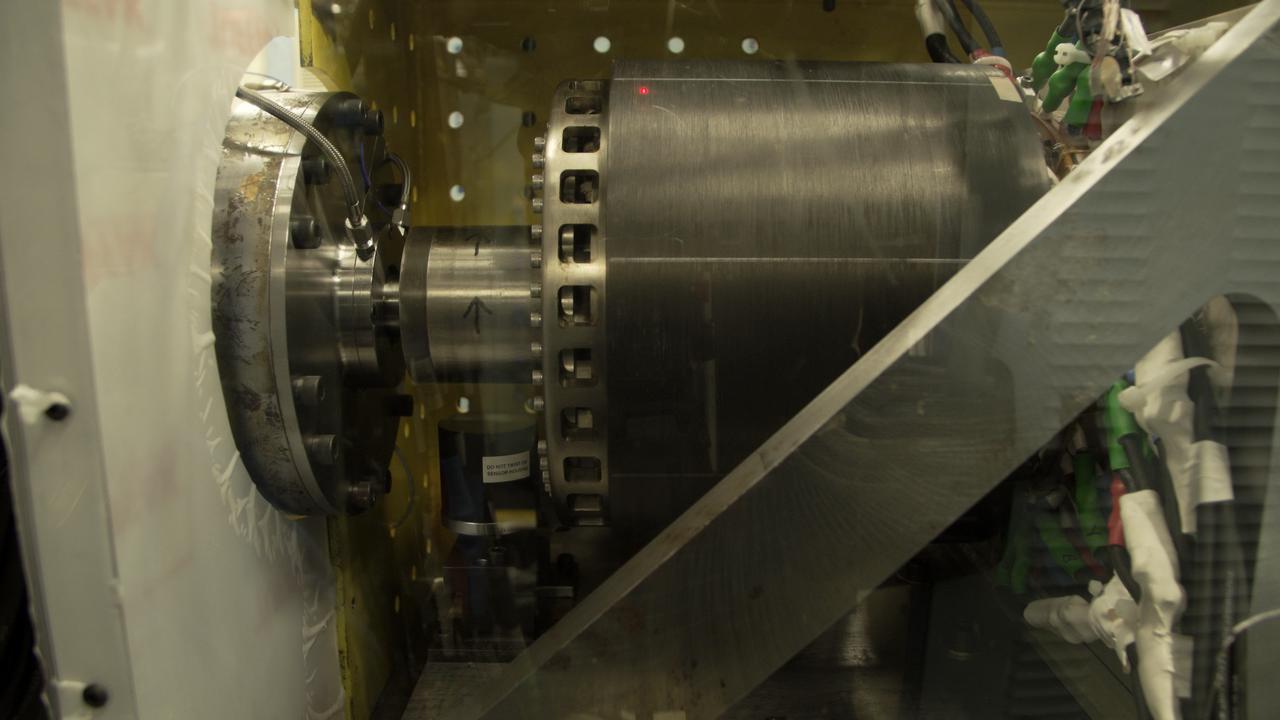

UIUC’s megawatt machine (right) was connected to a dynamometer (left) to test its effectiveness as an electric generator in a safety enclosure at a Collins Aerospace test facility in Rockford, Illinois. This unusual design has its rotating parts on the outside, so that both the cylinder on the right and the cylinder with arrows spin during operation.

Deputy Administrator Pam Melroy tours the General Electric exhibit on Friday, July 29, 2022 at EAA AirVenture.

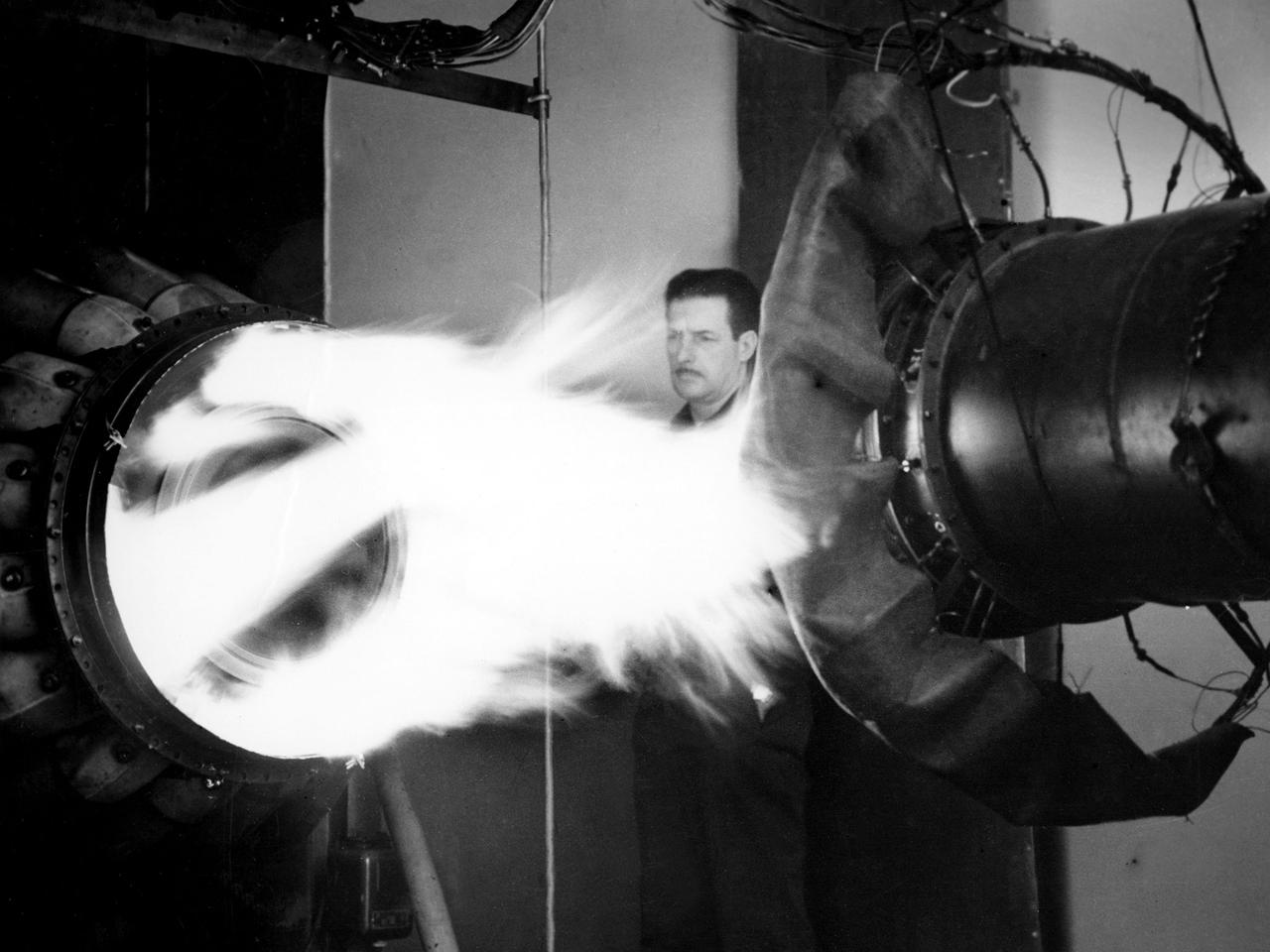

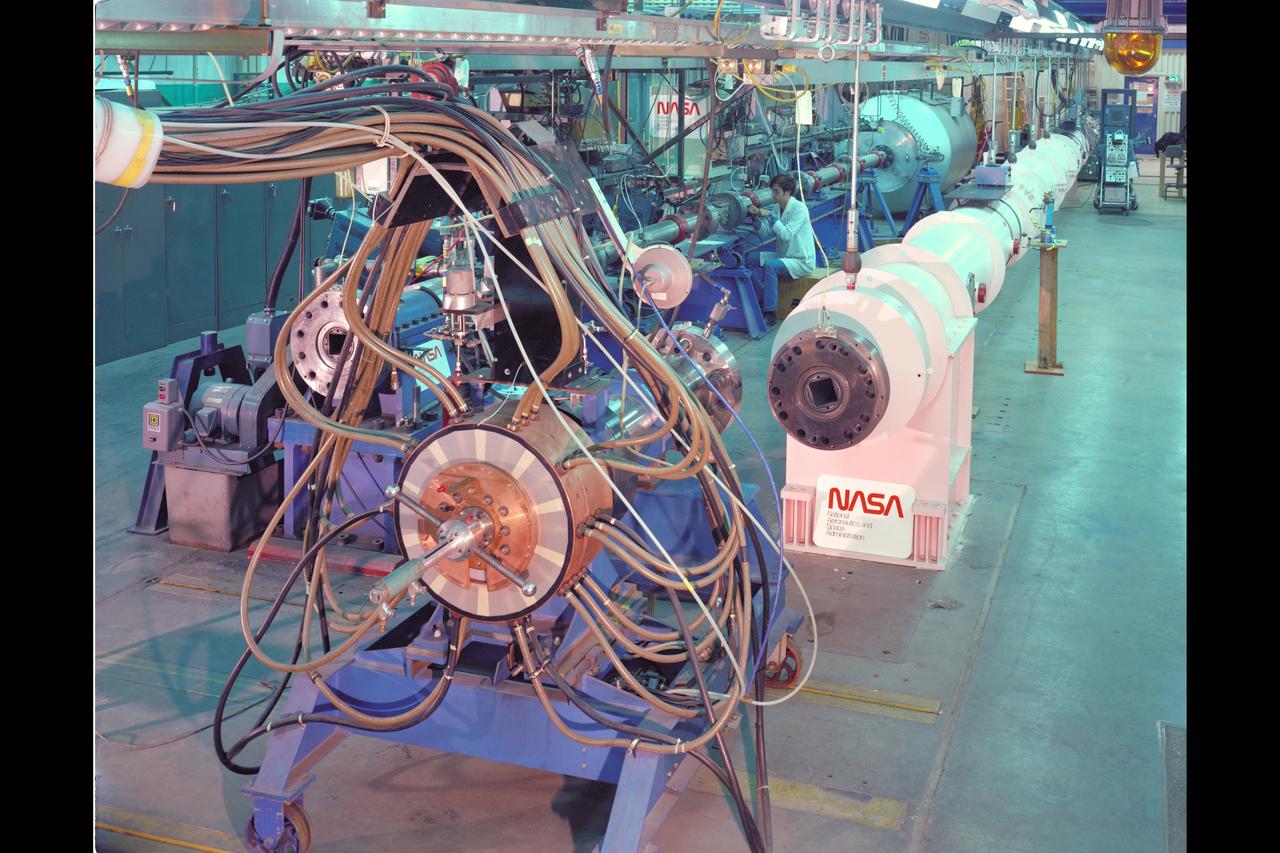

A mechanic watches the firing of a General Electric I-40 turbojet at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. The military selected General Electric’s West Lynn facility in 1941 to secretly replicate the centrifugal turbojet engine designed by British engineer Frank Whittle. General Electric’s first attempt, the I-A, was fraught with problems. The design was improved somewhat with the subsequent I-16 engine. It was not until the engine's next reincarnation as the I-40 in 1943 that General Electric’s efforts paid off. The 4000-pound thrust I-40 was incorporated into the Lockheed Shooting Star airframe and successfully flown in June 1944. The Shooting Star became the US’s first successful jet aircraft and the first US aircraft to reach 500 miles per hour. NACA Lewis studied all of General Electric’s centrifugal turbojet models during the 1940s. In 1945 the entire Shooting Star aircraft was investigated in the Altitude Wind Tunnel. Engine compressor performance and augmentation by water injection; comparison of different fuel blends in a single combustor; and air-cooled rotors were studied. The mechanic in this photograph watches the firing of a full-scale I-40 in the Jet Propulsion Static Laboratory. The facility was quickly built in 1943 specifically in order to test the early General Electric turbojets. The I-A was secretly analyzed in the facility during the fall of 1943.

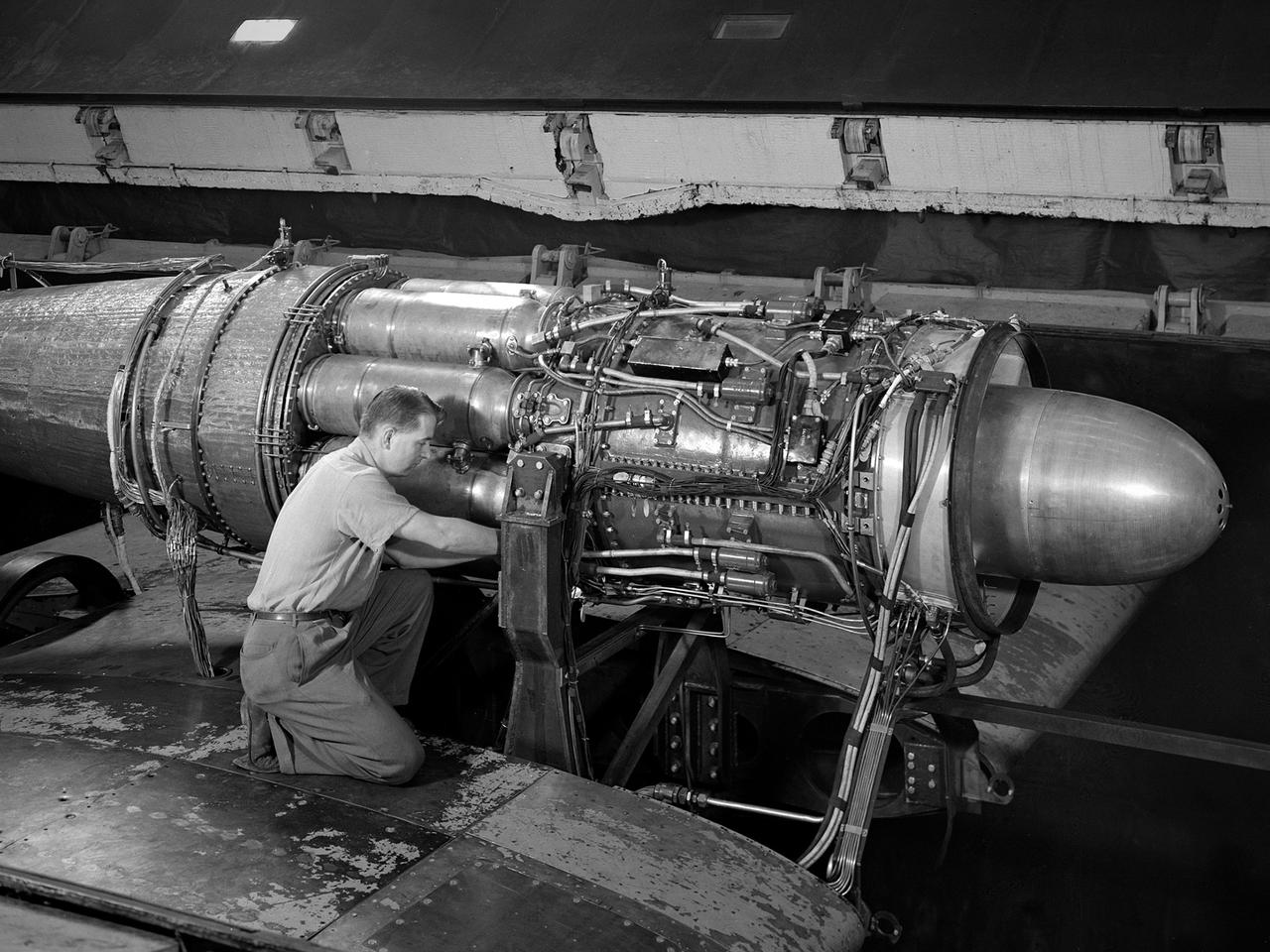

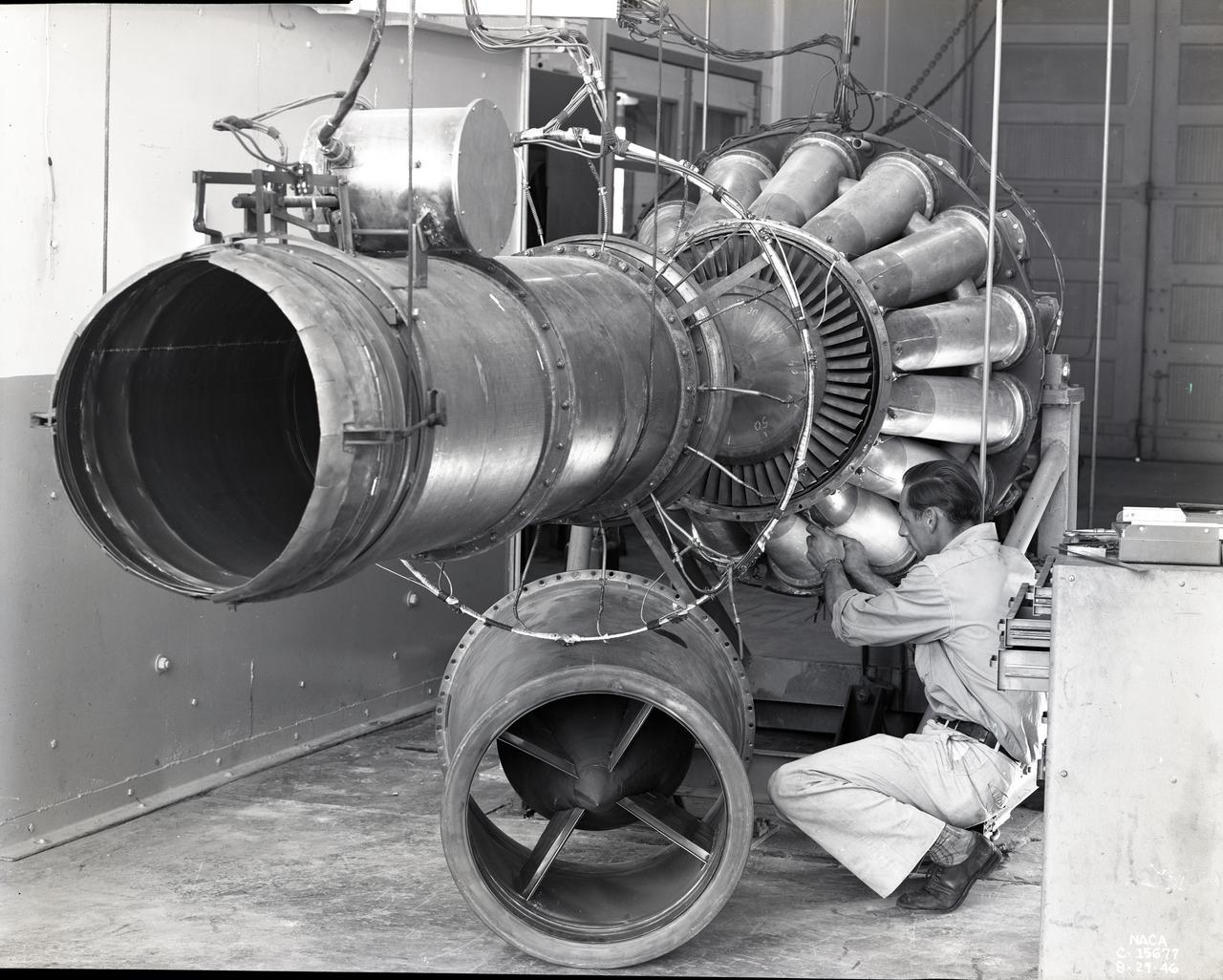

A mechanic works on a General Electric I-40 turbojet at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. The military selected General Electric’s West Lynn facility in 1941 to secretly replicate the centrifugal turbojet engine designed by British engineer Frank Whittle. General Electric’s first attempt, the I-A, was fraught with problems. The design was improved somewhat with the subsequent I-16 engine. It was not until the engine's next reincarnation as the I-40 in 1943 that General Electric’s efforts paid off. The 4000-pound thrust I-40 was incorporated into the Lockheed Shooting Star airframe and successfully flown in June 1944. The Shooting Star became the US’s first successful jet aircraft and the first US aircraft to reach 500 miles per hour. The NACA’s Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory studied all of General Electric’s centrifugal turbojets both during World War II and afterwards. The entire Shooting Star aircraft was investigated in the Altitude Wind Tunnel during 1945. The researchers studied the engine compressor performance, thrust augmentation using a water injection, and compared different fuel blends in a single combustor. The mechanic in this photograph is inserting a combustion liner into one of the 14 combustor cans. The compressor, which is not yet installed in this photograph, pushed high pressure air into these combustors. There the air mixed with the fuel and was heated. The hot air was then forced through a rotating turbine that powered the engine before being expelled out the nozzle to produce thrust.

3/4 front view VZ-11 ground test - variable height struts. Engines of the VZ-11 are a pair of General Electric J85-5 turbojets, mounted in high in the centre fuselage, well away from fan disturbance. Designed in the Ames 40x80 foot wind tunnel.

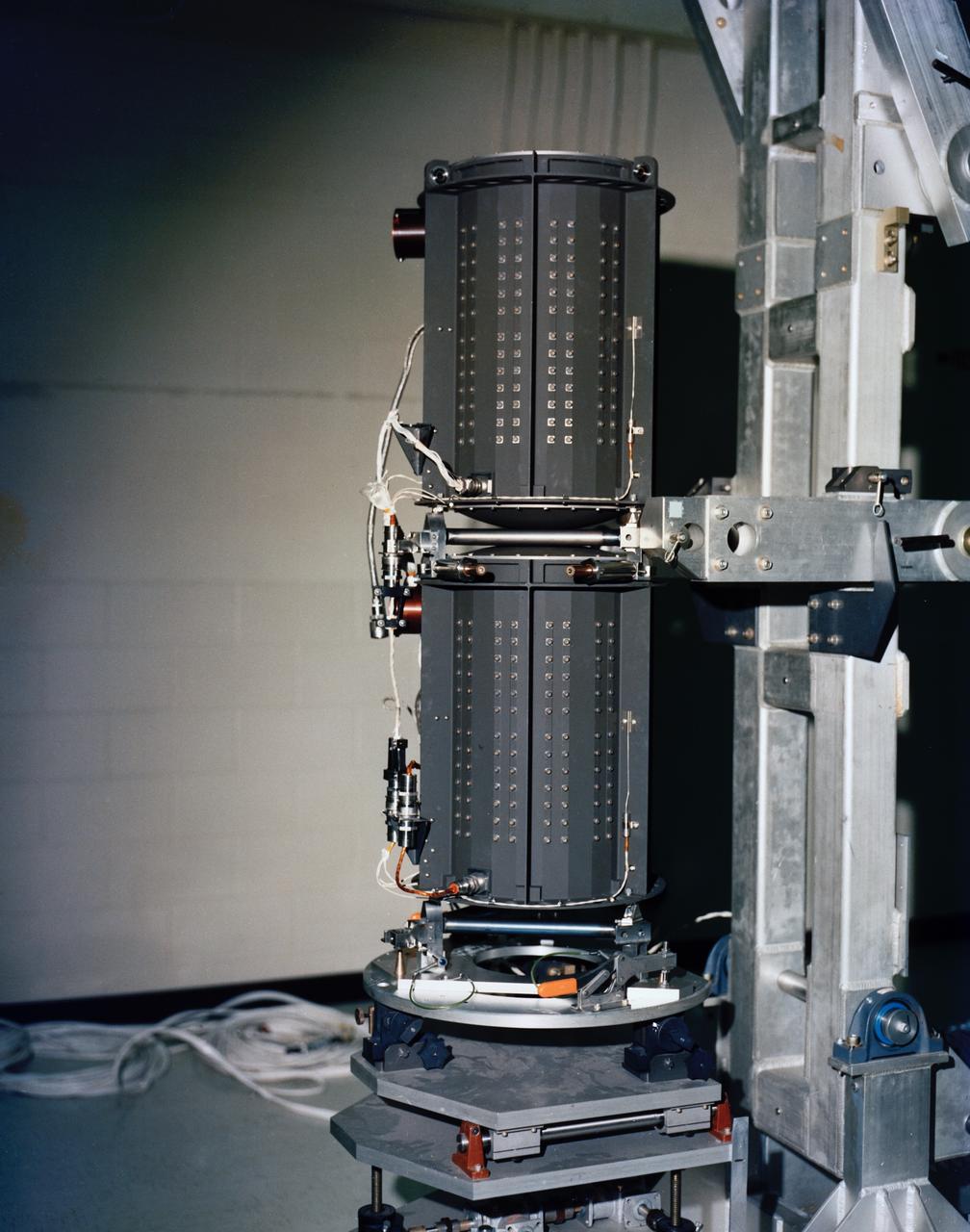

A General Electric TG-180 turbojet installed in the Altitude Wind Tunnel at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. In 1943 the military asked General Electric to develop an axial-flow jet engine which became the TG-180. The military understood that the TG-180 would not be ready during World War II but recognized the axial-flow compressor’s long-term potential. Although the engine was bench tested in April 1944, it was not flight tested until February 1946. The TG-180 was brought to the Altitude Wind Tunnel in 1945 for a series of investigations. The studies, which continued intermittently into 1948, analyzed an array of performance issues. NACA modifications steadily improved the TG-180’s performance, including the first successful use of an afterburner. The Lewis researchers studied a 29-inch diameter afterburner over a range of altitude conditions using several different types of flameholders and fuel systems. Lewis researchers concluded that a three-stage flameholder with its largest stage upstream was the best burner configuration. Although the TG-180 (also known as the J35) was not the breakthrough engine that the military had hoped for, it did power the Douglas D-558-I Skystreak to a world speed record on August 20, 1947. The engines were also used on the Republic F-84 Thunderjet and the Northrup F-89 Scorpion.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Convair F-106B Delta Dart with a 32-spoke nozzle installed on its General Electric J85 test engine. Lewis acquired a Delta Dart fighter in 1966 to study the components for propulsion systems that could be applied to supersonic transport aircraft at transonic speeds. The F-106B was modified with two General Electric J85-13 engines under its wings to study these components. The original test plan was expanded to include the study of boattail drag, noise reduction, and inlets. From February to July 1971 the modified F-106B was used to study different ejector nozzles. Researchers conducted both acoustic and aerodynamic tests on the ground and in flight. Several models were created to test different suppression methods. NASA Lewis’ conical nozzle was used as the baseline configuration. Flightline and sideline microphones were set up on the ground. The F-106B would idle its own engine and buzz the recording station from an altitude of 300 feet at Mach 0.4 with the test engines firing. Researchers found that the suppression of the perceived noise level was usually lower during flight than the researchers had statistically predicted. The 64 and 32-spoke nozzles performed well in actual flight, but the others nozzles tended to negatively affect the engine’s performance. Different speeds or angles- -of-attack sometimes changed the noise levels. In the end, no general conclusions could be applied to all the nozzles.

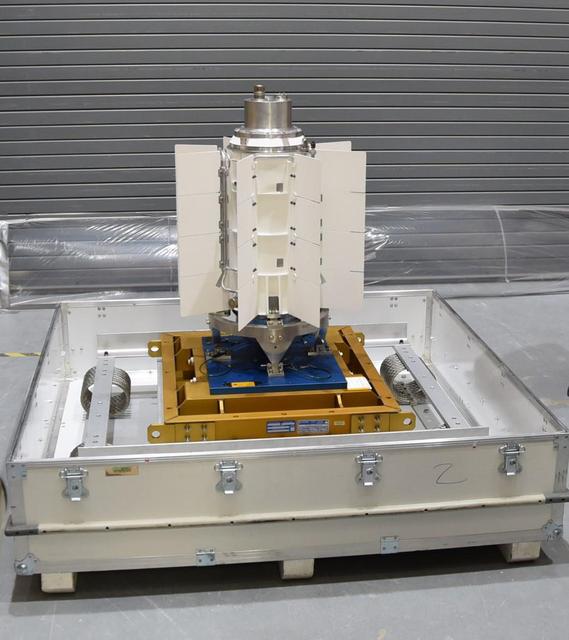

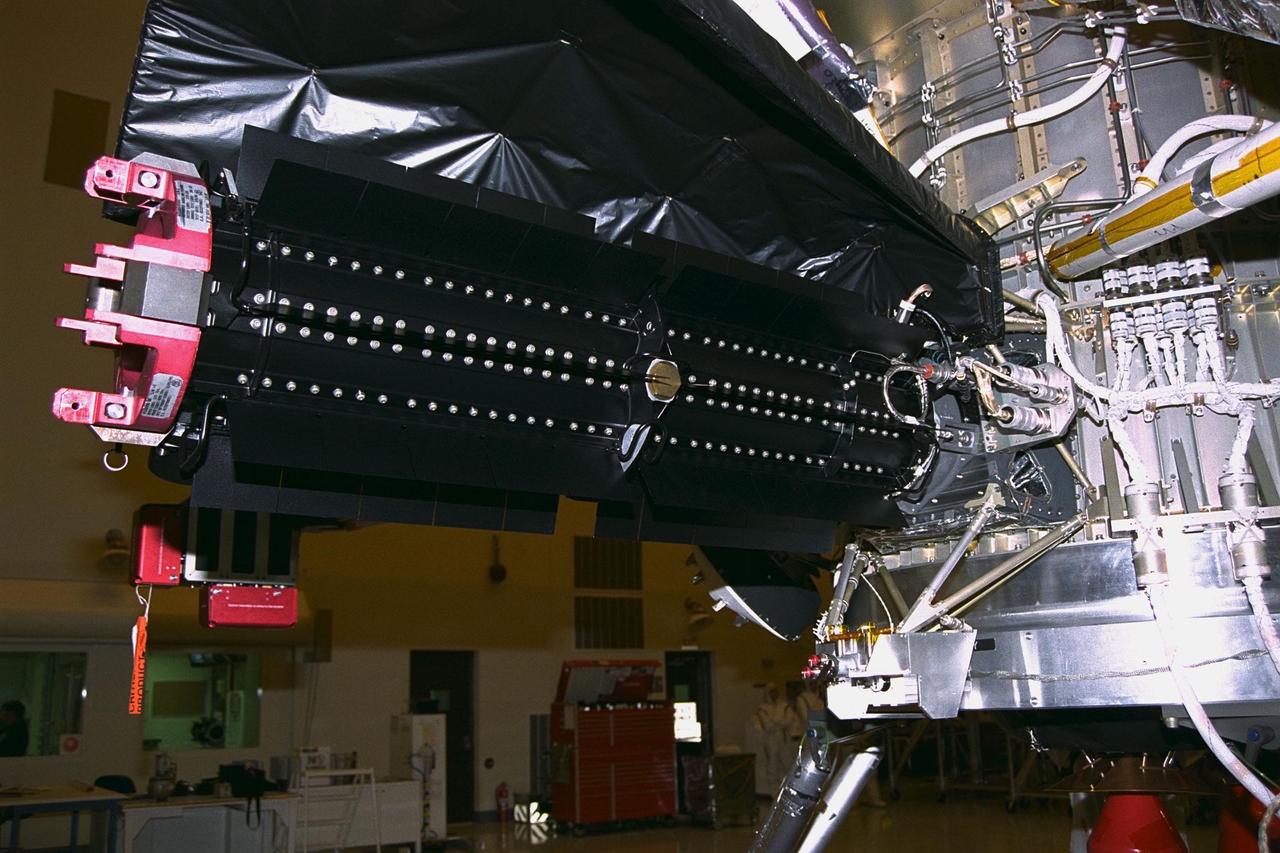

The electricity for NASA's Mars 2020 rover is provided by a power system called a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator, or MMRTG. Essentially a nuclear battery, an MMRTG uses the heat from the natural radioactive decay of plutonium-238 to generate about 110 watts of electricity at the start of a mission. Besides generating electrical power, the MMRTG produces heat. Some of this heat can be used to maintain the rover's systems at the proper operating temperatures in the frigid cold of space and on the surface of Mars. This device, seen here before fueling and testing at the U.S. Department of Energy's Idaho National Laboratory, has "fins" that radiate excess heat. MMRTGs are provided to NASA for civil space applications by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). The radioisotope fuel is inserted into the MMRTG at the DOE's Idaho National Laboratory before the MMRTG is shipped to the launch site. Electrically heated versions of the MMRTG are used at JPL to verify and practice integration of the power system with the rover. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23306

A General Electric TG-100A seen from the rear in the test section of the Altitude Wind Tunnel at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio. The Altitude Wind Tunnel was used to study almost every model of US turbojet that emerged in the 1940s, as well as some ramjets and turboprops. In the early 1940s the military was interested in an engine that would use less fuel than the early jets but would keep up with them performance-wise. Turboprops seemed like a plausible solution. They could move a large volume of air and thus required less engine speed and less fuel. Researchers at General Electric’s plant in Schenectady, New York worked on the turboprop for several years in the 1930s. They received an army contract in 1941 to design a turboprop engine using an axial-flow compressor. The result was the 14-stage TG-100, the nation's first turboprop aircraft engine. Development of the engine was slow, however, and the military asked NACA Lewis to analyze the engine’s performance. The TG-100A was tested in the Altitude Wind Tunnel and it was determined that the compressors, combustion chamber, and turbine were impervious to changes in altitude. The researchers also established the optimal engine speed and propeller angle at simulated altitudes up to 35,000 feet. Despite these findings, development of the TG-100 was cancelled in May 1947. Twenty-eight of the engines were produced, but they were never incorporated into production aircraft.

NASA’s all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA’s first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA’s all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA’s first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA’s all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA’s first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA’s all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA’s first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA’s all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA’s first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASAâ's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA’s all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA’s first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA's first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

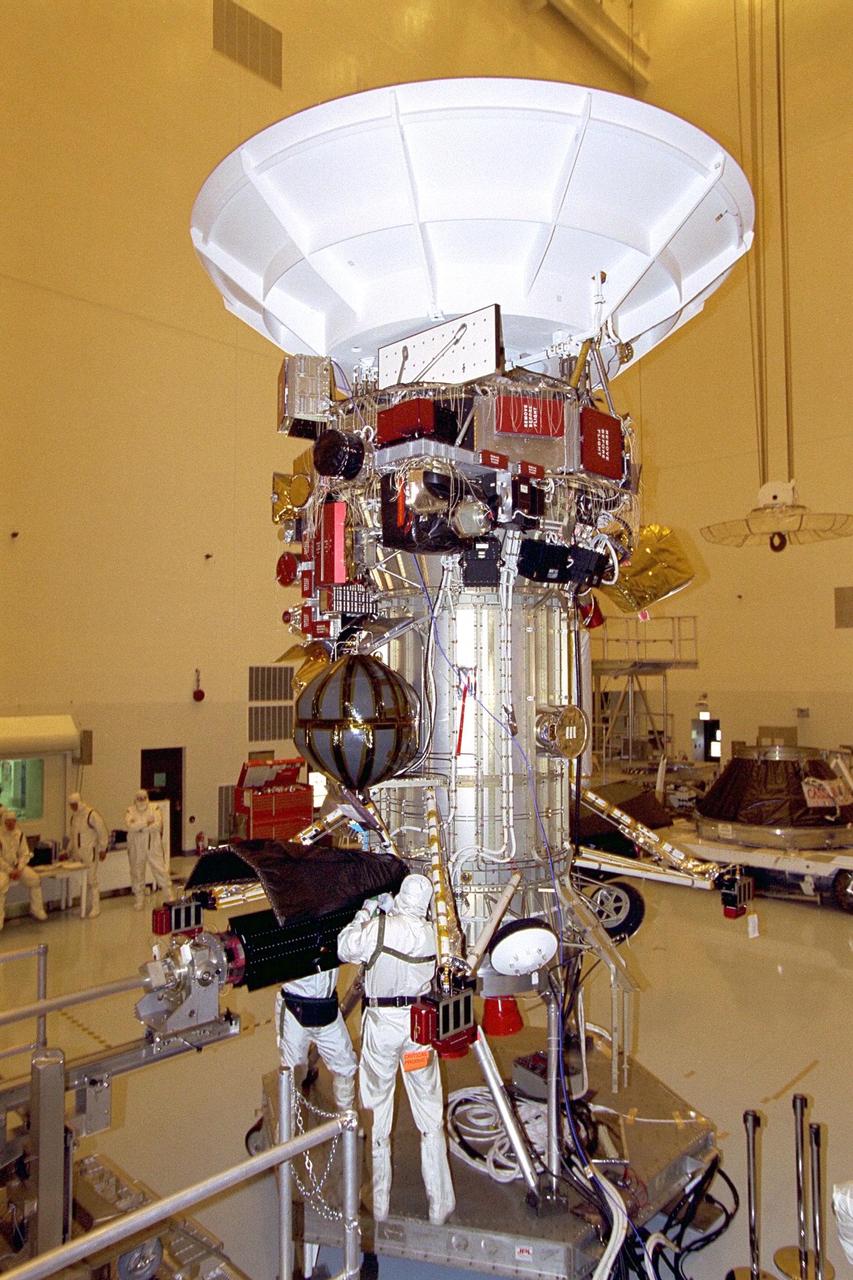

The electricity needed to operate NASA's Mars 2020 rover is provided by a power system called a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator, or MMRTG. The MMRTG will be inserted into the aft end of the rover between the panels with gold tubing visible at the rear, which are called heat exchangers. Essentially a nuclear battery, an MMRTG uses the heat from the natural radioactive decay of plutonium-238 to generate about 110 watts of electricity at the start of a mission. Besides generating useful electrical power, the MMRTG produces heat. Some of this heat can be used to maintain the rover's systems at the proper operating temperatures in the frigid cold of space and on the surface of Mars. Some of it is rejected into space via the rover's Heat Rejection System. The gold-colored tubing on the heat exchangers form part of the cooling loops of that system. The tubes carry a fluid coolant called Trichlorofluoromethane (CFC-11) that helps dissipate the excess heat. The same tubes are used to pipe some of the heat back into the belly of the rover. MMRTGs are provided to NASA for civil space applications by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). The radioisotope fuel is inserted into the MMRTG at the DOE's Idaho National Laboratory before the MMRTG is shipped to the launch site. Electrically heated versions of the MMRTG are used at JPL to verify and practice integration of the power system with the rover. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23305

NASA’s all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, departs Scaled Composites’ facility at Mojave Air and Space Port, en route to NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California for delivery. The aircraft, shipped as two parts – the fuselage and the wing – was delivered to NASA Armstrong’s Research Aircraft Integration Facility, where it will be reintegrated to begin ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57’s Mod II configuration, the first of three primary modifications for the project, involves testing of the aircraft’s cruise electric propulsion system. The goal of the X-57 project is to share the aircraft’s electric-propulsion-focused design and airworthiness process with regulators, to advance certification approaches for distributed electric propulsion in general aviation.

NASA’s all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, departs Scaled Composites’ facility at Mojave Air and Space Port, en route to NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California for delivery. The aircraft, shipped as two parts – the fuselage and the wing – was delivered to NASA Armstrong’s Research Aircraft Integration Facility, where it will be reintegrated to begin ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57’s Mod II configuration, the first of three primary modifications for the project, involves testing of the aircraft’s cruise electric propulsion system. The goal of the X-57 project is to share the aircraft’s electric-propulsion-focused design and airworthiness process with regulators, to advance certification approaches for distributed electric propulsion in general aviation.

NASA's all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, departs Scaled Composites' facility at Mojave Air and Space Port, en route to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California for delivery. The aircraft, shipped as two parts - the fuselage and the wing - was delivered to NASA Armstrong's Research Aircraft Integration Facility, where it will be reintegrated to begin ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's Mod II configuration, the first of three primary modifications for the project, involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. The goal of the X-57 project is to share the aircraft's electric-propulsion-focused design and airworthiness process with regulators, to advance certification approaches for distributed electric propulsion in general aviation.

NASA’s all-electric X-57 Maxwell, in its Mod II configuration, arrives at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California. The X-plane was delivered by prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, in two parts, with the wing separated from the fuselage, to aid in a more timely delivery. X-57 is NASA’s first crewed X-plane in two decades, and seeks to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA’s X-57 Maxwell, the agency’s first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft’s cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57’s goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA’s X-57 Maxwell, the agency’s first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft’s cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57’s goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA’s X-57 Maxwell, the agency’s first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft’s cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57’s goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA’s X-57 Maxwell, the agency’s first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft’s cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57’s goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA’s X-57 Maxwell, the agency’s first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft’s cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57’s goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA’s X-57 Maxwell, the agency’s first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft’s cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57’s goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA's X-57 Maxwell, the agency's first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft's cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57's goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

NASA’s X-57 Maxwell, the agency’s first all-electric X-plane and first crewed X-planed in two decades, is delivered to NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California in its Mod II configuration. The first of three primary modifications for the project, Mod II involves testing of the aircraft’s cruise electric propulsion system. Delivery to NASA from prime contractor Empirical Systems Aerospace of San Luis Obispo, California, marks a major milestone for the project, at which point the vehicle is reintegrated for ground tests, to be followed by taxi tests, and eventually, flight tests. X-57’s goal is to further advance the design and airworthiness process for distributed electric propulsion technology for general aviation aircraft, which can provide multiple benefits to efficiency, emissions, and noise.

Each of NASA's Voyager probes are equipped with three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), including the one shown here at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The RTGs provide power for the spacecraft by converting the heat generated by the decay of plutonium-238 into electricity. Launched in 1977, the Voyager mission is managed for NASA by the agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25782

REMOVAL OF GE - GENERAL ELECTRIC - DRIVERS

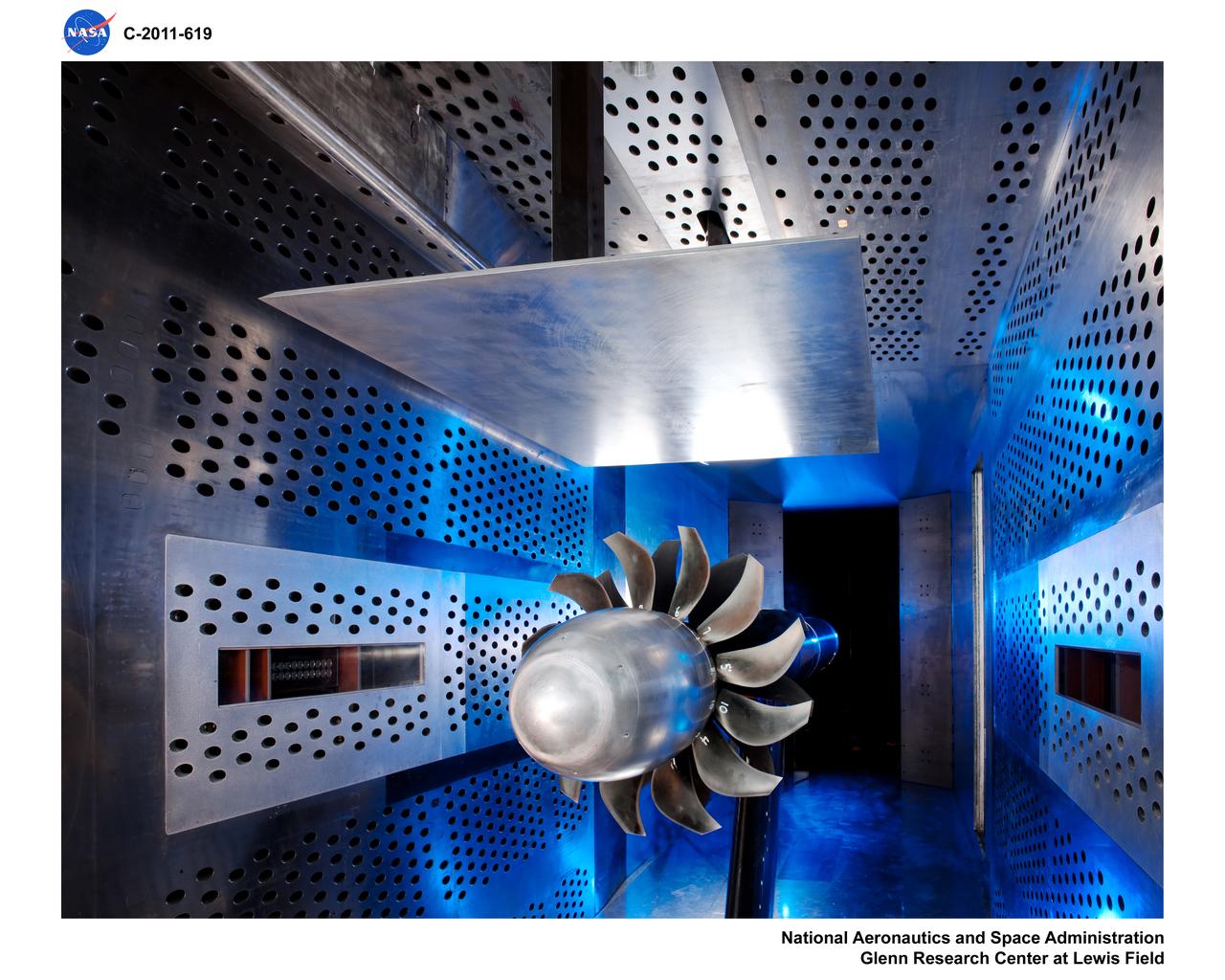

GENERAL ELECTRIC HIGH SPEED FAN

GENERAL ELECTRIC HIGH SPEED FAN

REMOVAL OF GE - GENERAL ELECTRIC - DRIVERS

GENERAL ELECTRIC GE 2 CUP SECTOR

G.E. Fan-in-fuselage model (lifting). 3/4 front view of fan at low G.P. position. Lift fan on variable height strut for ground effects studies. T-Tail

G.E fan-in-fuselage model (lifting) 3/4 front view of fan at low G.P. position

G.E. Fan-in-fuselage model (lifting). 3/4 rear view of fan at low G.P. position. Lift fan on variable height strut for ground effects studies with reaction control. T-Tail.

General Electric Aviation - Engine Splitter Booster Model in the Icing Research Tunnel

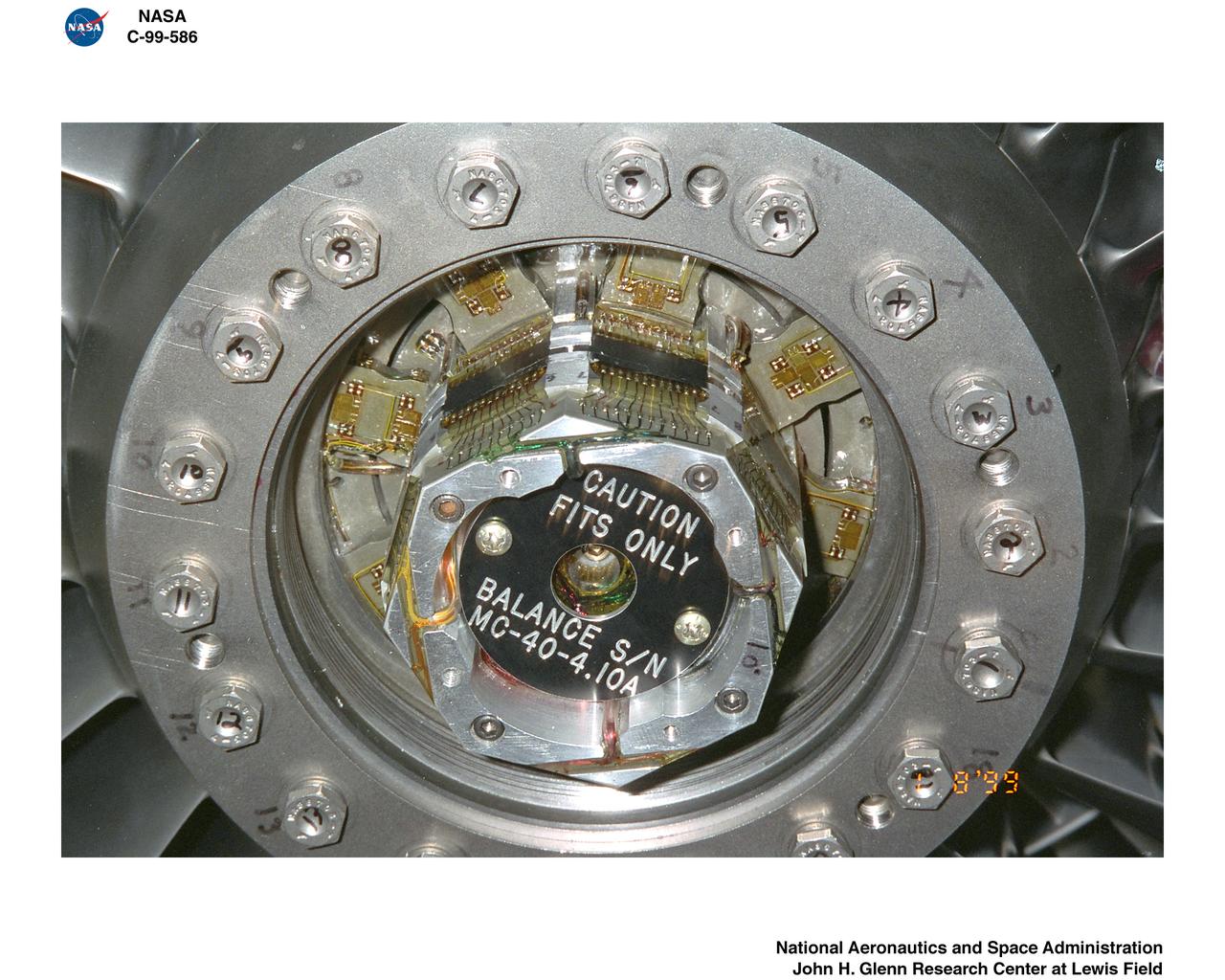

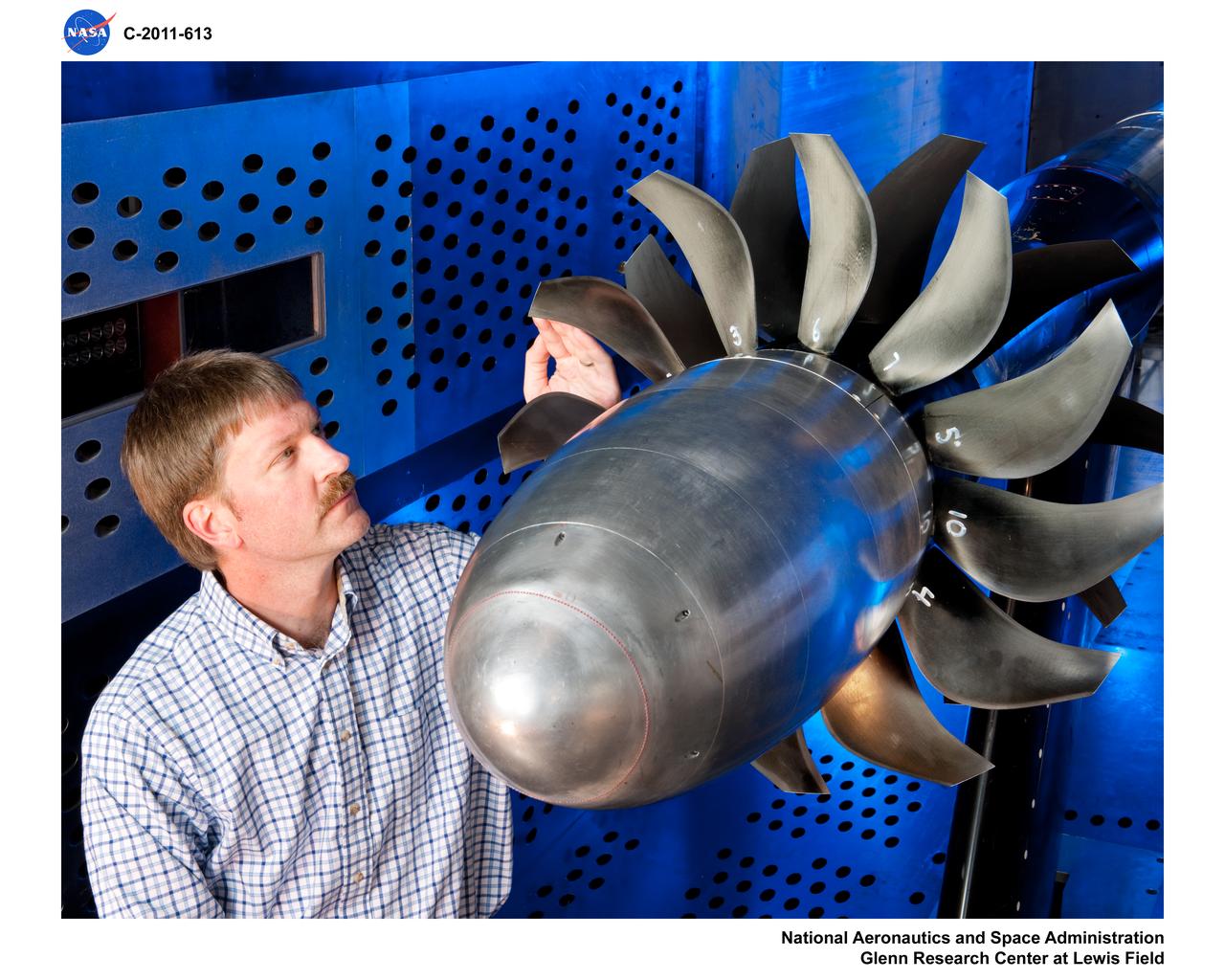

General Electric Open Rotor Model in the 8x6-Foot Supersonic Wind Tunnel

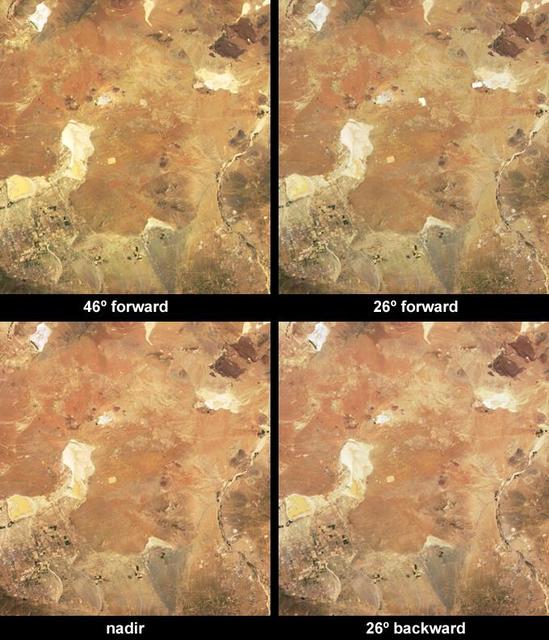

These images, from 8 April 2003 show that depending upon the position of the Sun, the solar power stations in California Mohave Desert can reflect solar energy from their large, mirror-like surfaces directly toward one of NASA Terra cameras.

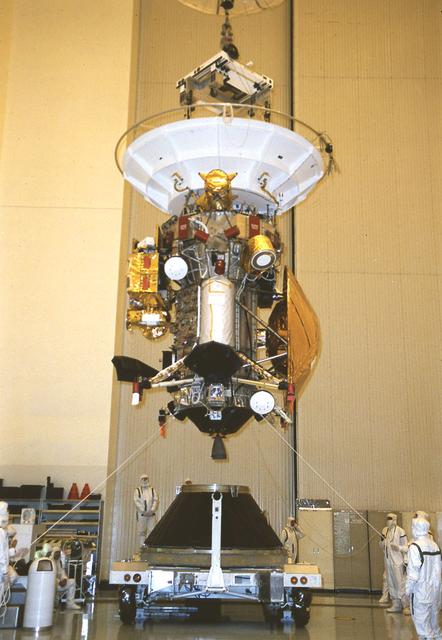

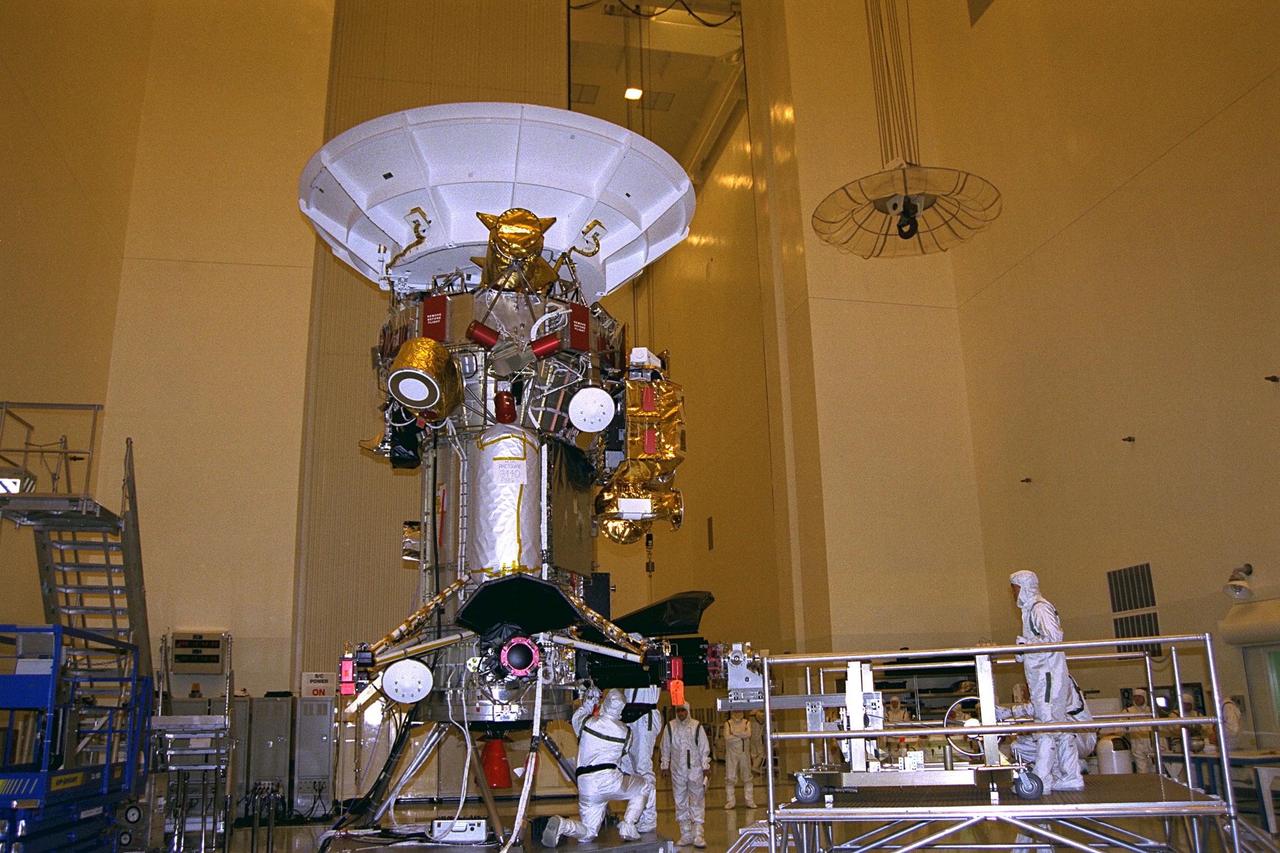

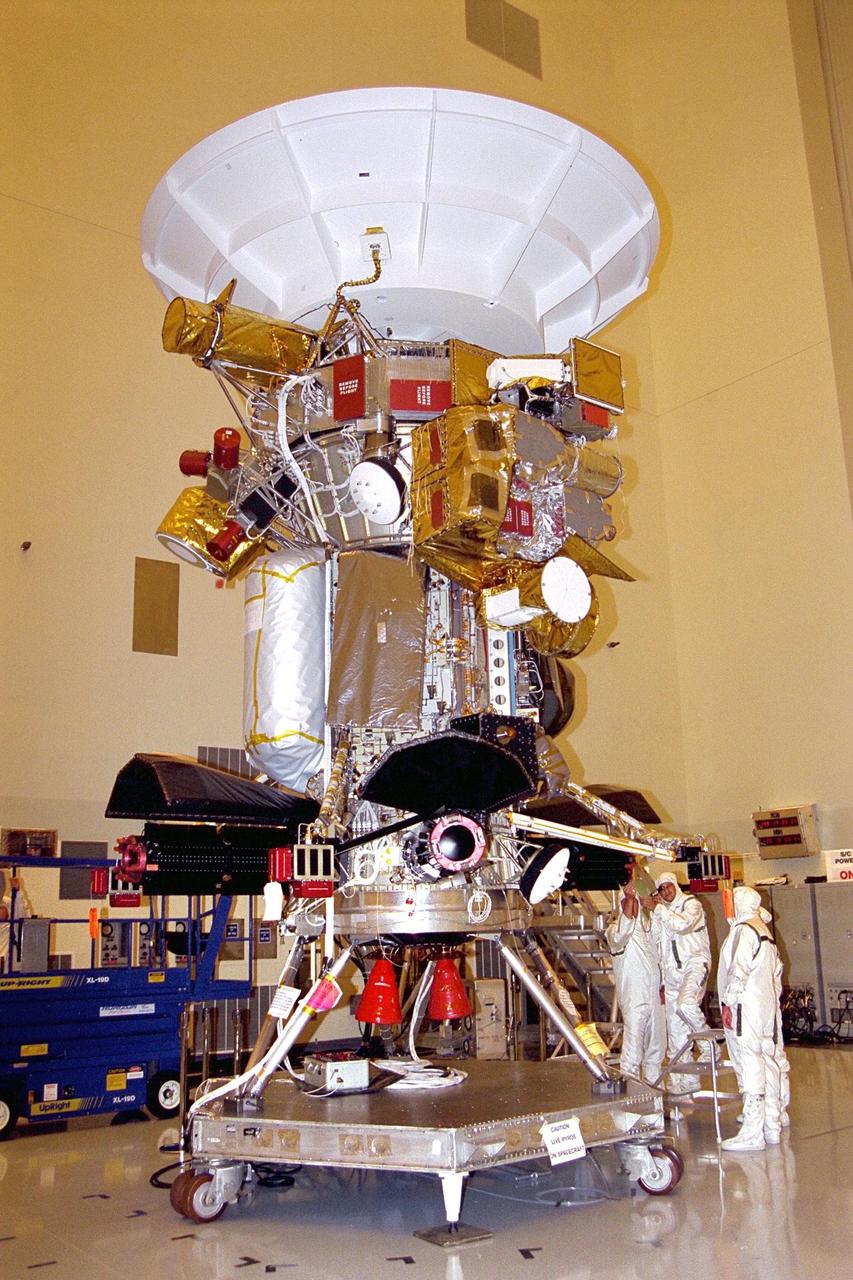

Workers in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility remove the storage collar from a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) in preparation for installation on the Cassini spacecraft. Cassini will be outfitted with three RTGs. The power units are undergoing mechanical and electrical verification tests in the PHSF. The RTGs will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate at great distances from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle

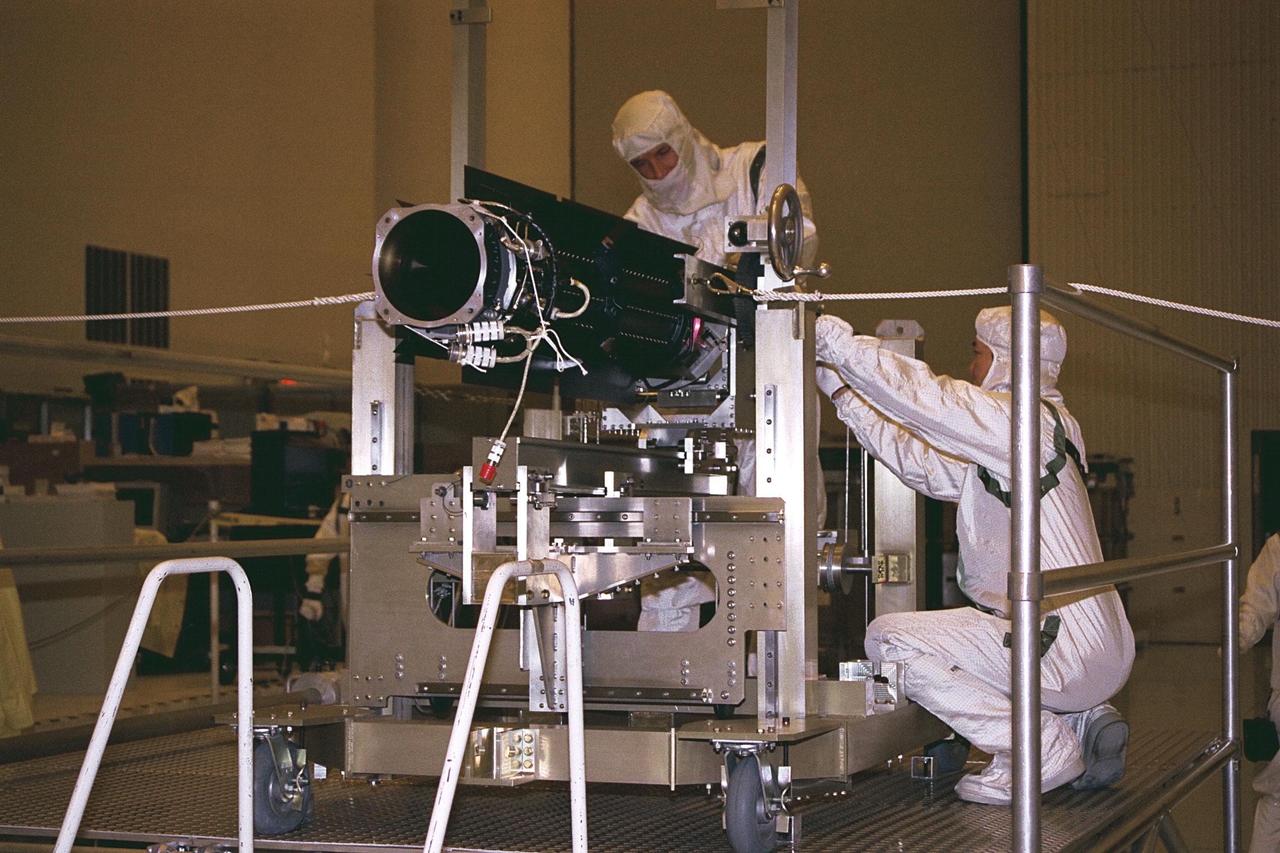

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) workers Dan Maynard and John Shuping prepare to install a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) on the Cassini spacecraft in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF). The three RTGs which will provide electrical power to Cassini on its mission to the Saturnian system are undergoing mechanical and electrical verification testing in the PHSF. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate far from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is scheduled for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed for NASA by JPL

Mechanic prepares a General Electric I-40 turbojet for testing (NASA C1946-15677).

Air-Breathing Propulsion - General Electric Open Rotor Model in the 8x6-Foot Supersonic Wind Tunnel

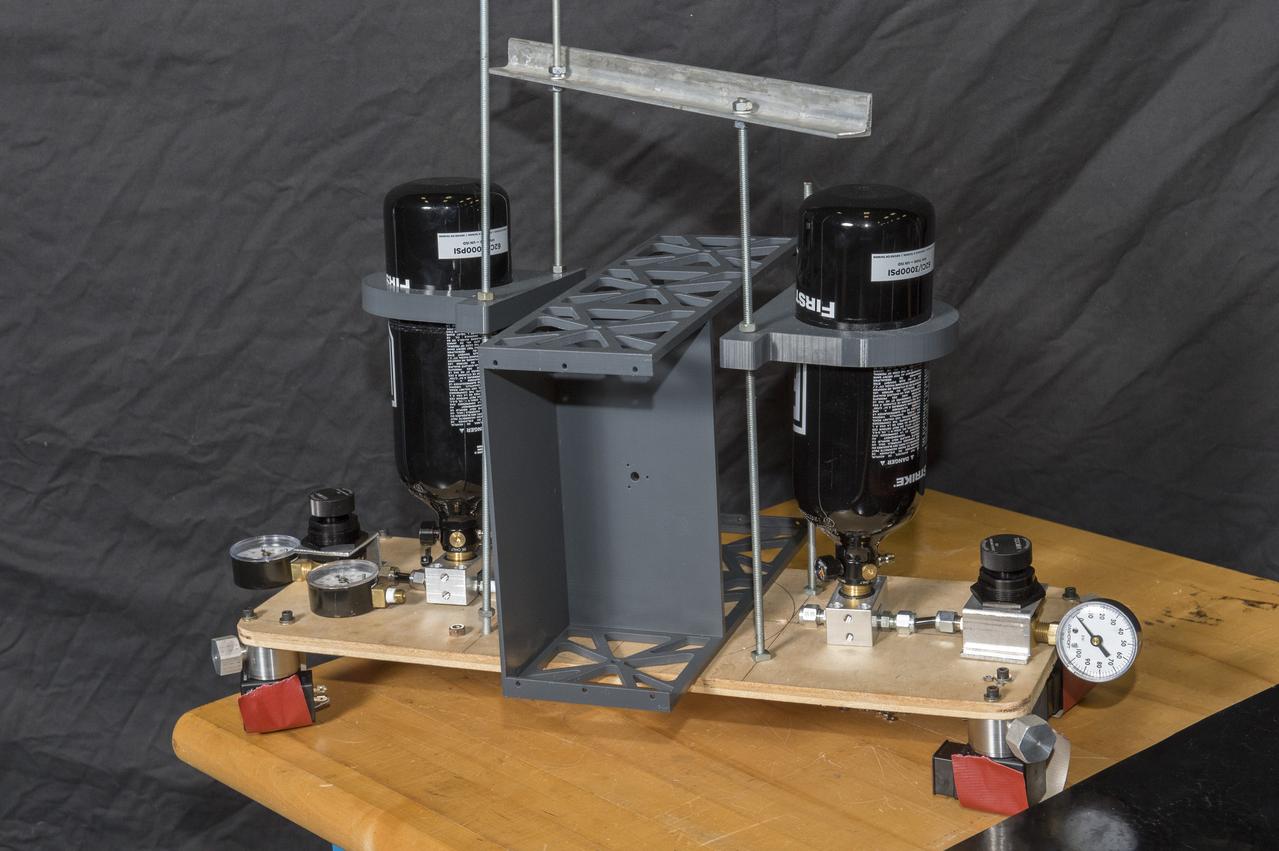

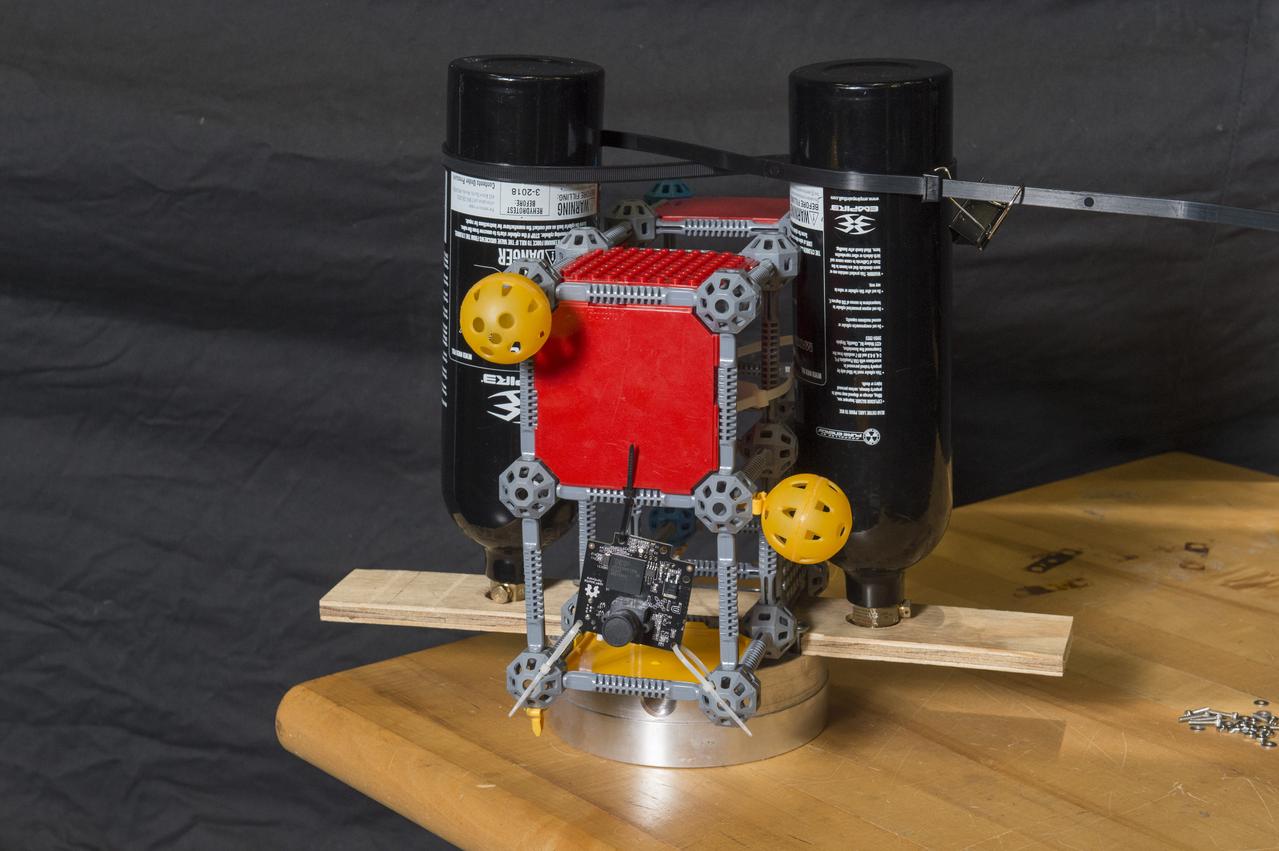

Second Generation Agile Engineering Prototype of Electric Sail 6U CubeSat Testbed Article

First Generation Agile Engineering Prototype of Electric Sail 6U CubeSat Testbed Article

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) workers David Rice, at left, and Johnny Melendez rotate a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) to the horizontal position on a lift fixture in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. The RTG is one of three generators which will provide electrical power for the Cassini spacecraft mission to the Saturnian system. The RTGs will be installed on the powered-up spacecraft for mechanical and electrical verification testing. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate far from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is scheduled for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed for NASA by JPL

AirVenture at Oshkosh 2023

Jet Propulsion Research Lab (JPL) workers use a borescope to verify the pressure relief device bellow's integrity on a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) that has been installed on the Cassini spacecraft in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. The activity is part of the mechanical and electrical verification testing of RTGs during prelaunch processing. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electrical power. The three RTGs on Cassini will enable the spacecraft to operate far from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. They will provide electrical power to Cassini on it seven year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four year mission at Saturn.

Jet Propulsion Research Lab (JPL) workers use a borescope to verify the pressure relief device bellow's integrity on a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) that has been installed on the Cassini spacecraft in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. The activity is part of the mechanical and electrical verification testing of RTGs during prelaunch processing. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electrical power. The three RTGs on Cassini will enable the spacecraft to operate far from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. They will provide electrical power to Cassini on it seven year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four year mission at Saturn.

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) engineers examine the interface surface on the Cassini spacecraft prior to installation of the third radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG). The other two RTGs, at left, already are installed on Cassini. The three RTGs will be used to power Cassini on its mission to the Saturnian system. They are undergoing mechanical and electrical verification testing in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate far from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is scheduled for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed for NASA by JPL

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) workers prepare the installation cart (atop the platform) for removal of a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) from the adjacent Cassini spacecraft. This is the second of three RTGs being removed from Cassini after undergoing mechanical and electrical verification tests in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. The third RTG to be removed is in background at left. The three RTGs will then be temporarily stored before being re-installed for flight. The RTGs will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate far from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is scheduled for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed for NASA by JPL

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) worker Mary Reaves mates connectors on a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) to power up the Cassini spacecraft, while quality assurance engineer Peter Sorci looks on. The three RTGs which will be used on Cassini are undergoing mechanical and electrical verification testing in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. The RTGs will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate at great distances from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed by JPL

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) workers carefully roll into place a platform with a second radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) for installation on the Cassini spacecraft. In background at left, the first of three RTGs already has been installed on Cassini. The RTGs will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. The power units are undergoing mechanical and electrical verification testing in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate far from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is scheduled for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed for NASA by JPL

Lockheed Martin Missile and Space Co. employees Joe Collingwood, at right, and Ken Dickinson retract pins in the storage base to release a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) in preparation for hoisting operations. This RTG and two others will be installed on the Cassini spacecraft for mechanical and electrical verification testing in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. The RTGs will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate at great distances from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

This radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), at center, is ready for electrical verification testing now that it has been installed on the Cassini spacecraft in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. A handling fixture, at far left, remains attached. This is the third and final RTG to be installed on Cassini for the prelaunch tests. The RTGs will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate at great distances from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle

Carrying a neutron radiation detector, Fred Sanders (at center), a health physicist with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and other health physics personnel monitor radiation in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility after three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) were installed on the Cassini spacecraft for mechanical and electrical verification tests. The RTGs will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate at great distances from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed by JPL

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) employees Norm Schwartz, at left, and George Nakatsukasa transfer one of three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) to be used on the Cassini spacecraft from the installation cart to a lift fixture in preparation for returning the power unit to storage. The three RTGs underwent mechanical and electrical verification testing in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. The RTGs will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate at great distances from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed by JPL

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) employees bolt a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) onto the Cassini spacecraft, at left, while other JPL workers, at right, operate the installation cart on a raised platform in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF). Cassini will be outfitted with three RTGs. The power units are undergoing mechanical and electrical verification tests in the PHSF. The RTGs will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate at great distances from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed by JPL

This radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), at center, will undergo mechanical and electrical verification testing now that it has been installed on the Cassini spacecraft in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. A handling fixture, at far left, is still attached. Three RTGs will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate far from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is scheduled for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed for NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Supported on a lift fixture, this radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), at center, is hoisted from its storage base using the airlock crane in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility (PHSF). Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) workers are preparing to install the RTG onto the Cassini spacecraft, in background at left, for mechanical and electrical verification testing. The three RTGs on Cassini will provide electrical power to the spacecraft on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The generators enable spacecraft to operate at great distances from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed by JPL

This is a photograph of a technician checking on a solar array wing for the Orbital Workshop as it is deployed. A solar array, consisting of two wings covered on one side with solar cells, was mounted outside the workshop to generate electrical power to augment the power generated by another solar array mounted on the solar observatory.

Johnson Space Center (JSC) engineers visit Houston area schools for National Engineers Week. Students examine a machine that generates static electricity (4296-7). Students examine model rockets (4298).

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) workers use a borescope to verify pressure relief device bellows integrity on a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) which has been installed on the Cassini spacecraft in the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. The activity is part of the mechanical and electrical verification testing of RTGs during prelaunch processing. RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. The three RTGs on Cassini will enable the spacecraft to operate far from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. They will provide electrical power to Cassini on its 6.7-year trip to the Saturnian system and during its four-year mission at Saturn. The Cassini mission is scheduled for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle. Cassini is built and managed for NASA by JPL

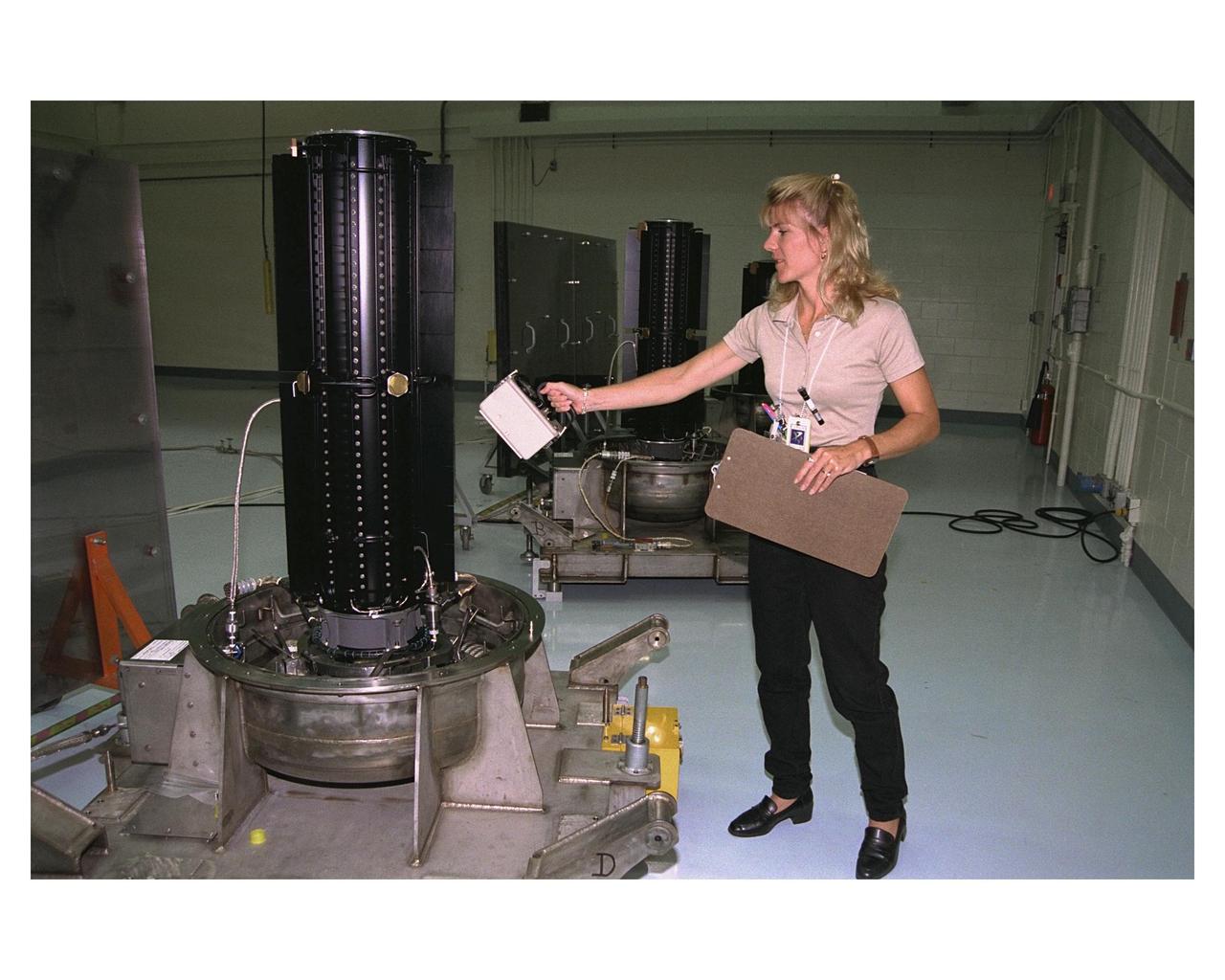

Environmental Health Specialist Jamie A. Keeley, of EG&G Florida Inc., uses an ion chamber dose rate meter to measure radiation levels in one of three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) that will provide electrical power to the Cassini spacecraft on its mission to explore the Saturnian system. The three RTGs and one spare are being tested and mointored in the Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator Storage Building in the KSC's Industrial Area. The RTGs use heat from the natural decay of plutonium to generate electric power. RTGs enable spacecraft to operate far from the Sun where solar power systems are not feasible. The RTGs on Cassini are of the same design as those flying on the already deployed Galileo and Ulysses spacecraft. The Cassini mission is targeted for an Oct. 6 launch aboard a Titan IVB/Centaur expendable launch vehicle.

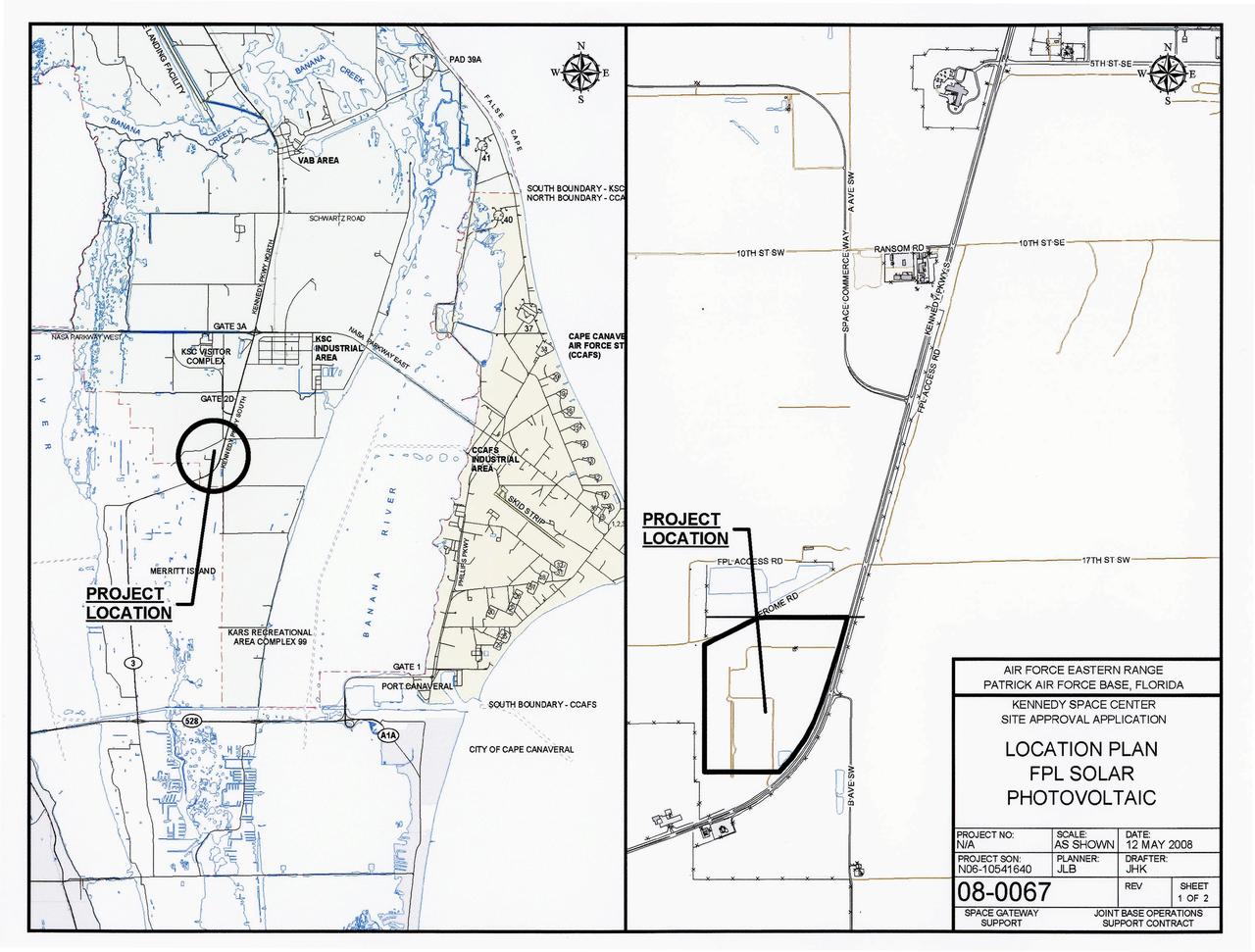

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – This photo shows the area within NASA's Kennedy Space Center where a solar photovoltaic power generation system will be built as the result of an agreement between NASA and Florida Power & Light. The agreement is part of a new initiative that will cut reliance on fossil fuels and improve the environment by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The major facility will produce an estimated 10 megawatts of electrical power, which can serve roughly 3,000 homes. A separate one-megawatt solar power facility will support the electrical needs of the center.

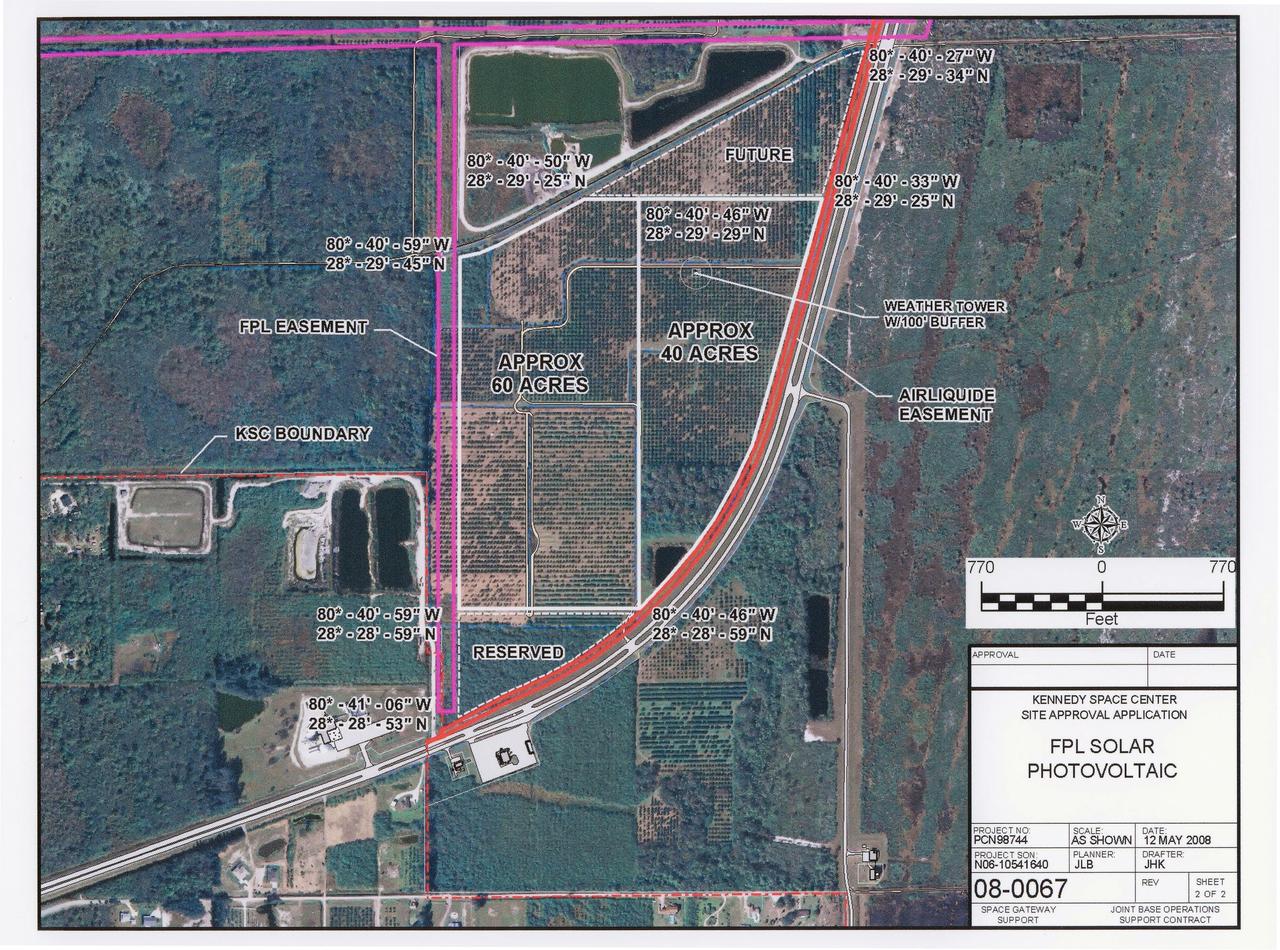

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – This map shows the area within NASA's Kennedy Space Center where a solar photovoltaic power generation system will be built as the result of an agreement between NASA and Florida Power & Light. The agreement is part of a new initiative that will cut reliance on fossil fuels and improve the environment by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The major facility will produce an estimated 10 megawatts of electrical power, which can serve roughly 3,000 homes. A separate one-megawatt solar power facility will support the electrical needs of the center.

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – This photo shows the area within NASA's Kennedy Space Center where a solar photovoltaic power generation system will be built as the result of an agreement between NASA and Florida Power & Light. The agreement is part of a new initiative that will cut reliance on fossil fuels and improve the environment by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The major facility will produce an estimated 10 megawatts of electrical power, which can serve roughly 3,000 homes. A separate one-megawatt solar power facility will support the electrical needs of the center.

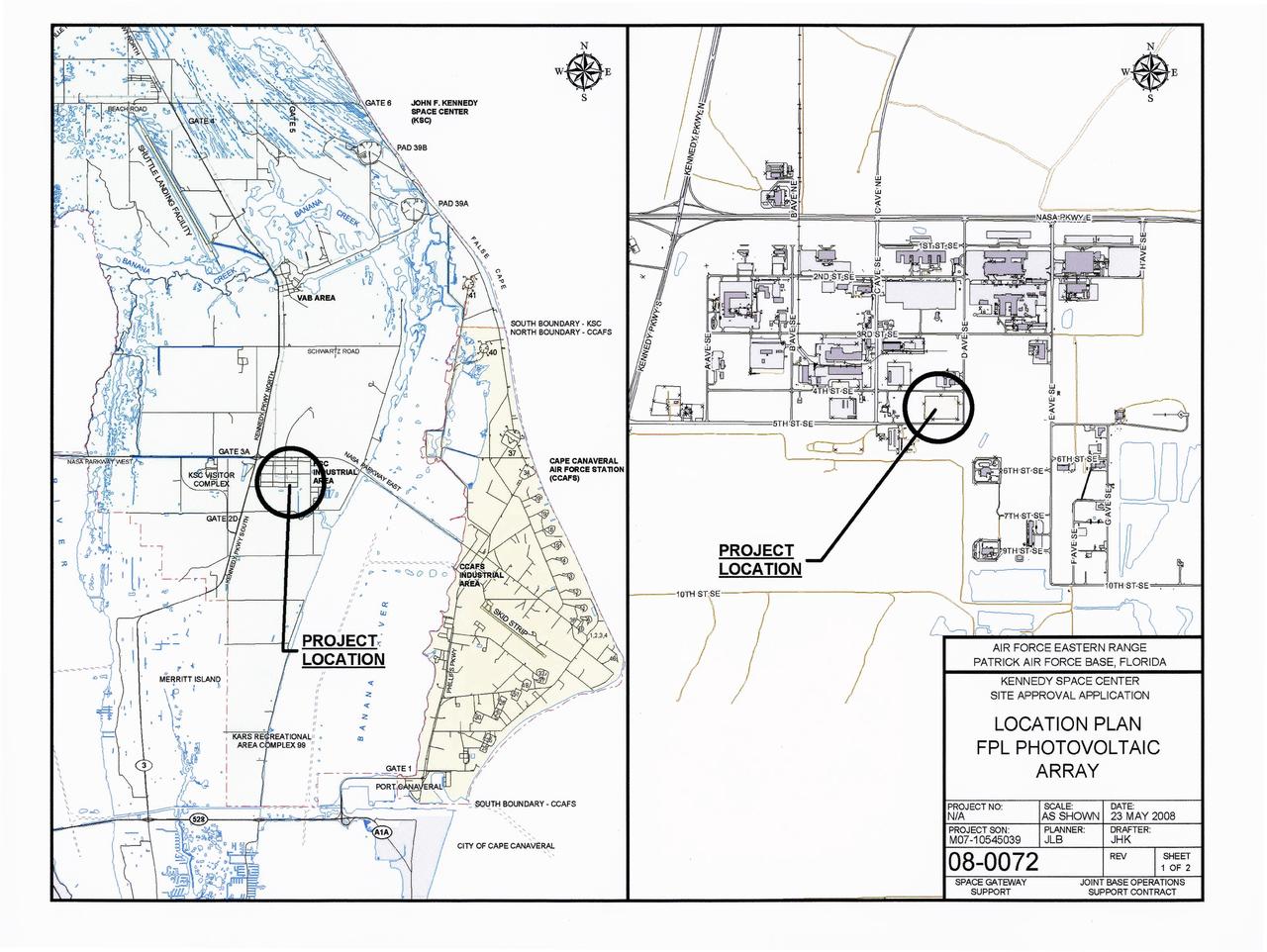

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – This map shows the two sites within NASA's Kennedy Space Center where a solar photovoltaic power generation system will be built as the result of an agreement between NASA and Florida Power & Light. The agreement is part of a new initiative that will cut reliance on fossil fuels and improve the environment by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The major facility will produce an estimated 10 megawatts of electrical power, which can serve roughly 3,000 homes. A separate one-megawatt solar power facility will support the electrical needs of the center.

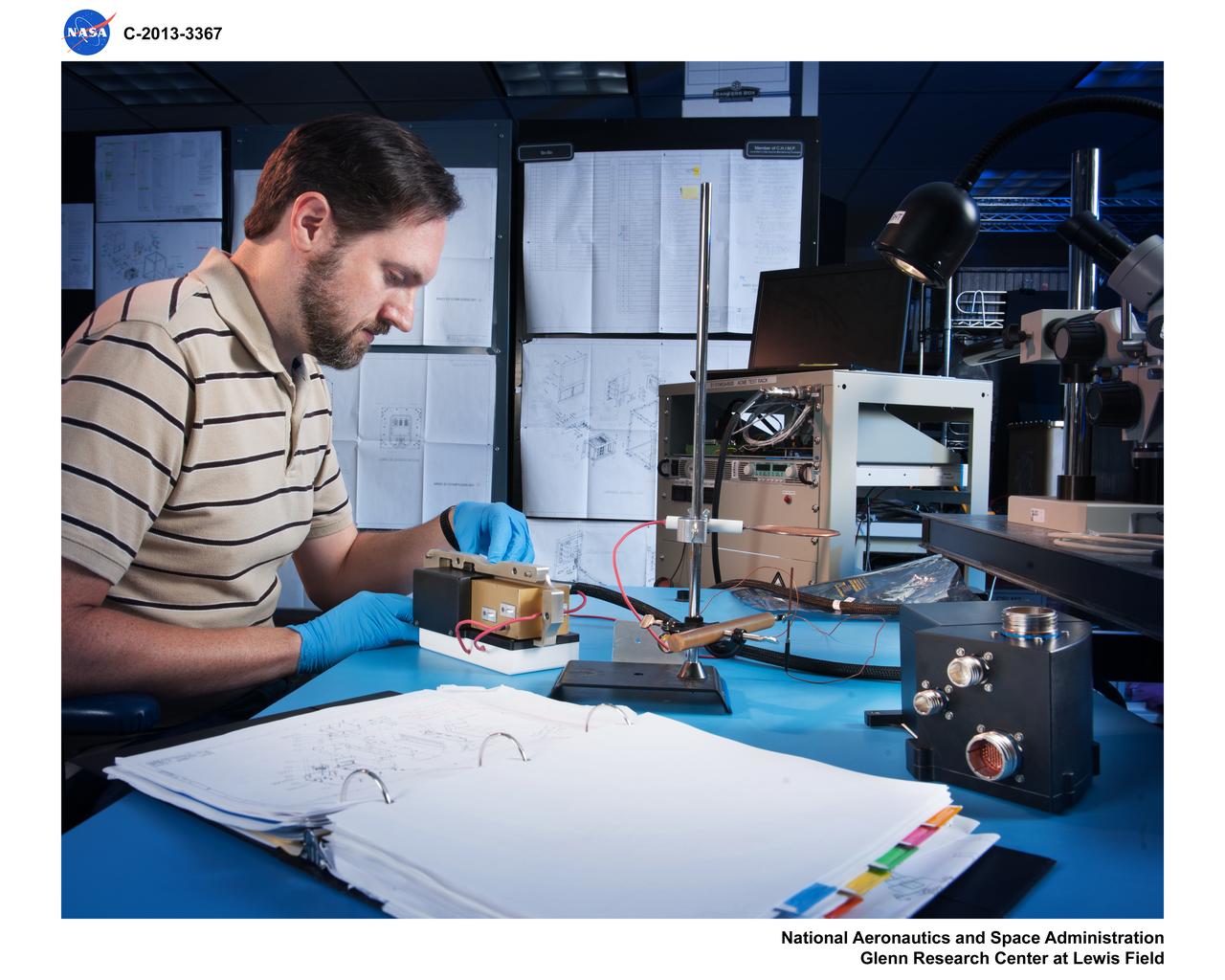

Mechanical Engineer Adrian Drake inspects engineering model hardware built to generate a high-voltage electric field for the Electric-Field Effects on Laminar Diffusion Flames (E-FIELD Flames) experiment of the Advanced Combustion via Microgravity Experiments (ACME) project. ACME’s small computer (i.e., the Cube) for data acquisition and control within the CIR combustion chamber is seen in the right foreground. The E-FIELD Flames tests were conducted in the Combustion Integrated Rack (CIR) on the International Space Station (ISS) in 2018.

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – This map shows the two sites within NASA's Kennedy Space Center where a solar photovoltaic power generation system will be built as the result of an agreement between NASA and Florida Power & Light. The agreement is part of a new initiative that will cut reliance on fossil fuels and improve the environment by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The major facility will produce an estimated 10 megawatts of electrical power, which can serve roughly 3,000 homes. A separate one-megawatt solar power facility will support the electrical needs of the center.

Here is an overhead view of the X-59 aircraft (left) prior to the installation of the General Electric F414 engine (center, located under the blue cover). After the engine is installed, the lower empennage (right), the last remaining major aircraft component, will be installed in preparation for integrated system checkouts. The X-59 is the centerpiece of the Quesst mission which plans to help enable commercial supersonic air travel over land.

Here is an image of the X-59’s 13-foot General Electric F414 engine as the team prepares for a fit check. Making sure components, like the aircraft’s hydraulic lines, which help control functions like brakes or landing gear, and wiring of the engine, fit properly is essential to the aircraft’s safety. Once complete, the X-59 aircraft will demonstrate the ability to fly supersonic while reducing the loud sonic boom to a quiet sonic thump and help enable commercial supersonic air travel over land.

4' and 24' Shock Tubes - Electric Arc Shock Tube Facililty N-229 (East) The facility is used to investigate the effects of radiation and ionization during outer planetary entries as well as for air-blast simualtion which requires the strongest possible shock generation in air at loadings of 1 atm or greater.

iss070e37241 (Nov. 1, 2023) --- Expedition 70 Flight Engineer and NASA astronaut Loral O'Hara is pictured during a spacewalk for maintenance on the International Space Station's port solar alpha rotary joint, which allows the solar arrays to track the Sun and generate electricity to power the orbital outpost.