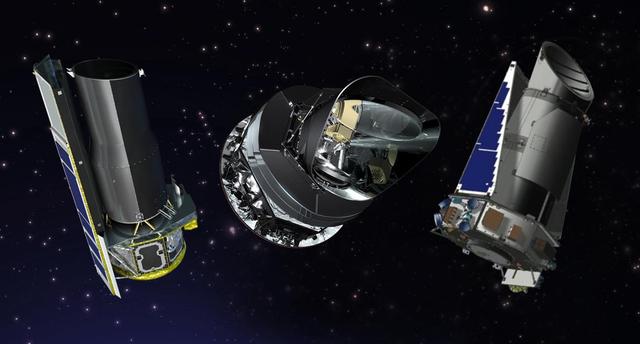

From left to right, artist concepts of the Spitzer, Planck and Kepler space telescopes. NASA extended Spitzer and Kepler for two additional years; and the U.S. portion of Planck, a European Space Agency mission, for one year.

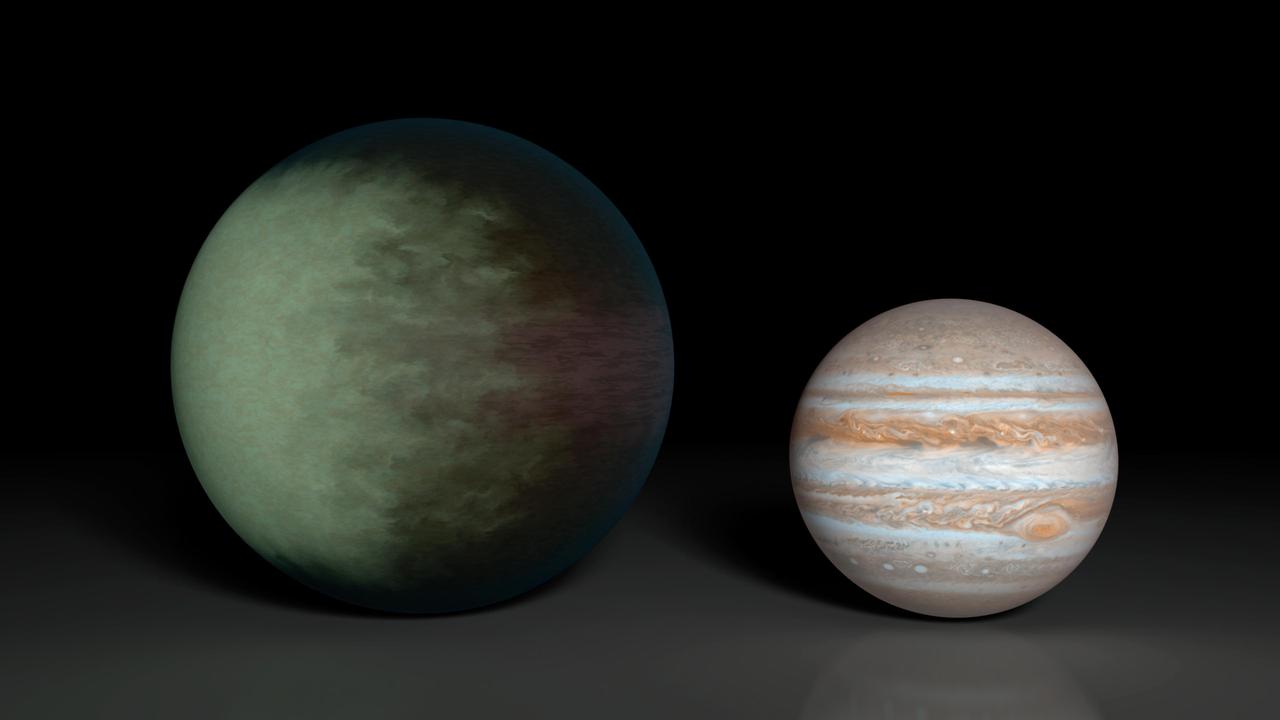

Kepler-7b right, which is 1.5 times the radius of Jupiter left, is the first exoplanet to have its clouds mapped. The cloud map was produced using data from NASA Kepler and Spitzer space telescopes.

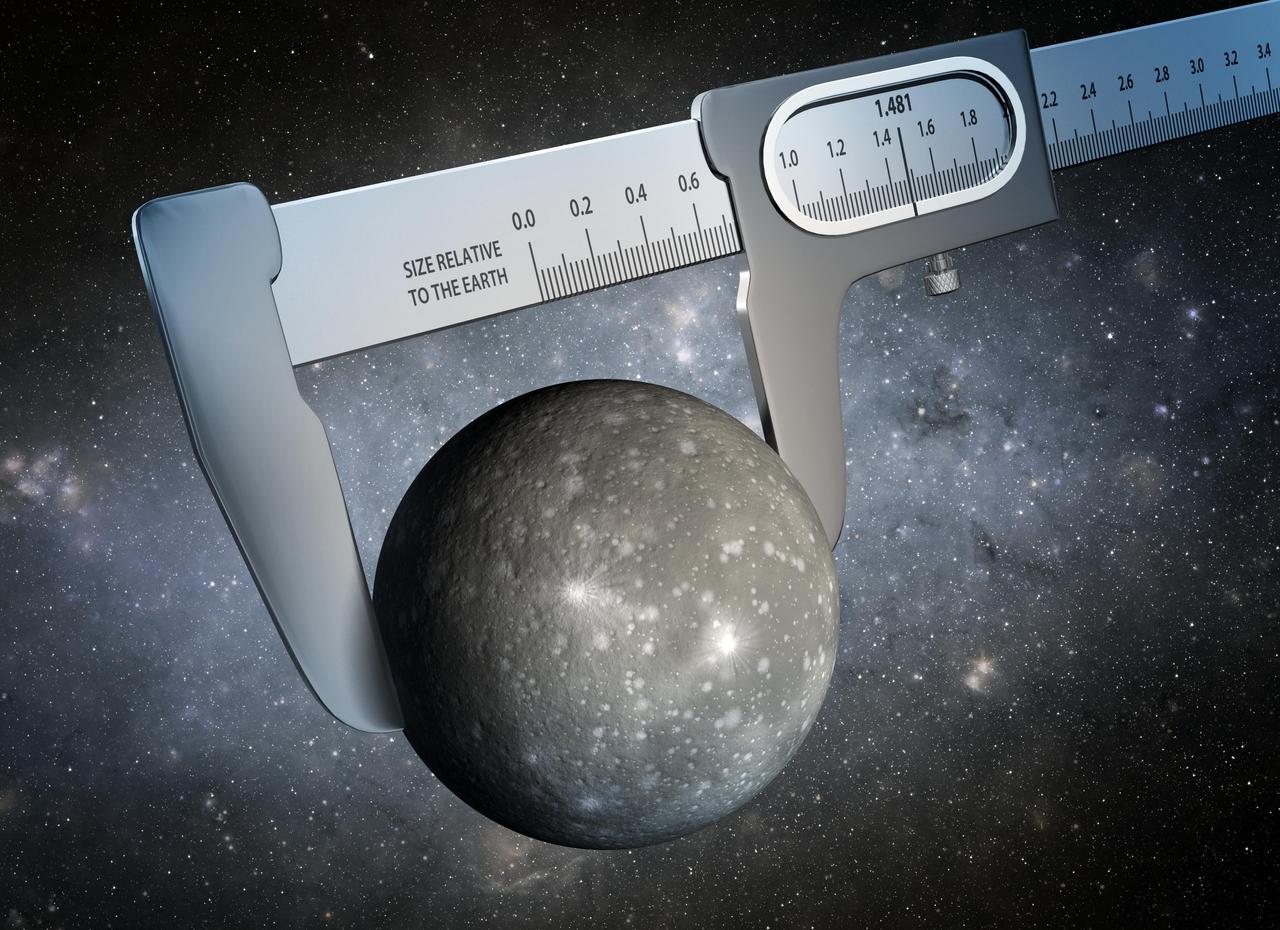

Using data from NASA Kepler and Spitzer Space Telescopes, scientists have made the most precise measurement ever of the size of a world outside our solar system, as illustrated in this artist conception.

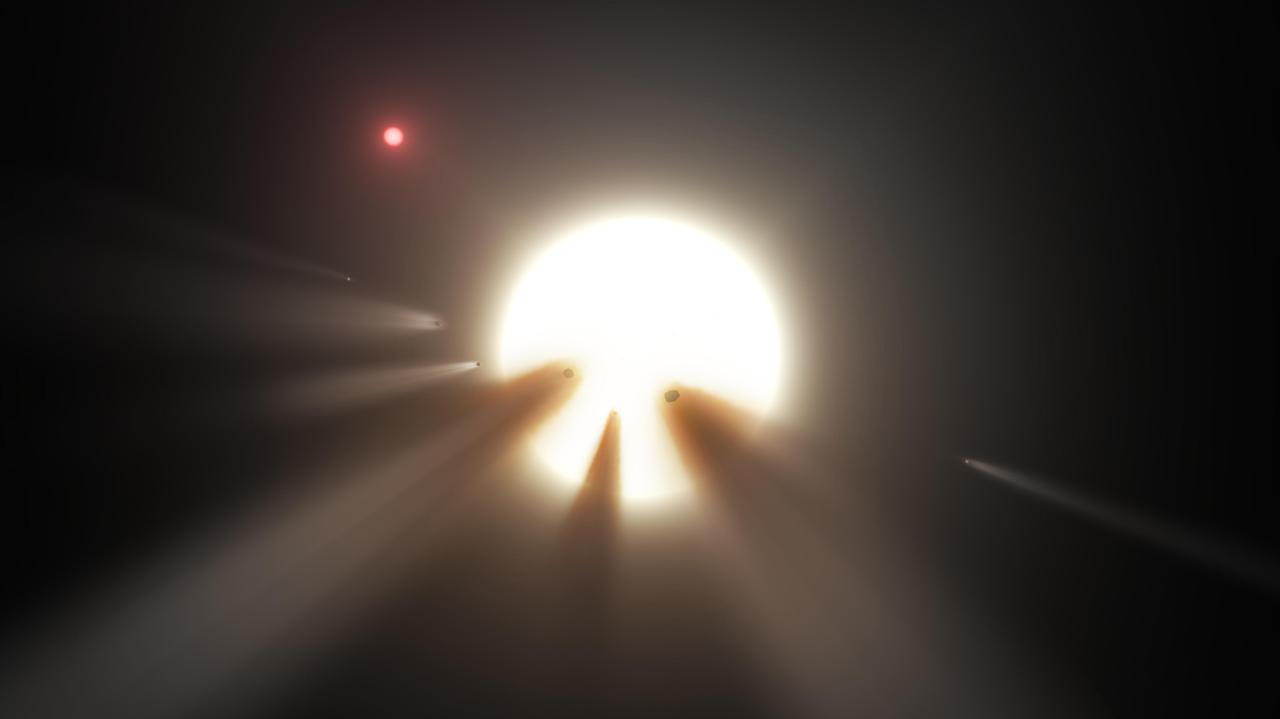

This illustration shows a star behind a shattered comet. Observations of the star KIC 8462852 by NASA's Kepler and Spitzer space telescopes suggest that its unusual light signals are likely from dusty comet fragments, which blocked the light of the star as they passed in front of it in 2011 and 2013. The comets are thought to be traveling around the star in a very long, eccentric orbit. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20053

Scientists were excited to discover clear skies on a relatively small planet, about the size of Neptune, using the combined power of NASA Hubble, Spitzer and Kepler space telescopes.

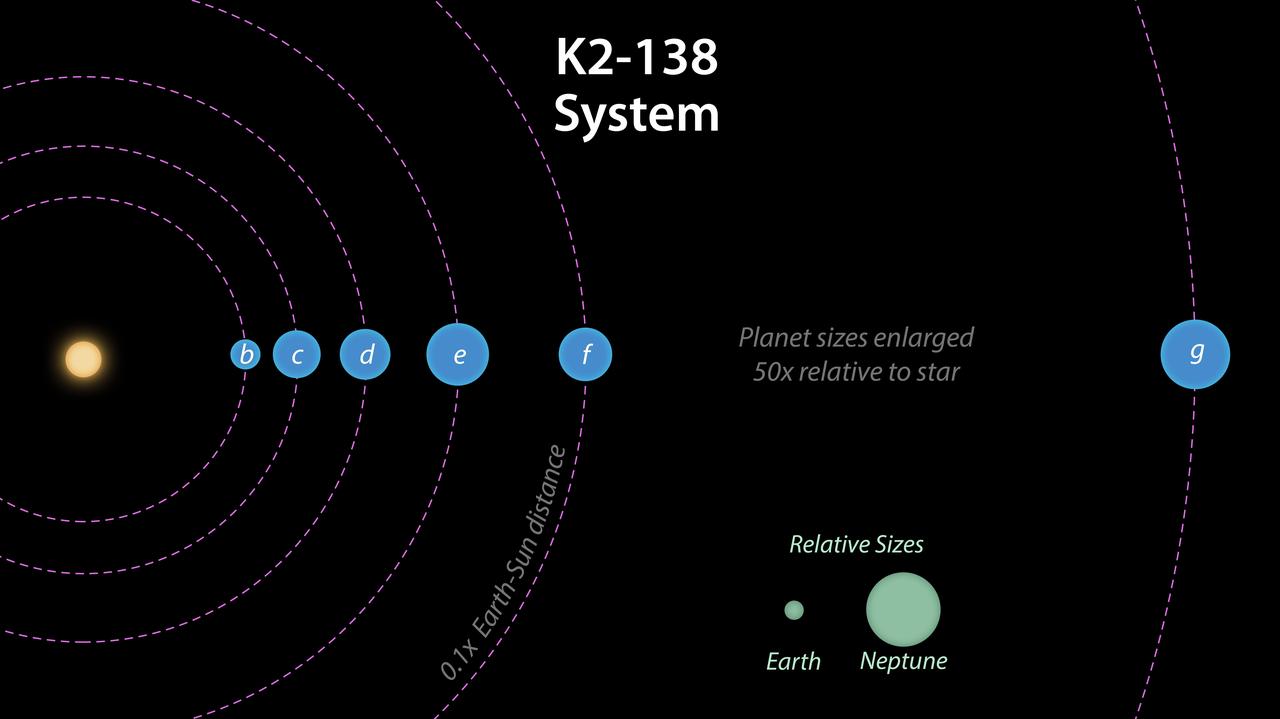

This artist's illustration shows the planetary system K2-138, which was discovered by citizen scientists in 2017 using data from NASA's Kepler space telescope. Five planets were initially detected in the system. In 2018, scientists using NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope found evidence of a sixth planet in the system. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23002

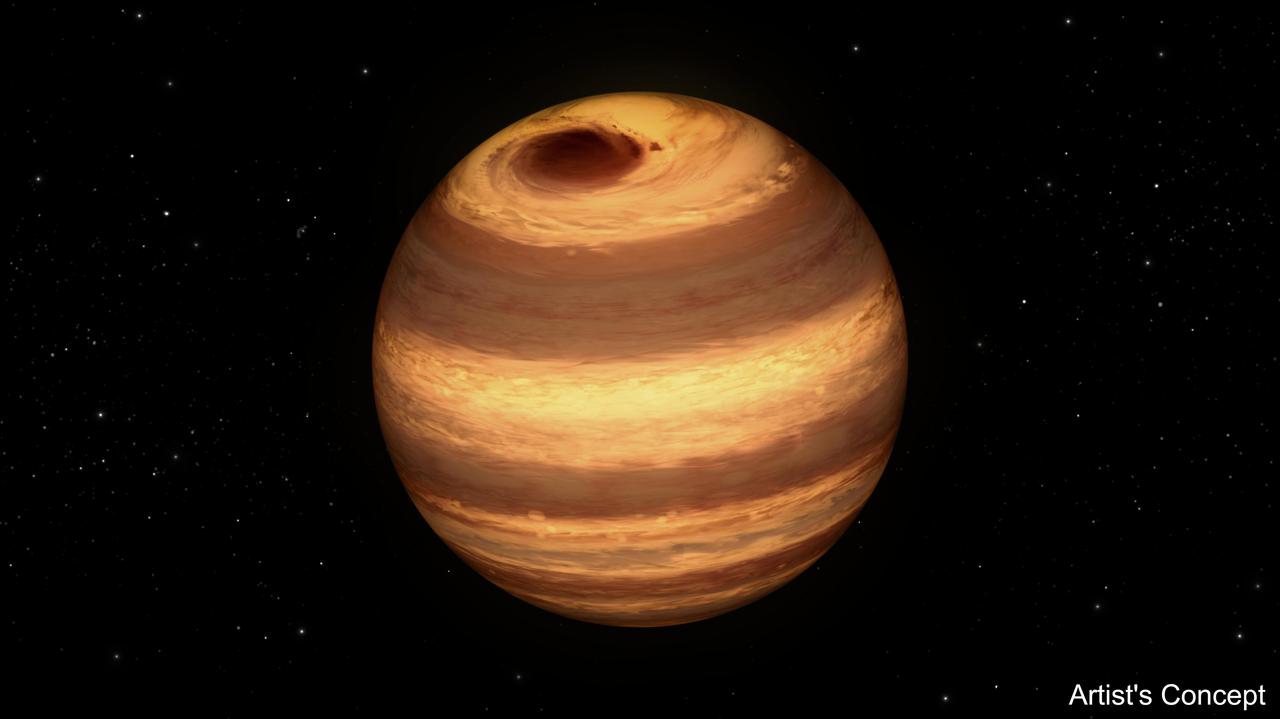

This illustration shows a cool star, called W1906+40, marked by a raging storm near one of its poles. The storm is thought to be similar to the Great Red Spot on Jupiter. Scientists discovered it using NASA's Kepler and Spitzer space telescopes. The location of the storm is estimated to be near the north pole of the star based on computer models of the data. The telescopes cannot see the storm itself, but learned of its presence after observing how the star's light changes over time. The storm travels around with the star, making a full lap about every 9 hours. When it passes into a telescope's field of view, it causes light of particular infrared and visible wavelengths to dip in brightness. The storm has persisted for at least two years. Astronomers aren't sure why it has lasted so long. While planets are known to have cloudy storms, this is the best evidence yet for a star with the same type of storm. The star, W1906+40, belongs to a thermally cool class of objects called L-dwarfs. Some L-dwarfs are considered stars because they fuse atoms and generate light, as our sun does, while others, called brown dwarfs, are known as "failed stars" for their lack of atomic fusion. The L-dwarf W1906+40 is thought to be a star based on estimates of its age (the older the L-dwarf, the more likely it is a star). Its temperature is about 2,200 Kelvin (3,500 degrees Fahrenheit). That may sound scorching hot, but as far as stars go, it is relatively cool. Cool enough, in fact, for clouds to form in its atmosphere. W1906+40 is located 53 light-years away in the constellation Lyra. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20055

This image shows the estimated radii of the six planets in the planetary system K2-128, as well as their distance from the parent star. The radii of the Earth and Neptune are shown for scale. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23003

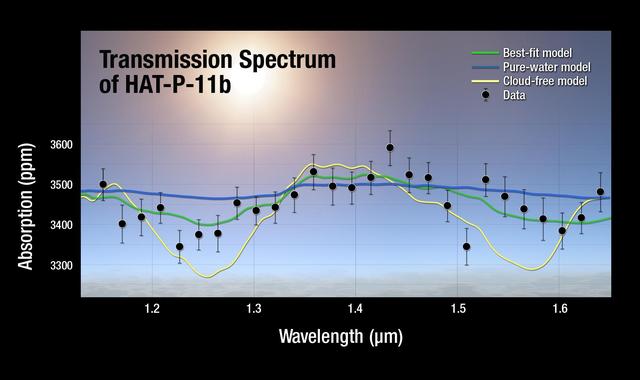

A plot of the transmission spectrum for exoplanet HAT-P-11b, with data from NASA Kepler, Hubble and Spitzer observatories combined. The results show a robust detection of water absorption in the Hubble data.

The newfound planet K2-288Bb, illustrated here, is slightly smaller than Neptune. Located about 226 light-years away, it orbits the fainter member of a pair of cool M-type stars every 31.3 days. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23004

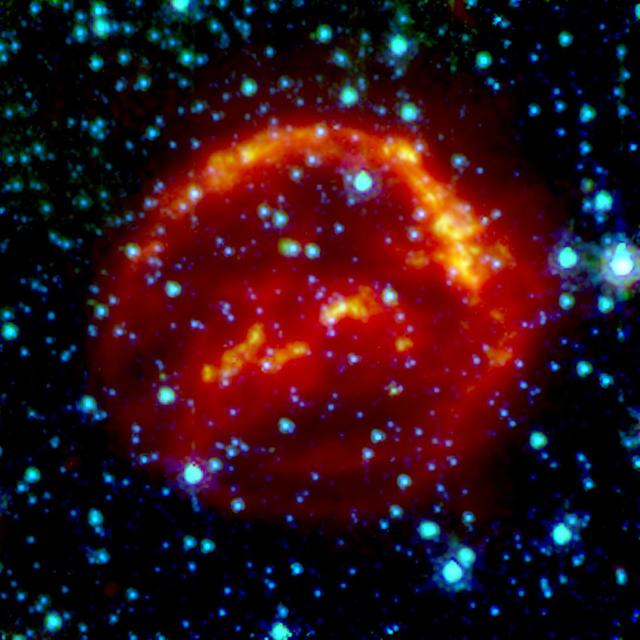

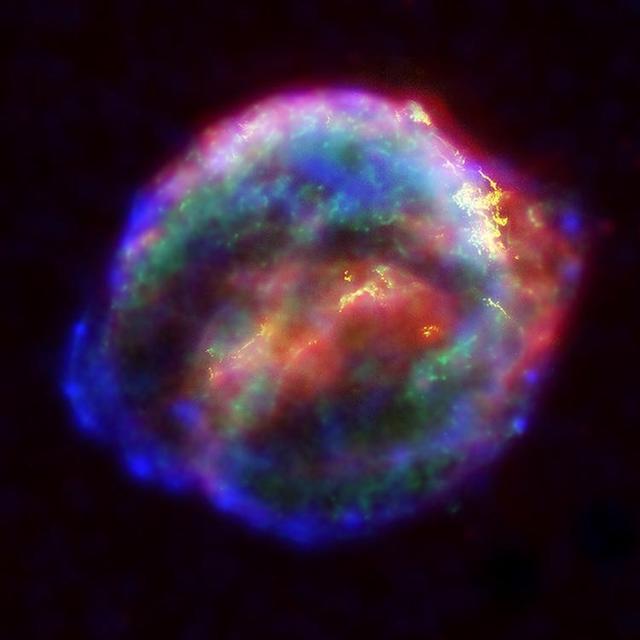

This Spitzer false-color image is a composite of data from the 24 micron channel of Spitzer's multiband imaging photometer (red), and three channels of its infrared array camera: 8 micron (yellow), 5.6 micron (blue), and 4.8 micron (green). Stars are most prominent in the two shorter wavelengths, causing them to show up as turquoise. The supernova remnant is most prominent at 24 microns, arising from dust that has been heated by the supernova shock wave, and re-radiated in the infrared. The 8 micron data shows infrared emission from regions closely associated with the optically emitting regions. These are the densest regions being encountered by the shock wave, and probably arose from condensations in the surrounding material that was lost by the supernova star before it exploded. The composite above (PIA06908, PIA06909, and PIA06910) represent views of Kepler's supernova remnant taken in X-rays, visible light, and infrared radiation. Each top panel in the composite above shows the entire remnant. Each color in the composite represents a different region of the electromagnetic spectrum, from X-rays to infrared light. The X-ray and infrared data cannot be seen with the human eye. Astronomers have color-coded those data so they can be seen in these images. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA06910

NASA Administrator Charles Bolden speaks at the 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Washington on Tuesday, Jan. 5, 2009. Throughout the meeting, NASA research and mission highlights will be presented from missions that include Kepler, the Spitzer Space Telescope, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the newly launched Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

NASA Administrator Charles Bolden speaks at the 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Washington on Tuesday, Jan. 5, 2009. Throughout the meeting, NASA research and mission highlights will be presented from missions that include Kepler, the Spitzer Space Telescope, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the newly launched Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

NASA Administrator Charles Bolden speaks at the 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Washington on Tuesday, Jan. 5, 2009. Throughout the meeting, NASA research and mission highlights will be presented from missions that include Kepler, the Spitzer Space Telescope, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the newly launched Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Astronomers have discovered one of the most distant planets known, a gas giant about 13,000 light-years from Earth, called OGLE-2014-BLG-0124L. The planet was discovered using a technique called microlensing, and the help of NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment, or OGLE. In this artist's illustration, planets discovered with microlensing are shown in yellow. The farthest lies in the center of our galaxy, 25,000 light-years away. Most of the known exoplanets, numbering in the thousands, have been discovered by NASA's Kepler space telescope, which uses a different strategy called the transit method. Kepler's cone-shaped field of view is shown in pink/orange. Ground-based telescopes, which use the transit and other planet-hunting methods, have discovered many exoplanets close to home, as shown by the pink/orange circle around the sun. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19333

NASA's three Great Observatories -- the Hubble Space Telescope, the SpitzerSpace Telescope, and the Chandra X-ray Observatory -- joined forces to probe theexpanding remains of a supernova, called Kepler's supernova remnant, first seen 400 years ago by sky watchers, including astronomer Johannes Kepler. The combined image unveils a bubble-shaped shroud of gas and dust that is 14light-years wide and is expanding at 4 million miles per hour (2,000 kilometersper second). Observations from each telescope highlight distinct features of thesupernova remnant, a fast-moving shell of iron-rich material from the explodedstar, surrounded by an expanding shock wave that is sweeping up interstellar gasand dust. Each color in this image represents a different region of the electromagneticspectrum, from X-rays to infrared light. These diverse colors are shown in thepanel of photographs below the composite image. The X-ray and infrared datacannot be seen with the human eye. By color-coding those data and combining themwith Hubble's visible-light view, astronomers are presenting a more completepicture of the supernova remnant. Visible-light images from the Hubble telescope (colored yellow) reveal where the supernova shock wave is slamming into the densest regions of surrounding gas.The bright glowing knots are dense clumps from instabilities that form behindthe shock wave. The Hubble data also show thin filaments of gas that look likerippled sheets seen edge-on. These filaments reveal where the shock wave isencountering lower-density, more uniform interstellar material. The Spitzer telescope shows microscopic dust particles (colored red) that havebeen heated by the supernova shock wave. The dust re-radiates the shock wave'senergy as infrared light. The Spitzer data are brightest in the regionssurrounding those seen in detail by the Hubble telescope. The Chandra X-ray data show regions of very hot gas, and extremely high-energyparticles. The hottest gas (higher-energy X-rays, colored blue) is locatedprimarily in the regions directly behind the shock front. These regions alsoshow up in the Hubble observations, and also align with the faint rim of glowingmaterial seen in the Spitzer data. The X-rays from the region on the lower left(colored blue) may be dominated by extremely high-energy electrons that wereproduced by the shock wave and are radiating at radio through X-ray wavelengthsas they spiral in the intensified magnetic field behind the shock front. CoolerX-ray gas (lower-energy X-rays, colored green) resides in a thick interior shelland marks the location of heated material expelled from the exploded star. Kepler's supernova, the last such object seen to explode in our Milky Waygalaxy, resides about 13,000 light-years away in the constellation Ophiuchus. The Chandra observations were taken in June 2000, the Hubble in August 2003;and the Spitzer in August 2004. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA06907

This artist's concept shows what the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system may look like, based on available data about the planets' diameters, masses and distances from the host star, as of February 2018. This image represents an updated version of PIA21422, which was created in 2017. The planets' appearances were re-imagined based on a 2018 study using additional observations from NASA's Spitzer and Kepler space telescopes, in addition to previous data from Spitzer, the ground-based TRAPPIST (TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope) telescope and other ground-based observatories. The system was named for the TRAPPIST telescope. The new analysis concludes that the seven planets of TRAPPIST-1 are all rocky, and some could contain significant amounts of water. TRAPPIST-1 is an ultra-cool dwarf star in the constellation Aquarius, and its planets orbit very close to it. The form that water would take on TRAPPIST-1 planets would depend on the amount of heat they receive from their star, which is a mere 9 percent as massive as our Sun. Planets closest to the star are more likely to host water in the form of atmospheric vapor, while those farther away may have water frozen on their surfaces as ice. TRAPPIST-1e is the rockiest planet of them all, but still is believed to have the potential to host some liquid water. In this illustration, the relative sizes of the planets and their host star, an ultracool dwarf, are all shown to scale. An annotated image is available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22093

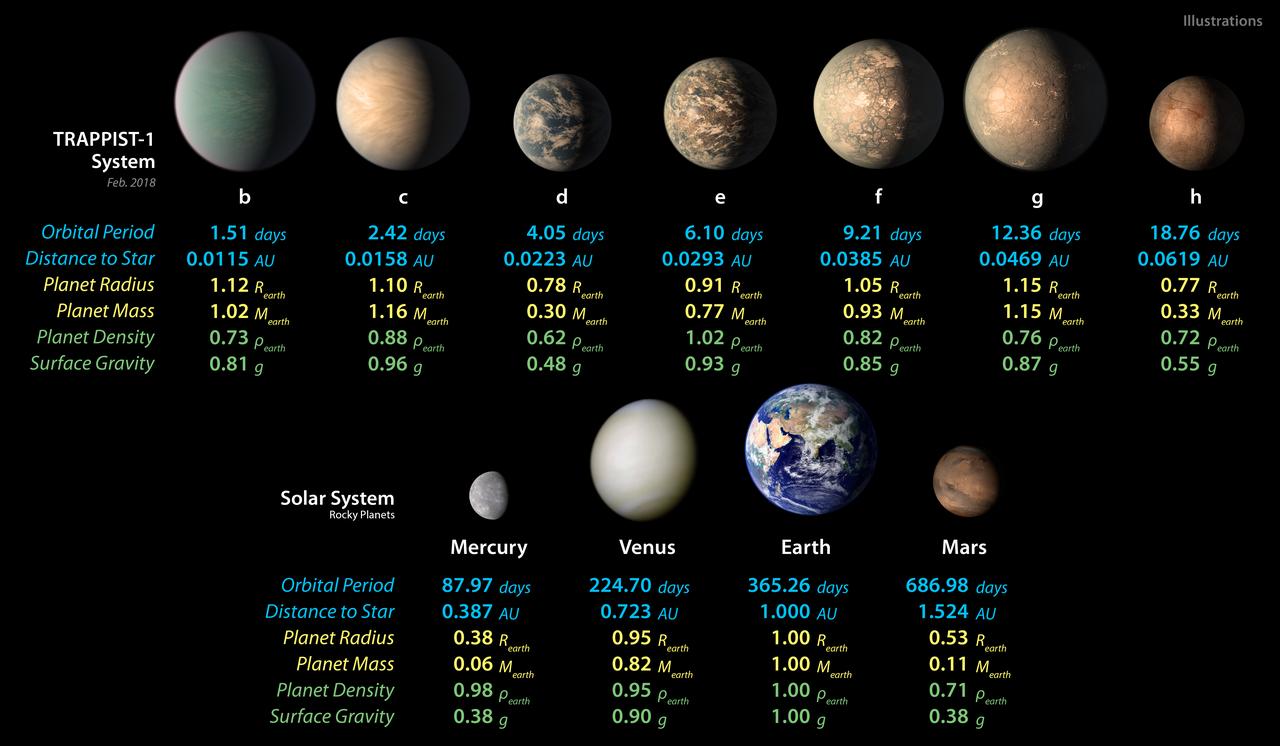

This chart shows, on the top row, artist concepts of the seven planets of TRAPPIST-1 with their orbital periods, distances from their star, radii, masses, densities and surface gravity as compared to those of Earth. These numbers are current as of February 2018. On the bottom row, the same numbers are displayed for the bodies of our inner solar system: Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. The TRAPPIST-1 planets orbit their star extremely closely, with periods ranging from 1.5 to only about 20 days. This is much shorter than the period of Mercury, which orbits our sun in about 88 days. The masses and densities of the TRAPPIST-1 planets were determined by careful measurements of slight variations in the timings of their orbits using extensive observations made by NASA's Spitzer and Kepler space telescopes, in combination with data from Hubble and a number of ground-based telescopes. These measurements are the most precise to date for any system of exoplanets. In this illustration, the relative sizes of the planets are all shown to scale. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22094

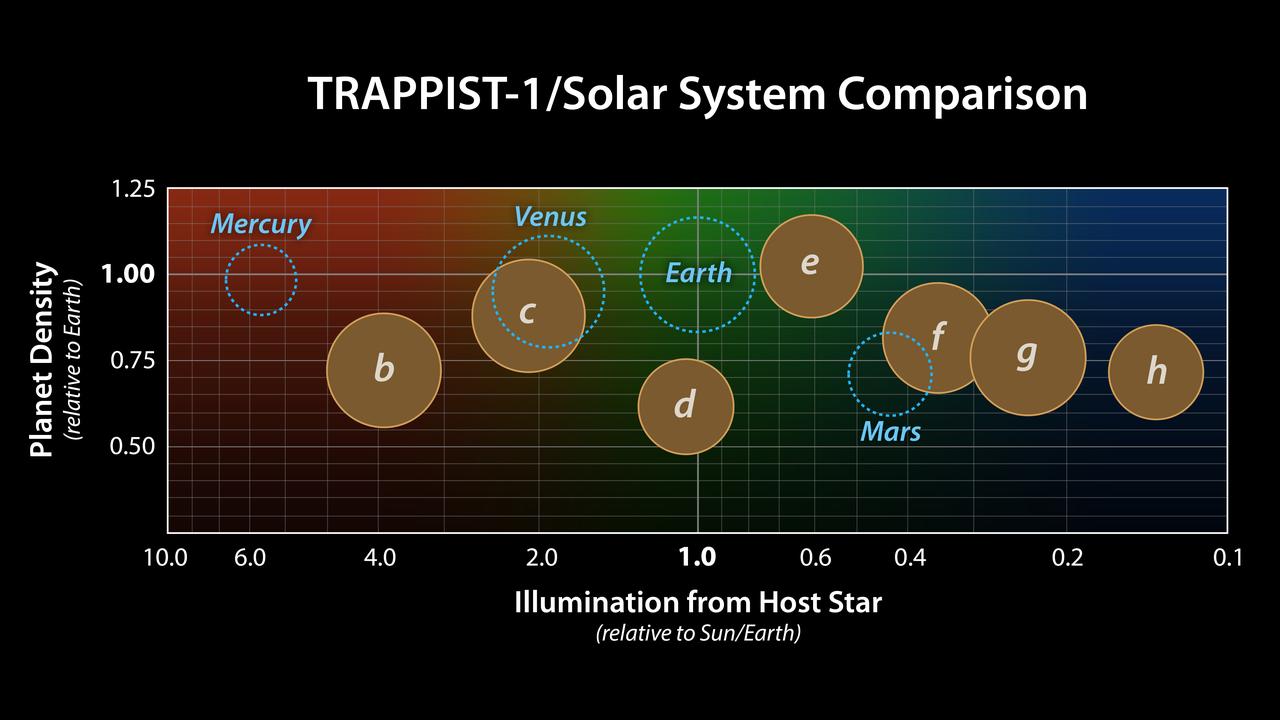

This graph presents measured properties of the seven TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets (labeled b through h), showing how they stack up with one another as well as with Earth and the other inner rocky worlds in our own solar system. The relative sizes of the planets are indicated by the circles. All of the known TRAPPIST-1 planets are larger than Mars, with five of them within 15% of the diameter of Earth. The vertical axis shows the uncompressed densities of the planets. Density, calculated from a planet's mass and volume, is the first important step in understanding its composition. Uncompressed density takes into account that the larger a planet is, the more its own gravity will pack the planet's material together and increase its density. Uncompressed density, therefore, usually provides a better means of comparing the composition of planets. The plot shows that the uncompressed densities of the TRAPPIST-1 planets are similar to one another, suggesting they may have all have a similar composition. The four rocky planets in our own solar system show more variation in density compared to the seven TRAPPIST-1 planets. Mercury, for example, contains a much higher percentage of iron than the other three rocky planets and thus has a much higher uncompressed density. The horizontal axis shows the level of illumination that each planet receives from its host star. The TRAPPIST-1 star is a mere 9% the mass of our Sun, and its temperature is much cooler. But because the TRAPPIST-1 planets orbit so closely to their star, they receive comparable levels of light and heat to Earth and its neighboring planets. The corresponding "habitable zones" — regions where an Earth-like planet could potentially support liquid water on its surface — of the two planetary systems are indicated near the top of the plot. The the two zones do not line up exactly because the cooler TRAPPIST-1 star emitting more of its light in the form of infrared radiation that is more efficiently absorbed by an Earth-like atmosphere. Since it takes less illumination to reach the same temperatures, the habitable zone shifts farther away from the star. The masses and densities of the TRAPPIST-1 planets were determined by measurements of slight variations in the timings of their orbits using extensive observations made by NASA's Spitzer and Kepler space telescopes, in combination with data from Hubble and a number of ground-based telescopes. The latest analysis, which includes Spitzer's complete record of over 1,000 hours of TRAPPIST-1 observations, has reduced the uncertainties of the mass measurements to a mere 3-6%. These are among the most accurate measurements of planetary masses anywhere outside of our solar system. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24371

This graph presents known properties of the seven TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets (labeled b through h), showing how they stack up to the inner rocky worlds in our own solar system. The horizontal axis shows the level of illumination that each planet receives from its host star. TRAPPIST-1 is a mere 9 percent the mass of our Sun, and its temperature is much cooler. But because the TRAPPIST-1 planets orbit so closely to their star, they receive comparable levels of light and heat to Earth and its neighboring planets. The vertical axis shows the densities of the planets. Density, calculated based on a planet's mass and volume, is the first important step in understanding a planet's composition. The plot shows that the TRAPPIST-1 planet densities range from being similar to Earth and Venus at the upper end, down to values comparable to Mars at the lower end. The relative sizes of the planets are indicated by the circles. The masses and densities of the TRAPPIST-1 planets were determined by careful measurements of slight variations in the timings of their orbits using extensive observations made by NASA's Spitzer and Kepler space telescopes, in combination with data from Hubble and a number of ground-based telescopes. These measurements are the most precise to date for any system of exoplanets. By comparing these measurements with theoretical models of how planets form and evolve, researchers have determined that they are all rocky in overall composition. Estimates suggest the lower-density planets could have large quantities of water -- as much as 5 percent by mass for TRAPPIST-1d. Earth, in comparison, has only about 0.02 percent of its mass in the form of water. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22095