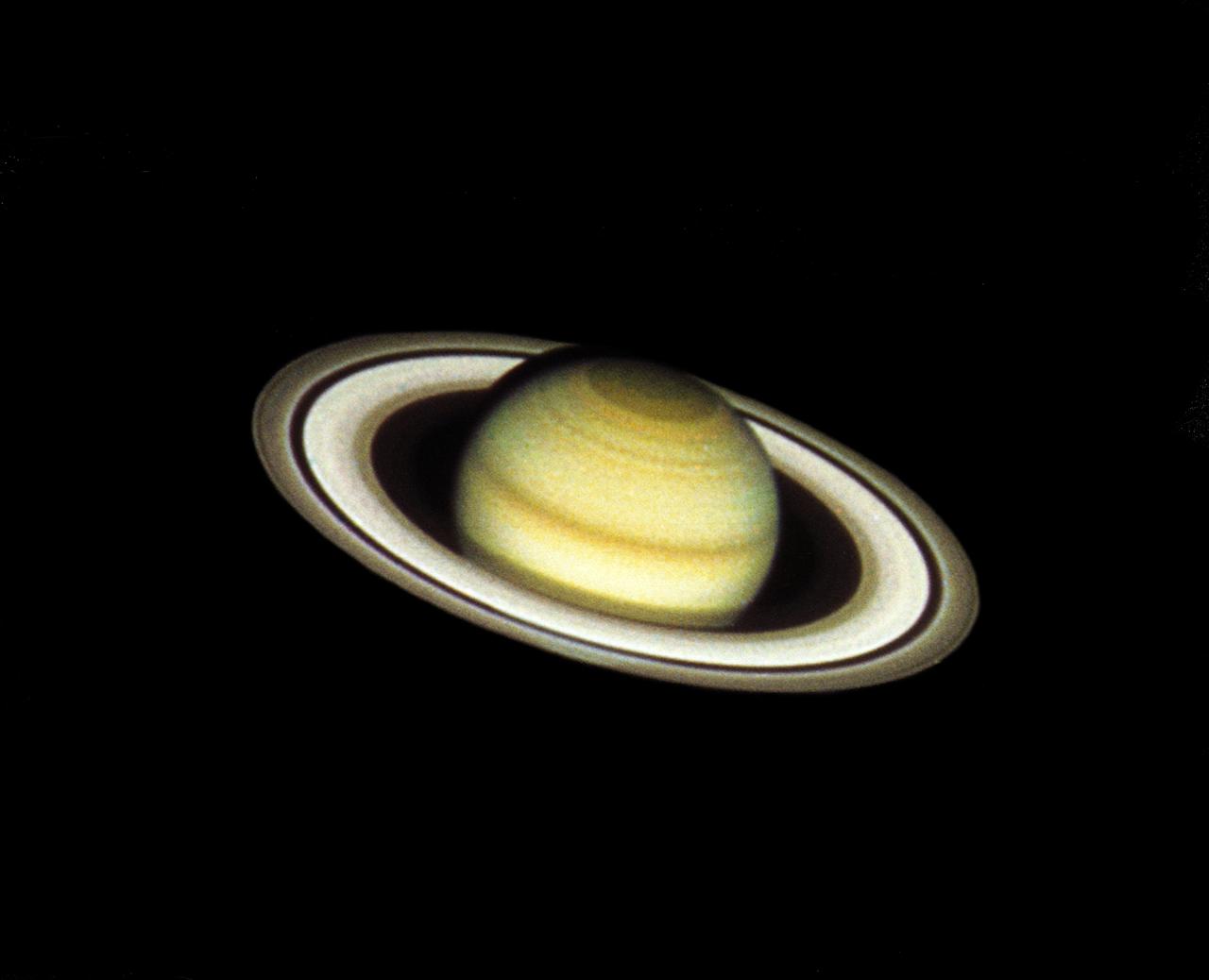

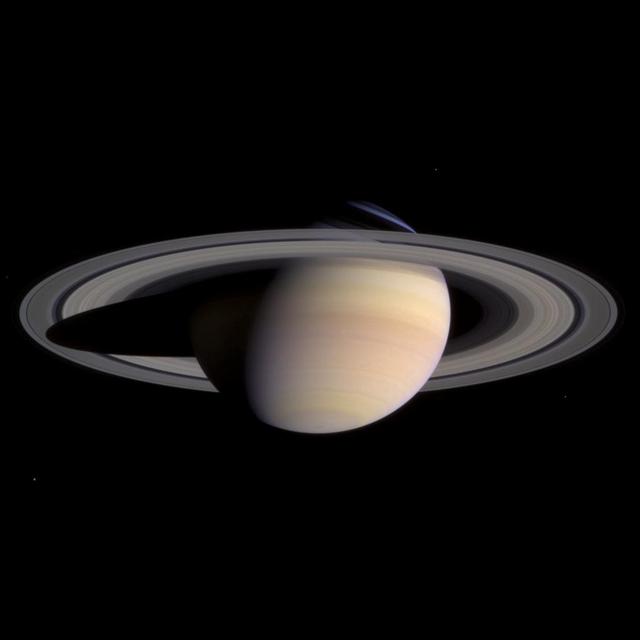

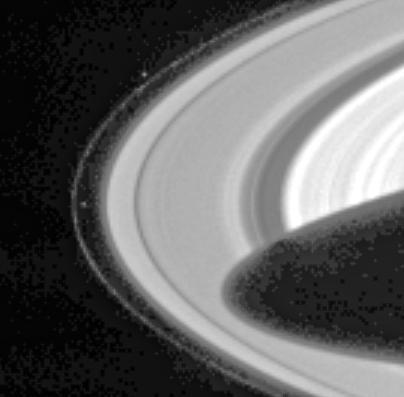

This color image of Saturn was taken with the Hubble Space Telescope's (HST's) Wide Field Camera (WFC) at 3:25 am EDT, August 26, 1990, when the planet was at a distance of 2.39 million km (360 million miles) from Earth. The color in the image is reconstructed by combining three different pictures, taken in blue, green and red light (4390, 5470 and 7180 angstroms). Because Saturn's north pole is currently tilted toward Earth (24 degrees), the HST image reveals unprecedented detail in atmospheric features at the northern polar hood, a region not extensively imaged by the Voyager space probes. The classic features of Saturn's vast ring system are also clearly seen from outer to irner edge; the bright A and B rings, divided by the Cassini division, and the very faint inner C ring. The Enche division, a dark gap near the outer edge of the A ring, has never before been photographed from Earth.

Saturn has long inspired astronomers, from Galileo’s first glimpse of its rings in 1610 to the last pictures taken by the Cassini spacecraft as it descended toward the planet’s atmosphere in 2017. But after four centuries of observing Saturn with telescopes, robotic flybys and orbiters, what might it look like to visit in person and witness the jewel of the solar system rising above one of its many natural satellites? Here we imagine the scene. Gazing over the south pole of the small moon Enceladus, geysers burst forth from cracks in the ice, scattering sunlight and forming a luminous veil around Saturn. In the distance, the large moons Rhea (right) and Titan (left) make their rounds of the gas giant’s far side. These bodies were discovered in the 17th century by astronomers Giovanni Domenico Cassini and Christiaan Huygens – the namesakes of the Cassini-Huygens mission, which explored the Saturn system from 2004 to 2017. The wealth of data and imagery returned by Cassini-Huygens vastly improved our understanding of the ringed planet and paved the way for future exploration.

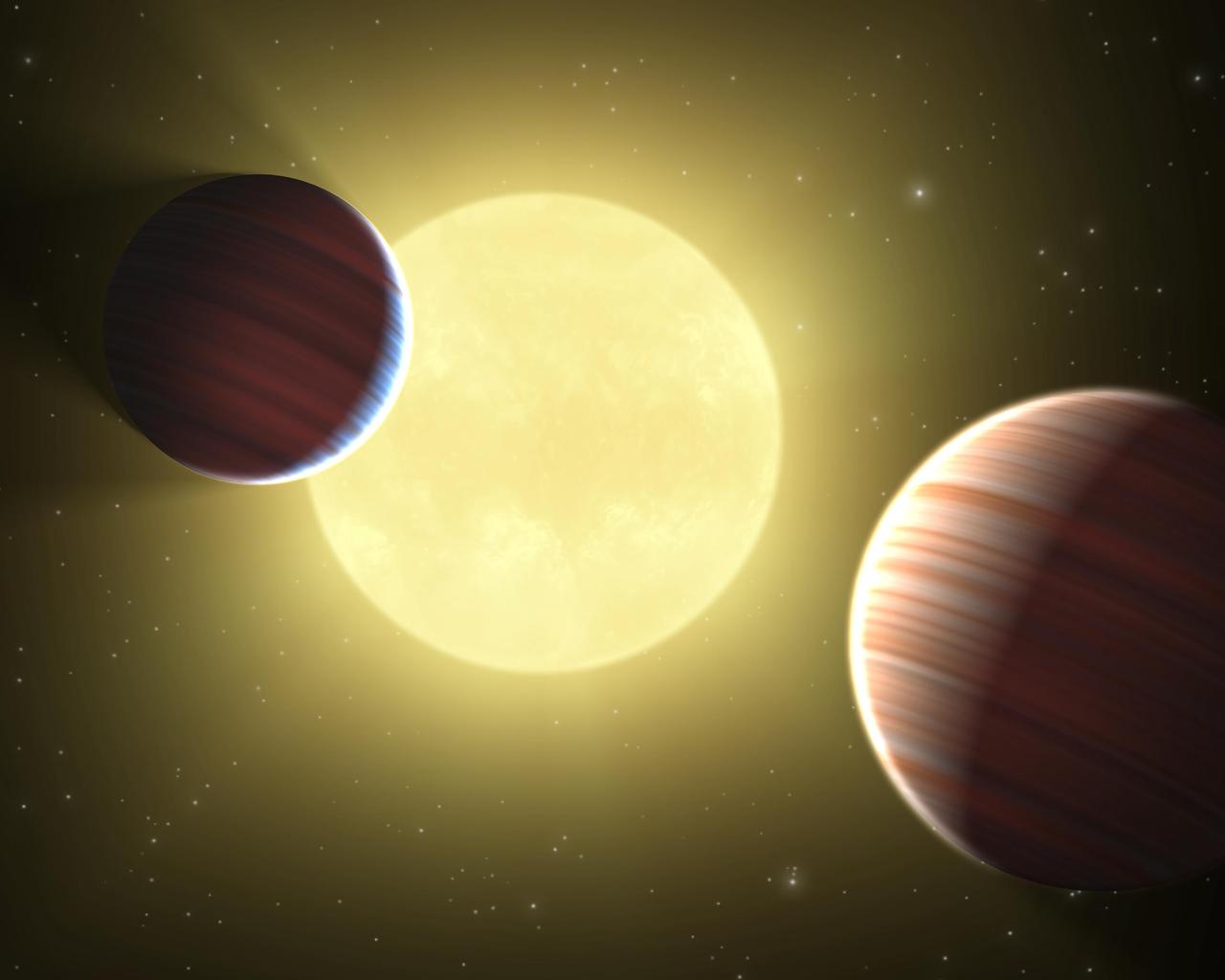

This artist concept illustrates the two Saturn-sized planets discovered by NASA Kepler mission. The star system is oriented edge-on, as seen by Kepler, such that both planets cross in front, or transit, their star, named Kepler-9.

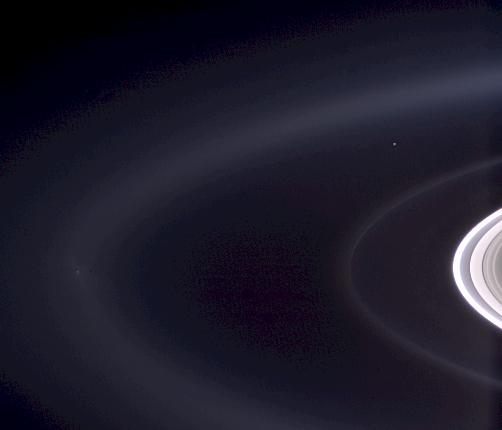

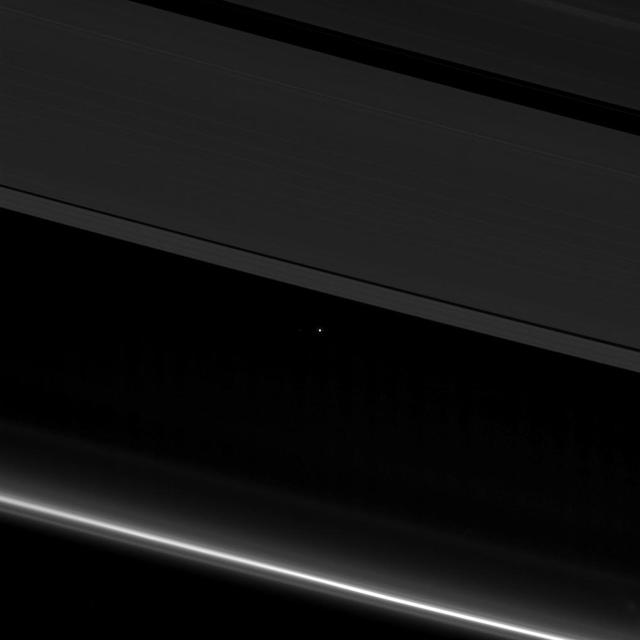

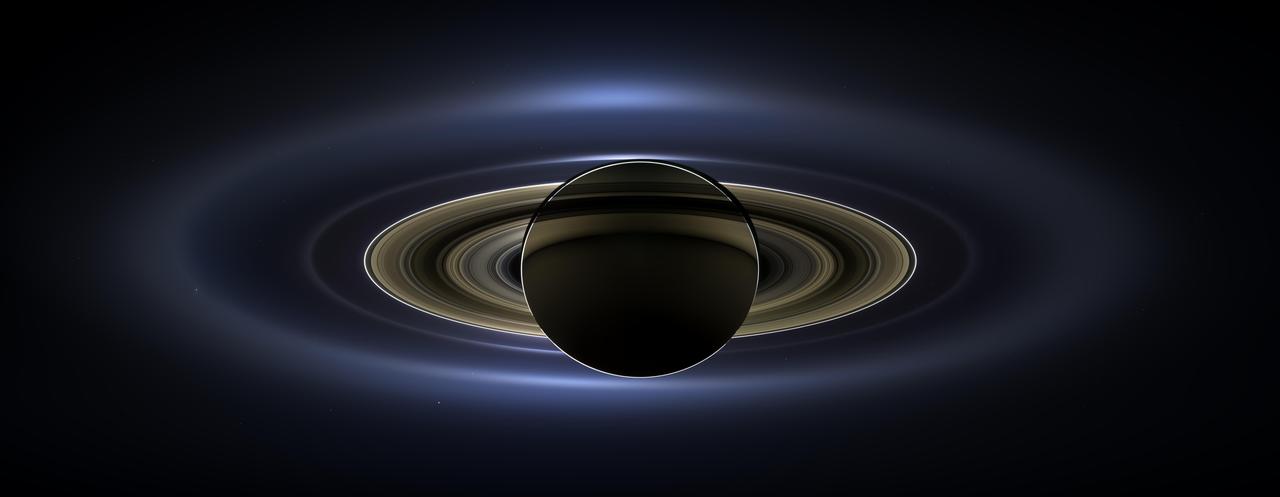

Cassini casts powerful eyes on our home planet, and captures Earth, a pale blue orb -- and a faint suggestion of our moon -- among the glories of the Saturn system.

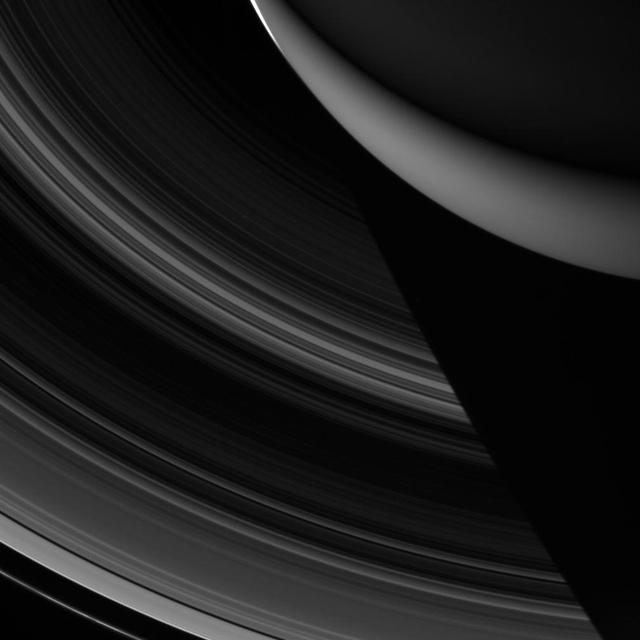

Saturn entire main ring system spreads out below Cassini in this night side view, which shows the rings disappearing into the planet shadow

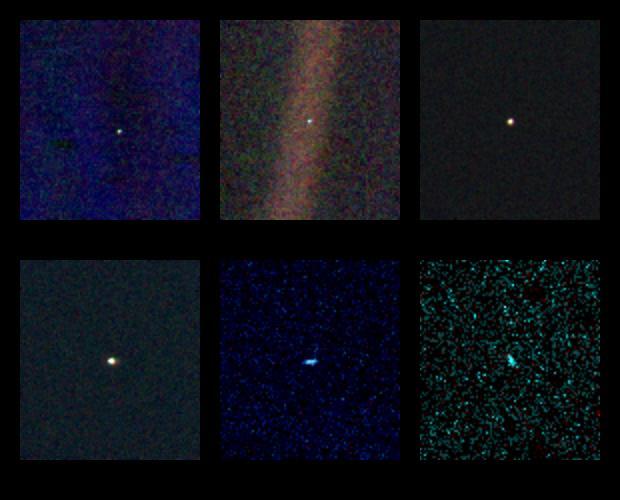

NASA Cassini casts powerful eyes on our home planet, and captures Earth, a pale blue orb, and a faint suggestion of our moon, among the glories of the Saturn system in this image taken Sept. 15, 2006.

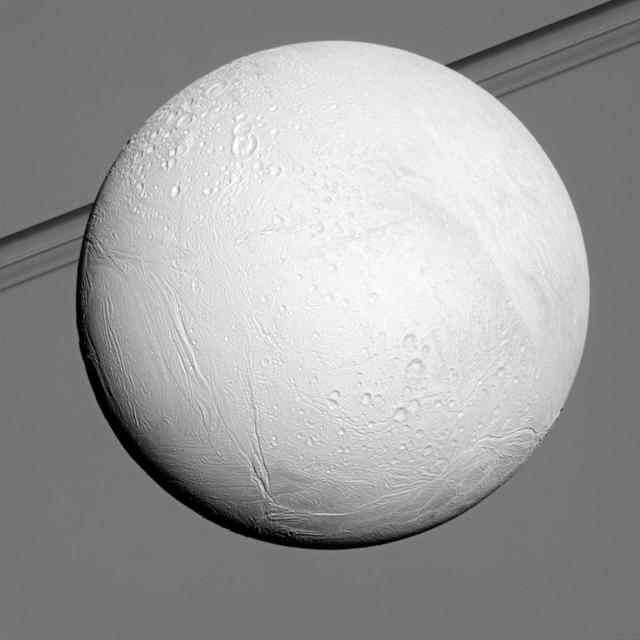

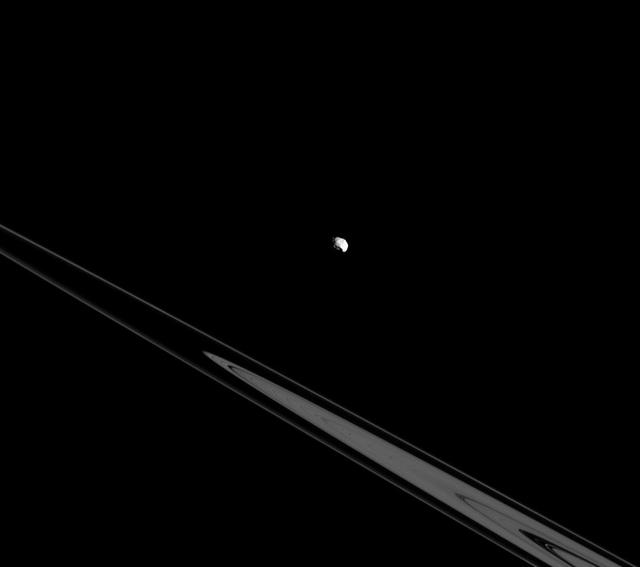

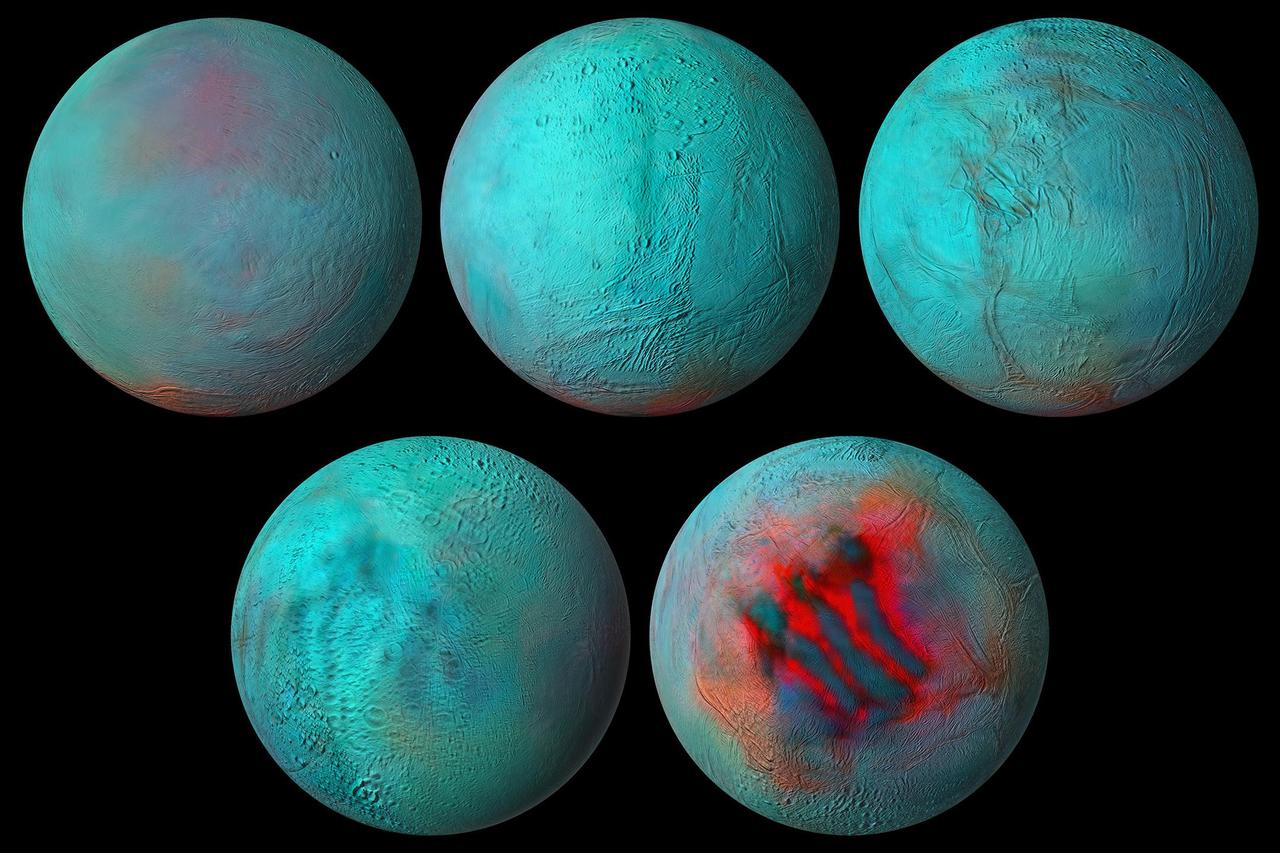

Saturn moon Enceladus reflects sunlight brightly while the planet and its rings fill the background in this view from NASA Cassini spacecraft. Enceladus is one of the most reflective bodies in the solar system.

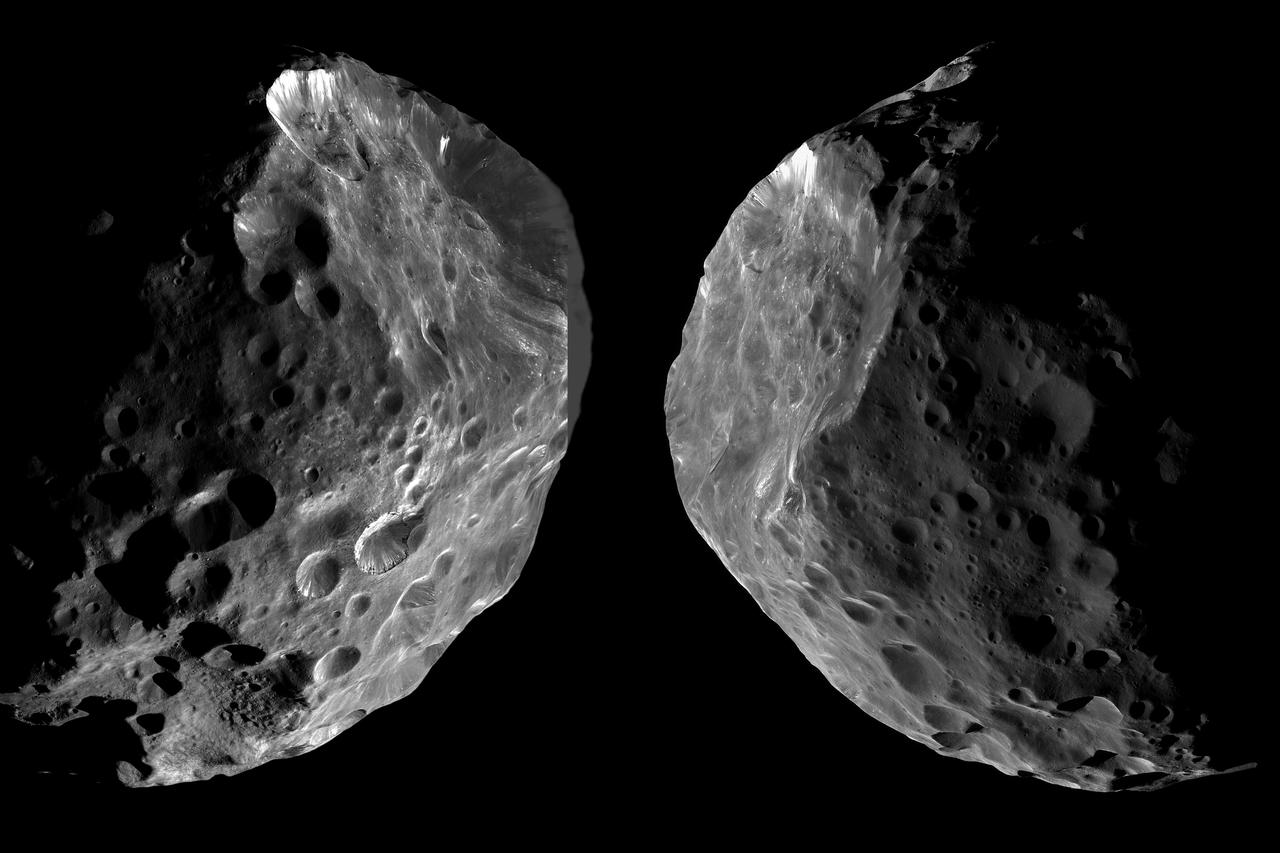

The image on the left shows Cassini view on approach to Phoebe, while the right shows the spacecraft departing perspective. As it entered the Saturn system, NASA Cassini spacecraft performed its first targeted flyby of one of the planet moons.

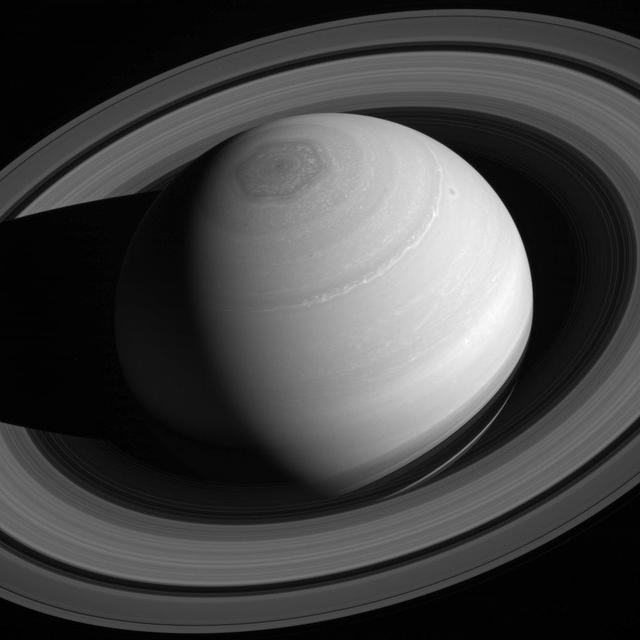

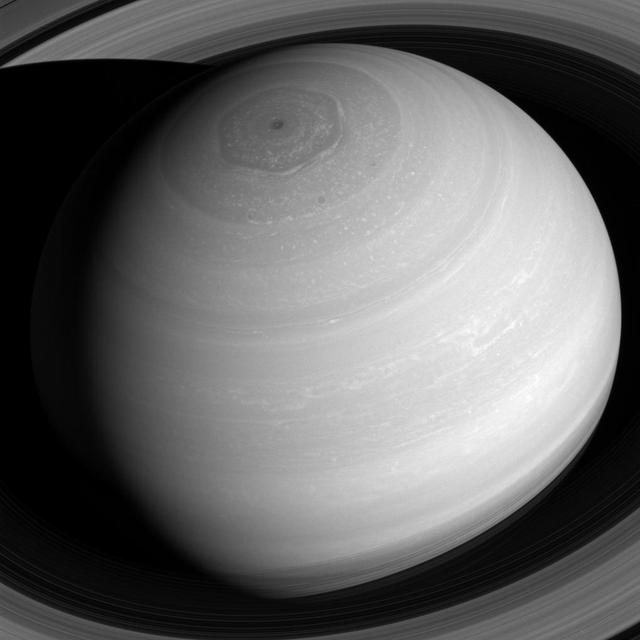

Saturn reigns supreme, encircled by its retinue of rings. Although all four giant planets have ring systems, Saturn's is by far the most massive and impressive. Scientists are trying to understand why by studying how the rings have formed and how they have evolved over time. Also seen in this image is Saturn's famous north polar vortex and hexagon. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 37 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on May 4, 2014 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 2 million miles (3 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 110 miles (180 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18278

MITZI ADAMS, MARSHALL SCIENTIST, TALKED WITH STUDENTS AT THE U.S. SPACE AND ROCKET CENTER ON FRIDAY, JULY 19 ABOUT THE PLANET SATURN. STUDENTS PARTICIPATED ALONG WITH LEGIONS OF SMILING EARTHLINGS IN A WAVE AT SATURN FOR A COSMIC PHOTO OP AS NASA’S CASSINI TOOK A COSMIC PHOTO OF THE WHOLE SATURN SYSTEM AND EARTH.

MITZI ADAMS, MARSHALL SCIENTIST, TALKED WITH STUDENTS AT THE U.S. SPACE AND ROCKET CENTER ON FRIDAY, JULY 19 ABOUT THE PLANET SATURN. STUDENTS PARTICIPATED ALONG WITH LEGIONS OF SMILING EARTHLINGS IN A WAVE AT SATURN FOR A COSMIC PHOTO OP AS NASA’S CASSINI TOOK A COSMIC PHOTO OF THE WHOLE SATURN SYSTEM AND EARTH.

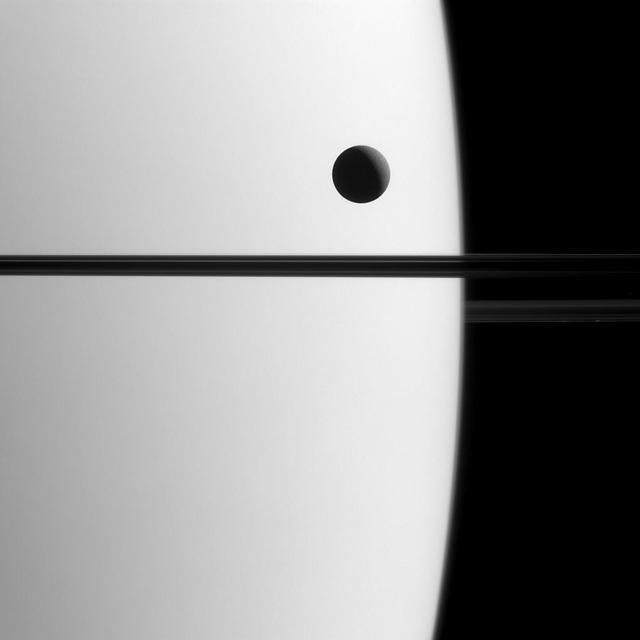

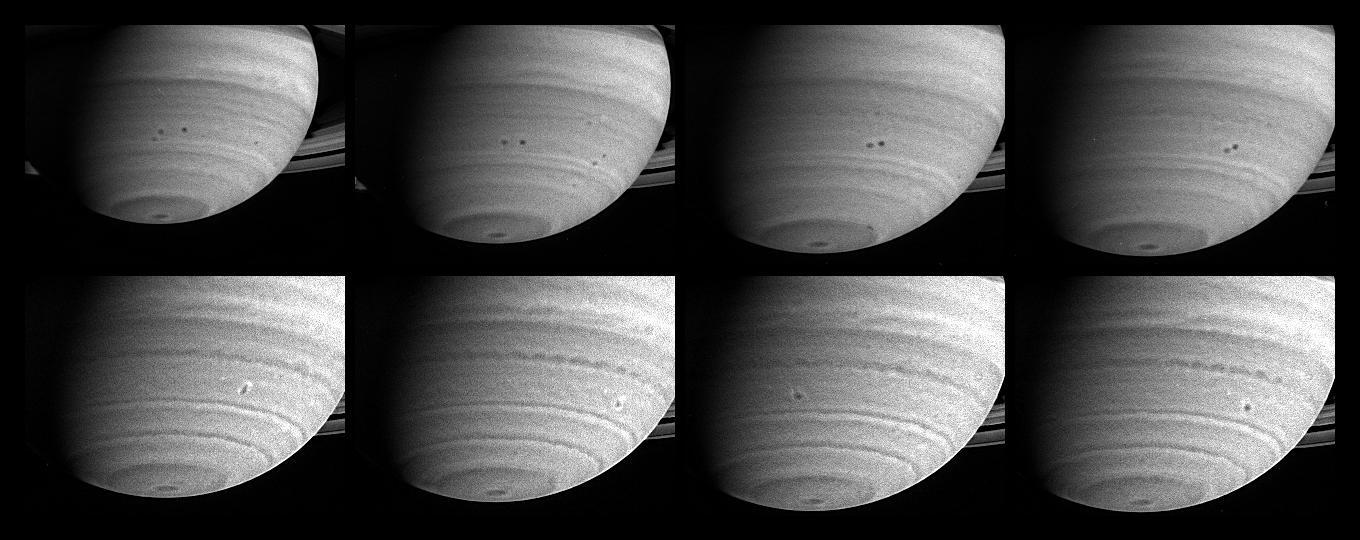

Saturn's moon Dione crosses the face of the giant planet in this view, a phenomenon astronomers call a transit. Transits play an important role in astronomy and can be used to study the orbits of planets and their atmospheres, both in our solar system and in others. By carefully timing and observing transits in the Saturn system, like that of Dione (698 miles or 1123 kilometers across), scientists can more precisely determine the orbital parameters of Saturn's moons. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 0.3 degrees below the ring plane. The image was taken in visible green light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on May 21, 2015. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.4 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 119 degrees. Image scale is 9 miles (14 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18330

On October of 1997, a two-story-tall robotic spacecraft will begin a journey of many years to reach and explore the exciting realm of Saturn, the most distant planet that can easily be seen by the unaided human eye. In addition to Saturn's interesting atmosphere and interior, its vast system contains the most spectacular of the four planetary ring systems, numerous icy satellites with a variety of unique surface features. A huge magnetosphere teeming with particles that interact with the rings and moons, and the intriguing moon Titan, which is slightly larger than the planet Mercury, and whose hazy atmosphere is denser than that of Earth, make Saturn a fascinating planet to study. The Cassini mission is an international venture involving NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), the Italian Space Agency (ASI), and several separate European academic and industrial partners. The mission is managed for NASA by JPL. The spacecraft will carry a sophisticated complement of scientific sensors to support 27 different investigations to probe the mysteries of the Saturn system. The large spacecraft will consist of an orbiter and ESA's Huygens Titan probe. The orbiter mass at launch will be nearly 5300 kg, over half of which is propellant for trajectory control. The mass of the Titan probe (2.7 m diameter) is roughly 350 kg. The mission is named in honor of the seventeenth-century, French-Italian astronomer Jean Dominique Cassini, who discovered the prominent gap in Saturn's main rings, as well as the icy moons Iapetus, Rhea, Dione, and Tethys. The ESA Titan probe is named in honor of the exceptional Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens, who discovered Titan in 1655, followed in 1659 by his announcement that the strange Saturn "moons" seen by Galileo in 1610 were actually a ring system surrounding the planet. Huygens was also famous for his invention of the pendulum clock, the first accurate timekeeping device. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04603

Saturn's shadow stretched beyond the edge of its rings for many years after Cassini first arrived at Saturn, casting an ever-lengthening shadow that reached its maximum extent at the planet's 2009 equinox. This image captured the moment in 2015 when the shrinking shadow just barely reached across the entire main ring system. The shadow will continue to shrink until the planet's northern summer solstice, at which point it will once again start lengthening across the rings, reaching across them in 2019. Like Earth, Saturn is tilted on its axis. And, just as on Earth, as the sun climbs higher in the sky, shadows get shorter. The projection of the planet's shadow onto the rings shrinks and grows over the course of its 29-year-long orbit, as the angle of the sun changes with respect to Saturn's equator. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 11 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Jan. 16, 2015. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.6 million miles (2.5 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is about 90 miles (150 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20498

Seen by NASA Cassini spacecraft, Tethys, like many moons in the solar system, keeps one face pointed towards the planet around which it orbits. Tethys anti-Saturn face is seen here, fully illuminated, basking in sunlight. The Odysseus crater is 280 miles (450 kilometers) across while Tethys is 660 miles (1,062 kilometers) across. See PIA07693 for a closer view and more information on the Odysseus crater. This view looks toward the anti-Saturn side of Tethys. North on Tethys is up and rotated 33 degrees to the right. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on June 15, 2013. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 503,000 miles (809,000 kilometers) from Tethys. Image scale is 3 miles (5 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18275

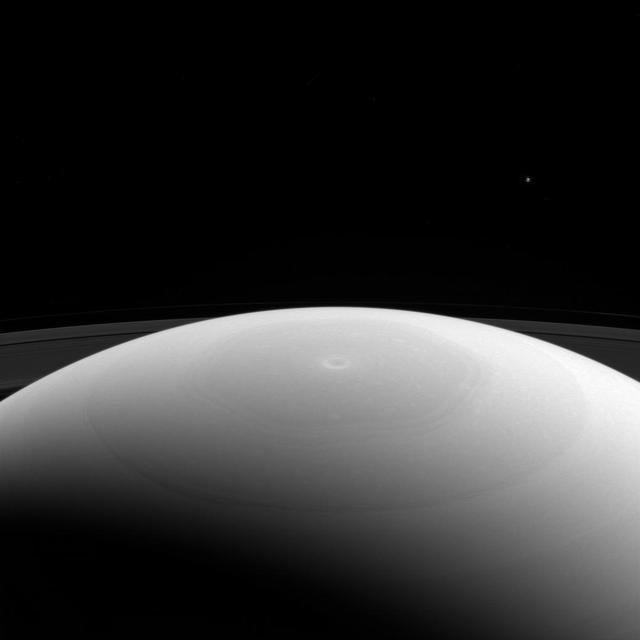

An illusion of perspective, Saturn's moon Tethys seems to hang above the planet's north pole in this view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft. Tethys (660 miles or 1,062 kilometers across) is actually farther away than Saturn in this image. Lacking visual clues about distance, our brains place the moon above Saturn's north pole. Tethys, like all of Saturn's major moons and its ring system, orbits almost exactly in the planet's equatorial plane. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 17 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft's wide-angle camera on Jan. 26, 2015 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 2.1 million miles (3.4 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale on Saturn is 120 miles (200 kilometers) per pixel. Tethys has been brightened by a factor of three relative to Saturn to enhance its visibility. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20488

The Titan IVB core vehicle and its twin Solid Rocket Motor Upgrades (SRMUs) which will be used to propel the Cassini spacecraft to its final destination, Saturn, approaches the pad at Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral Air Station. At the pad, the Centaur upper stage will be added and, eventually, the prime payload, the Cassini spacecraft. Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6

The Titan IVB core vehicle and its twin Solid Rocket Motor Upgrades (SRMUs) which will be used to propel the Cassini spacecraft to its final destination, Saturn, arrive at the pad at Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral Air Station. At the pad, the Centaur upper stage will be added and, eventually, the prime payload, the Cassini spacecraft. Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6

The Titan IVB core vehicle and its twin Solid Rocket Motor Upgrades (SRMUs) which will be used to propel the Cassini spacecraft to its final destination, Saturn, arrive at the pad at Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral Air Station. At the pad, the Centaur upper stage will be added and, eventually, the prime payload, the Cassini spacecraft. Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6

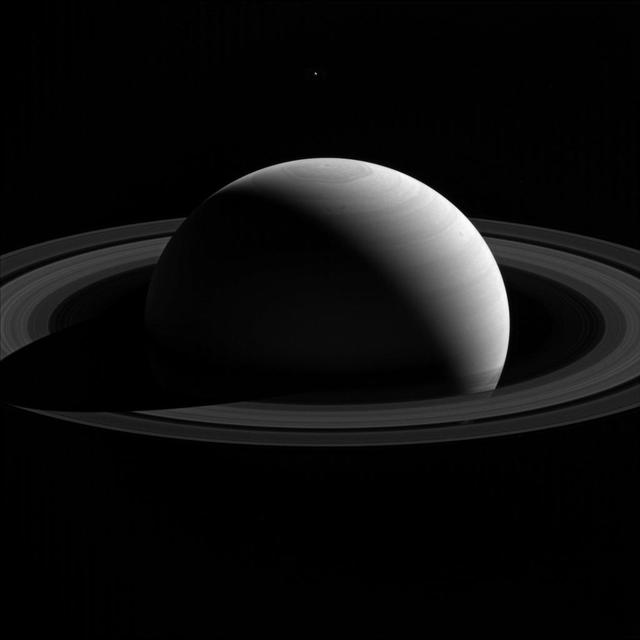

Saturn appears as a serene globe amid tranquil rings in this view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft. In reality, the planet's atmosphere is an ever-changing scene of high-speed winds and evolving weather patterns, punctuated by occasional large storms (see PIA14901). The rings, consist of countless icy particles, which are continually colliding. Such collisions play a key role in the rings' numerous waves and wakes, which are the manifestation of the subtle influence of Saturn's moons and, indeed, the planet itself. The long duration of the Cassini mission has allowed scientists to study how the atmosphere and rings of Saturn change over time, providing much-needed insights into this active planetary system. The view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 41 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on July 16, 2016 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1 million miles (2 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 68 miles (110 kilometers) per pixel. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 752,000 miles (1.21 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 6 degrees. Image scale is 45 miles (72 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20502

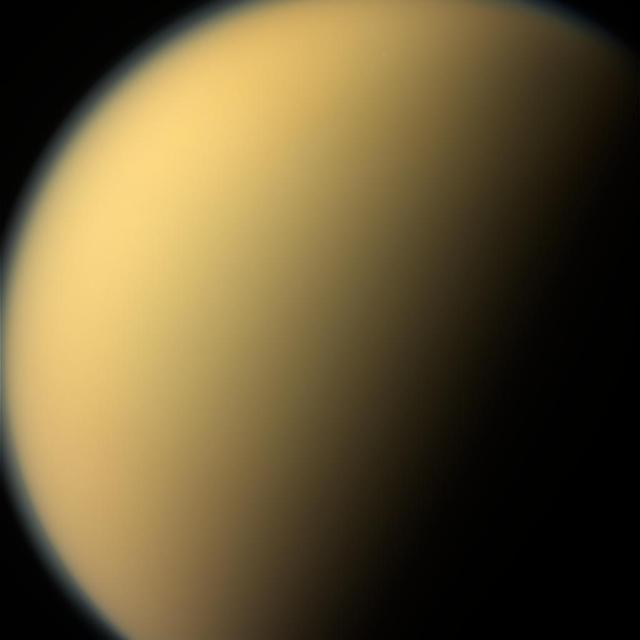

Titan may be a "large" moon -- its name even implies it! -- but it is still dwarfed by its parent planet, Saturn. As it turns out, this is perfectly normal. Although Titan (3200 miles or 5150 kilometers across) is the second-largest moon in the solar system, Saturn is still much bigger, with a diameter almost 23 times larger than Titan's. This disparity between planet and moon is the norm in the solar system. Earth's diameter is "only" 3.7 times our moon's diameter, making our natural satellite something of an oddity. (Another exception to the rule: dwarf planet Pluto's diameter is just under two times that of its moon.) So the question isn't why is Titan so small (relatively speaking), but why is Earth's moon so big? This view looks toward the anti-Saturn hemisphere of Titan. North on Titan is up. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on April 18, 2015 using a near-infrared spectral filter with a passband centered at 752 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Titan. Image scale is 56 miles (90 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18326

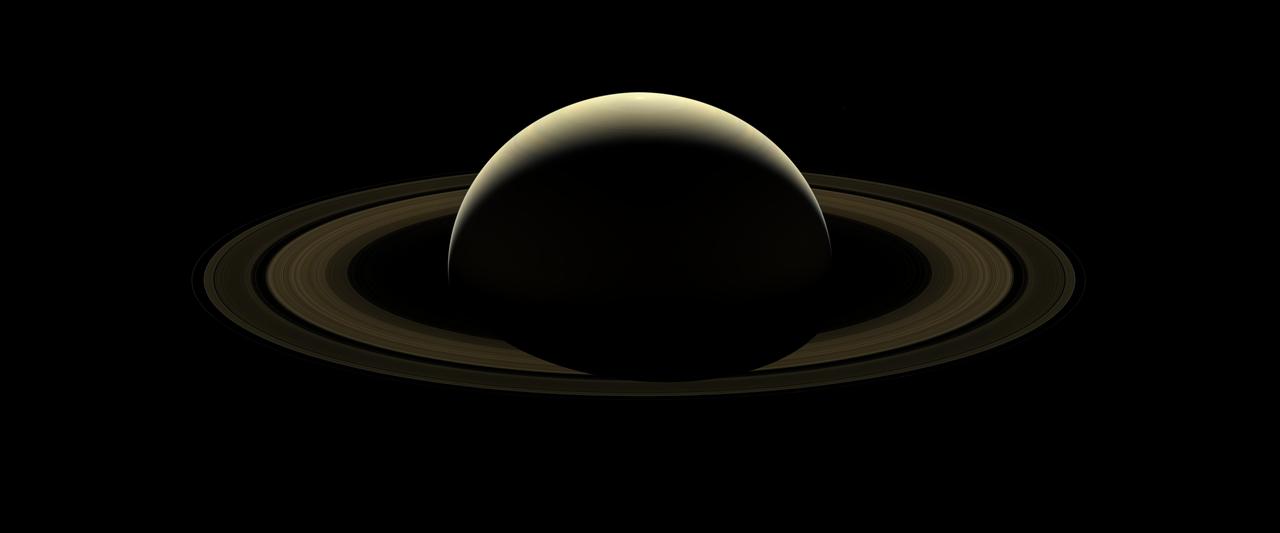

With this view, Cassini captured one of its last looks at Saturn and its main rings from a distance. The Saturn system has been Cassini's home for 13 years, but that journey is nearing its end. Cassini has been orbiting Saturn for nearly a half of a Saturnian year but that journey is nearing its end. This extended stay has permitted observations of the long-term variability of the planet, moons, rings, and magnetosphere, observations not possible from short, fly-by style missions. When the spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004, the planet's northern hemisphere, seen here at top, was in darkness, just beginning to emerge from winter. Now at journey's end, the entire north pole is bathed in the continuous sunlight of summer. Images taken on Oct. 28, 2016 with the wide angle camera using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this color view. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 25 degrees above the ringplane. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 870,000 miles (1.4 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 50 miles (80 kilometers) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21345

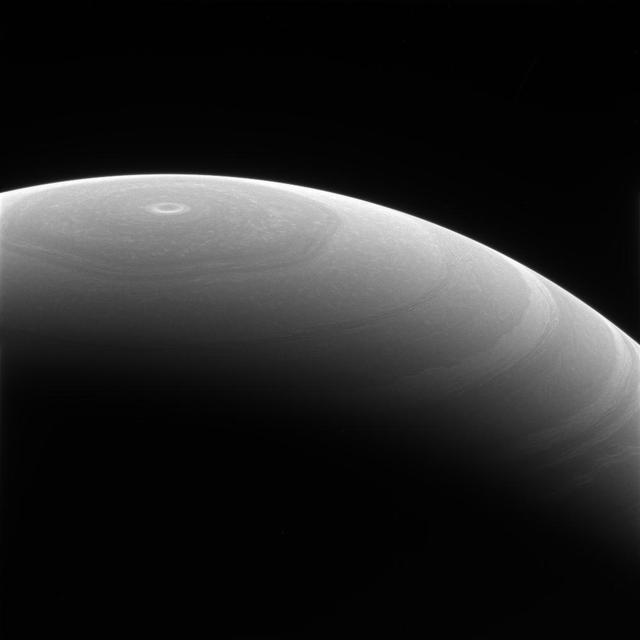

When imaged by NASA Cassini spacecraft at infrared wavelengths that pierce the planet upper haze layer, the high-speed winds of Saturn atmosphere produce watercolor-like patterns. With no solid surface creating atmospheric drag, winds on Saturn can reach speeds of more than 1,100 miles per hour (1,800 kilometers per hour) -- some of the fastest in the solar system. This view was taken from a vantage point about 28 degrees above Saturn's equator. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Dec. 2, 2016, with a combination of spectral filters which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 728 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 592,000 miles (953,000 kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 35 miles (57 kilometers) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20528

This view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft shows planet Earth as a point of light between the icy rings of Saturn. The spacecraft captured the view on April 12, 2017 at 10:41 p.m. PDT (1:41 a.m. EDT). Cassini was 870 million miles (1.4 billion kilometers) away from Earth when the image was taken. Although far too small to be visible in the image, the part of Earth facing toward Cassini at the time was the southern Atlantic Ocean. Earth's moon is also visible to the left of our planet in a cropped, zoomed-in version of the image (Figure 1). The rings visible here are the A ring (at top) with the Keeler and Encke gaps visible, and the F ring (at bottom). During this observation Cassini was looking toward the backlit rings, making a mosaic of multiple images, with the sun blocked by the disk of Saturn. Seen from Saturn, Earth and the other inner solar system planets are all close to the sun, and are easily captured in such images, although these opportunities have been somewhat rare during the mission. The F ring appears especially bright in this viewing geometry. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21445

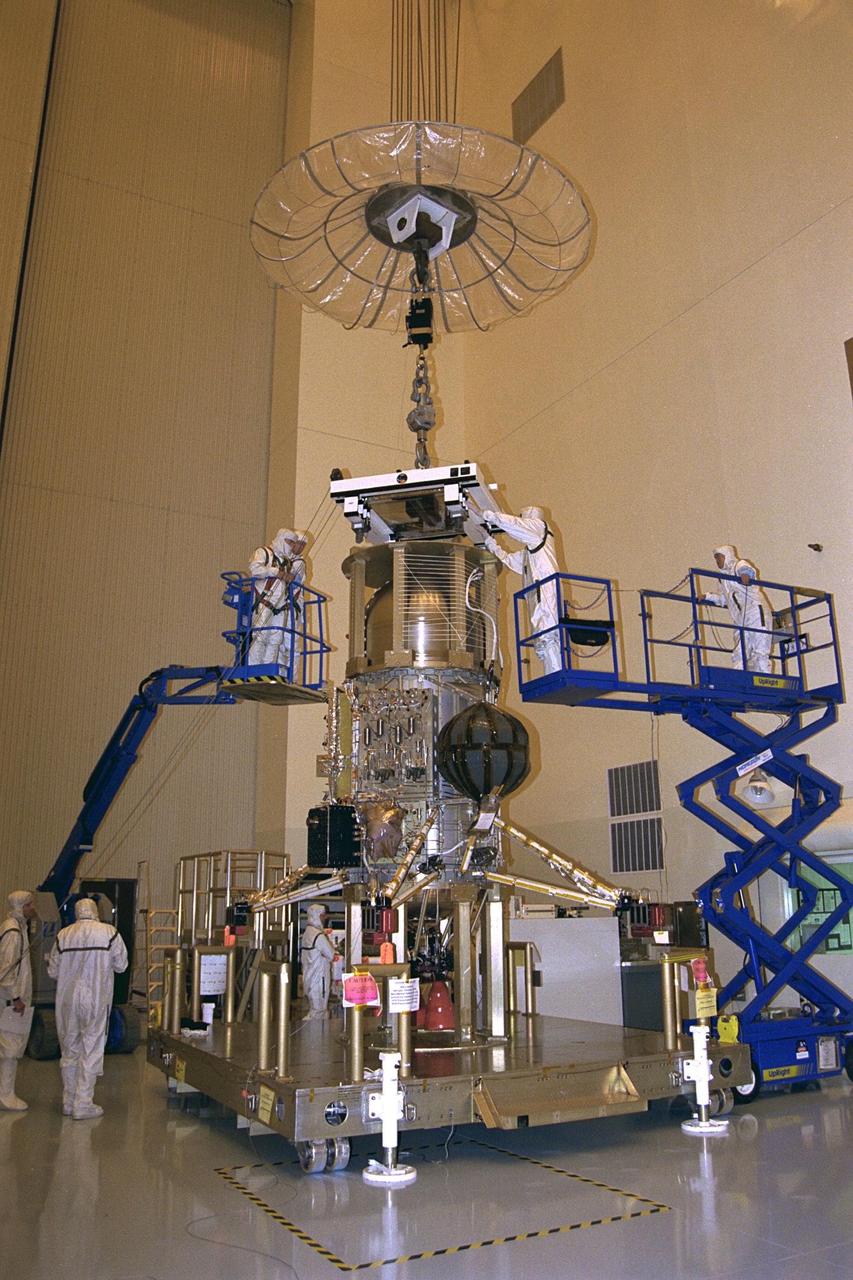

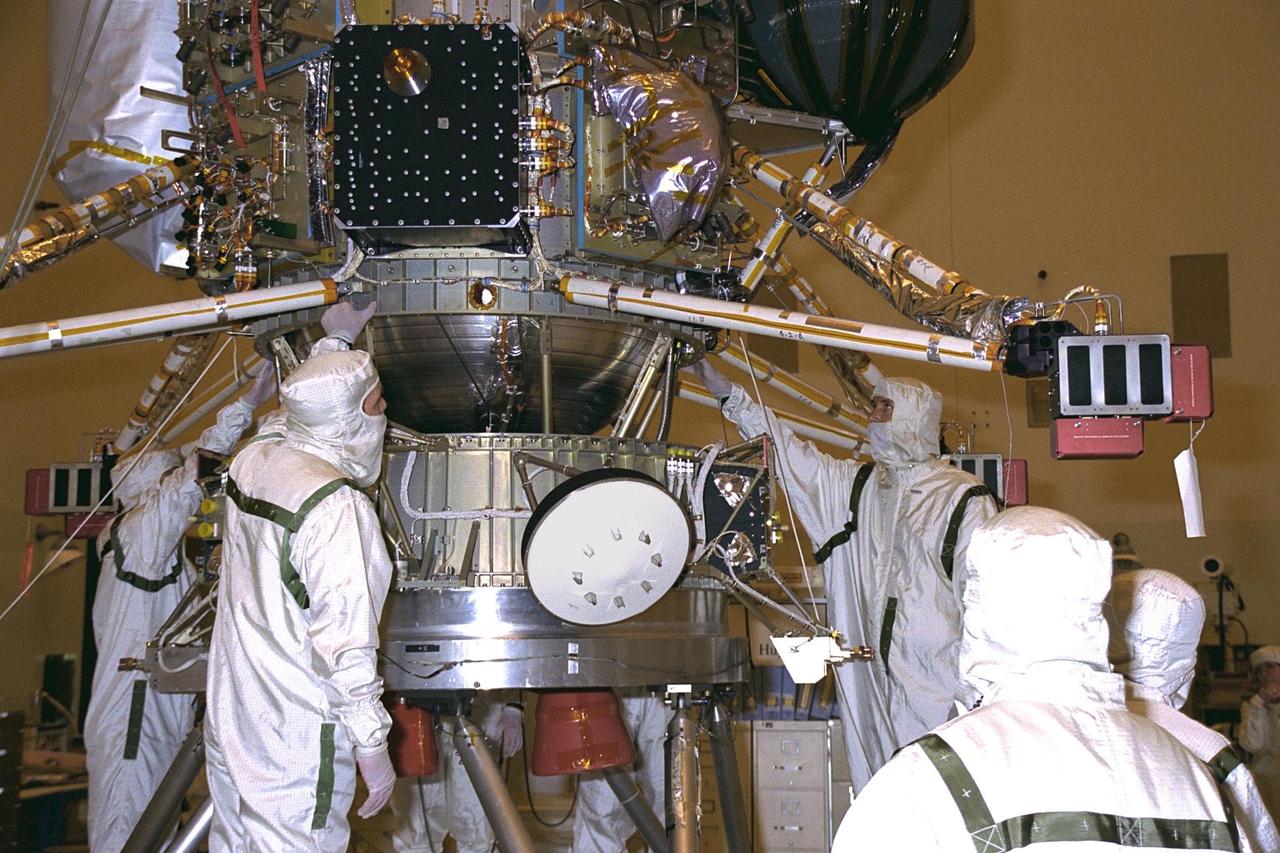

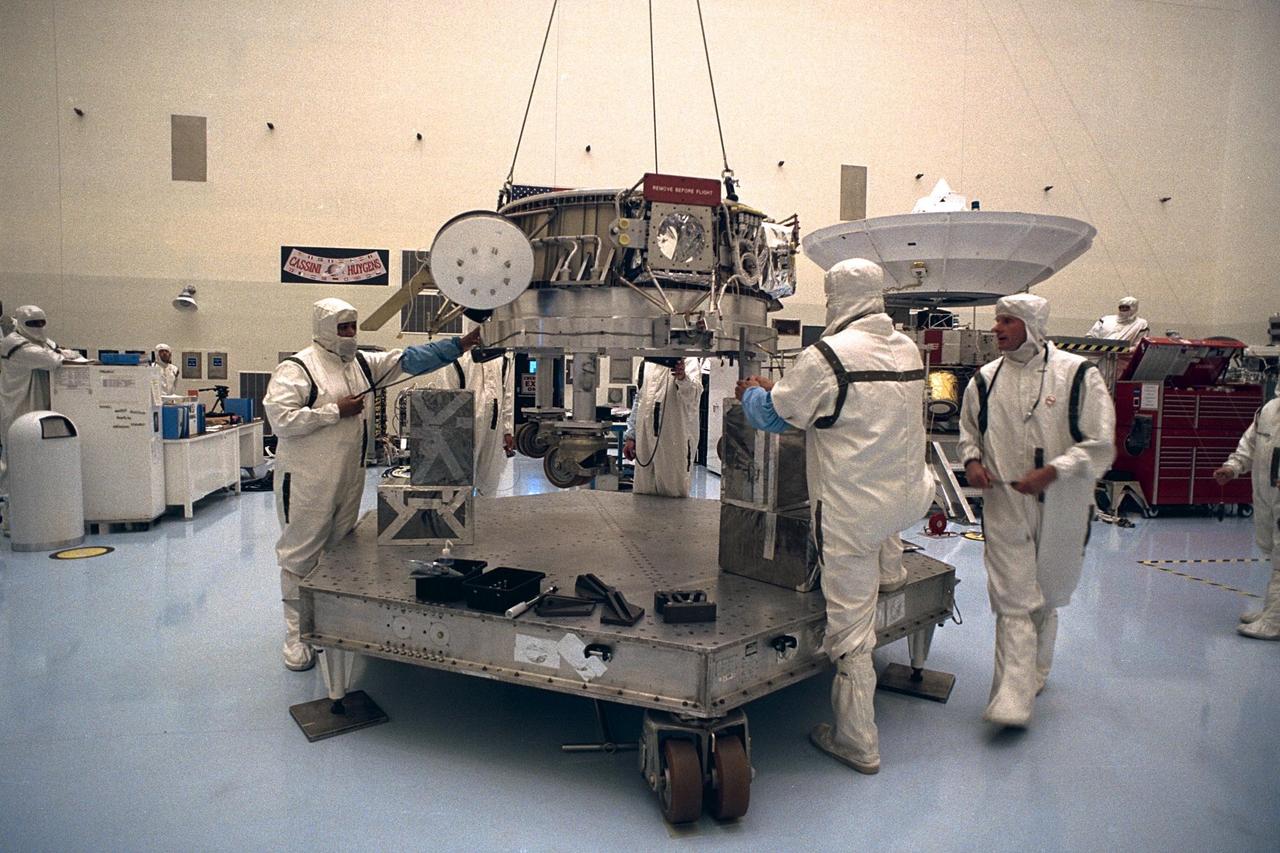

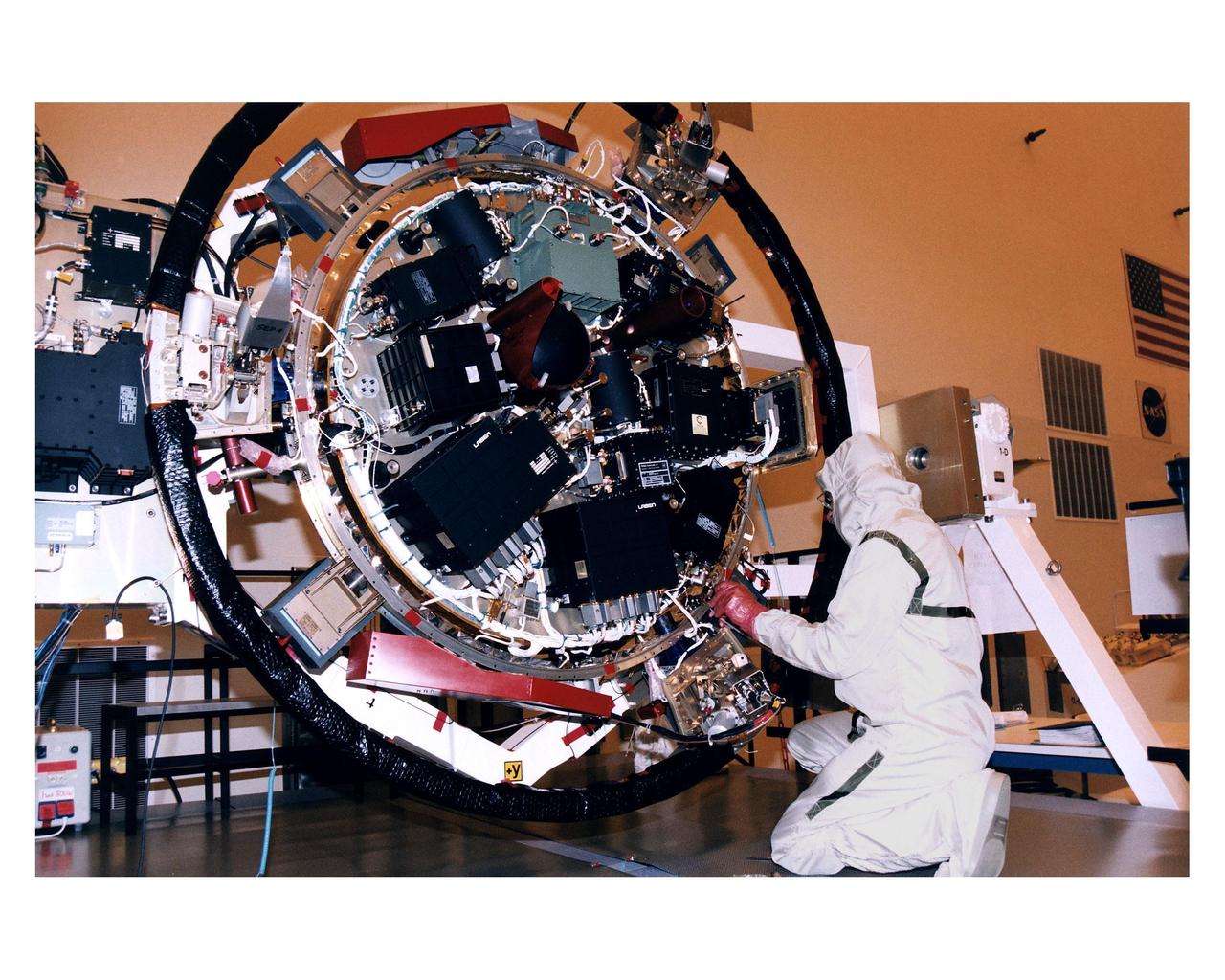

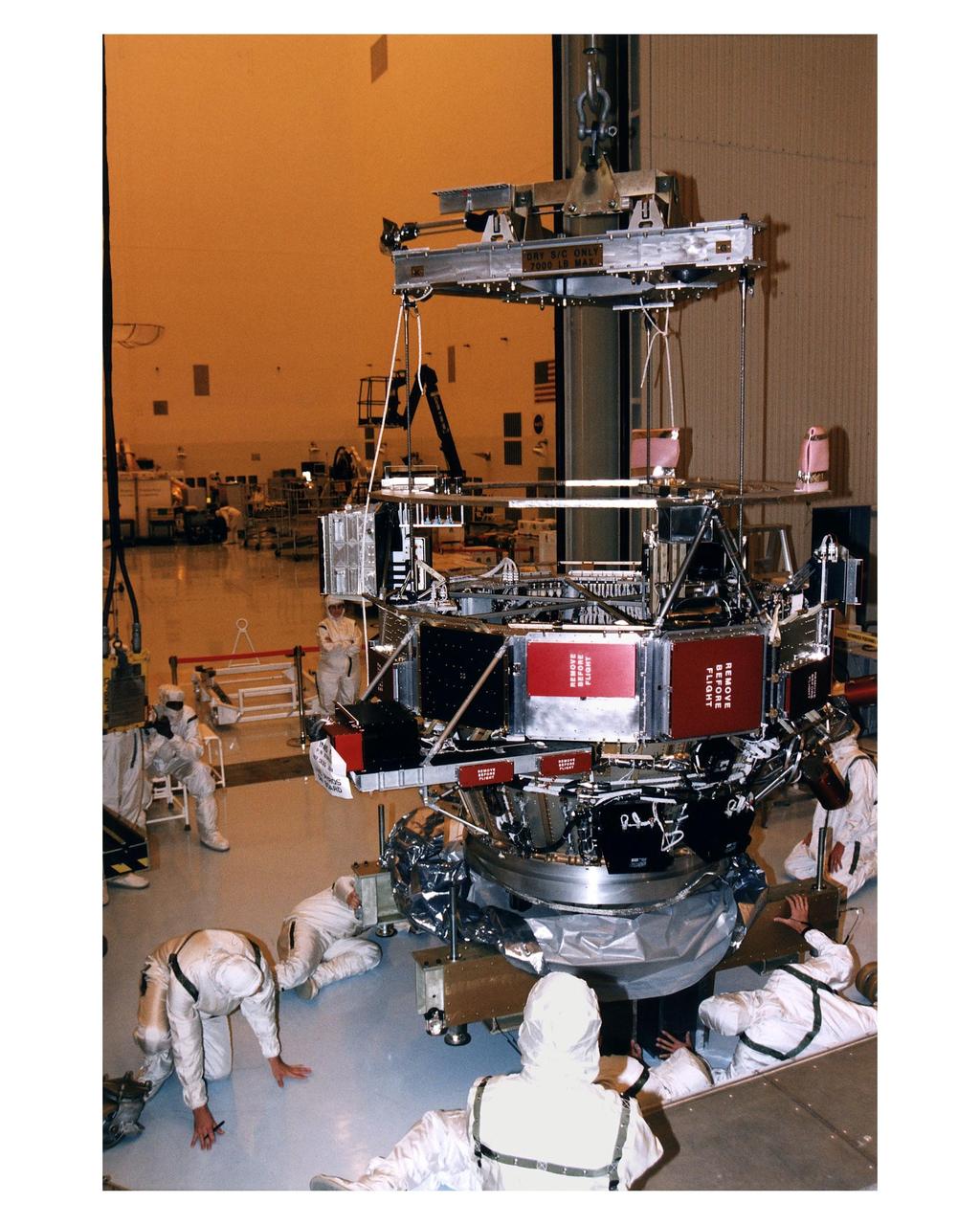

The propulsion system is mated to the Lower Equipment Module of the Cassini spacecraft in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF). Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and its moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6 from Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral Air Station, aboard a Titan IVB unmanned vehicle

The propulsion system is mated to the Lower Equipment Module of the Cassini spacecraft in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF). Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and its moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6 from Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral Air Station, aboard a Titan IVB unmanned vehicle

The propulsion system is mated to the Lower Equipment Module of the Cassini spacecraft in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF). Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and its moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6 from Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral Air Station, aboard a Titan IVB unmanned vehicle

The propulsion system is mated to the Lower Equipment Module of the Cassini spacecraft in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF). Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and its moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6 from Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral Air Station, aboard a Titan IVB unmanned vehicle

Saturn and its rings completely fill the field of view of Cassini's narrow angle camera in this natural color image taken on March 27, 2004. This is the last single 'eyeful' of Saturn and its rings achievable with the narrow angle camera on approach to the planet. From now until orbit insertion, Saturn and its rings will be larger than the field of view of the narrow angle camera. Color variations between atmospheric bands and features in the southern hemisphere of Saturn, as well as subtle color differences across the planet's middle B ring, are now more distinct than ever. Color variations generally imply different compositions. The nature and causes of any compositional differences in both the atmosphere and the rings are major questions to be investigated by Cassini scientists as the mission progresses. The bright blue sliver of light in the northern hemisphere is sunlight passing through the Cassini Division in Saturn's rings and being scattered by the cloud-free upper atmosphere. Two faint dark spots are visible in the southern hemisphere. These spots are close to the latitude where Cassini saw two storms merging in mid-March. The fate of the storms visible here is unclear. They are getting close and will eventually merge or squeeze past each other. Further analysis of such dynamic systems in Saturn's atmosphere will help scientists understand their origins and complex interactions. Moons visible in this image are (clockwise from top right): Enceladus (499 kilometers or 310 miles across), Mimas (398 kilometers or 247 miles across), Tethys (1060 kilometers or 659 miles across) and Epimetheus (116 kilometers or 72 miles across). Epimetheus is dim and appears just above the left edge of the rings. Brightnesses have been exaggerated to aid visibility. The image is a composite of three exposures, in red, green and blue, taken when the spacecraft was 47.7 million kilometers (29.7 million miles) from the planet. The image scale is 286 kilometers (178 miles) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05389

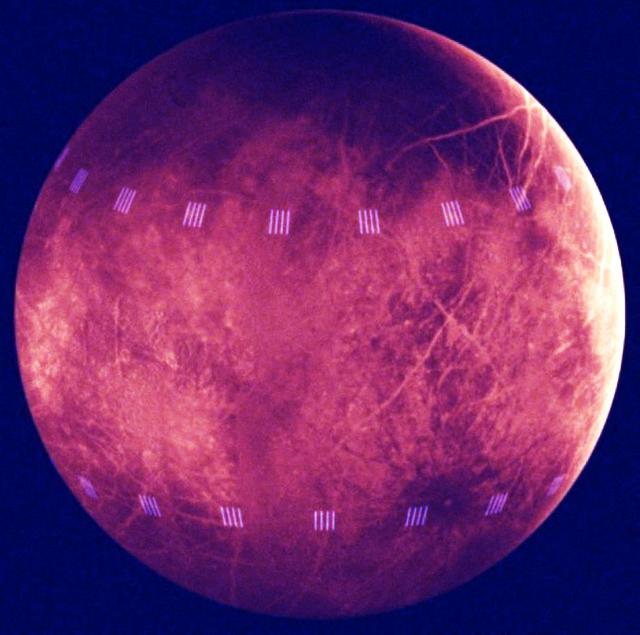

As it glanced around the Saturn system one final time, NASA's Cassini spacecraft captured this view of the planet's giant moon Titan. Interest in mysterious Titan was a major motivating factor to return to Saturn with Cassini-Huygens following the Voyager mission flybys of the early 1980s. Cassini and its Huygens probe, supplied by European Space Agency, revealed the moon to be every bit as fascinating as scientists had hoped. These views were obtained by Cassini's narrow-angle camera on Sept. 13, 2017. They are among the last images Cassini sent back to Earth. This natural color view, made from images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters, shows Titan much as Voyager saw it -- a mostly featureless golden orb, swathed in a dense atmospheric haze. An enhanced-color view (Figure 1) adds to this color a separate view taken using a spectral filter (centered at 938 nanometers) that can partially see through the haze. The views were acquired at a distance of 481,000 miles (774,000 kilometers) from Titan. The image scale is about 3 miles (5 kilometers) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21890

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. -- A Centaur upper stage is prepared for hoisting at Launch Pad 40 at Cape Canaveral Air Station to be mated with the Titan IV expendable launch vehicle that will propel the Cassini spacecraft and the European Space Agency's Huygens probe to Saturn and its moon Titan. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. The Cassini mission is targeted for an October 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004.

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. -- A Centaur upper stage is hoisted at Launch Pad 40 at Cape Canaveral Air Station for mating with the Titan IV expendable launch vehicle that will propel the Cassini spacecraft and the European Space Agency's Huygens probe to Saturn and its moon Titan. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. The Cassini mission is targeted for an October 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004.

In this rare image taken on July 19, 2013, the wide-angle camera on NASA's Cassini spacecraft has captured Saturn's rings and our planet Earth and its moon in the same frame. It is only one footprint in a mosaic of 33 footprints covering the entire Saturn ring system (including Saturn itself). At each footprint, images were taken in different spectral filters for a total of 323 images: some were taken for scientific purposes and some to produce a natural color mosaic. This is the only wide-angle footprint that has the Earth-moon system in it. The dark side of Saturn, its bright limb, the main rings, the F ring, and the G and E rings are clearly seen; the limb of Saturn and the F ring are overexposed. The "breaks" in the brightness of Saturn's limb are due to the shadows of the rings on the globe of Saturn, preventing sunlight from shining through the atmosphere in those regions. The E and G rings have been brightened for better visibility. Earth, which is 898 million miles (1.44 billion kilometers) away in this image, appears as a blue dot at center right; the moon can be seen as a fainter protrusion off its right side. An arrow indicates their location in the annotated version. (The two are clearly seen as separate objects in the accompanying composite image PIA14949.) The other bright dots nearby are stars. This is only the third time ever that Earth has been imaged from the outer solar system. The acquisition of this image, along with the accompanying composite narrow- and wide-angle image of Earth and the moon and the full mosaic from which both are taken, marked the first time that inhabitants of Earth knew in advance that their planet was being imaged. That opportunity allowed people around the world to join together in social events to celebrate the occasion. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 20 degrees below the ring plane. Images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this natural color view. The images were obtained with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on July 19, 2013 at a distance of approximately 753,000 miles (1.212 million kilometers) from Saturn, and approximately 898.414 million miles (1.445858 billion kilometers) from Earth. Image scale on Saturn is 43 miles (69 kilometers) per pixel; image scale on the Earth is 53,820 miles (86,620 kilometers) per pixel. The illuminated areas of neither Earth nor the Moon are resolved here. Consequently, the size of each "dot" is the same size that a point of light of comparable brightness would have in the wide-angle camera. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17171

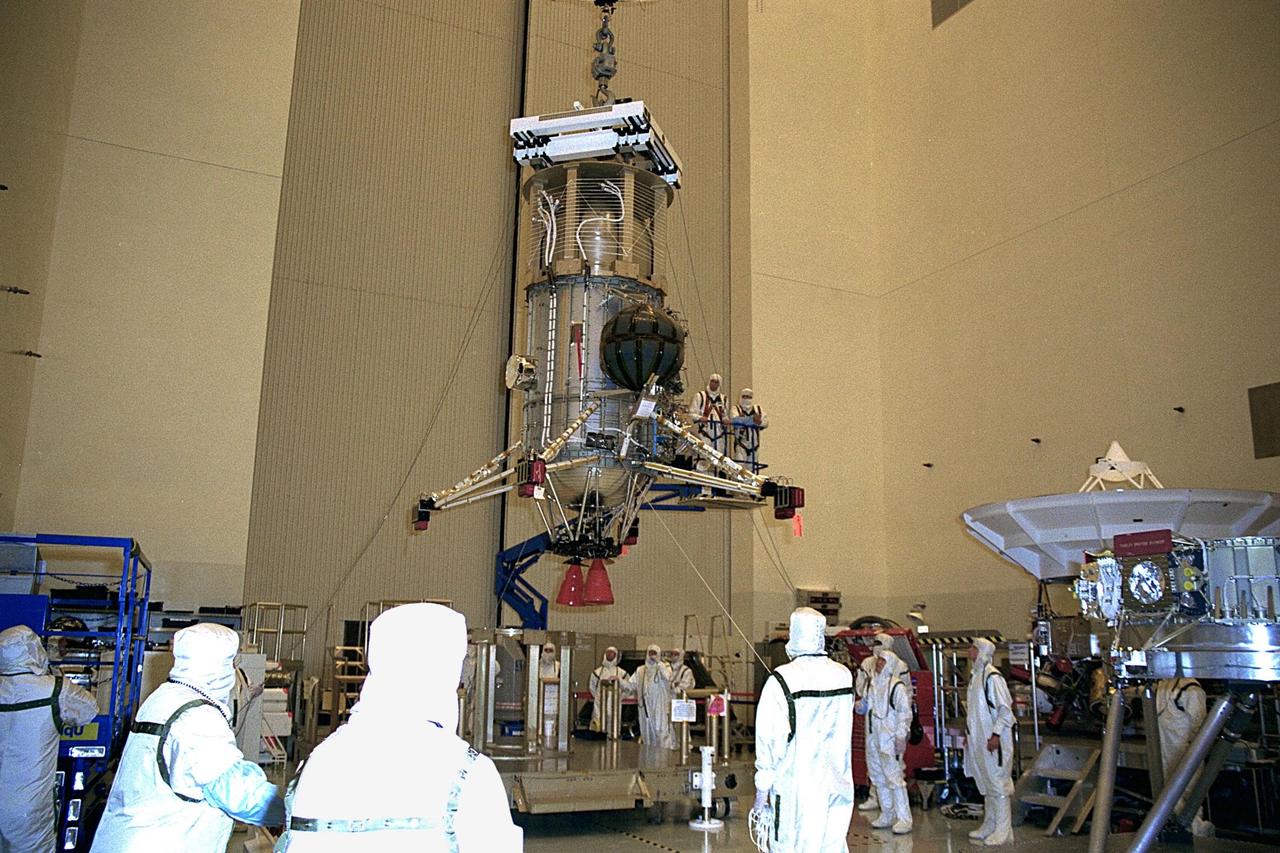

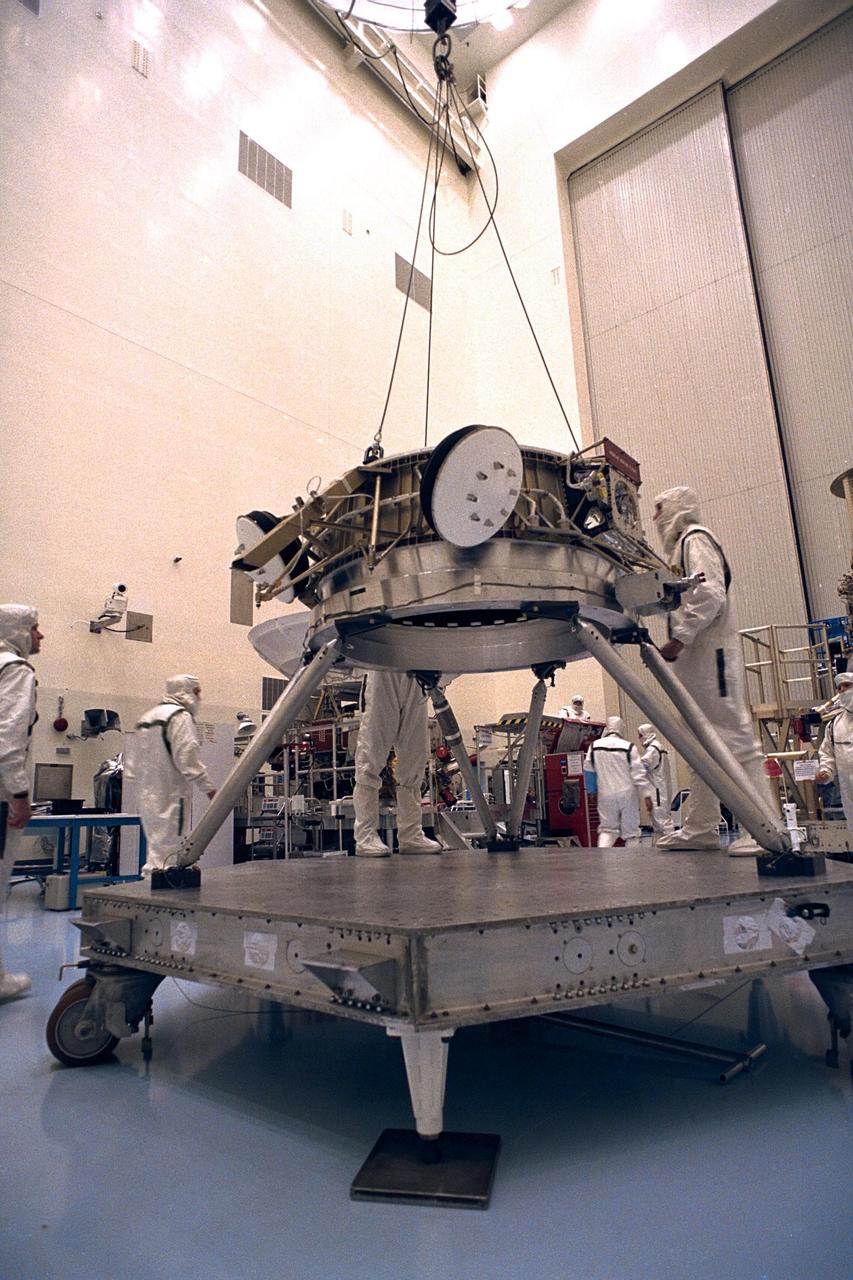

The Lower Equipment Module of the Cassini spacecraft is lifted into a workstand in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF). Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and its moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6 from Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral Air Station, aboard a Titan IVB unmanned vehicle

Scientists from the Cassini project at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the European Space Agency talk to photojournalists, news reporters, writers, television broadcasters, and cameramen in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) during the Cassini press showing. Cassini will launch on Oct. 6, 1997, on an Air Force Titan IV/Centaur launch vehicle and will arrive at Saturn in July 2004 to begin an international scientific mission to study the planet and its systems. Cassini is managed for NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Pasadena, Calif

The Lower Equipment Module of the Cassini spacecraft is lifted into a workstand in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF). Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and its moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6 from Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral Air Station, aboard a Titan IVB unmanned vehicle

A Titan IVB core vehicle and its twin Solid Rocket Motor Upgrades (SRMUs) depart from the Solid Rocket Motor Assembly and Readiness Facility (SMARF), Cape Canaveral Air Station (CCAS), en route to Launch Complex 40. At the pad, the Centaur upper stage will be added and, eventually, the prime payload, the Cassini spacecraft. Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6 from Pad 40, CCAS

The Lower Equipment Module of the Cassini spacecraft is lifted into a workstand in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF). Cassini will explore the Saturnian system, including the planet’s rings and its moon, Titan. Launch of the Cassini mission to Saturn is scheduled for Oct. 6 from Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral Air Station, aboard a Titan IVB unmanned vehicle

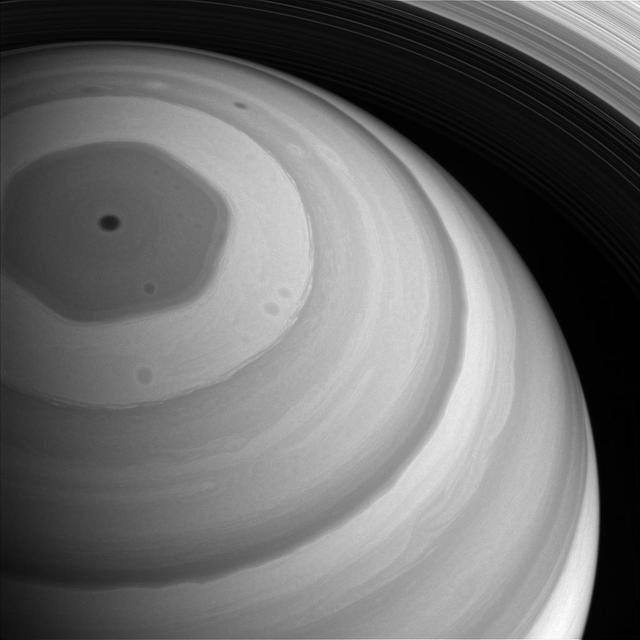

Saturn's cloud belts generally move around the planet in a circular path, but one feature is slightly different. The planet's wandering, hexagon-shaped polar jet stream breaks the mold -- a reminder that surprises lurk everywhere in the solar system. This atmospheric feature was first observed by the Voyager mission in the early 1980s, and was dubbed "the hexagon." Cassini's visual and infrared mapping spectrometer was first to spy the hexagon during the mission, since it could see the feature's outline while the pole was still immersed in wintry darkness. The hexagon became visible to Cassini's imaging cameras as sunlight returned to the northern hemisphere. This view looks toward the northern hemisphere of Saturn -- in summer when this view was acquired -- from above 65 degrees north latitude. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on June 28, 2017 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 536,000 miles (862,000 kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 32 miles (52 kilometers) per pixel. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21348

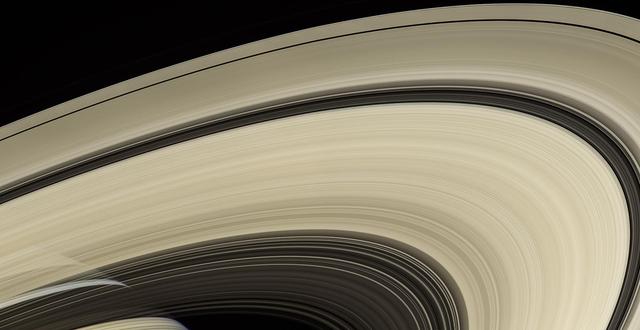

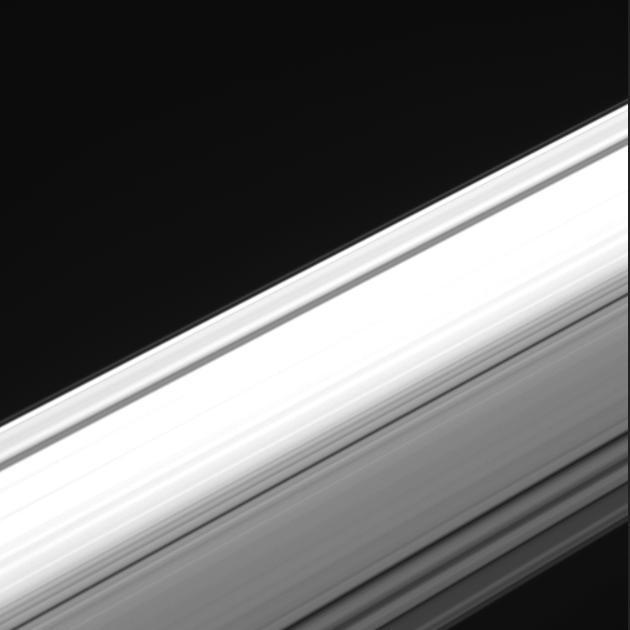

Saturn's rings are perhaps the most recognized feature of any world in our solar system. Cassini spent more than a decade examining them more closely than any spacecraft before it. The rings are made mostly of particles of water ice that range in size from smaller than a grain of sand to as large as mountains. The ring system extends up to 175,000 miles (282,000 kilometers) from the planet, but for all their immense width, the rings are razor-thin, about 30 feet (10 meters) thick in most places. From the right angle you can see straight through the rings, as in this natural-color view that looks from south to north. Cassini obtained the images that comprise this mosaic on April 25, 2007, at a distance of approximately 450,000 miles (725,000 kilometers) from Saturn. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA14943

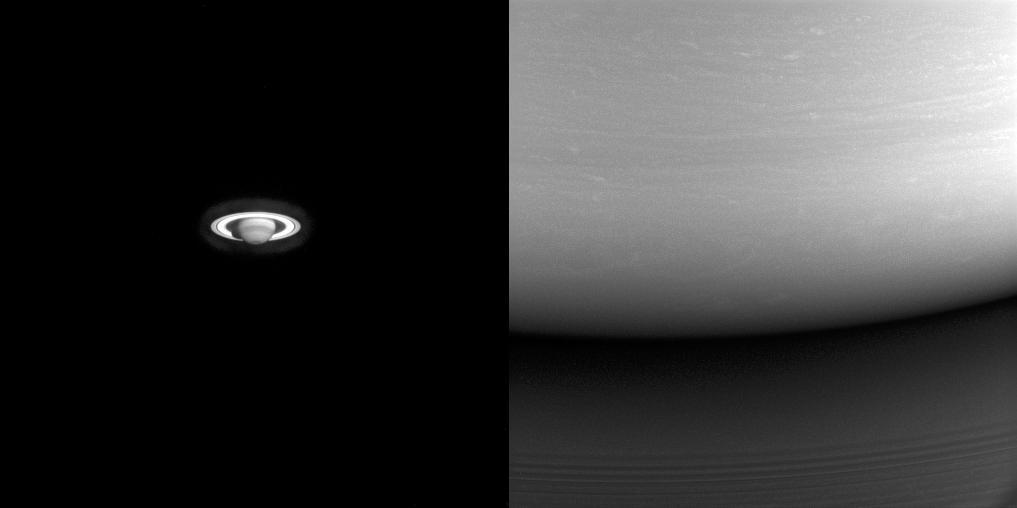

These two images illustrate just how far Cassini traveled to get to Saturn. On the left is one of the earliest images Cassini took of the ringed planet, captured during the long voyage from the inner solar system. On the right is one of Cassini's final images of Saturn, showing the site where the spacecraft would enter the atmosphere on the following day. In the left image, taken in 2001, about six months after the spacecraft passed Jupiter for a gravity assist flyby, the best view of Saturn using the spacecraft's high-resolution (narrow-angle) camera was on the order of what could be seen using the Earth-orbiting Hubble Space Telescope. At the end of the mission (at right), from close to Saturn, even the lower resolution (wide-angle) camera could capture just a tiny part of the planet. The left image looks toward Saturn from 20 degrees below the ring plane and was taken on July 13, 2001 in wavelengths of infrared light centered at 727 nanometers using the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The view at right is centered on a point 6 degrees north of the equator and was taken in visible light using the wide-angle camera on Sept. 14, 2017. The view on the left was acquired at a distance of approximately 317 million miles (510 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is about 1,900 miles (3,100 kilometers) per pixel. The view at right was acquired at a distance of approximately 360,000 miles (579,000 kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 22 miles (35 kilometers) per pixel. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21353

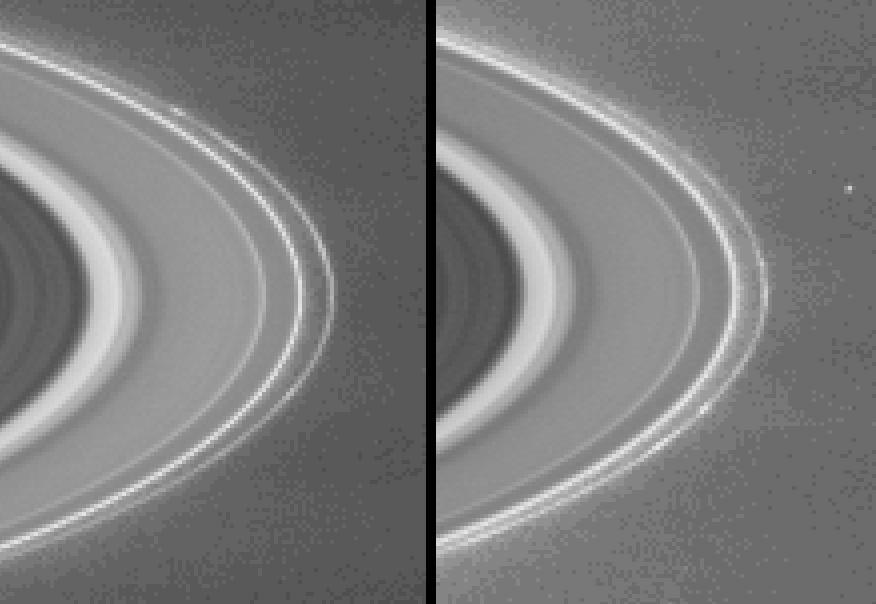

Scientists have only a rough idea of the lifetime of clumps in Saturn's rings - a mystery that Cassini may help answer. The latest images taken by the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft show clumps seemingly embedded within Saturn's narrow, outermost F ring. The narrow angle camera took the images on Feb. 23, 2004, from a distance of 62.9 million kilometers (39 million miles). The two images taken nearly two hours apart show these clumps as they revolve about the planet. The small dot at center right in the second image is one of Saturn's small moons, Janus, which is 181 kilometers, (112 miles) across. Like all particles in Saturn's ring system, these clump features orbit the planet in the same direction in which the planet rotates. This direction is clockwise as seen from Cassini's southern vantage point below the ring plane. Two clumps in particular, one of them extended, is visible in the upper part of the F ring in the image on the left, and in the lower part of the ring in the image on the right. Other knot-like irregularities in the ring's brightness are visible in the image on the right. The core of the F ring is about 50 kilometers (31miles) wide, and from Cassini's current distance, is not fully visible. The imaging team enhanced the contrast of the images and magnified them to aid visibility of the F ring and the clump features. The camera took the images with the green filter, which is centered at 568 nanometers. The image scale is 377 kilometers (234 miles) per pixel. NASA's two Voyager spacecraft that flew past Saturn in 1980 and 1981 were the first to see these clumps. The Voyager data suggest that the clumps change very little and can be tracked as they orbit for 30 days or more. No clump survived from the time of the first Voyager flyby to the Voyager 2 flyby nine months later. Scientists are not certain of the cause of these features. Among the theories proposed are meteoroid bombardments and inter-particle collisions in the F ring. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05382

Sunlight truly has come to Saturn's north pole. The whole northern region is bathed in sunlight in this view from late 2016, feeble though the light may be at Saturn's distant domain in the solar system. The hexagon-shaped jet-stream is fully illuminated here. In this image, the planet appears darker in regions where the cloud deck is lower, such the region interior to the hexagon. Mission experts on Saturn's atmosphere are taking advantage of the season and Cassini's favorable viewing geometry to study this and other weather patterns as Saturn's northern hemisphere approaches Summer solstice. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 51 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Sept. 9, 2016 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 728 nanometers. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 750,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 46 miles (74 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20513

From high above Saturn's northern hemisphere, NASA's Cassini spacecraft gazes over the planet's north pole, with its intriguing hexagon and bullseye-like central vortex. Saturn's moon Mimas is visible as a mere speck near upper right. At 246 miles (396 kilometers across) across, Mimas is considered a medium-sized moon. It is large enough for its own gravity to have made it round, but isn't one of the really large moons in our solar system, like Titan. Even enormous Titan is tiny beside the mighty gas giant Saturn. This view looks toward Saturn from the sunlit side of the rings, from about 27 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in green light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on March 27, 2017. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 617,000 miles (993,000 kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 37 miles (59 kilometers) per pixel. Mimas' brightness has been enhanced by a factor of 3 in this image to make it easier to see. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21331

This image from NASA's Cassini spacecraft offers a unique perspective on Saturn's ring system. Cassini captured images from within the gap between the planet and its rings, looking outward as the spacecraft made one of its final dives through the gap as part of the mission's Grand Finale. Using its wide-angle camera, Cassini took the 21 images in the sequence over a span of about four minutes during its dive through the gap on Aug. 20, 2017. The images have an original size of 512 x 512 pixels; the smaller image size allowed for more images to be taken over the short span of time. The entirety of the main rings can be seen here, but due to the low viewing angle, the rings appear extremely foreshortened. The perspective shifts from the sunlit side of the rings to the unlit side, where sunlight filters through. On the sunlit side, the grayish C ring looks larger in the foreground because it is closer; beyond it is the bright B ring and slightly less-bright A ring, with the Cassini Division between them. The F ring is also fairly easy to make out. A movie is available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21886

After more than 13 years at Saturn, and with its fate sealed, NASA's Cassini spacecraft bid farewell to the Saturnian system by firing the shutters of its wide-angle camera and capturing this last, full mosaic of Saturn and its rings two days before the spacecraft's dramatic plunge into the planet's atmosphere. During the observation, a total of 80 wide-angle images were acquired in just over two hours. This view is constructed from 42 of those wide-angle shots, taken using the red, green and blue spectral filters, combined and mosaicked together to create a natural-color view. Six of Saturn's moons -- Enceladus, Epimetheus, Janus, Mimas, Pandora and Prometheus -- make a faint appearance in this image. (Numerous stars are also visible in the background.) A second version of the mosaic is provided in which the planet and its rings have been brightened, with the fainter regions brightened by a greater amount. (The moons and stars have also been brightened by a factor of 15 in this version.) The ice-covered moon Enceladus -- home to a global subsurface ocean that erupts into space -- can be seen at the 1 o'clock position. Directly below Enceladus, just outside the F ring (the thin, farthest ring from the planet seen in this image) lies the small moon Epimetheus. Following the F ring clock-wise from Epimetheus, the next moon seen is Janus. At about the 4:30 position and outward from the F ring is Mimas. Inward of Mimas and still at about the 4:30 position is the F-ring-disrupting moon, Pandora. Moving around to the 10 o'clock position, just inside of the F ring, is the moon Prometheus. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 15 degrees above the ring plane. Cassini was approximately 698,000 miles (1.1 million kilometers) from Saturn, on its final approach to the planet, when the images in this mosaic were taken. Image scale on Saturn is about 42 miles (67 kilometers) per pixel. The image scale on the moons varies from 37 to 50 miles (59 to 80 kilometers) pixel. The phase angle (the Sun-planet-spacecraft angle) is 138 degrees. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17218

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. - Reporters (bottom) take notes during an informal briefing concerning NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, launched aboard an Air Force Titan IV rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Oct. 15, 1997. Cassini launch team members seen here discussed the challenge and experience of preparing Cassini for launch, integrating it with the Titan IV rocket and the countdown events of launch day. Facing the camera (from left) are Ron Gillett, NASA Safety and Lead Federal Agency official; Omar Baez, mechanical and propulsion systems engineer; Ray Lugo, NASA launch manager; Chuck Dovale, chief, Avionics Branch; George Haddad, Integration and Ground Systems mechanical engineer; and Ken Carr, Cassini assistant launch site support manager. Approximately 10:36 p.m. EDT, June 30, the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft will arrive at Saturn. After nearly a seven-year journey, it will be the first mission to orbit Saturn. The international cooperative mission plans a four-year tour of Saturn, its rings, icy moons, magnetosphere, and Titan, the planet’s largest moon.

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. - Reporters (left) take notes during an informal briefing concerning NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, launched aboard an Air Force Titan IV rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Oct. 15, 1997. Cassini launch team members at right discussed the challenge and experience of preparing Cassini for launch, integrating it with the Titan IV rocket and the countdown events of launch day. From left are Ron Gillett, NASA Safety and Lead Federal Agency official; Omar Baez, mechanical and propulsion systems engineer; Ray Lugo, NASA launch manager; Chuck Dovale, chief, Avionics Branch; George Haddad, Integration and Ground Systems mechanical engineer; and Ken Carr, Cassini assistant launch site support manager. Approximately 10:36 p.m. EDT, June 30, the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft will arrive at Saturn. After nearly a seven-year journey, it will be the first mission to orbit Saturn. The international cooperative mission plans a four-year tour of Saturn, its rings, icy moons, magnetosphere, and Titan, the planet’s largest moon.

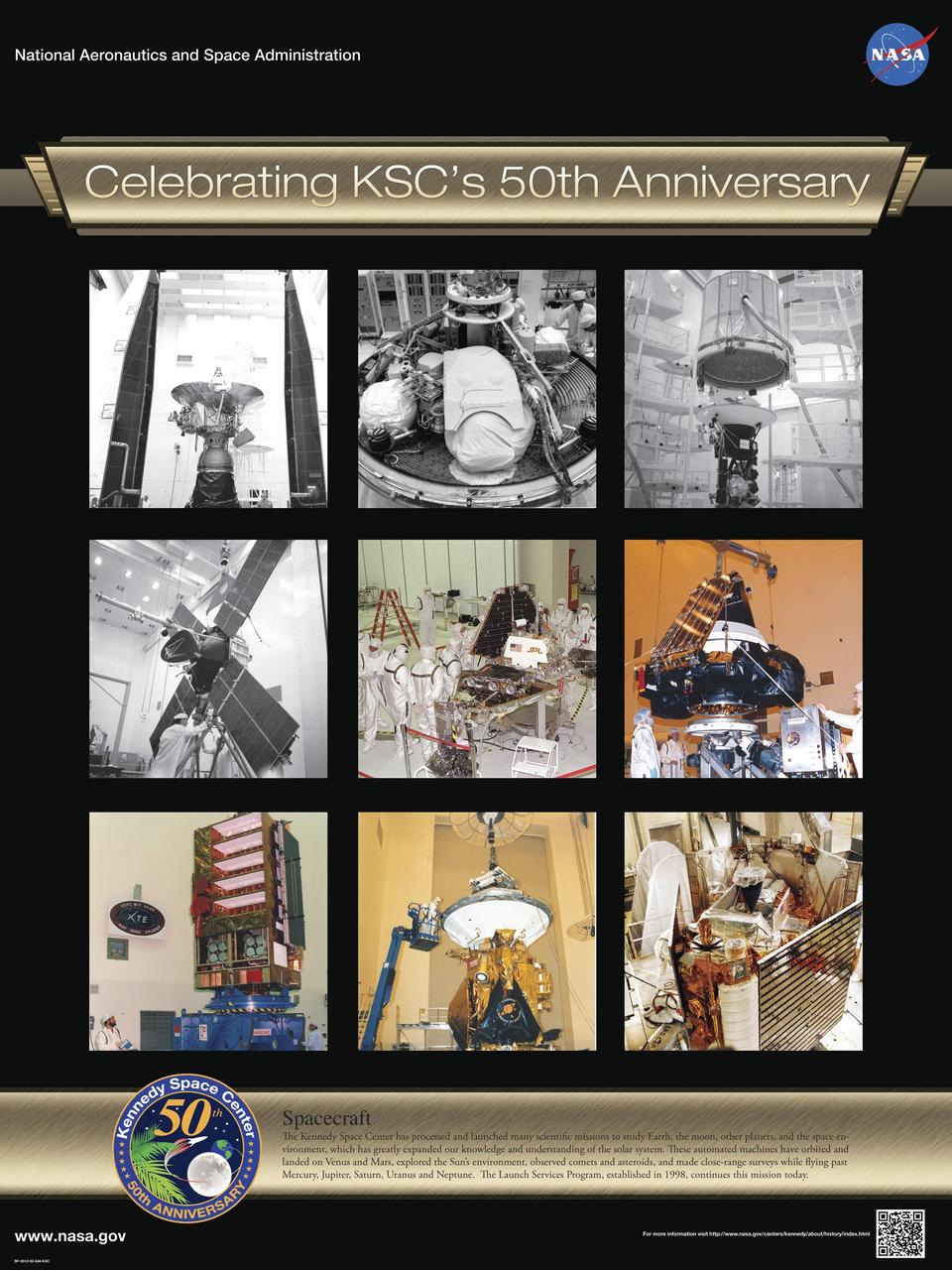

Spacecraft: The Kennedy Space Center has processed and launched many scientific missions to study Earth, the moon, other planets, and the space environment, which has greatly expanded our knowledge and understanding of the solar system. These automated machines have orbited and landed on Venus and Mars, explored the Sun’s environment, observed comets and asteroids, and made close-range surveys while flying past Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. The Launch Services Program, established in 1998, continues this mission today. Poster designed by Kennedy Space Center Graphics Department/Greg Lee. Credit: NASA

In this artist's conception, a possible newfound planet spins through a clearing in a nearby star's dusty, planet-forming disc. This clearing was detected around the star CoKu Tau 4 by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope. Astronomers believe that an orbiting massive body, like a planet, may have swept away the star's disc material, leaving a central hole. The possible planet is theorized to be at least as massive as Jupiter, and may have a similar appearance to what the giant planets in our own solar system looked like billions of years ago. A graceful ring, much like Saturn's, spins high above the planet's cloudy atmosphere. The ring is formed from countless small orbiting particles of dust and ice, leftovers from the initial gravitational collapse that formed the possible giant planet. If we were to visit a planet like this, we would have a very different view of the universe. The sky, instead of being the familiar dark expanse lit by distant stars, would be dominated by the thick disc of dust that fills this young planetary system. The view looking toward CoKu Tau 4 would be relatively clear, as the dust in the interior of the disc has fallen into the accreting star. A bright band would seem to surround the central star, caused by light scattered back by the dust in the disc. Looking away from CoKu Tau 4, the dusty disc would appear dark, blotting out light from all the stars in the sky except those which lie well above the plane of the disc. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA05988

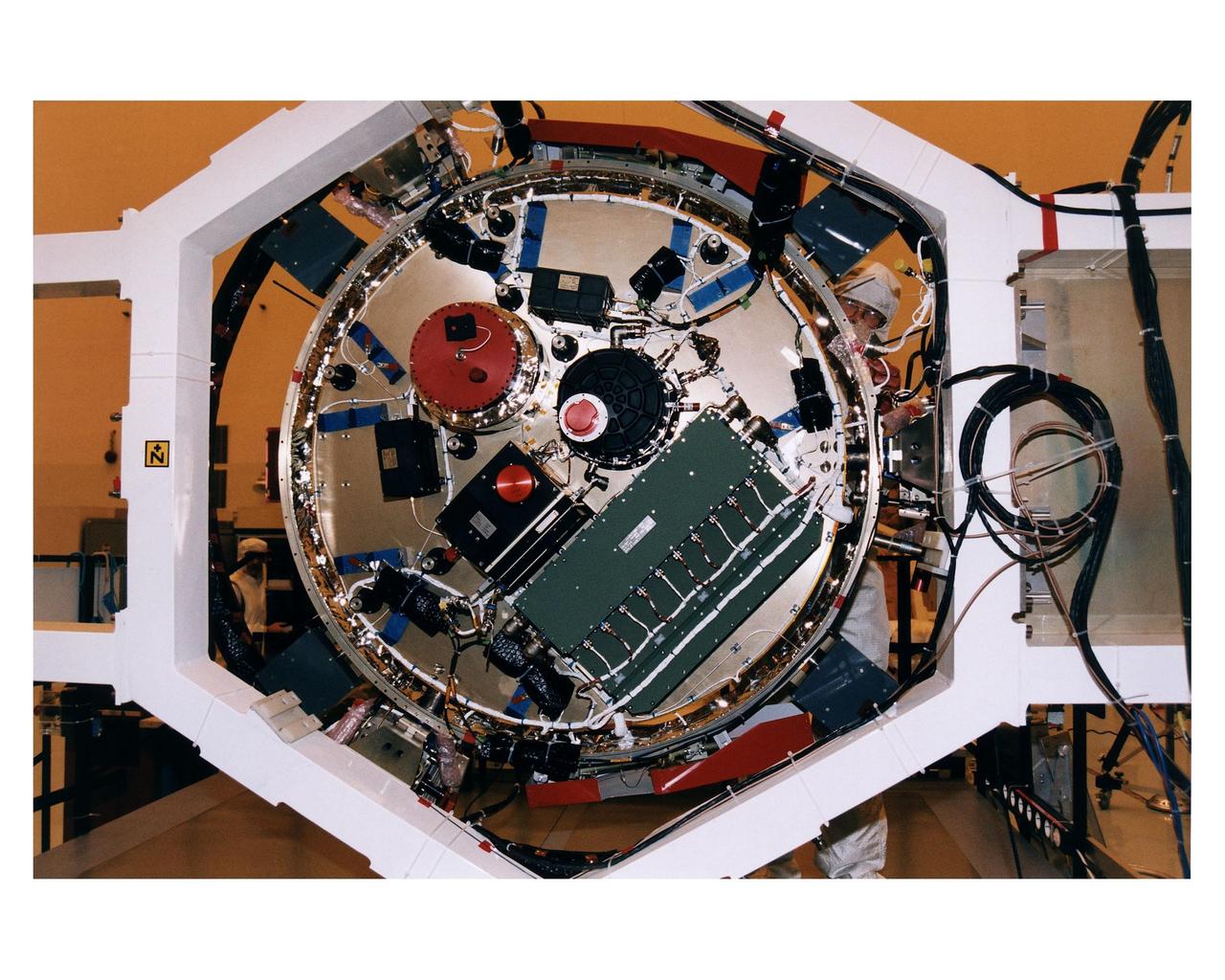

An employee in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) works on the top side of the experiment platform for the Huygens probe that will accompany the Cassini orbiter to Saturn during prelaunch processing, testing and integration in that facility. The Huygens probe and the Cassini orbiter being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

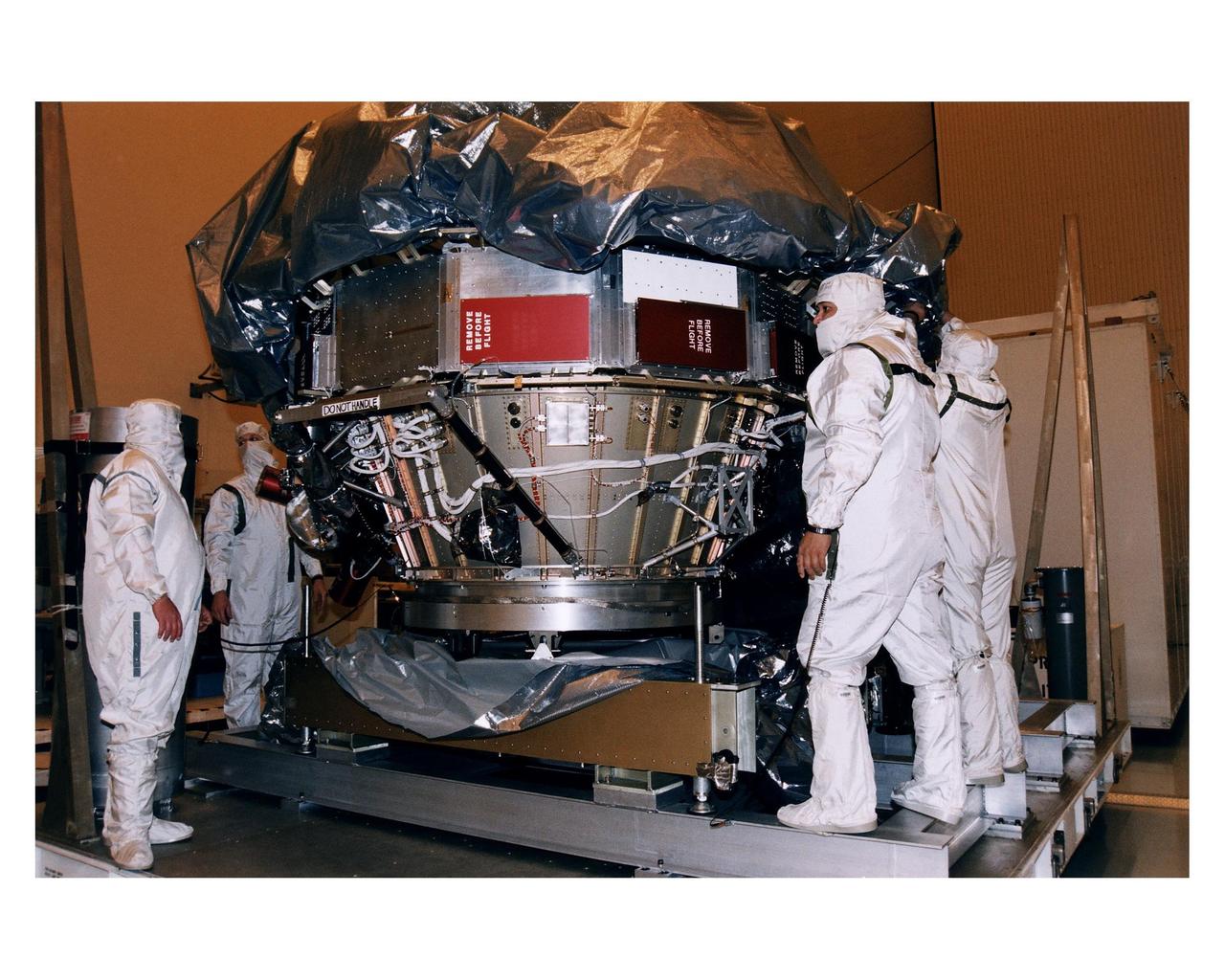

A worker in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) stands behind the bottom side of the experiment platform for the Huygens probe that will accompany the Cassini orbiter to Saturn during prelaunch processing testing and integration in that facility. The Huygens probe and the Cassini orbiter being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

The cameras of Voyager 1 on Feb. 14, 1990, pointed back toward the sun and took a series of pictures of the sun and the planets, making the first ever portrait of our solar system as seen from the outside. In the course of taking this mosaic consisting of a total of 60 frames, Voyager 1 made several images of the inner solar system from a distance of approximately 4 billion miles and about 32 degrees above the ecliptic plane. Thirty-nine wide angle frames link together six of the planets of our solar system in this mosaic. Outermost Neptune is 30 times further from the sun than Earth. Our sun is seen as the bright object in the center of the circle of frames. The wide-angle image of the sun was taken with the camera's darkest filter (a methane absorption band) and the shortest possible exposure (5 thousandths of a second) to avoid saturating the camera's vidicon tube with scattered sunlight. The sun is not large as seen from Voyager, only about one-fortieth of the diameter as seen from Earth, but is still almost 8 million times brighter than the brightest star in Earth's sky, Sirius. The result of this great brightness is an image with multiple reflections from the optics in the camera. Wide-angle images surrounding the sun also show many artifacts attributable to scattered light in the optics. These were taken through the clear filter with one second exposures. The insets show the planets magnified many times. Narrow-angle images of Earth, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune were acquired as the spacecraft built the wide-angle mosaic. Jupiter is larger than a narrow-angle pixel and is clearly resolved, as is Saturn with its rings. Uranus and Neptune appear larger than they really are because of image smear due to spacecraft motion during the long (15 second) exposures. From Voyager's great distance Earth and Venus are mere points of light, less than the size of a picture element even in the narrow-angle camera. Earth was a crescent only 0.12 pixel in size. Coincidentally, Earth lies right in the center of one of the scattered light rays resulting from taking the image so close to the sun. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00451

The Cassini spacecraft is closing in fast on its first target of observation in the Saturn system: the small, mysterious moon Phoebe, only 220 kilometers (137 miles) across. The three images shown here, the latest of which is twice as good as any image returned by the Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1981, were captured in the past week on approach to this outer moon of Saturn. Phoebe's surface is already showing a great deal of contrast, most likely indicative of topography, such as tall sunlit peaks and deep shadowy craters, as well as genuine variation in the reflectivity of its surface materials. Left to right, the three views were captured at a phase (Sun-Saturn-spacecraft) angle of 87 degrees between June 4 and June 7, from distances ranging from 4.1 million kilometers (2.6 million miles) to 2.5 million kilometers (1.5 million miles). The image scale ranges from 25 to 15 kilometers per pixel. Phoebe rotates once every nine hours and 16 minutes; each of these images shows a different region on Phoebe. Phoebe was the discovered in 1898. It has a very dark surface. Cassini's powerful cameras will provide the best-ever look at this moon on Friday, June 11, when the spacecraft will streak past Phoebe at a distance of only about 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles) from the moon's surface. The current images, and the presence of large craters, promise a heavily cratered surface which will come into sharp view over the next few days when image scales should get as small as a few tens of meters. Phoebe orbits Saturn in a direction opposite to that of the larger interior Saturnian moons. Because of its small size and retrograde orbit Phoebe is believed to be a body from the distant outer solar system, perhaps one of the building blocks of the outer planets that were captured into orbit around Saturn. If true, the little moon will provide information about these primitive pieces of material. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA06062

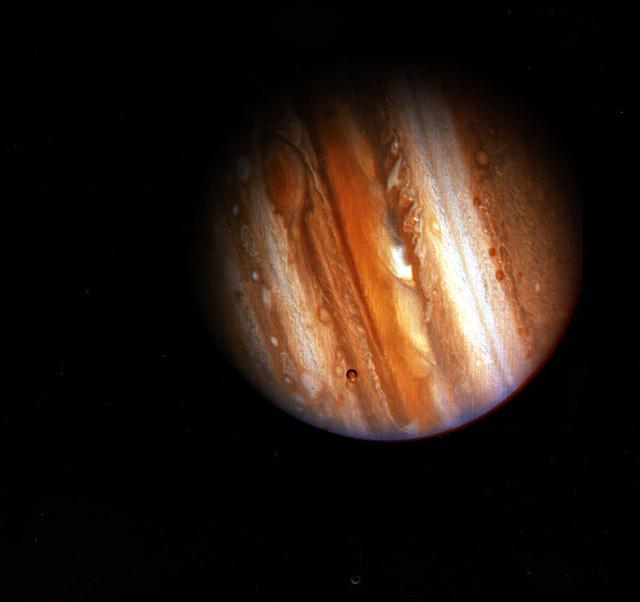

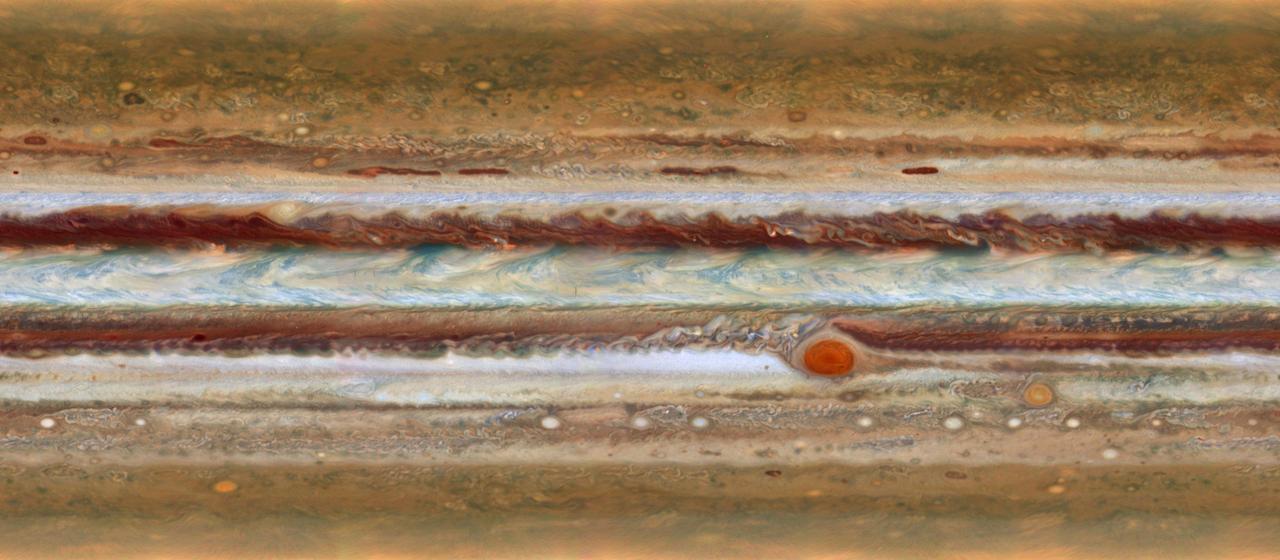

On February 5, 1979, Voyager 1 made its closest approach to Jupiter since early 1974 and 1975 when Pioneers 10 and 11 made their voyages to Jupiter and beyond. Voyager 1 completed its Jupiter encounter in early April, after taking almost 19,000 pictures and recording many other scientific measurements. Although astronomers had studied Jupiter from Earth for several centuries, scientists were surprised by many of Voyager 1 and 2's findings. They now understand that important physical, geological, and atmospheric processes go on that they had never observed from Earth. Discovery of active volcanism on the satellite Io was probably the greatest surprise. It was the first time active volcanoes had been seen on another body in the solar system. Voyager also discovered a ring around Jupiter. Thus Jupiter joins Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune as a ringed planet -- although each ring system is unique and distinct from the others.

Composite Pioneer 10 imagery Excitement rose as the PICS displayed images of Jupiter of ever-increasing size as Pioneer 10 plunged at high speed toward its closest approach to the planet. The most dramatic moment was perhaps after closest approach and after the spacecraft has been hidden behind Jupiter. PICS (Pioneer Image Converter System) began to show a few spots on the screens, which gradually built up into a very distorted crescent-shaped Jupiter. 'Sunrise on Jupiter,' exclaimed an experimenter excitedly. 'We've made it safely through periapsis.' Subsequent PICS images were of a crescent Jupiter gradually decreasing in size as the spacecraft sped away out of the Jovian system. Note: used in NASA SP-349 'Pioneer Odyssey - Encounter with a Giant' fig. 5-15 and SP-446 ' Pioneer - First to Jupiter, Saturn, and Beyond' fig. 5-16.

Two's company, but three might not always be a crowd — at least in space. Astronomers using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, and a trick of nature, have confirmed the existence of a planet orbiting two stars in the system OGLE-2007-BLG-349, located 8,000 light-years away towards the center of our galaxy. The planet orbits roughly 300 million miles from the stellar duo, about the distance from the asteroid belt to our sun. It completes an orbit around both stars roughly every seven years. The two red dwarf stars are a mere 7 million miles apart, or 14 times the diameter of the moon's orbit around Earth. The Hubble observations represent the first time such a three-body system has been confirmed using the gravitational microlensing technique. Gravitational microlensing occurs when the gravity of a foreground star bends and amplifies the light of a background star that momentarily aligns with it. The particular character of the light magnification can reveal clues to the nature of the foreground star and any associated planets. The three objects were discovered in 2007 by an international collaboration of five different groups: Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA), the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE), the Microlensing Follow-up Network (MicroFUN), the Probing Lensing Anomalies Network (PLANET), and the Robonet Collaboration. These ground-based observations uncovered a star and a planet, but a detailed analysis also revealed a third body that astronomers could not definitively identify. Image caption: This artist's illustration shows a gas giant planet circling a pair of red dwarf stars in the system OGLE-2007-BLG-349, located 8,000 light-years away. The Saturn-mass planet orbits roughly 300 million miles from the stellar duo. The two red dwarf stars are 7 million miles apart. Credit: NASA, ESA, and G. Bacon (STScI) Read more: <a href="http://go.nasa.gov/2dcfMns" rel="nofollow">go.nasa.gov/2dcfMns</a> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagrid.me/nasagoddard/?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

On July 19, 2013, in an event celebrated the world over, NASA's Cassini spacecraft slipped into Saturn's shadow and turned to image the planet, seven of its moons, its inner rings -- and, in the background, our home planet, Earth. With the sun's powerful and potentially damaging rays eclipsed by Saturn itself, Cassini's onboard cameras were able to take advantage of this unique viewing geometry. They acquired a panoramic mosaic of the Saturn system that allows scientists to see details in the rings and throughout the system as they are backlit by the sun. This mosaic is special as it marks the third time our home planet was imaged from the outer solar system; the second time it was imaged by Cassini from Saturn's orbit; and the first time ever that inhabitants of Earth were made aware in advance that their photo would be taken from such a great distance. With both Cassini's wide-angle and narrow-angle cameras aimed at Saturn, Cassini was able to capture 323 images in just over four hours. This final mosaic uses 141 of those wide-angle images. Images taken using the red, green and blue spectral filters of the wide-angle camera were combined and mosaicked together to create this natural-color view. A brightened version with contrast and color enhanced (Figure 1), a version with just the planets annotated (Figure 2), and an annotated version (Figure 3) are shown above. This image spans about 404,880 miles (651,591 kilometers) across. The outermost ring shown here is Saturn's E ring, the core of which is situated about 149,000 miles (240,000 kilometers) from Saturn. The geysers erupting from the south polar terrain of the moon Enceladus supply the fine icy particles that comprise the E ring; diffraction by sunlight gives the ring its blue color. Enceladus (313 miles, or 504 kilometers, across) and the extended plume formed by its jets are visible, embedded in the E ring on the left side of the mosaic. At the 12 o'clock position and a bit inward from the E ring lies the barely discernible ring created by the tiny, Cassini-discovered moon, Pallene (3 miles, or 4 kilometers, across). (For more on structures like Pallene's ring, see PIA08328). The next narrow and easily seen ring inward is the G ring. Interior to the G ring, near the 11 o'clock position, one can barely see the more diffuse ring created by the co-orbital moons, Janus (111 miles, or 179 kilometers, across) and Epimetheus (70 miles, or 113 kilometers, across). Farther inward, we see the very bright F ring closely encircling the main rings of Saturn. Following the outermost E ring counter-clockwise from Enceladus, the moon Tethys (662 miles, or 1,066 kilometers, across) appears as a large yellow orb just outside of the E ring. Tethys is positioned on the illuminated side of Saturn; its icy surface is shining brightly from yellow sunlight reflected by Saturn. Continuing to about the 2 o'clock position is a dark pixel just outside of the G ring; this dark pixel is Saturn's Death Star moon, Mimas (246 miles, or 396 kilometers, across). Mimas appears, upon close inspection, as a very thin crescent because Cassini is looking mostly at its non-illuminated face. The moons Prometheus, Pandora, Janus and Epimetheus are also visible in the mosaic near Saturn's bright narrow F ring. Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers, across) is visible as a faint black dot just inside the F ring and at the 9 o'clock position. On the opposite side of the rings, just outside the F ring, Pandora (50 miles, or 81 kilometers, across) can be seen as a bright white dot. Pandora and Prometheus are shepherd moons and gravitational interactions between the ring and the moons keep the F ring narrowly confined. At the 11 o'clock position in between the F ring and the G ring, Janus (111 miles, or 179 kilometers, across) appears as a faint black dot. Janus and Prometheus are dark for the same reason Mimas is mostly dark: we are looking at their non-illuminated sides in this mosaic. Midway between the F ring and the G ring, at about the 8 o'clock position, is a single bright pixel, Epimetheus. Looking more closely at Enceladus, Mimas and Tethys, especially in the brightened version of the mosaic, one can see these moons casting shadows through the E ring like a telephone pole might cast a shadow through a fog. In the non-brightened version of the mosaic, one can see bright clumps of ring material orbiting within the Encke gap near the outer edge of the main rings and immediately to the lower left of the globe of Saturn. Also, in the dark B ring within the main rings, at the 9 o'clock position, one can see the faint outlines of two spoke features, first sighted by NASA's Voyager spacecraft in the early 1980s and extensively studied by Cassini. Finally, in the lower right of the mosaic, in between the bright blue E ring and the faint but defined G ring, is the pale blue dot of our planet, Earth. Look closely and you can see the moon protruding from the Earth's lower right. (For a higher resolution view of the Earth and moon taken during this campaign, see PIA14949.) Earth's twin, Venus, appears as a bright white dot in the upper left quadrant of the mosaic, also between the G and E rings. Mars also appears as a faint red dot embedded in the outer edge of the E ring, above and to the left of Venus. For ease of visibility, Earth, Venus, Mars, Enceladus, Epimetheus and Pandora were all brightened by a factor of eight and a half relative to Saturn. Tethys was brightened by a factor of four. In total, 809 background stars are visible and were brightened by a factor ranging from six, for the brightest stars, to 16, for the faintest. The faint outer rings (from the G ring to the E ring) were also brightened relative to the already bright main rings by factors ranging from two to eight, with the lower-phase-angle (and therefore fainter) regions of these rings brightened the most. The brightened version of the mosaic was further brightened and contrast-enhanced all over to accommodate print applications and a wide range of computer-screen viewing conditions. Some ring features -- such as full rings traced out by tiny moons -- do not appear in this version of the mosaic because they require extreme computer enhancement, which would adversely affect the rest of the mosaic. This version was processed for balance and beauty. This view looks toward the unlit side of the rings from about 17 degrees below the ring plane. Cassini was approximately 746,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from Saturn when the images in this mosaic were taken. Image scale on Saturn is about 45 miles (72 kilometers) per pixel. This mosaic was made from pictures taken over a span of more than four hours while the planets, moons and stars were all moving relative to Cassini. Thus, due to spacecraft motion, these objects in the locations shown here were not in these specific places over the entire duration of the imaging campaign. Note also that Venus appears far from Earth, as does Mars, because they were on the opposite side of the sun from Earth. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17172

In this rare image taken on 19 July, the wide-angle camera on the international Cassini spacecraft has captured Saturn’s rings and our planet Earth and Moon in the same frame. The dark side of Saturn, its bright limb, the main rings, the F ring, and the G and E rings are clearly seen; the limb of Saturn and the F ring are overexposed. The ‘breaks’ in the brightness of Saturn’s limb are due to the shadows of the rings on the globe of Saturn, preventing sunlight from shining through the atmosphere in those regions. The E and G rings have been brightened for better visibility. Earth, 1.44 billion km away in this image, appears as a blue dot at centre right; the Moon can be seen as a fainter protrusion off its right side. The other bright dots nearby are stars. <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagrid.me/nasagoddard/?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

Workers in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) stand around the upper experiment module and base of the Cassini orbiter during prelaunch processing, testing and integration in that facility. The Cassini orbiter and Huygens probe being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Employees in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) lower the upper experiment module and base of the Cassini orbiter onto a work stand during prelaunch processing, testing and integration work in that facility. The Cassini orbiter and Huygens probe being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers begin unloading the Cassini orbiter from a U.S. Air Force C-17 air cargo plane after its <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">arrival</a> at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers prepare to tow away the large container with the Cassini orbiter from KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility. The orbiter <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">just arrived</a> on the U.S. Air Force C-17 air cargo plane, shown here, from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers prepare to move the shipping container with the Cassini orbiter inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) for prelaunch processing, testing and integration. The <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">orbiter arrived</a> at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility in a U.S. Air Force C-17 air cargo plane from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers prepare to move the shipping container with the Cassini orbiter inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) for prelaunch processing, testing and integration. The <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">orbiter arrived</a> at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility in a U.S. Air Force C-17 air cargo plane from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

P-34712 Range: 1.1 million kilometers (683,000 miles) This wide-angle Voyager 2 image, taken through the camera's clear filter, is the first to show Neptune's rings in detail. The two main rings, about 53,000 km (33,000 miles) and 63,000 km (39,000 miles) from Neptune, are 5 to 10 times brighter than in earlier images. The difference is due to lighting and viewing geometry. In approach images, the rings were seen in light scattered backward toward the spacecraft at a 15° phase angle. However, this image was taken at a 135° phase angle as Voyager left the planet. That geometry is ideal for detecting microscopic particles that forward scatter light preferentially. The fact that Neptune's rings are so much brighter at that angle means the particle-size distribution is quite different from most of Uranus' and Saturn's rings, which contain fewer dust-size grains. However, a few componenets of the Saturian and Uranian ring systems exhibit forward-scattering behavior: The F ring and the Encke Gap ringlet at Saturn and 1986U1R at Uranus. They are also narrow, clumpy ringlets with kinks, and are associated with nearby moonlets too small to detect directly. In this image, the main clumpy arc, composed of three features each about 6 to 8 degrees long, is clearly seen. Exposure time for this image was 111 seconds.

An employee in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) sews thermal insulation material on the front heat shield of the Huygens probe during prelaunch processing testing and integration in that facility, with the probe’s back cover in the background. The Huygens probe and the Cassini orbiter being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers prepare to move the shipping container with the Cassini orbiter inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) for prelaunch processing, testing and integration. The <a href="http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/kscpao/release/1997/66-97.htm">orbiter arrived</a> at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility in a U.S. Air Force C-17 air cargo plane from Edwards Air Force Base, California. The orbiter and the Huygens probe already being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

An employee in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) sews thermal insulation material on the back cover and heat shield of the Huygens probe during prelaunch processing, testing and integration in that facility. The Huygens probe and the Cassini orbiter being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004

Workers in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF) perform checkouts of the upper experiment module and base of the Cassini orbiter during prelaunch processing, testing and integration in that facility. The Cassini orbiter and Huygens probe being processed at KSC are the two primary components of the Cassini spacecraft, which will be launched on a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle from Cape Canaveral Air Station. Cassini will explore Saturn, its rings and moons for four years. The Huygens probe, designed and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA), will be deployed from the orbiter to study the clouds, atmosphere and surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The orbiter was designed and assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Following postflight inspections, integration of the 12 science instruments not already installed on the orbiter will be completed. Then, the parabolic high-gain antenna and the propulsion module will be mated to the orbiter, followed by the Huygens probe, which will complete spacecraft integration. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch to begin its 6.7-year journey to the Saturnian system. Arrival at the planet is expected to occur around July 1, 2004