NASA Dryden flight test engineer Marta Bohn-Meyer is suited up for a research flight in the F-16XL laminar-flow control experiment in this 1993 photo.

Four different versions of the F-16 were used by Dryden in the 1990s. On the left and right sides are two F-16XLs. On the left is the F-16XL #2 (NASA 848), which is the two-seat version, used for advanced laminar flow studies until late 1996. On the right is the single-seat F-16XL #1 (NASA 849), used for laminar flow research and sonic boom research. (Laminar flow refers to smooth airflow over a wing, which increases lift and reduces drag compared to turbulent airflow). Between them at center left is an F-16A (NASA 816), the only civilian operated F-16. Next to it at center right is the U.S. Air Force Advance Fighter Technology Integration (AFTI) F-16, a program to test new sensor and control technologies for future fighter aircraft. Both F-16XLs are in storage at Dryden. The F-16A was never flown at Dryden, and was parked by the entrance to the center. The AFTI F-16 is in the Air Force Museum.

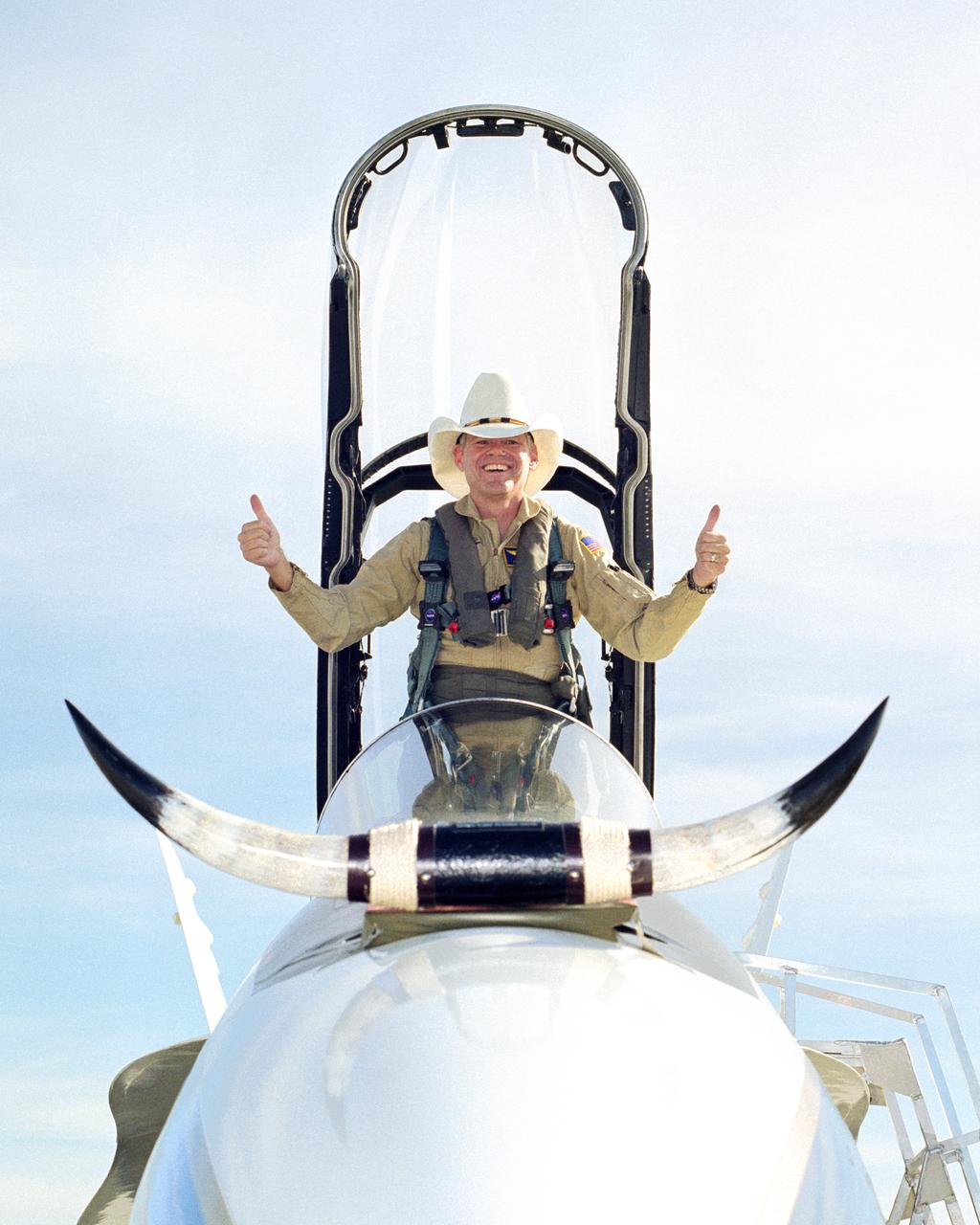

In a lighter mood, Ed Schneider gives a "thumbs-up" after his last flight at the Dryden Flight Research Center on September 19, 2000. Schneider arrived at the NASA Ames-Dryden Flight Research Facility on July 5, 1982, as a Navy Liaison Officer, becoming a NASA research pilot one year later. He has been project pilot for the F-18 High Angle-of-Attack program (HARV), the F-15 aeronautical research aircraft, the NASA B-52 launch aircraft, and the SR-71 "Blackbird" aircraft. He also participated in such programs as the F-8 Digital Fly-By-Wire, the FAA/NASA 720 Controlled Impact Demonstration, the F-14 Automatic Rudder Interconnect and Laminar Flow, and the F-104 Aeronautical Research and Microgravity projects.

A technician prepares a test sample in the Zero Gravity Research Facility clean room at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Lewis Research Center. The Zero Gravity Research Facility contained a drop tower which provided five seconds of microgravity during freefall in its 450-foot deep vacuum chamber. The facility has been used for a variety of studies relating to the behavior of fluids and flames in microgravity. During normal operations, a cylindrical 3-foot diameter and 11-foot long vehicle was used to house the experiments, instrumentation, and high speed cameras. The 4.5-foot long and 1.5-foot wide rectangular vehicle, seen in this photograph, was used less frequently. A 3-foot diameter orb was used for the special ten-second drops in which the package was pneumatically shot to the top of the tower then dropped. The facility also contained a control room, shop offices, tool and equipment rooms, and this clean room. The 242.5-foot long and 19.5-foot wide clean room was equipped with specialized cleaning equipment. In the 1960s the room was rated as a class 10,000 clean room, but I was capable of meeting the class 100 requirements. The room included a fume hood, ultrasonic cleaner, and a laminar flow station which operated as a class 100 environment. The environment in the clean room was maintained at 71° F and a relative humidity of 45- percent.

In this photo of the C-140 JetStar on the Dryden Ramp, a subscale propeller has been fitted to the upper fuselage of the aircraft.

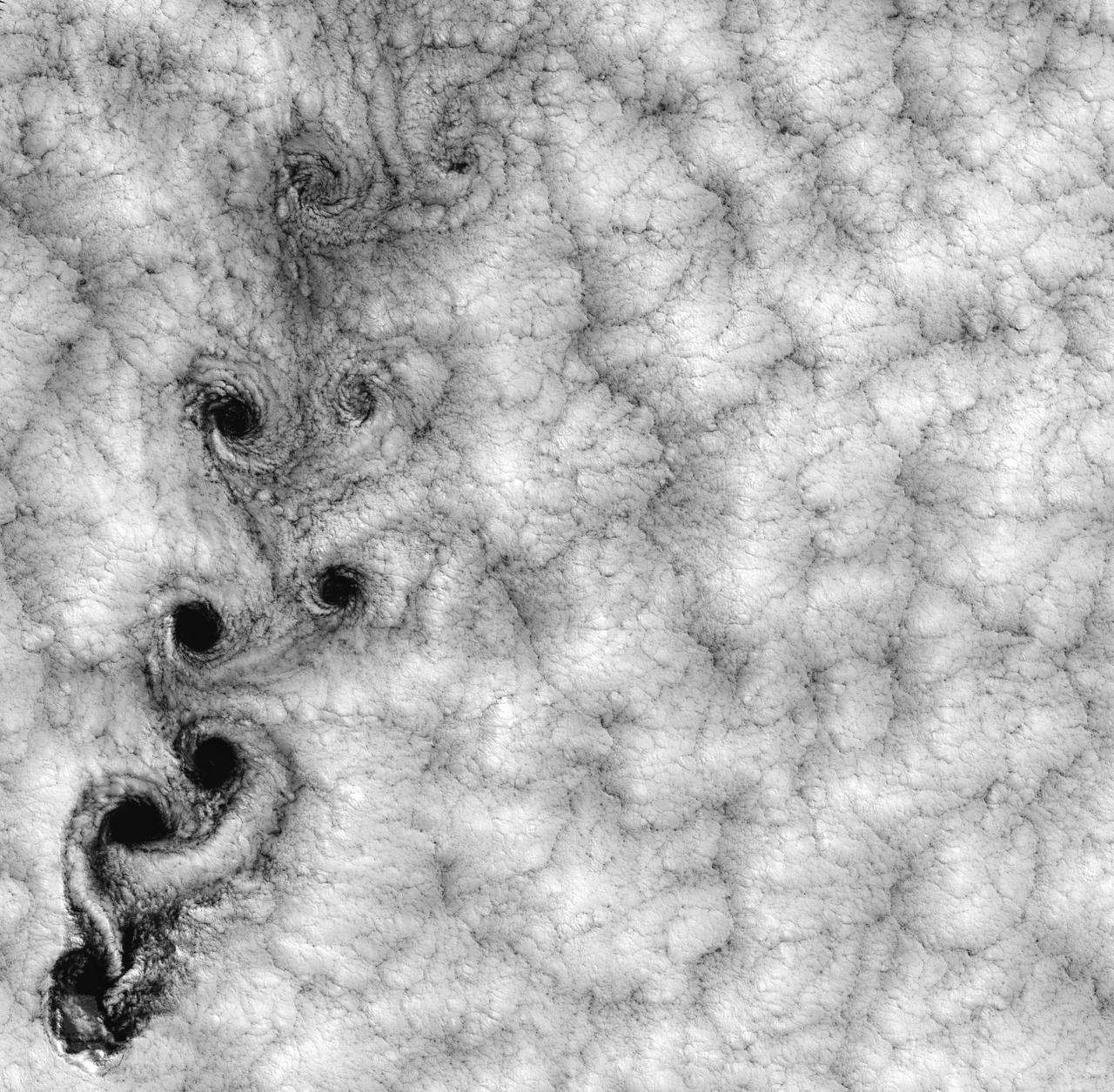

NASA image acquired September 15, 1999 This Landsat 7 image of clouds off the Chilean coast near the Juan Fernandez Islands (also known as the Robinson Crusoe Islands) on September 15, 1999, shows a unique pattern called a “von Karman vortex street.” This pattern has long been studied in the laboratory, where the vortices are created by oil flowing past a cylindrical obstacle, making a string of vortices only several tens of centimeters long. Study of this classic “flow past a circular cylinder” has been very important in the understanding of laminar and turbulent fluid flow that controls a wide variety of phenomena, from the lift under an aircraft wing to Earth’s weather. Here, the cylinder is replaced by Alejandro Selkirk Island (named after the true “Robinson Crusoe,” who was stranded here for many months in the early 1700s). The island is about 1.5 km in diameter, and rises 1.6 km into a layer of marine stratocumulus clouds. This type of cloud is important for its strong cooling of the Earth’s surface, partially counteracting the Greenhouse warming. An extended, steady equatorward wind creates vortices with clockwise flow off the eastern edge and counterclockwise flow off the western edge of the island. The vortices grow as they advect hundreds of kilometers downwind, making a street 10,000 times longer than those made in the laboratory. Observing the same phenomenon extended over such a wide range of sizes dramatizes the “fractal” nature of atmospheric convection and clouds. Fractals are characteristic of fluid flow and other dynamic systems that exhibit “chaotic” motions. Both clockwise and counter-clockwise vortices are generated by flow around the island. As the flow separates from the island’s leeward (away from the source of the wind) side, the vortices “swallow” some of the clear air over the island. (Much of the island air is cloudless due to a local “land breeze” circulation set up by the larger heat capacity of the waters surrounding the island.) The “swallowed” gulps of clear island air get carried along within the vortices, but these are soon mixed into the surrounding clouds. Landsat is unique in its ability to image both the small-scale eddies that mix clear and cloudy air, down to the 30 meter pixel size of Landsat, but also having a wide enough field-of-view, 180 km, to reveal the connection of the turbulence to large-scale flows such as the subtropical oceanic gyres. Landsat 7, with its new onboard digital recorder, has extended this capability away from the few Landsat ground stations to remote areas such as Alejandro Island, and thus is gradually providing a global dynamic picture of evolving human-scale phenomena. For more details on von Karman vortices, refer to <a href="http://climate.gsfc.nasa.gov/~cahalan" rel="nofollow">climate.gsfc.nasa.gov/~cahalan</a>. Image and caption courtesy Bob Cahalan, NASA GSFC Instrument: Landsat 7 - ETM+ Credit: NASA/GSFC/Landsat <b><a href="http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/home/index.html" rel="nofollow">NASA Goddard Space Flight Center</a></b> enables NASA’s mission through four scientific endeavors: Earth Science, Heliophysics, Solar System Exploration, and Astrophysics. Goddard plays a leading role in NASA’s accomplishments by contributing compelling scientific knowledge to advance the Agency’s mission. <b>Follow us on <a href="http://twitter.com/NASA_GoddardPix" rel="nofollow">Twitter</a></b> <b>Join us on <a href="http://www.facebook.com/pages/Greenbelt-MD/NASA-Goddard/395013845897?ref=tsd" rel="nofollow">Facebook</a></b>

The Dryden C-140 JetStar during testing of advanced propfan designs. Dryden conducted flight research in 1981-1982 on several designs. The technology was developed under the direction of the Lewis Research Center (today the Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, OH) under the Advanced Turboprop Program. Under that program, Langley Research Center in Virginia oversaw work on accoustics and noise reduction. These efforts were intended to develop a high-speed and fuel-efficient turboprop system.

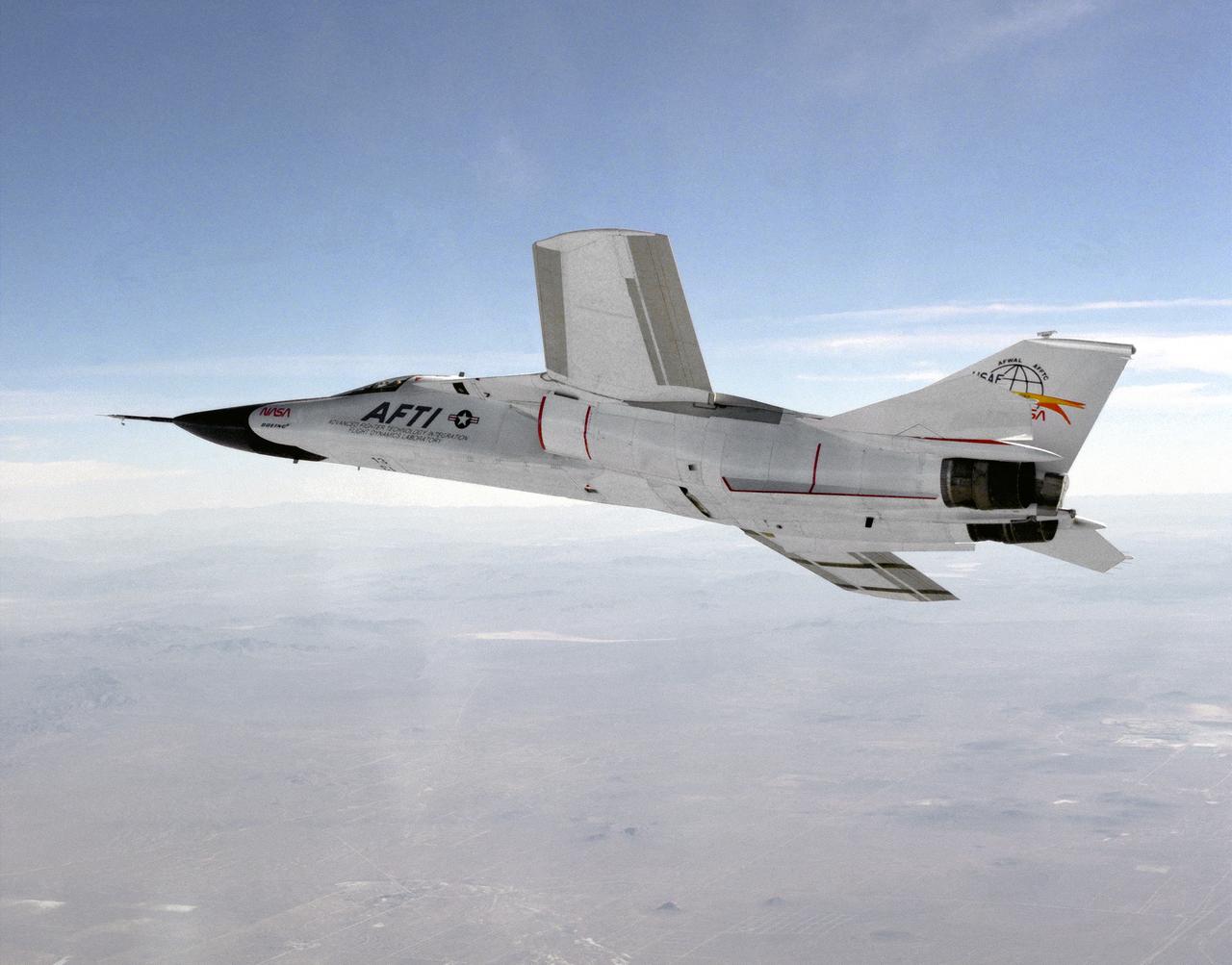

This photograph shows a modified General Dynamics AFTI/F-111A Aardvark with supercritical mission adaptive wings (MAW) installed. The four dark bands on the right wing are the locations of pressure orifices used to measure surface pressures and shock locations on the MAW. The El Paso Mountains and Red Rock Canyon State Park Califonia, about 30 miles northwest of Edwards Air Force Base, are seen directly in the background. With the phasing out of the TACT program came a renewed effort by the Air Force Flight Dynamics Laboratory to extend supercritical wing technology to a higher level of performance. In the early 1980s the supercritical wing on the F-111A aircraft was replaced with a wing built by Boeing Aircraft Company System called a “mission adaptive wing” (MAW), and a joint NASA and Air Force program called Advanced Fighter Technology Integration (AFTI) was born.

This photograph shows a modified General Dynamics TACT/F-111A Aardvaark with supercritical wings installed. The aircraft, with flaps and landing gear down, is in a decending turn over Rogers Dry Lakebed at Edwards Air Force Base. Starting in 1971 the NASA Flight Research Center and the Air Force undertook a major research and flight testing program, using F-111A (#63-9778), which would span almost 20 years before completion. Intense interest over the results coming from the NASA F-8 supercritical wing program spurred NASA and the Air Force to modify the General Dynamics-Convair F-111A to explore the application of supercritical wing technology to maneuverable military aircraft. This flight program was called Transonic Aircraft Technology (TACT).

This photograph shows a modified General Dynamics AFTI/F-111A Aardvark with supercritical mission adaptive wings (MAW) installed. The AFTI/F111A is seen banking towards Rodgers Dry Lake and Edwards Air Force Base. With the phasing out of the TACT program came a renewed effort by the Air Force Flight Dynamics Laboratory to extend supercritical wing technology to a higher level of performance. In the early 1980s the supercritical wing on the F-111A aircraft was replaced with a wing built by Boeing Aircraft Company System called a “mission adaptive wing” (MAW), and a joint NASA and Air Force program called Advanced Fighter Technology Integration (AFTI) was born.

The General Dynamics TACT/F-111A Aardvark is seen In a banking-turn over the California Mojave desert. This photograph affords a good view of the supercritical wing airfoil shape. Starting in 1971 the NASA Flight Research Center and the Air Force undertook a major research and flight testing program, using F-111A (#63-9778), which would span almost 20 years before completion. Intense interest over the results coming from the NASA F-8 supercritical wing program spurred NASA and the Air Force to modify the General Dynamics F-111A to explore the application of supercritical wing technology to maneuverable military aircraft. This flight program was called Transonic Aircraft Technology (TACT).

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of sp

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of

Long-time NASA Dryden research pilot and former astronaut C. Gordon Fullerton capped an almost 50-year flying career, including more than 38 years with NASA, with a final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007. Fullerton and Dryden research pilot Jim Smolka flew a 90-minute pilot proficiency formation aerobatics flight with another Dryden F/A-18 and a Dryden T-38 before concluding with two low-level formation flyovers of Dryden before landing. Fullerton was honored with a water-cannon spray arch provided by two fire trucks from the Edwards Air Force Base fire department as he taxied the F/A-18 up to the Dryden ramp, and was then greeted by his wife Marie and several hundred Dryden staff after his final flight. Fullerton began his flying career with the U.S. Air Force in 1958 after earning bachelor's and master's degrees in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. Initially trained as a fighter pilot, he later transitioned to multi-engine bombers and became a bomber operations test pilot after attending the Air Force Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. He then was assigned to the flight crew for the planned Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory in 1966. Upon cancellation of that program, the Air Force assigned Fullerton to NASA's astronaut corps in 1969. He served on the support crews for the Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17 lunar missions, and was later assigned to one of the two flight crews that piloted the space shuttle prototype Enterprise during the Approach and Landing Test program at Dryden. He then logged some 382 hours in space when he flew on two early space shuttle missions, STS-3 on Columbia in 1982 and STS-51F on Challenger in 1985. He joined the flight crew branch at NASA Dryden after leaving the astronaut corps in 1986. During his 21 years at Dryden, Fullerton was project pilot on a number of high-profile research efforts, including the Propulsion Controlled Aircraft, the high-speed landing tests of

NASA Dryden research pilot Gordon Fullerton is greeted by his wife Marie on the Dryden ramp after his final flight in a NASA F/A-18 on Dec. 21, 2007.