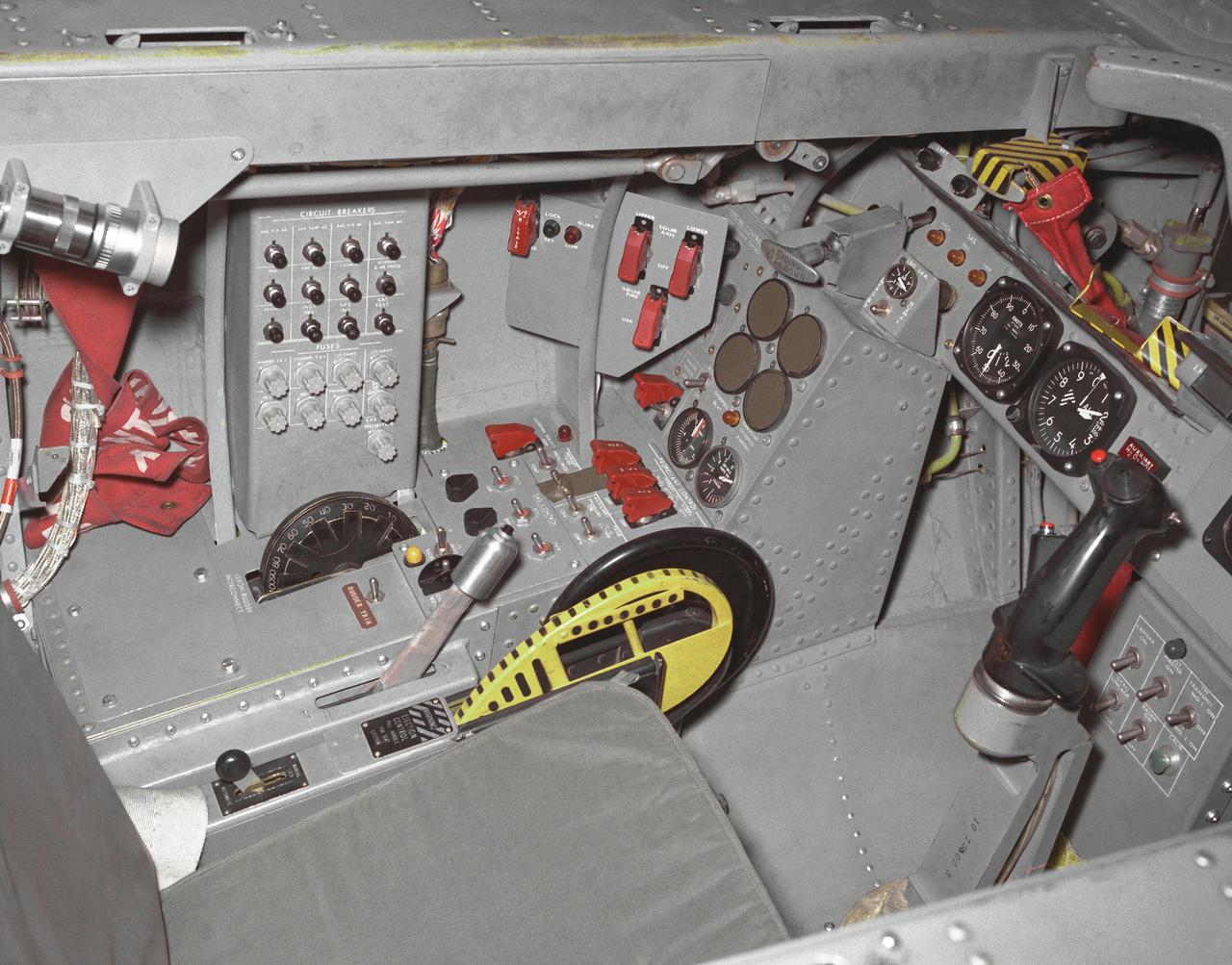

This photo shows the cockpit instrument panel of the M2-F3 Lifting Body.

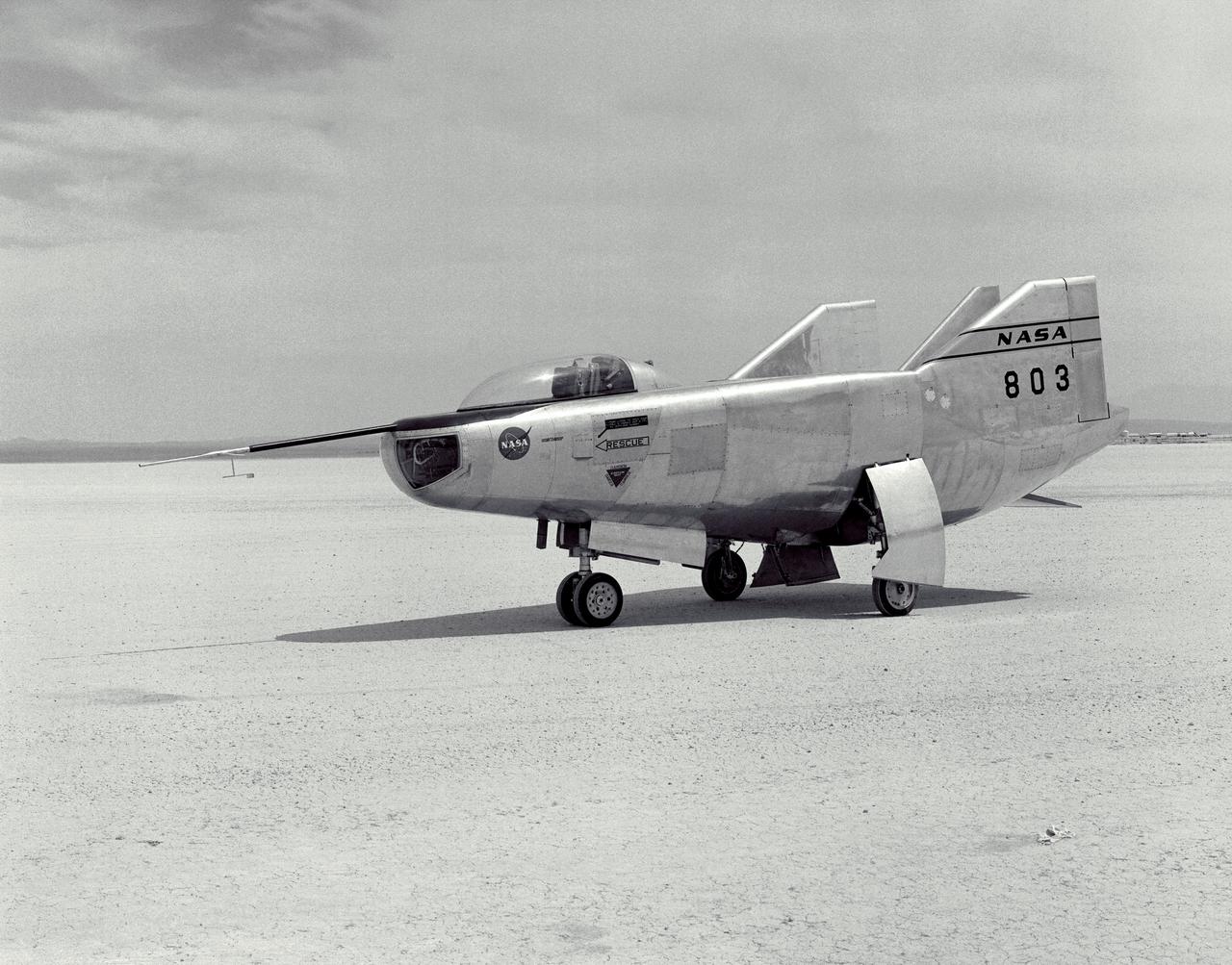

The M2-F3 Lifting Body is seen here on the lakebed at the NASA Flight Research Center (FRC--later the Dryden Flight Research Center), Edwards, California. After a three-year-long redesign and rebuilding effort, the M2-F3 was ready to fly. The May 1967 crash of the M2-F2 had damaged both the external skin and the internal structure of the lifting body. At first, it seemed that the vehicle had been irreparably damaged, but the original manufacturer, Northrop, did the repair work and returned the redesigned M2-F3 with a center fin for stability to the FRC.

The M2-F3 Lifting Body is seen here on the lakebed next to the NASA Flight Research Center (later the Dryden Flight Research Center), Edwards, California. Redesigned and rebuilt from the M2-F2, the M2-F3 featured as its most visible change a center fin for greater stability. While the M2-F3 was still demanding to fly, the center fin eliminated the high risk of pilot induced oscillation (PIO) that was characteristic of the M2-F2.

The M2-F3 Lifting Body is seen here on the lakebed next to the NASA Flight Research Center (FRC--later Dryden Flight Research Center), Edwards, California. The May 1967 crash of the M2-F2 had torn off the left fin and landing gear. It had also damaged the external skin and internal structure. Flight Research Center engineers worked with Ames Research Center and the Air Force in redesigning the vehicle with a center fin to provide greater stability. Then Northrop Corporation cooperated with the FRC in rebuilding the vehicle. The entire process took three years.

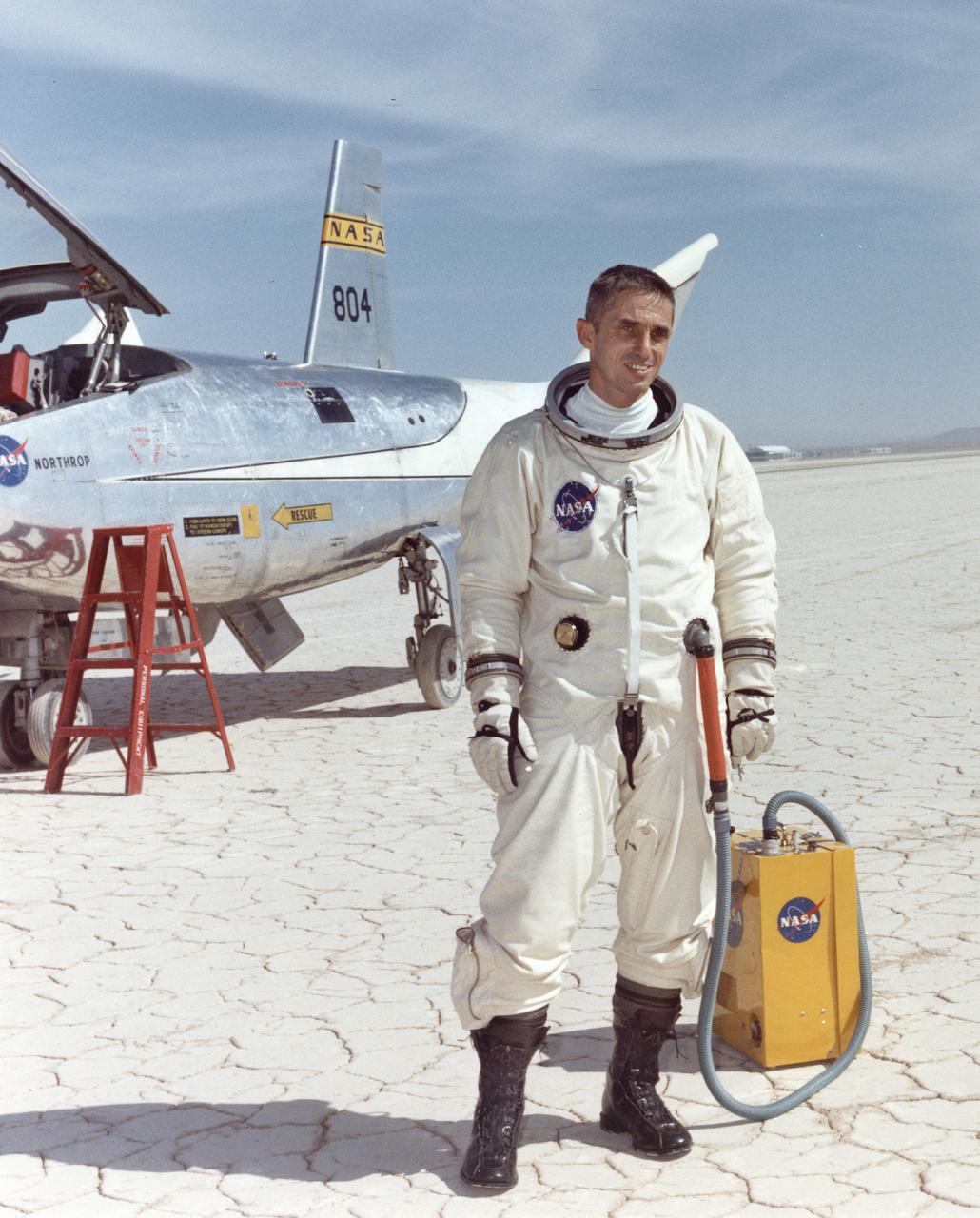

NASA research pilot John A. Manke is seen here in front of the M2-F3 Lifting Body. Manke was hired by NASA on May 25, 1962, as a flight research engineer. He was later assigned to the pilot's office and flew various support aircraft including the F-104, F5D, F-111 and C-47. After leaving the Marine Corps in 1960, Manke worked for Honeywell Corporation as a test engineer for two years before coming to NASA. He was project pilot on the X-24B and also flew the HL-10, M2-F3, and X-24A lifting bodies. John made the first supersonic flight of a lifting body and the first landing of a lifting body on a hard surface runway. Manke served as Director of the Flight Operations and Support Directorate at the Dryden Flight Research Center prior to its integration with Ames Research Center in October 1981. After this date John was named to head the joint Ames-Dryden Directorate of Flight Operations. He also served as site manager of the NASA Ames-Dryden Flight Research Facility. John is a member of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots. He retired on April 27, 1984.

The M2-F2 Lifting Body is seen here on the ramp at the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center. The success of Dryden's M2-F1 program led to NASA's development and construction of two heavyweight lifting bodies based on studies at NASA's Ames and Langley research centers -- the M2-F2 and the HL-10, both built by the Northrop Corporation. The "M" refers to "manned" and "F" refers to "flight" version. "HL" comes from "horizontal landing" and 10 is for the tenth lifting body model to be investigated by Langley. The first flight of the M2-F2 -- which looked much like the "F1" -- was on July 12, 1966. Milt Thompson was the pilot. By then, the same B-52 used to air launch the famed X-15 rocket research aircraft was modified to also carry the lifting bodies. Thompson was dropped from the B-52's wing pylon mount at an altitude of 45,000 feet on that maiden glide flight. The M2-F2 weighed 4,620 pounds, was 22 feet long, and had a width of about 10 feet. On May 10, 1967, during the sixteenth glide flight leading up to powered flight, a landing accident severely damaged the vehicle and seriously injured the NASA pilot, Bruce Peterson. NASA pilots and researchers realized the M2-F2 had lateral control problems, even though it had a stability augmentation control system. When the M2-F2 was rebuilt at Dryden and redesignated the M2-F3, it was modified with an additional third vertical fin -- centered between the tip fins -- to improve control characteristics. The M2-F2/F3 was the first of the heavy-weight, entry-configuration lifting bodies. Its successful development as a research test vehicle answered many of the generic questions about these vehicles. NASA donated the M2-F3 vehicle to the Smithsonian Institute in December 1973. It is currently hanging in the Air and Space Museum along with the X-15 aircraft number 1, which was its hangar partner at Dryden from 1965 to 1969.

This photo shows the left side cockpit instrumentation panel of the M2-F2 Lifting Body. The success of Dryden's M2-F1 program led to NASA's development and construction of two heavyweight lifting bodies based on studies at NASA's Ames and Langley research centers -- the M2-F2 and the HL-10, both built by the Northrop Corporation. The "M" refers to "manned" and "F" refers to "flight" version. "HL" comes from "horizontal landing" and 10 is for the tenth lifting body model to be investigated by Langley. The first flight of the M2-F2 -- which looked much like the "F1" -- was on July 12, 1966. Milt Thompson was the pilot. By then, the same B-52 used to air launch the famed X-15 rocket research aircraft was modified to also carry the lifting bodies. Thompson was dropped from the B-52's wing pylon mount at an altitude of 45,000 feet on that maiden glide flight. The M2-F2 weighed 4,620 pounds, was 22 feet long, and had a width of about 10 feet. On May 10, 1967, during the sixteenth glide flight leading up to powered flight, a landing accident severely damaged the vehicle and seriously injured the NASA pilot, Bruce Peterson. NASA pilots and researchers realized the M2-F2 had lateral control problems, even though it had a stability augmentation control system. When the M2-F2 was rebuilt at Dryden and redesignated the M2-F3, it was modified with an additional third vertical fin -- centered between the tip fins -- to improve control characteristics. The M2-F2/F3 was the first of the heavy-weight, entry-configuration lifting bodies. Its successful development as a research test vehicle answered many of the generic questions about these vehicles. NASA donated the M2-F3 vehicle to the Smithsonian Institute in December 1973. It is currently hanging in the Air and Space Museum along with the X-15 aircraft number 1, which was its hangar partner at Dryden from 1965 to 1969.

This photo shows the right side cockpit instrumentation panel of the M2-F2 Lifting Body. The success of Dryden's M2-F1 program led to NASA's development and construction of two heavyweight lifting bodies based on studies at NASA's Ames and Langley research centers -- the M2-F2 and the HL-10, both built by the Northrop Corporation. The "M" refers to "manned" and "F" refers to "flight" version. "HL" comes from "horizontal landing" and 10 is for the tenth lifting body model to be investigated by Langley. The first flight of the M2-F2 -- which looked much like the "F1" -- was on July 12, 1966. Milt Thompson was the pilot. By then, the same B-52 used to air launch the famed X-15 rocket research aircraft was modified to also carry the lifting bodies. Thompson was dropped from the B-52's wing pylon mount at an altitude of 45,000 feet on that maiden glide flight. The M2-F2 weighed 4,620 pounds, was 22 feet long, and had a width of about 10 feet. On May 10, 1967, during the sixteenth glide flight leading up to powered flight, a landing accident severely damaged the vehicle and seriously injured the NASA pilot, Bruce Peterson. NASA pilots and researchers realized the M2-F2 had lateral control problems, even though it had a stability augmentation control system. When the M2-F2 was rebuilt at Dryden and redesignated the M2-F3, it was modified with an additional third vertical fin -- centered between the tip fins -- to improve control characteristics. The M2-F2/F3 was the first of the heavy-weight, entry-configuration lifting bodies. Its successful development as a research test vehicle answered many of the generic questions about these vehicles. NASA donated the M2-F3 vehicle to the Smithsonian Institute in December 1973. It is currently hanging in the Air and Space Museum along with the X-15 aircraft number 1, which was its hangar partner at Dryden from 1965 to 1969.

The HL-10, seen here parked on the ramp at NASA's Flight Research Center in 1966, had a radically different shape from that of the M2-F2/F3. While the M2s were flat on top and had rounded undersides (giving them a bathtub shape), the HL-10 had a flat lower surface and a rounded top. Both shapes provided lift without wings, however. This photo was taken before the HL-10's fins were modified.

The wingless, lifting body aircraft sitting on Rogers Dry Lake at what is now NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, from left to right are the X-24A, M2-F3 and the HL-10. The lifting body aircraft studied the feasibility of maneuvering and landing an aerodynamic craft designed for reentry from space. These lifting bodies were air launched by a B-52 mother ship, then flew powered by their own rocket engines before making an unpowered approach and landing. They helped validate the concept that a space shuttle could make accurate landings without power. The X-24A flew from April 17, 1969 to June 4, 1971. The M2-F3 flew from June 2, 1970 until December 22, 1972. The HL-10 flew from December 22, 1966 until July 17, 1970, and logged the highest and fastest records in the lifting body program.

The wingless, lifting body aircraft sitting on Rogers Dry Lake at what is now NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, from left to right are the X-24A, M2-F3 and the HL-10. The lifting body aircraft studied the feasibility of maneuvering and landing an aerodynamic craft designed for reentry from space. These lifting bodies were air launched by a B-52 mother ship, then flew powered by their own rocket engines before making an unpowered approach and landing. They helped validate the concept that a space shuttle could make accurate landings without power. The X-24A flew from April 17, 1969 to June 4, 1971. The M2-F3 flew from June 2, 1970 until December 21, 1971. The HL-10 flew from December 22, 1966 until July 17, 1970, and logged the highest and fastest records in the lifting body program.

The wingless, lifting body aircraft sitting on Rogers Dry Lake at what is now NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, from left to right are the X-24A, M2-F3 and the HL-10. The lifting body aircraft studied the feasibility of maneuvering and landing an aerodynamic craft designed for reentry from space. These lifting bodies were air launched by a B-52 mother ship, then flew powered by their own rocket engines before making an unpowered approach and landing. They helped validate the concept that a space shuttle could make accurate landings without power. The X-24A flew from April 17, 1969 to June 4, 1971. The M2-F3 flew from June 2, 1970 until December 20, 1972. The HL-10 flew from December 22, 1966 until July 17, 1970 and logged the highest and fastest records in the lifting body program.

The wingless, lifting body aircraft sitting on Rogers Dry Lake at what is now NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, from left to right are the X-24A, M2-F3 and the HL-10. The lifting body aircraft studied the feasibility of maneuvering and landing an aerodynamic craft designed for reentry from space. These lifting bodies were air launched by a B-52 mother ship, then flew powered by their own rocket engines before making an unpowered approach and landing. They helped validate the concept that a space shuttle could make accurate landings without power. The X-24A flew from April 17, 1969 to June 4, 1971. The M2-F3 flew from June 2, 1970 until December 20, 1972. The HL-10 flew from December 22, 1966 until July 17, 1970 and logged the highest and fastest records in the lifting body program.

NASA research pilot Bill Dana after his fourth free flight (1 glide and 3 powered) in the HL-10. This particular flight reached a maximum speed of Mach 1.45. Dana made a total of nine HL-10 flights (1 glide and 8 powered), and his lifting body experience as a whole included several car tow and 1 air tow flights in the M2-F1; 4 glide and 15 powered flights in the M2-F3; and 2 powered flights in the X-24B. He is wearing a pressure suit for protection against the cockpit depressurizing at high altitudes. The air conditioner box held by the ground crewman provides cool air to prevent overheating.

The HL-10 was one of five heavyweight lifting-body designs flown at NASA's Flight Research Center (FRC--later Dryden Flight Research Center), Edwards, California, from July 1966 to November 1975 to study and validate the concept of safely maneuvering and landing a low lift-over-drag vehicle designed for reentry from space. Northrop Corporation built the HL-10 and M2-F2, the first two of the fleet of "heavy" lifting bodies flown by the NASA Flight Research Center. The contract for construction of the HL-10 and the M2-F2 was $1.8 million. "HL" stands for horizontal landing, and "10" refers to the tenth design studied by engineers at NASA's Langley Research Center, Hampton, Va. After delivery to NASA in January 1966, the HL-10 made its first flight on Dec. 22, 1966, with research pilot Bruce Peterson in the cockpit. Although an XLR-11 rocket engine was installed in the vehicle, the first 11 drop flights from the B-52 launch aircraft were powerless glide flights to assess handling qualities, stability, and control. In the end, the HL-10 was judged to be the best handling of the three original heavy-weight lifting bodies (M2-F2/F3, HL-10, X-24A). The HL-10 was flown 37 times during the lifting body research program and logged the highest altitude and fastest speed in the Lifting Body program. On Feb. 18, 1970, Air Force test pilot Peter Hoag piloted the HL-10 to Mach 1.86 (1,228 mph). Nine days later, NASA pilot Bill Dana flew the vehicle to 90,030 feet, which became the highest altitude reached in the program. Some new and different lessons were learned through the successful flight testing of the HL-10. These lessons, when combined with information from it's sister ship, the M2-F2/F3, provided an excellent starting point for designers of future entry vehicles, including the Space Shuttle.

NASA research pilot Bill Dana stands in front of the HL-10 Lifting Body following his first glide flight on April 25, 1969. Dana later retired as Chief Engineer at NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, (called the NASA Flight Research Center in 1969). Prior to his lifting body assignment, Dana flew the X-15 research airplane. He flew the rocket-powered aircraft 16 times, reaching a top speed of 3,897 miles per hour and a peak altitude of 310,000 feet (almost 59 miles high).

The HL-10, seen here parked on the ramp, was one of five lifting body designs flown at NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, from July 1966 to November 1975 to study and validate the concept of safely maneuvering and landing a low lift-over-drag vehicle designed for reentry from space.

The HL-10 Lifting Body is seen here in powered flight shortly after launch from the B-52 mothership. When HL-10 powered flights began on October 23, 1968, the vehicle used the same basic XLR-11 rocket engine that powered the original X-1s. A total of five powered flights were made before the HL-10 first flew supersonically on May 9, 1969, with John Manke in the pilot's seat.

The HL-10 Lifting Body is seen here parked on Rogers Dry Lake, the unique location where it landed after research flights. This 1968 photo shows the vehicle after the fins were modified to remove instabilities encountered on the first flight. It involved a change to the shape of the leading edge of the fins to eliminate flow separation. It required extensive wind-tunnel testing at Langley Research Center, Hampton, Va. NASA Flight Research Center (FRC) engineer Bob Kempel than plotted thousands of data points by hand to come up with the modification, which involved a fiberglass glove backed with a metal structure on each fin's leading edge. This transformed the vehicle from a craft that was difficult to control into the best handling of the original group of lifting bodies at the FRC.

As shown in this photo of the HL-10 flight simulator, the lifting-body pilots and engineers made use of early simulators for both training and the determination of a given vehicle's handling at various speeds, attitudes, and altitudes. This provided warning of possible problems.

John Manke is shown here on the lakebed next to the HL-10, one of four different lifting-body vehicles he flew, including the X-24B, which he flew 16 times. His final total was 42 lifting-body flights.

This photo shows the HL-10 in flight, turning to line up with lakebed runway 18. The pilot for this flight, the 29th of the HL-10 series, was Bill Dana. The HL-10 reached a peak altitude of 64,590 feet and a top speed of Mach 1.59 on this particular flight.