Amazing Icy Moons

Icy Old Moon

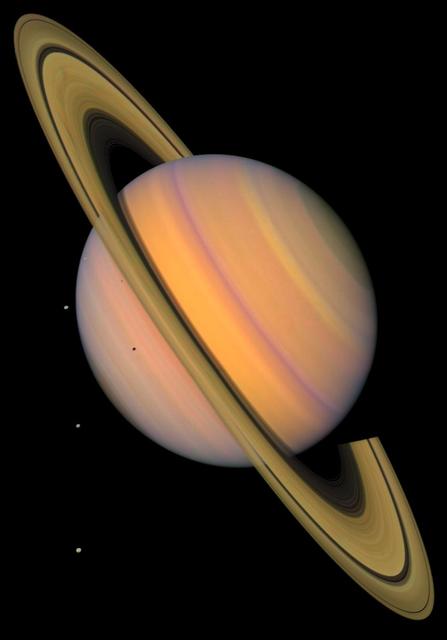

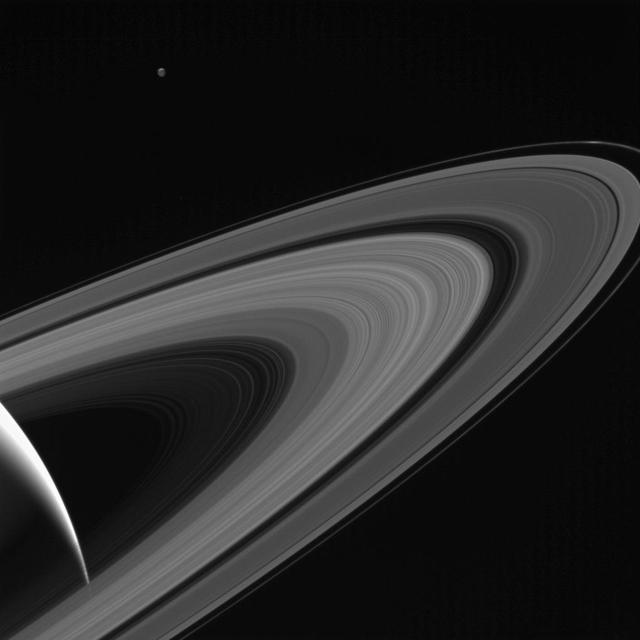

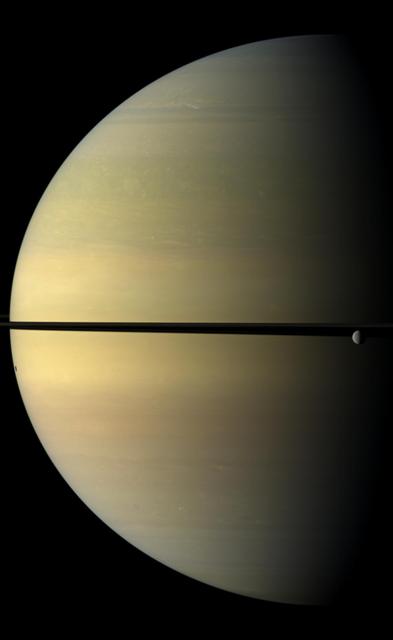

Saturn and 4 Icy Moons, Enhanced Color http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00349

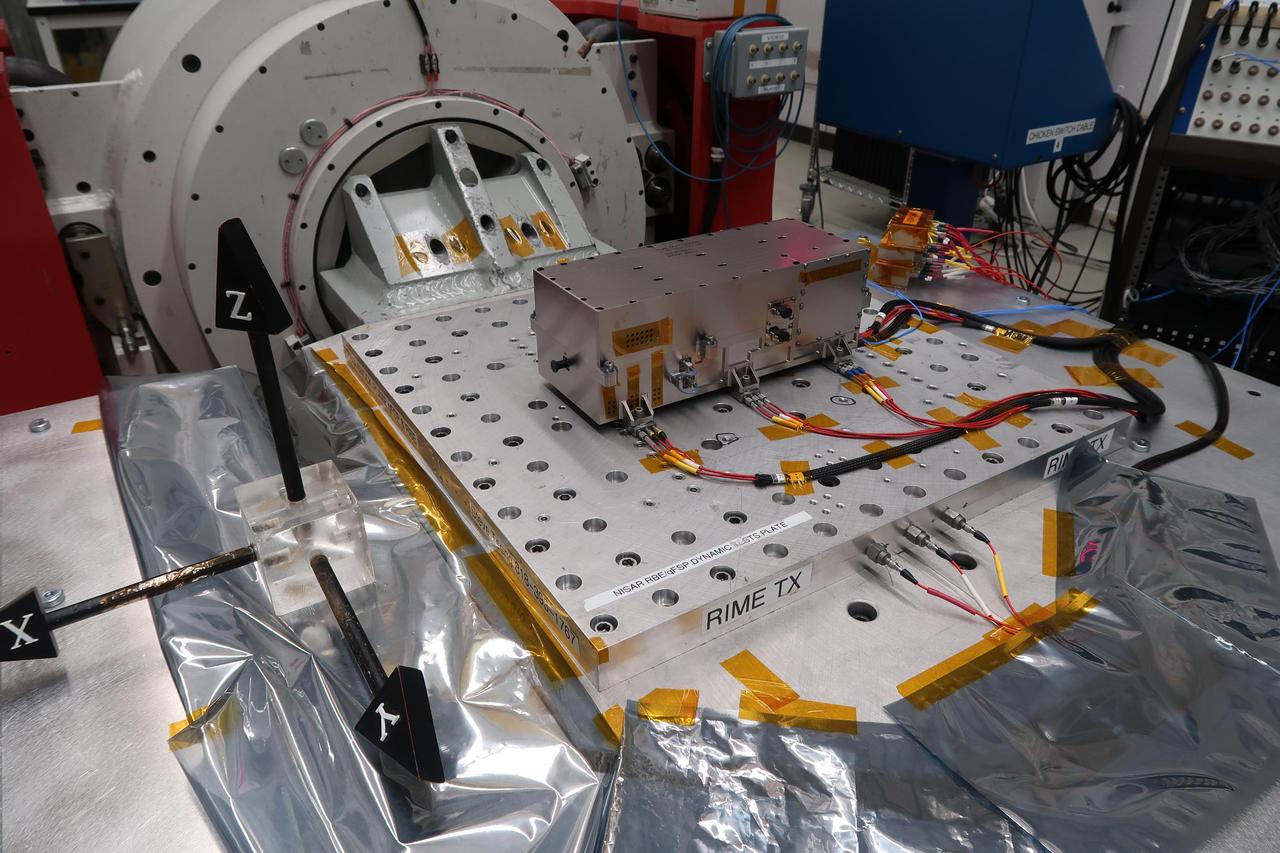

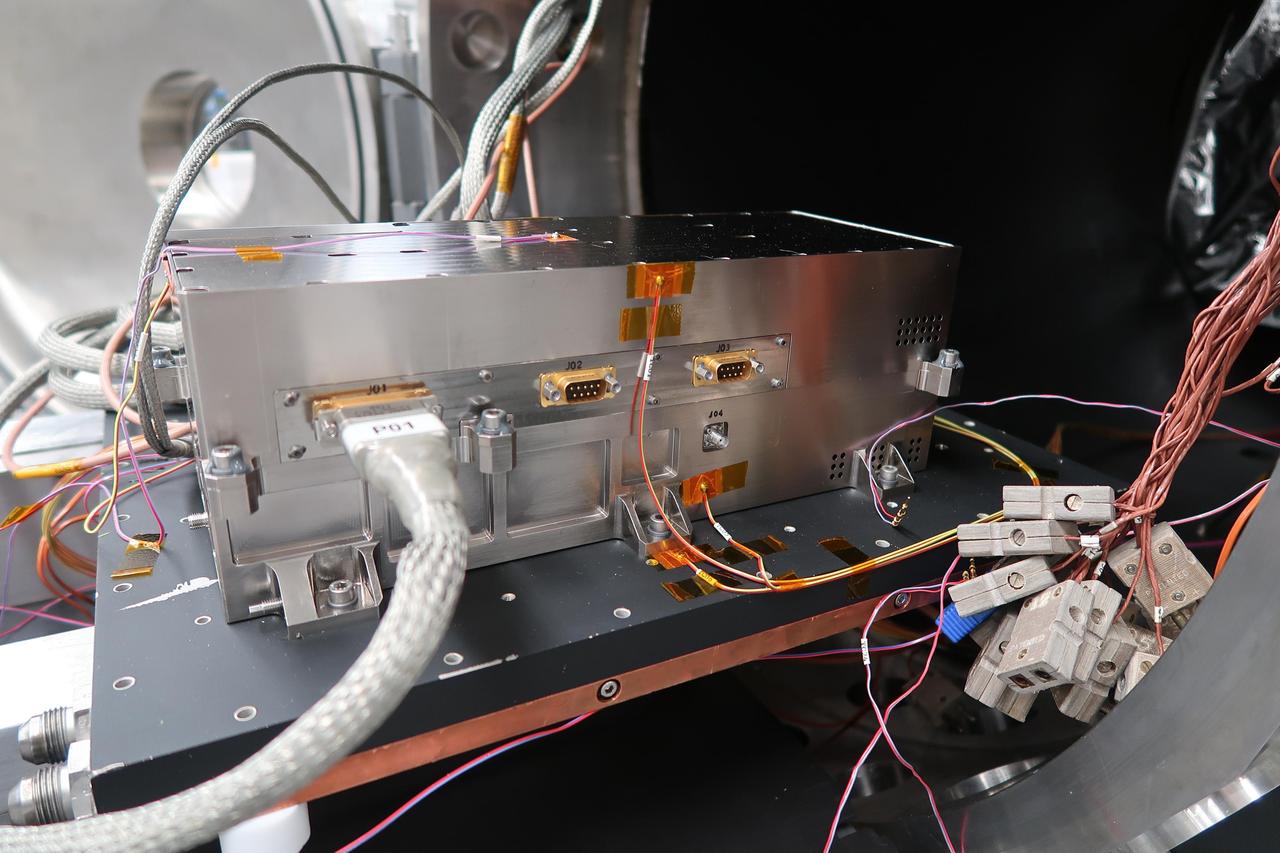

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory built and shipped the receiver, transmitter, and electronics necessary to complete the radar instrument for Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), the ESA (European Space Agency) mission to explore Jupiter and its three large icy moons. In this photo, shot at JPL on April 27, 2020, the transmitter undergoes random vibration testing to ensure the instrument can survive the shaking that comes with launch. Part of an instrument called Radar for Icy Moon Exploration, or RIME, the transmitter sends out radio waves, which can penetrate surfaces of icy moons and help scientists "see" underneath. A collaboration between JPL and the Italian Space Agency (ASI), RIME is one of 10 instruments that will fly aboard ESA's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission, set to launch in 2022. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24024

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory built and shipped the receiver, transmitter and electronics necessary to complete the radar instrument for ESA's (European Space Agency's) Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission. Set to launch in 2022, JUICE will explore Jupiter and its three large icy moons. The transmitter works by sending out radio waves, which can penetrate surfaces of icy moons so that scientists "see" underneath. The instrument, called Radar for Icy Moon Exploration, or RIME, is a collaboration by JPL and the Italian Space Agency (ASI) and is one of ten instruments that will fly aboard. This photo, shot at JPL on July 23, 2020, shows the transmitter as it exits a thermal vacuum chamber. The test is one of several designed to ensure the hardware can survive the conditions of space travel. The thermal chamber simulates deep space by creating a vacuum and by varying the temperatures to match those the instrument will experience over the life of the mission. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24025

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory built and shipped the receiver, transmitter and electronics necessary to complete the radar instrument for the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission. Set to launch in 2022, JUICE is the ESA (European Space Agency) mission to explore Jupiter and its three large icy moons. From front: JPL engineers and technicians Jeremy Steinert, Jordan Tanabe, Glenn Jeffery, and Robert Johnson follow COVID-19 Safe-at-Work guidelines as they transport the transmitter and electronics on Aug. 19, 2020, for shipping to the Italian Space Agency (ASI). ASI is collaborating with JPL to build the instrument, called Radar for Icy Moon Exploration (RIME). It is one of 10 instruments that will fly aboard JUICE. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24026

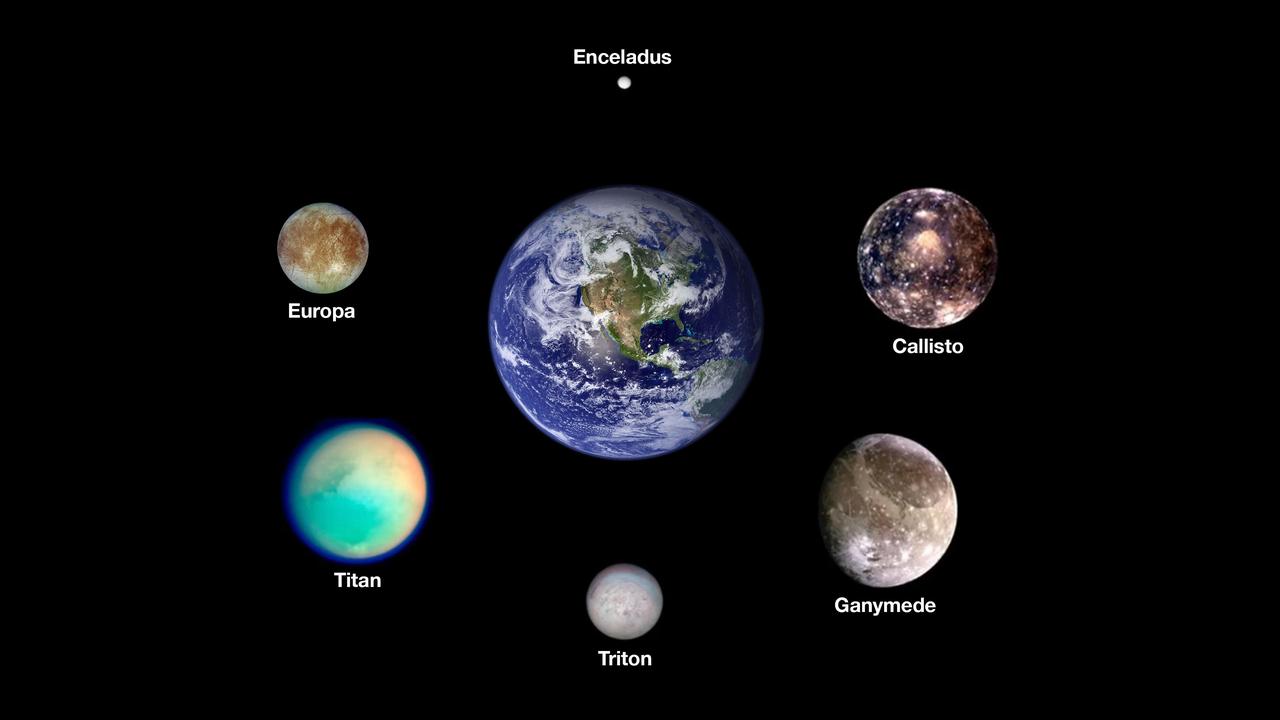

Scientists think six icy moons in our solar system may currently host oceans of liquid water beneath their outer surfaces. Arranged around Earth are images from NASA spacecraft of, clockwise from the top, Saturn's moon Enceladus, Jupiter's moons Callisto and Ganymede, Neptune's moon Triton, Saturn's moon Titan, and Jupiter's moon Europa, the target of NASA's Europa Clipper mission. The worlds here are shown to scale. The images of the Saturnian moons were taken by NASA's Cassini mission. The images of the Jovian moons were taken by NASA's Galileo mission. The image of Triton was taken by NASA's Voyager 2 mission. The image of Earth was stitched together using months of satellite-based observations, mostly using data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra satellite. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26103

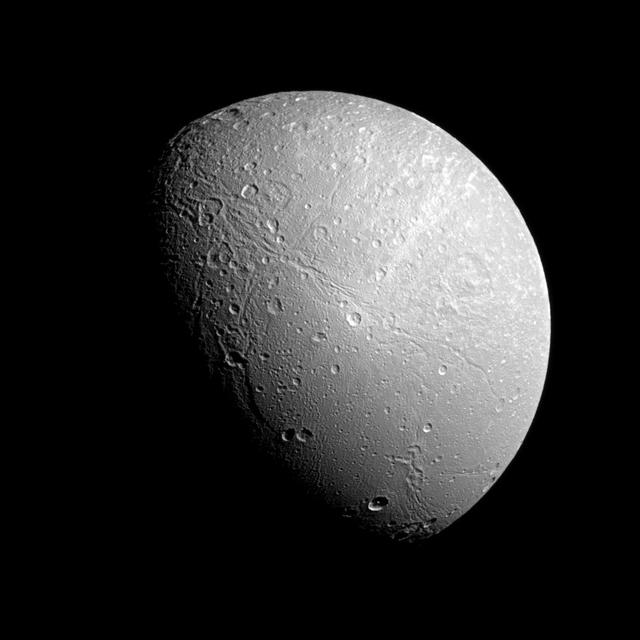

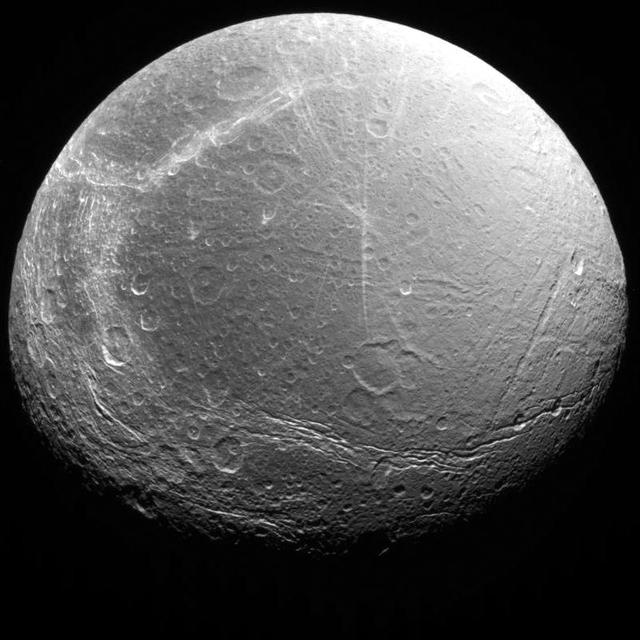

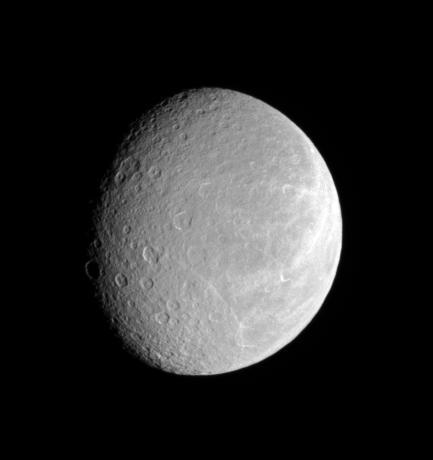

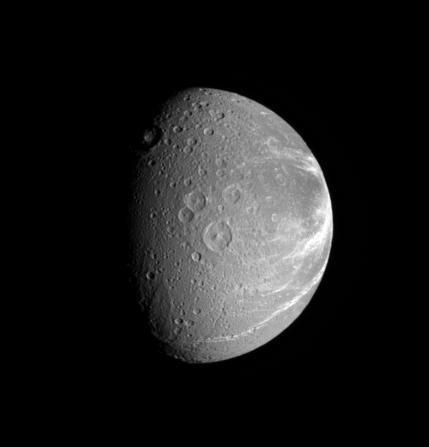

Bright icy fractures, or linea, cover the trailing hemisphere of Saturn moon, Dione

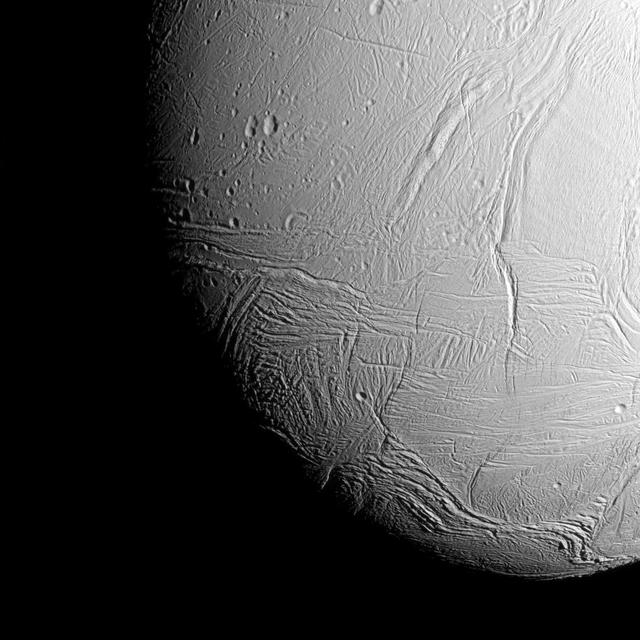

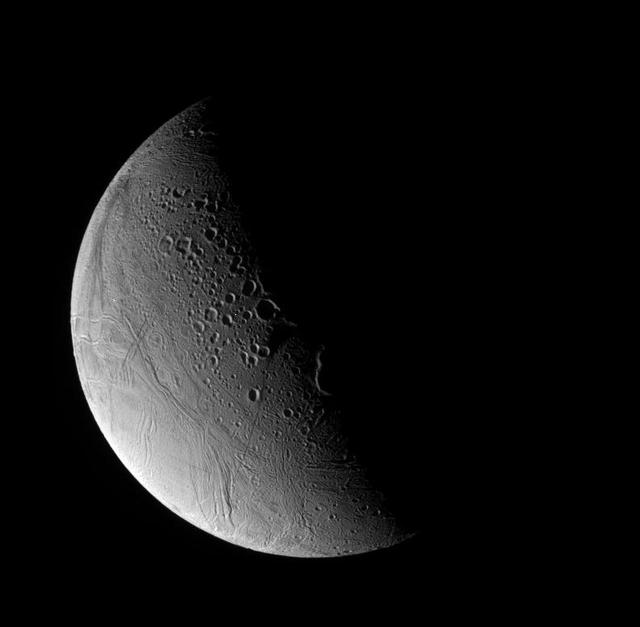

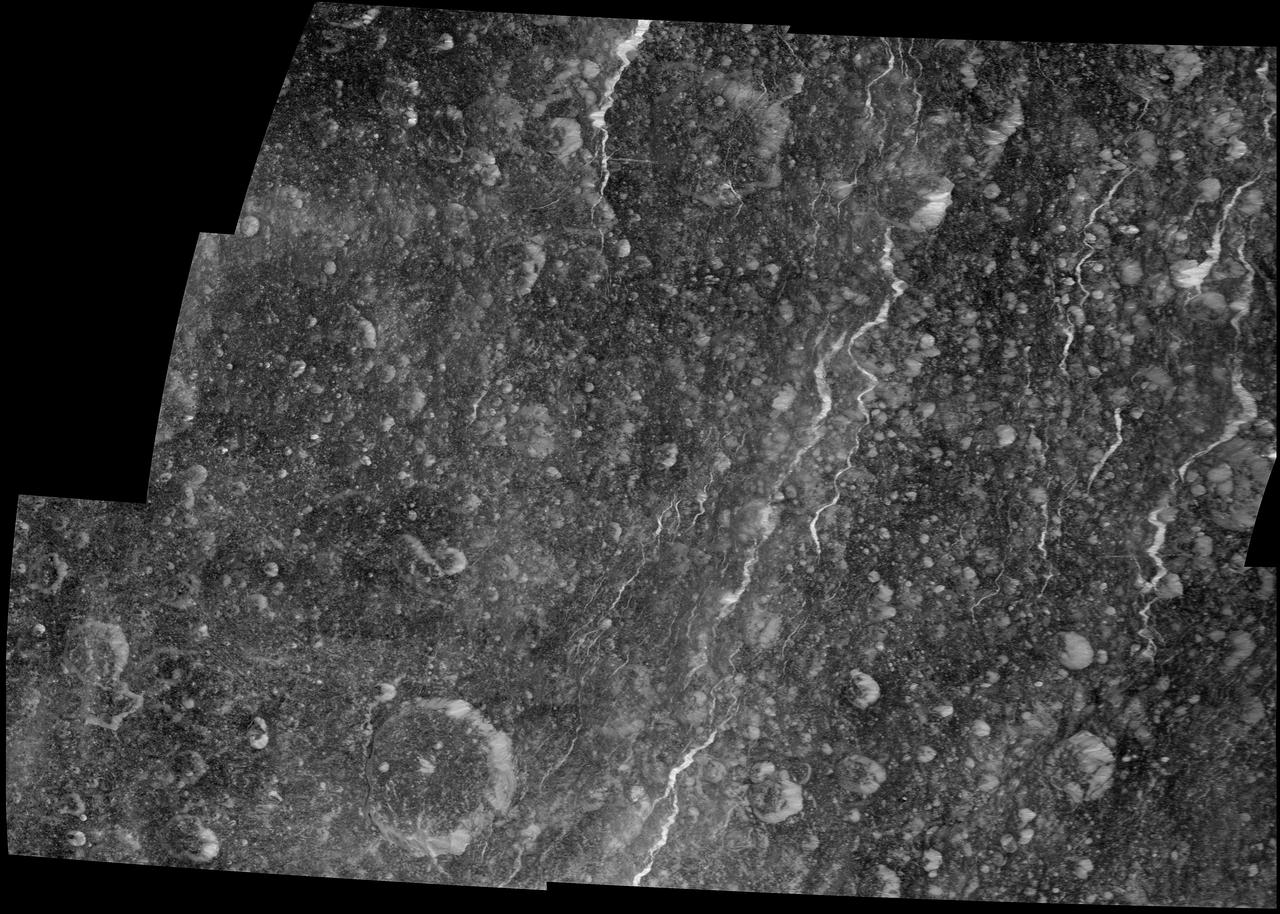

The south polar region of Saturn active, icy moon Enceladus awaits NASA Cassini spacecraft in this view, acquired on approach to the mission deepest-ever dive through the moon plume of icy spray.

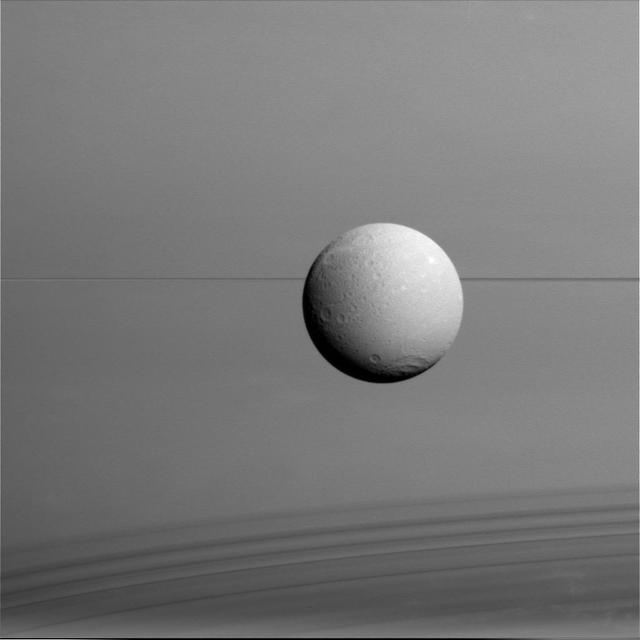

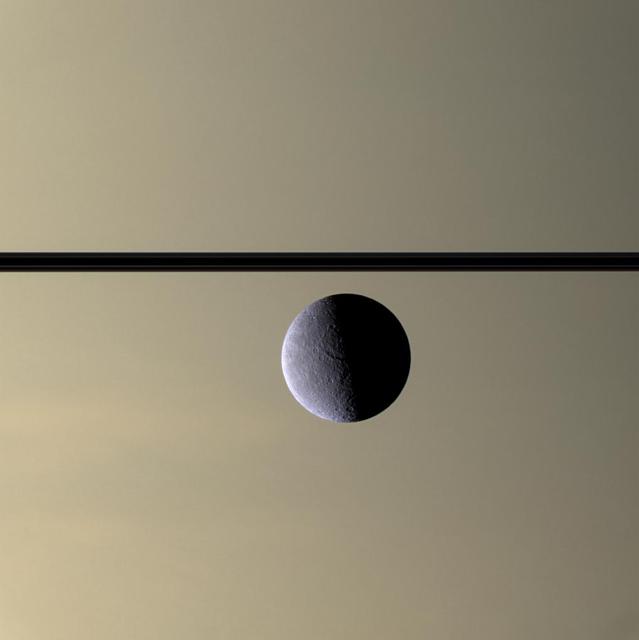

Dione hangs in front of Saturn and its icy rings in this view, captured during Cassini final close flyby of the icy moon. North on Dione is up.

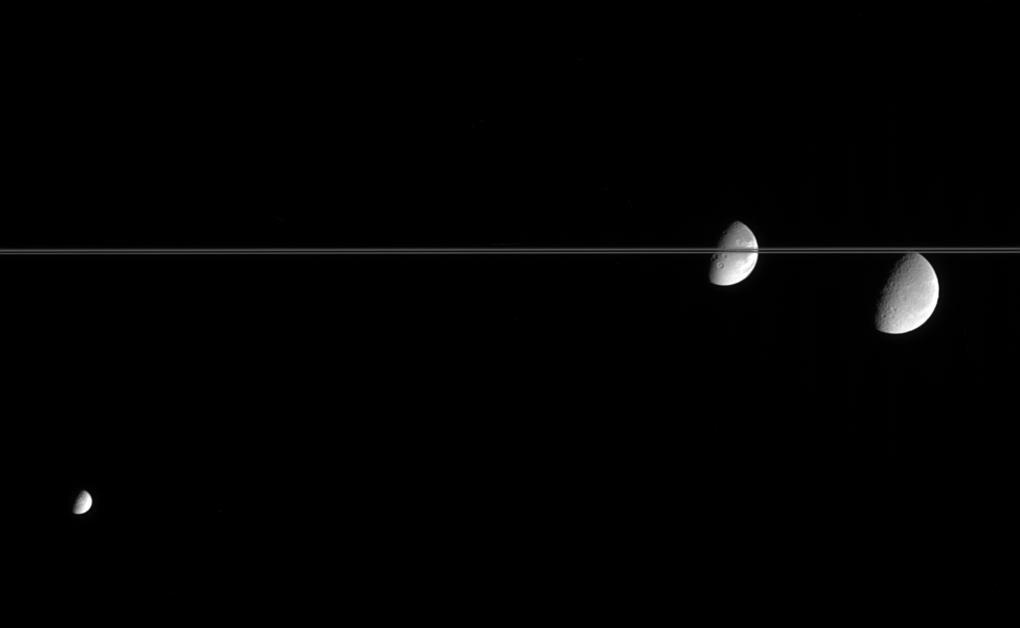

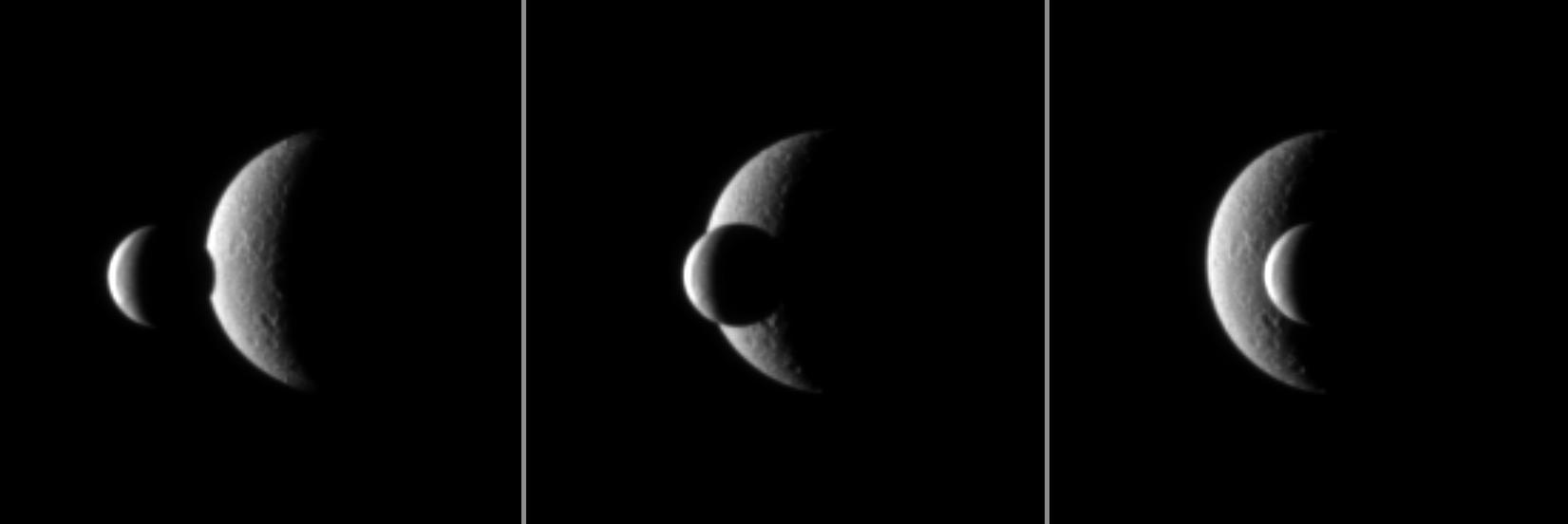

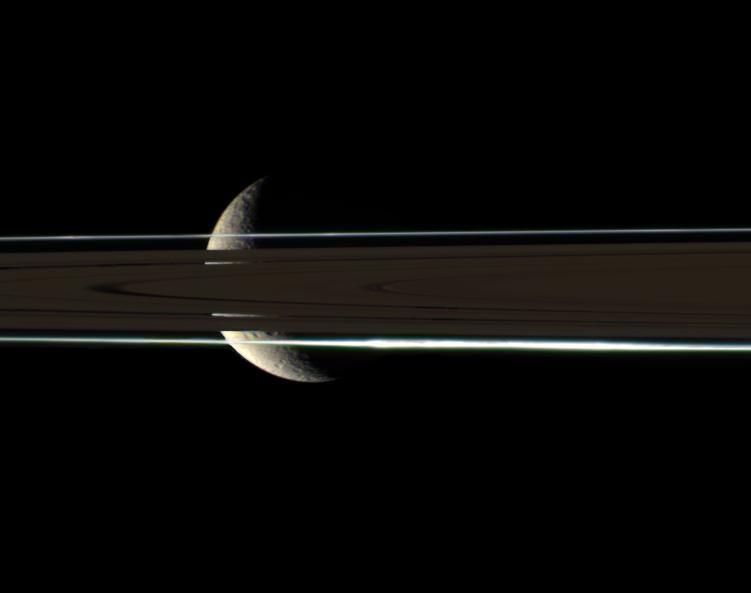

Two of Saturn icy moons pass each other in a mutual event recorded by NASA Cassini spacecraft. The smaller moon Enceladus passes in front of the larger moon Rhea.

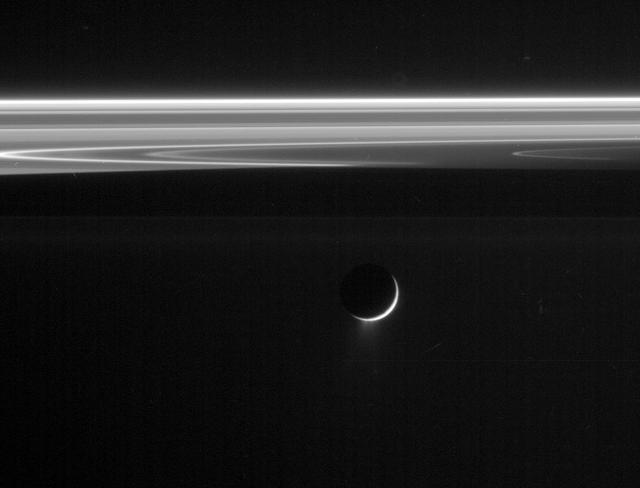

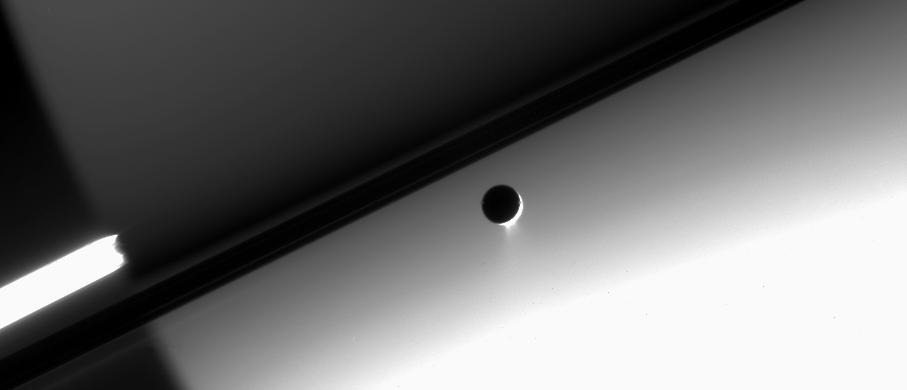

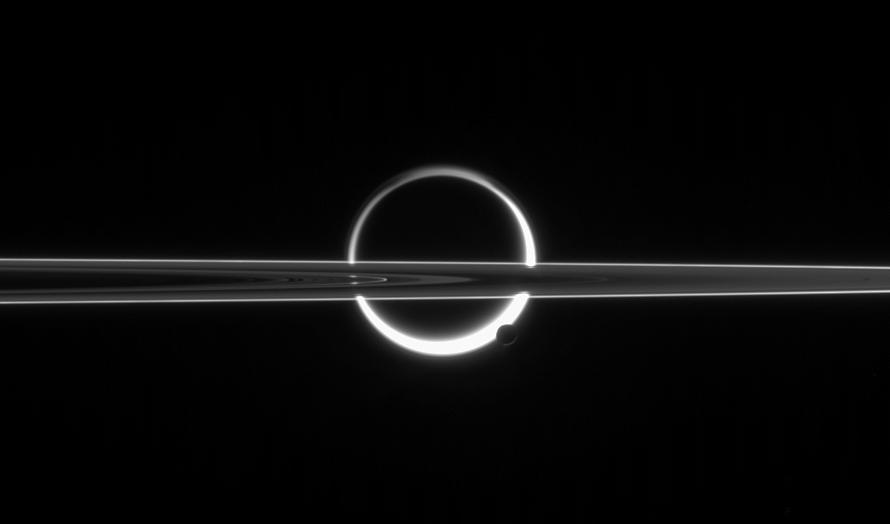

Cassini stares toward the night side of Saturn, seen here on the right, as the active icy moon Enceladus glides past

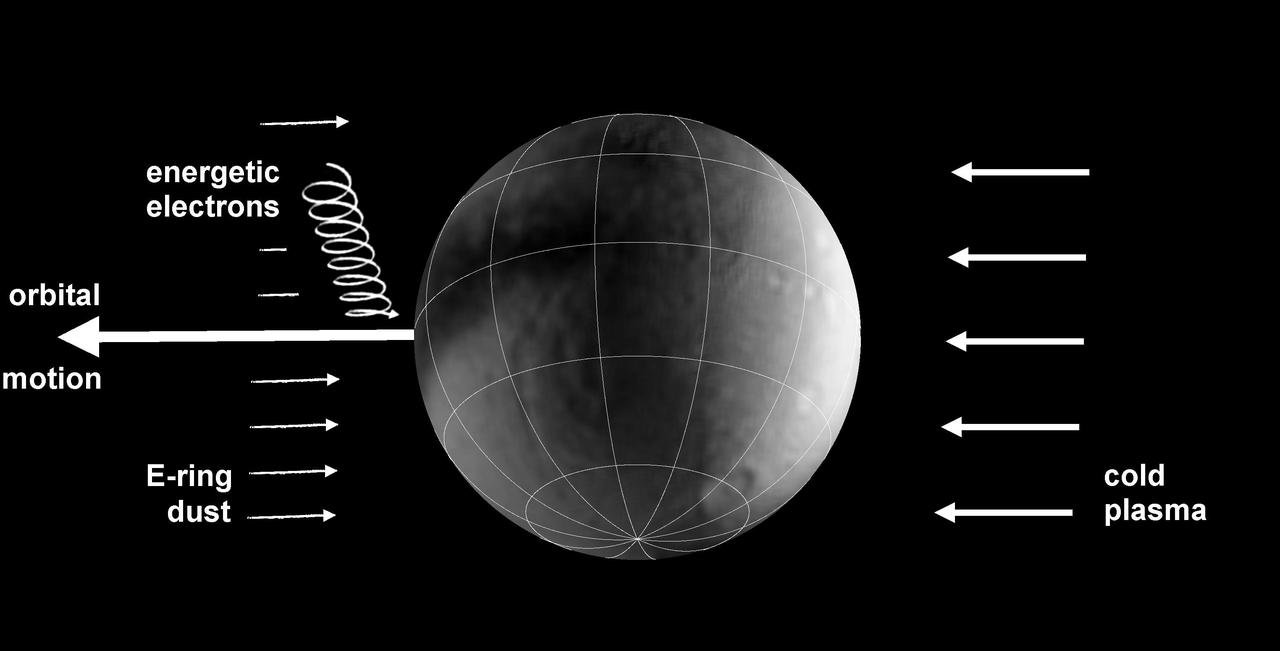

This schematic graphic illustrates the bombardments that lead to colorful splotches and bands on the surfaces of several icy moons of Saturn.

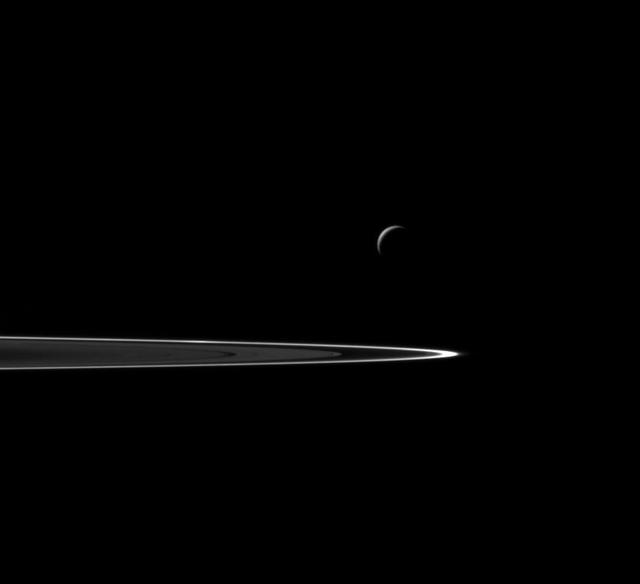

Blazing like an icy torch, the plume of Enceladus shines in scattered sunlight as the moon casts a shadow onto Saturn E ring

Uranus icy moon Miranda is seen in this image from Voyager 2 on January 24, 1986. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18185

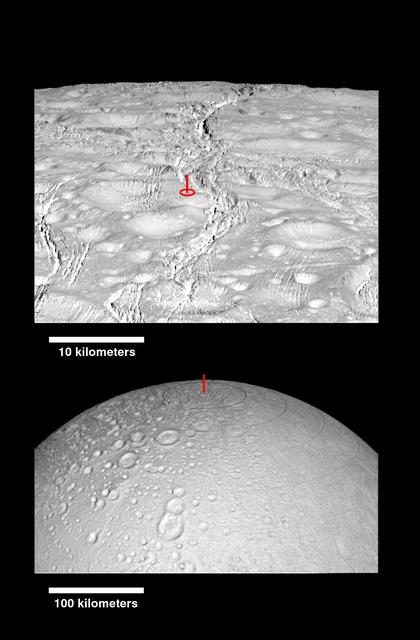

This montage of images from NASA Cassini orbiter shows the precise location of the north pole on Saturn icy moon Enceladus.

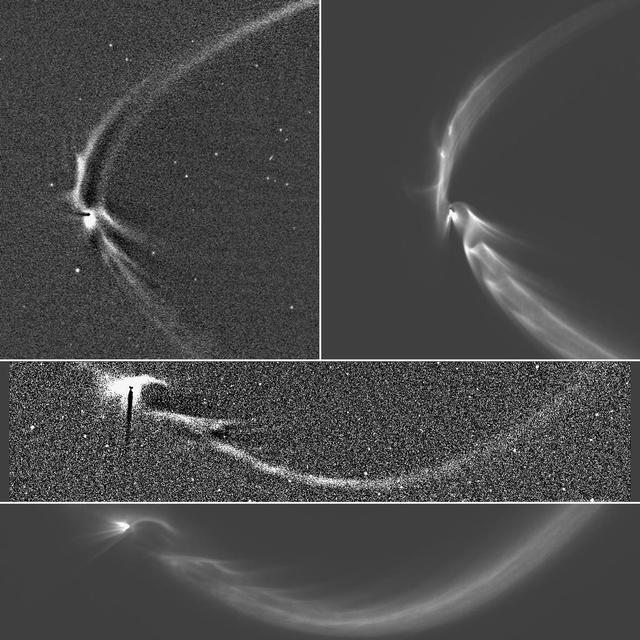

Multiple jets of icy particles are blasted into space by the active venting on Saturn moon Enceladus

Gazing across the plains of Saturn icy rings, Cassini catches the F ring shepherd moon Pandora hovering in the distance

Following a successful close flyby of Enceladus, NASA Cassini spacecraft captured this artful composition of the icy moon with Saturn rings beyond.

This frame from an animation shows the Cassini spacecraft approaching Saturn's icy moon Enceladus. It shows the highest resolution images obtained of the moon's surface. This is followed by a depiction of Saturn's magnetic field, which interacts with Enceladus' atmosphere and presumed plume coming from the south pole. An animation is available at http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA03554

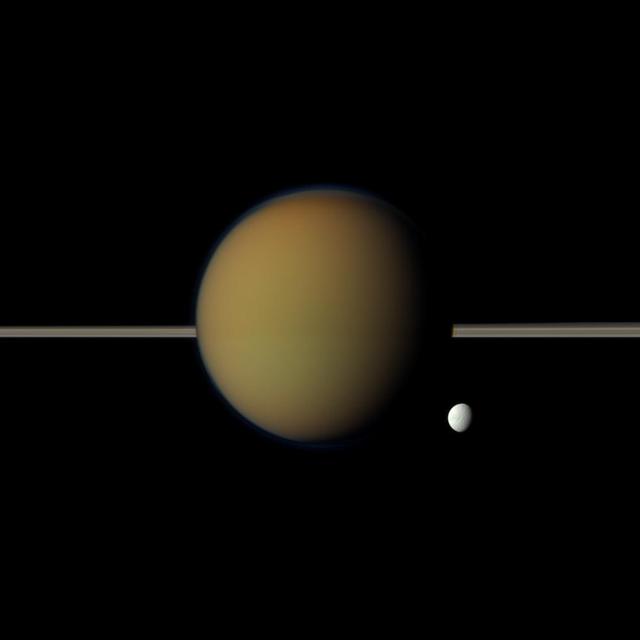

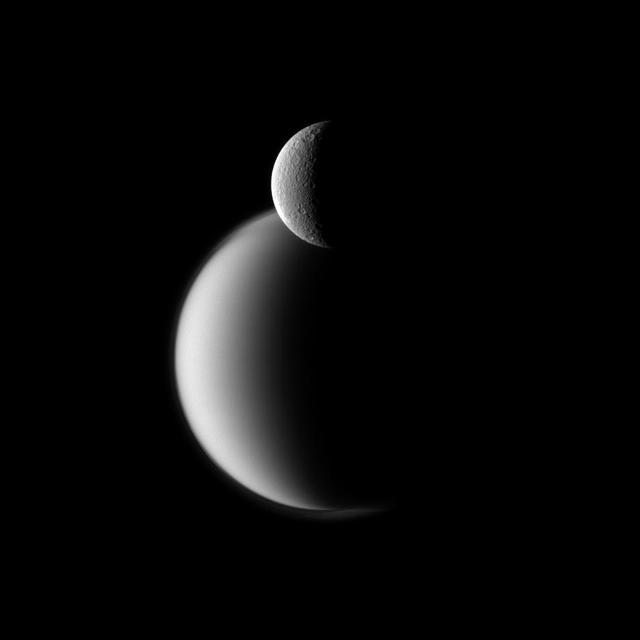

Saturn moon Tethys, with its stark white icy surface, peeps out from behind the larger, hazy, colorful Titan in this view of the two moons obtained by NASA Cassini spacecraft. Saturn rings lie between the two.

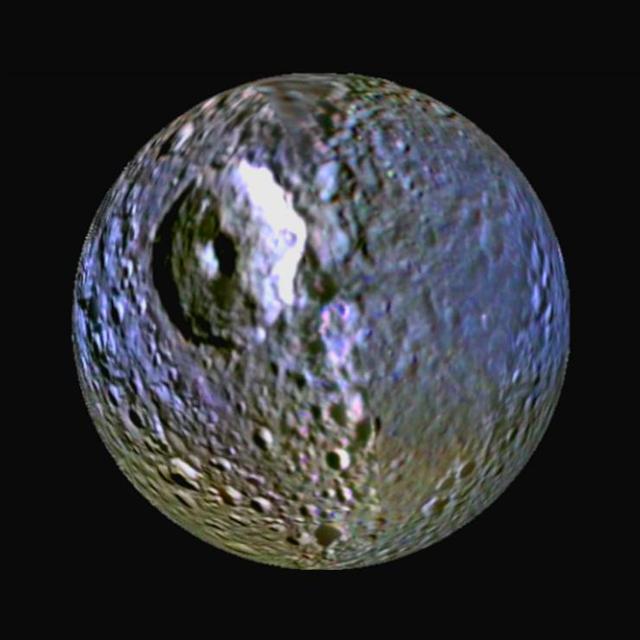

This enhanced-color view of Saturn moon Mimas was made from images obtained by NASA Cassini spacecraft. It highlights the bluish band around the icy moon equator. The large round gouge on the surface is Herschel Crater.

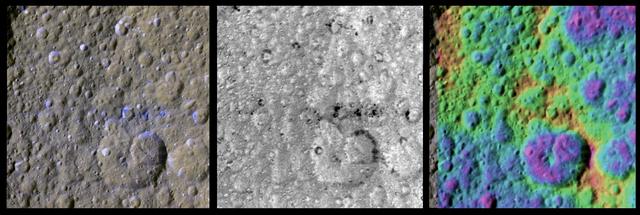

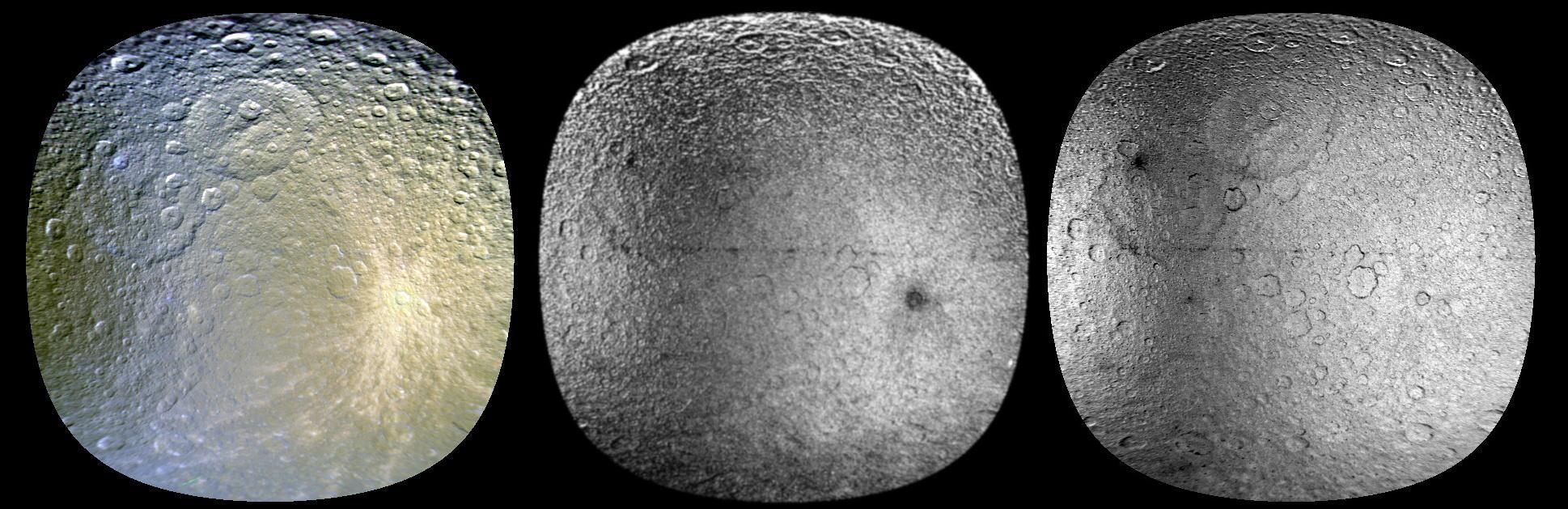

These three enhanced-color views of an equatorial region on Saturn moon Rhea were made from data obtained by NASA Cassini spacecraft. The colors have been enhanced to show colorful splotches and bands on the icy moon surface.

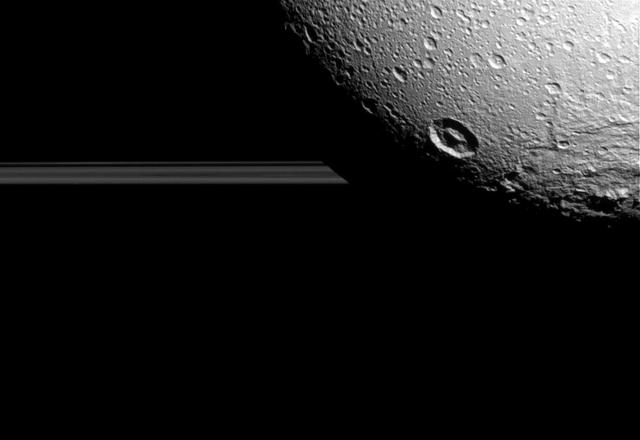

Saturn moon Dione hangs in front of Saturn rings in this view taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft during the inbound leg of its last close flyby of the icy moon.

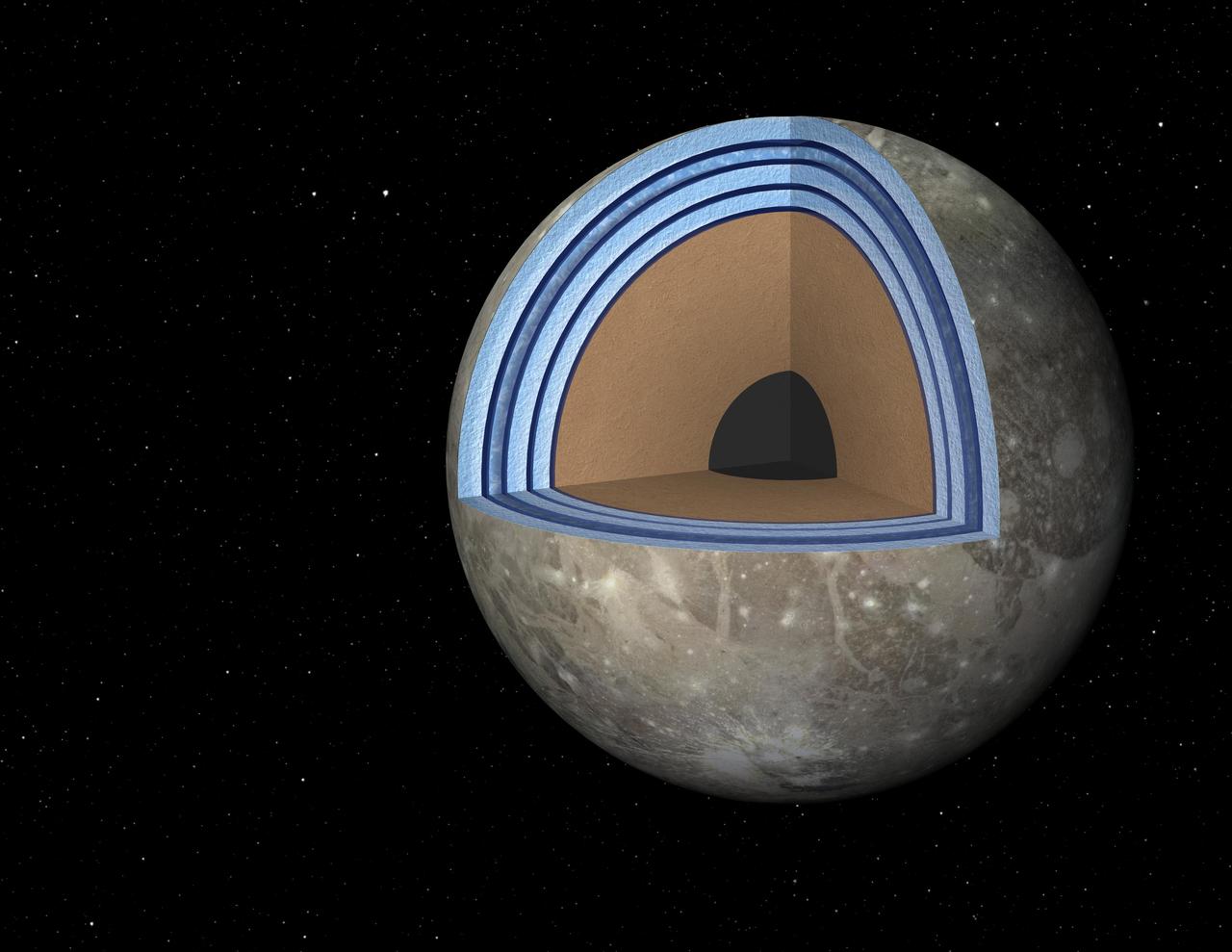

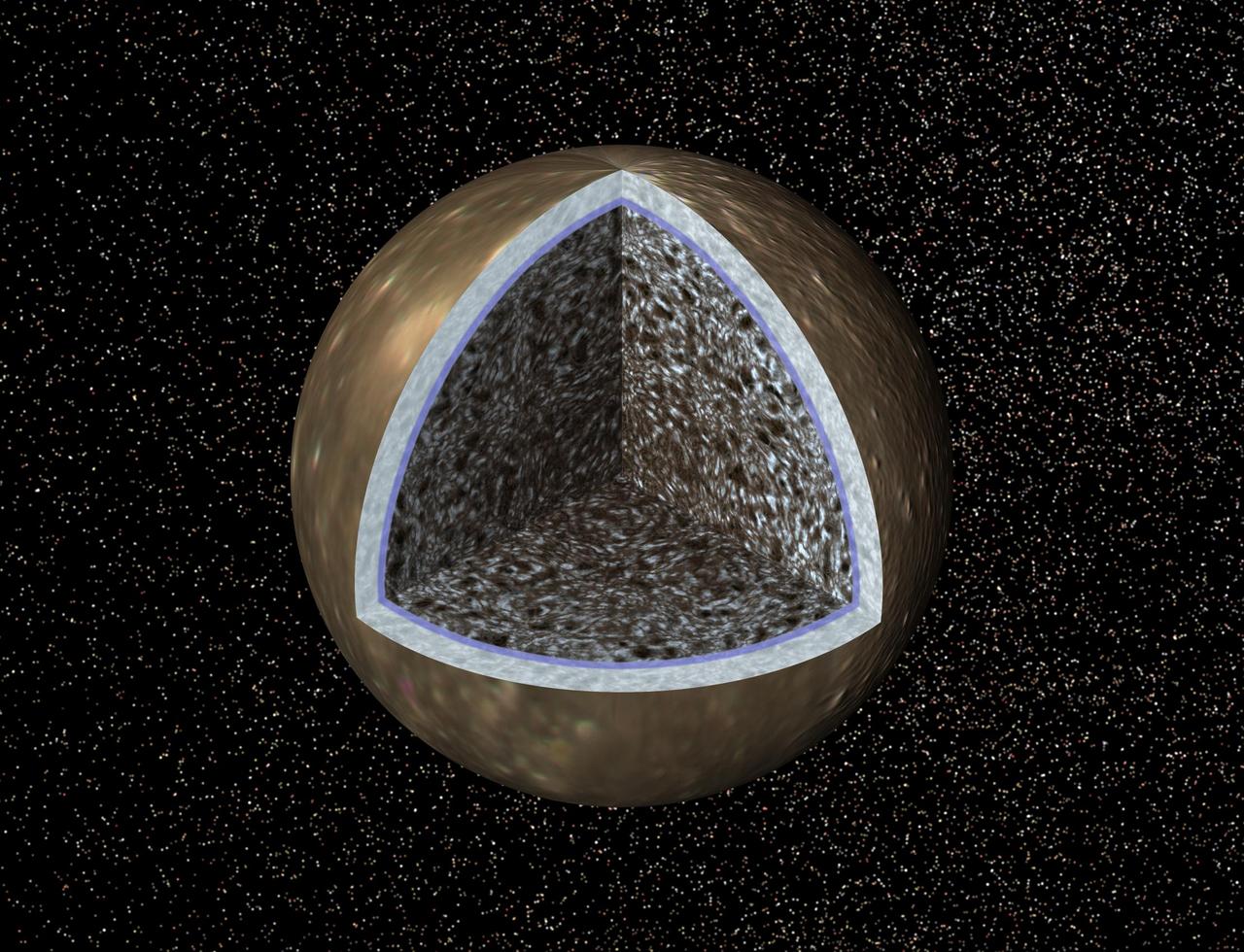

This artist concept of Jupiter moon Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system, illustrates the club sandwich model of its interior oceans. Scientists suspect Ganymede has a massive ocean under an icy crust.

The famed wispy terrain on Saturn moon Dione is front and center in this recent image captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft. The wisps are fresh fractures on the trailing hemisphere of the moon icy surface.

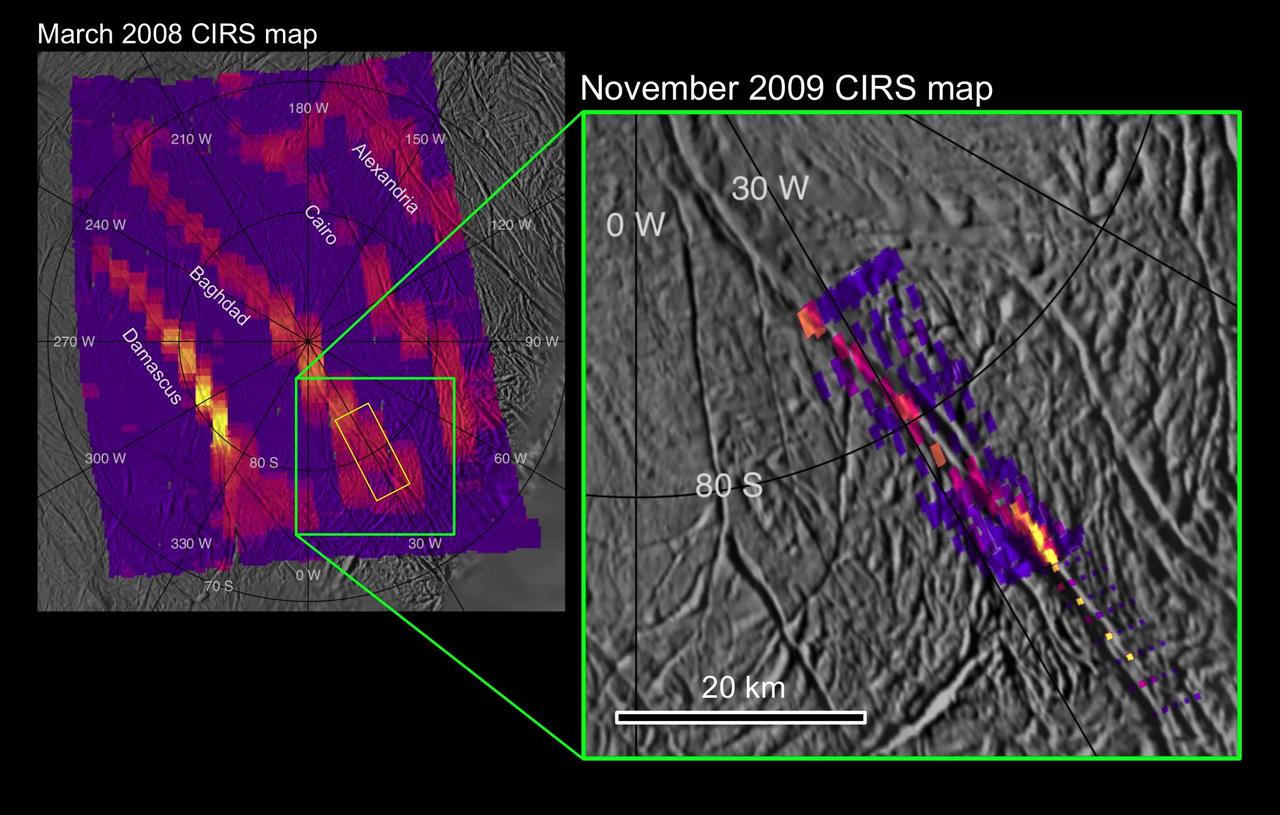

This map shows a dramatically improved view of heat radiation from a warm fissure near the south pole of Saturn icy moon Enceladus. It was obtained by NASA Cassini spacecraft during its Nov. 21, 2009, flyby of that moon.

NASA Cassini orbiter shows its final close flyby of Enceladus to focus on the icy moon craggy, dimly lit limb, with the planet Saturn beyond.

This mosaic of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede consists of more than 100 images acquired with NASA’s Voyager and Galileo spacecrafts, showing irregular lumps beneath the icy surface.

Cracks, canyons, craters, and streaks are seen in this image of Saturn icy moon, Dione, taken from Voyager 2 on August 3, 2005.

This three dimensional effect is created by superimposing images of Jupiter icy moon, Europa, taken by NASA Galileo Orbiter. 3D glasses are necessary to identify surface detail.

The plumes of Enceladus continue to gush icy particles into Saturn orbit, making this little moon one of a select group of geologically active bodies in the solar system

Craters appear well defined on icy Rhea in front of the hazy orb of the much larger moon Titan in this view from NASA Cassini spacecraft.

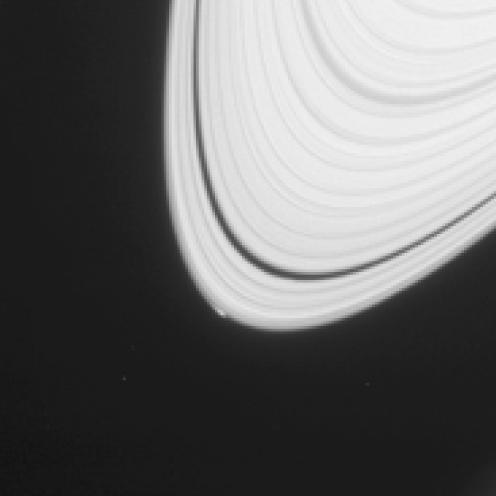

The disturbance visible at the outer edge of Saturn A ring in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft could be caused by an object replaying the birth process of icy moons.

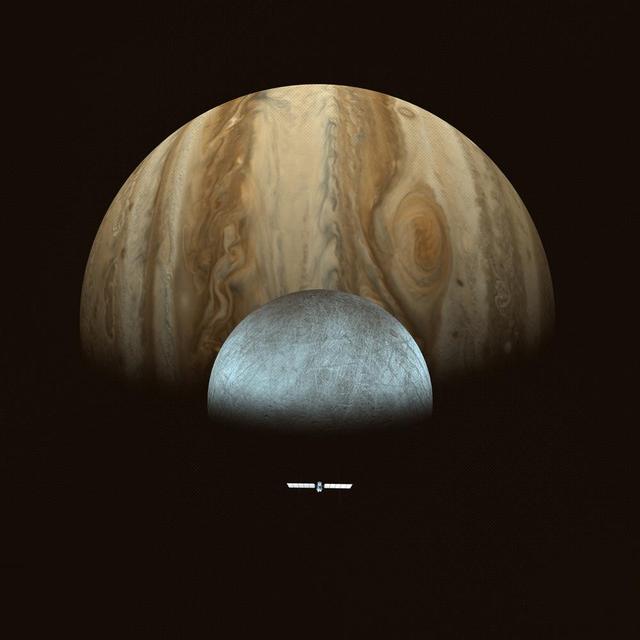

This artist's concept depicts NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft in orbit at Jupiter as it passes over the gas giant's icy moon Europa (lower right). Scheduled to arrive at Jupiter in April 2030, the mission will be the first to specifically target Europa for detailed science investigation. Europa Clipper's three main science objectives are to determine the thickness of the moon's icy shell and its interactions with the ocean below, to investigate its composition, and to characterize its geology. The mission's detailed exploration of Europa will help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26431

This artist's concept depicts NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft approaching Jupiter and its icy moon Europa. Scheduled to arrive at Jupiter in April 2030, Europa Clipper will orbit the gas giant, and will be the first mission to specifically target Europa for detailed science investigation. Europa Clipper's three main science objectives are to determine the thickness of the moon's icy shell and its interactions with the ocean below, to investigate its composition, and to characterize its geology. The mission's detailed exploration of Europa will help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26445

This artist's concept depicts NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft performing a close flyby of Jupiter's icy moon Europa. Scheduled to arrive at Jupiter in April 2030, Europa Clipper will orbit the gas giant and be the first mission to specifically target Europa for detailed science investigation. Europa Clipper's three main science objectives are to determine the thickness of the moon's icy shell and its interactions with the ocean below, to investigate its composition, and to characterize its geology. The mission's detailed exploration of Europa will help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26443

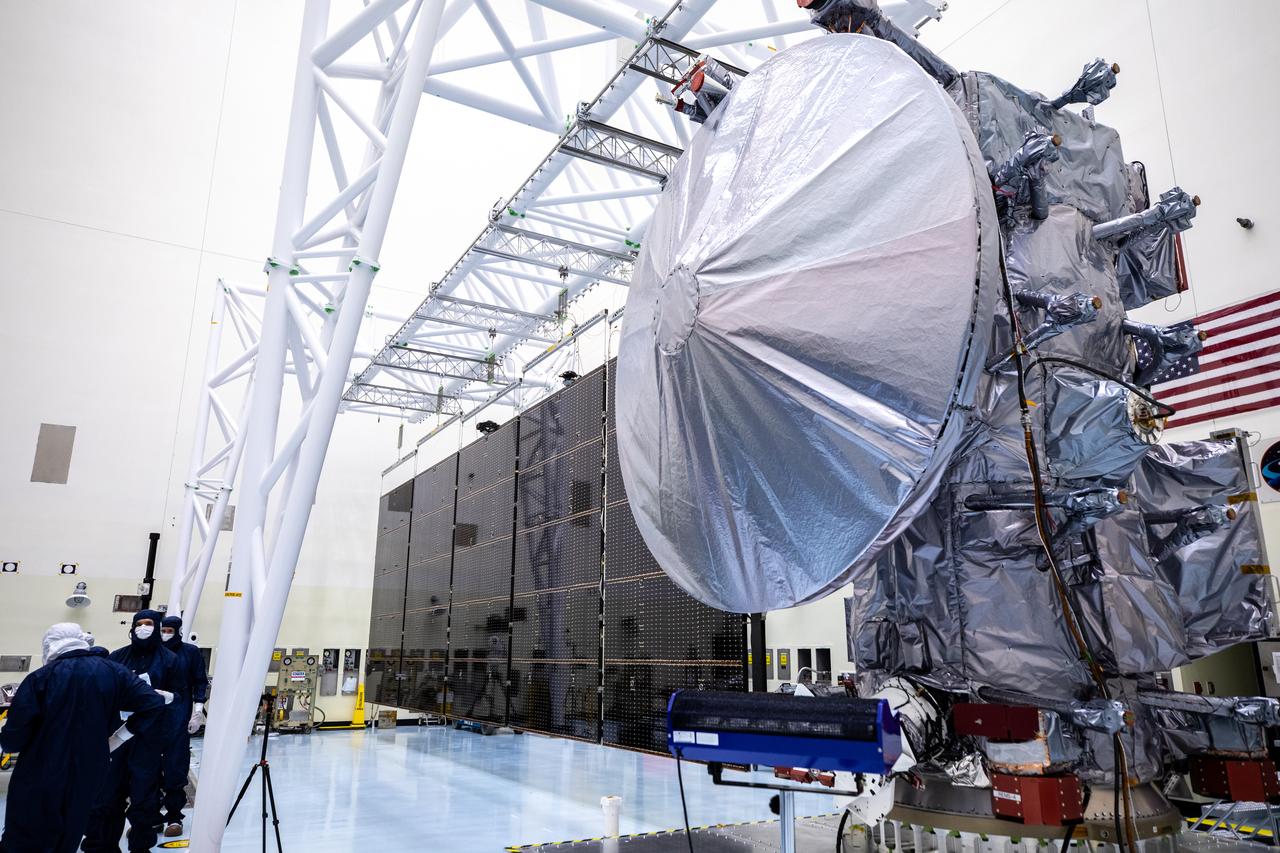

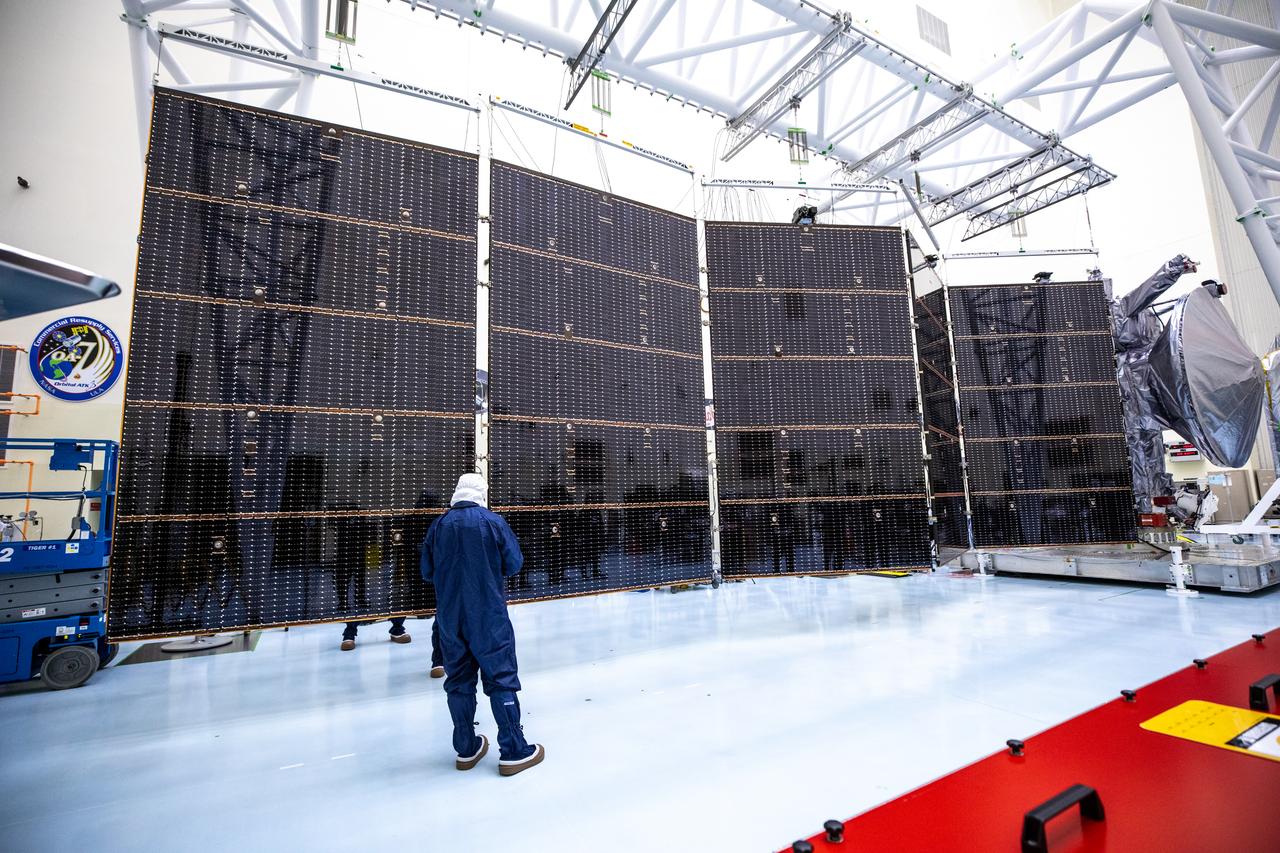

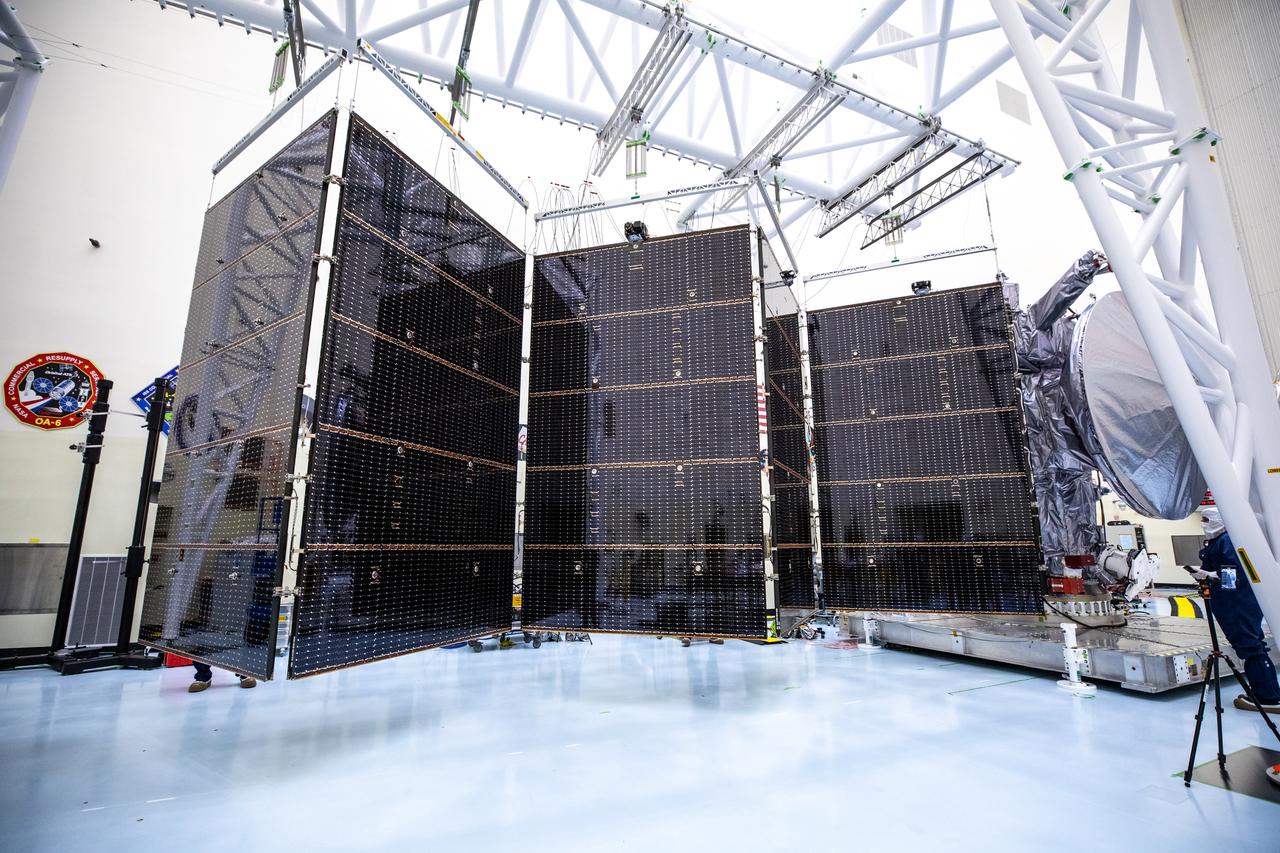

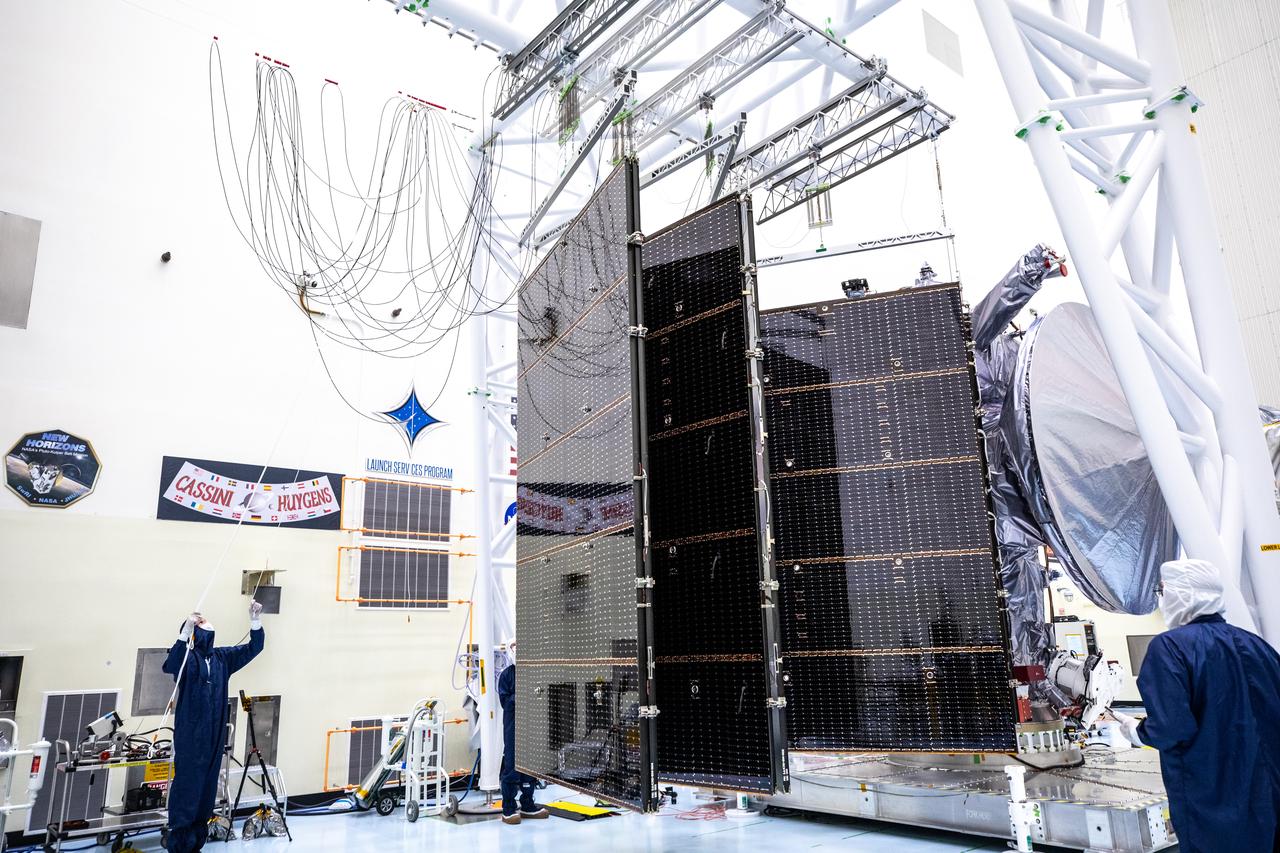

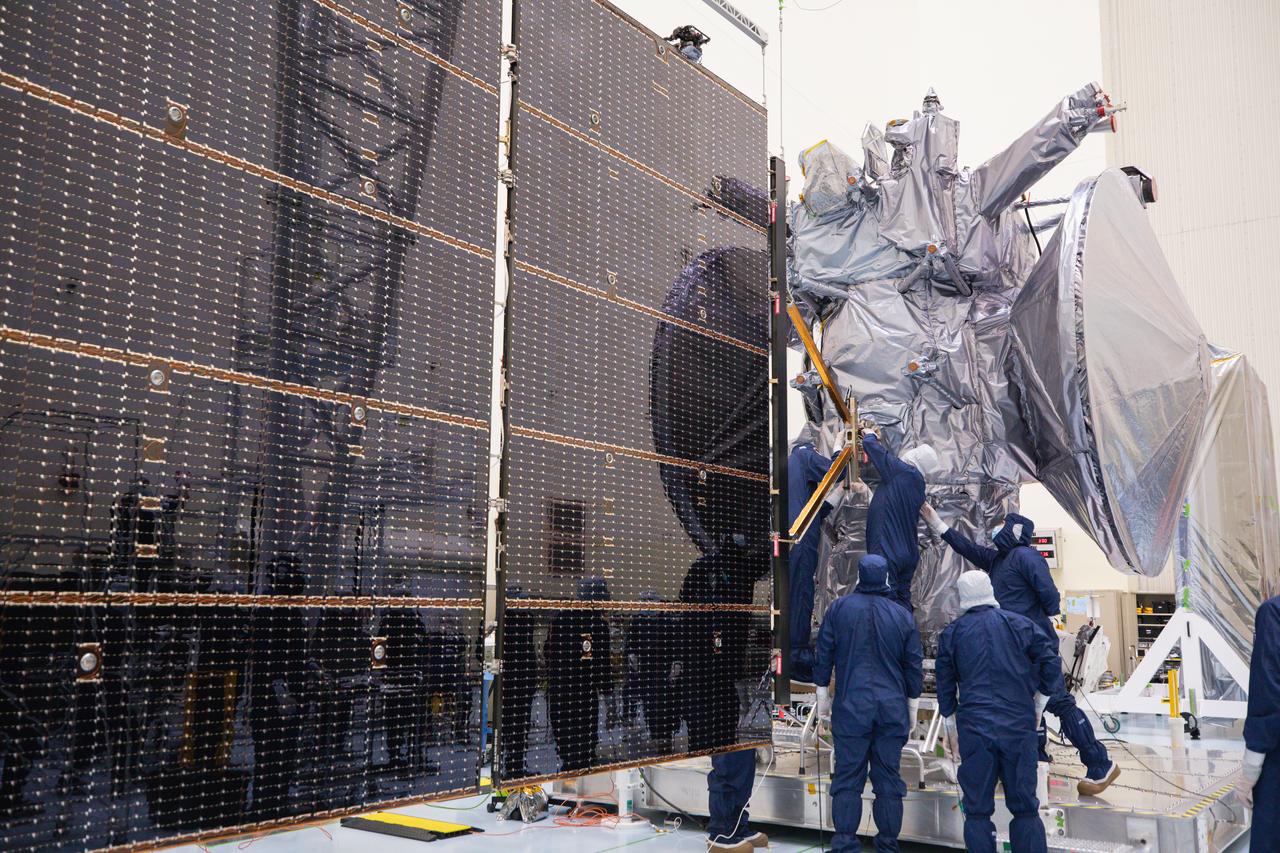

Technicians tested deploying a set of massive solar arrays measuring about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. Once launched to study Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, the solar arrays will fully extend to power the spacecraft to perform flybys to gather science and data to determine if the moon can support habitable conditions.

Technicians tested deploying a set of massive solar arrays measuring about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. Once launched to study Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, the solar arrays will fully extend to power the spacecraft to perform flybys to gather science and data to determine if the moon can support habitable conditions.

Technicians tested deploying a set of massive solar arrays measuring about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. Once launched to study Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, the solar arrays will fully extend to power the spacecraft to perform flybys to gather science and data to determine if the moon can support habitable conditions.

Technicians tested deploying a set of massive solar arrays measuring about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. Once launched to study Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, the solar arrays will fully extend to power the spacecraft to perform flybys to gather science and data to determine if the moon can support habitable conditions.

Technicians tested deploying a set of massive solar arrays measuring about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. Once launched to study Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, the solar arrays will fully extend to power the spacecraft to perform flybys to gather science and data to determine if the moon can support habitable conditions.

Technicians tested deploying a set of massive solar arrays measuring about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. Once launched to study Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, the solar arrays will fully extend to power the spacecraft to perform flybys to gather science and data to determine if the moon can support habitable conditions.

Technicians tested deploying a set of massive solar arrays measuring about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. Once launched to study Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, the solar arrays will fully extend to power the spacecraft to perform flybys to gather science and data to determine if the moon can support habitable conditions.

Technicians tested deploying a set of massive solar arrays measuring about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. Once launched to study Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, the solar arrays will fully extend to power the spacecraft to perform flybys to gather science and data to determine if the moon can support habitable conditions.

Technicians tested deploying a set of massive solar arrays measuring about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. Once launched to study Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, the solar arrays will fully extend to power the spacecraft to perform flybys to gather science and data to determine if the moon can support habitable conditions.

Technicians tested deploying a set of massive solar arrays measuring about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. Once launched to study Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, the solar arrays will fully extend to power the spacecraft to perform flybys to gather science and data to determine if the moon can support habitable conditions.

Science instruments and other hardware for NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft will come together in the mission's final phase before launching to Jupiter's icy moon Europa in 2024. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25125

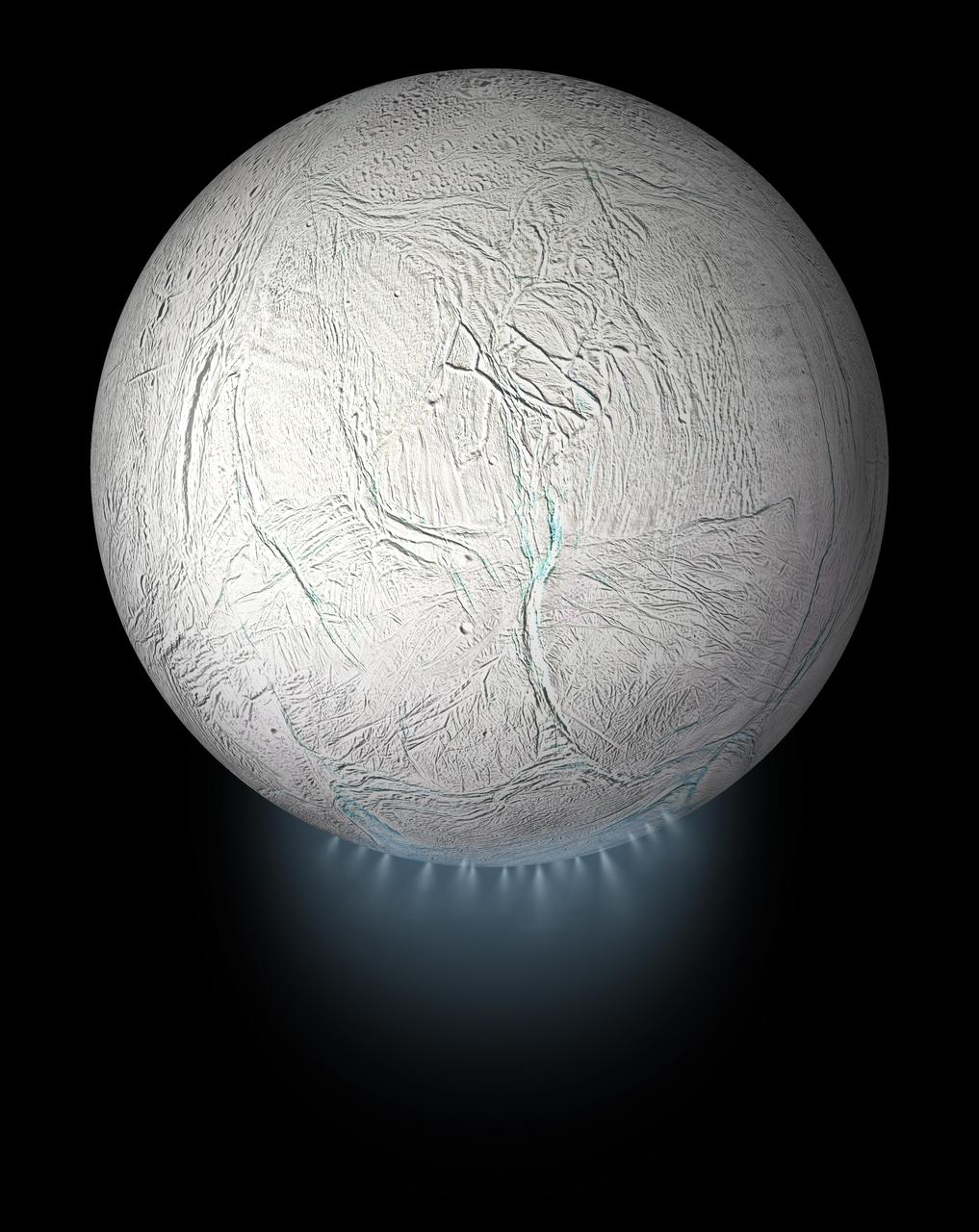

This illustration shows Saturn's icy moon Enceladus with the plume of ice particles, water vapor and organic molecules that sprays from fractures in the moon's south polar region. A cutaway version of this graphic is also available, showing the moon's interior ocean and hydrothermal activity — both of which were discovered by NASA's Cassini mission (see PIA20013). This global view was created using a Cassini-derived map of Enceladus (see PIA18435). More information about Enceladus is available at https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/saturn-moons/enceladus/in-depth/. For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/missions/cassini/overview/. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23175

This artist's concept depicts NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft silhouetted against Jupiter as it passes over the gas giant's icy moon Europa (bottom center). Scheduled to orbit Jupiter beginning in April 2030, the mission will be the first to specifically target Europa for detailed science investigation. Europa Clipper's three main science objectives are to determine the thickness of the moon's icy shell and its interactions with the ocean below, to investigate its composition, and to characterize its geology. The mission's detailed exploration of Europa will help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26442

NASA's Cassini gazes across the icy rings of Saturn toward the icy moon Tethys, whose night side is illuminated by Saturnshine, or sunlight reflected by the planet. Tethys was on the far side of Saturn with respect to Cassini here; an observer looking upward from the moon's surface toward Cassini would see Saturn's illuminated disk filling the sky. Tethys was brightened by a factor of two in this image to increase its visibility. A sliver of the moon's sunlit northern hemisphere is seen at top. A bright wedge of Saturn's sunlit side is seen at lower left. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 10 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on May 13, 2017. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 750,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 140 degrees. Image scale is 43 miles (70 kilometers) per pixel on Saturn. The distance to Tethys was about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers). The image scale on Tethys is about 56 miles (90 kilometers) per pixel. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21342

A world whose mysteries are just coming to light, Enceladus has enchanted scientists and non-scientists alike. With its potential for near-surface liquid water, the icy moon may be the latest addition to the list of possible abodes for life

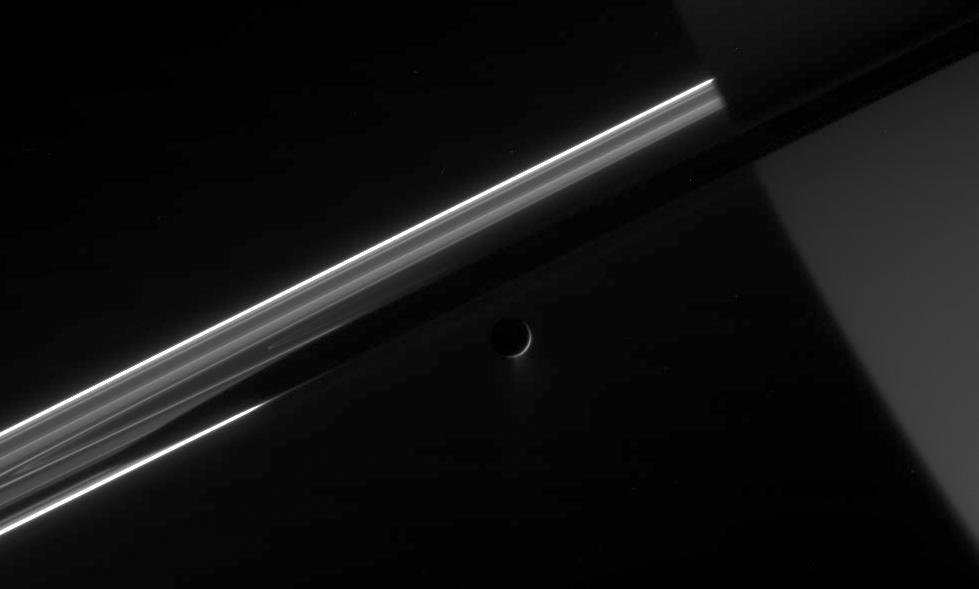

Saturn rings cut across an eerie scene that is ruled by Titan luminous crescent and globe-encircling haze, broken by the small moon Enceladus, whose icy jets are dimly visible at its south pole. North is up

NASACassini spacecraft captures this dual portrait of an apparently dead moon and one that is very much alive. Tethys, shows no signs of recent geologic activity. Enceladus, however, is covered in fractures and faults and spews icy particles into space

This artist concept, a cutaway view of Jupiter moon Callisto, is based on recent data from NASA Galileo spacecraft which indicates a salty ocean may lie beneath Callisto icy crust.

This image of Oberon, Uranus outermost moon, was captured by NASA Voyager 2 on Jan. 24, 1986. Clearly visible are several large impact craters in Oberon icy surface surrounded by bright rays. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00034

This collage of NASA Cassini spacecraft images and computer simulations shows how long, sinuous features from Enceladus can be modeled by tracing the trajectories of tiny, icy grains ejected from the moon south polar geysers.

Saturn, stately and resplendent in this natural color view taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft, dwarfs the icy moon Rhea. Rhea orbits beyond the rings on the right of the image. Tethys shadow is visible on the planet on the left of the image.

Icy fractures on Saturn moon Rhea reflect sunlight brightly in this high-resolution mosaic created from images captured by NASA Cassini spacecraft during its March 2, 2010, flyby.

This enhanced-color view obtained on September 25, 1998 from NASA Galileo spacecraft shows an intricate pattern of linear fractures on the icy surface of Jupiter moon Europa.

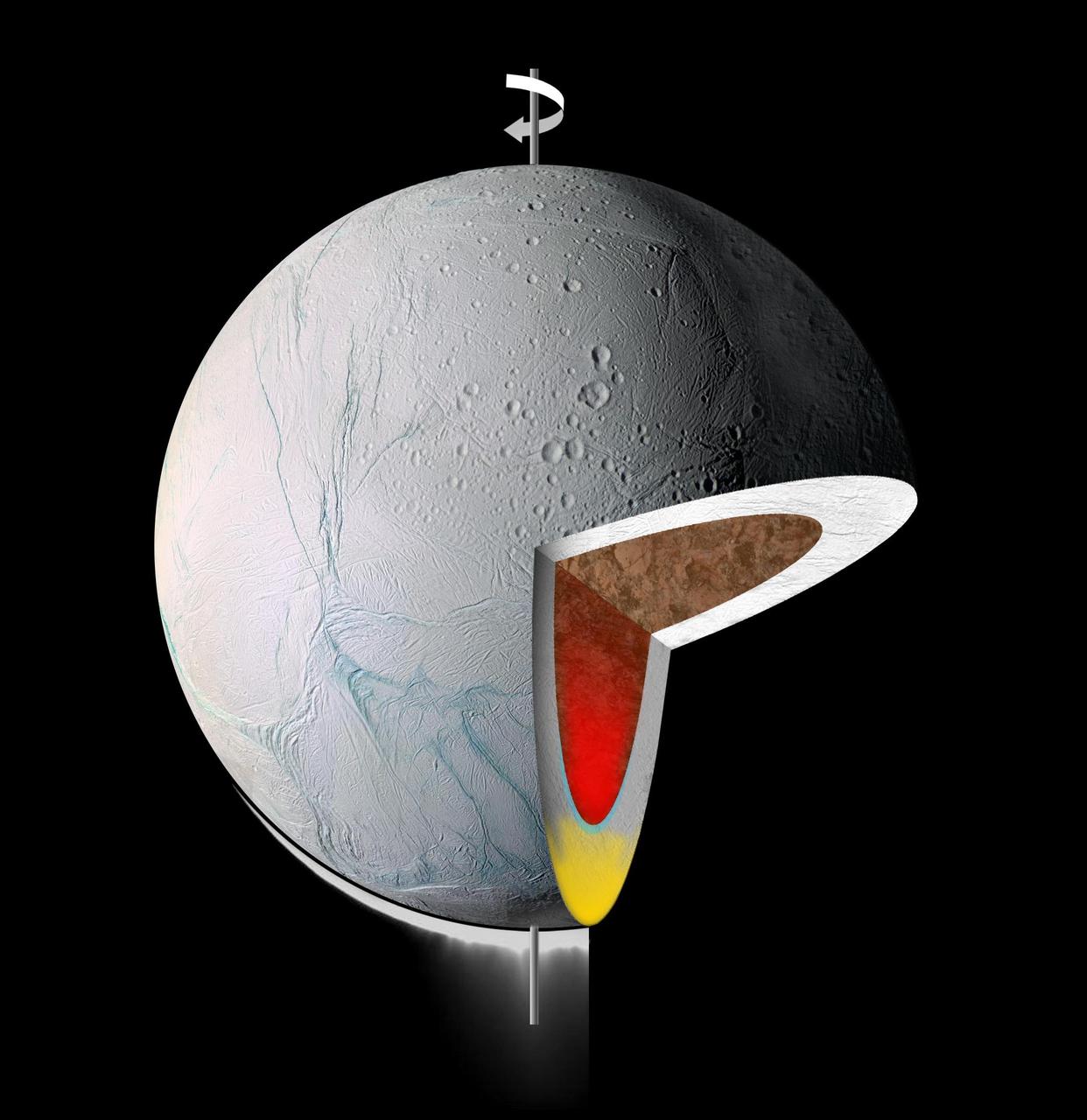

This graphic illustrates the interior of Saturn moon Enceladus. It shows warm, low-density material rising to the surface from within, in its icy shell yellow and/or its rocky core red

The Cassini spacecraft looks toward Rhea cratered, icy landscape with the dark line of Saturn ringplane and the planet murky atmosphere as a background. Rhea is Saturn second-largest moon, at 1,528 kilometers 949 miles across.

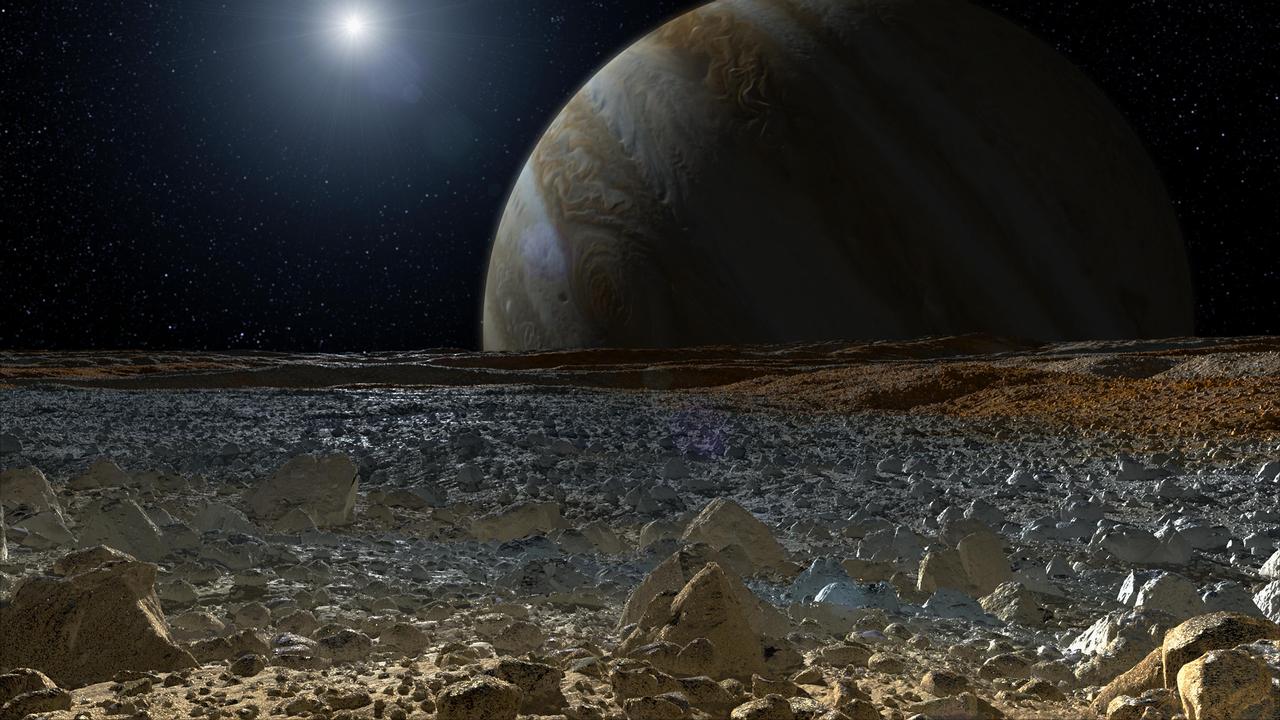

This artist concept shows a simulated view from the surface of Jupiter moon Europa. Europa potentially rough, icy surface, tinged with reddish areas that scientists hope to learn more about.

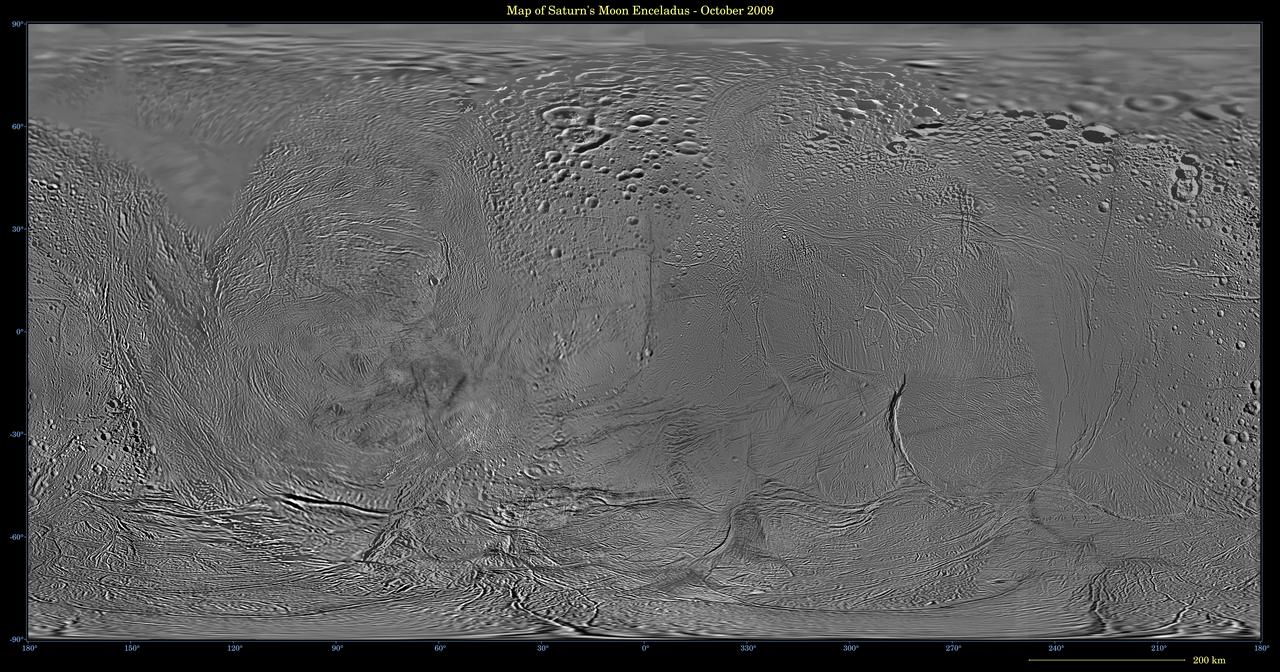

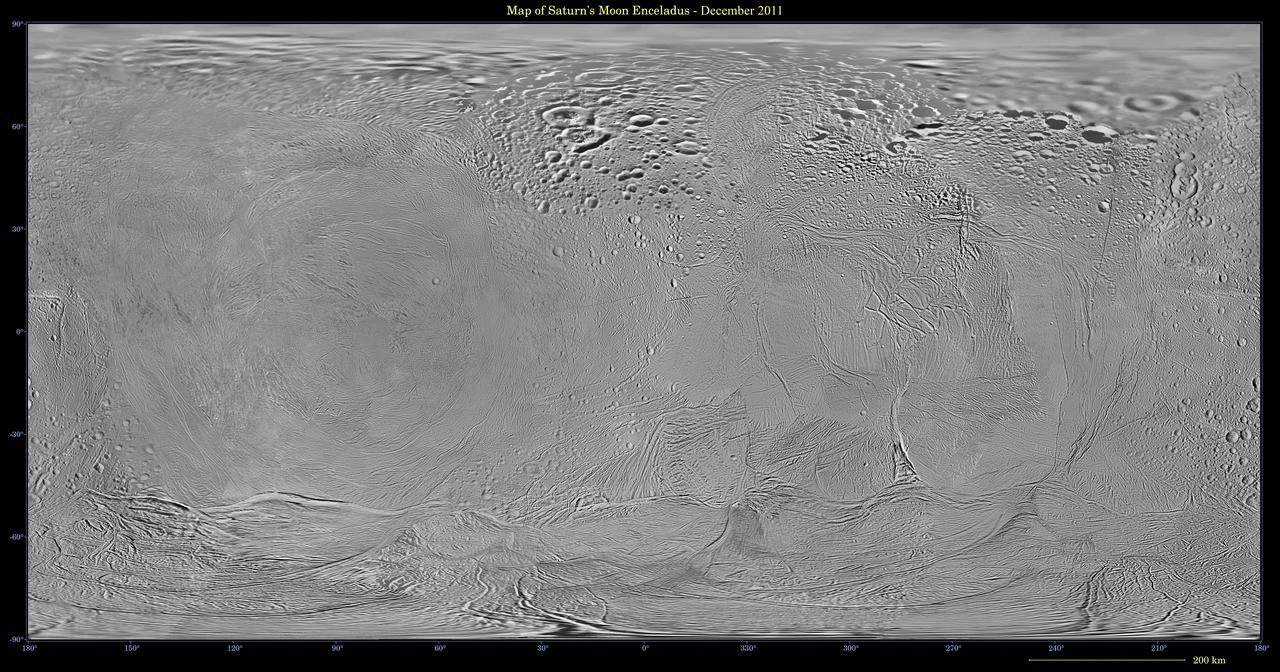

This image shows an updated map of Saturn icy moon Enceladus, generated by NASA Cassini imaging team. The map incorporates new images taken in 2008, with better image processing techniques.

After nearly three years at Saturn, the Cassini spacecraft continues to observe the planet retinue of icy moons. Rhea cratered face attests to its great age, while its bright wisps hint at tectonic activity in the past

Bright fractures creep across the surface of icy Dione. This extensive canyon system is centered on a region of terrain that is significantly darker that the rest of the moon. Part of the darker terrain is visible at right

Saturn outermost large moon, Iapetus, has a bright, heavily cratered icy terrain and a dark terrain, as shown in this NASA Voyager 2 image taken on Aug. 22, 1981. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00348

The rings cannot hide the ragged, icy crescent of Rhea, here imaged in color by the Cassini spacecraft. The second-largest moon of Saturn shines brightly through gaps in the rings

This mosaic shows an updated global map of Saturn icy moon Enceladus, created using images taken during flybys of NASA Cassini spacecraft. The map incorporates new images taken during flybys in December 2011.

A ghostly view of Enceladus reveals the specter of the moon icy plume of fine particles. Scientists continue to monitor the plume, where mission planning allows, using the Cassini spacecraft imaging cameras

This is an artist concept of a plume of water vapor thought to be ejected off the frigid, icy surface of the Jovian moon Europa, located about 500 million miles 800 million kilometers from the sun.

Canyons and mountain peaks snake along the terminator on the crater-covered, icy moon Dione. With the Sun at a low angle on their local horizon, the line of mountain ridges above center casts shadows toward the east

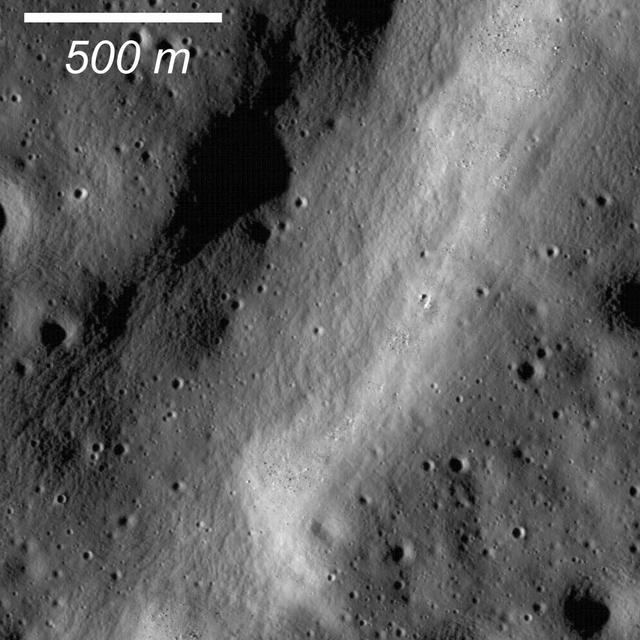

Graben are common extensional features on the Moon as well as the other terrestrial planets and icy satellites. This graben formed within a larger graben as captured by NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

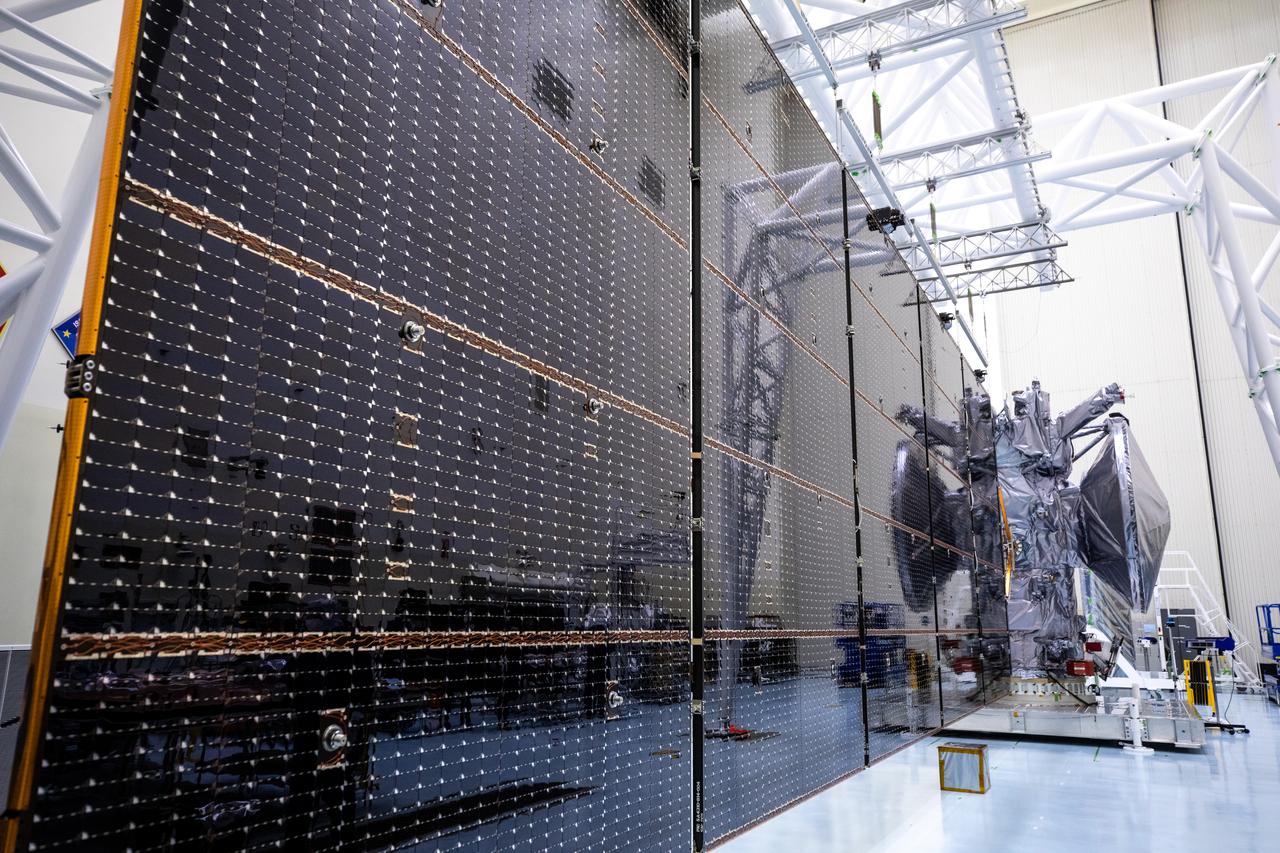

Technicians install and align the second set of solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Thursday, Aug. 15, 2024. The Europa Clipper spacecraft will need the 46.5 feet (14.2 meter) long, five-panel solar arrays on each side, to gather enough sunlight to power the spacecraft to perform flybys around Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, so science instruments aboard the spacecraft can determine if the moon could hold the building blocks necessary to sustain life.

Technicians install and align the second set of solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Thursday, Aug. 15, 2024. The Europa Clipper spacecraft will need the 46.5 feet (14.2 meter) long, five-panel solar arrays on each side, to gather enough sunlight to power the spacecraft to perform flybys around Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, so science instruments aboard the spacecraft can determine if the moon could hold the building blocks necessary to sustain life.

Technicians install and align the second set of solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Thursday, Aug. 15, 2024. The Europa Clipper spacecraft will need the 46.5 feet (14.2 meter) long, five-panel solar arrays on each side, to gather enough sunlight to power the spacecraft to perform flybys around Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, so science instruments aboard the spacecraft can determine if the moon could hold the building blocks necessary to sustain life.

Technicians install and align the second set of solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Thursday, Aug. 15, 2024. The Europa Clipper spacecraft will need the 46.5 feet (14.2 meter) long, five-panel solar arrays on each side, to gather enough sunlight to power the spacecraft to perform flybys around Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, so science instruments aboard the spacecraft can determine if the moon could hold the building blocks necessary to sustain life.

Technicians install and align the second set of solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Thursday, Aug. 15, 2024. The Europa Clipper spacecraft will need the 46.5 feet (14.2 meter) long, five-panel solar arrays on each side, to gather enough sunlight to power the spacecraft to perform flybys around Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, so science instruments aboard the spacecraft can determine if the moon could hold the building blocks necessary to sustain life.

Technicians install and align the second set of solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Thursday, Aug. 15, 2024. The Europa Clipper spacecraft will need the 46.5 feet (14.2 meter) long, five-panel solar arrays on each side, to gather enough sunlight to power the spacecraft to perform flybys around Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, so science instruments aboard the spacecraft can determine if the moon could hold the building blocks necessary to sustain life.

Technicians install and align the second set of solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Thursday, Aug. 15, 2024. The Europa Clipper spacecraft will need the 46.5 feet (14.2 meter) long, five-panel solar arrays on each side, to gather enough sunlight to power the spacecraft to perform flybys around Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, so science instruments aboard the spacecraft can determine if the moon could hold the building blocks necessary to sustain life.

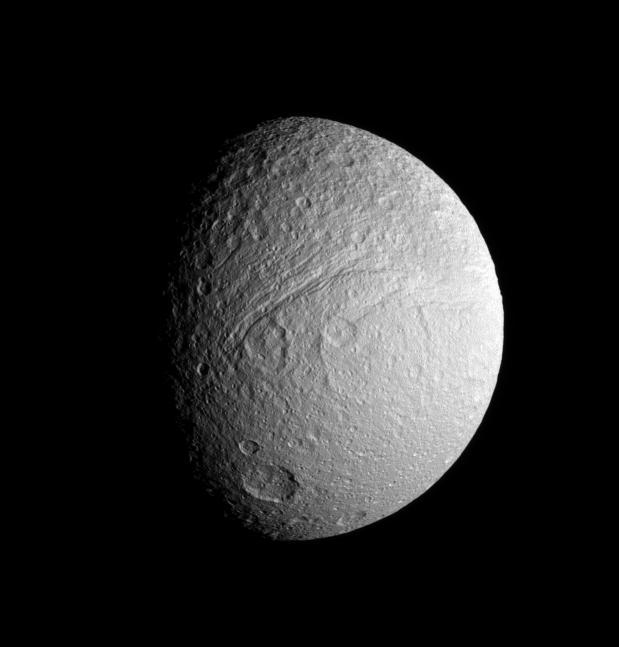

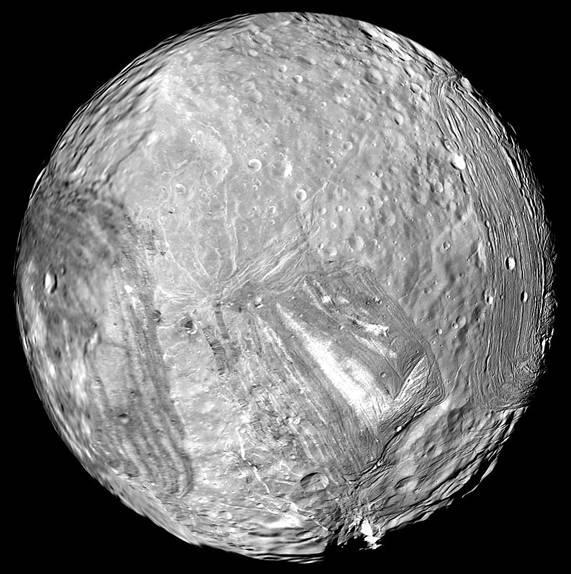

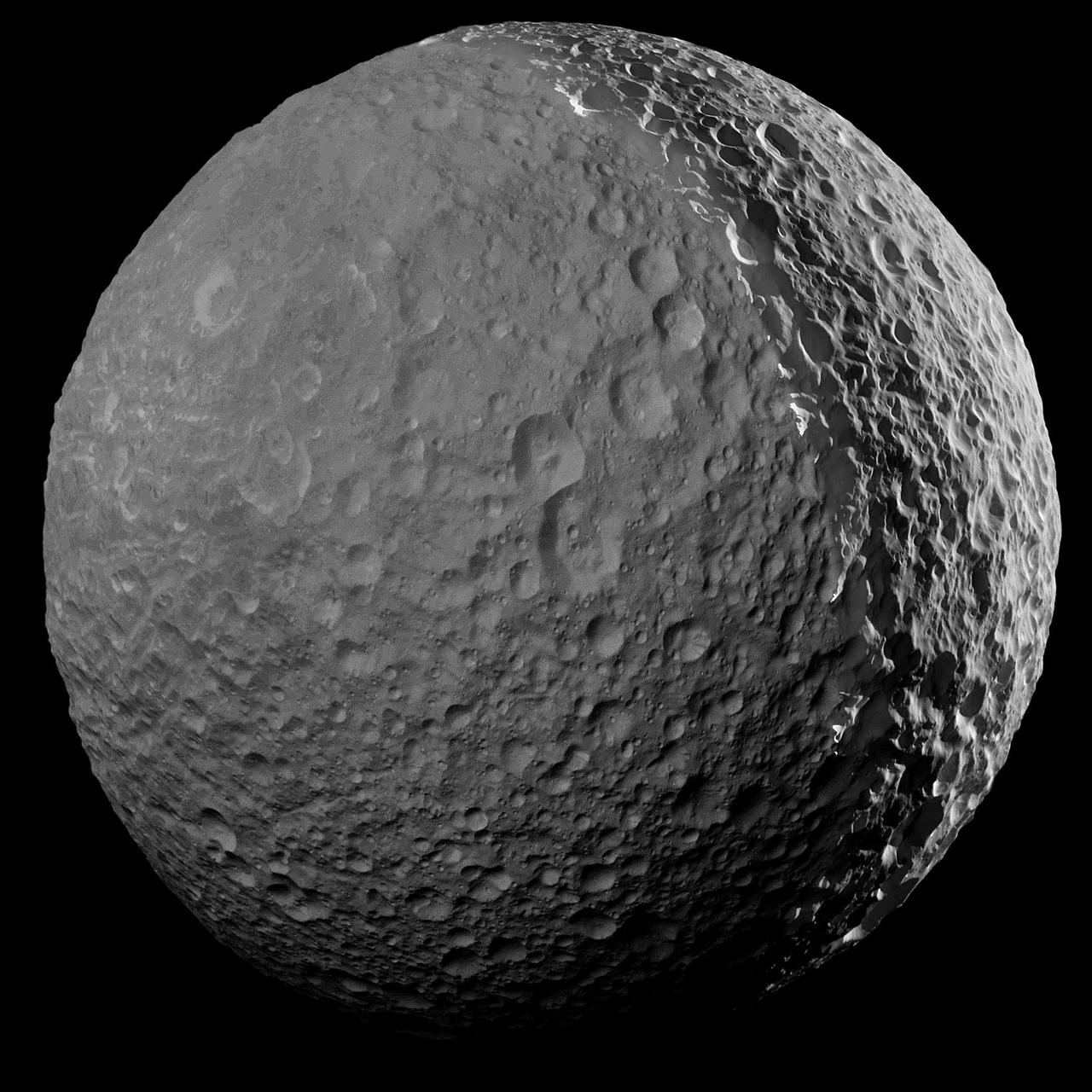

In its season of "lasts," NASA's Cassini spacecraft made its final close approach to Saturn's moon Mimas on January 30, 2017. At closest approach, Cassini passed 25,620 miles (41,230 kilometers) from Mimas. All future observations of Mimas will be from more than twice this distance. This mosaic is one of the highest resolution views ever captured of the icy moon. Close approaches to Mimas have been somewhat rare during Cassini's mission, with only seven flybys at distances of less than 31,000 miles (50,000 kilometers). Mimas' surface is pockmarked with countless craters, the largest of which gives the icy moon its distinctive appearance. Imaging scientists combined ten narrow-angle camera images to create this mosaic view. The scene is an orthographic projection centered on terrain at 17.5 degrees south latitude, 325.4 degrees west longitude on Mimas. An orthographic view is most like the view seen by a distant observer looking through a telescope. This mosaic was acquired at a distance of approximately 28,000 miles (45,000 kilometers) from Mimas. Image scale is approximately 820 feet (250 meters) per pixel. The images were taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Jan. 30, 2017. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17213

Three views of Saturn moon Rhea made from data obtained by NASA Cassini spacecraft, were enhanced to show colorful splotches and bands on the icy moon surface. Scientists believe the reddish and bluish tints came from bombardments large and small.

Technicians test and extend one of the two “wings” comprising the solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft on Friday, Aug. 23, 2024, at the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Each array measures about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high. The spacecraft needs the massive solar arrays to power to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa to help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet.

Technicians attach the five-panel solar arrays to NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it explores Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.

Technicians attach the five-panel solar arrays to NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it explores Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.

Technicians attach the five-panel solar arrays to NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it explores Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.

Technicians pose for a photo in front of one of the two “wings” comprising the solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft on Friday, Aug. 23, 2024, at the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Each array measures about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high. The spacecraft needs the massive solar arrays to power to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa to help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet.

Technicians attach the five-panel solar arrays to NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it explores Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.

Technicians test and extend one of the two “wings” comprising the solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft on Friday, Aug. 23, 2024, at the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Each array measures about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high. The spacecraft needs the massive solar arrays to power to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa to help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet.

Technicians test and extend one of the two “wings” comprising the solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft on Friday, Aug. 23, 2024, at the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Each array measures about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high. The spacecraft needs the massive solar arrays to power to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa to help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet.

Technicians attach the five-panel solar arrays to NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it explores Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.

Technicians attach the five-panel solar arrays to NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it explores Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.

Technicians attach the five-panel solar arrays to NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it explores Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.

Technicians attach the five-panel solar arrays to NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it explores Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.

Technicians attach the five-panel solar arrays to NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it explores Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.

Technicians test and extend one of the two “wings” comprising the solar arrays for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft on Friday, Aug. 23, 2024, at the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Each array measures about 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high. The spacecraft needs the massive solar arrays to power to Jupiter’s icy moon Europa to help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet.

Technicians attach the five-panel solar arrays to NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it explores Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.

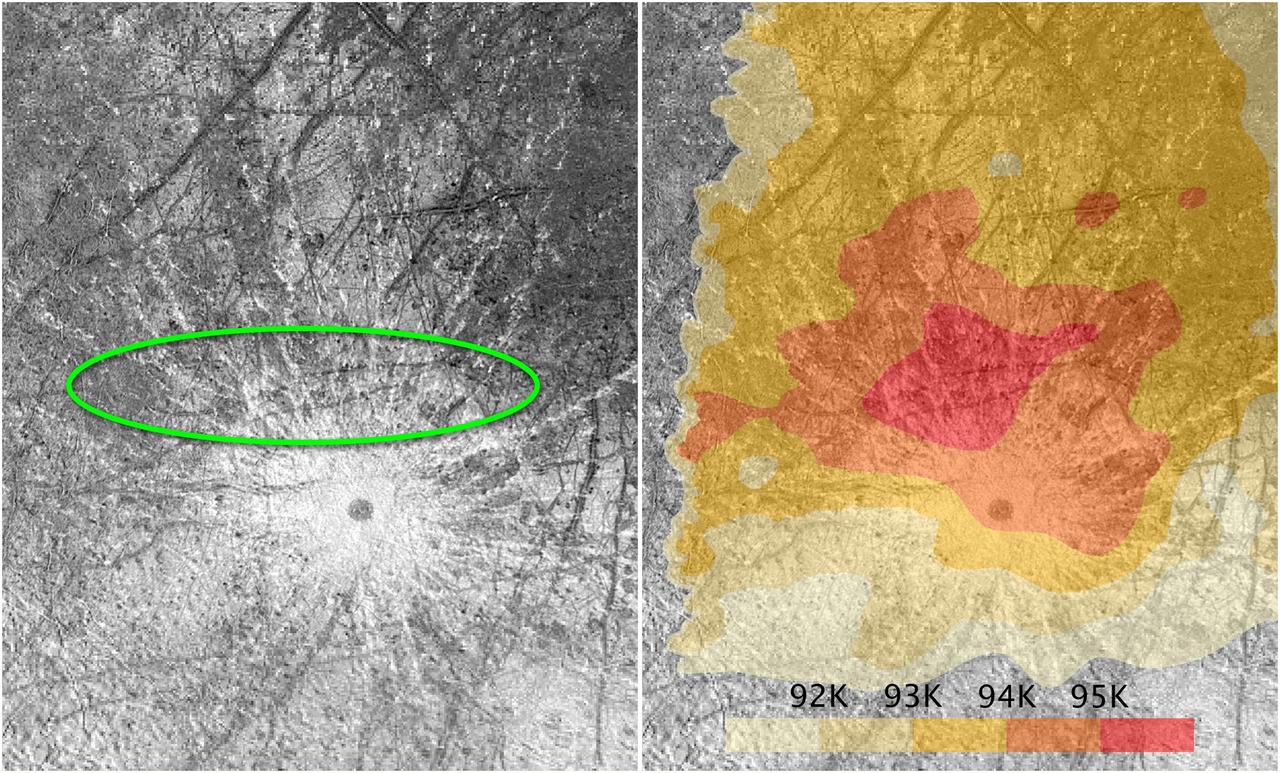

These images of the surface of the Jovian moon Europa, taken by NASA's Galileo spacecraft, focus on a "region of interest" on the icy moon. The image at left traces the location of the erupting plumes of material, observed by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope in 2014 and again in 2016. The plumes are located inside the area surrounded by the green oval. The green oval also corresponds to a warm region on Europa's surface, as identified by the temperature map at right. The map is based on observations by the Galileo spacecraft. The warmest area is colored bright red. Researchers speculate these data offer circumstantial evidence for unusual activity that may be related to a subsurface ocean on Europa. The dark circle just below center in both images is a crater and is not thought to be related to the warm spot or the plume activity. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21444

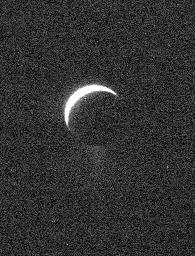

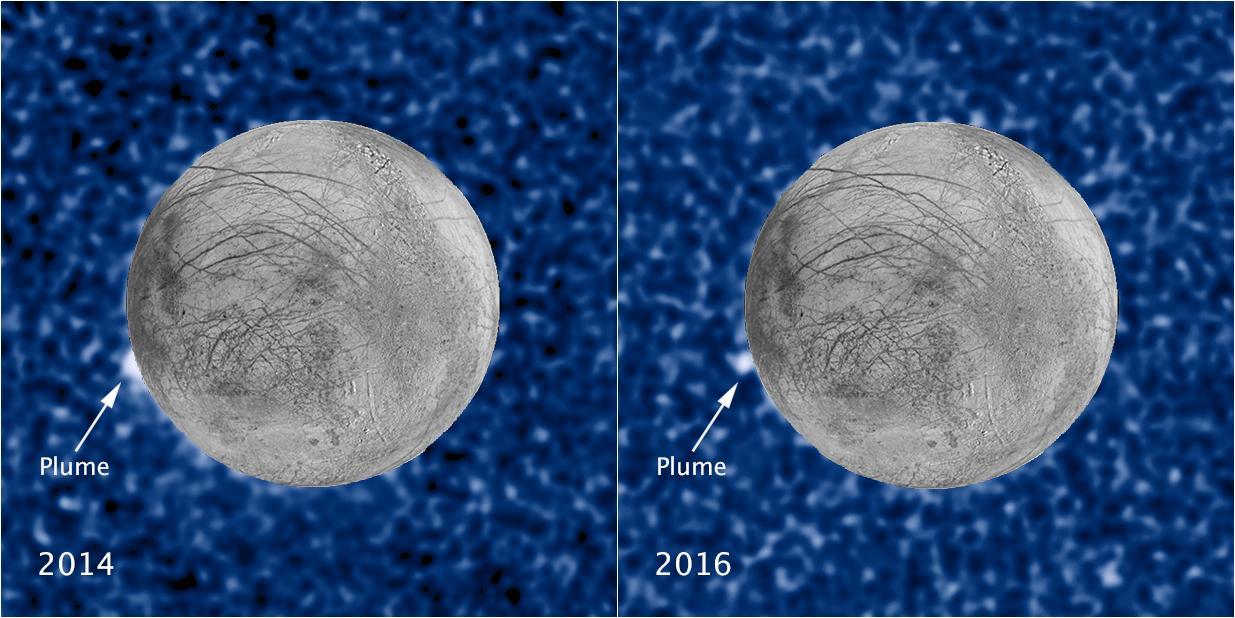

These composite images show a suspected plume of material erupting two years apart from the same location on Jupiter's icy moon Europa. The images bolster evidence that the plumes are a real phenomenon, flaring up intermittently in the same region on the satellite. Both plumes, photographed in ultraviolet light by NASA's Hubble's Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph, were seen in silhouette as the moon passed in front of Jupiter. The newly imaged plume, shown at right, rises about 62 miles (100 kilometers) above Europa's frozen surface. The image was taken Feb. 22, 2016. The plume in the image at left, observed by Hubble on March 17, 2014, originates from the same location. It is estimated to be about 30 miles (50 kilometers) high. The snapshot of Europa, superimposed on the Hubble image, was assembled from data from NASA's Galileo mission to Jupiter. The plumes correspond to the location of an unusually warm spot on the moon's icy crust, seen in the late 1990s by the Galileo spacecraft (see PIA21444). Researchers speculate that this might be circumstantial evidence for water venting from the moon's subsurface. The material could be associated with the global ocean that is believed to be present beneath the frozen crust. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21443

Technicians align, install, and then extend the second set of solar arrays, measuring 46.5 feet (14.2 meters) long and about 13.5 feet (4.1 meters) high, for NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft inside the agency’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Thursday, Aug. 15, 2024. The huge arrays – spanning more than 100 feet when fully deployed, or about the length of a basketball court – will collect sunlight to power the spacecraft as it flies multiple times around Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa, conducting science investigations to determine its potential to support life.