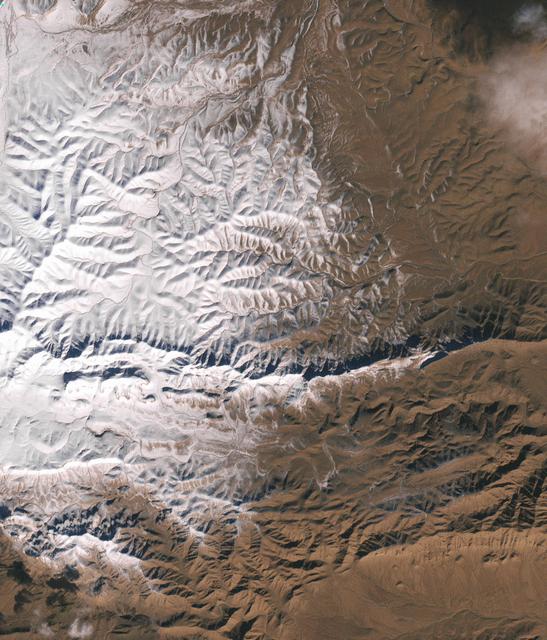

In December 2016, snow fell in the Sahara for the first time since 1979. In 1984, the charitable supergroup Band Aid sang: “There won’t be snow in Africa this Christmas time.” In fact, it does snow in Africa at high elevations. Kilimanjaro has long had a cap of snow and ice, though it has been shrinking. Skiiers travel for natural and manufactured snow in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco and Algeria, as well as a few spots in South Africa and Lesotho. Nonetheless, snow on the edge of the Sahara Desert is rare. On December 19, 2016, snow fell on the Algerian town of Ain Sefra, which is sometimes referred to as the “gateway to the desert.” The town of roughly 35,000 people sits between the Atlas Mountains and the northern edge of the Sahara. The last recorded snowfall in Ain Sefra occurred in February 1979. The Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) on the Landsat 7 satellite acquired this natural-color image of snow in North Africa on December 19, 2016. This scene shows an area near the border of Morocco and Algeria, south of the city of Bouarfa and southwest of Ain Sefra. Though the news has been dominated by snow in the Saharan city, a review of several years of satellite data suggests that snow is also pretty rare in this section of the Atlas range. Read more: <a href="http://go.nasa.gov/2hIH4Xe" rel="nofollow">go.nasa.gov/2hIH4Xe</a> NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Caption by Mike Carlowicz. b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagrid.me/nasagoddard/?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

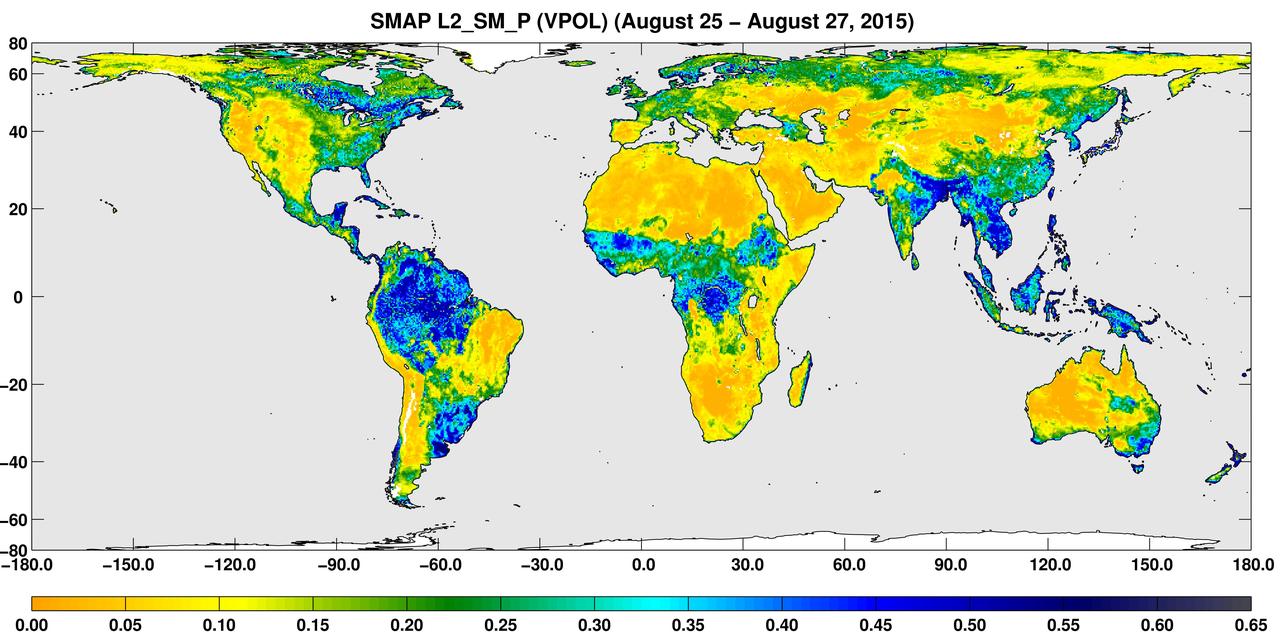

A three-day composite global map of surface soil moisture as retrieved from NASA SMAP radiometer instrument between Aug. 25-27, 2015. Dry areas appear yellow/orange, such as the Sahara Desert, western Australia and the western U.S. Wet areas appear blue, representing the impacts of localized storms. White areas indicate snow, ice or frozen ground. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19877

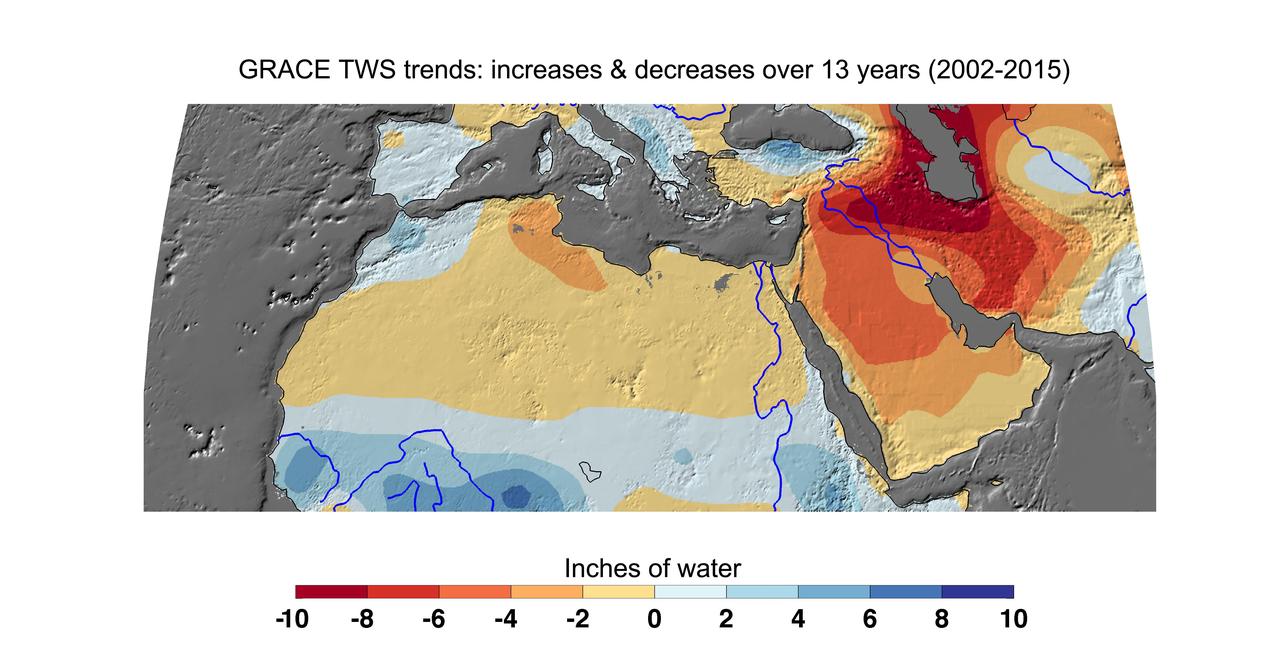

Cumulative total freshwater losses in North Africa and the Middle East from 2002 to 2015 (in inches) observed by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission. Total water refers to all of the snow, surface water, soil water and groundwater combined. Groundwater depletion in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran, and along the Arabian Peninsula, are leading to large changes in total water storage in the region. Likewise, drought and groundwater pumping is contributing to the drying of the Caspian Sea Region. The Northwest Sahara Aquifer System, which underlies Tunisia and Libya, is also experiencing increasing water stress as shown in the map. Image updated from Voss et al., 2013. Citation of Record: Voss, K. A., J. S. Famiglietti, M. Lo, C. R. de Linage, M. Rodell and S. C. Swenson, Groundwater depletion in the Middle East from GRACE with Implications for Transboundary Water Management in the Tigris-Euphrates-Western Iran Region, Wat. Resour. Res., 49(2), 904-914, DOI: 10.1002/wrcr.20078. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20207

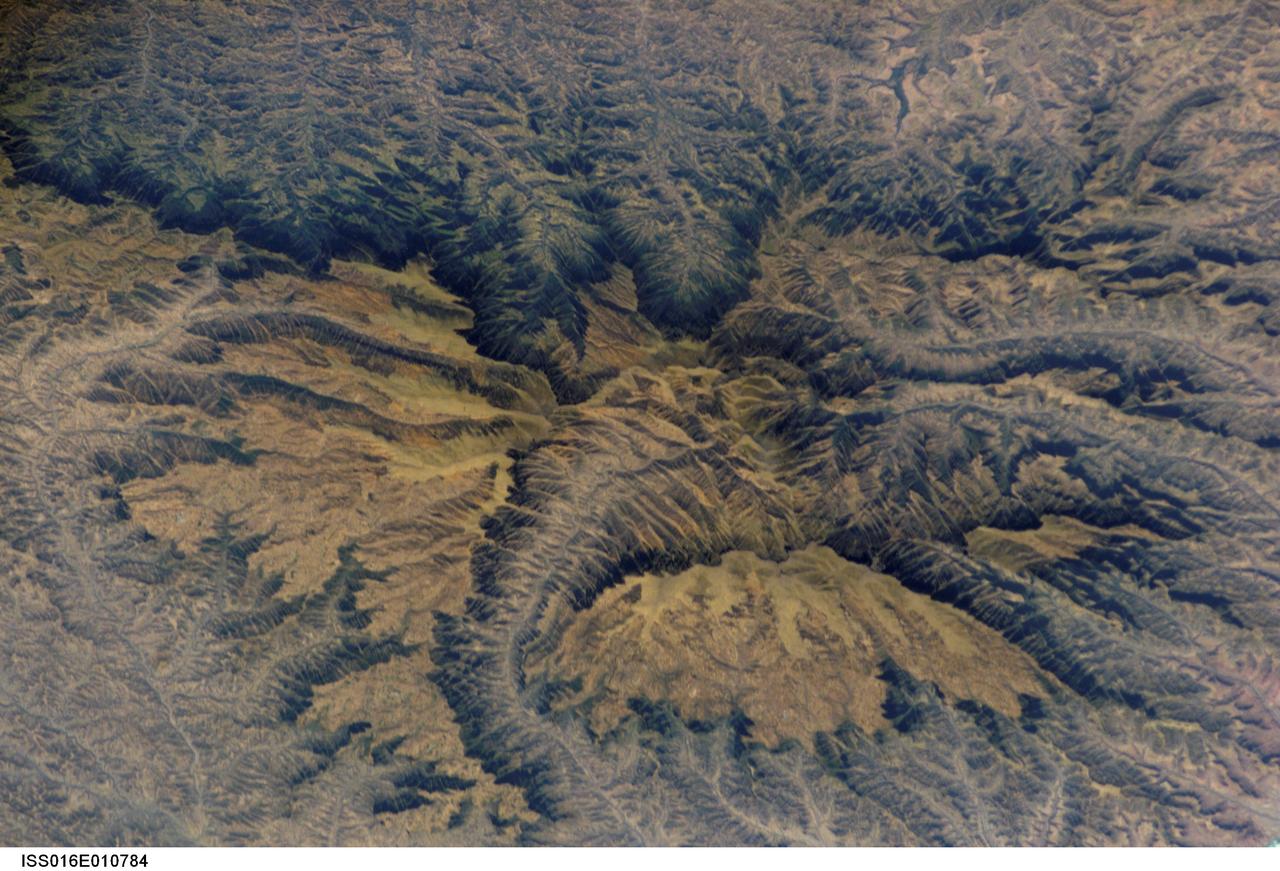

ISS016-E-010784 (16 Nov. 2007) --- Semien Mountains, Gonder, northern Ethiopia are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 16 crewmember on the International Space Station. The Semien Mountains, the highest parts of the Ethiopian Plateau (above 2,000 meters--6,560 feet), are surrounded by a steep, ragged escarpment (step) with dramatic vertical cliffs, pinnacles, and rock spires - scenery that draws international tourists. Included in the range is the highest point in Ethiopia, Ras Dashen at 4,533 meters (14,926 feet) - an altitude only recently computed with any accuracy. The plateau and surrounding areas are made up of numerous flood basalts, totaling probably more than 3,000 meters in thickness. According to scientists, the lavas erupted quickly (in about one million years) 31 million years ago, as Ethiopia passed above what is known as the Afar "hotspot." The hotspot caused the general region of Ethiopia to be elevated, which encouraged extensive river erosion. This erosion has cut the highly dramatic canyons that ring the plateau. Although the plateau lies in the latitude of the Sahara--Arabia deserts, its great altitude makes for a cool, wet climate. This is shown by light green vegetation, compared with the brown canyons which are hot and dry. The green tinge on the biggest escarpment (trending across the top third of the image) is also vegetation, showing that this part of the escarpment also receives more rain than other parts of the escarpment wall. The Semien Mountains are one of the few places in Africa to regularly receive snow, and they receive plentiful rainfall (more than 1,280 millimeters--55 inches). A major canyon cuts the flatter plateau surface (center), with several more surrounding the plateau. These canyons are hot because they reach low altitudes, more than 2,000 meters below the plateau surface. The Semien Mountains National Park has been declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO for its rugged beauty. In addition, several extremely rare species are found here, such as the Gelada baboon with its thick coat to protect against the cold; the critically-endangered Walia ibex with long, heavy scimitar-like horns; and the Ethiopian wolf--also known as the Semien jackal, the "most endangered canid."