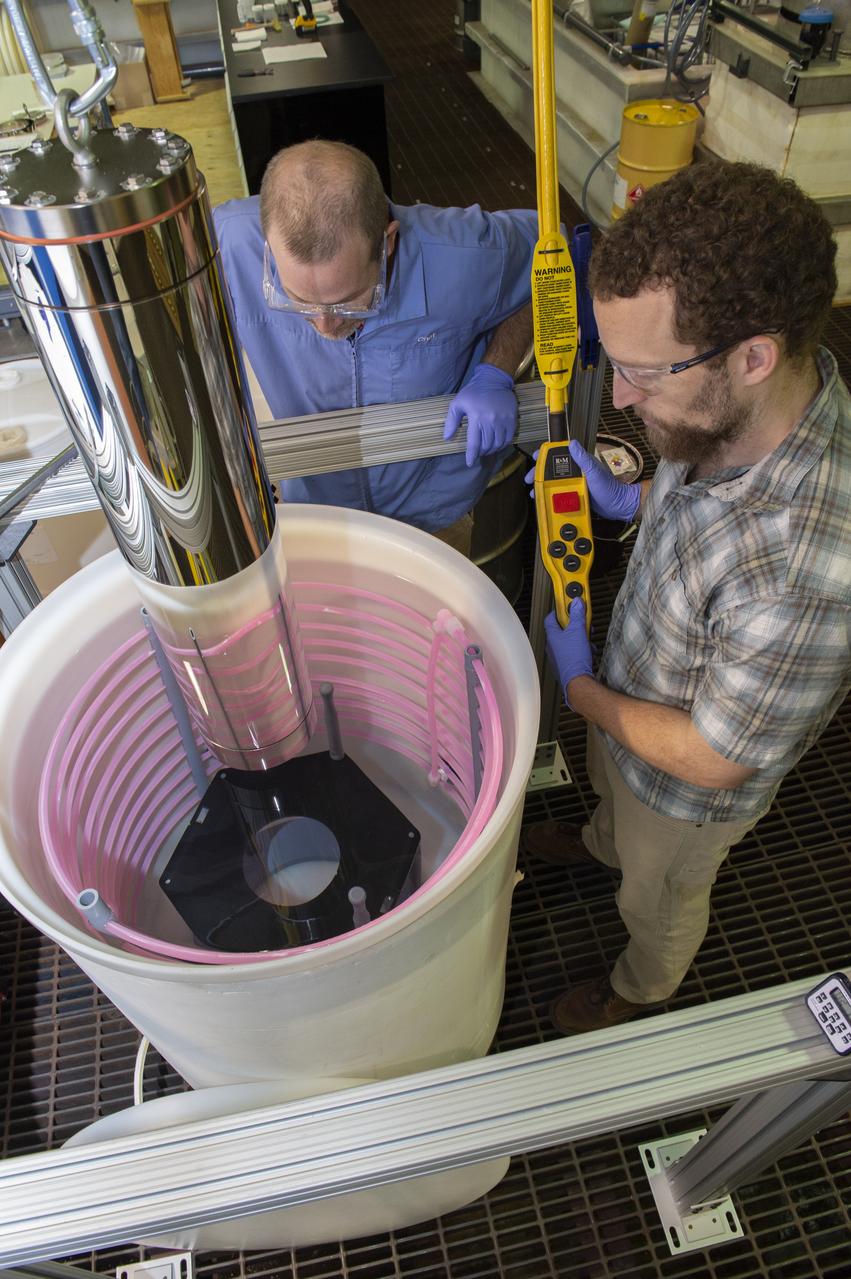

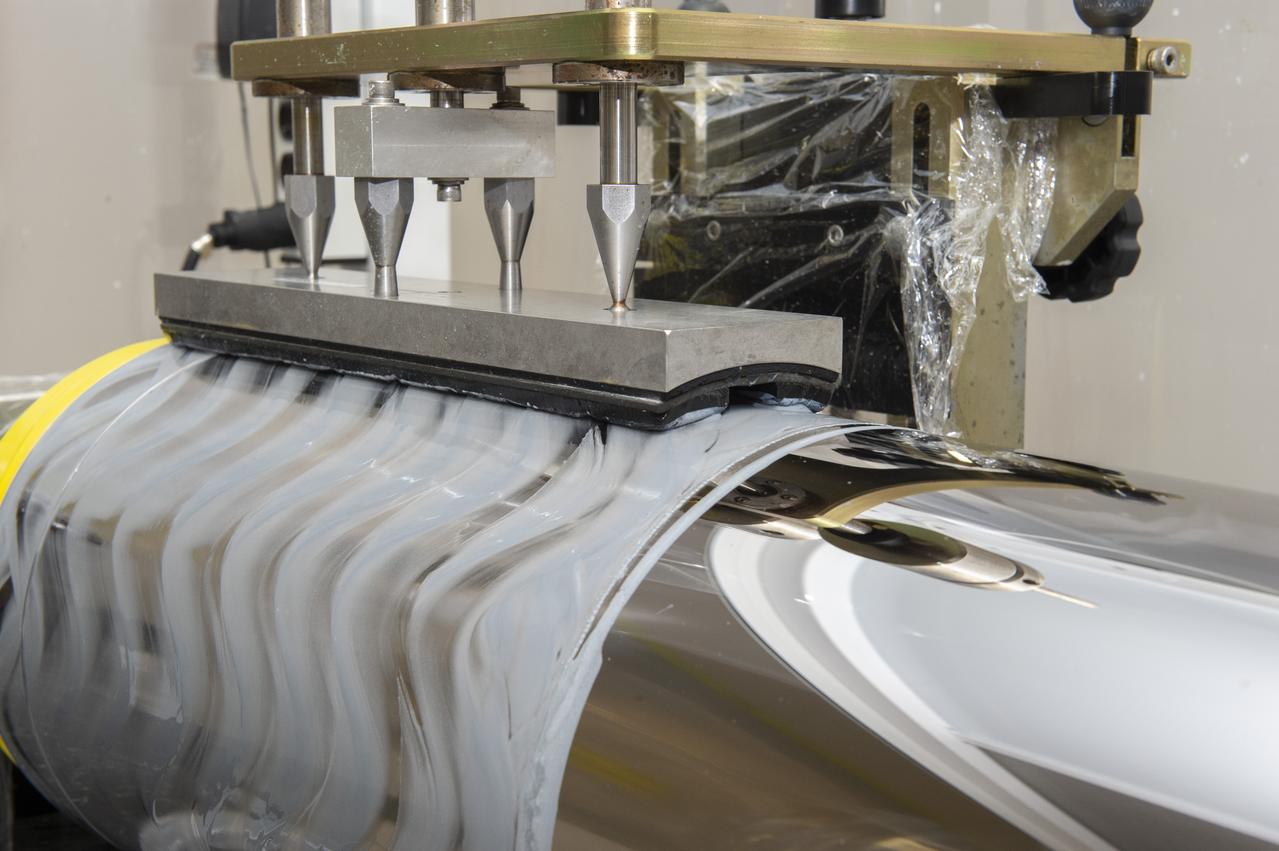

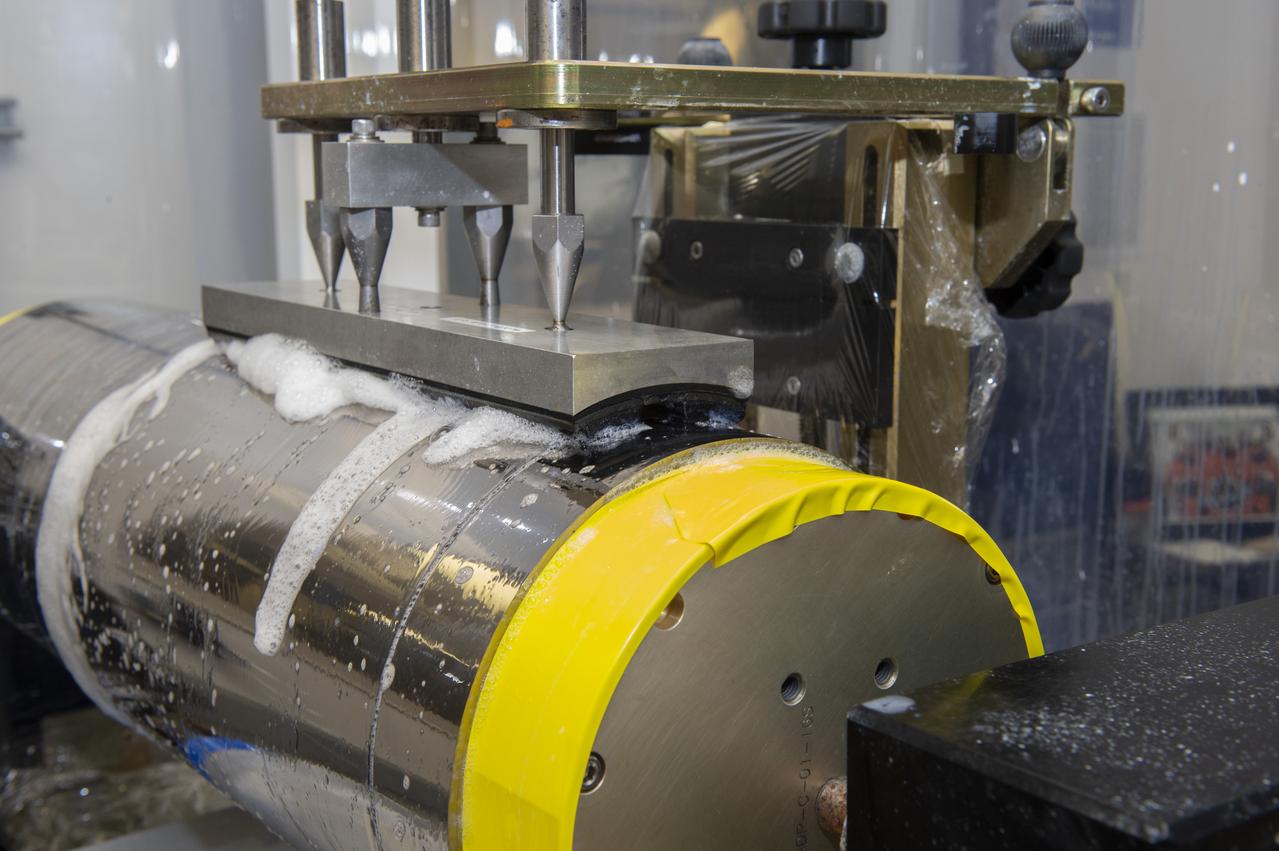

X-RAY MIRROR REPLICATION AND SHELL SEPARATION PROCESS: CHET SPEEGLE, JOHN HOOD, KEITH BOWEN, CARL WIDRIG, RATANA MEEKHAM, AMY MEEKHAM

X-RAY MIRROR REPLICATION AND SHELL SEPARATION PROCESS: CHET SPEEGLE, JOHN HOOD, KEITH BOWEN, CARL WIDRIG, RATANA MEEKHAM, AMY MEEKHAM

X-RAY MIRROR REPLICATION AND SHELL SEPARATION PROCESS: CHET SPEEGLE, JOHN HOOD, KEITH BOWEN, CARL WIDRIG, RATANA MEEKHAM, AMY MEEKHAM

X-RAY MIRROR REPLICATION AND SHELL SEPARATION PROCESS: CHET SPEEGLE, JOHN HOOD, KEITH BOWEN, CARL WIDRIG, RATANA MEEKHAM, AMY MEEKHAM

X-RAY MIRROR REPLICATION AND SHELL SEPARATION PROCESS: CHET SPEEGLE, JOHN HOOD, KEITH BOWEN, CARL WIDRIG, RATANA MEEKHAM, AMY MEEKHAM

X-RAY MIRROR REPLICATION AND SHELL SEPARATION PROCESS: CHET SPEEGLE, JOHN HOOD, KEITH BOWEN, CARL WIDRIG, RATANA MEEKHAM, AMY MEEKHAM

X-RAY MIRROR REPLICATION AND SHELL SEPARATION PROCESS: CHET SPEEGLE, JOHN HOOD, KEITH BOWEN, CARL WIDRIG, RATANA MEEKHAM, AMY MEEKHAM

X-RAY MIRROR REPLICATION AND SHELL SEPARATION PROCESS: CHET SPEEGLE, JOHN HOOD, KEITH BOWEN, CARL WIDRIG, RATANA MEEKHAM, AMY MEEKHAM

X-RAY MIRROR REPLICATION AND SHELL SEPARATION PROCESS: CHET SPEEGLE, JOHN HOOD, KEITH BOWEN, CARL WIDRIG, RATANA MEEKHAM, AMY MEEKHAM

X-RAY MIRROR REPLICATION AND SHELL SEPARATION PROCESS: CHET SPEEGLE, JOHN HOOD, KEITH BOWEN, CARL WIDRIG, RATANA MEEKHAM, AMY MEEKHAM

NASA Phoenix Mars Lander will be in free fall after it separates from its back shell and parachute, but not for long.

The Mars 2020 Perseverance rover mission's disk-shaped cruise stage sits atop the bell-shaped back shell, which contains the powered descent stage and Perseverance rover. Below is the brass-colored heat shield that is about to be attached to the back shell. The image was taken on May 28, 2020, at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The next time the back shell and cruise stage will separate will be about 6 miles (9 kilometers) above Mars' Jezero Crater on Feb. 18, 2021. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23925

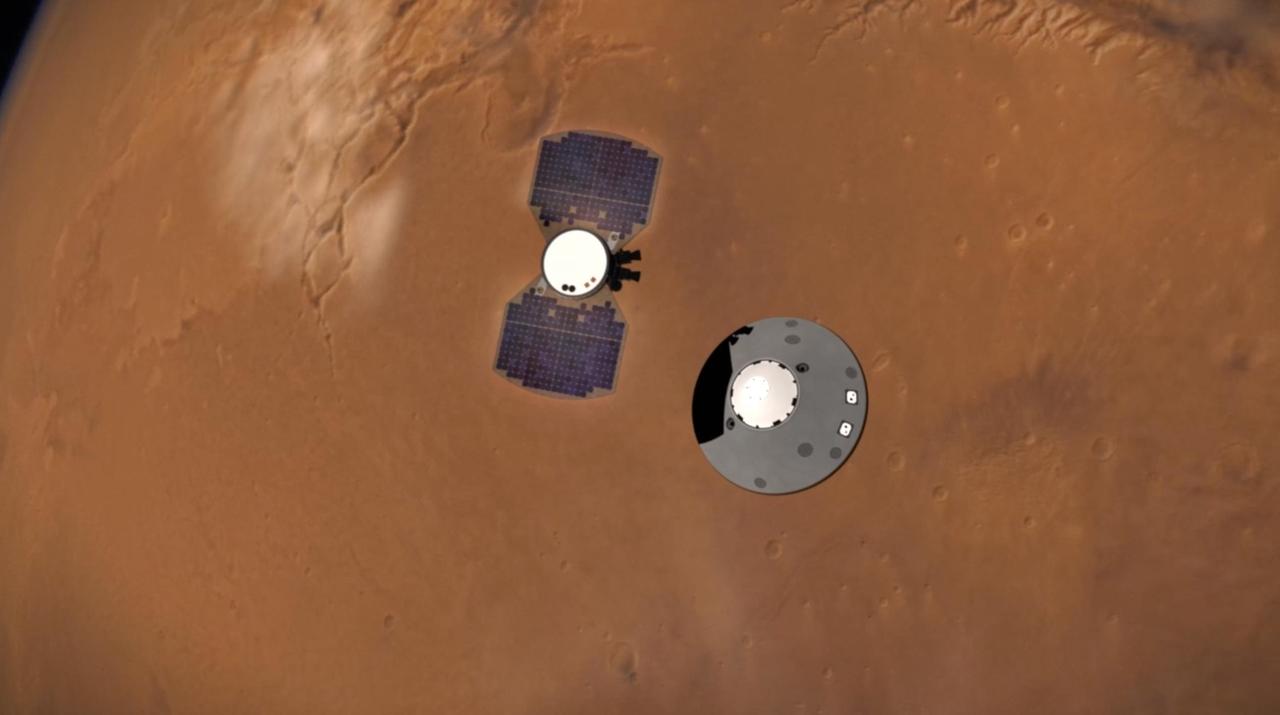

This illustration shows NASA's InSight lander separating from its cruise stage as it prepares to enter Mars' atmosphere. The InSight lander is on the right, tucked inside a protective heat shield and back shell. The cruise stage with solar panels is on the left. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22828

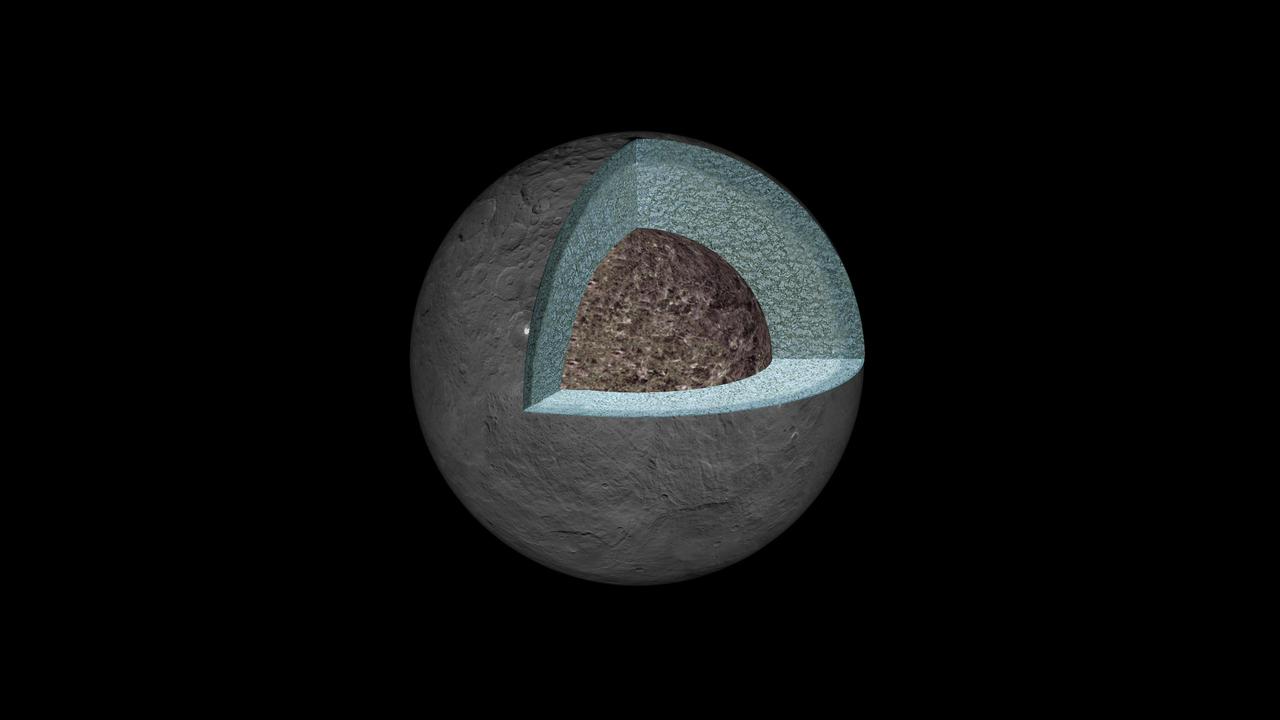

This artist's concept shows a diagram of how the inside of Ceres could be structured, based on data about the dwarf planet's gravity field from NASA's Dawn mission. Using information about Ceres' gravity and topography, scientists found that Ceres is "differentiated," which means that it has compositionally distinct layers at different depths. The densest layer is at the core, which scientists suspect is made of hydrated silicates. Above that is a volatile-rich shell, topped with a crust of mixed materials. This research teaches scientists about what internal processes could have occurred during the early history of Ceres. It appears that, during a heating phase early in the history of Ceres, water and other light materials partially separated from rock. These light materials and water then rose to the outer layer of Ceres. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20867

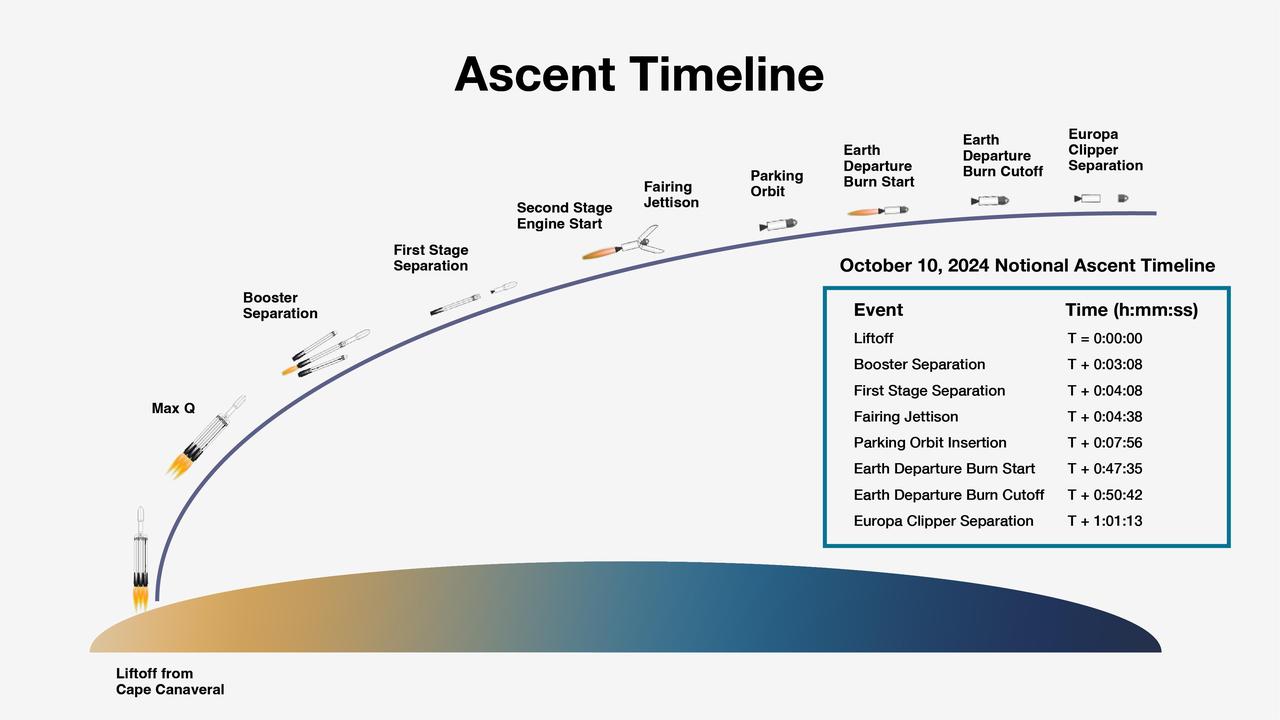

NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft will be launched on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket from the agency's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. This graphic shows the expected timeline of milestones immediately following liftoff if the mission launches at the beginning of its launch period on Oct. 10, 2024. The actual times of milestones will differ slightly depending on the launch day. Regardless of launch date within the launch period, the spacecraft's separation from the rocket is expected to occur a little over an hour after liftoff. Europa Clipper is bound for the Jupiter system, where it will study the gas giant's icy moon Europa. The mission's three main science objectives are to determine the thickness of the moon's icy shell and its interactions with the ocean below, to investigate its composition, and to characterize its geology. The mission's detailed exploration of Europa will help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26437

![This is one of three views of locations where hardware from the European Space Agency's Schiaparelli test lander reached the surface of Mars on Oct. 19, 2016, combine two orbital views from different angles as a stereo pair. The view was created to appear three-dimensional when seen through red-blue glasses with the red lens on the left, though the scene is too flat to show much relief. The stereo preparation uses images taken on Oct. 25, 2016, [PIA21131] and Nov. 1, 2016, [PIA21132] by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The left-eye (red-tinted) component of the stereo is from the earlier observation, which was taken from farther west than the second observation. These views shows three sites where parts of the Schiaparelli spacecraft hit the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The parachute's shape on the ground changed between the two observation dates, cancelling the three-dimensional effect of having views from different angles. The scale bar of 20 meters (65.6 feet) applies to all three portions. Schiaparelli was one component of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. The ExoMars project received data from Schiaparelli during its descent through the atmosphere. ESA has reported that the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). More views are available at http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21135](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21135/PIA21135~thumb.jpg)

This is one of three views of locations where hardware from the European Space Agency's Schiaparelli test lander reached the surface of Mars on Oct. 19, 2016, combine two orbital views from different angles as a stereo pair. The view was created to appear three-dimensional when seen through red-blue glasses with the red lens on the left, though the scene is too flat to show much relief. The stereo preparation uses images taken on Oct. 25, 2016, [PIA21131] and Nov. 1, 2016, [PIA21132] by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The left-eye (red-tinted) component of the stereo is from the earlier observation, which was taken from farther west than the second observation. These views shows three sites where parts of the Schiaparelli spacecraft hit the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The parachute's shape on the ground changed between the two observation dates, cancelling the three-dimensional effect of having views from different angles. The scale bar of 20 meters (65.6 feet) applies to all three portions. Schiaparelli was one component of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. The ExoMars project received data from Schiaparelli during its descent through the atmosphere. ESA has reported that the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). More views are available at http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21135

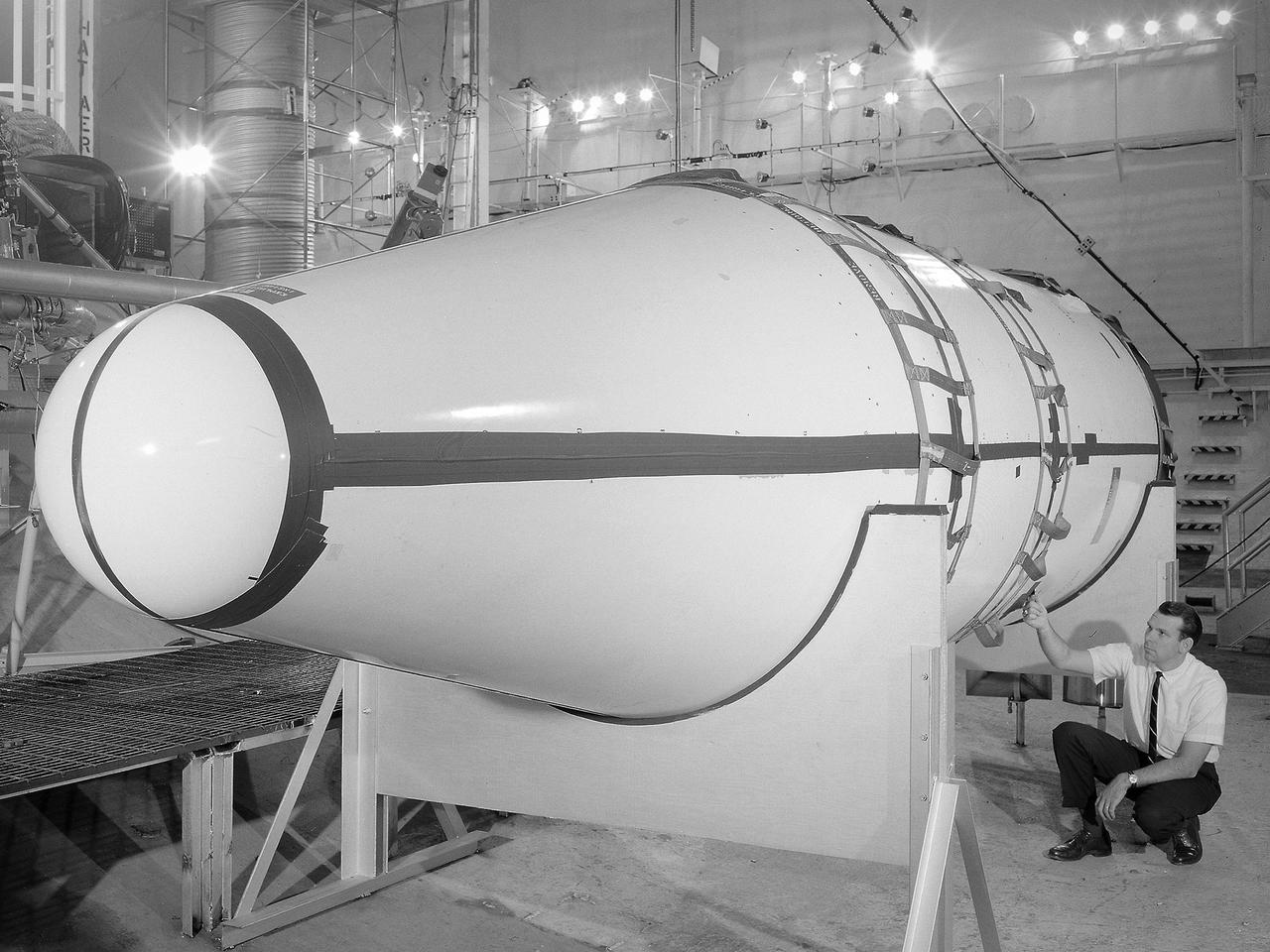

Setup of a Surveyor/Atlas/Centaur shroud in the Space Power Chambers for a leak test at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Lewis Research Center. Centaur was a 15,000-pound thrust second-stage rocket designed for the military in 1957 and 1958 by General Dynamics. It was the first major rocket to use the liquid hydrogen technology developed by Lewis in the 1950s. The Centaur Program suffered numerous problems before being transferred to Lewis in 1962. Several test facilities at Lewis’ main campus and Plum Brook Station were built or modified specifically for Centaur, including the Space Power Chambers. In 1961, NASA Lewis management decided to convert its Altitude Wind Tunnel into two large test chambers and later renamed it the Space Power Chambers. The conversion, which took over 2 years, included the removal of the tunnel’s internal components and insertion of bulkheads to seal off the new chambers. The larger chamber, seen here, could simulate altitudes of 100,000 feet. It was used for Centaur shroud separation and propellant management studies until the early 1970s. The leak test in this photograph was likely an attempt to verify that the shroud’s honeycomb shell did not seep any of its internal air when the chamber was evacuated to pressures similar to those found in the upper atmosphere.

This Oct. 25, 2016, image shows the area where the European Space Agency's Schiaparelli test lander reached the surface of Mars, with magnified insets of three sites where components of the spacecraft hit the ground. It is the first view of the site from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter taken after the Oct. 19, 2016, landing event. The Schiaparelli test lander was one component of ESA's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. This HiRISE observation adds information to what was learned from observation of the same area on Oct. 20 by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's Context Camera (CTX). Of these two cameras, CTX covers more area and HiRISE shows more detail. A portion of the HiRISE field of view also provides color information. The impact scene was not within that portion for the Oct. 25 observation, but an observation with different pointing to add color and stereo information is planned. This Oct. 25 observation shows three locations where hardware reached the ground, all within about 0.9 mile (1.5 kilometer) of each other, as expected. The annotated version includes insets with six-fold enlargement of each of those three areas. Brightness is adjusted separately for each inset to best show the details of that part of the scene. North is about 7 degrees counterclockwise from straight up. The scale bars are in meters. At lower left is the parachute, adjacent to the back shell, which was its attachment point on the spacecraft. The parachute is much brighter than the Martian surface in this region. The smaller circular feature just south of the bright parachute is about the same size and shape as the back shell, (diameter of 7.9 feet or 2.4 meters). At upper right are several bright features surrounded by dark radial impact patterns, located about where the heat shield was expected to impact. The bright spots may be part of the heat shield, such as insulation material, or gleaming reflections of the afternoon sunlight. According to the ExoMars project, which received data from the spacecraft during its descent through the atmosphere, the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). At mid-upper left are markings left by the lander's impact. The dark, approximately circular feature is about 7.9 feet (2.4 meters) in diameter, about the size of a shallow crater expected from impact into dry soil of an object with the lander's mass -- about 660 pounds (300 kilograms) -- and calculated velocity. The resulting crater is estimated to be about a foot and a half (half a meter) deep. This first HiRISE observation does not show topography indicating the presence of a crater. Stereo information from combining this observation with a future one may provide a way to check. Surrounding the dark spot are dark radial patterns expected from an impact event. The dark curving line to the northeast of the dark spot is unusual for a typical impact event and not yet explained. Surrounding the dark spot are several relatively bright pixels or clusters of pixels. They could be image noise or real features, perhaps fragments of the lander. A later image is expected to confirm whether these spots are image noise or actual surface features. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21131

![On Nov. 1, 2016, the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter observed the impact site of Europe's Schiaparelli test lander, gaining the first color view of the site since the lander's Oct. 19, 2016, arrival. These cutouts from the observation cover three locations where parts of the spacecraft reached the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The heat shield location was outside of the area covered in color. The scale bar of 10 meters (32.8 feet) applies to all three cutouts. Schiaparelli was one component of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. The ExoMars project received data from Schiaparelli during its descent through the atmosphere. ESA reports that the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). Information gained from the Nov. 1 observation supplements what was learned from an Oct. 25 HiRISE observation, at PIA21131, which also shows the locations of these three cutouts relative to each other. Where the lander module struck the ground, dark radial patterns that extend from a dark spot are interpreted as "ejecta," or material thrown outward from the impact, which may have excavated a shallow crater. From the earlier image, it was not clear whether the relatively bright pixels and clusters of pixels scattered around the lander module's impact site are fragments of the module or image noise. Now it is clear that at least the four brightest spots near the impact are not noise. These bright spots are in the same location in the two images and have a white color, unusual for this region of Mars. The module may have broken up at impact, and some fragments might have been thrown outward like impact ejecta. The parachute has a different shape in the Nov. 1 image than in the Oct. 25 one, apparently from shifting in the wind. Similar shifting was observed in the parachute of NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission during the first six months after the Mars arrival of that mission's Curiosity rover in 2012 [PIA16813]. At lower right are several bright features surrounded by dark radial impact patterns, located where the heat shield was expected to impact. The bright spots appear identical in the Nov. 1 and Oct. 25 images, which were taken from different angles, so these spots are now interpreted as bright material, such as insulation layers, not glinting reflections. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21132](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21132/PIA21132~thumb.jpg)

On Nov. 1, 2016, the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter observed the impact site of Europe's Schiaparelli test lander, gaining the first color view of the site since the lander's Oct. 19, 2016, arrival. These cutouts from the observation cover three locations where parts of the spacecraft reached the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The heat shield location was outside of the area covered in color. The scale bar of 10 meters (32.8 feet) applies to all three cutouts. Schiaparelli was one component of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. The ExoMars project received data from Schiaparelli during its descent through the atmosphere. ESA reports that the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). Information gained from the Nov. 1 observation supplements what was learned from an Oct. 25 HiRISE observation, at PIA21131, which also shows the locations of these three cutouts relative to each other. Where the lander module struck the ground, dark radial patterns that extend from a dark spot are interpreted as "ejecta," or material thrown outward from the impact, which may have excavated a shallow crater. From the earlier image, it was not clear whether the relatively bright pixels and clusters of pixels scattered around the lander module's impact site are fragments of the module or image noise. Now it is clear that at least the four brightest spots near the impact are not noise. These bright spots are in the same location in the two images and have a white color, unusual for this region of Mars. The module may have broken up at impact, and some fragments might have been thrown outward like impact ejecta. The parachute has a different shape in the Nov. 1 image than in the Oct. 25 one, apparently from shifting in the wind. Similar shifting was observed in the parachute of NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission during the first six months after the Mars arrival of that mission's Curiosity rover in 2012 [PIA16813]. At lower right are several bright features surrounded by dark radial impact patterns, located where the heat shield was expected to impact. The bright spots appear identical in the Nov. 1 and Oct. 25 images, which were taken from different angles, so these spots are now interpreted as bright material, such as insulation layers, not glinting reflections. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21132

Taken by the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), this image of MyCn18, a young planetary nebula located about 8,000 light-years away, reveals its true shape to be an hourglass with an intricate pattern of "etchings" in its walls. The arc-like etchings could be the remnants of discrete shells ejected from the star when it was younger, flow instabilities, or could result from the action of a narrow beam of matter impinging on the hourglass walls. According to one theory on the formation of planetary nebulae, the hourglass shape is produced by the expansion of a fast stellar wind within a slowly expanding cloud, which is denser near its equator than near its poles. Hubble has also revealed other features in MyCn18 which are completely new and unexpected. For example, there is a pair of intersecting elliptical rings in the central region which appear to be the rims of a smaller hourglass. This picture has been composed from three separate images taken in the light of ionized nitrogen (represented by red), hydrogen (green) and doubly-ionized oxygen (blue). The results are of great interest because they shed new light on the poorly understood ejection of stellar matter which accompanies the slow death of sun-like stars. An unseen companion star and accompanying gravitational effects may well be necessary in order to explain the structure of MyCn18. The Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) had responsibility for design, development, and construction of the HST.

This composite picture is a seamless blend of ultra-sharp NASA Hubble Space Telescope (HST) images combined with the wide view of the Mosaic Camera on the National Science Foundation's 0.9-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, part of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, near Tucson, Ariz. Astronomers at the Space Telescope Science Institute assembled these images into a mosaic. The mosaic was then blended with a wider photograph taken by the Mosaic Camera. The image shows a fine web of filamentary "bicycle-spoke" features embedded in the colorful red and blue gas ring, which is one of the nearest planetary nebulae to Earth. Because the nebula is nearby, it appears as nearly one-half the diameter of the full Moon. This required HST astronomers to take several exposures with the Advanced Camera for Surveys to capture most of the Helix. HST views were then blended with a wider photo taken by the Mosaic Camera. The portrait offers a dizzying look down what is actually a trillion-mile-long tunnel of glowing gases. The fluorescing tube is pointed nearly directly at Earth, so it looks more like a bubble than a cylinder. A forest of thousands of comet-like filaments, embedded along the inner rim of the nebula, points back toward the central star, which is a small, super-hot white dwarf. The tentacles formed when a hot "stellar wind" of gas plowed into colder shells of dust and gas ejected previously by the doomed star. Ground-based telescopes have seen these comet-like filaments for decades, but never before in such detail. The filaments may actually lie in a disk encircling the hot star, like a collar. The radiant tie-die colors correspond to glowing oxygen (blue) and hydrogen and nitrogen (red). Valuable Hubble observing time became available during the November 2002 Leonid meteor storm. To protect the spacecraft, including HST's precise mirror, controllers turned the aft end into the direction of the meteor stream for about half a day. Fortunately, the Helix Nebula was almost exactly in the opposite direction of the meteor stream, so Hubble used nine orbits to photograph the nebula while it waited out the storm. To capture the sprawling nebula, Hubble had to take nine separate snapshots. Planetary nebulae like the Helix are sculpted late in a Sun-like star's life by a torrential gush of gases escaping from the dying star. They have nothing to do with planet formation, but got their name because they look like planetary disks when viewed through a small telescope. With higher magnification, the classic "donut-hole" in the middle of a planetary nebula can be resolved. Based on the nebula's distance of 650 light-years, its angular size corresponds to a huge ring with a diameter of nearly 3 light-years. That's approximately three-quarters of the distance between our Sun and the nearest star. The Helix Nebula is a popular target of amateur astronomers and can be seen with binoculars as a ghostly, greenish cloud in the constellation Aquarius. Larger amateur telescopes can resolve the ring-shaped nebula, but only the largest ground-based telescopes can resolve the radial streaks. After careful analysis, astronomers concluded the nebula really isn't a bubble, but is a cylinder that happens to be pointed toward Earth. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18164