Raymond Lewis, son-in-law of Mary W. Jackson, takes a picture of the Mary W. Jackson NASA Headquarters sign following a ceremony officially naming the building, Friday, Feb. 26, 2021, at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. Mary W. Jackson, the first African American female engineer at NASA, began her career with the agency in the segregated West Area Computing Unit of NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. The mathematician and aerospace engineer went on to lead programs influencing the hiring and promotion of women in NASA's science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers. In 2019, she posthumously received the Congressional Gold Medal. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Bryan Jackson, grandson of Mary W. Jackson, left, and Raymond Lewis, son-in-law of Mary W. Jackson, right, unveil the Mary W. Jackson NASA Headquarters sign during a ceremony officially naming the building, Friday, Feb. 26, 2021, at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. Mary W. Jackson, the first African American female engineer at NASA, began her career with the agency in the segregated West Area Computing Unit of NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. The mathematician and aerospace engineer went on to lead programs influencing the hiring and promotion of women in NASA's science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers. In 2019, she posthumously received the Congressional Gold Medal. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Myrtle Lewis and three of her sons visit the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio. The Flight Propulsion Research Laboratory was renamed in Lewis’ honor in September 1948. Lewis served as the NACA’s Director of Aeronautical Research for over 20 years. Lewis joined the NACA as Executive Officer in 1919 and was named Director of Aeronautical Research in 1924. In this role Lewis served as the liaison between the Executive Committee and the research laboratories. His most important accomplishment may have been the investigative tours of German research facilities in 1936 and 1939. The visits resulted in the NACA’s physical expansion and the broadening of its scope of research. Lewis did not take a day of leave between the Pearl Harbor attack and the Armistice, but began suffering health problems in 1945. He was forced to retire two years later and passed in July 1948. Front row, left to right: Lewis Director Raymond Sharp, Mrs. Lewis, NACA Executive Secretary John Victory; back row: Executive Officer Robert Sessions, Armand Lewis, Harvey Lewis, and George Lewis II. Harvey and George Lewis II were employed at NACA Lewis in the Instrument Service and Applied Compressor sections, respectively.

Addison Rothrock, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics’s (NACA) Assistant Director of Research, speaks at the groundbreaking ceremony for the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory’s new test reactor at Plum Brook Station. This dedication event was held almost exactly one year after the NACA announced that it would build its $4.5 million nuclear reactor on 500 acres of the army’s 9000-acre Plum Brook Ordnance Works. The site was located in Sandusky, Ohio, approximately 60 miles west of the NACA Lewis laboratory in Cleveland. Lewis Director Raymond Sharp is seated to the left of Rothrock, Congressman Albert Baumhart and NACA Secretary John Victory are to the right. Many government and local officials were on hand for the press conference and ensuing luncheon. In the wake of World War II the military, the Atomic Energy Commission, and the NACA became interested in the use of atomic energy for propulsion and power. A Nuclear Division was established at NACA Lewis in the early 1950s. The division’s request for a 60-megawatt research reactor was approved in 1955. The semi-remote Plum Brook location was selected over 17 other possible sites. Construction of the Plum Brook Reactor Facility lasted five years. By the time of its first trial runs in 1961 the aircraft nuclear propulsion program had been cancelled. The space age had arrived, however, and the reactor would be used to study materials for a nuclear powered rocket.

Construction Manager Raymond Sharp and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Director of Research George Lewis speak to employees during the May 8, 1942, Initiation of Research ceremony at the Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory. The event marked the first operation of a test facility at the new laboratory. The overall laboratory was still under construction, however, and behind schedule. Lewis traveled from his office in Washington, DC every week to personally assess the progress. Drastic measures were undertaken to accelerate the lab’s construction schedule. The military provided special supplies, contractors were given new agreements and pressured to meet deadlines, and Congress approved additional funds. The effort paid off and much of the laboratory was operational in early 1943. George Lewis managed the NACA’s aeronautical research for over 20 years. Lewis joined the NACA as Executive Officer in 1919, and was named Director of Aeronautical Research in 1924. In this role Lewis served as the liaison between the Executive Committee and the research laboratories. His most important accomplishment may have been the investigative tours of the research facilities in Germany in 1936 and 1939. The visits resulted in the NACA’s physical expansion and the broadening of the scope of its research. Lewis did not take a day of leave between the Pearl Harbor attack and the Armistice. He began suffering health problems in 1945 and was forced to retire two years later. The Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory was renamed the NACA Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in September 1948.

General Dwight Eisenhower addressed the staff of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory during an April 11, 1946 visit to Cleveland. The former supreme commander of Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe was on a tour of several US cities in the months following the end of World War II. The general arrived in Cleveland on his Douglas C-54 Skymaster, the 'Sunflower II'. Eisenhower employed this aircraft while leading forces during the war. Skymasters, the military version of the DC–4 transport aircraft, were used extensively by both the army and navy throughout the war years. NACA Secretary John Victory, Lewis Director Raymond Sharp, and local politicians formally greeted Eisenhower as he deplaned at the NACA hangar. After patiently posing for the press photographers, Eisenhower accompanied Victory and Sharp to the Administration Building for a press conference. The general made a point of downplaying the prospects for another imminent war. Afterwards Eisenhower was given a tour of the laboratory and addressed the NACA Lewis staff assembled outside the Administration Building on the importance of research and development. Eisenhower left the laboratory in a motorcade for a banquet being held in his honor downtown with the Cleveland Aviation Club.

Attendees listen during the May 22, 1956 Inspection of the new 10- by 10-Foot Supersonic Wind Tunnel at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. The facility, known at the time as the Lewis Unitary Plan Tunnel, was in its initial stages of operation. The $33 million 10- by 10 was the most powerful wind tunnel in the nation. Over 150 guests from industry, other NACA laboratories, and the media attended the event. The speakers, from left to right in the front row, addressed the crowd before the tour. Lewis Director Raymond Sharp began the event by welcoming the visitors to the laboratory. NACA Director Hugh Dryden discussed Congress’ Unitary Plan Act and its effect on the creation of the facility. Lewis Associate Director Abe Silverstein discussed the need for research tools and the 10- by 10’s place among the NACA’s other research facilities. Lewis Assistant Director Eugene Wasielewski described the detailed design work that went into the facility. Carl Schueller, Chief of the 10- by 10, described the tunnel’s components and how the facility operated. Robert Godman led the tour afterwards. The 10- by 10 can test engines up to five feet in diameter at supersonic speeds and simulated altitudes of 30 miles. Its main purpose is to investigate problems relating to engine inlet and outlet geometry, engine matching and interference effects, and overall drag. The tunnel’s 250,000-horsepower electric motor drive, the most powerful of its kind in the world, creates air speeds between Mach 2.0 and 3.5.

ALL Singularity University Students, Founding Members, Faculty/TP Leads, TF and Staff; Founders, Peter Diamandis, Ray Kurzweil, Salim, Bruce/Susan Faculty, Bob Richards, Dan Barry, Rob Freitas, Andrew Hessel, Jim Hurd, Neil Jacobstein, Raymond McCauley, Michael McCullough, Ralph Merkle, David Orban, David S. Rose, Chris Lewicki, David Dell,Robert A Freitas, Jr,.Staff, Tasha McCauley, Manuel Zaera-Sanz, David Ayotte, Jose Cordeiro, Sarah Russell, Candi Sterling, Marco Chacin, Ola Abraham, Jonathan Badal, Eric Dahlstrom, Susan Fonseca-Klein, Emeline Paat-Dahlstrom, Keith Powers, Bruce Klein, Tracy Nguyen, Kelly Lewis, Ken Hurst, Paul Sieveke, Kathryn Myronuk, Andy Barry. Associate Faculty, Adriana Cardenas

The Mary W. Jackson NASA Headquarters sign is seen after being unveiled by Bryan Jackson, grandson of Mary W. Jackson, and Raymond Lewis, son-in-law of Mary W. Jackson, during a ceremony officially naming the building, Friday, Feb. 26, 2021, at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. Mary W. Jackson, the first African American female engineer at NASA, began her career with the agency in the segregated West Area Computing Unit of NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. The mathematician and aerospace engineer went on to lead programs influencing the hiring and promotion of women in NASA's science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers. In 2019, she posthumously received the Congressional Gold Medal. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Singularity University Founding Members,Faculty/TP Leads, TF's, GSP10 Directors Founders, Peter Diamandis, Ray Kurzweil. Faculty, Bob Richards, Dan Barry, Rob Freitas, Andrew Hessel, Jim Hurd, Neil Jacobstein, Raymond McCauley, Michael McCullough, Ralph Merkle, David Orban, David S. Rose, Chris Lewicki, David Dell,Robert A Freitas, Jr,. Staff, Tasha McCauley, Manuel Zaera-Sanz, David Ayotte, Jose Cordeiro, Sarah Russell, Candi Sterling, Marco Chacin, Ola Abraham, Jonathan Badal, Eric Dahlstrom, Susan Fonseca-Klein, Emeline Paat-Dahlstrom, Keith Powers, Bruce Klein, Tracy Nguyen, Kelly Lewis, Ken Hurst, Paul Sieveke, Kathryn Myronuk, Andy Barry. Associate Faculty, Adriana Cardenas

Singularity University Founding Members,Faculty/TP Leads, TF's, GSP10 Directors Founders, Peter Diamandis, Ray Kurzweil. Faculty, Bob Richards, Dan Barry, Rob Freitas, Andrew Hessel, Jim Hurd, Neil Jacobstein, Raymond McCauley, Michael McCullough, Ralph Merkle, David Orban, David S. Rose, Chris Lewicki, David Dell,Robert A Freitas, Jr,. Staff, Tasha McCauley, Manuel Zaera-Sanz, David Ayotte, Jose Cordeiro, Sarah Russell, Candi Sterling, Marco Chacin, Ola Abraham, Jonathan Badal, Eric Dahlstrom, Susan Fonseca-Klein, Emeline Paat-Dahlstrom, Keith Powers, Bruce Klein, Tracy Nguyen, Kelly Lewis, Ken Hurst, Paul Sieveke, Kathryn Myronuk, Andy Barry. Associate Faculty, Adriana Cardenas

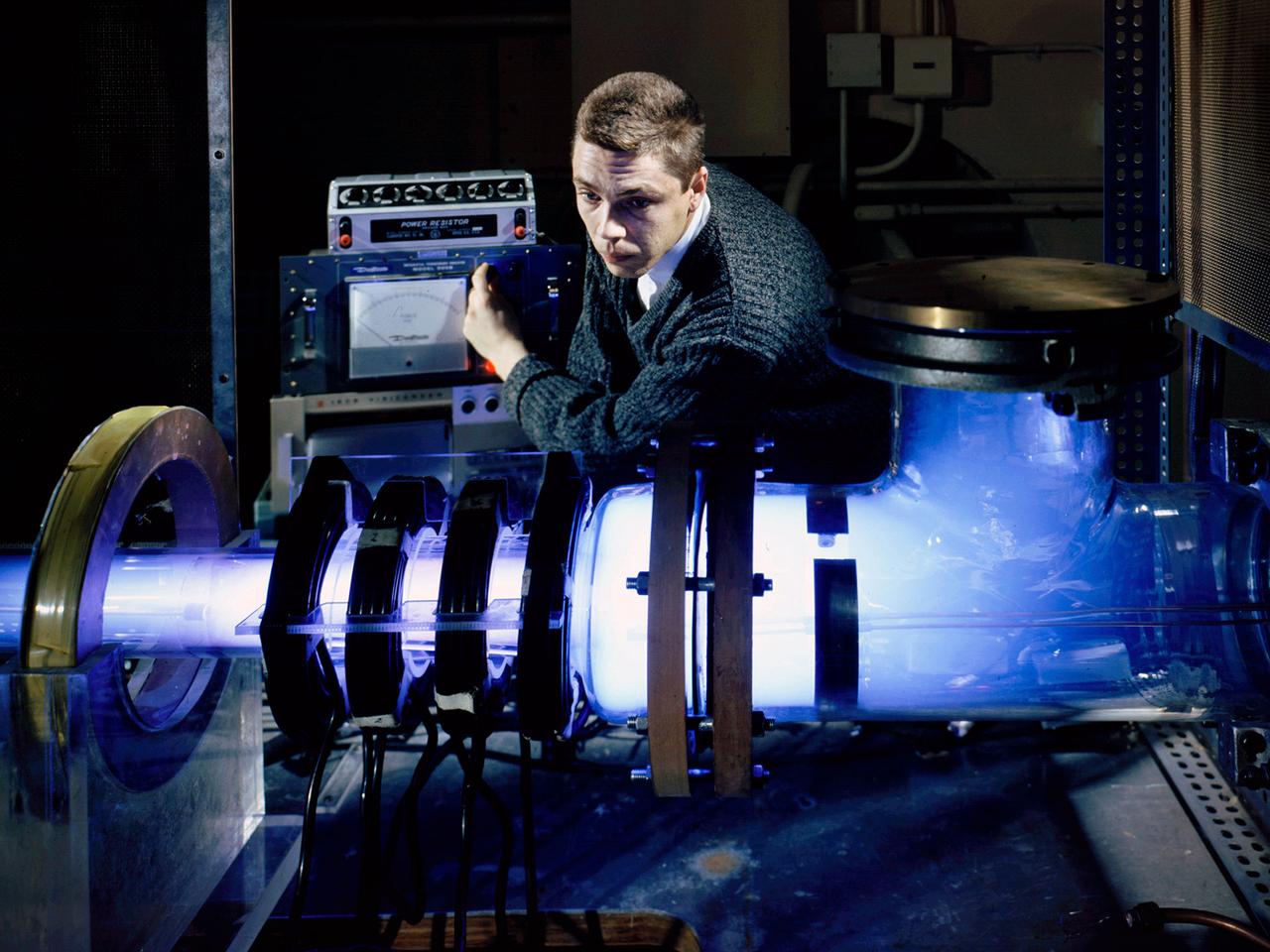

Raymond Palmer, of the Electromagnetic Propulsion Division’s Plasma Flow Section, adjusts the traveling magnetic wave plasma engine being operated in the Electric Power Conversion at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Lewis Research Center. During the 1960s Lewis researchers were exploring several different methods of creating electric propulsion systems, including the traveling magnetic wave plasma engine. The device operated similarly to alternating-current motors, except that a gas, not a solid, was used to conduct the electricity. A magnetic wave induced a current as it passed through the plasma. The current and magnetic field pushed the plasma in one direction. Palmer and colleague Robert Jones explored a variety of engine configurations in the Electric Propulsion Research Building. The engine is seen here mounted externally on the facility’s 5-foot diameter and 16-foot long vacuum tank. The four magnetic coils are seen on the left end of the engine. The researchers conducted two-minute test runs with varying configurations and used of both argon and xenon as the propellant. The Electric Propulsion Research Building was built in 1942 as the Engine Propeller Research Building, often called the Prop House. It contained four test cells to study large reciprocating engines with their propellers. After World War II, the facility was modified to study turbojet engines. By the 1960s, the facility was modified again for electric propulsion research and given its current name.

A group of 60 Army Air Forces officers visited the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory on August 27, 1945. The laboratory enacted strict security regulations throughout World War II. During the final months of the war, however, the NACA began opening its doors to groups of writers, servicemen, and aviation industry leaders. These events were the first exposure of the new engine laboratory to the outside world. Grandstands were built alongside the Altitude Wind Tunnel specifically for group photographs. George Lewis, Raymond Sharp, and Addison Rothrock (right to left) addressed this group of officers in the Administration Building auditorium. Lewis was the NACA’s Director of Aeronautical Research, Sharp was the lab’s manager, and Rothrock was the lab’s chief of research. Abe Silverstein, Jesse Hall and others watch from the rear of the room. The group toured several facilities after the talks, including the Altitude Wind Tunnel and a new small supersonic wind tunnel. The visit concluded with a NACA versus Army baseball game and cookout.

National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Chairman James Doolittle and Thompson Products Chairman of the Board Frederick Crawford receive a tour of the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory during the last few months of the NACA. Lewis mechanic Leonard Tesar demonstrates the machining of a 20,000-pound thrust rocket engine for the group in the Fabrication Shop. From left to right, Associate Director Eugene Manganiello, researcher Edward Baehr, Doolittle, NACA Executive Secretary John Victory, Crawford, Tesar, Lewis Director Raymond Sharp, and mechanic Curtis Strawn. Doolittle began his career as a test pilot and air racer. In 1942 he famously flew a B-25 Mitchell on a daring raid over Tokyo. Doolittle also worked with the aviation industry on the development of aircraft fuels and instrumentation. After the war he served as vice president of Shell Oil and as a key government advisor. In this capacity he also served on the NACA’s Executive Committee for a number of years and served as its Chairman in 1957 and 1958. Tesar was a supervisor at the Sheet Metal Shop in the Fabrication Building. He joined the laboratory in 1948 and enrolled in their Apprentice Program. He graduated from the school three years later as an aviation metalsmith. The Fabrication Branch created a wide variety of hardware for the laboratory’s research projects. Requests from research divisions ranged from sheetmetal manufacturing for aircraft to fabrication of rocket engines. Tesar retired in 1982 after 37 years of service.

A group of National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) officials and local dignitaries were on hand on May 8, 1942, to witness the Initiation of Research at the NACA's new Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio. The group in this photograph was in the control room of the laboratory's first test facility, the Engine Propeller Research Building. The NACA press release that day noted, "First actual research activities in what is to be the largest aircraft engine research laboratory in the world was begun today at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics laboratory at the Cleveland Municipal Airport.” The ceremony, however, was largely symbolic since most of the laboratory was still under construction. Dr. George W. Lewis, the NACA's Director of Aeronautical Research, and John F. Victory, NACA Secretary, are at the controls in this photograph. Airport Manager John Berry, former City Manager William Hopkins, NACA Assistant Secretary Ed Chamberlain, Langley Engineer-in-Charge Henry Reid, Executive Engineer Carlton Kemper, and Construction Manager Raymond Sharp are also present. The propeller building contained two torque stands to test complete engines at ambient conditions. The facility was primarily used at the time to study engine lubrication and cooling systems for World War II aircraft, which were required to perform at higher altitudes and longer ranges than previous generations.