Pat Doty (right) of NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) demonstrates the greater bounce to the ounce of metal made from a supercooled bulk metallic glass alloy that NASA is studying in space experiments. The metal plates at the bottom of the plexiglass tubes are made of three different types of metal. Bulk metallic glass is more resilient and, as a result, the dropped ball bearing bounces higher. Experiments in space allow scientists to study fundamental properties that carnot be observed on Earth. This demonstration was at the April 200 conference of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) in Chicago. photo credit: NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC)

Pat Doty (right) of NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) demonstrates the greater bounce to the ounce of metal made from a supercooled bulk metallic glass alloy that NASA is studying in space experiments. The metal plates at the bottom of the plexiglass tubes are made of three different types of metal. Bulk metallic glass is more resilient and, as a result, the dropped ball bearing bounces higher. Experiments in space allow scientists to study fundamental properties that carnot be observed on Earth. This demonstration was at the April 2000 conference of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics in Chicago. Photo credit: NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC)

Pat Doty (right) of NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) demonstrates the greater bounce to the ounce of metal made from a supercooled bulk metallic glass alloy that NASA is studying in space expepriments. The metal plates at the bottom of plexiglass tubes are made of three different types of metal. Bulk mettalic glass is more resilient and, as a result, the dropped ball bearing bounces higher. Experiments in space allow scientists to study fundamental properties that carnot be observed on Earth. This demonstration was at the April 2000 conference of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) in Chicago. Photo credit: NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC)

A.J. Nick, left, and Drew Smith, robotics engineers with the Exploration Research and Technology programs at NASA's Kennedy Space Center, test Bulk Metallic Glass Gears (BMGGs) in a vacuum inside a cryogenic cooler at Kennedy's Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations lab on June 17, 2021. Made from a custom bulk metallic glass alloy, BMGGs could be used in heater-free gearboxes at extremely low temperatures in locations such as the Moon, Mars, and Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory is working with commercial partners to create the gears.

Drew Smith, a robotics engineer and lab manager with the Exploration Research and Technology programs at NASA's Kennedy Space Center, prepares a Bulk Metallic Glass Gear (BMGG) for ambient temperature tests in a vacuum inside a cryogenic cooler at Kennedy's Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations lab on June 17, 2021. Made from a custom bulk metallic glass alloy, BMGGs could be used in heater-free gearboxes at extremely low temperatures in locations such as the Moon, Mars, and Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory is working with commercial partners to create the gears.

Drew Smith, a robotics engineer and lab manager with the Exploration Research and Technology programs at NASA's Kennedy Space Center, prepares a Bulk Metallic Glass Gear (BMGG) for ambient temperature tests in a vacuum inside a cryogenic cooler at Kennedy's Granular Mechanics and Regolith Operations lab on June 17, 2021. Made from a custom bulk metallic glass alloy, BMGGs could be used in heater-free gearboxes at extremely low temperatures in locations such as the Moon, Mars, and Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory is working with commercial partners to create the gears.

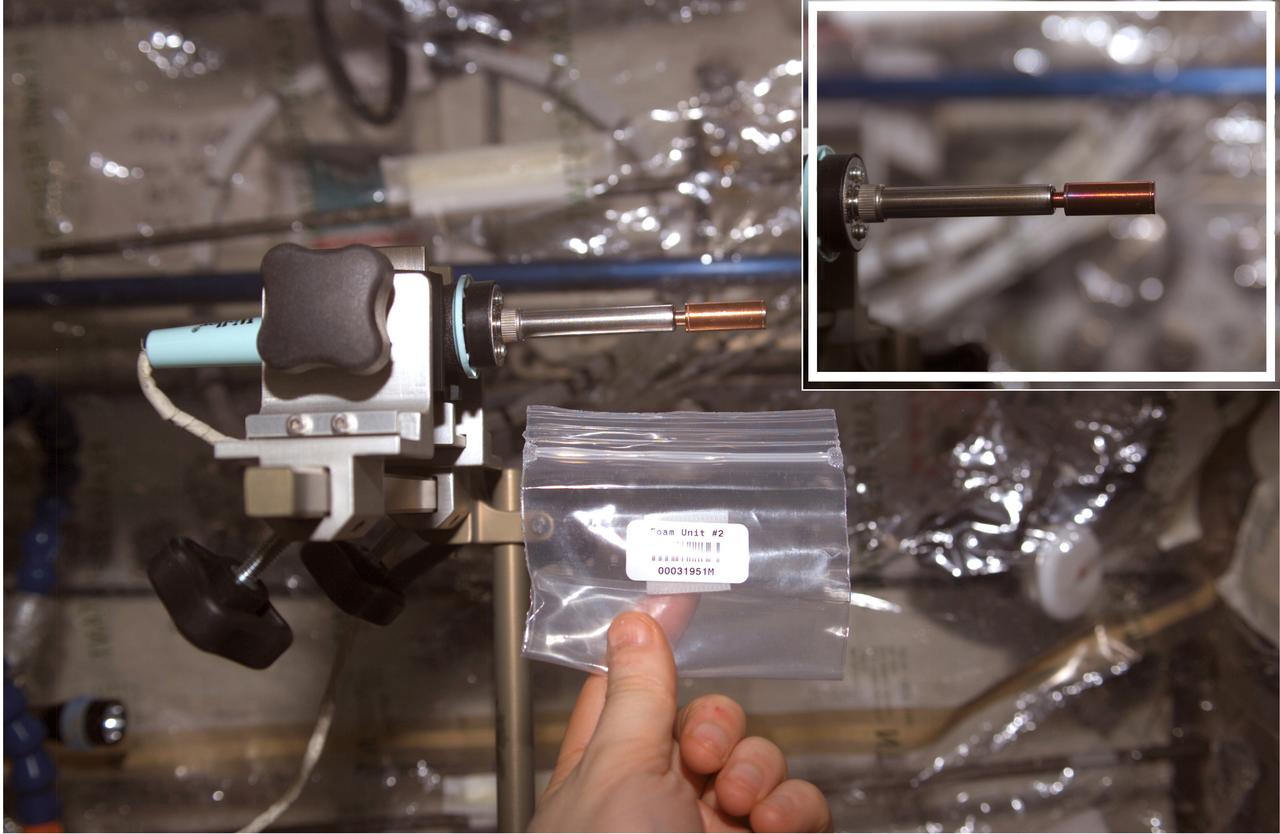

This soldering iron has an evacuated copper capsule at the tip that contains a pellet of Bulk Metallic Glass (BMG) aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Prior to flight, researchers sealed a pellet of bulk metallic glass mixed with microscopic gas-generating particles into the copper ampoule under vacuum. Once heated in space, such as in this photograph, the particles generated gas and the BMG becomes a viscous liquid. The released gas made the sample foam within the capsule where each microscopic particle formed a gas-filled pore within the foam. The inset image shows the oxidation of the sample after several minutes of applying heat. Although hidden within the brass sleeve, the sample retained the foam shape when cooled, because the viscosity increased during cooling until it was solid.

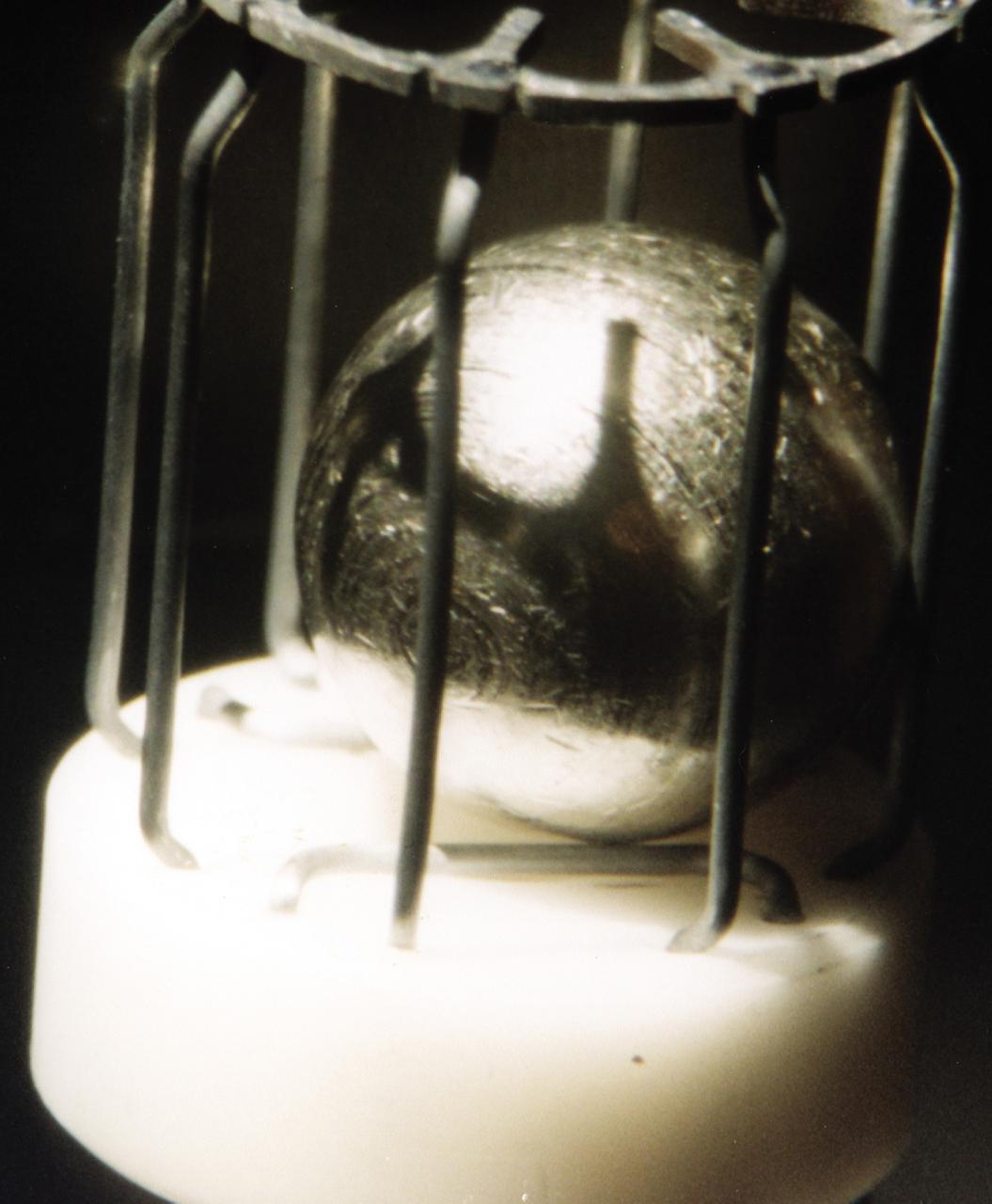

This metal sample, which is approximately 1 cm in diameter, is typical of the metals that were studied using the German designed electromagnetic containerless processing facility. The series of experiments that use this device is known as TEMPUS which is the acronym that stands for the German Tiegelfreies Elektromanetisches Prozessieren Unter Schwerelosigkeit. Most of the TEMPUS experiments focused on various aspects of undercooling liquid metal and alloys. Undercooling is the process of melting a material and then cooling it to a temperature that is below its normal freezing or solidification point. The TEMPUS experiments that used the metal cages as shown in the photograph, often studied bulk metallic glass, a solid material with no crystalline structures. We study metals and alloys not only to build things in space, but to improve things that are made on Earth. Metals and alloys are everywhere around us; in our automobiles, in the engines of aircraft, in our power-plants, and elsewhere. Despite their presence in everyday life, there are many scientific aspects of metals that we do not understand.

In early 2022, the Cold Operable Lunar Deployable Arm (COLDArm) project – led by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California – successfully integrated special gears into pieces of a robotic arm that is planned to perform a robot-controlled lunar surface experiment with imagery in the coming years. These bulk metallic glass (BMG) gears, integrated into COLDArm's joints and actuators, were developed through the Game Changing Development bulk metallic glass gears project to operate at extreme temperatures below minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 173 degrees Celsius). The gear alloys have a disordered atomic-scale structure, making them both strong and elastic enough to withstand these exceptionally low temperatures. Typical gearboxes require heating to operate at such cryogenic temperatures. The BMG gear motors have been tested and successfully operated at roughly minus 279 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 173 degrees Celsius) without heating assistance. This gear motor is one of the key technologies to enable the robotic arm to operate in extremely cold environments, such as during lunar night. Each of the four joints containing BMG gears will be tested once the arm is fully assembled, which is scheduled for spring of 2022. Robotic joint testing will include dynamometer testing to measure torque/rotational speed, as well as cryogenic thermal vacuum testing to understand how the equipment would perform in an environment similar to space. Once proven, the BMG gears and COLDArm capabilities will enable future missions to work in extreme environments on the Moon, Mars, and ocean worlds. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24567

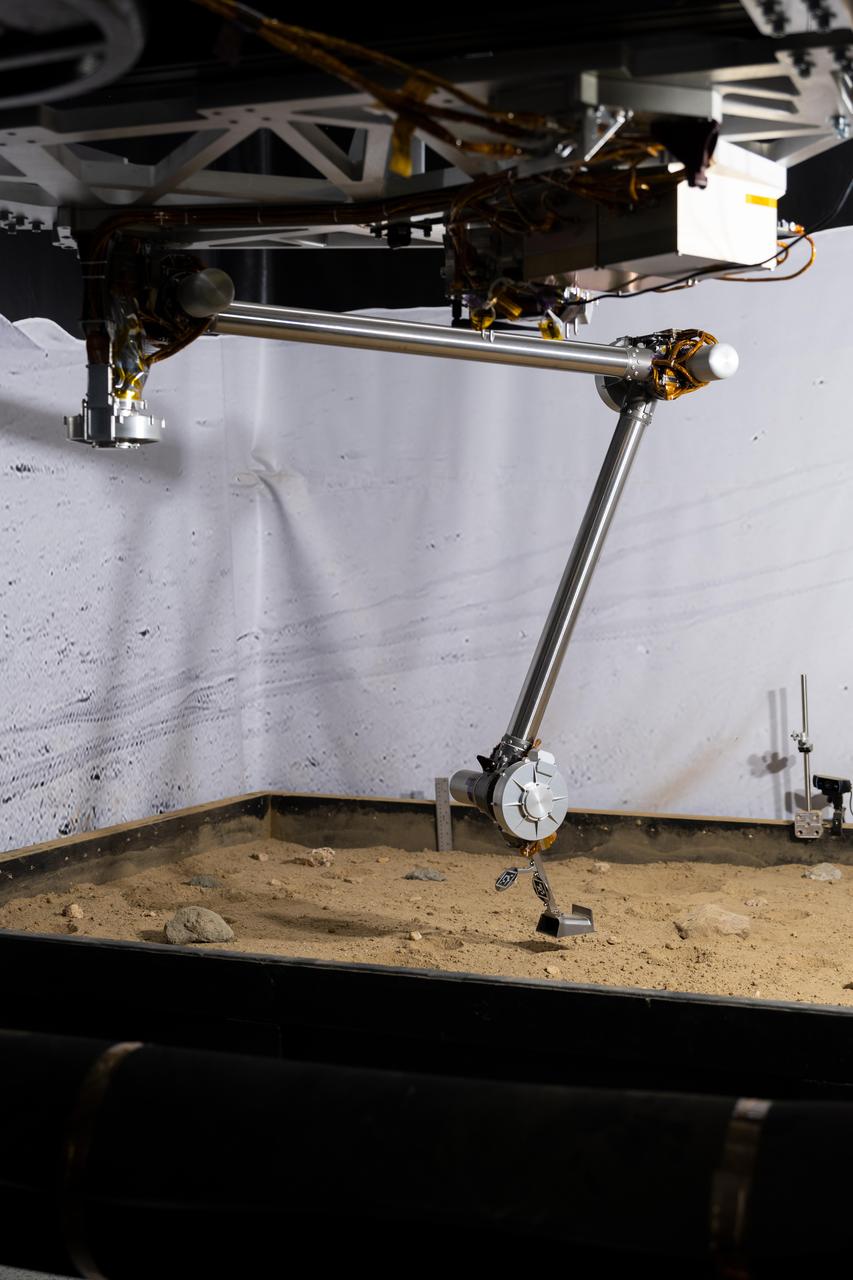

The 3D-printed titanium scoop of the Cold Operable Lunar Deployable Arm (COLDArm) robotic arm system is poised above a test bed filled with material to simulate lunar regolith (broken rocks and dust) at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. COLDArm can function in temperatures as cold as minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 173 degrees Celsius). COLDArm is designed to go on a Moon lander and operate during lunar night, a period that lasts about 14 Earth days. Frigid temperatures during lunar night would stymie current spacecraft, which must rely on energy-consuming heaters to stay warm. To operate in the cold, the 6-foot-6-inch (2-meter) arm combines several key new technologies: gears made of bulk metallic glass that require no lubrication or heating, cold motor controllers that don't need to be kept warm in an electronics box near the core of the spacecraft, and a cryogenic six-axis force torque sensor that lets the arm "feel" what it's doing and make adjustments. A variety of attachments and small instruments could go on the end of the arm, including the scoop, which could be used for collecting samples from a planet's surface. Like the arm on NASA's InSight Mars lander, COLDArm could deploy science instruments to the surface. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25317

Engineers and technicians prepare NASA's Cold Operable Lunar Deployable Arm (COLDArm) robotic arm system for testing in a thermal vacuum chamber at the agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California in November 2023. Successful testing in this chamber, which was reduced to minus 292 F (minus 180 C), demonstrates the arm can withstand the conditions it would face on the surface of the Moon. To operate in the cold, COLDArm combines several key new technologies: gears made of bulk metallic glass, which require no wet lubrication or heating; cold motor controllers that don't need to be kept warm in an electronics box near the core of the spacecraft, and a cryogenic six-axis force torque sensor that lets the arm "feel" what it's doing and make adjustments. A variety of attachments and small instruments could go on the end of the arm, including a 3D-printed titanium scoop that could be used for collecting samples from a celestial body's surface. Like the arm on NASA's InSight Mars lander, COLDArm could deploy science instruments to the surface. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26162

The 3D-printed titanium scoop of the Cold Operable Lunar Deployable Arm (COLDArm) robotic arm system is poised above a test bed filled with material to simulate lunar regolith (broken rocks and dust) at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. COLDArm can function in temperatures as cold as minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 173 degrees Celsius). COLDArm is designed to go on a Moon lander and operate during lunar night, a period that lasts about 14 Earth days. Frigid temperatures during lunar night would stymie current spacecraft, which must rely on energy-consuming heaters to stay warm. To operate in the cold, the 6-foot-6-inch (2-meter) arm combines several key new technologies: gears made of bulk metallic glass that require no lubrication or heating, cold motor controllers that don't need to be kept warm in an electronics box near the core of the spacecraft, and a cryogenic six-axis force torque sensor that lets the arm "feel" what it's doing and make adjustments. A variety of attachments and small instruments could go on the end of the arm, including the scoop, which could be used for collecting samples from a planet's surface. Like the arm on NASA's InSight Mars lander, COLDArm could deploy science instruments to the surface. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25318

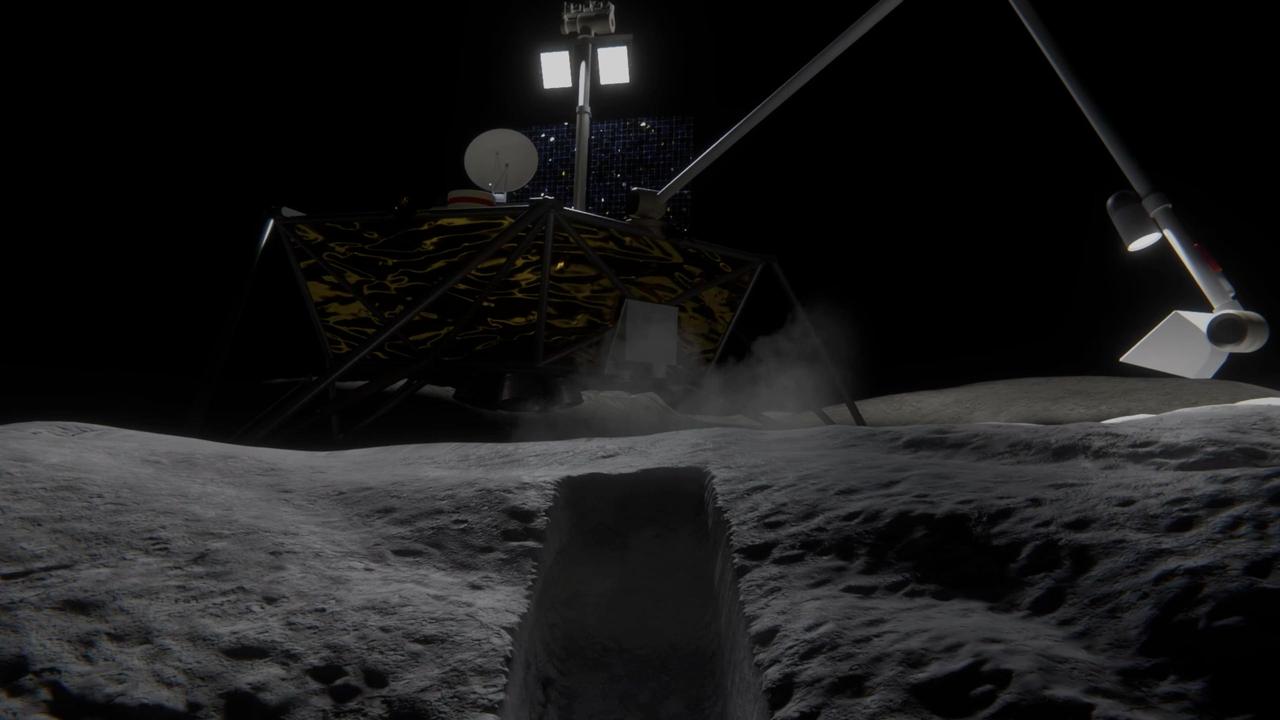

NASA's Cold Operable Lunar Deployable Arm (COLDArm) robotic arm system reaches out from a lander on the Moon and scoops up regolith (broken rock and dust). Managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, COLDArm is designed to operate during lunar night, a period that lasts about 14 Earth days. It can function in temperatures as cold as minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 173 degrees Celsius). Frigid temperatures during lunar night would stymie the arms on current spacecraft, which must rely on energy-consuming heaters to stay warm. To operate in the cold, the 6-foot-6-inch (2-meter) arm combines several key new technologies: gears made of bulk metallic glass that require no wet lubrication or heating, cold motor controllers that don't need to be kept warm in an electronics box near the core of the spacecraft, and a cryogenic six-axis force torque sensor that lets the arm "feel" what it's doing and make adjustments. A variety of attachments and small instruments could go on the end of the arm, such as a 3D-printed titanium scoop that could collect samples from a planet's surface, similar to what's depicted here. Like the arm on NASA's now-retired InSight Mars lander, COLDArm is also capable of deploying science instruments to the surface. The arm system could be attached to a stationary lander or to a rover. Motiv Space Systems, a partner on COLDArm, developed the cold motor controllers, and also built sections of the arm and assembled it from JPL-supplied parts at the company's Pasadena, California, facility. The COLDArm project is funded through the Lunar Surface Innovation Initiative and managed by the Game Changing Development program in NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate. Animation available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26347

The 3D-printed titanium scoop of the Cold Operable Lunar Deployable Arm (COLDArm) robotic arm system is poised above a test bed filled with material to simulate lunar regolith (broken rocks and dust) at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. COLDArm can function in temperatures as cold as minus 280 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 173 degrees Celsius). Robotics engineer David E. Newill-Smith looks on during testing in September 2022. COLDArm is designed to go on a Moon lander and operate during lunar night, a period that lasts about 14 Earth days. Frigid temperatures during lunar night would stymie current spacecraft, which must rely on energy-consuming heaters to stay warm. To operate in the cold, the 6-foot-6-inch (2-meter) arm combines several key new technologies: gears made of bulk metallic glass that require no lubrication or heating, cold motor controllers that don't need to be kept warm in an electronics box near the core of the spacecraft, and a cryogenic six-axis force torque sensor that lets the arm "feel" what it's doing and make adjustments. A variety of attachments and small instruments could go on the end of the arm, including the scoop, which could be used for collecting samples from a planet's surface. Like the arm on NASA's InSight Mars lander, COLDArm could deploy science instruments to the surface. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25316