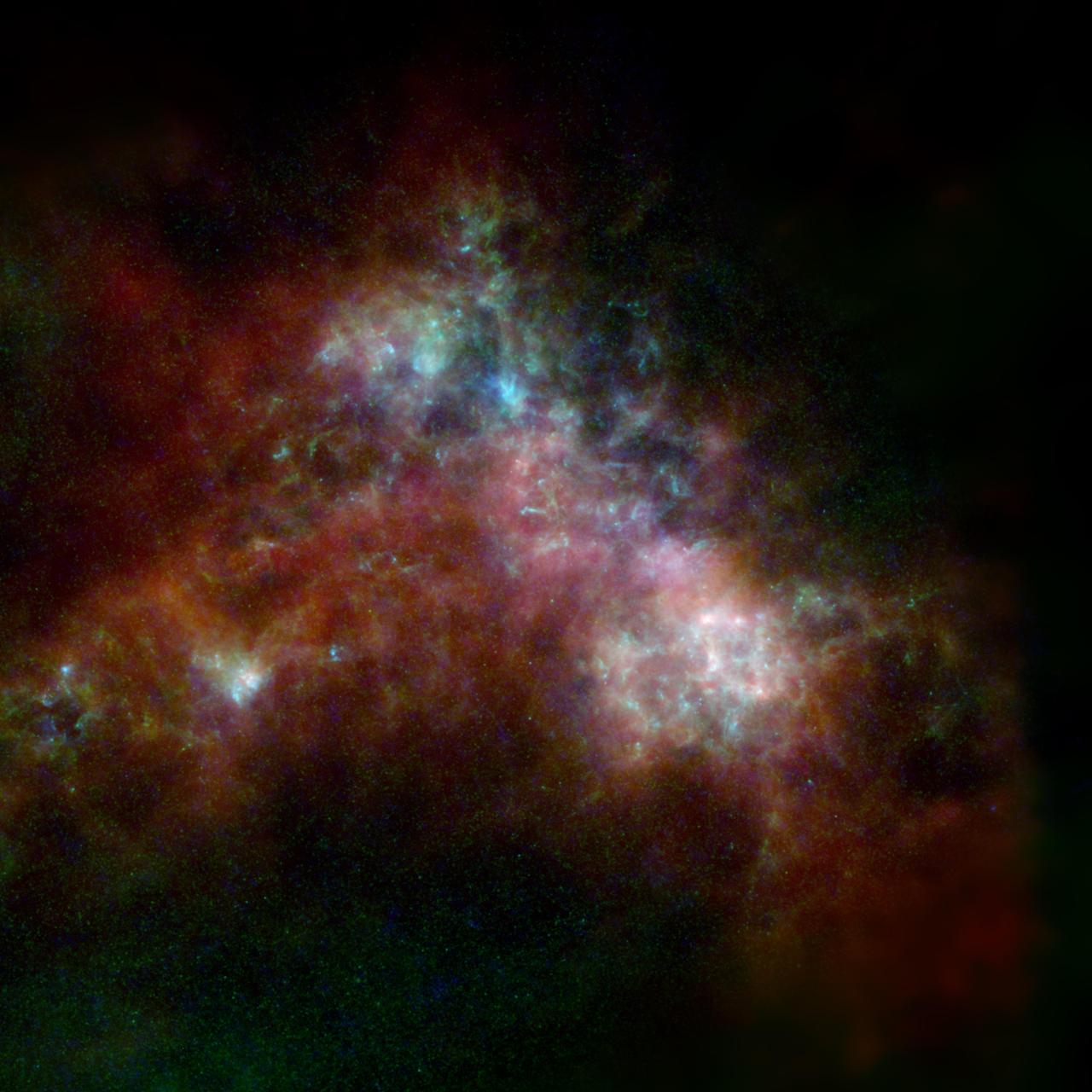

The Small Magellanic Cloud, shown here, is a dwarf galaxy orbiting the Milky Way. The image includes data from the ESA (European Space Agency) Herschel mission, supplemented with data from ESA's retired Planck observatory and two retired NASA missions: the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) and Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE). Operated from 2009 to 2013, Herschel detected wavelengths of light in the far-infrared and microwave ranges, and was ideal for studying dust in nearby galaxies because it could capture small-scale structures in the dust clouds in high resolution. However, Herschel often couldn't detect light from diffuse dust clouds – especially in the outer regions of galaxies, where the gas and dust become sparse and thus fainter. As a result, the mission missed up to 30% of all the light given off by dust. Combining the Herschel observations with data from other observatories creates a more complete picture of the dust in the galaxy. In the image, red indicates hydrogen gas; green indicates cold dust; and warmer dust is shown in blue. Launched in 1983, IRAS was the first space telescope to detect infrared light, setting the stage for future observatories like NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and James Webb Space Telescope. The Planck observatory, launched in 2009, and COBE, launched in 1989, both studied the cosmic microwave background, or light left over from the big bang. The hydrogen gas was detected using the Parkes Radio Telescope and the Australia Compact Telescope Array, located in Australia and managed by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO); and the NANTEN2 Observatory in the Atacama Desert in Chile. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25164

This image of the Andromeda galaxy, or M31, includes data from the ESA (European Space Agency) Herschel mission, supplemented with data from ESA's retired Planck observatory and two retired NASA missions: the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) and Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE). Operated from 2009 to 2013, Herschel detected wavelengths of light in the far-infrared and microwave ranges, and was ideal for studying dust in nearby galaxies because it could capture small-scale structures in the dust clouds in high resolution. However, Herschel often couldn't detect light from diffuse dust clouds – especially in the outer regions of galaxies, where the gas and dust become sparse and thus fainter. As a result, the mission missed up to 30% of all the light given off by dust. Combining the Herschel observations with data from other observatories creates a more complete picture of the dust in the galaxy. In the image, red indicates hydrogen gas; green indicates cold dust; and warmer dust is shown in blue. Launched in 1983, IRAS was the first space telescope to detect infrared light, setting the stage for future observatories like NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and James Webb Space Telescope. The Planck observatory, launched in 2009, and COBE, launched in 1989, both studied the cosmic microwave background, or light left over from the big bang. Red indicates hydrogen gas detected using the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, the Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope in the Netherlands, and the Institute for Radio Astronomy in the Millimeter Range 30-meter telescope in Spain. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25163

This image of the Triangulum galaxy, or M33, includes data from the ESA (European Space Agency) Herschel mission, supplemented with data from ESA's retired Planck observatory and two retired NASA missions: the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) and Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE). Operated from 2009 to 2013, Herschel detected wavelengths of light in the far-infrared and microwave ranges, and was ideal for studying dust in nearby galaxies because it could capture small-scale structures in the dust clouds in high resolution. However, Herschel often couldn't detect light from diffuse dust clouds – especially in the outer regions of galaxies, where the gas and dust become sparse and thus fainter. As a result, the mission missed up to 30% of all the light given off by dust. Combining the Herschel observations with data from other observatories creates a more complete picture of the dust in the galaxy. In the image, red indicates hydrogen gas; green indicates cold dust; and warmer dust is shown in blue. Launched in 1983, IRAS was the first space telescope to detect infrared light, setting the stage for future observatories like NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and James Webb Space Telescope. The Planck observatory, launched in 2009, and COBE, launched in 1989, both studied the cosmic microwave background, or light left over from the big bang. The hydrogen gas was detected using the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array in New Mexico, and the Institute for Radio Astronomy in the Millimeter Range 30-meter telescope in Spain. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25165