Saturn Rings

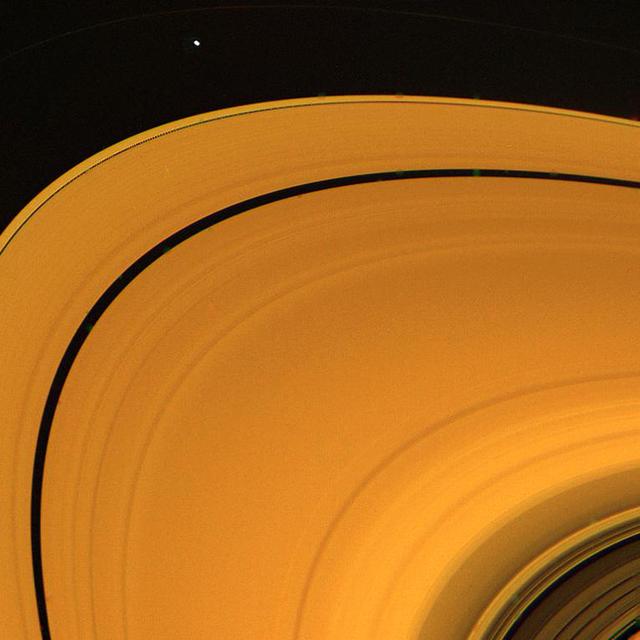

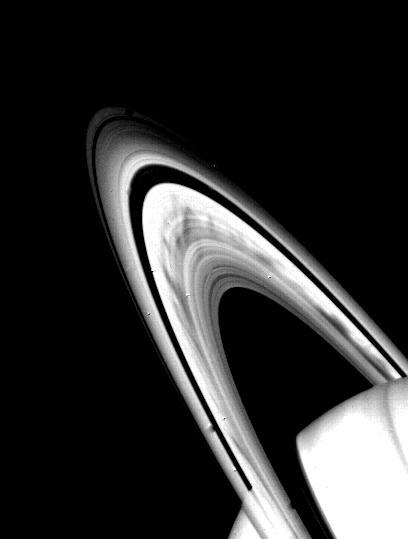

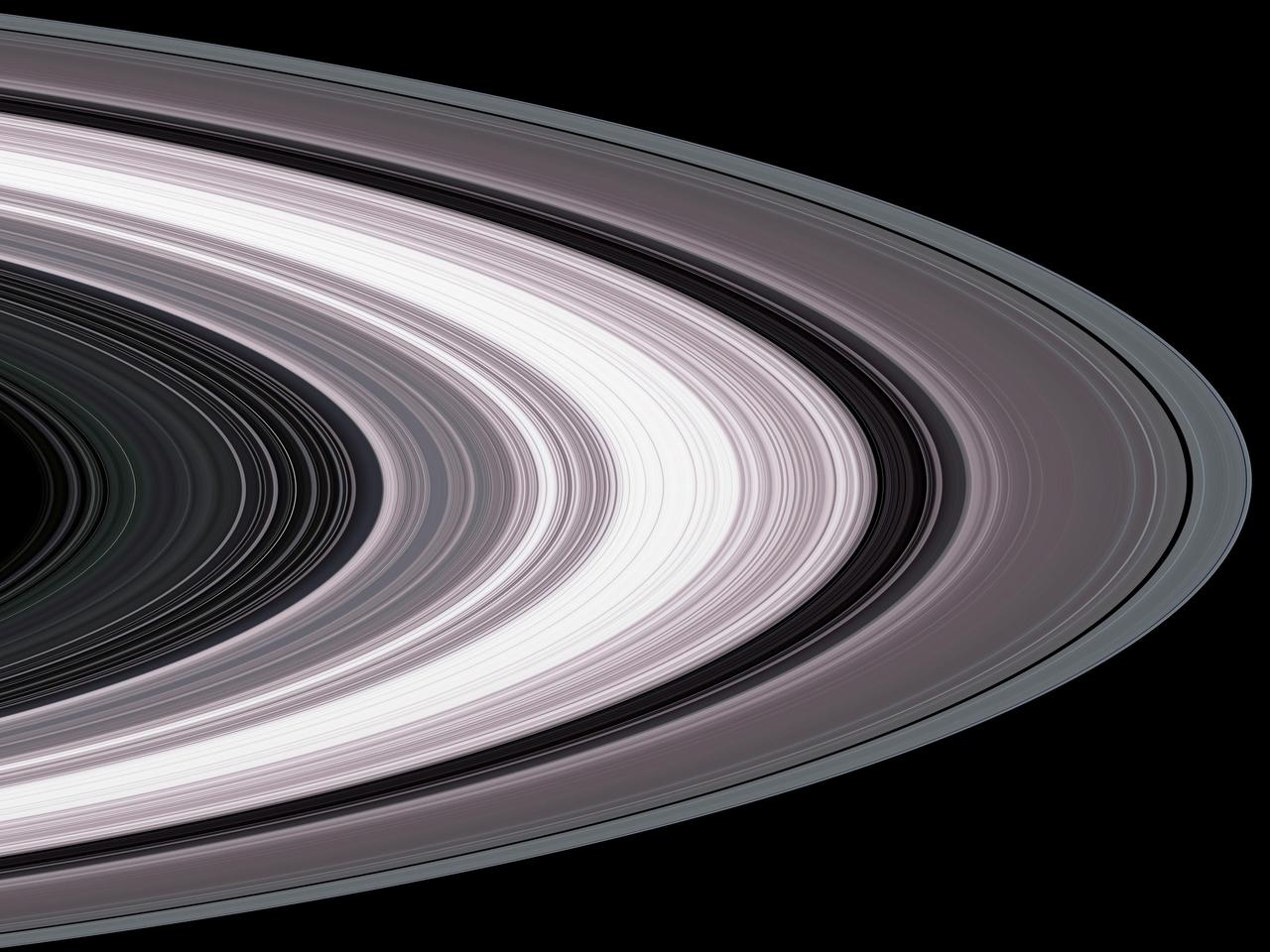

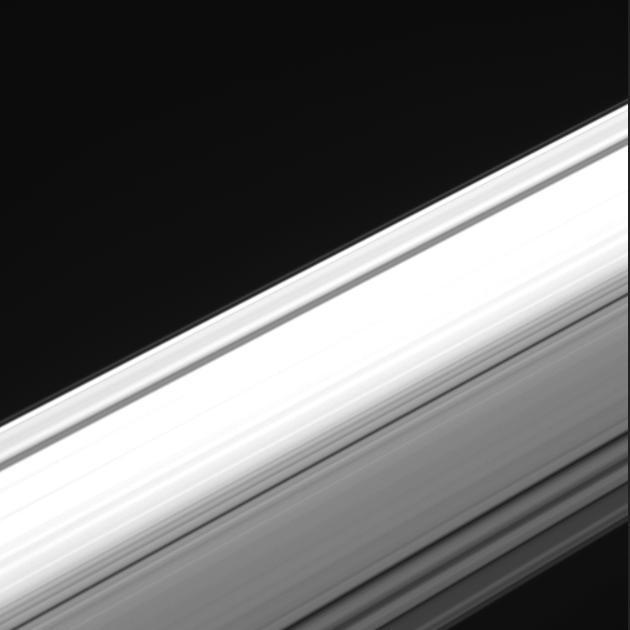

Saturn A-Ring

Saturn A-ring

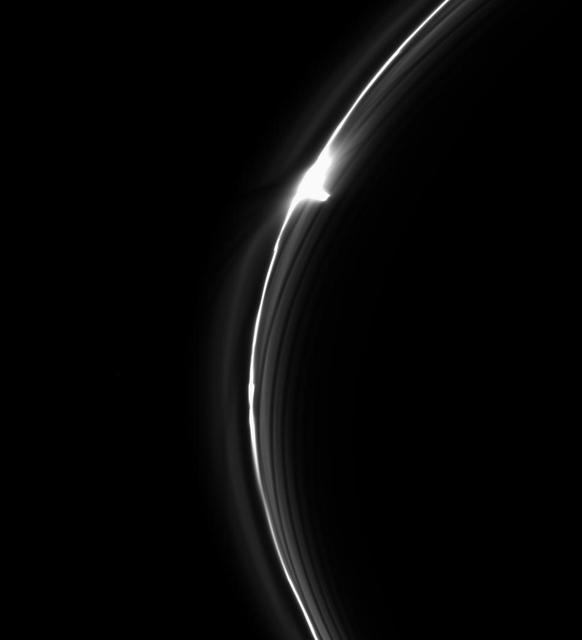

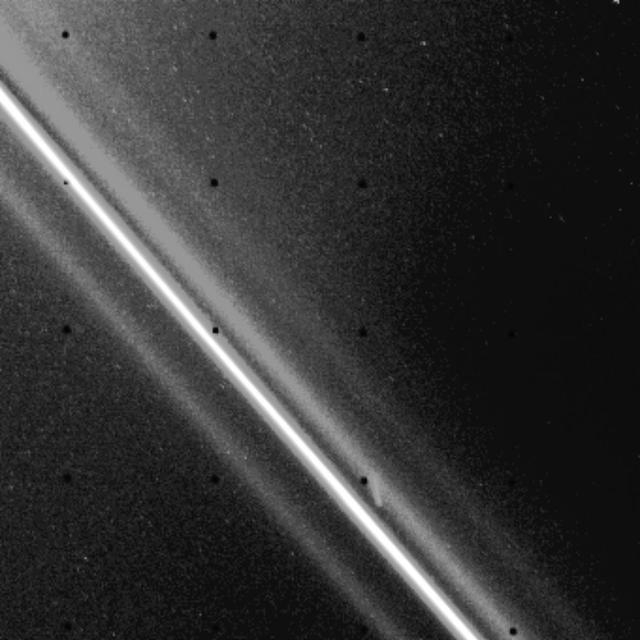

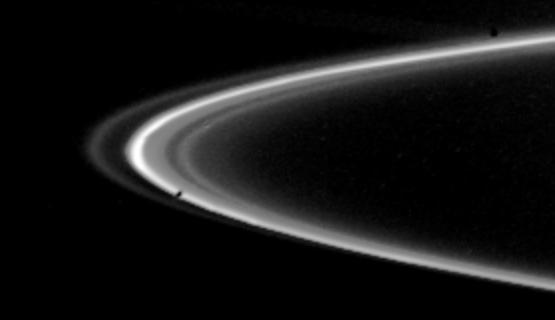

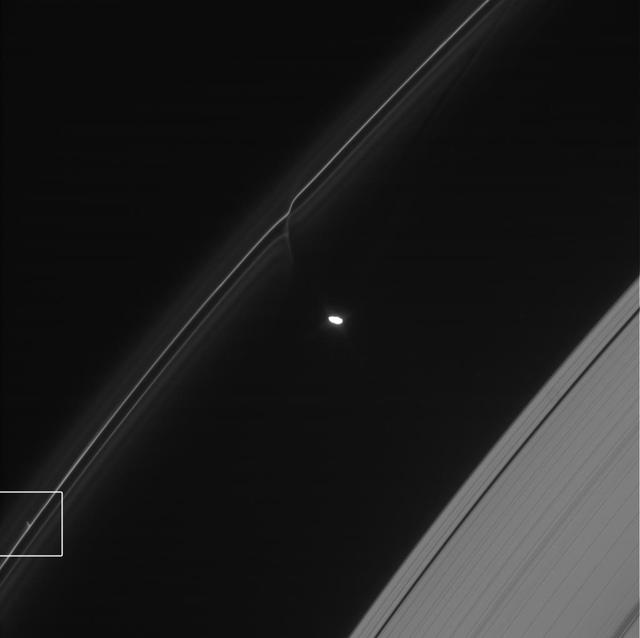

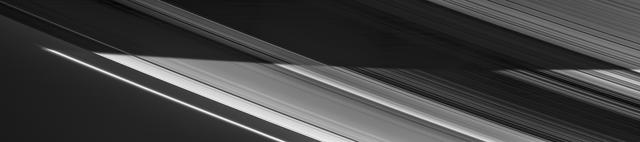

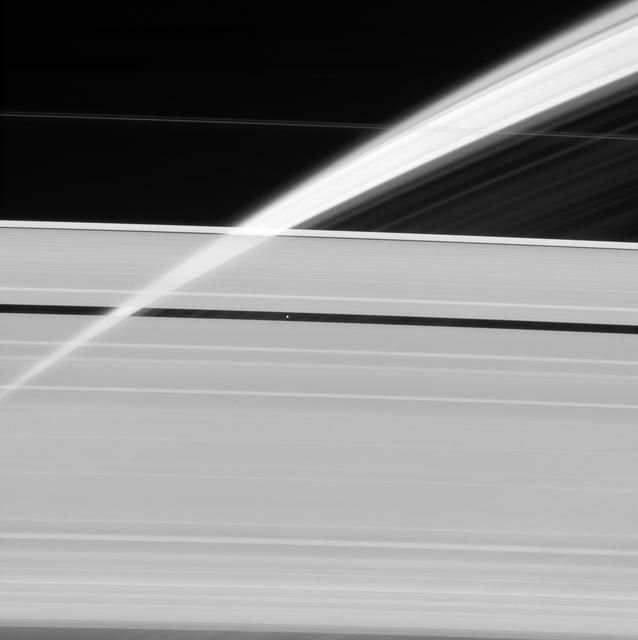

Saturn's dynamic F ring contains many different types of features to keep scientists perplexed. In this image we see features ring scientists call "gores," to the right of the bright clump, and a "jet," to the left of the bright spot. Thanks to the ring's interaction with the moons Prometheus and Pandora, and perhaps a host of smaller moonlets hidden in its core, the F ring is a constantly changing structure, with features that form, fade and re-appear on timescales of hours to days. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 7 degrees below the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on March 15, 2015. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 295,000 miles (475,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-ring-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 117 degrees. Image scale is 1.8 miles (2.9 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18337

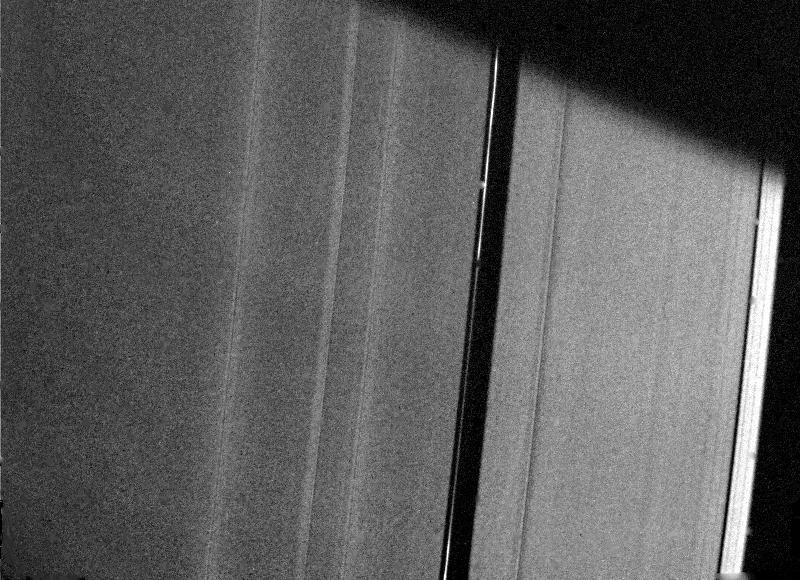

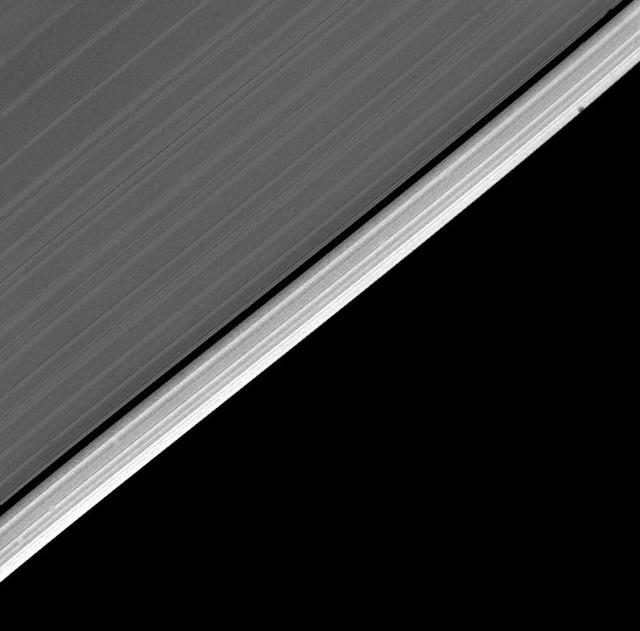

Saturn Outer C Ring

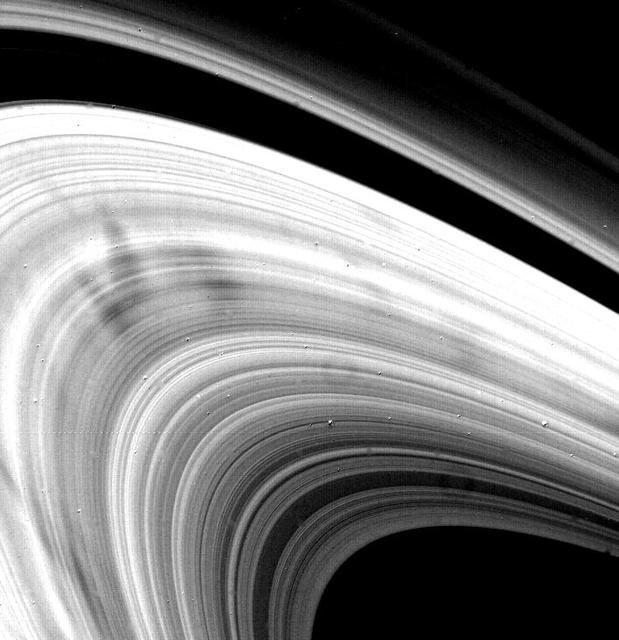

Spokes on Side of Saturn Rings

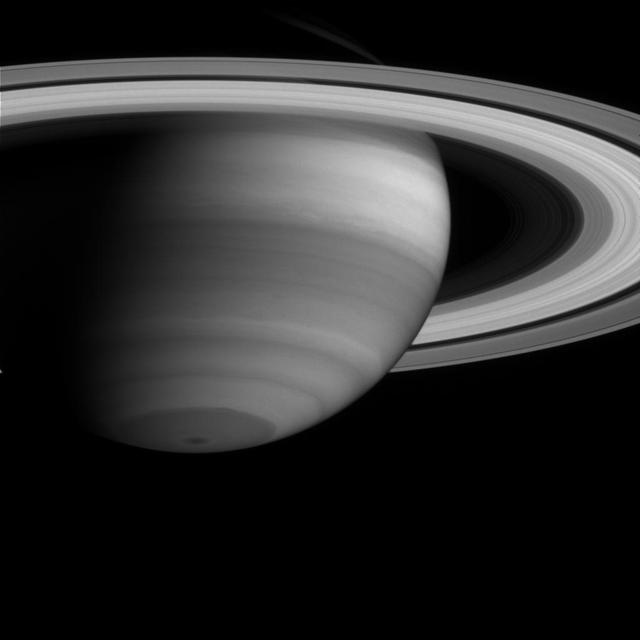

Saturn and its Ring System

Saturn and its Rings

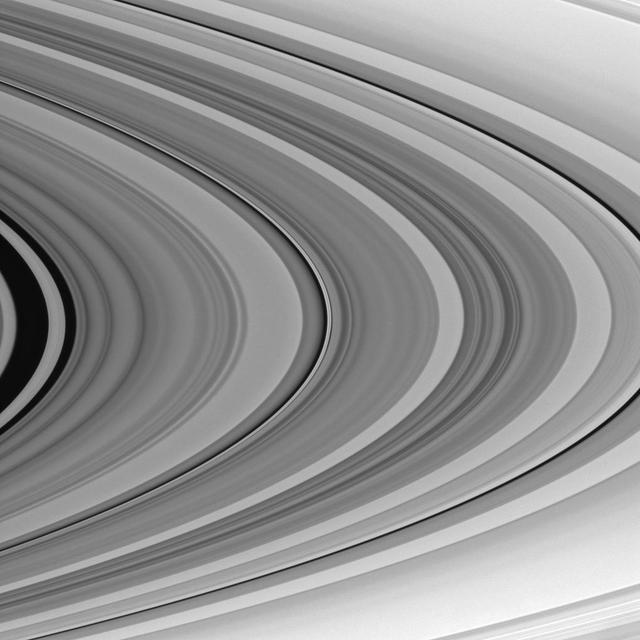

Saturn Ring Patterns

Saturn Rings Edge-on

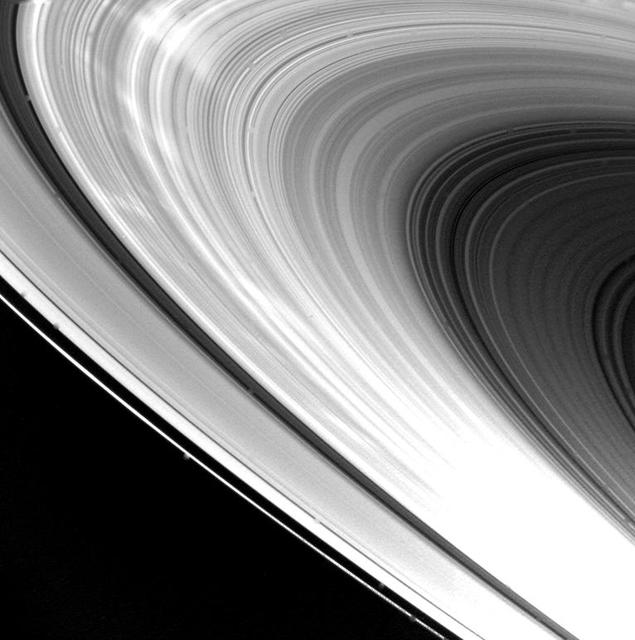

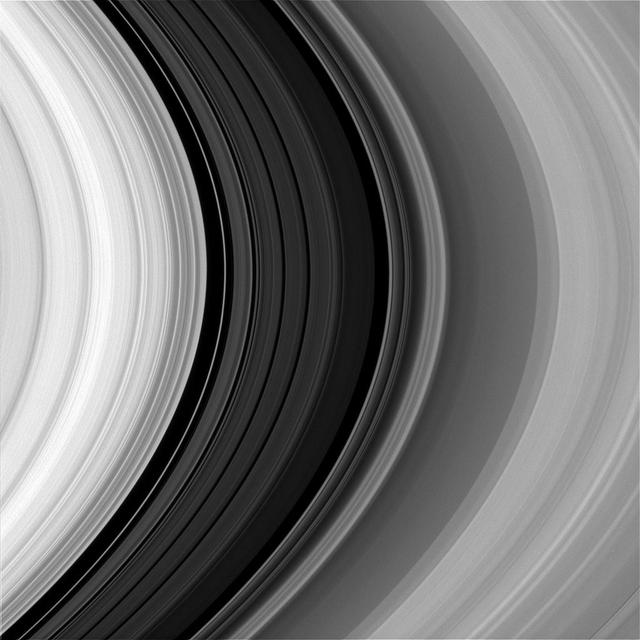

A View of Saturn B-ring

Saturn B and C-rings

Sunset on Saturn Rings

Saturn Recycling Rings

Saturn F-Ring

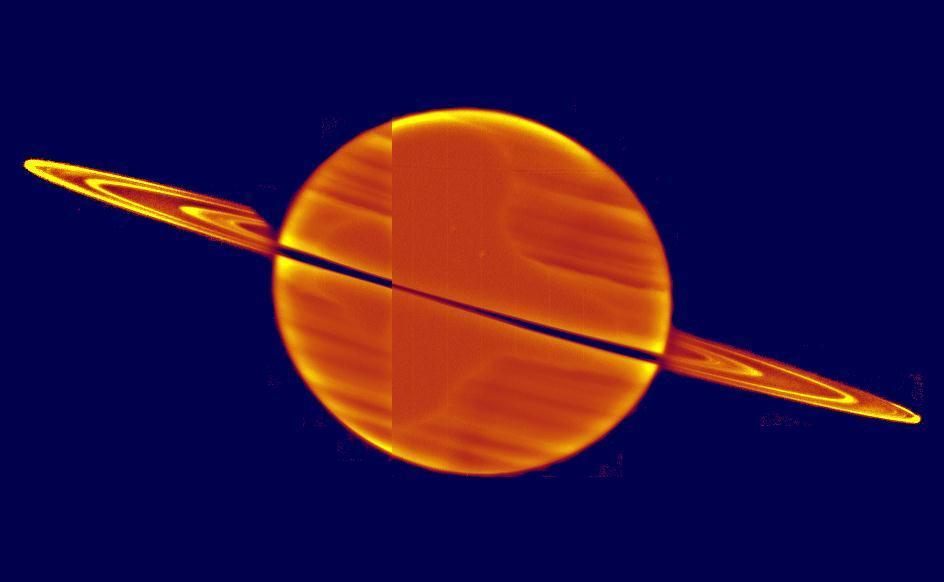

Saturn Rings, Cold and Colder

Saturn F-Ring

Catching Saturn Ring Waves

Saturn Rings - High Resolution

Saturn F Ring

Saturn B-ring

Saturn Ring System

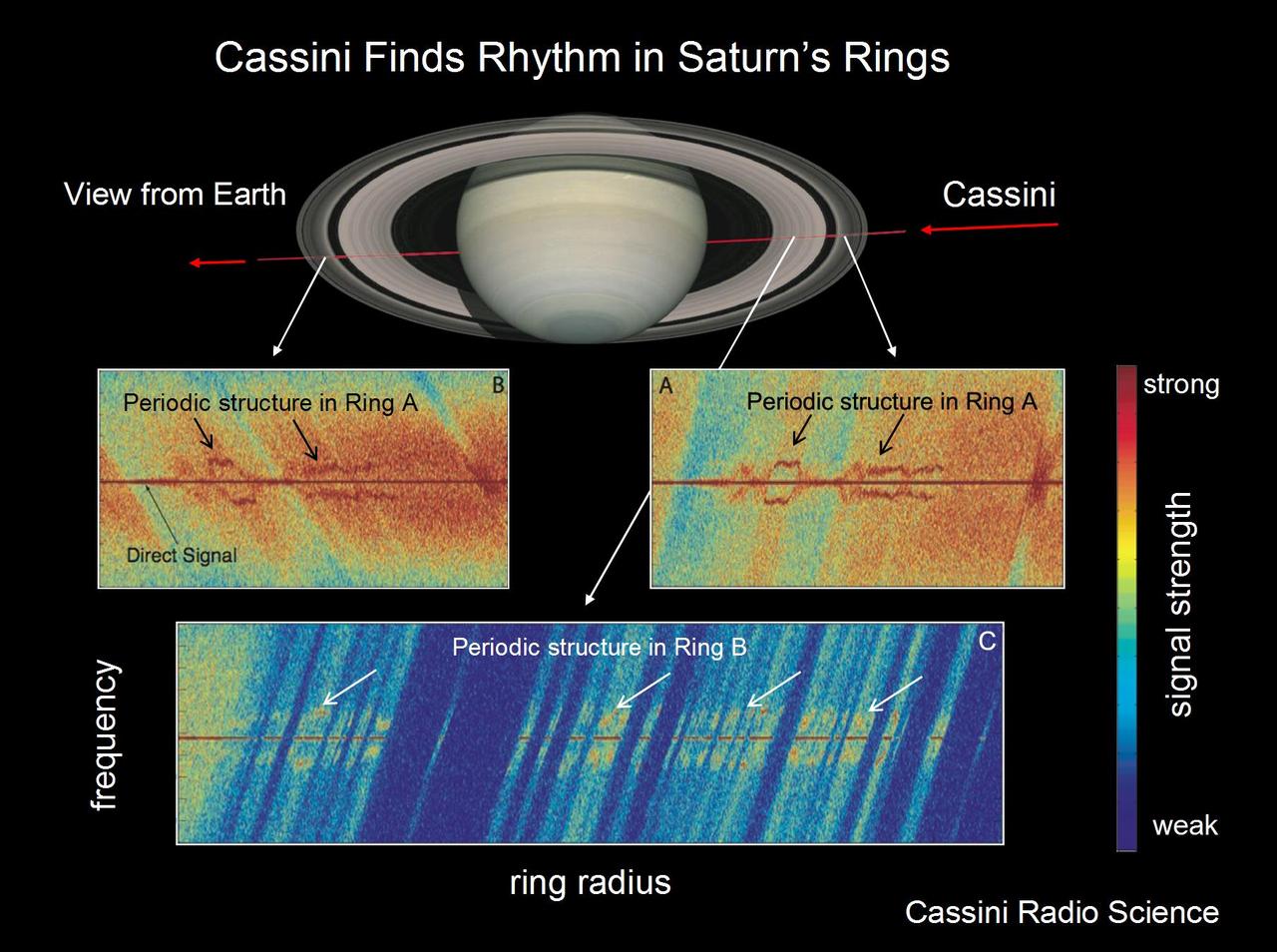

Saturn Ring Rhythm #2

Edge-on View of Saturn Rings

Saturn F-ring

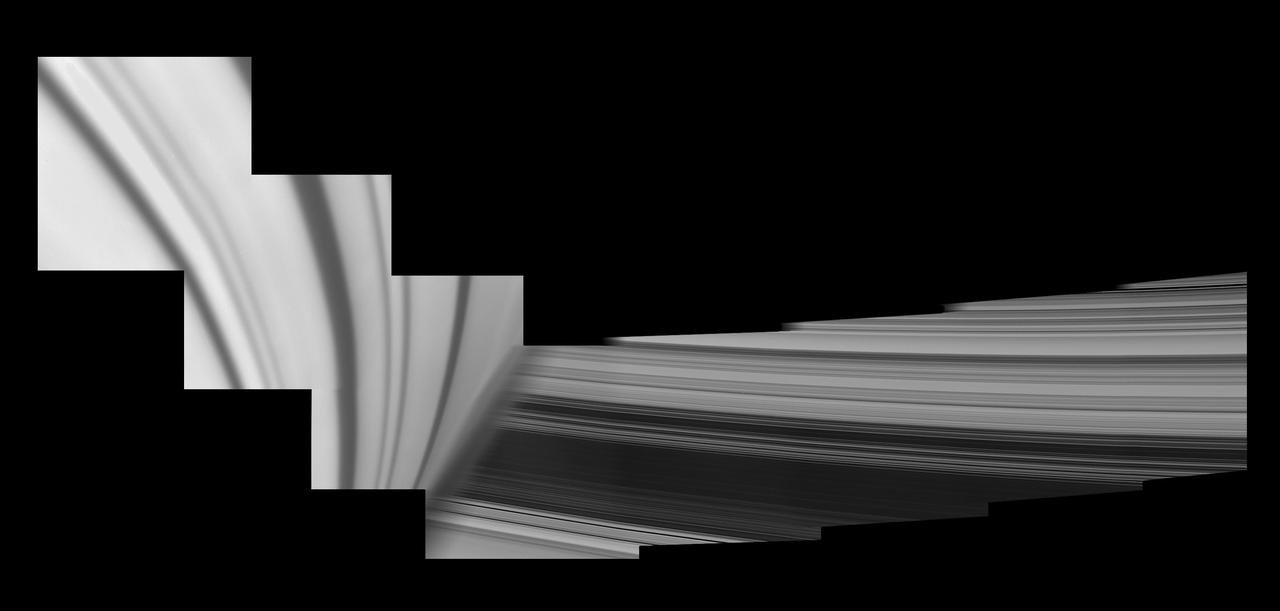

A Full Sweep of Saturn Rings

Thin Ringlet of Saturn A-ring

Saturn Ring Rhythm

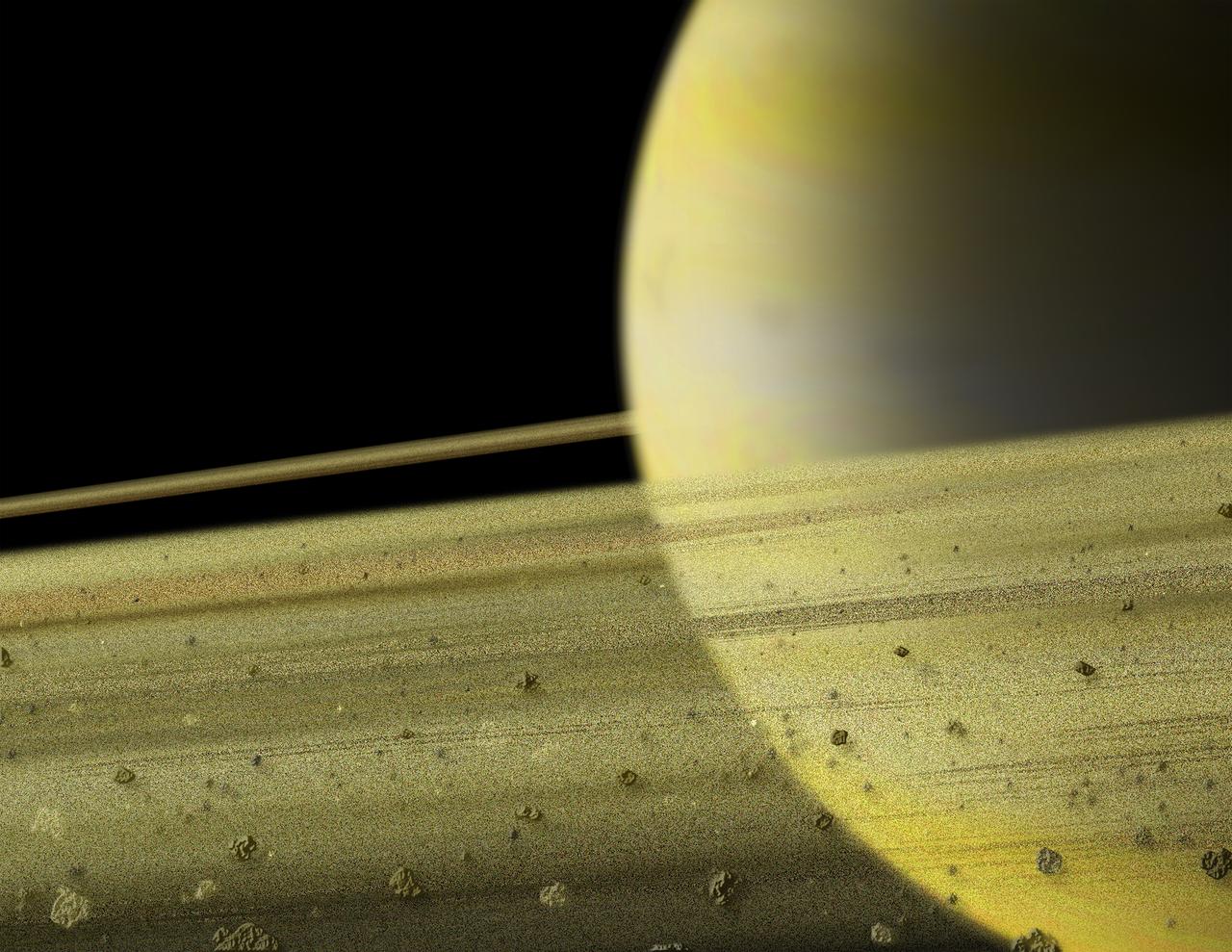

Saturn Rings Artist Concept

Small Particles in Saturn Rings

Saturn Atmosphere and Rings

Image of Saturn F-ring

Outer Edge of Saturn A-ring

A View of Saturn F-ring

Tilting Saturn Rings

Saturn B rings

Saturn Shadow Upon the Rings

Saturn Ring Shadow, Then and Now

Mapping Clumps in Saturn Rings

Mosaic of Saturn Rings

Saturn Ring Region

Two-image Mosaic of Saturn Rings

High-resolution View of Saturn Rings

Outer edge of Saturn B-ring

Wide-Angle Image of Saturn Rings

Saturn Faint Inner D-ring

Wide View of Saturn F Ring

Saturn A Ring From the Inside Out

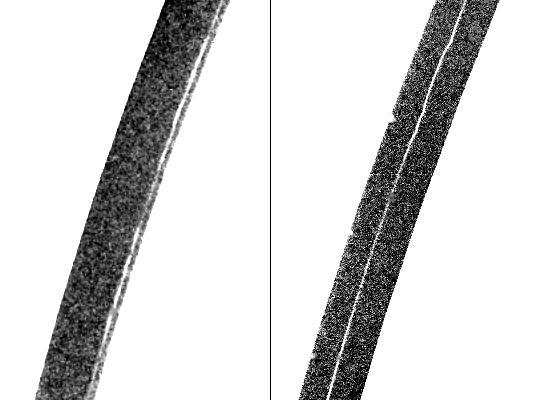

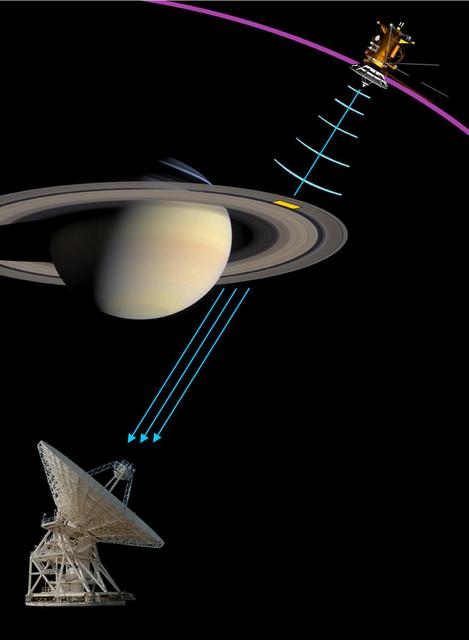

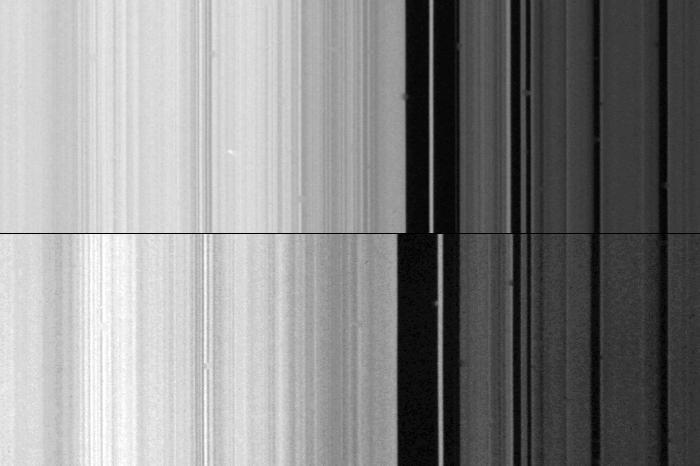

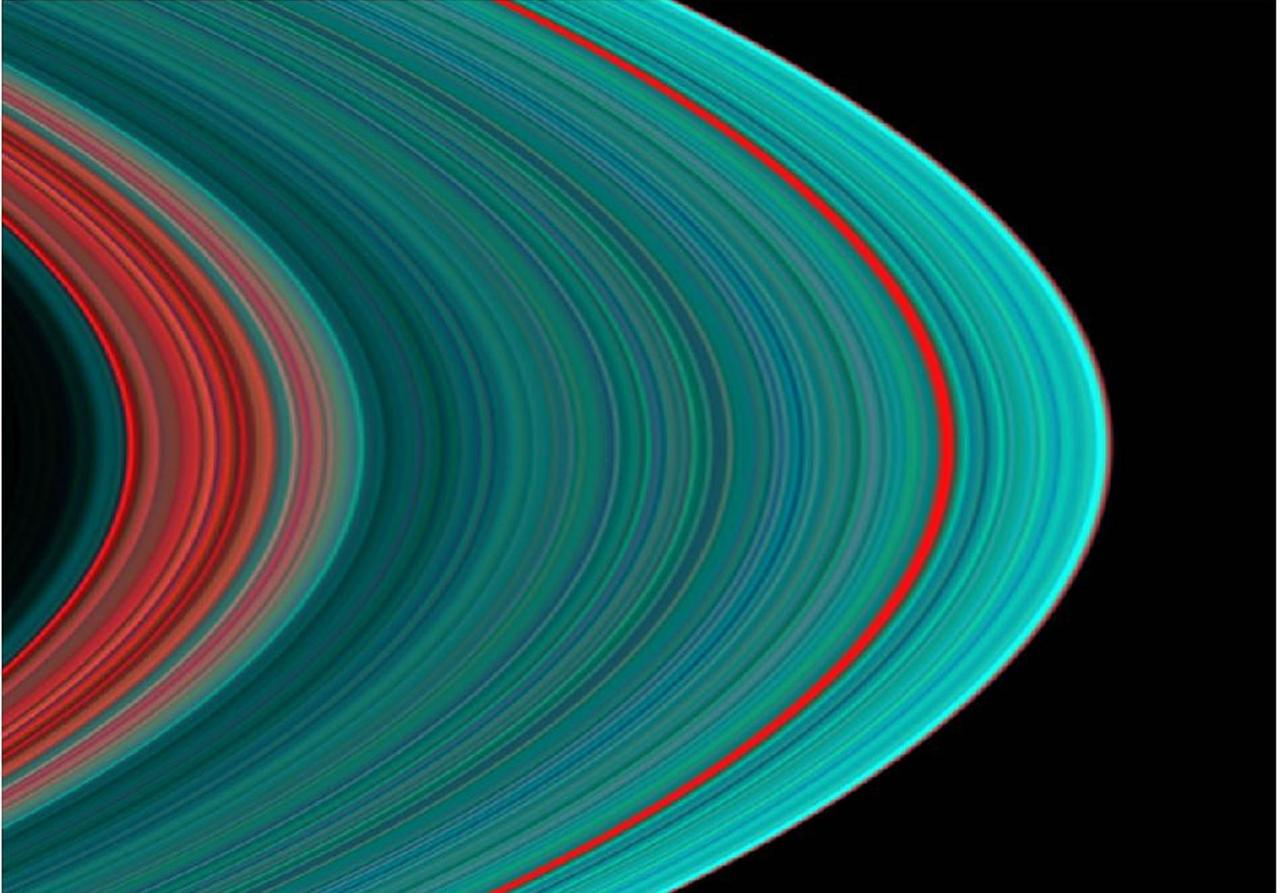

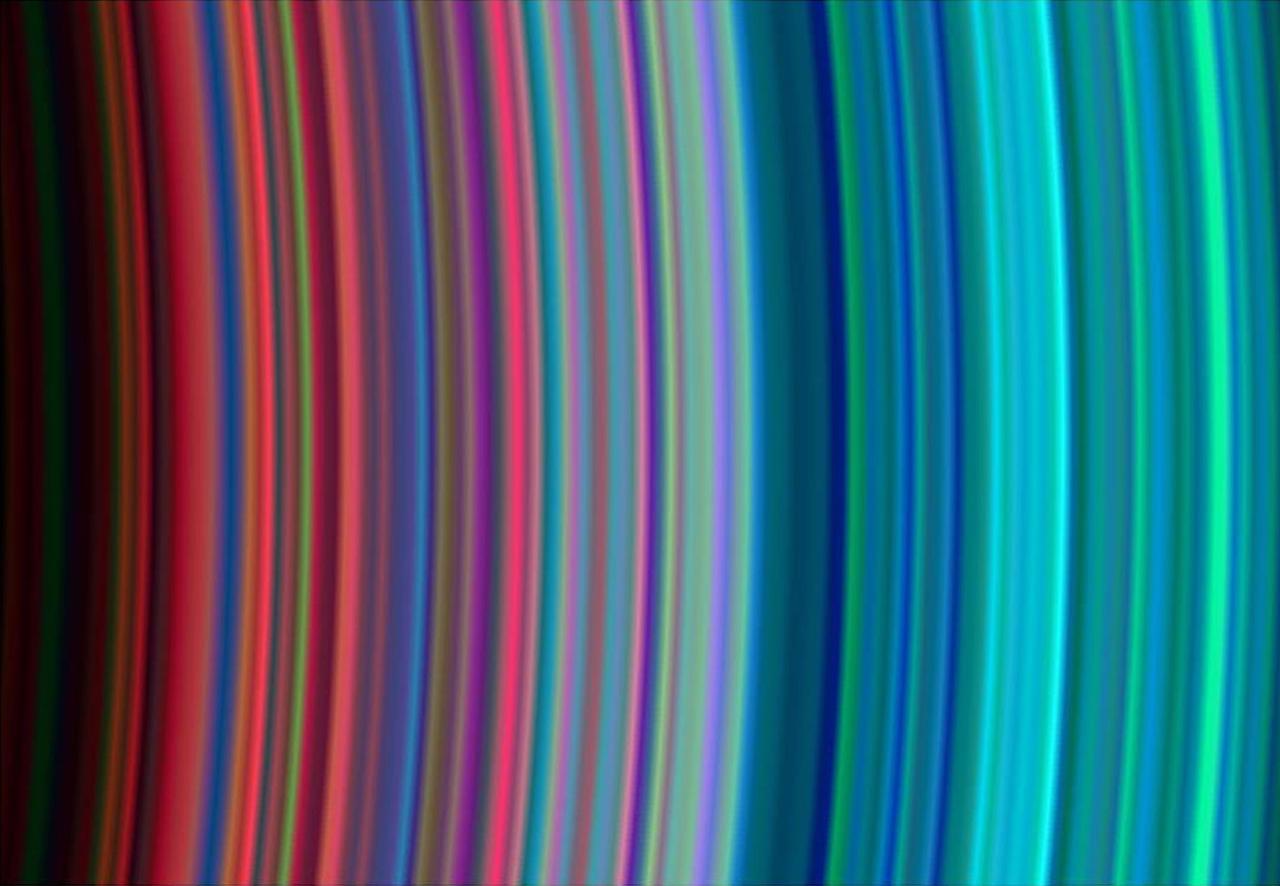

Radio Occultation: Unraveling Saturn Rings

Saturn F-ring and Inner Satellite

One of the glittering trails caused by small objects punching through Saturn F ring is highlighted in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft. These trails show how the F ring, the outermost of Saturn main rings, is constantly changing.

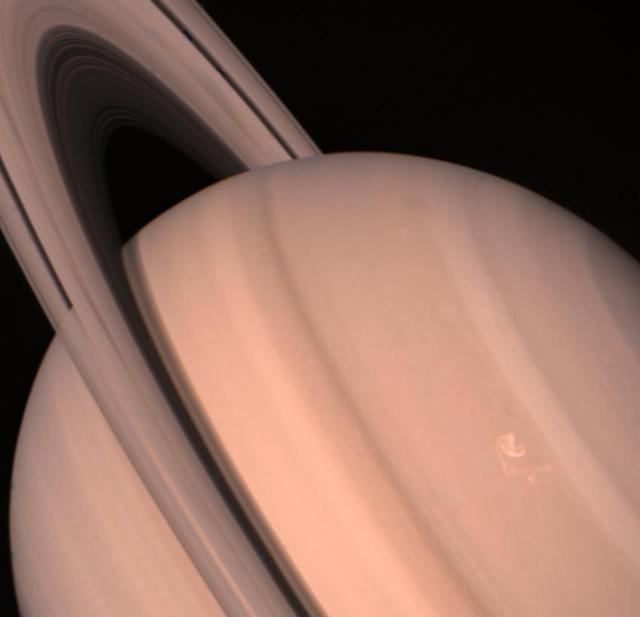

Full-disk Color Image of Crescent Saturn with Rings and Ring Shadows http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00335

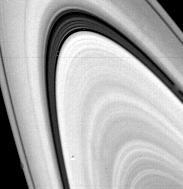

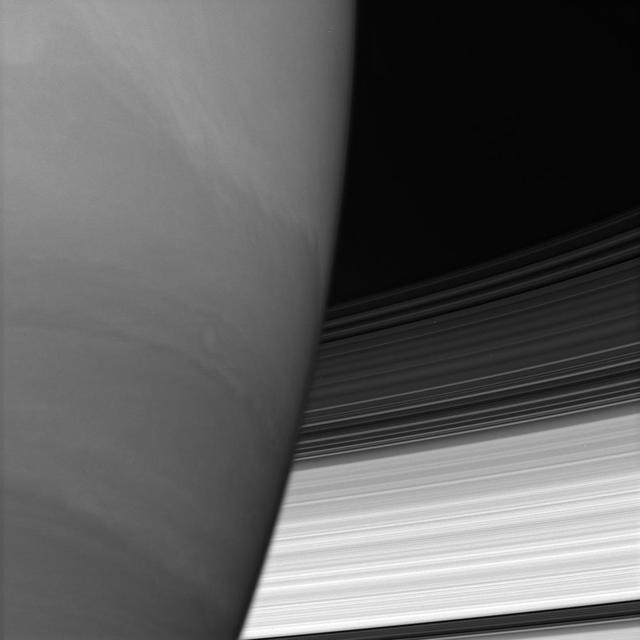

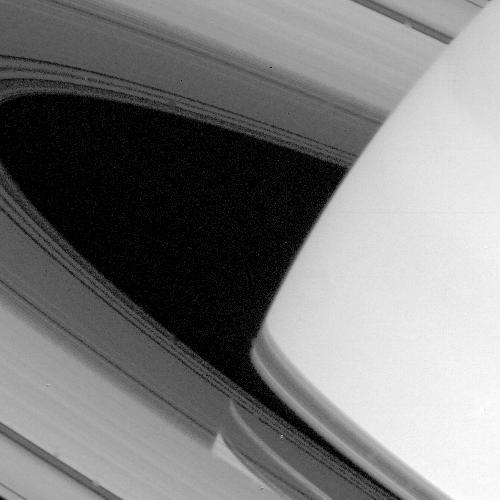

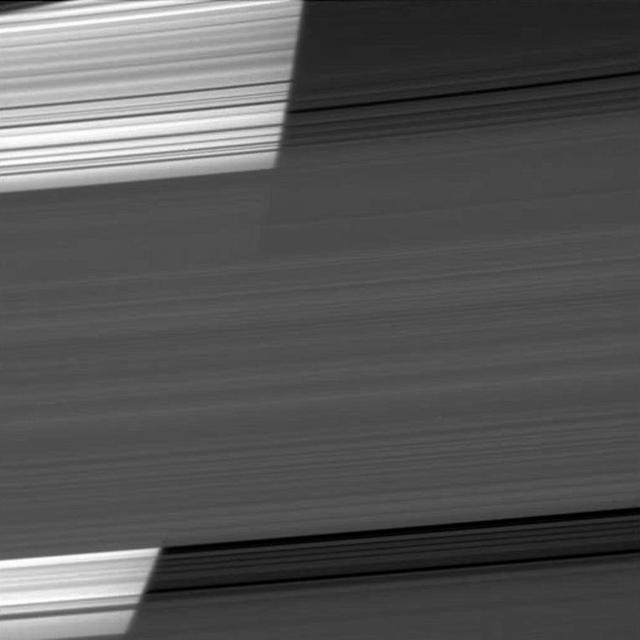

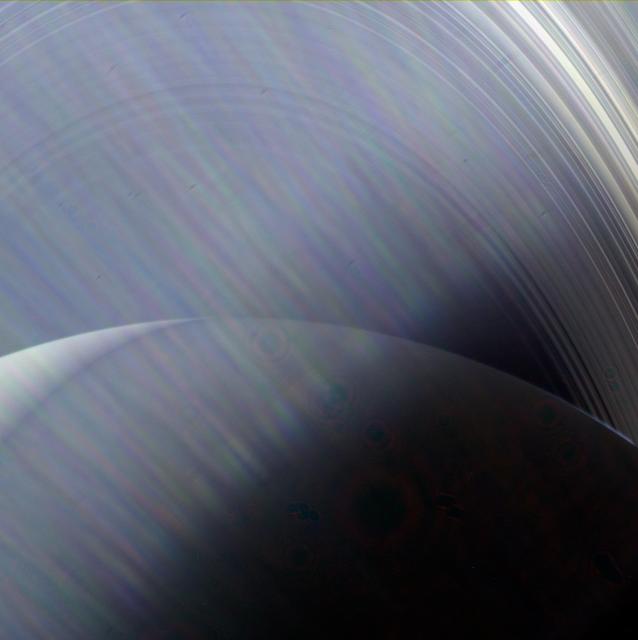

Sometimes at Saturn you can see things almost as if from every angle at once, the way a Cubist might imagine things. For example, in this image, we're seeing Saturn's A ring in the lower part of the image and the limb of Saturn in the upper. In addition, the rings cast their shadows onto the portion of the planet imaged here, creating alternating patterns of light and dark. This pattern is visible even through the A ring, which, unlike the core of the nearby B ring, is not completely opaque. The ring shadows on Saturn often appear to cross the surface at confusing angles in close-ups like this one. The visual combination of Saturn's oblateness, the varying opacity of its rings and the shadows cast by those rings, sometimes creates elaborate and complicated patterns from Cassini's perspective. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Dec. 5, 2014. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.2 million miles (2 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 7 miles (11 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18303

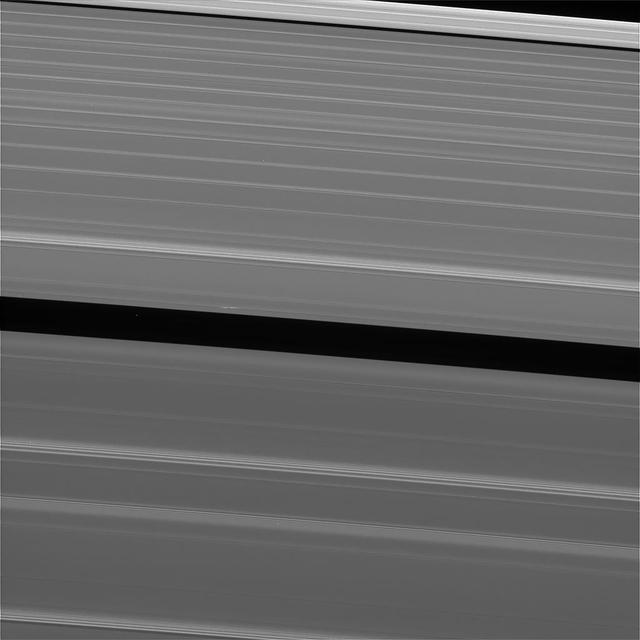

Saturn B and C rings disappear behind the immense planet. Where they meet the limb, the rings appear to bend slightly owing to upper-atmospheric refraction

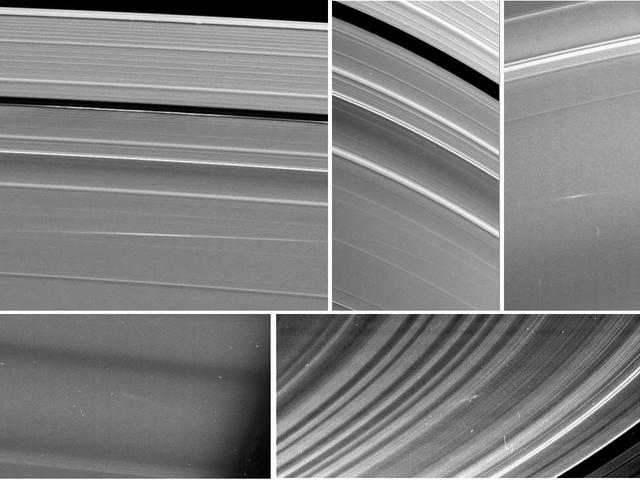

Five images of Saturn rings, taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft between 2009 and 2012, show clouds of material ejected from impacts of small objects into the rings.

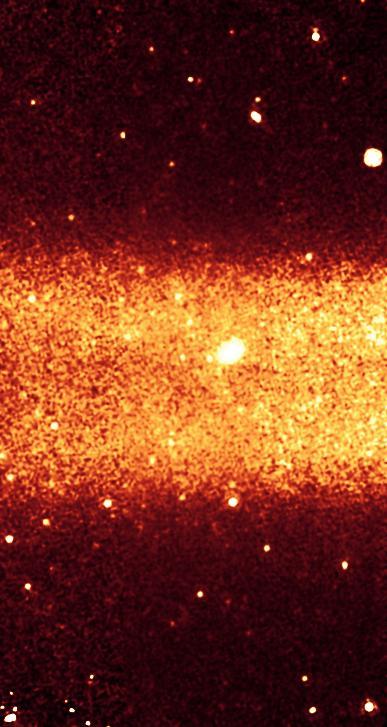

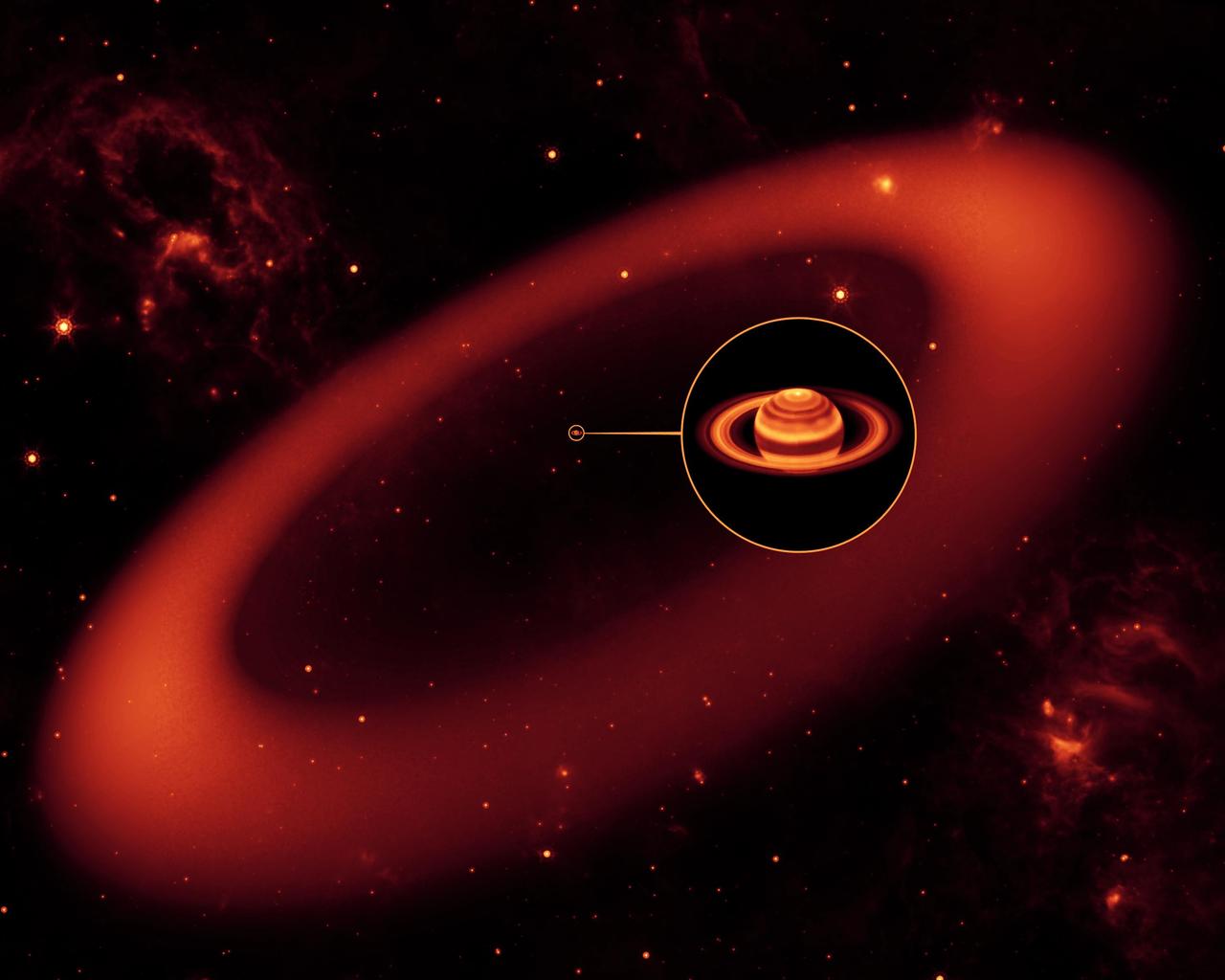

This picture highlights a slice of Saturn largest ring. The ring red band was discovered by NASA Spitzer Space Telescope, which detected infrared light, or heat, from the dusty ring material.

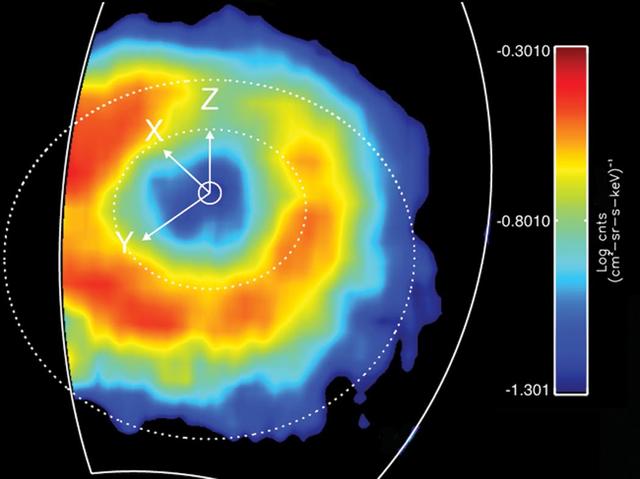

Like Earth, Saturn has an invisible ring of energetic ions trapped in its magnetic field. This feature is known as a "ring current." This ring current has been imaged with a special camera on Cassini sensitive to energetic neutral atoms. This is a false color map of the intensity of the energetic neutral atoms emitted from the ring current through a processed called charged exchange. In this process a trapped energetic ion steals and electron from cold gas atoms and becomes neutral and escapes the magnetic field. The Cassini Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument's ion and neutral camera records the intensity of the escaping particles, which provides a map of the ring current. In this image, the colors represent the intensity of the neutral emission, which is a reflection of the trapped ions. This "ring" is much farther from Saturn (roughly five times farther) than Saturn's famous icy rings. Red in the image represents the higher intensity of the particles, while blue is less intense. Saturn's ring current had not been mapped before on a global scale, only "snippets" or areas were mapped previously but not in this detail. This instrument allows scientists to produce movies (see PIA10083) that show how this ring changes over time. These movies reveal a dynamic system, which is usually not as uniform as depicted in this image. The ring current is doughnut shaped but in some instances it appears as if someone took a bite out of it. This image was obtained on March 19, 2007, at a latitude of about 54.5 degrees and radial distance 1.5 million kilometres (920,000 miles). Saturn is at the center, and the dotted circles represent the orbits of the moon's Rhea and Titan. The Z axis points parallel to Saturn's spin axis, the X axis points roughly sunward in the sun-spin axis plane, and the Y axis completes the system, pointing roughly toward dusk. The ion and neutral camera's field of view is marked by the white line and accounts for the cut-off of the image on the left. The image is an average of the activity over a (roughly) 3-hour period. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA10094

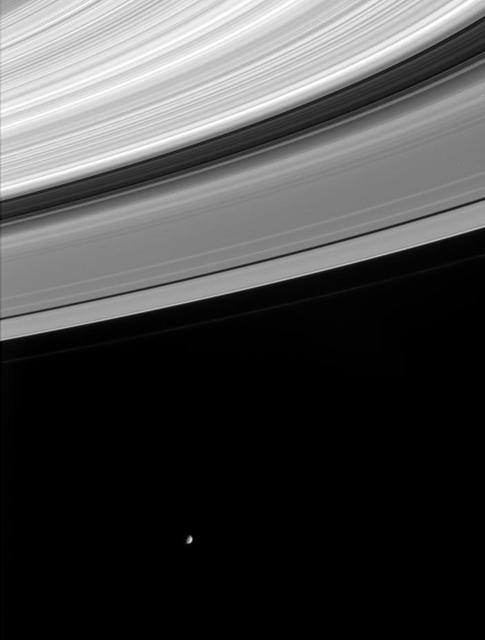

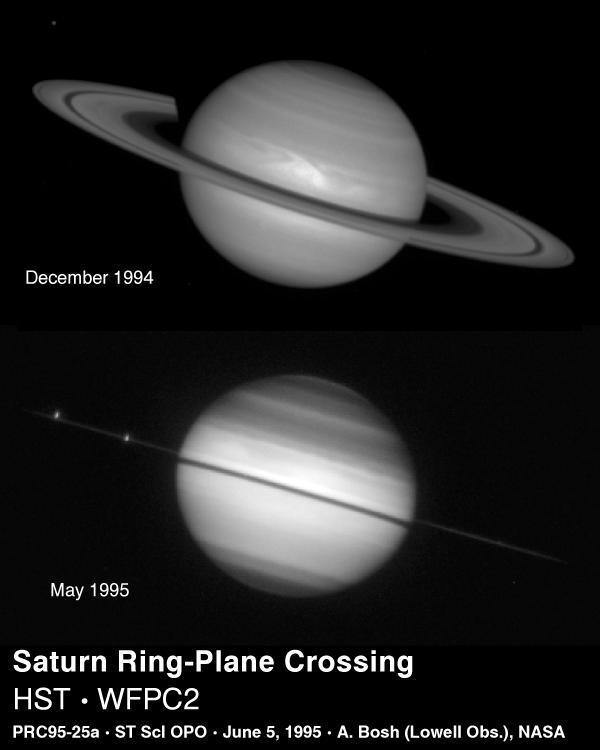

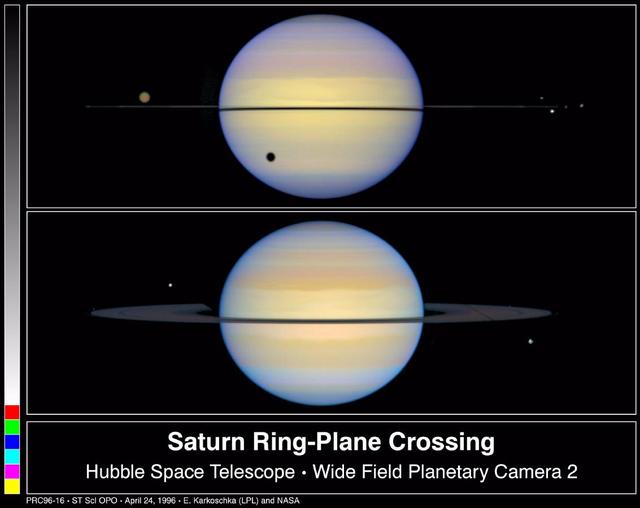

Hubble Views Saturn Ring-Plane Crossing

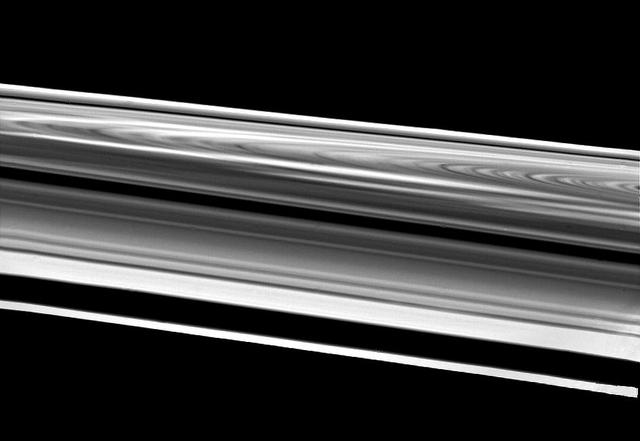

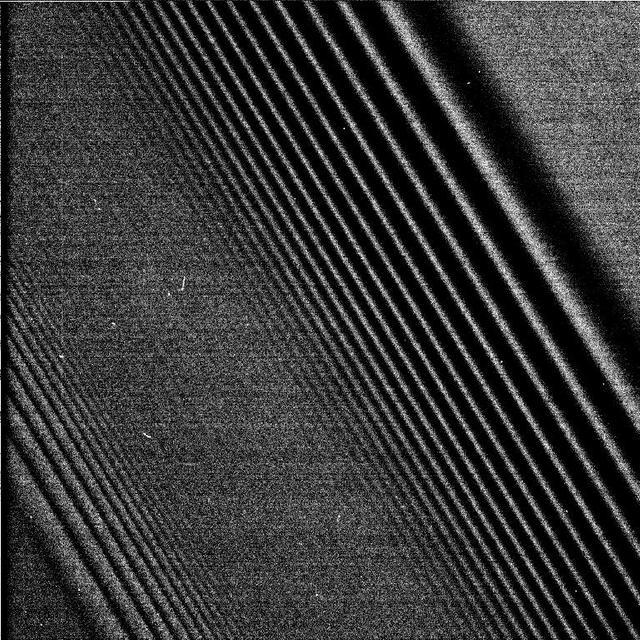

Two Waves in One Spectacular Image of Saturn Rings

Hubble again views Saturn Rings Edge-on

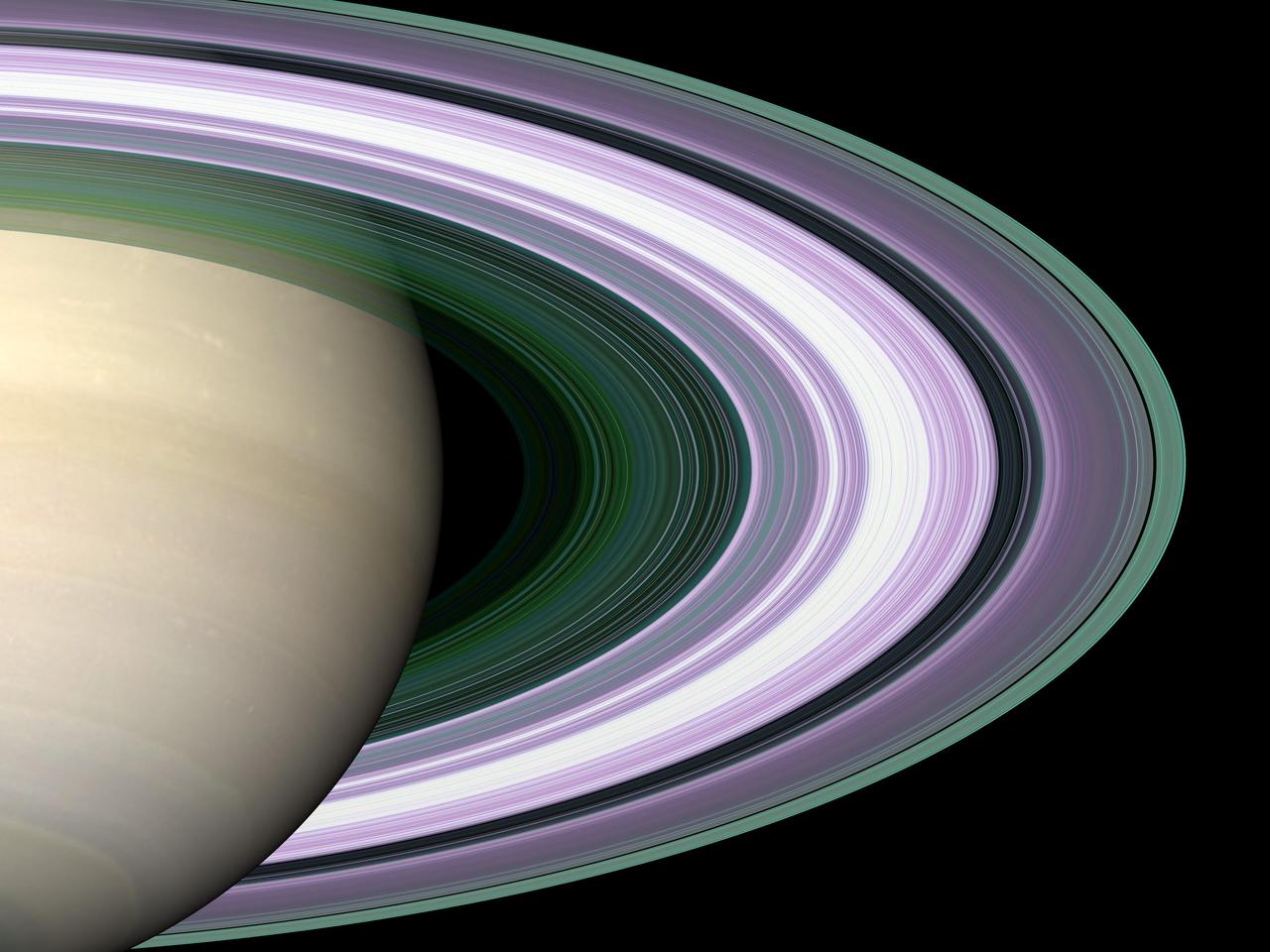

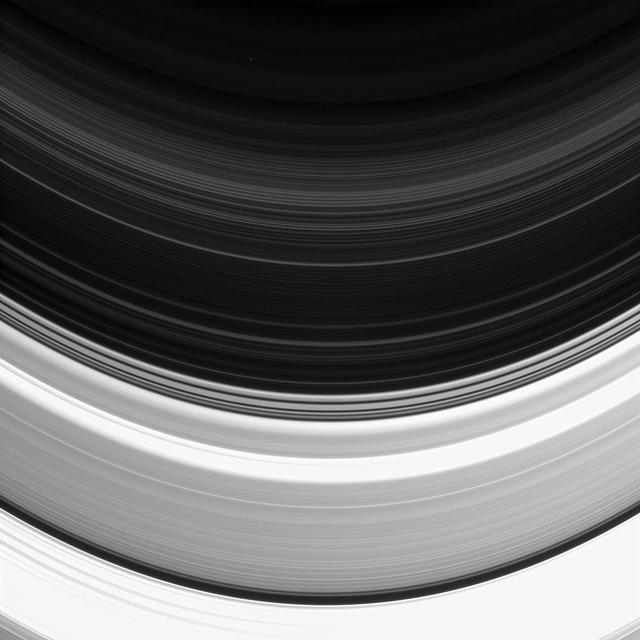

Saturn C and B Rings From the Inside Out

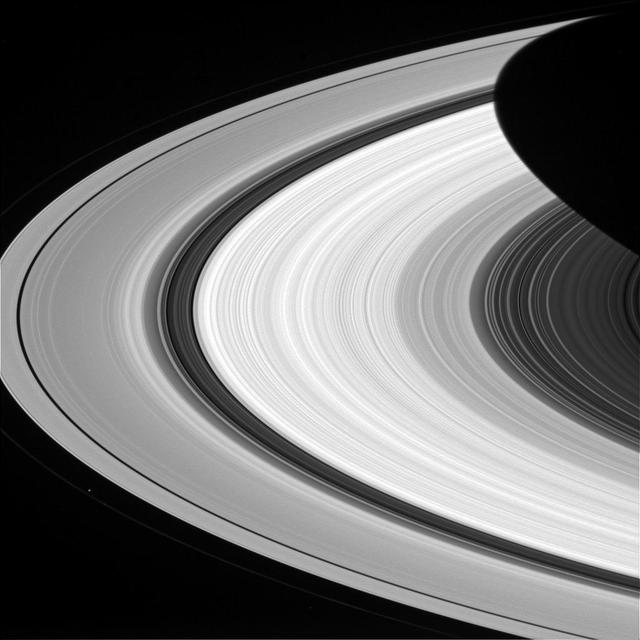

Although solid-looking in many images, Saturn's rings are actually translucent. In this picture, we can glimpse the shadow of the rings on the planet through (and below) the A and C rings themselves, towards the lower right hand corner. For centuries people have studied Saturn's rings, but questions about the structure and composition of the rings lingered. It was only in 1857 when the physicist James Clerk Maxwell demonstrated that the rings must be composed of many small particles and not solid rings around the planet, and not until the 1970s that spectroscopic evidence definitively showed that the rings are composed mostly of water ice. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 17 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Aug. 12, 2014 in near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.4 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 24 degrees. Image scale is 85 miles (136 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18295

Not all of Saturn's rings are created equal: here the C and D rings appear side-by-side, but the C ring, which occupies the bottom half of this image, clearly outshines its neighbor. The D ring appears fainter than the C ring because it is comprised of less material. However, even rings as thin as the D ring can pose hazards to spacecraft. Given the high speeds at which Cassini travels, impacts with particles just fractions of a millimeter in size have the potential to damage key spacecraft components and instruments. Nonetheless, near the end of Cassini's mission, navigators plan to thread the spacecraft's orbit through the narrow region between the D ring and the top of Saturn's atmosphere. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 12 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 11, 2015. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 372,000 miles (599,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 133 degrees. Image scale is 2.2 miles (3.6 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18313

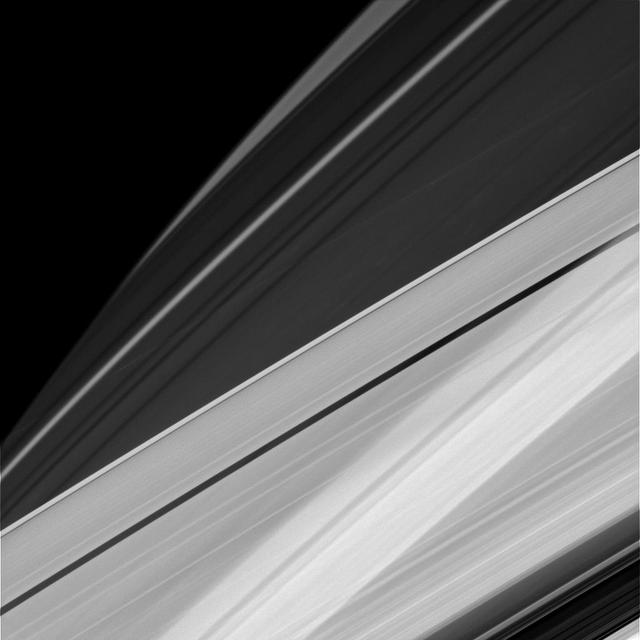

Many of the features seen in Saturn's rings are shaped by the planet's moons. This view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft shows two different effects of moons that cause waves in the A ring and kinks in a faint ringlet. The view captures the outer edge of the 200-mile-wide (320-kilometer-wide) Encke Gap, in the outer portion of Saturn's A ring. This is the same region features the large propeller called Earhart. Also visible here is one of several kinked and clumpy ringlets found within the gap. Kinks and clumps in the Encke ringlet move about, and even appear and disappear, in part due to the gravitational effects of Pan -- which orbits in the gap and whose gravitational influence holds it open. The A ring, which takes up most of the image on the left side, displays wave features caused by Pan, as well as the moons Pandora and Prometheus, which orbit a bit farther from Saturn on both sides of the planet's F ring. This view was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on March 22, 2017, and looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 22 degrees above the ring plane. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 63,000 miles (101,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a phase angle (the angle between the sun, the rings and the spacecraft) of 59 degrees. Image scale is 1,979 feet (603 meters) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21333

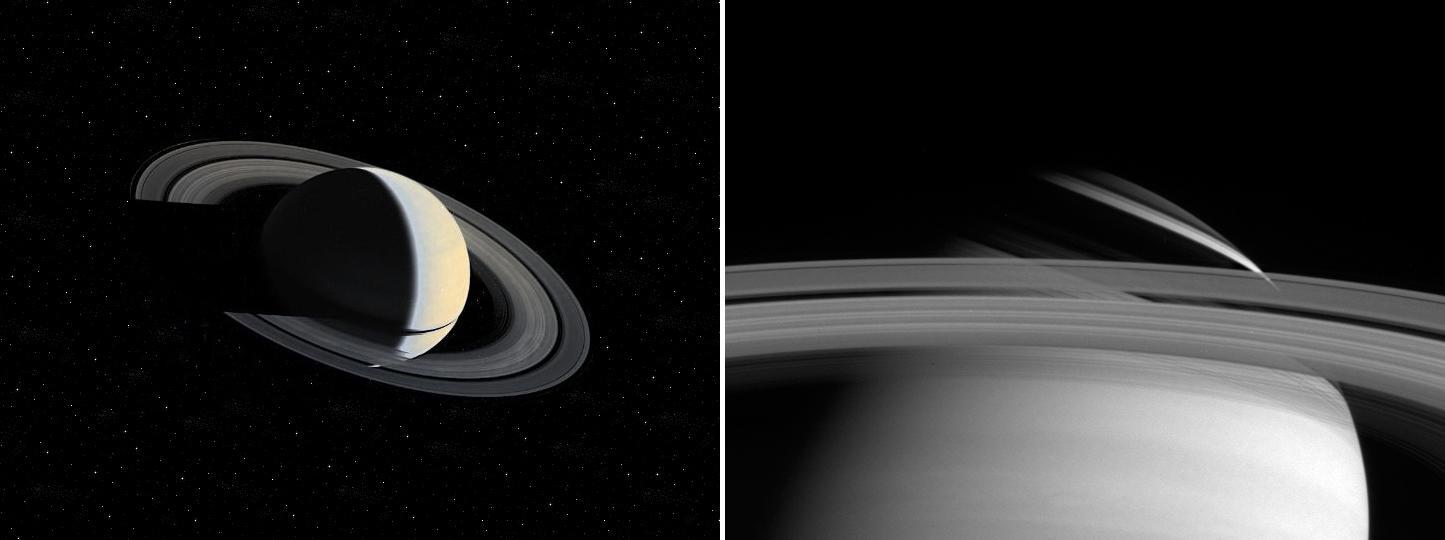

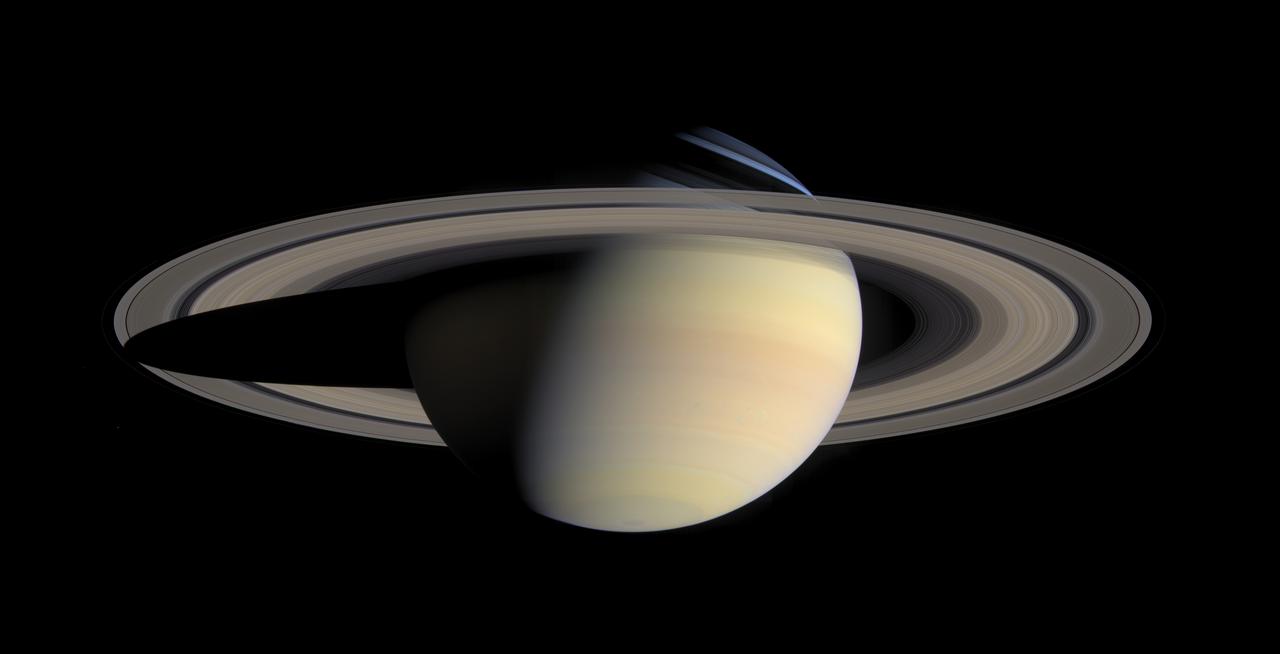

While cruising around Saturn in early October 2004, Cassini captured a series of images that have been composed into the largest, most detailed, global natural color view of Saturn and its rings ever made. This grand mosaic consists of 126 images acquired in a tile-like fashion, covering one end of Saturn's rings to the other and the entire planet in between. The images were taken over the course of two hours on Oct. 6, 2004, while Cassini was approximately 6.3 million kilometers (3.9 million miles) from Saturn. Since the view seen by Cassini during this time changed very little, no re-projection or alteration of any of the images was necessary. Three images (red, green and blue) were taken of each of 42 locations, or "footprints," across the planet. The full color footprints were put together to produce a mosaic that is 8,888 pixels across and 4,544 pixels tall. The smallest features seen here are 38 kilometers (24 miles) across. Many of Saturn's splendid features noted previously in single frames taken by Cassini are visible in this one detailed, all-encompassing view: subtle color variations across the rings, the thread-like F ring, ring shadows cast against the blue northern hemisphere, the planet's shadow making its way across the rings to the left, and blue-grey storms in Saturn's southern hemisphere to the right. Tiny Mimas and even smaller Janus are both faintly visible at the lower left. The Sun-Saturn-Cassini, or phase, angle at the time was 72 degrees; hence, the partial illumination of Saturn in this portrait. Later in the mission, when the spacecraft's trajectory takes it far from Saturn and also into the direction of the Sun, Cassini will be able to look back and view Saturn and its rings in a more fully-illuminated geometry. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA06193

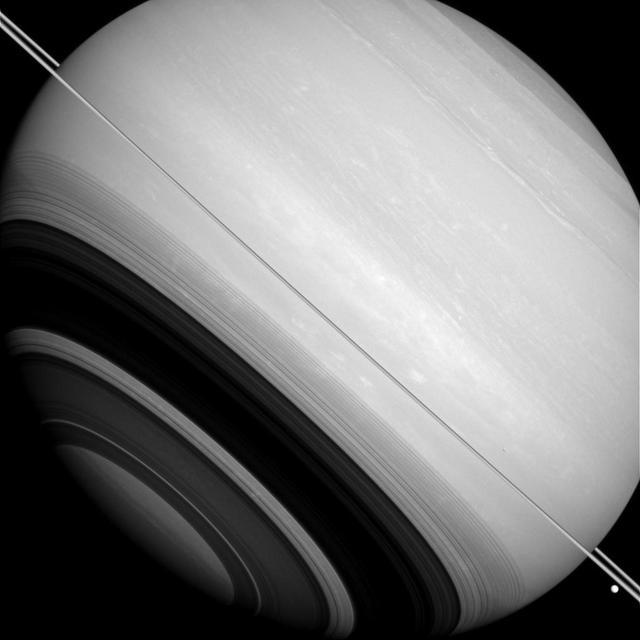

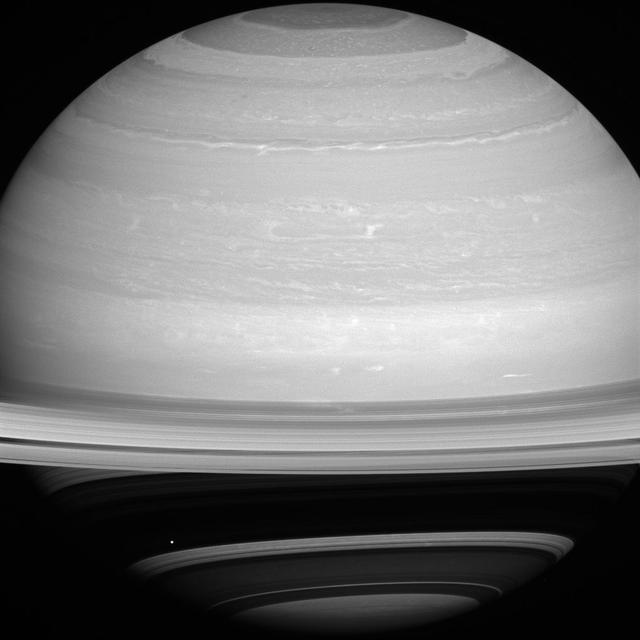

Saturn's shadow sweeps across the rings in a view captured on Nov. 5, 2006 by NASA's Cassini spacecraft. In the bottom half of the image, the countless icy particles that make up the rings bask in full daylight. In the top half, they move through Saturn's shadow. On the right side of the image, the planet's night side, dimly lit by reflected ringshine, can be seen through gaps in the darkened rings. This view is a mosaic of four visible light images taken with Cassini's narrow-angle camera at a distance of approximately 932,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Saturn. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17199

Saturn is circled by its rings (seen nearly edge-on in this image), as well as by the moons Tethys (the large bright body near the lower right hand corner of this image) and Mimas (seen as a slight crescent against Saturn's disk above the rings, at about 4 o'clock). The shadows of the rings, each ringlet delicately recorded across Saturn's face, also circle around Saturn's south pole. Although the rings and larger moons of Saturn mostly orbit very near the planet's equatorial plane, this image shows that they do not all lie precisely in the orbital plane. Part of the reason that Mimas (246 miles, or 396 kilometers across) and Tethys (660 miles, or 1062 kilometers across) appear above and below the ring plane because their orbits are slightly inclined (about 1 to 1.5 degrees) relative to the rings. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from slightly above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Aug. 14, 2014. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 1.1 million miles (1.7 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 23 degrees. Image scale is 63 miles (102 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18288

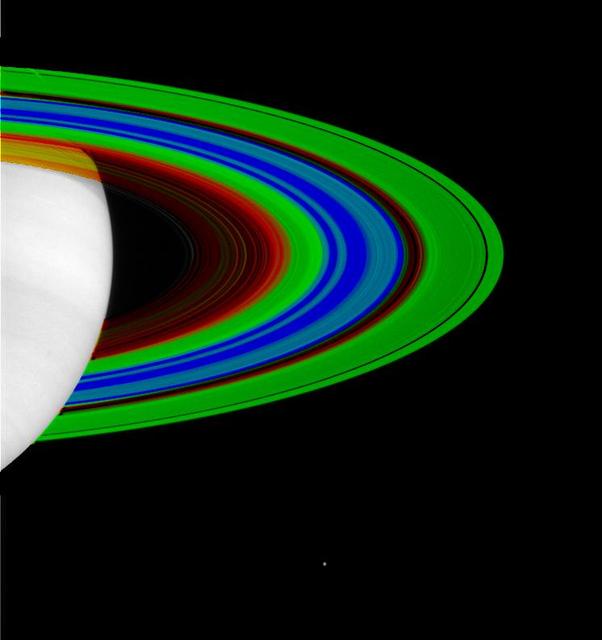

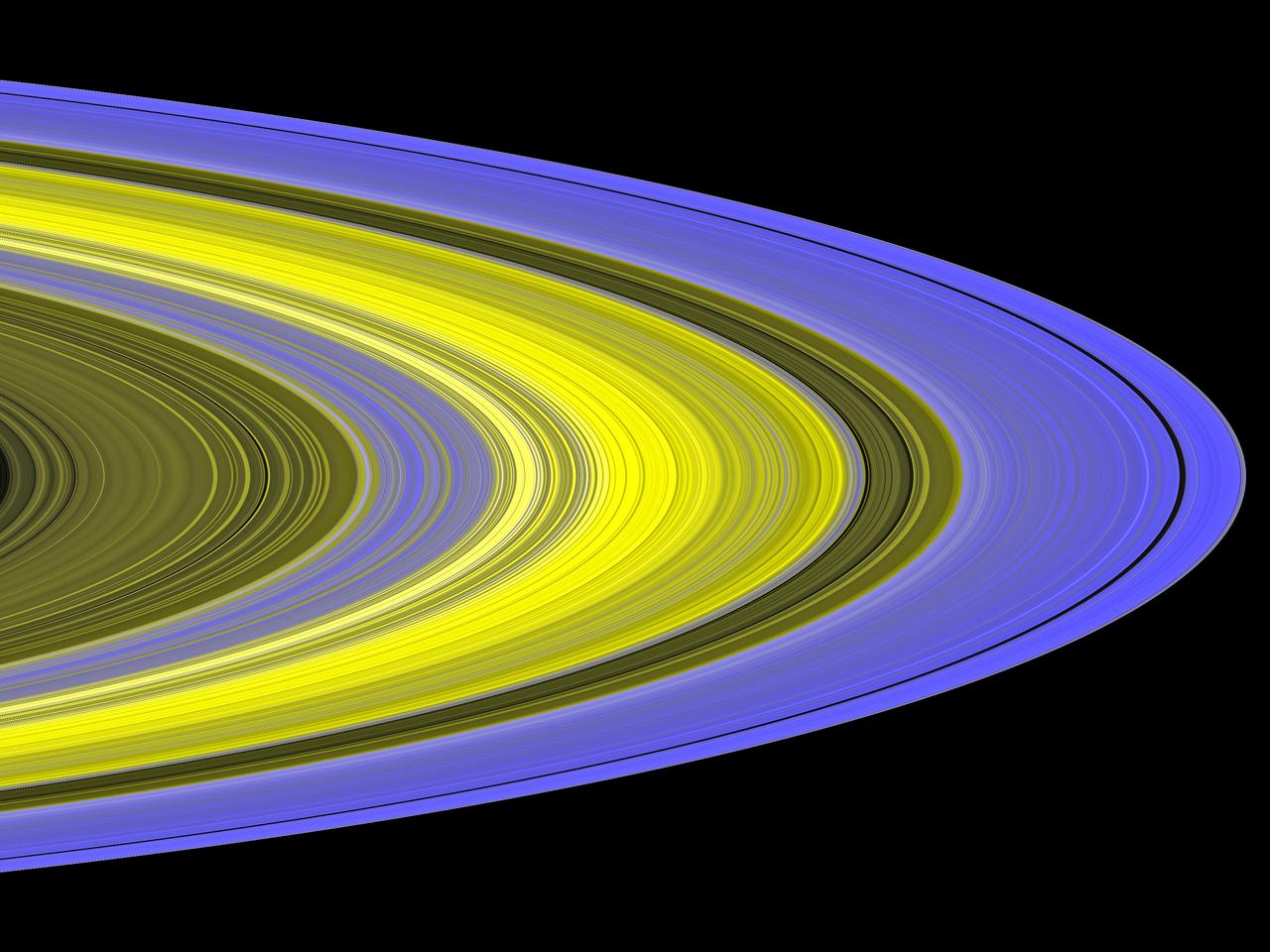

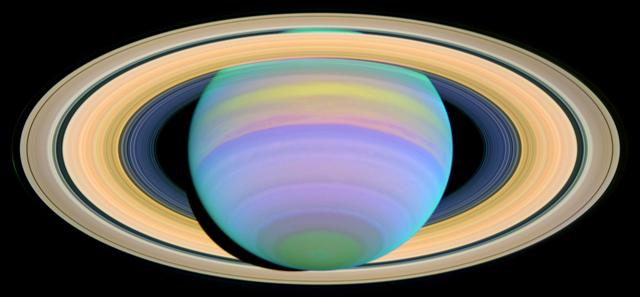

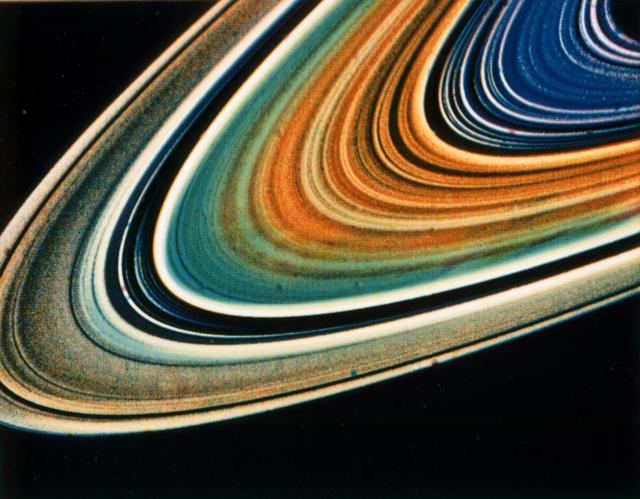

Saturn's Rings in Ultraviolet Light Credit: NASA and E. Karkoschka (University of Arizona) The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute conducts Hubble science operations. Goddard is responsible for HST project management, including mission and science operations, servicing missions, and all associated development activities. To learn more about the Hubble Space Telescope go here: <a href="http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hubble/main/index.html" rel="nofollow">www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hubble/main/index.html</a>

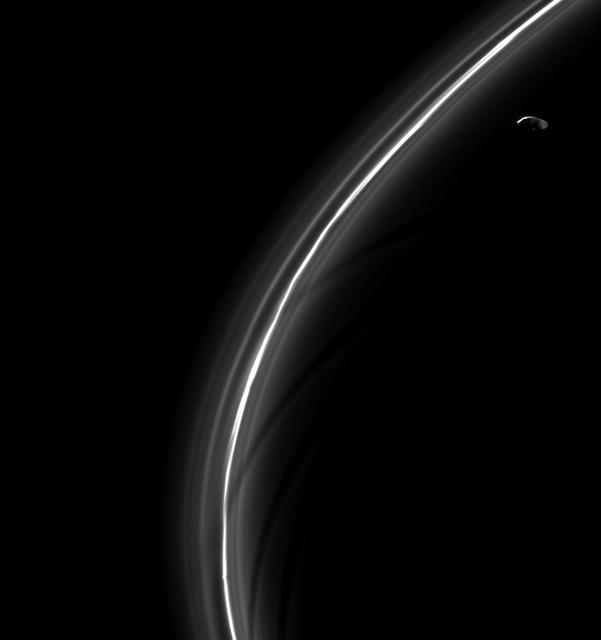

Saturn's rings, made of countless icy particles, form a translucent veil in this view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft. Saturn's tiny moon Pan, about 17 miles (28 kilometers) across, orbits within the Encke Gap in the A ring. Beyond, we can see the arc of Saturn itself, its cloud tops streaked with dark shadows cast by the rings. This image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Feb. 12, 2016, at a distance of approximately 746,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from Pan. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21901

This view of Saturn's A ring features a lone "propeller" -- one of many such features created by small moonlets embedded in the rings as they attempt, unsuccessfully, to open gaps in the ring material. The image was taken by NASA's Cassini spacecraft on Sept. 13, 2017. It is among the last images Cassini sent back to Earth. The view was taken in visible light using the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera at a distance of 420,000 miles (676,000 kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 2.3 miles (3.7 kilometers). https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21894

From afar, Saturn's rings look like a solid, homogenous disk of material. But upon closer examination from Cassini, we see that there are varied structures in the rings at almost every scale imaginable. Structures in the rings can be caused by many things, but often times Saturn's many moons are the culprits. The dark gaps near the left edge of the A ring (the broad, outermost ring here) are caused by the moons (Pan and Daphnis) embedded in the gaps, while the wider Cassini division (dark area between the B ring and A ring here) is created by a resonance with the medium-sized moon Mimas (which orbits well outside the rings). Prometheus is seen orbiting just outside the A ring in the lower left quadrant of this image; the F ring can be faintly seen to the left of Prometheus. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 15 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in red light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Jan. 8, 2015. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 566,000 miles (911,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 37 degrees. Image scale is 34 miles (54 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/pia18308

Saturn's moon Prometheus, seen here looking suspiciously blade-like, is captured near some of its sculpting in the F ring. Prometheus' (53 miles or 86 kilometers across) orbit sometimes takes it into the F ring. When it enters the ring, it leaves a gore where its gravitational influence clears out some of the smaller ring particles. Below Prometheus, the dark lanes interior to the F ring's bright core provide examples of previous ring-moon interactions. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 7 degrees below the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on March 15, 2015. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 286,000 miles (461,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 115 degrees. Image scale is 1.7 miles (2.8 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18324

This artist conception shows a nearly invisible ring around Saturn -- the largest of the giant planet many rings. It was discovered by NASA Spitzer Space Telescope.

Although the rings lack the many colors of the rainbow, they arc across the sky of Saturn. From equatorial locations on the planet, they'd appear very thin since they would be seen edge-on. Closer to the poles, the rings would appear much wider; in some locations (for parts of the Saturn's year), they would even block the sun for part of each day. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on April 10, 2017. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 680,000 miles (1.1 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 128 degrees. Image scale is 43 miles (69 kilometers) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21339

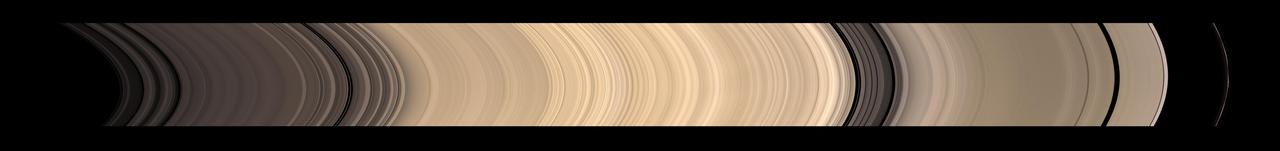

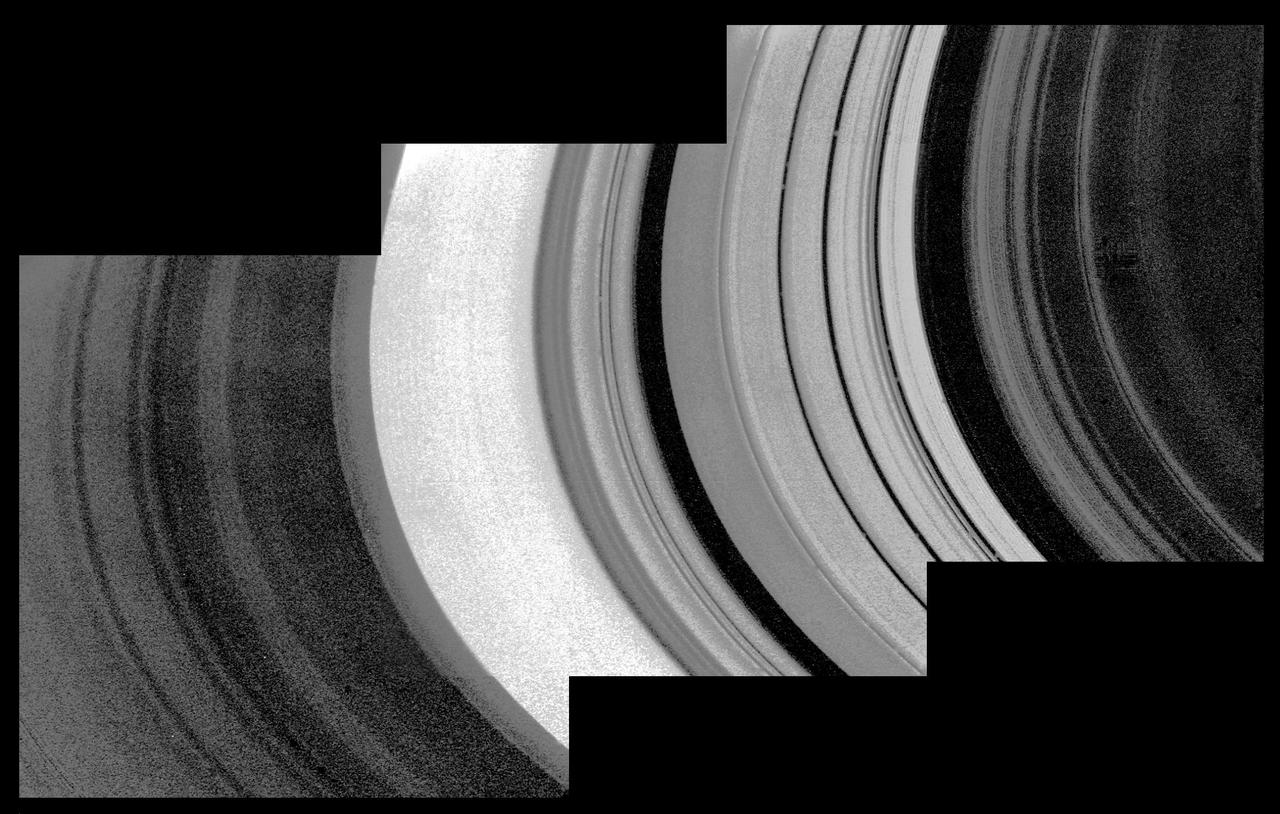

This mosaic of Saturn rings was acquired by NASA Cassini visual and infrared mapping spectrometer instrument on Sept. 15, 2006, while the spacecraft was in the shadow of the planet looking back towards the rings

Cassini obtained this panoramic view of Saturn's rings on Sept. 9, 2017, just minutes after it passed through the ring plane. The view looks upward at the southern face of the rings from a vantage point above Saturn's southern hemisphere. The entirety of the main rings can be seen here, but due to the low viewing angle, the rings appear extremely foreshortened. The C ring, with its sharp, bright plateaus (see PIA20529), appears at left; the B ring is the darkened region stretching from bottom center toward upper right; the A ring is seen at far right. This view shows the rings' unilluminated face, where sunlight filters through from the other side. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21898

Both the limb of Saturn and the shadow of its ring system are seen through the transparent C-ring in this striking picture taken by NASA Voyager 1 on Nov. 9, 1980. Gaps and regions of high transparency are seen throughout the C-ring, especially in the a

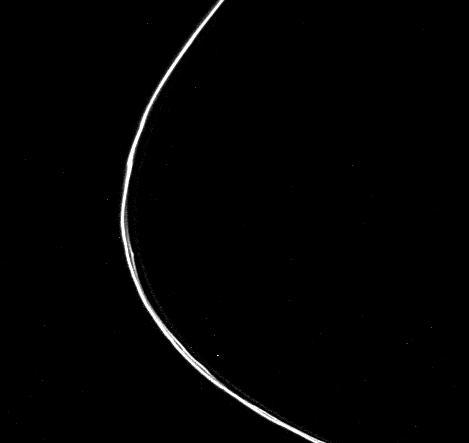

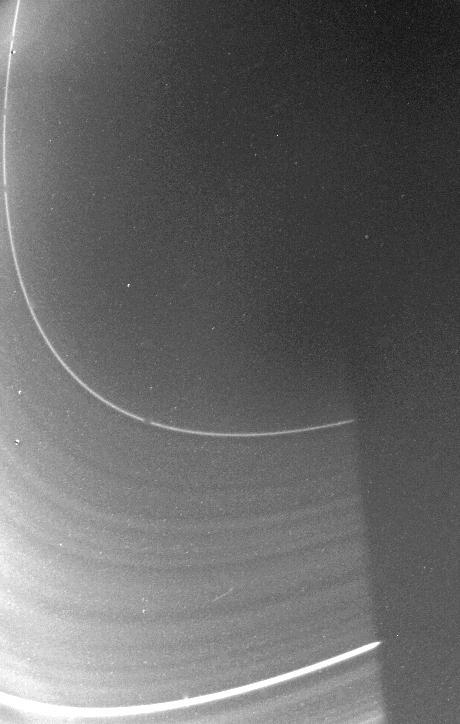

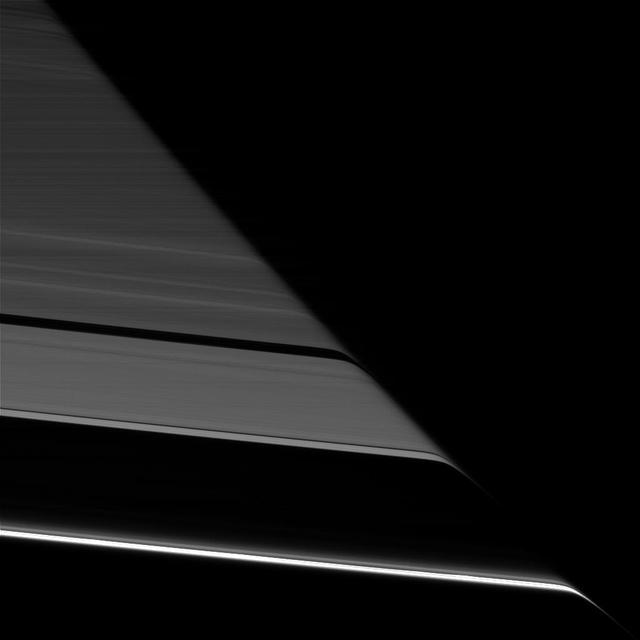

Saturn's rings appear to bend as they pass behind the planet's darkened limb due to refraction by Saturn's upper atmosphere. The effect is the same as that seen in an earlier Cassini view (see PIA20491), except this view looks toward the unlit face of the rings, while the earlier image viewed the rings' sunlit side. The difference in illumination brings out some noticeable differences. The A ring is much darker here, on the rings' unlit face, since its larger particles primarily reflect light back toward the sun (and away from Cassini's cameras in this view). The narrow F ring (at bottom), which was faint in the earlier image, appears brighter than all of the other rings here, thanks to the microscopic dust that is prevalent within that ring. Small dust tends to scatter light forward (meaning close to its original direction of travel), making it appear bright when backlit. (A similar effect has plagued many a driver with a dusty windshield when driving toward the sun.) This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 19 degrees below the ring plane. The image was taken in red light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on July 24, 2016. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 527,000 miles (848,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 169 degrees. Image scale is 3 miles (5 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20497

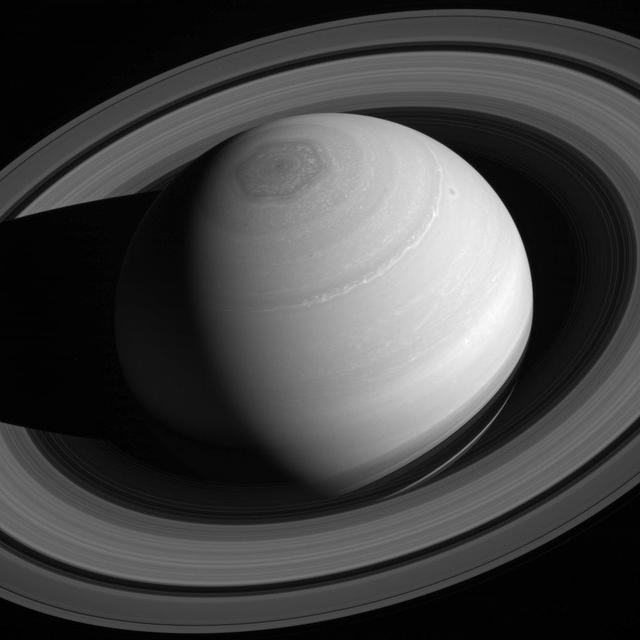

Saturn reigns supreme, encircled by its retinue of rings. Although all four giant planets have ring systems, Saturn's is by far the most massive and impressive. Scientists are trying to understand why by studying how the rings have formed and how they have evolved over time. Also seen in this image is Saturn's famous north polar vortex and hexagon. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 37 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on May 4, 2014 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 2 million miles (3 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 110 miles (180 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18278

This illustration shows a close-up of Saturn's rings. These rings are thought to have formed from material that was unable to form into a Moon because of tidal forces from Saturn, or from a Moon that was broken up by Saturn's tidal forces.

As if trying to get our attention, Mimas is positioned against the shadow of Saturn's rings, bright on dark. As we near summer in Saturn's northern hemisphere, the rings cast ever larger shadows on the planet. With a reflectivity of about 96 percent, Mimas (246 miles, or 396 kilometers across) appears bright against the less-reflective Saturn. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 10 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on July 13, 2014 using a spectral filter which preferentially admits wavelengths of near-infrared light centered at 752 nanometers. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.1 million miles (1.8 million kilometers) from Saturn and approximately 1 million miles (1.6 million kilometers) from Mimas. Image scale is 67 miles (108 kilometers) per pixel at Saturn and 60 miles (97 kilometers) per pixel at Mimas. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18282

The limb of Saturn appears bright as NASA Cassini spacecraft peers through several of the planet rings. The curvature of the planet can be seen on the bright left half of the image.

Saturn's main rings, seen here on their "lit" face, appear much darker than normal. That's because they tend to scatter light back toward its source -- in this case, the Sun. Usually, when taking images of the rings in geometries like this, exposures times are increased to make the rings more visible. Here, the requirement to not over-expose Saturn's lit crescent reveals just how dark the rings actually become. Scientists are interested in images in this sunward-facing ("high phase") geometry because the way that the rings scatter sunlight can tell us much about the ring particles' physical make-up. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 6 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Jan. 12, 2014. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.4 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 152 degrees. Image scale is 86 miles (138 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18294

Saturn's graceful lanes of orbiting ice -- its iconic rings -- wind their way around the planet to pass beyond the horizon in this view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft. And diminutive Pandora, scarcely larger than a pixel here, can be seen orbiting just beyond the F ring in this image. Also in this image is the gap between Saturn's cloud tops and its innermost D ring through which Cassini would pass 22 times before ending its mission in spectacular fashion in Sept. 15, 2017. Scientists scoured images of this region, particularly those taken at the high phase (spacecraft-ring-Sun) angles, looking for material that might pose a hazard to the spacecraft. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 19 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in green light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Aug. 12, 2017. Pandora was brightened by a factor of 2 to increase its visibility. The view was obtained at a distance to Saturn of approximately 581,000 miles (935,000 kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 35 miles (56 kilometers) per pixel. The distance to Pandora was 691,000 miles (1.1 million kilometers) for a scale of 41 miles (66 kilometers) per pixel. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21352

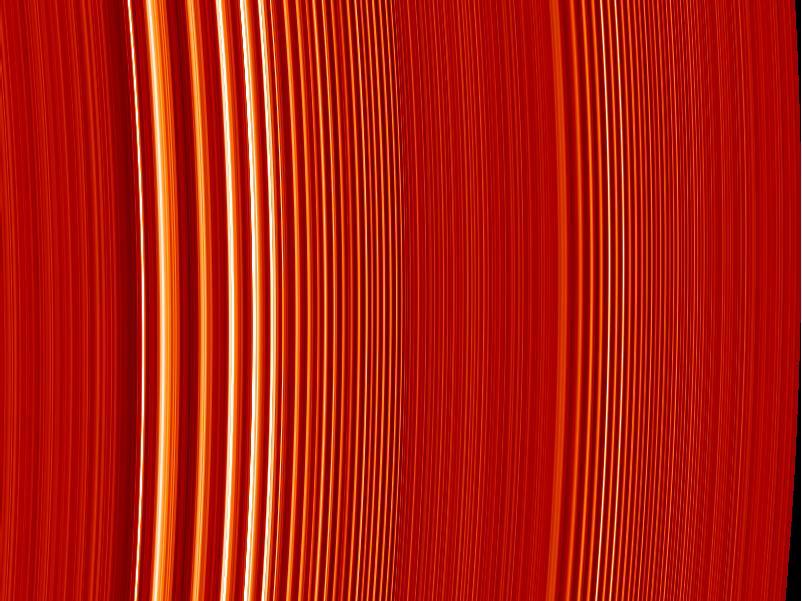

If your eyes could only see the color red, this is how Saturn's rings would look. Many Cassini color images, like this one, are taken in red light so scientists can study the often subtle color variations of Saturn's rings. These variations may reveal clues about the chemical composition and physical nature of the rings. For example, the longer a surface is exposed to the harsh environment in space, the redder it becomes. Putting together many clues derived from such images, scientists are coming to a deeper understanding of the rings without ever actually visiting a single ring particle. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 11 degrees above the ringplane. The image was taken in red light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Dec. 6, 2014. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 870,000 miles (1.4 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 27 degrees. Image scale is 5 miles (8 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18301

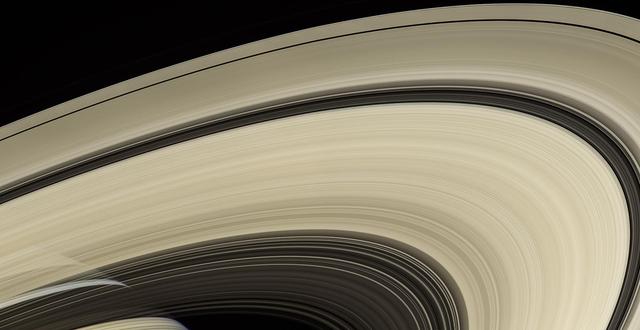

Cassini obtained the images in this mosaic on May 28, 2017, looking over the horizon just after its sixth pass through the gap between Saturn and its rings as part of the mission's Grand Finale. In this view, Saturn looms in the foreground on the left, adorned by ring shadows. To the right, the rings emerge from behind the planet's hazy limb, stretching outward from Cassini's perspective. The view is of the rings' unilluminated face, where sunlight filters through from the other side. The part of the planet seen here is in the southern hemisphere. . For another mosaic showing the view from between Saturn and the rings, see PIA21898. A previously released movie sequence showed Cassini's changing view, gazing out upon the rings as the spacecraft passed through the ring plane from north to south (see PIA21886). The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. A wider, uncropped version of the mosaic, which shows more of the rings, is also available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21897

In this image, NASA's Cassini sees Saturn and its rings through a haze of Sun glare on the camera lens. If you could travel to Saturn in person and look out the window of your spacecraft when the Sun was at a certain angle, you might see a view very similar to this one. Images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to show the scene in natural color. The images were taken with Cassini's wide-angle camera on June 23, 2013, at a distance of approximately 491,200 miles (790,500 kilometers) from Saturn. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17185

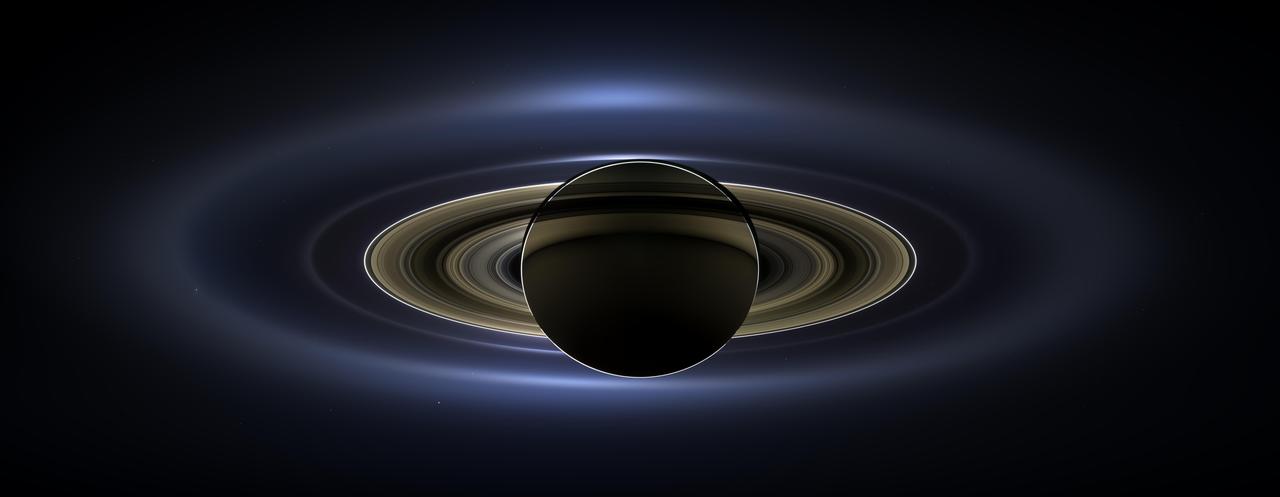

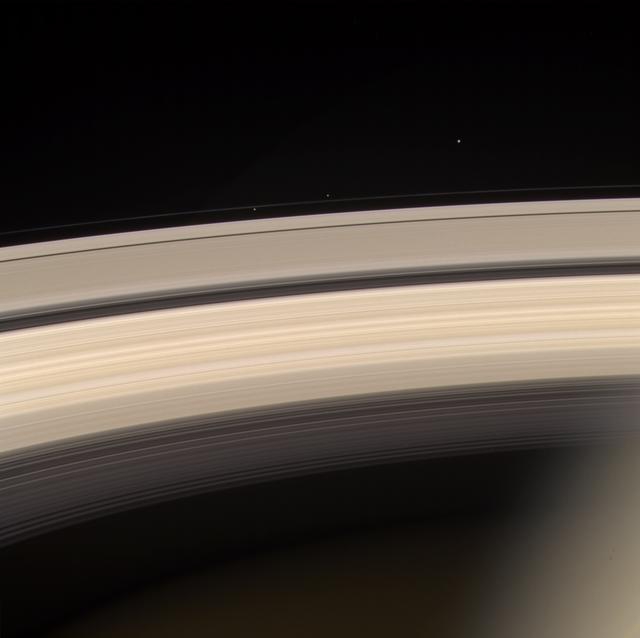

On July 19, 2013, in an event celebrated the world over, NASA's Cassini spacecraft slipped into Saturn's shadow and turned to image the planet, seven of its moons, its inner rings -- and, in the background, our home planet, Earth. With the sun's powerful and potentially damaging rays eclipsed by Saturn itself, Cassini's onboard cameras were able to take advantage of this unique viewing geometry. They acquired a panoramic mosaic of the Saturn system that allows scientists to see details in the rings and throughout the system as they are backlit by the sun. This mosaic is special as it marks the third time our home planet was imaged from the outer solar system; the second time it was imaged by Cassini from Saturn's orbit; and the first time ever that inhabitants of Earth were made aware in advance that their photo would be taken from such a great distance. With both Cassini's wide-angle and narrow-angle cameras aimed at Saturn, Cassini was able to capture 323 images in just over four hours. This final mosaic uses 141 of those wide-angle images. Images taken using the red, green and blue spectral filters of the wide-angle camera were combined and mosaicked together to create this natural-color view. A brightened version with contrast and color enhanced (Figure 1), a version with just the planets annotated (Figure 2), and an annotated version (Figure 3) are shown above. This image spans about 404,880 miles (651,591 kilometers) across. The outermost ring shown here is Saturn's E ring, the core of which is situated about 149,000 miles (240,000 kilometers) from Saturn. The geysers erupting from the south polar terrain of the moon Enceladus supply the fine icy particles that comprise the E ring; diffraction by sunlight gives the ring its blue color. Enceladus (313 miles, or 504 kilometers, across) and the extended plume formed by its jets are visible, embedded in the E ring on the left side of the mosaic. At the 12 o'clock position and a bit inward from the E ring lies the barely discernible ring created by the tiny, Cassini-discovered moon, Pallene (3 miles, or 4 kilometers, across). (For more on structures like Pallene's ring, see PIA08328). The next narrow and easily seen ring inward is the G ring. Interior to the G ring, near the 11 o'clock position, one can barely see the more diffuse ring created by the co-orbital moons, Janus (111 miles, or 179 kilometers, across) and Epimetheus (70 miles, or 113 kilometers, across). Farther inward, we see the very bright F ring closely encircling the main rings of Saturn. Following the outermost E ring counter-clockwise from Enceladus, the moon Tethys (662 miles, or 1,066 kilometers, across) appears as a large yellow orb just outside of the E ring. Tethys is positioned on the illuminated side of Saturn; its icy surface is shining brightly from yellow sunlight reflected by Saturn. Continuing to about the 2 o'clock position is a dark pixel just outside of the G ring; this dark pixel is Saturn's Death Star moon, Mimas (246 miles, or 396 kilometers, across). Mimas appears, upon close inspection, as a very thin crescent because Cassini is looking mostly at its non-illuminated face. The moons Prometheus, Pandora, Janus and Epimetheus are also visible in the mosaic near Saturn's bright narrow F ring. Prometheus (53 miles, or 86 kilometers, across) is visible as a faint black dot just inside the F ring and at the 9 o'clock position. On the opposite side of the rings, just outside the F ring, Pandora (50 miles, or 81 kilometers, across) can be seen as a bright white dot. Pandora and Prometheus are shepherd moons and gravitational interactions between the ring and the moons keep the F ring narrowly confined. At the 11 o'clock position in between the F ring and the G ring, Janus (111 miles, or 179 kilometers, across) appears as a faint black dot. Janus and Prometheus are dark for the same reason Mimas is mostly dark: we are looking at their non-illuminated sides in this mosaic. Midway between the F ring and the G ring, at about the 8 o'clock position, is a single bright pixel, Epimetheus. Looking more closely at Enceladus, Mimas and Tethys, especially in the brightened version of the mosaic, one can see these moons casting shadows through the E ring like a telephone pole might cast a shadow through a fog. In the non-brightened version of the mosaic, one can see bright clumps of ring material orbiting within the Encke gap near the outer edge of the main rings and immediately to the lower left of the globe of Saturn. Also, in the dark B ring within the main rings, at the 9 o'clock position, one can see the faint outlines of two spoke features, first sighted by NASA's Voyager spacecraft in the early 1980s and extensively studied by Cassini. Finally, in the lower right of the mosaic, in between the bright blue E ring and the faint but defined G ring, is the pale blue dot of our planet, Earth. Look closely and you can see the moon protruding from the Earth's lower right. (For a higher resolution view of the Earth and moon taken during this campaign, see PIA14949.) Earth's twin, Venus, appears as a bright white dot in the upper left quadrant of the mosaic, also between the G and E rings. Mars also appears as a faint red dot embedded in the outer edge of the E ring, above and to the left of Venus. For ease of visibility, Earth, Venus, Mars, Enceladus, Epimetheus and Pandora were all brightened by a factor of eight and a half relative to Saturn. Tethys was brightened by a factor of four. In total, 809 background stars are visible and were brightened by a factor ranging from six, for the brightest stars, to 16, for the faintest. The faint outer rings (from the G ring to the E ring) were also brightened relative to the already bright main rings by factors ranging from two to eight, with the lower-phase-angle (and therefore fainter) regions of these rings brightened the most. The brightened version of the mosaic was further brightened and contrast-enhanced all over to accommodate print applications and a wide range of computer-screen viewing conditions. Some ring features -- such as full rings traced out by tiny moons -- do not appear in this version of the mosaic because they require extreme computer enhancement, which would adversely affect the rest of the mosaic. This version was processed for balance and beauty. This view looks toward the unlit side of the rings from about 17 degrees below the ring plane. Cassini was approximately 746,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from Saturn when the images in this mosaic were taken. Image scale on Saturn is about 45 miles (72 kilometers) per pixel. This mosaic was made from pictures taken over a span of more than four hours while the planets, moons and stars were all moving relative to Cassini. Thus, due to spacecraft motion, these objects in the locations shown here were not in these specific places over the entire duration of the imaging campaign. Note also that Venus appears far from Earth, as does Mars, because they were on the opposite side of the sun from Earth. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17172

This image from NASA's Cassini spacecraft offers a unique perspective on Saturn's ring system. Cassini captured images from within the gap between the planet and its rings, looking outward as the spacecraft made one of its final dives through the gap as part of the mission's Grand Finale. Using its wide-angle camera, Cassini took the 21 images in the sequence over a span of about four minutes during its dive through the gap on Aug. 20, 2017. The images have an original size of 512 x 512 pixels; the smaller image size allowed for more images to be taken over the short span of time. The entirety of the main rings can be seen here, but due to the low viewing angle, the rings appear extremely foreshortened. The perspective shifts from the sunlit side of the rings to the unlit side, where sunlight filters through. On the sunlit side, the grayish C ring looks larger in the foreground because it is closer; beyond it is the bright B ring and slightly less-bright A ring, with the Cassini Division between them. The F ring is also fairly easy to make out. A movie is available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21886

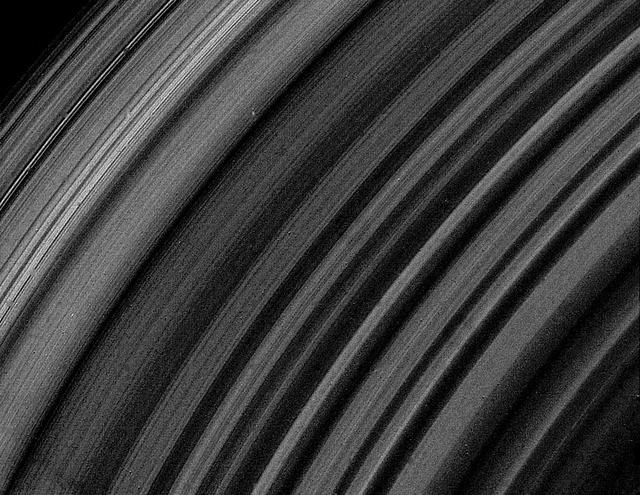

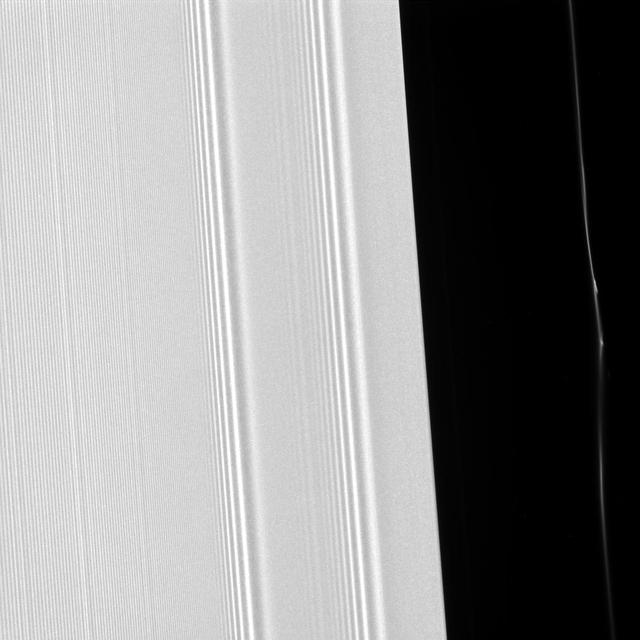

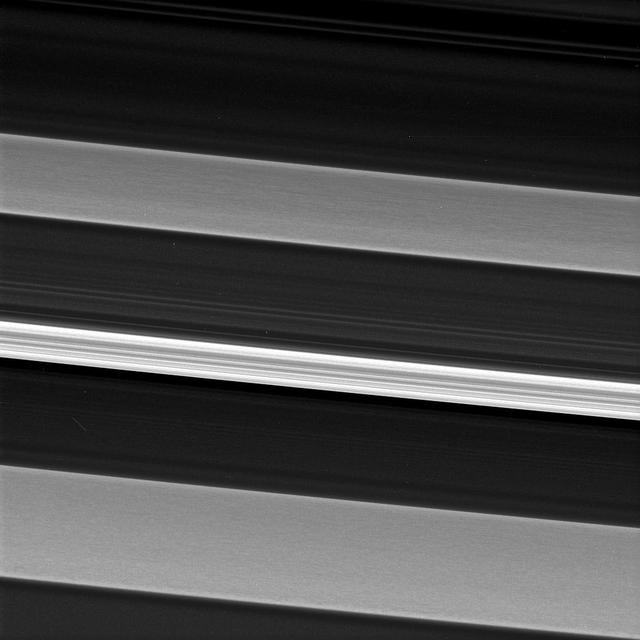

![Recent images of features in Saturn's C ring called "plateaus" have deepened the mystery surrounding them. It turns out that these bright bands have a streaky texture that is very different from the textures of the regions around them. The central feature in this image, called Plateau P5, is found approximately 52,700 miles (84,800 kilometers) from Saturn's center. It is situated amid some undulating structure that characterizes this region of the C ring. None of this structure is well understood. This image reveals that the plateau itself is shot through with elongated streaks. This provides information about ways in which the ring particles are interacting with each other, though scientists have not yet worked out what it all means. A more clumpy texture, similar to the "straw" seen previously in the A ring. Plateau regions are brighter than their surroundings, and have sharp edges. Recent evidence indicates that the plateaus do not actually contain more material than their surroundings, nor are they different in their chemical composition, which would mean that their greater brightness is likely due to smaller particle sizes. (If a given amount of mass is broken into smaller particles, it will spread out more [i.e., it will have more surface area].) These texture differences may give a clue about processes at the particle level that create the larger structures that Cassini has observed from greater distance throughout its mission at Saturn. These images were taken with the camera moving in sync with the orbits of individual ring particles. Therefore, any elongated structures are truly there in the rings, and are not an artifact of particles moving during the exposure (i.e., smear). This image was taken on the unilluminated side of the rings, with sunlight filtering through the rings as it would through a translucent bathroom window. Brighter regions in the image indicate more material scattering light toward the camera. This image was taken on May 29, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of about 39,800 miles (64,100 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,460 feet (445 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 137 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21619](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21619/PIA21619~small.jpg)

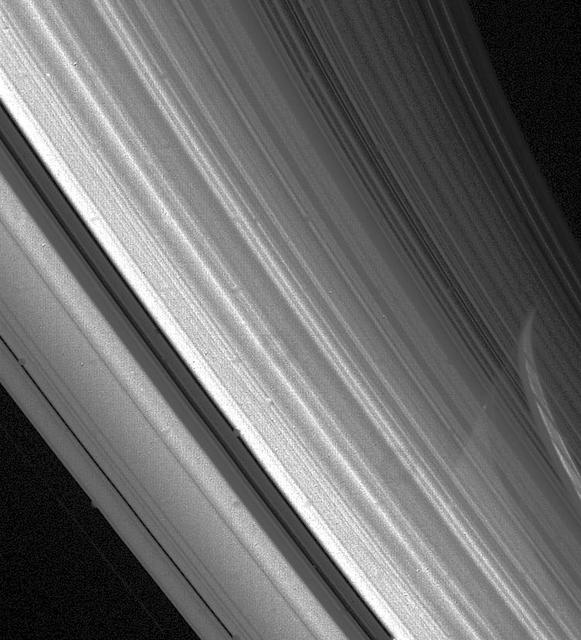

Recent images of features in Saturn's C ring called "plateaus" have deepened the mystery surrounding them. It turns out that these bright bands have a streaky texture that is very different from the textures of the regions around them. The central feature in this image, called Plateau P5, is found approximately 52,700 miles (84,800 kilometers) from Saturn's center. It is situated amid some undulating structure that characterizes this region of the C ring. None of this structure is well understood. This image reveals that the plateau itself is shot through with elongated streaks. This provides information about ways in which the ring particles are interacting with each other, though scientists have not yet worked out what it all means. A more clumpy texture, similar to the "straw" seen previously in the A ring. Plateau regions are brighter than their surroundings, and have sharp edges. Recent evidence indicates that the plateaus do not actually contain more material than their surroundings, nor are they different in their chemical composition, which would mean that their greater brightness is likely due to smaller particle sizes. (If a given amount of mass is broken into smaller particles, it will spread out more [i.e., it will have more surface area].) These texture differences may give a clue about processes at the particle level that create the larger structures that Cassini has observed from greater distance throughout its mission at Saturn. These images were taken with the camera moving in sync with the orbits of individual ring particles. Therefore, any elongated structures are truly there in the rings, and are not an artifact of particles moving during the exposure (i.e., smear). This image was taken on the unilluminated side of the rings, with sunlight filtering through the rings as it would through a translucent bathroom window. Brighter regions in the image indicate more material scattering light toward the camera. This image was taken on May 29, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of about 39,800 miles (64,100 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,460 feet (445 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 137 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21619

With this view, Cassini captured one of its last looks at Saturn and its main rings from a distance. The Saturn system has been Cassini's home for 13 years, but that journey is nearing its end. Cassini has been orbiting Saturn for nearly a half of a Saturnian year but that journey is nearing its end. This extended stay has permitted observations of the long-term variability of the planet, moons, rings, and magnetosphere, observations not possible from short, fly-by style missions. When the spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004, the planet's northern hemisphere, seen here at top, was in darkness, just beginning to emerge from winter. Now at journey's end, the entire north pole is bathed in the continuous sunlight of summer. Images taken on Oct. 28, 2016 with the wide angle camera using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this color view. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 25 degrees above the ringplane. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 870,000 miles (1.4 million kilometers) from Saturn. Image scale is 50 miles (80 kilometers) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21345

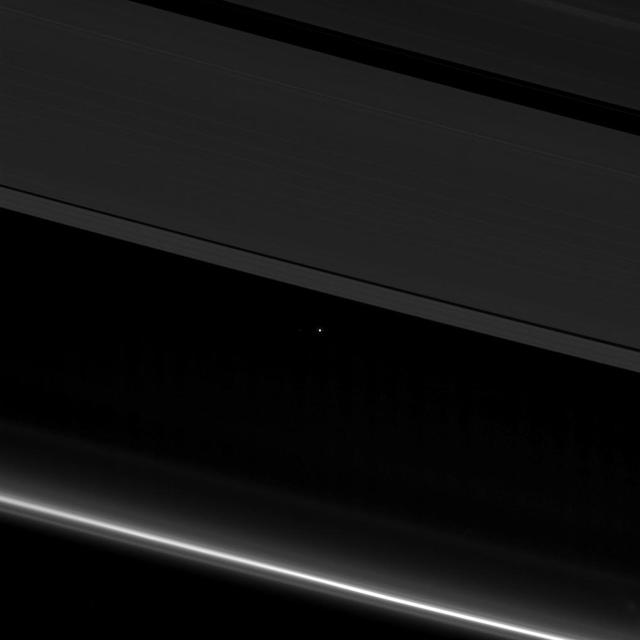

This view from NASA's Cassini spacecraft shows planet Earth as a point of light between the icy rings of Saturn. The spacecraft captured the view on April 12, 2017 at 10:41 p.m. PDT (1:41 a.m. EDT). Cassini was 870 million miles (1.4 billion kilometers) away from Earth when the image was taken. Although far too small to be visible in the image, the part of Earth facing toward Cassini at the time was the southern Atlantic Ocean. Earth's moon is also visible to the left of our planet in a cropped, zoomed-in version of the image (Figure 1). The rings visible here are the A ring (at top) with the Keeler and Encke gaps visible, and the F ring (at bottom). During this observation Cassini was looking toward the backlit rings, making a mosaic of multiple images, with the sun blocked by the disk of Saturn. Seen from Saturn, Earth and the other inner solar system planets are all close to the sun, and are easily captured in such images, although these opportunities have been somewhat rare during the mission. The F ring appears especially bright in this viewing geometry. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21445

Saturn and its rings are prominently shown in this color image, along with three of Saturn's smaller moons. From left to right, they are Prometheus, Pandora and Janus. Prometheus and Pandora are often called the "F ring shepherds" as they control and interact with Saturn's interesting F ring, seen between them. This image was taken on June 18, 2004, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow angle camera 8.2 million kilometers (5.1 million miles) from Saturn. It was created using the red, green, and blue filters. Contrast has been enhanced to aid visibility. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA06422

Saturn's C ring is home to a surprisingly rich array of structures and textures. Much of the structure seen in the outer portions of Saturn's rings is the result of gravitational perturbations on ring particles by moons of Saturn. Such interactions are called resonances. However, scientists are not clear as to the origin of the structures seen in this image which has captured an inner ring region sparsely populated with particles, making interactions between ring particles rare, and with few satellite resonances. In this image, a bright and narrow ringlet located toward the outer edge of the C ring is flanked by two broader features called plateaus, each about 100 miles (160 kilometers) wide. Plateaus are unique to the C ring. Cassini data indicates that the plateaus do not necessarily contain more ring material than the C ring at large, but the ring particles in the plateaus may be smaller, enhancing their brightness. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 53 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in green light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Aug. 14, 2017. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 117,000 miles (189,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 74 degrees. Image scale is 3,000 feet (1 kilometer) per pixel. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21356

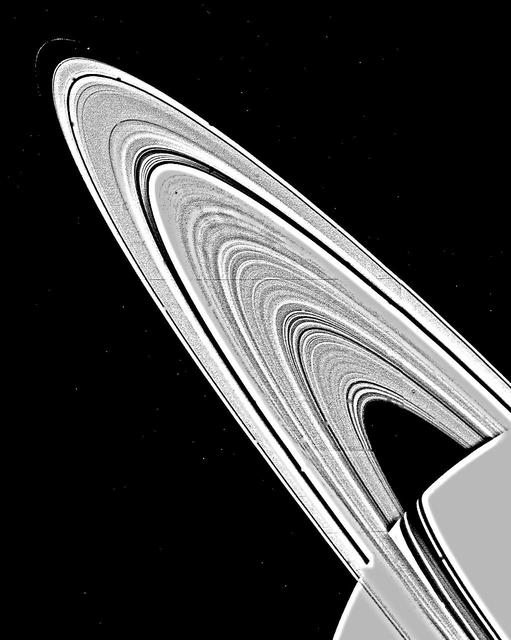

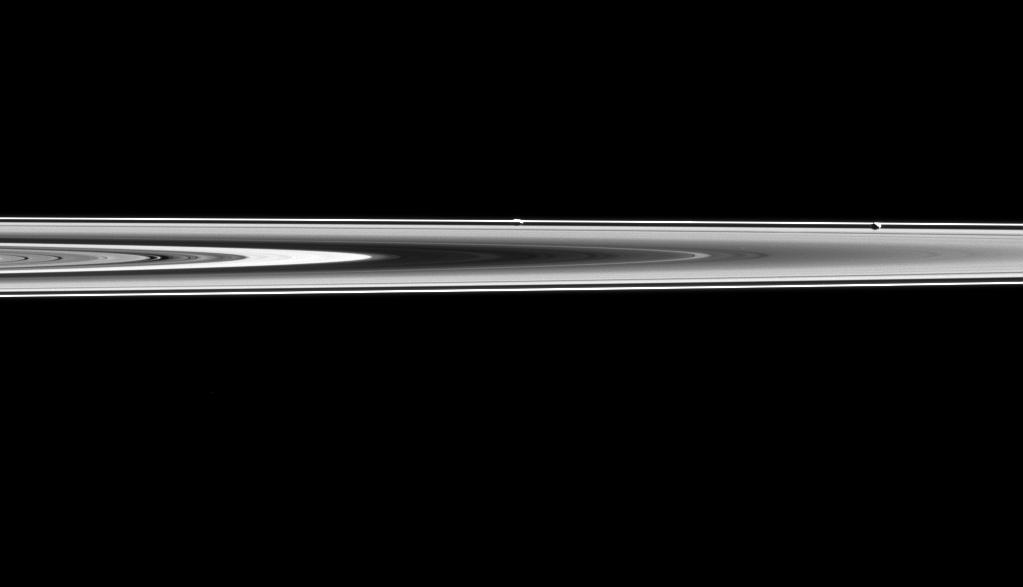

Saturn's rings are perhaps the most recognized feature of any world in our solar system. Cassini spent more than a decade examining them more closely than any spacecraft before it. The rings are made mostly of particles of water ice that range in size from smaller than a grain of sand to as large as mountains. The ring system extends up to 175,000 miles (282,000 kilometers) from the planet, but for all their immense width, the rings are razor-thin, about 30 feet (10 meters) thick in most places. From the right angle you can see straight through the rings, as in this natural-color view that looks from south to north. Cassini obtained the images that comprise this mosaic on April 25, 2007, at a distance of approximately 450,000 miles (725,000 kilometers) from Saturn. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA14943

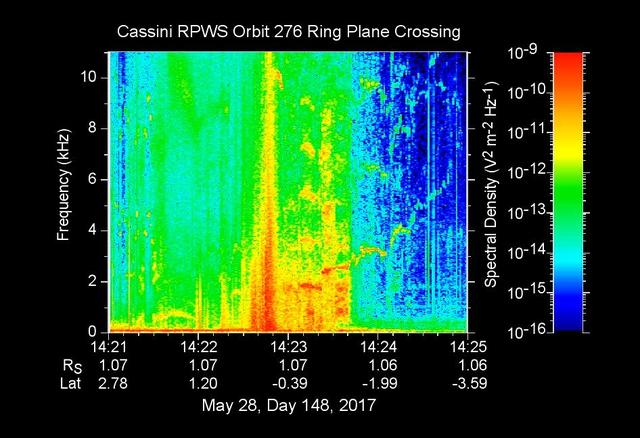

The sounds and colorful spectrogram in this still image and video represent data collected by the Radio and Plasma Wave Science, or RPWS, instrument on NASA's Cassini spacecraft, as it crossed through Saturn's D ring on May 28, 2017. This was the first of four passes through the inner edge of the D ring during the 22 orbits of Cassini's final mission phase, called the Grand Finale. During this ring plane crossing, the spacecraft was oriented so that its large high-gain antenna was used as a shield to protect more sensitive components from possible ring-particle impacts. The three 33-foot-long (10-meter-long) RPWS antennas were exposed to the particle environment during the pass. As tiny, dust-sized particles strike Cassini and the RPWS antennas, the particles are vaporized into tiny clouds of plasma, or electrically excited gas. These tiny explosions make a small electrical signal (a voltage impulse) that RPWS can detect. Researchers on the RPWS team convert the data into visible and audio formats, some like those seen here, for analysis. Ring particle hits sound like pops and cracks in the audio. Particle impacts are seen to increase in frequency in the spectrogram and in the audible pops around the time of ring crossing as indicated by the red/orange spike just before 14:23 on the x-axis. Labels on the x-axis indicate time (top line), distance from the planet's center in Saturn radii, or Rs (middle), and latitude on Saturn beneath the spacecraft (bottom). These data can be compared to those recorded during Cassini's first dive through the gap between Saturn and the D ring, on April 26. While it appeared from those earlier data that there were essentially no particles in the gap, scientists later determined the particles there are merely too small to create a voltage detectable by RPWS, but could be detected using Cassini's dust analyzer instrument. After ring plane crossing (about 14:23 onward) a series of high pitched whistles are heard. The RPWS instrument detects such tones during each of the Grand Finale orbits and the team is working to understand their source. The D ring proved to contain larger ring particles, as expected and recorded here, although the environment was determined to be relatively benign -- with less dust than other faint Saturnian rings Cassini has flown through. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21620

Hubble Views Saturn Ring-Plane Crossing Satellites Labeled

Possible variations in chemical composition from one part of Saturn ring system to another are visible in this archival image from NASA Voyager 2.

Prometheus and Pandora are almost hidden in Saturn's rings in this image. Prometheus (53 miles or 86 kilometers across) and Pandora (50 miles or 81 kilometers across) orbit along side Saturn's narrow F ring, which is shaped, in part, by their gravitational influences help to shape that ring. Their proximity to the rings also means that they often lie on the same line of sight as the rings, sometimes making them difficult to spot. In this image, Prometheus is the left most moon in the ring plane, roughly in the center of the image. Pandora is towards the right. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 0.3 degrees below the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on May 6, 2015. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 994,000 miles (1.6 million kilometers) from Prometheus and at a Sun-Prometheus-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 106 degrees. Image scale is 6 miles (10 kilometers) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18334

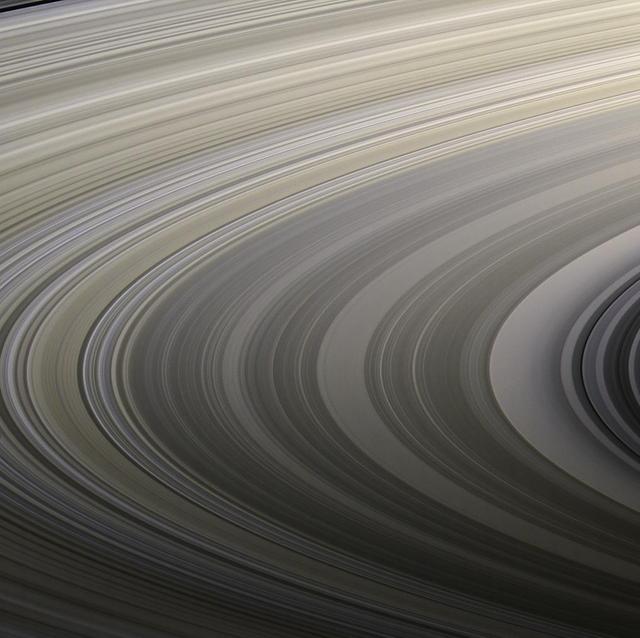

Saturn's rings display their subtle colors in this view captured on Aug. 22, 2009, by NASA's Cassini spacecraft. The particles that make up the rings range in size from smaller than a grain of sand to as large as mountains, and are mostly made of water ice. The exact nature of the material responsible for bestowing color on the rings remains a matter of intense debate among scientists. Images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this natural color view. Cassini's narrow-angle camera took the images at a distance of approximately 1.27 million miles (2.05 million kilometers) from the center of the rings. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22418