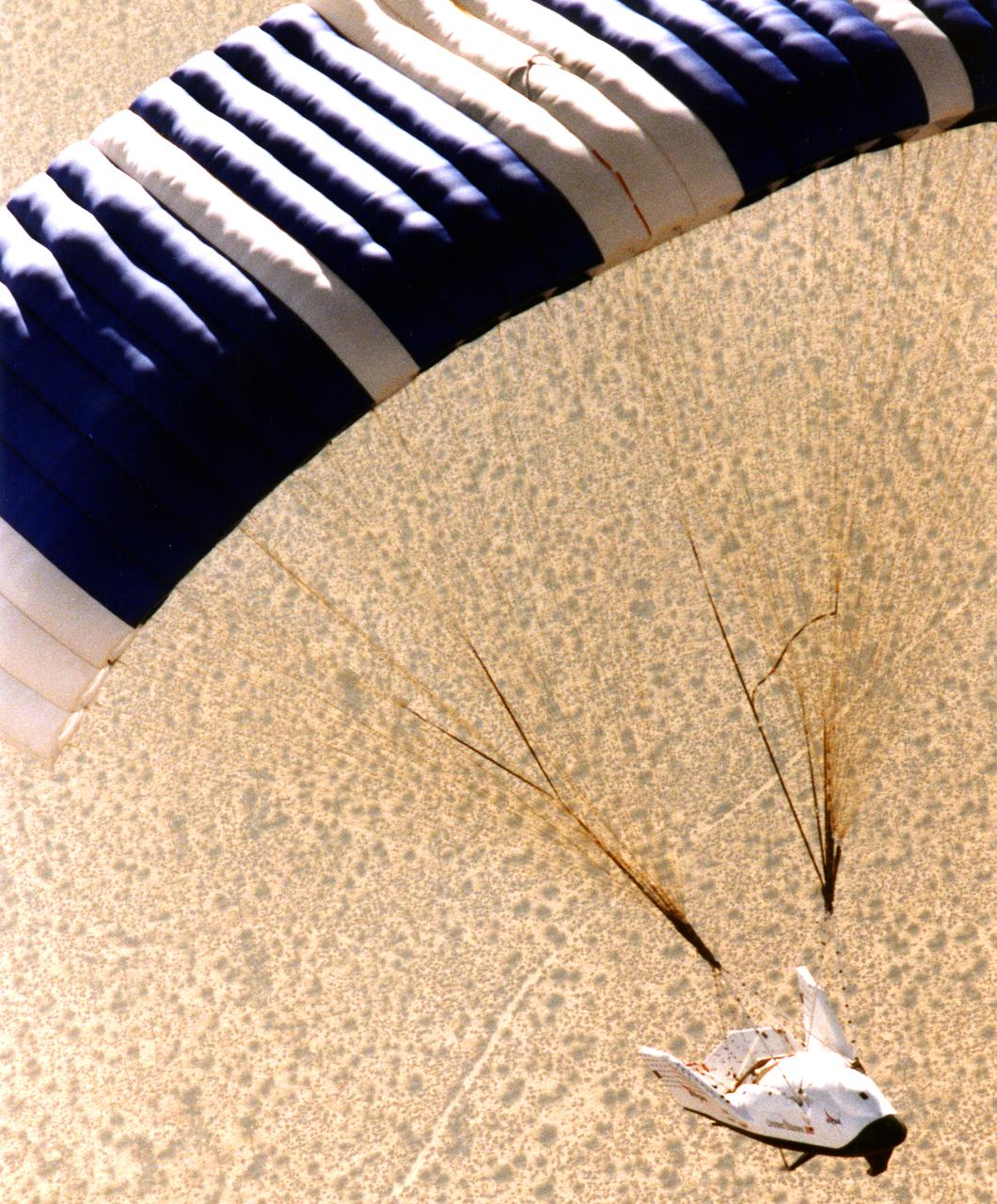

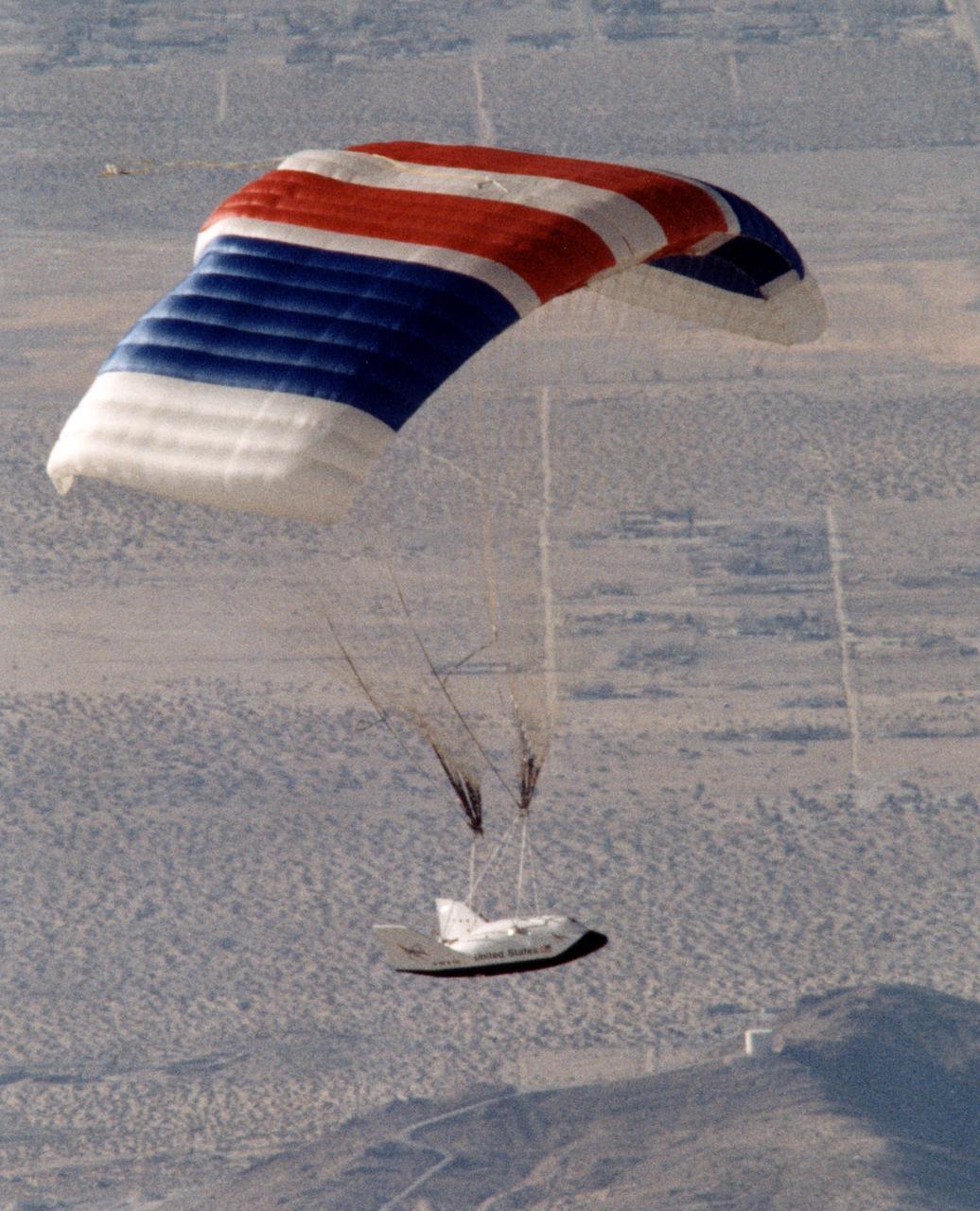

The second free-flight test of an evolving series of X-38 prototypes took place July 10, 2001 when the X-38 was released from NASA's B-52 mothership over the Edwards Air Force Base range in California's Mojave Desert. Shortly after the photo was taken, a sequenced deployment of a drogue parachute followed by a large parafoil fabric wing slowed the X-38 to enable it to land safely on Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards. NASA engineers from the Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards, and the Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas, are developing a "lifeboat" for the International Space Station based on X-38 research.

The seventh free flight of an X-38 prototype for an emergency space station crew return vehicle culminated in a graceful glide to landing under the world's largest parafoil. The mission began when the X-38 was released from NASA's B-52 mother ship over Edwards Air Force Base, California, where NASA Dryden Flight Research Center is located. The July 10, 2001 flight helped researchers evaluate software and deployment of the X-38's drogue parachute and subsequent parafoil. NASA intends to create a space-worthy Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) to be docked to the International Space Station as a "lifeboat" to enable a full seven-person station crew to evacuate in an emergency.

The X-38, mounted beneath the right wing of NASA's B-52, climbed from the runway at Edwards Air Force Base for the seventh free flight test of the X-38, July 10, 2001. The X-38 was released at 37,500 feet and completed a thirteen minute glide flight to a landing on Rogers Dry Lake.

The X-38, a research vehicle built to help develop technology for an emergency Crew Return Vehicle (CRV), descends under its steerable parachute during a July 1999 test flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California. It was the fourth free flight of the test vehicles in the X-38 program, and the second free flight test of Vehicle 132 or Ship 2. The goal of this flight was to release the vehicle from a higher altitude -- 31,500 feet -- and to fly the vehicle longer -- 31 seconds -- than any previous X-38 vehicle had yet flown. The project team also conducted aerodynamic verification maneuvers and checked improvements made to the drogue parachute.

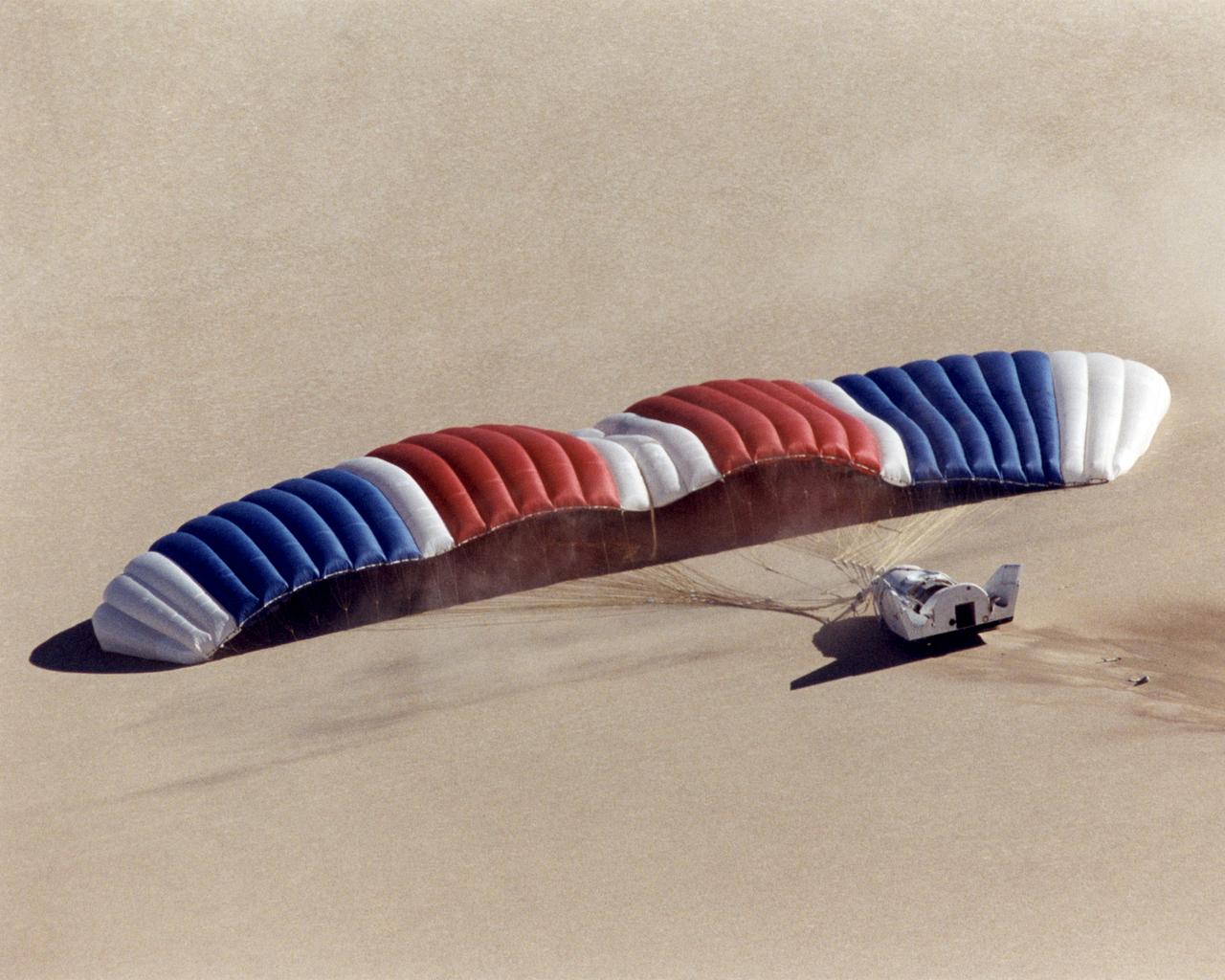

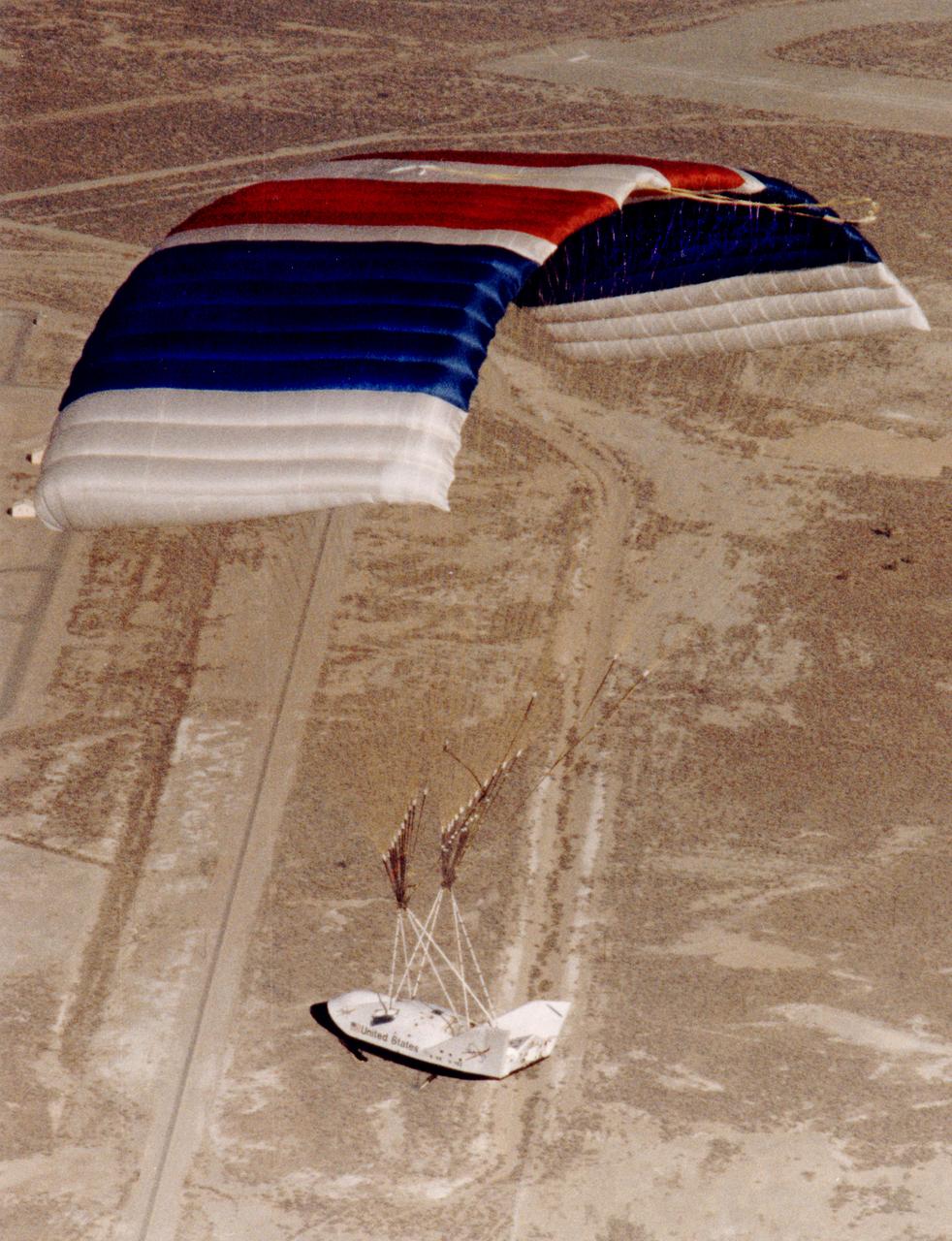

The third iteration of the X-38, V-131R, glides down under a giant parafoil towards a landing on Rogers Dry Lake near NASAÕs Dryden Flight Research Center during its first free flight Nov. 2, 2000. The X-38 prototypes are intended to perfect technology for a planned Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) ÒlifeboatÓ to carry a crew to safety in the event of an emergency on the International Space Station. Free-flight tests of X-38 V-131R are evaluating upgraded avionics and control systems and the aerodynamics of the modified upper body, which is more representative of the final design of the CRV than the two earlier X-38 test craft, including a simulated hatch atop the body. The huge 7,500 square-foot parafoil will enable the CRV to land in the length of a football field after returning from space. The first three X-38Õs are air-launched from NASAÕs venerable NB-52B mother ship, while the last version, V-201, will be carried into space by a Space Shuttle and make a fully autonomous re-entry and landing.

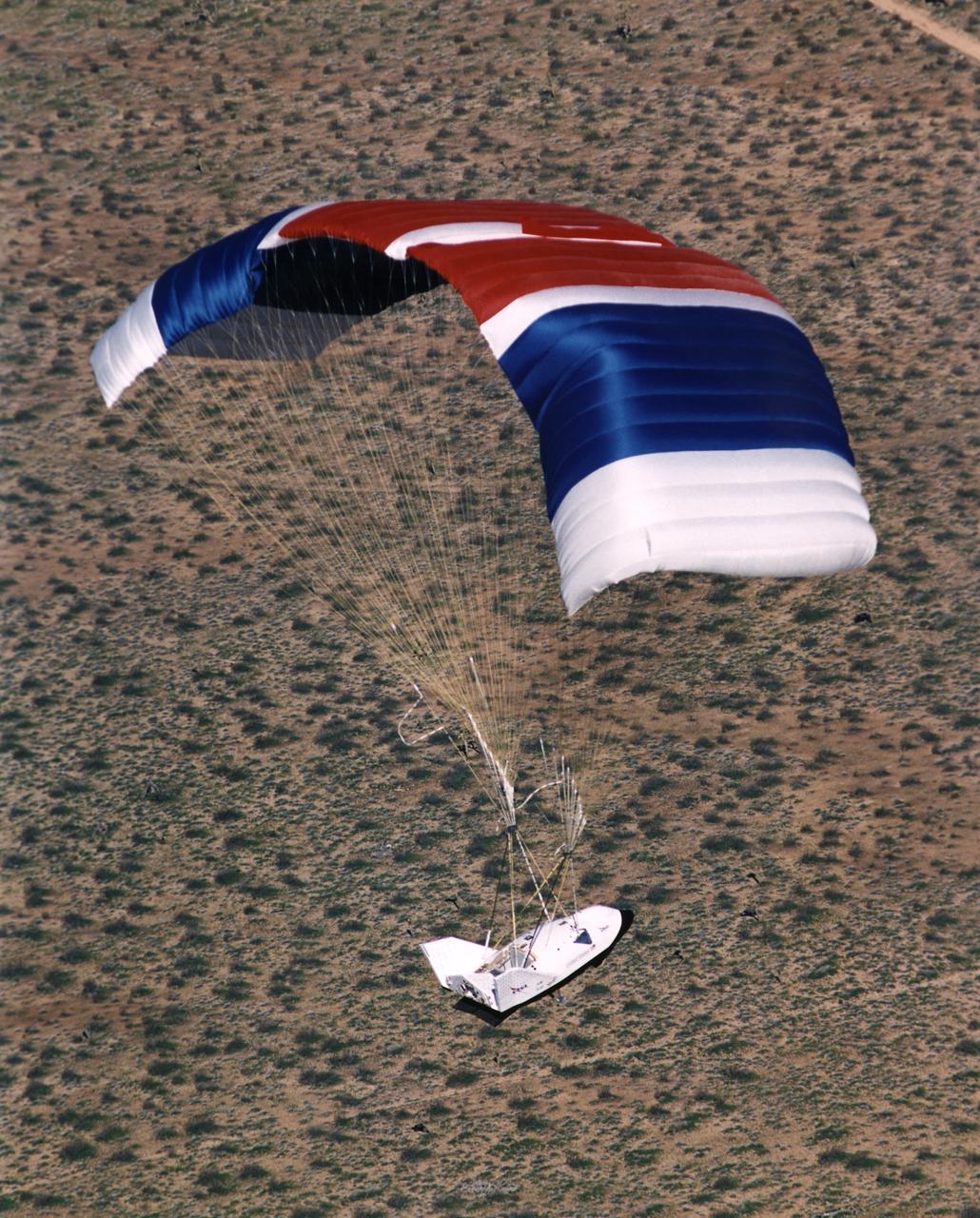

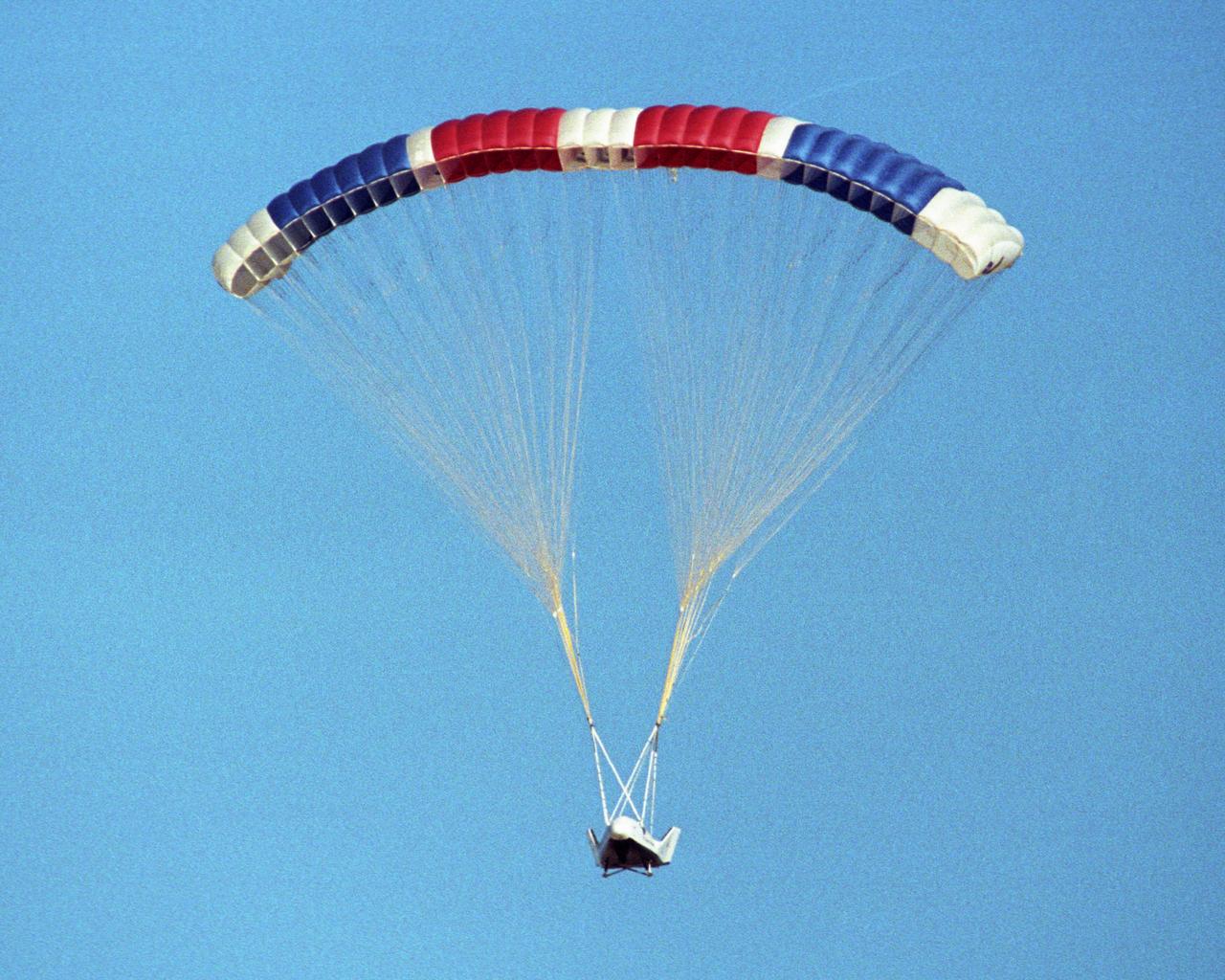

NASA's X-38, a research vehicle developed as part of an effort to build an emergency Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) for the International Space Station, descends toward the desert floor under its steerable parafoil on its second free flight. The X-38 was launched from NASA Dryden's B-52 Mothership on Saturday, February 6, 1999, from an altitude of approximately 23,000 feet.

NASA's X-38, a research vehicle developed as part of an effort to build an emergency Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) for the International Space Station, descends toward the desert floor under its steerable parafoil on its second free flight. The X-38 was launched from NASA Dryden's B-52 Mothership on Saturday, February 6, 1999, from an altitude of approximately 23,000 feet.

NASA's X-38, a research vehicle developed as part of an effort to build an emergency Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) for the International Space Station, descends toward a desert lakebed under its steerable parafoil on its second free flight. The X-38 was launched from NASA Dryden's B-52 Mothership on Saturday, February 6, 1999, from an altitude of approximately 23,000 feet.

NASA's X-38 glided high over California desert test ranges as it descended from 37,500 feet to land on Rogers Dry Lake for the seventh free flight of the program July 10, 2001.

A close-up view of the X-38 research vehicle mounted under the wing of the B-52 mothership prior to a 1997 test flight. The X-38, which was designed to help develop technology for an emergency crew return vehicle (CRV) for the International Space Station, is one of many research vehicles the B-52 has carried aloft over the past 40 years.

Dale Reed, a NASA engineer who worked on the original lifting-body research programs in the 1960s and 1970s, stands with a scale-model X-38 that was used in 1995 research flights, with a full-scale X-38 (80 percent of the size of a potential Crew Return Vehicle) behind him.

NASA's X-38, a prototype of a Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) resting on the lakebed near the Dryden Flight Research Center after the completion of its second free flight. The X-38 was launched from NASA Dryden's B-52 Mothership on Saturday, February 6, 1999, from an altitude of approximately 23,000 feet.

A unique, close-up view of the X-38 under the wing of NASA's B-52 mothership prior to launch of the lifting-body research vehicle. The photo was taken from the observation window of the B-52 bomber as it banked in flight.

The NASA X-38 is picked up from its dry lakebed landing site following its successful eighth free flight test mission December 13, 2001. Skid marks in the ground show the X-38's landing path.

NASA's Super Guppy transport aircraft landed at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. on July 11, 2000, to deliver the latest version of the X-38 drop vehicle to Dryden. The X-38s are intended as prototypes for a possible "crew lifeboat" for the International Space Station. The X-38 vehicle 131R will demonstrate a huge 7,500 square-foot parafoil that will that will enable the potential crew return vehicle to land on the length of a football field after returning from space. The crew return vehicle is intended to serve as a possible emergency transport to carry a crew to safety in the event of problems with the International Space Station. The Super Guppy evolved from the 1960s-vintage Pregnant Guppy, used for transporting outsized sections of the Apollo moon rocket. The Super Guppy was modified from 1950s-vintage Boeing C-97. NASA acquired its Super Guppy from the European Space Agency in 1997.

The latest version of the X-38, V-131R, touches down on Rogers Dry Lake adjacent to NASAÕs Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards, California, at the end of its first free flight under a giant parafoil on Nov. 2, 2000. The X-38 prototypes are intended to perfect technology for a planned Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) ÒlifeboatÓ to carry a crew to safety in the event of an emergency on the International Space Station. Free-flight tests of X-38 V-131R are evaluating upgraded avionics and control systems and the aerodynamics of the modified upper body, which is more representative of the final design of the CRV than the two earlier X-38 test craft, including a simulated hatch atop the body. The huge 7,500 square-foot parafoil will enable the CRV to land in the length of a football field after returning from space. The first three X-38Õs are air-launched from NASAÕs venerable NB-52B mother ship, while the last version, V-201, will be carried into space by a Space Shuttle and make a fully autonomous re-entry and landing.

The X-38 Crew Return Vehicle touches down amidst the California desert scrubbrush at the end of its first free flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, in March 1998.

The X-38, a research vehicle built to help develop technology for an emergency Crew Return Vehicle (CRV), flares for its lakebed landing at the end of a March 1999 test flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California.

The X-38 Crew Return Vehicle descends under its steerable parafoil over the California desert during its first free flight in March 1998 at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California.

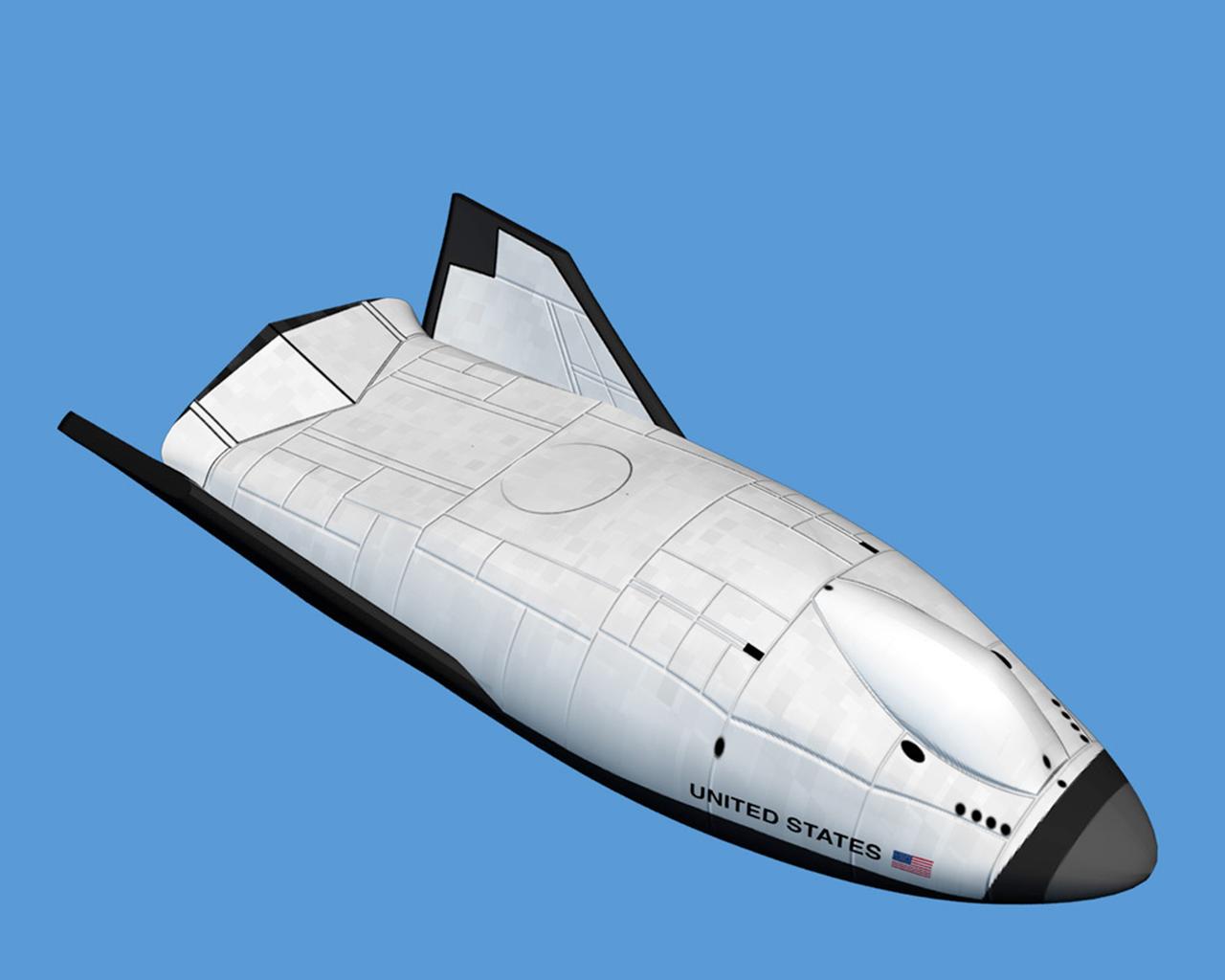

This is an artist's concept of the X-38 Crew Return Vehicle (CRV). The X-38 will take place of the Russian Soyuz capsule and is well underway on development for the International Space Station. The Soyuz can only stay on orbit for six months as opposed to three years for the CRV.

The X-38 prototype of the Crew Return Vehicle for the International Space Station drops away from its launch pylon on the wing of NASA's NB-52B mothership as it begins its eighth free flight on Thursday, Dec. 13, 2001. The 13-minute test flight of X-38 vehicle 131R was the longest and fastest and was launched from the highest altitude to date in the X-38's atmospheric flight test program. A portion of the descent was flown under remote control by a NASA astronaut from a ground vehicle configured like the CRV's interior before the X-38 made an autonomous landing on Rogers Dry Lake.

The X-38 Vehicle 131R, intended to prove the utility of a "lifeboat" crew return vehicle to bring crews home from the International Space Station in the event of an emergency, was unloaded from NASA's Super Guppy transport aircraft on July 11, 2000. The newest X-38 version arrived at Dryden for drop tests from NASA's venerable B-52 mother ship. The tests will evaluate a 7,500 square-foot parafoil intended to permit the CRV to return from space and land in the length of a football field.

The X-38 Vehicle 131R, intended to prove the utility of a "lifeboat" crew return vehicle to bring crews home from the International Space Station in the event of an emergency, was unloaded from NASA's Super Guppy transport aircraft on July 11, 2000. The newest X-38 version arrived at Dryden for drop tests from NASA's venerable B-52 mother ship. The tests will evaluate a 7,500 square-foot parafoil intended to permit the crew return vehicle to return from space and land in the length of a football field.

Looking like a giant air mattress, the world's largest parafoil slowly deflates seconds after it carried the latest version of the X-38, V-131R, to a landing on Rogers Dry Lake adjacent to NASAÕs Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards, California, at the end of its first free flight, November 2, 2000. The X-38 prototypes are intended to perfect technology for a planned Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) "lifeboat" to carry a crew to safety in the event of an emergency on the International Space Station. Free-flight tests of X-38 V-131R are evaluating upgraded avionics and control systems and the aerodynamics of the modified upper body, which is more representative of the final design of the CRV than the two earlier X-38 test craft, including a simulated hatch atop the body. The huge 7,500 square-foot parafoil will enable the CRV to land in the length of a football field after returning from space. The first three X-38's are air-launched from NASA's venerable NB-52B mother ship, while the last version, V-201, will be carried into space by a Space Shuttle and make a fully autonomous re-entry and landing.

The X-38 technology demonstrator descends under its steerable parafoil toward a lakebed landing in a March 2000 test flight.

The X-38 technology demonstrator descends under its steerable parafoil toward a lakebed landing in a March 2000 test flight.

The X-38 Crew Return Vehicle descends under its steerable parafoil over the California desert in its first free flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California. The flight took place March 12, 1998.

The X-38 Crew Return Vehicle descends under its steerable parafoil over the California desert in its first free flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California. The flight took place March 12, 1998.

The X-38 Crew Return Vehicle descends under its steerable parafoil over the California desert in its first free flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California. The flight took place March 12, 1998.

Crew members surround the X-38 lifting body research vehicle after a successful test flight and landing in March 1998. The flight was the first free flight for the vehicle and took place at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California.

The X-38 Crew Return Vehicle descends under its steerable parafoil over the California desert in its first free flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California. The flight took place March 12, 1998.

This photo shows one of the X-38 lifting-body research vehicles mated to NASA's B-52 mothership in flight prior to launch. The B-52 has been a workhorse for the Dryden Flight Research Center for more than 40 years, carrying numerous research vehicles aloft and conducting a variety of other research flight experiments.

The X-38 prototype of the Crew Return Vehicle for the International Space Station is suspended under its giant 7,500-square-foot parafoil during its eighth free flight on Thursday, Dec. 13, 2001. A portion of the descent was flown by remote control by a NASA astronaut from a ground vehicle configured like the CRV's interior before the X-38 made an autonomous landing on Rogers Dry Lake.

The X-38 prototype of the Crew Return Vehicle for the International Space Station is suspended under its giant 7,500-square-foot parafoil during its eighth free flight on Thursday, Dec. 13, 2001. A portion of the descent was flown by remote control by a NASA astronaut from a ground vehicle configured like the CRV's interior before the X-38 made an autonomous landing on Rogers Dry Lake.

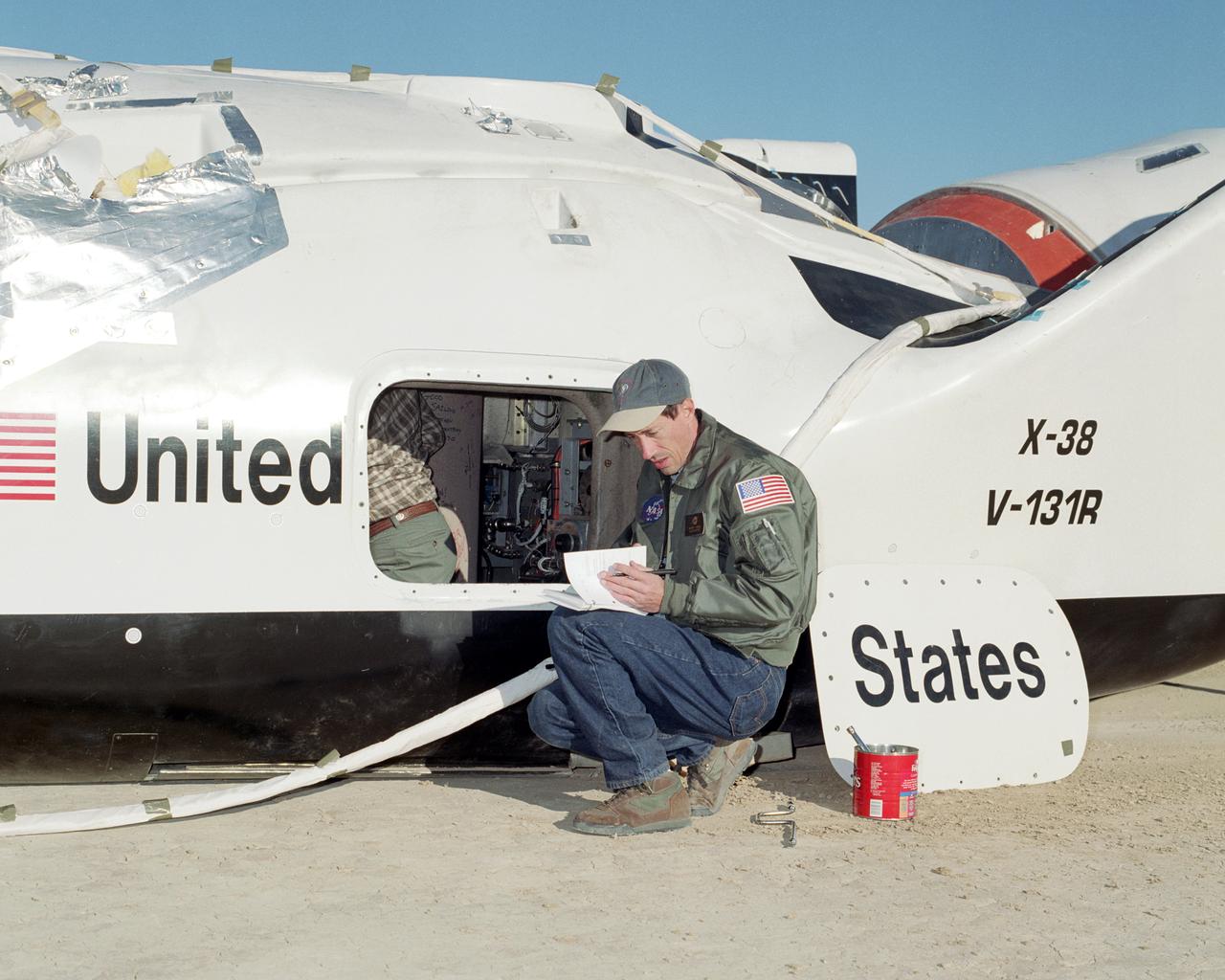

NASA engineer Wayne Peterson from the Johnson Space Center reviews postflight checklists following a spectacular flight of the X-38 prototype for a crew recovery vehicle that may be built for the International Space Station. The X-38 tested atmospheric flight characteristics on December 13, 2001, in a descent from 45,000 feet to Rogers Dry Lake at the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center/Edwards Air Force Base complex in California.

B-52 008 landing on runway 04 at Edwards Air Force Base after first free flight of X-38 vehicle #131R

The X-38 prototypes are intended to perfect a "crew lifeboat" for the International Space Station. The X-38 vehicle 131R demonstrates a huge 7,500 square-foot parafoil that will that will enable the Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) to land on the length of a football field after returning from space. The CRV is intended to serve as an emergency transport to carry a crew to safety in the event of problems with the International Space Station.

The X-38, a research vehicle built to help develop technology for an emergency Crew Return Vehicle (CRV), descends under its steerable parafoil on a March 1999 test flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California.

The X-38, a research vehicle built to help develop technology for an emergency Crew Return Vehicle (CRV), maneuvers toward landing at the end of a March 1999 test flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California.

The X-38, a research vehicle built to help develop technology for an emergency Crew Return Vehicle (CRV), descends under its steerable parafoil on a March 1999 test flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California.

The X-38, a research vehicle built to help develop technology for an emergency Crew Return Vehicle (CRV), descends under its steerable parafoil on a March 1999 test flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California.

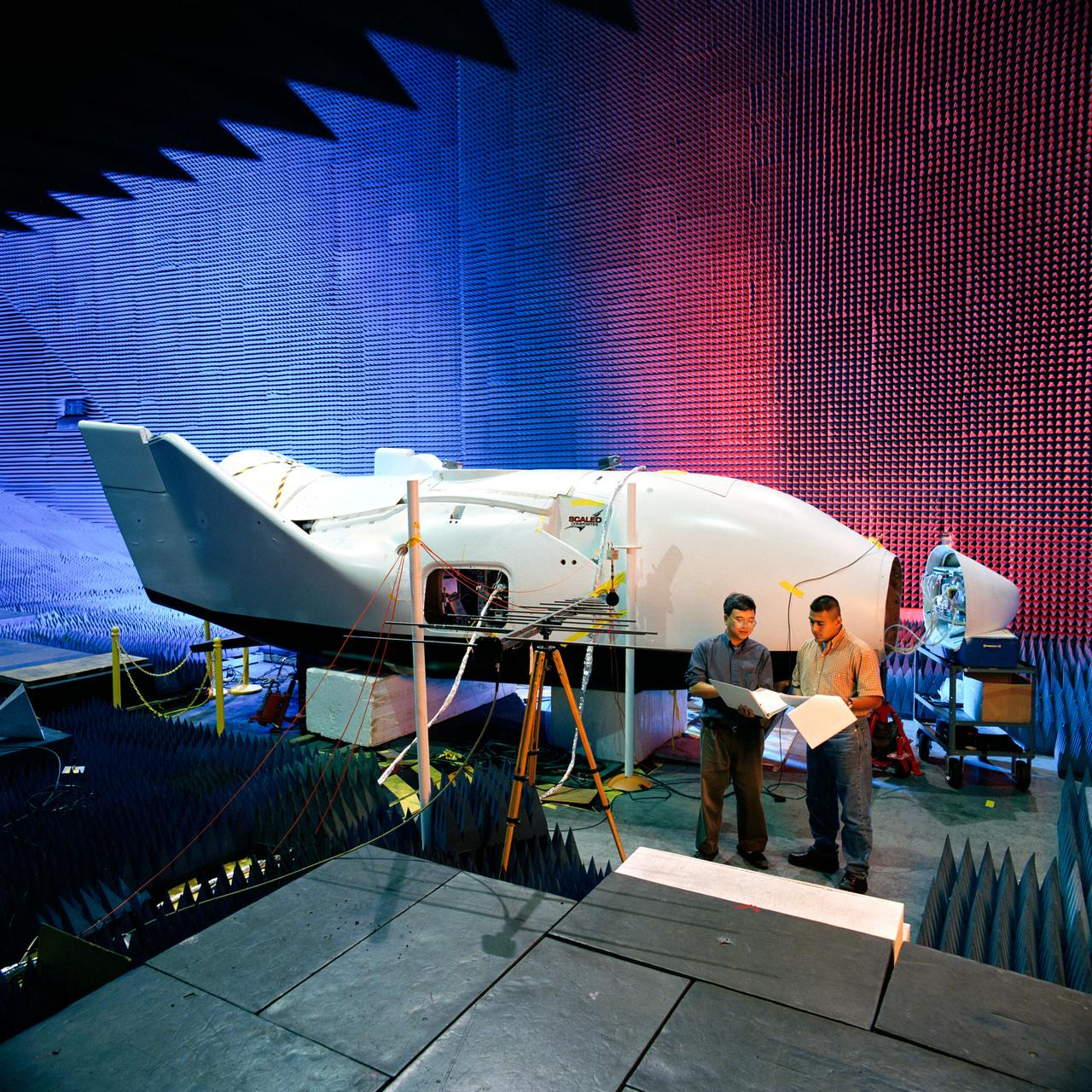

Photographic documentation showing the X-38 Crew Return Vehicle (CRV) undergoing testing in the anechoic chamber in bldg. 14.

The X-38, a research vehicle built to help develop technology for an emergency Crew Return Vehicle from the International Space Station, is seen just before touchdown on a lakebed near the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards California, at the end of a March 2000 test flight.

The X-38's blue and white parafoil spreads out in front of the research vehicle as it sits on a lakebed near the Dryden Flight Research Center after a March 2000 test flight.

A collection of NASA's research aircraft on the ramp at the Dryden Flight Research Center in July 1997: X-31, F-15 ACTIVE, SR-71, F-106, F-16XL Ship #2, X-38, Radio Controlled Mothership and X-36.

NASA's B377SGT Super Guppy Turbine cargo aircraft touches down at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. on June 11, 2000 to deliver the latest version of the X-38 flight test vehicle to NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center.

Members of the flight and ground crews prepare to unload equipment from NASA's B377SGT Super Guppy Turbine cargo aircraft on the ramp at NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. The outsize cargo plane had delivered the latest version of the X-38 flight test vehicle to NASA Dryden when this photo was taken on June 11, 2000.

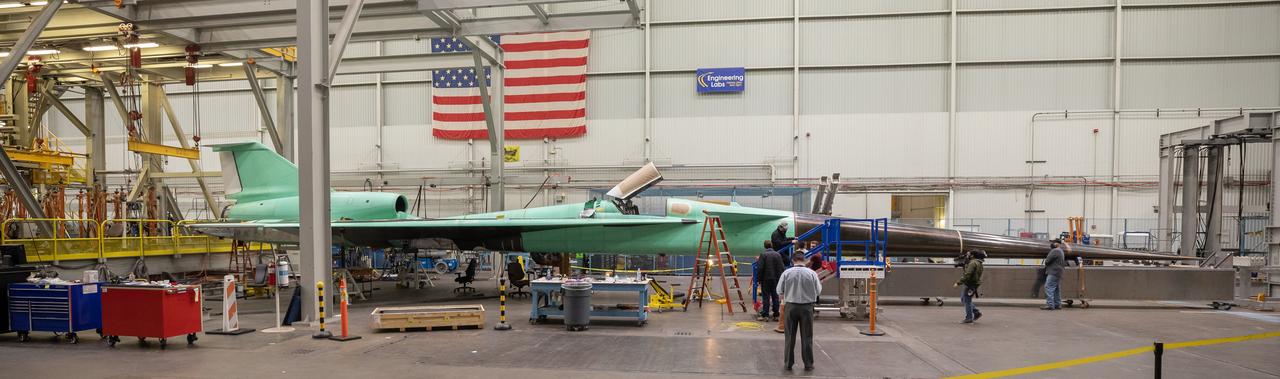

A panoramic view of NASA’s X-59 in Fort Worth, Texas to undergo structural and fuel testing. The X-59’s nose makes up one third of the aircraft, at 38-feet in length. The X-59 is a one-of-a-kind airplane designed to fly at supersonic speeds without making a startling sonic boom sound for the communities below. This is part of NASA’s Quesst mission which plans to help enable supersonic air travel over land.

NASA’s X-59 undergoes a structural stress test at Lockheed Martin’s facility in Fort Worth, Texas. The X-59’s nose makes up one third of the aircraft, at 38-feet in length. The X-59 is a one-of-a-kind airplane designed to fly at supersonic speeds without making a startling sonic boom sound for the communities below. This is part of NASA’s Quesst mission, which plans to help enable supersonic air travel over land

NASA’s X-59 undergoes a structural stress test at a Lockheed Martin facility in Fort Worth, Texas. The X-59’s nose makes up one third of the aircraft, at 38-feet in length. The X-59 is a one-of-a-kind airplane designed to fly at supersonic speeds without making aa startling sonic boom sound for the communities below. This is part of NASA’s Quesst mission which plans to help enable supersonic air travel over land

Event: Manufacturing Area From Above A overhead view of the X-59 with its nose on. The X-59’s nose is 38-feet long – approximately one third of the length of the entire aircraft. The aircraft, under construction at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California, will demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic while reducing the loud sonic boom to a quiet sonic thump.

NASA Aircraft on ramp (Aerial view) Sides: (L) QSRA (R) C-8A AWJSRA - Back to Front: CV-990 (711) C-141 KAO, CV-990 (712) Galileo, T-38, YO-3A, Lear Jet, X-14, U-2, OH-6, CH-47, SH-3G, RSRA, AH-1G, XV-15, UH-1H

A Rans S-12 remotely piloted "mothership" takes off from a lakebed runway carrying a Spacewedge research model during 1992 flight tests. The Spacewedge was lauched in flight from the Rans S-12 aircraft and then glided back to a landing under a steerable parafoil. Technology tested in the Spacewedge program was used in developing the X-38 research vehicle.

NASA Aircraft on ramp (Aerial view) Sides: (L) QSRA (R) C-8A AWJSRA - Back to Front: CV-990 (711) C-141 KAO, CV-990 (712) Galileo, T-38, YO-3A, Lear Jet, X-14, U-2, OH-6, CH-47, SH-3G, RSRA, AH-1G, XV-15, UH-1H

A overhead view of the X-59 with its nose on. The X-59’s nose is 38-feet long – approximately one third of the length of the entire aircraft. The plane is under construction at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California, will fly to demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic while reducing the loud sonic boom to a quiet sonic thump.

Event: SEG 230 Nose - Craned Onto Tooling A close up of the X-59’s duckbill nose, which is a crucial part of its supersonic design shaping. The team prepares the nose for a fit check. The X-59’s nose is 38-feet long – approximately one third of the length of the entire aircraft. The aircraft, under construction at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California, will demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic while reducing the loud sonic boom to a quiet sonic thump.

Event: SEG 230 Nose - Craned Onto Tooling A close-up of the X-59’s duckbill nose, which is a crucial part of its supersonic design shaping. The team prepares the nose for a fit check. The X-59’s nose is 38-feet long – approximately one third of the length of the entire aircraft. The aircraft, under construction at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California, will demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic while reducing the loud sonic boom to a quiet sonic thump.

A panoramic side view of the left top of the X-59 supersonic plane with the tail on and the nose in the process of installation. The X-59’s nose is 38-feet long – approximately one third of the length of the entire aircraft. The aircraft, under construction at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California, will demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic while reducing the loud sonic boom to a quiet sonic thump.

Event: SEG 230 Nose The X-59’s nose is wrapped up safely and rests on a dolly before the team temporarily attaches it to the aircraft for fit checks at Lockheed Martin in Palmdale, California. The full length of the X-plane’s nose is 38-feet – making up one third of the plane’s full length. The aircraft, under construction at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California, once in the air will demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic while reducing the loud sonic boom to a quiet sonic thump.

An overhead view of the X-59 supersonic plane with the tail on and the nose in the process of installation. The X-59’s nose is 38-feet long – approximately one third of the length of the entire aircraft. The aircraft, under construction at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California, will demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic while reducing the loud sonic boom to a quiet sonic thump.

NASA test pilot Nils Larson gets an initial look at the painted X-59 as it sits on the ramp at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California. Larson, one of three test pilots training to fly the X-59 inspects the side of the 38-foot-long nose; a primary design feature to the X-59’s purpose of demonstrating the ability to fly supersonic, or faster than sound, without creating a loud sonic boom. The X-59 is the centerpiece of NASA’s Quesst mission, which seeks to solve one of the major barriers to supersonic flight over land, currently banned in the United States, by making sonic booms quieter.

NASA test pilot Nils Larson gets an initial look at the painted X-59 as it sits on the ramp at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California. Larson, one of three test pilots training to fly the X-59 inspects the side of the 38-foot-long nose; a primary design feature to the X-59’s purpose of demonstrating the ability to fly supersonic, or faster than sound, without creating a loud sonic boom. The X-59 is the centerpiece of NASA’s Quesst mission, which seeks to solve one of the major barriers to supersonic flight over land, currently banned in the United States, by making sonic booms quieter.

NASA’s X-59 quiet supersonic research aircraft sits on the ramp at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California during sunrise, shortly after completion of painting. With its unique design, including a 38-foot-long nose, the X-59 was built to demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic, or faster than the speed of sound, while reducing the typically loud sonic boom produced by aircraft at such speeds to a quieter sonic “thump”. The X-59 is the centerpiece of NASA’s Quesst mission, which seeks to solve one of the major barriers to supersonic flight over land, currently banned in the United States, by making sonic booms quieter.

NASA’s X-59 quiet supersonic research aircraft sits on the ramp at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California during sunrise, shortly after completion of painting. With its unique design, including a 38-foot-long nose, the X-59 was built to demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic, or faster than the speed of sound, while reducing the typically loud sonic boom produced by aircraft at such speeds to a quieter sonic “thump”. The X-59 is the centerpiece of NASA’s Quesst mission, which seeks to solve one of the major barriers to supersonic flight over land, currently banned in the United States, by making sonic booms quieter.

NASA’s X-59 quiet supersonic research aircraft sits on the ramp at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California during sunrise, shortly after completion of painting. With its unique design, including a 38-foot-long nose, the X-59 was built to demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic, or faster than the speed of sound, while reducing the typically loud sonic boom produced by aircraft at such speeds to a quieter sonic “thump”. The X-59 is the centerpiece of NASA’s Quesst mission, which seeks to solve one of the major barriers to supersonic flight over land, currently banned in the United States, by making sonic booms quieter.

NASA’s X-59 quiet supersonic research aircraft sits on the ramp at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California during sunrise, shortly after completion of painting. With its unique design, including a 38-foot-long nose, the X-59 was built to demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic, or faster than the speed of sound, while reducing the typically loud sonic boom produced by aircraft at such speeds to a quieter sonic “thump”. The X-59 is the centerpiece of NASA’s Quesst mission, which seeks to solve one of the major barriers to supersonic flight over land, currently banned in the United States, by making sonic booms quieter.

NASA’s X-59 quiet supersonic research aircraft sits on the ramp at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California during sunrise, shortly after completion of painting. With its unique design, including a 38-foot-long nose, the X-59 was built to demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic, or faster than the speed of sound, while reducing the typically loud sonic boom produced by aircraft at such speeds to a quieter sonic “thump”. The X-59 is the centerpiece of NASA’s Quesst mission, which seeks to solve one of the major barriers to supersonic flight over land, currently banned in the United States, by making sonic booms quieter.

NASA’s X-59 quiet supersonic research aircraft sits on the ramp at Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Palmdale, California during sunrise, shortly after completion of painting. With its unique design, including a 38-foot-long nose, the X-59 was built to demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic, or faster than the speed of sound, while reducing the typically loud sonic boom produced by aircraft at such speeds to a quieter sonic “thump”. The X-59 is the centerpiece of NASA’s Quesst mission, which seeks to solve one of the major barriers to supersonic flight over land, currently banned in the United States, by making sonic booms quieter.

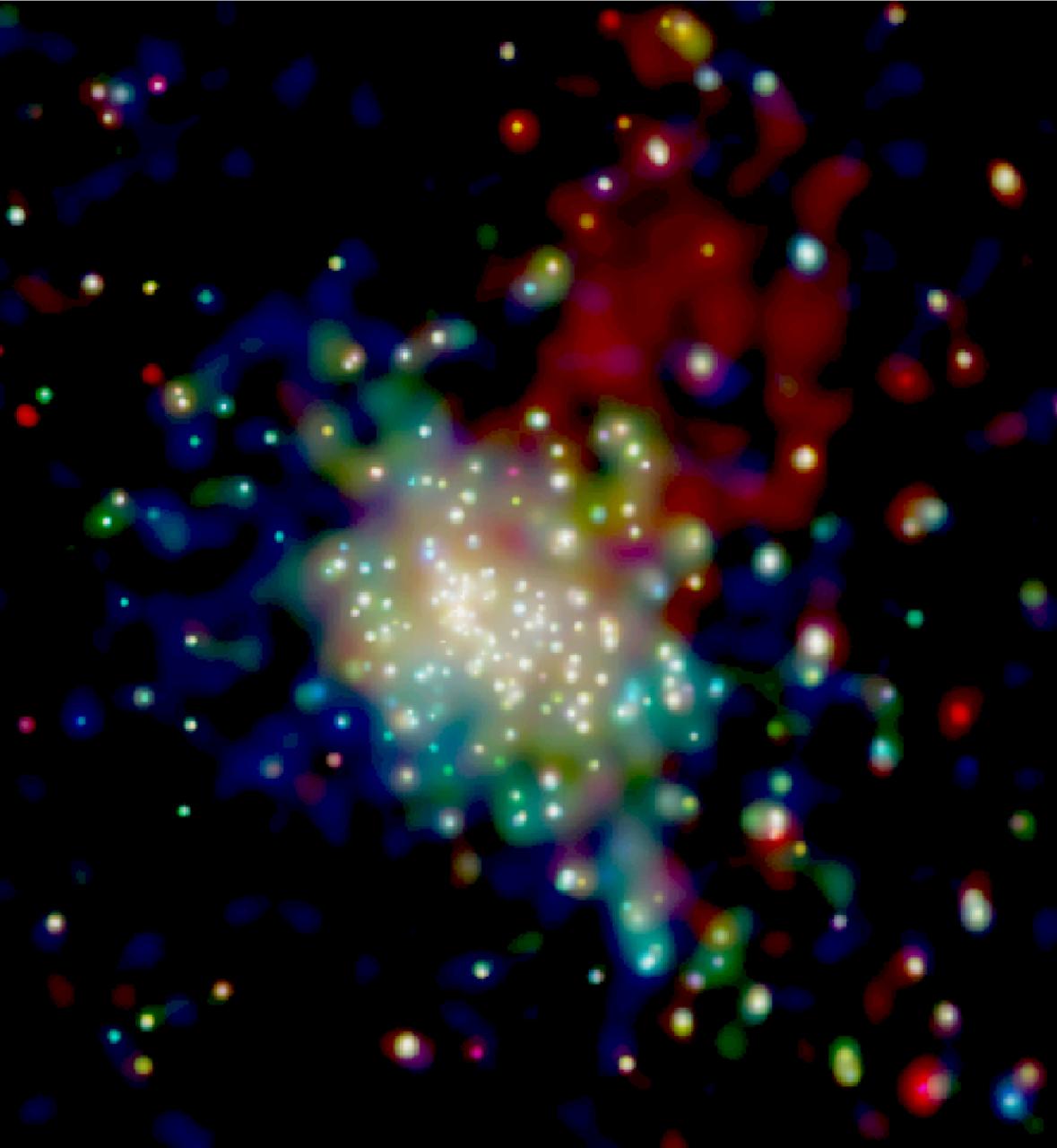

At a distance of 6,000 light years from Earth, the star cluster RCW 38 is a relatively close star-forming region. This area is about 5 light years across, and contains thousands of hot, very young stars formed less than a million years ago, 190 of which exposed x-rays to Chandra. Enveloping the star cluster, the diffused cloud of x-rays shows an excess of high energy x-rays, which indicates that the x-rays come from trillion-volt electrons moving in a magnetic field. Such particles are typically produced by exploding stars, or in the strong magnetic fields around neutron stars or black holes, none of which are evident in RCW 38. One possible origin for the particles, could be an undetected supernova that occurred in the cluster, possibly thousands of years ago, producing a shock wave that is interacting with the young stars. Regardless of the origin of these energetic electrons, their presence could change the chemistry of the disks that will eventually form planets around the stars in the cluster.

NASA research pilot Milt Thompson sits in the M2-F2 "heavyweight" lifting body research vehicle before a 1966 test flight. The M2-F2 and the other lifting-body designs were all attached to a wing pylon on NASA’s B-52 mothership and carried aloft. The vehicles were then drop-launched and, at the end of their flights, glided back to wheeled landings on the dry lake or runway at Edwards AFB. The lifting body designs influenced the design of the Space Shuttle and were also reincarnated in the design of the X-38 in the 1990s.

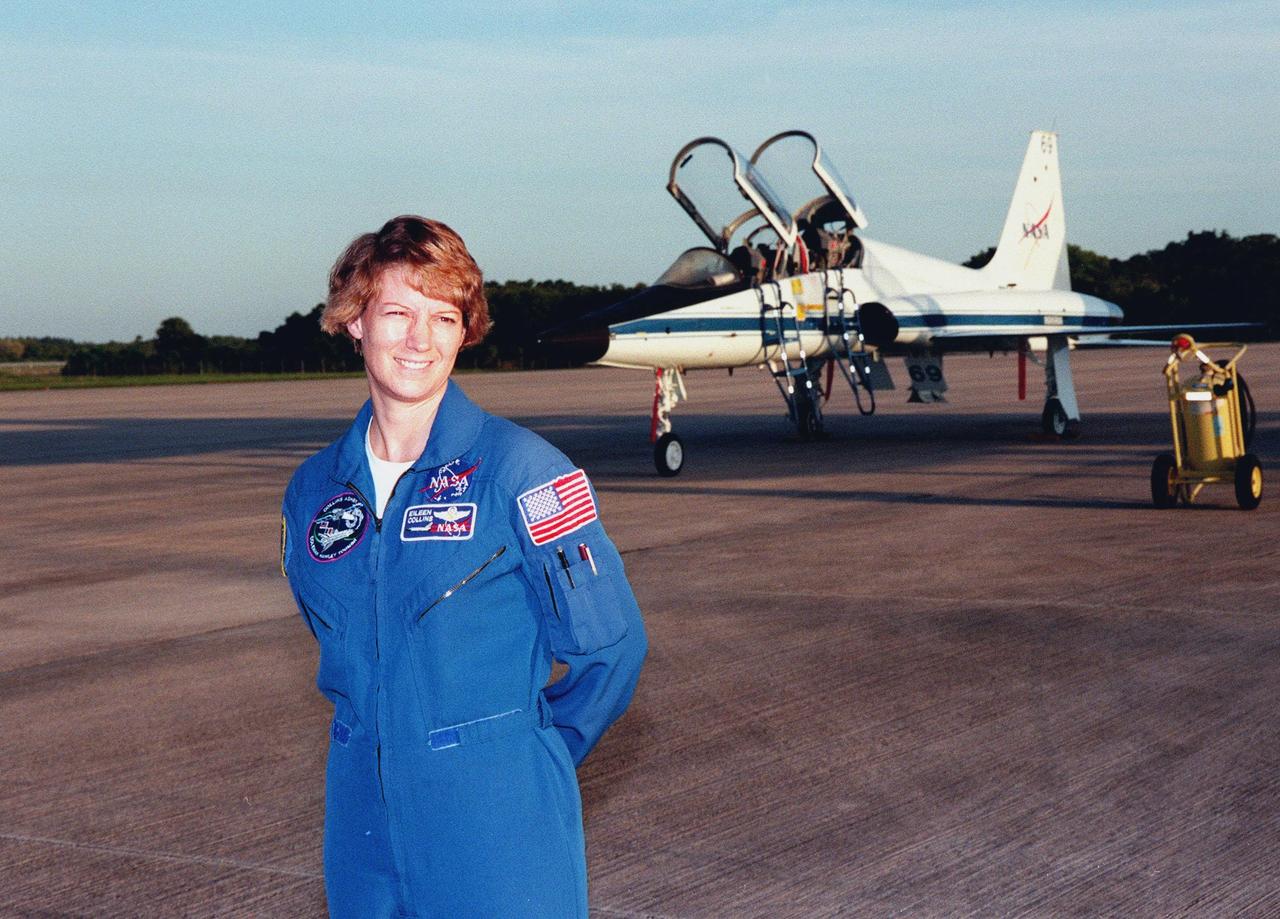

STS-93 Commander Eileen Collins poses for photographers in the early morning sun after landing at Kennedy Space Center's Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) aboard a T-38 jet aircraft (background). She and other crew members Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.), Catherine G. "Cady" Coleman (Ph.D.) and Michel Tognini of France, with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES), are arriving for pre-launch activities. Collins is the first woman to serve as mission commander. This is her third Shuttle flight. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to study some of the most distant, powerful and dynamic objects in the universe. The new telescope is 20 to 50 times more sensitive than any previous X-ray telescope and is expected to unlock the secrets of supernovae, quasars and black holes

Center Director Roy D. Bridges Jr. greets STS-93 Commander Eileen M. Collins after her arrival at KSC's Shuttle Landing Facility aboard a T-38 jet aircraft (behind her). She and other crew members Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.), Catherine G. "Cady" Coleman (Ph.D.) and Michel Tognini of France, with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES), are arriving for pre-launch activities. Collins is the first woman to serve as mission commander. This is her third Shuttle flight. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to study some of the most distant, powerful and dynamic objects in the universe. The new telescope is 20 to 50 times more sensitive than any previous X-ray telescope and is expected to unlock the secrets of supernovae, quasars and black holes

STS-93 Mission Specialist Catherine G. "Cady" Coleman (Ph.D.) shows her sense of humor upon arriving at KSC's Shuttle Landing Facility aboard a T-38 jet aircraft. She and other crew members Commander Eileen Collins, Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby, and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.) and Michel Tognini of France, with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES), are arriving for pre-launch activities. Coleman is making her second Shuttle flight. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to study some of the most distant, powerful and dynamic objects in the universe. The new telescope is 20 to 50 times more sensitive than any previous X-ray telescope and is expected to unlock the secrets of supernovae, quasars and black holes

STS-93 Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby lands at Kennedy Space Center's Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) aboard a T-38 jet aircraft. He and other crew members Commander Eileen Collins and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.), Catherine G. "Cady" Coleman (Ph.D.) and Michel Tognini of France, with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES), are arriving for pre-launch activities. STS-93 is Ashby's inaugural Shuttle flight. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to study some of the most distant, powerful and dynamic objects in the universe. The new telescope is 20 to 50 times more sensitive than any previous X-ray telescope and is expected to unlock the secrets of supernovae, quasars and black holes

STS-93 Mission Specialist Catherine G. 'Cady' Coleman (Ph.D.) smiles upon her arrival at KSC's Shuttle Landing Facility aboard a T-38 jet aircraft. She and other crew members Commander Eileen Collins, Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby, and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.) and Michel Tognini of France, with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES), are arriving for pre-launch activities. Coleman is making her second Shuttle flight. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to study some of the most distant, powerful and dynamic objects in the universe. The new telescope is 20 to 50 times more sensitive than any previous X-ray telescope and is expected to unlock the secrets of supernovae, quasars and black holes

STS-93 Commander Eileen Collins waves to spectators after landing at Kennedy Space Center's Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) aboard a T-38 jet aircraft. She and other crew members Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.), Catherine G. "Cady" Coleman (Ph.D.) and Michel Tognini of France, with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES), are arriving for pre-launch activities. Collins is the first woman to serve as mission commander. This is her third Shuttle flight. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to study some of the most distant, powerful and dynamic objects in the universe. The new telescope is 20 to 50 times more sensitive than any previous X-ray telescope and is expected to unlock the secrets of supernovae, quasars and black holes

STS-93 Mission Specialist Michel Tognini of France, with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES), prepares to leave the T-38 jet aircraft that brought him to KSC's Shuttle Landing Facility. He and other crew members Commander Eileen Collins, Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby, and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.) and Catherine G. "Cady" Coleman (Ph.D.) are arriving for pre-launch activities. Tognini is making his inaugural Shuttle flight. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to study some of the most distant, powerful and dynamic objects in the universe. The new telescope is 20 to 50 times more sensitive than any previous X-ray telescope and is expected to unlock the secrets of supernovae, quasars and black holes

STS-93 Commander Eileen Collins peers into the eastern early morning sky after landing at Kennedy Space Center's Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) aboard a T-38 jet aircraft (background). She and other crew members Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.), Catherine G. "Cady" Coleman (Ph.D.) and Michel Tognini of France, with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES), are arriving for pre-launch activities. Collins is the first woman to serve as mission commander. This is her third Shuttle flight. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to study some of the most distant, powerful and dynamic objects in the universe. The new telescope is 20 to 50 times more sensitive than any previous X-ray telescope and is expected to unlock the secrets of supernovae, quasars and black holes

Joseph A. Walker was a Chief Research Pilot at the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center during the mid-1960s. He joined the NACA in March 1945, and served as project pilot at the Edwards flight research facility on such pioneering research projects as the D-558-1, D-558-2, X-1, X-3, X-4, X-5, and the X-15. He also flew programs involving the F-100, F-101, F-102, F-104, and the B-47. Walker made the first NASA X-15 flight on March 25, 1960. He flew the research aircraft 24 times and achieved its fastest speed and highest altitude. He attained a speed of 4,104 mph (Mach 5.92) during a flight on June 27, 1962, and reached an altitude of 354,300 feet on August 22, 1963 (his last X-15 flight). He was the first man to pilot the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV) that was used to develop piloting and operational techniques for lunar landings. Walker was born February 20, 1921, in Washington, Pa. He lived there until graduating from Washington and Jefferson College in 1942, with a B.A. degree in Physics. During World War II he flew P-38 fighters for the Air Force, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with Seven Oak Clusters. Walker was the recipient of many awards during his 21 years as a research pilot. These include the 1961 Robert J. Collier Trophy, 1961 Harmon International Trophy for Aviators, the 1961 Kincheloe Award and 1961 Octave Chanute Award. He received an honorary Doctor of Aeronautical Sciences degree from his alma mater in June of 1962. Walker was named Pilot of the Year in 1963 by the National Pilots Association. He was a charter member of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, and one of the first to be designated a Fellow. He was fatally injured on June 8, 1966, in a mid-air collision between an F-104 he was piloting and the XB-70.

S66-46122 (18 July 1966) --- Agena Target Docking Vehicle 5005 is photographed from the Gemini-Titan 10 (GT-10) spacecraft during rendezvous in space. The two spacecraft are about 38 feet apart. After docking with the Agena, astronauts John W. Young, command pilot, and Michael Collins, pilot, fired the 16,000 pound thrust engine of Agena X's primary propulsion system to boost the combined vehicles into an orbit with an apogee of 413 nautical miles to set a new altitude record for manned spaceflight. Photo credit: NASA

STS-93 Mission Specialist Catherine G. Coleman (Ph.D.) grins on her arrival at KSC's Shuttle Landing Facility aboard a T-38 jet to participate in Terminal Countdown Demonstration Tests (TCDT) this week. TCDT activities familiarize the crew with the mission, provide training in emergency exit from the orbiter and launch pad, and include a launch-day dress rehearsal culminating with a simulated main engine cut-off. Joining Coleman are Commander Eileen M. Collins, Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.) and Michel Tognini of France, who is with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES). Collins is the first woman to serve as mission commander. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to obtain unprecedented X-ray images of exotic environments in space to help understand the structure and evolution of the universe. Chandra is expected to provide unique and crucial information on the nature of objects ranging from comets in our solar system to quasars at the edge of the observable universe. Since X-rays are absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, space-based observatories are necessary to study these phenomena and allow scientists to analyze some of the greatest mysteries of the universe

STS-93 Commander Eileen M. Collins smiles on her arrival at KSC's Shuttle Landing Facility aboard a T-38 jet aircraft to participate in Terminal Countdown Demonstration Tests (TCDT) this week. TCDT activities familiarize the crew with the mission, provide training in emergency exit from the orbiter and launch pad, and include a launch-day dress rehearsal culminating with a simulated main engine cut-off. Joining Collins are Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby and Mission Specialists Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.), Catherine G. Coleman (Ph.D.) and Michel Tognini of France, with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES). Collins is the first woman to serve as mission commander. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to obtain unprecedented X-ray images of exotic environments in space to help understand the structure and evolution of the universe. Chandra is expected to provide unique and crucial information on the nature of objects ranging from comets in our solar system to quasars at the edge of the observable universe. Since X-rays are absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, space-based observatories are necessary to study these phenomena and allow scientists to analyze some of the greatest mysteries of the universe

STS-93 Mission Specialist Steven A. Hawley (Ph.D.) grins as he steps down from a T-38 jet aircraft after landing at KSC's Shuttle Landing Facility. The STS-93 crew are at KSC to participate in Terminal Countdown Demonstration Tests (TCDT) this week. TCDT activities familiarize the crew with the mission, provide training in emergency exit from the orbiter and launch pad, and include a launch-day dress rehearsal culminating with a simulated main engine cut-off. Joining Hawley are Commander Eileen M. Collins, Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby, and Mission Specialists Catherine G. Coleman (Ph.D.) and Michel Tognini of France, with the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES). Collins is the first woman to serve as mission commander. The primary mission of STS-93 is the release of the Chandra X-ray Observatory, which will allow scientists from around the world to obtain unprecedented X-ray images of exotic environments in space to help understand the structure and evolution of the universe. Chandra is expected to provide unique and crucial information on the nature of objects ranging from comets in our solar system to quasars at the edge of the observable universe. Since X-rays are absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, space-based observatories are necessary to study these phenomena and allow scientists to analyze some of the greatest mysteries of the universe

Before leaving KSC, STS-93 Commander Eileen M. Collins poses by a T-38 jet trainer aircraft at the Shuttle Landing Facility. She and the rest of the STS-93 crew spent two days visiting mission-related sites, including the Vertical Processing Facility where the Chandra X-ray Observatory is undergoing testing. STS-93 is scheduled to launch July 9 aboard Space Shuttle Columbia and has the primary mission of the deployment of the observatory. Formerly called the Advanced X-ray Astrophysics Facility, Chandra comprises three major elements: the spacecraft, the science instrument module (SIM), and the world's most powerful X-ray telescope. Chandra will allow scientists from around the world to see previously invisible black holes and high-temperature gas clouds, giving the observatory the potential to rewrite the books on the structure and evolution of our universe. Collins is the first woman to serve as commander of a Space Shuttle. Other STS-93 crew members are Pilot Jeffrey S. Ashby and Mission Specialists Catherine G. Coleman, Steven A. Hawley, and Michel Tognini of France, who represents the Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales (CNES)

This side-rear view of the X-24A Lifting Body on the lakebed by the NASA Flight Research Center shows its control surfaces used for subsonic flight.

ISS008-E-12555 (22 January 2004) --- This photo of melt-water pooled on the surface of iceberg A-39D, a 2 x 11 kilometers iceberg currently located near South Georgia Island, was taken by an Expedition 8 crewmember on the International Space Station (ISS). The different intensities of blue are interpreted as different water depths. From the orientation of the iceberg, the deepest water (darkest blue) lies at the westernmost end of the iceberg. The water pools have formed from snowmelt – late January is the peak of the southern summer. This iceberg was part of the original A-38 iceberg that calved from the Ronne Ice Shelf in October 1998. Originally the ice was between 200 and 350 meters thick. This piece of that iceberg is now probably about 150 meters thick, with around 15 meters sticking up above the surface of the water.

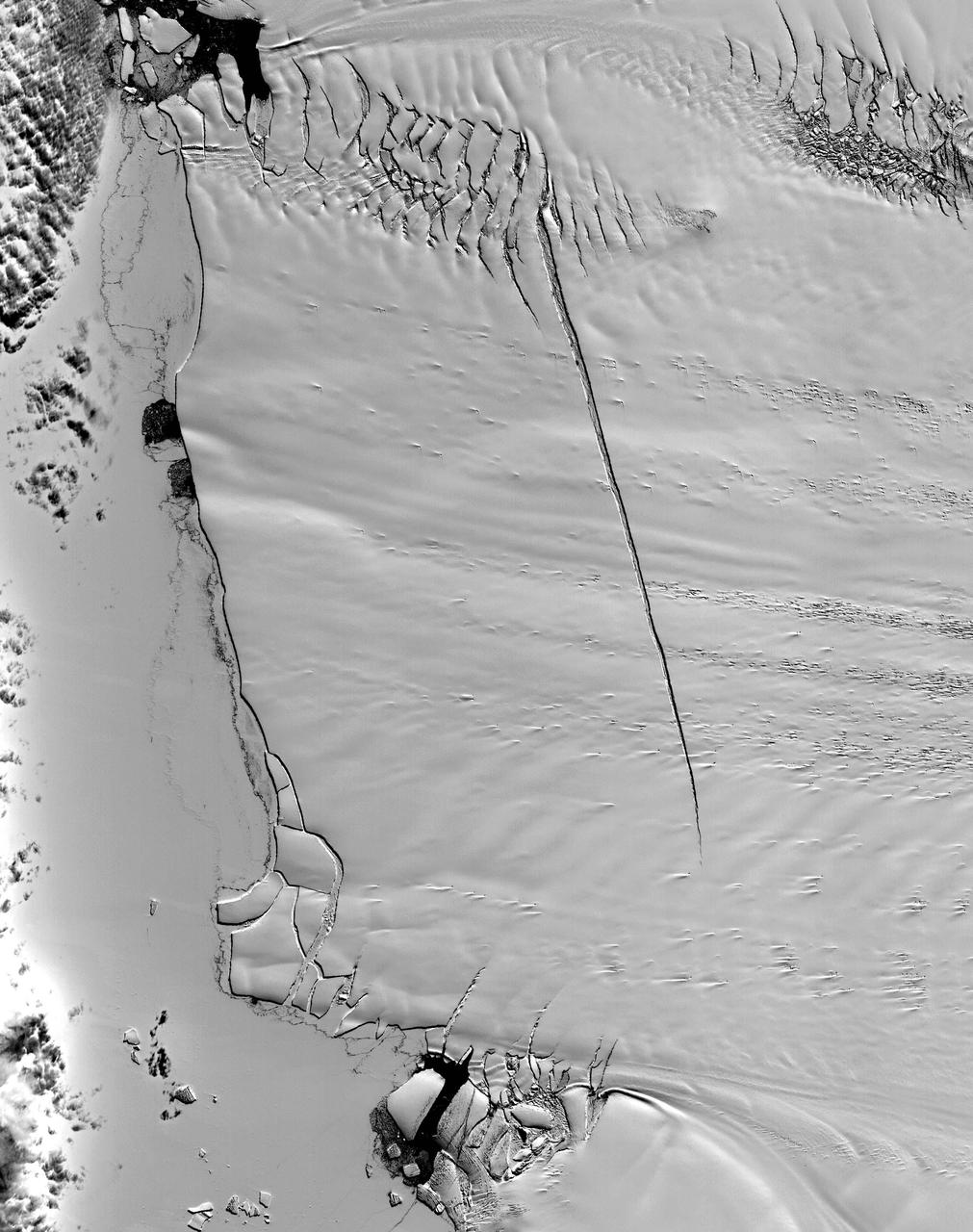

This ASTER image was acquired on December 12, 2000, and covers an area of 38 x 48 km. Pine Island Glacier has undergone a steady loss of elevation with retreat of the grounding line in recent decades. Now, space imagery has revealed a wide new crack that some scientists think will soon result in a calving event. Glaciologist Robert Bindschadler of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center predicts this crack will result in the calving of a major iceberg, probably in less than 18 months. Discovery of the crack was possible due to multi-year image archives and high resolution imagery. This image is located at 74.1 degrees south latitude and 105.1 degrees west longitude. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA11095

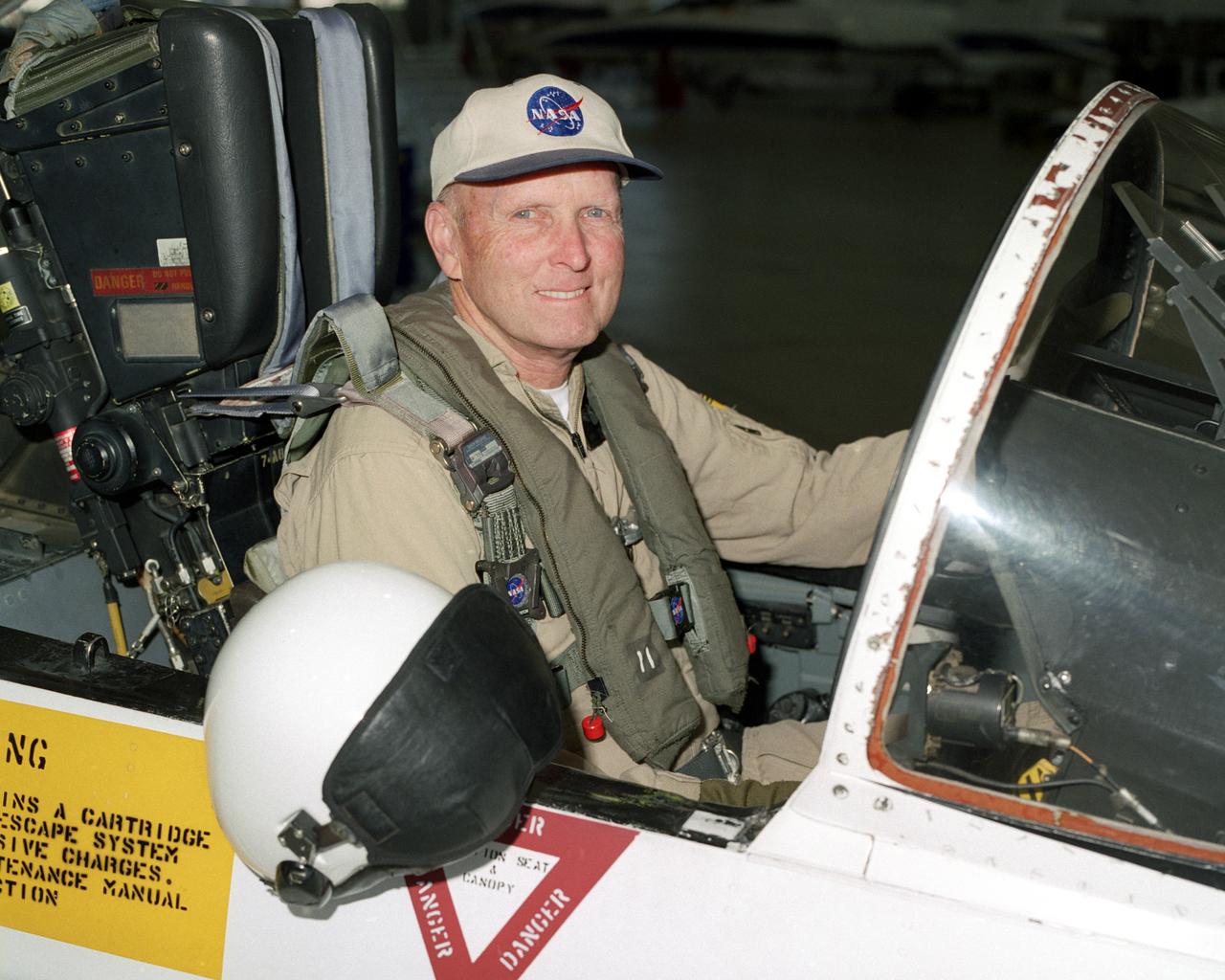

Former NASA astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton, seated in the cockpit of an F/A-18, is a research pilot at NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, Calif. Since transferring to Dryden in 1986, his assignments have included a variety of flight research and support activities piloting NASA's B-52 launch aircraft, the 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), and other multi-engine and high performance aircraft. He flew a series of development air launches of the X-38 prototype Crew Return Vehicle and in the launches for the X-43A Hyper-X project. Fullerton also flies Dryden's DC-8 Airborne Science aircraft in support a variety of atmospheric physics, ground mapping and meteorology studies. Fullerton also was project pilot on the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft program, during which he successfully landed both a modified F-15 and an MD-11 transport with all control surfaces neutralized, using only engine thrust modulation for control. Fullerton also evaluated the flying qualities of the Russian Tu-144 supersonic transport during two flights in 1998, one of only two non-Russian pilots to fly that aircraft. With more than 15,000 hours of flying time, Fullerton has piloted 135 different types of aircraft in his career. As an astronaut, Fullerton served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16, and 17 lunar missions. In 1977, Fullerton was on one of the two flight crews that piloted the Space Shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test Program at Dryden. Fullerton was the pilot on the STS-3 Space Shuttle orbital flight test mission in 1982, and commanded the STS-51F Spacelab 2 mission in 1985. He has logged 382 hours in space flight. In July 1988, he completed a 30-year career with the U.S. Air Force and retired as a colonel.

The wingless, lifting body aircraft sitting on Rogers Dry Lake at what is now NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, from left to right are the X-24A, M2-F3 and the HL-10. The lifting body aircraft studied the feasibility of maneuvering and landing an aerodynamic craft designed for reentry from space. These lifting bodies were air launched by a B-52 mother ship, then flew powered by their own rocket engines before making an unpowered approach and landing. They helped validate the concept that a space shuttle could make accurate landings without power. The X-24A flew from April 17, 1969 to June 4, 1971. The M2-F3 flew from June 2, 1970 until December 22, 1972. The HL-10 flew from December 22, 1966 until July 17, 1970, and logged the highest and fastest records in the lifting body program.

The wingless, lifting body aircraft sitting on Rogers Dry Lake at what is now NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, from left to right are the X-24A, M2-F3 and the HL-10. The lifting body aircraft studied the feasibility of maneuvering and landing an aerodynamic craft designed for reentry from space. These lifting bodies were air launched by a B-52 mother ship, then flew powered by their own rocket engines before making an unpowered approach and landing. They helped validate the concept that a space shuttle could make accurate landings without power. The X-24A flew from April 17, 1969 to June 4, 1971. The M2-F3 flew from June 2, 1970 until December 21, 1971. The HL-10 flew from December 22, 1966 until July 17, 1970, and logged the highest and fastest records in the lifting body program.

The wingless, lifting body aircraft sitting on Rogers Dry Lake at what is now NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, from left to right are the X-24A, M2-F3 and the HL-10. The lifting body aircraft studied the feasibility of maneuvering and landing an aerodynamic craft designed for reentry from space. These lifting bodies were air launched by a B-52 mother ship, then flew powered by their own rocket engines before making an unpowered approach and landing. They helped validate the concept that a space shuttle could make accurate landings without power. The X-24A flew from April 17, 1969 to June 4, 1971. The M2-F3 flew from June 2, 1970 until December 20, 1972. The HL-10 flew from December 22, 1966 until July 17, 1970 and logged the highest and fastest records in the lifting body program.

The wingless, lifting body aircraft sitting on Rogers Dry Lake at what is now NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, from left to right are the X-24A, M2-F3 and the HL-10. The lifting body aircraft studied the feasibility of maneuvering and landing an aerodynamic craft designed for reentry from space. These lifting bodies were air launched by a B-52 mother ship, then flew powered by their own rocket engines before making an unpowered approach and landing. They helped validate the concept that a space shuttle could make accurate landings without power. The X-24A flew from April 17, 1969 to June 4, 1971. The M2-F3 flew from June 2, 1970 until December 20, 1972. The HL-10 flew from December 22, 1966 until July 17, 1970 and logged the highest and fastest records in the lifting body program.

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. - STS-129 Pilot Barry E. Wilmore arrives at the Shuttle Landing Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida aboard a T-38 jet. The six astronauts for space shuttle Atlantis’ STS-129 mission are at Kennedy for their launch dress rehearsal, the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test. Additional training associated with the test was done last month, but the simulated countdown was postponed because of a scheduling conflict with the launch of NASA’s Ares I-X test rocket. Launch of Atlantis on its STS-129 mission to the International Space Station is set for Nov. 16. On STS-129, the crew will deliver to the station two spare gyroscopes, two nitrogen tank assemblies, two pump modules, an ammonia tank assembly and a spare latching end effector for the station's robotic arm. For information on the STS-129 mission objectives and crew, visit http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/shuttlemissions/sts129/index.html. Photo credit: NASA/Troy Cryder

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. - STS-129 Commander Charles O. Hobaugh disembarks from a T-38 jet at the Shuttle Landing Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The six astronauts for space shuttle Atlantis’ STS-129 mission have arrived at Kennedy for their launch dress rehearsal, the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test. Additional training associated with the test was done last month, but the simulated countdown was postponed because of a scheduling conflict with the launch of NASA’s Ares I-X test rocket. Launch of Atlantis on its STS-129 mission to the International Space Station is set for Nov. 16. On STS-129, the crew will deliver to the station two spare gyroscopes, two nitrogen tank assemblies, two pump modules, an ammonia tank assembly and a spare latching end effector for the station's robotic arm. For information on the STS-129 mission objectives and crew, visit http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/shuttlemissions/sts129/index.html. Photo credit: NASA/Troy Cryder

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. - STS-129 Mission Specialist Randy Bresnik disembarks from a T-38 jet at the Shuttle Landing Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The six astronauts for space shuttle Atlantis’ STS-129 mission have arrived at Kennedy for their launch dress rehearsal, the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test. Additional training associated with the test was done last month, but the simulated countdown was postponed because of a scheduling conflict with the launch of NASA’s Ares I-X test rocket. Launch of Atlantis on its STS-129 mission to the International Space Station is set for Nov. 16. On STS-129, the crew will deliver to the station two spare gyroscopes, two nitrogen tank assemblies, two pump modules, an ammonia tank assembly and a spare latching end effector for the station's robotic arm. For information on the STS-129 mission objectives and crew, visit http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/shuttlemissions/sts129/index.html. Photo credit: NASA/Troy Cryder

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. - STS-129 Mission Specialist Mike Foreman arrives at the Shuttle Landing Facility at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida aboard a T-38 jet. The six astronauts for space shuttle Atlantis’ STS-129 mission are at Kennedy for their launch dress rehearsal, the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test. Additional training associated with the test was done last month, but the simulated countdown was postponed because of a scheduling conflict with the launch of NASA’s Ares I-X test rocket. Launch of Atlantis on its STS-129 mission to the International Space Station is set for Nov. 16. On STS-129, the crew will deliver to the station two spare gyroscopes, two nitrogen tank assemblies, two pump modules, an ammonia tank assembly and a spare latching end effector for the station's robotic arm. For information on the STS-129 mission objectives and crew, visit http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/shuttlemissions/sts129/index.html. Photo credit: NASA/Troy Cryder

Nils Larson is a research pilot in the Flight Crew Branch of NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, Calif. Larson joined NASA in February 2007 and will fly the F-15, F-18, T-38 and ER-2. Prior to joining NASA, Larson was on active duty with the U.S. Air Force. He has accumulated more that 4,900 hours of military and civilian flight experience in more than 70 fixed and rotary winged aircraft. Larson completed undergraduate pilot training at Williams Air Force Base, Chandler, Ariz., in 1987. He remained at Williams as a T-37 instructor pilot. In 1991, Larson was assigned to Beale Air Force Base, Calif., as a U-2 pilot. He flew 88 operational missions from Korea, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, Panama and other locations. Larson graduated from the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., in Class 95A. He became a flight commander and assistant operations officer for the 445th squadron at Edwards. He flew the radar, avionics integration and engine tests in F-15 A-D, the early flights of the glass cockpit T-38C and airworthiness flights of the Coast Guard RU-38. He was selected to serve as an Air Force exchange instructor at the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School, Patuxent River, Md. He taught systems and fixed-wing flight test and flew as an instructor pilot in the F-18, T-2, U-6A Beaver and X-26 Schweizer sailplane. Larson commanded U-2 operations for Warner Robins Air Logistics Center's Detachment 2 located in Palmdale, Calif. In addition to flying the U-2, Larson supervised the aircraft's depot maintenance and flight test. He was the deputy group commander for the 412th Operations Group at Edwards before retiring from active duty in 2007 with the rank of lieutenant colonel. His first experience with NASA was at the Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, where he served a college summer internship working on arcjet engines. Larson is a native of Bethany, W.Va,, and received his commission from the U.S. Air Force Academy in 1986 with a

This image of Houston, Texas, shows the amount of detail that is possible to obtain using spaceborne radar imaging. Images such as this -- obtained by the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C/X-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SIR-C/X-SAR) flying aboard the space shuttle Endeavor last fall -- can become an effective tool for urban planners who map and monitor land use patterns in urban, agricultural and wetland areas. Central Houston appears pink and white in the upper portion of the image, outlined and crisscrossed by freeways. The image was obtained on October 10, 1994, during the space shuttle's 167th orbit. The area shown is 100 kilometers by 60 kilometers (62 miles by 38 miles) and is centered at 29.38 degrees north latitude, 95.1 degrees west longitude. North is toward the upper left. The pink areas designate urban development while the green-and blue-patterned areas are agricultural fields. Black areas are bodies of water, including Galveston Bay along the right edge and the Gulf of Mexico at the bottom of the image. Interstate 45 runs from top to bottom through the image. The narrow island at the bottom of the image is Galveston Island, with the city of Galveston at its northeast (right) end. The dark cross in the upper center of the image is Hobby Airport. Ellington Air Force Base is visible below Hobby on the other side of Interstate 45. Clear Lake is the dark body of water in the middle right of the image. The green square just north of Clear Lake is Johnson Space Center, home of Mission Control and the astronaut training facilities. The black rectangle with a white center that appears to the left of the city center is the Houston Astrodome. The colors in this image were obtained using the follow radar channels: red represents the L-band (horizontally transmitted, vertically received); green represents the C-band (horizontally transmitted, vertically received); blue represents the C-band (horizontally transmitted and received). http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01783

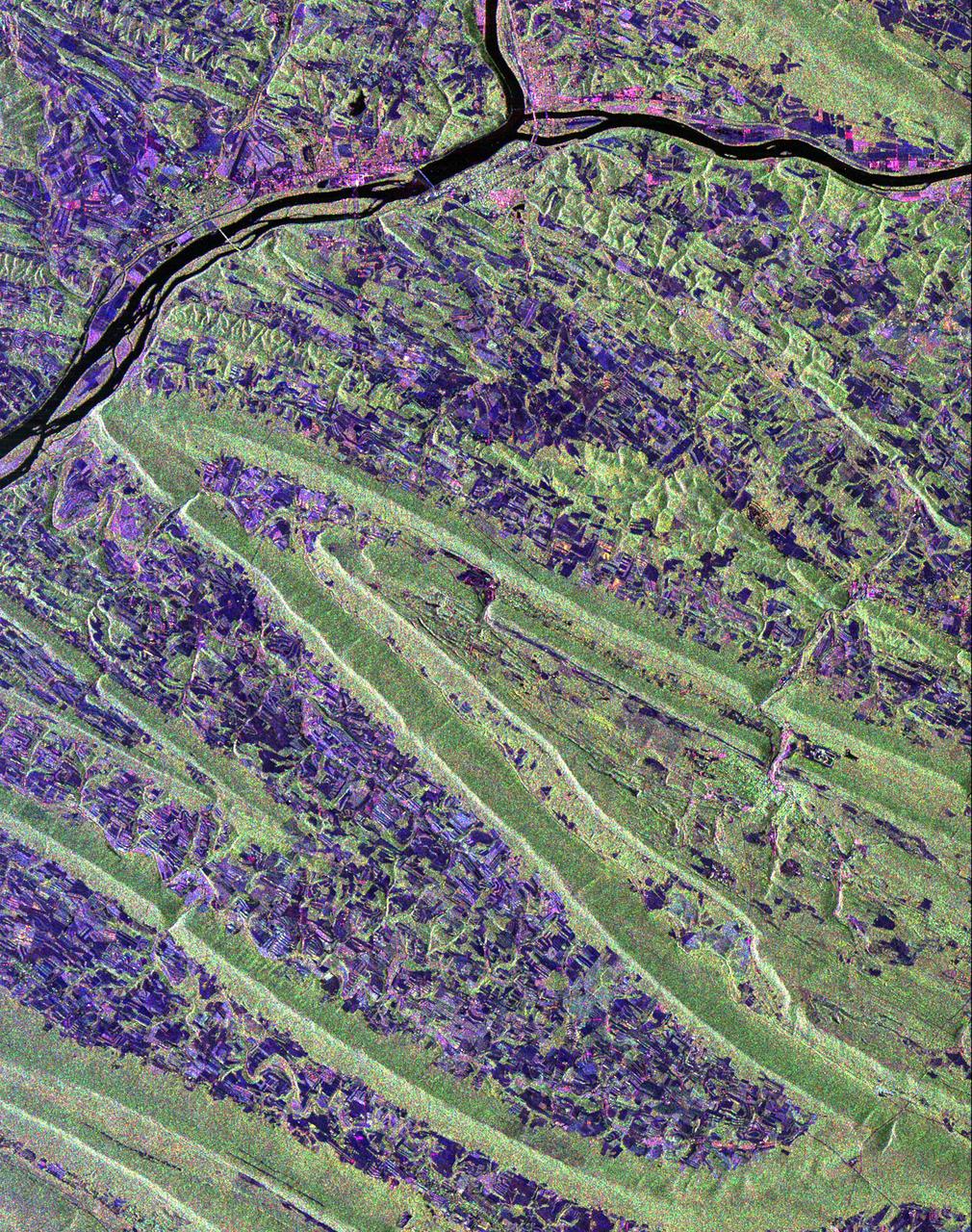

Scientists are using this radar image of the area surrounding Sunbury, Pennsylvania to study the geologic structure and land use patterns in the Appalachian Valley and Ridge province. This image was collected on October 6, 1994 by the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C/ X-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SIR-C/X-SAR) on orbit 102 of the space shuttle Endeavour. The image is centered on latitude 40.85 degrees North latitude and 76.79 degrees West longitude. The area shown is approximately 30.5 km by 38 km. (19 miles by 24 miles). North is towards the upper right of the image. The Valley and Ridge province occurs in the north-central Appalachians, primarily in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. It is an area of adjacent valleys and ridges that formed when the Appalachian mountain were created some 370 to 390 million years ago. During the continental collision that formed the Appalachians, the rocks in this area were pushed from the side and buckled much like a rug when pushed from one end. Subsequent erosion has produced the landscape we see in this image. The more resistant rocks, such as sandstone, form the tops of the ridges which appear as forested greenish areas on this image. The less resistant rocks, such as limestone, form the lower valleys which are cleared land and farm fields and are purple in this image. Smaller rivers and streams in the area flow along the valleys and in places cut across the ridges in "water gaps." In addition to defining the geography of this region, the Valley and Ridge province also provides this area with natural resources. The valleys provide fertile farmland and the folded mountains form natural traps for oil and gas accumulation; coal deposits are also found in the mountains. The colors in the image are assigned to different frequencies and polarizations of the SIR-C radar as follows: red is L-band horizontally transmitted, horizontally received; green is L-band horizontally transmitted, vertically received; blue is C-band horizontally transmitted, horizontally received. The river junction near the top of the image is where the West Branch River flows into the Susquehanna River, which then flows to the south-southwest past the state capitol of Harrisburg, 70 km (43 miles) to the south and not visible in this image. The town of Sunbury is shown along the Susquehanna on the east just to the southeast of the junction with West Branch. Three structures that cross the Susquehanna; the northern and southern of these structures are bridges and middle structure is the Shamokin Dam which confines the Susquehanna just south of the junction with West Branch. The prominent S-shaped mountain ridge in the center of the image is, from north to south, Little Mountain (the top of the S), Line Mountain (the middle of the S), and Mahantango Mountain (the bottom of the S). http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01306

ISS038-E-047324 (13 Feb. 2014) --- This grand panorama of the Southern Patagonia Icefield (center) was imaged by an Expedition 38 crew member on the International Space Station on one of the rare clear days in the southern Andes Mountains. With an area of 13,000 square kilometers, the icefield is the largest temperate ice sheet in the Southern Hemisphere. Storms that swirl into the region from the southern Pacific Ocean (top) bring rain and snow (equivalent to a total of 2-11 meters of rainfall per year) resulting in the buildup of the ice sheet shown here (center). During the ice ages the glaciers were far larger. Geologists now know that ice tongues extended far onto the plains in the foreground, completely filling the great Patagonian lakes on repeated occasions. Similarly, ice tongues extended into the dense network of fjords (arms of the sea) on the Pacific side of the icefield. Ice tongues today appear tiny compared to the view that an "ice age" astronaut would have seen. A study of the surface topography of sixty-three glaciers, based on Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) data, compared data from 2000 to data from studies going back about 30 years (1968-1975). Many glacier tongues showed significant annual "retreat" of their ice fronts, a familiar signal of climate change. The study also revealed that the almost invisible loss by glacier thinning is far more significant in explaining ice loss. The researchers concluded that volume loss by frontal collapse is 4-10 times smaller than that caused by thinning. Scaled over the entire icefield, including frontal loss (so-called calving when ice masses collapse into the lakes), it was calculated that 13.5 cubic kilometers of ice was lost each year over the study period. This number becomes more meaningful compared with the rate measured in the last five years of the study (1995-2000), when the rate increased almost threefold, averaging 38.7 cubic kilometers per year. Extrapolating results from the low altitude glacier tongues implies that the high plateau ice on the spine of the Andes is thinning as well. In the decade since this study the often-imaged Upsala Glacier has retreated a further three kilometers, as shown recently in images taken by crew members aboard the space station. Glacier Pio X, named for Pope Pius X, is the only large glacier that is growing in length.