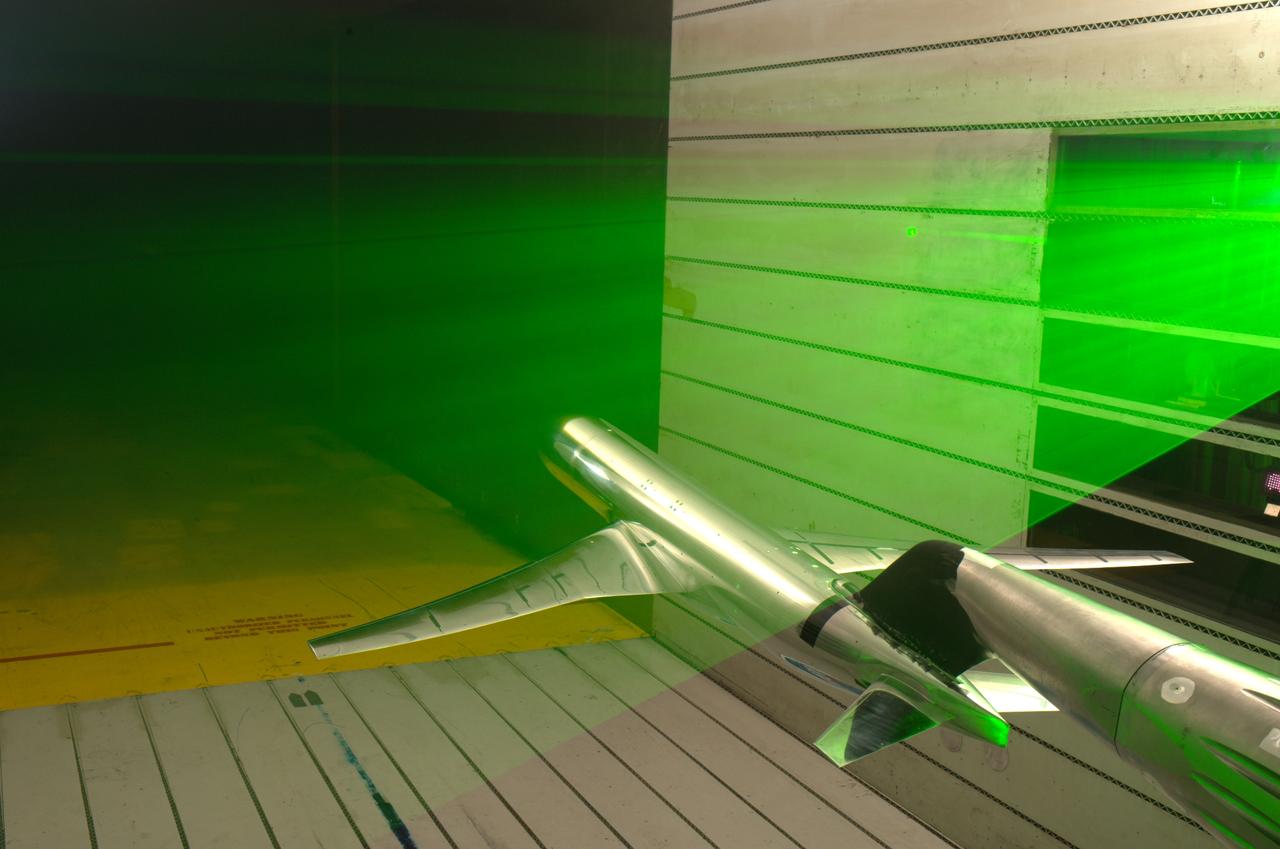

Particle-image velocimetry (PIV) is performed on the upper surface of a pitching airfoil in the NASA Glenn Icing Research Tunnel. PIV is a laser-based flow velocity measurement technique used widely in wind tunnels. These experiments were conducted as part of a research project focused on enhancing rotorcraft speed, efficiency and maneuverability by suppressing dynamic stall.

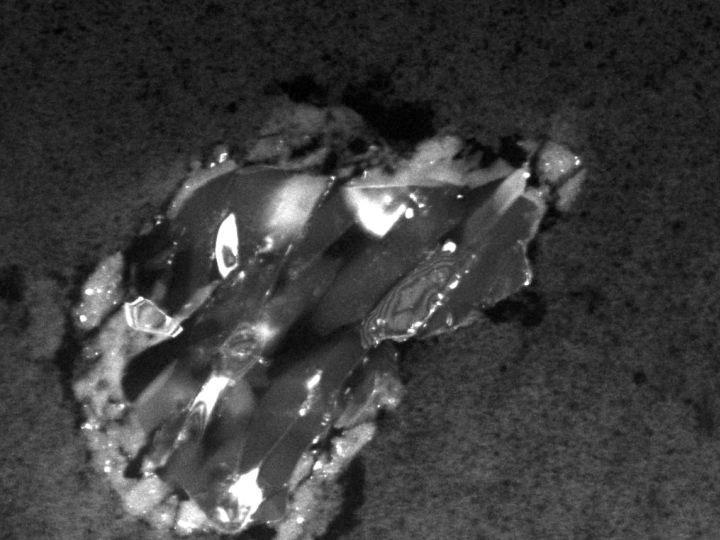

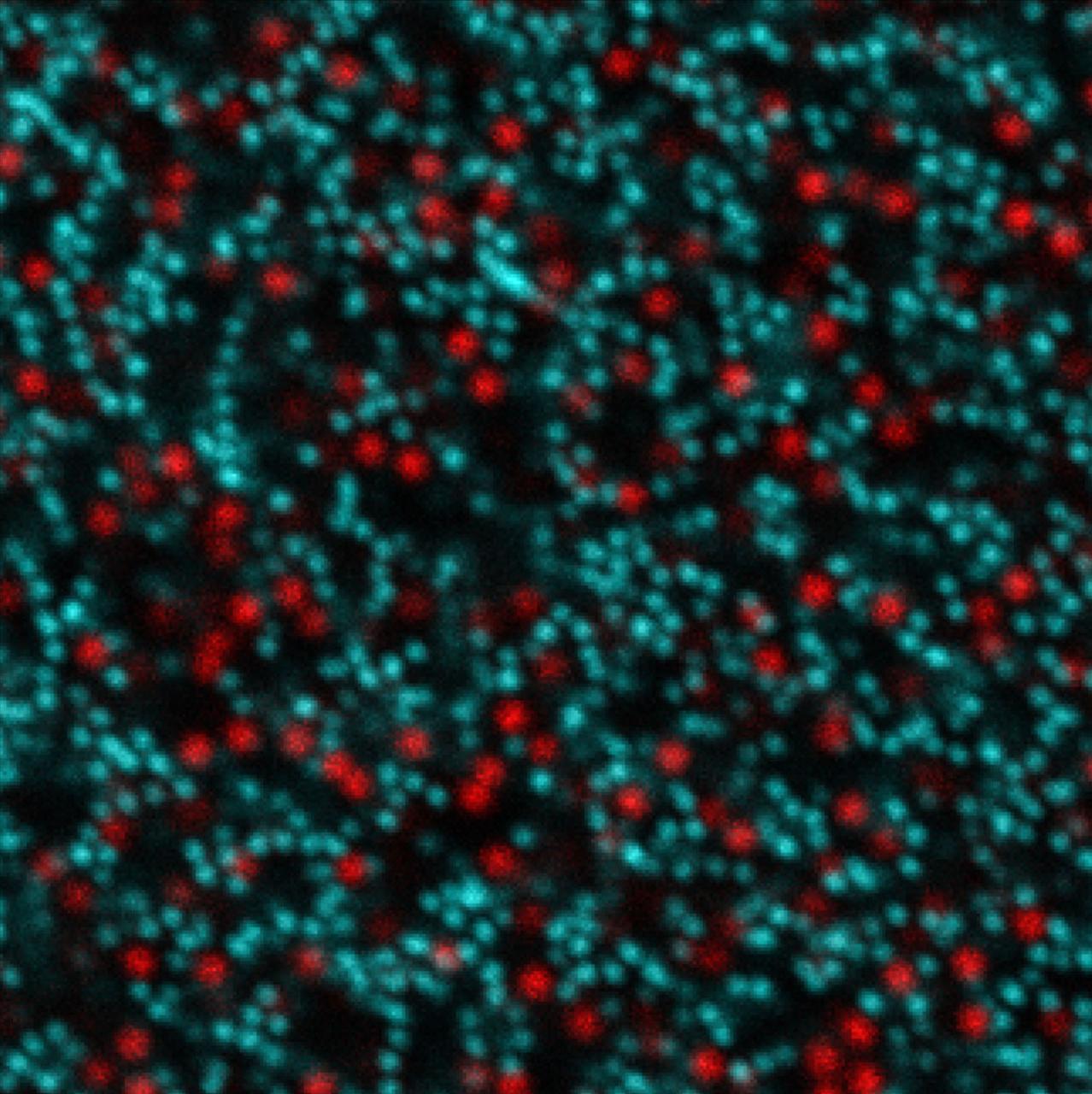

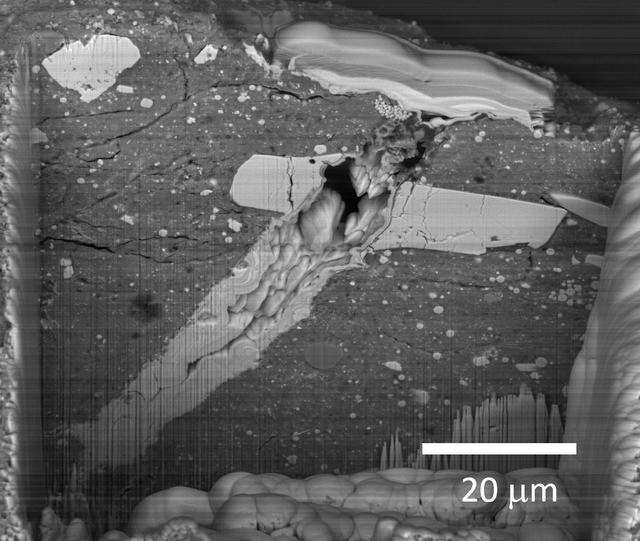

Microscope Image of Scavenged Particles

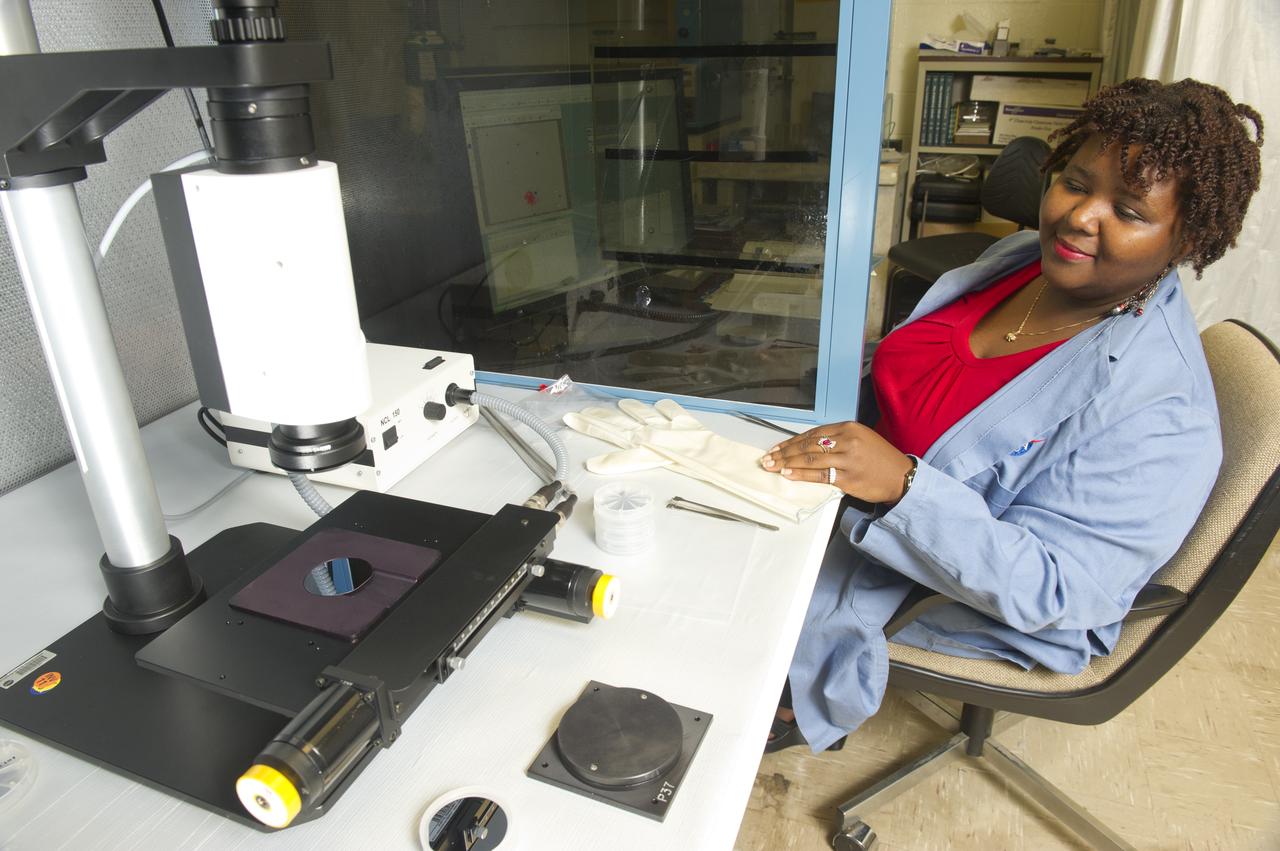

LAQUIETA HUEY WITH IMAGE ANALYSIS SYSTEM FOR AUTOMATED PARTICLE COUNTING.

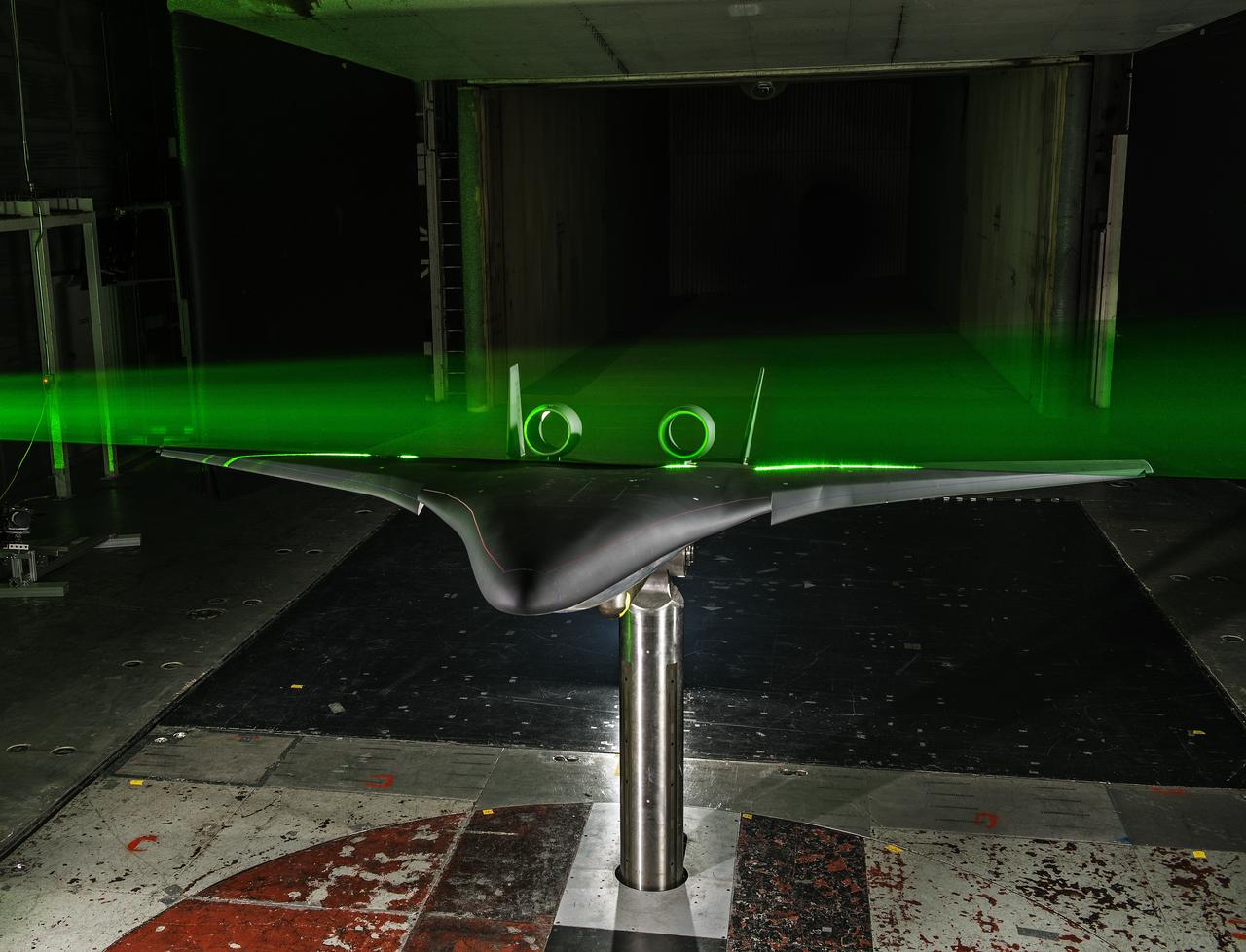

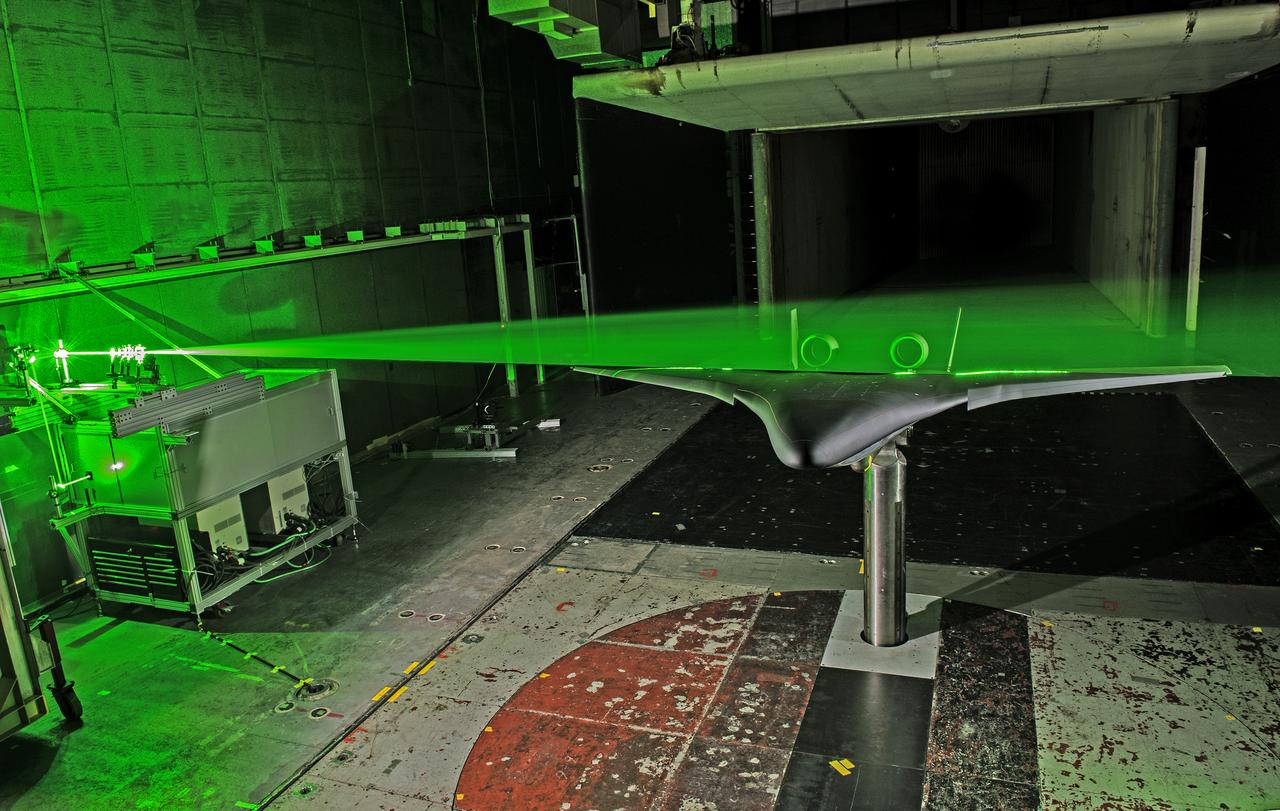

Hybrid Wing Body Particle Image Velocimetry Test in LaRC 14x22 Foot Tunnel: PIV measurement of HWB-N2A model in Langley 14x22 Foot Tunnel

Hybrid Wing Body Particle Image Velocimetry Test in LaRC 14x22 Foot Tunnel: PIV measurement of HWB-N2A model in Langley 14x22 Foot Tunnel

Hybrid Wing Body Particle Image Velocimetry Test in LaRC 14x22 Foot Tunnel: PIV measurement of HWB-N2A model in Langley 14x22 Foot Tunnel

Hybrid Wing Body Particle Image Velocimetry Test in LaRC 14x22 Foot Tunnel: PIV measurement of HWB-N2A model in Langley 14x22 Foot Tunnel

Hybrid Wing Body Particle Image Velocimetry Test in LaRC 14x22 Foot Tunnel: PIV measurement of HWB-N2A model in Langley 14x22 Foot Tunnel

Hybrid Wing Body Particle Image Velocimetry Test in LaRC 14x22 Foot Tunnel: PIV measurement of HWB-N2A model in Langley 14x22 Foot Tunnel

Hybrid Wing Body Particle Image Velocimetry Test in LaRC 14x22 Foot Tunnel: PIV measurement of HWB-N2A model in Langley 14x22 Foot Tunnel

This image shows a comet particle collected by NASA’s Stardust spacecraft. The particle is made up of the silicate mineral forsterite, also known as peridot in its gem form.

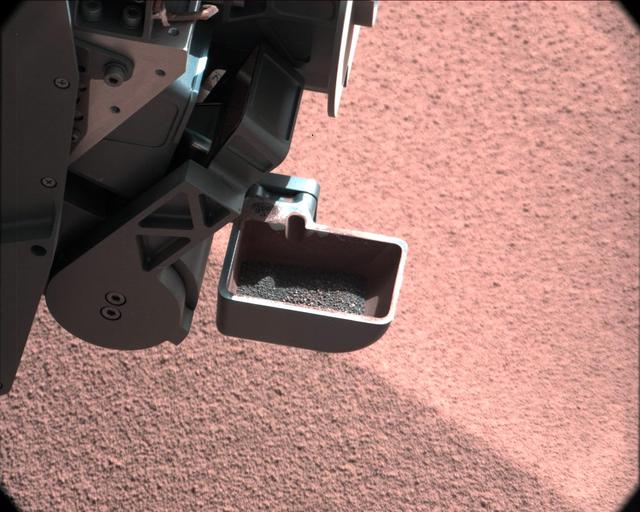

In this image, the scoop on NASA Curiosity rover shows the larger soil particles that were too big to filter through a sample-processing sieve that is porous only to particles less than 0.006 inches 150 microns across.

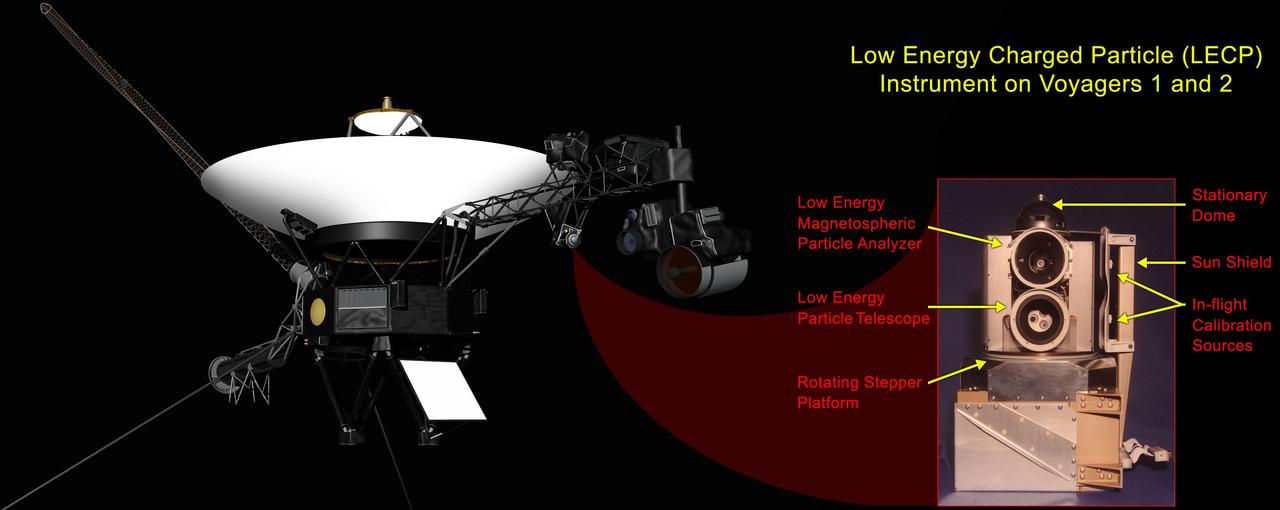

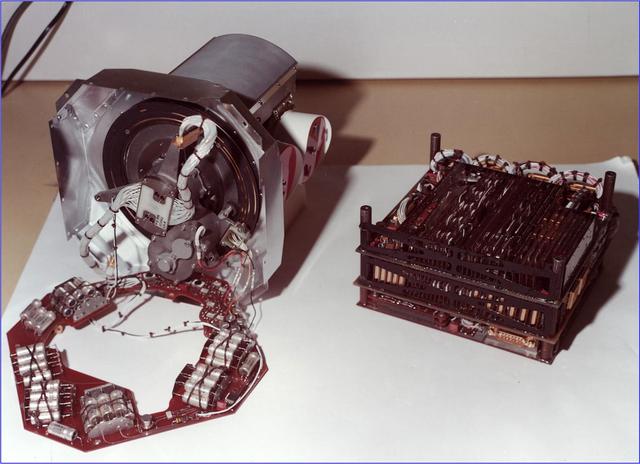

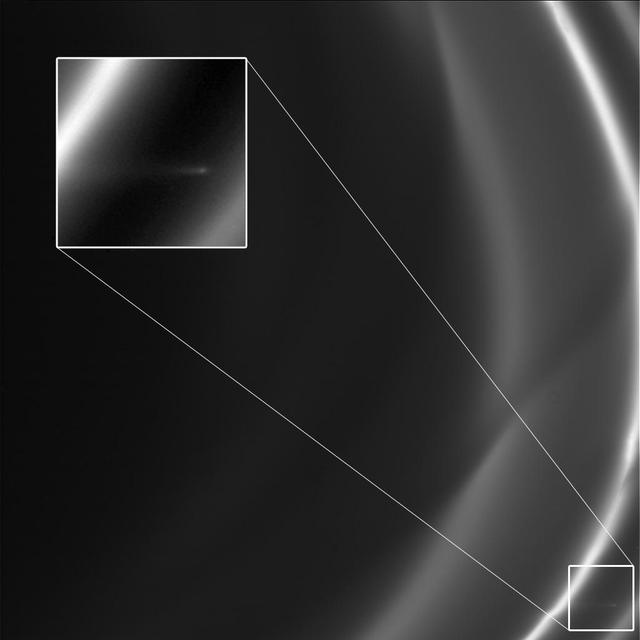

This graphic shows the NASA Voyager 1 spacecraft and the location of its low-energy charged particle instrument. A labeled close-up of the low-energy charged particle instrument appears as the inset image.

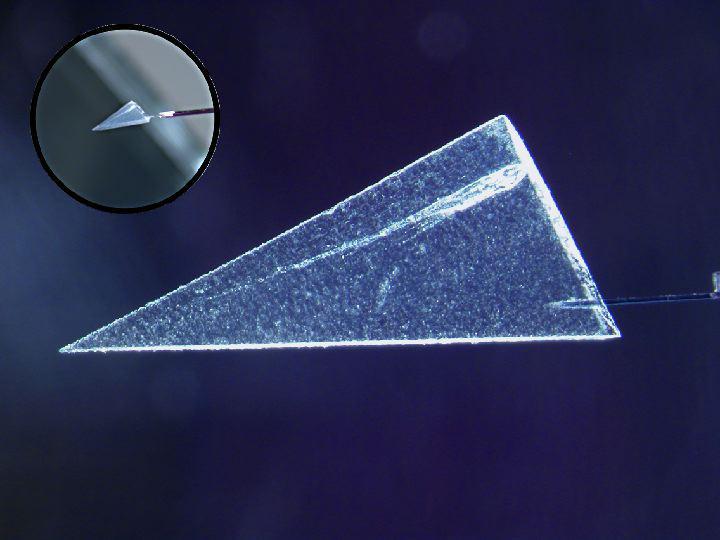

This image illustrates one of several ways scientists have begun extracting comet particles from NASAa Stardust spacecraft collector. First, a particle and its track are cut out of the collector material, called aerogel.

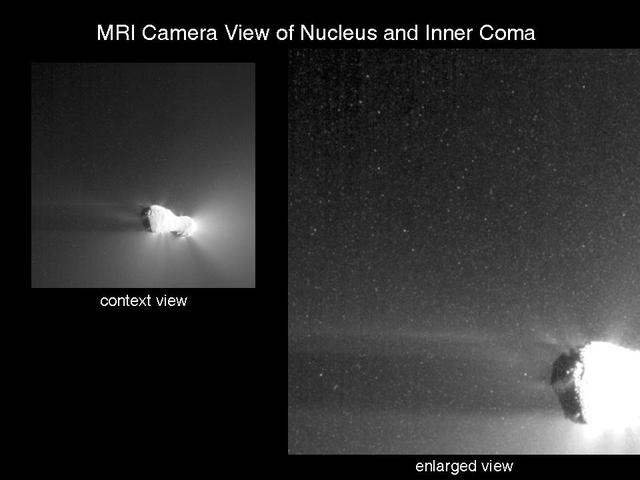

NASA EPOXI mission spacecraft obtained these views of the icy particle cloud around comet Hartley 2. The image on the left is the full image of comet Hartley 2 for context, and the image on the right was enlarged and cropped.

This zoomed-in image from the High-Resolution Instrument on NASA EPOXI mission spacecraft shows the particles swirling in a now storm around the nucleus of comet Hartley 2.

This image contributed to an interpretation by NASA Mars rover Curiosity science team that some of the bright particles on the ground near the rover are native Martian material.

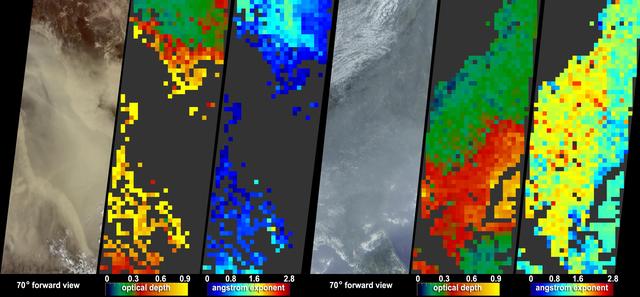

How precisely do the size of the aerosol particles comprising the dust that obscured the Red Sea on July 26, 2005? This image is from NASA Terra spacecraft.

The small parallel ridges in this image captured by NASA 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft were created by the erosive power of wind blown particles.

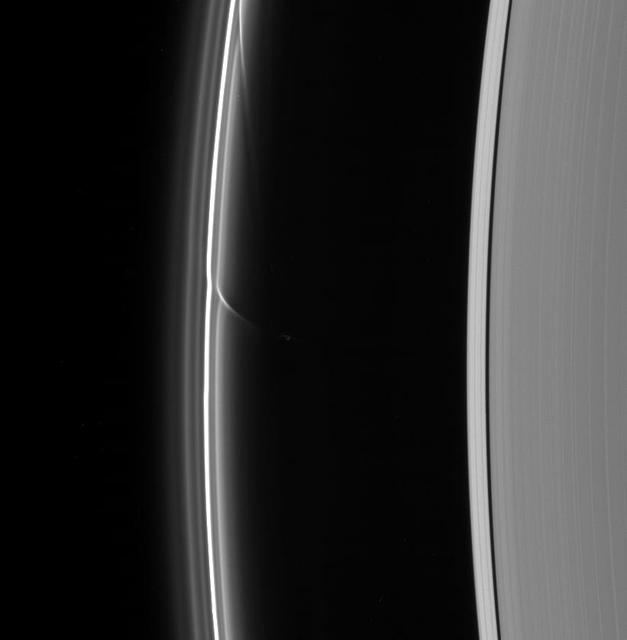

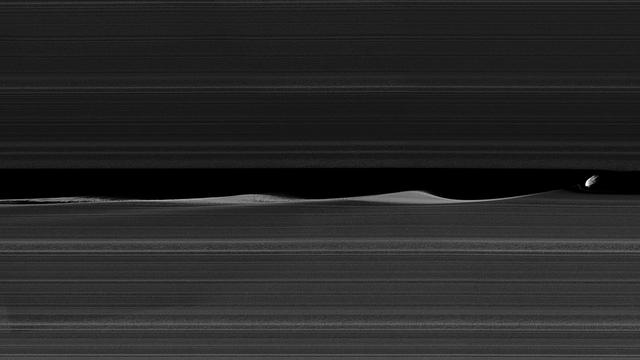

A shepherd moon can do more to define ring structures than just keep the flock of particles in line, as Cassini spacecraft images such as this have shown

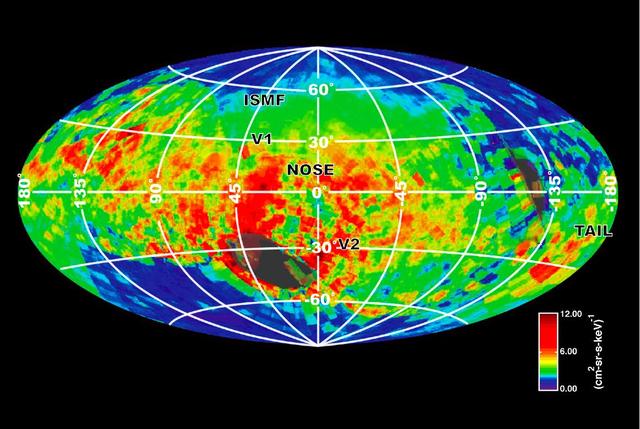

NASA Cassini spacecraft created this image of the bubble around our solar system based on emissions of particles known as energetic neutral atoms.

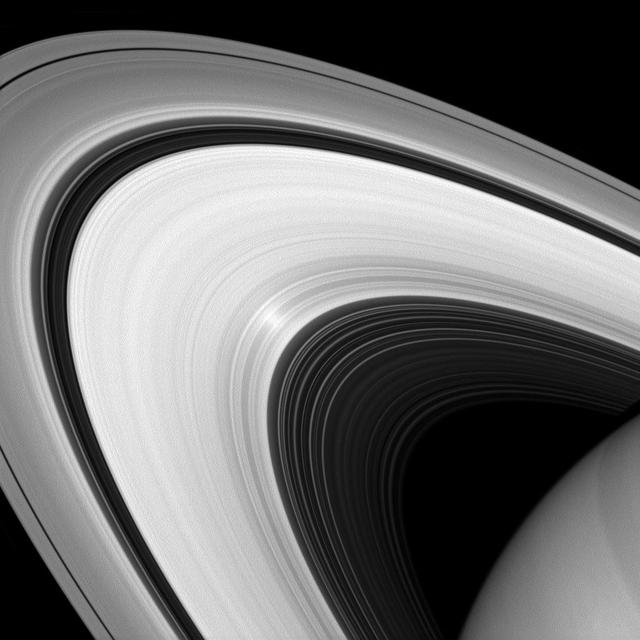

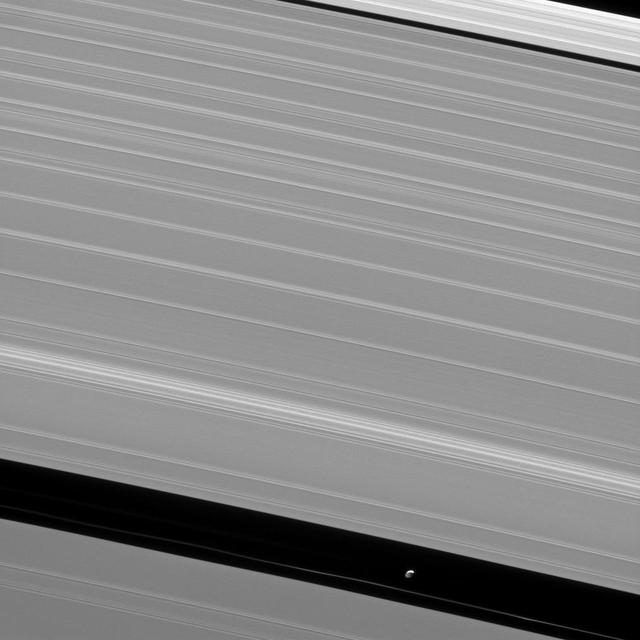

Scientists can use images such as this one from NASA Cassini spacecraft to learn more about the nature of the particles that make up Saturn rings.

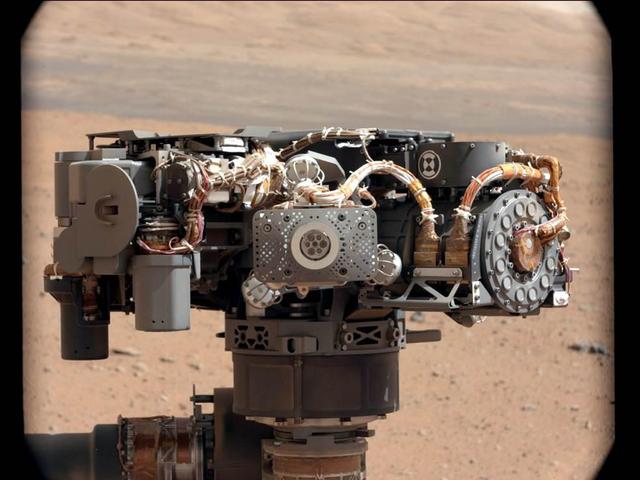

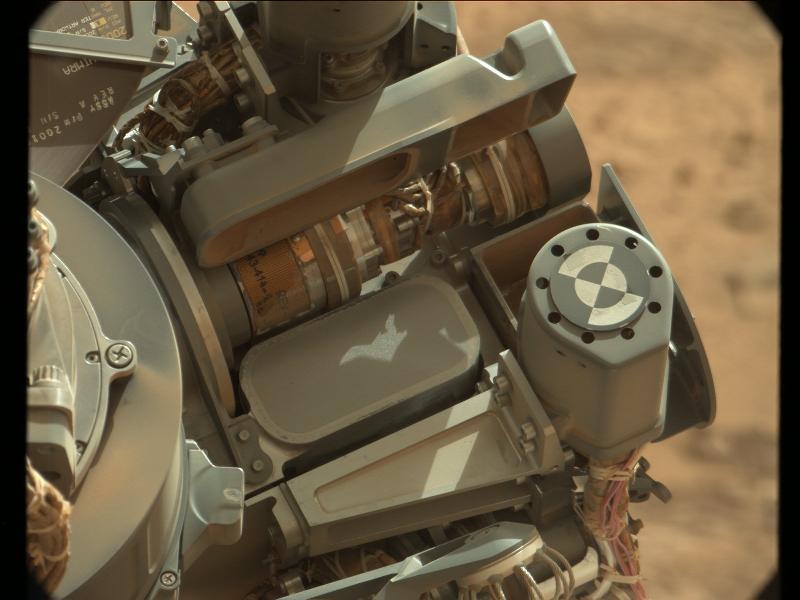

This image shows the Alpha Particle X-Ray Spectrometer APXS on NASA Curiosity rover, with the Martian landscape in the background. This image let researchers know that the APXS instrument had not become caked with dust during Curiosity landing.

NASA Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity found this image of a meteorite. The science team used two tools on Opportunity arm, the microscopic imager and the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer, to inspect the rock texture and composition.

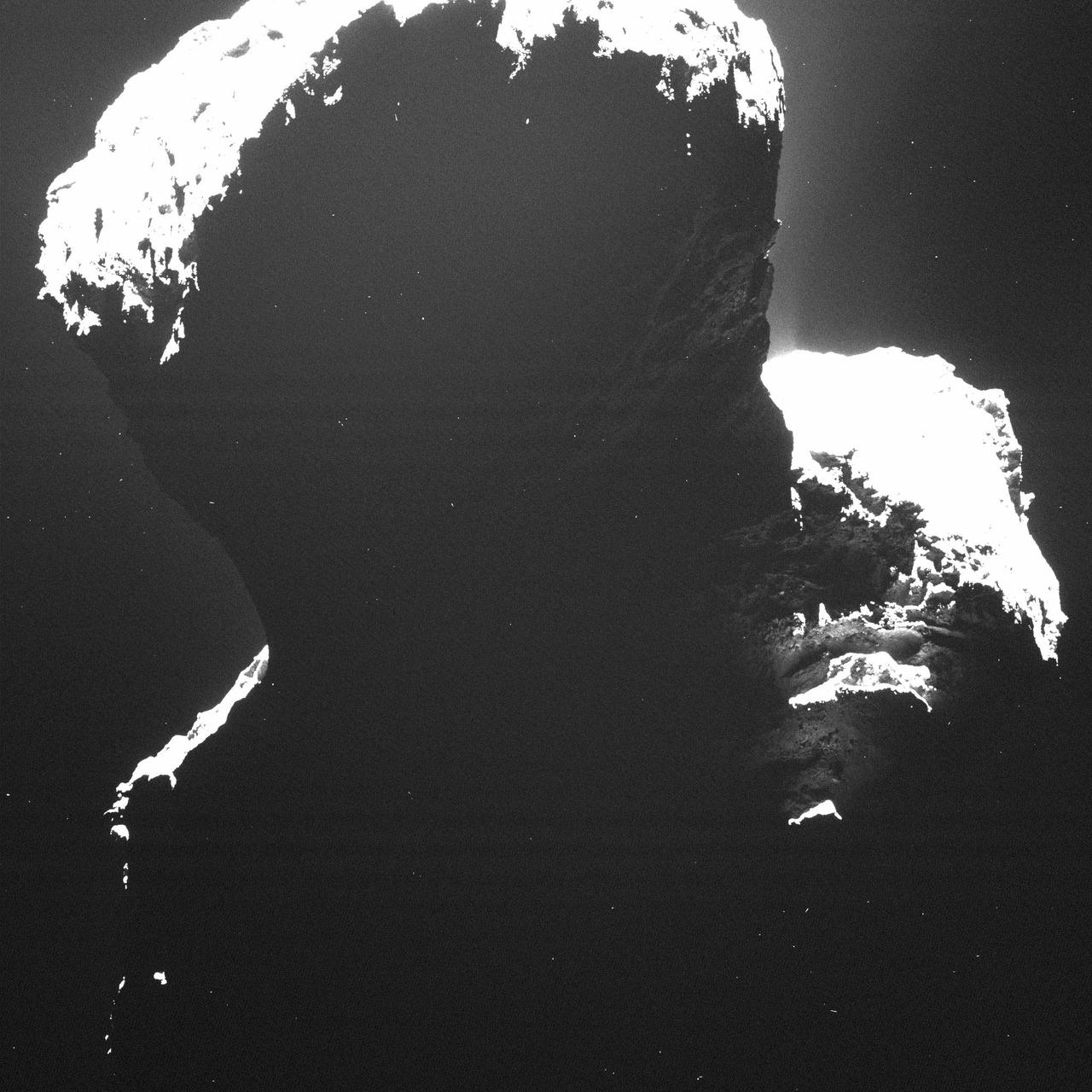

This is a rare glance at the dark side of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Light backscattered from dust particles in the comet coma reveals a hint of surface structures. This image was taken by OSIRIS, Rosetta scientific imaging system.

Images obtained by NASA EPOXI mission spacecraft show an active end of the nucleus of comet Hartley 2. Icy particles spew from the surface. Most of these particles are traveling with the nucleus; fluffy nowballs about 3 centimeters to 30 centimeters.

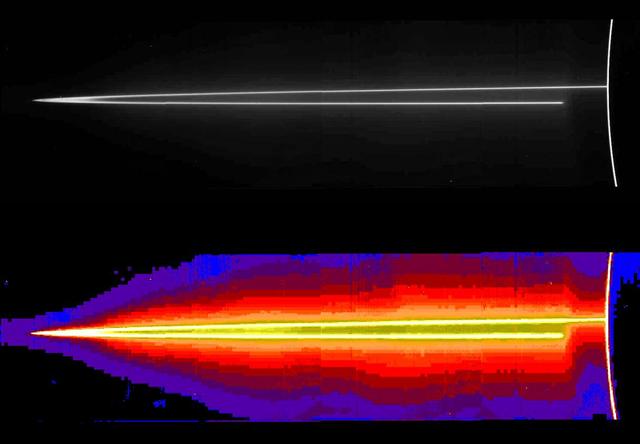

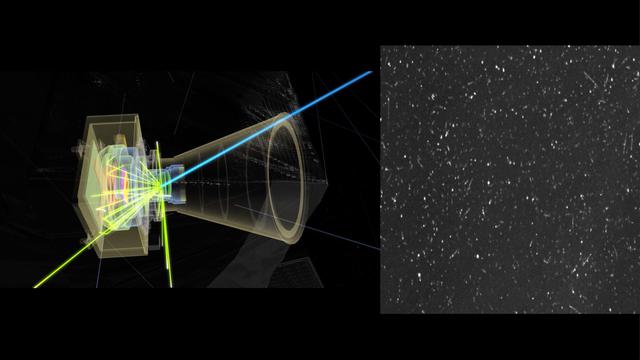

NASA's Curiosity Mars rover captured evidence of a solar storm's charged particles arriving at the Martian surface in this three-frame video taken by one of the rover's navigation cameras on May 20, 2024, the 4,190th Martian day, or sol, of the mission. The mission regularly captures videos to try and catch dust devils, or dust-bearing whirlwinds. While none were spotted in this particular sequence of images, engineers did see streaks and specks – visual artifacts created when charged particles from the Sun hit the camera's image detector. The particles do not damage the detector. The images in this sequence appear grainy because navigation-camera images are processed to highlight changes in the landscape from frame to frame. When there isn't much change – in this case, the rover was parked &ndash more noise appears in the image. Curiosity's Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) measured a sharp increase in radiation at this time – the biggest radiation surge the mission has seen since landing in 2012. Animation available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26302

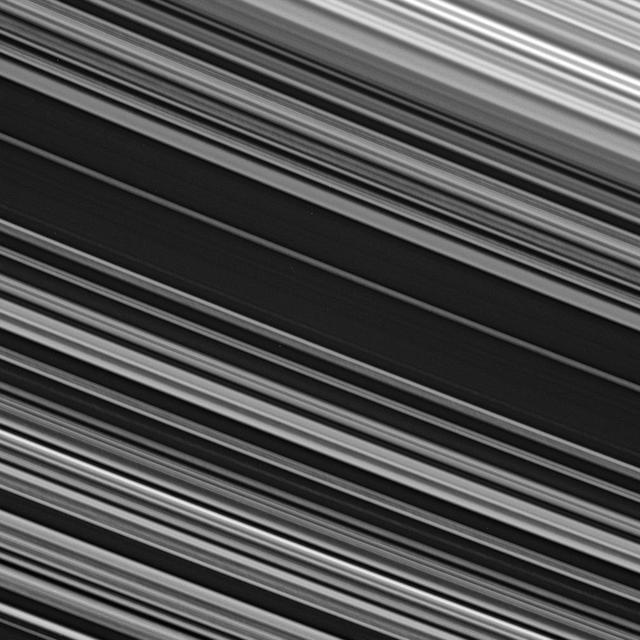

The spoke-producing region of the B ring displays fine-scale asymmetry in the azimuthal direction -- the direction along which the ring particles orbit Saturn -- from upper left to lower right across the image

This image from NASA shows a particle impact on the aluminum frame that holds the aerogel tiles. The debris from the impact shot into the adjacent aerogel tile producing the explosion pattern of ejecta framents captured in the material.

This image shows the low-energy charged particle instrument before it was installed on one of NASA Voyager spacecraft in 1977. The instrument includes a stepper motor that turns the platform on which the sensors are mounted.

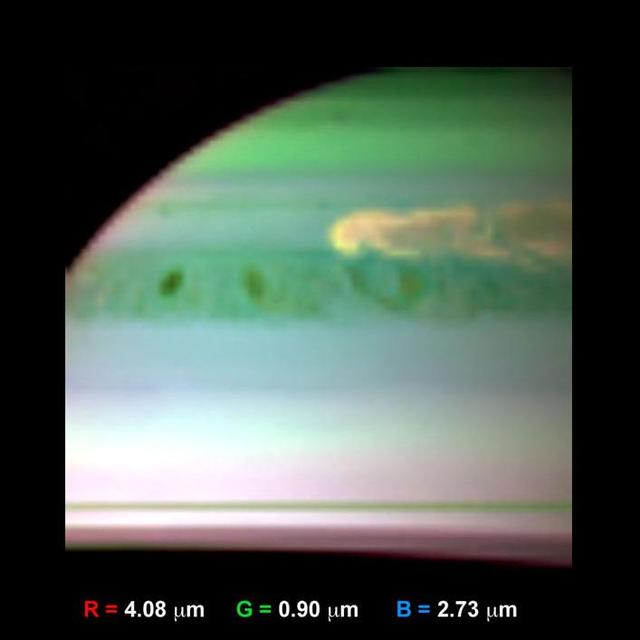

This false-color infrared image, obtained by NASA Cassini spacecraft, shows clouds of large ammonia ice particles dredged up by a powerful storm in Saturn northern hemisphere.

The mission science team assessed the bright particles in this scooped pit to be native Martian material rather than spacecraft debris as seen in this image from NASA Mars rover Curiosity as it collected its second scoop of Martian soil.

Clumps of ring material are revealed along the edge of Saturn A ring in this image taken during the planet August 2009 equinox. The granular appearance of the outer edge of the A ring is likely created by gravitational clumping of particles there.

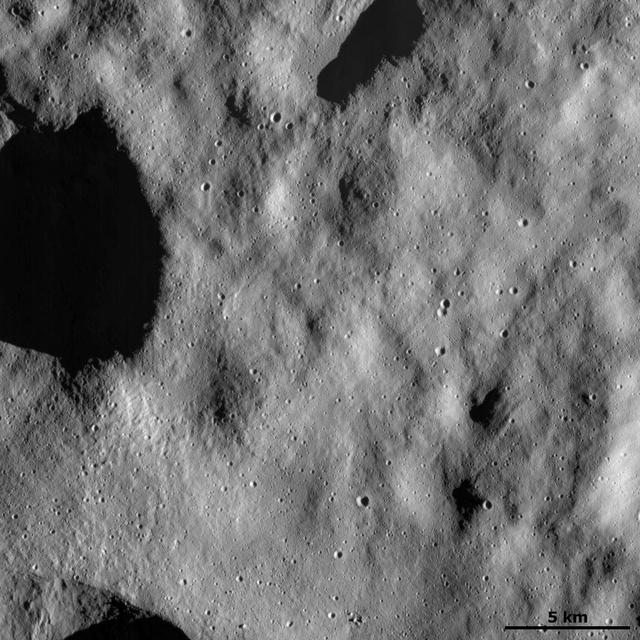

This image from NASA Dawn spacecraft shows a relatively smooth part of asteroid Vesta surface. This smooth texture is probably due to the surface being covered in a layer of tiny dust particles.

This new false-colored image from NASA Hubble, Chandra and Spitzer space telescopes shows a giant jet of particles that has been shot out from the vicinity of a type of supermassive black hole called a quasar.

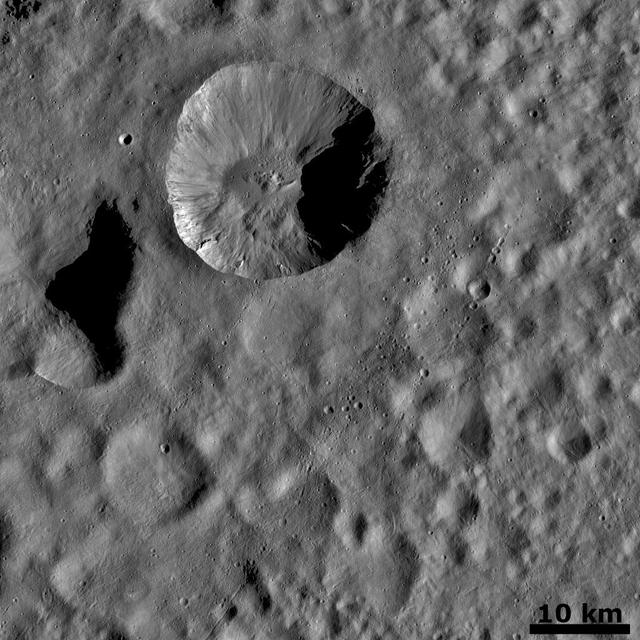

This image from NASA Dawn spacecraft is dominated by a wide, young, fresh crater on asteroid Vesta. Surrounding this crater is its ejecta blanket, a covering of small particles that were thrown out during the impact that formed the crater.

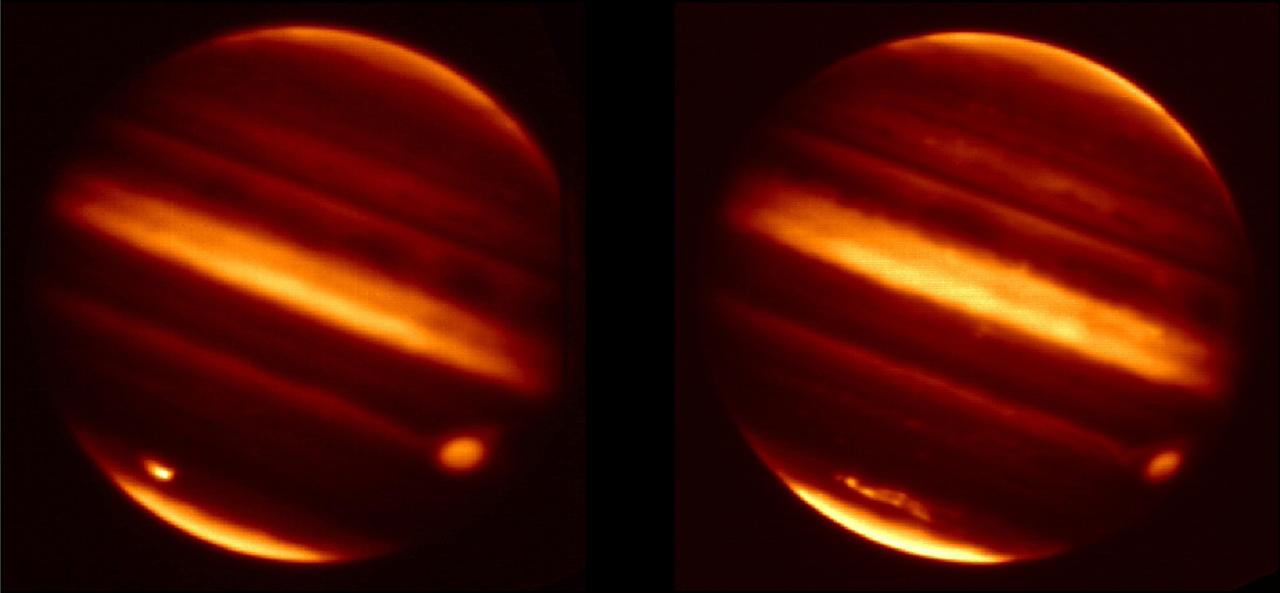

These infrared images obtained from NASA Infrared Telescope Facility in Mauna Kea, Hawaii, show before and aftereffects from particle debris in Jupiter atmosphere after an object hurtled into the atmosphere on July 19, 2009.

This image from the High-Resolution Instrument on NASA EPOXI mission spacecraft shows part of the nucleus of comet Hartley 2. The sun is illuminating the nucleus from the right. A distinct cloud of individual particles is visible.

This image shows the location of the 150-micrometer sieve screen on NASA Mars rover Curiosity, a device used to remove larger particles from samples before delivery to science instruments.

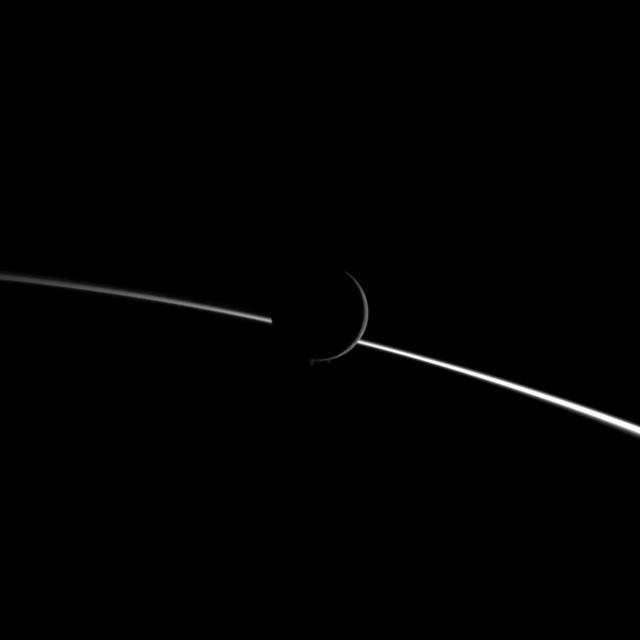

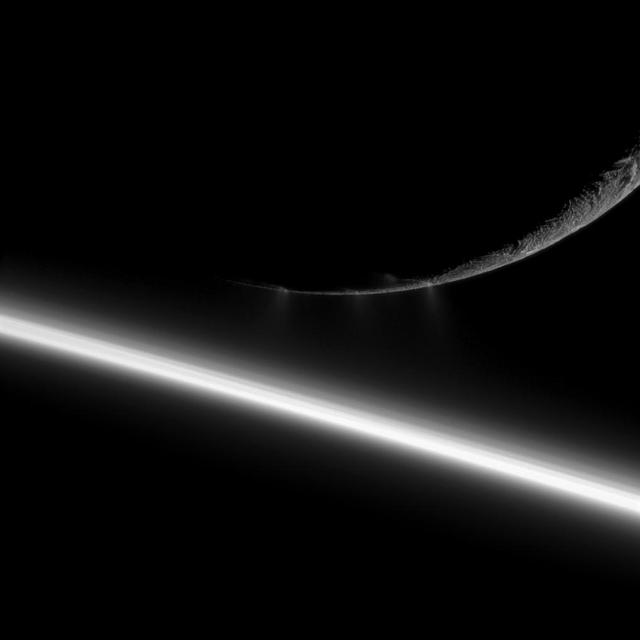

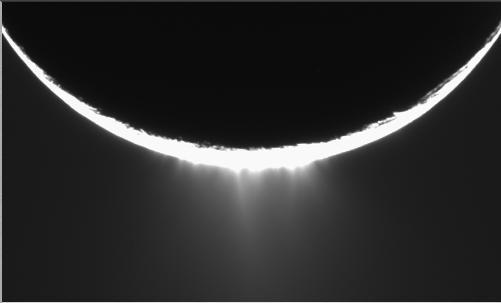

Jets of water ice particles spew from Saturn moon Enceladus in this image obtained by NASA Cassini spacecraft on Aug. 13, 2010. A crescent of the moon appears dimly illuminated in front of the bright limb of Saturn.

This mosaic of nine images taken at a location called Darwin, inside Gale Crater, were taken by NASA Mars rover Curiosity and shows detailed texture in a conglomerate rock bearing small pebbles and sand-size particles.

This composite image comes from the ESA Planck shows a festive portrait of our Milky Way galaxy shows a mishmash of gas, charged particles and several types of dust.

This image, acquired by NASA Terra spacecraft, is of the CERN Large Hadron Collider, the world largest and highest-energy particle accelerator laying beneath the French-Swiss border northwest of Geneva yellow circle.

An enhanced close-up view shows at least two distinct jets spraying a mist of fine particles from the south polar region of Enceladus. This image shows the night side of Saturn and the active moon against dark sky

NASA Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity found and examined this meteorite. The science team used two tools on Opportunity arm, the microscopic imager and the alpha particle X-ray spectrometer, to inspect the rock texture and composition.

A ghostly view of Enceladus reveals the specter of the moon icy plume of fine particles. Scientists continue to monitor the plume, where mission planning allows, using the Cassini spacecraft imaging cameras

This image obtained by NASA Cassini spacecraft around the time it went into orbit around Saturn in 2004 shows a short trail of icy particles dragged out from Saturn F ring.

This image taken by NASA Cassini spacecraft shows that rather than being an unchanging disk of peaceful particles, the material that makes up Saturn rings is constantly pushed and pulled into spectacular shapes. At left is the moon Daphnis.

Small water ice particles fly from fissures in the south polar region of Saturn moon Enceladus in this image taken during the Aug. 13, 2010, flyby of the moon by NASA Cassini spacecraft.

The shepherd moon Pan orbits Saturn in the Encke gap while the A ring surrounding the gap displays wave features created by interactions between the ring particles and Saturnian moons in this image from NASA Cassini spacecraft.

The sharp outer boundary of Saturn B ring, which is the bright ring region seen to the right in this image, is maintained by a strong resonance with the moon Mimas. For every two orbits made by particles at this distance from Saturn

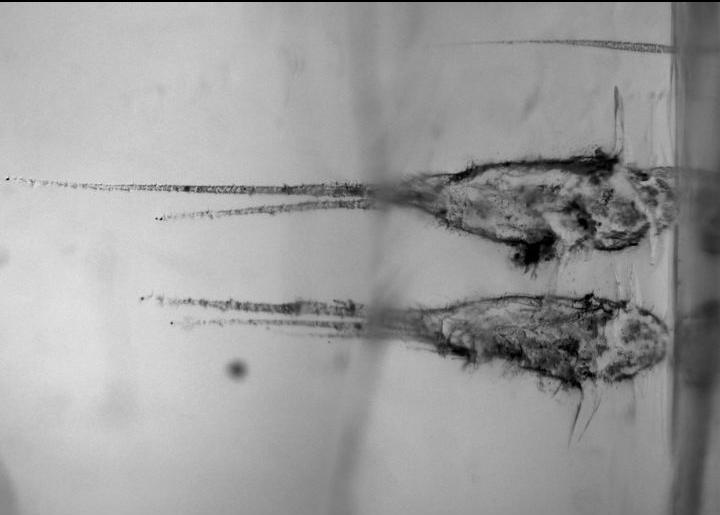

This image shows the tracks left by two comet particles after they impacted NASA Stardust spacecraft comet dust collector. The collector is made up of a low-density glass material called aerogel.

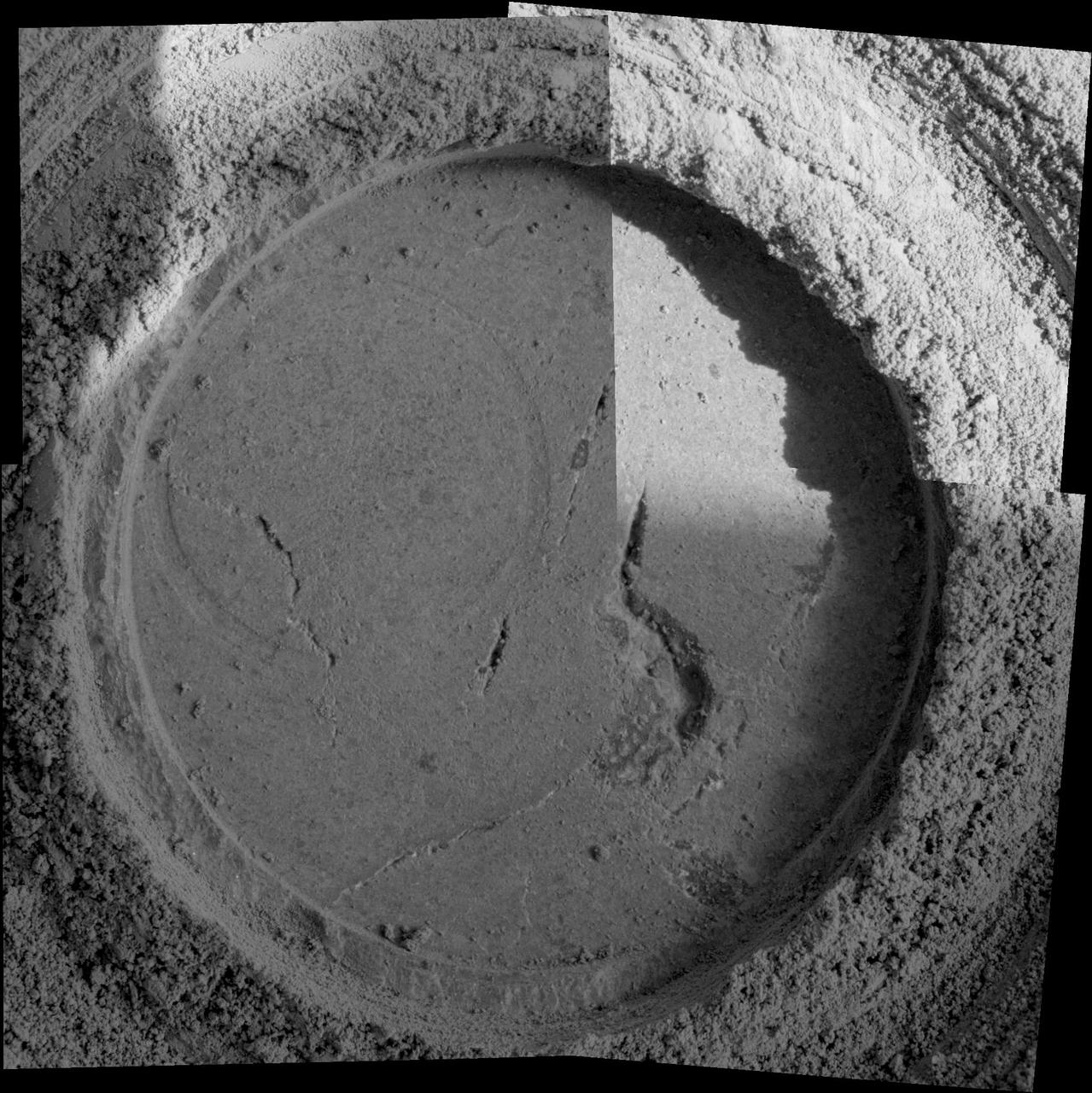

Close-up examination of a freshly exposed area of a rock called "Uchben" in the "Columbia Hills" of Mars reveals an assortment of particle shapes and sizes in the rock's makeup. NASA's Mars Exploration Rover Spirit used its microscopic imager during the rover's 286th martian day (Oct. 22, 2004) to take the frames assembled into this view. The view covers a circular hole ground into a target spot called "Koolik" on Uchben by the rover's rock abrasion tool. The circle is 4.5 centimeters (1.8 inches) in diameter. Particles in the rock vary in shape from angular to round, and range in size from about 0.5 millimeter (0.2 inch) to too small to be seen. This assortment suggests that the rock originated from particles that had not been transported much by wind or water, because such a transport process would likely have resulted in more sorting of the particles by size and shape. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA07023

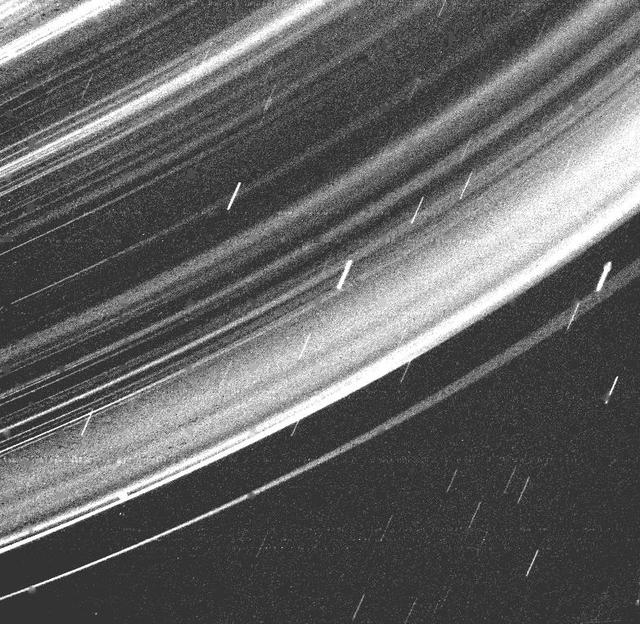

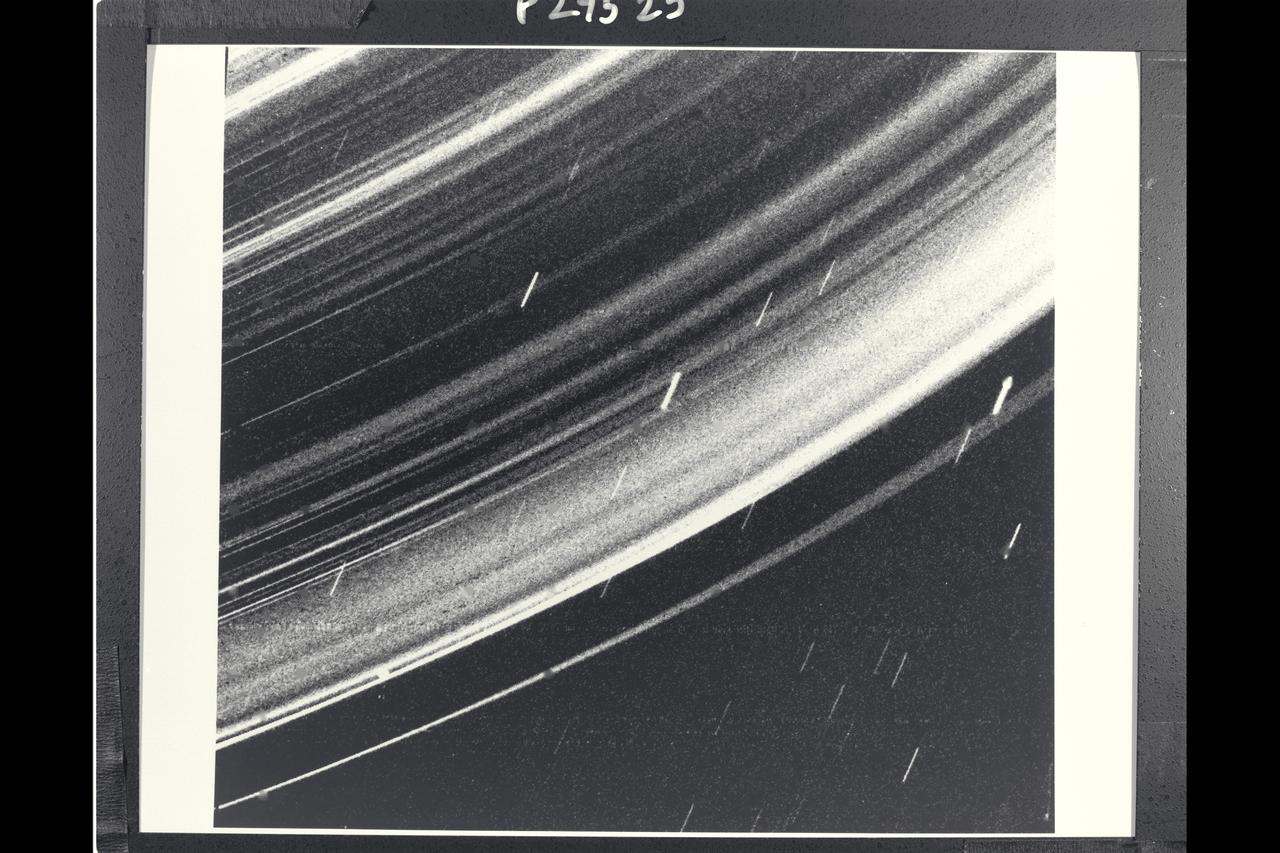

This image captured by NASA's Voyager 2 in 1986 revealed a continuous distribution of small particles throughout the Uranus ring system. This unique geometry, the highest phase angle at which Voyager imaged the rings, allowed us to see lanes of fine dust. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00142

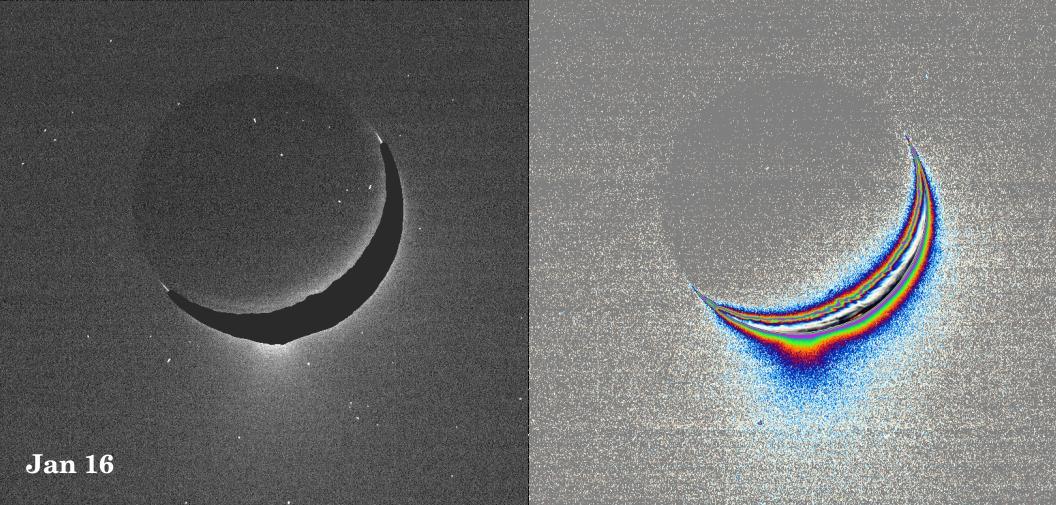

A fine spray of small, icy particles emanating from the warm, geologically unique province surrounding the south pole of Saturn’s moon Enceladus was observed in a Cassini narrow-angle camera image of the crescent moon taken on Jan. 16, 2005. Taken from a high-phase angle of 148 degrees -- a viewing geometry in which small particles become much easier to see -- the plume of material becomes more apparent in images processed to enhance faint signals. Imaging scientists have measured the light scattered by the plume's particles to determine their abundance and fall-off with height. Though the measurements of particle abundance are more certain within 100 kilometers (60 miles) of the surface, the values measured there are roughly consistent with the abundance of water ice particles measured by other Cassini instruments (reported in September, 2005) at altitudes as high as 400 kilometers (250 miles) above the surface. Imaging scientists, as reported in the journal Science on March 10, 2006, believe that the jets are geysers erupting from pressurized subsurface reservoirs of liquid water above 273 degrees Kelvin (0 degrees Celsius). The image at the left was taken in visible green light. A dark mask was applied to the moon's bright limb in order to make the plume feature easier to see. The image at the right has been color-coded to make faint signals in the plume more apparent. Images of other satellites (such as Tethys and Mimas) taken in the last 10 months from similar lighting and viewing geometries, and with identical camera parameters as this one, were closely examined to demonstrate that the plume towering above Enceladus' south pole is real and not a camera artifact. The images were acquired at a distance of about 209,400 kilometers (130,100 miles) from Enceladus. Image scale is about 1 kilometer (0.6 mile) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA07760

This processed image is the highest-resolution color look yet at the haze layers in Pluto's atmosphere. Shown in approximate true color, the picture was constructed from a mosaic of four panchromatic images from the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) splashed with Ralph/Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC) four-color filter data, all acquired by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft on July 14, 2015. The resolution is 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) per pixel; the sun illuminates the scene from the right. Scientists believe the haze is a photochemical smog resulting from the action of sunlight on methane and other molecules in Pluto's atmosphere, producing a complex mixture of hydrocarbons such as acetylene and ethylene. These hydrocarbons accumulate into small particles, a fraction of a micrometer in size, and scatter sunlight to make the bright blue haze seen in this image. As they settle down through the atmosphere, the haze particles form numerous intricate, horizontal layers, some extending for hundreds of miles around Pluto. The haze layers extend to altitudes of over 200 kilometers (120 miles). Adding to the stark beauty of this image are mountains on Pluto's limb (on the right, near the 4 o'clock position), surface features just within the limb to the right, and crepuscular rays (dark finger-like shadows to the left) extending from Pluto's topographic features. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA20362

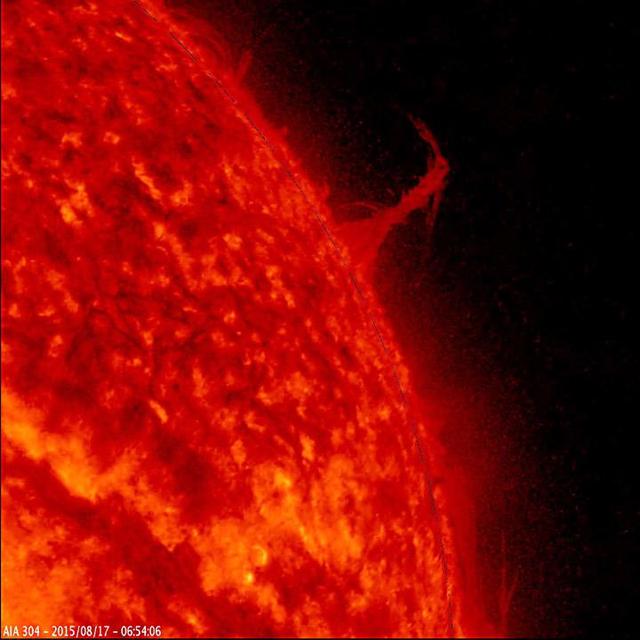

This still image from an animation from NASA GSFC Solar Dynamics Observatory shows a single plume of plasma, many times taller than the diameter of Earth, spewing streams of particles for over two days Aug. 17-19, 2015 before breaking apart. At times, its shape resembled the Eiffel Tower. Other lesser plumes and streams of particles can be seen dancing above the solar surface as well. The action was observed in a wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19875

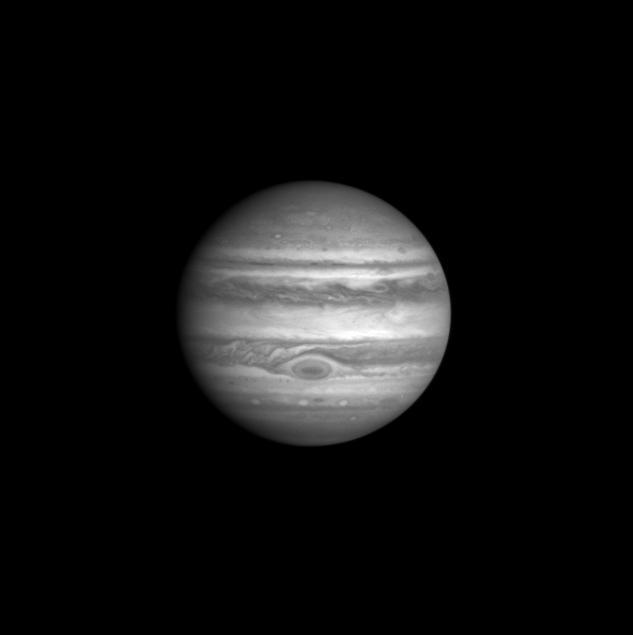

This image of Jupiter was taken by the Cassini Imaging Science narrow angle camera through the blue filter (centered at 445 nanometers) on October 1, 2000, 15:26 UTC at a distance of 84.1million km from Jupiter. The smallest features that can be seen are 500 kilometers across. The contrast between bright and dark features in this region of the spectrum is determined by the different light absorbing properties of the particles composing Jupiter's clouds. Ammonia ice particles are white, reflecting all light that falls on them. But some particles are red, and absorb mostly blue light. The composition of these red particles and the processes which determine their distribution are two of the long-standing mysteries of Jovian meteorology and chemistry. Note that the Great Red Spot contains a dark core of absorbing particles. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA02666

![Recent images of features in Saturn's C ring called "plateaus" have deepened the mystery surrounding them. It turns out that these bright bands have a streaky texture that is very different from the textures of the regions around them. The central feature in this image, called Plateau P5, is found approximately 52,700 miles (84,800 kilometers) from Saturn's center. It is situated amid some undulating structure that characterizes this region of the C ring. None of this structure is well understood. This image reveals that the plateau itself is shot through with elongated streaks. This provides information about ways in which the ring particles are interacting with each other, though scientists have not yet worked out what it all means. A more clumpy texture, similar to the "straw" seen previously in the A ring. Plateau regions are brighter than their surroundings, and have sharp edges. Recent evidence indicates that the plateaus do not actually contain more material than their surroundings, nor are they different in their chemical composition, which would mean that their greater brightness is likely due to smaller particle sizes. (If a given amount of mass is broken into smaller particles, it will spread out more [i.e., it will have more surface area].) These texture differences may give a clue about processes at the particle level that create the larger structures that Cassini has observed from greater distance throughout its mission at Saturn. These images were taken with the camera moving in sync with the orbits of individual ring particles. Therefore, any elongated structures are truly there in the rings, and are not an artifact of particles moving during the exposure (i.e., smear). This image was taken on the unilluminated side of the rings, with sunlight filtering through the rings as it would through a translucent bathroom window. Brighter regions in the image indicate more material scattering light toward the camera. This image was taken on May 29, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of about 39,800 miles (64,100 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,460 feet (445 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 137 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21619](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21619/PIA21619~small.jpg)

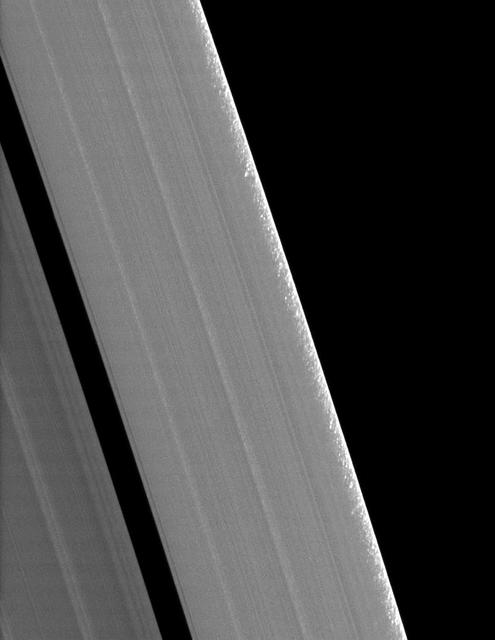

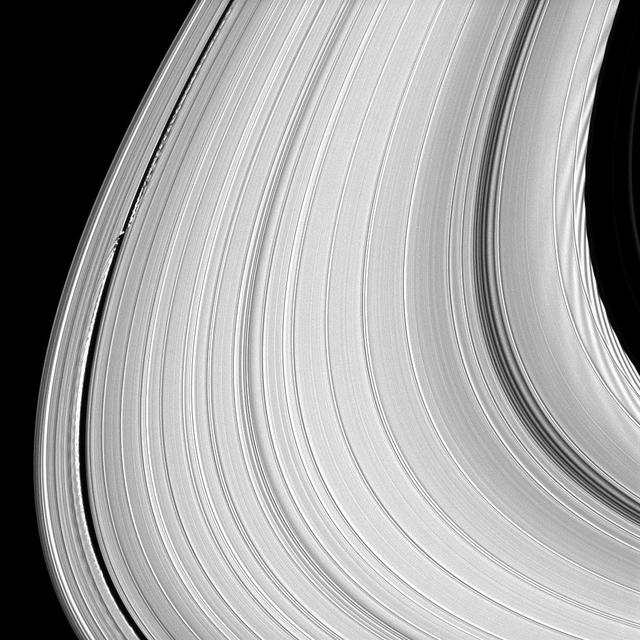

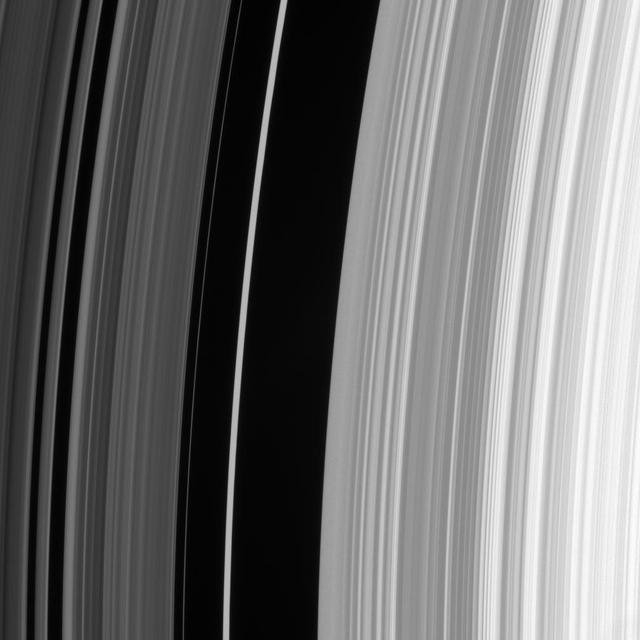

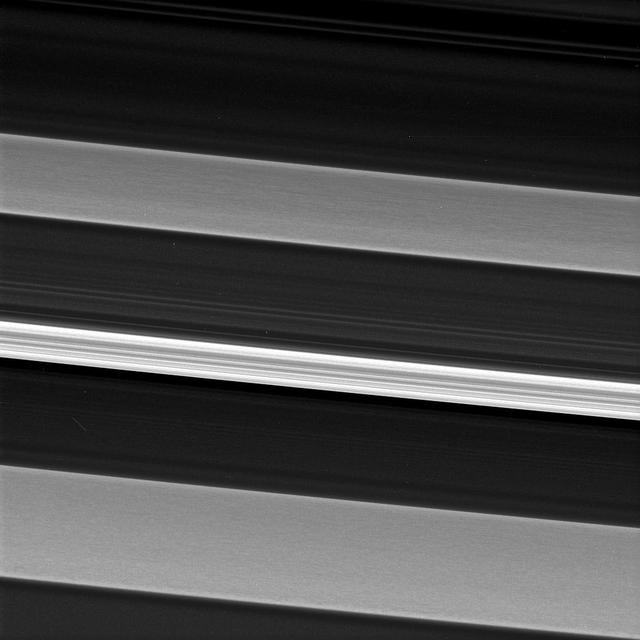

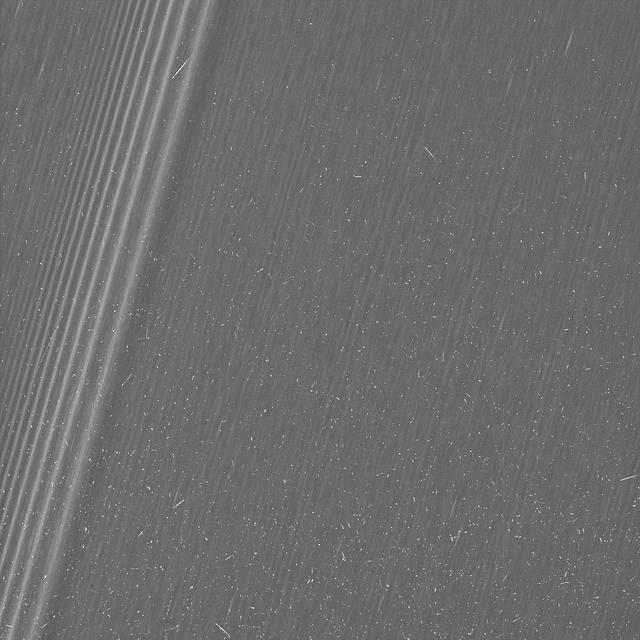

Recent images of features in Saturn's C ring called "plateaus" have deepened the mystery surrounding them. It turns out that these bright bands have a streaky texture that is very different from the textures of the regions around them. The central feature in this image, called Plateau P5, is found approximately 52,700 miles (84,800 kilometers) from Saturn's center. It is situated amid some undulating structure that characterizes this region of the C ring. None of this structure is well understood. This image reveals that the plateau itself is shot through with elongated streaks. This provides information about ways in which the ring particles are interacting with each other, though scientists have not yet worked out what it all means. A more clumpy texture, similar to the "straw" seen previously in the A ring. Plateau regions are brighter than their surroundings, and have sharp edges. Recent evidence indicates that the plateaus do not actually contain more material than their surroundings, nor are they different in their chemical composition, which would mean that their greater brightness is likely due to smaller particle sizes. (If a given amount of mass is broken into smaller particles, it will spread out more [i.e., it will have more surface area].) These texture differences may give a clue about processes at the particle level that create the larger structures that Cassini has observed from greater distance throughout its mission at Saturn. These images were taken with the camera moving in sync with the orbits of individual ring particles. Therefore, any elongated structures are truly there in the rings, and are not an artifact of particles moving during the exposure (i.e., smear). This image was taken on the unilluminated side of the rings, with sunlight filtering through the rings as it would through a translucent bathroom window. Brighter regions in the image indicate more material scattering light toward the camera. This image was taken on May 29, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of about 39,800 miles (64,100 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,460 feet (445 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 137 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21619

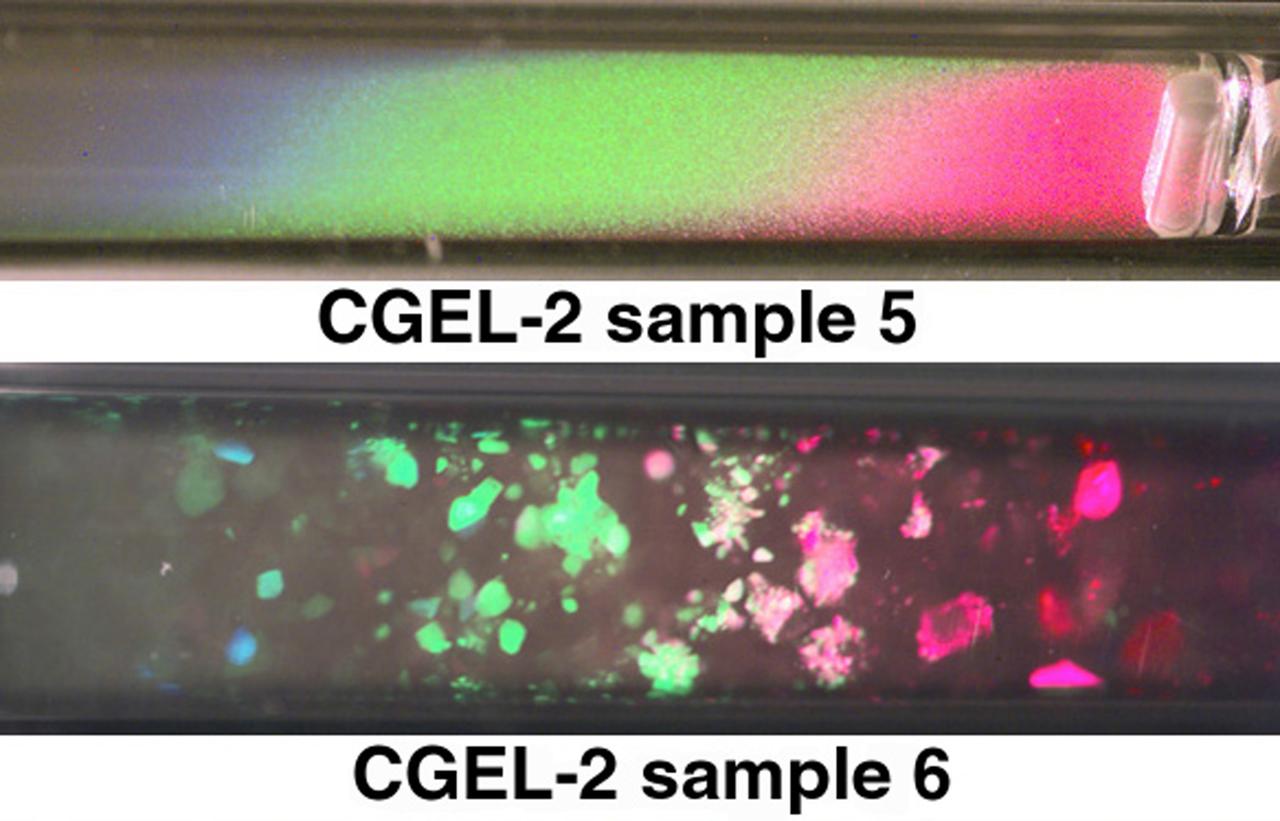

These are images of CGEL-2 samples taken during STS-95. They show binary colloidal suspensions that have formed ordered crystalline structures in microgravity. In sample 5, there are more particles therefore, many, many crystallites (small crystals) form. In sample 6, there are less particles therefore, the particles are far apart and few, much larger crystallites form. The white object in the right corner of sample 5 is the stir bar used to mix the sample at the begirning of the mission.

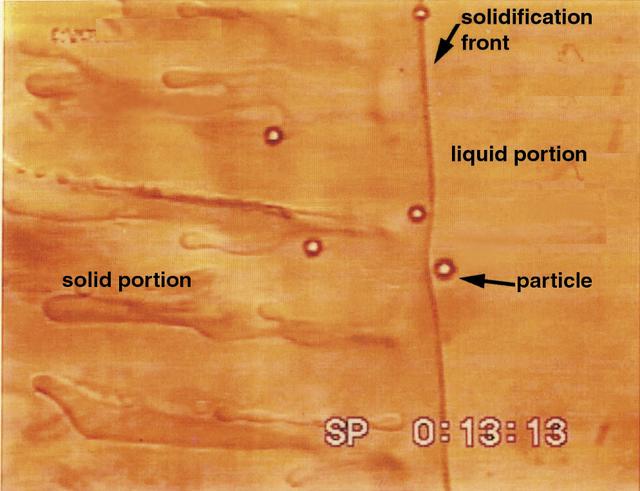

As a liquefied metal solidifies, particles dispersed in the liquid are either pushed ahead of or engulfed by the moving solidification front. Similar effects can be seen when the ground freezes and pushes large particles out of the soil. The Particle Engulfment and Pushing (PEP) experiment, conducted aboard the fourth U.S. Microgravity Payload (USMP-4) mission in 1997, used a glass and plastic beads suspended in a transparent liquid. The liquid was then frozen, trapping or pushing the particles as the solidifying front moved. This simulated the formation of advanced alloys and composite materials. Such studies help scientists to understand how to improve the processes for making advanced materials on Earth. The principal investigator is Dr. Doru Stefanescu of the University of Alabama. This image is from a video downlink.

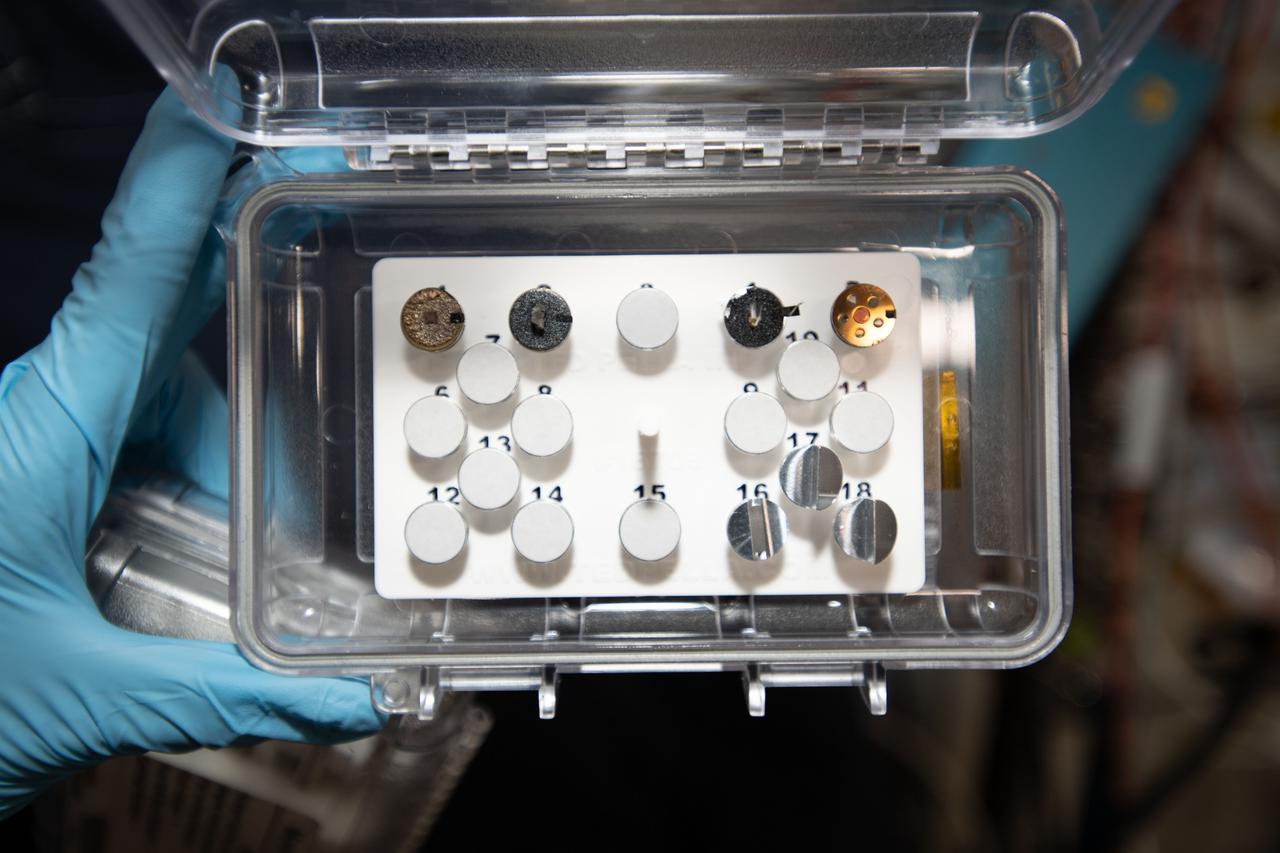

jsc2025e036188 (2/3/2025) --- A preflight image of the Exploration Aerosol Monitors (ExAM) hardware which includes the Moderated Aerosol Growth with Internal water Cycling (MAGIC) particle counter, the OPto-electrical Realtime Aerosol classifier (OPERA), the Mobile Aerosol Reference Samplers (MARS). Aerosol Monitors demonstrates technologies to continuously monitor the concentration of airborne pollutant particles, which must be kept within safe ranges, inside the International Space Station. Image courtesy of BioServe.

![Recent images of features in Saturn's C ring called "plateaus" have deepened the mystery surrounding them. It turns out that these bright bands have a streaky texture that is very different from the textures of the regions around them. The central feature in this image, called Plateau P1, is found approximately 47,300 miles (76,200 kilometers) from Saturn's center. It is situated amid some undulating structure that characterizes this region of the C ring. None of this structure is well understood. This image reveals three different textures with different kinds of structure. The plateau itself is shot through with elongated streaks, while the brighter parts of the undulating structure have more clumpy texture that is similar to the "straw" seen previously in the A ring, and the dimmer parts of the undulating structure have no apparent texture at all. These textures provide information about different ways in which the ring particles are interacting with each other, though scientists have not yet worked out what it all means. Plateau regions are brighter than their surroundings, and have sharp edges. Recent evidence indicates that the plateaus do not actually contain more material than their surroundings, nor are they different in their chemical composition, which would mean that their greater brightness is likely due to smaller particle sizes. (If a given amount of mass is broken into smaller particles, it will spread out more [i.e., it will have more surface area].) These texture differences may give a clue about processes at the particle level that create the larger structures that Cassini has observed from greater distance throughout its mission at Saturn. These images were taken with the camera moving in sync with the orbits of individual ring particles. Therefore, any elongated structures are truly there in the rings, and are not an artifact of particles moving during the exposure (i.e., smear). This image was taken on June 4, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of (51,830 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,070 feet (325 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 80 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21618](https://images-assets.nasa.gov/image/PIA21618/PIA21618~small.jpg)

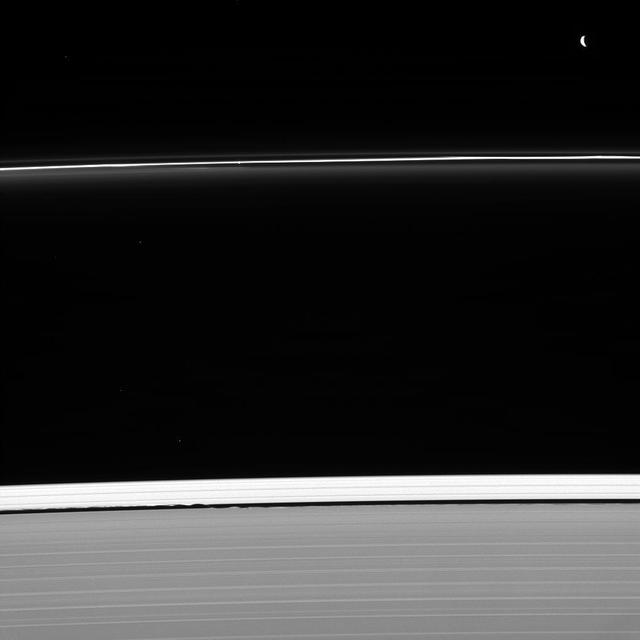

Recent images of features in Saturn's C ring called "plateaus" have deepened the mystery surrounding them. It turns out that these bright bands have a streaky texture that is very different from the textures of the regions around them. The central feature in this image, called Plateau P1, is found approximately 47,300 miles (76,200 kilometers) from Saturn's center. It is situated amid some undulating structure that characterizes this region of the C ring. None of this structure is well understood. This image reveals three different textures with different kinds of structure. The plateau itself is shot through with elongated streaks, while the brighter parts of the undulating structure have more clumpy texture that is similar to the "straw" seen previously in the A ring, and the dimmer parts of the undulating structure have no apparent texture at all. These textures provide information about different ways in which the ring particles are interacting with each other, though scientists have not yet worked out what it all means. Plateau regions are brighter than their surroundings, and have sharp edges. Recent evidence indicates that the plateaus do not actually contain more material than their surroundings, nor are they different in their chemical composition, which would mean that their greater brightness is likely due to smaller particle sizes. (If a given amount of mass is broken into smaller particles, it will spread out more [i.e., it will have more surface area].) These texture differences may give a clue about processes at the particle level that create the larger structures that Cassini has observed from greater distance throughout its mission at Saturn. These images were taken with the camera moving in sync with the orbits of individual ring particles. Therefore, any elongated structures are truly there in the rings, and are not an artifact of particles moving during the exposure (i.e., smear). This image was taken on June 4, 2017, with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera. The image was acquired on the sunlit side of the rings from a distance of (51,830 kilometers) away from the area pictured. The image scale is 1,070 feet (325 meters) per pixel. The phase angle, or sun-ring-spacecraft angle, is 80 degrees. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21618

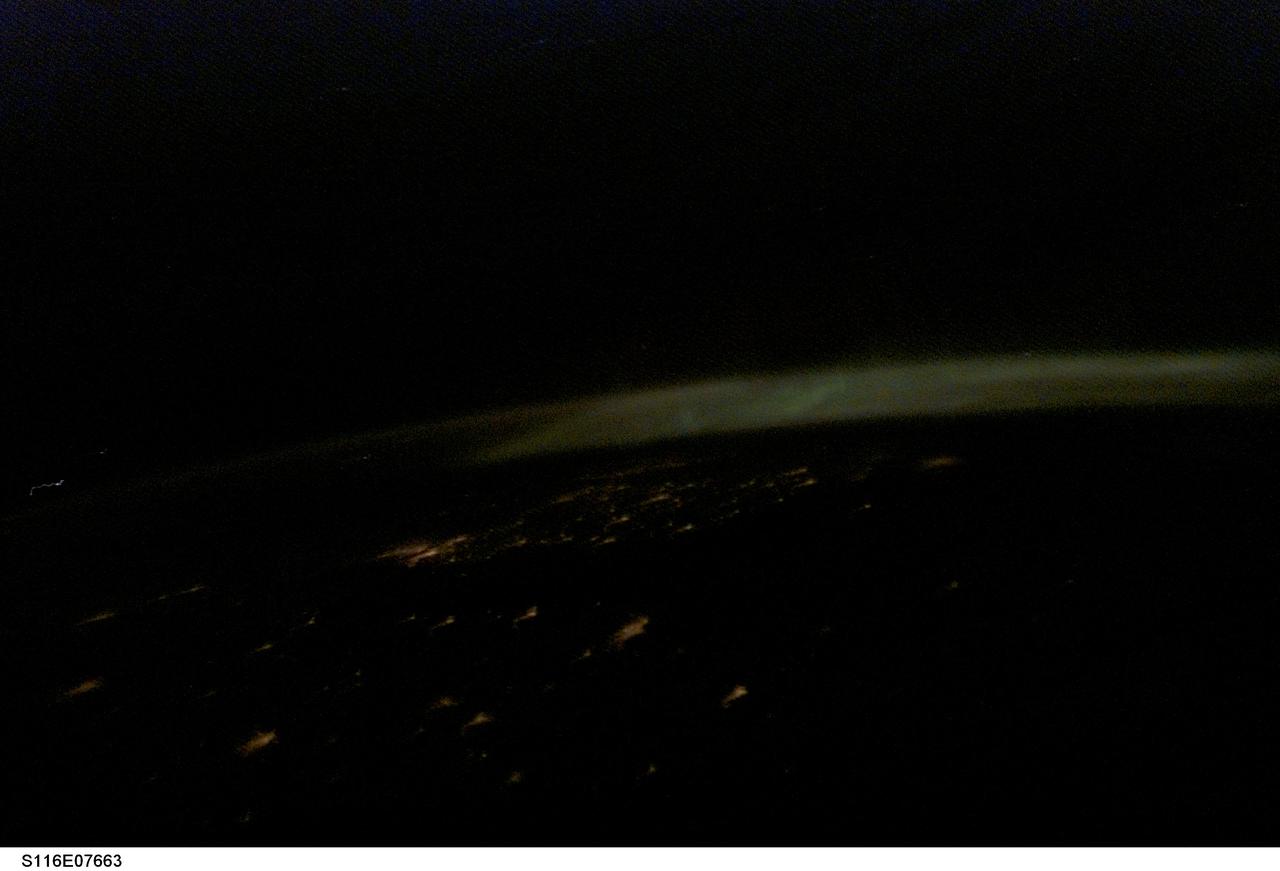

S116-E-07663 (20 Dec. 2006) --- One of the STS-116 crewmembers onboard the Space Shuttle Discovery captured this picture of Aurora Borealis over Norway, Poland and Sweden, as the crew made preparations for a Dec. 22 landing. European Space Agency astronaut Christer Fuglesang onboard the shuttle noted the rarity of pictures over this area from shuttle missions, and especially pictures that included the Northern Lights. Fuglesang is from Sweden. The city lights of Copenhagen (bright cluster of lights in the middle left portion of the image), Stockholm (under the aurora on the far right side of the image), and Gdansk (in the center forefront) are seen. The formation of the aurora starts with the sun releasing solar particles. The Earth's magnetic field captures and channels the solar particles toward the Earth's two magnetic poles (north and south). As the solar particles move towards the poles they collide with the Earth's atmosphere, which acts as an effective shield against these deadly particles. The collision between the solar particles and the atmospheric gas molecule emits a light particle (photon). When there are many collisions the aurora is formed.

Saturn's C ring is home to a surprisingly rich array of structures and textures. Much of the structure seen in the outer portions of Saturn's rings is the result of gravitational perturbations on ring particles by moons of Saturn. Such interactions are called resonances. However, scientists are not clear as to the origin of the structures seen in this image which has captured an inner ring region sparsely populated with particles, making interactions between ring particles rare, and with few satellite resonances. In this image, a bright and narrow ringlet located toward the outer edge of the C ring is flanked by two broader features called plateaus, each about 100 miles (160 kilometers) wide. Plateaus are unique to the C ring. Cassini data indicates that the plateaus do not necessarily contain more ring material than the C ring at large, but the ring particles in the plateaus may be smaller, enhancing their brightness. This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 53 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in green light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Aug. 14, 2017. The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 117,000 miles (189,000 kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 74 degrees. Image scale is 3,000 feet (1 kilometer) per pixel. The Cassini spacecraft ended its mission on Sept. 15, 2017. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21356

Two masters of their craft are caught at work shaping Saturn's rings. Pandora (upper right) sculpts the F ring, as does nearby Prometheus (not seen in this image). Meanwhile, Daphnis is busy holding open the Keeler gap (bottom center), its presence revealed here by the waves it raises on the gap's edge. The faint moon is located where the inner and outer waves appear to meet. Also captured in this image, shining through the F ring above the image center, is a single star. Although gravity is by its very nature an attractive force, moons can interact with ring particles in such a way that they effectively push ring particles away from themselves. Ring particles experience tiny gravitational "kicks" from these moons and subsequently collide with other ring particles, losing orbital momentum. The net effect is for moons like Pandora (50 miles or 81 kilometers across) and Daphnis (5 miles or 8 kilometers across) to push ring edges away from themselves. The Keeler gap is the result of just such an interaction. This view looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings from about 50 degrees below the ringplane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on Jan. 30, 2013. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA18298

Common Research Model (CRM) Test t11-0216 in the NASA Ames 11x11_foot Transonic Wind Tunnel with PIV laser sheet over model. (3D PIV Particle Image Velosymetry Equipment)

jsc2024e043753 (7/10/2024) --- Confocal microscopy image of a bimodal attractive colloidal suspension with size ratio R = 2 for the ISS Bimodal Colloidal Assembly, Coarsening, and Failure: Decoupling Sedimentation and Particle Size Effects (Bimodal Colloid) investigation. Image courtesy of Calvin Zhuang.

The specks in the sequence of images in this video were caused by charged particles from a solar storm hitting one of the navigation cameras aboard NASA's Curiosity Mars rover. The mission uses the rover's navigation cameras to try capturing images of dust devils (dust-bearing whirlwinds) and wind gusts, like the gust seen here. By chance, the gust occurred at the same time that charged particles began to strike the Martian surface on May 20, 2024, the 4,190th Martian day, or sol, of the mission. The particles do not damage the camera. Curiosity's Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) measured a sharp increase in radiation at this time – the biggest radiation surge the mission has seen since landing in 2012. Animation available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26303

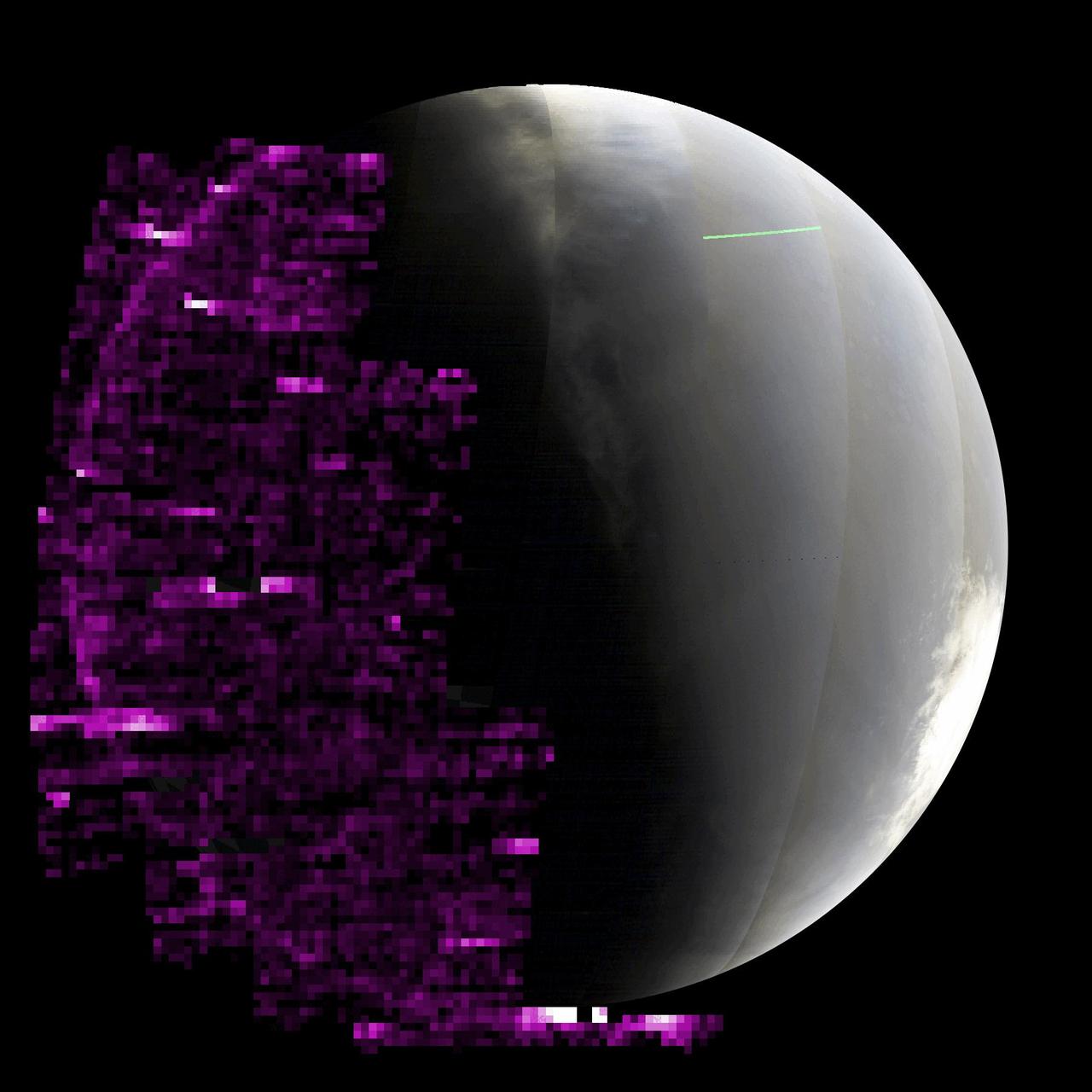

The purple color in this animated GIF shows auroras across Mars' nightside as detected by the Imaging Ultraviolet Spectrograph instrument aboard NASA's MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN) orbiter. The brighter the purple, the more auroras were present. Taken as waves of energetic particles from a solar storm were arriving at Mars, the sequence pauses at the end, when the wave of the most energetic particles arrived and overwhelmed the instrument with noise. MAVEN took these images between May 14 and 20, 2024, as the spacecraft orbited below Mars, looking up at the nightside of the planet (Mars' south pole can be seen on the right, in full sunlight). Animation available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA26304

A mosaic of four images taken through the clear filter (610 nanometers) of the solid state imaging (CCD) system aboard NASA's Galileo spacecraft on November 8, 1996, at a resolution of approximately 46 kilometers (28.5 miles) per picture element (pixel) along Jupiter's rings. Because the spacecraft was only about 0.5 degrees above the ring plane, the image is highly foreshortened in the vertical direction. The images were obtained when Galileo was in Jupiter's shadow, peering back toward the Sun; the ring was approximately 2.3 million kilometers (1.4 million miles) away. The arc on the far right of the image is produced when sunlight is scattered by small particles comprising Jupiter's upper atmospheric haze. The ring also efficiently scatters light, indicating that much of its brightness is due to particles that are microns or less in diameter. Such small particles are believed to have human-scale lifetimes, i.e., very brief compared to the solar system's age. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00701

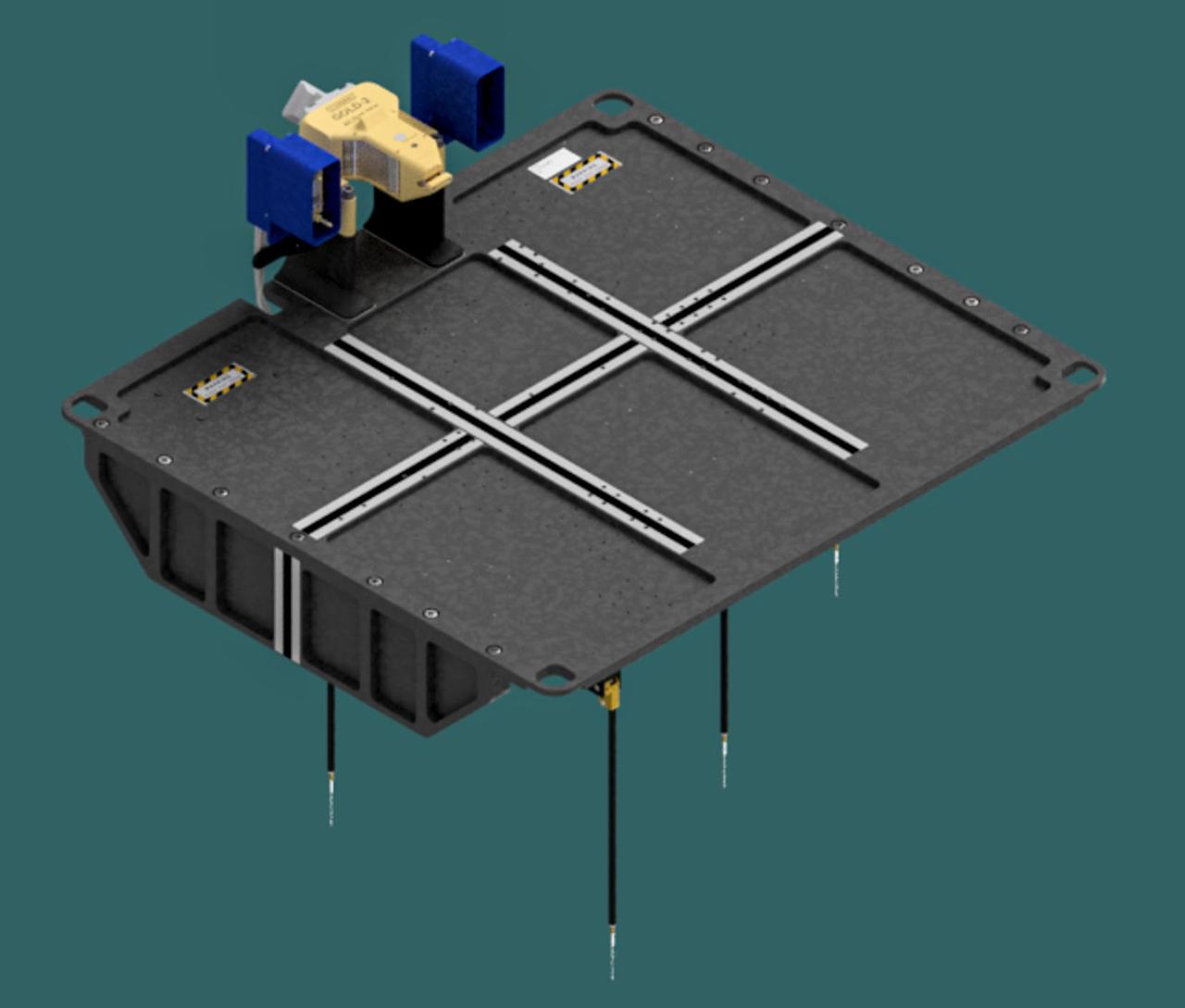

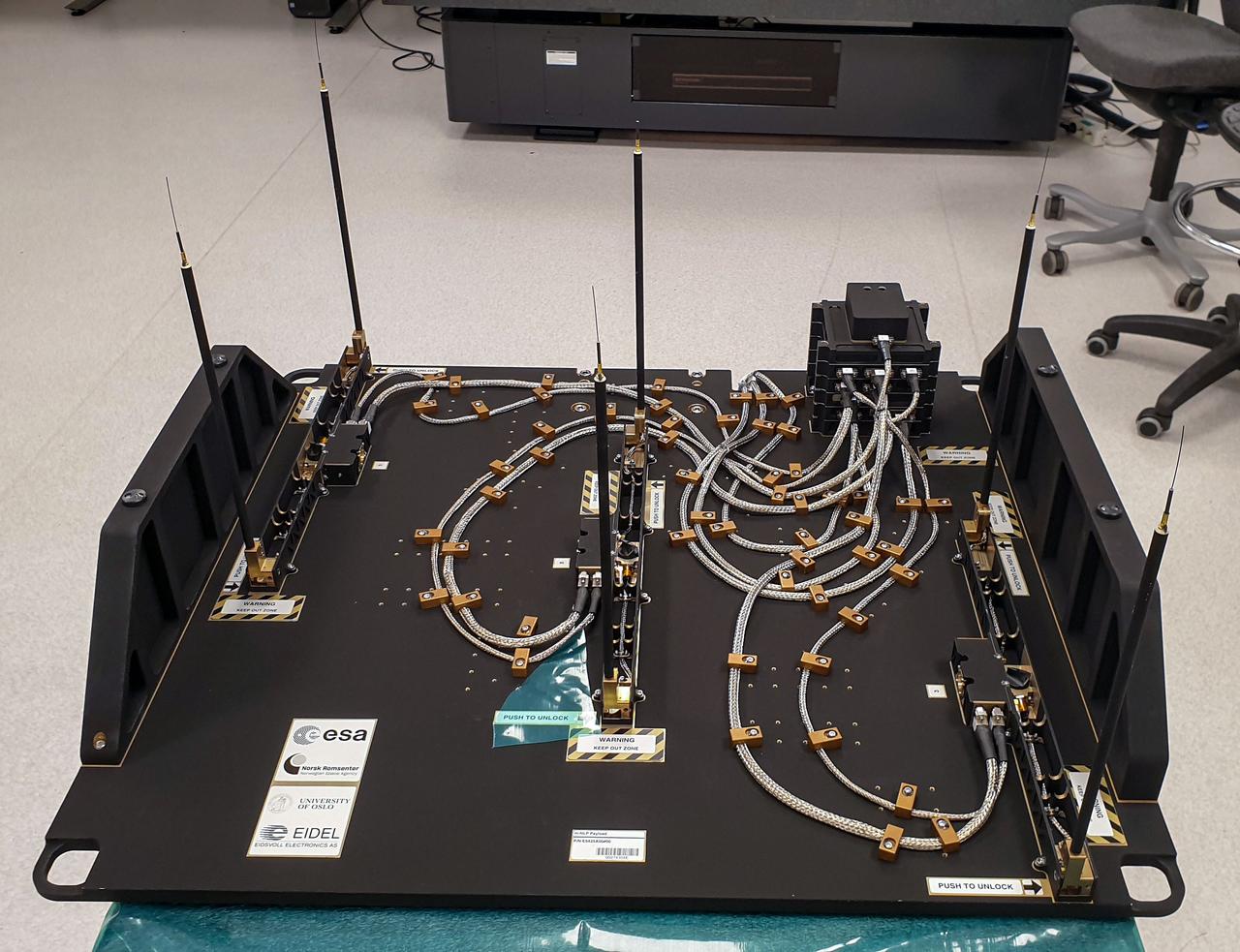

jsc2023e046374 (7/25/2023) --- Artistic rendering of the rear side of the Multi-Needle Langmuir Probe (m-NLP). The m-NLP measures plasma density in the ionosphere, where Earth's atmosphere meets the beginning of space. Researchers aim to study electrically charged particles and increase their understanding of how particle phenomena affects radio communications and global navigation satellite system (GNSS) signals. Image courtesy of the University of Oslo, Maren C. Lithun.

jsc2023e046372 (9/30/2022) --- The Multi-Needle Langmuir Probe (m-NLP) is shown from the ram facing side with booms in deployed position. The m-NLP measures plasma density in the ionosphere, where Earth's atmosphere meets the beginning of space. Researchers aim to study electrically charged particles and increase their understanding of how particle phenomena affect radio communications and global navigation satellite system (GNSS) signals. Image courtesy of the University of Oslo, Espen Trondsen.

iss068e016422 (Oct. 12, 2022) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 68 Flight Engineer Jessica Watkins works with Mochii, a miniature scanning electron microscope (SEM) with spectroscopy to conduct real-time, on-site imaging and compositional measurements of particles on the International Space Station (ISS). Such particles can cause vehicle and equipment malfunctions and threaten crew health, but currently, samples must be returned to Earth for analysis, leaving crew and vehicle at risk. Mochii also provides a powerful new analysis platform to support novel microgravity science and engineering.

Located in the center of this VIS image is a group of sand dunes. With enough wind and sand, sand dunes are formed. Dune morphology typically has a shallow slope on the side the wind is blowing from and a steep face on the other side. The darker part of the dunes in this image are the steep slopes. Wind blows sand particles up the shallow slope and then the particles 'fall' off the crest of the dune down the steep side. With time, the constant wind will move the crest of the dune forward. Depending on the amount of available sand, dunes can grow to large heights and sizes. In the case of this image, the dunes are moving toward the top of the image, which means up the surface slope. In cases like this, the dunes 'climb' up hills. Orbit Number: 74955 Latitude: -50.2322 Longitude: 292.058 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2018-11-07 00:56 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22975

This image of the active galaxy Centaurus A was taken by NASA's Galaxy Evolution Explorer on June 7, 2003. The galaxy is located 30 million light-years from Earth and is seen edge on, with a prominent dust lane across the major axis. In this image the near ultraviolet emission is represented as green, and the far ultraviolet emission as blue. The galaxy exhibits jets of high energy particles, which were traced by the X-ray emission and measured by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory. These X-ray emissions are seen as red in the image. Several regions of ultraviolet emission can be seen where the jets of high energy particles intersect with hydrogen clouds in the upper left corner of the image. The emission shown may be the result of recent star formation triggered by the compression of gas by the jet. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA04624

This animation gives an X-ray view of the Juno spacecraft's Stellar Reference Unit (SRU) star camera (left) as it is bombarded by high-energy particles in Jupiter's inner radiation belts. Even though the SRU camera head is six times more heavily shielded than Juno's radiation vault, the highest-energy particles in Jupiter's extreme radiation environment can still penetrate, striking the imaging sensor inside. The signatures from high-energy electron and ion hits appear as dots, squiggles, and streaks (right) in the images collected by the SRU, like static on a television screen. Juno's Radiation Monitoring Investigation collects SRU images and uses image processing to extract these radiation-induced noise signatures to profile the radiation levels encountered by Juno during its close flybys of Jupiter. Animation available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24436

Several small sunspots appeared this week, giving NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory a chance to illustrate their sources Mar. 2, 2017. The first image is a magnetogram or magnetic image of the sun's surface. The MDI instrument can observe where positive and negative particles are moving toward or away from strong magnetic areas. These active regions have stronger magnetic fields and appear as strongly black or white. The yellow image shows the surface in filtered light, and there the same active regions appear as dark, cooler splotches called sunspots. Higher up in the sun's atmosphere, the golden image (in extreme ultraviolet light) shows arches of light above the active regions, which are charged particles spinning along magnetic field lines. Note that they all align very well with each other. Magnetic forces are the dynamic drivers here in these regions of the sun. Movies are available at http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21557

This still image from an animation from NASA GSFC Solar Dynamics Observatory shows magnetically charged particles forming a nicely symmetrical arch at the edge of the Sun as they followed the magnetic field lines of an active region Aug.4-5, 2015. Before long the arch begins to fade, but a fainter and taller arch appears for a time in the same place. Note that several other bright active regions display similar kinds of loops above them. These images of ionized iron at about one million degrees were taken in a wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light. The video covers about 30 hours of activity. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19874

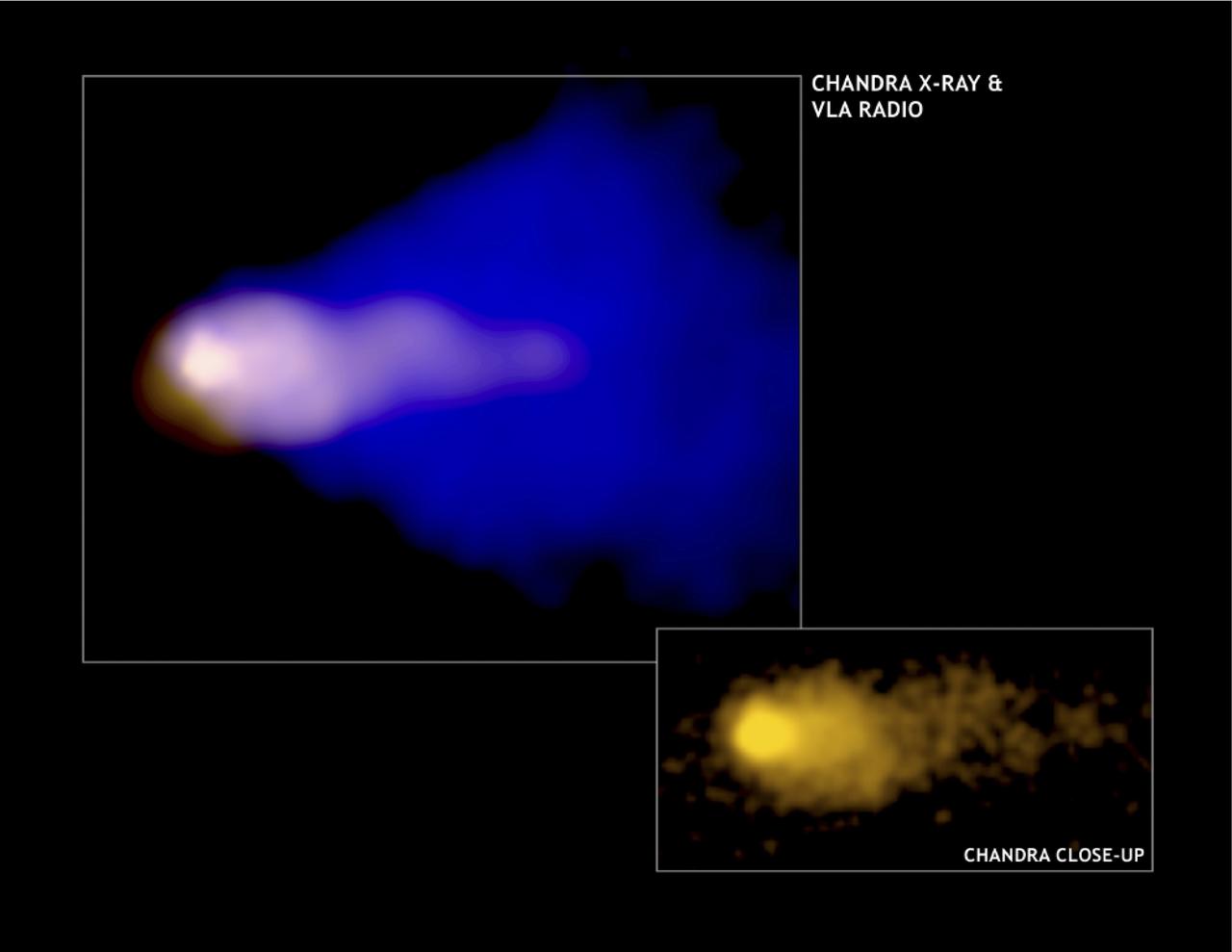

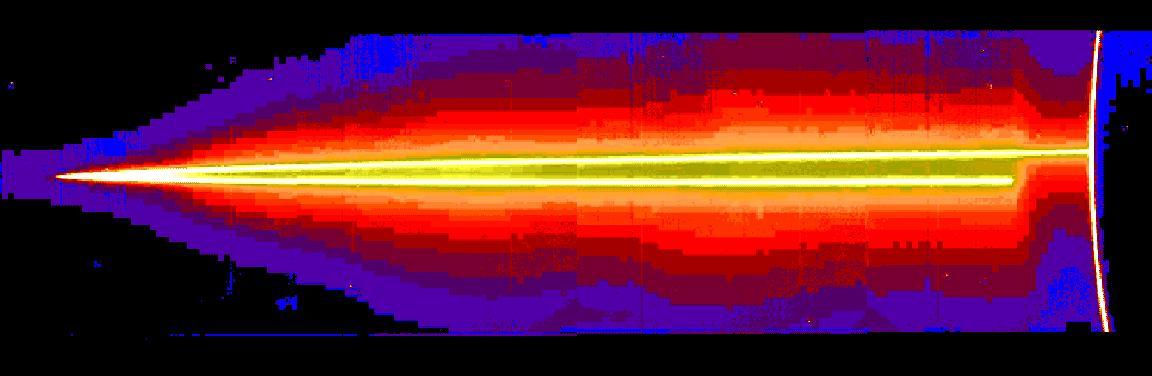

Astronomers have used an x-ray image to make the first detailed study of the behavior of high-energy particles around a fast moving pulsar. This image, from NASA's Chandra X-Ray Observatory (CXO), shows the shock wave created as a pulsar plows supersonically through interstellar space. These results will provide insight into theories for the production of powerful winds of matter and antimatter by pulsars. Chandra's image of the glowing cloud, known as the Mouse, shows a stubby bright column of high-energy particles, about four light years in length, swept back by the pulsar's interaction with interstellar gas. The intense source at the head of the X-ray column is the pulsar, estimated to be moving through space at about 1.3 million miles per hour. A cone-shaped cloud of radio-wave-emitting particles envelopes the x-ray column. The Mouse, a.k.a. G359.23-0.82, was discovered in 1987 by radio astronomers using the National Science Foundation's Very Large Array in New Mexico. G359.23-0.82 gets its name from its appearance in radio images that show a compact snout, a bulbous body, and a remarkable long, narrow, tail that extends for about 55 light years. NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama manages the Chandler program.

Daphnis, one of Saturn's ring-embedded moons, is featured in this view, kicking up waves as it orbits within the Keeler gap. The mosaic combines several images to show more waves in the gap edges. Daphnis is a small moon at 5 miles (8 kilometers) across, but its gravity is powerful enough to disrupt the tiny particles of the A ring that form the Keeler gap's edge. As the moon moves through the Keeler gap, wave-like features are created in both the horizontal and vertical plane. Images like this provide scientists with a close-up view of the complicated interactions between a moon and the rings, as well as the interactions between the ring particles themselves, in the wake of the moon's passage. Three wave crests of diminishing sizes trail Daphnis here. In each subsequent crest, the shape of the wave evolves, as the ring particles within the crests collide with one another. Close examination of Daphnis' immediate vicinity also reveals a faint, thin strand of ring material that almost appears to have been directly ripped out of the A ring by Daphnis. The images in this mosaic were taken in visible light, using the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera at a distance of approximately 17,000 miles (28,000 kilometers) from Daphnis and at a Sun-Daphnis-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 71 degrees. Image scale is 551 feet (168 meters) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17212

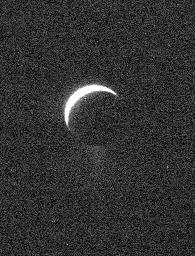

Jets of icy particles burst from Saturn’s moon Enceladus in this brief movie sequence of four images taken on Nov. 27, 2005. The sensational discovery of active eruptions on a third outer solar system body (Io and Triton are the others) is surely one of the great highlights of the Cassini mission. Imaging scientists, as reported in the journal Science on March 10, 2006, believe that the jets are geysers erupting from pressurized subsurface reservoirs of liquid water above 273 degrees Kelvin (0 degrees Celsius). Images taken in January 2005 appeared to show the plume emanating from the fractured south polar region of Enceladus, but the visible plume was only slightly brighter than the background noise in the image, because the lighting geometry was not suitable to reveal the true details of the feature. This potential sighting, in addition to the detection of the icy particles in the plume by other Cassini instruments, prompted imaging scientists to target Enceladus again with exposures designed to confirm the validity of the earlier plume sighting. The new views show individual jets, or plume sources, that contribute to the plume with much greater visibility than the earlier images. The full plume towers over the 505-kilometer-wide (314-mile) moon and is at least as tall as the moon's diameter. The four 10-second exposures were taken over the course of about 36 minutes at approximately 12 minute intervals. Enceladus rotates about 7.5 degrees in longitude over the course of the frames, and most of the observed changes in the appearances of the jets is likely attributable to changes in the viewing geometry. However, some of the changes may be due to actual variation in the flow from the jets on a time scale of tens of minutes. Additionally, the shift of the sources seen here should provide information about their location in front of and behind the visible limb (edge) of Enceladus. These images were obtained using the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera at distances between 144,350 and 149,520 kilometers (89,695 and 92,907 miles) from Enceladus and at a phase angle of about 161 degrees. Image scale is about 900 meters (2,950 feet) per pixel on Enceladus. A movie is available at http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA07762

A mosaic of four images taken through the clear filter (610 nanometers) of the solid state imaging (CCD) system aboard NASA's Galileo spacecraft on November 8, 1996, at a resolution of approximately 46 kilometers (km) per picture element (pixel) along the rings; however, because the spacecraft was only about 0.5 degrees above the ring plane, the image is highly foreshortened in the vertical direction. The images were obtained when Galileo was in Jupiter's shadow peering back toward the Sun; the ring was approximately 2,300,000 kilometers (km) away. The arc on the far right of the image is produced by sunlight scattered by small particles comprising Jupiter's upper atmospheric haze. The ring also efficiently scatters light, indicating that much of its brightness is due to particles that are microns or less in diameter. Such small particles are believed to have human-scale lifetimes, i.e., very brief compared to the solar system's age. Jupiter's ring system is composed of three parts -- a flat main ring, a lenticular halo interior to the main ring, and the gossamer ring, which lies exterior to the main ring. The near and far arms of Jupiter's main ring extend horizontally across the mosaic, joining together at the ring's ansa, on the far left side of the figure. The near arm of the ring appears to be abruptly truncated close to the planet, at the point where it passes into Jupiter's shadow. A faint mist of particles can be seen above and below the main rings; this vertically extended, toroidal "halo" is unusual in planetary rings, and is probably caused by electromagnetic forces which can push small grains out of the ring plane. Halo material is present across this entire image, implying that it reaches more than 27,000 km above the ring plane. Because of shadowing, the halo is not visible close to Jupiter in the lower right part of the mosaic. In order to accentuate faint features in the image, different brightnesses are shown through color, with the brightest being white or yellow and the faintest purple. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA00658

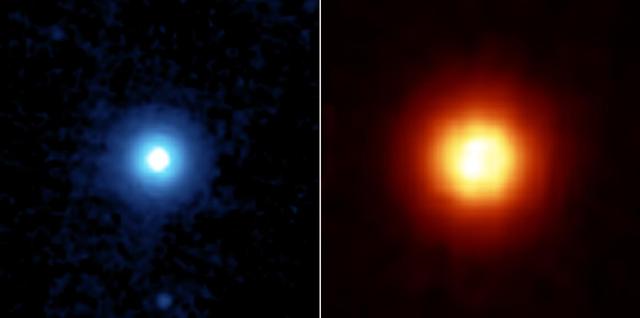

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope recently captured these images of the star Vega, located 25 light years away in the constellation Lyra. Spitzer was able to detect the heat radiation from the cloud of dust around the star and found that the debris disc is much larger than previously thought. This side by side comparison, taken by Spitzer's multiband imaging photometer, shows the warm infrared glows from dust particles orbiting the star at wavelengths of 24 microns (figure 2 in blue) and 70 microns (figure 3 in red). Both images show a very large, circular and smooth debris disc. The disc radius extends to at least 815 astronomical units. (One astronomical unit is the distance from Earth to the Sun, which is 150-million kilometers or 93-million miles). Scientists compared the surface brightness of the disc in the infrared wavelengths to determine the temperature distribution of the disc and then infer the corresponding particle size in the disc. Most of the particles in the disc are only a few microns in size, or 100 times smaller than a grain of Earth sand. These fine dust particles originate from collisions of embryonic planets near the star at a radius of approximately 90 astronomical units, and are then blown away by Vega's intense radiation. The mass and short lifetime of these small particles indicate that the disc detected by Spitzer is the aftermath of a large and relatively recent collision, involving bodies perhaps as big as the planet Pluto. The images are 3 arcminutes on each side. North is oriented upward and east is to the left. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA07218

Range : 236,000 km. ( 147,000 mi. ) Resolution : 33 km. ( 20 mi. ) P-29525B/W This Voyager 2 image reveals a contiuos distribution of small particles throughout the Uranus ring system. This unigue geometry, the highest phase angle at which Voyager imaged the rings, allows us to see lanes of fine dust particles not visible from other viewing angles. All the previously known rings are visible. However, some of the brightest features in the image are bright dust lanes not previously seen. the combination of this unique geometry and a long, 96 second exposure allowed this spectacular observation, acquired through the clear filter if Voyager 2's wide angle camera. the long exposure produced a noticable, non-uniform smear, as well as streaks due to trailed stars.

This image from NASA's Cassini mission shows a region in Saturn's A ring. The level of detail is twice as high as this part of the rings has ever been seen before. The view contains many small, bright blemishes due to cosmic rays and charged particle radiation near the planet. The view shows a section of the A ring known to researchers for hosting belts of propellers -- bright, narrow, propeller-shaped disturbances in the ring produced by the gravity of unseen embedded moonlets. Several small propellers are visible in this view. These are on the order of 10 times smaller than the large, bright propellers whose orbits scientists have routinely tracked (and which are given nicknames for famous aviators). This image is a lightly processed version, with minimal enhancement, preserving all original details present in the image. he image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on Dec. 18, 2016. The view was obtained at a distance of approximately 33,000 miles (54,000 kilometers) from the rings and looks toward the unilluminated side of the rings. Image scale is about a quarter-mile (330 meters) per pixel. http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21059

iss066e110545 (1/10/2022) --- A view of the Mochii microscope aboard the International Space Station (ISS. Mochii is a miniature scanning electron microscope (SEM) with spectroscopy to conduct real-time, on-site imaging and compositional measurements of particles on the International Space Station (ISS).

iss066e110547 (1/10/2022) --- A view of the Mochii microscope sample load aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Mochii is a miniature scanning electron microscope (SEM) with spectroscopy to conduct real-time, on-site imaging and compositional measurements of particles on the International Space Station (ISS)

iss066e110566 (1/10/2022) --- NASA astronaut Kayla Barron sets up the Mochii microscope. Mochii is a miniature scanning electron microscope (SEM) with spectroscopy to conduct real-time, on-site imaging and compositional measurements of particles on the International Space Station (ISS).

iss066e110556 (1/10/2022) --- NASA astronaut Kayla Barron sets up the Mochii microscope. Mochii is a miniature scanning electron microscope (SEM) with spectroscopy to conduct real-time, on-site imaging and compositional measurements of particles on the International Space Station (ISS).

iss066e110531_alt (1/10/2022) --- NASA astronaut Kayla Barron sets up the Mochii microscope. Mochii is a miniature scanning electron microscope (SEM) with spectroscopy to conduct real-time, on-site imaging and compositional measurements of particles on the International Space Station (ISS).

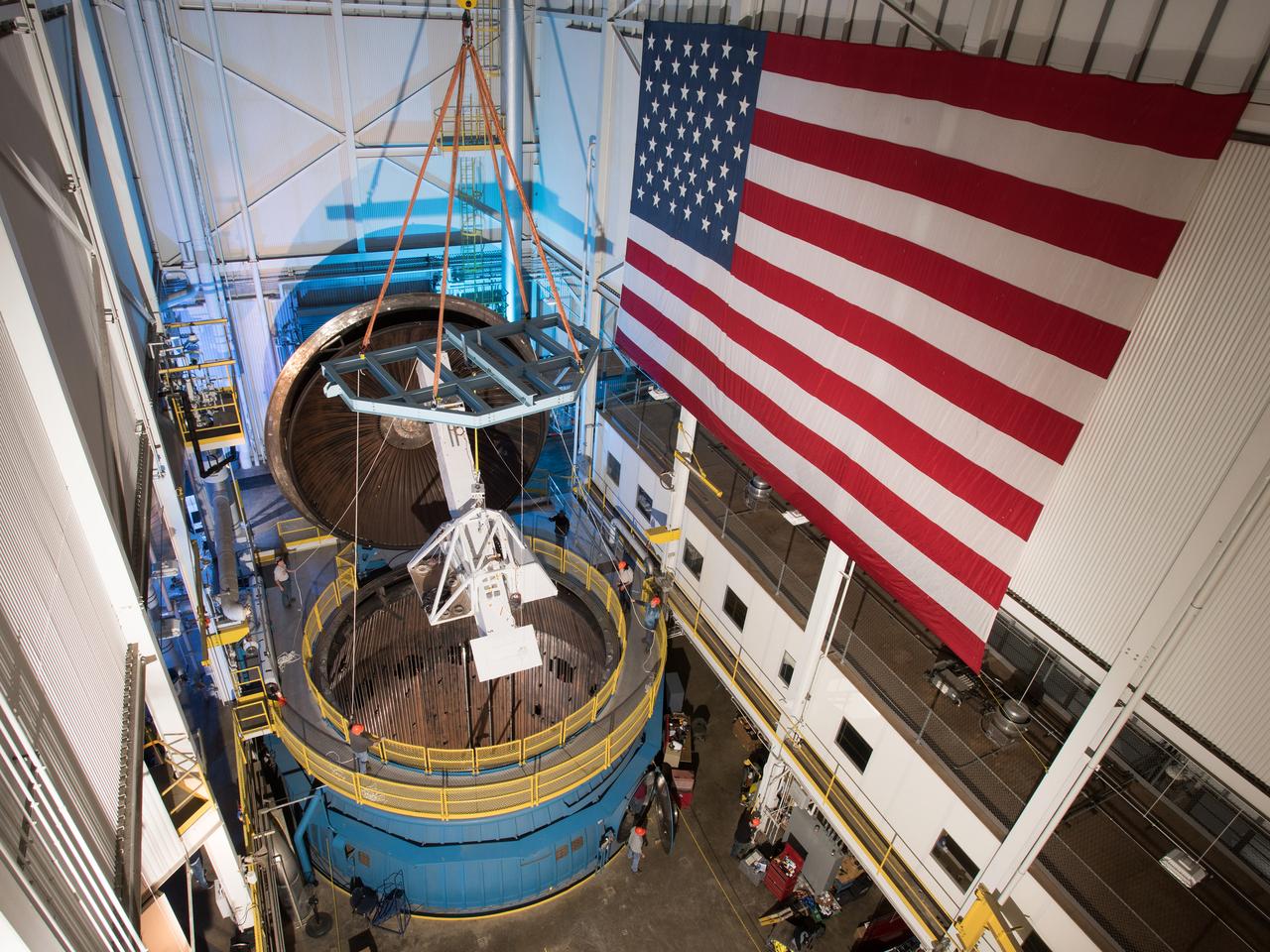

The Gamma-Ray Imager/Polarimeter for Solar flares (GRIPS) instrument is installed in the B-2 vacuum chamber for a full-instrument thermal-vacuum test in 2015. The GRIPS telescope was launched via balloon in January 2016 on a high-altitude flight over Antarctica to study the acceleration and transport of solar flare particles.

A scanning electron microscope image of a micrometeorite impact crater in a particle of asteroid Bennu material. Scientists found microscopic craters and tiny splashes of once-molten rock – known as impact melts – on the surfaces of samples, signs that the asteroid was bombarded by micrometeorites.

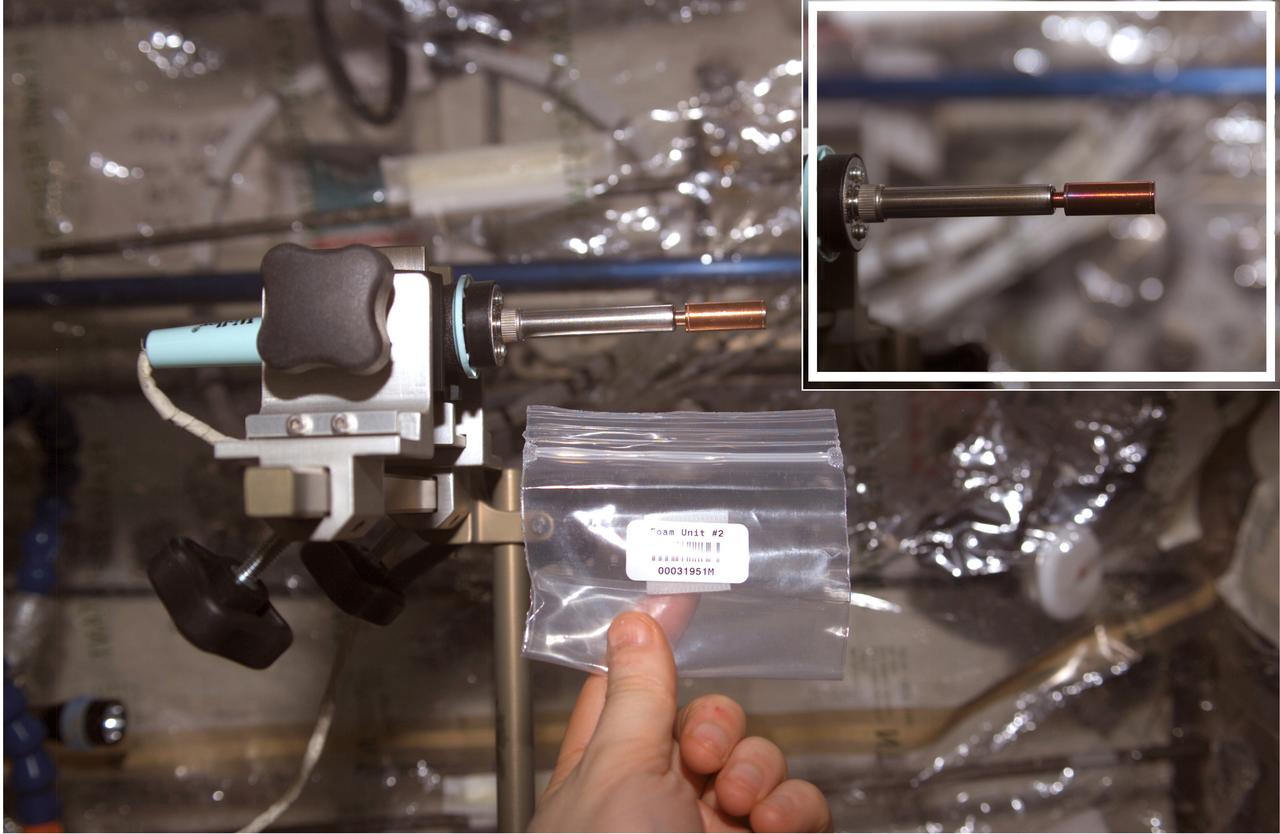

This soldering iron has an evacuated copper capsule at the tip that contains a pellet of Bulk Metallic Glass (BMG) aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Prior to flight, researchers sealed a pellet of bulk metallic glass mixed with microscopic gas-generating particles into the copper ampoule under vacuum. Once heated in space, such as in this photograph, the particles generated gas and the BMG becomes a viscous liquid. The released gas made the sample foam within the capsule where each microscopic particle formed a gas-filled pore within the foam. The inset image shows the oxidation of the sample after several minutes of applying heat. Although hidden within the brass sleeve, the sample retained the foam shape when cooled, because the viscosity increased during cooling until it was solid.

jsc2022e072960 (9/16/2022) --- Front view of flow of mixture of hydrophobic medium sand particles, water, and air. After mixing hydrophobic medium sand particles with water and air, researchers flow the mixture through the pipe. Both agglomerates and excess free sand particles are visible. Researchers also observe the segregation phenomenon during the flow of this particular mixture. Agglomerates do not occupy the pipe uniformly and do not always flow at the same speed. Catastrophic Post-Wildfire Mudflows studies the formation and stability of this bubble-sand structure in microgravity. A better understanding of these phenomena could improve the understanding, modeling, and predicting of mudflows and support development of innovative solutions to prevent catastrophic post-fire events. Image courtesy of the UCSD Geo-Micromechanics Research Group.

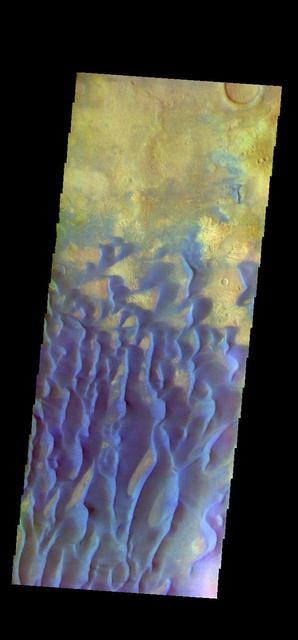

The THEMIS VIS camera contains 5 filters. The data from different filters can be combined in multiple ways to create a false color image. These false color images may reveal subtle variations of the surface not easily identified in a single band image. This false color image shows part of the floor of Kaiser Crater. Kaiser Crater is 207 km (129 miles) in diameter and is located in Noachis Terra west of Hellas Planitia. This sand dune field is one of several regions of sand dunes located in the southern part of the crater floor. With enough wind and sand, sand dunes are formed. Dune morphology typically has a shallow slope on the side the wind is blowing from and a steep face on the other side. The lighter part of the dunes in this image are the steep slopes. Wind blows sand particles up the shallow slope and then the particles 'fall' off the crest of the dune down the steep side. With time, the constant wind will move the crest of the dune forward. Depending on the amount of available sand, dunes can grow to large heights and sizes. The dunes in this image are moving west - towards the left side of the image. Dark blue in this false color combination are typically basaltic sand. Orbit Number: 83387 Latitude: -46.8031 Longitude: 19.7369 Instrument: VIS Captured: 2020-10-01 08:54 https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA24708

Range : 900,000 miles A brilliant halo around Jupiter, the thin ring of particles discovered by Voyager 1 four months ago, is seen here unusually bright due to forward scattering of the particles within it. Similiarly, the planet is outlined by sunlight scattered toward the spacecraft from a haze layer high in jupiter's atmosphere. The arms of the ring are cut off on each sideby the planet's shadow as they approach the brightly outlined disk. The night side of the planet appears completly dark in this reproduction, but later will be specially reprocessed to search for evidence of lightning sorms and auroras. This 4 image mosaic was obtained with Voyager 2's wide angle camera.

A prominence at the edge of the sun provided us with a splendid view of solar plasma as it churned and streamed over less than one day (June 25-26, 2017). The charged particles of plasma were being manipulated by strong magnetic forces. When viewed in this wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light, we can trace the movements of the particles. Such occurrences are fairly common but much easier to see when they are near the sun's edge. For a sense of scale, the arch of prominence in the still image has risen up several times the size of Earth. Movies are available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21768

A flare medium-sized (M2) flare and a coronal mass ejection erupted from the same, large active region (July 14, 2017). The flare lasted almost two hours, quite a long duration. Coronagraphs on the SOHO spacecraft show a substantial cloud of charged particles blasting into space just after the blast. The coils arcing over this active region are particles spiraling along magnetic field lines, which were reorganizing themselves after the magnetic field was disrupted by the blast. Images were taken in a wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light. Movies are available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21836

A prominence at the edge of the sun provided us with a splendid view of solar plasma as it churned and streamed over less than one day (June 25-26, 2017). The charged particles of plasma were being manipulated by strong magnetic forces. When viewed in this wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light, we can trace the movements of the particles. Such occurrences are fairly common but much easier to see when they are near the sun's edge. For a sense of scale, the arch of prominence in the still image has risen up several times the size of Earth. Movies are available at https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA21783