jsc2025e044837 2/19/2019) --- Shown is the SV104A noise dosimeter that measures noise dose and noise levels in the large measurement range of 55 dB to 140 dB aboard the International Space Station. This dosimeter is part of A Next Generation Crew Health & Performance Acoustic Monitoring Capability for Exploration: An International Space Station Technology Demonstration (Wireless Acoustics) investigation. Image courtesy of SVANTEK.

The augmentor wing concept was introduced during the early 1960s to enhance the performance of vertical and short takeoff (VSTOL) aircraft. The leading edge of the wing has full-span vertical flaps, and the trailing edge has double-slotted flaps. This provides aircraft with more control in takeoff and landing conditions. The augmentor wing also produced lower noise levels than other VSTOL designs. In the early 1970s Boeing Corporation built a Buffalo C-8A augmentor wing research aircraft for Ames Research Center. Researches at Lewis Research Center concentrated their efforts on reducing the noise levels of the wing. They initially used small-scale models to develop optimal nozzle screening methods. They then examined the nozzle designs on a large-scale model, seen here on an external test stand. This test stand included an airflow system, nozzle, the augmentor wing, and a muffler system below to reduce the atmospheric noise levels. The augmentor was lined with noise-reducing acoustic panels. The Lewis researchers were able to adjust the airflow to simulate conditions at takeoff and landing. Once the conditions were stabilized they took noise measurements from microphones placed in all directions from the wing, including an aircraft flying over. They found that the results coincided with the earlier small-scale studies for landing situations but not takeoffs. The acoustic panels were found to be successful.

A Lockheed F-94B Starfire being equipped with an audio recording machine and sensors at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory. The NACA was investigating the acoustic effects caused by the engine’s nozzle and the air flowing along the fuselage. Airline manufacturers would soon be introducing jet engines on their passenger aircraft, and there was concern regarding the noise levels for both the passengers and public on the ground. NACA Lewis conducted a variety of noise reduction studies in its wind tunnels, laboratories, and on a F2H-2B Banshee aircraft. The F2H-2B Banshee’s initial test flights in 1955 and 1956 measured the noise emanating directly from airflow over the aircraft’s surfaces, particularly the wings. This problem was particularly pronounced at high subsonic speeds. The researchers found the majority of the noise occurred in the low and middle octaves. These investigations were enhanced with a series of flights using the F-94B Starfire. The missions measured wall-pressure, turbulence fluctuations, and mean velocity profiles. Mach 0.3 to 0.8 flights were flown at altitudes of 10,000, 20,000, and 30,000 feet with microphones mounted near the forward fuselage and on a wing. The results substantiated the wind tunnel findings. This photograph shows the tape recorder being installed in the F-94B’s nose.

Support personnel prepare noise level measuring equipment along the runway for the 2011 Green Flight Challenge, sponsored by Google, at the Charles M. Schulz Sonoma County Airport in Santa Rosa, Calif. on Monday, Sept. 26, 2011. NASA and the Comparative Aircraft Flight Efficiency (CAFE) Foundation are having the challenge with the goal to advance technologies in fuel efficiency and reduced emissions with cleaner renewable fuels and electric aircraft. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Sid Siddiqi, seated, and other support personnel prepare noise level measuring equipment for the 2011 Green Flight Challenge, sponsored by Google, at the Charles M. Schulz Sonoma County Airport in Santa Rosa, Calif. on Monday, Sept. 26, 2011. NASA and the Comparative Aircraft Flight Efficiency (CAFE) Foundation are having the challenge with the goal to advance technologies in fuel efficiency and reduced emissions with cleaner renewable fuels and electric aircraft. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

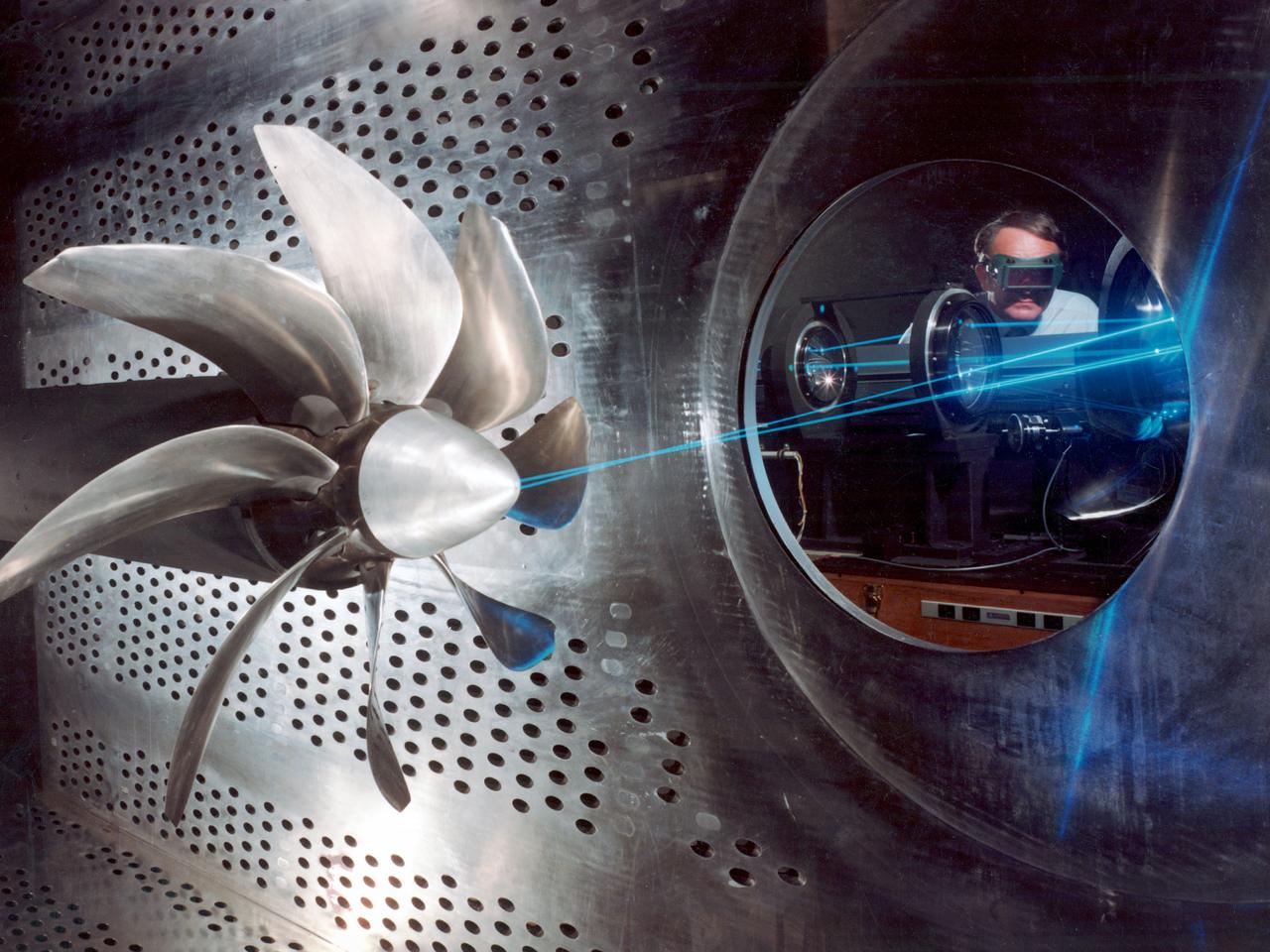

NASA Lewis Research Center researcher, John S. Sarafini, uses a laser doppler velocimeter to analyze a Hamilton Standard SR-2 turboprop design in the 8- by 6-Foot foot Supersonic Wind Tunnel. Lewis researchers were analyzing a series of eight-bladed propellers in their wind tunnels to determine their operating characteristics at speeds up to Mach 0.8. The program, which became the Advanced Turboprop (ATP), was part of a NASA-wide Aircraft Energy Efficiency Program undertaken to reduce aircraft fuel costs by 50 percent. The ATP concept was different from the turboprops in use in the 1950s. The modern versions had at least eight blades and were swept back for better performance. Bell Laboratories developed the laser doppler velocimeter technology in the 1960s to measure velocity of transparent fluid flows or vibration motion on reflective surfaces. Lewis researchers modified the device to measure the flow field of turboprop configurations in the transonic speed region. The modifications were necessary to overcome the turboprop’s vibration and noise levels. The laser beam was split into two beams which were crossed at a specific point. This permits researchers to measure two velocity components simultaneously. This data measures speeds both ahead and behind the propeller blades. Researchers could use this information as they sought to advance flow fields and to verify computer modeling codes.

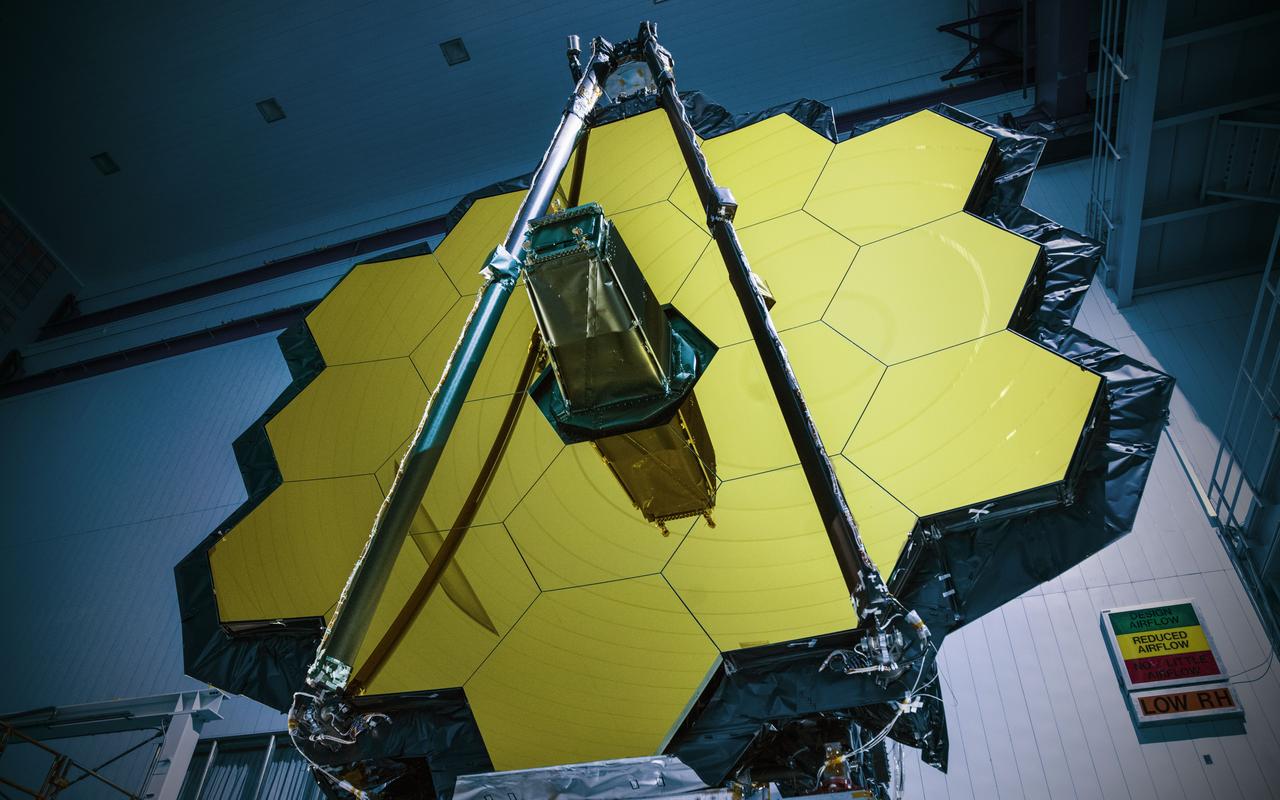

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has successfully passed the center of curvature test, an important optical measurement of Webb’s fully assembled primary mirror prior to cryogenic testing, and the last test held at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, before the spacecraft is shipped to NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston for more testing. After undergoing rigorous environmental tests simulating the stresses of its rocket launch, the Webb telescope team at Goddard analyzed the results from this critical optical test and compared it to the pre-test measurements. The team concluded that the mirrors passed the test with the optical system unscathed. “The Webb telescope is about to embark on its next step in reaching the stars as it has successfully completed its integration and testing at Goddard. It has taken a tremendous team of talented individuals to get to this point from all across NASA, our industry and international partners, and academia,” said Bill Ochs, NASA’s Webb telescope project manager. “It is also a sad time as we say goodbye to the Webb Telescope at Goddard, but are excited to begin cryogenic testing at Johnson.” Rocket launches create high levels of vibration and noise that rattle spacecraft and telescopes. At Goddard, engineers tested the Webb telescope in vibration and acoustics test facilities that simulate the launch environment to ensure that functionality is not impaired by the rigorous ride on a rocket into space. Before and after these environmental tests took place, optical engineers set up an interferometer, the main device used to measure the shape of the Webb telescope’s mirror. An interferometer gets its name from the process of recording and measuring the ripple patterns that result when different beams of light mix and their waves combine or “interfere.” Waves of visible light are less than a thousandth of a millimeter long and optics on the Webb telescope need to be shaped and aligned even more accurately than that to work correctly. Making measurements of the mirror shape and position by lasers prevents physical contact and damage (scratches to the mirror). So, scientists use wavelengths of light to make tiny measurements. By measuring light reflected off the optics using an interferometer, they are able to measure extremely small changes in shape or position that may occur after exposing the mirror to a simulated launch or temperatures that simulate the subfreezing environment of space. During a test conducted by a team from Goddard, Ball Aerospace of Boulder, Colorado, and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, temperature and humidity conditions in the clean room were kept incredibly stable to minimize fluctuations in the sensitive optical measurements over time. Even so, tiny vibrations are ever-present in the clean room that cause jitter during measurements, so the interferometer is a “high-speed” one, taking 5,000 “frames” every second, which is a faster rate than the background vibrations themselves. This allows engineers to subtract out jitter and get good, clean results on any changes to the mirror's shape. Credit: NASA/Goddard/Chris Gunn Read more: <a href="https://go.nasa.gov/2oPqHwR" rel="nofollow">go.nasa.gov/2oPqHwR</a> NASA’s Webb Telescope Completes Goddard Testing

The aircraft in this 1953 photo of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) hangar at South Base of Edwards Air Force Base showed the wide range of research activities being undertaken. On the left side of the hangar are the three D-558-2 research aircraft. These were designed to test swept wings at supersonic speeds approaching Mach 2. The front D-558-2 is the third built (NACA 145/Navy 37975). It has been modified with a leading-edge chord extension. This was one of a number of wing modifications, using different configurations of slats and/or wing fences, to ease the airplane's tendency to pitch-up. NACA 145 had both a jet and a rocket engine. The middle aircraft is NACA 144 (Navy 37974), the second built. It was all-rocket powered, and Scott Crossfield made the first Mach 2 flight in this aircraft on November 20, 1953. The aircraft in the back is D-558-2 number 1. NACA 143 (Navy 37973) was also carried both a jet and a rocket engine in 1953. It had been used for the Douglas contractor flights, then was turned over to the NACA. The aircraft was not converted to all-rocket power until June 1954. It made only a single NACA flight before NACA's D-558-2 program ended in 1956. Beside the three D-558-2s is the third D-558-1. Unlike the supersonic D-558-2s, it was designed for flight research at transonic speeds, up to Mach 1. The D-558-1 was jet-powered, and took off from the ground. The D-558-1's handling was poor as it approached Mach 1. Given the designation NACA 142 (Navy 37972), it made a total of 78 research flights, with the last in June 1953. In the back of the hangar is the X-4 (Air Force 46-677). This was a Northrop-built research aircraft which tested a swept wing design without horizontal stabilizers. The aircraft proved unstable in flight at speeds above Mach 0.88. The aircraft showed combined pitching, rolling, and yawing motions, and the design was considered unsuitable. The aircraft, the second X-4 built, was then used as a pilot traine