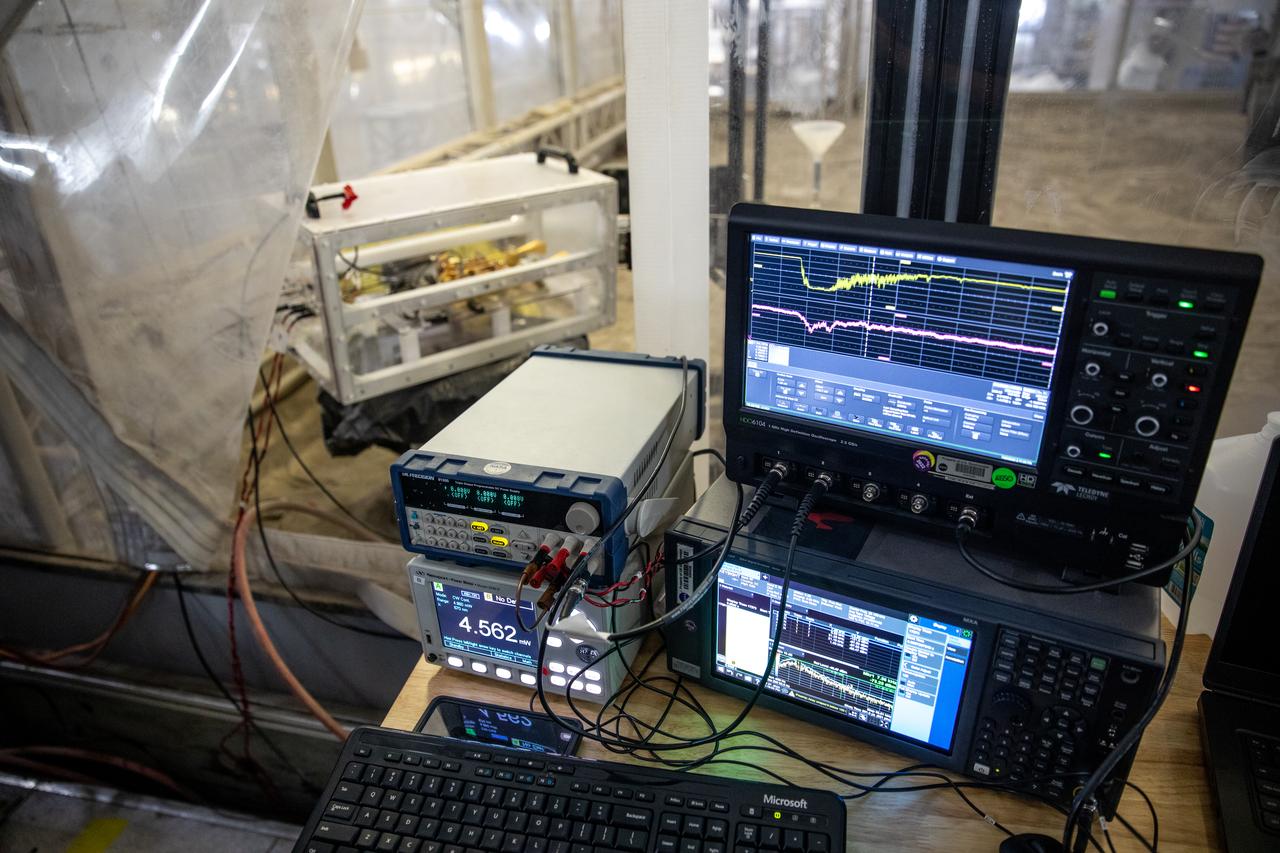

A team at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida assesses the Dust Concentration Monitor and the Millimeter Wave Doppler Radar inside a regolith bin at the Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations (GMRO) lab at the spaceport’s Swamp Works on July 28, 2022, as part of Plume Surface Interaction (PSI) Instrumentation testing. The PSI Project is advancing both modeling and testing capabilities to understand exactly how rocket exhaust plumes affect a planetary landing site. This advanced modeling will help engineers evaluate the risks of various plumes on planetary surfaces, which will help them more accurately design landers for particular locations.

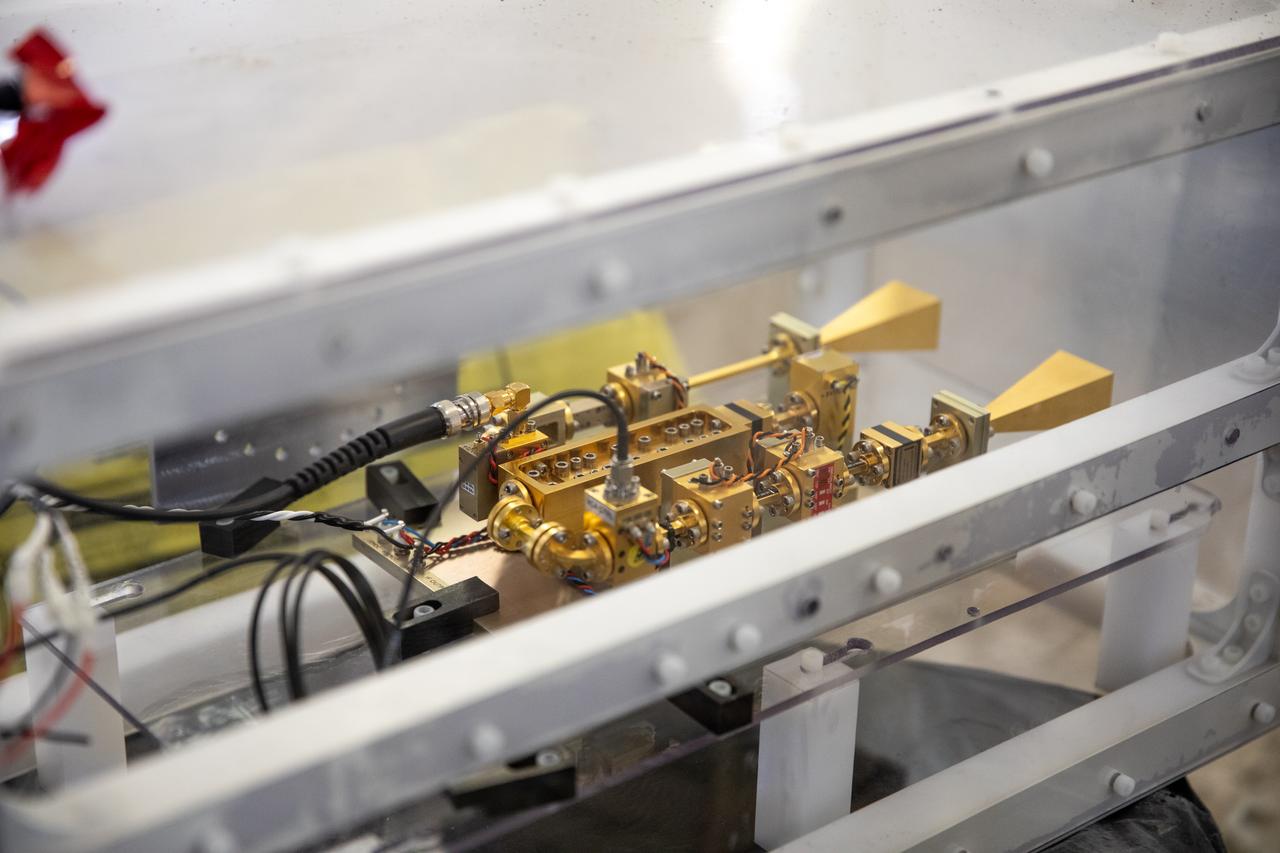

The Dust Concentration Monitor and the Millimeter Wave Doppler Radar undergo testing inside a regolith bin at the Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations (GMRO) lab at the Kennedy Space Center’s Swamp Works on July 28, 2022, as part of Plume Surface Interaction (PSI) Instrumentation testing. The PSI Project is advancing both modeling and testing capabilities to understand exactly how rocket exhaust plumes affect a planetary landing site. This advanced modeling will help engineers evaluate the risks of various plumes on planetary surfaces, which will help them more accurately design landers for particular locations.

A team at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida assesses the Dust Concentration Monitor and the Millimeter Wave Doppler Radar inside a regolith bin at the Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations (GMRO) lab at the spaceport’s Swamp Works on July 28, 2022, as part of Plume Surface Interaction (PSI) Instrumentation testing. The PSI Project is advancing both modeling and testing capabilities to understand exactly how rocket exhaust plumes affect a planetary landing site. This advanced modeling will help engineers evaluate the risks of various plumes on planetary surfaces, which will help them more accurately design landers for particular locations.

The Dust Concentration Monitor and the Millimeter Wave Doppler Radar undergo testing inside a regolith bin at the Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations (GMRO) lab at the Kennedy Space Center’s Swamp Works on July 28, 2022, as part of Plume Surface Interaction (PSI) Instrumentation testing. The PSI Project is advancing both modeling and testing capabilities to understand exactly how rocket exhaust plumes affect a planetary landing site. This advanced modeling will help engineers evaluate the risks of various plumes on planetary surfaces, which will help them more accurately design landers for particular locations.

A team at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida assesses the Dust Concentration Monitor and the Millimeter Wave Doppler Radar inside a regolith bin at the Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations (GMRO) lab at the spaceport’s Swamp Works on July 28, 2022, as part of Plume Surface Interaction (PSI) Instrumentation testing. The PSI Project is advancing both modeling and testing capabilities to understand exactly how rocket exhaust plumes affect a planetary landing site. This advanced modeling will help engineers evaluate the risks of various plumes on planetary surfaces, which will help them more accurately design landers for particular locations.

A team at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida assesses the Dust Concentration Monitor and the Millimeter Wave Doppler Radar inside a regolith bin at the Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations (GMRO) lab at the spaceport’s Swamp Works on July 28, 2022, as part of Plume Surface Interaction (PSI) Instrumentation testing. The PSI Project is advancing both modeling and testing capabilities to understand exactly how rocket exhaust plumes affect a planetary landing site. This advanced modeling will help engineers evaluate the risks of various plumes on planetary surfaces, which will help them more accurately design landers for particular locations.

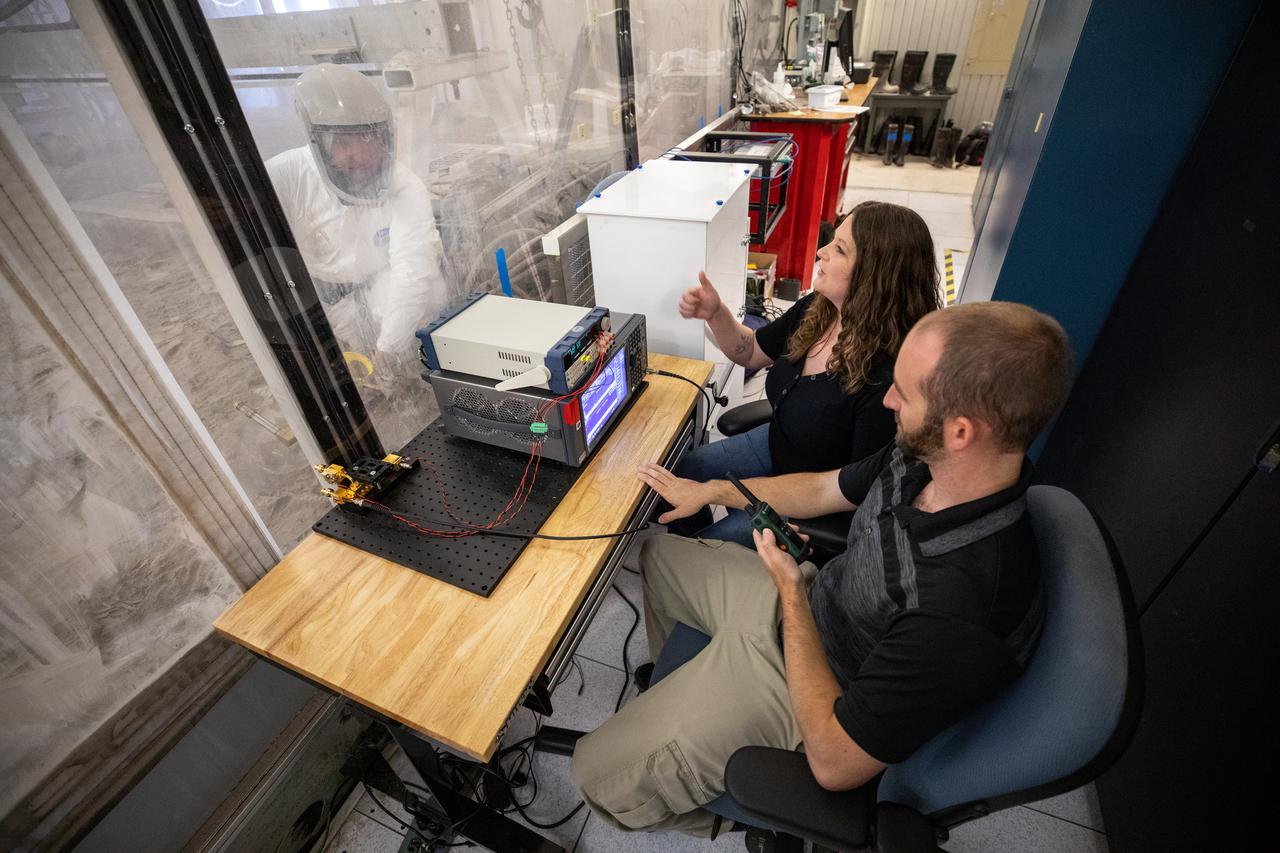

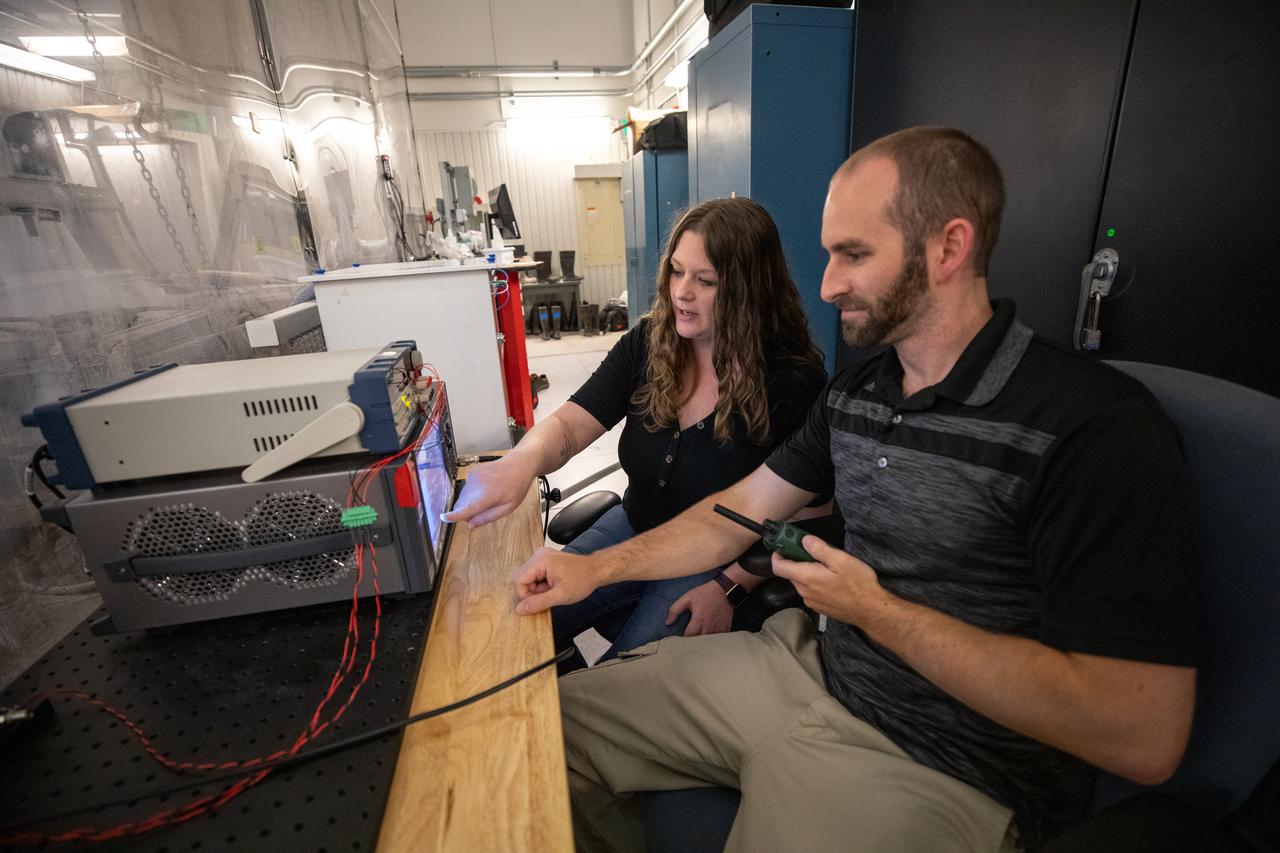

Beverly Kemmerer and Austin Adkins, right, and Austin Langton, perform testing with a Millimeter Wave Doppler Radar at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center’s Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations Lab on July 16, 2021. The testing at the Florida spaceport is part of a project to identify a suite of instrumentation capable of acquiring a comprehensive set of flight data from a lunar lander. Researchers at NASA will use that data to validate computational models being developed to predict plume surface interaction effects on the Moon.

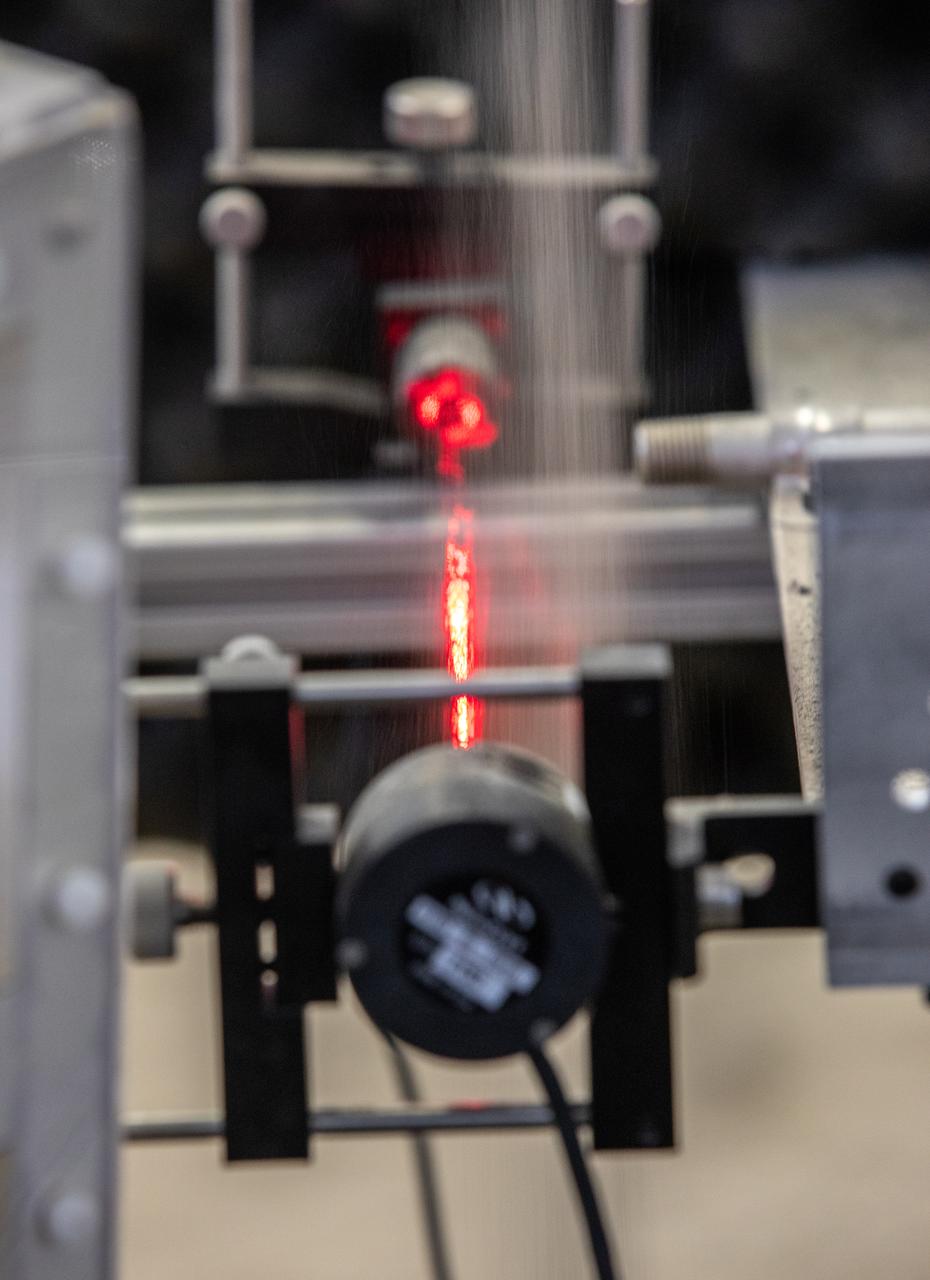

Austin Langton, a researcher at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, creates a fine spray of the regolith simulant BP-1, to perform testing with a Millimeter Wave Doppler Radar at the Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations Lab on July 16, 2021. The testing occurred inside the "Big Bin," an enclosure at Swamp Works that holds 120 tons of regolith simulant. The testing at the Florida spaceport is part of a project to predict plume surface interaction effects on the Moon, with testing happening at Kennedy, and NASA's Marshal Space Flight Center and Glenn Research Center.

Beverly Kemmerer and Austin Adkins perform testing with a Millimeter Wave Doppler Radar at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center’s Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations Lab on July 16, 2021. The testing at the Florida spaceport is part of a project to identify a suite of instrumentation capable of acquiring a comprehensive set of flight data from a lunar lander. Researchers at NASA will use that data to validate computational models being developed to predict plume surface interaction effects on the Moon.

ISS033-E-018010 (3 Nov. 2012) --- Volcanoes in central Kamchatka are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 33 crew member on the International Space Station. The snow-covered peaks of several volcanoes of the central Kamchatka Peninsula are visible standing above a fairly uniform cloud deck that obscures the surrounding lowlands. In addition to the rippled cloud patterns caused by interactions of air currents and the volcanoes, a steam and ash plume is visible at center extending north-northeast from the relatively low summit (2,882 meters above sea level) of Bezymianny volcano. Volcanic activity in this part of Russia is relatively frequent, and well monitored by Russia’s Kamchatka Volcanic Eruption Response Team (KVERT). The KVERT website provides updated information about the activity levels on the peninsula, including aviation alerts and webcams. Directly to the north and northeast of Bezymianny, the much larger and taller stratovolcanoes Kamen (4,585 meters above sea level) and Kliuchevskoi (4,835 meters above sea level) are visible. Kliuchevskoi, Kamchatka’s most active volcano, last erupted in 2011 whereas neighboring Kamen has not erupted during the recorded history of the region. An explosive eruption from the summit of the large volcanic massif of Ushkovsky (3,943 meters above sea level; left) northwest of Bezymianny occurred in 1890; this is the most recent activity at this volcano. To the south of Bezymianny, the peaks of Zimina (3,081 meters above sea level) and Udina (2,923 meters above sea level) volcanoes are just visible above the cloud deck; no historical eruptions are known from either volcanic center. While the large Tobalchik volcano to the southwest (bottom center) is largely formed from a basaltic shield volcano, its highest peak (3,682 meters above sea level) is formed from an older stratovolcano. Tobalchik last erupted in 1976. While this image may look like it was taken from the normal altitude of a passenger jet, the space station was located approximately 417 kilometers above the southeastern Sea of Okhotsk; projected downwards to Earth’s surface, the space station was located over 700 kilometers to the southwest of the volcanoes in the image. The combination of low viewing angle from the orbital outpost, shadows, and height and distance from the volcanoes contributes to the appearance of topographic relief visible in the image.