The X-1B reaction control system thrusters are tested in 1958 and later proven on the X-15 as a way to control a vehicle in the absence of dynamic pressure.

Bell X-1B fitted with a reaction control system on the lakebed

X-1B engine run on Air Force thrust stand.

Lee Adelsbach and Bob Cook work on the instrumentation on the Bell X-1B.

B-29 #800 with X-1B attached taxis in off of the lakebed.

Bell X-1B fitted with a reaction control system on the lakebed.

B-29 #800 with X-1B attached taxi's in off of the lakebed.

Early NACA research aircraft on the lakebed at the High Speed Research Station in 1955: Left to right: X-1E, D-558-II, X-1B

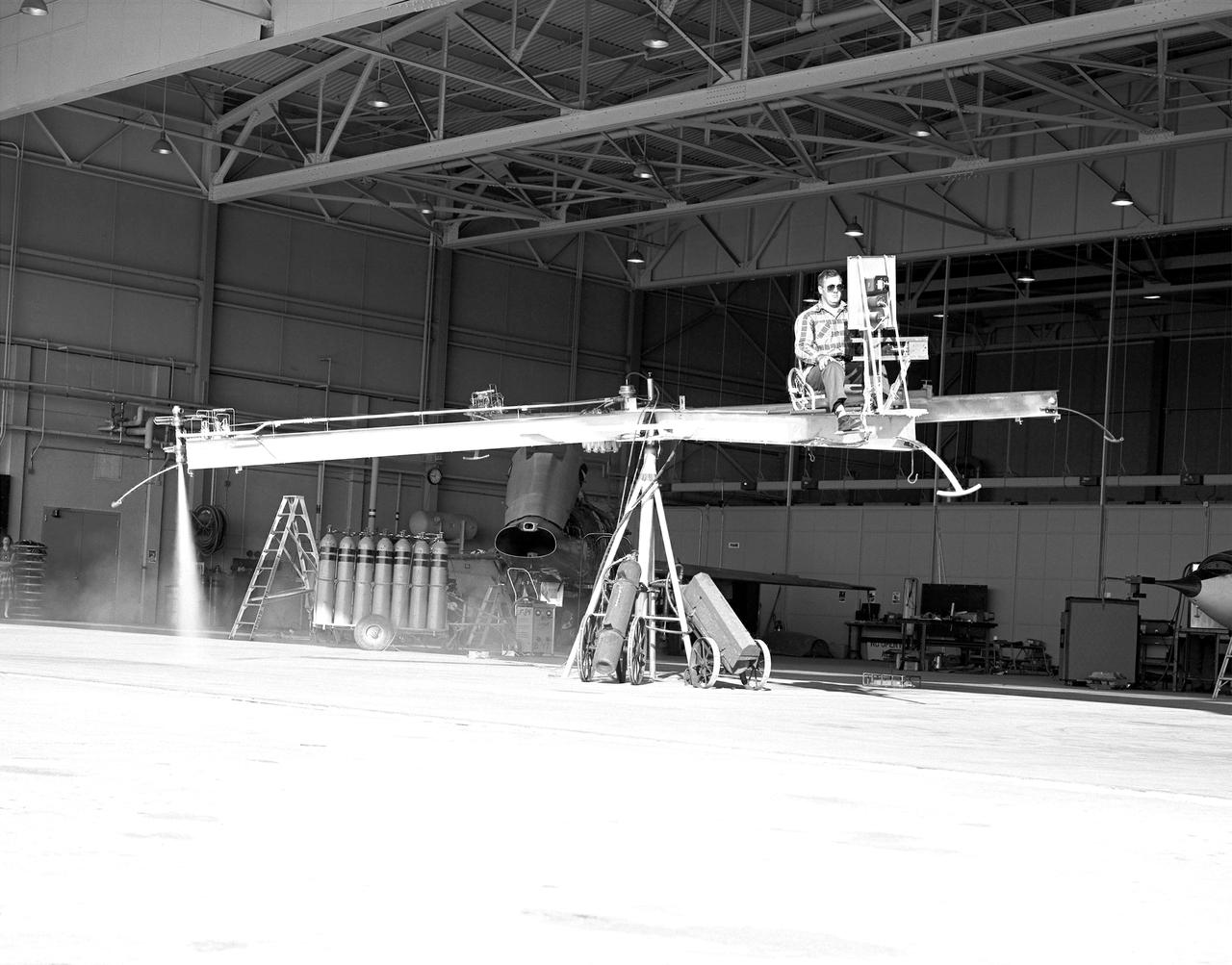

NACA High-Speed Flight Station test pilot Stan Butchart flying the Iron Cross, the mechanical reaction control simulator. High-pressure nitrogen gas expanded selectively, by the pilot, through the small reaction control thrusters maneuvered the Iron Cross through the three axes. The exhaust plume can be seen from the aft thruster. The tanks containing the gas can be seen on the cart at the base of the pivot point of the Iron Cross. NACA technicians built the iron-frame simulator, which matched the inertia ratios of the Bell X-1B airplane, installing six jet nozzles to control the movement about the three axes of pitch, roll, and yaw.

Famed astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, the first man to set foot on the moon during the historic Apollo 11 space mission in July 1969, served for seven years as a research pilot at the NACA-NASA High-Speed Flight Station, now the Dryden Flight Research Center, at Edwards, California, before he entered the space program. Armstrong joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) at the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory (later NASA's Lewis Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio, and today the Glenn Research Center) in 1955. Later that year, he transferred to the High-Speed Flight Station at Edwards as an aeronautical research scientist and then as a pilot, a position he held until becoming an astronaut in 1962. He was one of nine NASA astronauts in the second class to be chosen. As a research pilot Armstrong served as project pilot on the F-100A and F-100C aircraft, F-101, and the F-104A. He also flew the X-1B, X-5, F-105, F-106, B-47, KC-135, and Paresev. He left Dryden with a total of over 2450 flying hours. He was a member of the USAF-NASA Dyna-Soar Pilot Consultant Group before the Dyna-Soar project was cancelled, and studied X-20 Dyna-Soar approaches and abort maneuvers through use of the F-102A and F5D jet aircraft. Armstrong was actively engaged in both piloting and engineering aspects of the X-15 program from its inception. He completed the first flight in the aircraft equipped with a new flow-direction sensor (ball nose) and the initial flight in an X-15 equipped with a self-adaptive flight control system. He worked closely with designers and engineers in development of the adaptive system, and made seven flights in the rocket plane from December 1960 until July 1962. During those fights he reached a peak altitude of 207,500 feet in the X-15-3, and a speed of 3,989 mph (Mach 5.74) in the X-15-1. Armstrong has a total of 8 days and 14 hours in space, including 2 hours and 48 minutes walking on the Moon. In March 1966 he was commander of the Gemini 8 or

From December 10, 1966, until his retirement on February 27, 1976, Stanley P. Butchart served as Chief (later, Director) of Flight Operations at NASA's Flight Research Center (renamed on March 26, 1976, the Hugh L. Dryden Flight Research Center). Initially, his responsibilities in this position included the Research Pilots Branch, a Maintenance and Manufacturing Branch, and an Operations Engineering Branch, the last of which not only included propulsion and electrical/electronic sections but project engineers for the X-15 and lifting bodies. During his tenure, however, the responsibilities of his directorate came to include not only Flight Test Engineering Support but Flight Systems and Loads laboratories. Before becoming Chief of Flight Operations, Butchart had served since June of 1966 as head of the Research Pilots Branch (Chief Pilot) and then as acting chief of Flight Operations. He had joined the Center (then known as the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics' High-Speed Flight Research Station) as a research pilot on May 10, 1951. During his career as a research pilot, he flew a great variety of research and air-launch aircraft including the D-558-I, D-558-II, B-29 (plus its Navy version, the P2B), X-4, X-5, KC-135, CV-880, CV-990, B-47, B-52, B-747, F-100A, F-101, F-102, F-104, PA-30 Twin Comanche, JetStar, F-111, R4D, B-720, and B-47. Although previously a single-engine pilot, he became the Center's principal multi-engine pilot during a period of air-launches in which the pilot of the air-launch aircraft (B-29 or P2B) basically directed the operations. It was he who called for the chase planes before each drop, directed the positioning of fire rescue vehicles, and released the experimental aircraft after ensuring that all was ready for the drop. As pilot of the B-29 and P2B, Butchart launched the X-1A once, the X-1B 13 times, the X-1E 22 times, and the D-558-II 102 times. In addition, he towed the M2-F1 lightweight lifting body 14 times behind an R4

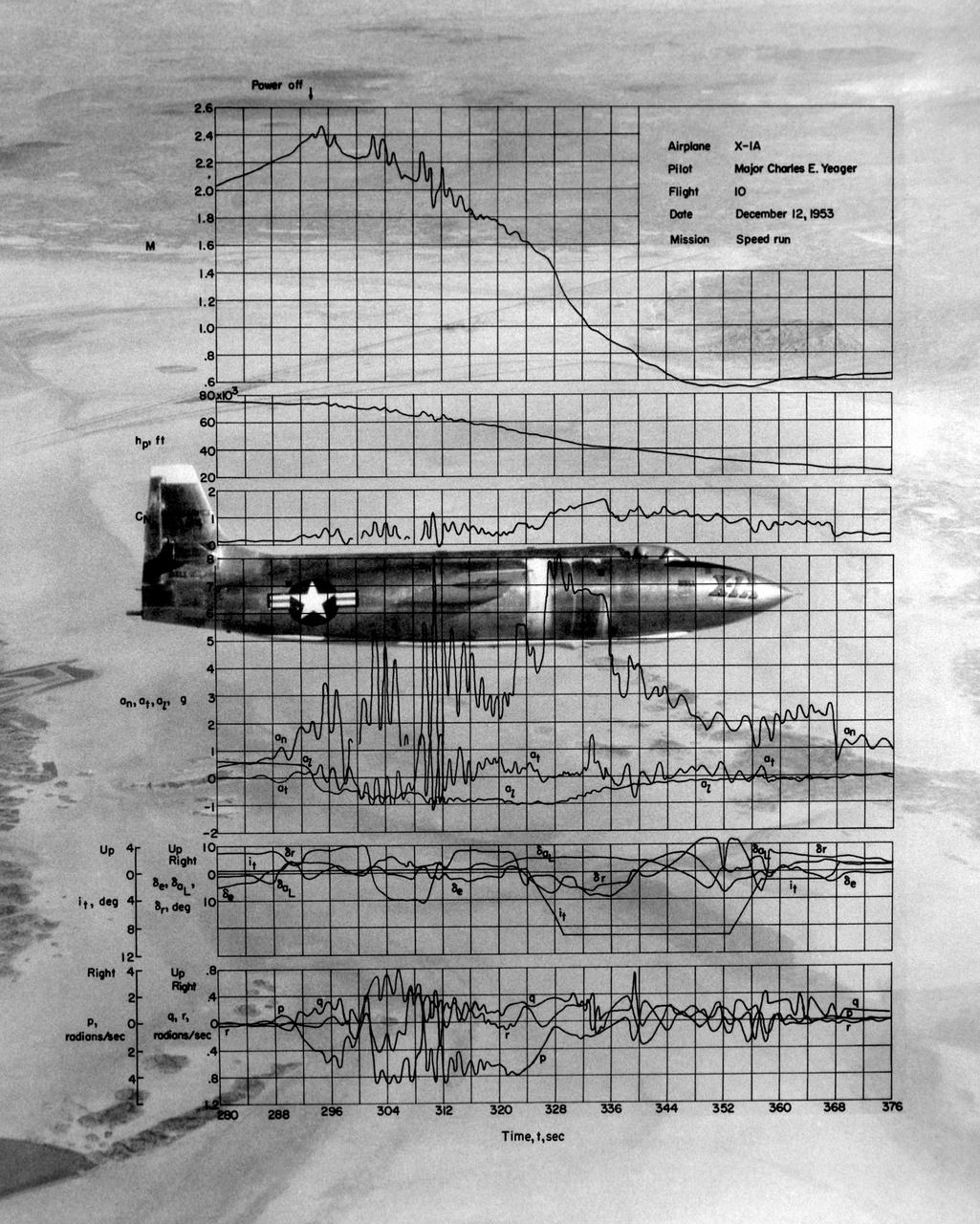

This photo of the X-1A includes graphs of the flight data from Maj. Charles E. Yeager's Mach 2.44 flight on December 12, 1953. (This was only a few days short of the 50th anniversary of the Wright brothers' first powered flight.) After reaching Mach 2.44, then the highest speed ever reached by a piloted aircraft, the X-1A tumbled completely out of control. The motions were so violent that Yeager cracked the plastic canopy with his helmet. He finally recovered from a inverted spin and landed on Rogers Dry Lakebed. Among the data shown are Mach number and altitude (the two top graphs). The speed and altitude changes due to the tumble are visible as jagged lines. The third graph from the bottom shows the G-forces on the airplane. During the tumble, these twice reached 8 Gs or 8 times the normal pull of gravity at sea level. (At these G forces, a 200-pound human would, in effect, weigh 1,600 pounds if a scale were placed under him in the direction of the force vector.) Producing these graphs was a slow, difficult process. The raw data from on-board instrumentation recorded on oscillograph film. Human computers then reduced the data and recorded it on data sheets, correcting for such factors as temperature and instrument errors. They used adding machines or slide rules for their calculations, pocket calculators being 20 years in the future.