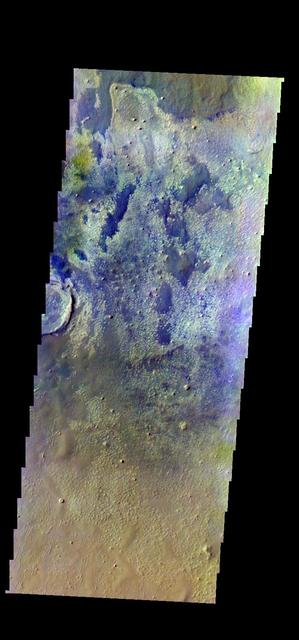

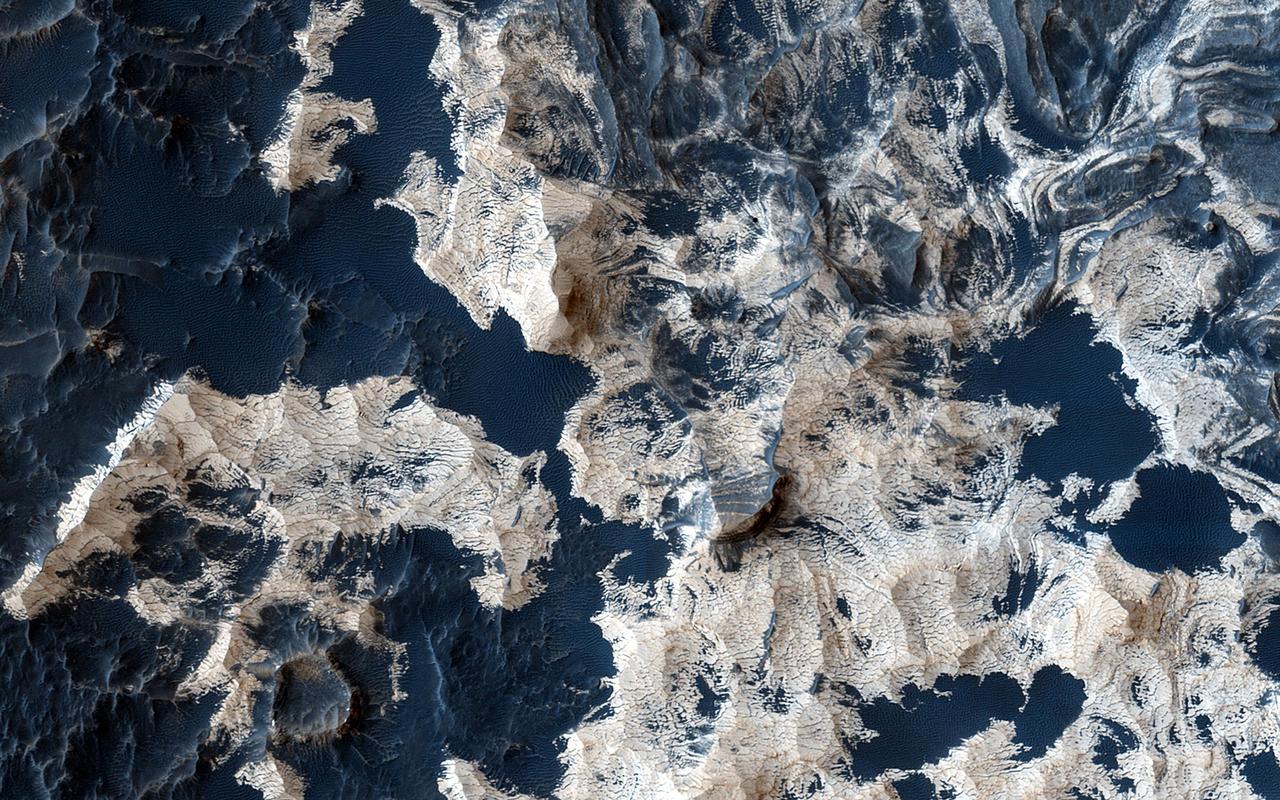

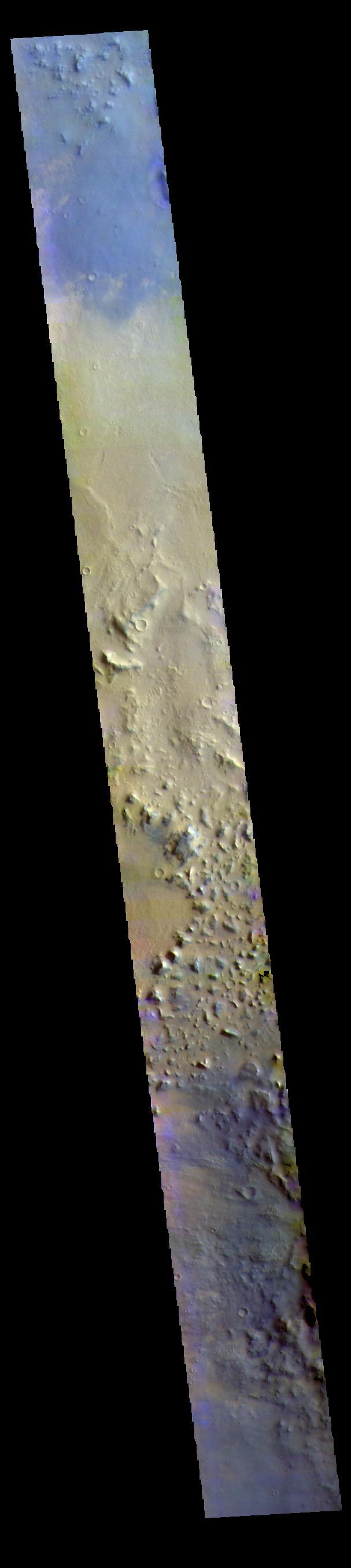

The THEMIS VIS camera contains 5 filters. The data from different filters can be combined in multiple ways to create a false color image. These false color images may reveal subtle variations of the surface not easily identified in a single band image. Today's false color image shows part of the floor of Schiaparelli Crater. Orbit Number: 44366 Latitude: -1.13235 Longitude: 14.4773 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2011-12-15 07:21 http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21163

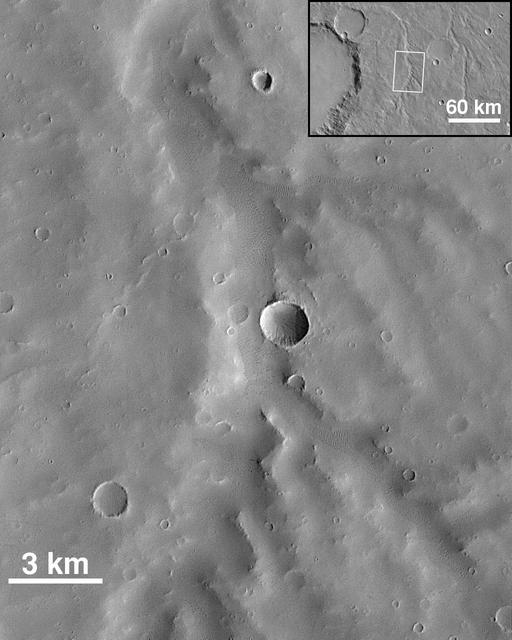

Schiaparelli Crater Rim and Interior Deposits

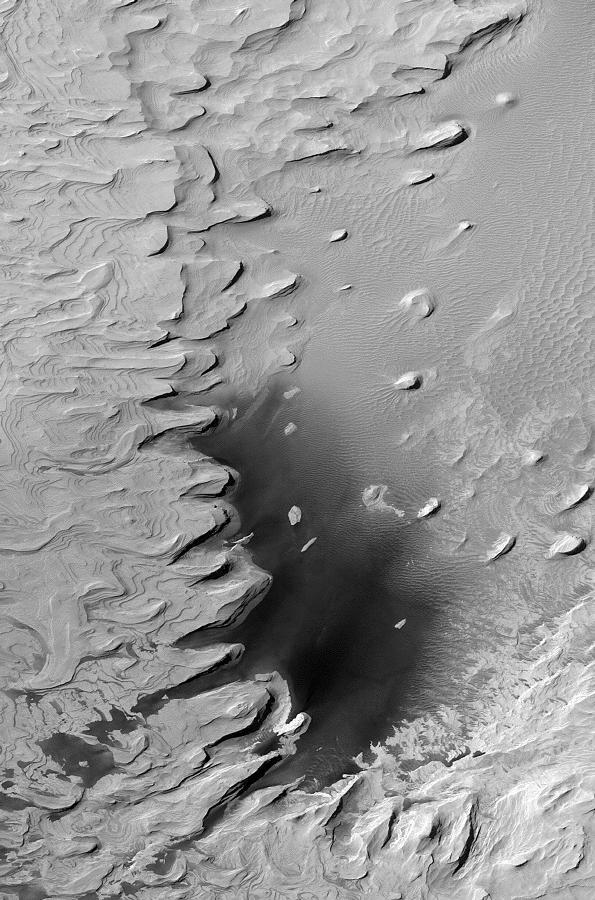

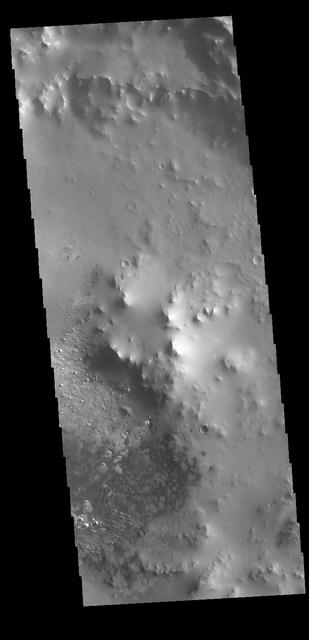

Ancient Layered Rocks in Schiaparelli Crater

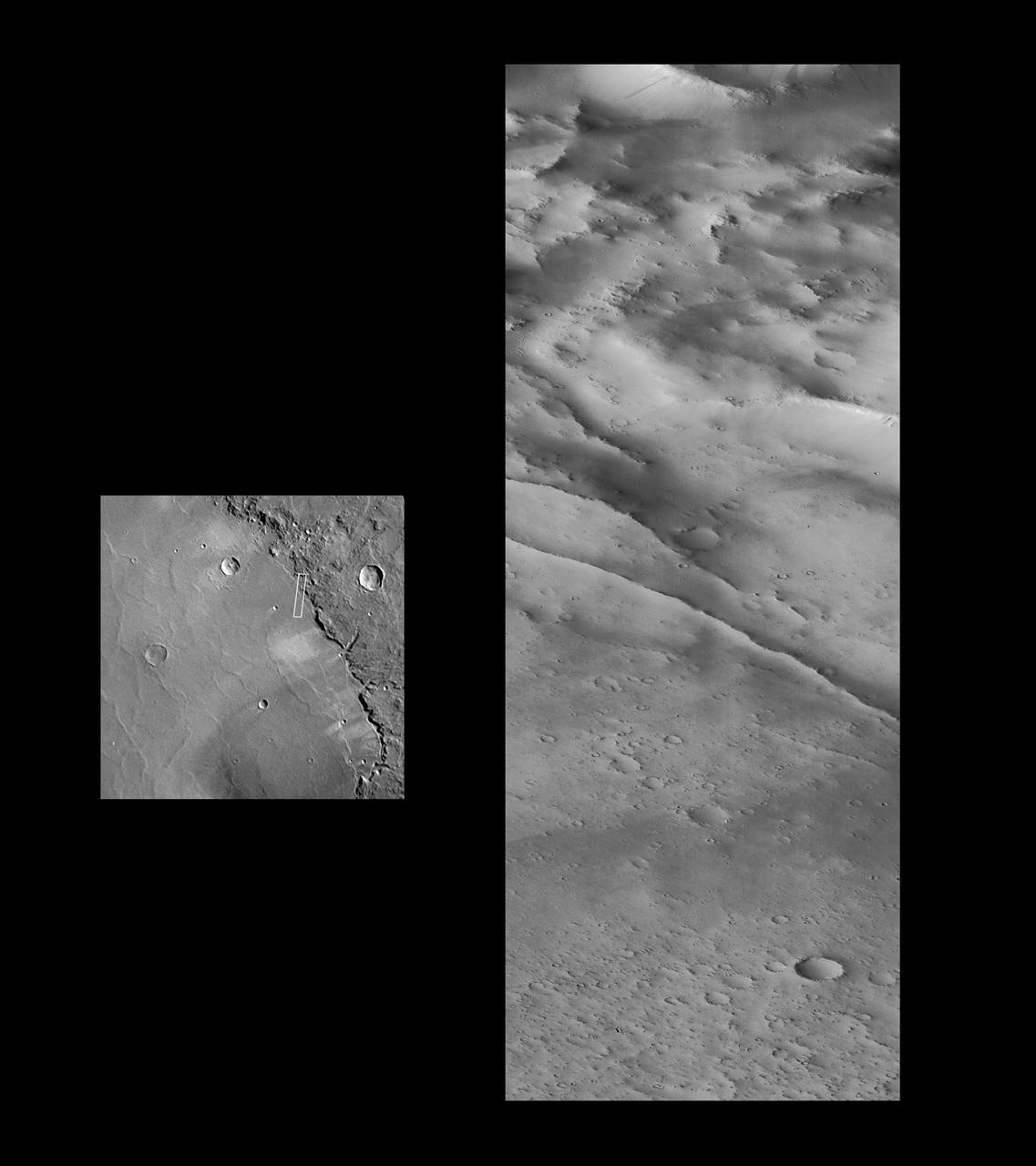

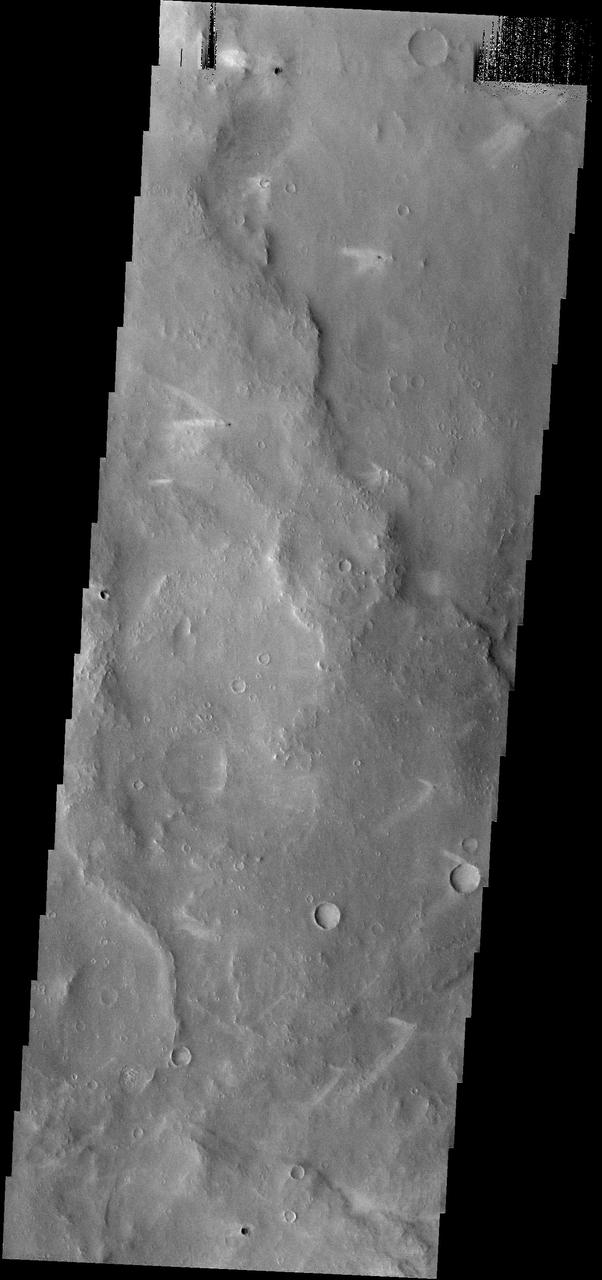

Small Valley Network Near Schiaparelli Crater

Valley and Surrounding Terrain Adjacent to Schiaparelli Crater

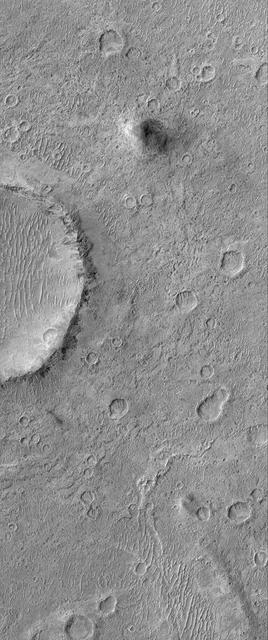

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows a crater within the larger Schiaparelli Crater.

Valley and Surrounding Terrain Adjacent to Schiaparelli Crater - High Resolution Image

Schiaparelli Crater Rim and Interior Deposits - High Resolution Image

Valley and Surrounding Terrain Adjacent to Schiaparelli Crater - High Resolution Image

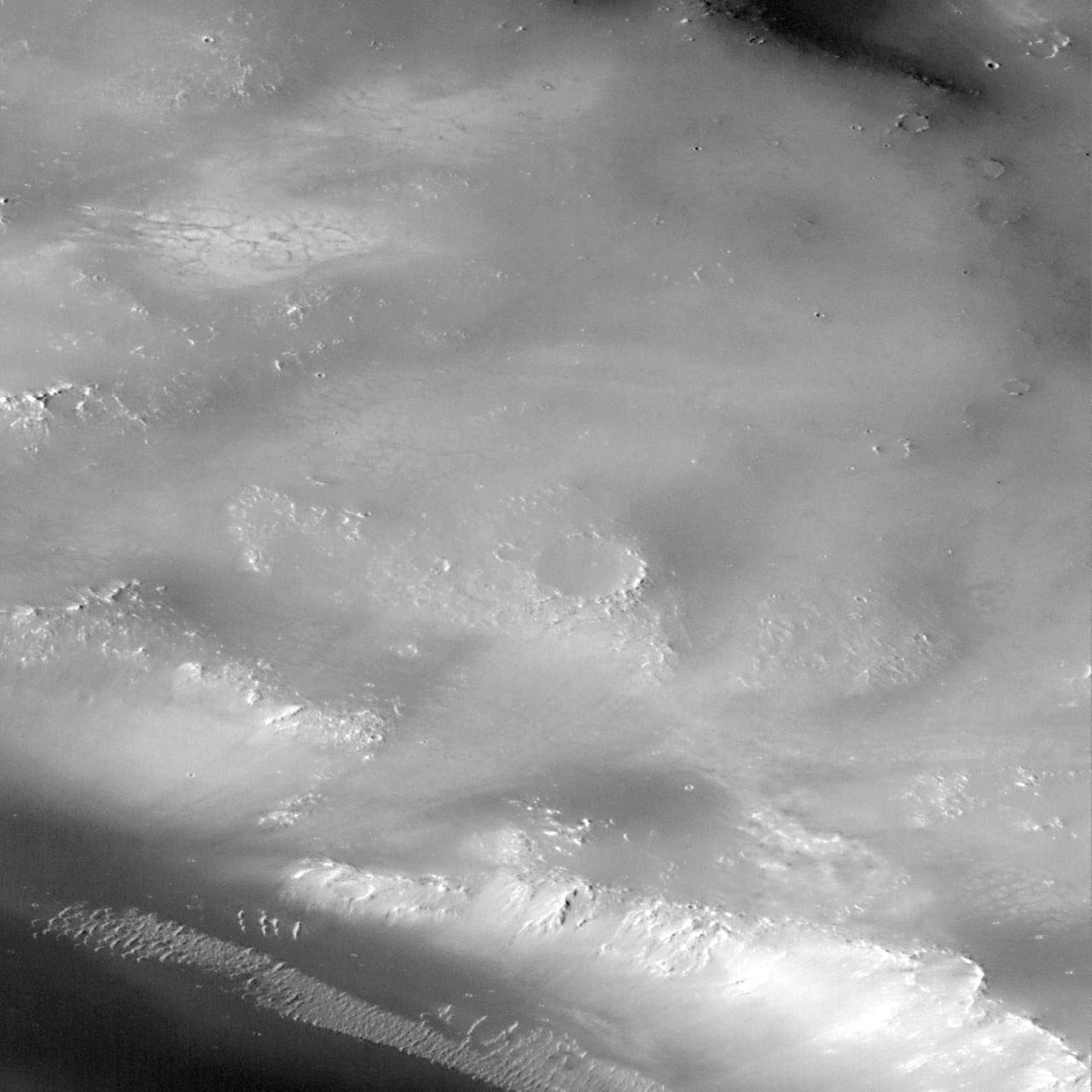

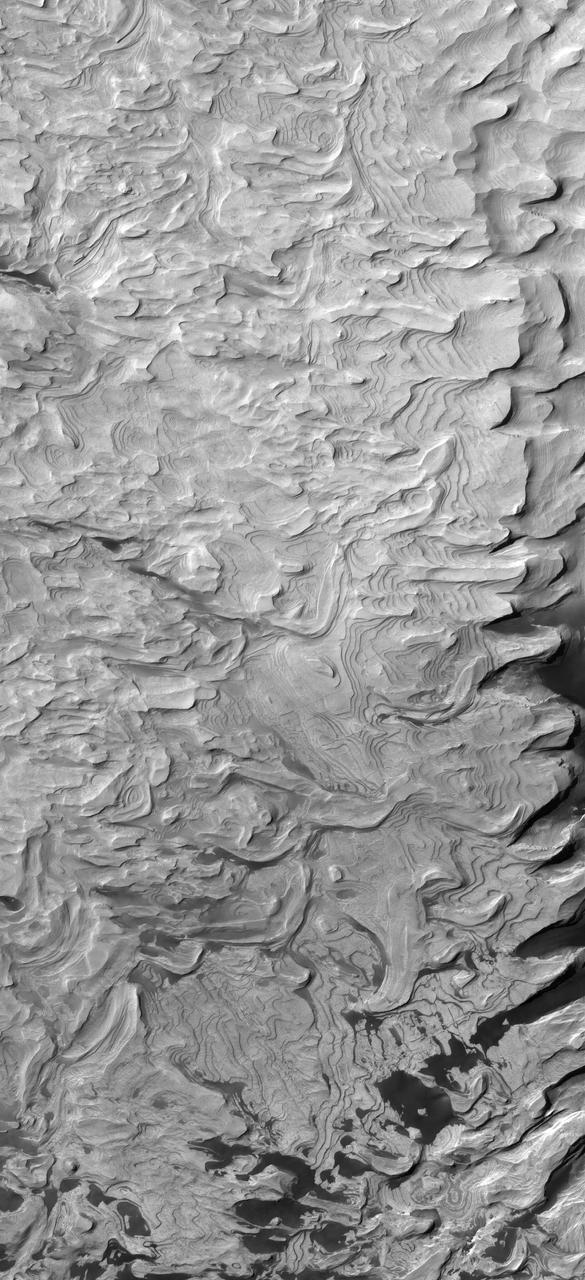

Schiaparelli Crater is a 460 kilometer 286 mile wide multi-ring structure. However, it is a very shallow crater, apparently filled by younger materials such as lava and/or fluvial and aeolian sediments as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

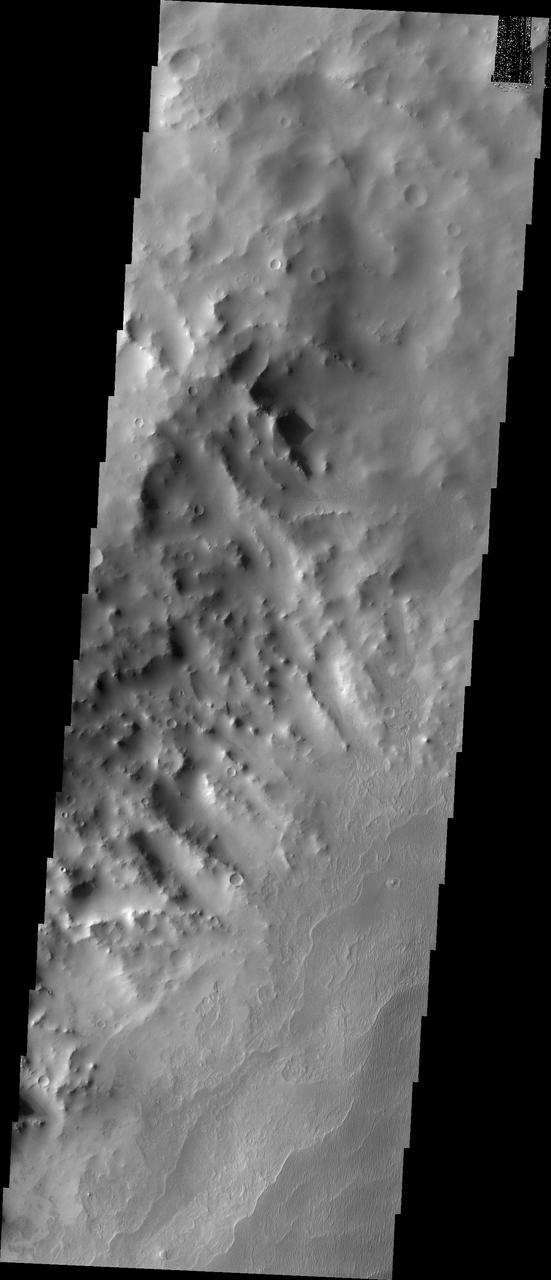

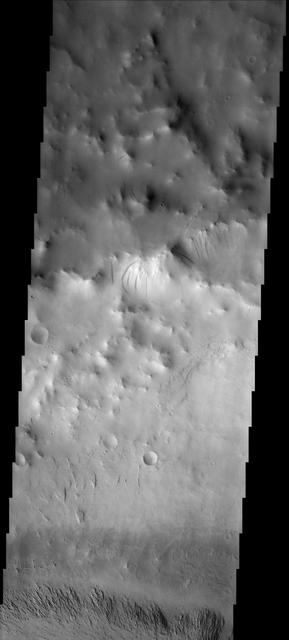

All this week, the THEMIS Image of the Day is following on the real Mars the path taken by fictional astronaut Mark Watney, stranded on the Red Planet in the book and movie, The Martian. Today's image shows part of the northwest rim of Schiaparelli Crater. Schiaparelli is a large, ancient impact scar, some 480 kilometers (280 miles) wide. It has been much modified by billions of years of erosion and deposition by wind and probably water. For astronaut Mark Watney, the descent from the rim onto the crater floor looks smooth and gradual. But it almost wrecks his rover vehicle when he drives into soft sediments. His goal? An automated rescue rocket, intended for the next Mars expedition, which stands about 250 kilometers (150 miles) away on the southern part of Schiaparelli's floor. Orbit Number: 10910 Latitude: -0.882761 Longitude: 13.4529 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2004-05-30 15:45 http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19799

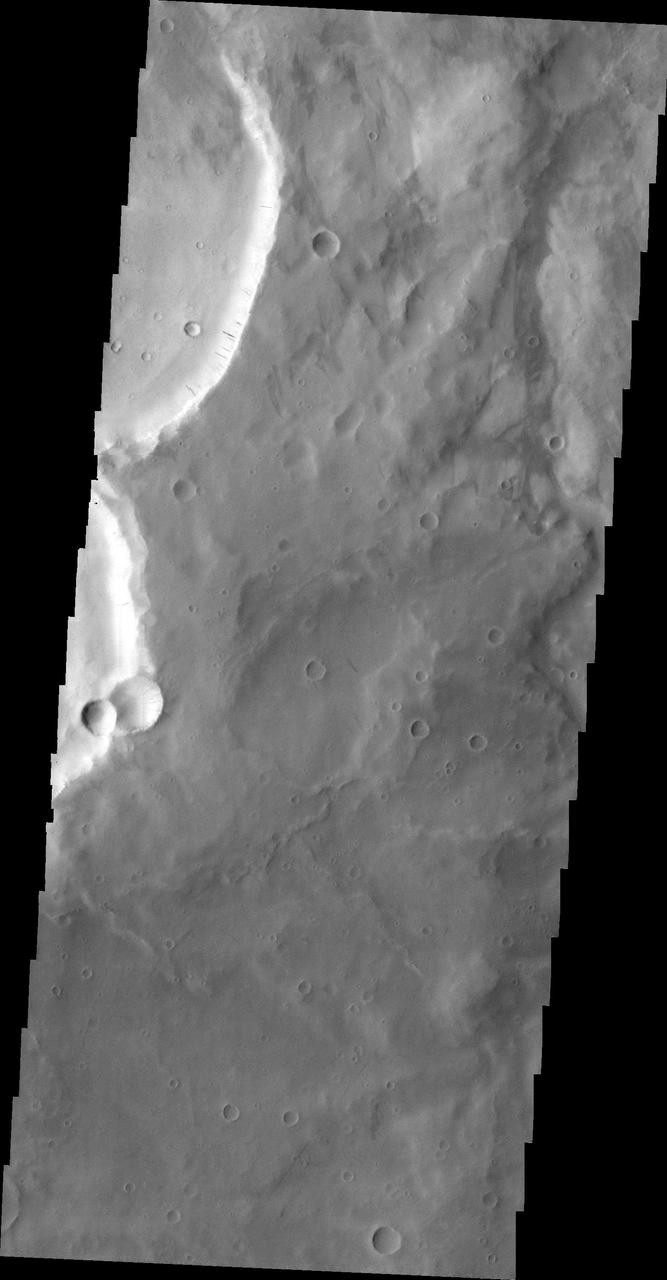

All this week, the THEMIS Image of the Day has been following on the real Mars the path taken by fictional astronaut Mark Watney, stranded on the Red Planet in the book and movie, The Martian. Generally smooth and rolling terrain covers most of this portion of Schiaparelli Crater's floor. Because the impact that made Schiaparelli occurred billions of years ago, nature has had ample time to leave lava and sediments in the crater and to erode them. The ridge in the image's southern end is part of an eroded crater rim, one of many such smaller impact craters that have collected on Schiaparelli's floor since it formed. (This image was taken as part of a study for the Mars Student Imaging Project by a high-school science class.) Here astronaut Mark Watney's great overland trek reaches its end. He arrives safely at the Mars Ascent Vehicle (MAV), which was sent in advance for the next Mars mission crew. The rocket will get him off the ground and into Mars orbit, where he can be picked up by a rescue ship coming from Earth. Orbit Number: 37215 Latitude: -4.03322 Longitude: 15.477 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2010-05-05 13:14 http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19800

The dark slope streaks in this image are located on the rim of an unnamed crater east of Schiaparelli Crater taken by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft.

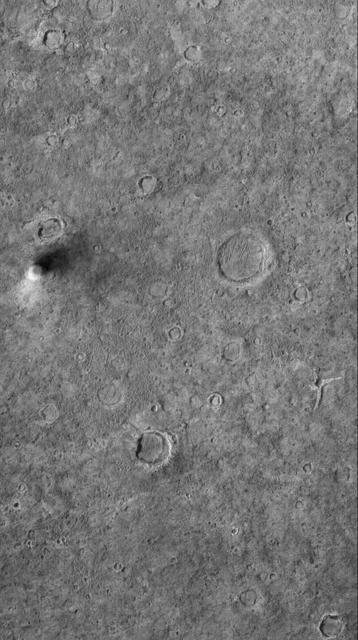

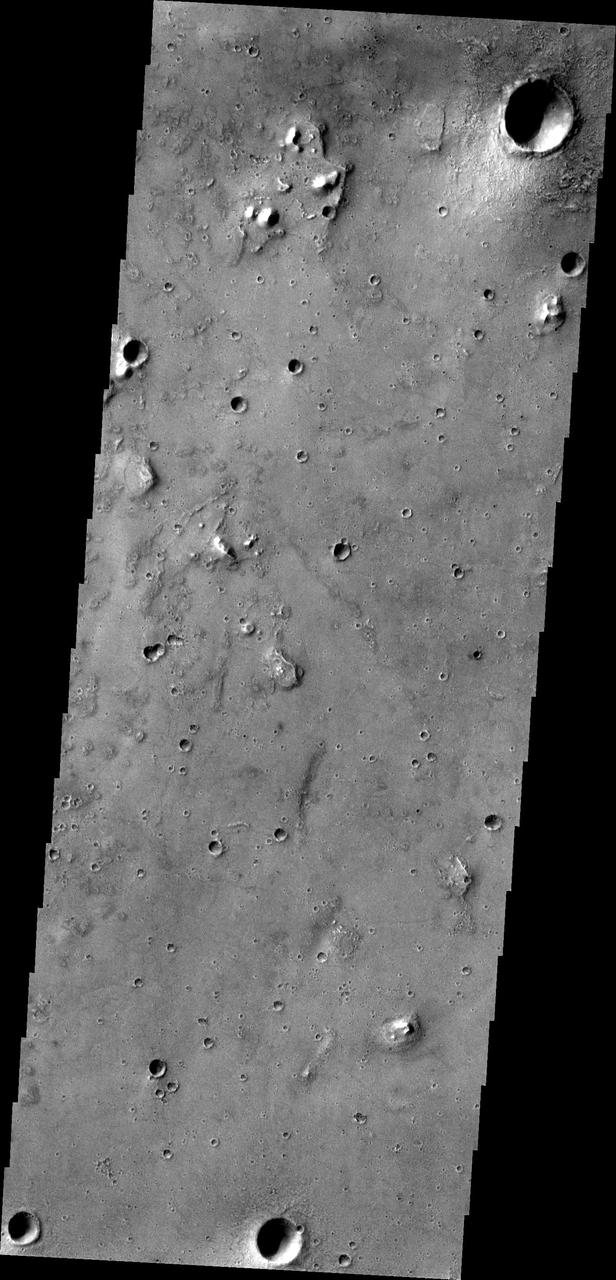

This MOC image shows a cratered plain west of Schiaparelli Crater, Mars. The area captured in this image, and areas adjacent to it, are known for high dust devil traffic

The windstreaks in this area northwest of Schiaparelli Crater point in three different directions. This indicates that the wind shifts/ed with time

NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows that the dust avalanches found on this crater rim have exposed darker rocky material on an otherwise dust coated slope. This unnamed crater is located east of Schiaparelli Crater.

Today's VIS image shows a field of dunes on the floor of an unnamed crater near Schiaparelli Crater in Noachis Terra. Orbit Number: 79163 Latitude: -3.81259 Longitude: 12.247 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2019-10-19 14:21 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23580

This MOC image shows light-toned, layered, sedimentary rocks in a crater in the northwestern part of Schiaparelli basin. The repetition of these horizontal layers suggests the sediments could have been deposited in an ancient crater lake

This MOC image shows a dust devil traveling across a plain west-southwest of Schiaparelli Crater, in far eastern Sinus Meridiani. The dust devil is casting a shadow toward the northeast, just south below of an egg-shaped crater

Today's false color image shows part of the plains of Noachis Terra southwest of Schiaparelli Crater. The THEMIS VIS camera contains 5 filters. The data from different filters can be combined in multiple ways to create a false color image. These false color images may reveal subtle variations of the surface not easily identified in a single band image. Orbit Number: 63097 Latitude: -6.20315 Longitude: 11.7459 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2016-03-05 04:38 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23217

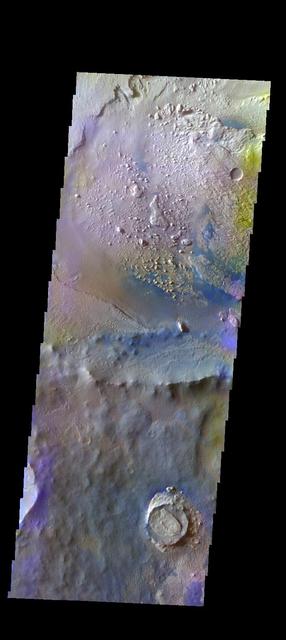

The THEMIS VIS camera contains 5 filters. The data from different filters can be combined in multiple ways to create a false color image. These false color images may reveal subtle variations of the surface not easily identified in a single band image. Today's false color image shows an unnamed crater located on the floor of the much larger Schiaparelli Crater. The dark blue material located in the topographic lows is basaltic sand. Orbit Number: 19495 Latitude: -0.402445 Longitude: 14.3131 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2006-05-07 13:43 http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20244

![In Andy Weir's "The Martian," stranded astronaut Mark Watney drives from the Ares 3 landing site in Acidalia Planitia towards the Ares 4 landing site in Schiaparelli Crater via Mawrth Vallis. This image covers the entrance to Mawrth Vallis. As you can tell, driving over this terrain will be much more difficult than it was depicted in the novel or the movie. The map is projected here at a scale of 50 centimeters (19.7 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 58.5 centimeters (19.1 inches) per pixel (with 2 x 2 binning); objects on the order of 176 centimeters (69.2 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21555](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21555/PIA21555~medium.jpg)

In Andy Weir's "The Martian," stranded astronaut Mark Watney drives from the Ares 3 landing site in Acidalia Planitia towards the Ares 4 landing site in Schiaparelli Crater via Mawrth Vallis. This image covers the entrance to Mawrth Vallis. As you can tell, driving over this terrain will be much more difficult than it was depicted in the novel or the movie. The map is projected here at a scale of 50 centimeters (19.7 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 58.5 centimeters (19.1 inches) per pixel (with 2 x 2 binning); objects on the order of 176 centimeters (69.2 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21555

All this week, the THEMIS Image of the Day is following on the real Mars the path taken by fictional astronaut Mark Watney, stranded on the Red Planet in the book and movie, The Martian. Today's image shows a part of the flat terrain of northern Meridiani Planum. This area lies about 300 kilometers (190 miles) north of where Mars rover Opportunity is currently exploring the rim rocks of Endeavour Crater. Meridiani is a large expanse of sedimentary rock, mostly flat-lying basalt sandstone with hematite nodules ("blueberries") embedded in it. Farther south from this scene, Opportunity has examined several craters like these that expose deeper rock layers. They show that the Meridiani sandstone is made of dune sands that were soaked in sulfur-rich water. Flat terrain may make for dull scenery, but the driving is easy. This area is where astronaut Mark Watney turns his vehicle east toward Schiaparelli Crater. Before arriving here, he was driving south to get out from under a dust storm that threatened to shut off power to the vehicle's solar cells. At this point he has journeyed about 2,300 kilometers (1,400 miles) from Acidalia. Orbit Number: 6304 Latitude: 2.51711 Longitude: 355.154 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2003-05-17 13:18 http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19798

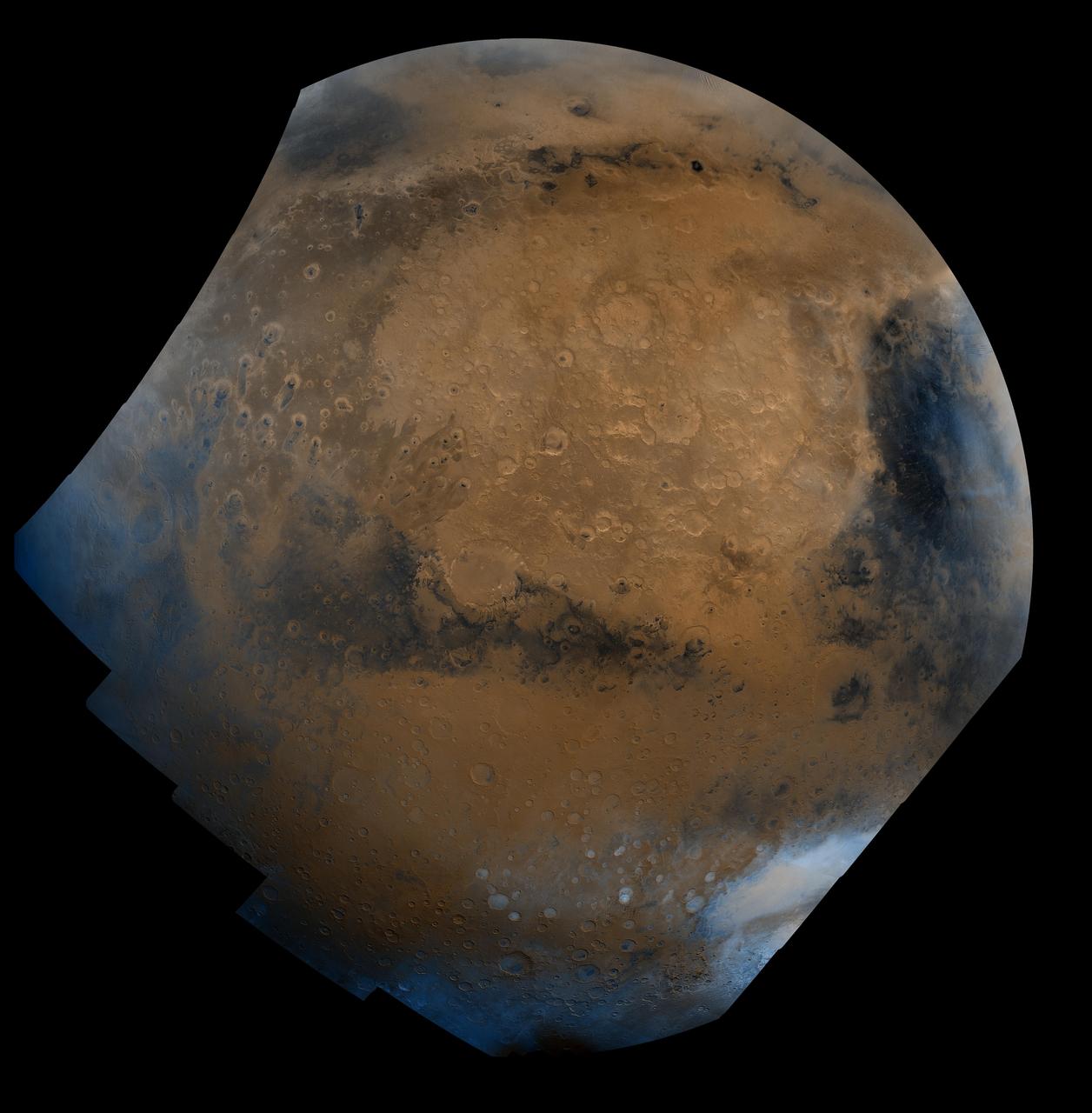

This mosaic is composed of about 100 red- and violet- filter Viking Orbiter images, digitally mosaiced in an orthographic projection at a scale of 1 km/pixel. The images were acquired in 1980 during mid northern summer on Mars (Ls = 89 degrees). The center of the image is near the impact crater Schiaparelli (latitude -3 degrees, longitude 343 degrees). The limits of this mosaic are approximately latitude -60 to 60 degrees and longitude 280 to 30 degrees. The color variations have been enhanced by a factor of two, and the large-scale brightness variations (mostly due to sun-angle variations) have been normalized by large-scale filtering. The large circular area with a bright yellow color (in this rendition) is known as Arabia. The boundary between the ancient, heavily-cratered southern highlands and the younger northern plains occurs far to the north (latitude 40 degrees) on this side of the planet, just north of Arabia. The dark streaks with bright margins emanating from craters in the Oxia Palus region (to the left of Arabia) are caused by erosion and/or deposition by the wind. The dark blue area on the far right, called Syrtis Major Planum, is a low-relief volcanic shield of probable basaltic composition. Bright white areas to the south, including the Hellas impact basin at the lower right, are covered by carbon dioxide frost. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00004

All this week, the THEMIS Image of the Day is following on the real Mars the path taken by fictional astronaut Mark Watney, stranded on the Red Planet in the book and movie, The Martian. Today's image shows a small portion of Acidalia Planitia, a largely flat plain that is part of Mars' vast northern lowlands. Scientists are debating the likelihood that the northern plains once contained a large ocean or other bodies of water, probably ice-covered. In the story, Acidalia Planitia is the landing site for a human expedition to Mars. After a dust storm damages the crew habitat and apparently kills Watney, the remaining crew abandon the expedition and leave for Earth. Watney however is still alive, and to save himself he must journey nearly 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles) east to Schiaparelli Crater, where a rescue rocket awaits. Orbit Number: 27733 Latitude: 31.218 Longitude: 332.195 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2008-03-15 20:24 http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19796

This image from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows a location on Mars associated with the best-selling novel and Hollywood movie, "The Martian." It is the science-fiction tale's planned landing site for the Ares 4 mission. The novel placed the Ares 4 site on the floor of a very shallow crater in the southwestern corner of Schiaparelli Crater. This HiRISE image shows a flat region there entirely mantled by bright Martian dust. There are no color variations, just uniform reddish dust. A pervasive, pitted texture visible at full resolution is characteristic of many dust deposits on Mars. No boulders are visible, so the dust is probably at least a meter thick. Past Martian rover and lander missions from NASA have avoided such pervasively dust-covered regions for two reasons. First, the dust has a low thermal inertia, meaning that it gets extra warm in the daytime and extra cold at night, a thermal challenge to survival of the landers and rovers (and people). Second, the dust hides the bedrock, so little is known about the bedrock composition and whether it is of scientific interest. This view is one image product from HiRISE observation ESP_042014_1760, taken July 14, 2015, at 3.9 degrees south latitude, 15.2 degrees east longitude. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19914

![On Nov. 1, 2016, the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter observed the impact site of Europe's Schiaparelli test lander, gaining the first color view of the site since the lander's Oct. 19, 2016, arrival. These cutouts from the observation cover three locations where parts of the spacecraft reached the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The heat shield location was outside of the area covered in color. The scale bar of 10 meters (32.8 feet) applies to all three cutouts. Schiaparelli was one component of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. The ExoMars project received data from Schiaparelli during its descent through the atmosphere. ESA reports that the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). Information gained from the Nov. 1 observation supplements what was learned from an Oct. 25 HiRISE observation, at PIA21131, which also shows the locations of these three cutouts relative to each other. Where the lander module struck the ground, dark radial patterns that extend from a dark spot are interpreted as "ejecta," or material thrown outward from the impact, which may have excavated a shallow crater. From the earlier image, it was not clear whether the relatively bright pixels and clusters of pixels scattered around the lander module's impact site are fragments of the module or image noise. Now it is clear that at least the four brightest spots near the impact are not noise. These bright spots are in the same location in the two images and have a white color, unusual for this region of Mars. The module may have broken up at impact, and some fragments might have been thrown outward like impact ejecta. The parachute has a different shape in the Nov. 1 image than in the Oct. 25 one, apparently from shifting in the wind. Similar shifting was observed in the parachute of NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission during the first six months after the Mars arrival of that mission's Curiosity rover in 2012 [PIA16813]. At lower right are several bright features surrounded by dark radial impact patterns, located where the heat shield was expected to impact. The bright spots appear identical in the Nov. 1 and Oct. 25 images, which were taken from different angles, so these spots are now interpreted as bright material, such as insulation layers, not glinting reflections. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21132](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21132/PIA21132~thumb.jpg)

On Nov. 1, 2016, the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter observed the impact site of Europe's Schiaparelli test lander, gaining the first color view of the site since the lander's Oct. 19, 2016, arrival. These cutouts from the observation cover three locations where parts of the spacecraft reached the ground: the lander module itself in the upper portion, the parachute and back shell at lower left, and the heat shield at lower right. The heat shield location was outside of the area covered in color. The scale bar of 10 meters (32.8 feet) applies to all three cutouts. Schiaparelli was one component of the European Space Agency's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. The ExoMars project received data from Schiaparelli during its descent through the atmosphere. ESA reports that the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). Information gained from the Nov. 1 observation supplements what was learned from an Oct. 25 HiRISE observation, at PIA21131, which also shows the locations of these three cutouts relative to each other. Where the lander module struck the ground, dark radial patterns that extend from a dark spot are interpreted as "ejecta," or material thrown outward from the impact, which may have excavated a shallow crater. From the earlier image, it was not clear whether the relatively bright pixels and clusters of pixels scattered around the lander module's impact site are fragments of the module or image noise. Now it is clear that at least the four brightest spots near the impact are not noise. These bright spots are in the same location in the two images and have a white color, unusual for this region of Mars. The module may have broken up at impact, and some fragments might have been thrown outward like impact ejecta. The parachute has a different shape in the Nov. 1 image than in the Oct. 25 one, apparently from shifting in the wind. Similar shifting was observed in the parachute of NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission during the first six months after the Mars arrival of that mission's Curiosity rover in 2012 [PIA16813]. At lower right are several bright features surrounded by dark radial impact patterns, located where the heat shield was expected to impact. The bright spots appear identical in the Nov. 1 and Oct. 25 images, which were taken from different angles, so these spots are now interpreted as bright material, such as insulation layers, not glinting reflections. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21132

This Oct. 25, 2016, image shows the area where the European Space Agency's Schiaparelli test lander reached the surface of Mars, with magnified insets of three sites where components of the spacecraft hit the ground. It is the first view of the site from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter taken after the Oct. 19, 2016, landing event. The Schiaparelli test lander was one component of ESA's ExoMars 2016 project, which placed the Trace Gas Orbiter into orbit around Mars on the same arrival date. This HiRISE observation adds information to what was learned from observation of the same area on Oct. 20 by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's Context Camera (CTX). Of these two cameras, CTX covers more area and HiRISE shows more detail. A portion of the HiRISE field of view also provides color information. The impact scene was not within that portion for the Oct. 25 observation, but an observation with different pointing to add color and stereo information is planned. This Oct. 25 observation shows three locations where hardware reached the ground, all within about 0.9 mile (1.5 kilometer) of each other, as expected. The annotated version includes insets with six-fold enlargement of each of those three areas. Brightness is adjusted separately for each inset to best show the details of that part of the scene. North is about 7 degrees counterclockwise from straight up. The scale bars are in meters. At lower left is the parachute, adjacent to the back shell, which was its attachment point on the spacecraft. The parachute is much brighter than the Martian surface in this region. The smaller circular feature just south of the bright parachute is about the same size and shape as the back shell, (diameter of 7.9 feet or 2.4 meters). At upper right are several bright features surrounded by dark radial impact patterns, located about where the heat shield was expected to impact. The bright spots may be part of the heat shield, such as insulation material, or gleaming reflections of the afternoon sunlight. According to the ExoMars project, which received data from the spacecraft during its descent through the atmosphere, the heat shield separated as planned, the parachute deployed as planned but was released (with back shell) prematurely, and the lander hit the ground at a velocity of more than 180 miles per hour (more than 300 kilometers per hour). At mid-upper left are markings left by the lander's impact. The dark, approximately circular feature is about 7.9 feet (2.4 meters) in diameter, about the size of a shallow crater expected from impact into dry soil of an object with the lander's mass -- about 660 pounds (300 kilograms) -- and calculated velocity. The resulting crater is estimated to be about a foot and a half (half a meter) deep. This first HiRISE observation does not show topography indicating the presence of a crater. Stereo information from combining this observation with a future one may provide a way to check. Surrounding the dark spot are dark radial patterns expected from an impact event. The dark curving line to the northeast of the dark spot is unusual for a typical impact event and not yet explained. Surrounding the dark spot are several relatively bright pixels or clusters of pixels. They could be image noise or real features, perhaps fragments of the lander. A later image is expected to confirm whether these spots are image noise or actual surface features. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21131

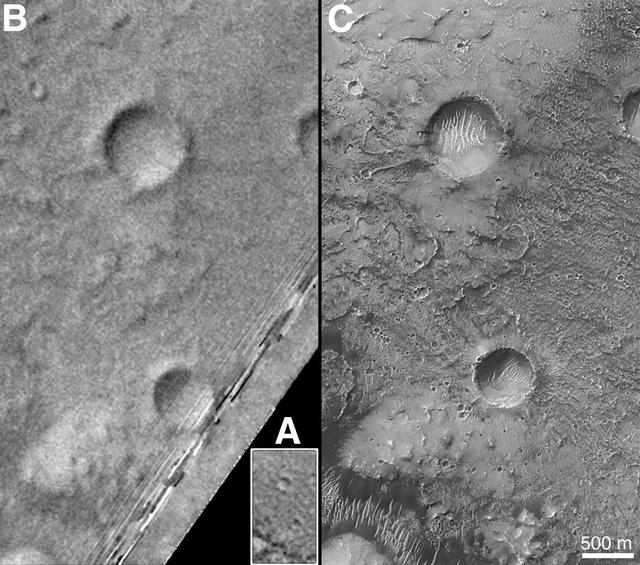

On Earth, the longitude of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England is defined as the "prime meridian," or the zero point of longitude. Locations on Earth are measured in degrees east or west from this position. The prime meridian was defined by international agreement in 1884 as the position of the large "transit circle," a telescope in the Observatory's Meridian Building. The transit circle was built by Sir George Biddell Airy, the 7th Astronomer Royal, in 1850. (While visual observations with transits were the basis of navigation until the space age, it is interesting to note that the current definition of the prime meridian is in reference to orbiting satellites and Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) measurements of distant radio sources such as quasars. This "International Reference Meridian" is now about 100 meters east of the Airy Transit at Greenwich.) For Mars, the prime meridian was first defined by the German astronomers W. Beer and J. H. Mädler in 1830-32. They used a small circular feature, which they designated "a," as a reference point to determine the rotation period of the planet. The Italian astronomer G. V. Schiaparelli, in his 1877 map of Mars, used this feature as the zero point of longitude. It was subsequently named Sinus Meridiani ("Middle Bay") by Camille Flammarion. When Mariner 9 mapped the planet at about 1 kilometer (0.62 mile) resolution in 1972, an extensive "control net" of locations was computed by Merton Davies of the RAND Corporation. Davies designated a 0.5-kilometer-wide crater (0.3 miles wide), subsequently named "Airy-0" (within the large crater Airy in Sinus Meridiani) as the longitude zero point. (Airy, of course, was named to commemorate the builder of the Greenwich transit.) This crater was imaged once by Mariner 9 (the 3rd picture taken on its 533rd orbit, 533B03) and once by the Viking 1 orbiter in 1978 (the 46th image on that spacecraft's 746th orbit, 746A46), and these two images were the basis of the martian longitude system for the rest of the 20th Century. The Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) has attempted to take a picture of Airy-0 on every close overflight since the beginning of the MGS mapping mission. It is a measure of the difficulty of hitting such a small target that nine attempts were required, since the spacecraft did not pass directly over Airy-0 until almost the end of the MGS primary mission, on orbit 8280 (January 13, 2001). In the left figure above, the outlines of the Mariner 9, Viking, and Mars Global Surveyor images are shown on a MOC wide angle context image, M23-00924. In the right figure, sections of each of the three images showing the crater Airy-0 are presented. A is a piece of the Mariner 9 image, B is from the Viking image, and C is from the MGS image. Airy-0 is the larger crater toward the top-center in each frame. The MOC observations of Airy-0 not only provide a detailed geological close-up of this historic reference feature, they will be used to improve our knowledge of the locations of all features on Mars, which will in turn enable more precise landings on the Red Planet by future spacecraft and explorers. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA03207