The M2-F2 Lifting Body is seen here on the ramp at the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center. The success of Dryden's M2-F1 program led to NASA's development and construction of two heavyweight lifting bodies based on studies at NASA's Ames and Langley research centers -- the M2-F2 and the HL-10, both built by the Northrop Corporation. The "M" refers to "manned" and "F" refers to "flight" version. "HL" comes from "horizontal landing" and 10 is for the tenth lifting body model to be investigated by Langley. The first flight of the M2-F2 -- which looked much like the "F1" -- was on July 12, 1966. Milt Thompson was the pilot. By then, the same B-52 used to air launch the famed X-15 rocket research aircraft was modified to also carry the lifting bodies. Thompson was dropped from the B-52's wing pylon mount at an altitude of 45,000 feet on that maiden glide flight. The M2-F2 weighed 4,620 pounds, was 22 feet long, and had a width of about 10 feet. On May 10, 1967, during the sixteenth glide flight leading up to powered flight, a landing accident severely damaged the vehicle and seriously injured the NASA pilot, Bruce Peterson. NASA pilots and researchers realized the M2-F2 had lateral control problems, even though it had a stability augmentation control system. When the M2-F2 was rebuilt at Dryden and redesignated the M2-F3, it was modified with an additional third vertical fin -- centered between the tip fins -- to improve control characteristics. The M2-F2/F3 was the first of the heavy-weight, entry-configuration lifting bodies. Its successful development as a research test vehicle answered many of the generic questions about these vehicles. NASA donated the M2-F3 vehicle to the Smithsonian Institute in December 1973. It is currently hanging in the Air and Space Museum along with the X-15 aircraft number 1, which was its hangar partner at Dryden from 1965 to 1969.

This photo shows the left side cockpit instrumentation panel of the M2-F2 Lifting Body. The success of Dryden's M2-F1 program led to NASA's development and construction of two heavyweight lifting bodies based on studies at NASA's Ames and Langley research centers -- the M2-F2 and the HL-10, both built by the Northrop Corporation. The "M" refers to "manned" and "F" refers to "flight" version. "HL" comes from "horizontal landing" and 10 is for the tenth lifting body model to be investigated by Langley. The first flight of the M2-F2 -- which looked much like the "F1" -- was on July 12, 1966. Milt Thompson was the pilot. By then, the same B-52 used to air launch the famed X-15 rocket research aircraft was modified to also carry the lifting bodies. Thompson was dropped from the B-52's wing pylon mount at an altitude of 45,000 feet on that maiden glide flight. The M2-F2 weighed 4,620 pounds, was 22 feet long, and had a width of about 10 feet. On May 10, 1967, during the sixteenth glide flight leading up to powered flight, a landing accident severely damaged the vehicle and seriously injured the NASA pilot, Bruce Peterson. NASA pilots and researchers realized the M2-F2 had lateral control problems, even though it had a stability augmentation control system. When the M2-F2 was rebuilt at Dryden and redesignated the M2-F3, it was modified with an additional third vertical fin -- centered between the tip fins -- to improve control characteristics. The M2-F2/F3 was the first of the heavy-weight, entry-configuration lifting bodies. Its successful development as a research test vehicle answered many of the generic questions about these vehicles. NASA donated the M2-F3 vehicle to the Smithsonian Institute in December 1973. It is currently hanging in the Air and Space Museum along with the X-15 aircraft number 1, which was its hangar partner at Dryden from 1965 to 1969.

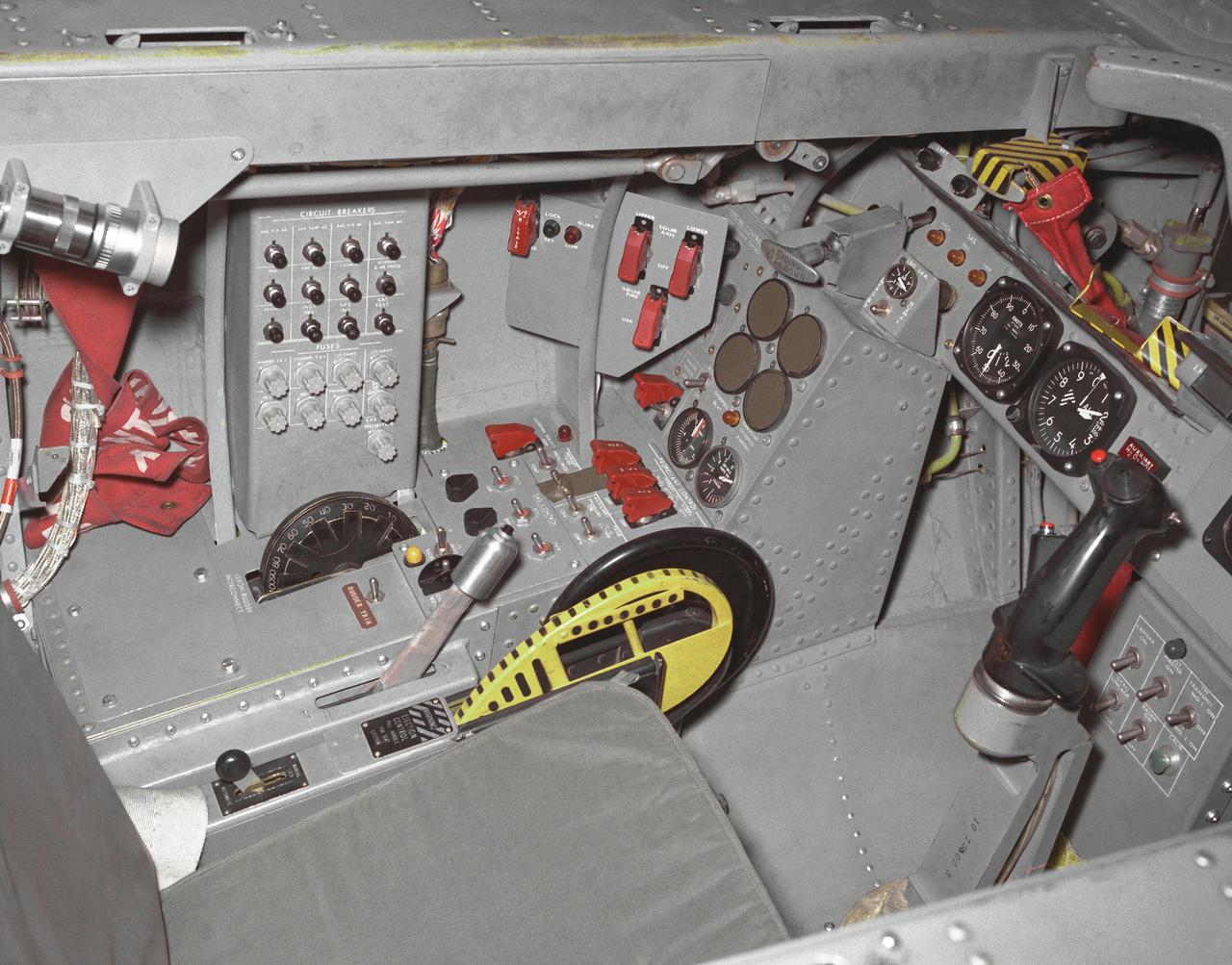

This photo shows the right side cockpit instrumentation panel of the M2-F2 Lifting Body. The success of Dryden's M2-F1 program led to NASA's development and construction of two heavyweight lifting bodies based on studies at NASA's Ames and Langley research centers -- the M2-F2 and the HL-10, both built by the Northrop Corporation. The "M" refers to "manned" and "F" refers to "flight" version. "HL" comes from "horizontal landing" and 10 is for the tenth lifting body model to be investigated by Langley. The first flight of the M2-F2 -- which looked much like the "F1" -- was on July 12, 1966. Milt Thompson was the pilot. By then, the same B-52 used to air launch the famed X-15 rocket research aircraft was modified to also carry the lifting bodies. Thompson was dropped from the B-52's wing pylon mount at an altitude of 45,000 feet on that maiden glide flight. The M2-F2 weighed 4,620 pounds, was 22 feet long, and had a width of about 10 feet. On May 10, 1967, during the sixteenth glide flight leading up to powered flight, a landing accident severely damaged the vehicle and seriously injured the NASA pilot, Bruce Peterson. NASA pilots and researchers realized the M2-F2 had lateral control problems, even though it had a stability augmentation control system. When the M2-F2 was rebuilt at Dryden and redesignated the M2-F3, it was modified with an additional third vertical fin -- centered between the tip fins -- to improve control characteristics. The M2-F2/F3 was the first of the heavy-weight, entry-configuration lifting bodies. Its successful development as a research test vehicle answered many of the generic questions about these vehicles. NASA donated the M2-F3 vehicle to the Smithsonian Institute in December 1973. It is currently hanging in the Air and Space Museum along with the X-15 aircraft number 1, which was its hangar partner at Dryden from 1965 to 1969.

Bruce A. Peterson standing beside the M2-F2 lifting body on Rogers Dry Lake. Peterson became the NASA project pilot for the lifting body program after Milt Thompson retired from flying in late 1966. Peterson had flown the M2-F1, and made the first glide flight of the HL-10 heavy-weight lifting body in December 1966. On May 10, 1967, Peterson made his fourth glide flight in the M2-F2. This was also the M2-F2's 16th glide flight, scheduled to be the last one before the powered flights began. However, as pilot Bruce Peterson neared the lakebed, the M2-F2 suffered a pilot induced oscillation (PIO). The vehicle rolled from side to side in flight as he tried to bring it under control. Peterson recovered, but then observed a rescue helicopter that seemed to pose a collision threat. Distracted, Peterson drifted in a cross-wind to an unmarked area of the lakebed where it was very difficult to judge the height over the lakebed because of a lack of the guidance the markers provided on the lakebed runway. Peterson fired the landing rockets to provide additional lift, but he hit the lakebed before the landing gear was fully down and locked. The M2-F2 rolled over six times, coming to rest upside down. Pulled from the vehicle by Jay King and Joseph Huxman, Peterson was rushed to the base hospital, transferred to March Air Force Base and then the UCLA Hospital. He recovered but lost vision in his right eye due to a staph infection.

NASA research pilot Milt Thompson is helped into the cockpit of the M2-F2 lifting body research aircraft at NASA’s Flight Research Center (now the Dryden Flight Research Center). The M2-F2 is attached to a wing pylon under the wing of NASA’s B-52 mothership. The flight was a captive flight with the pilot on-board. Milt Thompson flew in the lifting body throughout the flight, but it was never dropped from the mothership.

The HL-10 was one of five heavyweight lifting-body designs flown at NASA's Flight Research Center (FRC--later Dryden Flight Research Center), Edwards, California, from July 1966 to November 1975 to study and validate the concept of safely maneuvering and landing a low lift-over-drag vehicle designed for reentry from space. Northrop Corporation built the HL-10 and M2-F2, the first two of the fleet of "heavy" lifting bodies flown by the NASA Flight Research Center. The contract for construction of the HL-10 and the M2-F2 was $1.8 million. "HL" stands for horizontal landing, and "10" refers to the tenth design studied by engineers at NASA's Langley Research Center, Hampton, Va. After delivery to NASA in January 1966, the HL-10 made its first flight on Dec. 22, 1966, with research pilot Bruce Peterson in the cockpit. Although an XLR-11 rocket engine was installed in the vehicle, the first 11 drop flights from the B-52 launch aircraft were powerless glide flights to assess handling qualities, stability, and control. In the end, the HL-10 was judged to be the best handling of the three original heavy-weight lifting bodies (M2-F2/F3, HL-10, X-24A). The HL-10 was flown 37 times during the lifting body research program and logged the highest altitude and fastest speed in the Lifting Body program. On Feb. 18, 1970, Air Force test pilot Peter Hoag piloted the HL-10 to Mach 1.86 (1,228 mph). Nine days later, NASA pilot Bill Dana flew the vehicle to 90,030 feet, which became the highest altitude reached in the program. Some new and different lessons were learned through the successful flight testing of the HL-10. These lessons, when combined with information from it's sister ship, the M2-F2/F3, provided an excellent starting point for designers of future entry vehicles, including the Space Shuttle.

NASA research pilot Milt Thompson sits in the M2-F2 "heavyweight" lifting body research vehicle before a 1966 test flight. The M2-F2 and the other lifting-body designs were all attached to a wing pylon on NASA’s B-52 mothership and carried aloft. The vehicles were then drop-launched and, at the end of their flights, glided back to wheeled landings on the dry lake or runway at Edwards AFB. The lifting body designs influenced the design of the Space Shuttle and were also reincarnated in the design of the X-38 in the 1990s.

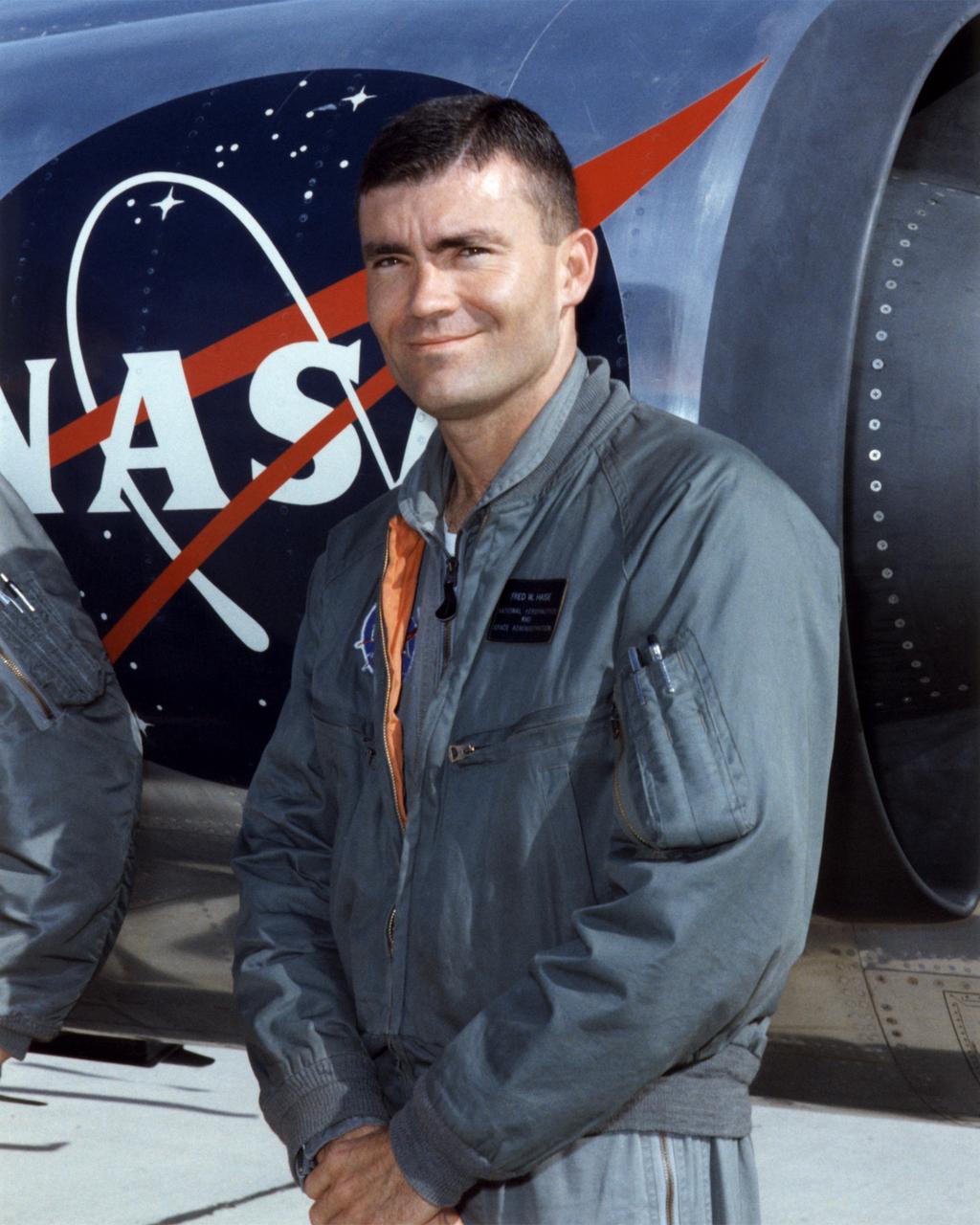

Fred W. Haise Jr. was a research pilot and an astronaut for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration from 1959 to 1979. He began flying at the Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio (today the Glenn Research Center), in 1959. He became a research pilot at the NASA Flight Research Center (FRC), Edwards, Calif., in 1963, serving NASA in that position for three years until being selected to be an astronaut in 1966 His best-known assignment at the FRC (later redesignated the Dryden Flight Research Center) was as a lifting body pilot. Shortly after flying the M2-F1 on a car tow to about 25 feet on April 22, 1966, he was assigned as an astronaut to the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. While at the FRC he had also flown a variety of other research and support aircraft, including the variable-stability T-33A to simulate the M2-F2 heavyweight lifting body, some light aircraft including the Piper PA-30 to evaluate their handling qualities, the Apache helicopter, the Aero Commander, the Cessna 310, the Douglas F5D, the Lockheed F-104 and T-33, the Cessna T-37, and the Douglas C-47. After becoming an astronaut, Haise served as a backup crewmember for the Apollo 8, 11, and 16 missions. He flew on the aborted Apollo 13 lunar mission in 1970, spending 142 hours and 54 minutes in space before returning safely to Earth. In 1977, he was the commander of three free flights of the Space Shuttle prototype Enterprise when it flew its Approach and Landing Tests at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. Meanwhile, from April 1973 to January 1976, Haise served as the Technical Assistant to the Manager of the Space Shuttle Orbiter Project. In 1979, he left NASA to become the Vice President for Space Programs with the Grumman Aerospace Corporation. He then served as President of Grumman Technical Services, an operating division of Northrop Grumman Corporation, from January 1992 until his retirement. Haise was born in Biloxi, Miss., on November 14, 1933. He underwent flight traini

A photo of model airplane builders James B. Newman and Robert L. McDonald preparing for a flight with models of the M2-F2 and a “Mothership”. In 1968 a test flight was made on the Rosamond dry lakebed, Rosamond, California. The original idea of lifting bodies was conceived about 1957 by Dr. Alfred J. Eggers, Jr., then the assistant director for Research and Development Analysis and Planning at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics' Ames Aeronautical Laboratory, Moffett Field, California. Nose cone studies led to the design known as the M-2, a modified half-cone, rounded on the bottom and flat on top, with a blunt, rounded nose and twin tail fins. To gather flight data on this configuration, models were found to be an effective method. A special twin-engined, 14-foot model “mothership” was used for carrying the M2-F2 model to altitude and a launch, much as was being done with the B-52 for the full-scale lifting bodies. Jim (on the left) will fly the “mothership” and Bob will take control of the M2-F2 at launch and fly it to a landing on the lakebed.