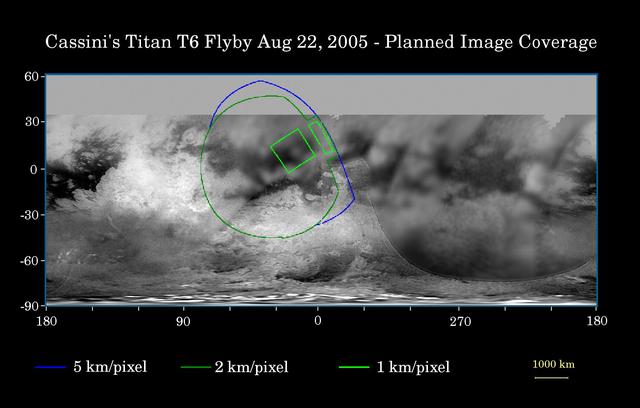

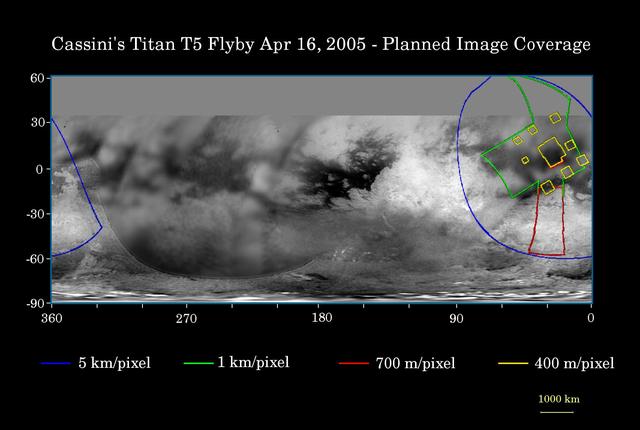

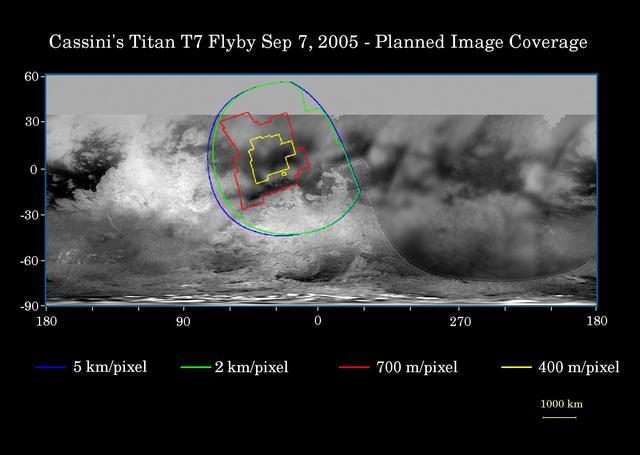

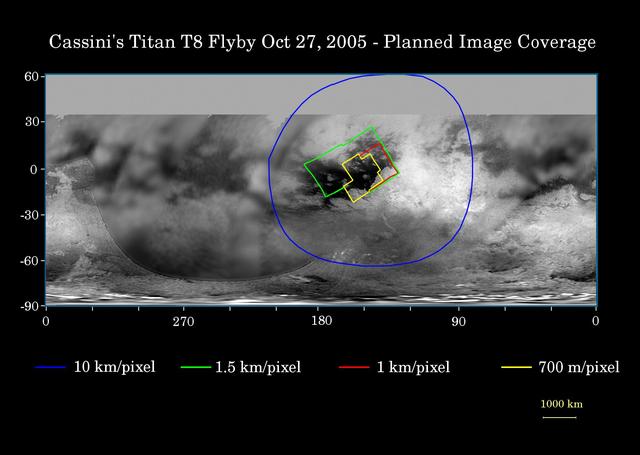

This map of Titan's surface illustrates the regions that will be imaged by Cassini during the spacecraft's close flyby of Titan on Aug. 22, 2005. At closest approach, the spacecraft is expected to pass approximately 3,800 kilometers (2,360 miles) above the moon's surface. At 5,150 kilometers (3,200 miles) across, Titan is one of the solar system's largest moons. The colored lines delineate the regions that will be imaged at differing resolutions. As Cassini continues its reconnaissance of Titan, maps of this haze-enshrouded world continue to improve. Images from this flyby will sharpen the moderate resolution coverage of terrain on the side of Titan that always faces Saturn. The highest resolution image planned for this encounter will cover a 215-kilometer-wide (134-mile) bright feature provisionally named "Bazaruto Facula." (A facula is the name chosen to denote a bright spot on Titan.) At the center of the facula is an 80-kilometer-wide (50-mile) crater (not yet named), seen by Cassini's radar experiment during a Titan flyby in February 2005 (see PIA07368). The imaging cameras and visual and infrared mapping spectrometer images taken in March and April 2005 also show this crater (see PIA06234). The southernmost corner of the highest resolution (1 kilometer per pixel) frame should also cover the northern portion of a large bright feature provisionally known as "Quivira." Wide-angle images obtained during this flyby should cover much of the Tsegihi-Aztlan-Quivira region (also known as the "H" region) at lower resolution. The map shows only brightness variations on Titan's surface (the illumination is such that there are no shadows and no shading from topographic variations). Previous observations indicate that, due to Titan's thick, hazy atmosphere, the sizes of surface features that can be resolved are up to five times larger than the actual pixel scale labeled on the map. The images for this global map were obtained using a narrow-band filter centered at 938 nanometers -- a near-infrared wavelength (invisible to the human eye) at which light can penetrate Titan's atmosphere. The images have been processed to enhance surface details. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA07711

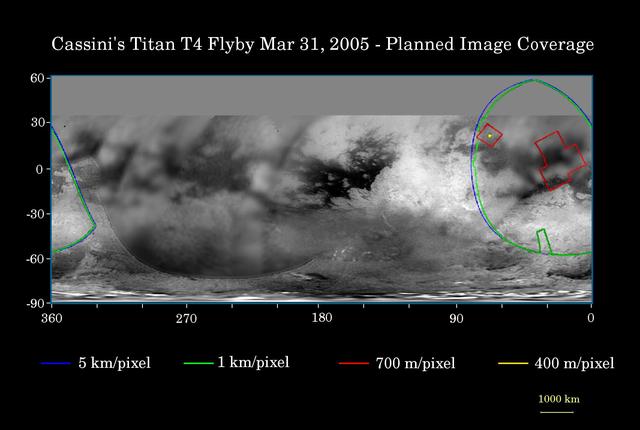

Cassini T4 Flyby

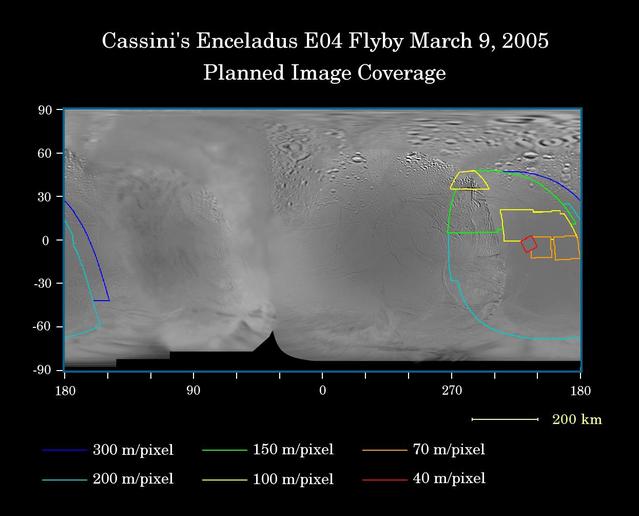

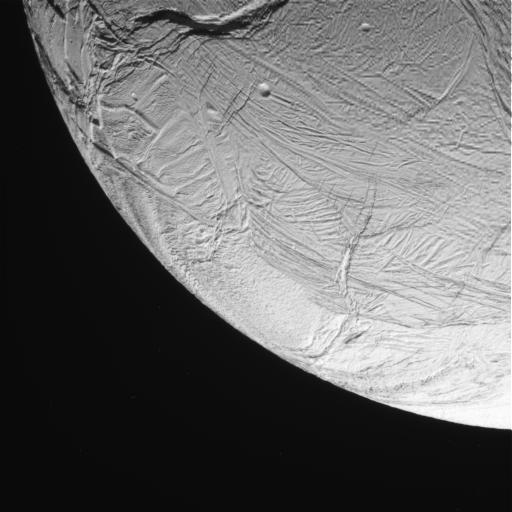

Enceladus First Flyby

A Flyby Tour of Spirit Descent

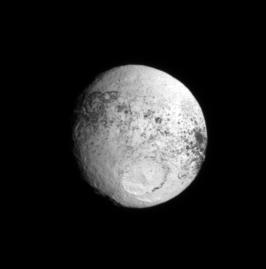

Iapetus New Year Flyby

Cassini Closest Enceladus Flyby

Titan Flyby Number Four

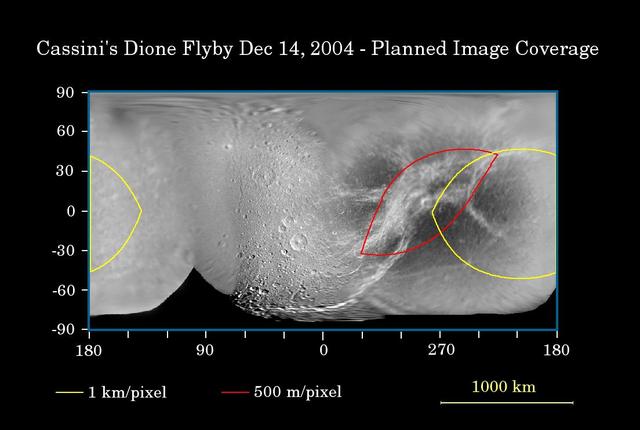

First Flyby of Dione

Flyby Follow-up

A Comparison of Flyby and Orbital Imaging

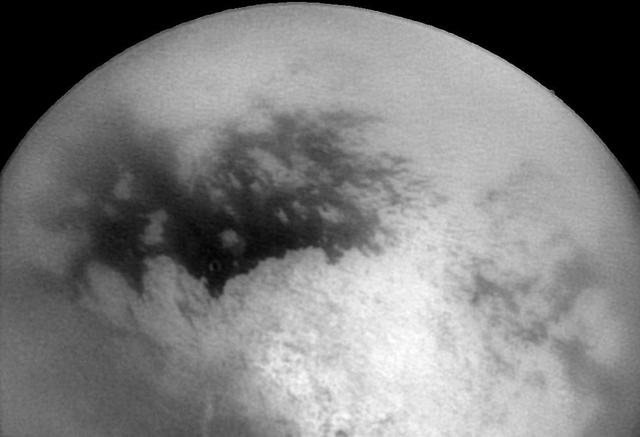

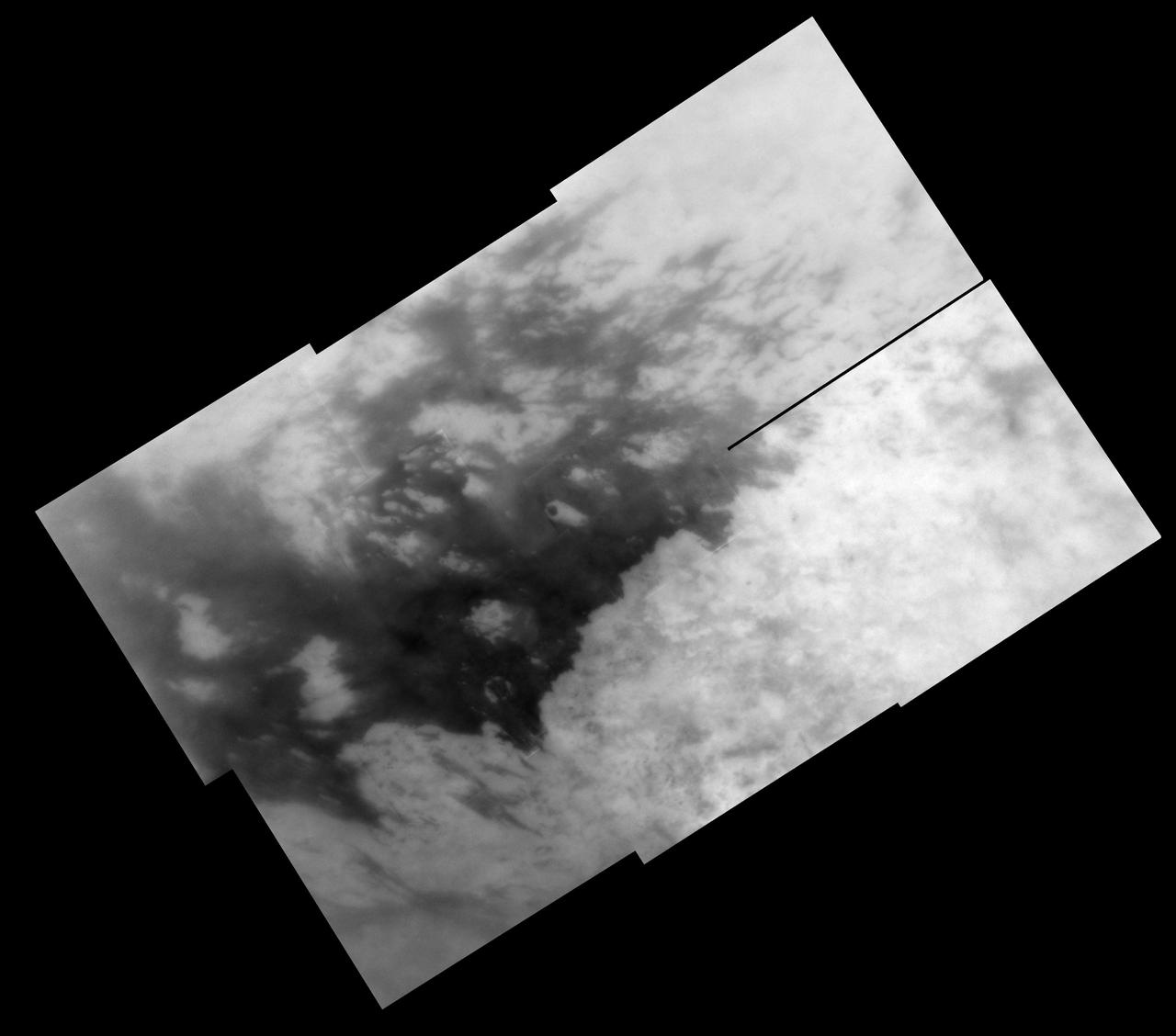

Cassini April 16 Flyby of Titan

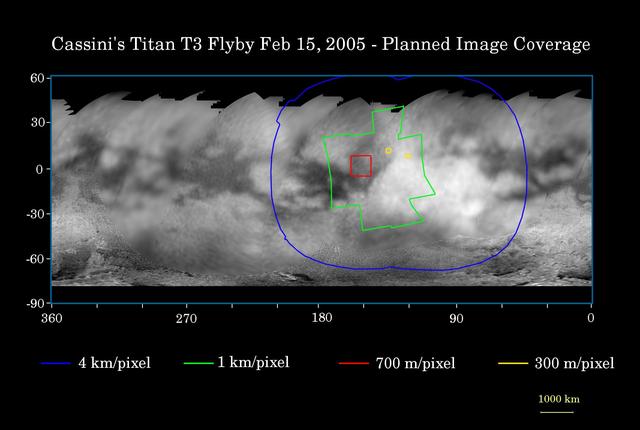

Second Titan Targeted Flyby #3

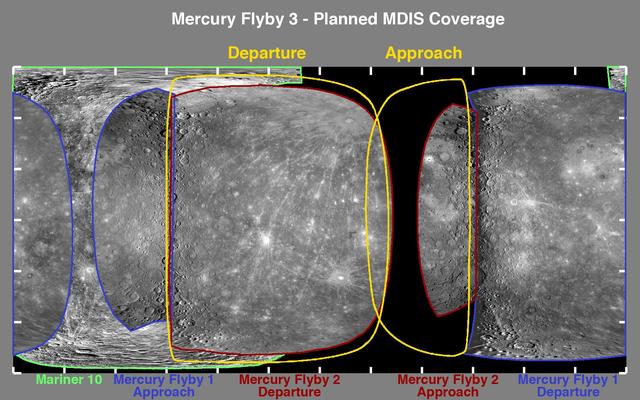

One Day to Mercury Flyby 3!

A Flyby Tour of Spirit Descent-2

Naming New Lands - September Flyby

Second Titan Targeted Flyby #1

Naming New Lands - October Flyby

Second Titan Targeted Flyby #2

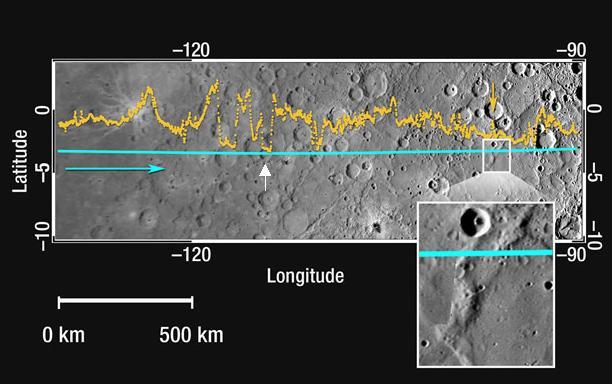

Mercury Topography from the Second Flyby

Pluto nearly fills the frame in this image from the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) aboard NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, taken on July 13, 2015, when the spacecraft was 476,000 miles (768,000 kilometers) from the surface. This is the last and most detailed image sent to Earth before the spacecraft’s closest approach to Pluto on July 14. The color image has been combined with lower-resolution color information from the Ralph instrument that was acquired earlier on July 13. This view is dominated by the large, bright feature informally named the “heart,” which measures approximately 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) across. The heart borders darker equatorial terrains, and the mottled terrain to its east (right) are complex. However, even at this resolution, much of the heart’s interior appears remarkably featureless—possibly a sign of ongoing geologic processes. CREDIT: NASA/APL/SwRI <b><a href="http://go.nasa.gov/1L5NU1J" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://go.nasa.gov/1L5NU1L" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://go.nasa.gov/1L5NU1N" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://go.nasa.gov/1L5NWqt" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://go.nasa.gov/1L5NWGJ" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b> <b><a href="http://go.nasa.gov/1L5NWGN" rel="nofollow">Credit: NOAA/NASA GOES Project</a></b>

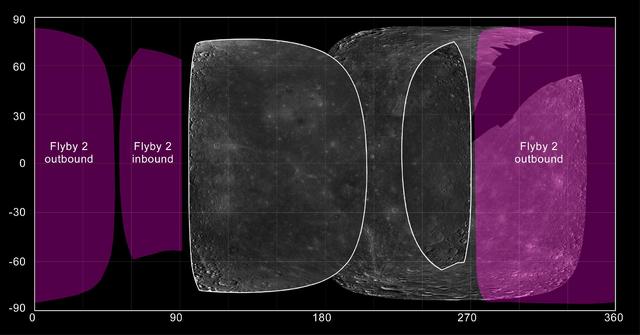

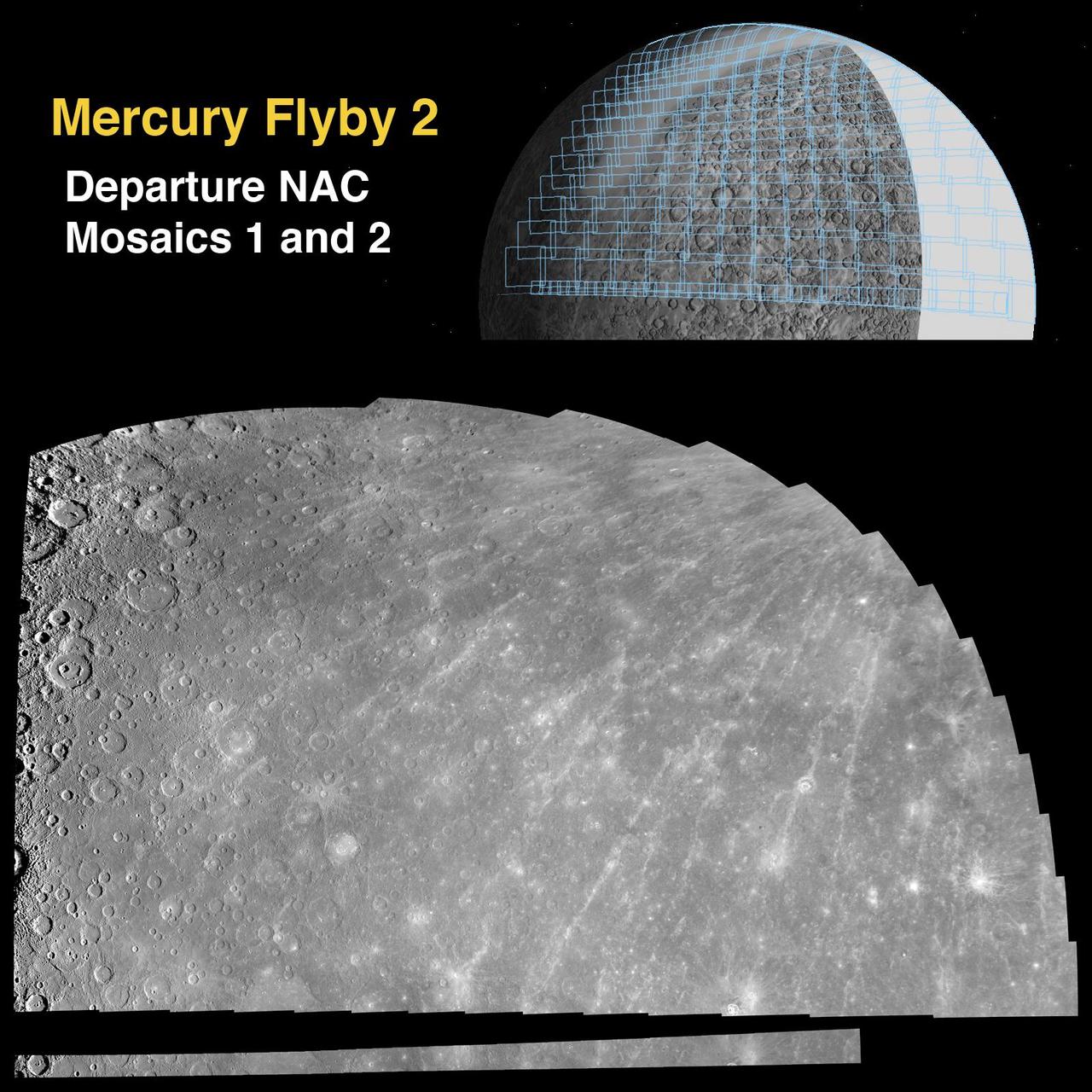

Imaging Plans for MESSENGER Second Mercury Flyby

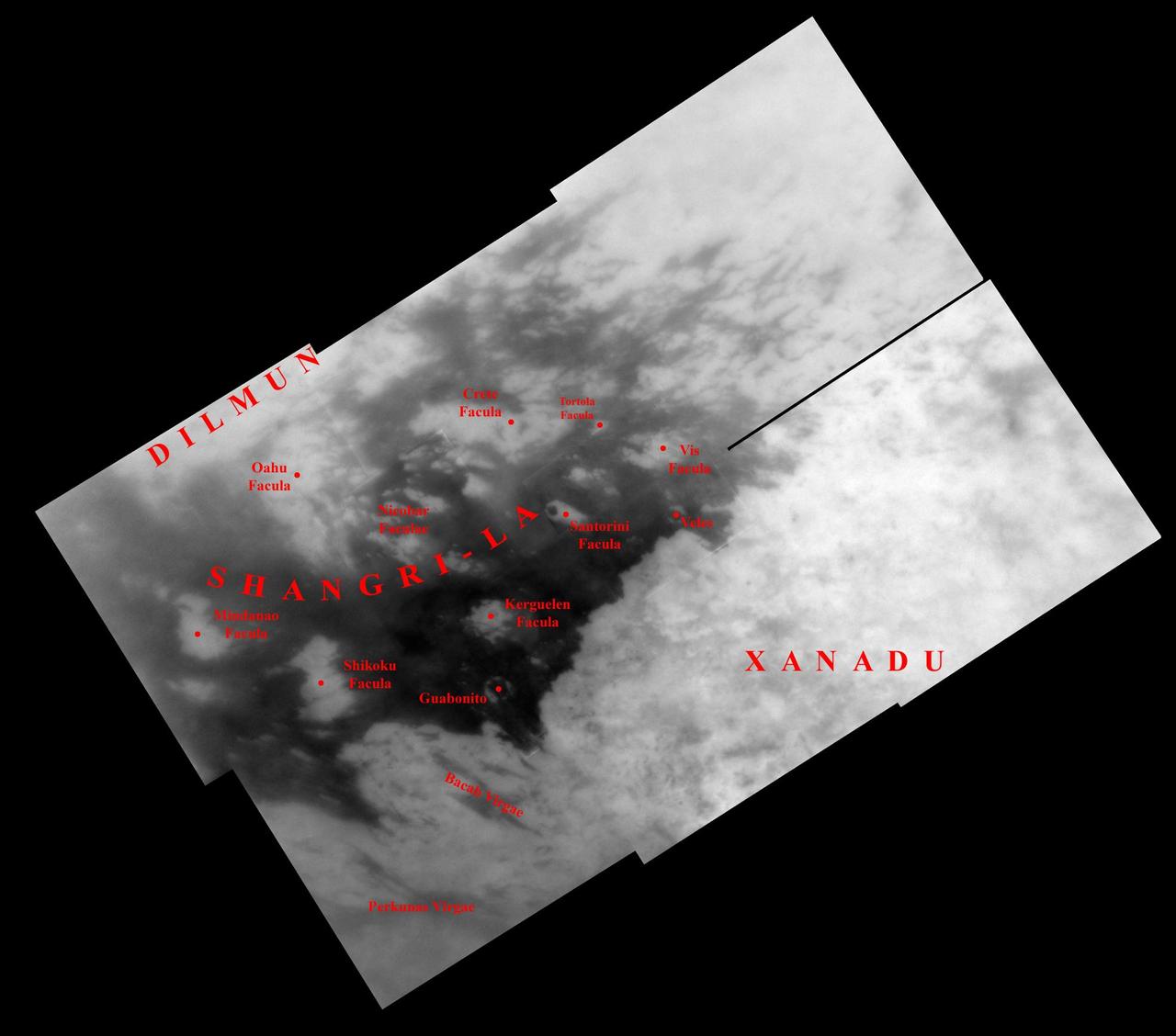

Naming New Lands - October Flyby annotated

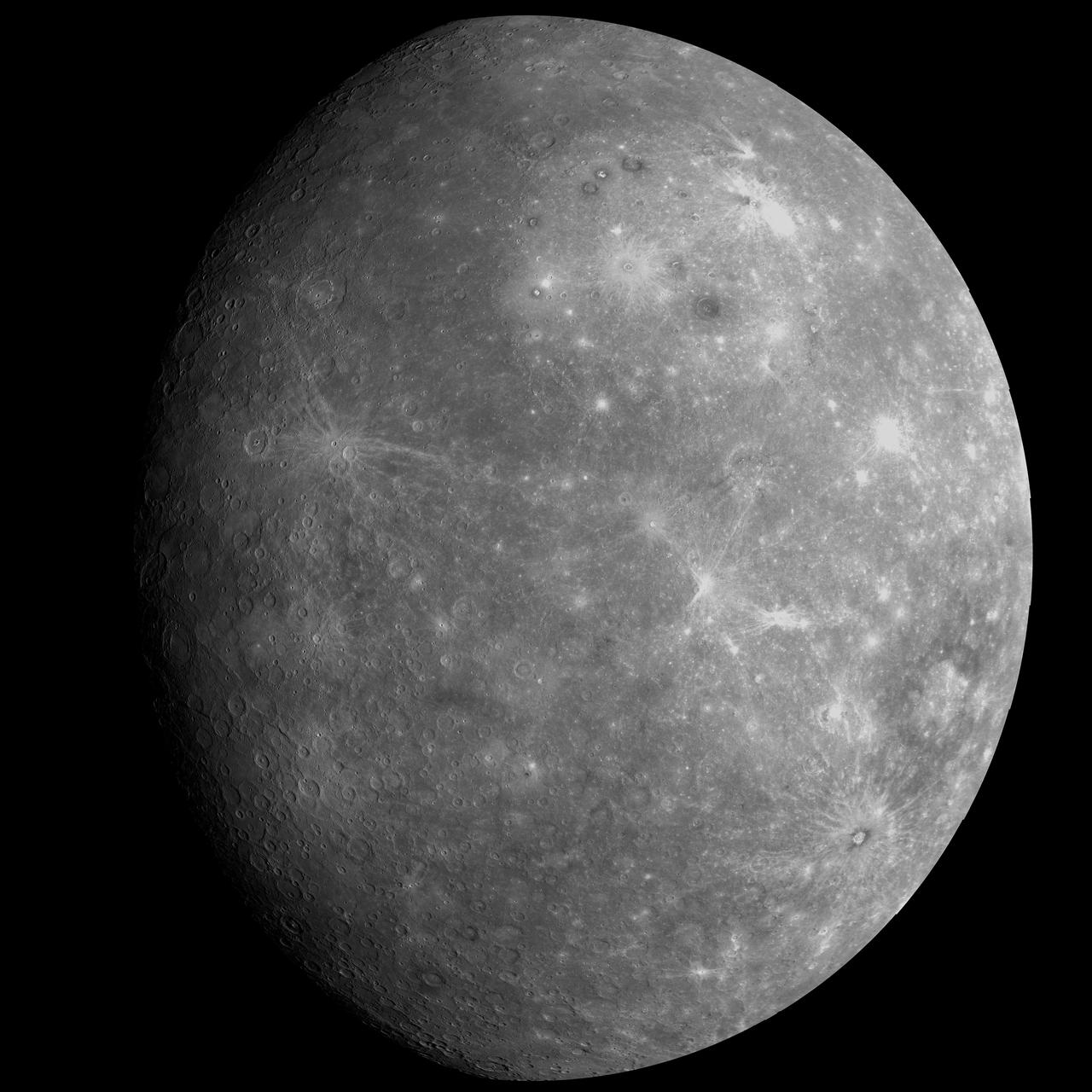

High-Resolution View from Mercury Flyby 1

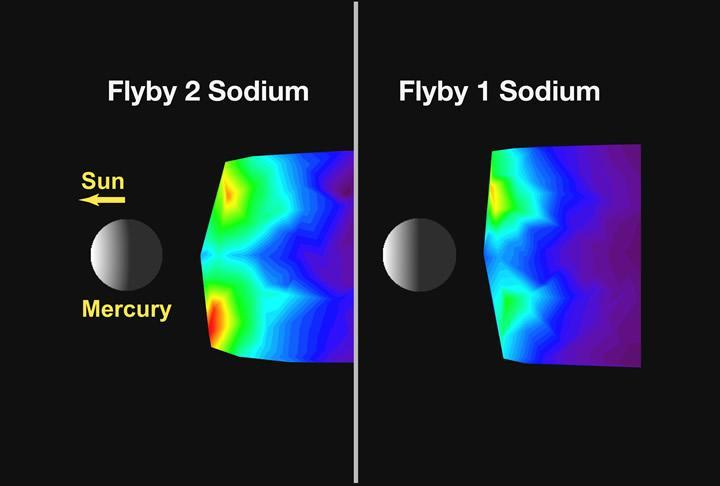

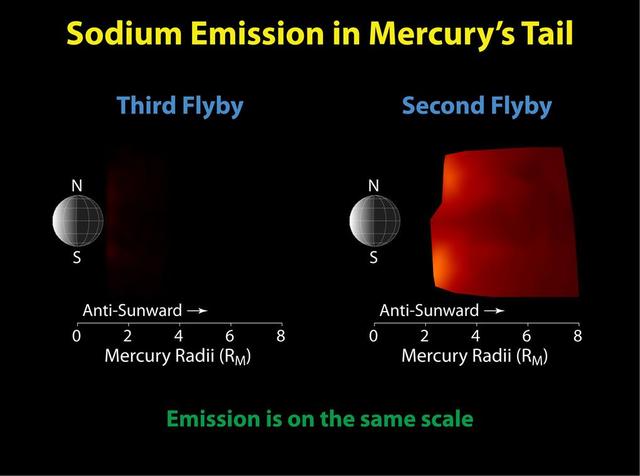

Comparing Mercury Exosphere between Two Flybys

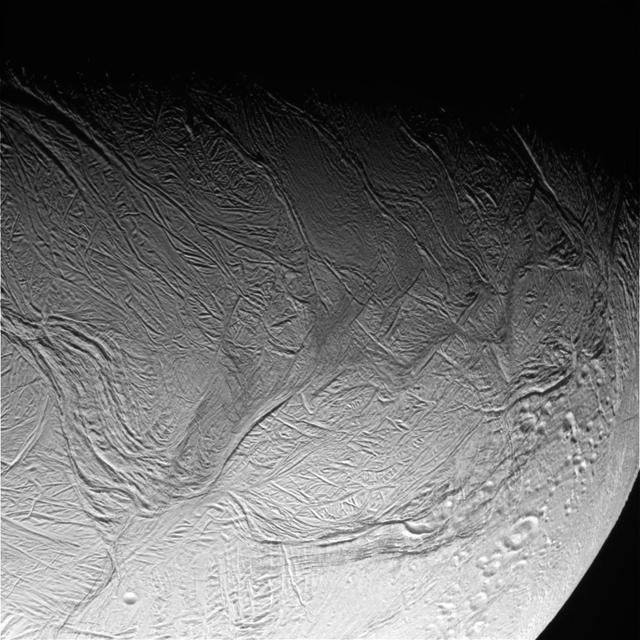

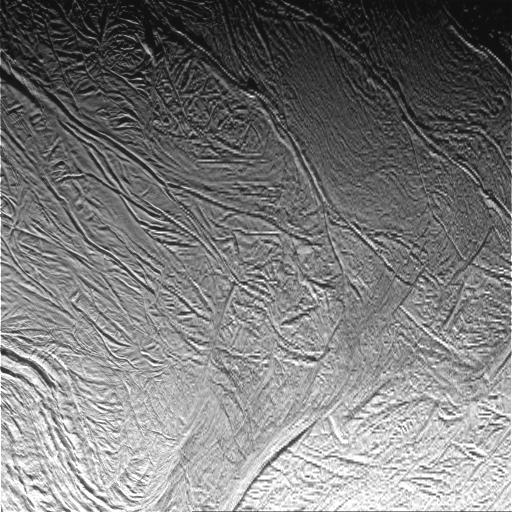

Enceladus Rev 91 Flyby - Skeet Shoot #8

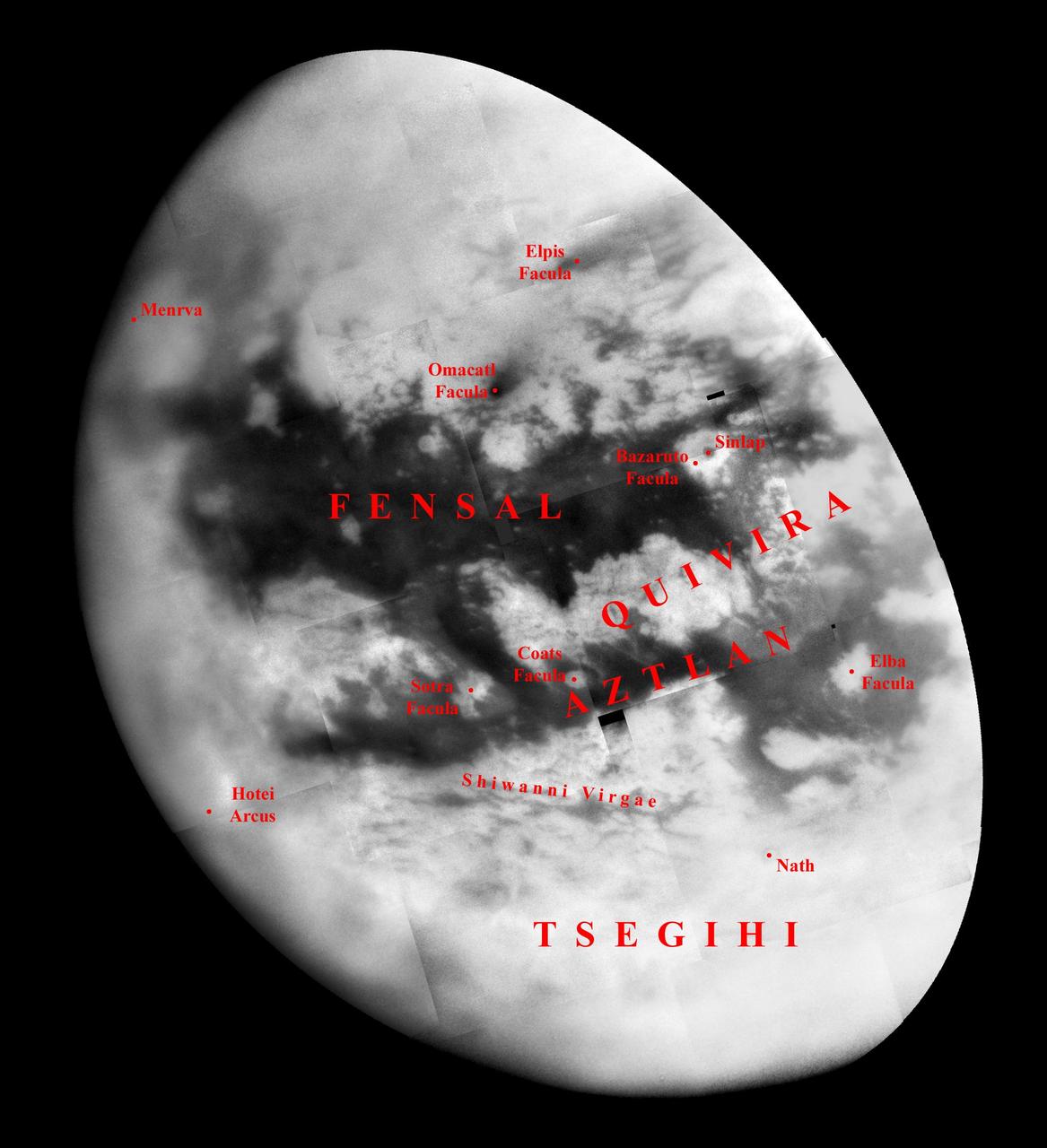

Naming New Lands - September Flyby annotated

Enceladus Rev 80 Flyby Skeet Shoot #3

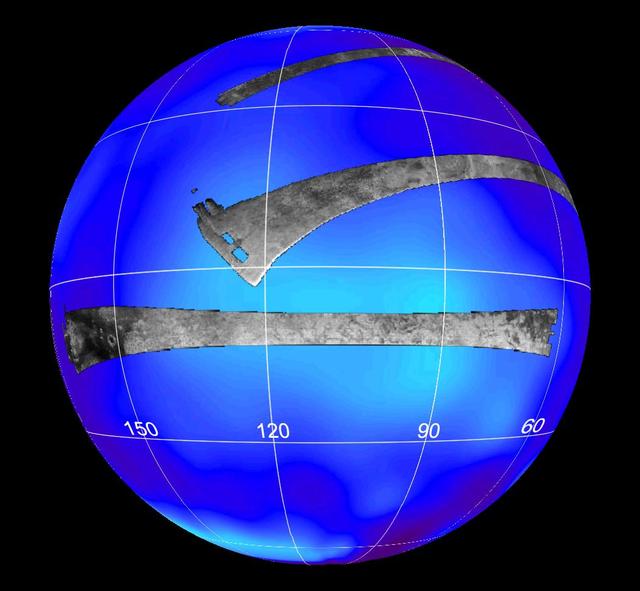

Radar Flyby of Titan - April 30, 2006

Enceladus Rev 91 Flyby - Skeet Shoot #4

Cassini Sept. 7, 2005, Titan Flyby

Approach Mosaic from Mercury Flyby 3

On Target for Mercury Flyby 3 - Two Weeks To Go!

Departure Mosaics from the Second Mercury Flyby

Cassini Oct. 28, 2005, Titan Flyby

Close Titan Flyby 3, Image #1

Enceladus Rev 91 Flyby - Skeet Shoot #9

Radar Swath of Oct. 28, 2005, Titan Flyby

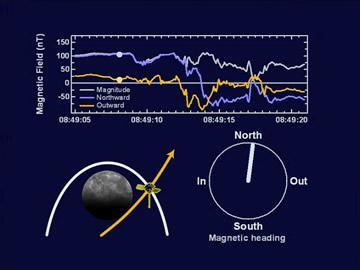

A Movie of Magnetometer Measurements from the Second Mercury Flyby

Enceladus Rev 91 Flyby - Skeet Shoot #1

Enceladus Rev 80 Flyby Skeet Shoot #1

Enceladus Rev 80 Flyby Skeet Shoot #7

A Southern Horizon as Seen during Mercury Flyby 3

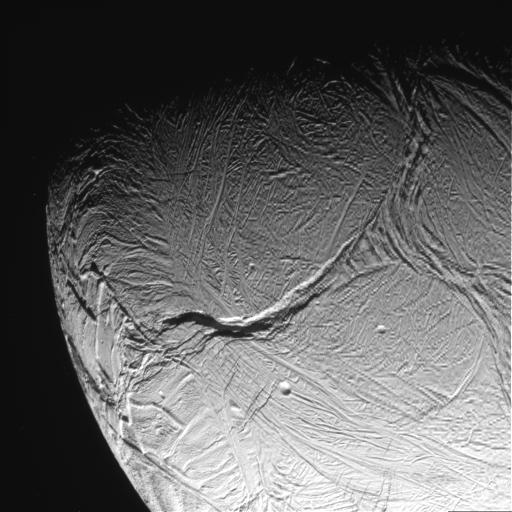

Enceladus Oct. 9, 2008 Flyby - Posted Image #3

Enceladus Oct. 9, 2008 Flyby - Posted Image #5

Enceladus Oct. 9, 2008 Flyby - Posted Image #2

Mercury Flyby 3 Reveals a Highly Diminished Sodium Tail

One Week to Mercury Flyby 3 - A Look at the Planned Imaging Coverage

Enceladus Oct. 9, 2008 Flyby - Posted Image #1

Enceladus Rev 91 Flyby - Skeet Shoot 1-4 Mosaic

Peak-Ring Basin Close-Up from the Second Mercury Flyby

Enceladus Oct. 9, 2008 Flyby - Posted Image #4

The Highest-resolution Image from MESSENGER Second Mercury Flyby

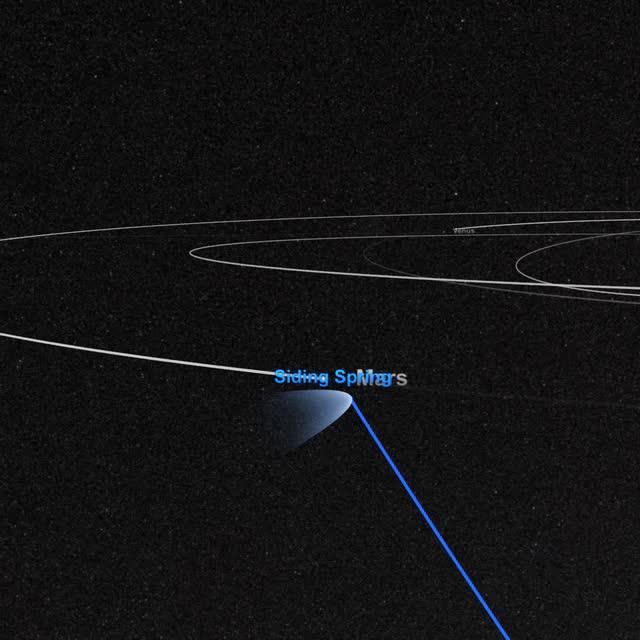

On October 19, Comet Siding Spring will pass within 88,000 miles of Mars – just one third of the distance from the Earth to the Moon! Traveling at 33 miles per second and weighing as much as a small mountain, the comet hails from the outer fringes of our solar system, originating in a region of icy debris known as the Oort cloud. Comets from the Oort cloud are both ancient and rare. Since this is Comet Siding Spring’s first trip through the inner solar system, scientists are excited to learn more about its composition and the effects of its gas and dust on the Mars upper atmosphere. NASA will be watching closely before, during, and after the flyby with its entire fleet of Mars orbiters and rovers, along with the Hubble Space Telescope and dozens of instruments on Earth. The encounter is certain to teach us more about Oort cloud comets, the Martian atmosphere, and the solar system’s earliest ingredients. Learn more: <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FG4KsatjFeI" rel="nofollow">www.youtube.com/watch?v=FG4KsatjFeI</a> Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagram.com/nasagoddard?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

During super-close flybys of Saturn's rings, NASA's Cassini spacecraft inspected the mini-moons Pan and Daphnis in the A ring; Atlas at the edge of the A ring; Pandora at the edge of the F ring; and Epimetheus, which is bathed in material that fans out from the moon Enceladus. The mini-moons' diameter ranges from 5 miles (8 kilometers) for Daphnis to 72 miles (116 kilometers) for Epimetheus. The rings and the moons depicted in this illustration are not to scale. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22772

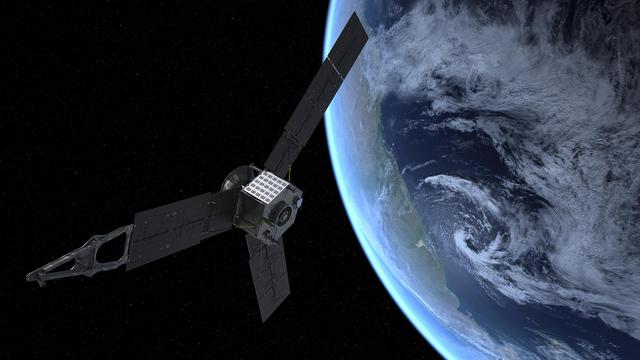

This artist rendering shows NASA Juno spacecraft during its Earth flyby gravity assist on Oct. 9, 2013. On Earth below, the southern Atlantic Ocean is visible, along with the coast of Argentina.

This image was obtained by NASA's Cassini radar instrument during a flyby on Dec. 20, 2007. South Polar Region, Western Mezzoramia. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01854

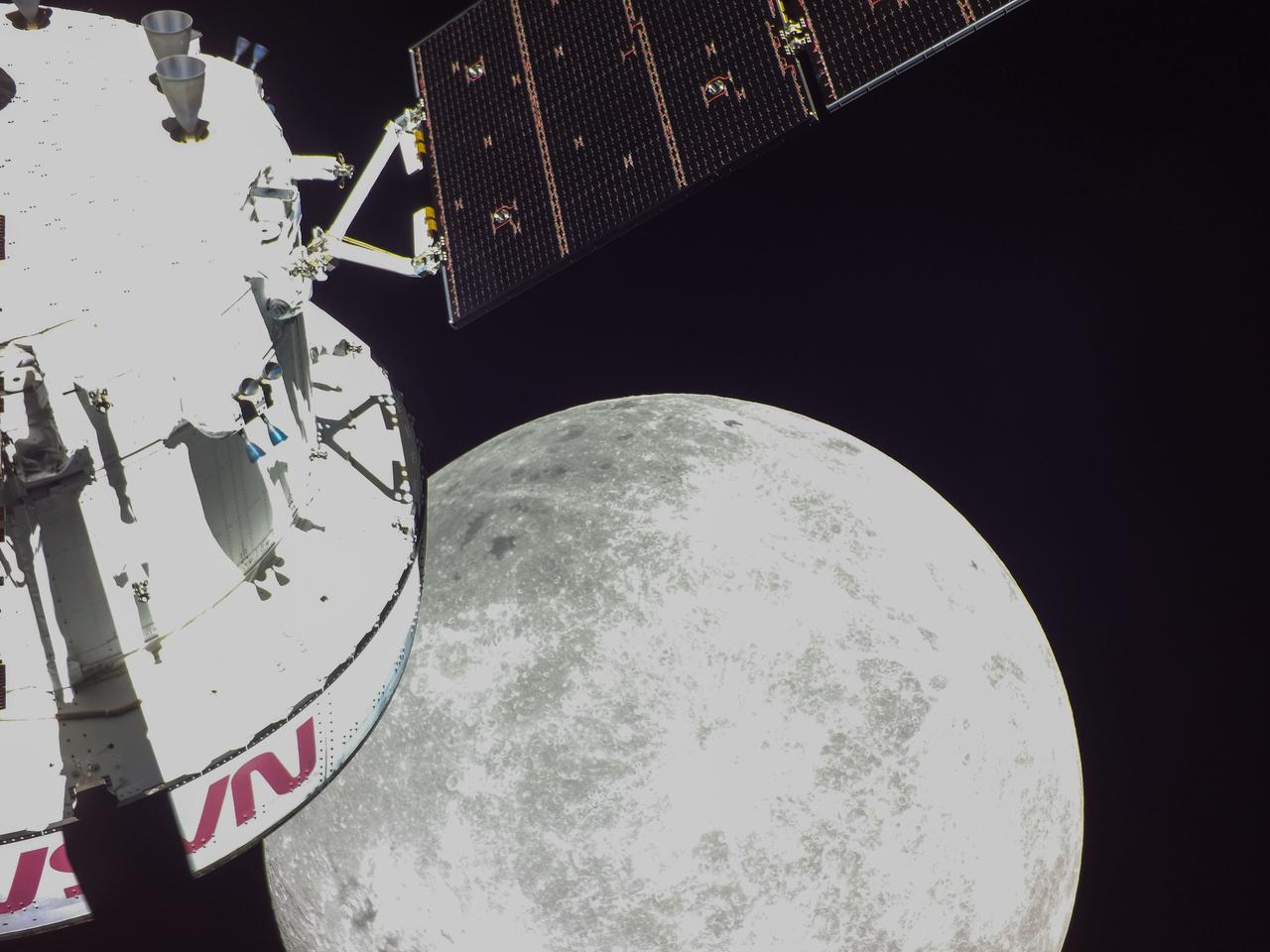

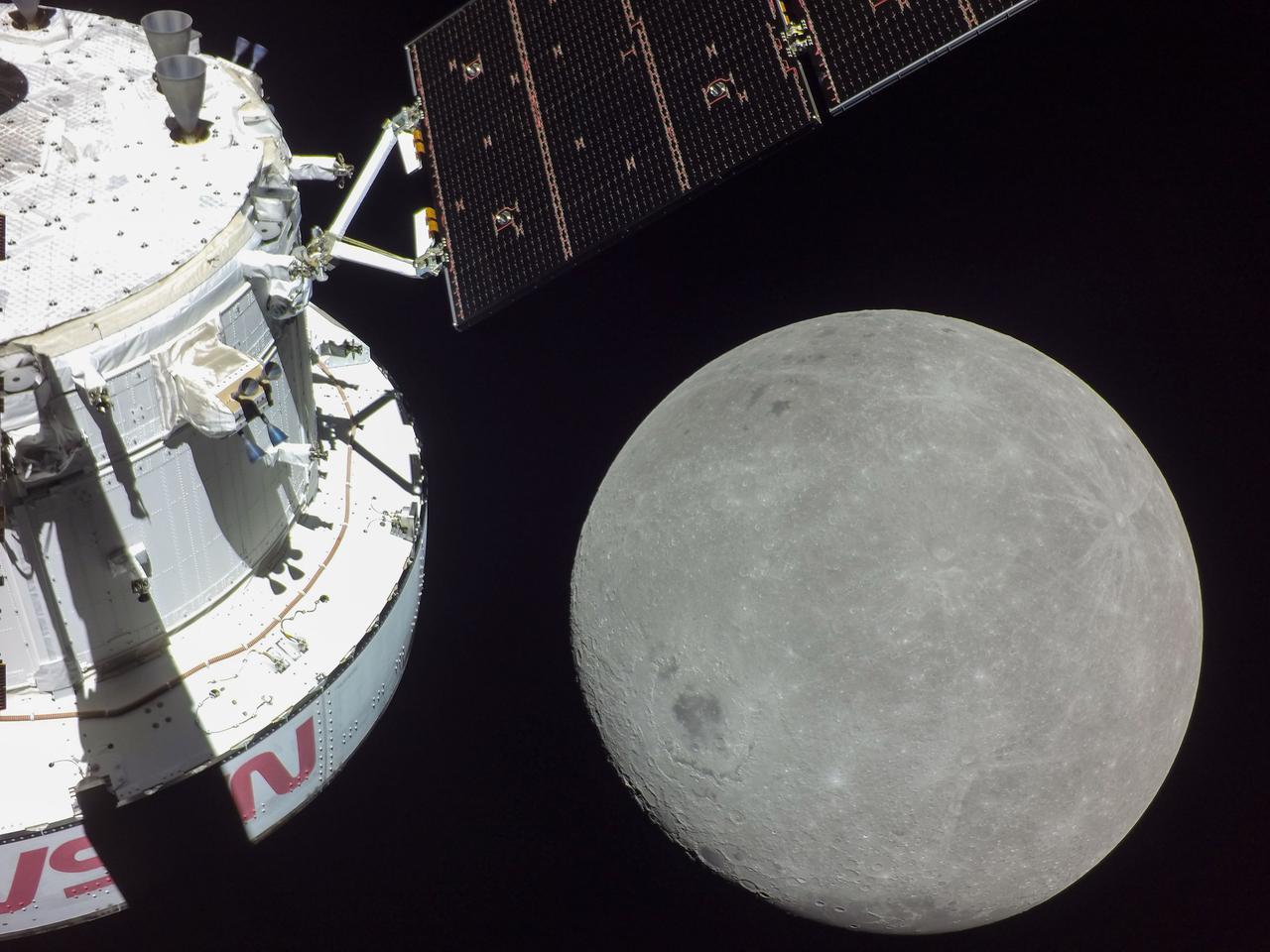

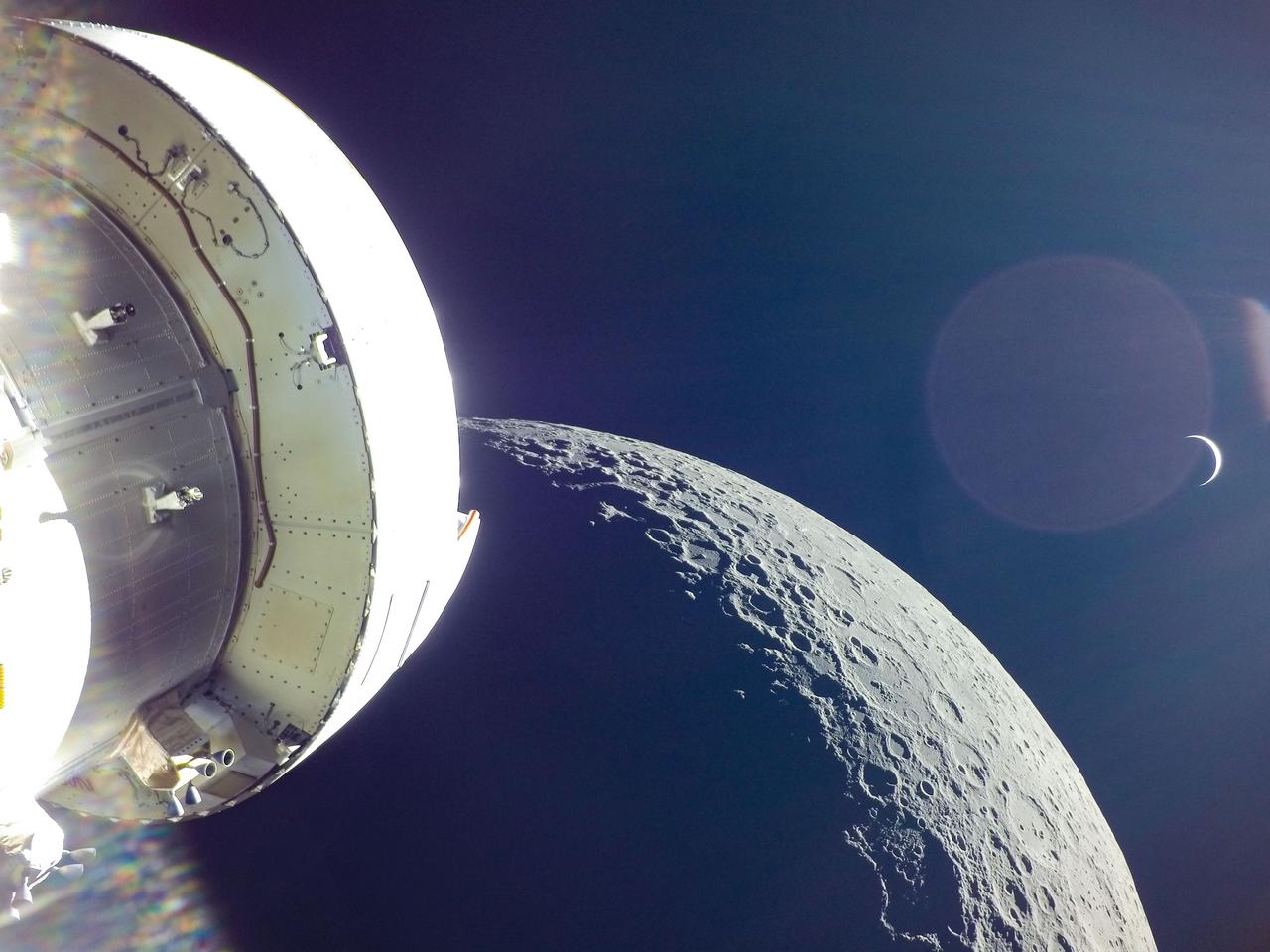

art001e000270 (Nov. 21, 2022) A portion of the far side of the Moon looms large just beyond the Orion spacecraft in this image taken on the sixth day of the Artemis I mission by a camera on the tip of one of Orion’s solar arrays. The spacecraft entered the lunar sphere of influence Sunday, Nov. 20, making the Moon, instead of Earth, the main gravitational force acting on the spacecraft. On Monday, Nov. 21, it came within 80 miles of the lunar surface, the closest approach of the uncrewed Artemis I mission, before moving into a distant retrograde orbit around the Moon.

art001e000268 (Nov. 21, 2022) A portion of the far side of the Moon looms large just beyond the Orion spacecraft in this image taken on the sixth day of the Artemis I mission by a camera on the tip of one of Orion’s solar arrays. The spacecraft entered the lunar sphere of influence Sunday, Nov. 20, making the Moon, instead of Earth, the main gravitational force acting on the spacecraft. On Monday, Nov. 21, it came within 80 miles of the lunar surface, the closest approach of the uncrewed Artemis I mission, before moving into a distant retrograde orbit around the Moon.

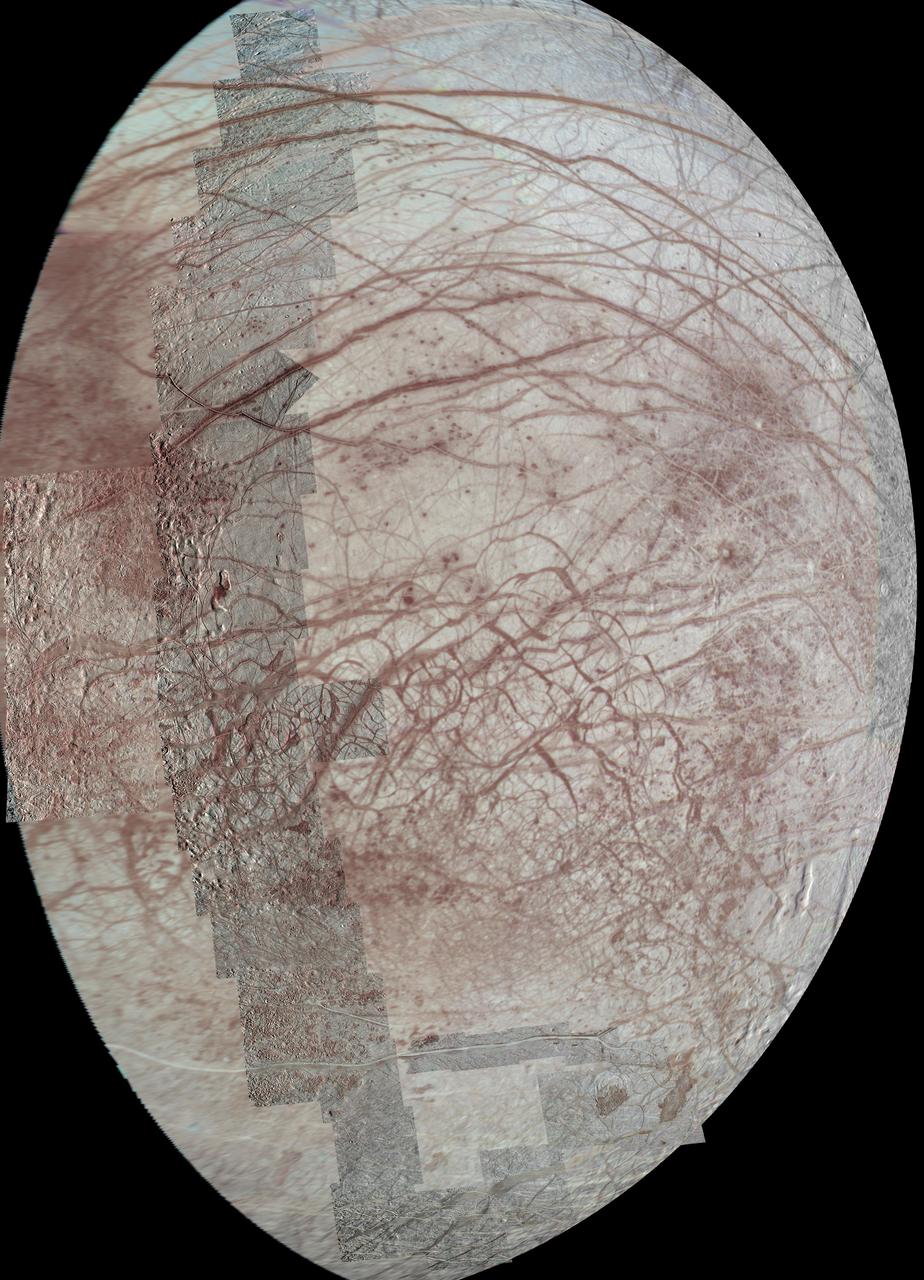

This view of Jupiter moon Europa features several regional-resolution mosaics overlaid on a lower resolution global view for context. The regional views were obtained during several different flybys of the moon by NASA Galileo mission.

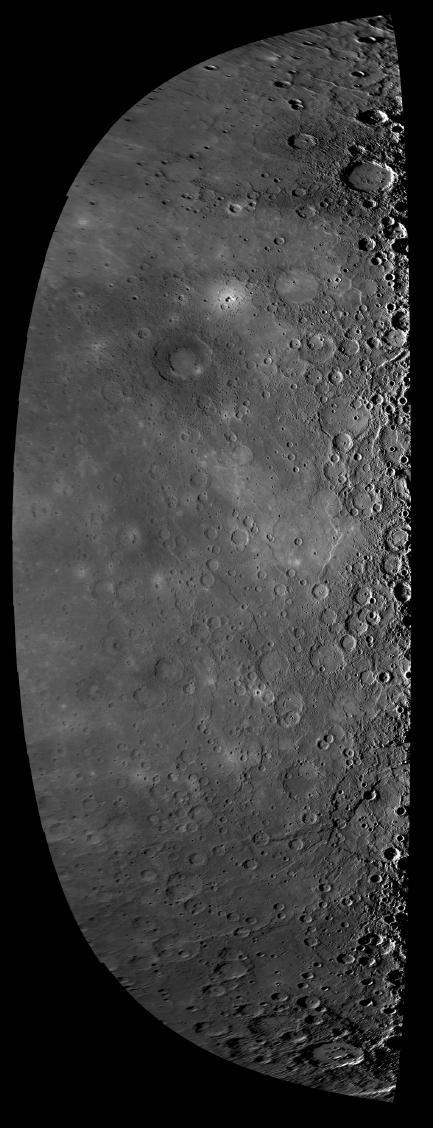

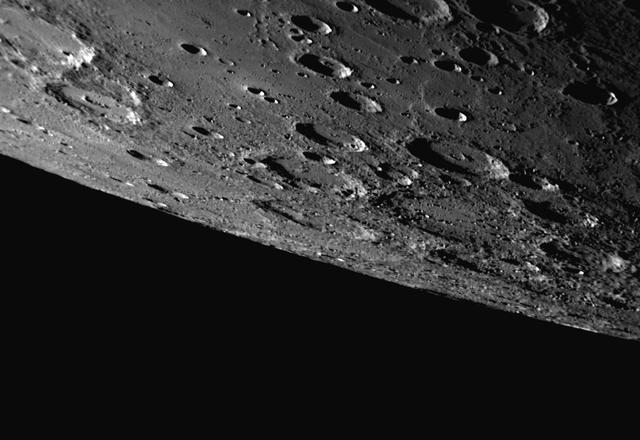

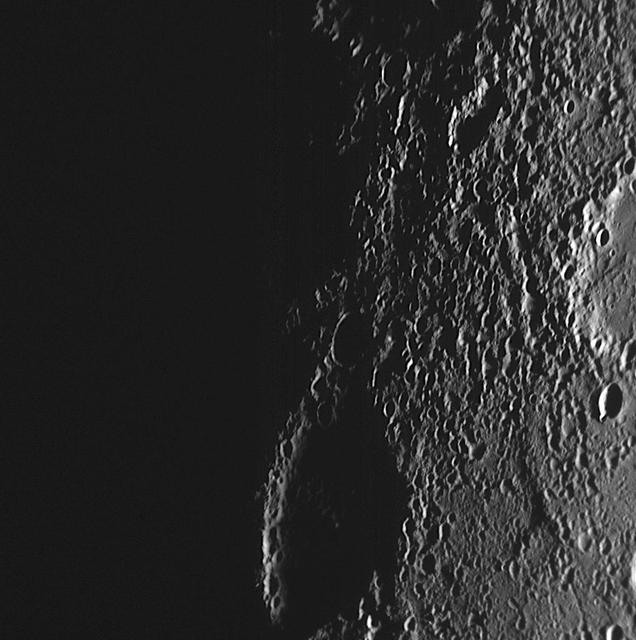

This high-resolution NAC image shows a view of Mercury dawn terminator, the division between the sunlit dayside and dark nightside of the planet, as seen as the MESSENGER spacecraft departed the planet during the mission second Mercury flyby.

Scaled Composites' Proteus aircraft with an F/A-18 Hornet and a Beechcraft KingAir from NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center during a low-level flyby at Mojave Airport in Southern California. The unique tandem-wing Proteus was the testbed for a series of UAV collision-avoidance flight demonstrations. An Amphitech 35GHz radar unit installed below Proteus' nose was the primary sensor for the Detect, See and Avoid tests.

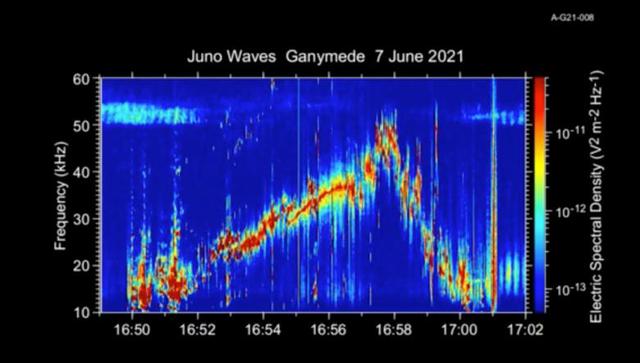

This 50-second animation provides an auditory as well as visual glimpse at data collected by Juno's Waves instrument as the spacecraft flew past the Jovian moon Ganymede on June 7, 2021. The abrupt change to higher frequencies around the midpoint of the recording represents the spacecraft's move from one region of Ganymede's magnetosphere to another. The audio track is made by shifting the frequency of those emissions – which range from 10 to 50 kHz – into the lower audio range. The animation is shorter than the duration of Juno's flyby because the Waves data is edited onboard to reduce telemetry requirements. Movie available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25030

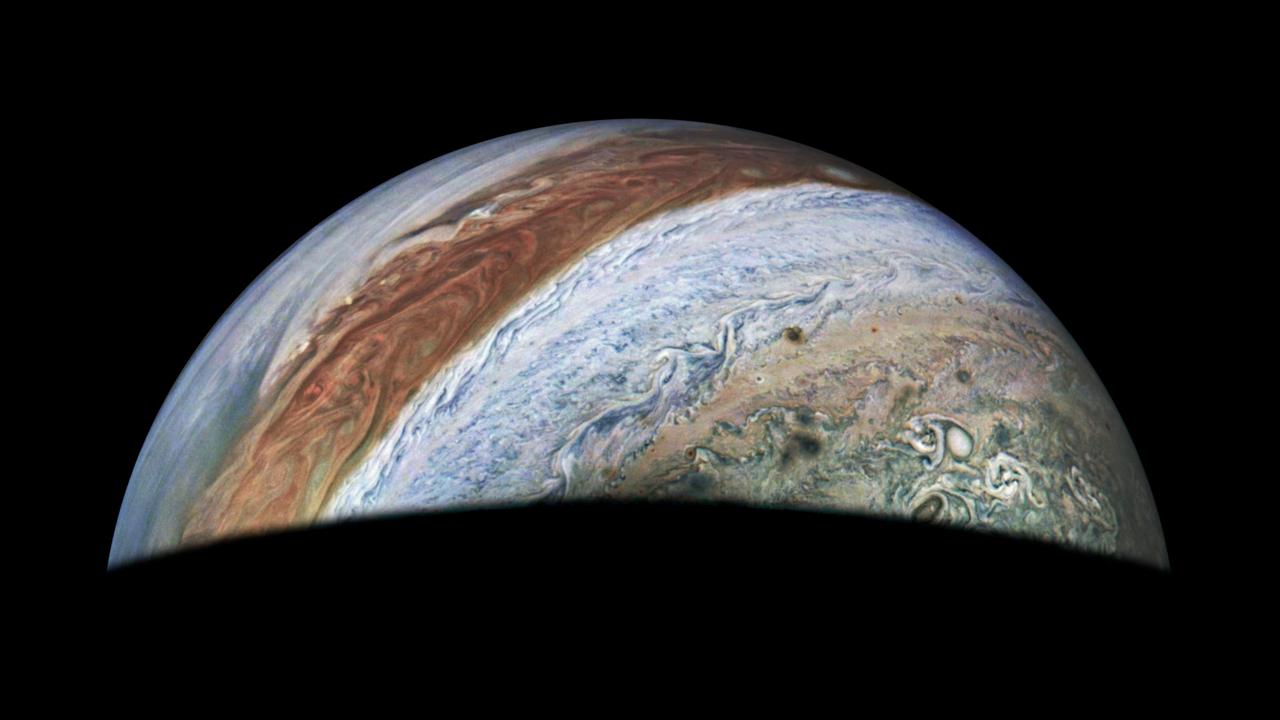

This view of Jupiter was captured by the JunoCam instrument aboard NASA's Juno spacecraft during the mission's 62nd close flyby of the giant planet on June 13, 2024. Citizen scientist Jackie Branc made the image using raw JunoCam data. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26350

A New Horizons Pluto flyby coffee mug is seen as team members wait for a signal from the spacecraft that it is healthy and collected data during the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at the Mission Operations Center of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

A new image of Ultima Thule is seen on a screen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO, New Horizons Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, New Horizons mission systems engineer Chris Hersman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, and New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, spoke about the flyby and new pre-flyby information that was downlinked from the spacecraft. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

A new image of Ultima Thule is seen on a screen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO, New Horizons Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, New Horizons mission systems engineer Chris Hersman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, and New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, spoke about the flyby and new pre-flyby information that was downlinked from the spacecraft. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

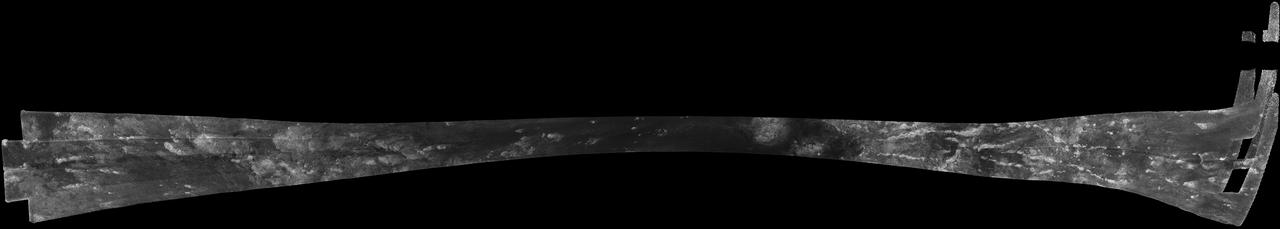

This image was obtained by NASA Cassini radar instrument during a flyby on July 7, 2010. Southern mid-latitudes trailing hemisphere, Northern Mezzoramia. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA06679

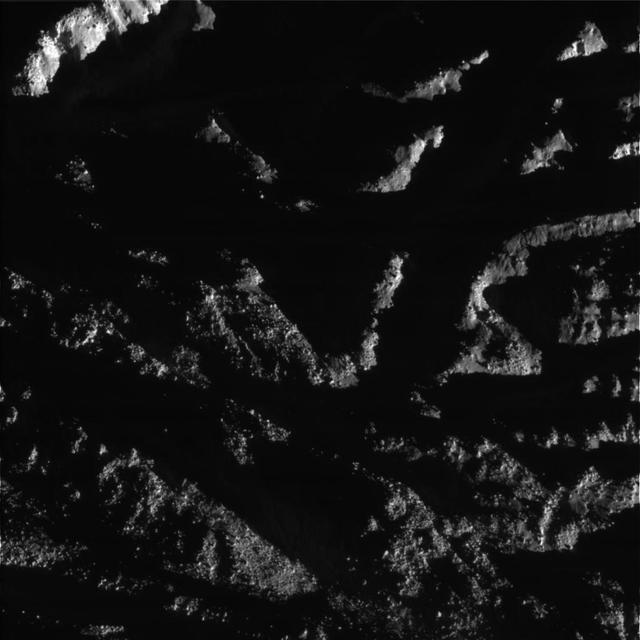

This image was obtained by NASA Cassini radar instrument during a flyby on Oct. 9, 2006. North Polar Pass Northern Lakes Region, Aaru. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA03187

This image was obtained by NASA Cassini radar instrument during a flyby on Dec. 12, 2006. North Polar Pass Northern Lakes Region, Aaru. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04308

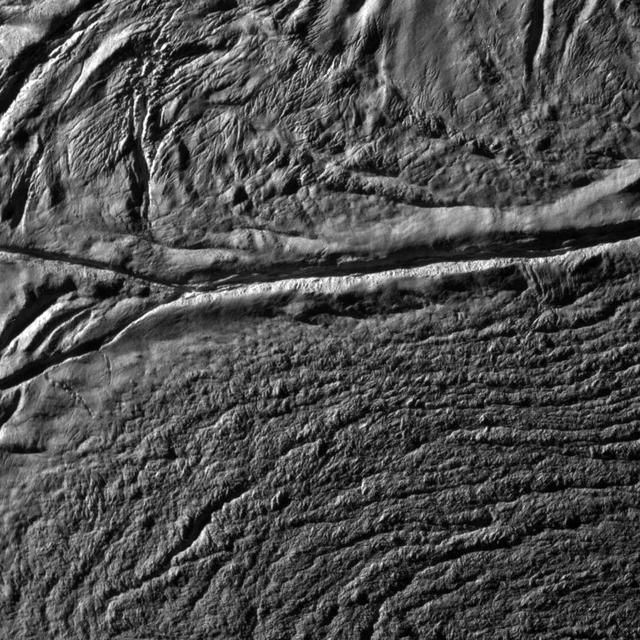

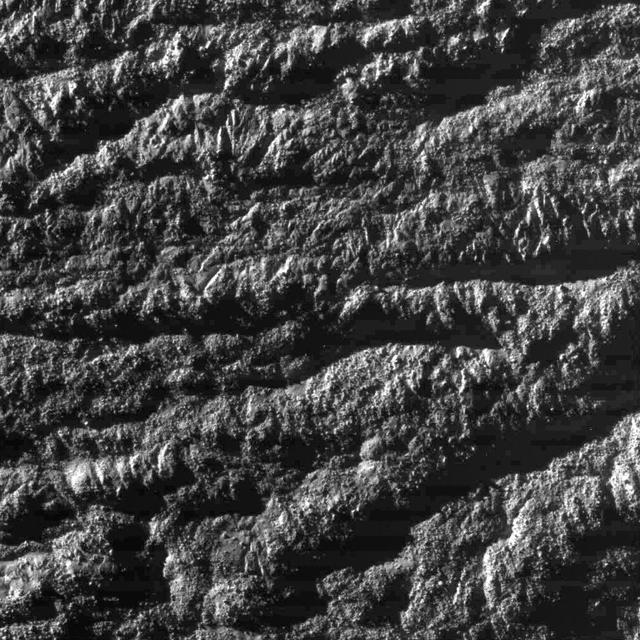

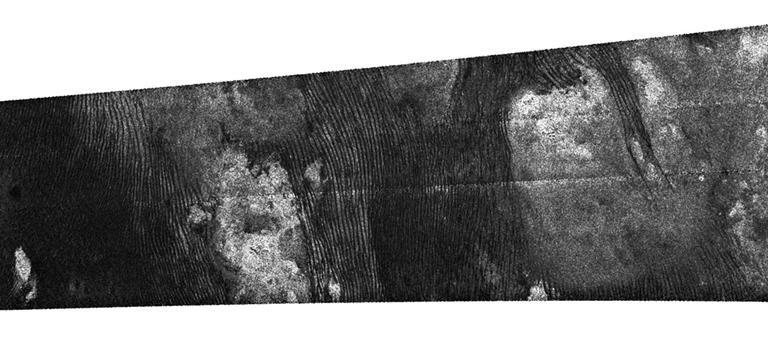

This image was obtained by NASA Cassini radar instrument during a flyby on Sept. 7, 2005. Southern Mid-latitudes Central Tsegihi, Mezzoramia. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01855

This image was obtained by NASA Cassini radar instrument during a flyby on Jan. 12, 2010. High southern latitudes Ontario Lacus, Mezzoramia. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00927

This image was obtained by NASA's Cassini radar instrument during a flyby on July 8, 2009. The radar antenna was pointing toward Titan at a 900 km altitude at the closest approach. The image has been processed with a resolution of 128 pixels/deg. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04398

Completed: 07-16-2009 Straddling the equator approximately 1000 kilometers to the west of the South American mainland, the Galapagos Islands lie within the heart of the equatorial current system. Rising from the sea floor, the volcanic islands of the Galapagos are set on top of a large submarine platform. The main portion of the Galapagos platform is relatively flat and less than 1000 meters in depth. The steepest slopes are found along the western and southern flanks of the platform with a gradual slope towards the east. The interactions of the Galapagos and the oceanic currents create vastly different environmental regimes which not only isolates one part of the Archipelago from the other but allows penguins to live along the equator on the western part of the Archipelago and tropical corals around the islands to the north. The islands are relatively new in geologic terms with the youngest islands in the west still exhibiting periodic eruptions from their massive volcanic craters. Please give credit for this item to: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, The SeaWiFS Project and GeoEye, Scientific Visualization Studio. NOTE: All SeaWiFS images and data presented on this web site are for research and educational use only. All commercial use of SeaWiFS data must be coordinated with GeoEye (http://www.geoeye.com). To download this video go to: <a href="http://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/goto?3628" rel="nofollow">svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/goto?3628</a> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> is home to the nation's largest organization of combined scientists, engineers and technologists that build spacecraft, instruments and new technology to study the Earth, the sun, our solar system, and the universe.

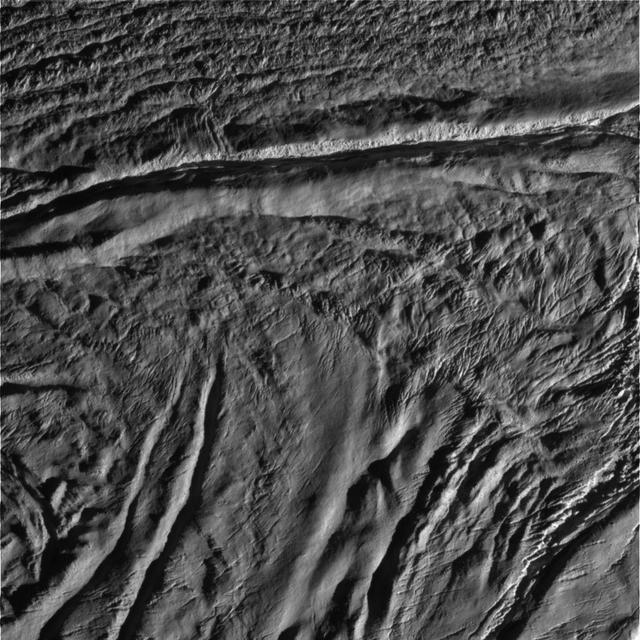

This image was obtained by NASA Cassini radar instrument during a flyby on Feb. 15, 2005. The radar antenna was pointing toward Titan at an altitude of 1,577 kilometers 890 miles during the closest approach. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04389

This image was obtained by NASA Cassini radar instrument during a flyby on Jan. 13, 2007. Northern mid-latitudes to equator Ganesa Macula, Aaru, western Senkyo, Tsegihi. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00928

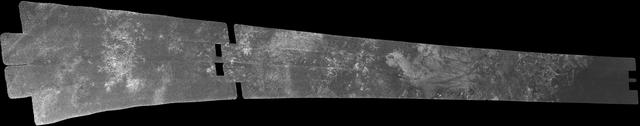

This image was obtained by NASA Cassini radar instrument during a flyby on Oct. 28, 2005. Equatorial Pass Trailing hemisphere, Central Adiri, Central Belet, Huygens Landing Site, Antillia Faculae.

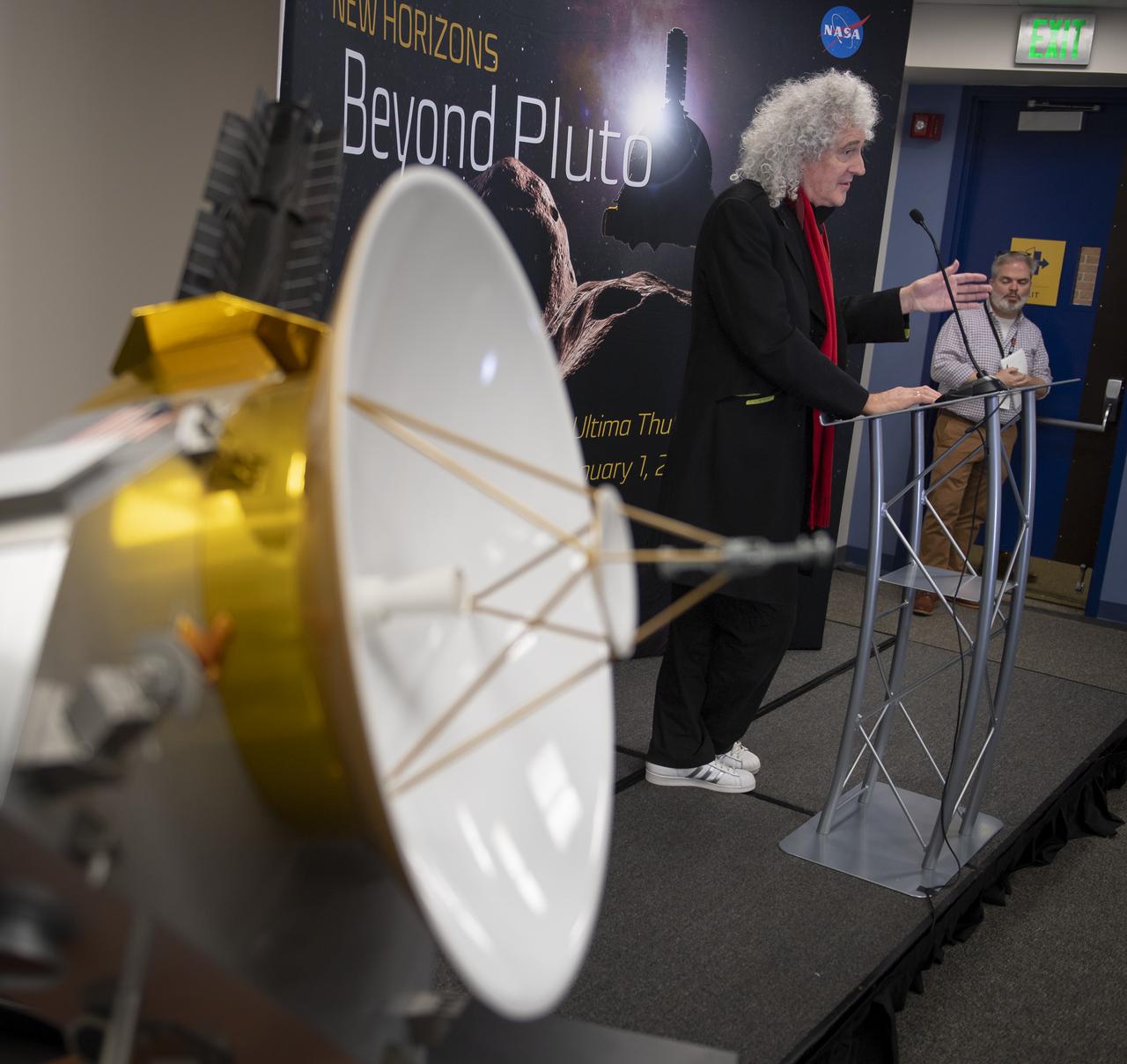

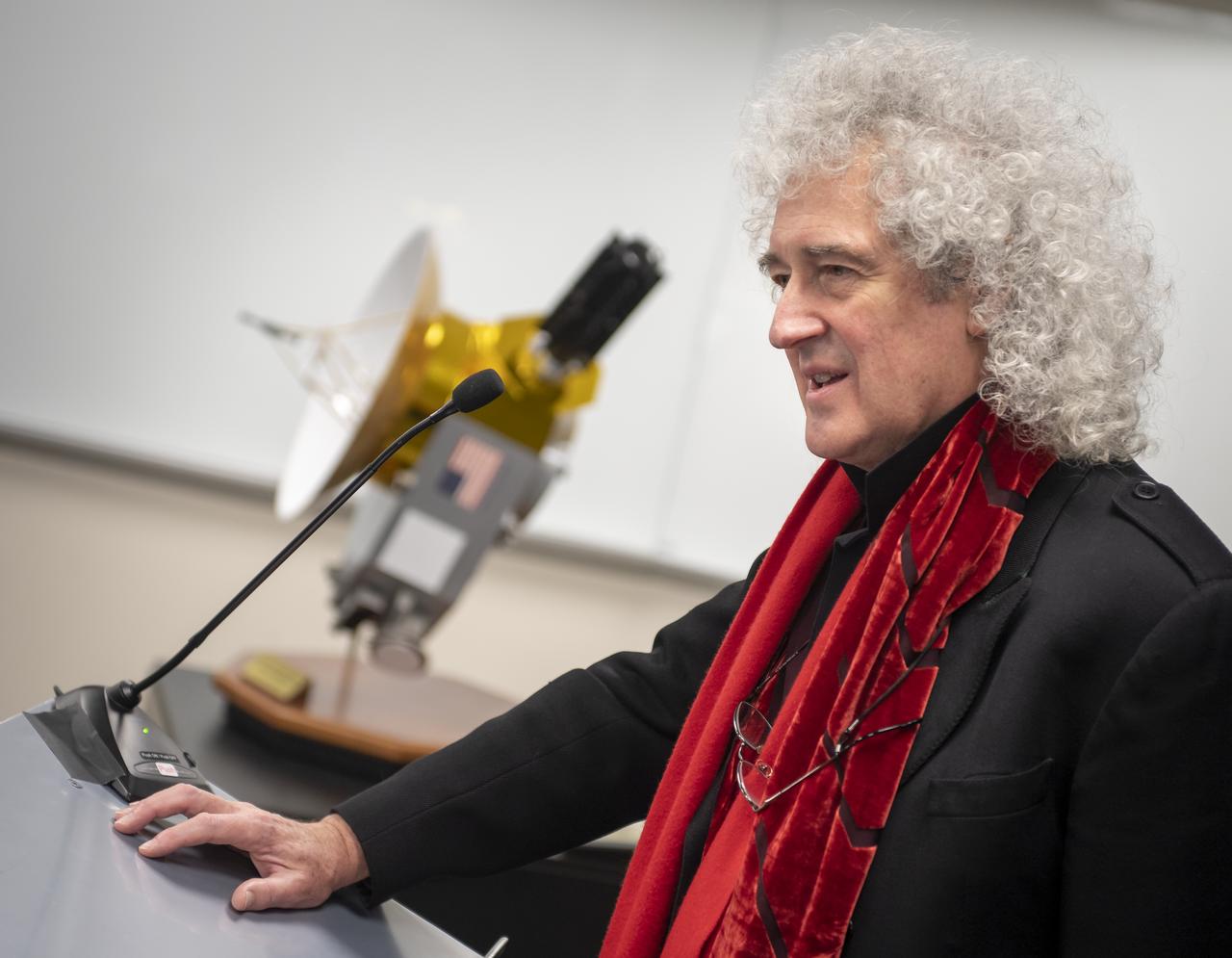

Brian May, lead guitarist of the rock band Queen and astrophysicist discusses the upcoming New Horizons flyby of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Brian May, lead guitarist of the rock band Queen and astrophysicist discusses the upcoming New Horizons flyby of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

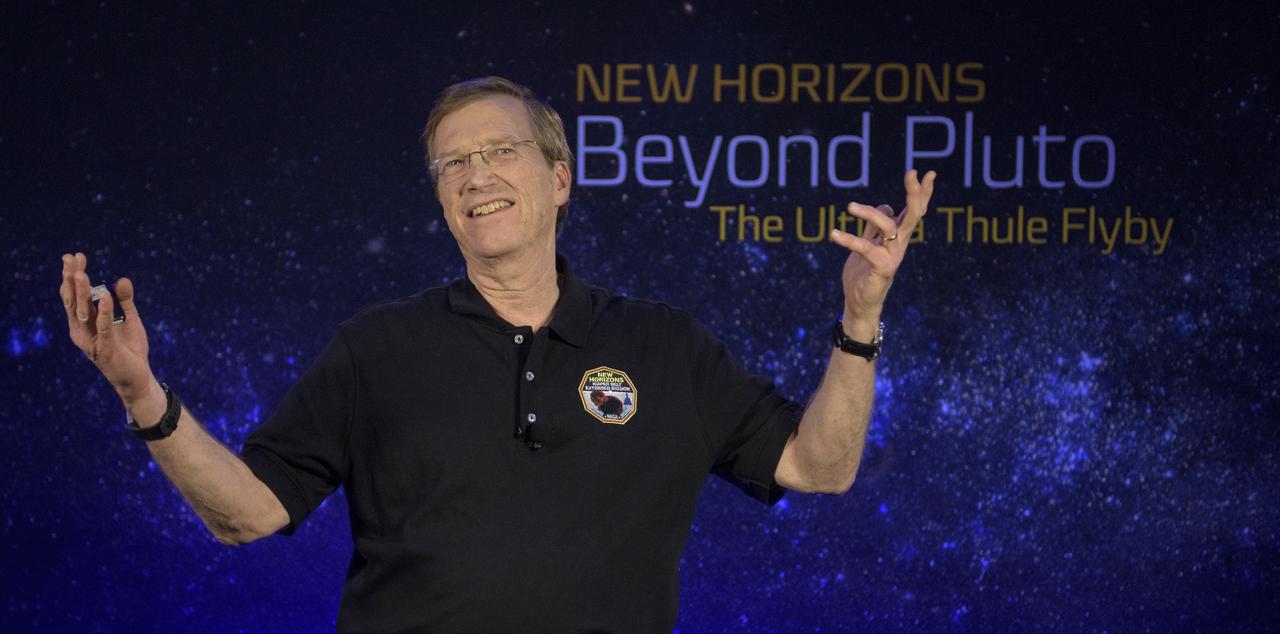

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO, speaks at a press conference prior to the flyby of Ultima Thule by the New Horizons spacecraft, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons team members wait for a signal from the spacecraft that it is healthy and collected data during the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at the Mission Operations Center of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons project manager Helene Winters of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory speaks at a press conference prior to the flyby of Ultima Thule by the New Horizons spacecraft, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

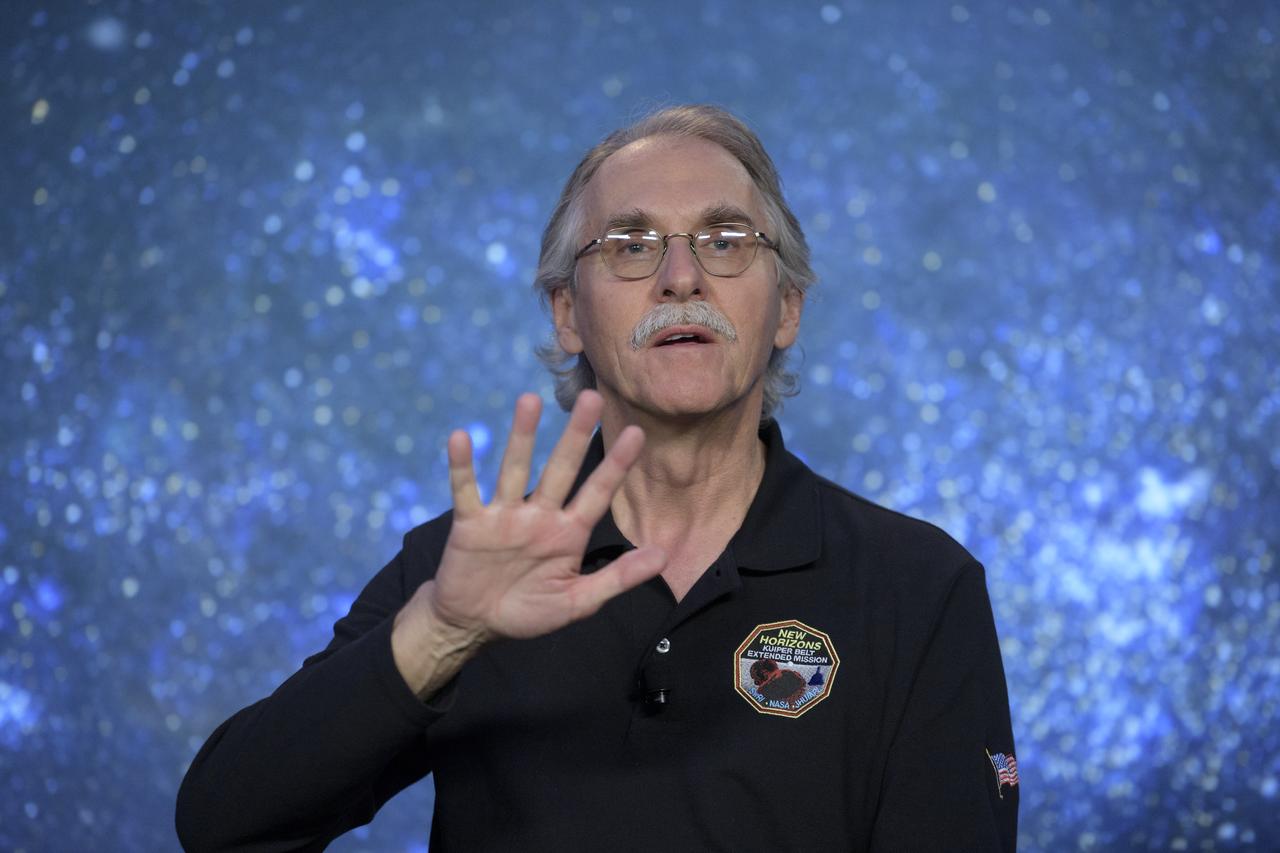

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory gives a talk titled "Pluto Flyby; Summer 2015", Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Brian May, lead guitarist of the rock band Queen and astrophysicist discusses the upcoming New Horizons flyby of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory gives a talk titled "Pluto Flyby; Summer 2015", Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons team members wait for a signal from the spacecraft that it is healthy and collected data during the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at the Mission Operations Center of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons project manager Helene Winters of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory speaks at a press conference prior to the flyby of Ultima Thule by the New Horizons spacecraft, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory gives a talk titled "Pluto Flyby; Summer 2015", Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Brian May, lead guitarist of the rock band Queen and astrophysicist discusses the upcoming New Horizons flyby of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons team members wait for a signal from the spacecraft that it is healthy and collected data during the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at the Mission Operations Center of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons deputy project scientist Cathy Olkin of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO discusses what they hope to learn from the flyby of Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Brian May, lead guitarist of the rock band Queen and astrophysicist discusses the upcoming New Horizons flyby of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Fred Pelletier, lead of the project navigation team at KinetX Inc. in Simi Valley, California, speaks at a press conference prior to the flyby of Ultima Thule by the New Horizons spacecraft, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons deputy project scientist John Spencer of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO discusses what they hope to learn from the flyby of Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

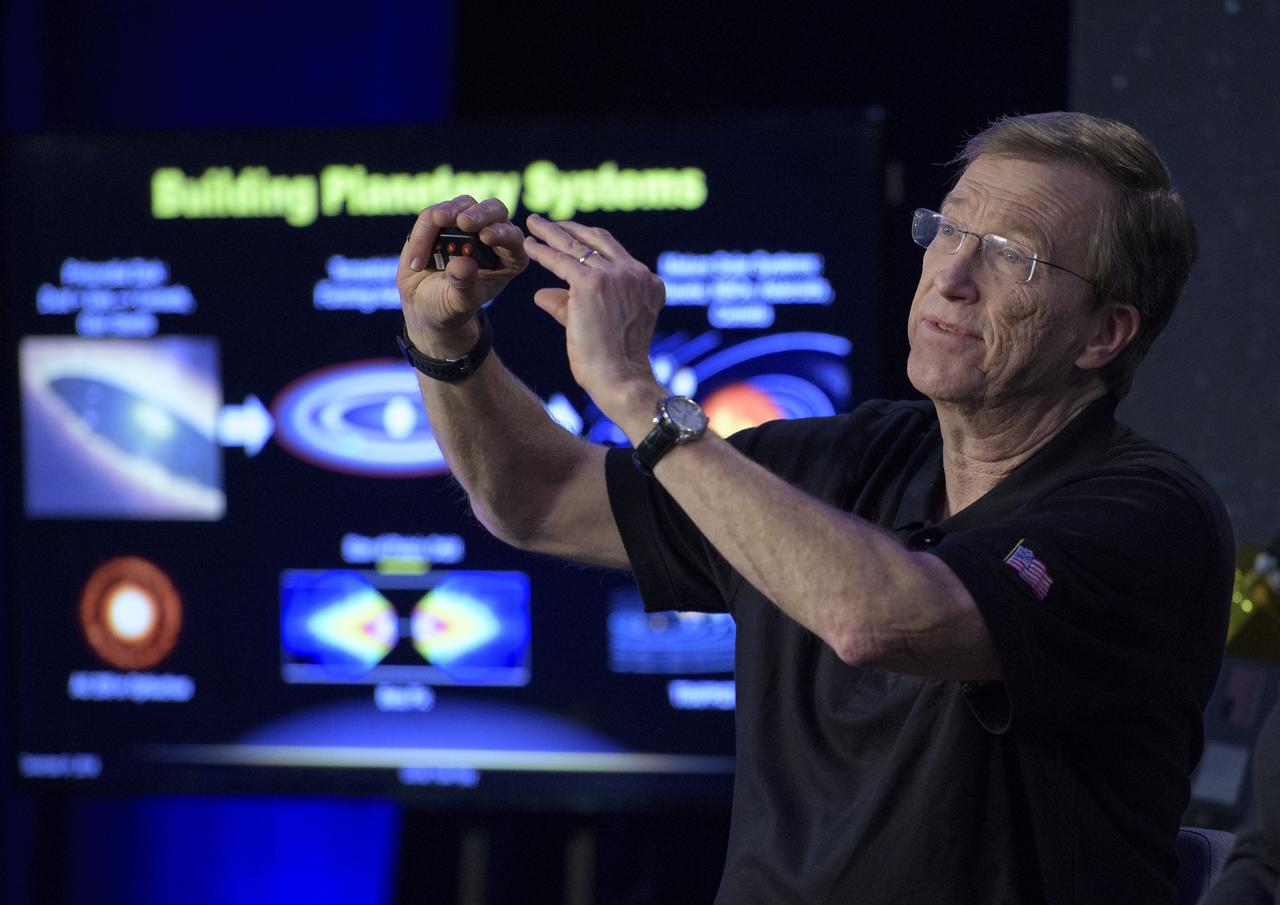

New Horizons co-investigator John Spencer of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO, speaks about the flyby of Ultima Thule during an overview of the New Horizons Mission, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons co-investigator Silvia Protopapa of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) discusses what they hope to learn from the flyby of Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory discusses what they hope to learn from the flyby of Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

art0001e002083 (Dec. 5, 2022) On the 20th day of the Artemis I mission, Orion captured the Earth rising behind the Moon following the return powered flyby. The 3 minute, 27 second, return powered flyby burn, committed the spacecraft to a Dec. 11 splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

art0001e002092 (Dec. 5, 2022) On the 20th day of the Artemis I mission, Orion captured the Earth rising behind the Moon following the return powered flyby. The 3 minute, 27 second, return powered flyby burn, committed the spacecraft to a Dec. 11 splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

NASA image release October 5, 2010 Hubble Space Telescope observations of comet 103P/Hartley 2, taken on September 25, are helping in the planning for a November 4 flyby of the comet by NASA's Deep Impact eXtended Investigation (DIXI) spacecraft. Analysis of the new Hubble data shows that the nucleus has a diameter of approximately 0.93 miles (1.5 km), which is consistent with previous estimates. The comet is in a highly active state, as it approaches the Sun. The Hubble data show that the coma is remarkably uniform, with no evidence for the types of outgassing jets seen from most "Jupiter Family" comets, of which Hartley 2 is a member. Jets can be produced when the dust emanates from a few specific icy regions, while most of the surface is covered with relatively inert, meteoritic-like material. In stark contrast, the activity from Hartley 2's nucleus appears to be more uniformly distributed over its entire surface, perhaps indicating a relatively "young" surface that hasn't yet been crusted over. Hubble's spectrographs - the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) and the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) -- are expected to provide unique information about the comet's chemical composition that might not be obtainable any other way, including measurements by DIXI. The Hubble team is specifically searching for emissions from carbon monoxide (CO) and diatomic sulfur (S2). These molecules have been seen in other comets but have not yet been detected in 103P/Hartley 2. 103P/Hartley has an orbital period of 6.46 years. It was discovered by Malcolm Hartley in 1986 at the Schmidt Telescope Unit in Siding Spring, Australia. The comet will pass within 11 million miles of Earth (about 45 times the distance to the Moon) on October 20. During that time the comet may be visible to the naked eye as a 5th magnitude "fuzzy star" in the constellation Auriga. Credit: NASA, ESA, and H. Weaver (The Johns Hopkins University/Applied Physics Lab) The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., in Washington, D.C. <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASA_GoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Join us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b>

Proteus aircraft low-level flyby at Las Cruces Airport.