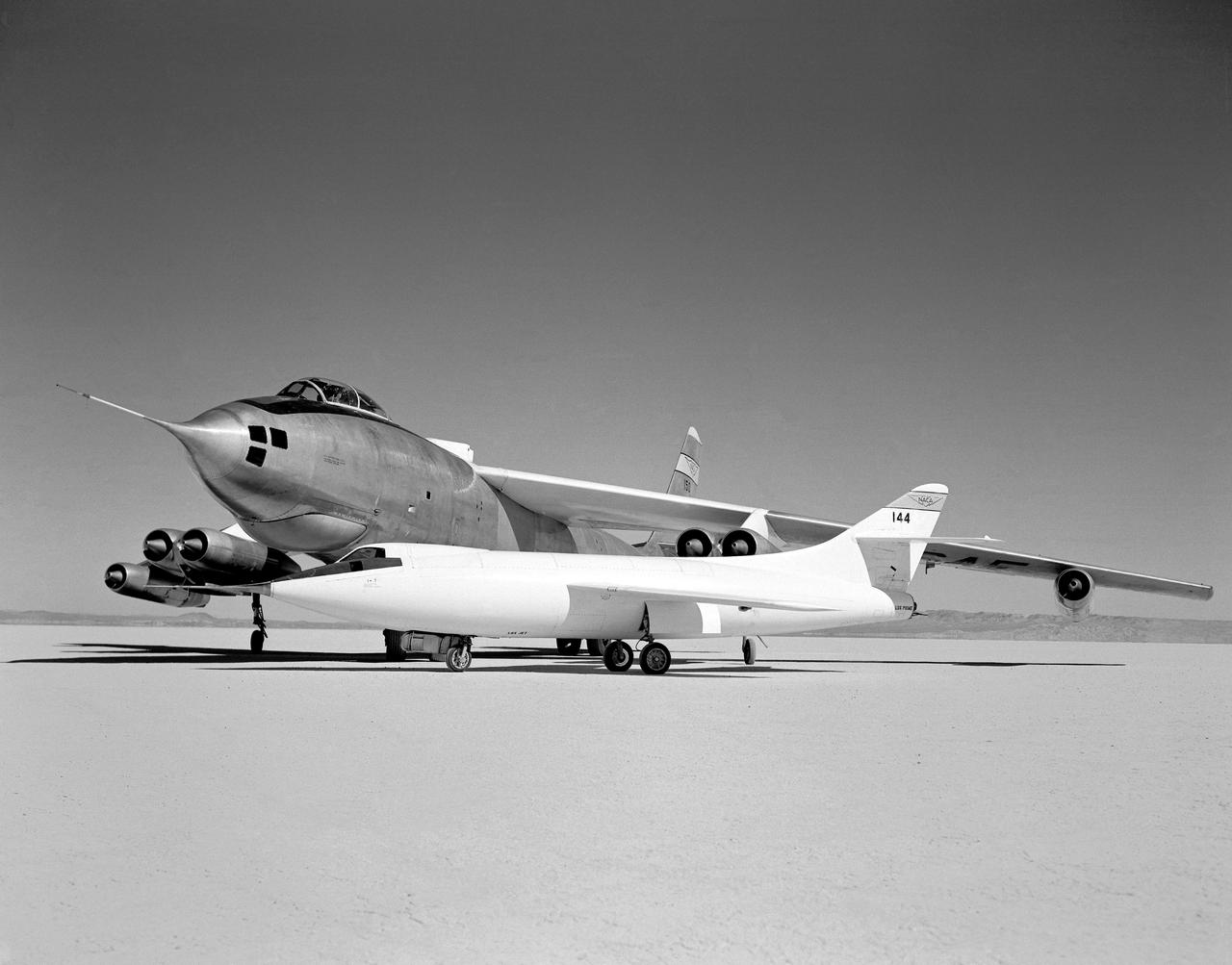

In 1954 this photo of two swept wing airplanes was taken on the ramp of NACA High-Speed Flight Research Station. The Douglas D-558-ll is a research aircraft while the Boeing B-47A Stratojet is a production bomber and very different in size. Both contributed to the studies for swept back wing research.

Hugh Dryden (far left) presents the NACA Exceptional Service Medal award at the NACA High Speed Flight Station. He awarded (L-R) Joe Walker (X-1A research pilot), Stan Butchart (pilot of the B-29 mothership),and Richard Payne (X-1A crew chief) in recognition of their research extending knowledge of swept wing flight.

The X-2, initially an Air Force program, was scheduled to be transferred to the civilian National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) for scientific research. The Air Force delayed turning the aircraft over to the NACA in the hope of attaining Mach 3 in the airplane. The service requested and received a two-month extension to qualify another Air Force test pilot, Capt. Miburn "Mel" Apt, in the X-2 and attempt to exceed Mach 3. After several ground briefings in the simulator, Apt (with no previous rocket plane experience) made his flight on 27 September 1956. Apt raced away from the B-50 under full power, quickly outdistancing the F-100 chase planes. At high altitude, he nosed over, accelerating rapidly. The X-2 reached Mach 3.2 (2,094 mph) at 65,000 feet. Apt became the first man to fly more than three times the speed of sound. Still above Mach 3, he began an abrupt turn back to Edwards. This maneuver proved fatal as the X-2 began a series of diverging rolls and tumbled out of control. Apt tried to regain control of the aircraft. Unable to do so, Apt separated the escape capsule. Too late, he attempted to bail out and was killed when the capsule impacted on the Edwards bombing range. The rest of the X-2 crashed five miles away. The wreckage of the X-2 rocket plane was later taken to NACA's High Speed Flight Station for analysis following the crash.

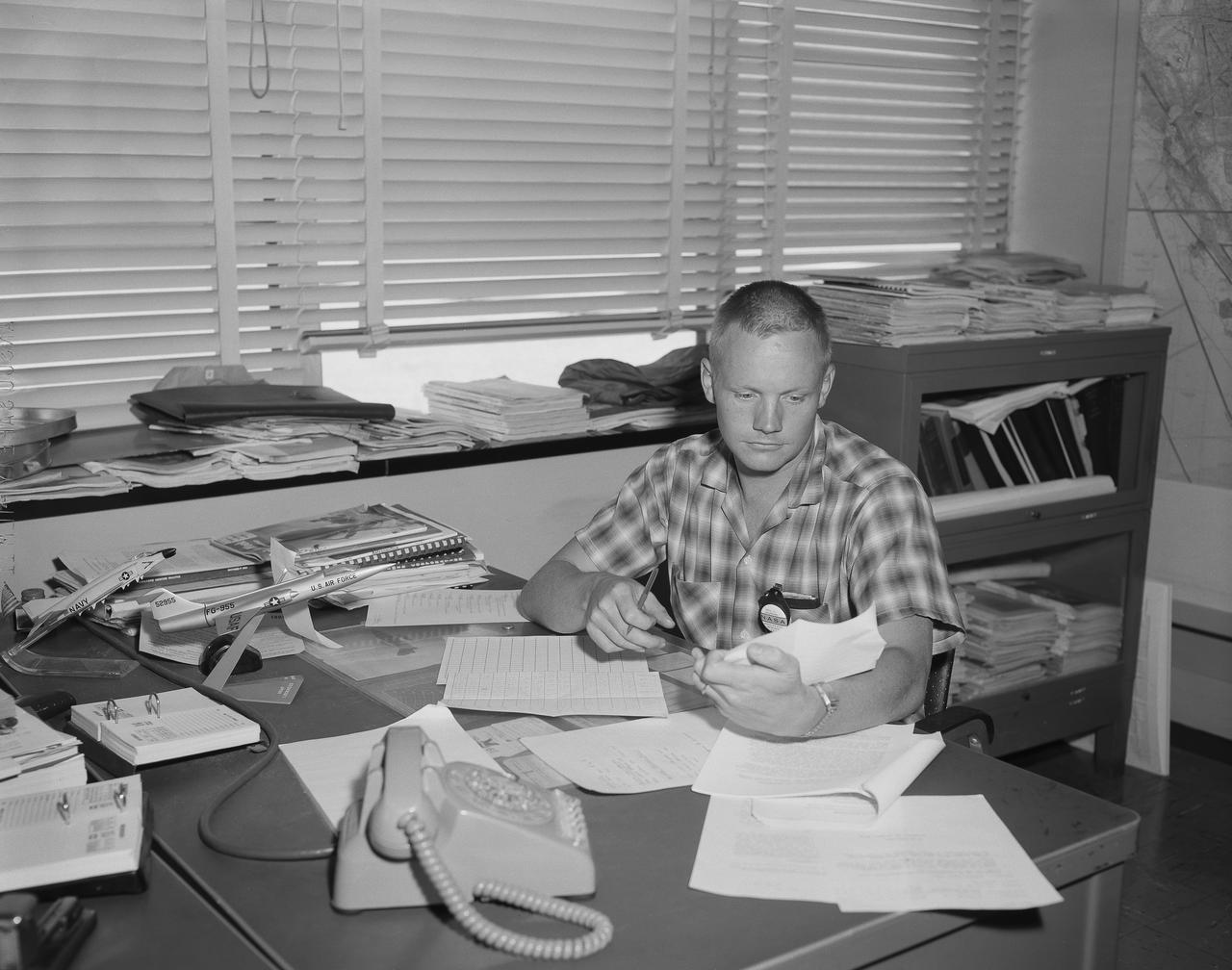

Famed astronaut Neil A. Armstrong – the first person to set foot on the Moon during the historic Apollo 11 mission in July 1969 – spent seven years as a research pilot at the NACA-NASA High-Speed Flight Station, now NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California, before joining the space program. During his tenure, Armstrong was actively engaged in both the piloting and engineering aspects of numerous NASA programs and projects.

In this 1950 view of the left side of the NACA High-Speed Flight Research Station's X-4 research aircraft, the low swept wing and horizontal taillest design are seen. The X-4 Bantam, a single-place, low swept-wing, semi-tailless aircraft, was designed and built by Northrop Aircraft, Inc. It had no horizontal tail surfaces and its mission was to obtain in-flight data on the stability and control of semi-tailless aircraft at high subsonic speeds.

High-Speed Research Station Director Walter C. Williams, NACA pilot A. Scott Crossfield, and Director of Flight Operations Joe Vensel in front of the Douglas D-558-2 after the first Mach 2 flight.

A 1953 photo of some of the research aircraft at the NACA High-Speed Flight Research Station (now known as the the Dryden Flight Research Center). The photo shows the X-3 (center) and, clockwise from left: X-1A (Air Force serial number 48-1384), the third D-558-1 (NACA tail number 142), XF-92A, X-5, D-558-2, and X-4.

Famed astronaut Neil A. Armstrong – the first person to set foot on the Moon during the historic Apollo 11 mission in July 1969 – spent seven years as a research pilot at the NACA-NASA High-Speed Flight Station, now NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California, before joining the space program. During his time there, he served as a project pilot on the F-100A, F-100C, F-101, and F-104A (pictured here).

The NACA High-Speed Flight Research Station, had initially been subordinate to the Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory near Hampton, Virginia, but as the flight research in the Mojave Desert increasingly proved its worth after 1946, it made sense to make the Flight Research Station a separate entity reporting directly to the headquarters of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. But an autonomous center required all the trappings of a major research facility, including good quarters. With the adoption of the Edwards “Master Plan,” the Air Force had committed itself to moving from its old South Base to a new location midway between the South and North Bases. The NACA would have to move also--so why not take advantage of the situation and move into a full-blown research facility. The Air Force issued a lease to NACA for a location on the northwestern shore of the Roger Dry Lake. Construction started on the NACA station in early February 1953. On a windy day, January 27, 1953, at a groundbreaking ceremony stood left to right: Gerald Truszynski, Head of Instrumentation Division; Joseph Vensel, Head of the Operations Branch; Walter Williams, Head of the Station, scooping the first shovel full of dirt; Marion Kent, Head of Personnel; and California state official Arthur Samet.

The Bell Aircraft Corporation X-1-2 aircraft on the ramp at NACA High Speed Flight Research Station located on the South Base of Muroc Army Air Field in 1947. The X-1-2 flew until October 23, 1951, completing 74 glide and powered flights with nine different pilots. The aircraft has white paint and the NACA tail band. The black Xs are reference markings for tracking purposes. They were widely used on NACA aircraft in the early 1950s.

Maintanence on the first F-107A. Apr. 9, 1958

The third F-107A parked on the ramp at the Flight Research Center. Jan. 7, 1959

F-107A ground loop landing mishap. Sept. 1, 1959

NACA High Speed Flight Station aircraft at South Base. Clockwise from far left: D-558-II, XF-92A, X-5, X-1, X-4, and D-558-I.

Arrival of first F-107A #118 (later NACA 207) to NASA FRC

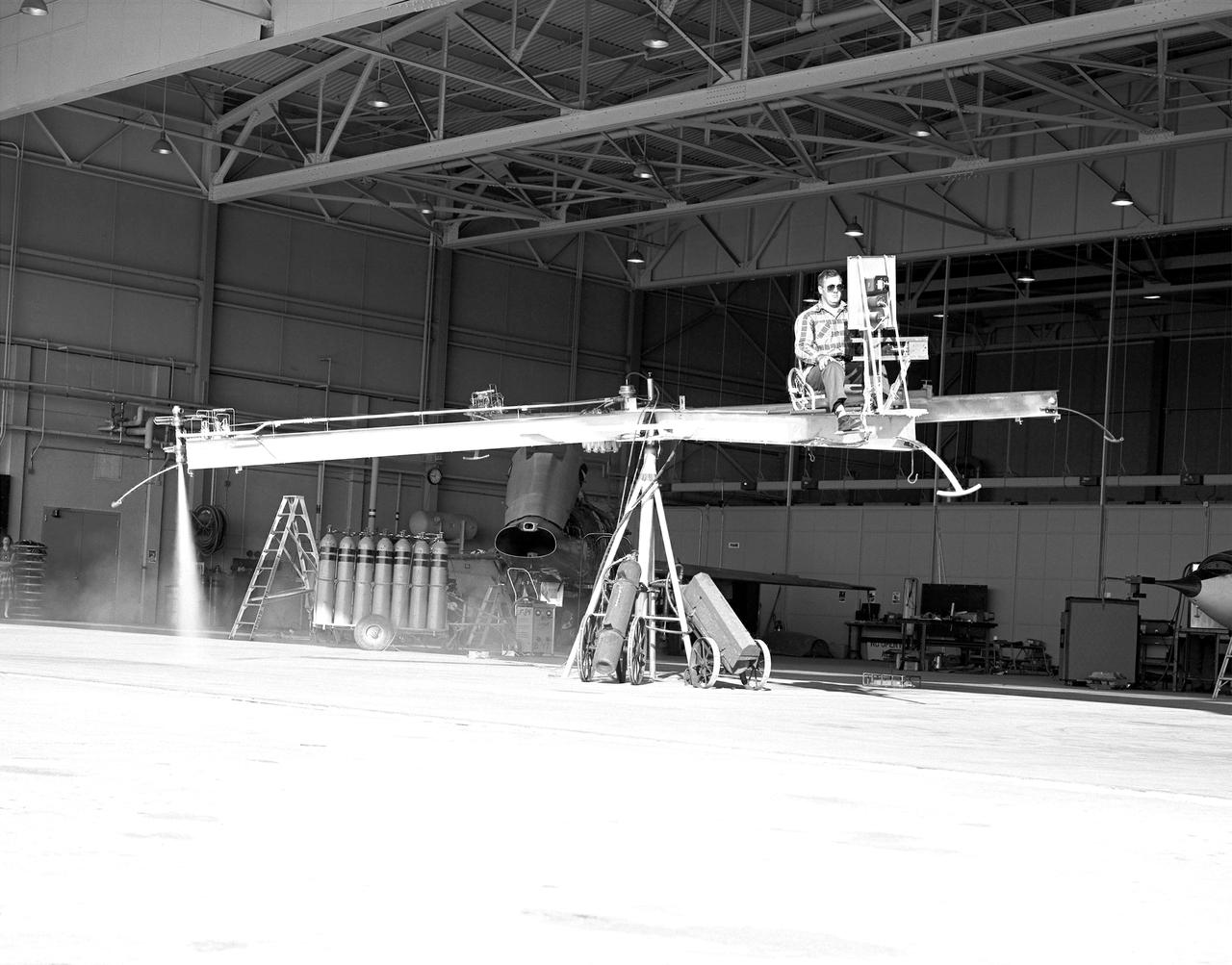

NACA High-Speed Flight Station test pilot Stan Butchart flying the Iron Cross, the mechanical reaction control simulator. High-pressure nitrogen gas expanded selectively, by the pilot, through the small reaction control thrusters maneuvered the Iron Cross through the three axes. The exhaust plume can be seen from the aft thruster. The tanks containing the gas can be seen on the cart at the base of the pivot point of the Iron Cross. NACA technicians built the iron-frame simulator, which matched the inertia ratios of the Bell X-1B airplane, installing six jet nozzles to control the movement about the three axes of pitch, roll, and yaw.

These people and this equipment supported the flight of the NACA D-558-2 Skyrocket at the High-Speed Flight Station at South Base, Edwards AFB. Note the two Sabre chase planes, the P2B-1S launch aircraft, and the profusion of ground support equipment, including communications, tracking, maintenance, and rescue vehicles. Research pilot A. Scott Crossfield stands in front of the Skyrocket.

Neil Armstrong, donned in his space suit, poses for his official Apollo 11 portrait. Armstrong began his flight career as a naval aviator. He flew 78 combat missions during the Korean War. Armstrong joined the NASA predecessor, NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics), as a research pilot at the Lewis Laboratory in Cleveland and later transferred to the NACA High Speed Flight Station at Edwards AFB, California. He was a project pilot on many pioneering high speed aircraft, including the 4,000 mph X-15. He has flown over 200 different models of aircraft, including jets, rockets, helicopters, and gliders. In 1962, Armstrong was transferred to astronaut status. He served as command pilot for the Gemini 8 mission, launched March 16, 1966, and performed the first successful docking of two vehicles in space. In 1969, Armstrong was commander of Apollo 11, the first manned lunar landing mission, and gained the distinction of being the first man to land a craft on the Moon and the first man to step on its surface. Armstrong subsequently held the position of Deputy Associate Administrator for Aeronautics, NASA Headquarters Office of Advanced Research and Technology, from 1970 to 1971. He resigned from NASA in 1971.

B-47A on ramp

Famed astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, the first man to set foot on the moon during the historic Apollo 11 space mission in July 1969, served for seven years as a research pilot at the NACA-NASA High-Speed Flight Station, now the Dryden Flight Research Center, at Edwards, California, before he entered the space program. Armstrong joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) at the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory (later NASA's Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio, and today the Glenn Research Center) in 1955. Later that year, he transferred to the High-Speed Flight Station at Edwards as an aeronautical research scientist and then as a pilot, a position he held until becoming an astronaut in 1962. He was one of nine NASA astronauts in the second class to be chosen. As a research pilot Armstrong served as project pilot on the F-100A and F-100C aircraft, F-101, and the F-104A. He also flew the X-1B, X-5, F-105, F-106, B-47, KC-135, and Paresev. He left Dryden with a total of over 2450 flying hours. He was a member of the USAF-NASA Dyna-Soar Pilot Consultant Group before the Dyna-Soar project was cancelled, and studied X-20 Dyna-Soar approaches and abort maneuvers through use of the F-102A and F5D jet aircraft. Armstrong was actively engaged in both piloting and engineering aspects of the X-15 program from its inception. He completed the first flight in the aircraft equipped with a new flow-direction sensor (ball nose) and the initial flight in an X-15 equipped with a self-adaptive flight control system. He worked closely with designers and engineers in development of the adaptive system, and made seven flights in the rocket plane from December 1960 until July 1962. During those fights he reached a peak altitude of 207,500 feet in the X-15-3, and a speed of 3,989 mph (Mach 5.74) in the X-15-1. Armstrong has a total of 8 days and 14 hours in space, including 2 hours and 48 minutes walking on the Moon. In March 1966 he was commander of the Gemini 8 or

NACA pilot A. Scott Crossfield next to the D-558-2 after first Mach 2 flight.

Scott Crossfield in cockpit of the Douglas D-558-2 after first Mach 2 flight.

Scott Crossfield talks to newsmen in front of NACA South Base hangar after his first flight to Mach 2 in the Douglas D-558-2.

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio as seen from the west in May 1946. The Cleveland Municipal Airport is located directly behind. The laboratory was built in the early 1940s to resolve problems associated with aircraft engines. The initial campus contained seven principal buildings: the Engine Research Building, hangar, Fuels and Lubricants Building, Administration Building, Engine Propeller Research Building, Altitude Wind Tunnel, and Icing Research Tunnel. These facilities and their associated support structures were located within an area occupying approximately one-third of the NACA’s property. After World War II ended, the NACA began adding new facilities to address different problems associated with the newer, more powerful engines and high speed flight. Between 1946 and 1955, four new world-class test facilities were built: the 8- by 6-Foot Supersonic Wind Tunnel, the Propulsion Systems Laboratory, the Rocket Engine Test Facility, and the 10- by 10-Foot Supersonic Wind Tunnel. These large facilities occupied the remainder of the NACA’s semicircular property. The Lewis laboratory expanded again in the late 1950s and early 1960s as the space program commenced. Lewis purchased additional land in areas adjacent to the original laboratory and acquired a large 9000-acre site located 60 miles to the west in Sandusky, Ohio. The new site became known as Plum Brook Station.

D-558-2 Aircraft on lakebed

D-558-2 being mounted to P2B-1S launch aircraft in hangar.

D-558-2 Aircraft on lakebed

Bell X-1A ejection seat test setup

Wing chord extension on D-558-2

D558-2 #143 LOX jettison with P2BS in background

The aircraft in this 1953 photo of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) hangar at South Base of Edwards Air Force Base showed the wide range of research activities being undertaken. On the left side of the hangar are the three D-558-2 research aircraft. These were designed to test swept wings at supersonic speeds approaching Mach 2. The front D-558-2 is the third built (NACA 145/Navy 37975). It has been modified with a leading-edge chord extension. This was one of a number of wing modifications, using different configurations of slats and/or wing fences, to ease the airplane's tendency to pitch-up. NACA 145 had both a jet and a rocket engine. The middle aircraft is NACA 144 (Navy 37974), the second built. It was all-rocket powered, and Scott Crossfield made the first Mach 2 flight in this aircraft on November 20, 1953. The aircraft in the back is D-558-2 number 1. NACA 143 (Navy 37973) was also carried both a jet and a rocket engine in 1953. It had been used for the Douglas contractor flights, then was turned over to the NACA. The aircraft was not converted to all-rocket power until June 1954. It made only a single NACA flight before NACA's D-558-2 program ended in 1956. Beside the three D-558-2s is the third D-558-1. Unlike the supersonic D-558-2s, it was designed for flight research at transonic speeds, up to Mach 1. The D-558-1 was jet-powered, and took off from the ground. The D-558-1's handling was poor as it approached Mach 1. Given the designation NACA 142 (Navy 37972), it made a total of 78 research flights, with the last in June 1953. In the back of the hangar is the X-4 (Air Force 46-677). This was a Northrop-built research aircraft which tested a swept wing design without horizontal stabilizers. The aircraft proved unstable in flight at speeds above Mach 0.88. The aircraft showed combined pitching, rolling, and yawing motions, and the design was considered unsuitable. The aircraft, the second X-4 built, was then used as a pilot traine

B-29 mothership with pilots - Dick Payne, Stan Butchart, Joe Walker, Charles Littleton, and John Moise

A group picture of Douglas Airplanes, taken for a photographic promotion in 1954, at what is now known as the Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The photo includes the X-3 (in front--Air Force serial number 49-2892) then clockwise D-558-I, XF4D-1 (a Navy jet fighter prototype not flown by the NACA), and the first D-558-II (NACA tail number 143, Navy serial number 37973), which was flown only once by the NACA.

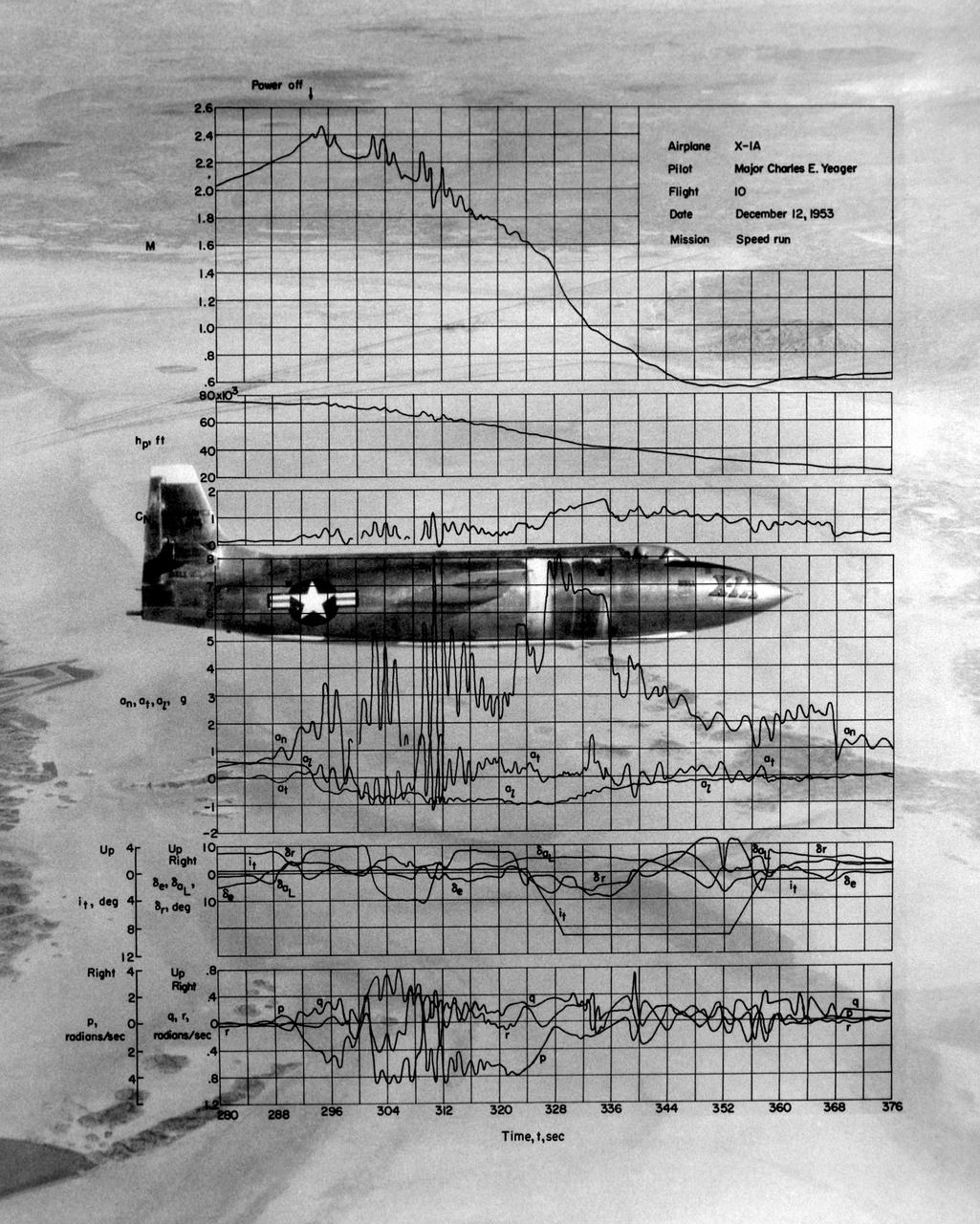

This photo of the X-1A includes graphs of the flight data from Maj. Charles E. Yeager's Mach 2.44 flight on December 12, 1953. (This was only a few days short of the 50th anniversary of the Wright brothers' first powered flight.) After reaching Mach 2.44, then the highest speed ever reached by a piloted aircraft, the X-1A tumbled completely out of control. The motions were so violent that Yeager cracked the plastic canopy with his helmet. He finally recovered from a inverted spin and landed on Rogers Dry Lakebed. Among the data shown are Mach number and altitude (the two top graphs). The speed and altitude changes due to the tumble are visible as jagged lines. The third graph from the bottom shows the G-forces on the airplane. During the tumble, these twice reached 8 Gs or 8 times the normal pull of gravity at sea level. (At these G forces, a 200-pound human would, in effect, weigh 1,600 pounds if a scale were placed under him in the direction of the force vector.) Producing these graphs was a slow, difficult process. The raw data from on-board instrumentation recorded on oscillograph film. Human computers then reduced the data and recorded it on data sheets, correcting for such factors as temperature and instrument errors. They used adding machines or slide rules for their calculations, pocket calculators being 20 years in the future.

In the center foreground of this 1953 hangar photo is the YF-84A (NACA 134/Air Force 45-59490) used for vortex generator research. It arrived on November 28, 1949, and departed on April 21, 1954. Beside it is the third D-558-1 aircraft (NACA 142/Navy 37972). This aircraft was used for a total of 78 transonic research flights from April 1949 to June 1954. It replaced the second D-558-1, lost in the crash which killed Howard Lilly. Just visible on the left edge is the nose of the first D-558-2 (NACA 143/Navy 37973). Douglas turned the aircraft over to NACA on August 31, 1951, after the contractor had completed its initial test flights. NACA only made a single flight with the aircraft, on September 17, 1956, before the program was cancelled. In the center of the photo is the B-47A (NACA 150/Air Force 49-1900). The B-47 jet bomber, with its thin, swept-back wings, and six podded engines, represented the state of the art in aircraft design in the early 1950s. The aircraft undertook a number of research activities between May 1953 and its 78th and final research flight on November 22, 1957. The tests showed that the aircraft had a buffeting problem at speeds above Mach 0.8. Among the pilots who flew the B-47 were later X-15 pilots Joe Walker, A. Scott Crossfield, John B. McKay, and Neil A. Armstrong. On the right side of the B-47 is NACA's X-1 (Air Force 46-063). The second XS-1 aircraft built, it was fitted with a thicker wing than that on the first aircraft, which had exceeded Mach 1 on October 14, 1947. Flight research by NACA pilots indicated that this thicker wing produced 30 percent more drag at transonic speeds compared to the thinner wing on the first X-1. After a final flight on October 23, 1951, the aircraft was grounded due to the possibility of fatigue failure of the nitrogen spheres used to pressurize the fuel tanks. At the time of this photo, in 1953, the aircraft was in storage. In 1955, the aircraft was extensively modified, becoming the X-1E. In front o