Marshall scientist practices working on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator.

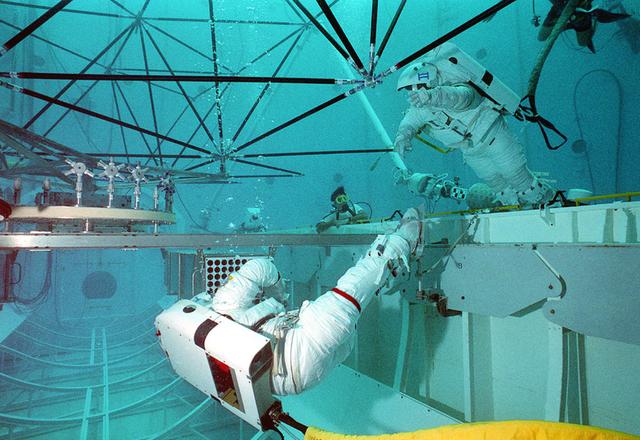

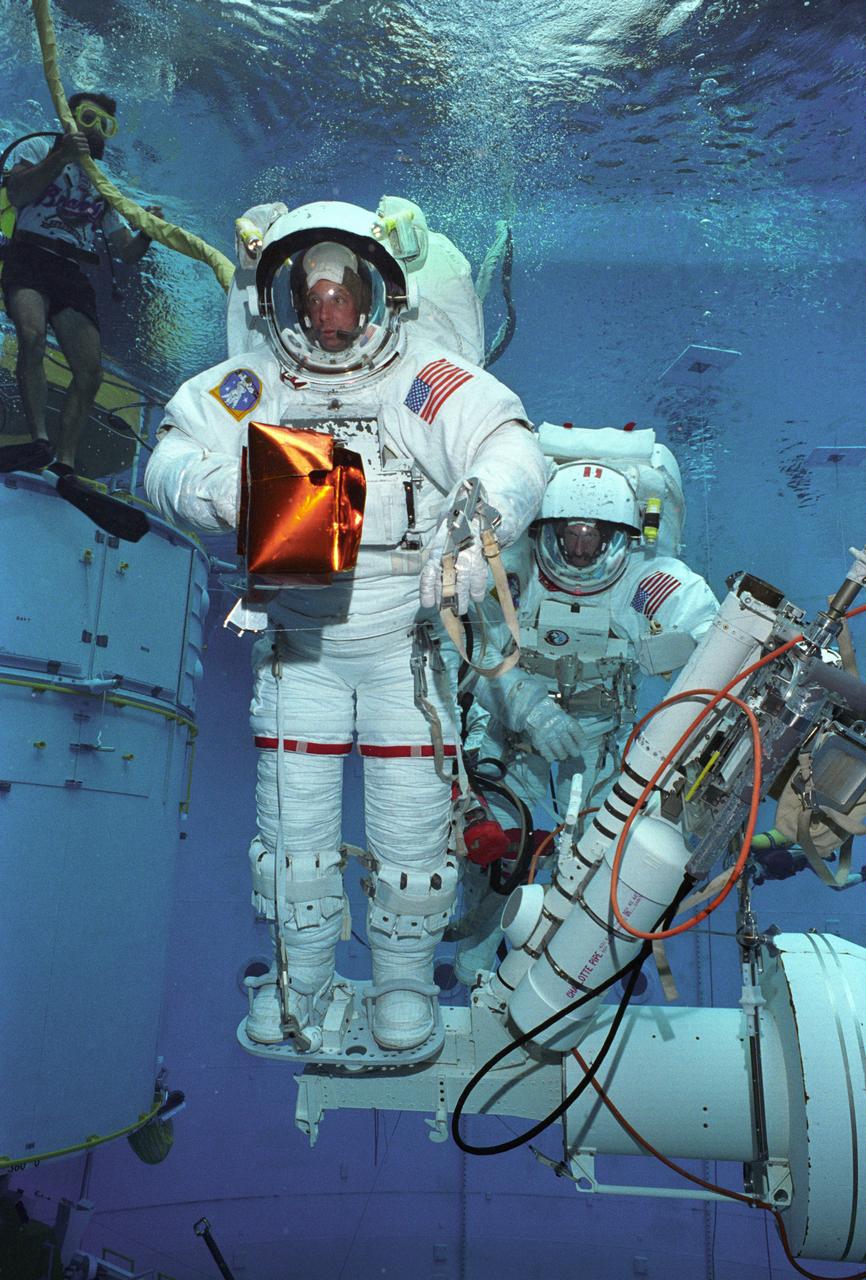

Astronaut Mark Lee participates in the Nitrox breathing system test in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

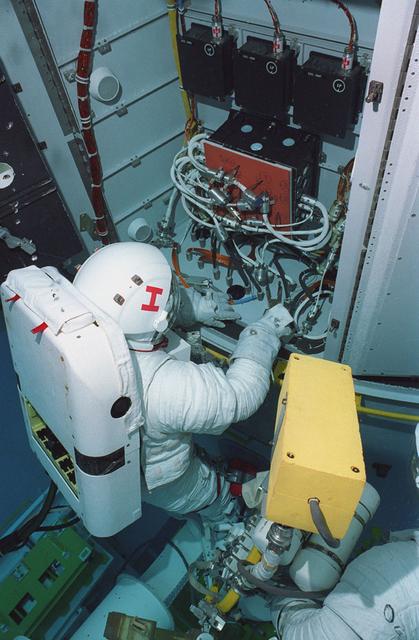

Astronaut Mark Lee participates in the Nitrox breathing system test in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

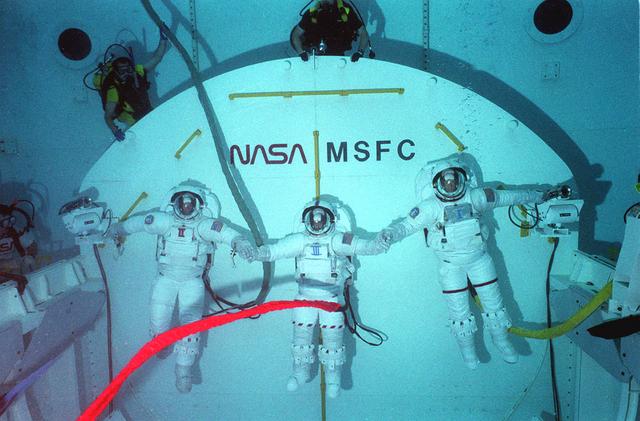

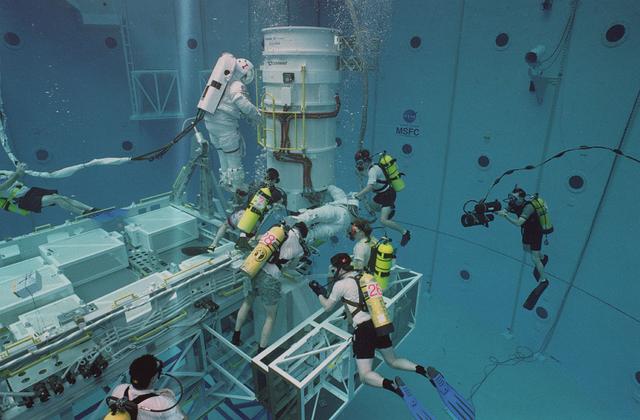

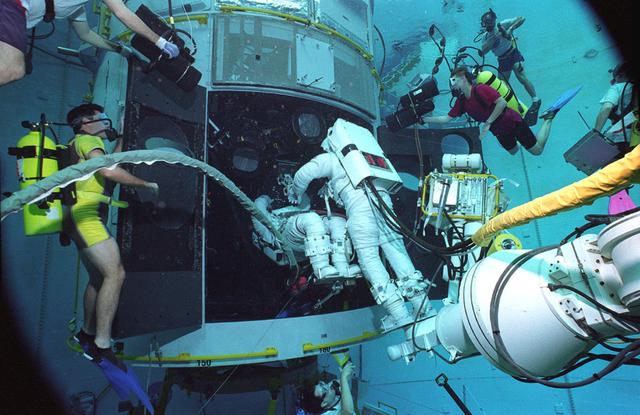

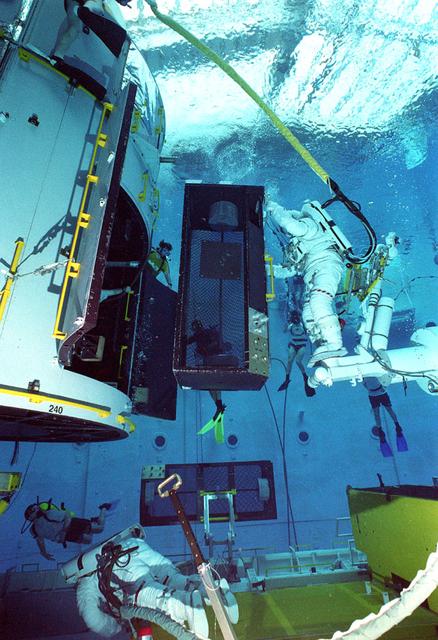

Astronauts Mark Lee and Mike Gerhardt, and a technician participate in the Nitrox breathing system test in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

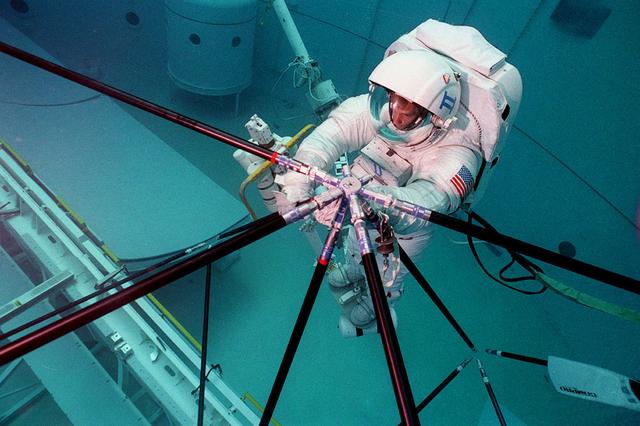

Astronaut Scott Parazynski participates in a Nitrox breathing system test in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Astronauts Mark Lee and Mike Gerhardt, and a technician participate in the Nitrox breathing system test in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

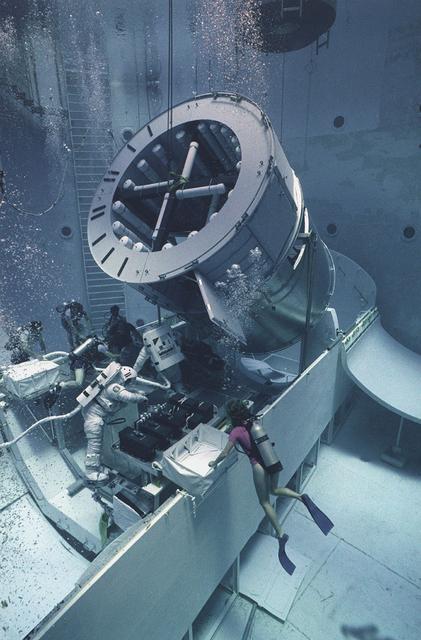

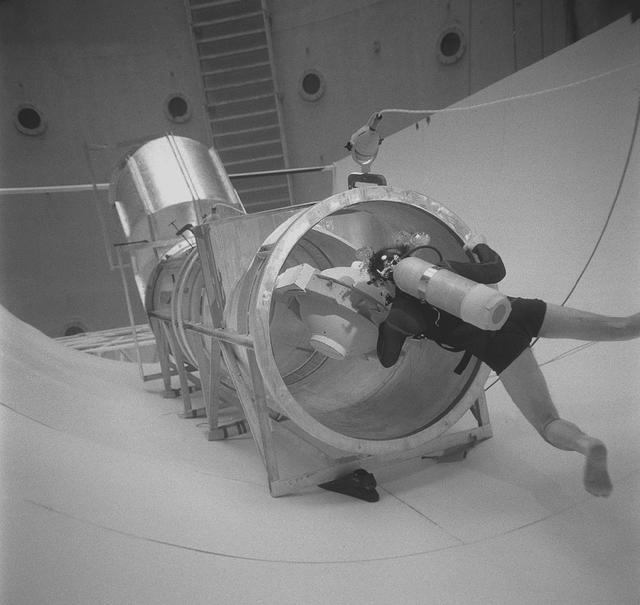

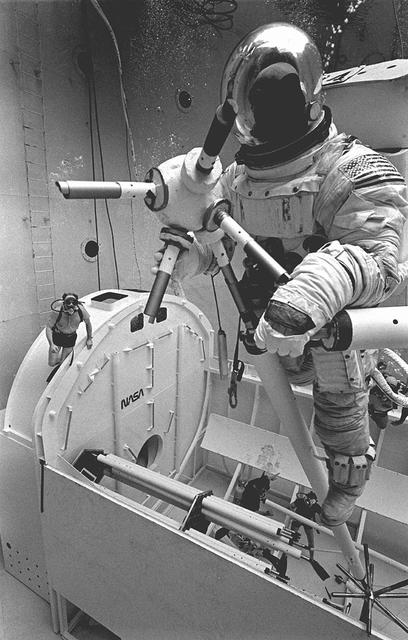

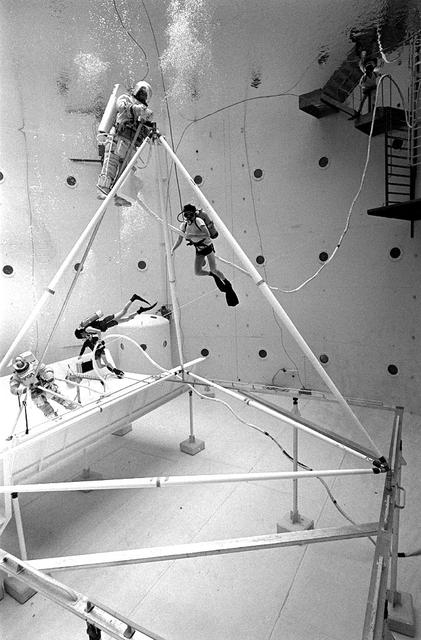

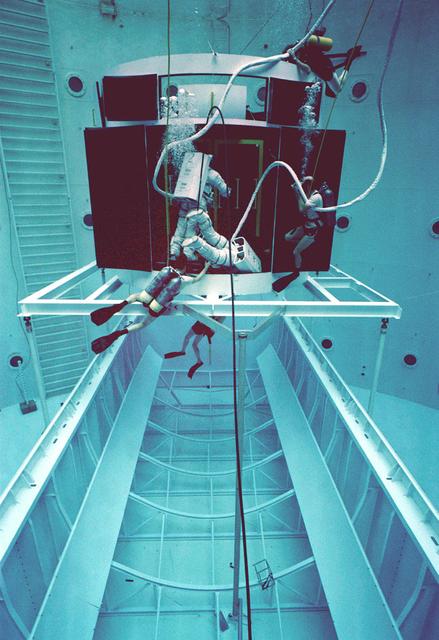

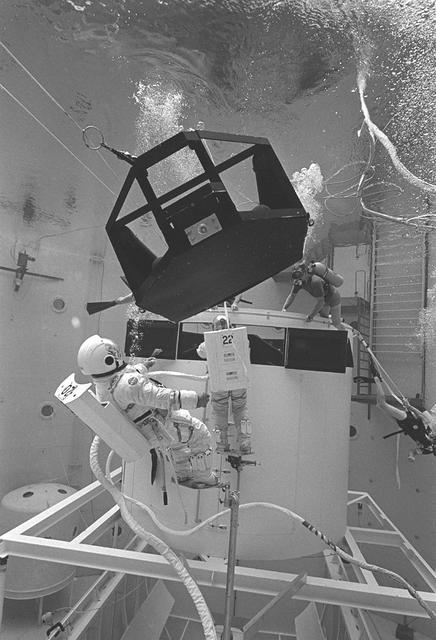

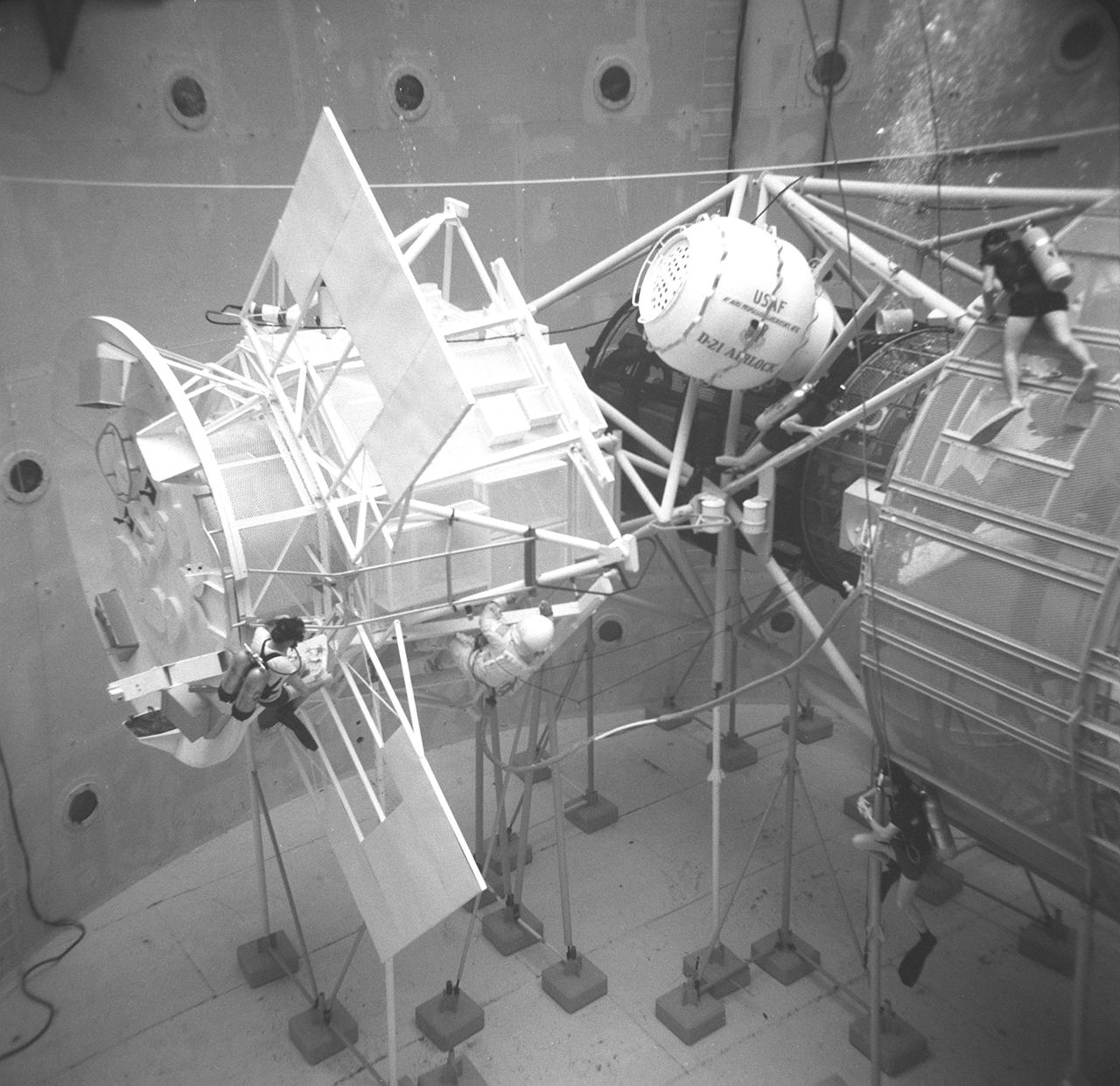

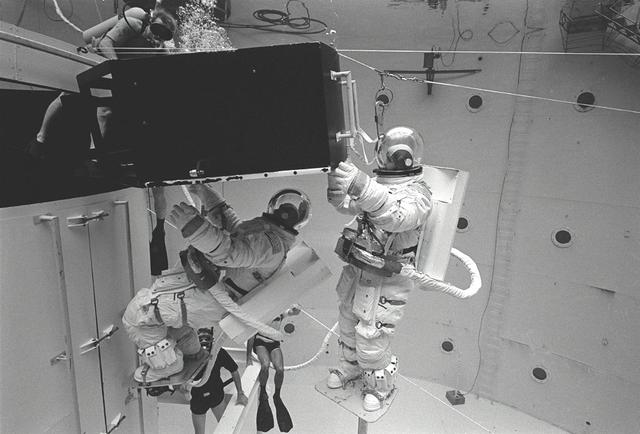

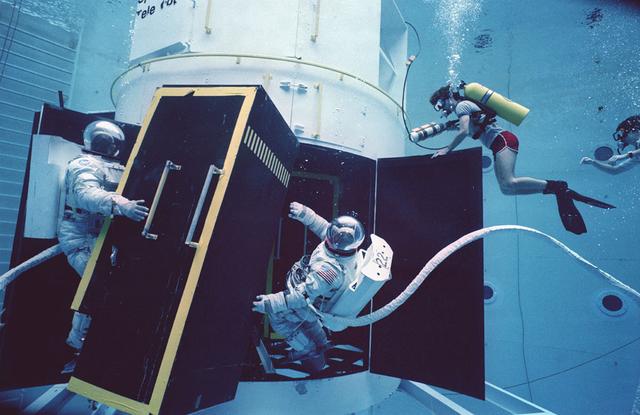

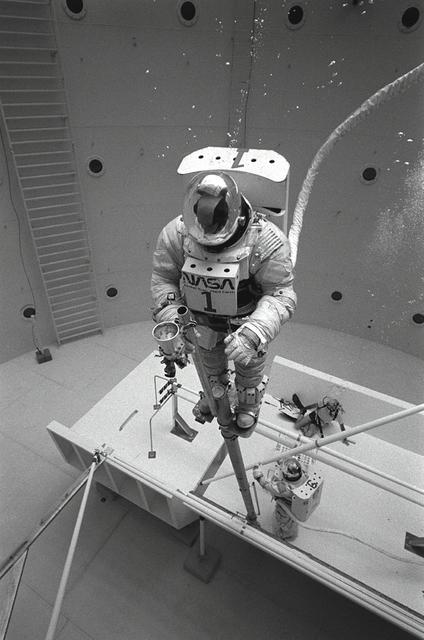

An astronaut wearing a pressurized space suit performed a work task while suspended in a “zero-gravity” simulator known as the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at Marshall Space Flight Center. This particular task was one of many performed by astronauts while checking out the mockup for the Apollo Telescope Mount.

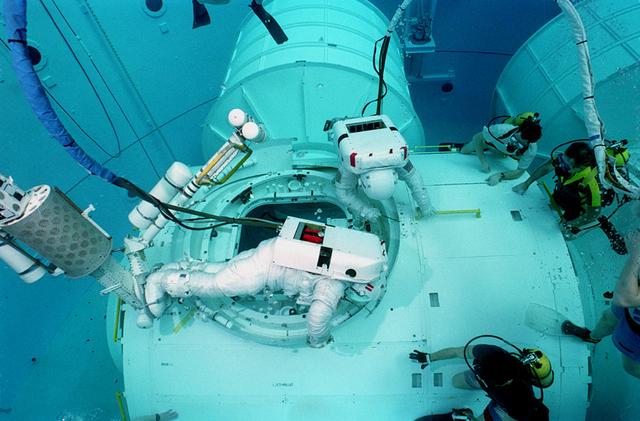

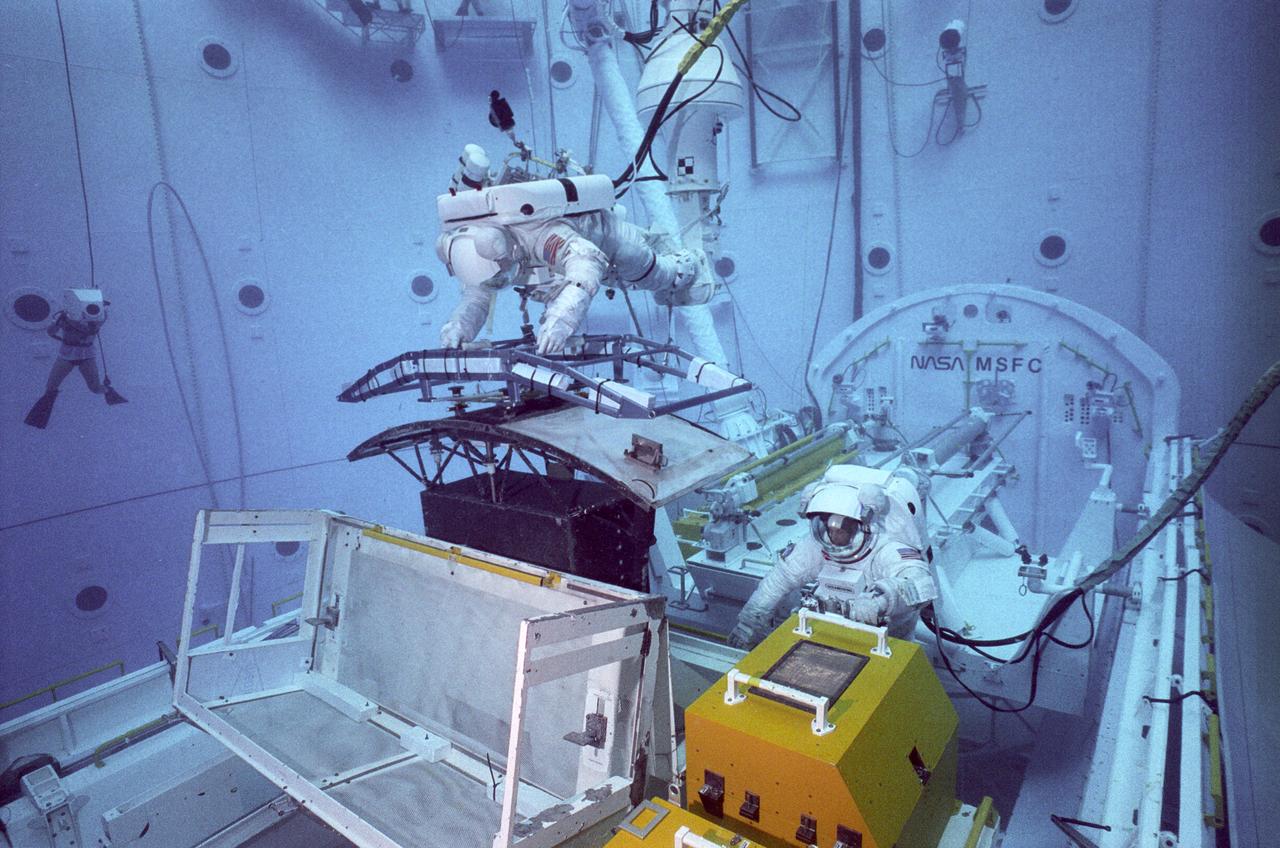

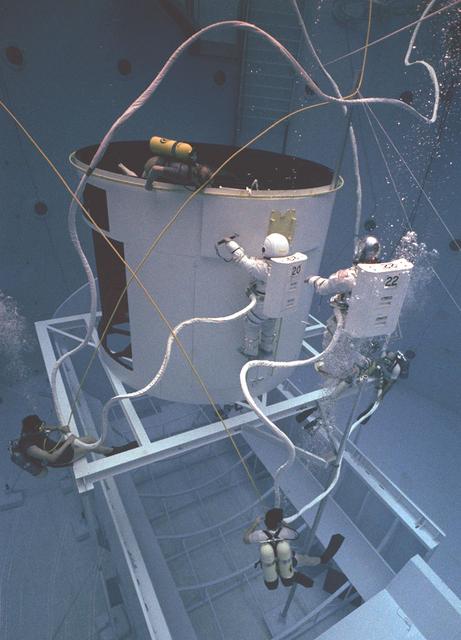

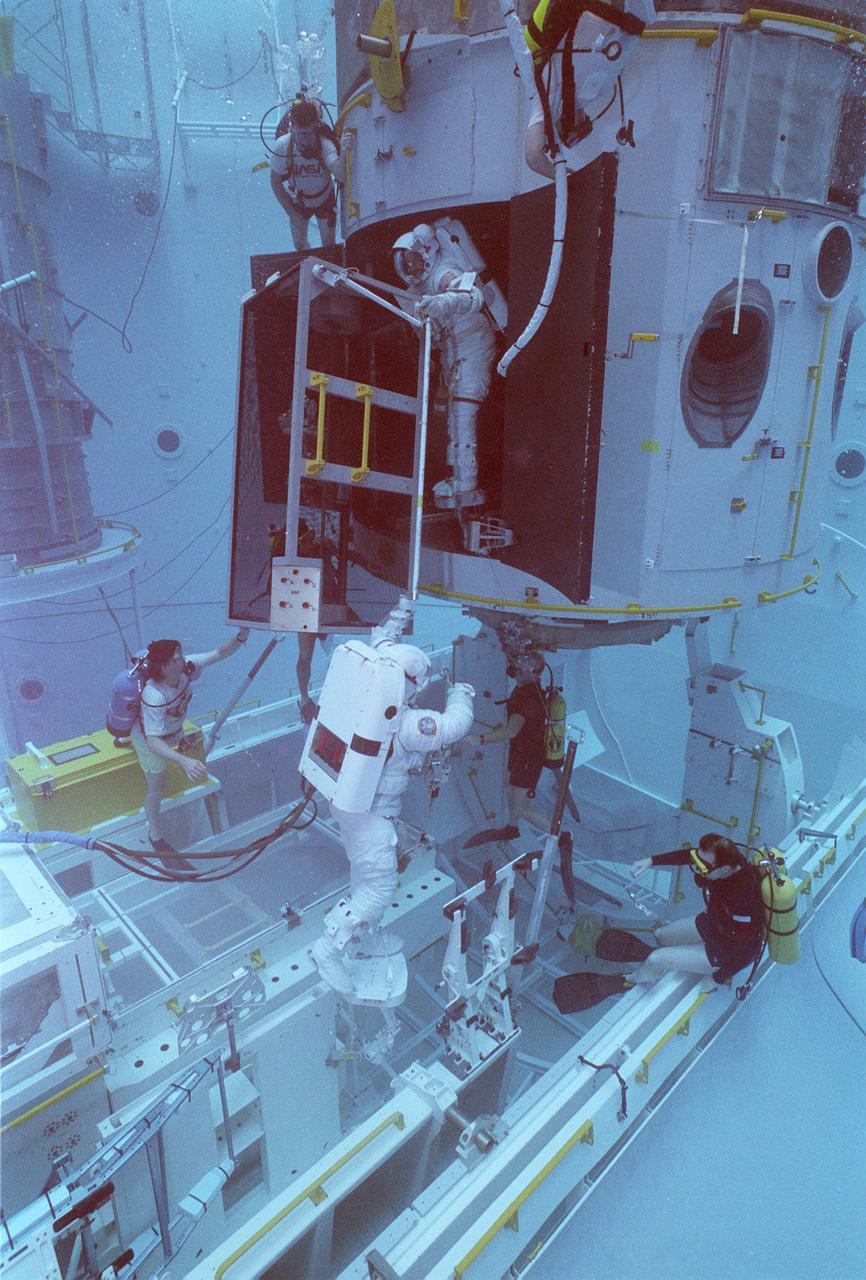

International Space Station testing is conducted in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

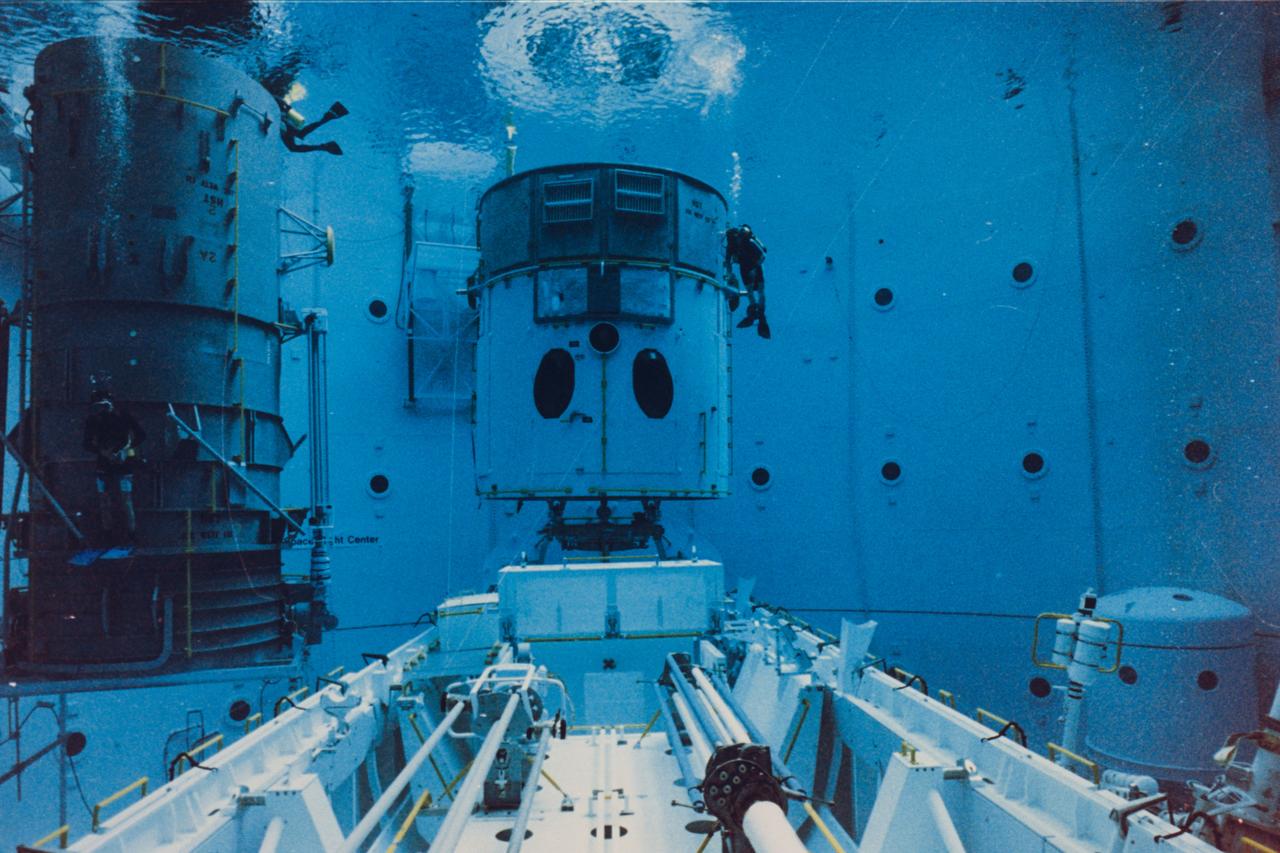

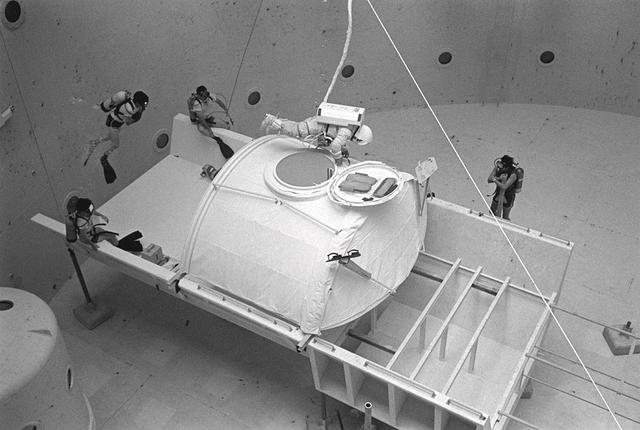

Japanese Experimental Module testing in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

International Space Station testing is conducted in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Photo Voltaic Module testing in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

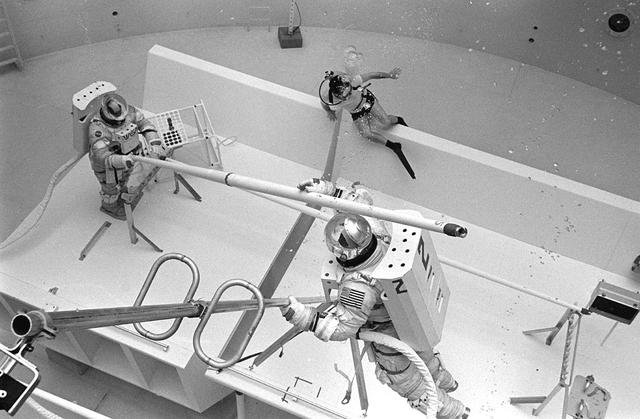

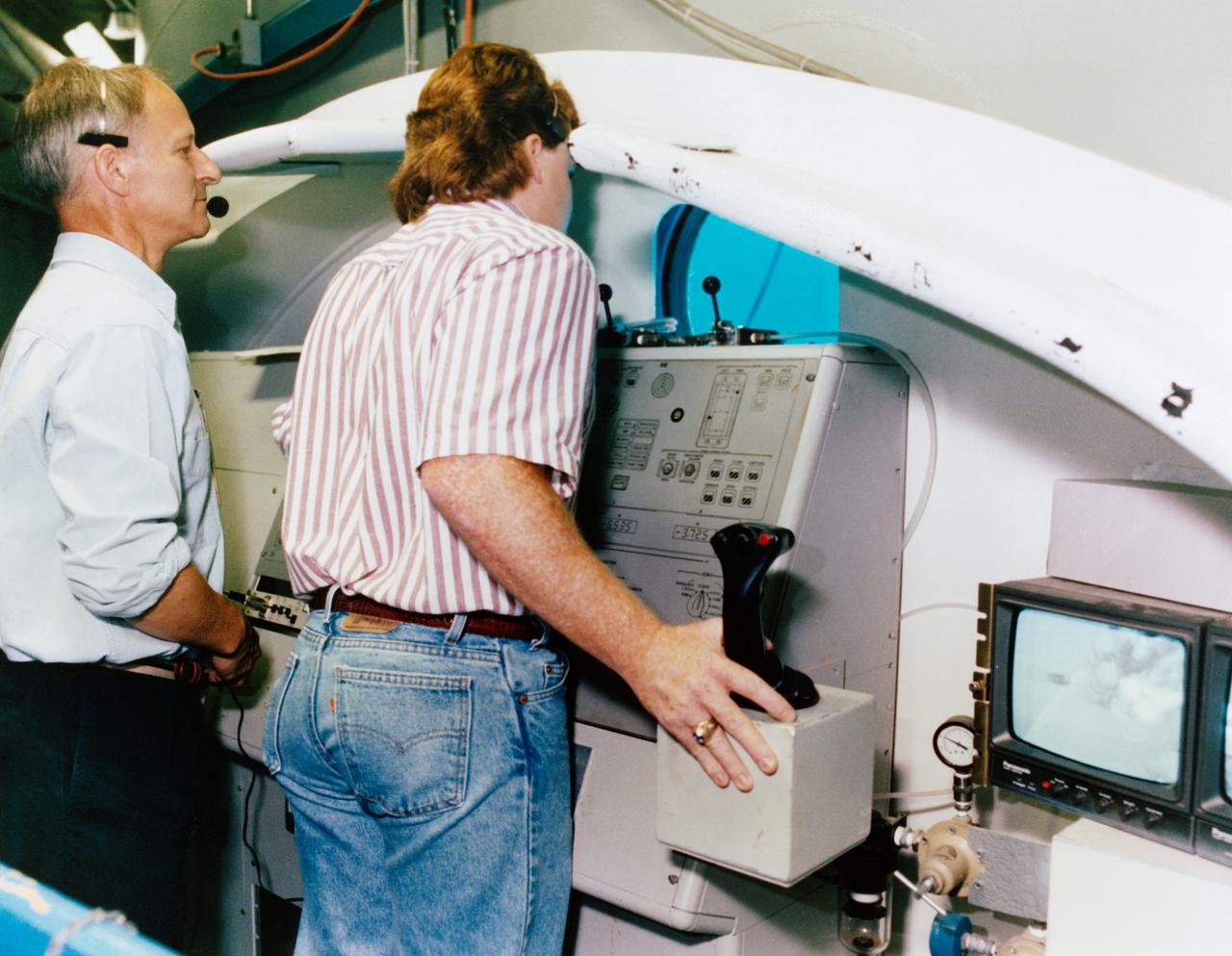

Astronauts Jeffrey A. Hoffman (far left) and F. Story Musgrave (second left) monitor a training session from consoles in the control room for the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC). Seen underwater in the NBS on the big screen and the monitors at the consoles is astronaut Thomas D. Akers. The three mission specialists, along with astronaut Kathryn C. Thornton, are scheduled to be involved in a total of five sessions of extravehicular activity (EVA) to service the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in orbit during the STS-61 mission, scheduled for December 1993.

Astronaut Mark Lee participates in the Photo Voltaic Module testing in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

A Marshall scientist practices transferring objects in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) for the Spacelab transfer tunnel test.

Underwater tests are conducted with Space Systems lab at Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

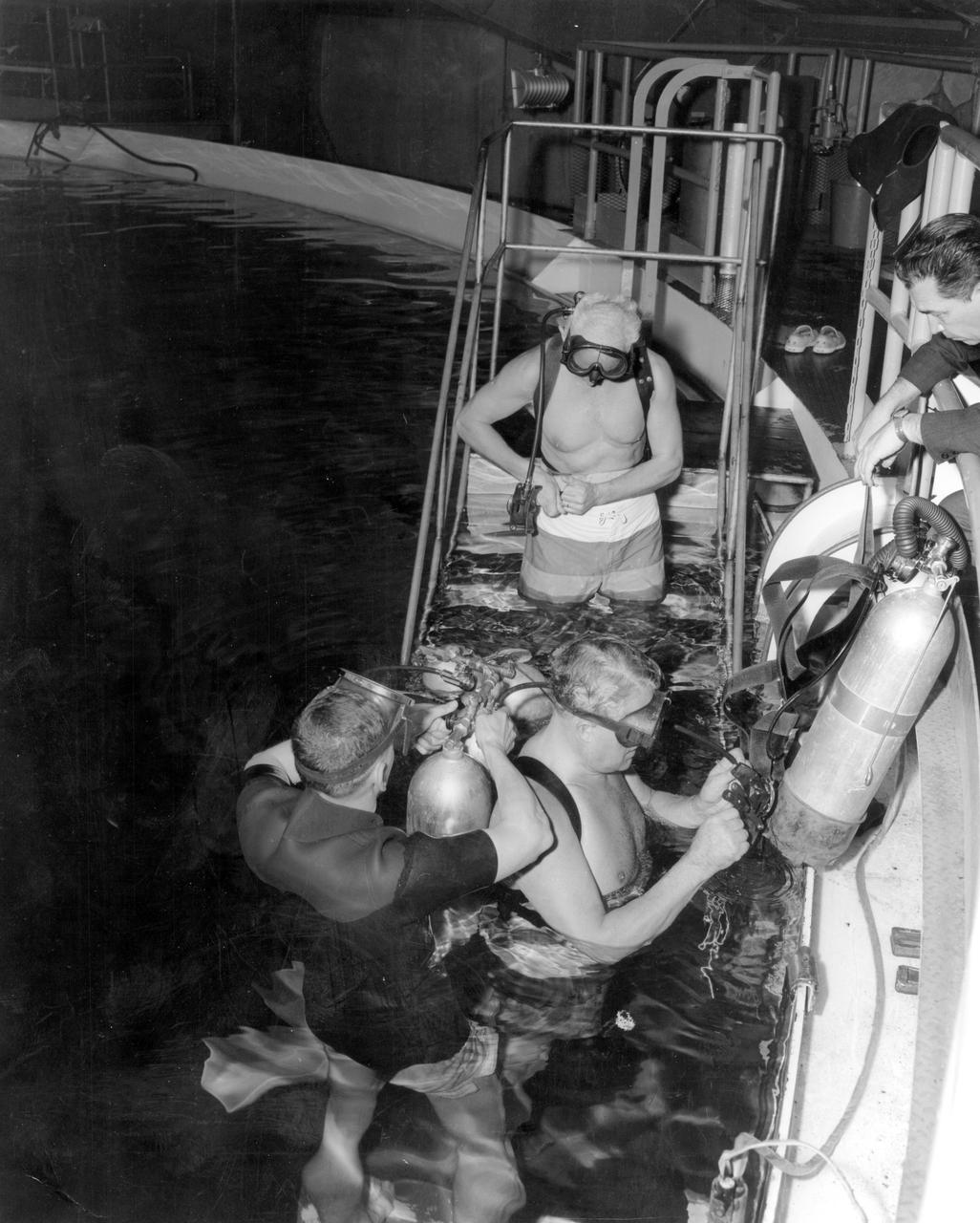

Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Director, Dr. von Braun, submerges after spending some time under water in the MSFC Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). Weighted to a neutrally buoyant condition, Dr. von Braun was able to perform tasks underwater which simulated weightless conditions found in space.

Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Director, Dr. von Braun, submerges after spending some time under water in the MSFC Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). Weighted to a neutrally buoyant condition, Dr. von Braun was able to perform tasks underwater which simulated weightless conditions found in space.

Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Director, Dr. von Braun, is shown fitted with suit and diving equipment as he prepares for a tryout in the MSFC Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). Weighted to a neutrally buoyant condition, Dr. von Braun was able to perform tasks underwater which simulated weightless conditions found in space.

Astronaut Joe Lindquist and Kate Rupley conduct underwater testing on the International Space Station's power module in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

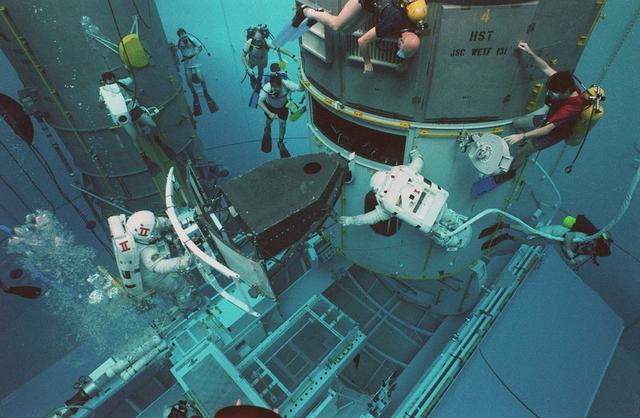

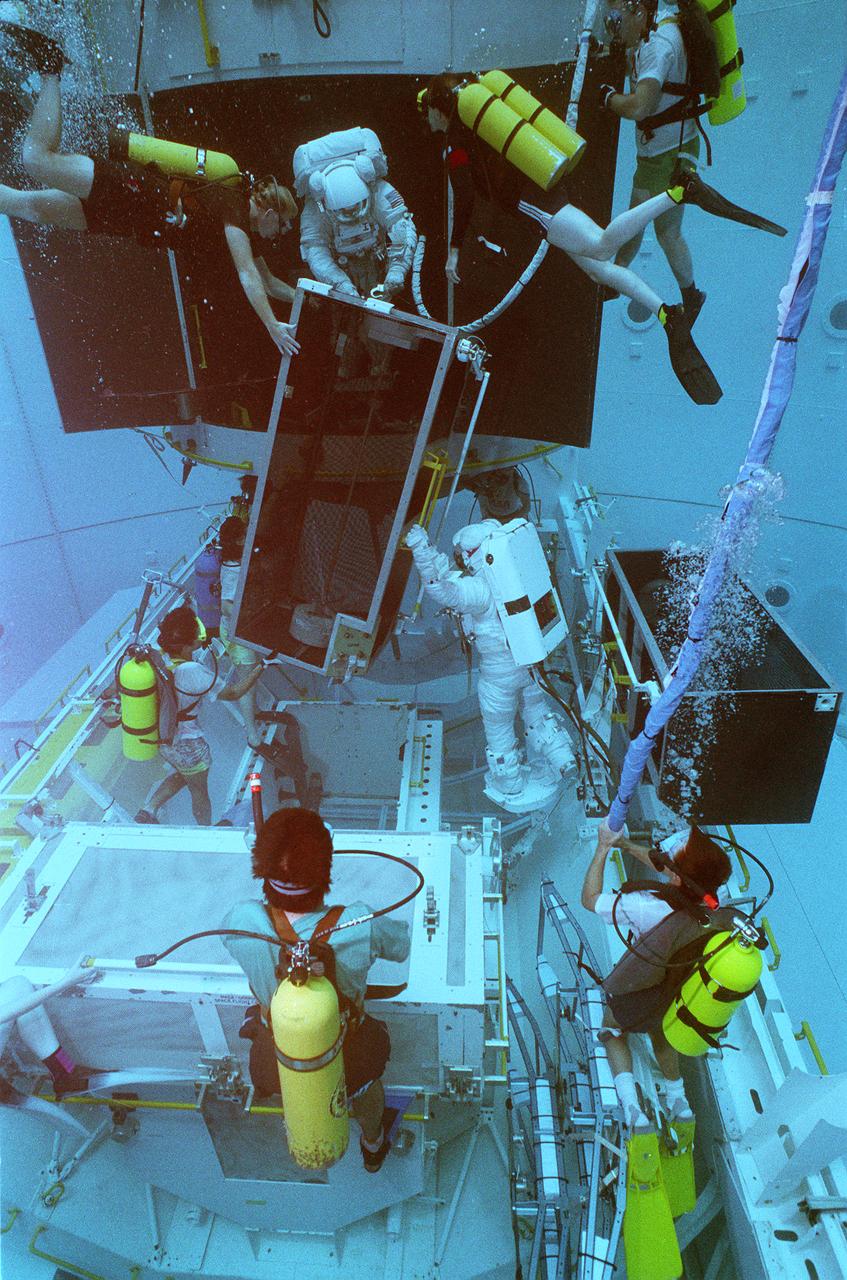

Safety divers in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) prepare a mockup of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) for one of 32 separate training sessions conducted by four of the STS-61 crew members in June. The three-week process allowed mission trainers to refine the timelines for the five separate spacewalks scheduled to be conducted on the actual mission scheduled for December 1993. The HST is separated into two pieces since the water tank depth cannot support the entire structure in one piece. The full length payload bay mockup shows the Solar Array Carrier in the foreground and the various containers that will house replacement hardware that will be carried on the mission.

Candid shots of Carolyn Griner (front), Drs. Mary-Helen Johnston and Ann Whitaker (L to R) wearing scuba gear at the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) for training.

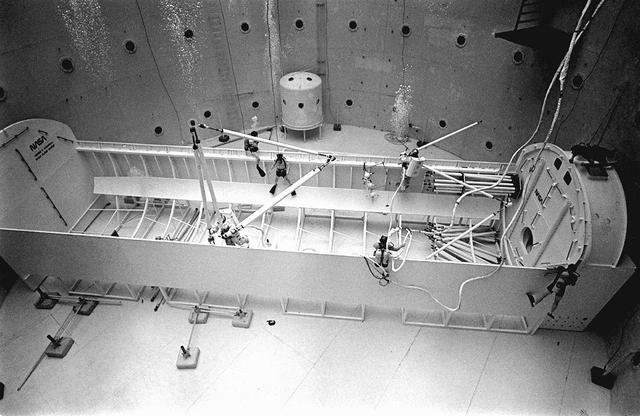

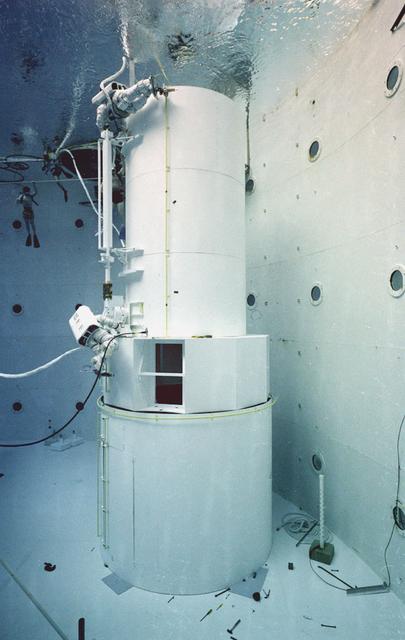

This photograph was taken in the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) during the testing of the Japanese Experimental Module. The NBS provided the weightless environment encountered in space needed for testing and the practices of extra-vehicular activities.

Marshall Space Flight Center’s (MSFC) Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger, Director of Research Projects Office; and Dr. Wernher von Braun, center director, along with others, took a swim in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at MSFC. A safety diver adjusts scuba equipment worn by von Braun, while Stuhlinger adjusts his weight belt prior to entering the tank. In the NBS, subjects were weighted to a neutrally buoyant condition underwater to perform and practice tasks in a simulated weightless condition as would be encountered in space.

Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Director, Dr. von Braun, is shown leaving the suiting-up van wearing a pressure suit prepared for a tryout in the MSFC Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). Weighted to a neutrally buoyant condition, Dr. von Braun was able to perform tasks underwater which simulated weightless conditions found in space.

Astronaut L. Gordon Cooper checks the neck ring of a space suit worn by Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Director, Dr. von Braun before he submerges into the water of the MSFC Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). Wearing a pressurized suit and weighted to a neutrally buoyant condition, Dr. von Braun was able to perform tasks underwater which simulated weightless conditions found in space.

Astronauts Greg Harbaugh and Joe Tarner conduct Hubble Space Telescope training in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Astronaut Jeff Hoffman conducts Hubble Space Telescope training in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS)

Underwater training is conducted in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) in preparation for on-orbit Hubble Space Telescope operations.

Astronaut Kathy Thornton conducts Hubble Space Telescope training in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Astronaut Storey Musgrave conducts Hubble Space Telescope (HST) training in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Astronauts Mark Lee and Joe Tarner conduct Hubble Space Telescope training in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Astronaut Mark Lee conducts Hubble Space Telescope training in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS)

Underwater training is conducted in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) in preparation for on-orbit Hubble Space Telescope operations.

Underwater crew training is conducted in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) in preparation for on-orbit Hubble Space Telescope (HST) operations.

Astronaut Mark Lee conducts Hubble Space Telescope training in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS)

Astronauts Greg Harbaugh and Steve Smith conduct Hubble Space Telescope (HST) training in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Astronauts Greg Harbaugh and Joe Tarner conduct Hubble Space Telescope training in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Astronauts Greg Harbaugh and Joe Tarner conduct Hubble Space Telescope training in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Underwater crew training is conducted in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) in preparation for on-orbit Hubble Space Telescope (HST) operations.

STS-61 astronauts practice installing the corrective optics module on a Hubble Space Telescope mockup in Marshall Space Flight Center's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator. Test activities for STS-61 were carried out at Marshall from June 21, 1993 through July 2, 1993 and again in October 1993.

Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) is used to simulate the gravitational fields and buoyancy effects outer space has on astronauts and their ability to perform tasks in this environment. In this example, a diver performs a temporary fluid line repair task using a repair kit developed by Marshall engineers. The analysis will determine the value of this repair kit and its feasibility.

Astronauts Kathy Thornton and Tom Akers practice installing the Wide Field Planetary camera into the Hubble Space Telescope at Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Marshall scientist practices assembling the solar panel array for the space station during the Collector Panel Assembly Test (COPAT) at Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

Astronauts Kathy Thornton and Tom Akers practice installing the Wide Field Planetary camera into the Hubble Space Telescope at Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).

This plaque, displayed on the grounds of Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama commemorates the Neutral Buoyancy Space Simulator as a National Historic Landmark. The site was designated as such in 1986 by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior.

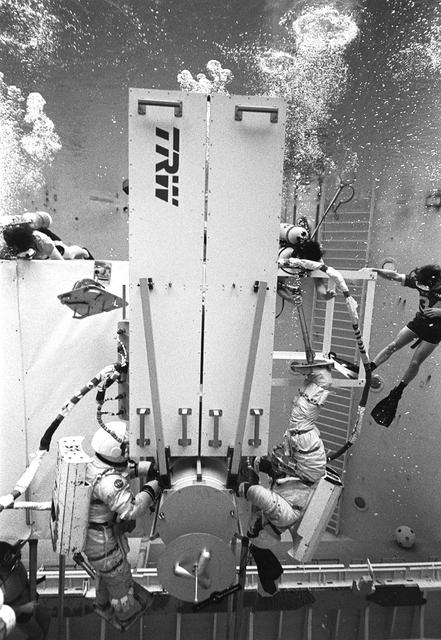

Two years prior to being used during a shuttle mission, the Transfer to Orbit System (TOS) is being demonstrated at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). TOS is an upper stage launch system used to place satellites into higher orbits. TOS was used only once, on September 12, 1993 when the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS51) deployed ACTS (Advanced Communications Technology Satellite). The test pictured was to provide an evaluation of the extravehicular activity (EVA) tools that were to be used by future shuttle crews.

Dr. E. Stuhlinger, Dr. W. von Braun, and Dr. J. Piccard, along with others, take a swim in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center. The NBS was instrumental in providing a zero-gravity environment where astronauts could practice tasks assigned for up coming space flights.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. And construction methods had to be efficient due to limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. Included in the plans for the space station was a space telescope. This telescope would be attached to the space station and directed towards outerspace. Astronomers hoped that the space telescope would provide a look at space that is impossible to see from Earth because of Earth's atmosphere and other man made influences. In an effort to make replacement and repairs easier on astronauts the space telescope was designed to be modular. Practice makes perfect as demonstrated in this photo: an astronaut practices moving modular pieces of the space telescope in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at MSFC. The space telescope was later deployed in April 1990 as the Hubble Space Telescope.

S95-04319 (22 Feb 1995) --- The neutral buoyancy facility at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Star City, Russia, is used for underwater training for missions aboard the Russian Mir Space Station. The facility is similar to NASA's Weightless Environment Training Facility (WET-F) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, and the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Alabama.

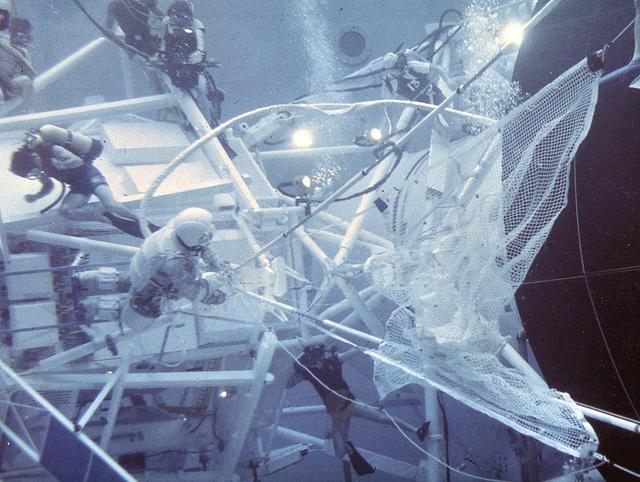

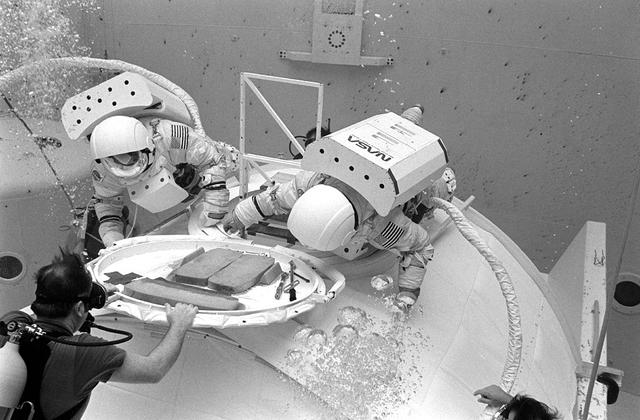

After its launch on May 14, 1973, it was immediately known that there were some major problems with Skylab. The large, delicate, meteoroid shield on the outside of the workshop was ripped off by the vibration of the launch. Its tearing off caused serious damage to the two wings of solar cells that were to supply most of the electric power to the workshop. Once in orbit, the news worsened. The loss of the big shade exposed the metal skin of the workshop to the sun. Internal temperatures soared to 126 degrees F. This heat not only threatened its habitation by astronauts, but if prolonged, would cause serious damage to instruments and film. After twice delaying the launch of the first astronaut crew, engineers worked frantically to develop solutions to these problems and salvage the Skylab. After designing a protective solar sail to cover the workshop, crews needed to practice using the specially designed tools and materials to facilitate the repair procedure. Marshall Space Flight Center's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS), was used to practice these maneuvers. Pictured here are the astronauts in the NBS deploying the protecticve solar sail. On may 25, 1973, an Apollo command and service module was launched and later docked with Skylab. The next day, astronauts Conrad and Kerwin were able to complete the needed repairs to Skylab, salvaging the entire program.

Astronaut Thomas D. Akers uses a power wrench to deploy one of the tools on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) during a training session in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator at Marshall Space Flight Center.

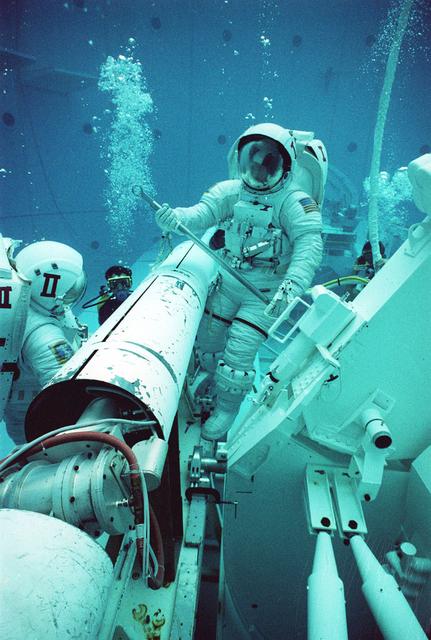

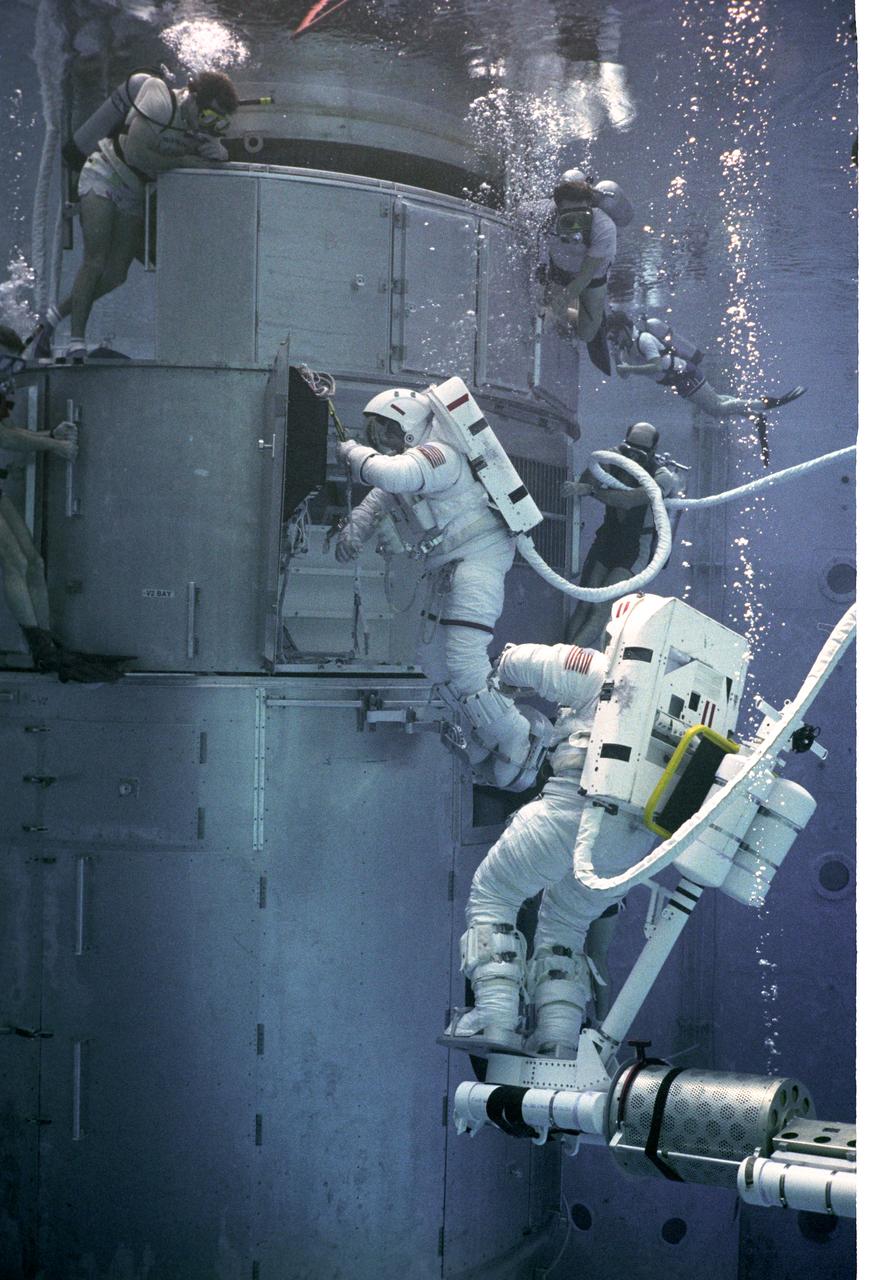

Preparing for the eventual launch of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), an astronaut prepares himself for the rigorous duties of maintenance and repairs after launch, at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). The NBS provided mock-ups of the HST, the Remote Manipulator System (RMS), the orbiter's cargo bay, and the low-gravity environment that the astronauts would encounter while working in space. All aspects of shuttle missions were pre-plarned and practiced at the NBS to forego any problems in space.

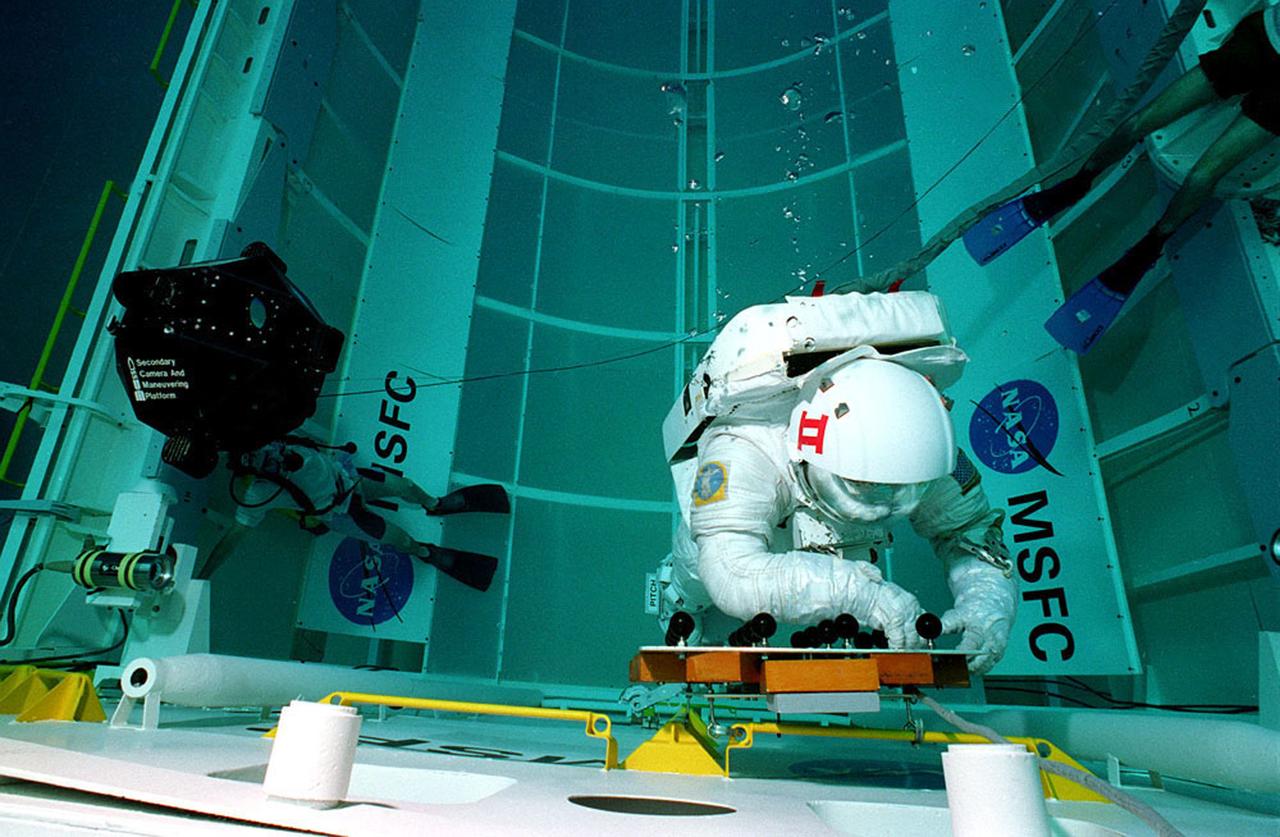

A diver tests a secondary camera and maneuvering platform in Marshall's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS).The secondary camera will be beneficial for recording repairs and other extra vehicular activities (EVA) the astronuats will perform while making repairs on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). The maneuvering platform was developed to give the astronauts something to stand on while performing maintenance tasks. These platforms were developed to be mobile so that the astronauts could move them to accommadate different sites.

The Space Platform was first conceived as a launching site for deep space exploration. The original idea was to build this space platform either on the moon's surface or near lunar orbit. It would be used as a staging base, where the reusable launch vehicles (later known as Space Shuttles) would ferry machinery and equipment to assemble deep space exploration vehicles. Replaced by the Space Station concept, the space platform idea was never completed. However, early in the space platform development, astronauts trained at the Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS), as pictured here, working on solar array equipment. This experiment was deployed from the shuttle to study the motions of large structures in space. Similar arrays will be used on the Space Station and large observatory spacecraft in the future.

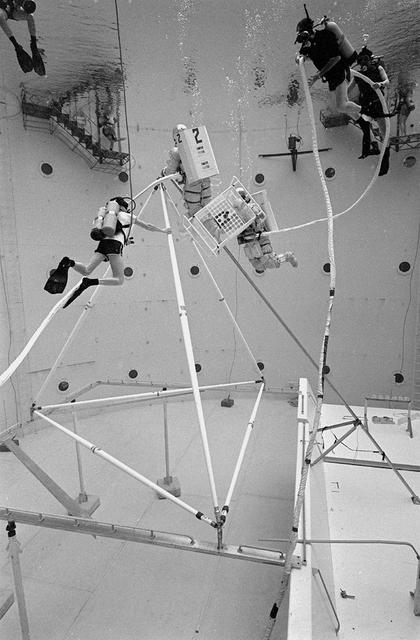

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. Construction methods had to be efficient due to the limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. Pictured is a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) student working in a spacesuit on the Experimental Assembly of Structures in Extravehicular Activity (EASE) project which was developed as a joint effort between MFSC and MIT. The EASE experiment required that crew members assemble small components to form larger components, working from the payload bay of the space shuttle. The MIT student in this photo is assembling two six-beam tetrahedrons.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. Construction methods had to be efficient due to the limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. Pictured is a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) student working in a spacesuit on the Experimental Assembly of Structures in Extravehicular Activity (EASE) project which was developed as a joint effort between MFSC and MIT. The EASE experiment required that crew members assemble small components to form larger components, working from the payload bay of the space shuttle. The MIT student in this photo is assembling two six-beam tetrahedrons.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. Construction methods had to be efficient due to the limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. Pictured is a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) student working in a spacesuit on the Experimental Assembly of Structures in Extravehicular Activity (EASE) project which was developed as a joint effort between MFSC and MIT. The EASE experiment required that crew members assemble small components to form larger components, working from the payload bay of the space shuttle. The MIT student in this photo is assembling two six-beam tetrahedrons.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. Construction methods had to be efficient due to the limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. As part of this experimentation, the Experimental Assembly of Structures in Extravehicular Activity (EASE) project was developed as a joint effort between MFSC and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The EASE experiment required that crew members assemble small components to form larger components, working from the payload bay of the space shuttle. Pictured is an entire unit that has been constructed and is sitting in the bottom of a mock-up shuttle cargo bay pallet.

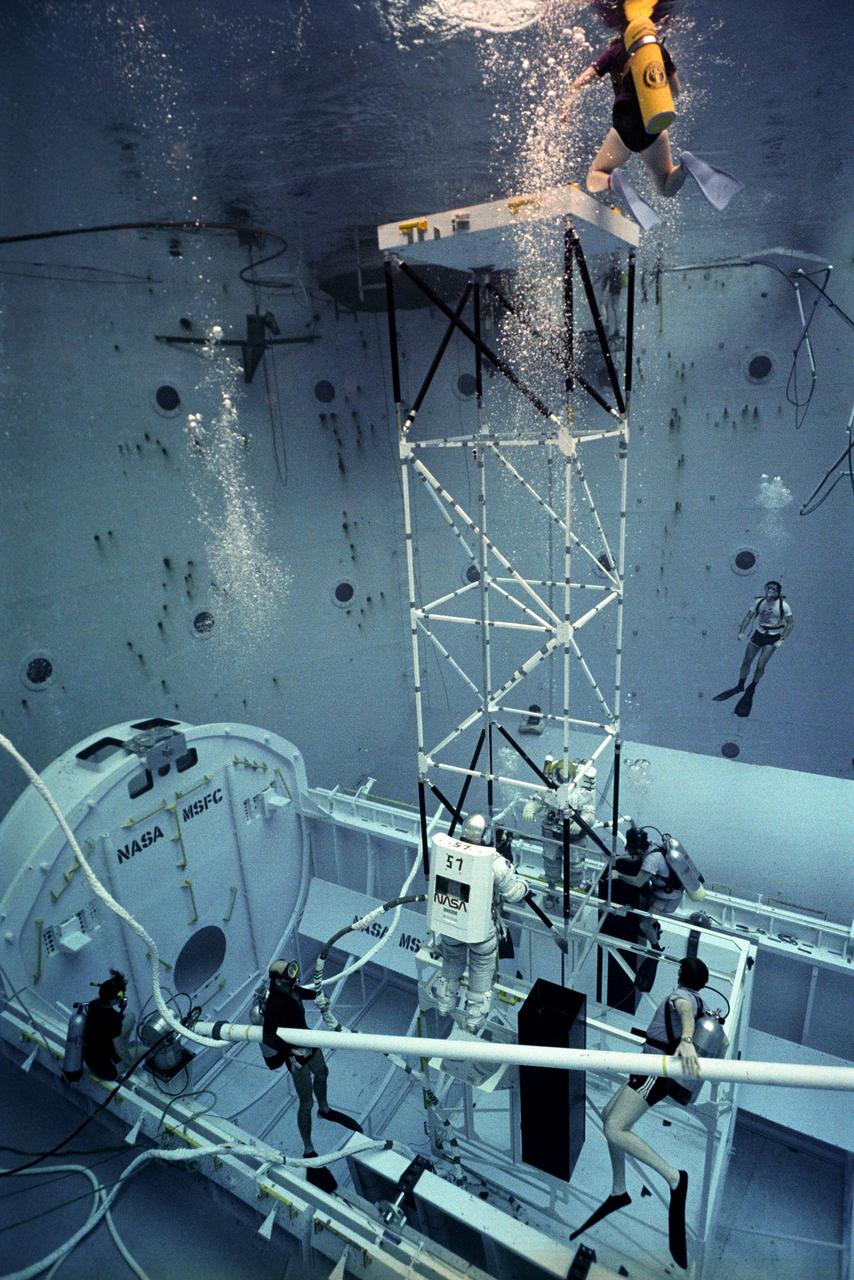

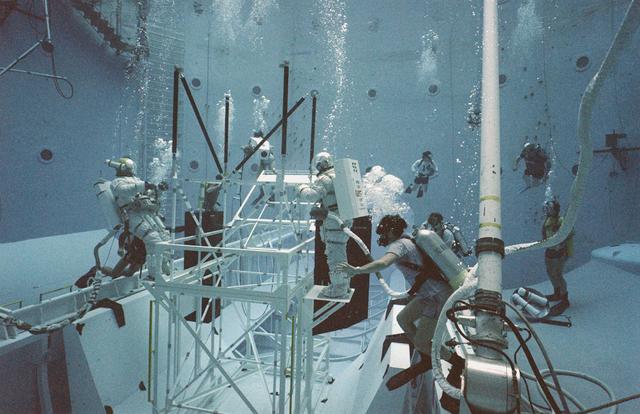

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. And construction methods had to be efficient due to limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. With the help of the NBS, building a space station became more of a reality. In a joint venture between NASA/Langley Research Center in Hampton, VA and MSFC, the Assembly Concept for Construction of Erectable Space Structures (ACCESS) was developed and demonstrated at MSFC's NBS. The primary objective of this experiment was to test the ACCESS structural assembly concept for suitability as the framework for larger space structures and to identify ways to improve the productivity of space construction. Pictured is a demonstration of ACCESS.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. And construction methods had to be efficient due to limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. With the help of the NBS, building a space station became more of a reality. In a joint venture between NASA/Langley Research Center in Hampton, VA and MSFC, the Assembly Concept for Construction of Erectable Space Structures (ACCESS) was developed and demonstrated at MSFC's NBS. The primary objective of this experiment was to test the ACCESS structural assembly concept for suitability as the framework for larger space structures and to identify ways to improve the productivity of space construction. Pictured is a demonstration of ACCESS.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. And construction methods had to be efficient due to limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. With the help of the NBS, building a space station became more of a reality. In a joint venture between NASA/Langley Research Center in Hampton, VA and MSFC, the Assembly Concept for Construction of Erectable Space Structures (ACCESS) was developed and demonstrated at MSFC's NBS. The primary objective of this experiment was to test the ACCESS structural assembly concept for suitability as the framework for larger space structures and to identify ways to improve the productivity of space construction. Pictured is a demonstration of ACCESS.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, theprospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. Construction methods had to be efficient due to the limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. Pictured is a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) student working in a spacesuit on the Experimental Assembly of Structures in Extravehicular Activity (EASE) project which was developed as a joint effort between MFSC and MIT. The EASE experiment required that crew members assemble small components to form larger components, working from the payload bay of the space shuttle. The MIT student in this photo is assembling two six-beam tetrahedrons.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. And construction methods had to be efficient due to limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. With the help of the NBS, building a space station became more of a reality. In a joint venture between NASA/Langley Research Center in Hampton, VA and MSFC, the Assembly Concept for Construction of Erectable Space Structures (ACCESS) was developed and demonstrated at MSFC's NBS. The primary objective of this experiment was to test the ACCESS structural assembly concept for suitability as the framework for larger space structures and to identify ways to improve the productivity of space construction. Pictured is a demonstration of ACCESS.

Swiss scientits Claude Nicollier (left), STS-61 mission specialist, waits his turn at the controls for the remote manipulator system (RMS) during a training session in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC). Mark Norman of MSFC has control of the RMS in this frame.

This photograph was taken in the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) during the testing of an emergency procedure to deploy a twin-pole sunshade to protect the orbiting workshop from overheating due to the loss of its thermal shield. The spacecraft suffered damage to its sunshield during its launch on May 14, 1973. This photograph shows the base plate used to hold the twin-pole in place, the bag to hold the fabric sail, and the lines that were used to draw the sail into place. Extensive testing and many hours of practice in simulators, such as the NBS, helped prepare the Skylab crewmen for extravehicular performance in the weightless environment. This huge water tank simulated the weightless environment that the astronauts would encounter in space.

This close-up of astronaut and mission specialist Kathryn Thornton readies herself for submersion into the water in the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) where she is participating in a training session for the STS-61 mission. The NBS provided the weightless environment encountered in space needed for testing and the practices of Extravehicular Activities (EVA). Launched on December 2, 1993 aboard the Space Shuttle Orbiter Endeavor, STS-61 was the first Hubble Space Telescope (HST) serving mission. During the 2nd EVA of the mission, Thornton, along with astronaut and mission specialist Thomas Akers, performed the task of replacing the solar arrays. The EVA lasted 6 hours and 35 minutes.

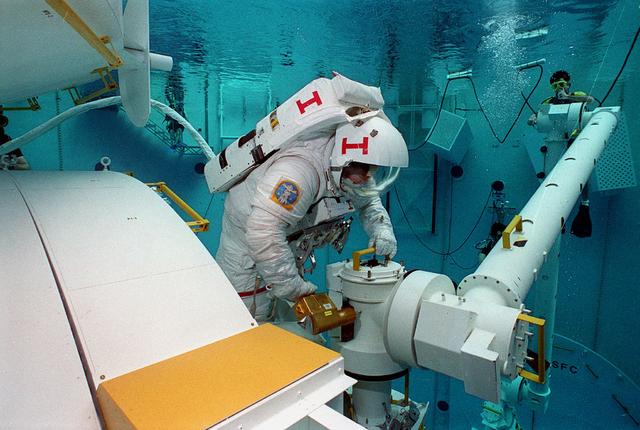

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory; it was the first and flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, HST was finally designed and built; and became operational in the 1990s. HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is MSFC's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator which served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is an astronaut training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST in removal/replacement of scientific instruments.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory; it was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, HST was finally designed and built; and it finally became operational in the 1990s. HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is MSFC's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator which served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown are astronauts McCandless and Nelson training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST in removal/replacement of scientific instruments.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory; it was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, HST was finally designed and built; and it finally became operational in the 1990s. HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. MSFC's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator served as the training facility for shuttle astronauts for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Sharnon Lucid having her life support system being checked prior to entering the NBS to begin training on the space telescope axial scientific instrument changeout.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory; it was the first and flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, HST was finally designed and built; and became operational in the 1990s. HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is MSFC's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator which served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is an astronaut training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST in removal/replacement of scientific instruments.

Skylab's success proved that scientific experimentation in a low gravity environment was essential to scientific progress. A more permanent structure was needed to provide this space laboratory. President Ronald Reagan, on January 25, 1984, during his State of the Union address, claimed that the United States should exploit the new frontier of space, and directed NASA to build a permanent marned space station within a decade. The idea was that the space station would not only be used as a laboratory for the advancement of science and medicine, but would also provide a staging area for building a lunar base and manned expeditions to Mars and elsewhere in the solar system. President Reagan invited the international community to join with the United States in this endeavour. NASA and several countries moved forward with this concept. By December 1985, the first phase of the space station was well underway with the design concept for the crew compartments and laboratories. Pictured are two NASA astronauts, at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS), practicing construction techniques they later used to construct the space station after it was deployed.

Prior to its launch in April 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) went through years of development and testing. The HST was the first of its kind and the scientific community could only imagine the fruits of their collective labors. However, prior to its launch, more practical procedures, such as astronaut training, had to be developed. As the HST was to remain in orbit for years, it became apparent that on-orbit maintenance routines would have to be developed. The best facility to develop these maintenance practices was at the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC). The NBS provided mock-ups of the HST (in sections), a Remote Manipulator System (RMS), and a shuttle's cargo bay pallet. This real life scenario provided scientists, engineers, and astronauts a practical environment to work out any problems with a plarned on-orbit maintenance mission. Pictured is an astronaut in training with a mock-up section of the HST, practicing using tools especially designed for the task being performed.

This photograph shows an STS-61 astronaut training for the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing mission (STS-61) in the Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). Two months after its deployment in space, scientists detected a 2-micron spherical aberration in the primary mirror of the HST that affected the telescope's ability to focus faint light sources into a precise point. This imperfection was very slight, one-fiftieth of the width of a human hair. A scheduled Space Service servicing mission (STS-61) in 1993 permitted scientists to correct the problem. The MSFC NBS provided an excellent environment for testing hardware to examine how it would operate in space and for evaluating techniques for space construction and spacecraft servicing.

This photograph was taken during testing of an emergency procedure to free jammed solar array panels on the Skylab workshop. A metal strap became tangled over one of the folded solar array panels when Skylab lost its micrometeoroid shield during the launch. This photograph shows astronauts Schweickart and Gibson in the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) using various cutting tools and methods developed by the MSFC to free the jammed solar wing. Extensive testing and many hours of practice in simulators such as the NBS tank helped prepare the Skylab crewmen for extravehicular performance in the weightless environment. This huge water tank simulated the weightless environment that the astronauts would encounter in space.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. Construction methods had to be efficient due to the limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. With the help of the NBS, building a space station became more of a reality. Pictured is Astronaut Paul Weitz training on a mock-up of Spacelab's airlock-hatch cover. Training was also done on the use of foot restraints which had recently been developed to help astronauts maintain their positions during space walks rather than having their feet float out from underneath them while they tried to perform maintenance and repair operations. Every aspect of every space mission was researched and demonstrated in the NBS. Using the airlock hatch cover and foot restraints were just a small example of the preparation that went into each mission.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. And construction methods had to be efficient due to limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. Another facet of the space station would be electrical cornectors which would be used for powering tools the astronauts would need for construction, maintenance and repairs. Shown is an astronaut training during an underwater electrical connector test in the NBS.

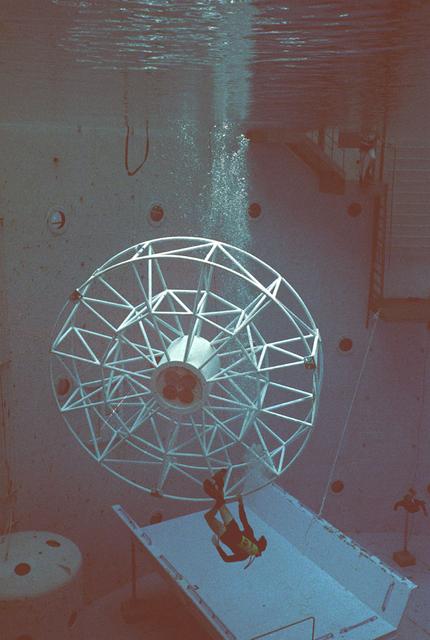

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. And construction methods had to be efficient due to limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. Included in the plans for the space station was a space telescope. This telescope would be attached to the space station and directed towards outerspace. Astronomers hoped that the space telescope would provide a look at space that is impossible to see from Earth because of Earth's atmosphere and other man made influences. Pictured is a large structure that is being used as the antenna base for the space telescope.

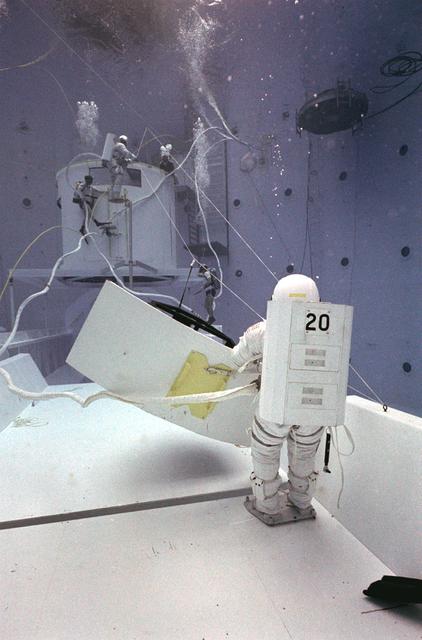

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. And construction methods had to be efficient due to limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built.Pictured is an experiment where the astronaut is required to move a large object which weighed 19,000 pounds. It was moved with realitive ease once the astronaut became familiar with his environment and his near weightless condition. Experiments of this nature provided scientists with the information needed regarding weight and mass allowances astronauts could manage in preparation for building a permanent space station in the future.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. And construction methods had to be efficient due to limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. Pictured is a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) student working in a spacesuit on the Experimental Assembly of Structures in Extravehicular Activity (EASE) project which was developed as a joint effort between MFSC and MIT. The EASE experiment required that crew members assemble small components to form larger components, working from the payload bay of the space shuttle.

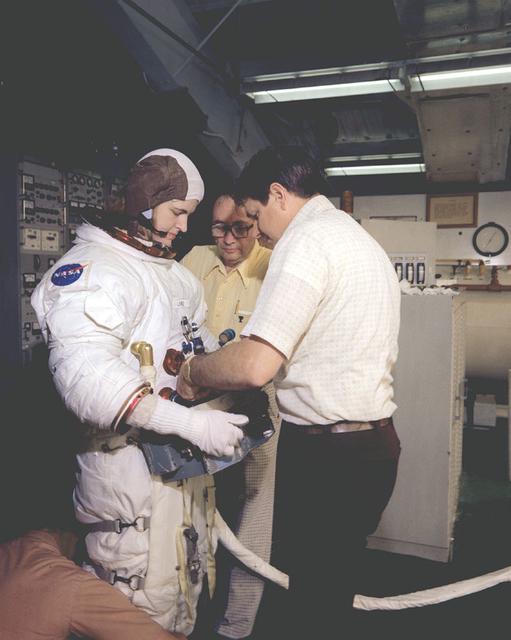

Astronaut Thomas D. Akers gets assistance in donning a training version of the Shuttle extravehicular mobility unit (EMU) space suit prior to a training session in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) (39735); Astronaut Kathryn C. Thornton (foreground) and Thomas Akers, STS-61 mission specialists scheduled for extravehicular activity (EVA) duty, prepare for an underwater rehearsal session. Thornton recieves assistance from a technician in donning her EMU gloves (39736).

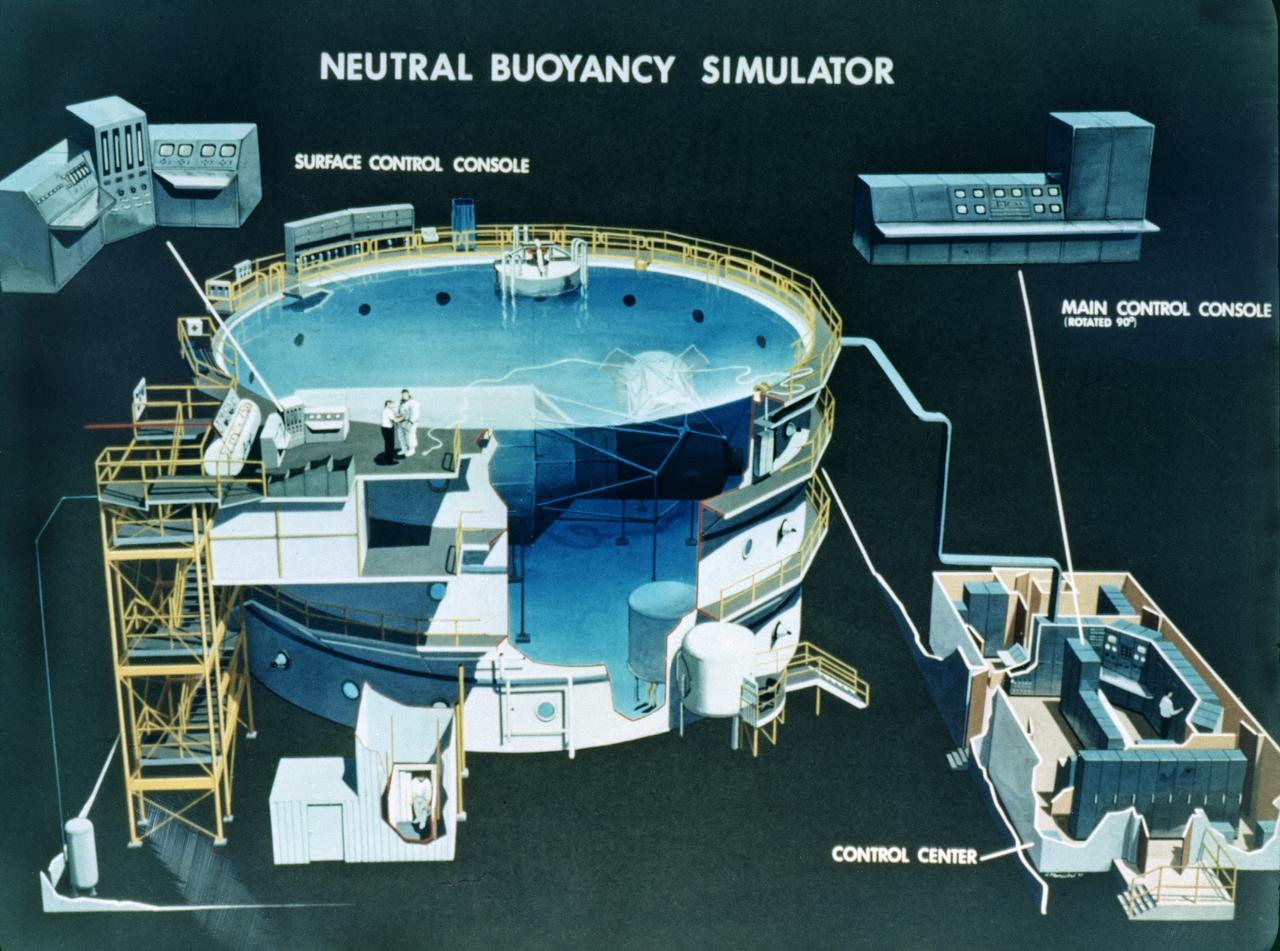

This is a cutaway illustration of the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC ). The MSFC NBS provided an excellent environment for testing hardware to examine how it would operate in space and for evaluating techniques for space construction and spacecraft servicing. Here, engineers, designers, and astronauts performed various tests to develop basic concepts, preliminary designs, final designs, and crew procedures. The NBS was constructed of welded steel with polyester-resin coating. The water tank was 75-feet (22.9- meters) in diameter, 40-feet (12.2-meters) deep, and held 1.32 million gallons of water. Since it opened for operation in 1968, the NBS had supported a number of successful space missions, such as the Skylab, Solar Maximum Mission Satellite, Marned Maneuvering Unit, Experimental Assembly of Structures in Extravehicular Activity/Assembly Concept for Construction of Erectable Space Structures (EASE/ACCESS), the Hubble Space Telescope, and the Space Station. The function of the MSFC NBS was moved to the larger simulator at the Johnson Space Center and is no longer operational.

After the end of the Apollo missions, NASA's next adventure into space was the marned spaceflight of Skylab. Using an S-IVB stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle, Skylab was a two-story orbiting laboratory, one floor being living quarters and the other a work room. The objectives of Skylab were to enrich our scientific knowledge of the Earth, the Sun, the stars, and cosmic space; to study the effects of weightlessness on living organisms, including man; to study the effects of the processing and manufacturing of materials utilizing the absence of gravity; and to conduct Earth resource observations. At the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), astronauts and engineers spent hundreds of hours in an MSFC Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) rehearsing procedures to be used during the Skylab mission, developing techniques, and detecting and correcting potential problems. The NBS was a 40-foot deep water tank that simulated the weightlessness environment of space. This photograph shows astronaut Ed Gibbon (a prime crew member of the Skylab-4 mission) during the neutral buoyancy Skylab extravehicular activity training at the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM) mockup. One of Skylab's major components, the ATM was the most powerful astronomical observatory ever put into orbit to date.

This photograph shows STS-61 crewmemmbers training for the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing mission in the Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). Two months after its deployment in space, scientists detected a 2-micron spherical aberration in the primary mirror of the HST that affected the telescope's ability to focus faint light sources into a precise point. This imperfection was very slight, one-fiftieth of the width of a human hair. A scheduled Space Service servicing mission (STS-61) in 1993 permitted scientists to correct the problem. The MSFC NBS provided an excellent environment for testing hardware to examine how it would operate in space and for evaluating techniques for space construction and spacecraft servicing.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the first and flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is MSFC's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator that served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is an astronaut training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST in the removal and replacement of scientific instruments.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Marshall Space Flight Center’s (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher suiting up for training on a mockup of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the first and flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is MSFC's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator that served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is an astronaut training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST in the removal and replacement of scientific instruments.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Marshall Space Flight Center’s (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. MSFC's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher suiting up for training on a mockup of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

One of the main components of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is the Solar Array Drive Electronics (SADE) system. This system interfaces with the Support System Module (SSM) for exchange of operational commands and telemetry data. SADE operates and controls the Solar Array Drive Mechanisms (SADM) for the orientation of the Solar Array Drive (SAD). It also monitors the position of the arrays and the temperature of the SADM. During the first HST servicing mission, the astronauts replaced the SADE component because of some malfunctions. This turned out to be a very challenging extravehicular activity (EVA). Two transistors and two diodes had been thermally stressed with the conformal coating discolored and charred. Soldered cornections became molten and reflowed between the two diodes. The failed transistors gave no indication of defective construction. All repairs were made and the HST was redeposited into orbit. Prior to undertaking this challenging mission, the orbiter's crew trained at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) to prepare themselves for working in a low gravity environment. They also practiced replacing HST parts and exercised maneuverability and equipment handling. Pictured is an astronaut practicing climbing a space platform that was necessary in making repairs on the HST.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is MSFC's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) that served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown are astronauts Arna Fisher and Joe Kerwin training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument changeout.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Marshall Space Flight Center’s (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher suiting up for training on a mockup of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) that served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown are astronauts Arna Fisher and Joe Kerwin training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument changeout.

One of the main components of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is the Solar Array Drive Electronics (SADE) system. This system interfaces with the Support System Module (SSM) for exchange of operational commands and telemetry data. SADE operates and controls the Solar Array Drive Mechanisms (SADM) for the orientation of the Solar Array Drive (SAD). It also monitors the position of the arrays and the temperature of the SADM. During the first HST servicing mission, the astronauts replaced the SADE component because of some malfunctions. This turned out to be a very challenging extravehicular activity (EVA). Two transistors and two diodes had been thermally stressed with the conformal coating discolored and charred. Soldered cornections became molten and reflowed between the two diodes. The failed transistors gave no indication of defective construction. All repairs were made and the HST was redeposited into orbit. Prior to undertaking this challenging mission, the orbiter's crew trained at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) to prepare themselves for working in a low gravity environment. They also practiced replacing HST parts and exercised maneuverability and equipment handling. Pictured are crew members practicing on a space platform.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Marshall SPace Flight Center’s (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher suited up for training on a mockup of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

Prior to its launch in April 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) went through years of development and testing. The HST was the first of its kind and the scientific community could only imagine the fruits of their collective labors. However, prior to its launch, more practical procedures, such as astronaut training, had to be developed. As the HST was to remain in orbit for years, it became apparent that on-orbit maintenance routines would have to be developed. The best facility to develop these maintenance practices was at the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC). The NBS provided mock-ups of the HST (in sections), a Remote Manipulator System (RMS), and a shuttle's cargo bay pallet. This real life scenario provided scientists, engineers, and astronauts a practical environment to work out any problems with a plarned on-orbit maintenance mission. Pictured are two astronauts training at MSFC's NBS. One astronaut is using a foot restraint system attached to the RMS, while the other astronaut performs maintenance techniques while attached to the surface of the HST mock-up.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Marshall Space Flight Center’s (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher suited up for training on a mockup of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is MSFC's Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) that served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown are astronauts Bruce McCandless and Sharnon Lucid being fitted for their space suits prior to entering the NBS to begin training on the space telescope axial scientific instrument changeout.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) that served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown are astronauts Arna Fisher and Joe Kerwin training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument changeout.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. Construction methods had to be efficient due to the limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. With the help of the NBS, building a space station became more of a reality. Pictured is Astronaut Paul Weitz training on a mock-up of Spacelab's airlock-hatch cover. Training was also done on the use of foot restraints which had recently been developed to help astronauts maintain their positions during space walks rather than having their feet float out from underneath them while they tried to perform maintenance and repair operations. Every aspect of every space mission was researched and demonstrated in the NBS. Using the airlock hatch cover and foot restraints were just a small example of the preparation that went into each mission.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. Construction methods had to be efficient due to the limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. With the help of the NBS, building a space station became more of a reality. In a joint venture between NASA/Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia and the MSFC, the Assembly Concept for Construction of Erectable Space Structures (ACCESS) was developed and demonstrated at MSFC's NBS. The primary objective of this experiment was to test the ACCESS structural assembly concept for suitability as the framework for larger space structures and to identify ways to improve the productivity of space construction. Pictured is a demonstration of ACCESS.