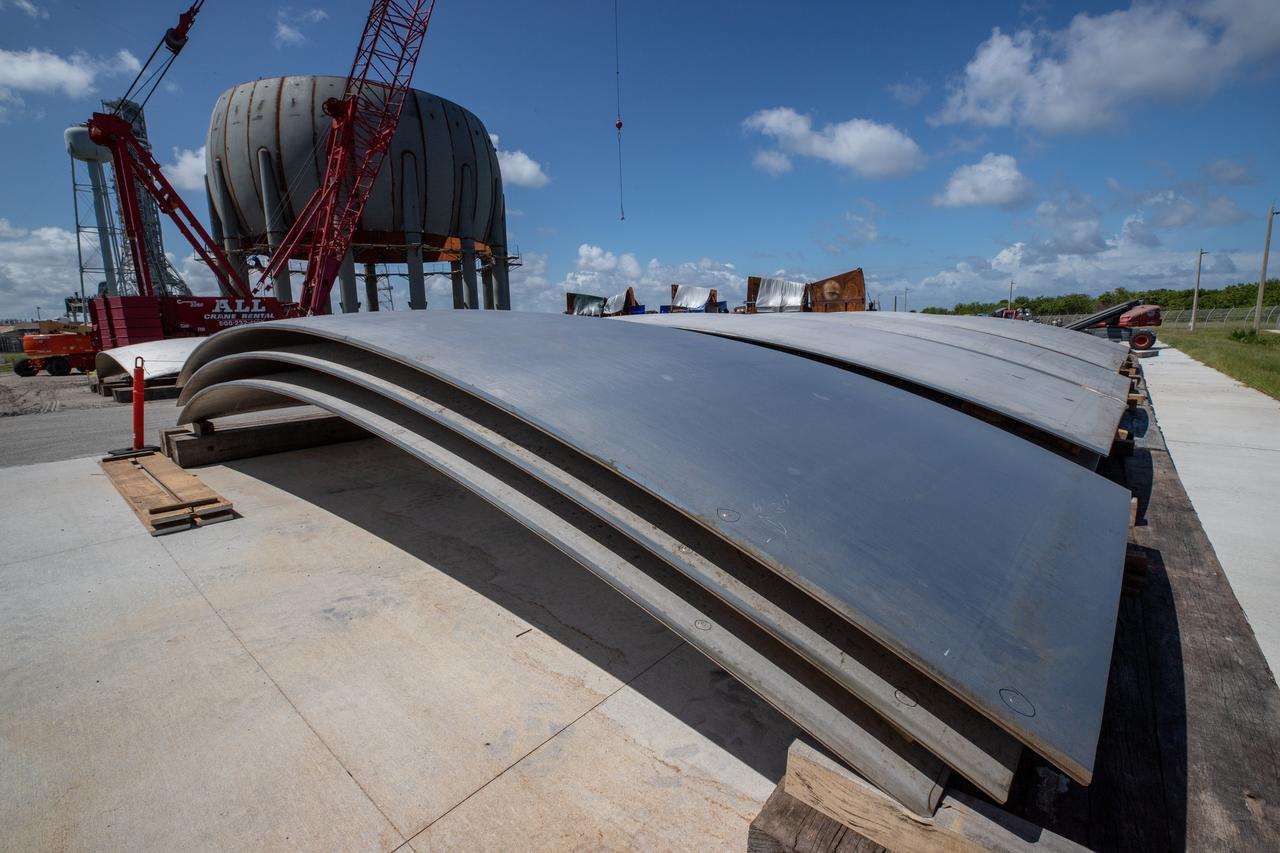

Build-up of a new liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank is in progress on Oct. 1, 2019, at Launch Complex 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The new tank will hold 1.25 million gallons of usable LH2 to support future launches from the pad, including Artemis missions to the Moon and on to Mars.

Build-up of a new liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank is in progress on Oct. 1, 2019, at Launch Complex 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The new tank will hold 1.25 million gallons of usable LH2 to support future launches from the pad, including Artemis missions to the Moon and on to Mars.

Build-up of a new liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank is in progress on Oct. 1, 2019, at Launch Complex 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The new tank will hold 1.25 million gallons of usable LH2 to support future launches from the pad, including Artemis missions to the Moon and on to Mars.

Build-up of a new liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank is in progress on Oct. 1, 2019, at Launch Complex 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The new tank will hold 1.25 million gallons of usable LH2 to support future launches from the pad, including Artemis missions to the Moon and on to Mars.

Build-up of a new liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank is in progress on Oct. 1, 2019, at Launch Complex 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The new tank will hold 1.25 million gallons of usable LH2 to support future launches from the pad, including Artemis missions to the Moon and on to Mars.

Build-up of a new liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank is in progress on Oct. 1, 2019, at Launch Complex 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The new tank will hold 1.25 million gallons of usable LH2 to support future launches from the pad, including Artemis missions to the Moon and on to Mars.

Build-up of a new liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank is in progress on Oct. 1, 2019, at Launch Complex 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The new tank will hold 1.25 million gallons of usable LH2 to support future launches from the pad, including Artemis missions to the Moon and on to Mars.

Build-up of a new liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank is in progress on Oct. 1, 2019, at Launch Complex 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The new tank will hold 1.25 million gallons of usable LH2 to support future launches from the pad, including Artemis missions to the Moon and on to Mars.

Move Crews at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans transport a liquid oxygen tank from a detached production building to the main 43-acre rocket factory on Mar. 26. Teams recently completed primer application on the tank, which will be used on the core stage of the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for its Artemis III mission. The tank will now undergo electrical installations before moving on to the next phase of production. The propellant tank is one of five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis.

Move Crews at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans transport a liquid oxygen tank from a detached production building to the main 43-acre rocket factory on Mar. 26. Teams recently completed primer application on the tank, which will be used on the core stage of the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for its Artemis III mission. The tank will now undergo electrical installations before moving on to the next phase of production. The propellant tank is one of five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis.

The core stage liquid hydrogen tank for the Artemis III mission completed proof testing, and technicians returned it to the main factory building at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans where it will undergo more outfitting. As part of proof testing, technicians apply a simple soap solution and check for leaks by observing any bubble formation on the welds. The technician removed the bubble solution with distilled water and then dried the area of application to prevent corrosion. To build the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket’s 130-foot core stage liquid hydrogen tank, engineers use robotic tools to weld five-barrel segments. This process results in a tank with around 1,900 feet, or more than six football fields, of welds that must be tested by hand. After the leak tests, the core stage lead, Boeing, pressurized the SLS tank to further ensure there were no leaks. After it passed proof testing, technicians moved the Artemis III liquid hydrogen tank to Michoud’s main factory. Soon, the technicians will prime and apply a foam-based thermal protection system that protects the tank during launch. Later, the tank will be joined with other parts of the core stage to form the entire 212-foot rocket stage with its four RS-25 engines that produce 2 million pounds of thrust to help launch the rocket. Artemis III will land the first astronauts on the lunar surface.

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The tank will be lifted and rotated for delivery to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The tank will be lifted and rotated for delivery to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The tank will be lifted and rotated for delivery to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A crane will be used to lift and rotate the tank for delivery to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A crane will be used to lift and rotate the tank for delivery to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

Seen here is a newly constructed liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank at Launch Pad 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Oct. 1, 2021. With construction now complete, teams will focus on painting the tank next. The storage tank, capable of holding 1.25 million gallons of LH2, will be used to support future Artemis missions to the Moon and, eventually, Mars. Through Artemis, NASA will land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon, paving the way for a long-term presence in lunar orbit.

Seen here is a newly constructed liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank at Launch Pad 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Oct. 1, 2021. With construction now complete, teams will focus on painting the tank next. The storage tank, capable of holding 1.25 million gallons of LH2, will be used to support future Artemis missions to the Moon and, eventually, Mars. Through Artemis, NASA will land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon, paving the way for a long-term presence in lunar orbit.

Seen here is a newly constructed liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank at Launch Pad 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Oct. 1, 2021. With construction now complete, teams will focus on painting the tank next. The storage tank, capable of holding 1.25 million gallons of LH2, will be used to support future Artemis missions to the Moon and, eventually, Mars. Through Artemis, NASA will land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon, paving the way for a long-term presence in lunar orbit.

Seen here is a newly constructed liquid hydrogen (LH2) storage tank at Launch Pad 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Oct. 1, 2021. With construction now complete, teams will focus on painting the tank next. The storage tank, capable of holding 1.25 million gallons of LH2, will be used to support future Artemis missions to the Moon and, eventually, Mars. Through Artemis, NASA will land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon, paving the way for a long-term presence in lunar orbit.

Workers install a bulk diesel storage tank for use at Stennis Space Center. Installation of additional diesel storage tanks is part of the center's hurricane-related risk mitigation work.

Photo shows how the Space Launch Sysetm (SLS) rocket liquid oxygen tank failed during a structural qualification test at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The photos show both the water flowing from the tank as it ruptured and the resultant tear left in the tank when it buckled during the test. Engineers pushed the liquid oxygen structural test article to the limits on purpose. The tank is a test article that is identical to tanks that are part of the SLS core stage that will produce 2 million pounds of thrust to help launch the rocket on the Artemis missions to the Moon. During the test, hydraulic cylinders were then calibrated and positioned along the tank to apply millions of pounds of crippling force from all sides while engineers measured and recorded the effects of the launch and flight forces. For the test, water used to simulate the liquid oxygen flows out of the tank after it ruptures. The structural test campaign was conducted on the rocket to ensure the SLS rocket’s structure can endure the rigors of launch and safely send astronauts to the Moon on the Artemis missions. For more information: https://www.nasa.gov/exploration/systems/sls/nasa-completes-artemis-sls-structural-testing-campaign.html

Move Crews at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans transport a liquid oxygen tank from a detached production building to the main 43-acre rocket factory on Mar. 26. Teams recently completed primer application on the tank, which will be used on the core stage of the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for its Artemis III mission. The tank will now undergo electrical installations before moving on to the next phase of production. The propellant tank is one of five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis.

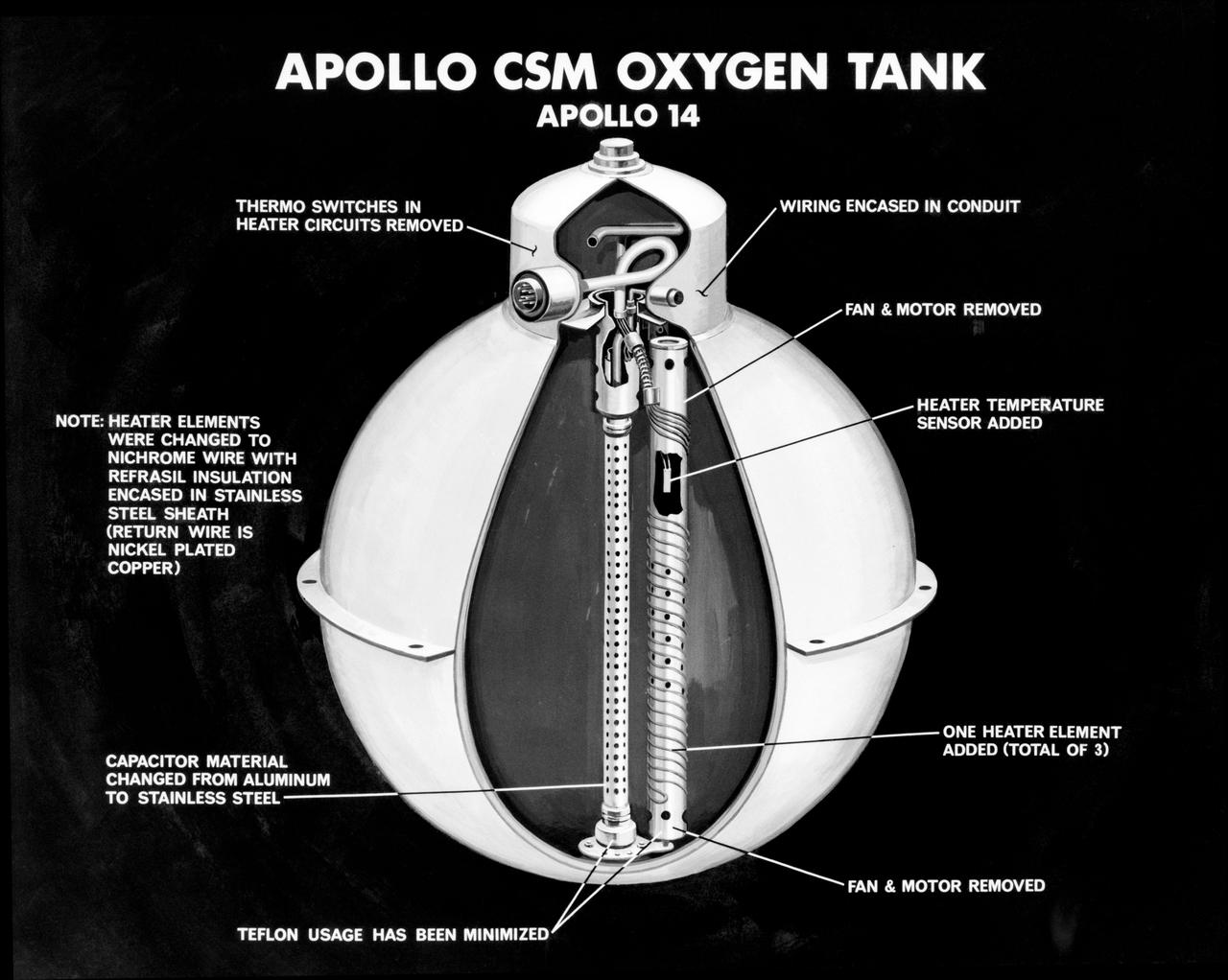

S71-16745 (January 1971) --- An artist's concept illustrating a cutaway view of one of the three oxygen tanks of the Apollo 14 spacecraft. This is the new Apollo oxygen tank design, developed since the Apollo 13 oxygen tank explosion. Apollo 14 has three oxygen tanks redesigned to eliminate ignition sources, minimize the use of combustible materials, and simplify the fabrication process. The third tank has been added to the Apollo 14 Service Module, located in the SM's sector one, apart from the pair of oxygen tanks in sector four. Arrows point out various features of the oxygen tank.

A water tank is lifted into place at the A-3 Test Stand being built at NASA's John C. Stennis Space Center. Fourteen water, liquid oxygen (LOX) and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) tanks are being installed to support the chemical steam generators to be used on the A-3 Test Stand. The IPA and LOX tanks will provide fuel for the generators. The water will allow the generators to produce steam that will be used to reduce pressure inside the stand's test cell diffuser, enabling operators to simulate altitudes up to 100,000 feet. In that way, operators can perform the tests needed on rocket engines being built to carry humans back to the moon and possibly beyond. The A-3 Test Stand is set for completion and activation in 2011.

A water tank is lifted into place at the A-3 Test Stand being built at NASA's John C. Stennis Space Center. Fourteen water, liquid oxygen (LOX) and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) tanks are being installed to support the chemical steam generators to be used on the A-3 Test Stand. The IPA and LOX tanks will provide fuel for the generators. The water will allow the generators to produce steam that will be used to reduce pressure inside the stand's test cell diffuser, enabling operators to simulate altitudes up to 100,000 feet. In that way, operators can perform the tests needed on rocket engines being built to carry humans back to the moon and possibly beyond. The A-3 Test Stand is set for completion and activation in 2011.

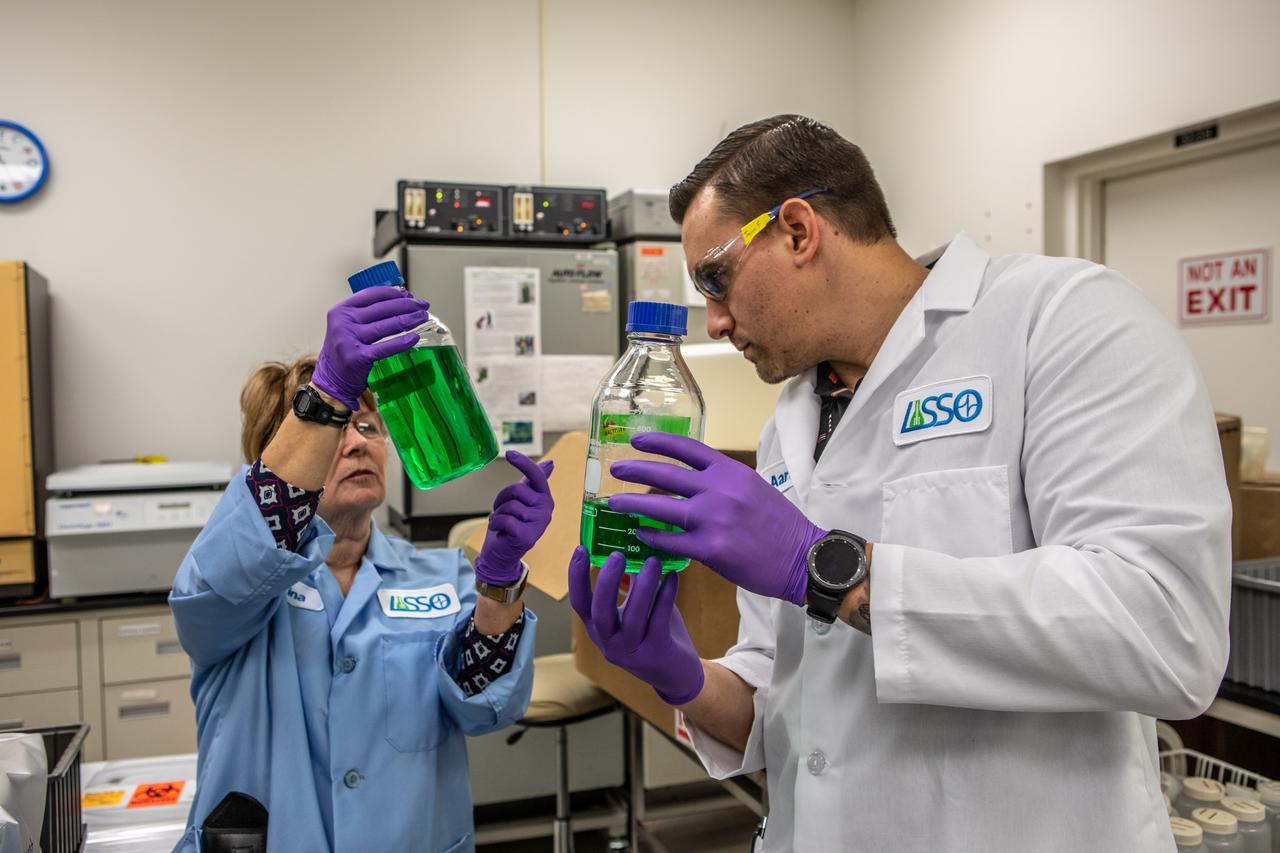

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., conducts a biological study on two tanks of water, filled with green dye, in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. The tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

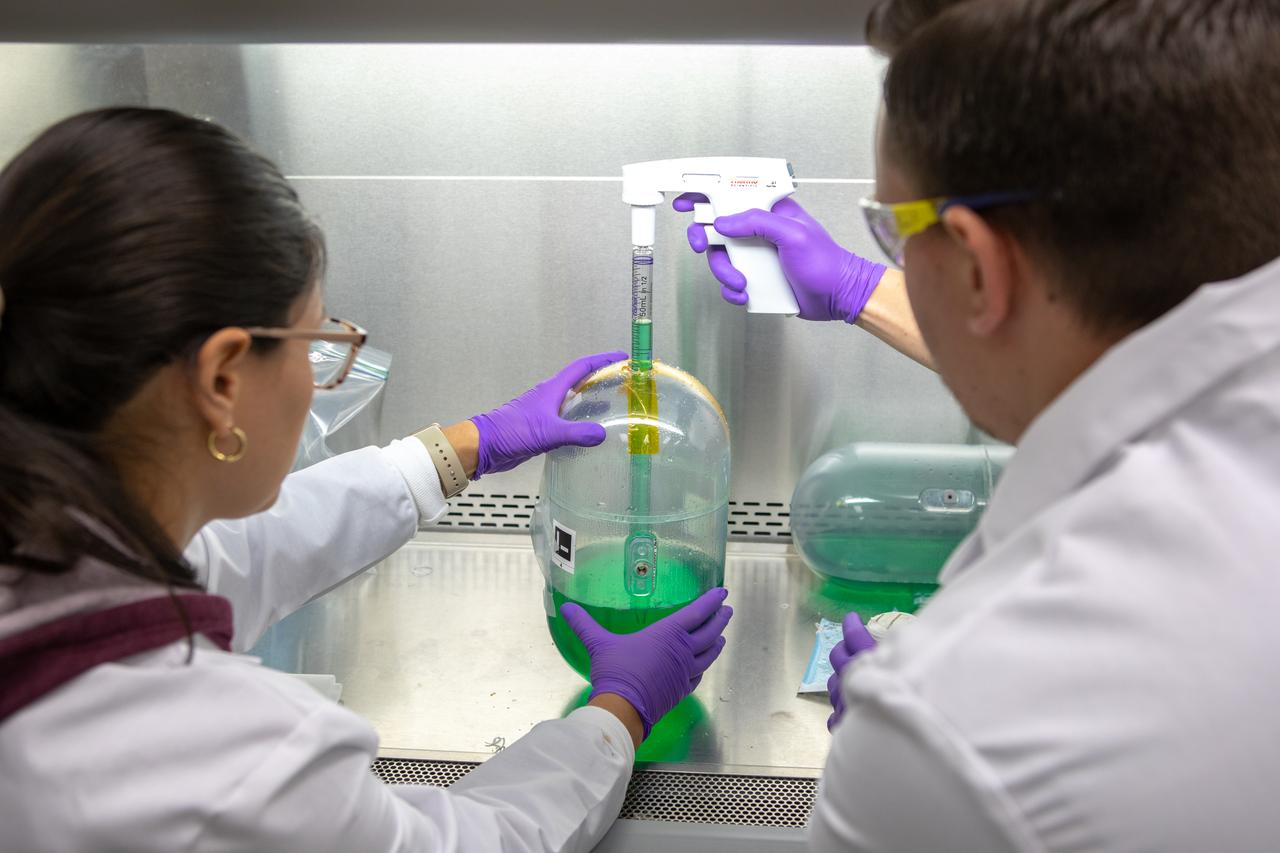

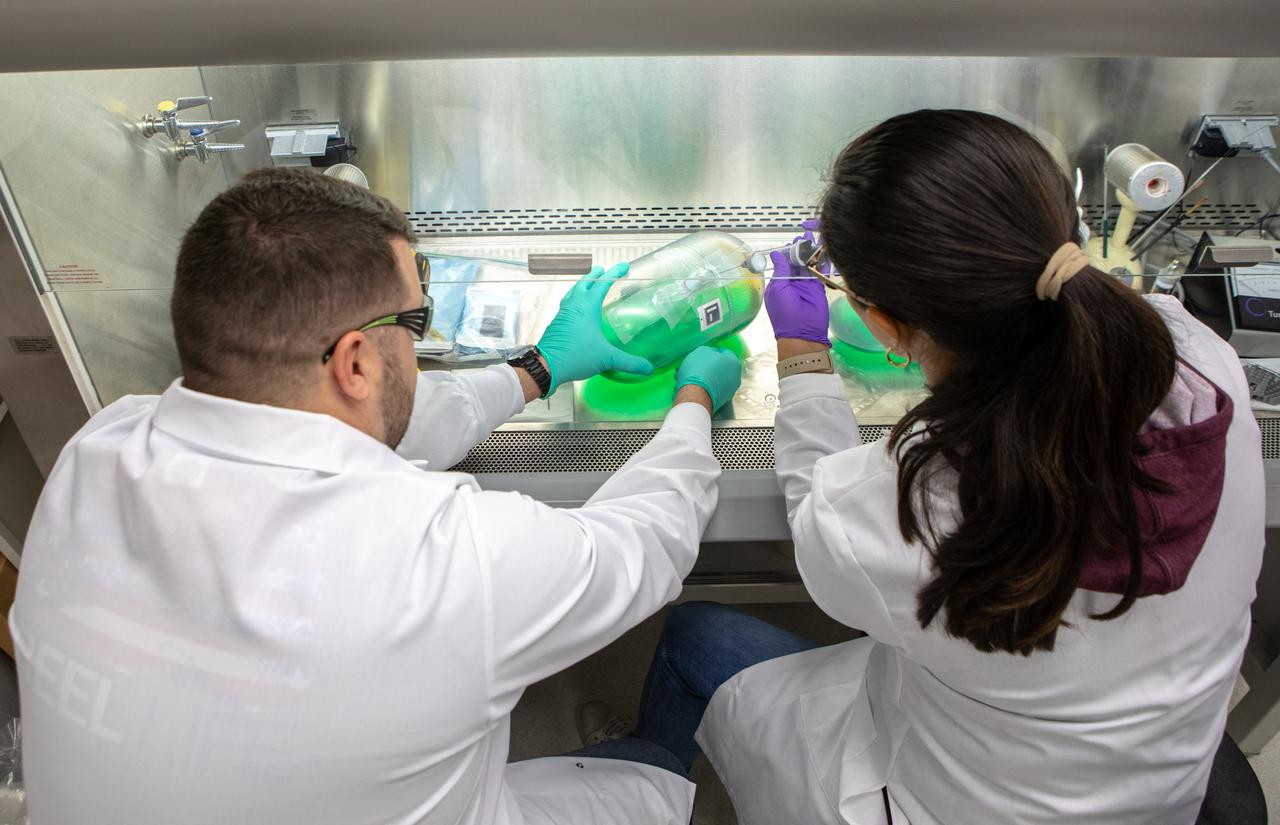

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., left, and Jason Fischer collect samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

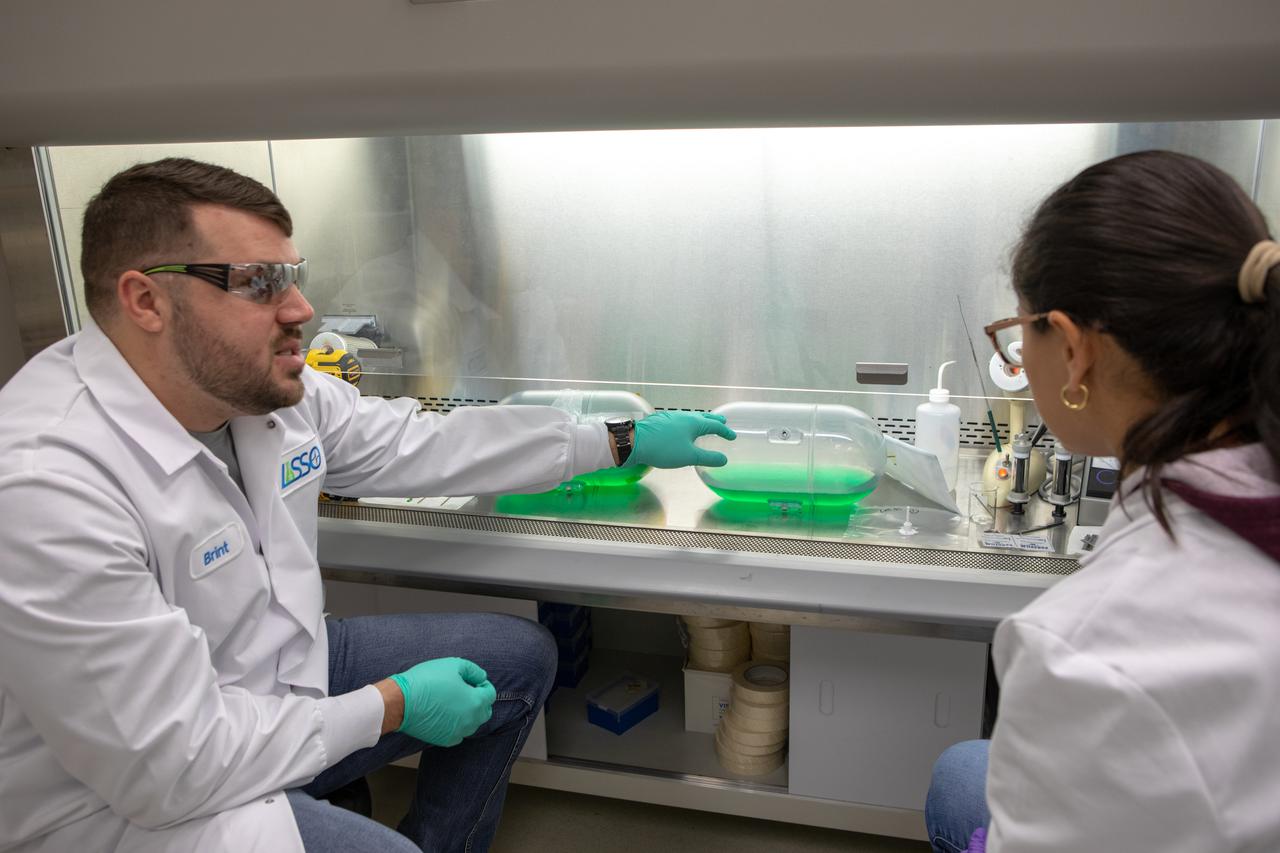

Kennedy Space Center’s Brint Bauer drills into a water tank, filled with green dye, in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

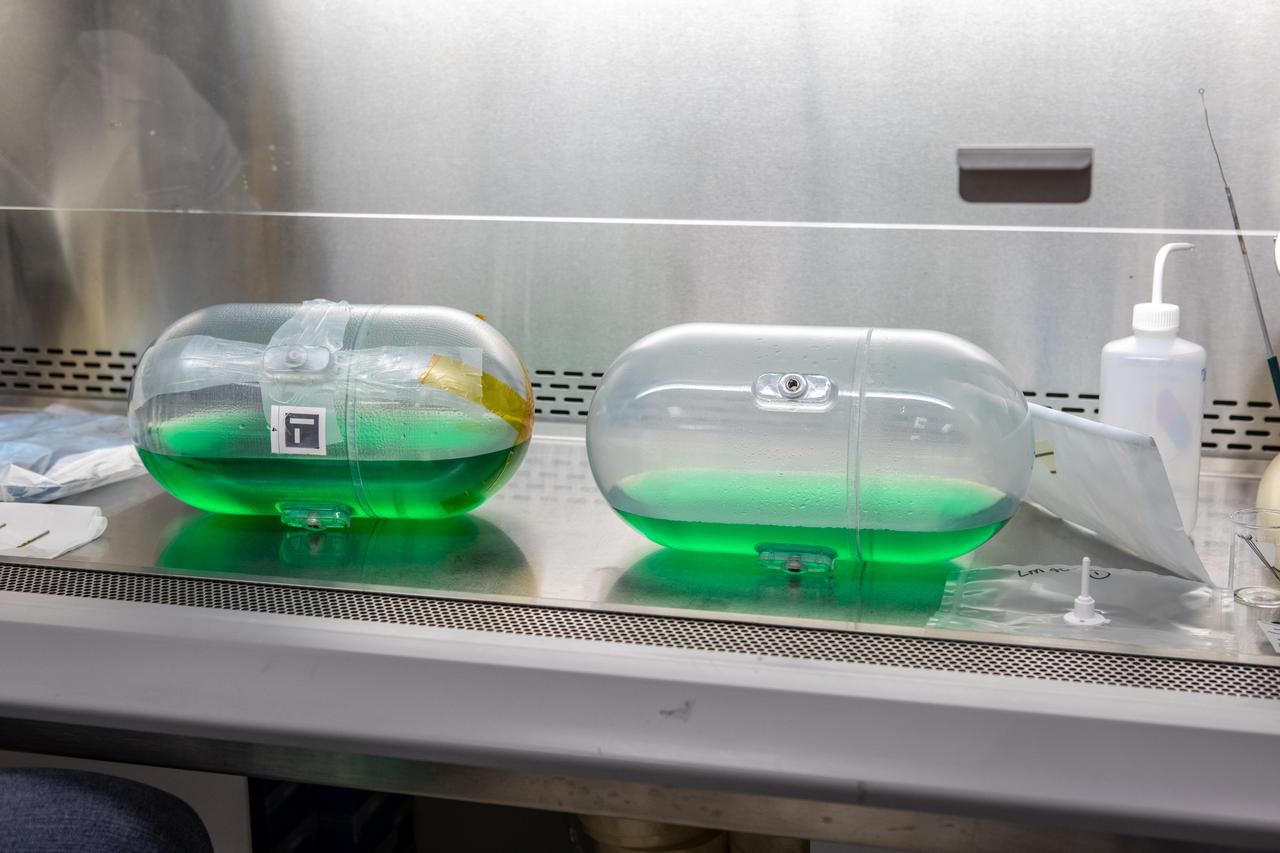

Kennedy Space Center’s Brint Bauer, left, and Carolina Franco, Ph.D., conduct a biological study on two tanks of water, filled with green dye, in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. The tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

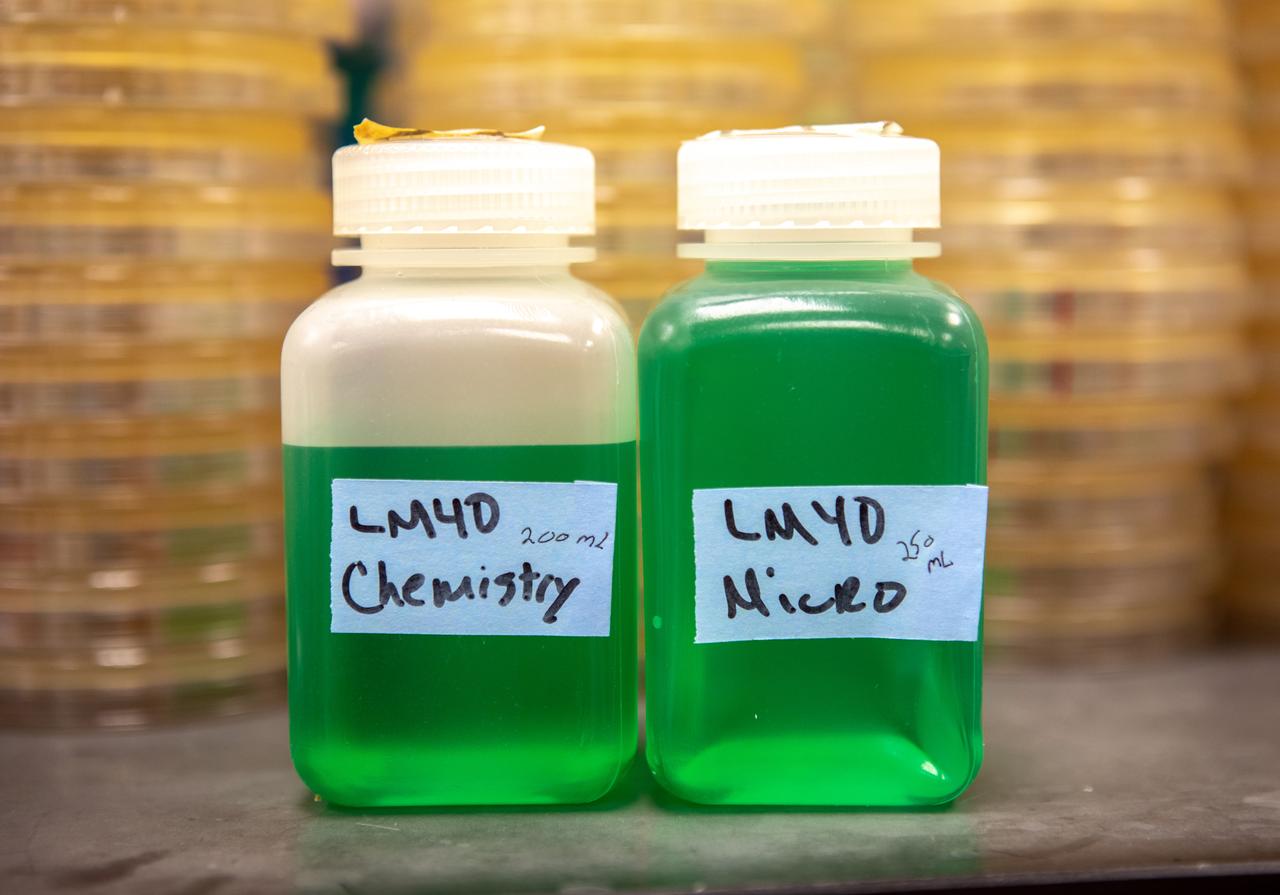

Samples of water, filled with green dye, gathered from two water tanks that have spent the past five years in space, are photographed inside the Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Nov. 13, 2019. The tanks were first sent to the International Space Station in 2014 to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded and the tanks recently returned to Kennedy, they are being utilized for a biological study to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

A Kennedy Space Center employee collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

A Kennedy Space Center employee collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, the tanks are being utilized to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

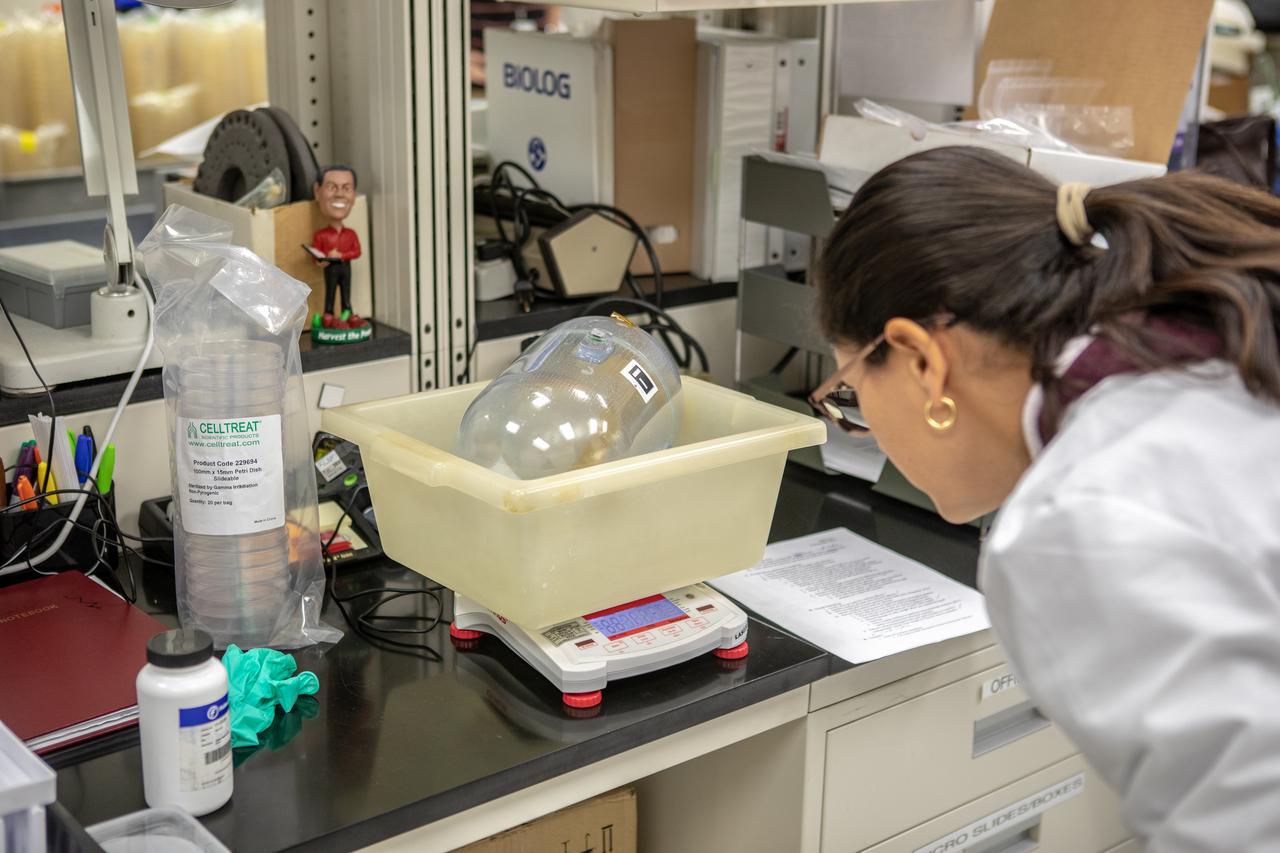

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., weighs one of the water tanks, recently returned to the center after remaining on the International Space Station for the past five years, in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks containing water were first sent to the orbiting laboratory in 2014 to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., left, and Jason Fischer collect samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

A Kennedy Space Center employee collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Brint Bauer, left, and Carolina Franco, Ph.D., collect samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Researchers from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center Air and Water Revitalization lab are studying two tanks, containing water with green dye, inside the Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building in Florida on Nov. 13, 2019. The tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after remaining on the International Space Station for the past five years, originally sent to space to study slosh – the movement of water – in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, the tanks are being examined to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Jason Fischer collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Carolina Franco, Ph.D., collects samples from a water tank, filled with green dye, for a biological study in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. With the slosh experiment now concluded, Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Christina Khodadad, Ph.D., left, and Jason Fischer hold samples of water in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks of water have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Kennedy Space Center’s Jason Fischer holds a sample of water in the Florida spaceport’s Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout Building on Nov. 13, 2019. Two tanks of water have recently returned to Kennedy after spending the last five years on the International Space Station for an experiment to study slosh, or the movement of water, in a zero-gravity environment to help engineers predict the movement of propellant in rocket tanks. Kennedy’s Air and Water Revitalization lab is studying the water tanks to determine if there is, or was, any microbial growth within them. The results will help NASA determine whether clean water can be stored in space for long-duration missions, an essential component to keeping astronauts safe and healthy as the agency prepares for missions to the Moon and beyond to Mars.

Technicians prepare to unpack and inspect a Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

Technicians unpack and inspect a Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

Technicians unpack and inspect a Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

A Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank is unpacked and readied for inspection inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

Technicians unpack and inspect a Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

Technicians unpack and inspect a Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

Technicians unpack and inspect a Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

Technicians unpack and inspect a Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

A technicians inspects a Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

Technicians unpack and inspect a Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

A Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank is unpacked and readied for inspection inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

Technicians unpack and inspect a Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

A Nitrogen/Oxygen Recharge System (NORS) tank is unpacked and readied for inspection inside the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 2020. The NORS tanks and their support fixtures are designed to connect to the International Space Station’s existing air supply network to refill the previous generation of tanks installed during construction of the space station. These reusable tanks measure 3 feet long and 21 inches in diameter, and weigh about 200 pounds when filled. Once onboard, the tanks will be used to fill the oxygen and nitrogen tanks that supply the needed gases to the space station’s airlock for spacewalks. They could also be used to replenish the atmosphere inside the station. The NORS tanks will launch to the station later in the year on a commercial resupply mission.

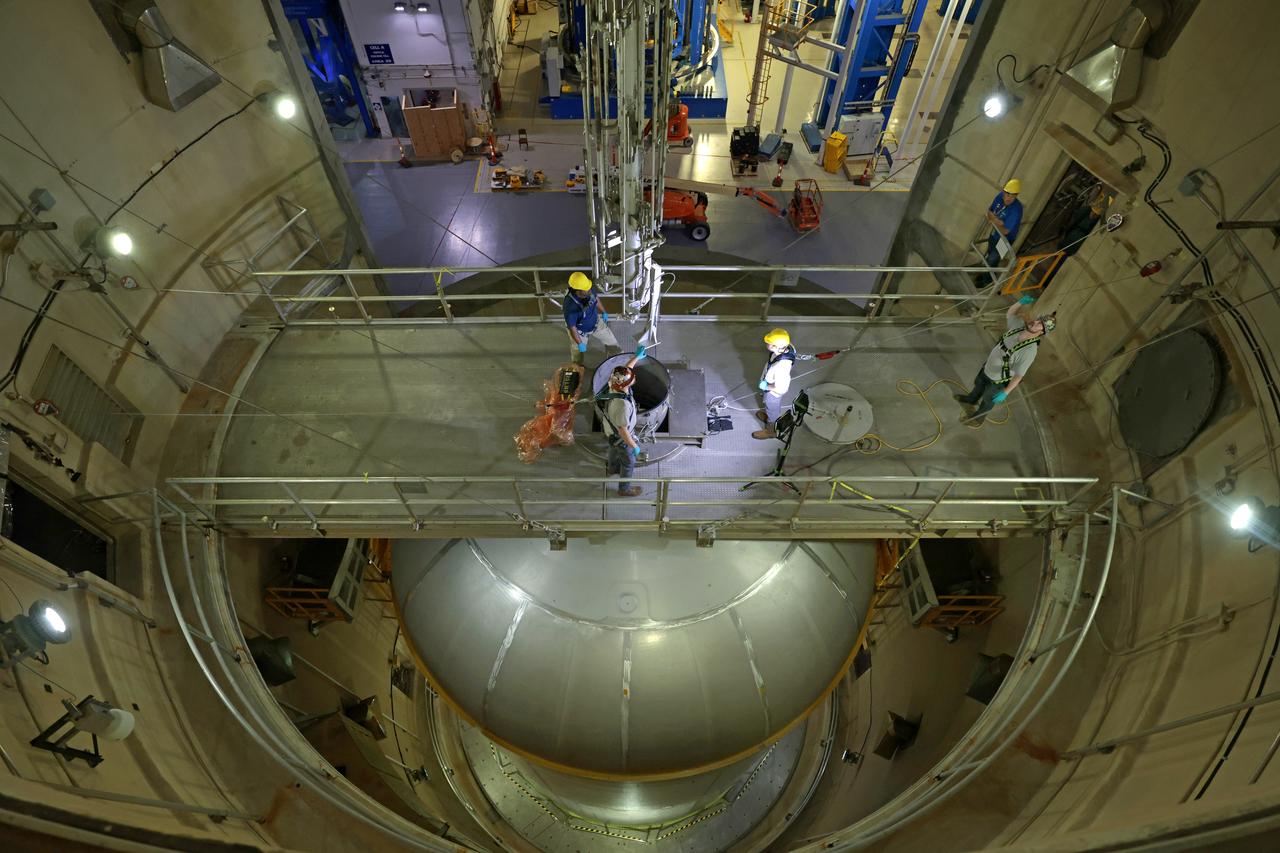

Teams at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans lift the 130-foot-tall liquid hydrogen tank off the vertical assembly center on Nov. 14. This is the fourth liquid hydrogen tank manufactured at the facility for the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket. The completed tank will be loaded into a production cell for technicians to remove the lift tool, perform dimensional scans, and then install brackets, which will allow the move crew to break the tank over from a vertical to a horizontal configuration.

Teams at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans lift the 130-foot-tall liquid hydrogen tank off the vertical assembly center on Nov. 14. This is the fourth liquid hydrogen tank manufactured at the facility for the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket. The completed tank will be loaded into a production cell for technicians to remove the lift tool, perform dimensional scans, and then install brackets, which will allow the move crew to break the tank over from a vertical to a horizontal configuration.

These photos show how teams moved and prepared a liquid hydrogen tank for the SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for priming in the Vertical Assembly Building at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans Nov. 14, 2023. The hardware will form part of the core stage for the SLS rocket that will power Artemis III. To prepare the flight hardware for primer, the tank underwent internal cleaning in nearby Cell E in October. Internal cleaning is part of the manufacturing process for the core stage. After testing, both of the stage’s propellant tanks and its dry structures – the elements that do not hold fuel – are cleaned, primed, and readied for the next phase of production Technichians will next sand down and prepare the surface of the tank before coating it in a primer. Primer is applied to the barrel section of the tank by an automated robotic tool, whereas the forward and aft domes are primed manually. The propellant tank is the largest of the five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall Moon rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

These photos show how teams moved and prepared a liquid hydrogen tank for the SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for priming in the Vertical Assembly Building at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans Nov. 14, 2023. The hardware will form part of the core stage for the SLS rocket that will power Artemis III. To prepare the flight hardware for primer, the tank underwent internal cleaning in nearby Cell E in October. Internal cleaning is part of the manufacturing process for the core stage. After testing, both of the stage’s propellant tanks and its dry structures – the elements that do not hold fuel – are cleaned, primed, and readied for the next phase of production Technichians will next sand down and prepare the surface of the tank before coating it in a primer. Primer is applied to the barrel section of the tank by an automated robotic tool, whereas the forward and aft domes are primed manually. The propellant tank is the largest of the five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall Moon rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

These photos show how teams moved and prepared a liquid hydrogen tank for the SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for priming in the Vertical Assembly Building at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans Nov. 14, 2023. The hardware will form part of the core stage for the SLS rocket that will power Artemis III. To prepare the flight hardware for primer, the tank underwent internal cleaning in nearby Cell E in October. Internal cleaning is part of the manufacturing process for the core stage. After testing, both of the stage’s propellant tanks and its dry structures – the elements that do not hold fuel – are cleaned, primed, and readied for the next phase of production Technichians will next sand down and prepare the surface of the tank before coating it in a primer. Primer is applied to the barrel section of the tank by an automated robotic tool, whereas the forward and aft domes are primed manually. The propellant tank is the largest of the five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall Moon rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

These photos show how teams moved and prepared a liquid hydrogen tank for the SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for priming in the Vertical Assembly Building at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans Nov. 14, 2023. The hardware will form part of the core stage for the SLS rocket that will power Artemis III. To prepare the flight hardware for primer, the tank underwent internal cleaning in nearby Cell E in October. Internal cleaning is part of the manufacturing process for the core stage. After testing, both of the stage’s propellant tanks and its dry structures – the elements that do not hold fuel – are cleaned, primed, and readied for the next phase of production Technichians will next sand down and prepare the surface of the tank before coating it in a primer. Primer is applied to the barrel section of the tank by an automated robotic tool, whereas the forward and aft domes are primed manually. The propellant tank is the largest of the five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall Moon rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

Teams at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans install wash probes into a liquid oxygen tank inside the factory’s cleaning cell on Oct. 25. The tank, which will be used on the core stage of the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for its Artemis III mission, will undergo an internal cleaning before moving on to its next phase of production. Inside the cleaning cell, a solution is sprayed into the tank to remove particulates which may collect during the manufacturing process. Once a tank is cleaned, teams use mobile clean rooms for internal access to the tank to prevent external contaminates from entering the hardware. The propellant tank is one of five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

Teams at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans install wash probes into a liquid oxygen tank inside the factory’s cleaning cell on Oct. 25. The tank, which will be used on the core stage of the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for its Artemis III mission, will undergo an internal cleaning before moving on to its next phase of production. Inside the cleaning cell, a solution is sprayed into the tank to remove particulates which may collect during the manufacturing process. Once a tank is cleaned, teams use mobile clean rooms for internal access to the tank to prevent external contaminates from entering the hardware. The propellant tank is one of five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

Teams at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans install wash probes into a liquid oxygen tank inside the factory’s cleaning cell on Oct. 25. The tank, which will be used on the core stage of the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for its Artemis III mission, will undergo an internal cleaning before moving on to its next phase of production. Inside the cleaning cell, a solution is sprayed into the tank to remove particulates which may collect during the manufacturing process. Once a tank is cleaned, teams use mobile clean rooms for internal access to the tank to prevent external contaminates from entering the hardware. The propellant tank is one of five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

Teams at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans install wash probes into a liquid oxygen tank inside the factory’s cleaning cell on Oct. 25. The tank, which will be used on the core stage of the agency’s SLS (Space Launch System) rocket for its Artemis III mission, will undergo an internal cleaning before moving on to its next phase of production. Inside the cleaning cell, a solution is sprayed into the tank to remove particulates which may collect during the manufacturing process. Once a tank is cleaned, teams use mobile clean rooms for internal access to the tank to prevent external contaminates from entering the hardware. The propellant tank is one of five major elements that make up the 212-foot-tall rocket stage. The core stage, along with its four RS-25 engines, produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit and to the lunar surface for Artemis. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

The liquid hydrogen tank that will be part of the Space Launch System rocket’s core stage is being prepared for the Artemis III mission at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. Eventually, the tank will be connected to the engine section that will house the four RS-25 engines. Once the aft simulator is attached, the LH2 tank undergoes non-destructive evaluation, which will test weld strength and ensure the tank is structurally sound. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The tank holds 537,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen cooled to minus 432 degrees Fahrenheit and sits between the core stage’s intertank and engine section. The liquid hydrogen hardware, along with the liquid oxygen tank, will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines at the bottom of the core stage to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch the Artemis III mission to the Moon. Together with its four RS-25 engines, the rocket’s massive 212-foot-tall core stage — the largest stage NASA has ever built — and its twin solid rocket boosters will produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust to send NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon.

Photo shows how the Space Launch Sysetm (SLS) rocket liquid oxygen tank failed during a structural qualification test at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The photos show both the water flowing from the tank as it ruptured and the resultant tear left in the tank when it buckled during the test. Engineers pushed the liquid oxygen structural test article to the limits on purpose. The tank is a test article that is identical to tanks that are part of the SLS core stage that will produce 2 million pounds of thrust to help launch the rocket on the Artemis missions to the Moon. During the test, hydraulic cylinders were then calibrated and positioned along the tank to apply millions of pounds of crippling force from all sides while engineers measured and recorded the effects of the launch and flight forces. For the test, water used to simulate the liquid oxygen flows out of the tank after it ruptures. The structural test campaign was conducted on the rocket to ensure the SLS rocket’s structure can endure the rigors of launch and safely send astronauts to the Moon on the Artemis missions. For more information: https://www.nasa.gov/exploration/systems/sls/nasa-completes-artemis-sls-structural-testing-campaign.html

Photo shows how the Space Launch Sysetm (SLS) rocket liquid oxygen tank failed during a structural qualification test at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The photos show both the water flowing from the tank as it ruptured and the resultant tear left in the tank when it buckled during the test. Engineers pushed the liquid oxygen structural test article to the limits on purpose. The tank is a test article that is identical to tanks that are part of the SLS core stage that will produce 2 million pounds of thrust to help launch the rocket on the Artemis missions to the Moon. During the test, hydraulic cylinders were then calibrated and positioned along the tank to apply millions of pounds of crippling force from all sides while engineers measured and recorded the effects of the launch and flight forces. For the test, water used to simulate the liquid oxygen flows out of the tank after it ruptures. The structural test campaign was conducted on the rocket to ensure the SLS rocket’s structure can endure the rigors of launch and safely send astronauts to the Moon on the Artemis missions. For more information: https://www.nasa.gov/exploration/systems/sls/nasa-completes-artemis-sls-structural-testing-campaign.html

Photo shows how the Space Launch Sysetm (SLS) rocket liquid oxygen tank failed during a structural qualification test at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The photos show both the water flowing from the tank as it ruptured and the resultant tear left in the tank when it buckled during the test. Engineers pushed the liquid oxygen structural test article to the limits on purpose. The tank is a test article that is identical to tanks that are part of the SLS core stage that will produce 2 million pounds of thrust to help launch the rocket on the Artemis missions to the Moon. During the test, hydraulic cylinders were then calibrated and positioned along the tank to apply millions of pounds of crippling force from all sides while engineers measured and recorded the effects of the launch and flight forces. For the test, water used to simulate the liquid oxygen flows out of the tank after it ruptures. The structural test campaign was conducted on the rocket to ensure the SLS rocket’s structure can endure the rigors of launch and safely send astronauts to the Moon on the Artemis missions. For more information: https://www.nasa.gov/exploration/systems/sls/nasa-completes-artemis-sls-structural-testing-campaign.html

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A crane is used to lift the tank and rotate it before it is delivered to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The tank has been lifted and rotated by crane and lowered back onto the flatbed truck for transport to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A crane is used to lift and rotate the tank before delivery to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Construction workers check lines as a crane is attached to the tank to lift and rotate it before it is delivered to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A crane has been attached to the tank to lift and rotate it before it is delivered to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

A new liquid hydrogen separator tank arrives at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A crane is used to lift and rotate the tank before it is delivered to Launch Pad 39B. The new separator/storage tank will be added to the pad's existing hydrogen vent system to assure gaseous hydrogen is delivered downstream to the flare stack. The 60,000 gallon tank was built by INOXCVA, in Baytown, Texas, a subcontractor of Precision Mechanical Inc. in Cocoa Florida. The new tank will support all future launches from the pad.

On Thursday, February 10, 2022, move crews at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility lift the core stage 3 liquid oxygen tank (LOX) aft barrel out of the vertical friction stir weld tool to be moved for its next phase of production. Eventually, the aft barrel will be mated with the forward barrel and forward and aft domes to create the LOX tank, which will be used for the Space Launch System’s Artemis III mission. The LOX tank holds 196,000 gallons of super-cooled liquid oxygen to help fuel four RS-25 engines. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The liquid oxygen hardware, along with the liquid hydrogen tank will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

On Thursday, February 10, 2022, move crews at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility lift the core stage 3 liquid oxygen tank (LOX) aft barrel out of the vertical friction stir weld tool to be moved for its next phase of production. Eventually, the aft barrel will be mated with the forward barrel and forward and aft domes to create the LOX tank, which will be used for the Space Launch System’s Artemis III mission. The LOX tank holds 196,000 gallons of super-cooled liquid oxygen to help fuel four RS-25 engines. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The liquid oxygen hardware, along with the liquid hydrogen tank will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

On Thursday, February 10, 2022, move crews at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility lift the core stage 3 liquid oxygen tank (LOX) aft barrel out of the vertical friction stir weld tool to be moved for its next phase of production. Eventually, the aft barrel will be mated with the forward barrel and forward and aft domes to create the LOX tank, which will be used for the Space Launch System’s Artemis III mission. The LOX tank holds 196,000 gallons of super-cooled liquid oxygen to help fuel four RS-25 engines. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The liquid oxygen hardware, along with the liquid hydrogen tank will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

On Thursday, February 10, 2022, move crews at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility lift the core stage 3 liquid oxygen tank (LOX) aft barrel out of the vertical friction stir weld tool to be moved for its next phase of production. Eventually, the aft barrel will be mated with the forward barrel and forward and aft domes to create the LOX tank, which will be used for the Space Launch System’s Artemis III mission. The LOX tank holds 196,000 gallons of super-cooled liquid oxygen to help fuel four RS-25 engines. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The liquid oxygen hardware, along with the liquid hydrogen tank will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker

On Thursday, February 10, 2022, move crews at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility lift the core stage 3 liquid oxygen tank (LOX) aft barrel out of the vertical friction stir weld tool to be moved for its next phase of production. Eventually, the aft barrel will be mated with the forward barrel and forward and aft domes to create the LOX tank, which will be used for the Space Launch System’s Artemis III mission. The LOX tank holds 196,000 gallons of super-cooled liquid oxygen to help fuel four RS-25 engines. The SLS core stage is made up of five unique elements: the forward skirt, liquid oxygen tank, intertank, liquid hydrogen tank, and the engine section. The liquid oxygen hardware, along with the liquid hydrogen tank will provide propellant to the four RS-25 engines to produce more than two million pounds of thrust to help launch NASA’s Orion spacecraft, astronauts, and supplies beyond Earth’s orbit to the Moon. Image credit: NASA/Michael DeMocker