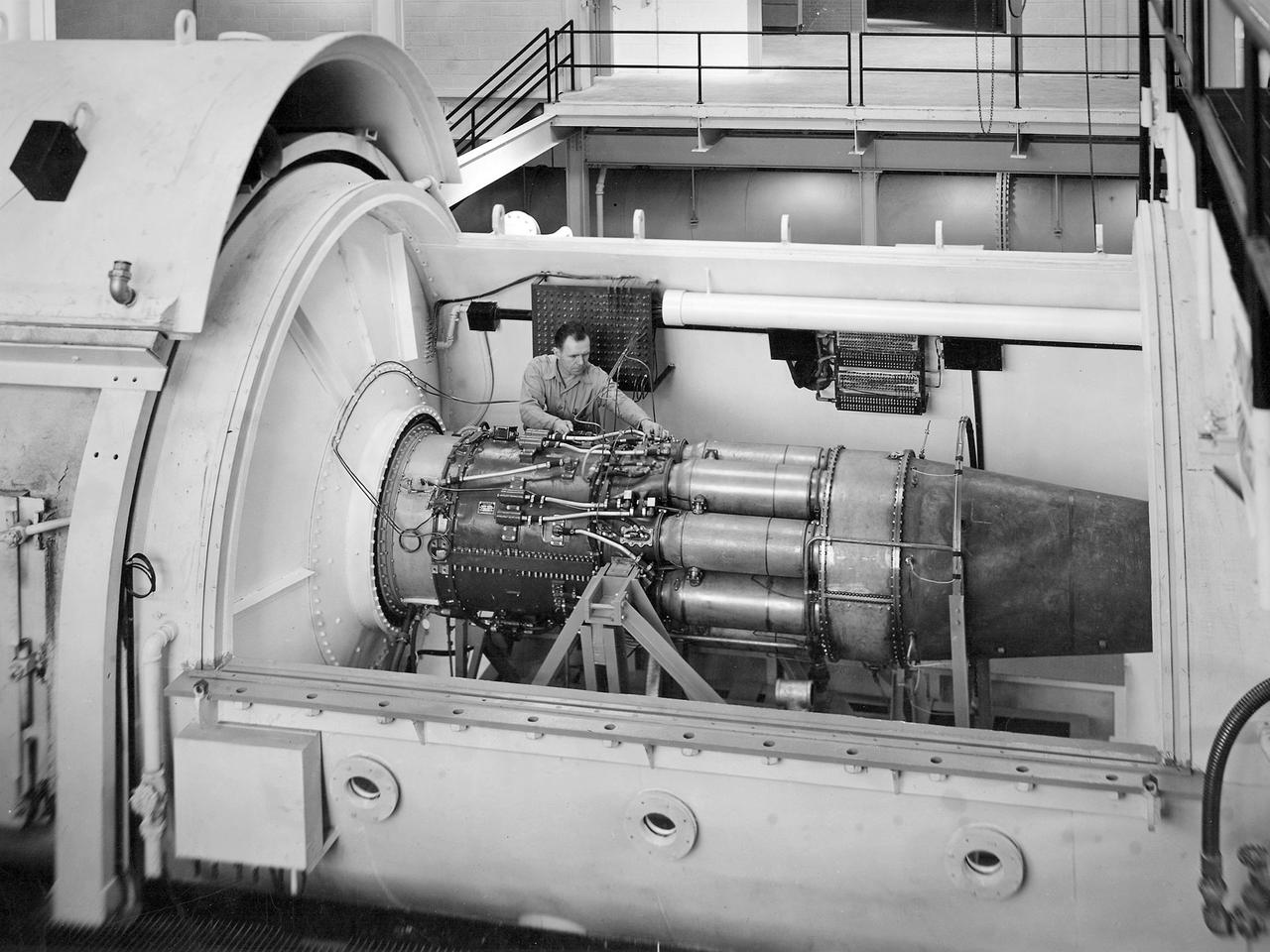

A Wright Aeronautical XRJ47-W-5 ramjet installed in a test chamber of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics’ (NACA) new Propulsion Systems Laboratory at the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. Construction of the facility had only recently been completed, and NACA engineers were still testing the various operating systems. The Propulsion Systems Laboratory was the NACA’s most powerful facility for testing full-scale engines in simulated flight altitudes. It contained two 14-foot diameter and 100-foot-long altitude chambers that ran parallel to one another with a control room in between. The engine being tested was installed inside the test section of one of the chambers, seen in this photograph. Extensive instrumentation was fitted onto the engine prior to the test. Once the chamber was sealed, the altitude conditions were introduced, and the engine was ignited. Operators in the control room could run the engine at the various speeds and adjust the altitude conditions to the desired levels. The engine’s exhaust was ejected into the cooling equipment. Two 48-inch diameter XRJ47-W-5 ramjets were used to power the North American Aviation Navaho Missile. The Navaho was a winged missile that was intended to travel up to 3000 miles carrying a nuclear warhead. It was launched using rocket booster engines that were ejected after the missile’s ramjet engines were ignited.

This 0.5-inch x 0.5-inch (1.3 x 1.3 centimeter) square of unbleached muslin material from the Wright brothers' first airplane was encapsulated in a protective polyamide film before being attached to a cable underneath the solar panel of NASA's Ingenuity Mars Helicopter. Procured by the Wrights from a local department store in downtown Dayton, Ohio, the cotton fabric (called "Pride of the West Muslin") was at the time mostly used for ladies undergarments. In the front parlor of their home, the Wrights cut the material into strips and used the family sewing machine to create wing coverings for their airplane Flyer 1, which achieved the first powered, controlled flight on Earth on Dec. 17, 1903. The swatch of material from the Wright brothers' first airplane was obtained from the Carillon Historical Park, in Dayton, Ohio — home to the Wright Brothers National Museum. The image was taken in a clean room at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory on January 15, 2020. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24438

NASA's Ingenuity Mars Helicopter carries a small swatch of muslin material from the lower-left wing of the Wright Brothers Flyer 1. Located on the underside of the helicopter's solar panel (the dark rectangle), the swatch is attached with dark orange polymide tape to a cable extending from the panel, and then further secured in place with white polyester cord used to bind cables together. A gray dot of epoxy at the intersection of the three wraps of cord prevents the lacing from loosening as the rotor blades (upper pair seen at bottom of image) rotate at up to 2,400 rpm. The entire process, from enclosing the material in the plastic to affixing it onto the helicopter took, approximately 30 minutes. The swatch of material from the Wright brothers' first airplane was obtained from the Carillon Historical Park, in Dayton, Ohio — home to the Wright Brothers National Museum. The image was taken in a clean room at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California on January 15, 2020. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24291

JSC2004-E-34992 (9 August 2004) --- Cosmonaut Salizhan S. Sharipov, Expedition 10 flight engineer representing Russia;s Federal Space Agency, gets help with final touches on a training version of the Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) spacesuit prior to being submerged in the waters of the Neutral Buoyancy laboratory (NBL) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC). Kevin Moore (left) and Carl Wright, both with United Space Alliance (USA), assisted Sharipov.

Interior view of the slotted throat test section installed in the 8-Foot High Speed Tunnel (HST) in 1950. The slotted region is about 160 inches in length. In this photograph, the sting-type model support is seen straight on. In a NASA report, the test section is described as follows: The test section of the Langley 8-foot transonic tunnel is dodecagonal in cross section and has a cross-sectional area of about 43 square feet. Longitudinal slots are located between each of the 12 wall panels to allow continuous operation through the transonic speed range. The slots contain about 11 percent of the total periphery of the test section. Six of the twelve panels have windows in them to allow for schlieren observations. The entire test section is enclosed in a hemispherical shaped chamber. John Becker noted that the tunnel s final achievement was the development and use in routine operations of the first transonic slotted throat. The investigations of wing-body shapes in this tunnel led to Whitcomb s discovery of the transonic area rule. James Hansen described the origins of the the slotted throat as follows: In 1946 Langley physicist Ray H. Wright conceived a way to do transonic research effectively in a wind tunnel by placing slots in the throat of the test section. The concept for what became known as the slotted-throat or slotted-wall tunnel came to Wright not as a solution to the chronic transonic problem, but as a way to get rid of wall interference (i.e., the mutual effect of two or more meeting waves or vibrations of any kind caused by solid boundaries) at subsonic speeds. For most of the year before Wright came up with this idea, he had been trying to develop a theoretical understanding of wall interference in the 8-Foot HST, which was then being repowered for Mach 1 capability. When Wright presented these ideas to John Stack, the response was enthusiastic but neither Wright nor Stack thought of slotted-throats as a solution to the transonic problem, only the wall interference problem. It was an accidental discovery which showed that slotted throats might solve the transonic problem. Most engineers were skeptical but Stack persisted. Initially, plans were to modify the 16-Foot tunnel but in the spring of 1948, Stack announced that the 8-Foot HST would also be modified. As Hansen notes: The 8-Foot HST began regular transonic operations for research purposes on 6 October 1950. The concept was a success and led to plans for a new wind tunnel which would be known as the 8-Foot Transonic Pressure Tunnel. -- Published in U.S., National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, Characteristics of Nine Research Wind Tunnels of the Langley Aeronautical Laboratory, 1957, pp. 17, 22 James R. Hansen, Engineer in Charge, NASA SP-4305, p. 454 and Chapter 11, The Slotted Tunnel and the Area Rule.

A Republic P-47G Thunderbolt is tested with a large blower on the hangar apron at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio. The blower could produce air velocities up to 250 miles per hour. This was strong enough to simulate take-off power and eliminated the need to risk flights with untried engines. The Republic P-47G was loaned to the laboratory to test NACA modifications to the Wright R-2800 engine’s cooling system at higher altitudes. The ground-based tests, seen here, were used to map the engine’s normal operating parameters. The P-47G then underwent an extensive flight test program to study temperature distribution among the engine’s 18 cylinders and develop methods to improve that distribution.

The Flight Operations crew stands before a Republic P-47G Thunderbolt at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio. The laboratory’s Flight Research Section was responsible for conducting a variety of research flights. During World War II most of the test flights complemented the efforts in ground-based facilities to improve engine cooling systems or study advanced fuel mixtures. The Republic P–47G was loaned to the laboratory to test NACA modifications to the Wright R–2800 engine’s cooling system at higher altitudes. The laboratory has always maintained a fleet of aircraft so different research projects were often conducted concurrently. The flight research program requires an entire section of personnel to accomplish its work. This staff generally consists of a flight operations group, which includes the section chief, pilots and administrative staff; a flight maintenance group with technicians and mechanics responsible for inspecting aircraft, performing checkouts and installing and removing flight instruments; and a flight research group that integrates the researchers’ experiments into the aircraft. The staff at the time of this March 1944 photograph included 3 pilots, 16 planning and analysis engineers, 36 mechanics and technicians, 10 instrumentation specialists, 6 secretaries and 5 computers.

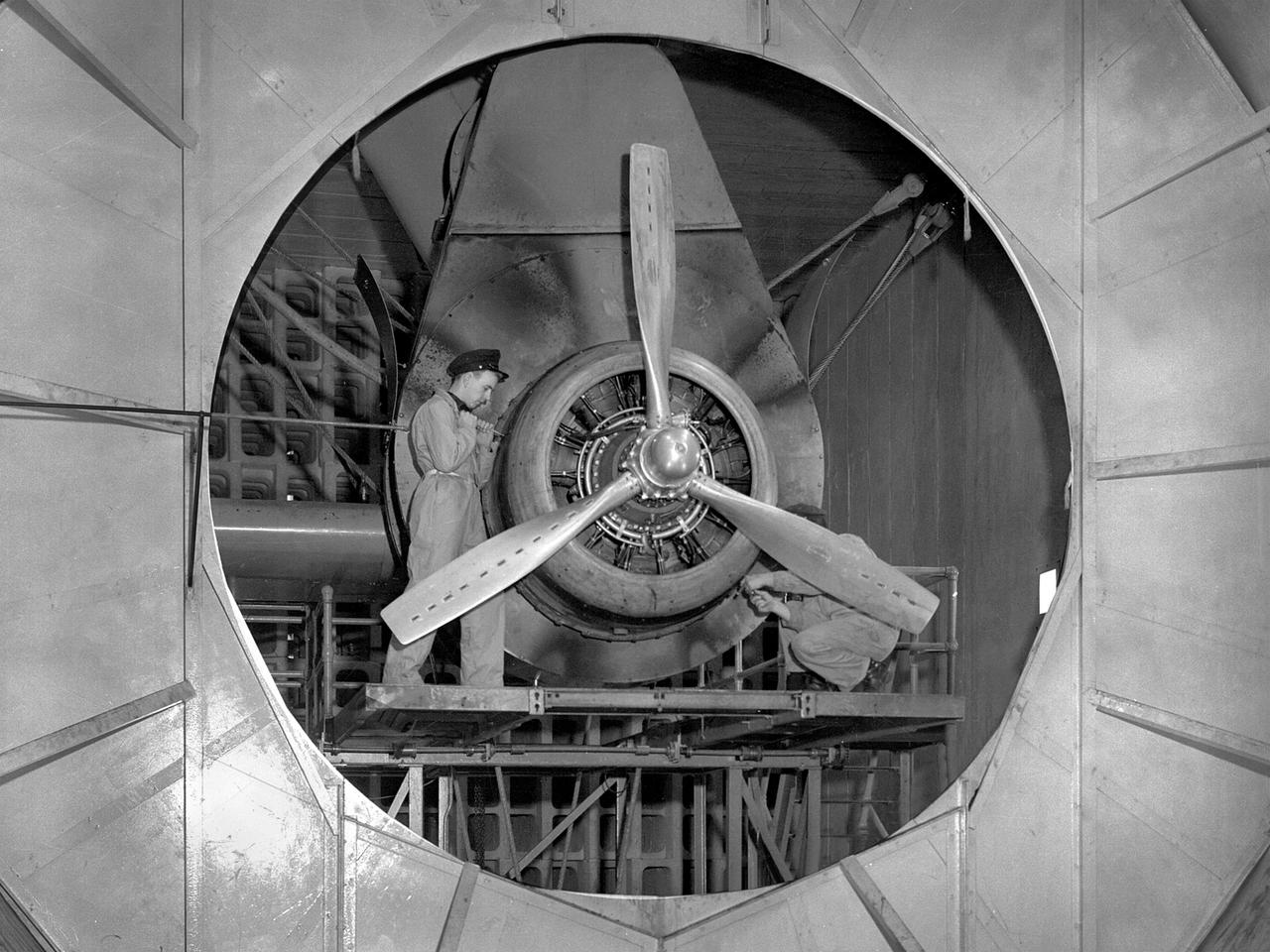

A Wright Aeronautical R–2600 Cyclone piston engine installed in the Engine Propeller Research Building, or Prop House, at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory. The R–2600 was among the most powerful engines that emerged during World War II. The engine, which was developed for commercial applications in 1939, was used to power the North American B–25 bomber and several other midsize military aircraft. The higher altitudes required by the military caused problems with the engine's cooling and fuel systems. The military requested that the Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory analyze the performance of the R–2600, improve its cooling system, and reduce engine knock. The NACA researchers subjected the engine to numerous tests in its Prop House. The R–2600 was the subject of the laboratory's first technical report, which was written by members of the Fuels and Lubricants Division. The Prop House contained soundproof test cells in which piston engines and propellers were mounted and operated at high powers. Electrically driven fans drew air through ducts to create a stream of cooling air over the engines. Researchers tested the performance of fuels, turbochargers, water-injection and cooling systems here during World War II. The facility was also investigated a captured German V–I buzz bomb during the war.

Frank Batteas is a research test pilot in the Flight Crew Branch of NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California. He is currently a project pilot for the F/A-18 and C-17 flight research projects. In addition, his flying duties include operation of the DC-8 Flying Laboratory in the Airborne Science program, and piloting the B-52B launch aircraft, the King Air, and the T-34C support aircraft. Batteas has accumulated more than 4,700 hours of military and civilian flight experience in more than 40 different aircraft types. Batteas came to NASA Dryden in April 1998, following a career in the U.S. Air Force. His last assignment was at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio, where Lieutenant Colonel Batteas led the B-2 Systems Test and Evaluation efforts for a two-year period. Batteas graduated from Class 88A of the Air Force Test Pilot School, Edwards Air Force Base, California, in December 1988. He served more than five years as a test pilot for the Air Force's newest airlifter, the C-17, involved in nearly every phase of testing from flutter and high angle-of-attack tests to airdrop and air refueling envelope expansion. In the process, he achieved several C-17 firsts including the first day and night aerial refuelings, the first flight over the North Pole, and a payload-to-altitude world aviation record. As a KC-135 test pilot, he also was involved in aerial refueling certification tests on a number of other Air Force aircraft. Batteas received his commission as a second lieutenant in the U. S. Air Force through the Reserve Officer Training Corps and served initially as an engineer working on the Peacekeeper and Minuteman missile programs at the Ballistic Missile Office, Norton Air Force Base, Calif. After attending pilot training at Williams Air Force Base, Phoenix, Ariz., he flew operational flights in the KC-135 tanker aircraft and then was assigned to research flying at the 4950th Test Wing, Wright-Patterson. He flew extensively modified C-135

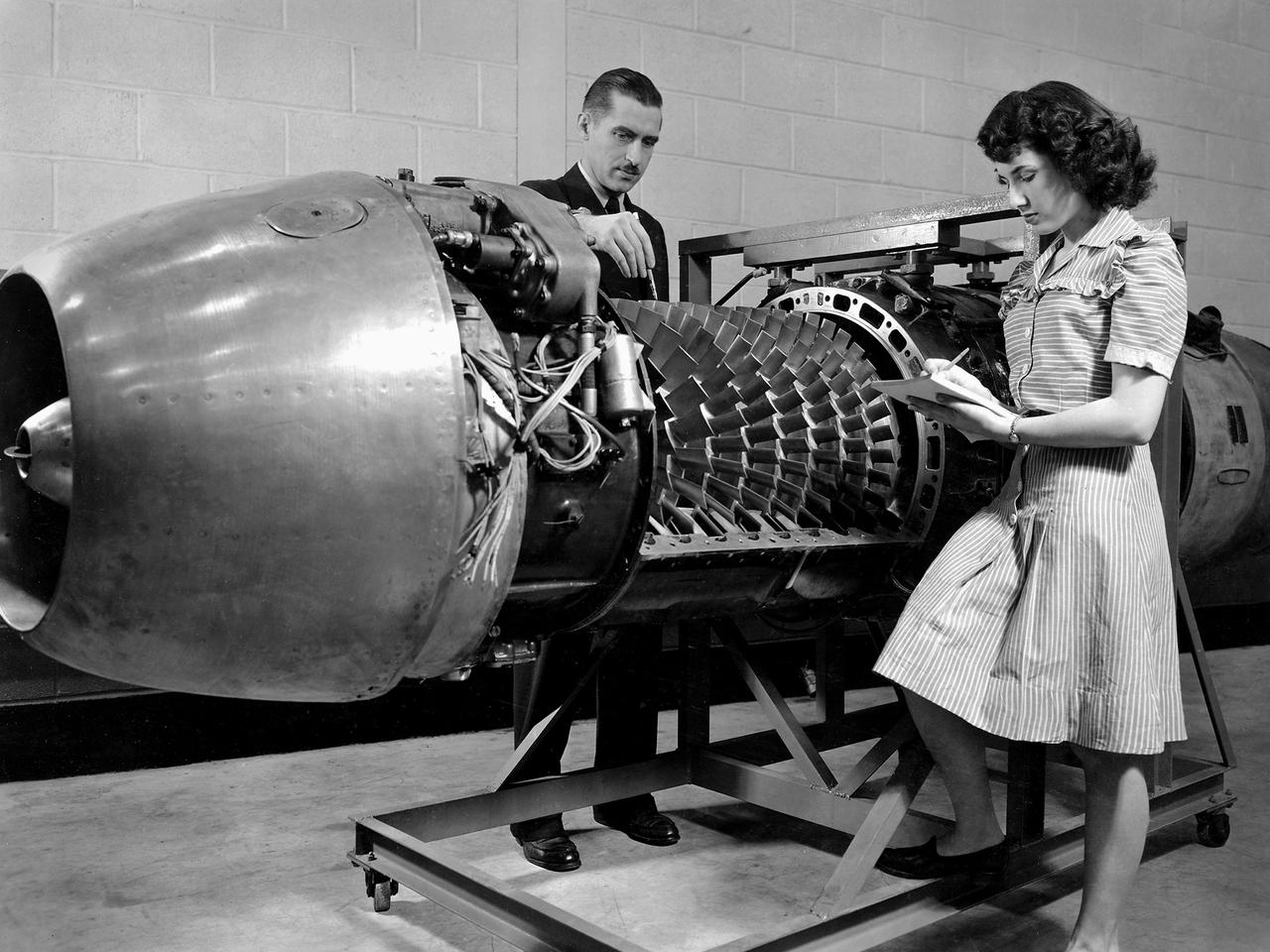

Researcher Robert Miller led an investigation into the combustor performance of a German Jumo 004 engine at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. The Jumo 004 powered the world's first operational jet fighter, the Messerschmitt Me 262, beginning in 1942. The Me 262 was the only jet aircraft used in combat during World War II. The eight-stage axial-flow compressor Jumo 004 produced 2000 pounds of thrust. The US Army Air Forces provided the NACA with a Jumo 004 engine in 1945 to study the compressor’s design and performance. Conveniently the engine’s designer Anselm Franz had recently arrived at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in nearby Dayton, Ohio as part of Project Paperclip. The Lewis researchers used a test rig in the Engine Research Building to analyze one of the six combustion chambers. It was difficult to isolate a single combustor’s performance when testing an entire engine. The combustion efficiency, outlet-temperature distribution, and total pressure drop were measured. The researchers determined the Jumo 004’s maximum performance was 5000 revolutions per minute at a 27,000 foot altitude and 11,000 revolutions per minute at a 45,000 foot altitude. The setup in this photograph was created for a tour of NACA Lewis by members of the Institute of Aeronautical Science on March 22, 1945.

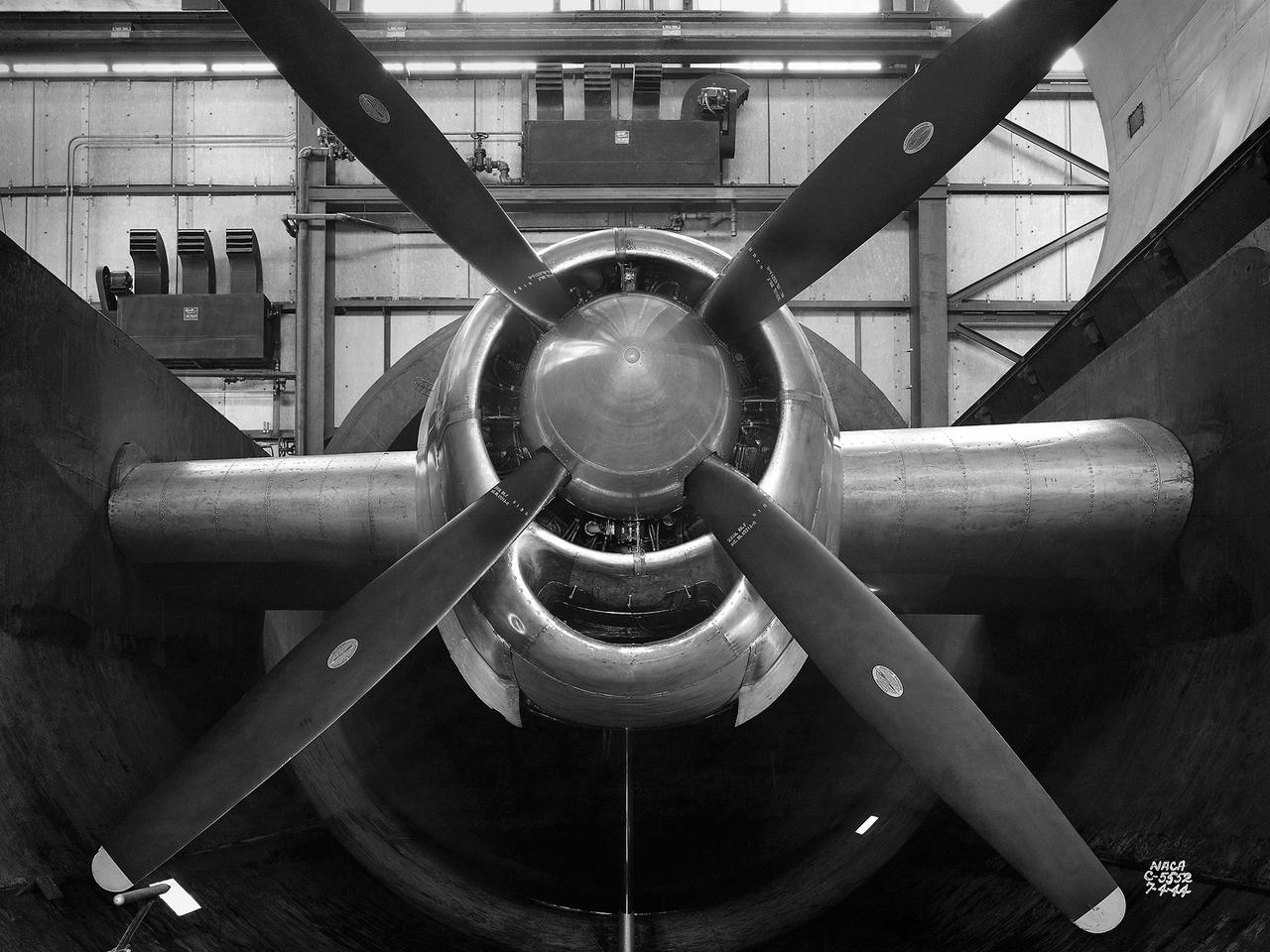

The resolution of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress’ engine cooling problems was one of the Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory’s (AERL) key contributions to the World War II effort. The B-29 leapfrogged previous bombers in size, speed, and altitude capabilities. The B–29 was intended to soar above anti-aircraft fire and make pinpoint bomb drops onto strategic targets. Four Wright Aeronautical R-3350 engines powered the massive aircraft. The engines, however, frequently strained and overheated due to payload overloading. This resulted in a growing number of engine fires that often resulted in crashes. The military asked the NACA to tackle the overheating issue. Full-scale engine tests on a R–3350 engine in the Prop House demonstrated that a NACA-designed impeller increased the fuel injection system’s flow rate. Single-cylinder studies resolved a valve failure problem by a slight extension of the cylinder head, and researchers in the Engine Research Building combated uneven heating with a new fuel injection system. Investigations during the summer of 1944 in the Altitude Wind Tunnel, which could simulate flight conditions at high altitudes, led to reduction of drag and improved air flow by reshaping the cowling inlet and outlet. The NACA modifications were then flight tested on a B-29 bomber that was brought to the AERL.

January 23, 1941 groundbreaking ceremony at the NACA Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory: left to right (does not include two individuals obscured from view behind Maj. Brett and Dr. Lewis): • William R. Hopkins – Cleveland City Manager from 1924-1930, was personally responsible for planning and acquiring the land for the Cleveland Airport. The airport’s huge capacity for handling aircraft was one factor in selecting Cleveland for the site of the research center. The Cleveland Airport was renamed Cleveland Hopkins airport in his honor in 1951. • Major John Berry – Cleveland Airport Manager • Edward R. Sharp – GRC’s first director, serving from 1942 to his retirement in 1961. He came to Cleveland in 1941 as the construction manager for the new facility. • Frederick C. Crawford – President of Thompson Products, which became the Thompson-Ramo-Woolridge Corporation (TRW) in 1958. Crawford was, at the time, also president of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce. He began in 1939 to campaign for Cleveland as the location for the new NACA facility. • Major George H. Brett – A Cleveland native, Brett served in WWI and was commanding officer at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio before becoming chief of the Army Air Corps. • Dr. Edward P. Warner – Acting chairman of the NACA. • Captain Sydney M. Kraus – Officer in charge of Navy procurement • Edward Blythin – Mayor of Cleveland • Dr. George Lewis – Director of Aeronautical Research for the NACA from 1924-1947, Lewis devoted his life to building a scientific basis for aeronautical engineering. The Cleveland laboratory was renamed the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in his honor in 1948. A description of the event, based on newspaper accounts and later NASA publications is as follows: On January 23, 1941, a brief groundbreaking ceremony at the site marked the start of construction. Dr. George W. Lewis, director of research for the NACA, loosened the soil with a

The Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory’s first aircraft, a Martin B–26B Marauder, parked in front of the Flight Research Building in September 1943. The military loaned the B–26B to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) to augment the lab’s studies of the Wright Aeronautical R–2800 engines. The military wanted to improve the engine cooling in order to increase the bomber’s performance. On March 17, 1943, the B–26B performed the very first research flight at the NACA’s new engine laboratory. The B–26B received its “Widowmaker” nickname during the rushed effort to transition the new aircraft from design to production and into the sky. During World War II, however, the B–26B proved itself to be a capable war machine. The U.S. lost fewer Marauders than any other type of bomber employed in the war. The B–26B was originally utilized at low altitudes in the Pacific but had its most success at high altitudes over Europe. The B–26B’s flight tests in Cleveland during 1943 mapped the R-2800 engine’s behavior at different altitudes and speeds. The researchers were then able to correlate engine performance in ground facilities to expected performance at different altitudes. They found that air speed, cowl flap position, angle of attack, propeller thrust, and propeller speed influenced inlet pressure recovery and exhaust distribution. The flight testing proceeded quickly, and the B–26B was transferred elsewhere in October 1943.

Because the number two X-29 at NASA's Ames-Dryden Flight Research Facility (later the Dryden Flight Research Center) flew at higher angles of attack than the number one aircraft, it required a spin chute system for safety. The system deployed a parachute for recovery of the aircraft if it inadvertently entered an uncontrolled spin. Most of the components of the spin chute system were located on a truss at the aft end of the aircraft. In addition, there were several cockpit modifications to facilitate use of the chute. The parachute was made of nylon and was of the conical ribbon type.

This photo shows the X-29 during a 1991 research flight. Smoke generators in the nose of the aircraft were used to help researchers see the behavior of the air flowing over the aircraft. The smoke here is demonstrating forebody vortex flow. This mission was flown September 10, 1991, by NASA research pilot Rogers Smith.

A Bell P-59B Airacomet sits beside the hangar at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. In 1942 the Bell XP-59A Airacomet became the first jet aircraft in the US. The Airacomet incorporated centrifugal turbojet engines that were based on British plans secretly brought to the US in 1941. A Bell test pilot flew the XP-59A for the first time at Muroc Lake, California in October 1942. The General Electric I-16 engines proved to be problematic. In an effort to increase the engine performance, an Airacomet was secretly brought to Cleveland in early 1944 for testing in the Altitude Wind Tunnel. A series of tunnel investigations in February and March resulted in a 25-percent increase in the I-16 engine’s performance. Nonetheless, Bell’s 66 Airacomets never made it into combat. A second, slightly improved Airacomet, a P-59B, was transferred to NACA Lewis just after the war in September 1945. The P-59B was used over the next three years to study general jet thrust performance and thrust augmentation devices such as afterburners and water/alcohol injection. The P-59B flights determined the proper alcohol and water mixture and injection rate to produce a 21-percent increase in thrust. Since the extra boost would be most useful for takeoffs, a series of ground-based tests with the aircraft ensued. It was determined that the runway length for takeoffs could be reduced by as much as 15 percent. The P-59B used for the tests is now on display at the Air Force Museum at Wright Patterson.

Operators in the control room for the Altitude Wind Tunnel at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory remotely operate a Wright R–3350 engine in the tunnel’s test section. Four of the engines were used to power the B–29 Superfortress, a critical weapon in the Pacific theater during World War II. The wind tunnel, which had been in operation for approximately six months, was the nation’s only wind tunnel capable of testing full-scale engines in simulated altitude conditions. The soundproof control room was used to operate the wind tunnel and control the engine being run in the test section. The operators worked with assistants in the adjacent Exhauster Building and Refrigeration Building to manage the large altitude simulation systems. The operator at the center console controlled the tunnel’s drive fan and operated the engine in the test section. Two sets of pneumatic levers near his right forearm controlled engine fuel flow, speed, and cooling. Panels on the opposite wall, out of view to the left, were used to manage the combustion air, refrigeration, and exhauster systems. The control panel also displayed the master air speed, altitude, and temperature gauges, as well as a plethora of pressure, temperature, and airflow readings from different locations on the engine. The operator to the right monitored the manometer tubes to determine the pressure levels. Despite just being a few feet away from the roaring engine, the control room remained quiet during the tests.

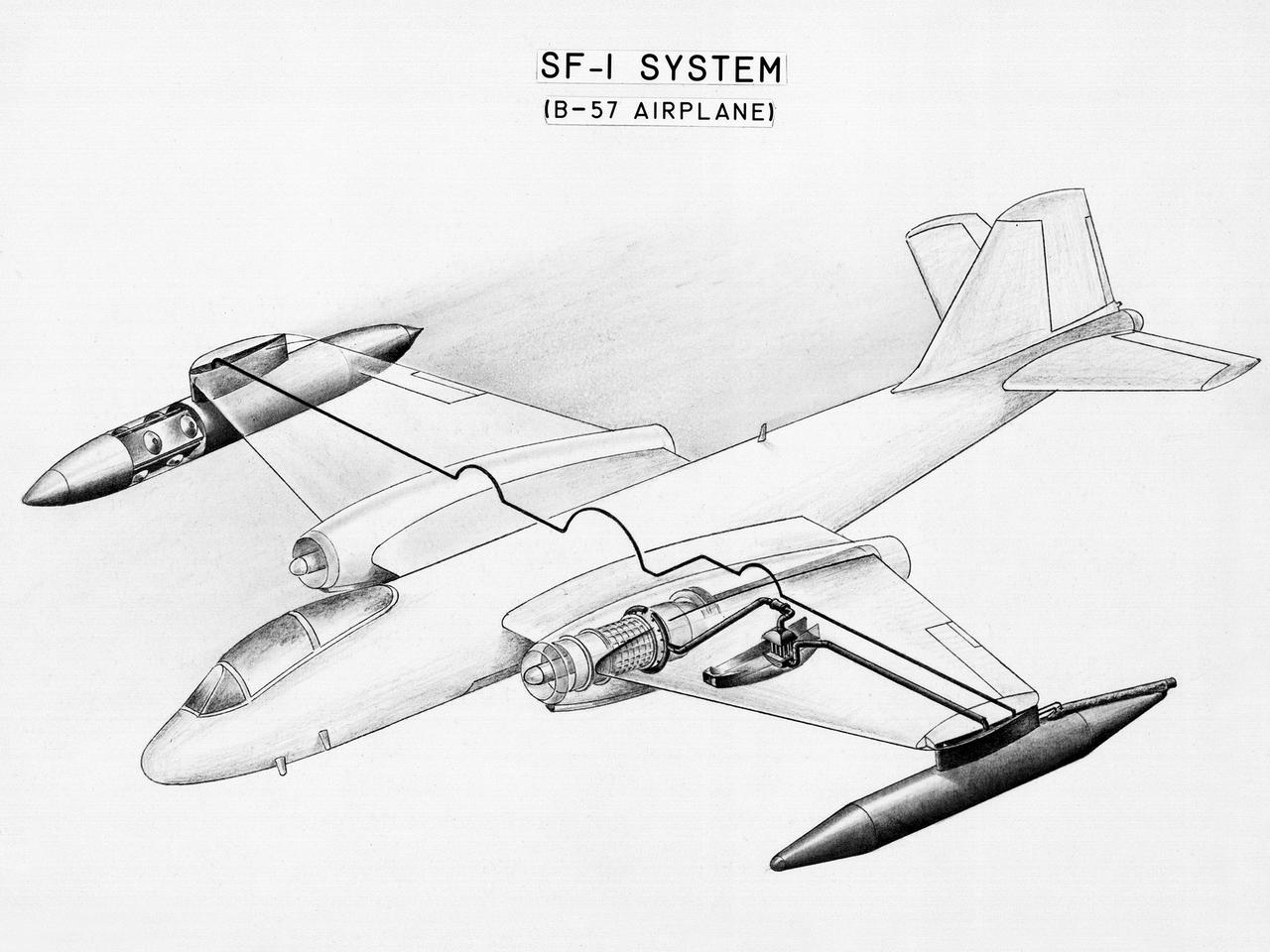

This diagram shows a hydrogen fuel system designed by researchers at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory and installed on a Martin B-57B Canberra aircraft. Lewis researchers accelerated their studies of high energy propellants in the early 1950s. In late 1954, Lewis researchers studied the combustion characteristics of gaseous hydrogen in a turbojet combustor. It was found that the hydrogen provided a very high efficiency. Almost immediately thereafter, Associate Director Abe Silverstein became focused on the possibilities of hydrogen for aircraft propulsion. That fall, Silverstein secured a contract to work with the air force to examine the practicality of liquid hydrogen aircraft. A B-57B Canberra was obtained by the air force especially for this project, referred to as Project Bee. The aircraft was powered by two Wright J65 engines, one of which was modified so that it could be operated using either traditional or liquid hydrogen propellants. The engine and its liquid hydrogen fuel system were tested extensively in the Altitude Wind Tunnel and the Four Burner Area test cells in 1955 and 1956. A B-57B flight program was planned to test the system on an actual aircraft. The aircraft would take off using jet fuel, switch to liquid hydrogen while over Lake Erie, then after burning the hydrogen supply switch back to jet fuel for the landing. The third test flight, in February 1957, was a success, and the ensuing B-57B flights remain the only demonstration of hydrogen-powered aircraft.

One of the two altitude simulating-test chambers in Engine Research Building at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. The two chambers were collectively referred to as the Four Burner Area. NACA Lewis’ Altitude Wind Tunnel was the nation’s first major facility used for testing full-scale engines in conditions that realistically simulated actual flight. The wind tunnel was such a success in the mid-1940s that there was a backlog of engines waiting to be tested. The Four Burner chambers were quickly built in 1946 and 1947 to ease the Altitude Wind Tunnel’s congested schedule. The Four Burner Area was located in the southwest wing of the massive Engine Research Building, across the road from the Altitude Wind Tunnel. The two chambers were 10 feet in diameter and 60 feet long. The refrigeration equipment produced the temperatures and the exhauster equipment created the low pressures present at altitudes up to 60,000 feet. In 1947 the Rolls Royce Nene was the first engine tested in the new facility. The mechanic in this photograph is installing a General Electric J-35 engine. Over the next ten years, a variety of studies were conducted using the General Electric J-47 and Wright Aeronautical J-65 turbojets. The two test cells were occasionally used for rocket engines between 1957 and 1959, but other facilities were better suited to the rocket engine testing. The Four Burner Area was shutdown in 1959. After years of inactivity, the facility was removed from the Engine Research Building in late 1973 in order to create the High Temperature and Pressure Combustor Test Facility.

A Boeing B–29 Superfortress at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio. The B–29 was the Army Air Forces’ deadliest weapon during the latter portion of World War II. The aircraft was significantly larger than previous bombers but could fly faster and higher. The B–29 was intended to soar above anti-aircraft fire and make pinpoint drops onto strategic targets. The bomber was forced to carry 20,000 pounds more armament than it was designed for. The extra weight pushed the B–29’s four powerful Wright R–3350 engines to their operating limits. The over-heating of the engines proved to be a dangerous problem. The military asked the NACA to tackle the issue. Full-scale engine tests on a R–3350 engine in the Prop House demonstrated that a NACA-designed impeller increased the flow rate of the fuel injection system. Altitude Wind Tunnel studies of the engine led to the reshaping of cowling inlet and outlet to improve airflow and reduce drag. Single-cylinder studies on valve failures were resolved by a slight extension of the cylinder head, and the Engine Research Building researchers combated uneven heating with a new fuel injection system. The modifications were then tried out on an actual B–29. The bomber arrived in Cleveland on June 22, 1944. The new injection impeller, ducted head baffles and instrumentation were installed on the bomber’s two left wing engines. Eleven test flights were flown over the next month with military pilots at the helm. Overall the flight tests corroborated the wind tunnel and test stand studies.

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of sp

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of

NASA Dryden research pilot Gordon Fullerton is greeted by his wife Marie on the Dryden ramp after his final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007.