Valles Marineris

Valles Marineris

Valles Marineris Wall Rock

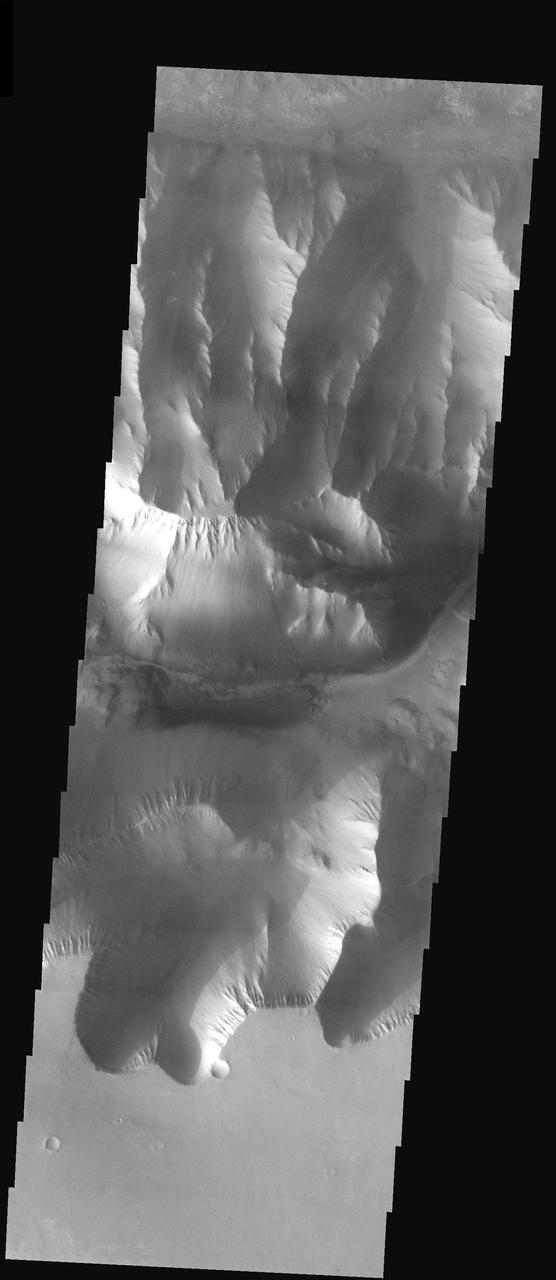

Valles Marineris Landforms

Valles Marineris Features

Valles Marineris Graben

Valles Marineris Mosaic

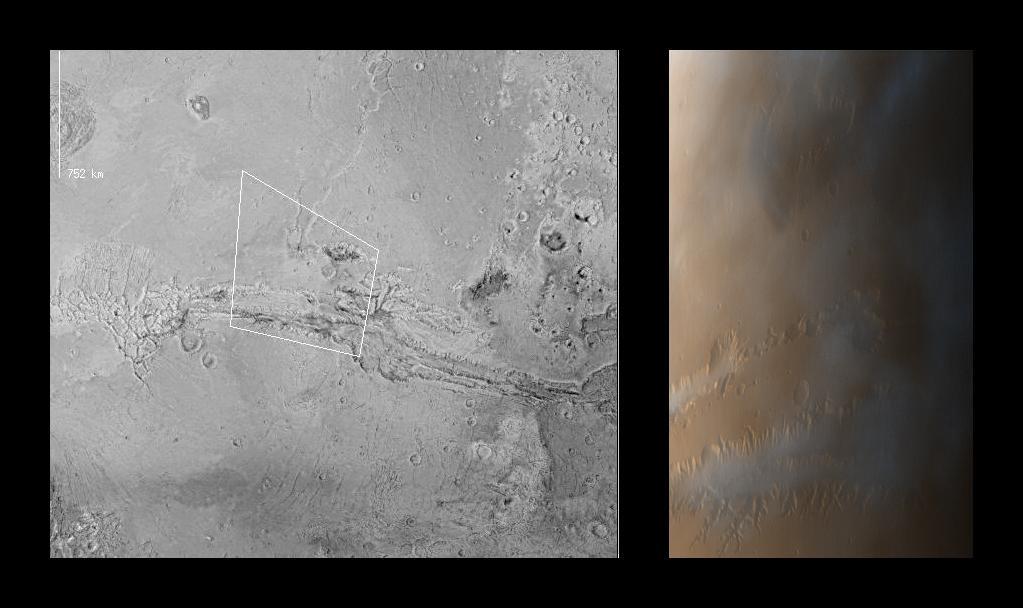

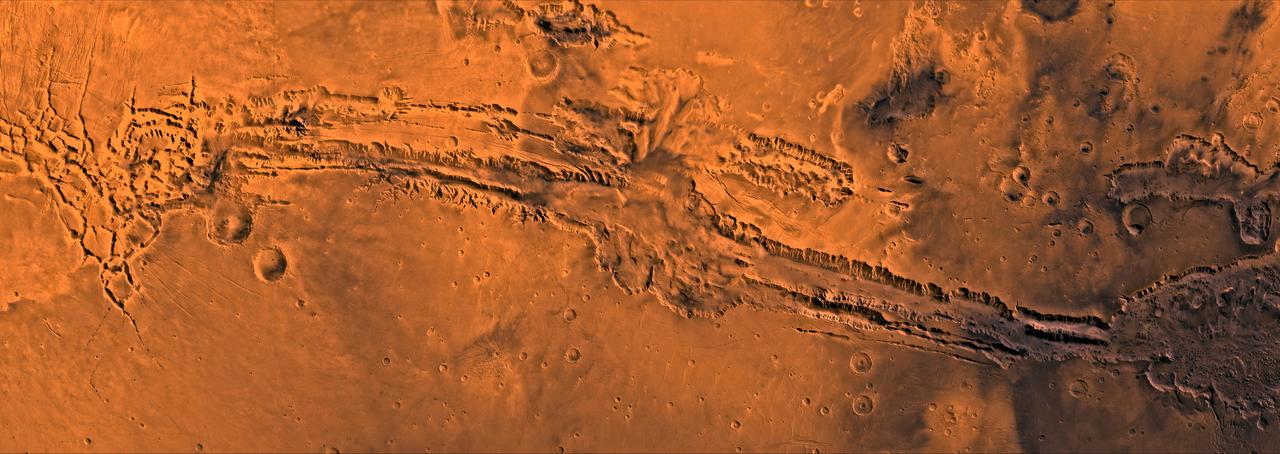

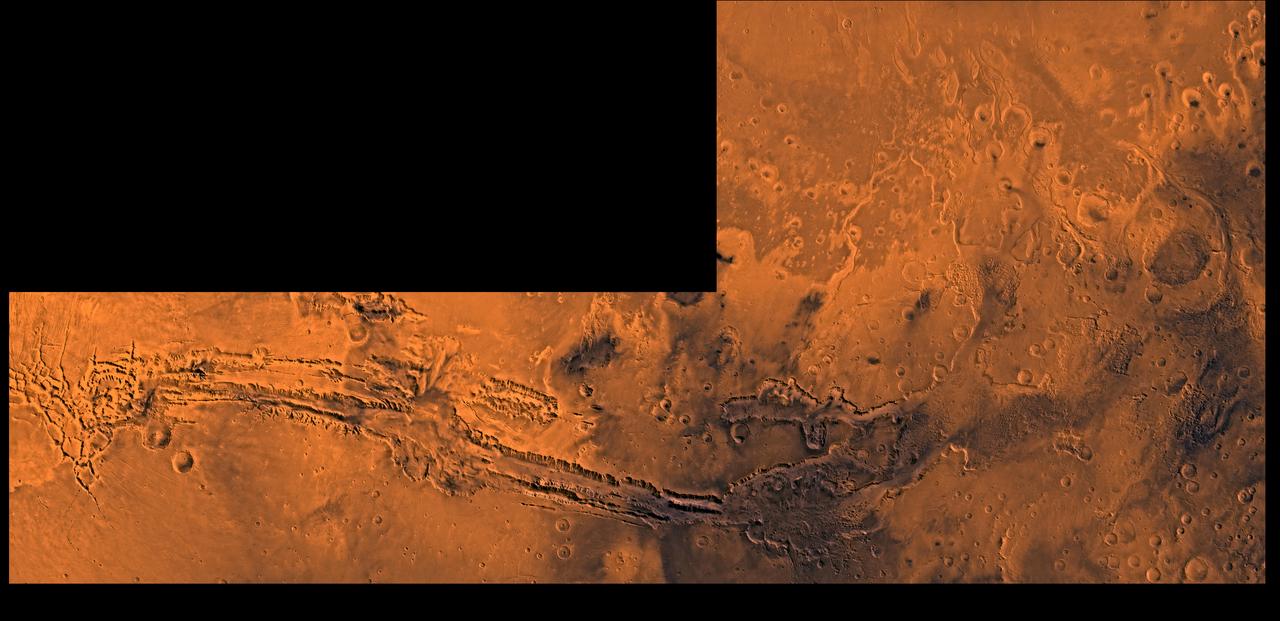

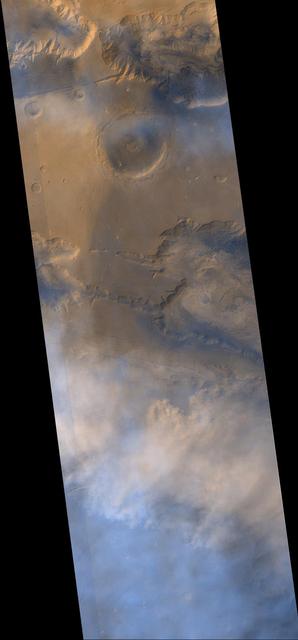

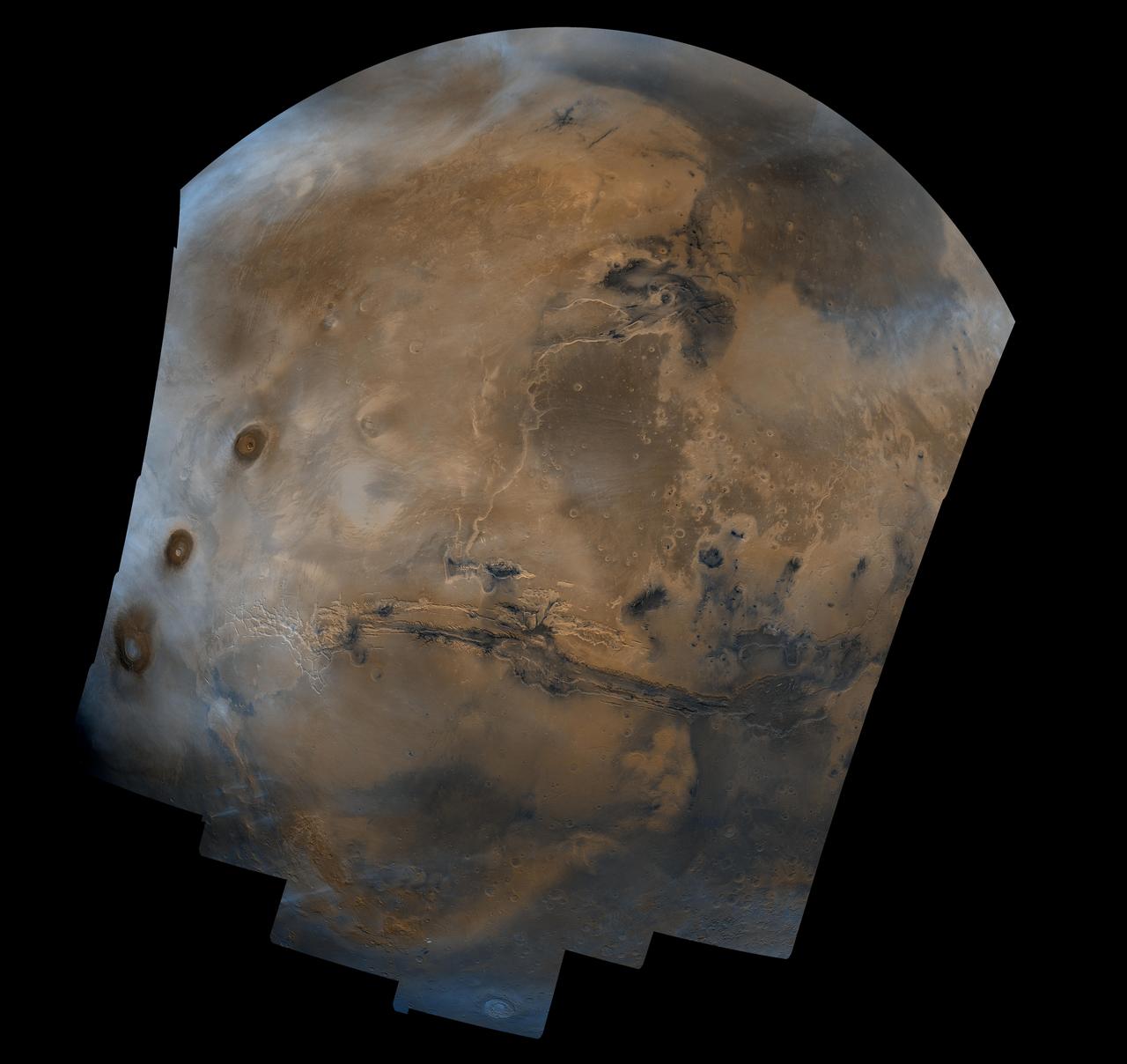

A color image of Valles Marineris, the great canyon of Mars; north toward top. The scene shows the entire canyon system, over 3,000 km long and averaging 8 km deep, extending from Noctis Labyrinthus, the arcuate system of graben to the west, to the chaotic terrain to the east. This image is a composite of Viking medium-resolution images in black and white and low-resolution images in color; Mercator projection. The image extends from latitude 0 degrees to 20 degrees S. and from longitude 45 degrees to 102.5 degrees. The connected chasma or valleys of Valles Marineris may have formed from a combination of erosional collapse and structural activity. Layers of material in the eastern canyons might consist of carbonates deposited in ancient lakes. Huge ancient river channels began from Valles Marineris and from adjacent canyons and ran north. Many of the channels flowed north into Chryse Basin, which contains the site of the Viking 1 Lander and the future site of the Mars Pathfinder Lander. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00422

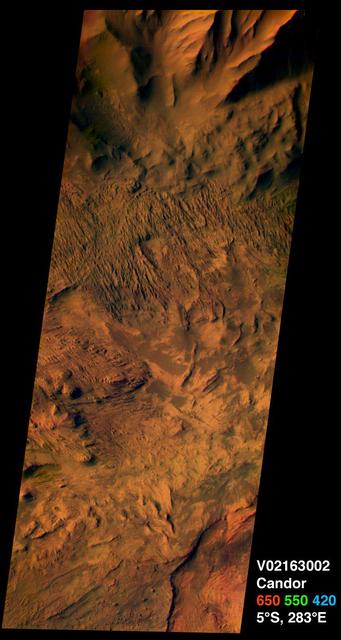

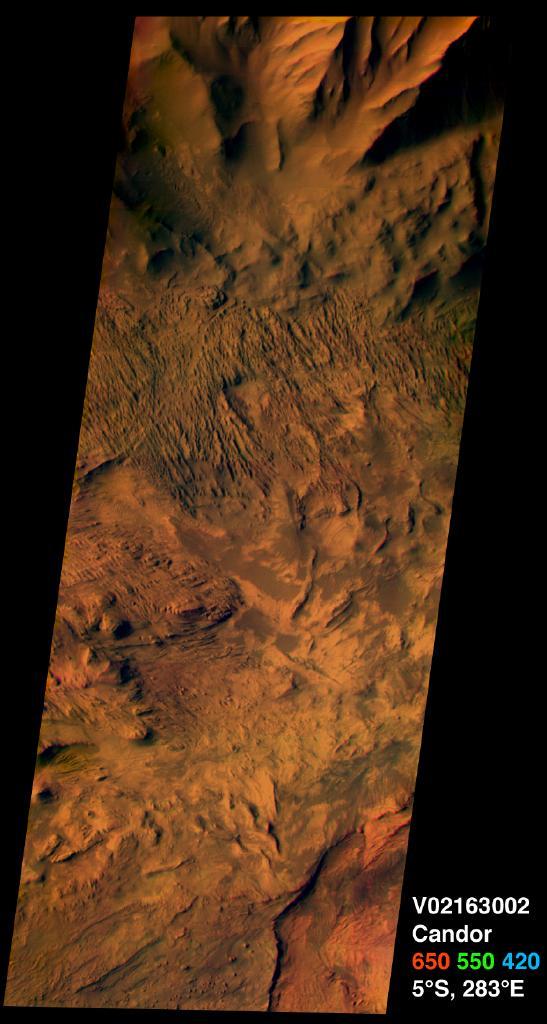

Western Candor Chasma, Valles Marineris

Light Layered Deposits in Valles Marineris

Tharsis Volcanoes and Valles Marineris, Mars

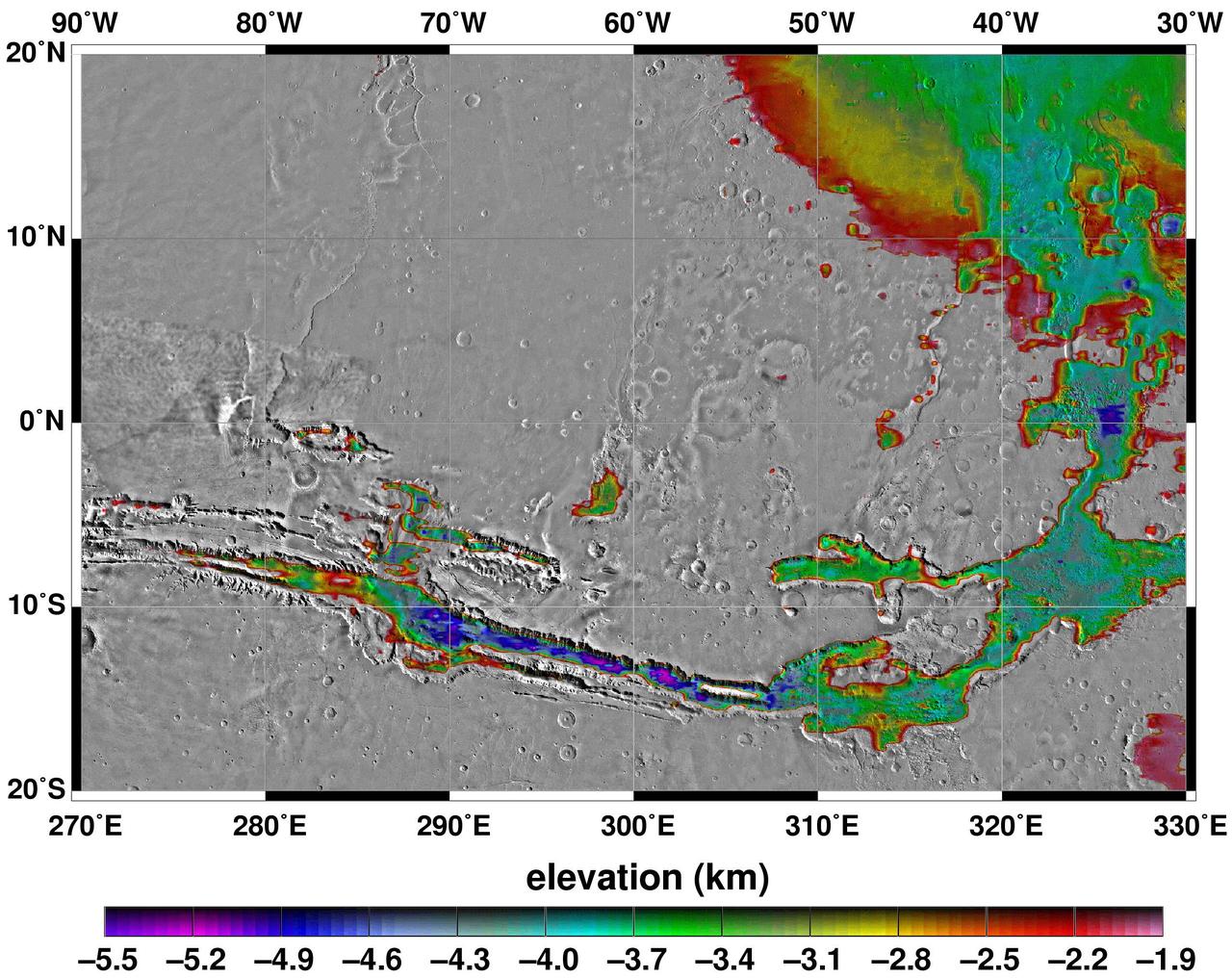

Elevations Within the Floor of the Valles Marineris

Exposed Layers in Central Valles Marineris

A color image of Valles Marineris, the great canyon and the south Chryse basin-Valles Marineris outflow channels of Mars; north toward top. The scene shows the entire Valles Marineris canyon system, over 3,000 km long and averaging 8 km deep, extending from Noctis Labyrinthus, the arcuate system of graben to the west, to the chaotic terrain to the east and related outflow canyons that drain toward the Chryse basin. Eos and Capri Chasmata (south to north) are two canyons connected to Valles Marineris. Ganges Chasma lies directly north. The chaos in the southeast part of the image gives rise to several outflow channels, Shalbatana, Simud, Tiu, and Ares Valles (left to right), that drained north into the Chryse basin. The mouth of Ares Valles is the site of the Mars Pathfinder lander. This image is a composite of Viking medium-resolution images in black and white and low-resolution images in color; Mercator projection. The image roughly extends from latitude 20 degrees S. to 20 degrees N. and from longitude 15 degrees to 102.5 degrees. The connected chasma or valleys of Valles Marineris may have formed from a combination of erosional collapse and structural activity. Layers of material in the eastern canyons might consist of carbonates deposited in ancient lakes, eolian deposits, or volcanic materials. Huge ancient river channels began from Valles Marineris and from adjacent canyons and ran north. Many of the channels flowed north into Chryse Basin. The south Chryse outflow channels are cut an average of 1 km into the cratered highland terrain. This terrain is about 9 km above datum near Valles Marineris and steadily decreases in elevation to 1 km below datum in the Chryse basin. Shalbatana is relatively narrow (10 km wide) but can reach 3 km in depth. The channel begins at a 2- to 3-km-deep circular depression within a large impact crater, whose floor is partly covered by chaotic material, and ends in Simud Valles. Tiu and Simud Valles consist of a complex of connected channel floors and chaotic terrain and extend as far south as and connect to eastern Valles Marineris. Ares Vallis originates from discontinuous patches of chaotic terrain within large craters. In the Chryse basin the Ares channel forks; one branch continues northwest into central Chryse Planitia and the other extends north into eastern Chryse Planitia. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00426

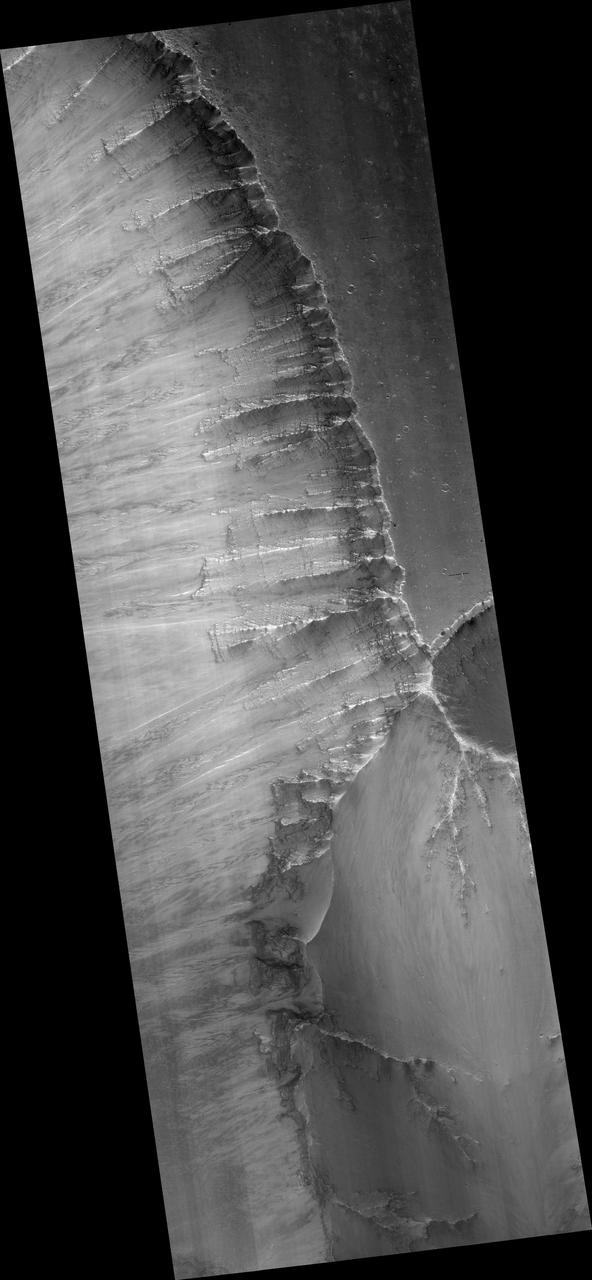

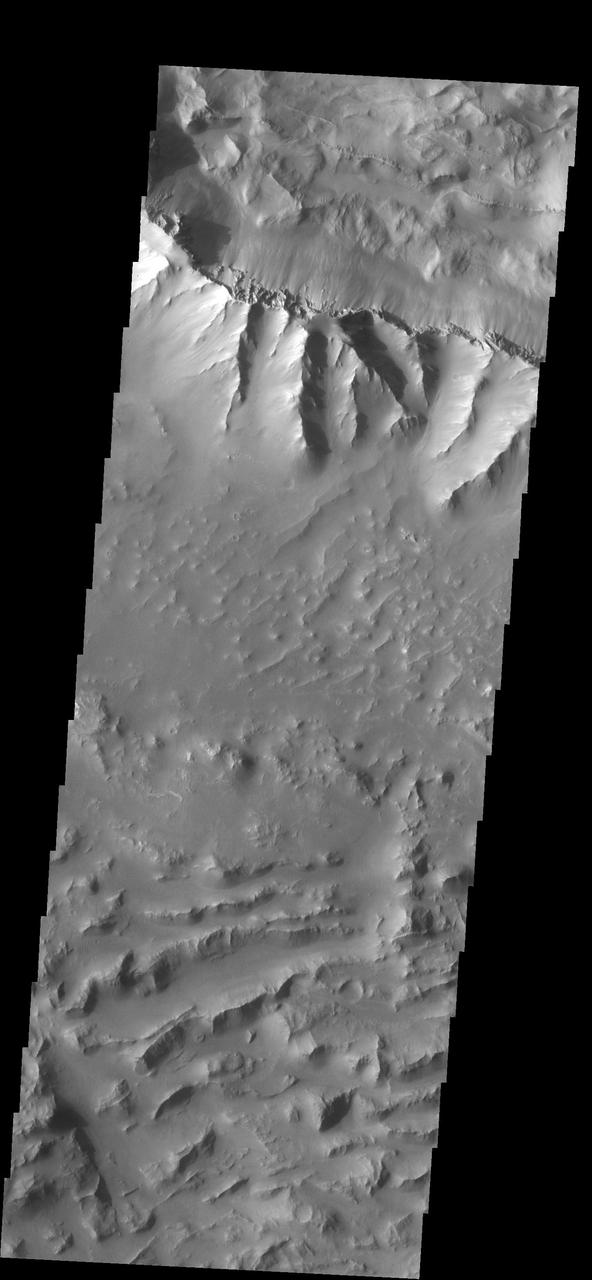

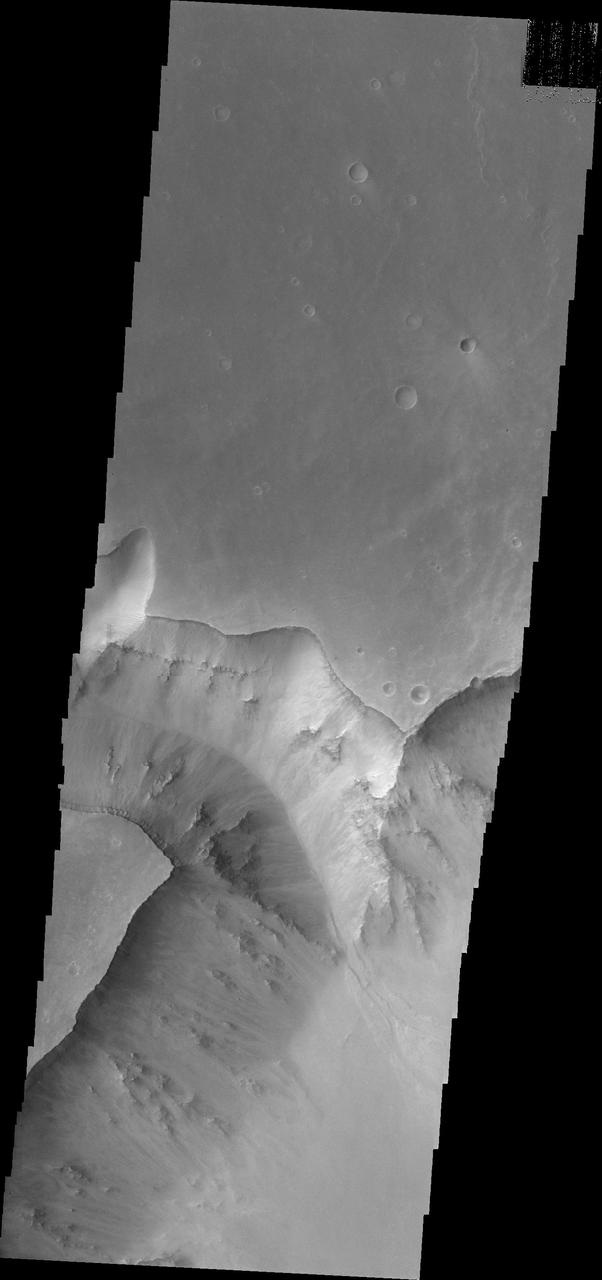

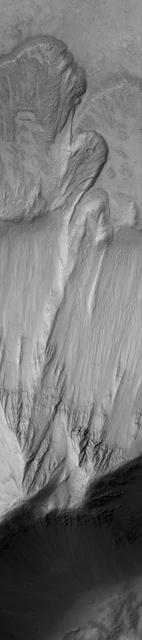

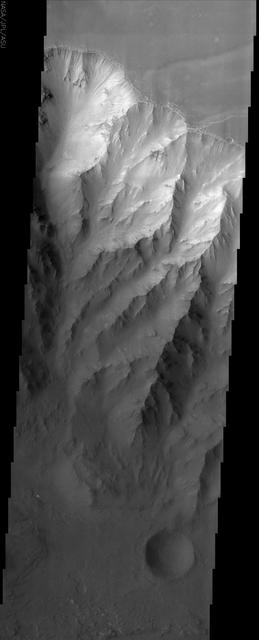

This image captured by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows part of the north wall of Valles Marineris near Melas Chasma.

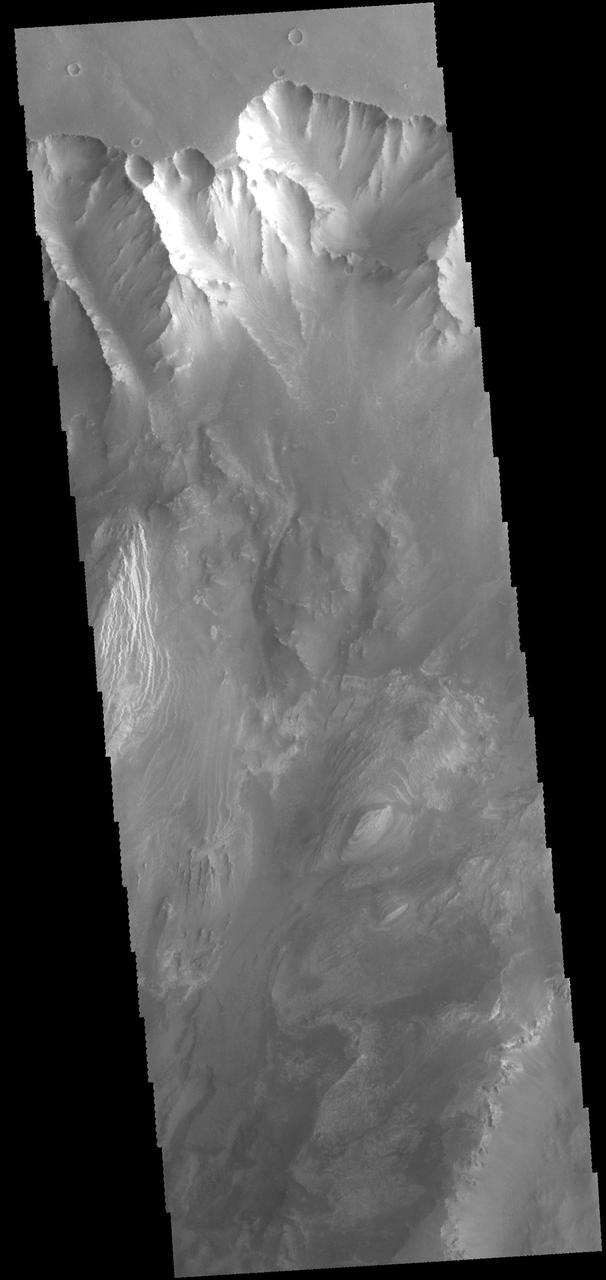

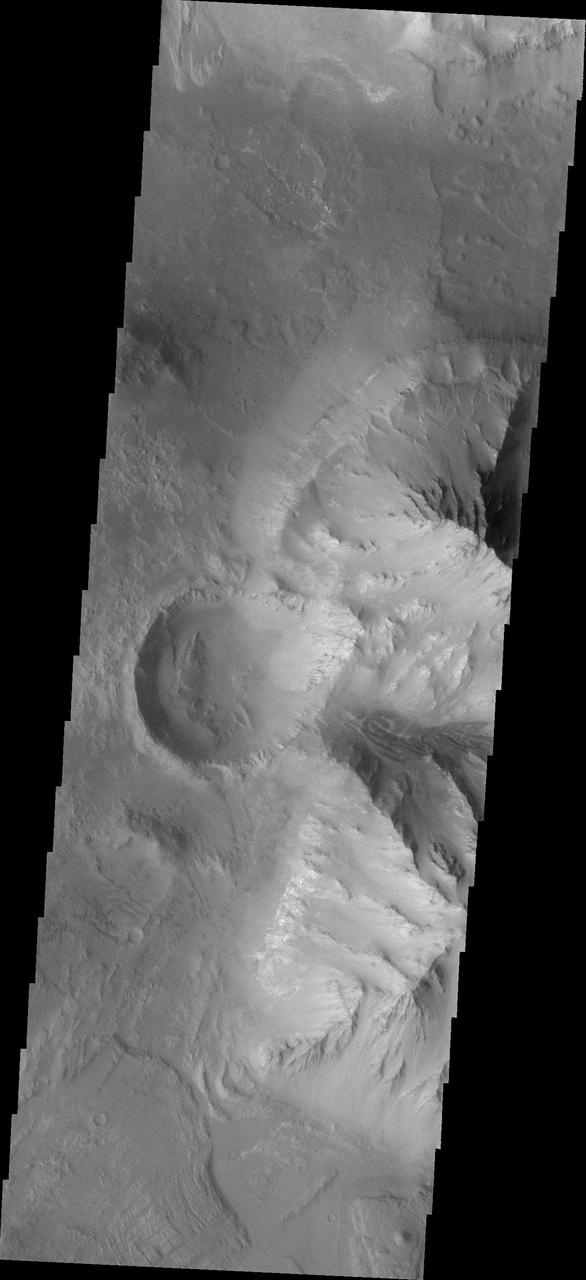

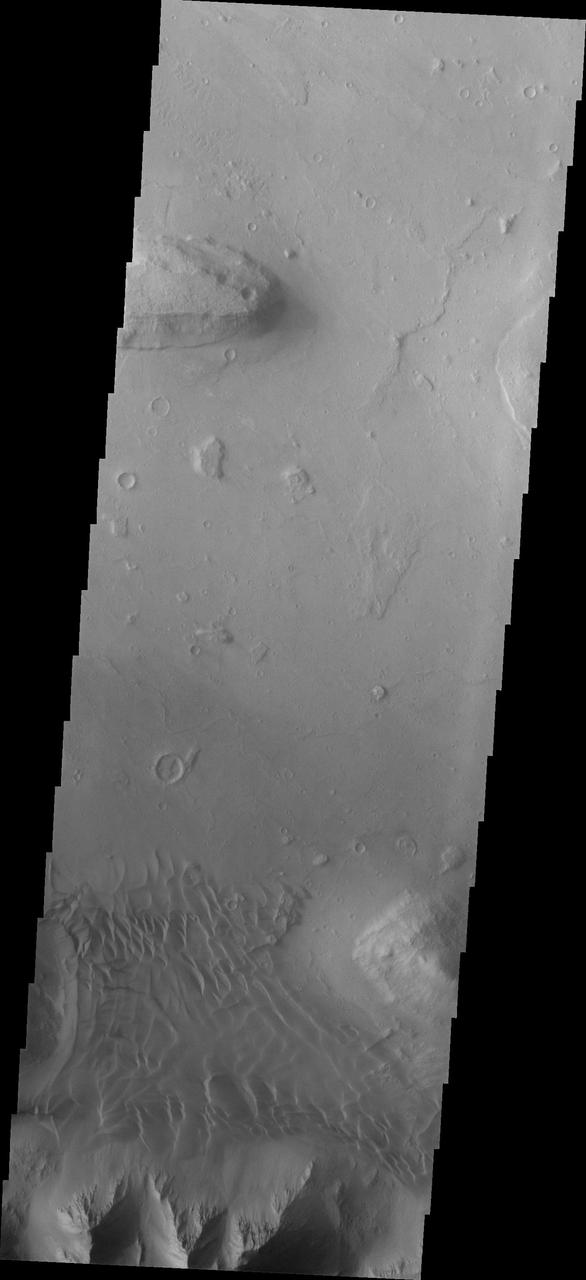

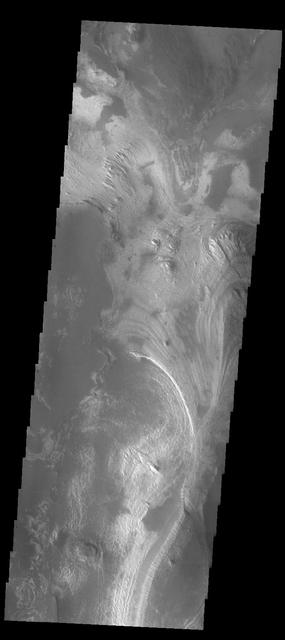

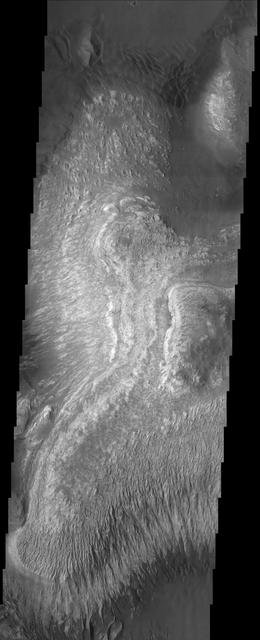

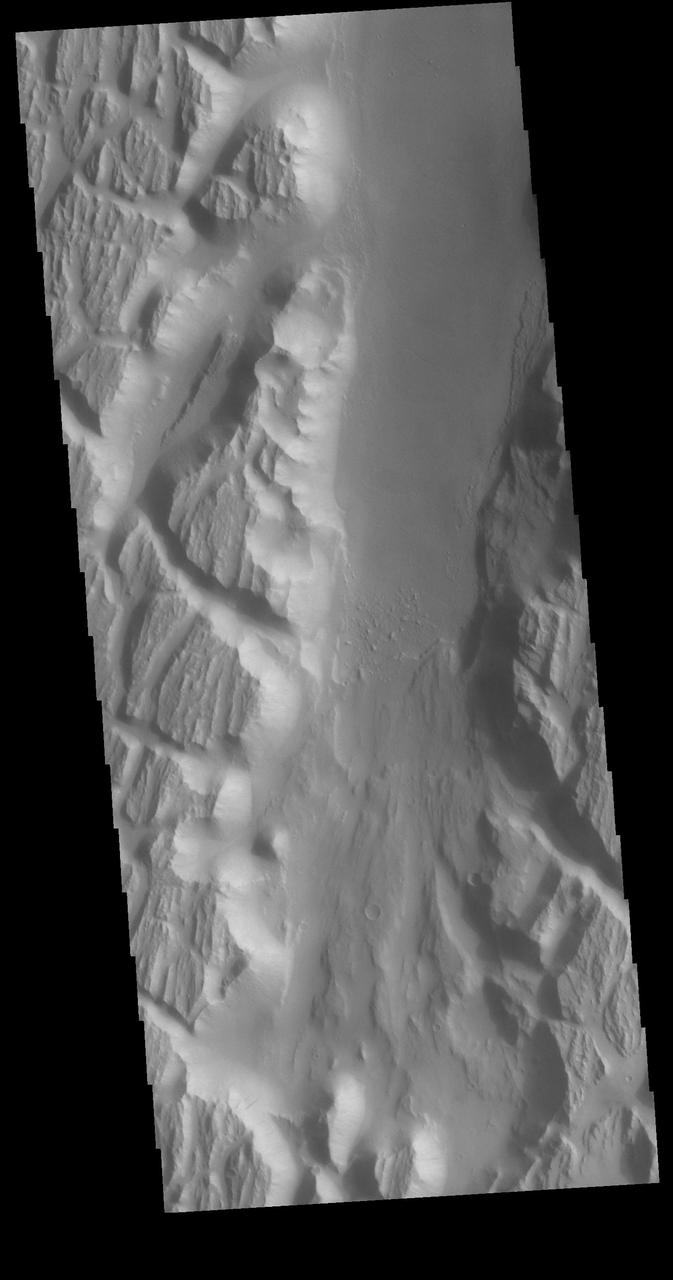

The landslide deposits in this VIS image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft are located in Valles Marineris and are called Coprates Labes.

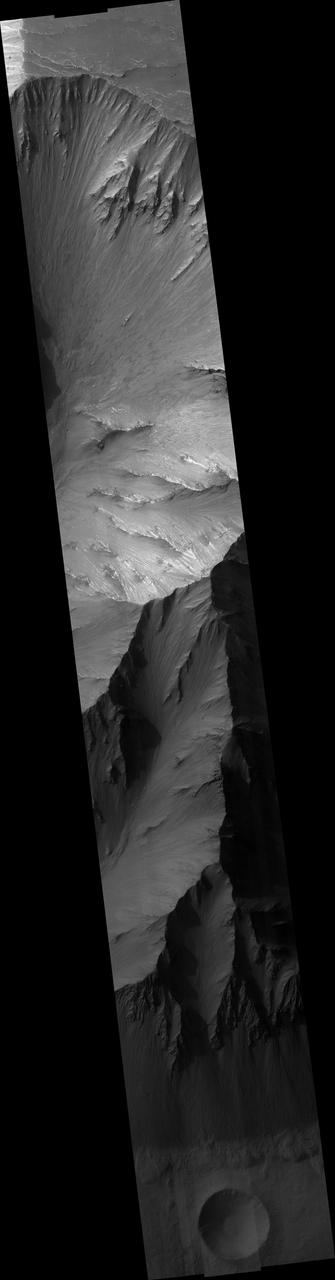

East Tithonium Chasma Wall, Valles Marineris

Light-toned Layered Outcrops in Valles Marineris Walls

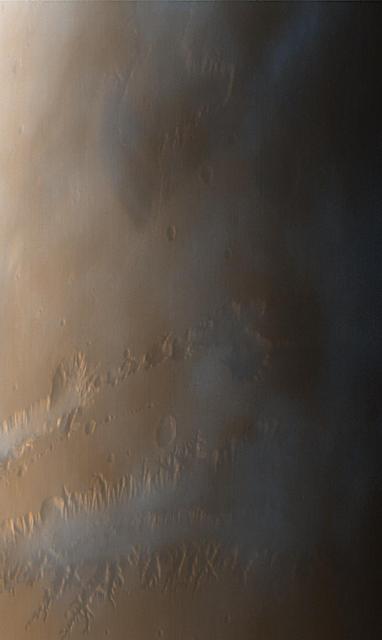

May 1999 Dust Storm in Valles Marineris

Western Tithonium Chasma/Ius Chasma, Valles Marineris

Western Melas and Candor Chasms, Valles Marineris

This image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows part of the Valles Marineris canyon system -- a mega gully enters Capri Chasma.

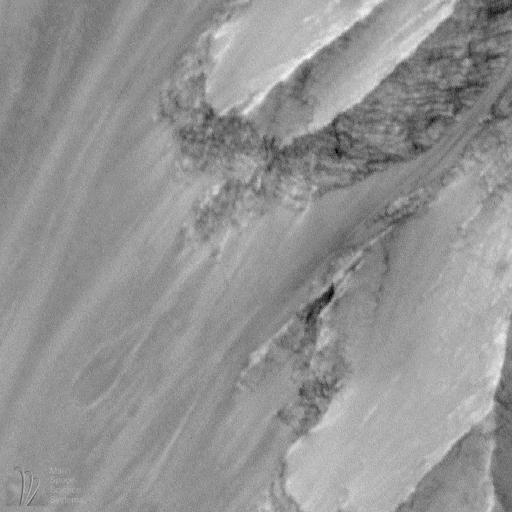

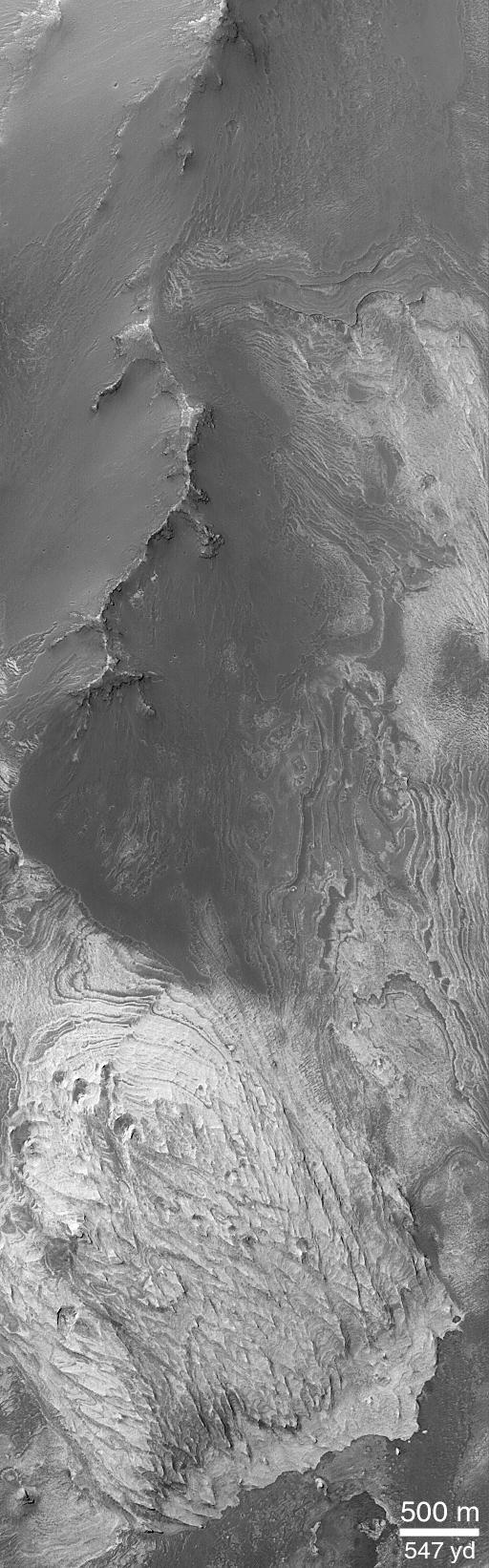

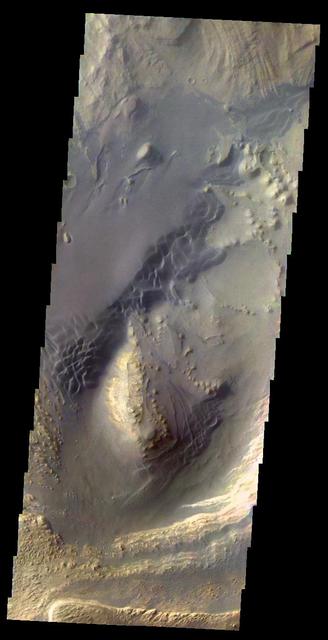

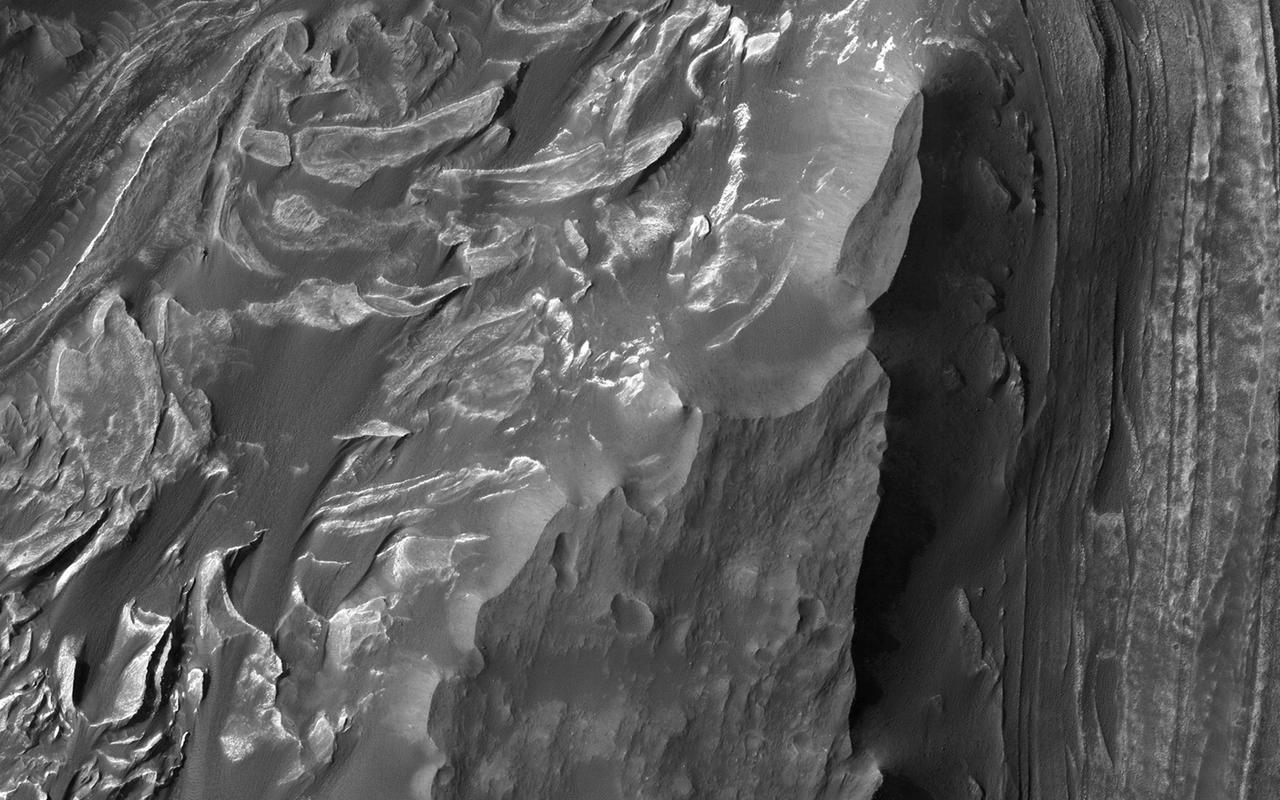

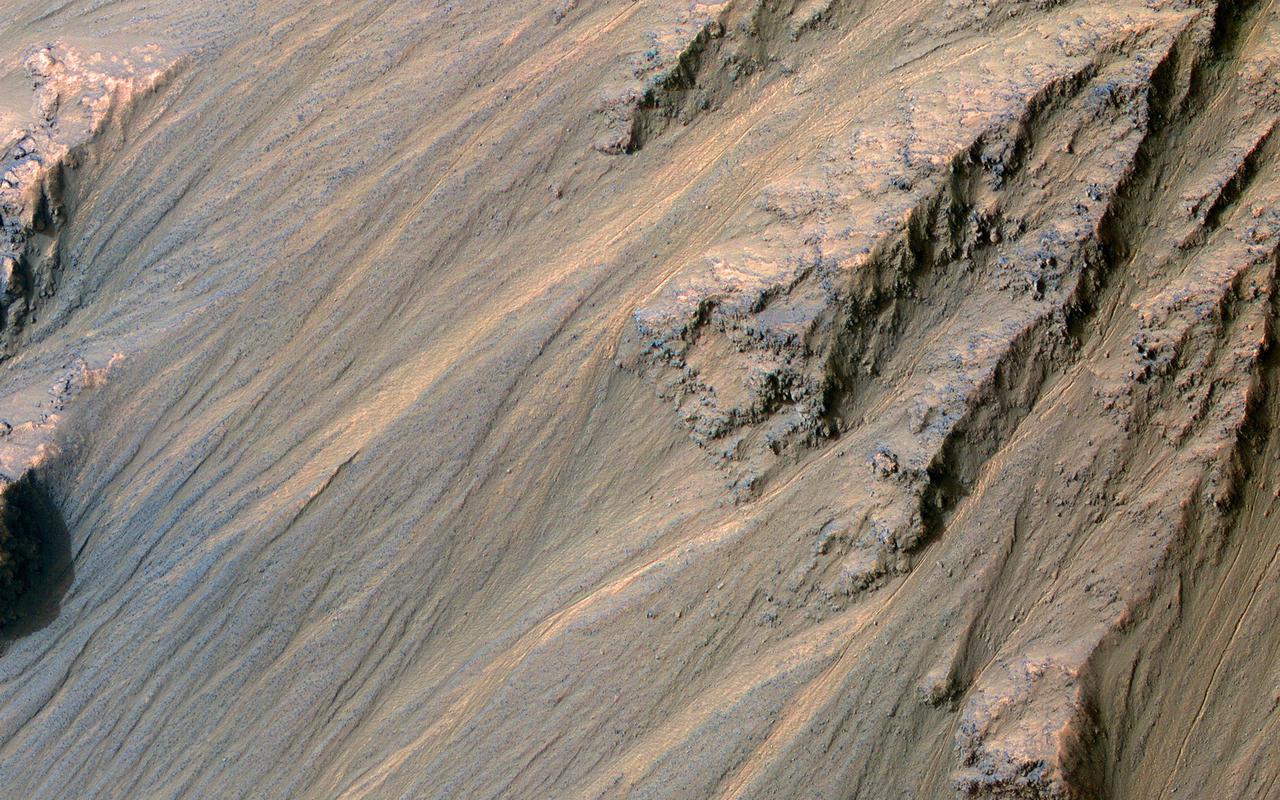

It has been known since the 1970s when the Viking orbiters took pictures of Mars that there are large (i.e., several kilometers-thick) mounds of light-toned deposits within the central portion of Valles Marineris. More recent higher resolution images of Mars, including this image of Melas Chasma, show that the wall rocks of Valles Mariners also contain similar, albeit thinner, light-toned deposits. Spectral data from the CRISM instrument indicate that the larger mounds are composed of sulfates. Some of the wall rock deposits are also made up of sulfates, but others contain clays or mixtures of several kinds of hydrated materials, suggesting that multiple aqueous processes, perhaps at different times within Valles Marineris, formed the variety of deposits we now observe. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21102

Part of Candor Chasm in Valles Marineris, Mars. Layered terrain is visible in the scene from NASA Viking Orbiter 1, perhaps due to a huge ancient lake. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00199

Complex Floor Deposits Within Western Ganges Chasma, Valles Marineris

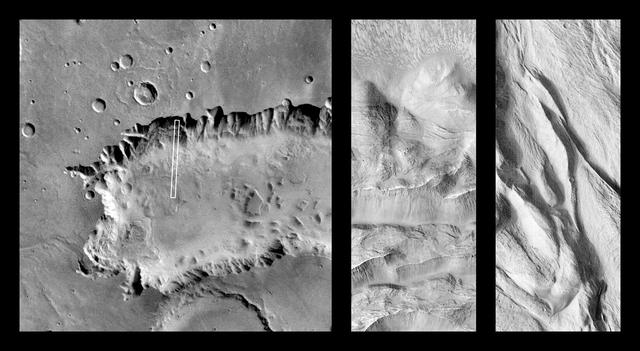

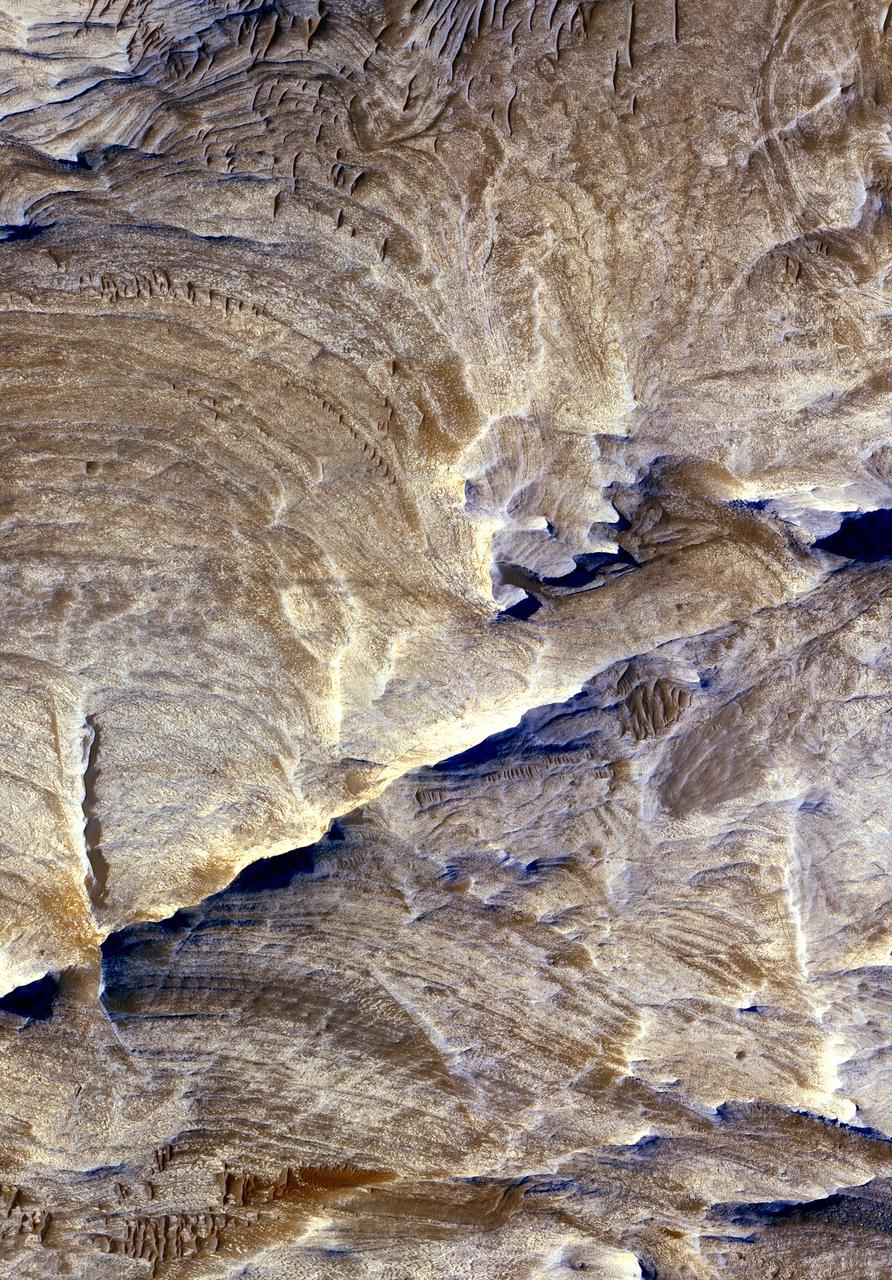

Layers within the Valles Marineris: Clues to the Ancient Crust of Mars

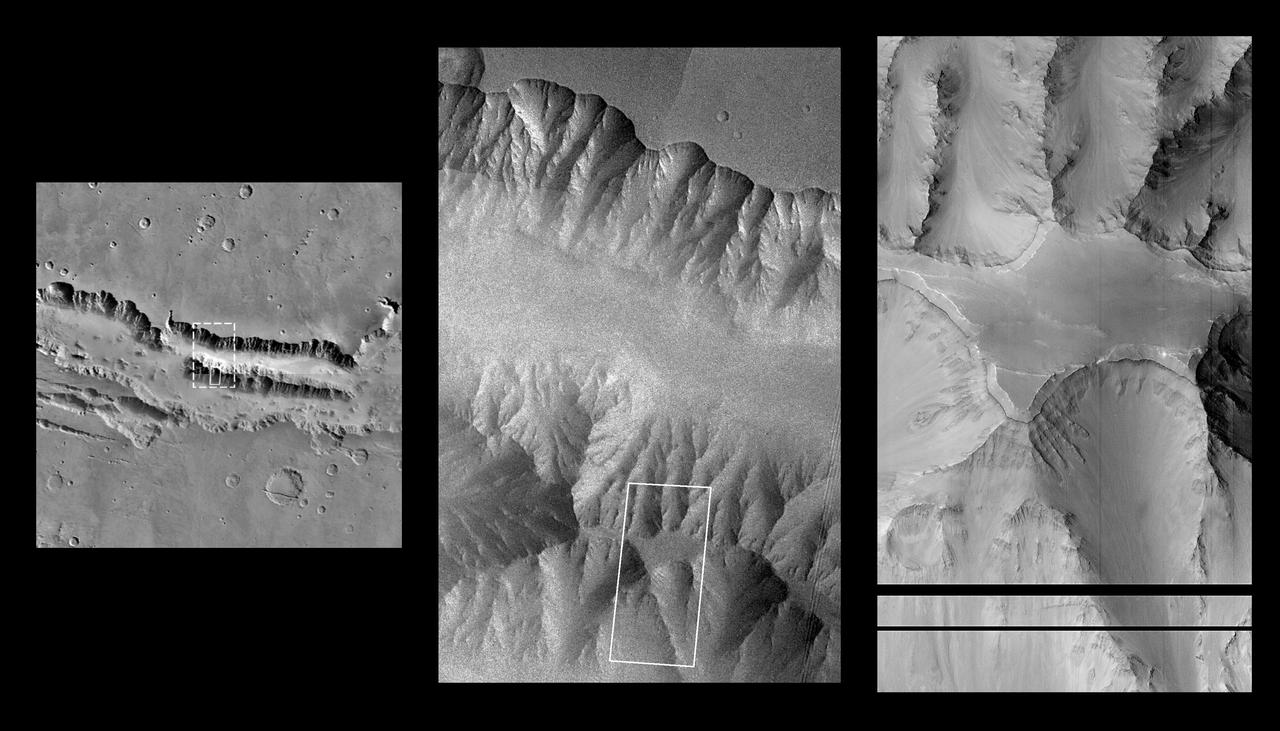

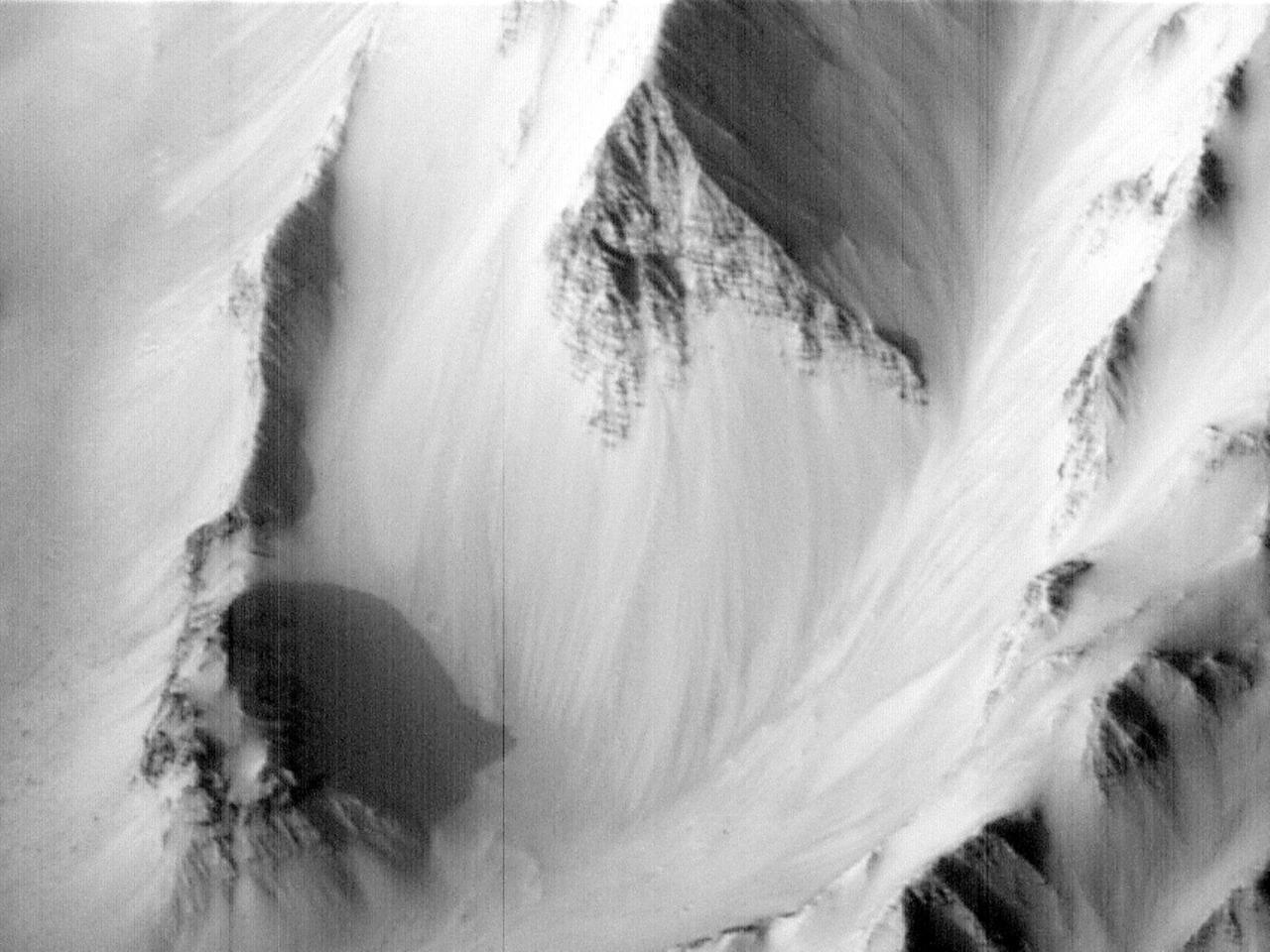

Western Tithonium Chasma/Ius Chasma, Valles Marineris - High Resolution Image

Western Tithonium Chasma/Ius Chasma, Valles Marineris - High Resolution Image

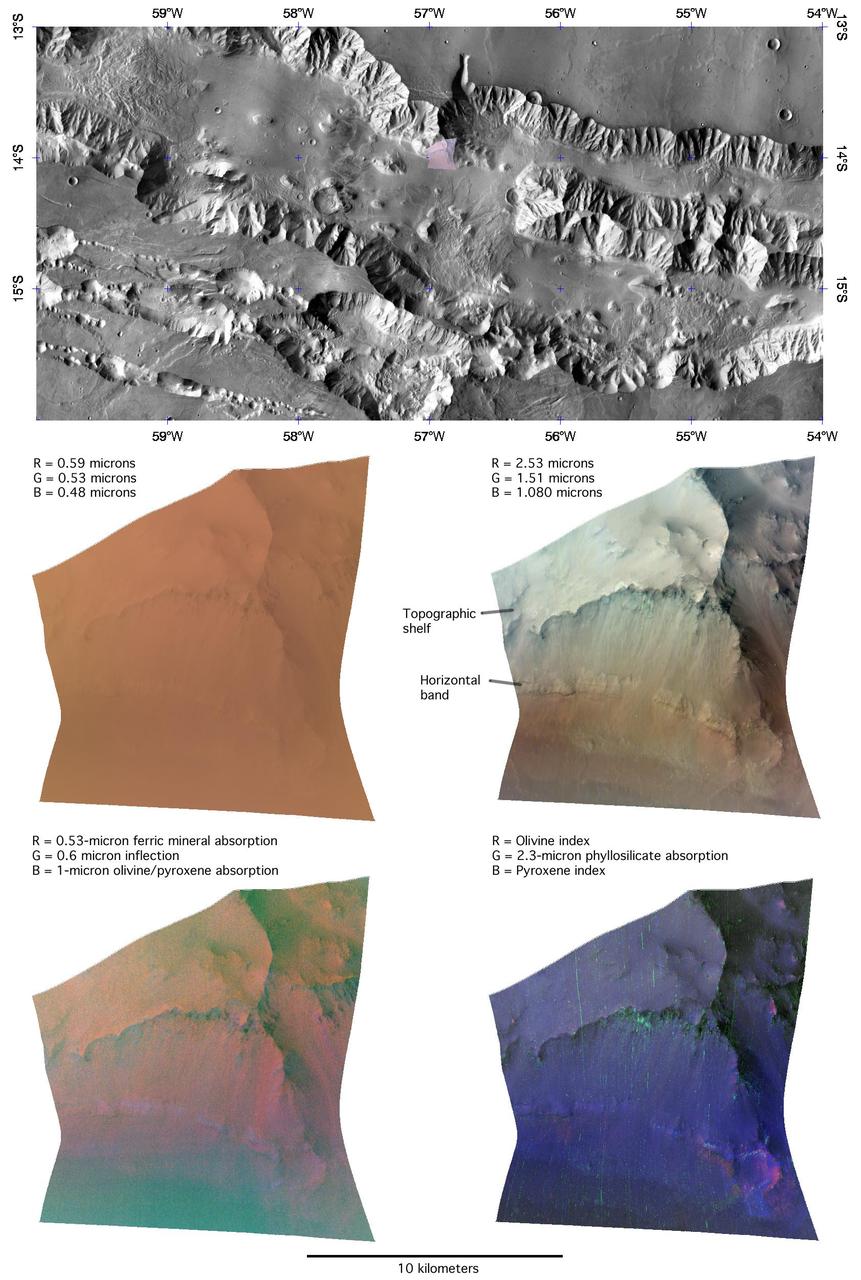

This image of the northern wall of Coprates Chasma, in Valles Marineris, was taken by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars CRISM on June 16, 2007.

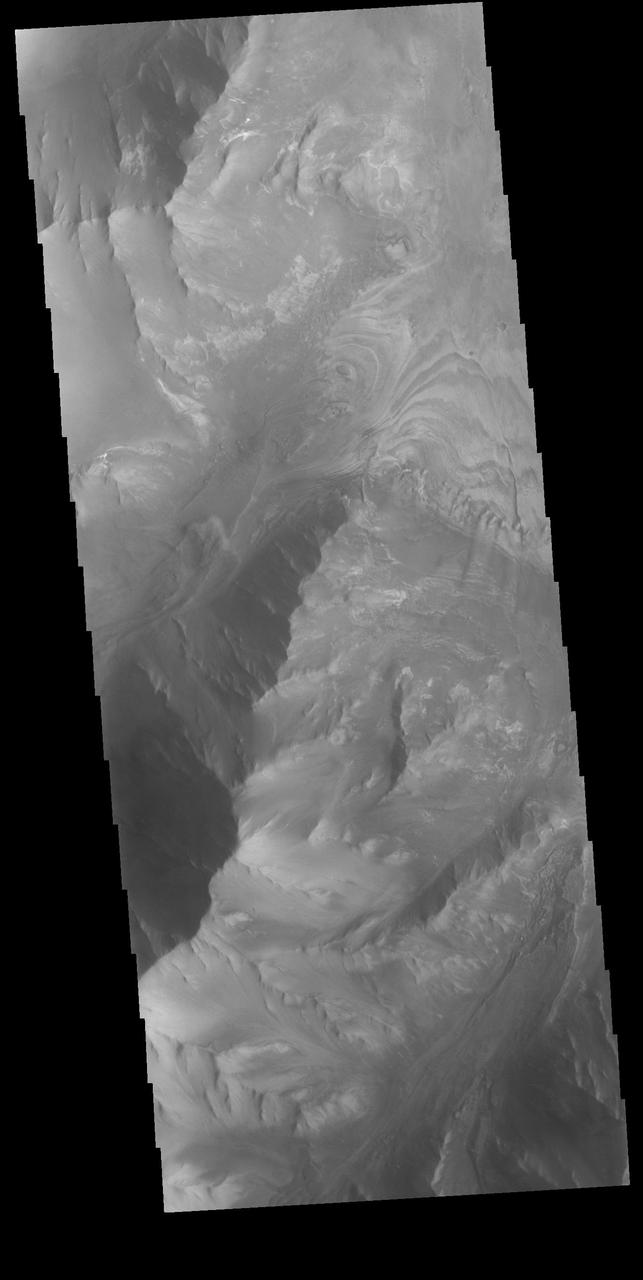

The top half of this NASA Mars Odyssey image shows interior layered deposits that have long been recognized in Valles Marineris. Upon close examination, the layers appear to be eroding differently, indicating different levels of competency.

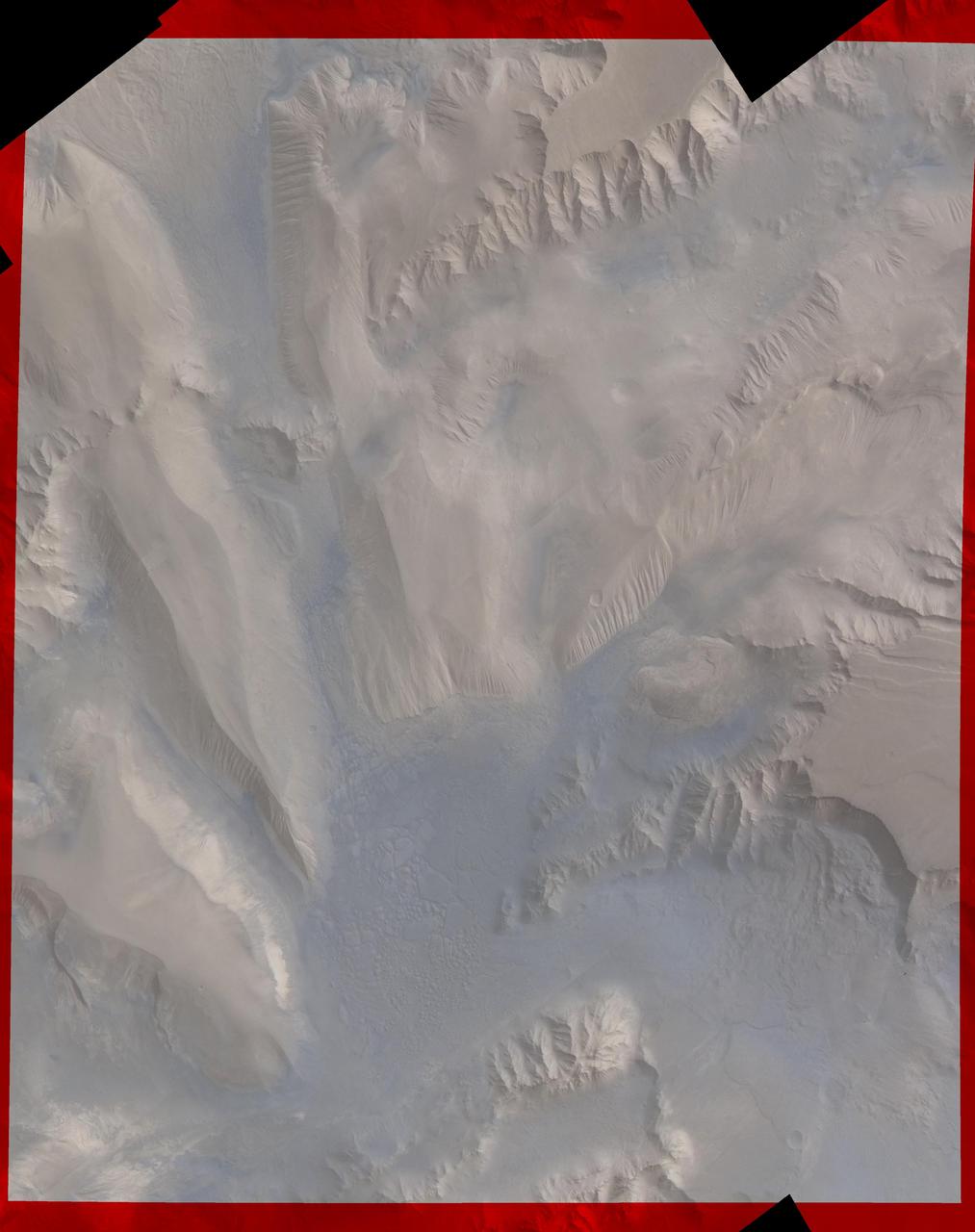

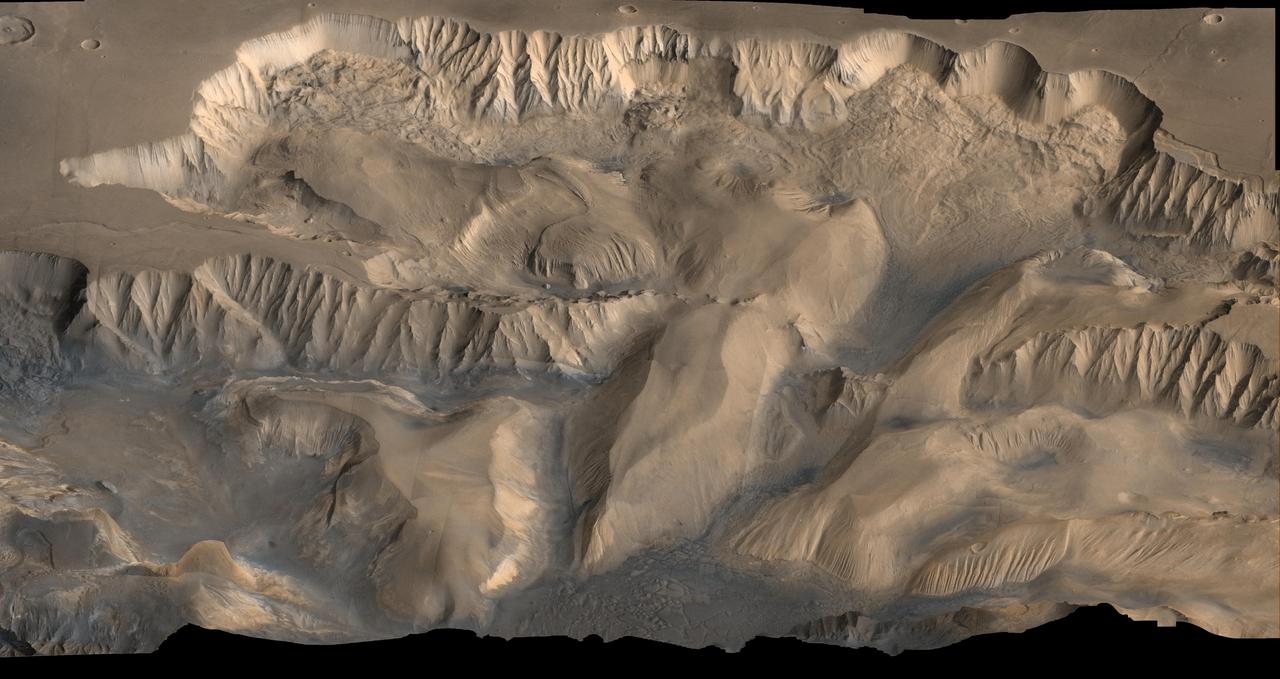

An oblique, color image of central Valles Marineris, Mars showing relief of Ophir and Candor Chasmata; view toward north. The photograph is a composite of Viking high-resolution images in black and white and low-resolution images in color. Ophir Chasma on the north is approximately 300 km across and as deep as 10 km. The connected chasma or valleys of Valles Marineris may have formed from a combination of erosional collapse and structural activity. Tongues of interior layered deposits on the floor of the chasmata can be observed as well as young landslide material along the base of Ophir Chasma's north wall. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00005

An oblique, color image of central Valles Marineris, Mars showing relief of Ophir and Candor Chasmata; view toward east. The photograph is a composite of Viking high-resolution images in black and white and low-resolution images in color. Ophir Chasma on the north (left side) is approximately 300 km across and as deep as 10 km. The connected chasma or valleys of Valles Marineris may have formed from a combination of erosional collapse and structural activity. Tongues of interior layered deposits on the floor of the chasmata can be observed as well as young landslide material along the base of Ophir Chasma's north wall. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00006

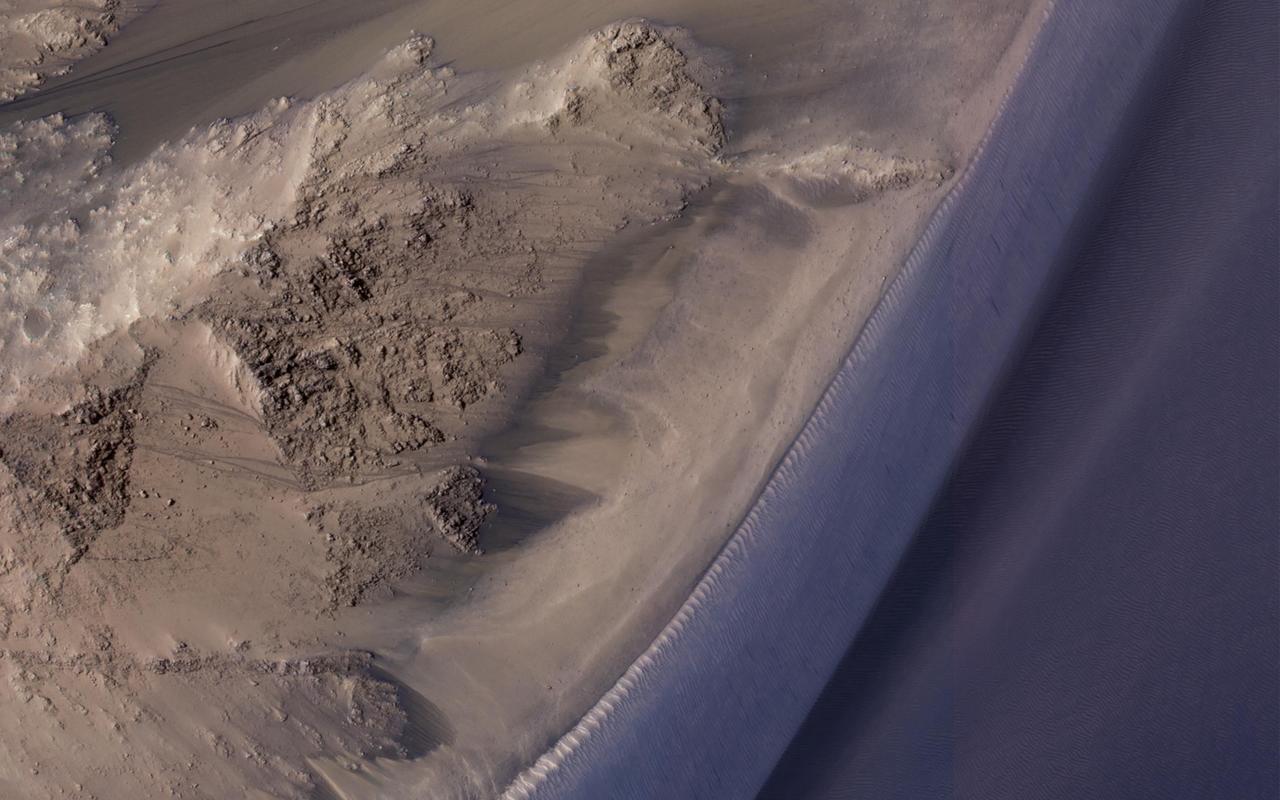

Dark, windblown sand covers intricate sedimentary rock layers in this image captured by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) from Ganges Chasma, a canyon in the Valles Marineris system. These features are at once familiar and unusual to those familiar with Earth's beaches and deserts. Most sand dunes on Earth are made of silica-rich sand, giving them a light color; these Martian dunes owe their dark color to the iron and magnesium-rich sand found in the region. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21600

Although large gullies (ravines) are concentrated at higher latitudes, there are gullies on steep slopes in equatorial regions, as seen in this image captured by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). The colors of the gully deposits match the colors of the eroded source materials. Krupac is a relatively young impact crater, but exposes ancient bedrock. Krupac Crater also hosts some of the most impressive recurring slope lineae (RSL) on equatorial Mars outside of Valles Marineris. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21605

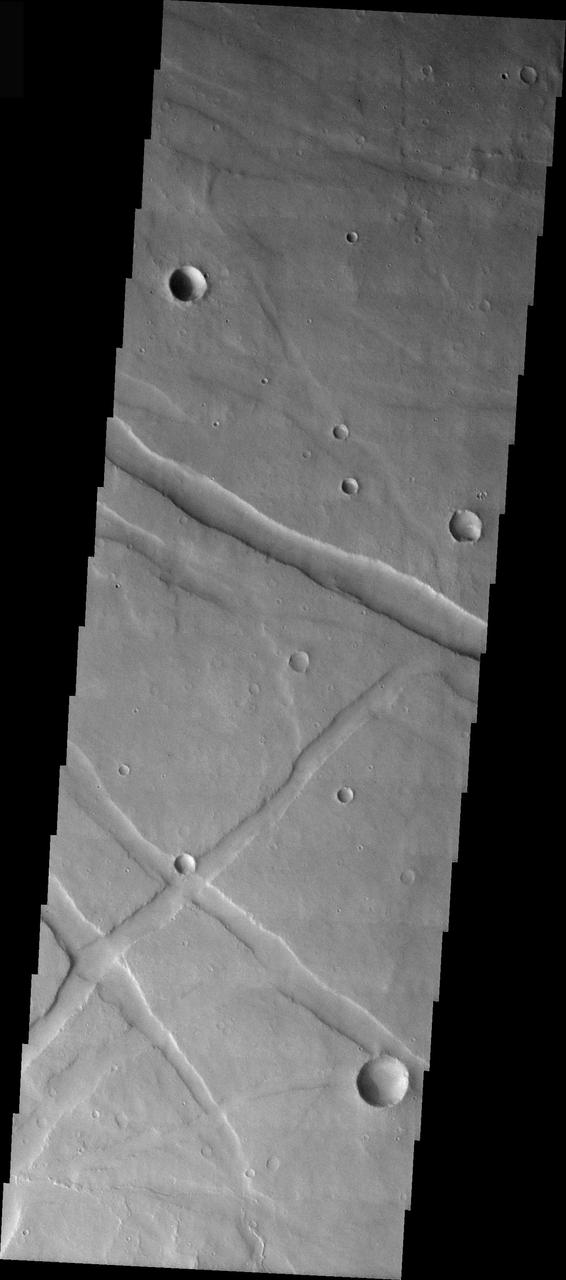

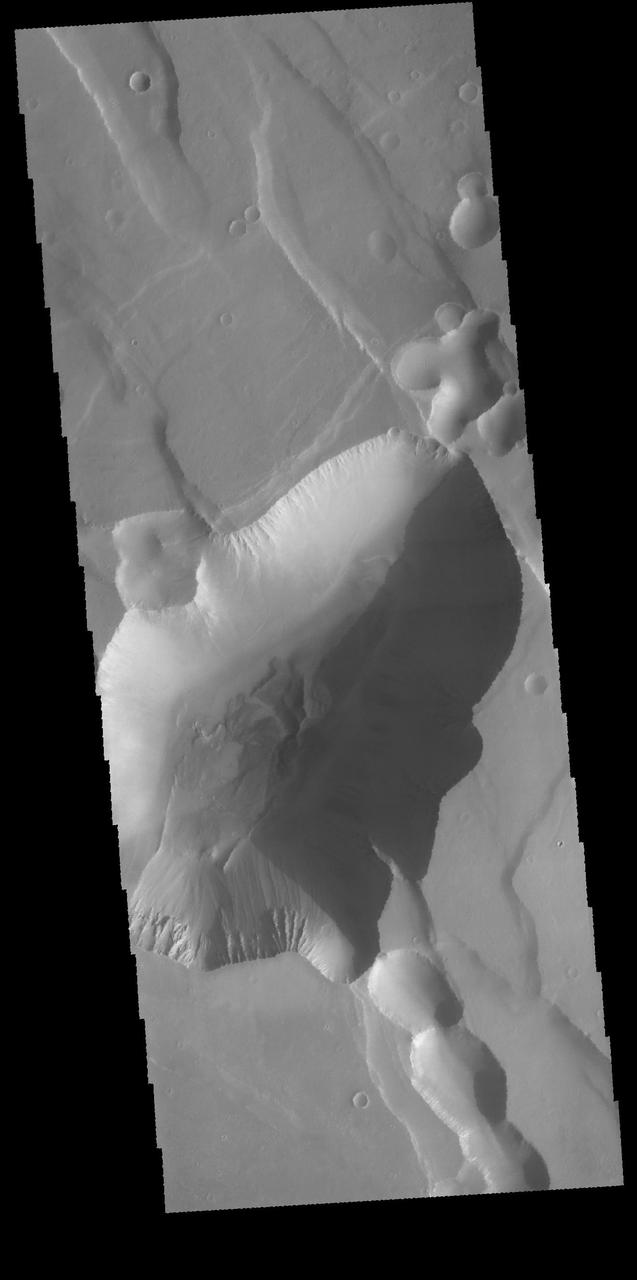

This image captured by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows a small portion of Noctis Labyrinthus. Noctis Labyrinthus is a network of tectonic graben and collapse valleys on the western margin of Valles Marineris. Orbit Number: 65633 Latitude: -12.6383 Longitude: 264.142 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2016-09-30 01:59 http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21176

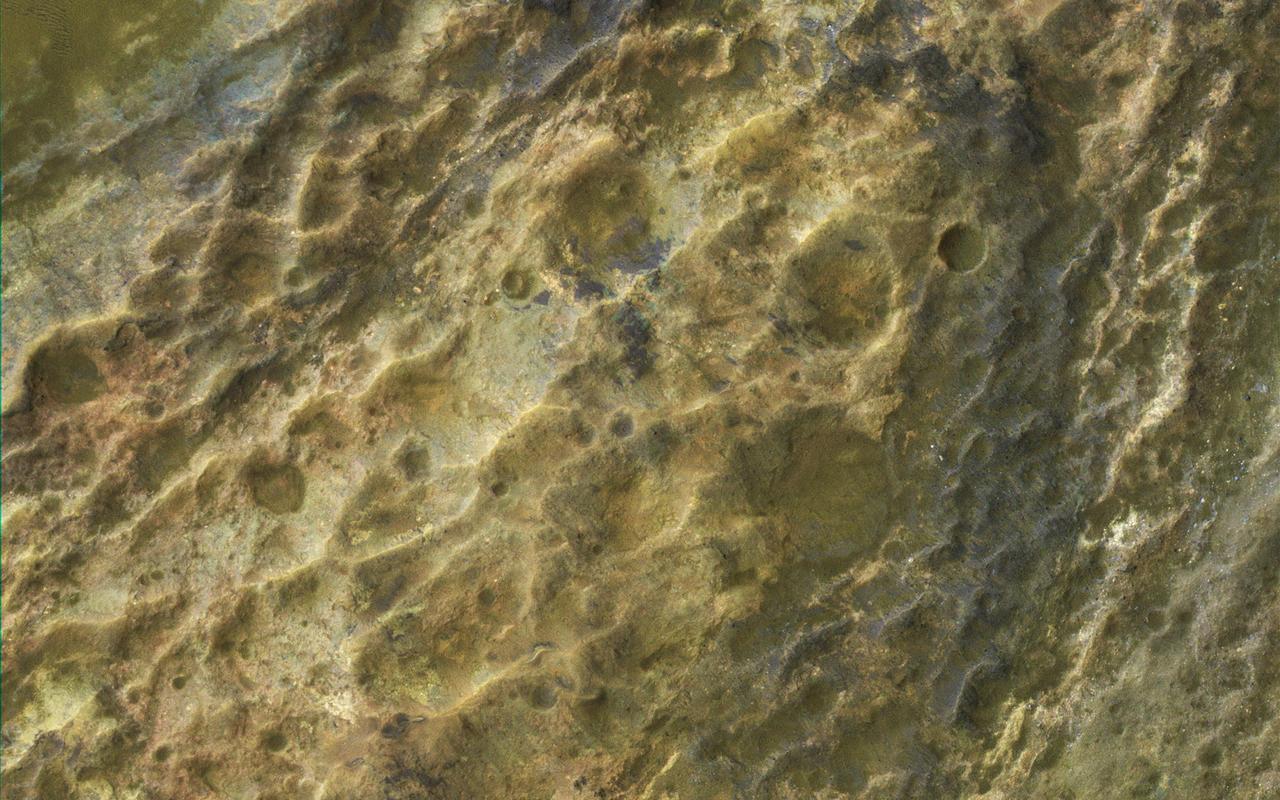

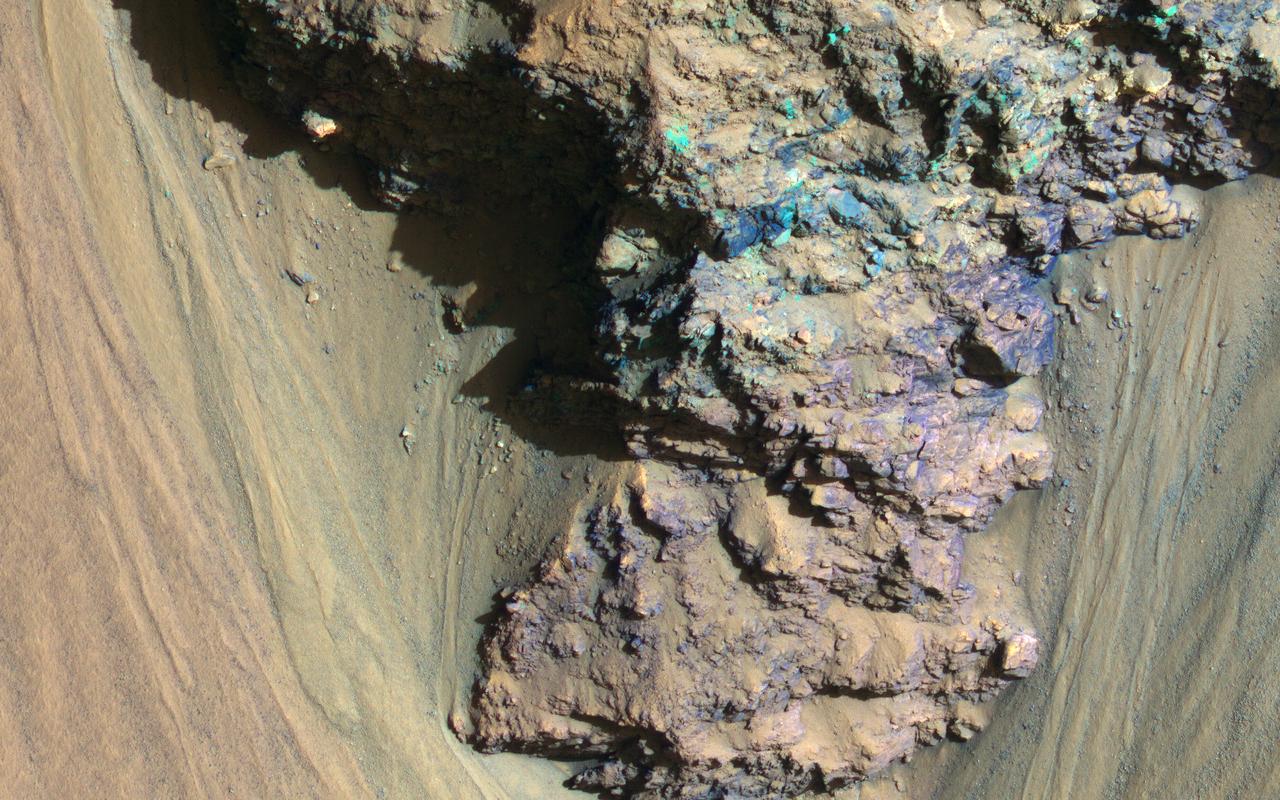

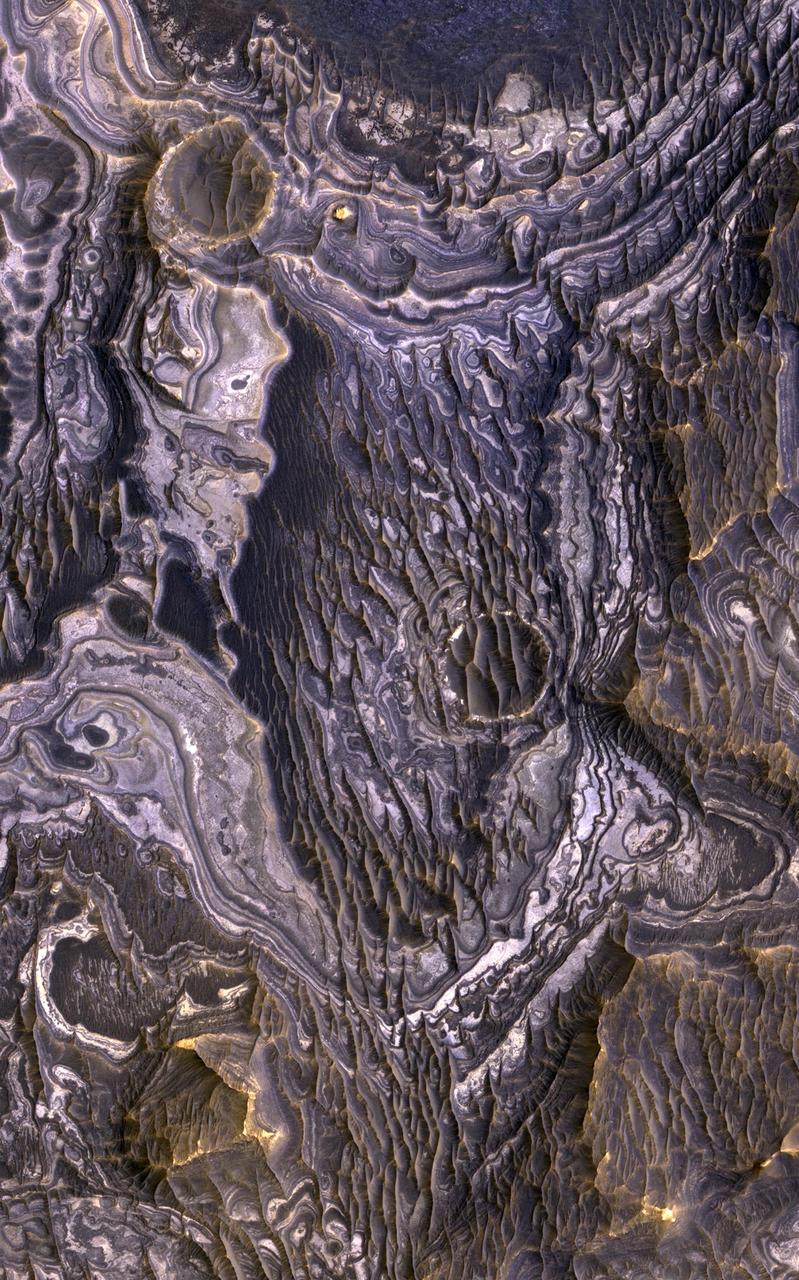

This image captured by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter MRO covers diverse surface units on the floor of eastern Coprates Chasma in eastern Valles Marineris. The bedrock has diverse minerals producing wonderful color contrasts. In over 10 years of orbiting Mars, HiRISE has acquired nearly 50,000 large images, but they cover less than 3 percent of the Martian surface. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21606

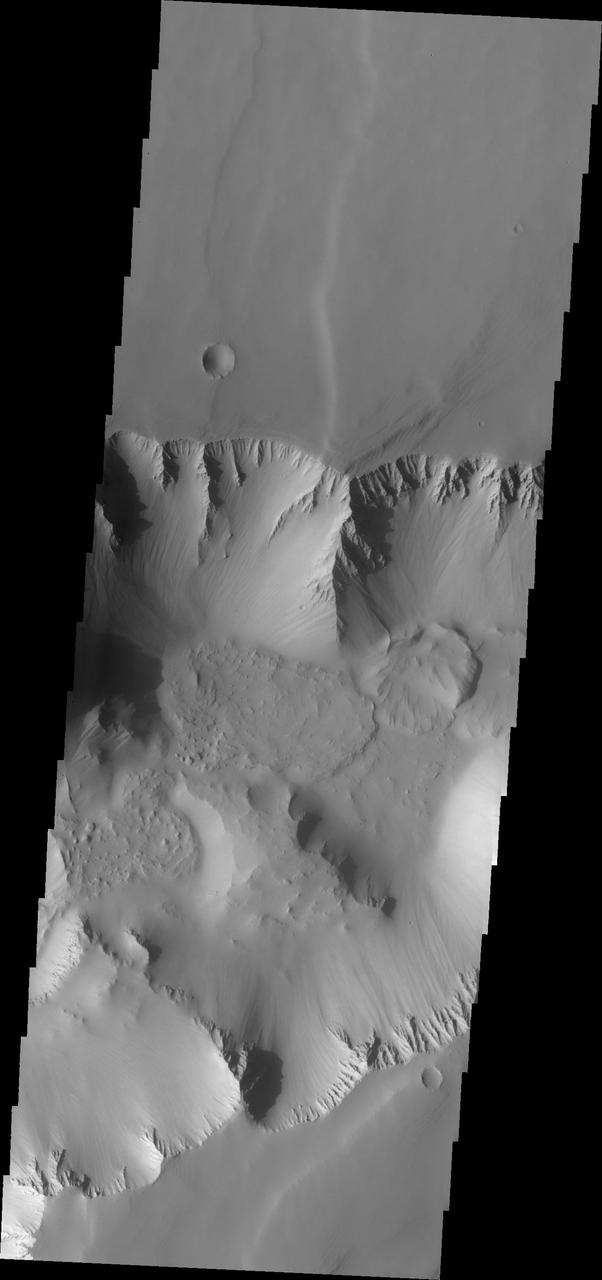

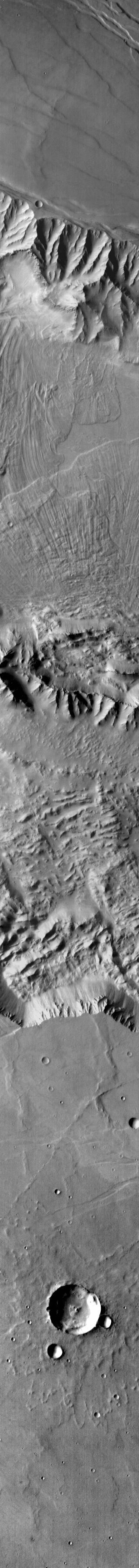

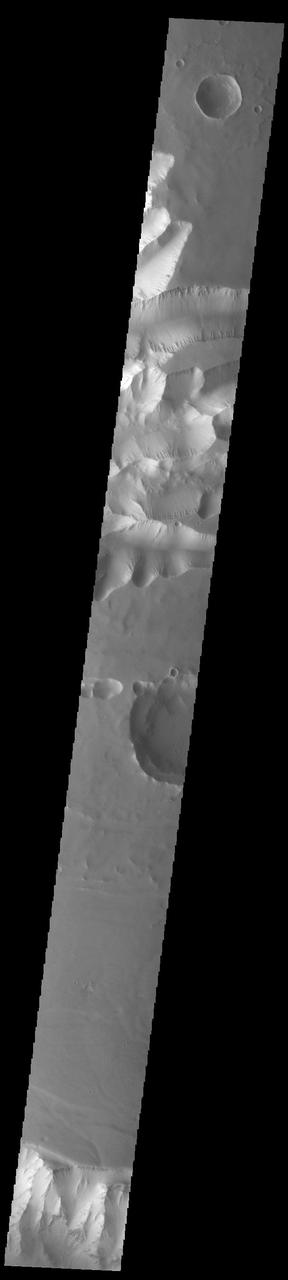

Coprates Chasma is one of the numerous canyons that make up Valles Marineris. The chasma stretches for 960 km (600 miles) from Melas Chasma to the west and Capri Chasma to the east. Landslide deposits, layered materials and sand dunes cover a large portion of the chasma floor. This image is located on the eastern side of Coprates Chasma, near Capri Chasma. The image shows multiple landslide features, which form lobed shaped deposits at the bottom of the canyon cliff face. Sand dunes are visible both on the landslide deposit and other parts of the canyon floor. The Odyssey spacecraft has spent over 15 years in orbit around Mars, circling the planet more than 69000 times. It holds the record for longest working spacecraft at Mars. THEMIS, the IR/VIS camera system, has collected data for the entire mission and provides images covering all seasons and lighting conditions. Over the years many features of interest have received repeated imaging, building up a suite of images covering the entire feature. From the deepest chasma to the tallest volcano, individual dunes inside craters and dune fields that encircle the north pole, channels carved by water and lava, and a variety of other feature, THEMIS has imaged them all. For the next several months the image of the day will focus on the Tharsis volcanoes, the various chasmata of Valles Marineris, and the major dunes fields. We hope you enjoy these images! Orbit Number: 16653 Latitude: -14.2759 Longitude: 303.707 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2005-09-15 12:01 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21991

This NASA Mars Odyssey image shows the transition zone between maze-like troughs of Noctis Labyrinthus and the main Valles Marineris canyon system. This huge system of troughs near the equator of Mars was most likely created by tectonic forces.

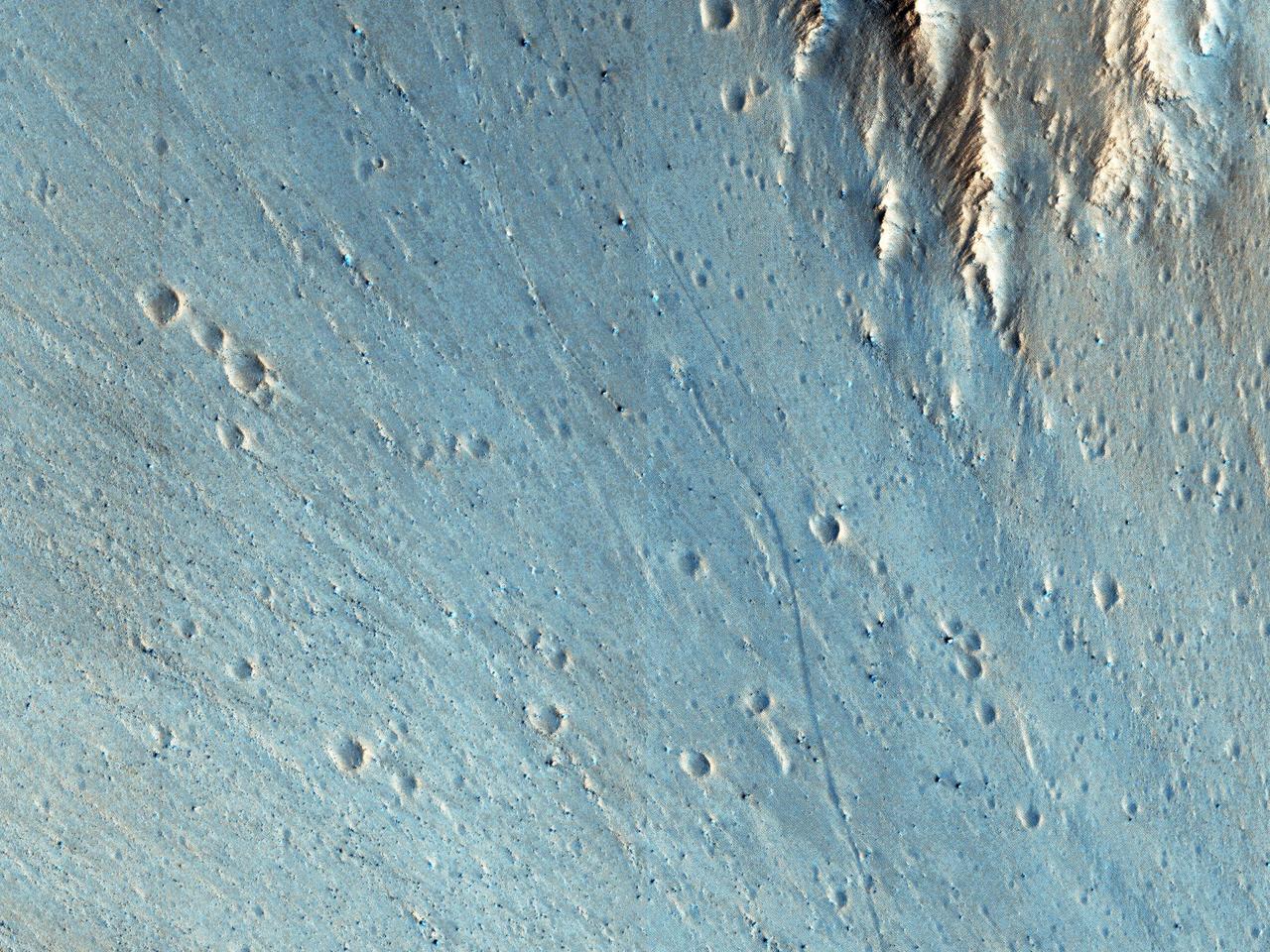

Recurring slope lineae (RSL) are seasonal flows on warm slopes, and are especially common in central and eastern Valles Marineris, as seen in this observation by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). This image covers a large area full of interesting features. Here, the RSL are active on east-facing slopes, extending from bouldery terrain and terminating on fans. Perhaps the fans themselves built up over time from the seasonal flows. Part of the fans with abundant RSL are dark, while the downhill portion of the fans are bright. The role of water in RSL activity is a matter of active debate. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21608

Sediments rich in hydrated sulfates may have filled central Valles Marineris, but debates persist as to how these deposits grew or formed. If they formed from deposition in a deep lake then the layers should be nearly horizontal. If the layers formed from airfall deposits such as volcanic pyroclastics or windblown dust, then the layers should drape over the pre-existing topography. Another possibility is that the layers were deformed by slumping. Stereo topographic data can be used to test these hypotheses. The cutout shows an area at full resolution. There are no detectable color variations within these layers, suggesting a uniform composition or the presence of a thin cover of dust over all surfaces. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25308

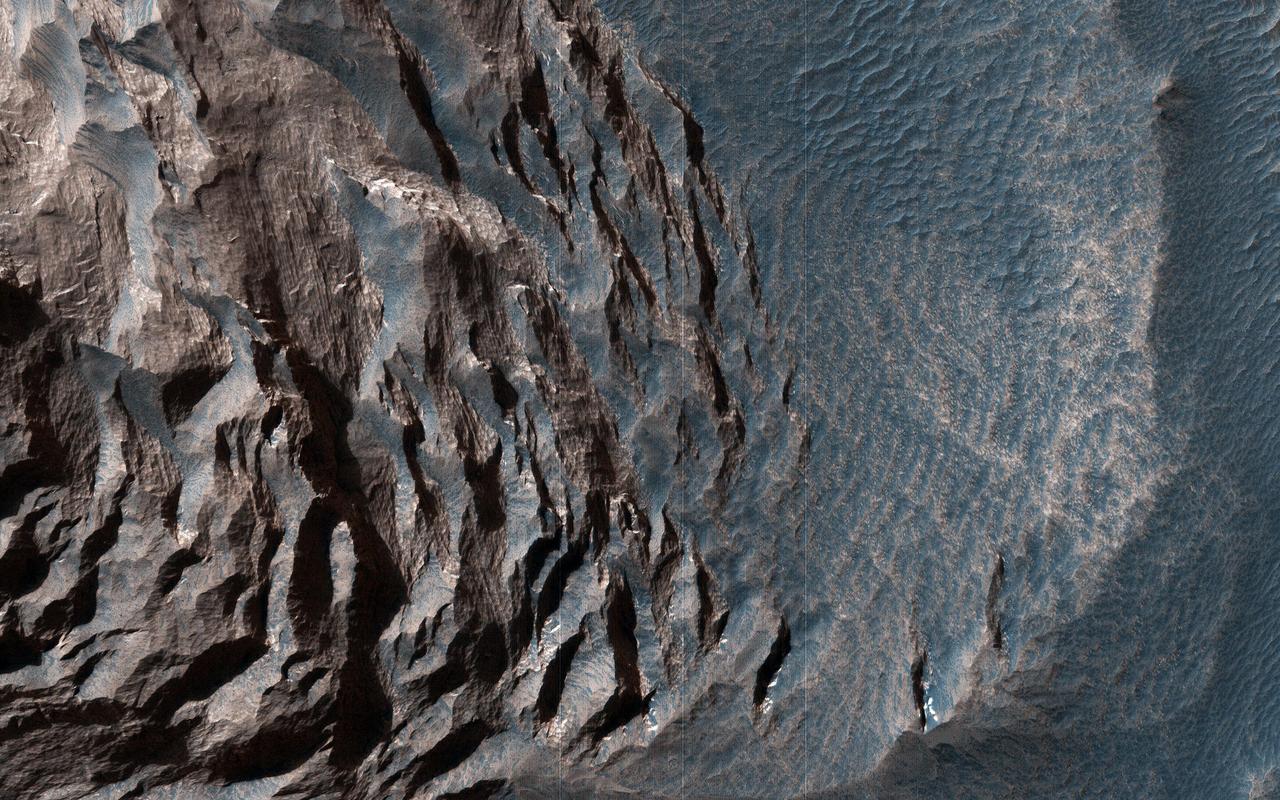

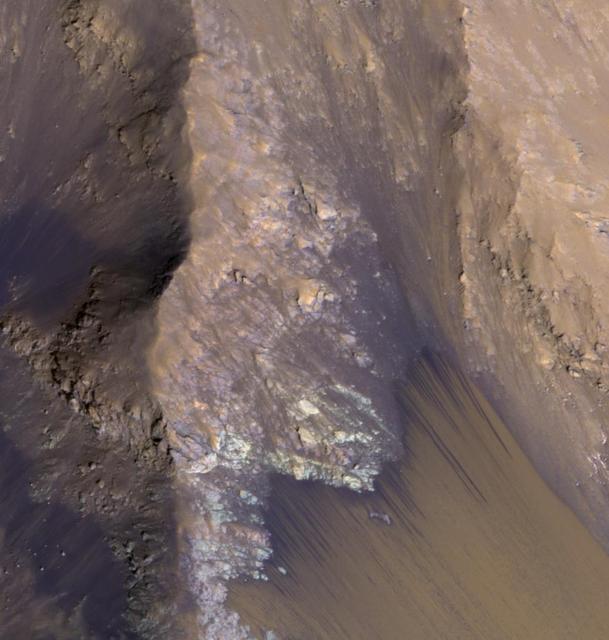

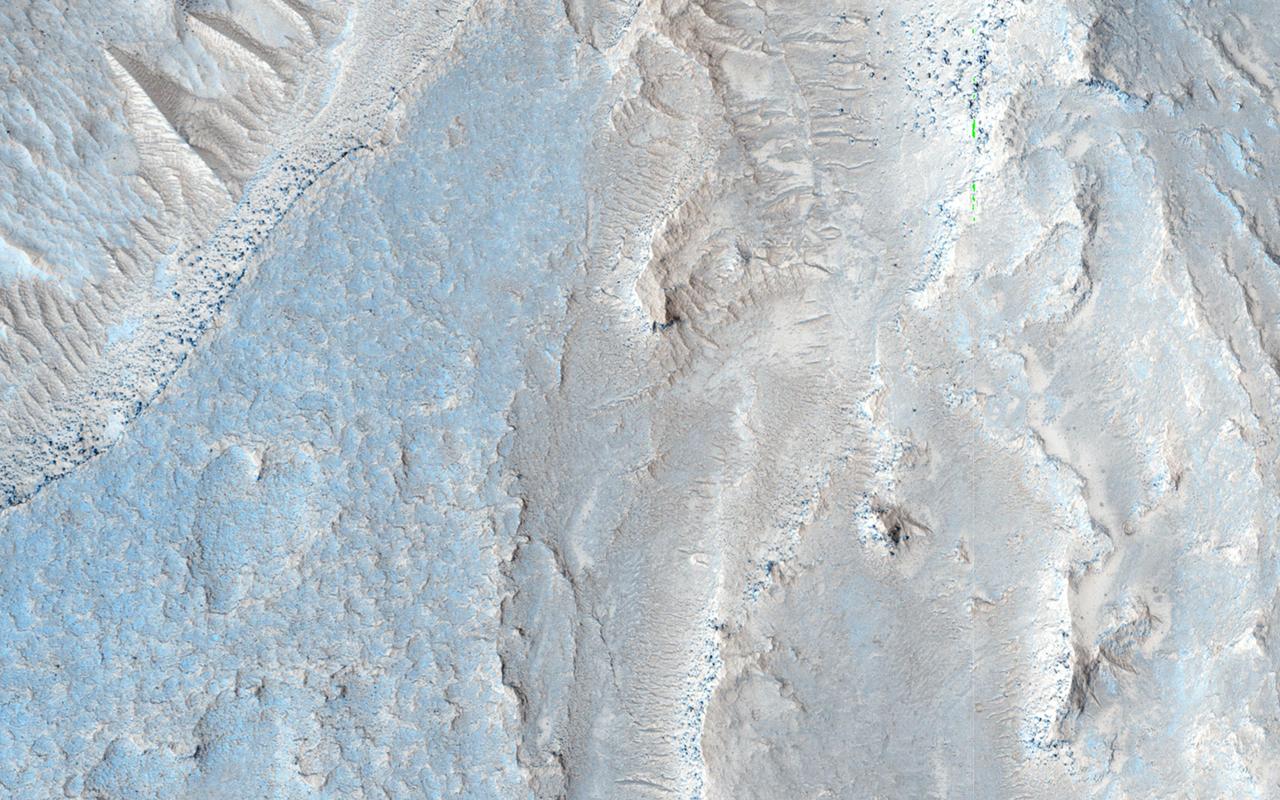

An enhanced-color image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) reveals bedrock that is several kilometers below the top of the giant Valles Marineris canyons. The upper layers have relatively little diversity of colors and textures, but deeper levels show more complex processes. The upper layers could be mostly volcanic while the lower layers were influenced by the period of heavy bombardment and greater interactions with water. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22238

Coprates Chasma is one of the numerous canyons that make up Valles Marineris. The chasma stretches for 960 km (600 miles) from Melas Chasma to the west and Capri Chasma to the east. Landslide deposits, layered materials and sand dunes cover a large portion of the chasma floor. This image is located on the eastern side of Coprates Chasma, near Capri Chasma. The image shows multiple landslide features, which form lobed shaped deposits at the bottom of the canyon cliff face. Sand dunes are visible both on the landslide deposit and other parts of the canyon floor. The Odyssey spacecraft has spent over 15 years in orbit around Mars, circling the planet more than 69000 times. It holds the record for longest working spacecraft at Mars. THEMIS, the IR/VIS camera system, has collected data for the entire mission and provides images covering all seasons and lighting conditions. Over the years many features of interest have received repeated imaging, building up a suite of images covering the entire feature. From the deepest chasma to the tallest volcano, individual dunes inside craters and dune fields that encircle the north pole, channels carved by water and lava, and a variety of other feature, THEMIS has imaged them all. For the next several months the image of the day will focus on the Tharsis volcanoes, the various chasmata of Valles Marineris, and the major dunes fields. We hope you enjoy these images! Orbit Number: 16628 Latitude: -15.4094 Longitude: 304.726 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2005-09-13 10:38 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21990

Layers within the Valles Marineris: Clues to the Ancient Crust of Mars - High Resolution Image

Complex Floor Deposits Within Western Ganges Chasma, Valles Marineris - High Resolution Image

Complex Floor Deposits Within Western Ganges Chasma, Valles Marineris - High Resolution Image

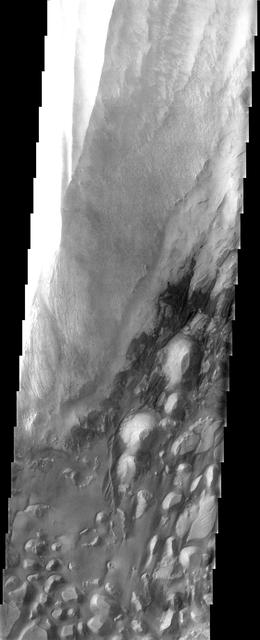

This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter covers a steep west-facing slope in southwestern Ganges Chasma, north of the larger canyons of Valles Marineris. The spot was targeted both for the bedrock exposures and to look for active slope processes. We see two distinct flow deposits: lobate flows that are relatively bright, sometimes with dark fringes, and very thin brownish lines that resemble recurring slope lineae (or 'RSL'). Both flows emanate from rocky alcoves. The RSL are superimposed on the lobate deposits (perhaps rocky debris flows), so they are younger and more active. The possible role of water in forming the debris flows and RSL are the subjects of continuing debate among scientists. We will acquire more images here to see if the candidate RSL are active. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21651

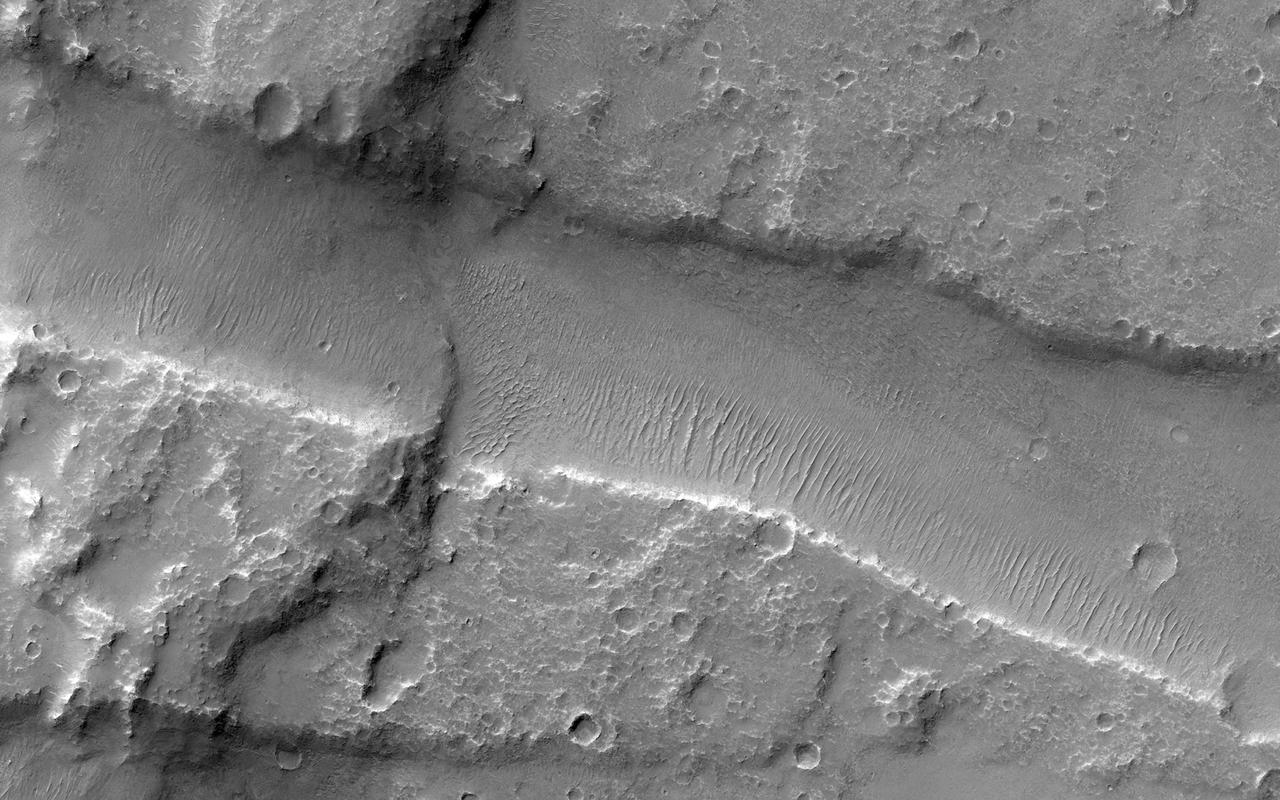

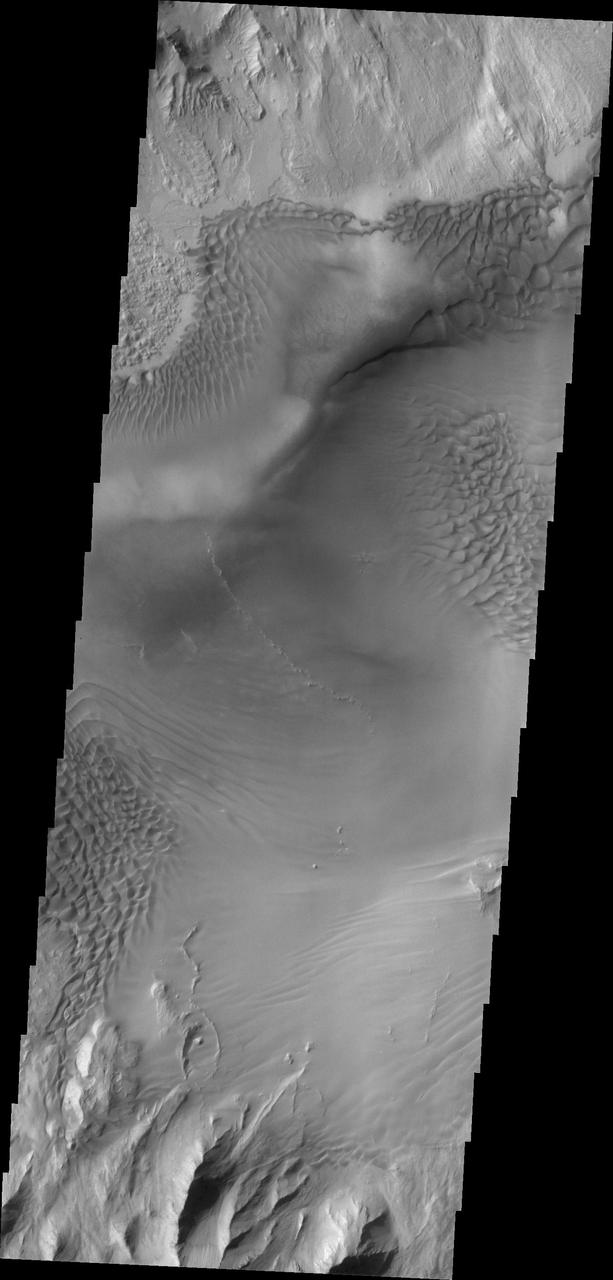

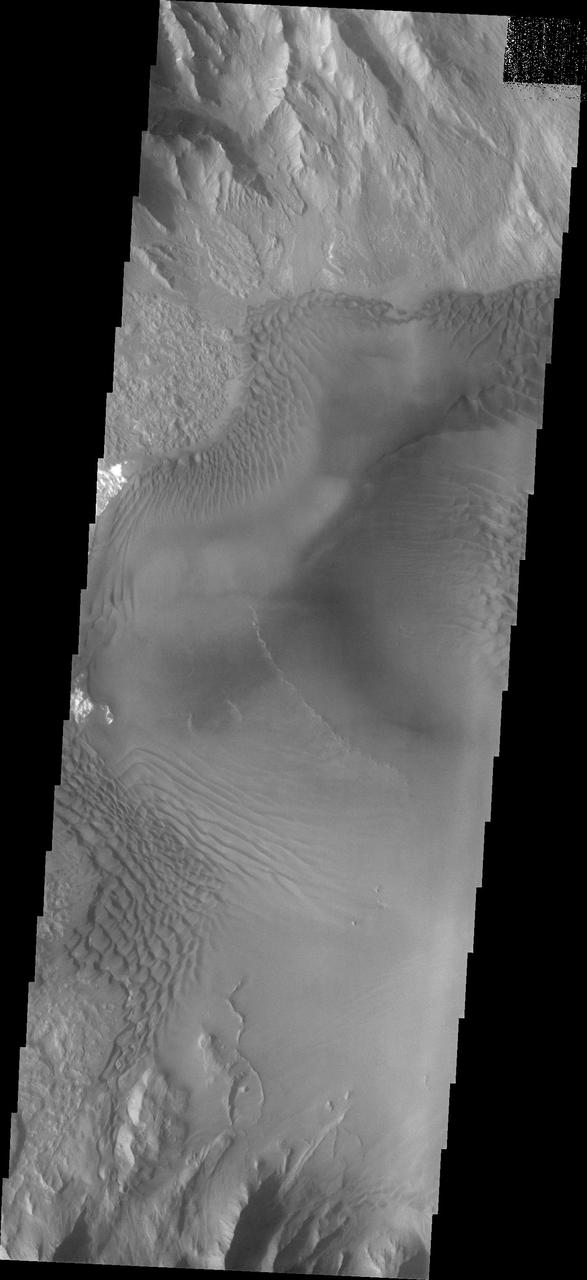

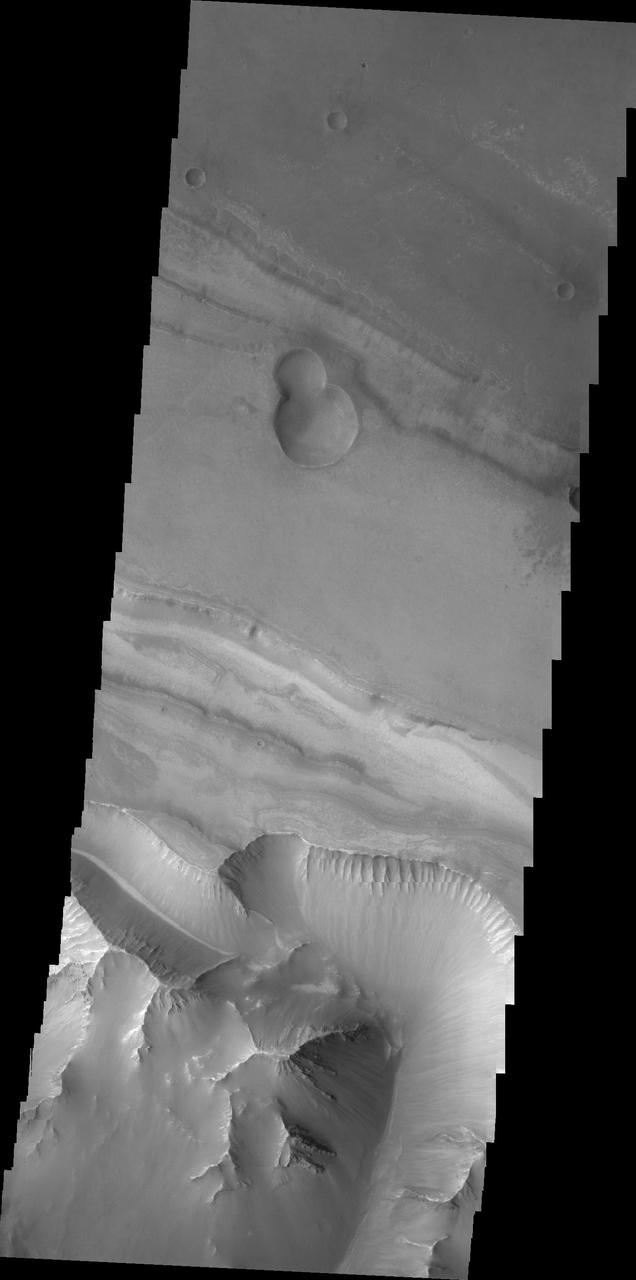

Coprates Chasma is one of the numerous canyons that make up Valles Marineris. The chasma stretches for 960 km (600 miles) from Melas Chasma to the west and Capri Chasma to the east. Landslide deposits, layered materials and sand dunes cover a large portion of the chasma floor. This image is located in eastern Coprates Chasma. The image shows a relatively smooth floor, with a group of sand dune forms located against the wall of the chasma (bottom of image). The Odyssey spacecraft has spent over 15 years in orbit around Mars, circling the planet more than 69000 times. It holds the record for longest working spacecraft at Mars. THEMIS, the IR/VIS camera system, has collected data for the entire mission and provides images covering all seasons and lighting conditions. Over the years many features of interest have received repeated imaging, building up a suite of images covering the entire feature. From the deepest chasma to the tallest volcano, individual dunes inside craters and dune fields that encircle the north pole, channels carved by water and lava, and a variety of other feature, THEMIS has imaged them all. For the next several months the image of the day will focus on the Tharsis volcanoes, the various chasmata of Valles Marineris, and the major dunes fields. We hope you enjoy these images! Orbit Number: 27061 Latitude: -13.9602 Longitude: 301.82 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2008-01-20 10:39 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21993

Layered sedimentary rocks are key to understanding the geologic history of a planet, recording the sequence of deposition and the changes over time in the materials that were deposited. These layered sediments are on the floor of eastern Coprates Chasma in Valles Marineris, the grandest canyon on Mars. They are erosional remnants of a formerly much more extensive sedimentary deposit that once filled the floor of the canyon but is nowadays reduced to isolated mesas. The origin of the deposits is not yet known. Various theories attribute the sediments to wind blown dust and sand, or to volcanic materials, or accumulations of debris from avalanches originating from the canyon walls, or even to lakebed sediments laid down when the canyons were filled with liquid water. Some sediments are devoid of boulders or blocks larger than the limit of resolution (about 0.5 meters), so avalanche debris is unlikely. We see fine laminations with a horizontal spacing of about 2 meters and a vertical separation less than 2 meters. No previous orbital observations were capable of resolving such fine scale layering. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23583

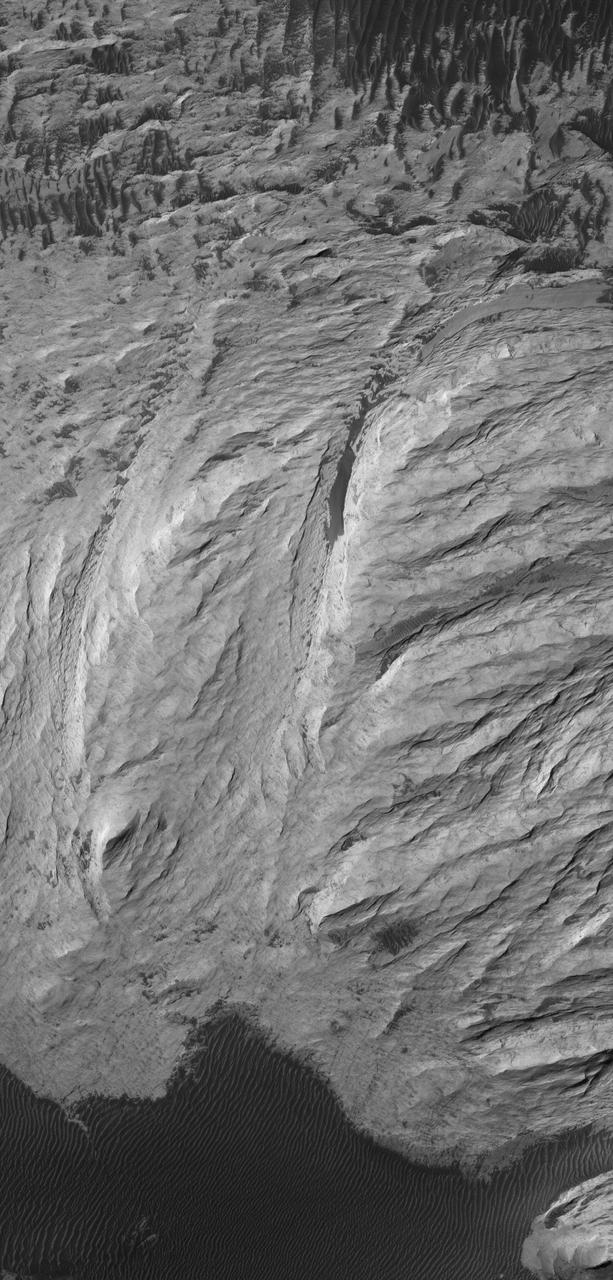

This picture of the rim of Eos Chasma in Valles Marineris shows active erosion of the Martian surface. Layered bedrock is exposed in a steep cliff on a spur of the canyon rim. Dark layers in this cliff are made up of large boulders up to 4 meters in diameter. The boulders are lined up along specific horizons, presumably individual lava flows, and are perched to descend down into the canyon upon the slightest disturbance. How long will the boulders remain poised to fall, and what will push them over the edge? Just as on Earth, the main factors that contribute to dry mass wasting erosion on Mars are frost heaving and thermal expansion and contraction due to changes in temperature. The temperature changes on Mars are extreme compared to Earth, because of the lack of humidity in the Martian atmosphere and the eccentricity of the Martian orbit. Each daily temperature cycle and each seasonal change from summer to winter produces a cycle of expansion and contraction that pushes the boulders gradually closer to the brink. Inevitably, the boulders fall from their precarious positions and plunge into the canyons below. Most simply slide down slope and collect just below the source layers. A few are launched along downward trajectories, travelling long distances before they settle on the slopes below. These trundling boulders left behind conspicuous tracks, up to a kilometer long. The tracks resemble dashed lines or perforations, indicating that the boulders bounced as they trundled down the slopes. The visibility of the boulder tracks suggests that this process may have taken place recently. The active Martian winds quickly erased the tracks of the rover Opportunity, for example. However, the gouges produced by trundling boulders probably go much deeper than the shallow compression of soil by the wheels of a relatively lightweight rover. The boulder tracks might persist for a much longer time span than the rover tracks for this reason. Nevertheless, the tracks of the boulders suggest that erosion of the rim of Eos Chasma is a process that continues today. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21203

Mosaic composed of 102 Viking Orbiter images of Mars, covering nearly a full hemisphere of the planet (approximate latitude -55 to 60 degrees, longitude 30 to 130 degrees). The mosaic is in a point-perspective projection with a scale of about 1 km/pixel. The color variations have been enhanced by a factor of about two, and the large-scale brightness variations (mostly due to sun-angle variations) have been normalized by large-scale filtering. The center of the scene shows the entire Valles Marineris canyon system, over 3,000 km long and up to 8 km deep, extending from Noctis Labyrinthus, the arcuate system of graben to the west, to the chaotic terrain to the east. Bright white layers of material in the eastern canyons may consist of carbonates deposited in ancient lakes. Huge ancient river channels begin from the chaotic terrain and from north-central canyons and run north. Many of the channels flowed into a basin called Acidalia Planitia, which is the dark area in the extreme north of this picture. The Viking 1 landing site (Mutch Memorial Station) is located in Chryse Planitia, south of Acidalia Planitia. The three Tharsis volcanoes (dark red spots), each about 25 km high, are visible to the west. The large crater with two prominent rings located at the bottom of this image is named Lowell, after the Flagstaff astronomer. The images were acquired by Viking Orbiter 1 in 1980 during early northern summer on Mars (Ls = 70 degrees); the atmosphere was relatively dust-free. A variety of clouds appear as bright blue streaks and hazes, and probably consist of water ice. Long, linear clouds north of central Valles Marineris appear to emanate from impact craters. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00003

This image shows the sand dunes and layered material common on the floor of Valles Marineris

NASA Mars Odyssey shows the location of the complexly fractured region called Noctis Labyrinthus at the westernmost end of Valles Marineris. The canyon systems in Noctis Labyrinthus do not reach the depths of the chasma of Valles Marineris.

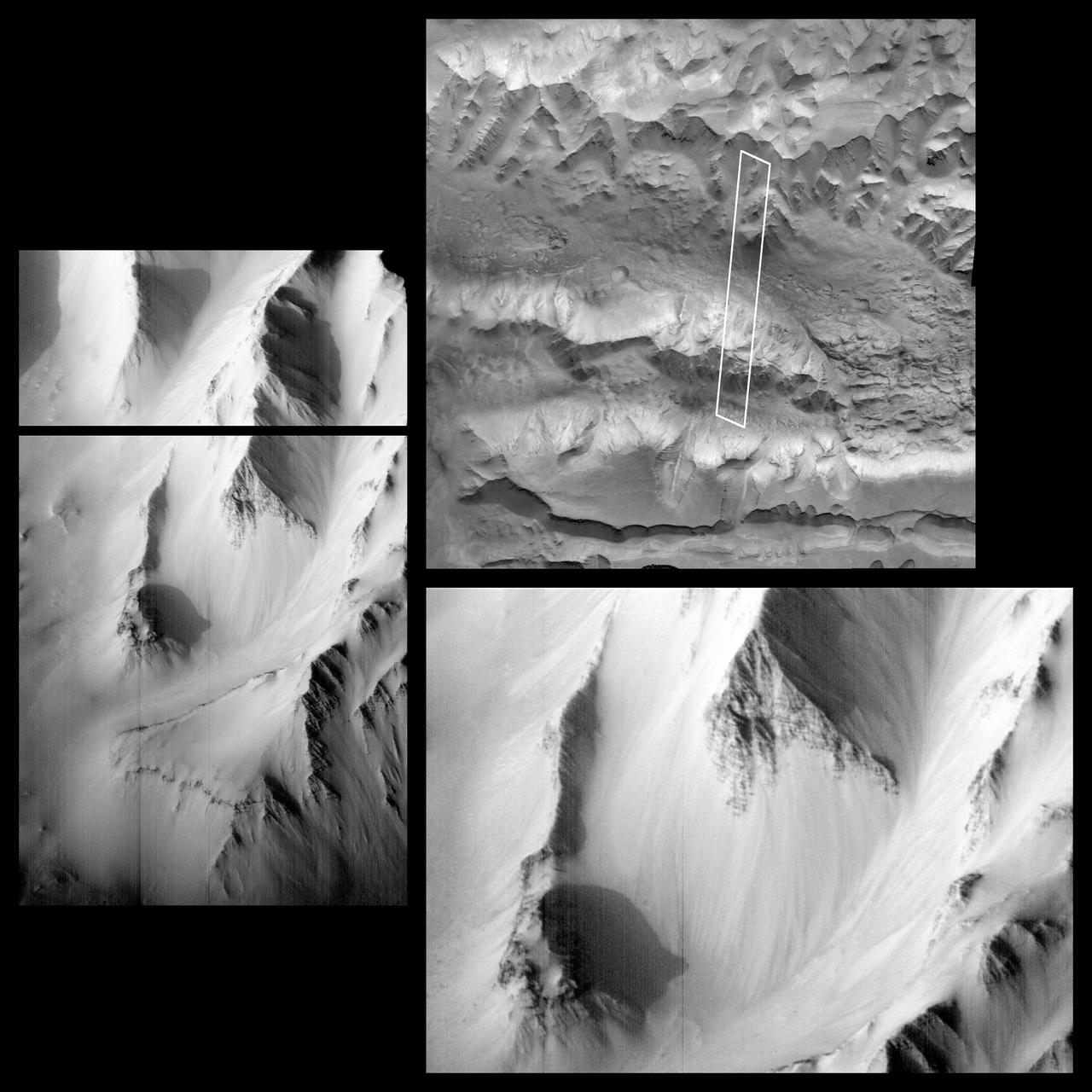

Capri Chasma is located in the eastern portion of the Valles Marineris canyon system, the largest known canyon system in the Solar System. Deeply incised canyons such as this are excellent targets for studying the Martian crust, as the walls may reveal many distinct types of bedrock. This section of the canyon was targeted by HiRISE based on a previous spectral detection of hematite-rich deposits in the area. Hematite, a common iron-oxide mineral, was first identified here by the Mars Global Surveyor Thermal Emission Spectrometer (TES). In this TES image, red pixels indicate higher abundances of hematite, while the blue and green pixels represent different types of volcanic rocks (e.g., basalt). Hematite in the Meridiani Planum region was also detected with the TES instrument (which we can see with the bright red spot on the Global TES mineral map). As a consequence, Meridiani Planum was the first landing site selected on Mars due to the spectral detection of a mineral that may have formed in the presence of liquid water. Shortly after landing, the Opportunity rover detected the presence of hematite in the form of concretions called "blueberries." The blueberries are found in association with layers of sulfate salt-rich rocks. The salts are hypothesized to have formed through the raising and lowering of the groundwater table. During one such an event, the rock altered to form the hematite-rich blueberries. As the rock was eroded away, the more resistant hematite-rich blueberries were plucked out and concentrated on the plains as a "lag" deposit. Martian blueberries are observed to be scattered across the plains of Meridiani along Opportunity's traverse from Eagle Crater to Endeavor Crater, where Opportunity continues to explore after its mission began over 10 years ago. This infrared-color image close-up highlights what is possibly the hematite-rich deposits nestled between different types of bedrock terraces in Capri Chasma. The bluish terrace is likely volcanic in origin, possibly basaltic, whereas the greenish rocks remain unidentified. The central reddish terrace is possibly where some of the hematite may be concentrated. The higher elevation terrace with the lighter-colored materials is likely a sulfate-rich rock (based on CRISM data in the area). Given the presence of both sulfate salts and hematite in this area, akin to the deposits and associations explored by the Opportunity rover in Meridiani Planum, it might be that these materials in Capri Chasma may share a similar origin. The yellow rectangular box shown on the TES spectral map outlines the corresponding location of the HiRISE image. Although the outline does not appear to contain a high hematite abundance, we note that the lower resolution of TES (about 3 to 6 kilometers per pixel) may exclude smaller exposures and finer sub-pixel details not-yet captured, but could be with HiRISE. A follow-up observation by the CRISM spectrometer may reveal additional details and a spectral signature for hematite in the vicinity at a finer resolution than TES. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21274

This HiRISE image shows the central pit feature of an approximately 20-kilometer diameter complex crater in located at 304.480 degrees east, -11.860 degrees south, just north of the Valles Marineris. Here we can observe a partial ring of light-toned, massive and fractured bedrock, which has been exposed by the impact-forming event, and via subsequent erosion that typically obscure the bedrock of complex central features. Features such as this one are of particular interest as they provide scientists with numerous exposures of bedrock that can be readily observed from orbit and originate from the deep Martian subsurface. Unlike on Earth, plate tectonics do not appear to be active on Mars. Thus, much of the Martian subsurface is not directly observable through uplift, erosion and exposure of mountain chains, which provide the majority of bedrock exposures on Earth. Exposures of subsurface materials generated by these features provides us with some of the only "windows" into the subsurface geology. This makes the study of impact craters an invaluable source of information when trying to understand, not only the impact process, but also the composition and history of Mars. Although much of what we see here is composed of massive and fractured bedrock, there are zones of rock fragmentation, called "brecciation." These fragmented rocks (a.k.a., breccias) are best viewed in the eastern portion of the central pit, which was captured in a previous HiRISE image. Additionally, we see some occurrences of impact melt-bearing deposits that surround and coat the bedrock exposed within the central pit. Several dunes are on the surface throughout the central pit and surrounding crater floor. The mechanisms behind the formation of central features, particularly central pits, are not completely understood. Geologic mapping of these circumferential "mega" blocks of bedrock indicate radial and concentric fracturing that is consistent with deformation through uplift. The exposed bedrock shows well-expressed lineament features that are likely fractures and faults formed during the uplift process. Studies of the bedrock, and such structures in this image, allows us better to understand the formative events and physical processes responsible for their formation. Current research suggests that their formation is the result of some component of uplift followed by collapse. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21205

This false-color infrared image from NASA Mars Odyssey was acquired over the region of Ophir and Candor Chasma in Valles Marineris.

The landslide in the center of this image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft occurred in the Melas Chasma region of Valles Marineris.

This MOC image shows a landslide that occurred off of a steep slope in Tithonium Chasma, part of the vast Valles Marineris trough system

This image captured by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft is part of Tithonium Chasma, part of the western side of Valles Marineris.

This image from NASA Mars Odyssey shows a portion of Tithonium Chasma, part of western Valles Marineris.

At the eastern end of Valles Marineris the chasma floors are typically filled with the hills and mounds of chaos terrain as seen by NASA Mars Odyssey.

The landslide deposits in this infrared image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft are located in Valles Marineris and are called Coprates Labes.

The landslide deposit in this image captured by NASA Mars Odyssey is located in shallow extension of Tithonium Chasma, in the western part of Valles Marineris.

Among the many discoveries by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter since the mission was launched on Aug. 12, 2005, are seasonal flows on some steep slopes. These flows have a set of characteristics consistent with shallow seeps of salty water. This July 21, 2015, image from the orbiter's High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera shows examples of these flows on a slope within Coprates Chasma, which is part of the grandest canyon system on Mars, Valles Marineris. The image covers an area of ground one-third of a mile (536 meters) wide. These flows are called recurring slope lineae because they fade and disappear during cold seasons and reappear in warm seasons, repeating this pattern every Martian year. The flows seen in this image are on a north-facing slope, so they are active in northern-hemisphere spring. The flows emanate from the relatively bright bedrock and flow onto sandy fans, where they are remarkably straight, following linear channels. Valles Marineris contains more of these flows than everywhere else on Mars combined. At any season, some are active, though on different slope aspects at different seasons. Future human explorers (and settlers?) will need water to drink, grow food, produce oxygen to breath, and make rocket fuel. Bringing all of that water from Earth would be extremely expensive, so using water on Mars is essential. Although there is plenty of water ice at high latitudes, surviving the cold winters would be difficult. An equatorial source of water would be preferable, so Valles Marineris may be the best destination. However, the chemistry of this water must be understood before betting any lives on it. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19805

Osuga Valles lies around 170 kilometers to the south of Eos Chasma, which is at the eastern end of the vast Valles Marineris canyon system as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Many of the Valles Marineris canyons, called chasmata, have kilometer-high, light-toned layered mounds made up of sulfate materials. Ius Chasma, near the western end of Valles Marineris, is an exception. The light-toned deposits here are thinner and occur along both the floor and walls, as we see in this HiRISE image. Additionally, the sulfates are mixed with other minerals like clays and hydrated silica. Scientists are trying to use the combination of mineralogy, morphology, and stratigraphy to understand how the deposits formed in Ius Chasma and why they differ from those found elsewhere in Valles Marineris. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25982

Ius Chasma is one of several canyons that make up Valles Marineris, the largest canyon system in the Solar System as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

This NASA Mars Odyssey image shows the effects of erosion on a beautiful sequence of dramatically layered rocks within Candor Chasma, which is part of the Valles Marineris.

This colorful scene is situated in the Noctis Labyrinthus, perched high on the Tharsis rise in the upper reaches of the Valles Marineris canyon system as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Melas Chasma is the widest segment of the Valles Marineris canyon, and is an area where NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has detected the presence of sulfates.

This image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft was acquired of Candor Chasma within Valles Marineris and shows the effects of erosion on a sequence of dramatically layered rocks.

This image from NASA Mars Odyssey was acquired of Candor Chasma within Valles Marineris and shows the effects of erosion on a sequence of dramatically layered rocks.

Tectonic fractures within the Candor Chasma region of Valles Marineris, Mars, retain ridge-like shapes as the surrounding bedrock erodes away

This image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows the northern interior wall of Coprates Chasma, one of the major canyons that form Valles Marineris.

This view, taken by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, shows color variations in bright layered deposits on a plateau near Juventae Chasma in the Valles Marineris region of Mars.

This image captured by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows part of the floor of Melas Chasma, which is part of the much larger Valles Marineris.

Melas Chasma is part of the Valles Marineris canyon system, the largest canyon in the Solar System. This image was taken by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

This image captured by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows the part of the floor of Melas Chasma. Melas Chasma in the central chasma of Valles Marineris.

Ages ago, a giant earthquake shook the walls of Valles Marineris, the Grand Canyon of Mars, and triggered a catastrophic landslide that crashed down 15,000 feet.

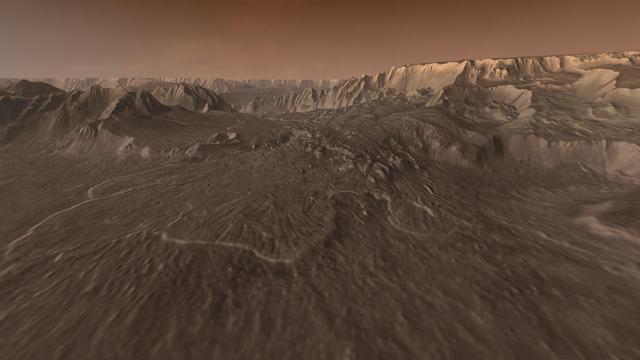

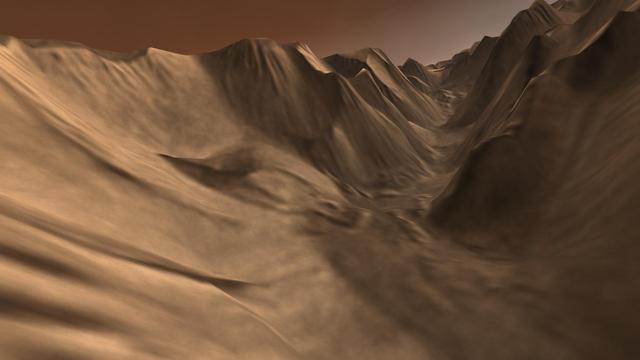

Flying through the canyons and over the ridges of Valles Marineris, viewers can experience some of the thrills that gripped explorers who pushed into unknown regions on Earth

The image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is approximately 6 by 6 kilometers and is located east of Noctis Labyrinthus, in a portion the large canyon system Valles Marineris.

This MOC image shows outcrops of light-toned, massively-bedded rock in western Candor Chasma, part of the Valles Marineris trough system

Baetis Chasma is a chasmata near but not directly connected to Valles Marineris. Dunes are prevalent on the floor of this portion of Juventae Chasma in this image taken by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey.

Viewers experience roller-coaster twists and turns as they fly up a winding tributary valley that feeds into Valles Marineris, the Grand Canyon of Mars.

These layered deposits are located on the floor of a large canyon called Ganges Chasma which is a part of the Valles Marineris in this image captured by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft.

This observation from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows one of the first close HiRISE views of the enigmatic Valles Marineris interior layered deposits.

This image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft covers part of Tithonium Chasma, which is part of the Valles Marineris system of canyons that stretch for thousands of kilometers.

This image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows part of Coprates Chasma, which is just one part of the extensive Valles Marineris canyon system.

Dune forms cover the top of this sand sheet on the floor of Juventae Chasma, a chasma north of the Valles Marineris canyon system in this image from NASA Mars Odyssey.

Juventae Chasma is a giant box canyon, yet a relatively small segment of the enormous Valles Marineris system, seen here by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

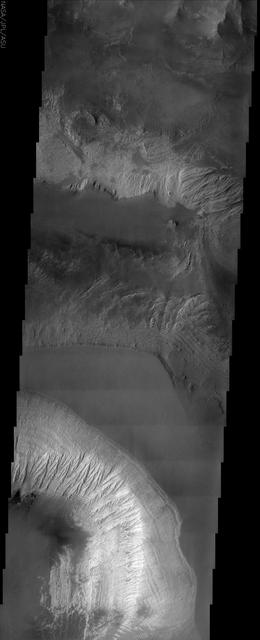

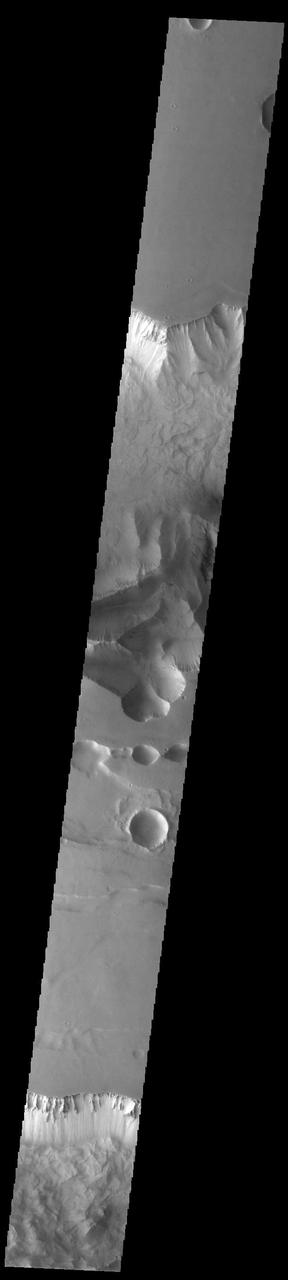

Today's VIS image shows the part of the eastern end of Tithonium Chasma. Tithonium Chasma is at the western end of Valles Marineris. Valles Marineris is over 4000 kilometers long, almost as wide as the United States. Tithonium Chasma is almost 810 kilometers long (499 miles), 50 kilometers wide and over 6 kilometers deep. In comparison, the Grand Canyon in Arizona is about 175 kilometers long, 30 kilometers wide, and only 2 kilometers deep. The canyons of Valles Marineris were formed by extensive fracturing and pulling apart of the crust during the uplift of the vast Tharsis plateau. In this image, the shallower regions of Tithonium are visible. The northern cliff of Ius Chasma is visible at the bottom of the image. Orbit Number: 92650 Latitude: -5.20867 Longitude: 275.913 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-11-03 01:37 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25767

Although actively-forming gullies are common in the middle latitudes of Mars, there are also pristine-looking gullies in equatorial regions. In this scene, the gullies have very sharp channels and different colors where the gullies have eroded and deposited material. Over time, the topography becomes smoothed over and the color variations disappear, unless there is recent activity. Changes have not been visible here from before-and-after images, and maybe such differences are apparent compared to older images, but nobody has done a careful comparison. What may be needed to see subtle changes is a new image that matches the lighting conditions of an older one. Equatorial gully activity is probably much less common — perhaps there is major downslope avalanching every few centuries — so we need to be lucky to see changes. MRO has now been imaging Mars for over 16 years, and the chance of seeing rare activity increases as the time interval widens between repeat images. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25309

![This is an odd-looking image. It shows gullies during the winter while entirely in the shadow of the crater wall. Illumination comes only from the winter skylight. We acquire such images because gullies on Mars actively form in the winter when there is carbon dioxide frost on the ground, so we image them in the winter, even though not well illuminated, to look for signs of activity. The dark streaks might be signs of current activity, removing the frost, but further analysis is needed. NB: North is down in the cutout, and the terrain slopes towards the bottom of the image. The map is projected here at a scale of 50 centimeters (19.7 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 62.3 centimeters (24.5 inches) per pixel (with 2 x 2 binning); objects on the order of 187 centimeters (73.6 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21568](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21568/PIA21568~medium.jpg)

This is an odd-looking image. It shows gullies during the winter while entirely in the shadow of the crater wall. Illumination comes only from the winter skylight. We acquire such images because gullies on Mars actively form in the winter when there is carbon dioxide frost on the ground, so we image them in the winter, even though not well illuminated, to look for signs of activity. The dark streaks might be signs of current activity, removing the frost, but further analysis is needed. NB: North is down in the cutout, and the terrain slopes towards the bottom of the image. The map is projected here at a scale of 50 centimeters (19.7 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 62.3 centimeters (24.5 inches) per pixel (with 2 x 2 binning); objects on the order of 187 centimeters (73.6 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21568

This VIS image shows a portion of Kasei Valles. In the region of this image Kasei Valles is flowing northward from Vallis Marineris. This image contains both fluvial features and tectonic features. The linear features running across the image from the lower right to the upper left are fractures created by tectonic forces. The ones running vertically were created by fluid flow. Kasei Valles is one of the largest outflow channels on Mars and catastrophic flooding carved this massive channel. Orbit Number: 79091 Latitude: 19.5912 Longitude: 286.26 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2019-10-13 16:12 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23565

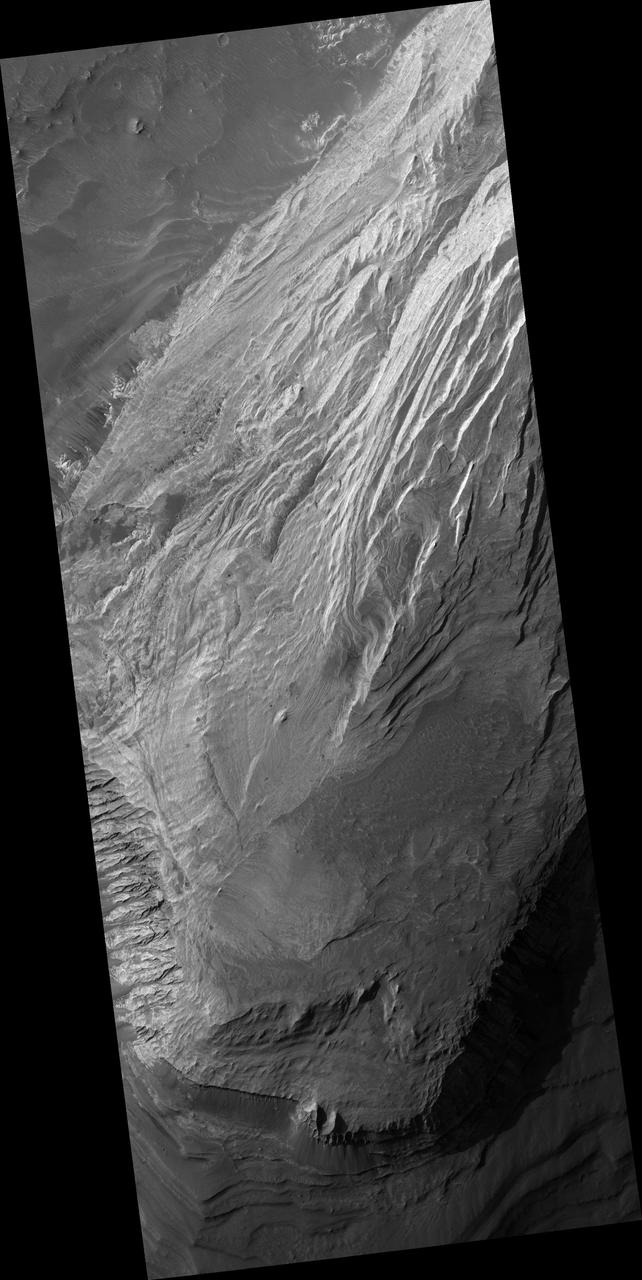

This VIS image shows part of the southern cliffside of Melas Chasma. Melas Chasma is part of the largest canyon system on Mars, Valles Marineris. At only 563 km long (349 miles) it is not the longest canyon, but it is the widest. Located in the center of Valles Marineris, it has depths up to 9 km below the surrounding plains, and is the location of many large landslide deposits, as will as layered materials and sand dunes. There is evidence of both water and wind action as modes of formation for many of the interior deposits. Orbit Number: 81537 Latitude: -11.3482 Longitude: 284.901 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2020-05-02 01:42 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23992

This image captured by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows the region between Candor Chasma and Melas Chasma.

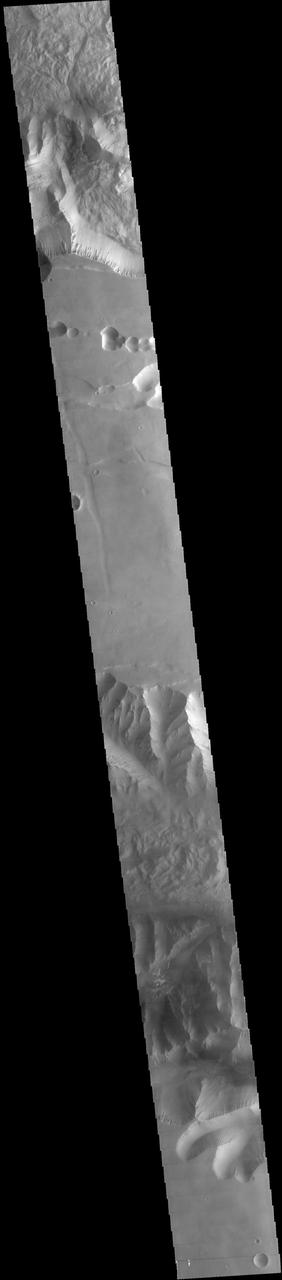

This image captured by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft spans from Tithonium Chasma top of image to Ius Chasma bottom of image.

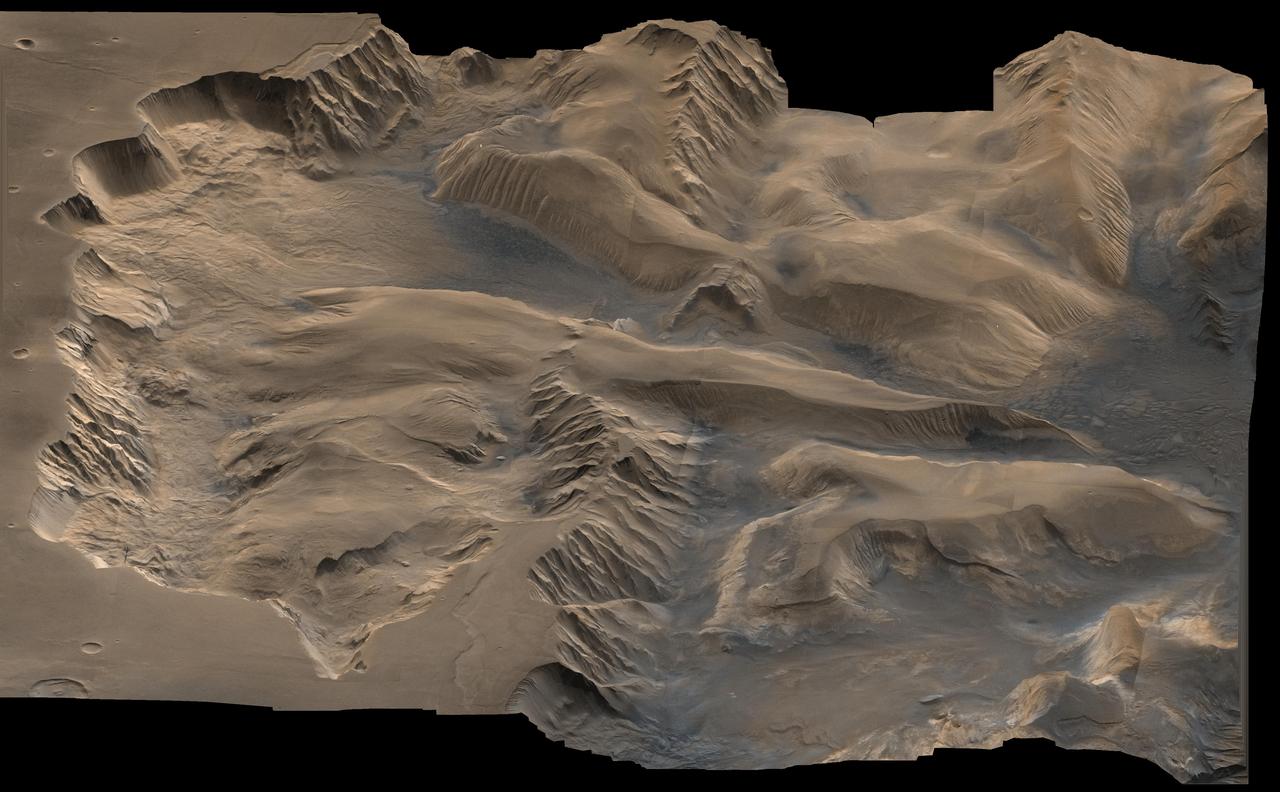

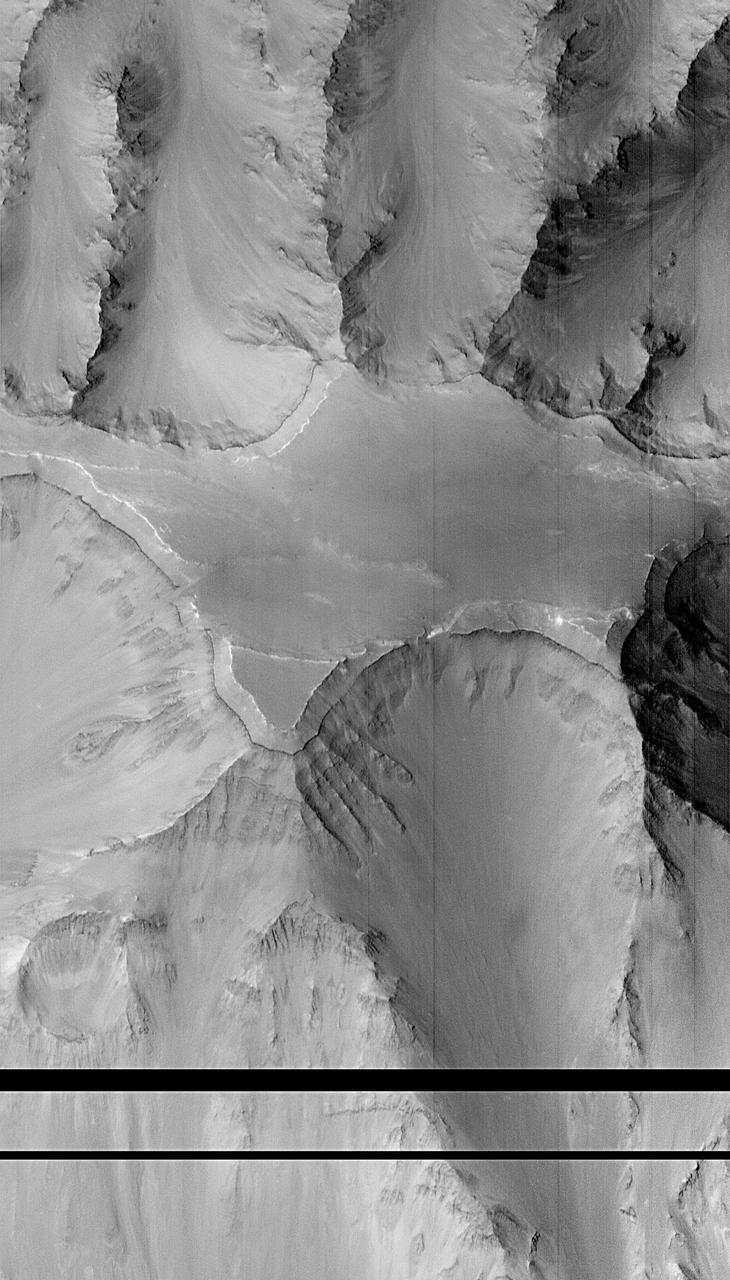

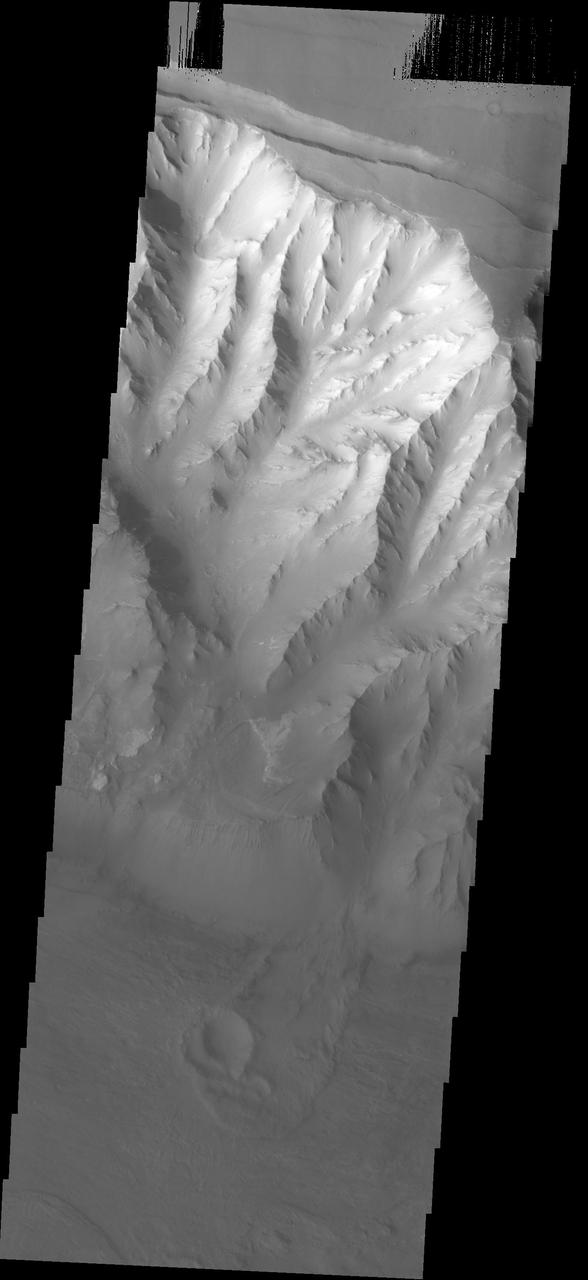

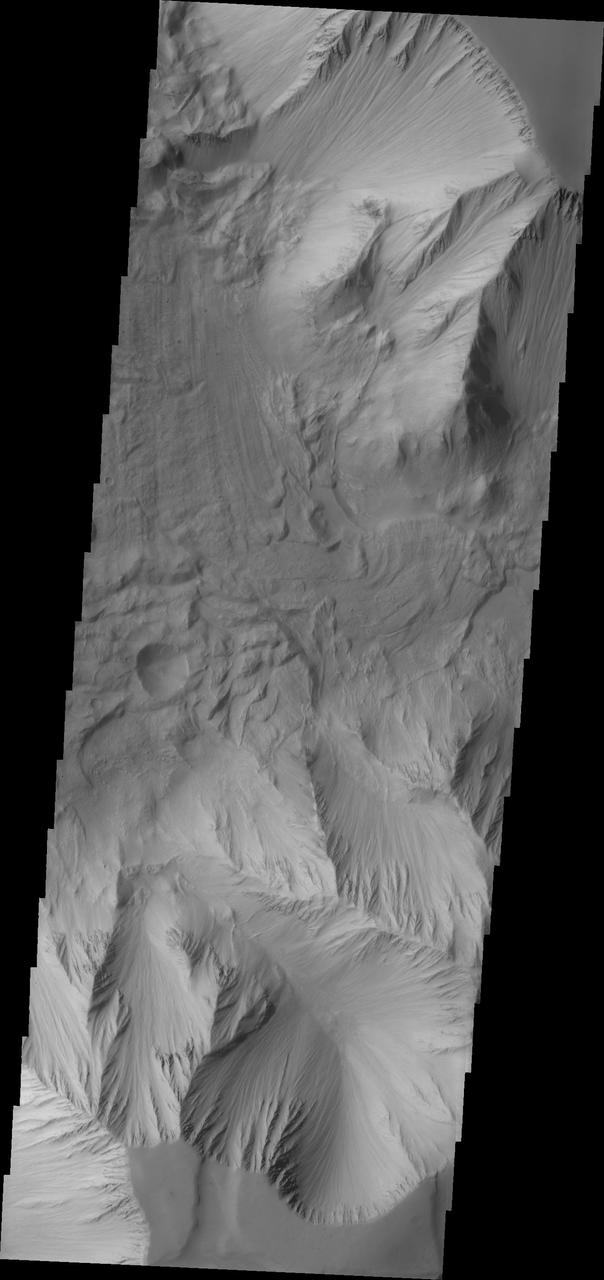

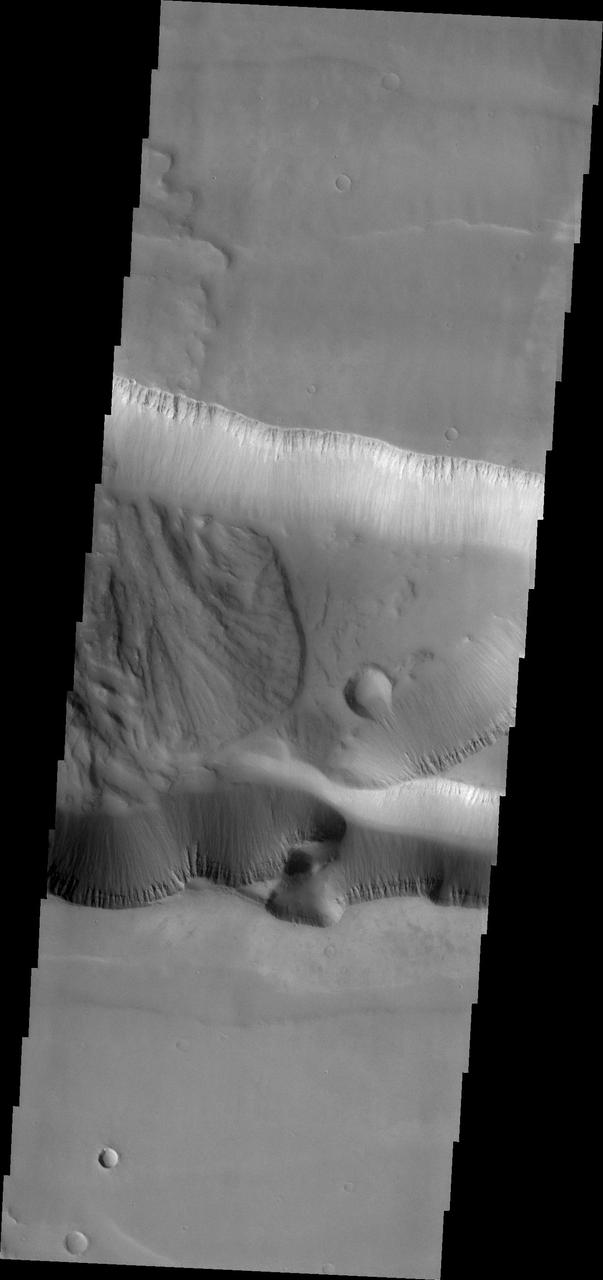

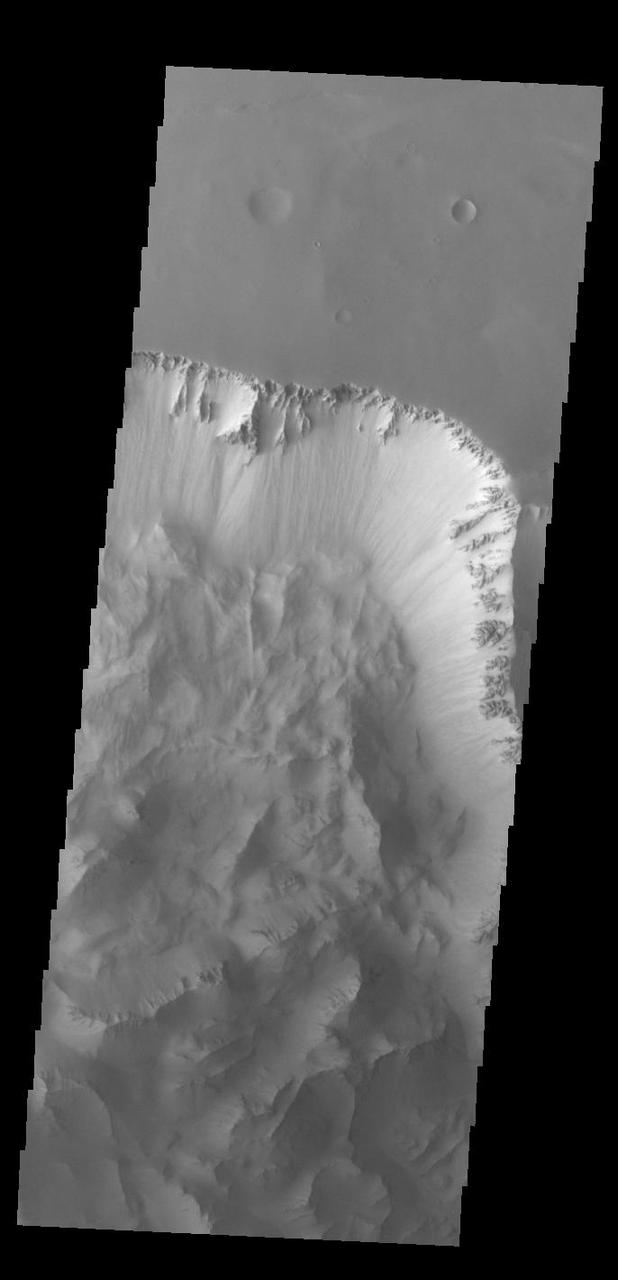

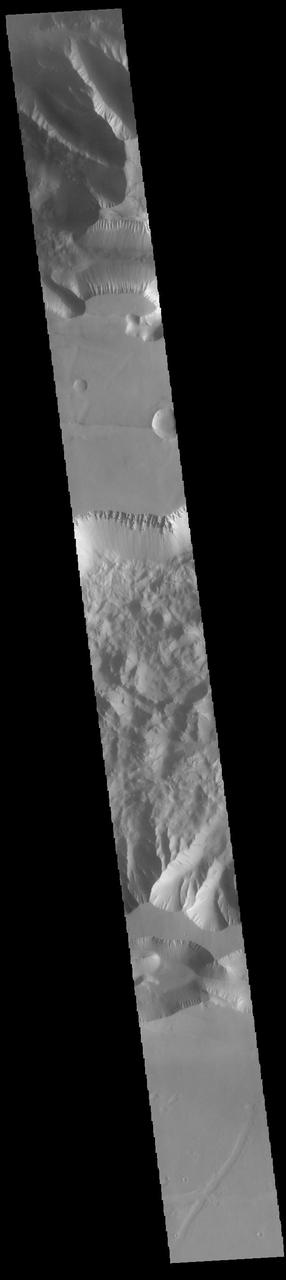

Today's VIS image shows part of Ius Chasma. Ius Chasma is at the western end of Valles Marineris. Valles Marineris is over 4000 kilometers long, wider than the United States. Ius Chasma is almost 850 kilometers long (528 miles), 120 kilometers wide and over 8 kilometers deep. In comparison, the Grand Canyon in Arizona is about 175 kilometers long, 30 kilometers wide, and only 2 kilometers deep. The canyons of Valles Marineris were formed by extensive fracturing and pulling apart of the crust during the uplift of the vast Tharsis plateau. Landslides have enlarged the canyon walls and created deposits on the canyon floor. Weathering of the surface and influx of dust and sand have modified the canyon floor, both creating and modifying layered materials. There are many features that indicate flowing and standing water played a part in the chasma formation. The rugged floor of Ius Chasma in this image is the result of many large landslides. Orbit Number: 92987 Latitude: -6.37421 Longitude: 273.45 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-11-30 19:36 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25808

Ius Chasma is at the western end of Valles Marineris, south of Tithonium Chasma. Valles Marineris is over 4000 kilometers long, almost as wide as the United States. Ius Chasma is almost 850 kilometers long (528 miles), 120 kilometers wide and over 8 kilometers deep. In comparison, the Grand Canyon in Arizona is about 175 kilometers long, 30 kilometers wide, and only 2 kilometers deep. The canyons of Valles Marineris were formed by extensive fracturing and pulling apart of the crust during the uplift of the vast Tharsis plateau. Landslides have enlarged the canyon walls and created deposits on the canyon floor. Weathering of the surface and influx of dust and sand have modified the canyon floor, both creating and modifying layered materials. There are many features that indicate flowing and standing water played a part in the chasma formation. The rugged floor of Ius Chasma in this image is the result of many large landslides. Orbit Number: 91839 Latitude: -7.09251 Longitude: 272.604 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-08-28 06:58 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25712

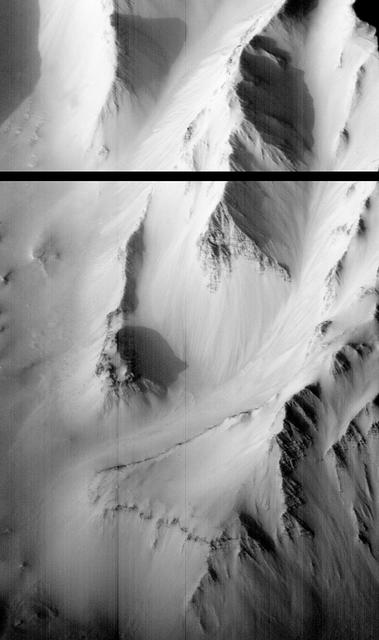

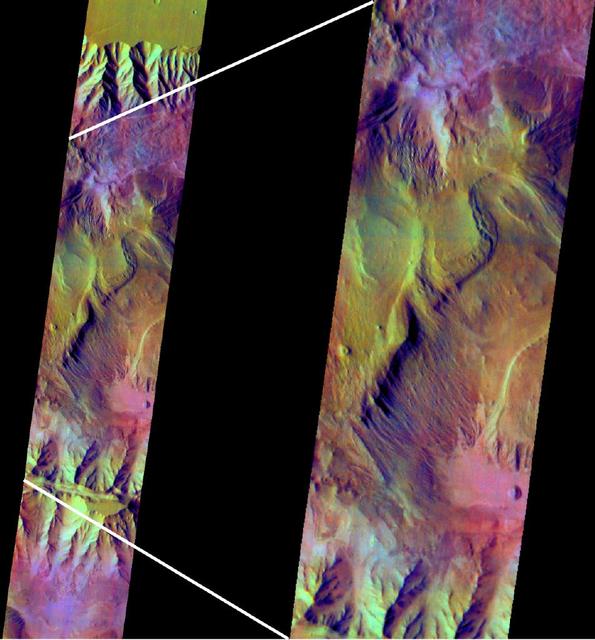

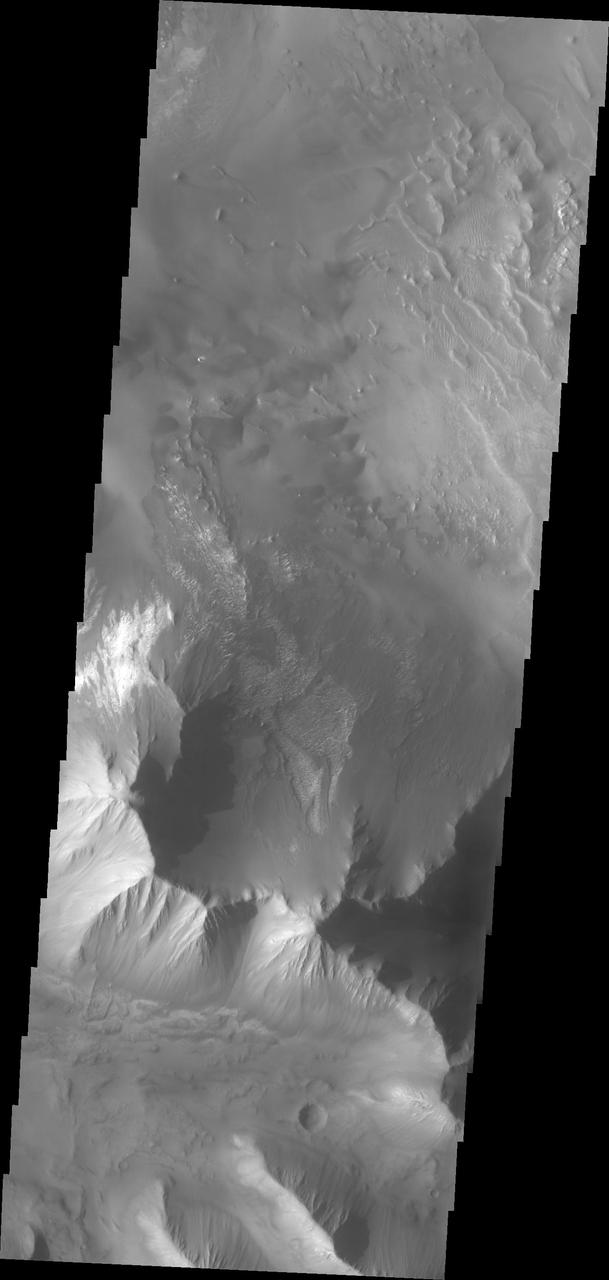

Ius and Tithonium Chasmata are located at the western end of Valles Marineris. Tithonium Chasma is north of Ius Chasma. Valles Marineris is over 4000 kilometers long (2495 miles), almost as wide as the United States. Ius Chasma is almost 840 kilometers long (522 miles), 120 kilometers wide and over 8 kilometers deep. Tithonium Chasma is 803 km (499 miles) long. In comparison, the Grand Canyon in Arizona is about 175 kilometers long (109 miles), 30 kilometers wide, and only 2 kilometers deep. The canyons of Valles Marineris were formed by extensive fracturing and pulling apart of the crust during the uplift of the vast Tharsis plateau. Landslides have enlarged the canyon walls and created deposits on the canyon floor. Weathering of the surface and influx of dust and sand have modified the canyon floor, both creating and modifying layered materials. There are many features that indicate flowing and standing water played a part in the chasma formation. The rugged floor of Ius Chasma (bottom of image) is comprised of large landslide deposits. Orbit Number: 92700 Latitude: -5.02133 Longitude: 273.439 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-11-07 04:26 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25769

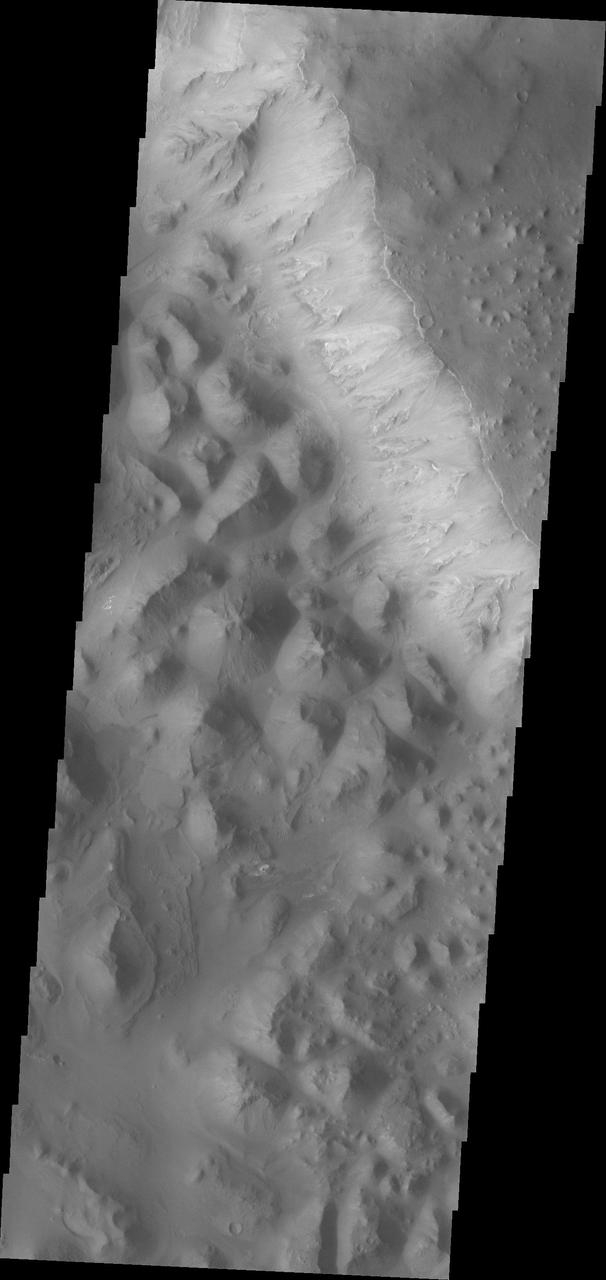

Ius and Tithonium Chasmata are located at the western end of Valles Marineris. Tithonium Chasma is north of Ius Chasma. Valles Marineris is over 4000 kilometers long (2495 miles), almost as wide as the United States. Ius Chasma is almost 840 kilometers long (522 miles), 120 kilometers wide and over 8 kilometers deep. Tithonium Chasma is 803 km (499 miles) long. In comparison, the Grand Canyon in Arizona is about 175 kilometers long (109 miles), 30 kilometers wide, and only 2 kilometers deep. The canyons of Valles Marineris were formed by extensive fracturing and pulling apart of the crust during the uplift of the vast Tharsis plateau. Landslides have enlarged the canyon walls and created deposits on the canyon floor. Weathering of the surface and influx of dust and sand have modified the canyon floor, both creating and modifying layered materials. There are many features that indicate flowing and standing water played a part in the chasma formation. The rugged floor of Ius Chasma (lower half of image) is comprised of large landslide deposits. Orbit Number: 89711 Latitude: -6.50729 Longitude: 272.316 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-03-06 02:35 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25459