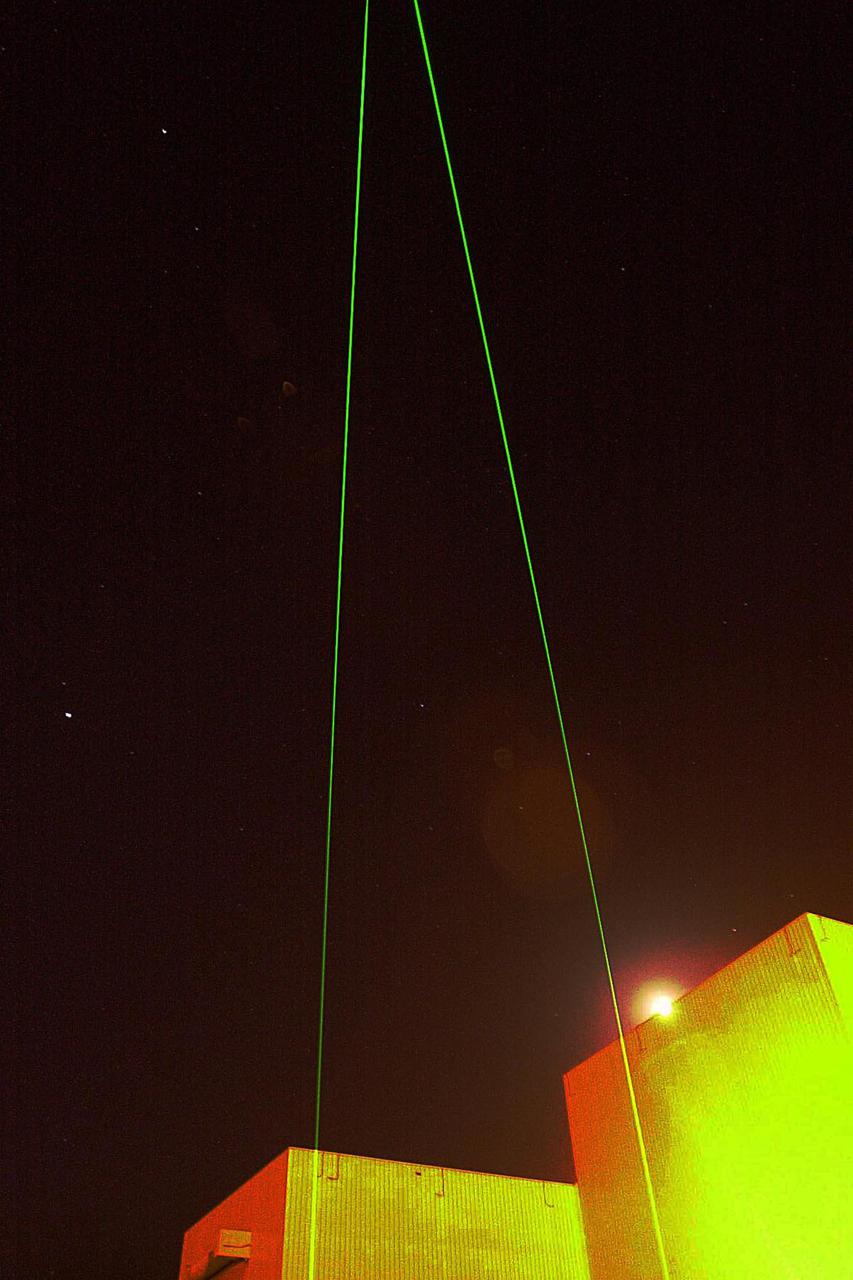

This infrared photograph shows the uplink laser beacon for NASA's Deep Space Optical Communications (DSOC) experiment beaming into the night sky from the Optical Communications Telescope Laboratory (OCTL) at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory's Table Mountain Facility near Wrightwood, California. Attached to the agency's Psyche spacecraft, the DSOC flight laser transceiver can receive and send data from Earth in encoded photons. As the experiment's ground laser transmitter, OCTL transmits at an infrared wavelength of 1,064 nanometers from its 3.3-foot-aperture (1-meter) telescope. The telescope can also receive faint infrared photons (at a wavelength of 1,550 nanometers) from the 4-watt flight laser transceiver on Psyche. Neither infrared wavelength is easily absorbed or scattered by Earth's atmosphere, making both ideal for deep space optical communications. To receive the most distant signals from Psyche, the project enlisted the powerful 200-inch-aperture (5-meter) Hale Telescope at Caltech's Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, California, as its primary downlink station, which provided adequate light-collecting area to capture the faintest photons. Those photons were then directed to a cryogenically cooled superconducting high-efficiency detector array at the observatory where the information encoded in the photons could be processed. Managed by JPL, DSOC was designed to demonstrate that data encoded in laser photons could be reliably transmitted, received, and then decoded after traveling millions of miles from Earth out to Mars distances. Nearly two years after launching aboard the agency's Psyche mission in 2023, the demonstration completed its 65th and final "pass" on Sept. 2, 2025, sending a laser signal to Psyche and receiving the return signal from 218 million miles (350 million kilometers) away. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26662

In this infrared photograph, the Optical Communications Telescope Laboratory (OCTL) at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory's Table Mountain Facility near Wrightwood, California, beams its eight-laser beacon (at a total power of 1.4 kilowatts) to the Deep Space Optical Communications (DSOC) flight laser transceiver aboard NASA's Psyche spacecraft. The photo was taken on June 2, 2025, when Psyche was about 143 million miles (230 million kilometers) from Earth. The faint purple crescent just left of center and near the laser beam is a lens flare caused by a bright light (out of frame) reflecting inside the camera lens. As the experiment's ground laser transmitter, OCTL transmits at an infrared wavelength of 1,064 nanometers from its 3.3-foot-aperture (1-meter) telescope. The telescope can also receive faint infrared photons (at a wavelength of 1,550 nanometers) from the 4-watt flight laser transceiver on Psyche. Neither infrared wavelength is easily absorbed or scattered by Earth's atmosphere, making both ideal for deep space optical communications. To receive the most distant signals from Psyche, the project enlisted the powerful 200-inch-aperture (5-meter) Hale Telescope at Caltech's Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, California, as its primary downlink station, which provided adequate light-collecting area to capture the faintest photons. Those photons were then directed to a cryogenically cooled superconducting high-efficiency detector array at the observatory where the information encoded in the photons could be processed. Managed by JPL, DSOC was designed to demonstrate that data encoded in laser photons could be reliably transmitted, received, and then decoded after traveling millions of miles from Earth out to Mars distances. Nearly two years after launching aboard the agency's Psyche mission in 2023, the demonstration completed its 65th and final "pass" on Sept. 2, 2025, sending a laser signal to Psyche and receiving the return signal from 218 million miles (350 million kilometers) away. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26661

NASA Mercury Laser Altimeter MLA is shown ranging to Mercury surface from orbit. In this animation, yellow flashes represent near-infrared laser pulses that can reflect off terrain in shadow as well as in sunlight.

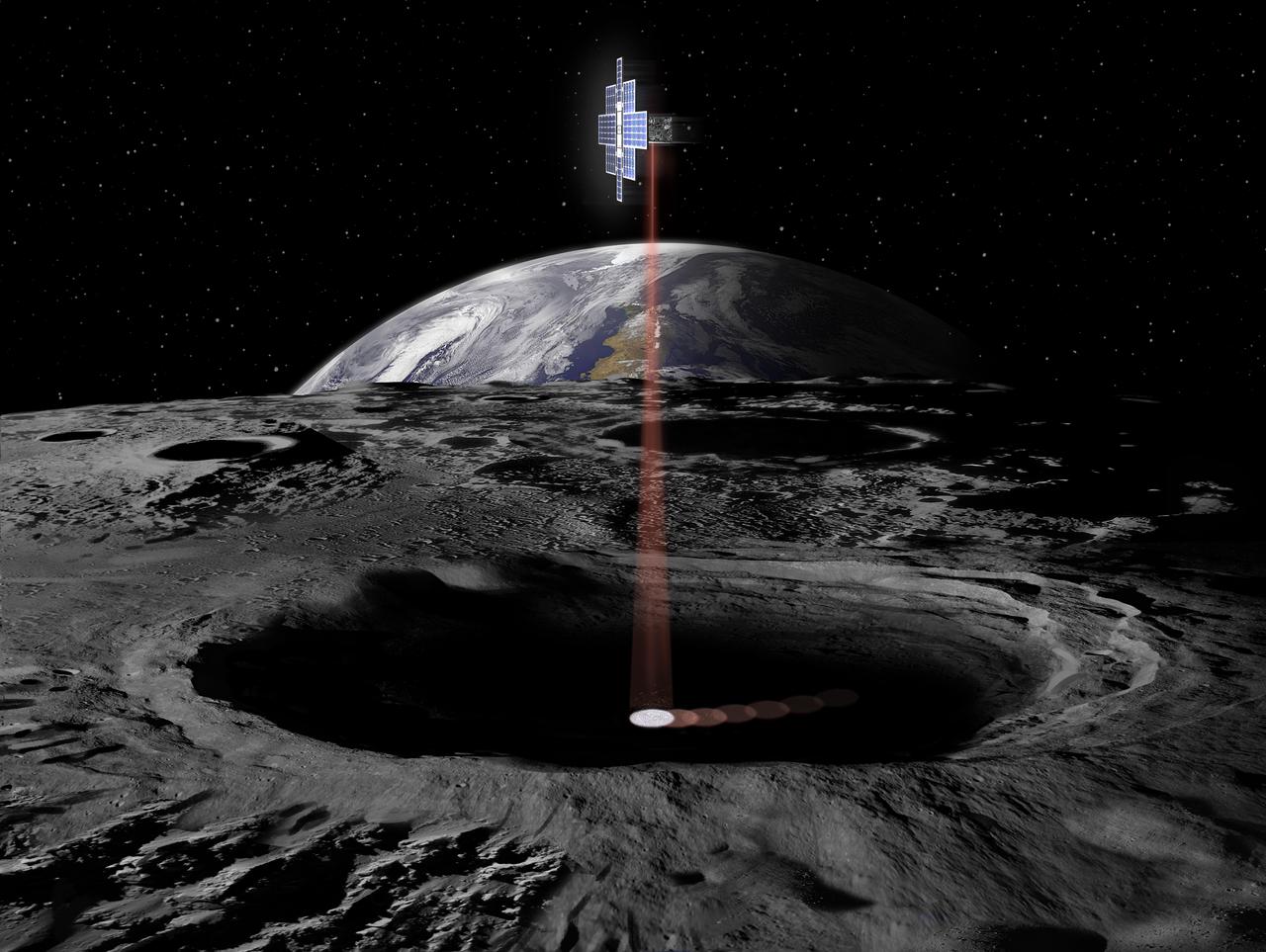

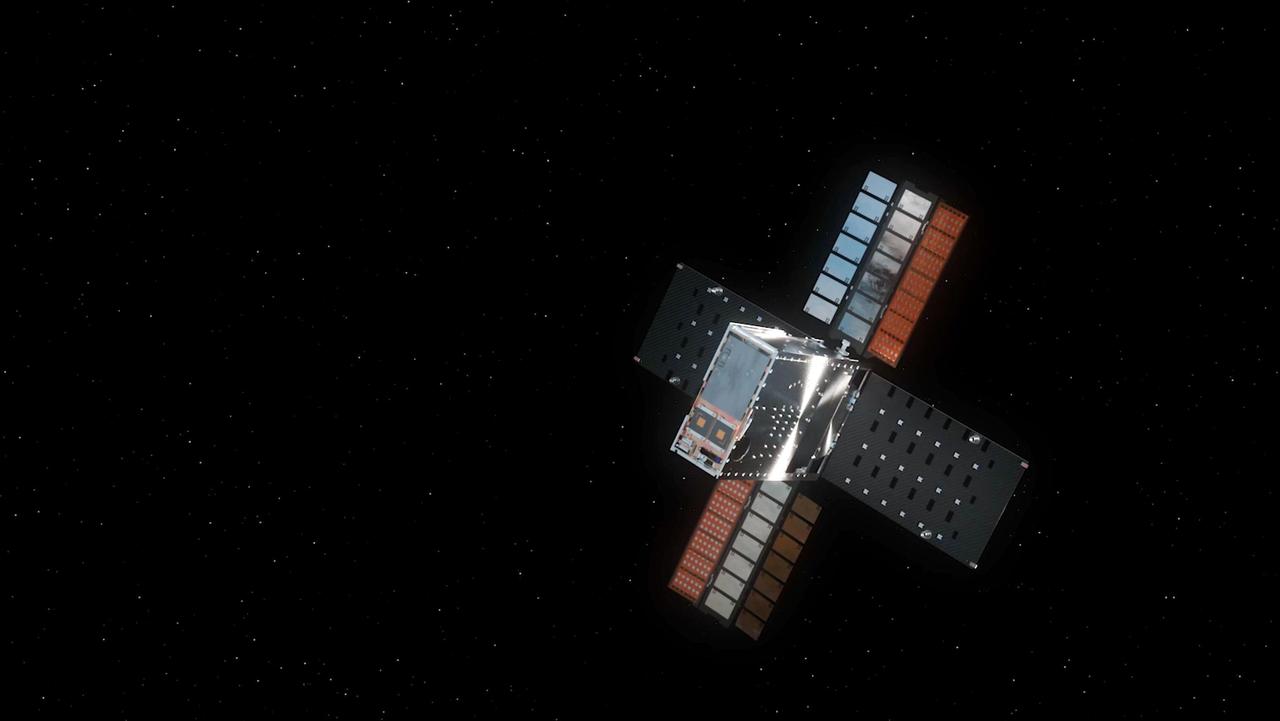

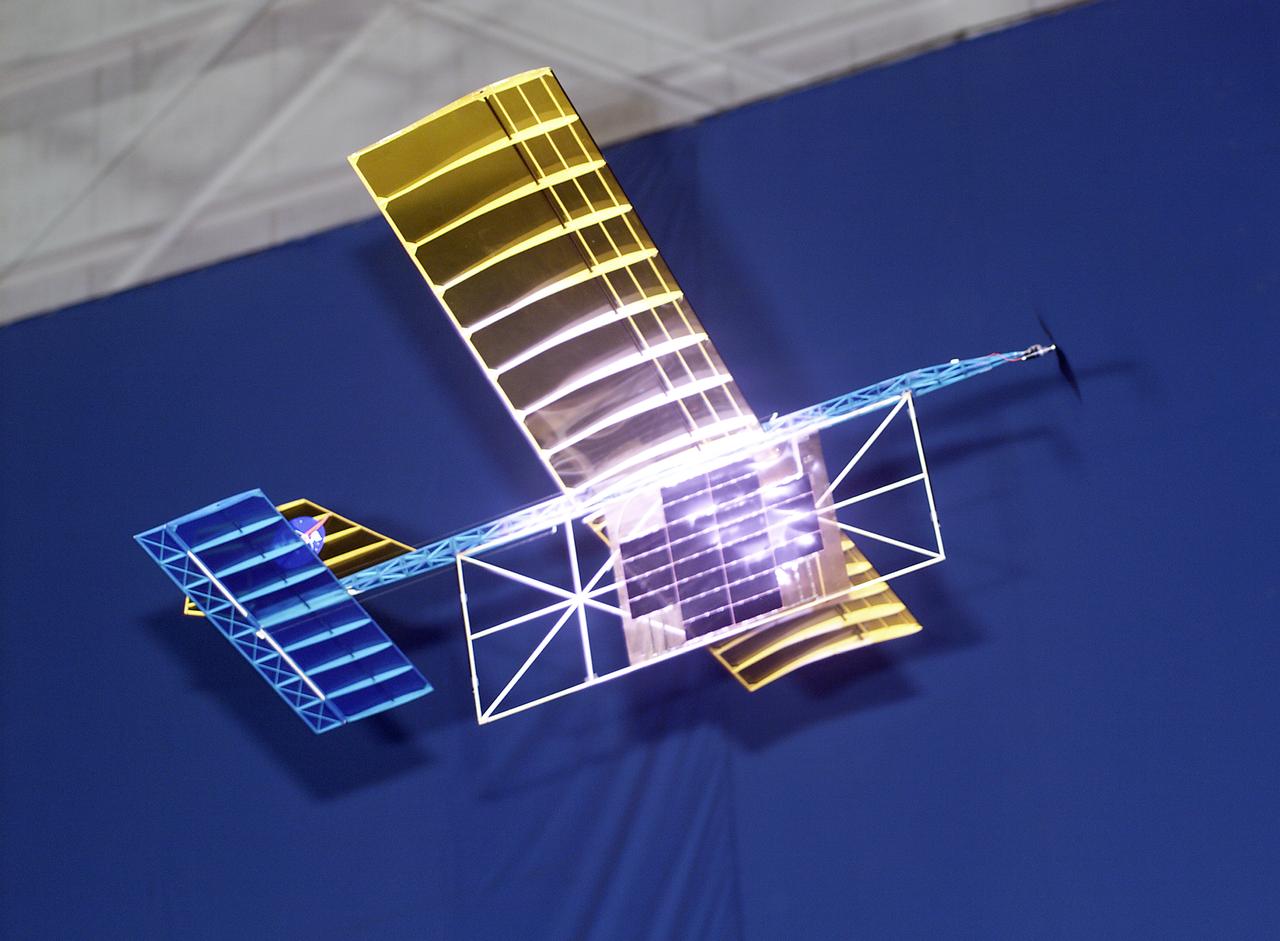

This artist's concept shows the Lunar Flashlight spacecraft, a six-unit CubeSat designed to search for ice on the Moon's surface using special lasers. The spacecraft will use its near-infrared lasers to shine light into shaded polar regions on the Moon, while an onboard reflectometer will measure surface reflection and composition. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23131

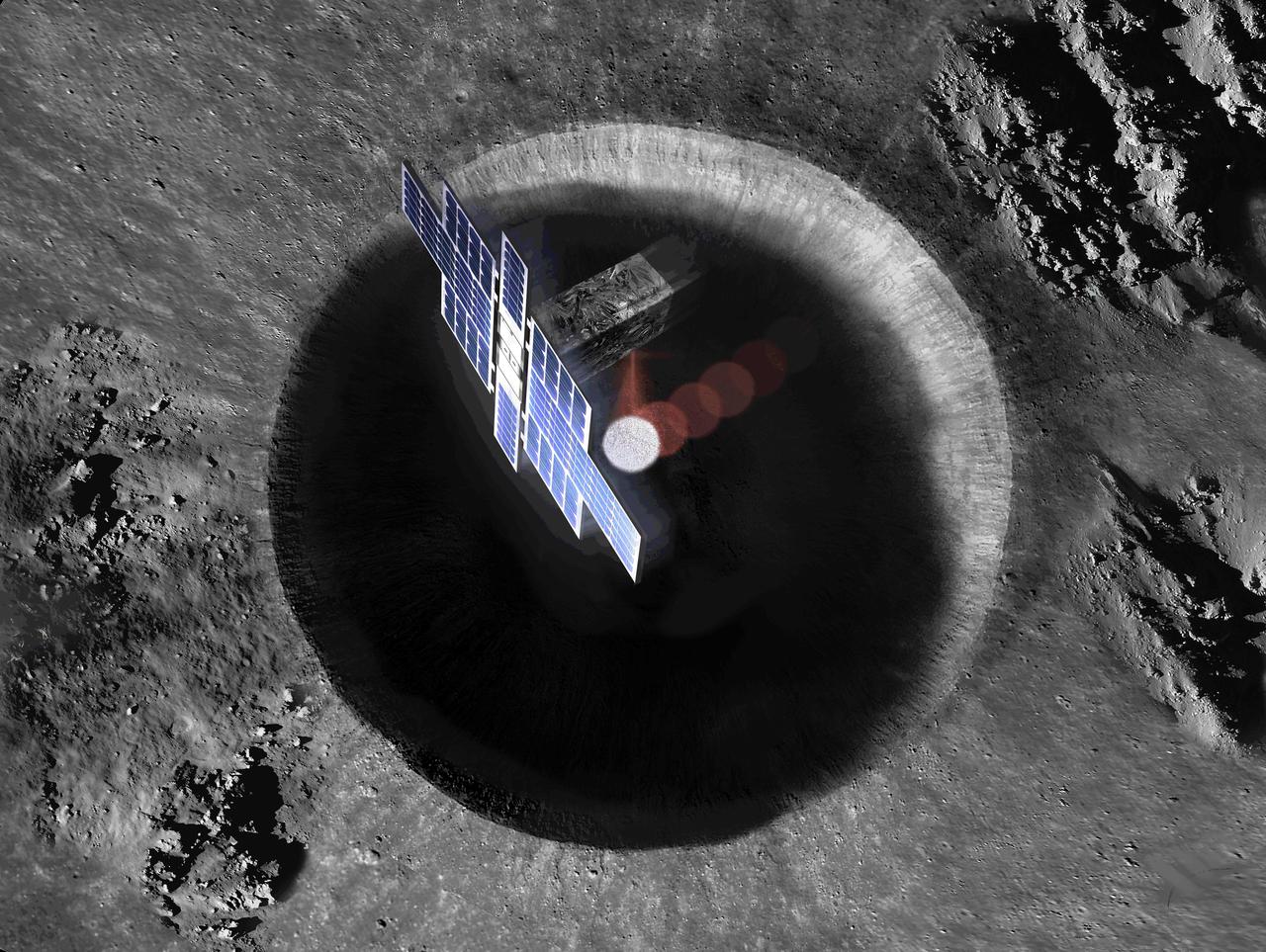

This artist's concept shows a view from above the Lunar Flashlight spacecraft, a six-unit CubeSat designed to search for ice on the Moon's surface using special lasers. The spacecraft uses its near-infrared lasers to shine light into shaded polar regions on the Moon, while an on-board reflectometer measures surface reflection and composition. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23132

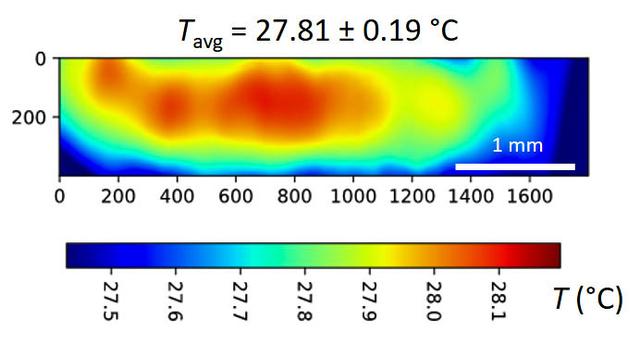

jsc2024e065172 (10/3/2024) --- A temperature map is seen within a microgel suspension illuminated by the Colloidal Solids (COLIS) near infrared laser (NIR). Reference ground tests for the Colloidal Solids (COLIS) investigation show spatial variation of the sample temperature while illuminating an aqueous, dense suspension of thermosensitive microgels with a 0.5 s pulse of NIR laser light. The NIR beam propagates from left to right. The sample temperature with no NIR laser is uniform and set to 27°C. The temperature values are inferred from the change in scattered intensity at a scattering angle of 90°, as recorded by one of the complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) cameras of COLIS. Results from this investigation are expected to provide a deeper understanding of soft solid interactions with gravity and microgravity, paving the way for the design of new materials. Image courtesy of Redwire Space Laboratories, Kruibeke – Belgium.

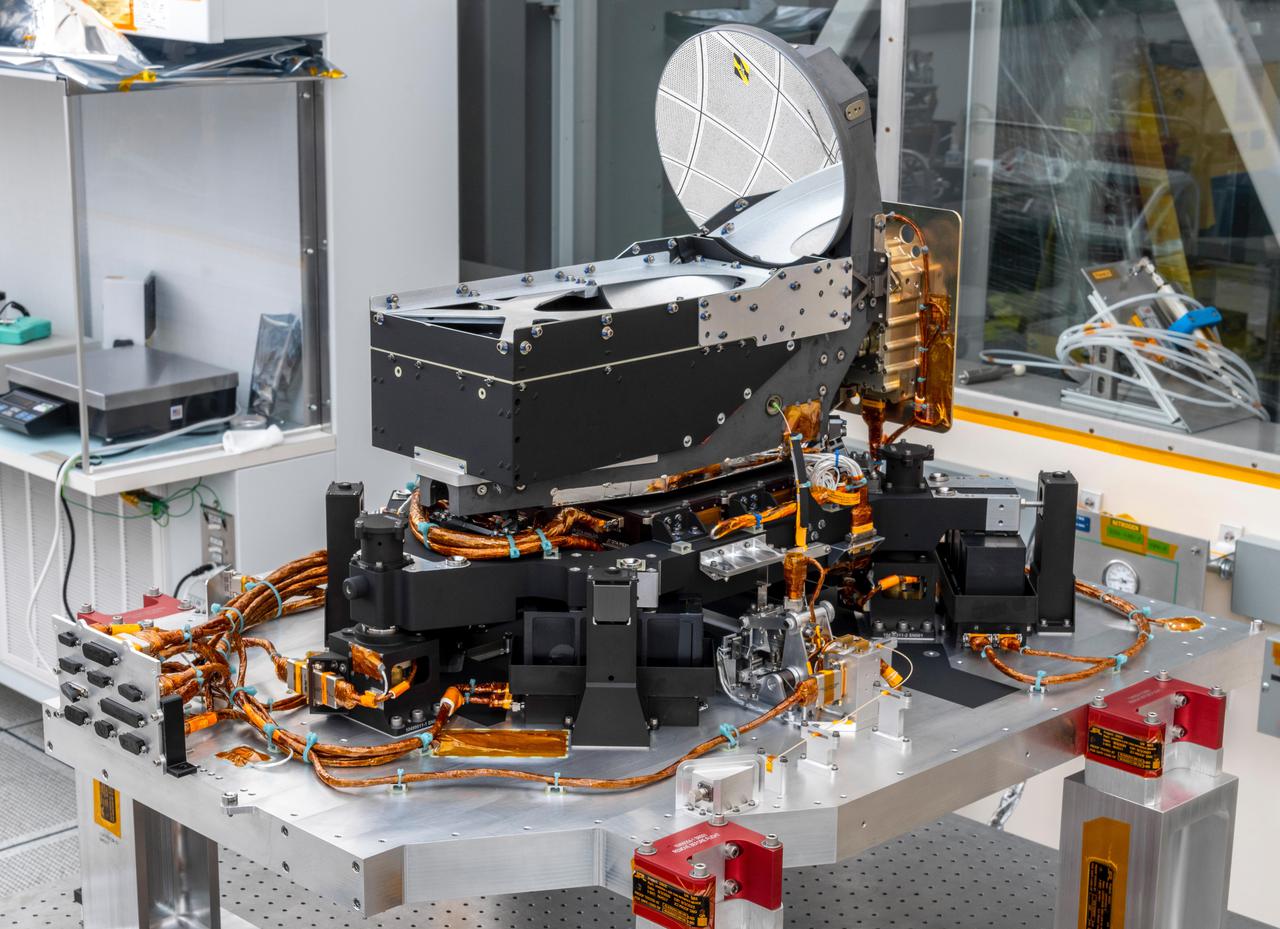

The Deep Space Optical Communications (DSOC) technology demonstration's flight laser transceiver is shown at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California in April 2021, before being installed inside its box-like enclosure that was later integrated with NASA's Psyche spacecraft. The transceiver consists of a near-infrared laser transmitter to send high-rate data to Earth, and a sensitive photon-counting camera to receive ground-transmitted low-rate data. The transceiver is mounted on an assembly of struts and actuators – shown in this photograph – that stabilizes the optics from spacecraft vibrations. The DSOC experiment is the agency's first demonstration of optical communications beyond the Earth-Moon system. DSOC is a system that consists of this flight laser transceiver, a ground laser transmitter, and a ground laser receiver. New advanced technologies have been implemented in each of these elements. The transceiver will "piggyback" on NASA's Psyche spacecraft when it launches in August 2022 to the metal-rich asteroid of the same name. The DSOC technology demonstration will begin shortly after launch and continue as the spacecraft travels from Earth to its gravity-assist flyby of Mars. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24569

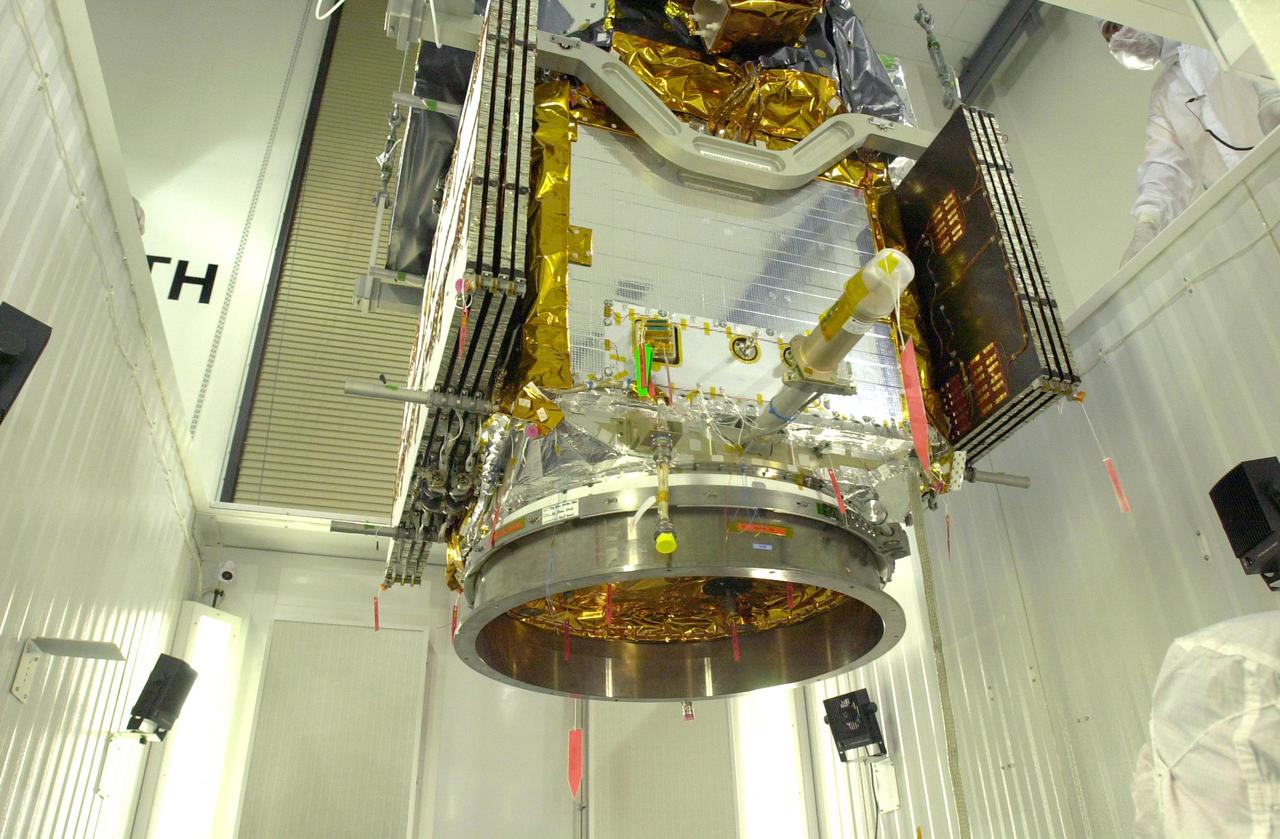

The Deep Space Optical Communications (DSOC) technology demonstration's flight laser transceiver can be easily identified on NASA's Psyche spacecraft, seen in this December 2021 photograph inside a clean room at the agency's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. DSOC's tube-like gray/silver sunshade can be seen protruding from the side of the spacecraft. The bulge to which the sunshade is attached is DSOC's transceiver, which consists of a near-infrared laser transmitter to send high-rate data to Earth and a sensitive photon-counting camera to receive ground-transmitted low-rate data. The DSOC experiment is the agency's first demonstration of optical communications beyond the Earth-Moon system. DSOC is a system that consists of this flight laser transceiver, a ground laser transmitter, and a ground laser receiver. New advanced technologies have been implemented in each of these elements. The transceiver will "piggyback" on NASA's Psyche spacecraft when it launches in August 2022 to the metal-rich asteroid of the same name. The DSOC technology demonstration will begin shortly after launch and continue as the spacecraft travels from Earth to its gravity-assist flyby of Mars. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24570

The purpose of the experiments for the Advanced Automated Directional Solidification Furnace (AADSF) is to determine how gravity-driven convection affects the composition and properties of alloys (mixtures of two or more materials, usually metal). During the USMP-4 mission, the AADSF will solidify crystals of lead tin telluride and mercury cadmium telluride, alloys of compound semiconductor materials used to make infrared detectors and lasers, as experiment samples. Although these materials are used for the same type application their properties and compositional uniformity are affected differently during the solidification process.

STS085-312-019 (7 - 19 August 1997) --- Astronaut Stephen K. Robinson, mission specialist, uses a battery-powered, hand held laser-ranging device at the Space Shuttle Discovery's aft overhead windows during operations with the Cryogenic Infrared Spectrometers and Telescopes for the Atmosphere-Shuttle Pallet Satellite-2 (CRISTA-SPAS-2).

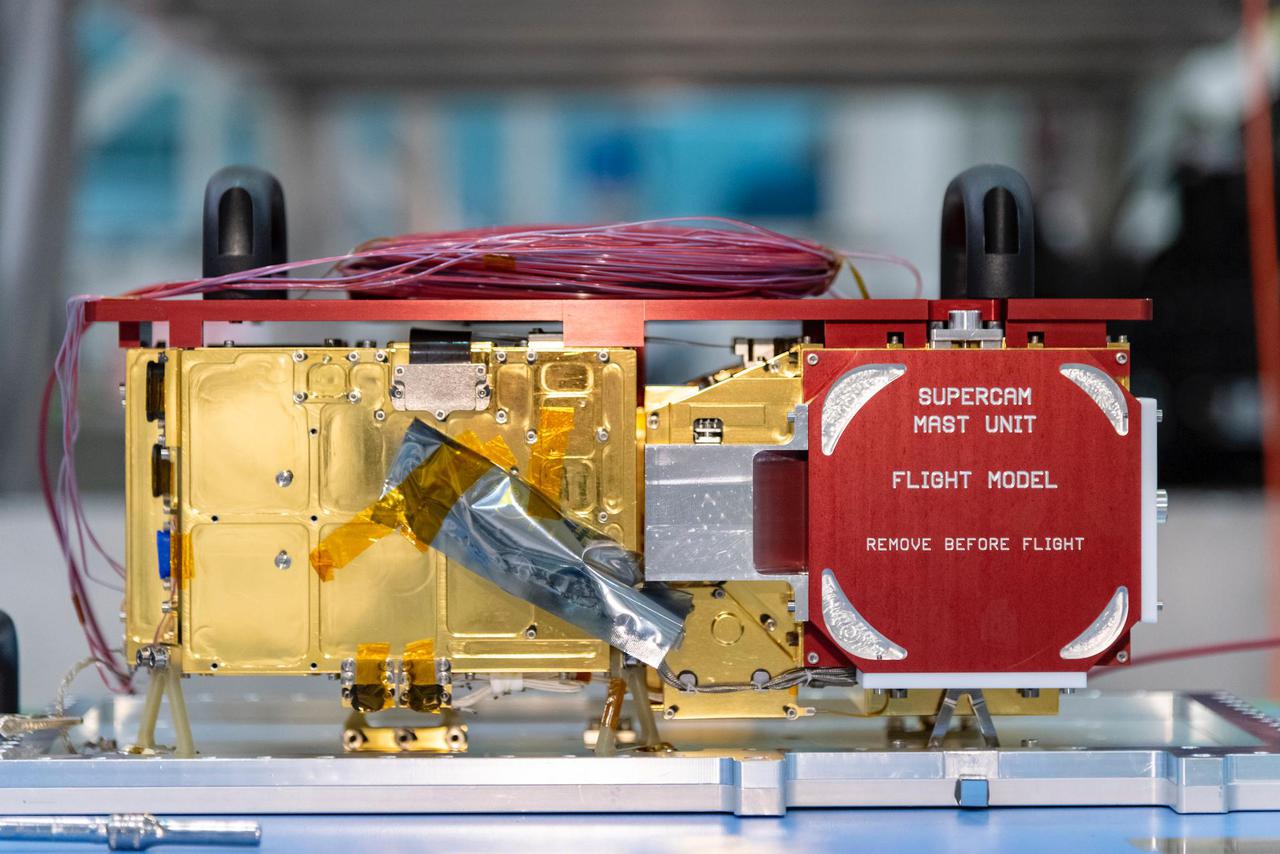

The mast-mounted portion of SuperCam awaits integration into the Perseverance rover. Part of SuperCam is contained in the belly of the rover, while this unit, containing the laser, infrared spectrometer, telescope, camera, and electronics, sits at the top of the remote sensing mast. The red "remove before flight" cover protects a clear window in front of the telescope and camera and was removed when SuperCam was installed in the rover. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24207

A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Pictured from Left to Right: James Demers, Adam Wroblewski, Shaun McKeehan, Kurt Blankenship. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data.

A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data.

Pilatus PC-12 Aircraft Being Prepped for Takeoff on June 12, 2024. A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data. Photo Credit: (NASA/Sara Lowthian-Hanna)

A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data.

A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data.

A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data.

A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data. Photo Credit: (NASA/Sara Lowthian-Hanna)

A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data. Photo Credit: (NASA/Sara Lowthian-Hanna)

A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data.

Adam Wroblewski p A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. Adam Wroblewski in the PC-12 over Lake Erie on June 13, 2024 sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data. Photo Credit: (NASA/Sara Lowthian-Hanna)

This illustration shows NASA's Lunar Flashlight, with its four solar arrays deployed, shortly after launch. The small satellite, or SmallSat, launched Nov. 30, 2022, aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket as a rideshare with ispace's HAKUTO-R Mission 1. It will take about three months to reach its science orbit to seek out surface water ice in the darkest craters of the Moon's South Pole. A technology demonstration, Lunar Flashlight will use a reflectometer equipped with four lasers that emit near-infrared light in wavelengths readily absorbed by surface water ice. This is the first time that multiple colored lasers will be used to seek out ice inside these dark regions on the Moon, which haven't seen sunlight in billions of years. Should the lasers hit bare rock or regolith (broken rock and dust), the light will reflect back to the spacecraft. But if the target absorbs the light, that would indicate the presence of water ice. The greater the absorption, the more ice there may be. The science data collected by the mission will be compared with observations made by other lunar missions to help reveal the distribution of surface water ice on the Moon for potential use by future astronauts. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25626

The Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) spacecraft embarks on a journey that will culminate in a close encounter with an asteroid. The launch of NEAR inaugurates NASA's irnovative Discovery program of small-scale planetary missions with rapid, lower-cost development cycles and focused science objectives. NEAR will rendezvous in 1999 with the asteroid 433 Eros to begin the first long-term, close-up look at an asteroid's surface composition and physical properties. NEAR's science payload includes an x-ray/gamma ray spectrometer, an near-infrared spectrograph, a laser rangefinder, a magnetometer, a radio science experiment and a multi-spectral imager.

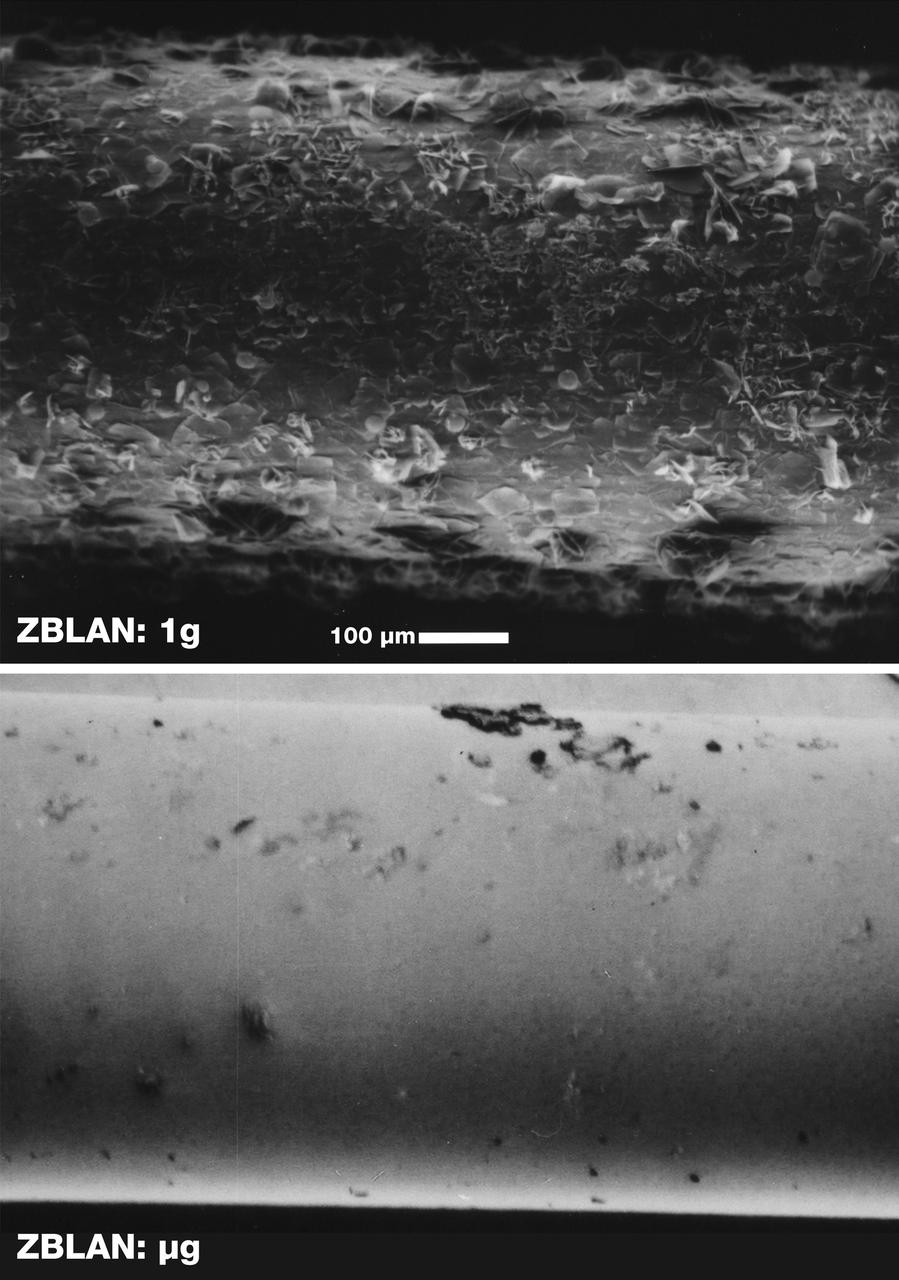

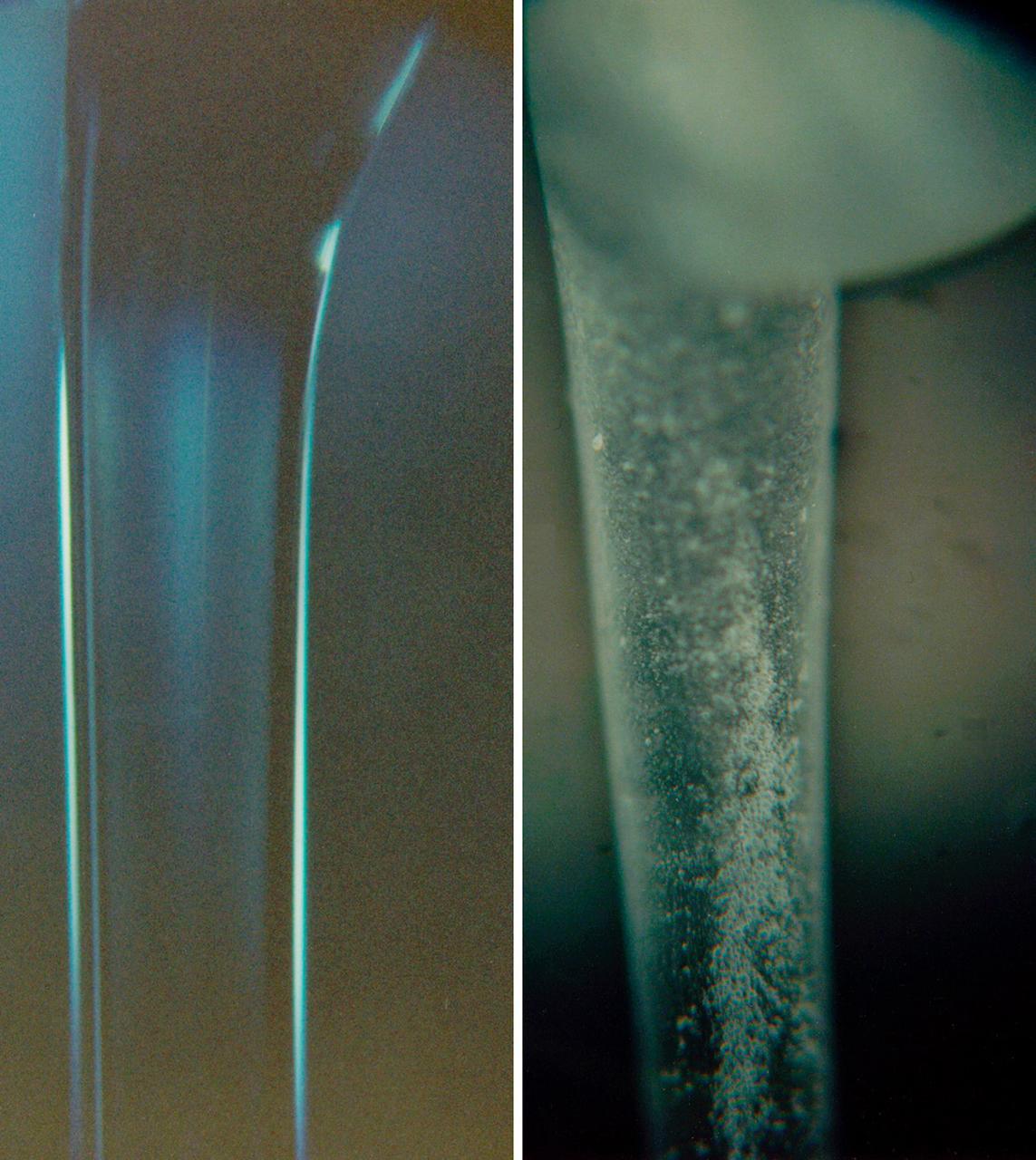

Scarning electron microscope images of the surface of ZBLAN fibers pulled in microgravity (ug) and on Earth (1g) show the crystallization that normally occurs in ground-based processing. The face of each crystal will reflect or refract a portion of the optical signal, thus degrading its quality. NASA is conducting research on pulling ZBLAN fibers in the low-g environment of space to prevent crystallization that limits ZBLAN's usefulness in optical fiber-based communications. ZBLAN is a heavy-metal fluoride glass that shows exdeptional promise for high-throughput communications with infrared lasers. Photo credit: NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center

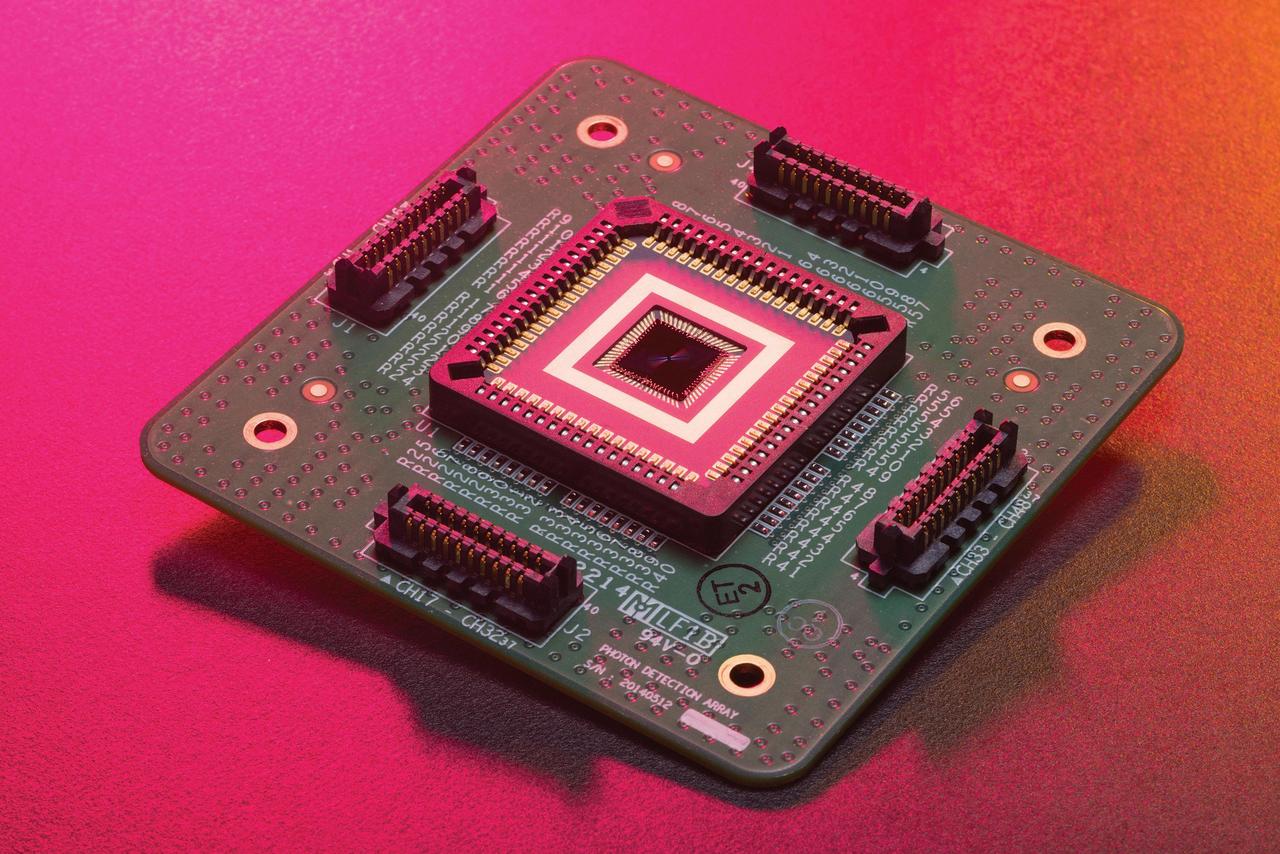

Shown here is a prototype of the Deep Space Optical Communications, or DSOC, ground receiver detector built by the Microdevices Laboratory at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. The prototype superconducting nanowire single-photon detector was used by JPL technologists to help develop the detector that – from a station on Earth – will receive near-infrared laser signals from the DSOC flight transceiver traveling with NASA's Psyche mission in deep space. DSOC will test key technologies that could enable high-bandwidth optical, or laser, communications from Mars distances. Bolted to the side of the spacecraft and operating for the first two years of Psyche's journey to the asteroid of the same name, the DSOC flight laser transceiver will transmit high-rate data to Caltech's Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, California, which houses the 200-inch (5.1-meter) Hale Telescope. The downlink detector converts optical signals to electrical signals, which can be processed and decoded. The detector is designed to be both sensitive enough to detect single photons (quantum particles of light) and able to detect many photons arriving all at once. At its farthest point during the technology demonstration's operations period, the transceiver will be up to 240 million miles (390 million kilometers) away, meaning that by the time its weak laser pulses arrive at Earth, the detector will need to efficiently detect a trickle of single photons. But when the spacecraft is closer to Earth and the flight transceiver is delivering its highest bit rate to Palomar, the detector is capable of detecting very high numbers of photons without becoming overwhelmed. Because data is encoded in the timing of the laser pulses, the detector must also be able to determine the time of a photon's arrival with a precision of 100 picoseconds (one picosecond is one trillionth of a second). DSOC is the latest in a series of optical communication technology demonstrations funded by NASA's Technology Demonstrations Missions (TDM) program and the agency's Space Communications and Navigation (SCaN) program. JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages DSOC for TDM within NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate and SCaN within the agency's Space Operations Mission Directorate. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25840

Aerial Photograph of Glenn Research Center With Downtown Cleveland in the Distance taken from the PC-12 on June 13, 2024. A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data. Photo Credit: (NASA/Sara Lowthian-Hanna)

Adam Wroblewski and Shaun McKeehan Working In PC-12 Aircraft during in flight testing on June 13, 2024. A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data. Photo Credit: (NASA/Sara Lowthian-Hanna)

A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Pictured here on June 13, 2024 from Left to Right: Kurt Blakenship, Adam Wroblewski, Shaun McKeehan. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data. Photo Credit: (NASA/Sara Lowthian-Hanna)

Kurt Blankenship and James Demers Fly PC-12 Aircraft During Testing on June 13, 2024. A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data. Photo Credit: (NASA/Sara Lowthian-Hanna)

View of the Glenn Research Center Hangar from the Cleveland Hopkins Airport Runway during a testing flight on June 13, 2024. A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data. Photo Credit: (NASA/Sara Lowthian-Hanna)

At Glenn Research Center, the PC-12 is Prepped for a flight and ready to takeoff on June 12, 2024. A team at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland streamed 4K video footage from an aircraft to the International Space Station and back for the first time using optical, or laser, communications. The feat was part of a series of tests on new technology that could provide live video coverage of astronauts on the Moon during the Artemis missions. Working with the Air Force Research Laboratory and NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research program, Glenn engineers temporarily installed a portable laser terminal on the belly of a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft. They then flew over Lake Erie sending data from the aircraft to an optical ground station in Cleveland. From there, it was sent over an Earth-based network to NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where scientists used infrared light signals to send the data. Photo Credit: (NASA/Sara Lowthian-Hanna)

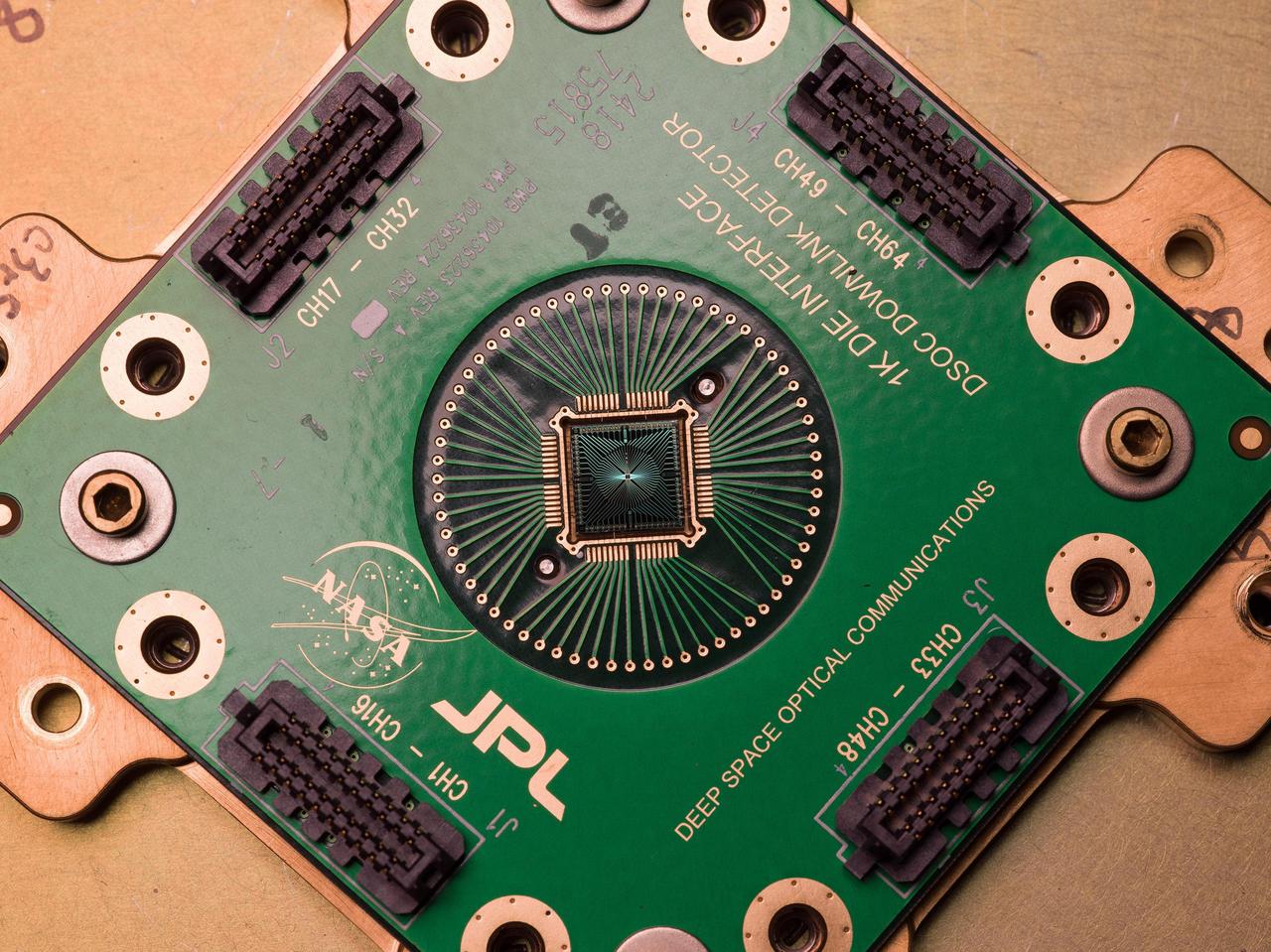

Shown here is an identical copy of the Deep Space Optical Communications, or DSOC, superconducting nanowire single-photon detector that is coupled to the 200-inch (5.1-meter) Hale Telescope located at Caltech's Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, California. Built by the Microdevices Laboratory at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, the detector is designed to receive near-infrared laser signals from the DSOC flight transceiver traveling with NASA's Psyche mission in deep space as a part of the technology demonstration. DSOC will test key technologies that could enable high-bandwidth optical, or laser, communications from Mars distances. Bolted to the side of the spacecraft and operating for the first two years of Psyche's journey to the asteroid of the same name, the DSOC flight laser transceiver will transmit high-rate data to Caltech's Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, California, which houses the 200-inch (5.1-meter) Hale Telescope. The downlink detector converts optical signals to electrical signals, which can be processed and decoded. The detector is designed to be both sensitive enough to detect single photons (quantum particles of light) and able to detect many photons arriving all at once. At its farthest point during the technology demonstration's operations period, the transceiver will be up to 240 million miles (390 million kilometers) away, meaning that by the time its weak laser pulses arrive at Earth, the detector will need to efficiently detect a trickle of single photons. But when the spacecraft is closer to Earth and the flight transceiver is delivering its highest bit rate to Palomar, the detector is capable of detecting very high numbers of photons without becoming overwhelmed. Because data is encoded in the timing of the laser pulses, the detector must also be able to determine the time of a photon's arrival with a precision of 100 picoseconds (one picosecond is one trillionth of a second). To sense single photons, the detector must be in a superconducting state (when electrical current flows with zero resistance), so it is cryogenically cooled to less than minus 458 degrees Fahrenheit (or 1 Kelvin), which is close to absolute zero, or the lowest temperature possible. A photon absorbed in the detector disrupts its superconducting state, creating a measurable electrical pulse as current leaves the detector. DSOC is the latest in a series of optical communication technology demonstrations funded by NASA's Technology Demonstrations Missions (TDM) program and the agency's Space Communications and Navigation (SCaN) program. JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages DSOC for TDM within NASA's Space Technology Mission Directorate and SCaN within the agency's Space Operations Mission Directorate. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26141

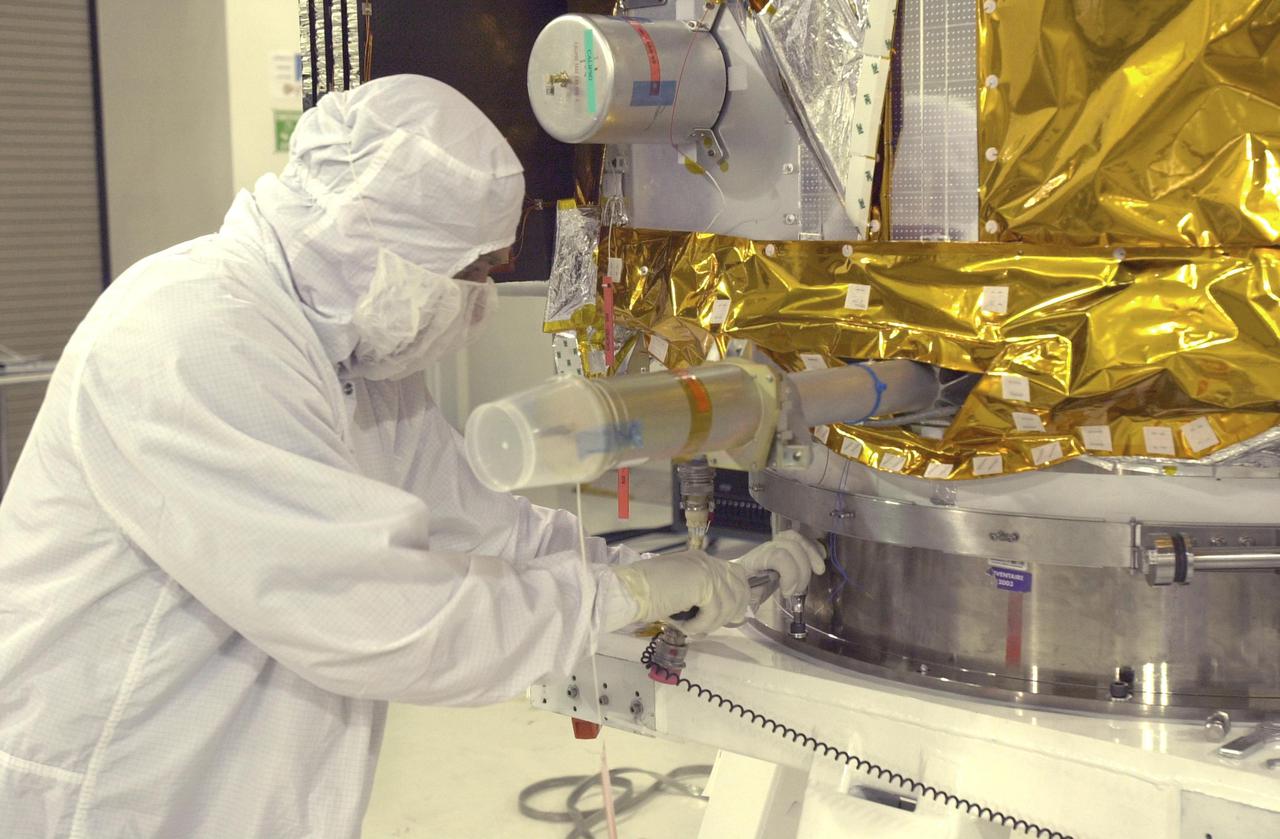

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, a worker prepares the CALIPSO spacecraft for a move to a specially modified container where LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing will take place. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, a light beam is emitted during LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing on the CALIPSO spacecraft. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, the CALIPSO spacecraft is being prepared for a move to a specially modified container where LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing will take place. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, workers help secure the CALIPSO spacecraft inside a specially modified container where LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing will take place. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, light beams are emitted during LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing on the CALIPSO spacecraft. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, an overhead crane lowers the suspended CALIPSO spacecraft into a specially modified container (lower right) where LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing will take place. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

AS17-145-22254 (14 Dec. 1972) --- An excellent view of the Apollo 17 Command and Service Modules (CSM) photographed from the Lunar Module (LM) "Challenger" during rendezvous and docking maneuvers in lunar orbit. The LM ascent stage, with astronauts Eugene A. Cernan and Harrison H. Schmitt aboard, had just returned from the Taurus-Littrow landing site on the lunar surface. Astronaut Ronald E. Evans remained with the CSM in lunar orbit. Note the exposed Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) Bay in Sector 1 of the Service Module (SM). Three experiments are carried in the SIM bay: S-209 lunar sounder, S-171 infrared scanning spectrometer, and the S-169 far-ultraviolet spectrometer. Also mounted in the SIM bay are the panoramic camera, mapping camera and laser altimeter used in service module photographic tasks. A portion of the LM is on the right.

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, the suspended CALIPSO spacecraft is moved toward a specially modified container (lower right) where LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing will take place. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, the CALIPSO spacecraft is lifted off a work stand for a move to a specially modified container where LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing will take place. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

Sections of ZBLAN fibers pulled in a conventional 1-g process (right) and in experiments aboard NASA's KC-135 low-gravity aircraft (left). The rough surface of the 1-g fiber indicates surface defects that would scatter an optical signal and greatly degrade its quality. ZBLAN is part of the family of heavy-metal fluoride glasses (fluorine combined zirconium, barium, lanthanum, aluminum, and sodium). NASA is conducting research on pulling ZBLAN fibers in the low-g environment of space to prevent crystallization that limits ZBLAN's usefulness in optical fiber-based communications. ZBLAN is a heavy-metal fluoride glass that shows exceptional promise for high-throughput communications with infrared lasers. Photo credit: NASA/Marshall Space Flight Center

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, the suspended CALIPSO spacecraft is lowered inside a specially modified container where LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing will take place. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, workers oversee the CALIPSO spacecraft as it is lowered inside a specially modified container where LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing will take place. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, CALIF. - At Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, the suspended CALIPSO spacecraft is moved toward a specially modified container (lower right) where LIDAR (LIght Detection And Ranging) laser testing will take place. CALIPSO stands for Cloud-Aerosol LIDAR and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation. LIDAR measures distance, speed, rotation, chemical composition and concentration. CALIPSO and CloudSat will fly in formation with three other satellites in the A-train constellation to enhance understanding of our climate system. They are highly complementary satellites and together they will provide never-before-seen 3-D perspectives of how clouds and aerosols form, evolve, and affect weather and climate. Launch of CALIPSO_CloudSat aboard a Boeing Delta II rocket is scheduled for 3:01 a.m. PDT Sept. 29.

Powered by a laser beam directed at it from a center pedestal, a lightweight model plane makes the first flight of an aircraft powered by laser energy inside a building at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center.

NASA Dryden project engineer Dave Bushman carefully aims the optics of a laser device at a solar cell panel on a model aircraft during the first flight demonstration of an aircraft powered by laser light.

With a laser beam centered on its panel of photovoltaic cells, a lightweight model plane makes the first flight of an aircraft powered by a laser beam inside a building at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center.

With a laser beam centered on its solar panel, a lightweight model aircraft is checked out by technician Tony Frakowiak and researcher Tim Blackwell before its power-beamed demonstration flight.

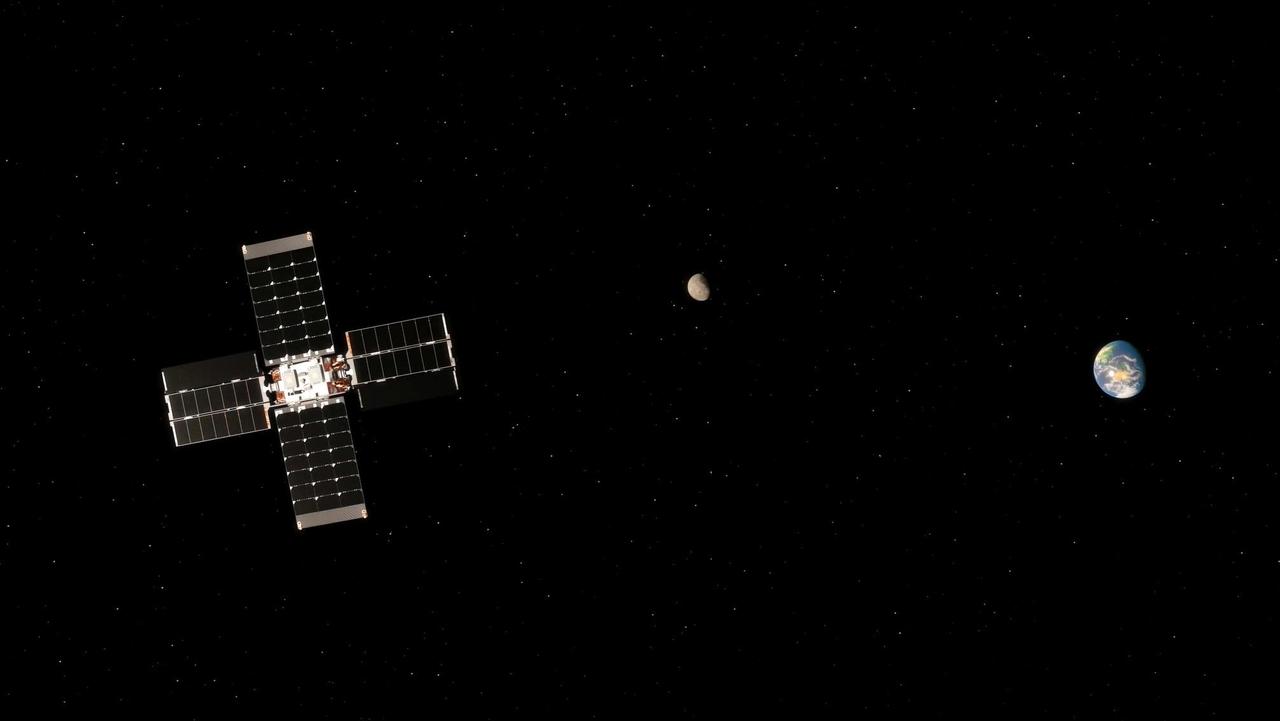

This illustration shows NASA's Lunar Flashlight carrying out a trajectory correction maneuver with the Moon and Earth in the background. Powered by the small satellite's four thrusters, the maneuver is needed to reach lunar orbit. Lunar Flashlight launched Nov. 30, 2022, and will take about four months to reach its science orbit to seek out surface water ice in the darkest craters of the Moon's South Pole. A technology demonstration, the small satellite, or SmallSat, will use a reflectometer equipped with four lasers that emit near-infrared light in wavelengths readily absorbed by surface water ice. To achieve the mission's goals with the satellite's limited amount of propellent, Lunar Flashlight will employ an energy-efficient near-rectilinear halo orbit, taking it within 9 miles (15 kilometers) of the lunar South Pole and 43,000 miles (70,000 kilometers) away at its farthest point. Only one other spacecraft has employed this type of orbit: NASA's Cislunar Autonomous Positioning System Technology Operations and Navigation Experiment (CAPSTONE) mission, which launched in June 2022. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25258

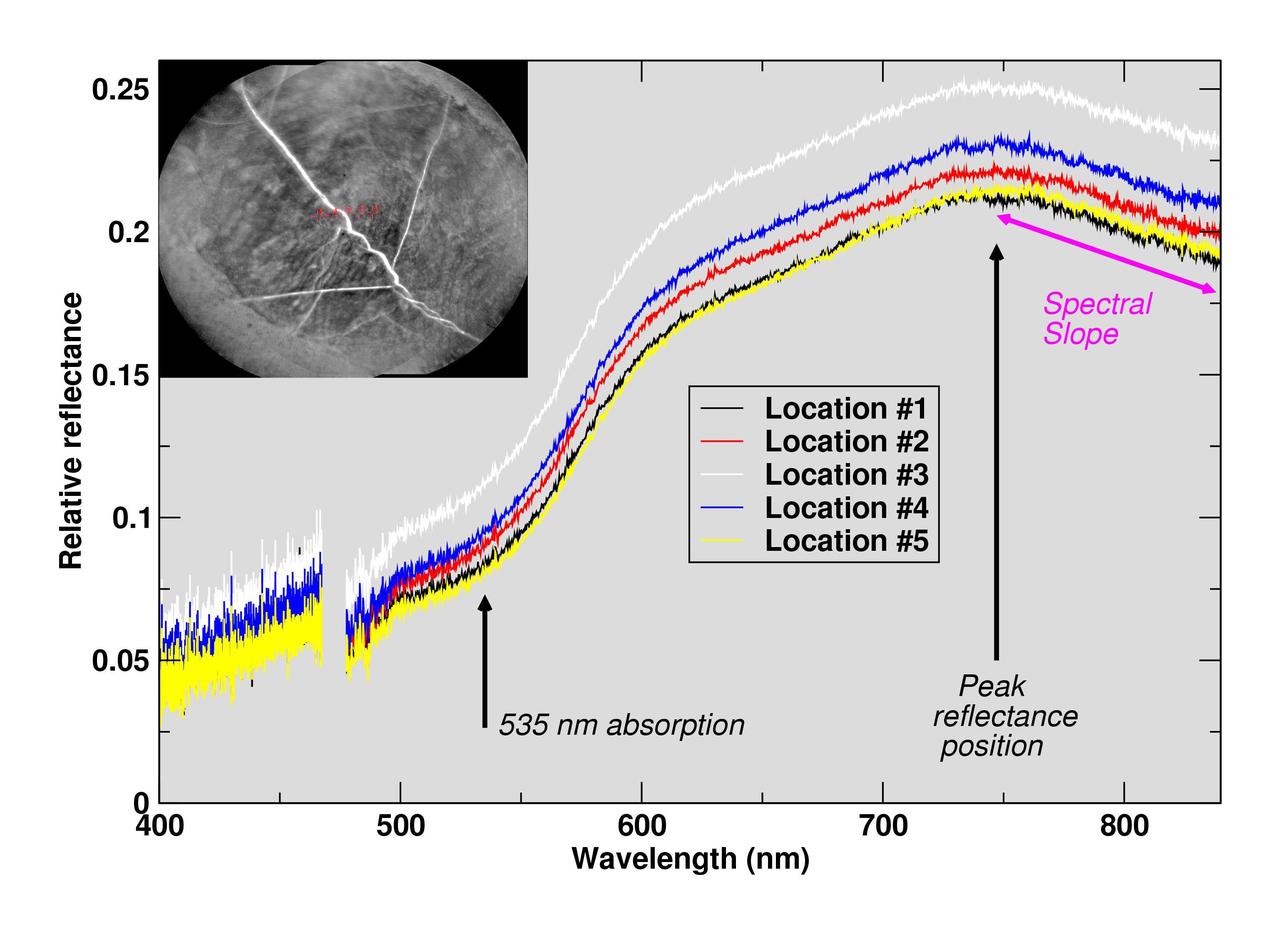

The Chemistry and Camera (ChemCam) instrument on NASA's Curiosity Mars rover examined a freshly brushed area on target rock "Christmas Cove" and found spectral evidence of hematite, an iron-oxide mineral. ChemCam sometimes zaps rocks with a laser, but can also be used, as in this case, in a "passive" mode. In this type of investigation, the instrument's telescope delivers to spectrometers the sunlight reflected from a small target point. The upper-left inset of this graphic is an image from ChemCam's Remote Micro-Imager with five labeled points that the instrument analyzed. The image covers an area about 2 inches (5 centimeters) wide, and the bright lines are fractures in the rock filled with calcium sulfate minerals. The five charted lines of the graphic correspond to those five points and show the spectrometer measurements of brightness at thousands of different wavelengths, from 400 nanometers (at the violet end of the visible-light spectrum) to 840 nanometers (in near-infrared). Sections of the spectrum measurements that are helpful for identifying hematite are annotated. These include a dip around 535 nanometers, the green-light portion of the spectrum at which fine-grained hematite tends to absorb more light and reflect less compared to other parts of the spectrum. That same green-absorbing characteristic of the hematite makes it appear purplish when imaged through special filters of Curiosity's Mast Camera and even in usual color images. The spectra also show maximum reflectance values near 750 nanometers, followed by a steep decrease in the spectral slope toward 840 nanometers, both of which are consistent with hematite. This ChemCam examination of Christmas Cove was part of an experiment to determine whether the rock had evidence of hematite under a tan coating of dust. The target area was brushed with Curiosity's Dust Removal Tool prior to these ChemCam passive observations on Sept. 17, 2017, during the 1,819th Martian day, or sol, of Curiosity's work on Mars. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22068

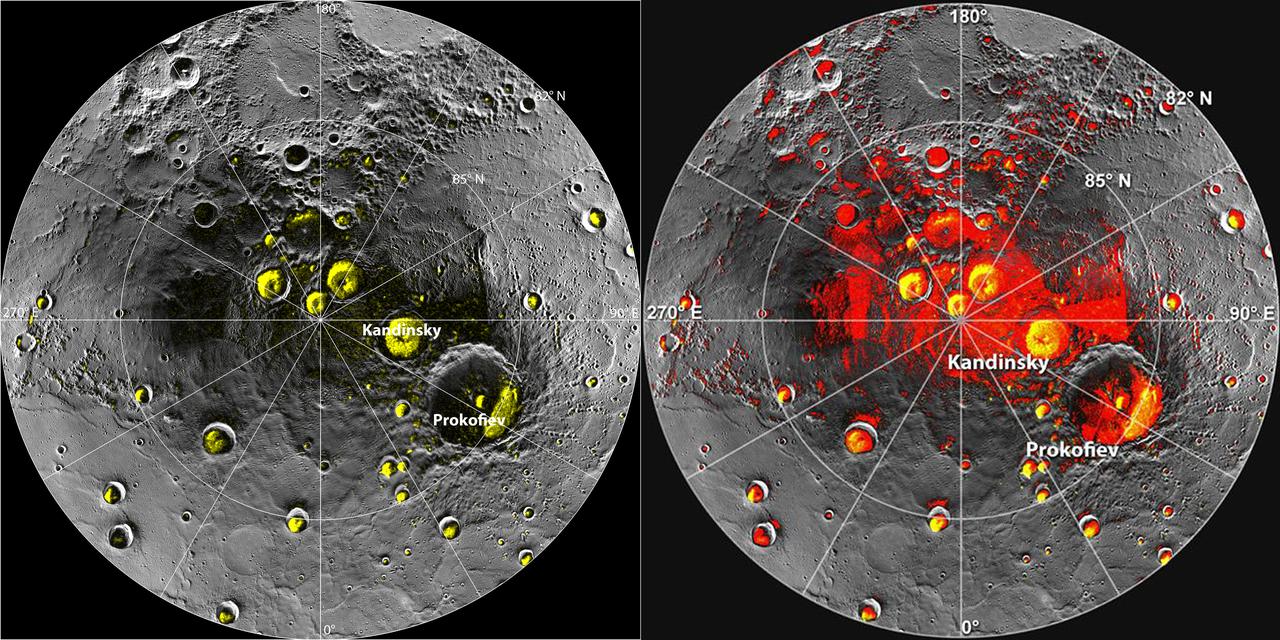

New observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft provide compelling support for the long-held hypothesis that Mercury harbors abundant water ice and other frozen volatile materials in its permanently shadowed polar craters. Three independent lines of evidence support this conclusion: the first measurements of excess hydrogen at Mercury's north pole with MESSENGER's Neutron Spectrometer, the first measurements of the reflectance of Mercury's polar deposits at near-infrared wavelengths with the Mercury Laser Altimeter (MLA), and the first detailed models of the surface and near-surface temperatures of Mercury's north polar regions that utilize the actual topography of Mercury's surface measured by the MLA. These findings are presented in three papers published online today in Science Express. Given its proximity to the Sun, Mercury would seem to be an unlikely place to find ice. But the tilt of Mercury's rotational axis is almost zero — less than one degree — so there are pockets at the planet's poles that never see sunlight. Scientists suggested decades ago that there might be water ice and other frozen volatiles trapped at Mercury's poles. The idea received a boost in 1991, when the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico detected unusually radar-bright patches at Mercury's poles, spots that reflected radio waves in the way one would expect if there were water ice. Many of these patches corresponded to the location of large impact craters mapped by the Mariner 10 spacecraft in the 1970s. But because Mariner saw less than 50 percent of the planet, planetary scientists lacked a complete diagram of the poles to compare with the images. MESSENGER's arrival at Mercury last year changed that. Images from the spacecraft's Mercury Dual Imaging System taken in 2011 and earlier this year confirmed that radar-bright features at Mercury's north and south poles are within shadowed regions on Mercury's surface, findings that are consistent with the water-ice hypothesis. To read more go to: <a href="http://1.usa.gov/TtNwM2" rel="nofollow">1.usa.gov/TtNwM2</a> Image Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington/National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center, Arecibo Observatory <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASA_GoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagram.com/nasagoddard?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>

This galaxy has a far more exciting and futuristic classification than most — it hosts a megamaser. Megamasers are intensely bright, around 100 million times brighter than the masers found in galaxies like the Milky Way. The entire galaxy essentially acts as an astronomical laser that beams out microwave emission rather than visible light (hence the ‘m’ replacing the ‘l’). A megamaser is a process that involves some components within the galaxy (like gas) that is in the right physical condition to cause the amplification of light (in this case, microwaves). But there are other parts of the galaxy (like stars for example) that aren’t part of the maser process. This megamaser galaxy is named IRAS 16399-0937 and is located over 370 million light-years from Earth. This NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image belies the galaxy’s energetic nature, instead painting it as a beautiful and serene cosmic rosebud. The image comprises observations captured across various wavelengths by two of Hubble’s instruments: the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), and the Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS). NICMOS’s superb sensitivity, resolution, and field of view gave astronomers the unique opportunity to observe the structure of IRAS 16399-0937 in detail. They found it hosts a double nucleus — the galaxy’s core is thought to be formed of two separate cores in the process of merging. The two components, named IRAS 16399N and IRAS 16399S for the northern and southern parts respectively, sit over 11,000 light-years apart. However, they are both buried deep within the same swirl of cosmic gas and dust and are interacting, giving the galaxy its peculiar structure. The nuclei are very different. IRAS 16399S appears to be a starburst region, where new stars are forming at an incredible rate. IRAS 16399N, however, is something known as a LINER nucleus (Low Ionization Nuclear Emission Region), which is a region whose emission mostly stems from weakly-ionized or neutral atoms of particular gases. The northern nucleus also hosts a black hole with some 100 million times the mass of the sun! Image credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, Acknowledgement: Judy Schmidt (geckzilla) <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/audience/formedia/features/MP_Photo_Guidelines.html" rel="nofollow">NASA image use policy.</a></b> <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASAGoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Like us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b> <b>Find us on <a href="http://instagrid.me/nasagoddard/?vm=grid" rel="nofollow">Instagram</a></b>