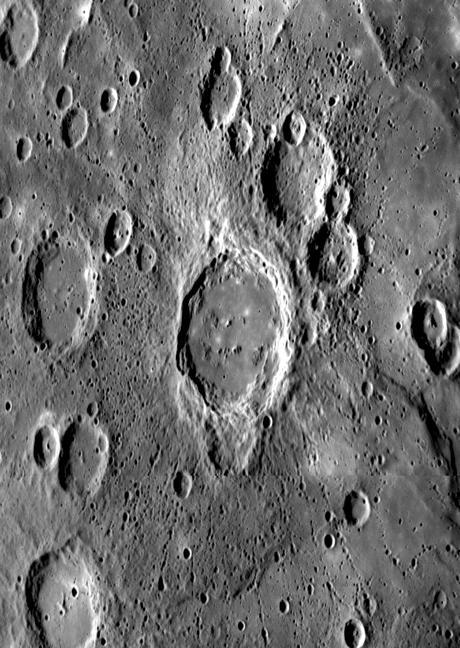

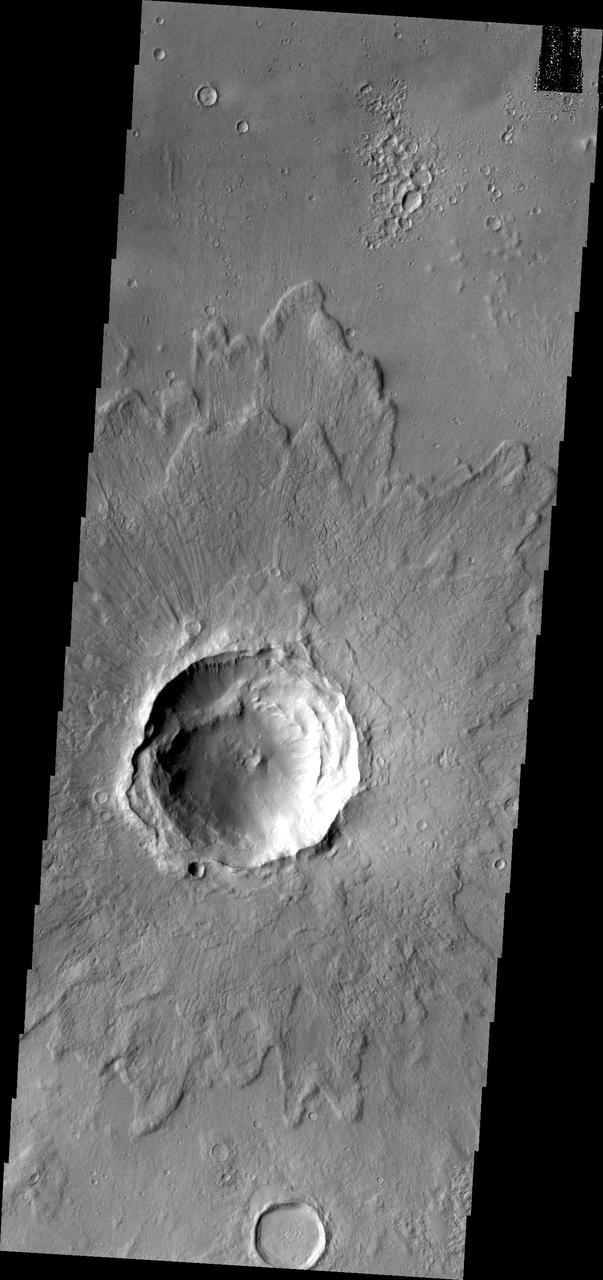

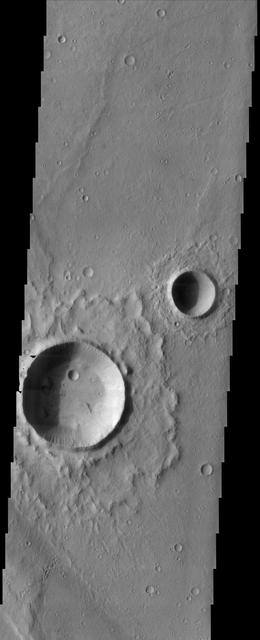

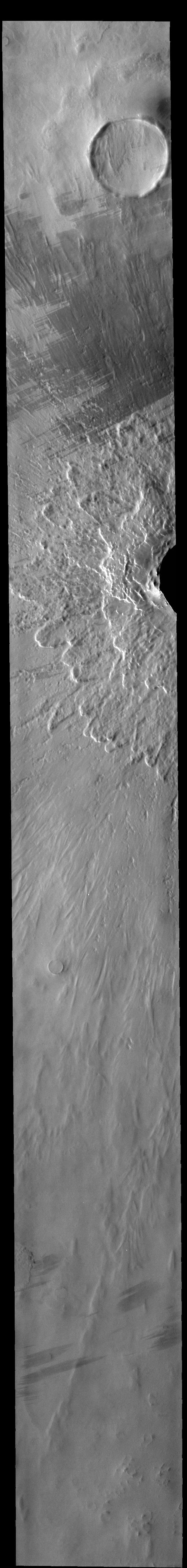

Impact Crater with Ejecta Blanket

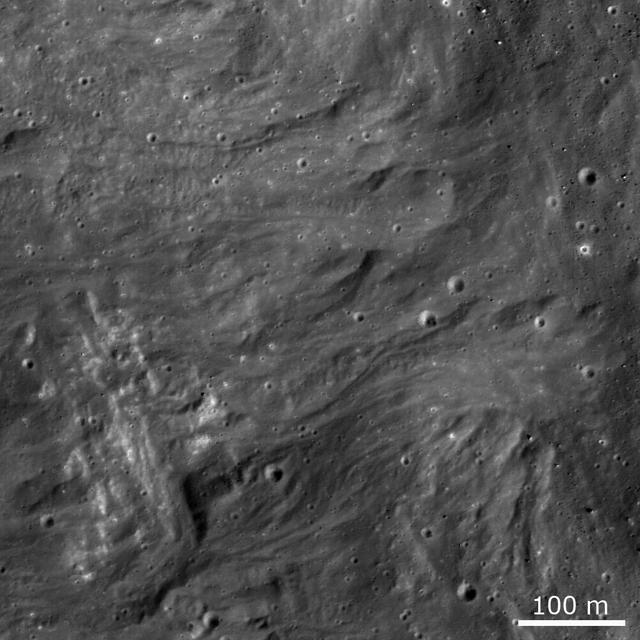

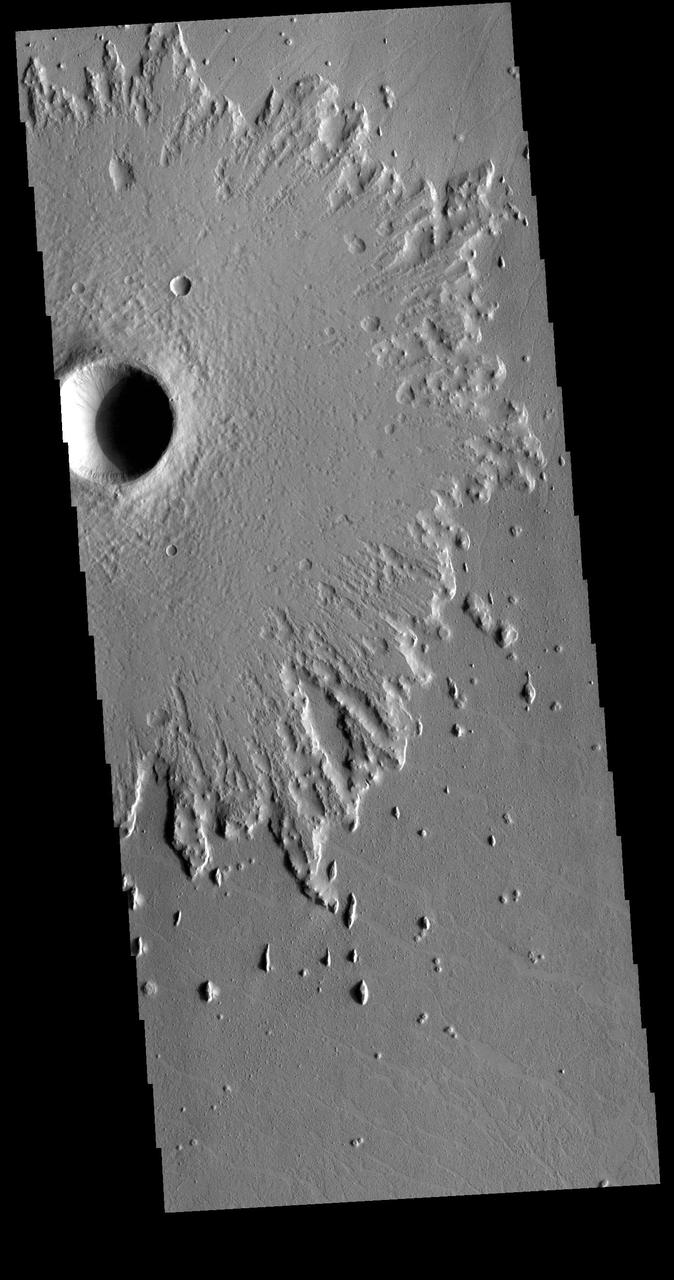

Bouldery Impact Ejecta

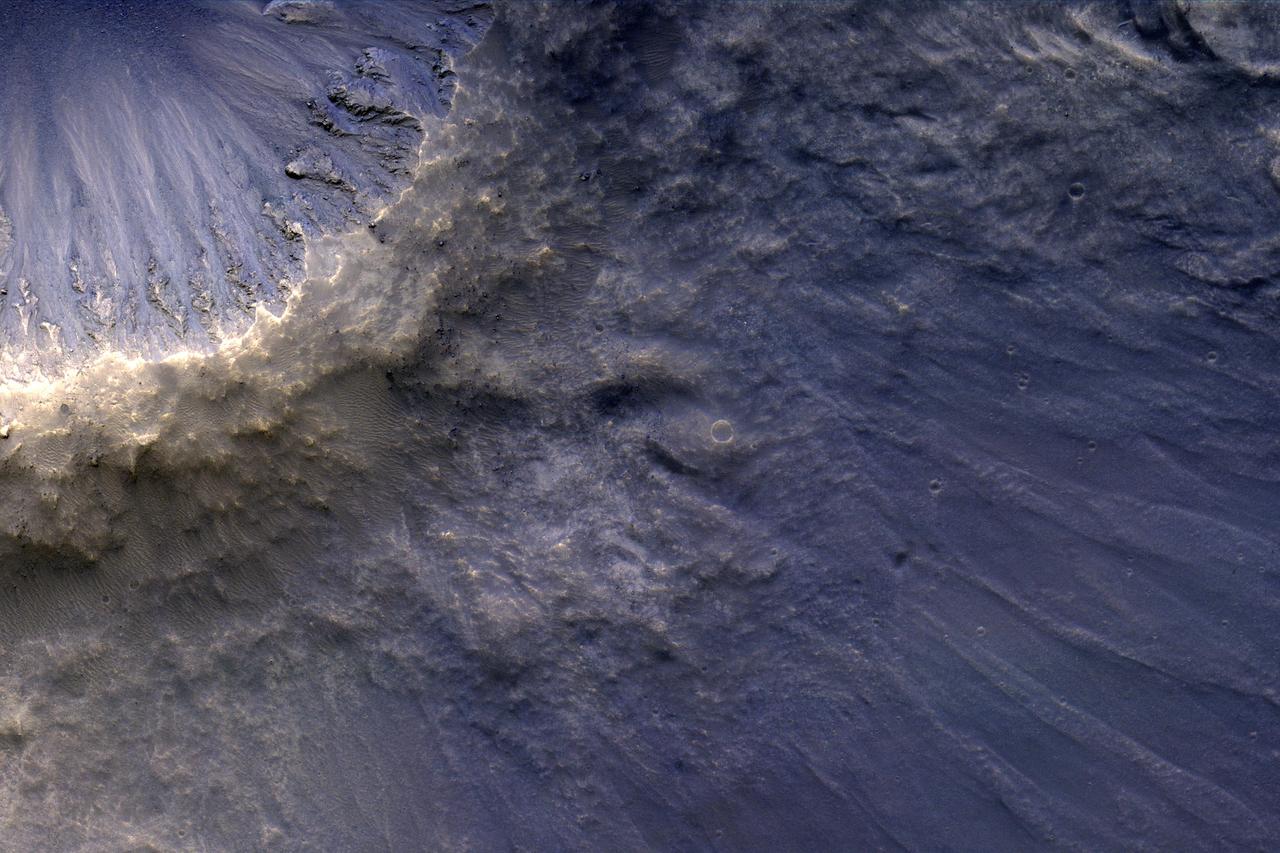

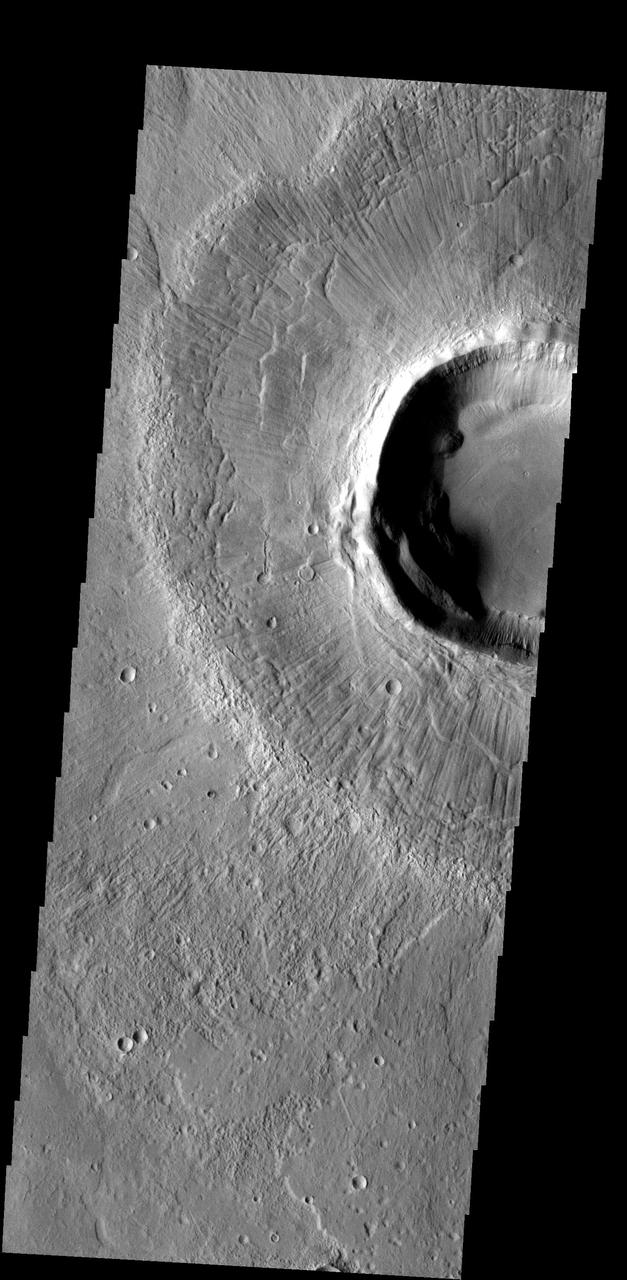

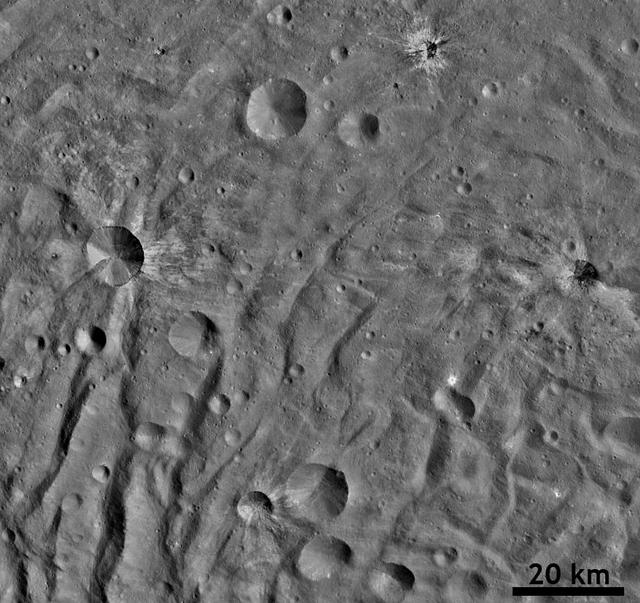

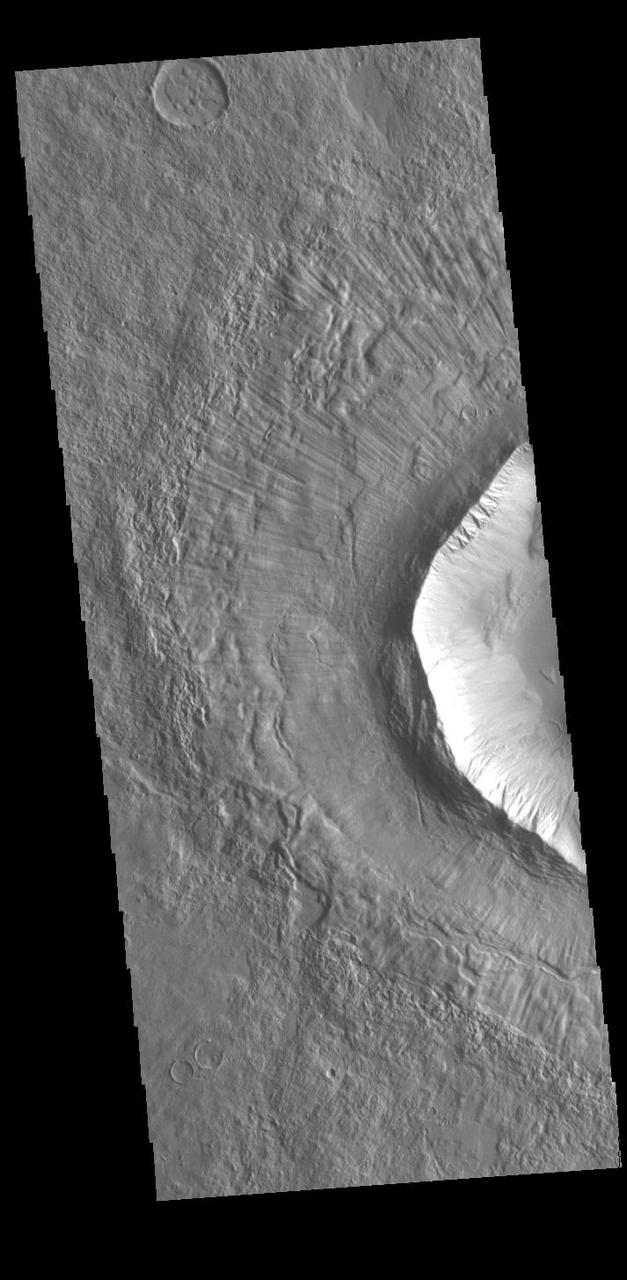

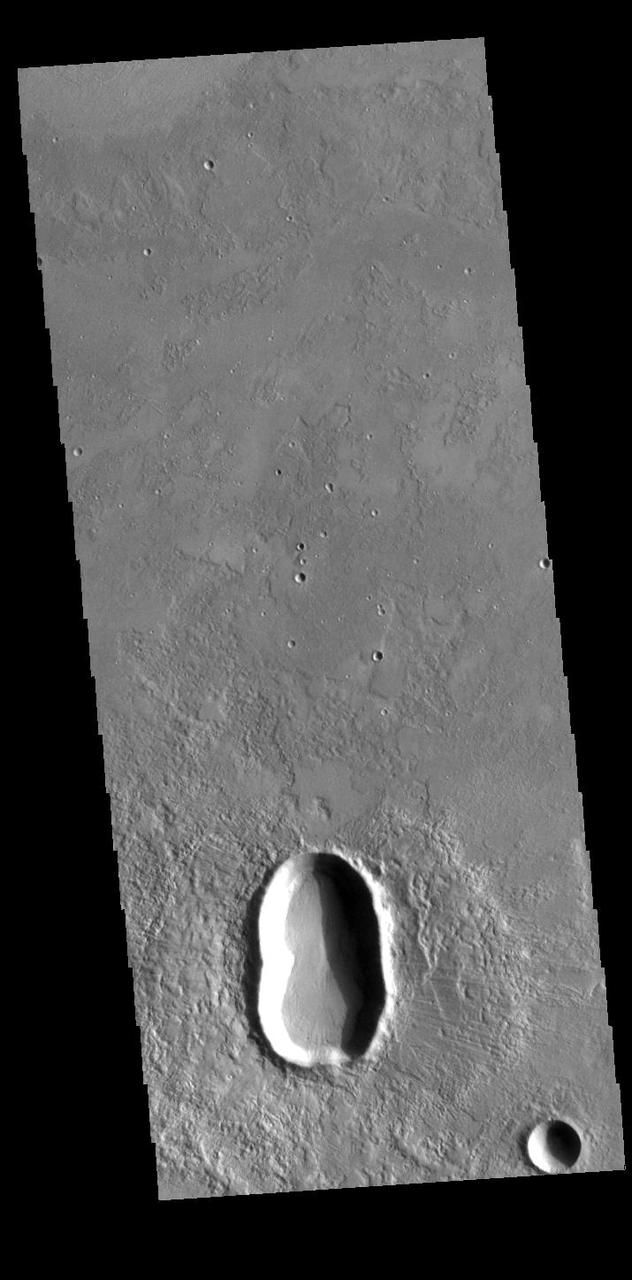

Crater Ejecta and Chains of Secondary Impacts

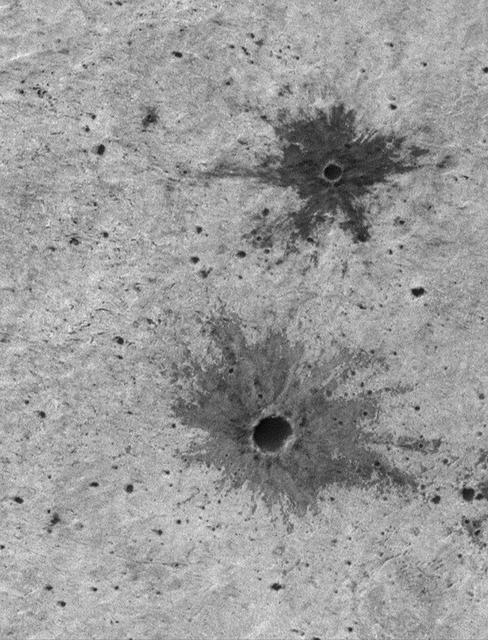

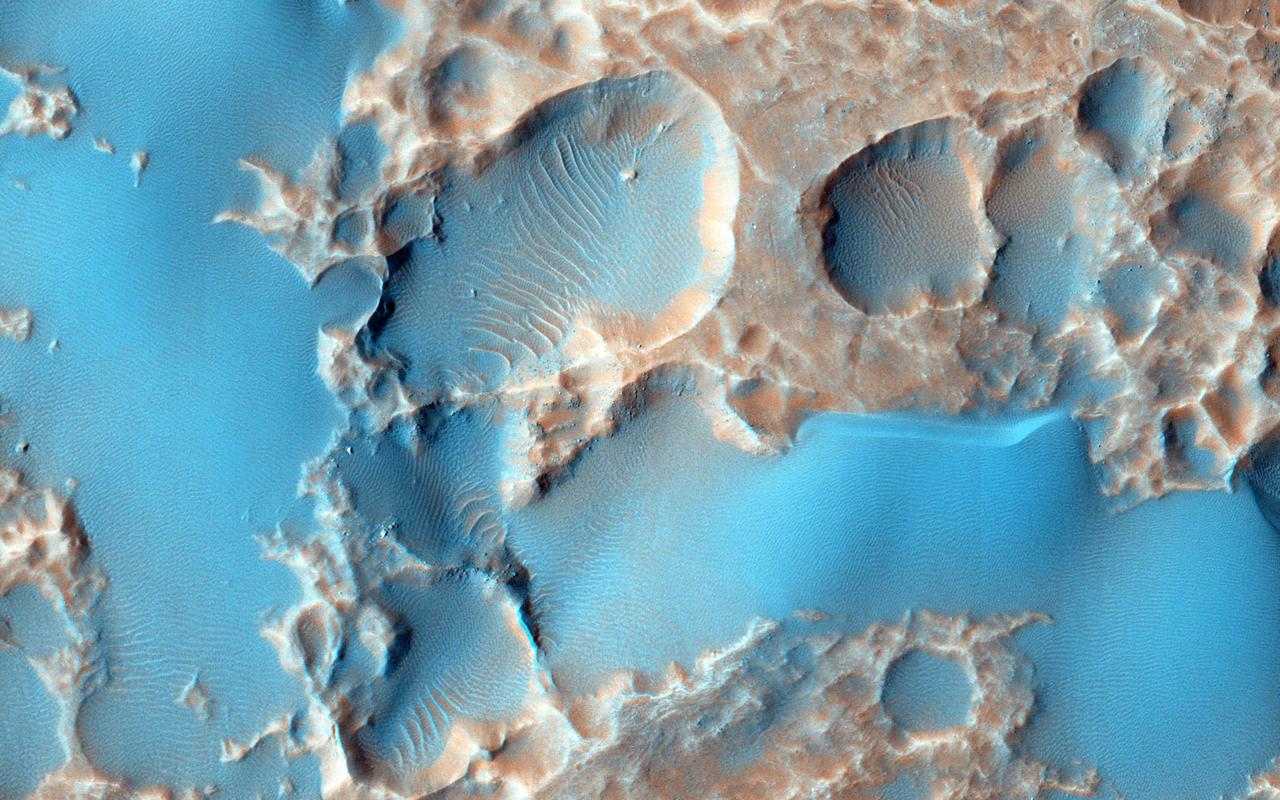

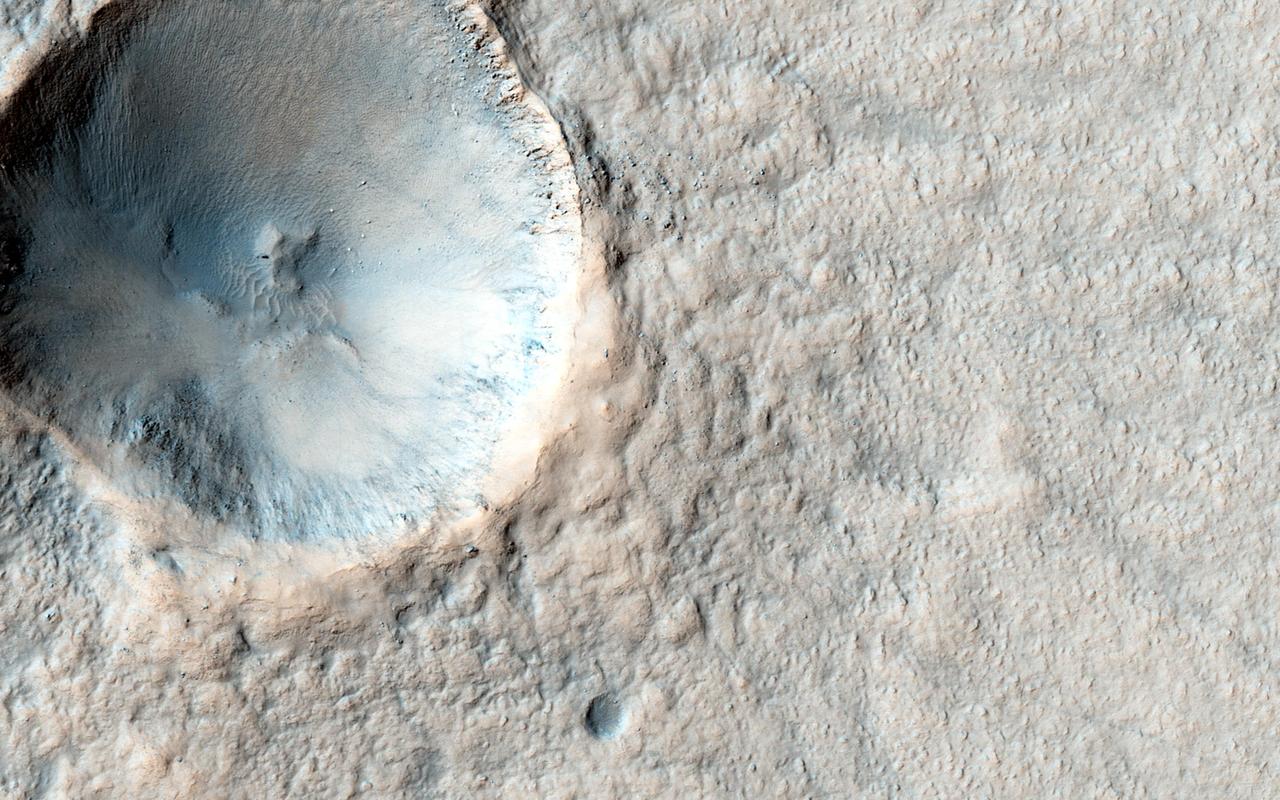

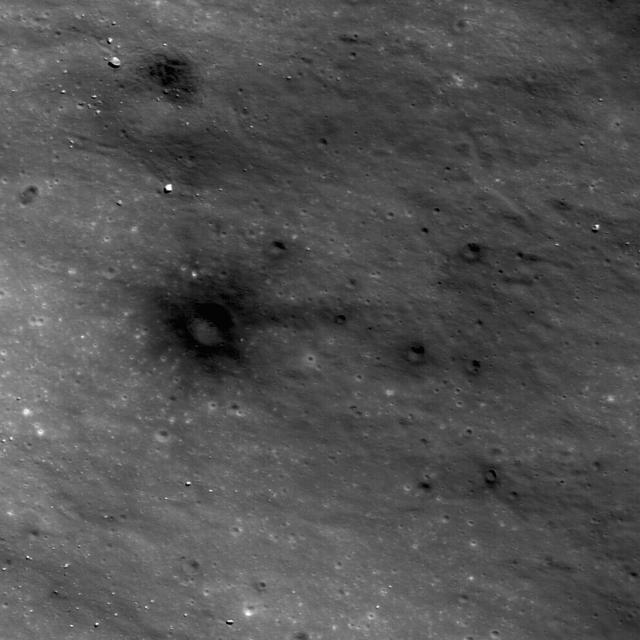

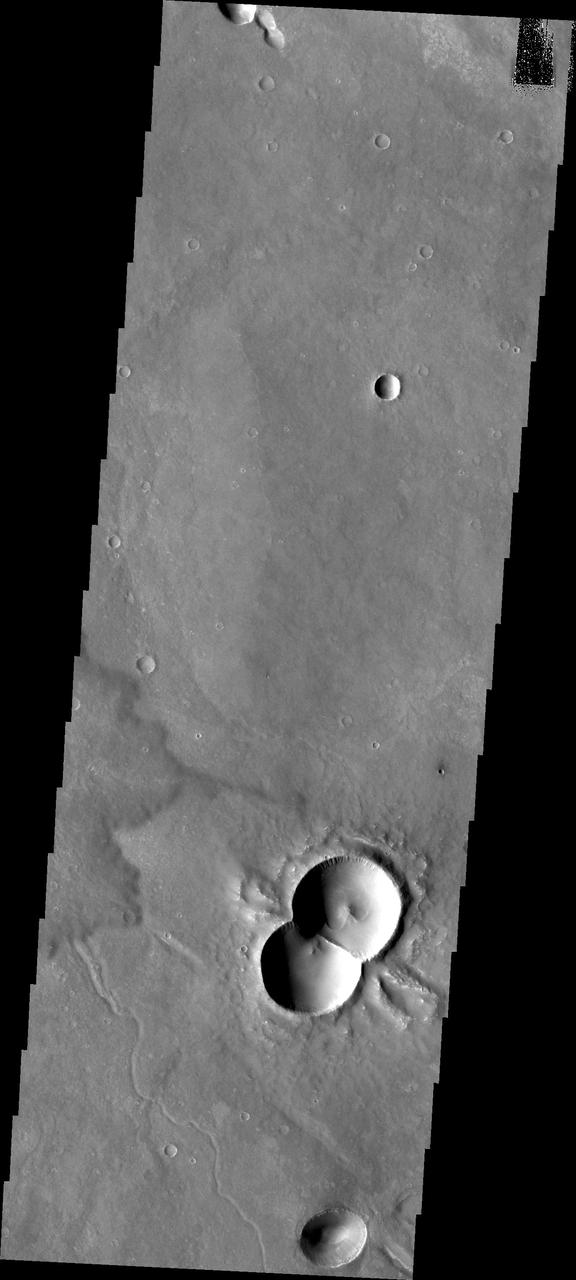

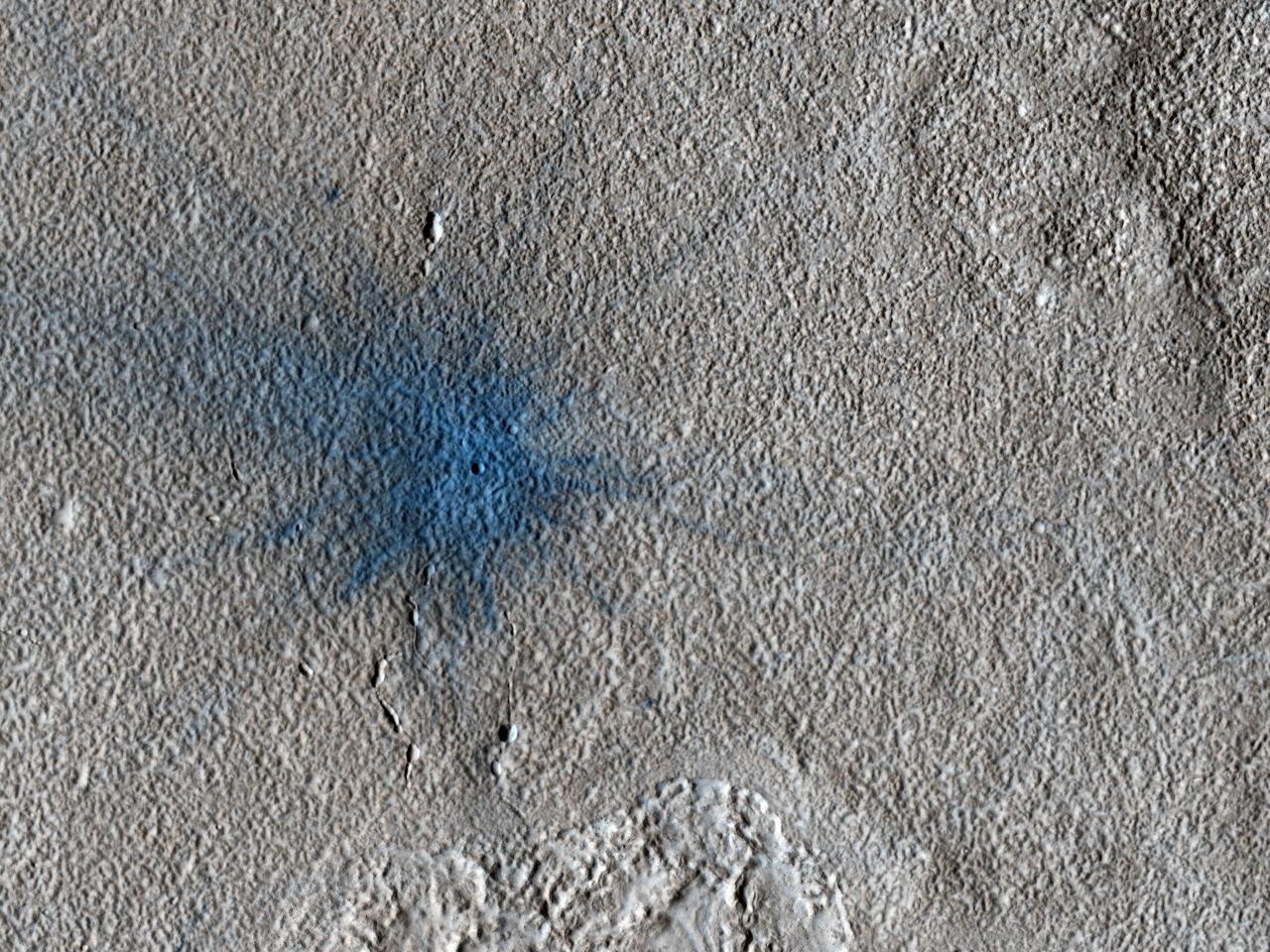

Small Impact Craters with Dark Ejecta Deposits

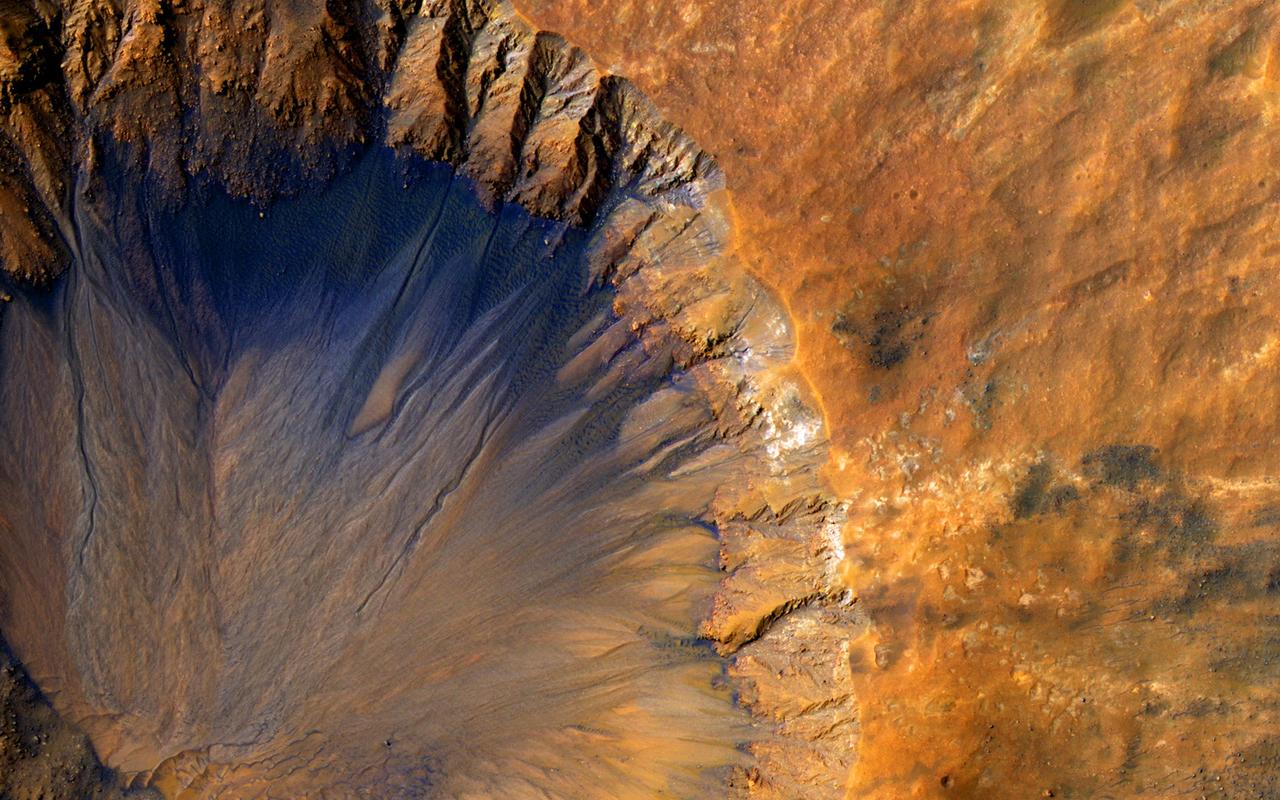

Small, Fresh Impact Crater With Dark Ejecta

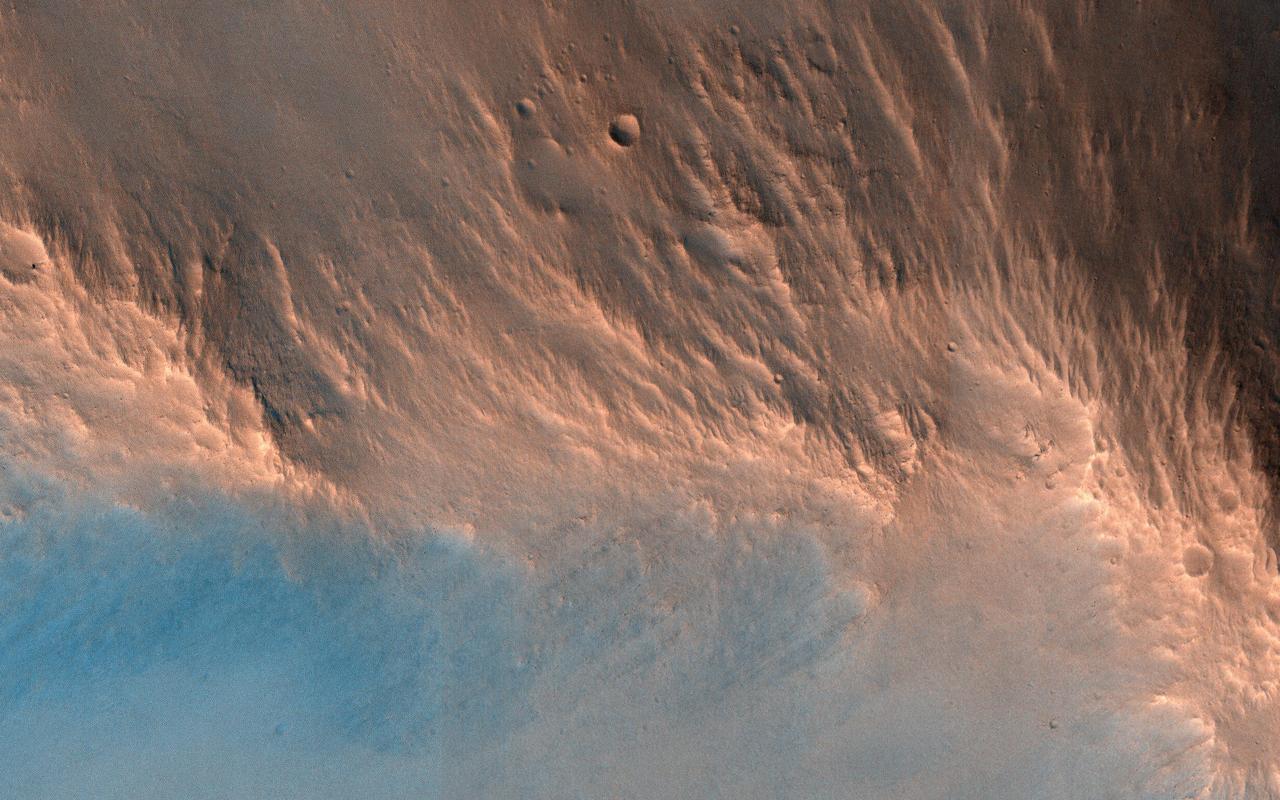

Impact ejecta is material that is thrown up and out of the surface of a planet as a result of the impact of an meteorite, asteroid or comet. The material that was originally beneath the surface of the planet then rains down onto the environs of the newly formed impact crater. Some of this material is deposited close to the crater, folding over itself to form the crater rim, visible here as a yellowish ring. Other material is ejected faster and falls down further from the crater rim creating two types of ejecta: a "continuous ejecta blanket" and "discontinuous ejecta." Both are shown in this image. The blocky area at the center of the image close to the yellowish crater rim is the "continuous" ejecta. The discontinuous ejecta is further from the crater rim, streaking away from the crater like spokes on a bicycle. (Note: North is to the right.) http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA11180

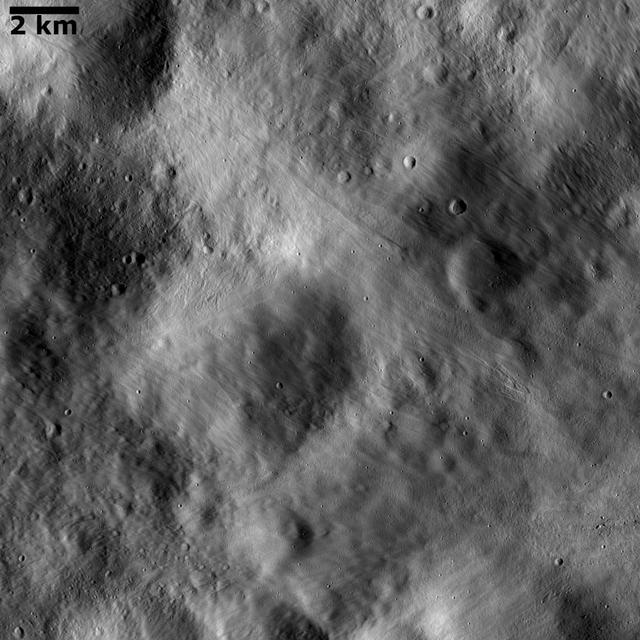

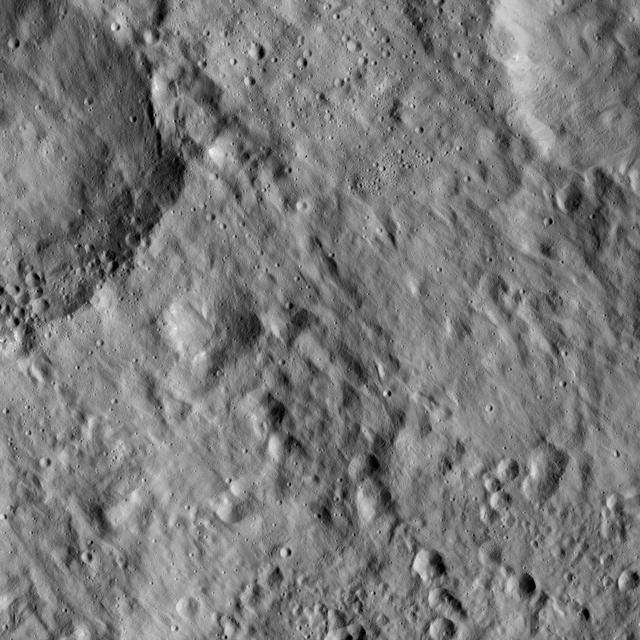

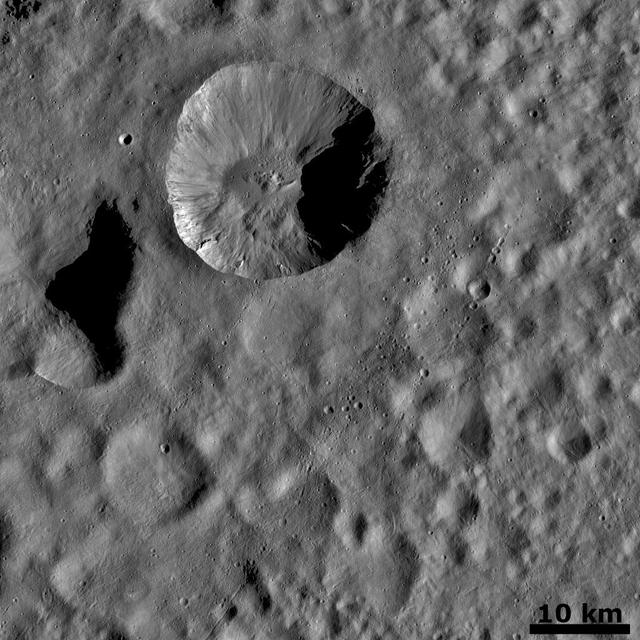

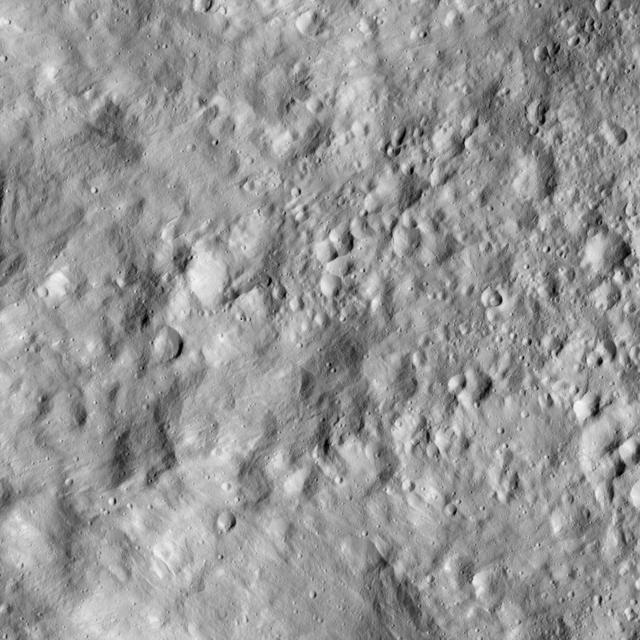

This image from NASA Dawn spacecraft shows impact ejecta deposits dominating asteroid Vesta landscape. This impact ejecta material was ejected from an impact crater located outside the imaged area.

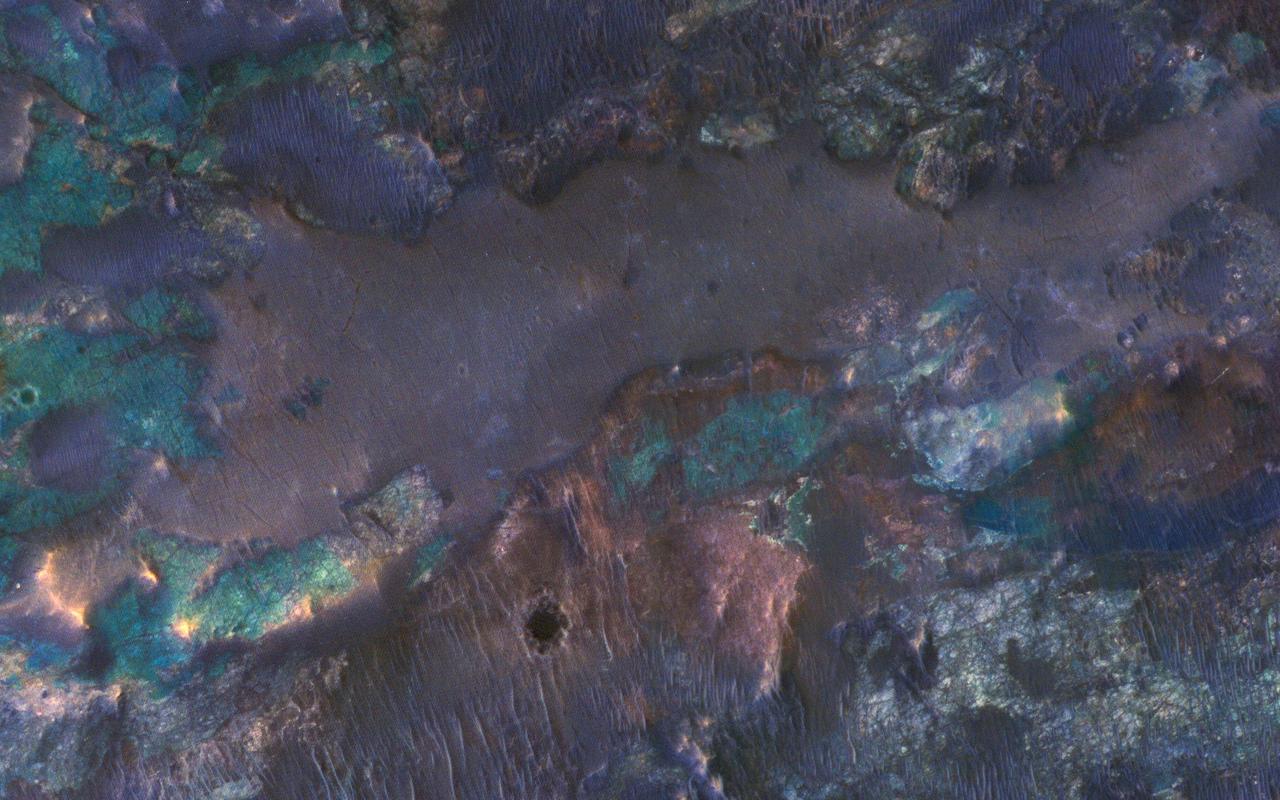

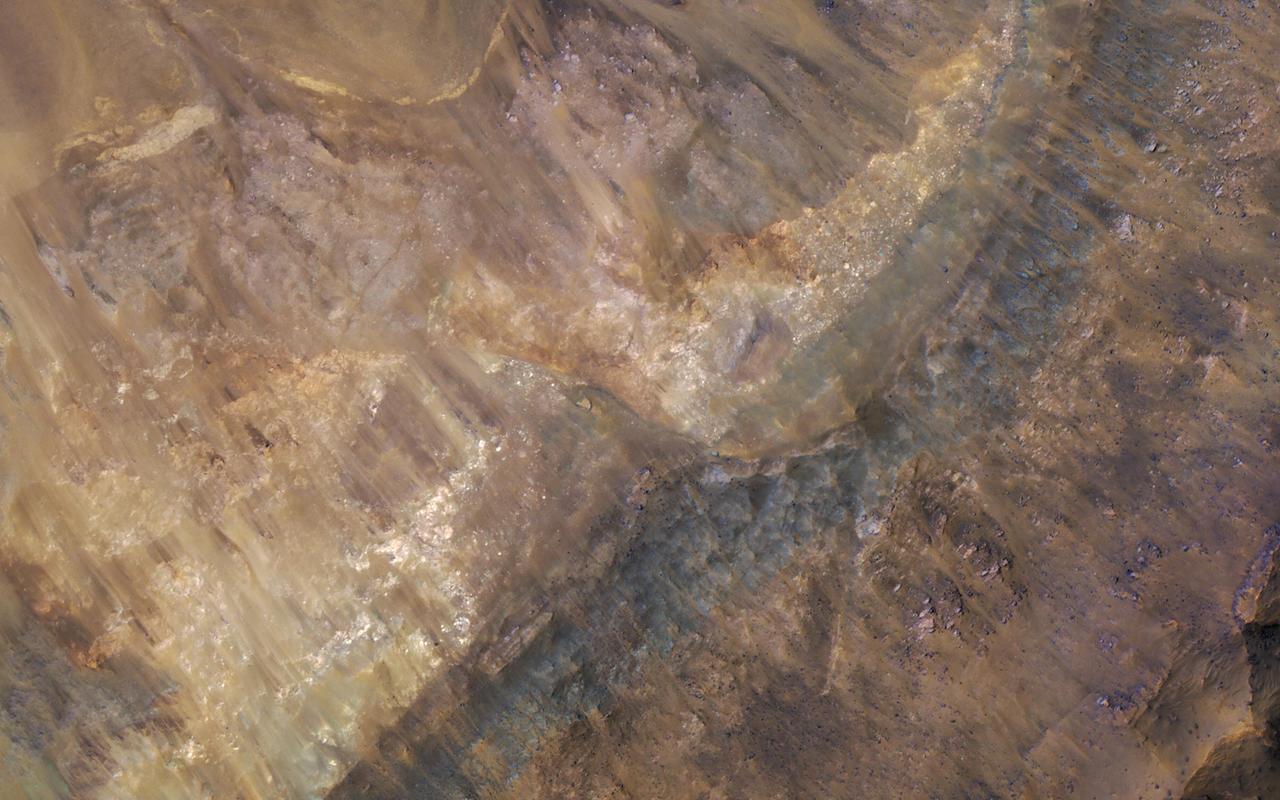

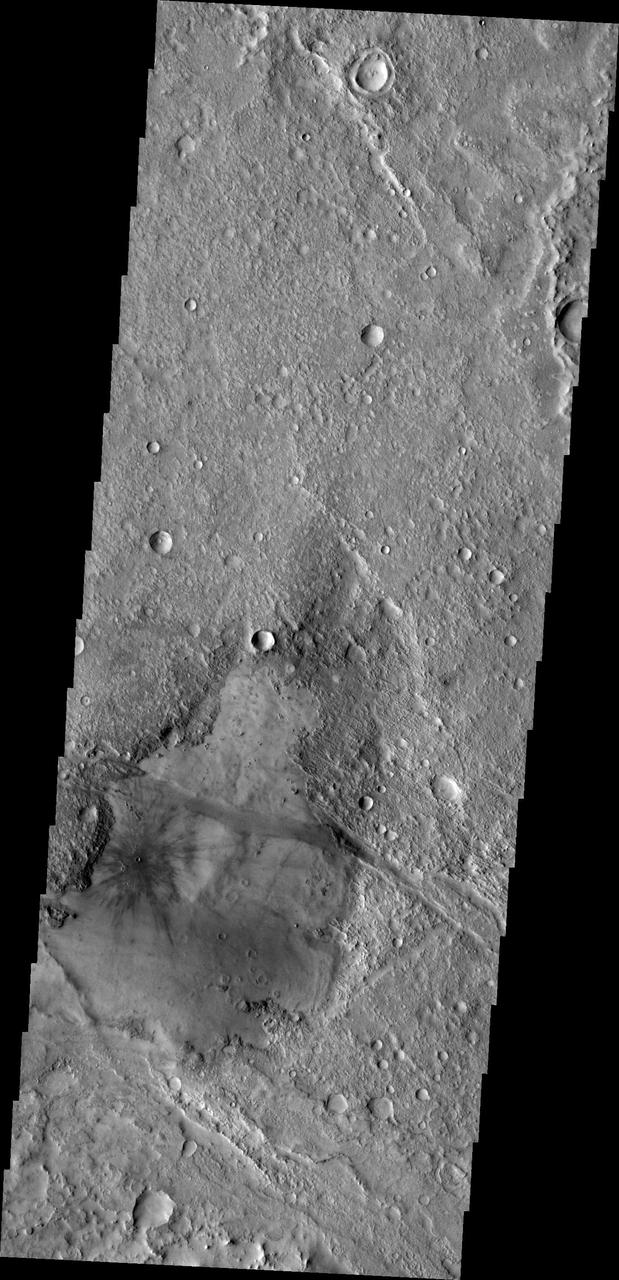

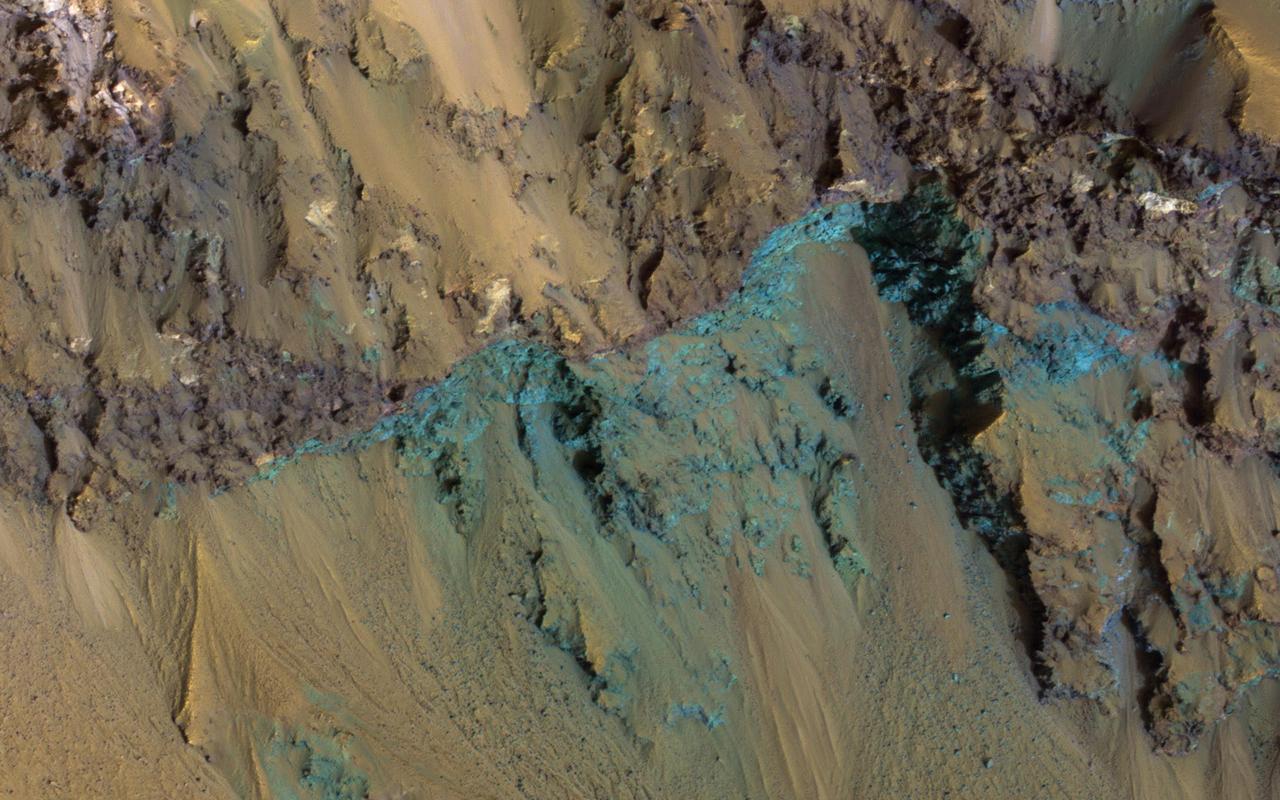

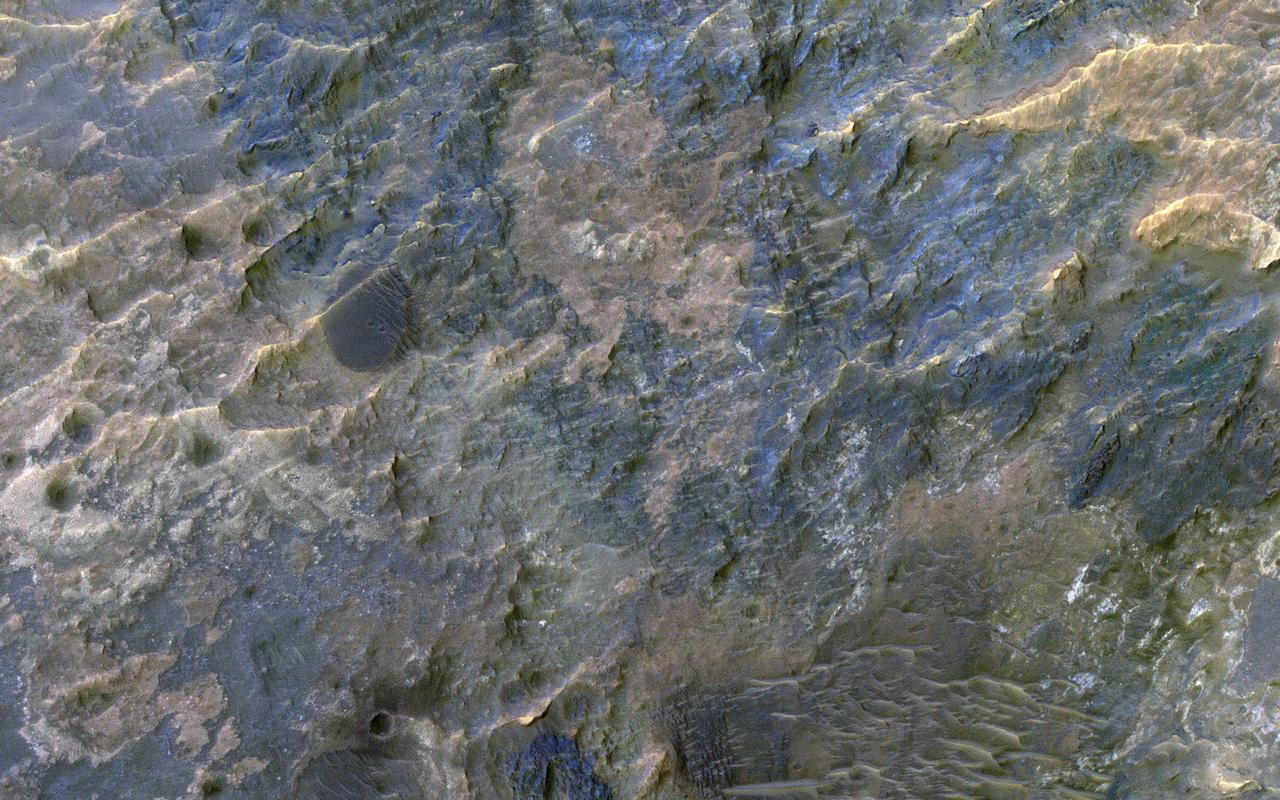

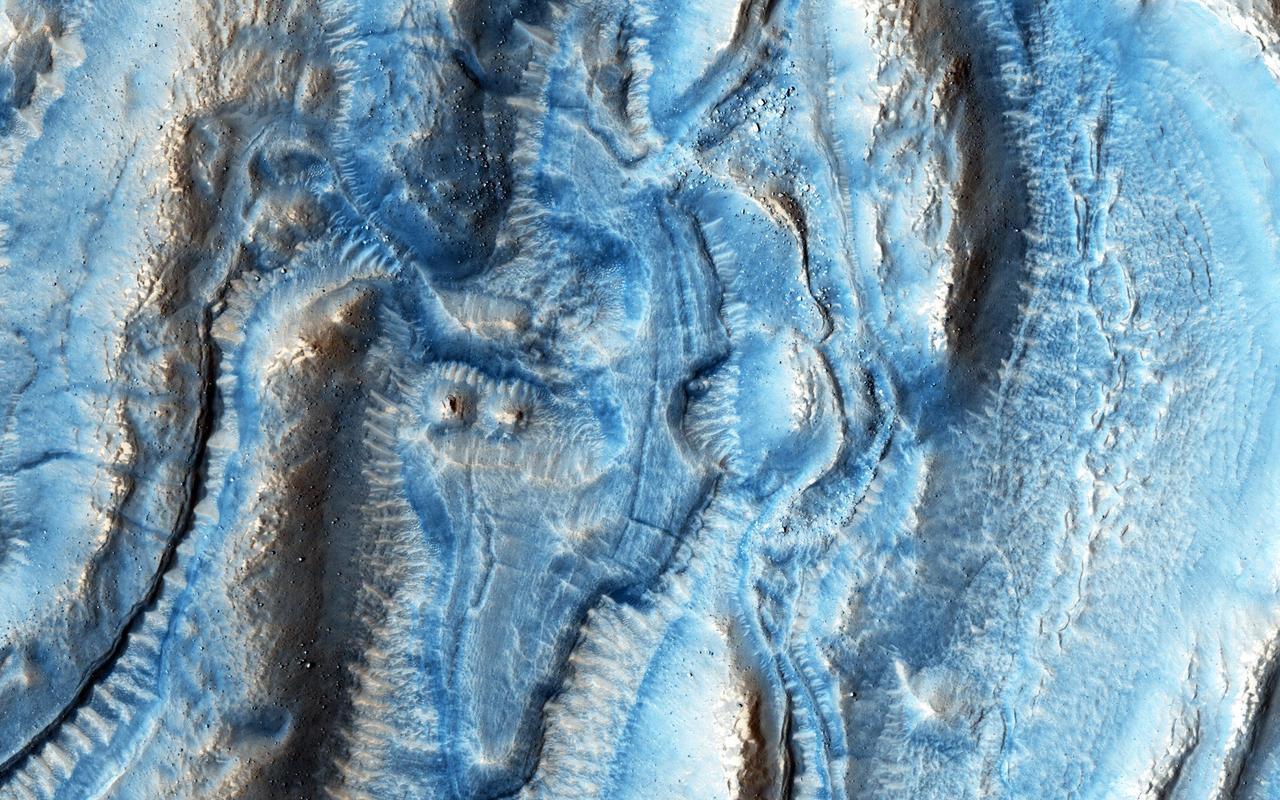

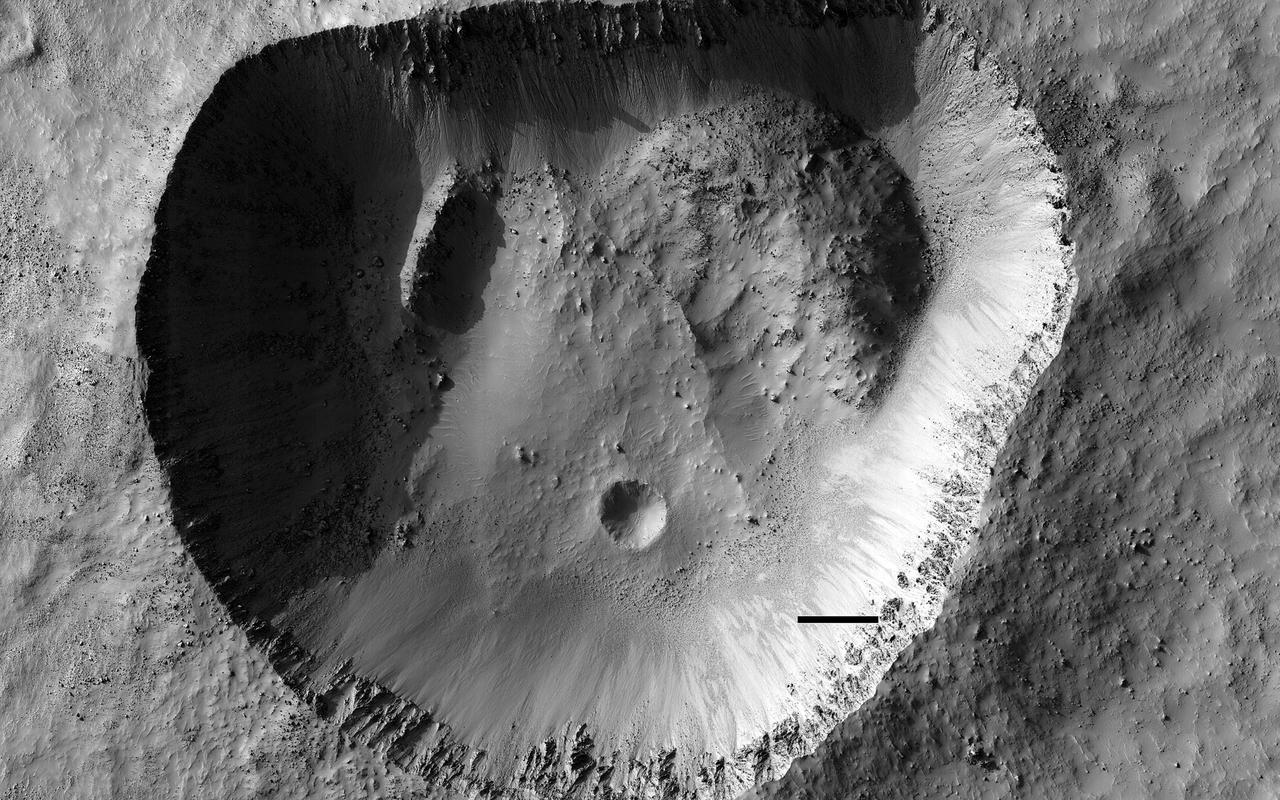

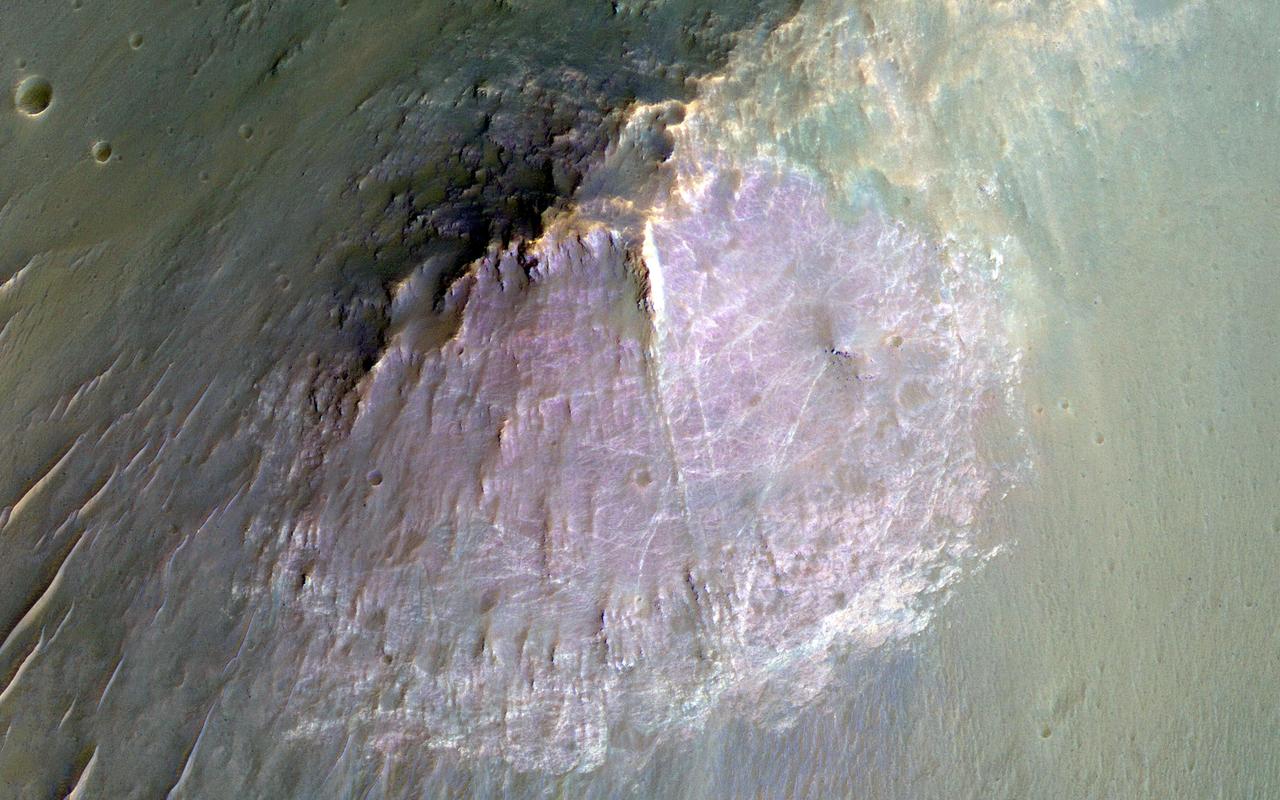

The collision that created Hargraves Crater impacted into diverse bedrock lithologies of ancient Mars; the impact ejecta is a rich mix of rock types with different colors and textures, as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The crater is named after Robert Hargraves who discovered and studied meteorite impacts on the Earth. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21609

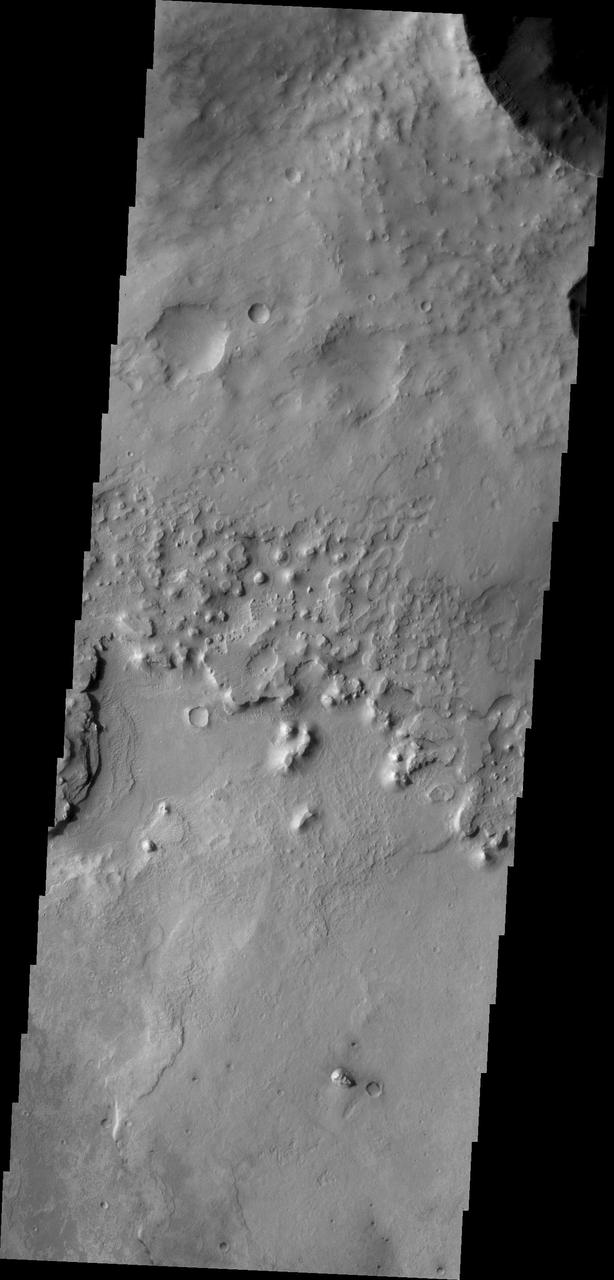

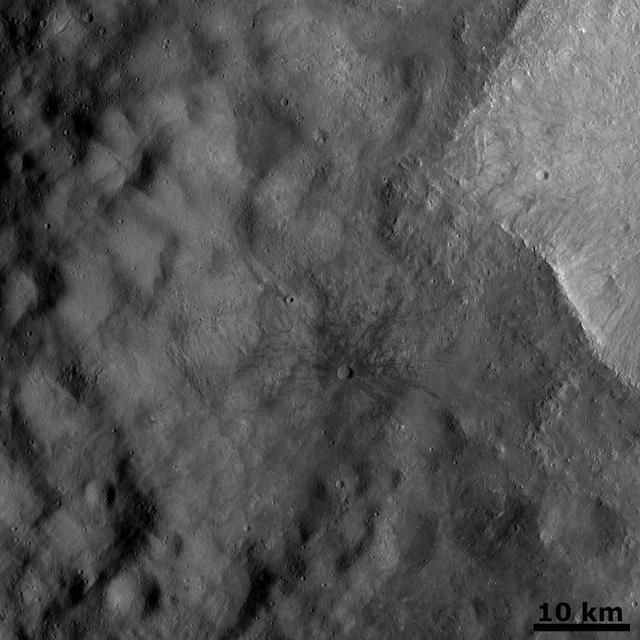

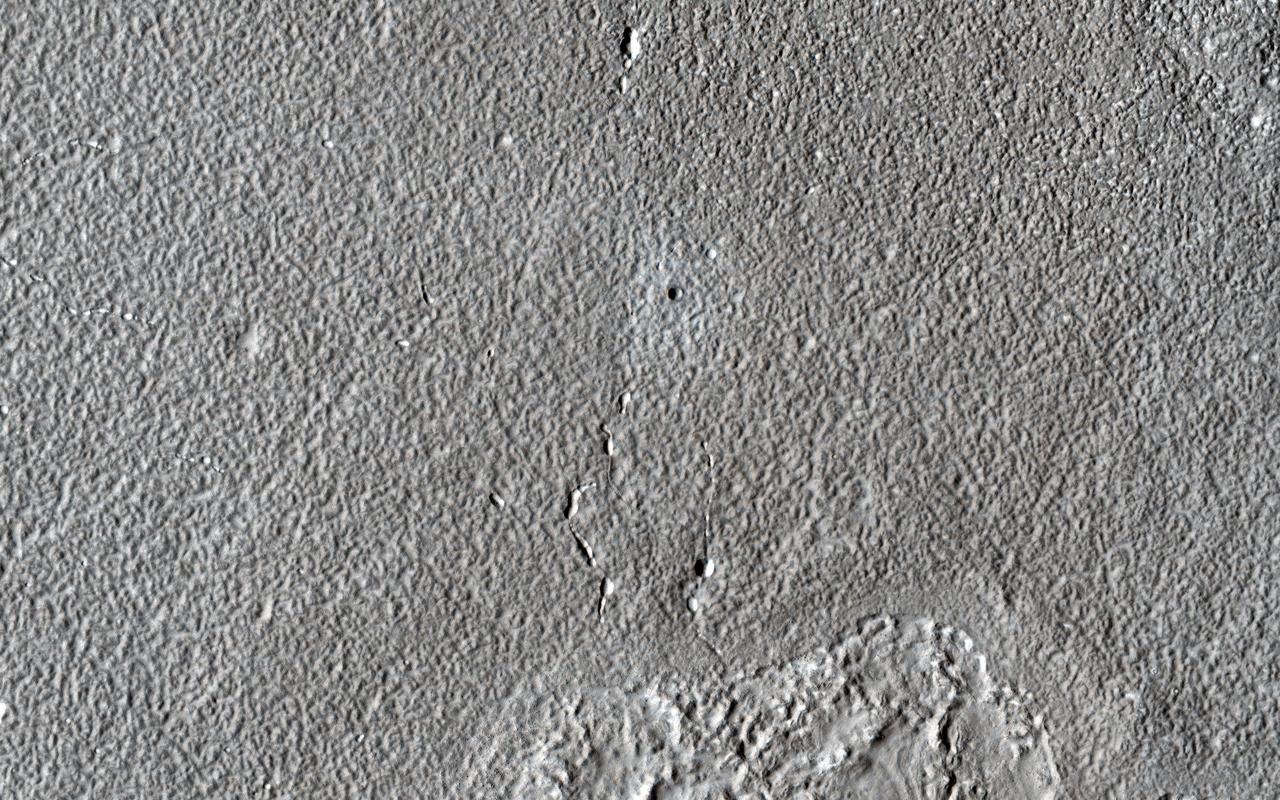

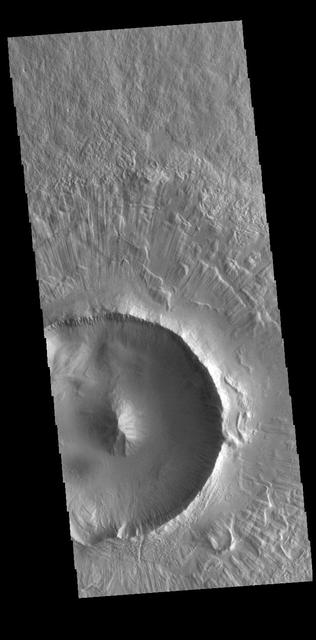

This image of a well-preserved unnamed elliptical crater in Terra Sabaea, is illustrative of the complexity of ejecta deposits forming as a by-product of the impact process that shapes much of the surface of Mars. Here we see a portion of the western ejecta deposits emanating from a 10-kilometer impact crater that occurs within the wall of a larger, 60-kilometer-wide crater. In the central part is a lobe-shaped portion of the ejecta blanket from the smaller crater. The crater is elliptical not because of an angled (oblique) impact, but because it occurred on the steep slopes of the wall of a larger crater. This caused it to be truncated along the slope and elongated perpendicular to the slope. As a result, any impact melt from the smaller crater would have preferentially deposited down slope and towards the floor of the larger crater (towards the west). Within this deposit, we can see fine-scale morphological features in the form of a dense network of small ridges and pits. These crater-related pitted materials are consistent with volatile-rich impact melt-bearing deposits seen in some of the best-preserved craters on Mars (e.g., Zumba, Zunil, etc.). These deposits formed immediately after the impact event, and their discernible presence relate to the preservation state of the crater. This image is an attempt to visualize the complex formation and emplacement history of these enigmatic deposits formed by this elliptical crater and to understand its degradation history. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA13078

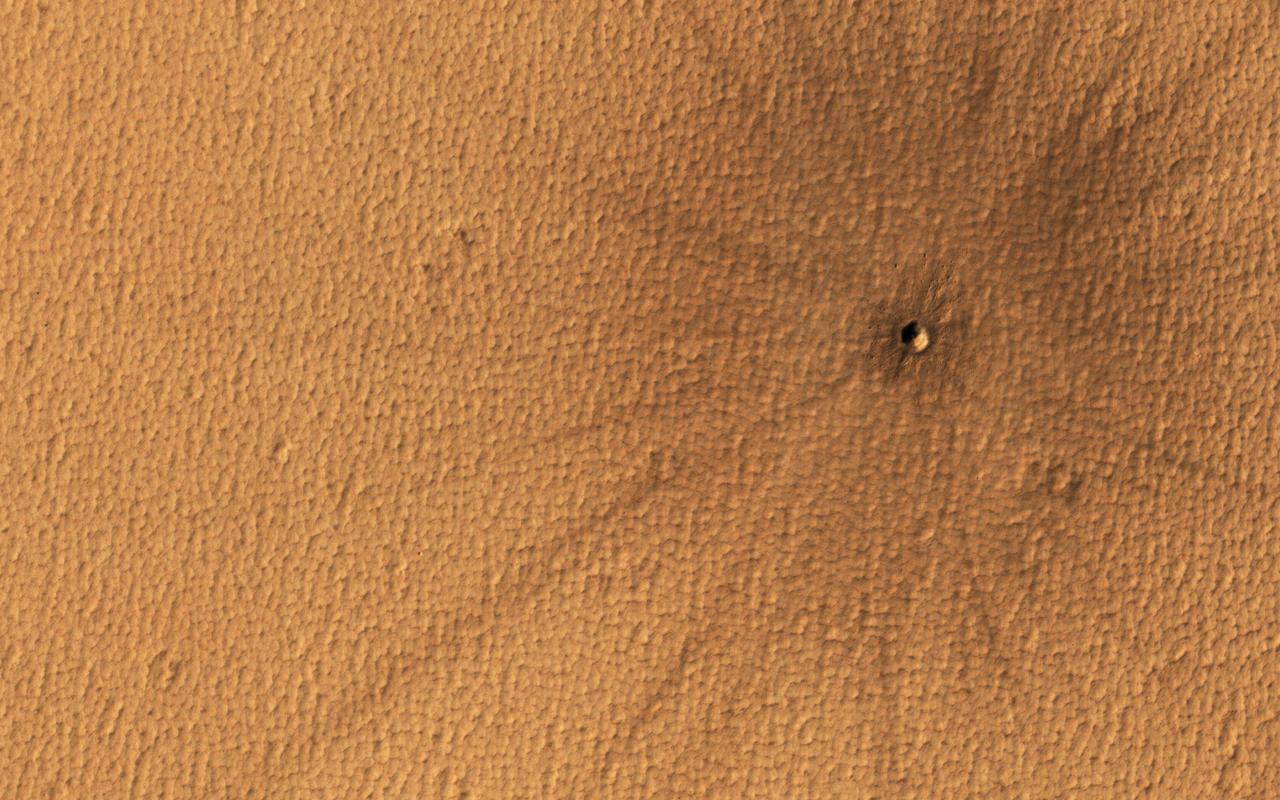

The Context Camera onboard MRO has been discovering new impact sites on Mars, followed up with HiRISE images. Usually these sites are discovered as new dark spots from removal or disturbance of bright dust, but a few show up as new bright spots. These craters may have bright ejecta from exposure of shallow subsurface materials, below a thin dark cover. An alternate theory—that this is a particle size effect—is unlikely because the bright materials are also distinctly redder than surrounding areas, and because ejecta is typically more coarse-grained, which would make the surface darker rather than brighter. The new crater visible here is about 13 meters in diameter. The color has been enhanced for this cutout. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24619

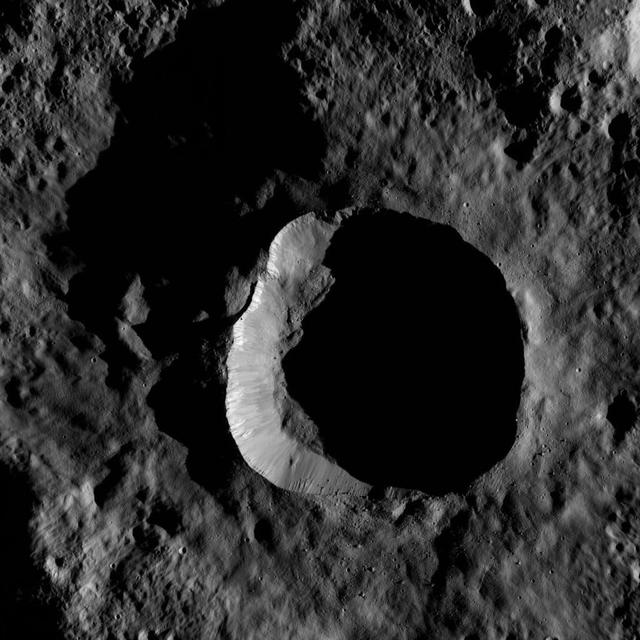

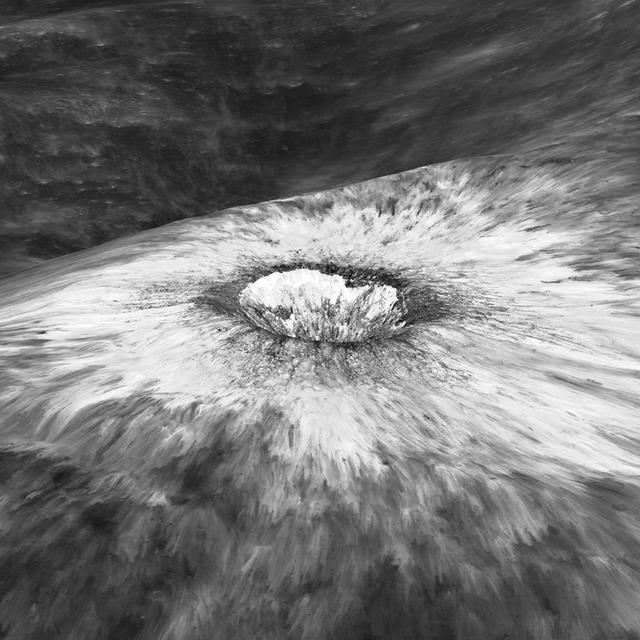

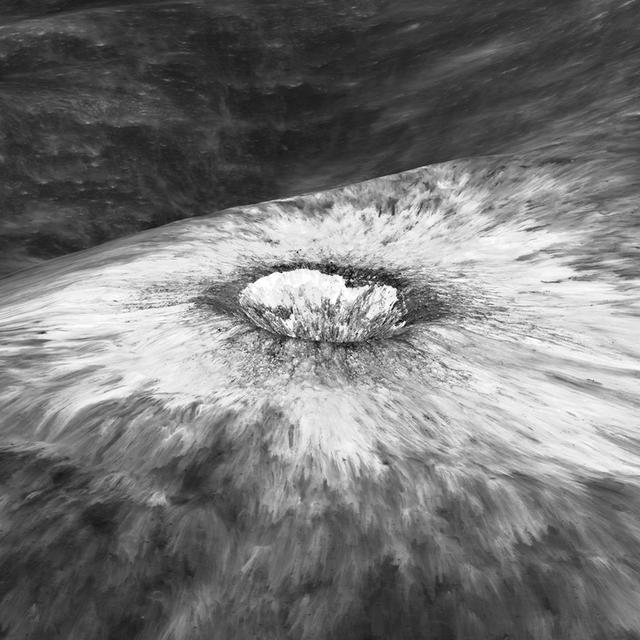

Overlapping petals of bright ejecta illustrate the complexity of ejecta emplacement, even in smaller impact events in image taken by NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Frozen impact melt flows on the ejecta blanket of the young impact crater Giordano Bruno in this image from NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

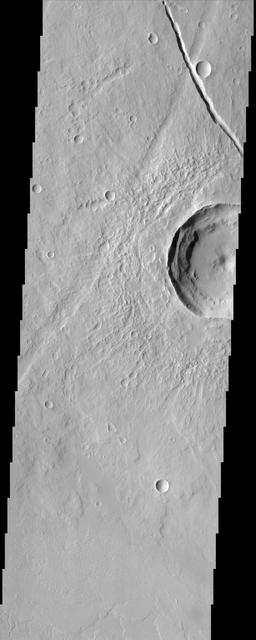

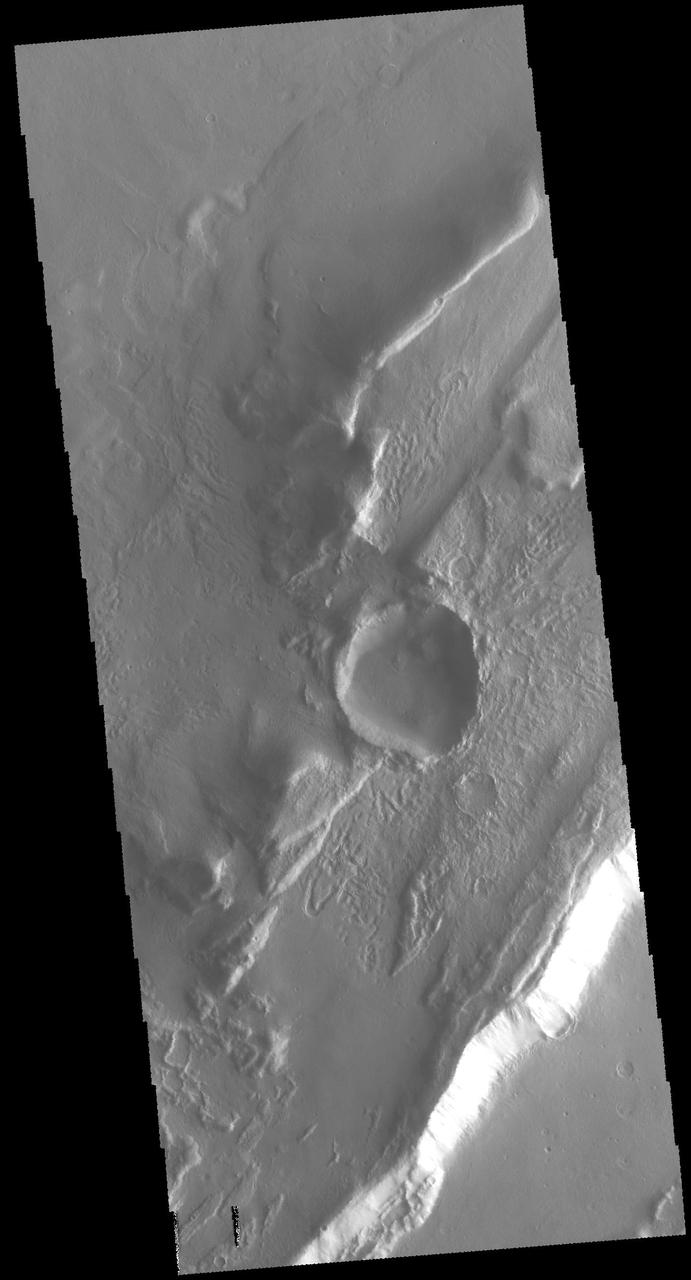

This image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft contains a relatively young crater and its ejecta. Layering in the ejecta is visible and relates to the shock waves from the impact. This unnamed crater is located in Arabia Terra.

This image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows an impact crater with a rampart ejecta blanket in Arabia Terra.

This impact crater, as seen by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, appears relatively recent as it has a sharp rim and well-preserved ejecta.

The surface of the ejecta surrounding this crater is scored with fine radial grooves. The grooves were formed during the impact event

The pits visible in this image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter arent impact craters. The material they are embedded into is ejecta stuff thrown out of an impact crater when it forms from a large crater called Hale not seen in this image. Substances called "volatiles" -- which can explode as gases when they're quickly warmed by the immense heat of an impact-exploded out of the ejecta and caused these pits. Unrelated sand dunes near the top of the image have since blown over portions of the pits. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19289

This image from NASA shows a particle impact on the aluminum frame that holds the aerogel tiles. The debris from the impact shot into the adjacent aerogel tile producing the explosion pattern of ejecta framents captured in the material.

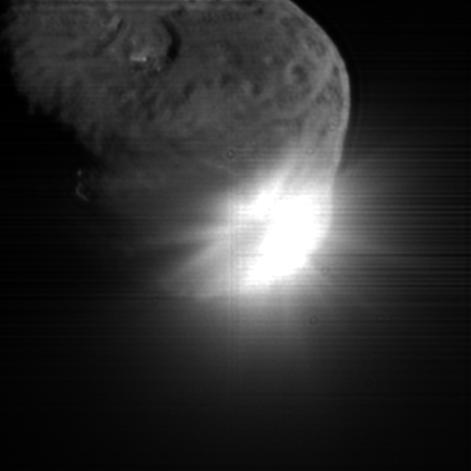

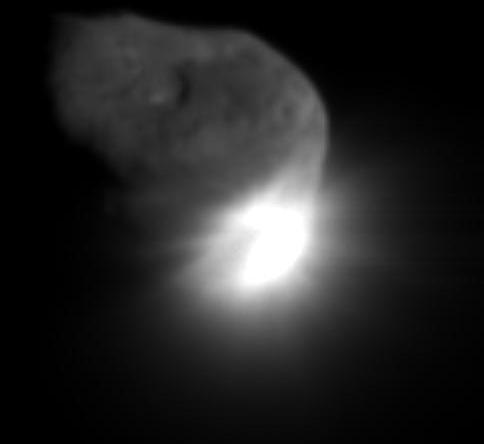

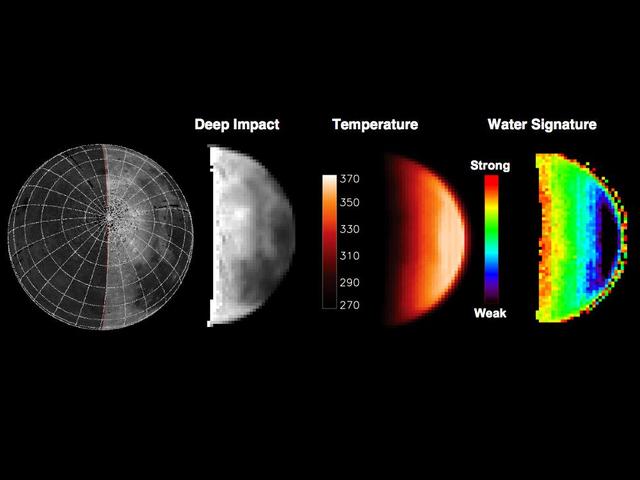

This image shows the initial ejecta that resulted when NASA Deep Impact probe collided with comet Tempel 1 on July 3, 2005. It was taken by the spacecraft high-resolution camera 13 seconds after impact.

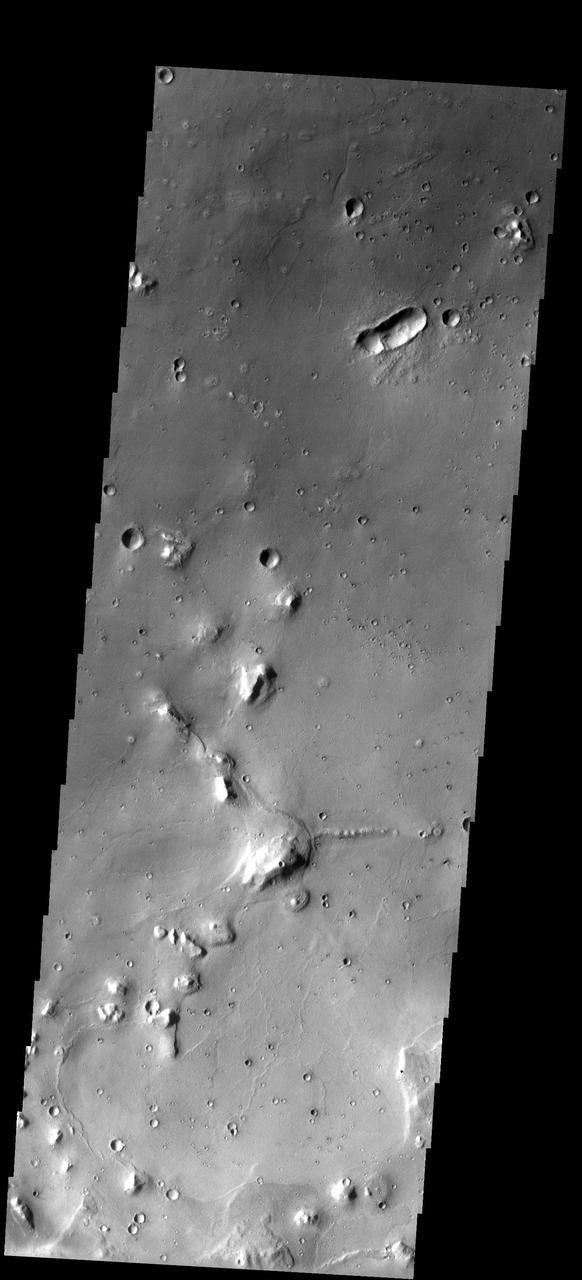

This area of Mars imaged by NASA Mars Odyssey shows a wonderful example of relative geologic dating. Ancient lava flows and escarpments are mantled by younger impact ejecta, which was cut by a younger graben and resurfaced by smaller impact craters.

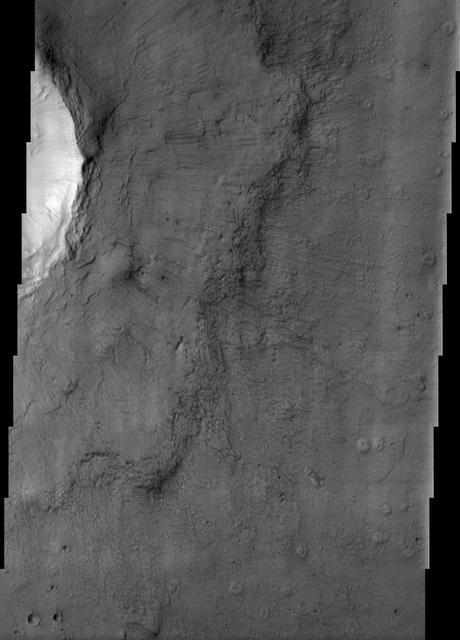

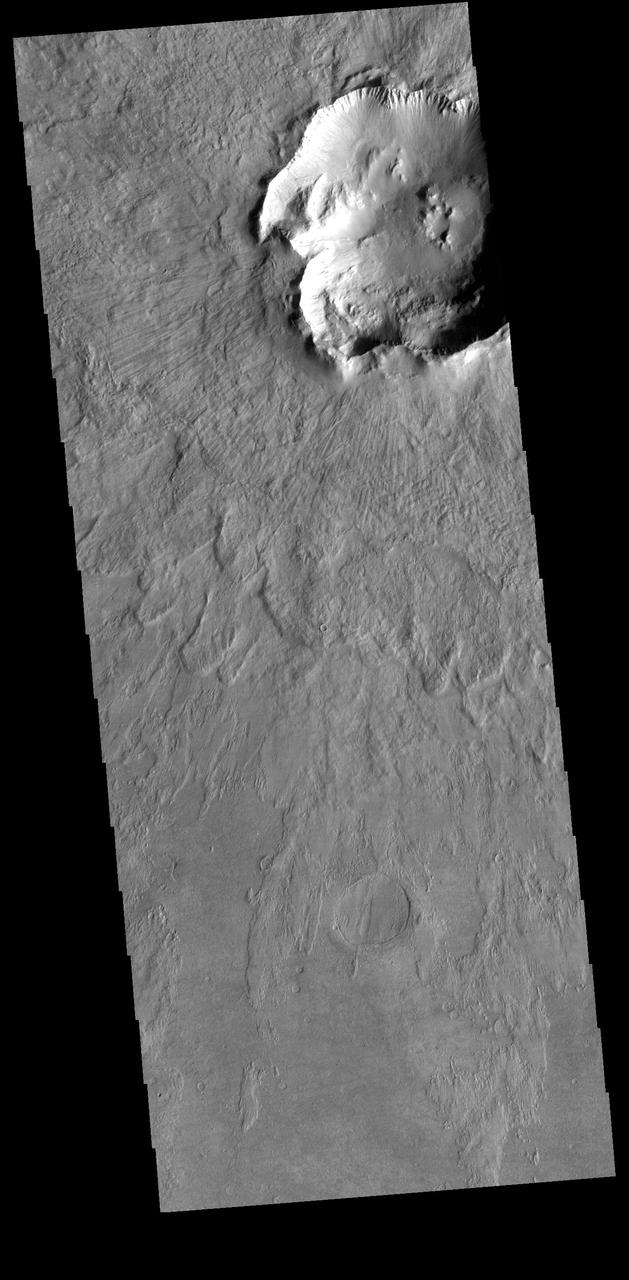

The objective of this observation by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter was to examine the edge of impact ejecta from a crater to the north-west of this area north is up, west is to the left.

The ejecta blanket created around impact craters is often much more resistant to erosion than surrounding surface materials. As seen by NASA Mars Odyssey, the ejecta material creates isolated highs as surrounding surface is eroded near Meridiani Planum.

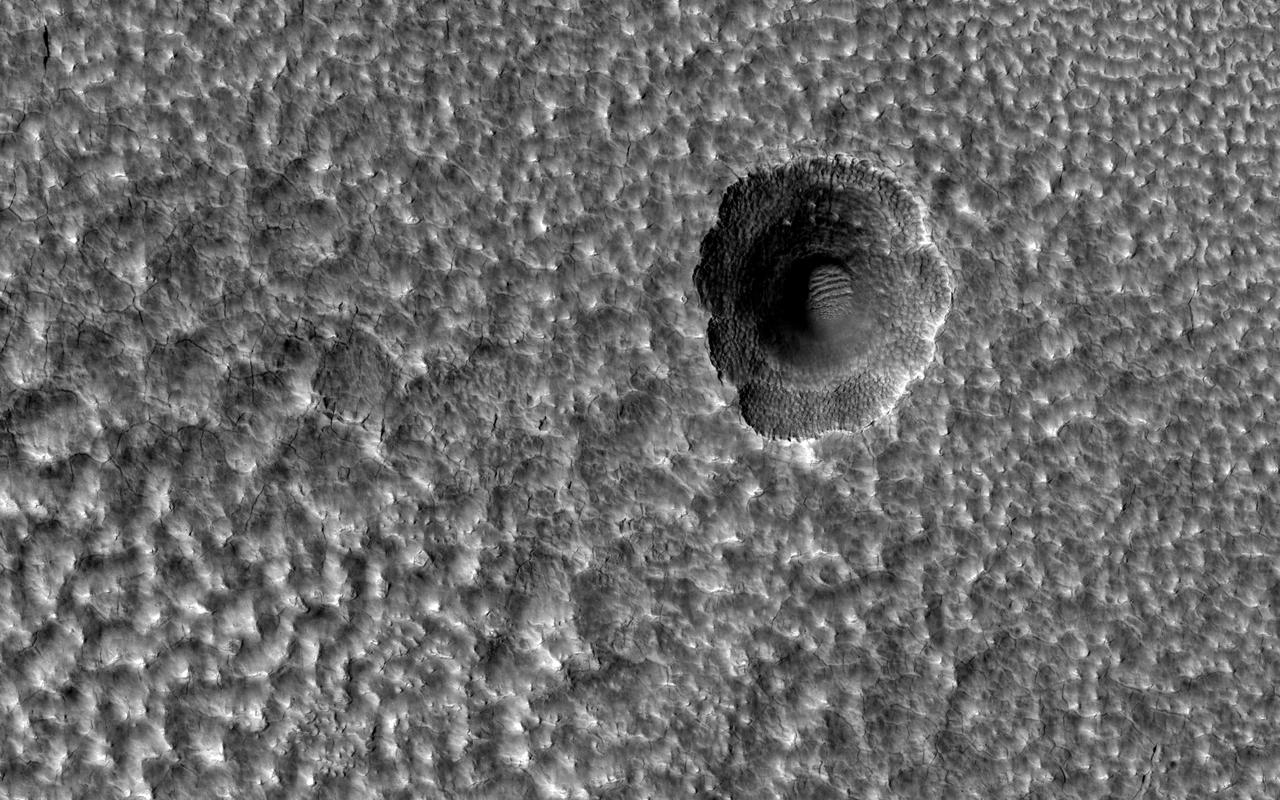

In this image, we see an approximately 500-meter crater that is fairly fresh (in geological terms), but the ejecta is already high-standing. Could this be an indication of early stage of pedestal development? A pedestal crater is when the ejecta from an impact settles around the new crater and is more erosion-resistant than the surrounding terrain. Over time, the surrounding terrain erodes much faster than the ejecta; in fact, some pedestal craters are measured to be hundreds of meters above the surrounding area. HiRISE has imaged many other pedestal craters before, and the ejecta isn't always symmetrical, as in this observation. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19849

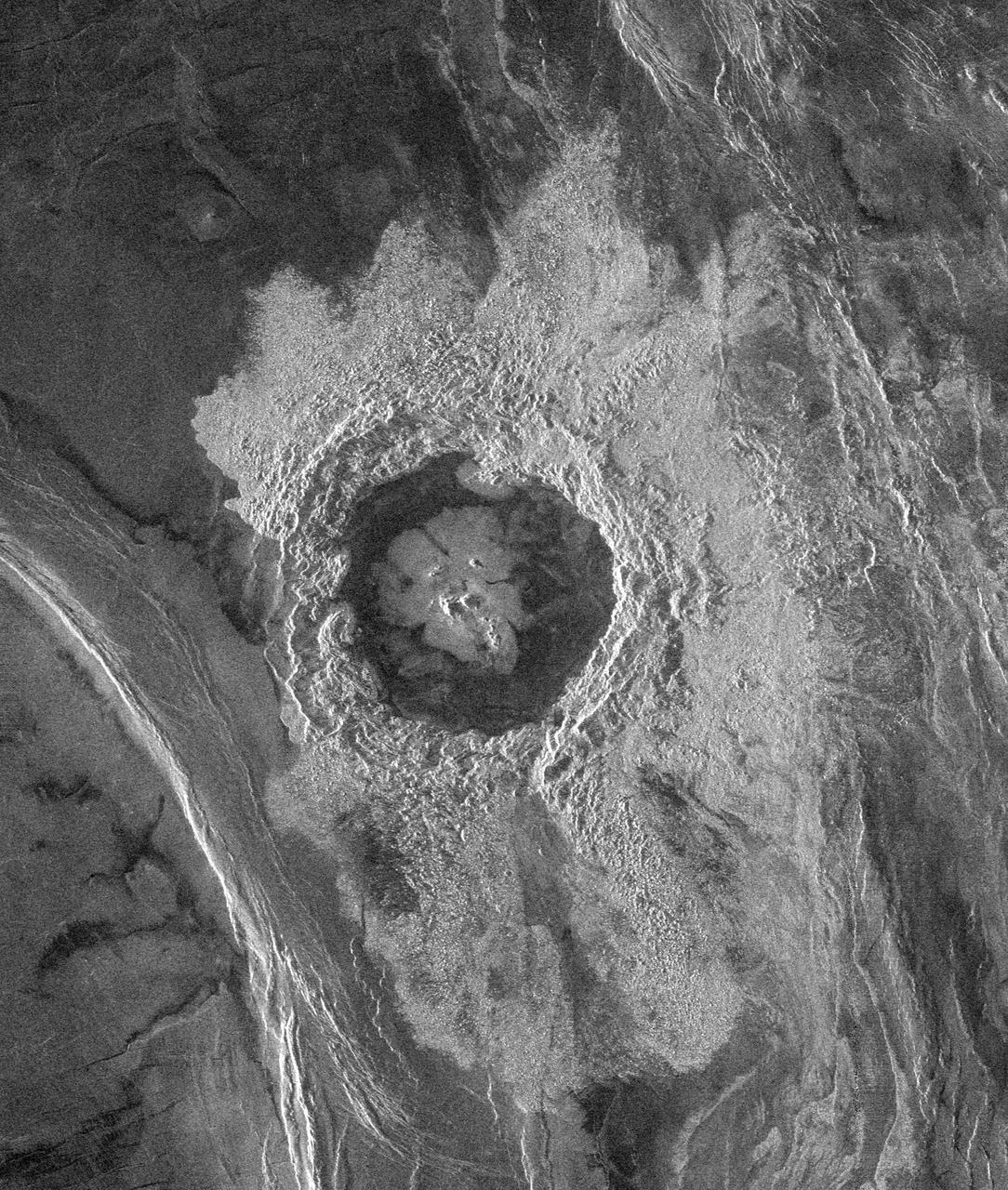

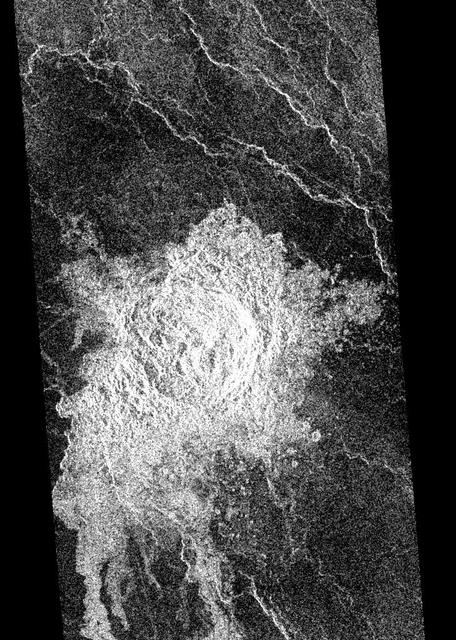

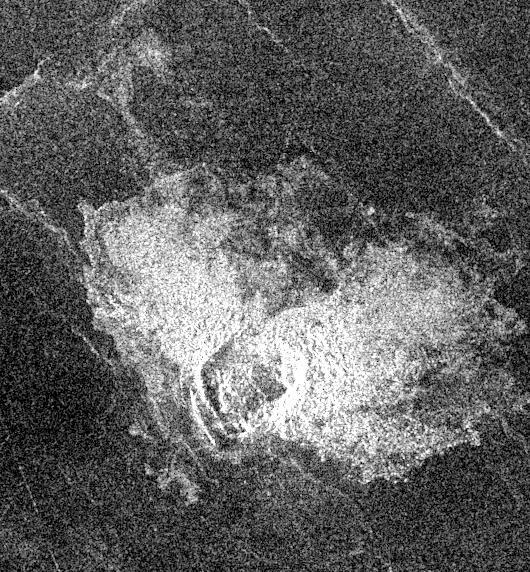

This full-resolution image from NASA Magellan spacecraft shows Jeanne crater, a 19.5 kilometer (12 mile) diameter impact crater. Jeanne crater is located at 40.0 degrees north latitude and 331.4 degrees longitude. The distinctive triangular shape of the ejecta indicates that the impacting body probably hit obliquely, traveling from southwest to northeast. The crater is surrounded by dark material of two types. The dark area on the southwest side of the crater is covered by smooth (radar-dark) lava flows which have a strongly digitate contact with surrounding brighter flows. The very dark area on the northeast side of the crater is probably covered by smooth material such as fine-grained sediment. This dark halo is asymmetric, mimicking the asymmetric shape of the ejecta blanket. The dark halo may have been caused by an atmospheric shock or pressure wave produced by the incoming body. Jeanne crater also displays several outflow lobes on the northwest side. These flow-like features may have formed by fine-grained ejecta transported by a hot, turbulent flow created by the arrival of the impacting object. Alternatively, they may have formed by flow of impact melt. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00472

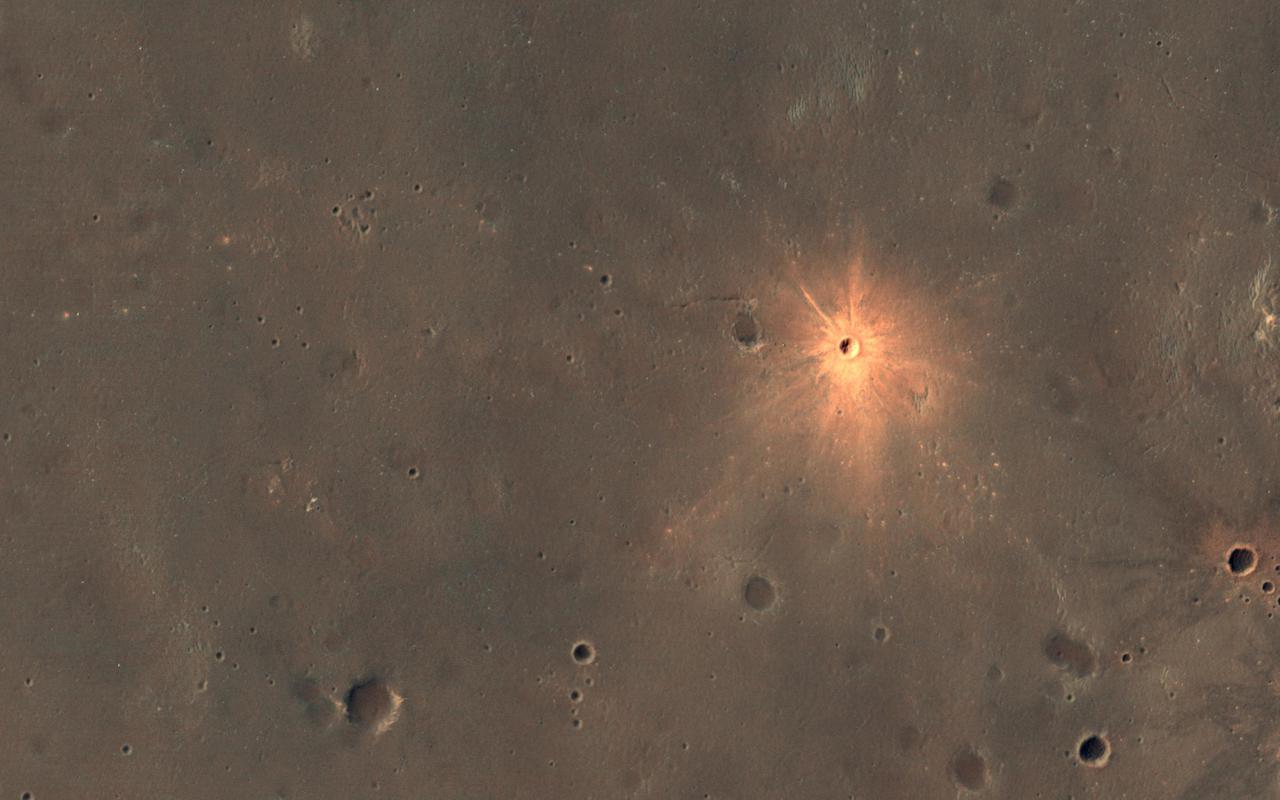

Mars and the Earth run into debris in space regularly, and on our planet, meteors usually vaporize in the atmosphere. On Mars however, with a surface pressure 1/100th that of the Earth, the impactors generally make it to the surface. This particular impact took place on Mars sometime in the last 5 years. Although the crater is small, the rays of ejecta thrown out by the impact are easy to spot, stretching out almost a kilometer. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24694

This MOC image shows a pedestal crater superposed on the floor of the much larger Mellish Crater. When an impact crater of this type forms, material is thrown onto the adjacent terrain to form portions of the ejecta blanket

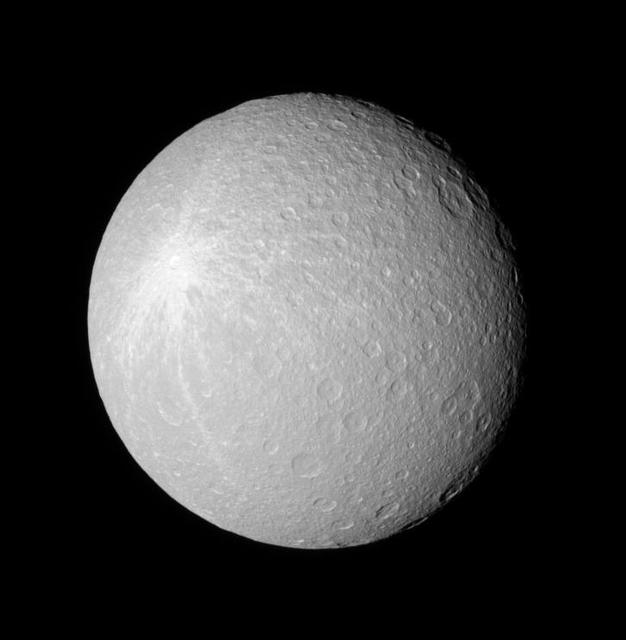

Rhea crater-saturated surface shows a large bright blotch, which was likely created when a geologically recent impact sprayed bright, fresh ice ejecta over the moon surface

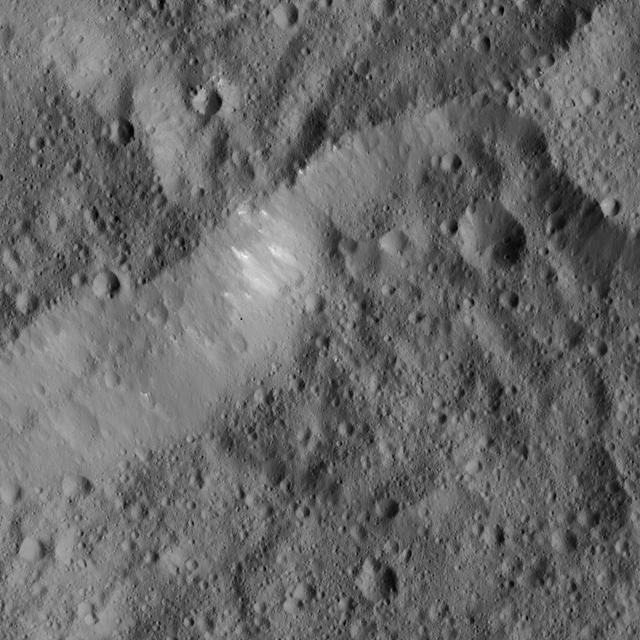

This view from NASA Dawn spacecraft shows a portion of Ertedank Planum, a large, generally flat area in the northern hemisphere of Ceres. Ejecta from a nearby impact has smoothed older features in this scene.

This image from NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter shows dark materials excavated by later small impacts show up clearly on the bright ejecta of a small lunar crater to the west.

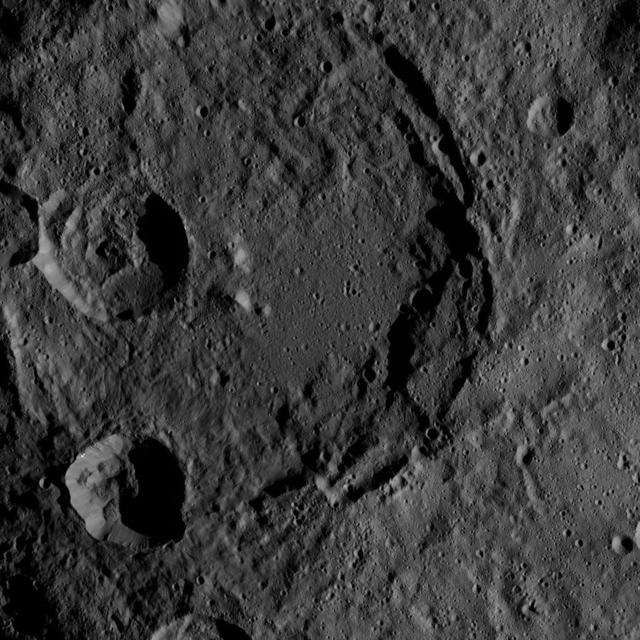

This view from NASA Dawn spacecraft shows an impact site at high southern latitude on Ceres. A smooth blanket of ejecta surrounds the crater. Many boulders can be seen around the crater rim and on the sunlit part of its floor.

This scene from Ceres, captured by NASA Dawn spacecraft, shows an older crater at top center that has been blanketed by impact ejecta from the younger crater to its right.

The ejecta of the impact crater shown in this image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft appears to have been modified after it was emplaced. This modification may be due to the presence of subsurface ground ice.

The fluidized impact crater ejecta and flat crater floors observed in this image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft suggest near-surface volatiles once played an important role in modifying the Martian surface.

This image from NASA Dawn spacecraft is dominated by a wide, young, fresh crater on asteroid Vesta. Surrounding this crater is its ejecta blanket, a covering of small particles that were thrown out during the impact that formed the crater.

This Mars Global Surveyor MGS Mars Orbiter Camera MOC image shows a pedestal crater in the Promethei Terra region. The ejecta from an impact crater is usually rocky

This image from NASA Dawn spacecraft shows many fresh craters, several with bright ejecta rays, which were formed by impacts into the floor of asteroid Vesta south polar basin.

This scene from Ceres, captured by NASA Dawn spacecraft, shows an older crater at top center that has been blanketed by impact ejecta from the younger crater to its right.

The crater on asteroid Vesta shown in this image from NASA Dawn spacecraft was emplaced onto the ejecta blanket of two large twin craters. Commonly, rays from impact craters are brighter than the surrounding surface.

This doublet crater was formed when two meteorites impacted at the same time. The shock waves interact to form the straight central rim and the wings of ejecta on the outside of the rims. This image is from NASA Mars Odyssey.

The ejecta blanket of the crater in this image from NASA Mars Odyssey spacecraft does not resemble the blocky, discontinuous ejecta associated with most fresh craters on Mars. Rather, the continuous lobes of material seen around this crater are evidence that the crater ejecta were fluidized upon impact of the meteor that formed this crater. Impact ejecta become fluidized when a meteor strikes a surface that has a considerable volatile content. The volatiles mixed with the ejecta form a flow of material that moves outward from the crater and produces the morphology seen in this THEMIS visible image. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04025

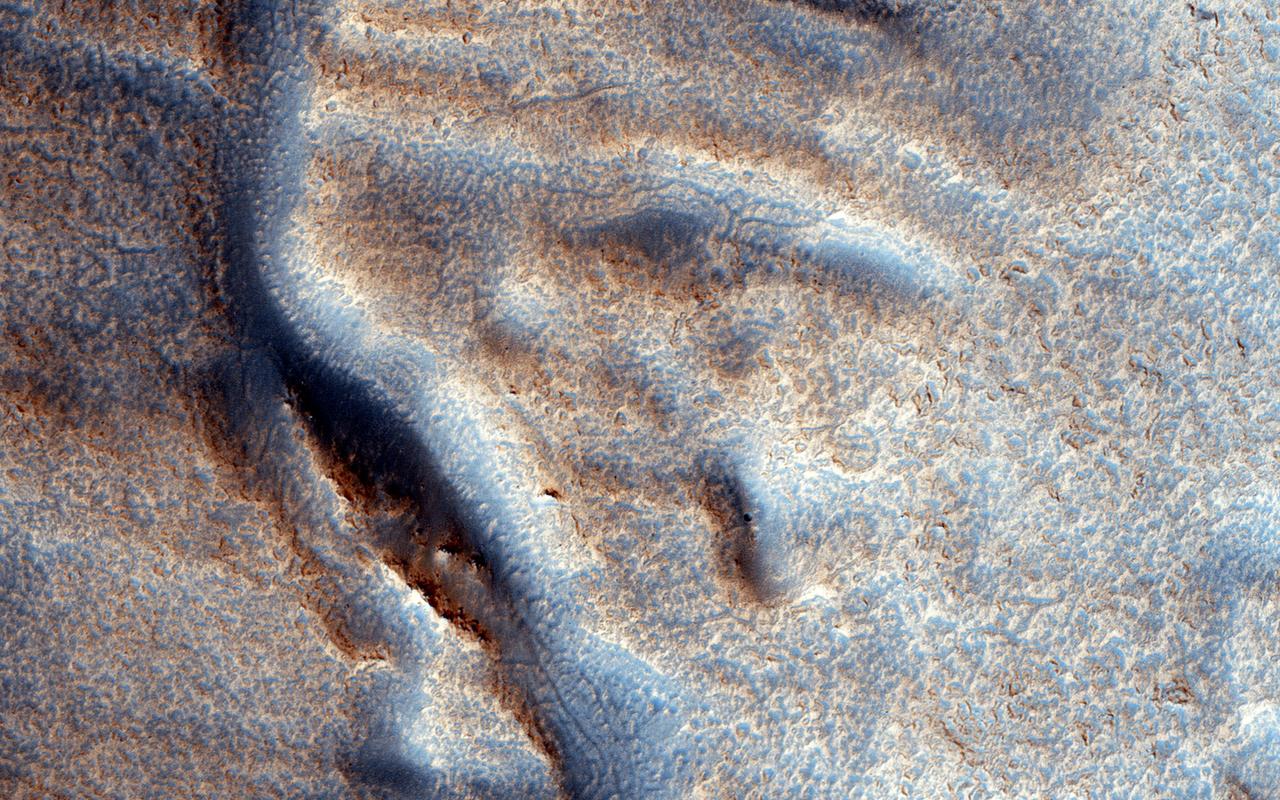

This image covers part of the ejecta from an impact crater (about 6-kilometers in diameter) to the west in Utopia Planitia. The ejecta lobes have morphologies suggesting icy flow. Several small (about 100 to 200 meters in diameter) craters on top of those lobes have a distinctive formation. One interpretation is that the impact crater exposed nearly pure water ice, which then sublimated away where exposed by the slopes of the crater, expanding the crater's diameter and producing a scalloped appearance. The small polygons are another indicator of shallow ice. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23759

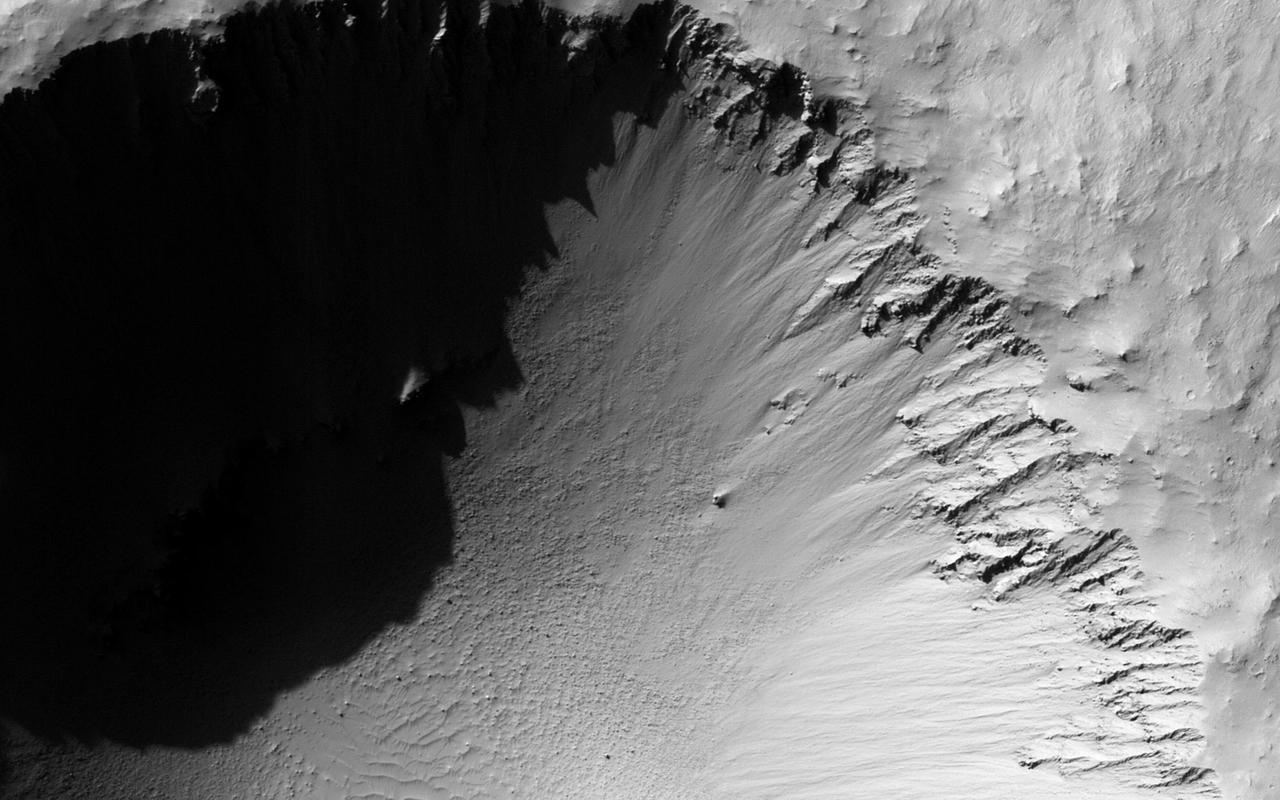

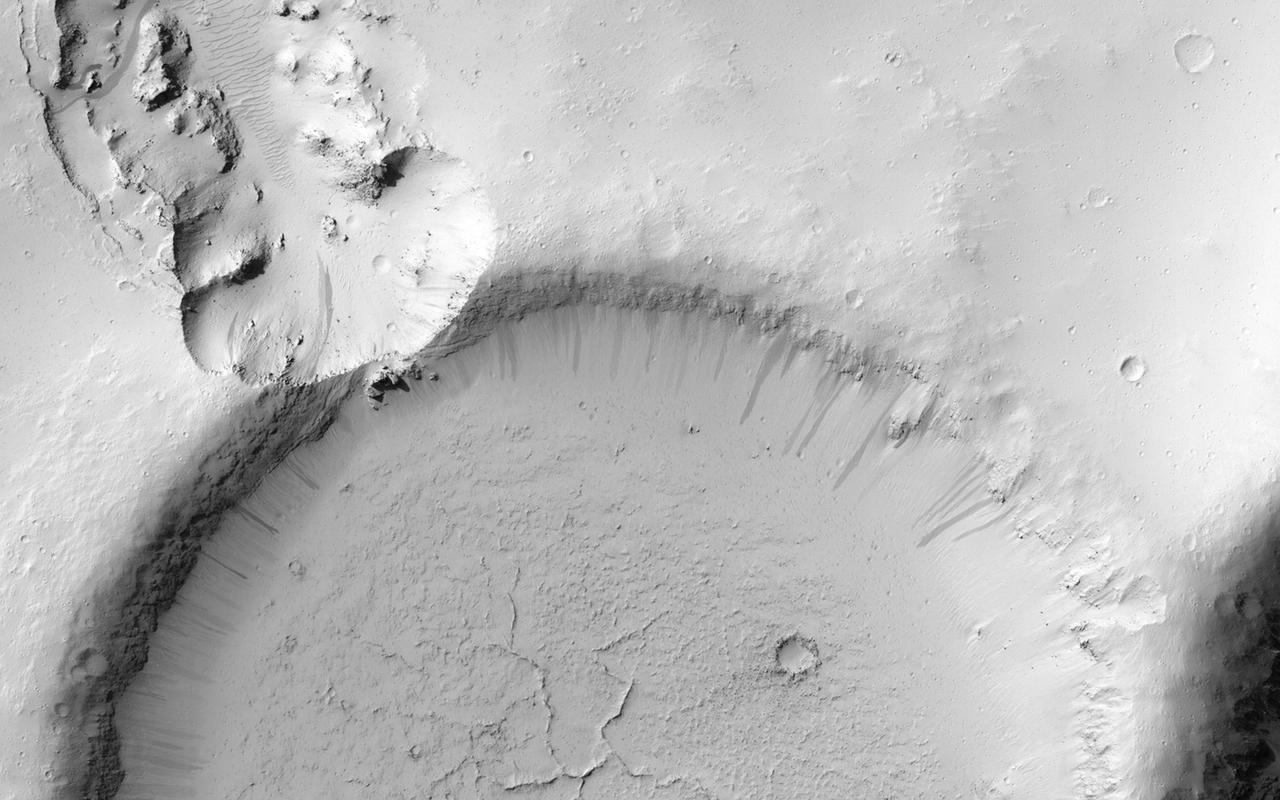

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft is of a morphologically fresh and simple impact crater in the Hellespontus region. At 1.3 kilometers in diameter, this unnamed crater is only slightly larger than Arizona's Barringer (aka Meteor) Crater, by about 200 meters. Note the simple bowl shape and the raised crater rim. Rock and soil excavated out of the crater by the impacting meteor -- called ejecta -- forms the ejecta deposit. It is continuous for about one crater radius away from the rim and is likely composed of about 90 percent ejecta and 10 percent in-place material that was re-worked by both the impact and the subsequently sliding ejecta. The discontinuous ejecta deposit extends from about one crater radius outward. Here, high velocity ejecta that was launched from close to the impact point -- and got the biggest kick -- flew a long way, landed, rolled, slid, and scoured the ground, forming long tendrils of ejecta and v-shaped ridges. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20340

Geologists love roadcuts because they reveal the bedrock stratigraphy (layering). Until we have highways on Mars, we can get the same information from fresh impact craters as shown in this image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. This image reveals these layers filling a larger crater, perhaps a combination of lava, impact ejecta, and sediments. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21631

Today's VIS image shows part of a crater and its ejecta. Located in Noachis Terra, this impact crater is not the typical round shape. Instead, the rim has scallops and indentations. In most instances it is heterogeneities in the preexisting surface that deflect the impact energies and create 'out of round' craters. Tectonic faults are just one of the subsurface features capable of causing non-round craters. Orbit Number: 91604 Latitude: -45.6956 Longitude: 25.6058 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2022-08-08 23:16 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25611

This image shows material almost completely filling an impact crater to the northeast of Hale Crater, perhaps water-rich ejecta from Hale itself. There is a pattern of fractures at two scales and many small cones. There are lots of strange terrains surrounding Hale Crater, perhaps the youngest impact crater on Mars larger than 100 kilometers in diameter. The body that hit Mars, creating Hale, may have impacted ice-rich ground. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24618

n this picture we can see a huge tongue-like form, which looks a like a mudflow with boulders on its surface. This "tongue" is only a small part of a larger deposit that completely surrounds Tooting Crater (not visible in this image). This is part of what is called an "ejecta blanket." The shape and form of the deposits in the ejecta blanket can tell us about the condition of the ground when the impact crater was formed. The presence of this tongue of ejecta is interpreted as a sign that the ground was frozen before impact. The force of the impact melted ice and mixed it with rock and dust as it was thrown away from the crater. It then settled to form these tongue-like lobes all around the crater. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23286

Tooting Crater is one of the youngest craters on Mars that is larger than 20-kilometers in diameter. Relatively low areas inside and outside the crater are covered by a distinctive pitted and ponded material. The pits are not impact craters, as they lack ejecta and are very closely spaced. There is one small impact crater near the lower right corner of our picture, which is much more circular than the pits and has a raised rim and ejecta. One interpretation is that this pitted and ponded material was hot impact ejecta from Tooting, and loss of volatiles from this material or underlying materials created the pits as it cooled. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23848

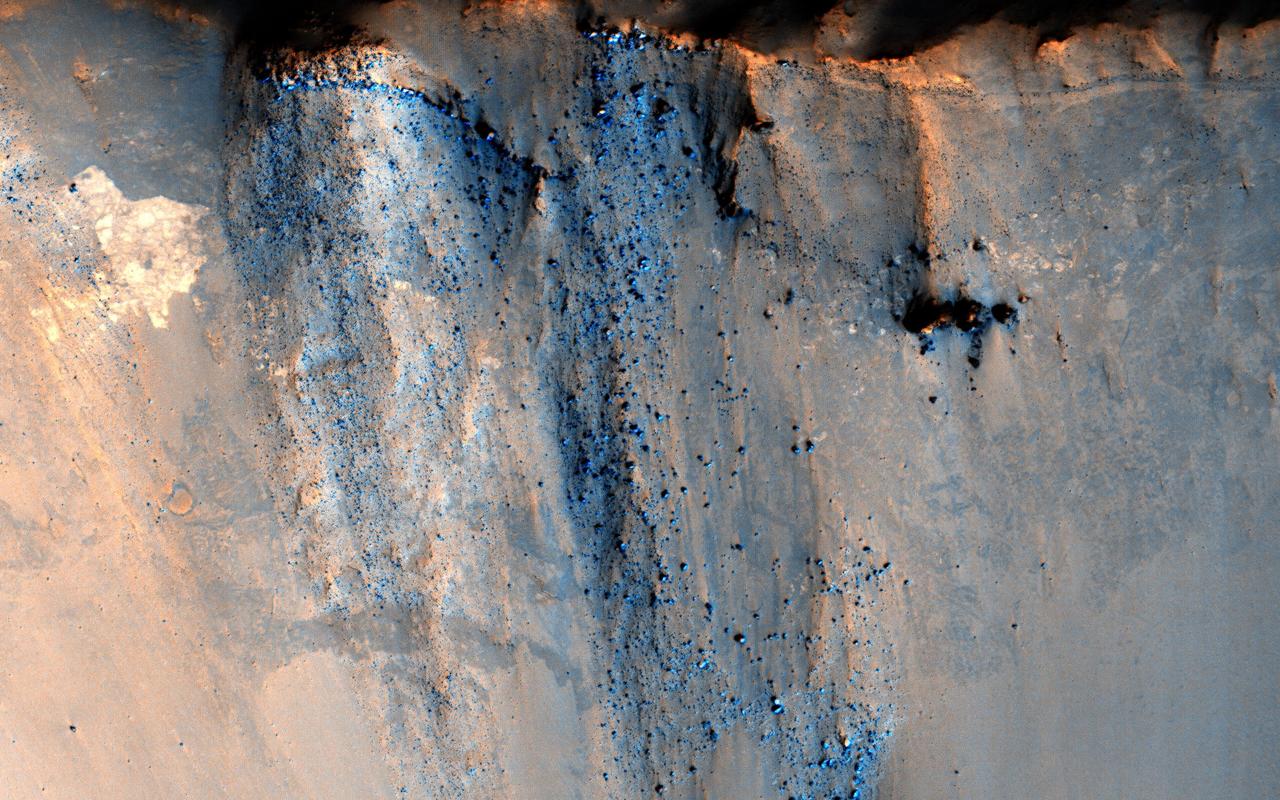

It's not that common to see craters on steep hills, partly because rocks falling downhill can quickly erase such craters. Here, however, NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) observes a small impact has occurred on the sloping wall of a larger crater and is well-preserved. Dark, blocky ejecta from the smaller crater has flowed downhill (to the west) toward the floor of the larger crater. Understanding the emplacement of such ejecta on steep hills is an area of ongoing research. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21758

This view of Ceres from NASA's Dawn spacecraft shows a fresh impact crater with a flat floor. The crater is surrounded by smooth, flow-like ejecta that covers adjacent older impact craters. The crater is about 16 miles (26 kilometers) in diameter. The image was taken Oct. 9, 2015, from an altitude of 915 miles (1,470 kilometers). It has a resolution of 450 feet (140 meters) per pixel. The image is located at 31 degrees south latitude, 176 degrees east longitude. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20124

This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows an elongated depression from three merged craters. The raised rims and ejecta indicate that these are impact craters rather than collapse or volcanic landforms. The pattern made by the ejecta and the craters suggest this was a highly oblique (low angle to the surface) impact, probably coming from the west. There may have been three major pieces flying in close formation to make this triple crater. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21652

This image shows the initial ejecta that resulted when NASA Deep Impact probe collided with comet Tempel 1 at 10:52 p.m. Pacific time, July 3 1:52 a.m. Eastern time, July 4, 2005.

Sandwiched between a crater nearly 4 kilometer across and a much larger and older crater over 15-kilometers in diameter is this small impact crater with light-toned material exposed in its ejecta. This image is from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

In this image from NASA Mars Odyssey, eroded mesas and secondary craters dot the landscape in an area of Cydonia Mensae. The single oval-shaped crater displays a butterfly ejecta pattern, indicating that the crater formed from a low-angle impact.

This image from NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft shows a young crater. Dark radial spokes are created by the explosive blast of an impact event. With time, only thick ejecta near the rim of the crater will be visible, and dark spokes will disappear.

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows an approximately 7-meter diameter fresh crater and dark ejecta blanket. These small impact craters continue to form on Mars, and are most easily recognized in areas covered by bright dust.

This image from NASA Mars Odyssey shows a region of Mars northern hemisphere called Ismenia Fossae. Most of the landforms are the degraded remains of impact crater rim and ejecta from an unnamed crater 75 km diameter just north of this scene.

This image shows the initial ejecta that resulted when NASA Deep Impact probe collided with comet Tempel 1 at 10:52 p.m. Pacific time, July 3 1:52 a.m. Eastern time, July 4, 2005.

This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) shows Hale Crater, a large impact crater (more than 100 kilometers) with a suite of interesting features such as active gullies, active recurring slope lineae, and extensive icy ejecta flows. There are also exposed diverse (colorful) bedrock units. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22465

![The broader scene for this image is the fluidized ejecta from Bakhuysen Crater to the southwest, but there's something very interesting going on here on a much smaller scale. A small impact crater, about 25 meters in diameter, with a gouged-out trench extends to the south. The ejecta (rocky material ejected from the crater) mostly extends to the east and west of the crater. This "butterfly" ejecta is very common for craters formed at low impact angles. Taken together, these observations suggest that the crater-forming impactor came in at a low angle from the north, hit the ground and ejected material to the sides. The top of the impactor may have sheared off ("decapitating" the impactor) and continued downrange, forming the trench. We can't prove that's what happened, but this explanation is consistent with the observations. Regardless of how it formed, it's quite an interesting-looking "dragonfly" crater. The map is projected here at a scale of 50 centimeters (19.69 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 55.7 centimeters (21.92 inches) per pixel (with 2 x 2 binning); objects on the order of 167 centimeters (65.7 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21454](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21454/PIA21454~medium.jpg)

The broader scene for this image is the fluidized ejecta from Bakhuysen Crater to the southwest, but there's something very interesting going on here on a much smaller scale. A small impact crater, about 25 meters in diameter, with a gouged-out trench extends to the south. The ejecta (rocky material ejected from the crater) mostly extends to the east and west of the crater. This "butterfly" ejecta is very common for craters formed at low impact angles. Taken together, these observations suggest that the crater-forming impactor came in at a low angle from the north, hit the ground and ejected material to the sides. The top of the impactor may have sheared off ("decapitating" the impactor) and continued downrange, forming the trench. We can't prove that's what happened, but this explanation is consistent with the observations. Regardless of how it formed, it's quite an interesting-looking "dragonfly" crater. The map is projected here at a scale of 50 centimeters (19.69 inches) per pixel. [The original image scale is 55.7 centimeters (21.92 inches) per pixel (with 2 x 2 binning); objects on the order of 167 centimeters (65.7 inches) across are resolved.] North is up. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21454

This image captured by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft targets a 3-kilometer diameter crater that occurs within the ejecta blanket of the much older Bakhuysen Crater, a 150-kilometer diameter impact crater in Noachis Terra. Impact craters are interesting because they provide a mechanism to uplift and expose underlying bedrock, allowing for the study of the subsurface and the geologic past. An enhanced color image shows the wall of the crater, which exposes layering as well as blocks of rock. There is a distinctive large block in the upper left of the crater wall, generally referred to as a "mega-block."Â It is an angular, light-toned, highly fragmented block, about 100 meters across. Several smaller light-toned blocks are also in the crater wall, possibly of the same rock type as the "mega-block." Ejecta blocks are thrown outward during the initial excavation of a crater, or are deposited as part of the ground-hugging flows of which the majority of the ejecta blanket is comprised. Through images like these, we are able to study the deeper subsurface of Mars that is not otherwise exposed. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20728

This VIS image shows the part of the crater rim and ejecta surrounding Lonar Crater in the northern plains of Vastitas Borealis. There is a fine scale, radial grooved outer layer of ejecta covered by lobate ejecta nearer the crater rim. The ends of the lobes are taller than the material just inside the end of the lobe. Often called rampart ejecta, this morphology can be caused by impact into a surface that includes volatiles such as sub-surface water or ice. Orbit Number: 71327 Latitude: 73.428 Longitude: 38.7539 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2018-01-12 05:31 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22386

This VIS image shows a double impact - two meteors hitting simultaneously. The two meteors would have started as a single object, at some point prior to impact the object separated into parts. The two parts followed the same path to the surface, hitting at the same time in close proximity. The linear feature at the center is where the shock waves intersect, its straightness showing the impacts were simultaneous (and nearly equal in size). The ejecta created from the impact tends to be focused to the sides of the doublet, often forming a butterfly-like ejecta blanket. The butterfly pattern is most common at oblique angle impacts, but can also form by the interaction of the impact shock waves. These craters are located in Utopia Planitia. Orbit Number: 72448 Latitude: 27.1977 Longitude: 95.4916 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2018-04-14 13:36 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22606

This image covers the western portion of a well-preserved (recent) impact crater in Ladon Basin. Ladon is filled by diverse materials including chemically-altered sediments and unaltered lava, so the impact event ejected and deposited a wide range of elements. This image is the first of a pair of images for stereo coverage, so check out the stereo anaglyph when completed. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23079

The dark spots in this enhanced-color infrared image are the recent impact craters that occurred in the Tharsis region between 2008 and 2014. These impact craters were first discovered by the Mars Context Camera (or CTX, also onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) as a cluster of dark spots. The meteoroid that formed these craters must have broken up upon atmospheric entry and fragmented into two larger masses along with several smaller fragments, spawning at least twenty or so smaller impact craters. The dark halos around the resulting impact craters are a combination of the light-toned dust being cleared from the impact event and the deposition of the underlying dark toned materials as crater ejecta. The distribution and the pattern of the rayed ejecta suggests that the meteoroid most-likely struck from the south. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA11176

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) keeps finding new impact sites on Mars. This one occurred within the dense secondary crater field of Corinto Crater, to the north-northeast. The new crater and its ejecta have distinctive color patterns. Once the colors have faded in a few decades, this new crater will still be distinctive compared to the secondaries by having a deeper cavity compared to its diameter. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22462

Today's VIS image shows part of an unnamed crater in Utopia Planitia. The ejecta surrounding the crater rim shows both layering and radial grooves. These features formed during the impact event. Orbit Number: 94546 Latitude: 38.5545 Longitude: 98.9045 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2023-04-08 05:31 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26034

This image from NASA's Dawn spacecraft shows terrain on Ceres covered by ejecta from a nearby impact, which has smoothed the appearance of older features. The image is centered at 21 degrees north latitude, 253 degrees east longitude. Dawn took this image on June 12, 2016, from its low-altitude mapping orbit, at a distance of about 240 miles (385 kilometers) above the surface. The image resolution is 120 feet (35 meters) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20964

This VIS image is located in Amazonis Planitia. Amazonis Planitia is host to many pedestal craters, which indicate the region has had significant erosion. A pedestal crater is one where the crater and inner ejecta are above the level of the surrounding plains. Impact events alter the surface by the heat and pressure of the actual impact, and the resultant crater and ejecta are often stronger than the surrounding unaltered surface. To form a pedestal crater the surrounding plains are eroded away, isolating the crater materials to form a platform above the plain surface. Orbit Number: 81203 Latitude: 12.4957 Longitude: 197.378 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2020-04-04 13:48 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23940

This unnamed crater in Utopia Planitia is shaped like a peanut shell, with an indentation in the crater rim at the middle of the crater. It is likely that this crater was created by a dual impact. In a dual (or double) impact the incoming meteor is broken into two or more pieces which impact together into the surface. This type of impact often has a unique ejecta blanket shape, pinched at the center making a butterfly shape, and a pronounced inner rim jutting out at the center. The ejecta blanket in this case does not show the butterfly shape, and the middle rim is on slightly visible on the left side of the crater. These irregularities may indicate the the meteor pieces were still very close together when they hit the surface. Orbit Number: 95144 Latitude: 31.6611 Longitude: 128.303 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2023-05-27 11:12 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26261

Off the image to the right is Yuty Crater, located between Simud and Tiu Valles. The crater ejcta forms the large lobes along the right side of this VIS image. This type of ejecta was created by surface flow rather than air fall. It is thought that the near surface materials contained volatiles (like water) which mixed with the ejecta at the time of the impact. Orbit Number: 68736 Latitude: 22.247 Longitude: 325.213 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2017-06-12 17:57 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22303

Today's image shows a portion of Phlegra Montes, a region of hills and ridges near Arcadia Planitia. Near the center of the image is a small impact crater, easily identified by it's radial ejecta pattern. This crater is relatively young. With time the radial nature of the ejecta will become less distinct. Orbit Number: 93926 Latitude: 39.3087 Longitude: 161.704 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2023-02-16 04:54 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25926

This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) shows two new craters, both with the same distinctive pattern of relatively blue (less red) ejecta surrounded by a dark blast zone (where dust has been removed or disturbed), and with arcing patterns extending northwest and northeast. This pattern indicates an oblique impact angle with the bolide coming from the north. MRO has discovered over 700 new impact sites on Mars. Often, a bolide breaks apart in the atmosphere and makes a tight cluster of new craters. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22453

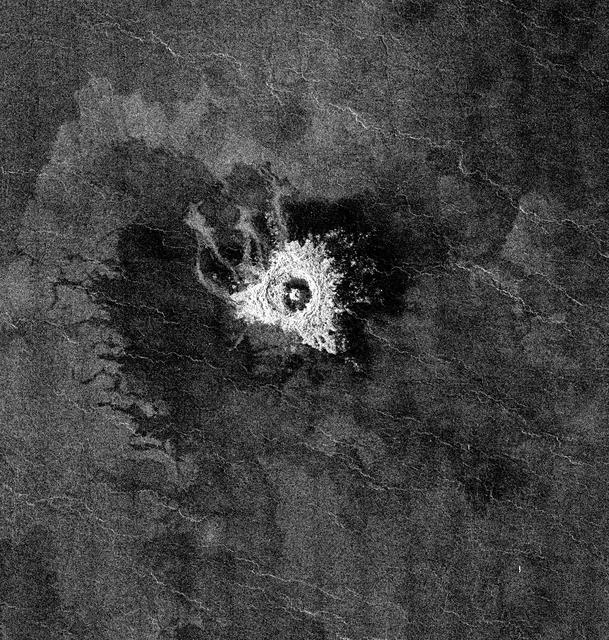

This Magellan image is centered at 74.6 degrees north latitude and 177.3 east longitude, in the northeastern Atalanta Region of Venus. The image is approximately 185 kilometers (115 miles) wide at the base and shows Dickinson, an impact crater 69 kilometers (43 miles) in diameter. The crater is complex, characterized by a partial central ring and a floor flooded by radar-dark and radar-bright materials. Hummocky, rough-textured ejecta extend all around the crater, except to the west. The lack of ejecta to the west may indicate that the impactor that produced the crater was an oblique impact from the west. Extensive radar-bright flows that emanate from the crater's eastern walls may represent large volumes of impact melt, or they may be the result of volcanic material released from the subsurface during the cratering event. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00479

This image NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows an impact crater that was cut by lava in the Elysium Planitia region of Mars. It looks relatively flat, with a shallow floor, rough surface texture, and possible cooling cracks seem to indicate that the crater was partially filled with lava. The northern part of the image also shows a more extensive lava flow deposit that surrounds the impact ejecta of the largest impact crater in the image. Which way did the lava flow? It might appear that the lava flowed from the north through the channel into the partially filled crater. However, if you look at the anaglyph with your red and blue 3D glasses, it becomes clear that the partially filled crater sits on top of the large crater's ejecta blanket, making it higher than the lava flow to the north. Since lava does not flow uphill, that means the explanation isn't so simple. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18887

This oblique view from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows a small part of the near-rim ejecta from Tooting Crater. The flow extending from upper left to lower right looks much like a typical lava flow, but doesn't emanate from a volcanic vent. Instead, this must be either melted rock from the impact event, or a wet debris flow from melting of ice. The surface is dusty so color variations are minor. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21648

A HiRISE observation in 2010 covered a new impact crater that formed after December 2007 and before August 2010, based on Context Camera images. HiRISE has been re-imaging these sites to see how rapidly the dark ejecta and blast zone markings disappear as dust is deposited or redistributed. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23760

S72-37257 (November 1972) --- The Lunar Ejecta and Meteorites Experiment (S-202), one of the experiments of the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package which will be carried on the Apollo 17 lunar landing mission. The purpose of this experiment is to measure the physical parameters of primary and secondary particles impacting the lunar surface.

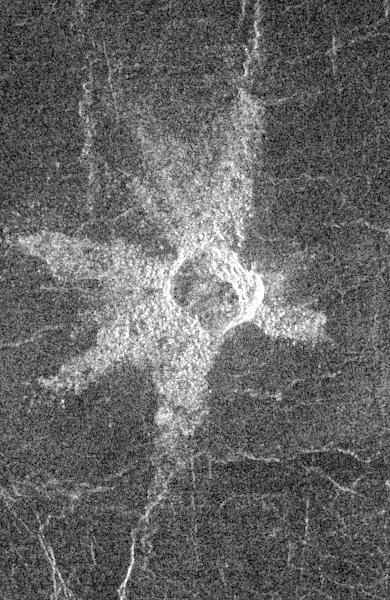

This image from NASA Magellan spacecraft shows the central Eistla Region of the equatorial highlands of Venus. It is centered at 15 degrees north latitude and 5 degrees east longitude. The image is 76.8 kilometers (48 miles) wide. The crater is slightly irregular in platform and approximately 6 kilometers (4 miles) in diameter. The walls appear terraced. Five or six lobes of radar-bright ejecta radiate up to 13.2 kilometers (8 miles) from the crater rim. These lobes are up to 3.5 kilometers (2 miles) in width and form a "starfish" pattern against the underlying radar-dark plains. The asymmetric pattern of the ejecta suggests the angle of impact was oblique. The alignment of two of the ejecta lobes along fractures in the underlying plains is apparently coincidental. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00466

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) captured this region of Mars, sprayed with secondary craters from 10-kilometer Zunil Crater to the northwest. Secondary craters form from rocks ejected at high speed from the primary crater, which then impact the ground at sufficiently high speed to make huge numbers of much smaller craters over a large region. In this scene, however, the secondary crater ejecta has an unusual raised-relief appearance like bas-relief sculpture. How did that happen? One idea is that the region was covered with a layer of fine-grained materials like dust or pyroclastics about 1 to 2 meters thick when the Zunil impact occurred (about a million years ago), and the ejecta served to harden or otherwise protect the fine-grained layer from later erosion by the wind. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21591

This image was taken in one of the regions on Mars well-known for its viscous flow features (VFF), which are massive flowing deposits believed to be composed of a mixture of ice and dust similar to glaciers on Earth. In this particular region, an impact event occurred creating ejecta deposits that also appear to flow (probably because of their similarly ice-rich composition), and interact with the flows from the VFF. Looking closer, we can see that the VFF deposits (on the right) appear to be rougher in appearance than those of the impact ejecta. We will need to study this image in more detail to understand how these flows have interacted with each other and what they can tell us about their composition and their flowing behavior properties. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20370

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows a portion of a long valley system in northern Arabia Terra. The valley must be relatively young because it cuts through the ejecta of an impact crater that still retains it entire ejecta blanket, indicating the crater is also fairly young and fresh. The valley is interesting because it transitions to an inverted channel near its end point. Inverted channels form when a valley fills with materials. Later, erosion removes the surrounding terrain leaving behind higher standing and more resistant material that filled the valley. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19861

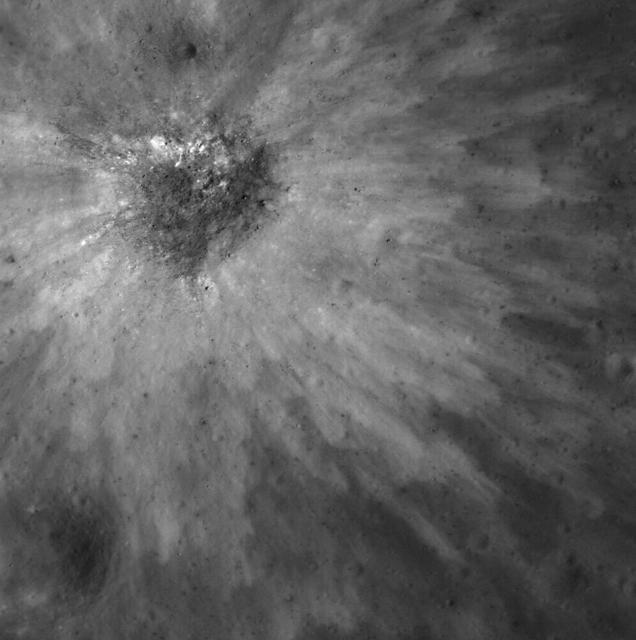

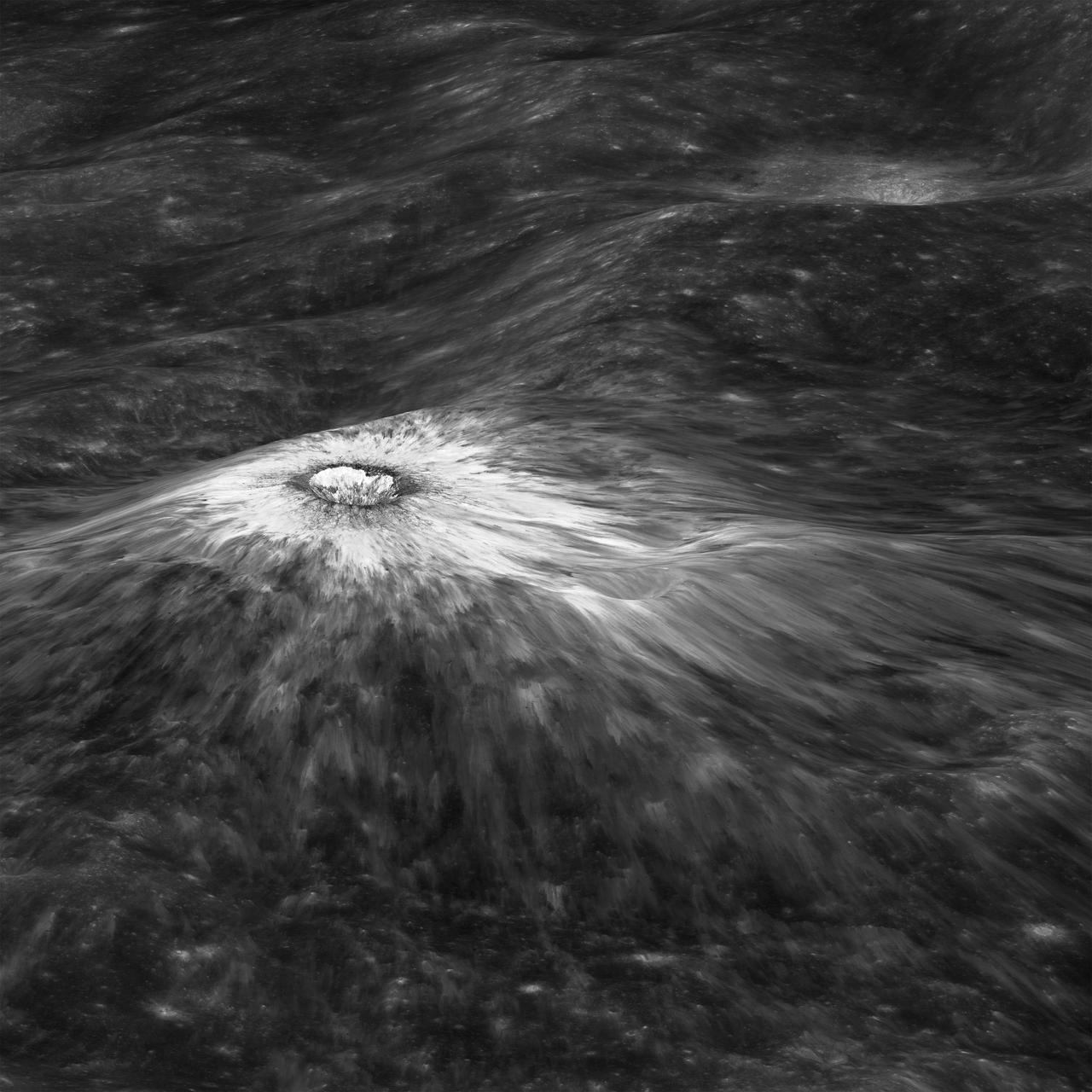

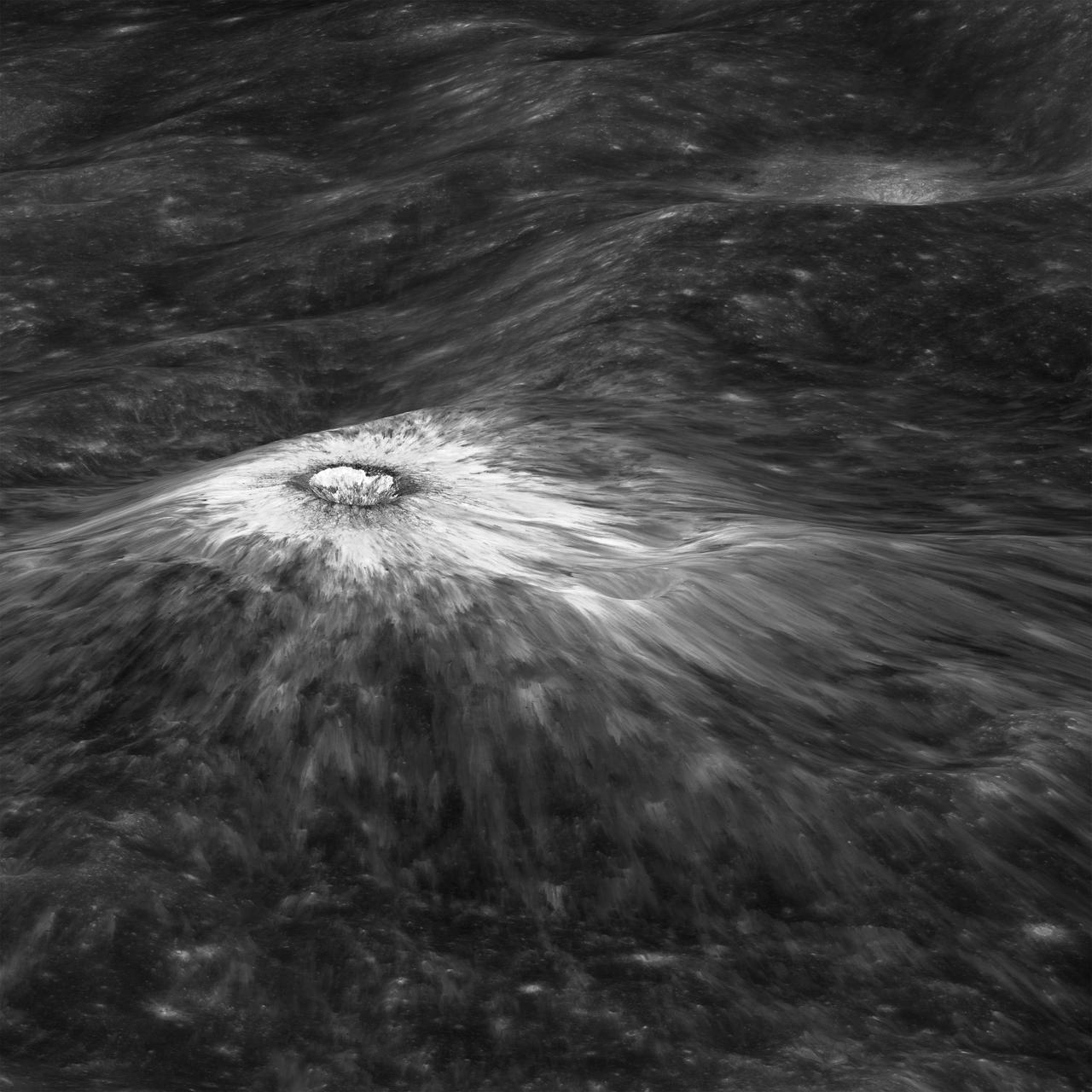

Looking east to west across the rim and down into Chaplygin crater reveals this beautiful example of a fresh young crater and its perfectly preserved ejecta blanket. The delicate patterns of flow across, over, and down local topography clearly show that ejecta traveled as a ground hugging flow for great distances, rather than simply being tossed out on a ballistic trajectory. Very near the rim lies a dark, lacy, discontinuous crust of now frozen impact melt. Clearly this dark material is on top of the bright material so it was the very last material ejected from the crater. The melt was formed as the tremendous energy of impact was converted to heat and the lunar crust was melted at the impact point. As the crater rebounded and material sloughed down the walls of the deforming crater the melt was splashed out over the rim and froze. Its low reflectance is mostly due to a high percentage of glass because the melt cooled so quickly that minerals did not have time to crystallize. The fact that the delicate splash patterns are so well preserved testifies to the very young age of this crater. But how young? For comparison "Chappy" (informal name) is 200 m larger than Meteor crater (1200 m diameter) in Arizona, which is about 50,000 years old. Craters of this size form every 100,000 years or so on the Moon and the Earth. Since there are very few superposed craters on Chappy, and its ejecta is so perfectly preserved it may be much younger than Meteor crater. However, we can't know the true true absolute age of "Chappy" until we can obtain a sample of its impact melt for radiometric age dating. Investigate all of Chappy's ejecta, at full resolution: <a href="http://lroc.sese.asu.edu/posts/901" rel="nofollow">lroc.sese.asu.edu/posts/901</a> Credit: NASA/Goddard/Arizona State University/LRO/LROC

Looking east to west across the rim and down into Chaplygin crater reveals this beautiful example of a fresh young crater and its perfectly preserved ejecta blanket. The delicate patterns of flow across, over, and down local topography clearly show that ejecta traveled as a ground hugging flow for great distances, rather than simply being tossed out on a ballistic trajectory. Very near the rim lies a dark, lacy, discontinuous crust of now frozen impact melt. Clearly this dark material is on top of the bright material so it was the very last material ejected from the crater. The melt was formed as the tremendous energy of impact was converted to heat and the lunar crust was melted at the impact point. As the crater rebounded and material sloughed down the walls of the deforming crater the melt was splashed out over the rim and froze. Its low reflectance is mostly due to a high percentage of glass because the melt cooled so quickly that minerals did not have time to crystallize. The fact that the delicate splash patterns are so well preserved testifies to the very young age of this crater. But how young? For comparison "Chappy" (informal name) is 200 m larger than Meteor crater (1200 m diameter) in Arizona, which is about 50,000 years old. Craters of this size form every 100,000 years or so on the Moon and the Earth. Since there are very few superposed craters on Chappy, and its ejecta is so perfectly preserved it may be much younger than Meteor crater. However, we can't know the true true absolute age of "Chappy" until we can obtain a sample of its impact melt for radiometric age dating. Investigate all of Chappy's ejecta, at full resolution: <a href="http://lroc.sese.asu.edu/posts/901" rel="nofollow">lroc.sese.asu.edu/posts/901</a> Credit: NASA/Goddard/Arizona State University/LRO/LROC

This odd-shaped hole in Noachis Terra is clearly an impact crater. It has the characteristic raised rim that distinguishes it from pits that have simply collapsed. In contrast to most impact craters though, it isn't round. What could have caused this odd shape? Sometimes craters can be elongated when the impact occurs at a very grazing angle, but that's not the case here as the rough ejecta blanket around the crater is mostly symmetric. Large blocks of material in the northeast and northwest corners look like they have slid into the crater. These collapses have extended the crater in those directions giving it an oblong appearance. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25307

This image from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows the exposed bedrock of an ejecta blanket of an unnamed crater in the Mare Serpentis region of Mars. Ejecta, when exposed, are truly an eye-opening feature, as they reveal the sometimes exotic subsurface, and materials created by impacts (close-up view). This ejecta shares similarities to others found elsewhere on Mars, which are of particular scientific interest for the extent of exposure and diverse colors. (For example, the Hargraves Crater ejecta, in the Nili Fossae trough region, was once considered as a candidate landing site for the next NASA Mars rover 2020.) The colors observed in this picture represent different rocks and minerals, now exposed on the surface. Blue in HiRISE infrared color images generally depicts iron-rich minerals, like olivine and pyroxene. Lighter colors, such as yellow, indicate the presence of altered rocks. The possible sources of the ejecta is most likely from two unnamed craters. How do we determine which crater deposited the ejecta? A full-scale image shows numerous linear features that are observed trending in an east-west direction. These linear features indicate the flow direction of the ejecta from its unnamed host crater. Therefore, if we follow them, we find that they emanate from the bottom of the two unnamed craters. If the ejecta had originated from the top crater, then we would expect the linear features at the location of our picture to trend northwest to southeast. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21782

This VIS image contains three craters. There is a quarter of the largest crater in the top half of the image, half of a smaller crater at the very top, and the full crater in the lower half of the image. Investigating the relative ages of each crater indicates the largest crater formed first followed at some point by the smaller craters -- the 1/2 crater at the top occurs on top of the big crater as does the ejecta from the bottom crater. Because the visible ejecta does not reach the smaller crater at the top it is difficult to determine the relative ages of the two smaller craters. Both have similar floor morphology, but different rim morphology. The crater in the bottom of the image has a very complex rim, including both rim gullies (top side) and ridge and spur eroded features (bottom side). These difference may be related to the different materials of the largest crater. One crater impacted into the floor and the other into the ejecta blanket of the largest crater. Near surface morphology as well as deeper materials can modify the pressure wave created by impact. These craters are located in Terra Cimmeria. Orbit Number: 75334 Latitude: -38.7393 Longitude: 157.653 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2018-12-08 06:01 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23074

During orbits 423 through 424 on 22 September 1990, NASA's Magellan imaged this impact crater that is located at latitude 10.7 degrees north and longitude 340.7 degrees east. This crater is shown as a representative of Venusian craters that are of the proper diameter (about 15 kilometers) to be 'transitional' in their morphology between 'complex' and irregular' craters. Complex craters account for about 96 percent of all craters on Venus with diameters larger than about 15 kilometers; they are thought to have been formed by the impact of a large, more or less intact, mass of asteroidal material that has not been excessively effected during its passage through the dense Venusian atmosphere. Complex craters are characterized by circular rims, terraced inner wall slopes, well developed ejecta deposits, and flat floors with a central peak or peak ring. Irregular craters make up about 60 percent of the craters with diameters less than about 15 kilometers. Irregular craters are thought to form as the result of the impact of asteroidal projectiles that have been aerodynamically crushed and fragmented during their passage through the atmosphere. Irregular craters are characterized by irregular and/or discontinuous rims and hummocky or multiple floors. The 'transitional' crater shown here has a somewhat circular rim like larger complex craters, but has the hummocky floor and asymmetric ejecta characteristic of smaller irregular craters. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00468

An impressionist painting? No, it's a new impact crater that has appeared on the surface of Mars, formed at most between September 2016 and February 2019. What makes this stand out is the darker material exposed beneath the reddish dust. It looks blue because it’s a false color image, which combines several color filters to enhance differences between material compositions. The light blue indicates an absence of brighter, redder dust where the impact blast scoured the surface, revealing bedrock below. The very bright blue could be ejecta with a different composition that was thrown by the impact. The blue color isn’t ice. This impact was near the equator, not in a region where we’d expect shallow ice below the surface. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23304

This image of Ceres, taken by NASA's Dawn spacecraft, shows a giant, ancient impact crater with smaller craters in its interior. The large crater shows partial terracing on its southeast rim, whereas the north part is almost fully degraded. Terraces -- generally level areas separated from lower areas by steep slopes -- are common features in large impact craters. The crater's floor is partly covered by smooth material. The smaller crater in the south (lower left) is the freshest impact seen here. The distinct rim of the young crater, along with impact ejecta, covers part of the big crater's floor. The image was taken on Oct. 3, 2015, from an altitude of 915 miles (1,470 kilometers), and has a resolution of 450 feet (140 meters) per pixel. The image is located at 53 degrees south latitude, 1 degrees east longitude. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20121

found across the Martian surface. Each impact crater on Mars possesses a unique origin and composition, which makes the HiRISE team very interested in sampling as many of them as possible! Like the impact of a droplet into fluid, once an impact has occurred on the surface of Mars, an ejecta curtain forms immediately after, contributing to the raised rim visible at the top of the crater's walls. After the formation of the initial crater, if it is large enough, then a central peak appears as the surface rebounds. These central peaks can expose rocks that were previously deeply buried beneath the Martian surface. The blue and red colors in this enhanced-contrast image reflect the effects of post-impact sedimentation and weathering over time. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA08395

NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbite observed this image of an isolated mountain in the Southern highlands reveals a large exposure of purplish bedrock. Since HiRISE color is shifted to longer wavelengths than visible color and given relative stretches, this really means that the bedrock is roughly dark in the broad red bandpass image compared to the blue-green and near-infrared bandpass images. In the RGB (red-green-blue) color image, which excludes the near-infrared bandpass image, the bedrock appears bluish in color. This small mountain is located near the northeastern rim of the giant Hellas impact basin, and could be impact ejecta. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19854

Range : 85,000 kilometers (53,000 miles) This photo of Jupiter's satellite Ganymede shows ancient cratered terrain. A variety of impact craters of different ages are shown. The brightest craters are the youngest. The ejecta blankets fade with age. The center shows a bright patch that represents the rebounding of the floor of the crater. The dirty ice has lost all topography except for faint circular patterns. Also shown are the 'Callisto type' curved troughs and ridges that mark an ancient enormous impact basin. The basin itself has been destroyed by later geologic processes. Only the ring features are preserved on the ancient surface. Near the bottom of the picture, these curved features are trumcated by the younger grooved terrain.

Looking east to west across the rim and down into Chaplygin crater reveals this beautiful example of a fresh young crater and its perfectly preserved ejecta blanket. The delicate patterns of flow across, over, and down local topography clearly show that ejecta traveled as a ground hugging flow for great distances, rather than simply being tossed out on a ballistic trajectory. Very near the rim lies a dark, lacy, discontinuous crust of now frozen impact melt. Clearly this dark material is on top of the bright material so it was the very last material ejected from the crater. The melt was formed as the tremendous energy of impact was converted to heat and the lunar crust was melted at the impact point. As the crater rebounded and material sloughed down the walls of the deforming crater the melt was splashed out over the rim and froze. Its low reflectance is mostly due to a high percentage of glass because the melt cooled so quickly that minerals did not have time to crystallize. The fact that the delicate splash patterns are so well preserved testifies to the very young age of this crater. But how young? For comparison "Chappy" (informal name) is 200 m larger than Meteor crater (1200 m diameter) in Arizona, which is about 50,000 years old. Craters of this size form every 100,000 years or so on the Moon and the Earth. Since there are very few superposed craters on Chappy, and its ejecta is so perfectly preserved it may be much younger than Meteor crater. However, we can't know the true true absolute age of "Chappy" until we can obtain a sample of its impact melt for radiometric age dating. Credit: NASA/Goddard/Arizona State University/LRO/LROC

Looking east to west across the rim and down into Chaplygin crater reveals this beautiful example of a fresh young crater and its perfectly preserved ejecta blanket. The delicate patterns of flow across, over, and down local topography clearly show that ejecta traveled as a ground hugging flow for great distances, rather than simply being tossed out on a ballistic trajectory. Very near the rim lies a dark, lacy, discontinuous crust of now frozen impact melt. Clearly this dark material is on top of the bright material so it was the very last material ejected from the crater. The melt was formed as the tremendous energy of impact was converted to heat and the lunar crust was melted at the impact point. As the crater rebounded and material sloughed down the walls of the deforming crater the melt was splashed out over the rim and froze. Its low reflectance is mostly due to a high percentage of glass because the melt cooled so quickly that minerals did not have time to crystallize. The fact that the delicate splash patterns are so well preserved testifies to the very young age of this crater. But how young? For comparison "Chappy" (informal name) is 200 m larger than Meteor crater (1200 m diameter) in Arizona, which is about 50,000 years old. Craters of this size form every 100,000 years or so on the Moon and the Earth. Since there are very few superposed craters on Chappy, and its ejecta is so perfectly preserved it may be much younger than Meteor crater. However, we can't know the true true absolute age of "Chappy" until we can obtain a sample of its impact melt for radiometric age dating. Credit: NASA/Goddard/Arizona State University/LRO/LROC

Today's VIS image shows part of an unnamed crater in Utopia Planitia. The ejecta surrounding the crater rim shows both layering and radial grooves. These features formed during the impact event. Orbit Number: 77363 Latitude: 38.7001 Longitude: 99.283 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2019-05-24 09:13 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23328

This VIS image shows where an impact created a crater on top of a group of ridges called Tanaica Montes. The slightly out-of-round shape and the distribution of the ejecta was likely all due to the pre-existing landforms. Orbit Number: 60555 Latitude: 39.6442 Longitude: 268.824 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2015-08-08 20:37 http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19780

This Magellan image, which is 50 kilometers (31 miles) in width and 80 kilometers (50 miles) in length, is centered at 11.9 degrees latitude, 352 degrees longitude in the eastern Navka Region of Venus. The crater, which is approximately 8 kilometers (5 miles) in diameter, displays a butterfly symmetry pattern. The ejecta pattern most likely results from an oblique impact, where the impactor came from the south and ejected material to the north. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00474

This image shows a recent impact in Noachis Terra in the southern mid-latitudes of Mars. The impact occurred in dark-toned ejecta material from a degraded, 60-kilometer crater to the south. Rather than a single impact crater, we see multiple impacts like a shotgun blast. This suggests that the impactor broke up in the atmosphere on entry. Although the atmosphere of Mars is thinner than Earth's, it still has the capacity to break up small impactors, especially ones comprised of weaker materials, like a stony meteoroid versus a iron-nickel one. Our image depicts 21 distinctive craters ranging in size from 1 to 7 meters in diameter. They are distributed over an area that spans about 305 meters. Most observed recent impacts expose darker-toned materials underlying bright dusty surfaces. However, this impact does the opposite, showing us lighter-toned materials that lie beneath a darker colored surface. The impact was initially discovered in a 2016 Context Camera image, and was not seen in a 2009 picture. This implies that the impact may be only two years old, but certainly no more than nine years. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23061

NASA MESSENGER is again sending images back to Earth after the spacecraft emerged from superior solar conjunction, when communication is largely blocked by the Sun. These will be some of our last views of Mercury from MESSENGER. Featured here is the ejecta blanket of a fresh impact crater located just outside the scene. Ejecta scoured the surface leaving behind beautiful patterns of secondary craters. Date acquired: April 16, 2015 Image Mission Elapsed Time (MET): 71544702 Image ID: 8343072 Instrument: Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) of the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) Center Latitude: 55.67° Center Longitude: 97.37° E Resolution: 19.9 meters/pixel Scale: This scene is approximately 20 km (12 miles) across http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19424

This image of the Nili Fossae region, to the west of the great Isidis basin, shows layered bedrock with many impact craters. Nili Fossae is one of the most mineralogically important sites on Mars. Remote observations by the infrared spectrometer onboard MRO (called CRISM) suggest the layers in the ancient craters contain clays, carbonates, and iron oxides, perhaps due to hydrothermal alteration of the crust. However, the impact craters have been degraded by many millions of years of erosion so the original sedimentary, impact ejecta, or lava flows are hard to distinguish. The bright linear features are sand dunes, also known as "transverse aeolian dunes," because the wind direction is at ninety degrees to their elongated orientation. This shows that the erosion of Nili Fossae continues to the present day with sand-sized particles broken off from the local rocks mobilized within the dunes. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23452