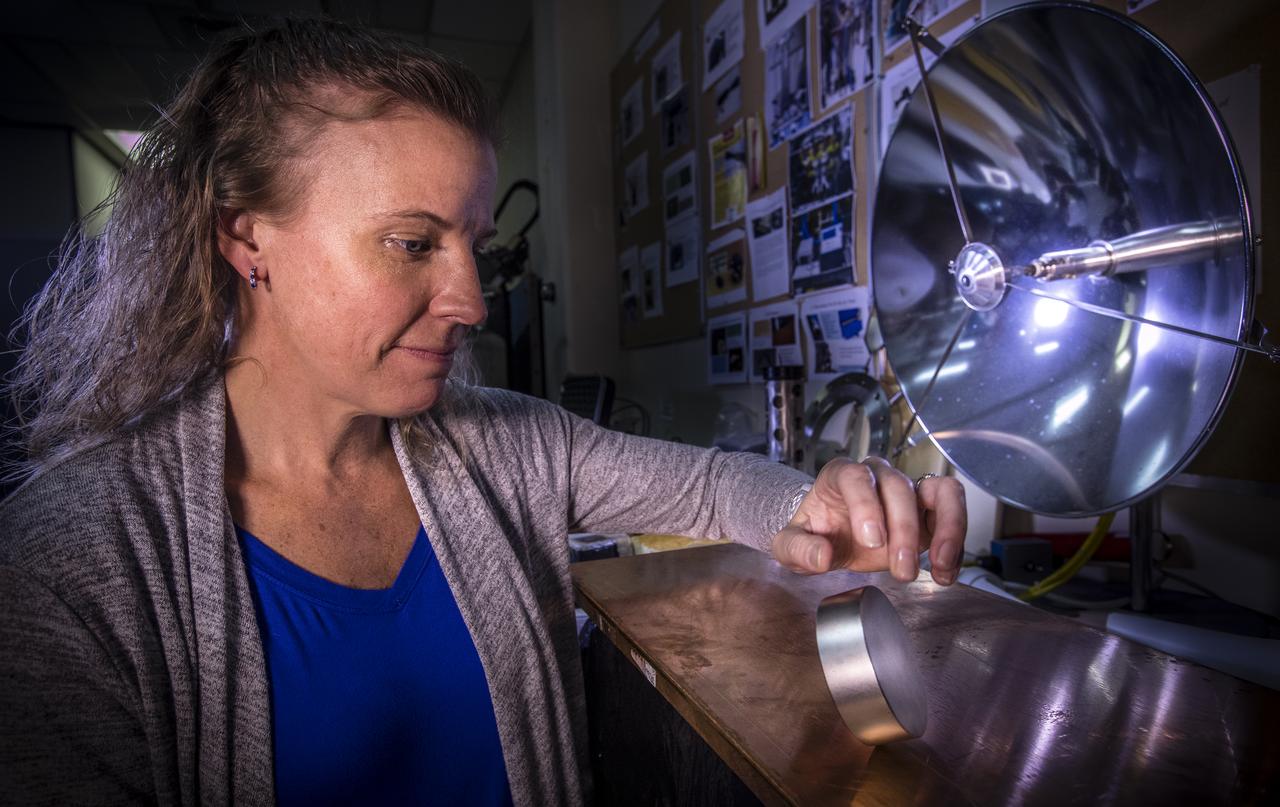

Principal investigator, Dr. Janine Captain, demonstrates the effects of moving a magnet against metal in the Applied Physics Laboratory at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center on Dec. 12, 2018. When dropped or tipped over on a plate of copper, the magnet decelerates and slowly touches down on the plate visually demonstrating the physics of the magnetic field.

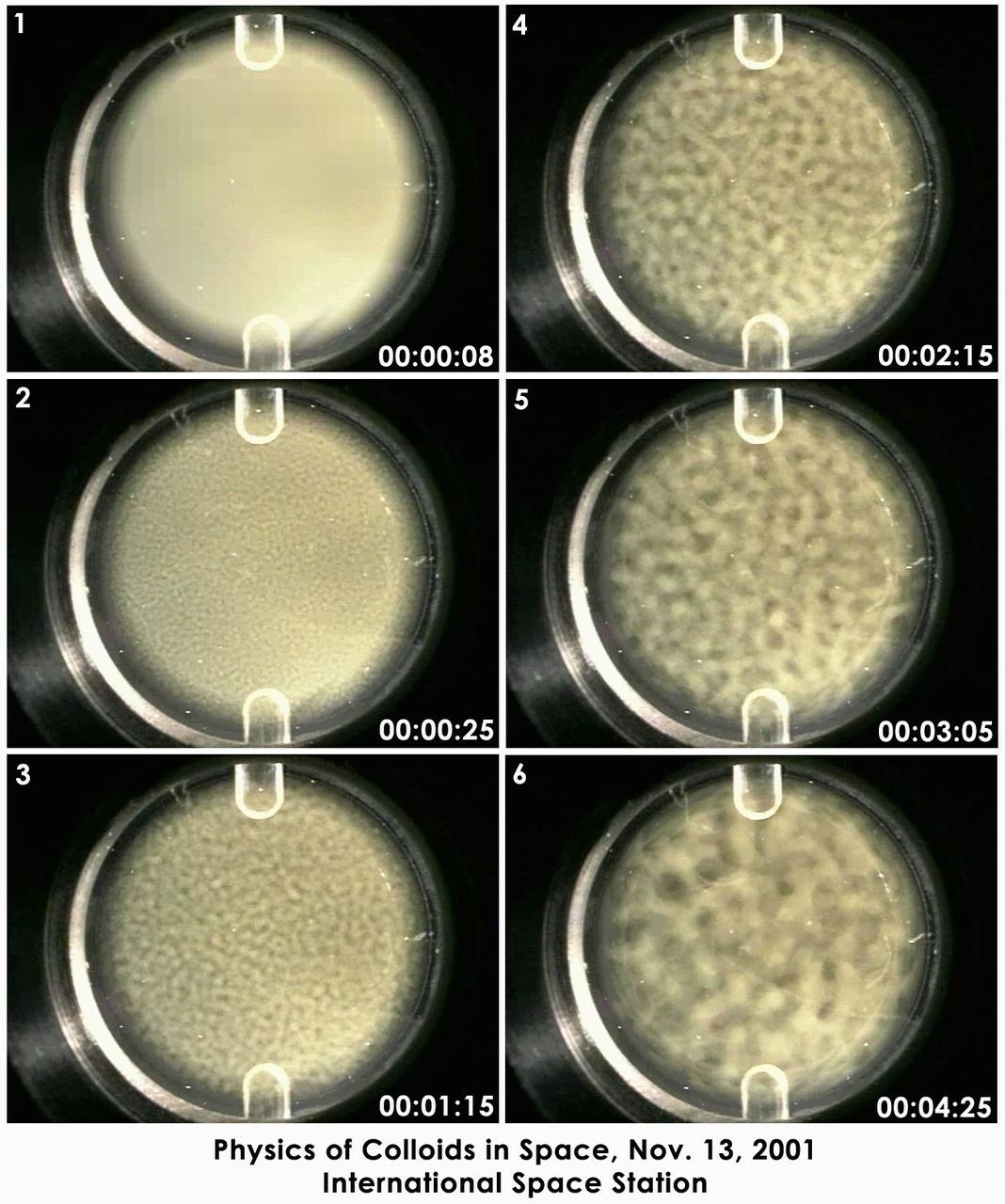

Still photographs taken over 16 hours on Nov. 13, 2001, on the International Space Station have been condensed into a few seconds to show the de-mixing -- or phase separation -- process studied by the Experiment on Physics of Colloids in Space. Commanded from the ground, dozens of similar tests have been conducted since the experiment arrived on ISS in 2000. The sample is a mix of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA or acrylic) colloids, polystyrene polymers and solvents. The circular area is 2 cm (0.8 in.) in diameter. The phase separation process occurs spontaneously after the sample is mechanically mixed. The evolving lighter regions are rich in colloid and have the structure of a liquid. The dark regions are poor in colloids and have the structure of a gas. This behavior carnot be observed on Earth because gravity causes the particles to fall out of solution faster than the phase separation can occur. While similar to a gas-liquid phase transition, the growth rate observed in this test is different from any atomic gas-liquid or liquid-liquid phase transition ever measured experimentally. Ultimately, the sample separates into colloid-poor and colloid-rich areas, just as oil and vinegar separate. The fundamental science of de-mixing in this colloid-polymer sample is the same found in the annealing of metal alloys and plastic polymer blends. Improving the understanding of this process may lead to improving processing of these materials on Earth.

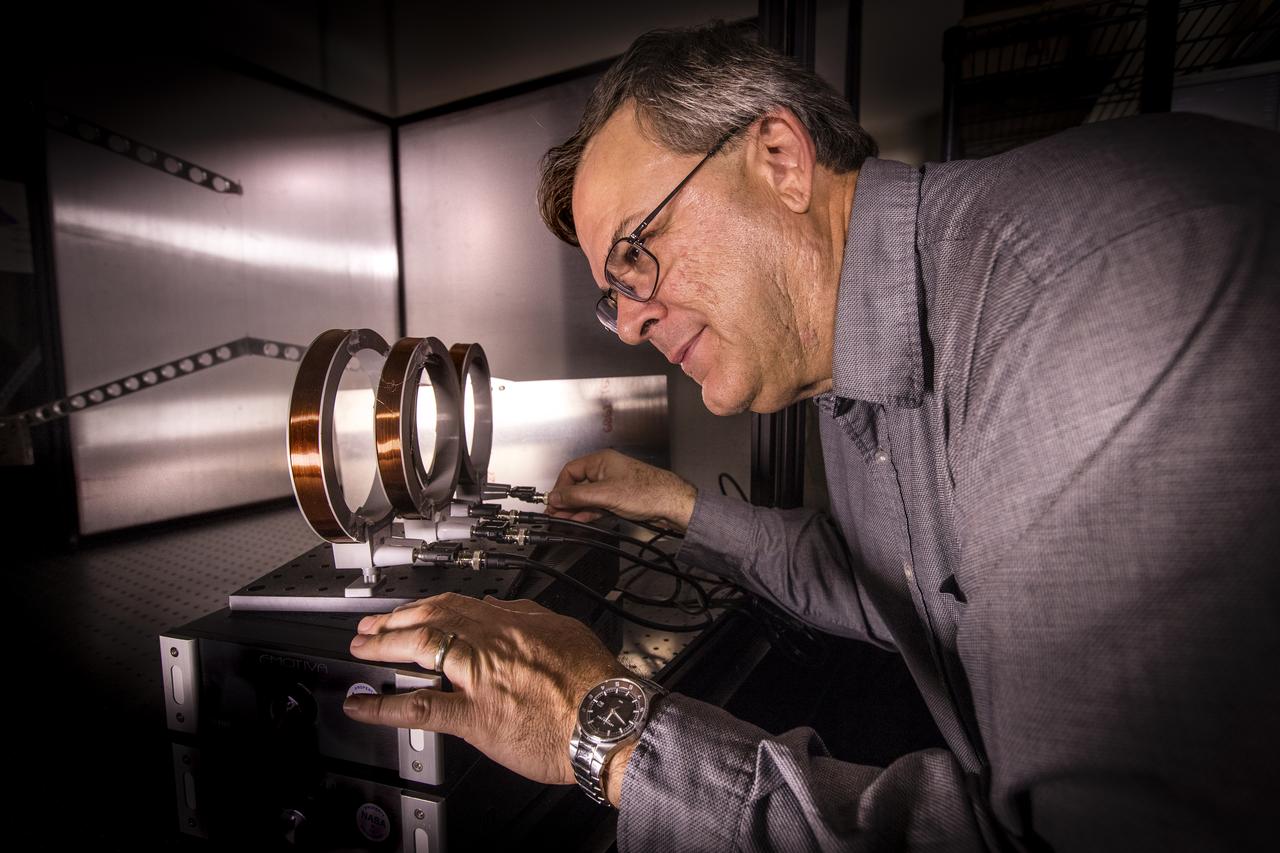

Dr. Mark Nurge, a physicist in the Applied Physics Laboratory at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center adjusted cables on an experiment setup on Dec. 12, 2018. The experiment seeks to find new methods of propulsion based on electromagnetism that could be used in robots to service the International Space Station.

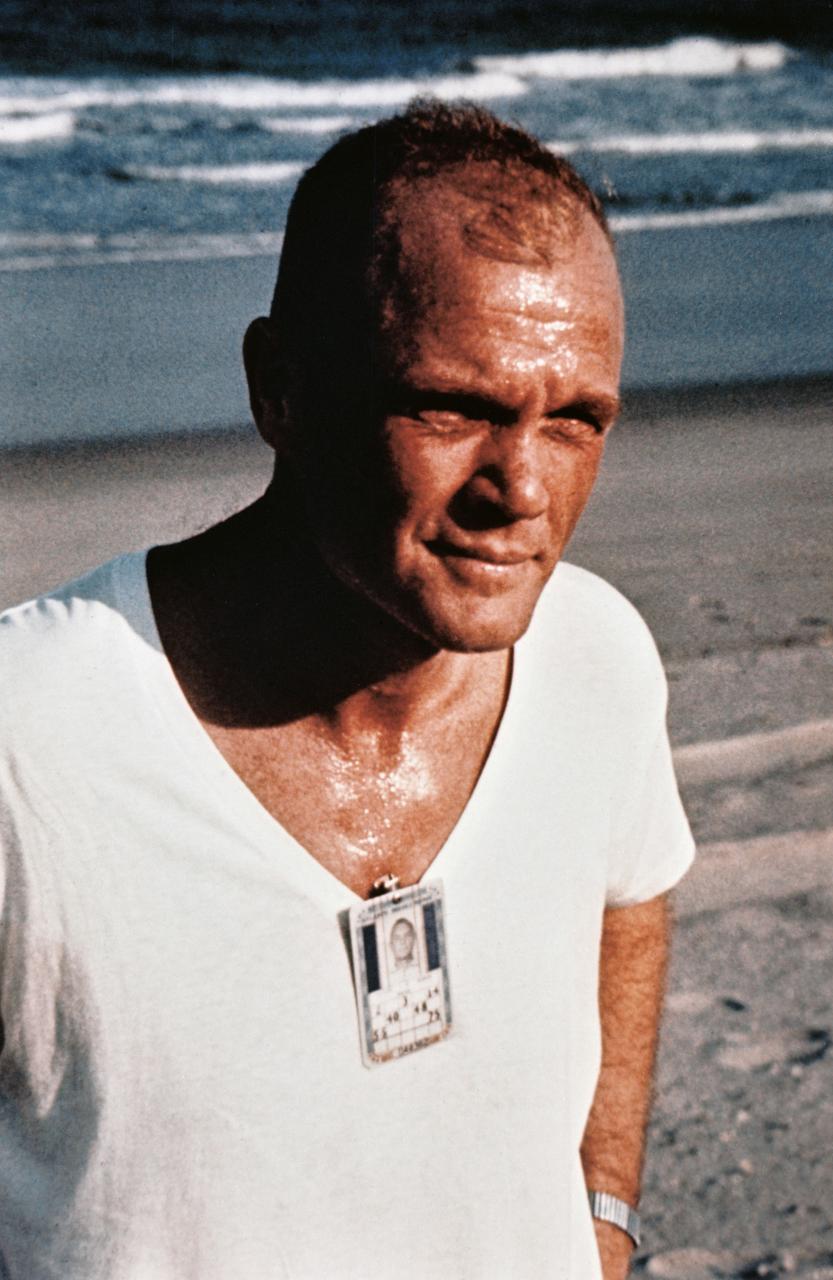

S64-14883 (1962) --- Astronaut John H. Glenn Jr., pilot of the Mercury-Atlas 6 mission, participates in a strict physical training program, as he exemplifies by frequent running. Here he pauses during an exercise period on the beach near Cape Canaveral, Florida. Photo credit: NASA

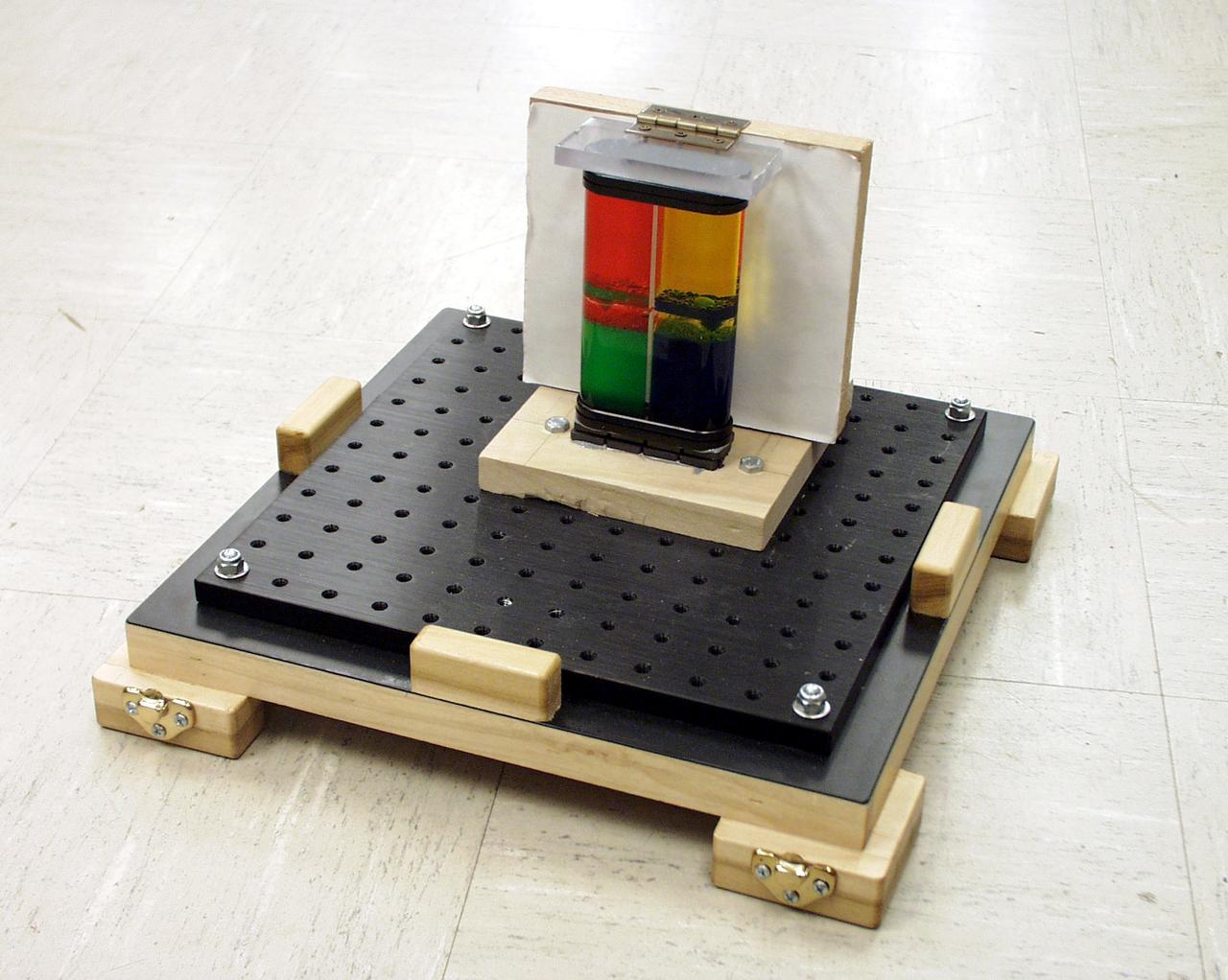

Colored oil flow toy was part of a student-designed apparatus used in the second Dropping in a Microgravity Environment (DIME) competition held April 23-25, 2002, at NASA's Glenn Research Center. Competitors included two teams from Sycamore High School, Cincinnati, OH, and one each from Bay High School, Bay Village, OH, and COSI Academy, Columbus, OH. DIME is part of NASA's education and outreach activities. Details are on line at http://microgravity.grc.nasa.gov/DIME_2002.html.

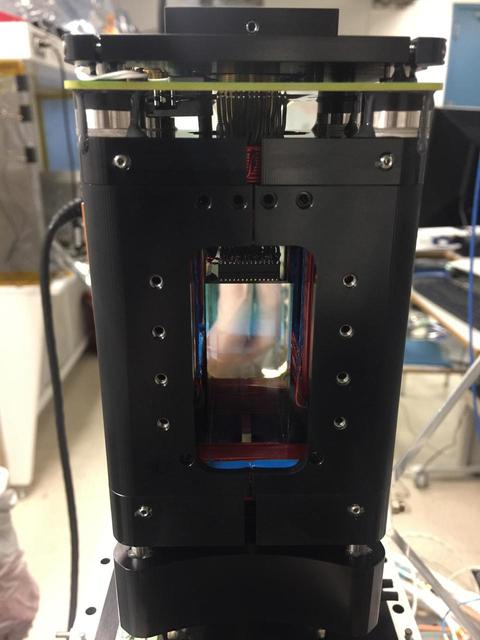

Shown here, the "physics package" inside NASA's Cold Atom Lab, where ultracold clouds of atoms called Bose-Einstein condensates are produced. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA22563

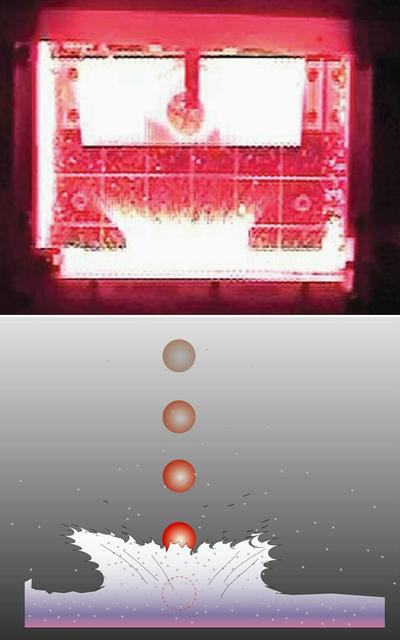

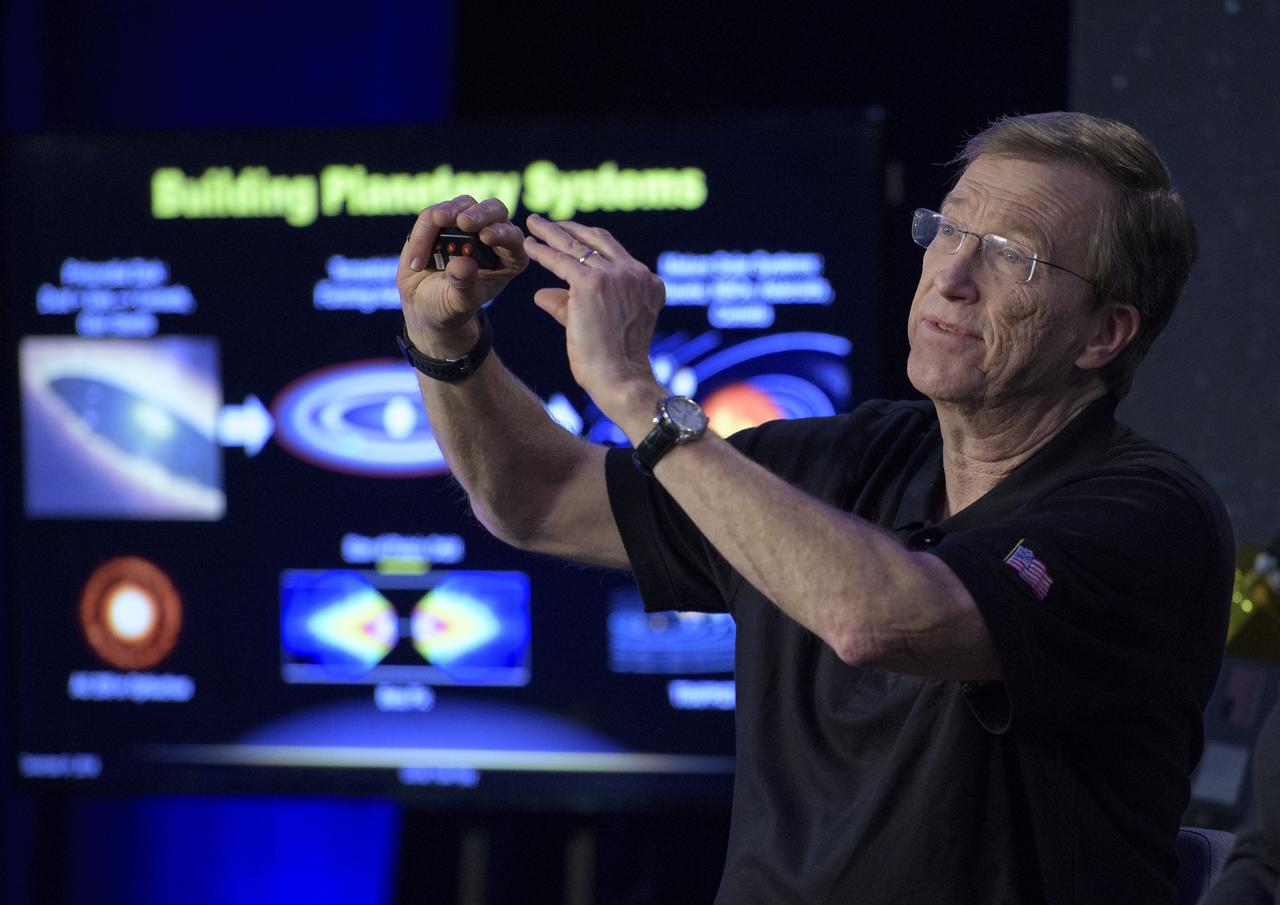

Clues to the formation of planets and planetary rings -- like Saturn's dazzling ring system -- may be found by studying how dust grains interact as they collide at low speeds. To study the question of low-speed dust collisions, NASA sponsored the COLLisions Into Dust Experiment (COLLIDE) at the University of Colorado. It was designed to spring-launch marble-size projectiles into trays of powder similar to space or lunar dust. COLLIDE-1 (1998) discovered that collisions below a certain energy threshold eject no material. COLLIDE-2 was designed to identify where the threshold is. In COLLIDE-2, scientists nudged small projectiles into dust beds and recorded how the dust splashed outward (video frame at top; artist's rendering at bottom). The slowest impactor ejected no material and stuck in the target. The faster impactors produced ejecta; some rebounded while others stuck in the target.

This image depicts the formation of multiple whirlpools in a sodium gas cloud. Scientists who cooled the cloud and made it spin created the whirlpools in a Massachusetts Institute of Technology laboratory, as part of NASA-funded research. This process is similar to a phenomenon called starquakes that appear as glitches in the rotation of pulsars in space. MIT's Wolgang Ketterle and his colleagues, who conducted the research under a grant from the Biological and Physical Research Program through NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., cooled the sodium gas to less than one millionth of a degree above absolute zero (-273 Celsius or -460 Fahrenheit). At such extreme cold, the gas cloud converts to a peculiar form of matter called Bose-Einstein condensate, as predicted by Albert Einstein and Satyendra Bose of India in 1927. No physical container can hold such ultra-cold matter, so Ketterle's team used magnets to keep the cloud in place. They then used a laser beam to make the gas cloud spin, a process Ketterle compares to stroking a ping-pong ball with a feather until it starts spirning. The spinning sodium gas cloud, whose volume was one- millionth of a cubic centimeter, much smaller than a raindrop, developed a regular pattern of more than 100 whirlpools.

Principal investigator, Dr. Janine Captain, attaches a mass spectrometer sensor to electronics inside a vacuum chamber in the Space Station Processing Facility high bay at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center on Dec. 12, 2018. The Mass Spectrometer observing lunar operations (MSolo) instrument is a commercial off-the-shelf mass instrument modified to work in space, and can identify molecules at lunar landing sites. These MSolo instruments are part of NASA’s efforts to return to the Moon with the Commercial Lunar Payload Services Landers Program.

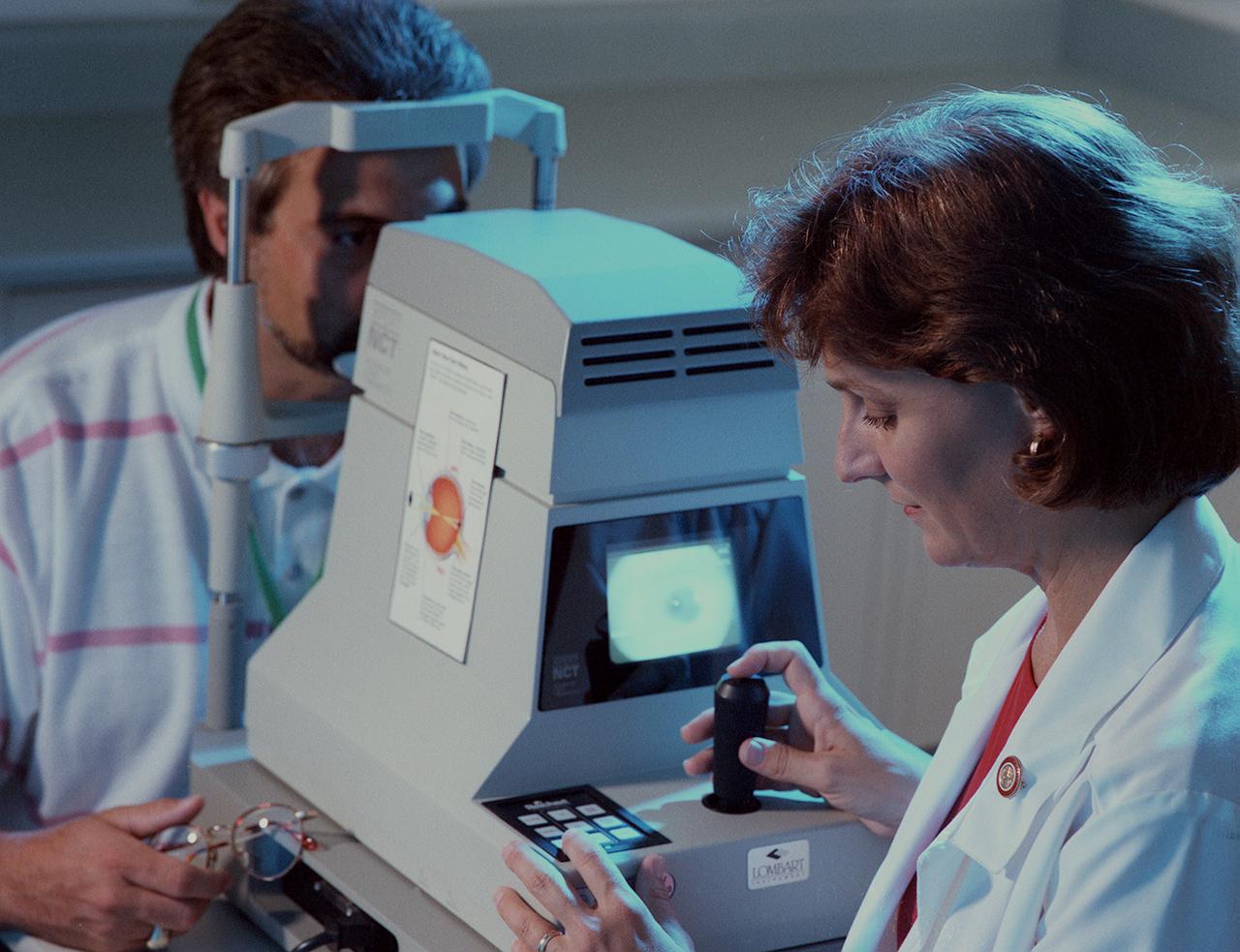

Nurse performs tonometry examination, which measure the tension of the eyeball, during an employee's arnual physical examination given by MSFC Occupational Medicine Environmental Health Services under the Center Operations Directorate.

ISS030-E-142784 (15 March 2012) --- European Space Agency astronaut Andre Kuipers, Expedition 30 flight engineer, works to remove the Marangoni Surface fluid physics experiment from the Fluid Physics Experiment Facility (FPEF) in the Kibo laboratory of the International Space Station.

ISS030-E-142785 (15 March 2012) --- European Space Agency astronaut Andre Kuipers, Expedition 30 flight engineer, works to remove the Marangoni Surface fluid physics experiment from the Fluid Physics Experiment Facility (FPEF) in the Kibo laboratory of the International Space Station.

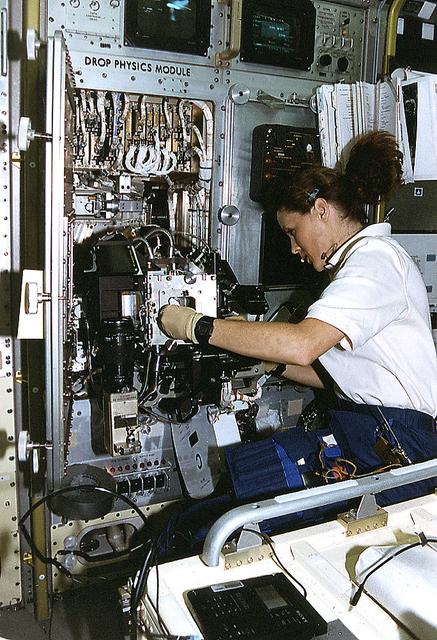

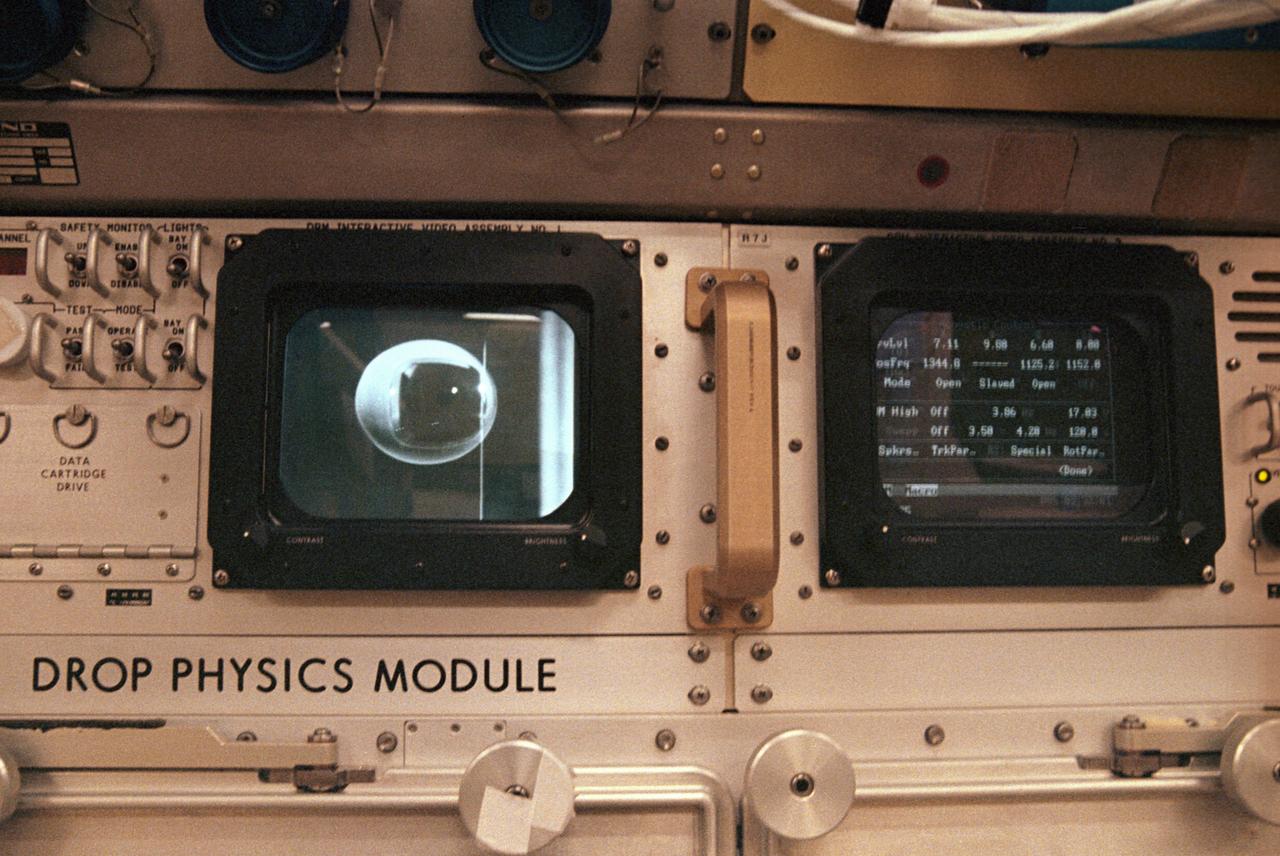

Onboard Space Shuttle Columbia (STS-73) Payload Commander Kathryn Thornton works with the Drop Physics Module (DPM) in the United States Microgravity Laboratory 2 (USML-2) Spacelab Science Module cleaning the experiment chamber of the DPM.

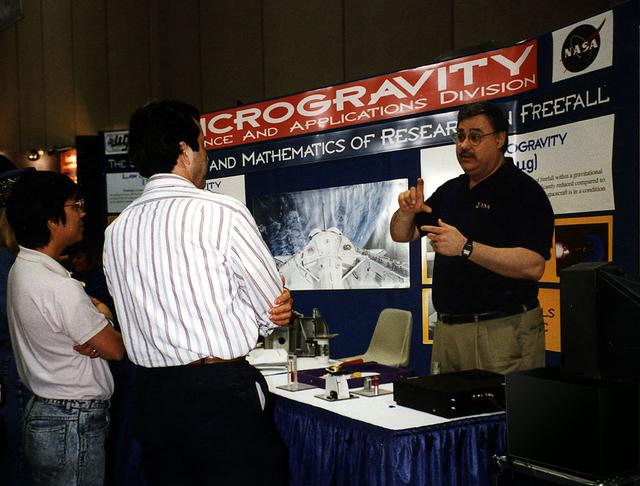

Dr. Michael Wargo, program scientist for materials science at NASA headquarters, explains the math and physics principles associated with freefall research to attendees at the arnual conference of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

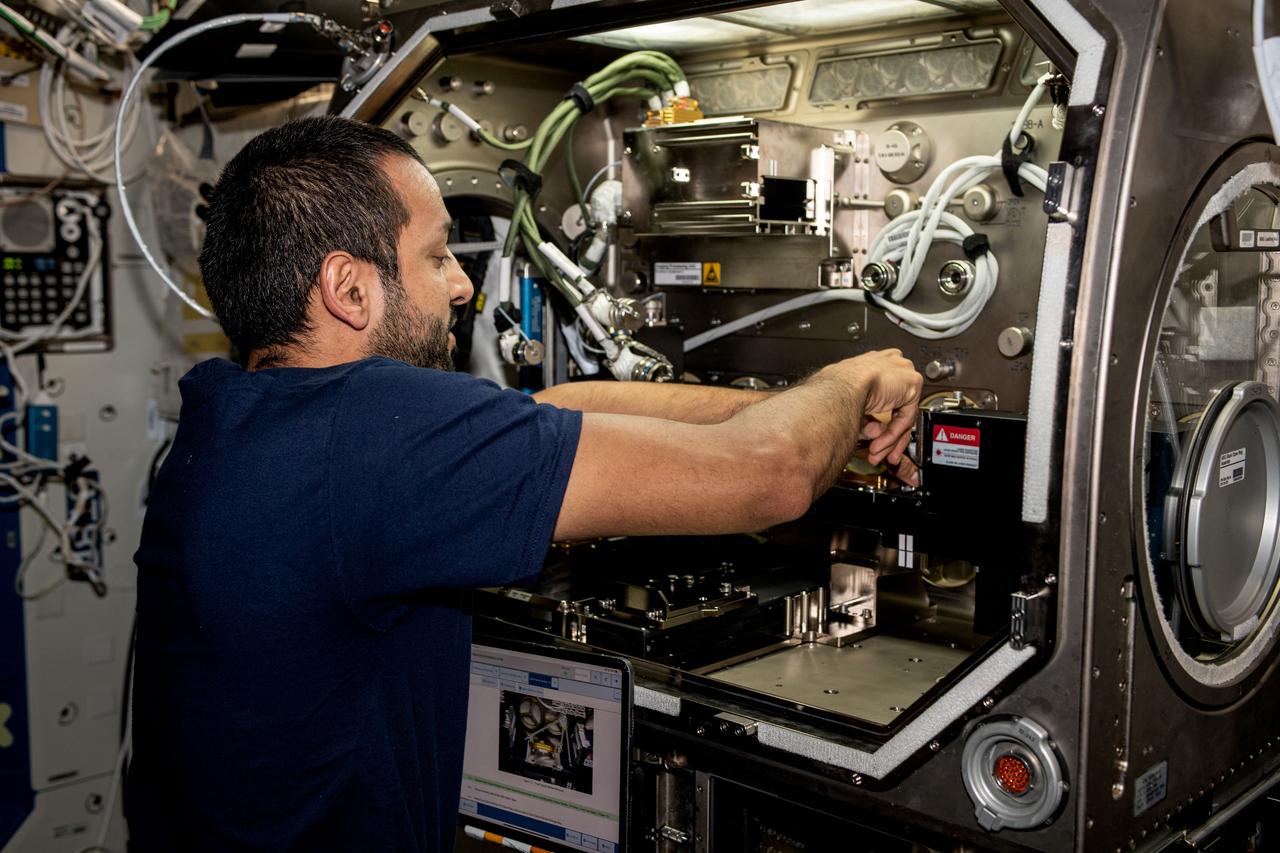

iss069e008883 (May 5, 2023) --- UAE (United Arab Emirates) astronaut and Expedition 69 Flight Engineer Sultan Alneyadi removes physics research hardware from inside the Destiny laboratory module's Microgravity Science Glovebox. The Particle Vibrations experiment investigated the self-organization mechanisms of particles in fluids potentially providing insights into new manufacturing techniques and the formation of planets and asteroids.

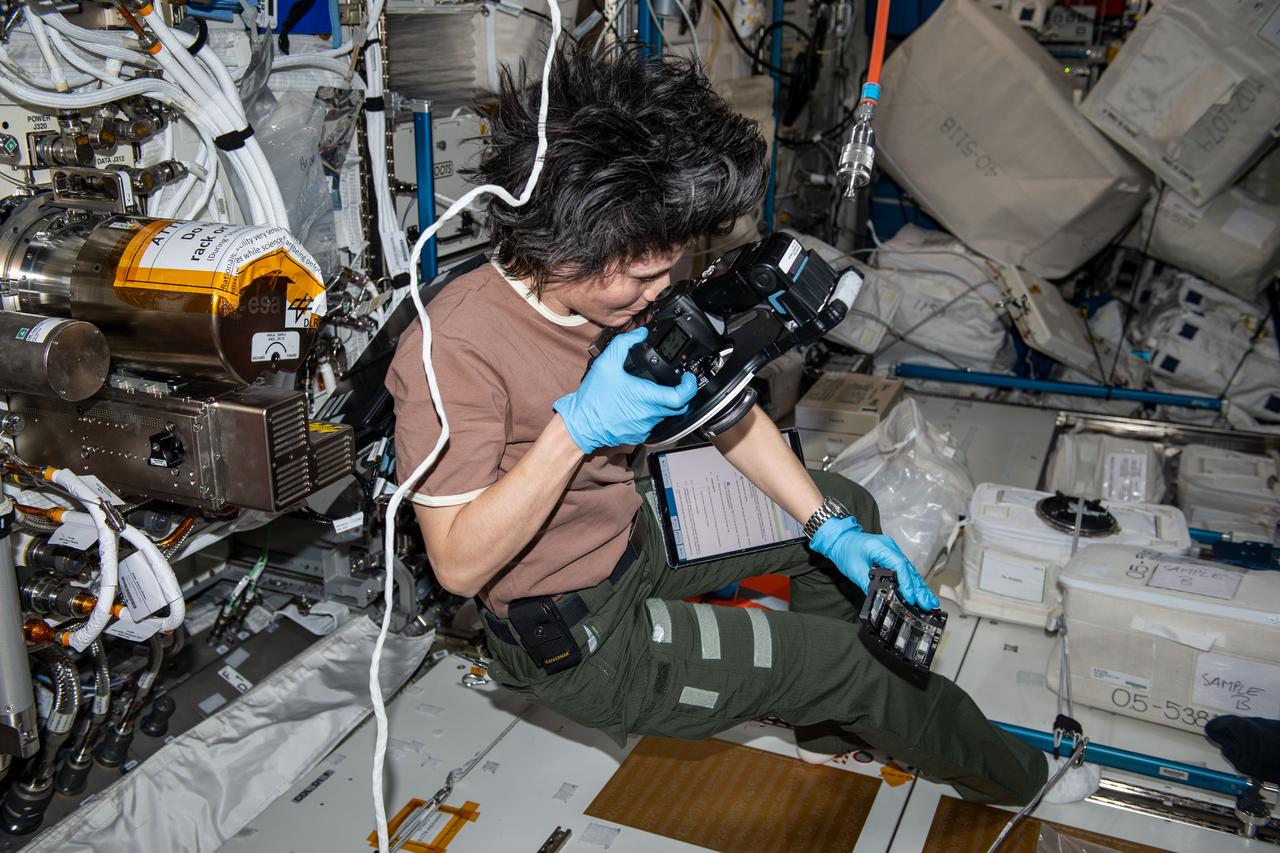

iss067e253397 (Dec. 2, 2024) --- ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut and Expedition 67 Flight Engineer Samantha Cristoforetti photographs and exchanges samples for the Fluids Science Laboratory Soft Matter Dynamics space physics experiment aboard the Intenational Space Station's Columbus laboratory module. The microgravity environment enables the observation of "wet" foams and the study of rearrangement phenomena, such as coarsening and coalescence, disentangled from drainage issues caused by Earth's gravity. Results may benefit Earth and space industries.

Students in the My Brother’s Keeper program listen as Jose Nunez of NASA Kennedy Space Center’s Exploration Research and Technology Programs explains some of the hardware in the Electrostatic and Surface Physics Lab at the Florida spaceport. Kennedy is one of six NASA centers that participated in My Brother’s Keeper National Lab Week. The event is a nationwide effort to bring youth from underrepresented communities into federal labs and centers for hands-on activities, tours and inspirational speakers. Sixty students from the nearby cities of Orlando and Sanford visited Kennedy, where they toured the Vehicle Assembly Building, the Space Station Processing Facility and the center’s innovative Swamp Works Labs. The students also had a chance to meet and ask questions of a panel of subject matter experts from across Kennedy.

Students in the My Brother’s Keeper program watch as Jose Nunez of NASA Kennedy Space Center’s Exploration Research and Technology Programs demonstrates some of the hardware in the Electrostatic and Surface Physics Lab at the Florida spaceport. Kennedy is one of six NASA centers that participated in My Brother’s Keeper National Lab Week. The event is a nationwide effort to bring youth from underrepresented communities into federal labs and centers for hands-on activities, tours and inspirational speakers. Sixty students from the nearby cities of Orlando and Sanford visited Kennedy, where they toured the Vehicle Assembly Building, the Space Station Processing Facility and the center’s innovative Swamp Works Labs. The students also had a chance to meet and ask questions of a panel of subject matter experts from across Kennedy.

ISS020-E-016214 (1 July 2009) --- Canadian Space Agency astronaut Robert Thirsk, Expedition 20 flight engineer, prepares the Fluid Physics Experiment Facility (FPEF) for the planned Marangoni Surface experiment in the Kibo laboratory of the International Space Station.

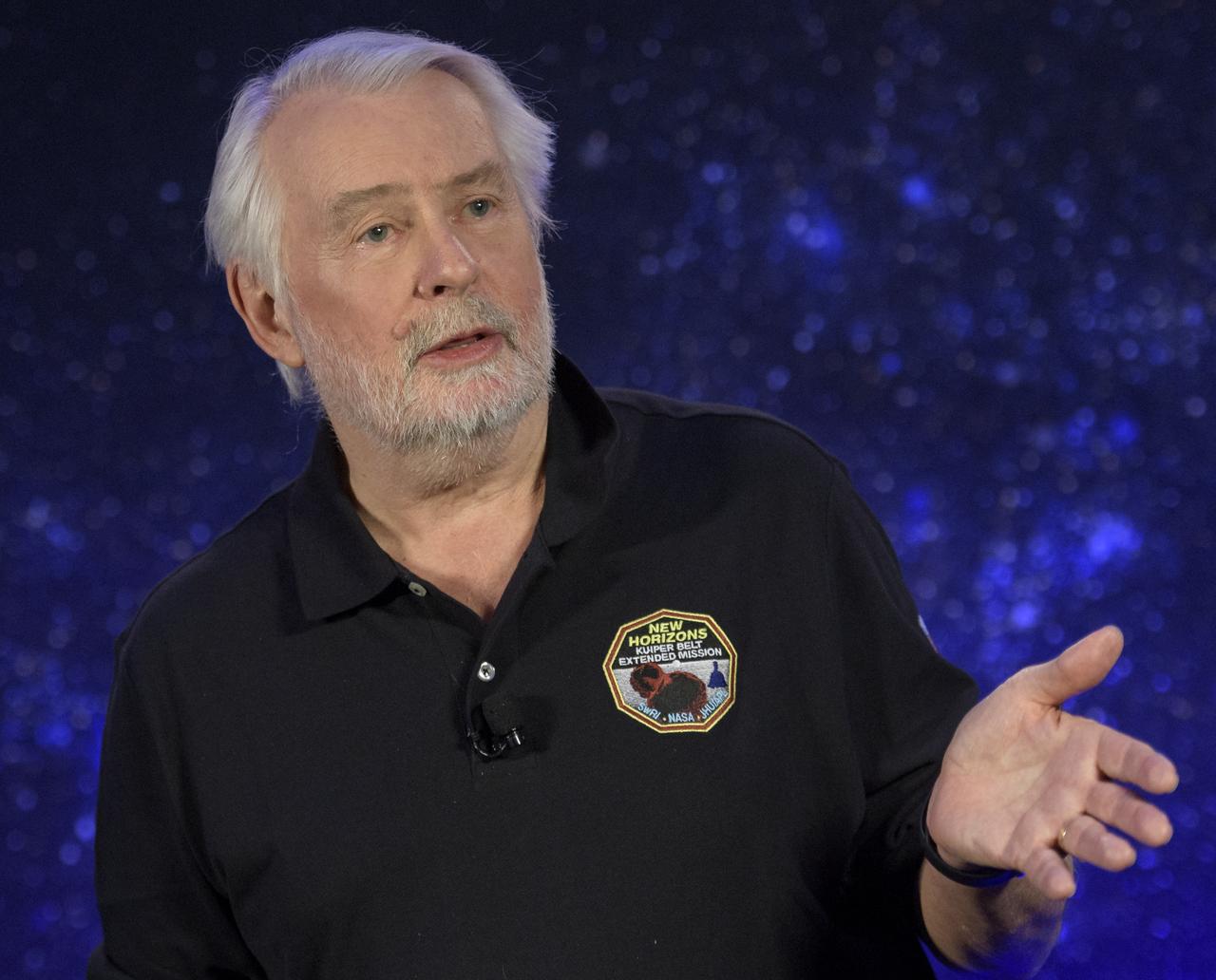

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory speaks about the Kuiper Belt during an overview of the New Horizons Mission, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory speaks about the Kuiper Belt during an overview of the New Horizons Mission, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory speaks about the Kuiper Belt during an overview of the New Horizons Mission, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project manager Helene Winters of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory speaks at a press conference prior to the flyby of Ultima Thule by the New Horizons spacecraft, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory gives a talk titled "Pluto Flyby; Summer 2015", Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory gives a talk titled "Pluto Flyby; Summer 2015", Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons project manager Helene Winters of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory speaks during an overview of the New Horizons Mission, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project manager Helene Winters of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory speaks at a press conference prior to the flyby of Ultima Thule by the New Horizons spacecraft, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory gives a talk titled "Pluto Flyby; Summer 2015", Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Director of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Ralph Semmel delivers remarks, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory discusses what they hope to learn from the flyby of Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

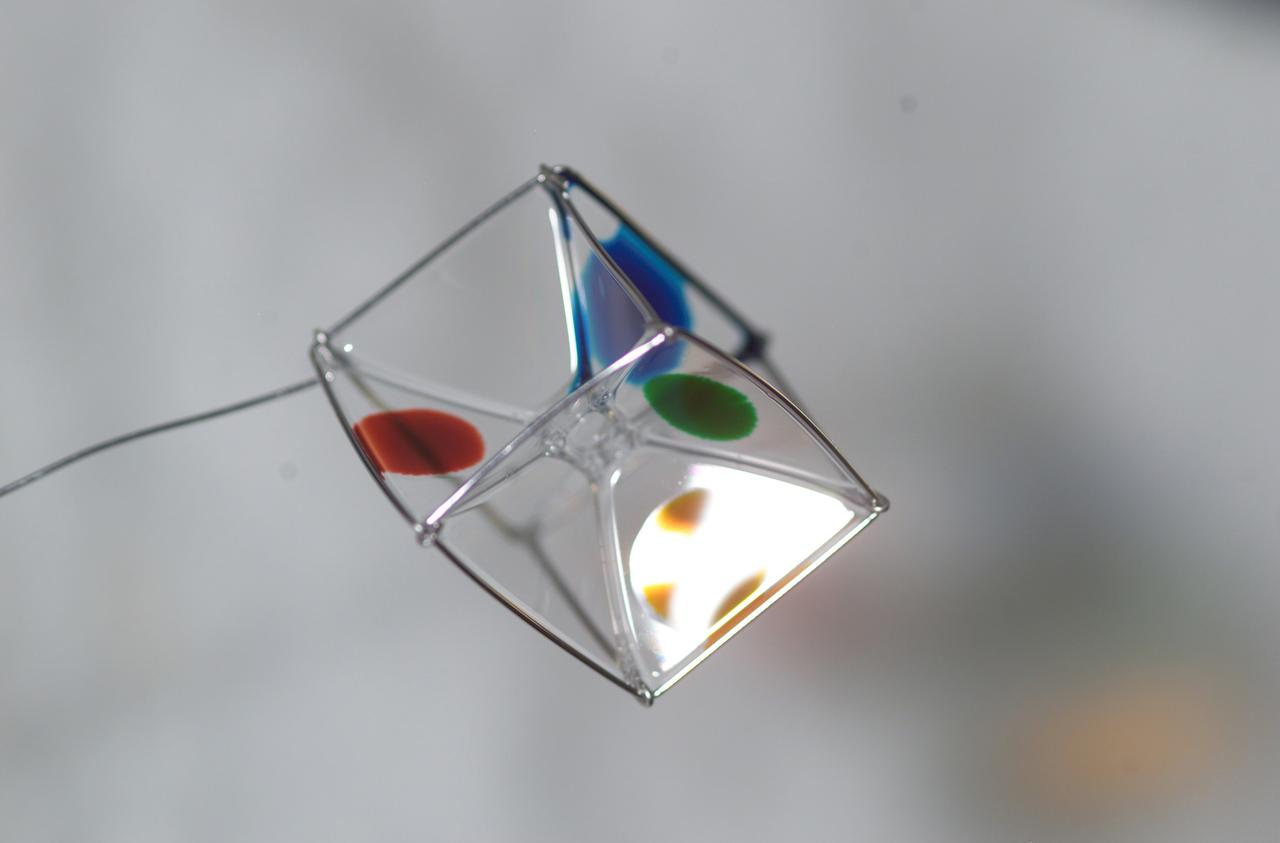

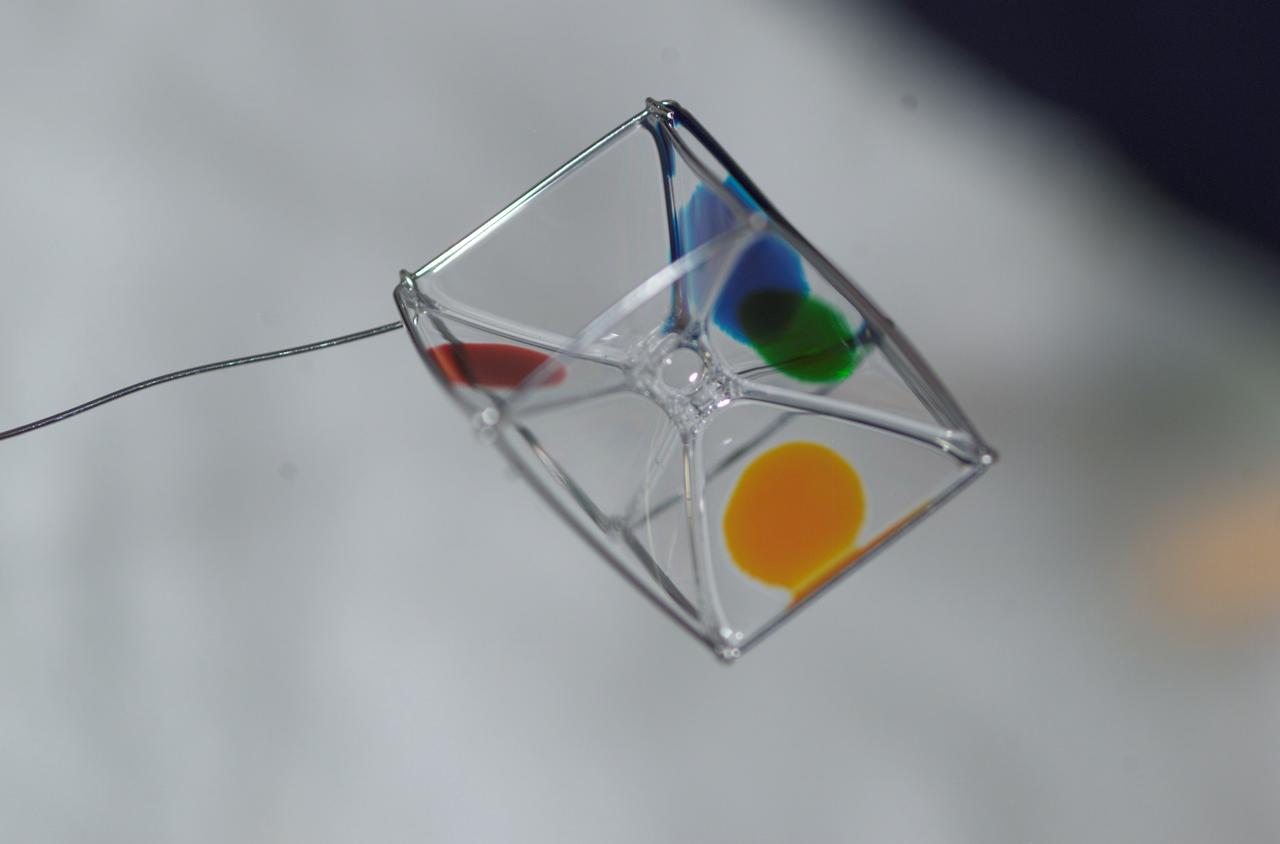

Expedition 6 astronaut Dr. Don Pettit photographed a cube shaped wire frame supporting a thin film made from a water-soap solution during his Saturday Morning Science aboard the International Space Station’s (ISS) Destiny Laboratory. Food coloring was added to several faces to observe the effects of diffusion within the film.

Expedition 6 astronaut Dr. Don Pettit photographed a cube shaped wire frame supporting a thin film made from a water-soap solution during his Saturday Morning Science aboard the International Space Station’s (ISS) Destiny Laboratory. Food coloring was added to several faces to observe the effects of diffusion within the film.

Whipped cream and the filling for pumpkin pie are two familiar materials that exhibit the shear-thinning effect seen in a range of industrial applications. It is thick enough to stand on its own atop a piece of pie, yet flows readily when pushed through a tube. This demonstrates the shear-thinning effect that was studied with the Critical Viscosity of Xenon Experiment (CVX-2) on the STS-107 Research 1 mission in 2002. CVX observed the behavior of xenon, a heavy inert gas used in flash lamps and ion rocket engines, at its critical point. The principal investigator was Dr. Robert Berg of the National Institutes of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, MD.

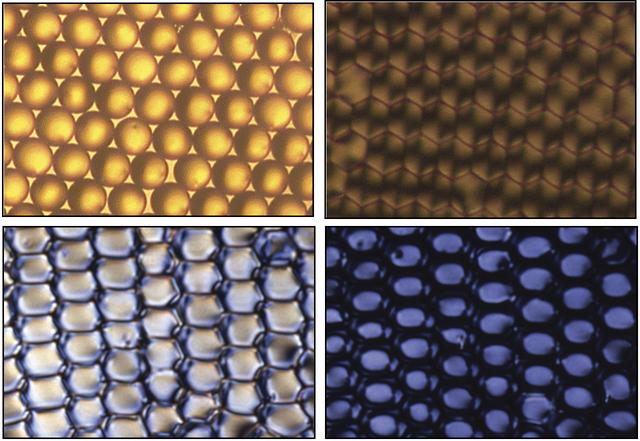

These images, from David Weitz’s liquid crystal research, show ordered uniform sized droplets (upper left) before they are dried from their solution. After the droplets are dried (upper right), they are viewed with crossed polarizers that show the deformation caused by drying, a process that orients the bipolar structure of the liquid crystal within the droplets. When an electric field is applied to the dried droplets (lower left), and then increased (lower right), the liquid crystal within the droplets switches its alignment, thereby reducing the amount of light that can be scattered by the droplets when a beam is shone through them.

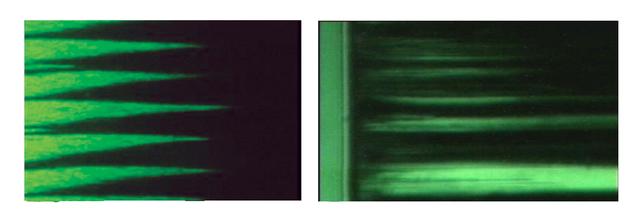

These are video microscope images of magnetorheological (MR) fluids, illuminated with a green light. Those on Earth, left, show the MR fluid forming columns or spikes structures. On the right, the fluids in microgravity aboard the International Space Station (ISS), formed broader columns.

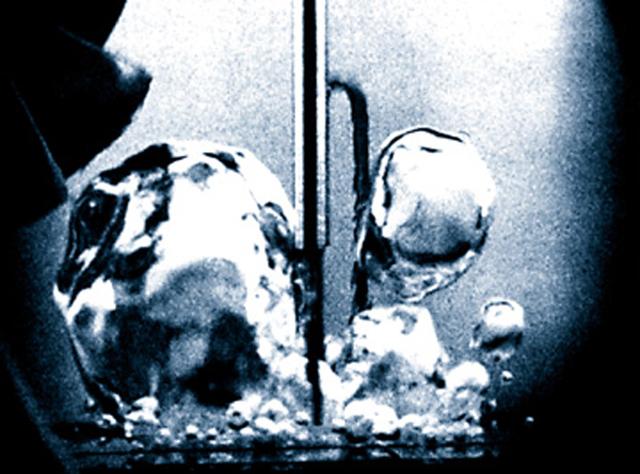

Fluid Physics is study of the motion of fluids and the effects of such motion. When a liquid is heated from the bottom to the boiling point in Earth's microgravity, small bubbles of heated gas form near the bottom of the container and are carried to the top of the liquid by gravity-driven convective flows. In the same setup in microgravity, the lack of convection and buoyancy allows the heated gas bubbles to grow larger and remain attached to the container's bottom for a significantly longer period.

iss073e1193970 (Nov. 25, 2025) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 73 Flight Engineer Mike Fincke smiles for a portrait during research operations for the Droplets fluid physics investigation. Fincke was inside the International Space Station's Destiny laboratory module exploring how particles behave inside fluids. The microgravity study may inform commercial in-space manufacturing techniques and improve optical materials and pollution removal operations.

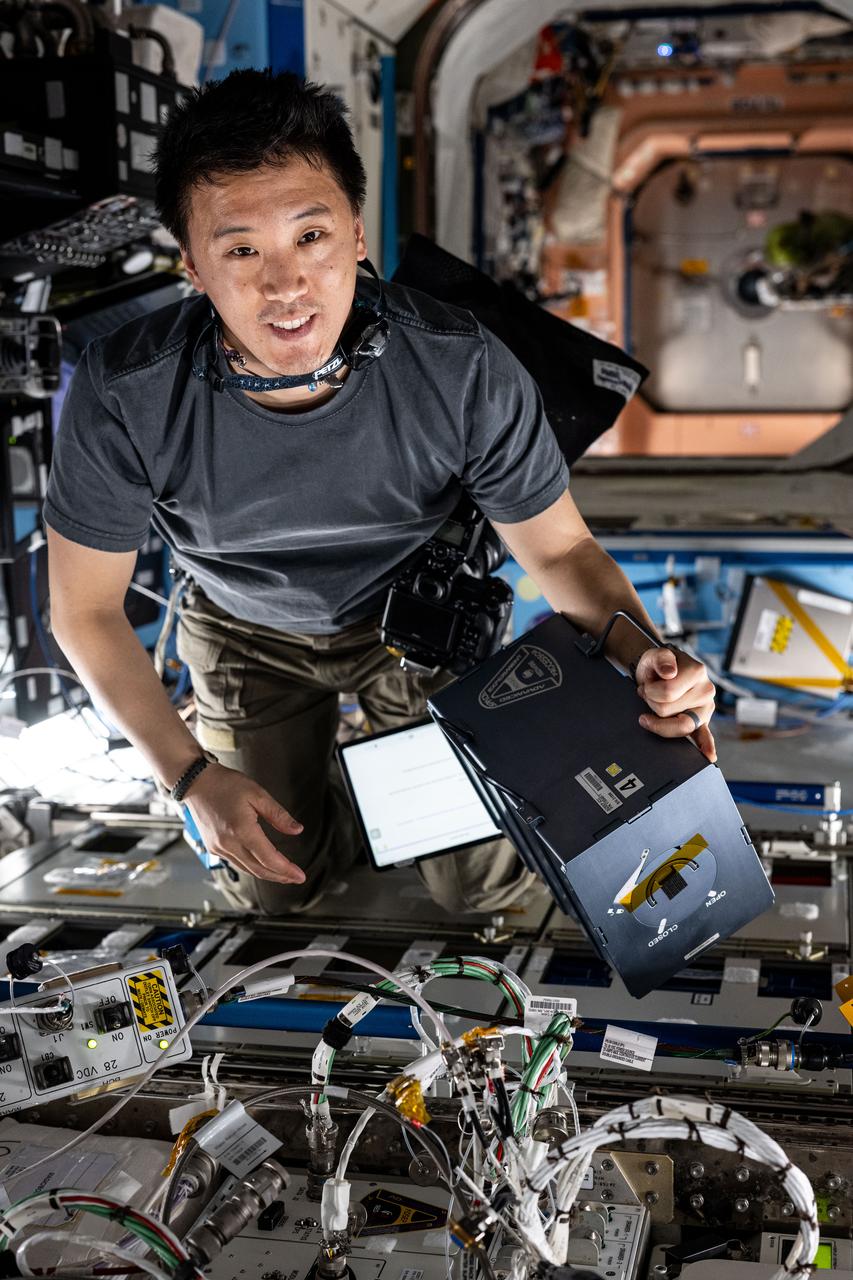

iss073e0032794 (May 16, 2025) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 73 Flight Engineer Jonny Kim swaps hardware that promotes physical science and crystalization research inside the Advanced Space Experiment Processor-4 (ADSEP-4) aboard the International Space Station. The ADSEP-4 is supporting a technology demonstration potentially enabling the synthesis of medications during deep space missions and improving the pharmaceutical industry on Earth.

iss066e078282 (November 17, 2021) --- NASA astronaut Tom Marshburn works on the SUBSA-BRAINS space physics experiment, which examines differences in capillary flow, interface reactions, and bubble formation during solidification of brazing alloys in microgravity. Brazing technology bonds similar materials (such as an aluminum alloy to aluminum) or dissimilar ones (such as aluminum alloy to ceramics) at temperatures above 450°C. It is a potential tool for construction of human space habitats and manufactured systems as well as to repair damage from micrometeoroids or space debris.

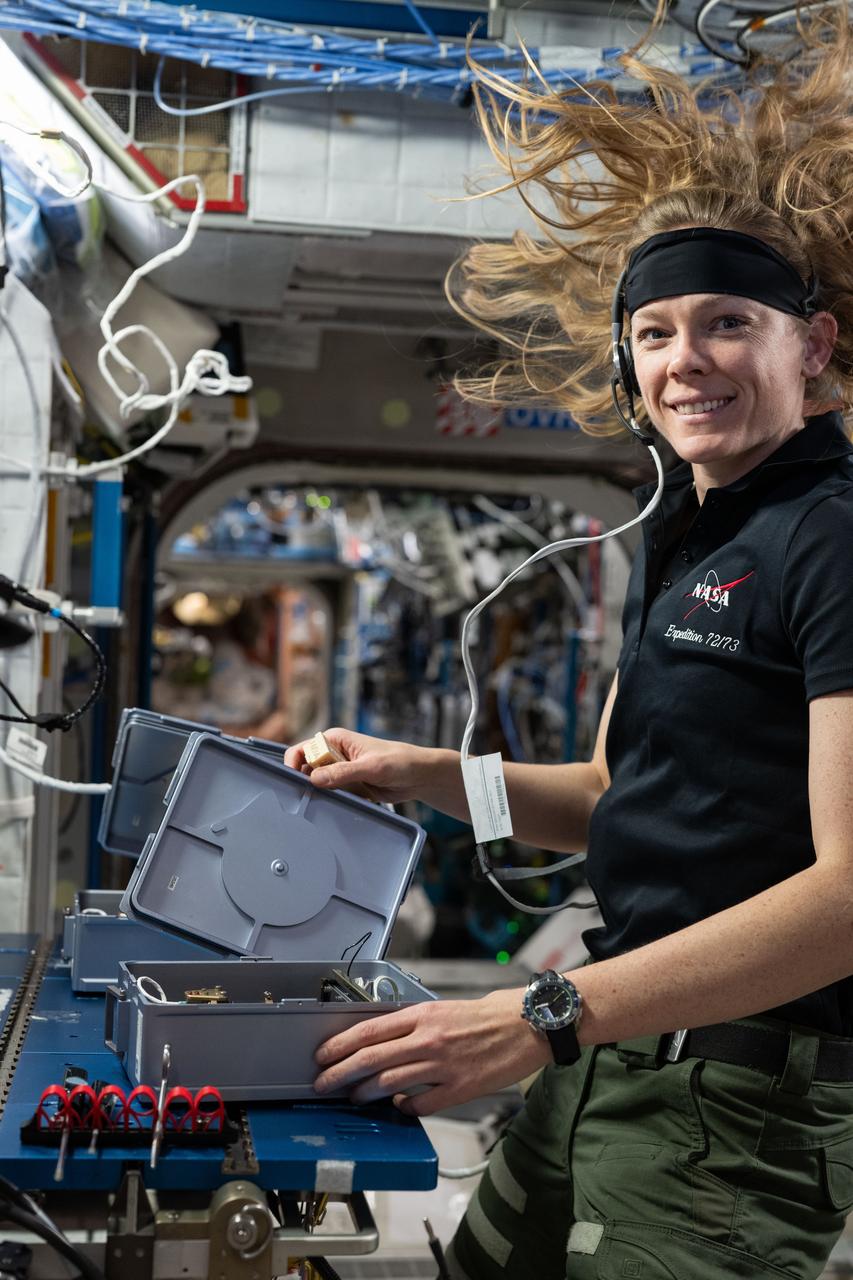

iss073e0030873 (May 14, 2025) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 73 Flight Engineer Nichole Ayers swaps hardware that promotes physical science and crystalization research inside the Advanced Space Experiment Processor-4 (ADSEP-4) aboard the International Space Station. The ADSEP-4 is supporting a technology demonstration potentially enabling the synthesis of medications during deep space missions and improving the pharmaceutical industry on Earth.

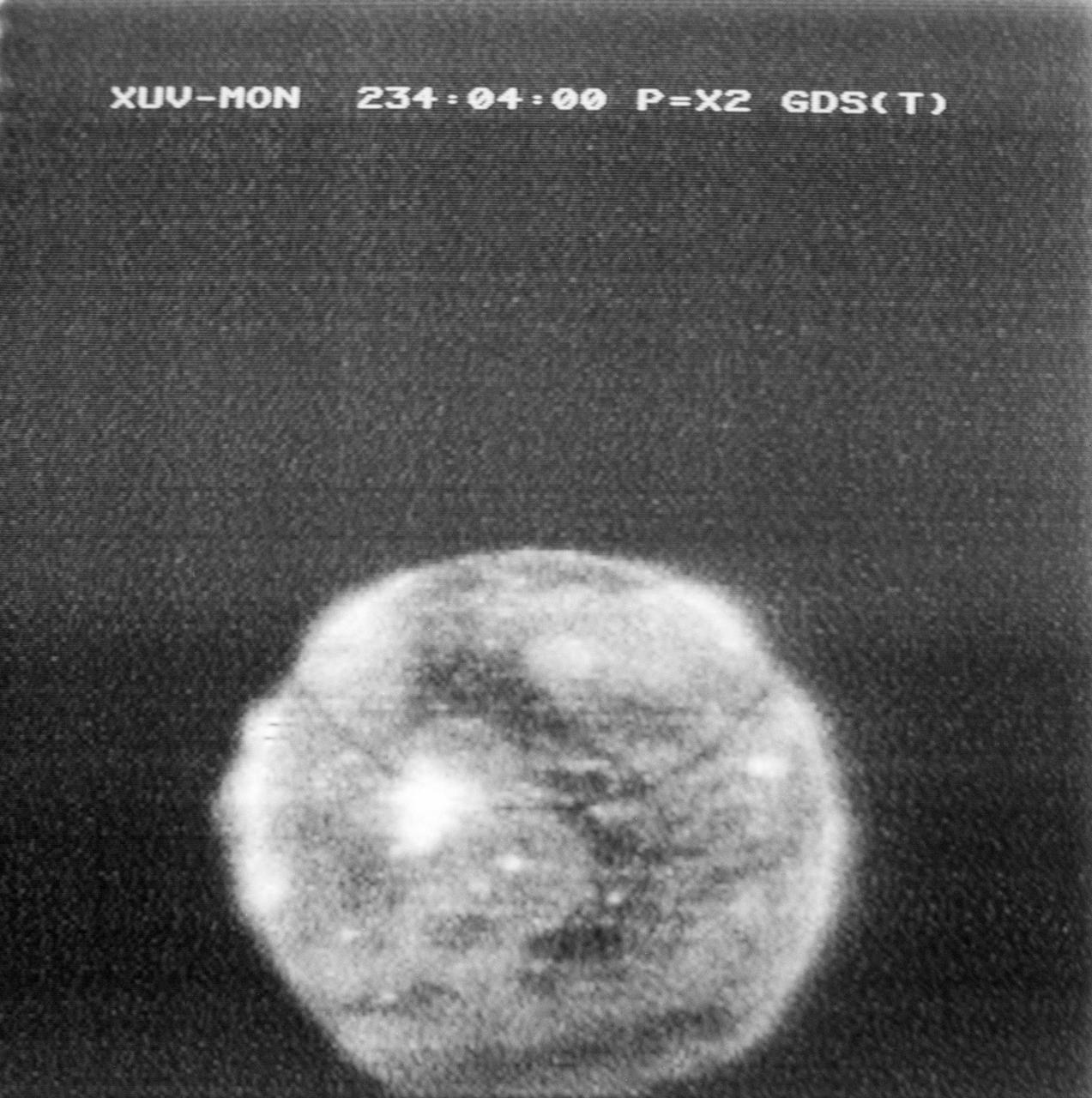

S73-32867 (21 Aug. 1973) --- The solar sphere viewed through the Skylab solar physics experiment (S082) Extreme Ultraviolet Spectroheliographis seen in this photographic reproduction taken from a color television transmission made by a TV camera aboard the Skylab space station in Earth orbit. The solar chromosphere and lower corona are much hotter than the surface of the sun characterized by the white light emissions. This image was recorded during the huge solar prominence which occurred on Aug. 21, 1973. Photo credit: NASA

iss073e0025362 (May 7, 2025) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 73 Flight Engineer Nichole Ayers swaps hardware that promotes physical science and crystalization research inside the Advanced Space Experiment Processor-4 (ADSEP-4) aboard the International Space Station. The ADSEP-4 is supporting a technology demonstration potentially enabling the synthesis of medications during deep space missions and improving the pharmaceutical industry on Earth.

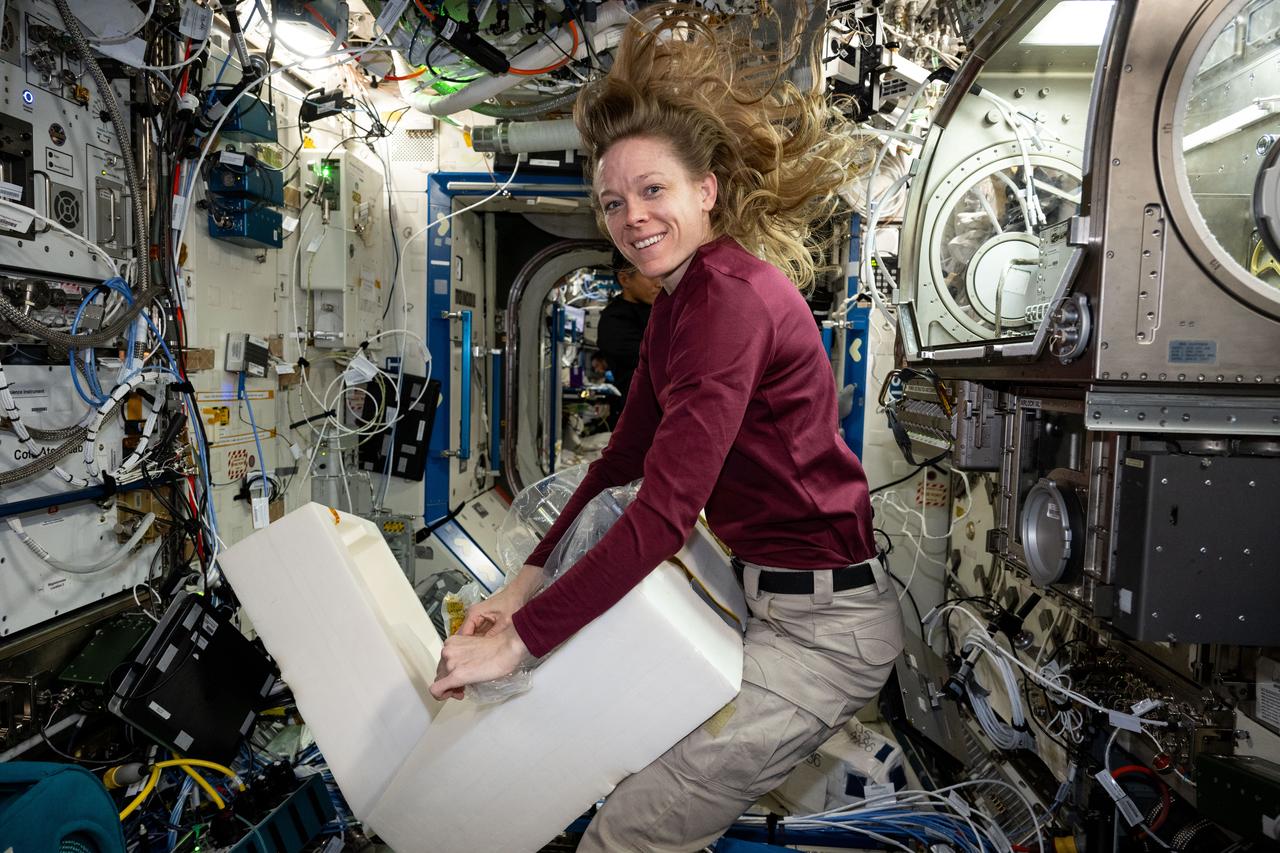

iss073e0253842 (July 1, 2025) --- NASA astronaut and Expedition 73 Flight Engineer Nichole Ayers stows physics research hardware from inside the Microgravity Science Glovebox located inside the International Space Station's Destiny laboratory module. Ayers was completing operations with the Ring Sheared Drop investigation that may benefit pharmaceutical manufacturing techniques and 3D printing in space.

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is seen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Michael Ryschkewitsch,head of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Space Exploration Sector, is seen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is seen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is seen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Mike Buckley, senior public information officer at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is seen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO and New Horizons project manager Helene Winters of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory discuss the various teams have helped work on New Horizons, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Michael Ryschkewitsch,head of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Space Exploration Sector, is seen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is seen before a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory speaks about new data received from the New Horizons spacecraft during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project manager Helene Winters of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory speaks during a press conference prior to the flyby of Ultima Thule by the New Horizons spacecraft, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Mike Buckley, senior public information office at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory speaks at the beginning of a press conference prior to the flyby of Ultima Thule by the New Horizons spacecraft, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons mission systems engineer Chris Hersman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is seen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory high-fives a New Horizons team member after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory is seen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory watches a live feed of the Mission Operations Center (MOC) as the team waits to receive confirmation from the spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Mike Buckley, senior public information officer at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, left, and New Horizons encounter mission manager Mark Holdridge of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, right, watch a live feed of the Mission Operations Center (MOC) along with guests and New Horizons team members as they wait to receive confirmation from the spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Guests celebrate New Years, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Guests celebrate New Years, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Guests celebrate New Years, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Musician Craig Werth introduces a song he made for the New Horizons mission, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Guests celebrate New Years, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Guests celebrate New Years, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Educators shine a flashlight onto a toy bear to simulate the physics behind solar eclipses.

Director of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory Ralph Semmel celebrates with other mission team members after they received signals from the spacecraft that it is healthy and collected data during the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at the Mission Operations Center of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO and New Horizons Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory are seen on a television screen as New Horizons team members and guests cheer as the team receives confirmation from the spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

A new image of Ultima Thule is seen on a screen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO, New Horizons Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, New Horizons mission systems engineer Chris Hersman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, and New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, spoke about the flyby and new pre-flyby information that was downlinked from the spacecraft. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO, left, New Horizons Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, second from left, New Horizons mission systems engineer Chris Hersman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, second from right, and New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, right, participate in a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

A new image of Ultima Thule is seen on a screen during a press conference after the team received confirmation from the New Horizons spacecraft that it has completed the flyby of Ultima Thule, Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO, New Horizons Mission Operations Manager Alice Bowman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, New Horizons mission systems engineer Chris Hersman of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, and New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, spoke about the flyby and new pre-flyby information that was downlinked from the spacecraft. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

The first United States Microgravity Laboratory (USML-1) was one of NASA's science and technology programs that provided scientists an opportunity to research various scientific investigations in a weightlessness environment inside the Spacelab module. It also provided demonstrations of new equipment to help prepare for advanced microgravity research and processing aboard the Space Station. The USML-1 flew in orbit for extended periods, providing greater opportunities for research in materials science, fluid dynamics, biotechnology (crystal growth), and combustion science. This is a close-up view of the Drop Physics Module (DPM) in the USML science laboratory. The DPM was dedicated to the detailed study of the dynamics of fluid drops in microgravity: their equilibrium shapes, the dynamics of their flows, and their stable and chaotic behaviors. It also demonstrated a technique known as containerless processing. The DPM and microgravity combine to remove the effects of the container, such as chemical contamination and shape, on the sample being studied. Sound waves, generating acoustic forces, were used to suspend a sample in microgravity and to hold a sample of free drops away from the walls of the experiment chamber, which isolated the sample from potentially harmful external influences. The DPM gave scientists the opportunity to test theories of classical fluid physics, which have not been confirmed by experiments conducted on Earth. This image is a close-up view of the DPM. The USML-1 flew aboard the STS-50 mission on June 1992, and was managed by the Marshall Space Flight Center.

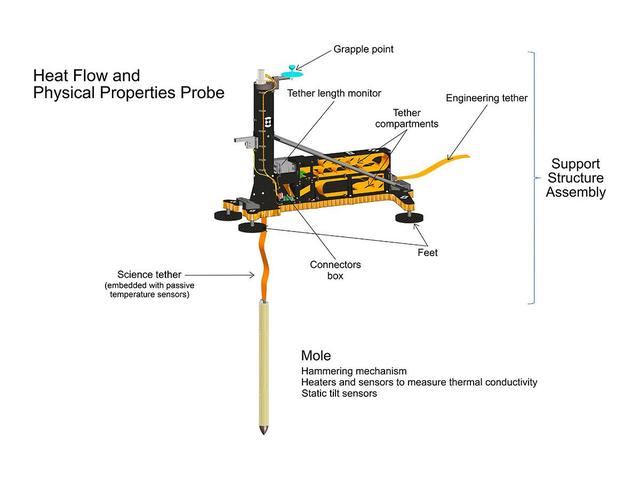

An artist's concept of InSight's heat probe, called the Heat and Physical Properties Package (HP3), annotates various parts inside of the instrument. https://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA23045

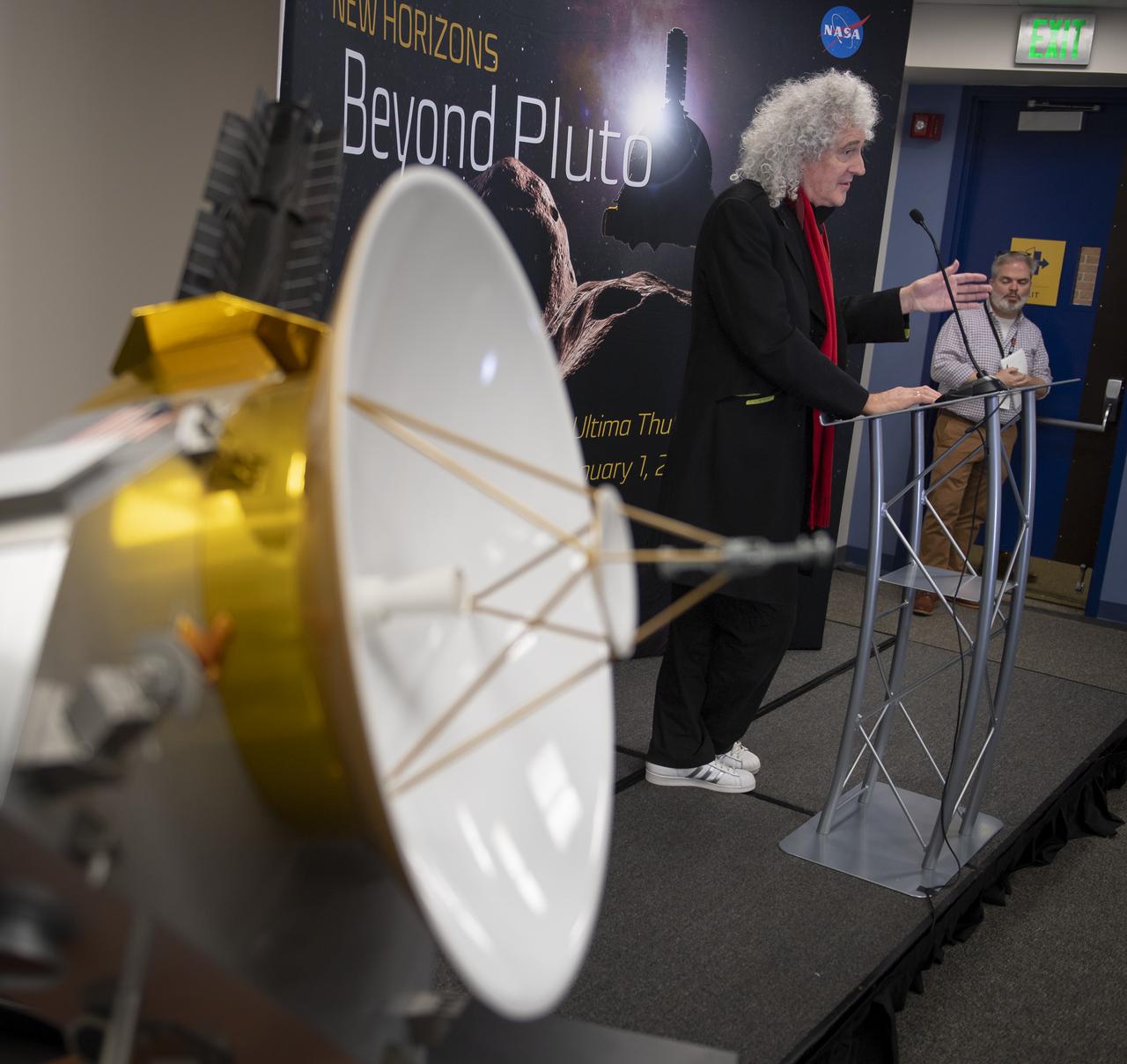

Brian May, lead guitarist of the rock band Queen and astrophysicist discusses the upcoming New Horizons flyby of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

David Grinspoon, senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute discusses Pluto and the Human Imagination, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

Brian May, lead guitarist of the rock band Queen and astrophysicist discusses the upcoming New Horizons flyby of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Harold "Hal" Levison from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado gives remarks about the Lucy mission during a briefing discussing small bodies missions, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Associate Administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate Thomas Zurbuchen is seen during a New Horizons briefing, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Associate Administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate Thomas Zurbuchen is seen during a New Horizons briefing, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO, speaks at a press conference prior to the flyby of Ultima Thule by the New Horizons spacecraft, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

Geoff Haines-Stiles, writer, producer, director, Passport to Knowledge, discusses documenting the New Horizons mission, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

Brian May, lead guitarist of the rock band Queen and astrophysicist discusses the upcoming New Horizons flyby of the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), Boulder, CO, speaks during an overview of the New Horizons Mission, Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Walter Alvarez professor in the Earth and Planetary Science department at the University of California, Berkeley, gives a presentation titled "Doing Geology by Looking Up; Doing Astronomy by Looking Down", Monday, Dec. 31, 2018 at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) command team at Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory monitoring the DART spacecraft’s impact into the asteroid Dimorphos. The operation is the first of its kind test to redirect deadly asteroids from hitting Earth.