The BICEP2 telescope at the South Pole used a specialized array of superconducting detectors to capture polarized light from billions of years ago. The detector array is shown here, under a microscope.

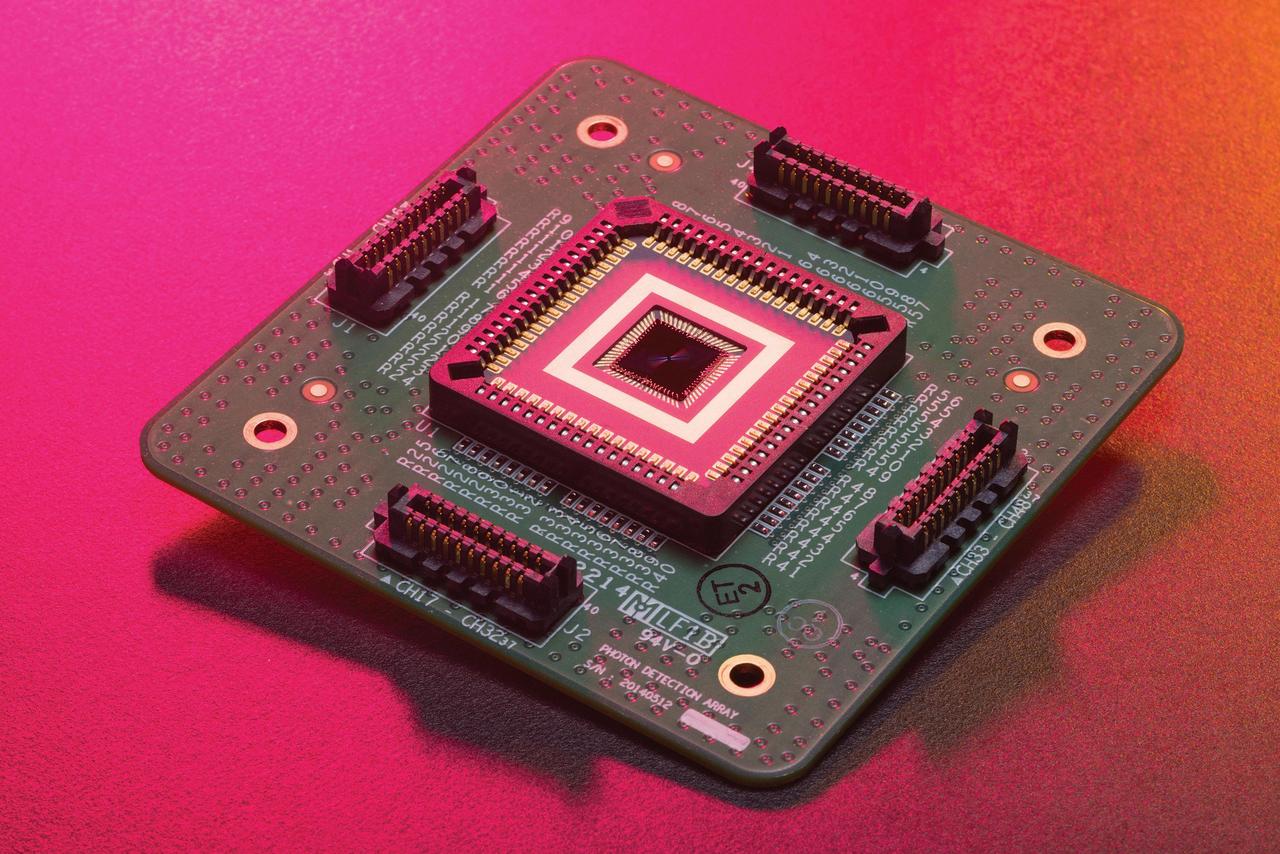

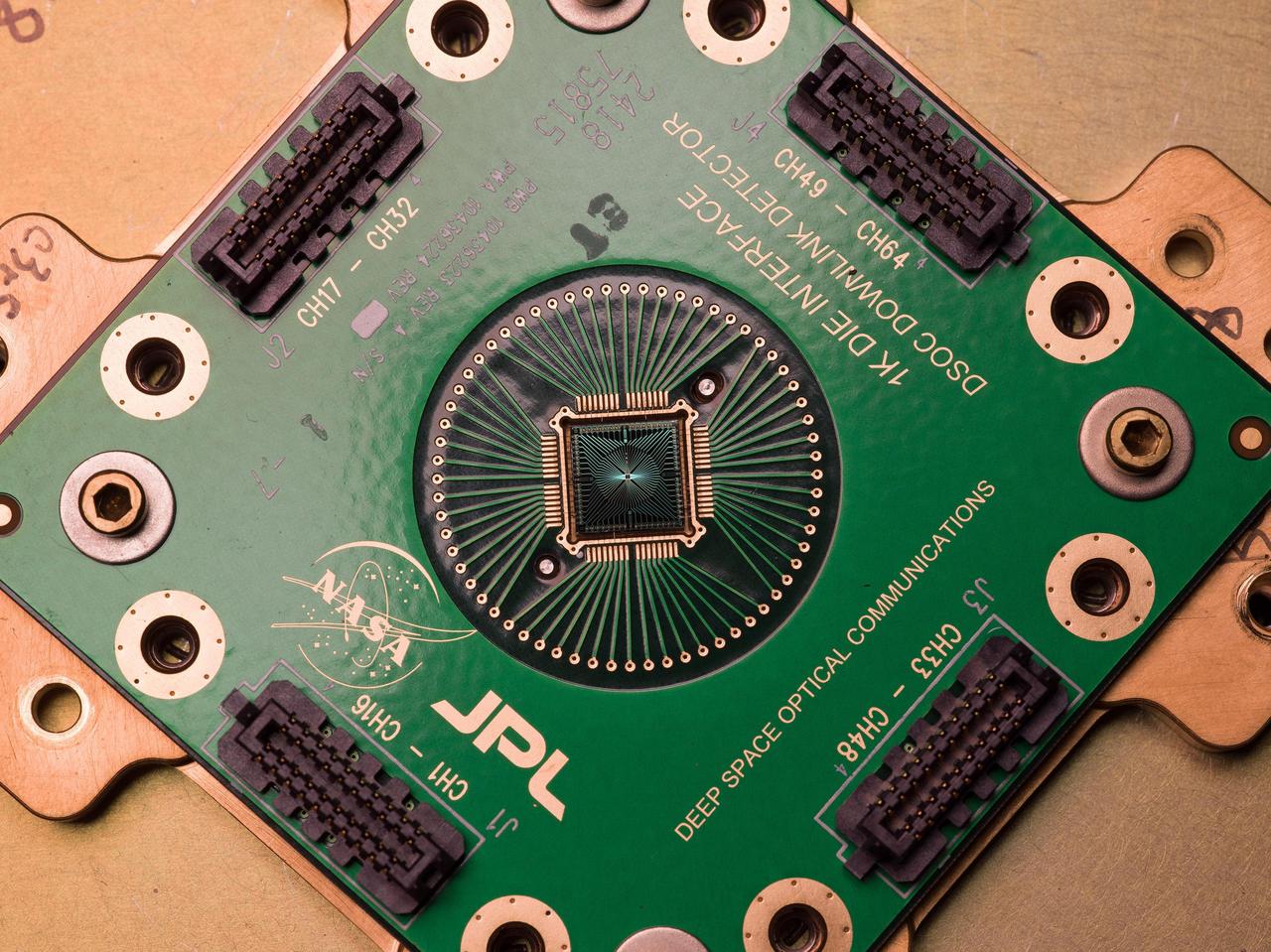

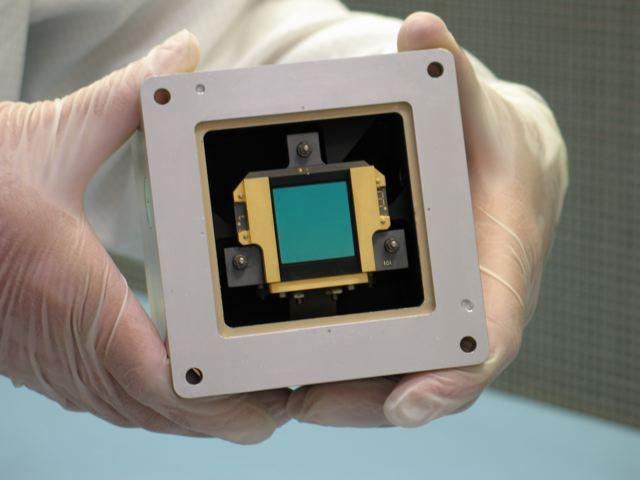

Shown here is a prototype of the Deep Space Optical Communications, or DSOC, ground receiver detector built by the Microdevices Laboratory at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. The prototype superconducting nanowire single-photon detector was used by JPL technologists to help develop the detector that – from a station on Earth – will receive near-infrared laser signals from the DSOC flight transceiver traveling with NASA's Psyche mission in deep space. DSOC will test key technologies that could enable high-bandwidth optical, or laser, communications from Mars distances. Bolted to the side of the spacecraft and operating for the first two years of Psyche's journey to the asteroid of the same name, the DSOC flight laser transceiver will transmit high-rate data to Caltech's Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, California, which houses the 200-inch (5.1-meter) Hale Telescope. The downlink detector converts optical signals to electrical signals, which can be processed and decoded. The detector is designed to be both sensitive enough to detect single photons (quantum particles of light) and able to detect many photons arriving all at once. At its farthest point during the technology demonstration's operations period, the transceiver will be up to 240 million miles (390 million kilometers) away, meaning that by the time its weak laser pulses arrive at Earth, the detector will need to efficiently detect a trickle of single photons. But when the spacecraft is closer to Earth and the flight transceiver is delivering its highest bit rate to Palomar, the detector is capable of detecting very high numbers of photons without becoming overwhelmed. Because data is encoded in the timing of the laser pulses, the detector must also be able to determine the time of a photon's arrival with a precision of 100 picoseconds (one picosecond is one trillionth of a second). DSOC is the latest in a series of optical communication technology demonstrations funded by NASA's Technology Demonstrations Missions (TDM) program and the agency's Space Communications and Navigation (SCaN) program. JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages DSOC for TDM within NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate and SCaN within the agency's Space Operations Mission Directorate. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25840

This image shows one of the NASA detectors from the BICEP2 project, developed in collaboration with the NSF. The sensors were used to make the first detection of gravitational waves in the ancient background light from the early universe.

Shown here is an identical copy of the Deep Space Optical Communications, or DSOC, superconducting nanowire single-photon detector that is coupled to the 200-inch (5.1-meter) Hale Telescope located at Caltech's Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, California. Built by the Microdevices Laboratory at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, the detector is designed to receive near-infrared laser signals from the DSOC flight transceiver traveling with NASA's Psyche mission in deep space as a part of the technology demonstration. DSOC will test key technologies that could enable high-bandwidth optical, or laser, communications from Mars distances. Bolted to the side of the spacecraft and operating for the first two years of Psyche's journey to the asteroid of the same name, the DSOC flight laser transceiver will transmit high-rate data to Caltech's Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, California, which houses the 200-inch (5.1-meter) Hale Telescope. The downlink detector converts optical signals to electrical signals, which can be processed and decoded. The detector is designed to be both sensitive enough to detect single photons (quantum particles of light) and able to detect many photons arriving all at once. At its farthest point during the technology demonstration's operations period, the transceiver will be up to 240 million miles (390 million kilometers) away, meaning that by the time its weak laser pulses arrive at Earth, the detector will need to efficiently detect a trickle of single photons. But when the spacecraft is closer to Earth and the flight transceiver is delivering its highest bit rate to Palomar, the detector is capable of detecting very high numbers of photons without becoming overwhelmed. Because data is encoded in the timing of the laser pulses, the detector must also be able to determine the time of a photon's arrival with a precision of 100 picoseconds (one picosecond is one trillionth of a second). To sense single photons, the detector must be in a superconducting state (when electrical current flows with zero resistance), so it is cryogenically cooled to less than minus 458 degrees Fahrenheit (or 1 Kelvin), which is close to absolute zero, or the lowest temperature possible. A photon absorbed in the detector disrupts its superconducting state, creating a measurable electrical pulse as current leaves the detector. DSOC is the latest in a series of optical communication technology demonstrations funded by NASA's Technology Demonstrations Missions (TDM) program and the agency's Space Communications and Navigation (SCaN) program. JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages DSOC for TDM within NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate and SCaN within the agency's Space Operations Mission Directorate. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26141

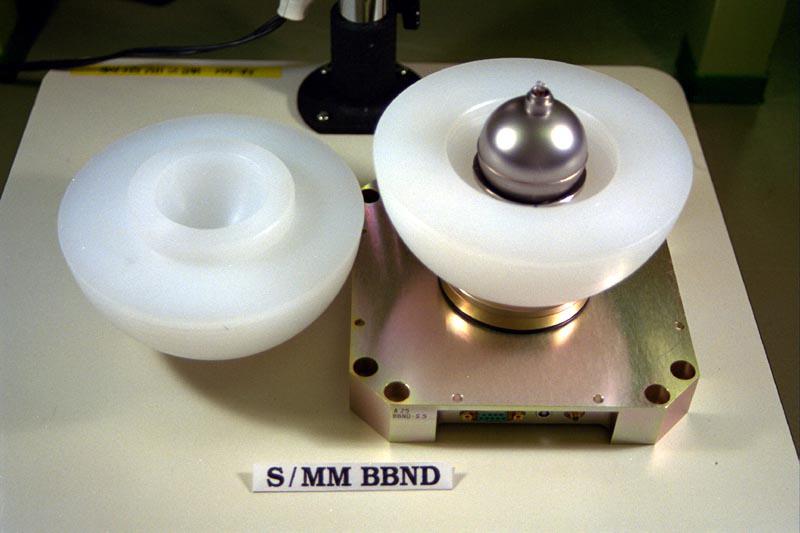

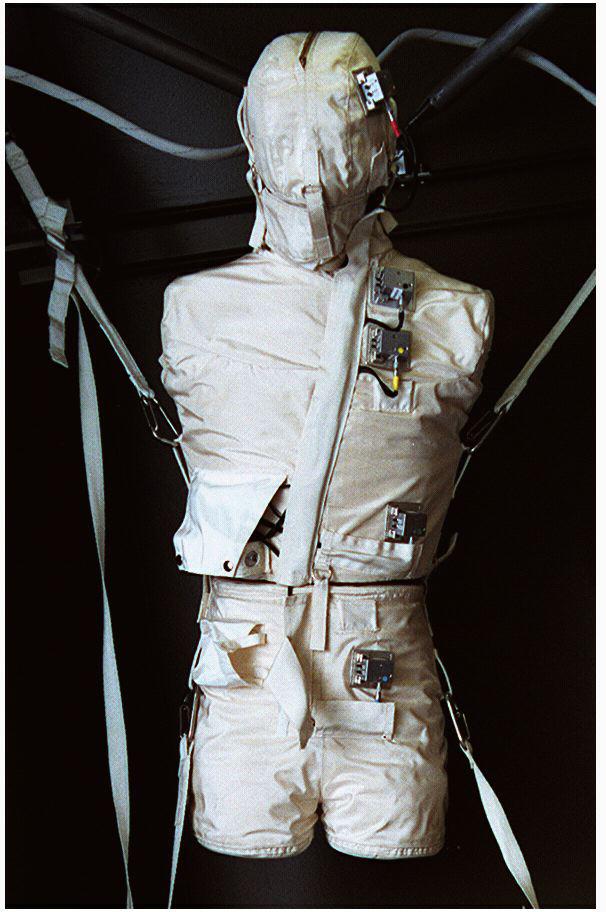

The Bonner Ball Neutron Detector measures neutron radiation. Neutrons are uncharged atomic particles that have the ability to penetrate living tissues, harming human beings in space. The Bonner Ball Neutron Detector is one of three radiation experiments during Expedition Two. The others are the Phantom Torso and Dosimetric Mapping.

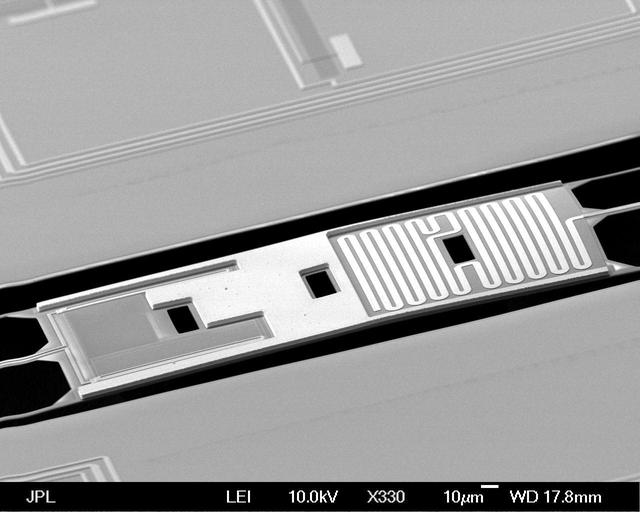

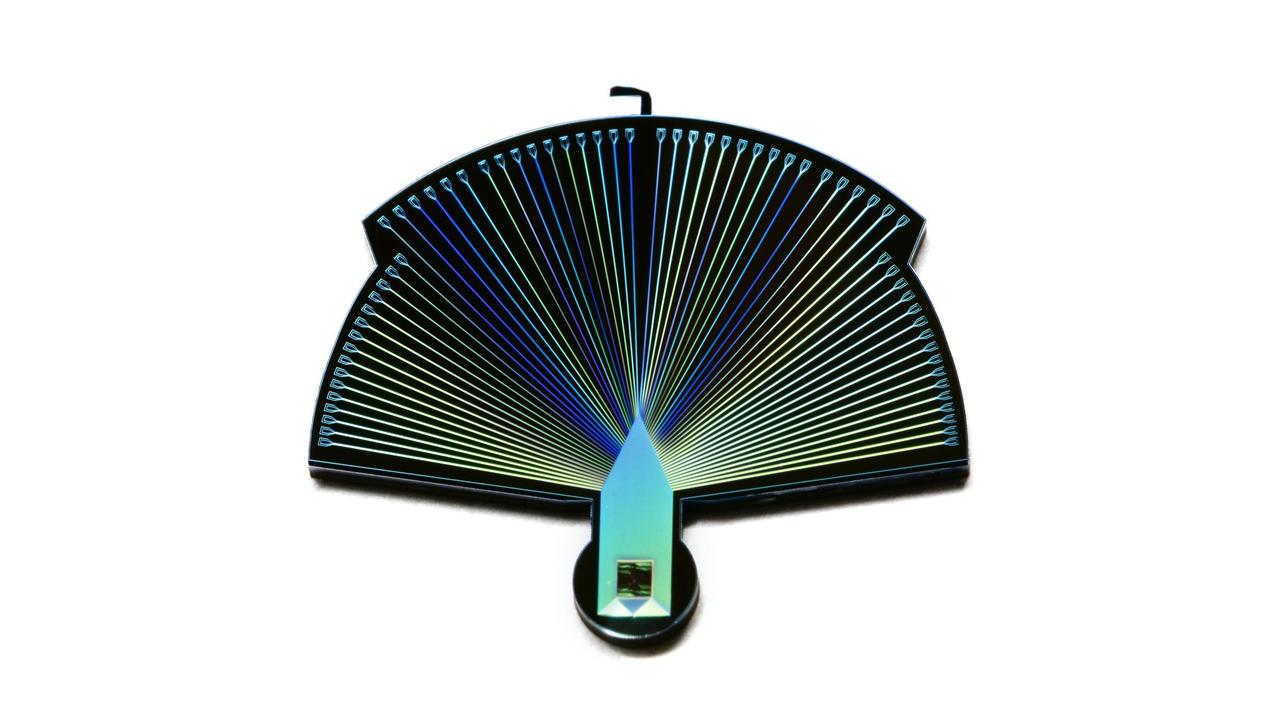

This close-up photograph shows a single Performance-Enhanced Array for Counting Optical Quanta (PEACOQ) detector. Smaller than a dime, a single detector consists of 32 niobium nitride superconducting nanowires on a silicon chip, which is attached to connectors that fan out like the plumage of the device's namesake. Each individual nanowire is about 10,000 times thinner than a human hair and the active detector (housed inside the green-black square at the bottom of the device) measures only 13 microns across. Figure A shows a silicon wafer that has had 32 PEACOQ detectors printed onto it by the Microdevices Laboratory at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. The exquisitely sensitive PEACOQ detector is being developed at JPL to detect single photons – quantum particles of light – at an extremely high rate. Like counting individual droplets of water while being sprayed by a firehose, each PEACOQ detector can measure the precise time each photon hits the detector (to within 100 trillionths of a second) at a rate of 1.5 billion photons per second. No other detector has achieved that rate. The detector could help form a global quantum communications network, facilitating the transfer of data between quantum computers that are separated by hundreds of miles. PEACOQ detectors could be located at ground-based terminals to receive photons encoded with quantum information transmitted from space "nodes" aboard satellites orbiting Earth. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25260

The Radiation Assessment Detector, shown prior to its September 2010 installation onto NASA Mars rover Curiosity, will aid future human missions to Mars by providing information about the radiation environment on Mars and on the way to Mars.

This image shows an array of the 512 superconducting detectors used on the BICEP2 telescope at the South Pole. The technology was key to detecting the effects of gravitational waves associated with the early epoch of our universe known as inflation.

ISS030-E-177101 (12 March 2012) --- European Space Agency astronaut Andre Kuipers, Expedition 30 flight engineer, sets up the Environmental Health System / Tissue Equivalent Proportional Counter (EHS/TEPC) spectrometer and detector assembly on panel 327 in the Zvezda Service Module of the International Space Station. The TEPC detector assembly is the primary radiation measurement tool on the space station.

ISS034-E-034506 (25 Jan. 2013) --- Canadian Space Agency astronaut Chris Hadfield, Expedition 34 flight engineer, holds bubble detectors for the RaDI-N experiment in the International Space Station?s Kibo laboratory. RaDI-N measures neutron radiation levels onboard the space station. RaDI-N uses bubble detectors as neutron monitors which have been designed to only detect neutrons and ignore all other radiation.

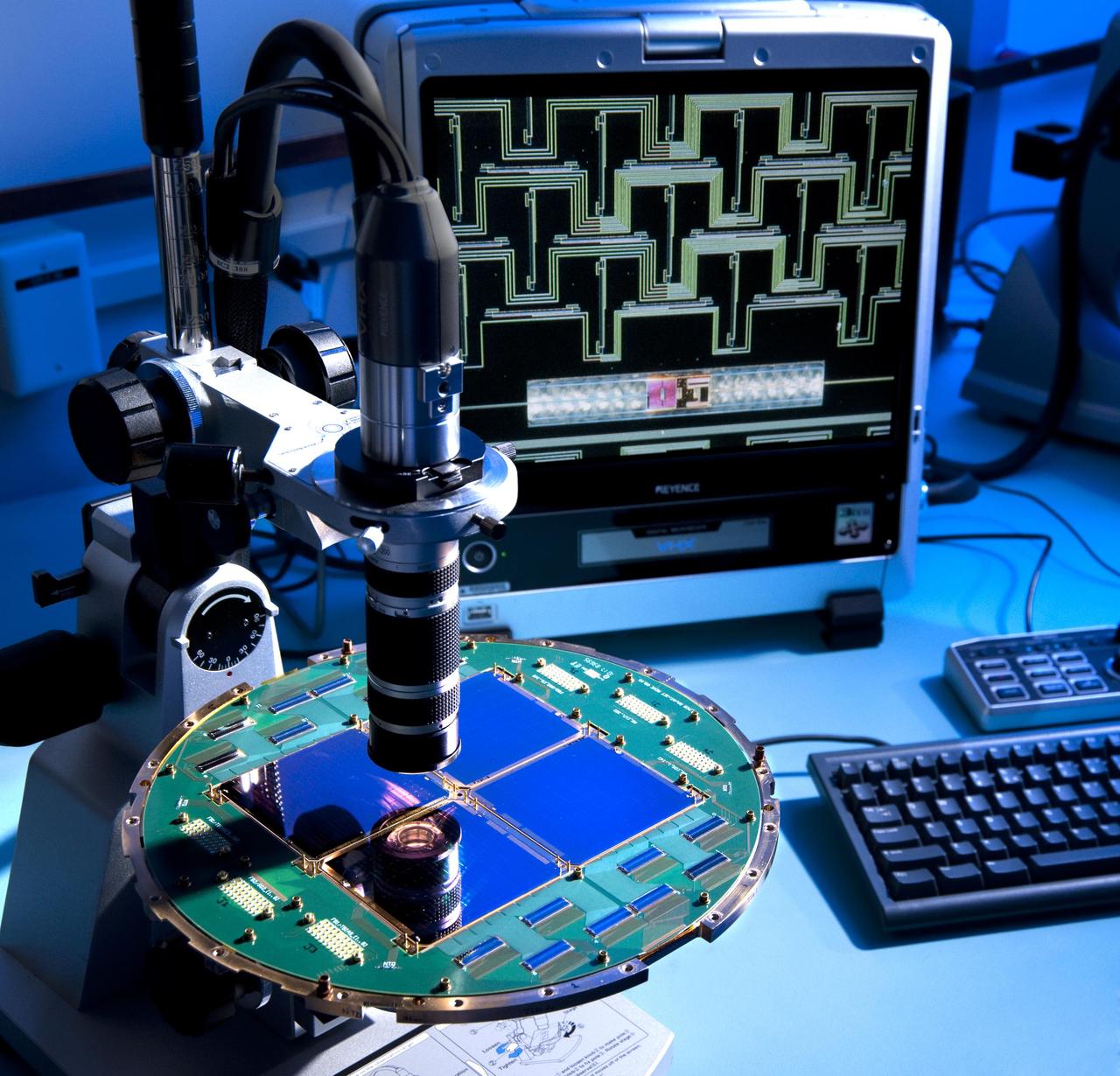

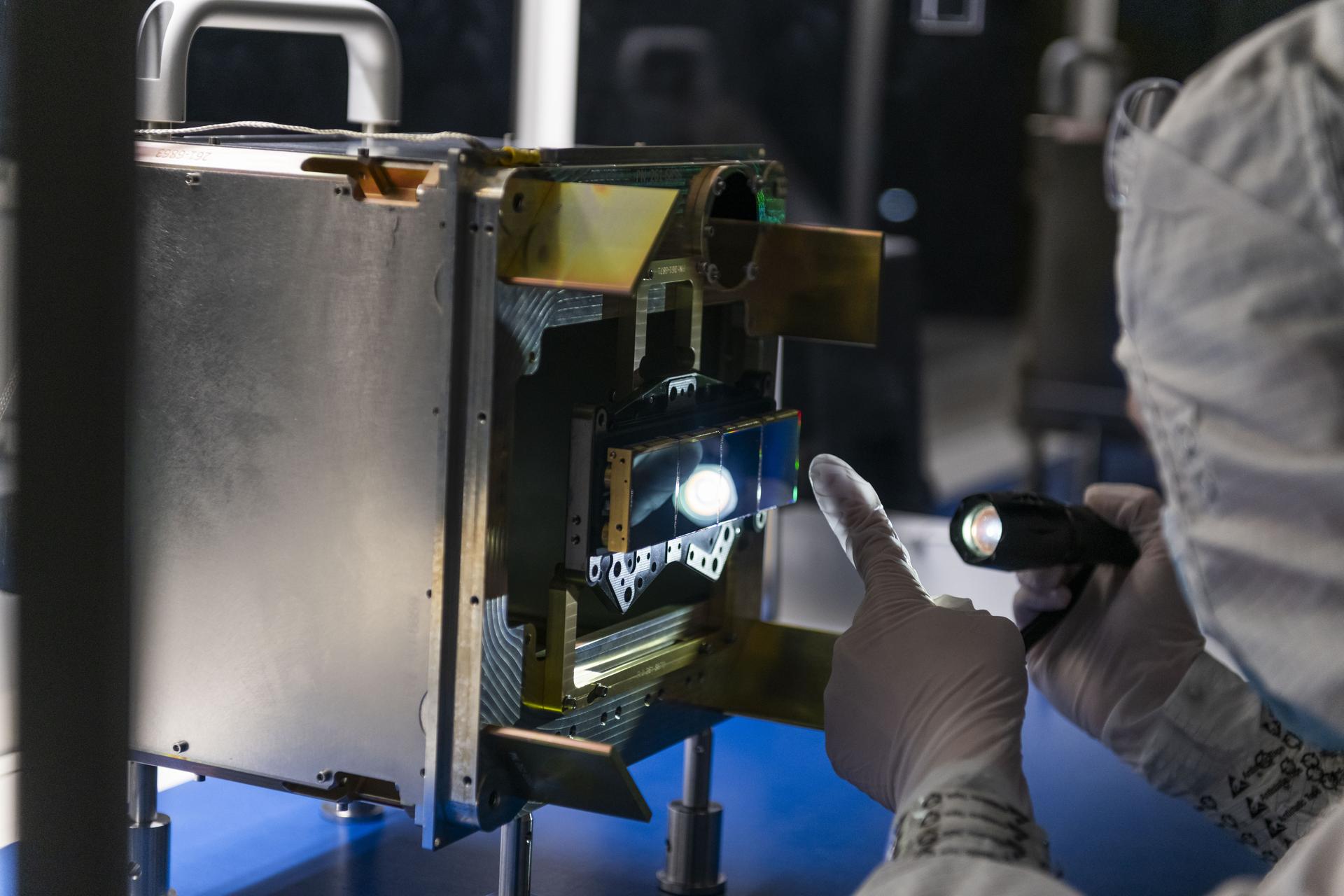

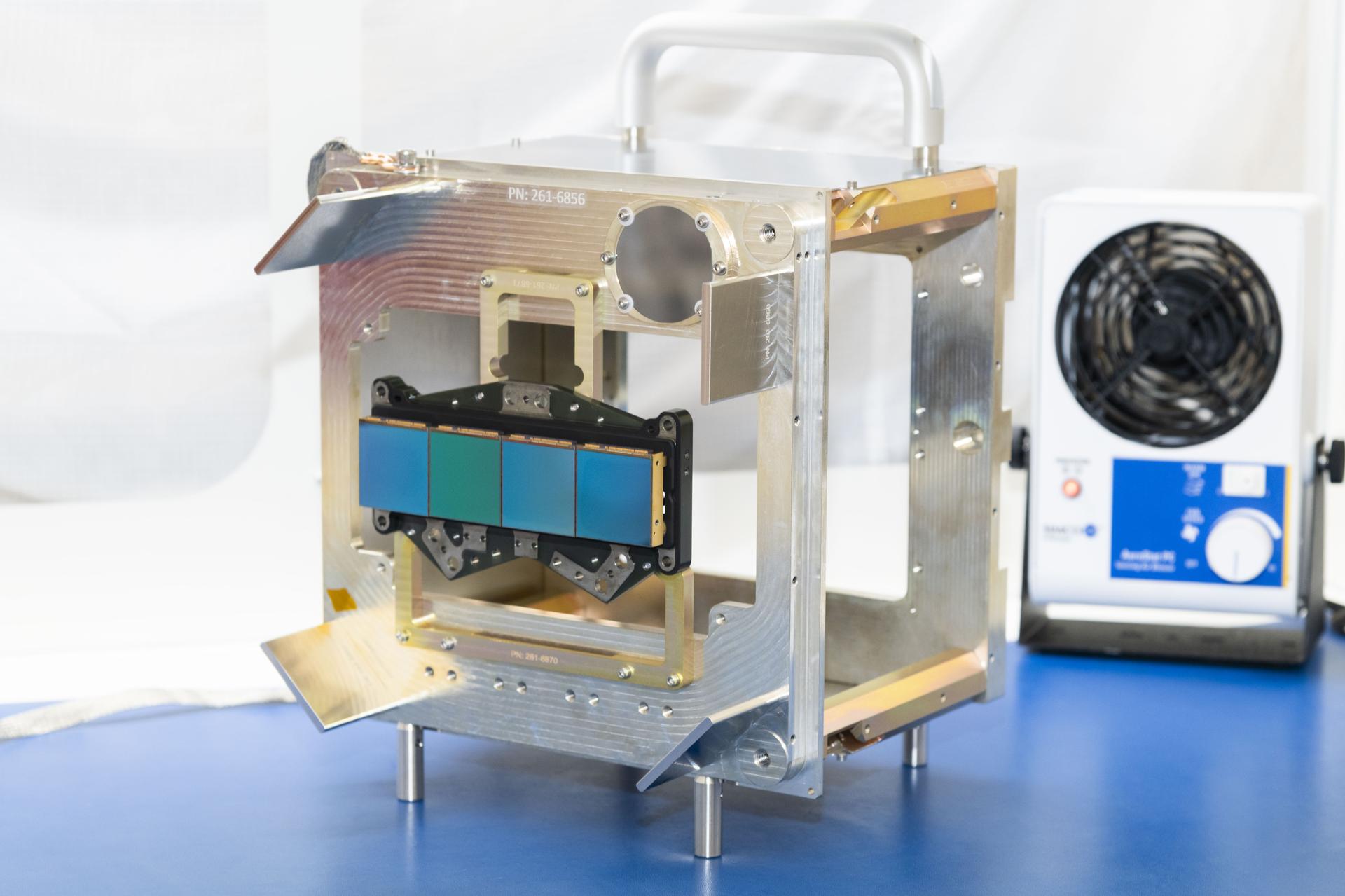

An engineer inspects the surface of four mid-wavelength infrared science detectors for NASA’s Near-Earth Object (NEO) Surveyor mission atop a clean room bench at the Space Dynamics Laboratory (SDL) in Logan, Utah. Mounted to a sensor chip assembly, the four blue-green-colored detectors are made with mercury cadmium telluride (HgCdTe), a versatile semiconducting alloy that is sensitive to infrared wavelengths. There are two such assemblies that form the heart of NEO Surveyor’s two science cameras. These state-of-the-art cameras sense solar heat re-radiated by near-Earth objects. The mission’s cameras and telescope, which has an aperture of nearly 20 inches (50 centimeters), will be housed inside the spacecraft’s instrument enclosure, a structure that is designed to ensure heat produced by the spacecraft and instrument during operations doesn’t interfere with its infrared observations. Targeting launch in late 2027, the NEO Surveyor mission is led by Professor Amy Mainzer at the University of California, Los Angeles for NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office and is being managed by the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California for the Planetary Missions Program Office at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. BAE Systems and the Space Dynamics Laboratory in Logan, Utah, and Teledyne are among the companies that were contracted to build the spacecraft and its instrumentation. The Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder will support operations, and IPAC at Caltech in Pasadena, California, is responsible for producing some of the mission’s data products. Caltech manages JPL for NASA. More information about NEO Surveyor is available at: https://science.nasa.gov/mission/neo-surveyor/

Four mid-wavelength infrared science detectors for NASA’s Near-Earth Object (NEO) Surveyor mission are shown here on a clean room bench at the Space Dynamics Laboratory (SDL) in Logan, Utah. Mounted to a sensor chip assembly, the four blue-green-colored detectors are made with mercury cadmium telluride (HgCdTe), a versatile semiconducting alloy that is sensitive to infrared wavelengths. There are two such assemblies that form the heart of NEO Surveyor’s two science cameras. These state-of-the-art cameras sense solar heat re-radiated by near-Earth objects. The mission’s cameras and telescope, which has an aperture of nearly 20 inches (50 centimeters), will be housed inside the spacecraft’s instrument enclosure, a structure that is designed to ensure heat produced by the spacecraft and instrument during operations doesn’t interfere with its infrared observations. Targeting launch in late 2027, the NEO Surveyor mission is led by Professor Amy Mainzer at the University of California, Los Angeles for NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office and is being managed by the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California for the Planetary Missions Program Office at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. BAE Systems and the Space Dynamics Laboratory in Logan, Utah, and Teledyne are among the companies that were contracted to build the spacecraft and its instrumentation. The Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder will support operations, and IPAC at Caltech in Pasadena, California, is responsible for producing some of the mission’s data products. Caltech manages JPL for NASA. More information about NEO Surveyor is available at: https://science.nasa.gov/mission/neo-surveyor/

The Phantom Torso is a tissue-muscle plastic anatomical model of a torso and head. It contains over 350 radiation measuring devices to calculate the radiation that penetrates internal organs in space travel. The Phantom Torso is one of three radiation experiments in Expedition Two including the Borner Ball Neutron Detector and Dosimetric Mapping.

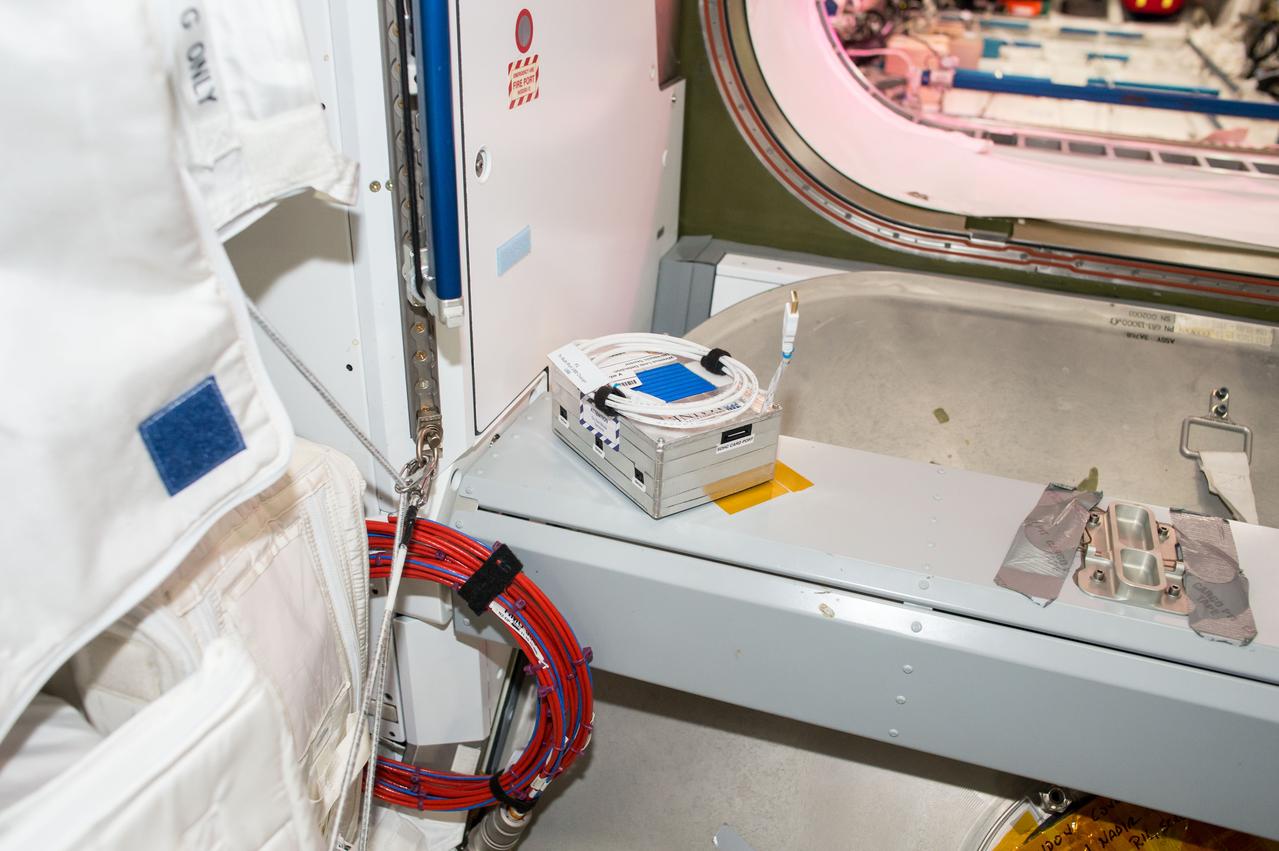

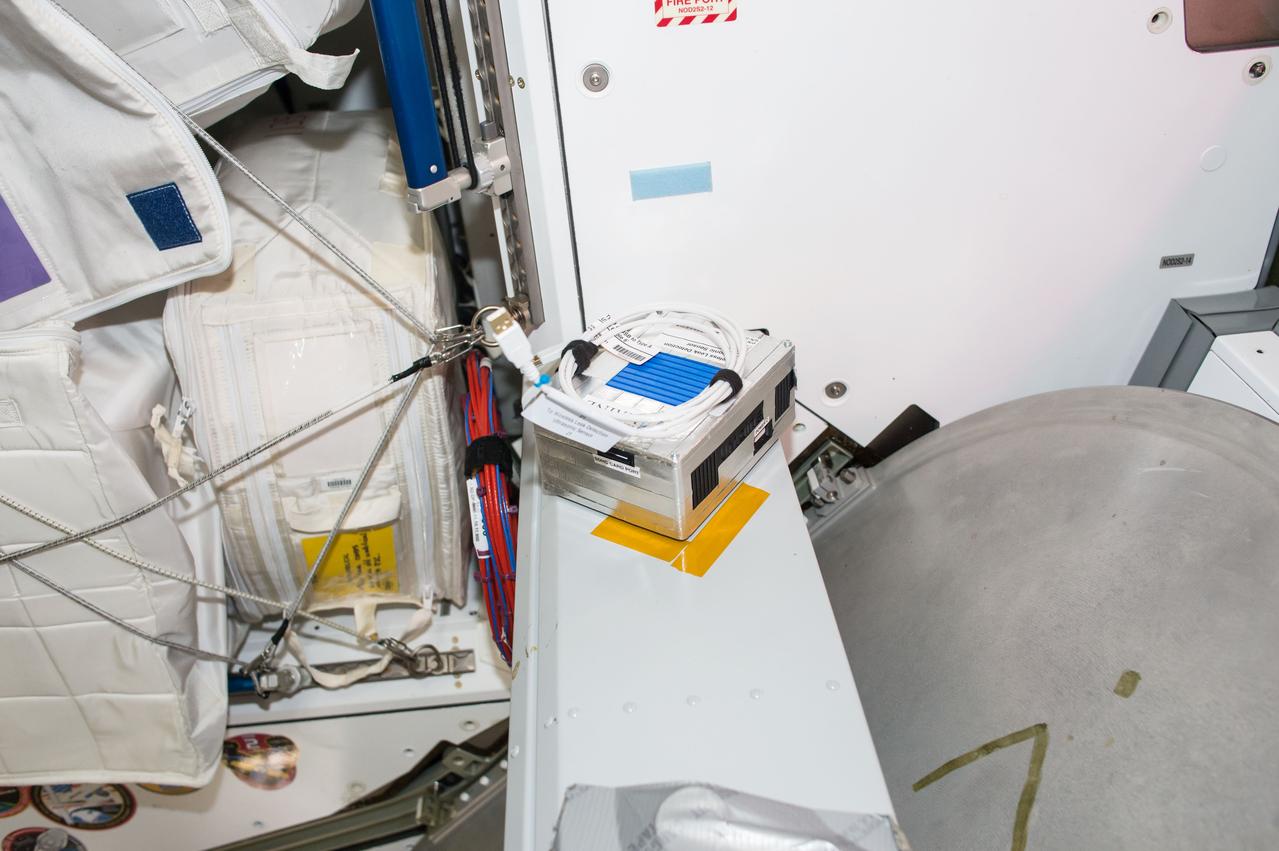

iss050e035315 (1/26/2017) --- A view of the Wireless Leak Detector Ultrasonic Sensor aboard the International Space Station (ISS). The Joint Leak Detection and Localization Based on Fast Bayesian Inference from Network of Ultrasonic Sensor Arrays in Microgravity Environment (Wireless Leak Detection) investigation compares signals received at various ultrasonic sensors to reveal the location of air leaks, which can then be repaired.

iss050e035314 (1/26/2017) --- A view of the Wireless Leak Detector Ultrasonic Sensor aboard the International Space Station (ISS). The Joint Leak Detection and Localization Based on Fast Bayesian Inference from Network of Ultrasonic Sensor Arrays in Microgravity Environment (Wireless Leak Detection) investigation compares signals received at various ultrasonic sensors to reveal the location of air leaks, which can then be repaired.

iss050e035313 (1/26/2017) --- A view of the Wireless Leak Detector Ultrasonic Sensor aboard the International Space Station (ISS). The Joint Leak Detection and Localization Based on Fast Bayesian Inference from Network of Ultrasonic Sensor Arrays in Microgravity Environment (Wireless Leak Detection) investigation compares signals received at various ultrasonic sensors to reveal the location of air leaks, which can then be repaired.

iss050e035316 (1/26/2017) --- A view of the Wireless Leak Detector Ultrasonic Sensor aboard the International Space Station (ISS). The Joint Leak Detection and Localization Based on Fast Bayesian Inference from Network of Ultrasonic Sensor Arrays in Microgravity Environment (Wireless Leak Detection) investigation compares signals received at various ultrasonic sensors to reveal the location of air leaks, which can then be repaired.

ISS002-E-5714 (23 March 2001) --- Astronaut James S. Voss, Expedition Two flight engineer, sets up the Bonner Ball Neutron Detector (BBND) in the Destiny laboratory. The BBND is connected to the Human Research Facility (HRF). This image was recorded with a digital still camera.

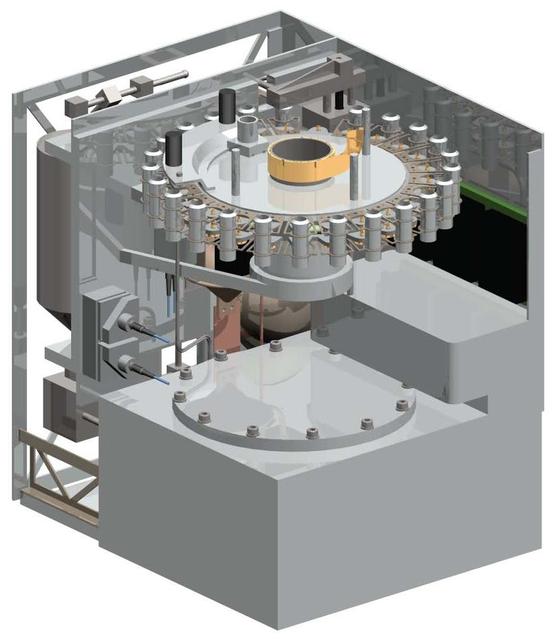

This image shows a model of one of three detectors for the Mid-Infrared Instrument on NASA James Webb Space Telescope.

This charged couple device CCD is part of the CheMin instrument on NASA Curiosity rover. When CheMin directs X-rays at a sample of soil, this imager, which is the size of a postage stamp, detects both the position and energy of each X-ray photon.

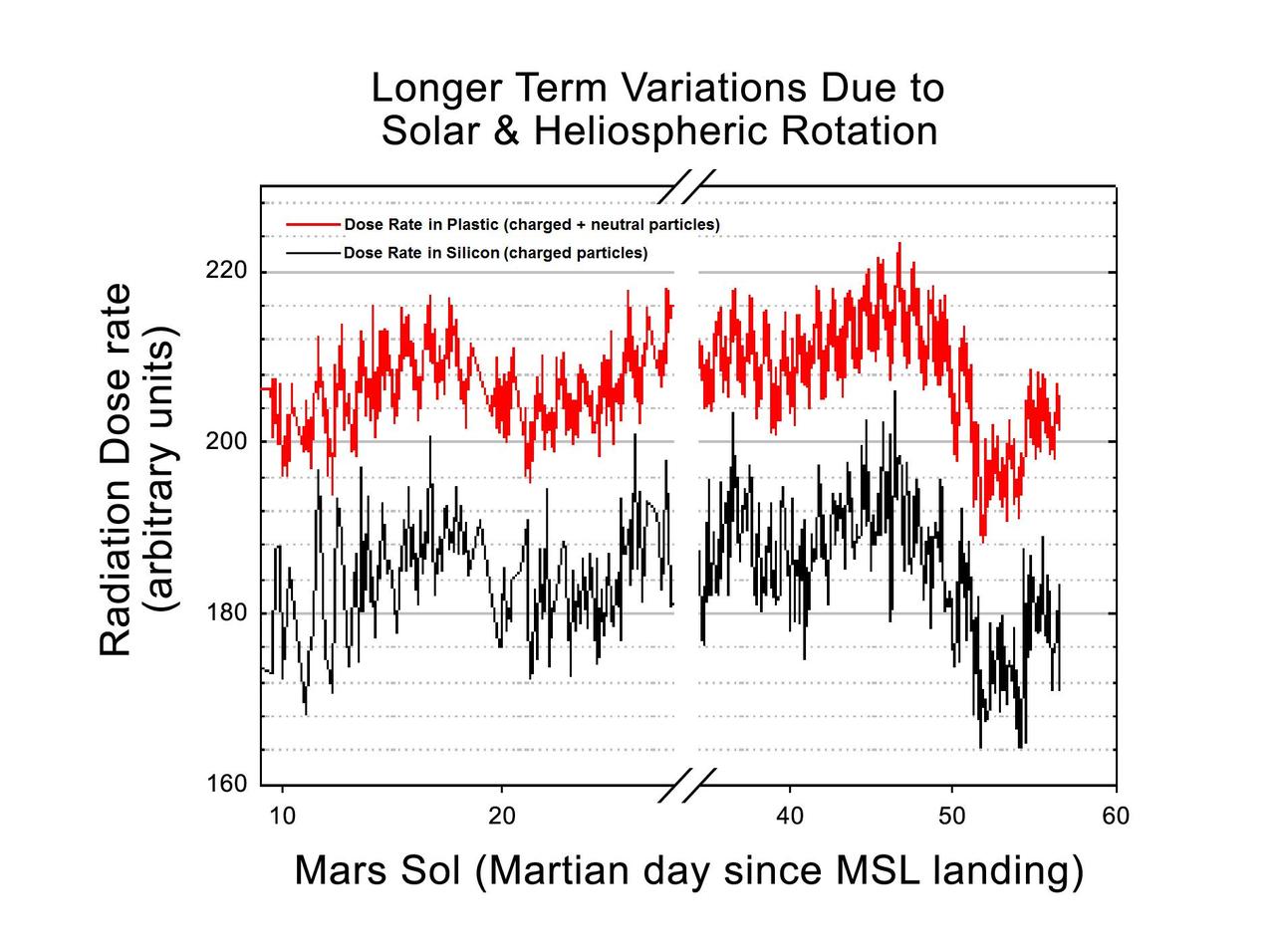

This graphic shows the variation of radiation dose measured by the Radiation Assessment Detector on NASA Curiosity rover over about 50 sols, or Martian days, on Mars.

This image of NASA Curiosity rover shows the location of the two components of the Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons instrument. The neutron generator is mounted on the right hip and the detectors are on the opposite hip.

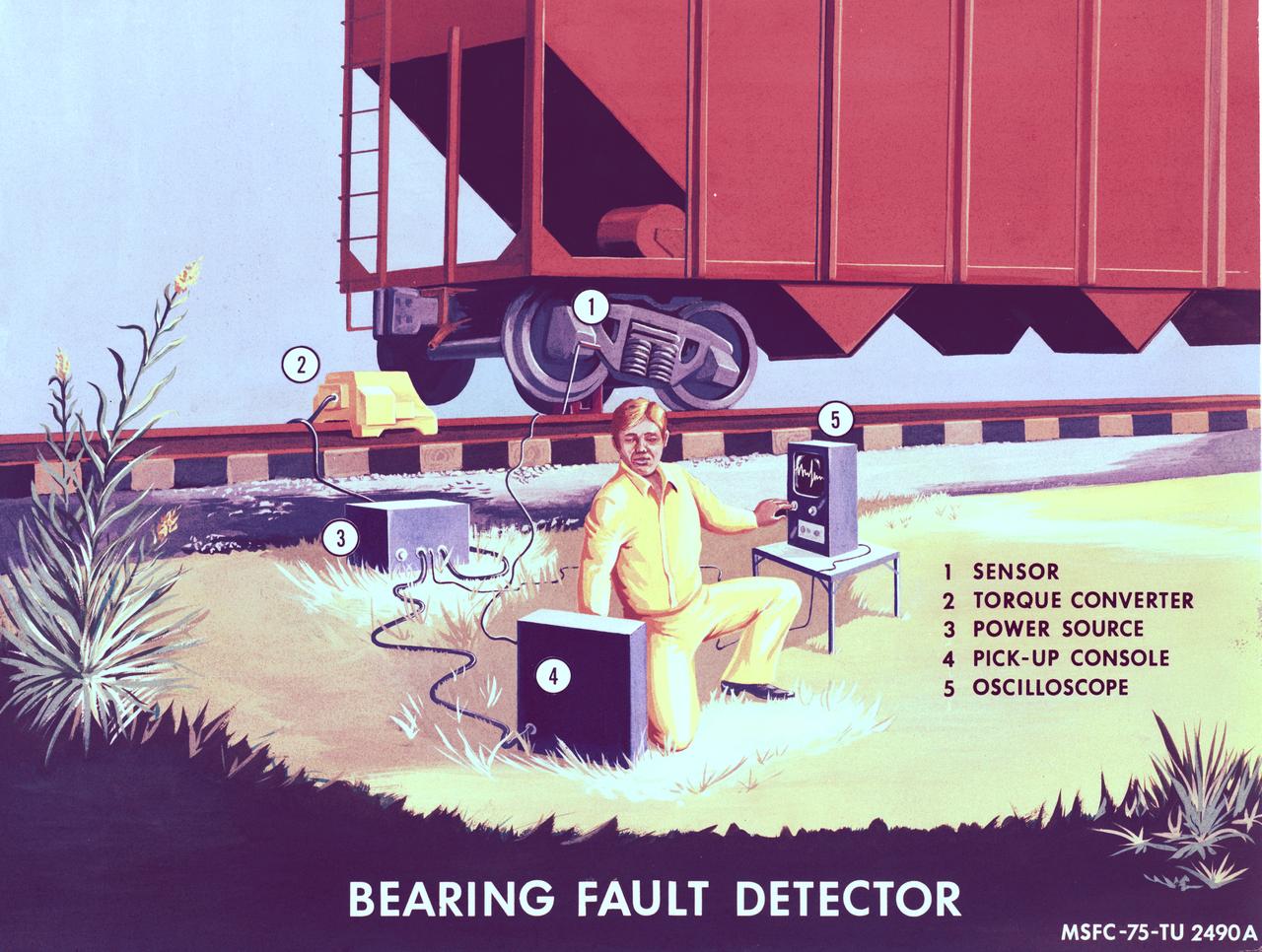

Technology derived by NASA for monitoring control gyros in the Skylab program is directly applicable to the problems of fault detection of railroad wheel bearings. Marhsall Space Flight Center's scientists have developed a detection concept based on the fact that bearing defects excite resonant frequency of rolling elements of the bearing as they impact the defect. By detecting resonant frequency and subsequently analyzing the character of this signal, bearing defects may be detected and identified as to source.

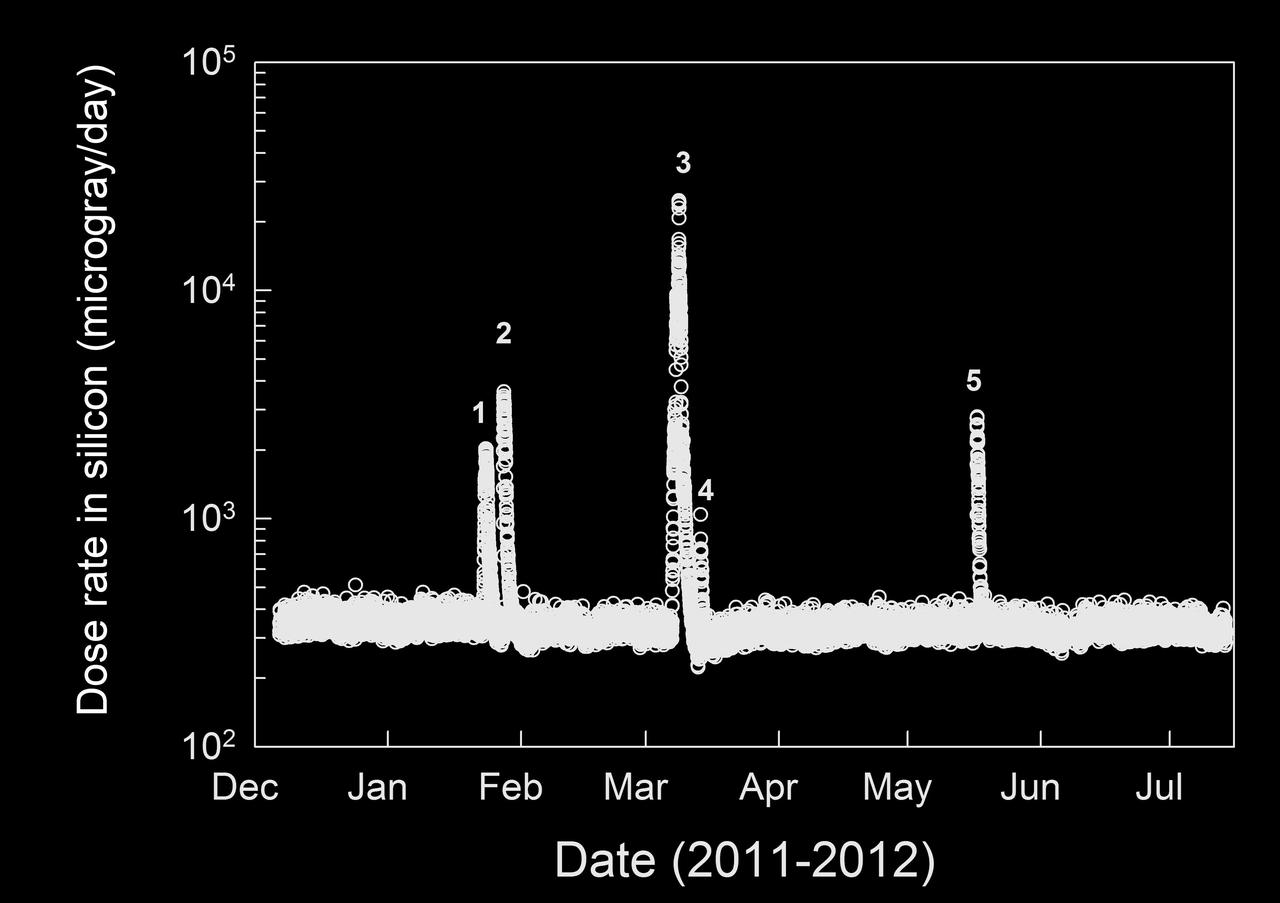

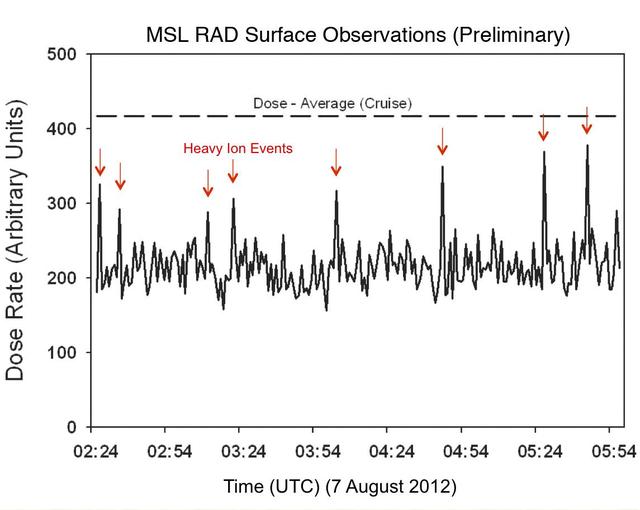

This graphic shows the level of natural radiation detected by the Radiation Assessment Detector shielded inside NASA Mars Science Laboratory on the trip from Earth to Mars from December 2011 to July 2012.

Some say the science instrument on NASA Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer mission resembles the Star Wars robot R2-D2. The instrument is enclosed in a solid-hydrogen cryostat, which cools the WISE telescope and detectors.

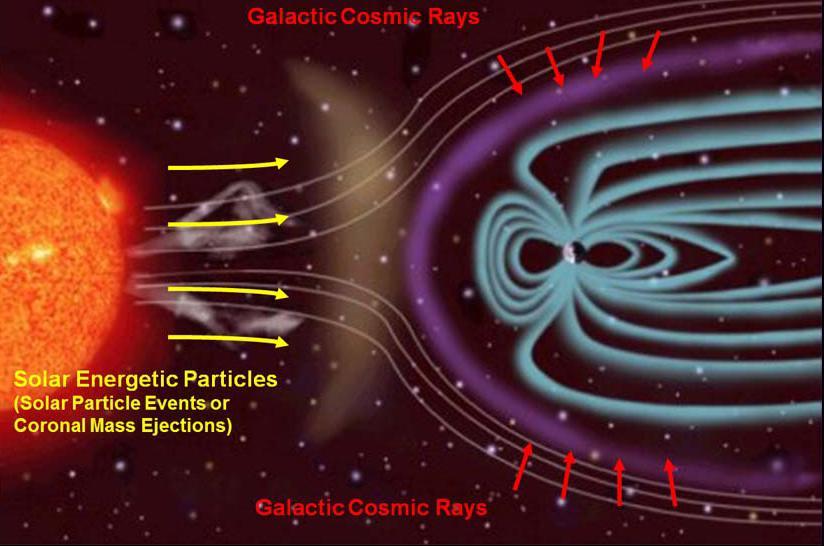

This illustration depicts the two main types of radiation that NASA Radiation Assessment Detector RAD onboard Curiosity monitors, and how the magnetic field around Earth affects the radiation in space near Earth.

NASA Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer captured this colorful image of the reflection nebula IRAS 12116-6001. This cloud of interstellar dust cannot be seen directly in visible light, but WISE detectors observed the nebula at infrared wavelengths.

This artist conception illustrates a storm of comets around a star near our own, called Eta Corvi. Evidence for this barrage comes from NASA Spitzer Space Telescope infrared detectors.

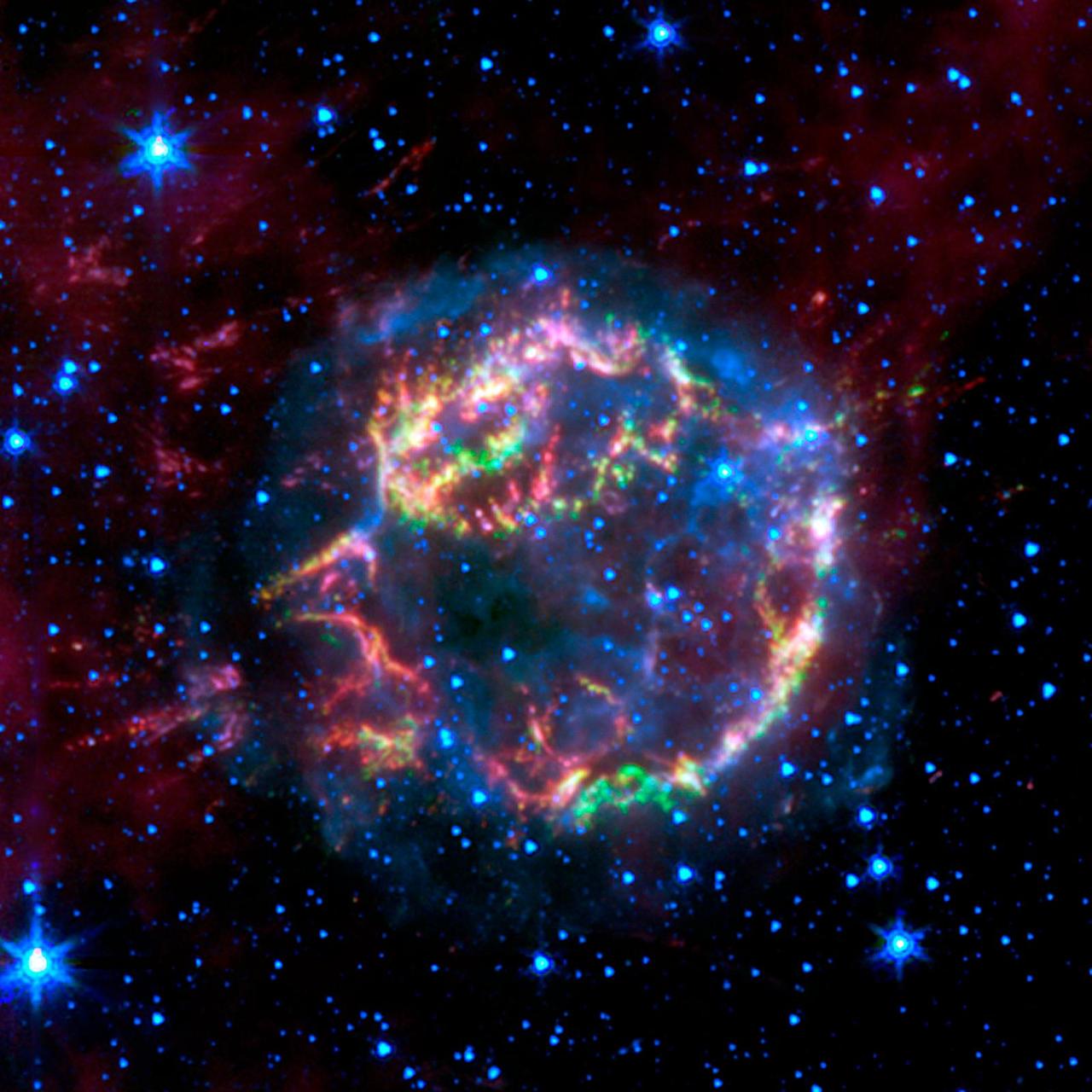

This image from NASA Spitzer Space Telescope shows the scattered remains of an exploded star named Cassiopeia A. Spitzer infrared detectors picked through these remains and found that much of the star original layering had been preserved.

Like a human working in a radiation environment, NASA Curiosity rover carries its own version of a dosimeter to measure radiation from outer space and the sun. This graphic shows the flux of radiation detected the rover Radiation Assessment Detector.

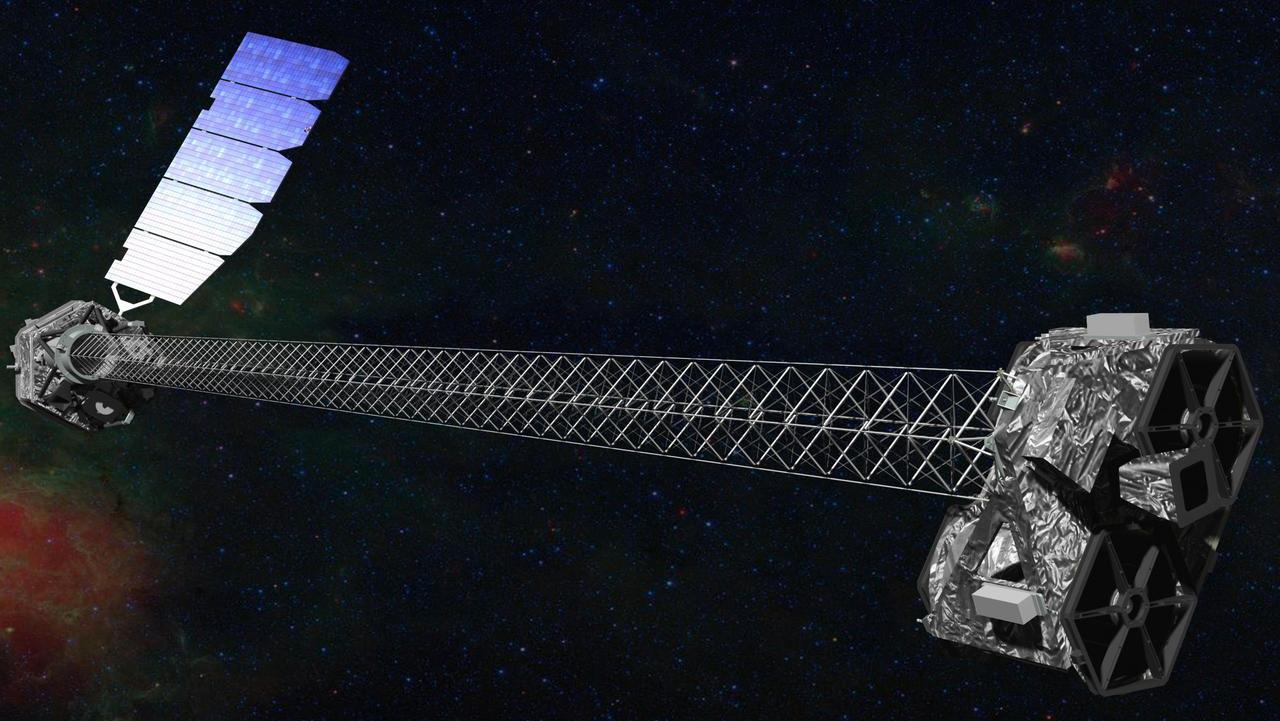

This is an artist concept of NASA NuSTAR spacecraft which has a 10-meter mast that deploys after launch to separate the optics modules right from the detectors in the focal plane left.

Initial assembly of NASA Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer cryostat. The cryostat is a 2-stage solid hydrogen dewar that is used to cool the WISE optics and detectors. Here the cryostat internal structures are undergoing their initial vacuum pumpdown.

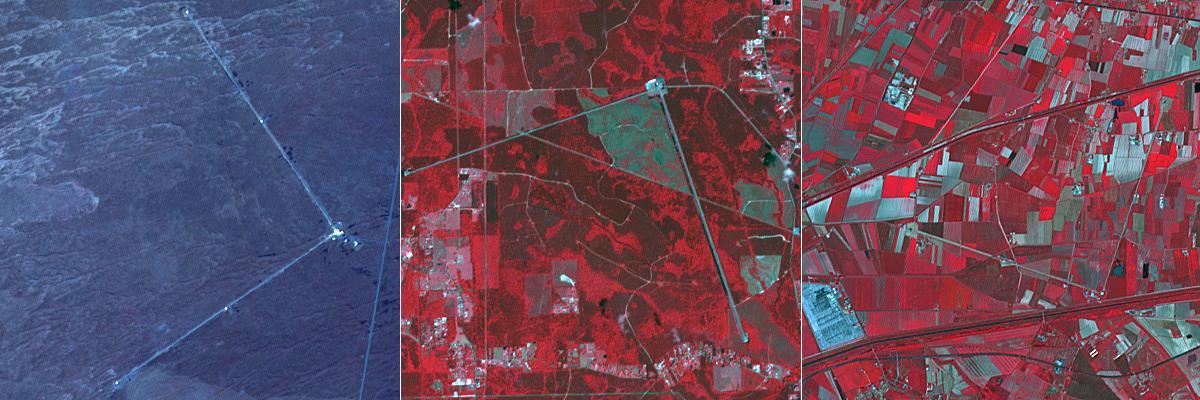

The biggest merger yet between two black holes produced gravity waves that were detected by gravitational wave detection systems. This analysis is the latest to come out of the international LIGO-VIRGO collaboration, which operates three super-sensitive gravitational wave-detection systems in America and Europe (Information from BBC News, September 2). The systems consist of two interferometers at right angles to each other. The two American LIGO systems are located near Livingston, LA (left image) and near Hanford, WA (center image); the European VIRGO system is located near Pisa, Italy (right image). The three ASTER cutouts each cover an area of 6 by 6 km. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24129

S128-E-007282 (4 Sept. 2009) --- Onboard the International Space Station since July, astronaut Tim Kopra is pictured on the orbital outpost a little less than a week before his scheduled return to Earth. Earlier this week, Kopra changed roles from Expedition 20 flight engineer to STS-128 mission specialist. Kopra came up to the station with the STS-127 crew and participated in a spacewalk on July 18. He will return to Earth aboard the Discovery on a scheduled Sept. 10 landing.

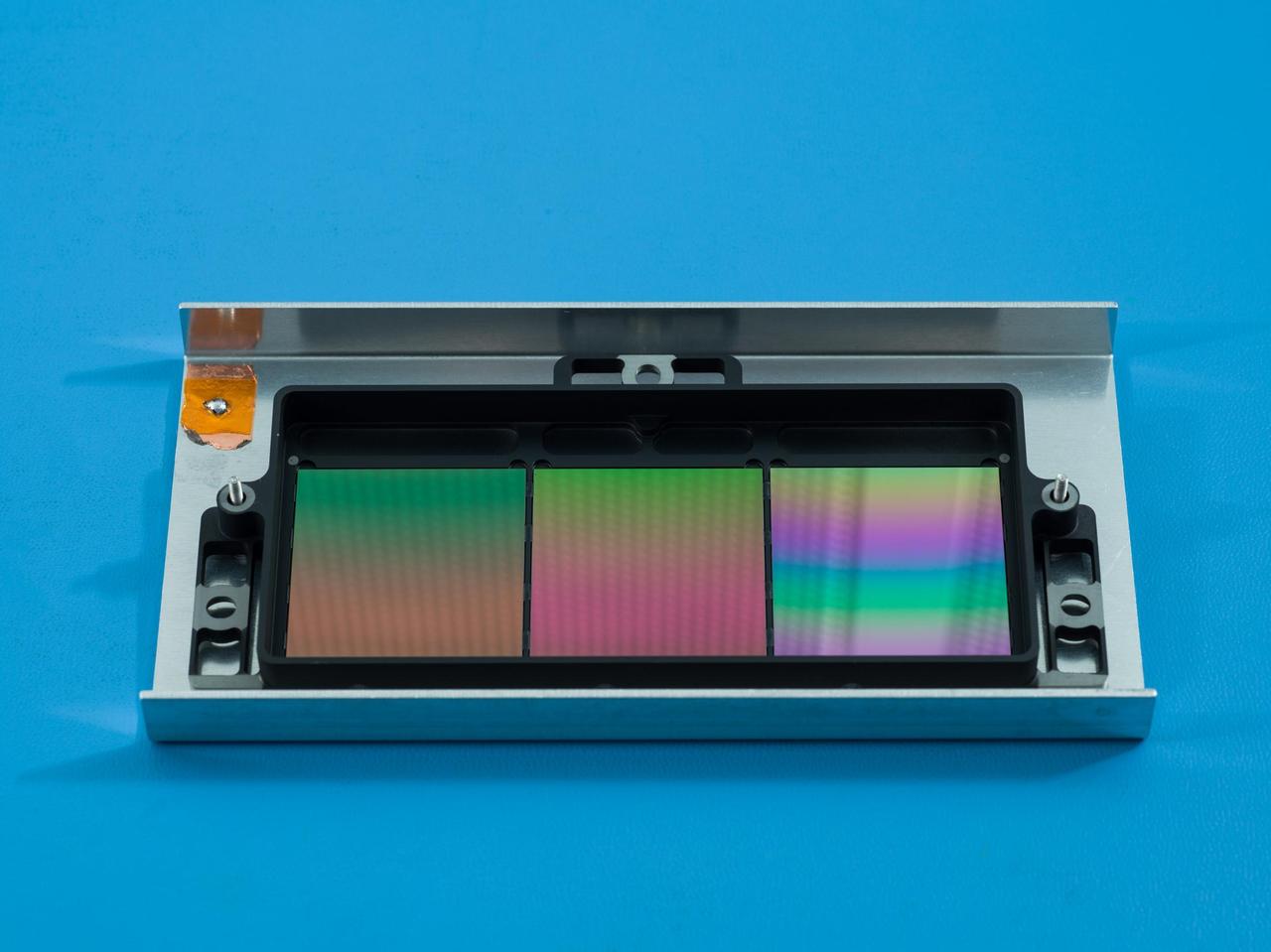

NASA's SPHEREx mission will use these filters to conduct spectroscopy, a technique that lets scientists measure individual wavelengths of light from a source, which can reveal information such as the chemical composition of the object or how far away it is. Each about the size of a cracker, the filters appear iridescent to the naked eye. The filters have multiple segments that block all but one specific wavelength of infrared light. Every object SPHEREx images will be observed by each segment, enabling scientists to see the specific infrared wavelengths emitted by every star or galaxy the telescope views. In total, SPHEREx can observe more than 100 distinct wavelengths. Short for Specto-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer, SPHEREx will create a map of the cosmos like no other, imaging the entire sky and gathering information about millions of galaxies. With this map, scientists will study what happened in the first fraction of a second after the big bang, the history of galaxy evolution, and the origins of water in planetary systems in our galaxy. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25788

In this photo, the Gravity Probe B (GP-B) detector mount assembly is shown in comparison to the size of a dime. The assembly is used to detect exactly how much starlight is coming through different beams from the beam splitter in the telescope. The measurements from the tiny chips inside are what keeps GP-B aimed at the guide star. The GP-B is the relativity experiment developed at Stanford University to test two extraordinary predictions of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. The experiment will measure, very precisely, the expected tiny changes in the direction of the spin axes of four gyroscopes contained in an Earth-orbiting satellite at a 400-mile altitude. So free are the gyroscopes from disturbance that they will provide an almost perfect space-time reference system. They will measure how space and time are very slightly warped by the presence of the Earth, and, more profoundly, how the Earth’s rotation very slightly drags space-time around with it. These effects, though small for the Earth, have far-reaching implications for the nature of matter and the structure of the Universe. GP-B is among the most thoroughly researched programs ever undertaken by NASA. This is the story of a scientific quest in which physicists and engineers have collaborated closely over many years. Inspired by their quest, they have invented a whole range of technologies that are already enlivening other branches of science and engineering. Launched April 20, 2004 , the GP-B program was managed for NASA by the Marshall Space Flight Center. Development of the GP-B is the responsibility of Stanford University along with major subcontractor Lockheed Martin Corporation. (Image credit to Paul Ehrensberger, Stanford University.)

N-213 detector set up for 3d LV (laser velocimeter)

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover captured evidence of a solar storm's charged particles arriving at the Martian surface in this three-frame video taken by one of the rover's navigation cameras on May 20, 2024, the 4,190th Martian day, or sol, of the mission. The mission regularly captures videos to try and catch dust devils, or dust-bearing whirlwinds. While none were spotted in this particular sequence of images, engineers did see streaks and specks – visual artifacts created when charged particles from the Sun hit the camera's image detector. The particles do not damage the detector. The images in this sequence appear grainy because navigation-camera images are processed to highlight changes in the landscape from frame to frame. When there isn't much change – in this case, the rover was parked &ndash more noise appears in the image. Curiosity's Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) measured a sharp increase in radiation at this time – the biggest radiation surge the mission has seen since landing in 2012. Animation available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26302

ISS037-E-003198 (27 Sept. 2013) --- Russian cosmonaut Oleg Kotov, Expedition 37 flight engineer, is pictured in the Zvezda Service Module of the International Space Station.

Some key components of a NASA-funded instrument being developed for the payload of the European Space Agency ExoMars mission stand out in thisillustration of the instrument

ISS020-E-050738 (10 Oct. 2009) --- Canadian Space Agency astronaut Robert Thirsk, Expedition 20/21 flight engineer, works in the Zvezda Service Module of the International Space Station.

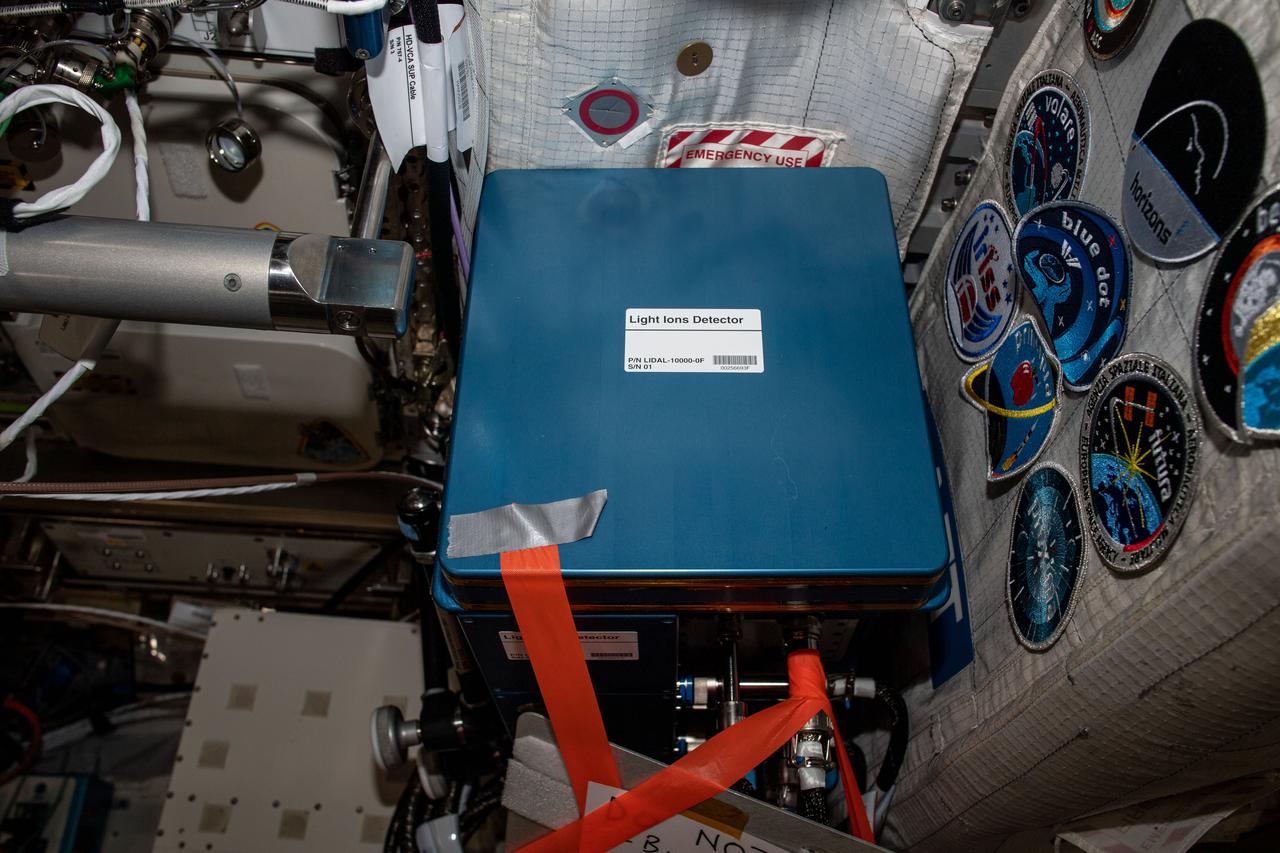

ISS064E011766 (12/11/2020) --- Documentation of the Light Ions Detector for ALTEA Facility (LIDAL Facility) in the Columbus European Laboratory.

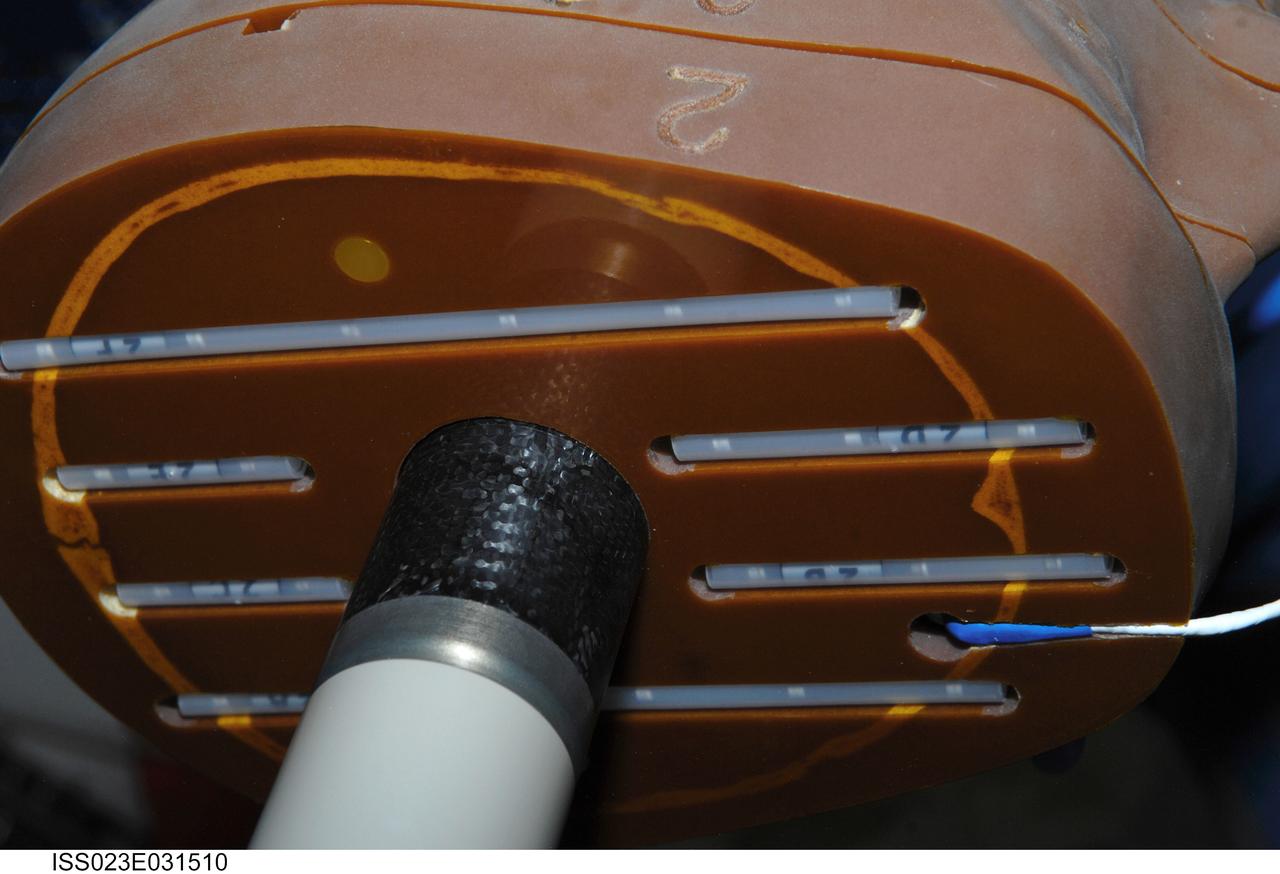

iss023e031510 (542010) --- A view of the detectors installed in the anthropomorphic Phantom for the Matroshka-2 Kibo experiment.

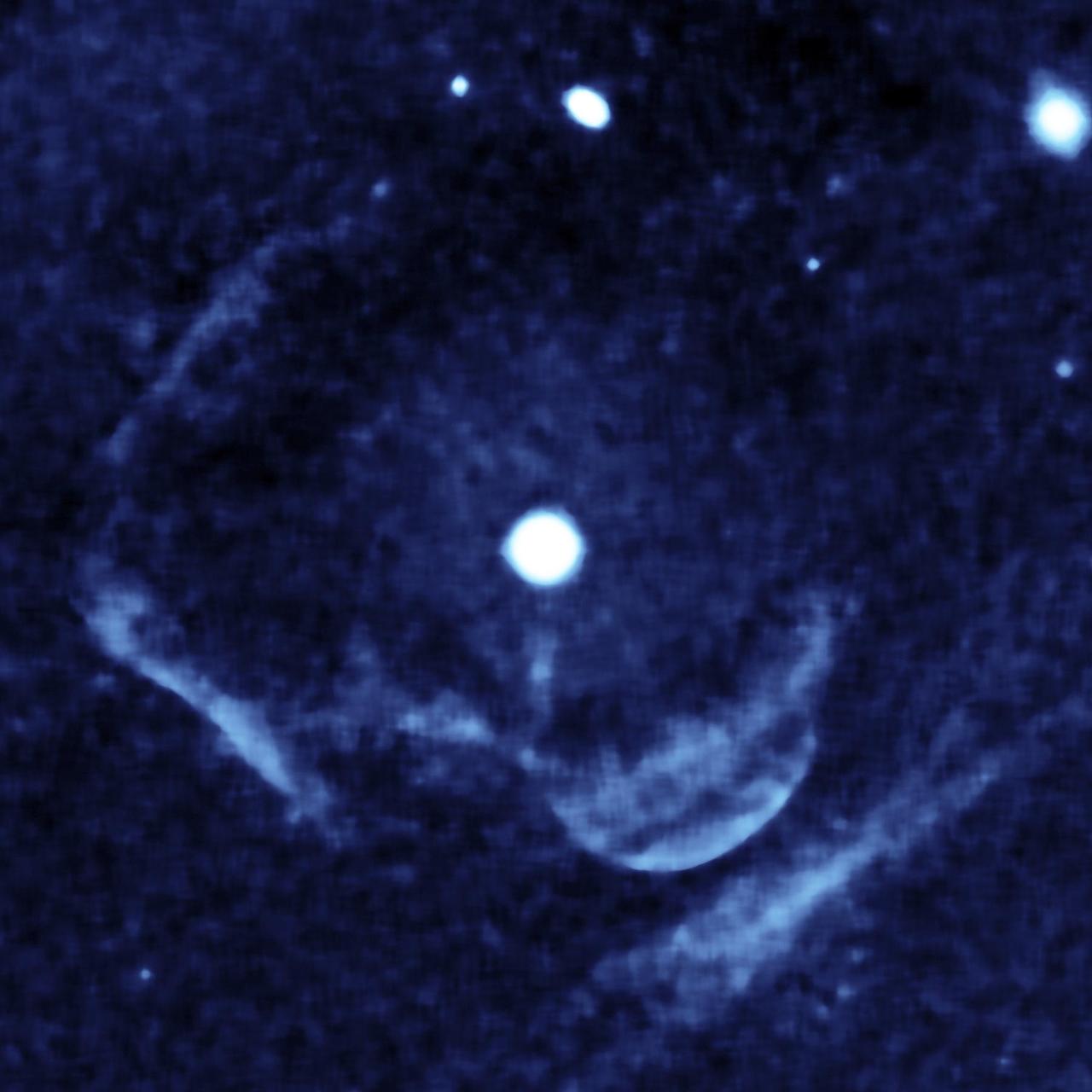

This enhanced image from the far-ultraviolet detector on NASA Galaxy Evolution shows a ghostly shell of ionized gas around Z Camelopardalis, a binary, or double-star system featuring a collapsed, dead star known as a white dwarf, and a companion star.

NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft produced this high-energy neutron detector map of neutrons in Mars southern hemisphere. The blue region around the south pole indicates a high content of hydrogen in the upper 2 to 3 meters 7 to 10 feet of the surface.

The objective of this facility is to investigate the potential of space grown semiconductor materials by the vapor transport technique and develop powdered metal and ceramic sintering techniques in microgravity. The materials processed or developed in the SEF have potential application for improving infrared detectors, nuclear particle detectors, photovoltaic cells, bearing cutting tools, electrical brushes and catalysts for chemical production. Flown on STS-60 Commercial Center: Consortium for Materials Development in Space - University of Alabama Huntsville (UAH)

Nobel laureate Professor Samuel C. C. Ting of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology pauses for a photo in the Space Station Processing Facility. Dr. Ting is directing an experiment, an international collaboration of some 37 universities and laboratories, using a state-of-the-art particle physics detector called the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS), which will fly on a future launch to the International Space Station. Using the unique environment of space, the AMS will study the properties and origin of cosmic particles and nuclei including antimatter and dark matter. AMS flew initially as a Space Shuttle payload on the June 1998 mission STS-91 that provided the investigating team with data on background sources and verified the detector’s performance under actual space flight conditions. The detector’s second space flight is scheduled to be launched on mission UF-4 October 2003 for installation on the Space Station as an attached payload. Current plans call for operating the detector for three years before it is returned to Earth on the Shuttle. Using the Space Station offers the science team the opportunity to conduct the long-duration research above the Earth’s atmosphere necessary to collect sufficient data required to accomplish the science objectives

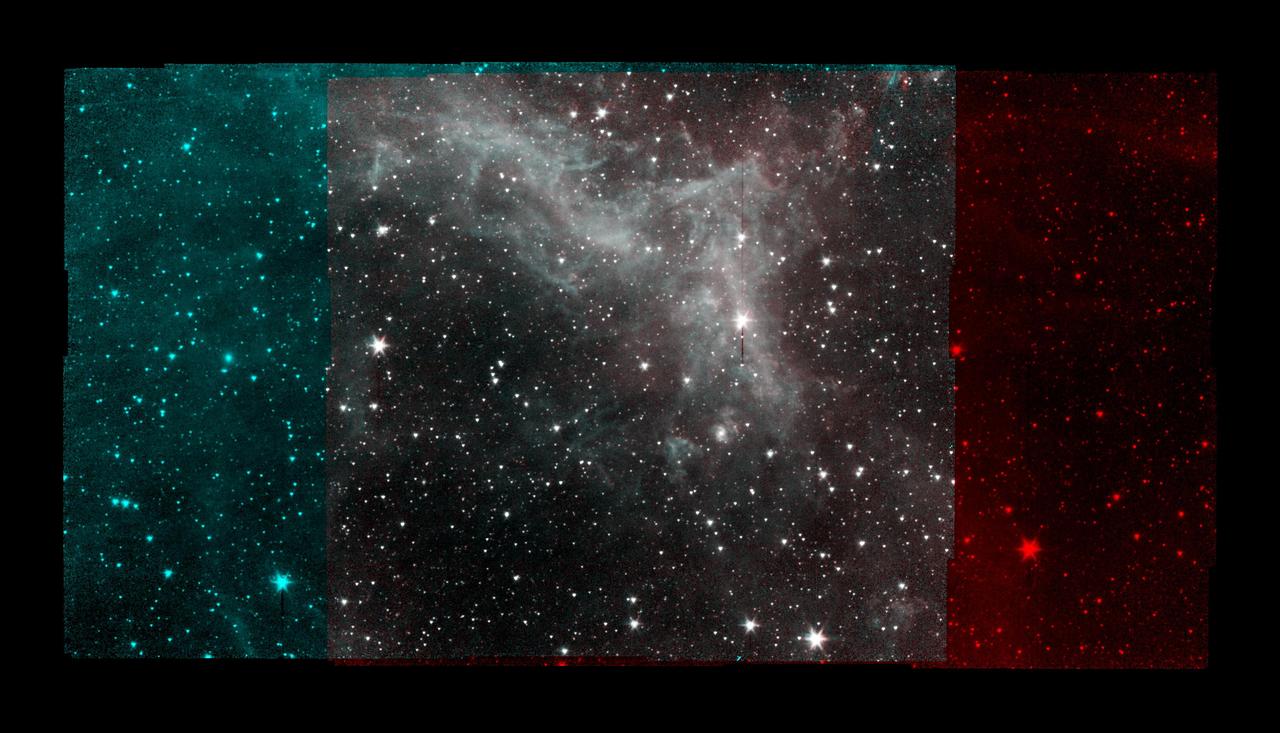

This series of image taken by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope on Jan. 25, 2020, shows part of the California Nebula, which is located about 1,000 light-years from Earth. This is the final mosaic taken by the mission before it was decommissioned on Jan. 30, 2020. Spitzer's infrared detectors reveal the presence of warm dust, similar to soot, mixed in with the gas. The dust absorbs visible and ultraviolet light from nearby stars and then re-emits the absorbed energy as infrared light. The image displays Spitzer's observations much the way that research astronomers would view them: From 2009 to 2020, Spitzer operated two detectors simultaneously that imaged adjacent areas of the sky. The detectors captured different wavelengths of infrared light (referred to by their physical wavelength): 3.6 micrometers (shown in cyan) and 4.5 micrometers (shown in red). Different wavelengths of light can reveal different objects or features. Spitzer would scan the sky, taking multiple pictures in a grid pattern, so that both detectors would image the region at the center of the grid. By combining those images into a mosaic, it was possible to see what a given region looked like in multiple wavelengths, such as in the gray-hued part of the image above. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23650

Nobel laureate Professor Samuel C. C. Ting of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology pauses for a photo in the Space Station Processing Facility. Dr. Ting is directing an experiment, an international collaboration of some 37 universities and laboratories, using a state-of-the-art particle physics detector called the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS), which will fly on a future launch to the International Space Station. Using the unique environment of space, the AMS will study the properties and origin of cosmic particles and nuclei including antimatter and dark matter. AMS flew initially as a Space Shuttle payload on the June 1998 mission STS-91 that provided the investigating team with data on background sources and verified the detector’s performance under actual space flight conditions. The detector’s second space flight is scheduled to be launched on mission UF-4 October 2003 for installation on the Space Station as an attached payload. Current plans call for operating the detector for three years before it is returned to Earth on the Shuttle. Using the Space Station offers the science team the opportunity to conduct the long-duration research above the Earth’s atmosphere necessary to collect sufficient data required to accomplish the science objectives

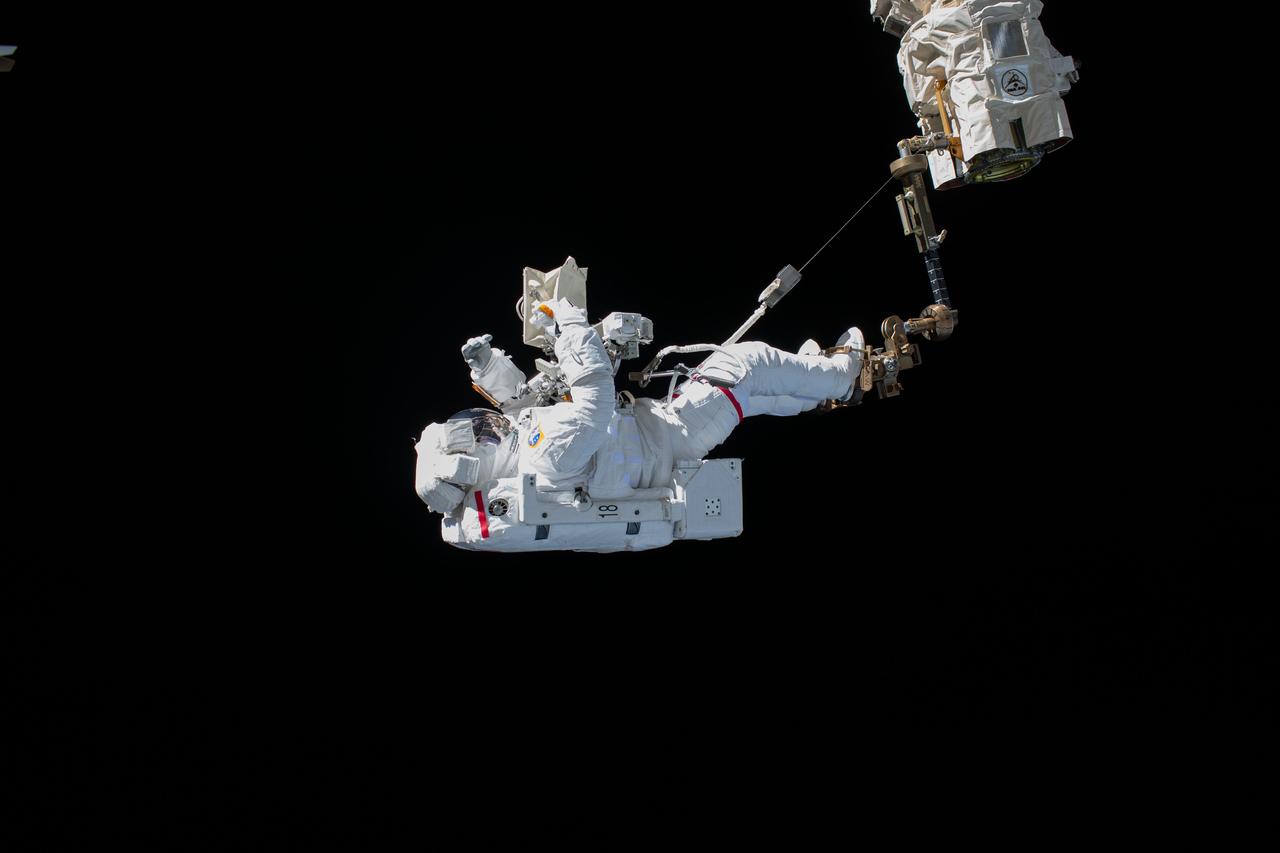

iss061e058236 (Nov. 22, 2019) --- Astronaut Andrew Morgan of NASA is tethered to the Starboard-3 truss segment work site during the second spacewalk to repair the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer.

iss061e143751 (Jan. 25, 2020) --- NASA astronaut Andrew Morgan takes pictures with a camera shielded from the effects of microgravity during a spacewalk to finalize thermal repairs on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a dark matter and antimatter detector.

ISS031-E-096064 (8 June 2012) --- European Space Agency astronaut Andre Kuipers, Expedition 31 flight engineer, works with the silicon detector unit in the Columbus laboratory of the International Space Station.

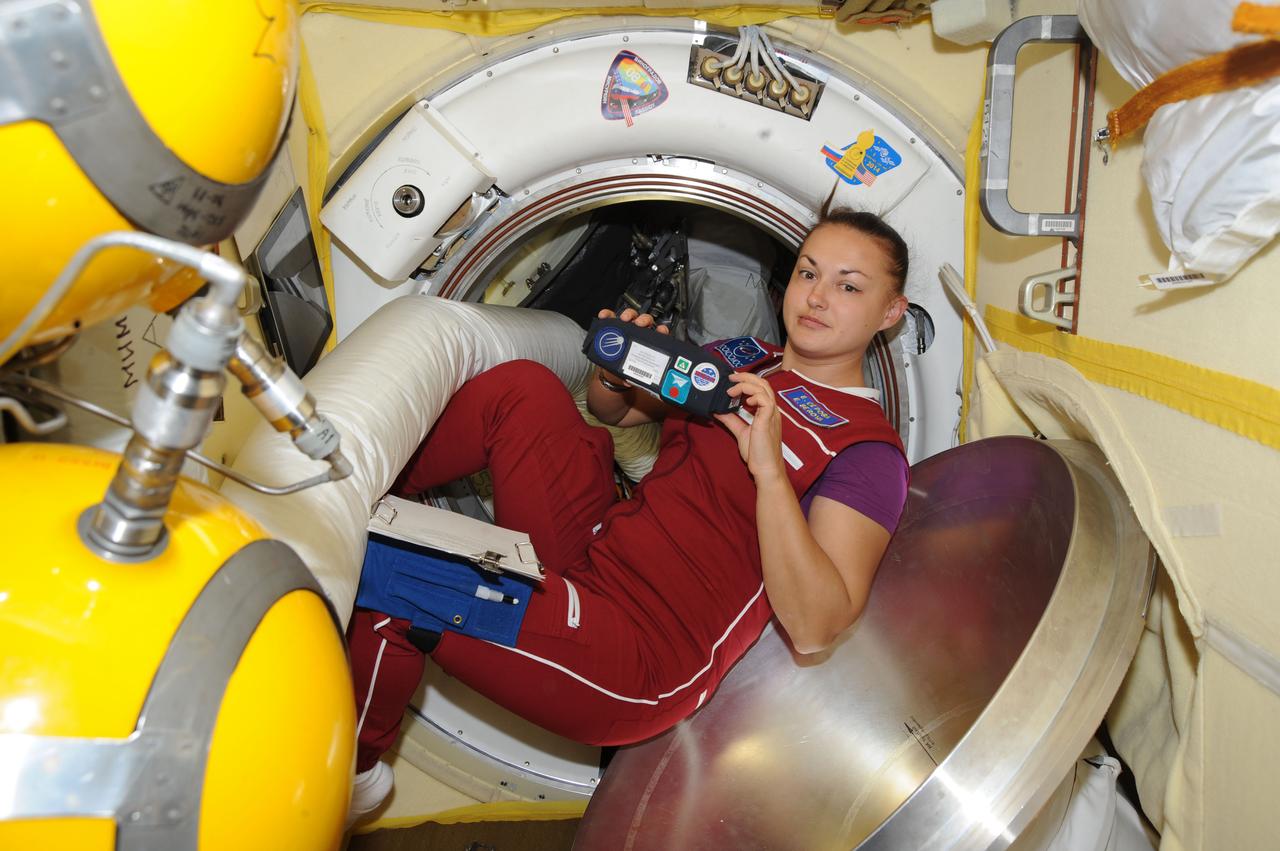

iss068e041015 (Jan. 19, 2023) --- Roscosmos cosmonaut and Expedition 68 Flight Engineer Anna Kikina installs dosimeters, or radiation detectors, and collects data from them aboard the International Space Station. Credit: Roscosmos

iss061e058144 (Nov. 22, 2019) --- Astronaut Andrew Morgan of NASA is tethered to the Starboard-3 truss segment work site during the second spacewalk to repair the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer.

iss061e142293 (Jan. 25, 2020) --- Spacewalkers Andrew Morgan (left) and Luca Parmitano (bottom right) work on get-ahead tasks after completing thermal repairs on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a dark matter and antimatter detector.

iss061e142299 (Jan. 25, 2020) --- Spacewalker (bottom left) Luca Parmitano works on get-ahead tasks after completing thermal repairs on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a dark matter and antimatter detector.

iss066e090268 (Dec. 13, 2021) --- Astronaut and Expedition 66 Flight Engineer Matthias Maurer of ESA (European Space Agency) inspects and cleans smoke detectors inside Columbus laboratory module.

iss061e142334 (Jan. 25, 2020) --- Spacewalkers Andrew Morgan and Luca Parmitano work on get-ahead tasks after completing thermal repairs on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a dark matter and antimatter detector.

iss061e040708 (Nov. 15, 2019) --- NASA astronaut Andrew Morgan waves as he is photographed during the first spacewalk to repair the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a cosmic particle detector on the International Space Station.

iss061e058179 (Nov. 22, 2019) --- Astronaut Andrew Morgan of NASA is tethered to the Starboard-3 truss segment work site during the second spacewalk to repair the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer.

iss065e045733 (May 14, 2021) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 65 Flight Engineer Shane Kimbrough relocates smoke detectors inside the International Space Station's Harmony module.

iss068e041021 (Jan. 19, 2023) --- Roscosmos cosmonaut and Expedition 68 Flight Engineer Anna Kikina installs dosimeters, or radiation detectors, and collects data from them aboard the International Space Station. Credit: Roscosmos

ISS015-E-26252 (1 Sept. 2007) --- Astronaut Clay Anderson, Expedition 15 flight engineer, works on the Smoke and Aerosol Measurement Experiment (SAME) hardware setup located in the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station. SAME will measure the smoke properties, or particle size distribution, of typical particles that are produced from different materials that can be found onboard station and other spacecrafts. SAME aims to test the performance of ionization smoke detectors and evaluate the performance of the photoelectric smoke detectors. The data will be used to develop a model that can predict smoke droplet growth that will be used to evaluate future smoke detection devices.

ISS015-E-27425 (8 Sept. 2007) --- NASA astronaut Clay Anderson, Expedition 15 flight engineer, works on the Smoke and Aerosol Measurement Experiment (SAME) hardware located in the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station. SAME will measure the smoke properties, or particle size distribution, of typical particles that are produced from different materials that can be found onboard station and other spacecrafts. SAME aims to test the performance of ionization smoke detectors and evaluate the performance of the photoelectric smoke detectors. The data will be used to develop a model that can predict smoke droplet growth that will be used to evaluate future smoke detection devices.

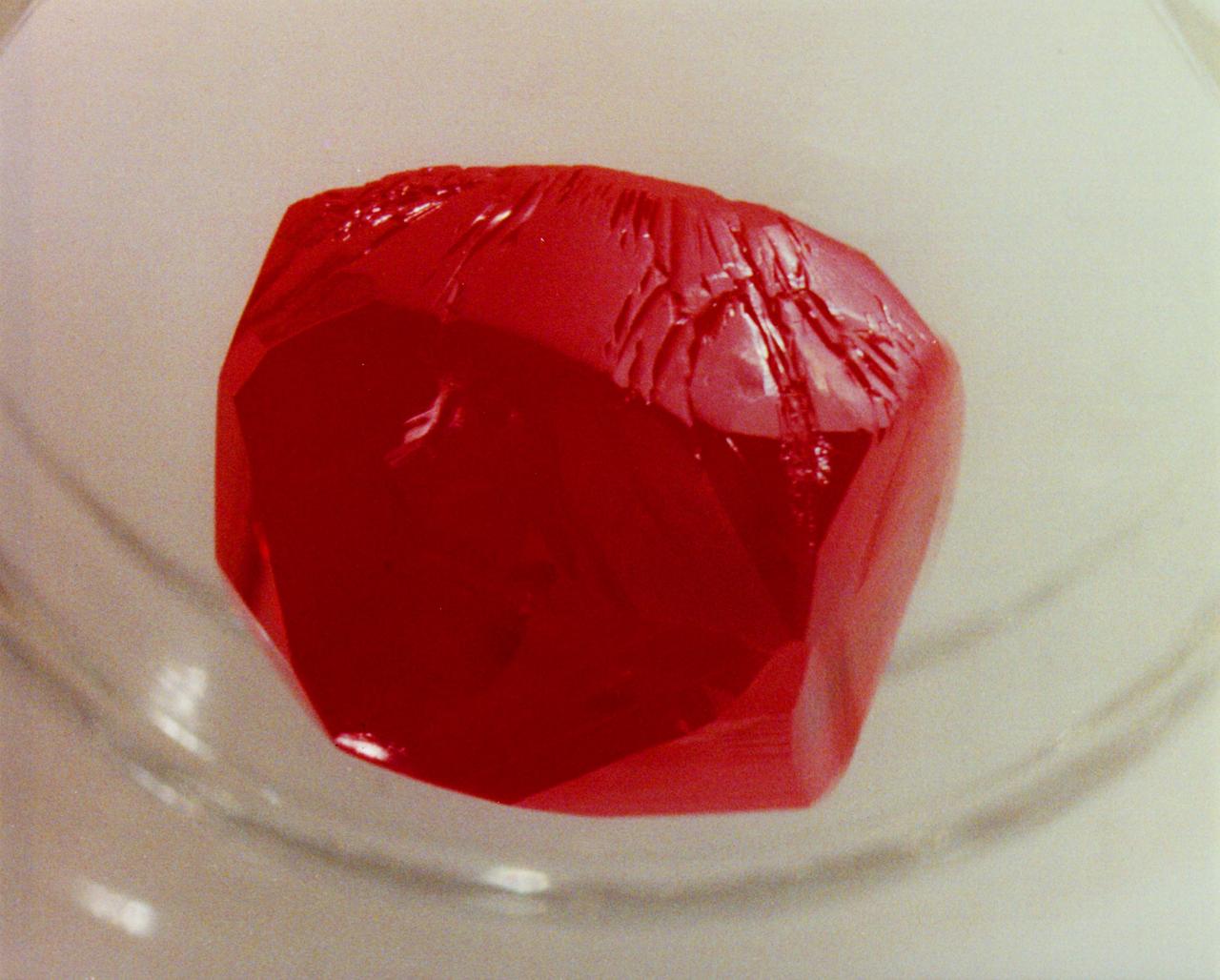

Vapor Crystal Growth System developed in IML-1, Mercuric Iodide Crystal grown in microgravity FES/VCGS (Fluids Experiment System/Vapor Crystal Growth Facility). During the mission, mercury iodide source material was heated, vaporized, and transported to a seed crystal where the vapor condensed. Mercury iodide crystals have practical uses as sensitive X-ray and gamma-ray detectors. In addition to their excellent optical properties, these crystals can operate at room temperature, which makes them useful for portable detector devices for nuclear power plant monitoring, natural resource prospecting, biomedical applications, and astronomical observing.

iss050e000936 (11/7/2016) --- View of eight bubble detectors in pack during Radi-N2 deployment in the U.S. Laboratory for RADI-N2 experiment. Radi-N2 Neutron Field Study (Radi-N2) is a follow on investigation designed to characterize the neutron radiation environment aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Eight neutron “bubble detectors” produced by the Canadian company Bubble Technology Industries are attached to fixed locations inside the ISS, including one carried by a crew member. The objective of this investigation is to better characterize the ISS neutron environment and define the risk posed to the crew members’ health and provide the data necessary to develop advanced protective measures for future spaceflight.

S73-36161 (November 1973) --- In the Radiation Counting Laboratory sixty feet underground at JSC, Dr. Robert S. Clark prepares to load pieces of iridium foil -- sandwiched between plastic sheets -- into the laboratory's radiation detector. The iridium foil strips were worn by the crew of the second Skylab flight in personal radiation dosimeters throughout their 59 1/2 days in space. Inside the radiation detector assembly surrounded by 28 tons of lead shielding, the sample will be tested to determine the total neutron dose to which the astronauts were exposed during their long stay aboard the space station. Photo credit: NASA

ISS015-E-27397 (8 Sept. 2007) --- NASA astronaut Clay Anderson, Expedition 15 flight engineer, pauses for a photo while working on the Smoke and Aerosol Measurement Experiment (SAME) hardware located in the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station. SAME will measure the smoke properties, or particle size distribution, of typical particles that are produced from different materials that can be found onboard station and other spacecrafts. SAME aims to test the performance of ionization smoke detectors and evaluate the performance of the photoelectric smoke detectors. The data will be used to develop a model that can predict smoke droplet growth that will be used to evaluate future smoke detection devices.

ISS015-E-27411 (8 Sept. 2007) --- NASA astronaut Clay Anderson, Expedition 15 flight engineer, works on the Smoke and Aerosol Measurement Experiment (SAME) hardware located in the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG) in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station. SAME will measure the smoke properties, or particle size distribution, of typical particles that are produced from different materials that can be found onboard station and other spacecrafts. SAME aims to test the performance of ionization smoke detectors and evaluate the performance of the photoelectric smoke detectors. The data will be used to develop a model that can predict smoke droplet growth that will be used to evaluate future smoke detection devices.

ISS040-E-130025 (9 Sept. 2014) --- European Space Agency astronaut Alexander Gerst (right) and Russian cosmonaut Alexander Skvortsov, both Expedition 40 flight engineers, work with a package of dosimeters in the Zvezda Service Module of the International Space Station.

ISS040-E-130020 (9 Sept. 2014) --- European Space Agency astronaut Alexander Gerst, Expedition 40 flight engineer, opens a package of dosimeters in the Zvezda Service Module of the International Space Station.

ISS041-E-037514 (27 Sept. 2014) --- Russian cosmonaut Elena Serova, Expedition 41 flight engineer, poses for a photo near a hatch in the Russian segment of the International Space Station.

ISS040-E-130021 (9 Sept. 2014) --- European Space Agency astronaut Alexander Gerst (left), writes a note while Russian cosmonaut Alexander Skvortsov, both Expedition 40 flight engineers, looks on in the Zvezda Service Module of the International Space Station.

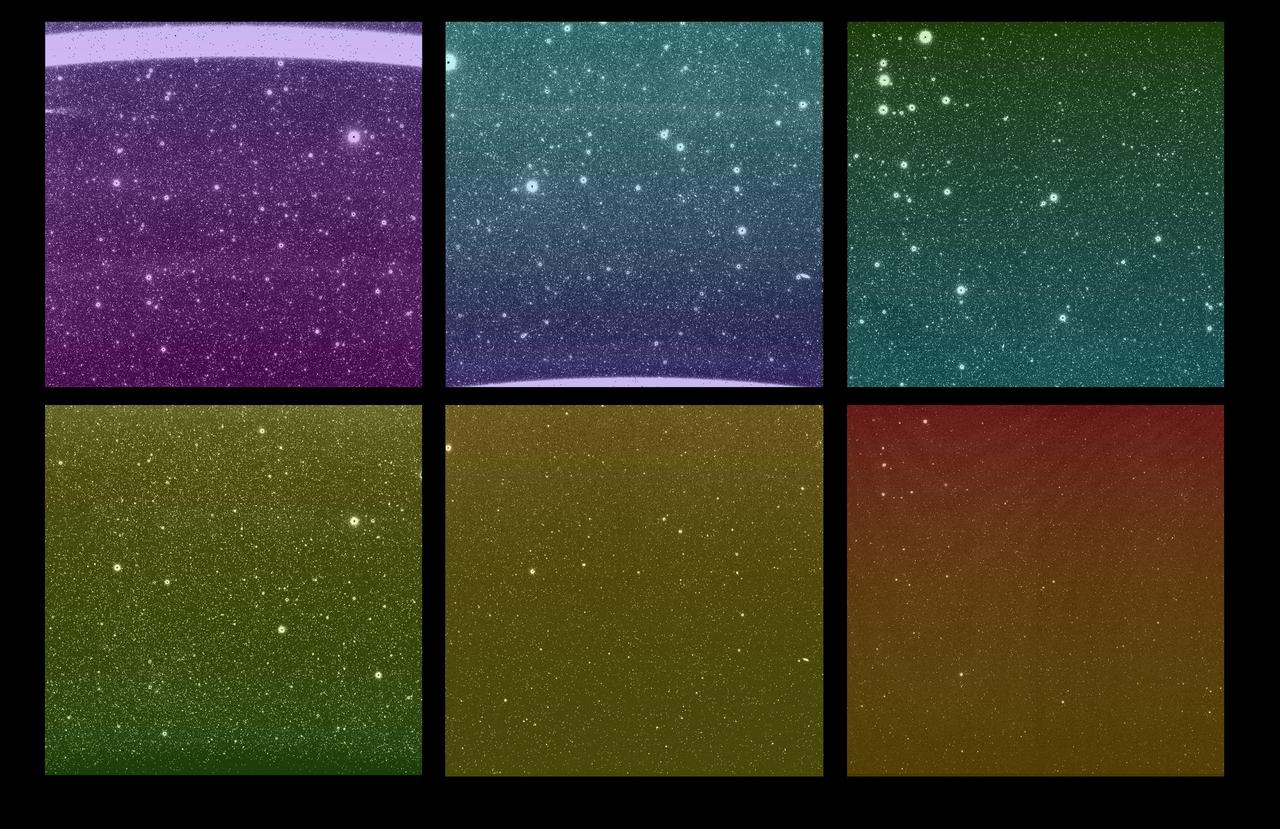

Some of the first images from NASA's SPHEREx (Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer) mission were captured March 27, 2025. Although the new images are uncalibrated and not yet ready to use for science, they give a tantalizing look at SPHEREx's wide view of the sky. Each bright spot is a source of light, like a star or galaxy, and each image is expected to contain more than 100,000 detected sources. There are six images in every SPHEREx exposure – one for each detector. The top three images show the same area of sky as the bottom three images; this is the observatory's full field of view, a rectangular area about 20 times wider than the full Moon. When the SPHEREx observatory begins routine science operations in April, it will take approximately 600 exposures every day. SPHEREx detects infrared light, which is invisible to the human eye. To make the images shown here, science team members assigned a visible color to each infrared wavelength captured by the observatory. With each detector capturing 17 unique infrared wavelength bands, there are 102 hues in this image. To detect so many infrared colors, SPHEREx uses color filters set on top of the detectors. (If the detectors are like SPHEREx's eyes, the filters are like color-tinted glasses). A standard color filter blocks all wavelengths but one, but the SPHEREx filters are more like rainbow-tinted glasses, in that the wavelengths they block change gradually from the top of the filter to the bottom. The legend at the top shows that the detectors are placed to observe infrared wavelengths from shortest to longest. Certain chemical elements are visible at specific wavelengths, as is the case with helium from Earth's atmosphere, which creates a bright line in the wavelength at the top of the top-left image. Breaking down color this way can reveal the composition of an object or the distance to a galaxy. With that data, scientists can study topics ranging from the physics that governed the universe less than a second after its birth to the origins of water in our galaxy. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26280

Sara Susca, deputy payload manager and payload systems engineer for the NASA's SPHEREx mission, looks up at one of the spacecraft's photon shields at the agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California in October 2023. Short for Specto-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer, SPHEREx will create a map of the cosmos like no other, imaging the entire sky and gathering information about millions of galaxies. With this map, scientists will study what happened in the first fraction of a second after the big bang, the history of galaxy evolution, and the origins of water in planetary systems in our galaxy. Three concentric photon shields will surround the SPHEREx telescope to protect it from nearby light sources that could overwhelm its detectors. The shields will primarily block light from the Sun and the Earth. They also block heat; SPHEREx needs to be kept cold – below minus 350 degrees Fahrenheit (about minus 210 degrees Celsius). That's because SPHEREx detects infrared light, which is sometimes called heat radiation because it's emitted by anything warm. The heat from SPHEREx's own detectors could overwhelm their ability to image faint cosmic objects, so the spacecraft needs a way to cool the detectors down. The spacecraft stands almost 8.5 feet tall (2.6 meters) and stretches nearly 10.5 feet (3.2 meters) wide. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25784

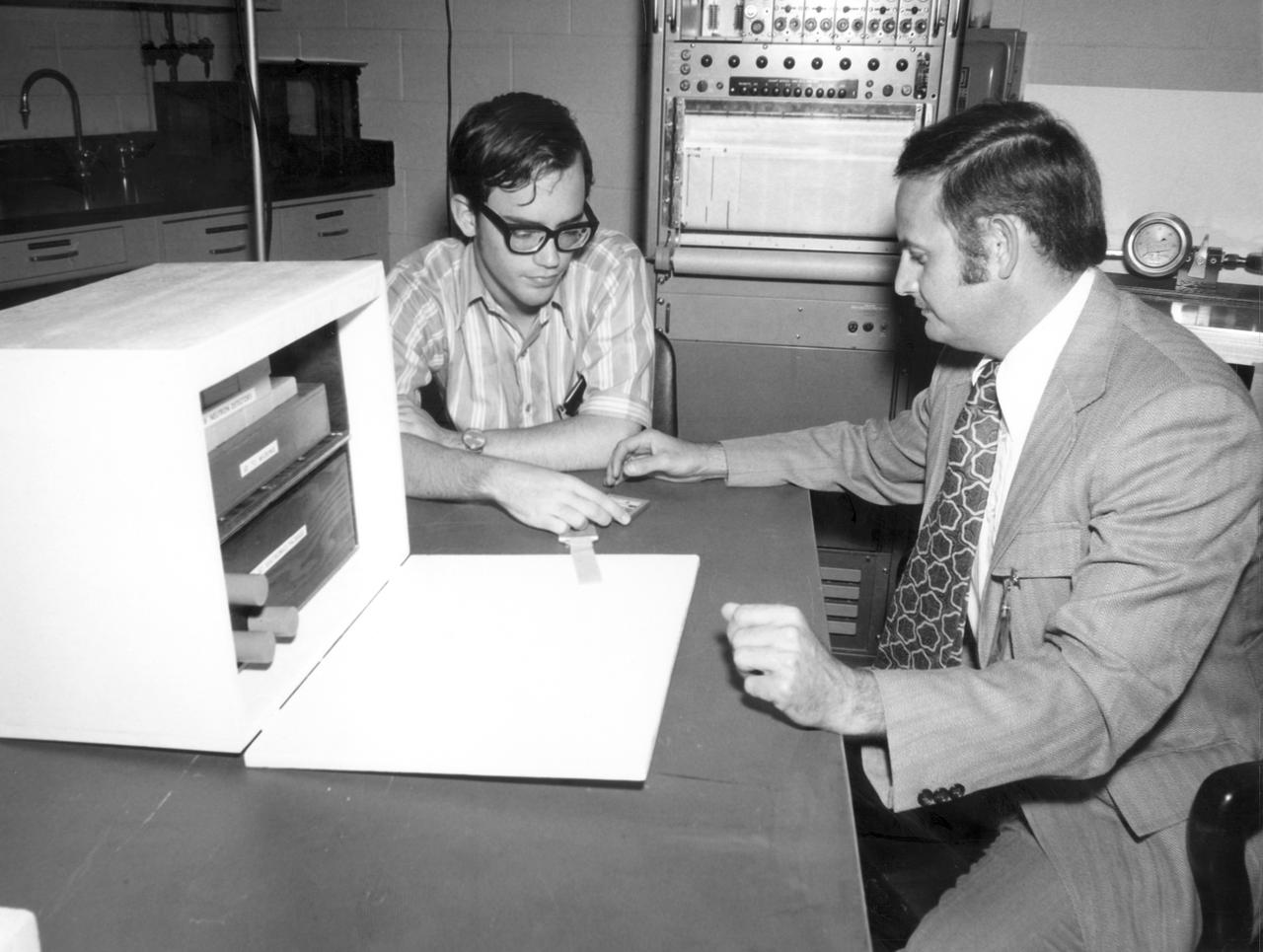

San Antonio, Texas high school student, Terry C. Quist (left), and Dr. Raymond Gause of the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), discuss the student’s experiment to be performed aboard the Skylab the following year. His experiment, “Earth Orbital Neutron Analysis” required detectors such as the one he is examining in this photo. The detector was to be attached to a water tank in Skylab. Neutrons striking the detectors left traces that were brought out by a chemical etching process after the Skylab mission. Quist’s experiment seeked to record neutron hits, count them, and determine their direction. This information was to help determine the source of neutrons in the solar system. Quist was among 25 winners of a contest in which some 3,500 high school students proposed experiments for the following year’s Skylab mission. The nationwide scientific competition was sponsored by the National Science Teachers Association and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The winning students, along with their parents and sponsor teachers, visited MSFC two months earlier where they met with scientists and engineers, participated in design reviews for their experiments, and toured MSFC facilities. Of the 25 students, 6 did not see their experiments conducted on Skylab because the experiments were not compatible with Skylab hardware and timelines. Of the 19 remaining, 11 experiments required the manufacture of additional equipment. The equipment for the experiments was manufactured at MSFC.

iss061e144253 (Jan. 25, 2020) --- NASA astronaut Andrew Morgan is pictured tethered to the International Space Station while finalizing thermal repairs on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a dark matter and antimatter detector, during a spacewalk that lasted 6 hours and 16 minutes.

This image is an artist's conception of the Pegasus, meteoroid detection satellite, in orbit with meteoroid detector extended. The satellite, a payload for Saturn I SA-8, SA-9, and SA-10 missions, was used to obtain data on frequency and penetration of the potentially hazardous micrometeoroids in low Earth orbits and to relay the information back to Earth.

iss061e058254 (Nov. 22, 2019) ---- Astronaut Andrew Morgan of NASA, whose U.S. spacesuit is outfitted with a variety of tools and cameras, holds on to a handrail during the second spacewalk to repair the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer.

iss061e144323 (Jan. 25, 2020) --- NASA astronaut Andrew Morgan is pictured tethered to the International Space Station while finalizing thermal repairs on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a dark matter and antimatter detector, during a spacewalk that lasted 6 hours and 16 minutes.

iss061e143462 (Jan. 25, 2020) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Luca Parmitano is pictured tethered to the International Space Station while finalizing thermal repairs on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a dark matter and antimatter detector, during a spacewalk that lasted 6 hours and 16 minutes.

iss061e143622 (Jan. 25, 2020) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Luca Parmitano is pictured tethered to the International Space Station while finalizing thermal repairs on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a dark matter and antimatter detector, during a spacewalk that lasted 6 hours and 16 minutes.

iss061e033522 (Nov. 11, 2019) --- NASA astronaut Jessica Meir reviews robotics procedures in the U.S. Destiny laboratory module. She will operate the Canadarm2 robotic arm to support a series of spacewalks by astronauts Luca Parmitano and Andrew Morgan to repair the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS).

iss061e038284 (Nov. 12, 2019) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Luca Parmitano tests the usage of specialized spacewalking tools while wearing U.S. spacesuit gloves. The tools were designed specifically for the complex repair work planned for the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer.

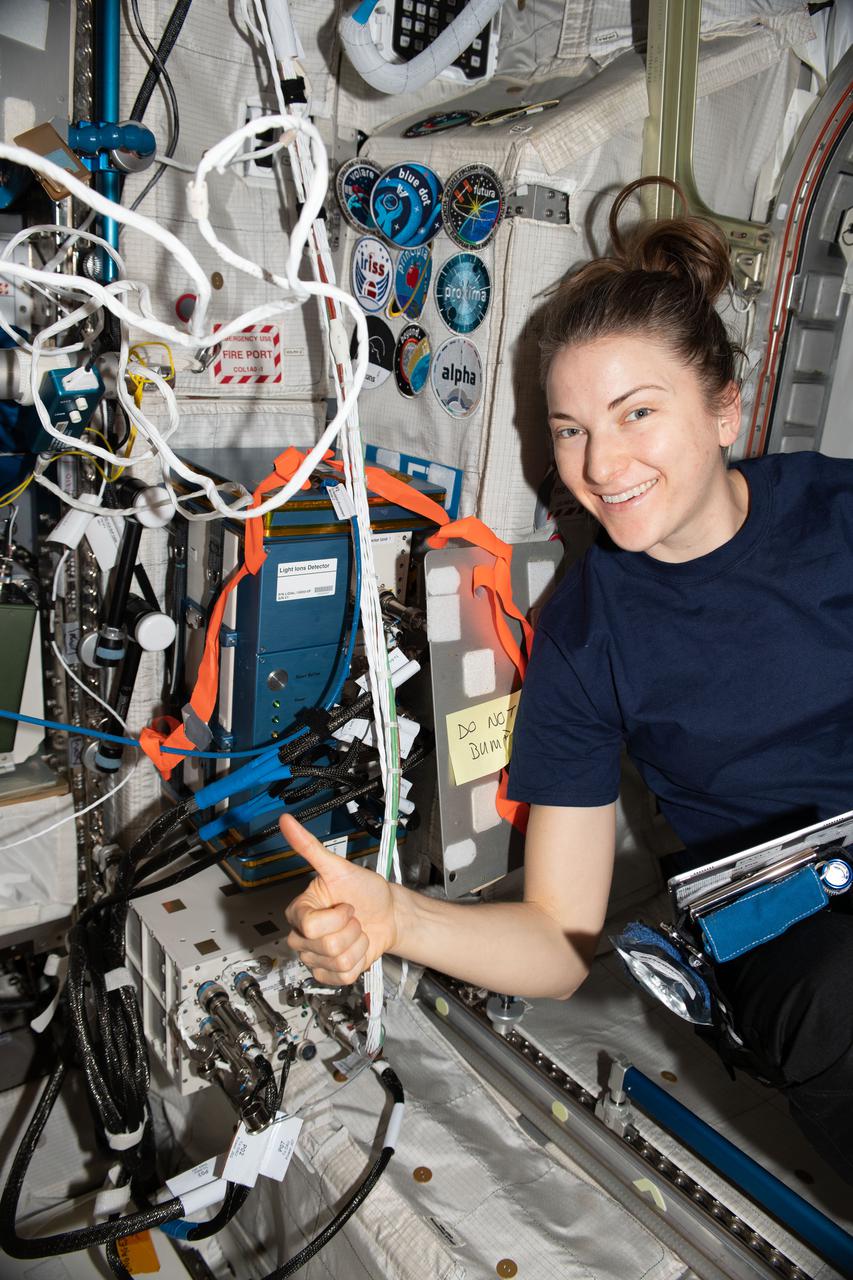

iss067e032549 (May 2, 2022) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 67 Flight Engineer Kayla Barron begins her work day inside the International Space Station's Columbus laboratory module. She gives a "thumbs up" and poses next to the Light Ions Detector that monitors the radiation environment aboard the orbiting lab.

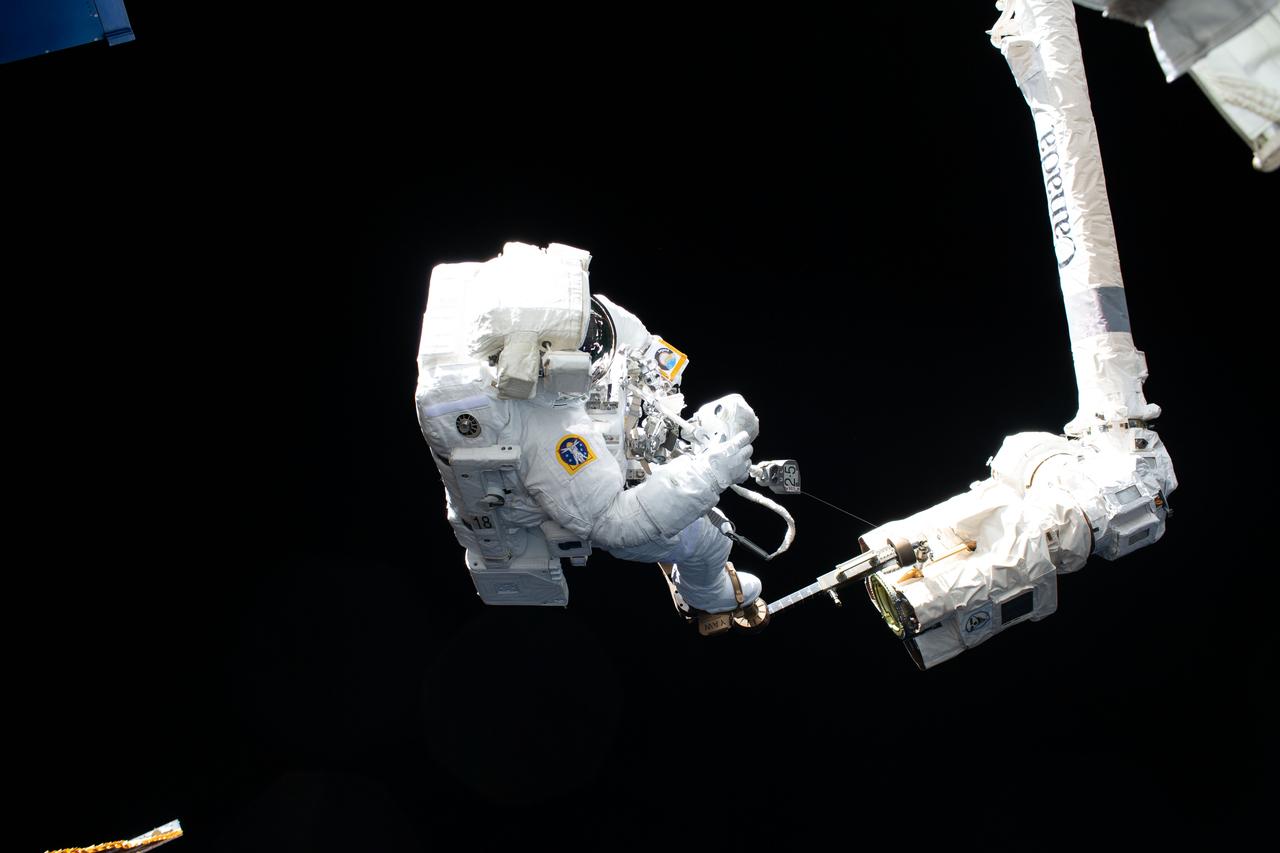

iss061e045275 (Nov. 15, 2019) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Luca Parmitano is pictured attached to the Canadarm2 robotic arm during the first spacewalk to repair the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector.

iss061e037472 (Nov. 12, 2019) --- Expedition 61 crewmembers (from left) Andrew Morgan, Jessica Meir, Luca Parmitano and Christina Koch gather inside the U.S. Destiny laboratory module to review spacewalk procedures for the complex repair work planned for the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer.

iss061e040949 (Nov. 15, 2019) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Luca Parmitano takes an out-of-this-world "space-selfie" with his spacesuit's helmet visor up during the first spacewalk to repair the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector.

iss061e040844 (Nov. 15, 2019) --- NASA astronaut Andrew Morgan waves as he is photographed seemingly camouflaged among the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (lower left) and other International Space Station hardware during the first spacewalk to repair the cosmic particle detector.

The High Altitude Lidar Observatory (HALO) instrument head, which houses the lidar instrument, is installed onto the DC-8 airborne science laboratory at NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The gold and blue casing holds the laser, optics, detectors, and electronics, which are at the heart of the lidar.

iss061e040912 (Nov. 15, 2019) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Luca Parmitano takes an out-of-this-world "space-selfie" with his spacesuit's helmet visor down during the first spacewalk to repair the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector.

iss061e033521 (Nov. 11, 2019) --- Astronauts Luca Parmitano (left) and Andrew Morgan review robotics procedures in the U.S. Destiny laboratory module. Astronaut Jessica Meir will operate the Canadarm2 robotic arm to support the duo during a series of spacewalks to repair the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS).

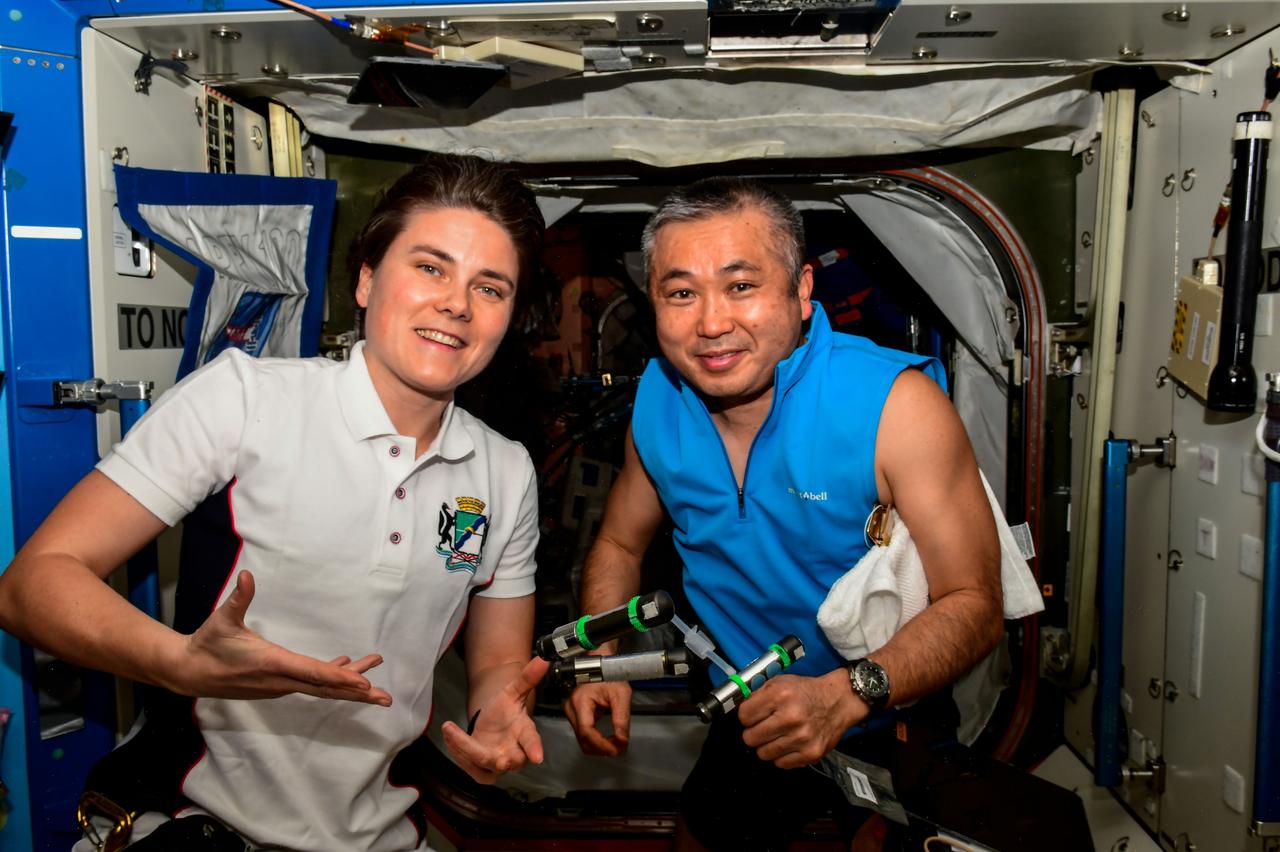

iss068e041017 (Jan. 19, 2023) --- Expedition 68 Flight Engineers Anna Kikina of Roscosmos and Koichi Wakata of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) pose together with dosimeters, or radiation detectors, floating weightlessly in the microgravity environment of the International Space Station. Credit: Roscosmos

iss061e065188 (Dec. 2, 2019) --- The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) is a cosmic particle detector attached to the International Space Station's Starboard Truss-3 structure and undergoing repairs to its thermal pump system during a series of spacewalks with astronauts Andrew Morgan and Luca Parmitano.

iss061e064794 (Dec. 2, 2019) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Luca Parmitano, attached to the Canadarm2 robotic arm, carries the new thermal pump system that was installed on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) during the third spacewalk to upgrade the AMS, the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector.

iss061e142964 (Jan. 25, 2020) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Luca Parmitano is pictured tethered to the International Space Station while finalizing thermal repairs on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a dark matter and antimatter detector, during a spacewalk that lasted 6 hours and 16 minutes.

iss061e058754 (Nov. 22, 2019) --- Astronaut Luca Parmitano of ESA (European Space Agency) is pictured holding a camera protected from the hazards of microgravity by shielding during the second spacewalk to repair the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer.

iss061e143112 (Jan. 25, 2020) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut Luca Parmitano is pictured attached to the Canadarm2 robotic arm while finalizing thermal repairs on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, a dark matter and antimatter detector, during a spacewalk that lasted 6 hours and 16 minutes.

iss061e057607 (Nov. 22, 2019) --- Astronaut Luca Parmitano of ESA (European Space Agency) takes an out-of-this-world "space-selfie" with his spacesuit's helmet visor down during the second spacewalk to repair the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer.

iss061e058345 (Nov. 22, 2019) --- NASA astronaut and spacewalker Andrew Morgan takes an out-of-this-world "space-selfie" with his spacesuit's helmet visor down during the second spacewalk to repair the International Space Station's cosmic particle detector, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer.