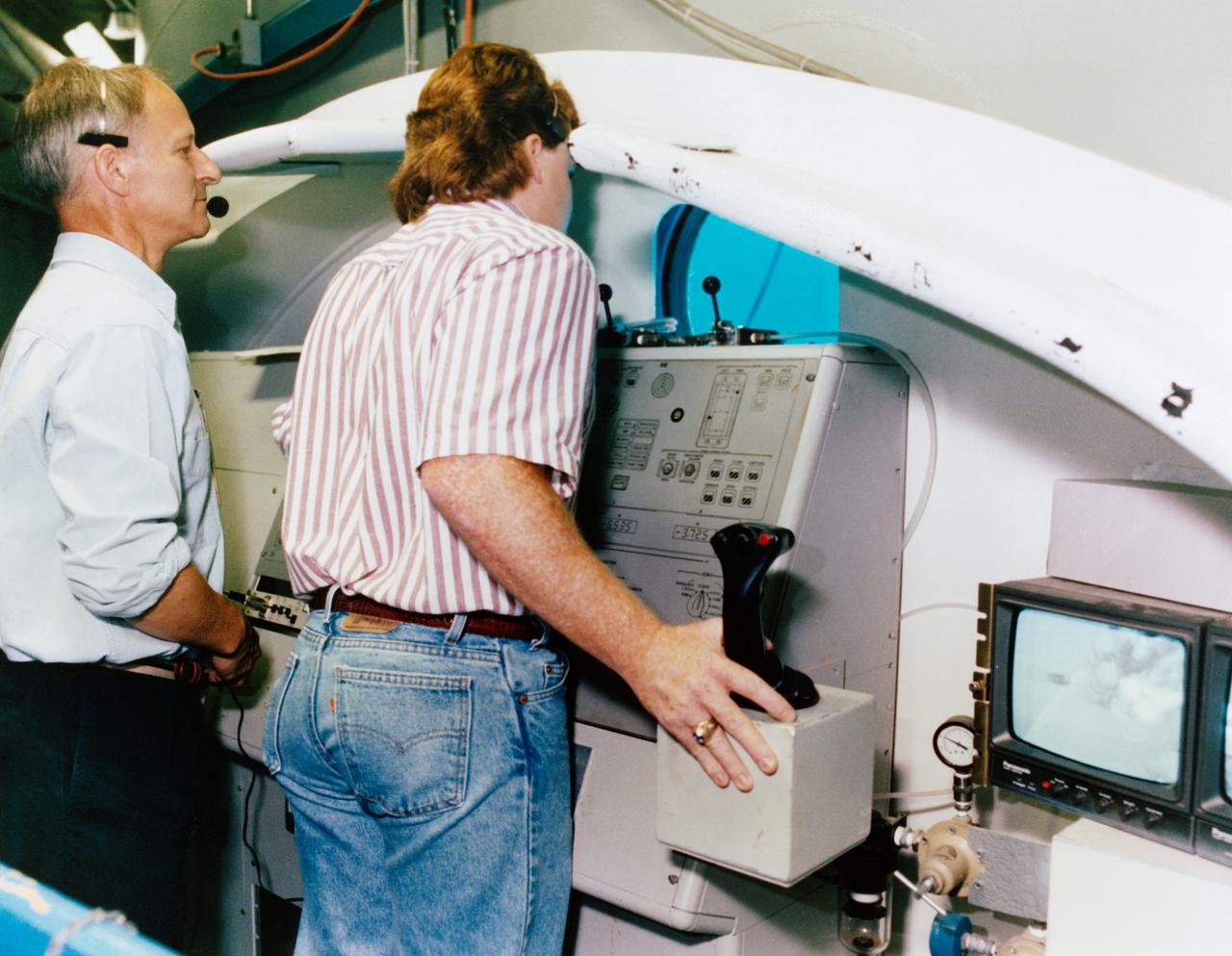

Astronauts Jeffrey A. Hoffman (far left) and F. Story Musgrave (second left) monitor a training session from consoles in the control room for the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC). Seen underwater in the NBS on the big screen and the monitors at the consoles is astronaut Thomas D. Akers. The three mission specialists, along with astronaut Kathryn C. Thornton, are scheduled to be involved in a total of five sessions of extravehicular activity (EVA) to service the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in orbit during the STS-61 mission, scheduled for December 1993.

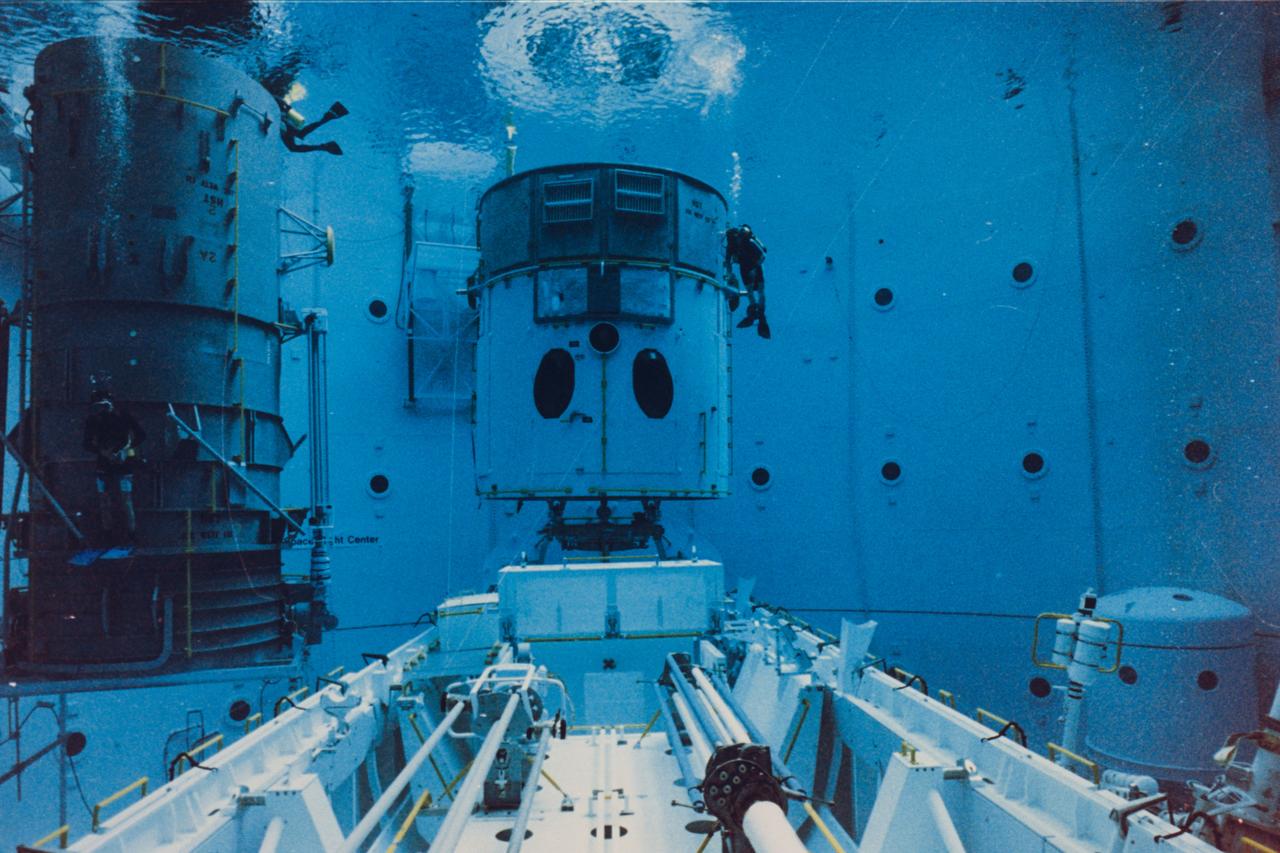

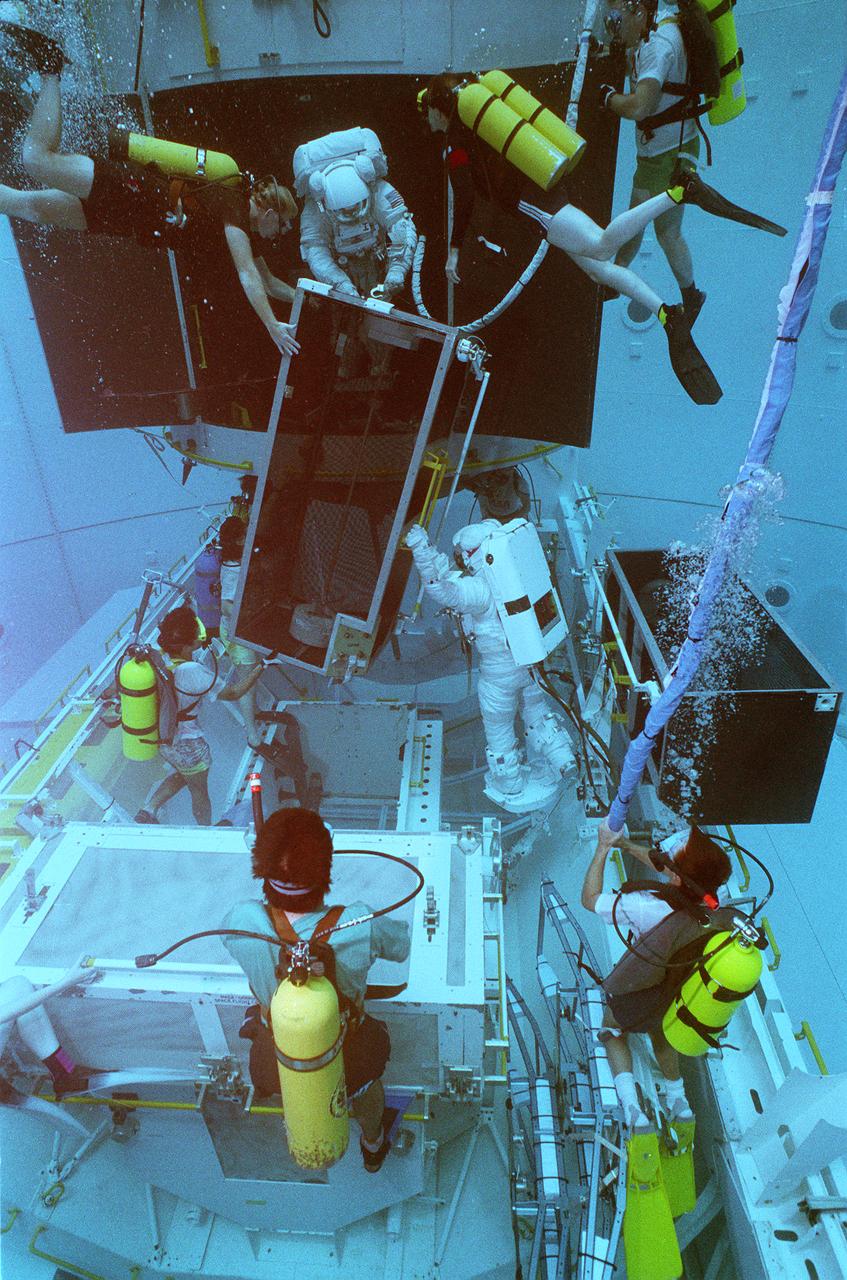

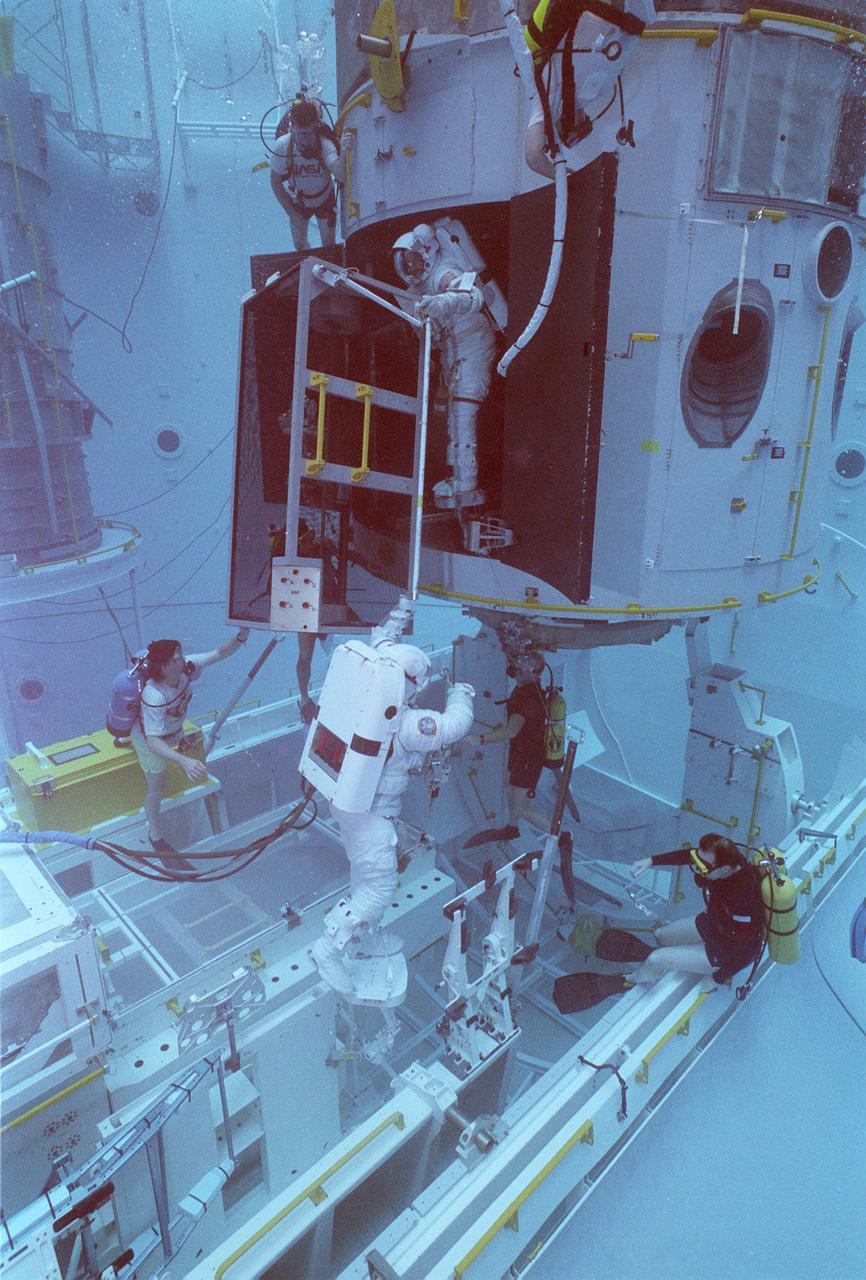

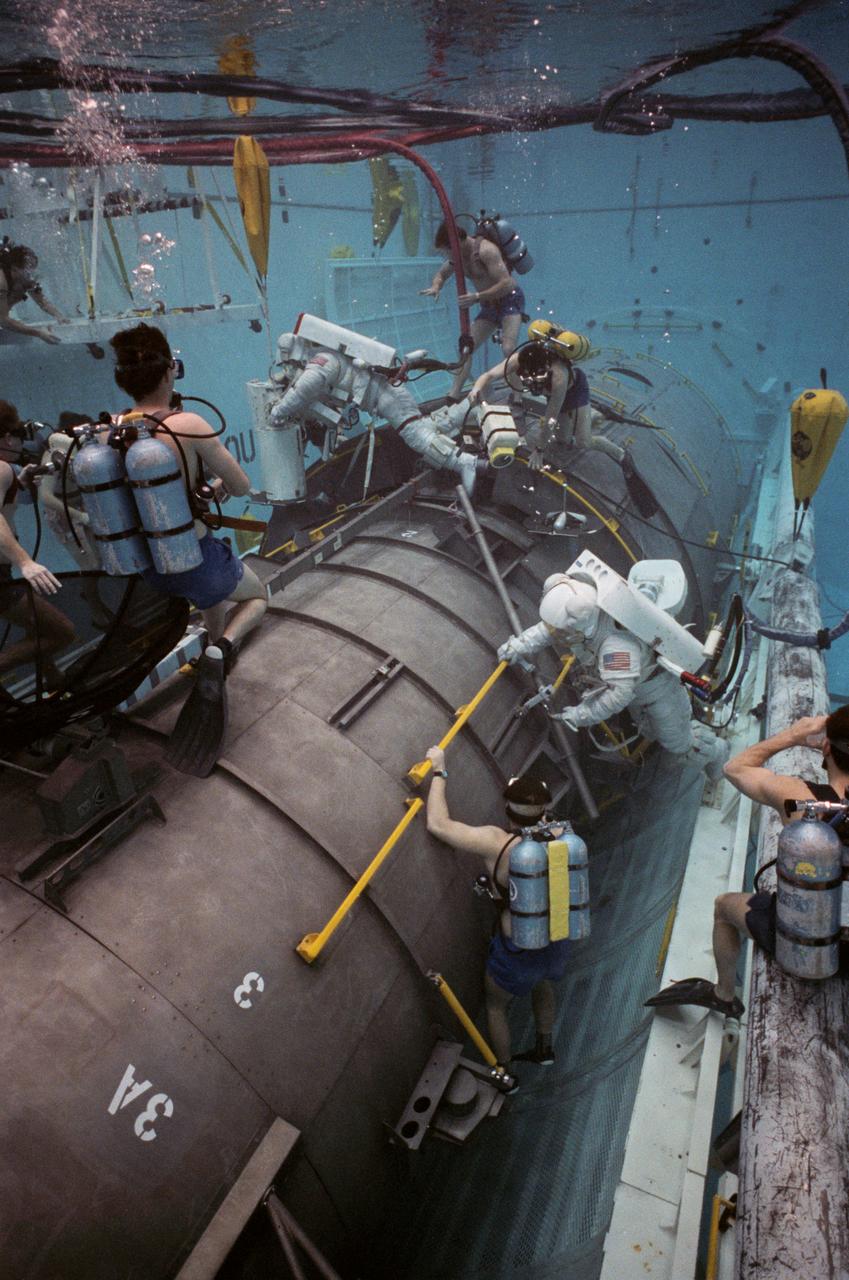

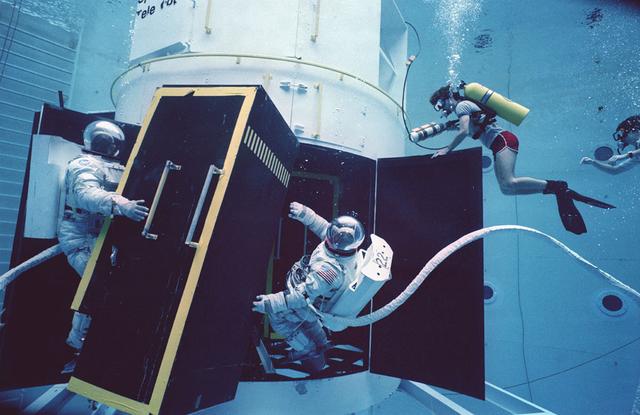

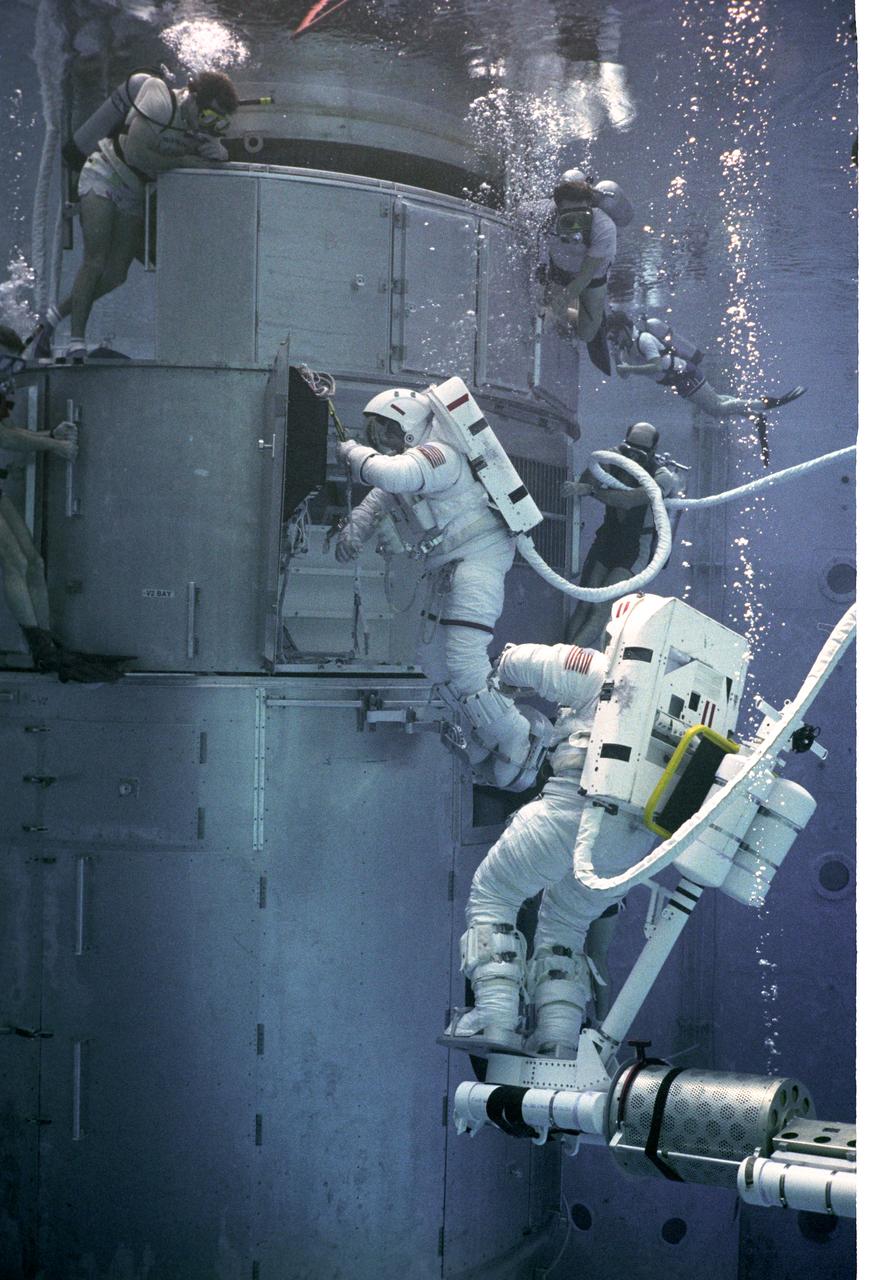

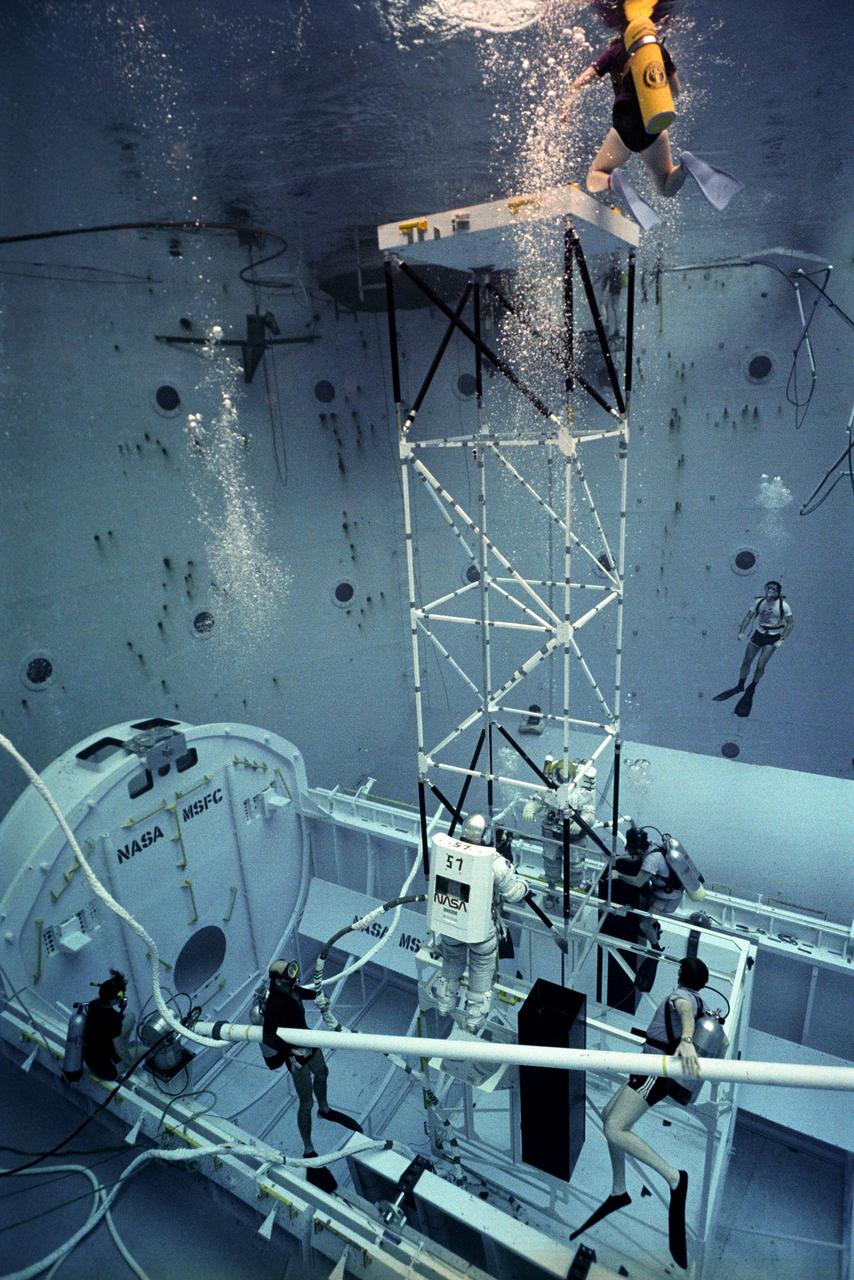

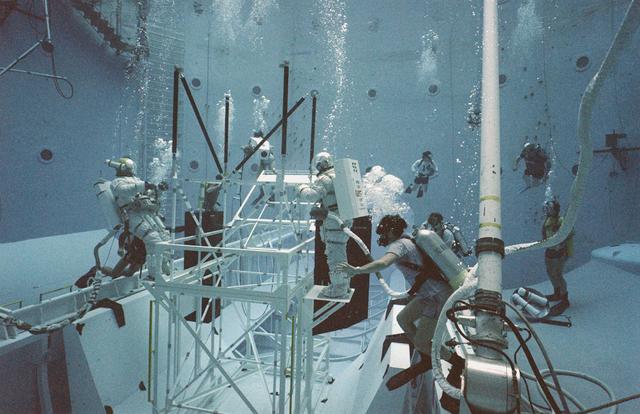

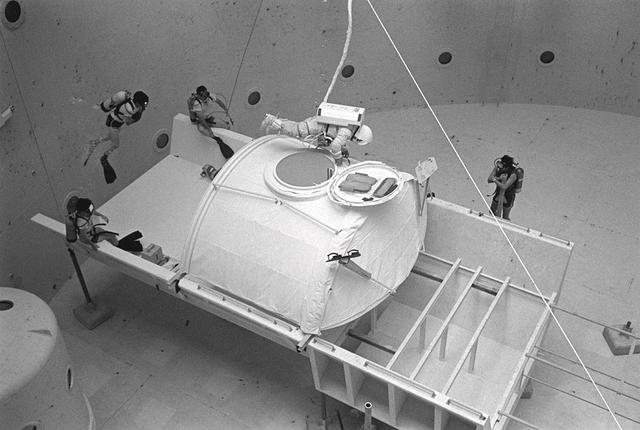

Safety divers in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) prepare a mockup of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) for one of 32 separate training sessions conducted by four of the STS-61 crew members in June. The three-week process allowed mission trainers to refine the timelines for the five separate spacewalks scheduled to be conducted on the actual mission scheduled for December 1993. The HST is separated into two pieces since the water tank depth cannot support the entire structure in one piece. The full length payload bay mockup shows the Solar Array Carrier in the foreground and the various containers that will house replacement hardware that will be carried on the mission.

S95-04319 (22 Feb 1995) --- The neutral buoyancy facility at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Star City, Russia, is used for underwater training for missions aboard the Russian Mir Space Station. The facility is similar to NASA's Weightless Environment Training Facility (WET-F) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, and the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Alabama.

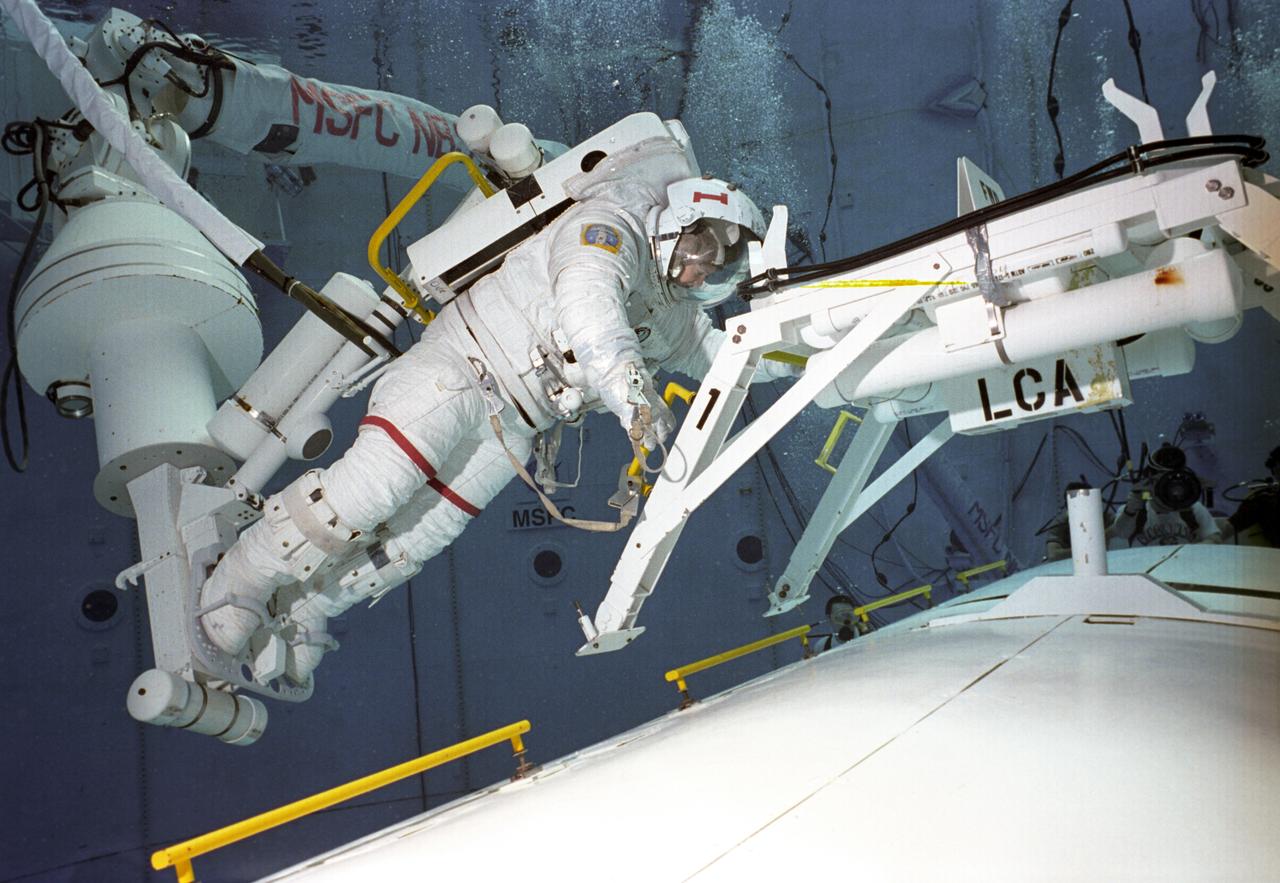

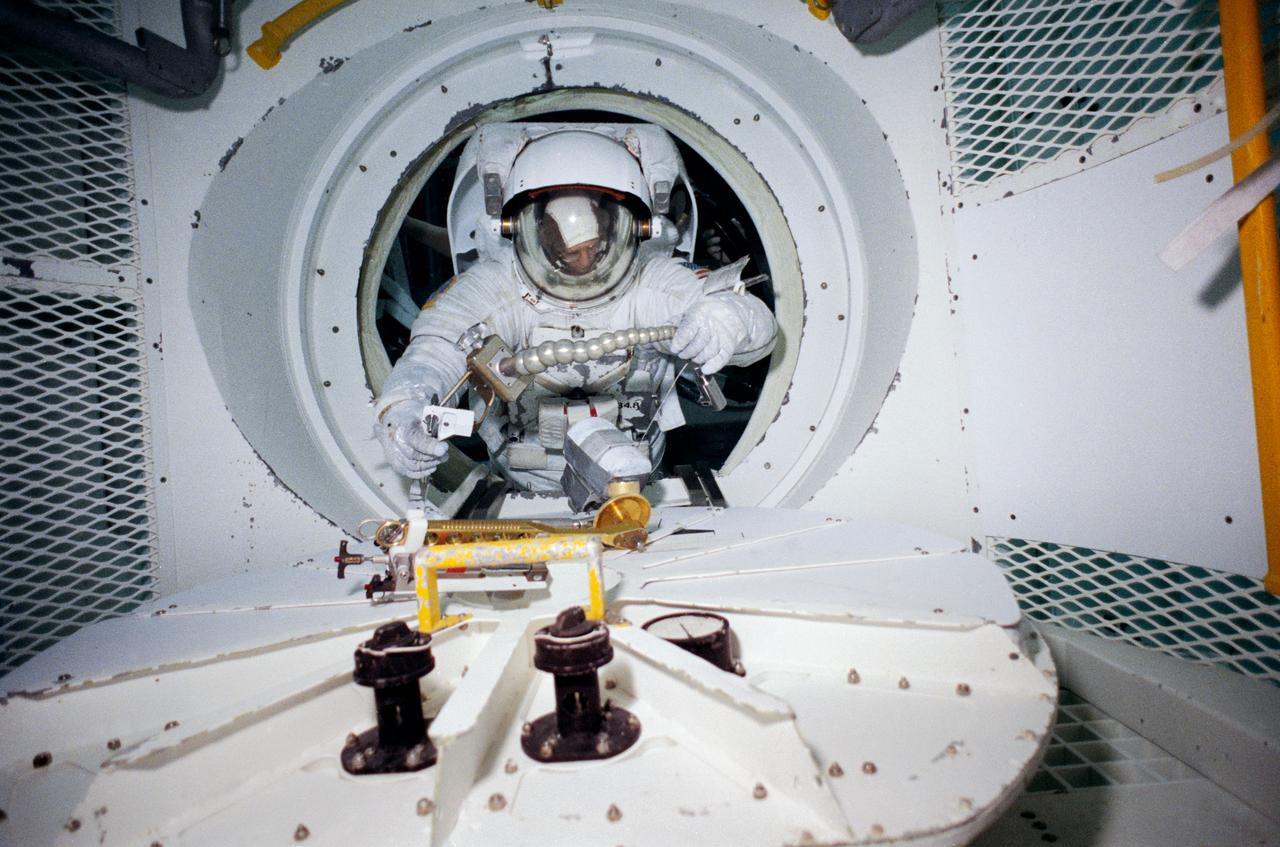

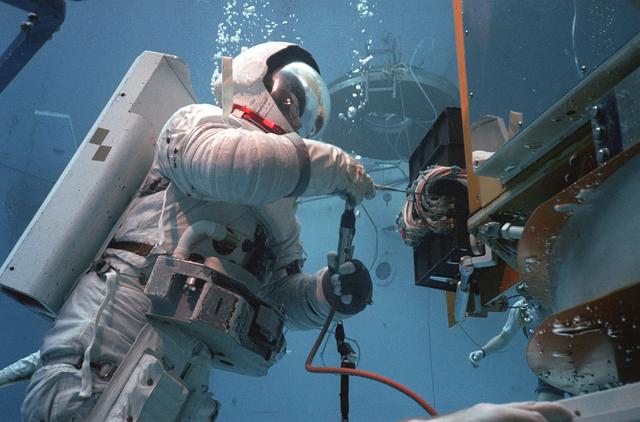

Astronaut Thomas D. Akers uses a power wrench to deploy one of the tools on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) during a training session in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator at Marshall Space Flight Center.

S98-08181 (March 1998) --- Standing on a mobile platform, astronaut Catherine G. Coleman is in the processing of being submerged in the deep pool of JSC's Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL). Coleman was participating in a simulation of a contingency space walk in preparation for the STS-93 mission next year. The mission specialist will join four other NASA astronauts for the Space Shuttle Columbia flight, scheduled for spring. The training version of the extravehicular mobility unit (EMU) that Coleman is wearing is weighted and otherwise accommodated to afford neutral buoyancy in the deep pool.

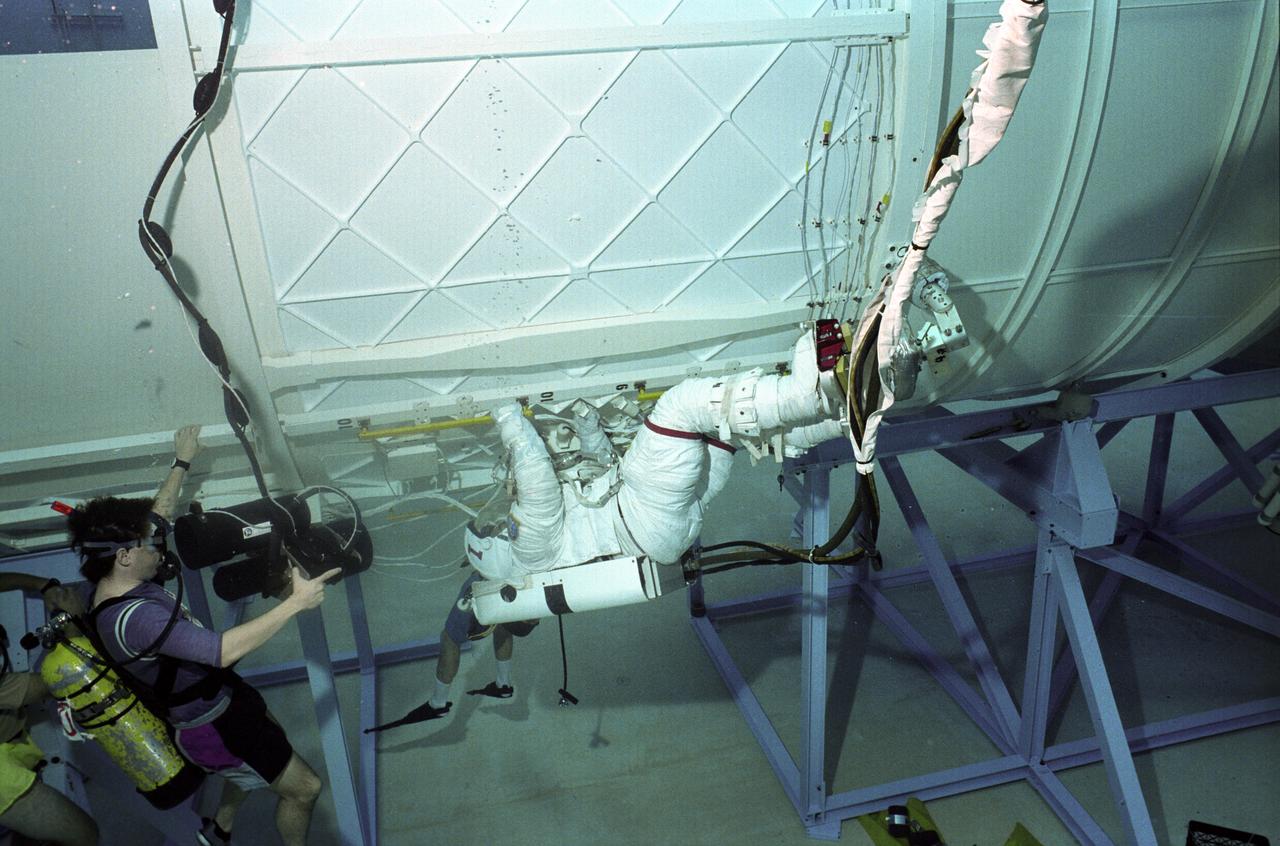

Astronauts Susan Helms (#1) and Carl Walz (#2) are training in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at Marshall Space Flight center with an exercise for International Space Station Alpha. The NBS provided the weightless environment encountered in space needed for testing and the practices of Extravehicular Activities (EVA).

Astronauts Tamara Jernigan (#1) and David Wolf (#2) are training in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at Marshall Space Flight center with an exercise for International Space Station Alpha. The NBS provided the weightless environment encountered in space needed for testing and the practices of Extravehicular Activities (EVA).

Swiss scientits Claude Nicollier (left), STS-61 mission specialist, waits his turn at the controls for the remote manipulator system (RMS) during a training session in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC). Mark Norman of MSFC has control of the RMS in this frame.

S98-08195 (March 1998) --- Standing on a mobile platform, astronaut Catherine G. Coleman is assisted with final touches for suiting up for a training exercise in the deep pool of JSC's Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL). Coleman was participating in a simulation of a contingency space walk in preparation for the STS-93 mission next year. The mission specialist will join four other NASA astronauts for the Space Shuttle Columbia flight, scheduled for spring. The training version of the extravehicular mobility unit (EMU) that Coleman is wearing is weighted and otherwise accommodated to afford neutral buoyancy in the deep pool.

S92-42755 (31 July 1992) --- Astronaut Susan J. Helms, mission specialist assigned to fly aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour for the STS-54 mission, completes the donning of her spacesuit before a training exercise. Though not assigned to the scheduled extravehicular activity (EVA), Helms is trained in the weightless environment training facility (WET-F). She will aid astronauts Gregory J. Harbaugh and Mario Runco Jr. in their planned EVA, scheduled for January of next year, and serve a backup role. Wearing this high fidelity training version of the extravehicular mobility unit (EMU), Helms was later lowered into the 25-ft. deep WET-F pool. The pressurized suit is weighted so as to allow Helms to achieve neutral buoyancy and simulate the various chores of the spacewalk.

S92-42754 (31 July 1992) --- Astronaut Susan J. Helms, mission specialist assigned to fly aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour for the STS-54 mission, gets assistance to complete the donning of her spacesuit. Though not assigned to the scheduled extravehicular activity (EVA), Helms is trained in the weightless environment training facility (WET-F). She will aid astronauts Gregory J. Harbaugh and Mario Runco Jr. in their planned EVA, scheduled for January of next year, and serve a backup role. Wearing this high fidelity training version of the extravehicular mobility unit (EMU), Helms was later lowered into the 25-ft. deep WET-F pool. The pressurized suit is weighted so as to allow Helms to achieve neutral buoyancy and simulate the various chores of the spacewalk.

S92-42753 (31 July 1992) --- Astronaut Susan J. Helms, mission specialist assigned to fly aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour for the STS-54 mission, gets assistance to complete the donning of her spacesuit. Though not assigned to the scheduled extravehicular activity (EVA), Helms is trained in the weightless environment training facility (WET-F). She will aid astronauts Gregory J. Harbaugh and Mario Runco Jr. in their planned EVA, scheduled for January of next year, and serve a backup role. Wearing this high fidelity training version of the extravehicular mobility unit (EMU), Helms was later lowered into the 25-ft. deep WET-F pool. The pressurized suit is weighted so as to allow Helms to achieve neutral buoyancy and simulate the various chores of the spacewalk.

Astronaut Thomas D. Akers gets assistance in donning a training version of the Shuttle extravehicular mobility unit (EMU) space suit prior to a training session in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) (39735); Astronaut Kathryn C. Thornton (foreground) and Thomas Akers, STS-61 mission specialists scheduled for extravehicular activity (EVA) duty, prepare for an underwater rehearsal session. Thornton recieves assistance from a technician in donning her EMU gloves (39736).

Astronaut Thomas D. Akers gets assistance in donning a training version of the Shuttle extravehicular mobility unit (EMU) space suit prior to a training session in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator at Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) (39735); Astronaut Kathryn C. Thornton (foreground) and Thomas Akers, STS-61 mission specialists scheduled for extravehicular activity (EVA) duty, prepare for an underwater rehearsal session. Thornton recieves assistance from a technician in donning her EMU gloves (39736).

S98-09501 (6-14-98) --- Astronaut Eileen M. Collins participates in a simulation of an emergency egress from a shuttle during preparations for her role as mission commander for next year's STS-93 flight. Collins was joined by four other crewmembers for the training session, held in and around the deep Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL)pool at the Johnson Space Center's Sonny Carter Training Center.

S98-09499 (6-24-98) --- Astronaut Eileen M. Collins gets a refresher course in water survival as part of her preparation for her role as commander in next year's scheduled STS-93 mission. Wearing a training version of the partial pressure launch and entry suit for Shuttle flights, Collins watches as a crew member simulates a parachute jump into the pool of the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL) at the Johnson Space Center's Sonny Carter Training Center.

JSC2000-07397 (1 December 2000)--- Astronaut Chris A. Hadfield, representing the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), is about to be submerged in a giant pool of water as part of a training session in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL) near the Johnson Space Center (JSC). Hadfield is designated for space walk duty on the STS-100 flight, and underwater simulations of his duties help prepare him for the mission, scheduled for spring of next year.

This photograph shows STS-61 crewmemmbers training for the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing mission in the Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). Two months after its deployment in space, scientists detected a 2-micron spherical aberration in the primary mirror of the HST that affected the telescope's ability to focus faint light sources into a precise point. This imperfection was very slight, one-fiftieth of the width of a human hair. A scheduled Space Service servicing mission (STS-61) in 1993 permitted scientists to correct the problem. The MSFC NBS provided an excellent environment for testing hardware to examine how it would operate in space and for evaluating techniques for space construction and spacecraft servicing.

S91-51058 (Dec 1991) --- Partially attired in a special training version of the Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) space suit, astronaut Bernard A. Harris Jr. is pictured before a training session at the Johnson Space Center's (JSC) Weightless Environment Training Facility (WET-F). Minutes later the STS-55 mission specialist was in a 25-feet deep pool simulating a contingency extravehicular activity (EVA). The platform on which he is standing was used to lower him into the water where, with the aid of weights on his environmentally-controlled pressurized suit, he was able to achieve neutral buoyancy. There is no scheduled EVA for the 1993 flight but each space flight crew includes astronauts trained for a variety of contingency tasks that could require exiting the shirt-sleeve environment of a Shuttle's cabin.

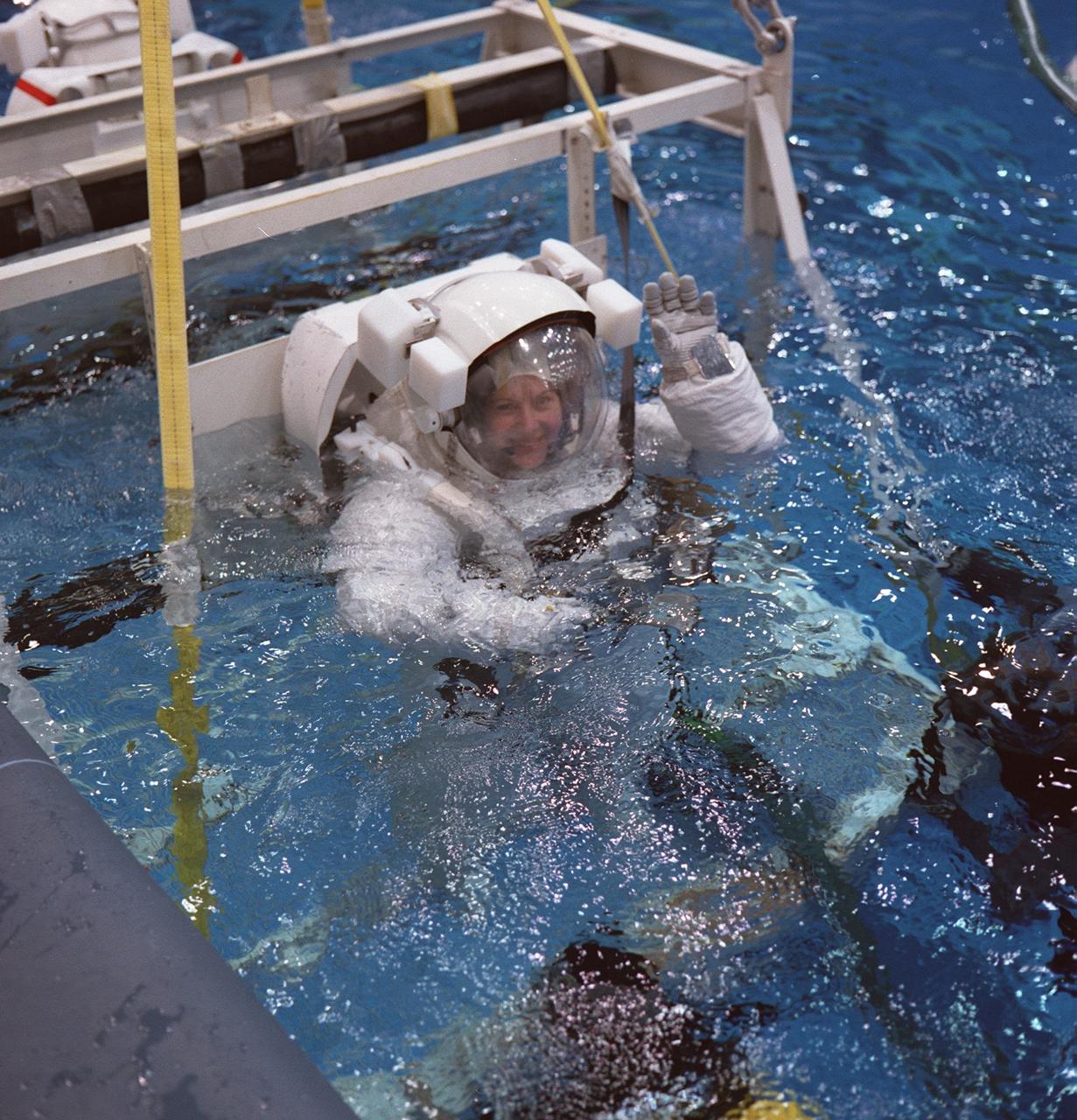

This close-up of astronaut and mission specialist Kathryn Thornton readies herself for submersion into the water in the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) where she is participating in a training session for the STS-61 mission. The NBS provided the weightless environment encountered in space needed for testing and the practices of Extravehicular Activities (EVA). Launched on December 2, 1993 aboard the Space Shuttle Orbiter Endeavor, STS-61 was the first Hubble Space Telescope (HST) serving mission. During the 2nd EVA of the mission, Thornton, along with astronaut and mission specialist Thomas Akers, performed the task of replacing the solar arrays. The EVA lasted 6 hours and 35 minutes.

JSC2000-07391 (1 December 2000)--- Astronaut Chris A. Hadfield, representing the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), puts final touches on the suit-up process in preparation for a training session in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL) near the Johnson Space Center (JSC). Hadfield is designated for space walk duty on the STS-100 flight, and underwater simulations of his duties help prepare him for the mission, scheduled for spring of next year. By coincidence, Hadfield is aligned beneath the Canadian flag, one of the many on NBL walls which pay tribute to the participating international partners.

STS-48 Mission Specialist (MS) James F. Buchli, wearing an extravehicular mobility unit (EMU), is watched by SCUBA-equipped divers as the platform he is standing on is lowered into JSC's Weightless Environment Training Facility (WETF) Bldg 29 pool. When completely underwater, Buchli will be released from the platform and will perform contingency extravehicular activity (EVA) operations. This underwater simulation of a spacewalk is part of the training required for Buchli's upcoming mission aboard Discovery, Orbiter Vehicle (OV) 103.

After the end of the Apollo missions, NASA's next adventure into space was the marned spaceflight of Skylab. Using an S-IVB stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle, Skylab was a two-story orbiting laboratory, one floor being living quarters and the other a work room. The objectives of Skylab were to enrich our scientific knowledge of the Earth, the Sun, the stars, and cosmic space; to study the effects of weightlessness on living organisms, including man; to study the effects of the processing and manufacturing of materials utilizing the absence of gravity; and to conduct Earth resource observations. At the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), astronauts and engineers spent hundreds of hours in an MSFC Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) rehearsing procedures to be used during the Skylab mission, developing techniques, and detecting and correcting potential problems. The NBS was a 40-foot deep water tank that simulated the weightlessness environment of space. This photograph shows astronaut Ed Gibbon (a prime crew member of the Skylab-4 mission) during the neutral buoyancy Skylab extravehicular activity training at the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM) mockup. One of Skylab's major components, the ATM was the most powerful astronomical observatory ever put into orbit to date.

JSC2002-E-27067 (1 July 2002) --- Astronaut Sandra H. Magnus prepares for the STS-112 mission by participating in a hardware-moving simulation. The mission specialist rehearses setting up work for assigned space-walking crewmates in the nearby giant pool of the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (NBL) at the Sonny Carter Training Facility. Magnus and Expedition Five flight engineer Peggy A. Whitson (already aboard the orbital outpost when this training took place) will be operating the controls of the Space Station Remote Manipulator System (SSRMS or Canadarm2) during the mission's task of installing the station's S-1 truss. Astronauts David A. Wolf and Piers J. Sellers, who would be suited up and standing by in the airlock during this activity, will follow Magnus' set-up work with a space walk.

Prior to its launch in April 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) went through years of development and testing. The HST was the first of its kind and the scientific community could only imagine the fruits of their collective labors. However, prior to its launch, more practical procedures, such as astronaut training, had to be developed. As the HST was to remain in orbit for years, it became apparent that on-orbit maintenance routines would have to be developed. The best facility to develop these maintenance practices was at the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC). The NBS provided mock-ups of the HST (in sections), a Remote Manipulator System (RMS), and a shuttle's cargo bay pallet. This real life scenario provided scientists, engineers, and astronauts a practical environment to work out any problems with a plarned on-orbit maintenance mission. Pictured is an astronaut in training with a mock-up section of the HST, practicing using tools especially designed for the task being performed.

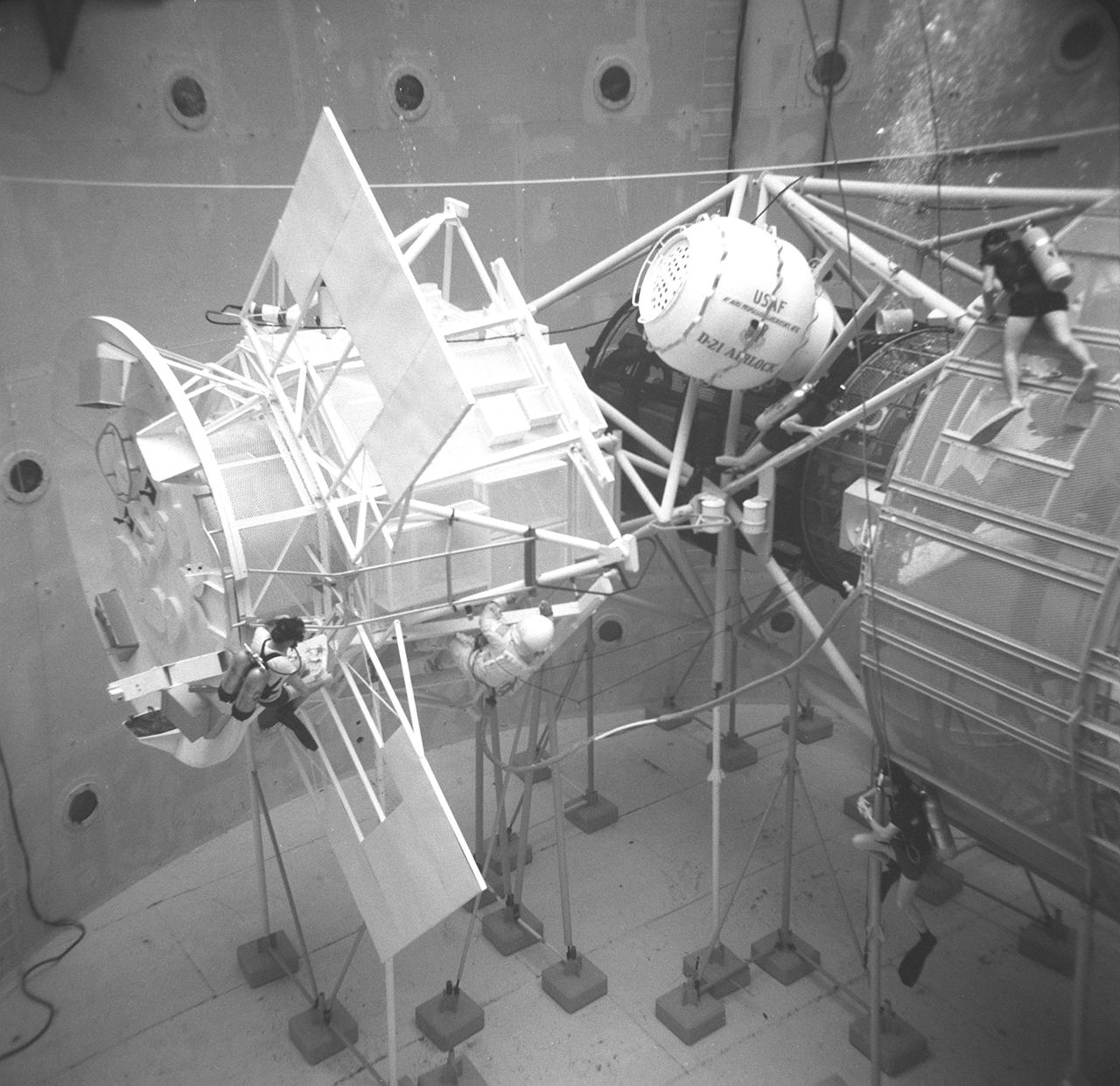

The Space Platform was first conceived as a launching site for deep space exploration. The original idea was to build this space platform either on the moon's surface or near lunar orbit. It would be used as a staging base, where the reusable launch vehicles (later known as Space Shuttles) would ferry machinery and equipment to assemble deep space exploration vehicles. Replaced by the Space Station concept, the space platform idea was never completed. However, early in the space platform development, astronauts trained at the Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS), as pictured here, working on solar array equipment. This experiment was deployed from the shuttle to study the motions of large structures in space. Similar arrays will be used on the Space Station and large observatory spacecraft in the future.

This photograph shows an STS-61 astronaut training for the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing mission (STS-61) in the Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS). Two months after its deployment in space, scientists detected a 2-micron spherical aberration in the primary mirror of the HST that affected the telescope's ability to focus faint light sources into a precise point. This imperfection was very slight, one-fiftieth of the width of a human hair. A scheduled Space Service servicing mission (STS-61) in 1993 permitted scientists to correct the problem. The MSFC NBS provided an excellent environment for testing hardware to examine how it would operate in space and for evaluating techniques for space construction and spacecraft servicing.

This overall view shows STS-31 Mission Specialist (MS) Bruce McCandless II (left) and MS Kathryn D. Sullivan making a practice space walk in JSC's Weightless Environment Training Facility (WETF) Bldg 29 pool. McCandless works with a mockup of the remote manipulator system (RMS) end effector which is attached to a grapple fixture on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) mockup. Sullivan manipulates HST hardware on the Support System Module (SSM) forward shell. SCUBA-equipped divers monitor the extravehicular mobility unit (EMU) suited crewmembers during this simulated extravehicular activity (EVA). No EVA is planned for the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) deployment, but the duo has trained for contingencies which might arise during the STS-31 mission aboard Discovery, Orbiter Vehicle (OV) 103. Photo taken by NASA JSC photographer Sheri Dunnette.

STS-31 Mission Specialist (MS) Bruce McCandless II (left), wearing an extravehicular mobility unit (EMU), maneuvers his way around a mockup of the remote manipulator system (RMS) end effector during an underwater simulation in JSC's Weightless Environment Training Facility (WETF) Bldg 29 pool. The end effector is attached to a grapple fixture on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) mockup. As McCandless performs contingency extravehicular activity (EVA) procedures, fellow crewmember MS Kathryn D. Sullivan, in EMU, works on the opposite side of the HST mockup, and SCUBA-equipped divers monitor the activity. Though no EVA is planned for STS-31, the two crewmembers train for contingencies that would necessitate leaving the shirt sleeve environment of Discovery's, Orbiter Vehicle (OV) 103's, crew cabin and performing chores with the HST payload or related hardware in the payload bay (PLB).

S90-30521 (20 Feb 1990) --- Though no extravehicular activity is planned for STS-31, two crewmembers train for contingencies that would necessitate leaving their shirt sleeve environment of Discovery's cabin and performing chores with their Hubble Space Telescope payload or related hardware. Astronaut Kathryn D. Sullivan, mission specialist, is seen egressing the hatchway of the airlock of a full scale mockup of a Shuttle cabin to interface with an HST mockup in JSC's 25.-ft. deep pool in the weightless environment training facility (WET-F). Two SCUBA-equipped divers who assisted in the training session are also seen. Astronaut Bruce McCandless II, mission specialist, is out of frame.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Marshall Space Flight Center’s (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher suiting up for training on a mockup of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Marshall Space Flight Center’s (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Marshall Space Flight Center’s (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher suiting up for training on a mockup of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) that served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown are astronauts Arna Fisher and Joe Kerwin training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument changeout.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Marshall SPace Flight Center’s (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher suited up for training on a mockup of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Marshall Space Flight Center’s (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown is astronaut Anna Fisher suited up for training on a mockup of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument change out.

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is a cooperative program of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) to operate a long-lived space-based observatory. It was the flagship mission of NASA's Great Observatories program. The HST program began as an astronomical dream in the 1940s. During the 1970s and 1980s, the HST was finally designed and built becoming operational in the 1990s. The HST was deployed into a low-Earth orbit on April 25, 1990 from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-31). The design of the HST took into consideration its length of service and the necessity of repairs and equipment replacement by making the body modular. In doing so, subsequent shuttle missions could recover the HST, replace faulty or obsolete parts and be re-released. Pictured is Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC's) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) that served as the test center for shuttle astronauts training for Hubble related missions. Shown are astronauts Arna Fisher and Joe Kerwin training on a mock-up of a modular section of the HST for an axial scientific instrument changeout.

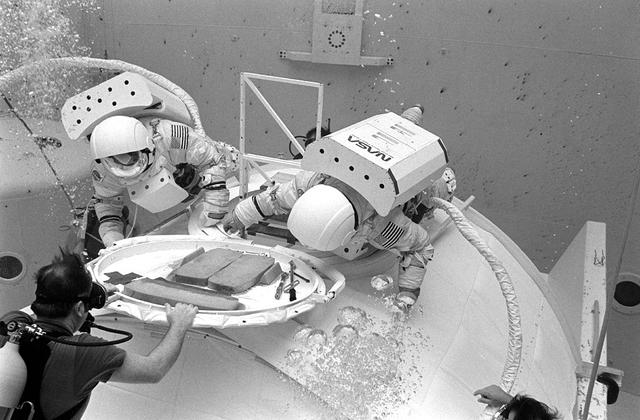

Prior to its launch in April 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) went through years of development and testing. The HST was the first of its kind and the scientific community could only imagine the fruits of their collective labors. However, prior to its launch, more practical procedures, such as astronaut training, had to be developed. As the HST was to remain in orbit for years, it became apparent that on-orbit maintenance routines would have to be developed. The best facility to develop these maintenance practices was at the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) at the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC). The NBS provided mock-ups of the HST (in sections), a Remote Manipulator System (RMS), and a shuttle's cargo bay pallet. This real life scenario provided scientists, engineers, and astronauts a practical environment to work out any problems with a plarned on-orbit maintenance mission. Pictured are two astronauts training at MSFC's NBS. One astronaut is using a foot restraint system attached to the RMS, while the other astronaut performs maintenance techniques while attached to the surface of the HST mock-up.

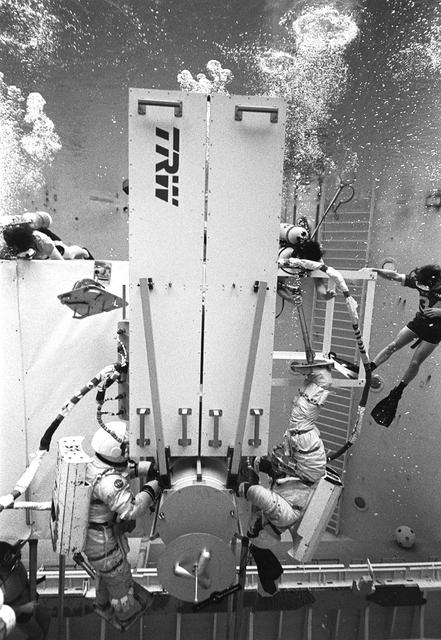

One of the main components of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is the Solar Array Drive Electronics (SADE) system. This system interfaces with the Support System Module (SSM) for exchange of operational commands and telemetry data. SADE operates and controls the Solar Array Drive Mechanisms (SADM) for the orientation of the Solar Array Drive (SAD). It also monitors the position of the arrays and the temperature of the SADM. During the first HST servicing mission, the astronauts replaced the SADE component because of some malfunctions. This turned out to be a very challenging extravehicular activity (EVA). Two transistors and two diodes had been thermally stressed with the conformal coating discolored and charred. Soldered cornections became molten and reflowed between the two diodes. The failed transistors gave no indication of defective construction. All repairs were made and the HST was redeposited into orbit. Prior to undertaking this challenging mission, the orbiter's crew trained at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) to prepare themselves for working in a low gravity environment. They also practiced replacing HST parts and exercised maneuverability and equipment handling. Pictured is an astronaut practicing climbing a space platform that was necessary in making repairs on the HST.

One of the main components of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is the Solar Array Drive Electronics (SADE) system. This system interfaces with the Support System Module (SSM) for exchange of operational commands and telemetry data. SADE operates and controls the Solar Array Drive Mechanisms (SADM) for the orientation of the Solar Array Drive (SAD). It also monitors the position of the arrays and the temperature of the SADM. During the first HST servicing mission, the astronauts replaced the SADE component because of some malfunctions. This turned out to be a very challenging extravehicular activity (EVA). Two transistors and two diodes had been thermally stressed with the conformal coating discolored and charred. Soldered cornections became molten and reflowed between the two diodes. The failed transistors gave no indication of defective construction. All repairs were made and the HST was redeposited into orbit. Prior to undertaking this challenging mission, the orbiter's crew trained at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) to prepare themselves for working in a low gravity environment. They also practiced replacing HST parts and exercised maneuverability and equipment handling. Pictured are crew members practicing on a space platform.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. Construction methods had to be efficient due to the limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. With the help of the NBS, building a space station became more of a reality. Pictured is Astronaut Paul Weitz training on a mock-up of Spacelab's airlock-hatch cover. Training was also done on the use of foot restraints which had recently been developed to help astronauts maintain their positions during space walks rather than having their feet float out from underneath them while they tried to perform maintenance and repair operations. Every aspect of every space mission was researched and demonstrated in the NBS. Using the airlock hatch cover and foot restraints were just a small example of the preparation that went into each mission.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. Construction methods had to be efficient due to the limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. With the help of the NBS, building a space station became more of a reality. Pictured is Astronaut Paul Weitz training on a mock-up of Spacelab's airlock-hatch cover. Training was also done on the use of foot restraints which had recently been developed to help astronauts maintain their positions during space walks rather than having their feet float out from underneath them while they tried to perform maintenance and repair operations. Every aspect of every space mission was researched and demonstrated in the NBS. Using the airlock hatch cover and foot restraints were just a small example of the preparation that went into each mission.

In February 1980, a satellite called Solar Maximum Mission Spacecraft, or Solar Max, was launched into Earth's orbit. Its primary objective was to provide a detailed study of solar flares, active regions on the Sun's surface, sunspots, and other solar activities. Additionally, it was to measure the total output of radiation from the Sun. Not much was known about solar activity at that time except for a slight knowledge of solar flares. After its launch, Solar Max fulfilled everyone's expectations. However, after a year in orbit, Solar Max's Altitude Control System malfunctioned, preventing the precise pointing of instruments at the Sun. NASA scientists were disappointed at the lost data, but not altogether dismayed because Solar Max had been designed for Space Shuttle retrievability enabling the repair of the satellite. On April 6, 1984, Space Shuttle Challenger (STS-41C), Commanded by astronaut Robert L. Crippen and piloted by Francis R. Scobee, launched on a historic voyage. This voyage initiated a series of firsts for NASA; the first satellite retrieval, the first service use of a new space system called the Marned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), the first in-orbit repair, the first use of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS), and the Space Shuttle Challenger's first space flight. The mission was successful in retrieving Solar Max. Mission Specialist Dr. George D. Nelson, using the MMU, left the orbiter's cargo bay and rendezvoused with Solar Max. After attaching himself to the satellite, he awaited the orbiter to maneuver itself nearby. Using the RMS, Solar Max was captured and docked in the cargo bay while Dr. Nelson replaced the altitude control system and the coronagraph/polarimeter electronics box. After the repairs were completed, Solar Max was redeposited in orbit with the assistance of the RMS. Prior to the April 1984 launch, countless man-hours were spent preparing for this mission. The crew of Challenger spent months at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) practicing retrieval maneuvers, piloting the MMU, and training on equipment so they could make the needed repairs to Solar Max. Pictured are crew members training for repair tasks.

In February 1980, a satellite called Solar Maximum Mission Spacecraft, or Solar Max, was launched into Earth's orbit. Its primary objective was to provide a detailed study of solar flares, active regions on the Sun's surface, sunspots, and other solar activities. Additionally, it was to measure the total output of radiation from the Sun. Not much was known about solar activity at that time except for a slight knowledge of solar flares. After its launch, Solar Max fulfilled everyone's expectations. However, after a year in orbit, Solar Max's Altitude Control System malfunctioned, preventing the precise pointing of instruments at the Sun. NASA scientists were disappointed at the lost data, but not altogether dismayed because Solar Max had been designed for Space Shuttle retrievability enabling the repair of the satellite. On April 6, 1984, Space Shuttle Challenger (STS-41C), Commanded by astronaut Robert L. Crippen and piloted by Francis R. Scobee, launched on a historic voyage. This voyage initiated a series of firsts for NASA; the first satellite retrieval, the first service use of a new space system called the Marned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), the first in-orbit repair, the first use of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS), and the Space Shuttle Challenger's first space flight. The mission was successful in retrieving Solar Max. Mission Specialist Dr. George D. Nelson, using the MMU, left the orbiter's cargo bay and rendezvoused with Solar Max. After attaching himself to the satellite, he awaited the orbiter to maneuver itself nearby. Using the RMS, Solar Max was captured and docked in the cargo bay while Dr. Nelson replaced the altitude control system and the coronagraph/polarimeter electronics box. After the repairs were completed, Solar Max was redeposited in orbit with the assistance of the RMS. Prior to the April 1984 launch, countless man-hours were spent preparing for this mission. The crew of Challenger spent months at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) practicing retrieval maneuvers, piloting the MMU, and training on equipment so they could make the needed repairs to Solar Max. Pictured are crew members training on repair tasks.

Once the United States' space program had progressed from Earth's orbit into outerspace, the prospect of building and maintaining a permanent presence in space was realized. To accomplish this feat, NASA launched a temporary workstation, Skylab, to discover the effects of low gravity and weightlessness on the human body, and also to develop tools and equipment that would be needed in the future to build and maintain a more permanent space station. The structures, techniques, and work schedules had to be carefully designed to fit this unique construction site. The components had to be lightweight for transport into orbit, yet durable. The station also had to be made with removable parts for easy servicing and repairs by astronauts. All of the tools necessary for service and repairs had to be designed for easy manipulation by a suited astronaut. And construction methods had to be efficient due to limited time the astronauts could remain outside their controlled environment. In lieu of all the specific needs for this project, an environment on Earth had to be developed that could simulate a low gravity atmosphere. A Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was constructed by NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in 1968. Since then, NASA scientists have used this facility to understand how humans work best in low gravity and also provide information about the different kinds of structures that can be built. Another facet of the space station would be electrical cornectors which would be used for powering tools the astronauts would need for construction, maintenance and repairs. Shown is an astronaut training during an underwater electrical connector test in the NBS.

In February 1980, a satellite called Solar Maximum Mission Spacecraft, or Solar Max, was launched into Earth's orbit. Its primary objective was to provide a detailed study of solar flares, active regions on the Sun's surface, sunspots, and other solar activities. Additionally, it was to measure the total output of radiation from the Sun. Not much was known about solar activity at that time except for a slight knowledge of solar flares. After its launch, Solar Max fulfilled everyone's expectations. However, after a year in orbit, Solar Max's Altitude Control System malfunctioned, preventing the precise pointing of instruments at the Sun. NASA scientists were disappointed at the lost data, but not altogether dismayed because Solar Max had been designed for Space Shuttle retrievability enabling repair of the satellite. On April 6, 1984, Space Shuttle Challenger (STS-41C), Commanded by astronaut Robert L. Crippen and piloted by Francis R. Scobee, launched on a historic voyage. This voyage initiated a series of firsts for NASA; the first satellite retrieval, the first service use of a new space system called the Marned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), the first in-orbit repair, the first use of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS), and the Space Shuttle Challenger's first space flight. The mission was successful in retrieving Solar Max. Mission Specialist Dr. George D. Nelson, using the MMU, left the orbiter's cargo bay and rendezvoused with Solar Max. After attaching himself to the satellite, he awaited the orbiter to maneuver itself nearby. Using the RMS, Solar Max was captured and docked in the cargo bay while Dr. Nelson replaced the altitude control system and the coronagraph/polarimeter electronics box. After the repairs were completed, Solar Max was redeposited in orbit with the assistance of the RMS. Prior to the April 1984 launch, countless man-hours were spent preparing for this mission. The crew of Challenger spent months at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) practicing retrieval maneuvers, piloting the MMU, and training on equipment so they could make the needed repairs to Solar Max. Pictured is Dr. Nelson performing a replacement task on the Solar Max mock-up in the NBS.

In February 1980, a satellite called Solar Maximum Mission Spacecraft, or Solar Max, was launched into Earth's orbit. Its primary objective was to provide a detailed study of solar flares,active regions on the Sun's surface, sunspots, and other solar activities. Additionally, it was to measure the total output of radiation from the Sun. Not much was known about solar activity at that time except for a slight knowledge of solar flares. After its launch, Solar Max fulfilled everyone's expectations. However, after a year in orbit, Solar Max's Altitude Control System malfunctioned, preventing the precise pointing of instruments at the Sun. NASA scientists were disappointed at the lost data, but not altogether dismayed because Solar Max had been designed for Space Shuttle retrievability enabling the repair of the satellite. On April 6, 1984, Space Shuttle Challenger (STS-41C), Commanded by astronaut Robert L. Crippen and piloted by Francis R. Scobee, launched on a historic voyage. This voyage initiated a series of firsts for NASA; the first satellite retrieval, the first service use of a new space system called the Marned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), the first in-orbit repair, the first use of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS), and the Space Shuttle Challenger's first space flight. The mission was successful in retrieving Solar Max. Mission Specialist Dr. George D. Nelson, using the MMU, left the orbiter's cargo bay and rendezvoused with Solar Max. After attaching himself to the satellite, he awaited the orbiter to maneuver itself nearby. Using the RMS, Solar Max was captured and docked in the cargo bay while Dr. Nelson replaced the altitude control system and the coronagraph/polarimeter electronics box. After the repairs were completed, Solar Max was redeposited in orbit with the assistance of the RMS. Prior to the April 1984 launch, countless man-hours were spent preparing for this mission. The crew of Challenger spent months at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) practicing retrieval maneuvers, piloting the MMU, and training on equipment so they could make the needed repairs to Solar Max. Pictured is Dr. Nelson performing a replacement task on the Solar Max mock-up in the NBS.

In February 1980, a satellite called Solar Maximum Mission Spacecraft, or Solar Max, was launched into Earth's orbit. Its primary objective was to provide a detailed study of solar flares, active regions on the Sun's surface, sunspots, and other solar activities. Additionally, it was to measure the total output of radiation from the Sun. Not much was known about solar activity at that time except for a slight knowledge of solar flares. After its launch, Solar Max fulfilled everyone's expectations. However, after a year in orbit, Solar Max's Altitude Control System malfunctioned, preventing the precise pointing of instruments at the Sun. NASA scientists were disappointed at the lost data, but not altogether dismayed because Solar Max had been designed for Space Shuttle retrievability enabling the repair of the satellite. On April 6, 1984, Space Shuttle Challenger (STS-41C), Commanded by astronaut Robert L. Crippen and piloted by Francis R. Scobee, launched on a historic voyage. This voyage initiated a series of firsts for NASA; the first satellite retrieval, the first service use of a new space system called the Marned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), the first in-orbit repair, the first use of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS), and the Space Shuttle Challenger's first space flight. The mission was successful in retrieving Solar Max. Mission Specialist Dr. George D. Nelson, using the MMU, left the orbiter's cargo bay and rendezvoused with Solar Max. After attaching himself to the satellite, he awaited the orbiter to maneuver itself nearby. Using the RMS, Solar Max was captured and docked in the cargo bay while Dr. Nelson replaced the altitude control system and the coronagraph/polarimeter electronics box. After the repairs were completed, Solar Max was redeposited in orbit with the assistance of the RMS. Prior to the April 1984 launch, countless man-hours were spent preparing for this mission. The crew of Challenger spent months at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) practicing retrieval maneuvers, piloting the MMU, and training on equipment so they could make the needed repairs to Solar Max. Pictured is Dr. Nelson performing a replacement task on the Solar Max mock-up in the NBS.

In February 1980, a satellite called Solar Maximum Mission Spacecraft, or Solar Max, was launched into Earth's orbit. Its primary objective was to provide a detailed study of solar flares,active regions on the Sun's surface, sunspots, and other solar activities. Additionally, it was to measure the total output of radiation from the Sun. Not much was known about solar activity at that time except for a slight knowledge of solar flares. After its launch, Solar Max fulfilled everyone's expectations. However, after a year in orbit, Solar Max's Altitude Control System malfunctioned, preventing the precise pointing of instruments at the Sun. NASA scientists were disappointed at the lost data, but not altogether dismayed because Solar Max had been designed for Space Shuttle retrievability, enabling repair to the satellite. On April 6, 1984, Space Shuttle Challenger (STS-41C), Commanded by astronaut Robert L. Crippen and piloted by Francis R. Scobee, launched on a historic voyage. This voyage initiated a series of firsts for NASA; the first satellite retrieval, the first service use of a new space system called the Marned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), the first in-orbit repair, the first use of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS), and the Space Shuttle Challenger's first space flight. The mission was successful in retrieving Solar Max. Mission Specialist Dr. George D. Nelson, using the MMU, left the orbiter's cargo bay and rendezvoused with Solar Max. After attaching himself to the satellite, he awaited the orbiter to maneuver itself nearby. Using the RMS, Solar Max was captured and docked in the cargo bay while Dr. Nelson replaced the altitude control system and the coronagraph/polarimeter electronics box. After the repairs were completed, Solar Max was redeposited in orbit with the assistance of the RMS. Prior to the April 1984 launch, countless man-hours were spent preparing for this mission. The crew of Challenger spent months at Marshall Space Flight Center's (MSFC) Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) practicing retrieval maneuvers, piloting the MMU, and training on equipment so they could make the needed repairs to Solar Max. Pictured is Dr. Nelson performing a replacement task on the Solar Max mock-up in the NBS.