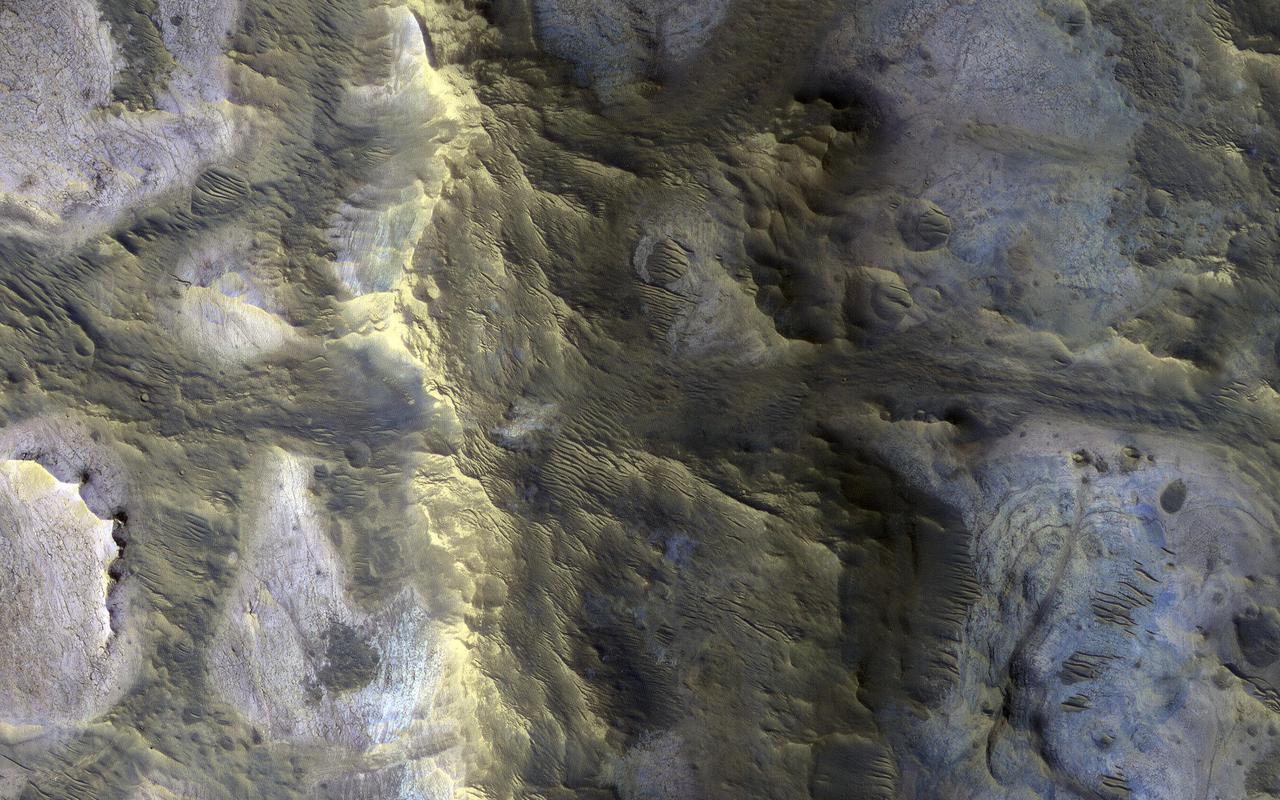

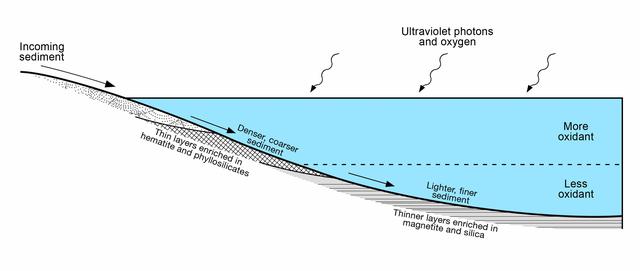

Investigation of exposed clay minerals at thousands of Martian sites by NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter suggests a long period of wet, warm conditions, mostly underground.

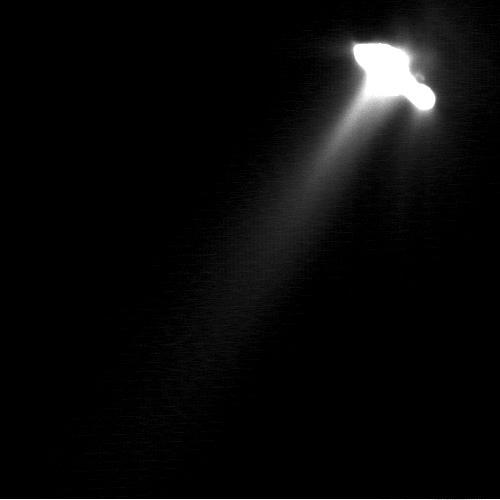

This very long exposure was taken by NASA Deep Space 1 to show detailed structures in the faint parts of comet Borrelly inner coma. As a result, the nucleus has been greatly over-exposed and its shape appears distorted.

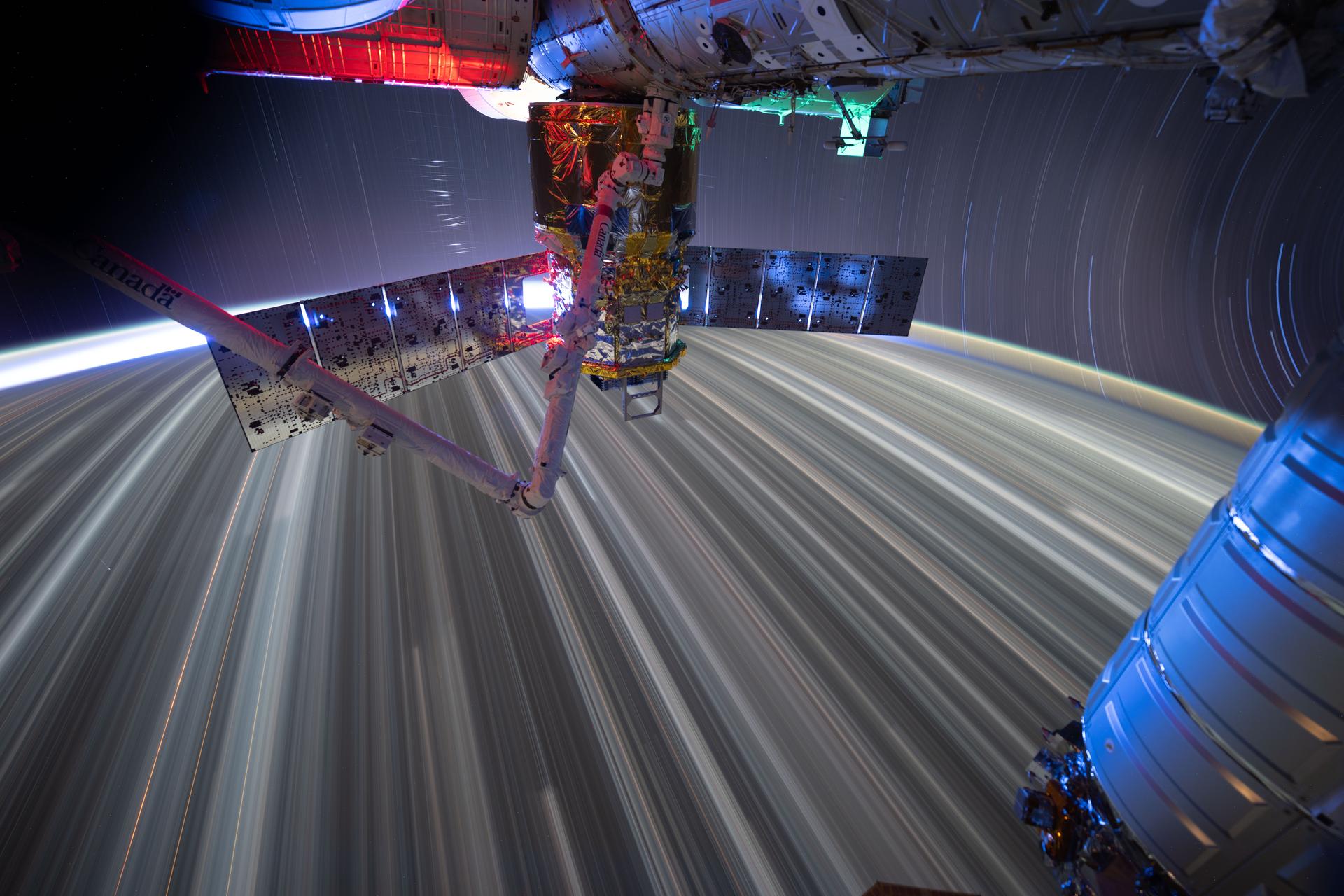

iss073e0427643 (July 26, 2025) --- This long-exposure photograph, taken over 31 minutes from a window inside the International Space Station’s Kibo laboratory module, captures the circular arcs of star trails. In the foreground is a portion of Kibo’s Exposed Facility, where various payloads and experiments are mounted to be exposed directly to the vacuum of space.

iss050e053932 (3/3/2017) --- A view of Long Duration Sorbent Testbed during Inlet Filter change. The Long Duration Sorbent Testbed (LDST) investigation exposes desiccants and CO2 sorbents to the ISS atmosphere for an extended period (such as one year) before returning them to earth for analysis of contamination level and capacity loss. The results will determine which types of sorbents would be most effective on long-term missions to Mars or other destinations.

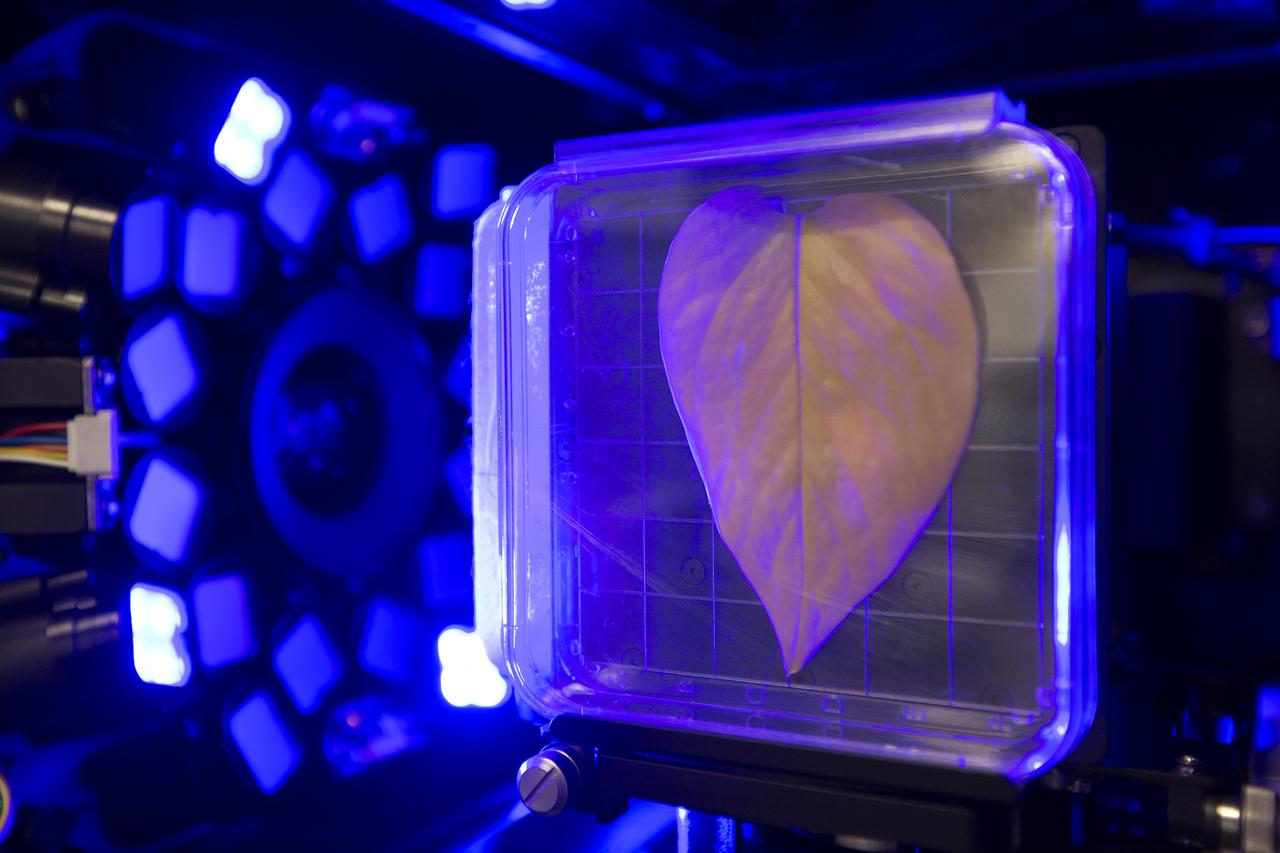

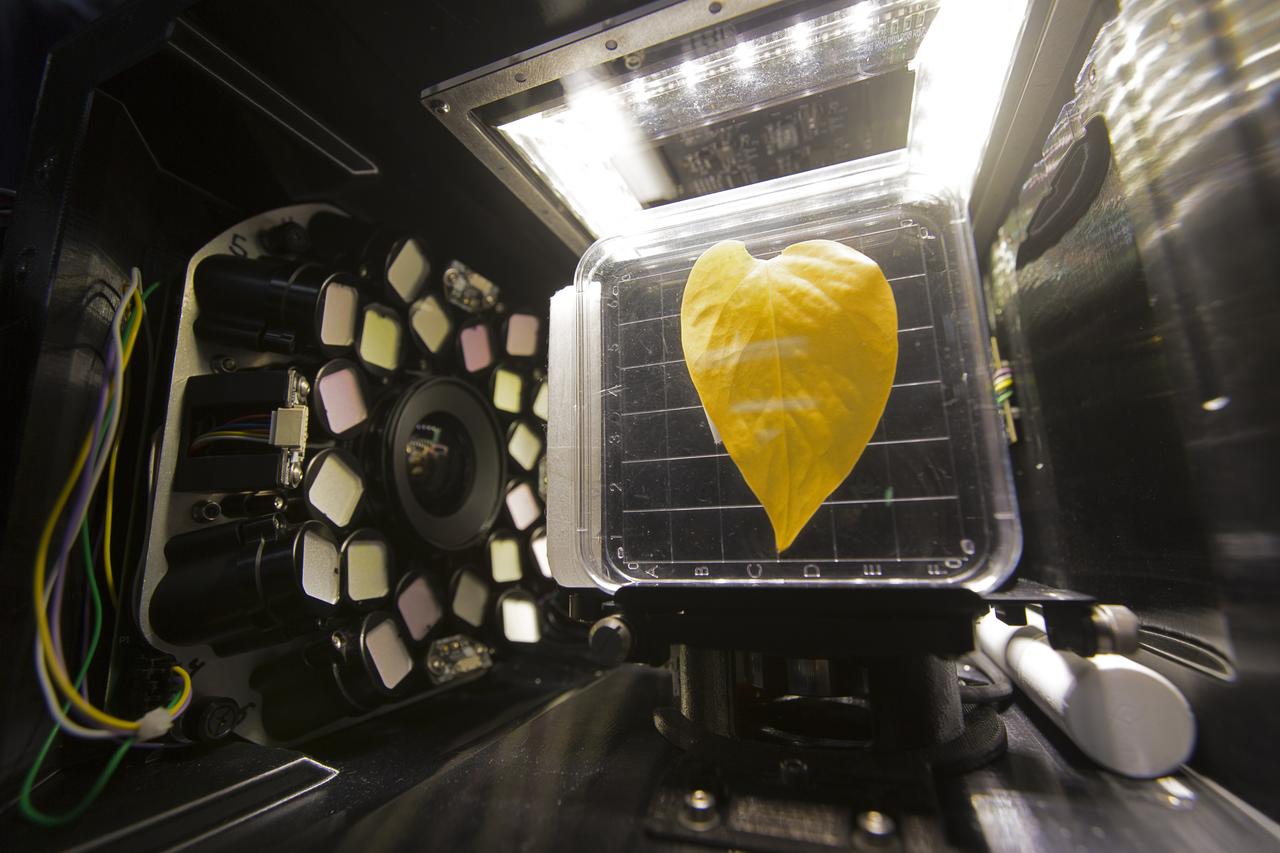

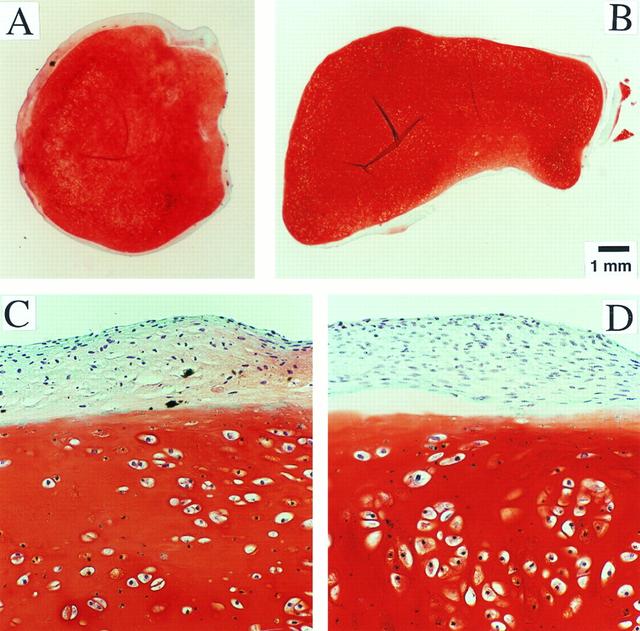

Inside the Spectrum prototype unit, organisms in a Petri plate are exposed to blue excitation lighting. The device works by exposing organisms to different colors of fluorescent light while a camera records what's happening with time-lapse photography. Results from the Spectrum project will shed light on which living things are best suited for long-duration flights into deep space.

Inside the Spectrum prototype unit, organisms in a Petri plate are exposed to blue excitation lighting. The device works by exposing organisms to different colors of fluorescent light while a camera records what's happening with time-lapse photography. Results from the Spectrum project will shed light on which living things are best suited for long-duration flights into deep space.

Inside the Spectrum prototype unit, organisms in a Petri plate are exposed to blue excitation lighting. The device works by exposing organisms to different colors of fluorescent light while a camera records what's happening with time-lapse photography. Results from the Spectrum project will shed light on which living things are best suited for long-duration flights into deep space.

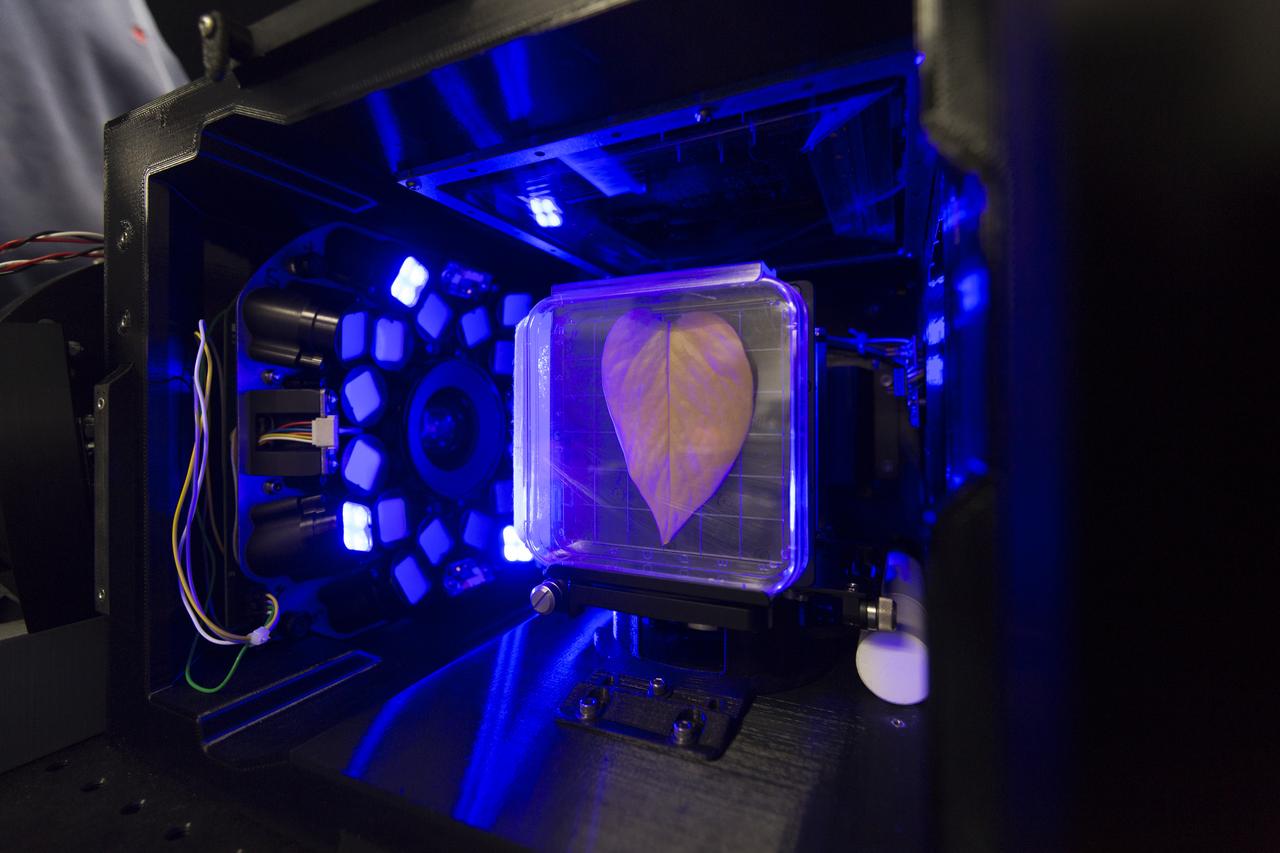

Inside the Spectrum prototype unit, organisms in a Petri plate are exposed to different colors of lighting. The device works by exposing organisms to different colors of fluorescent light while a camera records what's happening with time-lapse photography. Results from the Spectrum project will shed light on which living things are best suited for long-duration flights into deep space.

Inside the Spectrum prototype unit, organisms in a Petri plate are exposed to different colors of lighting. The device works by exposing organisms to different colors of fluorescent light while a camera records what's happening with time-lapse photography. Results from the Spectrum project will shed light on which living things are best suited for long-duration flights into deep space.

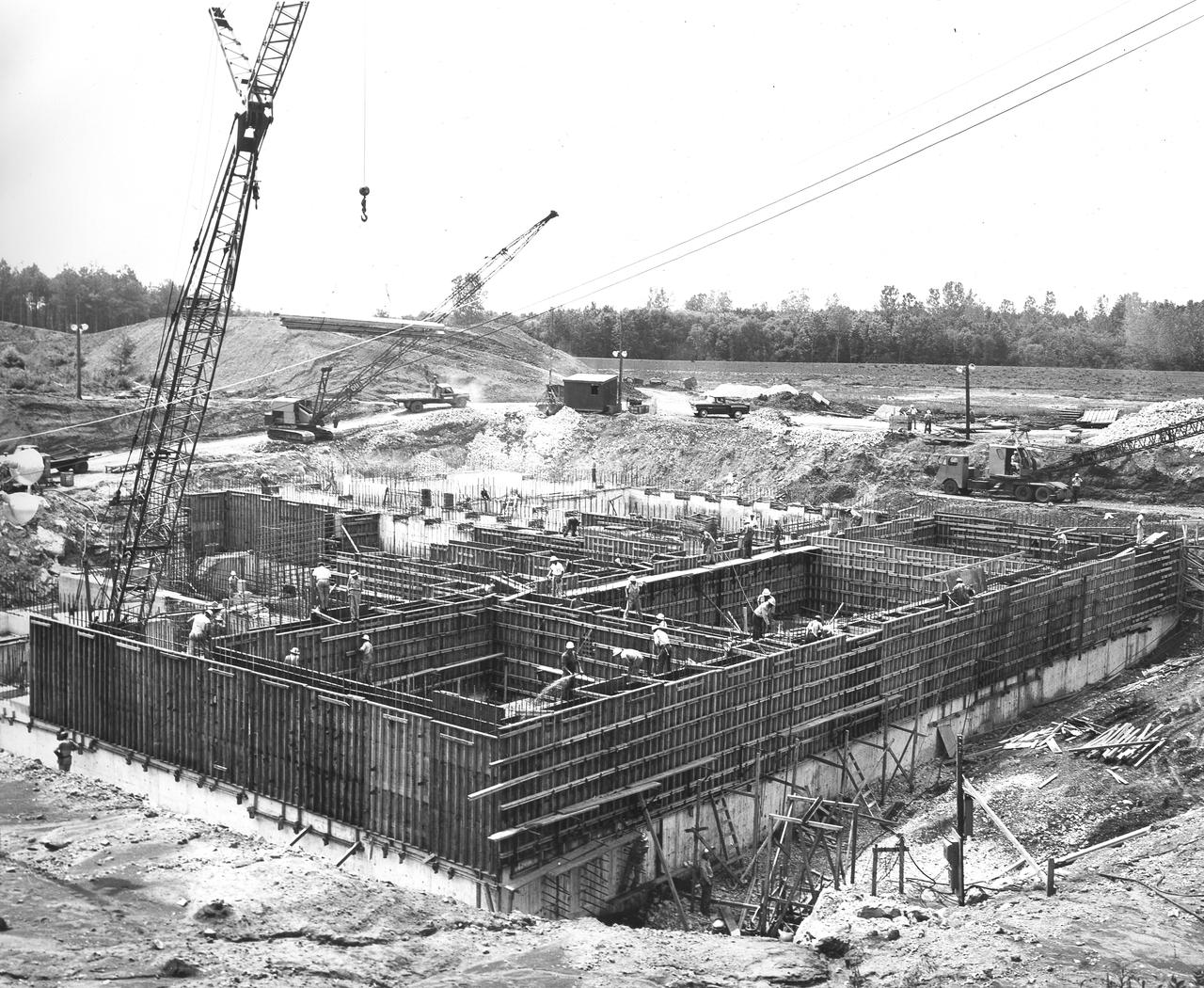

Aerial view looking North West of the nearly completed 40 x 80 foot wind tunnel. Drive and test section exposed. The facility covered 8 acres, and the air circuit was just over 1/2 mile long (2700 feet).

STS073-E-5098 (30 Oct. 1995) --- Long Island, New York stretches across the scene. The New York City metropolitan complex is at the left; Central Park can be seen as a dark rectangle between the Hudson and East Rivers. Sandy beaches of the Long Island barrier islands mark the boundary between Atlantic Ocean and quiet lagoons and marshes. The frame was exposed with the Electronic Still Camera (ESC).

ISS024-E-016051 (27 Aug. 2010) --- This night time view captured by one of the Expedition 24 crew members aboard the International Space Station some 220 miles above Earth is looking down upon New York City. The actual nadir estimate is 39.1 degrees north latitude and 71.2 degrees west longitude or about 170 miles southeast of the city over the Atlantic. Philadelphia is also visible to the right. Long Island and the Connecticut coastal cities mark Long Island Sound. Atlantic City is that small bright spot in the upper right corner. The image was exposed in August and was physically brought back to Earth on a disk with the return of the Expedition 25 crew in November 2010.

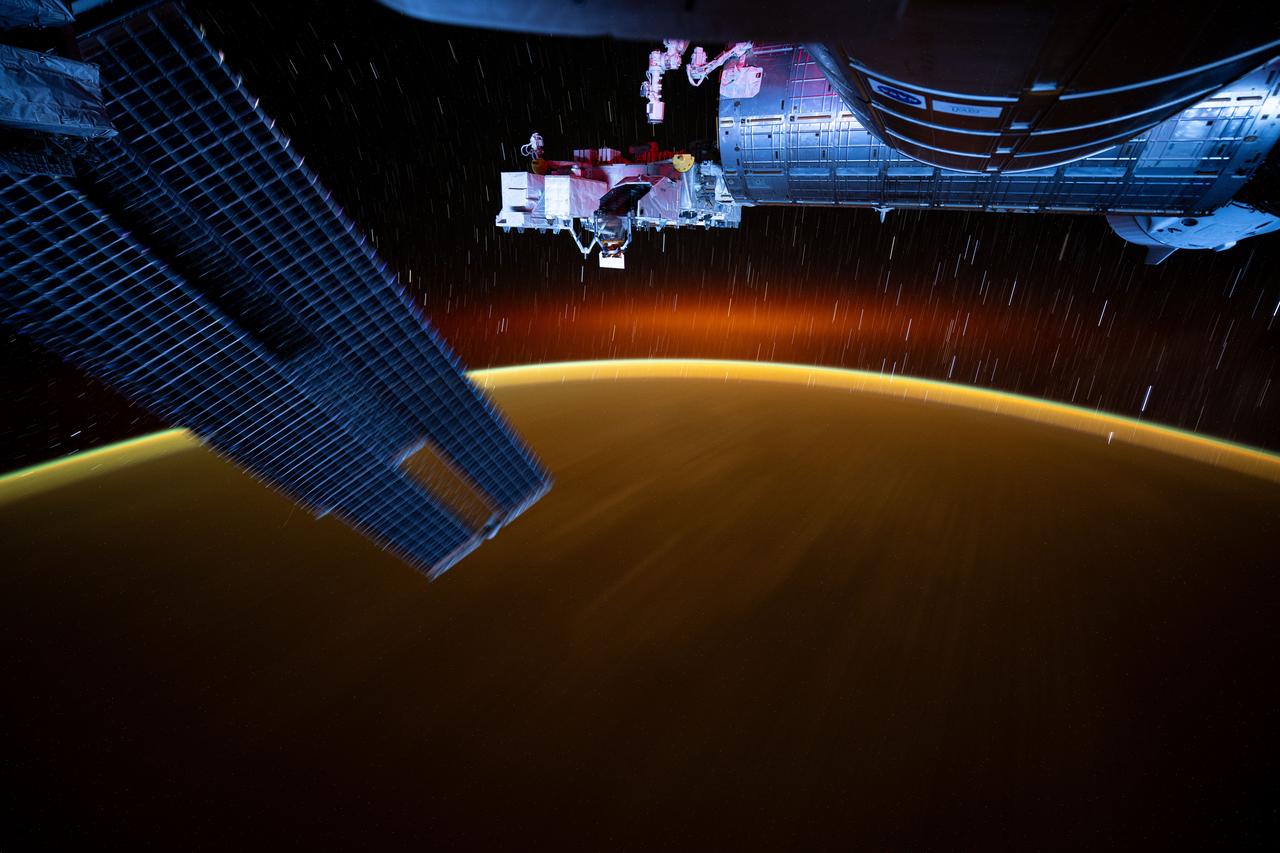

iss072e940709 (April 2, 2025) --- This long duration photograph looks out from a window on the cupola revealing Earth's atmopsheric glow underneath star trails as the International Space Station orbited 258 miles above the Pacific Ocean southeast of Hawaii at approximately 8:15 p.m. local time. In the foreground, is the Kibo laboratory module (left), and Kibo's External Platform (center) that houses experiments exposed to the vacuum of space, and a set of the space station's main solar arrays (right).

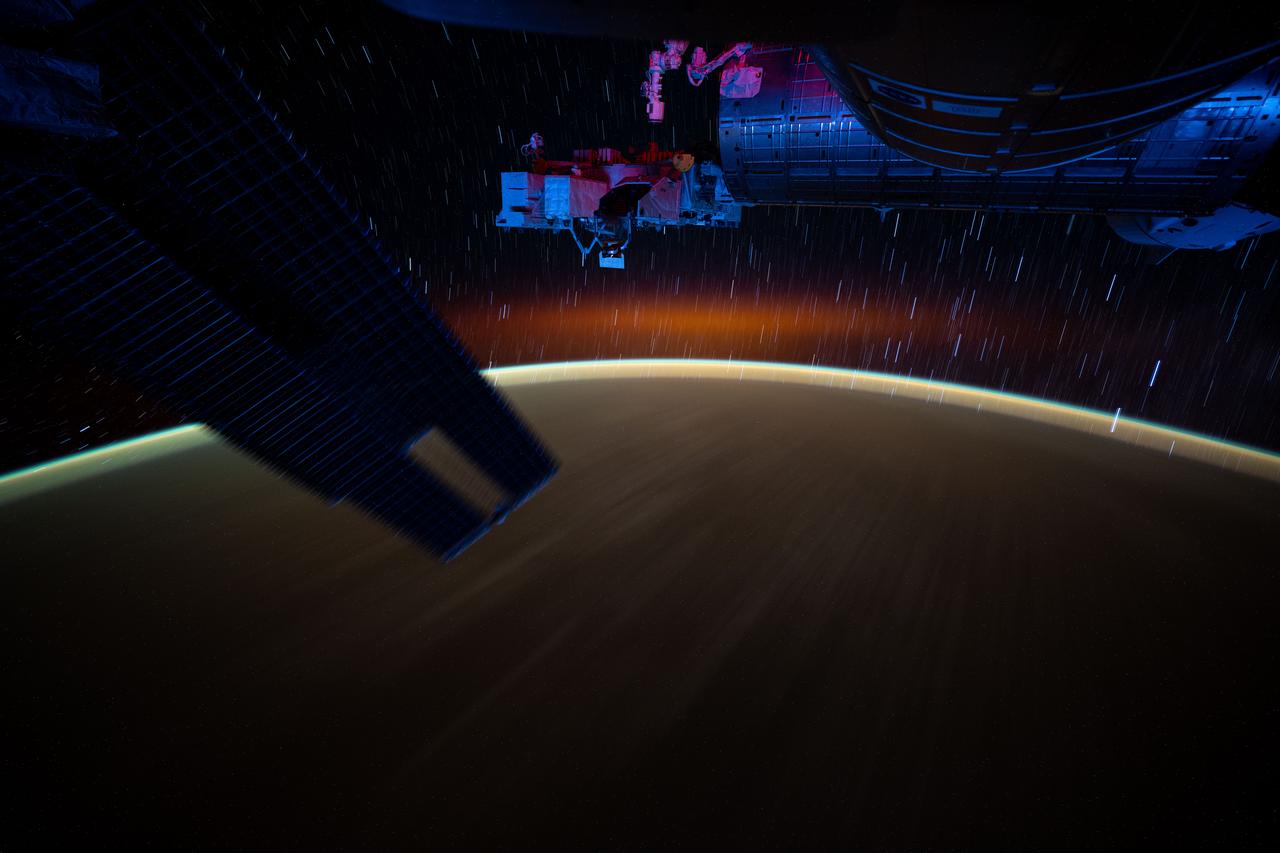

iss072e921627 (March 30, 2025) --- This long-duration photograph from the International Space Station highlights star trails and an atmospheric glow blanketing Earth's horizon. In the foreground, is a set of the space station's main solar arrays (left), the Kibo laboratory module (right), and Kibo's External Platform that houses experiments exposed to the vacuum of space. The orbital outpost was soaring 259 miles above the Pacific Ocean southeast of Japan going into a sunset.

STS064-72-093 (10 Sept. 1994) --- With the blue and white Earth as a backdrop 130 miles below, the Shuttle Plume Impingement Flight Experiment (SPIFEX) is at work on the end of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm. The 50-feet-long arm is extended to 80 feet with the temporary addition of the SPIFEX hardware. The image was exposed with a 70mm handheld Hasselblad camera from inside the space shuttle Discovery's crew cabin. Photo credit: NASA or National Aeronautics and Space Administration

iss068e018681 (Oct. 25, 2022) --- View of tomatoes growing in the eXposed Root On-Orbit Test System (XROOTS) facility. The tomatoes were grown without soil using hydroponic and aeroponic nourishing techniques to demonstrate space agricultural methods to sustain crews on long term space flights farther away from Earth where resupply missions become impossible.

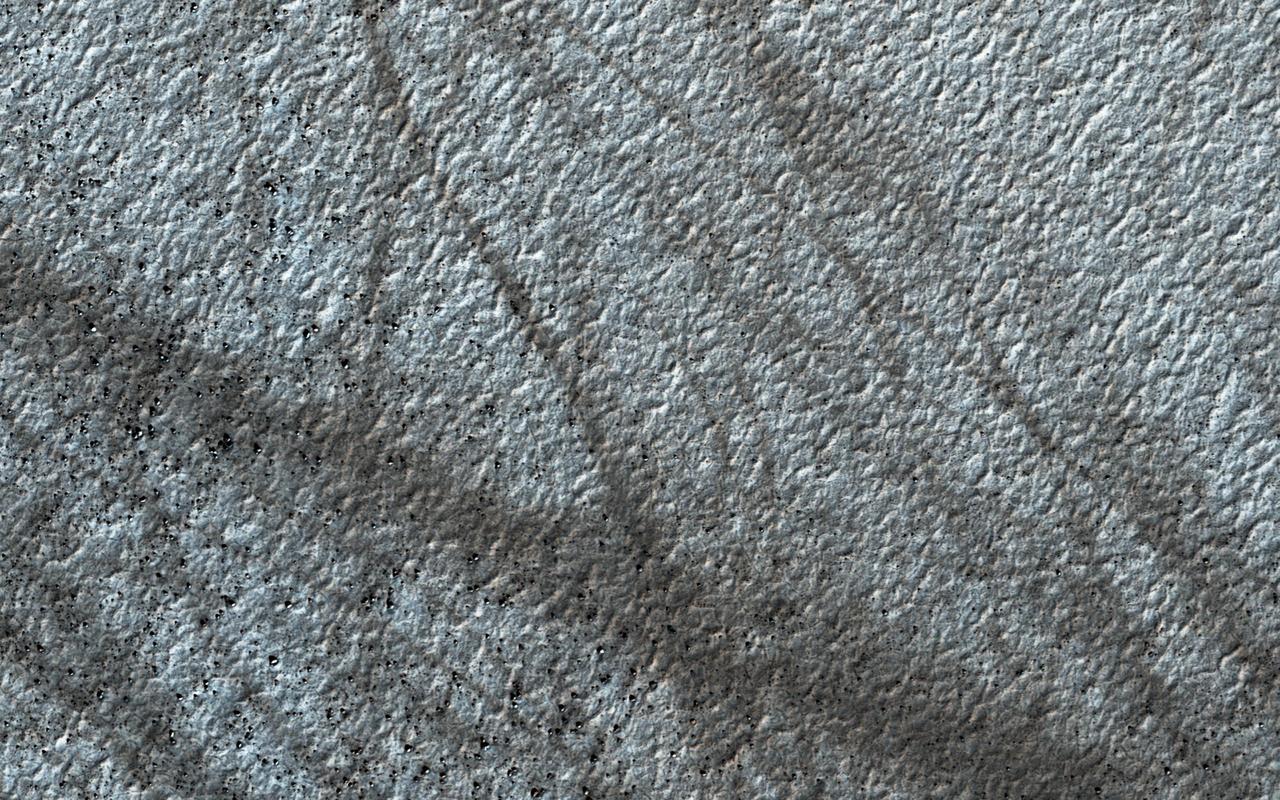

Dust devils on Mars often create long, dark markings where they pull a thin coat of dust off the surface. This image shows a cluster of these tracks on the flat ground below the south polar layered deposits, but none on the layers themselves. This tells us that either dust devils do not cross the layers, or they do not leave a track there. There are several possible reasons for this. For instance, the dust might be thick enough that the vortex of the dust devil doesn't expose darker material from underneath the surface. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23064

iss072e921629 (March 30, 2025) --- This long-duration photograph from the International Space Station highlights star trails and an atmospheric glow blanketing Earth's horizon. In the foreground, is a set of the space station's main solar arrays (left), the Kibo laboratory module (right), and Kibo's External Platform that houses experiments exposed to the vacuum of space. The orbital outpost was soaring 259 miles above the Pacific Ocean southeast of Japan after sunset.

iss072e921628 (March 30, 2025) --- This long-duration photograph from the International Space Station highlights star trails and an atmospheric glow blanketing Earth's horizon. In the foreground, is a set of the space station's main solar arrays (left), the Kibo laboratory module (right), and Kibo's External Platform that houses experiments exposed to the vacuum of space. The orbital outpost was soaring 259 miles above the Pacific Ocean southeast of Japan just after sunset.

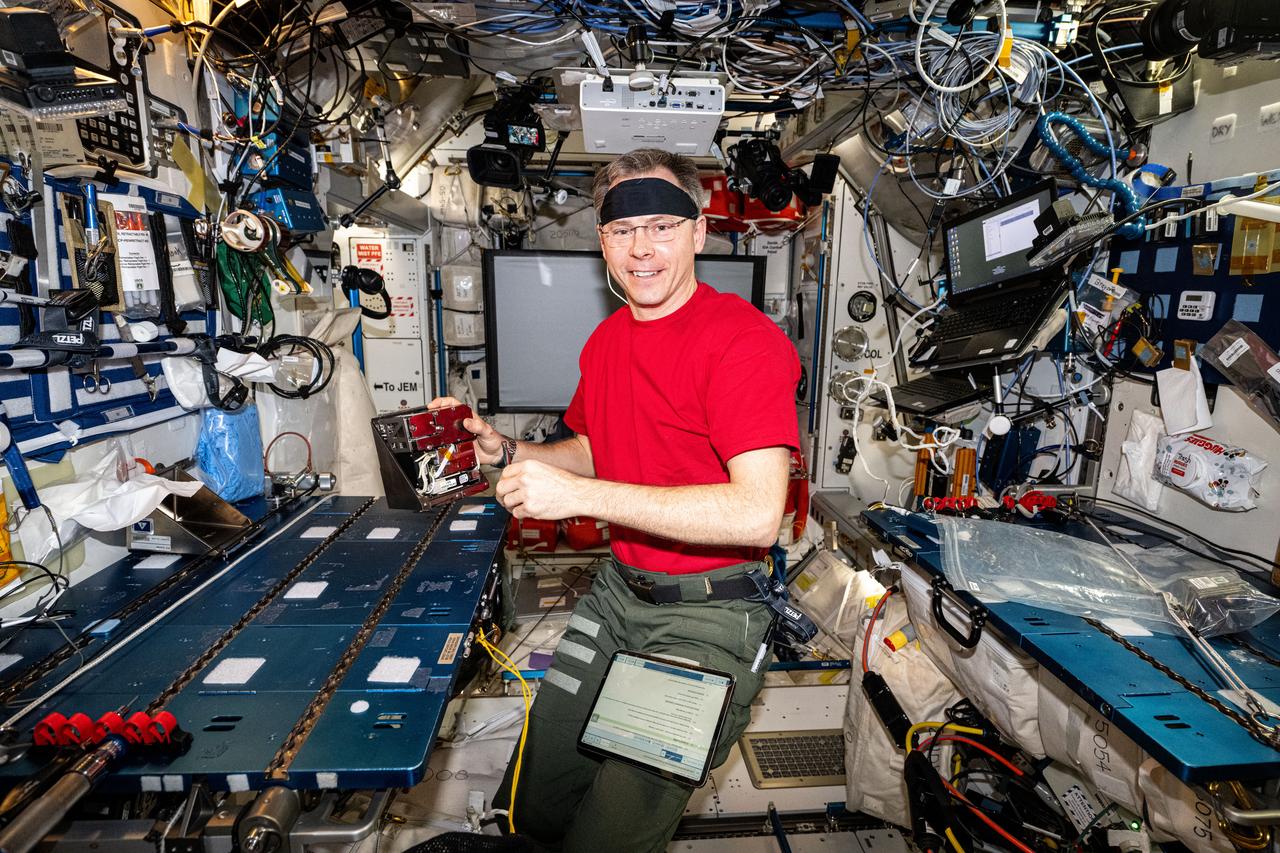

iss072e452598 (Jan. 10, 2025) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 72 Flight Engineer Nick Hague processes samples of micro-algae at the Harmony module's maintenance work area aboard the International Space Station. The Arthrospira C biotechnology investigation exposes micro-algae to cosmic radiation and microgravity to learn how to revitalize the spacecraft environment using photosynthesis and produce fresh food on long-term space missions.

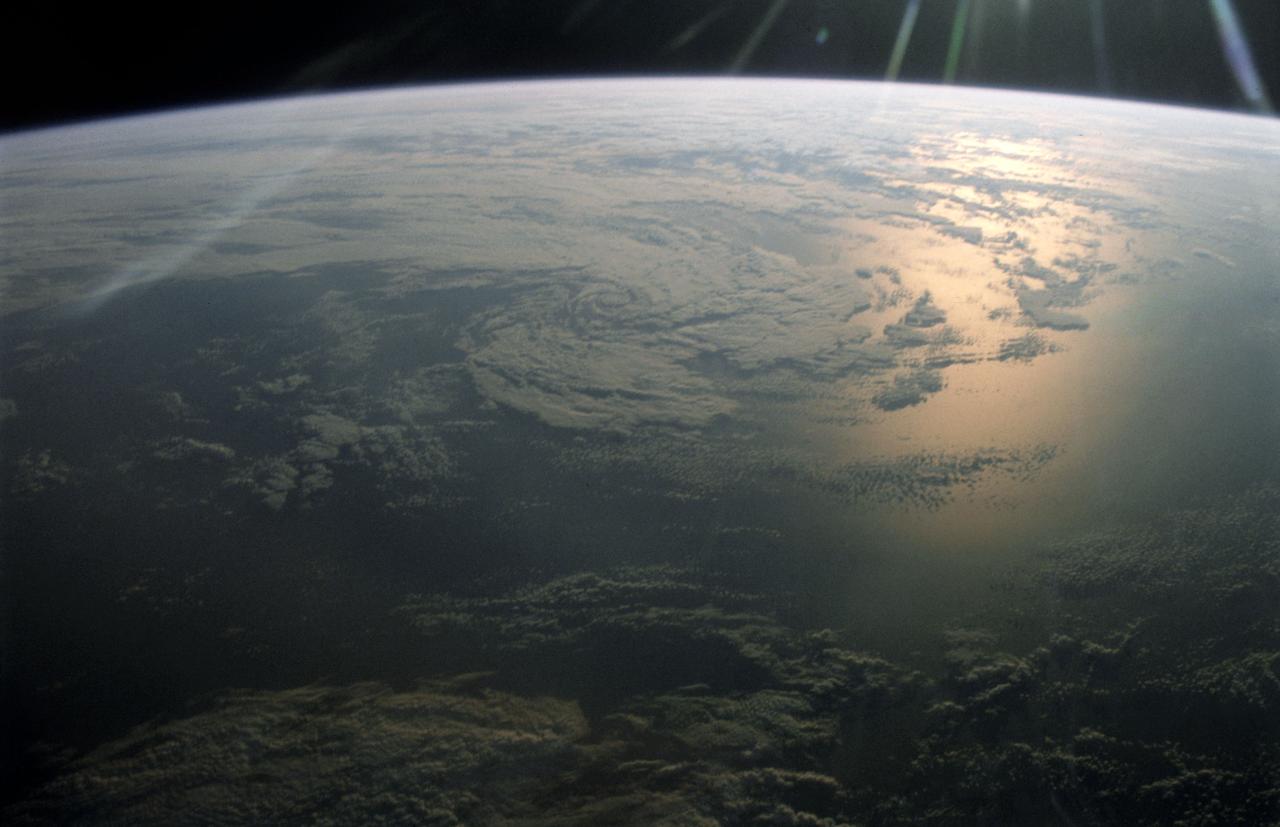

STS005-14-514 (11-16 Nov. 1982) --- This 35mm frame, taken against sunglint, shows clouds over the Pacific Ocean. A Nikon F-3 35mm modified camera and Type 5017, medium speed Ektachrome film were used to record the frame. Approximately 20 frames of 35mm and several dozen frames of 70mm photography of Earth were exposed on the week-long mission aboard the space shuttle Columbia (STS-5). Photo credit: NASA

iss072e921626 (March 30, 2025) --- This long-duration photograph from the International Space Station highlights star trails and an atmospheric glow blanketing Earth's horizon. In the foreground, is a set of the space station's main solar arrays (left), the Kibo laboratory module (right), and Kibo's External Platform that houses experiments exposed to the vacuum of space. The orbital outpost was soaring 259 miles above the Pacific Ocean southeast of Japan moments before sunset.

Dr. Scott Shipley of Ascentech Enterprises makes an adjustment to the Spectrum unit. He is the project engineer for the effort working under the Engineering Services Contract at NASA's Kennedy Space Center. The device is being built for use aboard the International Space Station and is designed to expose different organisms to different color of fluorescent light while a camera records what's happening with time-laps imagery. Results from the Spectrum project will shed light on which living things are best suited for long-duration flights into deep space.

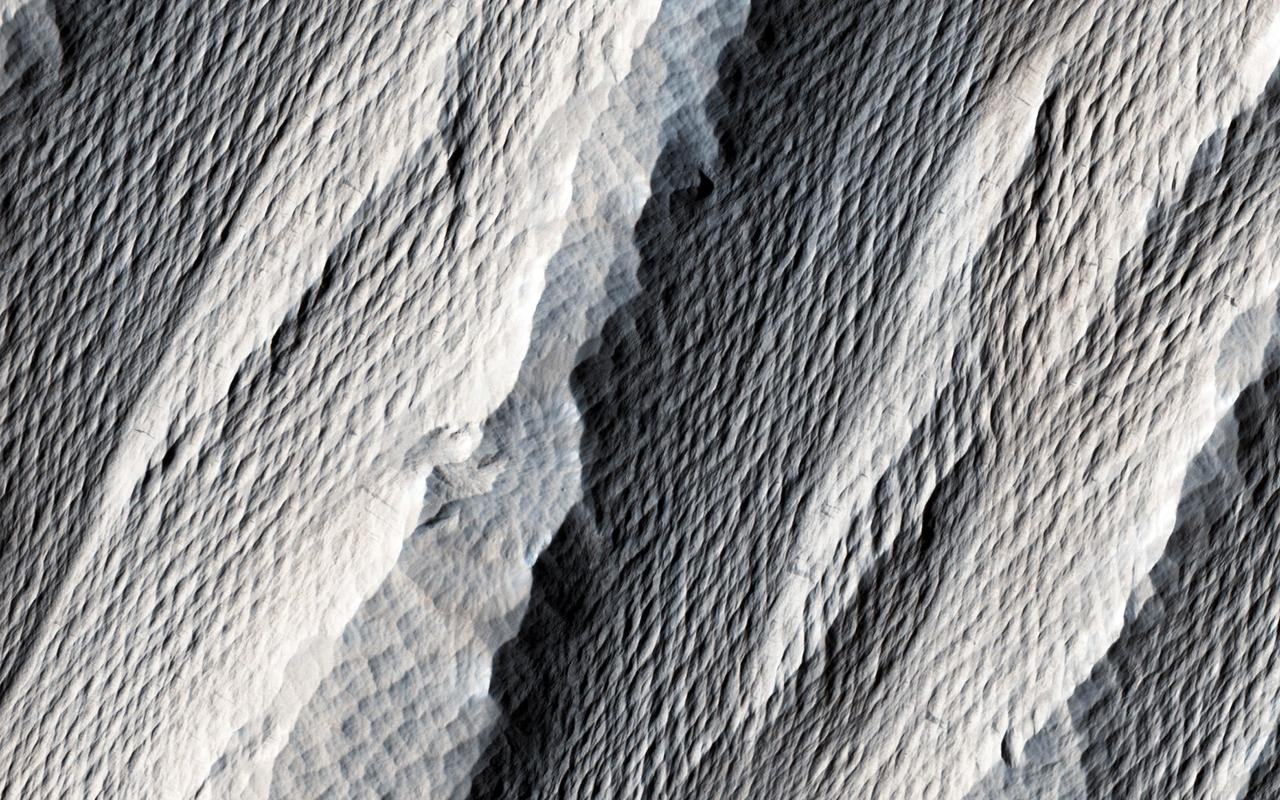

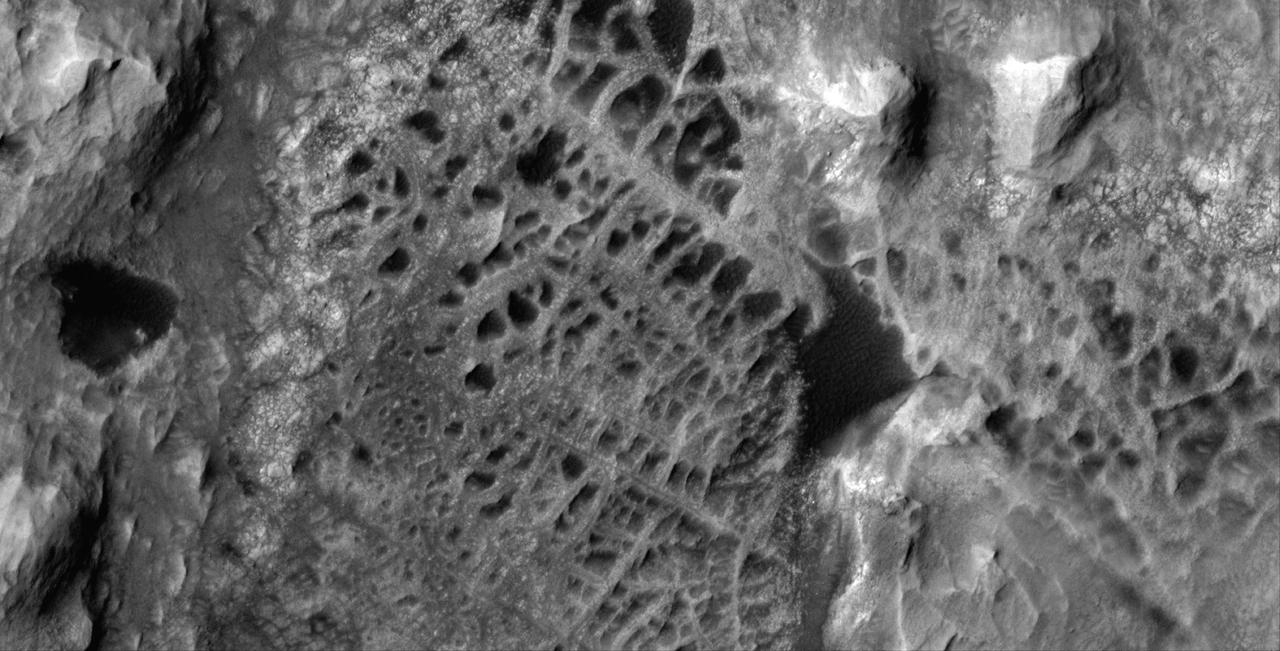

This intriguing, almost cartoon-like terrain is composed of coalescing pits and smooth-topped mesas, forming part of what is known as the Residual South Polar Cap (RSPC) of Mars. The RSPC is a permanent deposit of carbon dioxide (dry) ice that is several kilometers thick and overlies a much larger water ice cap. This part of the RSPC lies at an elevation of about 6.5 kilometers. The mesas are several kilometers long while the pits range in diameter up to several hundred meters. The dark regions surrounding the mesas are thought to be exposed water ice. This image was taken during southern summer when the brighter-appearing dry ice cap sublimates (evaporates directly from ice to vapor) exposing the darker, underlying water ice cap. Understanding the seasonal and yearly volumes of carbon dioxide exchange between the surface and the atmosphere provides important insights into Mars' climate. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24463

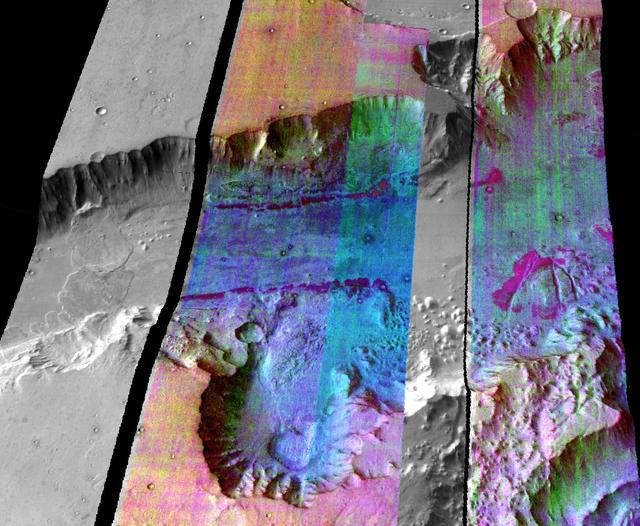

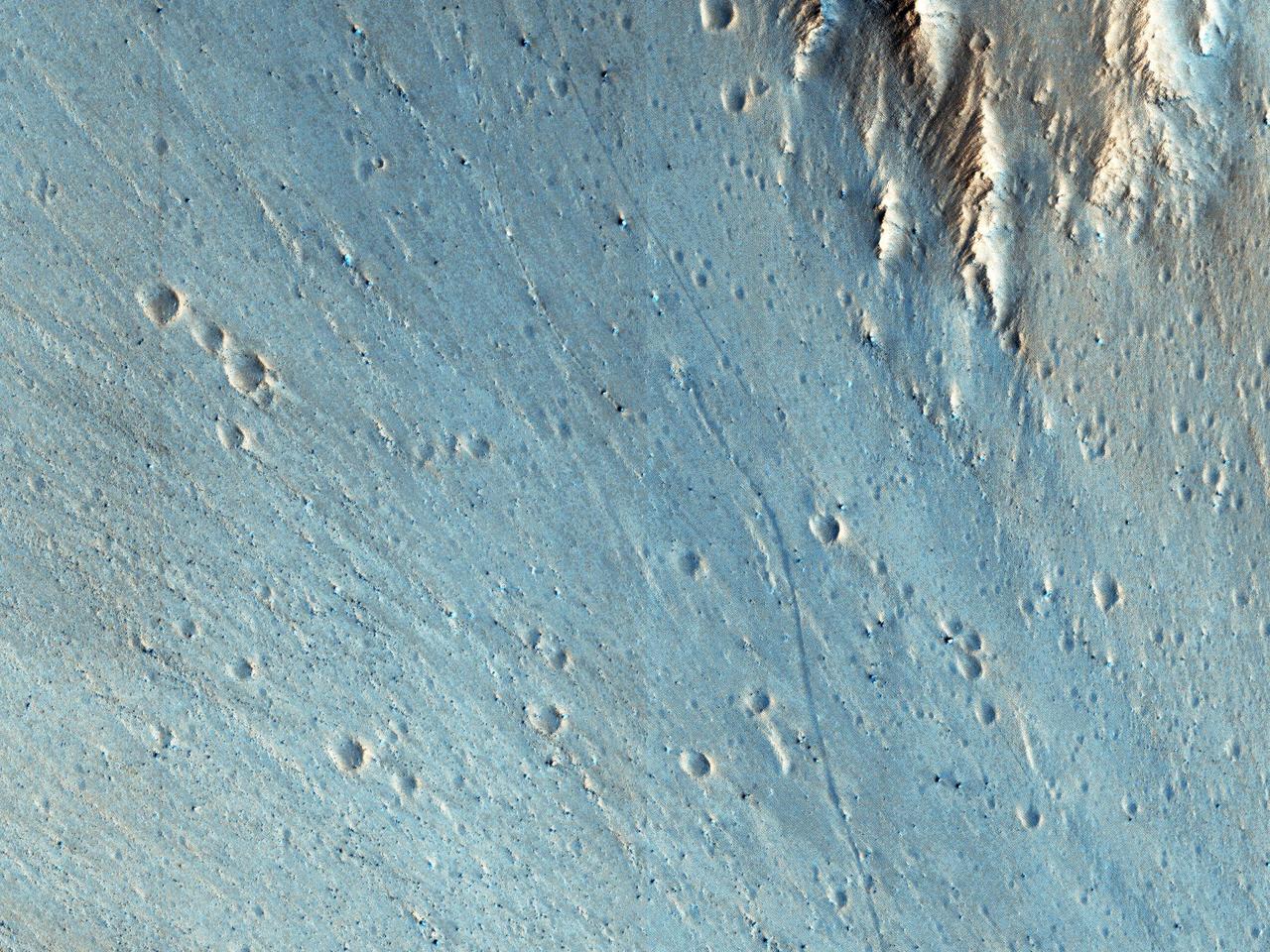

This image covers channels cutting through the ancient rim of Savich Crater, a 188 kilometer-wide depression near the northeastern edge of the much larger Hellas impact basin. The channels were likely eroded by water flowing into Savich Crater long ago. Our image reveals layers of varying brightness and texture exposed along the channels. Individual boulders are visible within the brighter layers (appearing blue-white in this enhanced color view), while redder layers lack distinct boulders. The meter-scale boulders could have been transported by floodwaters, or perhaps could be an even more ancient rock unit broken apart by impacts that these channels subsequently exposed. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25502

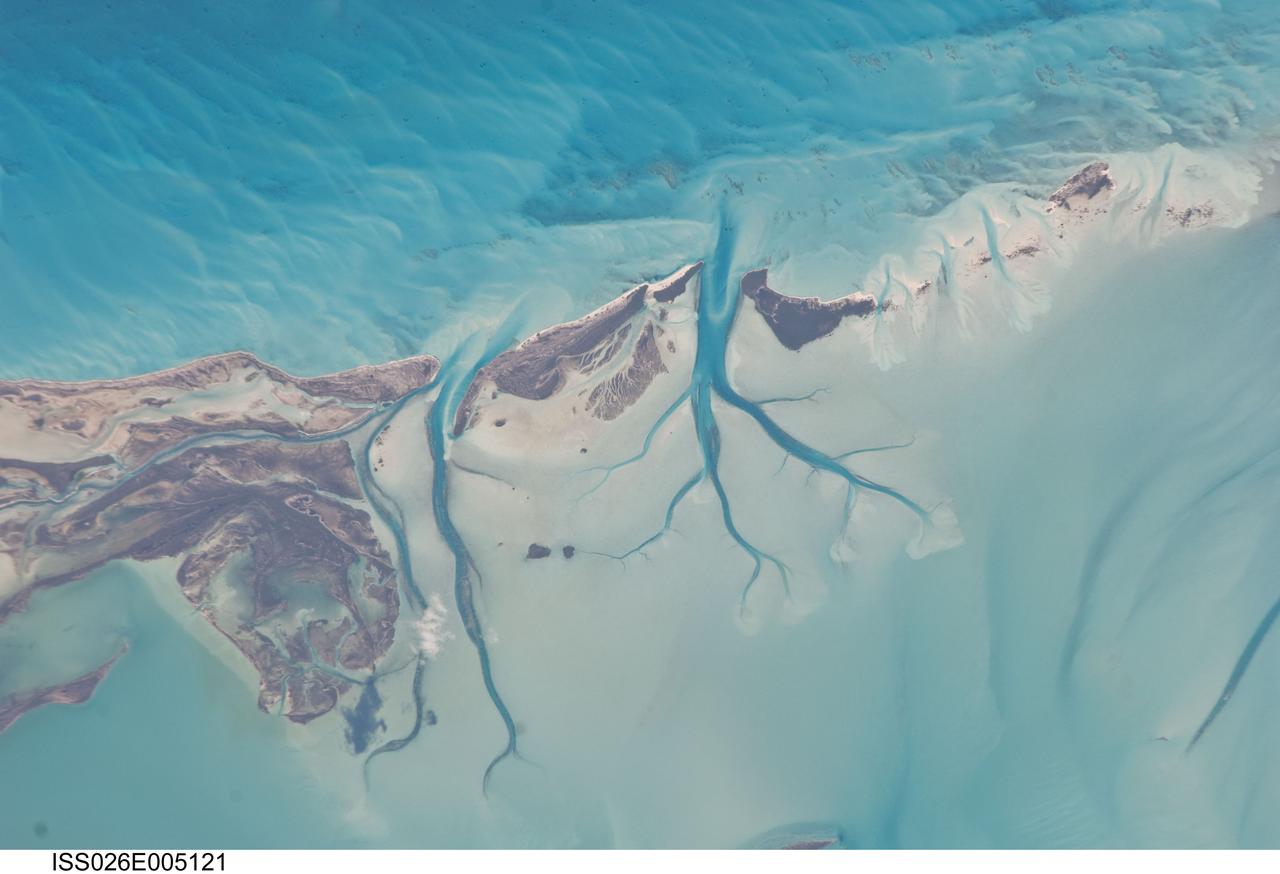

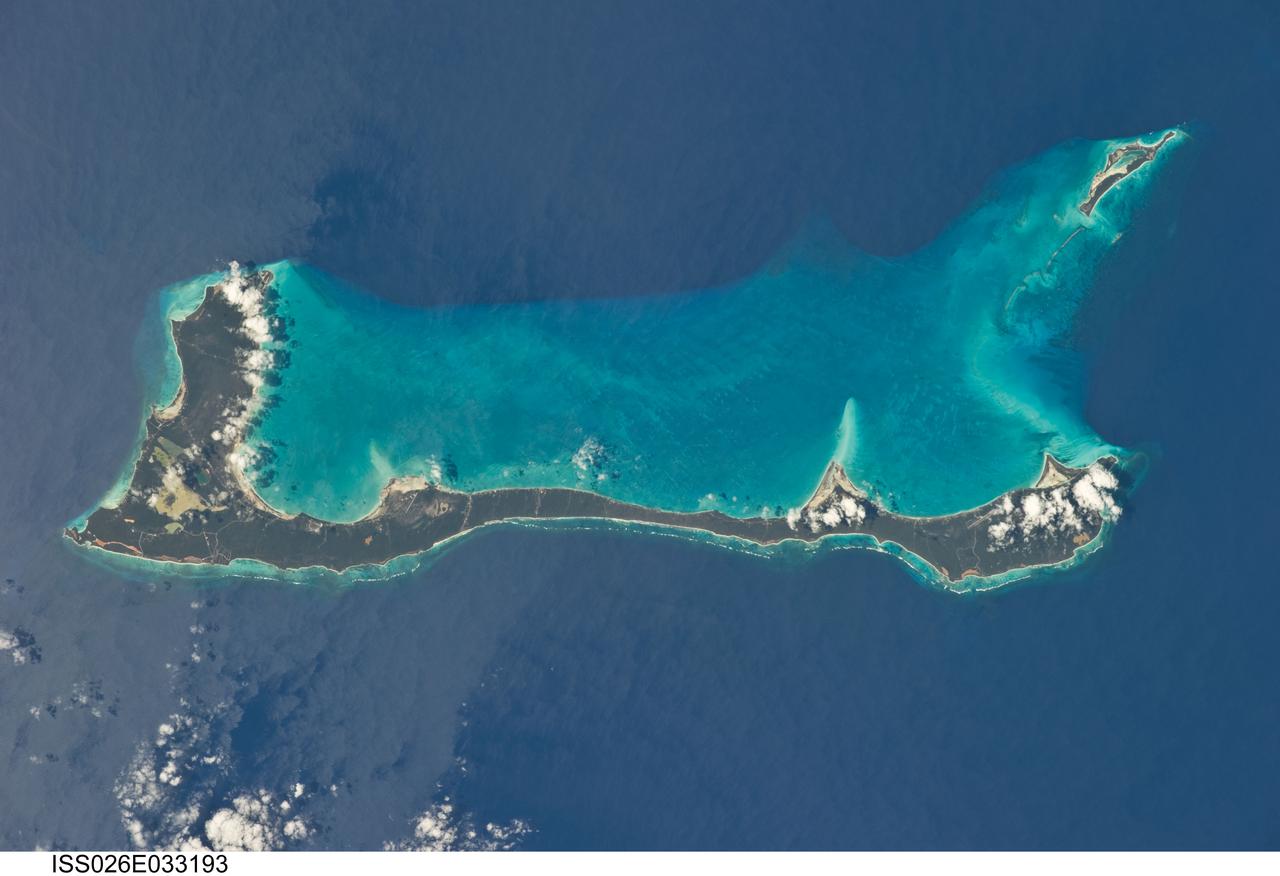

ISS026-E-005121 (27 Nov. 2010) --- Tidal flats and channels on Long Island, Bahamas are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 26 crew member on the International Space Station. The islands of the Bahamas in the Caribbean Sea are situated on large depositional platforms (the Great and Little Bahama Banks) composed mainly of carbonate sediments ringed by fringing reefs – the islands themselves are only the parts of the platform currently exposed above sea level. The sediments are formed mostly from the skeletal remains of organisms settling to the sea floor; over geologic time, these sediments will consolidate to form carbonate sedimentary rocks such as limestone. This detailed photograph provides a view of tidal flats and tidal channels near Sandy Cay on the western side of Long Island, located along the eastern margin of the Great Bahama Bank. The continually exposed parts of the island have a brown coloration in the image, a result of soil formation and vegetation growth (left). To the north of Sandy Cay an off-white tidal flat composed of carbonate sediments is visible; light blue-green regions indicate shallow water on the tidal flat. Tidal flow of seawater is concentrated through gaps in the anchored land surface, leading to formation of relatively deep tidal channels that cut into the sediments of the tidal flat. The channels, and areas to the south of the island, have a vivid blue coloration that provides a clear indication of deeper water (center).

S127-E-007100 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007149 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

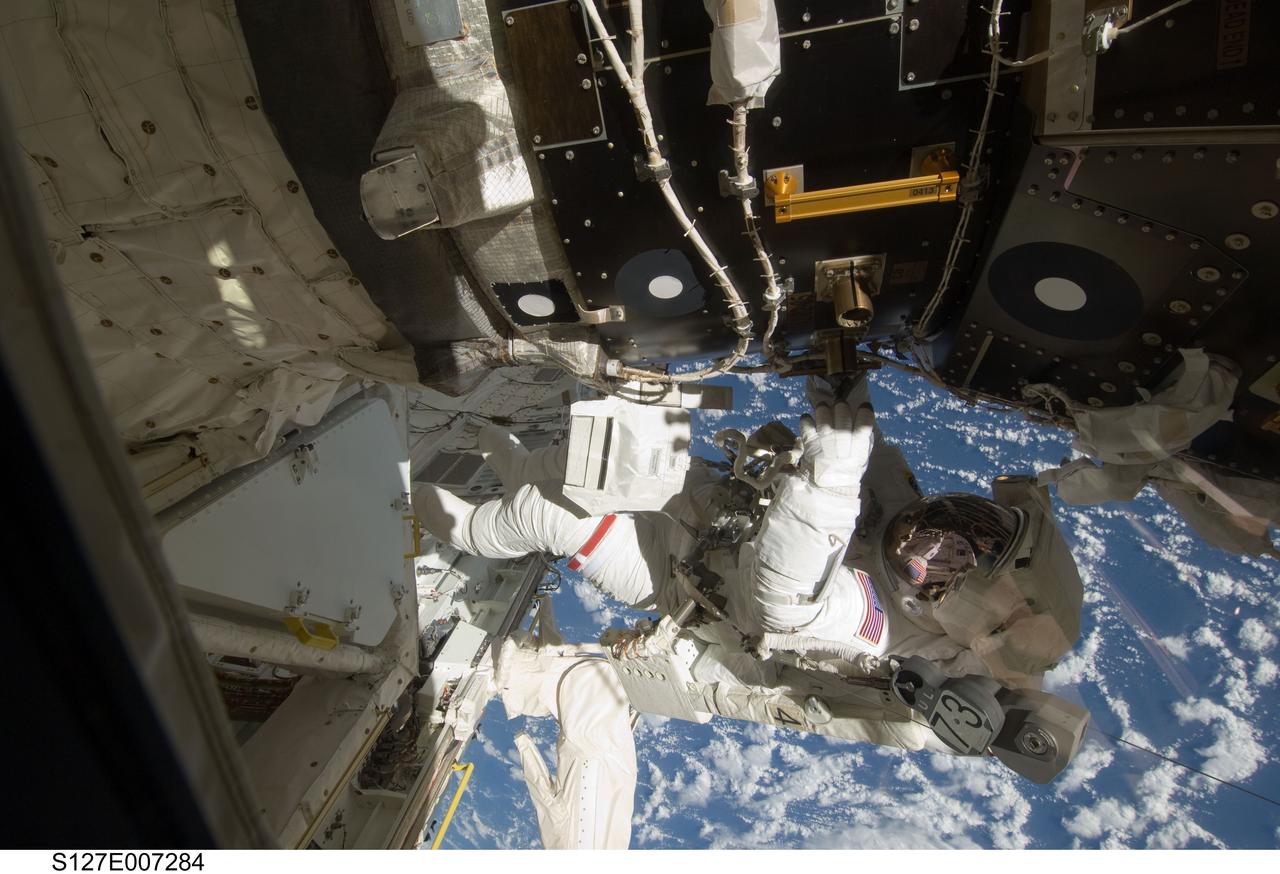

S127-E-007204 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Tom Marshburn performing his first spacewalk and the Endeavour crew’s second of the scheduled five overall in a little more than a week to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Marshburn and Dave Wolf (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007154 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007139 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007170 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

An isolated, elongated mound (about 1 mile wide and 3.75 miles long) rises above the smooth, surrounding plains. Horizontal layers are exposed at the northern end of the mound, and its surface is characterized by a very unusual quasi-circular pattern with varying colors that likely reflect diverse mineral compositions. A closer view shows that the rock has a range of textures, from massive and fractured on the left, to subtle banding or layering on the right. The origin of this mound is unknown, but its formation may be related to the clay-bearing rocks in the nearby Oxia Planum region. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24387

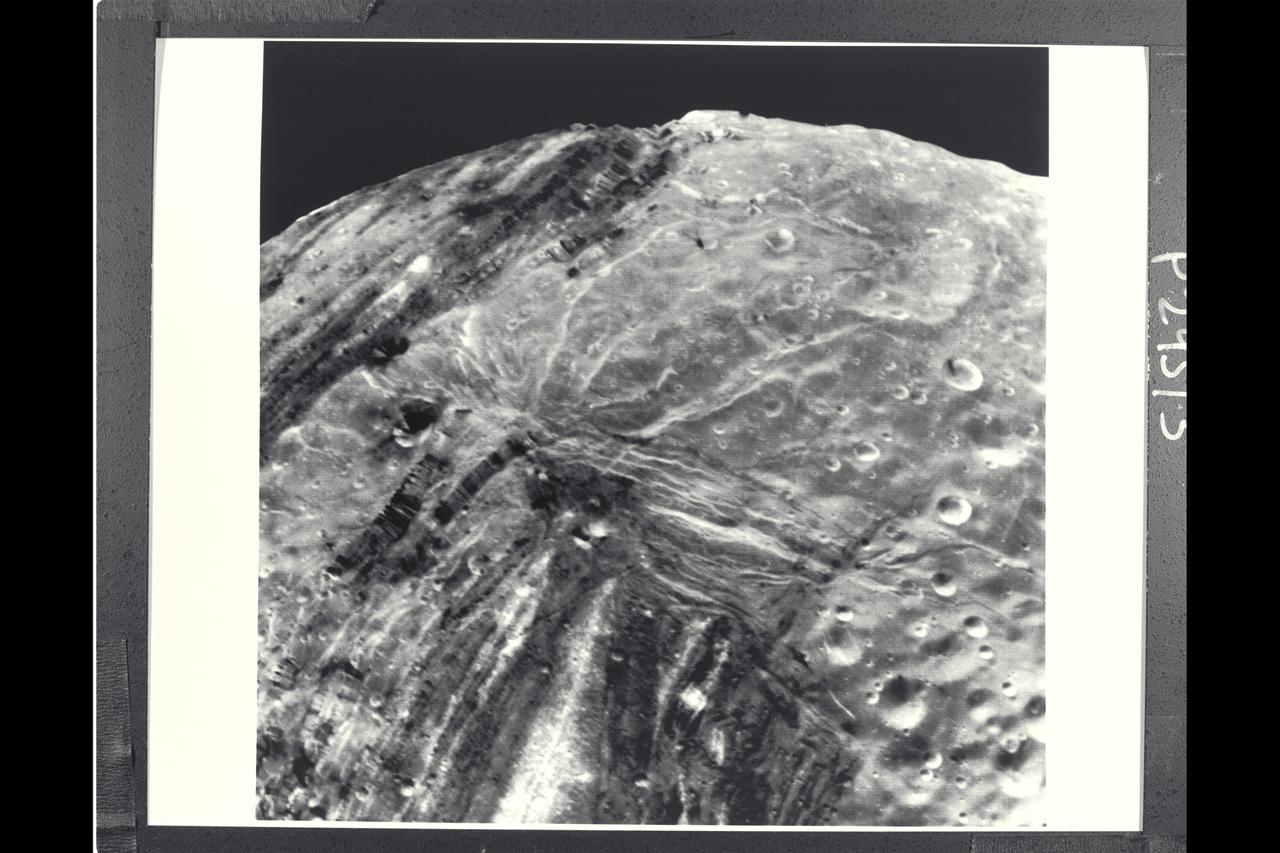

P-29513 BW Range: 31,000 kilometers (19,000 miles) This Voyager 2 image of Miranda was taken shortly before the spacecraft's closet approach to the Uranian moon.The high resolution of 600 meters (2,000 feet) reveals a bewildering variety of fractures, grooves and craters, as well as features of different albedos (reflectances). This clear-filter, narrow-angle view encompasses areas of older, heavily cratered terrain with a wide variety of forms. The grooves and troughs reach depths of a few kilometers and expose materials of different albedos. The great variety of directions of fracture and troughs, and the different densities of impact craters on them, signify a long, complex geologic evolution of this satellite.

S127-E-007173 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

STS006-22-038 (7 April 1983) --- Astronaut F. Story Musgrave, one of two STS-6 mission specialists who performed a long, successful extravehicular activity (EVA) in the cargo bay of the Earth-orbiting space shuttle Challenger, moves along a slide wire near the now vacated inertial upper stage’s (ISU) airborne support equipment (ASE). Astronaut Donald H. Peterson, sharing the cargo bay with Dr. Musgrave, exposed this frame with a 35mm camera, while astronauts Paul J. Weitz, commander; Karol J. Bobko, pilot, remained in the cabin. Photo credit: NASA

S127-E-007140 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S73-36161 (November 1973) --- In the Radiation Counting Laboratory sixty feet underground at JSC, Dr. Robert S. Clark prepares to load pieces of iridium foil -- sandwiched between plastic sheets -- into the laboratory's radiation detector. The iridium foil strips were worn by the crew of the second Skylab flight in personal radiation dosimeters throughout their 59 1/2 days in space. Inside the radiation detector assembly surrounded by 28 tons of lead shielding, the sample will be tested to determine the total neutron dose to which the astronauts were exposed during their long stay aboard the space station. Photo credit: NASA

S127-E-007284 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Tom Marshburn performing his first spacewalk and the Endeavour crew’s second of the scheduled five overall in a little more than a week to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Marshburn and Dave Wolf (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007179 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

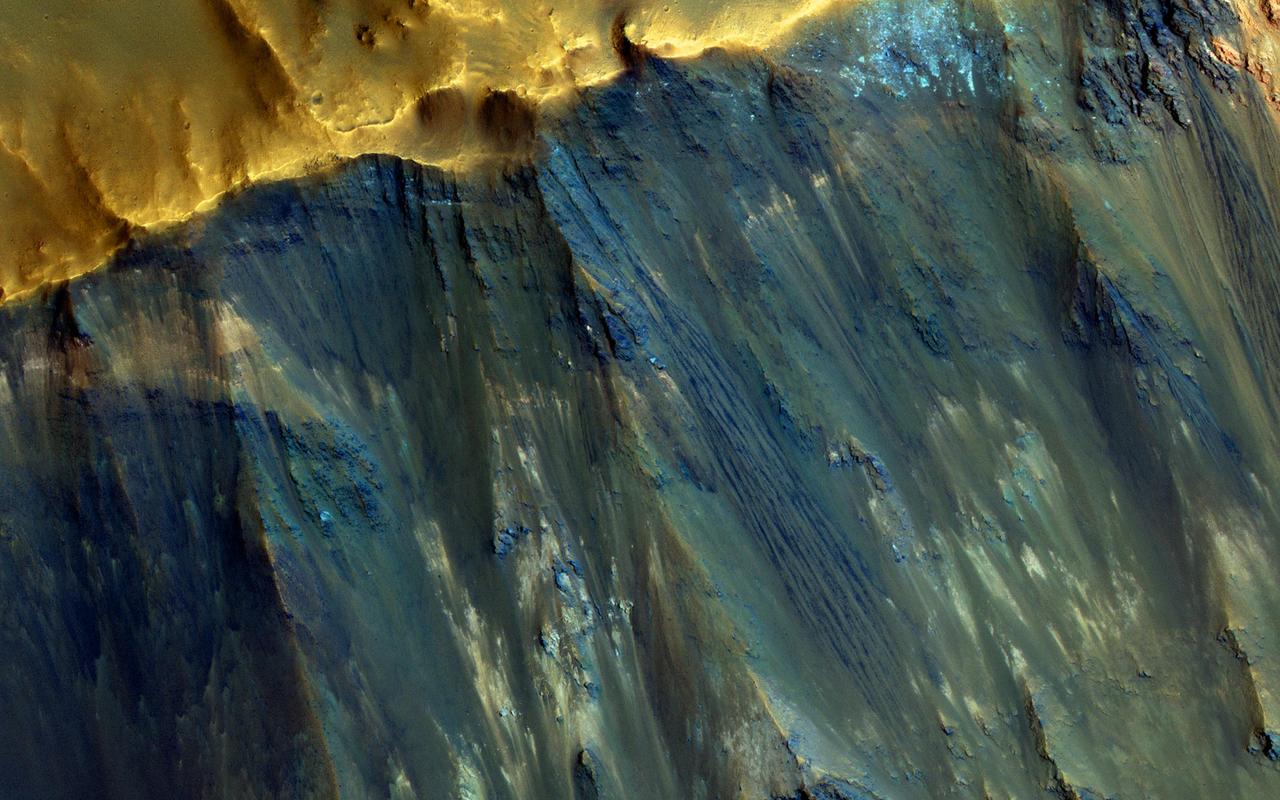

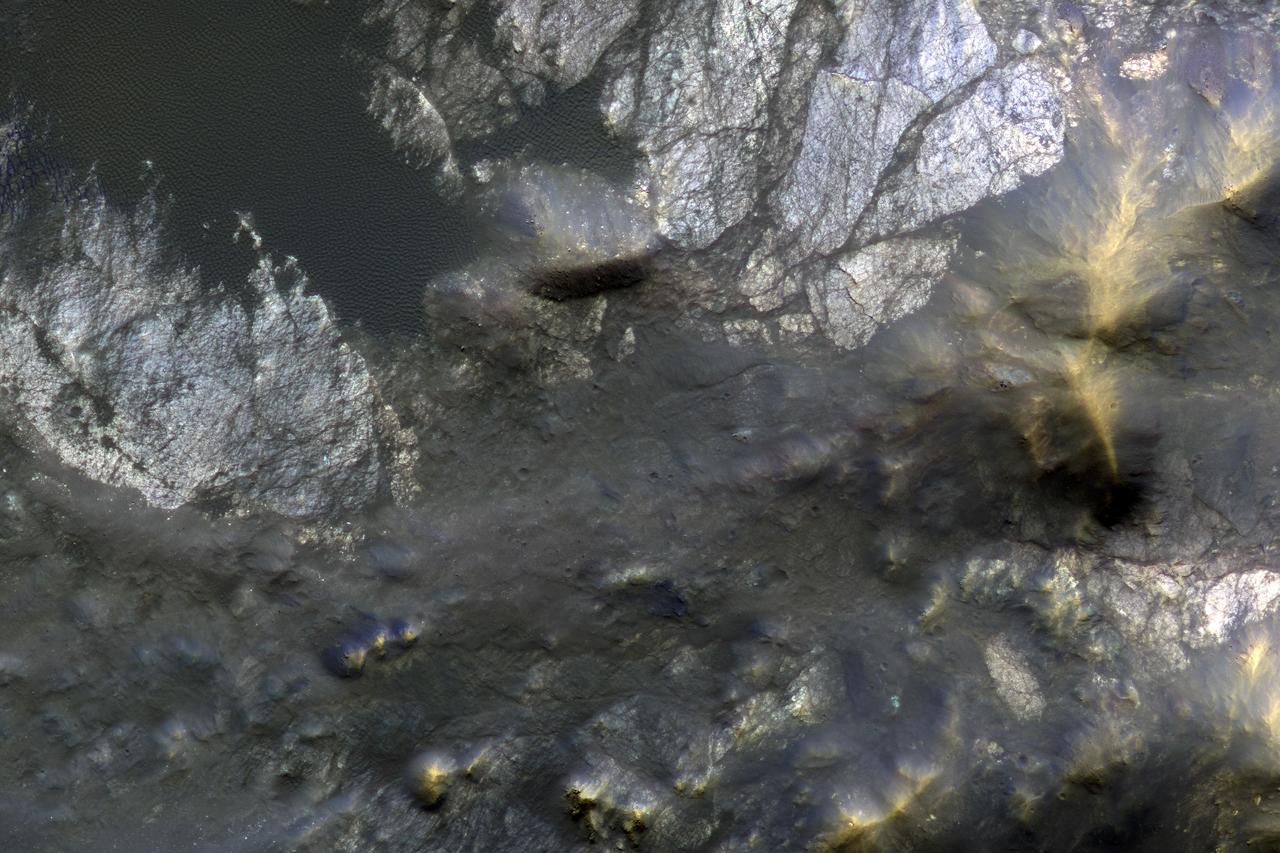

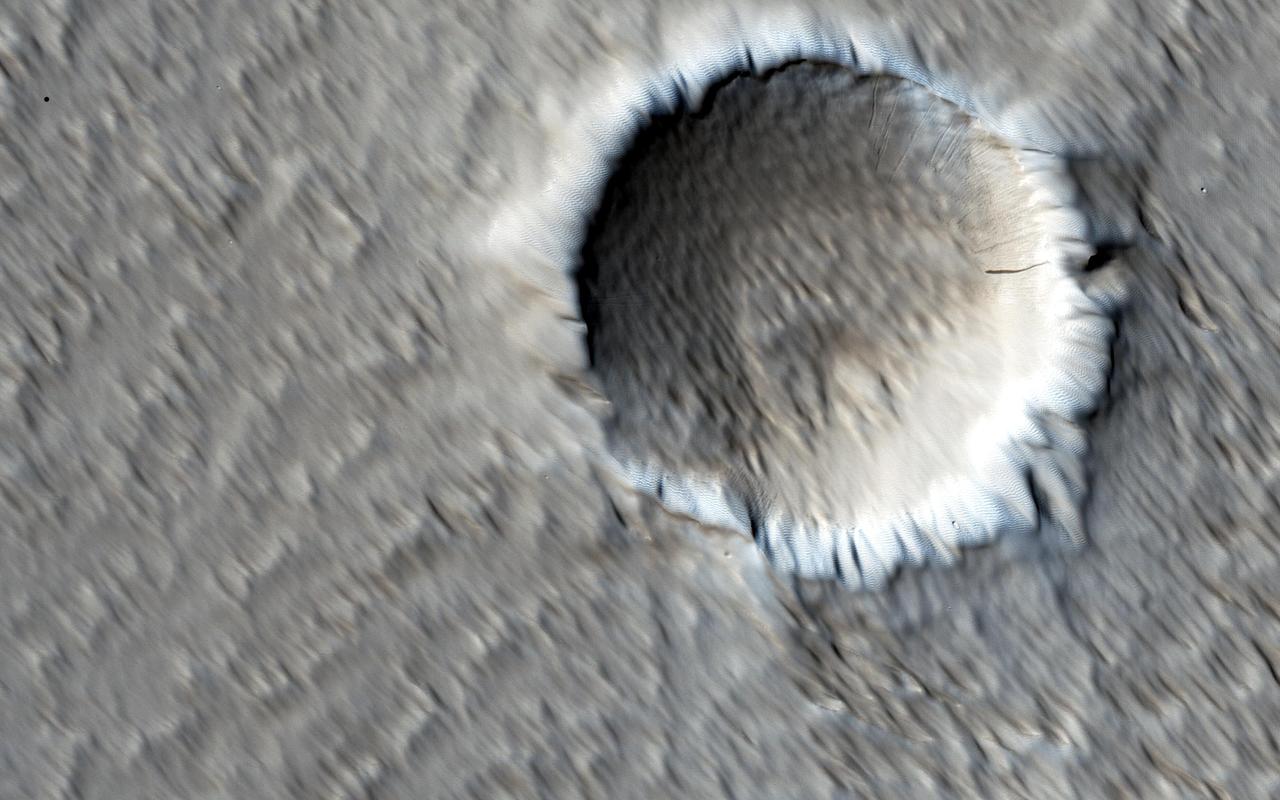

Impact craters expose the subsurface materials on steep slopes. However, these slopes often experience rockfalls and debris avalanches that keep the surface clean of dust, revealing a variety of hues, like in this enhanced-color image, representing different rock types. The bright reddish material at the top of the crater rim is from a coating of the Martian dust. The long streamers of material are from downslope movements. Also revealed in this slope are a variety of bedrock textures, with a mix of layered and jumbled deposits. This sample is typical of the Martian highlands, with lava flows and water-lain materials depositing layers, then broken up and jumbled by many impact events. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA14454

S127-E-007174 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

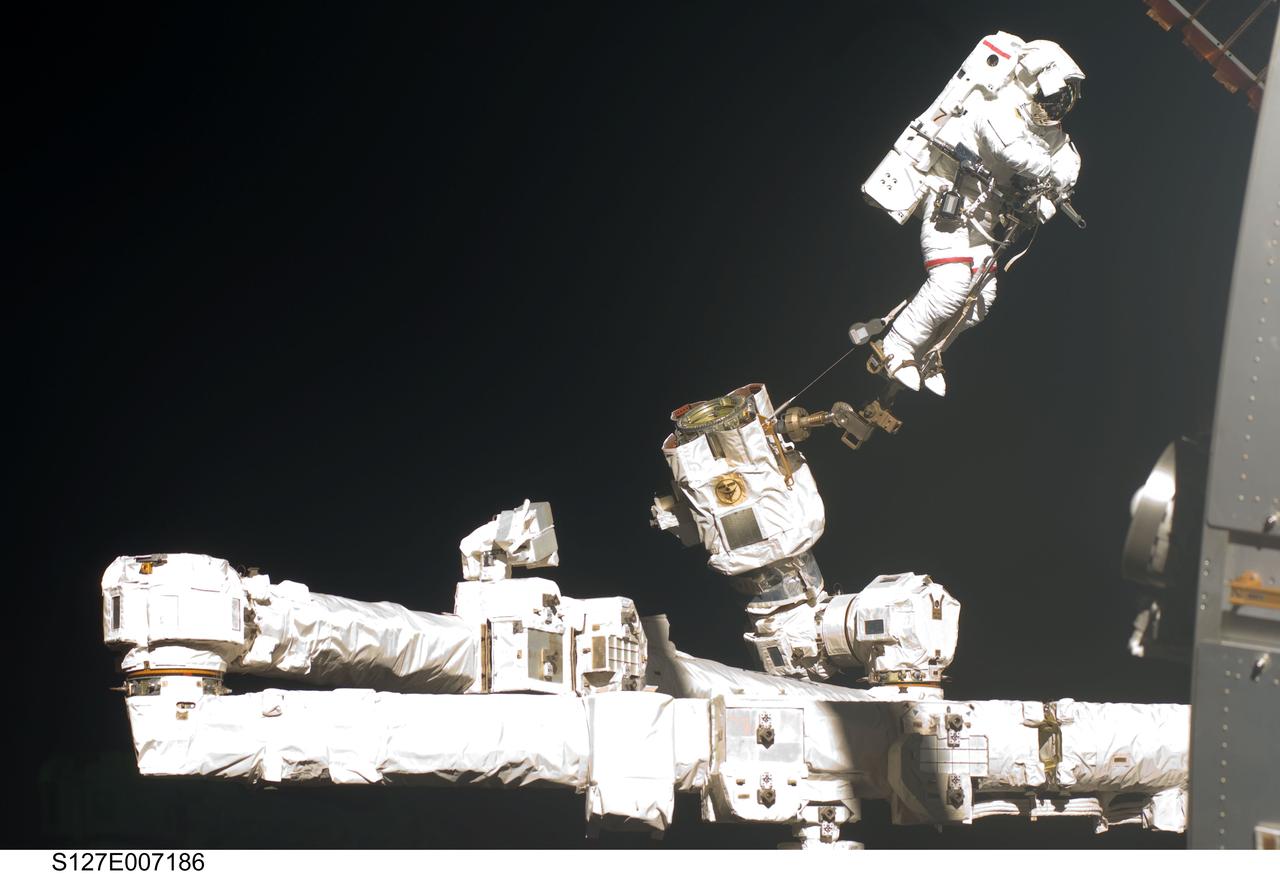

S127-E-007186 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

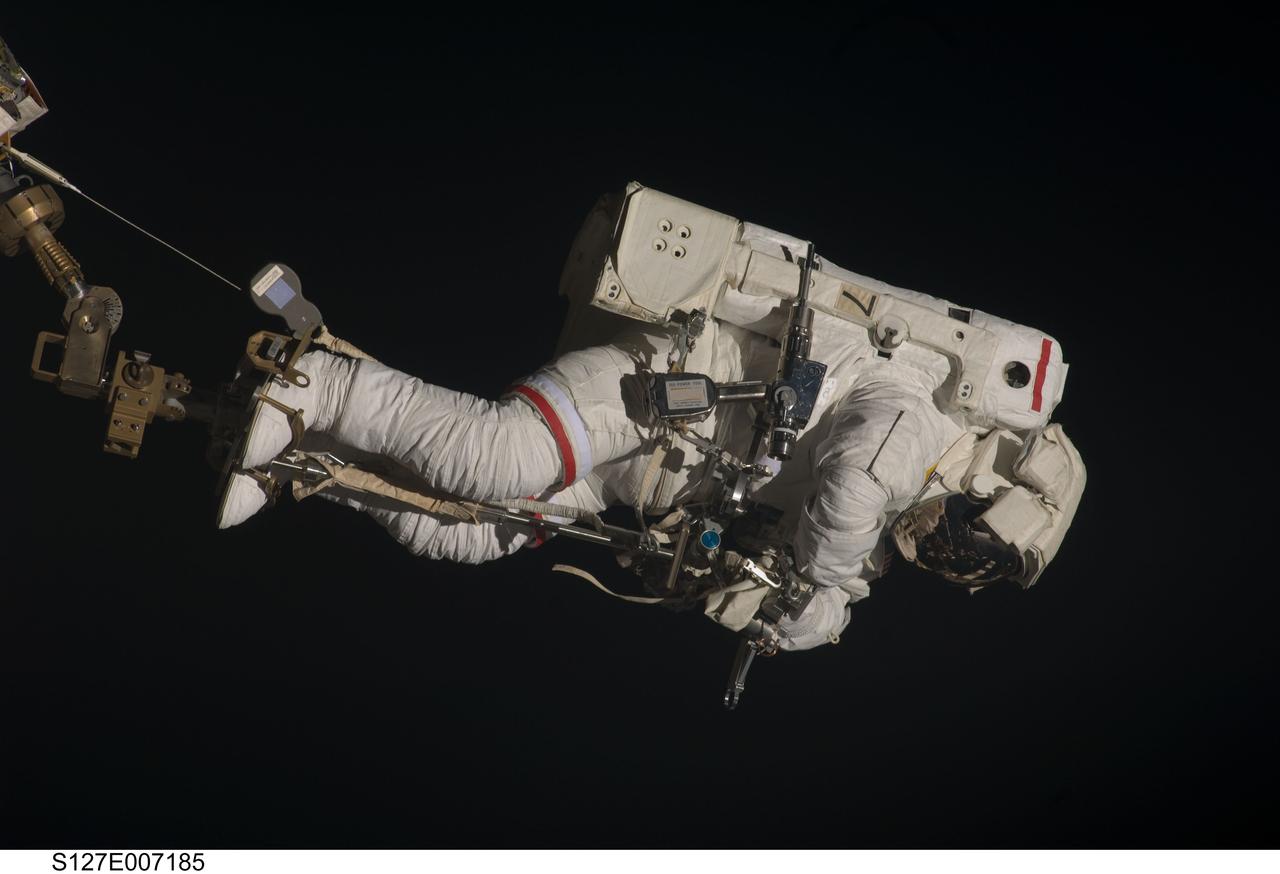

S127-E-007185 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both STS-127 mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

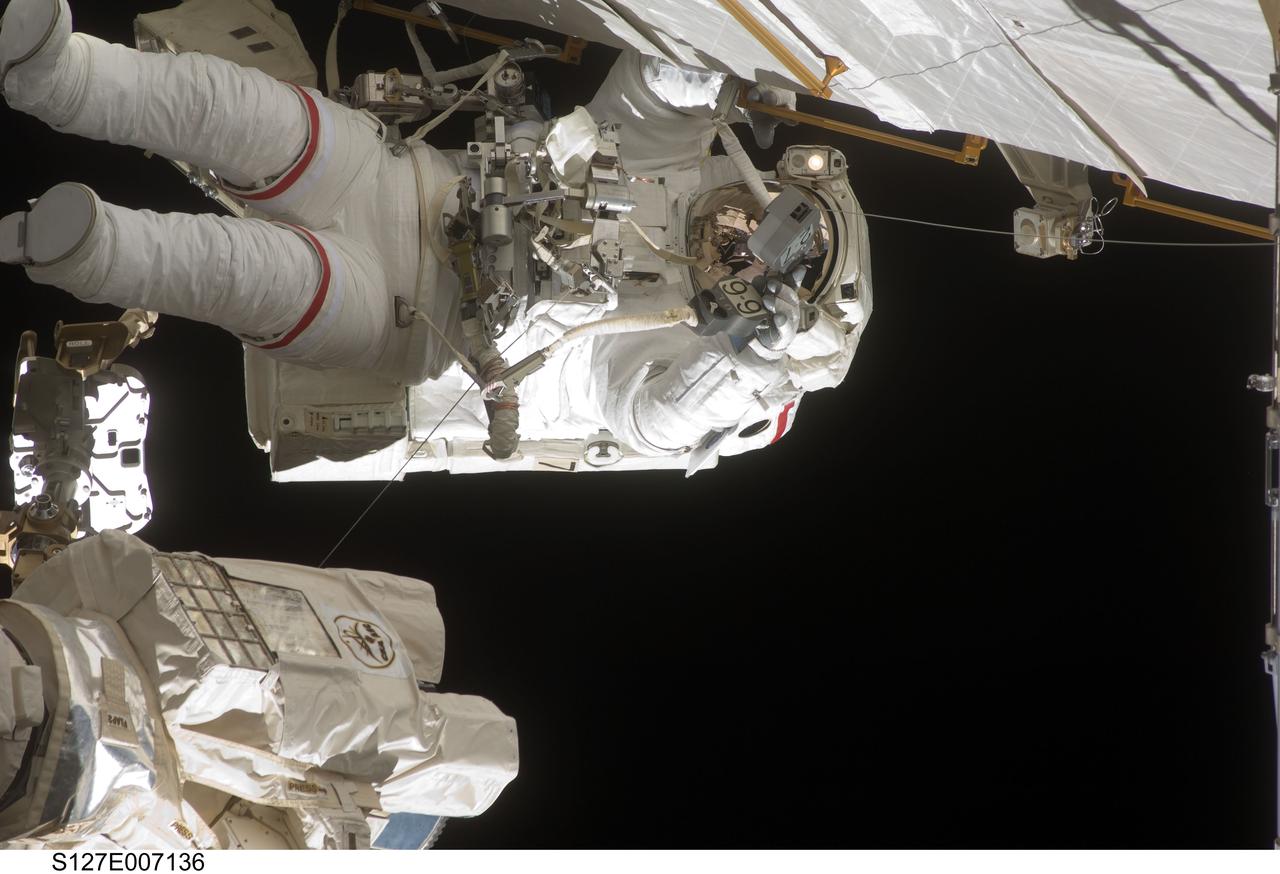

S127-E-007136 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

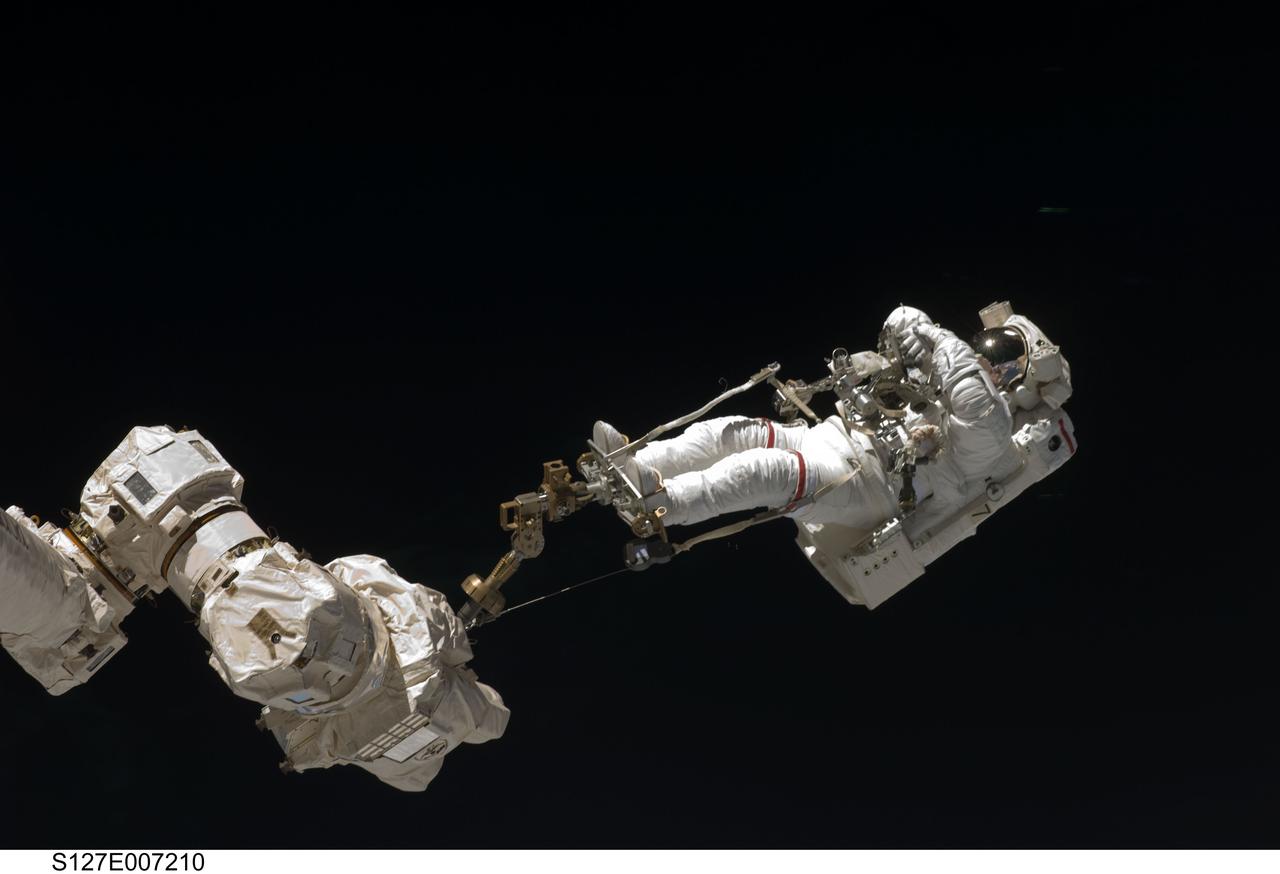

S127-E-007210 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007131 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

ISS011-E-07865 (3 June 2005) --- Aral Sea coastlines in Kazakhstan are featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 11 crewmember on the International Space Station. The arrow-shaped island in the Aral Sea once was a 35 kilometer-long visual marker, indicating the Aral Sea to astronauts. This 2005 image shows how much the coastline has changed as the sea level has dropped during the last three decades and shows that the island is now part of the mainland. Deep blues and greens indicate the water-covered areas. The exposed sea floor is characterized by old shorelines (parallel lines surrounding the island) and outlines of ancient deltas.

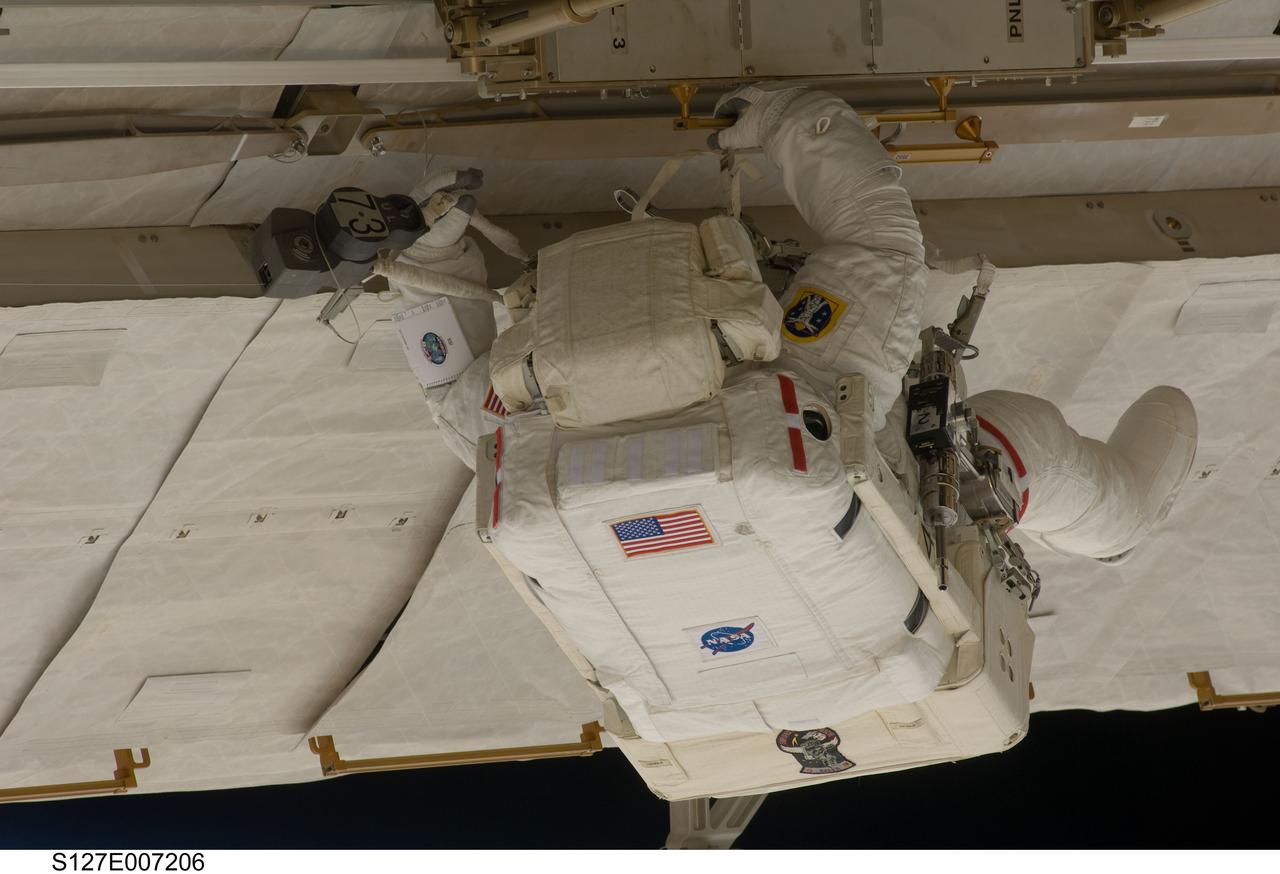

S127-E-007206 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Tom Marshburn performing his first spacewalk and the Endeavour crew’s second of the scheduled five overall in a little more than a week to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Marshburn and Dave Wolf (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007135 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007265 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Tom Marshburn performing his first spacewalk and the Endeavour crew’s second of the scheduled five overall in a little more than a week to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Marshburn and Dave Wolf (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007236 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Tom Marshburn performing his first spacewalk and the Endeavour crew’s second of the scheduled five overall in a little more than a week to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Marshburn and Dave Wolf (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007156 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

ISS036-E-036611 (23 Aug. 2013) --- One of the Expedition 36 crew members aboard the International Space Station on Aug. 23 exposed this image of the Strait of Gibraltar, where Europe and Africa meet and where the Atlantic Ocean waters flow through the strait into the Mediterranean Sea. A popular photographic target of astronauts has always been the Strait of Gibraltar, easily spotted at left center in this wide photograph, shot from the International Space Station. Spain is to the north (top) and Morocco to the south. The strait is 36 miles (58 kilometers) long and slims down to 8 miles (13 kilometers) at it?s most narrow point. The British colony of Gibraltar is north of the strait.

This is an image of the rover Sojourner at the feature called Mermaid Dune at the MPF landing site. Mermaid is thought to be a low, transverse dune ridge, with its long (approximately 2 meters) axis transverse to the wind, which is thought to come from the lower left of the image and blow toward the upper right. The rover is facing to the lower left, the "upwind" direction. The rover's middle wheels are at the crestline of the small dune, and the rear wheels are on the lee side of the feature. A soil mechanics experiment was performed to dig into the dune and examine the sediments exposed. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00794

S127-E-007289 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Tom Marshburn performing his first spacewalk and the Endeavour crew’s second of the scheduled five overall in a little more than a week to continue work on the International Space Station. Astronauts Marshburn and Dave Wolf (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

iss074e0319988 (Feb. 19, 2026) --- Star trails and city lights streak by in this long-duration photograph—exposed for nearly nine-and-a-half minutes—taken from the International Space Station as it orbited 260 miles above the Middle East. In the upper foreground is JAXA’s (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) HTV-X1 cargo craft, berthed to the Harmony module’s Earth-facing port, with the Canadarm2 robotic arm attached to a portable data grapple fixture in front. At bottom right is a portion of the Northrop Grumman Cygnus XL cargo craft. Credit: NASA/Chris Williams

A long exposure photo shows the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carrying the internation Sentinel-6B spacecraft lifting off from Space Launch Complex 4 East at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California on Sunday, Nov. 16, 2025. A collaboration between NASA, ESA (European Space Agency), EUMETSAT (European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Sentinel-6B is designed to measure sea levels down to roughly an inch for about 90% of the world’s oceans.

The distinctively fluted surface and elongated hills in this image in Medusae Fossae are caused by wind erosion of a soft fine-grained rock. Called yardangs, these features are aligned with the prevailing wind direction. This wind direction would have dominated for a very long time to carve these large-scale features into the exposed rock we see today. Yardangs not only reveal the strength and direction of historic winds, but also reveal something of the host rock itself. Close inspection by HiRISE shows an absence of boulders or rubble, especially along steep yardang cliffs and buttresses. The absence of rubble and the scale of the yardangs tells us that the host rock consists only of weakly cemented fine granules in tens of meters or more thick deposits. Such deposits could have come from extended settling of volcanic ash, atmospheric dust, or accumulations of wind deposited fine sands. After a time these deposits became cemented and cohesive, illustrated by the high standing relief and exposed cliffs. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21111

This false-color infrared image was taken by the camera system on the Mars Odyssey spacecraft over part of Ganges Chasma in Valles Marineris (approximately 13 degrees S, 318 degrees E). The infrared image has been draped over topography data obtained by Mars Global Surveyor. The color differences in this image show compositional variations in the rocks exposed in the wall and floor of Ganges (blue and purple) and in the dust and sand on the rim of the canyon (red and orange). The floor of Ganges is covered by rocks and sand composed of basaltic lava that are shown in blue. A layer that is rich in the mineral olivine can be seen as a band of purple in the walls on both sides of the canyon, and is exposed as an eroded layer surrounding a knob on the floor. Olivine is easily destroyed by liquid water, so its presence in these ancient rocks suggests that this region of Mars has been very dry for a very long time. The mosaic was constructed using infrared bands 5, 7, and 8, and covers an area approximately 150 kilometers (90 miles) on each side. This simulated view is toward the north. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04262

STS031-S-131 (29 April 1990) --- Low angle view of the Space Shuttle Discovery as it approaches for landing on a concrete runway at Edwards Air Force Base to complete a highly successful five-day mission. It was a long awaited Earth orbital flight during which the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) was sent toward its 15-year mission. Discovery's wheels came to a complete stop at 6:51:00 a.m. (PDT), April 29, 1990. The landing gear was deployed just moments after this frame was exposed. Inside the spacecraft for STS-31 were astronauts Loren J. Shriver, Charles F. Bolden, Bruce McCandless II, Kathryn D. Sullivan and Steven A. Hawley.

S127-E-007094 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. The equipment floating in front of Wolf is tethered to his spacesuit. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

S127-E-007096 (20 July 2009) --- This is one of a series of digital still images showing astronaut Dave Wolf performing his second spacewalk and the Endeavour’s second also of the scheduled five overall in a little over a week’s time to continue work on the International Space Station. The equipment floating in front of Wolf is tethered to his spacesuit. Astronauts Wolf and Tom Marshburn (out of frame), both mission specialists, successfully transferred a spare KU-band antenna to long-term storage on the space station, along with a backup coolant system pump module and a spare drive motor for the station's robot arm transporter. Installation of a television camera on the Japanese Exposed Facility experiment platform was deferred to a later spacewalk.

This is an onboard photo of the deployment of the Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) from the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Orbiter Challenger STS-41C mission, April 7, 1984. After a five year stay in space, the LDEF was retrieved during the STS-32 mission by the Space Shuttle Orbiter Columbia in January 1990 and was returned to Earth for close examination and analysis. The LDEF was designed by the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) to test the performance of spacecraft materials, components, and systems that have been exposed to the environment of micrometeoroids, space debris, radiation particles, atomic oxygen, and solar radiation for an extended period of time. Proving invaluable to the development of both future spacecraft and the International Space Station (ISS), the LDEF carried 57 science and technology experiments, the work of more than 200 investigators, 33 private companies, 21 universities, 7 NASA centers, 9 Department of Defense laboratories, and 8 forein countries.

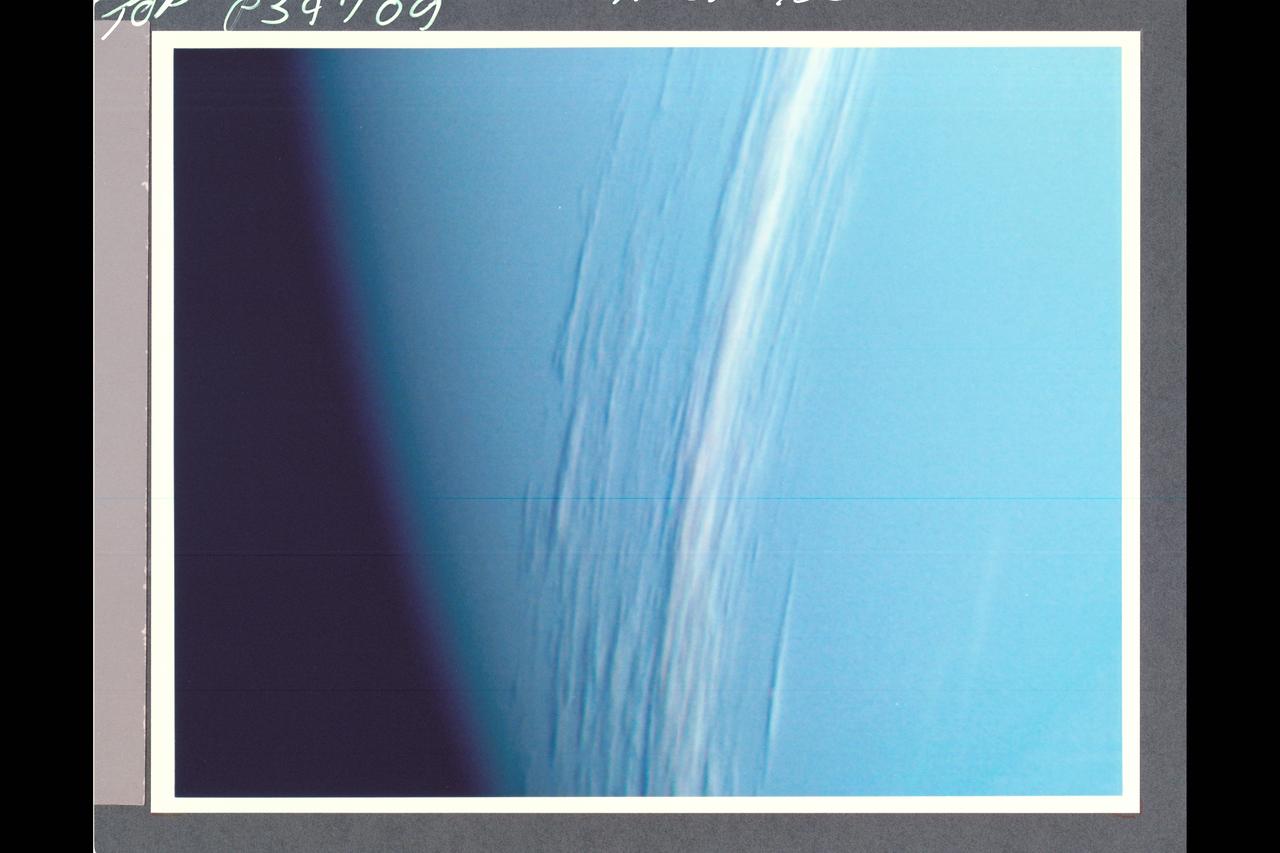

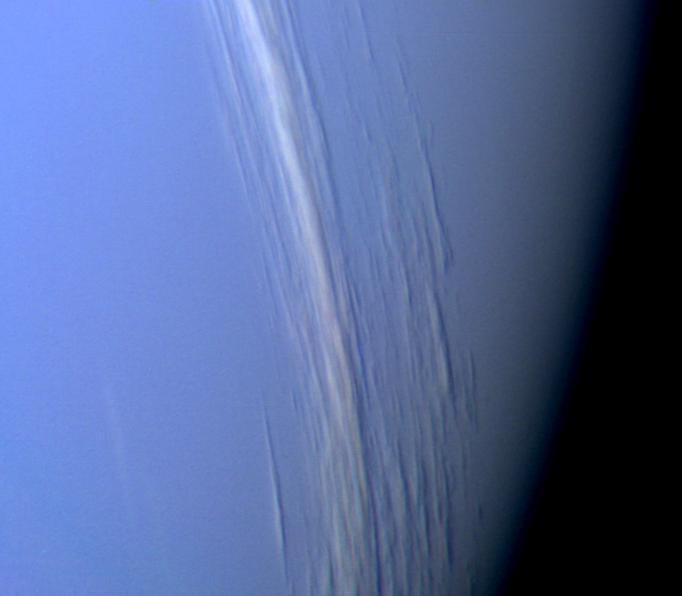

Range : 2.77 million miles (1.72 million miles) resolution : 51 km. (32 mi.) P-29495C This Voyager 2 photograph of the outermost Uranian satellite, Oberon is a computer reconstruction of three frames , exposed through the narrow angle camera's blue, green, and orange filters. the grayness or apparent lack of strong color is a distinctive characteristic of the satellites and the rings of Uranus and can serve as one indicator of the possible composition of the satellites' surfaces. Oberon has a diameter of about 1,600 km. (1,000 mi.) and orbits the planet at a radial distance of 586,000 km. (364,000 mi.). Oberon's surface displays areas of lighter and darker material, probably associated in part with impact craters formed during its long exposure to bombardment by cosmic debris. Thr resolution of this particular image is not sufficient, however, to reveal with confidece the nature of these features.

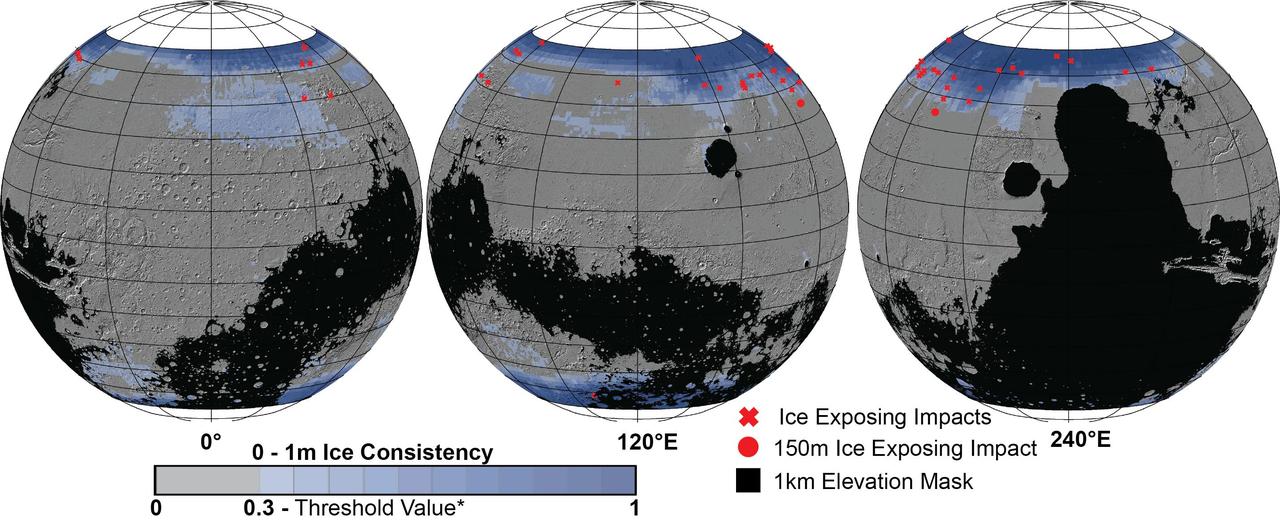

These Mars global maps show the likely distribution of water ice buried within the upper 3 feet (1 meter) of the planet's surface and represent the latest data from the Subsurface Water Ice Mapping project, or SWIM. SWIM uses data acquired by science instruments aboard three NASA orbital missions to estimate where ice may be hiding below the surface. Superimposed on the globes are the locations of ice-exposing meteoroid impacts, which provide an independent means to test the mapping results. The ice-exposing impacts were spotted by the High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE), a camera aboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. While other instruments at Mars can only suggest where buried water ice is located, HiRISE's imagery of ice-exposing impacts can confirm where ice is present. Most of these craters are no more than 33 feet (10 meters) in diameter, although in 2022 HiRISE captured a 492-foot-wide (150-meter-wide) impact crater that revealed a motherlode of ice that had been hiding beneath the surface. This crater is indicated with a circle in the upper-left portion of the right-most globe above. Scientists can use mapping data like this to decide where the first astronauts on Mars should land: Buried ice will be a vital resource for the first people to set foot on Mars, serving as drinking water and a key ingredient for rocket fuel. It would also be a major scientific target: Astronauts or robots could one day drill ice cores much as scientists do on Earth, uncovering the climate history of Mars and exploring potential habitats (past or present) for microbial life. The need to look for subsurface ice arises because liquid water isn't stable on the Martian surface: The atmosphere is so thin that water immediately vaporizes. There's plenty of ice at the Martian poles – mostly made of water, although carbon dioxide, or dry ice, can be found as well – but those regions are too cold for astronauts (or robots) to survive for long. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26046

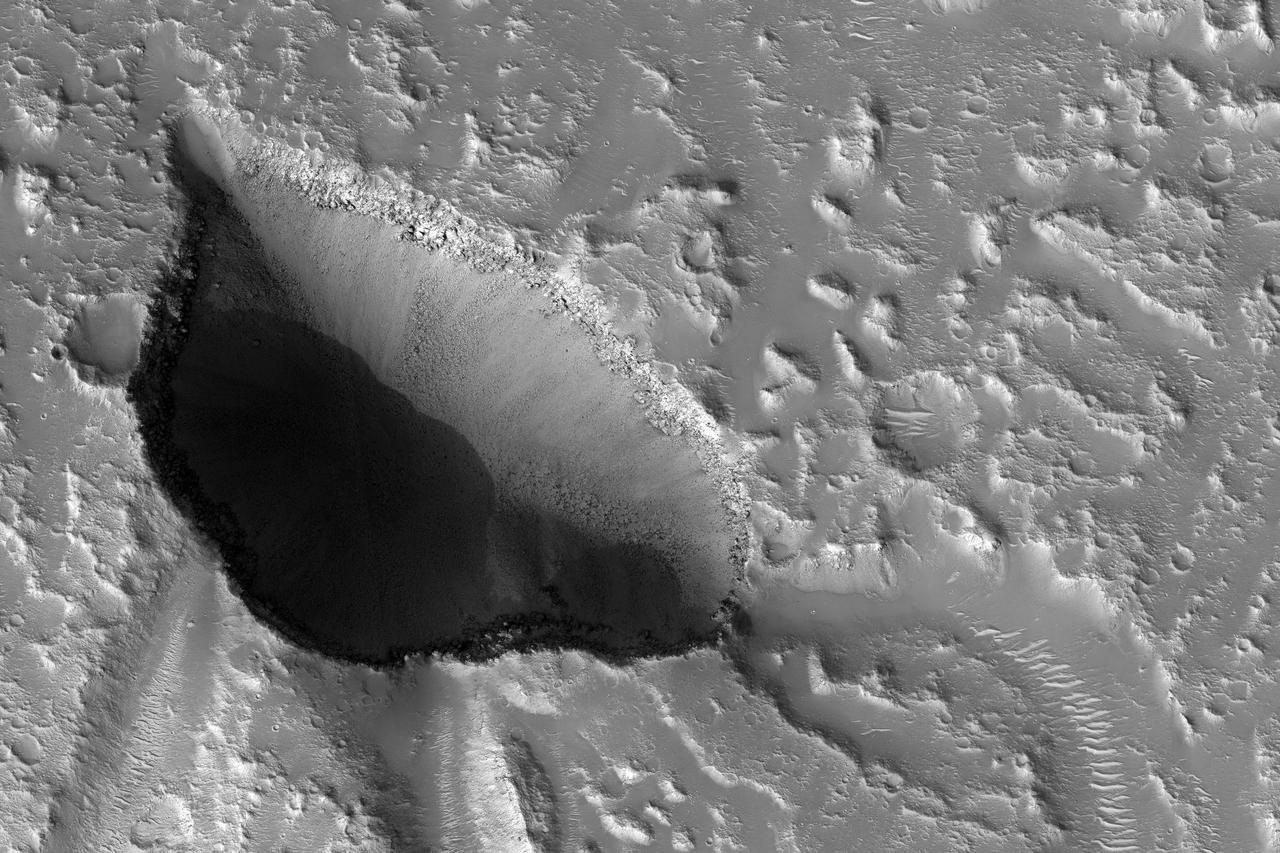

The drainages in this image are part of Hebrus Valles, an outflow channel system likely formed by catastrophic floods. Hebrus Valles is located in the plains of the Northern lowlands, just west of the Elysium volcanic region. Individual channels range from several hundred meters to several kilometers wide and form multi-threaded (anastamosing) patterns. Separating the channels are streamlined forms, whose tails point downstream and indicate that channel flow is to the north. The channels seemingly terminate in an elongated pit that is approximately 1875 meters long and 1125 meters wide. Using the shadow that the wall has cast on the floor of the pit, we can estimate that the pit is nearly 500 meters deep. The pit, which formed after the channels, exposes a bouldery layer below the dusty surface mantle and is underlain by sediments. Boulders several meters in diameter litter the slopes down into the pit. Pits such as these are of interest as possible candidate landing sites for human exploration because they might retain subsurface water ice (Schulze-Makuch et al. 2016, 6th Mars Polar Conf.) that could be utilized by future long-term human settlements. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA11704

This image shows some beautiful lava flows in Amazonis Planitia. Lava isn't moving around on Mars today, but it certainly once did, and images like this one are evidence of that. A thick lava flow came in from the west, and you can see the cooled flow lobes and wrinkled upper surface. East of the flow margin, this most recent flow also coursed over an older lava surface which shows some long, north-south breaks, and in the southeast corner, an arrowhead-shaped set of ridges. These textures are most likely from rafted slabs of lava. Under certain conditions, a large piece of lava can cool, but then detach and move like an iceberg over a cushion of still-molten lava. The long, narrow north-south smooth areas are probably where two of these plates rafted away from one another exposing the lava below. The arrowhead-shaped ridges are probably from when one of these plates pushed up against another one and caused a pile-up before cooling. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21113

Mamers Valles is a long sinuous canyon beginning in Arabia Terra and ending in the Northern lowlands of Deuteronilus Mensae. This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter features the southern facing slope of the canyon wall. The northern half (top) has a rough, pitted texture with numerous impact craters, while the middle section shows the steep canyon wall. Streaks of slightly different colors show slope material eroding onto the canyon floor. Though the canyon itself was formed long ago, the material deposited on the canyon floor has been laid down over time, creating a much younger surface. The difference in age of the surfaces can also be indicated by the presence or absence of impact craters. The longer a surface has been exposed, the more impact craters it will accumulate. Counting craters to determine age estimates of planetary surfaces has been used throughout the solar system. This method is based on the assumption that the youngest, freshly formed surfaces will have no impact craters, and as time progresses crater impacts will accumulate at a predictable rate. This concept has been calibrated using crater counts on the Moon and the measured age of the rocks brought back by the Apollo missions. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21603

This picture of the rim of Eos Chasma in Valles Marineris shows active erosion of the Martian surface. Layered bedrock is exposed in a steep cliff on a spur of the canyon rim. Dark layers in this cliff are made up of large boulders up to 4 meters in diameter. The boulders are lined up along specific horizons, presumably individual lava flows, and are perched to descend down into the canyon upon the slightest disturbance. How long will the boulders remain poised to fall, and what will push them over the edge? Just as on Earth, the main factors that contribute to dry mass wasting erosion on Mars are frost heaving and thermal expansion and contraction due to changes in temperature. The temperature changes on Mars are extreme compared to Earth, because of the lack of humidity in the Martian atmosphere and the eccentricity of the Martian orbit. Each daily temperature cycle and each seasonal change from summer to winter produces a cycle of expansion and contraction that pushes the boulders gradually closer to the brink. Inevitably, the boulders fall from their precarious positions and plunge into the canyons below. Most simply slide down slope and collect just below the source layers. A few are launched along downward trajectories, travelling long distances before they settle on the slopes below. These trundling boulders left behind conspicuous tracks, up to a kilometer long. The tracks resemble dashed lines or perforations, indicating that the boulders bounced as they trundled down the slopes. The visibility of the boulder tracks suggests that this process may have taken place recently. The active Martian winds quickly erased the tracks of the rover Opportunity, for example. However, the gouges produced by trundling boulders probably go much deeper than the shallow compression of soil by the wheels of a relatively lightweight rover. The boulder tracks might persist for a much longer time span than the rover tracks for this reason. Nevertheless, the tracks of the boulders suggest that erosion of the rim of Eos Chasma is a process that continues today. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21203

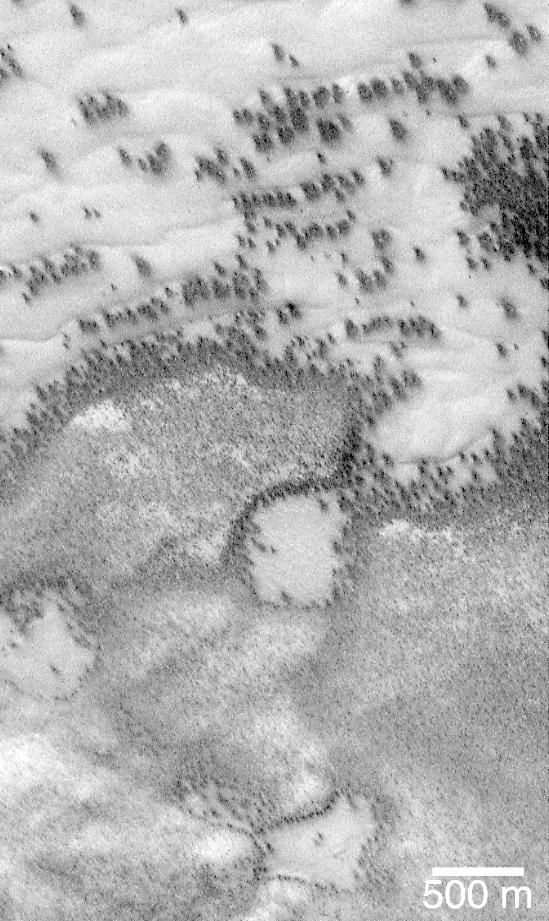

"They look like bushes!" That's what almost everyone says when they see the dark features found in pictures taken of sand dunes in the polar regions as they are beginning to defrost after a long, cold winter. It is hard to escape the fact that, at first glance, these images acquired by the Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) over both polar regions during the spring and summer seasons, do indeed resemble aerial photographs of sand dune fields on Earth -- complete with vegetation growing on and around them! Of course, this is not what the features are, as we describe below and in related picture captions. Still, don't they look like vegetation to you? Shown here are two views of the same MGS MOC image. On the left is the full scene, on the right is an expanded view of a portion of the scene on the left. The bright, smooth surfaces that are dotted with occasional, nearly triangular dark spots are sand dunes covered by winter frost. The MGS MOC has been used over the past several months (April-August 1999) to monitor dark spots as they form and evolve on polar dune surfaces. The dark spots typically appear first along the lower margins of a dune -- similar to the position of bushes and tufts of grass that occur in and among some sand dunes on Earth. Because the martian air pressure is very low -- 100 times lower than at Sea Level on Earth -- ice on Mars does not melt and become liquid when it warms up. Instead, ice sublimes -- that is, it changes directly from solid to gas, just as "dry ice" does on Earth. As polar dunes emerge from the months-long winter night, and first become exposed to sunlight, the bright winter frost and snow begins to sublime. This process is not uniform everywhere on a dune, but begins in small spots and then over several months it spreads until the entire dune is spotted like a leopard. The early stages of the defrosting process -- as in the picture shown here -- give the impression that something is "growing" on the dunes. The sand underneath the frost is dark, just like basalt beach sand in Hawaii. Once it is exposed to sunlight, the dark sand probably absorbs sunlight and helps speed the defrosting of each sand dune. This picture was taken by MGS MOC on July 21, 1999. The dunes are located in the south polar region and are expected to be completely defrosted by November or December 1999. North is approximately up, and sunlight illuminates the scene from the upper left. The 500 meter scale bar equals 547 yards; the 300 meter scale is also 328 yards. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA02300

The Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) was designed by the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) to test the performance of spacecraft materials, components, and systems that have been exposed to the environment of micrometeoroids and space debris for an extended period of time. The LDEF proved invaluable to the development of future spacecraft and the International Space Station (ISS). The LDEF carried 57 science and technology experiments, the work of more than 200 investigators. MSFC`s experiments included: Trapped Proton Energy Determination to determine protons trapped in the Earth's magnetic field and the impact of radiation particles; Linear Energy Transfer Spectrum Measurement Experiment which measures the linear energy transfer spectrum behind different shielding configurations; Atomic oxygen-Simulated Out-gassing, an experiment that exposes thermal control surfaces to atomic oxygen to measure the damaging out-gassed products; Thermal Control Surfaces Experiment to determine the effects of the near-Earth orbital environment and the shuttle induced environment on spacecraft thermal control surfaces; Transverse Flat-Plate Heat Pipe Experiment, to evaluate the zero-gravity performance of a number of transverse flat plate heat pipe modules and their ability to transport large quantities of heat; Solar Array Materials Passive LDEF Experiment to examine the effects of space on mechanical, electrical, and optical properties of lightweight solar array materials; and the Effects of Solar Radiation on Glasses. Launched aboard the Space Shuttle Orbiter Challenger's STS-41C mission April 6, 1984, the LDEF remained in orbit for five years until January 1990 when it was retrieved by the Space Shuttle Orbiter Columbia STS-32 mission and brought back to Earth for close examination and analysis.

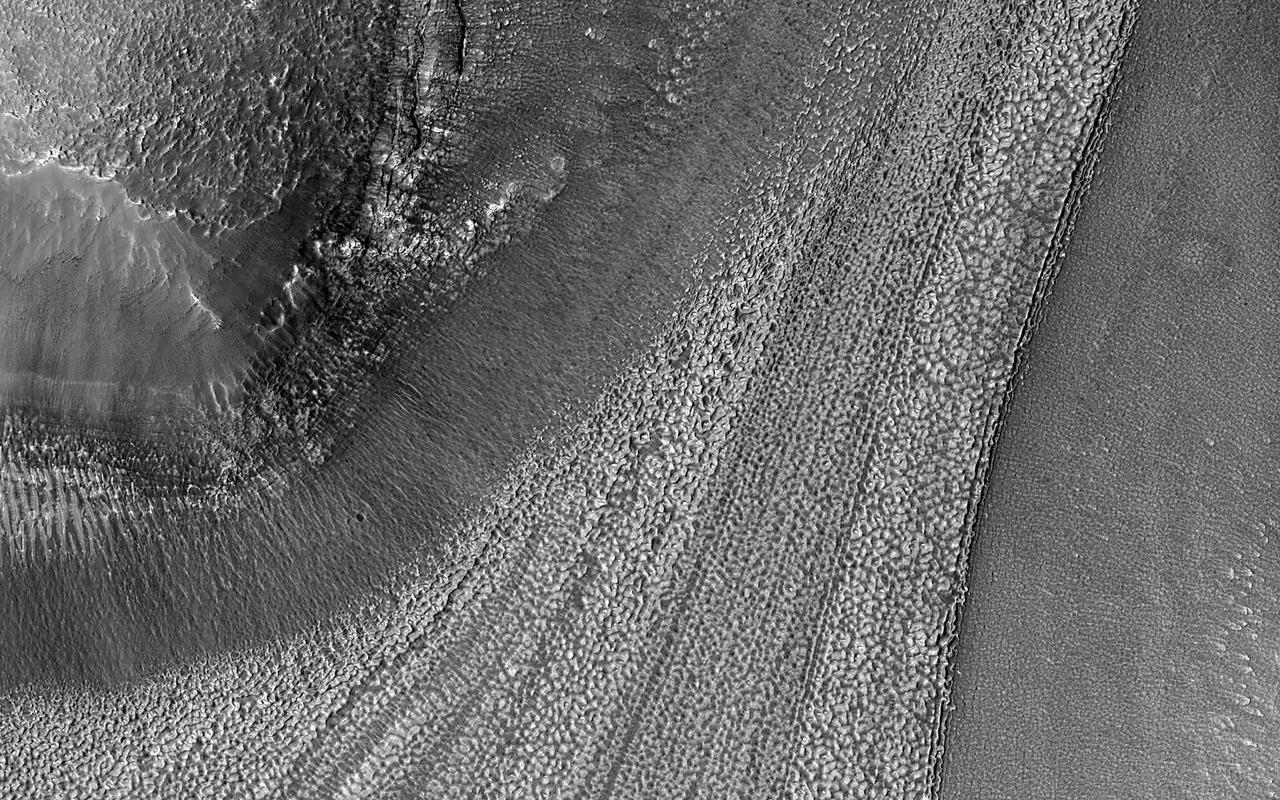

This image from NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft nicely captures several influential geologic processes that have shaped the landscape of Lycus Sulci. Our observation covers an area of about 7.5 by 5.4 kilometers in Lycus Sulci, located just to the northwest of Olympus Mons in the Tharsis region of Mars. "Sulci" is a Latin term meaning "furrow" or "groove." In this case, Lycus Sulci is a region comprised of a series of depressions and ridges. Like most of the Tharsis region, Lycus Sulci exhibits thick deposits of light-toned Martian dust; the slopes on ridges in this region feature abundant streaks. These streaks are long, thin dark-toned features. They appear when the superficial light-tone fine-grained materials (i.e., Martian dust) suddenly move down slope and expose the darker underlying volcanic surfaces. Repeat imaging shows that dust streaks are consistently dark when they are initially formed and become lighter over time. This is due to the steady deposition of dust from the atmosphere. Slope streaks are also visible along the slopes of ridges and shallow depressions. Two ridges here exhibit partially exposed bedrock. These outcrops are interpreted to still have abundant coatings and dust, obscuring the underlying bedrock. This interpretation is based on the lack of bluish color for volcanic bedrock from the infrared-red-blue swath of our camera, and consistent with the homogenous tannish color we see throughout the same swath. It's possible that the ridges here and throughout the Lycus Sulci region formed via volcanic and tectonic processes, which have been further sculpted by wind erosion and other mass wasting processes. For example, talus slopes, which appear as fine-grained fans or conical-shaped deposits, originate from the steepest portions of the ridges. These form when the rocks or deposits on the steepest slopes of a ridge fail under the influence of Martian gravity and their own mass, causing an avalanche of these materials, which then accumulate downslope. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19870

The surface of Mars is littered with examples of glacier-like landforms. While surface ice deposits are mostly limited to the polar caps, patterns of slow, viscous flow abound in many non-polar regions of Mars. Streamlines that appear as linear ridges in the surface soils and rocky debris are often exposed on top of infilling deposits that coat crater and valley floors. We see such patterns on the surfaces of Earth's icy glaciers and debris-covered "rock glaciers." As ice flows downhill, rock and soil are plucked from the surrounding landscape and ferried along the flowing ice surface and within the icy subsurface. While this process is gradual, taking perhaps thousands of years or longer, it creates a network of linear patterns that reveal the history of ice flow. Later and under warmer conditions, the ice may be lost through melting or sublimation. (Sublimation is the evaporation of ice directly from solid to gas without the presence of liquid.) Rock and minerals concentrated in these long ridges are then left behind, draped over the preexisting landscape. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA25984

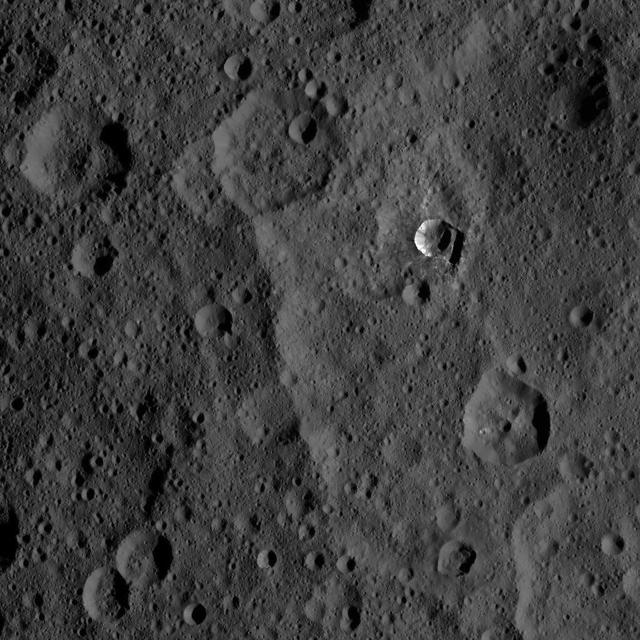

The 6-mile-wide (10-kilometer-wide) Oxo Crater stands out on the dark landscape of Ceres in this view from NASA's Dawn spacecraft. Oxo is one of several sites at which ice has been identified by Dawn's visible and infrared mapping spectrometer. The crater is located at mid-latitudes (42 degrees North, 0 degrees East), and the presence of ice there is consistent with the recent mapping of hydrogen by Dawn's GRaND instrument (Gamma Ray and Neutron Detector). Ice is likely to be present at shallow depths in this region, waiting to be exposed via small impacts or landslides, as is believed to be the case for Oxo. Ice is not stable for long periods of time on Ceres' surface, thus its exposure at Oxo must be a relatively recent event. Dawn took this image on Oct. 25, 2016, during its second extended-mission science orbit (XMO2), from a distance of about 920 miles (1,480 kilometers) above the surface of Ceres. The image resolution is about 460 feet (140 meters) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21250

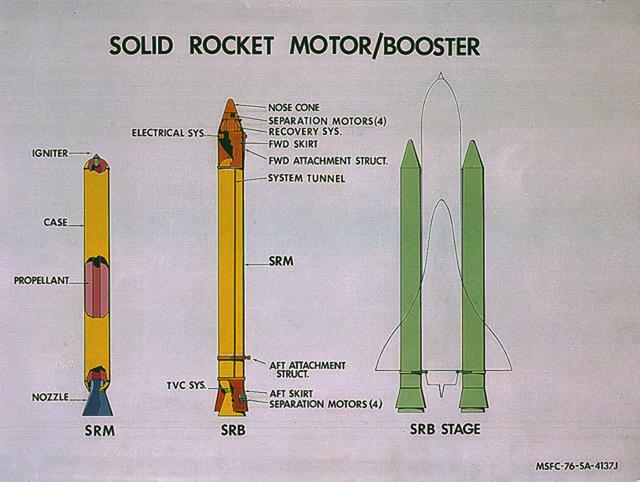

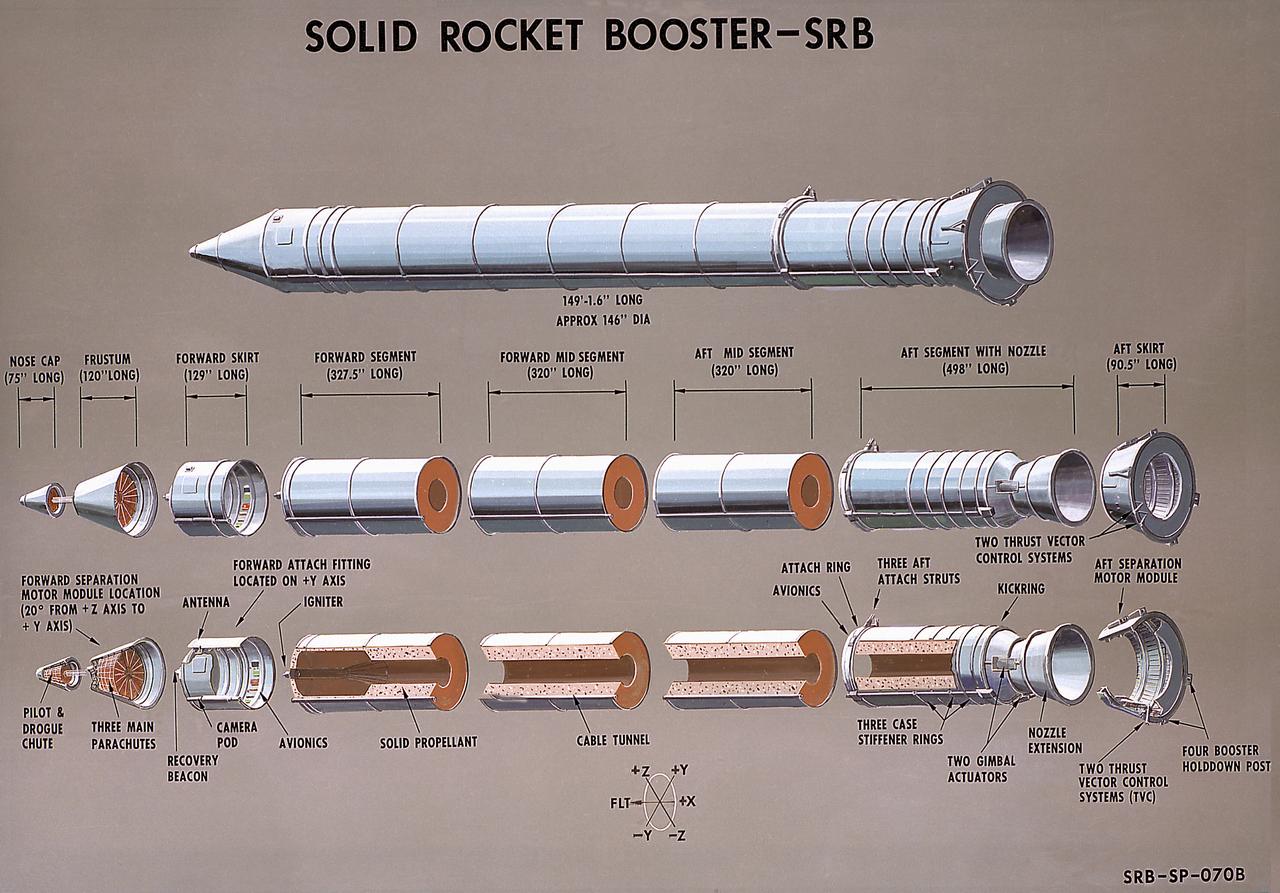

This image illustrates the solid rocket motor (SRM)/solid rocket booster (SRB) configuration. The Shuttle's two SRB's are the largest solids ever built and the first designed for refurbishment and reuse. Standing nearly 150-feet high, the twin boosters provide the majority of thrust for the first two minutes of flight, about 5.8 million pounds, augmenting the Shuttle's main propulsion system during liftoff. The major design drivers for the SRM's were high thrust and reuse. The desired thrust was achieved by using state-of-the-art solid propellant and by using a long cylindrical motor with a specific core design that allows the propellant to burn in a carefully controlled marner. At burnout, the boosters separate from the external tank and drop by parachute to the ocean for recovery and subsequent refurbishment. The boosters are designed to survive water impact at almost 60 miles per hour, maintain flotation with minimal damage, and preclude corrosion of the hardware exposed to the harsh seawater environment. Under the project management of the Marshall Space Flight Center, the SRB's are assembled and refurbished by the United Space Boosters. The SRM's are provided by the Morton Thiokol Corporation.

Roadside bedrock outcrops are all too familiar for many who have taken a long road trip through mountainous areas on Earth. Martian craters provide what tectonic mountain building and man's TNT cannot: crater-exposed bedrock outcrops. Although crater and valley walls offer us roadside-like outcrops from just below the Martian surface, their geometry is not always conducive to orbital views. On the other hand, a crater central peak -- a collection of mountainous rocks that have been brought up from depth, but also rotated and jumbled during the cratering process -- produce some of the most spectacular views of bedrock from orbit. This color composite cutout shows an example of such bedrock that may originate from as deep as 2 miles beneath the surface. The bedrock at this scale is does not appear to be layered or made up of grains, but has a massive appearance riddled with cross-cutting fractures, some of which have been filled by dark materials and rock fragments (impact melt and breccias) generated by the impact event. A close inspection of the image shows that these light-toned bedrock blocks are partially to fully covered by sand dunes and coated with impact melt bearing breccia flows. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA12291

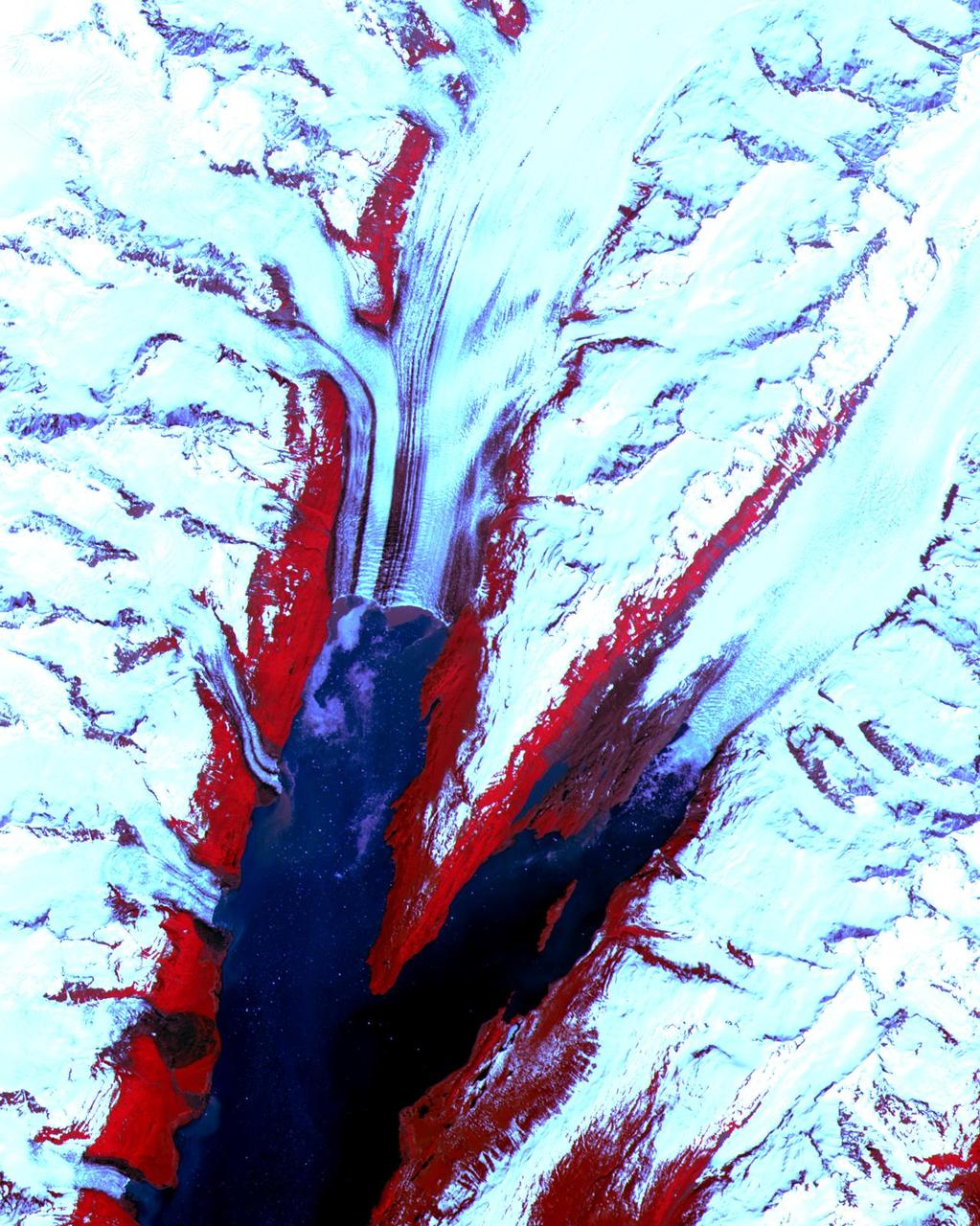

The College Fjord with its glaciers was imaged by ASTER on June 24, 2000. This image covers an area 20 kilometers (13 miles) wide and 24 kilometers (15 miles) long in three bands of the reflected visible and infrared wavelength region. College Fjord is located in Prince Williams Sound, east of Seward, Alaska. Vegetation is in red, and snow and ice are white and blue. Ice bergs calved off of the glaciers can be seen as white dots in the water. At the head of the fjord, Harvard Glacier (left) is one of the few advancing glaciers in the area; dark streaks on the glacier are medial moraines: rock and dirt that indicate the incorporated margins of merging glaciers. Yale Glacier to the right is retreating, exposing (now vegetated) bedrock where once there was ice. On the west edge of the fjord, several small glaciers enter the water. This fjord is a favorite stop for cruise ships plying Alaska's inland passage. This image is located at 61.2 degrees north latitude and 147.7 degrees west longitude. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA02664

This illustration is a cutaway of the solid rocket booster (SRB) sections with callouts. The Shuttle's two SRB's are the largest solids ever built and the first designed for refurbishment and reuse. Standing nearly 150-feet high, the twin boosters provide the majority of thrust for the first two minutes of flight, about 5.8 million pounds, augmenting the Shuttle's main propulsion system during liftoff. The major design drivers for the solid rocket motors (SRM's) were high thrust and reuse. The desired thrust was achieved by using state-of-the-art solid propellant and by using a long cylindrical motor with a specific core design that allows the propellant to burn in a carefully controlled marner. At burnout, the boosters separate from the external tank and drop by parachute to the ocean for recovery and subsequent refurbishment. The boosters are designed to survive water impact at almost 60 miles per hour, maintain flotation with minimal damage, and preclude corrosion of the hardware exposed to the harsh seawater environment. Under the project management of the Marshall Space Flight Center, the SRB's are assembled and refurbished by the United Space Boosters. The SRM's are provided by the Morton Thiokol Corporation.

Click on the image for larger version This image shows a circular impact crater and an oval volcanic caldera on the southern flank of a large volcano on Mars called Pavonis Mons. The caldera is also the source of numerous finger-like lava flows and at least one sinuous lava channel. Both the caldera and the crater are degraded by aeolian (wind) erosion. The strong prevailing winds have apparently carved deep grooves into the terrain. When looking at the scene for the first time, the image seems motion blurred. However, upon a closer look, the smaller, young craters are pristine, so the image must be sharp and the "blurriness" is due to the processes acting on the terrain. This suggests that the deflation-produced grooves, along with the crater and the caldera, are old features and deflation is not very active today. Alternatively, perhaps these craters are simply too young to show signs of degradation. This deeply wind-scoured terrain type is unique to Mars. Wind-carved stream-lined landforms on Earth are called "yardangs," but they don't form extensive terrains like this one. The basaltic lavas on the flanks of this volcano have been exposed to wind for such a long time that there are no parallels on Earth. Terrestrial landscapes and terrestrial wind patterns change much more rapidly than on Mars. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21064

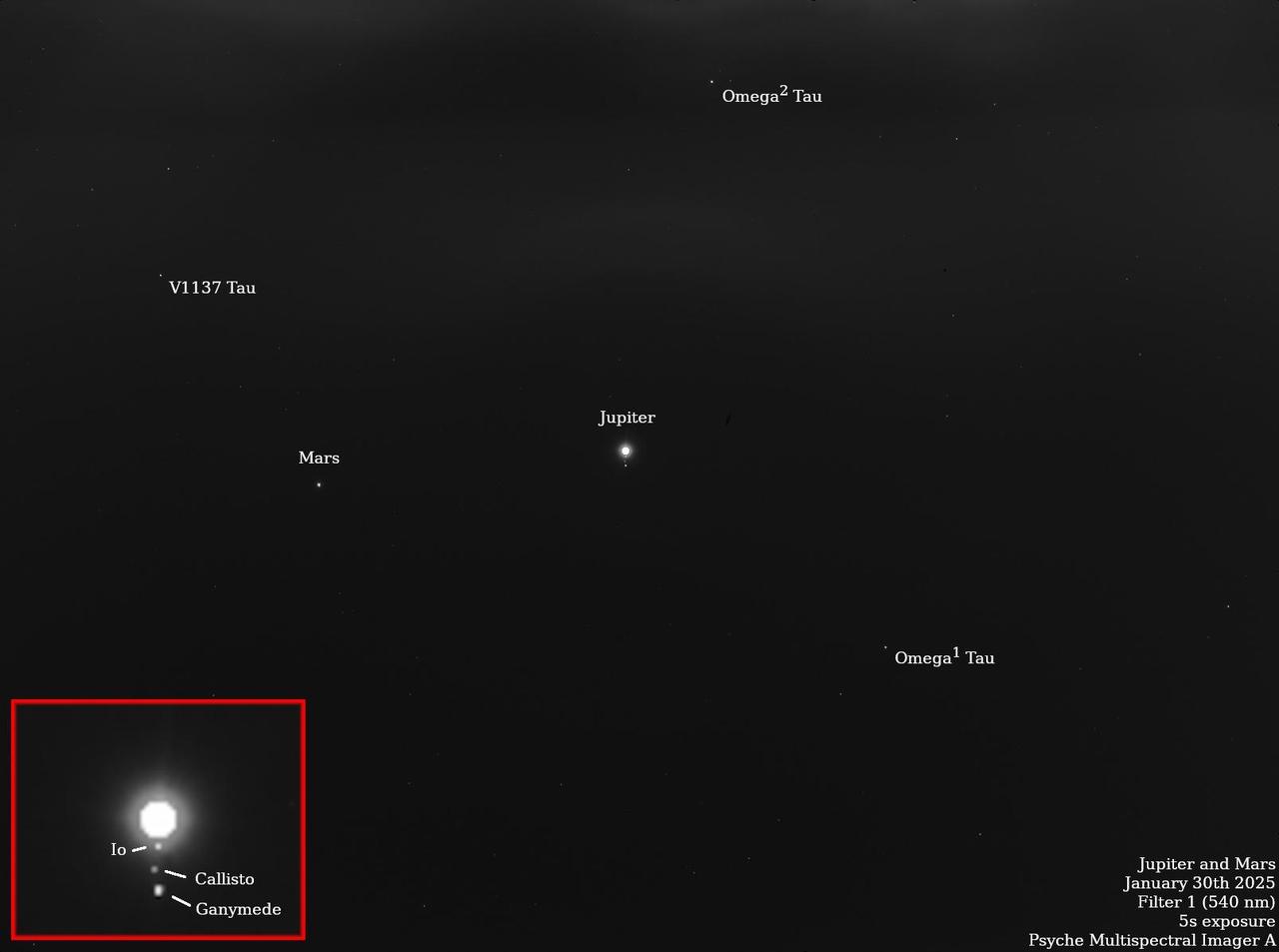

NASA's Psyche spacecraft captured multiple star and planet images in late January 2025 that include notable appearances by Mars, Jupiter, and the Jovian moons Io, Ganymede, Callisto, and Europa. The planned observation by Psyche's imaging instrument was part of a periodic maintenance and calibration test for the twin cameras that make up the imager instrument. Scientists on the imaging team, led by Arizona State University, also took images of the bright stars Vega and Canopus, which have served as standard calibration sources for astronomers for decades. The team is also using the data to assess the effects of minor wiggles or "jitter" in the spacecraft's pointing system as it points the cameras to different places in the sky. The observations of Jupiter and Mars also help the team determine how the cameras respond to solar system objects that shine by reflected sunlight, just like the Psyche asteroid. The starfield pictures shown here are long-exposure (five-second) images captured by each camera. By over-exposing Jupiter to bring out some of the background stars in the Taurus constellation, the imagers were able to capture Jupiter's fainter Galilean moons as well. The image was captured by the Psyche mission's primary camera, Imager-A, on Jan. 30. The image was obtained using the camera's "clear" filter, to provide maximum sensitivity for both bright and faint stars and solar system objects. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26563

ISS013-E-14843 (6 May 2006) --- Calcite Quarry, Michigan is featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 13 crewmember on the International Space Station. While the Great Lakes region of North America is well known for its importance to shipping between the United States, Canada, and the Atlantic Ocean, it is also the location of an impressive structure in the continent's bedrock -- the Michigan Basin, NASA scientists point out. The Basin looks much like a large bull's-eye defined by the arrangement of exposed rock layers, which all tilt inwards towards the center forming a huge bowl-shaped structure. While this "bowl" is not readily apparent while on the ground, detailed mapping of the rock units on a regional scale revealed the structure to geologists. The outer layers of the Basin include thick deposits of carbonates (limestone and dolomite). These carbonate rocks are mined throughout the Great Lakes region using large open-pit mines. The largest carbonate mine in the world, Calcite Quarry, is depicted in this image. The mine has been active for over 85 years; the worked area (grey region in image center) measures approximately 7 kilometers long by 4 kilometers wide, and is crossed by several access roads (white) into various areas of the mine.

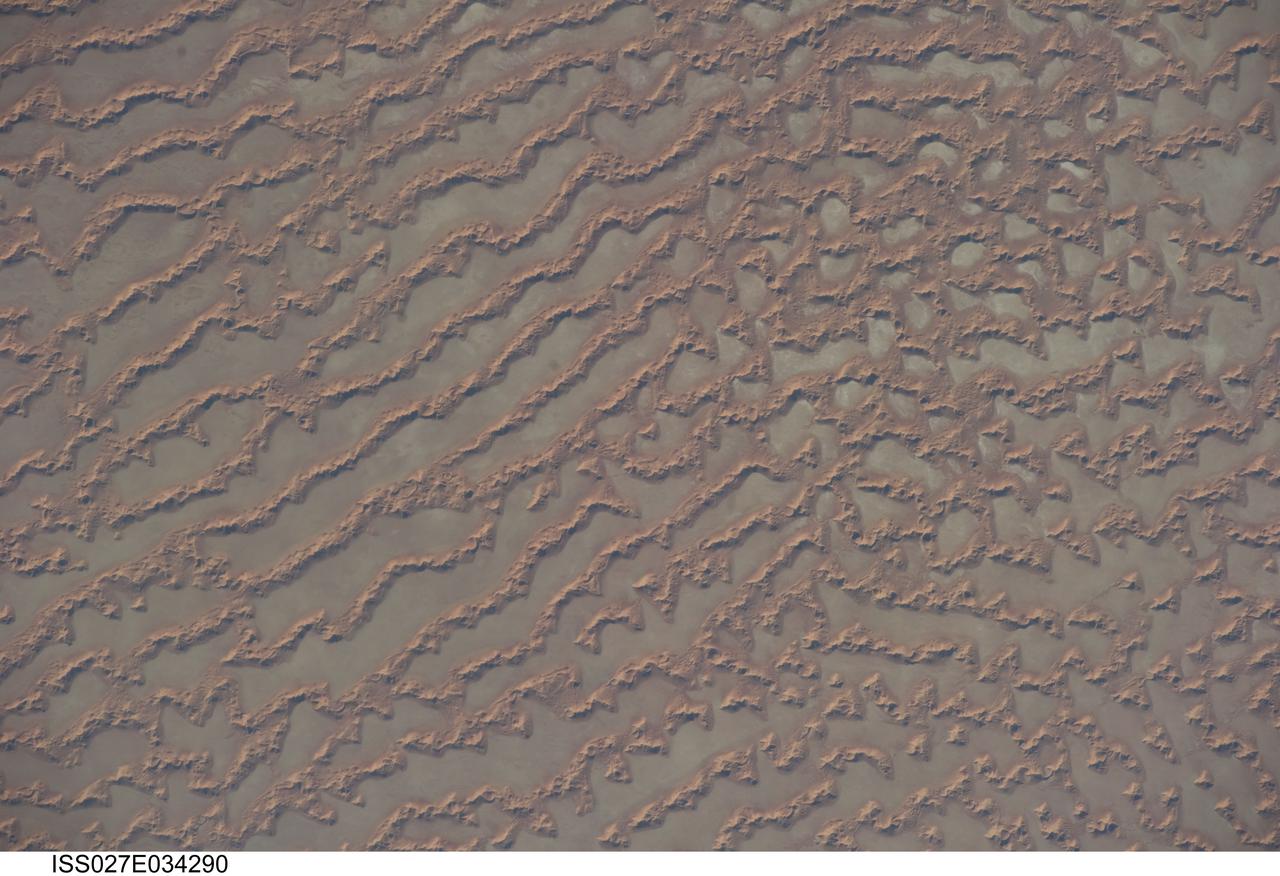

ISS027-E-034290 (16 May 2011) --- Ar Rub al Khali Sand Sea, Arabian Peninsula is featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 27 crew member on the International Space Station. The Ar Rub al Khali, also known as the “Empty Quarter”, is a large region of sand dunes and interdune flats known as a sand sea (or erg). This photograph highlights a part of the Ar Rub al Khali located close to its southeastern margin in the Sultanate of Oman. Reddish-brown, large linear sand dunes alternate with blue-gray interdune salt flats known as sabkhas at left. The major trend of the linear dunes is transverse to northwesterly trade winds that originate in Iraq (known as the Shamal winds). Formation of secondary barchan (crescent-shaped) and star dunes (dune crests in several directions originating from a single point, looking somewhat like a starfish from above) on the linear dunes is supported by southwesterly winds that occur during the monsoon season (Kharif winds). The long linear dunes begin to break up into isolated large star dunes to the northeast and east (right). This is likely a result of both wind pattern interactions and changes in the sand supply to the dunes. The Empty Quarter covers much of the south-central portion of the Arabian Peninsula, and with an area of approximately 660,000 square kilometers it is the largest continuous sand desert on Earth. The Empty Quarter is so called as the dominantly hyperarid climate and difficulty of travel through the dunes has not encouraged permanent settlement within the region. There is geological and archeological evidence to support cooler and wetter past climates in the region together with human settlement. This evidence includes exposed lakebed sediments, scattered stone tools, and the fossils of hippopotamus, water buffalo, and long-horned cattle.

STS089-743-004 (22-31 Jan. 1998) --- This picture showing Auckland Island, New Zealand was photographed with a 70mm handheld camera from the Earth-orbiting space shuttle Endeavour. A spectacular occurrence of internal waves in the ocean is visible in the wake of the island. These waves can be generated by currents or, in some cases, wind across the island. In this case, the observation was that these waves were visible after the sunglint disappeared, suggesting current generated effects. If so, the circum-polar current that moves west-east around Antarctica would generate the scalloped appearance in the water east of the island. There is characteristically very little surface expression to these waves so they would not be noticed by a ship in this region. Fundamental processes of oceanic circulation and interaction are poorly understood. These shots help oceanographers model the dynamics of the open ocean and work out mixing models for ocean layer and ocean-air interaction (important for modeling CO2 budget, for example). The long linear valleys and bays have been excavated by glaciers cutting into this long-extinct volcano. This island is located on the submerged Campbell Plateau, which is an area almost as large as the exposed land of South Island, New Zealand. Scientists report that the plateau was submerged when New Zealand, Antarctica and Australia separated "around 75 million years ago." This could be viewed as one of the tallest mountains on the plateau. Usually the weather in this area is bad so this photo opportunity was considered a "great catch." Photo credit: NASA

Tithonium Chasma is a part of Valles Marineris, the largest canyon in the Solar System. If Valles Marineris was located on Earth, at more than 4,000 kilometers long and 200 kilometers wide, it would span across almost the entire United States. Tithonium Chasma is approximately 800 kilometers long. A "chasma," as defined by the International Astronomical Union, is an elongate, steep-sided depression. The walls of canyons often contain bedrock exposing numerous layers. In some regions, light-toned layered deposits erode faster than the darker-toned ones. The layered deposits in the canyons are of great interest to scientists, as these exposures may shed light on past water activity on Mars. The CRISM instrument on MRO indicates the presence of sulfates, hydrated sulfates, and iron oxides in Tithonium Chasma. Because sulfates generally form from water, the light-toned sulfate rich deposits in the canyons may contain traces of ancient life. The mid-section of this image is an excellent example of the numerous layered deposits, known as interior layered deposits. The exact nature of their formation is still unclear. However, some layered regions display parallelism between strata while other regions are more chaotic, possibly due to past tectonic activity. Lobe-shaped deposits are associated with depositional morphologies, considered indicative of possible periglacial activity. Overall, the morphological and lithological features we see today are the result of numerous geological processes, indicating that Mars experienced a diverse and more active geological past. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19868

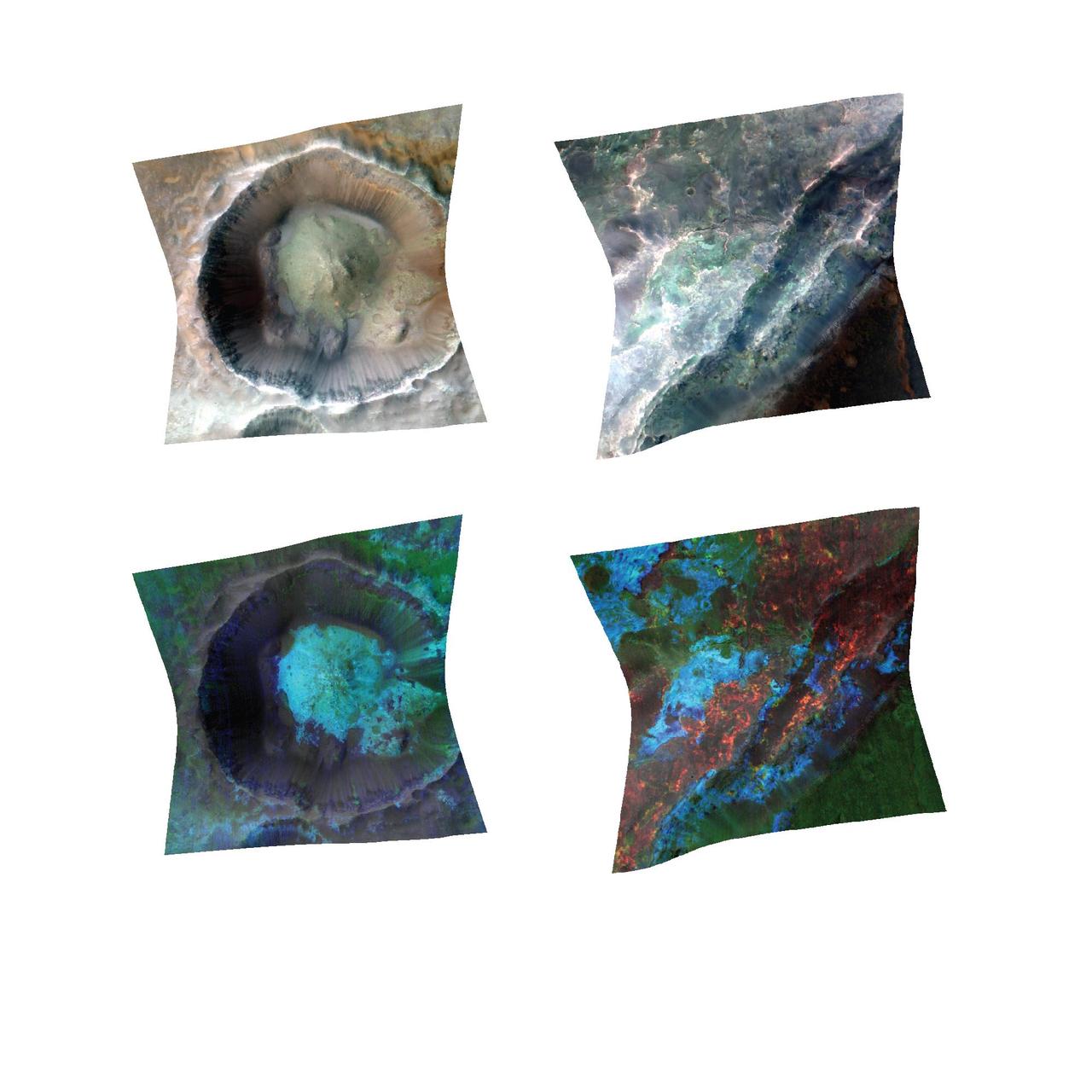

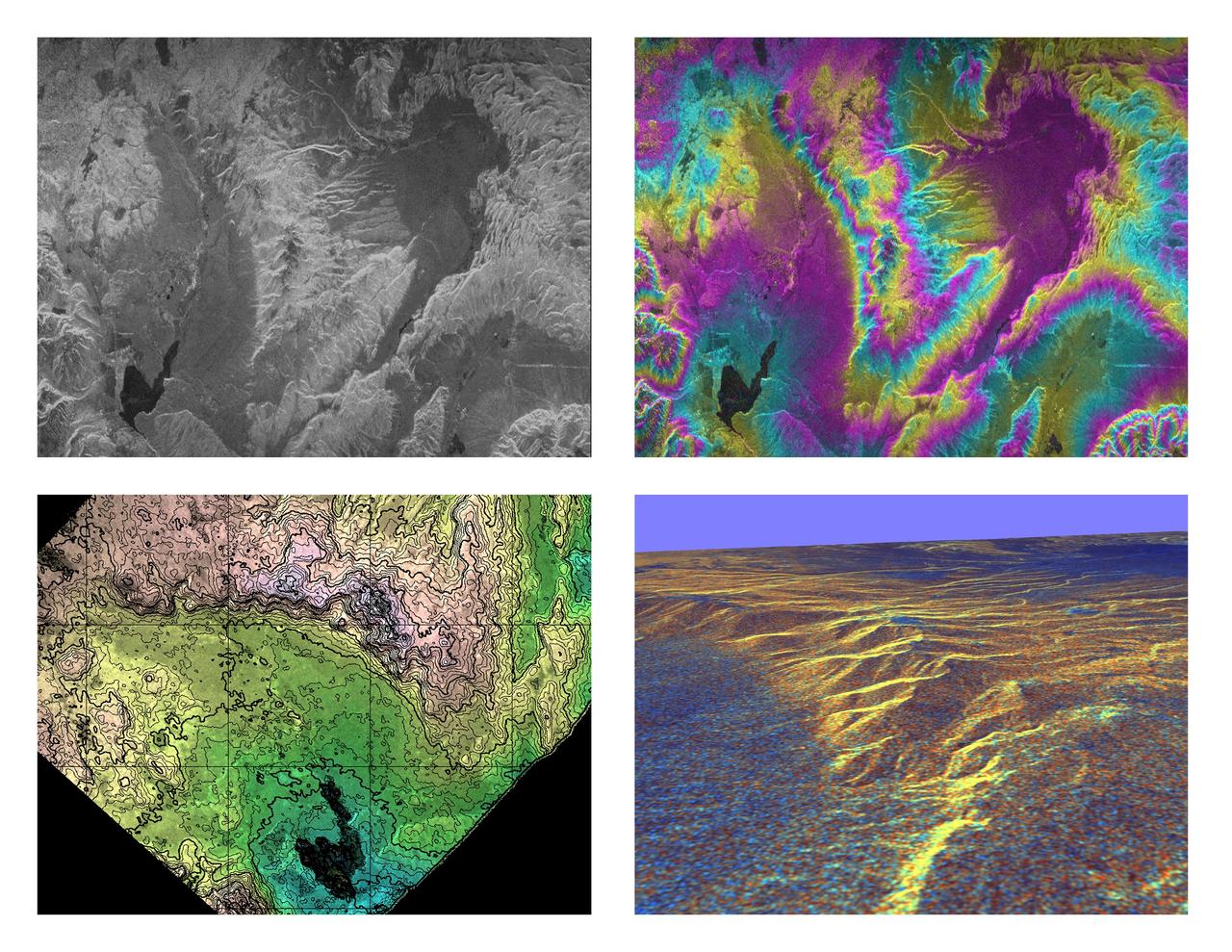

These four images of the Long Valley region of east-central California illustrate the steps required to produced three dimensional data and topographics maps from radar interferometry. All data displayed in these images were acquired by the Spaceborne Imaging Radar-C/X-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SIR-C/X-SAR) aboard the space shuttle Endeavour during its two flights in April and October, 1994. The image in the upper left shows L-band (horizontally transmitted and received) SIR-C radar image data for an area 34 by 59 kilometers (21 by 37 miles). North is toward the upper right; the radar illumination is from the top of the image. The bright areas are hilly regions that contain exposed bedrock and pine forest. The darker gray areas are the relatively smooth, sparsely vegetated valley floors. The dark irregular patch near the lower left is Lake Crowley. The curving ridge that runs across the center of the image from top to bottom is the northeast rim of the Long Valley Caldera, a remnant crater from a massive volcanic eruption that occurred about 750,000 years ago. The image in the upper right is an interferogram of the same area, made by combining SIR-C L-band data from the April and October flights. The colors in this image represent the difference in the phase of the radar echoes obtained on the two flights. Variations in the phase difference are caused by elevation differences. Formation of continuous bands of phase differences, known as interferometric "fringes," is only possible if the two observations were acquired from nearly the same position in space. For these April and October data takes, the shuttle tracks were less than 100 meters (328 feet) apart. The image in the lower left shows a topographic map derived from the interferometric data. The colors represent increments of elevation, as do the thin black contour lines, which are spaced at 50-meter (164-foot) elevation intervals. Heavy contour lines show 250-meter intervals (820-foot). Total relief in this area is about 1,320 meters (4,330 feet). Brightness variations come from the radar image, which has been geometrically corrected to remove radar distortions and rotated to have north toward the top. The image in the lower right is a three-dimensional perspective view of the northeast rim of the Long Valley caldera, looking toward the northwest. SIR-C C-band radar image data are draped over topographic data derived from the interferometry processing. No vertical exaggeration has been applied. Combining topographic and radar image data allows scientists to examine relationships between geologic structures and landforms, and other properties of the land cover, such as soil type, vegetation distribution and hydrologic characteristics. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA01770

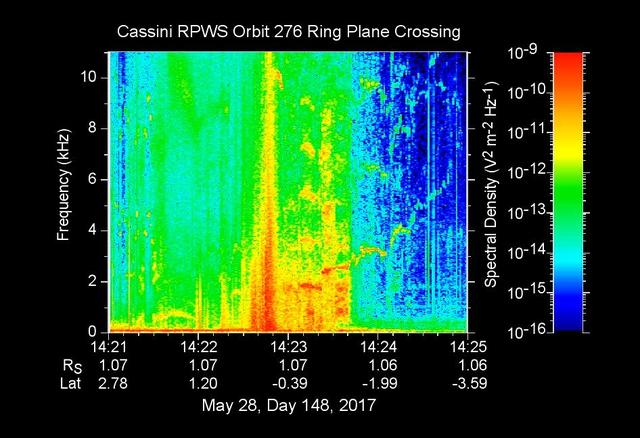

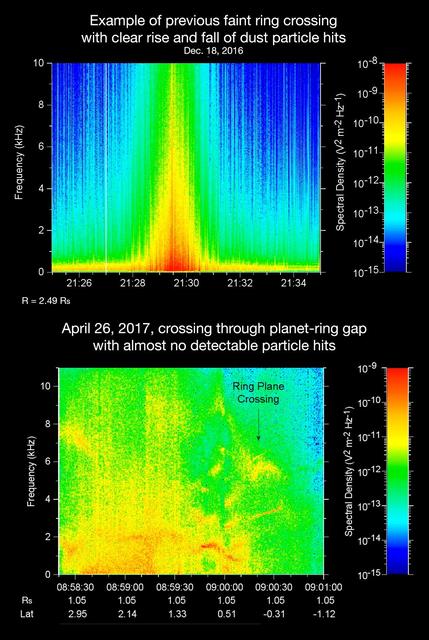

The sounds and colorful spectrogram in this still image and video represent data collected by the Radio and Plasma Wave Science, or RPWS, instrument on NASA's Cassini spacecraft, as it crossed through Saturn's D ring on May 28, 2017. This was the first of four passes through the inner edge of the D ring during the 22 orbits of Cassini's final mission phase, called the Grand Finale. During this ring plane crossing, the spacecraft was oriented so that its large high-gain antenna was used as a shield to protect more sensitive components from possible ring-particle impacts. The three 33-foot-long (10-meter-long) RPWS antennas were exposed to the particle environment during the pass. As tiny, dust-sized particles strike Cassini and the RPWS antennas, the particles are vaporized into tiny clouds of plasma, or electrically excited gas. These tiny explosions make a small electrical signal (a voltage impulse) that RPWS can detect. Researchers on the RPWS team convert the data into visible and audio formats, some like those seen here, for analysis. Ring particle hits sound like pops and cracks in the audio. Particle impacts are seen to increase in frequency in the spectrogram and in the audible pops around the time of ring crossing as indicated by the red/orange spike just before 14:23 on the x-axis. Labels on the x-axis indicate time (top line), distance from the planet's center in Saturn radii, or Rs (middle), and latitude on Saturn beneath the spacecraft (bottom). These data can be compared to those recorded during Cassini's first dive through the gap between Saturn and the D ring, on April 26. While it appeared from those earlier data that there were essentially no particles in the gap, scientists later determined the particles there are merely too small to create a voltage detectable by RPWS, but could be detected using Cassini's dust analyzer instrument. After ring plane crossing (about 14:23 onward) a series of high pitched whistles are heard. The RPWS instrument detects such tones during each of the Grand Finale orbits and the team is working to understand their source. The D ring proved to contain larger ring particles, as expected and recorded here, although the environment was determined to be relatively benign -- with less dust than other faint Saturnian rings Cassini has flown through. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21620

ISS018-E-018129 (6 Jan. 2009) --- Atafu Atoll in the Southern Pacific Ocean is featured in this image photographed by an Expedition 18 crewmember on the International Space Station. At roughly eight kilometers wide, Atafu Atoll is the smallest of three atolls (with Nukunonu and Fakaofo atolls to the southeast, not shown) comprising the Tokelau Islands group located in the southern Pacific Ocean. Swains Island to the south (not shown) is also considered part of the Tokelau group. The political entity of Tokelau is currently a territory of New Zealand. In recent years, public referendums on independence within the islands have been held, but have not received sufficient support to move forward. The primary settlement on Atafu is a village located at the northwestern corner of the atoll ? indicated by an area of light gray dots in this photograph. The typical ring shape of the atoll is the result of coral reefs building up around a former volcanic island. Over geologic time, the central volcano has subsided beneath the water surface, leaving the fringing reefs and a central lagoon that contains submerged coral reefs. Erosion and soil development on the surfaces of the exposed fringing reefs has lead to formation of tan to light brown beach deposits (southern and western sides of the atoll) and green vegetation cover (northern and eastern sides of the atoll). The Tokelau Islands, including Atafu Atoll, suffered significant inundation and erosion during Tropical Cyclone Percy in 2005. The approximate elevation of Atafu Atoll is only two meters above the tidal high water level. Vulnerability to tropical cyclones and potential sea level rise makes the long-term habitability of the atoll uncertain.