DR. CHING-HUA SU, MATERIALS RESEARCHER, AT IN-SITU X-RAY DIFFRACTION IMAGING AND SCATTERING FACILITY, BLDG.. 4602

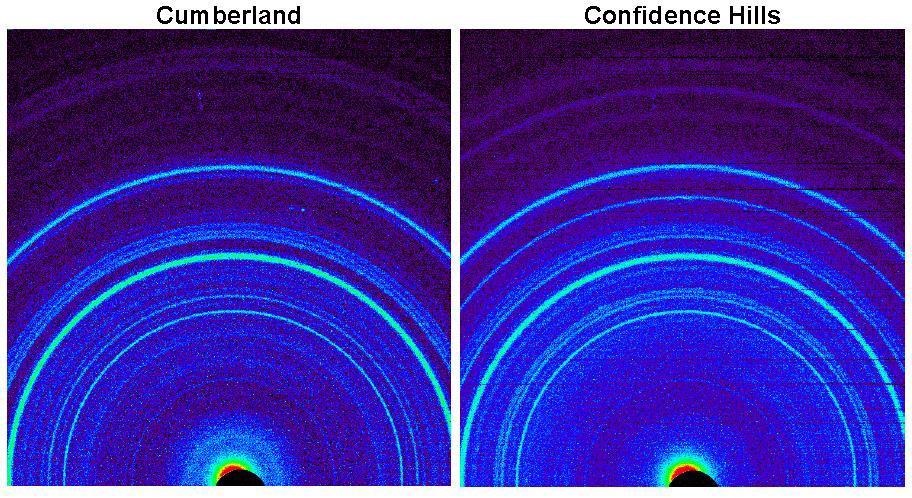

This side-by-side comparison shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of two different samples collected from rocks on Mars by NASA Curiosity rover. The images present data obtained by Curiosity Chemistry and Mineralogy instrument CheMin.

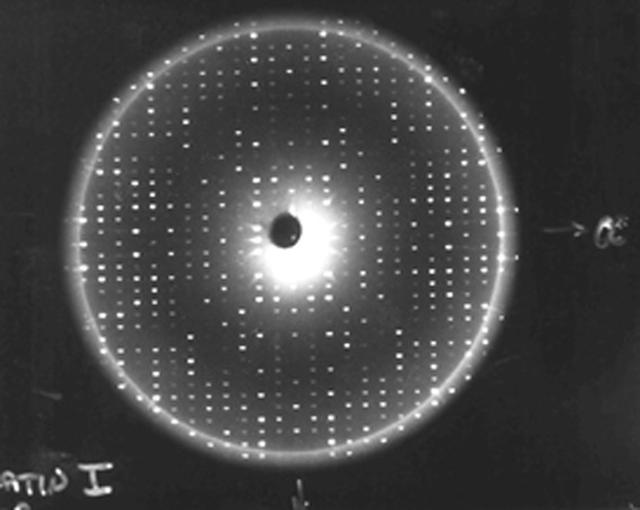

X-rays diffracted from a well-ordered protein crystal create sharp patterns of scattered light on film. A computer can use these patterns to generate a model of a protein molecule. To analyze the selected crystal, an X-ray crystallographer shines X-rays through the crystal. Unlike a single dental X-ray, which produces a shadow image of a tooth, these X-rays have to be taken many times from different angles to produce a pattern from the scattered light, a map of the intensity of the X-rays after they diffract through the crystal. The X-rays bounce off the electron clouds that form the outer structure of each atom. A flawed crystal will yield a blurry pattern; a well-ordered protein crystal yields a series of sharp diffraction patterns. From these patterns, researchers build an electron density map. With powerful computers and a lot of calculations, scientists can use the electron density patterns to determine the structure of the protein and make a computer-generated model of the structure. The models let researchers improve their understanding of how the protein functions. They also allow scientists to look for receptor sites and active areas that control a protein's function and role in the progress of diseases. From there, pharmaceutical researchers can design molecules that fit the active site, much like a key and lock, so that the protein is locked without affecting the rest of the body. This is called structure-based drug design.

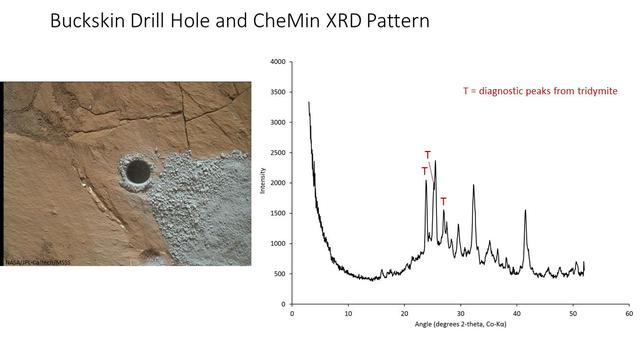

The graph at right presents information from the NASA Curiosity Mars rover's onboard analysis of rock powder drilled from the "Buckskin" target location, shown at left. X-ray diffraction analysis of the Buckskin sample inside the rover's Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument revealed the presence of a silica-containing mineral named tridymite. This is the first detection of tridymite on Mars. Peaks in the X-ray diffraction pattern are from minerals in the sample, and every mineral has a diagnostic set of peaks that allows identification. The image of Buckskin at left was taken by the rover's Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) camera on July 30, 2015, and is also available at PIA19804. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20271

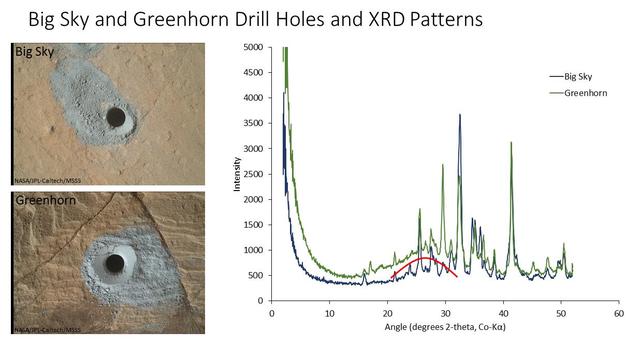

The graph at right presents information from the NASA Curiosity Mars rover's onboard analysis of rock powder drilled from the "Big Sky" and "Greenhorn" target locations, shown at left. X-ray diffraction analysis of the Greenhorn sample inside the rover's Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument revealed an abundance of silica in the form of noncrystalline opal. The broad hump in the background of the X-ray diffraction pattern for Greenhorn, compared to Big Sky, is diagnostic of opal. The image of Big Sky at upper left was taken by the rover's Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) camera the day the hole was drilled, Sept. 29, 2015, during the mission's 1,119th Martian day, or sol. The Greenhorn hole was drilled, and the MAHLI image at lower left was taken, on Oct. 18, 2015 (Sol 1137). http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20272

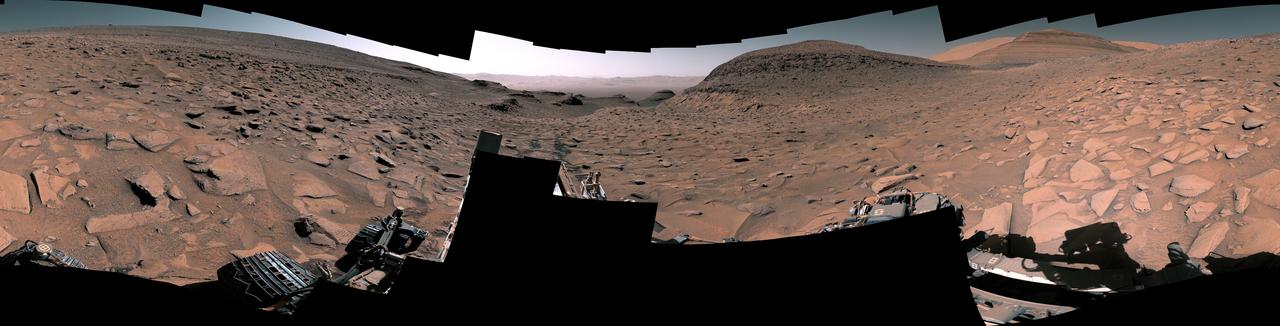

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover captured this 360-degree panorama at a site nicknamed "Ubajara" on April 30, 2023, the 3,815th Martian day, or sol, of the mission. Taken by the rover's Mastcam, this panorama was stitched together from 141 images after they were sent to Earth. Dark rover tracks recede into the distance in the center of the scene. Curiosity used the drill on the end of its robotic arm to take a sample from Ubajara, then dropped the pulverized rock into instruments within the rover's body. One of those instruments, called CheMin (Chemistry & Mineralogy), used X-ray diffraction to discover the presence of an iron carbonate mineral called siderite in samples from this site and two others: one above and one below Ubajara in a region enriched with salty minerals called sulfates. The discovery of siderite may help solve one of Mars' mysteries: There is strong evidence that liquid water coursed over the planet's surface billions of years ago, suggesting Mars had a thick, carbon-rich atmosphere rather than the wispy one it has today (a thicker carbon dioxide atmosphere is required to provide enough pressure and warmth for water to remain liquid on a planet's surface; otherwise, it rapidly vaporizes or freezes – which is the case on Mars today). That carbon dioxide and water should have reacted with Martian rocks to create carbonate minerals. However, when scientists study the planet with satellites that ample carbonate hasn't been apparent – even at Curiosity's site. It's possible that other minerals may be masking carbonate from satellite near-infrared analysis, particularly in sulfate-rich areas. If other such layers across Mars also contain hidden carbonates, the amount of stored carbon dioxide would be part of that needed in the ancient atmosphere to create conditions warm enough to support liquid water. The rest could be hidden in other deposits or have been lost to space over time. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26554