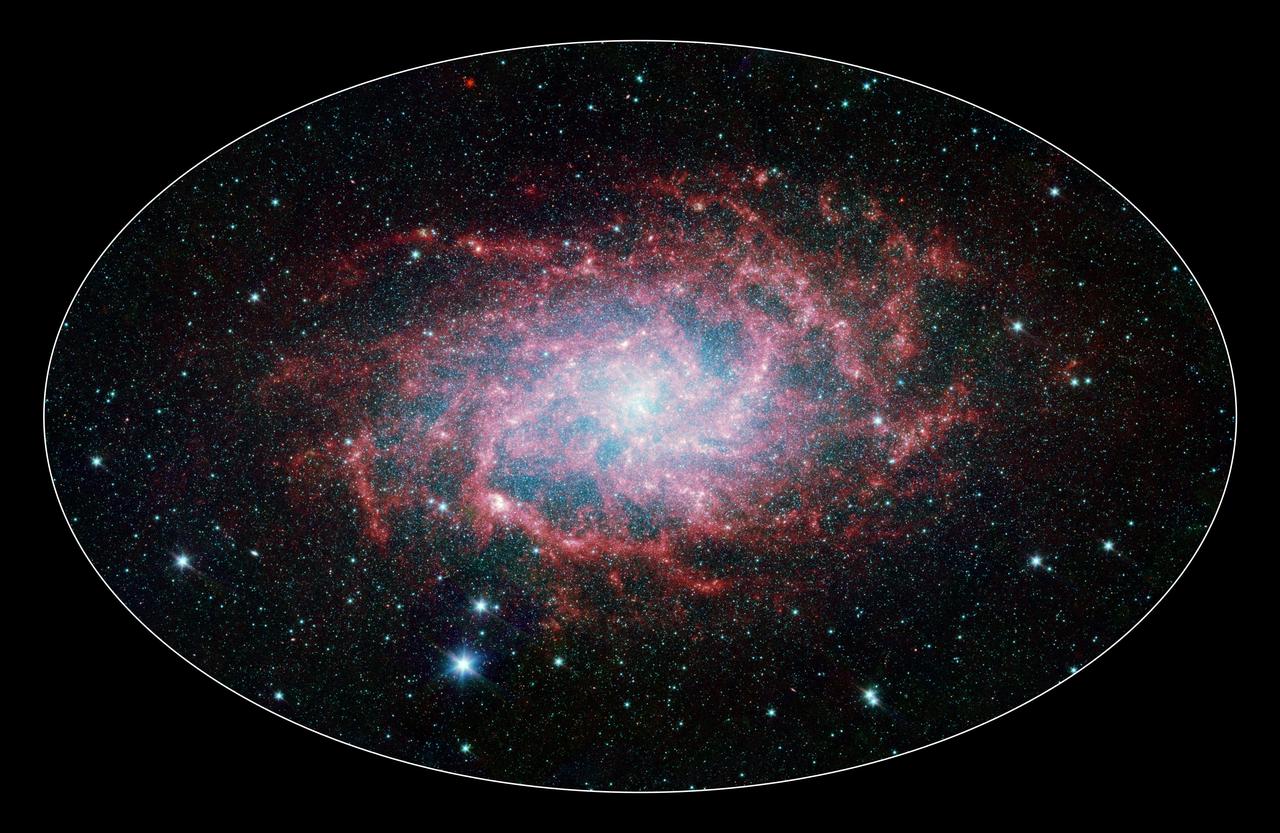

One of our closest galactic neighbors shows its awesome beauty in this new image from NASA Spitzer Space Telescope. M33, also known as the Triangulum Galaxy, is a member of what known as our Local Group of galaxies.

One of our closest galactic neighbors shows its awesome beauty in this new image from NASA Spitzer Space Telescope. M33, also known as the Triangulum Galaxy, is a member of what known as our Local Group of galaxies.

This image from NASA Galaxy Evolution Explorer shows M33, the Triangulum Galaxy, is a perennial favorite of amateur and professional astronomers alike, due to its orientation and relative proximity to us.

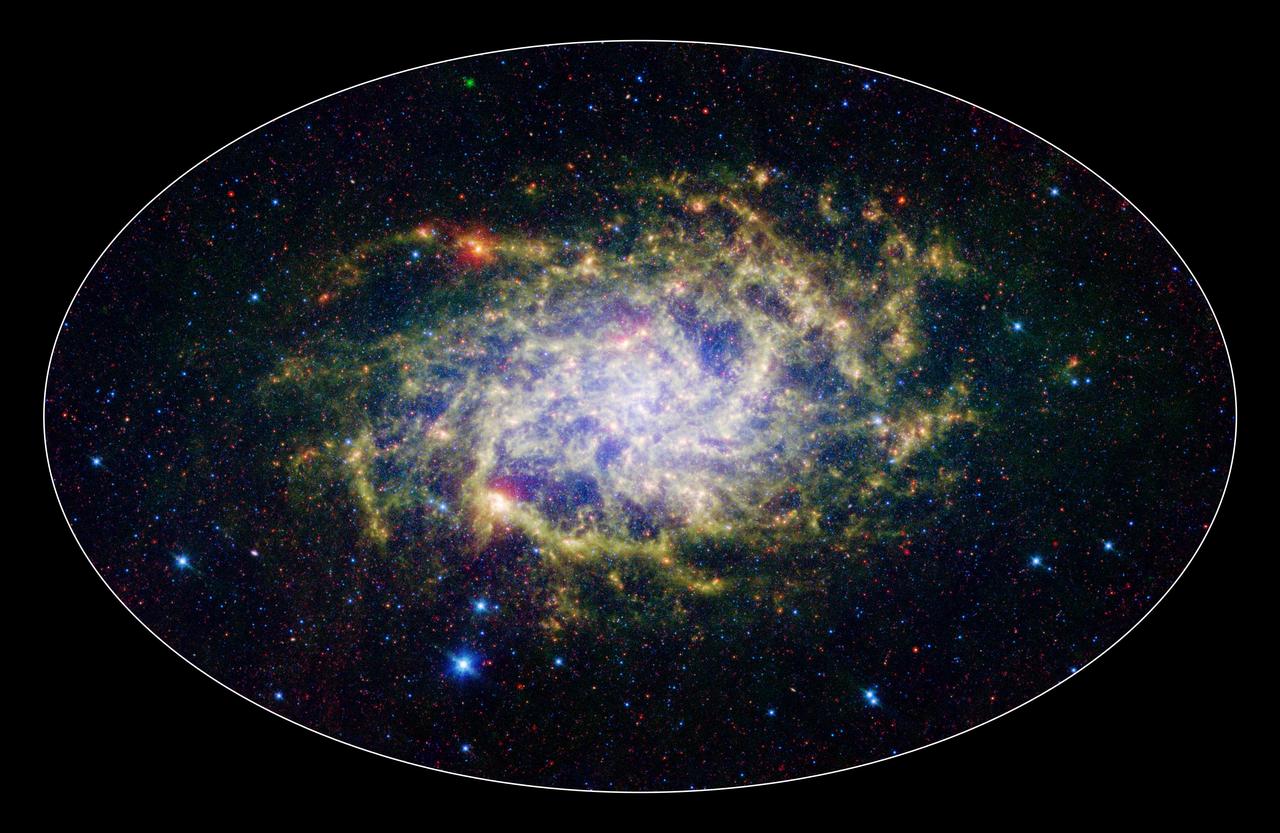

NASA Galaxy Evolution Explorer Mission celebrates its sixth anniversary studying galaxies beyond our Milky Way through its sensitive ultraviolet telescope, the only such far-ultraviolet detector in space. Pictured here, the galaxy NGC598 known as M33. The mission studies the shape, brightness, size and distance of distant galaxies across 10 billion years of cosmic history, giving scientists a wealth of data to help us better understand the origins of the universe. One such object is pictured here, the galaxy NGC598, more commonly known as M33. This image is a blend of the Galaxy Evolution Explorer's M33 image and another taken by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope. M33, one of our closest galactic neighbors, is about 2.9 million light-years away in the constellation Triangulum, part of what's known as our Local Group of galaxies. Together, the Galaxy Evolution Explorer and Spitzer can see a broad spectrum of sky. Spitzer, for example, can detect mid-infrared radiation from dust that has absorbed young stars' ultraviolet light. That's something the Galaxy Evolution Explorer cannot see. This combined image shows in amazing detail the beautiful and complicated interlacing of the heated dust and young stars. In some regions of M33, dust gathers where there is very little far-ultraviolet light, suggesting that the young stars are obscured or that stars farther away are heating the dust. In some of the outer regions of the galaxy, just the opposite is true: There are plenty of young stars and very little dust. Far-ultraviolet light from young stars glimmers blue, near-ultraviolet light from intermediate age stars glows green, and dust rich in organic molecules burns red. This image is a 3-band composite including far infrared as red. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA11998

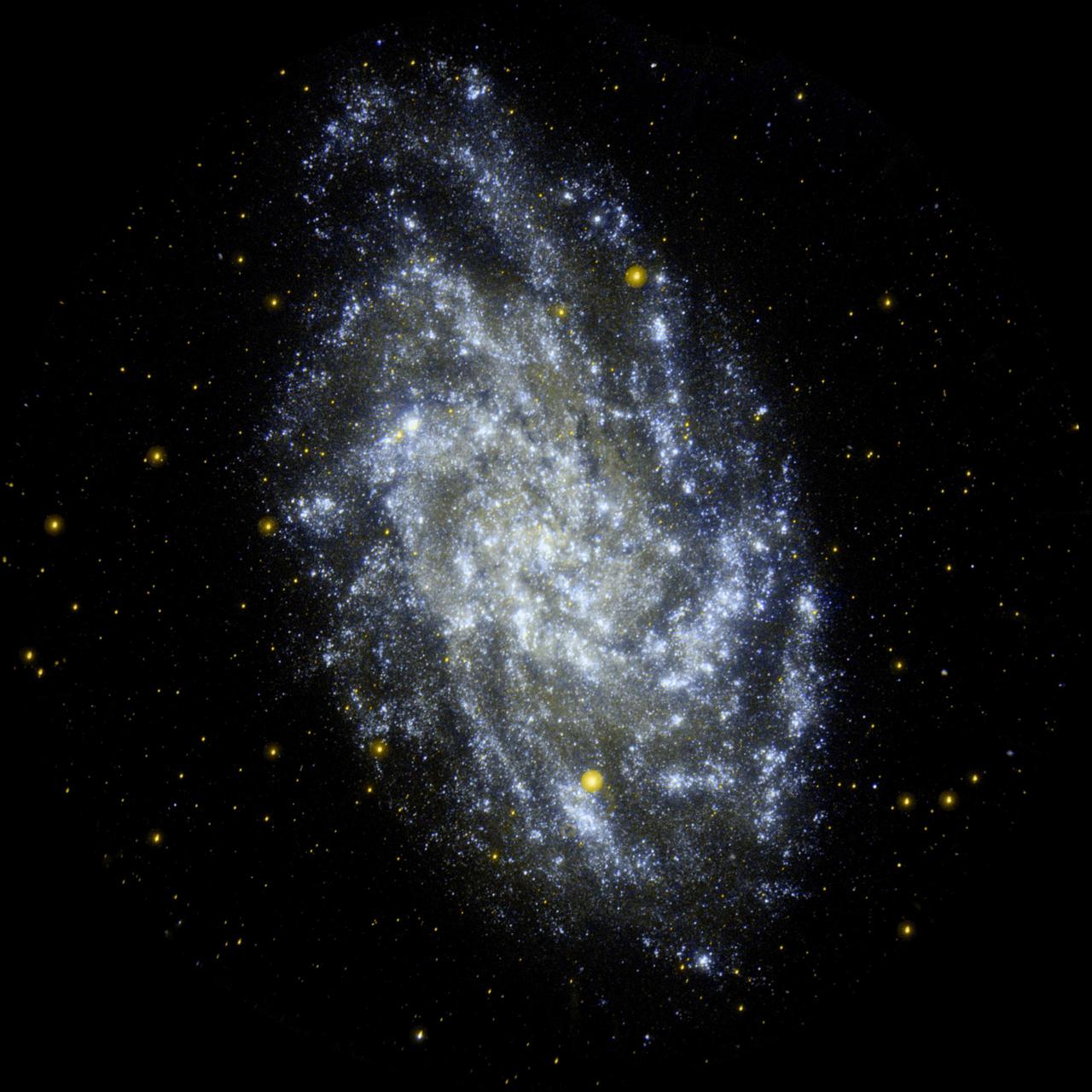

NASA Galaxy Evolution Explorer Mission celebrates its sixth anniversary studying galaxies beyond our Milky Way through its sensitive ultraviolet telescope, the only such far-ultraviolet detector in space. The mission studies the shape, brightness, size and distance of distant galaxies across 10 billion years of cosmic history, giving scientists a wealth of data to help us better understand the origins of the universe. One such object is pictured here, the galaxy NGC598, more commonly known as M33. The image shows a map of the recent star formation history of M33. The bright blue and white areas are where star formation has been extremely active over the past few million years. The patches of yellow and gold are regions where star formation was more active 100 million years ago. In addition, the ultraviolet image shows the most massive young stars in M33. These stars burn their large supply of hydrogen fuel quickly, burning hot and bright while emitting most of their energy at ultraviolet wavelengths. Compared with low-mass stars like our sun, which live for billions of years, these massive stars never reach old age, having a lifespan as short as a few million years. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA12000

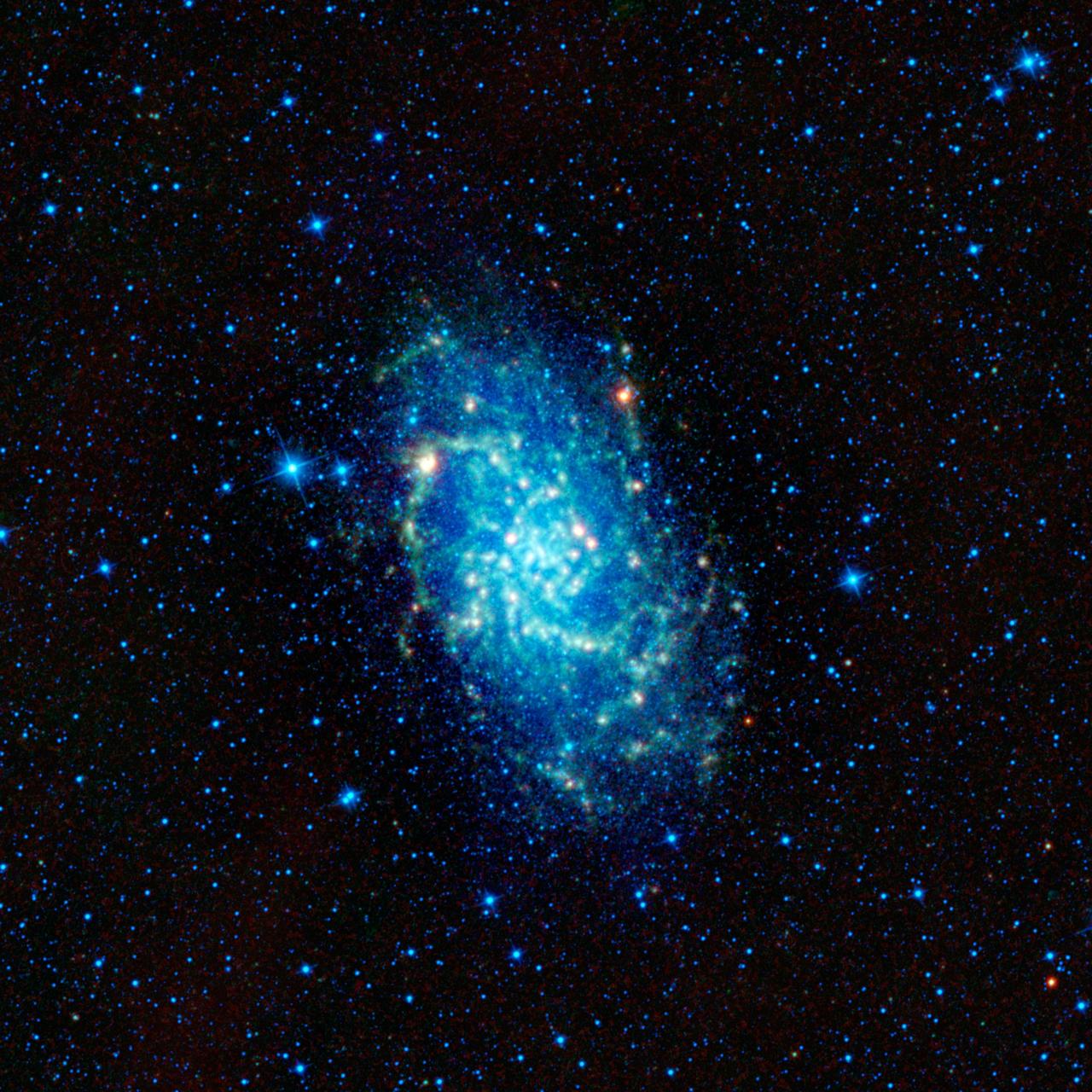

This image captured by NASA Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer shows of one of our closest neighboring galaxies, Messier 33. Also named the Triangulum galaxy, M33 is one of largest members in our small neighborhood of galaxies -- the Local Group.

This image of the Triangulum galaxy, or M33, includes data from the ESA (European Space Agency) Herschel mission, supplemented with data from ESA's retired Planck observatory and two retired NASA missions: the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) and Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE). Operated from 2009 to 2013, Herschel detected wavelengths of light in the far-infrared and microwave ranges, and was ideal for studying dust in nearby galaxies because it could capture small-scale structures in the dust clouds in high resolution. However, Herschel often couldn't detect light from diffuse dust clouds – especially in the outer regions of galaxies, where the gas and dust become sparse and thus fainter. As a result, the mission missed up to 30% of all the light given off by dust. Combining the Herschel observations with data from other observatories creates a more complete picture of the dust in the galaxy. In the image, red indicates hydrogen gas; green indicates cold dust; and warmer dust is shown in blue. Launched in 1983, IRAS was the first space telescope to detect infrared light, setting the stage for future observatories like NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and James Webb Space Telescope. The Planck observatory, launched in 2009, and COBE, launched in 1989, both studied the cosmic microwave background, or light left over from the big bang. The hydrogen gas was detected using the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array in New Mexico, and the Institute for Radio Astronomy in the Millimeter Range 30-meter telescope in Spain. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25165