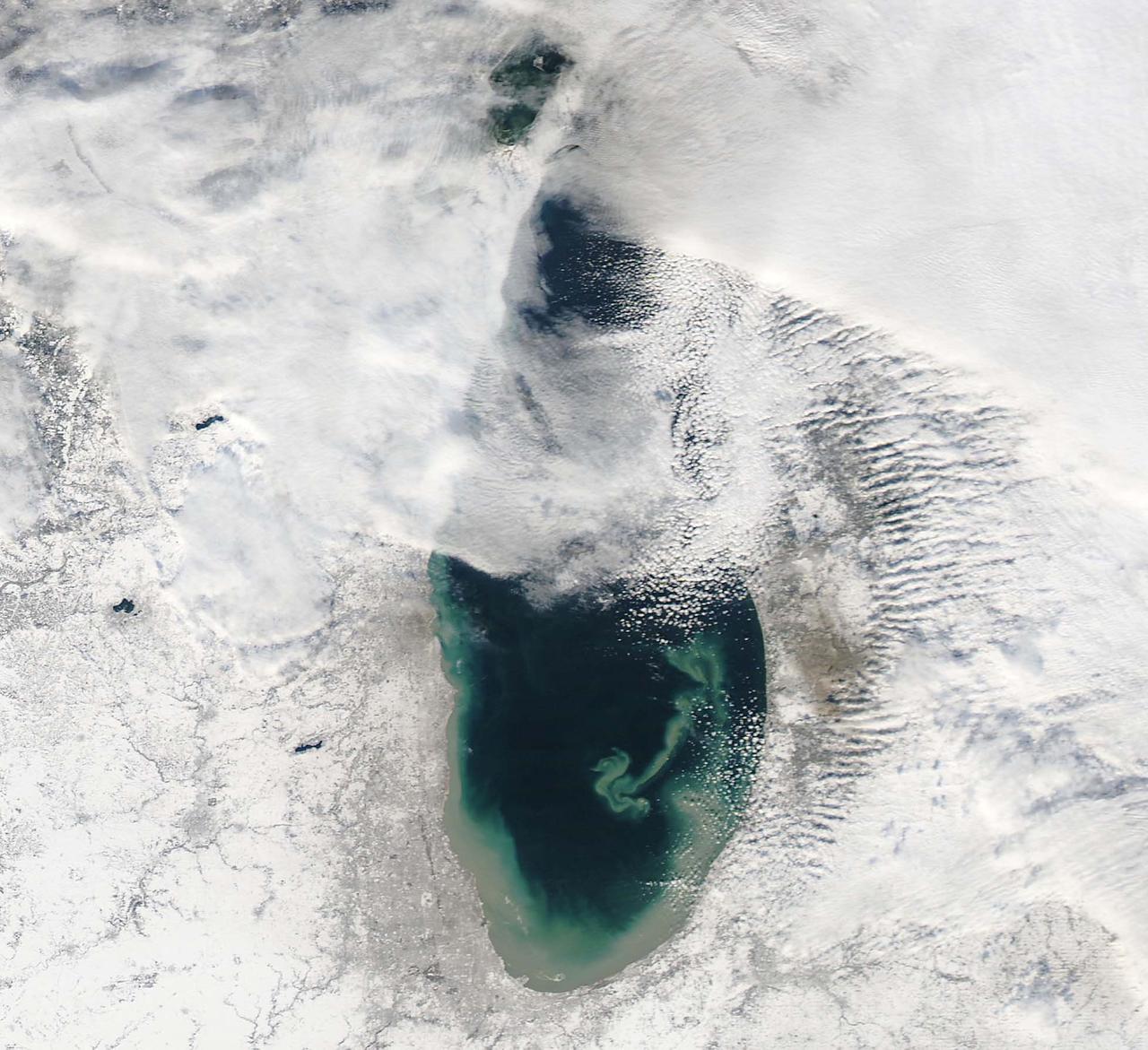

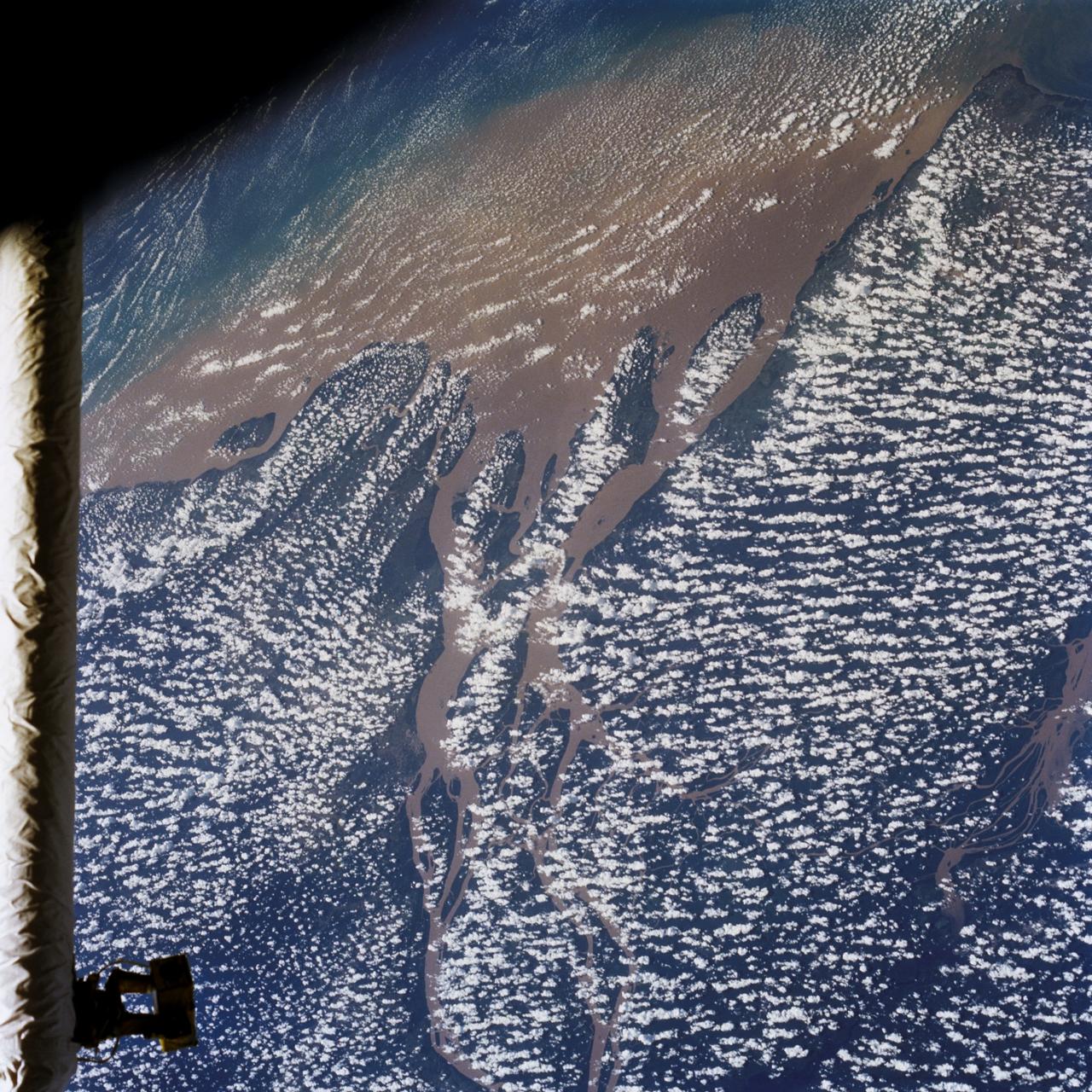

NASA image acquired December 17, 2010 In mid-December 2010, suspended sediments transformed the southern end of Lake Michigan. Ranging in color from brown to green, the sediment filled the surface waters along the southern coastline and formed a long, curving tendril extending toward the middle of the lake. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite captured these natural-color images on December 17, 2010 (top), and December 10, 2010 (bottom). Such sediment clouds are not uncommon in Lake Michigan, where winds influence lake circulation patterns. A scientificpaper published in 2007 described a model of the circulation, noting that while the suspended particles mostly arise from lake-bottom sediments along the western shoreline, they tend to accumulate on the eastern side. When northerly winds blow, two circulation gyres, rotating in opposite directions, transport sediment along the southern shoreline. As the northerly winds die down, the counterclockwise gyre predominates, and the smaller, clockwise gyre dissipates. Clear water—an apparent remnant of the small clockwise gyre—continues to interrupt the sediment plume. George Leshkevich, a researcher with the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, explains that the wind-driven gyres erode lacustrine clay (very fine lakebed sediment) on the western shore before transporting it, along with re-suspended lake sediments, to the eastern shore. On the eastern side, the gyre encounters a shoreline bulge that pushes it toward the lake’s central southern basin, where it deposits the sediments. The sediment plume on December 17 followed a windy weather front in the region on December 16. NASA image courtesy MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. Caption by Michon Scott. Instrument: Aqua - MODIS <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASA_GoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Join us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> To read more about this image go to: <a href="http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=48511" rel="nofollow">earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=48511</a>

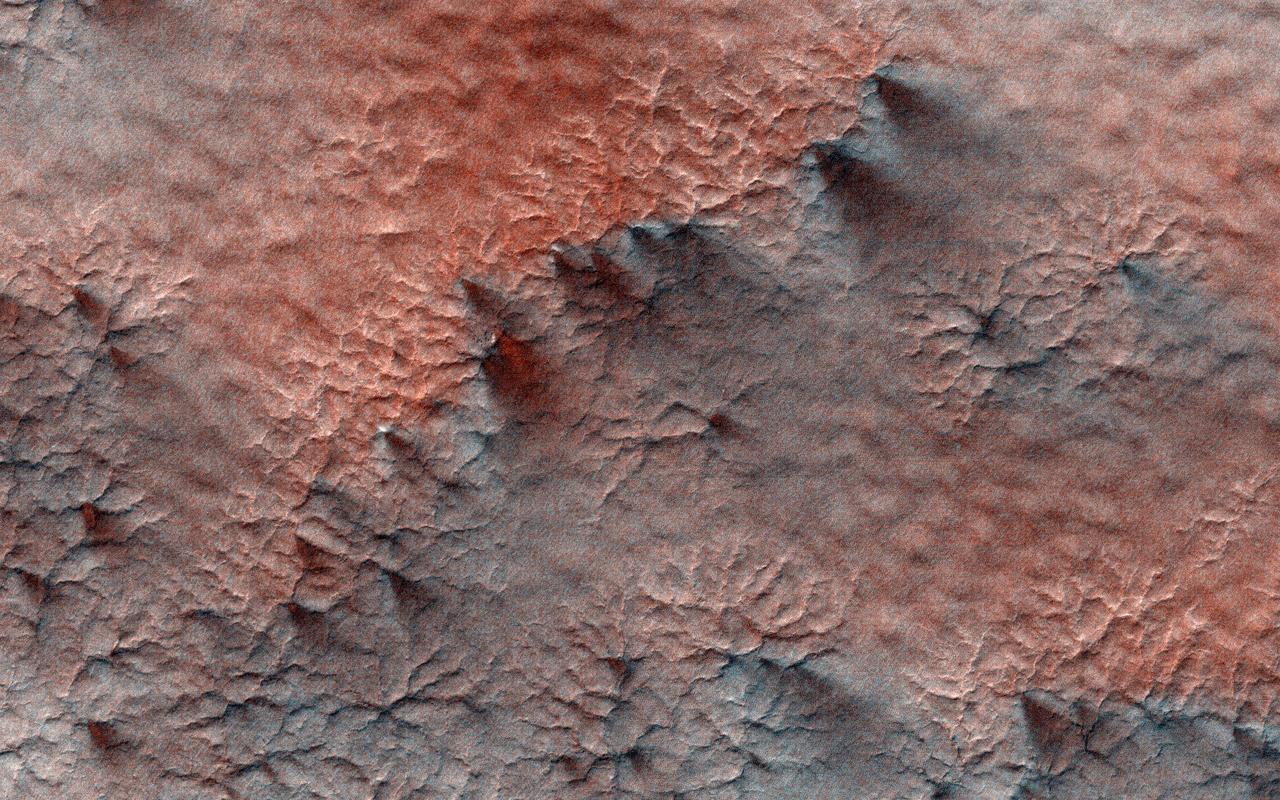

Sediments of Arabia

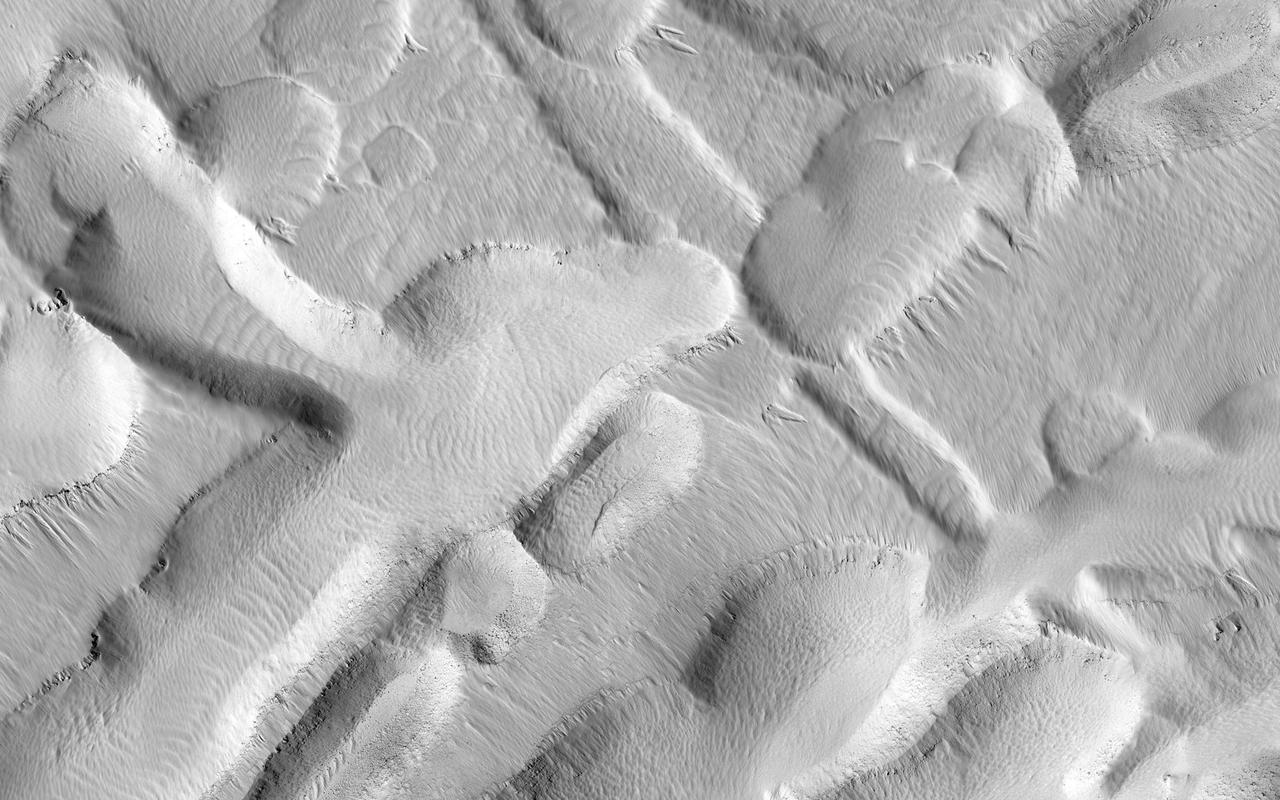

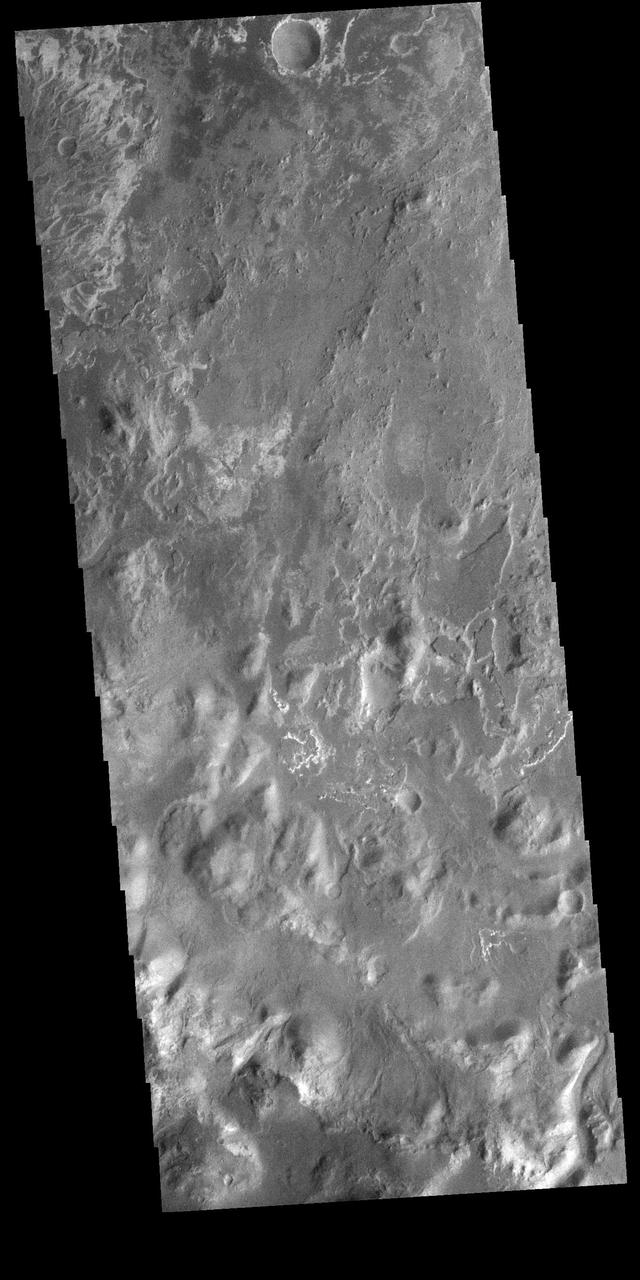

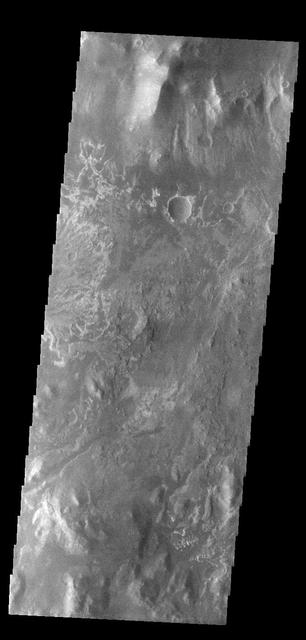

Sediments of Terby

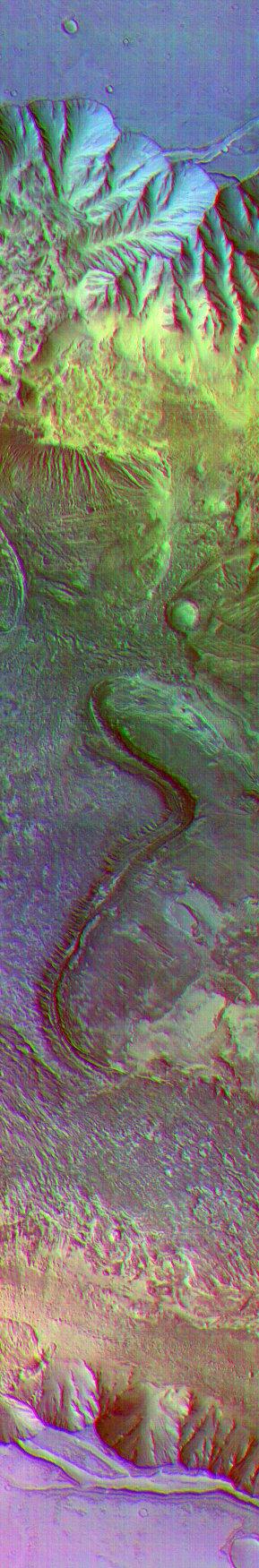

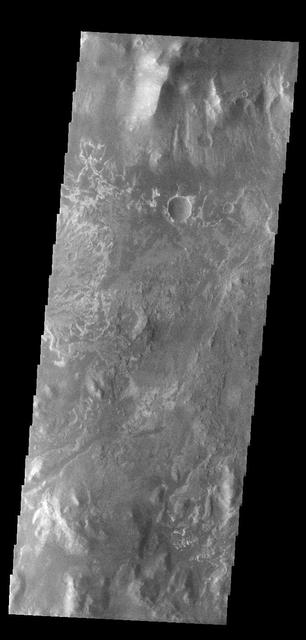

Sediments of Ophir

Becquerel Sediment

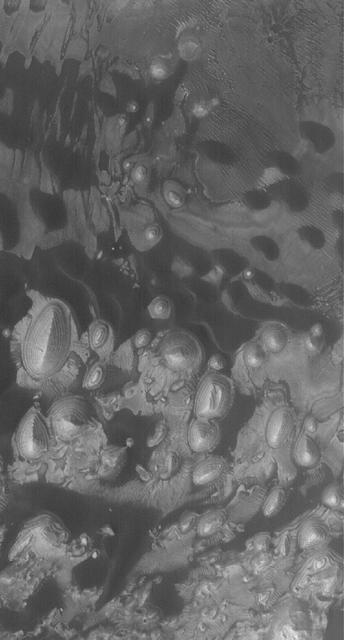

Aram Chaos Sediments

Sediment History Preserved in Gale Crater Central Mound

Sediment History Preserved in Gale Crater Central Mound

Sediment History Preserved in Gale Crater Central Mound

Sediment History Preserved in Gale Crater Central Mound

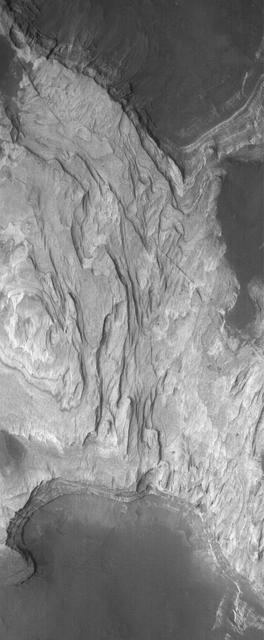

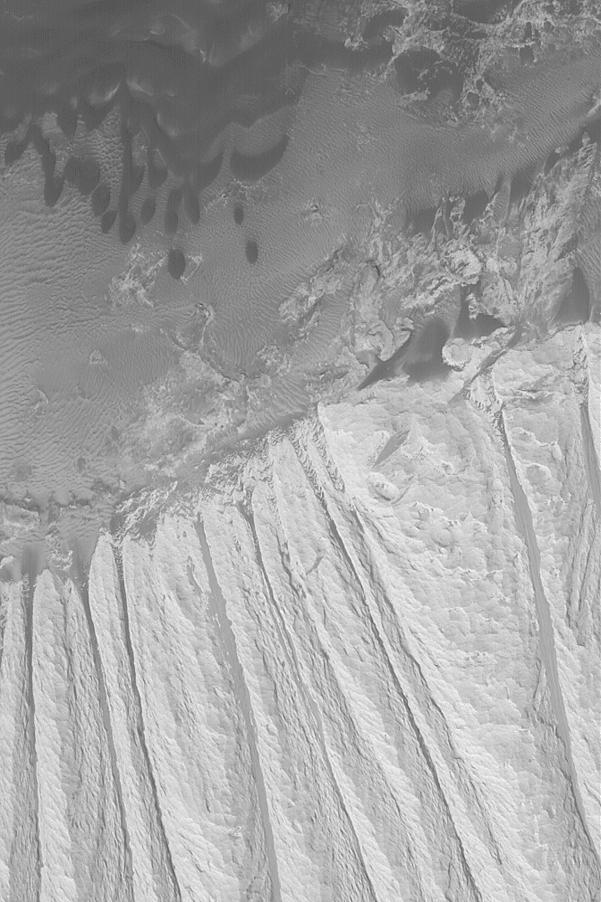

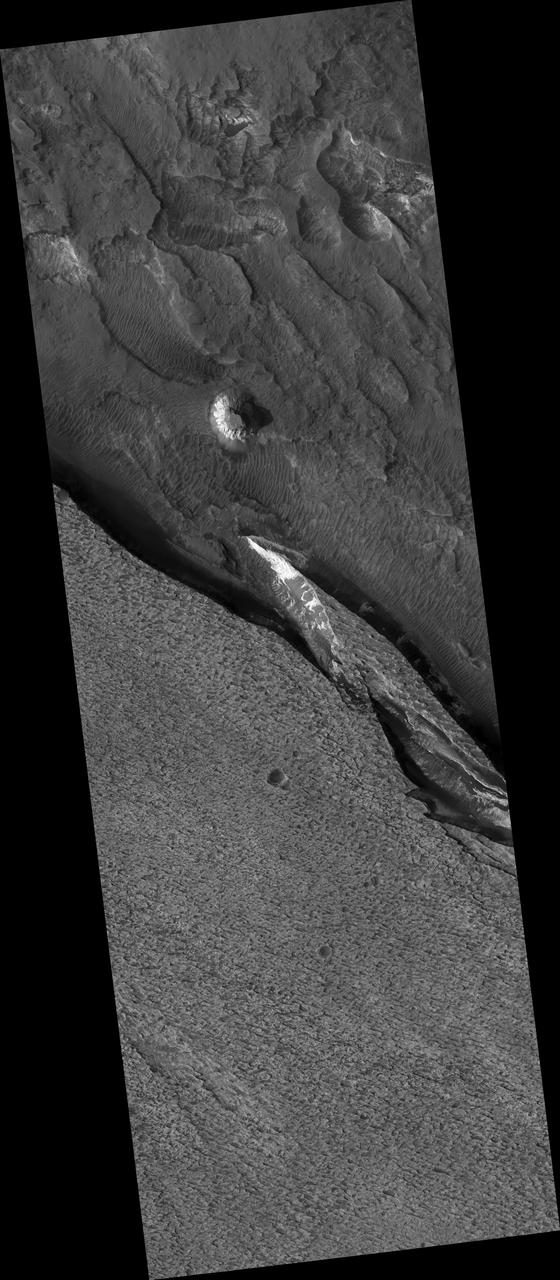

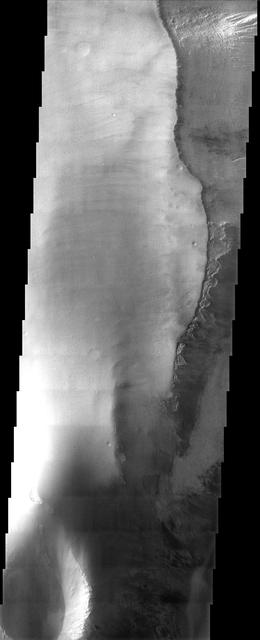

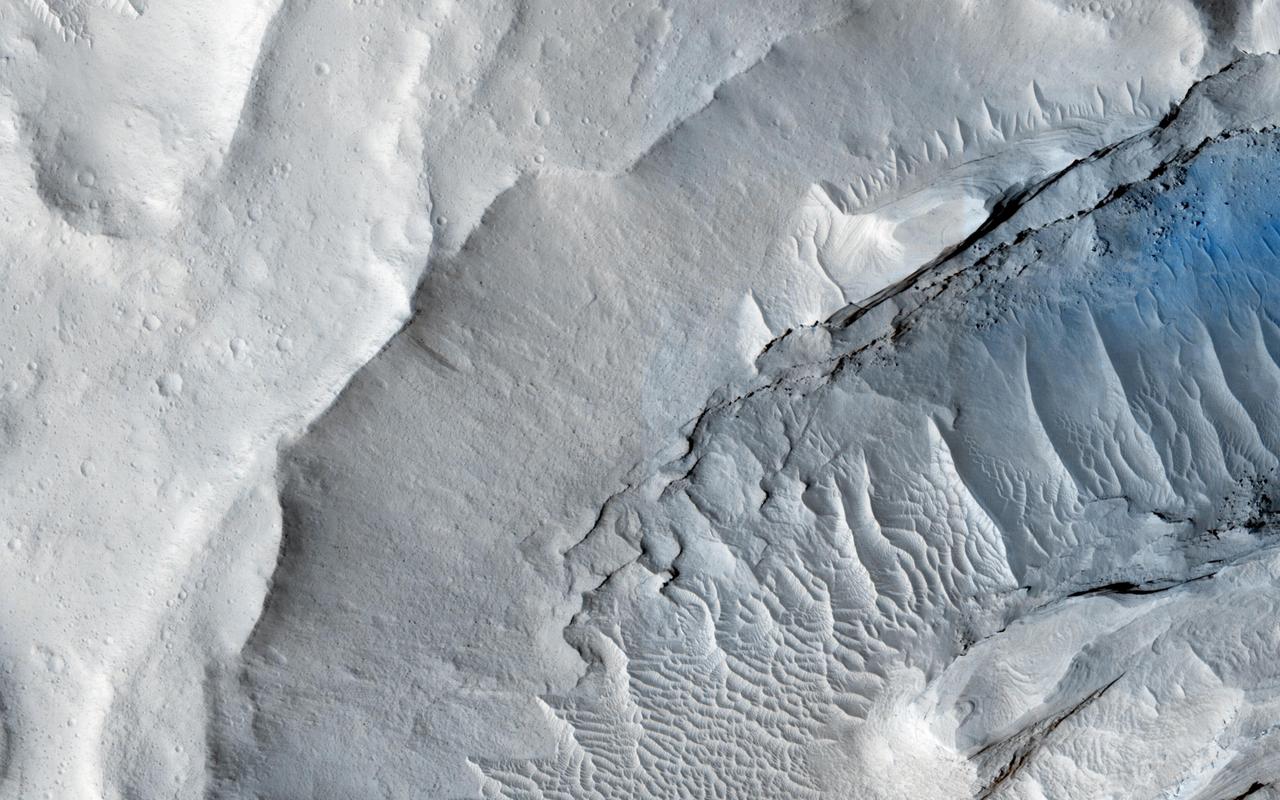

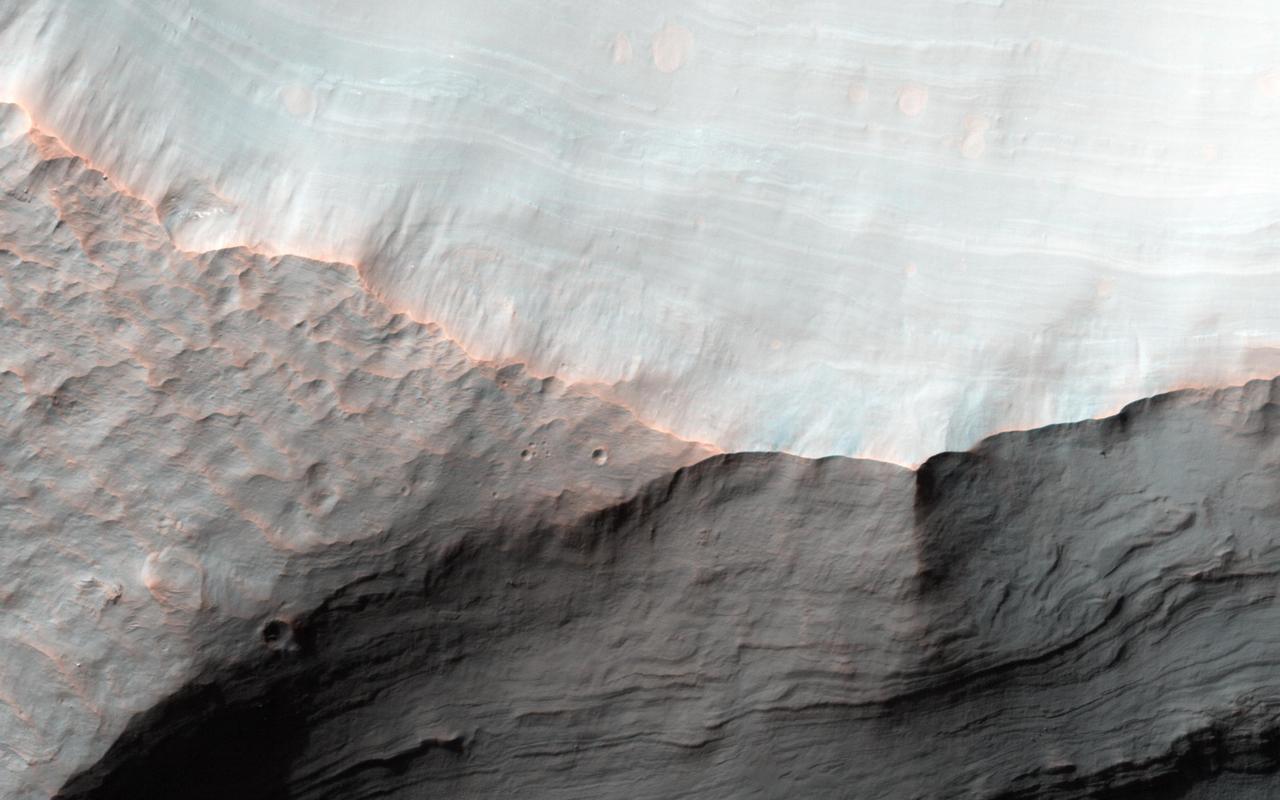

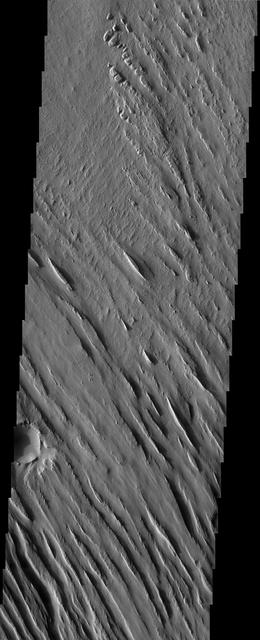

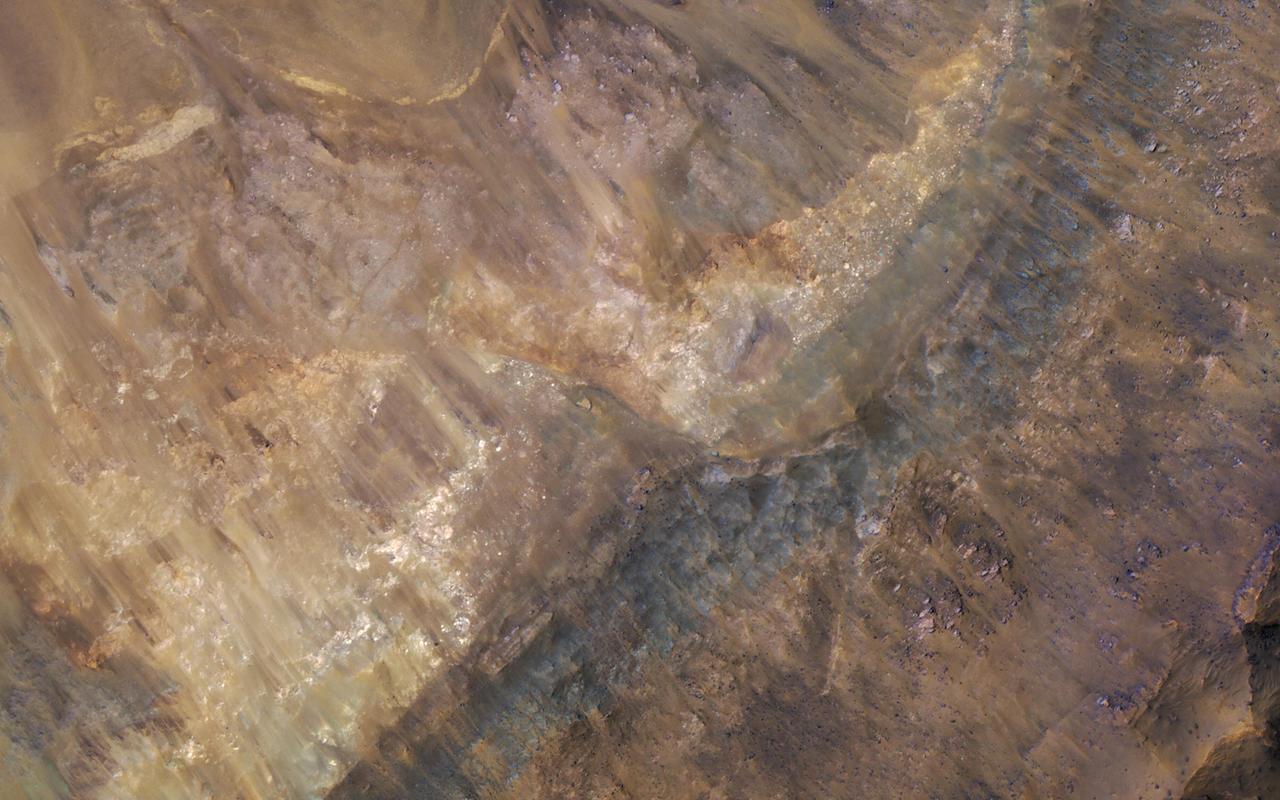

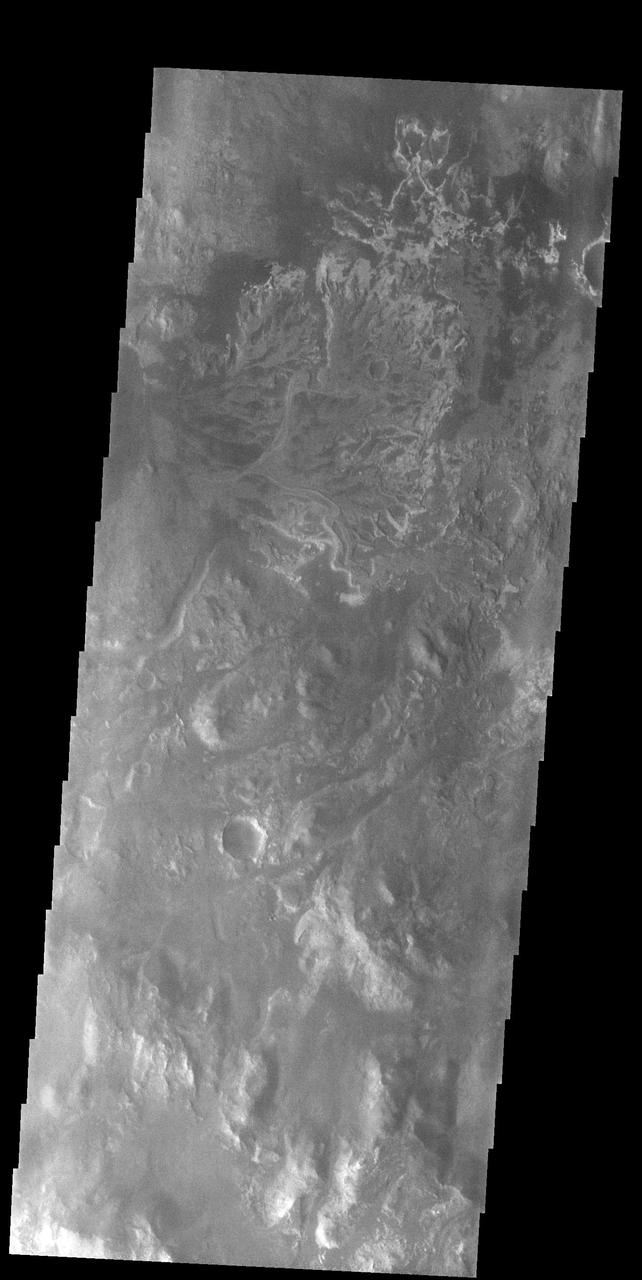

Massive deposits of sediments rich in hydrated sulfates are found in central Valles Marineris. Such deposits on Earth are soft and easily eroded, and that appears to be true on Mars as well. There are large gullies and sediment fans along the steepest slopes. Elsewhere on Mars, such slopes are actively eroding in before-and-after HiRISE images, so this would be a good location to observe again in a future year. Linear gaps in data coverage on the bright sun-facing slopes are locations where the image data is saturated. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25352

NASA image acquired September 2, 2011 To download the full high res go to: <a href="http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=52059" rel="nofollow">earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=52059</a> Nearly a week after Hurricane Irene drenched New England with rainfall in late August 2011, the Connecticut River was spewing muddy sediment into Long Island Sound and wrecking the region's farmland just before harvest. The Thematic Mapper on the Landsat 5 satellite acquired this true-color satellite image on September 2, 2011. With its headwaters near the Canadian border, the Connecticut River drains nearly 11,000 square miles (28,500 square kilometers) and receives water from at least 33 tributaries in Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. The 410-mile river—New England's longest—enters Long Island Sound near Old Lyme, Connecticut, and is estimated to provide 70 percent of the fresh water entering the Sound. When Irene blew through the region on August 27-28, substantial portions of the Connecticut River watershed received more than 6 to 8 inches (15-20 centimeters) of rainfall, and several locations received more than 10 inches (25 centimeters). Whole towns were cut off from overland transportation—particularly upstream in Vermont, which suffered its worst flooding in 80 years. Thousands of people saw their homes flooded, if not washed off their foundations, at a time of year when rivers are usually at their lowest. Preliminary estimates of river flow at Thompsonville, Connecticut, (not shown in this image) reached 128,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) on August 30, nearly 64 times the usual flow (2,000 cfs) for early fall and the highest flow rate since May 1984. At the mouth of the river—where flow is tidal, and therefore not gauged—the peak water height reached 6.9 feet (2.1 meters) above sea level, almost a foot higher than at any time in the past 10 years. According to Suzanne O'Connell, an environmental scientist working along the Connecticut River at Wesleyan University, the torrent of water coursing through New England picked up silt and clay from the river valleys, giving it the tan color shown in the image above. At Essex, Connecticut, the turbidity (muddiness) of the water was 50 times higher than pre-Irene values. To the east, the Thames River appears to be carrying very little sediment at all on September 2. According to O'Connell, the Thames "drains glaciated terrain, so fine sediment was removed long ago." Most of the land surface in the Thames basin is "just bedrock, till, and glacial erratics." Unlike the Connecticut, areas within the Thames watershed only received 2 to 4 inches of rain in most locations. The flooding that occurred in the aftermath of Hurricane Irene inundated farmland in Massachusetts and Connecticut just before harvest time, the Associated Press noted. Crops were drowned under inches to feet of water. The substantial amounts of soil, sediment, and water deposited on land during the flood could also pose trouble for farmers in coming seasons. "It's notable that whole segments of river bank are just gone," said Andrew Fisk of the Connecticut River Watershed Council. "That's not just loss of sediment. That's land disappearing down river." <b>NASA Earth Observatory image by Robert Simmon, using Landsat 5 data from the U.S. Geological Survey Global Visualization Viewer. Caption by Michael Carlowicz, with interpretation help from Suzanne O'Connell, Wesleyan University, and Andrew Fisk, Connecticut River Watershed Council.</b> Instrument: Landsat 5 - TM Credit: <b><a href="http://www.earthobservatory.nasa.gov/" rel="nofollow"> NASA Earth Observatory</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASA_GoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://web.stagram.com/n/nasagoddard/?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

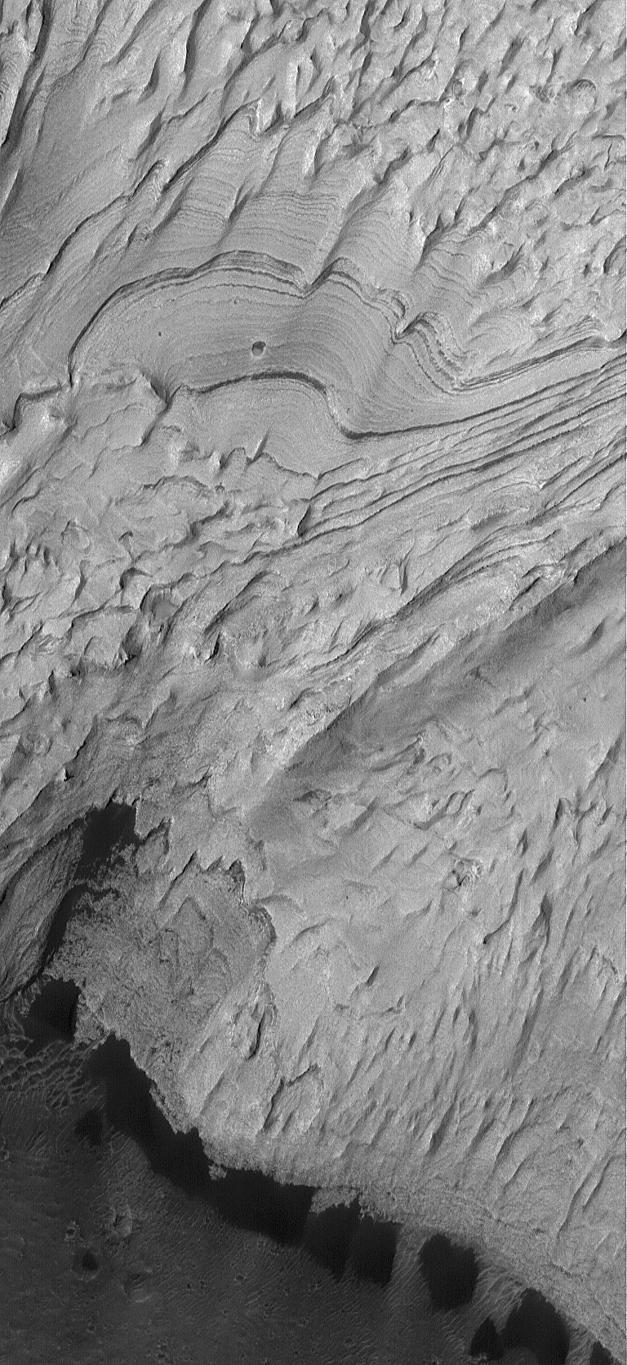

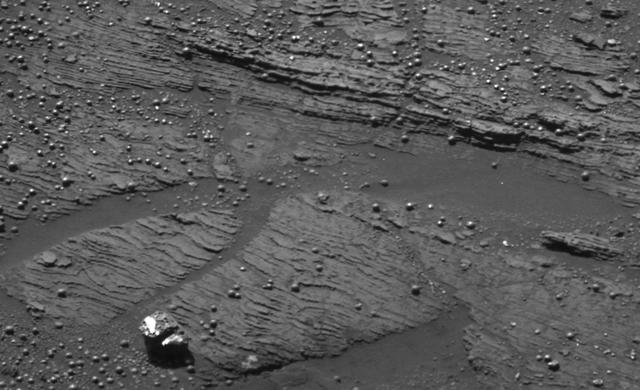

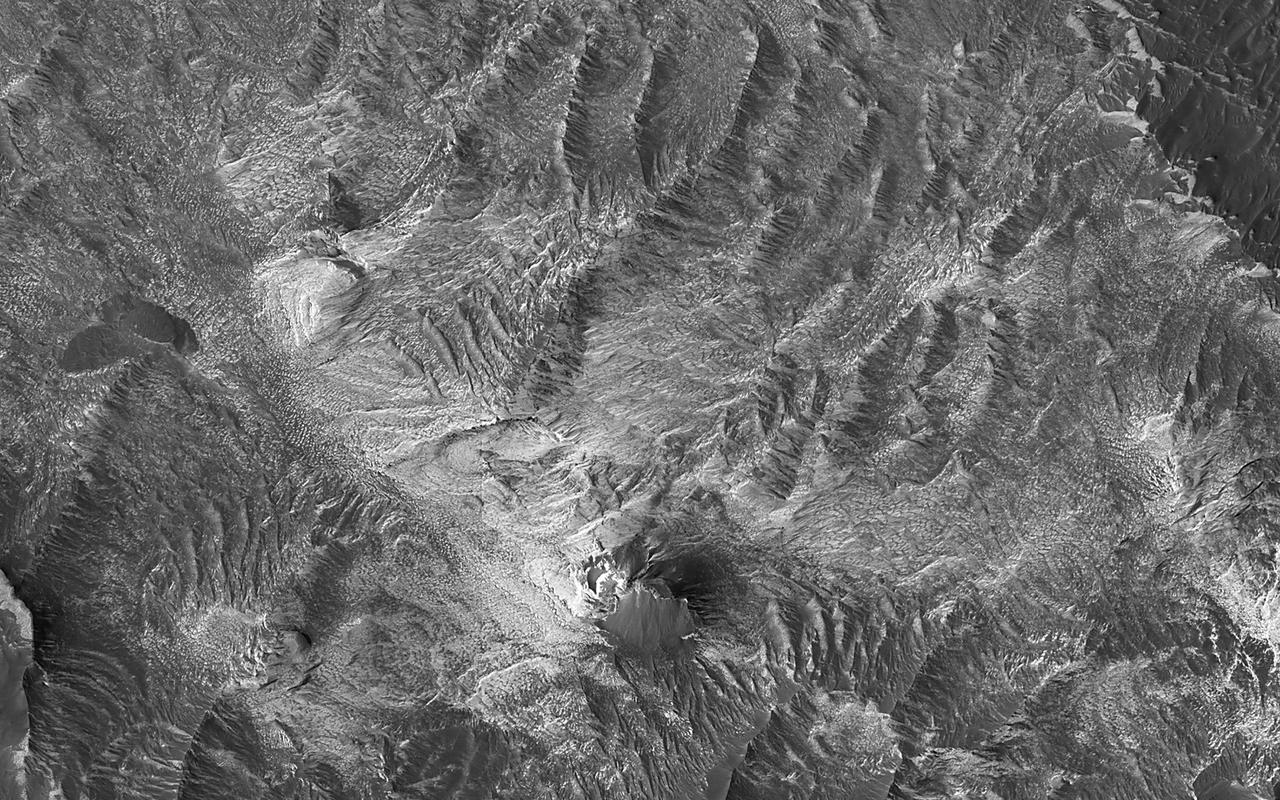

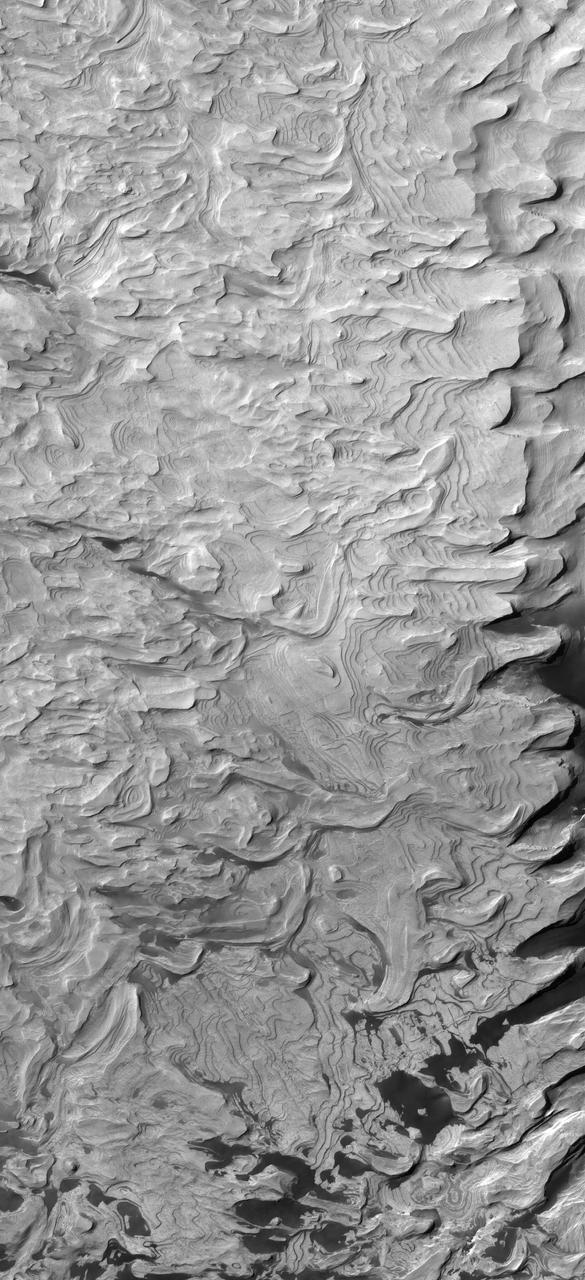

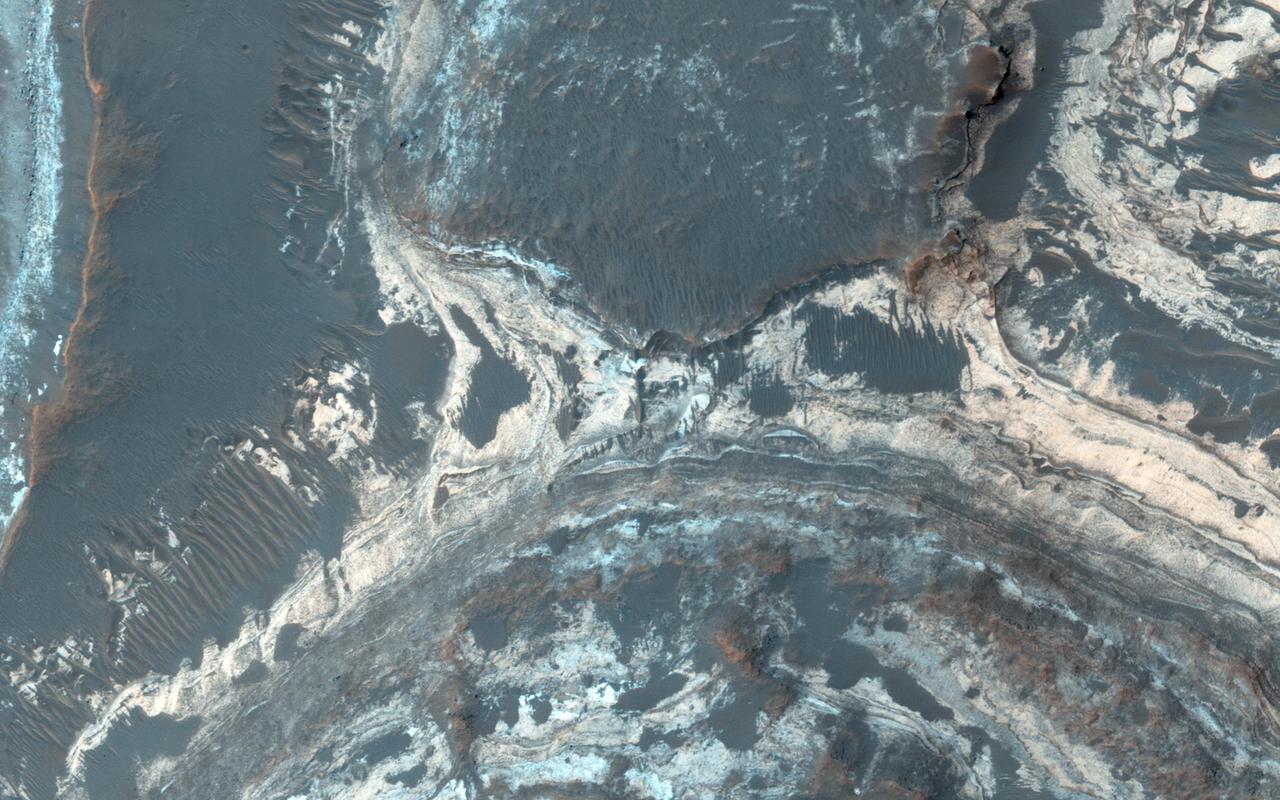

Layered sedimentary rocks are key to understanding the geologic history of a planet, recording the sequence of deposition and the changes over time in the materials that were deposited. These layered sediments are on the floor of eastern Coprates Chasma in Valles Marineris, the grandest canyon on Mars. They are erosional remnants of a formerly much more extensive sedimentary deposit that once filled the floor of the canyon but is nowadays reduced to isolated mesas. The origin of the deposits is not yet known. Various theories attribute the sediments to wind blown dust and sand, or to volcanic materials, or accumulations of debris from avalanches originating from the canyon walls, or even to lakebed sediments laid down when the canyons were filled with liquid water. Some sediments are devoid of boulders or blocks larger than the limit of resolution (about 0.5 meters), so avalanche debris is unlikely. We see fine laminations with a horizontal spacing of about 2 meters and a vertical separation less than 2 meters. No previous orbital observations were capable of resolving such fine scale layering. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23583

Signs of Soft-Sediment Deformation at Slickrock

This image depicts how a mountain inside a Mars Gale Crater might have formed. At left, the crater fills with layers of sediment. Yellow is for deposits in alluvial fans, deltas, and drifts during both wet and dry periods.

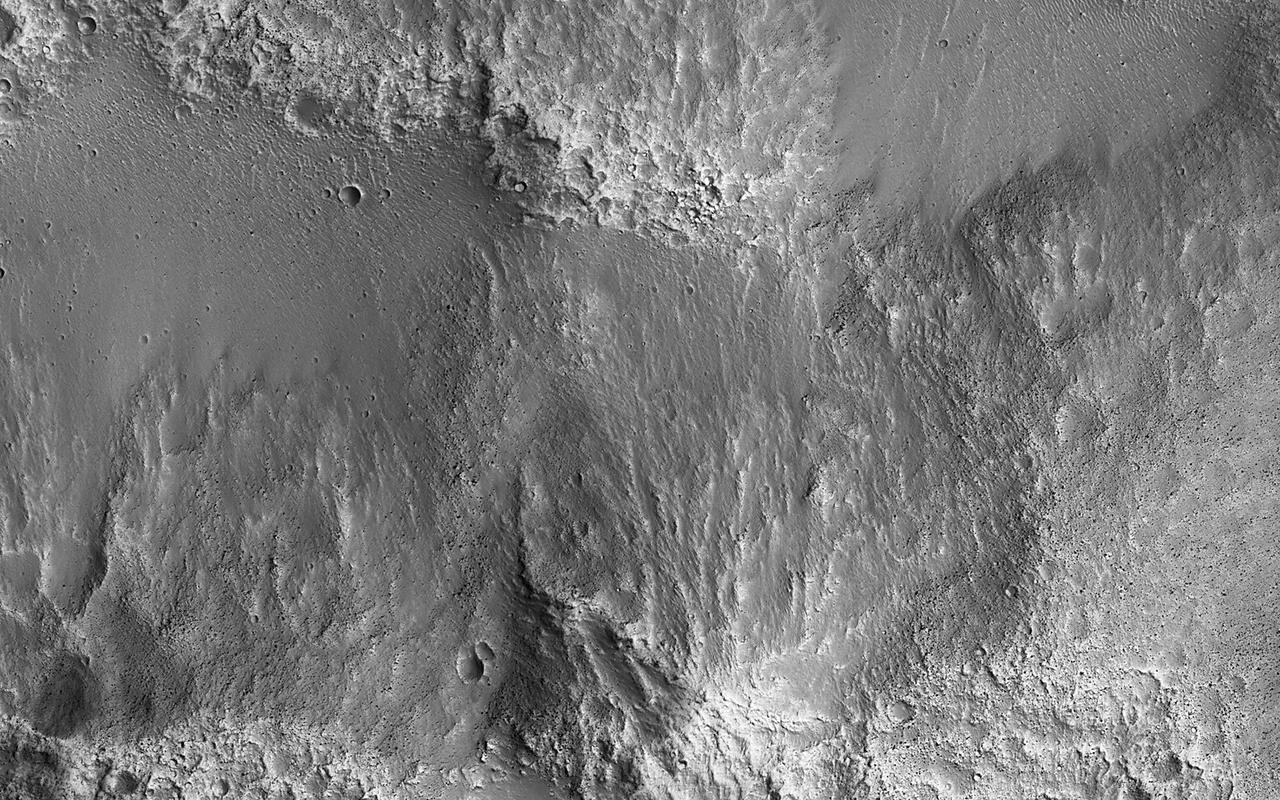

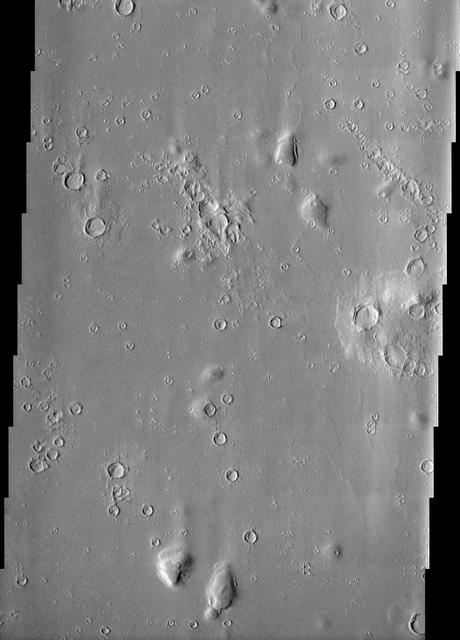

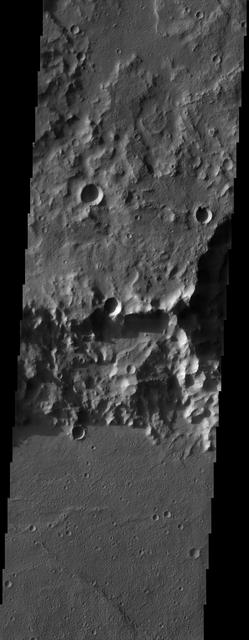

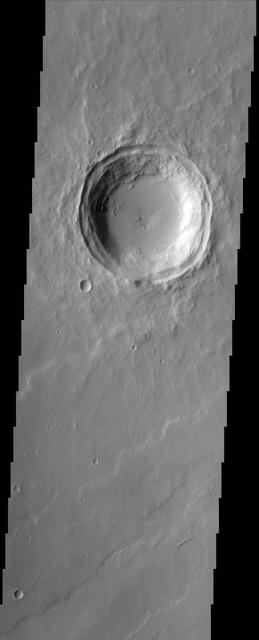

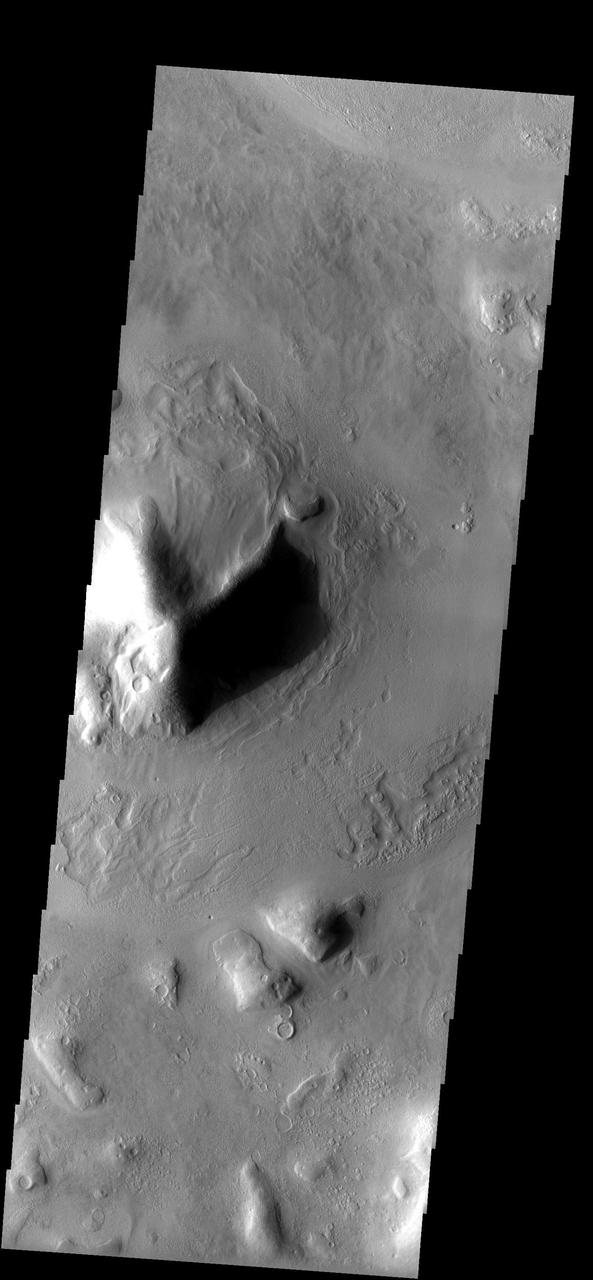

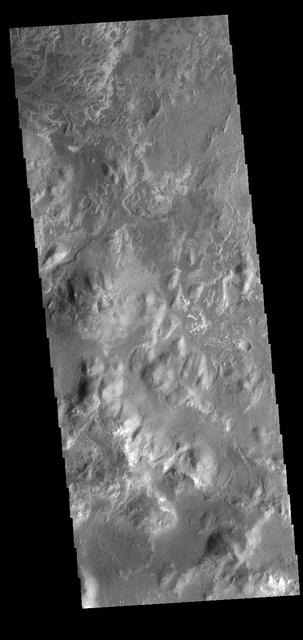

This image shows evidence of a complex cycle of cratering and erosion. The center of the image covers an old impact crater, roughly 6 to 7 kilometers in diameter. This can actually be easier to see in lower-resolution images that cover more area, like those from MRO's Context Camera. The crater was later filled by sediments. Erosion then occurred across the region. The crater rim was left high-standing even though material outside the rim was eroded down to the level of the crater floor. The sediments filling the crater also eroded from the rim inwards, leaving a circular pancake of sedimentary rock. Similar "rim-inwards" erosion has been hypothesized for the (much larger) Gale Crater where the Curiosity rover is operating. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24462

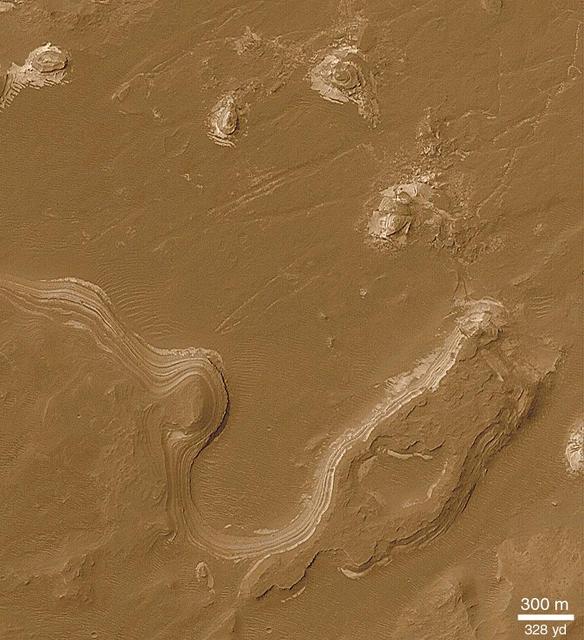

Sediments rich in hydrated sulfates may have filled central Valles Marineris, but debates persist as to how these deposits grew or formed. If they formed from deposition in a deep lake then the layers should be nearly horizontal. If the layers formed from airfall deposits such as volcanic pyroclastics or windblown dust, then the layers should drape over the pre-existing topography. Another possibility is that the layers were deformed by slumping. Stereo topographic data can be used to test these hypotheses. The cutout shows an area at full resolution. There are no detectable color variations within these layers, suggesting a uniform composition or the presence of a thin cover of dust over all surfaces. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25308

This survey of the canyon floor of Tithonium Chasma in Valles Marineris reveals terrain of two distinct ages. The slopes and hilltops here are made up of rough rocky outcrop that was sculpted by impact craters of all sizes. In contrast, the valley floors are filled with light toned, smooth materials with far fewer large craters. At HiRISE resolution, we can see that the "smooth" materials are in fact littered with boulders and small impact craters, so they cannot have been emplaced very recently. However, the absence of larger craters tells us that the smooth materials are much younger than the ancient rocky outcrops of the canyon floor. The smooth materials appear to be sediments that were deposited possibly by the wind, long after the canyon was formed. The sediments filled in the low lying spots in the canyon floor, leaving a landscape that resembles lakes and ponds but is made up of dust and sand instead of water. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26328

In this image from NASA Mars Odyssey, a mantling layer of sediment slumps off the edge of a mesa in Candor Chasma producing a ragged pattern of erosion that hints at the presence of a volatile component mixed in with the sediment.

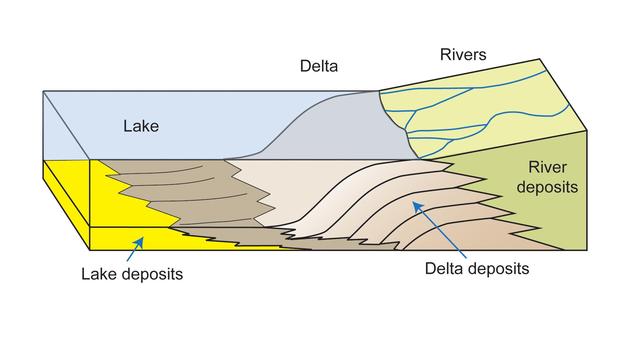

This diagram depicts rivers entering a lake. Where the water flow decelerates, sediments drop out, and a delta forms, depositing a prism of sediment that tapers out toward the lake interior.

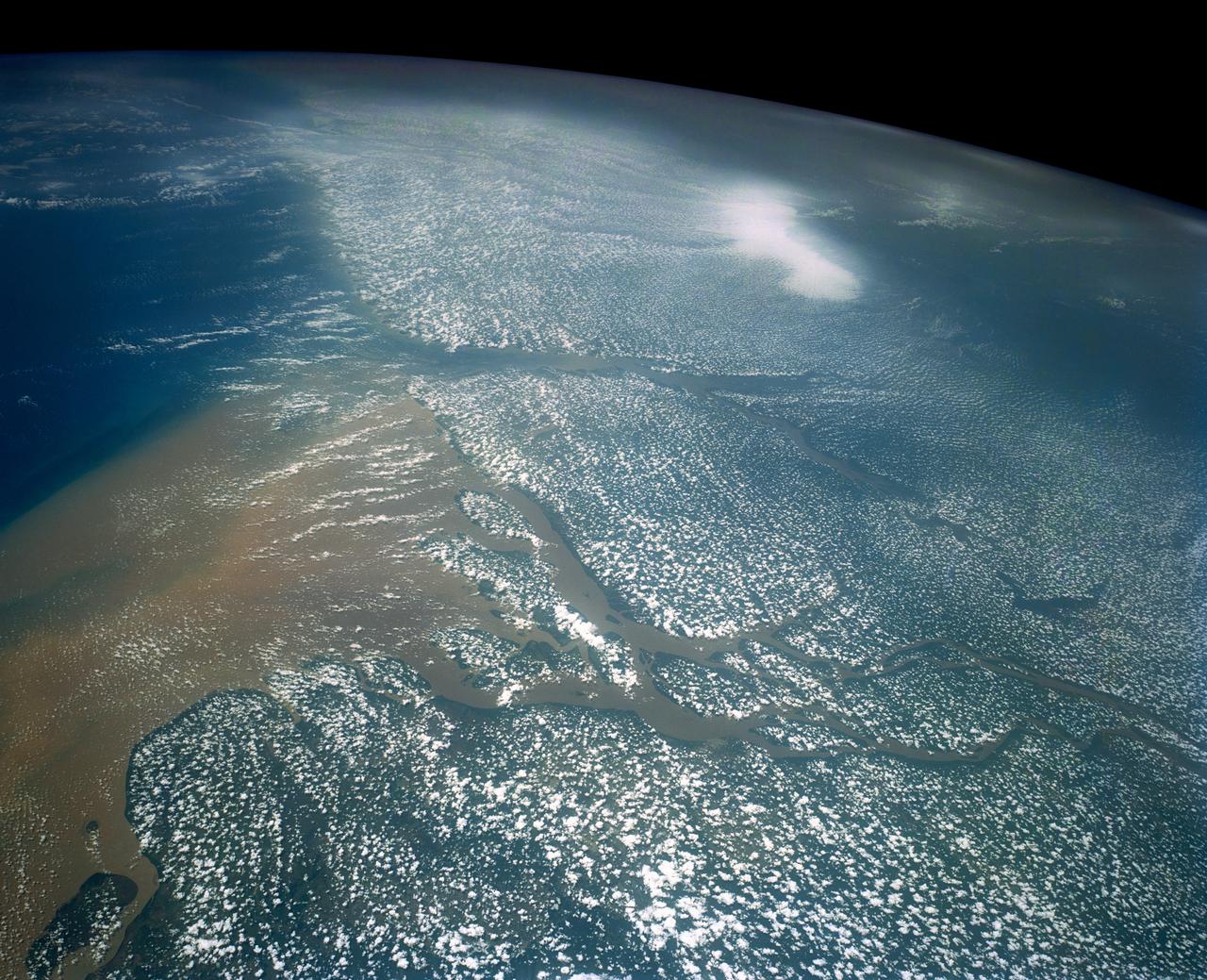

STS046-80-009 (31 July-8 Aug. 1992) --- A view of the mouth of the Amazon River and the Amazon Delta shows a large sediment plume expanding outward into the Atlantic Ocean. The sediment plume can be seen hugging the coast north of the Delta. This is caused by the west-northwest flowing Guyana Current. The large island of Marajo is partially visible through the clouds.

This terrain looks like lumpy sediment on top of patterned ground. The lumpy sediment is likely just loosely consolidated because it is covered with spidery channels. This landform is uniquely Martian, formed in the spring as seasonal dry ice turns directly into gas that erodes channels in the surface. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA14452

STS054-86-001 (13-19 Jan. 1993) --- This 70mm view shows a spectacular multiple spit on the coast of Brazil, about halfway between Rio de Janeiro and the mouth of the Amazon River. Over a few thousand years, according to NASA scientists, shifting regimes of wave and current patterns piled up sand onto a series of beach ridges and tidal lagoons. The present swirls of sediment along the coast evidently were derived from beach erosion, because streams flowing into the Atlantic contain dark, clear water. Offshore, reefs and sandbanks parallel the coast. The largest is the Recife da Pedra Grande (Big Rocks Reef).

This cross-section graphic provides an interpretation of the geologic relationship between the Murray Formation, the crater floor sediments, and the hematite ridge.

This observation from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows an incredible diversity of ancient lava tubes and impact craters filled with sediment on the flank of Arsia Mons.

Color differences in this daytime infrared image taken by NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft represent differences in the mineral composition of the rocks, sediments and dust on the surface.

Impact craters in Hecates Tholus, as seen in this image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft, appear to be filled with sediment derived from erosion of the surrounding terrain.

The irregularly shaped rim of the bowl-shaped impact crater in this NASA Mars Odyssey image is most likely due to erosion and the subsequent infilling of sediment.

Color differences in this daytime infrared image taken by the camera on NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft represent differences in the mineral composition of the rocks, sediments and dust on the surface.

This image was acquired to get more information about a site where the CRISM instrument detected hydrated sulfates. The bright materials are likely to be sediments rich in the hydrated sulfates, and this image shows that most of the material is covered by a thin deposit of dark material, perhaps sand. We also see streamlined patterns that suggest fluvial processes were involved in depositing or eroding the sulfate-rich sediments. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26327

A delta is a pile of sediment dumped by a river where it enters a standing body of water. Evidence for deltas that formed billions of years ago on Mars has been mounting in recent years. One line of evidence not yet investigated is to search for what are called clinoforms. In geology, a clinoform refers to a steep slope of sediment on the outer margin of a delta. This image seeks to test whether those features are visible and help confirm that Mars in ancient times had a standing body of water in this location. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19848

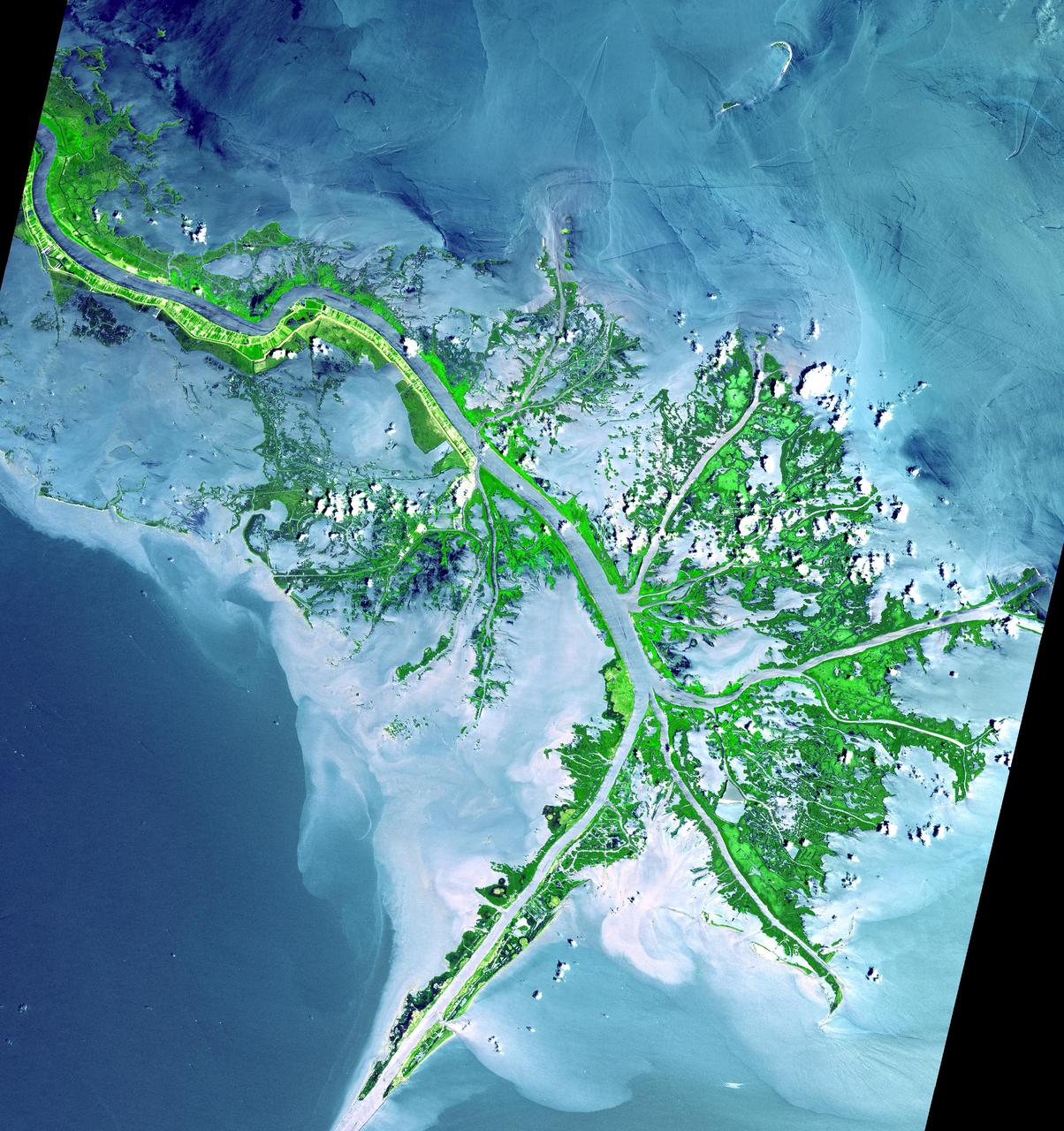

As the Mississippi River enters the Gulf of Mexico, it loses energy and dumps its load of sediment that it has carried on its journey through the mid continent. This pile of sediment, or mud, accumulates over the years building up the delta front. As one part of the delta becomes clogged with sediment, the delta front will migrate in search of new areas to grow. The area shown on this image is the currently active delta front of the Mississippi. The migratory nature of the delta forms natural traps for oil. Most of the land in the image consists of mud flats and marsh lands. There is little human settlement in this area due to the instability of the sediments. The main shipping channel of the Mississippi River is the broad stripe running northwest to southeast. This image was acquired on May 24, 2001 by the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) on NASA's Terra satellite. With its 14 spectral bands from the visible to the thermal infrared wavelength region, and its high spatial resolution of 15 to 90 meters (about 50 to 300 feet), ASTER will image Earth for the next 6 years to map and monitor the changing surface of our planet. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA03497

Nothing gets a geologist more excited than layered bedrock, except perhaps finding a fossil or holding a meteorite in your hand. All of these things create a profound feeling of history, the sense of a story that took place ages ago, long before we came appeared. Layered bedrock in particular tells a story that was set out chapter by chapter as each new layer was deposited on top of older, previously deposited layers. Here in Nili Fossae, we see layered bedrock as horizontal striations in the light toned sediments in the floor of a canyon near Syrtis Major. (Note: illumination is from the top of the picture) The ancient layered rocks appear in pale whitish and bluish tones. They are partially covered by much younger ripples made up of dust and other wind blown sediments. The rock of the nearby canyon wall is severely fractured and appears to have shed sand and rocks and boulders onto the floor. This canyon did not form by fluvial erosion: it is part of a system of faults that formed a series of graben like this one, but water probably flowed through Nili Fossae in the distant past. Orbital spectral measurements by the OMEGA instrument on Mars Express and CRISM on MRO detected an abundance of clay minerals of different types in the layered sediments inside Nili Fossae, along with other minerals that are typical of sediments that were deposited by water. The various colors and tones of the layered rocks record changes in the composition of the sediments, details that can tell us about changes in the Martian environment eons ago. Nili Fossae is a candidate site for a future landed robotic mission that could traverse across these layers and make measurements that could be used to unravel a part of the early history of Mars. Nili Fossae is a history book that is waiting to be read. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21206

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows some interesting fractured materials on the floor of an impact crater in Arabia Terra.

This colorful scene is situated in the Noctis Labyrinthus, perched high on the Tharsis rise in the upper reaches of the Valles Marineris canyon system as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

This observation from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows light-toned layered deposits at the contact between the Ladon Valles channel and Ladon Basin.

This color HiRISE view shows a pitted, blocky surface, but also more unusually, it has contorted, irregular features. Although there are impact craters in this area, some of the features (like in the lower center of the cutout) are too irregular to be relic impact craters or river channels. One possibility is that sedimentary layers have been warped from below to create these patterns. The freezing and thawing of subsurface ice is a mechanism that could have caused this. Acidalia Planitia is part of the northern plains of Mars, at a latitude of 44 degrees north. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23855

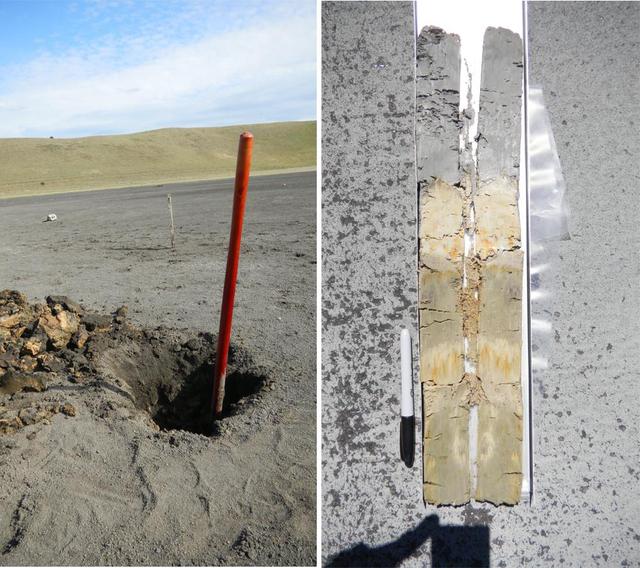

A sampling pit exposing clay-bearing lake sediments, deposited in a basaltic basin in southern Australia -- a modern terrestrial analog to the Yellowknife Bay area that NASA Curiosity rover is exploring.

The impact crater observed in this NASA Mars Odyssey image taken in Terra Cimmeria suggests sediments have filled the crater due to the flat and smooth nature of the floor compared to rougher surfaces at higher elevations.

This MOC image shows blocky remnants of a material that was once more laterally extensive on the floor of an impact crater located northwest of Herschel Crater on Mars. Large ripples of windblown sediment have accumulated around and between the blocks

The floors of these craters imaged by NASA Mars Odyssey contain very interesting and enigmatic materials that may hold shallow subsurface ground ice with varying amounts of a sediment covering mantle.

The relatively flat floor and terrace walls of this impact crater imaged by NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft suggest the crater was partly infilled with sediment and subsequently eroded to its present day form.

On Oct. 25, 2011, the Chao Phraya River was in flood stage as NASA Terra spacecraft imaged flooded agricultural fields and villages depicted here in dark blue, and the sediment-laden water in shades of tan.

Cross-bedding seen in the layers of this Martian rock is evidence of movement of water recorded by the waves or ripples of loose sediment the water passed over, such as a current in a lake. This image is from NASA Curiosity Mars rover.

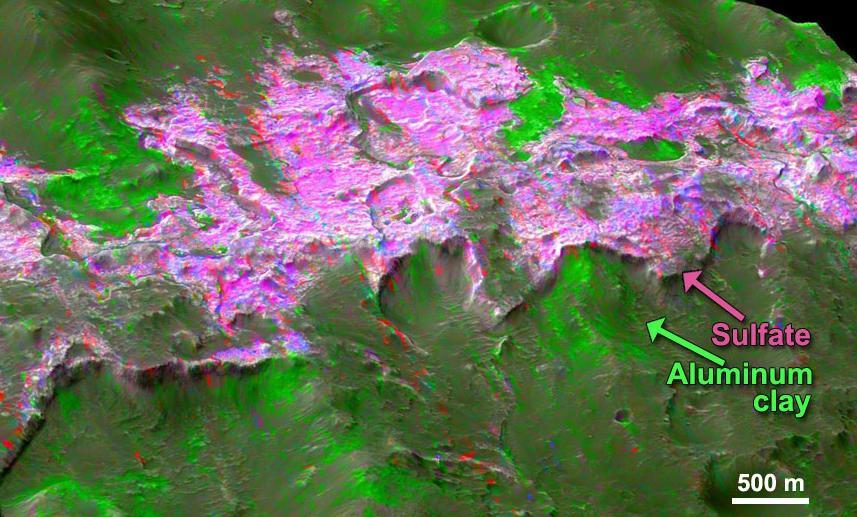

Sulfates are found overlying clay minerals in sediments within Columbus Crater, a depression that likely hosted a lake in the past in this image based on information from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

On ancient Mars, water carved channels and transported sediments to form fans and deltas within lake basins. Spectral data acquired by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, indicate chemical alteration by water.

Alluvial fans are gently-sloping wedges of sediments deposited by flowing water. Some of the best-preserved alluvial fans on Mars are in Saheki Crater, seen here by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft.

The mottled surface texture and flow features observed in this NASA Mars Odyssey image suggest materials may be, or have been, mixed with ice. There is also evidence in some areas for infilling of sediments as crater rims and ridges appear covered.

Schiaparelli Crater is a 460 kilometer 286 mile wide multi-ring structure. However, it is a very shallow crater, apparently filled by younger materials such as lava and/or fluvial and aeolian sediments as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

This MOC image shows light-toned, layered, sedimentary rocks in a crater in the northwestern part of Schiaparelli basin. The repetition of these horizontal layers suggests the sediments could have been deposited in an ancient crater lake

NASA Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity studied layers in the Burns Cliff slope of Endurance Crater in 2004. The layers show different types of deposition of sulfate-rich sediments. Opportunity panoramic camera recorded this image.

Scientist hypothesize that a lake of liquid water once filled Gale crater, and the layers in the mound formed as sediment settled down through the water to the bottom of the lake in this image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

The Medusae Fossae formation, seen in this NASA Mars Odyssey image, is an enigmatic pile of eroding sediments that spans over 5,000 km 3,107 miles in discontinuous masses along the Martian equator.

Erosion of the interior layered deposits of Melas Chasma, part of the huge Valles Marineris canyon system, has produced cliffs with examples of spur and gulley morphology and exposures of finely layered sediments, as seen in this NASA Mars Odyssey image.

In this image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, lower wall rock spurs are found that spread dark materials onto a dune field, suggesting local wall materials are a nearby sediment source for dunes.

This image, acquired by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, in southern winter over part of Asimov Crater, shows the crater appears to have been completely filled by a thick sequence of materials, perhaps including sediments and lava flows.

Streamlined buttes and mesas are left as remnants of an erosive wind that has carried away sediments and even the rim of a small crater in this image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft.

On March 25, 2014, view from the Mastcam on NASA Curiosity Mars rover looks southward at the Kimberley waypoint. Multiple sandstone beds show systematic inclination to the south suggesting progressive build-out of delta sediments.

SL2-16-174 (22 June 1973) --- Norfolk and the lower Chesapeake Bay, VA (37.5N, 75.5W) at the interface of the Atlantic Ocean can be seen to be a mixture of complex currents. Outgoing tides from the bay generate considerable turbulence as they encounter coastal currents and can be observed by the sediment plumes stirred up as a result of current dynamics. Smooth flowing water has less sediment and appears darker. Turbulent water has lots of sediment and appears lighter in color. Photo credit: NASA

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is part of a proposed landing site in Aram Dorsum for the ExoMars Rover, planned for launch in 2018. Upper layers of light toned sediments have been eroded, leaving a lower surface which appears dark. The retreating sediment scarp slopes would be an important target for the rover if it ends up going to Aram Dorsum. The retreating scarps will be relatively recent compared to the ancient age of the terrain. That means that organic compounds-which is what ExoMars is designed to drill to 2 meters depth and analyze-will not have been exposed to the full effects of solar and galactic radiation for their entire history. Such radiation can break down organic compounds. Prior to this later erosion, the rocks formed in the ancient, Noachian era as alluvial deposits of fine grained sediment. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19859

Made from fossilized microbes and sediment, these rounded rocks are stromatolites that were found in a dry lakebed during the field exercise. Scientists hope to find something similar in the dry lakebed Perseverance will be exploring on Mars. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23779

This un-named crater in southwestern Arabia Terra contains a treasure! Layered sediments are the key to the puzzle of Martian history. They tell us about the conditions that existed when the sediments were deposited, and how they changed over time. This image shows an eroded mesa made up of rhythmically layered bedrock that seems to indicate cyclic deposition. The layers are accentuated by recent dark sand deposits that have accumulated on the benches of the brighter sediments. The plateau is topped by a younger set of layers that appear to be finer and less blocky than the older layers below, suggesting a different depositional environment. Similar layered sediments are found in nearby craters in southwestern Arabia Terra. This image was requested by a member of the public who is interested in these deposits and will study them further by making a digital elevation model and measuring the thickness of the layers. Everyone is welcome to suggest interesting targets for HiRISE observations! https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24946

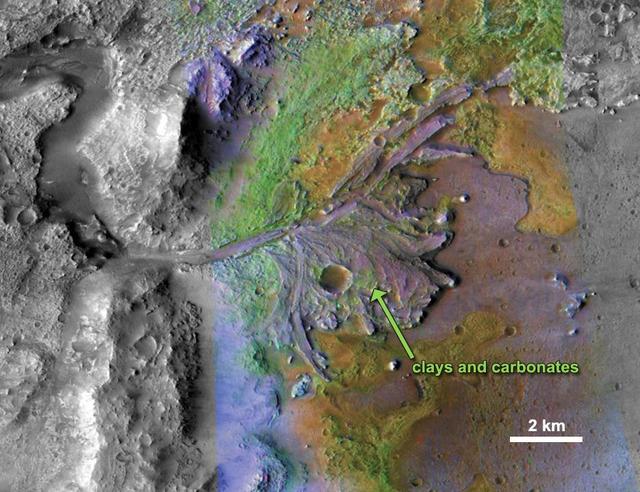

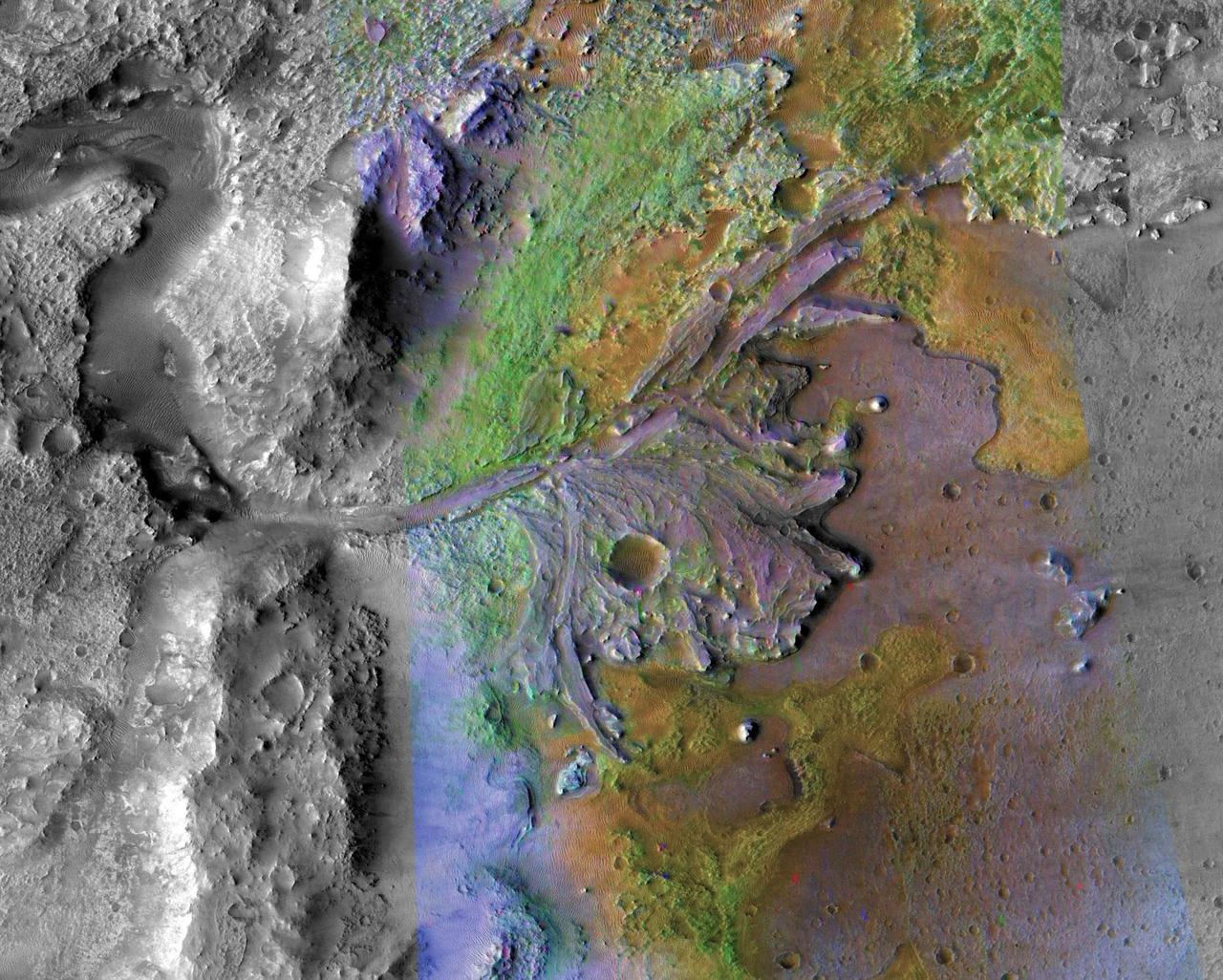

This image is of Jezero Crater on Mars, the landing site for NASA's Mars 2020 mission. It was taken by instruments on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), which regularly takes images of potential landing sites for future missions. On ancient Mars, water carved channels and transported sediments to form fans and deltas within lake basins. Examination of spectral data acquired from orbit show that some of these sediments have minerals that indicate chemical alteration by water. Here in Jezero Crater delta, sediments contain clays and carbonates. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23239

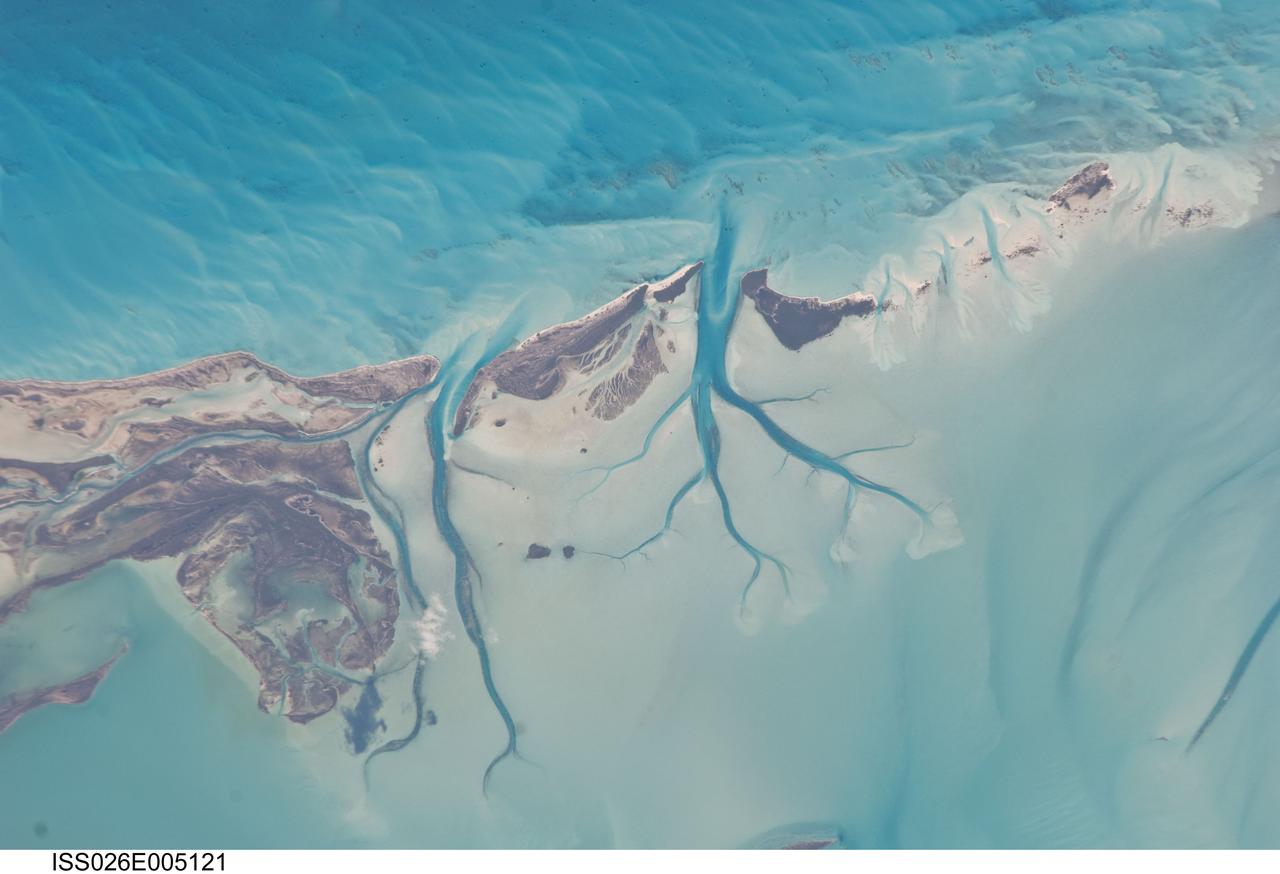

ISS026-E-005121 (27 Nov. 2010) --- Tidal flats and channels on Long Island, Bahamas are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 26 crew member on the International Space Station. The islands of the Bahamas in the Caribbean Sea are situated on large depositional platforms (the Great and Little Bahama Banks) composed mainly of carbonate sediments ringed by fringing reefs – the islands themselves are only the parts of the platform currently exposed above sea level. The sediments are formed mostly from the skeletal remains of organisms settling to the sea floor; over geologic time, these sediments will consolidate to form carbonate sedimentary rocks such as limestone. This detailed photograph provides a view of tidal flats and tidal channels near Sandy Cay on the western side of Long Island, located along the eastern margin of the Great Bahama Bank. The continually exposed parts of the island have a brown coloration in the image, a result of soil formation and vegetation growth (left). To the north of Sandy Cay an off-white tidal flat composed of carbonate sediments is visible; light blue-green regions indicate shallow water on the tidal flat. Tidal flow of seawater is concentrated through gaps in the anchored land surface, leading to formation of relatively deep tidal channels that cut into the sediments of the tidal flat. The channels, and areas to the south of the island, have a vivid blue coloration that provides a clear indication of deeper water (center).

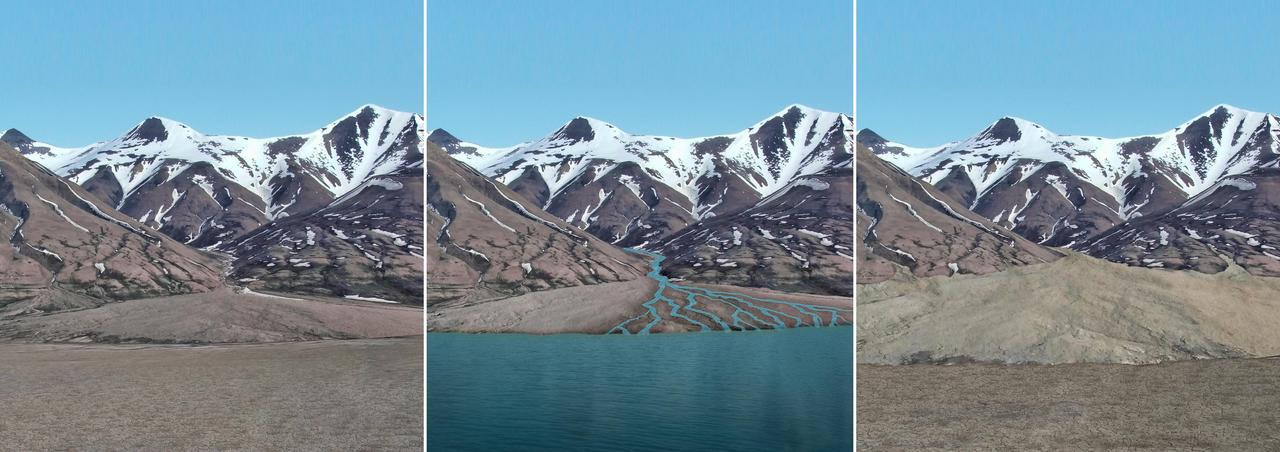

This series of images reconstructs the geology of the region around Mars Mount Sharp, where NASA Curiosity Mars rover landed and is now driving. The images were taken on Earth and have been altered for the illustration.

Excellent exposures of light-toned layered deposits occur along the northern edge of Hellas Basin as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

This image shows some bright layered deposits exposed within a linear trough along the floor of the Ladon Basin as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

This view from the NASA Curiosity Mars rover shows an example of cross-bedding that results from water passing over a loose bed of sediment. It was taken at a target called Whale Rock within the Pahrump Hills outcrop at the base of Mount Sharp.

Brown and tan muddy water flows down the Hudson River are seen in this image acquired by NASA Terra spacecraft on Sept. 1, 2011. After the torrential rains from Hurricane Irene, many rivers in the eastern United States were filled with sediment.

In this NASA Mars Odyssey image of eastern Arabia Terra, remnants of a once vast layered terrain are evident as isolated buttes, mesas, and deeply-filled craters. The origin of the presumed sediments that created the layers is unknown, but those same sediments, now eroded, may be the source of the thick mantle of dust that covers much of Arabia Terra today. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04400

STS035-81-040 (2-10 Dec 1990) --- Numerous algae reefs are seen in Shark Bay, Western Australia, Australia (26.0S, 113.5E) especially in the southern portions of the bay. The south end is more saline because tidal flow in and out of the bay is restricted by sediment deposited at the north and central end of the bay opposite the mouth of the Wooramel River. This extremely arid region produces little sediment runoff so that the waters are very clear, saline and rich in algae.

Huge sediment loads from the interior of the country flow through the Mouths of the Amazon River, Brazil (0.5S, 50.0W). The river current carries hundreds of tons of sediment through the multiple outlets of the great river over 100 miles from shore before it is carried northward by oceanic currents. The characteristic "fair weather cumulus" pattern of low clouds over the land but not over water may be observed in this scene.

Geologists love roadcuts because they reveal the bedrock stratigraphy (layering). Until we have highways on Mars, we can get the same information from fresh impact craters as shown in this image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. This image reveals these layers filling a larger crater, perhaps a combination of lava, impact ejecta, and sediments. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21631

This part of Melas Chasma has been the target for many previous HiRISE images due to its diversity of terrains and materials. This observation covers an area not previously imaged, revealing a chaotic jumble of bright layered sediments, perhaps resulting from large landslides. In a closeup with enhanced colors, we can see an assortment of materials. Dark sand covers the low areas of the scene. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23063

There is a circular feature in this observation from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft that appears to stand above the surrounding terrain. This feature is probably an inverted crater that was filled in with sediment. The fill became indurated, or hardened, until it was more resistant to subsequent erosion than the surrounding material. Other craters in this image are not inverted or substantially infilled. This suggests that they were formed after the events that filled in and later exposed the inverted crater. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20729

Planetary protection engineers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California swab engineering models of the tubes that will store Martian rock and sediment samples as part of NASA’s Mars 2020 Perseverance mission. Team members wanted to understand the transport of biological particles when the rover is taking rock cores. These measurements helped the rover team design hardware and sampling methods that meet stringent biological contamination control requirements. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23718

Gale Crater is well-known as the landing site of NASA's Curiosity rover, which has explored the northwest crater floor since 2012. But the entire crater is full of fascinating geology, some beyond the rover's reach. This image covers a fan of sedimentary rock on the southeast crater floor. Ridges on the fan surface may be composed of coarse-grained sediment deposited in ancient streams. More recent wind erosion of the surrounding finer sediments could have left these channel deposits elevated in "inverted relief." A closeup shows some of these ridges, as well as light-toned layers of sediment exposed along the fan edge. The fan is also punctured by scattered circular impact craters. One of these craters appears to have a circular deposit of sedimentary rock filling its floor, suggesting that it formed during the span of time that streams were active here. Features like this help scientists to infer the geologic history of the region. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25988

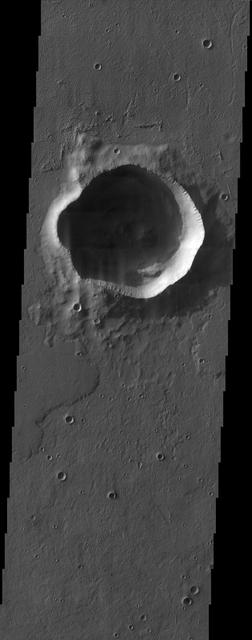

This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows a roundish crater with three channels breaching the rim and extending to the south. The crater has been filled by sediments and may have been an ancient lake. When the water began to overtop the crater rim, it would rapidly erode a channel and, at least, partially drain the lake. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22347

This mosaic of images shows layers of ancient sediment on a boulder-sized rock called "Strathdon," as seen by the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) camera on the end of the robotic arm on NASA's Curiosity rover. The images were taken on July 10, 2019, the 2,462nd Martian day, or sol, of the mission. The images were acquired from about 4 inches (10 centimeters) away and processed to adjust brightness and remove blemishes. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23347

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover used its Mast Camera, or Mastcam, to capture this detailed view of jagged rocks and sediment exposed along the side of a mound called "Fascination Turret." Made up of 32 individual images that were stitched together after being sent back to Earth, this panorama was taken on March 24, 2024, the 4,135th Martian day, or sol, of the mission. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26364

It drains a watershed that spans eight countries and nearly 1.6 million square kilometers 600,000 square miles. The Zambezi also Zambeze is the fourth largest river in Africa, and the largest east-flowing waterway. The Operational Land Imager on the Landsat 8 satellite acquired this natural-color image of the Zambezi Delta on August 29, 2013. Sandbars and barrier spits stretch across the mouths of the delta, and suspended sediment extends tens of kilometers out into the sea. The sandy outflow turns the coastal waters to a milky blue-green compared to the deep blue of open water in the Indian Ocean. The Zambezi Delta includes 230 kilometers of coastline fronting 18,000 square kilometers (7,00 square miles) of swamps, floodplains, and even savannahs (inland). The area has long been prized by subsistence fishermen and farmers, who find fertile ground for crops like sugar and fertile waters for prawns and fish. Two species of endangered cranes and one of the largest concentration of buffalo in Africa -- among many other species of wildlife -- have found a haven in this internationally recognized wetland. However, the past six decades have brought great changes to the Zambezi Delta, which used to pour more water and sediment off of the continent. Hydropower dams upstream-most prominently, the Kariba and the Cahora Bassa-greatly reduce river flows during the wet season; they also trap sediments that would otherwise flow downstream. The result has been less water reaching the delta and the floodplains, which rely on pulses of nutrients and sediments from annual (and mostly benign) natural flooding. The change in the flow of the river affects freshwater availability and quality in the delta. Strong flows push fresh water further out into the sea and naturally keep most of a delta full of fresh (or mostly fresh) water. When that fresh flow eases, the wetlands become drier and more prone to fire. Salt water from the Indian Ocean also can penetrate further into the marsh, upsetting the ecological balance for aquatic plant and animal species. Researchers have found that the freshwater table in the delta has dropped as much as five meters in the 50 years since dams were placed on the river. Less river flow also affects the shape and extent of the delta. Today there is less sediment replenishing the marshes and beaches as they are scoured by ocean waves and tides. "What strikes me in this image is the suspended sediment offshore," said Liviu Giosan, a delta geologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. "Sediment appears to be transferred from the delta offshore in plumes that not only originate in active river mouths but also from deactivated former mouths, now tidal channels. This shows the power of tidal scouring contributing to the slow but relentless erosion of the delta." http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18155

A nearly vertical view of Disappointment Reach and surroundings. Ripple-like patterns extending at right angles to the tidal flow can be discerned on shoals. Relict sand dune patterns, crests unvegetated, are evident on the western side of the estuary. Red mud brought down the Mooramel River on the east side of the estuary does extend into the shallow water of the inter-tidal lagoons. Most of the light-colored water along the coast, represents shoals of lime sediment. Patterns of sediment distribution by tides, waves, streams, and wind combine to create a complex and colorful scene.

STS072-738-019 (11-20 Jan. 1996) --- The Delta of the Paraiba do Sul River, northeast of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, stands out in this 70mm frame exposed from the Earth-orbiting Space Shuttle Endeavour. The brown color of the river water and offshore sediment plume show that the river is in flood stage. This delta attracts much attention from orbit because of its prominent beach ridges either side of the river mouth. River sediment from inland supplies the material which is redistributed by coastal currents to form the parallel beach ridges. The lower 20 miles of the river appear in this scene. The river flows into the Atlantic in an easterly direction.

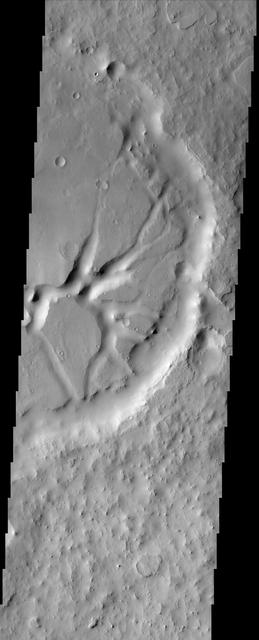

At the top of today's VIS image is the delta deposit on the floor of Eberswalde Crater. Deltas are formed when sediment laden rivers slow down — either due to a flattening of topography, or entering a standing body of water. The reduction in velocity causes the sediments to be deposited. The main channel often diverges into numerous smaller channel that spread apart to form the typical fan shape of a delta. The Eberswalde Crater delta is one of the best preserved on Mars. Orbit Number: 82771 Latitude: -24.1614 Longitude: 326.528 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2020-08-11 16:12 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24157

At the top left corner of today's VIS image is the delta deposit located on the floor of Eberswalde Crater. Deltas are formed when sediment laden rivers slow down – either due to a flattening of topography, or entering a standing body of water. The reduction in velocity causes the sediments to be deposited. The main channel often diverges into numerous smaller channel that spread apart to form the typical fan shape of a delta. The Eberswalde Crater delta is one of the best preserved on Mars. Orbit Number: 90982 Latitude: -24.1271 Longitude: 326.604 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-06-18 18:13 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25520

On the left side of today's VIS image is part of the delta deposit on the floor of Eberswalde Crater. Deltas are formed when sediment laden rivers slow down – either due to a flattening of topography, or entering a standing body of water. The reduction in velocity causes the sediments to be deposited. The main channel often diverges into numerous smaller channel that spread apart to form the typical fan shape of a delta. The Eberswalde Crater delta is one of the best preserved on Mars. Orbit Number: 84562 Latitude: -23.912 Longitude: 326.56 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2021-01-06 02:41 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24718

The southern section of Cydonia Region is dominated by both a series of craters and the remnants of channels that may be from a past fluvial system as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft. The paleochannel system has wind-blown bedforms in its interior, with crests oriented approximately perpendicular to the channel walls. The large rocky patch near the center of the image shows some evidence of bedding as would be expected for a river delta or other water-lain sediments, but the rough dissected nature of outcrops and superimposed aeolian bedforms and other sediments makes identification of this feature difficult. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20046

This image shows the transition from a regular channel to an inverted channel in Arabia Terra. The channel was once flowing with water that carved down into the bedrock to produce a depression. As the water flow slowed down, sediment became deposited within the channel that caused it to partially fill up. Over time, the landscape around the channel eroded away faster than the sediments within the channel, leaving behind a portion that now stands above the terrain, called an inverted channel. Why only one section of the channel is inverted while the rest is still a depression is unclear, but may reflect the local topography and hardness of the neighboring materials that only protected the channel in some places. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25983

In the top half of today's VIS image is the delta deposit on the floor of Eberswalde Crater. Deltas are formed when sediment laden rivers slow down – either due to a flattening of topography, or entering a standing body of water. The reduction in velocity causes the sediments to be deposited. The main channel often diverges into numerous smaller channel that spread apart to form the typical fan shape of a delta. The Eberswalde Crater delta is one of the best preserved on Mars. Orbit Number: 91288 Latitude: -23.9644 Longitude: 326.398 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-07-13 22:12 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25543

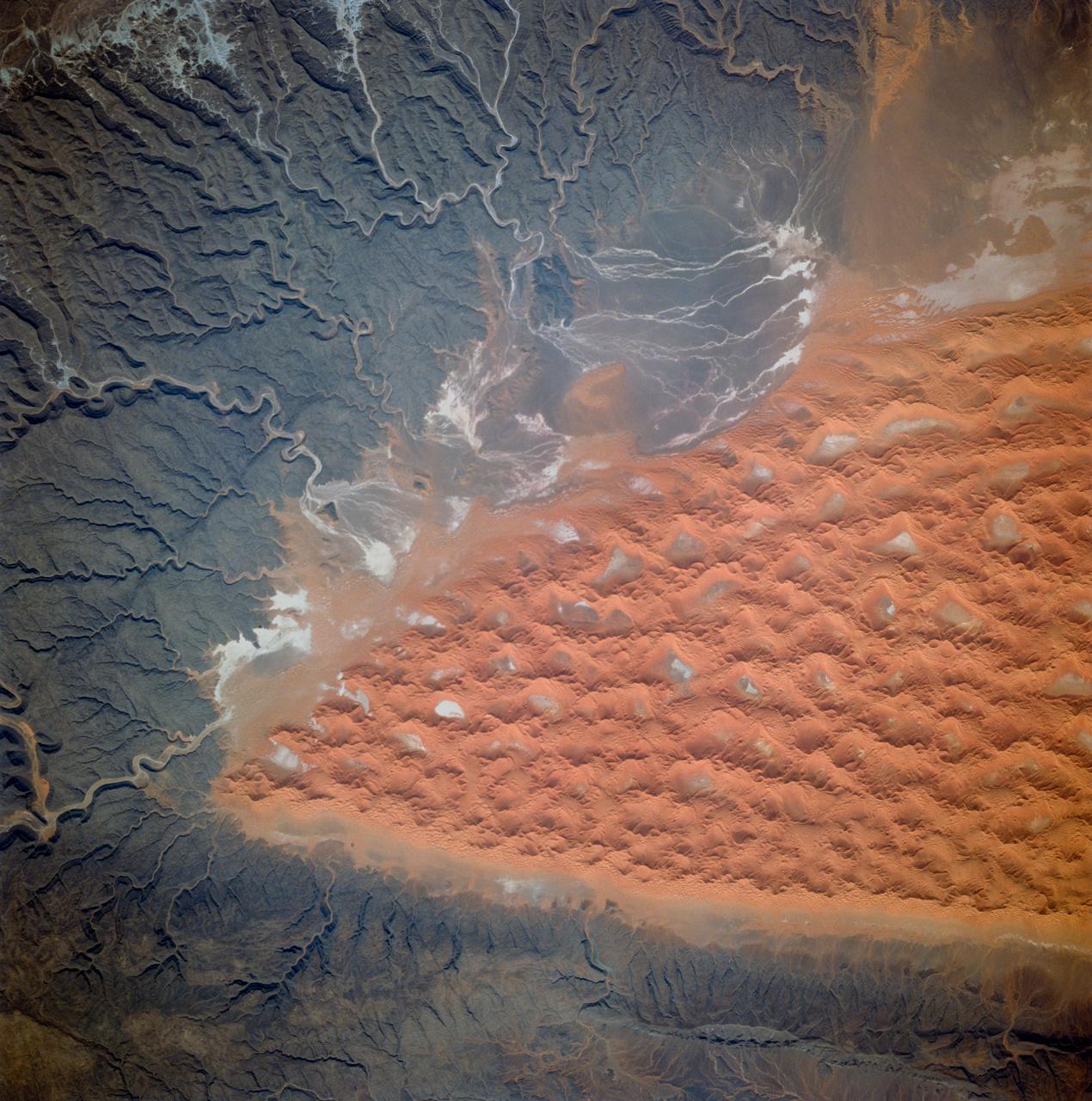

STS070-705-094 (13-22 JULY 1995) --- The southern half (about 70 miles in this view) of the Tifernine dunes of east-central Algeria appears on this view. The Tifernine dune-sea is one of the more dramatic features visible from the Shuttle when flying over the Sahara Desert. The dunes lie in a basin of dark-colored rocks heavily cut by winding stream courses (top right). Very occasional storms allow the streams to erode the dark rocks and transport the sediment to the basin. Westerly winds then mold the stream sediments into the complex dune shapes so well displayed here. North at bottom.

Today's VIS image shows two unnamed channels on the western edge of Claritas Fossae. The small channel joins the larger one close the the crater rim. The main channel has formed a delta in the crater. Deltas are formed when sediment laden rivers slow down – either due to a flattening of topography, or entering a standing body of water. The reduction in velocity causes the sediments to be deposited. The main channel often diverges into numerous smaller channel that spread apart to form the typical fan shape of a delta. Orbit Number: 92145 Latitude: -39.0947 Longitude: 256.903 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-09-22 12:24 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25747

At the top of today's VIS image is the delta deposit on the floor of Eberswalde Crater. Deltas are formed when sediment laden rivers slow down — either due to a flattening of topography, or entering a standing body of water. The reduction in velocity causes the sediments to be deposited. The main channel often diverges into numerous smaller channel that spread apart to form the typical fan shape of a delta. The Eberswalde Crater delta is one of the best preserved on Mars. Orbit Number: 84562 Latitude: -23.9124 Longitude: 326.56 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2021-01-06 02:41 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24362

The fishing and tourist village of Nazare, Portugal was practically unknown, until 2000, when surfers first braved its monstrous winter waves. Since then, world records for surviving surfing the 30m+ high waves have fallen, and movies have been made, celebrating the brave (crazy?) surfers willing to risk their lives to challenge the world's tallest waves. Sediment highlights off-shore current patterns in the image. The image was acquired November 24, 2009, covers an area of 18 by 25.7 km, and is located at 39.6 degrees north, 9.1 degrees west. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25121

The rocks seen here along the shoreline of Lake Salda in Turkey were formed over time by microbes that trap minerals and sediments in the water. These so-called microbialites were once a major form of life on Earth and provide some of the oldest known fossilized records of life on our planet. NASA's Mars 2020 Perseverance mission will search for signs of ancient life on the Martian surface. Studying these microbial fossils on Earth has helped scientists prepare for the mission. Today, the Martian surface is devoid of lakes and rivers, but billions of years ago it may have looked like this aqueous location on Earth. NASA's Perseverance Mars rover will land in Jezero Crater, which scientists believe was home to a lake and river delta about 3.5 billion years ago. Together, they could have collected and preserved ancient organic molecules and other potential signs of microbial life from the water and sediments that flowed into the crater billions of years ago. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24374

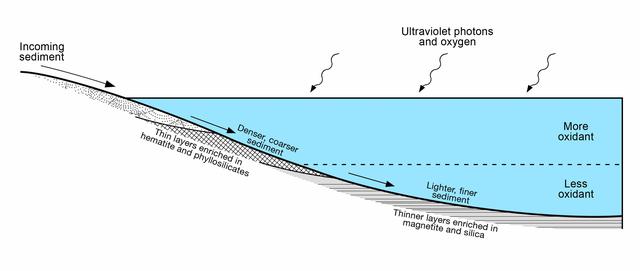

This diagram presents some of the processes and clues related to a long-ago lake on Mars that became stratified, with the shallow water richer in oxidants than deeper water was. The sedimentary rocks deposited within a lake in Mars' Gale Crater more than three billion years ago differ from each other in a pattern that matches what is seen in lakes on Earth. As sediment-bearing water flows into a lake, bedding thickness and particle size progressively decrease as sediment is deposited in deeper and deeper water as seen in examples of thick beds (PIA19074) from shallowest water, thin beds (PIA19075) from deeper water and even thinner beds (PIA19828) from deepest water. At sites on lower Mount Sharp, inside the crater, measurements of chemical and mineral composition by NASA's Curiosity Mars rover reveal a clear correspondence between the physical characteristics of sedimentary rock from different parts of the lake and how strongly oxidized the sediments were. Rocks with textures indicating that the sediments were deposited near the edge of a lake have more strongly oxidized composition than rocks with textures indicating sedimentation in deep water. For example, the iron mineral hematite is more oxidized than the iron mineral magnetite. An explanation for why such chemical stratification occurs in a lake is that the water closer to the surface is more exposed to oxidizing effects of oxygen in the atmosphere and ultraviolet light. On Earth, a stratified lake with a distinct boundary between oxidant-rich shallows and oxidant-poor depths provides a diversity of environments suited to different types of microbes. If Mars has ever hosted microbial live, the stratified lake at Gale Crater may have similarly provided a range of different habitats for life. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21500

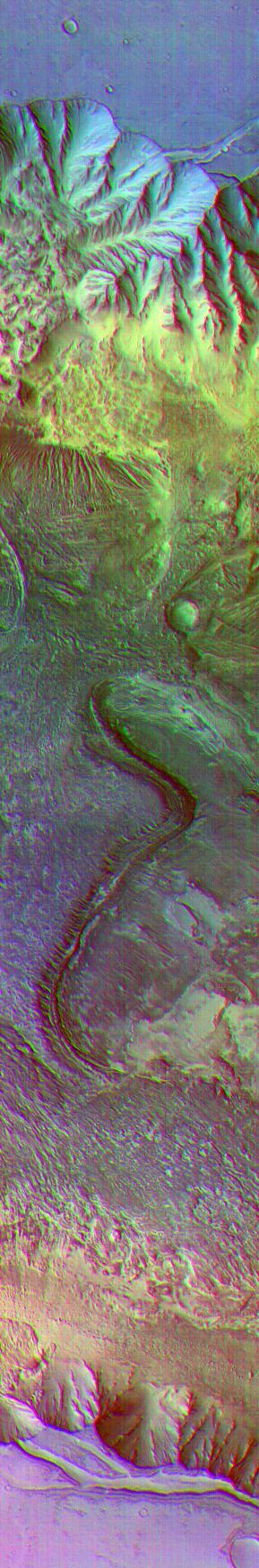

It's spring in the Northern Hemisphere of Mars (when this image was taken), and this area was recently completely covered by the seasonal frost cap. Here, we see polygonal patterns that are highlighted by carbon dioxide frost that has not entirely sublimed away. These organized patterns are likely caused by differences in the soil (regolith) characteristics such as grain size, density, even grain-shape and orientation in the underlying landforms and geologic materials. Variations in these characteristics strongly influence the strength of the ice-rich permafrost. This gives a preferred orientation to the stress field that produces the polygonal patterns. In this case, there appears to have been a meander in a fluvial channel in which sediments that differ from the native soil were deposited. The physical properties of these sediments probably change near the channel banks where flow rate drops off. Additionally, a high ice content might have resulted from a sediment-rich slurry flow that froze in place. Higher ice content will produce a weaker stress field and larger polygons, more so than just changes in grain size or orientation. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23581

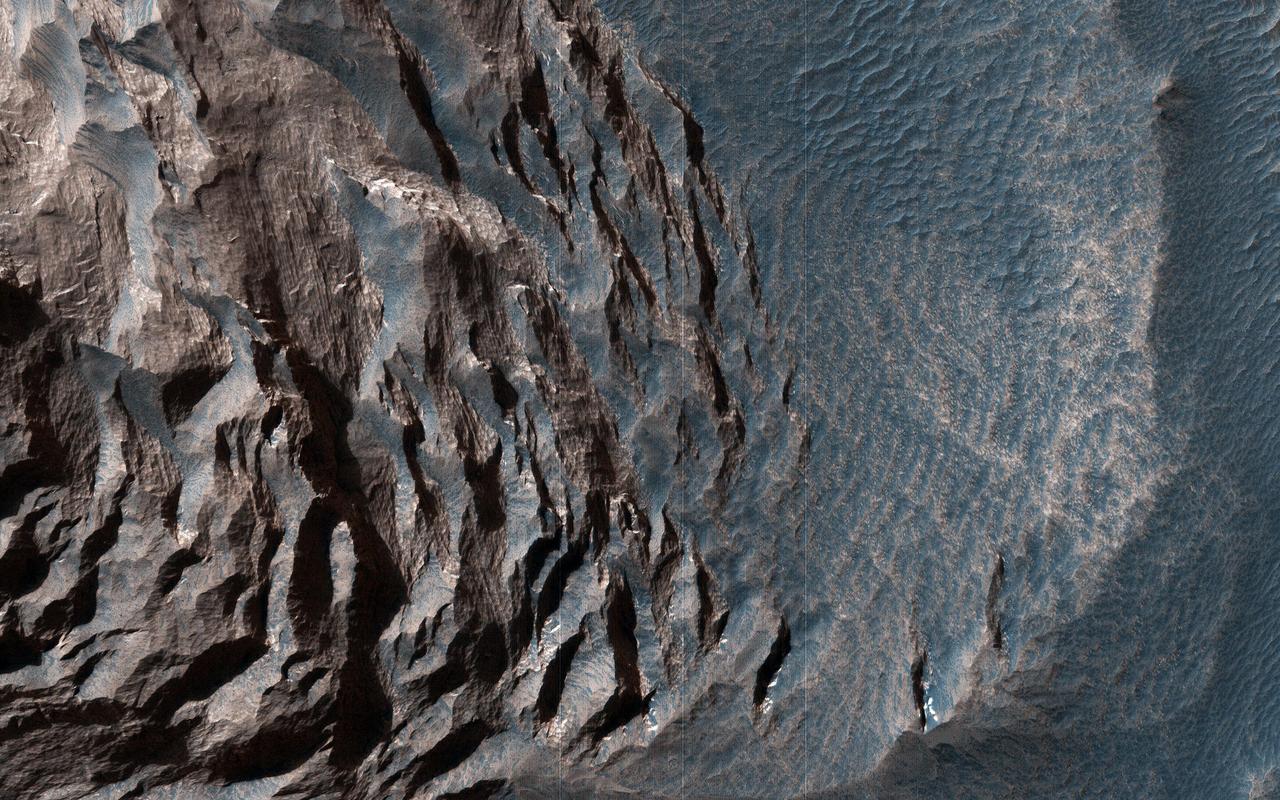

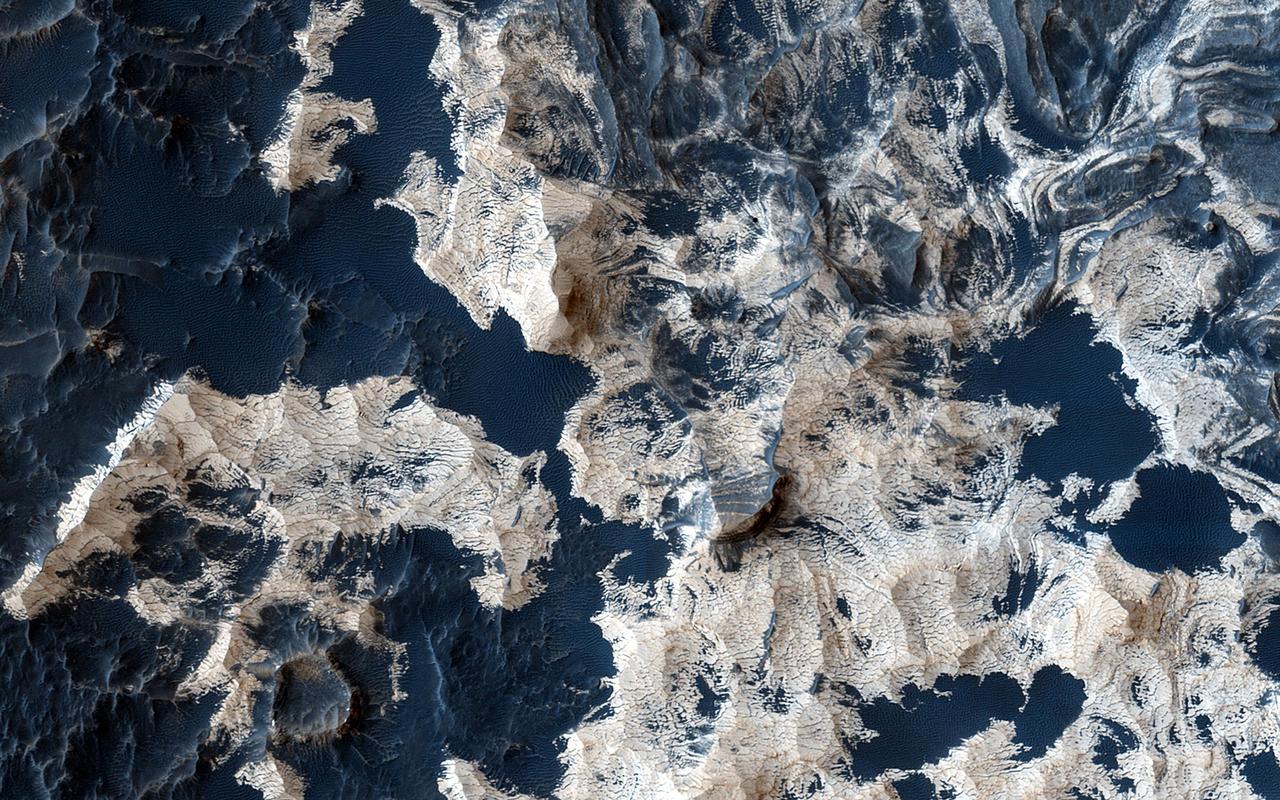

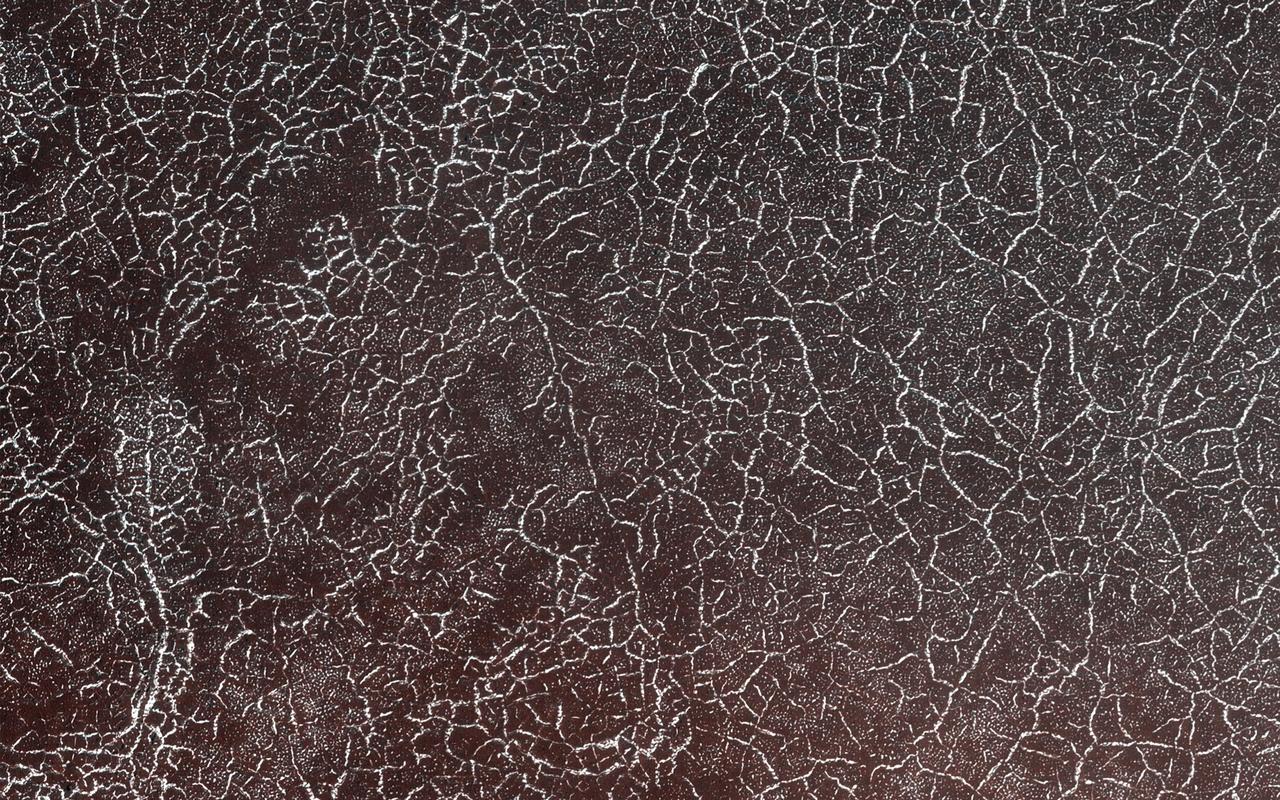

Sometimes Mars' surface is just beautiful as seen through the eyes of HiRISE. This is one example on the floor of Ius Chasma, part of Valles Marineris. The region has had a complex history of sediment deposition, deformation, erosion, and alteration. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23183

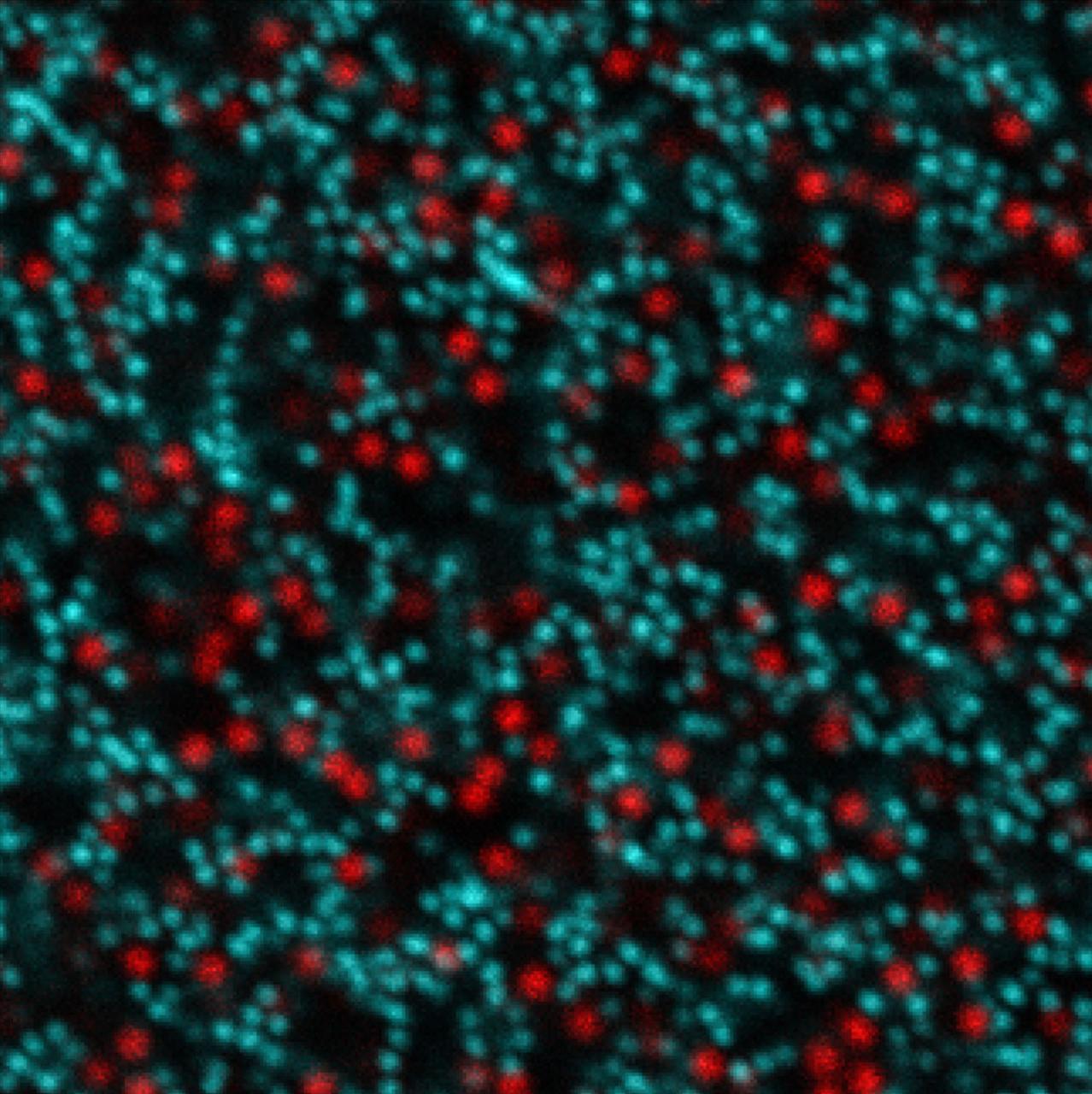

jsc2024e043753 (7/10/2024) --- Confocal microscopy image of a bimodal attractive colloidal suspension with size ratio R = 2 for the ISS Bimodal Colloidal Assembly, Coarsening, and Failure: Decoupling Sedimentation and Particle Size Effects (Bimodal Colloid) investigation. Image courtesy of Calvin Zhuang.

ISS002-E-6239 (14 May 2001) --- This digital still camera's image, recorded by one of the Expedition Two crew members aboard the International Space Station, features the mouth of the Mississippi River. The distribution of riverborne sediments is clearly evident in the Gulf of Mexico. This delta area is often referred to as the "crow's foot."

This long image is entirely over the extensive central peak complex of Hale Crater. Of particular interest are bedrock outcrops and associated fine-grained sediments with different colors. This 153-kilometer diameter crater was named after American astronomer George Ellery Hale. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23101