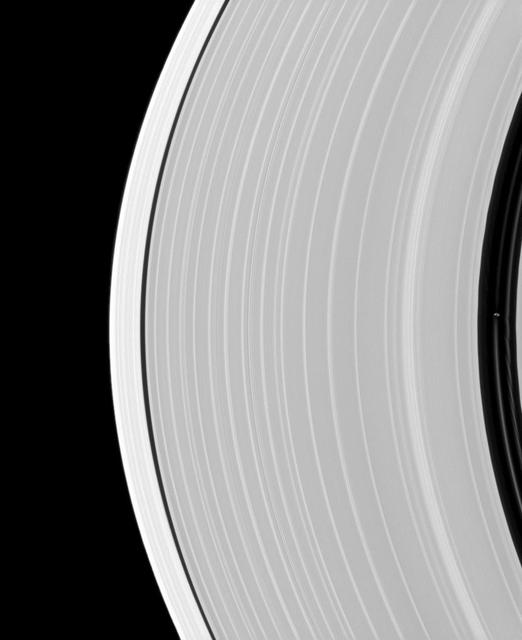

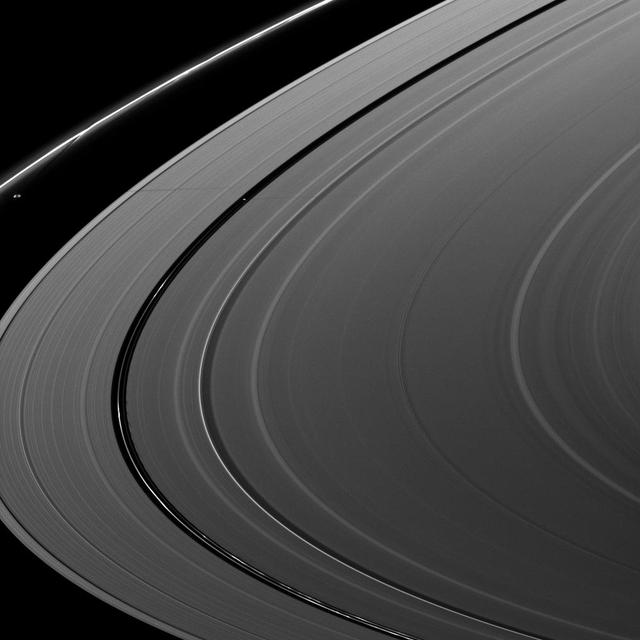

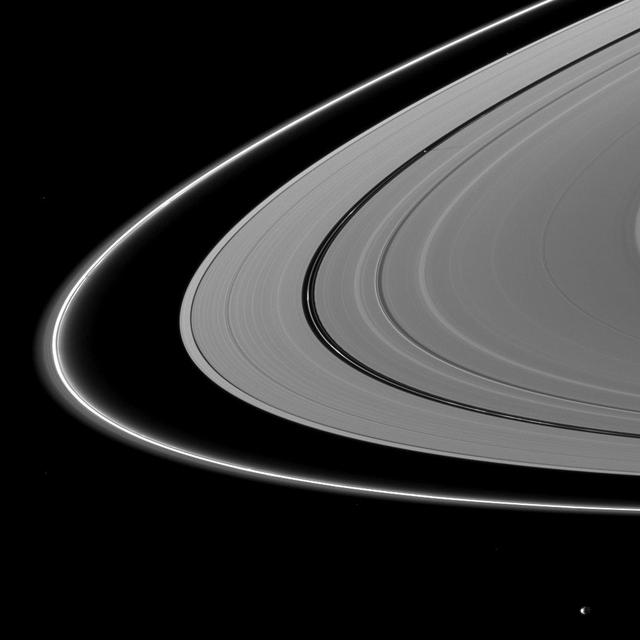

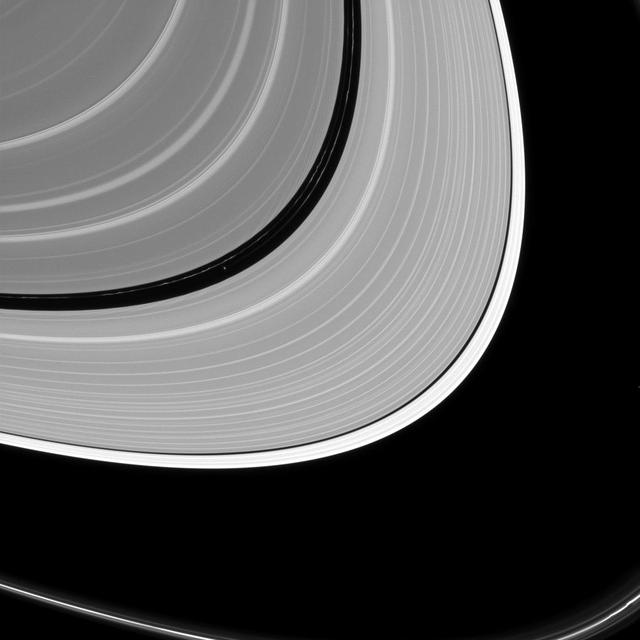

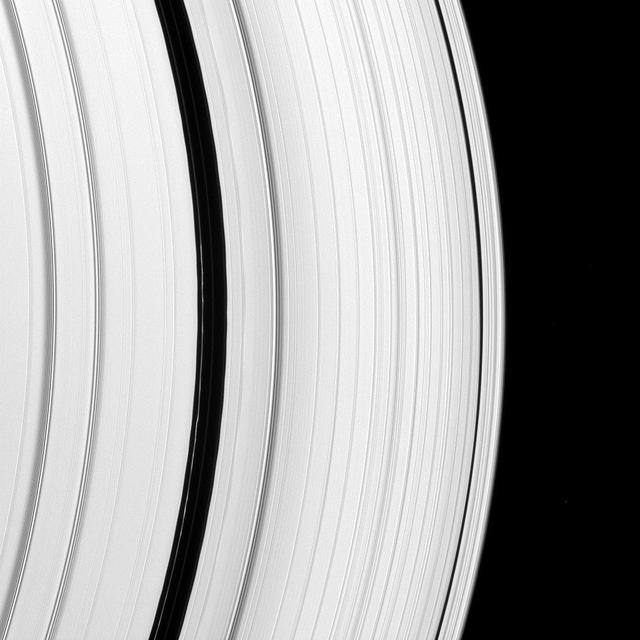

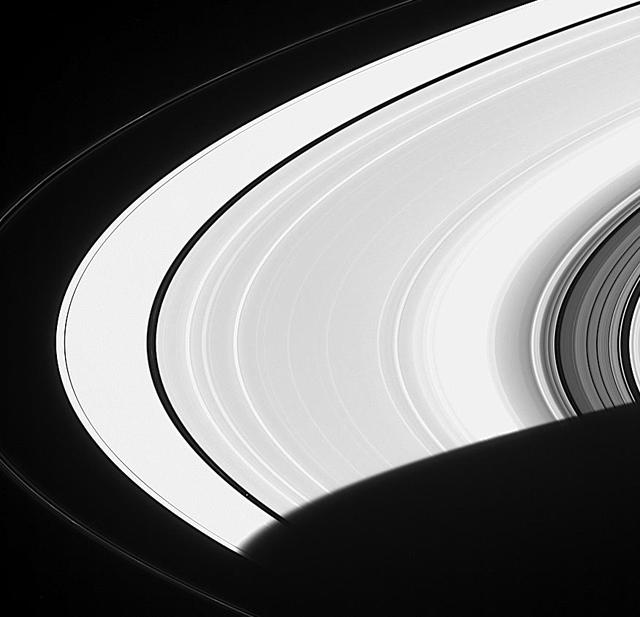

Pan Ringlet

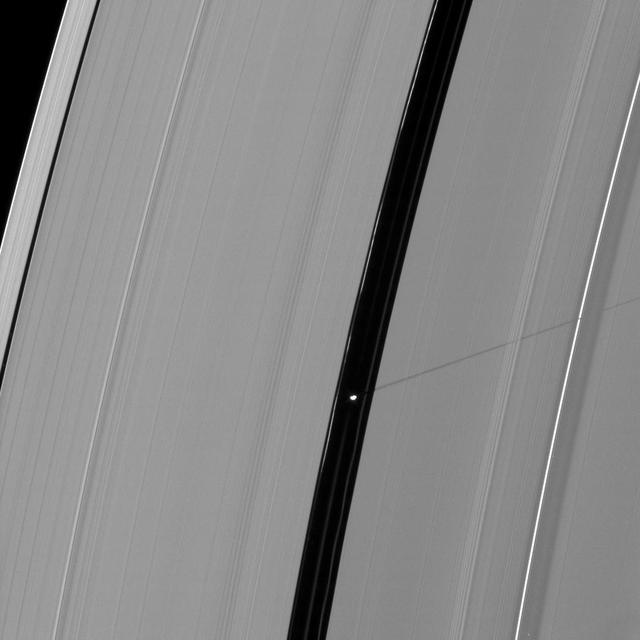

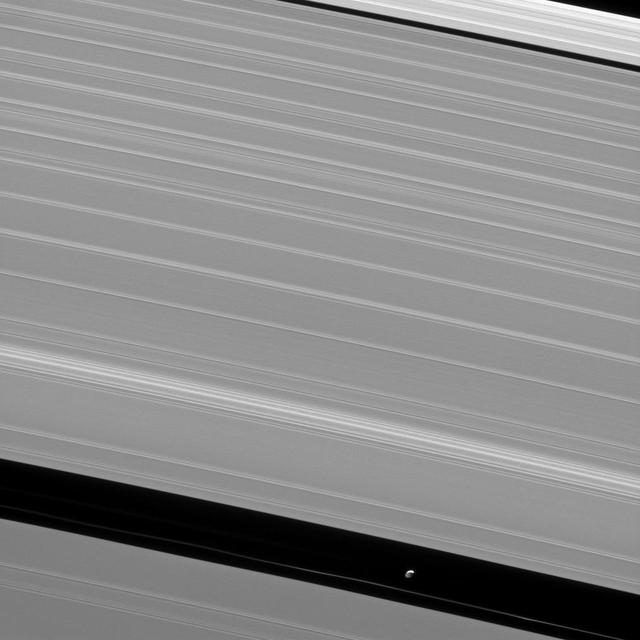

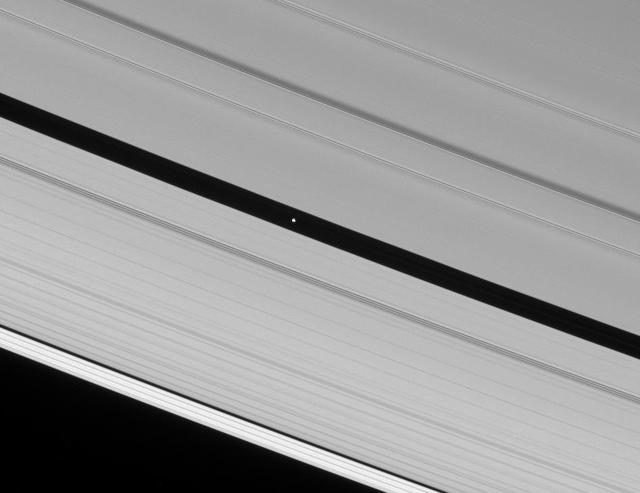

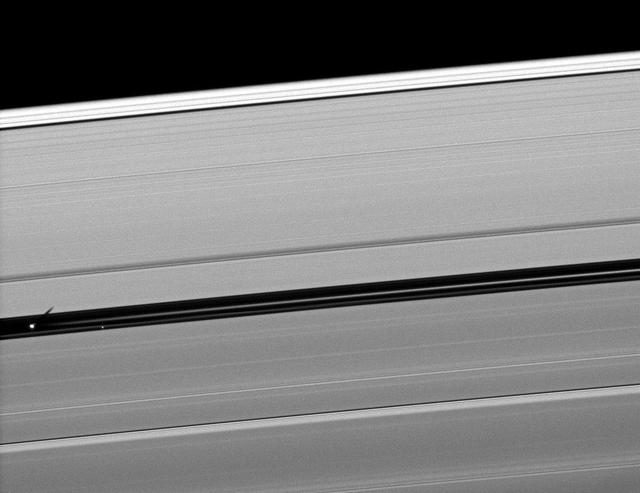

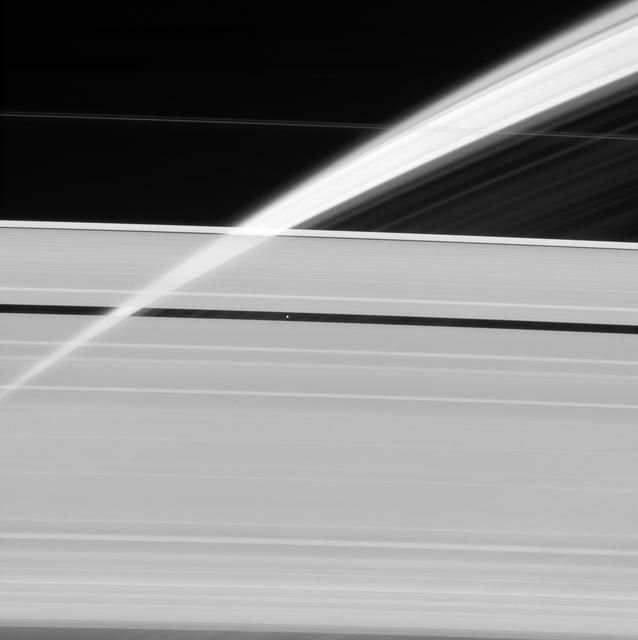

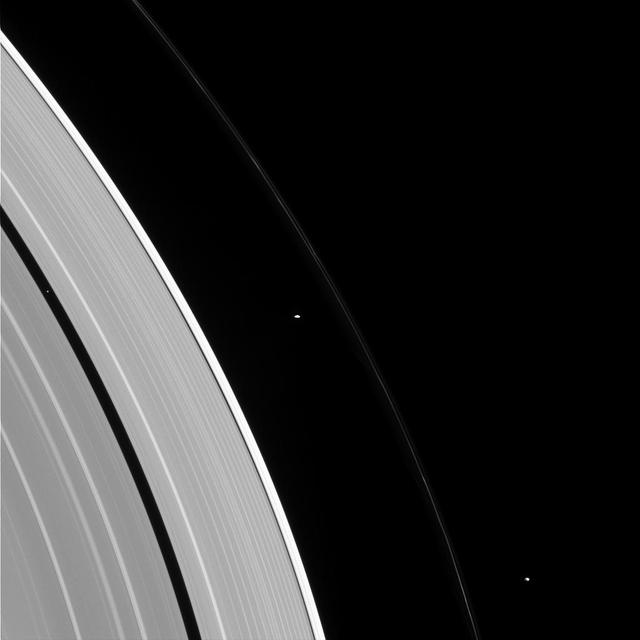

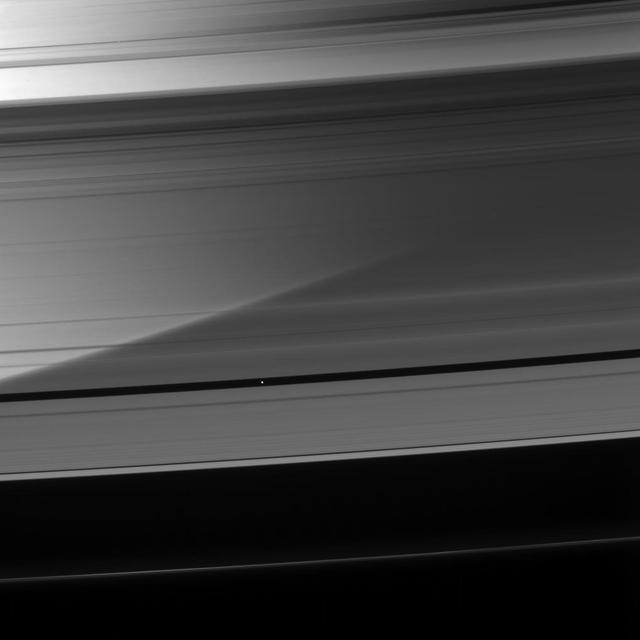

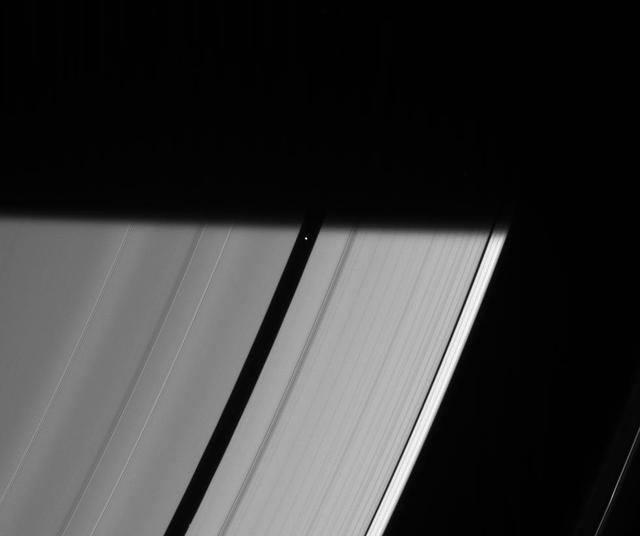

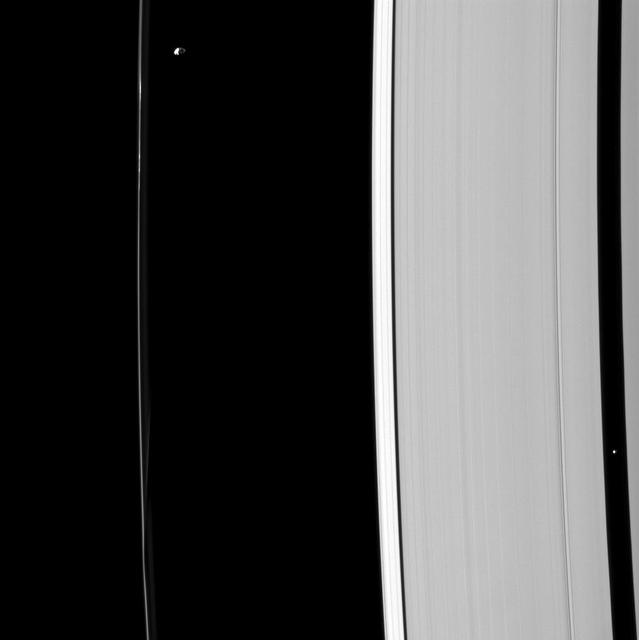

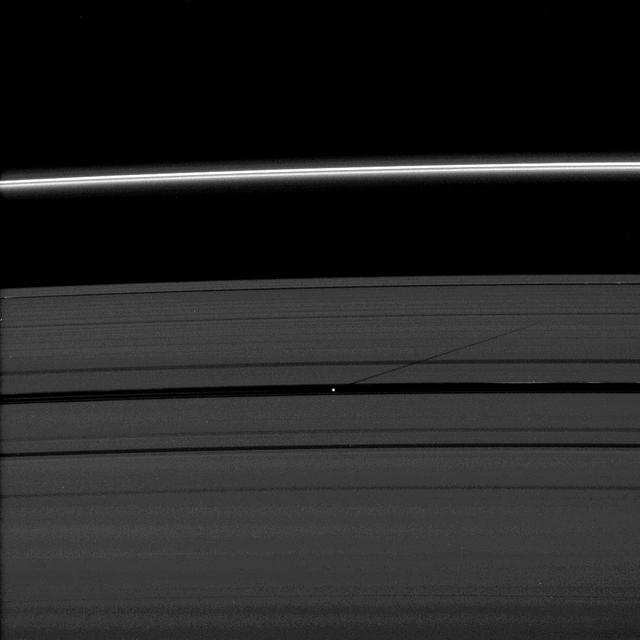

Pan Corridor

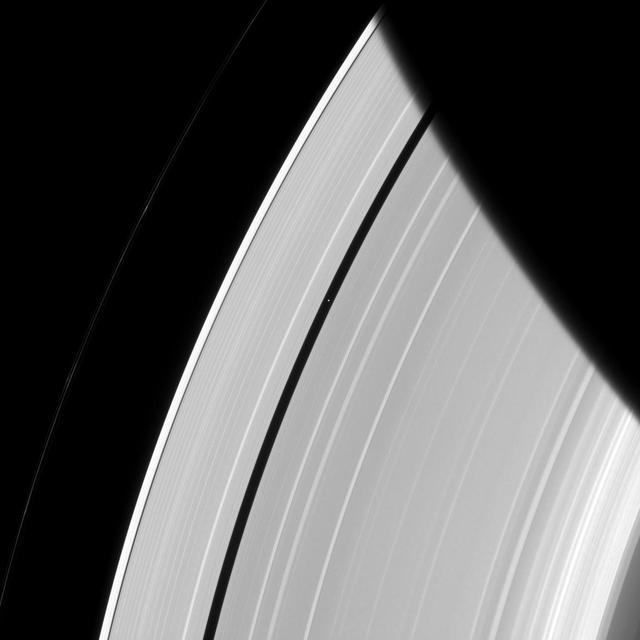

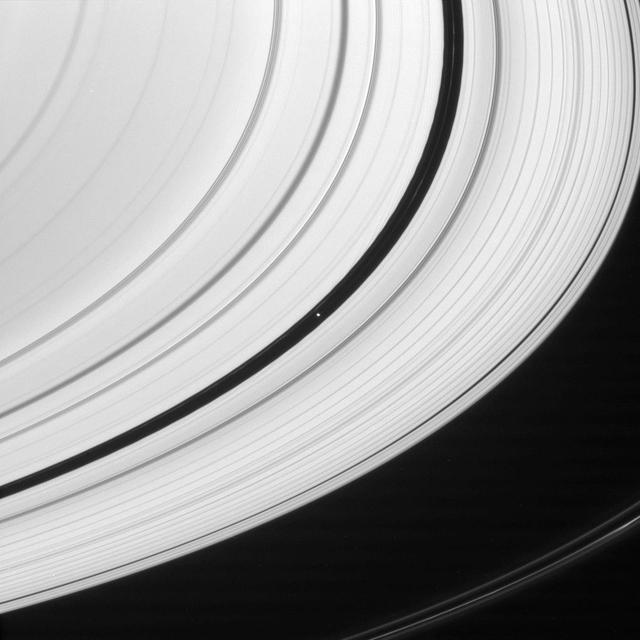

Cruising with Pan

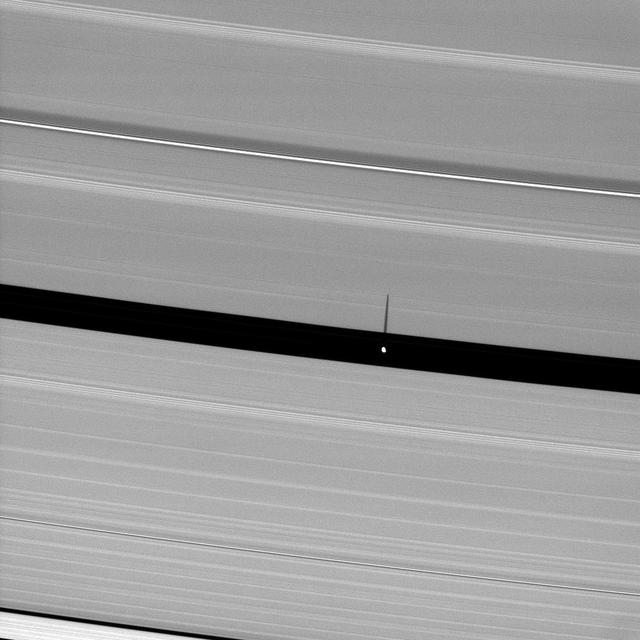

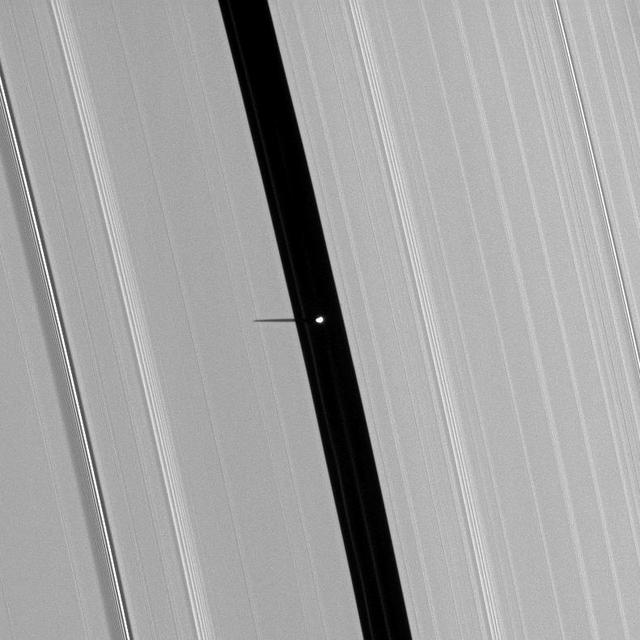

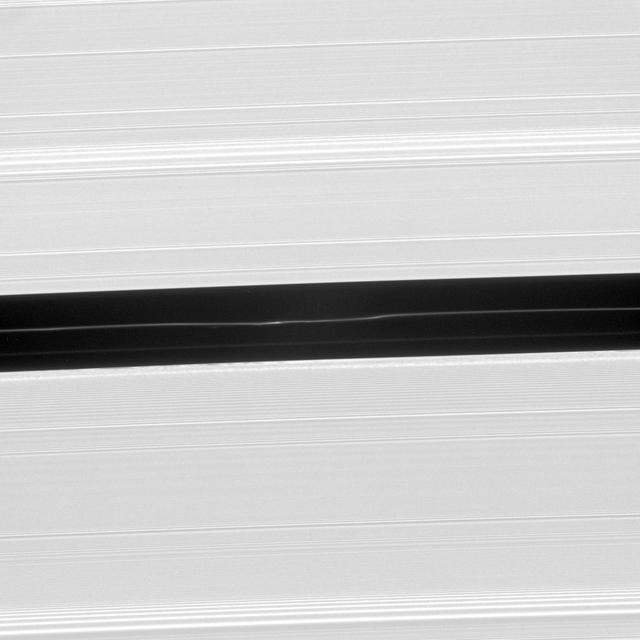

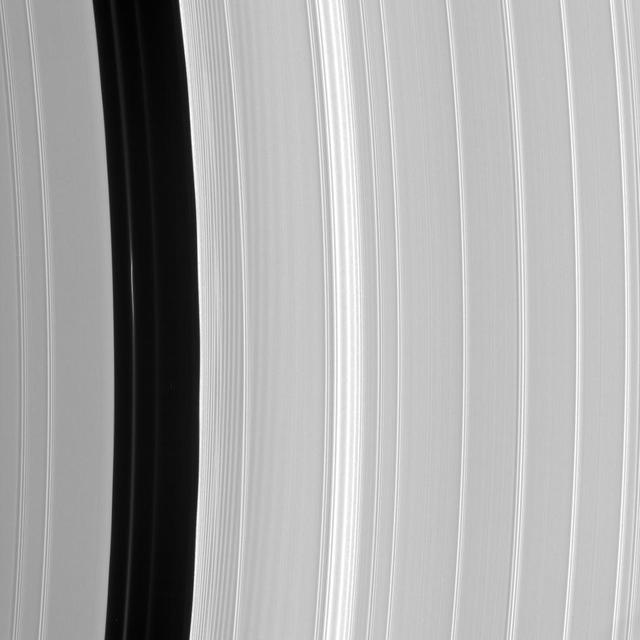

Pan Slender Shadow

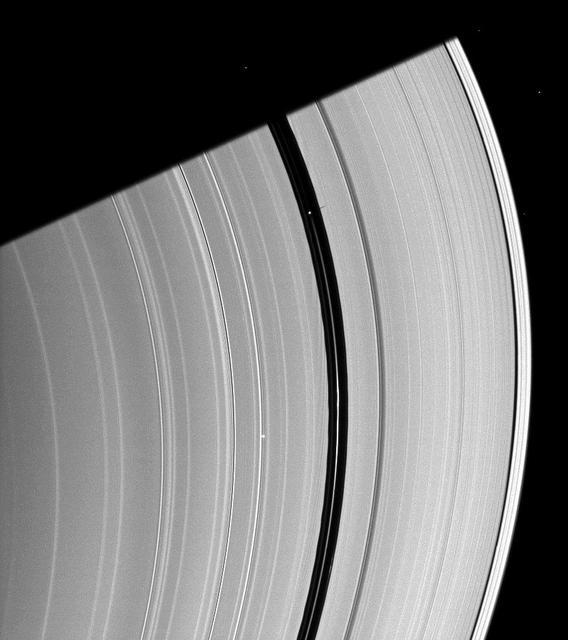

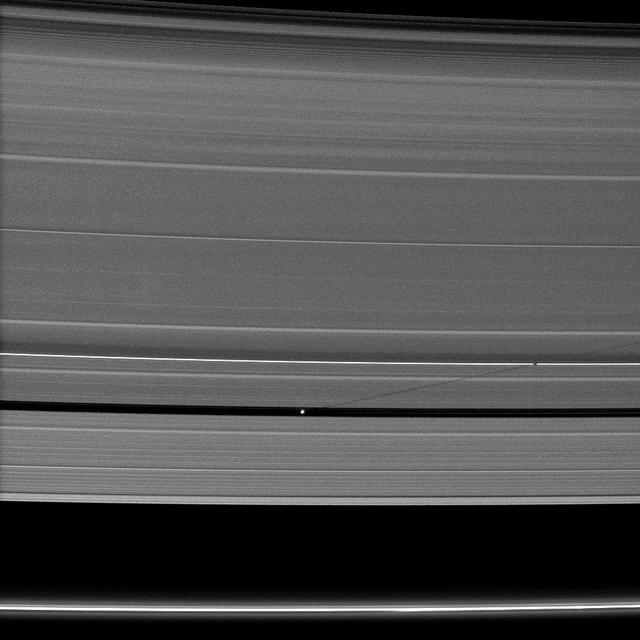

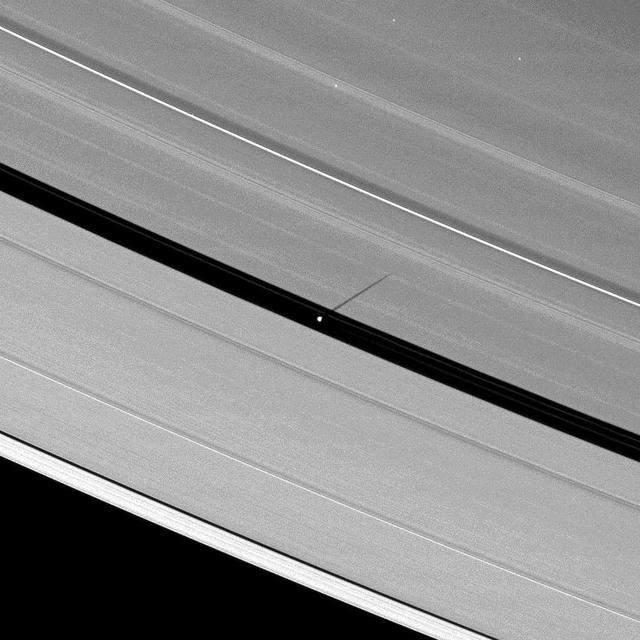

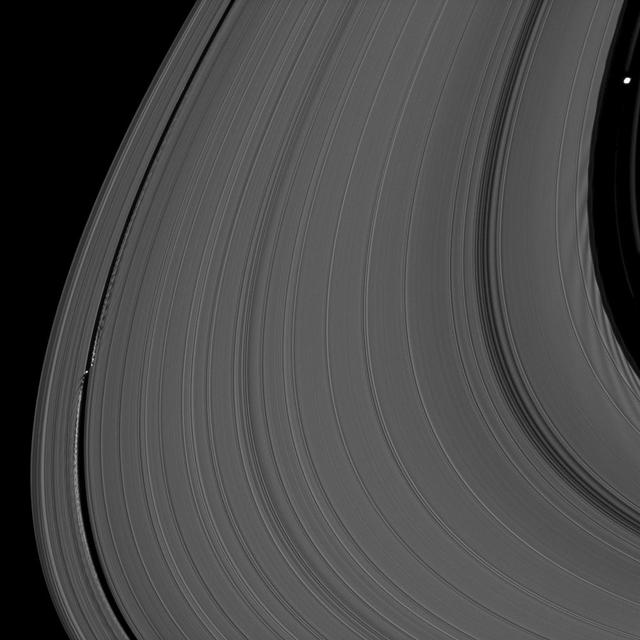

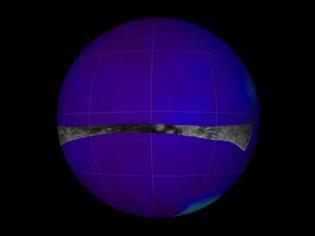

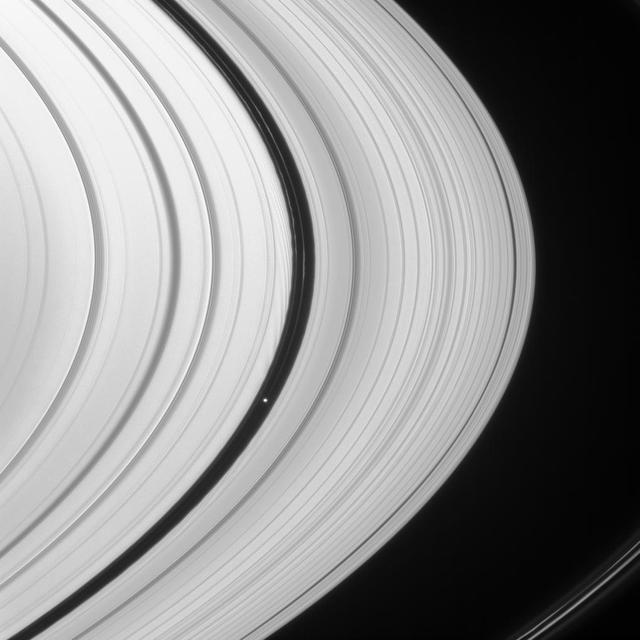

Revealing Pan Influence

Pan Very Own Shadow

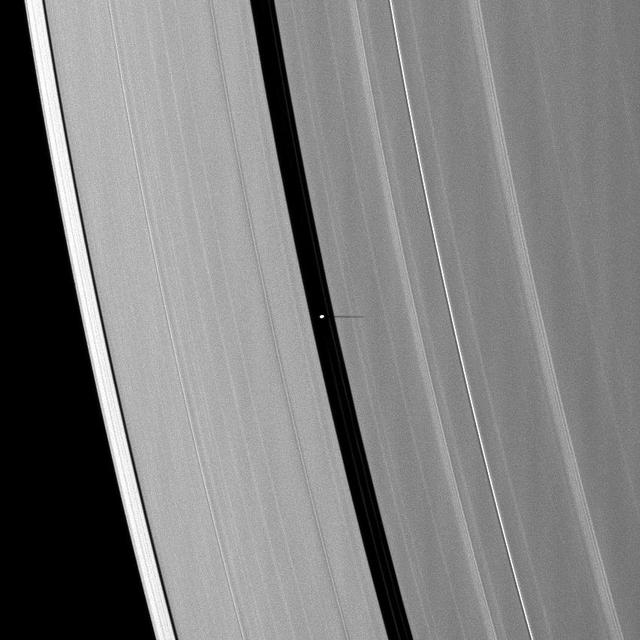

Pan in the Driver Seat

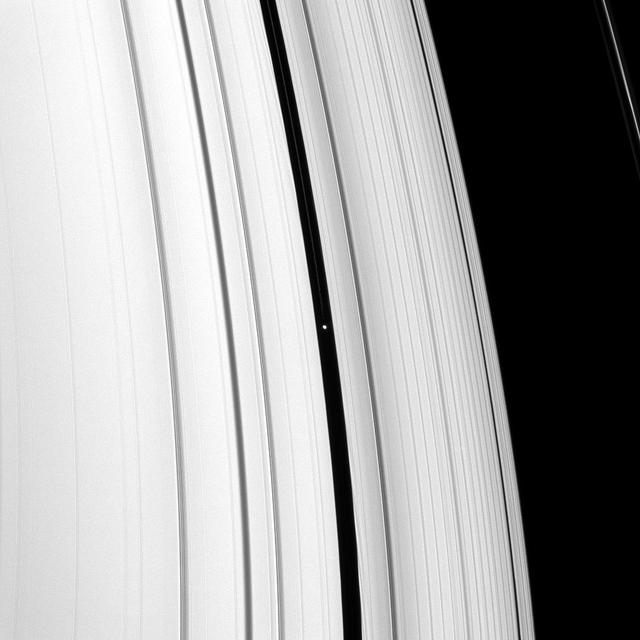

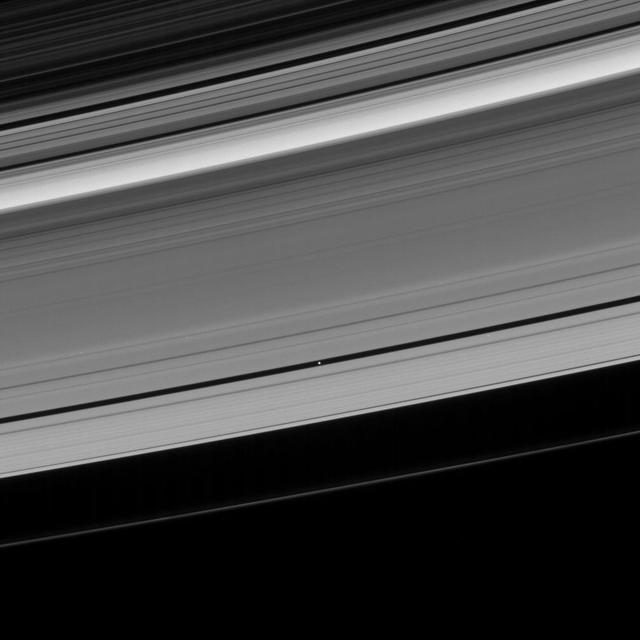

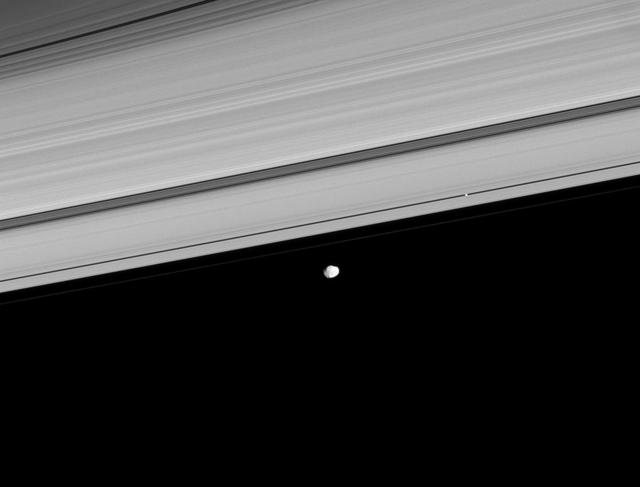

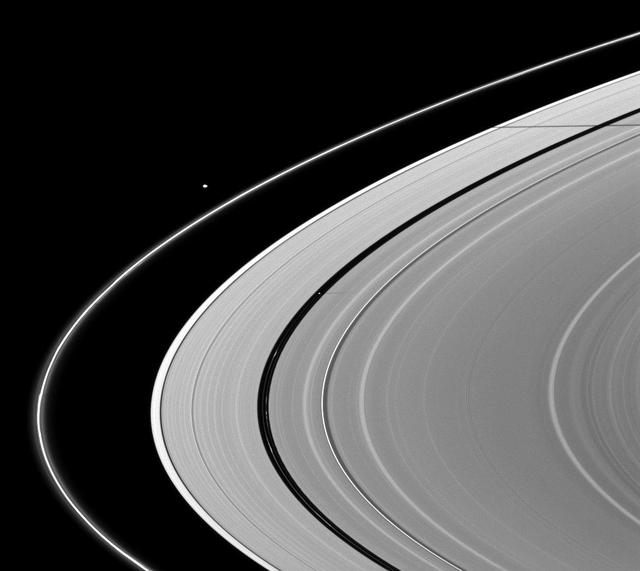

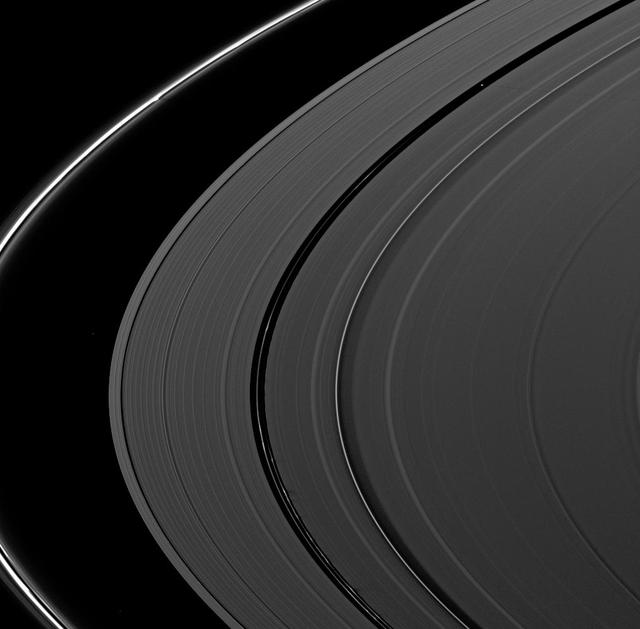

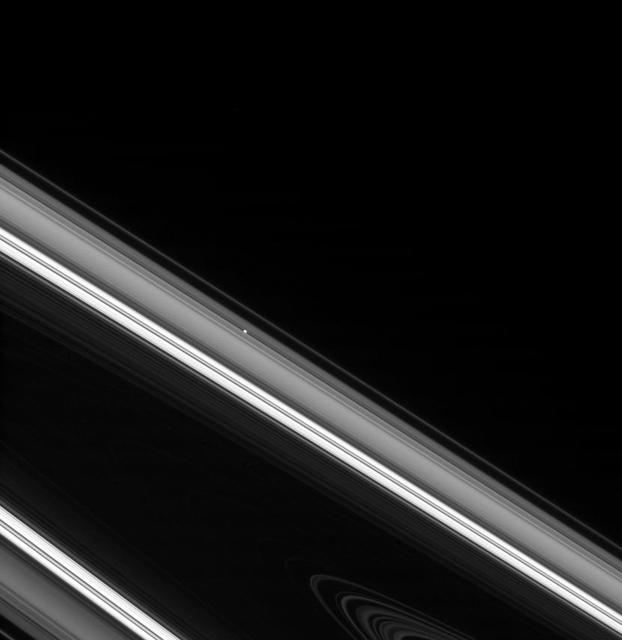

Saturn tiny moon Pan orbits in the middle of the Encke Gap of the planet A ring in this image from the Cassini spacecraft. Pan is visible as a bright dot in the gap near the center of this view.

Hiding within the Encke gap is the small moon Pan, partly in shadow and party cut off by the outer A ring in this view. Similar to Atlas, Pan appears to have a slight ridge around its middle; and like Atlas, Pan orbit also coincides with a faint ringlet

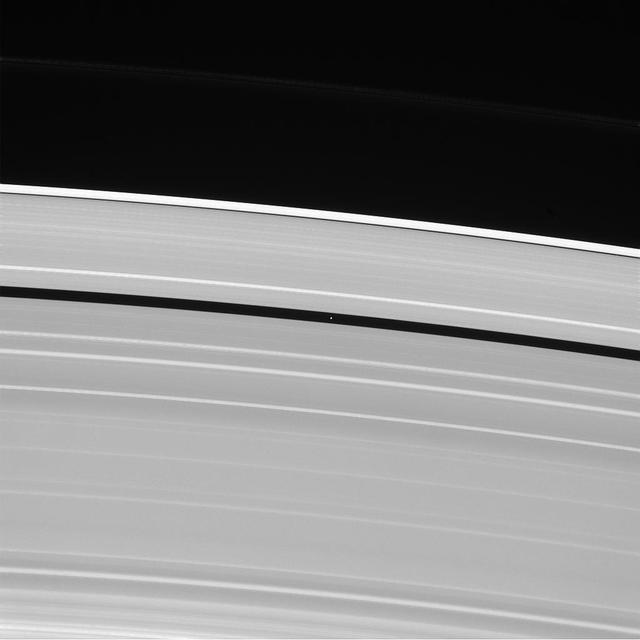

The Cassini spacecraft looks toward the unilluminated side of Saturn rings to spy on the moon Pan as it cruises through the Encke Gap

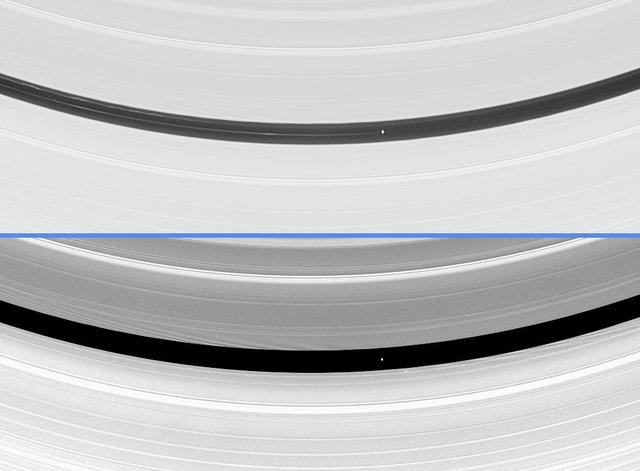

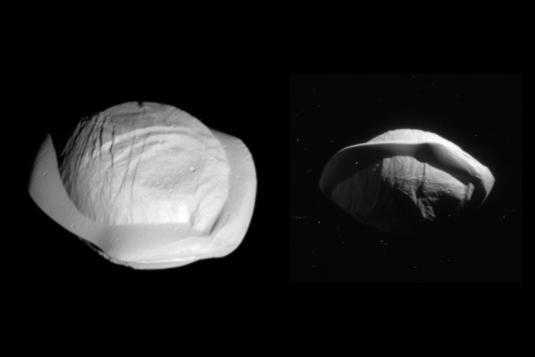

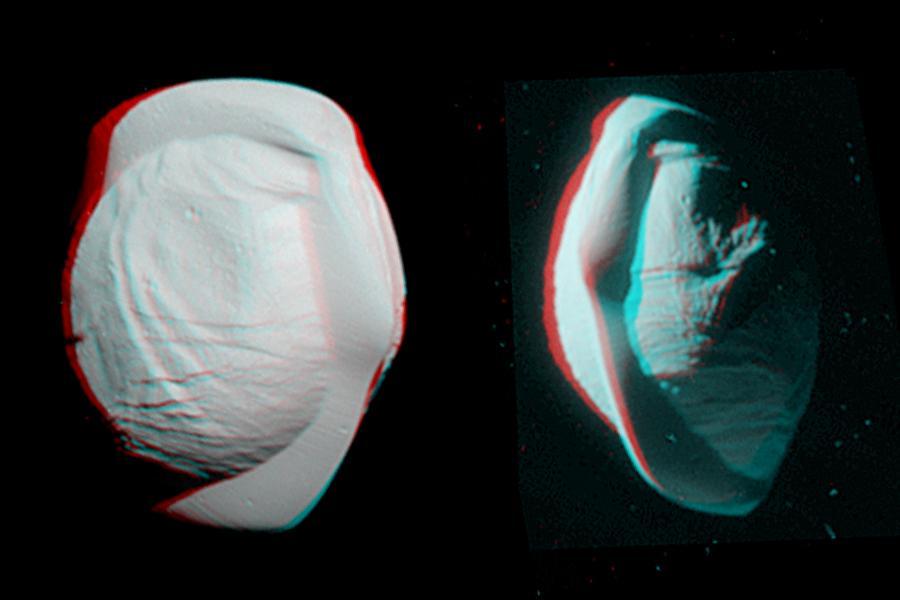

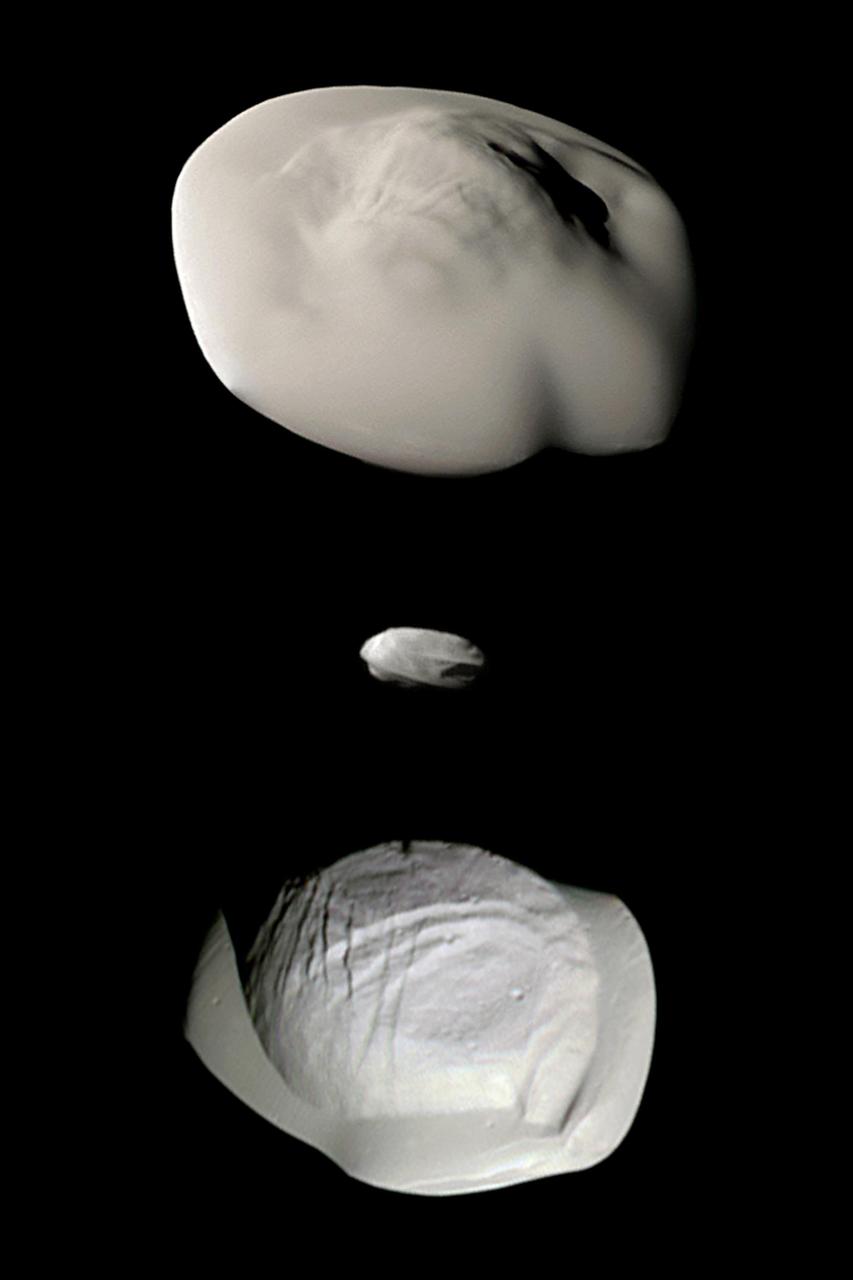

These two images from NASA's Cassini spacecraft show how the spacecraft's perspective changed as it passed within 15,300 miles (24,600 kilometers) of Saturn's moon Pan on March 7, 2017. This was Cassini's closest-ever encounter with Pan, improving the level of detail seen on the little moon by a factor of eight over previous observations. The views show the northern and southern hemispheres of Pan, at left and right, respectively. Both views look toward Pan's trailing side, which is the side opposite the moon's direction of motion as it orbits Saturn. Cassini imaging scientists think that Pan formed within Saturn's rings, with ring material accreting onto it and forming the rounded shape of its central mass, when the outer part of the ring system was quite young and the ring system was vertically thicker. Thus, Pan probably has a core of icy material that is denser than the softer mantle around it. The distinctive, thin ridge around Pan's equator is thought to have come after the moon formed and had cleared the gap in the rings in which it resides today. At that point the ring was as thin as it is today, yet there was still ring material accreting onto Pan. However, at the tail end of the process, that material was raining down on the moon solely in (or close to) its equatorial region. Thus, the infalling material formed a tall, narrow ridge of material. On a larger, more massive body, this ridge would not be so tall (relative to the body) because gravity would cause it to flatten out. But Pan's gravity is so feeble that the ring material simply settles onto Pan and builds up. Other dynamical forces keep the ridge from growing indefinitely. The images are presented here at their original size. The views were acquired by the Cassini narrow-angle camera at distances of 15,275 miles or 24,583 kilometers (left view) and 23,199 miles or 37,335 kilometers (right view). Image scale is 482 feet or 147 meters per pixel (left view) and about 735 feet or 224 meters per pixel (right view). http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21436

This Cassini spacecraft view of Pan in the Encke gap shows hints of detail on the moon dark side, which is lit by saturnshine -- sunlight reflected off Saturn.

Saturn moon Pan casts a longer shadow across the A ring as the planet August 2009 equinox draws near.

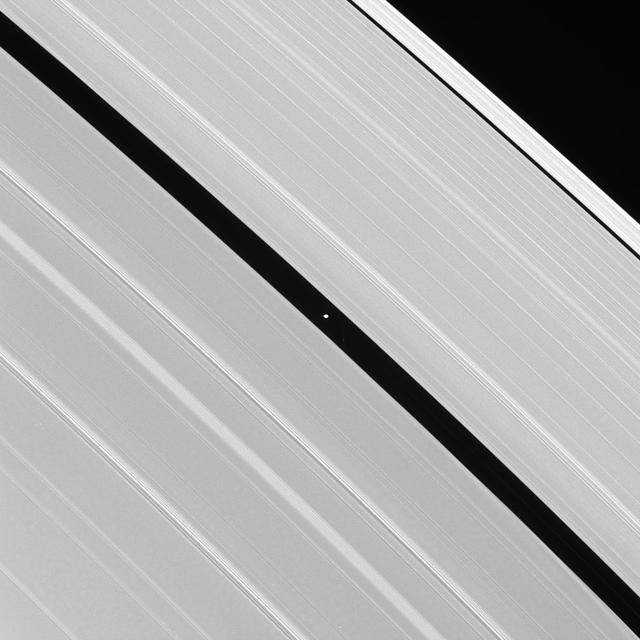

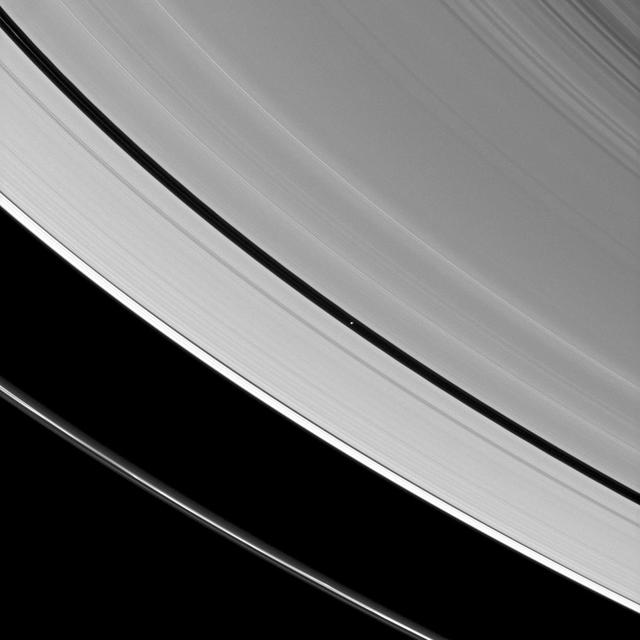

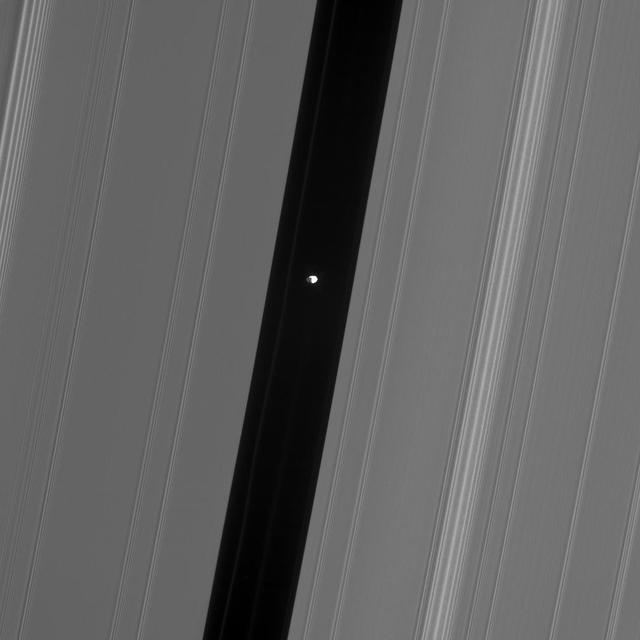

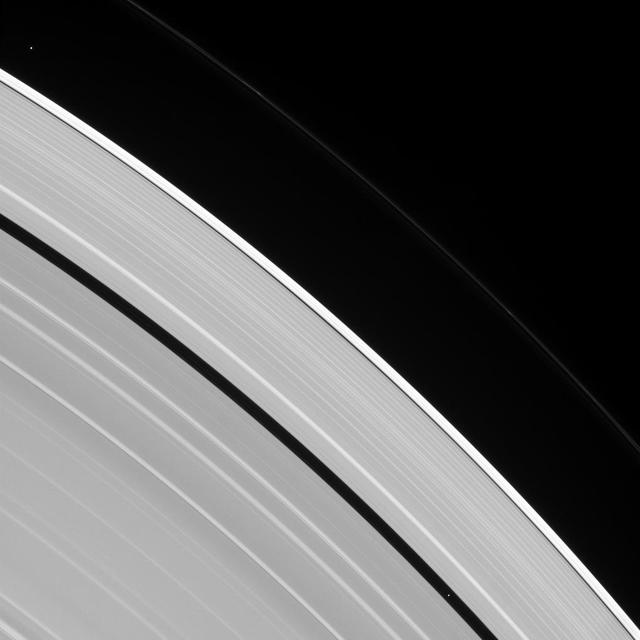

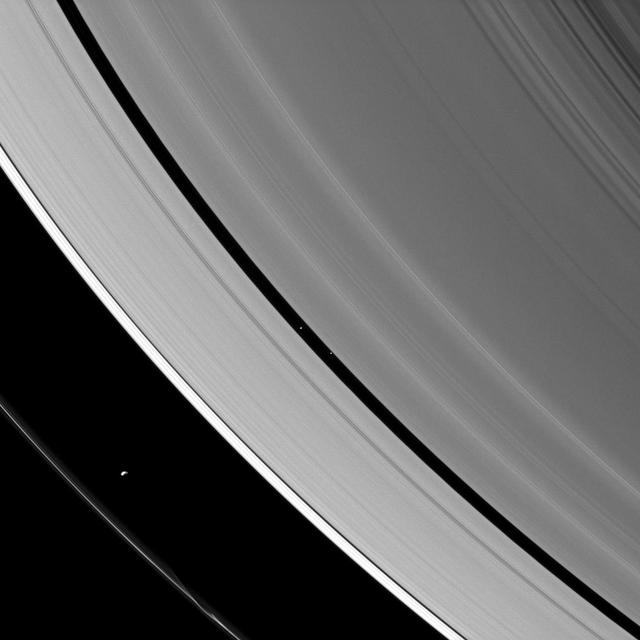

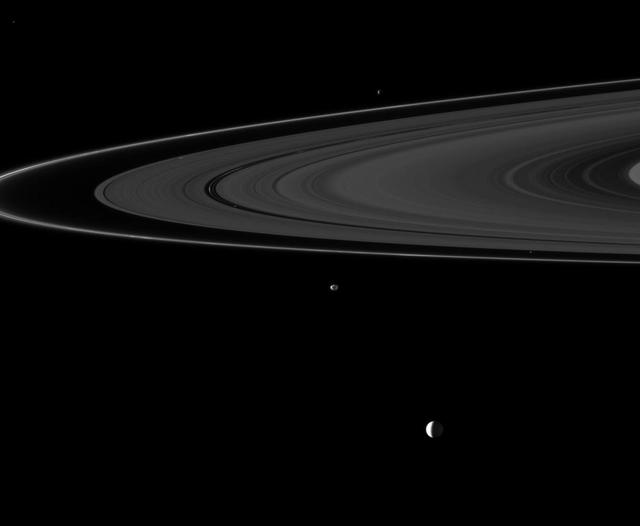

Saturn's innermost moon Pan orbits the giant planet seemingly alone in a ring gap its own gravity creates. Pan (17 miles, or 28 kilometers across) maintains the Encke Gap in Saturn's A ring by gravitationally nudging the ring particles back into the rings when they stray in the gap. Scientists think similar processes might be at work as forming planets clear gaps in the circumstellar disks from which they form. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 38 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on May 3, 2014. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 2 million miles (3.2 million kilometers) from Pan and at a Sun-Pan-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 56 degrees. Image scale is 12 miles (19 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18281

Saturn moon Pan, orbiting in the Encke Gap near the top of the image, casts a short shadow on the A ring in this image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft about six months after the planet August 2009 equinox.

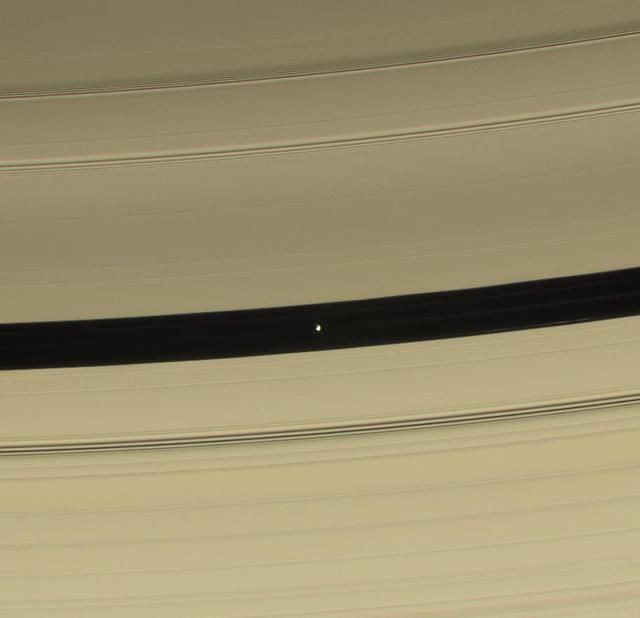

Pan is seen in this color view as it sweeps through the Encke Gap with its attendant ringlets. As the lemon-shaped little moon orbits Saturn, it always keeps its long axis pointed along a line toward the planet

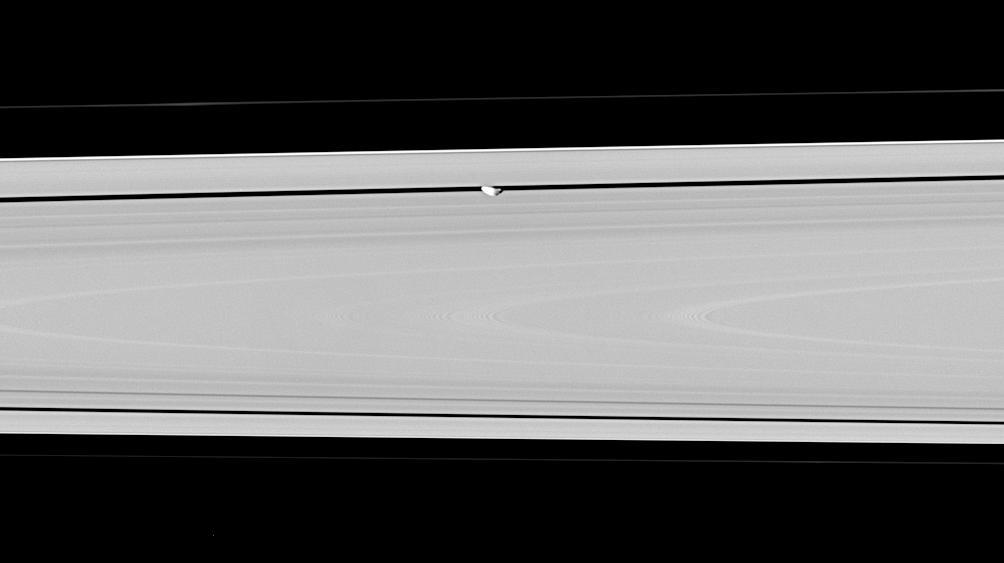

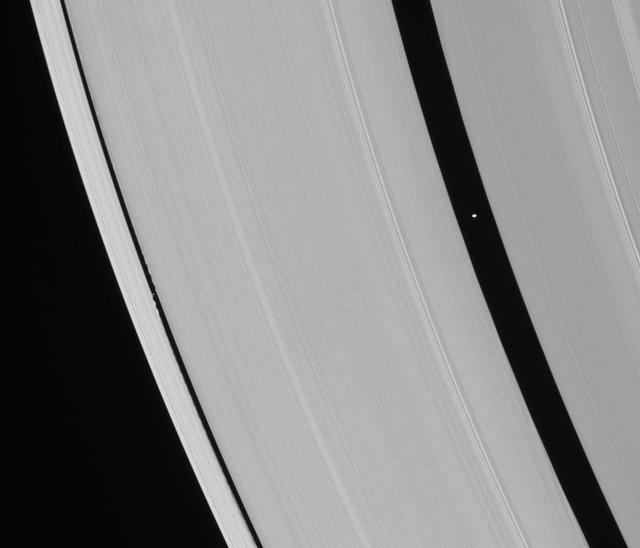

The shepherd moon Pan orbits Saturn in the Encke gap while the A ring surrounding the gap displays wave features created by interactions between the ring particles and Saturnian moons in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft.

Saturn small, ring-embedded moon Pan, on the extreme right of this NASA Cassini spacecraft image, can be seen interacting with the ringlets that share the Encke Gap of the A ring with this moon.

Saturn small moon Pan casts a long shadow across the A ring in this image captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft a few days after the planet August 2009 equinox.

The small moon Pan casts a short shadow on Saturn A ring in this image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft as the planet approached its August 2009 equinox.

Pan and Janus

Pan Gap

Daphnis and Pan

Pan in View

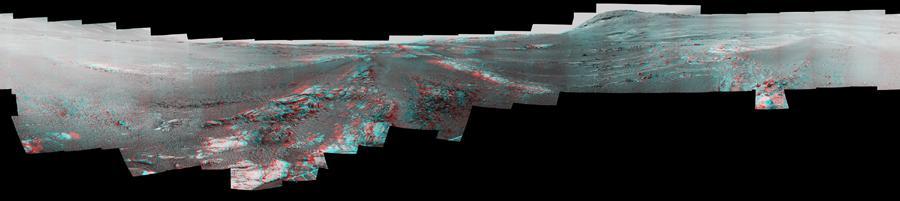

These stereo views, or anaglyphs, highlight the unusual, quirky shape of Saturn's moon Pan. They appear three-dimensional when viewed through red-blue glasses with the red lens on the left. The views show the northern and southern hemispheres of Pan, at left and right, respectively. They have been rotated to maximize the stereo effect. Pan has an average diameter of 17 miles (28 kilometers). The moon orbits within the Encke Gap in Saturn's A ring. Both of these views look toward Pan's trailing side, which is the side opposite the moon's direction of motion as it orbits Saturn. These views were acquired by the Cassini narrow-angle camera on March 7, 2017, at distances of approximately 16,000 miles or 25,000 kilometers (left view) and 21,000 miles or 34,000 kilometers (right view). Image scale in the original images is about 500 feet (150 meters) per pixel (left view) and about 650 feet (200 meters) per pixel (right view). The images have been magnified by a factor of two from their original size. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21435

Prometheus and Pan Pair

Pan in the Fast Lane

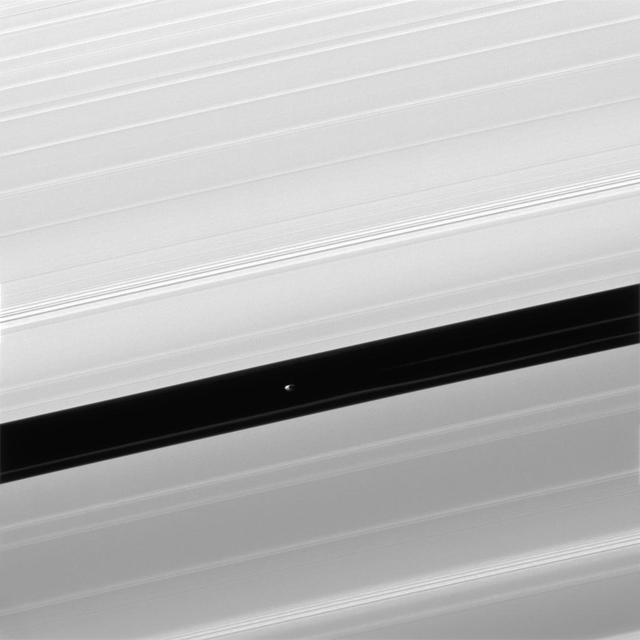

The Cassini spacecraft spies Pan speeding through the Encke Gap, its own private path around Saturn

Saturn moon Pan, orbiting in the Encke Gap, casts a slender shadow onto the A ring.

As Saturn equinox continues to approach, the moon Pan casts a slightly longer shadow on the A ring.

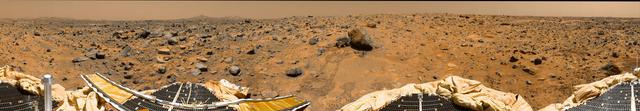

Portion of Enhanced 360-degree Gallery Pan

Pan is nearly lost within Saturn rings in this view captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft of a small section of the rings from just above the ringplane.

Saturn small moon Pan, brightly overexposed, casts a short shadow on the A ring in this image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft before the planet August 2009 equinox.

About a month after Saturn August 2009 equinox, shadows continue to grace the planet rings in this image taken by NASA Cassini Orbiter. Pan runs through the center of this image.

Orbiting in the Encke Gap of Saturn A ring, the moon Pan casts a shadow on the ring in this image taken about six months after the planet August 2009 equinox by NASA Cassini spacecraft.

Saturn moon Pan, named for the Greek god of shepherds, rules over quite a different domain: the Encke gap in Saturn rings. This image is from NASA Cassini spacecraft.

NASA Cassini spacecraft looks down at the unlit side of the rings as Pan heads into Saturn shadow. The moon is accompanied by faint ringlets in the Encke Gap.

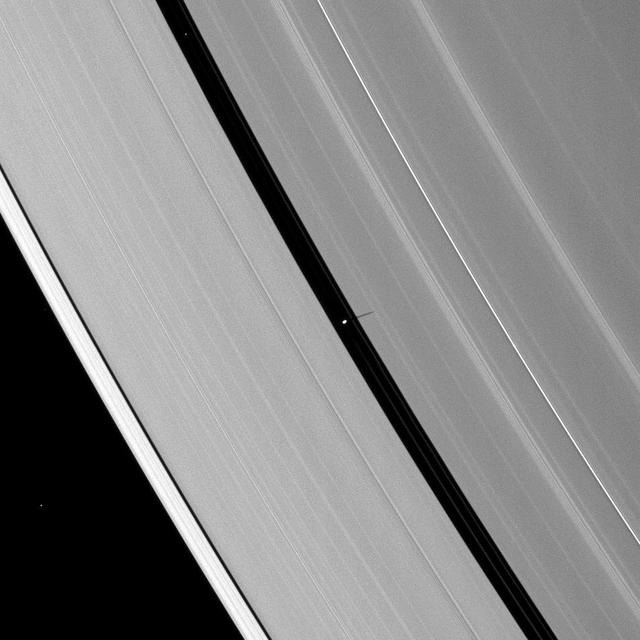

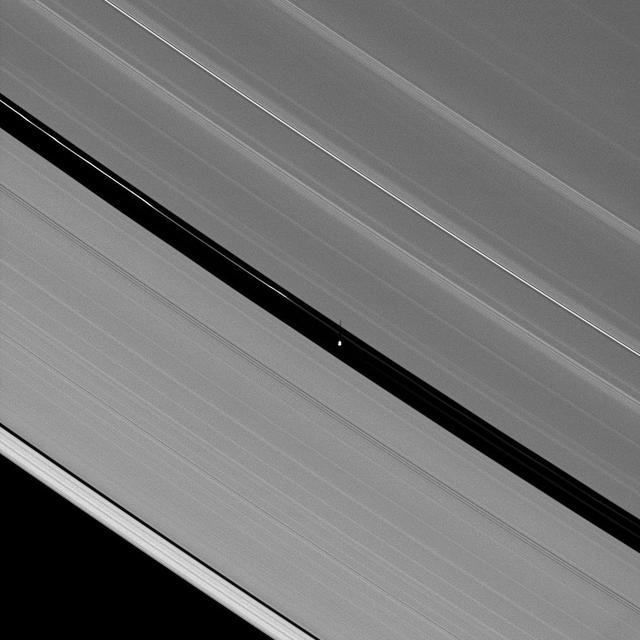

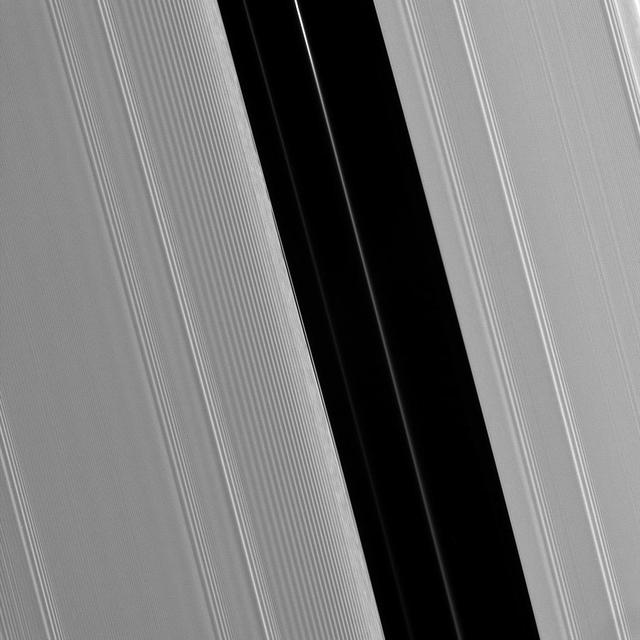

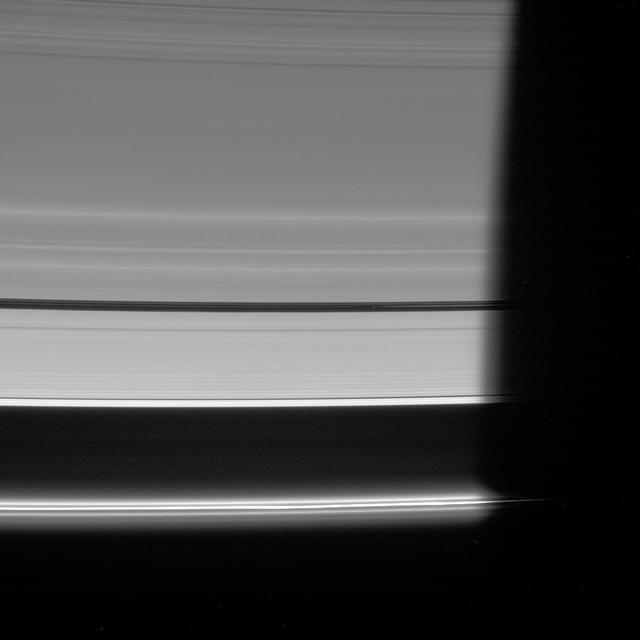

Pan and moons like it have profound effects on Saturn's rings. The effects can range from clearing gaps, to creating new ringlets, to raising vertical waves that rise above and below the ring plane. All of these effects, produced by gravity, are seen in this image. Pan (17 miles or 28 kilometers across), seen in image center, maintains the Encke Gap in which it orbits, but it also helps create and shape the narrow ringlets that appear in the Encke gap. Two faint ringlets are visible in this image, below and to the right of Pan. Many moons, Pan included, create waves at distant points in Saturn's rings where ring particles and the moons have orbital resonances. Many such waves are visible here as narrow groupings of brighter and darker bands. Studying these waves can provide information on local ring conditions. The view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 22 degrees below the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on April 3, 2016. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 232,000 miles (373,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 140 degrees. Image scale is 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20490

This view of scientists taking a break during the Pan Pacific Microgravity Conference on May 2-3, 2001, in Pasadena, CA, shows some of the diversity of the researchers attracted to the field.

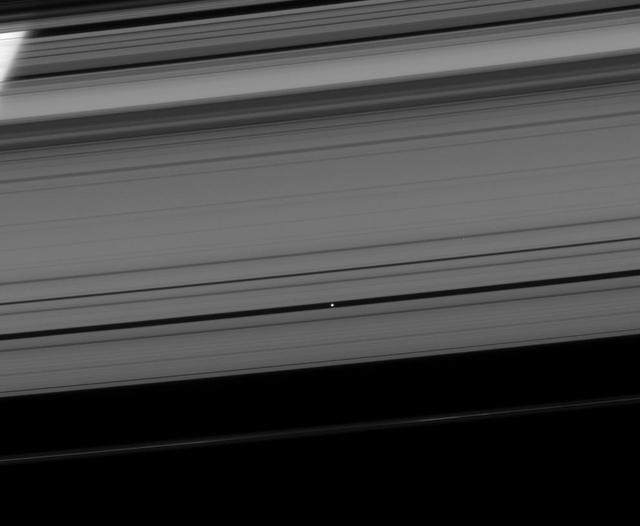

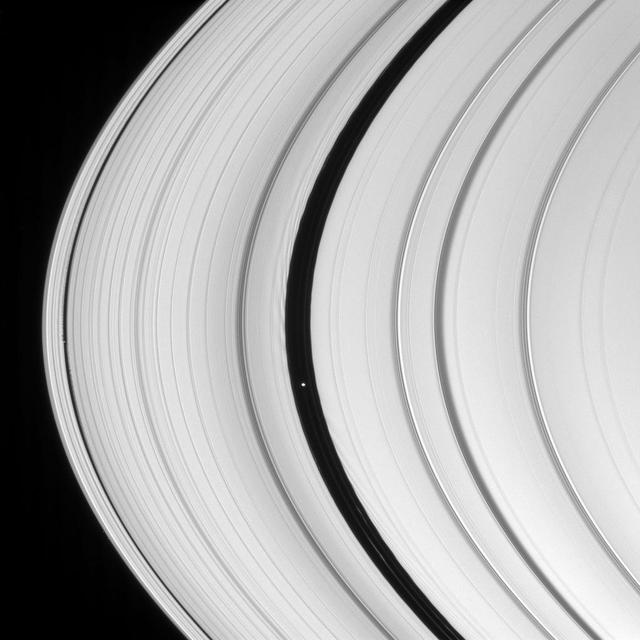

Pan may be small as satellites go, but like many of Saturn's ring moons, it has a has a very visible effect on the rings. Pan (17 miles or 28 kilometers across, left of center) holds open the Encke gap and shapes the ever-changing ringlets within the gap (some of which can be seen here). In addition to raising waves in the A and B rings, other moons help shape the F ring, the outer edge of the A ring and open the Keeler gap. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 8 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 2, 2016. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 840,000 miles (1.4 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 128 degrees. Image scale is 5 miles (8 kilometers) per pixel. Pan has been brightened by a factor of two to enhance its visibility. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20499

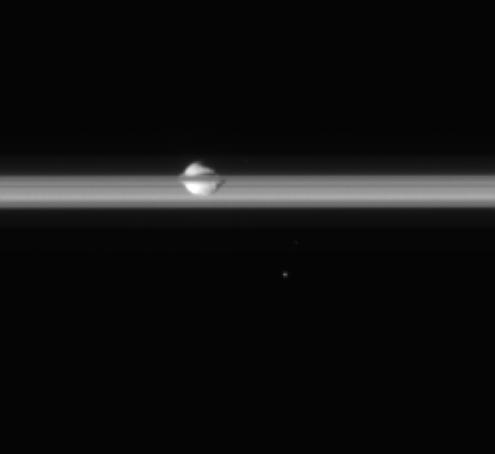

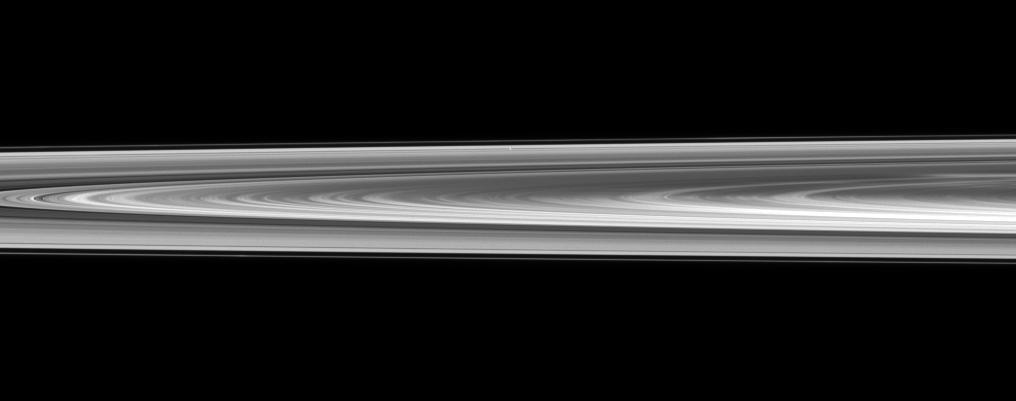

Saturn's rings, made of countless icy particles, form a translucent veil in this view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft. Saturn's tiny moon Pan, about 17 miles (28 kilometers) across, orbits within the Encke Gap in the A ring. Beyond, we can see the arc of Saturn itself, its cloud tops streaked with dark shadows cast by the rings. This image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 12, 2016, at a distance of approximately 746,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from Pan. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21901

This montage of views from NASA's Cassini spacecraft shows three of Saturn's small ring moons: Atlas, Daphnis and Pan at the same scale for ease of comparison. Two differences between Atlas and Pan are obvious in this montage. Pan's equatorial band is much thinner and more sharply defined, and the central mass of Atlas (the part underneath the smooth equatorial band) appears to be smaller than that of Pan. Images of Atlas and Pan taken using infrared, green and ultraviolet spectral filters were combined to create enhanced-color views, which highlight subtle color differences across the moons' surfaces at wavelengths not visible to human eyes. (The Daphnis image was colored using the same green filter image for all three color channels, adjusted to have a realistic appearance next to the other two moons.) All of these images were taken using the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The images of Atlas were acquired on April 12, 2017, at a distance of 10,000 miles (16,000 kilometers) and at a sun-moon-spacecraft angle (or phase angle) of 37 degrees. The images of Pan were taken on March 7, 2017, at a distance of 16,000 miles (26,000 kilometers) and a phase angle of 21 degrees. The Daphnis image was obtained on Jan. 16, 2017, at a distance of 17,000 miles (28,000 kilometers) and at a phase angle of 71 degrees. All images are oriented so that north is up. A monochrome version is available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21449

Two tiny moons of Saturn, almost lost amid the planet's enormous rings, are seen orbiting in this image. Pan, visible within the Encke Gap near lower-right, is in the process of overtaking the slower Atlas, visible at upper-left. All orbiting bodies, large and small, follow the same basic rules. In this case, Pan (17 miles or 28 kilometers across) orbits closer to Saturn than Atlas (19 miles or 30 kilometers across). According to the rules of planetary motion deduced by Johannes Kepler over 400 years ago, Pan orbits the planet faster than Atlas does. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 39 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 9, 2016. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 3.4 million miles (5.5 million kilometers) from Atlas and at a Sun-Atlas-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 71 degrees. Image scale is 21 miles (33 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20501

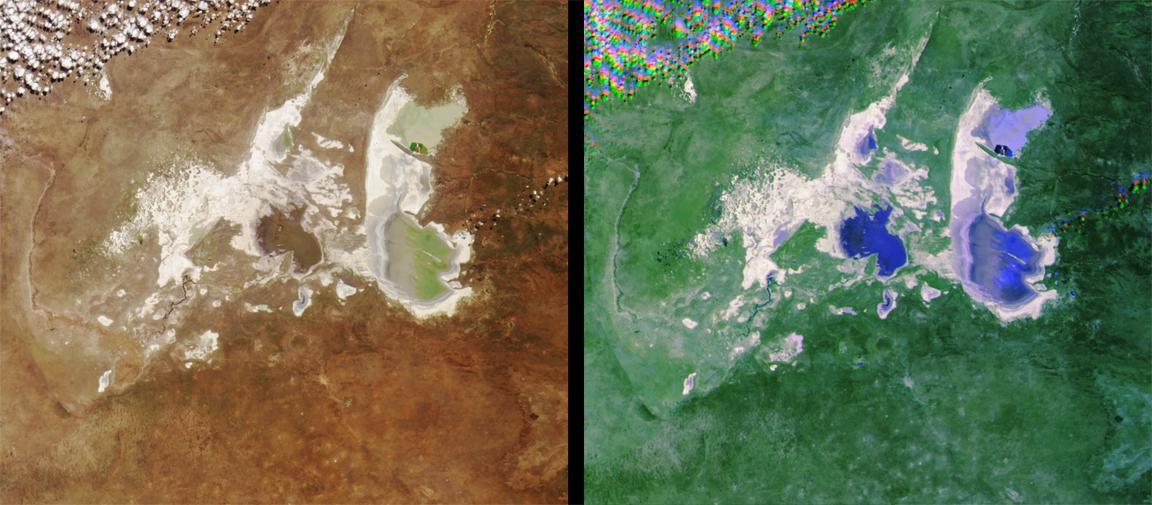

STS054-151-015 (13-19 Jan 1993) --- The Makgadikgadi Salt Pan is one of the largest features in Botswana visible from space. Any water that spills out of the Okavango Swamplands flows down to the Makgadikgadi where it evaporates. An ancient beach line can be seen as a smooth line around the west (left) side of the Pan. Orapa diamond mine can be detected due south of the pan as a small rectangle. The large geological feature known as the Great Dike of Zimbabwe can be seen far right. This large panorama shows clouds in southern Angola, Zambia and Zimbabwe in the distance.

People with similar jobs or interests hold conventions and meetings, so why shouldn't moons? Pandora, Prometheus, and Pan -- seen here, from right to left -- also appear to be holding some sort of convention in this image. Some moons control the structure of nearby rings via gravitational "tugs." The cumulative effect of the moon's tugs on the ring particles can keep the rings' edges from spreading out as they are naturally inclined to do, much like shepherds control their flock. Pan is a prototypical shepherding moon, shaping and controlling the locations of the inner and outer edges of the Encke gap through a mechanism suggested in 1978 to explain the narrow Uranian rings. However, though Prometheus and Pandora have historically been called "the F ring shepherd moons" due to their close proximity to the ring, it has long been known that the standard shepherding mechanism that works so well for Pan does not apply to these two moons. The mechanism for keeping the F ring narrow, and the roles played -- if at all -- by Prometheus and Pandora in the F ring's configuration are not well understood. This is an ongoing topic for study by Cassini scientists. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 29 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Jan. 2, 2015. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.6 million miles (2.6 million kilometers) from the rings and at a Sun-ring-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 86 degrees. Image scale is 10 miles (15 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18306

S132-E-005110 (15 May 2010) --- While preparing for the routine inspection of Atlantis’ thermal protection system on Flight Day 2, the STS-132 crew discovered a cable was being pinched and preventing the sensor package pan and tilt unit from moving properly. There are alternate sensor packages that do not require the pan and tilt function; and personnel in the Johnson Space Center’s Mission Control Center are evaluating those procedures. Photo credit: NASA or National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Saturn moons Daphnis and Pan demonstrate their effects on the planet rings in this view from NASA Cassini spacecraft. Daphnis, at left, orbits in the Keeler Gap of the A ring; Pan at right, orbits in the Encke Gap of the A ring.

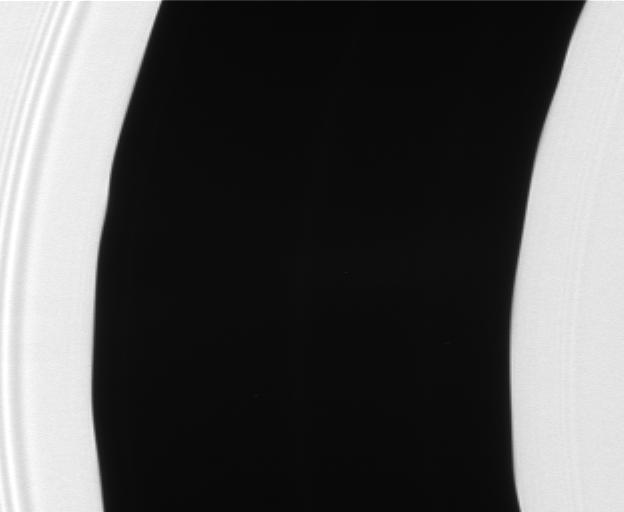

Bright undulations disturb a faint ringlet drifting through the center of the Encke Gap. This ring structure shares the orbit of the moon Pan

Immense Saturn is visible through the A ring as Pan coasts along its private corridor

Saturn ring-embedded moons, Pan and Daphnis, are captured in an alignment they repeat with the regularity of a precise cosmic clock

The ring-region Saturnian moons Prometheus and Pan are both caught herding their respective rings in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft.

The Encke gap displays gentle waves in its inner and outer edges that are caused by gravitational tugs from the small moon Pan

Pan prepares to be engulfed by the darkness of Saturn shadow, visible here as it stretches across the rings

Pan Conrad, deputy principal investigator, Sample Analysis at Mars team, NASA‘s Goddard Space Flight Center, discusses what we’ve learned from Curiosity and the other Mars rovers during a “Mars Up Close” panel discussion, Tuesday, August 5, 2014, at the National Geographic Society headquarters in Washington. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Pan Conrad, deputy principal investigator, Sample Analysis at Mars team, NASA‘s Goddard Space Flight Center, discusses what we’ve learned from Curiosity and the other Mars rovers during a “Mars Up Close” panel discussion, Tuesday, August 5, 2014, at the National Geographic Society headquarters in Washington. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Pan Conrad, deputy principal investigator, Sample Analysis at Mars team, NASA‘s Goddard Space Flight Center, discusses what we’ve learned from Curiosity and the other Mars rovers during a “Mars Up Close” panel discussion, Tuesday, August 5, 2014, at the National Geographic Society headquarters in Washington. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Six of Saturn moons orbiting within and beyond the planet rings are collected in this Cassini spacecraft image; they include Enceladus, Epimetheus, Atlas, Daphnis, Pan, and Janus.

These images from NASA Terra satellite images of the Ntwetwe and Sua Pans in northeastern Botswana were acquired on August 18, 2000 Terra orbit 3553.

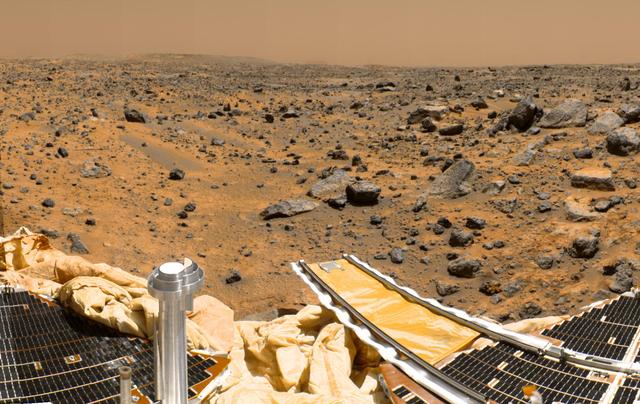

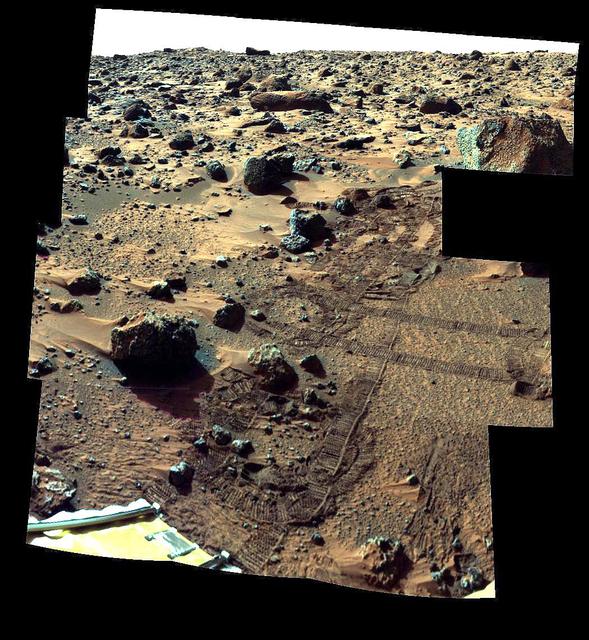

This is a more recent geometrically improved, color enhanced version of the 360-degree Gallery Pan, the first contiguous, uniform panorama taken by the Imager for Mars IMP over the course of Sols 8, 9, and 10.

The Encke Gap moon, Pan, has left its mark on a scalloped ringlet of the Encke Gap. The moon creates these perturbations as it sweeps through the 325-kilometer 200-mile gap in the A ring

Although their gravitational effects on nearby ring material look quite different, Prometheus and Pan are both shepherd moons, holding back nearby ring edges in this image captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft.

Although the embedded moon Pan is nowhere to be seen, there is a bright clump-like feature visible here, within the Encke Division. Also discernable are periodic brightness variations along the outer right side gap edge

This image showcases the Saturnian system, beginning with the planet itself and panning out to its newest addition -- an enormous ring discovered in infrared light by NASA Spitzer Space Telescope.

Cassini powerful radar eyes have uncovered a geologic goldmine in a region called Xanadu on Saturn moon Titan. Panning west to east, the geologic features include river channels, mountains and hills, a crater and possible lakes

A pair of Saturn moons, Pan and Janus, cast their shadows on the A ring in this NASA Cassini spacecraft image taken about a month and a half after Saturn August 2009 equinox.

Shadows seem ubiquitous in this view from NASA Cassini spacecraft of Saturn rings. The moon Pan casts a long shadow towards the right from where it orbits in the Encke Gap of the A ring in the upper right of the image.

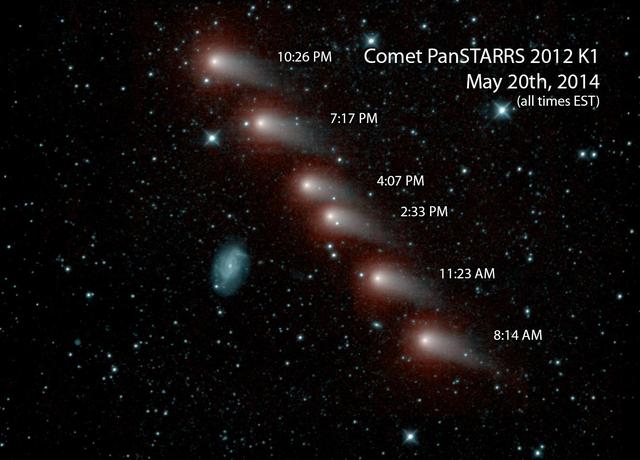

NASA NEOWISE mission captured this series of pictures of comet C/2012 K1 -- also known as comet Pan-STARRS -- as it swept across our skies on May 20, 2014.

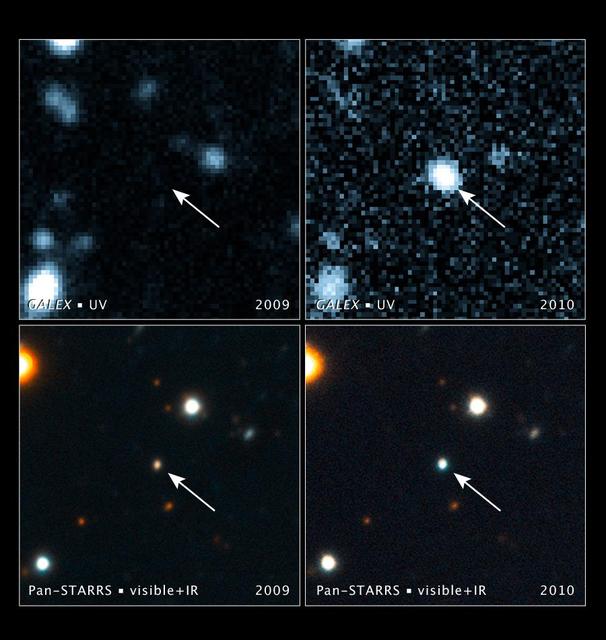

These images, taken with NASA Galaxy Evolution Explorer and the Pan-STARRS1 telescope in Hawaii, show a brightening inside a galaxy caused by a flare from its nucleus. The arrow in each image points to the galaxy.

NASA Cassini spacecraft captures a couple of small moons in this image taken while the spacecraft was nearly in the plane of Saturn rings.

ISS018-E-043947 (26 March 2009) --- Etosha Pan in Namibia is featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 18 crewmember on the International Space Station. Etosha Pan is a large dry lake about 130 kilometers long that dominates Namibia?s Etosha National Park (the sharp edge of the park fence can be seen at right). Small related dry lake beds appear as bright shapes top left, a portion of the International Space Station appears at top right. This view shows the pan as it appeared almost ten years ago. The pan is the low point in a major inland basin in northern Namibia. During occasional flood events, such those experienced in the last nine months, rivers from Angola (the Namibia?Angola boundary lies just outside the top of the image) deliver large quantities of water to the pan. In this image flood water in the Oshigambo River, resulting from recent heavy rains in Angola, appears as a gray stream entering the northwest corner of the pan (top left). The floodwater becomes a thin sheet on the vast salt flat of the pan floor. Algae blooms in the warm water have produced a light-green tinge. Another image of the Oshigambo River mouth in flood can be seen here. Reports on the ground, augmented with orbital unmanned satellite imagery acquired subsequent to this photograph, show that the plains north of the pan are now flooded, causing damage to homesteads, crops and roads. More than 340,000 people have been affected in northern Namibia and approximately 250,000 in southern Angola.

Faint Ring Details

Round the Outside

Encke Inhabitants

Waking the A Ring

Lighthouse Moon

The shadow of the moon Mimas is cast on Saturn outer A ring in this image which also shows a couple of moons and a collection of stars.

This is an image from the super-pan sequence. Of importance are some of the features around the rock nicknamed Barnacle Bill in the left foreground. The rock shows a "streamlined tail" composed of particles deposited by wind on the leeward (downwind) side of the rock. Also seen is a "moat" around the opposite (windward) side of the rock where either erosion (or non-deposition) of fine sediment has occurred. Mars Pathfinder scientist believe that the wind blowing over and around rocks like Barnacle Bill creates an airflow pattern wherein a buffer zone is formed immediately upwind of the rock and airflow patterns keep sediment from being deposited directly upwind of Barnacle Bill. On the downwind side, however, the airflow is complex and a small wake and tapered "dead air zone" form. Sediment can be deposited within this region, the shape of the formed deposit corresponds to the airflow patterns that exist behind the rock. Similar features have been observed at the Viking landing sites, and are thought to form under high wind conditions during the autumn and winter seasons in the northern hemisphere. This image mosaic was processed by the U.S. Geological Survey in support of the NASA/JPL Mars Pathfinder Mars Mission. Sojourner spent 83 days of a planned seven-day mission exploring the Martian terrain, acquiring images, and taking chemical, atmospheric and other measurements. The final data transmission received from Pathfinder was at 10:23 UTC on September 27, 1997. Although mission managers tried to restore full communications during the following five months, the successful mission was terminated on March 10, 1998. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00982

ISS030-E-234965 (30 Dec. 2011) --- The Etosha Pan in Namibia is featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 30 crew member on the International Space Station. This photograph shows the white, salt-covered floor of the northwest corner of the great dry lake in northern Namibia known as the Etosha Pan (left margin). Two rivers, the Ekuma and Oshigambo, transport water from the north down to the Etosha Pan proper. In a relatively rare event, water from recent rains has flowed down the larger Ekuma River?in which it appears as a thin blue line within the generally light grey-green floodplain?and fills a lobe of the lake with light green water (lower right quarter of image). Water has also flowed into a small offshoot dry lake where it appears a brighter green (upper right quarter of image). Other smaller lakes at center and top center show red and brown water colors. The different colors of lake water are determined by the interplay of water depth and resident organisms such as algae; the algae color varies depending on water temperature and salinity. A similar process is observed in pink and red floodwaters ponded in Lake Eyre, a usually dry lake in Australia?s arid center. In this case it is known that the coloration is indeed due to algae growth. Typically, little river water or sediment reaches the floor of the Etosha dry lake because water seeps into the riverbeds along their courses. The floor of the pan itself is seldom seen with even a thin sheet of water. In this image, there was enough surface flow to reach the pan, but too little to flow beyond the inlet bay. A prior flood event, when water entered the pan via the Oshigambo River, was documented in astronaut imagery in 2006. The straight line that crosses the image from top center to bottom is the northern fence line of Namibia?s Etosha National Park. This straight, three-meter-high fence keeps wildlife from crossing into the numerous small farms of the relatively densely populated Owambo region of Namibia, north of the pan. The large Etosha dry lakebed (120 kilometers or 75 miles long) is the center of Namibia?s largest wildlife park, a major tourist attraction.

From on high, the Cassini spacecraft spies a group of three ring moons in their travels around Saturn. Janus is seen at top, while Pandora hugs the outer edge of the narrow F ring. More difficult to spot is Pan, which is a mere speck in this view.

<p> The Cassini spacecraft looks toward the unilluminated side of Saturn rings to spy on the moon Pan as it cruises through the Encke Gap. </p> <p> This view looks toward the rings from about 13 degrees above the ringplane. At the top of the image

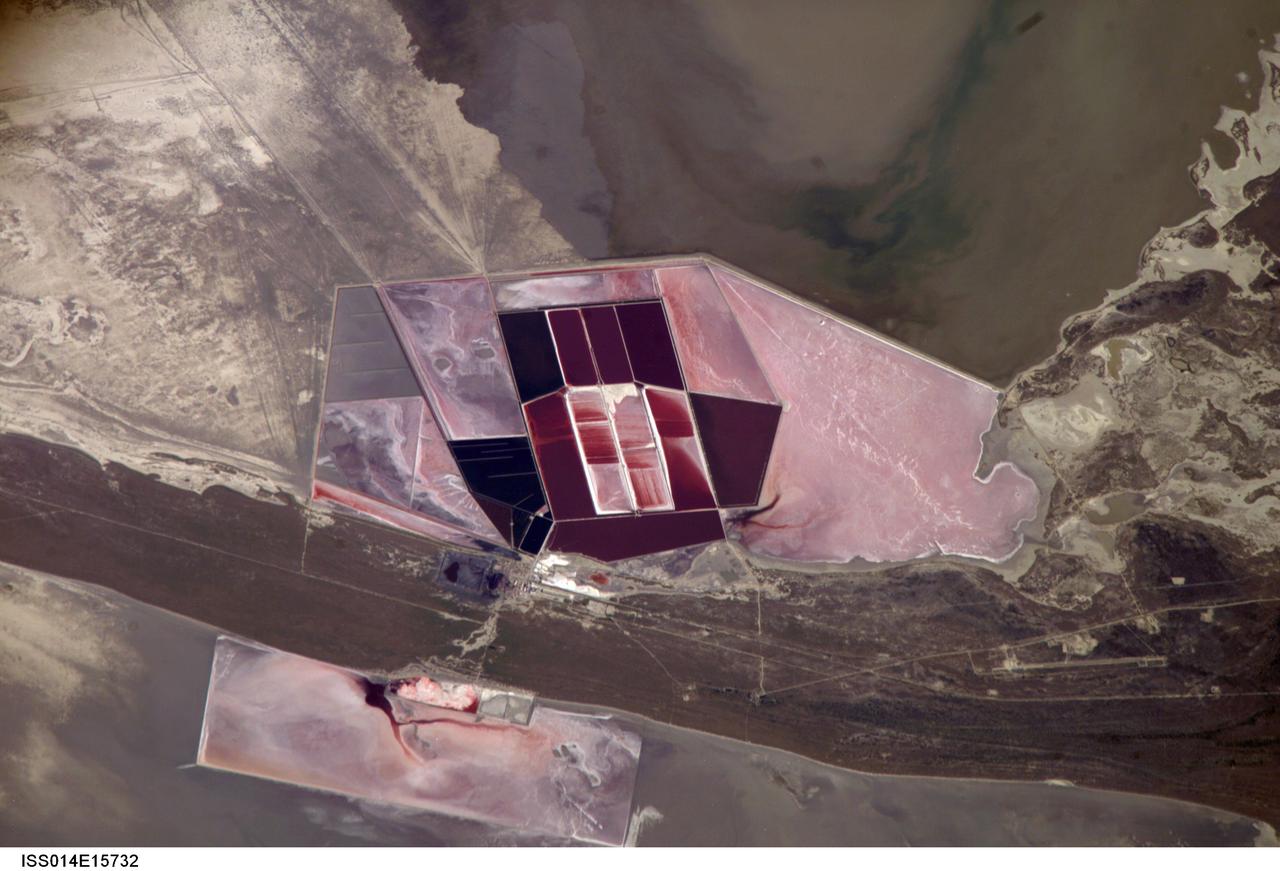

ISS014-E-15732 (1 March 2007) --- Salt ponds of Botswana are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 14 crewmember on the International Space Station. This recent, detailed view shows the salt ponds of one of Africa's major producers of soda ash (sodium carbonate) and salt. Soda ash is used for glass making, in metallurgy, in the detergent industry, and in chemical manufacture. The image shows a small part of the great salt flats of central Botswana known as the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans. The soda ash and salt are both mainly exported (since 1989) to most countries in southern and central Africa. Brines from just beneath the pan floor are evaporated to produce the soda ash and salt -- a process for which the semiarid climate of Botswana is ideal. Red salt-loving algae in the ponds indicate that the salinity of the evaporating brines is medium to high. The salt pans of Botswana--a prominent visual photo target of interest for astronauts aboard the station--lie at the low point of a vast shallow continental basin. Rivers draining from as far away as central Angola - more than 1,000 kilometers away - supply water to the pans. According to scientists, during several wet climatic phases in the recent geological past the pans were permanently filled with water, for thousands of years, only to dry out when climates fluctuated to drier conditions. During dry phases water only reaches the pans underground. These are the brines that support the ash and salt industry. During wet phases when open water exists, beach ridges are constructed by wave action. One of these crosses the lower part of the view.

ISS012-E-23057 (2 March 2006) --- Ekuma River and Etosha Pan, Namibia are featured in this close-up image photographed by an Expedition 12 crewmember on the International Space Station. Etosha Pan, northern Namibia, is a large (120 kilometers or 75 mile long) dry lakebed in the Kalahari Desert. The lake and surrounds are protected today as one of Namibia’s largest wildlife parks. Herds of elephant occupy the dense mopane woodland on the south side of the lake. Mopane trees are common throughout south-central Africa, and host the mopane worm (the larval form of the Mopane Emperor Moth)–an important source of protein for rural communities. According to scientists, about 16,000 years ago, when ice sheets were melting across Northern Hemisphere land masses, a wet climate phase in southern Africa filled Etosha Lake. Today, Etosha Pan is seldom seen with even a thin sheet of water covering the salt pan. This view shows the point where the Ekuma River flows into the salt lake. The Ekuma River is almost never seen with water, but in early 2006 rainfall twice the average amount in the river’s catchment generated flow. Greens and browns show vegetation and algae growing in different depths of water where the river enters the dry lake. Typically, little river water or sediment reaches the dry lake because water seeps into the riverbed along its 250 kilometers (155 miles) course, reducing discharge along the way. In this image, there was enough surface flow to reach the Pan, but too little water reached the mouth of the river to flow beyond the inlet bay. The unusual levels of precipitation also filled several small, usually dry lakes to the north of Etosha Pan.

ISS011-E-09504 (24 June 2005) --- Ekuma River and Etosha Pan, Namibia are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 11 crewmember on the International Space Station. Etosha Pan, northern Namibia, is a large (120 kilometers or 75 mile long) dry lakebed in the Kalahari Desert. The lake and surrounds are protected today as one of Namibia’s largest wildlife parks. Herds of elephants occupy the dense mopane woodland on the south side of the lake. Mopane trees are common throughout south-central Africa, and host the mopane worm (the larval form of the Mopane Emperor Moth)–an important source of protein for rural communities. According to scientists, about 16,000 years ago, when ice sheets were melting across Northern Hemisphere land masses, a wet climate phase in southern Africa filled Etosha Lake. Today, Etosha Pan is seldom seen with even a thin sheet of water covering the salt pan. Typically, little river water or sediment reaches the dry lake because water seeps into the riverbed along its 250 kilometers (155 miles) course, reducing discharge along the way.

This image is a shortened version of a 360-degree panorama taken by the Opportunity rover's Panoramic Camera (Pancam) from May 13 through June 10, 2018, or sols (Martian days) 5,084 through 5,111. This is the last panorama Opportunity acquired before the solar-powered rover succumbed to a global Martian dust storm on the same June 10. The panorama appears in 3D when seen through blue-red glasses with the red lens on the left. To the right of center and near the top of the frame, the rim of Endeavour Crater rises in the distance. Just to the left of that, rover tracks begin their descent from over the horizon towards the location that would become Opportunity's final resting spot in Perseverance Valley, where the panorama was taken. At the bottom, just left of center, is the rocky outcrop Opportunity was investigating with the instruments on its robotic arm. To the right of center and halfway down the of the frame is another rocky outcrop about 23 feet (7 meters) distant from the camera called "Ysleta del Sur" that Opportunity investigated from March 3 through 29, 2018, or sols 5,015 through 5,038. In the far right and left of the frame are the bottom of Perseverance Valley and the floor of Endeavour Crater. Located on the inner slope of the western rim of Endeavour Crater, Perseverance Valley is a system of shallow troughs descending eastward about the length of two football fields from the crest of Endeavour's rim to its floor. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22910

On Aug. 17 and 18, 2023, engineers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California tested the landing system for a proposed future mission that would touch down on Jupiter's icy moon Europa. This system for the proposed Europa Lander is an evolution of hardware used on previous NASA lander missions. It includes the architecture used for the "sky crane maneuver" that helped lower NASA's Curiosity and Perseverance rovers onto the Martian surface, which would give the lander the stability it needs during touchdown. Although this landing architecture was developed with Europa as the target, it could be adapted for use at other moons and celestial bodies with challenging terrain. Four bridles, suspended from an overhead simulated propulsive descent stage, maintain a level lander body. The four legs conform passively to the terrain they encounter as the lander body continues to descend toward the surface. Each leg consists of a four-bar linkage mechanism that controls the leg's pose before and during landing. The legs are preloaded downward with a constant force spring to help them rearrange and compress the surface they encounter prior to landing, giving them extra traction and stability during and after the landing event. Acting like a skid plate, the belly pan provides the underside of the spacecraft with protection from potentially harmful terrain. The belly pan also resists shear motion on the terrain it interacts with. Once the belly pan contacts the surface, sensors trigger a mechanism that quickly locks the legs' "hip" and "knee" rotary joints, resulting in a table-like stance. At this point, the job of ensuring lander stability shifts from the bridles to the legs. This shift keeps the lander level after the bridles are unloaded. In the event the belly pan does not encounter terrain during the touchdown process, sensors in each leg can also declare touchdown. After the leg joints lock, the belly pan would be suspended above the landed terrain, and the lander would be supported only by the four legs. Not pictured in the video is the period after the bridles are offloaded and flyaway is commanded. The bridles would then be cut, and the hovering propulsive stage would fly away, leaving the lander in a stable stance on the surface. Movie available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26010

These side-by-side images were taken by the Pan Camera (Pancam) on NASA's Opportunity rover. They're actually the same image; the left version is how the image originally came down, due to data dropouts. The right shows the same image after processing all the data. The image is from the 4,493rd Martian day, or sol, of the mission. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23248

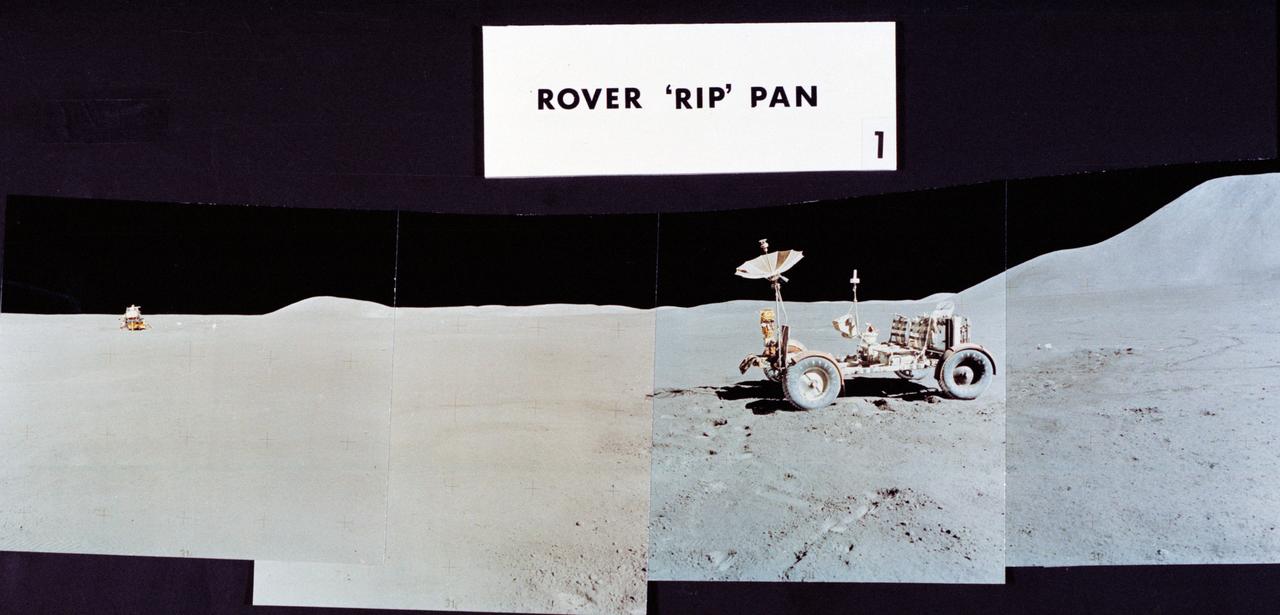

S71-43942 (2 Aug. 1971) --- This view is the second of a series of three mosaic photographs which compose a 360-degree panoramic view of the Apollo 15 Hadley-Apennine landing site, taken near the close of the third and final lunar surface extravehicular activity (EVA) by astronauts David R. Scott, commander, and James B. Irwin, lunar module pilot. This group of photographs was designated the Rover "RIP" Pan because the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) was parked in its final position prior to the two crew men returning to the Lunar Module (LM). The astronaut taking the pan was standing about 325 feet east of the LM. The LRV was parked about 300 feet east of the LM. This mosaic covers a field of view from about southeast to about west by northwest. Visible on the horizon from left to right are: Sliver Spur on the Apennine Front; Hadley Delta Mountain and St. George Crater; Bennett Hill; and the LM. The other two views which compose the 360-degree pan are S71-43940 and S71-43943.

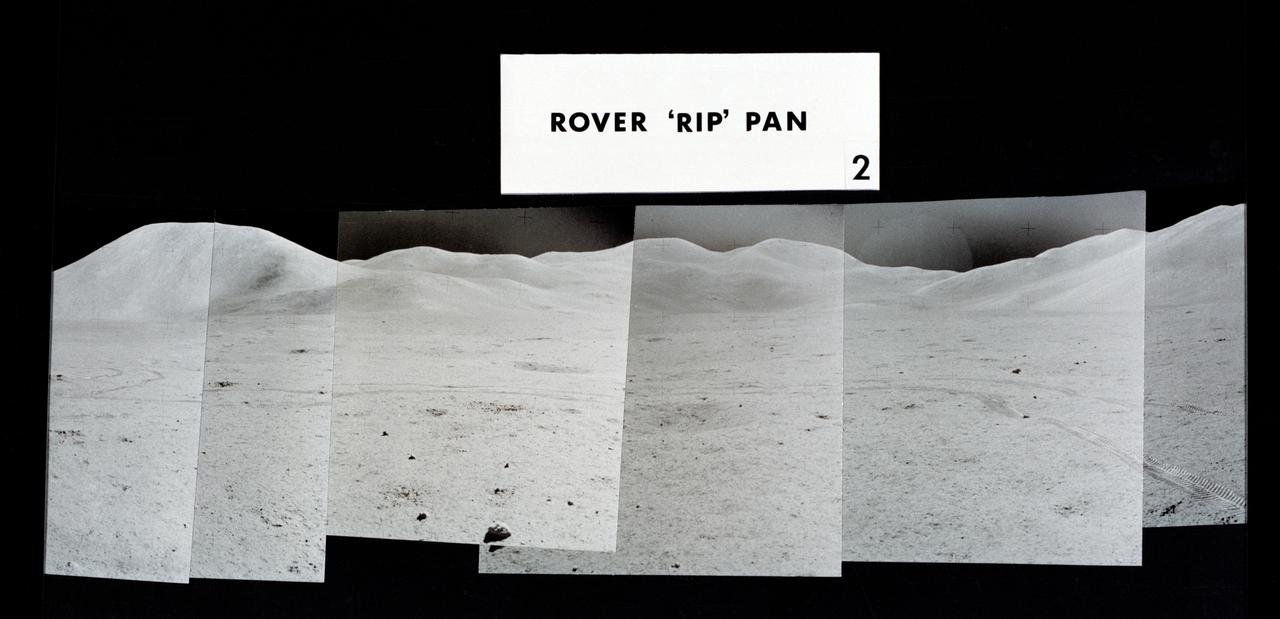

S71-43943 (2 Aug. 1971) --- Mosaic photographs which compose a 360-degree panoramic view of the Apollo 15 Hadley-Apennine landing site, taken near the close of the third lunar surface extravehicular activity (EVA) by astronauts David Scott and James Irwin. This group of photographs was designated the Rover "RIP" Pan because the Lunar Roving Vehicle was parked in its final position prior to the two crewmen returning to the Lunar Module. The astronaut taking the pan was standing 325 feet east of the Lunar Module (LM). The Rover was parked about 300 feet east of the LM. This mosaic covers a field of view from about north-northeast to about south. Visible on the horizon from left to right are: Mount Hadley; high peaks of the Apennine Mountains which are farther in the distance than either Mount Hadley or Hadley Delta Mountain; Silver Spur on the Apennine Front; and the eastern portion of Hadley Delta. Note Rover tracks in the foreground. The numbers of the other two views composing the 360-degree pan are S71-43940 and S71-43942.

Teachers, students, and parents listen as scientists explain what is different about the microgravity envirornment of space and why it is a valuable tool for research. This was part of the outreach session of the Pan Pacific Microgravity Conference on May 2, 2001, at the California Science Center.

Christened "Clipper Lindbergh" when it flew for Pan American Airways in the 1970s, the SOFIA 747SP shows evidence of modification to its aft fuselage contours to accommodate a 16-foot-tall opening for a 45,000-pound infrared telescope. This inflight photo was taken on SOFIA's first flight since its modification to become an airborne observatory.

Christened "Clipper Lindbergh" when it flew for Pan American Airways in the 1970s, the SOFIA 747SP shows evidence of modification to its aft fuselage contours to accommodate a 16-foot-tall opening for a 45,000-pound infrared telescope. This inflight photo was taken on SOFIA's first flight since its modification to become an airborne observatory.

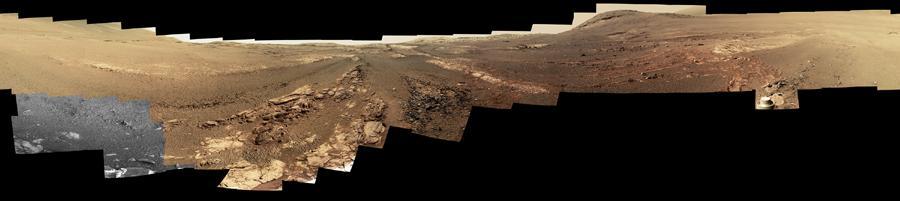

This 360-degree panorama is composed of 354 images taken by the Opportunity rover's Panoramic Camera (Pancam) from May 13 through June 10, 2018, or sols (Martian days) 5,084 through 5,111. This is the last panorama Opportunity acquired before the solar-powered rover succumbed to a global Martian dust storm on the same June 10. The view is presented in false color to make some differences between materials easier to see. To the right of center and near the top of the frame, the rim of Endeavour Crater rises in the distance. Just to the left of that, rover tracks begin their descent from over the horizon towards the location that would become Opportunity's final resting spot in Perseverance Valley, where the panorama was taken. At the bottom, just left of center, is the rocky outcrop Opportunity was investigating with the instruments on its robotic arm. To the right of center and halfway down the frame is another rocky outcrop - about 23 feet (7 meters) distant from the camera - called "Ysleta del Sur," which Opportunity investigated from March 3 through 29, 2018, or sols 5,015 through 5,038. In the far right and left of the frame are the bottom of Perseverance Valley and the floor of Endeavour Crater. Located on the inner slope of the western rim of Endeavour Crater, Perseverance Valley is a system of shallow troughs descending eastward about the length of two football fields from the crest of Endeavour's rim to its floor. This view combines images collected through three Pancam filters. The filters admit light centered on wavelengths of 753 nanometers (near-infrared), 535 nanometers (green) and 432 nanometers (blue). The three-color bands are combined. A few frames (bottom left) remain black and white, as the solar-powered rover did not have the time to photograph those locations using the green and violet filters before a severe Mars-wide dust storm swept in on June 2018. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22908

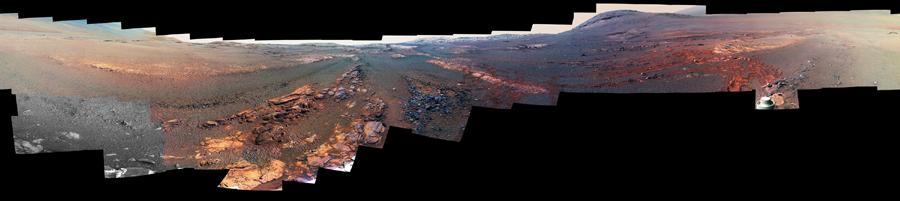

This 360-degree panorama is composed of 354 images taken by the Opportunity rover's Panoramic Camera (Pancam) from May 13 through June 10, 2018, or sols (Martian days) 5,084 through 5,111. This is the last panorama Opportunity acquired before the solar-powered rover succumbed to a global Martian dust storm on the same June 10. This version of the scene is presented in approximate true color. To the right of center and near the top of the frame, the rim of Endeavour Crater rises in the distance. Just to the left of that, rover tracks begin their descent from over the horizon towards the location that would become Opportunity's final resting spot in Perseverance Valley, where the panorama was taken. At the bottom, just left of center, is the rocky outcrop Opportunity was investigating with the instruments on its robotic arm. To the right of center and halfway down the frame is another rocky outcrop - about 23 feet (7 meters) distant from the camera - called "Ysleta del Sur," which Opportunity investigated from March 3 through 29, 2018, or sols 5,015 through 5,038. In the far right and left of the frame are the bottom of Perseverance Valley and the floor of Endeavour Crater. Located on the inner slope of the western rim of Endeavour Crater, Perseverance Valley is a system of shallow troughs descending eastward about the length of two football fields from the crest of Endeavour's rim to its floor. This true-color version combines images collected through three Pancam filters. The filters admit light centered on wavelengths of 753 nanometers (near-infrared), 535 nanometers (green) and 432 nanometers (blue). The three-color bands are combined. A few frames (bottom left) remain black and white, as the solar-powered rover did not have the time to photograph those locations using the green and violet filters before a severe Mars-wide dust storm swept in on June 2018. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22909

This image shows a microscopic view of fine-grained material at the tip of the Robotic Arm scoop as seen by the Robotic Arm Camera RAC aboard NASA Phoenix Mars Lander on June 20, 2008, the 26th Martian day, or sol, of the mission.

Marshall Space Flight Center employees visited DuPont Manual High School in Louisville, Kentucky. NASA's Mini Drop Tower was used to demonstrate free fall and a presentation was given on microgravity and the science performed in a microgravity environment. The visit coincided with the Pan-Pacific Basin Workshop on Microgravity Sciences held in Pasadena, California. Materials engineer Chris Cochrane explains the operation of the mini-drop tower. This image is from a digital still camera; higher resolution is not available.

Students from DuPont Manual High School in Louisville, Kentucky participated in a video-teleconference during the Pan-Pacific Basin Workshop on Microgravity Sciences held in Pasadena, California. The event originated at the California Science Center in Los Angeles. The DuPont Manual students patched in to the event through the distance learning lab at the Louisville Science Center. Education coordinator Twila Schneider (left) of Infinity Technology and NASA materials engineer Chris Cochrane prepare students for the on-line workshop. This image is from a digital still camera; higher resolution is not available.

Students from DuPont Manual High School in Louisville, Kentucky participated in a video-teleconference during the Pan-Pacific Basin Workshop on Microgravity Sciences held in Pasadena, California. The event originated at the California Science Center in Los Angeles. The DuPont Manual students patched in to the event through the distance learning lab at the Louisville Science Center. This image is from a digital still camera; higher resolution is not available.

Suzarne Nichols (12th grade) from DuPont Manual High School in Louisville, Kentucky, asks a question of on of the on-line lecturers during the Pan-Pacific Basin Workshop on Microgravity Sciences held in Pasadena, California. The event originated at the California Science Center in Los Angeles. The DuPont Manual students patched in to the event through the distance learning lab at the Louisville Science Center. Jie Ma (grade 10, at right) waits her turn to ask a question. This image is from a digital still camera; higher resolution is not available.

Sutta Chernubhotta (grade 10) from DuPont Manual High School in Louisville, Kentucky, asks a question of on of the on-line lecturers during the Pan-Pacific Basin Workshop on Microgravity Sciences held in Pasadena, California. The event originated at the California Science Center in Los Angeles. The DuPont Manual students patched in to the event through the distance learning lab at the Louisville Science Center. This image is from a digital still camera; higher resolution is not available.

Marshall Space Flight Center employees visited DuPont Manual High School in Louisville, Kentucky. NASA's Mini Drop Tower was used to demonstrate free fall and a presentation was given on microgravity and the science performed in a microgravity environment. The visit coincided with the Pan-Pacific Basin Workshop on Microgravity Sciences held in Pasadena, California. Students watch the playback of video from the mini-drop tower. This image is from a digital still camera; higher resolution is not available.