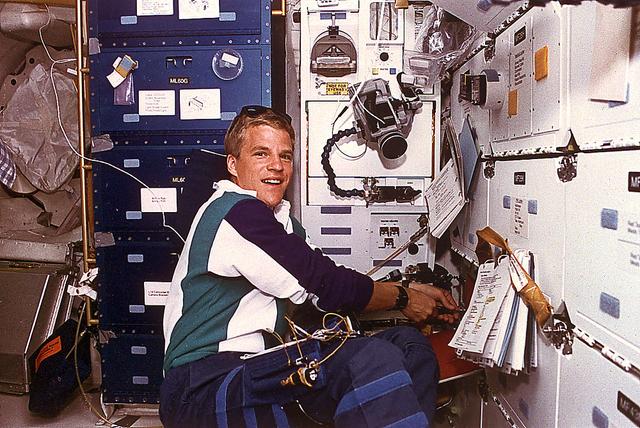

This is an onboard photo of space shuttle Atlantis (STS-66) astronaut Scott E. Parazynski, in the International Microgravity Laboratory (IML), performing a series of experiments devoted to material and life sciences studies using the Spacelab Long Module (SLM). STS-066 was launched on November 3, 1994.

The first International Space Station experiment facility--the Microgravity Glovebox Ground Unit--has been delivered to Marshall Space Flight Center's Microgravity Development Laboratory. The glovebox is a facility that provides a sealed work area accessed by the crew in gloves. This glovebox will be used at the Marshall laboratory throughout the Space Station era.

This is a Space Shuttle Columbia (STS-65) onboard photo of the second International Microgravity Laboratory (IML-2) in the cargo bay with Earth in the background. Mission objectives of IML-2 were to conduct science and technology investigations that required the low-gravity environment of space, with emphasis on experiments that studied the effects of microgravity on materials processes and living organisms. Materials science and life sciences are two of the most exciting areas of microgravity research because discoveries in these fields could greatly enhance the quality of life on Earth. If the structure of certain proteins can be determined by examining high-quality protein crystals grown in microgravity, advances can be made to improve the treatment of many human diseases. Electronic materials research in space may help us refine processes and make better products, such as computers, lasers, and other high-tech devices. The 14-nation European Space Agency (ESA), the Canadian Space Agency (SCA), the French National Center for Space Studies (CNES), the German Space Agency and the German Aerospace Research Establishment (DARA/DLR), and the National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA) participated in developing hardware and experiments for the IML missions. The missions were managed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. The Orbiter Columbia was launched from the Kennedy Space Center on July 8, 1994 for the IML-2 mission.

Astronaut Carl E. Walz, mission specialist, flies through the second International Microgravity Laboratory (IML-2) science module, STS-65 mission. IML was dedicated to study fundamental materials and life sciences in a microgravity environment inside Spacelab, a laboratory carried aloft by the Shuttle. The mission explored how life forms adapt to weightlessness and investigated how materials behave when processed in space. The IML program gave a team of scientists from around the world access to a unique environment, one that is free from most of Earth's gravity. Managed by the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, the 14-nation European Space Agency (ESA), the Canadian Space Agency (SCA), the French National Center for Space Studies (CNES), the German Space Agency and the German Aerospace Research Establishment (DARA/DLR), and the National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA) participated in developing hardware and experiments for the IML missions. The missions were managed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. The Orbiter Columbia was launched on July 8, 1994 for the IML-2 mission.

In this photograph, astronaut David Hilmers conducts a life science experiment by using the Biorack Glovebox (GBX) during the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1) mission. The Biorack was a large multipurpose facility designed for studying the effects of microgravity and cosmic radiation on numerous small life forms such as cells, tissues, small organisms, and plants. Located at the Biorack, the GBX was an enclosed environment that protected samples from contamination and prevented liquid from escaping. Crewmembers handled the specimens with their hands inside gloves that extended into the sealed work area. A microscope and video camera mounted on the GBX door were used to observe and document experiments. Managed by the Marshall Space Flight Center, the IML-1 mission was the first in a series of Shuttle flights dedicated to fundamental materials and life sciences research and was launched aboard the Shuttle Orbiter Discovery (STS-42) on January 22, 1992.

In this photograph, astronaut Roberta Bondar conducts a life science experiment by using the Biorack Glovebox (GBX) during the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1) mission. The Biorack was a large multipurpose facility designed for studying the effects of microgravity and cosmic radiation on numerous small life forms such as cells, tissues, small organisms, and plants. Located at the Biorack, the GBX was an enclosed environment that protected samples from contamination and prevented liquid from escaping. Crewmembers handled the specimens with their hands inside gloves that extended into the sealed work area. A microscope and video camera mounted on the GBX door were used to observe and document experiments. Managed by the Marshall Space Flight Center, the IML-1 mission was the first in a series of Shuttle flights dedicated to fundamental materials and life sciences research and was launched aboard the Shuttle Orbiter Discovery (STS-42) on January 22, 1992.

International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1) was the first in a series of Shuttle flights dedicated to fundamental materials and life sciences research with the international partners. The participating space agencies included: NASA, the 14-nation European Space Agency (ESA), the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the French National Center of Space Studies (CNES), the German Space Agency and the German Aerospace Research Establishment (DAR/DLR), and the National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA). Dedicated to the study of life and materials sciences in microgravity, the IML missions explored how life forms adapt to weightlessness and investigated how materials behave when processed in space. Both life and materials sciences benefited from the extended periods of microgravity available inside the Spacelab science module in the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Orbiter. In this photograph, Astronauts Stephen S. Oswald and Norman E. Thagard handle ampoules used in the Mercuric Iodide Crystal Growth (MICG) experiment. Mercury Iodide crystals have practical uses as sensitive x-ray and gamma-ray detectors. In addition to their exceptional electronic properties, these crystals can operate at room temperature rather than at the extremely low temperatures usually required by other materials. Because a bulky cooling system is urnecessary, these crystals could be useful in portable detector devices for nuclear power plant monitoring, natural resource prospecting, biomedical applications in diagnosis and therapy, and astronomical observation. Managed by the Marshall Space Flight Center, IML-1 was launched on January 22, 1992 aboard the Space Shuttle Orbiter Discovery (STS-42 mission).

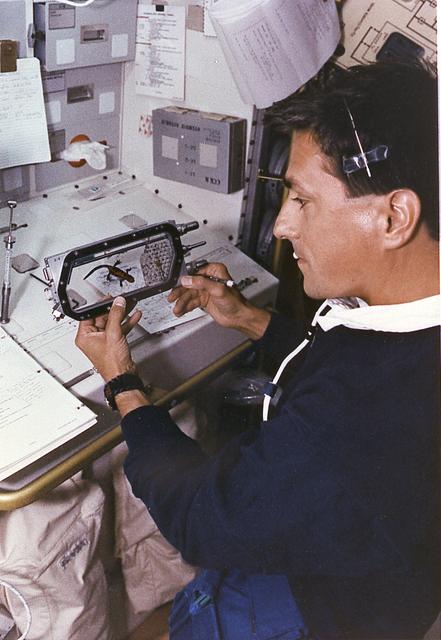

Astronaut Donald Thomas conducts the Fertilization and Embryonic Development of Japanese Newt in Space (AstroNewt) experiment at the Aquatic Animal Experiment Unit (AAEU) inside the International Microgravity Laboratory-2 (IML-2) science module. The AstroNewt experiment aims to know the effects of gravity on the early developmental process of fertilized eggs using a unique aquatic animal, the Japanese red-bellied newt. The newt egg is a large single cell at the begirning of development. The Japanese newt mates in spring and autumn. In late autumn, female newts enter hibernation with sperm in their body cavity and in spring lay eggs and fertilized them with the stored sperm. The experiment takes advantage of this feature of the newt. Groups of newts were sent to the Kennedy Space Center and kept in hibernation until the mission. The AAEU cassettes carried four newts aboard the Space Shuttle. Two newts in one cassette are treated by hormone injection on the ground to simulate egg laying. The other two newts are treated on orbit by the crew. The former group started maturization of eggs before launch. The effects of gravity on that early process were differentiated by comparison of the two groups. The IML-2 was the second in a series of Spacelab flights designed to conduct research by the international science community in a microgravity environment. Managed by the Marshall Space Flight Center, the IML-2 was launch on July 8, 1994 aboard the STS-65 Space Shuttle Orbiter Columbia mission.

Astronaut Donald Thomas conducts the Fertilization and Embryonic Development of Japanese Newt in Space (AstroNewt) experiment at the Aquatic Animal Experiment Unit (AAEU) inside the International Microgravity Laboratory-2 (IML-2) science module. The AstroNewt experiment aims to know the effects of gravity on the early developmental process of fertilized eggs using a unique aquatic animal, the Japanese red-bellied newt. The newt egg is a large single cell at the begirning of development. The Japanese newt mates in spring and autumn. In late autumn, female newts enter hibernation with sperm in their body cavity and in spring lay eggs and fertilize them with the stored sperm. The experiment takes advantage of this feature of the newt. Groups of newts were sent to the Kennedy Space Center and kept in hibernation until the mission. The AAEU cassettes carried four newts aboard the Space Shuttle. Two newts in one cassette are treated by hormone injection on the ground to simulate egg laying. The other two newts are treated on orbit by the crew. The former group started maturization of eggs before launch. The effects of gravity on that early process were differentiated by comparison of the two groups. The IML-2 was the second in a series of Spacelab flights designed to conduct research by the international science community in a microgravity environment. Managed by the Marshall Space Flight Center, the IML-2 was launched on July 8, 1994 aboard the STS-65 Space Shuttle mission, Orbiter Columbia.

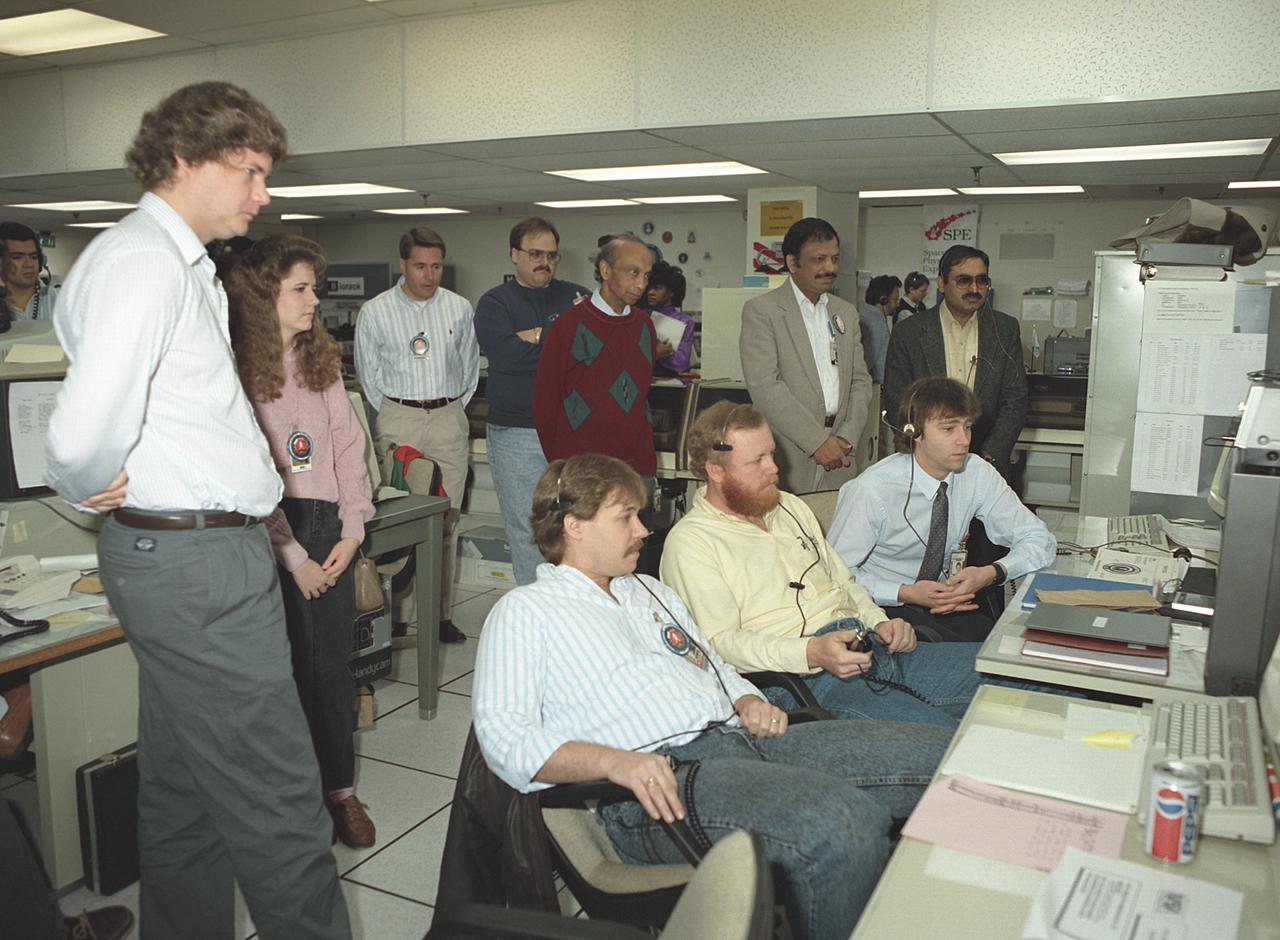

This photograph shows activities during the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1) mission (STS-42) in the Payload Operations Control Center (POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center. The IML-1 mission was the first in a series of Shuttle flights dedicated to fundamental materials and life sciences research. The mission was to explore, in depth, the complex effects of weightlessness on living organisms and materials processing. The crew conducted experiments on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and the effects on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Low gravity materials processing experiments included crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury, iodine, and virus. The International space science research organizations that participated in this mission were: The U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the European Space Agency, the Canadian Space Agency, the French National Center for Space Studies, the German Space Agency, and the National Space Development Agency of Japan. The POCC was the air/ground communication charnel used between the astronauts aboard the Spacelab and scientists, researchers, and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. The facility made instantaneous video and audio communications possible for scientists on the ground to follow the progress and to send direct commands of their research almost as if they were in space with the crew.

This photograph shows activities during the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1) mission (STS-42) in the Payload Operations Control Center (POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center. Members of the Fluid Experiment System (FES) group monitor the progress of their experiment through video at the POCC. The IML-1 mission was the first in a series of Shuttle flights dedicated to fundamental materials and life sciences research. The mission was to explore, in depth, the complex effects of weightlessness on living organisms and materials processing. The crew conducted experiments on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and the effects on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Low gravity materials processing experiments included crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury, iodine, and virus. The International space science research organizations that participated in this mission were: The U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administion, the European Space Agency, the Canadian Space Agency, the French National Center for Space Studies, the German Space Agency, and the National Space Development Agency of Japan. The POCC was the air/ground communication charnel used between astronauts aboard the Spacelab and scientists, researchers, and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. The facility made instantaneous video and audio communications possible for scientists on the ground to follow the progress and to send direct commands of their research almost as if they were in space with the crew.

Astronaut Chiaki Mukai conducts the Lower Body Negative Pressure (LBNP) experiment inside the International Microgravity Laboratory-2 (IML-2) mission science module. Dr. Chiaki Mukai is one of the National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA) astronauts chosen by NASA as a payload specialist (PS). She was the second NASDA PS who flew aboard the Space Shuttle, and was the first female astronaut in Asia. When humans go into space, the lack of gravity causes many changes in the body. One change is that fluids normally kept in the lower body by gravity shift upward to the head and chest. This is why astronauts' faces appear chubby or puffy. The change in fluid volume also affects the heart. The reduced fluid volume means that there is less blood to circulate through the body. Crewmembers may experience reduced blood flow to the brain when returning to Earth. This leads to fainting or near-fainting episodes. With the use of the LBNP to simulate the pull of gravity in conjunction with fluids, salt tablets can recondition the cardiovascular system. This treatment, called "soak," is effective up to 24 hours. The LBNP uses a three-layer collapsible cylinder that seals around the crewmember's waist which simulates the effects of gravity and helps pull fluids into the lower body. The data collected will be analyzed to determine physiological changes in the crewmembers and effectiveness of the treatment. The IML-2 was the second in a series of Spacelab flights designed by the international science community to conduct research in a microgravity environment Managed by the Marshall Space Flight Center, the IML-2 was launched on July 8, 1994 aboard the STS-65 Space Shuttle Orbiter Columbia mission.

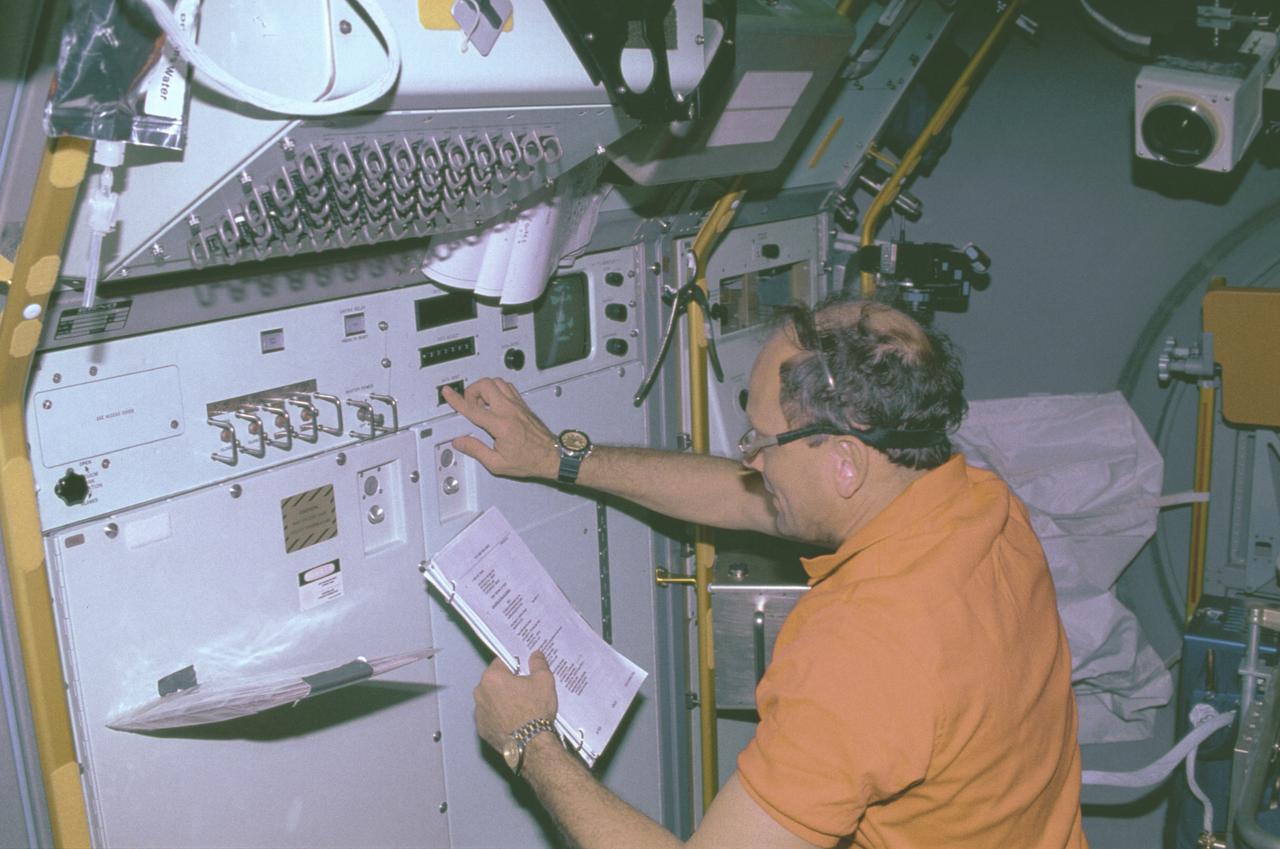

The IML-1 mission was the first in a series of Shuttle flights dedicated to fundamental materials and life sciences research with the international partners. The participating space agencies included: NASA, the 14-nation European Space Agency (ESA), the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), The French National Center of Space Studies (CNES), the German Space Agency and the German Aerospace Research Establishment (DAR/DLR), and the National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA). Dedicated to the study of life and materials sciences in microgravity, the IML missions explored how life forms adapt to weightlessness and investigated how materials behave when processed in space. Both life and materials sciences benefited from the extended periods of microgravity available inside the Spacelab science module in the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Orbiter. This photograph shows Astronaut Norman Thagard performing the fluid experiment at the Fluid Experiment System (FES) facility inside the laboratory module. The FES facility had sophisticated optical systems for imaging fluid flows during materials processing, such as experiments to grow crystals from solution and solidify metal-modeling salts. A special laser diagnostic technique recorded the experiments, holograms were made for post-flight analysis, and video was used to view the samples in space and on the ground. Managed by the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), the IML-1 mission was launched on January 22, 1992 aboard the Shuttle Orbiter Discovery (STS-42).

The primary payload for Space Shuttle Mission STS-42, launched January 22, 1992, was the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1), a pressurized manned Spacelab module. The goal of IML-1 was to explore in depth the complex effects of weightlessness of living organisms and materials processing. Around-the-clock research was performed on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and effects of microgravity on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Materials processing experiments were also conducted, including crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury iodide, and a virus. The Huntsville Operations Support Center (HOSC) Spacelab Payload Operations Control Center (SL POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) was the air/ground communication channel used between the astronauts and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. Featured are activities in the SL POCC during STS-42, IML-1 mission.

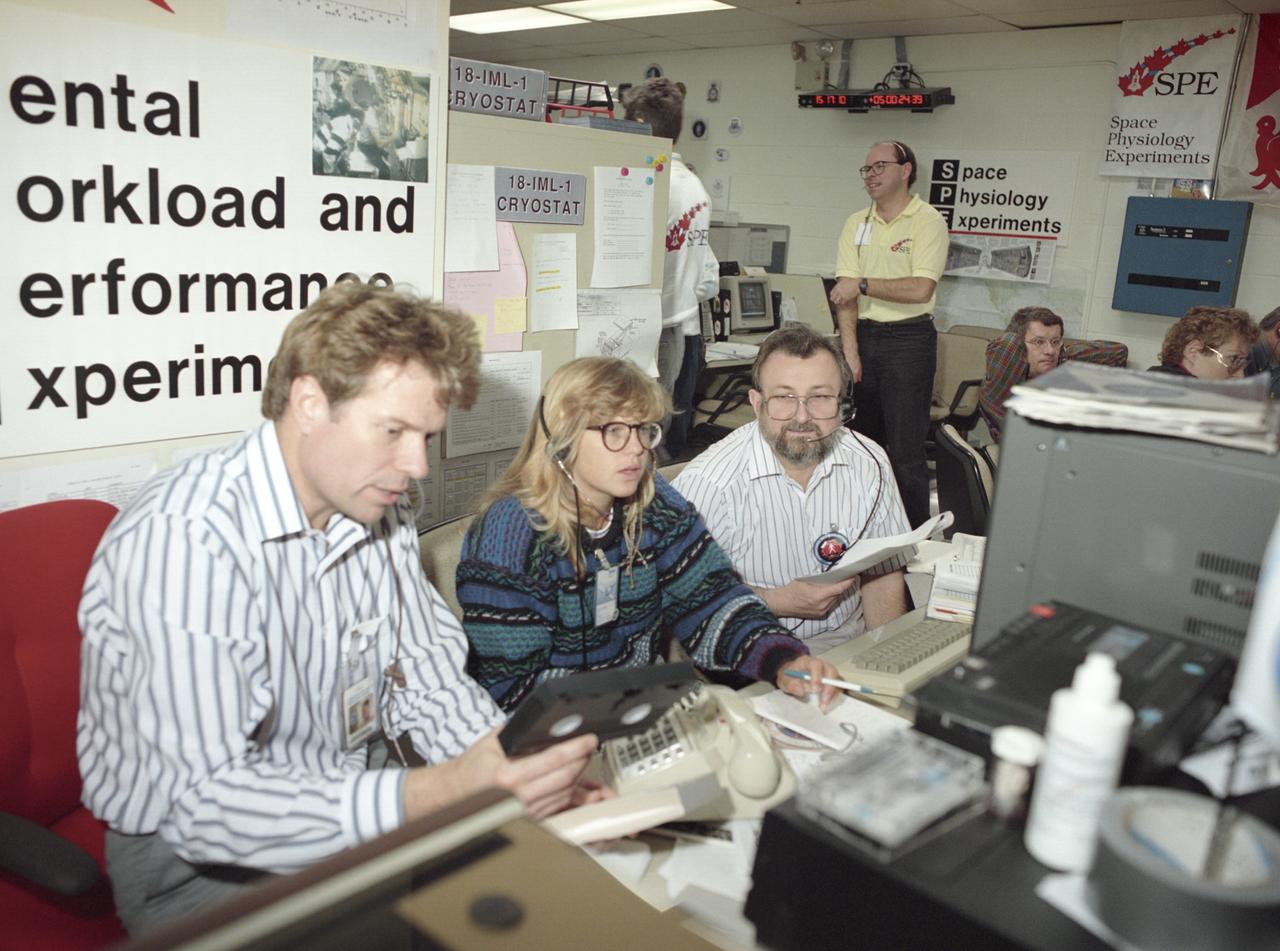

The primary payload for Space Shuttle Mission STS-42, launched January 22, 1992, was the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1), a pressurized manned Spacelab module. The goal of IML-1 was to explore in depth the complex effects of weightlessness of living organisms and materials processing. Around-the-clock research was performed on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and effects of microgravity on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Materials processing experiments were also conducted, including crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury iodide, and a virus. The Huntsville Operations Support Center (HOSC) Spacelab Payload Operations Control Center (SL POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) was the air/ground communication channel used between the astronauts and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. Featured activities are of the Mental Workload and Performance Experiment (MWPE) team in the SL POCC during the IML-1 mission.

The primary payload for Space Shuttle Mission STS-42, launched January 22, 1992, was the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1), a pressurized manned Spacelab module. The goal of IML-1 was to explore in depth the complex effects of weightlessness of living organisms and materials processing. Around-the-clock research was performed on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and effects of microgravity on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Materials processing experiments were also conducted, including crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury iodide, and a virus. The Huntsville Operations Support Center (HOSC) Spacelab Payload Operations Control Center (SL POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) was the air/ground communication channel used between the astronauts and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. Featured are activities of the Organic Crystal Growth Facility (OCGF) and Radiation Monitoring Container Device (RMCD) groups in the SL POCC during the IML-1 mission.

A versatile experiment facility for the International Space Station moved closer to flight recently with delivery of the ground-test model to NASA's Marshall Flight Center. The Microgravity Science Glovebox Ground Unit was delivered to the Microgravity Development Laboratory will be used to test hardware and procedures for the flight model of the glovebox aboard the ISS's Laboratory Module, Destiny.

Astronaut David C. Hilmers conducts the Microgravity Vestibular Investigations (MVI) sitting in its rotator chair inside the IML-1 science module. When environmental conditions change so that the body receives new stimuli, the nervous system responds by interpreting the incoming sensory information differently. In space, the free-fall environment of an orbiting spacecraft requires that the body adapts to the virtual absence of gravity. Early in flights, crewmembers may feel disoriented or experience space motion sickness. MVI examined the effects of orbital flight on the human orientation system to obtain a better understanding of the mechanisms of adaptation to weightlessness. By provoking interactions among the vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive systems and then measuring the perceptual and sensorimotor reactions, scientists can study changes that are integral to the adaptive process. The IML-1 mission was the first in a series of Shuttle flights dedicated to fundamental materials and life sciences research with the international partners. The participating space agencies included: NASA, the 14-nation European Space Agency (ESA), the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the French National Center of Space Studies (CNES), the German Space Agency and the German Aerospace Research Establishment (DAR/DLR), and the National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA). Both life and materials sciences benefited from the extended periods of microgravity available inside the Spacelab science module in the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Orbiter. Managed by the Marshall Space Flight Center, IML-1 was launched on January 22, 1992 aboard the Space Shuttle Orbiter Discovery (STS-42 mission).

STS-42, Viewing earth with lots of snow, partial view of IML-1 (International Microgravity Laboratory) in cargo bay.

STS-42, Astronauts Steve Oswald and Canadian Roberta Bondar working in IML-1 (International Microgravity Laboratory).

Documentation of the AFE (Aero Flight Experiment) - IML (International Microgravity Laboratory) construction progress through the year 1988.

The primary payload for Space Shuttle Mission STS-42, launched January 22, 1992, was the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1), a pressurized manned Spacelab module. The goal of IML-1 was to explore in depth the complex effects of weightlessness of living organisms and materials processing. Around-the-clock research was performed on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and effects of microgravity on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Materials processing experiments were also conducted, including crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury iodide and a virus. The Huntsville Operations Support Center (HOSC) Spacelab Payload Operations Control Center (SL POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) was the air/ground communication channel used between the astronauts aboard the Spacelab and scientists, researchers, and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. The facility made instantaneous video and audio communications possible for scientists on the ground to follow the progress and to send direct commands of their research almost as if they were in space with the crew. Teams of controllers and researchers directed on-orbit science operations, sent commands to the spacecraft, received data from experiments aboard the Space Shuttle, adjusted mission schedules to take advantage of unexpected science opportunities or unexpected results, and worked with crew members to resolve problems with their experiments. In this photograph the Payload Operations Director (POD) views the launch.

iss071e403579 (July 23, 2024) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 71 Flight Engineer Tracy C. Dyson unpacks and examines research gear that is part of the BioFabrication Facility (BFF) located inside the International Space Station's Columbus laboratory module. The BFF is a research device being tested for its ability to print organ-like tissues in microgravity.

The primary payload for Space Shuttle Mission STS-42, launched January 22, 1992, was the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1), a pressurized manned Spacelab module. The goal of IML-1 was to explore in depth the complex effects of weightlessness of living organisms and materials processing. Around-the-clock research was performed on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and effects of microgravity on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Materials processing experiments were also conducted, including crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury iodide, and a virus. The Huntsville Operations Support Center (HOSC) Spacelab Payload Operations Control Center (SL POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) was the air/ground communication channel used between the astronauts and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. Featured is the Critical Point Facility (CPF) team in the SL POCC during the IML-1 mission.

The primary payload for Space Shuttle Mission STS-42, launched January 22, 1992, was the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1), a pressurized manned Spacelab module. The goal of IML-1 was to explore in depth the complex effects of weightlessness of living organisms and materials processing. Around-the-clock research was performed on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and effects of microgravity on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Materials processing experiments were also conducted, including crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury iodide, and a virus. The Huntsville Operations Support Center (HOSC) Spacelab Payload Operations Control Center (SL POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) was the air/ground communication channel used between the astronauts and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. Featured is the Vapor Crystal Growth System (VCGS) team in SL POCC), during STS-42, IML-1 mission.

The primary payload for Space Shuttle Mission STS-42, launched January 22, 1992, was the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1), a pressurized manned Spacelab module. The goal of IML-1 was to explore in depth the complex effects of weightlessness of living organisms and materials processing. Around-the-clock research was performed on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and effects of microgravity on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Materials processing experiments were also conducted, including crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury iodide, and a virus. The Huntsville Operations Support Center (HOSC) Spacelab Payload Operations Control Center (SL POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) was the air/ground communication channel used between the astronauts and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. Featured is the Crystal Growth team in the SL POCC during STS-42, IML-1 mission.

The primary payload for Space Shuttle Mission STS-42, launched January 22, 1992, was the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1), a pressurized manned Spacelab module. The goal of IML-1 was to explore in depth the complex effects of weightlessness of living organisms and materials processing. Around-the-clock research was performed on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and effects of microgravity on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Materials processing experiments were also conducted, including crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury iodide, and a virus. The Huntsville Operations Support Center (HOSC) Spacelab Payload Operations Control Center (SL POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) was the air/ground communication channel used between the astronauts and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. Featured is the Spacelab Operations Support Room Space Engineering Support team in the SL POCC during STS-42, IML-1 mission.

The primary payload for Space Shuttle Mission STS-42, launched January 22, 1992, was the International Microgravity Laboratory-1 (IML-1), a pressurized manned Spacelab module. The goal of IML-1 was to explore in depth the complex effects of weightlessness of living organisms and materials processing. Around-the-clock research was performed on the human nervous system's adaptation to low gravity and effects of microgravity on other life forms such as shrimp eggs, lentil seedlings, fruit fly eggs, and bacteria. Materials processing experiments were also conducted, including crystal growth from a variety of substances such as enzymes, mercury iodide, and a virus. The Huntsville Operations Support Center (HOSC) Spacelab Payload Operations Control Center (SL POCC) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) was the air/ground communication channel used between the astronauts and ground control teams during the Spacelab missions. Featured is the Critical Point Facility (CPE) group in the SL POCC during STS-42, IML-1 mission.

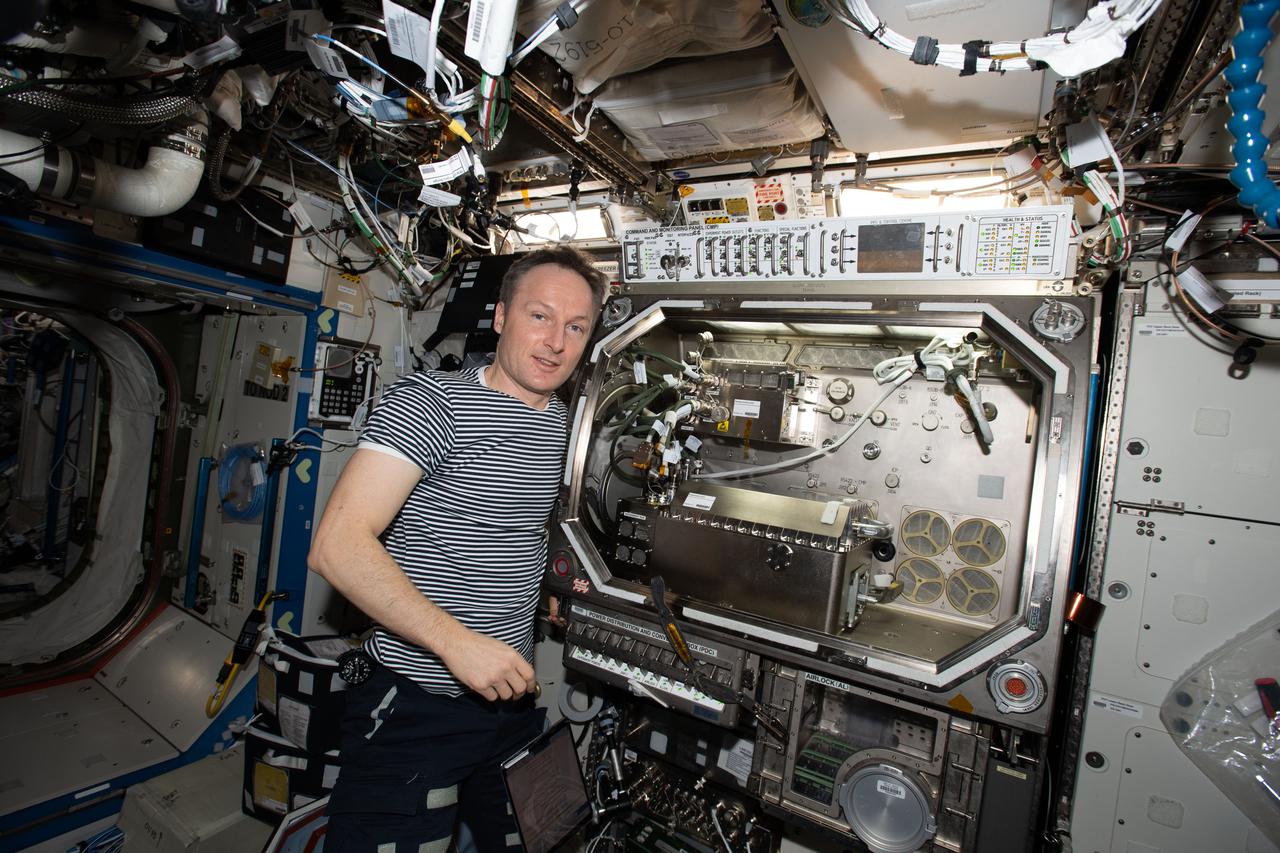

ISS036-E-034881 (20 Aug. 2013) --- European Space Agency astronaut Luca Parmitano, Expedition 36 flight engineer, works with Microgravity Science Laboratory (MSL) hardware in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

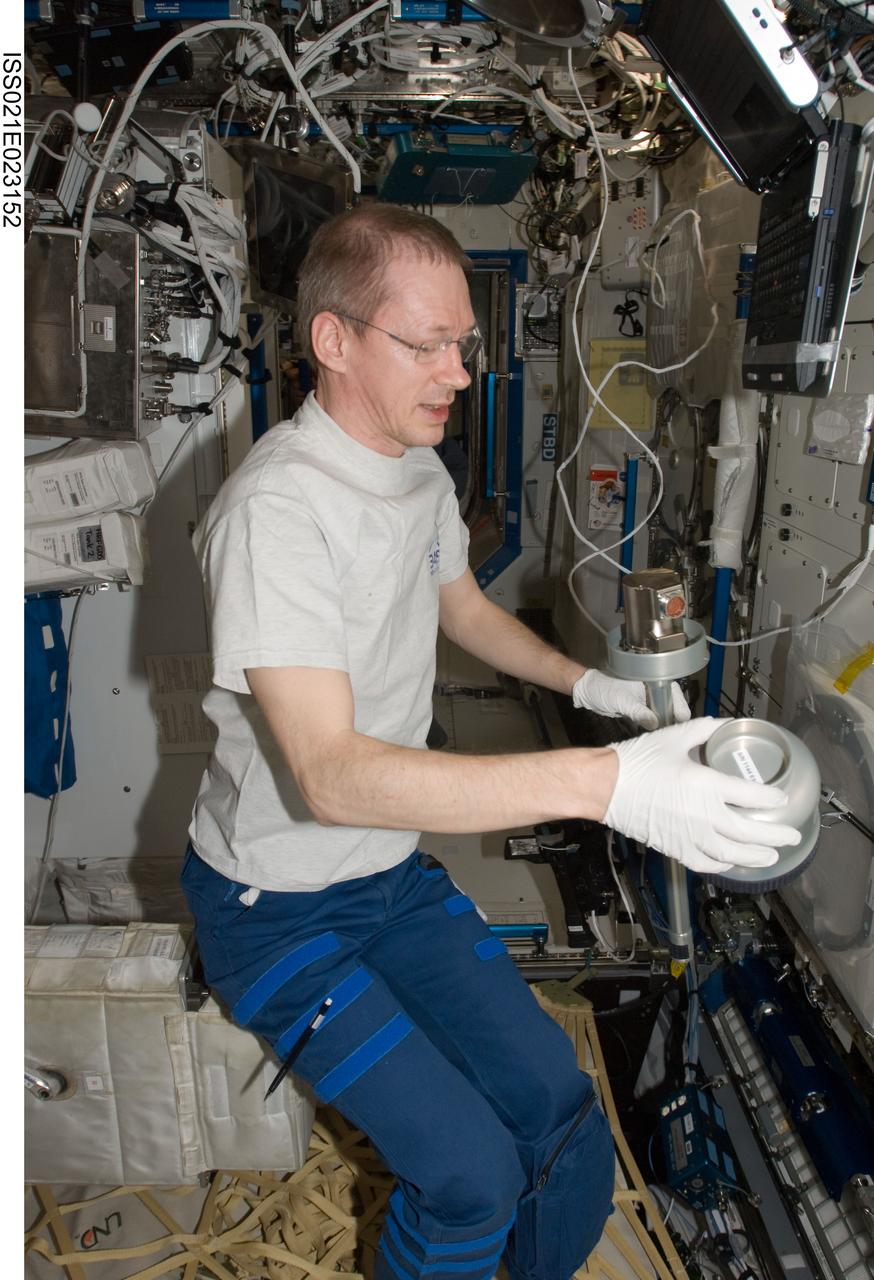

ISS021-E-023152 (8 Nov. 2009) --- European Space Agency astronaut Frank De Winne, Expedition 21 commander, works with Microgravity Science Laboratory (MSL) hardware in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

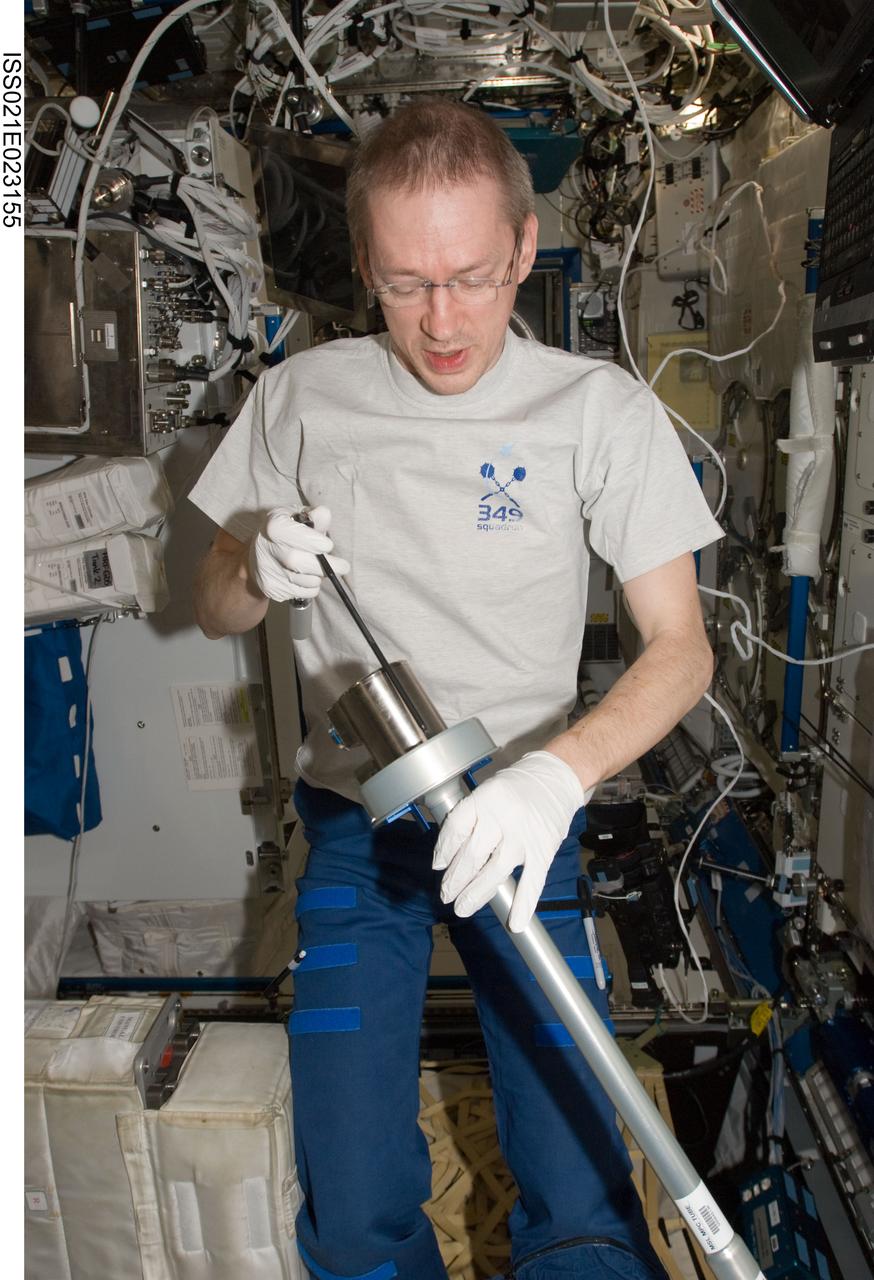

ISS021-E-023155 (8 Nov. 2009) --- European Space Agency astronaut Frank De Winne, Expedition 21 commander, works with Microgravity Science Laboratory (MSL) hardware in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS021-E-023158 (8 Nov. 2009) --- European Space Agency astronaut Frank De Winne, Expedition 21 commander, works with Microgravity Science Laboratory (MSL) hardware in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

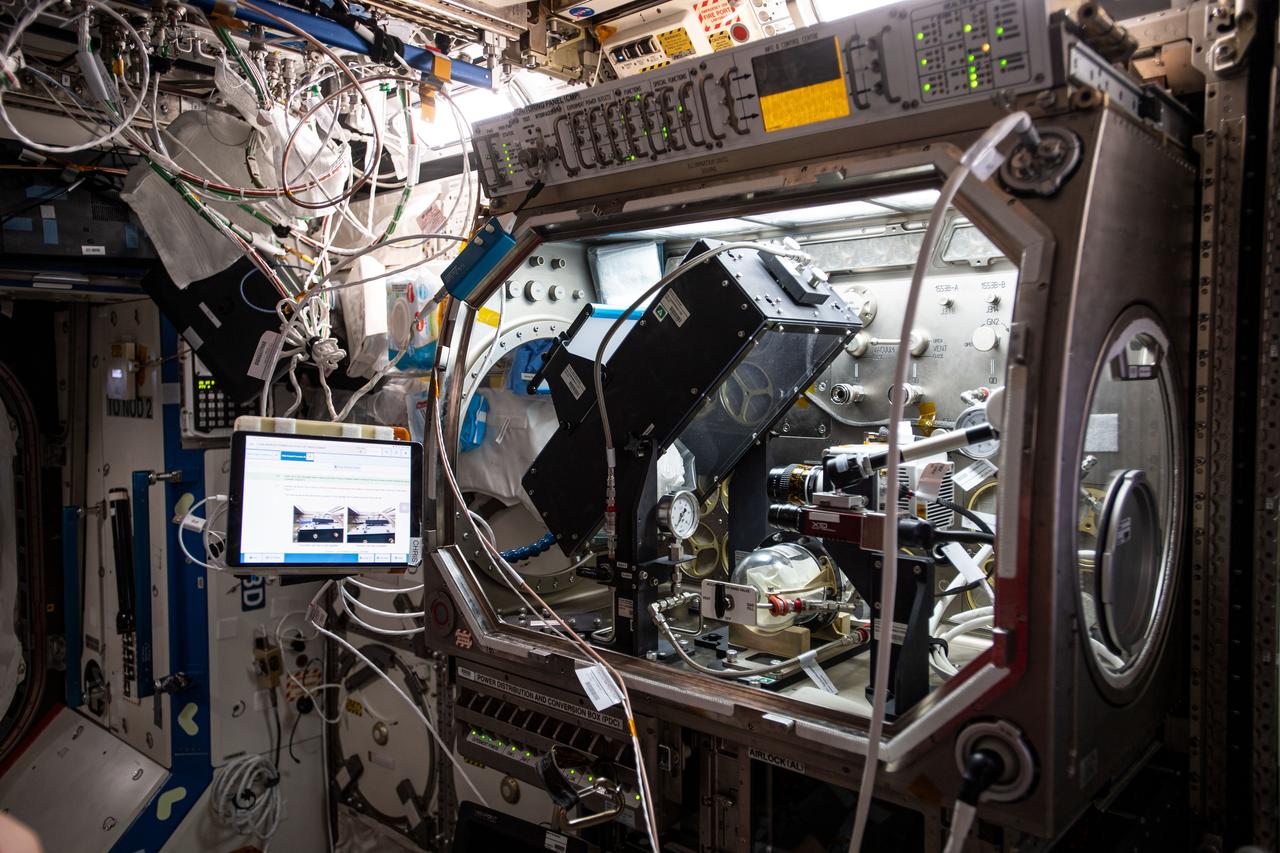

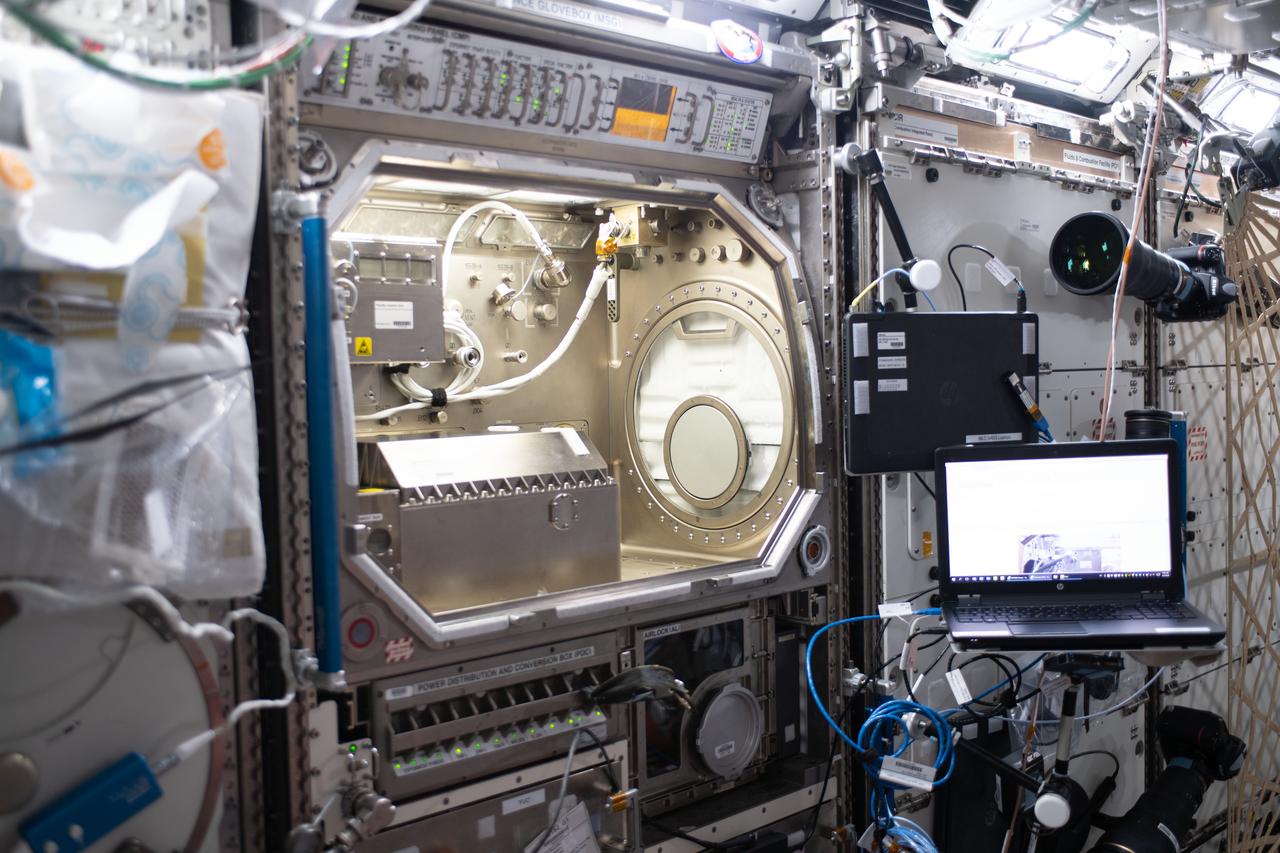

iss063e062018 (7/29/2020) --- Photo documentation of the Droplet Formation Study inside the U.S. Destiny laboratory module's Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) aboard the International Space Station (ISS). The Droplet Formation Study observes how microgravity shapes water droplets, possibly improving water conservation and water pressure techniques on Earth.

iss069e060322 (August 15, 2023) -- NASA astronaut Woody Hoburg swaps samples for a space manufacturing study inside the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the International Space Station's U.S. Destiny Laboratory Module. MSG allows crews to investigate physical science and biological research in a safe, contained environment in microgravity.

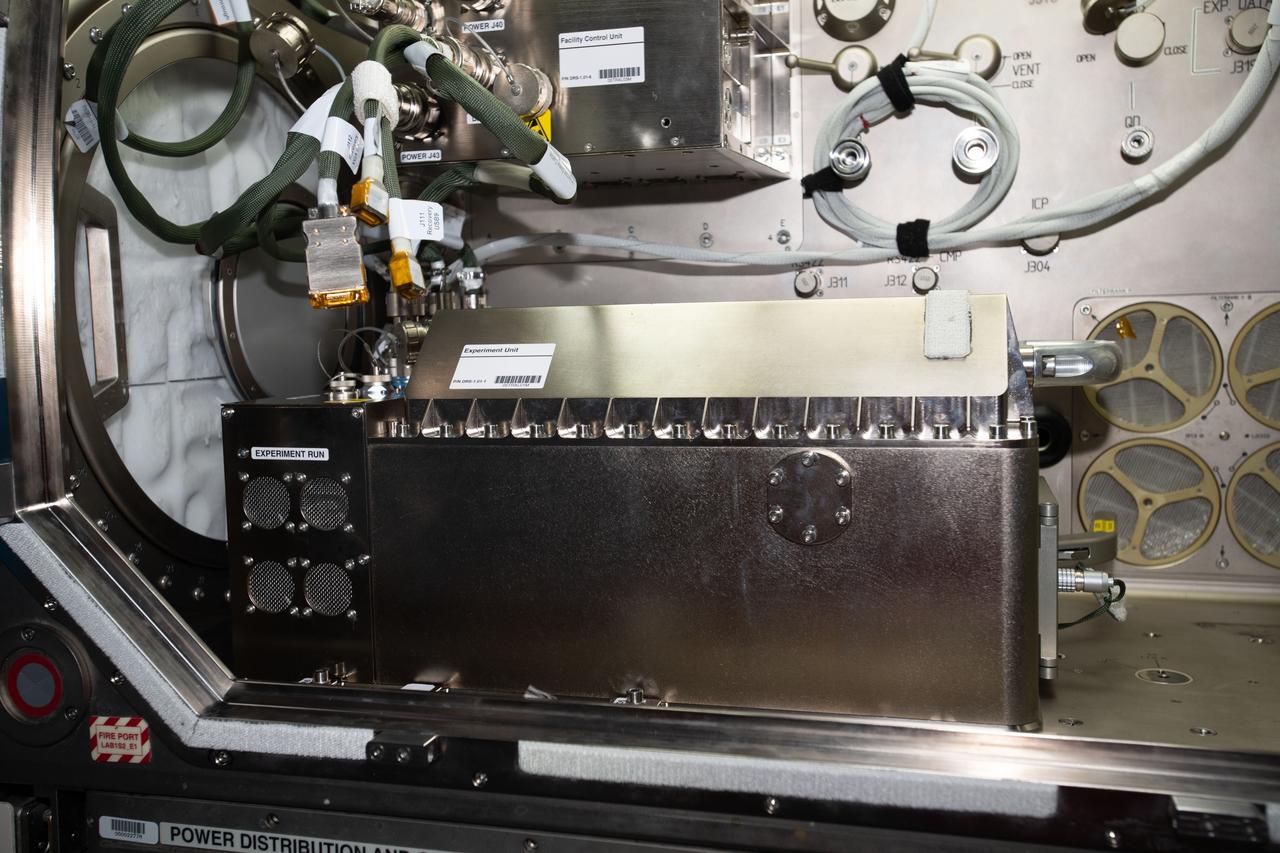

The Microgravity Science Glovebox Ground Unit, delivered to the Marshall Space Flight Center on August 30, 2002, will be used at Marshall's Microgravity Development Laboratory to test experiment hardware before it is installed in the flight glovebox aboard the International Space Station (ISS) U.S. Laboratory Module, Destiny. The glovebox is a sealed container with built in gloves on its sides and fronts that enables astronauts to work safely with experiments that involve fluids, flames, particles, and fumes that need to be safely contained.

ISS028-E-031895 (20 Aug. 2011) --- NASA astronaut Mike Fossum, Expedition 28 flight engineer, works with hardware in the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) located in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

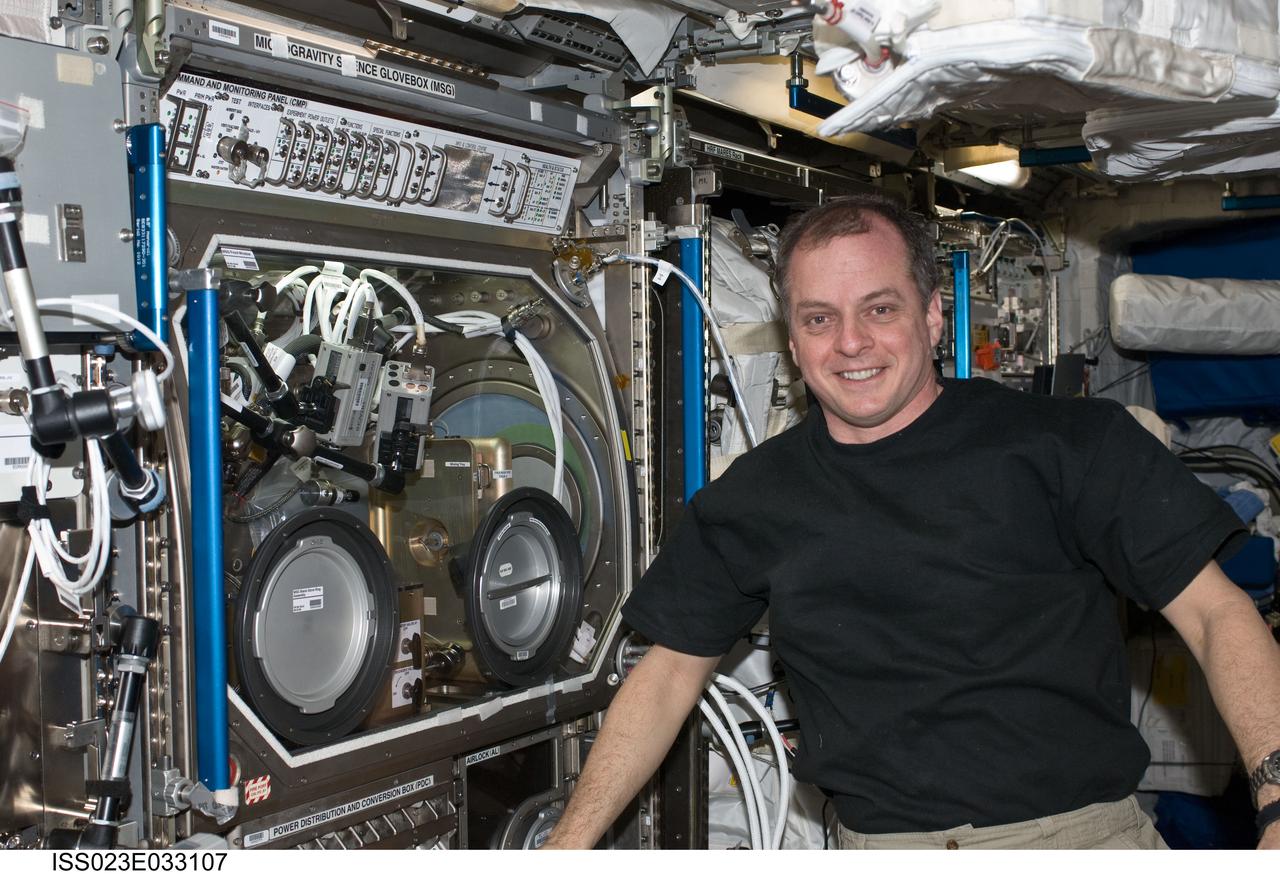

ISS023-E-033107 (6 May 2010) --- NASA astronaut T.J. Creamer, Expedition 23 flight engineer, is pictured near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) located in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

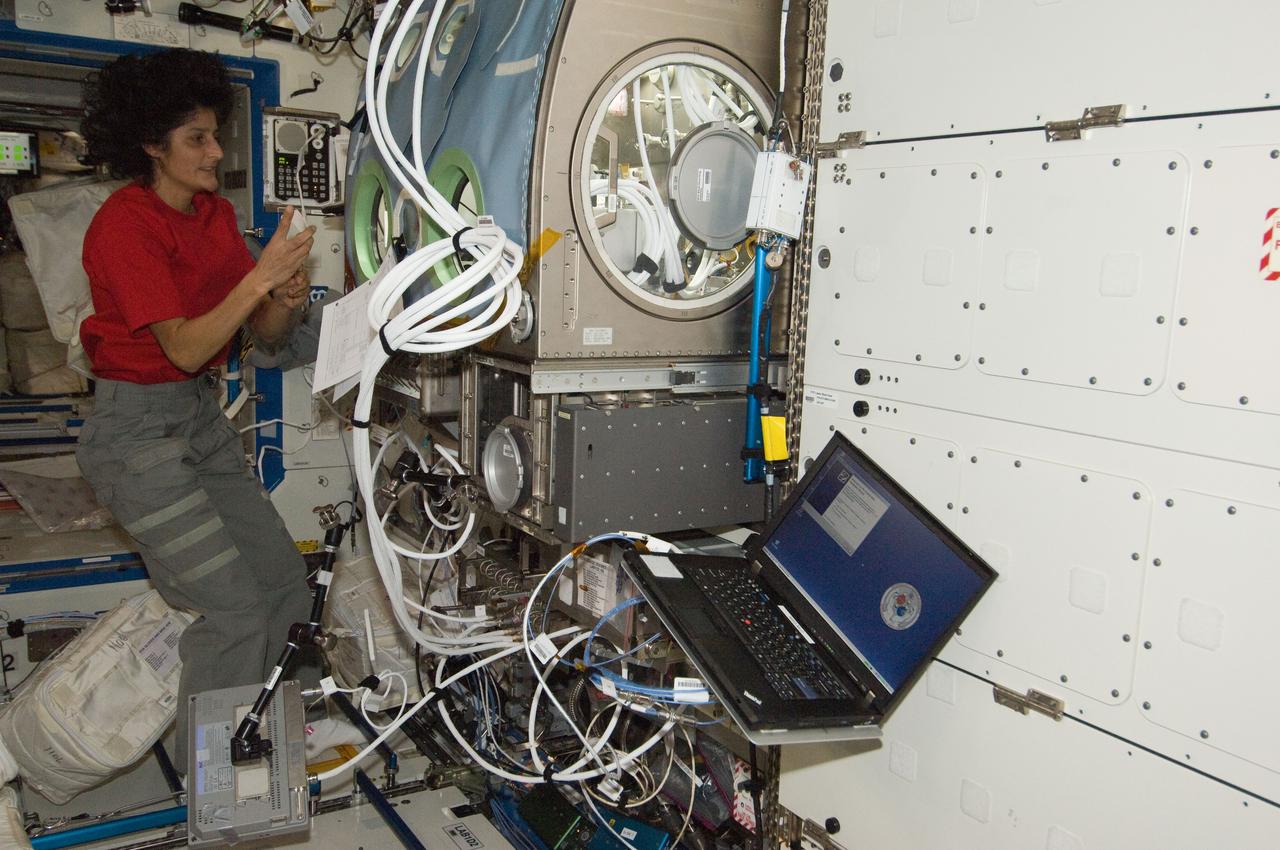

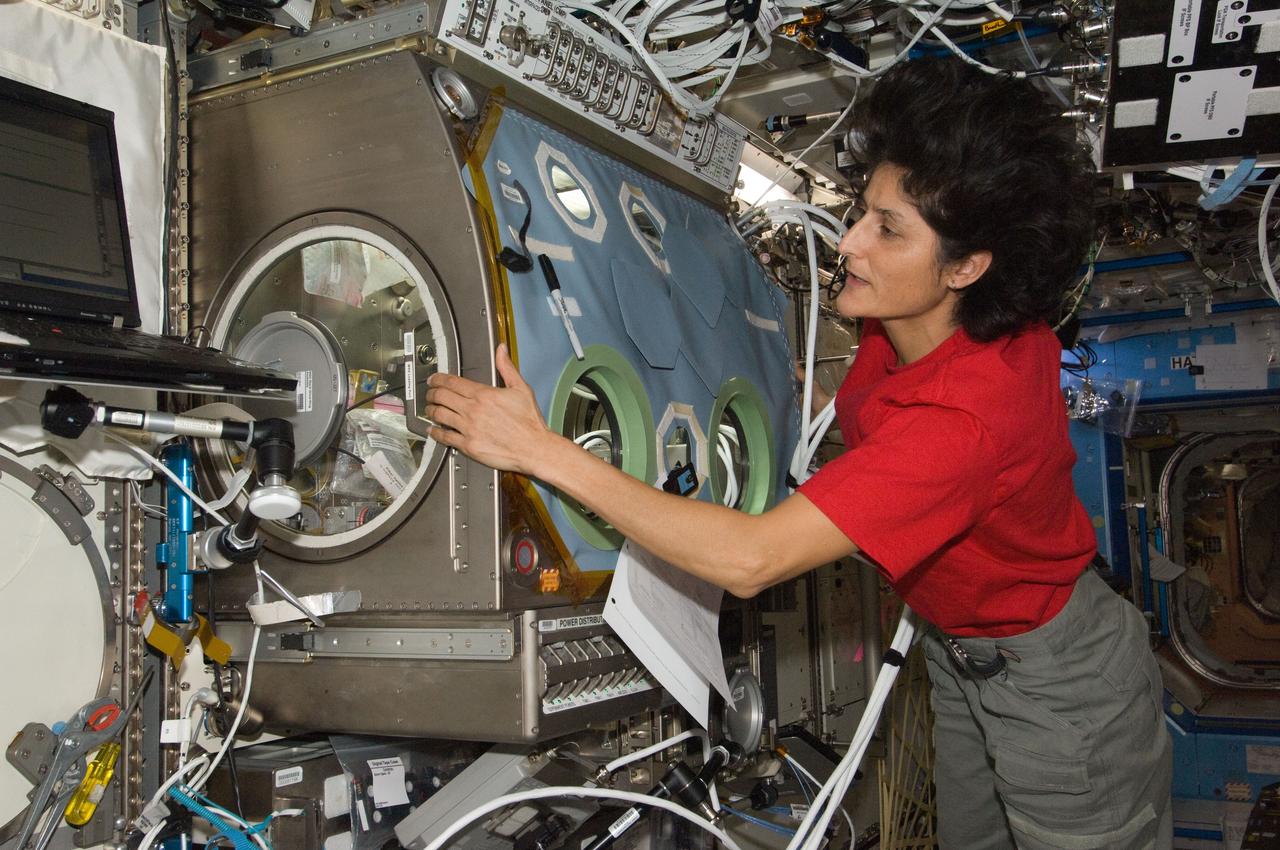

ISS032-E-022630 (23 Aug. 2012) --- NASA astronaut Sunita Williams, Expedition 32 flight engineer, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

iss062e004933 (Feb. 9, 2020) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 62 Flight Engineer Jessica Meir observes a floating sphere of water formed by microgravity inside the International Space Station's Kibo laboratory module.

Space Shuttle Columbia (STS-65) onboard photo of Payload specialist Richard J. Hieb (right) and Shuttle Pilot James D. Halsell Jr. working on experiments in the Spacelab in the International Microgravity Laboratory (IML-2).

ISS029-E-040013 (7 Nov. 2011) --- Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency astronaut Satoshi Furukawa, Expedition 29 flight engineer, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS008-E-05009 (27 October 2003) --- European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut Pedro Duque of Spain works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS008-E-22134 (24 April 2004) --- European Space Agency (ESA) astronaut Andre Kuipers of the Netherlands is pictured near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS032-E-022637 (23 Aug. 2012) --- NASA astronaut Sunita Williams, Expedition 32 flight engineer, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

Official portrait of STS-65 International Microgravity Laboratory 2 (IML-2) backup Payload Specialist Jean-Jacques Favier. Favier is a member of the Centre National D'Etudes Spatiales (CNES), the French space agency.

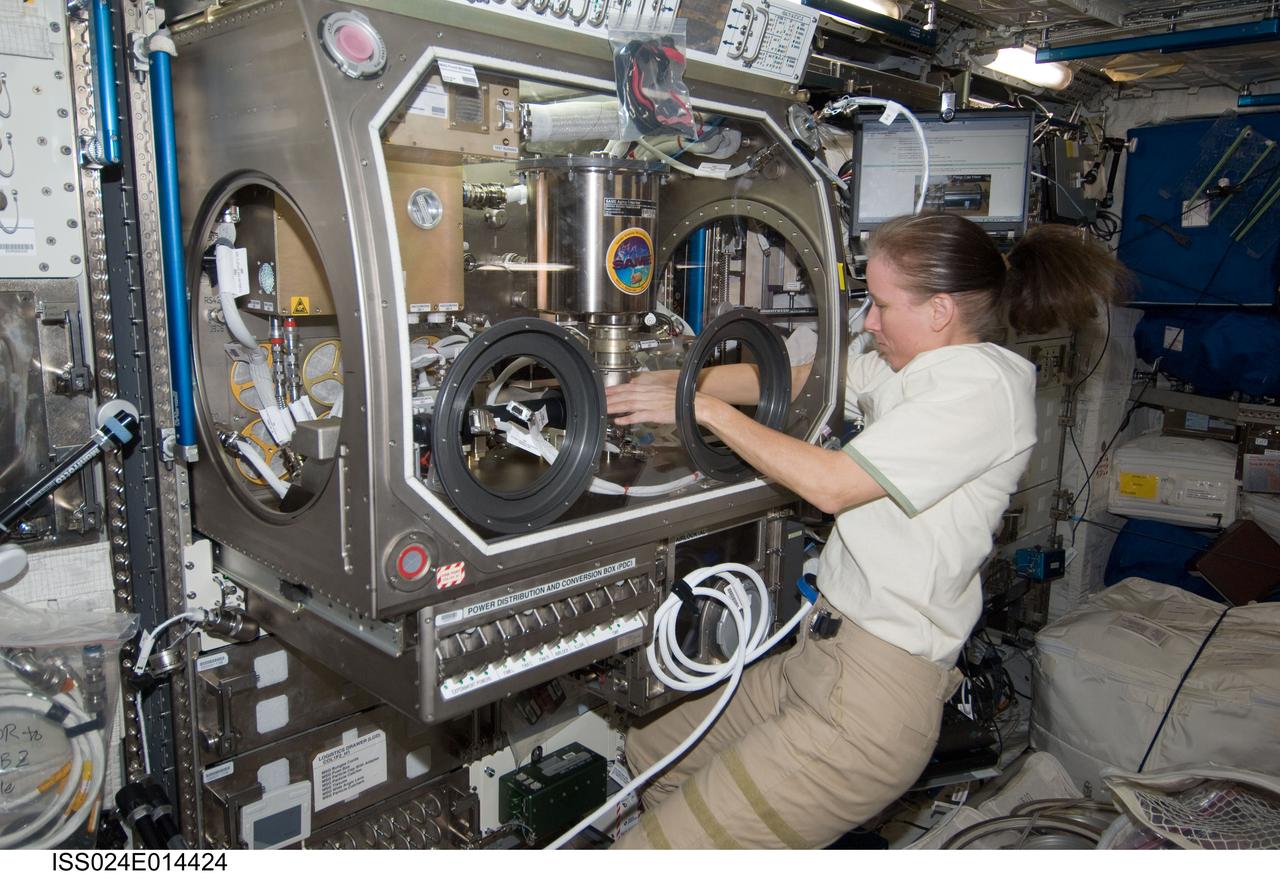

ISS024-E-014428 (13 Sept. 2010) --- NASA astronaut Shannon Walker, Expedition 24 flight engineer, works on the COLLOID experiment inside the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS037-E-006458 (3 Oct. 2013) --- NASA astronaut Karen Nyberg, Expedition 37 flight engineer, enters data into a computer near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS006-E-34567 (27 February 2003) --- Astronaut Donald R. Pettit, Expedition Six NASA ISS science officer, works on the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS018-E-024515 (30 Jan. 2009) --- Astronaut Sandra Magnus, Expedition 18 flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS037-E-028590 (10 Nov. 2013) --- NASA astronaut Michael Hopkins, Expedition 37/38 flight engineer, enters data into a computer near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS028-E-047464 (12 Sept. 2011) --- NASA astronaut Ron Garan, Expedition 28 flight engineer, works behind the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) rack located in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS027-E-017809 (28 April 2011) --- European Space Agency astronaut Paolo Nespoli, Expedition 27 flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

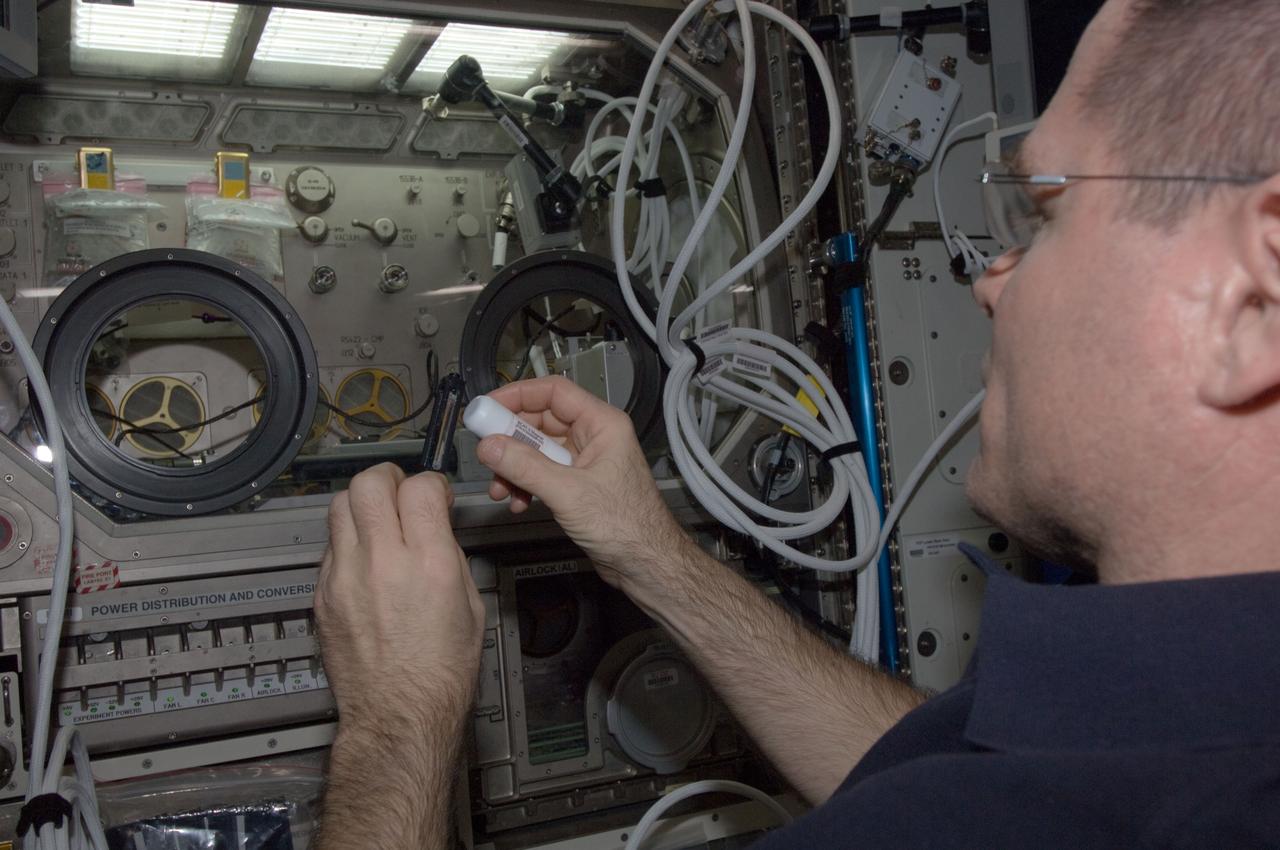

ISS016-E-021064 (5 Jan. 2008) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition 16 commander, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS027-E-017810 (28 April 2011) --- European Space Agency astronaut Paolo Nespoli, Expedition 27 flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS034-E-036867 (29 Jan. 2013) --- NASA astronaut Kevin Ford, Expedition 34 commander, works near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

S91-52649 (Nov 1991) ---- Astronaut Ulf Merbold, PhD, European Space Agency (ESA) Payload Specialist for STS-42, International Microgravity Laboratory (IML-1).

iss067e008088 (April 10, 2022) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut and Expedition Flight Engineer Matthias Maurer is pictured in front of the Microgravity Science Glovebox located inside the International Space Station's U.S. Destiny laboratory module.

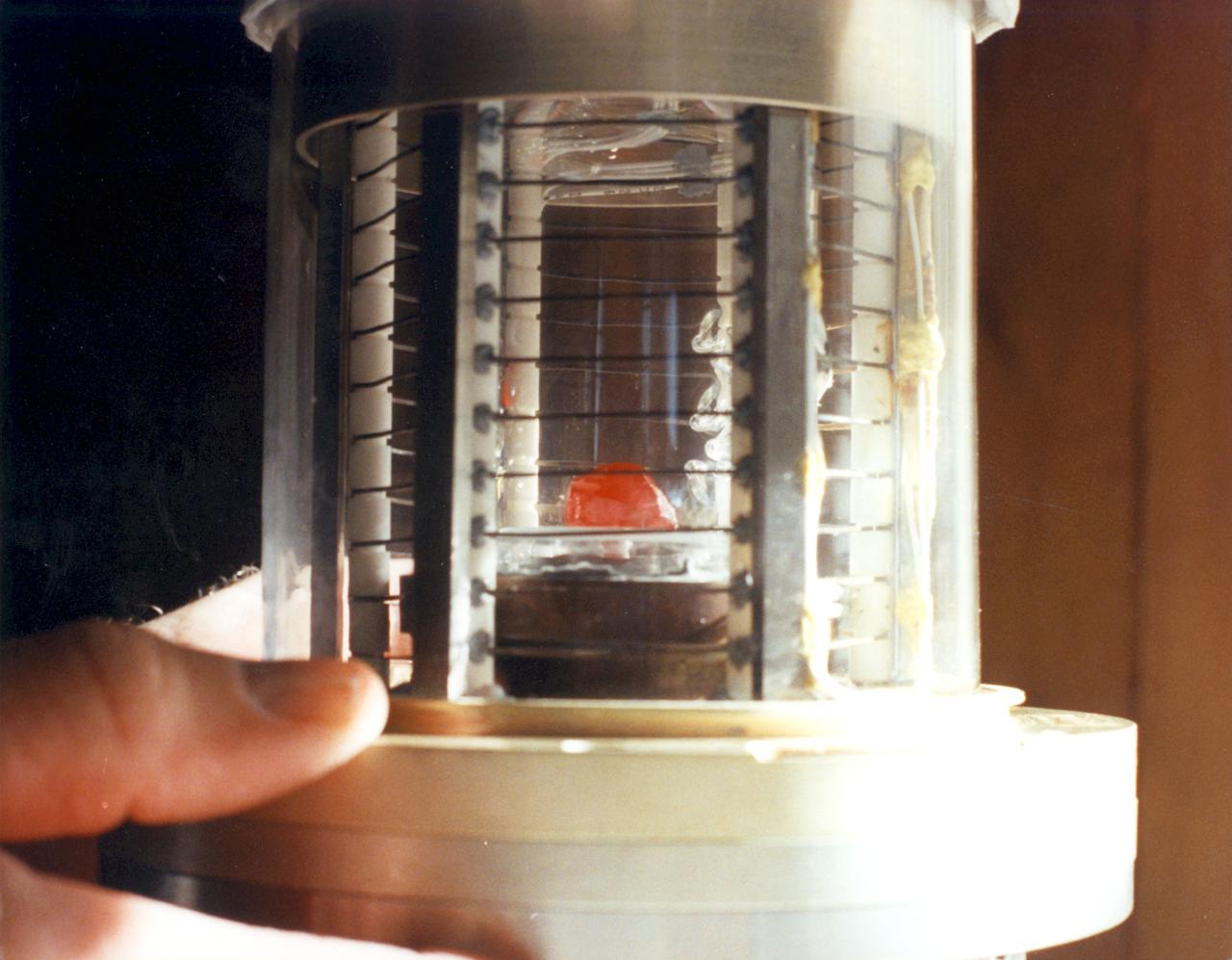

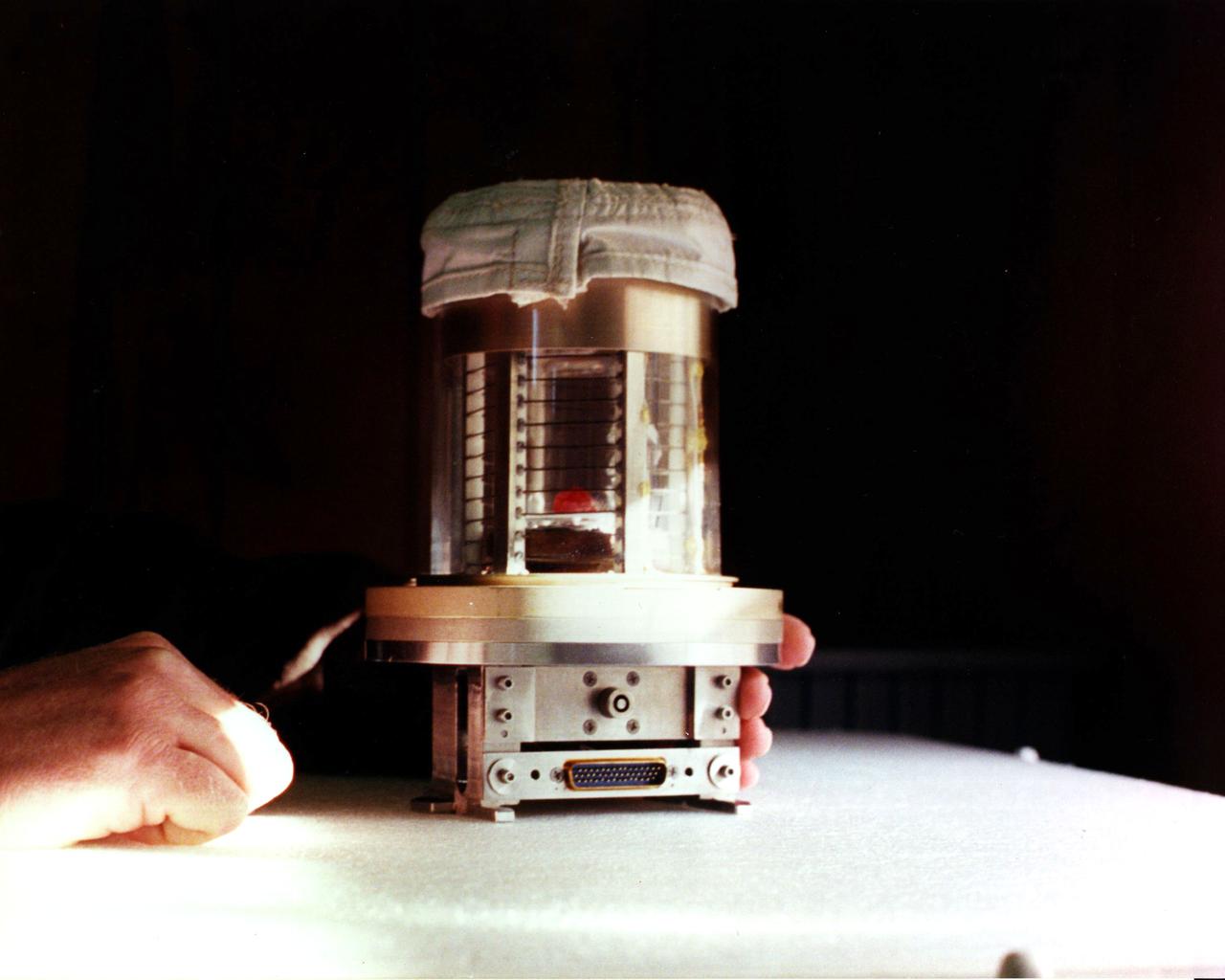

Ampoule view of the Vapor Crystal Growth System (VCGS) Furnace. Used on IML-1 International Microgravity Laboratory Spacelab 3. Prinicipal Investigator and Payload Specialist was Lodewijk van den Berg.

STS112-E-06078 (15 October 2002) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition Five flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS032-E-022628 (23 Aug. 2012) --- NASA astronaut Sunita Williams, Expedition 32 flight engineer, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS028-E-047462 (12 Sept. 2011) --- NASA astronaut Ron Garan, Expedition 28 flight engineer, works behind the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) rack located in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

STS112-E-06083 (15 October 2002) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition Five flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS).

iss062e080867 (3/5/2020) --- A view of the Transparent Alloys Hardware Setup in the Microgravity Sciences Glovebox (MSG) Work Volume (WV) in the U.S. Destiny Laboratory aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS016-E-021059 (5 Jan. 2008) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition 16 commander, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

STS111-E-5121 (9 June 2002) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition Five flight engineer, floats near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS005-E-13706 (11 September 2002) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition Five flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS005-E-13704 (11 September 2002) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition Five flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS023-E-033108 (6 May 2010) --- NASA astronaut T.J. Creamer, Expedition 23 flight engineer, is pictured near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) located in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS005-E-07157 (8 July 2002) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition Five flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS024-E-014424 (13 Sept. 2010) --- NASA astronaut Shannon Walker, Expedition 24 flight engineer, works on the COLLOID experiment inside the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS024-E-014421 (13 Sept. 2010) --- NASA astronaut Shannon Walker, Expedition 24 flight engineer, works on the COLLOID experiment inside the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

iss062e081047 (3/5/2020) --- A view of the Transparent Alloys Hardware Setup in the Microgravity Sciences Glovebox (MSG) Work Volume (WV) in the U.S. Destiny Laboratory aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS019-E-017339 (16 May 2009) --- Astronaut Michael Barratt, Expedition 19/20 flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS023-E-030740 (3 May 2010) --- NASA astronaut Tracy Caldwell Dyson, Expedition 23 flight engineer, works with experiment hardware in the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) located in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS034-E-010876 (28 Dec. 2012) --- NASA astronaut Kevin Ford, Expedition 34 commander, works near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS028-E-047461 (12 Sept. 2011) --- NASA astronaut Ron Garan, Expedition 28 flight engineer, works behind the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) rack located in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS005-E-07142 (8 July 2002) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition Five flight engineer, works near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS).

ISS017-E-014001 (23 Aug. 2008) --- Astronaut Greg Chamitoff, Expedition 17 flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Sciences Glovebox and the Commercial Generic Bioprocessing Apparatus in the Columbus laboratory on the International Space Station.

ISS030-E-032779 (16 Jan. 2012) --- European Space Agency astronaut Andre Kuipers, Expedition 30 flight engineer, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS019-E-017334 (16 May 2009) --- Astronaut Michael Barratt, Expedition 19/20 flight engineer, uses a computer near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS028-E-047468 (12 Sept. 2011) --- NASA astronaut Ron Garan, Expedition 28 flight engineer, works behind the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) rack located in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS028-E-031889 (20 Aug. 2011) --- NASA astronaut Mike Fossum, Expedition 28 flight engineer, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) located in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS034-E-010875 (28 Dec. 2012) --- NASA astronaut Kevin Ford, Expedition 34 commander, works near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS016-E-036417 (14 April 2008) --- NASA astronaut Garrett Reisman, Expedition 16/17 flight engineer, is pictured near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) located in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

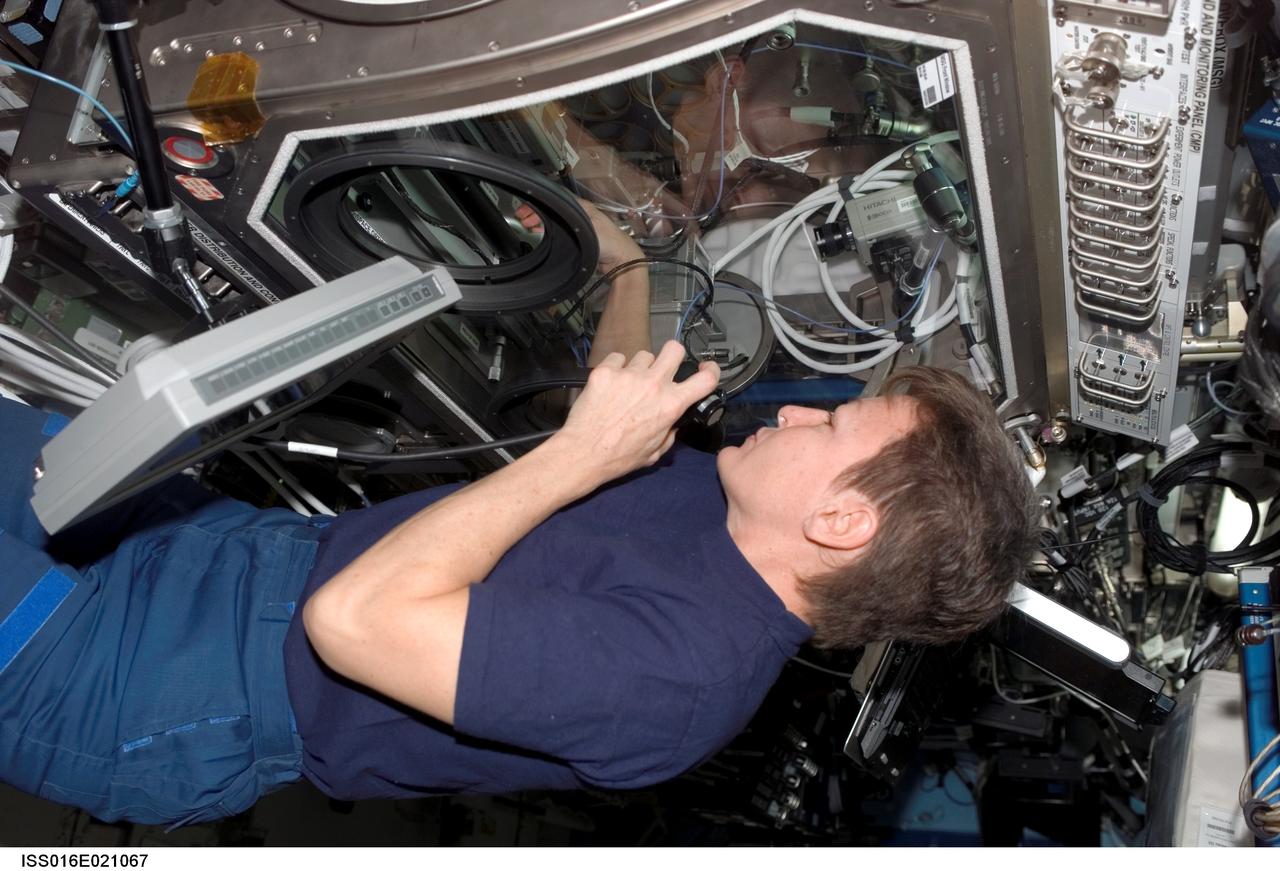

ISS016-E-021067 (5 Jan. 2008) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition 16 commander, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

Overall view of the Vapor Crystal Growth System (VCGS) Furnace. Used on IML-1 International Microgravity Laboratory Spacelab 3. Principal Investigator and Payload Specialist was Lodewijk van den Berg.

iss065e012827 (May 3, 2021) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 65 Flight Engineer Megan McArthur stows science hardware and reconfigures the Microgravity Science Glovebox inside the International Space Station's U.S. Destiny laboratory module.

ISS016-E-021060 (5 Jan. 2008) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition 16 commander, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS037-E-006456 (3 Oct. 2013) --- NASA astronaut Karen Nyberg, Expedition 37 flight engineer, enters data into a computer near the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS015-E-14705 (28 June 2007) --- Astronaut Clayton C. Anderson, Expedition 15 flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

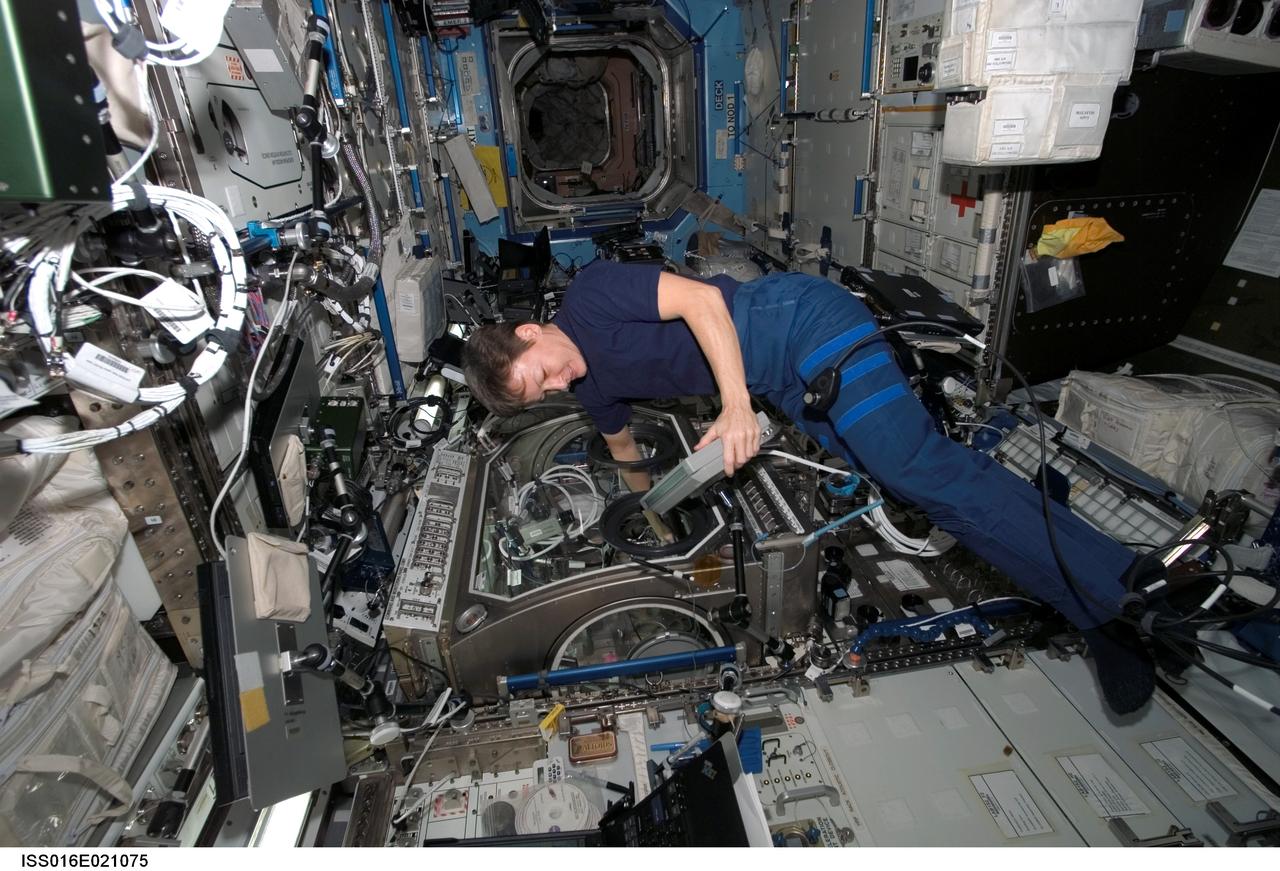

ISS016-E-021075 (5 Jan. 2008) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition 16 commander, works at the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS030-E-049556 (17 Jan. 2012) --- NASA astronaut Don Pettit, Expedition 30 flight engineer, holds a Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) glove in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

STS112-E-05145 (11 October 2002) --- Astronaut Peggy A. Whitson, Expedition Five flight engineer, works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory on the International Space Station (ISS).

iss073e0379975 (July 17, 2025) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 73 Flight Engineer Nichole Ayers works inside the International Space Station's Destiny laboratory module and cleans components behind the Microgravity Science Glovebox.

iss073e0002614 (April 28, 2025) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 73 Flight Engineer Nichole Ayers shows off research hardware inside the International Space Station's Columbus laboratory module. The Space Automated Bioproduct Laboratory is a research incubator that enables biology investigations into the effects of microgravity on cells, microbes, plants, and more.

iss069e004389 (April 20, 2023) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 69 Flight Engineer Frank Rubio works to install the NanoRacks CubeSat Deployer inside the Kibo laboratory module's airlock. After the airlock is depressurized, the Japanese robotic arm grapples the deployer and places it outside in the vacuum of microgravity pointing it away from the International Space Station. CubeSats from private, governmental, and academic organizations are then deployed into Earth orbit for a variety of research objectives.

iss069e004397 (April 20, 2023) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 69 Flight Engineer Frank Rubio works to install the NanoRacks CubeSat Deployer inside the Kibo laboratory module's airlock. After the airlock is depressurized, the Japanese robotic arm grapples the deployer and places it outside in the vacuum of microgravity pointing it away from the International Space Station. CubeSats from private, governmental, and academic organizations are then deployed into Earth orbit for a variety of research objectives.

This excellent shot of Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC's) Mark Whorton, testing experiment hardware in the Microgravity Science Glovebox Ground Unit delivered to MSFC on August 30, 2002, reveals a close look at the components inside of the Glovebox. The unit is being used at Marshall's Microgravity Development Laboratory to test experiment hardware before it is installed in the flight Glovebox aboard the International Space Station (ISS) U.S. Laboratory Module, Destiny. The glovebox is a sealed container with built in gloves on its sides and fronts that enables astronauts to work safely with experiments that involve fluids, flames, particles, and fumes that need to be safely contained.

ISS038-E-053250 (18 Feb. 2014) --- NASA astronaut Rick Mastracchio, Expedition 38 flight engineer, works with the Burning and Suppression of Solids (BASS-II) experiment in the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) located in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station. BASS-II explores how different substances burn in microgravity with benefits for combustion on Earth and fire safety in space.

ISS038-E-046385 (12 Feb. 2014) --- NASA astronaut Rick Mastracchio, Expedition 38 flight engineer, uses a computer while setting up the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) for the Burning and Suppression of Solids (BASS-II) experiment in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station. BASS-II explores how different substances burn in microgravity with benefits for combustion on Earth and fire safety in space.